User login

“Spry” Woman Reports Rapid Heart Rate

ANSWER

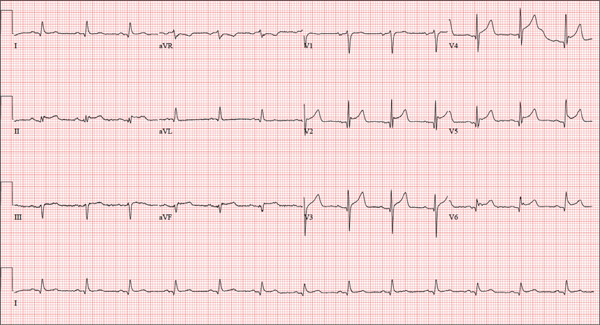

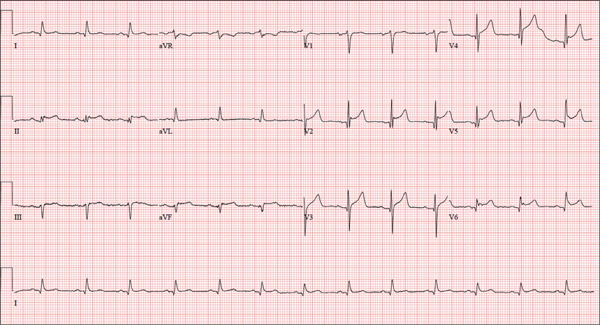

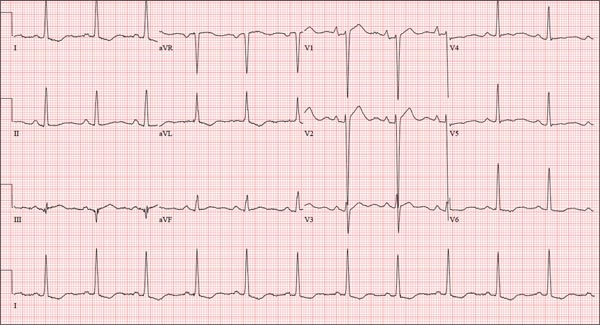

The correct interpretation includes atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and aberrantly conducted complexes, left axis deviation, and a left bundle branch block.

Atrial fibrillation is evidenced by the irregularly irregular heart rhythm without a measurable PR interval, and the rapid ventricular response is indicated by a ventricular rate > 100 beats/min.

Aberrant conduction, caused by conduction delay down the His-Purkinje system, is evidenced by the wide QRS complexes with a normally conducted beat (see first beat in leads V1-V3). Criteria for left axis deviation include an R axis between –30° and –90°, and left bundle branch block criteria include a QRS duration > 120 ms, a dominant S wave in V1, and broad monophasic R waves in leads I, aVL, and V5-V6.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and aberrantly conducted complexes, left axis deviation, and a left bundle branch block.

Atrial fibrillation is evidenced by the irregularly irregular heart rhythm without a measurable PR interval, and the rapid ventricular response is indicated by a ventricular rate > 100 beats/min.

Aberrant conduction, caused by conduction delay down the His-Purkinje system, is evidenced by the wide QRS complexes with a normally conducted beat (see first beat in leads V1-V3). Criteria for left axis deviation include an R axis between –30° and –90°, and left bundle branch block criteria include a QRS duration > 120 ms, a dominant S wave in V1, and broad monophasic R waves in leads I, aVL, and V5-V6.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and aberrantly conducted complexes, left axis deviation, and a left bundle branch block.

Atrial fibrillation is evidenced by the irregularly irregular heart rhythm without a measurable PR interval, and the rapid ventricular response is indicated by a ventricular rate > 100 beats/min.

Aberrant conduction, caused by conduction delay down the His-Purkinje system, is evidenced by the wide QRS complexes with a normally conducted beat (see first beat in leads V1-V3). Criteria for left axis deviation include an R axis between –30° and –90°, and left bundle branch block criteria include a QRS duration > 120 ms, a dominant S wave in V1, and broad monophasic R waves in leads I, aVL, and V5-V6.

An 84-year-old woman who recently relocated to be closer to her children presents to your practice as a new patient. She is a resident of an assisted living facility near your office, and although she has no specific complaints, she does report that her home health nurse observed a rapid heart rate and recommended she get it checked. A comprehensive medical history—provided by the patient, her daughter, and the aforementioned nurse—includes hypertension, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, hypothyroidism, and type 2 diabetes. She has taken medication for these diagnoses for more than 30 years. Surgical history is remarkable for cholecystectomy, appendectomy, and abdominal hysterectomy and oophorectomy, all of which were performed in the 1970s. Her current medication list—confirmed by the assisted living facility—includes furosemide, glyburide, metoprolol, potassium, and levothyroxine. She has not missed any doses. She is allergic to sulfa. The patient, a retired teacher, has never smoked, but she does “enjoy” one martini at dinner on a regular basis. She is widowed; her two daughters and four sons are all alive and well. The review of systems is remarkable for corrective lenses, bilateral hearing aids, and chronic joint pain. The patient does not routinely weigh herself but thinks, based on the fit of her clothes, that she may have gained some weight. She denies constitutional symptoms and shortness of breath. She thinks she may have a urinary tract infection, as she’s had burning with urination for several days, but says this is beginning to improve. Physical exam reveals a blood pressure of 168/90 mm Hg; pulse, 106 beats/min; temperature, 98.4° F; and O2 saturation, 94% on room air. Her weight is 132 lb and her height, 60 in. She is alert and quite spry, with a lot of energy. She wears glasses and bilateral hearing aids. Jugular distention is present to the angle of the jaw. There is no thyromegaly. The pulmonary exam is remarkable for crackles in both lung bases. The heart rhythm is irregularly irregular at a rate of 110 beats/min, and a grade II/VI murmur of mitral regurgitation is heard at the left lower sternal border. The abdomen is soft and nontender, with multiple surgical scars. The lower extremities are remarkable for 2+ pitting edema bilaterally to the level of the mid-calf. Osteoarthritic changes are present in both hands. The neurologic exam is grossly intact. An ECG reveals a ventricular rate of 110 beats/min; PR interval, not measured; QRS duration, 144 ms; QT/QTc interval, 298/403 ms; no P axis; R axis, –36°; and T axis, 169°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Painful Lesion Hasn’t Responded to Antibiotics

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema nodosum (EN; choice “c”), a reactive form of septal panniculitis with many potential triggers.

Erythema induratum (choice “a”) is a manifestation of lobular panniculitis, which affects the fat lobules but not the septae. It too has numerous triggers, but it tends to manifest with more discrete nodules, which eventually open and drain. It is far less common than EN.

Urticaria (choice “b”), also known as hives, presents as itchy, stingy wheals that are typically evanescent (eg, they appear suddenly, within seconds, and disappear within hours). Despite the itching and stinging, urticaria rarely hurts when it presents on the skin.

Erysipelas (choice “d”) is a superficial form of skin infection. More superficial than cellulitis, it usually is caused by a member of the Streptococcus family. It has a bright red appearance and sharply demarcated margins, with a peau d’orange (dimpled, like an orange peel) effect on its surface. It is acute in origin and responds readily to most common antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum, a reactive process involving fibrous septae that support and separate subcutaneous adipocytes, is notable for the complete lack of epidermal change (eg, scaling, broken skin, pointing, draining). The incidence is about 2 in 10,000 population, with women outnumbering men at a rate of 4:1 and the 18-to-34 age-group most affected. The anterior leg is involved in the vast majority of cases.

EN often starts with flulike symptoms, followed by the appearance of discrete, bright red nodules, measuring 2 to 4 cm, on the anterior legs; these darken and coalesce over a period of seven to 10 weeks. New lesions can continue to appear for up to six weeks. As they progress, the lesions often become ecchymotic. Idiopathic cases (at least 20%) can last months.

Notable triggers include Crohn disease flares and use of drugs such as sulfa, gold salts, and oral contraceptives. Several infections have been identified as triggers, including strep, mycoplasma, and campylobacter, as well as deep fungal infections (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sporotrichosis). More unusual causes include pregnancy and diseases such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Behçet disease, and leukemia/lymphoma.

The diagnostic workup for EN includes punch biopsy of deep adipose tissue and throat culture, and when indicated, ASO titer (if strep is suspected) and chest films (to rule out tuberculosis and sarcoid). In most cases, the diagnosis can be made on clinical grounds alone, although the triggering entity may be difficult to identify. The identification and elimination of the underlying trigger is nonetheless crucial for diagnosis and treatment.

