User login

Finding Spot-on Treatment for Acne

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

An 18-year-old woman is brought in by her mother for evaluation of longstanding acne. Although she is otherwise healthy, the patient has a significant family history of acne and recounts an extensive personal history of treatment attempts with both OTC and prescription products. Among these are several different benzoyl peroxide–based formulations (including one she bought after seeing an ad on TV) and devices including an electric scrub brush. None has had a significant impact. Tretinoin gel and oral erythromycin—prescribed by the patient’s primary care provider—haven’t helped much, either. The patient’s periods are regular and normal. She claims to be sexually abstinent. Examination reveals moderately severe acne confined to the patient’s face. Numerous open and closed comedones can be seen, as well as several pus-filled pimples. Scarring is minimal but present, especially on the sides of the face.

Subcutaneous Tortuous Nodules on the Posterior Lower Extremity

The Diagnosis: Plexiform Neurofibroma as a Manifestation of Neurofibromatosis Type I

Physical examination revealed a large 10×8-cm subcutaneous nodule that was boggy and resembled a bag of worms on palpation. It was covered by slightly hyperpigmented skin. He also had numerous (>20) café au lait spots measuring 2 to 3 cm across the body and several others on the axillae. There were no gross eye findings. Otherwise the examination was unremarkable on the rest of the body. The patient’s paternal grandfather and aunt had similar macules and multiple nodules. The patient had mild to moderate learning difficulties. He was subsequently referred for genetic and ophthalmology evaluation.

Plexiform neurofibromas are usually benign nerve sheath tumors that are elongated and are multinodular, forming when the tumor involves either multiple trunks of a plexus or multiple fascicles of a large nerve such as the sciatic. Some plexiform neurofibromas resemble a bag of worms; others produce a massive ropy enlargement of the nerve.1,2 Plexiform neurofibromas are associated with cases of neurofibromatosis type I (NFI) and are themselves one of the diagnostic criteria for NFI.1

Plexiform neurofibromas are benign tumors that are the result of a genetic mutation in which loss of heterozygosity occurs, as is the case with the other predominant neoplasms of NFI, that results in unrestricted cell growth.3,4 Some patients have a loss of heterozygosity of this tumor suppression gene with overgrowth of neurofibromatosis on a Blaschko segment. One study in mouse models showed that stromal mast cells were involved in promoting inflammation and increasing tumor growth by mediation of mitogenic signals involved in vascular ingrowth, collagen deposition, and cellular proliferation.5 Plexiform neurofibromas are a presenting feature in 30% of NFI cases within the first year of life. They are extensive nerve sheath tumors with an unpredictable growth pattern that can involve multiple fascicles (ie, large nerves and their branches). Five percent become malignant and the transformation is often heralded by rapid growth and pain.6 If malignant transformation is suspected, biopsy is diagnostic. Magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast can categorize them into 3 growth categories: superficial, displacing, and invasive.7 Because plexiform neurofibromas are rare tumors, it previously was common practice to delay surgical intervention until disfigurement or disability arose. Complete surgical resection at more advanced stages is nearly impossible given the networklike growth pattern that commonly encapsulates vital structures.8,9 Therefore, surgery has been used in the past for debulking the large growths that eventually will recur. A study of 9 small superficial plexiform neurofibromas in children aged 3 to 15 years documented treatment with early surgical resection, which showed complete resection and no relapse at 4 years. This study showed a promising strategy to prevent future extension of these fast-growing tumors into vital structures.8 There also are current clinical trials investigating sirolimus and peginterferon alfa-2b in patients with more invasive plexiform neurofibromas that are unable to undergo surgical resection due to encapsulation or proximity to essential anatomical structures (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT00652990 and NCT00678951, respectively).

Pain, development of a neurologic deficit, or enlargement of a preexisting plexiform neurofibroma may signal a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) and require immediate evaluation.10 Examination by magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography is useful in distinguishing benign and MPNSTs,8,11,12 but definitive differentiation can only be made by histologic examination of the tumor. Complete surgical excision, when possible, is the only treatment that offers the possibility of cure of MPNSTs. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy also is sometimes used, though benefit has not been clearly established.8,9,13,14

Death certificate and population-based studies have shown that approximately 10% of patients with NFI have a reduced life expectancy due to MPNSTs; indeed, these tumors arising from plexiform neurofibromas are the main cause of death in adults with NFI. In 2003, Mautner et al7 studied 50 individuals with NFI. The objective was to establish magnetic resonance imaging criteria for MPNST and to test their usefulness in detecting early malignant change in plexiform neurofibromas. This study found that MPNST in patients with NFI frequently showed inhomogeneous contrast enhancement. This inhomogeneity was due to necrosis and hemorrhage, as shown by macroscopic and histologic analysis of amputated limbs in 2 patients within the study. The investigators found it to be possible to detect malignant transformation at an early stage in patients with no overt clinical signs of progression.7 Careful follow-up will determine how frequently early malignancy can be detected and if it is worthwhile carrying out magnetic resonance imaging at defined intervals.2,7,10,15,16

- Friedman JM. Neurofibromatosis 1. In: Pagon RA, ed. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1109/. Updated September 4, 2014. Accessed April 6, 2015.

- Friedman JM, Riccardi VM. Clinical epidemiological features. In: Friedman JM, Gutmann DH, MacCollin M, et al, eds. Neurofibromatosis: Phenotype, Natural History, and Pathogenesis. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999:29-86.

- Bausch B, Borozdin W, Mautner VF, et al; European-American Phaeochromocytoma Registry Study Group. Germline NF1 mutational spectra and loss-of-heterozygosity analyses in patients with phaeochromocytoma and neurofibromatosis type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2784-2792.

- Bottillo I, Ahlquist T, Brekke H, et al. Germline and somatic NF1 mutations in sporadic and NF1-associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. J Pathol. 2009;217:693-701.

- Staser K, Yang FC, Clapp DW. Pathogenesis of plexiform neurofibroma: tumor-stromal/hematopoietic interactions in tumor progression. Ann Rev Pathol. 2012;7:469-495.

