User login

Perception of Executive Order on Medicare Pay for Advanced Practice Providers: A Study of Comments From Medical Professionals

The ability of advanced practice providers (APPs) to practice independently has been a recent topic of discussion among both the medical community and legislatures. Advanced practice provider is an umbrella term that includes physician assistants (PAs) and advanced practice registered nurses, including nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical nurse specialists, certified nurse-midwives, and certified registered nurse anesthetists. Since Congress passed the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, APPs can bill and be paid independently if they are not practicing incident to a physician or in a facility.1 Currently, NPs can practice independently in 27 states and Washington, DC. Physician assistants are required to practice under the supervision of a physician; however, the extent of supervision varies by state.2 Advocates for broadening the scope of practice for APPs argue that NPs and PAs will help to fill the physician deficit, particularly in primary care and rural regions. It has been projected that by 2025, the United States will require an additional 46,000 primary care providers to meet growing medical needs.3

On October 3, 2019, President Donald Trump issued the Executive Order on Protecting and Improving Medicare for Our Nation’s Seniors, in which he proposed an alternative to “Medicare for all.”4 This order instructed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to prepare a regulation that would “eliminate burdensome regulatory billing requirements, conditions of participation, supervision requirements, benefit definitions and all other licensure requirements . . . that are more stringent than applicable Federal or State laws require and that limit professionals from practicing at the top of their field.” Furthermore, President Trump proposed that “services provided by clinicians, including physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners, are appropriately reimbursed in accordance with the work performed rather than the clinician’s occupation.”4

In response to the executive order, members of the medical community utilized Reddit, an online public forum, and Medscape, a medical news website, to vocalize opinions on the executive order.5,6 Our goal was to analyze the characteristics of those who participated in the discussion and their points of view on the plan to broaden the scope of practice and change the Medicare reimbursement plans for APPs.

Methods

All comments on the October 3, 2019, Medscape article, “Trump Executive Order Seeks Proposals on Medicare Pay for NPs, PAs,”5 and the corresponding Reddit discussion on this article6 were reviewed and characterized by the type of commenter—doctor of medicine (MD)/doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO), NP/RN/certified registered nurse anesthetist, PA, medical student, PA student, NP student, pharmacist, dietician, emergency medical technician, scribe, or unknown—as identified in their username, title, or in the text of the comment. Gender of the commenter was recorded when provided. Commenters were further grouped by their support or lack of support for the executive order based on their comments. Patients’ comments underwent further qualitative analysis to identify general themes.

All analyses were conducted with RStudio statistical software. Analyses were reported as proportions. Variables were compared by χ2 and Fisher exact tests. Odds ratios with 95% CIs were calculated. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

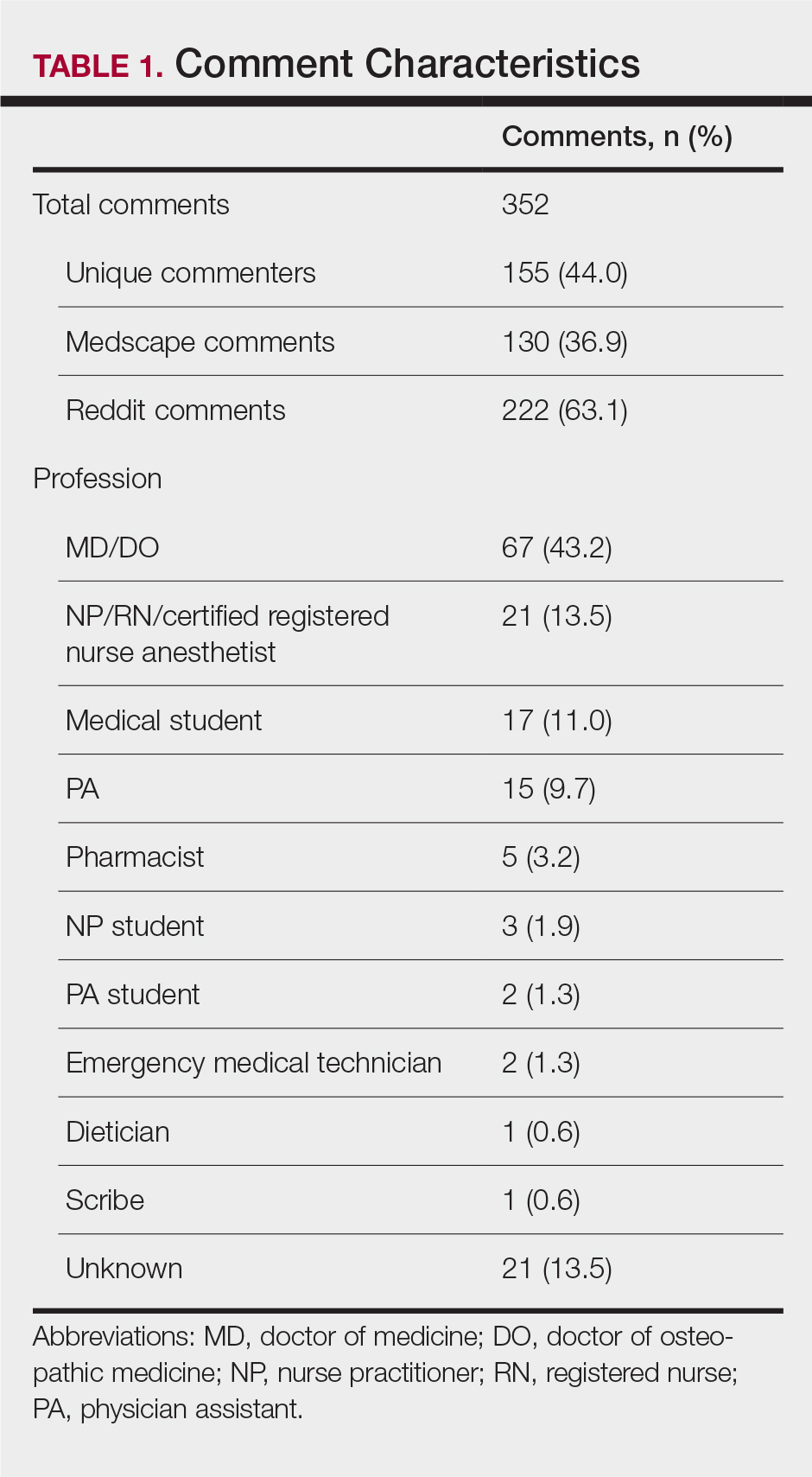

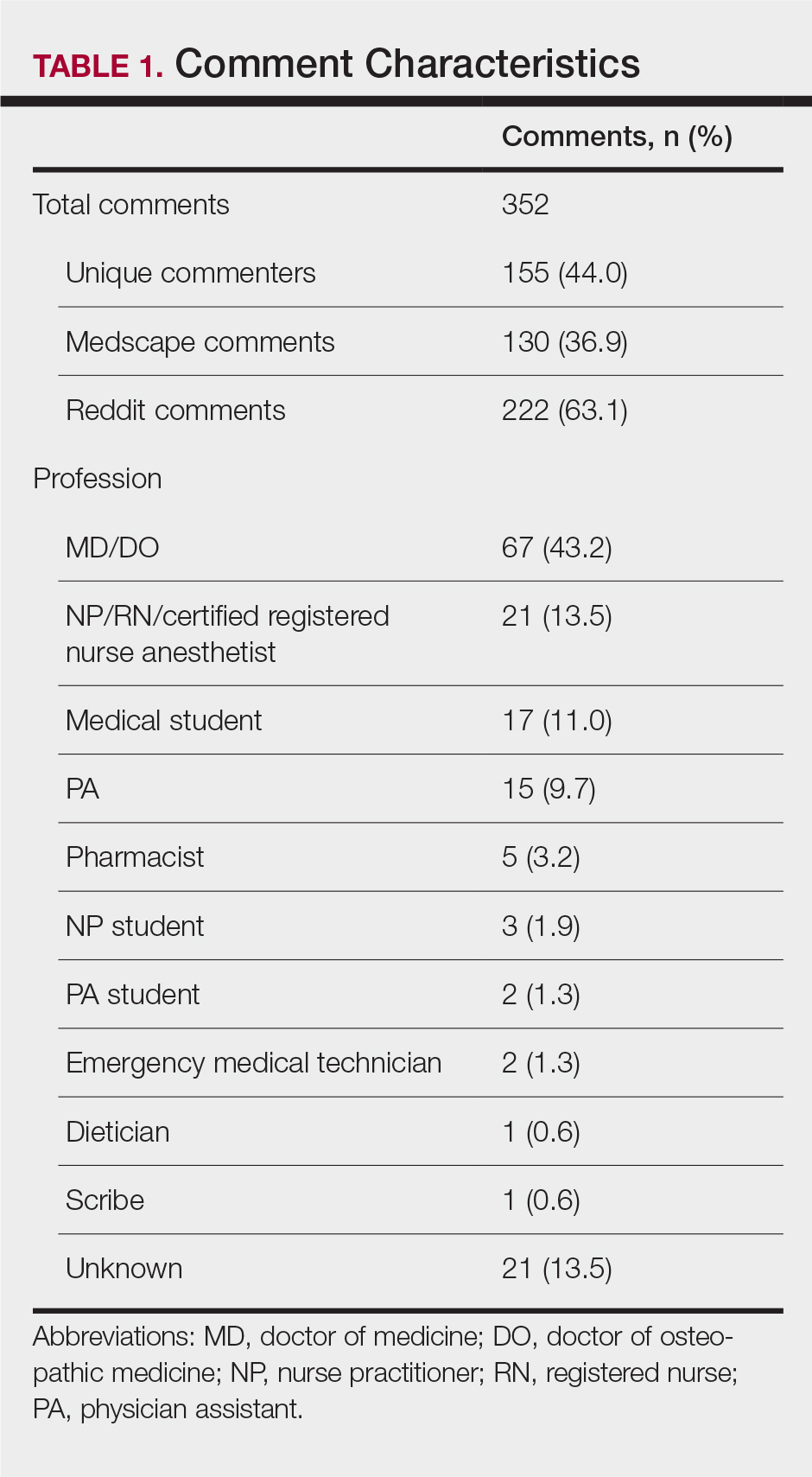

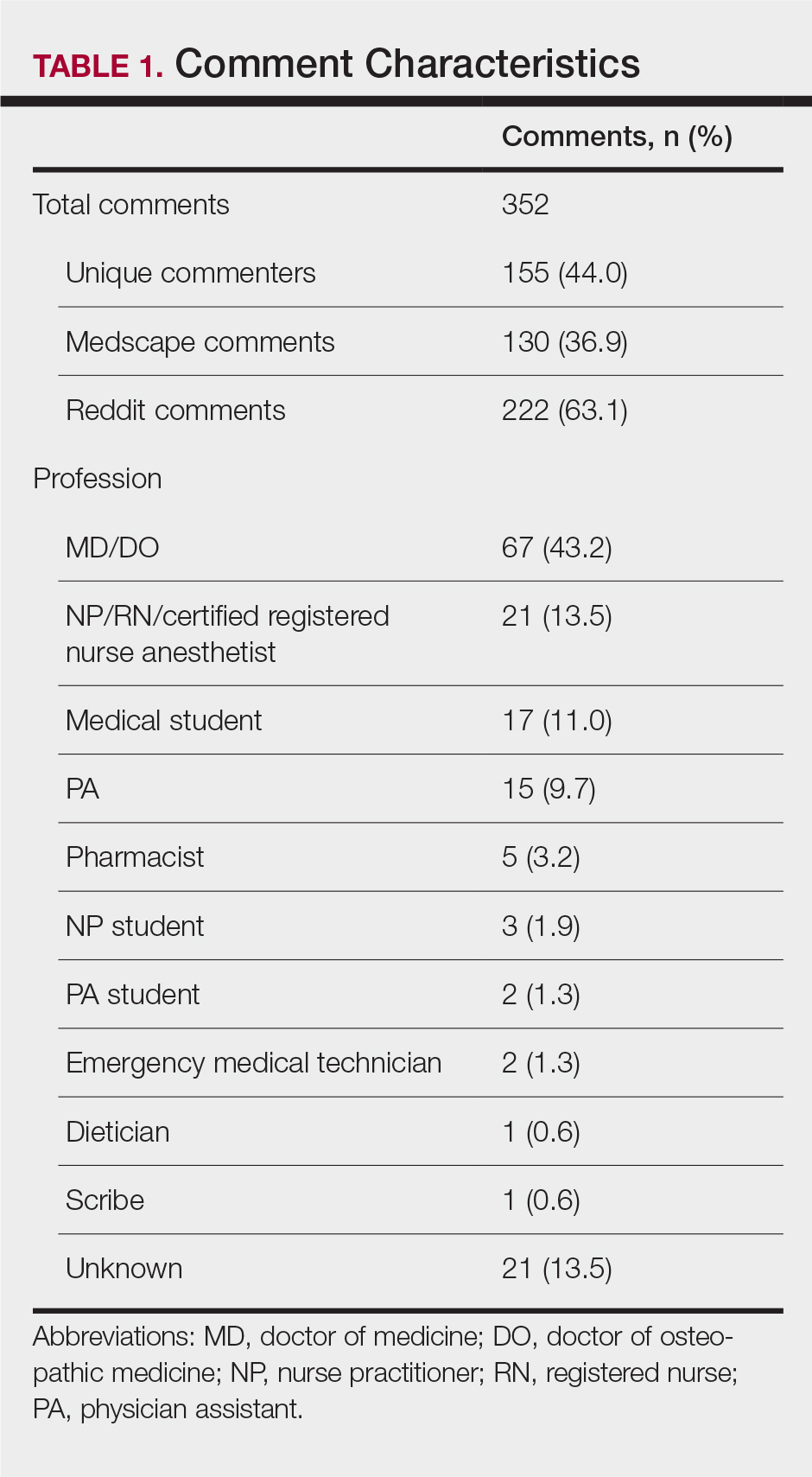

A total of 352 comments (130 on Medscape and 222 on Reddit) posted by 155 unique users (57 on Medscape and 98 on Reddit) were included in the analysis (Table 1). Of the 51 Medscape commenters who identified a gender, 60.7% were male and 39.2% were female. Reddit commenters did not identify a gender. Commenters included MD and DO physicians (43.2%), NPs/RNs/certified registered nurse anesthetists (13.5%), medical students (11.0%), PAs (9.7%), pharmacists (3.2%), NP students (1.9%), PA students (1.3%), emergency medical technicians (1.3%), dieticians (0.6%), and scribes (0.6%). Physicians (54.5% vs 36.73%; P=.032) and NPs (22.8% vs 8.2%; P=.009) made up a larger percentage of all comments on Medscape compared to Reddit, where medical students were more prevalent (16.3% vs 1.8%; P=.005). Nursing students and PA students more commonly posted on Reddit (4.08% of Reddit commenters vs 1.75% of Medscape commenters), though this difference did not achieve statistical significance.

