User login

Nail Changes Associated With Thyroid Disease

The major classifications of thyroid disease include hyperthyroidism, which is seen in Graves disease, and hypothyroidism due to iodine deficiency and Hashimoto thyroiditis, which have potentially devastating health consequences. The prevalence of hyperthyroidism ranges from 0.2% to 1.3% in iodine-sufficient parts of the world, and the prevalence of hypothyroidism in the general population is 5.3% in Europe and 3.7% in the United States.1 Thyroid hormones physiologically potentiate α- and β-adrenergic receptors by increasing their sensitivity to catecholamines. Excess thyroid hormones manifest as tachycardia, increased cardiac output, increased body temperature, hyperhidrosis, and warm moist skin. Reduced sensitivity of adrenergic receptors to catecholamines from insufficient thyroid hormones results in a lower metabolic rate and decreases response to the sympathetic nervous system.2 Nail changes in thyroid patients have not been well studied.3 Our objectives were to characterize nail findings in patients with thyroid disease. Early diagnosis of thyroid disease and prompt referral for treatment may be instrumental in preventing serious morbidities and permanent sequelae.

Methods

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched for the terms nail + thyroid, nail + hyperthyroid, nail + hypothyroid, nail + Graves, and nail + Hashimoto on June 10, 2020, and then updated on November 18, 2020. All English-language articles were included. Non–English-language articles and those that did not describe clinical trials of nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were excluded. One study that utilized survey-based data for nail changes without corroboration with physical examination findings was excluded. Hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism was defined by all authors as measurement of serum thyroid hormones triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone outside of the normal range. Eight studies were included in the final analysis. Patient demographics, thyroid disease type, physical examination findings, nail clinical findings, age at diagnosis, age at onset of nail changes, treatments/medications, and comorbidities were recorded and analyzed.

Results

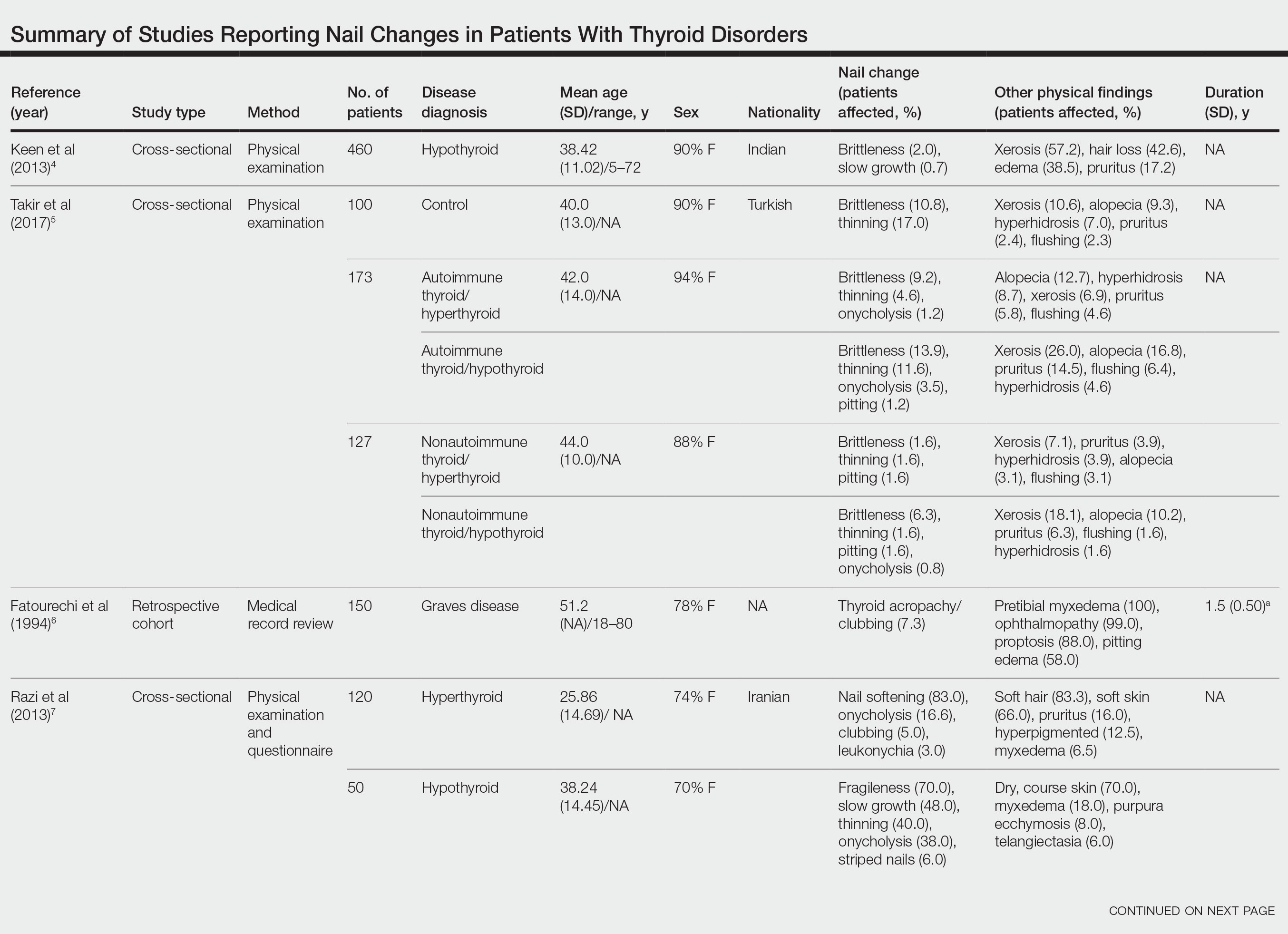

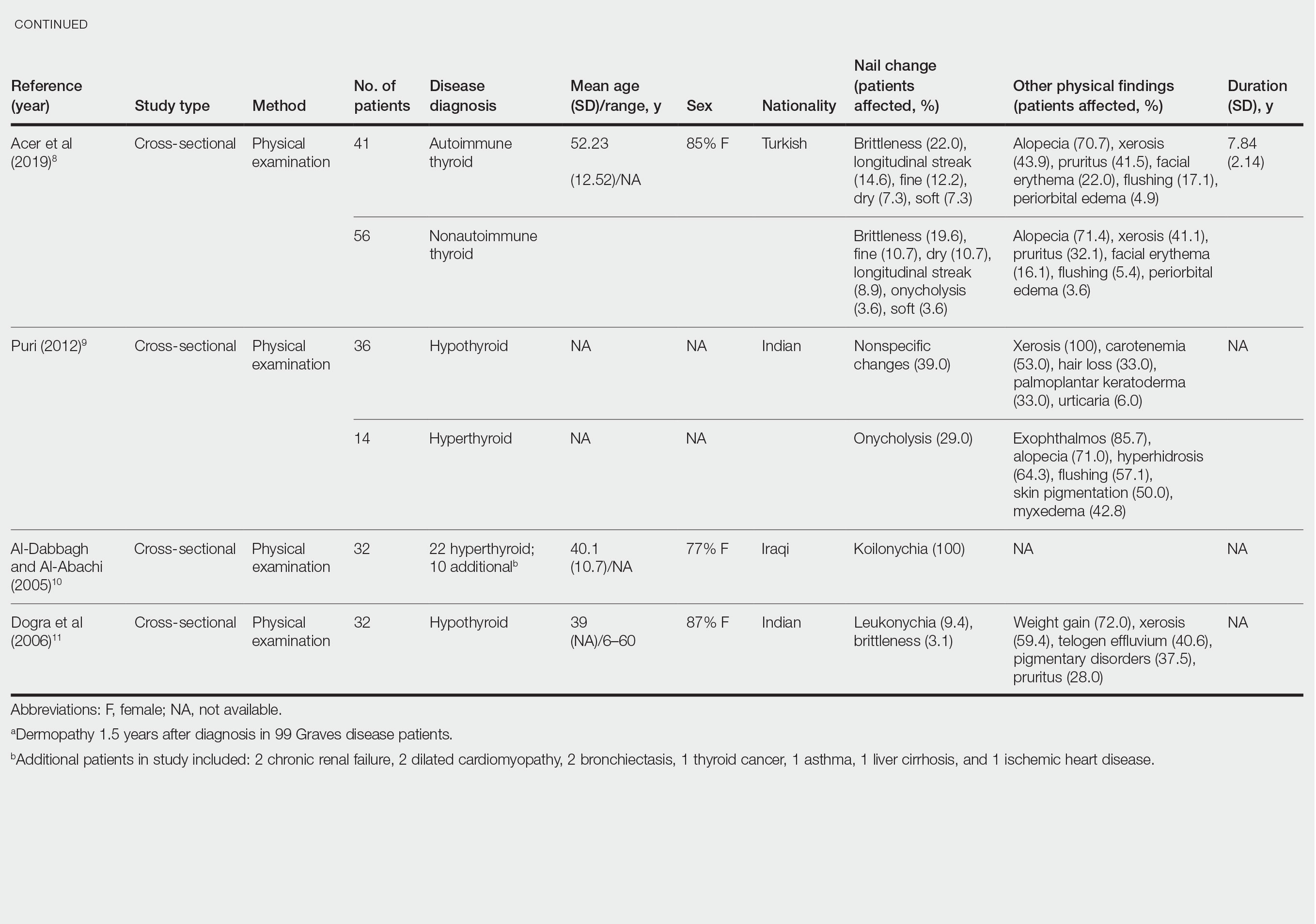

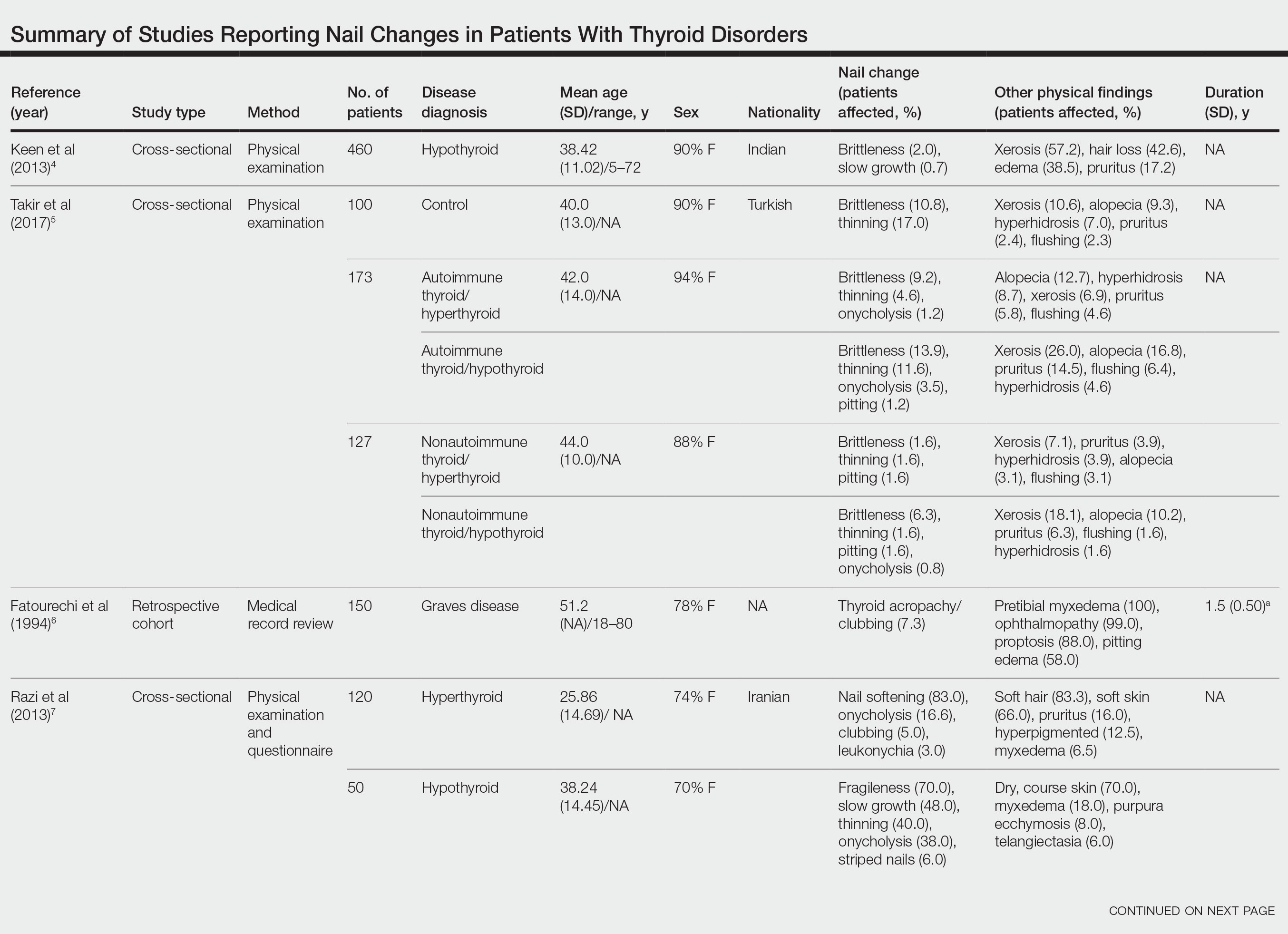

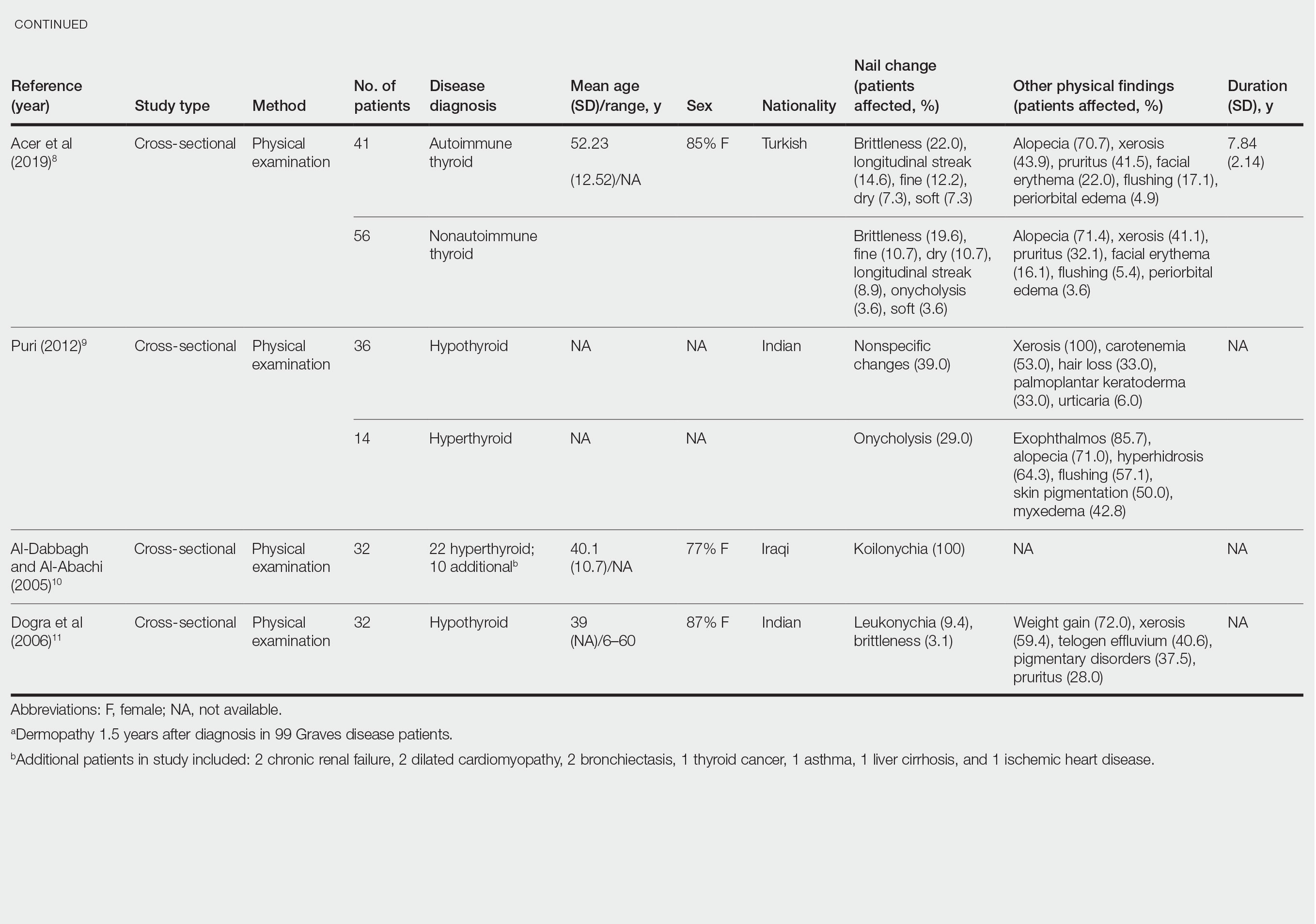

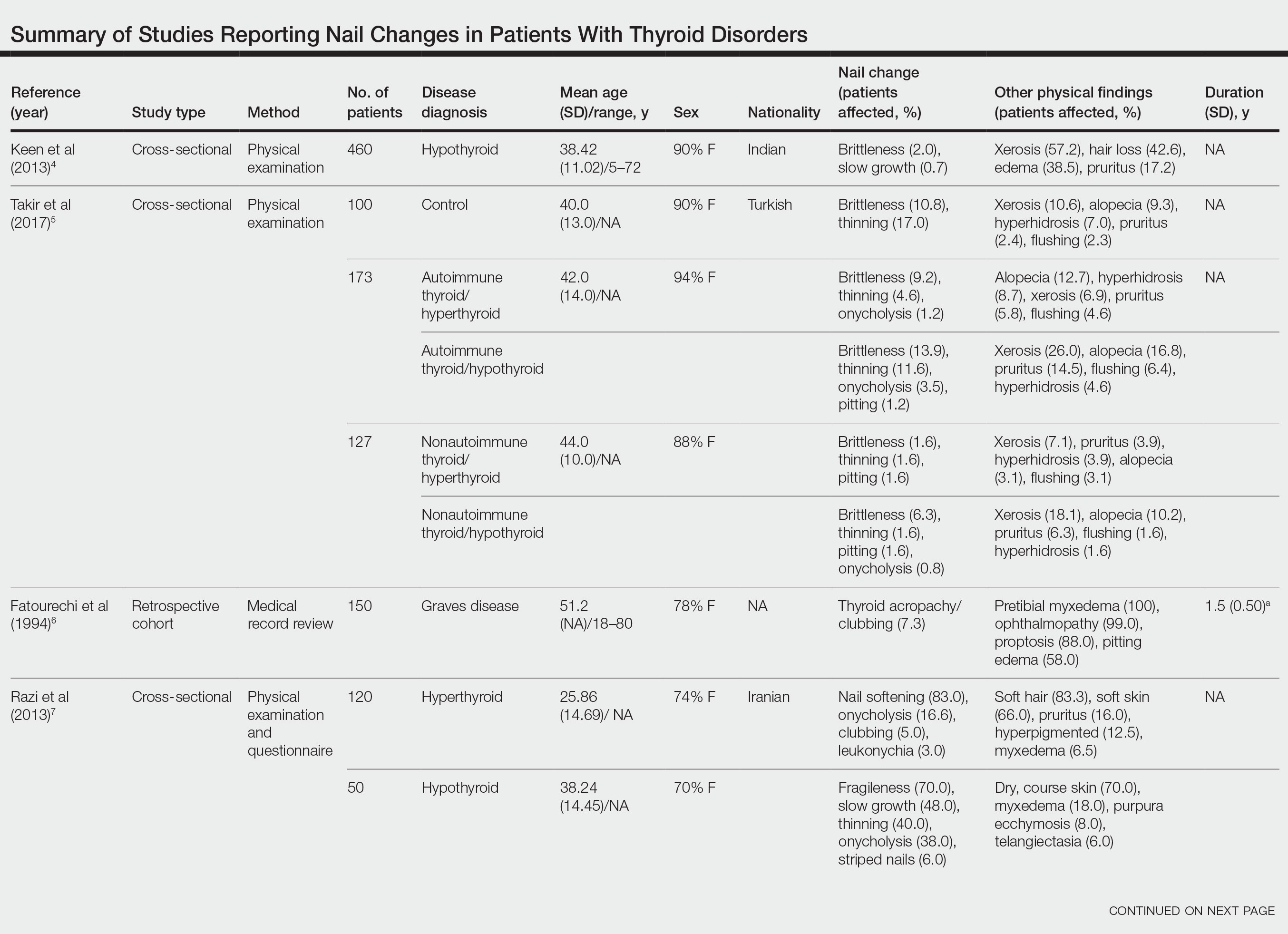

Nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were reported in 8 studies (7 cross-sectional, 1 retrospective cohort) and are summarized in the Table.4-11 The mean age was 41.2 years (range, 5–80 years), with a higher representation of females (range, 70%–94% female). The most common nail changes in thyroid patients were koilonychia, clubbing, and nail brittleness. Other changes included onycholysis, thin nails, dryness, and changes in nail growth rate. Frequent physical findings were xerosis, pruritus, and alopecia.