- Murphey MD, Smith WS, Smith SE, et al. From the archives of the AFIP: imaging of musculoskeletal neurogenic tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:1253-1280.

- Mautner VF, Friedrich RE, von Deimling A, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis type 1: MRI supports the diagnosis of malignant plexiform neurofibroma. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:618-625.

- Friedrich RE, Schmelzle R, Hartmann M, et al. Resection of small plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1 children. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:6.

- Gottfried ON, Viskochil DH, Fults DW, et al. Molecular, genetic, and cellular pathogenesis of neurofibromas and surgical implications. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:1-16.

- Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaïli N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumours: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:79-82.

- Bensaid B, Giammarile F, Mognetti T, et al. Utility of 18 FDG positron emission tomography in detection of sarcomatous transformation in neurofibromatosis type 1. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2007;134:735-741.

- Ferner RE, Lucas JD, O’Doherty MJ, et al. Evaluation of (18)fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ((18)FDG PET) in the detection of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours arising from within plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:3353-3357.

- Baujat B, Krastinova-Lolov D, Blumen M, et al. Radiofrequency in the treatment of craniofacial plexiform neurofibromatosis: a pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1261-1268.

- Hummel T, Anyane-Yeboa A, Mo J, et al. Response of NF1-related plexiform neurofibroma to high-dose carboplatin. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:488-490.

- Feldmann R, Schuierer G, Wessel A, et al. Development of MRI T2 hyperintensities and cognitive functioning in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1657-1660.

- Blazo MA, Lewis RA, Chintagumpala MM, et al. Outcomes of systematic screening for optic pathway tumors in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;127A:224-229.

The Diagnosis: Plexiform Neurofibroma as a Manifestation of Neurofibromatosis Type I

Physical examination revealed a large 10×8-cm subcutaneous nodule that was boggy and resembled a bag of worms on palpation. It was covered by slightly hyperpigmented skin. He also had numerous (>20) café au lait spots measuring 2 to 3 cm across the body and several others on the axillae. There were no gross eye findings. Otherwise the examination was unremarkable on the rest of the body. The patient’s paternal grandfather and aunt had similar macules and multiple nodules. The patient had mild to moderate learning difficulties. He was subsequently referred for genetic and ophthalmology evaluation.

Plexiform neurofibromas are usually benign nerve sheath tumors that are elongated and are multinodular, forming when the tumor involves either multiple trunks of a plexus or multiple fascicles of a large nerve such as the sciatic. Some plexiform neurofibromas resemble a bag of worms; others produce a massive ropy enlargement of the nerve.1,2 Plexiform neurofibromas are associated with cases of neurofibromatosis type I (NFI) and are themselves one of the diagnostic criteria for NFI.1

Plexiform neurofibromas are benign tumors that are the result of a genetic mutation in which loss of heterozygosity occurs, as is the case with the other predominant neoplasms of NFI, that results in unrestricted cell growth.3,4 Some patients have a loss of heterozygosity of this tumor suppression gene with overgrowth of neurofibromatosis on a Blaschko segment. One study in mouse models showed that stromal mast cells were involved in promoting inflammation and increasing tumor growth by mediation of mitogenic signals involved in vascular ingrowth, collagen deposition, and cellular proliferation.5 Plexiform neurofibromas are a presenting feature in 30% of NFI cases within the first year of life. They are extensive nerve sheath tumors with an unpredictable growth pattern that can involve multiple fascicles (ie, large nerves and their branches). Five percent become malignant and the transformation is often heralded by rapid growth and pain.6 If malignant transformation is suspected, biopsy is diagnostic. Magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast can categorize them into 3 growth categories: superficial, displacing, and invasive.7 Because plexiform neurofibromas are rare tumors, it previously was common practice to delay surgical intervention until disfigurement or disability arose. Complete surgical resection at more advanced stages is nearly impossible given the networklike growth pattern that commonly encapsulates vital structures.8,9 Therefore, surgery has been used in the past for debulking the large growths that eventually will recur. A study of 9 small superficial plexiform neurofibromas in children aged 3 to 15 years documented treatment with early surgical resection, which showed complete resection and no relapse at 4 years. This study showed a promising strategy to prevent future extension of these fast-growing tumors into vital structures.8 There also are current clinical trials investigating sirolimus and peginterferon alfa-2b in patients with more invasive plexiform neurofibromas that are unable to undergo surgical resection due to encapsulation or proximity to essential anatomical structures (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT00652990 and NCT00678951, respectively).

Pain, development of a neurologic deficit, or enlargement of a preexisting plexiform neurofibroma may signal a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) and require immediate evaluation.10 Examination by magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography is useful in distinguishing benign and MPNSTs,8,11,12 but definitive differentiation can only be made by histologic examination of the tumor. Complete surgical excision, when possible, is the only treatment that offers the possibility of cure of MPNSTs. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy also is sometimes used, though benefit has not been clearly established.8,9,13,14

Death certificate and population-based studies have shown that approximately 10% of patients with NFI have a reduced life expectancy due to MPNSTs; indeed, these tumors arising from plexiform neurofibromas are the main cause of death in adults with NFI. In 2003, Mautner et al7 studied 50 individuals with NFI. The objective was to establish magnetic resonance imaging criteria for MPNST and to test their usefulness in detecting early malignant change in plexiform neurofibromas. This study found that MPNST in patients with NFI frequently showed inhomogeneous contrast enhancement. This inhomogeneity was due to necrosis and hemorrhage, as shown by macroscopic and histologic analysis of amputated limbs in 2 patients within the study. The investigators found it to be possible to detect malignant transformation at an early stage in patients with no overt clinical signs of progression.7 Careful follow-up will determine how frequently early malignancy can be detected and if it is worthwhile carrying out magnetic resonance imaging at defined intervals.2,7,10,15,16

The Diagnosis: Plexiform Neurofibroma as a Manifestation of Neurofibromatosis Type I

Physical examination revealed a large 10×8-cm subcutaneous nodule that was boggy and resembled a bag of worms on palpation. It was covered by slightly hyperpigmented skin. He also had numerous (>20) café au lait spots measuring 2 to 3 cm across the body and several others on the axillae. There were no gross eye findings. Otherwise the examination was unremarkable on the rest of the body. The patient’s paternal grandfather and aunt had similar macules and multiple nodules. The patient had mild to moderate learning difficulties. He was subsequently referred for genetic and ophthalmology evaluation.