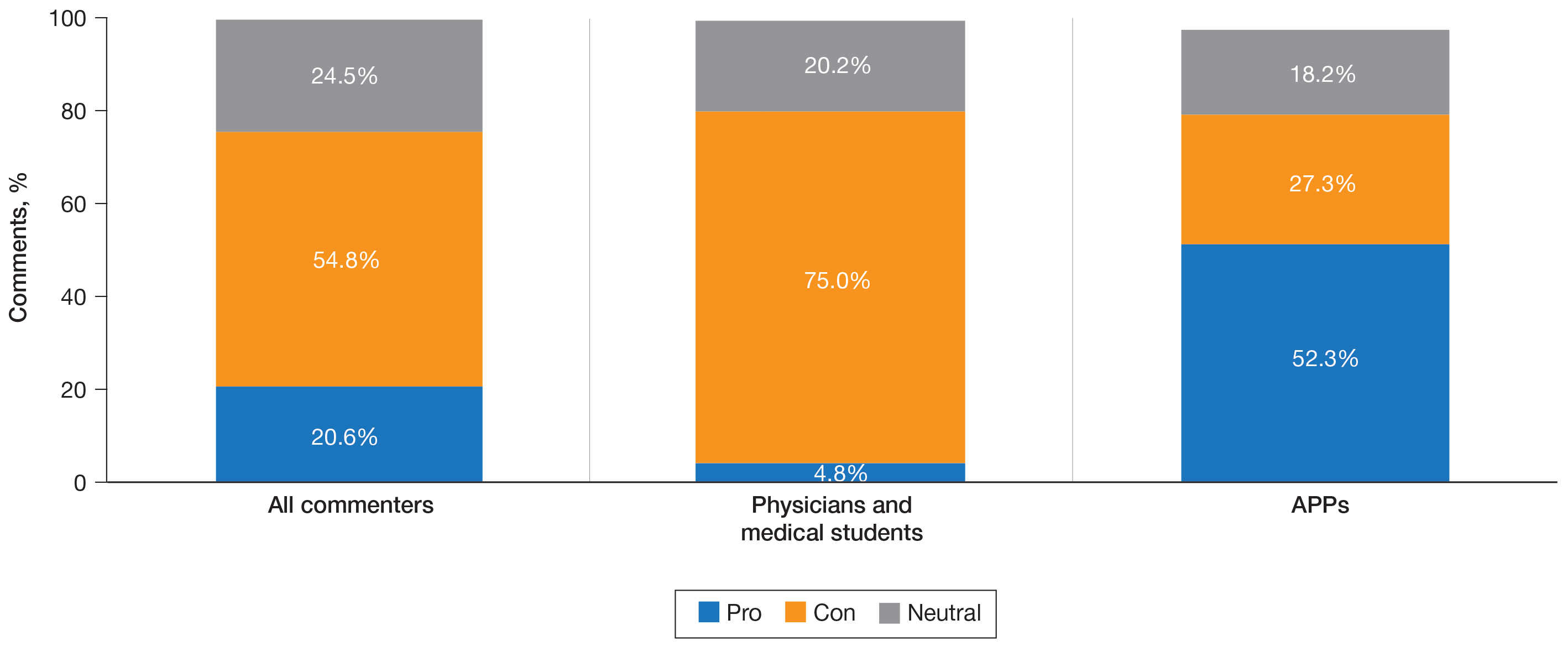

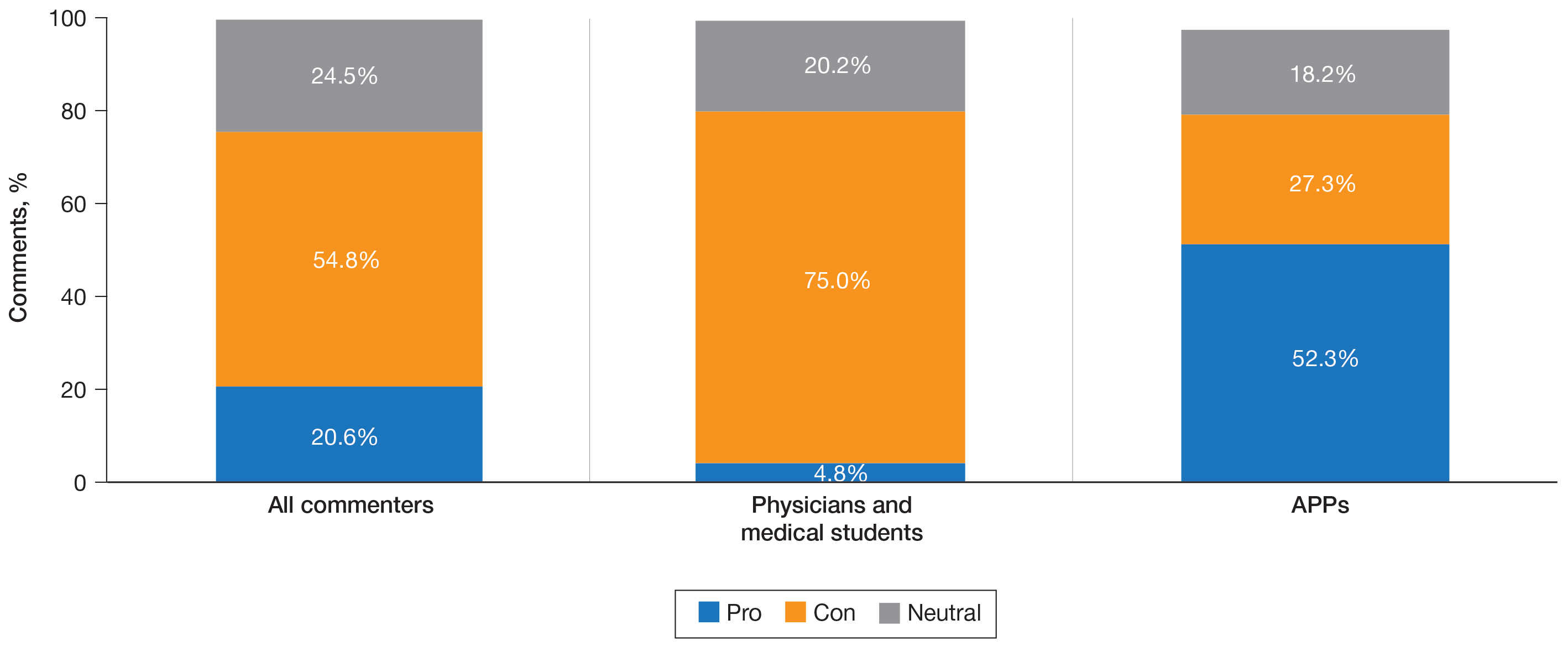

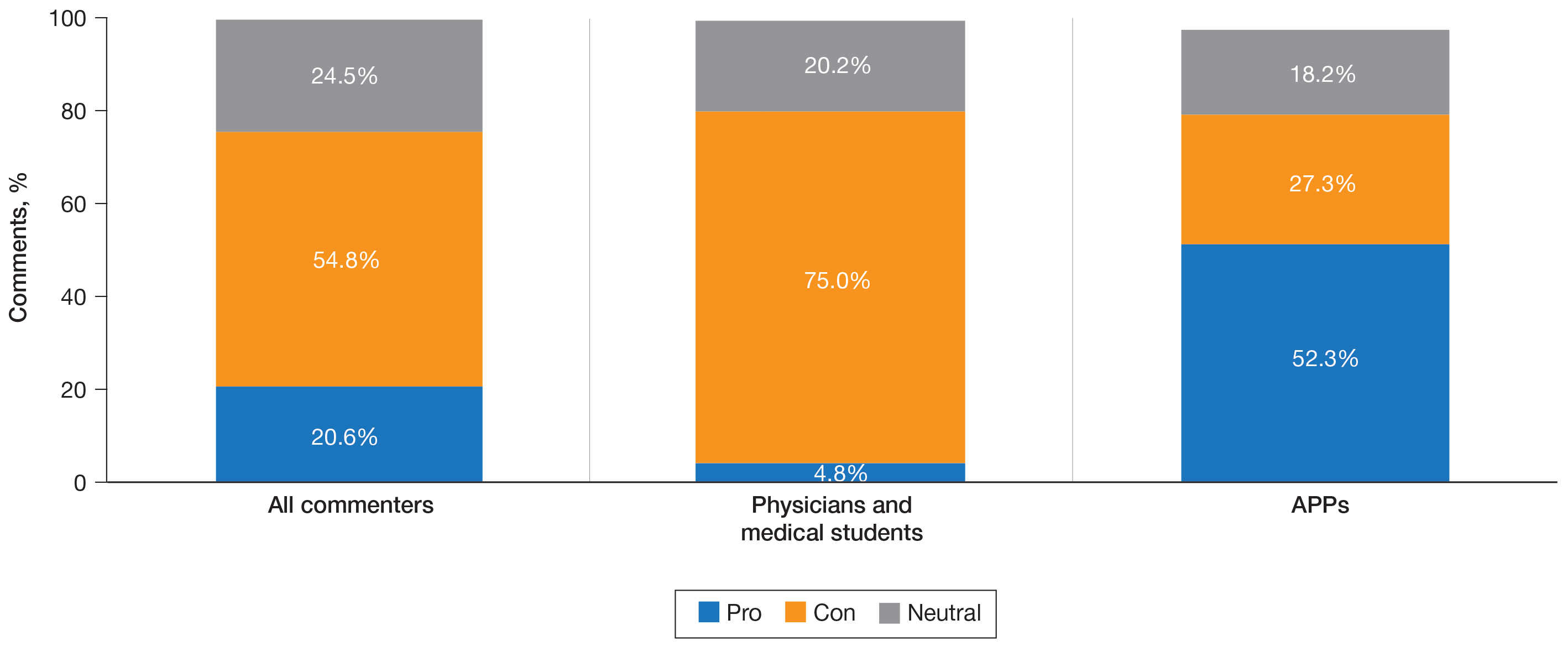

A majority of commenters did not support the executive order, with only 20.6% approving of the plan, 54.8% disapproving, and 24.5% remaining neutral (Figure). Advanced practice providers—NPs, PAs, NP/PA students, and APPs not otherwise specified—were more likely to support the executive order, with 52.3% voicing their support compared to only 4.8% of physicians and medical students expressing support (P<.0001). Similarly, physicians and medical students were more likely to disapprove of the order, with 75.0% voicing concerns compared to only 27.3% of APPs dissenting (P<.0001). A similar percentage of both physicians/medical students and APPs remained neutral (20.2% vs 18.2%). Commenters on Medscape were more likely to voice support for the executive order than those on Reddit (36.8% vs 11.2%; P=.0002), likely due to the higher percentage of NP and PA comments on the former.

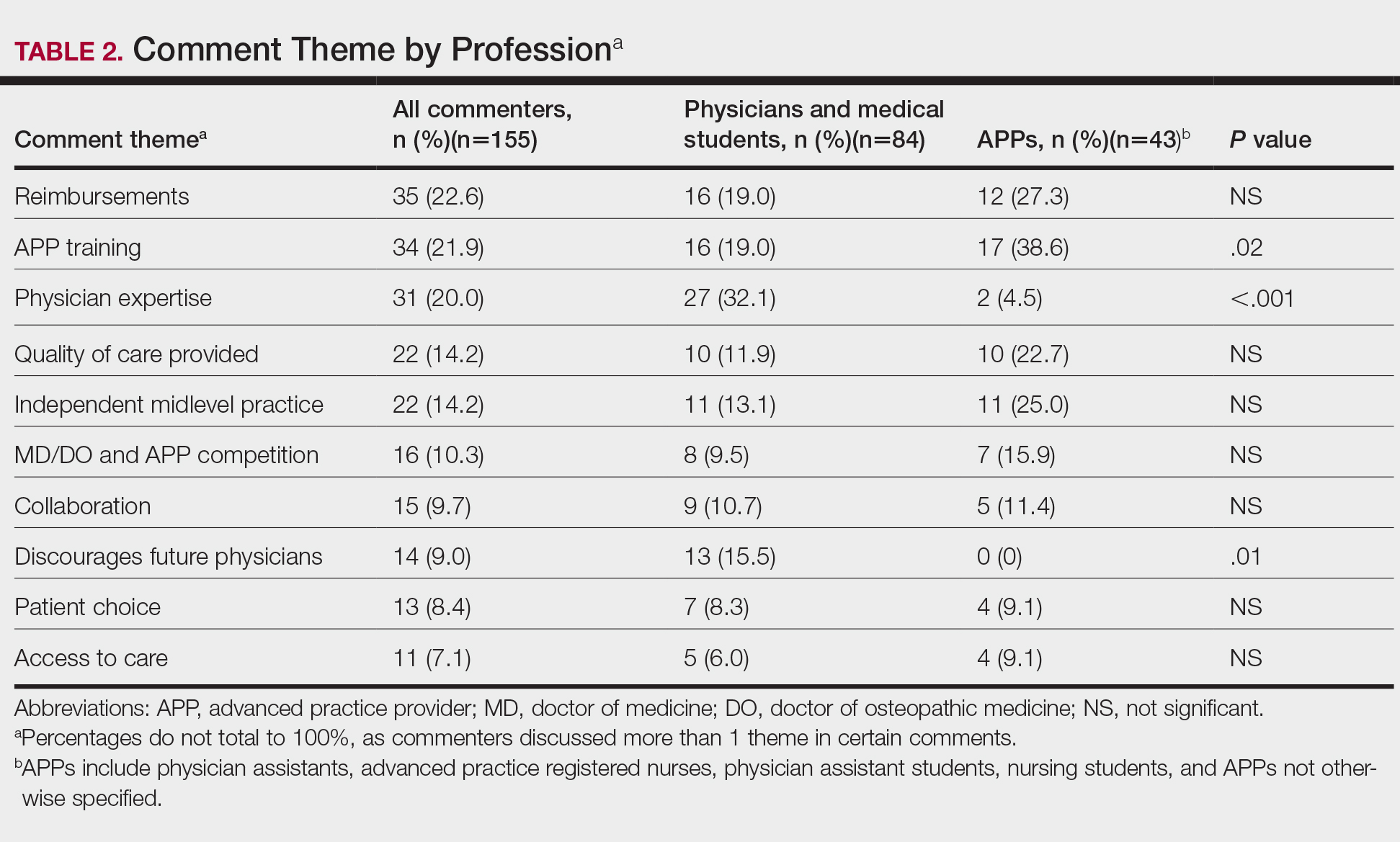

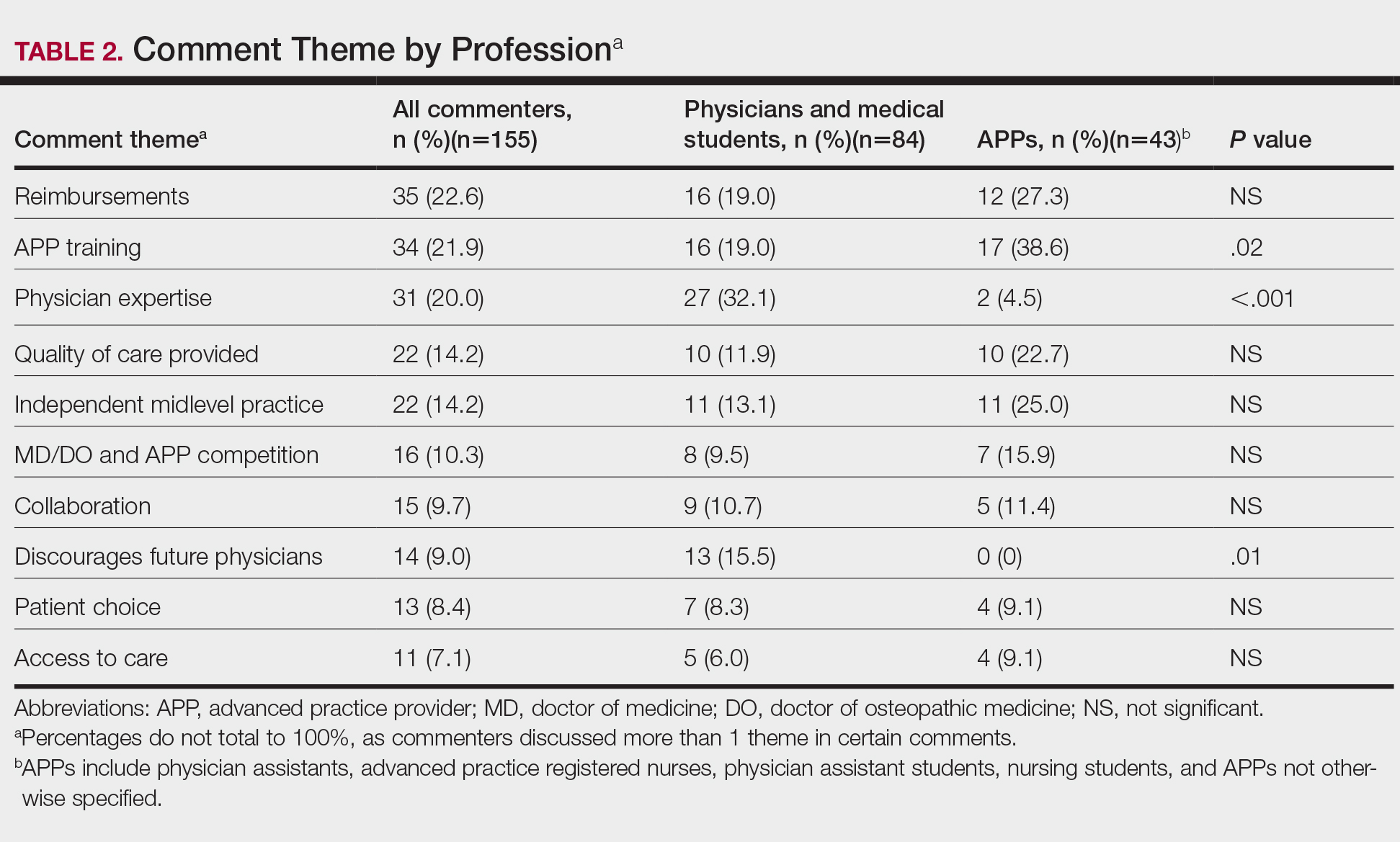

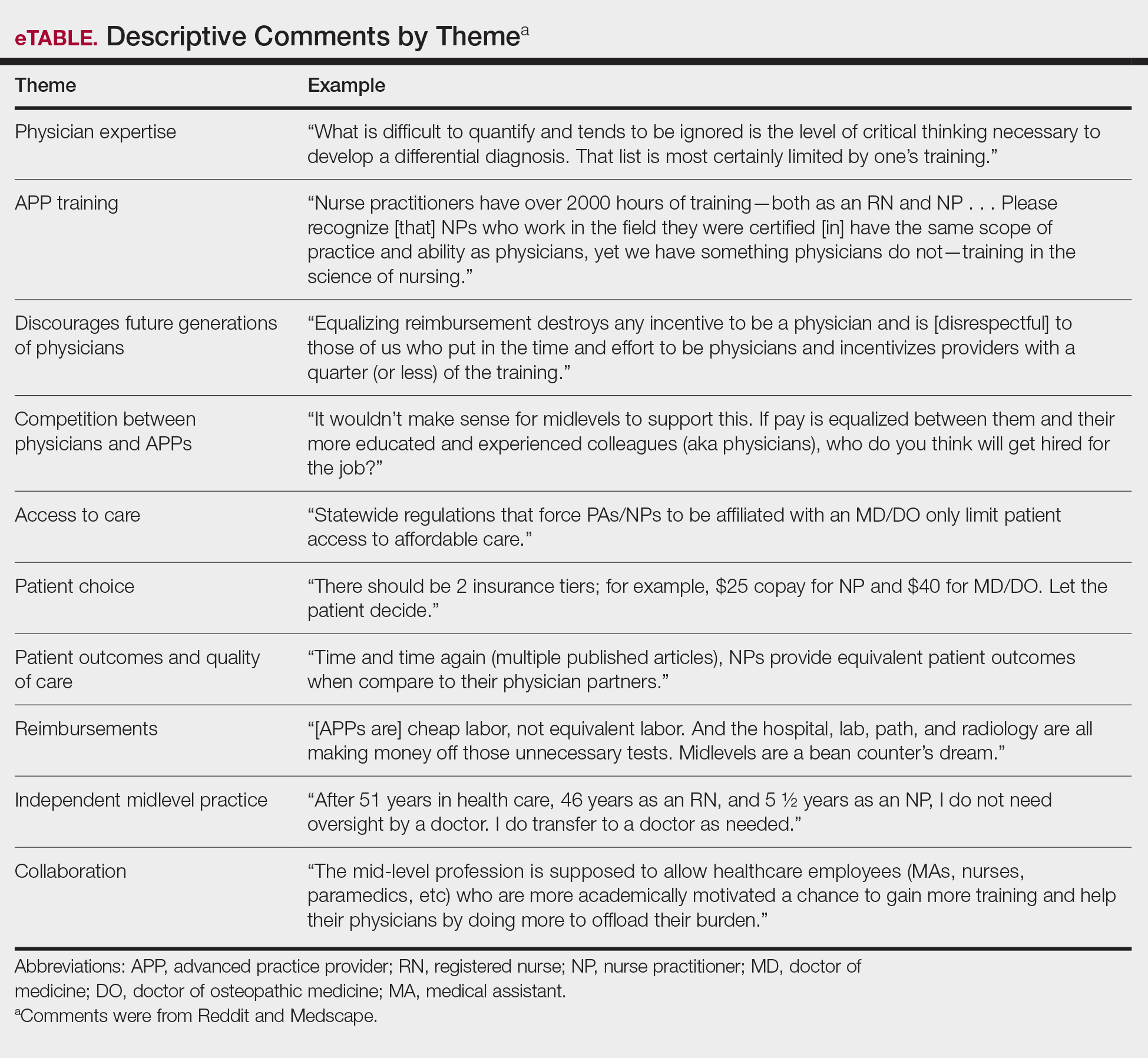

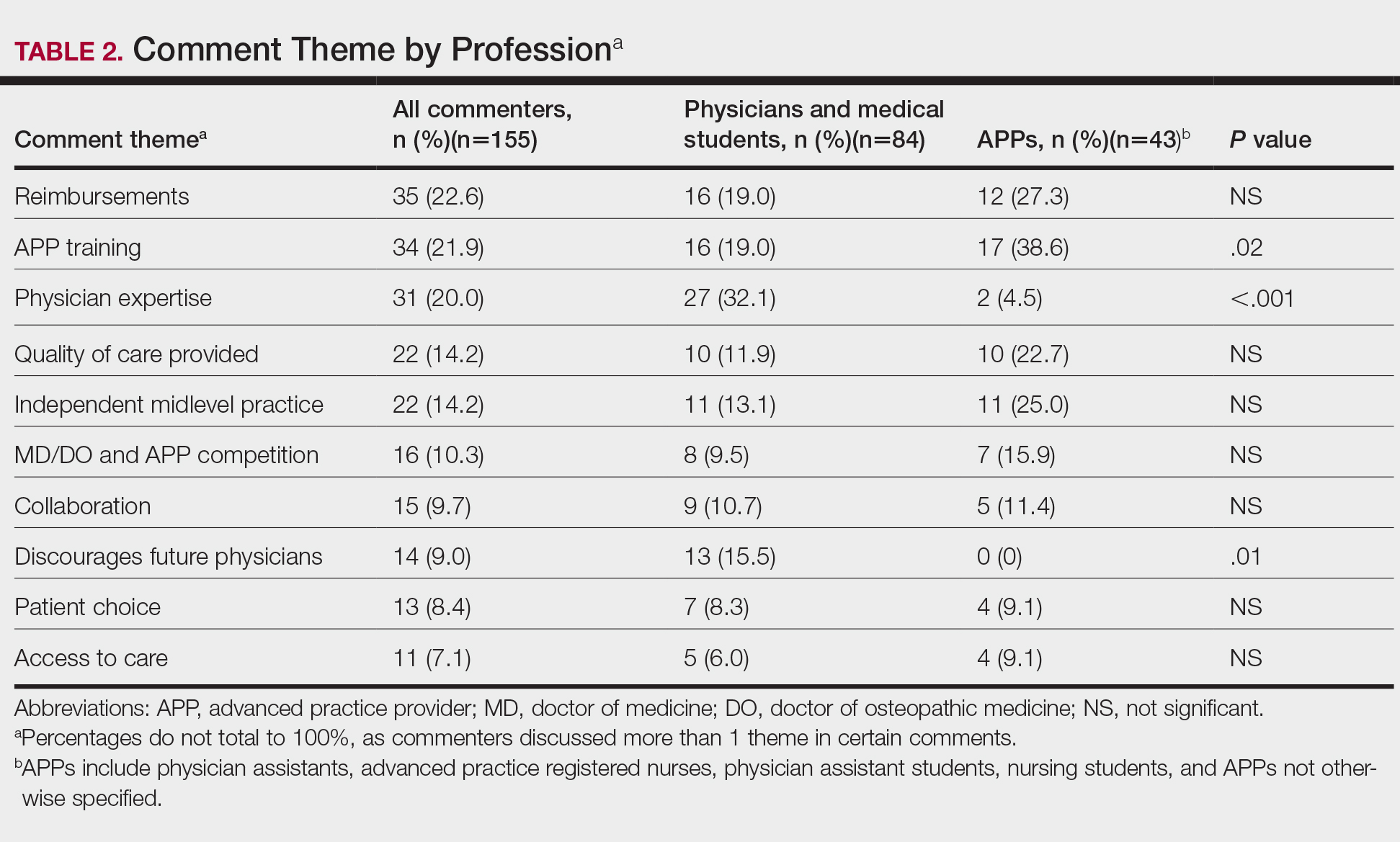

Overall, the most commonly discussed topic was provider reimbursement (22.6% of all comments)(Table 2). Physicians and medical students were more likely to discuss physician expertise compared to APPs (32.1% vs 4.5%; P<.001). They also were more likely to raise concerns that the executive order would discourage future generations of physicians from pursuing medicine (15.5% vs 0%; P=.01). Advanced practice providers were more likely than physicians/medical students to comment on the breadth of NP and/or PA training (38.6% vs 19.0%; P=.02). The eTable shows representative comments for each theme encountered.

