User login

Preoperative MRI may allow radiotherapy omission in some women with early BC

Key clinical point: Women with apparently unifocal, non–triple-negative breast cancer (BC) who underwent preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and did not have any occult malignancy may safely forgo radiation therapy.

Major finding: Preoperative MRI detected malignant occult lesions in 11% of patients with BC. At 5 years, the ipsilateral invasive recurrence rate was very low (1.0%; upper 95% CI 5.4%) in patients with no occult malignancy who did not receive adjuvant radiotherapy.

Study details: Findings are from the prospective 2-arm PROSPECT study that included 443 patients with non–triple-negative, clinical stage T1N0, apparently unifocal BC who underwent MRI, of whom 201 patients underwent breast-conserving surgery without radiotherapy and 242 women were deemed ineligible for radiotherapy omission.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Breast Cancer Trials, Australia, and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mann GB et al. Postoperative radiotherapy omission in selected patients with early breast cancer following preoperative breast MRI (PROSPECT): Primary results of a prospective two-arm study. Lancet. 2023 (Dec 5). doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02476-5

Key clinical point: Women with apparently unifocal, non–triple-negative breast cancer (BC) who underwent preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and did not have any occult malignancy may safely forgo radiation therapy.

Major finding: Preoperative MRI detected malignant occult lesions in 11% of patients with BC. At 5 years, the ipsilateral invasive recurrence rate was very low (1.0%; upper 95% CI 5.4%) in patients with no occult malignancy who did not receive adjuvant radiotherapy.

Study details: Findings are from the prospective 2-arm PROSPECT study that included 443 patients with non–triple-negative, clinical stage T1N0, apparently unifocal BC who underwent MRI, of whom 201 patients underwent breast-conserving surgery without radiotherapy and 242 women were deemed ineligible for radiotherapy omission.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Breast Cancer Trials, Australia, and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mann GB et al. Postoperative radiotherapy omission in selected patients with early breast cancer following preoperative breast MRI (PROSPECT): Primary results of a prospective two-arm study. Lancet. 2023 (Dec 5). doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02476-5

Key clinical point: Women with apparently unifocal, non–triple-negative breast cancer (BC) who underwent preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and did not have any occult malignancy may safely forgo radiation therapy.

Major finding: Preoperative MRI detected malignant occult lesions in 11% of patients with BC. At 5 years, the ipsilateral invasive recurrence rate was very low (1.0%; upper 95% CI 5.4%) in patients with no occult malignancy who did not receive adjuvant radiotherapy.

Study details: Findings are from the prospective 2-arm PROSPECT study that included 443 patients with non–triple-negative, clinical stage T1N0, apparently unifocal BC who underwent MRI, of whom 201 patients underwent breast-conserving surgery without radiotherapy and 242 women were deemed ineligible for radiotherapy omission.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Breast Cancer Trials, Australia, and other sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mann GB et al. Postoperative radiotherapy omission in selected patients with early breast cancer following preoperative breast MRI (PROSPECT): Primary results of a prospective two-arm study. Lancet. 2023 (Dec 5). doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02476-5

Cholesterol-lowering interventions with statins may improve prognosis in BC

Key clinical point: The post-diagnostic use of statins lowered the risk for mortality in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer (BC) only in case of a subsequent lowering of serum cholesterol levels.

Major finding: Compared with patients who did not receive statins, the risk for BC-specific mortality was significantly reduced in those who received statins after BC diagnosis and reported a subsequent reduction in the median total cholesterol level (adjusted hazard ratio 0.49; P = .001). No mortality-risk reduction was observed in patients whose cholesterol levels did not decrease after the post-diagnostic initiation of statins (P = .30).

Study details: This retrospective population-based cohort study included 13,378 patients with newly diagnosed invasive BC, of whom 980 patients initiated statins after BC diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was supported by research funds and a grant from the Pirkanmaa Hospital District and Duodecim, Finland, respectively. Two authors declared receiving grants or personal fees from various sources, including the Pirkanmaa Hospital District. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Murto MO et al. Statin use, cholesterol level, and mortality among females with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2343861 (Nov 17). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.43861

Key clinical point: The post-diagnostic use of statins lowered the risk for mortality in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer (BC) only in case of a subsequent lowering of serum cholesterol levels.

Major finding: Compared with patients who did not receive statins, the risk for BC-specific mortality was significantly reduced in those who received statins after BC diagnosis and reported a subsequent reduction in the median total cholesterol level (adjusted hazard ratio 0.49; P = .001). No mortality-risk reduction was observed in patients whose cholesterol levels did not decrease after the post-diagnostic initiation of statins (P = .30).

Study details: This retrospective population-based cohort study included 13,378 patients with newly diagnosed invasive BC, of whom 980 patients initiated statins after BC diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was supported by research funds and a grant from the Pirkanmaa Hospital District and Duodecim, Finland, respectively. Two authors declared receiving grants or personal fees from various sources, including the Pirkanmaa Hospital District. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Murto MO et al. Statin use, cholesterol level, and mortality among females with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2343861 (Nov 17). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.43861

Key clinical point: The post-diagnostic use of statins lowered the risk for mortality in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer (BC) only in case of a subsequent lowering of serum cholesterol levels.

Major finding: Compared with patients who did not receive statins, the risk for BC-specific mortality was significantly reduced in those who received statins after BC diagnosis and reported a subsequent reduction in the median total cholesterol level (adjusted hazard ratio 0.49; P = .001). No mortality-risk reduction was observed in patients whose cholesterol levels did not decrease after the post-diagnostic initiation of statins (P = .30).

Study details: This retrospective population-based cohort study included 13,378 patients with newly diagnosed invasive BC, of whom 980 patients initiated statins after BC diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was supported by research funds and a grant from the Pirkanmaa Hospital District and Duodecim, Finland, respectively. Two authors declared receiving grants or personal fees from various sources, including the Pirkanmaa Hospital District. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Murto MO et al. Statin use, cholesterol level, and mortality among females with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2343861 (Nov 17). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.43861

Pemetrexed + vinorelbine bests vinolrelbine monotherapy in metastatic BC in phase 2

Key clinical point: Pemetrexed + vinorelbine vs vinorelbine monotherapy led to a greater improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) outcomes and had a manageable safety profile in patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC) previously treated with anthracycline and taxane.

Major finding: The median PFS improved by 45% with pemetrexed + vinorelbine vs vinorelbine monotherapy (5.7 vs 1.6 months; hazard ratio 0.55; P = .001). Pemetrexed + vinorelbine also had a manageable safety profile in general.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2 KCSG-BR15-17 trial including 125 patients with metastatic BC who had been treated with anthracycline and taxane previously and were randomly assigned to receive pemetrexed + vinorelbine or vinorelbine monotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. Two authors declared receiving research funding or research drug supply from or serving in consulting or advisory roles for various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lee DW, Jung KH, et al. Pemetrexed plus vinorelbine versus vinorelbine monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer (KCSG-BR15-17): A randomized, open label, multicenter, phase II trial. Eur J Cancer. 2023;113456 (Nov 20). doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113456

Key clinical point: Pemetrexed + vinorelbine vs vinorelbine monotherapy led to a greater improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) outcomes and had a manageable safety profile in patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC) previously treated with anthracycline and taxane.

Major finding: The median PFS improved by 45% with pemetrexed + vinorelbine vs vinorelbine monotherapy (5.7 vs 1.6 months; hazard ratio 0.55; P = .001). Pemetrexed + vinorelbine also had a manageable safety profile in general.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2 KCSG-BR15-17 trial including 125 patients with metastatic BC who had been treated with anthracycline and taxane previously and were randomly assigned to receive pemetrexed + vinorelbine or vinorelbine monotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. Two authors declared receiving research funding or research drug supply from or serving in consulting or advisory roles for various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lee DW, Jung KH, et al. Pemetrexed plus vinorelbine versus vinorelbine monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer (KCSG-BR15-17): A randomized, open label, multicenter, phase II trial. Eur J Cancer. 2023;113456 (Nov 20). doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113456

Key clinical point: Pemetrexed + vinorelbine vs vinorelbine monotherapy led to a greater improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) outcomes and had a manageable safety profile in patients with metastatic breast cancer (BC) previously treated with anthracycline and taxane.

Major finding: The median PFS improved by 45% with pemetrexed + vinorelbine vs vinorelbine monotherapy (5.7 vs 1.6 months; hazard ratio 0.55; P = .001). Pemetrexed + vinorelbine also had a manageable safety profile in general.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 2 KCSG-BR15-17 trial including 125 patients with metastatic BC who had been treated with anthracycline and taxane previously and were randomly assigned to receive pemetrexed + vinorelbine or vinorelbine monotherapy.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. Two authors declared receiving research funding or research drug supply from or serving in consulting or advisory roles for various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lee DW, Jung KH, et al. Pemetrexed plus vinorelbine versus vinorelbine monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer (KCSG-BR15-17): A randomized, open label, multicenter, phase II trial. Eur J Cancer. 2023;113456 (Nov 20). doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113456

Young BRCA carriers with BC history may safely opt for pregnancy

Key clinical point: Women with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic mutations who had a pregnancy after diagnosis of early breast cancer (BC) reported prognostic outcomes similar to that of women without a pregnancy.

Major finding: The cumulative incidence of pregnancy was 22% at 10 years. The disease-free survival outcomes were comparable between patients with BC who did vs did not become pregnant (adjusted hazard ratio 0.99; P = .90).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 4732 young women age ≤ 40 years with a history of BC who had germline pathogenic BRCA mutations, of whom 659 women reported ≥1 pregnancy after BC.

Disclosures: The study was partly supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research and the 2022 Gilead Research Scholars Program in Solid Tumors. The authors declared receiving speaker honoraria, travel grants, research funding, or speaker fees from and having other ties with Gilead and several other sources.

Source: Lambertini M et al. Pregnancy after breast cancer in young BRCA carriers: An international hospital-based cohort study. JAMA. 2023 (Dec 7). doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.25463

Key clinical point: Women with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic mutations who had a pregnancy after diagnosis of early breast cancer (BC) reported prognostic outcomes similar to that of women without a pregnancy.

Major finding: The cumulative incidence of pregnancy was 22% at 10 years. The disease-free survival outcomes were comparable between patients with BC who did vs did not become pregnant (adjusted hazard ratio 0.99; P = .90).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 4732 young women age ≤ 40 years with a history of BC who had germline pathogenic BRCA mutations, of whom 659 women reported ≥1 pregnancy after BC.