Plexiform neurofibromas are usually benign nerve sheath tumors that are elongated and are multinodular, forming when the tumor involves either multiple trunks of a plexus or multiple fascicles of a large nerve such as the sciatic. Some plexiform neurofibromas resemble a bag of worms; others produce a massive ropy enlargement of the nerve.1,2 Plexiform neurofibromas are associated with cases of neurofibromatosis type I (NFI) and are themselves one of the diagnostic criteria for NFI.1

Plexiform neurofibromas are benign tumors that are the result of a genetic mutation in which loss of heterozygosity occurs, as is the case with the other predominant neoplasms of NFI, that results in unrestricted cell growth.3,4 Some patients have a loss of heterozygosity of this tumor suppression gene with overgrowth of neurofibromatosis on a Blaschko segment. One study in mouse models showed that stromal mast cells were involved in promoting inflammation and increasing tumor growth by mediation of mitogenic signals involved in vascular ingrowth, collagen deposition, and cellular proliferation.5 Plexiform neurofibromas are a presenting feature in 30% of NFI cases within the first year of life. They are extensive nerve sheath tumors with an unpredictable growth pattern that can involve multiple fascicles (ie, large nerves and their branches). Five percent become malignant and the transformation is often heralded by rapid growth and pain.6 If malignant transformation is suspected, biopsy is diagnostic. Magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast can categorize them into 3 growth categories: superficial, displacing, and invasive.7 Because plexiform neurofibromas are rare tumors, it previously was common practice to delay surgical intervention until disfigurement or disability arose. Complete surgical resection at more advanced stages is nearly impossible given the networklike growth pattern that commonly encapsulates vital structures.8,9 Therefore, surgery has been used in the past for debulking the large growths that eventually will recur. A study of 9 small superficial plexiform neurofibromas in children aged 3 to 15 years documented treatment with early surgical resection, which showed complete resection and no relapse at 4 years. This study showed a promising strategy to prevent future extension of these fast-growing tumors into vital structures.8 There also are current clinical trials investigating sirolimus and peginterferon alfa-2b in patients with more invasive plexiform neurofibromas that are unable to undergo surgical resection due to encapsulation or proximity to essential anatomical structures (registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with the identifiers NCT00652990 and NCT00678951, respectively).

Pain, development of a neurologic deficit, or enlargement of a preexisting plexiform neurofibroma may signal a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) and require immediate evaluation.10 Examination by magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography is useful in distinguishing benign and MPNSTs,8,11,12 but definitive differentiation can only be made by histologic examination of the tumor. Complete surgical excision, when possible, is the only treatment that offers the possibility of cure of MPNSTs. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy also is sometimes used, though benefit has not been clearly established.8,9,13,14

Death certificate and population-based studies have shown that approximately 10% of patients with NFI have a reduced life expectancy due to MPNSTs; indeed, these tumors arising from plexiform neurofibromas are the main cause of death in adults with NFI. In 2003, Mautner et al7 studied 50 individuals with NFI. The objective was to establish magnetic resonance imaging criteria for MPNST and to test their usefulness in detecting early malignant change in plexiform neurofibromas. This study found that MPNST in patients with NFI frequently showed inhomogeneous contrast enhancement. This inhomogeneity was due to necrosis and hemorrhage, as shown by macroscopic and histologic analysis of amputated limbs in 2 patients within the study. The investigators found it to be possible to detect malignant transformation at an early stage in patients with no overt clinical signs of progression.7 Careful follow-up will determine how frequently early malignancy can be detected and if it is worthwhile carrying out magnetic resonance imaging at defined intervals.2,7,10,15,16

- Friedman JM. Neurofibromatosis 1. In: Pagon RA, ed. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1109/. Updated September 4, 2014. Accessed April 6, 2015.

- Friedman JM, Riccardi VM. Clinical epidemiological features. In: Friedman JM, Gutmann DH, MacCollin M, et al, eds. Neurofibromatosis: Phenotype, Natural History, and Pathogenesis. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999:29-86.

- Bausch B, Borozdin W, Mautner VF, et al; European-American Phaeochromocytoma Registry Study Group. Germline NF1 mutational spectra and loss-of-heterozygosity analyses in patients with phaeochromocytoma and neurofibromatosis type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2784-2792.

- Bottillo I, Ahlquist T, Brekke H, et al. Germline and somatic NF1 mutations in sporadic and NF1-associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. J Pathol. 2009;217:693-701.

- Staser K, Yang FC, Clapp DW. Pathogenesis of plexiform neurofibroma: tumor-stromal/hematopoietic interactions in tumor progression. Ann Rev Pathol. 2012;7:469-495.

- Murphey MD, Smith WS, Smith SE, et al. From the archives of the AFIP: imaging of musculoskeletal neurogenic tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:1253-1280.

- Mautner VF, Friedrich RE, von Deimling A, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis type 1: MRI supports the diagnosis of malignant plexiform neurofibroma. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:618-625.

- Friedrich RE, Schmelzle R, Hartmann M, et al. Resection of small plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1 children. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:6.

- Gottfried ON, Viskochil DH, Fults DW, et al. Molecular, genetic, and cellular pathogenesis of neurofibromas and surgical implications. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:1-16.

- Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaïli N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumours: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:79-82.

- Bensaid B, Giammarile F, Mognetti T, et al. Utility of 18 FDG positron emission tomography in detection of sarcomatous transformation in neurofibromatosis type 1. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2007;134:735-741.