A subgroup analysis of the comments written by physicians supporting the executive order (n=4) and APPs disapproving of the order (n=12) was performed to identify the dissenting opinions. Physicians who supported the order discussed the need for improved pay for equal work (n=3), the competency of NP and PA training (n=2), the ability of a practice to generate more profit from APPs (n=1), and possible benefits of APPs providing primary care while MDs perform more specialized care (n=1). Of the APPs who did not support the order, there were 4 PAs, 2 registered nurses, 2 NPs, 2 NP students, and 2 PA students. The most common themes discussed were the differences in APP education and training (n=6), lack of desire for further responsibilities (n=4), and the adequacy of the current scope of practice (n=3).

Comment

President Trump’s executive order follows a trend of decreasing required oversight of APPs; however, this study indicates that these policies would face pushback from many physicians. These results are consistent with a prior study that analyzed 309 comments on an article in The New York Times made by physicians, APPs, patients, and laypeople, in which 24.7% had mistrust of APPs and 14.9% had concerns over APP supervision compared to 9% who supported APP independent practice.7 It is clear that there is a serious divide in opinion that threatens to harm the existing collaborations between physicians and APPs.

Primary Care Coverage With APPs

In the comments analyzed in our study, supporters of the executive order argued that an increase in APPs practicing independently would provide much-needed primary care coverage to patients in underserved regions. However, APPs are instead well represented across most specialties, with a majority in dermatology. Of the 4 million procedures billed independently by APPs in 2012, 54.8% were in the field of dermatology.8 The employment of APPs by dermatologists has grown from 28% of practices in 2005 to 46% in 2014, making this issue of particular importance to our field.9,10

Education and Training of APPs

In our analysis, many physicians cited concerns about the education and training of APPs. Dermatologists receive approximately 10,000 hours of training over the course of residency. Per the American Academy of Physician Assistants, PAs spend more than 2000 hours over a 26-month period on various clinical rotations, “with an emphasis on primary care.”11 There are multiple routes to become an advanced practice RN with varying classroom and clinical requirements, with one pathway requiring a bachelor of science in nursing, followed by a master’s degree requiring 500 to 700 hours of supervised clinical work. Although the Dermatology Nurses’ Association and Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants (http://www.dermpa.org) provide online modules, annual conventions with training workshops, and short fellowship programs, neither have formal guidelines on minimum requirements to diagnose and treat dermatologic conditions.2 Despite the lack of formalized dermatologic training, APPs billed for 13.4% of all dermatology procedures submitted to Medicare in 2015.12

Quality of Patient Care

In our study, physicians also voiced concern over reduced quality of patient care. In a review of 33,647 skin cancer screening examinations, PAs biopsied an average of 39.4 skin lesions, while dermatologists biopsied an average of 25.4 skin lesions to diagnose 1 case of melanoma.13 In addition, nonphysician providers accounted for 37.9% of defendants in 174 legal cases related to injury from cutaneous laser surgery.14 Before further laws are enacted regarding the independent practice and billing by NPs and PAs in the field of dermatology, further research is needed to address patient outcomes and safety.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. Because of a lack of other sources offering discussions on the topic, our sample size was limited. Self-identification of users presents a challenge, as an individual can pose as a physician or APP without validation of credentials. Although great care was taken to minimize bias, grouping comments into broad categories may misinterpret a poster’s intentions. Furthermore, the data collected represent only a small proportion of the medical community—readers of Medscape and Reddit who have the motivation to create a user profile and post a comment rather than put their efforts into lobbying or contacting legislators. Those posting may have stronger political opinions or more poignant experiences than the general public. Although selection bias impacts the generalizability of our findings, this analysis allows for deeper insight into the beliefs of a vocal subset of the medical community who may not have the opportunity to present their opinions elsewhere.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the response to President Trump’s executive order reveals that a rollout of these regulations would be met with strong opposition. On October 29, 2019, more than 100 professional organizations, including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Dermatology, wrote a letter to the Secretary of Health and Human Services that eloquently echoed the sentiments of the physician commenters in this study: “Scope of practice of health care professionals should be based on standardized, adequate training and demonstrated competence in patient care, not politics. While all health care professionals share an important role in providing care to patients, their skillset is not interchangeable with that of a fully trained physician.”15 The executive order would lead to a major shift in the current medical landscape, and as such, it is prudent that these concerns are addressed.

- Balanced Budget Act of 1997, 42 USC §1395x (1997). Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-105publ33/html/PLAW-105publ33.htm

- State practice environment. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Updated October 20, 2020. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state-practice-environment

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, et al. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2015. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:503-509.

- United States, Executive Office of the President [Donald Trump]. Executive Order 13890: Protecting and Improving Medicare for Our Nation’s Seniors. October 3, 2019. Fed Regist. 2019;84:53573-53576.

- Young KD. Trump executive order seeks proposals on Medicare pay for NPs, PAs. Medscape. Published October 3, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/919415

- Trump seeks proposals on Medicare pay for NPs, PAs. Reddit. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.reddit.com/r/medicine/comments/ddy03w/trump_seeks_proposals_on_medicare_pay_for_nps_pas/

- Martin E, Huang WW, Strowd LC, et al. Public perception of ethical issues in dermatology: evidenced by New York Times commenters. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1571-1577.

- Coldiron B, Ratnarathorn M. Scope of physician procedures independently billed by mid-level providers in the office setting. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1153-1159.

- Resneck JS Jr. Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:13-14.

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752.

- Become a PA. American Academy of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.aapa.org/career-central/become-a-pa/.

- Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1040-1044.

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis of physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573.

- Jalian HR, Jalian CA, Avram MM. Common causes of injury and legal action in laser surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:188-193.

- American Medical Association. Open letter to the Honorable Alex M. Azar II. Published October 29, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://searchlf.ama-assn.org/undefined/documentDownload?uri=%2Funstructured%2Fbinary%2Fletter%2FLETTERS%2F2019-10-29-Final-Sign-on-re-10-3-Executive-Order.pdf

The ability of advanced practice providers (APPs) to practice independently has been a recent topic of discussion among both the medical community and legislatures. Advanced practice provider is an umbrella term that includes physician assistants (PAs) and advanced practice registered nurses, including nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical nurse specialists, certified nurse-midwives, and certified registered nurse anesthetists. Since Congress passed the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, APPs can bill and be paid independently if they are not practicing incident to a physician or in a facility.1 Currently, NPs can practice independently in 27 states and Washington, DC. Physician assistants are required to practice under the supervision of a physician; however, the extent of supervision varies by state.2 Advocates for broadening the scope of practice for APPs argue that NPs and PAs will help to fill the physician deficit, particularly in primary care and rural regions. It has been projected that by 2025, the United States will require an additional 46,000 primary care providers to meet growing medical needs.3

On October 3, 2019, President Donald Trump issued the Executive Order on Protecting and Improving Medicare for Our Nation’s Seniors, in which he proposed an alternative to “Medicare for all.”4 This order instructed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to prepare a regulation that would “eliminate burdensome regulatory billing requirements, conditions of participation, supervision requirements, benefit definitions and all other licensure requirements . . . that are more stringent than applicable Federal or State laws require and that limit professionals from practicing at the top of their field.” Furthermore, President Trump proposed that “services provided by clinicians, including physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners, are appropriately reimbursed in accordance with the work performed rather than the clinician’s occupation.”4

In response to the executive order, members of the medical community utilized Reddit, an online public forum, and Medscape, a medical news website, to vocalize opinions on the executive order.5,6 Our goal was to analyze the characteristics of those who participated in the discussion and their points of view on the plan to broaden the scope of practice and change the Medicare reimbursement plans for APPs.

Methods

All comments on the October 3, 2019, Medscape article, “Trump Executive Order Seeks Proposals on Medicare Pay for NPs, PAs,”5 and the corresponding Reddit discussion on this article6 were reviewed and characterized by the type of commenter—doctor of medicine (MD)/doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO), NP/RN/certified registered nurse anesthetist, PA, medical student, PA student, NP student, pharmacist, dietician, emergency medical technician, scribe, or unknown—as identified in their username, title, or in the text of the comment. Gender of the commenter was recorded when provided. Commenters were further grouped by their support or lack of support for the executive order based on their comments. Patients’ comments underwent further qualitative analysis to identify general themes.

All analyses were conducted with RStudio statistical software. Analyses were reported as proportions. Variables were compared by χ2 and Fisher exact tests. Odds ratios with 95% CIs were calculated. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 352 comments (130 on Medscape and 222 on Reddit) posted by 155 unique users (57 on Medscape and 98 on Reddit) were included in the analysis (Table 1). Of the 51 Medscape commenters who identified a gender, 60.7% were male and 39.2% were female. Reddit commenters did not identify a gender. Commenters included MD and DO physicians (43.2%), NPs/RNs/certified registered nurse anesthetists (13.5%), medical students (11.0%), PAs (9.7%), pharmacists (3.2%), NP students (1.9%), PA students (1.3%), emergency medical technicians (1.3%), dieticians (0.6%), and scribes (0.6%). Physicians (54.5% vs 36.73%; P=.032) and NPs (22.8% vs 8.2%; P=.009) made up a larger percentage of all comments on Medscape compared to Reddit, where medical students were more prevalent (16.3% vs 1.8%; P=.005). Nursing students and PA students more commonly posted on Reddit (4.08% of Reddit commenters vs 1.75% of Medscape commenters), though this difference did not achieve statistical significance.

A majority of commenters did not support the executive order, with only 20.6% approving of the plan, 54.8% disapproving, and 24.5% remaining neutral (Figure). Advanced practice providers—NPs, PAs, NP/PA students, and APPs not otherwise specified—were more likely to support the executive order, with 52.3% voicing their support compared to only 4.8% of physicians and medical students expressing support (P<.0001). Similarly, physicians and medical students were more likely to disapprove of the order, with 75.0% voicing concerns compared to only 27.3% of APPs dissenting (P<.0001). A similar percentage of both physicians/medical students and APPs remained neutral (20.2% vs 18.2%). Commenters on Medscape were more likely to voice support for the executive order than those on Reddit (36.8% vs 11.2%; P=.0002), likely due to the higher percentage of NP and PA comments on the former.

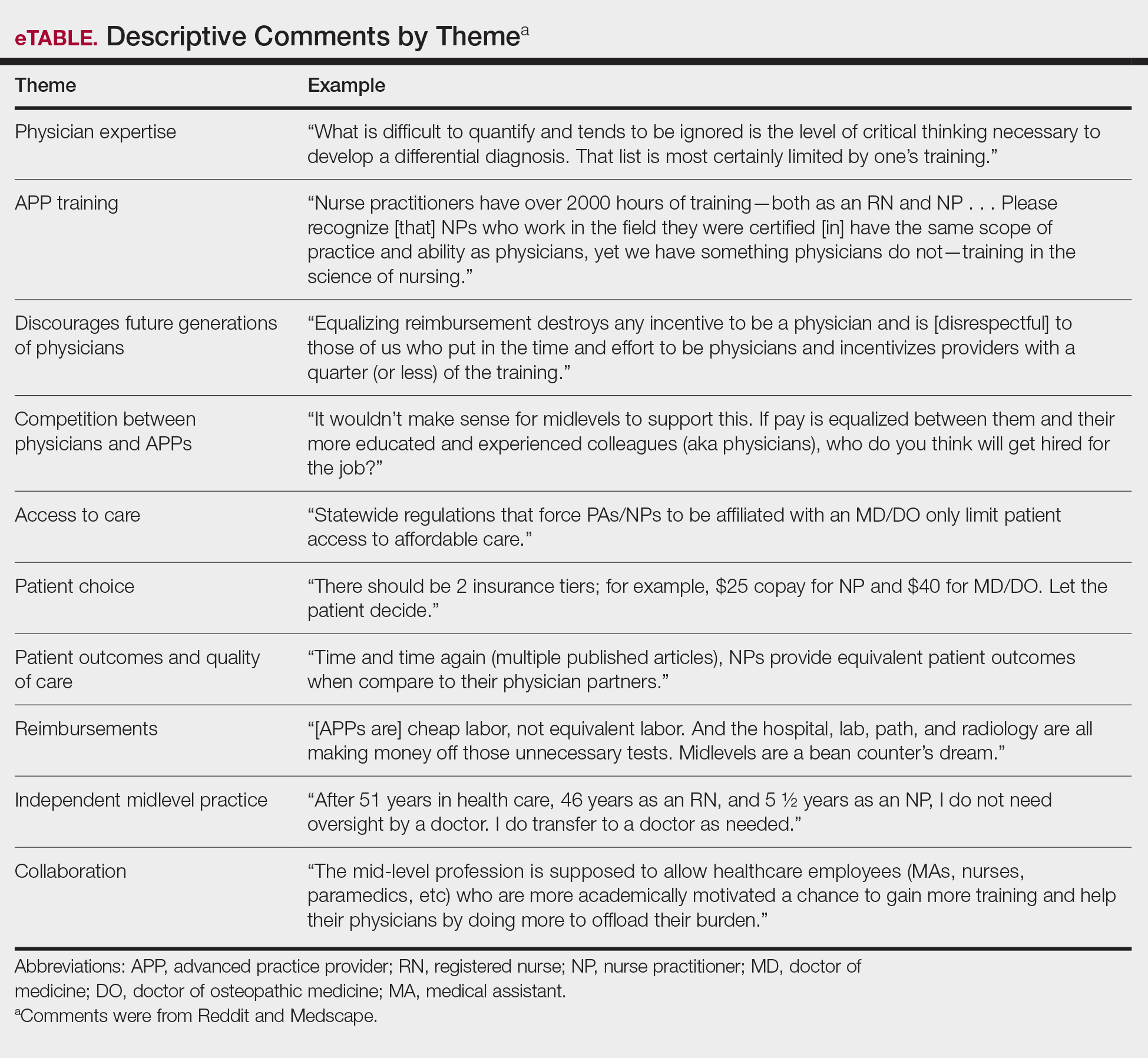

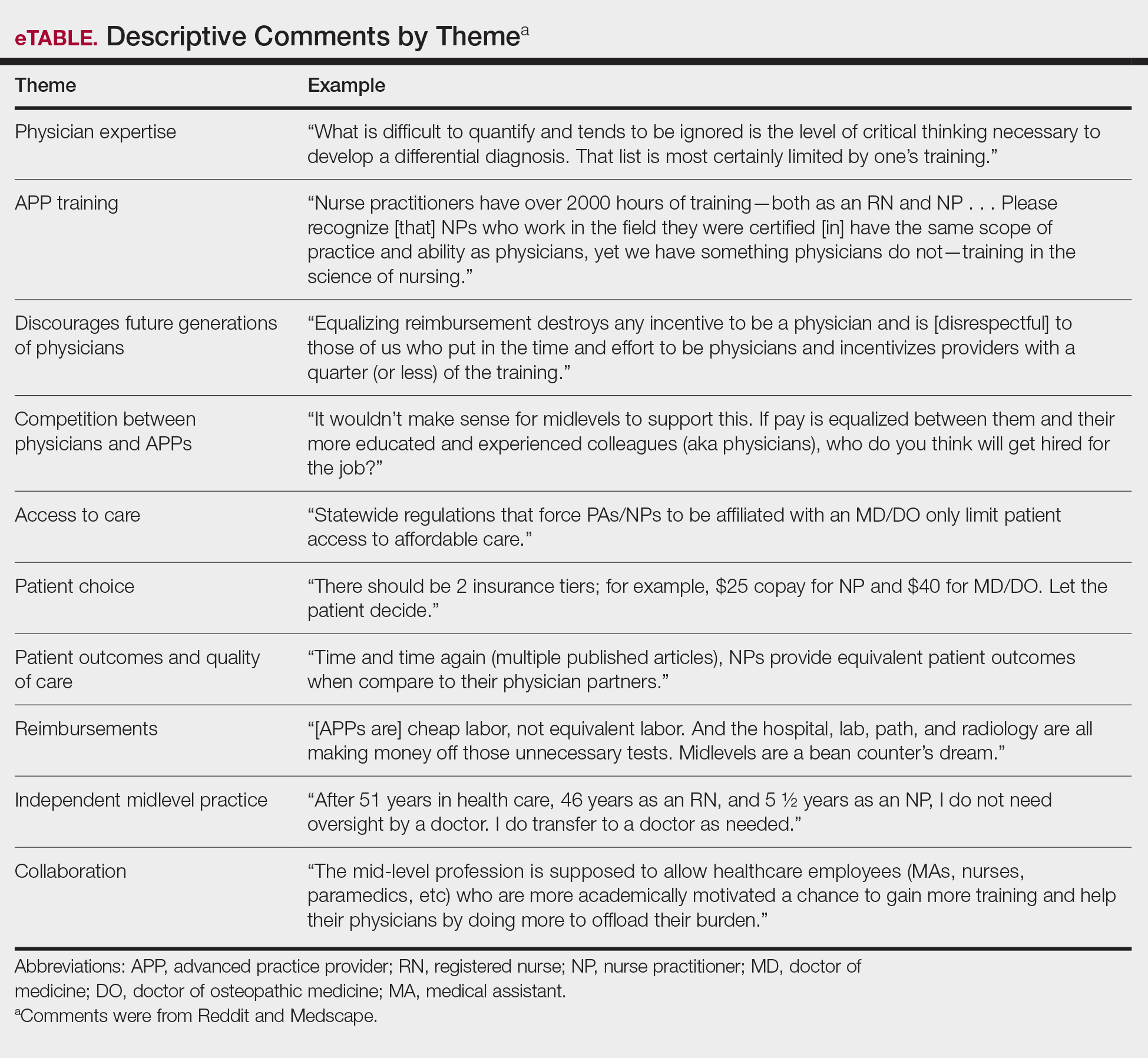

Overall, the most commonly discussed topic was provider reimbursement (22.6% of all comments)(Table 2). Physicians and medical students were more likely to discuss physician expertise compared to APPs (32.1% vs 4.5%; P<.001). They also were more likely to raise concerns that the executive order would discourage future generations of physicians from pursuing medicine (15.5% vs 0%; P=.01). Advanced practice providers were more likely than physicians/medical students to comment on the breadth of NP and/or PA training (38.6% vs 19.0%; P=.02). The eTable shows representative comments for each theme encountered.

