User login

Confusion Follows Malaise and Pain

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates innumerable small lytic defects throughout the calvarium. The patient’s confusion is most likely secondary to profound metabolic abnormalities. However, in the setting of lytic bone lesions, metabolic abnormalities of renal insufficiency, severe hypercalcemia, and hypomagnesemia, one must be concerned about an occult myeloma, and appropriate work-up must be done.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates innumerable small lytic defects throughout the calvarium. The patient’s confusion is most likely secondary to profound metabolic abnormalities. However, in the setting of lytic bone lesions, metabolic abnormalities of renal insufficiency, severe hypercalcemia, and hypomagnesemia, one must be concerned about an occult myeloma, and appropriate work-up must be done.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates innumerable small lytic defects throughout the calvarium. The patient’s confusion is most likely secondary to profound metabolic abnormalities. However, in the setting of lytic bone lesions, metabolic abnormalities of renal insufficiency, severe hypercalcemia, and hypomagnesemia, one must be concerned about an occult myeloma, and appropriate work-up must be done.

A 70-year-old woman is brought to the emergency department by her family for evaluation of acute altered mental status. According to the family, the patient has been complaining of general malaise, back pain, and severe joint pain for the past few days. Her confusion has increased in the past 24 hours. Medical history is significant for hypertension. Physical exam reveals an elderly female who appears somewhat uncomfortable. Vital signs are normal. Overall, her exam is stable. She has tenderness throughout her back and several of her joints, but no abnormal effusion or swelling is noted. While the patient is in triage, baseline labwork is ordered. The results indicate a serum creatinine of 1.83 mg/dL; serum calcium, 16.7 mg/dL; and serum magnesium, 1.4 mEq/L. Radiograph of the skull is obtained. What is your impression?

During Veggie Harvest, Chest Pain Hits

ANSWER

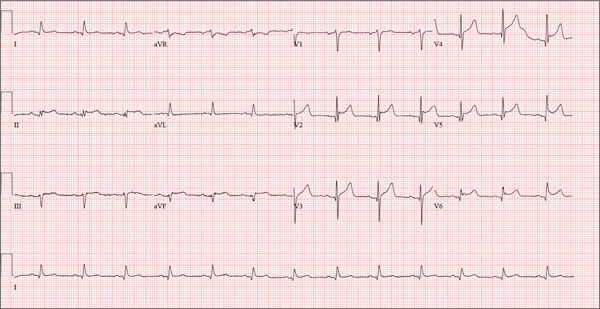

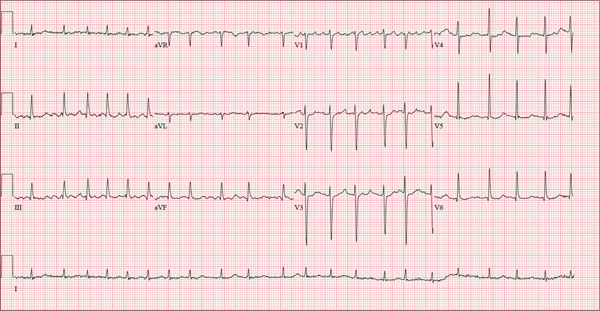

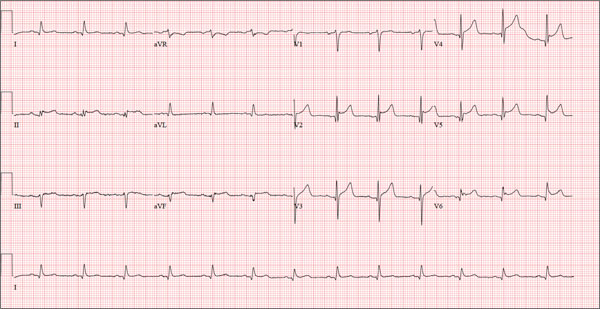

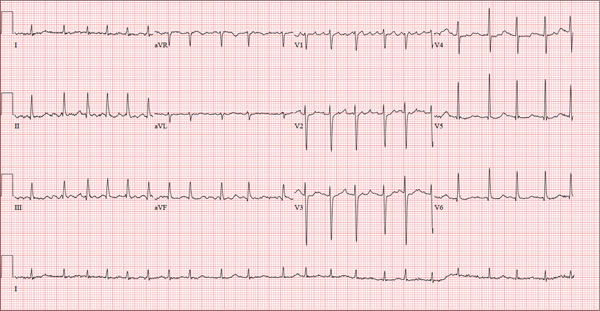

This ECG is representative of an acute anterior MI. This is evidenced by ST segment elevation in leads V2 through V4. Inferolateral injury is indicated by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF, as well as in leads V5 and V6.

Infarction was confirmed via laboratory data. Subsequent cardiac catheterization documented occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery.

ANSWER

This ECG is representative of an acute anterior MI. This is evidenced by ST segment elevation in leads V2 through V4. Inferolateral injury is indicated by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF, as well as in leads V5 and V6.

Infarction was confirmed via laboratory data. Subsequent cardiac catheterization documented occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery.

ANSWER

This ECG is representative of an acute anterior MI. This is evidenced by ST segment elevation in leads V2 through V4. Inferolateral injury is indicated by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF, as well as in leads V5 and V6.

Infarction was confirmed via laboratory data. Subsequent cardiac catheterization documented occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery.

A 48-year-old man arrives at your facility via emergency medical service (EMS). He is alert, oriented, and cooperative but reports substernal chest pain despite receiving two nitroglycerin tablets from the paramedics. The problem started while the patient was working in his garden, harvesting tomatoes and peppers but not doing anything particularly strenuous. The abrupt onset of chest pain caused him to stand up to catch his breath; he immediately became diaphoretic. The pain rated 10 out of 10 in severity and made him feel as if he’d been stabbed in the chest. After 10 minutes of persistent pain, he called to his neighbor, who contacted 911. The EMS arrived within six minutes. The paramedics found the patient conscious, profusely diaphoretic, and in severe pain; he was clutching his chest with his right fist. IV access was obtained, oxygen started, and sublingual nitroglycerin and aspirin given. The patient declined morphine due to a previous anaphylactic reaction to it. The pain subsided significantly, and the patient was loaded for transfer. During the 17-minute trip, his chest pain increased, and a second nitroglycerin tablet was given. It provided less relief than the previous one had. Medical history is remarkable for hypertension, smoking, adult-onset diabetes, and morbid obesity. The man has a primary care provider but hasn’t been seen in six years. He admits he is noncompliant with his medications because he just doesn’t like to take drugs—in fact, he hasn’t taken any of his prescribed medications for the past two years. He has never had chest pain prior to this event. Surgical history is remarkable for a cholecystectomy and a right knee replacement. His (unfilled) prescribed medications include a b-blocker, metformin, and a calcium channel blocker. He is allergic to morphine sulfate. He smokes marijuana on a daily basis because it calms his nerves. Review of systems is remarkable for multiple ulcers on the patient’s legs. He says he doesn’t require a cane for ambulation but prefers to walk with one. He also describes himself as a “nervous worrier,” hence his use of marijuana. Physical examination reveals an alert, anxious, and apprehensive man. His weight is 342 lb and his height, 70 in. He is afebrile and diaphoretic. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 164/98 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 97.4°F. Pertinent physical findings include no evidence of jugular venous distention or thyromegaly, clear lung sounds bilaterally, a regular rate and rhythm with distant muffled heart sounds, and no extra heart sounds or murmurs. The abdomen is obese, soft, and nontender. The peripheral pulses are equal bilaterally, and there is 2+ pitting edema present to the level of the knees. Multiple shallow ulcers are present on both lower legs, and a deep ulcer is present on the inferior surface of the left foot. After the patient is attached to telemetry monitoring and blood samples are drawn for analysis, an ECG is obtained. It reveals a ventricular rate of 80 beats/min; PR interval, 162 ms; QRS duration, 106 ms; QT/QTc interval, 370/426 ms; P axis, 51°; R axis, –20°; and T axis, 70°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Is It Ringworm, Herpes— Or Something Else Entirely?