Both koilonychia and clubbing were reported in patients with hyperthyroidism. In a study of 32 patients with koilonychia, 22 (68.8%) were diagnosed with hyperthyroidism.10 Nail clubbing affected 7.3% of Graves disease patients (n=150)6 and 5.0% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120).7 Dermopathy presented more than 1 year after diagnosis of Graves disease in 99 (66%) of 150 patients as a late manifestation of thyrotoxicosis.6 Additional physical features in patients with Graves disease (n=150) were pretibial myxedema (100%), ophthalmopathy (99.0%), and proptosis (88.0%). Non–Graves hyperthyroid patients showed physical features of soft hair (83.3%) and soft skin (66.0%).7

Nail brittleness was a frequently reported nail change in thyroid patients (4/8 studies, 50%), most often seen in 22% of autoimmune patients, 19.6% of nonautoimmune patients, 13.9% of hypothyroid patients, and 9.2% of hyperthyroid patients.5,8 For comparison, brittle nails presented in 10.8% of participants in a control group.5 Brittle nails in thyroid patients often are accompanied by other nail findings such as thinning, onycholysis, and pitting.

Among hypothyroid patients, nail changes included fragility (70%; n=50), slow growth (48%; n=50), thinning (40%; n=50), onycholysis (38%; n=50),7 and brittleness (13.9%; n=173).5 Less common nail changes in hypothyroid patients were leukonychia (9.4%; n=32), striped nails (6%; n=50), and pitting (1.2%; n=173).5,7,11 Among hyperthyroid patients, the most common nail changes were koilonychia (100%; n=22), softening (83%; n=120), onycholysis (29%; n=14), and brittleness (9.2%; n=173).5,7,9,10 Less common nail changes in hyperthyroid patients were clubbing (5%; n=120), thinning (4.6%; n=173), and leukonychia (3%; n=120).5,7

Additional cutaneous findings of thyroid disorder included xerosis, alopecia, pruritus, and weight change. Xerosis was most common in hypothyroid disease (57.2%; n=460).4 In 2 studies,8,9 alopecia affected approximately 70% of autoimmune, nonautoimmune, and hyperthyroid patients. Hair loss was reported in 42.6% (n=460)4 and 33.0% (n=36)9 of hypothyroid patients. Additionally, pruritus affected up to 28% (n=32)11 of hypothyroid and 16.0% (n=120)7 of hyperthyroid patients and was more common in autoimmune (41%) vs nonautoimmune (32%) thyroid patients.8 Weight gain was seen in 72% of hypothyroid patients (n=32),11 and soft hair and skin were reported in 83.3% and 66% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120), respectively.7 Flushing was a less common physical finding in thyroid patients (usually affecting <10%); however, it also was reported in 17.1% of autoimmune and 57.1% of hyperthyroid patients from 2 separate studies.8,9

Comment

There are limited data describing nail changes with thyroid disease. Singal and Arora3 reported in their clinical review of nail changes in systemic disease that koilonychia, onycholysis, and melanonychia are associated with thyroid disorders. We similarly found that koilonychia and onycholysis are associated with thyroid disorders without an association with melanonychia.

In his clinical review of thyroid hormone action on the skin, Safer12 described hypothyroid patients having coarse, dull, thin, and brittle nails, whereas in thyrotoxicosis, patients had shiny, soft, and concave nails with onycholysis; however, the author commented that there were limited data on the clinical findings in thyroid disorders. These nail findings are consistent with our results, but onycholysis was more common in hypothyroid patients than in hyperthyroid patients in our review. Fox13 reported on 30 cases of onycholysis, stating that it affected patients with hypothyroidism and improved with thyroid treatment. In a clinical review of 8 commonly seen nail abnormalities, Fowler et al14 reported that hyperthyroidism was associated with nail findings in 5% of cases and may result in onycholysis of the fourth and fifth nails or all nails. They also reported that onychorrhexis may be seen in patients with hypothyroidism, a finding that differed from our results.14

The mechanism of nail changes in thyroid disease has not been well studied. A protein/amino acid–deficiency state may contribute to the development of koilonychia. Hyperthyroid patients, who have high metabolic activity, may have hypoalbuminemia, leading to koilonychia.15 Hypothyroidism causes hypothermia from decreased metabolic rate and secondary compensatory vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction decreases blood flow of nutrients and oxygen to cutaneous structures and may cause slow-growing, brittle nails. In hyperthyroidism, vasodilation alternatively may contribute to the fast-growing nails. Anti–thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies in Graves disease may increase the synthesis of hyaluronic acid and glycosaminoglycans from fibroblasts, keratinocytes, adipocytes, or endothelial cells in the dermis and may contribute to development of clubbing.16

Our review is subject to several limitations. We recorded nail findings as they were described in the original studies; however, we could not confirm the accuracy of these descriptions. In addition, some specific nail changes were not described in sufficient detail. In all but 1 study, dermatologists performed the physical examination. In the study by Al-Dabbagh and Al-Abachi,10 the physical examinations were performed by general medicine physicians, but they selected only for patients with koilonychia and did not assess for other skin findings. Fragile nails and brittle nails were described in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid patients, but these nail changes were not described in detail. There also were studies describing nail changes in thyroid patients; some studies had small numbers of patients, and many did not have a control group.

Conclusion

Nail changes may be early clinical presenting signs of thyroid disorders and may be the clue to prompt diagnosis of thyroid disease. Dermatologists should be mindful that fragile, slow-growing, thin nails and onycholysis are associated with hypothyroidism and that koilonychia, softening, onycholysis, and brittle nail changes may be seen in hyperthyroidism. Our review aimed to describe nail changes associated with thyroid disease to guide dermatologists on diagnosis and promote future research on dermatologic manifestations of thyroid disease. Future research is necessary to explore the association between koilonychia and hyperthyroidism as well as the association of nail changes with thyroid disease duration and severity.

- Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:301-316.

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Faith EF. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Keen MA, Hassan I, Bhat MH. A clinical study of the cutaneous manifestations of hypothyroidism in Kashmir Valley. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:326.

- Takir M, Özlü E, Köstek O, et al. Skin findings in autoimmune and nonautoimmune thyroid disease with respect to thyroid functional status and healthy controls. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47:764-770.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

- Razi A, Golforoushan F, Nejad AB, et al. Evaluation of dermal symptoms in hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Pak J Biol Sci. 2013;16:541-544.

- Acer E, Ag˘aog˘lu E, Yorulmaz G, et al. Evaluation of cutaneous manifestations in patients under treatment with thyroid disease. Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2019;54:46-50.

- Puri N. A study on cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:247-248.

- Al-Dabbagh TQ, Al-Abachi KG. Nutritional koilonychia in 32 Iraqi subjects. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:154-157.

- Dogra A, Dua A, Singh P. Thyroid and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:96-99.

- Safer JD. Thyroid hormone action on skin. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:211-215.

- Fox EC. Diseases of the nails: report of cases of onycholysis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1940;41:98-112.

- Fowler JR, Stern E, English JC 3rd, et al. A hand surgeon’s guide to common onychodystrophies. Hand (N Y). 2014;9:24-28.

- Truswell AS. Nutritional factors in disease. In: Edwards CRW, Bouchier IAD, Haslett C, et al, eds. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. 17th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 1995:554.

- Heymann WR. Cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:885-902.

The major classifications of thyroid disease include hyperthyroidism, which is seen in Graves disease, and hypothyroidism due to iodine deficiency and Hashimoto thyroiditis, which have potentially devastating health consequences. The prevalence of hyperthyroidism ranges from 0.2% to 1.3% in iodine-sufficient parts of the world, and the prevalence of hypothyroidism in the general population is 5.3% in Europe and 3.7% in the United States.1 Thyroid hormones physiologically potentiate α- and β-adrenergic receptors by increasing their sensitivity to catecholamines. Excess thyroid hormones manifest as tachycardia, increased cardiac output, increased body temperature, hyperhidrosis, and warm moist skin. Reduced sensitivity of adrenergic receptors to catecholamines from insufficient thyroid hormones results in a lower metabolic rate and decreases response to the sympathetic nervous system.2 Nail changes in thyroid patients have not been well studied.3 Our objectives were to characterize nail findings in patients with thyroid disease. Early diagnosis of thyroid disease and prompt referral for treatment may be instrumental in preventing serious morbidities and permanent sequelae.

Methods

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched for the terms nail + thyroid, nail + hyperthyroid, nail + hypothyroid, nail + Graves, and nail + Hashimoto on June 10, 2020, and then updated on November 18, 2020. All English-language articles were included. Non–English-language articles and those that did not describe clinical trials of nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were excluded. One study that utilized survey-based data for nail changes without corroboration with physical examination findings was excluded. Hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism was defined by all authors as measurement of serum thyroid hormones triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone outside of the normal range. Eight studies were included in the final analysis. Patient demographics, thyroid disease type, physical examination findings, nail clinical findings, age at diagnosis, age at onset of nail changes, treatments/medications, and comorbidities were recorded and analyzed.

Results

Nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were reported in 8 studies (7 cross-sectional, 1 retrospective cohort) and are summarized in the Table.4-11 The mean age was 41.2 years (range, 5–80 years), with a higher representation of females (range, 70%–94% female). The most common nail changes in thyroid patients were koilonychia, clubbing, and nail brittleness. Other changes included onycholysis, thin nails, dryness, and changes in nail growth rate. Frequent physical findings were xerosis, pruritus, and alopecia.

Both koilonychia and clubbing were reported in patients with hyperthyroidism. In a study of 32 patients with koilonychia, 22 (68.8%) were diagnosed with hyperthyroidism.10 Nail clubbing affected 7.3% of Graves disease patients (n=150)6 and 5.0% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120).7 Dermopathy presented more than 1 year after diagnosis of Graves disease in 99 (66%) of 150 patients as a late manifestation of thyrotoxicosis.6 Additional physical features in patients with Graves disease (n=150) were pretibial myxedema (100%), ophthalmopathy (99.0%), and proptosis (88.0%). Non–Graves hyperthyroid patients showed physical features of soft hair (83.3%) and soft skin (66.0%).7

Nail brittleness was a frequently reported nail change in thyroid patients (4/8 studies, 50%), most often seen in 22% of autoimmune patients, 19.6% of nonautoimmune patients, 13.9% of hypothyroid patients, and 9.2% of hyperthyroid patients.5,8 For comparison, brittle nails presented in 10.8% of participants in a control group.5 Brittle nails in thyroid patients often are accompanied by other nail findings such as thinning, onycholysis, and pitting.

Among hypothyroid patients, nail changes included fragility (70%; n=50), slow growth (48%; n=50), thinning (40%; n=50), onycholysis (38%; n=50),7 and brittleness (13.9%; n=173).5 Less common nail changes in hypothyroid patients were leukonychia (9.4%; n=32), striped nails (6%; n=50), and pitting (1.2%; n=173).5,7,11 Among hyperthyroid patients, the most common nail changes were koilonychia (100%; n=22), softening (83%; n=120), onycholysis (29%; n=14), and brittleness (9.2%; n=173).5,7,9,10 Less common nail changes in hyperthyroid patients were clubbing (5%; n=120), thinning (4.6%; n=173), and leukonychia (3%; n=120).5,7

Additional cutaneous findings of thyroid disorder included xerosis, alopecia, pruritus, and weight change. Xerosis was most common in hypothyroid disease (57.2%; n=460).4 In 2 studies,8,9 alopecia affected approximately 70% of autoimmune, nonautoimmune, and hyperthyroid patients. Hair loss was reported in 42.6% (n=460)4 and 33.0% (n=36)9 of hypothyroid patients. Additionally, pruritus affected up to 28% (n=32)11 of hypothyroid and 16.0% (n=120)7 of hyperthyroid patients and was more common in autoimmune (41%) vs nonautoimmune (32%) thyroid patients.8 Weight gain was seen in 72% of hypothyroid patients (n=32),11 and soft hair and skin were reported in 83.3% and 66% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120), respectively.7 Flushing was a less common physical finding in thyroid patients (usually affecting <10%); however, it also was reported in 17.1% of autoimmune and 57.1% of hyperthyroid patients from 2 separate studies.8,9

Comment

There are limited data describing nail changes with thyroid disease. Singal and Arora3 reported in their clinical review of nail changes in systemic disease that koilonychia, onycholysis, and melanonychia are associated with thyroid disorders. We similarly found that koilonychia and onycholysis are associated with thyroid disorders without an association with melanonychia.

In his clinical review of thyroid hormone action on the skin, Safer12 described hypothyroid patients having coarse, dull, thin, and brittle nails, whereas in thyrotoxicosis, patients had shiny, soft, and concave nails with onycholysis; however, the author commented that there were limited data on the clinical findings in thyroid disorders. These nail findings are consistent with our results, but onycholysis was more common in hypothyroid patients than in hyperthyroid patients in our review. Fox13 reported on 30 cases of onycholysis, stating that it affected patients with hypothyroidism and improved with thyroid treatment. In a clinical review of 8 commonly seen nail abnormalities, Fowler et al14 reported that hyperthyroidism was associated with nail findings in 5% of cases and may result in onycholysis of the fourth and fifth nails or all nails. They also reported that onychorrhexis may be seen in patients with hypothyroidism, a finding that differed from our results.14

The mechanism of nail changes in thyroid disease has not been well studied. A protein/amino acid–deficiency state may contribute to the development of koilonychia. Hyperthyroid patients, who have high metabolic activity, may have hypoalbuminemia, leading to koilonychia.15 Hypothyroidism causes hypothermia from decreased metabolic rate and secondary compensatory vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction decreases blood flow of nutrients and oxygen to cutaneous structures and may cause slow-growing, brittle nails. In hyperthyroidism, vasodilation alternatively may contribute to the fast-growing nails. Anti–thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies in Graves disease may increase the synthesis of hyaluronic acid and glycosaminoglycans from fibroblasts, keratinocytes, adipocytes, or endothelial cells in the dermis and may contribute to development of clubbing.16

Our review is subject to several limitations. We recorded nail findings as they were described in the original studies; however, we could not confirm the accuracy of these descriptions. In addition, some specific nail changes were not described in sufficient detail. In all but 1 study, dermatologists performed the physical examination. In the study by Al-Dabbagh and Al-Abachi,10 the physical examinations were performed by general medicine physicians, but they selected only for patients with koilonychia and did not assess for other skin findings. Fragile nails and brittle nails were described in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid patients, but these nail changes were not described in detail. There also were studies describing nail changes in thyroid patients; some studies had small numbers of patients, and many did not have a control group.

Conclusion

Nail changes may be early clinical presenting signs of thyroid disorders and may be the clue to prompt diagnosis of thyroid disease. Dermatologists should be mindful that fragile, slow-growing, thin nails and onycholysis are associated with hypothyroidism and that koilonychia, softening, onycholysis, and brittle nail changes may be seen in hyperthyroidism. Our review aimed to describe nail changes associated with thyroid disease to guide dermatologists on diagnosis and promote future research on dermatologic manifestations of thyroid disease. Future research is necessary to explore the association between koilonychia and hyperthyroidism as well as the association of nail changes with thyroid disease duration and severity.

The major classifications of thyroid disease include hyperthyroidism, which is seen in Graves disease, and hypothyroidism due to iodine deficiency and Hashimoto thyroiditis, which have potentially devastating health consequences. The prevalence of hyperthyroidism ranges from 0.2% to 1.3% in iodine-sufficient parts of the world, and the prevalence of hypothyroidism in the general population is 5.3% in Europe and 3.7% in the United States.1 Thyroid hormones physiologically potentiate α- and β-adrenergic receptors by increasing their sensitivity to catecholamines. Excess thyroid hormones manifest as tachycardia, increased cardiac output, increased body temperature, hyperhidrosis, and warm moist skin. Reduced sensitivity of adrenergic receptors to catecholamines from insufficient thyroid hormones results in a lower metabolic rate and decreases response to the sympathetic nervous system.2 Nail changes in thyroid patients have not been well studied.3 Our objectives were to characterize nail findings in patients with thyroid disease. Early diagnosis of thyroid disease and prompt referral for treatment may be instrumental in preventing serious morbidities and permanent sequelae.

Methods

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched for the terms nail + thyroid, nail + hyperthyroid, nail + hypothyroid, nail + Graves, and nail + Hashimoto on June 10, 2020, and then updated on November 18, 2020. All English-language articles were included. Non–English-language articles and those that did not describe clinical trials of nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were excluded. One study that utilized survey-based data for nail changes without corroboration with physical examination findings was excluded. Hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism was defined by all authors as measurement of serum thyroid hormones triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone outside of the normal range. Eight studies were included in the final analysis. Patient demographics, thyroid disease type, physical examination findings, nail clinical findings, age at diagnosis, age at onset of nail changes, treatments/medications, and comorbidities were recorded and analyzed.