A subgroup analysis of the comments written by physicians supporting the executive order (n=4) and APPs disapproving of the order (n=12) was performed to identify the dissenting opinions. Physicians who supported the order discussed the need for improved pay for equal work (n=3), the competency of NP and PA training (n=2), the ability of a practice to generate more profit from APPs (n=1), and possible benefits of APPs providing primary care while MDs perform more specialized care (n=1). Of the APPs who did not support the order, there were 4 PAs, 2 registered nurses, 2 NPs, 2 NP students, and 2 PA students. The most common themes discussed were the differences in APP education and training (n=6), lack of desire for further responsibilities (n=4), and the adequacy of the current scope of practice (n=3).

Comment

President Trump’s executive order follows a trend of decreasing required oversight of APPs; however, this study indicates that these policies would face pushback from many physicians. These results are consistent with a prior study that analyzed 309 comments on an article in The New York Times made by physicians, APPs, patients, and laypeople, in which 24.7% had mistrust of APPs and 14.9% had concerns over APP supervision compared to 9% who supported APP independent practice.7 It is clear that there is a serious divide in opinion that threatens to harm the existing collaborations between physicians and APPs.

Primary Care Coverage With APPs

In the comments analyzed in our study, supporters of the executive order argued that an increase in APPs practicing independently would provide much-needed primary care coverage to patients in underserved regions. However, APPs are instead well represented across most specialties, with a majority in dermatology. Of the 4 million procedures billed independently by APPs in 2012, 54.8% were in the field of dermatology.8 The employment of APPs by dermatologists has grown from 28% of practices in 2005 to 46% in 2014, making this issue of particular importance to our field.9,10

Education and Training of APPs

In our analysis, many physicians cited concerns about the education and training of APPs. Dermatologists receive approximately 10,000 hours of training over the course of residency. Per the American Academy of Physician Assistants, PAs spend more than 2000 hours over a 26-month period on various clinical rotations, “with an emphasis on primary care.”11 There are multiple routes to become an advanced practice RN with varying classroom and clinical requirements, with one pathway requiring a bachelor of science in nursing, followed by a master’s degree requiring 500 to 700 hours of supervised clinical work. Although the Dermatology Nurses’ Association and Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants (http://www.dermpa.org) provide online modules, annual conventions with training workshops, and short fellowship programs, neither have formal guidelines on minimum requirements to diagnose and treat dermatologic conditions.2 Despite the lack of formalized dermatologic training, APPs billed for 13.4% of all dermatology procedures submitted to Medicare in 2015.12

Quality of Patient Care

In our study, physicians also voiced concern over reduced quality of patient care. In a review of 33,647 skin cancer screening examinations, PAs biopsied an average of 39.4 skin lesions, while dermatologists biopsied an average of 25.4 skin lesions to diagnose 1 case of melanoma.13 In addition, nonphysician providers accounted for 37.9% of defendants in 174 legal cases related to injury from cutaneous laser surgery.14 Before further laws are enacted regarding the independent practice and billing by NPs and PAs in the field of dermatology, further research is needed to address patient outcomes and safety.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. Because of a lack of other sources offering discussions on the topic, our sample size was limited. Self-identification of users presents a challenge, as an individual can pose as a physician or APP without validation of credentials. Although great care was taken to minimize bias, grouping comments into broad categories may misinterpret a poster’s intentions. Furthermore, the data collected represent only a small proportion of the medical community—readers of Medscape and Reddit who have the motivation to create a user profile and post a comment rather than put their efforts into lobbying or contacting legislators. Those posting may have stronger political opinions or more poignant experiences than the general public. Although selection bias impacts the generalizability of our findings, this analysis allows for deeper insight into the beliefs of a vocal subset of the medical community who may not have the opportunity to present their opinions elsewhere.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the response to President Trump’s executive order reveals that a rollout of these regulations would be met with strong opposition. On October 29, 2019, more than 100 professional organizations, including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Dermatology, wrote a letter to the Secretary of Health and Human Services that eloquently echoed the sentiments of the physician commenters in this study: “Scope of practice of health care professionals should be based on standardized, adequate training and demonstrated competence in patient care, not politics. While all health care professionals share an important role in providing care to patients, their skillset is not interchangeable with that of a fully trained physician.”15 The executive order would lead to a major shift in the current medical landscape, and as such, it is prudent that these concerns are addressed.

The ability of advanced practice providers (APPs) to practice independently has been a recent topic of discussion among both the medical community and legislatures. Advanced practice provider is an umbrella term that includes physician assistants (PAs) and advanced practice registered nurses, including nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical nurse specialists, certified nurse-midwives, and certified registered nurse anesthetists. Since Congress passed the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, APPs can bill and be paid independently if they are not practicing incident to a physician or in a facility.1 Currently, NPs can practice independently in 27 states and Washington, DC. Physician assistants are required to practice under the supervision of a physician; however, the extent of supervision varies by state.2 Advocates for broadening the scope of practice for APPs argue that NPs and PAs will help to fill the physician deficit, particularly in primary care and rural regions. It has been projected that by 2025, the United States will require an additional 46,000 primary care providers to meet growing medical needs.3

On October 3, 2019, President Donald Trump issued the Executive Order on Protecting and Improving Medicare for Our Nation’s Seniors, in which he proposed an alternative to “Medicare for all.”4 This order instructed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to prepare a regulation that would “eliminate burdensome regulatory billing requirements, conditions of participation, supervision requirements, benefit definitions and all other licensure requirements . . . that are more stringent than applicable Federal or State laws require and that limit professionals from practicing at the top of their field.” Furthermore, President Trump proposed that “services provided by clinicians, including physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners, are appropriately reimbursed in accordance with the work performed rather than the clinician’s occupation.”4

In response to the executive order, members of the medical community utilized Reddit, an online public forum, and Medscape, a medical news website, to vocalize opinions on the executive order.5,6 Our goal was to analyze the characteristics of those who participated in the discussion and their points of view on the plan to broaden the scope of practice and change the Medicare reimbursement plans for APPs.

Methods

All comments on the October 3, 2019, Medscape article, “Trump Executive Order Seeks Proposals on Medicare Pay for NPs, PAs,”5 and the corresponding Reddit discussion on this article6 were reviewed and characterized by the type of commenter—doctor of medicine (MD)/doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO), NP/RN/certified registered nurse anesthetist, PA, medical student, PA student, NP student, pharmacist, dietician, emergency medical technician, scribe, or unknown—as identified in their username, title, or in the text of the comment. Gender of the commenter was recorded when provided. Commenters were further grouped by their support or lack of support for the executive order based on their comments. Patients’ comments underwent further qualitative analysis to identify general themes.

All analyses were conducted with RStudio statistical software. Analyses were reported as proportions. Variables were compared by χ2 and Fisher exact tests. Odds ratios with 95% CIs were calculated. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 352 comments (130 on Medscape and 222 on Reddit) posted by 155 unique users (57 on Medscape and 98 on Reddit) were included in the analysis (Table 1). Of the 51 Medscape commenters who identified a gender, 60.7% were male and 39.2% were female. Reddit commenters did not identify a gender. Commenters included MD and DO physicians (43.2%), NPs/RNs/certified registered nurse anesthetists (13.5%), medical students (11.0%), PAs (9.7%), pharmacists (3.2%), NP students (1.9%), PA students (1.3%), emergency medical technicians (1.3%), dieticians (0.6%), and scribes (0.6%). Physicians (54.5% vs 36.73%; P=.032) and NPs (22.8% vs 8.2%; P=.009) made up a larger percentage of all comments on Medscape compared to Reddit, where medical students were more prevalent (16.3% vs 1.8%; P=.005). Nursing students and PA students more commonly posted on Reddit (4.08% of Reddit commenters vs 1.75% of Medscape commenters), though this difference did not achieve statistical significance.

A majority of commenters did not support the executive order, with only 20.6% approving of the plan, 54.8% disapproving, and 24.5% remaining neutral (Figure). Advanced practice providers—NPs, PAs, NP/PA students, and APPs not otherwise specified—were more likely to support the executive order, with 52.3% voicing their support compared to only 4.8% of physicians and medical students expressing support (P<.0001). Similarly, physicians and medical students were more likely to disapprove of the order, with 75.0% voicing concerns compared to only 27.3% of APPs dissenting (P<.0001). A similar percentage of both physicians/medical students and APPs remained neutral (20.2% vs 18.2%). Commenters on Medscape were more likely to voice support for the executive order than those on Reddit (36.8% vs 11.2%; P=.0002), likely due to the higher percentage of NP and PA comments on the former.

Overall, the most commonly discussed topic was provider reimbursement (22.6% of all comments)(Table 2). Physicians and medical students were more likely to discuss physician expertise compared to APPs (32.1% vs 4.5%; P<.001). They also were more likely to raise concerns that the executive order would discourage future generations of physicians from pursuing medicine (15.5% vs 0%; P=.01). Advanced practice providers were more likely than physicians/medical students to comment on the breadth of NP and/or PA training (38.6% vs 19.0%; P=.02). The eTable shows representative comments for each theme encountered.

A subgroup analysis of the comments written by physicians supporting the executive order (n=4) and APPs disapproving of the order (n=12) was performed to identify the dissenting opinions. Physicians who supported the order discussed the need for improved pay for equal work (n=3), the competency of NP and PA training (n=2), the ability of a practice to generate more profit from APPs (n=1), and possible benefits of APPs providing primary care while MDs perform more specialized care (n=1). Of the APPs who did not support the order, there were 4 PAs, 2 registered nurses, 2 NPs, 2 NP students, and 2 PA students. The most common themes discussed were the differences in APP education and training (n=6), lack of desire for further responsibilities (n=4), and the adequacy of the current scope of practice (n=3).

Comment

President Trump’s executive order follows a trend of decreasing required oversight of APPs; however, this study indicates that these policies would face pushback from many physicians. These results are consistent with a prior study that analyzed 309 comments on an article in The New York Times made by physicians, APPs, patients, and laypeople, in which 24.7% had mistrust of APPs and 14.9% had concerns over APP supervision compared to 9% who supported APP independent practice.7 It is clear that there is a serious divide in opinion that threatens to harm the existing collaborations between physicians and APPs.

Primary Care Coverage With APPs

In the comments analyzed in our study, supporters of the executive order argued that an increase in APPs practicing independently would provide much-needed primary care coverage to patients in underserved regions. However, APPs are instead well represented across most specialties, with a majority in dermatology. Of the 4 million procedures billed independently by APPs in 2012, 54.8% were in the field of dermatology.8 The employment of APPs by dermatologists has grown from 28% of practices in 2005 to 46% in 2014, making this issue of particular importance to our field.9,10

Education and Training of APPs

In our analysis, many physicians cited concerns about the education and training of APPs. Dermatologists receive approximately 10,000 hours of training over the course of residency. Per the American Academy of Physician Assistants, PAs spend more than 2000 hours over a 26-month period on various clinical rotations, “with an emphasis on primary care.”11 There are multiple routes to become an advanced practice RN with varying classroom and clinical requirements, with one pathway requiring a bachelor of science in nursing, followed by a master’s degree requiring 500 to 700 hours of supervised clinical work. Although the Dermatology Nurses’ Association and Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants (http://www.dermpa.org) provide online modules, annual conventions with training workshops, and short fellowship programs, neither have formal guidelines on minimum requirements to diagnose and treat dermatologic conditions.2 Despite the lack of formalized dermatologic training, APPs billed for 13.4% of all dermatology procedures submitted to Medicare in 2015.12

Quality of Patient Care

In our study, physicians also voiced concern over reduced quality of patient care. In a review of 33,647 skin cancer screening examinations, PAs biopsied an average of 39.4 skin lesions, while dermatologists biopsied an average of 25.4 skin lesions to diagnose 1 case of melanoma.13 In addition, nonphysician providers accounted for 37.9% of defendants in 174 legal cases related to injury from cutaneous laser surgery.14 Before further laws are enacted regarding the independent practice and billing by NPs and PAs in the field of dermatology, further research is needed to address patient outcomes and safety.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. Because of a lack of other sources offering discussions on the topic, our sample size was limited. Self-identification of users presents a challenge, as an individual can pose as a physician or APP without validation of credentials. Although great care was taken to minimize bias, grouping comments into broad categories may misinterpret a poster’s intentions. Furthermore, the data collected represent only a small proportion of the medical community—readers of Medscape and Reddit who have the motivation to create a user profile and post a comment rather than put their efforts into lobbying or contacting legislators. Those posting may have stronger political opinions or more poignant experiences than the general public. Although selection bias impacts the generalizability of our findings, this analysis allows for deeper insight into the beliefs of a vocal subset of the medical community who may not have the opportunity to present their opinions elsewhere.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the response to President Trump’s executive order reveals that a rollout of these regulations would be met with strong opposition. On October 29, 2019, more than 100 professional organizations, including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Dermatology, wrote a letter to the Secretary of Health and Human Services that eloquently echoed the sentiments of the physician commenters in this study: “Scope of practice of health care professionals should be based on standardized, adequate training and demonstrated competence in patient care, not politics. While all health care professionals share an important role in providing care to patients, their skillset is not interchangeable with that of a fully trained physician.”15 The executive order would lead to a major shift in the current medical landscape, and as such, it is prudent that these concerns are addressed.

- Balanced Budget Act of 1997, 42 USC §1395x (1997). Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-105publ33/html/PLAW-105publ33.htm

- State practice environment. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Updated October 20, 2020. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state-practice-environment

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, et al. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2015. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:503-509.

- United States, Executive Office of the President [Donald Trump]. Executive Order 13890: Protecting and Improving Medicare for Our Nation’s Seniors. October 3, 2019. Fed Regist. 2019;84:53573-53576.

- Young KD. Trump executive order seeks proposals on Medicare pay for NPs, PAs. Medscape. Published October 3, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/919415

- Trump seeks proposals on Medicare pay for NPs, PAs. Reddit. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.reddit.com/r/medicine/comments/ddy03w/trump_seeks_proposals_on_medicare_pay_for_nps_pas/

- Martin E, Huang WW, Strowd LC, et al. Public perception of ethical issues in dermatology: evidenced by New York Times commenters. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1571-1577.

- Coldiron B, Ratnarathorn M. Scope of physician procedures independently billed by mid-level providers in the office setting. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1153-1159.

- Resneck JS Jr. Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:13-14.

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752.

- Become a PA. American Academy of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.aapa.org/career-central/become-a-pa/.

- Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1040-1044.

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis of physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573.

- Jalian HR, Jalian CA, Avram MM. Common causes of injury and legal action in laser surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:188-193.

- American Medical Association. Open letter to the Honorable Alex M. Azar II. Published October 29, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://searchlf.ama-assn.org/undefined/documentDownload?uri=%2Funstructured%2Fbinary%2Fletter%2FLETTERS%2F2019-10-29-Final-Sign-on-re-10-3-Executive-Order.pdf

- Balanced Budget Act of 1997, 42 USC §1395x (1997). Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-105publ33/html/PLAW-105publ33.htm

- State practice environment. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Updated October 20, 2020. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state-practice-environment

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, et al. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2015. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:503-509.

- United States, Executive Office of the President [Donald Trump]. Executive Order 13890: Protecting and Improving Medicare for Our Nation’s Seniors. October 3, 2019. Fed Regist. 2019;84:53573-53576.

- Young KD. Trump executive order seeks proposals on Medicare pay for NPs, PAs. Medscape. Published October 3, 2019. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/919415

- Trump seeks proposals on Medicare pay for NPs, PAs. Reddit. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.reddit.com/r/medicine/comments/ddy03w/trump_seeks_proposals_on_medicare_pay_for_nps_pas/

- Martin E, Huang WW, Strowd LC, et al. Public perception of ethical issues in dermatology: evidenced by New York Times commenters. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:1571-1577.

- Coldiron B, Ratnarathorn M. Scope of physician procedures independently billed by mid-level providers in the office setting. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1153-1159.

- Resneck JS Jr. Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:13-14.

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752.

- Become a PA. American Academy of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 8, 2020. https://www.aapa.org/career-central/become-a-pa/.

- Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1040-1044.

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis of physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573.

- Jalian HR, Jalian CA, Avram MM. Common causes of injury and legal action in laser surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:188-193.

- American Medical Association. Open letter to the Honorable Alex M. Azar II. Published October 29, 2019. Accessed December 11, 2020. https://searchlf.ama-assn.org/undefined/documentDownload?uri=%2Funstructured%2Fbinary%2Fletter%2FLETTERS%2F2019-10-29-Final-Sign-on-re-10-3-Executive-Order.pdf

Practice Points

- On October 3, 2019, President Donald Trump issued the Executive Order on Protecting and Improving Medicare for Our Nation’s Seniors, in which he proposed eliminating supervision requirements for advanced practice providers (APPs) and equalizing Medicare reimbursements among APPs and physicians.

- In a review of comments posted on online forums for medical professionals, a majority of medical professionals disapproved of the executive order.

- Advanced practice providers were more likely to support the plan, citing the breadth of their experience, whereas physicians were more likely to disapprove based on their extensive training within their specialty.