Disclosures: The study was partly supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research and the 2022 Gilead Research Scholars Program in Solid Tumors. The authors declared receiving speaker honoraria, travel grants, research funding, or speaker fees from and having other ties with Gilead and several other sources.

Source: Lambertini M et al. Pregnancy after breast cancer in young BRCA carriers: An international hospital-based cohort study. JAMA. 2023 (Dec 7). doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.25463

Key clinical point: Women with germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic mutations who had a pregnancy after diagnosis of early breast cancer (BC) reported prognostic outcomes similar to that of women without a pregnancy.

Major finding: The cumulative incidence of pregnancy was 22% at 10 years. The disease-free survival outcomes were comparable between patients with BC who did vs did not become pregnant (adjusted hazard ratio 0.99; P = .90).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 4732 young women age ≤ 40 years with a history of BC who had germline pathogenic BRCA mutations, of whom 659 women reported ≥1 pregnancy after BC.

Disclosures: The study was partly supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research and the 2022 Gilead Research Scholars Program in Solid Tumors. The authors declared receiving speaker honoraria, travel grants, research funding, or speaker fees from and having other ties with Gilead and several other sources.

Source: Lambertini M et al. Pregnancy after breast cancer in young BRCA carriers: An international hospital-based cohort study. JAMA. 2023 (Dec 7). doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.25463

