User login

Do Nausea and Vomiting Have Cardiac Cause?

ANSWER

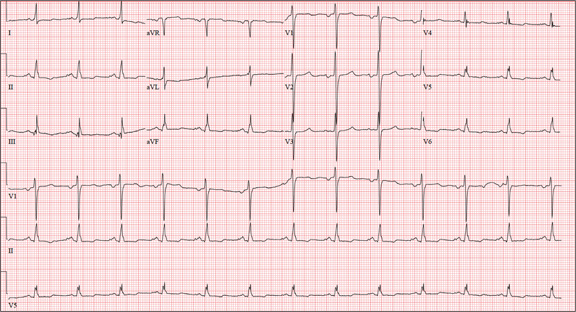

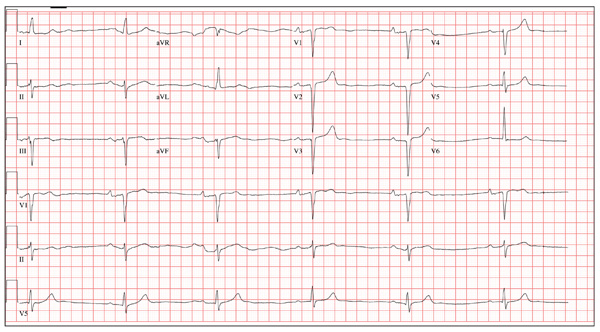

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and nonspecific T-wave abnormalities.

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by an atrial and ventricular rate of 77 beats/min with one-to-one association. Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by the presence of a biphasic P wave in lead V1 with a negative terminal portion of the P wave ≥ 1 mm2. (P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms are also seen in left atrial enlargement, but are not evident in this ECG.) The small or inverted appearance of T waves in the inferior and lateral leads indicates nonspecific T waves.

These ECG findings are typical of patients with mitral valve disease, but were of no benefit in diagnosing acute pancreatitis in this patient. By the time she had the ECG done, she had been given sedation sufficient to reduce her heart rate from the 118 beats/min it had been at the time of examination.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and nonspecific T-wave abnormalities.

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by an atrial and ventricular rate of 77 beats/min with one-to-one association. Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by the presence of a biphasic P wave in lead V1 with a negative terminal portion of the P wave ≥ 1 mm2. (P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms are also seen in left atrial enlargement, but are not evident in this ECG.) The small or inverted appearance of T waves in the inferior and lateral leads indicates nonspecific T waves.

These ECG findings are typical of patients with mitral valve disease, but were of no benefit in diagnosing acute pancreatitis in this patient. By the time she had the ECG done, she had been given sedation sufficient to reduce her heart rate from the 118 beats/min it had been at the time of examination.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, left atrial enlargement, and nonspecific T-wave abnormalities.

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by an atrial and ventricular rate of 77 beats/min with one-to-one association. Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by the presence of a biphasic P wave in lead V1 with a negative terminal portion of the P wave ≥ 1 mm2. (P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms are also seen in left atrial enlargement, but are not evident in this ECG.) The small or inverted appearance of T waves in the inferior and lateral leads indicates nonspecific T waves.

These ECG findings are typical of patients with mitral valve disease, but were of no benefit in diagnosing acute pancreatitis in this patient. By the time she had the ECG done, she had been given sedation sufficient to reduce her heart rate from the 118 beats/min it had been at the time of examination.

A 58-year-old woman presents with epigastric pain that began gradually about four hours ago, re-maining constant for the past two. She describes it as a “dull, steady, aching” pain directly beneath her lower sternum. It is neither exacerbated by exertion nor relieved by rest, but it does improve if she bends from the waist. She denies radiation of pain into her neck or upper extremities but describes a band of pain radiating to her back. Additionally, she has experienced nausea and vomiting, starting about 12 hours before her pain, with a single episode of emesis immediately upon presentation. She has a history of mitral valve prolapse, which was surgically corrected with a mechanical heart valve two years ago. She also has a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation for which she has been cardioverted on two separate occasions. Her last episode was six months ago. Social history reveals that she is divorced, has smoked one pack of cigarettes a day for the past 30 years, and is a heavy alcohol user. She states she went on a binge last weekend (72 hours ago), drinking one bottle of whiskey and half a bottle of vodka over the course of one day. She has tried heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamines in the past and currently uses marijuana when she can get it. The patient has a primary care provider who prescribed aspirin, atorvastatin, clonidine, gabapentin, metoprolol, and warfarin; however, she hasn’t taken or refilled any of these prescriptions for approx-imately six months. She is allergic to codeine, erythromycin, and azithromycin. The review of sys-tems is positive for difficulty sleeping, anxiety, diffuse abdominal pain not related to her current symp-toms, dyspnea on exertion, “typical smoker’s cough,” and burning with urination. The physical examination reveals an unkempt, thin woman who is restless and easily agitated. Her weight is 125 lb, and her height, 64”. Her vital signs include a blood pressure of 168/102 mm Hg; pulse, 118 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 99.9°F. She has poor den-tition. There is no thyromegaly or jugular venous distention. Her respirations are shallow, and there are coarse rhonchi in both bases that change with coughing. The cardiac exam reveals a regular tachy-cardia with mechanical heart sounds and a grade II/VI systolic murmur. A well-healed median ster-notomy scar is present. The abdominal exam is remarkable for tenderness to palpation in the epigas-trium, with no evidence of rebound. There are no palpable masses. Bowel tones are present in all quadrants. The extremities are positive for 2+ pitting edema to the knees bilaterally. The neurologic exam is grossly intact. Following acute management of her pain, laboratory blood work, abdominal ultrasound and CT, chest x-ray, and ECG are ordered. The ECG is the last test to be obtained and reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 77 beats/min; PR interval, 142 ms; QRS duration, 104 ms; QT/QTc interval, 402/454 ms; P axis, 66°; R axis, 57°; and T axis, –11°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Unresponsive Woman Extricated From Car

An unidentified female is brought in as a trauma code. She was apparently in a motor vehicle crash, the specific details of which are unclear. Emergency medical personnel describe extensive damage to her vehicle, which resulted in a pro-longed extrication time. Due to unresponsiveness at the scene, she was intubated in the field. The patient is probably in her late 30s to early 40s. She has two large-bore IV lines with normal saline infusing at a wide-open rate. Blood pressure is 90/60 mm Hg and heart rate, 140 beats/min. She has several superficial lacerations on her head, her pupils are fixed and dilated, and there is minimal withdrawal to pain in her extremities. No other trauma is im-mediately evident. Portable radiographs of her chest and pelvis are obtained prior to sending her for CT. Pelvis radiograph is shown. What is your impression?

After 15 Years, Still Losing Hair, Only Faster

ANSWER

This is a classic clinical picture of androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”). See discussion for more details.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”) usually manifests acutely and leads to complete hair loss in a well-defined, annular pattern. It typically resolves on its own, with or without treatment.