- Ferner RE, Lucas JD, O’Doherty MJ, et al. Evaluation of (18)fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ((18)FDG PET) in the detection of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours arising from within plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:3353-3357.

- Baujat B, Krastinova-Lolov D, Blumen M, et al. Radiofrequency in the treatment of craniofacial plexiform neurofibromatosis: a pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1261-1268.

- Hummel T, Anyane-Yeboa A, Mo J, et al. Response of NF1-related plexiform neurofibroma to high-dose carboplatin. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:488-490.

- Feldmann R, Schuierer G, Wessel A, et al. Development of MRI T2 hyperintensities and cognitive functioning in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1657-1660.

- Blazo MA, Lewis RA, Chintagumpala MM, et al. Outcomes of systematic screening for optic pathway tumors in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;127A:224-229.

- Friedman JM. Neurofibromatosis 1. In: Pagon RA, ed. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1109/. Updated September 4, 2014. Accessed April 6, 2015.

- Friedman JM, Riccardi VM. Clinical epidemiological features. In: Friedman JM, Gutmann DH, MacCollin M, et al, eds. Neurofibromatosis: Phenotype, Natural History, and Pathogenesis. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1999:29-86.

- Bausch B, Borozdin W, Mautner VF, et al; European-American Phaeochromocytoma Registry Study Group. Germline NF1 mutational spectra and loss-of-heterozygosity analyses in patients with phaeochromocytoma and neurofibromatosis type 1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2784-2792.

- Bottillo I, Ahlquist T, Brekke H, et al. Germline and somatic NF1 mutations in sporadic and NF1-associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. J Pathol. 2009;217:693-701.

- Staser K, Yang FC, Clapp DW. Pathogenesis of plexiform neurofibroma: tumor-stromal/hematopoietic interactions in tumor progression. Ann Rev Pathol. 2012;7:469-495.

- Murphey MD, Smith WS, Smith SE, et al. From the archives of the AFIP: imaging of musculoskeletal neurogenic tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:1253-1280.

- Mautner VF, Friedrich RE, von Deimling A, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis type 1: MRI supports the diagnosis of malignant plexiform neurofibroma. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:618-625.

- Friedrich RE, Schmelzle R, Hartmann M, et al. Resection of small plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1 children. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:6.

- Gottfried ON, Viskochil DH, Fults DW, et al. Molecular, genetic, and cellular pathogenesis of neurofibromas and surgical implications. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:1-16.

- Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaïli N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumours: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:79-82.

- Bensaid B, Giammarile F, Mognetti T, et al. Utility of 18 FDG positron emission tomography in detection of sarcomatous transformation in neurofibromatosis type 1. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2007;134:735-741.

- Ferner RE, Lucas JD, O’Doherty MJ, et al. Evaluation of (18)fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ((18)FDG PET) in the detection of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours arising from within plexiform neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:3353-3357.

- Baujat B, Krastinova-Lolov D, Blumen M, et al. Radiofrequency in the treatment of craniofacial plexiform neurofibromatosis: a pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1261-1268.

- Hummel T, Anyane-Yeboa A, Mo J, et al. Response of NF1-related plexiform neurofibroma to high-dose carboplatin. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:488-490.

- Feldmann R, Schuierer G, Wessel A, et al. Development of MRI T2 hyperintensities and cognitive functioning in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1657-1660.

- Blazo MA, Lewis RA, Chintagumpala MM, et al. Outcomes of systematic screening for optic pathway tumors in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;127A:224-229.

An 11-year-old boy presented for evaluation of a 10×8-cm tortuous lesion on the right posterior leg. Although it had been present since birth, the patient’s mother reported recent growth of the lesion. The lesion was noted to occasionally become irritated and pruritic. The patient’s history was remarkable for asthma.

Patient Has No Complaints, But Family Is Concerned

ANSWER

The radiograph shows diffuse osteopenia and spondylosis. Of note is a moderate to severe compression deformity of the T8 vertebral body. However, by plain radiograph, it is age indeterminate as to its acuity. For definitive diagnosis, MRI without contrast is required to assess for marrow edema, which then suggests an acute fracture.

This patient was admitted for further workup. MRI was ultimately obtained and revealed marrow edema within that vertebral body. She was treated with a rigid custom-made brace.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows diffuse osteopenia and spondylosis. Of note is a moderate to severe compression deformity of the T8 vertebral body. However, by plain radiograph, it is age indeterminate as to its acuity. For definitive diagnosis, MRI without contrast is required to assess for marrow edema, which then suggests an acute fracture.

This patient was admitted for further workup. MRI was ultimately obtained and revealed marrow edema within that vertebral body. She was treated with a rigid custom-made brace.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows diffuse osteopenia and spondylosis. Of note is a moderate to severe compression deformity of the T8 vertebral body. However, by plain radiograph, it is age indeterminate as to its acuity. For definitive diagnosis, MRI without contrast is required to assess for marrow edema, which then suggests an acute fracture.

This patient was admitted for further workup. MRI was ultimately obtained and revealed marrow edema within that vertebral body. She was treated with a rigid custom-made brace.

An 80-year-old woman presents to the emergency department for evaluation. Her family reports that she has baseline dementia and resides in an assisted living facility. Staff there report that recently the patient has fallen multiple times. The patient herself does not voice any specific complaints, but her family has noticed she is not as active or walking as much as usual. Medical history is significant for mild hypertension. On physical exam, you note that the patient is awake and alert but oriented only to person. Her vital signs are stable. Primary and secondary survey do not demonstrate any obvious injury or trauma. You order some basic blood work, as well as some imaging studies—including thoracic and lumbar radiographs. The lateral thoracic radiograph is shown. What is your impression?