Results

Nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were reported in 8 studies (7 cross-sectional, 1 retrospective cohort) and are summarized in the Table.4-11 The mean age was 41.2 years (range, 5–80 years), with a higher representation of females (range, 70%–94% female). The most common nail changes in thyroid patients were koilonychia, clubbing, and nail brittleness. Other changes included onycholysis, thin nails, dryness, and changes in nail growth rate. Frequent physical findings were xerosis, pruritus, and alopecia.

Both koilonychia and clubbing were reported in patients with hyperthyroidism. In a study of 32 patients with koilonychia, 22 (68.8%) were diagnosed with hyperthyroidism.10 Nail clubbing affected 7.3% of Graves disease patients (n=150)6 and 5.0% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120).7 Dermopathy presented more than 1 year after diagnosis of Graves disease in 99 (66%) of 150 patients as a late manifestation of thyrotoxicosis.6 Additional physical features in patients with Graves disease (n=150) were pretibial myxedema (100%), ophthalmopathy (99.0%), and proptosis (88.0%). Non–Graves hyperthyroid patients showed physical features of soft hair (83.3%) and soft skin (66.0%).7

Nail brittleness was a frequently reported nail change in thyroid patients (4/8 studies, 50%), most often seen in 22% of autoimmune patients, 19.6% of nonautoimmune patients, 13.9% of hypothyroid patients, and 9.2% of hyperthyroid patients.5,8 For comparison, brittle nails presented in 10.8% of participants in a control group.5 Brittle nails in thyroid patients often are accompanied by other nail findings such as thinning, onycholysis, and pitting.

Among hypothyroid patients, nail changes included fragility (70%; n=50), slow growth (48%; n=50), thinning (40%; n=50), onycholysis (38%; n=50),7 and brittleness (13.9%; n=173).5 Less common nail changes in hypothyroid patients were leukonychia (9.4%; n=32), striped nails (6%; n=50), and pitting (1.2%; n=173).5,7,11 Among hyperthyroid patients, the most common nail changes were koilonychia (100%; n=22), softening (83%; n=120), onycholysis (29%; n=14), and brittleness (9.2%; n=173).5,7,9,10 Less common nail changes in hyperthyroid patients were clubbing (5%; n=120), thinning (4.6%; n=173), and leukonychia (3%; n=120).5,7

Additional cutaneous findings of thyroid disorder included xerosis, alopecia, pruritus, and weight change. Xerosis was most common in hypothyroid disease (57.2%; n=460).4 In 2 studies,8,9 alopecia affected approximately 70% of autoimmune, nonautoimmune, and hyperthyroid patients. Hair loss was reported in 42.6% (n=460)4 and 33.0% (n=36)9 of hypothyroid patients. Additionally, pruritus affected up to 28% (n=32)11 of hypothyroid and 16.0% (n=120)7 of hyperthyroid patients and was more common in autoimmune (41%) vs nonautoimmune (32%) thyroid patients.8 Weight gain was seen in 72% of hypothyroid patients (n=32),11 and soft hair and skin were reported in 83.3% and 66% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120), respectively.7 Flushing was a less common physical finding in thyroid patients (usually affecting <10%); however, it also was reported in 17.1% of autoimmune and 57.1% of hyperthyroid patients from 2 separate studies.8,9

Comment

There are limited data describing nail changes with thyroid disease. Singal and Arora3 reported in their clinical review of nail changes in systemic disease that koilonychia, onycholysis, and melanonychia are associated with thyroid disorders. We similarly found that koilonychia and onycholysis are associated with thyroid disorders without an association with melanonychia.

In his clinical review of thyroid hormone action on the skin, Safer12 described hypothyroid patients having coarse, dull, thin, and brittle nails, whereas in thyrotoxicosis, patients had shiny, soft, and concave nails with onycholysis; however, the author commented that there were limited data on the clinical findings in thyroid disorders. These nail findings are consistent with our results, but onycholysis was more common in hypothyroid patients than in hyperthyroid patients in our review. Fox13 reported on 30 cases of onycholysis, stating that it affected patients with hypothyroidism and improved with thyroid treatment. In a clinical review of 8 commonly seen nail abnormalities, Fowler et al14 reported that hyperthyroidism was associated with nail findings in 5% of cases and may result in onycholysis of the fourth and fifth nails or all nails. They also reported that onychorrhexis may be seen in patients with hypothyroidism, a finding that differed from our results.14

The mechanism of nail changes in thyroid disease has not been well studied. A protein/amino acid–deficiency state may contribute to the development of koilonychia. Hyperthyroid patients, who have high metabolic activity, may have hypoalbuminemia, leading to koilonychia.15 Hypothyroidism causes hypothermia from decreased metabolic rate and secondary compensatory vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction decreases blood flow of nutrients and oxygen to cutaneous structures and may cause slow-growing, brittle nails. In hyperthyroidism, vasodilation alternatively may contribute to the fast-growing nails. Anti–thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies in Graves disease may increase the synthesis of hyaluronic acid and glycosaminoglycans from fibroblasts, keratinocytes, adipocytes, or endothelial cells in the dermis and may contribute to development of clubbing.16

Our review is subject to several limitations. We recorded nail findings as they were described in the original studies; however, we could not confirm the accuracy of these descriptions. In addition, some specific nail changes were not described in sufficient detail. In all but 1 study, dermatologists performed the physical examination. In the study by Al-Dabbagh and Al-Abachi,10 the physical examinations were performed by general medicine physicians, but they selected only for patients with koilonychia and did not assess for other skin findings. Fragile nails and brittle nails were described in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid patients, but these nail changes were not described in detail. There also were studies describing nail changes in thyroid patients; some studies had small numbers of patients, and many did not have a control group.

Conclusion

Nail changes may be early clinical presenting signs of thyroid disorders and may be the clue to prompt diagnosis of thyroid disease. Dermatologists should be mindful that fragile, slow-growing, thin nails and onycholysis are associated with hypothyroidism and that koilonychia, softening, onycholysis, and brittle nail changes may be seen in hyperthyroidism. Our review aimed to describe nail changes associated with thyroid disease to guide dermatologists on diagnosis and promote future research on dermatologic manifestations of thyroid disease. Future research is necessary to explore the association between koilonychia and hyperthyroidism as well as the association of nail changes with thyroid disease duration and severity.

- Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:301-316.

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Faith EF. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Keen MA, Hassan I, Bhat MH. A clinical study of the cutaneous manifestations of hypothyroidism in Kashmir Valley. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:326.

- Takir M, Özlü E, Köstek O, et al. Skin findings in autoimmune and nonautoimmune thyroid disease with respect to thyroid functional status and healthy controls. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47:764-770.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

- Razi A, Golforoushan F, Nejad AB, et al. Evaluation of dermal symptoms in hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Pak J Biol Sci. 2013;16:541-544.

- Acer E, Ag˘aog˘lu E, Yorulmaz G, et al. Evaluation of cutaneous manifestations in patients under treatment with thyroid disease. Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2019;54:46-50.

- Puri N. A study on cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:247-248.

- Al-Dabbagh TQ, Al-Abachi KG. Nutritional koilonychia in 32 Iraqi subjects. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:154-157.

- Dogra A, Dua A, Singh P. Thyroid and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:96-99.

- Safer JD. Thyroid hormone action on skin. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:211-215.

- Fox EC. Diseases of the nails: report of cases of onycholysis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1940;41:98-112.

- Fowler JR, Stern E, English JC 3rd, et al. A hand surgeon’s guide to common onychodystrophies. Hand (N Y). 2014;9:24-28.

- Truswell AS. Nutritional factors in disease. In: Edwards CRW, Bouchier IAD, Haslett C, et al, eds. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. 17th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 1995:554.

- Heymann WR. Cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:885-902.

- Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:301-316.

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Faith EF. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Keen MA, Hassan I, Bhat MH. A clinical study of the cutaneous manifestations of hypothyroidism in Kashmir Valley. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:326.

- Takir M, Özlü E, Köstek O, et al. Skin findings in autoimmune and nonautoimmune thyroid disease with respect to thyroid functional status and healthy controls. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47:764-770.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

- Razi A, Golforoushan F, Nejad AB, et al. Evaluation of dermal symptoms in hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Pak J Biol Sci. 2013;16:541-544.

- Acer E, Ag˘aog˘lu E, Yorulmaz G, et al. Evaluation of cutaneous manifestations in patients under treatment with thyroid disease. Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2019;54:46-50.

- Puri N. A study on cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:247-248.

- Al-Dabbagh TQ, Al-Abachi KG. Nutritional koilonychia in 32 Iraqi subjects. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:154-157.

- Dogra A, Dua A, Singh P. Thyroid and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:96-99.

- Safer JD. Thyroid hormone action on skin. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:211-215.

- Fox EC. Diseases of the nails: report of cases of onycholysis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1940;41:98-112.

- Fowler JR, Stern E, English JC 3rd, et al. A hand surgeon’s guide to common onychodystrophies. Hand (N Y). 2014;9:24-28.

- Truswell AS. Nutritional factors in disease. In: Edwards CRW, Bouchier IAD, Haslett C, et al, eds. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. 17th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 1995:554.

- Heymann WR. Cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:885-902.

Practice Points

- Koilonychia is associated with hyperthyroidism.

- Clubbing is a manifestation of thyroid acropachy in Graves disease and also affects other patients with hyperthyroidism.

- Onycholysis improves in patients with hypothyroidism treated with thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Online Information About Hydroquinone: An Assessment of Accuracy and Readability

To the Editor:

The internet is a popular resource for patients seeking information about dermatologic treatments. Hydroquinone (HQ) cream 4% is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for skin hyperpigmentation.1 The agency enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform on September 25, 2020, to restrict distribution of OTC HQ.2 Exogenous ochronosis is listed as a potential adverse effect in the prescribing information for HQ.1