Telogen effluvium (choice “c”) involves generalized hair loss without a pattern. The hair is actually “lost,” meaning markedly increased amounts of hair are seen in the comb, brush, sink, or shower. This results in an increasingly visible scalp.

Without a clear clinical picture of alopecia, a biopsy might have been indicated—primarily to rule out conditions such as lupus erythematosus (choice “d”), which can involve hair loss of various kinds. The negative ANA result obtained by the patient’s primary care provider helped rule out this diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) affects both men and women, though the latter begin to develop it about 10 years later, on average, than men do. Among women, 13% develop AGA before menopause, while 75% note its appearance postmenopausally.

In both sexes, AGA results from the gradual conversion of terminal hairs to vellus hairs, with miniaturization of the follicles. Hair loss in men starts in the vertex, followed by bitemporal recession. In women, AGA primarily affects the crown of the scalp, often with partial preservation of the frontal hairline.

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) appears to be the main culprit; testosterone is converted to DHT by means of the enzyme 5α-reductase. One of the most effective medications for AGA in men has been finasteride, which blocks the effects of 5α-reductase and can at least slow the rate of hair loss. Unfortunately, finasteride does not appear to be effective in treating AGA in women.

Women do, however, appear to respond to minoxidil, a topically applied solution, better than men. The response is moderate at best, and any hair gained is lost if the treatment is discontinued. Interestingly, the stronger 5% solution of minoxidil in women does not produce any demonstrable improvement over that seen with the 2% solution.

From a practical diagnostic standpoint, it is quite common for women with longstanding mild to moderate AGA to present with an acute episode of telogen effluvium (TE), in which hair all over the scalp falls out. Careful history taking is necessary to tease these stories apart, since TE will typically resolve on its own. The most common causes of TE, in my experience, are stress, extreme weight loss, and as a consequence of general anesthesia. For unknown reasons, TE is almost nonexistent in men.

TREATMENT

This patient chose to use 5% OTC minoxidil, an antihypertensive with an unknown mode of action in AGA. She’ll confine its application to the affected areas of the scalp, since unwanted hair growth has been reported on the face with the use of this medication.

ANSWER

This is a classic clinical picture of androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”). See discussion for more details.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”) usually manifests acutely and leads to complete hair loss in a well-defined, annular pattern. It typically resolves on its own, with or without treatment.

Telogen effluvium (choice “c”) involves generalized hair loss without a pattern. The hair is actually “lost,” meaning markedly increased amounts of hair are seen in the comb, brush, sink, or shower. This results in an increasingly visible scalp.

Without a clear clinical picture of alopecia, a biopsy might have been indicated—primarily to rule out conditions such as lupus erythematosus (choice “d”), which can involve hair loss of various kinds. The negative ANA result obtained by the patient’s primary care provider helped rule out this diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) affects both men and women, though the latter begin to develop it about 10 years later, on average, than men do. Among women, 13% develop AGA before menopause, while 75% note its appearance postmenopausally.

In both sexes, AGA results from the gradual conversion of terminal hairs to vellus hairs, with miniaturization of the follicles. Hair loss in men starts in the vertex, followed by bitemporal recession. In women, AGA primarily affects the crown of the scalp, often with partial preservation of the frontal hairline.

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) appears to be the main culprit; testosterone is converted to DHT by means of the enzyme 5α-reductase. One of the most effective medications for AGA in men has been finasteride, which blocks the effects of 5α-reductase and can at least slow the rate of hair loss. Unfortunately, finasteride does not appear to be effective in treating AGA in women.

Women do, however, appear to respond to minoxidil, a topically applied solution, better than men. The response is moderate at best, and any hair gained is lost if the treatment is discontinued. Interestingly, the stronger 5% solution of minoxidil in women does not produce any demonstrable improvement over that seen with the 2% solution.

From a practical diagnostic standpoint, it is quite common for women with longstanding mild to moderate AGA to present with an acute episode of telogen effluvium (TE), in which hair all over the scalp falls out. Careful history taking is necessary to tease these stories apart, since TE will typically resolve on its own. The most common causes of TE, in my experience, are stress, extreme weight loss, and as a consequence of general anesthesia. For unknown reasons, TE is almost nonexistent in men.

TREATMENT

This patient chose to use 5% OTC minoxidil, an antihypertensive with an unknown mode of action in AGA. She’ll confine its application to the affected areas of the scalp, since unwanted hair growth has been reported on the face with the use of this medication.

ANSWER

This is a classic clinical picture of androgenetic alopecia (choice “a”). See discussion for more details.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”) usually manifests acutely and leads to complete hair loss in a well-defined, annular pattern. It typically resolves on its own, with or without treatment.

Telogen effluvium (choice “c”) involves generalized hair loss without a pattern. The hair is actually “lost,” meaning markedly increased amounts of hair are seen in the comb, brush, sink, or shower. This results in an increasingly visible scalp.

Without a clear clinical picture of alopecia, a biopsy might have been indicated—primarily to rule out conditions such as lupus erythematosus (choice “d”), which can involve hair loss of various kinds. The negative ANA result obtained by the patient’s primary care provider helped rule out this diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) affects both men and women, though the latter begin to develop it about 10 years later, on average, than men do. Among women, 13% develop AGA before menopause, while 75% note its appearance postmenopausally.

In both sexes, AGA results from the gradual conversion of terminal hairs to vellus hairs, with miniaturization of the follicles. Hair loss in men starts in the vertex, followed by bitemporal recession. In women, AGA primarily affects the crown of the scalp, often with partial preservation of the frontal hairline.

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) appears to be the main culprit; testosterone is converted to DHT by means of the enzyme 5α-reductase. One of the most effective medications for AGA in men has been finasteride, which blocks the effects of 5α-reductase and can at least slow the rate of hair loss. Unfortunately, finasteride does not appear to be effective in treating AGA in women.

Women do, however, appear to respond to minoxidil, a topically applied solution, better than men. The response is moderate at best, and any hair gained is lost if the treatment is discontinued. Interestingly, the stronger 5% solution of minoxidil in women does not produce any demonstrable improvement over that seen with the 2% solution.

From a practical diagnostic standpoint, it is quite common for women with longstanding mild to moderate AGA to present with an acute episode of telogen effluvium (TE), in which hair all over the scalp falls out. Careful history taking is necessary to tease these stories apart, since TE will typically resolve on its own. The most common causes of TE, in my experience, are stress, extreme weight loss, and as a consequence of general anesthesia. For unknown reasons, TE is almost nonexistent in men.

TREATMENT

This patient chose to use 5% OTC minoxidil, an antihypertensive with an unknown mode of action in AGA. She’ll confine its application to the affected areas of the scalp, since unwanted hair growth has been reported on the face with the use of this medication.

