User login

The Potential Benefits of Dietary Changes in Psoriasis Patients

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease for which several lifestyle factors—smoking, alcohol use, and psychological stress—are associated with higher incidence and more severe disease.1-3 Diet also has been implicated as a factor that can affect psoriasis,4 and many patients have shown interest in possible dietary interventions to help their disease.5

In 2018, the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) presented dietary recommendations for patients based on results from a systematic review. From the available literature, only dietary weight reduction with hypocaloric diets in overweight or obese patients could be strongly recommended, and it has been proven that obesity is associated with worse psoriasis severity.6 Other more recent studies have shown that dietary modifications such as intermittent fasting and the ketogenic diet also led to weight loss and improved psoriasis severity in overweight patients; however, it is difficult to discern if the improvement was due to weight loss alone or if the dietary patterns themselves played a role.7,8 The paucity of well-designed studies evaluating the effects of other dietary changes has prevented further guidelines from being written. We propose that dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet (MeD) and vegan/vegetarian diets—even without strong data showing benefits in skin disease—may help to decrease systemic inflammation, improve gut dysbiosis, and help decrease the risk for cardiometabolic comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis.

Mediterranean Diet

The MeD is based on the dietary tendencies of inhabitants from the regions surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and is centered around nutrient-rich foods such as vegetables, olive oil, and legumes while limiting meat and dairy.9 The NPF recommended considering a trial of the MeD based on low-quality evidence.6 Observational studies have indicated that psoriasis patients are less likely to adhere to the MeD, but those who do have less severe disease.8 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Mediterranean diet and psoriasis yielded no prospective interventional studies. Given the association of the MeD with less severe disease, it is important to understand which specific foods in the MeD could be beneficial. Intake of omega-3 fatty acids, such as those found in fatty fish, are important for modulation of systemic inflammation.7 High intake of polyphenols—found in fruits and vegetables, extra-virgin olive oil, and wine—also have been implicated in improving inflammatory diseases due to potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Individually, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and sea fish have been associated with lowering C-reactive protein levels, which also is indicative of the benefits of these foods on systemic inflammation.7

Vegan/Vegetarian Diets

Although fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains are a substantial component of the MeD, there are limited data on vegetarian or purely vegan plant-based diets. An observational study from the NPF found that only 48.4% (15/31) of patients on the MeD vs 69.0% (20/29) on a vegan diet reported a favorable skin response.5 Two case reports also have shown beneficial results of a strict vegan diet for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, where whole-food plant-based diets also improved joint symptoms.10-12 As with any diet, those who pursue a plant-based diet should strive to consume a variety of foods to avoid nutrient deficiencies. A recent systematic meta-analysis of 141 studies evaluated nutrient status of vegan and vegetarian diets compared to pescovegetarians and those who consume meat. All dietary patterns showed varying degrees of low levels of different nutrients.13 Of note, the researchers found that vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, and docosahexaenoic acid were lower in plant-based diets. In contrast, folate; vitamins B1, B6, C, and E; polyunsaturated fatty acids; α-linolenic acid; and magnesium intake were higher. Those who consumed meat were at risk for inadequate intake of fiber, polyunsaturated fatty acids, α-linolenic acid, folate, vitamin E, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D, though vitamin D intake was higher than in vegans/vegetarians.13 The results of this meta-analysis indicated the importance of educating patients on what constitutes a well-rounded, micronutrient-rich diet or appropriate supplementation for any diet.

Effects on Gut Microbiome

Any changes in diet can lead to alterations in the gut microbiome, which may impact skin disease, as evidence indicates a bidirectional relationship between gut and skin health.10 A metagenomic analysis of the gut microbiota in patients with untreated plaque psoriasis revealed a signature dysbiosis for which the researchers developed a psoriasis microbiota index, suggesting the gut microbiota may play a role in psoriasis pathophysiology.14 Research shows that both the MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets, which are relatively rich in fiber and omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated fat and animal protein compared to many diets, cause increases in dietary fiber–metabolizing bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids. These short-chain fatty acids improve gut epithelial integrity and alleviate both gut and systemic inflammation.10

The changes to the gut microbiome induced by a high-fat diet also are concerning. In contrast to the MeD or vegan/vegetarian diets, consumption of a high-fat diet induces alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota that in turn increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines and promote higher intestinal permeability.10 Similarly, high sugar consumption promotes increased intestinal permeability and shifts the gut microbiota to organisms that can rapidly utilize simple carbohydrates at the expense of other beneficial organisms, reducing bacterial diversity.15 The Western diet, which is notable for both high fat and high sugar content, is sometimes referred to as a proinflammatory diet and has been shown to worsen psoriasiformlike lesions in mice.16 Importantly, most research indicates that high fat and high sugar consumption appear to be more prevalent in psoriasis patients,8 but the type of fat consumed in the diet matters. The Western diet includes abundant saturated fat found in meat, dairy products, palm and coconut oils, and processed foods, as well as omega-6 fatty acids that are found in meat, poultry, and eggs. Saturated fat has been shown to promote helper T cell (TH17) accumulation in the skin, and omega-6 fatty acids serve as precursors to various inflammatory lipid mediators.4 This distinction of sources of fat between the Western diet and MeD is important in understanding the diets’ different effects on psoriasis and overall health. As previously discussed, the high intake of omega-3 acids in the MeD is one of the ways it may exert its anti-inflammatory benefits.7