Bilateral Burning Palmoplantar Lesions

The Diagnosis: Lichen Sclerosus

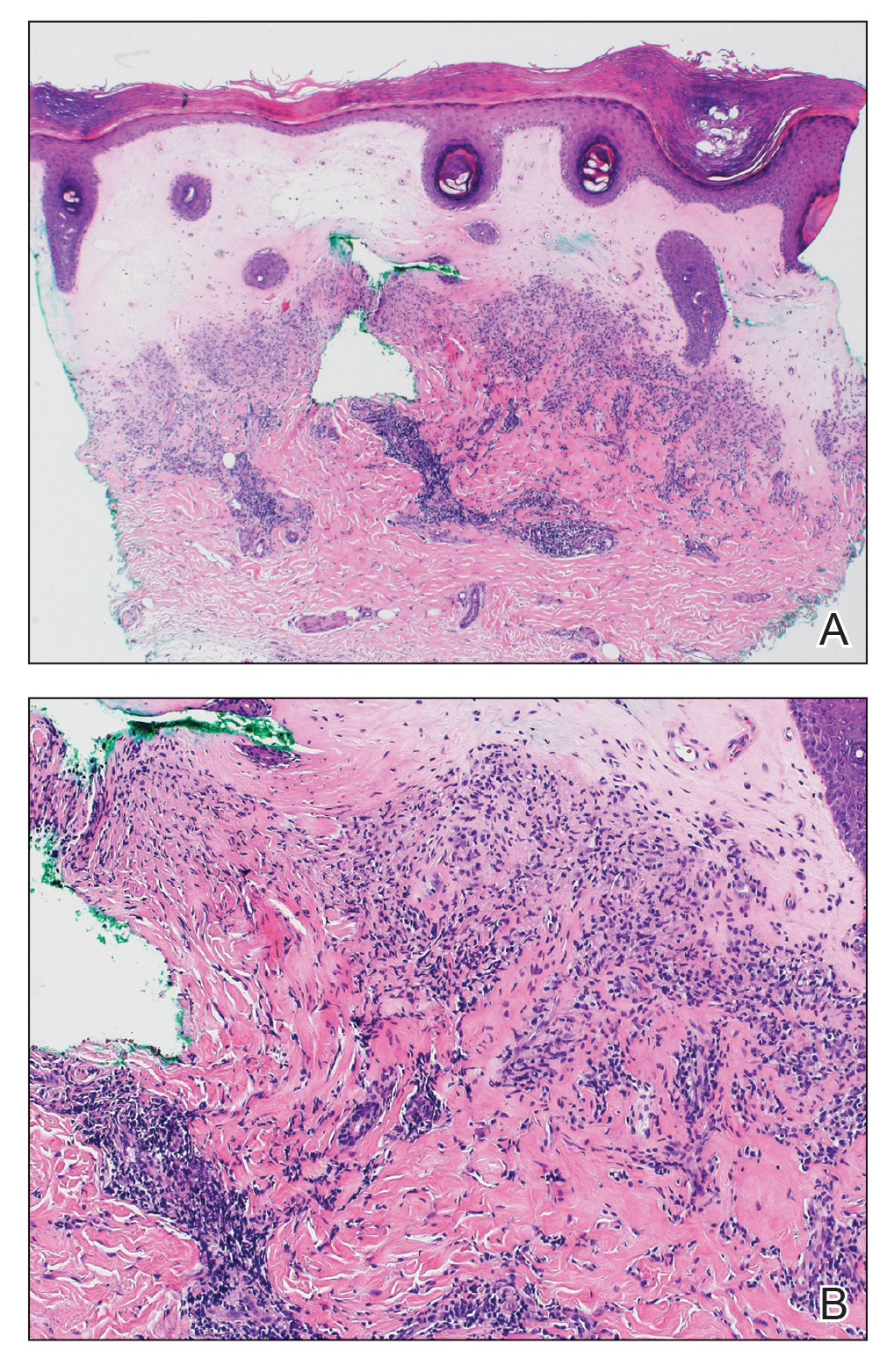

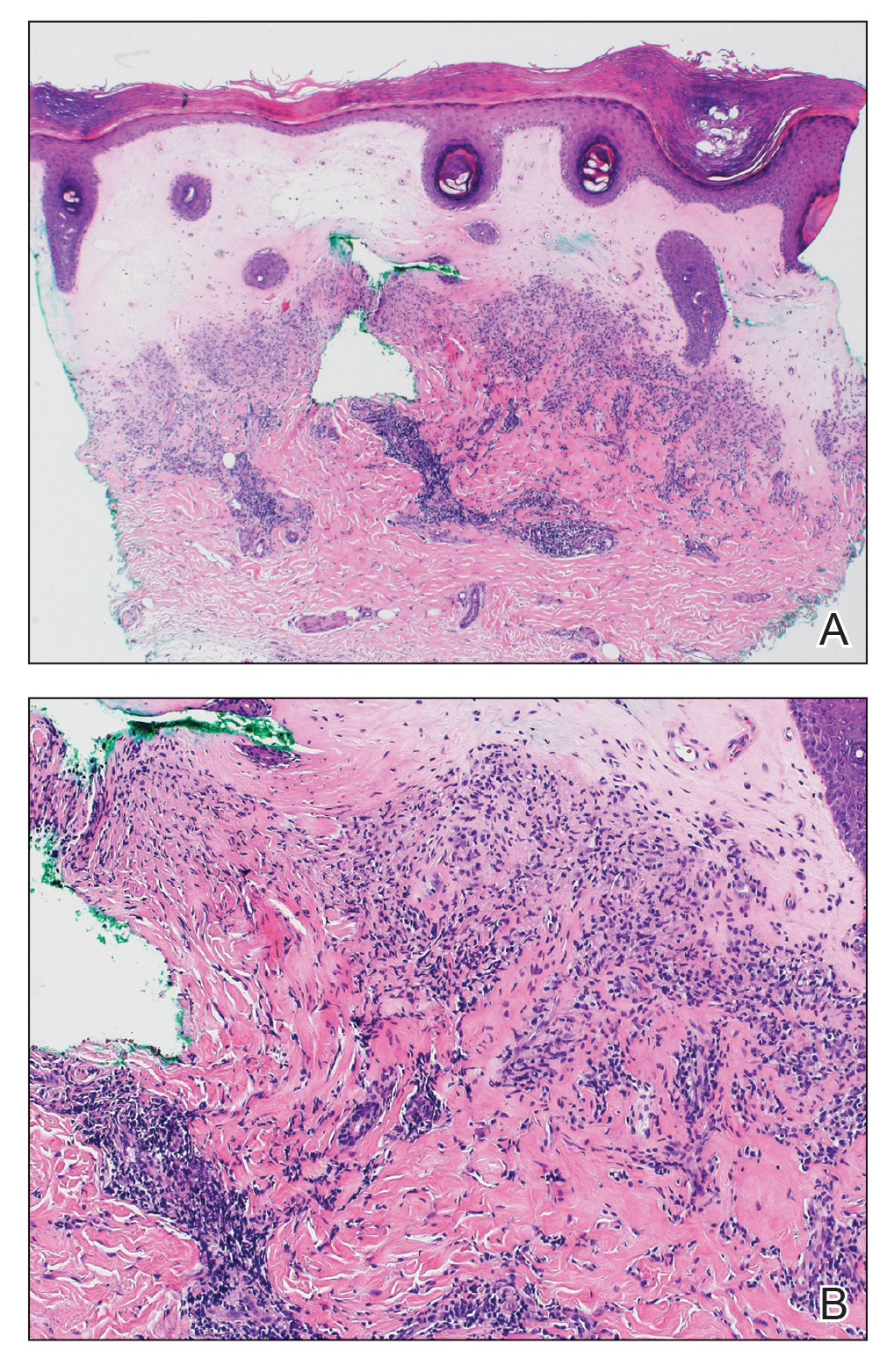

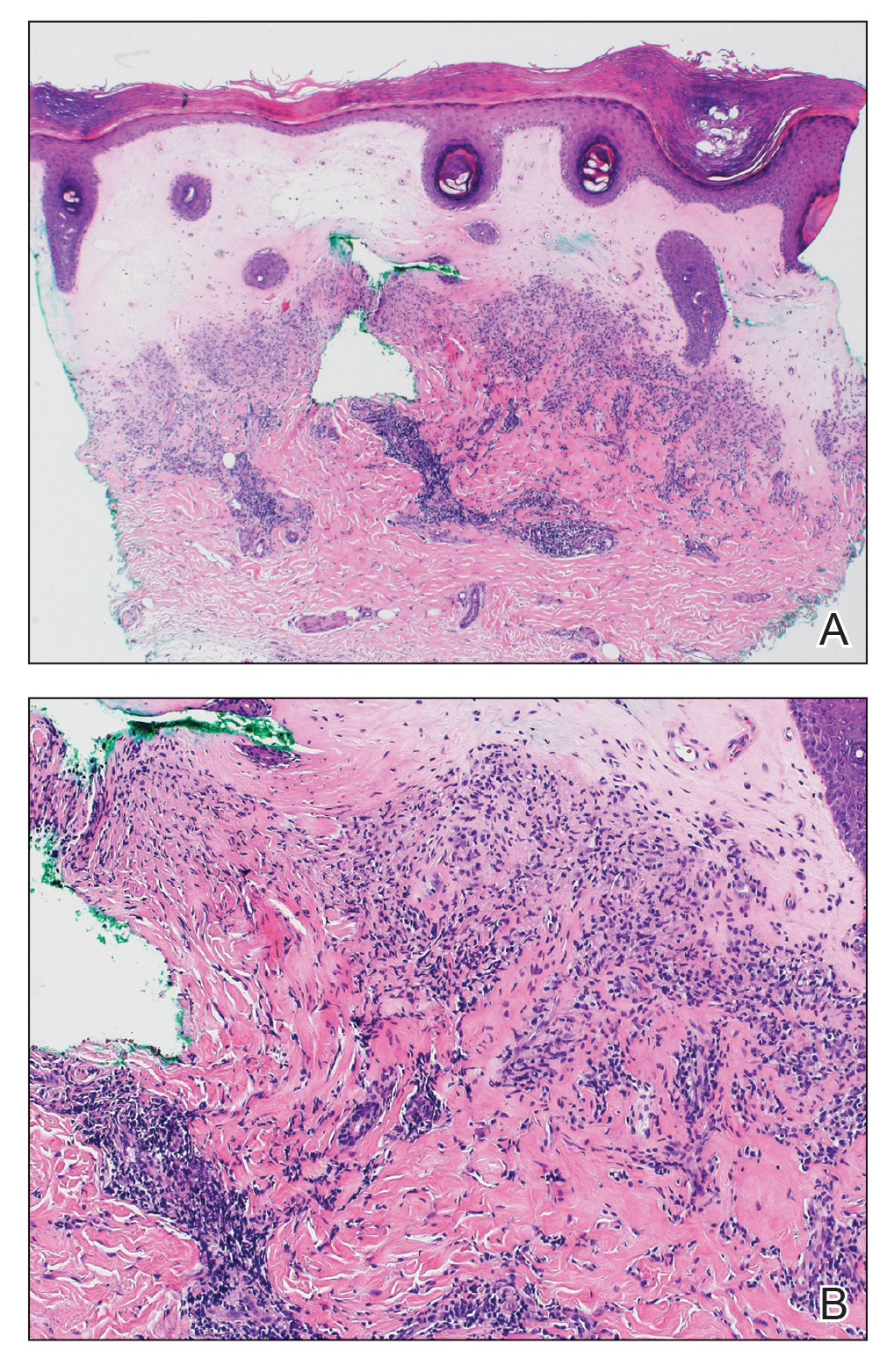

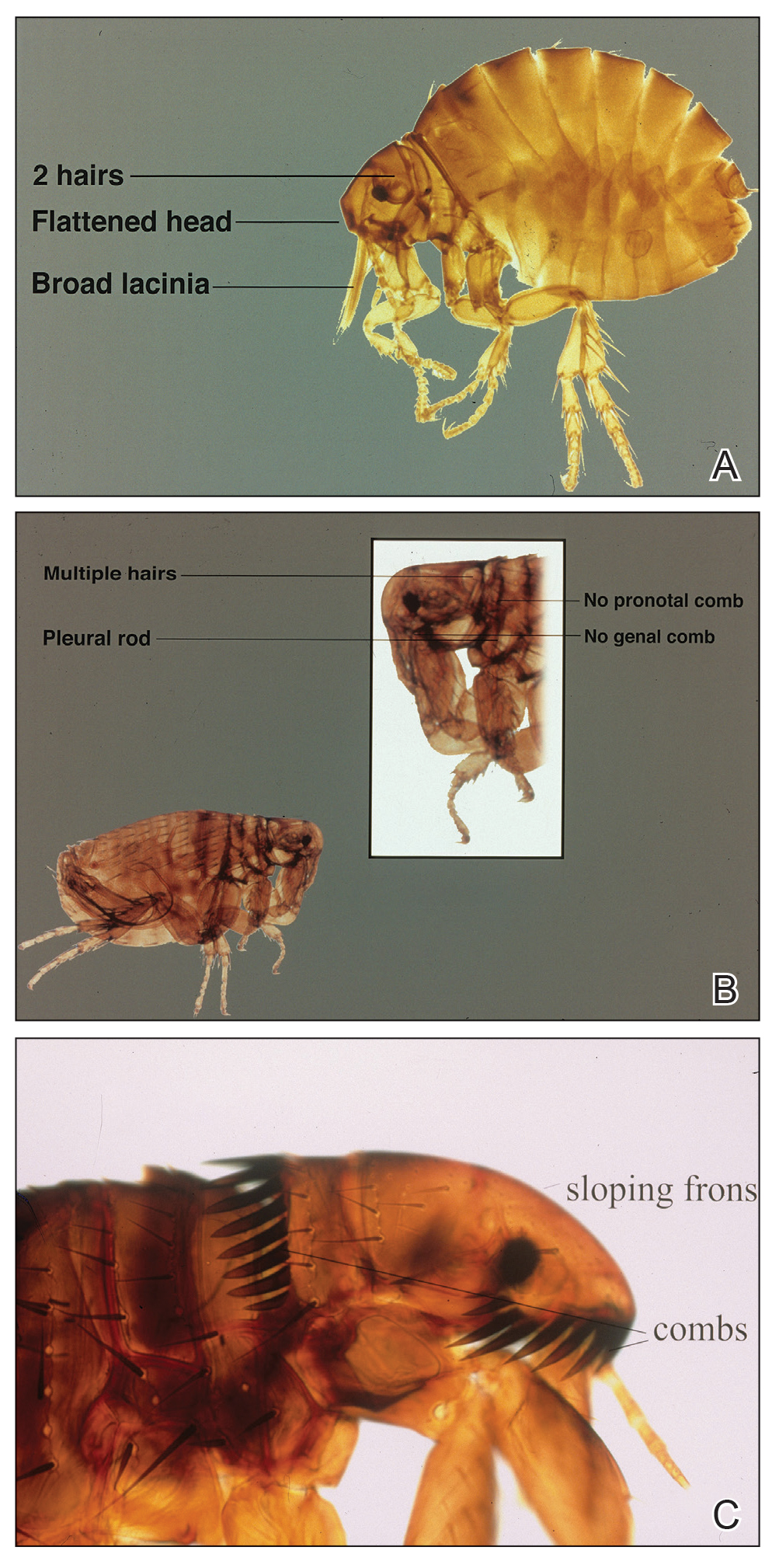

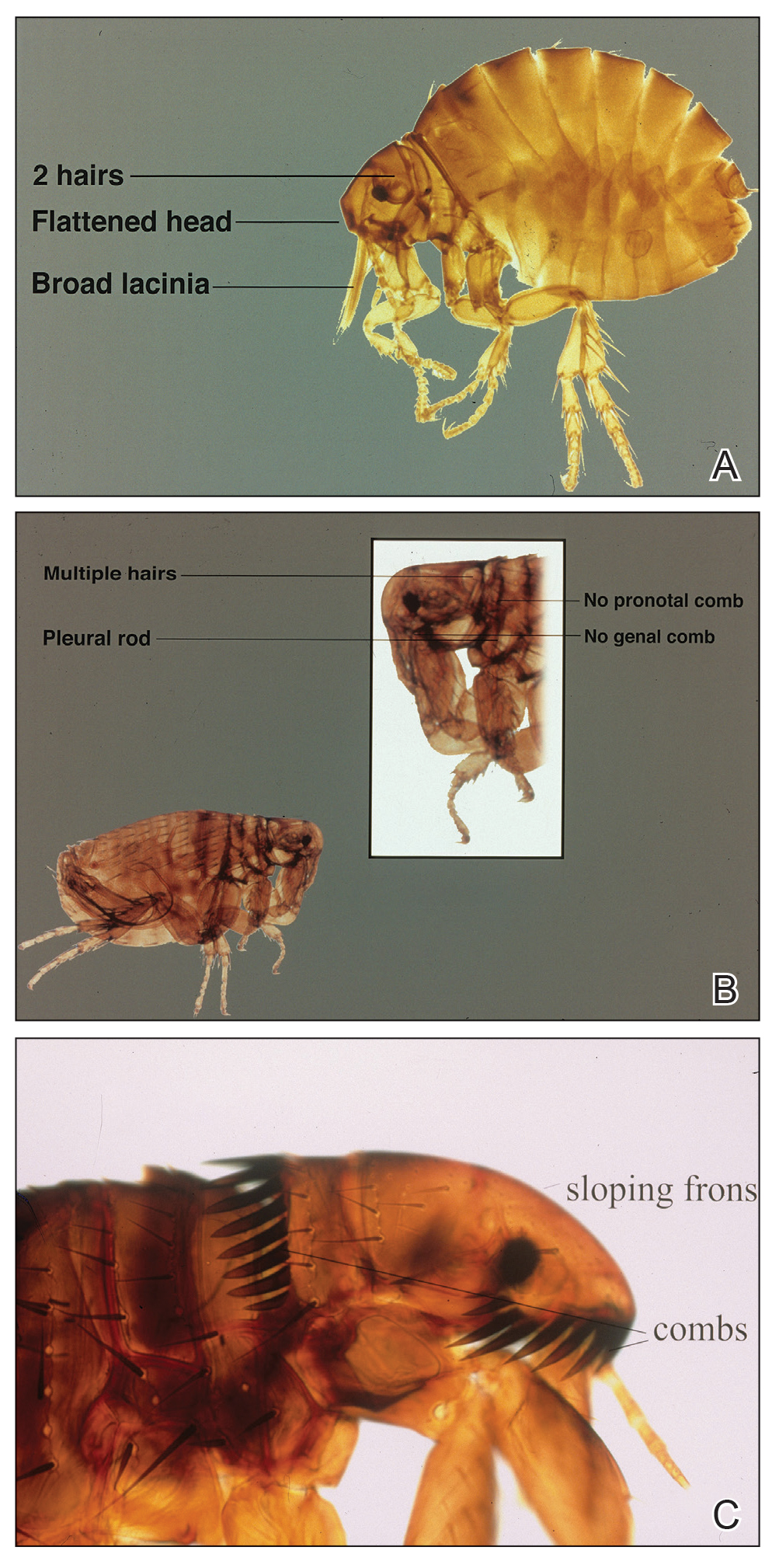

Histopathology revealed a thin epidermis with homogenization of the upper dermal collagen. By contrast, the lower dermis was sclerotic with patchy chronic dermal infiltrate (Figure). Ultimately, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS).

