User login

Data Trends 2023: PTSD and Psychedelic Treatments

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. How common is PTSD in veterans? Updated February 3, 2023. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp

16. Murphy D, Smith KV. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(5):753-763. doi:10.1002/jts.22333

17. Gray JC et al. Mil Med. 2022;usac400. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac400

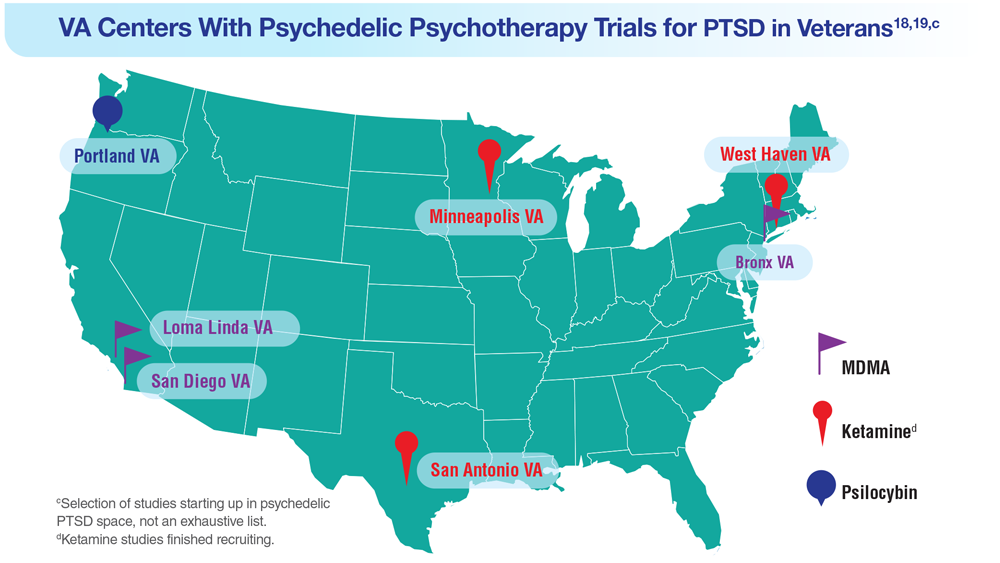

18. Herrington AJ. VA studying psychedelics as mental health treatment for veterans. Forbes. Published June 24, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ajherrington/2022/06/24/va-studying-psychedelics-as-mental-health-treatment-for-veterans/?sh=149266f6c0d4

19. Search of: Veterans: Ketamine - list results. ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=ketamine&term=veterans&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=. Accessed March 23, 2023.

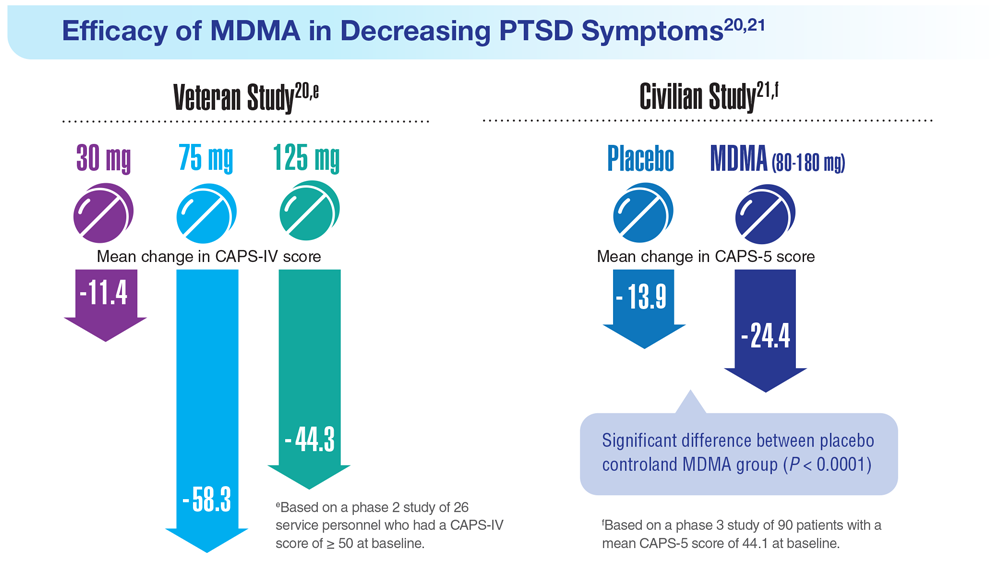

20. Mithoefer MC et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30135-4

21. Mitchell JM et al. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1025-1033. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3

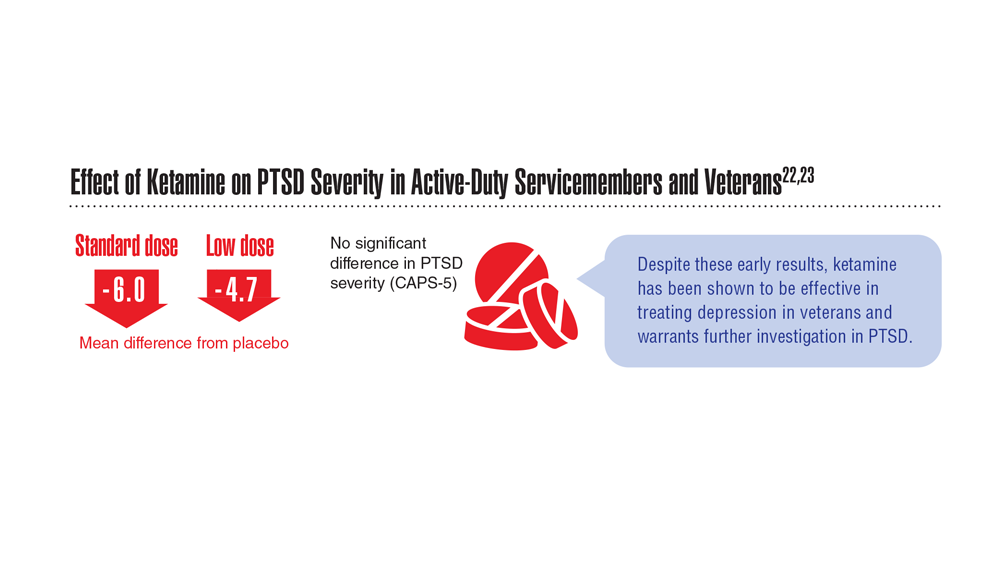

22. Abdallah CG et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(8):1574-1581. doi:10.1038/s41386-022-01266-9

23. Artin H et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;48:101439. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101439

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. How common is PTSD in veterans? Updated February 3, 2023. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp

16. Murphy D, Smith KV. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(5):753-763. doi:10.1002/jts.22333

17. Gray JC et al. Mil Med. 2022;usac400. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac400

18. Herrington AJ. VA studying psychedelics as mental health treatment for veterans. Forbes. Published June 24, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ajherrington/2022/06/24/va-studying-psychedelics-as-mental-health-treatment-for-veterans/?sh=149266f6c0d4

19. Search of: Veterans: Ketamine - list results. ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=ketamine&term=veterans&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=. Accessed March 23, 2023.

20. Mithoefer MC et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30135-4

21. Mitchell JM et al. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1025-1033. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3

22. Abdallah CG et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(8):1574-1581. doi:10.1038/s41386-022-01266-9

23. Artin H et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;48:101439. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101439

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. How common is PTSD in veterans? Updated February 3, 2023. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp

16. Murphy D, Smith KV. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(5):753-763. doi:10.1002/jts.22333

17. Gray JC et al. Mil Med. 2022;usac400. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac400

18. Herrington AJ. VA studying psychedelics as mental health treatment for veterans. Forbes. Published June 24, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ajherrington/2022/06/24/va-studying-psychedelics-as-mental-health-treatment-for-veterans/?sh=149266f6c0d4

19. Search of: Veterans: Ketamine - list results. ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=ketamine&term=veterans&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=. Accessed March 23, 2023.

20. Mithoefer MC et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486-497. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30135-4

21. Mitchell JM et al. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1025-1033. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01336-3

22. Abdallah CG et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47(8):1574-1581. doi:10.1038/s41386-022-01266-9

23. Artin H et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;48:101439. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101439

Data Trends 2023: HPV and Related Cancers

- Van Dyne EA et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):918-924. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2

- Nsouli-Maktabi H et al. MSMR. 2013;20(2):17-20. Published February 20, 2013. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23461306/

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Saxena K et al. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):299-308. doi:10.1080/13696998.2022.2041855

- Chidambaram S et al. JAMA Oncol. 2023;e227944. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

- Meites E et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698-702.