The Ears Have It (and She Doesn’t Want It)

ANSWER

The correct answer is to obtain a biopsy (choice “d”), the results of which would likely dictate rational and effective treatment. The other choices are largely empirical and not based on available evidence.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the biopsy (with samples from the arm rash as well as from the ears) showed unequivocal evidence of connective tissue disease—almost certainly lupus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has protean manifestations because it can affect so many different organs in so many different ways. Reduced to its simplest elements, lupus is an autoimmune process that results in a form of vasculitis that can affect any perfused tissue.

In terms of the skin, the visible manifestations of lupus are numerous and not always obvious. Sun is a known exacerbating factor, as this case demonstrated quite well: The patient’s rash was pronounced on sun-exposed skin but spared covered skin. When this was brought to her attention, the patient recalled a baby-sitting job earlier in the year (summer) that had required her to spend time outdoors. She also acknowledged that her smoking habit often took her into the backyard, where she would stand in the sun.

That being said, neither the arm rash nor the ear changes are “typical” of lupus (although the latter did include patulous follicular orifices, enlarged pores often seen focally with lupus). The effect is simply the result of the patient’s normal dark skin color; on a white person, the discoloration would have been pink or red.

Although these changes were suspicious for lupus, it was necessary to establish the diagnosis by biopsy—especially since the patient was already being treated for the disease. With that accomplished, the patient was sent back to her rheumatologist, who indicated he would probably treat her with a biologic, plus or minus methotrexate.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to obtain a biopsy (choice “d”), the results of which would likely dictate rational and effective treatment. The other choices are largely empirical and not based on available evidence.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the biopsy (with samples from the arm rash as well as from the ears) showed unequivocal evidence of connective tissue disease—almost certainly lupus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has protean manifestations because it can affect so many different organs in so many different ways. Reduced to its simplest elements, lupus is an autoimmune process that results in a form of vasculitis that can affect any perfused tissue.

In terms of the skin, the visible manifestations of lupus are numerous and not always obvious. Sun is a known exacerbating factor, as this case demonstrated quite well: The patient’s rash was pronounced on sun-exposed skin but spared covered skin. When this was brought to her attention, the patient recalled a baby-sitting job earlier in the year (summer) that had required her to spend time outdoors. She also acknowledged that her smoking habit often took her into the backyard, where she would stand in the sun.

That being said, neither the arm rash nor the ear changes are “typical” of lupus (although the latter did include patulous follicular orifices, enlarged pores often seen focally with lupus). The effect is simply the result of the patient’s normal dark skin color; on a white person, the discoloration would have been pink or red.

Although these changes were suspicious for lupus, it was necessary to establish the diagnosis by biopsy—especially since the patient was already being treated for the disease. With that accomplished, the patient was sent back to her rheumatologist, who indicated he would probably treat her with a biologic, plus or minus methotrexate.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to obtain a biopsy (choice “d”), the results of which would likely dictate rational and effective treatment. The other choices are largely empirical and not based on available evidence.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the biopsy (with samples from the arm rash as well as from the ears) showed unequivocal evidence of connective tissue disease—almost certainly lupus.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has protean manifestations because it can affect so many different organs in so many different ways. Reduced to its simplest elements, lupus is an autoimmune process that results in a form of vasculitis that can affect any perfused tissue.

In terms of the skin, the visible manifestations of lupus are numerous and not always obvious. Sun is a known exacerbating factor, as this case demonstrated quite well: The patient’s rash was pronounced on sun-exposed skin but spared covered skin. When this was brought to her attention, the patient recalled a baby-sitting job earlier in the year (summer) that had required her to spend time outdoors. She also acknowledged that her smoking habit often took her into the backyard, where she would stand in the sun.

That being said, neither the arm rash nor the ear changes are “typical” of lupus (although the latter did include patulous follicular orifices, enlarged pores often seen focally with lupus). The effect is simply the result of the patient’s normal dark skin color; on a white person, the discoloration would have been pink or red.

Although these changes were suspicious for lupus, it was necessary to establish the diagnosis by biopsy—especially since the patient was already being treated for the disease. With that accomplished, the patient was sent back to her rheumatologist, who indicated he would probably treat her with a biologic, plus or minus methotrexate.

A 34-year-old black woman is sent to dermatology by her rheumatologist for evaluation of changes to her ears that began several months ago. The patient reports no symptoms, but she is quite distressed by the appearance of her ears. She has been under the care of the rheumatologist for several years for her systemic lupus erythematosus. She takes hydroxychloroquine (400 mg/d), which she says controls most of her systemic symptoms (ie, joint pain and malaise). Further history taking reveals that, within the time frame of the ear changes, the patient also developed an itchy rash on both arms. Application of triamcinolone 0.1% cream has not helped. On examination, the changes to the patient’s ears are immediately obvious: the dark brown to black discoloration contrasts sharply with her light brown skin. In addition to the color change, the surface of the ears is scaly and rough, with enlarged pores evident. There is no redness or swelling noted; palpation elicits neither increased warmth nor adenopathy around the ears or on the adjacent neck. The scaly rash on the patient’s arms is remarkably symmetrical. It affects the sun-exposed lateral portions of both arms, sparing the skin on the medial aspects and on the proximal portions normally covered by clothing.