Lichen sclerosus is a rare chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically is characterized by porcelainwhite atrophic plaques on the skin, most often involving the external female genitalia including the vulva and perianal area.1 It is thought to be underdiagnosed and underreported.2 Extragenital manifestations may occur, though some cases are characterized by concomitant genital involvement.3,4 Our patient presented with palmoplantar distribution of plaques without genitalia involvement. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with extragenital LS do not have genital involvement at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Furthermore, LS involving the palms and soles is exceedingly rare.2 Although extragenital LS may be asymptomatic, patients can experience debilitating pruritus; bullae with hemorrhage and erosion; plaque thickening with repeated excoriations; and painful fissuring, especially if lesions are in areas that are susceptible to friction or tension.3,6 New lesions on previously unaffected skin also may develop secondary to trauma through the Koebner phenomenon.1,6

Histologically, LS is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis accompanied by follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal epidermis, marked edema in the superficial dermis (in early lesions) or homogenized collagen in the upper dermis (in established lesions), and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized collagen. Although the pathogenesis of LS is unclear, purported etiologic factors from studies in genital disease include immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infection, and trauma.6 Lichen sclerosus is associated strongly with autoimmune diseases including alopecia areata, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia, indicating its potential multifactorial etiology and linkage to T-lymphocyte dysfunction.1 Early LS lesions often appear as flat-topped and slightly scaly, hypopigmented, white or mildly erythematous, polygonal papules that coalesce to form larger plaques with peripheral erythema. With time, the inflammation subsides, and lesions become porcelain-white with varying degrees of palpable sclerosis, resembling thin paperlike wrinkles indicative of epidermal atrophy.6

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), morphea, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and vitiligo.3 Lesions of LP commonly are described as flat-topped, polygonal, pink-purple papules localized mostly along the volar wrists, shins, presacral area, and hands.7 Lichen planus is considered to be more pruritic3 than LS and can be further distinguished by biopsy through identifying a well-formed granular layer and numerous cytoid bodies. Unlike LS, LP is not characterized by basement membrane thickening or epidermal atrophy.8

Skin lesions seen in morphea may resemble the classic atrophic white lesions of extragenital LS; however, it is unclear if the appearance of LS-like lesions with morphea is a simultaneous occurrence of 2 separate disorders or the development of clinical findings resembling LS in lesions of morphea.6 Furthermore, morphea involves deep inflammation and sclerosis of the dermis that may extend into subcutaneous fat without follicular plugging of the epidermis.3,9 In contrast, LS primarily affects the epidermis and dermis with the presence of epidermal follicular plugging.6

Lesions seen in DLE are characterized as well-defined, annular, erythematous patches and plaques followed by follicular hyperkeratosis with adherent scaling. Upon removal of the scale, follicle-sized keratotic spikes (carpet tacks) are present.10 Scaling of lesions and the carpet tack sign were absent in our patient. In addition, DLE typically reveals surrounding pigmentation and scarring over plaques,3 which were not observed in our patient.

Vitiligo commonly is associated with extragenital LS. As with LS, vitiligo can be explained by mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced cytotoxicity as well as perforin and granzyme-B expression.11 Although vitiligo resembles the late hypopigmented lesions of extragenital LS, there are no plaques or surface changes, and a larger, more generalized area of the skin typically is involved.3

- Chamli A, Souissi A. Lichen sclerosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538246/

- Gaddis KJ, Huang J, Haun PL. An atrophic and spiny eruption of the palms. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1344-1345. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1265

- Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review [published online August 11, 2022]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.13890

- Heibel HD, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ. A case of acral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;8:26-27. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.12.008

- Seyffert J, Bibliowicz N, Harding T, et al. Palmar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:697-699. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.06.005

- Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated July 11, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus?search=Lichen%20sclerosus&source =search_result&selectedTitle=2~66&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Mostow E. Lichen planus. UpToDate. Updated October 25, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planus?search=lichen%20 sclerosus&topicRef=15838&source=see_link

- Tallon B. Lichen sclerosus pathology. DermNet NZ website. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lichen-sclerosus-pathology

- Jacobe H. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. UpToDate. Updated November 15, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/13776

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Veronesi G, Scarfì F, Misciali C, et al. An unusual skin reaction in uveal melanoma during treatment with nivolumab: extragenital lichen sclerosus. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:969-972. doi:10.1097/ CAD.0000000000000819

The Diagnosis: Lichen Sclerosus

Histopathology revealed a thin epidermis with homogenization of the upper dermal collagen. By contrast, the lower dermis was sclerotic with patchy chronic dermal infiltrate (Figure). Ultimately, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS).

Lichen sclerosus is a rare chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically is characterized by porcelainwhite atrophic plaques on the skin, most often involving the external female genitalia including the vulva and perianal area.1 It is thought to be underdiagnosed and underreported.2 Extragenital manifestations may occur, though some cases are characterized by concomitant genital involvement.3,4 Our patient presented with palmoplantar distribution of plaques without genitalia involvement. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with extragenital LS do not have genital involvement at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Furthermore, LS involving the palms and soles is exceedingly rare.2 Although extragenital LS may be asymptomatic, patients can experience debilitating pruritus; bullae with hemorrhage and erosion; plaque thickening with repeated excoriations; and painful fissuring, especially if lesions are in areas that are susceptible to friction or tension.3,6 New lesions on previously unaffected skin also may develop secondary to trauma through the Koebner phenomenon.1,6

Histologically, LS is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis accompanied by follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal epidermis, marked edema in the superficial dermis (in early lesions) or homogenized collagen in the upper dermis (in established lesions), and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized collagen. Although the pathogenesis of LS is unclear, purported etiologic factors from studies in genital disease include immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infection, and trauma.6 Lichen sclerosus is associated strongly with autoimmune diseases including alopecia areata, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia, indicating its potential multifactorial etiology and linkage to T-lymphocyte dysfunction.1 Early LS lesions often appear as flat-topped and slightly scaly, hypopigmented, white or mildly erythematous, polygonal papules that coalesce to form larger plaques with peripheral erythema. With time, the inflammation subsides, and lesions become porcelain-white with varying degrees of palpable sclerosis, resembling thin paperlike wrinkles indicative of epidermal atrophy.6

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), morphea, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and vitiligo.3 Lesions of LP commonly are described as flat-topped, polygonal, pink-purple papules localized mostly along the volar wrists, shins, presacral area, and hands.7 Lichen planus is considered to be more pruritic3 than LS and can be further distinguished by biopsy through identifying a well-formed granular layer and numerous cytoid bodies. Unlike LS, LP is not characterized by basement membrane thickening or epidermal atrophy.8

Skin lesions seen in morphea may resemble the classic atrophic white lesions of extragenital LS; however, it is unclear if the appearance of LS-like lesions with morphea is a simultaneous occurrence of 2 separate disorders or the development of clinical findings resembling LS in lesions of morphea.6 Furthermore, morphea involves deep inflammation and sclerosis of the dermis that may extend into subcutaneous fat without follicular plugging of the epidermis.3,9 In contrast, LS primarily affects the epidermis and dermis with the presence of epidermal follicular plugging.6

Lesions seen in DLE are characterized as well-defined, annular, erythematous patches and plaques followed by follicular hyperkeratosis with adherent scaling. Upon removal of the scale, follicle-sized keratotic spikes (carpet tacks) are present.10 Scaling of lesions and the carpet tack sign were absent in our patient. In addition, DLE typically reveals surrounding pigmentation and scarring over plaques,3 which were not observed in our patient.

Vitiligo commonly is associated with extragenital LS. As with LS, vitiligo can be explained by mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced cytotoxicity as well as perforin and granzyme-B expression.11 Although vitiligo resembles the late hypopigmented lesions of extragenital LS, there are no plaques or surface changes, and a larger, more generalized area of the skin typically is involved.3

The Diagnosis: Lichen Sclerosus

Histopathology revealed a thin epidermis with homogenization of the upper dermal collagen. By contrast, the lower dermis was sclerotic with patchy chronic dermal infiltrate (Figure). Ultimately, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus (LS).

Lichen sclerosus is a rare chronic inflammatory skin condition that typically is characterized by porcelainwhite atrophic plaques on the skin, most often involving the external female genitalia including the vulva and perianal area.1 It is thought to be underdiagnosed and underreported.2 Extragenital manifestations may occur, though some cases are characterized by concomitant genital involvement.3,4 Our patient presented with palmoplantar distribution of plaques without genitalia involvement. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with extragenital LS do not have genital involvement at the time of diagnosis.3,5 Furthermore, LS involving the palms and soles is exceedingly rare.2 Although extragenital LS may be asymptomatic, patients can experience debilitating pruritus; bullae with hemorrhage and erosion; plaque thickening with repeated excoriations; and painful fissuring, especially if lesions are in areas that are susceptible to friction or tension.3,6 New lesions on previously unaffected skin also may develop secondary to trauma through the Koebner phenomenon.1,6

Histologically, LS is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis accompanied by follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolization of the basal epidermis, marked edema in the superficial dermis (in early lesions) or homogenized collagen in the upper dermis (in established lesions), and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate beneath the homogenized collagen. Although the pathogenesis of LS is unclear, purported etiologic factors from studies in genital disease include immune dysfunction, genetic predisposition, infection, and trauma.6 Lichen sclerosus is associated strongly with autoimmune diseases including alopecia areata, vitiligo, autoimmune thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, and pernicious anemia, indicating its potential multifactorial etiology and linkage to T-lymphocyte dysfunction.1 Early LS lesions often appear as flat-topped and slightly scaly, hypopigmented, white or mildly erythematous, polygonal papules that coalesce to form larger plaques with peripheral erythema. With time, the inflammation subsides, and lesions become porcelain-white with varying degrees of palpable sclerosis, resembling thin paperlike wrinkles indicative of epidermal atrophy.6

The differential diagnosis of LS includes lichen planus (LP), morphea, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), and vitiligo.3 Lesions of LP commonly are described as flat-topped, polygonal, pink-purple papules localized mostly along the volar wrists, shins, presacral area, and hands.7 Lichen planus is considered to be more pruritic3 than LS and can be further distinguished by biopsy through identifying a well-formed granular layer and numerous cytoid bodies. Unlike LS, LP is not characterized by basement membrane thickening or epidermal atrophy.8

Skin lesions seen in morphea may resemble the classic atrophic white lesions of extragenital LS; however, it is unclear if the appearance of LS-like lesions with morphea is a simultaneous occurrence of 2 separate disorders or the development of clinical findings resembling LS in lesions of morphea.6 Furthermore, morphea involves deep inflammation and sclerosis of the dermis that may extend into subcutaneous fat without follicular plugging of the epidermis.3,9 In contrast, LS primarily affects the epidermis and dermis with the presence of epidermal follicular plugging.6

Lesions seen in DLE are characterized as well-defined, annular, erythematous patches and plaques followed by follicular hyperkeratosis with adherent scaling. Upon removal of the scale, follicle-sized keratotic spikes (carpet tacks) are present.10 Scaling of lesions and the carpet tack sign were absent in our patient. In addition, DLE typically reveals surrounding pigmentation and scarring over plaques,3 which were not observed in our patient.