- González-Moles MÁ et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4967. doi:10.3390/cancers14194967

- Mazul AL et al. Cancer. 2022;128(18):3310-3318. doi:10.1002/cncr.34387

- Clark E et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(9):e359-e366. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1162

- Rohner E et al. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(3):601-609. doi:10.1002/ijc.32260

- Guiguet M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(12):1152-1159. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70282-7

- Abraham AG et al. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):405-413. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828177d7

- Massad LS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):606.e1-e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.003

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection – basic fact sheet. Updated April 12, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm

- US Department of Defense. 2021 Demographics: profile of the military community. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2021-demographics-report.pdf

- National Cancer Institute. HPV and cancer. Updated April 4, 2023. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causesprevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer

- de Martel C et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(4):664-670. doi:10.1002/ijc.30716

- Daly CM et al. J Community Health. 2018;43(3):441-447. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0447-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Mashberg A et al. Cancer. 1993;72(4):1369-1375. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1369::AID-CNCR2820720436>3.0.CO;2-L

- Agha Z et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Singh JA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):108-113. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53020.x

- Morgan RO et al. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 pt 2):1573-1583. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00448.x

- National Cancer Institute. Head and neck cancers. Updated May 25, 2021. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet

- Odani S et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(1):7-12. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a2

- Ames G, Cunradi C. Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28(4):252-257.

- Di Credico G et al. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(9):1456-1463. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-01031-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated cancer risks. Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/index.htm

- Sandulache VC et al. Head Neck. 2015;37(9):1246-1253. doi:10.1002/hed.23740

- Van Dyne EA et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):918-924. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2

- Nsouli-Maktabi H et al. MSMR. 2013;20(2):17-20. Published February 20, 2013. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23461306/

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Saxena K et al. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):299-308. doi:10.1080/13696998.2022.2041855

- Chidambaram S et al. JAMA Oncol. 2023;e227944. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

- Meites E et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698-702.

- González-Moles MÁ et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4967. doi:10.3390/cancers14194967

- Mazul AL et al. Cancer. 2022;128(18):3310-3318. doi:10.1002/cncr.34387

- Clark E et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(9):e359-e366. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1162

- Rohner E et al. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(3):601-609. doi:10.1002/ijc.32260

- Guiguet M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(12):1152-1159. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70282-7

- Abraham AG et al. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):405-413. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828177d7

- Massad LS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):606.e1-e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.003

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection – basic fact sheet. Updated April 12, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm

- US Department of Defense. 2021 Demographics: profile of the military community. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2021-demographics-report.pdf

- National Cancer Institute. HPV and cancer. Updated April 4, 2023. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causesprevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer

- de Martel C et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(4):664-670. doi:10.1002/ijc.30716

- Daly CM et al. J Community Health. 2018;43(3):441-447. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0447-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Mashberg A et al. Cancer. 1993;72(4):1369-1375. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1369::AID-CNCR2820720436>3.0.CO;2-L

- Agha Z et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Singh JA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):108-113. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53020.x

- Morgan RO et al. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 pt 2):1573-1583. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00448.x

- National Cancer Institute. Head and neck cancers. Updated May 25, 2021. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet

- Odani S et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(1):7-12. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a2

- Ames G, Cunradi C. Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28(4):252-257.

- Di Credico G et al. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(9):1456-1463. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-01031-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated cancer risks. Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/index.htm

- Sandulache VC et al. Head Neck. 2015;37(9):1246-1253. doi:10.1002/hed.23740

- Van Dyne EA et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):918-924. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2

- Nsouli-Maktabi H et al. MSMR. 2013;20(2):17-20. Published February 20, 2013. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23461306/

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Saxena K et al. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):299-308. doi:10.1080/13696998.2022.2041855

- Chidambaram S et al. JAMA Oncol. 2023;e227944. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7944

- Meites E et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698-702.

- González-Moles MÁ et al. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4967. doi:10.3390/cancers14194967

- Mazul AL et al. Cancer. 2022;128(18):3310-3318. doi:10.1002/cncr.34387

- Clark E et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(9):e359-e366. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1162

- Rohner E et al. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(3):601-609. doi:10.1002/ijc.32260

- Guiguet M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(12):1152-1159. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70282-7

- Abraham AG et al. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):405-413. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828177d7

- Massad LS et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):606.e1-e8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.003

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection – basic fact sheet. Updated April 12, 2022. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm

- US Department of Defense. 2021 Demographics: profile of the military community. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2021-demographics-report.pdf

- National Cancer Institute. HPV and cancer. Updated April 4, 2023. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causesprevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer

- de Martel C et al. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(4):664-670. doi:10.1002/ijc.30716

- Daly CM et al. J Community Health. 2018;43(3):441-447. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0447-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How many cancers are linked with HPV each year? Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm

- Zevallos JP et al. Head Neck. 2021;43(1):108-115. doi:10.1002/hed.26465

- Mashberg A et al. Cancer. 1993;72(4):1369-1375. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930815)72:4<1369::AID-CNCR2820720436>3.0.CO;2-L

- Agha Z et al. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252

- Singh JA et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):108-113. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53020.x

- Morgan RO et al. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 pt 2):1573-1583. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00448.x

- National Cancer Institute. Head and neck cancers. Updated May 25, 2021. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/head-neck-fact-sheet

- Odani S et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(1):7-12. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a2

- Ames G, Cunradi C. Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28(4):252-257.

- Di Credico G et al. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(9):1456-1463. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-01031-z

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated cancer risks. Updated October 3, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/index.htm

- Sandulache VC et al. Head Neck. 2015;37(9):1246-1253. doi:10.1002/hed.23740

Impact of Liraglutide to Semaglutide Conversion on Glycemic Control and Cost Savings at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Semaglutide and liraglutide are glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as subcutaneous injections for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Both are recommended by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) as first-line options for patients with concomitant atherosclerotic cardiovascular (CV) disease and exert therapeutic effect via incretin-like mechanisms.1 These agents lower blood glucose levels by stimulating insulin release, increasing the body’s sensitivity to insulin, and inhibiting inappropriate glucagon secretion.2,3 They also slow gastric emptying, resulting in decreased appetite and potential weight loss.4

The SUSTAIN (1-7) trials concluded that semaglutide presented an equivalent safety profile and greater efficacy compared with other GLP-1 RAs, including exenatide and dulaglutide.2 The SUSTAIN-10 open-label, head-to-head trial evaluating 1 mg semaglutide once weekly vs 1.2 mg liraglutide daily concluded that semaglutide was superior in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and body weight reduction compared with liraglutide, with slightly increased gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects (AEs).5 Similar to the LEADER trial assessing liraglutide, SUSTAIN-6 evaluated semaglutide in patients at increased CV risk and found that compared with placebo, semaglutide decreased rates of serious CV events, such as CV death, myocardial infarction, and stroke and were similar to the CV outcomes in the LEADER trial.2,6 Although initial results of the SUSTAIN-6 trial were thought to be nearly equivalent to the LEADER trial, analyses later published comparing both trials noted that semaglutide had more potent HbA1c lowering and weight loss benefit when compared with liraglutide.2,6 The cardioprotective outcomes of SUSTAIN-6 qualified semaglutide for inclusion in the current ADA Standards of Medical Care recommendations for CV risk reduction.6,7 However, despite the CV safety profile and efficacy associated with semaglutide, the SUSTAIN-6 trial noted an increased risk of diabetic retinopathy (DR) complications in 50 of 1648 patients (3%) treated with semaglutide compared with 29 of 1649 (1.8%) who received placebo (P = .02; hazard ratio, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.11-2.78).6 Of the 79 total patients who experienced retinopathy complications, 66 had retinopathy at baseline (42 of 50 [84%]) in the semaglutide group; 24 of 29 [83%] in the placebo group).6 Worsening of DR became one of the most notable AEs of semaglutide evaluated in clinical trials. This further deemed the effect as a warning in the semaglutide package insert to assist clinicians with treatment decisions.

As part of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Lost Opportunity Cost Savings Initiative, which encompasses administrative efforts to promote more cost-effective yet safe and efficacious therapy options for veterans, the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, converted a portion of patients with T2DM established on liraglutide to semaglutide. The 30-day supply cost of the 2-pack liraglutide 6 mg/mL (3 mL) injection pens for the MEDVAMC was $197.64. The 30-day supply cost for the singular multidose semaglutide 0.5 mg/0.375 mL (1.5 mL) injection pen was $115.15. Cost savings for the MEDVAMC facility were initially estimated to reach $642,522.