Erythematous Scaly Papules on the Shins and Calves

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

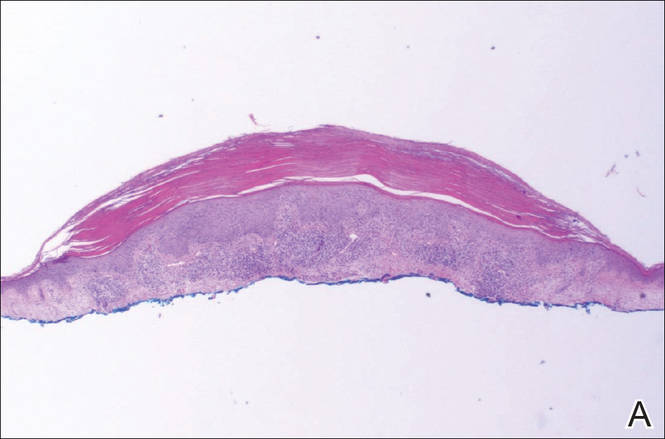

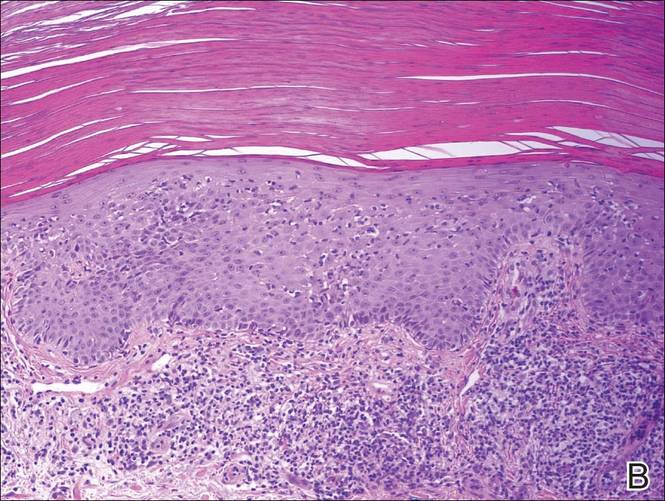

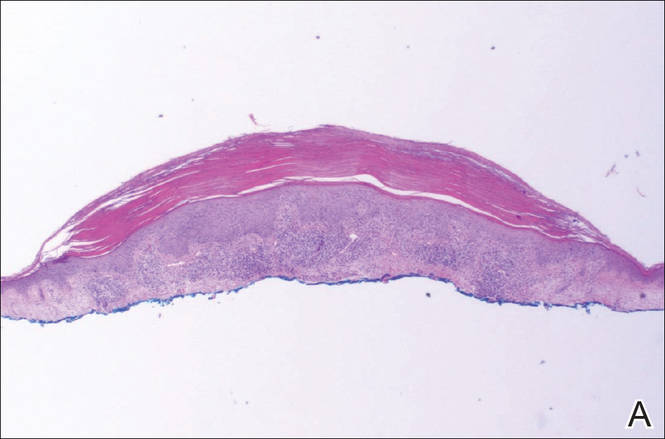

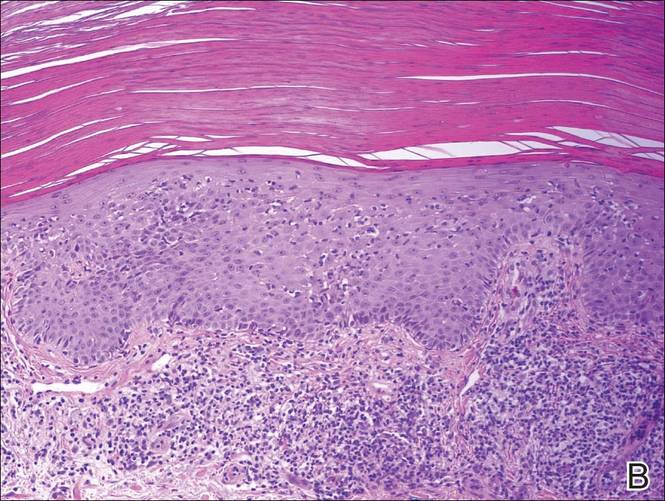

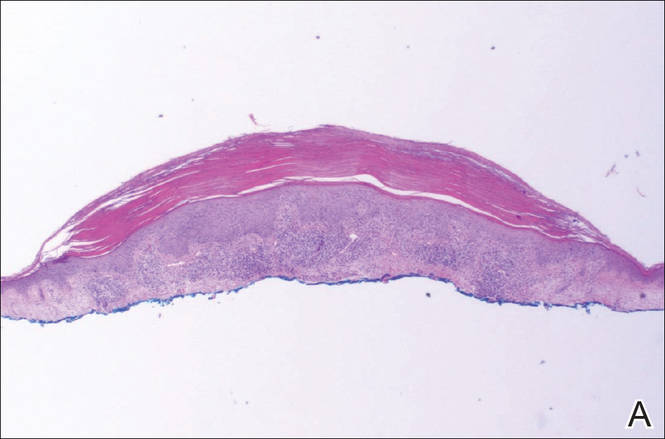

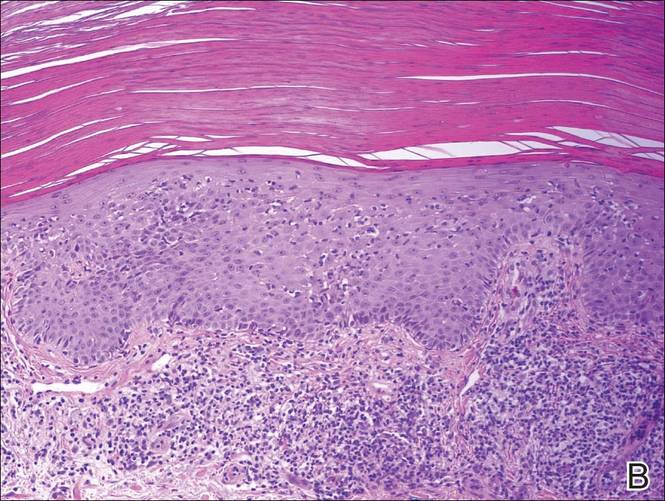

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

Holiday Trip Marred by Illness

ANSWER

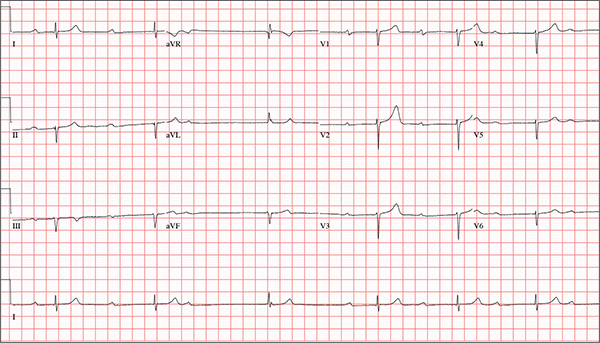

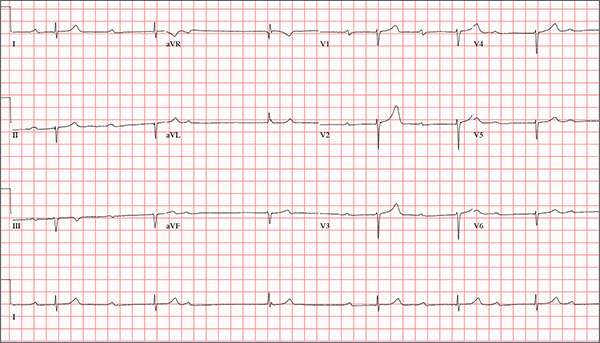

This ECG is representative of marked sinus bradycardia with second-degree atrioventricular block (Mobitz I) with an occasional junctional escape, left-axis deviation, and poor R-wave progression in the precordial leads.

Marked sinus bradycardia is evidenced by P waves that are regular except where expected, prior to the third QRS complex on the rhythm strip (lead 1).

Second-degree Mobitz I (Wenckebach) block is indicated by a gradual prolonging of the PR interval until there is loss of conduction from the atria to the ventricle (following the third P wave). Careful inspection of the third QRS complex shows a slight difference in the normally conducted sinus beat, indicative of a junctional escape beat. Left-axis deviation entails an R-wave axis of –78°.

Finally, there is poor R-wave progression in the precordial leads, including the lateral leads.

Although Mobitz I block is not an indication for pacemaker placement, symptomatic bradycardia is. The patient underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker, with complete resolution of symptoms.

ANSWER

This ECG is representative of marked sinus bradycardia with second-degree atrioventricular block (Mobitz I) with an occasional junctional escape, left-axis deviation, and poor R-wave progression in the precordial leads.

Marked sinus bradycardia is evidenced by P waves that are regular except where expected, prior to the third QRS complex on the rhythm strip (lead 1).

Second-degree Mobitz I (Wenckebach) block is indicated by a gradual prolonging of the PR interval until there is loss of conduction from the atria to the ventricle (following the third P wave). Careful inspection of the third QRS complex shows a slight difference in the normally conducted sinus beat, indicative of a junctional escape beat. Left-axis deviation entails an R-wave axis of –78°.

Finally, there is poor R-wave progression in the precordial leads, including the lateral leads.

Although Mobitz I block is not an indication for pacemaker placement, symptomatic bradycardia is. The patient underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker, with complete resolution of symptoms.

ANSWER

This ECG is representative of marked sinus bradycardia with second-degree atrioventricular block (Mobitz I) with an occasional junctional escape, left-axis deviation, and poor R-wave progression in the precordial leads.

Marked sinus bradycardia is evidenced by P waves that are regular except where expected, prior to the third QRS complex on the rhythm strip (lead 1).

Second-degree Mobitz I (Wenckebach) block is indicated by a gradual prolonging of the PR interval until there is loss of conduction from the atria to the ventricle (following the third P wave). Careful inspection of the third QRS complex shows a slight difference in the normally conducted sinus beat, indicative of a junctional escape beat. Left-axis deviation entails an R-wave axis of –78°.