Vitiligo commonly is associated with extragenital LS. As with LS, vitiligo can be explained by mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced cytotoxicity as well as perforin and granzyme-B expression.11 Although vitiligo resembles the late hypopigmented lesions of extragenital LS, there are no plaques or surface changes, and a larger, more generalized area of the skin typically is involved.3

- Chamli A, Souissi A. Lichen sclerosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538246/

- Gaddis KJ, Huang J, Haun PL. An atrophic and spiny eruption of the palms. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1344-1345. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1265

- Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review [published online August 11, 2022]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.13890

- Heibel HD, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ. A case of acral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;8:26-27. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.12.008

- Seyffert J, Bibliowicz N, Harding T, et al. Palmar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:697-699. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.06.005

- Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated July 11, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus?search=Lichen%20sclerosus&source =search_result&selectedTitle=2~66&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Mostow E. Lichen planus. UpToDate. Updated October 25, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planus?search=lichen%20 sclerosus&topicRef=15838&source=see_link

- Tallon B. Lichen sclerosus pathology. DermNet NZ website. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lichen-sclerosus-pathology

- Jacobe H. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. UpToDate. Updated November 15, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/13776

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Veronesi G, Scarfì F, Misciali C, et al. An unusual skin reaction in uveal melanoma during treatment with nivolumab: extragenital lichen sclerosus. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:969-972. doi:10.1097/ CAD.0000000000000819

- Chamli A, Souissi A. Lichen sclerosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538246/

- Gaddis KJ, Huang J, Haun PL. An atrophic and spiny eruption of the palms. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1344-1345. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2018.1265

- Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: a comprehensive review [published online August 11, 2022]. Australas J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ajd.13890

- Heibel HD, Styles AR, Cockerell CJ. A case of acral lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;8:26-27. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.12.008

- Seyffert J, Bibliowicz N, Harding T, et al. Palmar lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:697-699. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.06.005

- Jacobe H. Extragenital lichen sclerosus: clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. Updated July 11, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/extragenital-lichen-sclerosus?search=Lichen%20sclerosus&source =search_result&selectedTitle=2~66&usage_type=default&display_ rank=2

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Mostow E. Lichen planus. UpToDate. Updated October 25, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lichen-planus?search=lichen%20 sclerosus&topicRef=15838&source=see_link

- Tallon B. Lichen sclerosus pathology. DermNet NZ website. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/lichen-sclerosus-pathology

- Jacobe H. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults. UpToDate. Updated November 15, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2023. https://medilib.ir/uptodate/show/13776

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed December 14, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Veronesi G, Scarfì F, Misciali C, et al. An unusual skin reaction in uveal melanoma during treatment with nivolumab: extragenital lichen sclerosus. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:969-972. doi:10.1097/ CAD.0000000000000819

A 59-year-old woman presented with atrophic, hypopigmented, ivory papules and plaques localized to the central palms and soles of 3 years’ duration. The lesions were associated with burning that was most notable after extended periods of ambulation. The lesions initially were diagnosed as plaque psoriasis by an external dermatology clinic. At the time of presentation to our clinic, treatment with several highpotency topical steroids and biologics approved for plaque psoriasis had failed. Her medical history and concurrent medical workup were notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver dysfunction, thyroid nodules overseen by an endocrinologist, vitamin B12 and vitamin D deficiencies managed with supplementation, and diffuse androgenic alopecia with suspected telogen effluvium. Physical examination revealed no plaque fissuring, pruritus, or scaling. She had no history of radiation therapy or organ transplantation. A punch biopsy of the left palm was performed.

Updates on Investigational Treatments for HR-Positive, HER2-Negative Breast Cancer

Results from TROPION-Breast01, EMBER, and OPERA were recently presented at ESMO Breast Cancer 2023.

A number of exciting updates on systemic therapies for the treatment of hormone receptor (HR)-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer were presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Breast Cancer 2023, including novel endocrine agents and antibody-drug conjugates (ADC). We have highlighted 3 key studies, including the phase III study of datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd), the new trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (TROP2)-directed ADC; the phase I study of imlunestrant, a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD); and phase I/II data evaluating OP-1250, a small molecule oral complete estrogen receptor antagonist (CERAN) and SERD.

TROPION-Breast01: Dato-DXd Improves Progression-Free Survival Compared With Systemic Chemotherapy

Study synopsis

Dato-DXd, an investigational TROP2 ADC, resulted in significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with investigator’s choice chemotherapy (ICC) in individuals with inoperable or metastatic HR-positive, HER2-low or HER2-negative breast cancer, according to a randomized phase III trial.

Participants in the study had progressed on or were not eligible for endocrine therapy and had received 1 or 2 prior lines of systemic chemotherapy. Patients were randomized to receive either 6 mg/kg of Dato-DXd once every 3 weeks (n=365; median age 56), or ICC with eribulin, vinorelbine, capecitabine, or gemcitabine (n=367; median age 54) until progression or unacceptable toxicity. Blinded independent review assessed PFS and overall survival. Among the results:

In the blinded independent review, PFS was 6.9 months for Dato-DXd and 4.9 months for ICC (HR 0.63 [95% CI: 0.52, 0.76]; p<0.0001)

At 6 months, 53% of participants receiving Dato-DXd achieved PFS, compared with 39% in the systemic chemotherapy contingent

In the Dato-DXd group, treatment-related adverse events led to dose reductions in 23% and discontinuation in 3% of patients

In the systemic chemotherapy cohort, the dose reduction and discontinuation rates were 32% and 3%, respectively

At the time data were reported at ESMO, overall survival data were not mature but trending favorably for Dato-DXd

The investigators concluded that Dato-DXd is a promising novel treatment option for individuals with inoperable or metastatic HR-positive, HER2-low or HER2-negative breast cancer who have received prior chemotherapy.

EMBER: Imlunestrant Alone or With a Kinase Inhibitor: Early Safety and Efficacy Results Are Encouraging

Study synopsis

The SERD imlunestrant—used either alone or combined with a kinase inhibitor—showed favorable efficacy in individuals with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, according to the first set of clinical data reported from the phase 1a/b EMBER study.

Key eligibility criteria for phase 1b enrollment included prior sensitivity to endocrine therapy, ≤2 prior therapies, and a PIK3CA mutation (alpelisib arm only). Prior therapies included endocrine therapy (100%), CDK4/6 inhibitors (100%), hormonal therapy with fulvestrant (35%), and chemotherapy (17%). At baseline, 46% of patients had visceral disease and 46% had an ESR1 mutation. Participants received imlunestrant alone (n=114) or with the kinase inhibitors everolimus (n=42) or alpelisib (n=21). Investigators assessed each regimen’s safety profile, as well as the objective response rate and clinical benefit rate.

The safety profile of each regimen was similar to those seen with everolimus and alpelisib alone. No cardiac or ocular toxicities were observed. Regarding grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events:

The imlunestrant alone group experienced fatigue (2%) and neutropenia (2%)

The imlunestrant + everolimus group experienced hypertriglyceridemia (5%) and aspartate aminotransferase increase (5%)

The imlunestrant + alpelisib cohort experienced rash (43%) and hyperglycemia (10%).

In the imlunestrant alone group, 2% of individuals had their doses reduced due to adverse events; none discontinued treatment

In the imlunestrant + everolimus cohort, 12% of patients experienced dose reduction due to everolimus and 2% due to both medications; 2% discontinued treatment due to everolimus

In the imlunestrant + alpelisib cohort, 24% of patients experienced dose reduction due to alpelisib and 14% due to both medications; 29% discontinued treatment due to alpelisib

Regarding efficacy:

The objective response rates in the imlunestrant alone, imlunestrant + everolimus, and imlunestrant + alpelisib groups were 9%, 21%, and 50%, respectively

The clinical benefit rates in the imlunestrant alone, imlunestrant + everolimus, and imlunestrant + alpelisib groups were 42%, 62%, and 62%, respectively

Investigators concluded that imlunestrant used alone or in combination with 1 of the 2 kinase inhibitors demonstrated robust efficacy in individuals with pretreated, ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer.

OPERA: OP-1250 Paired With a CDK4/6 Inhibitor: Anti-Tumor Activity With No Dose-Limiting Toxicities

Study synopsis

OP-1250, a CERAN and SERD, continues to show promising results when paired with a CDK4/6 inhibitor. The combination of OP-1250 and the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib appears to be well tolerated and has a similar safety profile to each drug when used alone, according to a phase I/II study involving 20 individuals with pretreated ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

Participants had advanced or metastatic ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer that progressed on ≤1 lines of endocrine therapy. Fourteen participants had received prior CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy, including 11 who were previously treated with palbociclib. Patients received escalating doses of OP-1250 with 125 mg of palbociclib orally daily for 21 of 28 days. OP-1250 doses were 30 mg (n=3), 60 mg (n=3), 90 mg (n=3), and 120 mg (n=11). Investigators assessed pharmacokinetics, drug-drug interactions, safety, and efficacy. Among the results observed to date:

Grade 3 neutropenia occurred in 55% of participants

There were no grade 4 treatment-related adverse events and no dose-limiting toxicities

OP-1250 exposure yielded similar results to what was seen in the previous monotherapy study

Palbociclib exposure was comparable to published monotherapy data when combined with OP-1250 for all dosages

Investigators observed antitumor activity, including partial responses

Researchers concluded that OP-1250 does not affect the pharmacokinetics of palbociclib, and there do not appear to be drug-drug interactions. Tumor response to this combination was encouraging and requires continued investigation.