The subset of patients converted had to have undergone teleretinal imaging and not have a diagnosis of nonproliferative DR (NPDR), proliferative DR (PDR), or PDR with or without

In the fall of 2021, there was also a standing list of patients on liraglutide who were not converted due to a lack of teleretinal imaging. As a result, there was potential for a quality improvement (QI) intervention to target this patient population, which could result in further cost savings for MEDVAMC and improved glycemic control because of increased conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide. The purpose of this project was to perform a QI assessment on this subset of patients both initially converted from liraglutide to semaglutide, and those who were yet to be converted due to a lack of teleretinal imaging to determine the impact on glycemic control and cost savings.

Methods

This QI project was a single-center, prospective cohort study with a retrospective chart review of veterans with T2DM converted from liraglutide to semaglutide at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were collected from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) between March 1, 2021, and November 30, 2021. An initial subset of patients was converted to semaglutide in March and April 2021. Patients initially excluded underwent a second chart review to determine whether they truly met exclusion criteria. Patients who did not have a definitive diagnosis of NPDR or PDR, those due for updated teleretinal imaging, as well as those with updated teleretinal imaging that excluded NPDR or PDR were targeted for clinician education interventions.

Following this intervention, a subset of patients with negative DR findings were converted from liraglutide to semaglutide. Primary care and endocrinology clinicians were notified that patients who met the criteria should be referred for teleretinal imaging if no updated results were present or that patients were eligible for semaglutide conversion based on negative findings. Both patients who were initially converted as well as those converted following education were included for data collection/analysis of glycemic control via HbA1c and blood glucose levels.

Cost savings were evaluated using outpatient pharmacy procurement pricing data. This project was approved by the MEDVAMC Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs Office.

Participants

Patients included in the study were adults aged ≥ 18 years with T2DM, converted from liraglutide 0.6 and 1.2 mg daily to semaglutide 0.25 mg weekly (titrated to 0.5 mg weekly after 4 weeks), and had an active prescription for semaglutide, with or without insulin or other oral antihyperglycemics. Patients with NPDR or PDR, type 1 DM, no HbA1c data, no filled semaglutide prescriptions, insulin pumps, and those without teleretinal imaging within the postintervention period or who died during the study period were excluded.

Patient baseline characteristics collected included demographic data, CV comorbidities, antihyperglycemic medications, and changes in insulin doses. Parameters analyzed at baseline and 3 to 12 months postconversion included body weight, HbA1c, and blood glucose levels.

Outcomes

The primary objectives of this QI project were to assess glycemic control (via changes in HbA1c levels) and cost savings following patient conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide. A second objective was to educate clinicians for referral of T2DM patients without teleretinal imaging in the past 2 years.

The purpose of the latter objective was to encourage conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide in the absence of DR. We predicted that 50% of patients with clinician education would be converted. Secondary objectives included assessing body weight differences, evaluating modifications in diabetes regimen, and documenting AEs. We predicted that glycemic control would either remain stable or improve with conversion to semaglutide.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Quantitative data (HbA1c, blood glucose, and body weight differences as continuous variables) were analyzed using a paired Student t test, and categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test.

Results

During the study period, 692 patients were identified with active liraglutide prescriptions (Figure). Of these, 49 patients who were initially excluded due to outdated teleretinal imaging or negative findings met the criteria for clinician education, and 14 of those 49 patients (28.6%) were converted from liraglutide to semaglutide. Thirty-three patients (67.3%) did not schedule teleretinal imaging or did not convert to semaglutide following negative teleretinal findings. Two patients (4.1%) either scheduled or proceeded with teleretinal imaging, without any further action from the clinician.

Including the 14 patients converted posteducational intervention, 425 patients were converted to semaglutide. Excluded from analysis were 121 patients: 57 for incomplete HbA1c data or no filled semaglutide prescription; 30 for HbA1c and weight data outside of the study timeframe; 25 died of causes unrelated to the project; 8 had insulin pumps; and 1 was diagnosed with late-onset type 1 DM. The final sample was 304 patients who underwent analysis.

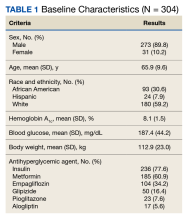

Two hundred seventy-three patients (89.8%) were male, and 180 (59.2%) were White (Table 1). The mean (SD) age of patients was 65.9 (9.6) years, and 236 (77.6%) were established on insulin therapy (either basal, bolus, or a combination). The 3 most common antihyperglycemic agents (other than insulin) that patients used included 185 metformin (60.9%), 104 empagliflozin (34.2%), and 50 glipizide (16.4%) prescriptions.

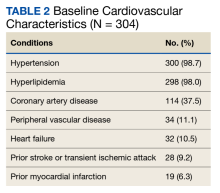

Most patients had CV disease. Three hundred patients (98.7%) had comorbid hypertension, 298 (98.0%) had hyperlipidemia, and 114 (37.5%) had coronary artery disease (Table 2). Other diseases that patients were concomitantly diagnosed with included peripheral vascular disease, heart failure, history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, and history of myocardial infarction.

Documented AEs included 83 patients (27.3%) with hypoglycemia at any point within 3 to 12 months of conversion and 25 patients (8.2%) with mainly GI-related events, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite, and abdominal pain. Six patients (2.0%) had a new diagnosis of DR 3 to 12 months postconversion.

Glycemic Control and Weight Changes

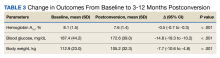

At baseline, mean (SD) HbA1c was 8.1% (1.5), blood glucose was 187.4 (44.2) mg/dL, and body weight was 112.9 (23.0) kg (Table 3). In the timeframe evaluated (3 to 12 months postconversion), patients’ mean (SD) HbA1c was found to have significantly decreased to 7.6% (1.4) (P < .001; 95% CI, -0.7 to -0.3), blood glucose decreased to 172.6 (39.0) mg/dL (P < .001; 95% CI, -19.3 to -10.2), and body weight decreased to 105.2 (32.3) kg (P < .001; 95% CI, -10.6 to -4.8). All parameters evaluated were deemed statistically significant.

Further analyses evaluating specific changes in HbA1c observed postconversion are as follows: 199 patients (65.5%) experienced a decrease, 92 (30.3%) experienced an increase, and 13 (4.3%) experienced no change in their HbA1c.

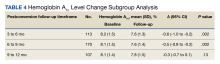

As the timeframe was fairly broad to assess HbA1c changes, a prespecified subgroup analysis was conducted to determine specific changes in HbA1c within 3 to 6, 6 to 9, and 9 to 12 months postconversion (Table 4). At 3 to 6 months postconversion, patient mean (SD) HbA1c levels significantly decreased from 8.2% (1.5) at baseline to 7.6% (1.3) postconversion (P = .002; 95% CI, -1.0 to -0.2). At 6 to 9 months postconversion, the mean (SD) HbA1c significantly decreased from 8.1% (1.5) at baseline to 7.6% (1.4) postconversion (P = .002; 95% CI, -0.8 to -0.2).

Glucose-Lowering Agent Adjustments

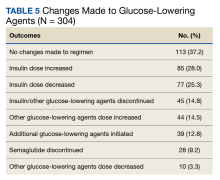

One hundred thirteen patients (37.2%) required no changes to their antihyperglycemic regimen with the conversion, 85 (28.0%) required increased insulin doses, and 77 (25.3%) required decreased insulin doses (Table 5). Forty-five (14.8%) patients underwent discontinuation of either insulin or other antihyperglycemic agents; 44 (14.5%) had other antihyperglycemic agents dose increased, 39 (12.8%) required adding other glucose-lowering agents, 28 (9.2%) discontinued semaglutide, and 10 (3.3%) had other glucose-lowering medication doses decreased.

Cost Savings

Cost savings were evaluated using the MEDVAMC outpatient pharmacy procurement service. The total cost savings per patient per month was $82.49. For the 411 preclinician education patients converted to semaglutide, this resulted in a prospective annual cost savings of $406,840.68. An additional $13,858.32 was saved due to the intervention/clinician education for 14 patients converted to semaglutide. The total annual cost savings was $420,699.00.