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “c”), a superficial infection usually caused by a combination of staph and strep organisms.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) would have presented with white, tenacious scaling and would not have been acute in onset.

Eczema (choice “b”) is definitely possible, but the patient’s rash has features not seen with this condition; see Discussion for details.

Fungal infection (choice “d”) is also definitely in the differential, but it is unlikely given the negative KOH, the lack of any source for such infection, and the complete lack of response to tolnaftate cream.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo has also been called impetiginized dermatitis because it almost always starts with minor breaks in the skin as a result of conditions such as eczema, acne, contact dermatitis, or insect bite. Thus provided with access to deeper portions of the epithelial surface, bacterial organisms that normally cause no problems on intact skin are able to create a minor but annoying condition we have come to call impetigo.

Mistakenly called infantigo in large parts of the United States, impetigo is quite common but nonetheless alarming. Rarely associated with morbidity, it tends to resolve in two to three weeks at most, even without treatment.

Impetigo has the reputation of being highly contagious; given enough heat and humidity, close living conditions, and lack of regular bathing and/or adequate treatment, it can spread rapidly. Those conditions existed commonly 100 years ago, when bathing was sporadic and often cursory, and multiple family members lived and slept in close quarters. In those days before the introduction of antibiotics, there were no good topical antimicrobial agents, either.

Another factor played a major role in impetigo, bolstering its fearsome reputation. The strains of strep (group A b-hemolytic strep) that caused most impetigo in those days included several so-called nephritogenic strains that could lead to a dreaded complication: acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN). Also called Bright disease, it could and did lead to fatal renal failure—about which little could be done at the time.

Fortunately, such nephritogenic strains of strep are unusual now, with APSGN occurring at a rate of about 1:1,000,000 in developed countries. In those locations, most people live far different lives today, bathing and changing clothes daily and living in much less cramped quarters.

The patient’s atopy likely had an impact, for several reasons: Since staph colonization of atopic persons is quite common, it’s more likely that an infection will develop. Also, thinner skin that is easily broken, a plethora of complicating problems (eg, dry skin, eczema, contact dermatitis, and exaggerated reactions to insect bites), and a lower threshold for itching all make atopic persons more susceptible to infection.

Most likely, our patient had a touch of eczema or dry skin and scratched it. Then, as the condition progressed, she scratched it more. The peroxide she used would have been highly irritating, serving only to worsen matters.

From a diagnostic point of view, the honey-colored crust covering the lesion and the context in which it developed led to a provisional diagnosis of impetiginized dermatitis. She was treated with oral cephalexin (500 mg tid for 7 d), topical mupirocin (applied bid), and topical hydrocortisone cream 2.5% (daily application). At one week’s follow-up, the patient’s skin was almost totally clear. It’s very unlikely she’ll have any residual scarring or blemish.

Had the diagnosis been unclear, or had the patient not responded to treatment, other diagnoses would have been considered. Among them: discoid lupus, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and Darier disease.

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “c”), a superficial infection usually caused by a combination of staph and strep organisms.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) would have presented with white, tenacious scaling and would not have been acute in onset.

Eczema (choice “b”) is definitely possible, but the patient’s rash has features not seen with this condition; see Discussion for details.

Fungal infection (choice “d”) is also definitely in the differential, but it is unlikely given the negative KOH, the lack of any source for such infection, and the complete lack of response to tolnaftate cream.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo has also been called impetiginized dermatitis because it almost always starts with minor breaks in the skin as a result of conditions such as eczema, acne, contact dermatitis, or insect bite. Thus provided with access to deeper portions of the epithelial surface, bacterial organisms that normally cause no problems on intact skin are able to create a minor but annoying condition we have come to call impetigo.

Mistakenly called infantigo in large parts of the United States, impetigo is quite common but nonetheless alarming. Rarely associated with morbidity, it tends to resolve in two to three weeks at most, even without treatment.

Impetigo has the reputation of being highly contagious; given enough heat and humidity, close living conditions, and lack of regular bathing and/or adequate treatment, it can spread rapidly. Those conditions existed commonly 100 years ago, when bathing was sporadic and often cursory, and multiple family members lived and slept in close quarters. In those days before the introduction of antibiotics, there were no good topical antimicrobial agents, either.

Another factor played a major role in impetigo, bolstering its fearsome reputation. The strains of strep (group A b-hemolytic strep) that caused most impetigo in those days included several so-called nephritogenic strains that could lead to a dreaded complication: acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN). Also called Bright disease, it could and did lead to fatal renal failure—about which little could be done at the time.

Fortunately, such nephritogenic strains of strep are unusual now, with APSGN occurring at a rate of about 1:1,000,000 in developed countries. In those locations, most people live far different lives today, bathing and changing clothes daily and living in much less cramped quarters.

The patient’s atopy likely had an impact, for several reasons: Since staph colonization of atopic persons is quite common, it’s more likely that an infection will develop. Also, thinner skin that is easily broken, a plethora of complicating problems (eg, dry skin, eczema, contact dermatitis, and exaggerated reactions to insect bites), and a lower threshold for itching all make atopic persons more susceptible to infection.

Most likely, our patient had a touch of eczema or dry skin and scratched it. Then, as the condition progressed, she scratched it more. The peroxide she used would have been highly irritating, serving only to worsen matters.

From a diagnostic point of view, the honey-colored crust covering the lesion and the context in which it developed led to a provisional diagnosis of impetiginized dermatitis. She was treated with oral cephalexin (500 mg tid for 7 d), topical mupirocin (applied bid), and topical hydrocortisone cream 2.5% (daily application). At one week’s follow-up, the patient’s skin was almost totally clear. It’s very unlikely she’ll have any residual scarring or blemish.

Had the diagnosis been unclear, or had the patient not responded to treatment, other diagnoses would have been considered. Among them: discoid lupus, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and Darier disease.

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “c”), a superficial infection usually caused by a combination of staph and strep organisms.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) would have presented with white, tenacious scaling and would not have been acute in onset.

Eczema (choice “b”) is definitely possible, but the patient’s rash has features not seen with this condition; see Discussion for details.

Fungal infection (choice “d”) is also definitely in the differential, but it is unlikely given the negative KOH, the lack of any source for such infection, and the complete lack of response to tolnaftate cream.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo has also been called impetiginized dermatitis because it almost always starts with minor breaks in the skin as a result of conditions such as eczema, acne, contact dermatitis, or insect bite. Thus provided with access to deeper portions of the epithelial surface, bacterial organisms that normally cause no problems on intact skin are able to create a minor but annoying condition we have come to call impetigo.

Mistakenly called infantigo in large parts of the United States, impetigo is quite common but nonetheless alarming. Rarely associated with morbidity, it tends to resolve in two to three weeks at most, even without treatment.

Impetigo has the reputation of being highly contagious; given enough heat and humidity, close living conditions, and lack of regular bathing and/or adequate treatment, it can spread rapidly. Those conditions existed commonly 100 years ago, when bathing was sporadic and often cursory, and multiple family members lived and slept in close quarters. In those days before the introduction of antibiotics, there were no good topical antimicrobial agents, either.