Conclusions

These 3 studies presented at ESMO 2023 highlight exciting novel therapies for the treatment of HR-positive, HER2-low, and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. The EMBER and OPERA updates provide support for the safety and efficacy of these novel endocrine agents in combination with kinase inhibitors and CDK4/6 inhibitors, respectively, in patients with endocrine-sensitive disease, while the TROPION-01 study demonstrates the encouraging efficacy and safety of a second TROP-2-directed ADC in a more heavily pretreated population.

Results from TROPION-Breast01, EMBER, and OPERA were recently presented at ESMO Breast Cancer 2023.

A number of exciting updates on systemic therapies for the treatment of hormone receptor (HR)-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer were presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Breast Cancer 2023, including novel endocrine agents and antibody-drug conjugates (ADC). We have highlighted 3 key studies, including the phase III study of datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd), the new trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (TROP2)-directed ADC; the phase I study of imlunestrant, a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD); and phase I/II data evaluating OP-1250, a small molecule oral complete estrogen receptor antagonist (CERAN) and SERD.

TROPION-Breast01: Dato-DXd Improves Progression-Free Survival Compared With Systemic Chemotherapy

Study synopsis

Dato-DXd, an investigational TROP2 ADC, resulted in significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with investigator’s choice chemotherapy (ICC) in individuals with inoperable or metastatic HR-positive, HER2-low or HER2-negative breast cancer, according to a randomized phase III trial.

Participants in the study had progressed on or were not eligible for endocrine therapy and had received 1 or 2 prior lines of systemic chemotherapy. Patients were randomized to receive either 6 mg/kg of Dato-DXd once every 3 weeks (n=365; median age 56), or ICC with eribulin, vinorelbine, capecitabine, or gemcitabine (n=367; median age 54) until progression or unacceptable toxicity. Blinded independent review assessed PFS and overall survival. Among the results:

In the blinded independent review, PFS was 6.9 months for Dato-DXd and 4.9 months for ICC (HR 0.63 [95% CI: 0.52, 0.76]; p<0.0001)

At 6 months, 53% of participants receiving Dato-DXd achieved PFS, compared with 39% in the systemic chemotherapy contingent

In the Dato-DXd group, treatment-related adverse events led to dose reductions in 23% and discontinuation in 3% of patients

In the systemic chemotherapy cohort, the dose reduction and discontinuation rates were 32% and 3%, respectively

At the time data were reported at ESMO, overall survival data were not mature but trending favorably for Dato-DXd

The investigators concluded that Dato-DXd is a promising novel treatment option for individuals with inoperable or metastatic HR-positive, HER2-low or HER2-negative breast cancer who have received prior chemotherapy.

EMBER: Imlunestrant Alone or With a Kinase Inhibitor: Early Safety and Efficacy Results Are Encouraging

Study synopsis

The SERD imlunestrant—used either alone or combined with a kinase inhibitor—showed favorable efficacy in individuals with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, according to the first set of clinical data reported from the phase 1a/b EMBER study.

Key eligibility criteria for phase 1b enrollment included prior sensitivity to endocrine therapy, ≤2 prior therapies, and a PIK3CA mutation (alpelisib arm only). Prior therapies included endocrine therapy (100%), CDK4/6 inhibitors (100%), hormonal therapy with fulvestrant (35%), and chemotherapy (17%). At baseline, 46% of patients had visceral disease and 46% had an ESR1 mutation. Participants received imlunestrant alone (n=114) or with the kinase inhibitors everolimus (n=42) or alpelisib (n=21). Investigators assessed each regimen’s safety profile, as well as the objective response rate and clinical benefit rate.

The safety profile of each regimen was similar to those seen with everolimus and alpelisib alone. No cardiac or ocular toxicities were observed. Regarding grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events:

The imlunestrant alone group experienced fatigue (2%) and neutropenia (2%)

The imlunestrant + everolimus group experienced hypertriglyceridemia (5%) and aspartate aminotransferase increase (5%)

The imlunestrant + alpelisib cohort experienced rash (43%) and hyperglycemia (10%).

In the imlunestrant alone group, 2% of individuals had their doses reduced due to adverse events; none discontinued treatment

In the imlunestrant + everolimus cohort, 12% of patients experienced dose reduction due to everolimus and 2% due to both medications; 2% discontinued treatment due to everolimus

In the imlunestrant + alpelisib cohort, 24% of patients experienced dose reduction due to alpelisib and 14% due to both medications; 29% discontinued treatment due to alpelisib

Regarding efficacy:

The objective response rates in the imlunestrant alone, imlunestrant + everolimus, and imlunestrant + alpelisib groups were 9%, 21%, and 50%, respectively

The clinical benefit rates in the imlunestrant alone, imlunestrant + everolimus, and imlunestrant + alpelisib groups were 42%, 62%, and 62%, respectively

Investigators concluded that imlunestrant used alone or in combination with 1 of the 2 kinase inhibitors demonstrated robust efficacy in individuals with pretreated, ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer.

OPERA: OP-1250 Paired With a CDK4/6 Inhibitor: Anti-Tumor Activity With No Dose-Limiting Toxicities

Study synopsis

OP-1250, a CERAN and SERD, continues to show promising results when paired with a CDK4/6 inhibitor. The combination of OP-1250 and the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib appears to be well tolerated and has a similar safety profile to each drug when used alone, according to a phase I/II study involving 20 individuals with pretreated ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

Participants had advanced or metastatic ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer that progressed on ≤1 lines of endocrine therapy. Fourteen participants had received prior CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy, including 11 who were previously treated with palbociclib. Patients received escalating doses of OP-1250 with 125 mg of palbociclib orally daily for 21 of 28 days. OP-1250 doses were 30 mg (n=3), 60 mg (n=3), 90 mg (n=3), and 120 mg (n=11). Investigators assessed pharmacokinetics, drug-drug interactions, safety, and efficacy. Among the results observed to date:

Grade 3 neutropenia occurred in 55% of participants

There were no grade 4 treatment-related adverse events and no dose-limiting toxicities

OP-1250 exposure yielded similar results to what was seen in the previous monotherapy study

Palbociclib exposure was comparable to published monotherapy data when combined with OP-1250 for all dosages

Investigators observed antitumor activity, including partial responses

Researchers concluded that OP-1250 does not affect the pharmacokinetics of palbociclib, and there do not appear to be drug-drug interactions. Tumor response to this combination was encouraging and requires continued investigation.

Conclusions

These 3 studies presented at ESMO 2023 highlight exciting novel therapies for the treatment of HR-positive, HER2-low, and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. The EMBER and OPERA updates provide support for the safety and efficacy of these novel endocrine agents in combination with kinase inhibitors and CDK4/6 inhibitors, respectively, in patients with endocrine-sensitive disease, while the TROPION-01 study demonstrates the encouraging efficacy and safety of a second TROP-2-directed ADC in a more heavily pretreated population.

Results from TROPION-Breast01, EMBER, and OPERA were recently presented at ESMO Breast Cancer 2023.

A number of exciting updates on systemic therapies for the treatment of hormone receptor (HR)-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer were presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Breast Cancer 2023, including novel endocrine agents and antibody-drug conjugates (ADC). We have highlighted 3 key studies, including the phase III study of datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd), the new trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (TROP2)-directed ADC; the phase I study of imlunestrant, a selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD); and phase I/II data evaluating OP-1250, a small molecule oral complete estrogen receptor antagonist (CERAN) and SERD.

TROPION-Breast01: Dato-DXd Improves Progression-Free Survival Compared With Systemic Chemotherapy

Study synopsis

Dato-DXd, an investigational TROP2 ADC, resulted in significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with investigator’s choice chemotherapy (ICC) in individuals with inoperable or metastatic HR-positive, HER2-low or HER2-negative breast cancer, according to a randomized phase III trial.

Participants in the study had progressed on or were not eligible for endocrine therapy and had received 1 or 2 prior lines of systemic chemotherapy. Patients were randomized to receive either 6 mg/kg of Dato-DXd once every 3 weeks (n=365; median age 56), or ICC with eribulin, vinorelbine, capecitabine, or gemcitabine (n=367; median age 54) until progression or unacceptable toxicity. Blinded independent review assessed PFS and overall survival. Among the results:

In the blinded independent review, PFS was 6.9 months for Dato-DXd and 4.9 months for ICC (HR 0.63 [95% CI: 0.52, 0.76]; p<0.0001)

At 6 months, 53% of participants receiving Dato-DXd achieved PFS, compared with 39% in the systemic chemotherapy contingent

In the Dato-DXd group, treatment-related adverse events led to dose reductions in 23% and discontinuation in 3% of patients

In the systemic chemotherapy cohort, the dose reduction and discontinuation rates were 32% and 3%, respectively

At the time data were reported at ESMO, overall survival data were not mature but trending favorably for Dato-DXd

The investigators concluded that Dato-DXd is a promising novel treatment option for individuals with inoperable or metastatic HR-positive, HER2-low or HER2-negative breast cancer who have received prior chemotherapy.

EMBER: Imlunestrant Alone or With a Kinase Inhibitor: Early Safety and Efficacy Results Are Encouraging

Study synopsis

The SERD imlunestrant—used either alone or combined with a kinase inhibitor—showed favorable efficacy in individuals with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, according to the first set of clinical data reported from the phase 1a/b EMBER study.

Key eligibility criteria for phase 1b enrollment included prior sensitivity to endocrine therapy, ≤2 prior therapies, and a PIK3CA mutation (alpelisib arm only). Prior therapies included endocrine therapy (100%), CDK4/6 inhibitors (100%), hormonal therapy with fulvestrant (35%), and chemotherapy (17%). At baseline, 46% of patients had visceral disease and 46% had an ESR1 mutation. Participants received imlunestrant alone (n=114) or with the kinase inhibitors everolimus (n=42) or alpelisib (n=21). Investigators assessed each regimen’s safety profile, as well as the objective response rate and clinical benefit rate.

The safety profile of each regimen was similar to those seen with everolimus and alpelisib alone. No cardiac or ocular toxicities were observed. Regarding grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events:

The imlunestrant alone group experienced fatigue (2%) and neutropenia (2%)

The imlunestrant + everolimus group experienced hypertriglyceridemia (5%) and aspartate aminotransferase increase (5%)

The imlunestrant + alpelisib cohort experienced rash (43%) and hyperglycemia (10%).