That issue aside, most cases of EN resolve with minimal treatment; this can include the use of NSAIDs and elevation of the limbs when possible. In this particular case, the intense pain the patient was experiencing called for stronger therapy (ibuprofen 800 mg tid, plus a two-week taper of prednisone 40 mg). She responded quite well, and the problem was almost totally resolved at a follow-up visit several weeks later.

In the absence of findings to the contrary, it is likely that the trigger for this patient’s EN was strep, given the timing of its manifestation after a sore throat.

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema nodosum (EN; choice “c”), a reactive form of septal panniculitis with many potential triggers.

Erythema induratum (choice “a”) is a manifestation of lobular panniculitis, which affects the fat lobules but not the septae. It too has numerous triggers, but it tends to manifest with more discrete nodules, which eventually open and drain. It is far less common than EN.

Urticaria (choice “b”), also known as hives, presents as itchy, stingy wheals that are typically evanescent (eg, they appear suddenly, within seconds, and disappear within hours). Despite the itching and stinging, urticaria rarely hurts when it presents on the skin.

Erysipelas (choice “d”) is a superficial form of skin infection. More superficial than cellulitis, it usually is caused by a member of the Streptococcus family. It has a bright red appearance and sharply demarcated margins, with a peau d’orange (dimpled, like an orange peel) effect on its surface. It is acute in origin and responds readily to most common antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum, a reactive process involving fibrous septae that support and separate subcutaneous adipocytes, is notable for the complete lack of epidermal change (eg, scaling, broken skin, pointing, draining). The incidence is about 2 in 10,000 population, with women outnumbering men at a rate of 4:1 and the 18-to-34 age-group most affected. The anterior leg is involved in the vast majority of cases.

EN often starts with flulike symptoms, followed by the appearance of discrete, bright red nodules, measuring 2 to 4 cm, on the anterior legs; these darken and coalesce over a period of seven to 10 weeks. New lesions can continue to appear for up to six weeks. As they progress, the lesions often become ecchymotic. Idiopathic cases (at least 20%) can last months.

Notable triggers include Crohn disease flares and use of drugs such as sulfa, gold salts, and oral contraceptives. Several infections have been identified as triggers, including strep, mycoplasma, and campylobacter, as well as deep fungal infections (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sporotrichosis). More unusual causes include pregnancy and diseases such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Behçet disease, and leukemia/lymphoma.

The diagnostic workup for EN includes punch biopsy of deep adipose tissue and throat culture, and when indicated, ASO titer (if strep is suspected) and chest films (to rule out tuberculosis and sarcoid). In most cases, the diagnosis can be made on clinical grounds alone, although the triggering entity may be difficult to identify. The identification and elimination of the underlying trigger is nonetheless crucial for diagnosis and treatment.

That issue aside, most cases of EN resolve with minimal treatment; this can include the use of NSAIDs and elevation of the limbs when possible. In this particular case, the intense pain the patient was experiencing called for stronger therapy (ibuprofen 800 mg tid, plus a two-week taper of prednisone 40 mg). She responded quite well, and the problem was almost totally resolved at a follow-up visit several weeks later.

In the absence of findings to the contrary, it is likely that the trigger for this patient’s EN was strep, given the timing of its manifestation after a sore throat.

ANSWER

The correct answer is erythema nodosum (EN; choice “c”), a reactive form of septal panniculitis with many potential triggers.

Erythema induratum (choice “a”) is a manifestation of lobular panniculitis, which affects the fat lobules but not the septae. It too has numerous triggers, but it tends to manifest with more discrete nodules, which eventually open and drain. It is far less common than EN.

Urticaria (choice “b”), also known as hives, presents as itchy, stingy wheals that are typically evanescent (eg, they appear suddenly, within seconds, and disappear within hours). Despite the itching and stinging, urticaria rarely hurts when it presents on the skin.

Erysipelas (choice “d”) is a superficial form of skin infection. More superficial than cellulitis, it usually is caused by a member of the Streptococcus family. It has a bright red appearance and sharply demarcated margins, with a peau d’orange (dimpled, like an orange peel) effect on its surface. It is acute in origin and responds readily to most common antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Erythema nodosum, a reactive process involving fibrous septae that support and separate subcutaneous adipocytes, is notable for the complete lack of epidermal change (eg, scaling, broken skin, pointing, draining). The incidence is about 2 in 10,000 population, with women outnumbering men at a rate of 4:1 and the 18-to-34 age-group most affected. The anterior leg is involved in the vast majority of cases.

EN often starts with flulike symptoms, followed by the appearance of discrete, bright red nodules, measuring 2 to 4 cm, on the anterior legs; these darken and coalesce over a period of seven to 10 weeks. New lesions can continue to appear for up to six weeks. As they progress, the lesions often become ecchymotic. Idiopathic cases (at least 20%) can last months.

Notable triggers include Crohn disease flares and use of drugs such as sulfa, gold salts, and oral contraceptives. Several infections have been identified as triggers, including strep, mycoplasma, and campylobacter, as well as deep fungal infections (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sporotrichosis). More unusual causes include pregnancy and diseases such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Behçet disease, and leukemia/lymphoma.

The diagnostic workup for EN includes punch biopsy of deep adipose tissue and throat culture, and when indicated, ASO titer (if strep is suspected) and chest films (to rule out tuberculosis and sarcoid). In most cases, the diagnosis can be made on clinical grounds alone, although the triggering entity may be difficult to identify. The identification and elimination of the underlying trigger is nonetheless crucial for diagnosis and treatment.

That issue aside, most cases of EN resolve with minimal treatment; this can include the use of NSAIDs and elevation of the limbs when possible. In this particular case, the intense pain the patient was experiencing called for stronger therapy (ibuprofen 800 mg tid, plus a two-week taper of prednisone 40 mg). She responded quite well, and the problem was almost totally resolved at a follow-up visit several weeks later.

In the absence of findings to the contrary, it is likely that the trigger for this patient’s EN was strep, given the timing of its manifestation after a sore throat.

A 57-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for “cellulitis” that has persisted despite several courses of oral antibiotics (including cephalexin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole). She denies taking any other medications and has no significant medical history. She states that the problem manifested as discrete red nodules, which eventually coalesced into a single large patch. At the time, she had just recovered from a sore throat and still felt a bit ill, although she denies cough, fever, and shortness of breath. Examination reveals a large (12 x 14 cm) red edematous plaque in the skin over her right anterior tibia. The deep intradermal and subdermal edema is exquisitely tender to touch, considerably warmer than the surrounding skin, and highly blanchable. No other changes are noted on the epidermal surface. A deep 5-mm punch biopsy is performed. Results show a dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the pannicular septae.

Solitary Lesion on the Left Ankle

The Diagnosis: Porokeratosis of Mibelli

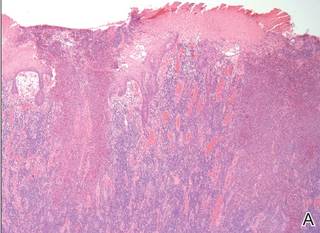

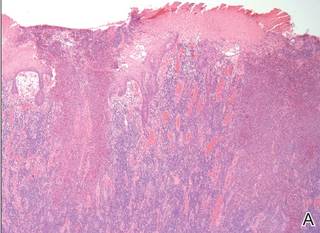

There are 5 variants of porokeratosis: disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), linear porokeratosis, porokeratosis of Mibelli, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, and punctate porokeratosis. The most common type is DSAP,1 which is characterized by multiple lesions on the body, particularly in sun-exposed areas. The distinguishing feature of porokeratosis is the cornoid lamella, which is made up of parakeratotic cells extending through the stratum corneum. There also is a thin or absent granular layer beneath it (Figure).2

Patients generally present in the third and fourth decades of life.1 Risk factors for porokeratosis include sun exposure, immunosuppression, and genetics.2-4 Overexpression of the protein p53 in porokeratosis lesions has been demonstrated in studies investigating the genetics of porokeratosis.5,6 A study of Chinese families with DSAP identified 3 different loci associated with DSAP: DSAP1, DSAP2, and DSAP3.2 The progression to cancer has been noted in all types of porokeratosis lesions. Malignancies include squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, and basal cell carcinoma.7,8

Many treatments have been tried for DSAP including cryotherapy, topical 5-fluorouracil, photodynamic therapy, and topical imiquimod with varying success.1 Our patient was treated with cryotherapy but had side effects from treatment including cellulitis and local infections with ulceration before finally healing.