A 43-year-old woman presents to dermatology with the extremely common complaint of hair loss. The problem is not new; she first noticed it 15 years ago. But the loss has now progressed to such an extent that the patient consulted her primary care provider. Blood tests were ordered, including complete blood count, antinuclear antibody (ANA), and thy-roid-stimulating hormone; all results were within normal limits. And so she decided to seek a specialist’s assessment. The patient is going through menopause—without the aid of medication—and claims to be otherwise healthy. She denies finding increased amounts of lost hair in her comb, brush, shower, or sink. She further denies any symptoms in her scalp. Her mother and one sister had similar problems with their scalp hair. Examination reveals extensive thinning of hair, which is almost totally confined to the crown of her scalp, with faint but obvious preservation of a thin band of the frontal hairline. There is no appreciable disruption of the skin surface in the scalp (eg, scaling, redness, edema, or scarring).

Chest Pain and Vomiting with Prior Heart Attack

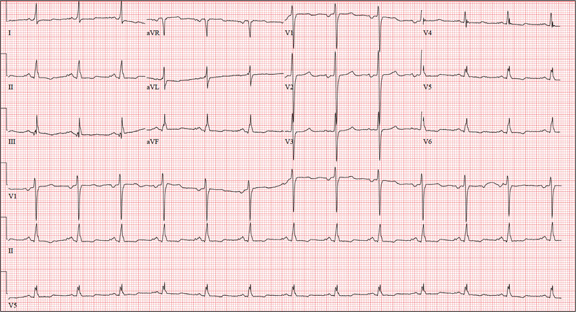

ANSWER

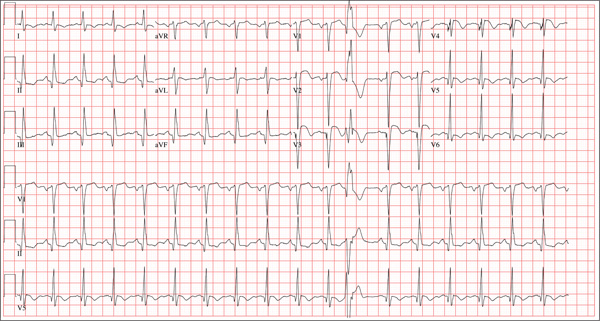

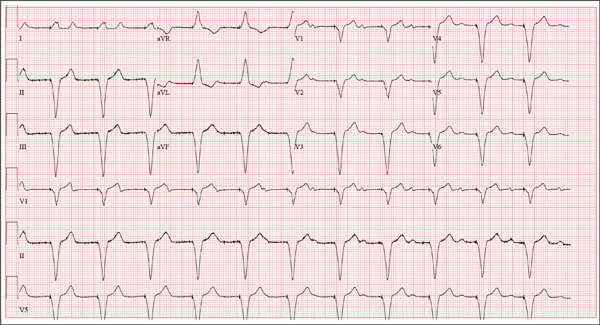

The correct interpretation includes sinus tachycardia with occasional premature ventricular complexes (PVCs), left atrial enlargement, evidence of a previous inferior MI, and an acute anterior MI. Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by a rate ≥ 100 beats/min and the presence of a P wave for every QRS complex with a constant PR interval. A single PVC is evident (12th beat of the rhythm strips V1, II, and V5).

Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by a large P wave in lead II and a biphasic P wave with the terminal portion larger than the initial portion in lead V1. An old inferior MI is evidenced by the presence of Q waves in leads II, III, and aVF.

An evolving anterior MI is diagnosed by the presence of poor R-wave progression with ST-segment elevations and T-wave inversion in leads V2, V3, and V4. This was subsequently confirmed by clinically significant elevations of serum troponin levels and by cardiac catheterization, which revealed occlusion of the left anterior descending artery distal to the internal mammary artery anastomosis.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes sinus tachycardia with occasional premature ventricular complexes (PVCs), left atrial enlargement, evidence of a previous inferior MI, and an acute anterior MI. Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by a rate ≥ 100 beats/min and the presence of a P wave for every QRS complex with a constant PR interval. A single PVC is evident (12th beat of the rhythm strips V1, II, and V5).

Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by a large P wave in lead II and a biphasic P wave with the terminal portion larger than the initial portion in lead V1. An old inferior MI is evidenced by the presence of Q waves in leads II, III, and aVF.

An evolving anterior MI is diagnosed by the presence of poor R-wave progression with ST-segment elevations and T-wave inversion in leads V2, V3, and V4. This was subsequently confirmed by clinically significant elevations of serum troponin levels and by cardiac catheterization, which revealed occlusion of the left anterior descending artery distal to the internal mammary artery anastomosis.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes sinus tachycardia with occasional premature ventricular complexes (PVCs), left atrial enlargement, evidence of a previous inferior MI, and an acute anterior MI. Sinus tachycardia is evidenced by a rate ≥ 100 beats/min and the presence of a P wave for every QRS complex with a constant PR interval. A single PVC is evident (12th beat of the rhythm strips V1, II, and V5).

Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by a large P wave in lead II and a biphasic P wave with the terminal portion larger than the initial portion in lead V1. An old inferior MI is evidenced by the presence of Q waves in leads II, III, and aVF.

An evolving anterior MI is diagnosed by the presence of poor R-wave progression with ST-segment elevations and T-wave inversion in leads V2, V3, and V4. This was subsequently confirmed by clinically significant elevations of serum troponin levels and by cardiac catheterization, which revealed occlusion of the left anterior descending artery distal to the internal mammary artery anastomosis.

Three hours ago, this 69-year-old man started to experience substernal chest pain, nausea, and vomiting. He had stopped for lunch after spending the morning raking leaves; his chest pain began while he was at the drive-through window at a local fast food restaurant. By the time he got home, he was nauseous and had an episode of emesis. The pain is described as a “dull, heavy ache” with radiation to the left neck and arm. The patient states he is diaphoretic, but attributes it to the labor associated with his yardwork. He recalls that his first heart attack started in a similar way and fears he is having another. Following the emesis, his nausea stopped, and he rested in his recliner, hoping his symptoms would resolve. Unfortunately, the chest pain worsened, and he drove himself to the clinic rather than calling 911. (He didn’t want to go to the ED or get billed for the ambulance ride.) Review of his medical history reveals coronary artery disease, evidenced by an inferior MI in 2008. This was treated with coronary artery bypass surgery with reversed saphenous vein grafts placed to the first and second obtuse marginal branches of the circumflex coronary artery, reversed saphenous vein graft to the posterior descending artery, and an internal mammary artery graft placed to the proximal left anterior descending artery. His history is also remarkable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and obesity. He is a retired postal worker who has lived alone since his wife died three years ago. He drinks a six-pack of beer daily and continues to smoke one to two packs of cigarettes per day, depending on his activities. His family history includes coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, and stroke. His current medications include aspirin, atorvastatin, clopidogrel, furosemide, isosorbide dinitrate, metoprolol, nicotine patch, potassium chloride, and valsartan. He is intolerant of ACE inhibitors, due to the resulting chronic, dry cough. The review of systems reveals that he has had headaches over the past week and that he recently recovered from the flu. He has had no changes in bowel or bladder function, shortness of breath, or recent weight loss or gain. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 168/100 mm Hg; pulse, 110 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; O2 saturation, 98% on room air; and temperature, 37.2°C. His weight is 108 kg, and his height is 170 cm. Physical findings show that the lungs are clear to auscultation; his rhythm is regular with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops; and the point of maximum impulse is not displaced. The neck veins are flat, and there is no peripheral edema. A well-healed median sternotomy scar is evident, as are bilateral lower extremity saphenous vein harvest scars. The abdomen is soft and nontender, and peripheral pulses are strong and equal bilaterally. There are no neurologic abnormalities noted. Laboratory samples and an ECG are obtained. The following findings are noted on the ECG: a ventricular rate of 108 beats/min; PR interval, 140 ms; QRS duration, 116 ms; QT/QTc interval, 372/498 ms; P axis, 70°; R axis, 75°; and T axis, 167°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Thumb: Scaling with Pitted Nail Plate

ANSWER

The most likely diagnosis is psoriasis (choice “d”), which can manifest with localized involvement (see discussion below).