Prescribing Patterns of Onychomycosis Therapies in the United States

To the Editor:

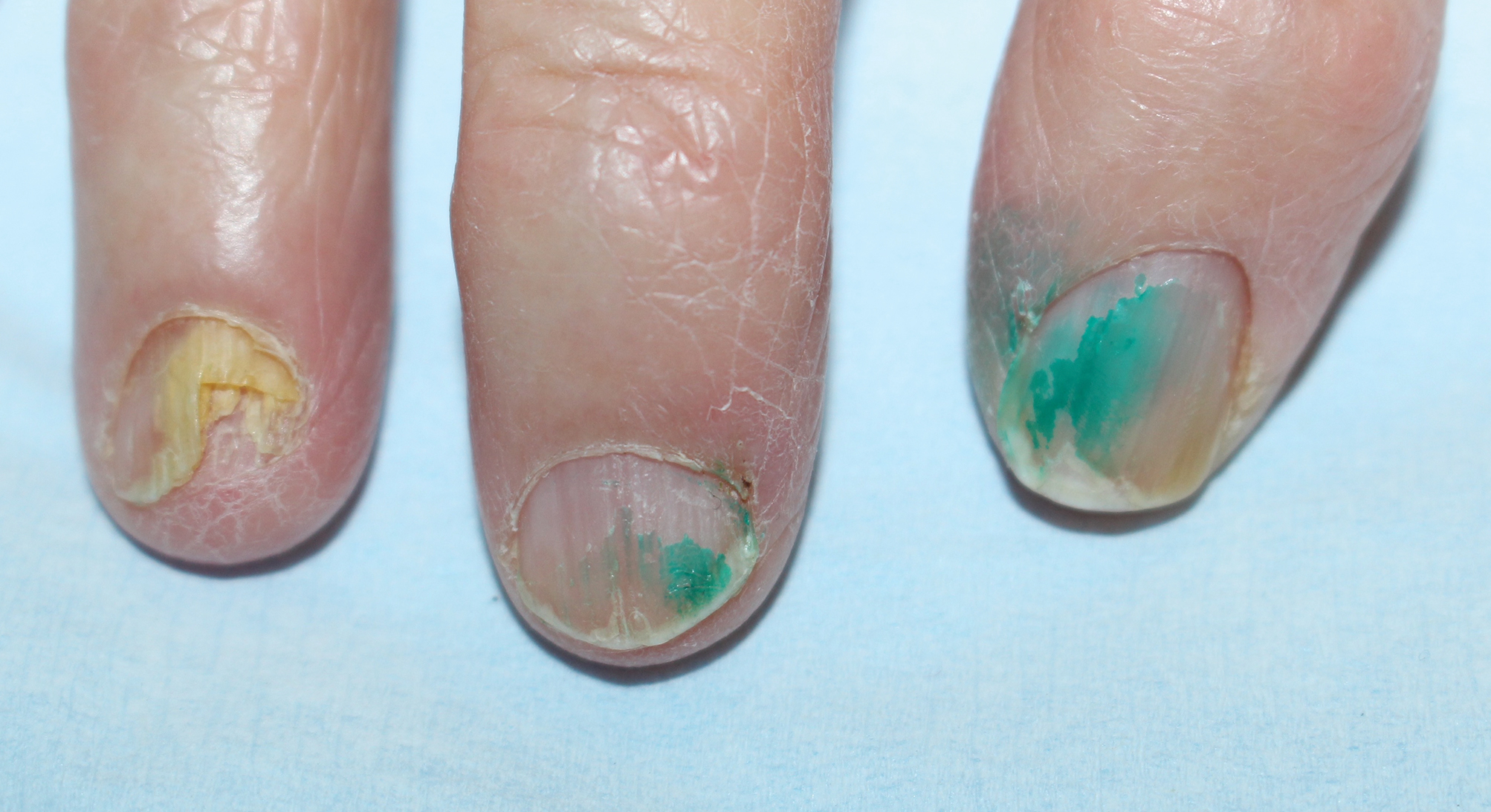

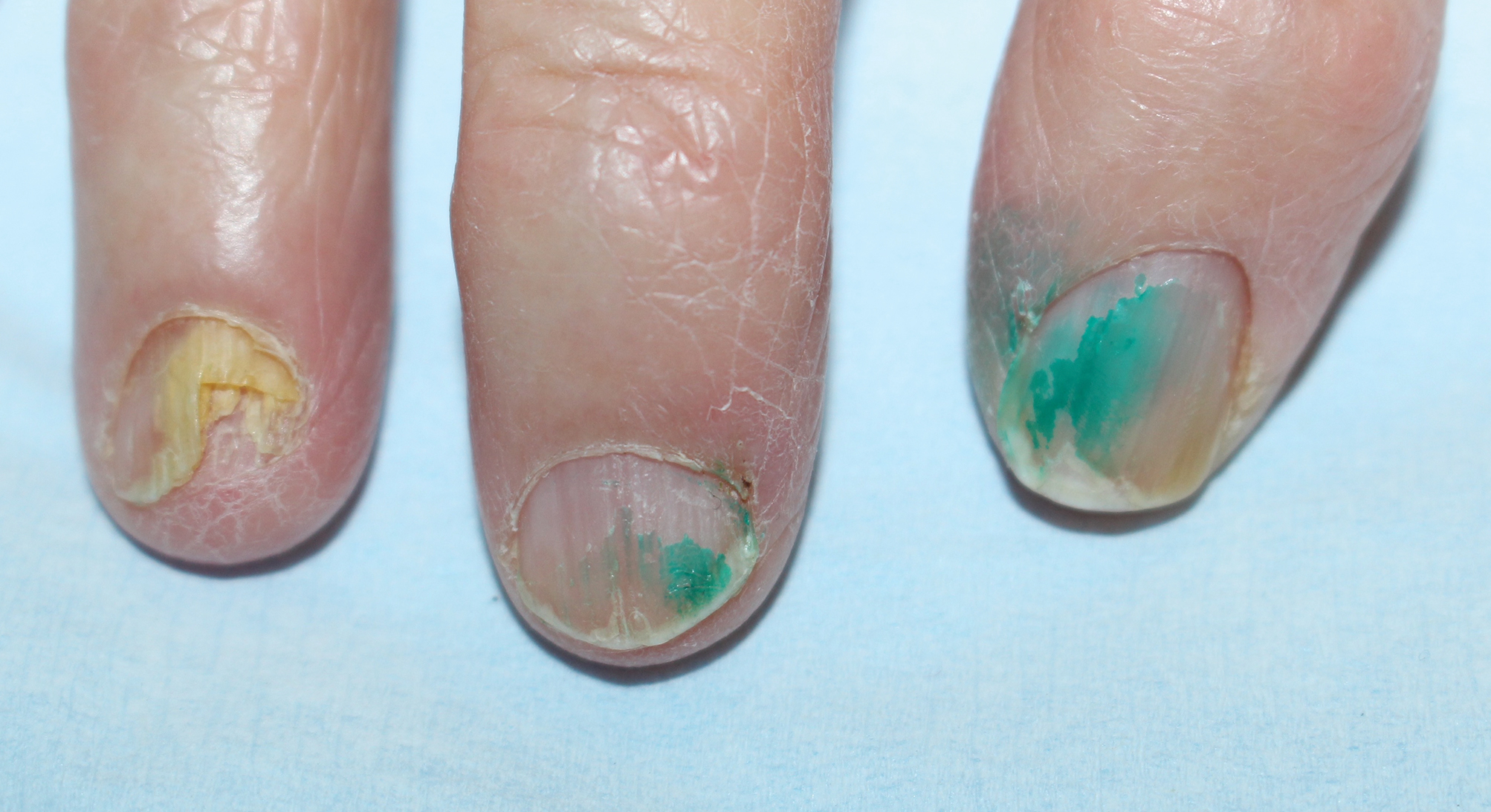

Onychomycosis is the most common nail disorder, affecting approximately 5.5% of the world’s population.1 There are a limited number of topical and systemic therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but no consensus guidelines exist for the management of onychomycosis. Therefore, we hypothesized that prescribing patterns would vary among different groups.

We examined data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Part D Prescriber Public Use Files for 2013 to 2016.2 Prescribing patterns were assessed for dermatologists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and podiatrists prescribing systemic (ie, terbinafine, itraconazole) or topical (ie, efinaconazole, tavaborole, ciclopirox) therapies. A cut-off of systemic therapy lasting 84 days or more (reflecting FDA-approved treatment regimens for toenail onychomycosis) was used to exclude prescriptions for other fungal conditions that require shorter treatment courses. Statistical analysis with χ2 tests identified differences among specialties’ prescribing patterns.