Interestingly, our patient had a single lesion with pathology findings most consistent with DSAP at a later age. Although the pathology suggested DSAP, the size and solitary lesion was more consistent with porokeratosis of Mibelli. Porokeratosis of Mibelli can occur concurrently with DSAP,9 but we have not seen other lesions in this patient. We have educated our patient to be aware of other lesions that may occur in the future. Due to risk for malignant conversion, it is generally viewed as beneficial to treat patients who present with porokeratosis lesions. Our patient’s lesion ultimately cleared and he has not developed new lesions at 1-year follow-up.

Although DSAP generally presents in the third and fourth decades of life and porokeratosis of Mibelli during childhood, it is important to educate both dermatologists and primary care physicians to be aware of the possibility of both diagnoses in the elderly population.

- Rouhani P, Fischer M, Meehan S, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:24.

- Murase J, Gilliam AC, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis co-existing with linear and verrucous porokeratosis in an elderly woman: update on the genetics and clinical expression of porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:886-891.

- Lederman JS, Sober AJ, Lederman GS. Immunosuppression: a cause of porokeratosis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:75-79.

- Hernandez MH, Lai CH, Mallory SB. Disseminated porokeratosis associated with chronic renal failure: a new type of disseminated porokeratosis? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1568-1569.

- Magee JW, McCalmont TH, LeBoit PE. Overexpression of p53 tumor suppressor protein in porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:187-190.

- Arranz-Salas I, Sanz-Trelles A, Ojeda DB. p53 alterations in porokeratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:455-458.

- Curnow P, Foley P, Baker C. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas complicating linear porokeratosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:136-139.

- Lee HR, Han TY, Son SJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:536-538.

- Mehta V, Balachandran C. Simultaneous co-occurrence of porokeratosis of Mibelli with disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:390-391.

The Diagnosis: Porokeratosis of Mibelli

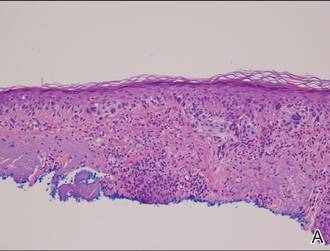

There are 5 variants of porokeratosis: disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), linear porokeratosis, porokeratosis of Mibelli, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, and punctate porokeratosis. The most common type is DSAP,1 which is characterized by multiple lesions on the body, particularly in sun-exposed areas. The distinguishing feature of porokeratosis is the cornoid lamella, which is made up of parakeratotic cells extending through the stratum corneum. There also is a thin or absent granular layer beneath it (Figure).2

Patients generally present in the third and fourth decades of life.1 Risk factors for porokeratosis include sun exposure, immunosuppression, and genetics.2-4 Overexpression of the protein p53 in porokeratosis lesions has been demonstrated in studies investigating the genetics of porokeratosis.5,6 A study of Chinese families with DSAP identified 3 different loci associated with DSAP: DSAP1, DSAP2, and DSAP3.2 The progression to cancer has been noted in all types of porokeratosis lesions. Malignancies include squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, and basal cell carcinoma.7,8

Many treatments have been tried for DSAP including cryotherapy, topical 5-fluorouracil, photodynamic therapy, and topical imiquimod with varying success.1 Our patient was treated with cryotherapy but had side effects from treatment including cellulitis and local infections with ulceration before finally healing.

Interestingly, our patient had a single lesion with pathology findings most consistent with DSAP at a later age. Although the pathology suggested DSAP, the size and solitary lesion was more consistent with porokeratosis of Mibelli. Porokeratosis of Mibelli can occur concurrently with DSAP,9 but we have not seen other lesions in this patient. We have educated our patient to be aware of other lesions that may occur in the future. Due to risk for malignant conversion, it is generally viewed as beneficial to treat patients who present with porokeratosis lesions. Our patient’s lesion ultimately cleared and he has not developed new lesions at 1-year follow-up.

Although DSAP generally presents in the third and fourth decades of life and porokeratosis of Mibelli during childhood, it is important to educate both dermatologists and primary care physicians to be aware of the possibility of both diagnoses in the elderly population.

The Diagnosis: Porokeratosis of Mibelli

There are 5 variants of porokeratosis: disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), linear porokeratosis, porokeratosis of Mibelli, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, and punctate porokeratosis. The most common type is DSAP,1 which is characterized by multiple lesions on the body, particularly in sun-exposed areas. The distinguishing feature of porokeratosis is the cornoid lamella, which is made up of parakeratotic cells extending through the stratum corneum. There also is a thin or absent granular layer beneath it (Figure).2

Patients generally present in the third and fourth decades of life.1 Risk factors for porokeratosis include sun exposure, immunosuppression, and genetics.2-4 Overexpression of the protein p53 in porokeratosis lesions has been demonstrated in studies investigating the genetics of porokeratosis.5,6 A study of Chinese families with DSAP identified 3 different loci associated with DSAP: DSAP1, DSAP2, and DSAP3.2 The progression to cancer has been noted in all types of porokeratosis lesions. Malignancies include squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, and basal cell carcinoma.7,8

Many treatments have been tried for DSAP including cryotherapy, topical 5-fluorouracil, photodynamic therapy, and topical imiquimod with varying success.1 Our patient was treated with cryotherapy but had side effects from treatment including cellulitis and local infections with ulceration before finally healing.

Interestingly, our patient had a single lesion with pathology findings most consistent with DSAP at a later age. Although the pathology suggested DSAP, the size and solitary lesion was more consistent with porokeratosis of Mibelli. Porokeratosis of Mibelli can occur concurrently with DSAP,9 but we have not seen other lesions in this patient. We have educated our patient to be aware of other lesions that may occur in the future. Due to risk for malignant conversion, it is generally viewed as beneficial to treat patients who present with porokeratosis lesions. Our patient’s lesion ultimately cleared and he has not developed new lesions at 1-year follow-up.

Although DSAP generally presents in the third and fourth decades of life and porokeratosis of Mibelli during childhood, it is important to educate both dermatologists and primary care physicians to be aware of the possibility of both diagnoses in the elderly population.

- Rouhani P, Fischer M, Meehan S, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:24.

- Murase J, Gilliam AC, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis co-existing with linear and verrucous porokeratosis in an elderly woman: update on the genetics and clinical expression of porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:886-891.

- Lederman JS, Sober AJ, Lederman GS. Immunosuppression: a cause of porokeratosis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:75-79.

- Hernandez MH, Lai CH, Mallory SB. Disseminated porokeratosis associated with chronic renal failure: a new type of disseminated porokeratosis? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1568-1569.

- Magee JW, McCalmont TH, LeBoit PE. Overexpression of p53 tumor suppressor protein in porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:187-190.

- Arranz-Salas I, Sanz-Trelles A, Ojeda DB. p53 alterations in porokeratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:455-458.

- Curnow P, Foley P, Baker C. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas complicating linear porokeratosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:136-139.

- Lee HR, Han TY, Son SJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:536-538.

- Mehta V, Balachandran C. Simultaneous co-occurrence of porokeratosis of Mibelli with disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:390-391.

- Rouhani P, Fischer M, Meehan S, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:24.

- Murase J, Gilliam AC, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis co-existing with linear and verrucous porokeratosis in an elderly woman: update on the genetics and clinical expression of porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:886-891.

- Lederman JS, Sober AJ, Lederman GS. Immunosuppression: a cause of porokeratosis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:75-79.

- Hernandez MH, Lai CH, Mallory SB. Disseminated porokeratosis associated with chronic renal failure: a new type of disseminated porokeratosis? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1568-1569.

- Magee JW, McCalmont TH, LeBoit PE. Overexpression of p53 tumor suppressor protein in porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:187-190.

- Arranz-Salas I, Sanz-Trelles A, Ojeda DB. p53 alterations in porokeratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:455-458.

- Curnow P, Foley P, Baker C. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas complicating linear porokeratosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:136-139.

- Lee HR, Han TY, Son SJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:536-538.

- Mehta V, Balachandran C. Simultaneous co-occurrence of porokeratosis of Mibelli with disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:390-391.

