User login

Polyglutamine diseases are rare, but not the mutations that cause them

Polyglutamine diseases are a group of hereditary neurodegenerative disorders caused by mutations in which a trinucleotide repeat expands pathologically on a disease-associated gene. The diseases are rare, with the most common among them – Huntington disease – affecting between 10 and 14 per 100,000 people in Western countries, where prevalence is highest.

In polyglutamine diseases, which include the spinocerebellar ataxias, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy, and spinal bulbar muscular atrophy, higher CAG (cytosine-adenine-guanine) repeat numbers are associated with greater disease severity, faster progression, or earlier age at onset.

In research published April 1 in JAMA Neurology, investigators report that more than one-tenth of the European population carries CAG expansions that fall short of the repeats needed to cause any of 9 polyglutamine diseases – but are enough to put them at risk of having children who develop one. A smaller number of people – about 1% – carry enough CAG repeats to cause one of the diseases late in life.

For their research, Sarah L. Gardiner, MD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University, and her colleagues looked at polyglutamine expansion variants for nine diseases in samples from 14,196 adults (56% of whom were women) from the Netherlands, Scotland, and Ireland. The samples were taken from five population-based cohort studies conducted between 1997 and 2012, and all subjects were without a history of polyglutamine disease or major depression.

Of these, 10.7% had a CAG repeat number on a disease-associated gene that was in the intermediate range, defined as a number of repeats that cannot cause disease but for which “expansion into the fully pathological range has been observed on intergenerational transmission,” Dr. Gardiner and her colleagues wrote. And some 1.3% of subjects were found to have CAG repeats within the disease-causing range, “mostly in the lower range associated with elderly onset.”

The investigators found no differences in sex, age, or body mass index between individuals with CAG repeat numbers within the pathological range and individuals with CAG repeat numbers within the normal or intermediate range.

Whether carriers of immediate or lower-range pathological CAG repeats went on to develop disease could not be measured, as follow-up data were not available. Another limitation of the study, the investigators acknowledged, was that the genotyping method used “did not allow us to determine the presence of trinucleotide interruptions,” which can affect disease penetrance.

“A late age at onset, a reduced penetrance, or the presence of interruptions could all explain the asymptomatic status of our carriers of intermediate and pathological polyglutamine disease–associated alleles at the time of assessment,” Dr. Gardiner and her colleagues wrote.

This study was funded by the European Union and Dutch government agencies; one of the population-based cohort studies from which the study sample was taken received some support from Bristol-Myers-Squibb. One of Dr. Gardiner’s coauthors, Raymund A. C. Roos, MD, PhD, disclosed being an adviser for UniQure, a gene-therapy firm, and no other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Gardiner et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.001/jamaneurol.2019.042.

Gardiner et al. describe the results of an appraisal of polyglutamine expansion variants in more than 14,000 individuals from the Netherlands, Scotland, and Ireland. Given the relative rarity of polyglutamine repeat disease, the first question that comes to mind is why were so many individuals identified with repeats in the pathogenic range? Based on our understanding of disease prevalence, it is unlikely that each of these individuals will become affected; therefore, this work suggests a reduced penetrance of these mutations. The findings are illustrative of a growing theme in human disease genetics: There are a very large number of apparently healthy individuals in the general population who carry mutations associated with various diseases. The phenomenon of reduced penetrance, where mutations cause disease in some but not all carriers, overlaps and arguably may be the same as that of variable expressivity, where the same mutation can lead to very different disease outcomes in different individuals. It is extremely likely that second-generation sequencing and population-scale screening will continue to reveal similar themes. We continue to appreciate the increasing complexity of the human genome and its relationship to disease, even those diseases we thought of previously as simple “single-gene” disorders.

Monia B. Hammer, PhD, and Andrew B. Singleton, PhD, are with the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. Dr. Hammer and Dr. Singleton report no financial conflicts of interest related to their editorial.

Gardiner et al. describe the results of an appraisal of polyglutamine expansion variants in more than 14,000 individuals from the Netherlands, Scotland, and Ireland. Given the relative rarity of polyglutamine repeat disease, the first question that comes to mind is why were so many individuals identified with repeats in the pathogenic range? Based on our understanding of disease prevalence, it is unlikely that each of these individuals will become affected; therefore, this work suggests a reduced penetrance of these mutations. The findings are illustrative of a growing theme in human disease genetics: There are a very large number of apparently healthy individuals in the general population who carry mutations associated with various diseases. The phenomenon of reduced penetrance, where mutations cause disease in some but not all carriers, overlaps and arguably may be the same as that of variable expressivity, where the same mutation can lead to very different disease outcomes in different individuals. It is extremely likely that second-generation sequencing and population-scale screening will continue to reveal similar themes. We continue to appreciate the increasing complexity of the human genome and its relationship to disease, even those diseases we thought of previously as simple “single-gene” disorders.

Monia B. Hammer, PhD, and Andrew B. Singleton, PhD, are with the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. Dr. Hammer and Dr. Singleton report no financial conflicts of interest related to their editorial.

Gardiner et al. describe the results of an appraisal of polyglutamine expansion variants in more than 14,000 individuals from the Netherlands, Scotland, and Ireland. Given the relative rarity of polyglutamine repeat disease, the first question that comes to mind is why were so many individuals identified with repeats in the pathogenic range? Based on our understanding of disease prevalence, it is unlikely that each of these individuals will become affected; therefore, this work suggests a reduced penetrance of these mutations. The findings are illustrative of a growing theme in human disease genetics: There are a very large number of apparently healthy individuals in the general population who carry mutations associated with various diseases. The phenomenon of reduced penetrance, where mutations cause disease in some but not all carriers, overlaps and arguably may be the same as that of variable expressivity, where the same mutation can lead to very different disease outcomes in different individuals. It is extremely likely that second-generation sequencing and population-scale screening will continue to reveal similar themes. We continue to appreciate the increasing complexity of the human genome and its relationship to disease, even those diseases we thought of previously as simple “single-gene” disorders.

Monia B. Hammer, PhD, and Andrew B. Singleton, PhD, are with the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. Dr. Hammer and Dr. Singleton report no financial conflicts of interest related to their editorial.

Polyglutamine diseases are a group of hereditary neurodegenerative disorders caused by mutations in which a trinucleotide repeat expands pathologically on a disease-associated gene. The diseases are rare, with the most common among them – Huntington disease – affecting between 10 and 14 per 100,000 people in Western countries, where prevalence is highest.

In polyglutamine diseases, which include the spinocerebellar ataxias, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy, and spinal bulbar muscular atrophy, higher CAG (cytosine-adenine-guanine) repeat numbers are associated with greater disease severity, faster progression, or earlier age at onset.

In research published April 1 in JAMA Neurology, investigators report that more than one-tenth of the European population carries CAG expansions that fall short of the repeats needed to cause any of 9 polyglutamine diseases – but are enough to put them at risk of having children who develop one. A smaller number of people – about 1% – carry enough CAG repeats to cause one of the diseases late in life.

For their research, Sarah L. Gardiner, MD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University, and her colleagues looked at polyglutamine expansion variants for nine diseases in samples from 14,196 adults (56% of whom were women) from the Netherlands, Scotland, and Ireland. The samples were taken from five population-based cohort studies conducted between 1997 and 2012, and all subjects were without a history of polyglutamine disease or major depression.

Of these, 10.7% had a CAG repeat number on a disease-associated gene that was in the intermediate range, defined as a number of repeats that cannot cause disease but for which “expansion into the fully pathological range has been observed on intergenerational transmission,” Dr. Gardiner and her colleagues wrote. And some 1.3% of subjects were found to have CAG repeats within the disease-causing range, “mostly in the lower range associated with elderly onset.”

The investigators found no differences in sex, age, or body mass index between individuals with CAG repeat numbers within the pathological range and individuals with CAG repeat numbers within the normal or intermediate range.