Discussion

Overall, glycemic control significantly improved with veterans’ conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide. Not only were significant changes noted with HbA1c levels and weight, but consistencies were noted with mean HbA1c decrease and weight loss expected of GLP-1 RAs noted in clinical trials. The typical range for HbA1c changes expected is -1% to -2% and weight loss of 1 to 6 kg.4,7 Data from the LEAD-5 and SUSTAIN-4 trials, evaluating glycemic control in liraglutide and semaglutide, respectively, have noted comparable yet slightly more potent HbA1c decreases (-1.33% for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily vs -1.2% and -1.6% for semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1 mg weekly, respectively).8,9 However, more robust weight loss has been noted with semaglutide vs liraglutide (-4.62 kg for semaglutide 0.5 mg weekly and -6.33 kg for semaglutide 1 mg weekly vs -3.43 kg for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily).8,9 Results from the SUSTAIN-10 trial also noted mean changes in HbA1c of -1.7% for semaglutide 1 mg weekly vs -1.0% for liraglutide 1.2 mg daily; mean body weight differences were -5.8 kg for semaglutide and -1.9 kg for liraglutide at their respective doses.5 The mean weight loss noted with this QI project is consistent with prior trials of semaglutide.

Of note, 44 patients (14.5%) required the dosage increase of either one or multiple additional glucose-lowering agents at any time point within the 3- to 12-month period. Of those patients, 38 (86.4%) underwent further semaglutide dose titration to 1 mg weekly. Common reasons for a further dose increase to 1 mg weekly were an indication for more robust HbA1c lowering, a desire to decrease patients’ either basal or bolus insulin requirements, or a treatment goal of completely titrating patients off insulin.

It is uncertain why 30.3% of patients experienced an increase in HbA1c and 4.3% experienced no change. However, possibilities for the divergence in HbA1c outcomes in these subsets of patients may include suboptimal adherence to semaglutide or other antihyperglycemic agents as indicated by clinicians or nonadherence to dietary and lifestyle modifications.

Most patients (65.5%) experienced a decrease in HbA1c because of conversion to semaglutide, and

At the MEDVAMC, liraglutide is a nonformulary agent and semaglutide is now the formulary-preferred option. For patients with uncontrolled T2DM, if a GLP-1 RA is desired for therapy, clinicians are to place a prior authorization drug request (PADR) consultation for semaglutide for further evaluation and review of VA Criteria for Use (CFU) by clinical pharmacist practitioners. Liraglutide is the alternative option if patients do not meet the CFU for semaglutide (ie, have a diagnosis of DR among other exclusions). However, the semaglutide CFU was updated in April 2022 to exclude those specifically diagnosed with PDR, severe NPDR, and macular edema unless an ophthalmologist deems semaglutide acceptable. This indicates that patients with mild-to-moderate NPDR (who were originally excluded from this QI project) are now eligible to receive semaglutide. The incidence of new DR diagnoses (2%) observed in this study could indicate an unclear relationship between semaglutide and increased rates of DR; however, no definitive correlation can be established due to the retrospective nature of this project. The implications of the results of this QI project in relation to the updated CFU remain undetermined.

Due to the comparable improvements in HbA1c and more robust weight loss noted with semaglutide vs liraglutide, we deem it appropriate to select semaglutide as the more cost-efficient GLP-1 RA and formulary preferred option. The data of this QI project supports the overall safety and treatment utility of this option. Although significant cost savings were achieved (> $400,000), the long-term benefit of the liraglutide to semaglutide conversion remains unknown.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this project include the large sample size, its setting in a large VA medical center, and the evaluation of multiple outcomes beyond HbA1c for assessment of glycemic control (ie, mean blood glucose, insulin titration, and dose adjustment of other glucose-lowering agents).

Limitations of this study include the retrospective chart review used for data collection, limited accuracy of objective data due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and inconsistencies with documentation in patients’ electronic health records. As a protective measure in the height of the pandemic between March 2021 and November 2021, the VA promoted using telephone and virtual-visit clinics to minimize exposure for patients with nonurgent follow-up needs. Patient hesitance to present to the clinic in person due to COVID-19 was also a significant factor in obtaining objective follow-up data. As a result, less accurate and timely baseline and postconversion weight and HbA1c data resulted, leading to our decision to extend the timeframe evaluated postconversion to 3 to 12 months. We also noted inconsistencies with documentation in CPRS. Unless veterans were closely followed by clinical pharmacist practitioners or endocrine consultation service clinicians, it was more difficult to follow and document trends of insulin titration to assess the impact of semaglutide conversion. The number of AEs, including hypoglycemia and GI intolerance, were also not consistently documented within the CPRS, and the frequency of AEs may be underestimated.

Another possible limitation regarding the interpretation of the results includes the portion of patients titrated up to semaglutide 1 mg weekly. As the focal point of this project was to review changes in glycemic control in the conversion to semaglutide 0.5 mg, this population of patients converted to 1 mg could potentially overestimate the HbA1c and weight changes described, as it is consistent with the SUSTAIN trials that show more robust decreases in those parameters described earlier.

Conclusions

A subset of patients with T2DM converted from liraglutide to semaglutide experienced significant changes in glycemic control and body weight. Significant differences were noted for a decreased HbA1c, decreased mean blood glucose, and weight loss. A fair portion of patients’ antihyperglycemic regimens required no changes on conversion to semaglutide. Although the semaglutide discontinuation rate neared 10%, AEs that may have contributed to this discontinuation rate included hypoglycemia and GI intolerance. Clinician education resulted in a substantial number of patients undergoing teleretinal imaging and further conversion to semaglutide; however, due to the low conversion response rate, a more effective method of educating clinicians is warranted. Although the semaglutide cost savings initiative at MEDVAMC resulted in significant savings, a full cost-effective analysis is needed to assess more comprehensive institution savings.

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S140-S157. doi:10.2337/dc23-S009

2. Aroda VR, Ahmann A, Cariou B, et al. Comparative efficacy, safety, and cardiovascular outcome with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: insights from the SUSTAIN 1-7 trials. Diabetes Metab. 2019;45(5):409-418. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2018.12.001

3. Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Smith BA. GLP-1 receptor agonists: an updated review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021;12:2042018821997320. Published 2021 Mar 9. doi:10.1177/2042018821997320

4. Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):740-756. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001

5. Capehorn MS, Catarig AM, Furberg JK, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide 1.0mg vs once-daily liraglutide 1.2mg as add-on to 1-3 oral antidiabetic drugs in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 10). Diabetes Metab. 2020;46(2):100-109. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2019.101117

6. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834-1844. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1607141

7. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S158-S190. doi:10.2337/dc23-S010

8. Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met+SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009;52(10):2046-2055. doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1472-y

9. Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus once-daily insulin glargine as add-on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(5):355-366. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30085-2

Semaglutide and liraglutide are glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as subcutaneous injections for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Both are recommended by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) as first-line options for patients with concomitant atherosclerotic cardiovascular (CV) disease and exert therapeutic effect via incretin-like mechanisms.1 These agents lower blood glucose levels by stimulating insulin release, increasing the body’s sensitivity to insulin, and inhibiting inappropriate glucagon secretion.2,3 They also slow gastric emptying, resulting in decreased appetite and potential weight loss.4

The SUSTAIN (1-7) trials concluded that semaglutide presented an equivalent safety profile and greater efficacy compared with other GLP-1 RAs, including exenatide and dulaglutide.2 The SUSTAIN-10 open-label, head-to-head trial evaluating 1 mg semaglutide once weekly vs 1.2 mg liraglutide daily concluded that semaglutide was superior in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and body weight reduction compared with liraglutide, with slightly increased gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects (AEs).5 Similar to the LEADER trial assessing liraglutide, SUSTAIN-6 evaluated semaglutide in patients at increased CV risk and found that compared with placebo, semaglutide decreased rates of serious CV events, such as CV death, myocardial infarction, and stroke and were similar to the CV outcomes in the LEADER trial.2,6 Although initial results of the SUSTAIN-6 trial were thought to be nearly equivalent to the LEADER trial, analyses later published comparing both trials noted that semaglutide had more potent HbA1c lowering and weight loss benefit when compared with liraglutide.2,6 The cardioprotective outcomes of SUSTAIN-6 qualified semaglutide for inclusion in the current ADA Standards of Medical Care recommendations for CV risk reduction.6,7 However, despite the CV safety profile and efficacy associated with semaglutide, the SUSTAIN-6 trial noted an increased risk of diabetic retinopathy (DR) complications in 50 of 1648 patients (3%) treated with semaglutide compared with 29 of 1649 (1.8%) who received placebo (P = .02; hazard ratio, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.11-2.78).6 Of the 79 total patients who experienced retinopathy complications, 66 had retinopathy at baseline (42 of 50 [84%]) in the semaglutide group; 24 of 29 [83%] in the placebo group).6 Worsening of DR became one of the most notable AEs of semaglutide evaluated in clinical trials. This further deemed the effect as a warning in the semaglutide package insert to assist clinicians with treatment decisions.