Fungal infection (choice “a”) is unlikely, given the negative results of the KOH prep and total lack of response to treatment for that diagnosis.

Eczema (choice “b”) does not manifest as such thick, adherent scale. If any nail changes were involved, they would likely consist of transverse nail ridges.

A variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”)—caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), for example—can produce somewhat similar changes in the skin. But it would be unlikely to lead to nail changes, and it would not be intermittent, as this rash was in apparent response to OTC cream.

DISCUSSION

A punch biopsy is sometimes required to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis, but this combination of skin and nail changes is quite suggestive of that entity. In this case, the confirmation was made by a different route: The rheumatologist judged that the patient’s arthritis was psoriatic in nature. The arthritis was treated with methotrexate, which soon cleared the skin disease without any help from dermatology.

This case serves to reinforce the possible mind-body role of stress in the genesis of this disease; however, at least 30% of the time, there is a positive family history. It also demonstrates the seemingly contradictory fact that the severity of the psoriasis doesn’t always correlate with the presence or absence of psoriatic arthritis.

Adding to the difficulty of making the diagnosis of psoriasis is the localized distribution of the scales, since it can usually be corroborated by finding lesions in their usual haunts—such as the extensor surfaces of arms, legs, on the trunk, or in the scalp. Cases such as this one force the provider to carefully consider the differential, which includes fungal infection. But the dermatophytes that cause ordinary fungal infections have to come from predictable sources (eg, children, pets, or farm animals), all missing from this patient’s history.

Had the rash been “fixed” (unchanging), the diagnosis of SCC would have to be considered more carefully. Superficial SCC is called Bowen’s disease, which, in cases such as this, is usually caused by HPV, not by the more typical overexposure to UV light. Though superficial, Bowen’s disease can become focally invasive and can even metastasize.

Had this patient not been treated with methotrexate, we would probably have used topical class 1 corticosteroid creams, which would have had a good chance to improve his skin but not his nail. The patient was also counseled regarding the role of stress and increased alcohol intake in the worsening of his disease. His prognosis for skin and joint disease is decent, though he will probably experience recurrences.

ANSWER

The most likely diagnosis is psoriasis (choice “d”), which can manifest with localized involvement (see discussion below).

Fungal infection (choice “a”) is unlikely, given the negative results of the KOH prep and total lack of response to treatment for that diagnosis.

Eczema (choice “b”) does not manifest as such thick, adherent scale. If any nail changes were involved, they would likely consist of transverse nail ridges.

A variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”)—caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), for example—can produce somewhat similar changes in the skin. But it would be unlikely to lead to nail changes, and it would not be intermittent, as this rash was in apparent response to OTC cream.

DISCUSSION

A punch biopsy is sometimes required to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis, but this combination of skin and nail changes is quite suggestive of that entity. In this case, the confirmation was made by a different route: The rheumatologist judged that the patient’s arthritis was psoriatic in nature. The arthritis was treated with methotrexate, which soon cleared the skin disease without any help from dermatology.

This case serves to reinforce the possible mind-body role of stress in the genesis of this disease; however, at least 30% of the time, there is a positive family history. It also demonstrates the seemingly contradictory fact that the severity of the psoriasis doesn’t always correlate with the presence or absence of psoriatic arthritis.

Adding to the difficulty of making the diagnosis of psoriasis is the localized distribution of the scales, since it can usually be corroborated by finding lesions in their usual haunts—such as the extensor surfaces of arms, legs, on the trunk, or in the scalp. Cases such as this one force the provider to carefully consider the differential, which includes fungal infection. But the dermatophytes that cause ordinary fungal infections have to come from predictable sources (eg, children, pets, or farm animals), all missing from this patient’s history.

Had the rash been “fixed” (unchanging), the diagnosis of SCC would have to be considered more carefully. Superficial SCC is called Bowen’s disease, which, in cases such as this, is usually caused by HPV, not by the more typical overexposure to UV light. Though superficial, Bowen’s disease can become focally invasive and can even metastasize.

Had this patient not been treated with methotrexate, we would probably have used topical class 1 corticosteroid creams, which would have had a good chance to improve his skin but not his nail. The patient was also counseled regarding the role of stress and increased alcohol intake in the worsening of his disease. His prognosis for skin and joint disease is decent, though he will probably experience recurrences.

ANSWER

The most likely diagnosis is psoriasis (choice “d”), which can manifest with localized involvement (see discussion below).

Fungal infection (choice “a”) is unlikely, given the negative results of the KOH prep and total lack of response to treatment for that diagnosis.

Eczema (choice “b”) does not manifest as such thick, adherent scale. If any nail changes were involved, they would likely consist of transverse nail ridges.

A variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; choice “c”)—caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), for example—can produce somewhat similar changes in the skin. But it would be unlikely to lead to nail changes, and it would not be intermittent, as this rash was in apparent response to OTC cream.

DISCUSSION

A punch biopsy is sometimes required to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis, but this combination of skin and nail changes is quite suggestive of that entity. In this case, the confirmation was made by a different route: The rheumatologist judged that the patient’s arthritis was psoriatic in nature. The arthritis was treated with methotrexate, which soon cleared the skin disease without any help from dermatology.

This case serves to reinforce the possible mind-body role of stress in the genesis of this disease; however, at least 30% of the time, there is a positive family history. It also demonstrates the seemingly contradictory fact that the severity of the psoriasis doesn’t always correlate with the presence or absence of psoriatic arthritis.

Adding to the difficulty of making the diagnosis of psoriasis is the localized distribution of the scales, since it can usually be corroborated by finding lesions in their usual haunts—such as the extensor surfaces of arms, legs, on the trunk, or in the scalp. Cases such as this one force the provider to carefully consider the differential, which includes fungal infection. But the dermatophytes that cause ordinary fungal infections have to come from predictable sources (eg, children, pets, or farm animals), all missing from this patient’s history.

Had the rash been “fixed” (unchanging), the diagnosis of SCC would have to be considered more carefully. Superficial SCC is called Bowen’s disease, which, in cases such as this, is usually caused by HPV, not by the more typical overexposure to UV light. Though superficial, Bowen’s disease can become focally invasive and can even metastasize.