Another factor played a major role in impetigo, bolstering its fearsome reputation. The strains of strep (group A b-hemolytic strep) that caused most impetigo in those days included several so-called nephritogenic strains that could lead to a dreaded complication: acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN). Also called Bright disease, it could and did lead to fatal renal failure—about which little could be done at the time.

Fortunately, such nephritogenic strains of strep are unusual now, with APSGN occurring at a rate of about 1:1,000,000 in developed countries. In those locations, most people live far different lives today, bathing and changing clothes daily and living in much less cramped quarters.

The patient’s atopy likely had an impact, for several reasons: Since staph colonization of atopic persons is quite common, it’s more likely that an infection will develop. Also, thinner skin that is easily broken, a plethora of complicating problems (eg, dry skin, eczema, contact dermatitis, and exaggerated reactions to insect bites), and a lower threshold for itching all make atopic persons more susceptible to infection.

Most likely, our patient had a touch of eczema or dry skin and scratched it. Then, as the condition progressed, she scratched it more. The peroxide she used would have been highly irritating, serving only to worsen matters.

From a diagnostic point of view, the honey-colored crust covering the lesion and the context in which it developed led to a provisional diagnosis of impetiginized dermatitis. She was treated with oral cephalexin (500 mg tid for 7 d), topical mupirocin (applied bid), and topical hydrocortisone cream 2.5% (daily application). At one week’s follow-up, the patient’s skin was almost totally clear. It’s very unlikely she’ll have any residual scarring or blemish.

Had the diagnosis been unclear, or had the patient not responded to treatment, other diagnoses would have been considered. Among them: discoid lupus, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, and Darier disease.

A 16-year-old girl is referred to dermatology by her pediatrician for evaluation of a rash on her face. She is currently taking acyclovir (dose unknown) as prescribed by her pediatrician for presumed herpetic infection. Previous treatment attempts with OTC tolnaftate cream and various OTC moisturizers have failed. The rash manifested several weeks ago with two scaly bumps on her left cheek and temple area, which the patient admits to “picking” at. Initially, the lesions itched a bit, but they became larger and more symptomatic after she applied hydrogen peroxide to them several times. She then began to scrub the lesions vigorously with antibacterial soap while continuing to apply the peroxide. Subsequently, she presented to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with “ringworm” (and advised to use tolnaftate cream), and then to her pediatrician, with the aforementioned result. Aside from seasonal allergies and periodic episodes of eczema, the patient’s health is excellent. She has no pets. Examination reveals large, annular, honey-colored crusts focally located on the left side of the patient’s face. Faint pinkness is noted peripherally around the lesions. Modest but palpable adenopathy is detected in the pretragal and submental nodal areas. Though symptomatic, the patient is in no distress. A KOH prep taken from the scaly periphery is negative for fungal elements.

Atrophic Plaques on the Back

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Pityriasis Versicolor

Pityriasis versicolor lesions accompanied by skin atrophy were first reported by De Graciansky and Mery1 in 1971. Since then, few reports have been described and it remains a rare condition.2-5 It manifests with oval to round, ivory-colored lesions with a typically depressed and sometimes finely pleated surface.3 The pathogenesis of the skin atrophy remains controversial. In some of the cases described, the onset of atrophy was related to long-term use of topical steroids.1 This fact as well as impaired barrier function due to fungal infection may explain the atrophy occurring only in the pityriasis versicolor lesions.2,6,7 Some authors call this disease “pityriasis versicolor pseudoatrophicans.”7 However, case reports have been described without use of topical corticosteroids. Crowson and Magro8 maintained that skin atrophy in these cases may occur due to mechanisms of delayed-type hypersensitivity and coined the term atrophying pityriasis versicolor as a variant of this disease. Our patient did not report prior use of topical corticosteroids.

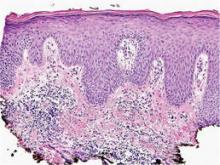

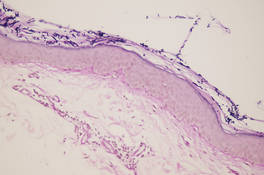

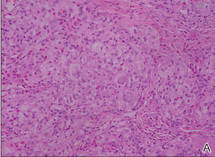

The differential diagnosis consists of other diseases that cause skin atrophy, such as collagen vascular diseases including anetoderma, morphea or atrophoderma, lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, and poikilodermatous T-cell dyscrasia; parapsoriasis or mycosis fungoides; sarcoidosis; cutis laxa; acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans; necrobiosis lipoidica; and atrophy due to intralesional steroid therapy.2,3,6-8 Histologic examination helps to achieve proper diagnosis. In our patient, cutaneous biopsy showed the presence of multiple short hyphae and spores in the horny layer with hematoxylin and eosin as well as periodic acid–Schiff stains, with typical “spaghetti and meatballs” appearance. Partial atrophy of the epidermis was observed with flattening of the epidermic ridges. A comparison with the normal areas could not be made because the biopsy was taken from cutaneous lesions without areas of uninvolved skin (Figure).

Treatment of this variant does not differ from conventional therapies for pityriasis versicolor, except that a longer treatment period might be required. Atrophy usually disappears, showing that atrophic pityriasis versicolor has a relatively good prognosis compared with other diseases that cause skin atrophy.2

Our patient was treated with ketoconazole gel 2% once daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions and no evidence of atrophy.

- De Graciansky P, Mery F. Atrophie sur pityriasis verscolor après corticotherapie locales prolongee. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971;78:295.

- Yang YS, Shin MK, Haw CR. Atrophying pityriasis versicolor: is this a new variant of pityriasis versicolor? Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:456-459.

- Romano C, Maritati E, Ghilardi A, et al. A case of pityriasis versicolor atrophicans. Mycoses. 2005;48:439-441.

- Park JS, Chae IS, Kim IY, et al. Achromatic atrophic macules and patches of upper extremities. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:270.

- Tellechea O, Cravo M, Brinca A, et al. Pityriasis versicolor atrophicans. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:287-288.

- Mazuecos Blanca J, García-Bravo B, Moreno Giménez JC, et al. Pseudoatrophic pityriasis versicolor. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1990;18:101-103.

- Tatnall FM, Rycroft RJ. Pityriasis versicolor with cutaneous atrophy induced by topical steroid application. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1985;10:258-261.

- Crowson AN, Magro CM. Atrophying tinea versicolor: a clinical and histological study of 12 patients. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:928-932.

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Pityriasis Versicolor

Pityriasis versicolor lesions accompanied by skin atrophy were first reported by De Graciansky and Mery1 in 1971. Since then, few reports have been described and it remains a rare condition.2-5 It manifests with oval to round, ivory-colored lesions with a typically depressed and sometimes finely pleated surface.3 The pathogenesis of the skin atrophy remains controversial. In some of the cases described, the onset of atrophy was related to long-term use of topical steroids.1 This fact as well as impaired barrier function due to fungal infection may explain the atrophy occurring only in the pityriasis versicolor lesions.2,6,7 Some authors call this disease “pityriasis versicolor pseudoatrophicans.”7 However, case reports have been described without use of topical corticosteroids. Crowson and Magro8 maintained that skin atrophy in these cases may occur due to mechanisms of delayed-type hypersensitivity and coined the term atrophying pityriasis versicolor as a variant of this disease. Our patient did not report prior use of topical corticosteroids.