A 69-year-old white man presented with a solitary lesion on the left ankle. His medical history included hypertension and arthritis. He resided in Florida for 11 years but denied tanning and has had sensitive skin throughout his life. He had no other notable skin conditions, except for nummular eczema. He did not have a family history of skin cancer. Physical examination showed the single lesion on the left ankle.

Erythematous Scaly Patch on the Jawline

The Diagnosis: Amelanotic Melanoma In Situ

Histopathology revealed a broad asymmetric melanocytic proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, consisting both of singly dispersed cells as well as randomly positioned nests (Figure 1). The single cells demonstrated junctional confluence and extension along adnexal structures highlighted by melan-A stain (Figure 2). The melanocytes were markedly atypical with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei containing multiple nucleoli. No dermal involvement was seen. There was papillary dermal fibrosis and an active host lymphocytic response. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma in situ was made.

|

Figure 1. Histopathology revealed confluence of atypical melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction and pagetoid scatter of melanocytes to the spinous layer (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). Higher-power magnification highlighted the atypia of the individual melanocytes (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

Subsequent scouting punch biopsies at the superior, anterior, and posterior aspects of the lesion were performed (Figure 3). All 3 revealed a similar nested and single cell proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, confirming residual amelanotic melanoma in situ. The patient was referred to the otolaryngology department and underwent wide local excision with 5-mm margins and reconstructive repair.

Amelanotic melanoma comprises 2% to 8% of cutaneous melanomas. It is more common in fair-skinned elderly women with an average age of diagnosis of 61.8 years. Because features typically associated with melanoma such as asymmetry, border irregularity, and color variegation often are absent, amelanotic melanoma represents a notable diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Lesions can present nonspecifically as erythematous macules, papules, patches, or plaques and can have associated pruritus and scale.1,2

Clinical misdiagnoses for amelanotic melanoma include Bowen disease, basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, lichenoid keratosis, intradermal nevus, dermatofibroma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, nummular dermatitis, pyogenic granuloma, and granuloma annulare.1-6 There have been few case reports of amelanotic melanoma in situ, with most being the lentigo maligna variant that were initially clinically diagnosed as superficial basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, or dermatitis.7,8 In one case report, an amelanotic lentigo maligna was incidentally discovered after performing a mapping shave biopsy on what was normal-appearing skin.9

Dermoscopic evidence of vascular structures in lesions, including the presence of dotted vessels, milky red areas, and/or serpentine (linear irregular) vessels, may be the only clues to suggest amelanotic melanoma before biopsy. However, these findings are nonspecific and can be seen in other benign and malignant skin conditions.2

Complete surgical excision is the standard treatment of amelanotic melanoma in situ given its potential for invasion. However, the lack of pigment can make margins difficult to define. Because of its ability to detect disease beyond visual margins, Mohs micrographic surgery may have better cure rates than conventional excision.4 Prognosis for amelanotic melanoma is the same as other melanomas of equal thickness and location, though delay in diagnosis can adversely affect outcomes. Furthermore, amelanotic melanoma in situ can rapidly progress to invasive melanoma.3,5 Thus it is important to maintain clinical suspicion for amelanotic melanoma in fair-skinned elderly women presenting with a persistent or recurring erythematous scaly lesion on sun-exposed skin.

- Rahbari H, Nabai H, Mehregan AH, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a diagnostic conundrum— presentation of four new cases. Cancer. 1996;77:2052-2057.

- Jaimes N, Braun RP, Thomas L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic characteristics of amelanotic melanomas that are not of the nodular subtype. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:591-596.

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:731-734.

- Conrad N, Jackson B, Goldberg L. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a unique case presentation. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:408-411.

- Cliff S, Otter M, Holden CA. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma of the face: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:177-179.

- Dalton SR, Fillman EP, Altman CE, et al. Atypical junctional melanocytic proliferations in benign lichenoid keratosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:706-709.

- Paver K, Stewart M, Kossard S, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna. Australas J Dermatol. 1981;22:106-108.

- Lewis JE. Lentigo maligna presenting as an eczematous lesion. Cutis. 1987;40:357-359.

- Perera E, Mellick N, Teng P, et al. A clinically invisible melanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:e58-e59.

The Diagnosis: Amelanotic Melanoma In Situ

Histopathology revealed a broad asymmetric melanocytic proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, consisting both of singly dispersed cells as well as randomly positioned nests (Figure 1). The single cells demonstrated junctional confluence and extension along adnexal structures highlighted by melan-A stain (Figure 2). The melanocytes were markedly atypical with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei containing multiple nucleoli. No dermal involvement was seen. There was papillary dermal fibrosis and an active host lymphocytic response. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma in situ was made.

|

Figure 1. Histopathology revealed confluence of atypical melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction and pagetoid scatter of melanocytes to the spinous layer (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). Higher-power magnification highlighted the atypia of the individual melanocytes (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

Subsequent scouting punch biopsies at the superior, anterior, and posterior aspects of the lesion were performed (Figure 3). All 3 revealed a similar nested and single cell proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, confirming residual amelanotic melanoma in situ. The patient was referred to the otolaryngology department and underwent wide local excision with 5-mm margins and reconstructive repair.

Amelanotic melanoma comprises 2% to 8% of cutaneous melanomas. It is more common in fair-skinned elderly women with an average age of diagnosis of 61.8 years. Because features typically associated with melanoma such as asymmetry, border irregularity, and color variegation often are absent, amelanotic melanoma represents a notable diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Lesions can present nonspecifically as erythematous macules, papules, patches, or plaques and can have associated pruritus and scale.1,2

Clinical misdiagnoses for amelanotic melanoma include Bowen disease, basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, lichenoid keratosis, intradermal nevus, dermatofibroma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, nummular dermatitis, pyogenic granuloma, and granuloma annulare.1-6 There have been few case reports of amelanotic melanoma in situ, with most being the lentigo maligna variant that were initially clinically diagnosed as superficial basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, or dermatitis.7,8 In one case report, an amelanotic lentigo maligna was incidentally discovered after performing a mapping shave biopsy on what was normal-appearing skin.9

Dermoscopic evidence of vascular structures in lesions, including the presence of dotted vessels, milky red areas, and/or serpentine (linear irregular) vessels, may be the only clues to suggest amelanotic melanoma before biopsy. However, these findings are nonspecific and can be seen in other benign and malignant skin conditions.2

Complete surgical excision is the standard treatment of amelanotic melanoma in situ given its potential for invasion. However, the lack of pigment can make margins difficult to define. Because of its ability to detect disease beyond visual margins, Mohs micrographic surgery may have better cure rates than conventional excision.4 Prognosis for amelanotic melanoma is the same as other melanomas of equal thickness and location, though delay in diagnosis can adversely affect outcomes. Furthermore, amelanotic melanoma in situ can rapidly progress to invasive melanoma.3,5 Thus it is important to maintain clinical suspicion for amelanotic melanoma in fair-skinned elderly women presenting with a persistent or recurring erythematous scaly lesion on sun-exposed skin.

The Diagnosis: Amelanotic Melanoma In Situ

Histopathology revealed a broad asymmetric melanocytic proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, consisting both of singly dispersed cells as well as randomly positioned nests (Figure 1). The single cells demonstrated junctional confluence and extension along adnexal structures highlighted by melan-A stain (Figure 2). The melanocytes were markedly atypical with enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei containing multiple nucleoli. No dermal involvement was seen. There was papillary dermal fibrosis and an active host lymphocytic response. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of amelanotic melanoma in situ was made.

|

Figure 1. Histopathology revealed confluence of atypical melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction and pagetoid scatter of melanocytes to the spinous layer (A)(H&E, original magnification ×4). Higher-power magnification highlighted the atypia of the individual melanocytes (B)(H&E, original magnification ×10). |

Subsequent scouting punch biopsies at the superior, anterior, and posterior aspects of the lesion were performed (Figure 3). All 3 revealed a similar nested and single cell proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, confirming residual amelanotic melanoma in situ. The patient was referred to the otolaryngology department and underwent wide local excision with 5-mm margins and reconstructive repair.