As part of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Lost Opportunity Cost Savings Initiative, which encompasses administrative efforts to promote more cost-effective yet safe and efficacious therapy options for veterans, the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, converted a portion of patients with T2DM established on liraglutide to semaglutide. The 30-day supply cost of the 2-pack liraglutide 6 mg/mL (3 mL) injection pens for the MEDVAMC was $197.64. The 30-day supply cost for the singular multidose semaglutide 0.5 mg/0.375 mL (1.5 mL) injection pen was $115.15. Cost savings for the MEDVAMC facility were initially estimated to reach $642,522.

The subset of patients converted had to have undergone teleretinal imaging and not have a diagnosis of nonproliferative DR (NPDR), proliferative DR (PDR), or PDR with or without

In the fall of 2021, there was also a standing list of patients on liraglutide who were not converted due to a lack of teleretinal imaging. As a result, there was potential for a quality improvement (QI) intervention to target this patient population, which could result in further cost savings for MEDVAMC and improved glycemic control because of increased conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide. The purpose of this project was to perform a QI assessment on this subset of patients both initially converted from liraglutide to semaglutide, and those who were yet to be converted due to a lack of teleretinal imaging to determine the impact on glycemic control and cost savings.

Methods

This QI project was a single-center, prospective cohort study with a retrospective chart review of veterans with T2DM converted from liraglutide to semaglutide at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were collected from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) between March 1, 2021, and November 30, 2021. An initial subset of patients was converted to semaglutide in March and April 2021. Patients initially excluded underwent a second chart review to determine whether they truly met exclusion criteria. Patients who did not have a definitive diagnosis of NPDR or PDR, those due for updated teleretinal imaging, as well as those with updated teleretinal imaging that excluded NPDR or PDR were targeted for clinician education interventions.

Following this intervention, a subset of patients with negative DR findings were converted from liraglutide to semaglutide. Primary care and endocrinology clinicians were notified that patients who met the criteria should be referred for teleretinal imaging if no updated results were present or that patients were eligible for semaglutide conversion based on negative findings. Both patients who were initially converted as well as those converted following education were included for data collection/analysis of glycemic control via HbA1c and blood glucose levels.

Cost savings were evaluated using outpatient pharmacy procurement pricing data. This project was approved by the MEDVAMC Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs Office.

Participants

Patients included in the study were adults aged ≥ 18 years with T2DM, converted from liraglutide 0.6 and 1.2 mg daily to semaglutide 0.25 mg weekly (titrated to 0.5 mg weekly after 4 weeks), and had an active prescription for semaglutide, with or without insulin or other oral antihyperglycemics. Patients with NPDR or PDR, type 1 DM, no HbA1c data, no filled semaglutide prescriptions, insulin pumps, and those without teleretinal imaging within the postintervention period or who died during the study period were excluded.

Patient baseline characteristics collected included demographic data, CV comorbidities, antihyperglycemic medications, and changes in insulin doses. Parameters analyzed at baseline and 3 to 12 months postconversion included body weight, HbA1c, and blood glucose levels.

Outcomes

The primary objectives of this QI project were to assess glycemic control (via changes in HbA1c levels) and cost savings following patient conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide. A second objective was to educate clinicians for referral of T2DM patients without teleretinal imaging in the past 2 years.

The purpose of the latter objective was to encourage conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide in the absence of DR. We predicted that 50% of patients with clinician education would be converted. Secondary objectives included assessing body weight differences, evaluating modifications in diabetes regimen, and documenting AEs. We predicted that glycemic control would either remain stable or improve with conversion to semaglutide.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Quantitative data (HbA1c, blood glucose, and body weight differences as continuous variables) were analyzed using a paired Student t test, and categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test.

Results

During the study period, 692 patients were identified with active liraglutide prescriptions (Figure). Of these, 49 patients who were initially excluded due to outdated teleretinal imaging or negative findings met the criteria for clinician education, and 14 of those 49 patients (28.6%) were converted from liraglutide to semaglutide. Thirty-three patients (67.3%) did not schedule teleretinal imaging or did not convert to semaglutide following negative teleretinal findings. Two patients (4.1%) either scheduled or proceeded with teleretinal imaging, without any further action from the clinician.

Including the 14 patients converted posteducational intervention, 425 patients were converted to semaglutide. Excluded from analysis were 121 patients: 57 for incomplete HbA1c data or no filled semaglutide prescription; 30 for HbA1c and weight data outside of the study timeframe; 25 died of causes unrelated to the project; 8 had insulin pumps; and 1 was diagnosed with late-onset type 1 DM. The final sample was 304 patients who underwent analysis.

Two hundred seventy-three patients (89.8%) were male, and 180 (59.2%) were White (Table 1). The mean (SD) age of patients was 65.9 (9.6) years, and 236 (77.6%) were established on insulin therapy (either basal, bolus, or a combination). The 3 most common antihyperglycemic agents (other than insulin) that patients used included 185 metformin (60.9%), 104 empagliflozin (34.2%), and 50 glipizide (16.4%) prescriptions.

Most patients had CV disease. Three hundred patients (98.7%) had comorbid hypertension, 298 (98.0%) had hyperlipidemia, and 114 (37.5%) had coronary artery disease (Table 2). Other diseases that patients were concomitantly diagnosed with included peripheral vascular disease, heart failure, history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, and history of myocardial infarction.

Documented AEs included 83 patients (27.3%) with hypoglycemia at any point within 3 to 12 months of conversion and 25 patients (8.2%) with mainly GI-related events, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite, and abdominal pain. Six patients (2.0%) had a new diagnosis of DR 3 to 12 months postconversion.

Glycemic Control and Weight Changes

At baseline, mean (SD) HbA1c was 8.1% (1.5), blood glucose was 187.4 (44.2) mg/dL, and body weight was 112.9 (23.0) kg (Table 3). In the timeframe evaluated (3 to 12 months postconversion), patients’ mean (SD) HbA1c was found to have significantly decreased to 7.6% (1.4) (P < .001; 95% CI, -0.7 to -0.3), blood glucose decreased to 172.6 (39.0) mg/dL (P < .001; 95% CI, -19.3 to -10.2), and body weight decreased to 105.2 (32.3) kg (P < .001; 95% CI, -10.6 to -4.8). All parameters evaluated were deemed statistically significant.

Further analyses evaluating specific changes in HbA1c observed postconversion are as follows: 199 patients (65.5%) experienced a decrease, 92 (30.3%) experienced an increase, and 13 (4.3%) experienced no change in their HbA1c.

As the timeframe was fairly broad to assess HbA1c changes, a prespecified subgroup analysis was conducted to determine specific changes in HbA1c within 3 to 6, 6 to 9, and 9 to 12 months postconversion (Table 4). At 3 to 6 months postconversion, patient mean (SD) HbA1c levels significantly decreased from 8.2% (1.5) at baseline to 7.6% (1.3) postconversion (P = .002; 95% CI, -1.0 to -0.2). At 6 to 9 months postconversion, the mean (SD) HbA1c significantly decreased from 8.1% (1.5) at baseline to 7.6% (1.4) postconversion (P = .002; 95% CI, -0.8 to -0.2).

Glucose-Lowering Agent Adjustments

One hundred thirteen patients (37.2%) required no changes to their antihyperglycemic regimen with the conversion, 85 (28.0%) required increased insulin doses, and 77 (25.3%) required decreased insulin doses (Table 5). Forty-five (14.8%) patients underwent discontinuation of either insulin or other antihyperglycemic agents; 44 (14.5%) had other antihyperglycemic agents dose increased, 39 (12.8%) required adding other glucose-lowering agents, 28 (9.2%) discontinued semaglutide, and 10 (3.3%) had other glucose-lowering medication doses decreased.

Cost Savings

Cost savings were evaluated using the MEDVAMC outpatient pharmacy procurement service. The total cost savings per patient per month was $82.49. For the 411 preclinician education patients converted to semaglutide, this resulted in a prospective annual cost savings of $406,840.68. An additional $13,858.32 was saved due to the intervention/clinician education for 14 patients converted to semaglutide. The total annual cost savings was $420,699.00.

Discussion

Overall, glycemic control significantly improved with veterans’ conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide. Not only were significant changes noted with HbA1c levels and weight, but consistencies were noted with mean HbA1c decrease and weight loss expected of GLP-1 RAs noted in clinical trials. The typical range for HbA1c changes expected is -1% to -2% and weight loss of 1 to 6 kg.4,7 Data from the LEAD-5 and SUSTAIN-4 trials, evaluating glycemic control in liraglutide and semaglutide, respectively, have noted comparable yet slightly more potent HbA1c decreases (-1.33% for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily vs -1.2% and -1.6% for semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1 mg weekly, respectively).8,9 However, more robust weight loss has been noted with semaglutide vs liraglutide (-4.62 kg for semaglutide 0.5 mg weekly and -6.33 kg for semaglutide 1 mg weekly vs -3.43 kg for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily).8,9 Results from the SUSTAIN-10 trial also noted mean changes in HbA1c of -1.7% for semaglutide 1 mg weekly vs -1.0% for liraglutide 1.2 mg daily; mean body weight differences were -5.8 kg for semaglutide and -1.9 kg for liraglutide at their respective doses.5 The mean weight loss noted with this QI project is consistent with prior trials of semaglutide.