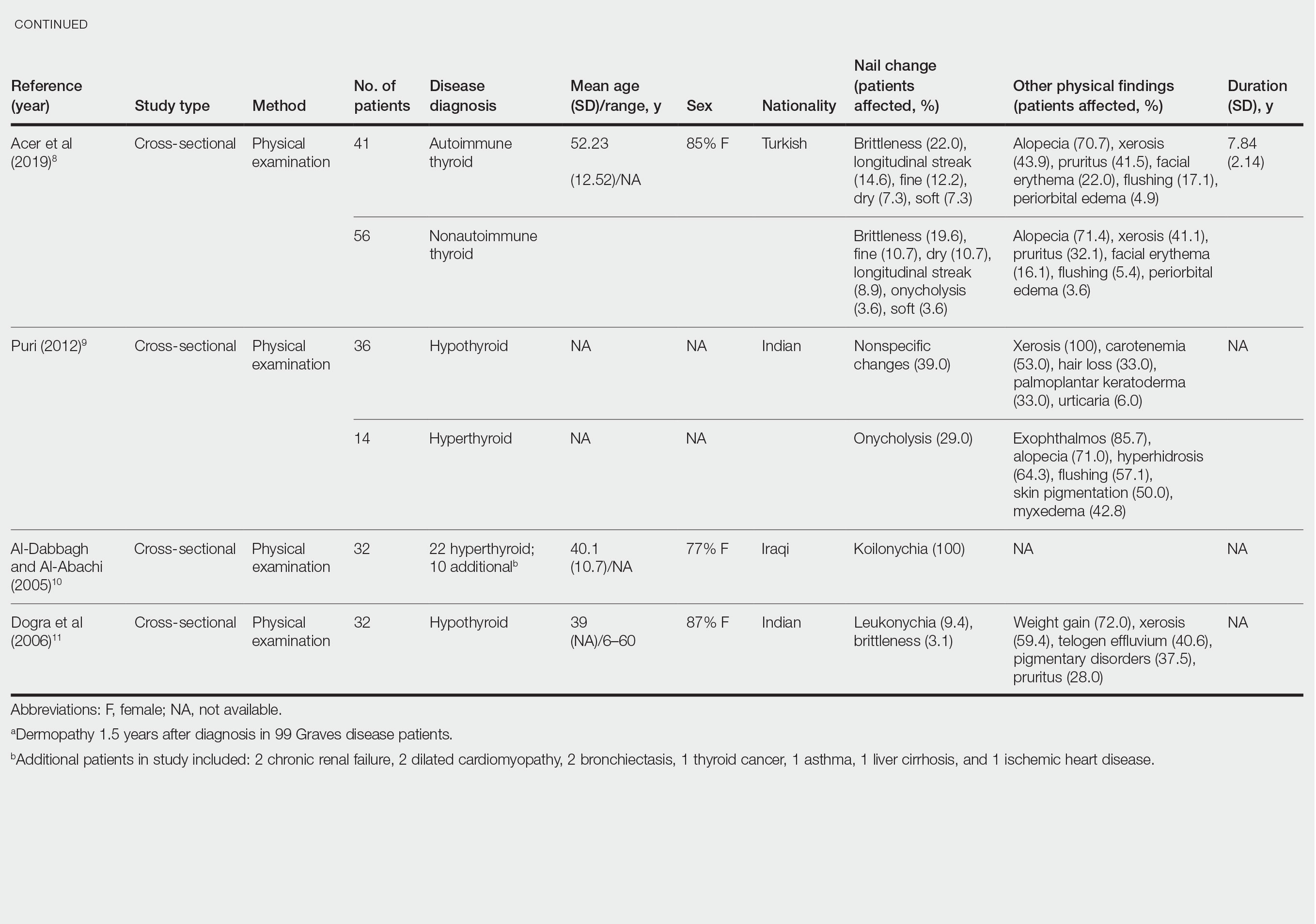

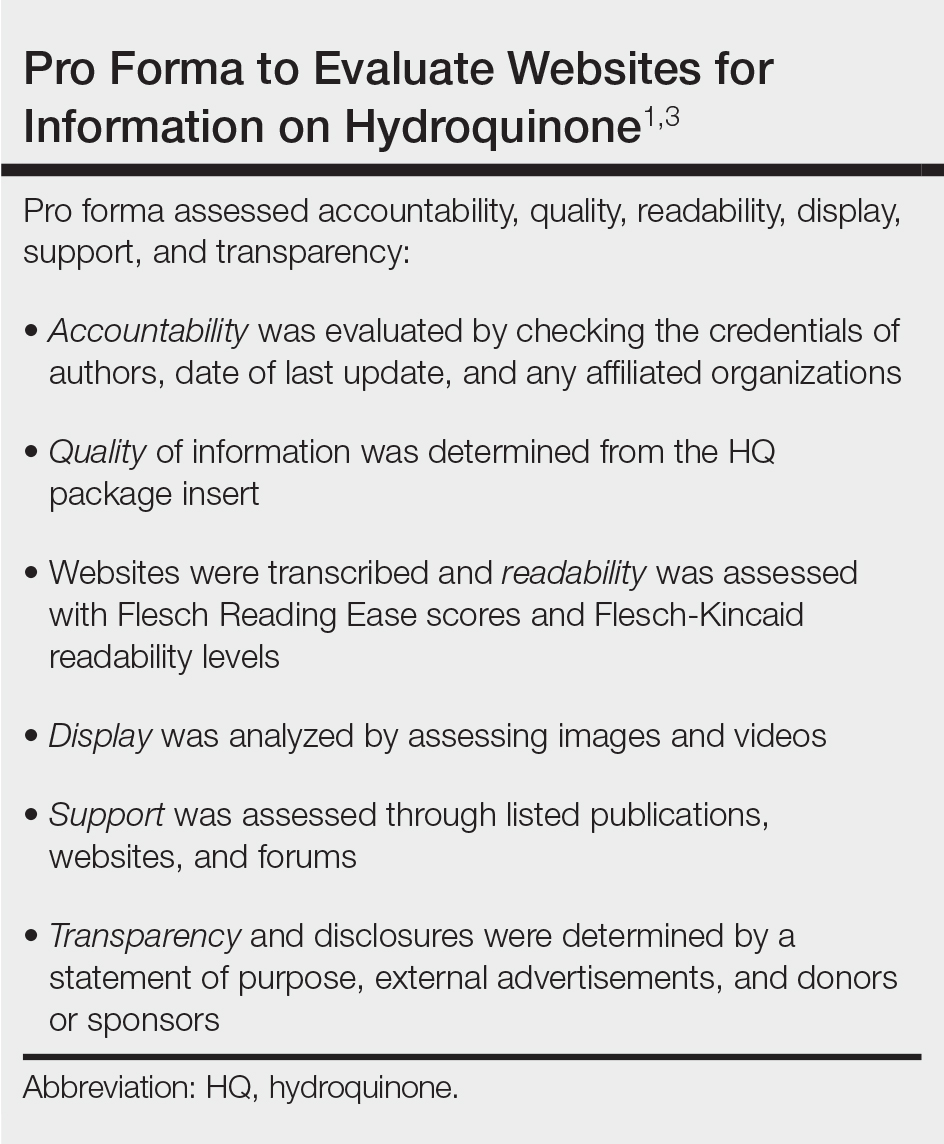

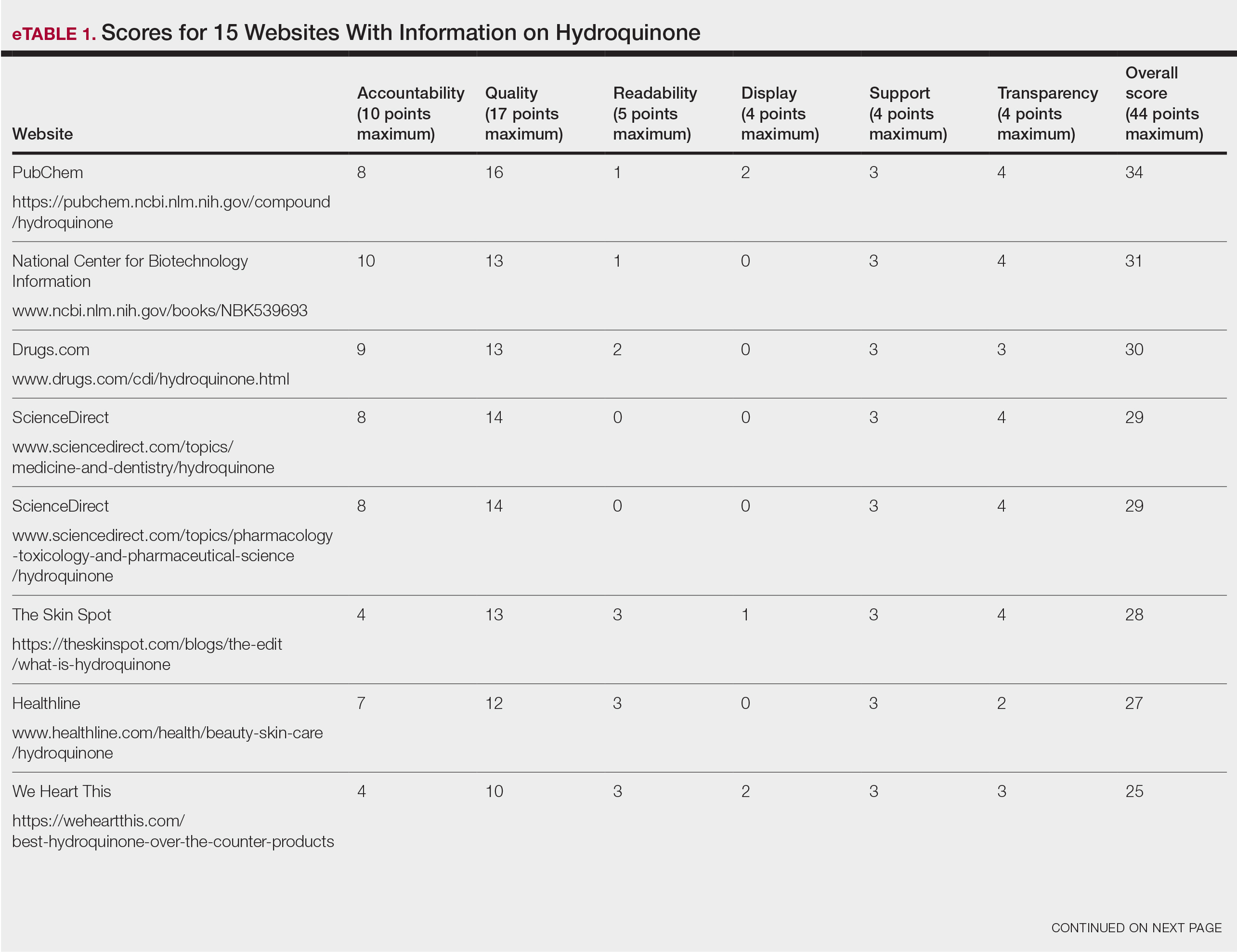

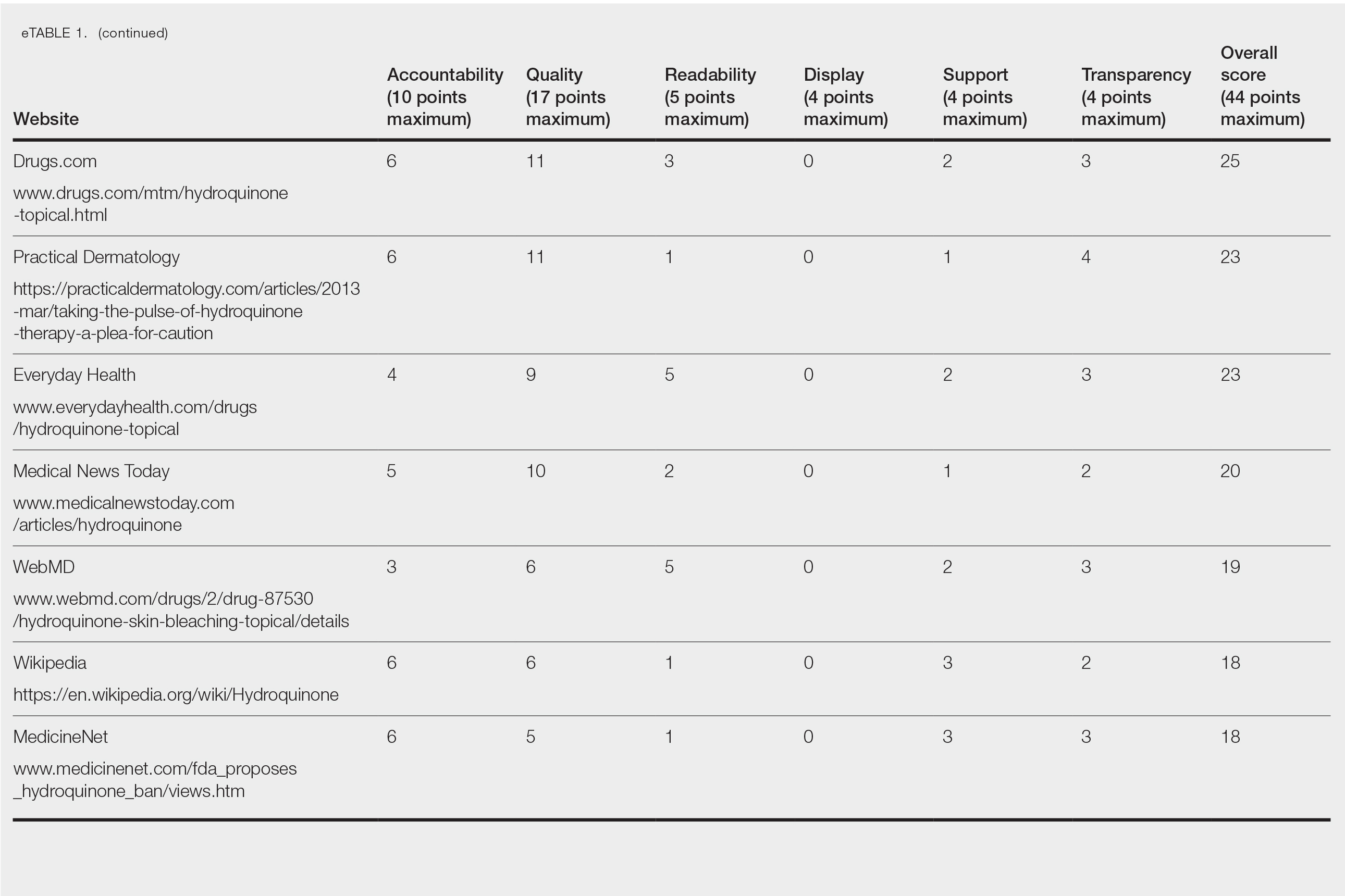

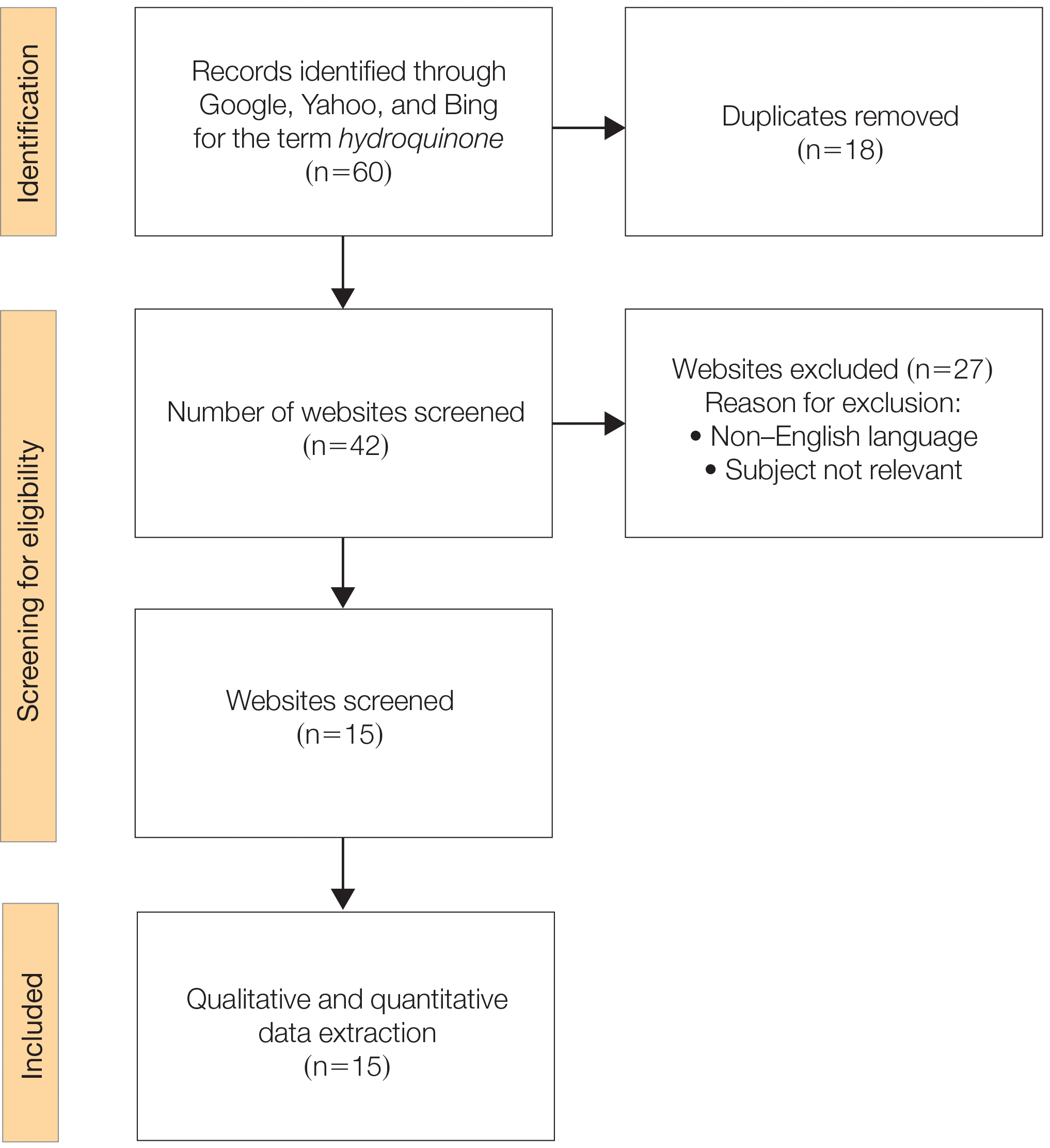

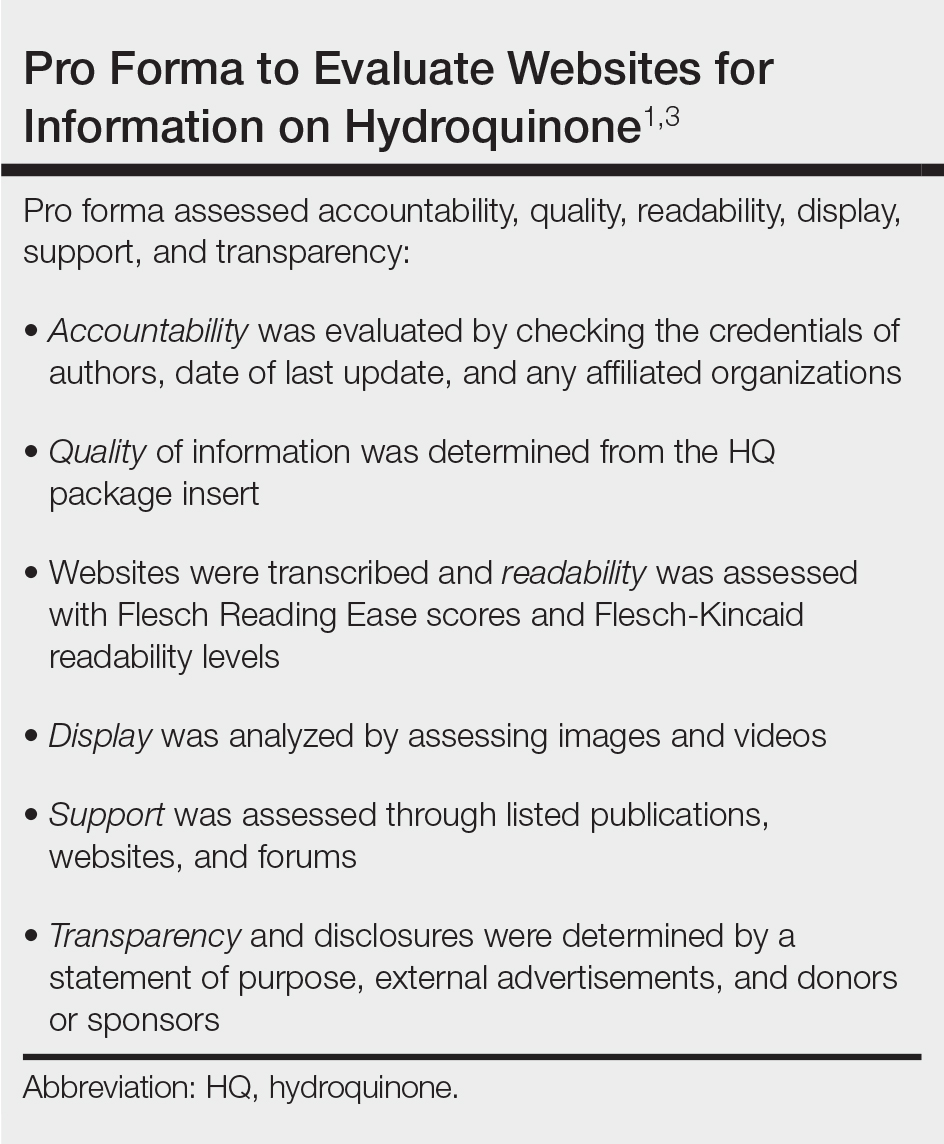

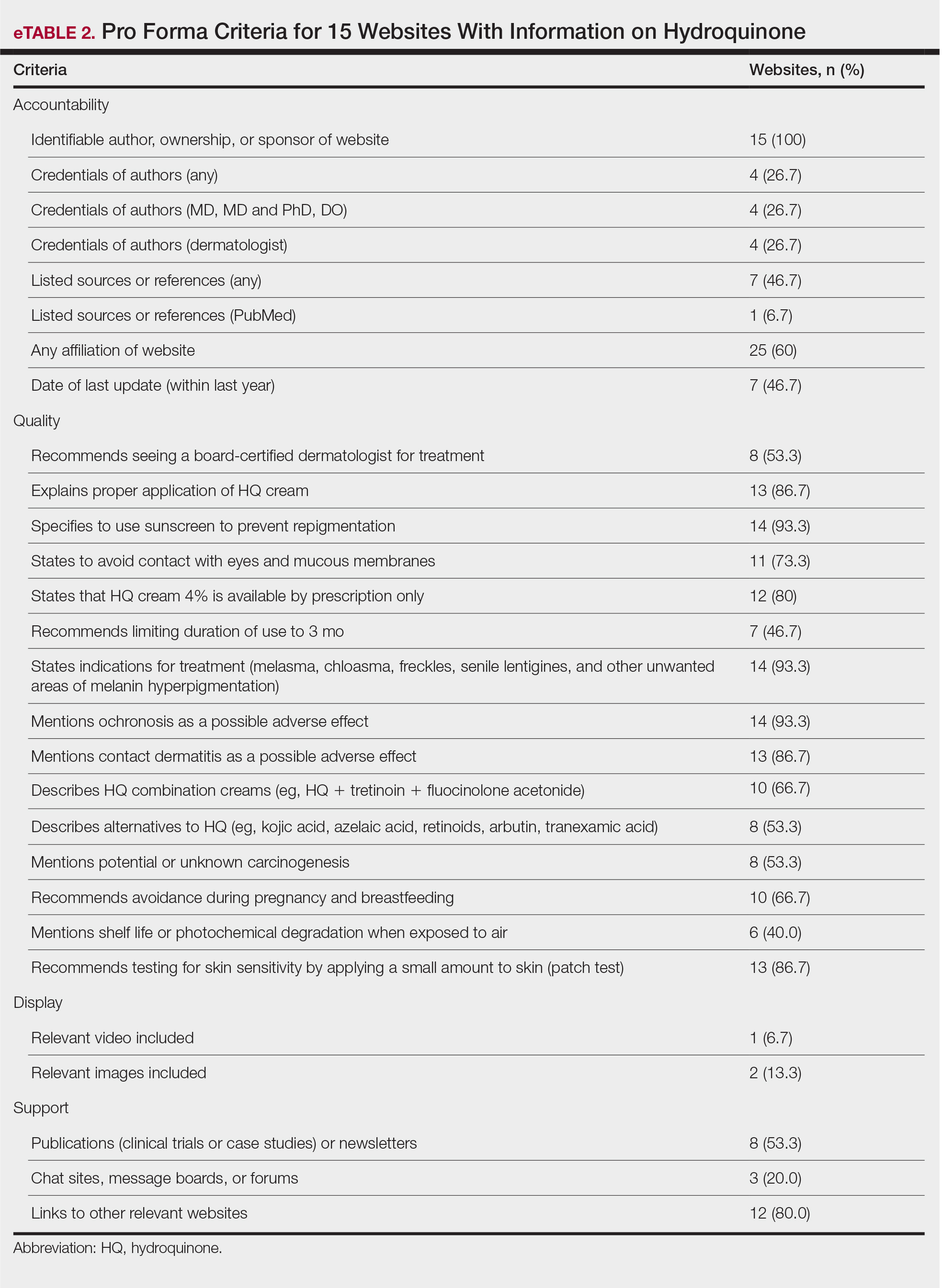

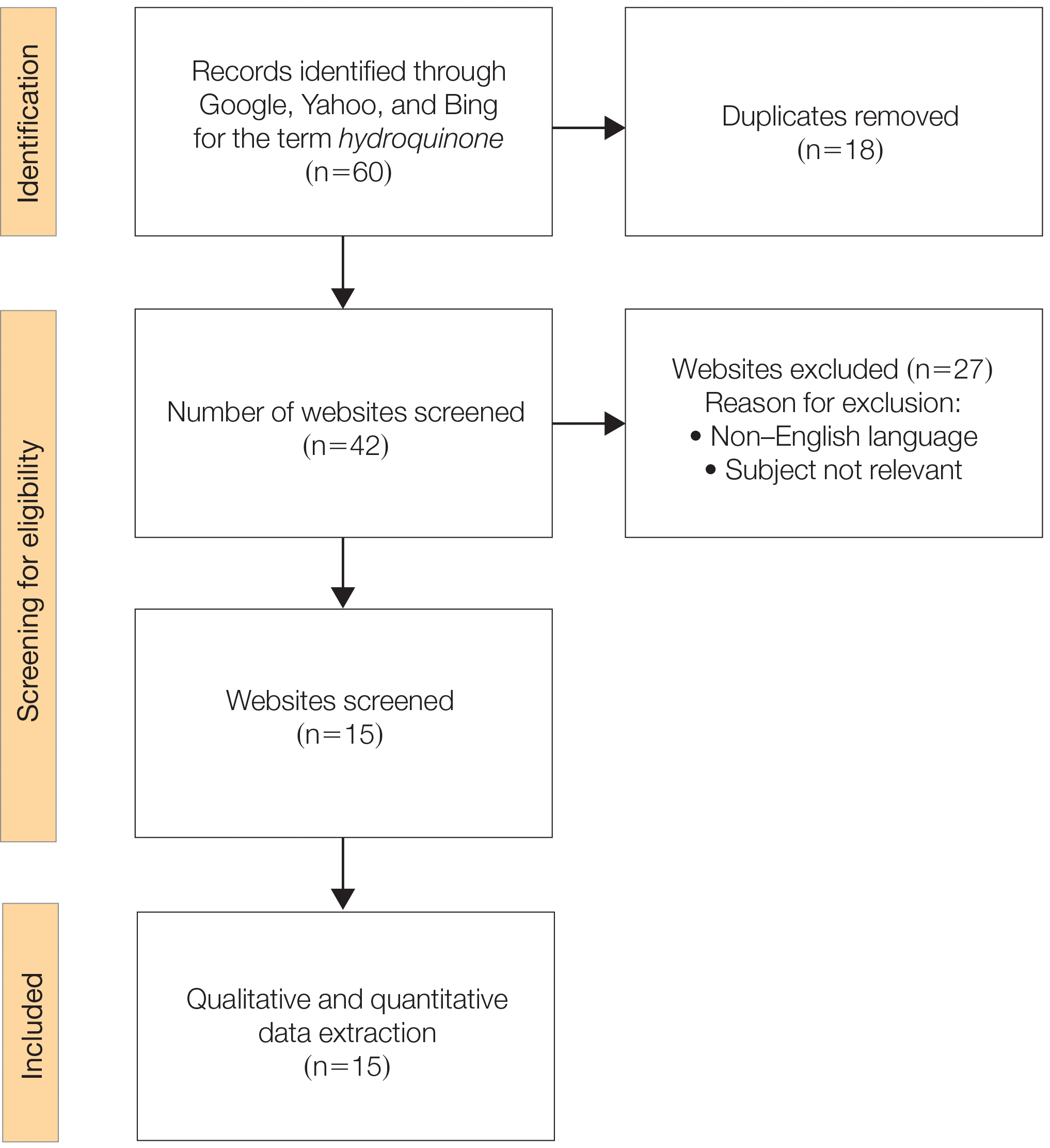

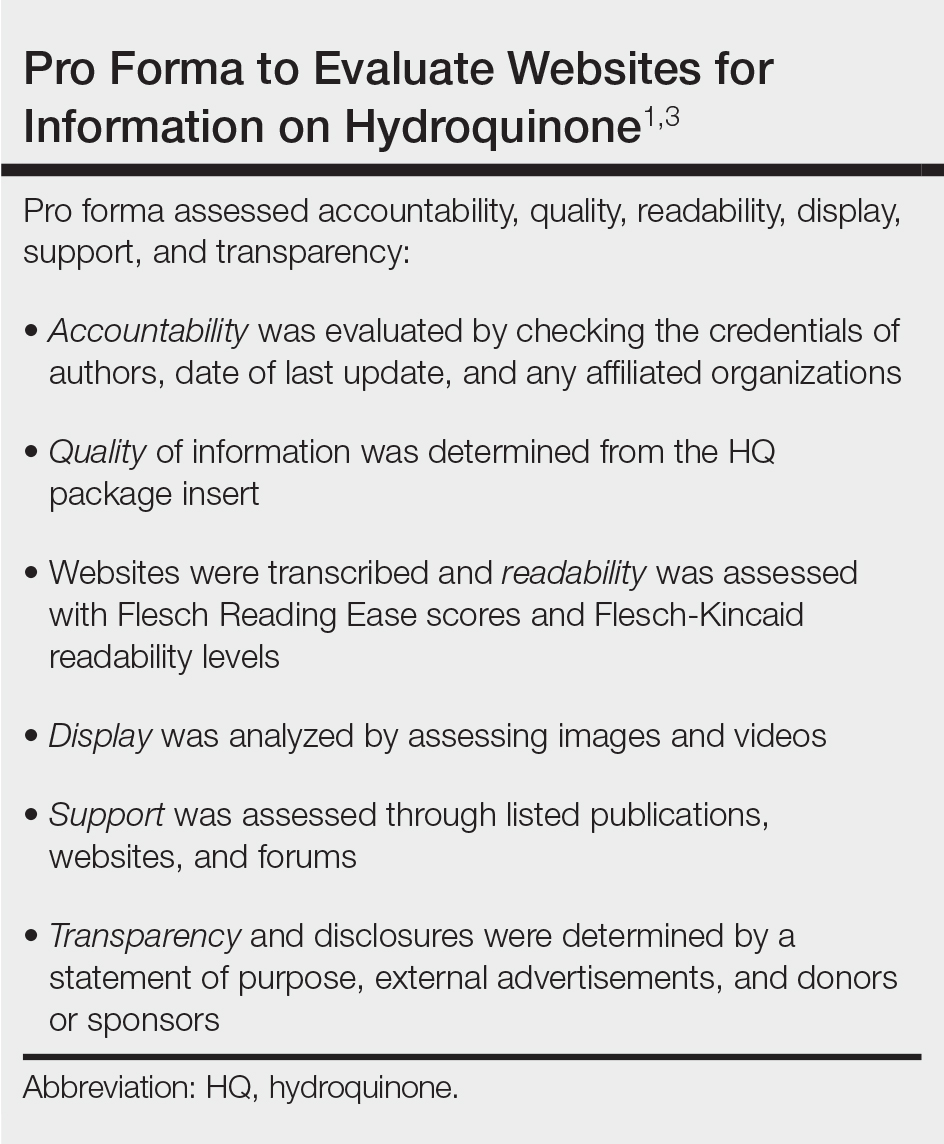

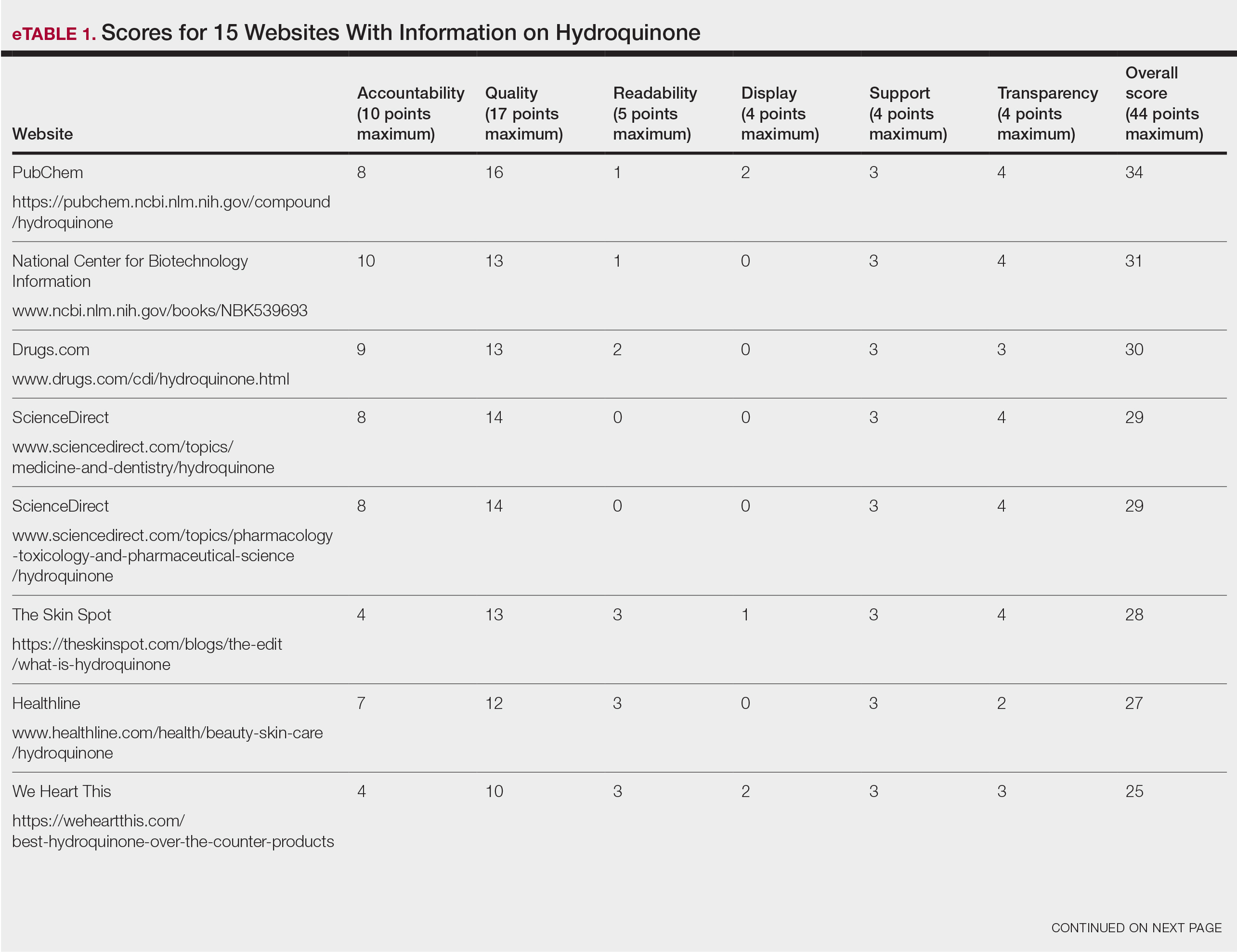

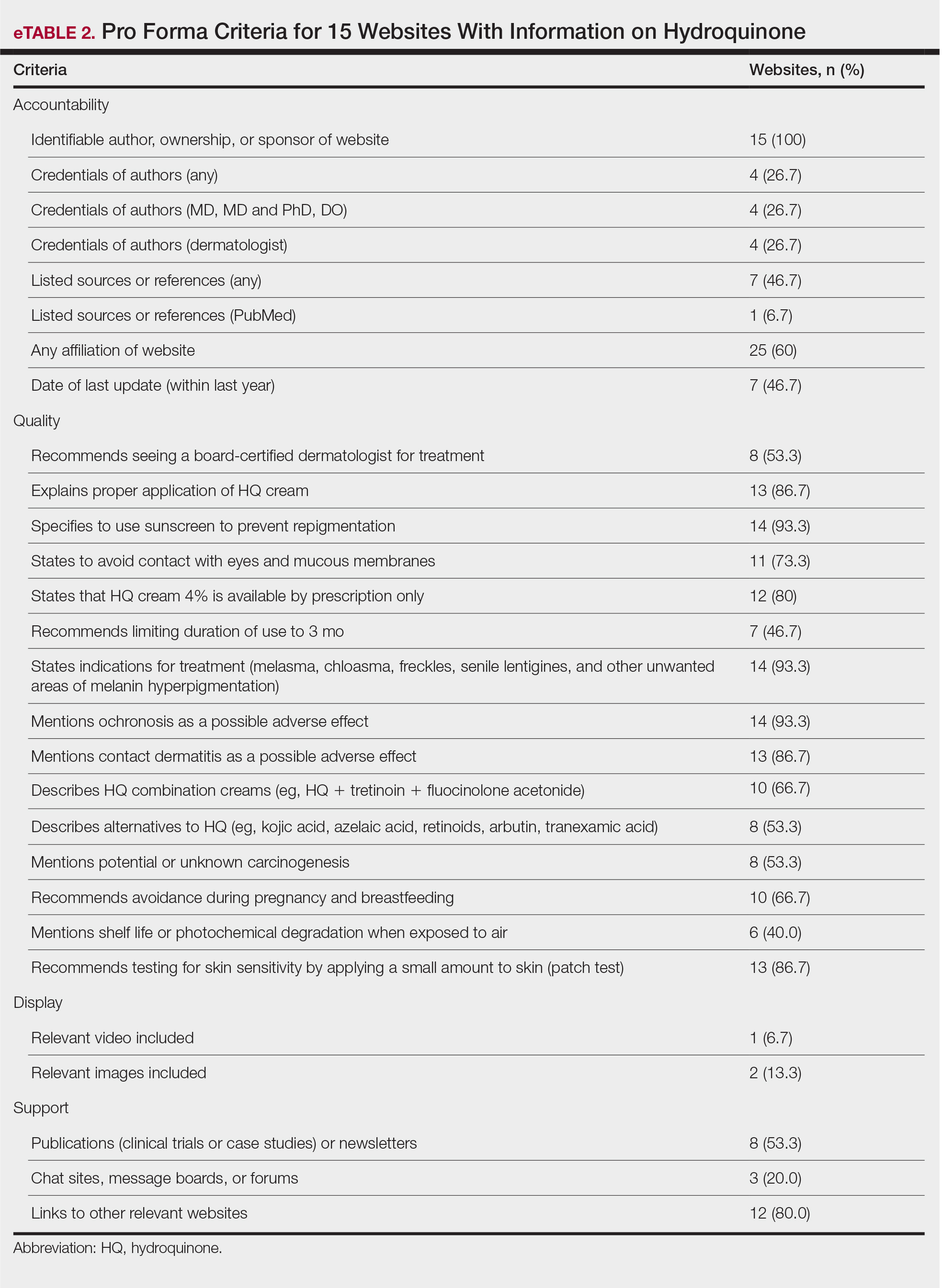

We sought to assess online resources on HQ for accuracy of information, including the recent OTC ban, as well as readability. The word hydroquinone was searched on 3 internet search engines—Google, Yahoo, and Bing—on December 12, 2020, each for the first 20 URLs (ie, websites)(total of 60 URLs). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)(Figure) reporting guidelines were used to assess a list of relevant websites to include in the final analysis. Website data were reviewed by both authors. Eighteen duplicates and 27 irrelevant and non–English-language URLs were excluded. The remaining 15 websites were analyzed. Based on a previously published and validated tool, a pro forma was designed to evaluate information on HQ for each website based on accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency (Table).1,3