Next Steps in Advising Psoriasis Patients

A major limitation of the data for MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets is limited randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of these diets on psoriasis. Thus, dietary recommendations for psoriasis are not as strong as for other diseases for which more conclusive data exist.8 Although the data on diet and psoriasis are not definitive, perhaps dermatologists should shift the question from “Does this diet definitely improve psoriasis?” to “Does this diet definitely improve my patient’s health as a whole and maybe also their psoriasis?” For instance, the MeD has been shown to reduce the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease as well as to slow cognitive decline.17 Vegan/vegetarian diets focusing on whole vs processed foods have been shown to be highly effective in combatting obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease including severe atherosclerosis, and hypertension.18 Psoriasis patients are at increased risk for many of the ailments that the MeD and plant-based diets protect against, making these diets potentially even more impactful than for someone without psoriasis.19 Dietary recommendations should still be made in conjunction with continuing traditional therapies for psoriasis and in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician and/or dietitian; however, rather than waiting for more randomized controlled trials before making health-promoting recommendations, what would be the downside of starting now? At worst, the dietary change decreases their risk for several metabolic conditions, and at best they may even see an improvement in their psoriasis.

- Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: results from an Italian case–control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:61-67. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23681.x

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, et al. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:304-314. doi:10.1111/bjd.12670

- Zhu K, Zhu C, Fan Y. Alcohol consumption and psoriatic risk: a meta‐analysis of case–control studies. J Dermatol. 2012;39:770-773. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01577.x

- Kanda N, Hoashi T, Saeki H. Nutrition and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5405. doi:10.3390/ijms21155405

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. national survey. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:227-242. doi:10.1007/s13555-017-0183-4

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al. Dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1412

- Duchnik E, Kruk J, Tuchowska A, et al. The impact of diet and physical activity on psoriasis: a narrative review of the current evidence. Nutrients. 2023;15:840. doi:10.3390/nu15040840

- Chung M, Bartholomew E, Yeroushalmi S, et al. Dietary intervention and supplements in the management of psoriasis: current perspectives. Psoriasis Targets Ther. 2022;12:151-176. doi:10.2147/PTT.S328581

- Mazza E, Ferro Y, Pujia R, et al. Mediterranean diet in healthy aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:1076-1083. doi:10.1007/s12603-021-1675-6

- Flores-Balderas X, Peña-Peña M, Rada KM, et al. Beneficial effects of plant-based diets on skin health and inflammatory skin diseases. Nutrients. 2023;15:2842. doi:10.3390/nu15132842

- Bonjour M, Gabriel S, Valencia A, et al. Challenging case in clinical practice: prolonged water-only fasting followed by an exclusively whole-plant-food diet in the management of severe plaque psoriasis. Integr Complement Ther. 2022;28:85-87. doi:10.1089/ict.2022.29010.mbo

- Lewandowska M, Dunbar K, Kassam S. Managing psoriatic arthritis with a whole food plant-based diet: a case study. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15:402-406. doi:10.1177/1559827621993435

- Neufingerl N, Eilander A. Nutrient intake and status in adults consuming plant-based diets compared to meat-eaters: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2021;14:29. doi:10.3390/nu14010029

- Dei-Cas I, Giliberto F, Luce L, et al. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota in non-treated plaque psoriasis patients stratified by disease severity: development of a new psoriasis-microbiome index. Sci Rep. 2020;10:12754. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69537-3

- Satokari R. High intake of sugar and the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory gut bacteria. Nutrients. 2020;12:1348. doi:10.3390/nu12051348

- Shi Z, Wu X, Santos Rocha C, et al. Short-term Western diet intake promotes IL-23–mediated skin and joint inflammation accompanied by changes to the gut microbiota in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:1780-1791. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.032

- Romagnolo DF, Selmin OI. Mediterranean diet and prevention of chronic diseases. Nutr Today. 2017;52:208-222. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000228

- Tuso PJ, Ismail MH, Ha BP, et al. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013;17:61-66. doi:10.7812/TPP/12-085

- Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease for which several lifestyle factors—smoking, alcohol use, and psychological stress—are associated with higher incidence and more severe disease.1-3 Diet also has been implicated as a factor that can affect psoriasis,4 and many patients have shown interest in possible dietary interventions to help their disease.5