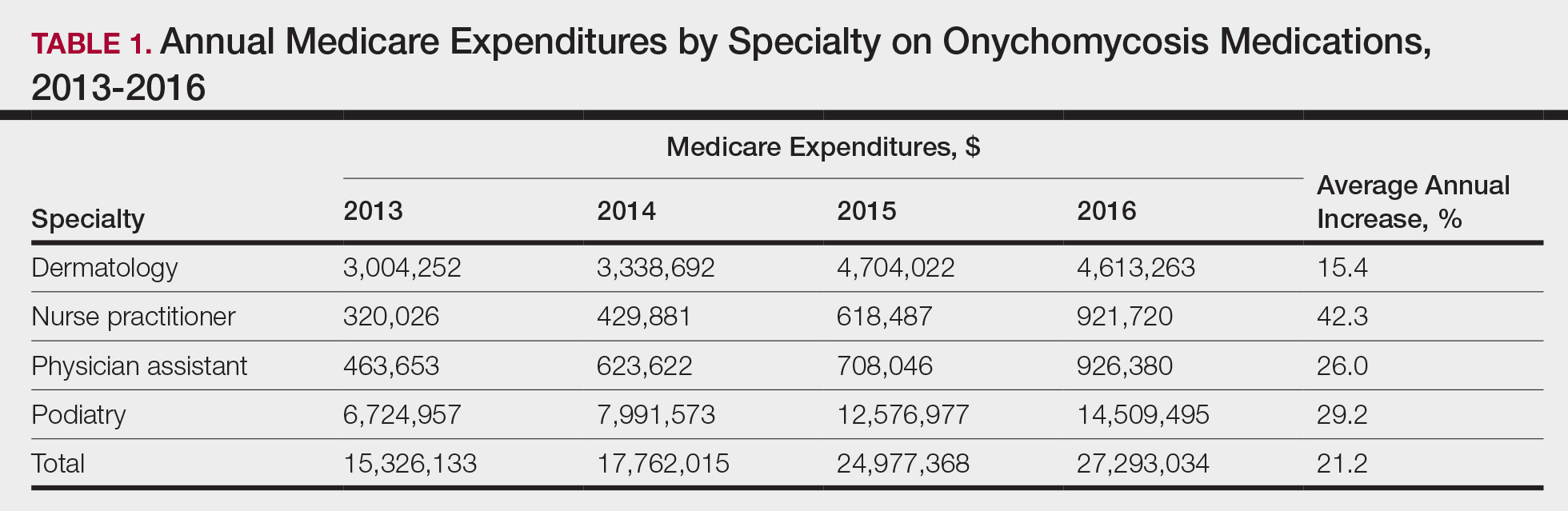

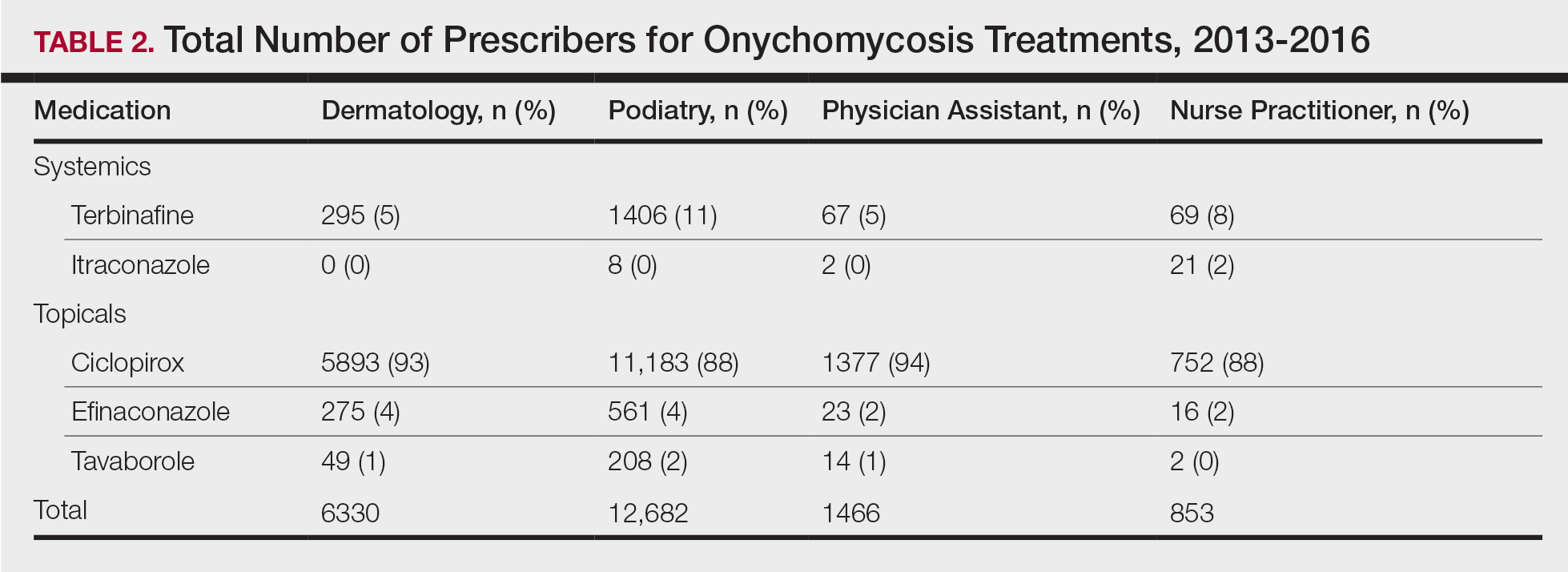

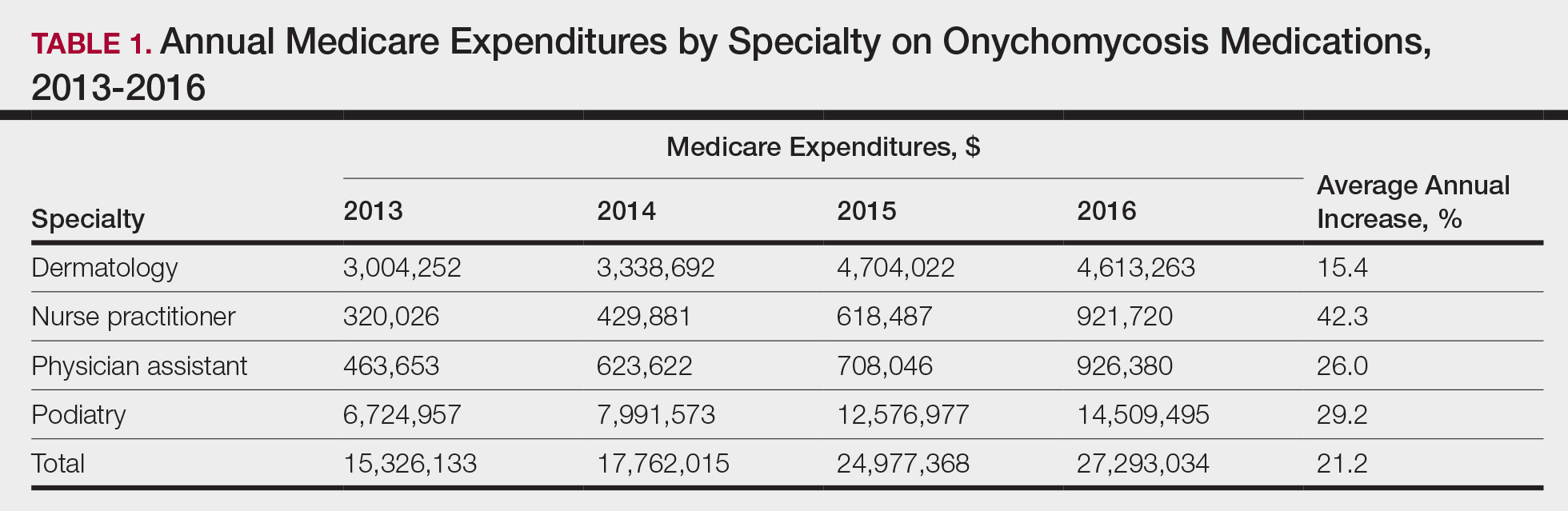

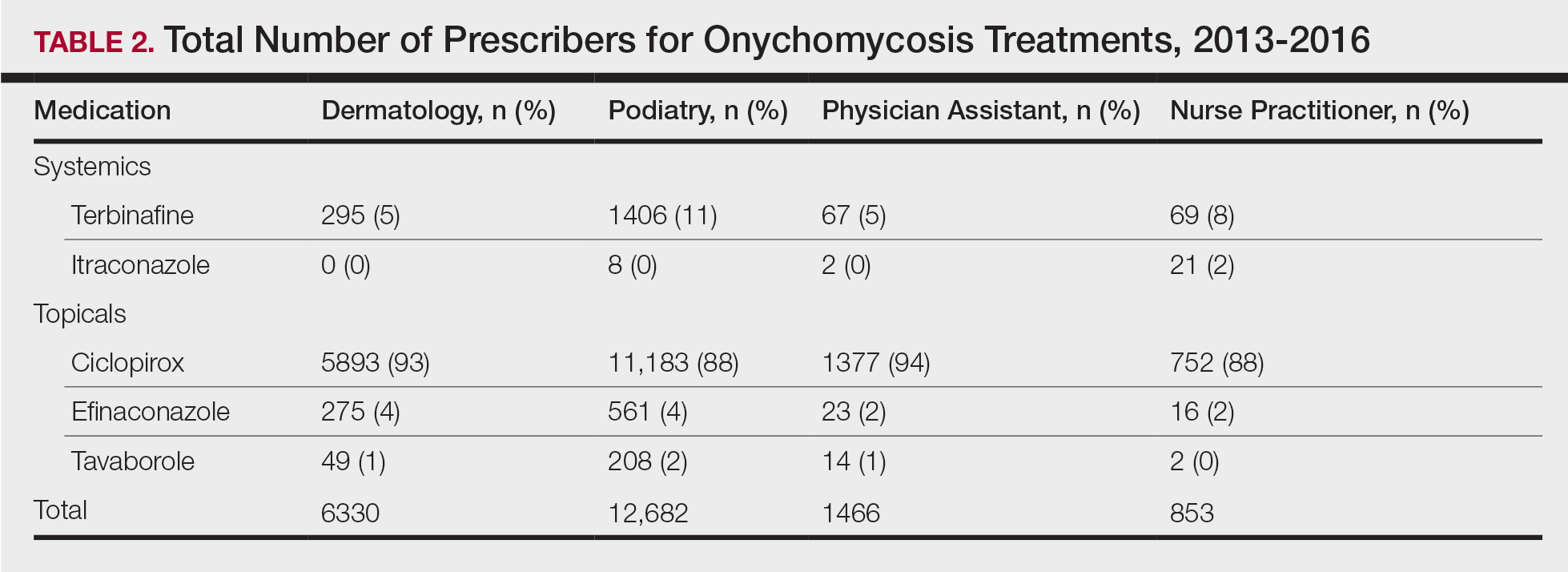

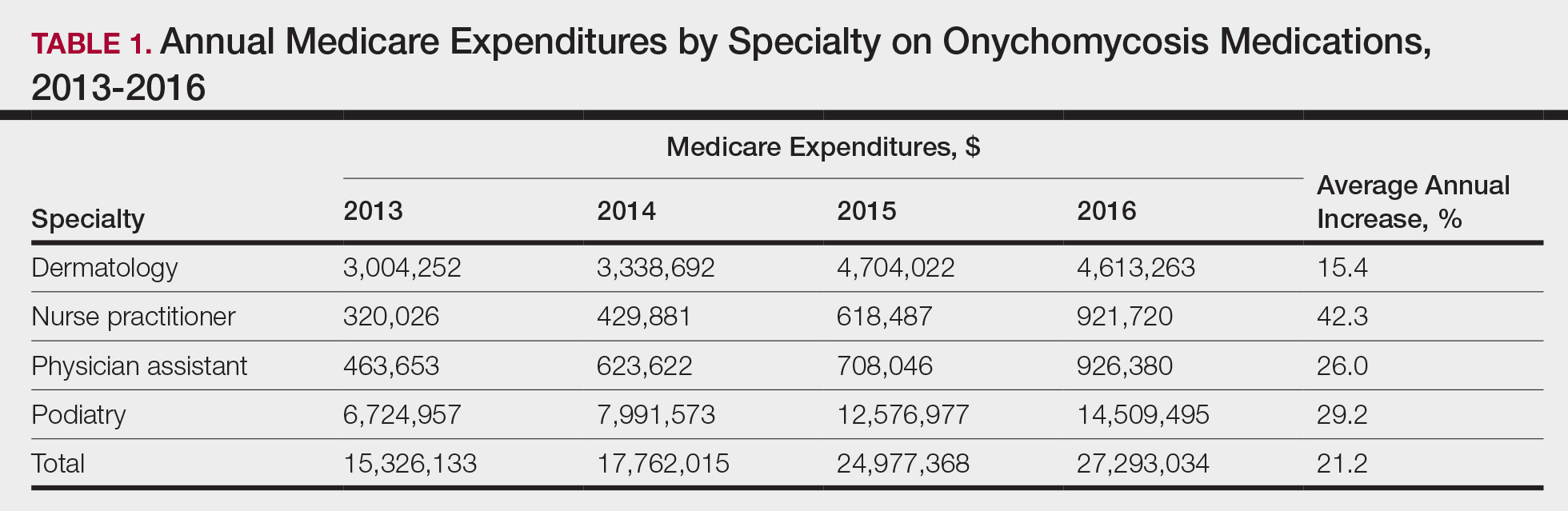

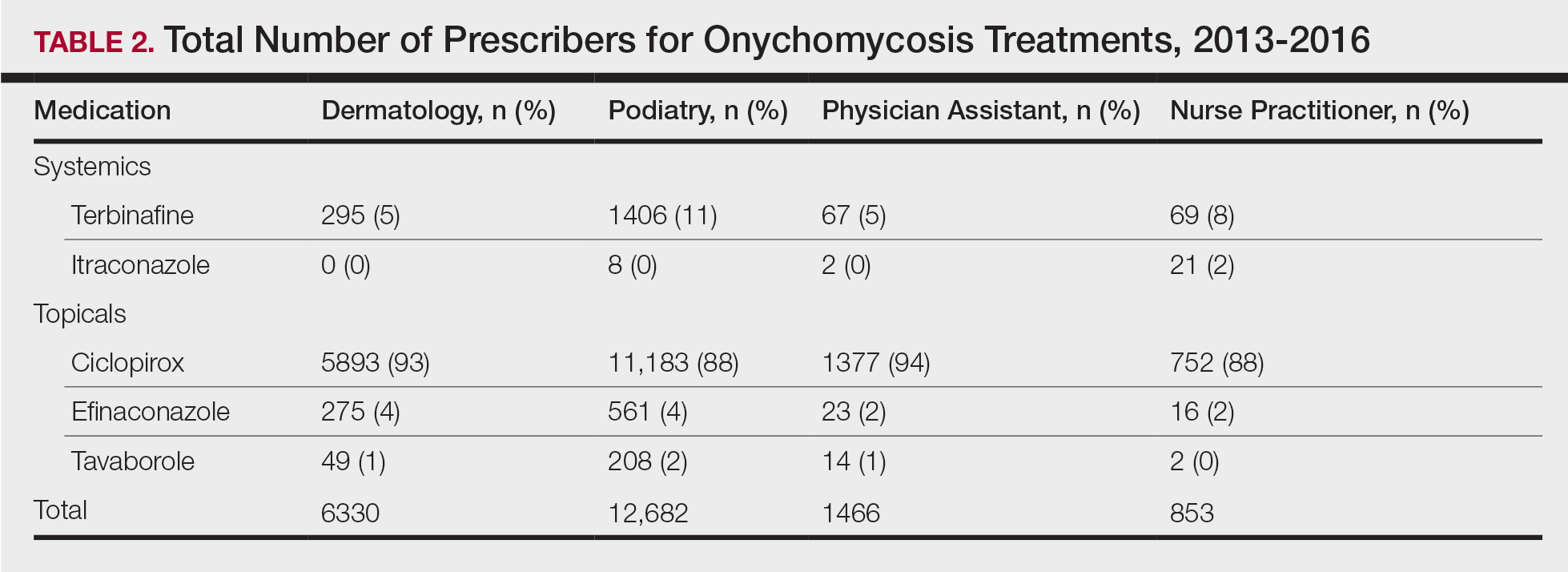

Overall, onychomycosis medications accounted for $85.4 million in expenditures from 2013 to 2016, with spending increasing at a rate of 21.2% annually (Table 1). The greatest single-year increase was observed from 2014 to 2015, with a 40.6% surge in overall expenditures for onychomycosis medications—increasing from $17.8 million to $25.0 million in spending. Dermatologists’ prescriptions accounted for 14.8% of all claims for onychomycosis medications and 18.3% of total expenditures during the study period, totaling $15.7 million in costs. Dermatologists’ claims increased at a rate of 7.4% annually, while expenditures increased at 15.4% annually. A greater proportion of dermatologists (96.4%) prescribed topicals for onychomycosis relative to nurse practitioners (90.2%) and podiatrists (91.3%)(P<.01)(Table 2). No significant difference was observed in the prescribing patterns of dermatologists and physician assistants (P=.99).

Per-claim spending for treating onychomycosis increased 7.4% annually for dermatologists, second only to podiatrists at 17.2% annually. Each analyzed group reported at least a 7% annual increase in the amount of topicals prescribed for onychomycosis. Following their FDA approvals in 2014, tavaborole and efinaconazole accounted for 0.9% and 2.3% of onychomycosis claims in 2016, respectively, and 15.0% and 25.1% of total Medicare expenditures on onychomycosis treatments that same year, respectively. Itraconazole also disproportionately contributed to expenditures, accounting for 1.3% of onychomycosis claims in 2016 while accounting for 9.5% of total expenditures.

The introduction of efinaconazole and tavaborole in 2014 resulted in large increases in Medicare spending for onychomycosis. Limited manufacturer competition due to patents may contribute to increased spending on these topicals in the future.3 A prior analysis demonstrated that podiatrists prescribe topicals more often than other clinicians,4 but after adjusting for the number of dermatologists managing onychomycosis, we found that a greater proportion of dermatologists (96.4%) are prescribing topicals for onychomycosis than other clinicians. This includes these newly approved, high-cost topicals, thus disproportionately contributing to the cost burden of onychomycosis treatment.

Ciclopirox is the most commonly prescribed therapy for onychomycosis across all groups, prescribed by more than 88% of prescribers in all studied specialties. Although ciclopirox is one of the least expensive treatment options available for onychomycosis, it has the lowest relative cure rate.5 Onychomycosis management requires understanding of drug efficacy and disease severity.6 Inappropriate treatment selection may result in prolonged treatment courses and increased costs. Consensus guidelines for onychomycosis therapies across specialties may yield more cost-effective treatment for this common nail condition.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Paul J. Christos, DrPH, MS (New York, New York), for his advisement regarding statistical analysis for this manuscript.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:835-851.

- Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Part-D-Prescriber. Updated November 27, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2020.

- Yang EJ, Lipner SR. Pharmacy costs of medications for the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:276-278.

- Singh P, Silverberg JI. Trends in utilization and expenditure for onychomycosis treatments in the United States in 2013-2016. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:311-313.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:853-867.

- Lipner SR. Pharmacotherapy for onychomycosis: new and emerging treatments. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20:725-735.

To the Editor:

Onychomycosis is the most common nail disorder, affecting approximately 5.5% of the world’s population.1 There are a limited number of topical and systemic therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but no consensus guidelines exist for the management of onychomycosis. Therefore, we hypothesized that prescribing patterns would vary among different groups.

We examined data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Part D Prescriber Public Use Files for 2013 to 2016.2 Prescribing patterns were assessed for dermatologists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and podiatrists prescribing systemic (ie, terbinafine, itraconazole) or topical (ie, efinaconazole, tavaborole, ciclopirox) therapies. A cut-off of systemic therapy lasting 84 days or more (reflecting FDA-approved treatment regimens for toenail onychomycosis) was used to exclude prescriptions for other fungal conditions that require shorter treatment courses. Statistical analysis with χ2 tests identified differences among specialties’ prescribing patterns.

Overall, onychomycosis medications accounted for $85.4 million in expenditures from 2013 to 2016, with spending increasing at a rate of 21.2% annually (Table 1). The greatest single-year increase was observed from 2014 to 2015, with a 40.6% surge in overall expenditures for onychomycosis medications—increasing from $17.8 million to $25.0 million in spending. Dermatologists’ prescriptions accounted for 14.8% of all claims for onychomycosis medications and 18.3% of total expenditures during the study period, totaling $15.7 million in costs. Dermatologists’ claims increased at a rate of 7.4% annually, while expenditures increased at 15.4% annually. A greater proportion of dermatologists (96.4%) prescribed topicals for onychomycosis relative to nurse practitioners (90.2%) and podiatrists (91.3%)(P<.01)(Table 2). No significant difference was observed in the prescribing patterns of dermatologists and physician assistants (P=.99).

Per-claim spending for treating onychomycosis increased 7.4% annually for dermatologists, second only to podiatrists at 17.2% annually. Each analyzed group reported at least a 7% annual increase in the amount of topicals prescribed for onychomycosis. Following their FDA approvals in 2014, tavaborole and efinaconazole accounted for 0.9% and 2.3% of onychomycosis claims in 2016, respectively, and 15.0% and 25.1% of total Medicare expenditures on onychomycosis treatments that same year, respectively. Itraconazole also disproportionately contributed to expenditures, accounting for 1.3% of onychomycosis claims in 2016 while accounting for 9.5% of total expenditures.

The introduction of efinaconazole and tavaborole in 2014 resulted in large increases in Medicare spending for onychomycosis. Limited manufacturer competition due to patents may contribute to increased spending on these topicals in the future.3 A prior analysis demonstrated that podiatrists prescribe topicals more often than other clinicians,4 but after adjusting for the number of dermatologists managing onychomycosis, we found that a greater proportion of dermatologists (96.4%) are prescribing topicals for onychomycosis than other clinicians. This includes these newly approved, high-cost topicals, thus disproportionately contributing to the cost burden of onychomycosis treatment.

Ciclopirox is the most commonly prescribed therapy for onychomycosis across all groups, prescribed by more than 88% of prescribers in all studied specialties. Although ciclopirox is one of the least expensive treatment options available for onychomycosis, it has the lowest relative cure rate.5 Onychomycosis management requires understanding of drug efficacy and disease severity.6 Inappropriate treatment selection may result in prolonged treatment courses and increased costs. Consensus guidelines for onychomycosis therapies across specialties may yield more cost-effective treatment for this common nail condition.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Paul J. Christos, DrPH, MS (New York, New York), for his advisement regarding statistical analysis for this manuscript.

To the Editor:

Onychomycosis is the most common nail disorder, affecting approximately 5.5% of the world’s population.1 There are a limited number of topical and systemic therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but no consensus guidelines exist for the management of onychomycosis. Therefore, we hypothesized that prescribing patterns would vary among different groups.

We examined data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Part D Prescriber Public Use Files for 2013 to 2016.2 Prescribing patterns were assessed for dermatologists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and podiatrists prescribing systemic (ie, terbinafine, itraconazole) or topical (ie, efinaconazole, tavaborole, ciclopirox) therapies. A cut-off of systemic therapy lasting 84 days or more (reflecting FDA-approved treatment regimens for toenail onychomycosis) was used to exclude prescriptions for other fungal conditions that require shorter treatment courses. Statistical analysis with χ2 tests identified differences among specialties’ prescribing patterns.

Overall, onychomycosis medications accounted for $85.4 million in expenditures from 2013 to 2016, with spending increasing at a rate of 21.2% annually (Table 1). The greatest single-year increase was observed from 2014 to 2015, with a 40.6% surge in overall expenditures for onychomycosis medications—increasing from $17.8 million to $25.0 million in spending. Dermatologists’ prescriptions accounted for 14.8% of all claims for onychomycosis medications and 18.3% of total expenditures during the study period, totaling $15.7 million in costs. Dermatologists’ claims increased at a rate of 7.4% annually, while expenditures increased at 15.4% annually. A greater proportion of dermatologists (96.4%) prescribed topicals for onychomycosis relative to nurse practitioners (90.2%) and podiatrists (91.3%)(P<.01)(Table 2). No significant difference was observed in the prescribing patterns of dermatologists and physician assistants (P=.99).

Per-claim spending for treating onychomycosis increased 7.4% annually for dermatologists, second only to podiatrists at 17.2% annually. Each analyzed group reported at least a 7% annual increase in the amount of topicals prescribed for onychomycosis. Following their FDA approvals in 2014, tavaborole and efinaconazole accounted for 0.9% and 2.3% of onychomycosis claims in 2016, respectively, and 15.0% and 25.1% of total Medicare expenditures on onychomycosis treatments that same year, respectively. Itraconazole also disproportionately contributed to expenditures, accounting for 1.3% of onychomycosis claims in 2016 while accounting for 9.5% of total expenditures.

The introduction of efinaconazole and tavaborole in 2014 resulted in large increases in Medicare spending for onychomycosis. Limited manufacturer competition due to patents may contribute to increased spending on these topicals in the future.3 A prior analysis demonstrated that podiatrists prescribe topicals more often than other clinicians,4 but after adjusting for the number of dermatologists managing onychomycosis, we found that a greater proportion of dermatologists (96.4%) are prescribing topicals for onychomycosis than other clinicians. This includes these newly approved, high-cost topicals, thus disproportionately contributing to the cost burden of onychomycosis treatment.

Ciclopirox is the most commonly prescribed therapy for onychomycosis across all groups, prescribed by more than 88% of prescribers in all studied specialties. Although ciclopirox is one of the least expensive treatment options available for onychomycosis, it has the lowest relative cure rate.5 Onychomycosis management requires understanding of drug efficacy and disease severity.6 Inappropriate treatment selection may result in prolonged treatment courses and increased costs. Consensus guidelines for onychomycosis therapies across specialties may yield more cost-effective treatment for this common nail condition.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Paul J. Christos, DrPH, MS (New York, New York), for his advisement regarding statistical analysis for this manuscript.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:835-851.

- Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Part-D-Prescriber. Updated November 27, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2020.

- Yang EJ, Lipner SR. Pharmacy costs of medications for the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:276-278.

- Singh P, Silverberg JI. Trends in utilization and expenditure for onychomycosis treatments in the United States in 2013-2016. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:311-313.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:853-867.

- Lipner SR. Pharmacotherapy for onychomycosis: new and emerging treatments. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20:725-735.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: clinical overview and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:835-851.

- Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Part-D-Prescriber. Updated November 27, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2020.

- Yang EJ, Lipner SR. Pharmacy costs of medications for the treatment of onychomycosis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:276-278.

- Singh P, Silverberg JI. Trends in utilization and expenditure for onychomycosis treatments in the United States in 2013-2016. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:311-313.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis: treatment and prevention of recurrence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:853-867.

- Lipner SR. Pharmacotherapy for onychomycosis: new and emerging treatments. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20:725-735.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should consider efficacy and cost of onychomycosis therapies, as inappropriate treatment selection results in longer treatment courses and increased costs.

- Creation of consensus guidelines for the management of onychomycosis may decrease the costs of treating this difficult-to-manage disease.

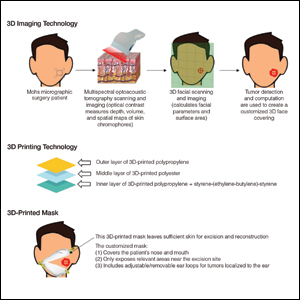

Use of 3D Technology to Support Dermatologists Returning to Practice Amid COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread across all 7 continents, including 185 countries, and infected more than 21.9 million individuals worldwide as of August 18, 2020, according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. It has strained our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology. Dermatologists have taken important safety measures by canceling/deferring elective and nonemergency procedures and diagnosing/treating patients via telemedicine. Many residents and attending dermatologists have volunteered to care for COVID-19 inpatients and donated

N95 masks are necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic because they effectively filter at least 95% of 0.3-μm airborne particles and provide adequate face seals.1 3-Dimensional imaging integrated with 3D printers can be used to scan precise facial parameters (eg, jawline, nose) and account for facial hair density and length to produce comfortable tailored N95 masks and face seals.1,2 3-Dimensional printing utilizes robotics and

Face shields offer an additional layer of safety for the face and mucosae and also may provide longevity for N95 masks. Using synthetic polymers such as polycarbonate and polyethylene, 3D printers can be used to construct face shields via fused deposition modeling.1 These face shields may be worn over N95 masks and then can be sanitized and reused.

Mohs surgeons and staff may be at particularly high risk for COVID-19 infection due to their close proximity to the face during surgery, use of cautery, and prolonged time spent with patients while taking layers and suturing.

As dermatologists reopen and ramp up practice volume, there will be increased PPE requirements. Using 3D technology and imaging to produce N95 masks, face shields, and face coverings, we can offer effective diagnosis and treatment while optimizing safety for dermatologists, staff, and patients.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19-related supply shortages [published online April 21, 2020]. Am J Med. 2020;133:771-773.

- Cai M, Li H, Shen S, et al. Customized design and 3D printing of face seal for an N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;3:226-234.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. A review of 3-dimensional skin bioprinting techniques: applications, approaches, and trends [published online March 17, 2020]. Dermatol Surg. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002378.

- Banerjee SS, Burbine S, Shivaprakash NK, et al. 3D-printable PP/SEBS thermoplastic elastomeric blends: preparation and properties [published online February 17, 2019]. Polymers (Basel). doi:10.3390/polym11020347.

- Chuah SY, Attia ABE, Long V. Structural and functional 3D mapping of skin tumours with non-invasive multispectral optoacoustic tomography [published online November 2, 2016]. Skin Res Technol. 2017;23:221-226.

Practice Points

- Coronavirus disease 19 has overwhelmed our health care system and affected all specialties, including dermatology.

- There are concerns about shortages of personal protective equipment to safely care for patients.

- 3-Dimensional imaging and printing technologies can be harnessed to create face coverings and face shields for the dermatology outpatient setting.

Approximation of Alcohol-Based Hand Sanitizer Volume Using a Toothpaste Cap

Practice Gap

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends handwashing with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand sanitizers to prevent transmission of coronavirus disease 2019. Five steps are delineated for effective handwashing: wetting, lathering, scrubbing, rinsing, and drying. Although alcohol-based sanitizers may be perceived as more damaging to the skin, they are less likely to cause dermatitis than handwashing with soap and water.1 Instructions are precise for handwashing, while there are no recommendations for effective use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers. A common inquiry regarding alcohol-based hand sanitizers is the volume needed for efficacy without causing skin irritation.