Amelanotic melanoma comprises 2% to 8% of cutaneous melanomas. It is more common in fair-skinned elderly women with an average age of diagnosis of 61.8 years. Because features typically associated with melanoma such as asymmetry, border irregularity, and color variegation often are absent, amelanotic melanoma represents a notable diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Lesions can present nonspecifically as erythematous macules, papules, patches, or plaques and can have associated pruritus and scale.1,2

Clinical misdiagnoses for amelanotic melanoma include Bowen disease, basal cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis, lichenoid keratosis, intradermal nevus, dermatofibroma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, nummular dermatitis, pyogenic granuloma, and granuloma annulare.1-6 There have been few case reports of amelanotic melanoma in situ, with most being the lentigo maligna variant that were initially clinically diagnosed as superficial basal cell carcinoma, Bowen disease, or dermatitis.7,8 In one case report, an amelanotic lentigo maligna was incidentally discovered after performing a mapping shave biopsy on what was normal-appearing skin.9

Dermoscopic evidence of vascular structures in lesions, including the presence of dotted vessels, milky red areas, and/or serpentine (linear irregular) vessels, may be the only clues to suggest amelanotic melanoma before biopsy. However, these findings are nonspecific and can be seen in other benign and malignant skin conditions.2

Complete surgical excision is the standard treatment of amelanotic melanoma in situ given its potential for invasion. However, the lack of pigment can make margins difficult to define. Because of its ability to detect disease beyond visual margins, Mohs micrographic surgery may have better cure rates than conventional excision.4 Prognosis for amelanotic melanoma is the same as other melanomas of equal thickness and location, though delay in diagnosis can adversely affect outcomes. Furthermore, amelanotic melanoma in situ can rapidly progress to invasive melanoma.3,5 Thus it is important to maintain clinical suspicion for amelanotic melanoma in fair-skinned elderly women presenting with a persistent or recurring erythematous scaly lesion on sun-exposed skin.

- Rahbari H, Nabai H, Mehregan AH, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a diagnostic conundrum— presentation of four new cases. Cancer. 1996;77:2052-2057.

- Jaimes N, Braun RP, Thomas L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic characteristics of amelanotic melanomas that are not of the nodular subtype. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:591-596.

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:731-734.

- Conrad N, Jackson B, Goldberg L. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a unique case presentation. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:408-411.

- Cliff S, Otter M, Holden CA. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma of the face: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:177-179.

- Dalton SR, Fillman EP, Altman CE, et al. Atypical junctional melanocytic proliferations in benign lichenoid keratosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:706-709.

- Paver K, Stewart M, Kossard S, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna. Australas J Dermatol. 1981;22:106-108.

- Lewis JE. Lentigo maligna presenting as an eczematous lesion. Cutis. 1987;40:357-359.

- Perera E, Mellick N, Teng P, et al. A clinically invisible melanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:e58-e59.

- Rahbari H, Nabai H, Mehregan AH, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a diagnostic conundrum— presentation of four new cases. Cancer. 1996;77:2052-2057.

- Jaimes N, Braun RP, Thomas L, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic characteristics of amelanotic melanomas that are not of the nodular subtype. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:591-596.

- Koch SE, Lange JR. Amelanotic melanoma: the great masquerader. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:731-734.

- Conrad N, Jackson B, Goldberg L. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma: a unique case presentation. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:408-411.

- Cliff S, Otter M, Holden CA. Amelanotic lentigo maligna melanoma of the face: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:177-179.

- Dalton SR, Fillman EP, Altman CE, et al. Atypical junctional melanocytic proliferations in benign lichenoid keratosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:706-709.

- Paver K, Stewart M, Kossard S, et al. Amelanotic lentigo maligna. Australas J Dermatol. 1981;22:106-108.

- Lewis JE. Lentigo maligna presenting as an eczematous lesion. Cutis. 1987;40:357-359.

- Perera E, Mellick N, Teng P, et al. A clinically invisible melanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:e58-e59.

Atypia of the individual melanocytes.

Melan-A stain highlighted the density and confluence of melanocytes within the epidermis.

Three scouting punch biopsies were performed along the periphery of the lesion.

A 70-year-old white woman with a history of basal cell carcinoma presented with a 2.7×1.9-cm ill-defined, erythematous, scaly patch along the left side of the jawline. Ten months prior to presentation, the lesion appeared as a grayish macule that was clinically diagnosed as a pigmented actinic keratosis and was treated with cryotherapy with resolution noted at 6-month follow-up. Differential diagnosis of the current lesion included actinic keratosis, lichenoid keratosis, and superficial basal cell carcinoma. A shave biopsy was performed.

Scalp Mass Is Painful and Oozes Pus

ANSWER

The correct answer is oral terbinafine or griseofulvin, plus a two-week taper of prednisone (choice “d”); further discussion follows. Most authorities recommend the use of oral steroids with terbinafine (choice “a”) or griseofulvin (choice “b”), to dampen the acute inflammatory reaction to the fungal antigen. Some sources advise the use of itraconazole (choice “c”) but not as a single agent.

DISCUSSION

This case is a classic representation of kerion, a type of tinea capitis. This distinctive presentation results from not only active localized fungal infection with one of the dermatophytes, but also an allergic response to the fungal antigen. (This antigen can also trigger a widespread eczematous rash called an id reaction.) The resulting boggy, tender mass often oozes pus and usually provokes significant localized adenopathy.

A more common type of tinea capitis is uncomplicated dermatophytic infection of the scalp, presenting as mild localized scaling and modest hair loss, with no edema or redness to speak of. Kerion, by contrast, is far more acute and involves an impressive amount of localized redness and edema, along with modest hair loss, purulence, bloody drainage, and marked tenderness. Untreated, kerion can result in permanent scarring alopecia.

Several different dermatophytes have been isolated from kerions, including Trichophyton tonsurans, T violaceum, and various members of the Microsporum family. These zoophilic or geophilic organisms affect children far more than adults. Distinguishing the causative type is significant, because different drugs are required to effectively treat each. This is why a fungal culture is done at the outset.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy may be necessary, with the sample divided for processing of default H&E stains and for fungal culture. Other information can be obtained by plucking a few hairs from the mass and examining them under 10x power to see if fungal hyphae are confined to the insides of the hair shafts (endothrix) or the outside of the shafts (ectothrix).

This is one situation in which KOH is not helpful for diagnosis: The organisms are too deep to obtain with a superficial scrape.

A number of scalp conditions can mimic a kerion, including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans. Several years ago, I had a patient who presented with a similar lesion that turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma—which eventually metastasized and led to his death.

TREATMENT

Treatment of more severe types of tinea capitis can be trying, even when the diagnosis is nailed down. The challenge becomes treating the problem long and strong enough to produce a cure.

In this case, I started the patient (who, at age 8, weighed 110 pounds) on a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) with a two-week taper of prednisone (40 mg). The expectation was that this would rapidly diminish the edema and pain while we waited for the culture results.

If the results showed the expected T tonsurans, treatment would continue as planned. If the cause turned out to be one of the Microsporum species, a switch to griseofulvin, at relatively high doses, would be considered.

ANSWER

The correct answer is oral terbinafine or griseofulvin, plus a two-week taper of prednisone (choice “d”); further discussion follows. Most authorities recommend the use of oral steroids with terbinafine (choice “a”) or griseofulvin (choice “b”), to dampen the acute inflammatory reaction to the fungal antigen. Some sources advise the use of itraconazole (choice “c”) but not as a single agent.

DISCUSSION

This case is a classic representation of kerion, a type of tinea capitis. This distinctive presentation results from not only active localized fungal infection with one of the dermatophytes, but also an allergic response to the fungal antigen. (This antigen can also trigger a widespread eczematous rash called an id reaction.) The resulting boggy, tender mass often oozes pus and usually provokes significant localized adenopathy.

A more common type of tinea capitis is uncomplicated dermatophytic infection of the scalp, presenting as mild localized scaling and modest hair loss, with no edema or redness to speak of. Kerion, by contrast, is far more acute and involves an impressive amount of localized redness and edema, along with modest hair loss, purulence, bloody drainage, and marked tenderness. Untreated, kerion can result in permanent scarring alopecia.

Several different dermatophytes have been isolated from kerions, including Trichophyton tonsurans, T violaceum, and various members of the Microsporum family. These zoophilic or geophilic organisms affect children far more than adults. Distinguishing the causative type is significant, because different drugs are required to effectively treat each. This is why a fungal culture is done at the outset.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy may be necessary, with the sample divided for processing of default H&E stains and for fungal culture. Other information can be obtained by plucking a few hairs from the mass and examining them under 10x power to see if fungal hyphae are confined to the insides of the hair shafts (endothrix) or the outside of the shafts (ectothrix).