Finally, there is poor R-wave progression in the precordial leads, including the lateral leads.

Although Mobitz I block is not an indication for pacemaker placement, symptomatic bradycardia is. The patient underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker, with complete resolution of symptoms.

While visiting family over the holidays, an 84-year-old man is (plaintively) informed by his wife that he appears unwell; she suspects he has the flu. The patient’s son, whom they are visiting, learns through conversation that his father has been feeling very tired and lethargic and becomes dizzy if he stands too quickly. The son, concerned for his father’s well-being, brings him to your clinic in the hope of obtaining a prescription for antibiotics. According to the patient, his symptoms, which have waxed and waned for several weeks, have become constant in the past week. He denies fever, cough, nausea, and vomiting, as well as chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, and lower extremity swelling. He reports that he has not recently changed his medication regimen and, aside from this current visit, has not traveled anywhere; he reiterates that his symptoms started prior to this trip. Medical history is remarkable for hypertension, peripheral atherosclerosis, osteoarthritis, gout, and pneumonia. Surgical history is remarkable for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and removal of multiple lipomas from the patient’s upper extremities. Via the family history, you learn that the man’s father had a myocardial infarction and died of complications from a stroke at age 92 and his mother died of complications of diabetes at age 87. The patient is married, with three sons and one daughter, all of whom are in good health. He is a retired owner of a hardware store. He has never smoked or used recreational drugs and says he rarely drinks alcohol. The patient’s medication list includes metoprolol, atorvastatin, furosemide, and a daily baby aspirin. He is allergic to sulfa, which causes shortness of breath and wheezing. Review of systems reveals that he wears corrective lenses and hearing aids. He walks with a cane due to pain in both knees but is not dependent on it. He denies constitutional symptoms. A review of cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, urologic, neurologic, and integumentary systems is noncontributory. Chest x-ray and laboratory testing, including complete blood count and chemistry panel, yield normal results. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 162/92 mm Hg; pulse, 40 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; temperature, 99.2°F; and O2 saturation, 97% on room air. Pertinent physical findings include clear lung fields bilaterally, no evidence of jugular venous distention, and a heart rate of 40 beats/min that is regular and without evidence of a murmur or rub. There are well-healed scars on the abdomen and no evidence of organomegaly. Peripheral pulses are diminished but present bilaterally in both lower extremities. The neurologic exam is grossly intact, and the patient is alert, cooperative, and cognizant. Your concern about the patient’s heart rate prompts you to order an ECG. It reveals a ventricular rate of 38 beats/min; no measurable PR interval; QRS duration, 78 ms; QT/QTc interval, 434/345 ms; P axis, 25°; R axis, –78°; and T axis, 13°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Friendly Advice Goes Awry