Whether carriers of immediate or lower-range pathological CAG repeats went on to develop disease could not be measured, as follow-up data were not available. Another limitation of the study, the investigators acknowledged, was that the genotyping method used “did not allow us to determine the presence of trinucleotide interruptions,” which can affect disease penetrance.

“A late age at onset, a reduced penetrance, or the presence of interruptions could all explain the asymptomatic status of our carriers of intermediate and pathological polyglutamine disease–associated alleles at the time of assessment,” Dr. Gardiner and her colleagues wrote.

This study was funded by the European Union and Dutch government agencies; one of the population-based cohort studies from which the study sample was taken received some support from Bristol-Myers-Squibb. One of Dr. Gardiner’s coauthors, Raymund A. C. Roos, MD, PhD, disclosed being an adviser for UniQure, a gene-therapy firm, and no other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Gardiner et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.001/jamaneurol.2019.042.

Polyglutamine diseases are a group of hereditary neurodegenerative disorders caused by mutations in which a trinucleotide repeat expands pathologically on a disease-associated gene. The diseases are rare, with the most common among them – Huntington disease – affecting between 10 and 14 per 100,000 people in Western countries, where prevalence is highest.

In polyglutamine diseases, which include the spinocerebellar ataxias, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy, and spinal bulbar muscular atrophy, higher CAG (cytosine-adenine-guanine) repeat numbers are associated with greater disease severity, faster progression, or earlier age at onset.

In research published April 1 in JAMA Neurology, investigators report that more than one-tenth of the European population carries CAG expansions that fall short of the repeats needed to cause any of 9 polyglutamine diseases – but are enough to put them at risk of having children who develop one. A smaller number of people – about 1% – carry enough CAG repeats to cause one of the diseases late in life.

For their research, Sarah L. Gardiner, MD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University, and her colleagues looked at polyglutamine expansion variants for nine diseases in samples from 14,196 adults (56% of whom were women) from the Netherlands, Scotland, and Ireland. The samples were taken from five population-based cohort studies conducted between 1997 and 2012, and all subjects were without a history of polyglutamine disease or major depression.

Of these, 10.7% had a CAG repeat number on a disease-associated gene that was in the intermediate range, defined as a number of repeats that cannot cause disease but for which “expansion into the fully pathological range has been observed on intergenerational transmission,” Dr. Gardiner and her colleagues wrote. And some 1.3% of subjects were found to have CAG repeats within the disease-causing range, “mostly in the lower range associated with elderly onset.”

The investigators found no differences in sex, age, or body mass index between individuals with CAG repeat numbers within the pathological range and individuals with CAG repeat numbers within the normal or intermediate range.

Whether carriers of immediate or lower-range pathological CAG repeats went on to develop disease could not be measured, as follow-up data were not available. Another limitation of the study, the investigators acknowledged, was that the genotyping method used “did not allow us to determine the presence of trinucleotide interruptions,” which can affect disease penetrance.

“A late age at onset, a reduced penetrance, or the presence of interruptions could all explain the asymptomatic status of our carriers of intermediate and pathological polyglutamine disease–associated alleles at the time of assessment,” Dr. Gardiner and her colleagues wrote.

This study was funded by the European Union and Dutch government agencies; one of the population-based cohort studies from which the study sample was taken received some support from Bristol-Myers-Squibb. One of Dr. Gardiner’s coauthors, Raymund A. C. Roos, MD, PhD, disclosed being an adviser for UniQure, a gene-therapy firm, and no other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Gardiner et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.001/jamaneurol.2019.042.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

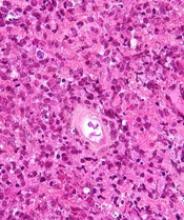

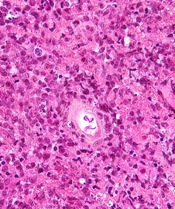

Non-TB mycobacteria infections rising in COPD patients

Veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen a sharp increase since 2012 in rates of non-TB mycobacteria infections, which carry a significantly higher risk of death in COPD patients, according to findings from a nationwide study.

For their research, published in Frontiers of Medicine, Fahim Pyarali, MD, and colleagues at the University of Miami, reviewed data from Veterans Affairs hospitals to identify non-TB mycobacteria (NTM) infections among more than 2 million COPD patients seen between 2000 and 2015. Incidence of NTM infections was 34.2 per 100,000 COPD patients in 2001, a rate that remained steady until 2012, when it began climbing sharply through 2015 to reach 70.3 per 100,000 (P = .035). Dr. Pyarali and colleagues also found that, during the study period, prevalence of NTM climbed from 93.1 infections per 100,000 population in 2001 to 277.6 per 100,000 in 2015.

Hotspots for NTM infections included Puerto Rico, which had the highest prevalence seen in the study at 370 infections per 100,000 COPD population; Florida, with 351 per 100,000; and Washington, D.C., with 309 per 100,000. Additional hotspots were identified around Lake Michigan, in coastal Louisiana, and in parts of the Southwest.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted that the geographical concentration of cases near oceans and lakes was “supported by previous findings that warmer temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen, and lower pH in the soils and waters provide a major environmental source for NTM organisms;” however, the study is the first to identify Puerto Rico as having exceptionally high prevalence. The reasons for this should be extensively investigated, the investigators argued.

The mortality risk was 43% higher among NTM-infected patients than in COPD patients without an NTM diagnosis (95% confidence interval, 1.31-1.58; P less than .001), independent of other comorbidities.

Though rates of NTM infection were seen rising steeply in men and women alike, Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted as a limitation of their study its use of an overwhelmingly male population, writing that this may obscure “the true reach of NTM disease and mortality” in the general population. The average age of NTM diagnosis remained steady throughout the study period, suggesting that rising incidence is not attributable to earlier diagnosis.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues reported no outside sources of funding or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pyarali F et al. Front Med. 2018 Nov 6. doi: 10.3389/fmed2018.00311.

Veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen a sharp increase since 2012 in rates of non-TB mycobacteria infections, which carry a significantly higher risk of death in COPD patients, according to findings from a nationwide study.

For their research, published in Frontiers of Medicine, Fahim Pyarali, MD, and colleagues at the University of Miami, reviewed data from Veterans Affairs hospitals to identify non-TB mycobacteria (NTM) infections among more than 2 million COPD patients seen between 2000 and 2015. Incidence of NTM infections was 34.2 per 100,000 COPD patients in 2001, a rate that remained steady until 2012, when it began climbing sharply through 2015 to reach 70.3 per 100,000 (P = .035). Dr. Pyarali and colleagues also found that, during the study period, prevalence of NTM climbed from 93.1 infections per 100,000 population in 2001 to 277.6 per 100,000 in 2015.

Hotspots for NTM infections included Puerto Rico, which had the highest prevalence seen in the study at 370 infections per 100,000 COPD population; Florida, with 351 per 100,000; and Washington, D.C., with 309 per 100,000. Additional hotspots were identified around Lake Michigan, in coastal Louisiana, and in parts of the Southwest.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted that the geographical concentration of cases near oceans and lakes was “supported by previous findings that warmer temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen, and lower pH in the soils and waters provide a major environmental source for NTM organisms;” however, the study is the first to identify Puerto Rico as having exceptionally high prevalence. The reasons for this should be extensively investigated, the investigators argued.

The mortality risk was 43% higher among NTM-infected patients than in COPD patients without an NTM diagnosis (95% confidence interval, 1.31-1.58; P less than .001), independent of other comorbidities.

Though rates of NTM infection were seen rising steeply in men and women alike, Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted as a limitation of their study its use of an overwhelmingly male population, writing that this may obscure “the true reach of NTM disease and mortality” in the general population. The average age of NTM diagnosis remained steady throughout the study period, suggesting that rising incidence is not attributable to earlier diagnosis.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues reported no outside sources of funding or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pyarali F et al. Front Med. 2018 Nov 6. doi: 10.3389/fmed2018.00311.

Veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen a sharp increase since 2012 in rates of non-TB mycobacteria infections, which carry a significantly higher risk of death in COPD patients, according to findings from a nationwide study.

For their research, published in Frontiers of Medicine, Fahim Pyarali, MD, and colleagues at the University of Miami, reviewed data from Veterans Affairs hospitals to identify non-TB mycobacteria (NTM) infections among more than 2 million COPD patients seen between 2000 and 2015. Incidence of NTM infections was 34.2 per 100,000 COPD patients in 2001, a rate that remained steady until 2012, when it began climbing sharply through 2015 to reach 70.3 per 100,000 (P = .035). Dr. Pyarali and colleagues also found that, during the study period, prevalence of NTM climbed from 93.1 infections per 100,000 population in 2001 to 277.6 per 100,000 in 2015.

Hotspots for NTM infections included Puerto Rico, which had the highest prevalence seen in the study at 370 infections per 100,000 COPD population; Florida, with 351 per 100,000; and Washington, D.C., with 309 per 100,000. Additional hotspots were identified around Lake Michigan, in coastal Louisiana, and in parts of the Southwest.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted that the geographical concentration of cases near oceans and lakes was “supported by previous findings that warmer temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen, and lower pH in the soils and waters provide a major environmental source for NTM organisms;” however, the study is the first to identify Puerto Rico as having exceptionally high prevalence. The reasons for this should be extensively investigated, the investigators argued.

The mortality risk was 43% higher among NTM-infected patients than in COPD patients without an NTM diagnosis (95% confidence interval, 1.31-1.58; P less than .001), independent of other comorbidities.

Though rates of NTM infection were seen rising steeply in men and women alike, Dr. Pyarali and colleagues noted as a limitation of their study its use of an overwhelmingly male population, writing that this may obscure “the true reach of NTM disease and mortality” in the general population. The average age of NTM diagnosis remained steady throughout the study period, suggesting that rising incidence is not attributable to earlier diagnosis.

Dr. Pyarali and colleagues reported no outside sources of funding or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pyarali F et al. Front Med. 2018 Nov 6. doi: 10.3389/fmed2018.00311.

FROM FRONTIERS IN MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Incidence and prevalence of non-TB mycobacteria infections rose sharply in a national veterans population with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after 2012.

Major finding: Incidence of non-TB mycobacteria infections doubled in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients between 2001 and 2015, with most of the increase seen after 2012

Study details: A retrospective, cross-sectional study using records from over 2 million, mostly male chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in a Veterans Affairs database.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no outside sources of funding or financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Pyarali F et al. Front Med. 2018 Nov 6. doi: 10.3389/fmed2018.00311.

Perioperative M&M similar for lobar, sublobar surgeries in early lung cancer

Though lobectomy is the long-held standard of care for people with early stage non–small cell lung cancer, a noninferiority study shows little difference in perioperative morbidity and mortality outcomes when sublobar resections are performed instead.

The study, published online in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, compared results from 697 functionally and physically fit patients with stage I cancer randomized over a 10-year period to lobar resection (n = 357) or sublobar resection (n = 340). Patients were analyzed for morbidity and mortality outcomes at 30 and 90 days post surgery. Nasser K. Altorki, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine–New York Presbyterian Hospital, led the study as a post hoc, exploratory analysis of CALGB/Alliance 140503, a multinational phase 3 trial whose primary outcome – still pending – is disease-free survival associated with the two different surgeries.

Dr. Altorki and his colleagues found 30- and 90-day survival to be comparable between surgery types. At 30 days, six patients in the study had died; four in the lobar resection group and two in the sublobar group (1.1% and 0.6%). At 90 days, 10 patients had died, or 1.4% of the cohort; 6 following lobar resection and 4 following sublobar resection. The between-group difference at 30 days was 0.5% (95% confidence interval, –1.1 to 2.3) and at 90 days remained 0.5% (95% CI, –1.5 to 2.6).

Similar rates of serious (grade 3 or worse) adverse advents were seen between surgery groups at 15% and 14%, respectively, and no differences were seen for cardiac or pulmonary complications. In the study, the type of sublobar approach was left to the surgeon’s discretion, and a majority of the sublobar procedures (59%) were found to comprise wedge resections, with the rest segmentectomies. Dr. Altorki and colleagues noted the high rate of wedge resections as striking, because “conventional wisdom … holds that an anatomical segmentectomy, involving individual ligation of segmental vessels and bronchi and wider parenchymal resection, is oncologically superior to nonanatomical wedge resections.” In their analysis the researchers conceded that a three-arm trial allocating patients to lobectomy, segmentectomy, or wedge resection “would have answered more precisely the posited research question,” but said that the sample size needed would have been too large.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Altorki reported a research grant from AstraZeneca unrelated to the study; two more coauthors disclosed funding from pharmaceutical or device manufacturers, and an additional 17 coauthors listed no competing interests.

SOURCE: Altorki NK et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Nov 12. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30411-9 .

Though lobectomy is the long-held standard of care for people with early stage non–small cell lung cancer, a noninferiority study shows little difference in perioperative morbidity and mortality outcomes when sublobar resections are performed instead.

The study, published online in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, compared results from 697 functionally and physically fit patients with stage I cancer randomized over a 10-year period to lobar resection (n = 357) or sublobar resection (n = 340). Patients were analyzed for morbidity and mortality outcomes at 30 and 90 days post surgery. Nasser K. Altorki, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine–New York Presbyterian Hospital, led the study as a post hoc, exploratory analysis of CALGB/Alliance 140503, a multinational phase 3 trial whose primary outcome – still pending – is disease-free survival associated with the two different surgeries.

Dr. Altorki and his colleagues found 30- and 90-day survival to be comparable between surgery types. At 30 days, six patients in the study had died; four in the lobar resection group and two in the sublobar group (1.1% and 0.6%). At 90 days, 10 patients had died, or 1.4% of the cohort; 6 following lobar resection and 4 following sublobar resection. The between-group difference at 30 days was 0.5% (95% confidence interval, –1.1 to 2.3) and at 90 days remained 0.5% (95% CI, –1.5 to 2.6).

Similar rates of serious (grade 3 or worse) adverse advents were seen between surgery groups at 15% and 14%, respectively, and no differences were seen for cardiac or pulmonary complications. In the study, the type of sublobar approach was left to the surgeon’s discretion, and a majority of the sublobar procedures (59%) were found to comprise wedge resections, with the rest segmentectomies. Dr. Altorki and colleagues noted the high rate of wedge resections as striking, because “conventional wisdom … holds that an anatomical segmentectomy, involving individual ligation of segmental vessels and bronchi and wider parenchymal resection, is oncologically superior to nonanatomical wedge resections.” In their analysis the researchers conceded that a three-arm trial allocating patients to lobectomy, segmentectomy, or wedge resection “would have answered more precisely the posited research question,” but said that the sample size needed would have been too large.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Altorki reported a research grant from AstraZeneca unrelated to the study; two more coauthors disclosed funding from pharmaceutical or device manufacturers, and an additional 17 coauthors listed no competing interests.

SOURCE: Altorki NK et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Nov 12. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30411-9 .

Though lobectomy is the long-held standard of care for people with early stage non–small cell lung cancer, a noninferiority study shows little difference in perioperative morbidity and mortality outcomes when sublobar resections are performed instead.

The study, published online in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, compared results from 697 functionally and physically fit patients with stage I cancer randomized over a 10-year period to lobar resection (n = 357) or sublobar resection (n = 340). Patients were analyzed for morbidity and mortality outcomes at 30 and 90 days post surgery. Nasser K. Altorki, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine–New York Presbyterian Hospital, led the study as a post hoc, exploratory analysis of CALGB/Alliance 140503, a multinational phase 3 trial whose primary outcome – still pending – is disease-free survival associated with the two different surgeries.