The differential diagnosis consists of other diseases that cause skin atrophy, such as collagen vascular diseases including anetoderma, morphea or atrophoderma, lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, and poikilodermatous T-cell dyscrasia; parapsoriasis or mycosis fungoides; sarcoidosis; cutis laxa; acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans; necrobiosis lipoidica; and atrophy due to intralesional steroid therapy.2,3,6-8 Histologic examination helps to achieve proper diagnosis. In our patient, cutaneous biopsy showed the presence of multiple short hyphae and spores in the horny layer with hematoxylin and eosin as well as periodic acid–Schiff stains, with typical “spaghetti and meatballs” appearance. Partial atrophy of the epidermis was observed with flattening of the epidermic ridges. A comparison with the normal areas could not be made because the biopsy was taken from cutaneous lesions without areas of uninvolved skin (Figure).

Treatment of this variant does not differ from conventional therapies for pityriasis versicolor, except that a longer treatment period might be required. Atrophy usually disappears, showing that atrophic pityriasis versicolor has a relatively good prognosis compared with other diseases that cause skin atrophy.2

Our patient was treated with ketoconazole gel 2% once daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions and no evidence of atrophy.

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Pityriasis Versicolor

Pityriasis versicolor lesions accompanied by skin atrophy were first reported by De Graciansky and Mery1 in 1971. Since then, few reports have been described and it remains a rare condition.2-5 It manifests with oval to round, ivory-colored lesions with a typically depressed and sometimes finely pleated surface.3 The pathogenesis of the skin atrophy remains controversial. In some of the cases described, the onset of atrophy was related to long-term use of topical steroids.1 This fact as well as impaired barrier function due to fungal infection may explain the atrophy occurring only in the pityriasis versicolor lesions.2,6,7 Some authors call this disease “pityriasis versicolor pseudoatrophicans.”7 However, case reports have been described without use of topical corticosteroids. Crowson and Magro8 maintained that skin atrophy in these cases may occur due to mechanisms of delayed-type hypersensitivity and coined the term atrophying pityriasis versicolor as a variant of this disease. Our patient did not report prior use of topical corticosteroids.

The differential diagnosis consists of other diseases that cause skin atrophy, such as collagen vascular diseases including anetoderma, morphea or atrophoderma, lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, and poikilodermatous T-cell dyscrasia; parapsoriasis or mycosis fungoides; sarcoidosis; cutis laxa; acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans; necrobiosis lipoidica; and atrophy due to intralesional steroid therapy.2,3,6-8 Histologic examination helps to achieve proper diagnosis. In our patient, cutaneous biopsy showed the presence of multiple short hyphae and spores in the horny layer with hematoxylin and eosin as well as periodic acid–Schiff stains, with typical “spaghetti and meatballs” appearance. Partial atrophy of the epidermis was observed with flattening of the epidermic ridges. A comparison with the normal areas could not be made because the biopsy was taken from cutaneous lesions without areas of uninvolved skin (Figure).

Treatment of this variant does not differ from conventional therapies for pityriasis versicolor, except that a longer treatment period might be required. Atrophy usually disappears, showing that atrophic pityriasis versicolor has a relatively good prognosis compared with other diseases that cause skin atrophy.2

Our patient was treated with ketoconazole gel 2% once daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions and no evidence of atrophy.

- De Graciansky P, Mery F. Atrophie sur pityriasis verscolor après corticotherapie locales prolongee. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971;78:295.

- Yang YS, Shin MK, Haw CR. Atrophying pityriasis versicolor: is this a new variant of pityriasis versicolor? Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:456-459.

- Romano C, Maritati E, Ghilardi A, et al. A case of pityriasis versicolor atrophicans. Mycoses. 2005;48:439-441.

- Park JS, Chae IS, Kim IY, et al. Achromatic atrophic macules and patches of upper extremities. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:270.

- Tellechea O, Cravo M, Brinca A, et al. Pityriasis versicolor atrophicans. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:287-288.

- Mazuecos Blanca J, García-Bravo B, Moreno Giménez JC, et al. Pseudoatrophic pityriasis versicolor. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1990;18:101-103.

- Tatnall FM, Rycroft RJ. Pityriasis versicolor with cutaneous atrophy induced by topical steroid application. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1985;10:258-261.

- Crowson AN, Magro CM. Atrophying tinea versicolor: a clinical and histological study of 12 patients. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:928-932.

- De Graciansky P, Mery F. Atrophie sur pityriasis verscolor après corticotherapie locales prolongee. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971;78:295.

- Yang YS, Shin MK, Haw CR. Atrophying pityriasis versicolor: is this a new variant of pityriasis versicolor? Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:456-459.

- Romano C, Maritati E, Ghilardi A, et al. A case of pityriasis versicolor atrophicans. Mycoses. 2005;48:439-441.

- Park JS, Chae IS, Kim IY, et al. Achromatic atrophic macules and patches of upper extremities. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:270.

- Tellechea O, Cravo M, Brinca A, et al. Pityriasis versicolor atrophicans. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:287-288.

- Mazuecos Blanca J, García-Bravo B, Moreno Giménez JC, et al. Pseudoatrophic pityriasis versicolor. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1990;18:101-103.

- Tatnall FM, Rycroft RJ. Pityriasis versicolor with cutaneous atrophy induced by topical steroid application. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1985;10:258-261.

- Crowson AN, Magro CM. Atrophying tinea versicolor: a clinical and histological study of 12 patients. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:928-932.

A 41-year-old woman presented with recurrent skin color and violaceous atrophic plaques that were slightly depressed and symmetrically distributed on the back and upper extremities. She had been given oral azithromycin for 3 days without improvement. Laboratory tests, including IgE levels, were within reference range. Her medical history was unremarkable.

Erythematous Seropurulent Ulcerations

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

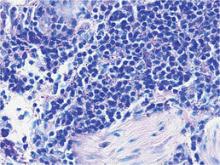

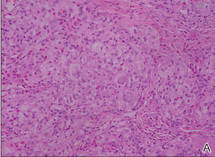

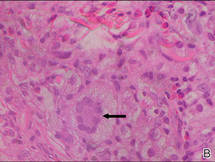

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.

1. Martin-Ezquerra G, Fisa R, Riera C, et al. Role of Leishmania spp. infestation in nondiagnostic cutaneous granulomatous lesions: report of a series of patients from a Western Mediterranean area. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:320-325.

2. Khatami A, Firooz A, Gorouhi F, et al. Treatment of acute old world cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systemic review of the randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:335.e1-335.e29.

3. Rojas R, Valderrama L, Valderrama M, et al. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1375-1383.

4. Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162.

5. Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126.

6. Croft S, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399-410.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.

1. Martin-Ezquerra G, Fisa R, Riera C, et al. Role of Leishmania spp. infestation in nondiagnostic cutaneous granulomatous lesions: report of a series of patients from a Western Mediterranean area. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:320-325.

2. Khatami A, Firooz A, Gorouhi F, et al. Treatment of acute old world cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systemic review of the randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:335.e1-335.e29.

3. Rojas R, Valderrama L, Valderrama M, et al. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1375-1383.

4. Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162.

5. Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126.

6. Croft S, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399-410.

1. Martin-Ezquerra G, Fisa R, Riera C, et al. Role of Leishmania spp. infestation in nondiagnostic cutaneous granulomatous lesions: report of a series of patients from a Western Mediterranean area. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:320-325.

2. Khatami A, Firooz A, Gorouhi F, et al. Treatment of acute old world cutaneous leishmaniasis: a systemic review of the randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:335.e1-335.e29.

3. Rojas R, Valderrama L, Valderrama M, et al. Resistance to antimony and treatment failure in human Leishmania (Viannia) infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1375-1383.

4. Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, et al. Unresponsiveness to glucantime treatment in Iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant Leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162.

5. Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111-126.

6. Croft S, Seifert K, Yardley V. Current scenario of drug development for leishmaniasis. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:399-410.

A 34-year-old male veteran who was otherwise healthy presented with multiple ulcerated skin lesions on the left arm and forearm as well as the chest. After returning to the United States from being stationed in Qatar and Saudi Arabia, he noticed multiple “bug bites” on the left arm that eventually progressed to larger crusted ulcerations. He denied fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, tenderness, or any other symptoms. He had been given doxycycline for a possible bacterial infection, but the lesions did not improve.

Asymptomatic Annular Plaques on the Neck

The Diagnosis: D-Penicillamine–Induced Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa

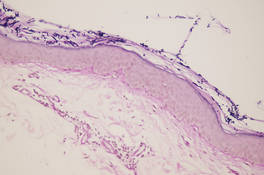

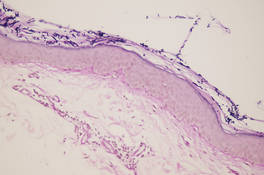

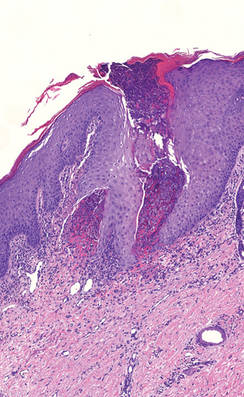

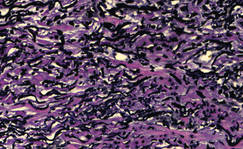

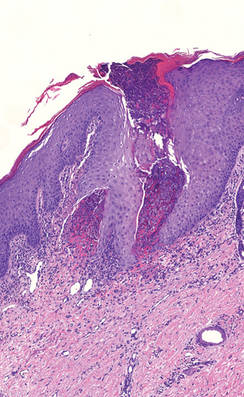

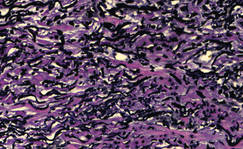

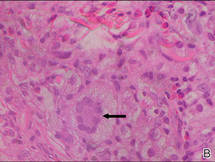

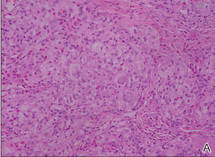

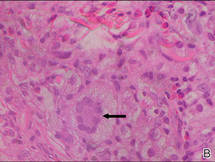

A 27-year-old woman was referred to our clinic by her rheumatologist with a 2×5-cm annular plaque on the right side of the lateral neck along with nummular plaques on the left side of 1 year’s duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for systemic sclerosis that had been treated with oral D-penicillamine (750 mg daily) for the last 10 years. Histopathologic examination of the skin biopsy specimen revealed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (Figure 3), which confirmed the diagnosis of D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS).

|

Figure 1. Nummular plaques on the left side of the |

|

Figure 2. A punch biopsy specimen showed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (H&E, original magnification ×10). |

|

Figure 3. Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (original magnification ×40). |

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is a rare entity that may present in many different settings. Some associated genetic conditions include Down syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, acrogeria, osteogenesis imperfecta, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, and moya-moya disease. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa also may be inherited in rare cases in an autosomal-dominant pattern.1 There are solitary reports of EPS in the setting of renal disease, morphea, and systemic sclerosis. Most cases of EPS are iatrogenically acquired. As first reported in 1973, long-term D-penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease has been classically associated with the rare development of EPS.2 Putative mechanisms include copper chelation by D-penicillamine in the setting of altered copper homeostasis in Wilson disease and subsequent inhibition of elastic fiber cross-linking by copper-dependent lysyl oxidase. Another proposed mechanism is the direct inhibition of collagen cross-linking by D-penicillamine resulting in abnormal elastic fiber maturation.3 Outside of the context of Wilson disease, D-penicillamine–induced EPS also has developed during the treatment of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and cystinuria.4 Our patient withsystemic sclerosis also exemplifies the possibility of developing EPS from long-term D-penicillamine therapy even in the absence of coexisting Wilson disease.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa lesions classically present as asymptomatic, serpiginously arranged, hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, and annular plaques in young adults and children. Lesions usually present on the neck, though other locations have been described. Histologically, transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers, degenerated keratinocytes, and collagen is seen in the background of a foreign-body reaction with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Elastin stains show increased thickened elastic fibers in the dermis underlying the perforation. The histology of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is distinctive in that the elastic fibers are arranged in a bramble bush pattern with lateral buds.

The clinical course of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is variable, ranging from slow to no resolution after drug discontinuation, with residual scarring, atrophy, and concern for systemic elastosis. Adjunctive therapies include oral and topical retinoids, cryotherapy, imiquimod, and CO2 laser.5 For our patient, tazarotene gel 0.1% was recommended, but the patient became pregnant soon after the diagnosis was made. Despite being untreated, her lesions have remarkably improved during her pregnancy.

1. Langeveld-Wildschut EG, Toonstra J, van Vloten WA, et al. Familial elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:205-207.

2. Pass F, Goldfischer S, Sternlieb I, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa during penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:713-715.

3. Deguti MM, Mucenic M, Cancado EL, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa secondary to D-penicillamine treatment in a Wilson’s disease patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2153-2154.

4. Sahn EE, Maize JC, Garen PD, et al. D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa in a child with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:979-988.

5. Atzori L, Pinna AL, Pau M, et al. D-penicillamine elastosis perforans serpiginosa: description of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:3.

The Diagnosis: D-Penicillamine–Induced Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa

A 27-year-old woman was referred to our clinic by her rheumatologist with a 2×5-cm annular plaque on the right side of the lateral neck along with nummular plaques on the left side of 1 year’s duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for systemic sclerosis that had been treated with oral D-penicillamine (750 mg daily) for the last 10 years. Histopathologic examination of the skin biopsy specimen revealed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (Figure 3), which confirmed the diagnosis of D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS).

|

Figure 1. Nummular plaques on the left side of the |

|

Figure 2. A punch biopsy specimen showed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (H&E, original magnification ×10). |

|

Figure 3. Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (original magnification ×40). |

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is a rare entity that may present in many different settings. Some associated genetic conditions include Down syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, acrogeria, osteogenesis imperfecta, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, and moya-moya disease. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa also may be inherited in rare cases in an autosomal-dominant pattern.1 There are solitary reports of EPS in the setting of renal disease, morphea, and systemic sclerosis. Most cases of EPS are iatrogenically acquired. As first reported in 1973, long-term D-penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease has been classically associated with the rare development of EPS.2 Putative mechanisms include copper chelation by D-penicillamine in the setting of altered copper homeostasis in Wilson disease and subsequent inhibition of elastic fiber cross-linking by copper-dependent lysyl oxidase. Another proposed mechanism is the direct inhibition of collagen cross-linking by D-penicillamine resulting in abnormal elastic fiber maturation.3 Outside of the context of Wilson disease, D-penicillamine–induced EPS also has developed during the treatment of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and cystinuria.4 Our patient withsystemic sclerosis also exemplifies the possibility of developing EPS from long-term D-penicillamine therapy even in the absence of coexisting Wilson disease.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa lesions classically present as asymptomatic, serpiginously arranged, hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, and annular plaques in young adults and children. Lesions usually present on the neck, though other locations have been described. Histologically, transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers, degenerated keratinocytes, and collagen is seen in the background of a foreign-body reaction with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Elastin stains show increased thickened elastic fibers in the dermis underlying the perforation. The histology of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is distinctive in that the elastic fibers are arranged in a bramble bush pattern with lateral buds.