The Technique

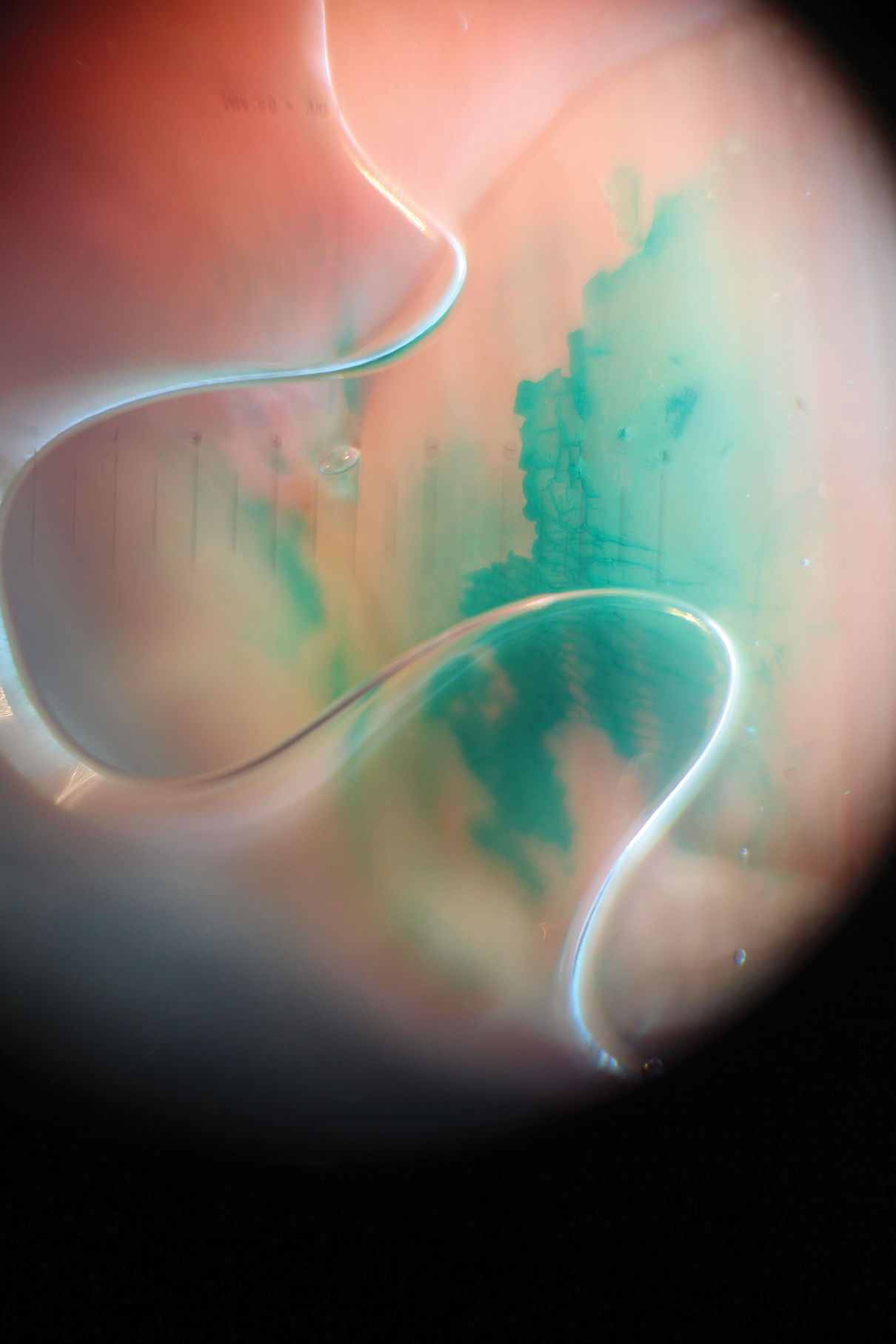

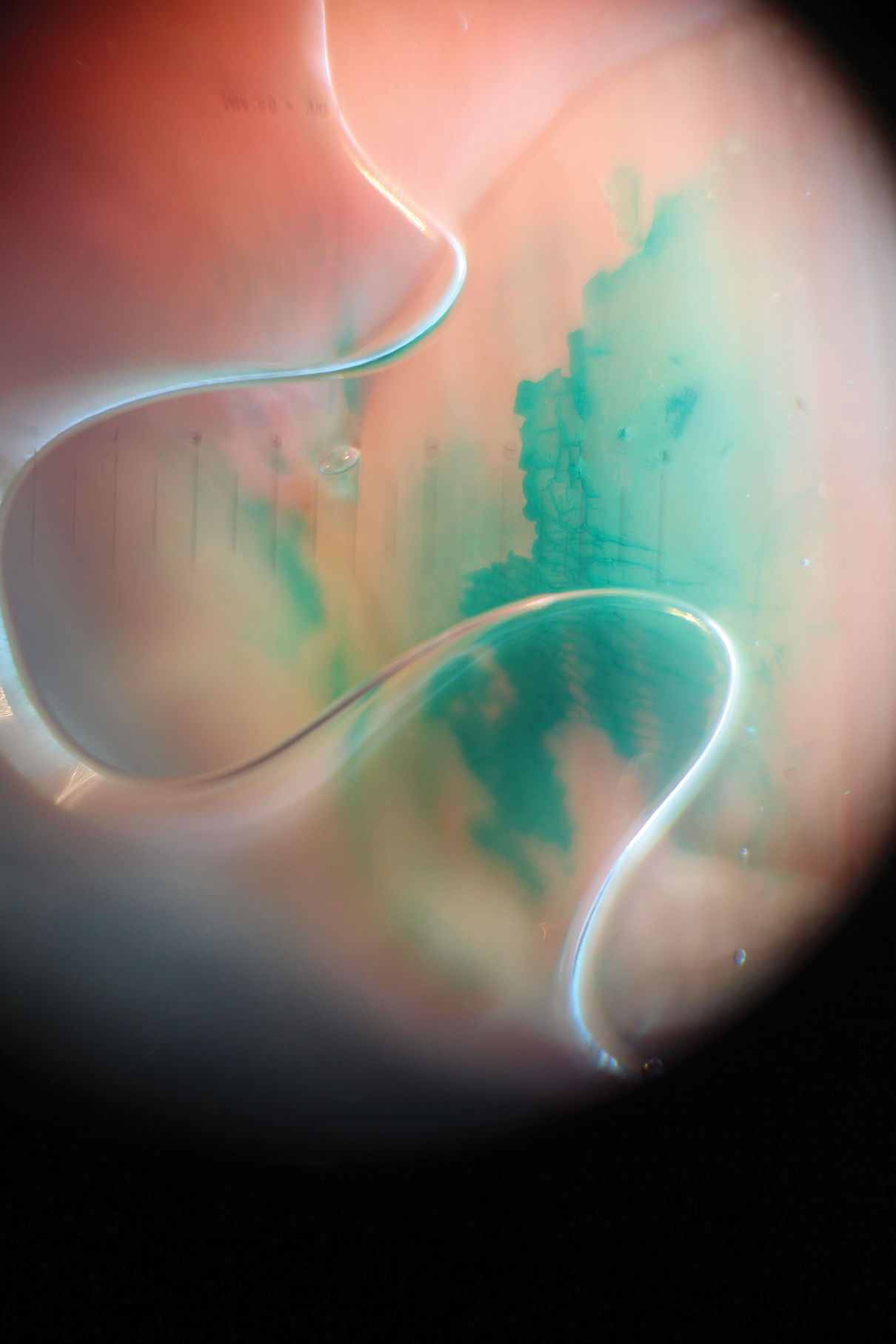

Approximately 1 mL of alcohol-based hand sanitizer is recommended by some manufacturers. However, abundant evidence refutes this recommendation, including a study that tested the microbial efficacy of alcohol-based sanitizers by volume. A volume of 2 mL was necessary to achieve the 2.0 log reduction of contaminants as required by the US Food and Drug Administration for antimicrobial efficacy.2 The precise measurement of hand sanitizer using a calibrated syringe before each use is impractical. Thus, we recommend using a screw-top toothpaste cap to assist in approximating the necessary volume (Figure). The cap holds approximately 1 mL of liquid as measured using a syringe; therefore, 2 caps filled with sanitizer should be used.

Practice Implications

The general public may be underutilizing hand sanitizer due to fear of excessive skin irritation or supply shortages, which will reduce efficacy. Patients and physicians can use this simple visual approximation to ensure adequate use of hand sanitizer volume.

- Stutz N, Becker D, Jappe U, et al. Nurses’ perceptions of the benefits and adverse effects of hand disinfection: alcohol-based hand rubs vs. hygienic handwashing: a multicentre questionnaire study with additional patch testing by the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:565-572.

- Kampf G, Ruselack S, Eggerstedt S, et al. Less and less-influence of volume on hand coverage and bactericidal efficacy in hand disinfection. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:472.

Practice Gap

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends handwashing with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand sanitizers to prevent transmission of coronavirus disease 2019. Five steps are delineated for effective handwashing: wetting, lathering, scrubbing, rinsing, and drying. Although alcohol-based sanitizers may be perceived as more damaging to the skin, they are less likely to cause dermatitis than handwashing with soap and water.1 Instructions are precise for handwashing, while there are no recommendations for effective use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers. A common inquiry regarding alcohol-based hand sanitizers is the volume needed for efficacy without causing skin irritation.

The Technique

Approximately 1 mL of alcohol-based hand sanitizer is recommended by some manufacturers. However, abundant evidence refutes this recommendation, including a study that tested the microbial efficacy of alcohol-based sanitizers by volume. A volume of 2 mL was necessary to achieve the 2.0 log reduction of contaminants as required by the US Food and Drug Administration for antimicrobial efficacy.2 The precise measurement of hand sanitizer using a calibrated syringe before each use is impractical. Thus, we recommend using a screw-top toothpaste cap to assist in approximating the necessary volume (Figure). The cap holds approximately 1 mL of liquid as measured using a syringe; therefore, 2 caps filled with sanitizer should be used.

Practice Implications

The general public may be underutilizing hand sanitizer due to fear of excessive skin irritation or supply shortages, which will reduce efficacy. Patients and physicians can use this simple visual approximation to ensure adequate use of hand sanitizer volume.

Practice Gap

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends handwashing with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand sanitizers to prevent transmission of coronavirus disease 2019. Five steps are delineated for effective handwashing: wetting, lathering, scrubbing, rinsing, and drying. Although alcohol-based sanitizers may be perceived as more damaging to the skin, they are less likely to cause dermatitis than handwashing with soap and water.1 Instructions are precise for handwashing, while there are no recommendations for effective use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers. A common inquiry regarding alcohol-based hand sanitizers is the volume needed for efficacy without causing skin irritation.

The Technique

Approximately 1 mL of alcohol-based hand sanitizer is recommended by some manufacturers. However, abundant evidence refutes this recommendation, including a study that tested the microbial efficacy of alcohol-based sanitizers by volume. A volume of 2 mL was necessary to achieve the 2.0 log reduction of contaminants as required by the US Food and Drug Administration for antimicrobial efficacy.2 The precise measurement of hand sanitizer using a calibrated syringe before each use is impractical. Thus, we recommend using a screw-top toothpaste cap to assist in approximating the necessary volume (Figure). The cap holds approximately 1 mL of liquid as measured using a syringe; therefore, 2 caps filled with sanitizer should be used.

Practice Implications

The general public may be underutilizing hand sanitizer due to fear of excessive skin irritation or supply shortages, which will reduce efficacy. Patients and physicians can use this simple visual approximation to ensure adequate use of hand sanitizer volume.

- Stutz N, Becker D, Jappe U, et al. Nurses’ perceptions of the benefits and adverse effects of hand disinfection: alcohol-based hand rubs vs. hygienic handwashing: a multicentre questionnaire study with additional patch testing by the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:565-572.

- Kampf G, Ruselack S, Eggerstedt S, et al. Less and less-influence of volume on hand coverage and bactericidal efficacy in hand disinfection. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:472.

- Stutz N, Becker D, Jappe U, et al. Nurses’ perceptions of the benefits and adverse effects of hand disinfection: alcohol-based hand rubs vs. hygienic handwashing: a multicentre questionnaire study with additional patch testing by the German Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:565-572.

- Kampf G, Ruselack S, Eggerstedt S, et al. Less and less-influence of volume on hand coverage and bactericidal efficacy in hand disinfection. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:472.

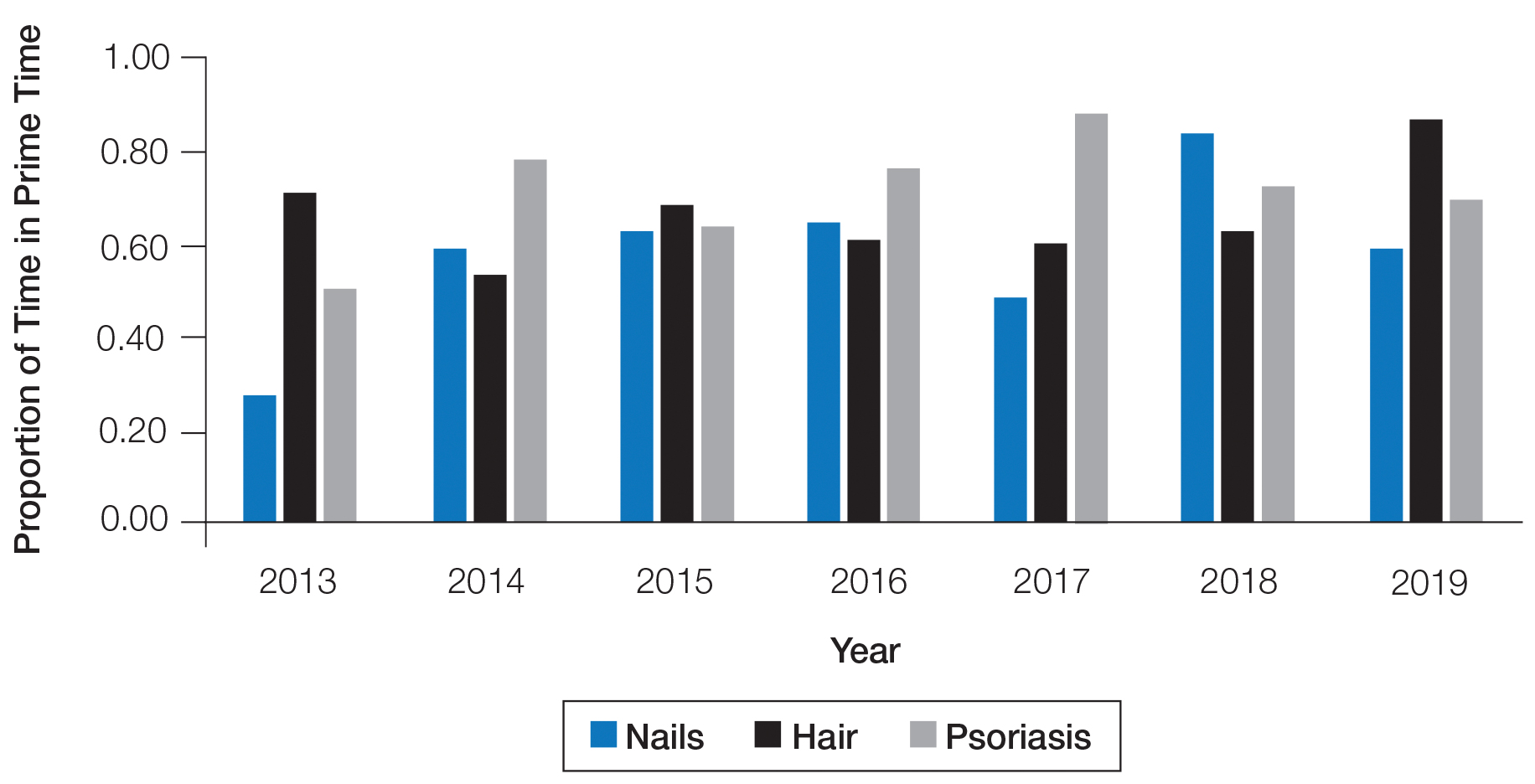

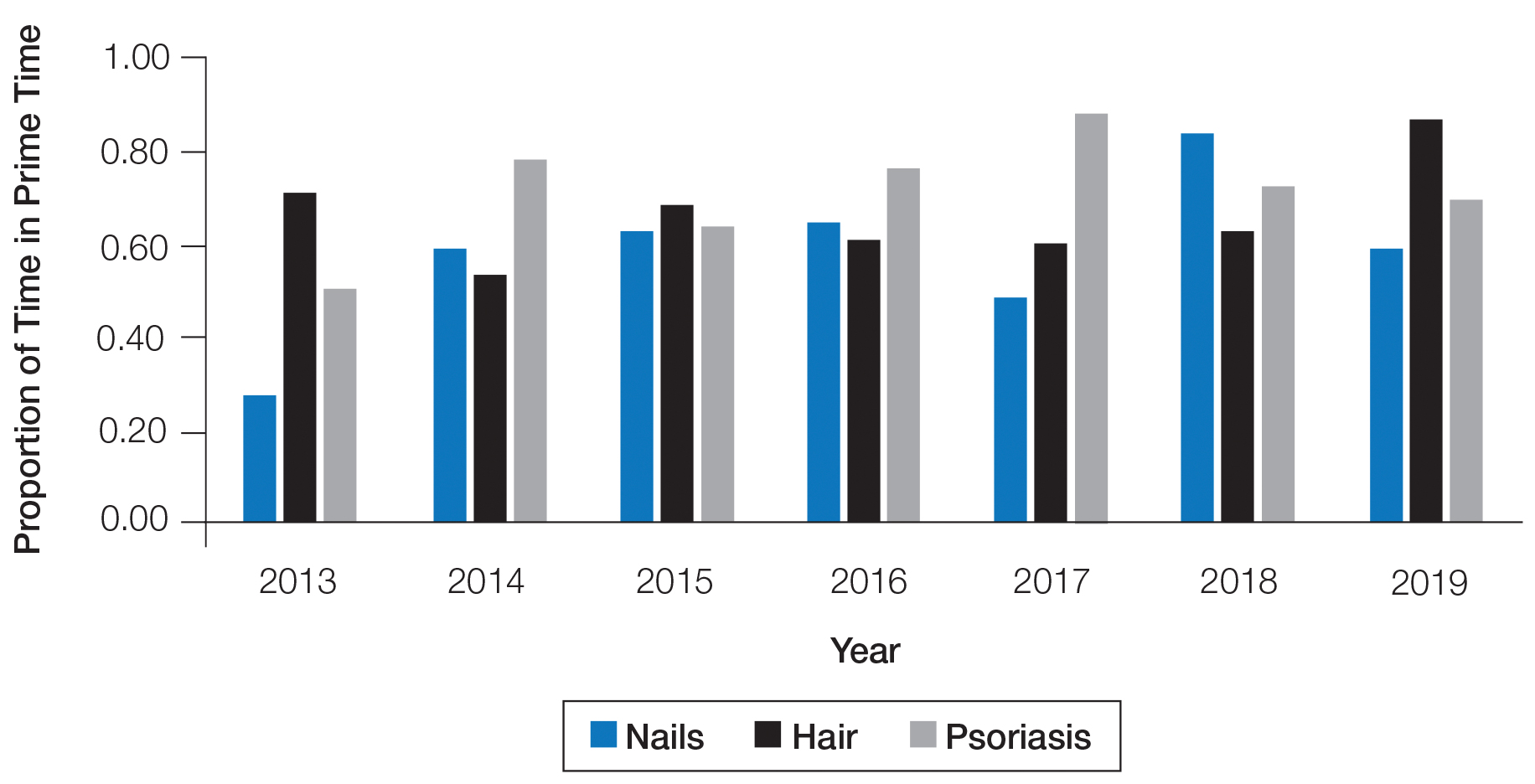

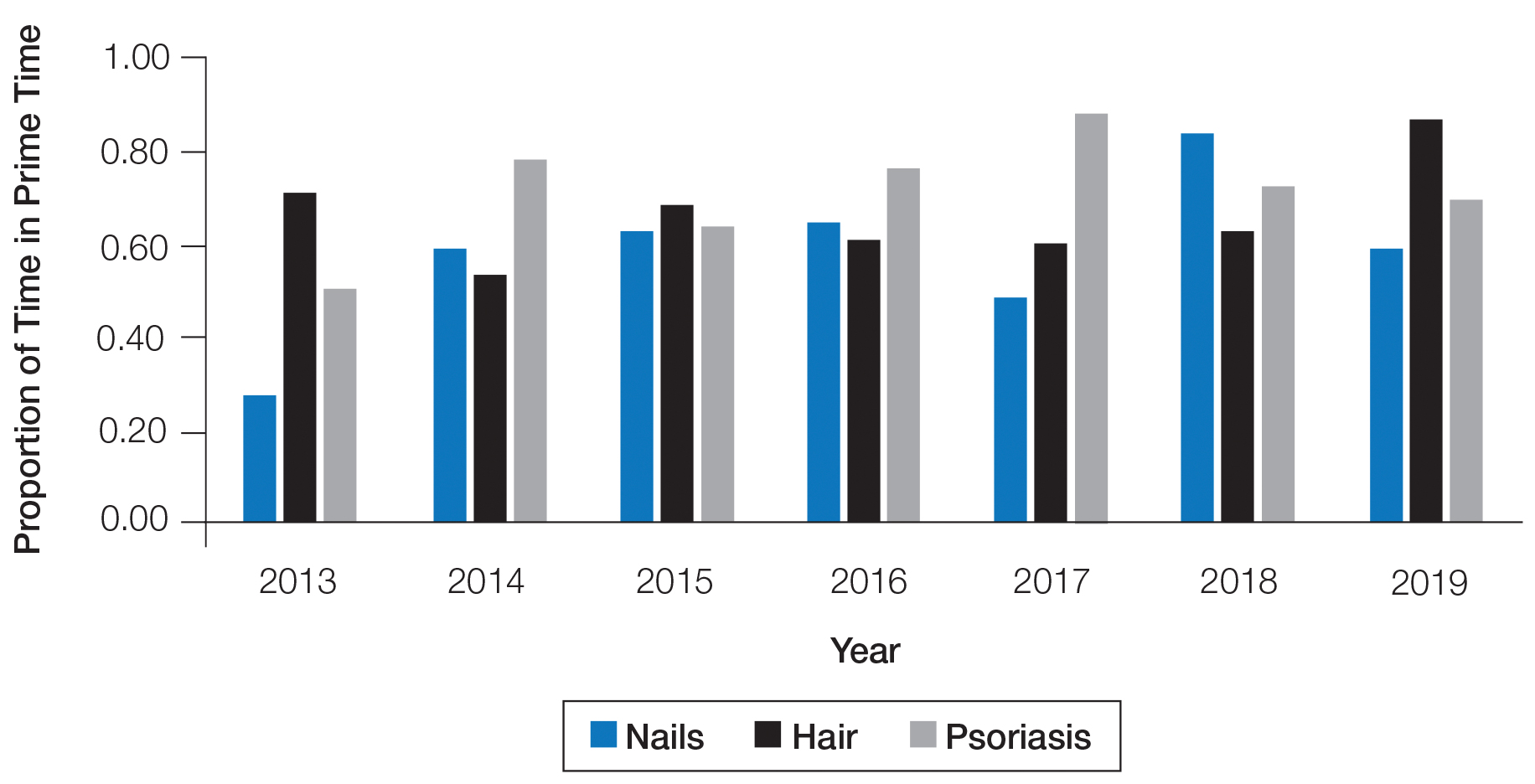

Assessment of Nail Content in the American Academy of Dermatology Patient Education Website

To the Editor:

Patients with skin, hair, or nail concerns often utilize online resources to self-diagnose or learn more about physician-diagnosed conditions. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website offers the public access to informational pages categorized by disease or treatment (https://www.aad.org/public). We sought to evaluate the nail content by searching the Patients and Public section of the AAD website to qualitatively and quantitatively describe mentions of nail conditions. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis, and ringworm content also were analyzed and compared to nail content. The analysis was performed on September 7, 2019.