Dr. Altorki and his colleagues found 30- and 90-day survival to be comparable between surgery types. At 30 days, six patients in the study had died; four in the lobar resection group and two in the sublobar group (1.1% and 0.6%). At 90 days, 10 patients had died, or 1.4% of the cohort; 6 following lobar resection and 4 following sublobar resection. The between-group difference at 30 days was 0.5% (95% confidence interval, –1.1 to 2.3) and at 90 days remained 0.5% (95% CI, –1.5 to 2.6).

Similar rates of serious (grade 3 or worse) adverse advents were seen between surgery groups at 15% and 14%, respectively, and no differences were seen for cardiac or pulmonary complications. In the study, the type of sublobar approach was left to the surgeon’s discretion, and a majority of the sublobar procedures (59%) were found to comprise wedge resections, with the rest segmentectomies. Dr. Altorki and colleagues noted the high rate of wedge resections as striking, because “conventional wisdom … holds that an anatomical segmentectomy, involving individual ligation of segmental vessels and bronchi and wider parenchymal resection, is oncologically superior to nonanatomical wedge resections.” In their analysis the researchers conceded that a three-arm trial allocating patients to lobectomy, segmentectomy, or wedge resection “would have answered more precisely the posited research question,” but said that the sample size needed would have been too large.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Altorki reported a research grant from AstraZeneca unrelated to the study; two more coauthors disclosed funding from pharmaceutical or device manufacturers, and an additional 17 coauthors listed no competing interests.

SOURCE: Altorki NK et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Nov 12. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30411-9 .

FROM THE LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Patients with 30 and 90 days post surgery.

Major finding: Mortality at 30 days and 90 days was 0.5% for both trial groups and serious adverse advents were similar between groups.

Study details: A post hoc analysis from a multinational trial randomizing about 700 stage I NSCLC patients to lobar or sublobar surgery

Disclosures: National Cancer Institute sponsored the study; three authors including the lead author reported financial ties to manufacturers.

Source: Altorki et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2018 Nov 12. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30411-9.

Huntington’s research returns to Latin America, as scientists tread with care

BARRANQUILLA, COLOMBIA – “We don’t like to call them brigades. That sounds militant,” said neuropsychologist Johan Acosta-López, PhD.

Dr. Acosta-López, the head of cognitive neurosciences at Simón Bolivar University in this city on Colombia’s Atlantic coast, was among five Colombian clinicians – neurologists, psychiatrists, and neuropsychologists – stuffed into a car on their way to a conference hotel in July 2018.

The following day they would be joined by clinicians and researchers from North America, other Latin American countries, and Europe for a first-of-its kind meeting on Huntington’s disease (HD) in the region, sponsored by Factor-H, an HD charity working in Latin America.

Once the talks wrapped up, the researchers – clinicians and basic scientists – were invited to see patients at a hospital in a town an hour inland with a large concentration of HD families, most of them extremely poor. For some, the Factor-H–sponsored “brigade” would be their first hands-on experience with HD patients in a developing country.

There was some debate in the car about what to call such events: brigades, “integrated health days,” or clinics. Around here – where HD abounded but patients were weary of researchers – terminology mattered.

“We’ve had so many investigators arrive in this area – foreigners and Colombians – telling people ‘we’ve got this huge, great project that you’ll benefit from.’ And they take blood samples and never return,” Dr. Acosta-López said.

Even as a local investigator, Dr. Acosta-López has faced challenges getting a new study off the ground. Dr. Acosta-López and his colleagues are working under a grant from the Colombian government to recruit 241 presymptomatic subjects with confirmed genetic markers for HD, and evaluate them for cognitive and neurologic changes preceding disease onset.

It’s a cross-sectional study, and such studies are usually funded for a year. But the investigators knew it would take much more than a year to recruit patients here, and planned their study for 3 years. As of July, the team had been engaging with the community for 6 months but still didn’t have a single blood sample.

“We’ve had to convince everyone that this time is different,” he said, “and that means focusing on the social aspect” – setting up a legal-assistance program through the university to help families claim health benefits and a job-training program sponsored by local businesses.

It’s unusual for researchers to find themselves playing such extensive roles in coordinating social and economic support for their subjects. But with HD, it’s happening across Latin America, where researchers speak frequently of a “debt” owed to HD families in this region.

Huntington’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease caused by a genetic mutation in the huntingtin (HTT) gene, changing the normal protein it expresses in the body to a toxic form that damages cortical and basal ganglia neurons. It affects between 0.5 to 1 in 10,000 people worldwide, with higher prevalence in the United States, Europe, and Australia.

HD is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; a child of a parent with the mutation has a 50% chance of developing the disease. Patients develop cognitive symptoms that progress to dementia, along with the debilitating involuntary, dancelike movements that gave the disease the name by which it was formerly known: Huntington’s chorea.

In the 1980s and 1990s, several generations of Latin American HD families provided data that allowed for some of the greatest research advances in the disease – and they may represent a large share of the world’s HD cases. Yet, they continue to live in extreme poverty and have benefited little from the findings of the past 3 decades.

Without recognizing this and working to improve the families’ well-being, the researchers at the conference said it’s unlikely that promising therapies in the pipeline will ever reach the populations that need them the most.

Discovery in Venezuela

Some 8 hours by car from Barranquilla sits Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela, home to the largest known clusters of HD patients worldwide. The disease is believed to have come to the shores of Lake Maracaibo with a lone European immigrant – a Spanish sailor, many claim – at the end of the 18th century. Cases were first described in the 1950s by a young Venezuelan physician named Américo Negrette, MD.

Dr. Negrette’s findings were ignored by health officials in Venezuela and went unnoticed in the international research community until 1972, when a student of Dr. Negrette’s presented at an HD conference in Ohio. There he drew the attention of the American neuropsychologist Nancy S. Wexler, PhD. Dr. Wexler’s own mother had died of HD, and her father Milton, a noted psychoanalyst, founded the first research foundation dedicated to the disease.

While prevalence of HD in North America, Australia, and Europe is about 1 in 10,000, the region around Lake Maracaibo saw 70 times that rate at the time, thanks to high birth rates, geographic isolation, and extensive intermarriage within a handful of families. The families comprised mostly poor fishermen who lived in makeshift homes in towns ringing the lake.

In 1979, Dr. Wexler, with funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, began making annual research visits to Lake Maracaibo, and in 1983, the research group she coordinated, using data from blood and tissue samples donated by affected families, identified the location of the huntingtin gene on chromosome 4 (Nature. 1983 Nov 17;306[5940]:234-8). A decade later, the researchers isolated the mutant version of the gene and found it to be a triplet (CAG) expansion mutation, with more CAG repetitions associated with earlier age at disease onset (Cell. 1993 Mar 26;72[6]:971-83). Dr. Wexler and her colleagues’ findings led to the first genetic tests for HD.

Nationalist policies in Venezuela ended Dr. Wexler and her colleagues’ annual visits to Lake Maracaibo in 2002, along with the food, clothing, and medicines that the group routinely distributed to the families when they came.

Over 23 years, the researchers obtained data from some 18,000 individuals, but the families did not benefit in any durable way from the research. Local investigators with whom Dr. Wexler’s group collaborated lacked the resources and training to continue independently.

Access to medications is limited in Venezuela, and there is no institutional support for hundreds of HD patients living in extreme poverty, many of them descendants of the patients who contributed to the research and generation of these samples. The families’ biological material was sent to labs abroad, where investigators continue to derive findings from it today. Though genetic testing was performed on thousands at risk for the disease, few received access to their results through genetic counseling. A hospice established by Dr. Wexler’s foundation limped along until 2014, when it was finally shuttered.

Rebuilding bridges

A handful of families from the Lake Maracaibo towns attended the conference in Barranquilla. Their travel costs were picked up by Factor-H, which sponsored the event.