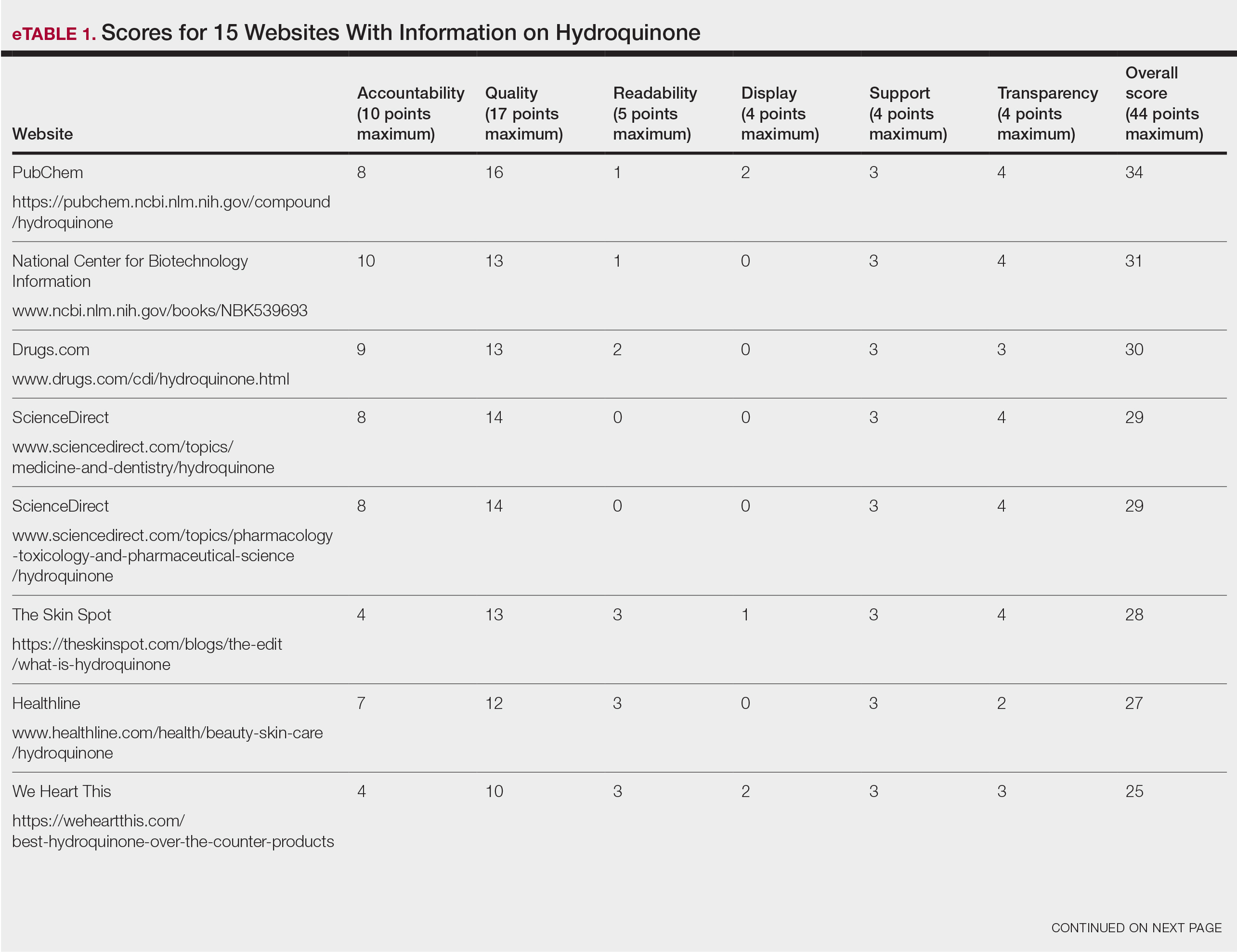

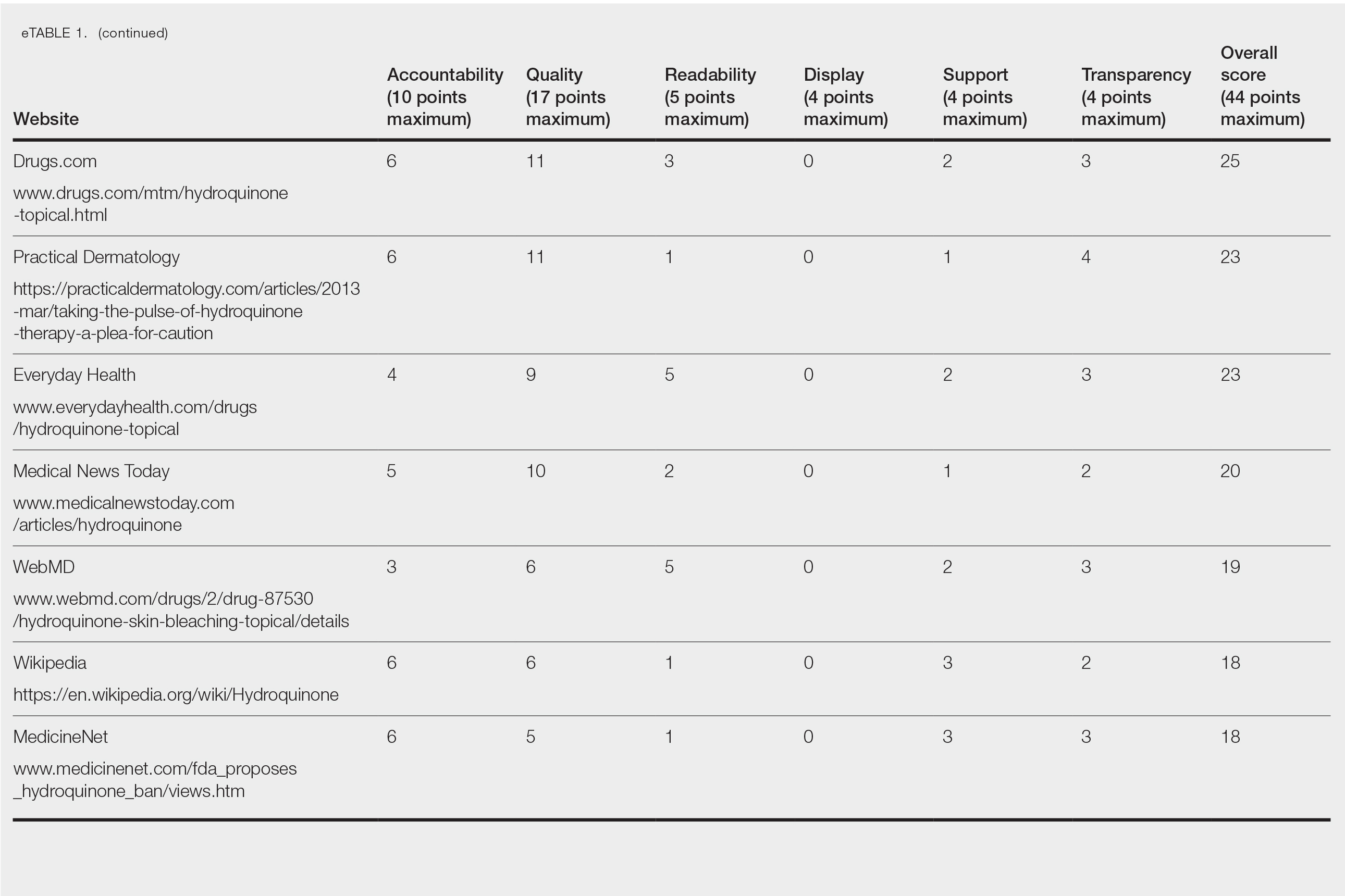

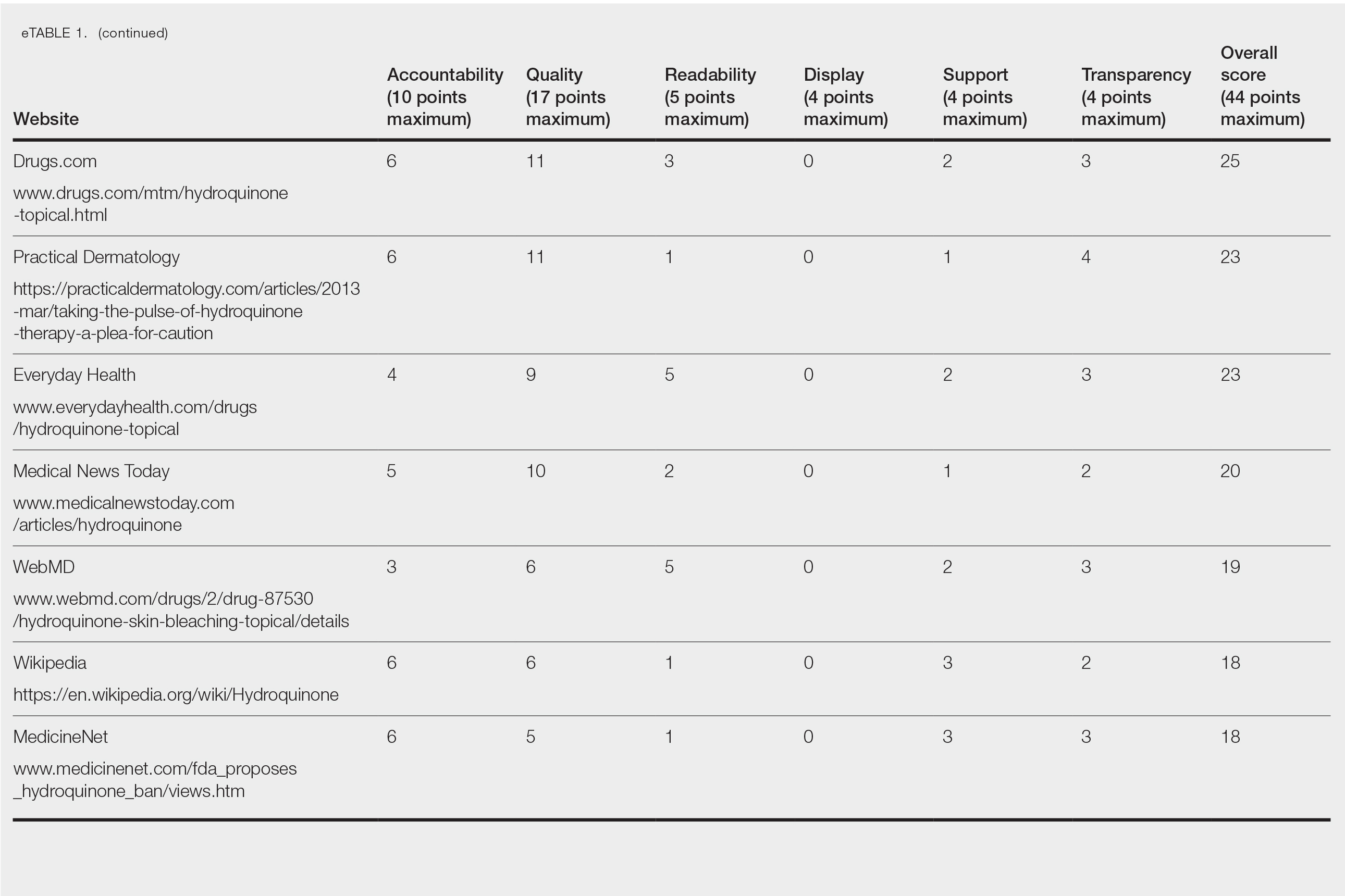

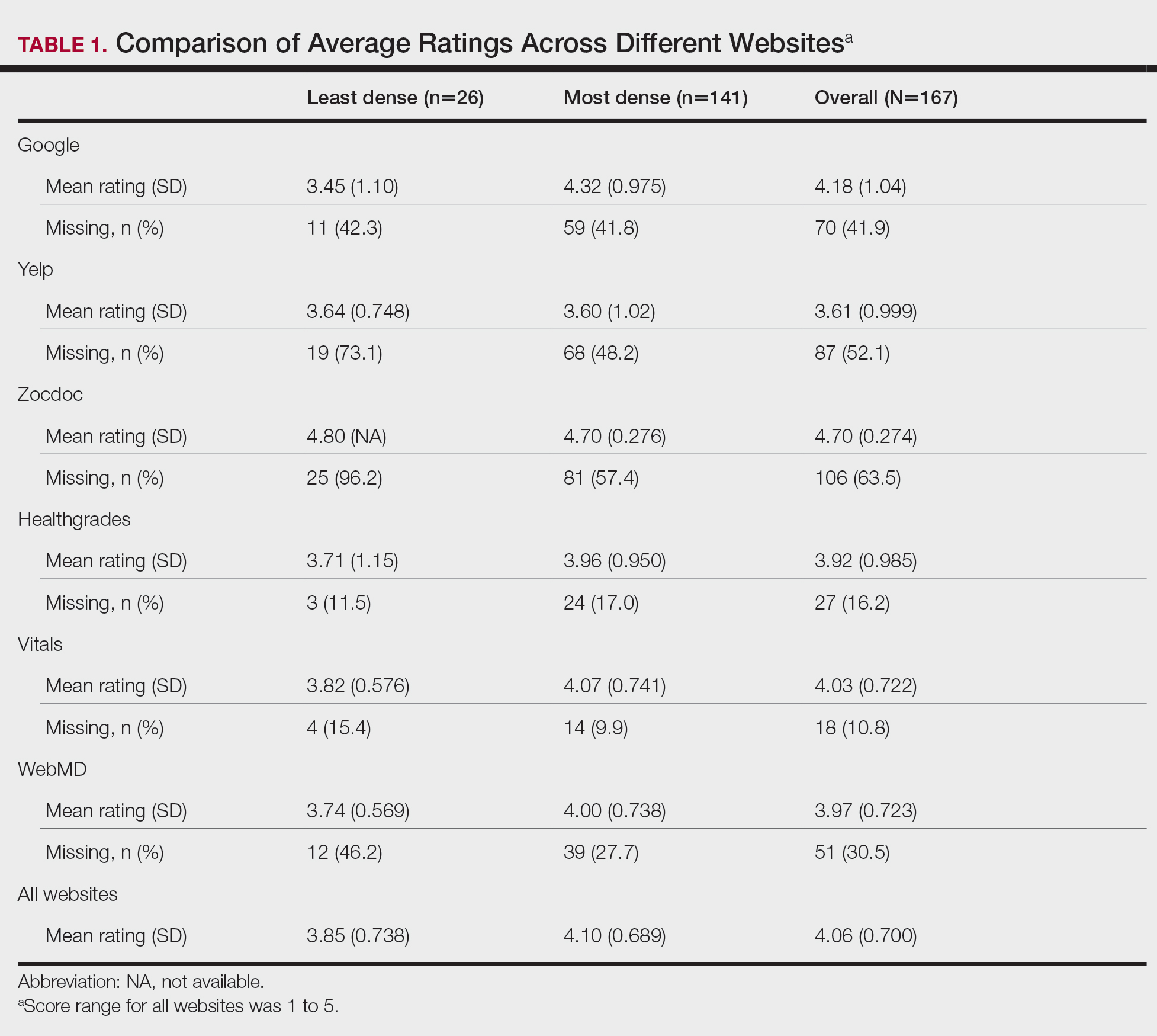

Scores for all 15 websites are listed in eTable 1. The mean overall (total) score was

The mean display score was 0.3 (of a possible 4; range, 0–2); 66.7% of websites (10/15) had advertisements or irrelevant material. Only 6.7% and 13.3% of websites included relevant videos or images, respectively, on applying HQ (eTable 2). We identified only 3 photographs—across all 15 websites—that depicted skin, all of which were Fitzpatrick skin types II or III. Therefore, none of the websites included a diversity of images to indicate broad ethnic relatability.

The average support score was 2.5 (of a possible 4; range, 1–3); 20% (3/15) of URLs included chat sites, message boards, or forums, and approximately half (8/15 [53.3%]) included references. Only 7 URLs (46.7%) had been updated in the last 12 months. Only 4 (26.7%) were written by a board-certified dermatologist (eTable 2). Most (60%) websites contained advertising, though none were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that manufactures HQ.

Only 46.7% (7/15) of websites recommended limiting a course of HQ treatment to 3 months; only 40% (6/15) mentioned shelf life or photochemical degradation when exposed to air. Although 93.3% (14/15) of URLs mentioned ochronosis, a clinical description of the condition was provided in only 33.3% (5/15)—none with images.

Only 2 sites (13.3%; Everyday Health and WebMD) met the accepted 7th-grade reading level for online patient education material; those sites scored lower on quality (9 of 17 and 6 of 17, respectively) than sites with higher overall scores.

None of the 15 websites studied, therefore, demonstrated optimal features on combined measures of accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency regarding HQ. Notably, the American Academy of Dermatology website (www.aad.org) was not among the 15 websites studied; the AAD website mentions HQ in a section on melasma, but only minimal detail is provided.

Limitations of this study include the small number of websites analyzed and possible selection bias because only 3 internet search engines were used to identify websites for study and analysis.

Previously, we analyzed content about HQ on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.4 The most viewed YouTube videos on HQ had poor-quality information (ie, only 20% mentioned ochronosis and only 28.6% recommended sunscreen [N=70]). However, average reading level of these videos was 7th grade.4,5 Therefore, YouTube HQ content, though comprehensible, generally is of poor quality.

By conducting a search for website content about HQ, we found that the most popular URLs had either accurate information with poor readability or lower-quality educational material that was more comprehensible. We conclude that there is a need to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality, up-to-date medical information; have been written by board-certified dermatologists; are comprehensible (ie, no more than approximately 1200 words and written at a 7th-grade reading level); and contain relevant clinical images and references. We encourage dermatologists to recognize the limitations of online patient education resources on HQ and educate patients on the proper use of the drug as well as its potential adverse effects

- US National Library of Medicine. Label: hydroquinone cream. DailyMed website. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=dc72c0b2-4505-4dcf-8a69-889cd9f41693

- US Congress. H.R.748 - CARES Act. 116th Congress (2019-2020). Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text?fbclid=IwAR3ZxGP6AKUl6ce-dlWSU6D5MfCLD576nWNBV5YTE7R2a0IdLY4Usw4oOv4

- Kang R, Lipner S. Evaluation of onychomycosis information on the internet. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:484-487.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Assessing the impact and educational value of YouTube as a source of information on hydroquinone: a content-quality and readability analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1-3. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782318

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf

To the Editor:

The internet is a popular resource for patients seeking information about dermatologic treatments. Hydroquinone (HQ) cream 4% is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for skin hyperpigmentation.1 The agency enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform on September 25, 2020, to restrict distribution of OTC HQ.2 Exogenous ochronosis is listed as a potential adverse effect in the prescribing information for HQ.1

We sought to assess online resources on HQ for accuracy of information, including the recent OTC ban, as well as readability. The word hydroquinone was searched on 3 internet search engines—Google, Yahoo, and Bing—on December 12, 2020, each for the first 20 URLs (ie, websites)(total of 60 URLs). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)(Figure) reporting guidelines were used to assess a list of relevant websites to include in the final analysis. Website data were reviewed by both authors. Eighteen duplicates and 27 irrelevant and non–English-language URLs were excluded. The remaining 15 websites were analyzed. Based on a previously published and validated tool, a pro forma was designed to evaluate information on HQ for each website based on accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency (Table).1,3

Scores for all 15 websites are listed in eTable 1. The mean overall (total) score was

The mean display score was 0.3 (of a possible 4; range, 0–2); 66.7% of websites (10/15) had advertisements or irrelevant material. Only 6.7% and 13.3% of websites included relevant videos or images, respectively, on applying HQ (eTable 2). We identified only 3 photographs—across all 15 websites—that depicted skin, all of which were Fitzpatrick skin types II or III. Therefore, none of the websites included a diversity of images to indicate broad ethnic relatability.

The average support score was 2.5 (of a possible 4; range, 1–3); 20% (3/15) of URLs included chat sites, message boards, or forums, and approximately half (8/15 [53.3%]) included references. Only 7 URLs (46.7%) had been updated in the last 12 months. Only 4 (26.7%) were written by a board-certified dermatologist (eTable 2). Most (60%) websites contained advertising, though none were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that manufactures HQ.

Only 46.7% (7/15) of websites recommended limiting a course of HQ treatment to 3 months; only 40% (6/15) mentioned shelf life or photochemical degradation when exposed to air. Although 93.3% (14/15) of URLs mentioned ochronosis, a clinical description of the condition was provided in only 33.3% (5/15)—none with images.

Only 2 sites (13.3%; Everyday Health and WebMD) met the accepted 7th-grade reading level for online patient education material; those sites scored lower on quality (9 of 17 and 6 of 17, respectively) than sites with higher overall scores.

None of the 15 websites studied, therefore, demonstrated optimal features on combined measures of accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency regarding HQ. Notably, the American Academy of Dermatology website (www.aad.org) was not among the 15 websites studied; the AAD website mentions HQ in a section on melasma, but only minimal detail is provided.

Limitations of this study include the small number of websites analyzed and possible selection bias because only 3 internet search engines were used to identify websites for study and analysis.

Previously, we analyzed content about HQ on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.4 The most viewed YouTube videos on HQ had poor-quality information (ie, only 20% mentioned ochronosis and only 28.6% recommended sunscreen [N=70]). However, average reading level of these videos was 7th grade.4,5 Therefore, YouTube HQ content, though comprehensible, generally is of poor quality.

By conducting a search for website content about HQ, we found that the most popular URLs had either accurate information with poor readability or lower-quality educational material that was more comprehensible. We conclude that there is a need to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality, up-to-date medical information; have been written by board-certified dermatologists; are comprehensible (ie, no more than approximately 1200 words and written at a 7th-grade reading level); and contain relevant clinical images and references. We encourage dermatologists to recognize the limitations of online patient education resources on HQ and educate patients on the proper use of the drug as well as its potential adverse effects

To the Editor:

The internet is a popular resource for patients seeking information about dermatologic treatments. Hydroquinone (HQ) cream 4% is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for skin hyperpigmentation.1 The agency enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform on September 25, 2020, to restrict distribution of OTC HQ.2 Exogenous ochronosis is listed as a potential adverse effect in the prescribing information for HQ.1

We sought to assess online resources on HQ for accuracy of information, including the recent OTC ban, as well as readability. The word hydroquinone was searched on 3 internet search engines—Google, Yahoo, and Bing—on December 12, 2020, each for the first 20 URLs (ie, websites)(total of 60 URLs). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)(Figure) reporting guidelines were used to assess a list of relevant websites to include in the final analysis. Website data were reviewed by both authors. Eighteen duplicates and 27 irrelevant and non–English-language URLs were excluded. The remaining 15 websites were analyzed. Based on a previously published and validated tool, a pro forma was designed to evaluate information on HQ for each website based on accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency (Table).1,3

Scores for all 15 websites are listed in eTable 1. The mean overall (total) score was

The mean display score was 0.3 (of a possible 4; range, 0–2); 66.7% of websites (10/15) had advertisements or irrelevant material. Only 6.7% and 13.3% of websites included relevant videos or images, respectively, on applying HQ (eTable 2). We identified only 3 photographs—across all 15 websites—that depicted skin, all of which were Fitzpatrick skin types II or III. Therefore, none of the websites included a diversity of images to indicate broad ethnic relatability.

The average support score was 2.5 (of a possible 4; range, 1–3); 20% (3/15) of URLs included chat sites, message boards, or forums, and approximately half (8/15 [53.3%]) included references. Only 7 URLs (46.7%) had been updated in the last 12 months. Only 4 (26.7%) were written by a board-certified dermatologist (eTable 2). Most (60%) websites contained advertising, though none were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that manufactures HQ.

Only 46.7% (7/15) of websites recommended limiting a course of HQ treatment to 3 months; only 40% (6/15) mentioned shelf life or photochemical degradation when exposed to air. Although 93.3% (14/15) of URLs mentioned ochronosis, a clinical description of the condition was provided in only 33.3% (5/15)—none with images.

Only 2 sites (13.3%; Everyday Health and WebMD) met the accepted 7th-grade reading level for online patient education material; those sites scored lower on quality (9 of 17 and 6 of 17, respectively) than sites with higher overall scores.

None of the 15 websites studied, therefore, demonstrated optimal features on combined measures of accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency regarding HQ. Notably, the American Academy of Dermatology website (www.aad.org) was not among the 15 websites studied; the AAD website mentions HQ in a section on melasma, but only minimal detail is provided.