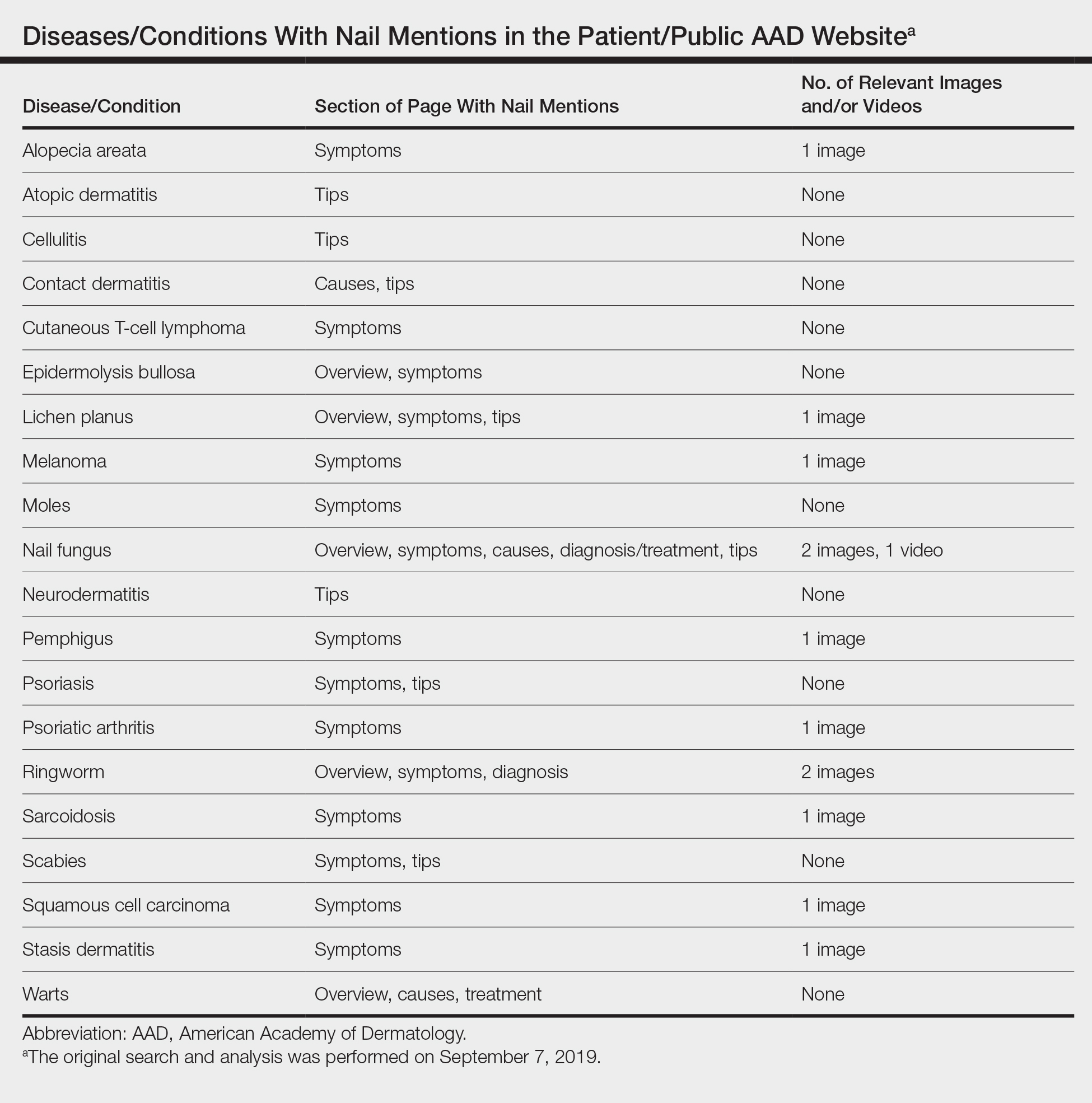

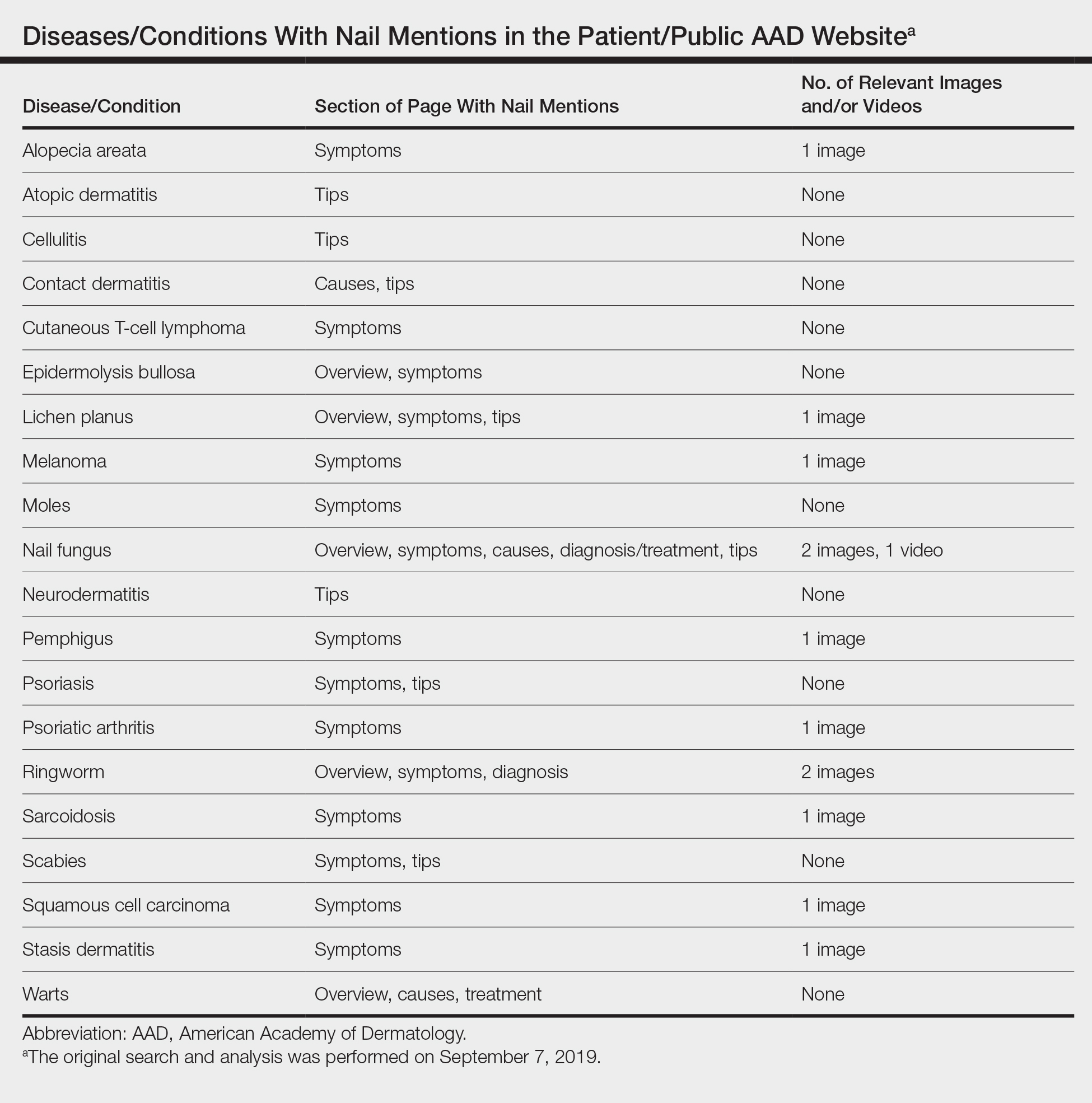

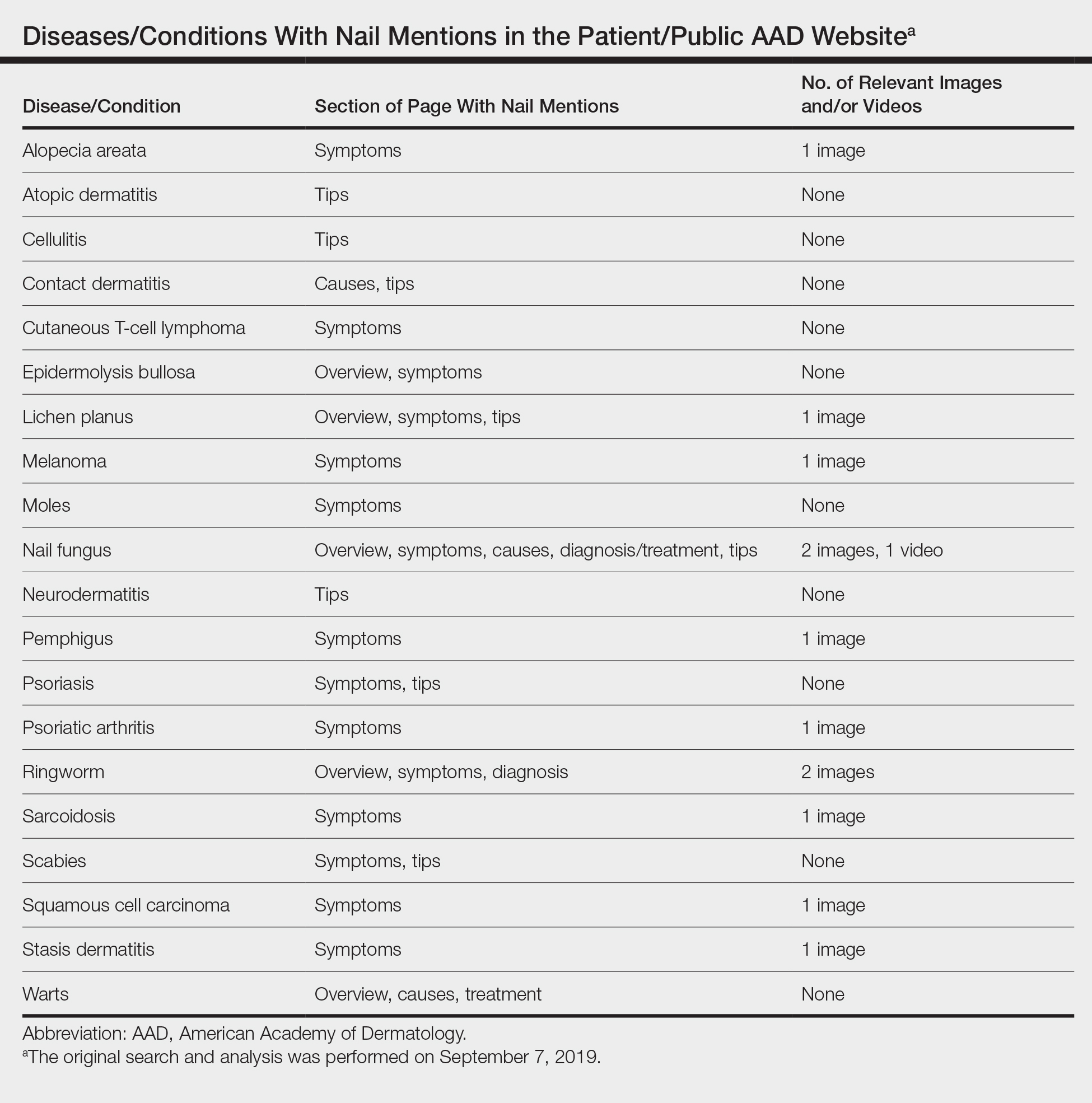

Of the 73 topics listed in the Diseases and Treatments section of the site, 17 (23%) specifically mentioned nail symptoms or pathology (Table). Three additional topics—atopic dermatitis, cellulitis, and neurodermatitis—recommended keeping nails short to prevent injury from scratching. There was 1 mention of obtaining fungal cultures, 2 of nail scraping microscopy, 2 of nail clippings, and 2 of nail-related cancers. There were no mentions of nail biopsies. The total number of unique clinical images across all sections was 300, with 12 of nails. The video library contained 84 videos, of which 6 focused on nail health.

Our study demonstrated that nail content is underrepresented in the public education section of the AAD website. If patients are unable to find nail disease material on the AAD website, they may seek alternative sources that are unreliable. Prior studies have shown that patient Internet resources for subungual melanoma and onychomycosis often are inadequate in quality and readability.1,2

Representative photographs and key information on common nail diseases could be added to improve patient education. The atopic dermatitis section should include text on related nail changes with accompanying images. We also recommend including paronychia information and images as either a separate topic or in the cellulitis section. The contact dermatitis section mentions nail cosmetics as causative factors, but an image of roller-coaster onycholysis may be more helpful.3 Although the alopecia areata section mentions nail changes, this information should be added to the general hair loss section of the site, as many patients may initially seek out the latter category. Herpes simplex may affect nails, and an image showing these changes would be instructive. In addition, pyogenic granulomas and paronychia occur with isotretinoin use.4

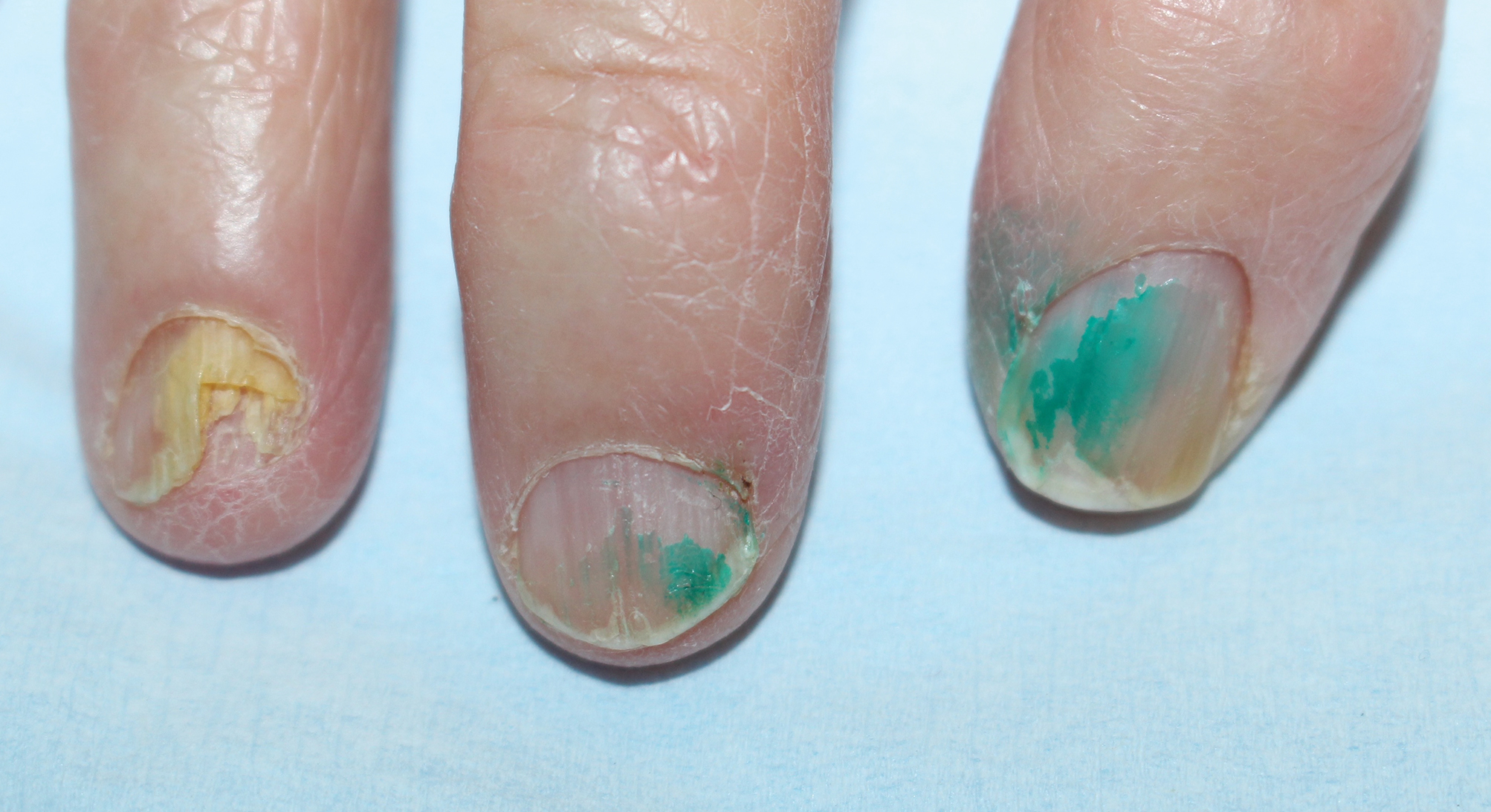

Many of the included images were not representative of common clinical findings. The nail lichen planus image showed pitting instead of more typical findings of nail plate atrophy and pterygium. The nail melanoma image showed thickened yellow toenails and the fifth toenail with a thin gray-brown band instead of an isolated wide black band. The nail fungus section included images of superficial onychomycosis and severe onychodystrophy instead of showing more common changes such as distal onycholysis with subungual hyperkeratosis, which is typical of the most common subtype, distal lateral subungual onychomycosis.5 Onychomycosis was referenced again in the ringworm section with 1 image repeated from the nail fungus section and another image that appeared to be a subungual hematoma.