Ignacio Muñoz-Sanjuán, PhD, Factor-H’s founder and president, knew the families personally. He’s visited them regularly for years. In 2017, Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán, a molecular biologist known affectionately in the HD community as “Nacho,” invited several to Rome for a meeting with Pope Francis, as part of an effort to raise awareness of HD and to request support from the Catholic Church for the Latin American families.

Humanitarian work is relatively new to Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán, who’s spent his career in drug development. In addition to his unpaid work with Factor-H, he is vice president of biology with the CHDI Foundation, a Los Angeles–based nonprofit that funds drug research in HD. CHDI is reported to have about $100 million in annual funding – about triple the NIH budget in recent years for HD research. Its major donors are a group of investors who for years have remained anonymous and do not publicly discuss their philanthropy.

The Spanish-born Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán had little direct experience with HD populations in Latin America until a few years ago, he said.

At a CHDI meeting in Brazil, he said, “I was talking with physicians and patient advocates from Latin America, telling them they had to be willing to be involved, that these communities with high prevalence had a lot to offer science,” Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán said in an interview. “I was told that it was me who needed to understand the conditions in which HD patients lived. It completely put me on the spot.”

HD tends to strike during the most productive years of a person’s life, from the late 30s onward, keeping them from working and obliging family members to stop working to care for them. In a poor community, it can condemn a family to a state of extreme poverty for generations. Tetrabenazine (Xenazine), a medication to quiet chorea symptoms, is costly enough that many patients must do without it. Ensuring adequate calorie intake is difficult in HD patients, whose constant movements cause them to lose weight.

Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán traveled to Colombia, Venezuela, and Brazil, meeting HD families and doctors like neurologist Gustavo Barrios, MD, of Hospital Occidente de Kennedy in Bogotá, Colombia. In a talk at the Barranquilla conference, Dr. Barrios related the experience of his first visit to El Dificil, a community in northern Colombia where some large HD families are forced to survive on the equivalent of $5 a day. “I had to confront not only the fact that these families were living with a terrible disease but in conditions of extreme deprivation,” he said. “My life as a doctor changed that day.”

Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán helped form a Latin American HD network to involve clinicians like Dr. Barrios who worked with HD clusters, most of them poorly studied. “These are all neglected communities that share similar features,” Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán said.

On Colombia’s Caribbean coast, for example, HD had been documented since the early 1990s, but genotyping was not performed until recently. Prevalence data are “virtually nonexistent” in Colombia, said Sonia Moreno, PhD, a neuropsychologist at the University of Antioquia in Medellin. In a pilot study presented this year at the CHDI Foundation’s Enroll-HD Congress, Dr. Moreno and her colleagues mined Colombian public health data for likely HD cases, and argued for the creation of a national registry.

In 2012, Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán founded Factor-H with the aim of improving living conditions for Latin American communities with HD.

Factor-H does not receive funds from CHDI Foundation and instead relies on donations from individuals and companies; its annual budget is less than $200,000. But through contracts with local nongovernmental organizations, it has sponsored health clinics and ongoing food assistance, delivered shipments of medicines and clothing, and started a sponsorship program for young people in HD families, whose studies often are interrupted caring for sick parents. It hopes to build permanent support centers in Colombia and Venezuela where HD families can get their food and medical needs met.

“The traditional thinking in the HD research community is that we’re helping people by doing the legwork to make medicine – and that’s not necessarily enough. You need a more holistic approach,” Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán said.

Lennie Pineda, MSc, who recently retired as a geneticist with the University of Zulia in Maracaibo, Venezuela, said that Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán was viewed skeptically when he first visited, in part because of his biomedical research background.

Ms. Pineda, who worked with the region’s HD families her whole career, has been wary of past research efforts in Venezuela. In 2010, she published a paper critical of Dr. Wexler’s and his colleagues’ approach (Revista Redbioética/UNESCO. 2010;1[2]:50-61), particularly regarding issues of informed consent.

“I was very cold to Nacho,” she laughed. “We all looked at him suspiciously.”

Ms. Pineda said Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán won her over with his interest and creativity in finding concrete ways improve the lives of families in the Lake Maracaibo towns.

In a talk at the conference, Edison Soto, a young man from San Luis, a town on Lake Maracaibo that is a key cluster of HD, said Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán’s visits had reawakened hope among the families there. “For years, no one thought about us, and because of the situation in the country it’s been hard, really hard,” he said.

“Nacho’s smart,” Ms. Pineda said. “He’s not coming to build a research cohort, he’s coming with genuine intention to help. But if one day conditions are adequate to support investigation, and the people here are well informed and volunteer for a study with full consent, well, all the better,” she said.

Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán acknowledged that his humanitarian work could be perceived as preparing the ground for future clinical trials.

“I’m not doing anything research oriented with Latin America,” he said. “I would never approach these communities and recommend they take part in a study or give samples, unless their conditions change significantly. But the idea of cross-contamination is a problem I might need to fix. There may come a day where I need to depersonalize Factor-H from me.”

A research platform, a novel agent

Though HD research in Latin America remains rife with challenges, a number of investigators at the conference talked optimistically about planned and ongoing HD studies in Latin America.

The biggest of these is ENROLL-HD, a long-term global observational study of families with HD that uses a standardized approach to data collection. The platform, launched in 2013, aims to enroll 20,000 participants for yearly (or more frequent) assessment. Data from ENROLL-HD will support a diverse range of studies on everything from biomarkers to genetic modifiers to quality of life measures in HD.

ENROLL-HD has opened study sites in Argentina, Chile, and Colombia, and plans to launch a site near Lima, Peru, that is home to an HD cluster. Venezuela is considered out of reach, at least for now.

In Barranquilla, Claudia Perandones, MD, PhD, a genetics researcher in Argentina who manages ENROLL-HD for Latin America and is a cofounder of Factor-H, explained why the kind of clusters seen in Latin America are so valuable scientifically.

The extended family groups share a disease haplotype, eat the same foods, and live in similar environments, Dr. Perandones noted. Because not all the variation in HD can be explained by the number of CAG repeats a patient has, having a large sample with a common haplotype would help researchers pinpoint other environmental and genetic factors that can modify the onset or progress of the disease.

Another key goal of ENROLL-HD, investigators say, is to speed recruitment into clinical trials as they arise. And for the first time in history, potentially game-changing therapies are being developed specifically for HD.

For the past 5 years the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche has worked with a smaller biotech firm, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, on an agent called RG6042, which was known until recently as IONIS-HTTRx. CHDI was extensively involved in the agent’s preclinical development, contributing some $10 million to get it off the ground.

RG6042 is an antisense oligonucleotide, delivered by spinal injection, which works by interrupting an mRNA signaling pathway to suppress production of mutant HTT (mHTT) protein in the brain. Antisense oligonucleotides, sometimes called gene silencing therapies, are a new and promising approach in neurodegenerative diseases. Two have received FDA approval to treat spinal muscular atrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

In April 2018, Roche announced positive results from phase 1/2a study in 46 HD patients in Europe and North America. Patients in that 13-week study saw significant (up to 60%) dose-dependent reductions of the mHTT in their cerebrospinal fluid; a post hoc analysis also found some evidence of functional improvement (Neurology. 2018;90[15 Supplement]:CT.002).

These encouraging findings led to Roche’s announcement of a global phase 3 randomized, controlled trial that is scheduled to begin enrolling in 2019. Roche hopes to randomize 660 patients with mild HD across 15 countries for the 2-year trial, called GENERATION-HD1.

Sites in Latin America are expected to include Argentina, Chile, and Colombia.

At the Barranquilla meeting, Daniel Ciriano, MD, Roche’s Argentina-based medical director for Latin America, extolled the company’s commitment to ethics and social welfare in the region. In recent years, Roche has increased its humanitarian commitments across Latin America, including helping rebuild a Chilean village after an earthquake and offering free breast cancer and kidney disease treatments.