This is one situation in which KOH is not helpful for diagnosis: The organisms are too deep to obtain with a superficial scrape.

A number of scalp conditions can mimic a kerion, including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans. Several years ago, I had a patient who presented with a similar lesion that turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma—which eventually metastasized and led to his death.

TREATMENT

Treatment of more severe types of tinea capitis can be trying, even when the diagnosis is nailed down. The challenge becomes treating the problem long and strong enough to produce a cure.

In this case, I started the patient (who, at age 8, weighed 110 pounds) on a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) with a two-week taper of prednisone (40 mg). The expectation was that this would rapidly diminish the edema and pain while we waited for the culture results.

If the results showed the expected T tonsurans, treatment would continue as planned. If the cause turned out to be one of the Microsporum species, a switch to griseofulvin, at relatively high doses, would be considered.

ANSWER

The correct answer is oral terbinafine or griseofulvin, plus a two-week taper of prednisone (choice “d”); further discussion follows. Most authorities recommend the use of oral steroids with terbinafine (choice “a”) or griseofulvin (choice “b”), to dampen the acute inflammatory reaction to the fungal antigen. Some sources advise the use of itraconazole (choice “c”) but not as a single agent.

DISCUSSION

This case is a classic representation of kerion, a type of tinea capitis. This distinctive presentation results from not only active localized fungal infection with one of the dermatophytes, but also an allergic response to the fungal antigen. (This antigen can also trigger a widespread eczematous rash called an id reaction.) The resulting boggy, tender mass often oozes pus and usually provokes significant localized adenopathy.

A more common type of tinea capitis is uncomplicated dermatophytic infection of the scalp, presenting as mild localized scaling and modest hair loss, with no edema or redness to speak of. Kerion, by contrast, is far more acute and involves an impressive amount of localized redness and edema, along with modest hair loss, purulence, bloody drainage, and marked tenderness. Untreated, kerion can result in permanent scarring alopecia.

Several different dermatophytes have been isolated from kerions, including Trichophyton tonsurans, T violaceum, and various members of the Microsporum family. These zoophilic or geophilic organisms affect children far more than adults. Distinguishing the causative type is significant, because different drugs are required to effectively treat each. This is why a fungal culture is done at the outset.

When the diagnosis is in doubt, a punch biopsy may be necessary, with the sample divided for processing of default H&E stains and for fungal culture. Other information can be obtained by plucking a few hairs from the mass and examining them under 10x power to see if fungal hyphae are confined to the insides of the hair shafts (endothrix) or the outside of the shafts (ectothrix).

This is one situation in which KOH is not helpful for diagnosis: The organisms are too deep to obtain with a superficial scrape.

A number of scalp conditions can mimic a kerion, including lichen planopilaris and folliculitis decalvans. Several years ago, I had a patient who presented with a similar lesion that turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma—which eventually metastasized and led to his death.

TREATMENT

Treatment of more severe types of tinea capitis can be trying, even when the diagnosis is nailed down. The challenge becomes treating the problem long and strong enough to produce a cure.

In this case, I started the patient (who, at age 8, weighed 110 pounds) on a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) with a two-week taper of prednisone (40 mg). The expectation was that this would rapidly diminish the edema and pain while we waited for the culture results.

If the results showed the expected T tonsurans, treatment would continue as planned. If the cause turned out to be one of the Microsporum species, a switch to griseofulvin, at relatively high doses, would be considered.

Four weeks ago, an 8-year-old boy developed a lesion in his scalp that manifested rather quickly and caused pain. Treatment with both topical medications (triple-antibiotic cream and mupirocin cream) and oral antibiotics (cephalexin and trimethoprim/sulfa) has failed to resolve the problem, so his mother brings him to dermatology for evaluation. The patient is afebrile but complains of fatigue. His mother denies any other health problems for the child. There is no history of foreign travel, and the patient’s brother is healthy. The boy is in no acute distress but complains of tenderness on palpation of the lesion. The mass in his left nuchal scalp, which measures 4 cm, is impressively swollen, boggy, wet, and inflamed. Numerous red folliculocentric papules—many oozing pus—are seen on the surface. Located inferiorly to the lesion on the neck is a firm, palpable subcutaneous mass. Examination of the rest of the scalp reveals nothing of note. The clinical presentation and lack of response to oral antibiotics yield a presumptive diagnosis of kerion. A fungal culture is taken, with plans to prescribe appropriate medication.

What’s Wrong With This Picture?

ANSWER

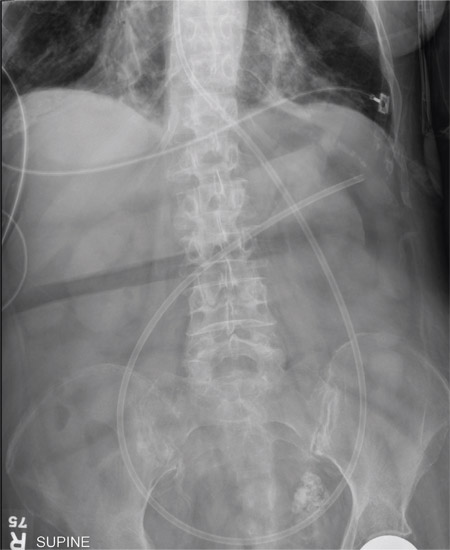

The radiograph shows an enteric tube passing through the gastrointestinal tract. However, it extends low into the left lower quadrant, loops around the right lower quadrant, and then heads up toward the left upper quadrant. Such a course is atypical and concerning for displaced position.

The radiologists concurred, and it was decided to instill some water-soluble contrast and repeat the KUB for further evaluation. That image is shown here. Note that the contrast does not appear to be in the stomach, as no gastric folds are visible. It accumulates in the left upper quadrant, under the diaphragm. Such a finding is concerning for possible gastric perforation.

The tube was promptly withdrawn, and urgent surgical consultation was obtained.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an enteric tube passing through the gastrointestinal tract. However, it extends low into the left lower quadrant, loops around the right lower quadrant, and then heads up toward the left upper quadrant. Such a course is atypical and concerning for displaced position.

The radiologists concurred, and it was decided to instill some water-soluble contrast and repeat the KUB for further evaluation. That image is shown here. Note that the contrast does not appear to be in the stomach, as no gastric folds are visible. It accumulates in the left upper quadrant, under the diaphragm. Such a finding is concerning for possible gastric perforation.

The tube was promptly withdrawn, and urgent surgical consultation was obtained.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an enteric tube passing through the gastrointestinal tract. However, it extends low into the left lower quadrant, loops around the right lower quadrant, and then heads up toward the left upper quadrant. Such a course is atypical and concerning for displaced position.

The radiologists concurred, and it was decided to instill some water-soluble contrast and repeat the KUB for further evaluation. That image is shown here. Note that the contrast does not appear to be in the stomach, as no gastric folds are visible. It accumulates in the left upper quadrant, under the diaphragm. Such a finding is concerning for possible gastric perforation.

The tube was promptly withdrawn, and urgent surgical consultation was obtained.

A 90-year-old woman, admitted for altered mental status, just had a nasogastric tube placed to facilitate nutrition and medication delivery. The ICU nurse asks you to review an abdominal radiograph to confirm correct placement, since several attempts by various hospital personnel were required before they felt they had the tube in place. The patient is otherwise currently stable, per the nurse’s report. Her vital signs are stable, and she will arouse to minimal stimulation, although she continues to demonstrate confusion. Portable KUB radiograph is shown. What is your impression?

Man Collapses While Playing Basketball

ANSWER

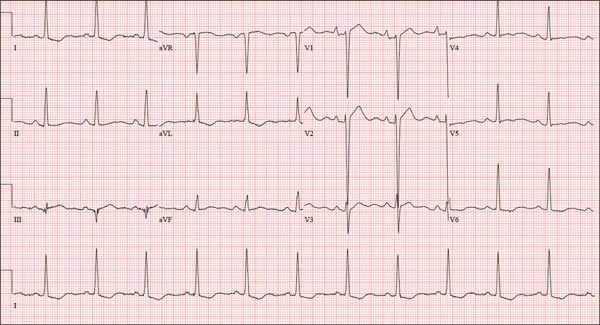

The correct interpretation is normal sinus rhythm with an acute anterior MI (STEMI) and inferolateral injury. In the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy and left bundle-branch block, an acute anterior MI manifests with new ST elevations ≥ 0.1 mV, measured at the J point in leads V2-V3. Inferolateral injury is indicated by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF, as well as ST elevations in leads V4-V6.