The clinical course of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is variable, ranging from slow to no resolution after drug discontinuation, with residual scarring, atrophy, and concern for systemic elastosis. Adjunctive therapies include oral and topical retinoids, cryotherapy, imiquimod, and CO2 laser.5 For our patient, tazarotene gel 0.1% was recommended, but the patient became pregnant soon after the diagnosis was made. Despite being untreated, her lesions have remarkably improved during her pregnancy.

The Diagnosis: D-Penicillamine–Induced Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa

A 27-year-old woman was referred to our clinic by her rheumatologist with a 2×5-cm annular plaque on the right side of the lateral neck along with nummular plaques on the left side of 1 year’s duration (Figure 1). Her medical history was notable for systemic sclerosis that had been treated with oral D-penicillamine (750 mg daily) for the last 10 years. Histopathologic examination of the skin biopsy specimen revealed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (Figure 2). Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (Figure 3), which confirmed the diagnosis of D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS).

|

Figure 1. Nummular plaques on the left side of the |

|

Figure 2. A punch biopsy specimen showed an epidermis with perforating channels of elastic fibers admixed with collagen (H&E, original magnification ×10). |

|

Figure 3. Verhoeff–van Gieson elastin stain highlighted “bramble bush or lumpy-bumpy” appearance of elastic fibers in the dermis (original magnification ×40). |

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is a rare entity that may present in many different settings. Some associated genetic conditions include Down syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, acrogeria, osteogenesis imperfecta, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, and moya-moya disease. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa also may be inherited in rare cases in an autosomal-dominant pattern.1 There are solitary reports of EPS in the setting of renal disease, morphea, and systemic sclerosis. Most cases of EPS are iatrogenically acquired. As first reported in 1973, long-term D-penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease has been classically associated with the rare development of EPS.2 Putative mechanisms include copper chelation by D-penicillamine in the setting of altered copper homeostasis in Wilson disease and subsequent inhibition of elastic fiber cross-linking by copper-dependent lysyl oxidase. Another proposed mechanism is the direct inhibition of collagen cross-linking by D-penicillamine resulting in abnormal elastic fiber maturation.3 Outside of the context of Wilson disease, D-penicillamine–induced EPS also has developed during the treatment of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and cystinuria.4 Our patient withsystemic sclerosis also exemplifies the possibility of developing EPS from long-term D-penicillamine therapy even in the absence of coexisting Wilson disease.

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa lesions classically present as asymptomatic, serpiginously arranged, hyperkeratotic papules, nodules, and annular plaques in young adults and children. Lesions usually present on the neck, though other locations have been described. Histologically, transepidermal elimination of elastic fibers, degenerated keratinocytes, and collagen is seen in the background of a foreign-body reaction with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Elastin stains show increased thickened elastic fibers in the dermis underlying the perforation. The histology of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is distinctive in that the elastic fibers are arranged in a bramble bush pattern with lateral buds.

The clinical course of D-penicillamine–induced EPS is variable, ranging from slow to no resolution after drug discontinuation, with residual scarring, atrophy, and concern for systemic elastosis. Adjunctive therapies include oral and topical retinoids, cryotherapy, imiquimod, and CO2 laser.5 For our patient, tazarotene gel 0.1% was recommended, but the patient became pregnant soon after the diagnosis was made. Despite being untreated, her lesions have remarkably improved during her pregnancy.

1. Langeveld-Wildschut EG, Toonstra J, van Vloten WA, et al. Familial elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:205-207.

2. Pass F, Goldfischer S, Sternlieb I, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa during penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:713-715.

3. Deguti MM, Mucenic M, Cancado EL, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa secondary to D-penicillamine treatment in a Wilson’s disease patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2153-2154.

4. Sahn EE, Maize JC, Garen PD, et al. D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa in a child with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:979-988.

5. Atzori L, Pinna AL, Pau M, et al. D-penicillamine elastosis perforans serpiginosa: description of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:3.

1. Langeveld-Wildschut EG, Toonstra J, van Vloten WA, et al. Familial elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:205-207.

2. Pass F, Goldfischer S, Sternlieb I, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa during penicillamine therapy for Wilson disease. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:713-715.

3. Deguti MM, Mucenic M, Cancado EL, et al. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa secondary to D-penicillamine treatment in a Wilson’s disease patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2153-2154.

4. Sahn EE, Maize JC, Garen PD, et al. D-penicillamine–induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa in a child with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:979-988.

5. Atzori L, Pinna AL, Pau M, et al. D-penicillamine elastosis perforans serpiginosa: description of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:3.

Postop Patient Reports “Wound Infection”

ANSWER

The correct answer is an allergic reaction to a contactant, most likely the triple-antibiotic ointment (choice “d”).

Irritant reactions to tape adhesive (choice “a”) are extremely common. However, the resultant rash would have been confined to the linear areas where the tape touched his skin.

Dissolving sutures, such as those used in this case, can provoke a “suture granuloma”—essentially a foreign body reaction to the suture material (choice “b”). But this would have caused a focal area of swelling and redness, and very possibly a show of pus.

Postop wound infections (choice “c”) are also quite common. However, they would not manifest solely with itching in a papulovesicular rash surrounding the wound. Had infection developed, the redness would have been broad-based, with ill-defined margins, and the patient’s complaint would have been of pain, not itching. No vesicles would have been seen with bacterial infection.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the phenomenon of “treatment as problem,” in which the medication the patient applies becomes more problematic than the condition being addressed. Reactions to the neomycin in triple-antibiotic ointment are common but still provoke considerable worry on the part of patients and providers alike, especially when mistaken for “infection.”

This patient, like many, was dubious of the diagnosis, pointing out that he had used this same topical medication on many occasions without incident (though not recently). What he didn’t know is that it takes repeated exposure to a given allergen to develop T-memory cells that eventually begin to react. This same phenomenon is seen with poison ivy; patients will recall the ability, as a child, to practically wallow in poison ivy with impunity, making them doubtful about being allergic to it as an adult.

Neomycin, an aminoglycoside with a fairly wide spectrum of antibacterial activity, was first noted as a contact allergen in 1952. It is such a notorious offender that it was named Allergen of the Year in 2010 by the American Contact Dermatology Society.

For the past 20 years, 7% to 13% of patch tests surveyed were positive for neomycin. For reasons not entirely clear, Americans older than 60 are 150% more likely to experience a reaction to neomycin than are younger patients. (It could simply be that they’ve had more chances for exposure.)

In another interesting twist, the ointment vehicle appears to play a role. A reaction to this preparation is considerably more likely than to the same drug in other forms (eg, powders, solutions, creams). This is true of most medications, such as topical steroids, which are effectively self-occluded by this vehicle.

Persons with impaired barrier function, such as those with atopic dermatitis or whose skin has been prepped for surgery, appear to be at increased risk for these types of contact dermatoses.

Though there are other items in the differential, the configuration of the papulovesicular rash and the sole symptom of itching are essentially pathognomic for contact dermatitis. Besides the use of potent topical steroids for a few days, the real “cure” for this problem is for the patient to switch to “double-antibiotic” creams or ointments that do not include neomycin.

ANSWER

The correct answer is an allergic reaction to a contactant, most likely the triple-antibiotic ointment (choice “d”).

Irritant reactions to tape adhesive (choice “a”) are extremely common. However, the resultant rash would have been confined to the linear areas where the tape touched his skin.

Dissolving sutures, such as those used in this case, can provoke a “suture granuloma”—essentially a foreign body reaction to the suture material (choice “b”). But this would have caused a focal area of swelling and redness, and very possibly a show of pus.