Of note, 44 patients (14.5%) required the dosage increase of either one or multiple additional glucose-lowering agents at any time point within the 3- to 12-month period. Of those patients, 38 (86.4%) underwent further semaglutide dose titration to 1 mg weekly. Common reasons for a further dose increase to 1 mg weekly were an indication for more robust HbA1c lowering, a desire to decrease patients’ either basal or bolus insulin requirements, or a treatment goal of completely titrating patients off insulin.

It is uncertain why 30.3% of patients experienced an increase in HbA1c and 4.3% experienced no change. However, possibilities for the divergence in HbA1c outcomes in these subsets of patients may include suboptimal adherence to semaglutide or other antihyperglycemic agents as indicated by clinicians or nonadherence to dietary and lifestyle modifications.

Most patients (65.5%) experienced a decrease in HbA1c because of conversion to semaglutide, and

At the MEDVAMC, liraglutide is a nonformulary agent and semaglutide is now the formulary-preferred option. For patients with uncontrolled T2DM, if a GLP-1 RA is desired for therapy, clinicians are to place a prior authorization drug request (PADR) consultation for semaglutide for further evaluation and review of VA Criteria for Use (CFU) by clinical pharmacist practitioners. Liraglutide is the alternative option if patients do not meet the CFU for semaglutide (ie, have a diagnosis of DR among other exclusions). However, the semaglutide CFU was updated in April 2022 to exclude those specifically diagnosed with PDR, severe NPDR, and macular edema unless an ophthalmologist deems semaglutide acceptable. This indicates that patients with mild-to-moderate NPDR (who were originally excluded from this QI project) are now eligible to receive semaglutide. The incidence of new DR diagnoses (2%) observed in this study could indicate an unclear relationship between semaglutide and increased rates of DR; however, no definitive correlation can be established due to the retrospective nature of this project. The implications of the results of this QI project in relation to the updated CFU remain undetermined.

Due to the comparable improvements in HbA1c and more robust weight loss noted with semaglutide vs liraglutide, we deem it appropriate to select semaglutide as the more cost-efficient GLP-1 RA and formulary preferred option. The data of this QI project supports the overall safety and treatment utility of this option. Although significant cost savings were achieved (> $400,000), the long-term benefit of the liraglutide to semaglutide conversion remains unknown.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this project include the large sample size, its setting in a large VA medical center, and the evaluation of multiple outcomes beyond HbA1c for assessment of glycemic control (ie, mean blood glucose, insulin titration, and dose adjustment of other glucose-lowering agents).

Limitations of this study include the retrospective chart review used for data collection, limited accuracy of objective data due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and inconsistencies with documentation in patients’ electronic health records. As a protective measure in the height of the pandemic between March 2021 and November 2021, the VA promoted using telephone and virtual-visit clinics to minimize exposure for patients with nonurgent follow-up needs. Patient hesitance to present to the clinic in person due to COVID-19 was also a significant factor in obtaining objective follow-up data. As a result, less accurate and timely baseline and postconversion weight and HbA1c data resulted, leading to our decision to extend the timeframe evaluated postconversion to 3 to 12 months. We also noted inconsistencies with documentation in CPRS. Unless veterans were closely followed by clinical pharmacist practitioners or endocrine consultation service clinicians, it was more difficult to follow and document trends of insulin titration to assess the impact of semaglutide conversion. The number of AEs, including hypoglycemia and GI intolerance, were also not consistently documented within the CPRS, and the frequency of AEs may be underestimated.

Another possible limitation regarding the interpretation of the results includes the portion of patients titrated up to semaglutide 1 mg weekly. As the focal point of this project was to review changes in glycemic control in the conversion to semaglutide 0.5 mg, this population of patients converted to 1 mg could potentially overestimate the HbA1c and weight changes described, as it is consistent with the SUSTAIN trials that show more robust decreases in those parameters described earlier.

Conclusions

A subset of patients with T2DM converted from liraglutide to semaglutide experienced significant changes in glycemic control and body weight. Significant differences were noted for a decreased HbA1c, decreased mean blood glucose, and weight loss. A fair portion of patients’ antihyperglycemic regimens required no changes on conversion to semaglutide. Although the semaglutide discontinuation rate neared 10%, AEs that may have contributed to this discontinuation rate included hypoglycemia and GI intolerance. Clinician education resulted in a substantial number of patients undergoing teleretinal imaging and further conversion to semaglutide; however, due to the low conversion response rate, a more effective method of educating clinicians is warranted. Although the semaglutide cost savings initiative at MEDVAMC resulted in significant savings, a full cost-effective analysis is needed to assess more comprehensive institution savings.

Semaglutide and liraglutide are glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as subcutaneous injections for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Both are recommended by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) as first-line options for patients with concomitant atherosclerotic cardiovascular (CV) disease and exert therapeutic effect via incretin-like mechanisms.1 These agents lower blood glucose levels by stimulating insulin release, increasing the body’s sensitivity to insulin, and inhibiting inappropriate glucagon secretion.2,3 They also slow gastric emptying, resulting in decreased appetite and potential weight loss.4

The SUSTAIN (1-7) trials concluded that semaglutide presented an equivalent safety profile and greater efficacy compared with other GLP-1 RAs, including exenatide and dulaglutide.2 The SUSTAIN-10 open-label, head-to-head trial evaluating 1 mg semaglutide once weekly vs 1.2 mg liraglutide daily concluded that semaglutide was superior in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and body weight reduction compared with liraglutide, with slightly increased gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects (AEs).5 Similar to the LEADER trial assessing liraglutide, SUSTAIN-6 evaluated semaglutide in patients at increased CV risk and found that compared with placebo, semaglutide decreased rates of serious CV events, such as CV death, myocardial infarction, and stroke and were similar to the CV outcomes in the LEADER trial.2,6 Although initial results of the SUSTAIN-6 trial were thought to be nearly equivalent to the LEADER trial, analyses later published comparing both trials noted that semaglutide had more potent HbA1c lowering and weight loss benefit when compared with liraglutide.2,6 The cardioprotective outcomes of SUSTAIN-6 qualified semaglutide for inclusion in the current ADA Standards of Medical Care recommendations for CV risk reduction.6,7 However, despite the CV safety profile and efficacy associated with semaglutide, the SUSTAIN-6 trial noted an increased risk of diabetic retinopathy (DR) complications in 50 of 1648 patients (3%) treated with semaglutide compared with 29 of 1649 (1.8%) who received placebo (P = .02; hazard ratio, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.11-2.78).6 Of the 79 total patients who experienced retinopathy complications, 66 had retinopathy at baseline (42 of 50 [84%]) in the semaglutide group; 24 of 29 [83%] in the placebo group).6 Worsening of DR became one of the most notable AEs of semaglutide evaluated in clinical trials. This further deemed the effect as a warning in the semaglutide package insert to assist clinicians with treatment decisions.

As part of a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Lost Opportunity Cost Savings Initiative, which encompasses administrative efforts to promote more cost-effective yet safe and efficacious therapy options for veterans, the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, converted a portion of patients with T2DM established on liraglutide to semaglutide. The 30-day supply cost of the 2-pack liraglutide 6 mg/mL (3 mL) injection pens for the MEDVAMC was $197.64. The 30-day supply cost for the singular multidose semaglutide 0.5 mg/0.375 mL (1.5 mL) injection pen was $115.15. Cost savings for the MEDVAMC facility were initially estimated to reach $642,522.

The subset of patients converted had to have undergone teleretinal imaging and not have a diagnosis of nonproliferative DR (NPDR), proliferative DR (PDR), or PDR with or without

In the fall of 2021, there was also a standing list of patients on liraglutide who were not converted due to a lack of teleretinal imaging. As a result, there was potential for a quality improvement (QI) intervention to target this patient population, which could result in further cost savings for MEDVAMC and improved glycemic control because of increased conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide. The purpose of this project was to perform a QI assessment on this subset of patients both initially converted from liraglutide to semaglutide, and those who were yet to be converted due to a lack of teleretinal imaging to determine the impact on glycemic control and cost savings.