Laboratory findings confirmed the diagnosis of a new infarction, and cardiac catheterization revealed significant blockage in the proximal left anterior descending and circumflex coronary arteries. These were treated percutaneously, and the patient recovered without sequelae.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is normal sinus rhythm with an acute anterior MI (STEMI) and inferolateral injury. In the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy and left bundle-branch block, an acute anterior MI manifests with new ST elevations ≥ 0.1 mV, measured at the J point in leads V2-V3. Inferolateral injury is indicated by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF, as well as ST elevations in leads V4-V6.

Laboratory findings confirmed the diagnosis of a new infarction, and cardiac catheterization revealed significant blockage in the proximal left anterior descending and circumflex coronary arteries. These were treated percutaneously, and the patient recovered without sequelae.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation is normal sinus rhythm with an acute anterior MI (STEMI) and inferolateral injury. In the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy and left bundle-branch block, an acute anterior MI manifests with new ST elevations ≥ 0.1 mV, measured at the J point in leads V2-V3. Inferolateral injury is indicated by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF, as well as ST elevations in leads V4-V6.

Laboratory findings confirmed the diagnosis of a new infarction, and cardiac catheterization revealed significant blockage in the proximal left anterior descending and circumflex coronary arteries. These were treated percutaneously, and the patient recovered without sequelae.

A 46-year-old man is playing intramural basketball when he suddenly collapses on the court. Bystander CPR is begun; the patient is revived immediately without need for cardioversion or defibrillation. He regains consciousness before EMS arrives and, although he does not recall collapsing, he is able to tell them that he has been experiencing chest discomfort all morning (but didn’t mention it to anyone). The patient is transported in stable condition to the emergency department (ED) via BLS ambulance. The total time from his collapse to hospital arrival is 77 minutes, due to the rural location of the high school where he was playing. When you see the patient in the ED, you learn that he has no prior history of cardiac symptoms. He specifically denies chest pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, or peripheral edema, although with additional questioning, he admits to having ongoing substernal pressure. There is no history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or thyroid disorder. Surgical history is remarkable for a left anterior cruciate repair that he underwent while in high school. He is employed as an assistant principal at a local high school, is married with two children, and is active in his community—a fact borne out by the volume of well-wishers in the waiting area, inquiring about his status. He does not smoke, drinks two or three beers on the weekend, and does not use recreational drugs, although he admits he tried marijuana in college and didn’t care for it. He is not taking any routine prescription or holistic medications and has no known drug allergies. He reports taking ibuprofen on occasion but adds that he hasn’t taken any in the past three weeks. Review of systems is remarkable for a recent cold. He says he has a residual cough and runny nose but does not feel like he’s currently sick. He considers himself to be very healthy and a role model for the students and faculty at his school. Physical exam reveals a blood pressure of 142/84 mm Hg; pulse, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 99% on 2 L of oxygen. His weight is 189 lb and his height, 74 in. He appears anxious and apprehensive but is alert and cooperative. Pertinent physical findings include a regular rate and rhythm, clear lungs, a soft, nontender abdomen, and no peripheral edema or jugular venous distention. The neurologic exam is intact. Specimens are drawn and sent to the lab for processing. While awaiting the results, you review the ECG taken at the time of arrival. It shows a ventricular rate of 80 beats/min; PR interval, 162 ms; QRS duration, 106 ms; QT/QTc interval, 370/426 ms; P axis, 51°; R axis, –20°; and T axis, 70°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Vegetative Sacral Plaque in a Patient With Human Immunodeficiency Virus

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Vegetans

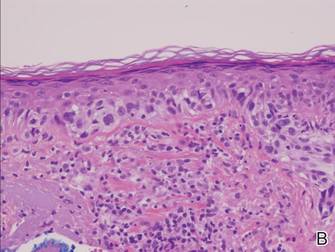

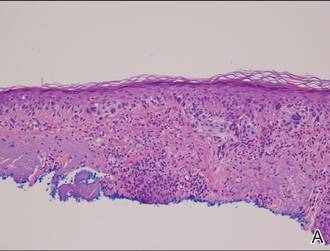

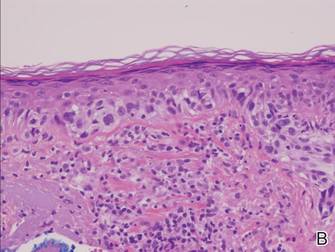

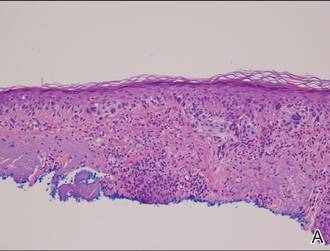

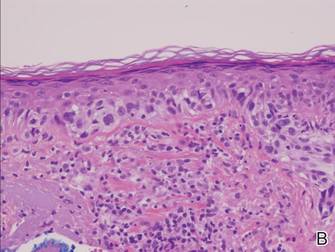

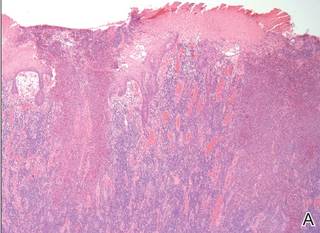

Histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulation tissue, ulceration, and abundant exudate joined by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate that included a myriad of eosinophils (Figure, A). At higher power (Figure, B), many single and multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes showed ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin within zones of ulceration and crust. Viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody assay identified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with herpes simplex vegetans. He was initially treated with oral acyclovir and then oral famciclovir but showed minimal improvement. Eventually, he was referred to surgery and the mass was totally excised with clear margins and no evidence of underlying malignancy.

|

| Histopathology revealed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Many multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes with ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin were shown (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with a notably increased incidence and prevalence among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 Although typical HSV manifestation in immunocompetent patients includes clustered vesicles and/or ulcerations, immunocompromised patients may have unusual presentations, such as persistent and extensive ulcerations or nodular hyperkeratotic lesions.2,3 Herpes vegetans, a term used to describe these atypical exophytic lesions, rarely has been reported in literature, but its presence should raise suspicion for possible underlying immunocompromise. The pathogenesis behind the hypertrophic nature of these lesions is not well understood, but it is postulated that the immune dysregulation from concomitant HIV and HSV infection plays a role.2 Overproduction of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 by HIV-infected dermal dendritic cells causes an increase in antiapoptotic factors within the epidermis, resulting in enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and clinical hyperkeratosis.2,4

The differential diagnosis for herpes vegetans is somewhat broad, owing to the verrucous and often eroded appearance of the lesions. Biopsy and cultures can be obtained to differentiate from condyloma acuminatum, condyloma latum (secondary syphilis), pyoderma vegetans, pemphigus vegetans, granuloma inguinale, extraintestinal Crohn disease, deep fungal infections, cutaneous tuberculosis, and malignancy.2-4 Histopathology shows epithelial hyperplasia and ulceration with scattered multinucleate keratinocytes, usually at the periphery of the ulcer, and intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV. In addition, a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils is usually present beneath the base of the ulcer.2,4

Treatment options for herpes vegetans are limited due to the high prevalence of acyclovir-resistant (ACV-R) HSV-2 strains in HIV patients. Valacyclovir and penciclovir have been largely ineffective against ACV-R HSV due to their dependence on the same enzyme—thymidine kinase—involved in the mechanism of acyclovir resistance. Intravenous foscarnet and cidofovir have shown efficacy against ACV-R virus, but concerns of nephrotoxicity have limited their use over prolonged intervals.5 Castelo-Soccio et al6 reported promising results with intralesional cidofovir. This route of administration provides the advantage of increased bioavailability with reduced risk for nephrotoxicity.6 Finally, surgical resection may be considered for refractory lesions to circumvent the toxicity from systemically administered drugs.3

- Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

- Patel AB, Rosen T. Herpes vegetans as a sign of HIV infection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Chung VQ, Parker DC, Parker SR. Surgical excision for vegetative herpes simplex virus infection. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1374-1379.

- Beasley KL, Cooley GE, Kao GF, et al. Herpes simplex vegetans: atypical genital herpes infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):860-863.