Postop wound infections (choice “c”) are also quite common. However, they would not manifest solely with itching in a papulovesicular rash surrounding the wound. Had infection developed, the redness would have been broad-based, with ill-defined margins, and the patient’s complaint would have been of pain, not itching. No vesicles would have been seen with bacterial infection.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the phenomenon of “treatment as problem,” in which the medication the patient applies becomes more problematic than the condition being addressed. Reactions to the neomycin in triple-antibiotic ointment are common but still provoke considerable worry on the part of patients and providers alike, especially when mistaken for “infection.”

This patient, like many, was dubious of the diagnosis, pointing out that he had used this same topical medication on many occasions without incident (though not recently). What he didn’t know is that it takes repeated exposure to a given allergen to develop T-memory cells that eventually begin to react. This same phenomenon is seen with poison ivy; patients will recall the ability, as a child, to practically wallow in poison ivy with impunity, making them doubtful about being allergic to it as an adult.

Neomycin, an aminoglycoside with a fairly wide spectrum of antibacterial activity, was first noted as a contact allergen in 1952. It is such a notorious offender that it was named Allergen of the Year in 2010 by the American Contact Dermatology Society.

For the past 20 years, 7% to 13% of patch tests surveyed were positive for neomycin. For reasons not entirely clear, Americans older than 60 are 150% more likely to experience a reaction to neomycin than are younger patients. (It could simply be that they’ve had more chances for exposure.)

In another interesting twist, the ointment vehicle appears to play a role. A reaction to this preparation is considerably more likely than to the same drug in other forms (eg, powders, solutions, creams). This is true of most medications, such as topical steroids, which are effectively self-occluded by this vehicle.

Persons with impaired barrier function, such as those with atopic dermatitis or whose skin has been prepped for surgery, appear to be at increased risk for these types of contact dermatoses.

Though there are other items in the differential, the configuration of the papulovesicular rash and the sole symptom of itching are essentially pathognomic for contact dermatitis. Besides the use of potent topical steroids for a few days, the real “cure” for this problem is for the patient to switch to “double-antibiotic” creams or ointments that do not include neomycin.

ANSWER

The correct answer is an allergic reaction to a contactant, most likely the triple-antibiotic ointment (choice “d”).

Irritant reactions to tape adhesive (choice “a”) are extremely common. However, the resultant rash would have been confined to the linear areas where the tape touched his skin.

Dissolving sutures, such as those used in this case, can provoke a “suture granuloma”—essentially a foreign body reaction to the suture material (choice “b”). But this would have caused a focal area of swelling and redness, and very possibly a show of pus.

Postop wound infections (choice “c”) are also quite common. However, they would not manifest solely with itching in a papulovesicular rash surrounding the wound. Had infection developed, the redness would have been broad-based, with ill-defined margins, and the patient’s complaint would have been of pain, not itching. No vesicles would have been seen with bacterial infection.

DISCUSSION

This case illustrates the phenomenon of “treatment as problem,” in which the medication the patient applies becomes more problematic than the condition being addressed. Reactions to the neomycin in triple-antibiotic ointment are common but still provoke considerable worry on the part of patients and providers alike, especially when mistaken for “infection.”

This patient, like many, was dubious of the diagnosis, pointing out that he had used this same topical medication on many occasions without incident (though not recently). What he didn’t know is that it takes repeated exposure to a given allergen to develop T-memory cells that eventually begin to react. This same phenomenon is seen with poison ivy; patients will recall the ability, as a child, to practically wallow in poison ivy with impunity, making them doubtful about being allergic to it as an adult.

Neomycin, an aminoglycoside with a fairly wide spectrum of antibacterial activity, was first noted as a contact allergen in 1952. It is such a notorious offender that it was named Allergen of the Year in 2010 by the American Contact Dermatology Society.

For the past 20 years, 7% to 13% of patch tests surveyed were positive for neomycin. For reasons not entirely clear, Americans older than 60 are 150% more likely to experience a reaction to neomycin than are younger patients. (It could simply be that they’ve had more chances for exposure.)

In another interesting twist, the ointment vehicle appears to play a role. A reaction to this preparation is considerably more likely than to the same drug in other forms (eg, powders, solutions, creams). This is true of most medications, such as topical steroids, which are effectively self-occluded by this vehicle.

Persons with impaired barrier function, such as those with atopic dermatitis or whose skin has been prepped for surgery, appear to be at increased risk for these types of contact dermatoses.

Though there are other items in the differential, the configuration of the papulovesicular rash and the sole symptom of itching are essentially pathognomic for contact dermatitis. Besides the use of potent topical steroids for a few days, the real “cure” for this problem is for the patient to switch to “double-antibiotic” creams or ointments that do not include neomycin.

A week ago, a 56-year-old man had a skin cancer surgically removed. Last night, he presented to an urgent care clinic for evaluation of a “wound infection” and received a prescription for double-strength trimethoprim/sulfa tablets (to be taken bid for 10 days). He is now in the dermatology office for follow-up. According to the patient, the problem manifested two days postop. There was no associated pain, only itching. The patient feels fine, with no fever or malaise, and there is no history of immunosuppression. He reports following his postop instructions well, changing his bandage daily and using triple-antibiotic ointment to dress the wound directly. The immediate peri-incisional area is indicated as the source of the problem. Surrounding the incision, which is healing well otherwise, is a sharply defined, bright pink, papulovesicular rash on a slightly edematous base. There is no tenderness on palpation, and no purulent material can be expressed from the wound. The area is only slightly warmer than the surrounding skin.

Rapidly Enlarging Noduloulcerative Lesions

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

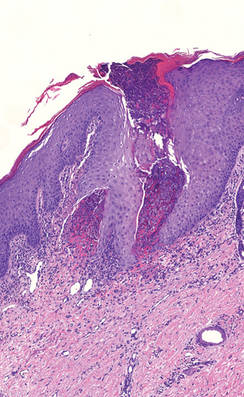

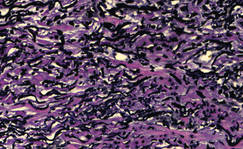

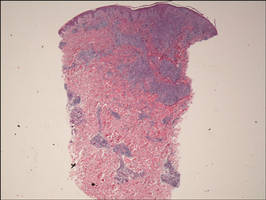

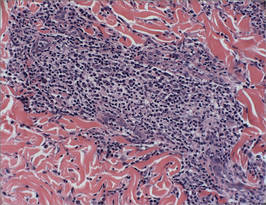

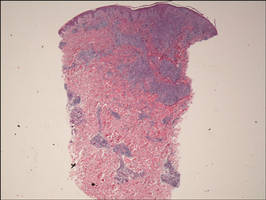

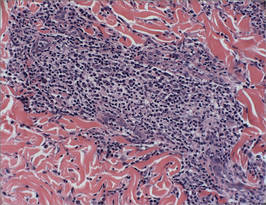

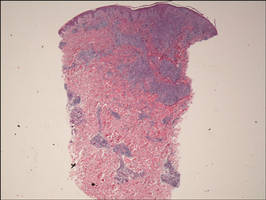

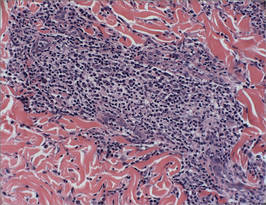

Biopsy revealed dense nodular aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and abundant plasma cells in both the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1). There were perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (Figure 2). Special stains for organisms, including Warthin-Starry silver, Giemsa, acid-fast bacilli, Gomori methenamine-silver, and Brown-Brenn stains were negative. Immunoperoxidase stain for Treponema pallidum also was negative. The patient’s rapid plasma reagin titer at the time of the fourth biopsy was 1:256, and appropriate treatment with penicillin resulted in complete clearance of the lesions in 3 to 4 weeks.

|

| Figure 1. Superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (H&E, original magnification ×2). |

|

| Figure 2. Perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum. Three stages typically are identified in immunocompetent hosts: primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis. Immunocompromised patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may have unusual presentations.