Had this patient not been treated with methotrexate, we would probably have used topical class 1 corticosteroid creams, which would have had a good chance to improve his skin but not his nail. The patient was also counseled regarding the role of stress and increased alcohol intake in the worsening of his disease. His prognosis for skin and joint disease is decent, though he will probably experience recurrences.

About a year ago, this 40-year-old man developed scaling on the distal one-third of his thumbnail. After an ini-tial apparent response to OTC hydrocortisone 1% cream, the condition began to worsen, spreading to more of the thumb. The patient’s primary care provider diagnosed fungal infection and prescribed a combination clotrima-zole/betamethasone cream, which had no effect. A subsequent four-month course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) also yielded no improvement. The patient then requested referral to dermatology. The patient considers himself “quite healthy,” aside from having moderately severe arthritis, for which he takes nabumetone (750 mg bid). His arthritis recently worsened, and he is scheduled to see a rheumatologist in two months. He admits to being under a great deal of stress shortly before his skin condition developed. As a result, he in-creased his alcohol intake for a few months, but he quit drinking altogether soon afterward. He denies any family history of skin disease and has no children or contact with animals. On examination, most of his thumb is covered by thick adherent white scales on a pinkish base. The margins are sharply defined. A KOH prep is performed, but no fungal elements are seen. The adjacent thumbnail has focal areas of pitting in the nail plate, as well as yellowish discoloration on the dis-tal edge. No such changes are seen on his other nails, and examination of his elbows, knees, trunk, and scalp fails to reveal any significant abnormalities.

Knee Pain After Falling Off Ladder

ANSWER

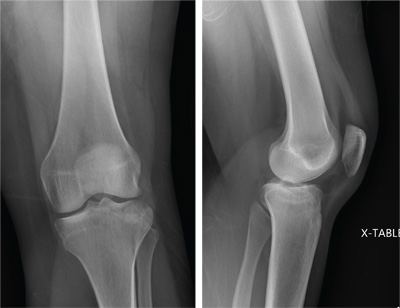

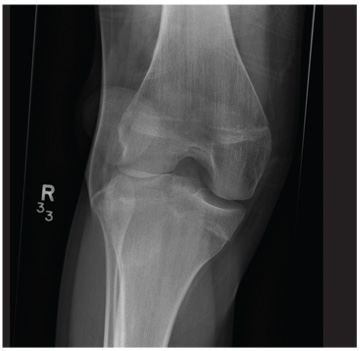

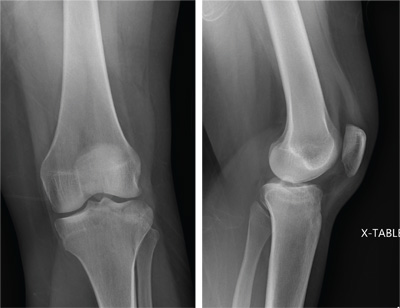

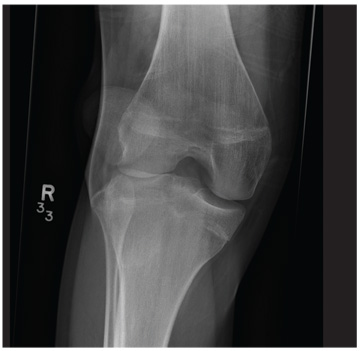

The radiograph shows a lucency within the lateral tibial plateau and tibial metaphysis, consistent with a fracture. It is mildly depressed and slightly comminuted.

Fluid collection is also evident on the lateral view, likely reflecting a lipohemarthrosis. The patient was placed in a knee immobilizer and made non–weight-bearing. She was instructed to follow up with an orthopedist when she returned home (as she was visiting from out of town).

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a lucency within the lateral tibial plateau and tibial metaphysis, consistent with a fracture. It is mildly depressed and slightly comminuted.

Fluid collection is also evident on the lateral view, likely reflecting a lipohemarthrosis. The patient was placed in a knee immobilizer and made non–weight-bearing. She was instructed to follow up with an orthopedist when she returned home (as she was visiting from out of town).

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a lucency within the lateral tibial plateau and tibial metaphysis, consistent with a fracture. It is mildly depressed and slightly comminuted.

Fluid collection is also evident on the lateral view, likely reflecting a lipohemarthrosis. The patient was placed in a knee immobilizer and made non–weight-bearing. She was instructed to follow up with an orthopedist when she returned home (as she was visiting from out of town).

A 25-year-old woman presents for evaluation of left knee pain secondary to a fall. She states she was descending a ladder when she missed a step while still several feet above the ground. She landed on her left foot, awkwardly twisting her leg. She now has swelling and pain in her knee and difficulty bearing weight on that leg. Her medical history is unremarkable. Examination reveals a moderate amount of swelling that limits her ability to flex her left knee. She has diffuse tenderness throughout the knee. Because of the swelling and the patient’s severe discomfort, instability tests are not performed. She has good distal pulses and sensation. Radiographs of the knee are obtained. What is your impression?

The Flu, or a Problem with His Pacemaker?

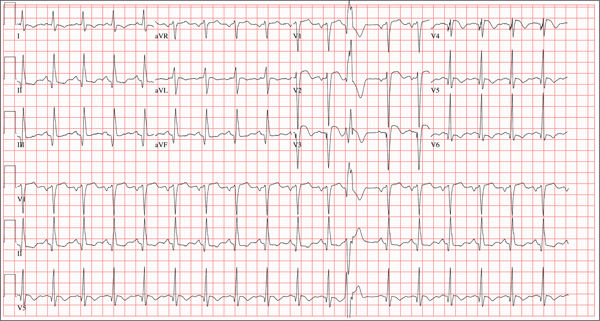

ANSWER

This ECG is remarkable for ventricular pacing at a rate of 70 beats/min, with an underlying sinus rhythm at the same rate as the pacemaker but dissociated from ventricular pacing. Ventricular pacing is evidenced by the presence of a pacing spike before each QRS complex, and the fact that each QRS complex in all leads is wide (200 ms) and does not demonstrate variability within an ECG lead. The T waves are similar in each lead as well. A left-axis deviation of –83° is attributable to pacing from the right ventricle.

What is interesting to note is that P waves are visible and are at a rate very close to that of the ventricular paced beats; however, they show no association with the pacing spike or the QRS complexes. This is most evident in lead V1 and the rhythm strip of lead I, which shows the P waves marching through the QRS and T-wave complexes without being associated with any ventricular conduction. This is an unusual situation in which the sinus rate and the paced ventricular rate are very similar.

Interrogation of the pacemaker generator revealed that the programming had been inadvertently changed from DDDR at a rate of 60 beats/min to VVI at a rate of 70 beats/min. After the device was reprogrammed to its original settings, the patient’s symptoms resolved.