In the imlunestrant alone group, 2% of individuals had their doses reduced due to adverse events; none discontinued treatment

In the imlunestrant + everolimus cohort, 12% of patients experienced dose reduction due to everolimus and 2% due to both medications; 2% discontinued treatment due to everolimus

In the imlunestrant + alpelisib cohort, 24% of patients experienced dose reduction due to alpelisib and 14% due to both medications; 29% discontinued treatment due to alpelisib

Regarding efficacy:

The objective response rates in the imlunestrant alone, imlunestrant + everolimus, and imlunestrant + alpelisib groups were 9%, 21%, and 50%, respectively

The clinical benefit rates in the imlunestrant alone, imlunestrant + everolimus, and imlunestrant + alpelisib groups were 42%, 62%, and 62%, respectively

Investigators concluded that imlunestrant used alone or in combination with 1 of the 2 kinase inhibitors demonstrated robust efficacy in individuals with pretreated, ER-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer.

OPERA: OP-1250 Paired With a CDK4/6 Inhibitor: Anti-Tumor Activity With No Dose-Limiting Toxicities

Study synopsis

OP-1250, a CERAN and SERD, continues to show promising results when paired with a CDK4/6 inhibitor. The combination of OP-1250 and the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib appears to be well tolerated and has a similar safety profile to each drug when used alone, according to a phase I/II study involving 20 individuals with pretreated ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer.

Participants had advanced or metastatic ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer that progressed on ≤1 lines of endocrine therapy. Fourteen participants had received prior CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy, including 11 who were previously treated with palbociclib. Patients received escalating doses of OP-1250 with 125 mg of palbociclib orally daily for 21 of 28 days. OP-1250 doses were 30 mg (n=3), 60 mg (n=3), 90 mg (n=3), and 120 mg (n=11). Investigators assessed pharmacokinetics, drug-drug interactions, safety, and efficacy. Among the results observed to date:

Grade 3 neutropenia occurred in 55% of participants

There were no grade 4 treatment-related adverse events and no dose-limiting toxicities

OP-1250 exposure yielded similar results to what was seen in the previous monotherapy study

Palbociclib exposure was comparable to published monotherapy data when combined with OP-1250 for all dosages

Investigators observed antitumor activity, including partial responses

Researchers concluded that OP-1250 does not affect the pharmacokinetics of palbociclib, and there do not appear to be drug-drug interactions. Tumor response to this combination was encouraging and requires continued investigation.

Conclusions

These 3 studies presented at ESMO 2023 highlight exciting novel therapies for the treatment of HR-positive, HER2-low, and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. The EMBER and OPERA updates provide support for the safety and efficacy of these novel endocrine agents in combination with kinase inhibitors and CDK4/6 inhibitors, respectively, in patients with endocrine-sensitive disease, while the TROPION-01 study demonstrates the encouraging efficacy and safety of a second TROP-2-directed ADC in a more heavily pretreated population.

Progressive joint pain and swelling

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is consistent with the patient's joint pain, dactylitis, enthesitis, skin plaques, and radiographic findings, making it the most likely diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is possible because of the patient's joint symptoms; however, it is not the correct answer because of negative RF and ACPA tests and skin plaques.

Osteoarthritis might cause joint pain but does not typically present with prolonged morning stiffness, skin plaques, or the "pencil-in-cup" radiographic finding.

Gout, an inflammatory arthritis, primarily affects the big toe and does not align with the patient's skin and radiographic manifestations.

PsA is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that often develops in people with psoriasis. It affects roughly 0.05%- 0.25% of the general population and up to 41% of people with psoriasis. PsA is most seen in White patients between 35 and 55 years and affects both men and women equally. PsA is linked to a higher risk for obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and other conditions, including uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Clinically, PsA presents with a diverse range of manifestations, encompassing peripheral joint inflammation, often with an asymmetric distribution; axial skeletal involvement reminiscent of spondylitis; dactylitis characterized by sausage-like swelling of fingers or toes; and enthesitis. Common symptoms or findings include early morning stiffness for > 30 minutes; joint pain, tenderness, and swelling; back pain aggravated by rest and relieved by exercise; limited joint motion; and deformity. Although most patients have a preceding condition in skin psoriasis, diagnosis of PsA is often delayed. Furthermore, nearly 80% of patients may exhibit nail changes, such as pitting or onycholysis, compared with about 40% of patients with psoriasis without arthritis. The heterogeneity of its clinical features often necessitates a comprehensive differential diagnosis to distinguish PsA from other spondyloarthropathies and rheumatic diseases. The most accepted classification criteria for PsA are the Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria, which have been used since 2006.

No laboratory tests are specific for PsA; however, a normal ESR and CRP level should not be used to rule out a diagnosis of PsA because these values are increased in only about 40% of patients. RF and ACPA are classically considered absent in PsA, and a negative RF is regarded as a criterion for diagnosing PsA per the CASPAR classification criteria. Radiographic changes show some characteristic patterns in PsA, including erosive damage, gross joint destruction, joint space narrowing, and "pencil-in-cup" deformity.

PsA treatment options have evolved over the years. Whereas in the past, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and cyclosporine were commonly prescribed, the development of immunologically targeted biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs since 2000 has revolutionized the treatment of PsA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (ie, etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab) have been shown to improve all domains (psoriatic and articular disease) of PsA and are considered a milestone in managing the condition. Other emerging therapeutic strategies in recent years have demonstrated efficacy in treating PsA, including monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin (IL)-12, IL-23, and IL-17, as well as small-molecule phosphodiesterase 4 and Janus kinase inhibitors.

Although most of these options have the potential to be effective in all clinical domains of the disease, their cross-domain efficacy can vary from patient to patient. In some cases, treatment may not be practical or can lose effectiveness over time, and true disease remission is rare. As a result, clinicians must regularly assess each domain and aim to achieve remission or low disease activity across the different active domains while also being aware of potential adverse events.

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, Consultant Dermatologist, ADI Dermatology LTD, Dublin, Ireland

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Serve(d) as a speaker or member of a speakers bureau for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is consistent with the patient's joint pain, dactylitis, enthesitis, skin plaques, and radiographic findings, making it the most likely diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is possible because of the patient's joint symptoms; however, it is not the correct answer because of negative RF and ACPA tests and skin plaques.

Osteoarthritis might cause joint pain but does not typically present with prolonged morning stiffness, skin plaques, or the "pencil-in-cup" radiographic finding.

Gout, an inflammatory arthritis, primarily affects the big toe and does not align with the patient's skin and radiographic manifestations.

PsA is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that often develops in people with psoriasis. It affects roughly 0.05%- 0.25% of the general population and up to 41% of people with psoriasis. PsA is most seen in White patients between 35 and 55 years and affects both men and women equally. PsA is linked to a higher risk for obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and other conditions, including uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Clinically, PsA presents with a diverse range of manifestations, encompassing peripheral joint inflammation, often with an asymmetric distribution; axial skeletal involvement reminiscent of spondylitis; dactylitis characterized by sausage-like swelling of fingers or toes; and enthesitis. Common symptoms or findings include early morning stiffness for > 30 minutes; joint pain, tenderness, and swelling; back pain aggravated by rest and relieved by exercise; limited joint motion; and deformity. Although most patients have a preceding condition in skin psoriasis, diagnosis of PsA is often delayed. Furthermore, nearly 80% of patients may exhibit nail changes, such as pitting or onycholysis, compared with about 40% of patients with psoriasis without arthritis. The heterogeneity of its clinical features often necessitates a comprehensive differential diagnosis to distinguish PsA from other spondyloarthropathies and rheumatic diseases. The most accepted classification criteria for PsA are the Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria, which have been used since 2006.

No laboratory tests are specific for PsA; however, a normal ESR and CRP level should not be used to rule out a diagnosis of PsA because these values are increased in only about 40% of patients. RF and ACPA are classically considered absent in PsA, and a negative RF is regarded as a criterion for diagnosing PsA per the CASPAR classification criteria. Radiographic changes show some characteristic patterns in PsA, including erosive damage, gross joint destruction, joint space narrowing, and "pencil-in-cup" deformity.

PsA treatment options have evolved over the years. Whereas in the past, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and cyclosporine were commonly prescribed, the development of immunologically targeted biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs since 2000 has revolutionized the treatment of PsA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (ie, etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab) have been shown to improve all domains (psoriatic and articular disease) of PsA and are considered a milestone in managing the condition. Other emerging therapeutic strategies in recent years have demonstrated efficacy in treating PsA, including monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin (IL)-12, IL-23, and IL-17, as well as small-molecule phosphodiesterase 4 and Janus kinase inhibitors.

Although most of these options have the potential to be effective in all clinical domains of the disease, their cross-domain efficacy can vary from patient to patient. In some cases, treatment may not be practical or can lose effectiveness over time, and true disease remission is rare. As a result, clinicians must regularly assess each domain and aim to achieve remission or low disease activity across the different active domains while also being aware of potential adverse events.

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, Consultant Dermatologist, ADI Dermatology LTD, Dublin, Ireland

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Serve(d) as a speaker or member of a speakers bureau for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is consistent with the patient's joint pain, dactylitis, enthesitis, skin plaques, and radiographic findings, making it the most likely diagnosis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is possible because of the patient's joint symptoms; however, it is not the correct answer because of negative RF and ACPA tests and skin plaques.

Osteoarthritis might cause joint pain but does not typically present with prolonged morning stiffness, skin plaques, or the "pencil-in-cup" radiographic finding.

Gout, an inflammatory arthritis, primarily affects the big toe and does not align with the patient's skin and radiographic manifestations.

PsA is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that often develops in people with psoriasis. It affects roughly 0.05%- 0.25% of the general population and up to 41% of people with psoriasis. PsA is most seen in White patients between 35 and 55 years and affects both men and women equally. PsA is linked to a higher risk for obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and other conditions, including uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Clinically, PsA presents with a diverse range of manifestations, encompassing peripheral joint inflammation, often with an asymmetric distribution; axial skeletal involvement reminiscent of spondylitis; dactylitis characterized by sausage-like swelling of fingers or toes; and enthesitis. Common symptoms or findings include early morning stiffness for > 30 minutes; joint pain, tenderness, and swelling; back pain aggravated by rest and relieved by exercise; limited joint motion; and deformity. Although most patients have a preceding condition in skin psoriasis, diagnosis of PsA is often delayed. Furthermore, nearly 80% of patients may exhibit nail changes, such as pitting or onycholysis, compared with about 40% of patients with psoriasis without arthritis. The heterogeneity of its clinical features often necessitates a comprehensive differential diagnosis to distinguish PsA from other spondyloarthropathies and rheumatic diseases. The most accepted classification criteria for PsA are the Classification of Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) criteria, which have been used since 2006.