Lues maligna is used to describe a rare noduloulcerative form of secondary syphilis.1 It was first described in 18592 and has been associated with other disorders such as diabetes mellitus3 and chronic alcoholism.4 Patients usually are gravely ill and develop polymorphic ulcerating lesions. Facial and scalp involvement are common, but patients typically do not have palmoplantar involvement in conventional presentations of secondary syphilis.

A scanning view of a punch biopsy from our patient revealed irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with long and thin rete pegs, a bandlike infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction, and a dense superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate. The histologic differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis, lymphoma, leishmaniasis, leprosy, yaws, and mycobacterial or fungal infections.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends screening of all HIV-positive indivi-duals for syphilis, and all sexually active individuals with syphilis should be screened for HIV.5 If clinical examination and findings suggest syphilis in the presence of negative serologic testing, then direct fluorescence assay for T pallidum staining of lesions, exudates or biopsy, or dark-field microscopic examination should be performed. In our case, dark-field microscopy was not performed and serologic tests were negative at presentation. Silver stains can detect T pallidum in tissue specimens, though detection may not be possible late in the course of disease.6

The morphology and rapid response to treatment confirmed the diagnosis in our patient. The incidence of syphilis in HIV-positive patients has risen substantially in the last 2 decades. This case illustrates an uncommon presentation that is increasing in prevalence.

1. Fisher DA, Chang LW, Tuffanelli DL. Lues maligna: presentation of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:70-73.

2. Passoni LF, de Menezes JA, Ribeiro SR, et al. Lues maligna in an HIV-infected patient [published online ahead of print March 30, 2005]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:181-184.

3. Hofmann UB, Hund M, Bröcker EB, et al. Lues maligna in a female patient with diabetes [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:780-782.

4. Bayramgürler D, Bilen N, Yildiz K, et al. Lues maligna in a chronic alcoholic patient. J Dermatol. 2005;32:217-219.

5. Centers for Disease Control. Recommendations for diagnosing and treating syphilis in HIV-infected patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:600-602.

6. Mannara GM. Bilateral secondary syphilis of the tonsil. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:1125-1127.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Biopsy revealed dense nodular aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and abundant plasma cells in both the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1). There were perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (Figure 2). Special stains for organisms, including Warthin-Starry silver, Giemsa, acid-fast bacilli, Gomori methenamine-silver, and Brown-Brenn stains were negative. Immunoperoxidase stain for Treponema pallidum also was negative. The patient’s rapid plasma reagin titer at the time of the fourth biopsy was 1:256, and appropriate treatment with penicillin resulted in complete clearance of the lesions in 3 to 4 weeks.

|

| Figure 1. Superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (H&E, original magnification ×2). |

|

| Figure 2. Perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum. Three stages typically are identified in immunocompetent hosts: primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis. Immunocompromised patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may have unusual presentations.

Lues maligna is used to describe a rare noduloulcerative form of secondary syphilis.1 It was first described in 18592 and has been associated with other disorders such as diabetes mellitus3 and chronic alcoholism.4 Patients usually are gravely ill and develop polymorphic ulcerating lesions. Facial and scalp involvement are common, but patients typically do not have palmoplantar involvement in conventional presentations of secondary syphilis.

A scanning view of a punch biopsy from our patient revealed irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with long and thin rete pegs, a bandlike infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction, and a dense superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate. The histologic differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis, lymphoma, leishmaniasis, leprosy, yaws, and mycobacterial or fungal infections.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends screening of all HIV-positive indivi-duals for syphilis, and all sexually active individuals with syphilis should be screened for HIV.5 If clinical examination and findings suggest syphilis in the presence of negative serologic testing, then direct fluorescence assay for T pallidum staining of lesions, exudates or biopsy, or dark-field microscopic examination should be performed. In our case, dark-field microscopy was not performed and serologic tests were negative at presentation. Silver stains can detect T pallidum in tissue specimens, though detection may not be possible late in the course of disease.6

The morphology and rapid response to treatment confirmed the diagnosis in our patient. The incidence of syphilis in HIV-positive patients has risen substantially in the last 2 decades. This case illustrates an uncommon presentation that is increasing in prevalence.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Biopsy revealed dense nodular aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and abundant plasma cells in both the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1). There were perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (Figure 2). Special stains for organisms, including Warthin-Starry silver, Giemsa, acid-fast bacilli, Gomori methenamine-silver, and Brown-Brenn stains were negative. Immunoperoxidase stain for Treponema pallidum also was negative. The patient’s rapid plasma reagin titer at the time of the fourth biopsy was 1:256, and appropriate treatment with penicillin resulted in complete clearance of the lesions in 3 to 4 weeks.

|

| Figure 1. Superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (H&E, original magnification ×2). |

|

| Figure 2. Perivascular and periadnexal aggregates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous plasma cells (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Syphilis is caused by T pallidum. Three stages typically are identified in immunocompetent hosts: primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis. Immunocompromised patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection may have unusual presentations.

Lues maligna is used to describe a rare noduloulcerative form of secondary syphilis.1 It was first described in 18592 and has been associated with other disorders such as diabetes mellitus3 and chronic alcoholism.4 Patients usually are gravely ill and develop polymorphic ulcerating lesions. Facial and scalp involvement are common, but patients typically do not have palmoplantar involvement in conventional presentations of secondary syphilis.

A scanning view of a punch biopsy from our patient revealed irregular acanthosis of the epidermis with long and thin rete pegs, a bandlike infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction, and a dense superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrate. The histologic differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, vasculitis, lymphoma, leishmaniasis, leprosy, yaws, and mycobacterial or fungal infections.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends screening of all HIV-positive indivi-duals for syphilis, and all sexually active individuals with syphilis should be screened for HIV.5 If clinical examination and findings suggest syphilis in the presence of negative serologic testing, then direct fluorescence assay for T pallidum staining of lesions, exudates or biopsy, or dark-field microscopic examination should be performed. In our case, dark-field microscopy was not performed and serologic tests were negative at presentation. Silver stains can detect T pallidum in tissue specimens, though detection may not be possible late in the course of disease.6

The morphology and rapid response to treatment confirmed the diagnosis in our patient. The incidence of syphilis in HIV-positive patients has risen substantially in the last 2 decades. This case illustrates an uncommon presentation that is increasing in prevalence.

1. Fisher DA, Chang LW, Tuffanelli DL. Lues maligna: presentation of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:70-73.

2. Passoni LF, de Menezes JA, Ribeiro SR, et al. Lues maligna in an HIV-infected patient [published online ahead of print March 30, 2005]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:181-184.

3. Hofmann UB, Hund M, Bröcker EB, et al. Lues maligna in a female patient with diabetes [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:780-782.

4. Bayramgürler D, Bilen N, Yildiz K, et al. Lues maligna in a chronic alcoholic patient. J Dermatol. 2005;32:217-219.

5. Centers for Disease Control. Recommendations for diagnosing and treating syphilis in HIV-infected patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:600-602.

6. Mannara GM. Bilateral secondary syphilis of the tonsil. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:1125-1127.