ANSWER

This ECG is remarkable for ventricular pacing at a rate of 70 beats/min, with an underlying sinus rhythm at the same rate as the pacemaker but dissociated from ventricular pacing. Ventricular pacing is evidenced by the presence of a pacing spike before each QRS complex, and the fact that each QRS complex in all leads is wide (200 ms) and does not demonstrate variability within an ECG lead. The T waves are similar in each lead as well. A left-axis deviation of –83° is attributable to pacing from the right ventricle.

What is interesting to note is that P waves are visible and are at a rate very close to that of the ventricular paced beats; however, they show no association with the pacing spike or the QRS complexes. This is most evident in lead V1 and the rhythm strip of lead I, which shows the P waves marching through the QRS and T-wave complexes without being associated with any ventricular conduction. This is an unusual situation in which the sinus rate and the paced ventricular rate are very similar.

Interrogation of the pacemaker generator revealed that the programming had been inadvertently changed from DDDR at a rate of 60 beats/min to VVI at a rate of 70 beats/min. After the device was reprogrammed to its original settings, the patient’s symptoms resolved.

ANSWER

This ECG is remarkable for ventricular pacing at a rate of 70 beats/min, with an underlying sinus rhythm at the same rate as the pacemaker but dissociated from ventricular pacing. Ventricular pacing is evidenced by the presence of a pacing spike before each QRS complex, and the fact that each QRS complex in all leads is wide (200 ms) and does not demonstrate variability within an ECG lead. The T waves are similar in each lead as well. A left-axis deviation of –83° is attributable to pacing from the right ventricle.

What is interesting to note is that P waves are visible and are at a rate very close to that of the ventricular paced beats; however, they show no association with the pacing spike or the QRS complexes. This is most evident in lead V1 and the rhythm strip of lead I, which shows the P waves marching through the QRS and T-wave complexes without being associated with any ventricular conduction. This is an unusual situation in which the sinus rate and the paced ventricular rate are very similar.

Interrogation of the pacemaker generator revealed that the programming had been inadvertently changed from DDDR at a rate of 60 beats/min to VVI at a rate of 70 beats/min. After the device was reprogrammed to its original settings, the patient’s symptoms resolved.

A 75-year-old man presents to your office with complaints of shortness of breath. He states he has had “the flu” for the past week, but it doesn’t seem to be getting any better. His shortness of breath has persisted without change, and he is concerned he may be developing pneumonia. He denies having a productive cough, fevers, chills, or night sweats. Medical history is remarkable for GERD, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and complete heart block with implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker in 2010. He has had several surgeries, including a right inguinal hernia repair and an appendectomy. Family history is positive for breast cancer, colon cancer, and stroke. There is no family history of cardiac or pulmonary disease. Social history reveals a retired accountant who lives at home with his wife. He has an occasional brandy in the evening and has never smoked. His current medications include metoprolol, rosu¬\vastatin, and omeprazole. He has no known drug allergies. The review of systems is unremarkable, with the exception of the shortness of breath. The patient is concerned, however, that since his pacemaker was interrogated one week ago, he hasn’t “felt the same.” Physical examination reveals a blood pressure of 130/70 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min-1; temperature, 36.6°C; and O2 saturation, 97% on room air. The patient’s weight is 105 kg. The cardiovascular exam reveals a regular rate of 70 beats/min, and a grade II/VI early systolic murmur best heard at the left upper sternal border and without radiation. There are no rubs, gallops, or bruits. The pulmonary exam reveals scattered crackles in the right lower chest, which clear with coughing. There are no rhonchi or bronchial breath sounds. All other exams yield normal results. The patient provides a copy of an interrogation report from one year ago, which states his pacemaker is programmed DDDR at a rate of 60 beats/min, with an upper tracking and sensing rate of 130 beats/min, a paced AV delay of 150 ms, and a sensed AV delay of 120 ms. Given the patient’s concern about his most recent interrogation, you call an experienced practitioner to determine whether the patient’s device is functioning appropriately. While waiting, you obtain an ECG, which reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 70 beats/min; PR interval, not measurable; QRS duration, 200 ms; QT/QTc interval, 500/540 ms; no P axis; R axis, –83°; and T axis, 71°. What is your interpretation, and is there any concern regarding his pacemaker function?

All of Her Friends Say She Has Ringworm

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (PR; choice “d”), which is commonly seen in patients ages 10 to 35 and is about twice as likely to occur in women as in men.

Lichen planus (LP; choice “a”) can mimic PR but lacks the peculiar centripetal scale and oval shape. Furthermore, it does not present with a herald patch.

Guttate psoriasis (choice “b”) could easily be confused for PR. However, it displays heavier white uniform scales with a salmon-pink base, tends to have a distinctly round configuration, and does not involve the appearance of a herald patch.

Secondary syphilis (choice “c”) can usually be ruled out by the sexual history, but also by the lack of a herald patch and the absence of centripetal scaling. Highly variable in appearance, the lesions of secondary syphilis are often seen on the palms.

DISCUSSION

PR was first described in 1860 by Camille Gibert, who used the term pityriasis to describe the fine scale seen with this condition, and chose the term rosea to denote the rosy or pink color.

For a variety of reasons, PR is assumed to be a viral exanthema since, as with many such eruptions, its incidence clusters in the fall and spring, it occurs in close contacts and families, and it is commonly seen in immunocompromised patients. In addition, acquiring the condition appears to confer lifelong immunity.

However, the jury is still out with regard to the exact virus responsible for the disease. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 are the strongest candidates in terms of antibody production, but no herpesviral particles have been detected in tissue samples.

The so-called herald patch appears initially, in a majority of cases, as a salmon-pink patch that can become as large as 5 to 10 cm, on the trunk or arms. The smaller oval lesions begin to appear within a week or two, averaging 1 to 2 cm in diameter; most display the characteristic “centripetal” scaling, clearly sparing the lesions’ periphery and serving as an essentially pathognomic finding.

On darker-skinned patients, the lesions (including the herald patch) will tend to be brown to black. The examiner must then look for the other characteristic aspects of PR, including the oval (as opposed to round) shape, the long axes of which will often parallel the skin tension lines on the back to produce what is termed the “Christmas tree pattern.” In the author’s experience, the most consistent diagnostic finding is the centripetal scaling seen in at least a few lesions.

Since secondary syphilis is a major item in the differential, obtaining a careful sexual history is essential. If this is uncertain, or if the lesions are not a good fit for PR, obtaining a punch biopsy and serum rapid plasma reagin is necessary. The biopsy in secondary syphilis will show an infiltrate largely composed of plasma cells.

TREATMENT

Once the diagnosis of PR is made, patient education is essential. Affected patients should be reassured about the benign and self-limiting nature of the problem, but also about the likelihood that the condition will persist for up to nine weeks. Darker-skinned patients need to understand that the hyperpigmentation will last for months after the condition has resolved.