Methods

This QI project was a single-center, prospective cohort study with a retrospective chart review of veterans with T2DM converted from liraglutide to semaglutide at the MEDVAMC. Patient data were collected from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) between March 1, 2021, and November 30, 2021. An initial subset of patients was converted to semaglutide in March and April 2021. Patients initially excluded underwent a second chart review to determine whether they truly met exclusion criteria. Patients who did not have a definitive diagnosis of NPDR or PDR, those due for updated teleretinal imaging, as well as those with updated teleretinal imaging that excluded NPDR or PDR were targeted for clinician education interventions.

Following this intervention, a subset of patients with negative DR findings were converted from liraglutide to semaglutide. Primary care and endocrinology clinicians were notified that patients who met the criteria should be referred for teleretinal imaging if no updated results were present or that patients were eligible for semaglutide conversion based on negative findings. Both patients who were initially converted as well as those converted following education were included for data collection/analysis of glycemic control via HbA1c and blood glucose levels.

Cost savings were evaluated using outpatient pharmacy procurement pricing data. This project was approved by the MEDVAMC Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs Office.

Participants

Patients included in the study were adults aged ≥ 18 years with T2DM, converted from liraglutide 0.6 and 1.2 mg daily to semaglutide 0.25 mg weekly (titrated to 0.5 mg weekly after 4 weeks), and had an active prescription for semaglutide, with or without insulin or other oral antihyperglycemics. Patients with NPDR or PDR, type 1 DM, no HbA1c data, no filled semaglutide prescriptions, insulin pumps, and those without teleretinal imaging within the postintervention period or who died during the study period were excluded.

Patient baseline characteristics collected included demographic data, CV comorbidities, antihyperglycemic medications, and changes in insulin doses. Parameters analyzed at baseline and 3 to 12 months postconversion included body weight, HbA1c, and blood glucose levels.

Outcomes

The primary objectives of this QI project were to assess glycemic control (via changes in HbA1c levels) and cost savings following patient conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide. A second objective was to educate clinicians for referral of T2DM patients without teleretinal imaging in the past 2 years.

The purpose of the latter objective was to encourage conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide in the absence of DR. We predicted that 50% of patients with clinician education would be converted. Secondary objectives included assessing body weight differences, evaluating modifications in diabetes regimen, and documenting AEs. We predicted that glycemic control would either remain stable or improve with conversion to semaglutide.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Quantitative data (HbA1c, blood glucose, and body weight differences as continuous variables) were analyzed using a paired Student t test, and categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test.

Results

During the study period, 692 patients were identified with active liraglutide prescriptions (Figure). Of these, 49 patients who were initially excluded due to outdated teleretinal imaging or negative findings met the criteria for clinician education, and 14 of those 49 patients (28.6%) were converted from liraglutide to semaglutide. Thirty-three patients (67.3%) did not schedule teleretinal imaging or did not convert to semaglutide following negative teleretinal findings. Two patients (4.1%) either scheduled or proceeded with teleretinal imaging, without any further action from the clinician.

Including the 14 patients converted posteducational intervention, 425 patients were converted to semaglutide. Excluded from analysis were 121 patients: 57 for incomplete HbA1c data or no filled semaglutide prescription; 30 for HbA1c and weight data outside of the study timeframe; 25 died of causes unrelated to the project; 8 had insulin pumps; and 1 was diagnosed with late-onset type 1 DM. The final sample was 304 patients who underwent analysis.

Two hundred seventy-three patients (89.8%) were male, and 180 (59.2%) were White (Table 1). The mean (SD) age of patients was 65.9 (9.6) years, and 236 (77.6%) were established on insulin therapy (either basal, bolus, or a combination). The 3 most common antihyperglycemic agents (other than insulin) that patients used included 185 metformin (60.9%), 104 empagliflozin (34.2%), and 50 glipizide (16.4%) prescriptions.

Most patients had CV disease. Three hundred patients (98.7%) had comorbid hypertension, 298 (98.0%) had hyperlipidemia, and 114 (37.5%) had coronary artery disease (Table 2). Other diseases that patients were concomitantly diagnosed with included peripheral vascular disease, heart failure, history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, and history of myocardial infarction.

Documented AEs included 83 patients (27.3%) with hypoglycemia at any point within 3 to 12 months of conversion and 25 patients (8.2%) with mainly GI-related events, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, decreased appetite, and abdominal pain. Six patients (2.0%) had a new diagnosis of DR 3 to 12 months postconversion.

Glycemic Control and Weight Changes

At baseline, mean (SD) HbA1c was 8.1% (1.5), blood glucose was 187.4 (44.2) mg/dL, and body weight was 112.9 (23.0) kg (Table 3). In the timeframe evaluated (3 to 12 months postconversion), patients’ mean (SD) HbA1c was found to have significantly decreased to 7.6% (1.4) (P < .001; 95% CI, -0.7 to -0.3), blood glucose decreased to 172.6 (39.0) mg/dL (P < .001; 95% CI, -19.3 to -10.2), and body weight decreased to 105.2 (32.3) kg (P < .001; 95% CI, -10.6 to -4.8). All parameters evaluated were deemed statistically significant.

Further analyses evaluating specific changes in HbA1c observed postconversion are as follows: 199 patients (65.5%) experienced a decrease, 92 (30.3%) experienced an increase, and 13 (4.3%) experienced no change in their HbA1c.

As the timeframe was fairly broad to assess HbA1c changes, a prespecified subgroup analysis was conducted to determine specific changes in HbA1c within 3 to 6, 6 to 9, and 9 to 12 months postconversion (Table 4). At 3 to 6 months postconversion, patient mean (SD) HbA1c levels significantly decreased from 8.2% (1.5) at baseline to 7.6% (1.3) postconversion (P = .002; 95% CI, -1.0 to -0.2). At 6 to 9 months postconversion, the mean (SD) HbA1c significantly decreased from 8.1% (1.5) at baseline to 7.6% (1.4) postconversion (P = .002; 95% CI, -0.8 to -0.2).

Glucose-Lowering Agent Adjustments

One hundred thirteen patients (37.2%) required no changes to their antihyperglycemic regimen with the conversion, 85 (28.0%) required increased insulin doses, and 77 (25.3%) required decreased insulin doses (Table 5). Forty-five (14.8%) patients underwent discontinuation of either insulin or other antihyperglycemic agents; 44 (14.5%) had other antihyperglycemic agents dose increased, 39 (12.8%) required adding other glucose-lowering agents, 28 (9.2%) discontinued semaglutide, and 10 (3.3%) had other glucose-lowering medication doses decreased.

Cost Savings

Cost savings were evaluated using the MEDVAMC outpatient pharmacy procurement service. The total cost savings per patient per month was $82.49. For the 411 preclinician education patients converted to semaglutide, this resulted in a prospective annual cost savings of $406,840.68. An additional $13,858.32 was saved due to the intervention/clinician education for 14 patients converted to semaglutide. The total annual cost savings was $420,699.00.

Discussion

Overall, glycemic control significantly improved with veterans’ conversion from liraglutide to semaglutide. Not only were significant changes noted with HbA1c levels and weight, but consistencies were noted with mean HbA1c decrease and weight loss expected of GLP-1 RAs noted in clinical trials. The typical range for HbA1c changes expected is -1% to -2% and weight loss of 1 to 6 kg.4,7 Data from the LEAD-5 and SUSTAIN-4 trials, evaluating glycemic control in liraglutide and semaglutide, respectively, have noted comparable yet slightly more potent HbA1c decreases (-1.33% for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily vs -1.2% and -1.6% for semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1 mg weekly, respectively).8,9 However, more robust weight loss has been noted with semaglutide vs liraglutide (-4.62 kg for semaglutide 0.5 mg weekly and -6.33 kg for semaglutide 1 mg weekly vs -3.43 kg for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily).8,9 Results from the SUSTAIN-10 trial also noted mean changes in HbA1c of -1.7% for semaglutide 1 mg weekly vs -1.0% for liraglutide 1.2 mg daily; mean body weight differences were -5.8 kg for semaglutide and -1.9 kg for liraglutide at their respective doses.5 The mean weight loss noted with this QI project is consistent with prior trials of semaglutide.

Of note, 44 patients (14.5%) required the dosage increase of either one or multiple additional glucose-lowering agents at any time point within the 3- to 12-month period. Of those patients, 38 (86.4%) underwent further semaglutide dose titration to 1 mg weekly. Common reasons for a further dose increase to 1 mg weekly were an indication for more robust HbA1c lowering, a desire to decrease patients’ either basal or bolus insulin requirements, or a treatment goal of completely titrating patients off insulin.