RG6042 is only one of a number of promising approaches to HD. Other therapies in the pipeline include gene silencing delivered by viral vectors instead of repeated spinal injections, an oral drug that interrupts mHTT production, immunotherapies, and even CRISPR gene–editing techniques.

Little was said at the conference, however, about how Latin American HD communities might be able to afford RG6042 or any other therapy that emerges from the pipeline.

Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán called the issue “a theme for future discussion.”

“This is an area that has to be handled carefully and not one we are heavily invested in yet, although it’s very important,” he said.

On the ground

Several of the European and North American scientists who presented in Barranquilla took pains to express their concern with the well-being of HD patients in Latin America and to demonstrate goodwill toward the local researchers and clinicians.

Hilal A. Lashuel, PhD, a molecular biologist working on the structure and behavior of the HTT protein, said his participation in the Factor-H event at the Vatican the year before had awakened him to “the real human part of HD,” and changed the way he does science.

Normally, Dr. Lashuel said, “we do research disconnected from the realities of the diseases we work with.”

“We need to not just to do research but [to ensure] that research is done right,” he said, which means also focusing on improving patients’ standard of living.

The room broke out in applause when Dr. Lashuel announced new internships for investigators from developing countries. He also presented a parting video from his research team at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (Switzerland), complete with music and affectionate messages in Spanish.

Pharmacologist Elena Cattaneo, PhD, a stem cell researcher long active in the HD community, and also a senator in Italy’s parliament, delivered a similarly warm, carefully choreographed video message from her laboratory at the University of Milan.

Just days later in the town of Juan de Acosta, an hour inland of Barranquilla, the same researchers sat down with patients and families who crowded the waiting room of the town’s only hospital, as the sun beat in through the windows and as mule carts, stray dogs, and buses passed by on the main drag outside.

The event had been titled a “brigade” after all, but the HD families did not seem to mind – and indeed so many showed up that a sign had to be placed on the door saying that no one who arrived after noon could be seen. Consults were not limited to HD-related matters, so families could be seen for any complaint.

HD was first documented in this town in the early 1990s, but much remains to be understood about the size of the cluster, the haplotype, and its relation to other clusters in Colombia or Venezuela. The families here share a handful of last names and likely share a common ancestor. In the early 19th century, the Barranquilla region was flooded with European migrants who reached the city by ship. (HD clusters in Latin America tend to be concentrated in coastal regions, possibly because of migration patterns.)

The waiting room of the hospital was loud with chatter. Small children played as their relatives waited for consults. Some showed the characteristic restless movements and emaciated bodies of people with advanced HD.

The foreign scientists were barred from taking any patient data out of the hospital or asking for samples. Even picture taking was prohibited. Instead they performed genetic counseling and neuropsychological tests; they sorted out differential diagnoses and advised on medications. Visiting Colombian and Venezuelan physicians did the same, while their assistants met with families in the waiting room, taking medical histories and sketching out basic genealogies.

Some of the foreign researchers reported fruitful interactions with patients, while others seemed perplexed by what they’d experienced. Alba di Pardo, PhD, a genetic epidemiologist at the Istituto Neurologico Mediterraneo Pozzilli (Italy), said she’d spent the morning doing genetic counseling with families and going over genealogies to assess risk. Yet, despite the fact that anyone with an HD parent has a 50% chance of developing the disease, some family members acted uninterested, she said.

Dr. di Pardo’s colleague at the Istituto, biologist Vittorio Maglione, PhD, reported having a similar experience. As he was counseling a young woman about her risk for HD, she scrolled indifferently through Facebook posts on her phone, he said.

On some level, Dr. Maglione said, he could understand patients’ reluctance to engage noting that, while there were many potential HD therapies to try, any new treatment paradigm for HD was many years away from a place like this – and potentially very costly. Dr. Maglione – along with Dr. di Pardo – is researching the SP1 axis, a sphingolipid pathway implicated in neurodegenerative such diseases as HD and which has potential as a drug target (Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39[5]:468-80).

Psychologist Pedro Puentes Rozo of Simón Bolivar University, who is working with Dr. Acosta-López on the local cohort study of presymptomatic HD patients, said that, for most of the families in the clinic that day, any seeming indifference probably masked deeper fears. People already were well aware of their risk. “They’ve known about it forever, said Dr. Puentes Rozo, who has been working with this HD population for a decade. “But this is a catastrophic illness and can generate a lot of anxiety.”

Dr. Puentes Rozo said the group’s planned study, unlike studies in the past, would be conducted under strict “international ethical norms and standards.” Subjects would receive ongoing psychological support, and the researchers were working to establish a genetic counseling center so that people who want to know their status “can be prepared,” he said, and plan for their lives and families.

By fall 2018, the cohort study was underway. The group had sponsored several more hospital brigades – or “integrated health days” as they preferred to call them, at the hospital in Juan de Acosta, giving them a chance to work face to face with families.

They drew no blood during the clinics, as investigators in the past had done. Instead, they explained the study to patients, performed the initial screenings, and invited them to designated study appointments at the university. Legal assistance was up and running, and the jobs program would start in 2019.

Enrollment was climbing. And the group was steadily accumulating data.

BARRANQUILLA, COLOMBIA – “We don’t like to call them brigades. That sounds militant,” said neuropsychologist Johan Acosta-López, PhD.

Dr. Acosta-López, the head of cognitive neurosciences at Simón Bolivar University in this city on Colombia’s Atlantic coast, was among five Colombian clinicians – neurologists, psychiatrists, and neuropsychologists – stuffed into a car on their way to a conference hotel in July 2018.

The following day they would be joined by clinicians and researchers from North America, other Latin American countries, and Europe for a first-of-its kind meeting on Huntington’s disease (HD) in the region, sponsored by Factor-H, an HD charity working in Latin America.

Once the talks wrapped up, the researchers – clinicians and basic scientists – were invited to see patients at a hospital in a town an hour inland with a large concentration of HD families, most of them extremely poor. For some, the Factor-H–sponsored “brigade” would be their first hands-on experience with HD patients in a developing country.

There was some debate in the car about what to call such events: brigades, “integrated health days,” or clinics. Around here – where HD abounded but patients were weary of researchers – terminology mattered.

“We’ve had so many investigators arrive in this area – foreigners and Colombians – telling people ‘we’ve got this huge, great project that you’ll benefit from.’ And they take blood samples and never return,” Dr. Acosta-López said.

Even as a local investigator, Dr. Acosta-López has faced challenges getting a new study off the ground. Dr. Acosta-López and his colleagues are working under a grant from the Colombian government to recruit 241 presymptomatic subjects with confirmed genetic markers for HD, and evaluate them for cognitive and neurologic changes preceding disease onset.

It’s a cross-sectional study, and such studies are usually funded for a year. But the investigators knew it would take much more than a year to recruit patients here, and planned their study for 3 years. As of July, the team had been engaging with the community for 6 months but still didn’t have a single blood sample.

“We’ve had to convince everyone that this time is different,” he said, “and that means focusing on the social aspect” – setting up a legal-assistance program through the university to help families claim health benefits and a job-training program sponsored by local businesses.

It’s unusual for researchers to find themselves playing such extensive roles in coordinating social and economic support for their subjects. But with HD, it’s happening across Latin America, where researchers speak frequently of a “debt” owed to HD families in this region.

Huntington’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease caused by a genetic mutation in the huntingtin (HTT) gene, changing the normal protein it expresses in the body to a toxic form that damages cortical and basal ganglia neurons. It affects between 0.5 to 1 in 10,000 people worldwide, with higher prevalence in the United States, Europe, and Australia.

HD is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; a child of a parent with the mutation has a 50% chance of developing the disease. Patients develop cognitive symptoms that progress to dementia, along with the debilitating involuntary, dancelike movements that gave the disease the name by which it was formerly known: Huntington’s chorea.