Relief of the itching experienced by 75% of PR patients can be achieved with topical steroids (eg, triamcinolone 0.1% cream) and oral antihistamines at bedtime (eg, hydroxyzine 25 to 50 mg) and/or during the daytime (cetirizine 10 mg/d), plus the liberal use of soothing OTC lotions (eg, those containing camphor and menthol). Systemic steroids appear to prolong the condition and are not terribly helpful in controlling the symptoms. In severe cases, phototherapy (narrow-band UVB) can be useful in controlling the itching.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (PR; choice “d”), which is commonly seen in patients ages 10 to 35 and is about twice as likely to occur in women as in men.

Lichen planus (LP; choice “a”) can mimic PR but lacks the peculiar centripetal scale and oval shape. Furthermore, it does not present with a herald patch.

Guttate psoriasis (choice “b”) could easily be confused for PR. However, it displays heavier white uniform scales with a salmon-pink base, tends to have a distinctly round configuration, and does not involve the appearance of a herald patch.

Secondary syphilis (choice “c”) can usually be ruled out by the sexual history, but also by the lack of a herald patch and the absence of centripetal scaling. Highly variable in appearance, the lesions of secondary syphilis are often seen on the palms.

DISCUSSION

PR was first described in 1860 by Camille Gibert, who used the term pityriasis to describe the fine scale seen with this condition, and chose the term rosea to denote the rosy or pink color.

For a variety of reasons, PR is assumed to be a viral exanthema since, as with many such eruptions, its incidence clusters in the fall and spring, it occurs in close contacts and families, and it is commonly seen in immunocompromised patients. In addition, acquiring the condition appears to confer lifelong immunity.

However, the jury is still out with regard to the exact virus responsible for the disease. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 are the strongest candidates in terms of antibody production, but no herpesviral particles have been detected in tissue samples.

The so-called herald patch appears initially, in a majority of cases, as a salmon-pink patch that can become as large as 5 to 10 cm, on the trunk or arms. The smaller oval lesions begin to appear within a week or two, averaging 1 to 2 cm in diameter; most display the characteristic “centripetal” scaling, clearly sparing the lesions’ periphery and serving as an essentially pathognomic finding.

On darker-skinned patients, the lesions (including the herald patch) will tend to be brown to black. The examiner must then look for the other characteristic aspects of PR, including the oval (as opposed to round) shape, the long axes of which will often parallel the skin tension lines on the back to produce what is termed the “Christmas tree pattern.” In the author’s experience, the most consistent diagnostic finding is the centripetal scaling seen in at least a few lesions.

Since secondary syphilis is a major item in the differential, obtaining a careful sexual history is essential. If this is uncertain, or if the lesions are not a good fit for PR, obtaining a punch biopsy and serum rapid plasma reagin is necessary. The biopsy in secondary syphilis will show an infiltrate largely composed of plasma cells.

TREATMENT

Once the diagnosis of PR is made, patient education is essential. Affected patients should be reassured about the benign and self-limiting nature of the problem, but also about the likelihood that the condition will persist for up to nine weeks. Darker-skinned patients need to understand that the hyperpigmentation will last for months after the condition has resolved.

Relief of the itching experienced by 75% of PR patients can be achieved with topical steroids (eg, triamcinolone 0.1% cream) and oral antihistamines at bedtime (eg, hydroxyzine 25 to 50 mg) and/or during the daytime (cetirizine 10 mg/d), plus the liberal use of soothing OTC lotions (eg, those containing camphor and menthol). Systemic steroids appear to prolong the condition and are not terribly helpful in controlling the symptoms. In severe cases, phototherapy (narrow-band UVB) can be useful in controlling the itching.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pityriasis rosea (PR; choice “d”), which is commonly seen in patients ages 10 to 35 and is about twice as likely to occur in women as in men.

Lichen planus (LP; choice “a”) can mimic PR but lacks the peculiar centripetal scale and oval shape. Furthermore, it does not present with a herald patch.

Guttate psoriasis (choice “b”) could easily be confused for PR. However, it displays heavier white uniform scales with a salmon-pink base, tends to have a distinctly round configuration, and does not involve the appearance of a herald patch.

Secondary syphilis (choice “c”) can usually be ruled out by the sexual history, but also by the lack of a herald patch and the absence of centripetal scaling. Highly variable in appearance, the lesions of secondary syphilis are often seen on the palms.

DISCUSSION

PR was first described in 1860 by Camille Gibert, who used the term pityriasis to describe the fine scale seen with this condition, and chose the term rosea to denote the rosy or pink color.

For a variety of reasons, PR is assumed to be a viral exanthema since, as with many such eruptions, its incidence clusters in the fall and spring, it occurs in close contacts and families, and it is commonly seen in immunocompromised patients. In addition, acquiring the condition appears to confer lifelong immunity.

However, the jury is still out with regard to the exact virus responsible for the disease. Human herpesviruses 6 and 7 are the strongest candidates in terms of antibody production, but no herpesviral particles have been detected in tissue samples.

The so-called herald patch appears initially, in a majority of cases, as a salmon-pink patch that can become as large as 5 to 10 cm, on the trunk or arms. The smaller oval lesions begin to appear within a week or two, averaging 1 to 2 cm in diameter; most display the characteristic “centripetal” scaling, clearly sparing the lesions’ periphery and serving as an essentially pathognomic finding.

On darker-skinned patients, the lesions (including the herald patch) will tend to be brown to black. The examiner must then look for the other characteristic aspects of PR, including the oval (as opposed to round) shape, the long axes of which will often parallel the skin tension lines on the back to produce what is termed the “Christmas tree pattern.” In the author’s experience, the most consistent diagnostic finding is the centripetal scaling seen in at least a few lesions.

Since secondary syphilis is a major item in the differential, obtaining a careful sexual history is essential. If this is uncertain, or if the lesions are not a good fit for PR, obtaining a punch biopsy and serum rapid plasma reagin is necessary. The biopsy in secondary syphilis will show an infiltrate largely composed of plasma cells.

TREATMENT

Once the diagnosis of PR is made, patient education is essential. Affected patients should be reassured about the benign and self-limiting nature of the problem, but also about the likelihood that the condition will persist for up to nine weeks. Darker-skinned patients need to understand that the hyperpigmentation will last for months after the condition has resolved.

Relief of the itching experienced by 75% of PR patients can be achieved with topical steroids (eg, triamcinolone 0.1% cream) and oral antihistamines at bedtime (eg, hydroxyzine 25 to 50 mg) and/or during the daytime (cetirizine 10 mg/d), plus the liberal use of soothing OTC lotions (eg, those containing camphor and menthol). Systemic steroids appear to prolong the condition and are not terribly helpful in controlling the symptoms. In severe cases, phototherapy (narrow-band UVB) can be useful in controlling the itching.