It is uncertain why 30.3% of patients experienced an increase in HbA1c and 4.3% experienced no change. However, possibilities for the divergence in HbA1c outcomes in these subsets of patients may include suboptimal adherence to semaglutide or other antihyperglycemic agents as indicated by clinicians or nonadherence to dietary and lifestyle modifications.

Most patients (65.5%) experienced a decrease in HbA1c because of conversion to semaglutide, and

At the MEDVAMC, liraglutide is a nonformulary agent and semaglutide is now the formulary-preferred option. For patients with uncontrolled T2DM, if a GLP-1 RA is desired for therapy, clinicians are to place a prior authorization drug request (PADR) consultation for semaglutide for further evaluation and review of VA Criteria for Use (CFU) by clinical pharmacist practitioners. Liraglutide is the alternative option if patients do not meet the CFU for semaglutide (ie, have a diagnosis of DR among other exclusions). However, the semaglutide CFU was updated in April 2022 to exclude those specifically diagnosed with PDR, severe NPDR, and macular edema unless an ophthalmologist deems semaglutide acceptable. This indicates that patients with mild-to-moderate NPDR (who were originally excluded from this QI project) are now eligible to receive semaglutide. The incidence of new DR diagnoses (2%) observed in this study could indicate an unclear relationship between semaglutide and increased rates of DR; however, no definitive correlation can be established due to the retrospective nature of this project. The implications of the results of this QI project in relation to the updated CFU remain undetermined.

Due to the comparable improvements in HbA1c and more robust weight loss noted with semaglutide vs liraglutide, we deem it appropriate to select semaglutide as the more cost-efficient GLP-1 RA and formulary preferred option. The data of this QI project supports the overall safety and treatment utility of this option. Although significant cost savings were achieved (> $400,000), the long-term benefit of the liraglutide to semaglutide conversion remains unknown.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this project include the large sample size, its setting in a large VA medical center, and the evaluation of multiple outcomes beyond HbA1c for assessment of glycemic control (ie, mean blood glucose, insulin titration, and dose adjustment of other glucose-lowering agents).

Limitations of this study include the retrospective chart review used for data collection, limited accuracy of objective data due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and inconsistencies with documentation in patients’ electronic health records. As a protective measure in the height of the pandemic between March 2021 and November 2021, the VA promoted using telephone and virtual-visit clinics to minimize exposure for patients with nonurgent follow-up needs. Patient hesitance to present to the clinic in person due to COVID-19 was also a significant factor in obtaining objective follow-up data. As a result, less accurate and timely baseline and postconversion weight and HbA1c data resulted, leading to our decision to extend the timeframe evaluated postconversion to 3 to 12 months. We also noted inconsistencies with documentation in CPRS. Unless veterans were closely followed by clinical pharmacist practitioners or endocrine consultation service clinicians, it was more difficult to follow and document trends of insulin titration to assess the impact of semaglutide conversion. The number of AEs, including hypoglycemia and GI intolerance, were also not consistently documented within the CPRS, and the frequency of AEs may be underestimated.

Another possible limitation regarding the interpretation of the results includes the portion of patients titrated up to semaglutide 1 mg weekly. As the focal point of this project was to review changes in glycemic control in the conversion to semaglutide 0.5 mg, this population of patients converted to 1 mg could potentially overestimate the HbA1c and weight changes described, as it is consistent with the SUSTAIN trials that show more robust decreases in those parameters described earlier.

Conclusions

A subset of patients with T2DM converted from liraglutide to semaglutide experienced significant changes in glycemic control and body weight. Significant differences were noted for a decreased HbA1c, decreased mean blood glucose, and weight loss. A fair portion of patients’ antihyperglycemic regimens required no changes on conversion to semaglutide. Although the semaglutide discontinuation rate neared 10%, AEs that may have contributed to this discontinuation rate included hypoglycemia and GI intolerance. Clinician education resulted in a substantial number of patients undergoing teleretinal imaging and further conversion to semaglutide; however, due to the low conversion response rate, a more effective method of educating clinicians is warranted. Although the semaglutide cost savings initiative at MEDVAMC resulted in significant savings, a full cost-effective analysis is needed to assess more comprehensive institution savings.

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S140-S157. doi:10.2337/dc23-S009

2. Aroda VR, Ahmann A, Cariou B, et al. Comparative efficacy, safety, and cardiovascular outcome with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: insights from the SUSTAIN 1-7 trials. Diabetes Metab. 2019;45(5):409-418. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2018.12.001

3. Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Smith BA. GLP-1 receptor agonists: an updated review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021;12:2042018821997320. Published 2021 Mar 9. doi:10.1177/2042018821997320

4. Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):740-756. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001

5. Capehorn MS, Catarig AM, Furberg JK, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide 1.0mg vs once-daily liraglutide 1.2mg as add-on to 1-3 oral antidiabetic drugs in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 10). Diabetes Metab. 2020;46(2):100-109. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2019.101117

6. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834-1844. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1607141

7. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S158-S190. doi:10.2337/dc23-S010

8. Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met+SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009;52(10):2046-2055. doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1472-y

9. Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus once-daily insulin glargine as add-on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(5):355-366. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30085-2

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S140-S157. doi:10.2337/dc23-S009

2. Aroda VR, Ahmann A, Cariou B, et al. Comparative efficacy, safety, and cardiovascular outcome with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: insights from the SUSTAIN 1-7 trials. Diabetes Metab. 2019;45(5):409-418. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2018.12.001

3. Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Smith BA. GLP-1 receptor agonists: an updated review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021;12:2042018821997320. Published 2021 Mar 9. doi:10.1177/2042018821997320

4. Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):740-756. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001

5. Capehorn MS, Catarig AM, Furberg JK, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide 1.0mg vs once-daily liraglutide 1.2mg as add-on to 1-3 oral antidiabetic drugs in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 10). Diabetes Metab. 2020;46(2):100-109. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2019.101117

6. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834-1844. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1607141

7. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S158-S190. doi:10.2337/dc23-S010

8. Russell-Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD-5 met+SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009;52(10):2046-2055. doi:10.1007/s00125-009-1472-y

9. Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus once-daily insulin glargine as add-on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(5):355-366. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30085-2

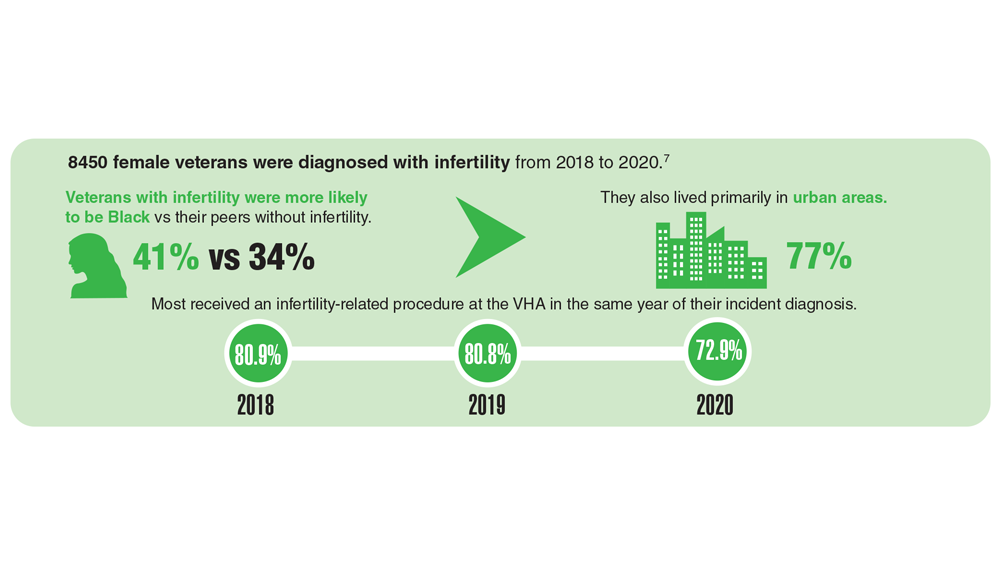

Data Trends 2023: Infertility

- US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics: women veterans in focus. Updated January 31, 2023. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/materials-and-resources/facts-and-statistics.asp

- US Department of Defense. Department of Defense Releases Annual Demographics Report — Upward Trend in Number of Women Serving Continues. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3246268/department-of-defense-releases-annual-demographics-report-upwardtrend-in-numbe/

- Meadows SO, Collins RL, Schuler MS, Beckman RL, Cefalu M. The Women’s Reproductive Health Survey (WRHS) of active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. Published 2022. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1031-1.html

- Congressional Research Service Report. Infertility in the military. Updated May 26, 2021. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11504