In the 1980s and 1990s, several generations of Latin American HD families provided data that allowed for some of the greatest research advances in the disease – and they may represent a large share of the world’s HD cases. Yet, they continue to live in extreme poverty and have benefited little from the findings of the past 3 decades.

Without recognizing this and working to improve the families’ well-being, the researchers at the conference said it’s unlikely that promising therapies in the pipeline will ever reach the populations that need them the most.

Discovery in Venezuela

Some 8 hours by car from Barranquilla sits Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela, home to the largest known clusters of HD patients worldwide. The disease is believed to have come to the shores of Lake Maracaibo with a lone European immigrant – a Spanish sailor, many claim – at the end of the 18th century. Cases were first described in the 1950s by a young Venezuelan physician named Américo Negrette, MD.

Dr. Negrette’s findings were ignored by health officials in Venezuela and went unnoticed in the international research community until 1972, when a student of Dr. Negrette’s presented at an HD conference in Ohio. There he drew the attention of the American neuropsychologist Nancy S. Wexler, PhD. Dr. Wexler’s own mother had died of HD, and her father Milton, a noted psychoanalyst, founded the first research foundation dedicated to the disease.

While prevalence of HD in North America, Australia, and Europe is about 1 in 10,000, the region around Lake Maracaibo saw 70 times that rate at the time, thanks to high birth rates, geographic isolation, and extensive intermarriage within a handful of families. The families comprised mostly poor fishermen who lived in makeshift homes in towns ringing the lake.

In 1979, Dr. Wexler, with funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, began making annual research visits to Lake Maracaibo, and in 1983, the research group she coordinated, using data from blood and tissue samples donated by affected families, identified the location of the huntingtin gene on chromosome 4 (Nature. 1983 Nov 17;306[5940]:234-8). A decade later, the researchers isolated the mutant version of the gene and found it to be a triplet (CAG) expansion mutation, with more CAG repetitions associated with earlier age at disease onset (Cell. 1993 Mar 26;72[6]:971-83). Dr. Wexler and her colleagues’ findings led to the first genetic tests for HD.

Nationalist policies in Venezuela ended Dr. Wexler and her colleagues’ annual visits to Lake Maracaibo in 2002, along with the food, clothing, and medicines that the group routinely distributed to the families when they came.

Over 23 years, the researchers obtained data from some 18,000 individuals, but the families did not benefit in any durable way from the research. Local investigators with whom Dr. Wexler’s group collaborated lacked the resources and training to continue independently.

Access to medications is limited in Venezuela, and there is no institutional support for hundreds of HD patients living in extreme poverty, many of them descendants of the patients who contributed to the research and generation of these samples. The families’ biological material was sent to labs abroad, where investigators continue to derive findings from it today. Though genetic testing was performed on thousands at risk for the disease, few received access to their results through genetic counseling. A hospice established by Dr. Wexler’s foundation limped along until 2014, when it was finally shuttered.

Rebuilding bridges

A handful of families from the Lake Maracaibo towns attended the conference in Barranquilla. Their travel costs were picked up by Factor-H, which sponsored the event.

Ignacio Muñoz-Sanjuán, PhD, Factor-H’s founder and president, knew the families personally. He’s visited them regularly for years. In 2017, Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán, a molecular biologist known affectionately in the HD community as “Nacho,” invited several to Rome for a meeting with Pope Francis, as part of an effort to raise awareness of HD and to request support from the Catholic Church for the Latin American families.

Humanitarian work is relatively new to Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán, who’s spent his career in drug development. In addition to his unpaid work with Factor-H, he is vice president of biology with the CHDI Foundation, a Los Angeles–based nonprofit that funds drug research in HD. CHDI is reported to have about $100 million in annual funding – about triple the NIH budget in recent years for HD research. Its major donors are a group of investors who for years have remained anonymous and do not publicly discuss their philanthropy.

The Spanish-born Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán had little direct experience with HD populations in Latin America until a few years ago, he said.

At a CHDI meeting in Brazil, he said, “I was talking with physicians and patient advocates from Latin America, telling them they had to be willing to be involved, that these communities with high prevalence had a lot to offer science,” Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán said in an interview. “I was told that it was me who needed to understand the conditions in which HD patients lived. It completely put me on the spot.”

HD tends to strike during the most productive years of a person’s life, from the late 30s onward, keeping them from working and obliging family members to stop working to care for them. In a poor community, it can condemn a family to a state of extreme poverty for generations. Tetrabenazine (Xenazine), a medication to quiet chorea symptoms, is costly enough that many patients must do without it. Ensuring adequate calorie intake is difficult in HD patients, whose constant movements cause them to lose weight.

Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán traveled to Colombia, Venezuela, and Brazil, meeting HD families and doctors like neurologist Gustavo Barrios, MD, of Hospital Occidente de Kennedy in Bogotá, Colombia. In a talk at the Barranquilla conference, Dr. Barrios related the experience of his first visit to El Dificil, a community in northern Colombia where some large HD families are forced to survive on the equivalent of $5 a day. “I had to confront not only the fact that these families were living with a terrible disease but in conditions of extreme deprivation,” he said. “My life as a doctor changed that day.”

Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán helped form a Latin American HD network to involve clinicians like Dr. Barrios who worked with HD clusters, most of them poorly studied. “These are all neglected communities that share similar features,” Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán said.

On Colombia’s Caribbean coast, for example, HD had been documented since the early 1990s, but genotyping was not performed until recently. Prevalence data are “virtually nonexistent” in Colombia, said Sonia Moreno, PhD, a neuropsychologist at the University of Antioquia in Medellin. In a pilot study presented this year at the CHDI Foundation’s Enroll-HD Congress, Dr. Moreno and her colleagues mined Colombian public health data for likely HD cases, and argued for the creation of a national registry.

In 2012, Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán founded Factor-H with the aim of improving living conditions for Latin American communities with HD.

Factor-H does not receive funds from CHDI Foundation and instead relies on donations from individuals and companies; its annual budget is less than $200,000. But through contracts with local nongovernmental organizations, it has sponsored health clinics and ongoing food assistance, delivered shipments of medicines and clothing, and started a sponsorship program for young people in HD families, whose studies often are interrupted caring for sick parents. It hopes to build permanent support centers in Colombia and Venezuela where HD families can get their food and medical needs met.

“The traditional thinking in the HD research community is that we’re helping people by doing the legwork to make medicine – and that’s not necessarily enough. You need a more holistic approach,” Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán said.

Lennie Pineda, MSc, who recently retired as a geneticist with the University of Zulia in Maracaibo, Venezuela, said that Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán was viewed skeptically when he first visited, in part because of his biomedical research background.

Ms. Pineda, who worked with the region’s HD families her whole career, has been wary of past research efforts in Venezuela. In 2010, she published a paper critical of Dr. Wexler’s and his colleagues’ approach (Revista Redbioética/UNESCO. 2010;1[2]:50-61), particularly regarding issues of informed consent.

“I was very cold to Nacho,” she laughed. “We all looked at him suspiciously.”

Ms. Pineda said Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán won her over with his interest and creativity in finding concrete ways improve the lives of families in the Lake Maracaibo towns.

In a talk at the conference, Edison Soto, a young man from San Luis, a town on Lake Maracaibo that is a key cluster of HD, said Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán’s visits had reawakened hope among the families there. “For years, no one thought about us, and because of the situation in the country it’s been hard, really hard,” he said.

“Nacho’s smart,” Ms. Pineda said. “He’s not coming to build a research cohort, he’s coming with genuine intention to help. But if one day conditions are adequate to support investigation, and the people here are well informed and volunteer for a study with full consent, well, all the better,” she said.

Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán acknowledged that his humanitarian work could be perceived as preparing the ground for future clinical trials.

“I’m not doing anything research oriented with Latin America,” he said. “I would never approach these communities and recommend they take part in a study or give samples, unless their conditions change significantly. But the idea of cross-contamination is a problem I might need to fix. There may come a day where I need to depersonalize Factor-H from me.”