Limitations of this study include the small number of websites analyzed and possible selection bias because only 3 internet search engines were used to identify websites for study and analysis.

Previously, we analyzed content about HQ on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.4 The most viewed YouTube videos on HQ had poor-quality information (ie, only 20% mentioned ochronosis and only 28.6% recommended sunscreen [N=70]). However, average reading level of these videos was 7th grade.4,5 Therefore, YouTube HQ content, though comprehensible, generally is of poor quality.

By conducting a search for website content about HQ, we found that the most popular URLs had either accurate information with poor readability or lower-quality educational material that was more comprehensible. We conclude that there is a need to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality, up-to-date medical information; have been written by board-certified dermatologists; are comprehensible (ie, no more than approximately 1200 words and written at a 7th-grade reading level); and contain relevant clinical images and references. We encourage dermatologists to recognize the limitations of online patient education resources on HQ and educate patients on the proper use of the drug as well as its potential adverse effects

- US National Library of Medicine. Label: hydroquinone cream. DailyMed website. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=dc72c0b2-4505-4dcf-8a69-889cd9f41693

- US Congress. H.R.748 - CARES Act. 116th Congress (2019-2020). Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text?fbclid=IwAR3ZxGP6AKUl6ce-dlWSU6D5MfCLD576nWNBV5YTE7R2a0IdLY4Usw4oOv4

- Kang R, Lipner S. Evaluation of onychomycosis information on the internet. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:484-487.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Assessing the impact and educational value of YouTube as a source of information on hydroquinone: a content-quality and readability analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1-3. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782318

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf

- US National Library of Medicine. Label: hydroquinone cream. DailyMed website. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=dc72c0b2-4505-4dcf-8a69-889cd9f41693

- US Congress. H.R.748 - CARES Act. 116th Congress (2019-2020). Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text?fbclid=IwAR3ZxGP6AKUl6ce-dlWSU6D5MfCLD576nWNBV5YTE7R2a0IdLY4Usw4oOv4

- Kang R, Lipner S. Evaluation of onychomycosis information on the internet. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:484-487.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Assessing the impact and educational value of YouTube as a source of information on hydroquinone: a content-quality and readability analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1-3. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782318

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf

Practice Points

- Hydroquinone (HQ) 4% is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for skin hyperpigmentation including melasma.

- In September 2020, the FDA enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform, announcing that HQ is not classified as Category II/not generally recognized as safe and effective, thus prohibiting the distribution of OTC HQ products.

- Exogenous ochronosis is a potential side effect associated with HQ.

- There is a need for dermatologists to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality and up-to-date medical information.

A Contrasting Dark Background for Nail Sampling

Practice Gap

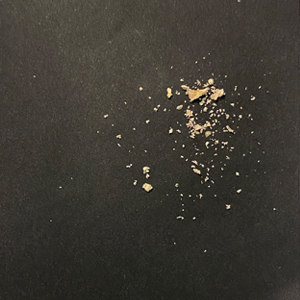

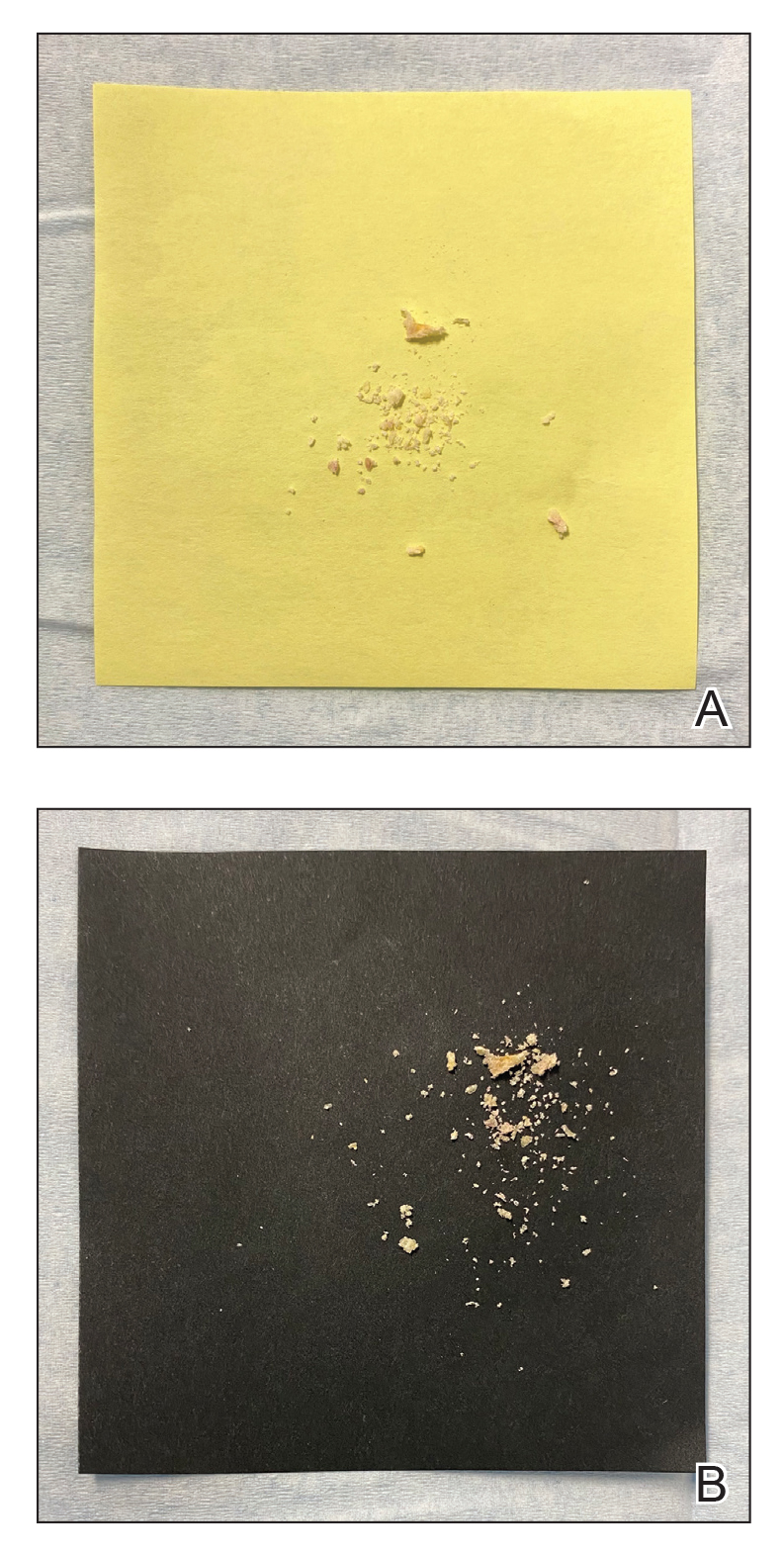

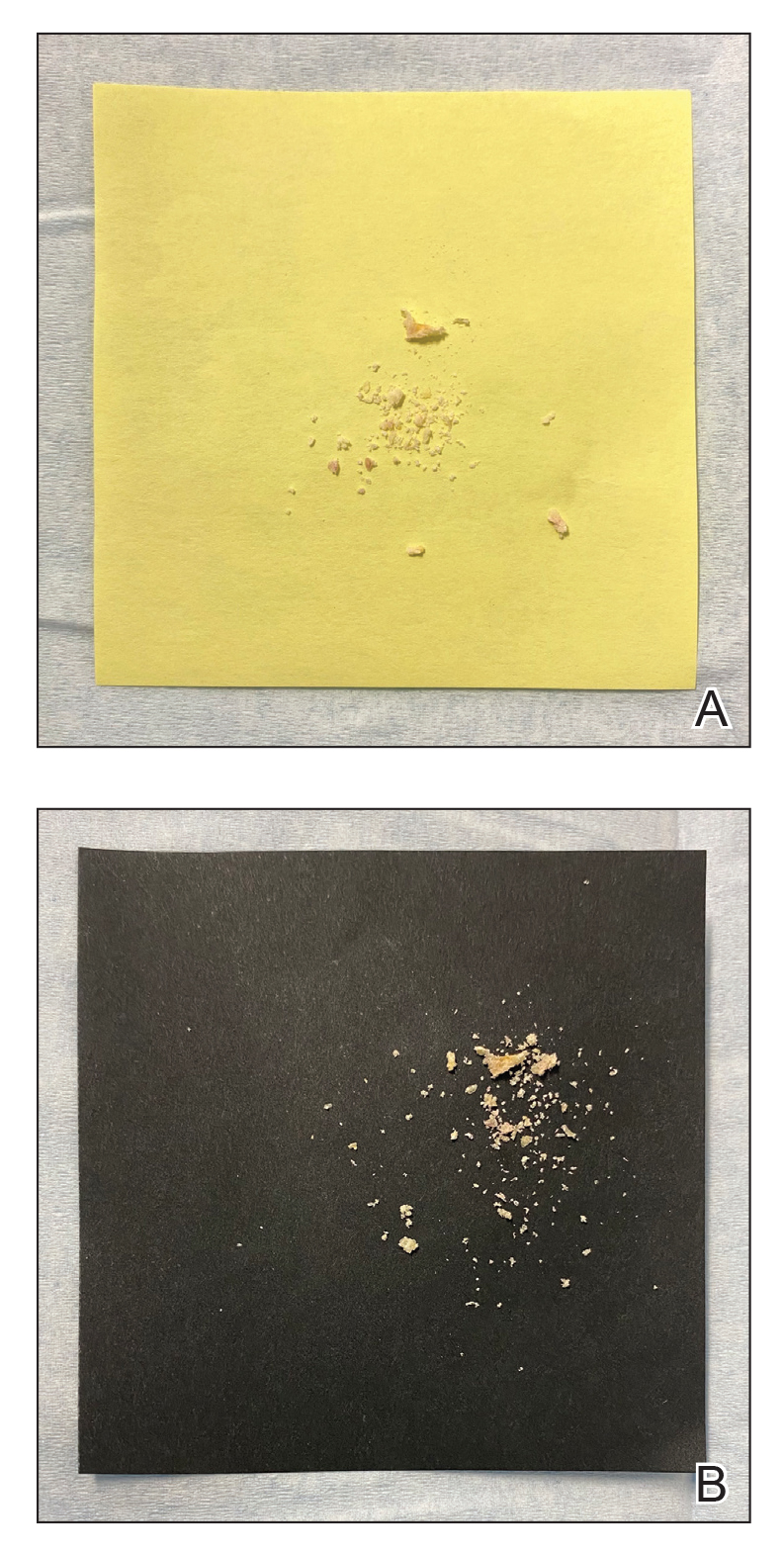

Mycologic testing is necessary and cost-effective1 for appropriate diagnosis and treatment of onychomycosis. Empiric treatment of onychodystrophy for presumed onychomycosis can result in misdiagnosis, treatment failure, or potential adverse effects caused by medications.2 Collection of ample subungual debris facilitates the sensitivity and specificity of fungal culture and fungal polymerase chain reaction. However, the naturally pale hue of subungual debris makes specimen estimation challenging, particularly when using a similarly light-colored gauze or piece of paper for collection (Figure, A).

The Technique

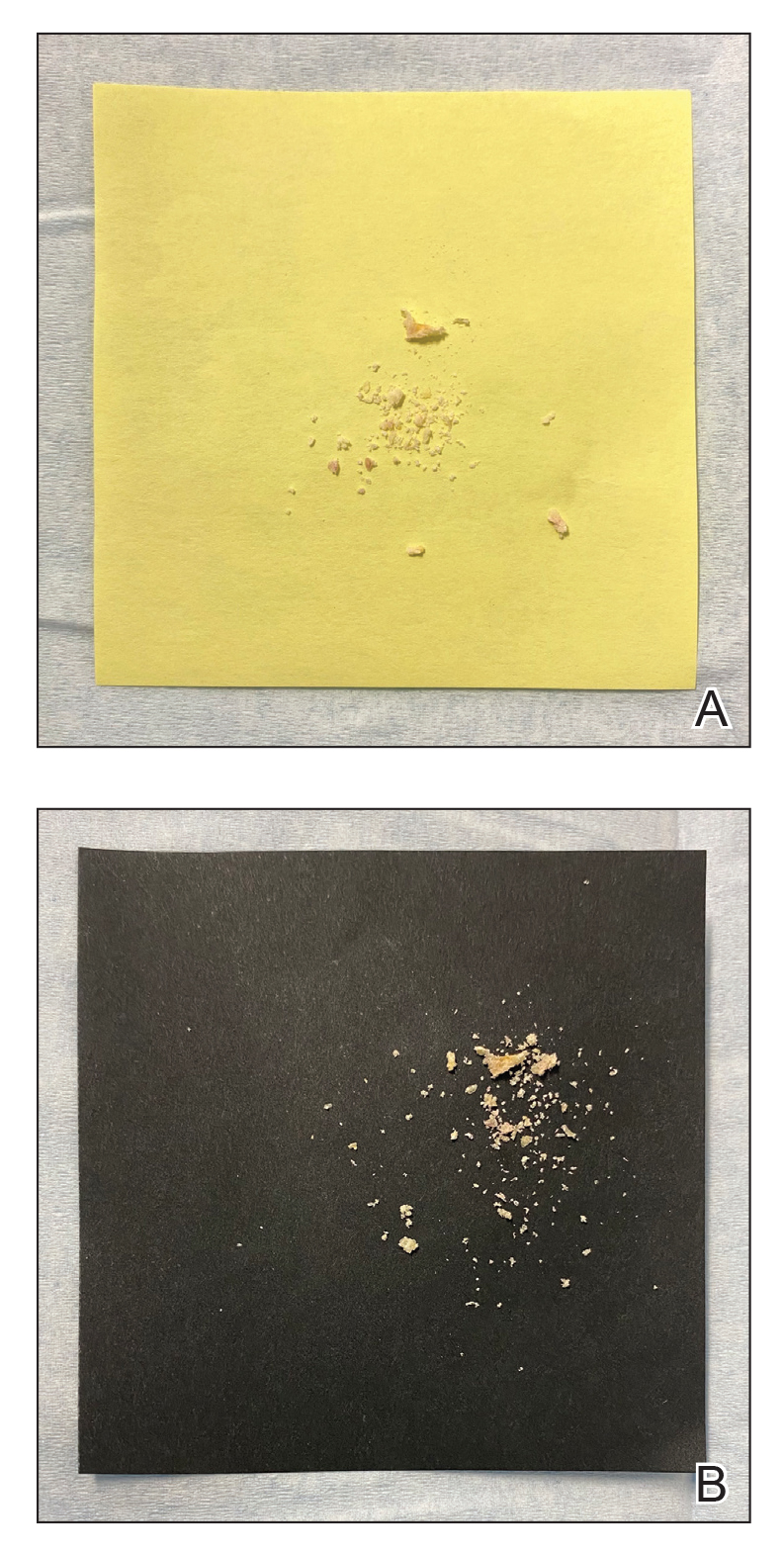

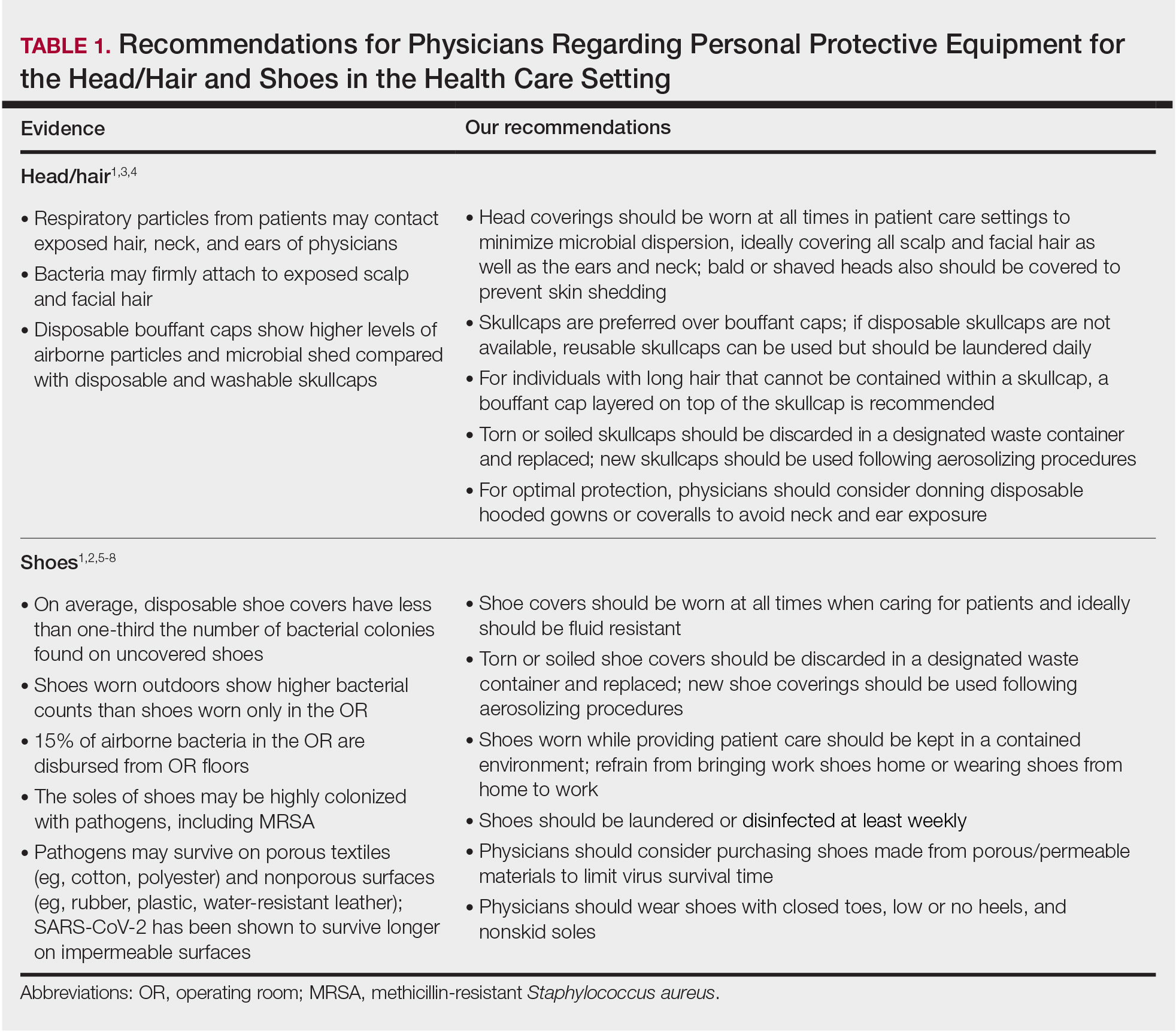

A sheet from a black sticky notepad (widely available and cost-effective) can be adapted for making a diagnosis of onychomycosis (Figure, B).