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Vegetans

Histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulation tissue, ulceration, and abundant exudate joined by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate that included a myriad of eosinophils (Figure, A). At higher power (Figure, B), many single and multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes showed ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin within zones of ulceration and crust. Viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody assay identified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with herpes simplex vegetans. He was initially treated with oral acyclovir and then oral famciclovir but showed minimal improvement. Eventually, he was referred to surgery and the mass was totally excised with clear margins and no evidence of underlying malignancy.

|

| Histopathology revealed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Many multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes with ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin were shown (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with a notably increased incidence and prevalence among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 Although typical HSV manifestation in immunocompetent patients includes clustered vesicles and/or ulcerations, immunocompromised patients may have unusual presentations, such as persistent and extensive ulcerations or nodular hyperkeratotic lesions.2,3 Herpes vegetans, a term used to describe these atypical exophytic lesions, rarely has been reported in literature, but its presence should raise suspicion for possible underlying immunocompromise. The pathogenesis behind the hypertrophic nature of these lesions is not well understood, but it is postulated that the immune dysregulation from concomitant HIV and HSV infection plays a role.2 Overproduction of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 by HIV-infected dermal dendritic cells causes an increase in antiapoptotic factors within the epidermis, resulting in enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and clinical hyperkeratosis.2,4

The differential diagnosis for herpes vegetans is somewhat broad, owing to the verrucous and often eroded appearance of the lesions. Biopsy and cultures can be obtained to differentiate from condyloma acuminatum, condyloma latum (secondary syphilis), pyoderma vegetans, pemphigus vegetans, granuloma inguinale, extraintestinal Crohn disease, deep fungal infections, cutaneous tuberculosis, and malignancy.2-4 Histopathology shows epithelial hyperplasia and ulceration with scattered multinucleate keratinocytes, usually at the periphery of the ulcer, and intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV. In addition, a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils is usually present beneath the base of the ulcer.2,4

Treatment options for herpes vegetans are limited due to the high prevalence of acyclovir-resistant (ACV-R) HSV-2 strains in HIV patients. Valacyclovir and penciclovir have been largely ineffective against ACV-R HSV due to their dependence on the same enzyme—thymidine kinase—involved in the mechanism of acyclovir resistance. Intravenous foscarnet and cidofovir have shown efficacy against ACV-R virus, but concerns of nephrotoxicity have limited their use over prolonged intervals.5 Castelo-Soccio et al6 reported promising results with intralesional cidofovir. This route of administration provides the advantage of increased bioavailability with reduced risk for nephrotoxicity.6 Finally, surgical resection may be considered for refractory lesions to circumvent the toxicity from systemically administered drugs.3

The Diagnosis: Herpes Simplex Vegetans

Histopathologic examination using hematoxylin and eosin stain demonstrated marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with granulation tissue, ulceration, and abundant exudate joined by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate that included a myriad of eosinophils (Figure, A). At higher power (Figure, B), many single and multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes showed ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin within zones of ulceration and crust. Viral culture and direct fluorescent antibody assay identified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. Based on the clinical and histopathologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with herpes simplex vegetans. He was initially treated with oral acyclovir and then oral famciclovir but showed minimal improvement. Eventually, he was referred to surgery and the mass was totally excised with clear margins and no evidence of underlying malignancy.

|

| Histopathology revealed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). Many multinucleate acantholytic keratinocytes with ground-glass nuclei and peripheral margination of chromatin were shown (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, with a notably increased incidence and prevalence among individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 Although typical HSV manifestation in immunocompetent patients includes clustered vesicles and/or ulcerations, immunocompromised patients may have unusual presentations, such as persistent and extensive ulcerations or nodular hyperkeratotic lesions.2,3 Herpes vegetans, a term used to describe these atypical exophytic lesions, rarely has been reported in literature, but its presence should raise suspicion for possible underlying immunocompromise. The pathogenesis behind the hypertrophic nature of these lesions is not well understood, but it is postulated that the immune dysregulation from concomitant HIV and HSV infection plays a role.2 Overproduction of tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 by HIV-infected dermal dendritic cells causes an increase in antiapoptotic factors within the epidermis, resulting in enhanced keratinocyte proliferation and clinical hyperkeratosis.2,4

The differential diagnosis for herpes vegetans is somewhat broad, owing to the verrucous and often eroded appearance of the lesions. Biopsy and cultures can be obtained to differentiate from condyloma acuminatum, condyloma latum (secondary syphilis), pyoderma vegetans, pemphigus vegetans, granuloma inguinale, extraintestinal Crohn disease, deep fungal infections, cutaneous tuberculosis, and malignancy.2-4 Histopathology shows epithelial hyperplasia and ulceration with scattered multinucleate keratinocytes, usually at the periphery of the ulcer, and intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV. In addition, a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils is usually present beneath the base of the ulcer.2,4

Treatment options for herpes vegetans are limited due to the high prevalence of acyclovir-resistant (ACV-R) HSV-2 strains in HIV patients. Valacyclovir and penciclovir have been largely ineffective against ACV-R HSV due to their dependence on the same enzyme—thymidine kinase—involved in the mechanism of acyclovir resistance. Intravenous foscarnet and cidofovir have shown efficacy against ACV-R virus, but concerns of nephrotoxicity have limited their use over prolonged intervals.5 Castelo-Soccio et al6 reported promising results with intralesional cidofovir. This route of administration provides the advantage of increased bioavailability with reduced risk for nephrotoxicity.6 Finally, surgical resection may be considered for refractory lesions to circumvent the toxicity from systemically administered drugs.3

- Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

- Patel AB, Rosen T. Herpes vegetans as a sign of HIV infection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Chung VQ, Parker DC, Parker SR. Surgical excision for vegetative herpes simplex virus infection. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1374-1379.

- Beasley KL, Cooley GE, Kao GF, et al. Herpes simplex vegetans: atypical genital herpes infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):860-863.

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126.

- Severson JL, Tyring SK. Relation between herpes simplex viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infections. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1393-1397.

- Patel AB, Rosen T. Herpes vegetans as a sign of HIV infection. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6.

- Chung VQ, Parker DC, Parker SR. Surgical excision for vegetative herpes simplex virus infection. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1374-1379.

- Beasley KL, Cooley GE, Kao GF, et al. Herpes simplex vegetans: atypical genital herpes infection in a patient with common variable immunodeficiency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5, pt 2):860-863.

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320.

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126.

A 53-year-old man presented to our clinic with a sacral mass that had progressively enlarged over 2 years. The patient reported occasional oozing from the mass as well as pain when laying flat but denied fever or other symptoms. His medical history was remarkable for human immunodeficiency virus infection with variable adherence to a highly active antiretroviral therapy regimen. At the time of presentation, the patient had a CD4 lymphocyte count of 78 cells/mm3 (reference range, 500–1400 cells/mm3) and a viral load of 290 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL). Physical examination revealed a 10-cm discrete, moist and pink, exophytic plaque on the sacrum with superficial erosions. The plaque was nontender and without associated lymphadenopathy. The skin and mucous membranes were otherwise clear. A cutaneous biopsy specimen was obtained from the tumor and sent for histopathologic analysis.

A Prescription for Trouble

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy, and a prolonged QT interval. Normal sinus rhythm is indicated by a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, with a constant PR interval (see rhythm strip of lead I).

Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by the tall P waves in leads II, III, aVF, and V1. Note that there is no biphasic P wave in lead V1, so there is no evidence of accompanying left atrial enlargement.

High-voltage limb leads (sum of R in lead I and S in lead III ≥ 25 mm) or precordial leads (sum of S in V1 and R in V5 or V6 ≥ 35 mm) are indicative of left ventricular hypertrophy.

The QTc interval of 653 ms with a normal sinus rate is worrisome for prolonged QT syndrome. A review of the history shows the patient to be taking two drugs (lithium, azithromycin) known to prolong the QT interval. Although it is not known whether this patient has inherent QT prolongation, use of these types of agents should be avoided.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy, and a prolonged QT interval. Normal sinus rhythm is indicated by a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, with a constant PR interval (see rhythm strip of lead I).

Right atrial enlargement is evidenced by the tall P waves in leads II, III, aVF, and V1. Note that there is no biphasic P wave in lead V1, so there is no evidence of accompanying left atrial enlargement.