A research platform, a novel agent

Though HD research in Latin America remains rife with challenges, a number of investigators at the conference talked optimistically about planned and ongoing HD studies in Latin America.

The biggest of these is ENROLL-HD, a long-term global observational study of families with HD that uses a standardized approach to data collection. The platform, launched in 2013, aims to enroll 20,000 participants for yearly (or more frequent) assessment. Data from ENROLL-HD will support a diverse range of studies on everything from biomarkers to genetic modifiers to quality of life measures in HD.

ENROLL-HD has opened study sites in Argentina, Chile, and Colombia, and plans to launch a site near Lima, Peru, that is home to an HD cluster. Venezuela is considered out of reach, at least for now.

In Barranquilla, Claudia Perandones, MD, PhD, a genetics researcher in Argentina who manages ENROLL-HD for Latin America and is a cofounder of Factor-H, explained why the kind of clusters seen in Latin America are so valuable scientifically.

The extended family groups share a disease haplotype, eat the same foods, and live in similar environments, Dr. Perandones noted. Because not all the variation in HD can be explained by the number of CAG repeats a patient has, having a large sample with a common haplotype would help researchers pinpoint other environmental and genetic factors that can modify the onset or progress of the disease.

Another key goal of ENROLL-HD, investigators say, is to speed recruitment into clinical trials as they arise. And for the first time in history, potentially game-changing therapies are being developed specifically for HD.

For the past 5 years the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche has worked with a smaller biotech firm, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, on an agent called RG6042, which was known until recently as IONIS-HTTRx. CHDI was extensively involved in the agent’s preclinical development, contributing some $10 million to get it off the ground.

RG6042 is an antisense oligonucleotide, delivered by spinal injection, which works by interrupting an mRNA signaling pathway to suppress production of mutant HTT (mHTT) protein in the brain. Antisense oligonucleotides, sometimes called gene silencing therapies, are a new and promising approach in neurodegenerative diseases. Two have received FDA approval to treat spinal muscular atrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

In April 2018, Roche announced positive results from phase 1/2a study in 46 HD patients in Europe and North America. Patients in that 13-week study saw significant (up to 60%) dose-dependent reductions of the mHTT in their cerebrospinal fluid; a post hoc analysis also found some evidence of functional improvement (Neurology. 2018;90[15 Supplement]:CT.002).

These encouraging findings led to Roche’s announcement of a global phase 3 randomized, controlled trial that is scheduled to begin enrolling in 2019. Roche hopes to randomize 660 patients with mild HD across 15 countries for the 2-year trial, called GENERATION-HD1.

Sites in Latin America are expected to include Argentina, Chile, and Colombia.

At the Barranquilla meeting, Daniel Ciriano, MD, Roche’s Argentina-based medical director for Latin America, extolled the company’s commitment to ethics and social welfare in the region. In recent years, Roche has increased its humanitarian commitments across Latin America, including helping rebuild a Chilean village after an earthquake and offering free breast cancer and kidney disease treatments.

RG6042 is only one of a number of promising approaches to HD. Other therapies in the pipeline include gene silencing delivered by viral vectors instead of repeated spinal injections, an oral drug that interrupts mHTT production, immunotherapies, and even CRISPR gene–editing techniques.

Little was said at the conference, however, about how Latin American HD communities might be able to afford RG6042 or any other therapy that emerges from the pipeline.

Dr. Muñoz-Sanjuán called the issue “a theme for future discussion.”

“This is an area that has to be handled carefully and not one we are heavily invested in yet, although it’s very important,” he said.

On the ground

Several of the European and North American scientists who presented in Barranquilla took pains to express their concern with the well-being of HD patients in Latin America and to demonstrate goodwill toward the local researchers and clinicians.

Hilal A. Lashuel, PhD, a molecular biologist working on the structure and behavior of the HTT protein, said his participation in the Factor-H event at the Vatican the year before had awakened him to “the real human part of HD,” and changed the way he does science.

Normally, Dr. Lashuel said, “we do research disconnected from the realities of the diseases we work with.”

“We need to not just to do research but [to ensure] that research is done right,” he said, which means also focusing on improving patients’ standard of living.

The room broke out in applause when Dr. Lashuel announced new internships for investigators from developing countries. He also presented a parting video from his research team at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (Switzerland), complete with music and affectionate messages in Spanish.

Pharmacologist Elena Cattaneo, PhD, a stem cell researcher long active in the HD community, and also a senator in Italy’s parliament, delivered a similarly warm, carefully choreographed video message from her laboratory at the University of Milan.

Just days later in the town of Juan de Acosta, an hour inland of Barranquilla, the same researchers sat down with patients and families who crowded the waiting room of the town’s only hospital, as the sun beat in through the windows and as mule carts, stray dogs, and buses passed by on the main drag outside.

The event had been titled a “brigade” after all, but the HD families did not seem to mind – and indeed so many showed up that a sign had to be placed on the door saying that no one who arrived after noon could be seen. Consults were not limited to HD-related matters, so families could be seen for any complaint.

HD was first documented in this town in the early 1990s, but much remains to be understood about the size of the cluster, the haplotype, and its relation to other clusters in Colombia or Venezuela. The families here share a handful of last names and likely share a common ancestor. In the early 19th century, the Barranquilla region was flooded with European migrants who reached the city by ship. (HD clusters in Latin America tend to be concentrated in coastal regions, possibly because of migration patterns.)

The waiting room of the hospital was loud with chatter. Small children played as their relatives waited for consults. Some showed the characteristic restless movements and emaciated bodies of people with advanced HD.

The foreign scientists were barred from taking any patient data out of the hospital or asking for samples. Even picture taking was prohibited. Instead they performed genetic counseling and neuropsychological tests; they sorted out differential diagnoses and advised on medications. Visiting Colombian and Venezuelan physicians did the same, while their assistants met with families in the waiting room, taking medical histories and sketching out basic genealogies.

Some of the foreign researchers reported fruitful interactions with patients, while others seemed perplexed by what they’d experienced. Alba di Pardo, PhD, a genetic epidemiologist at the Istituto Neurologico Mediterraneo Pozzilli (Italy), said she’d spent the morning doing genetic counseling with families and going over genealogies to assess risk. Yet, despite the fact that anyone with an HD parent has a 50% chance of developing the disease, some family members acted uninterested, she said.

Dr. di Pardo’s colleague at the Istituto, biologist Vittorio Maglione, PhD, reported having a similar experience. As he was counseling a young woman about her risk for HD, she scrolled indifferently through Facebook posts on her phone, he said.

On some level, Dr. Maglione said, he could understand patients’ reluctance to engage noting that, while there were many potential HD therapies to try, any new treatment paradigm for HD was many years away from a place like this – and potentially very costly. Dr. Maglione – along with Dr. di Pardo – is researching the SP1 axis, a sphingolipid pathway implicated in neurodegenerative such diseases as HD and which has potential as a drug target (Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39[5]:468-80).

Psychologist Pedro Puentes Rozo of Simón Bolivar University, who is working with Dr. Acosta-López on the local cohort study of presymptomatic HD patients, said that, for most of the families in the clinic that day, any seeming indifference probably masked deeper fears. People already were well aware of their risk. “They’ve known about it forever, said Dr. Puentes Rozo, who has been working with this HD population for a decade. “But this is a catastrophic illness and can generate a lot of anxiety.”

Dr. Puentes Rozo said the group’s planned study, unlike studies in the past, would be conducted under strict “international ethical norms and standards.” Subjects would receive ongoing psychological support, and the researchers were working to establish a genetic counseling center so that people who want to know their status “can be prepared,” he said, and plan for their lives and families.

By fall 2018, the cohort study was underway. The group had sponsored several more hospital brigades – or “integrated health days” as they preferred to call them, at the hospital in Juan de Acosta, giving them a chance to work face to face with families.