No laboratory tests are specific for PsA; however, a normal ESR and CRP level should not be used to rule out a diagnosis of PsA because these values are increased in only about 40% of patients. RF and ACPA are classically considered absent in PsA, and a negative RF is regarded as a criterion for diagnosing PsA per the CASPAR classification criteria. Radiographic changes show some characteristic patterns in PsA, including erosive damage, gross joint destruction, joint space narrowing, and "pencil-in-cup" deformity.

PsA treatment options have evolved over the years. Whereas in the past, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and cyclosporine were commonly prescribed, the development of immunologically targeted biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs since 2000 has revolutionized the treatment of PsA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (ie, etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab) have been shown to improve all domains (psoriatic and articular disease) of PsA and are considered a milestone in managing the condition. Other emerging therapeutic strategies in recent years have demonstrated efficacy in treating PsA, including monoclonal antibodies targeting interleukin (IL)-12, IL-23, and IL-17, as well as small-molecule phosphodiesterase 4 and Janus kinase inhibitors.

Although most of these options have the potential to be effective in all clinical domains of the disease, their cross-domain efficacy can vary from patient to patient. In some cases, treatment may not be practical or can lose effectiveness over time, and true disease remission is rare. As a result, clinicians must regularly assess each domain and aim to achieve remission or low disease activity across the different active domains while also being aware of potential adverse events.

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, Consultant Dermatologist, ADI Dermatology LTD, Dublin, Ireland

Alan Irvine, MD, DSc, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Serve(d) as a speaker or member of a speakers bureau for: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Sanofi; Abbvie; Regeneron; Leo; Pfizer; Janssen.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 45-year-old man visited the rheumatology clinic with a 6-month history of progressive joint pain and swelling. He described experiencing morning stiffness that lasted about an hour, with the pain showing improvement with activity. Interestingly, he also mentioned having rashes for the past 10 years, which he initially attributed to eczema and managed with over-the-counter creams.

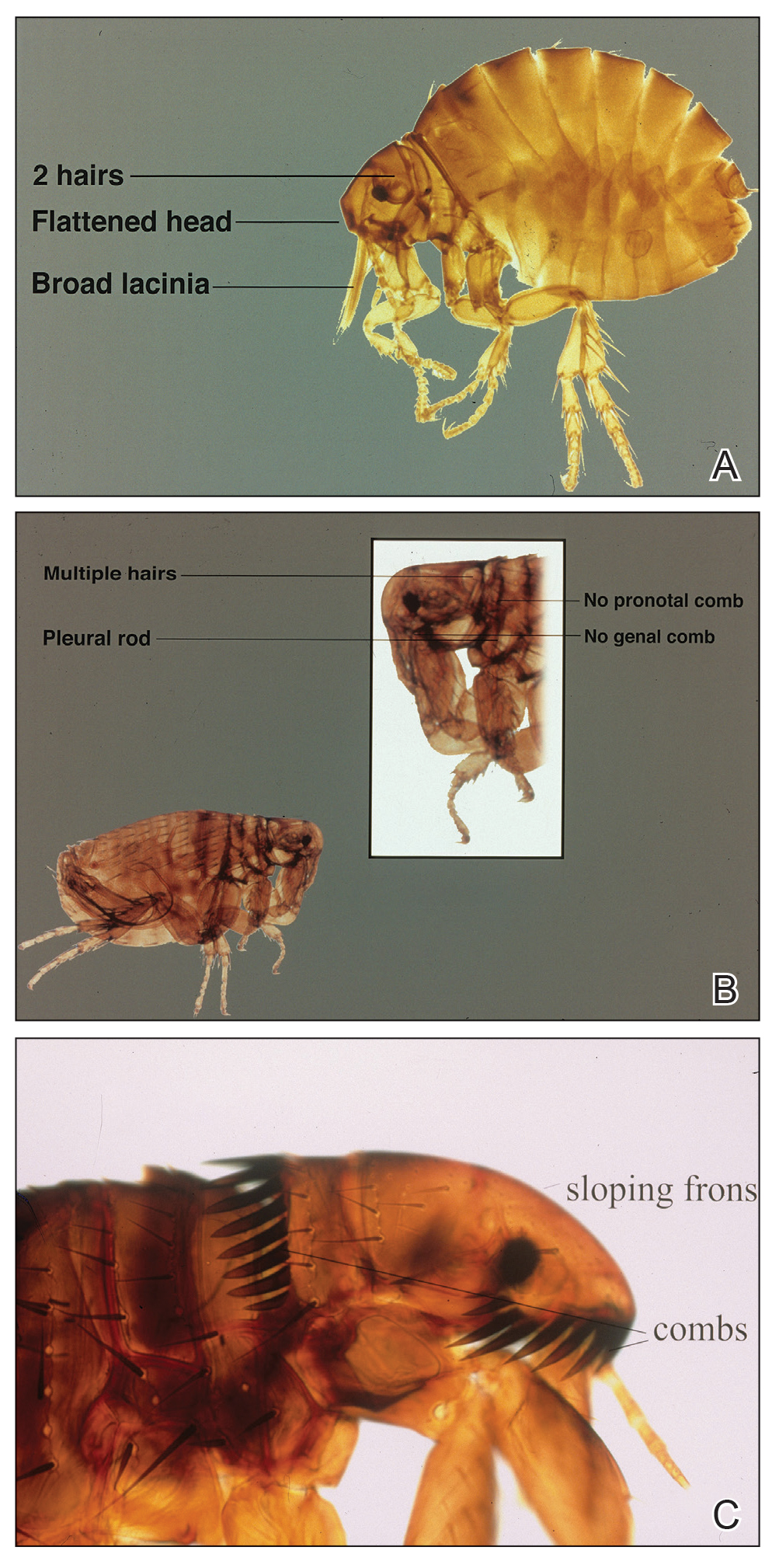

On physical examination, there was noticeable swelling and tenderness in the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints of both hands. The fourth finger on the right hand exhibited dactylitis with a well-circumscribed, erythematous, scaly lesion (see image). Physical exam suggested enthesitis at the insertion of the Achilles tendon. Skin examination revealed plaques with a characteristic silver scaling on the elbows and knees. Laboratory tests indicated elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Notably, both the rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) tests returned negative results. Radiography of the hands showed periarticular erosions and a "pencil-in-cup" deformity at the DIP joints.

Diffuse Capillary Malformation With Undergrowth of a Limb in a Boy

To the Editor:

Capillary malformations (CMs), the most common vascular malformations that can affect the skin,1 present clinically as macules and patches of various colors, shapes, and sizes. Congenital structural abnormalities are associated with conditions such as Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS), cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC), and megalencephaly–capillary malformation syndrome.2 Diffuse CM with overgrowth (DCMO) of the soft tissue and bones is an established association of CMs; however, diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth (DCMU) is a more recent term that describes the lesser-recognized counterpart to DCMO.3 Herein, we describe a case of CM with left-sided undergrowth.

An 11-year-old boy presented to our clinic with asymptomatic vascular patterning on the left side of the body that had been present since birth. He previously was diagnosed with congenital right hemihypertrophy. He reported that the areas gradually lightened over time, and he denied any history of ulceration or venous or lymphatic malformations. Additionally, he explained how the left arm and leg have been noticeably smaller than the right extremities throughout his life. Physical examination revealed superficial, violaceous, reticulated patches along the left upper back tracking down the arm, abdomen (Figure 1A), and anterior thigh (Figure 1B) without crossing the midline. A few dilated veins were noted in the same region as the patches. There was no evidence of scarring or depression found in the skin. The right arms and legs were visibly larger compared to the left side (Figure 2A), and there also was macrodactyly of the third digit of the left hand (Figure 2B). Radiography confirmed the limb length discrepancy and showed the right and left legs to measure 73.2 cm and 71.3 cm, respectively. Given the patient’s multifocal reticulated CMs and ipsilateral undergrowth, a diagnosis of DCMU was rendered. The superficial vascular pattern is likely to fade over time, which will partially be hidden by his darker complexion. He also was advised to continue to see an orthopedist to monitor the limb length incongruity. Surgical intervention was not recommended.

It ordinarily is thought that vascular anomalies of a limb may result in hypertrophy due to increased blood flow such as in KTS, but there are occasions where the affected limb(s) are inexplicably smaller.2,4 Cubiró et al3 observed that in 6 patients with unilateral CMs, all had ipsilateral limb undergrowth. They proposed the term diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth as a distinct counterpart to DCMO. Diffuse capillary malformation with undergrowth is most similar to CMTC, as both can present with patchy or reticulated capillary staining with ipsilateral limb hypotrophy, but girth more often is affected than length; CMTC also may be associated with dermal atrophy and ulceration.2 The lesions of CMTC typically diminish within the first few years of life whereas those in DCMU tend to persist. Patients with KTS also can exhibit soft-tissue and bony undergrowth, which is termed inverse Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome3; however, the lack of the triad of capillary-lymphatic-venous malformation in our patient made this condition less likely. Additionally, it appears that our patient had left-sided undergrowth rather than the previously diagnosed right hemihypertrophy. The ipsilateral macrodactyly of the third digit of the left hand was an interesting observation and contrasted the undergrowth apparent in the rest of the left limb, which could be caused by increased blood flow specifically to the third digit resembling DCMO.4

Of note, genetic mutations have been implicated as a cause of vascular malformations and growth abnormalities. Specifically, mutations in the phosphoinositide-3-kinase–AKT pathway have been reported in these cases likely due its role in cell growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis.3,4 Future studies should investigate genetic associations in patients with DCMU to determine if there is a robust genotypic-phenotypic link.

Although CMs are a common occurrence in pediatric dermatology, CMs with concurrent limb undergrowth are rare. Our patient’s unique features included involvement of both an arm and leg as well as the presence of macrodactyly. We agree with the terminology for DCMU to describe multifocal reticulated vascular patterning with ipsilateral undergrowth.3

- Huang JT, Liang MG. Vascular malformations. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1091-1110. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2010.08.003

- Lee MS, Liang MG, Mulliken JB. Diffuse capillary malformation with overgrowth: a clinical subtype of vascular anomalies with hypertrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:589-594. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.030