Practical Implication

Use of a dark background that contrasts with light-hued nail debris is valuable to ensure an adequate specimen for fungal culture and polymerase chain reaction.

- Gupta AK, Versteeg SG, Shear NH. Confirmatory testing prior to initiating onychomycosis therapy is cost effective. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:129-141. doi:10.1177/1203475417733461

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis—a small step for quality of care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:865-867. doi:10.1185/03007995.2016.1147026

Practice Gap

Mycologic testing is necessary and cost-effective1 for appropriate diagnosis and treatment of onychomycosis. Empiric treatment of onychodystrophy for presumed onychomycosis can result in misdiagnosis, treatment failure, or potential adverse effects caused by medications.2 Collection of ample subungual debris facilitates the sensitivity and specificity of fungal culture and fungal polymerase chain reaction. However, the naturally pale hue of subungual debris makes specimen estimation challenging, particularly when using a similarly light-colored gauze or piece of paper for collection (Figure, A).

The Technique

A sheet from a black sticky notepad (widely available and cost-effective) can be adapted for making a diagnosis of onychomycosis (Figure, B).

Practical Implication

Use of a dark background that contrasts with light-hued nail debris is valuable to ensure an adequate specimen for fungal culture and polymerase chain reaction.

Practice Gap

Mycologic testing is necessary and cost-effective1 for appropriate diagnosis and treatment of onychomycosis. Empiric treatment of onychodystrophy for presumed onychomycosis can result in misdiagnosis, treatment failure, or potential adverse effects caused by medications.2 Collection of ample subungual debris facilitates the sensitivity and specificity of fungal culture and fungal polymerase chain reaction. However, the naturally pale hue of subungual debris makes specimen estimation challenging, particularly when using a similarly light-colored gauze or piece of paper for collection (Figure, A).

The Technique

A sheet from a black sticky notepad (widely available and cost-effective) can be adapted for making a diagnosis of onychomycosis (Figure, B).

Practical Implication

Use of a dark background that contrasts with light-hued nail debris is valuable to ensure an adequate specimen for fungal culture and polymerase chain reaction.

- Gupta AK, Versteeg SG, Shear NH. Confirmatory testing prior to initiating onychomycosis therapy is cost effective. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:129-141. doi:10.1177/1203475417733461

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis—a small step for quality of care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:865-867. doi:10.1185/03007995.2016.1147026

- Gupta AK, Versteeg SG, Shear NH. Confirmatory testing prior to initiating onychomycosis therapy is cost effective. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:129-141. doi:10.1177/1203475417733461

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Onychomycosis—a small step for quality of care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:865-867. doi:10.1185/03007995.2016.1147026

The Top 100 Most-Cited Articles on Nail Psoriasis: A Bibliometric Analysis

To the Editor:

Nail psoriasis is highly prevalent in patients with cutaneous psoriasis and also may present as an isolated finding. There is a strong association between nail psoriasis and development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, publications on nail psoriasis are sparse compared with articles describing cutaneous psoriasis.1 Our objectives were to analyze the nail psoriasis literature for content, citations, and media attention.

The Web of Science database was searched for the term nail psoriasis on April 27, 2020, and publications by year, subject, and article type were compiled. Total and average yearly citations were calculated to create a list of the top 100 most-cited articles (eTable). First and last authors, sex, and Altmetric Attention Scores were then recorded. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was calculated to compare the relationship of Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific references and others on the list.

In our data set, the average total number of citations was 134.09 (range, 42–1617), with average yearly citations ranging from 2 to 108. Altmetric scores—measures of media attention of scholarly work—were available for 58 of 100 papers (58%), with an average score of 33.2 (range, 1–509).

Of the top 100 most-cited articles using the search term nail psoriasis, only 20% focused on nail psoriasis, with the remainder concentrating on psoriasis/PsA. Only 32% and 24% of first and last authors, respectively, were female. Fifty-two percent and 31% of the articles were published in dermatology and arthritis/rheumatology journals, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific and other articles in our data set (P=.7551).

For the nail psoriasis–specific articles, all 20 highlighted a lack of nail clinical trials, a positive association with PsA, and a correlation of increased cutaneous psoriasis body surface area with increased onychodystrophy likelihood.2 Three of 20 (15%) articles stated that nail psoriasis often is overlooked, despite the negative impact on quality of life,1 and emphasized the importance of patient compliance owing to the chronic nature of the disease. Only 1 of 20 (5%) articles focused on nail psoriasis treatments.3 There was no overlap between the 100 most-cited psoriasis articles from 1970 to 2012 and our top 100 articles on nail psoriasis.4

Treatment recommendations for nail psoriasis by consensus were published by a nail expert group in 2019.5 For 3 or fewer nails involved, suggested first-line treatment is intralesional matrix injections with triamcinolone acetonide. For more than 3 affected nails, systemic treatment with oral or biologic therapy is recommended.5 Although this article is likely to change clinical practice, it did not qualify for our list because it did not garner sufficient citations in the brief period between its publication date and our search (July 2019–April 2020).

This study is subject to several limitations. Only the Web of Science database was utilized, and only the term nail psoriasis was searched, potentially excluding relevant articles. Using total citations biases toward older articles.

Our bibliometric analysis highlights a lack of publications on nail psoriasis, with most articles focusing on psoriasis and PsA. This deficiency in highly cited nail psoriasis references is likely to be a barrier to physicians in managing patients with nail disease. There is a need for controlled clinical trials and better mechanisms to disseminate information on management of nail psoriasis to practicing physicians.

- Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease in psoriatic arthritis—clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:790-794. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh198

- Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 1):15-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x

- de Berker D. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357-362. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Marczynski W. The 100 most cited psoriasis articles in clinical dermatologic journals, 1970 to 2012. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-19.

- Rigopoulos D, Baran R, Chiheb S, et al. Recommendations for the definition, evaluation, and treatment of nail psoriasis in adult patients with no or mild skin psoriasis: a dermatologist and nail expert group consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:228-240. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.072

To the Editor:

Nail psoriasis is highly prevalent in patients with cutaneous psoriasis and also may present as an isolated finding. There is a strong association between nail psoriasis and development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, publications on nail psoriasis are sparse compared with articles describing cutaneous psoriasis.1 Our objectives were to analyze the nail psoriasis literature for content, citations, and media attention.

The Web of Science database was searched for the term nail psoriasis on April 27, 2020, and publications by year, subject, and article type were compiled. Total and average yearly citations were calculated to create a list of the top 100 most-cited articles (eTable). First and last authors, sex, and Altmetric Attention Scores were then recorded. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was calculated to compare the relationship of Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific references and others on the list.

In our data set, the average total number of citations was 134.09 (range, 42–1617), with average yearly citations ranging from 2 to 108. Altmetric scores—measures of media attention of scholarly work—were available for 58 of 100 papers (58%), with an average score of 33.2 (range, 1–509).

Of the top 100 most-cited articles using the search term nail psoriasis, only 20% focused on nail psoriasis, with the remainder concentrating on psoriasis/PsA. Only 32% and 24% of first and last authors, respectively, were female. Fifty-two percent and 31% of the articles were published in dermatology and arthritis/rheumatology journals, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific and other articles in our data set (P=.7551).

For the nail psoriasis–specific articles, all 20 highlighted a lack of nail clinical trials, a positive association with PsA, and a correlation of increased cutaneous psoriasis body surface area with increased onychodystrophy likelihood.2 Three of 20 (15%) articles stated that nail psoriasis often is overlooked, despite the negative impact on quality of life,1 and emphasized the importance of patient compliance owing to the chronic nature of the disease. Only 1 of 20 (5%) articles focused on nail psoriasis treatments.3 There was no overlap between the 100 most-cited psoriasis articles from 1970 to 2012 and our top 100 articles on nail psoriasis.4

Treatment recommendations for nail psoriasis by consensus were published by a nail expert group in 2019.5 For 3 or fewer nails involved, suggested first-line treatment is intralesional matrix injections with triamcinolone acetonide. For more than 3 affected nails, systemic treatment with oral or biologic therapy is recommended.5 Although this article is likely to change clinical practice, it did not qualify for our list because it did not garner sufficient citations in the brief period between its publication date and our search (July 2019–April 2020).

This study is subject to several limitations. Only the Web of Science database was utilized, and only the term nail psoriasis was searched, potentially excluding relevant articles. Using total citations biases toward older articles.

Our bibliometric analysis highlights a lack of publications on nail psoriasis, with most articles focusing on psoriasis and PsA. This deficiency in highly cited nail psoriasis references is likely to be a barrier to physicians in managing patients with nail disease. There is a need for controlled clinical trials and better mechanisms to disseminate information on management of nail psoriasis to practicing physicians.

To the Editor:

Nail psoriasis is highly prevalent in patients with cutaneous psoriasis and also may present as an isolated finding. There is a strong association between nail psoriasis and development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, publications on nail psoriasis are sparse compared with articles describing cutaneous psoriasis.1 Our objectives were to analyze the nail psoriasis literature for content, citations, and media attention.

The Web of Science database was searched for the term nail psoriasis on April 27, 2020, and publications by year, subject, and article type were compiled. Total and average yearly citations were calculated to create a list of the top 100 most-cited articles (eTable). First and last authors, sex, and Altmetric Attention Scores were then recorded. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was calculated to compare the relationship of Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific references and others on the list.

In our data set, the average total number of citations was 134.09 (range, 42–1617), with average yearly citations ranging from 2 to 108. Altmetric scores—measures of media attention of scholarly work—were available for 58 of 100 papers (58%), with an average score of 33.2 (range, 1–509).

Of the top 100 most-cited articles using the search term nail psoriasis, only 20% focused on nail psoriasis, with the remainder concentrating on psoriasis/PsA. Only 32% and 24% of first and last authors, respectively, were female. Fifty-two percent and 31% of the articles were published in dermatology and arthritis/rheumatology journals, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific and other articles in our data set (P=.7551).

For the nail psoriasis–specific articles, all 20 highlighted a lack of nail clinical trials, a positive association with PsA, and a correlation of increased cutaneous psoriasis body surface area with increased onychodystrophy likelihood.2 Three of 20 (15%) articles stated that nail psoriasis often is overlooked, despite the negative impact on quality of life,1 and emphasized the importance of patient compliance owing to the chronic nature of the disease. Only 1 of 20 (5%) articles focused on nail psoriasis treatments.3 There was no overlap between the 100 most-cited psoriasis articles from 1970 to 2012 and our top 100 articles on nail psoriasis.4

Treatment recommendations for nail psoriasis by consensus were published by a nail expert group in 2019.5 For 3 or fewer nails involved, suggested first-line treatment is intralesional matrix injections with triamcinolone acetonide. For more than 3 affected nails, systemic treatment with oral or biologic therapy is recommended.5 Although this article is likely to change clinical practice, it did not qualify for our list because it did not garner sufficient citations in the brief period between its publication date and our search (July 2019–April 2020).

This study is subject to several limitations. Only the Web of Science database was utilized, and only the term nail psoriasis was searched, potentially excluding relevant articles. Using total citations biases toward older articles.

Our bibliometric analysis highlights a lack of publications on nail psoriasis, with most articles focusing on psoriasis and PsA. This deficiency in highly cited nail psoriasis references is likely to be a barrier to physicians in managing patients with nail disease. There is a need for controlled clinical trials and better mechanisms to disseminate information on management of nail psoriasis to practicing physicians.

- Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease in psoriatic arthritis—clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:790-794. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh198

- Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 1):15-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x

- de Berker D. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357-362. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Marczynski W. The 100 most cited psoriasis articles in clinical dermatologic journals, 1970 to 2012. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-19.

- Rigopoulos D, Baran R, Chiheb S, et al. Recommendations for the definition, evaluation, and treatment of nail psoriasis in adult patients with no or mild skin psoriasis: a dermatologist and nail expert group consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:228-240. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.072

- Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease in psoriatic arthritis—clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:790-794. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh198

- Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 1):15-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x

- de Berker D. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357-362. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Marczynski W. The 100 most cited psoriasis articles in clinical dermatologic journals, 1970 to 2012. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-19.

- Rigopoulos D, Baran R, Chiheb S, et al. Recommendations for the definition, evaluation, and treatment of nail psoriasis in adult patients with no or mild skin psoriasis: a dermatologist and nail expert group consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:228-240. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.072

Utilizing a Sleep Mask to Reduce Patient Anxiety During Nail Surgery

Practice Gap

Perioperative anxiety is common in patients undergoing nail surgery. Patients might worry about seeing blood; about the procedure itself, including nail avulsion; and about associated pain and disfigurement. Nail surgery causes a high level of anxiety that correlates positively with postoperative pain1 and overall patient dissatisfaction. Furthermore, surgery-related anxiety is a predictor of increased postoperative analgesic use2 and delayed recovery.3

Therefore, implementing strategies that reduce perioperative anxiety may help minimize postoperative pain. Squeezing a stress ball, hand-holding, virtual reality, and music are tools that have been studied to reduce anxiety in the context of Mohs micrographic surgery; these strategies have not been studied for nail surgery.

The Technique

Using a sleep mask is a practical solution to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. A minority of patients will choose to watch their surgical procedure; most become unnerved observing their nail surgery. Using a sleep mask diverts visual attention from the surgical field without physically interfering with the nail surgeon. Utilizing a sleep mask is cost-effective, with disposable sleep masks available online for less than $0.30 each. Patients can bring their own mask, or a mask can be offered prior to surgery.

If desired, patients are instructed to wear the sleep mask during the entirety of the procedure, starting from anesthetic infiltration until wound closure and dressing application. Any adjustments can be made with the patient’s free hand. The sleep mask can be offered to patients of all ages undergoing nail surgery under local anesthesia, except babies and young children, who require general anesthesia.

Practical Implications

Distraction is an important strategy to reduce anxiety and pain in patients undergoing surgical procedures. In an observational study of 3087 surgical patients, 36% reported that self-distraction was the most helpful strategy for coping with preoperative anxiety.4 In a randomized, open-label clinical trial of 72 patients undergoing peripheral venous catheterization, asking the patients simple questions during the procedure was more effective than local anesthesia in reducing the perception of pain.5

It is crucial to implement strategies to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing nail surgery. Using a sleep mask impedes direct visualization of the surgical field, thus distracting the patient’s sight and attention from the procedure. Furthermore, this technique is safe and cost-effective.

Controlled clinical trials are necessary to assess the efficacy of this method in reducing nail surgery–related anxiety in comparison to other techniques.

- Navarro-Gastón D, Munuera-Martínez PV. Prevalence of preoperative anxiety and its relationship with postoperative pain in foot nail surgery: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4481. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124481

- Ip HYV, Abrishami A, Peng PWH, et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657-677. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Aust H, Rüsch D, Schuster M, et al. Coping strategies in anxious surgical patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:250. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1492-5

- Balanyuk I, Ledonne G, Provenzano M, et al. Distraction technique for pain reduction in peripheral venous catheterization: randomized, controlled trial. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(suppl 4):55-63. doi:10.23750/abmv89i4-S.7115

Practice Gap

Perioperative anxiety is common in patients undergoing nail surgery. Patients might worry about seeing blood; about the procedure itself, including nail avulsion; and about associated pain and disfigurement. Nail surgery causes a high level of anxiety that correlates positively with postoperative pain1 and overall patient dissatisfaction. Furthermore, surgery-related anxiety is a predictor of increased postoperative analgesic use2 and delayed recovery.3

Therefore, implementing strategies that reduce perioperative anxiety may help minimize postoperative pain. Squeezing a stress ball, hand-holding, virtual reality, and music are tools that have been studied to reduce anxiety in the context of Mohs micrographic surgery; these strategies have not been studied for nail surgery.

The Technique

Using a sleep mask is a practical solution to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. A minority of patients will choose to watch their surgical procedure; most become unnerved observing their nail surgery. Using a sleep mask diverts visual attention from the surgical field without physically interfering with the nail surgeon. Utilizing a sleep mask is cost-effective, with disposable sleep masks available online for less than $0.30 each. Patients can bring their own mask, or a mask can be offered prior to surgery.

If desired, patients are instructed to wear the sleep mask during the entirety of the procedure, starting from anesthetic infiltration until wound closure and dressing application. Any adjustments can be made with the patient’s free hand. The sleep mask can be offered to patients of all ages undergoing nail surgery under local anesthesia, except babies and young children, who require general anesthesia.

Practical Implications

Distraction is an important strategy to reduce anxiety and pain in patients undergoing surgical procedures. In an observational study of 3087 surgical patients, 36% reported that self-distraction was the most helpful strategy for coping with preoperative anxiety.4 In a randomized, open-label clinical trial of 72 patients undergoing peripheral venous catheterization, asking the patients simple questions during the procedure was more effective than local anesthesia in reducing the perception of pain.5

It is crucial to implement strategies to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing nail surgery. Using a sleep mask impedes direct visualization of the surgical field, thus distracting the patient’s sight and attention from the procedure. Furthermore, this technique is safe and cost-effective.

Controlled clinical trials are necessary to assess the efficacy of this method in reducing nail surgery–related anxiety in comparison to other techniques.

Practice Gap

Perioperative anxiety is common in patients undergoing nail surgery. Patients might worry about seeing blood; about the procedure itself, including nail avulsion; and about associated pain and disfigurement. Nail surgery causes a high level of anxiety that correlates positively with postoperative pain1 and overall patient dissatisfaction. Furthermore, surgery-related anxiety is a predictor of increased postoperative analgesic use2 and delayed recovery.3

Therefore, implementing strategies that reduce perioperative anxiety may help minimize postoperative pain. Squeezing a stress ball, hand-holding, virtual reality, and music are tools that have been studied to reduce anxiety in the context of Mohs micrographic surgery; these strategies have not been studied for nail surgery.

The Technique

Using a sleep mask is a practical solution to reduce patient anxiety during nail surgery. A minority of patients will choose to watch their surgical procedure; most become unnerved observing their nail surgery. Using a sleep mask diverts visual attention from the surgical field without physically interfering with the nail surgeon. Utilizing a sleep mask is cost-effective, with disposable sleep masks available online for less than $0.30 each. Patients can bring their own mask, or a mask can be offered prior to surgery.

If desired, patients are instructed to wear the sleep mask during the entirety of the procedure, starting from anesthetic infiltration until wound closure and dressing application. Any adjustments can be made with the patient’s free hand. The sleep mask can be offered to patients of all ages undergoing nail surgery under local anesthesia, except babies and young children, who require general anesthesia.

Practical Implications

Distraction is an important strategy to reduce anxiety and pain in patients undergoing surgical procedures. In an observational study of 3087 surgical patients, 36% reported that self-distraction was the most helpful strategy for coping with preoperative anxiety.4 In a randomized, open-label clinical trial of 72 patients undergoing peripheral venous catheterization, asking the patients simple questions during the procedure was more effective than local anesthesia in reducing the perception of pain.5