Three weeks ago, a 25-year-old woman noticed an asymp¬tomatic lesion of unknown origin on her chest. Since then, smaller versions have appeared in “crops” on her trunk, arms, and lower neck. Friends were unanimous in their opinion that she had “ringworm,” so she consulted her pharmacist, who recommended clotrimazole cream. Despite her use of it, however, the lesions continue to increase in number. Her original lesion has become less red and scaly, though. The patient has felt fine from the outset and maintains that she is “quite healthy” in other respects. Employed as an IT technician, she denies any exposure to children, pets, or sexually transmitted diseases. The patient, who is African-American, has type V skin. Her original lesion—located on her left inframammary chest—is dark brown, macular, oval to round, and measures about 3.8 cm. On her trunk, arms, and lower neck, 15 to 20 oval, papulosquamous lesions are seen; these are widely scattered, all hyperpigmented (brown), and average 1.5 cm in diameter. Several of these smaller lesions have scaly centers that spare the peripheral margins. The long axes of her oval back lesions are parallel with natural lines of cleavage in the skin.

Chest Wall and Knee Pain Following Motor Vehicle Collision

A 20-year-old man presents following a motor vehicle collision in which the car he was driving was broadsided by another vehicle. His air bag deployed, and the patient is now complaining of right-sided chest wall pain and right knee pain. His medical history is unremarkable. In a primary survey, the patient appears stable, with normal vital signs. Inspection of his right knee shows some deformity of the joint, with mild swelling and moderate tenderness. The patient is unable to perform flexion with his right knee. Good distal pulses are present, and sensation is intact. Radiograph of the right knee is obtained. What is your impression?

Man Waits Until Follow-up to Reveal Chest Pain

ANSWER

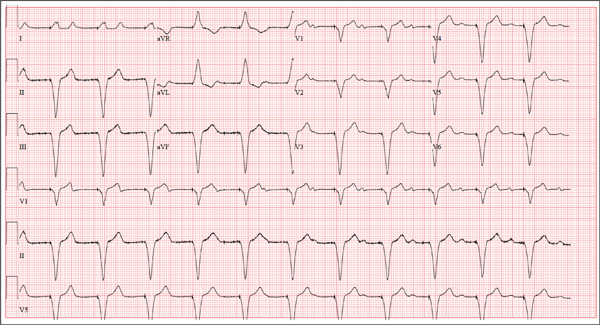

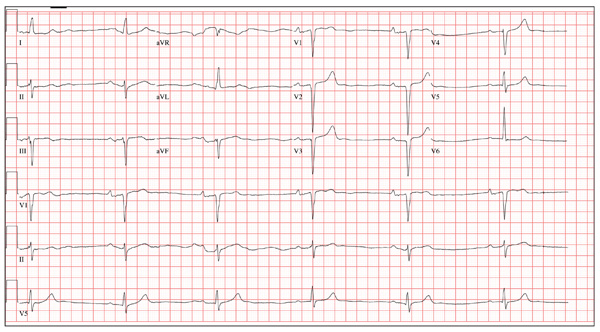

The correct interpretation includes marked sinus bradycardia with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, left anterior fascicular block, and evidence of an anteroseptal MI. Marked sinus bradycardia is evidenced by a heart rate significantly less than 60 beats/min (in this case, almost half the rate). A first-degree AV block is apparent by the presence of a PR interval > 200 ms. The presence of a left anterior fascicular block (or left anterior hemiblock) includes a left-axis deviation between –45° and –90°, small Q waves with tall R waves in leads I and aVL, small R waves with deep S waves in leads II, III, and aVF, and a normal or slightly prolonged QRS duration. Finally, an anteroseptal MI is evident from the presence of deep S waves in leads V1 to V3.

The patient was directly admitted to the cardiology service for definitive workup and treatment.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes marked sinus bradycardia with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, left anterior fascicular block, and evidence of an anteroseptal MI. Marked sinus bradycardia is evidenced by a heart rate significantly less than 60 beats/min (in this case, almost half the rate). A first-degree AV block is apparent by the presence of a PR interval > 200 ms. The presence of a left anterior fascicular block (or left anterior hemiblock) includes a left-axis deviation between –45° and –90°, small Q waves with tall R waves in leads I and aVL, small R waves with deep S waves in leads II, III, and aVF, and a normal or slightly prolonged QRS duration. Finally, an anteroseptal MI is evident from the presence of deep S waves in leads V1 to V3.

The patient was directly admitted to the cardiology service for definitive workup and treatment.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes marked sinus bradycardia with a first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, left anterior fascicular block, and evidence of an anteroseptal MI. Marked sinus bradycardia is evidenced by a heart rate significantly less than 60 beats/min (in this case, almost half the rate). A first-degree AV block is apparent by the presence of a PR interval > 200 ms. The presence of a left anterior fascicular block (or left anterior hemiblock) includes a left-axis deviation between –45° and –90°, small Q waves with tall R waves in leads I and aVL, small R waves with deep S waves in leads II, III, and aVF, and a normal or slightly prolonged QRS duration. Finally, an anteroseptal MI is evident from the presence of deep S waves in leads V1 to V3.

The patient was directly admitted to the cardiology service for definitive workup and treatment.

A 64-year-old man presents for follow-up to an appointment one month ago in which he reported a history of acute-onset shortness of breath, fatigue, and exercise intolerance. His health prior to that visit was described as “normal”; he had not seen a clinician since having his tonsils out at age 14. At the previous visit, a complete history documented that the patient is a rancher and farmer who makes his living from his crops and animals. He has never been married and lives out in the country. He has a history of several broken bones that he set himself, with no resultant sequelae. Aside from routine colds and flu, he has not been ill. He stopped smoking 10 years ago when it “got to be too expensive,” and he drinks one shot of whiskey at bedtime each night. He denies any drug allergies; he was taking no medications when he presented for that visit. A physical examination during that appointment revealed the presence of an irregularly irregular rhythm with a ventricular rate of 120 beats/min, a grade II/VI decrescendo diastolic murmur best heard at the right upper sternal border, a grade II/VI mid-systolic murmur best heard at the apex, a large point of maximum impulse (PMI) palpable at the anterior axillary line, and 3+ pitting edema to the level of the knees in both lower extremities. Subsequent workup, including an ECG, echocardiogram, chest x-ray, complete blood count, and chemistry panel, was performed—much to the patient’s displeasure. Pertinent results included a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, a bicuspid aortic valve, aortic insufficiency, and mitral regurgitation. He was prescribed metoprolol and warfarin and referred to a cardiologist. During the current visit, you learn that he did not continue to take his warfarin, because his shortness of breath went away the day after the previous appointment. He states he doesn’t always remember to take his metoprolol, but when he does, he’ll often take enough to “catch up on” his dosage. He did not follow up with a cardiologist as scheduled. Additionally, he reveals that he experienced chest pain two weeks ago, which he describes as a “sharp, sticking” pain in his left chest. He did not come in because he thought he’d wait until this appointment to discuss it. He remembers being “all sweaty” when he had his chest pain, but adds that it hasn’t happened again. His review of symptoms is remarkable for fatigue since his chest pain. Physical exam reveals cardiac changes. His rhythm is now regular, but at a rate of 40 beats/min. His murmurs are unchanged from the previous visit. Another ECG is obtained, which reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 35 beats/min; PR interval, 258 ms; QRS duration, 116 ms; QT/QTc interval, 532/406 ms; P axis, 74°; R axis, –47°; and T axis, 45°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?