ANSWER

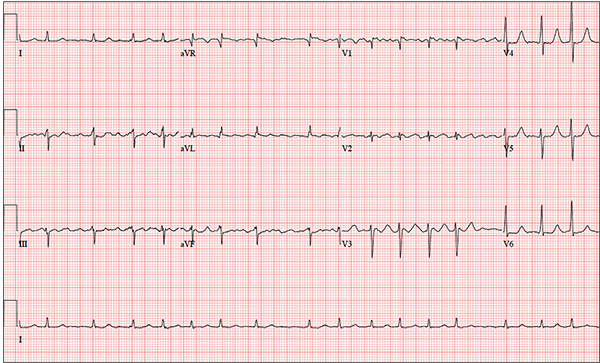

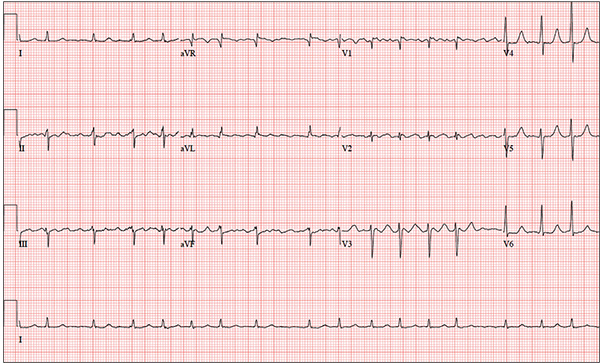

The correct interpretation is coarse atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and left-axis deviation.

Coarse atrial fibrillation is evidenced by the irregularly irregular rhythm with a normal QRS duration and flutter/fibrillation waves arising from the atria. Rapid ventricular response is defined as a ventricular response > 100 beats/min (seen in this case). Finally, an R-wave axis between –30° and –90° is indicative of left-axis deviation.

Correcting the patient’s hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia resulted in a return to normal sinus rhythm. At one-year follow-up, he had had no further episodes of atrial fibrillation.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is coarse atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and left-axis deviation.

Coarse atrial fibrillation is evidenced by the irregularly irregular rhythm with a normal QRS duration and flutter/fibrillation waves arising from the atria. Rapid ventricular response is defined as a ventricular response > 100 beats/min (seen in this case). Finally, an R-wave axis between –30° and –90° is indicative of left-axis deviation.

Correcting the patient’s hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia resulted in a return to normal sinus rhythm. At one-year follow-up, he had had no further episodes of atrial fibrillation.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is coarse atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and left-axis deviation.

Coarse atrial fibrillation is evidenced by the irregularly irregular rhythm with a normal QRS duration and flutter/fibrillation waves arising from the atria. Rapid ventricular response is defined as a ventricular response > 100 beats/min (seen in this case). Finally, an R-wave axis between –30° and –90° is indicative of left-axis deviation.

Correcting the patient’s hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia resulted in a return to normal sinus rhythm. At one-year follow-up, he had had no further episodes of atrial fibrillation.

You have been following a 57-year-old man for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). He presents for routine follow-up stating that his reflux has subsided; you presume this is a result of the 14-day course of a proton pump inhibitor that you prescribed. However, the patient confesses that, for about three months, he’s taken his omeprazole at twice the dose—because a friend told him that OTC medications are half the dose of the prescription versions. His primary concern today is that his heart has started flip-flopping in his chest for brief periods at bedtime. The symptoms typically last for 30 to 60 minutes and recur when he wakes in the morning—particularly if he is startled by his alarm clock. They began approximately a week ago, and he reports that they start and stop abruptly. The patient denies chest pain, dyspnea, and syncope or near-syncope, but he does note that it feels like something is “sticking in his throat.” His active medical problems include GERD, hypertension, and obesity. Surgical history is remarkable for repair of bilateral ankle fractures and a left femur fracture sustained in a motorcycle accident six years ago. Current medications include omeprazole, metoprolol, furosemide, and potassium chloride. He says he ran out of his potassium about a month ago and hasn’t refilled it yet. He also reports that he hasn’t taken his metoprolol in more than six months, because it makes him lethargic. He has no known drug allergies. The patient, who works as a welder, is married and has one son. He drinks approximately one six-pack of beer per week and smokes half a pack of cigarettes per day. He uses marijuana recreationally once or twice a month but denies use of any other illicit or naturopathic drugs. Review of systems is remarkable for a smoker’s cough, which clears with coughing. He also states his right eye twitches uncontrollably, and he feels weak and washed out. He denies nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. While you are conducting the review, he states, “It just started again.” You immediately check the patient’s pulse; it is 110 beats/min and irregular. Additional vital statistics include a blood pressure of 124/74 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; O2 saturation, 96% on room air; and temperature, 98.4°F. His weight is 245 lb and his height, 72 in. Pertinent physical findings include inspiratory and expiratory crackles that change with coughing, an irregularly irregular rhythm without evidence of a murmur or rub, a soft abdomen, and no evidence of jugular venous distention or peripheral edema. Laboratory values are within normal limits, with the exception of the potassium (2.8 mmol/L; normal range, 3.6-5.2 mmol/L) and magnesium (0.9 mg/dL; normal range, 1.8-2.6 mg/dL). An ECG reveals a ventricular rate of 108 beats/min; PR interval, not measured; QRS duration, 78 ms; QT/QTc interval, 352/471 ms; no P axis; R axis, –64°; and T axis, –58°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Secondary Survey of Trauma Patient

You are assisting in the evaluation and management of a trauma patient who was brought to your facility earlier today, following a motor vehicle collision. He is estimated to be in his 30s and is presumed to have been ejected, as he was found outside the vehicle. He was intubated in the field, and primary survey and resuscitation have been completed. History is otherwise unknown. The patient’s vital signs are currently stable. As you perform your secondary survey, you note that his right hand and wrist appear to be moderately swollen. He has been placed in a splint. You order a radiograph of the hand. What is your impression?

Boy Wrestles With Scalp Problem

ANSWER