In 2018, the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) presented dietary recommendations for patients based on results from a systematic review. From the available literature, only dietary weight reduction with hypocaloric diets in overweight or obese patients could be strongly recommended, and it has been proven that obesity is associated with worse psoriasis severity.6 Other more recent studies have shown that dietary modifications such as intermittent fasting and the ketogenic diet also led to weight loss and improved psoriasis severity in overweight patients; however, it is difficult to discern if the improvement was due to weight loss alone or if the dietary patterns themselves played a role.7,8 The paucity of well-designed studies evaluating the effects of other dietary changes has prevented further guidelines from being written. We propose that dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet (MeD) and vegan/vegetarian diets—even without strong data showing benefits in skin disease—may help to decrease systemic inflammation, improve gut dysbiosis, and help decrease the risk for cardiometabolic comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis.

Mediterranean Diet

The MeD is based on the dietary tendencies of inhabitants from the regions surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and is centered around nutrient-rich foods such as vegetables, olive oil, and legumes while limiting meat and dairy.9 The NPF recommended considering a trial of the MeD based on low-quality evidence.6 Observational studies have indicated that psoriasis patients are less likely to adhere to the MeD, but those who do have less severe disease.8 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Mediterranean diet and psoriasis yielded no prospective interventional studies. Given the association of the MeD with less severe disease, it is important to understand which specific foods in the MeD could be beneficial. Intake of omega-3 fatty acids, such as those found in fatty fish, are important for modulation of systemic inflammation.7 High intake of polyphenols—found in fruits and vegetables, extra-virgin olive oil, and wine—also have been implicated in improving inflammatory diseases due to potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Individually, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and sea fish have been associated with lowering C-reactive protein levels, which also is indicative of the benefits of these foods on systemic inflammation.7

Vegan/Vegetarian Diets

Although fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains are a substantial component of the MeD, there are limited data on vegetarian or purely vegan plant-based diets. An observational study from the NPF found that only 48.4% (15/31) of patients on the MeD vs 69.0% (20/29) on a vegan diet reported a favorable skin response.5 Two case reports also have shown beneficial results of a strict vegan diet for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, where whole-food plant-based diets also improved joint symptoms.10-12 As with any diet, those who pursue a plant-based diet should strive to consume a variety of foods to avoid nutrient deficiencies. A recent systematic meta-analysis of 141 studies evaluated nutrient status of vegan and vegetarian diets compared to pescovegetarians and those who consume meat. All dietary patterns showed varying degrees of low levels of different nutrients.13 Of note, the researchers found that vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, and docosahexaenoic acid were lower in plant-based diets. In contrast, folate; vitamins B1, B6, C, and E; polyunsaturated fatty acids; α-linolenic acid; and magnesium intake were higher. Those who consumed meat were at risk for inadequate intake of fiber, polyunsaturated fatty acids, α-linolenic acid, folate, vitamin E, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D, though vitamin D intake was higher than in vegans/vegetarians.13 The results of this meta-analysis indicated the importance of educating patients on what constitutes a well-rounded, micronutrient-rich diet or appropriate supplementation for any diet.

Effects on Gut Microbiome

Any changes in diet can lead to alterations in the gut microbiome, which may impact skin disease, as evidence indicates a bidirectional relationship between gut and skin health.10 A metagenomic analysis of the gut microbiota in patients with untreated plaque psoriasis revealed a signature dysbiosis for which the researchers developed a psoriasis microbiota index, suggesting the gut microbiota may play a role in psoriasis pathophysiology.14 Research shows that both the MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets, which are relatively rich in fiber and omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated fat and animal protein compared to many diets, cause increases in dietary fiber–metabolizing bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids. These short-chain fatty acids improve gut epithelial integrity and alleviate both gut and systemic inflammation.10

The changes to the gut microbiome induced by a high-fat diet also are concerning. In contrast to the MeD or vegan/vegetarian diets, consumption of a high-fat diet induces alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota that in turn increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines and promote higher intestinal permeability.10 Similarly, high sugar consumption promotes increased intestinal permeability and shifts the gut microbiota to organisms that can rapidly utilize simple carbohydrates at the expense of other beneficial organisms, reducing bacterial diversity.15 The Western diet, which is notable for both high fat and high sugar content, is sometimes referred to as a proinflammatory diet and has been shown to worsen psoriasiformlike lesions in mice.16 Importantly, most research indicates that high fat and high sugar consumption appear to be more prevalent in psoriasis patients,8 but the type of fat consumed in the diet matters. The Western diet includes abundant saturated fat found in meat, dairy products, palm and coconut oils, and processed foods, as well as omega-6 fatty acids that are found in meat, poultry, and eggs. Saturated fat has been shown to promote helper T cell (TH17) accumulation in the skin, and omega-6 fatty acids serve as precursors to various inflammatory lipid mediators.4 This distinction of sources of fat between the Western diet and MeD is important in understanding the diets’ different effects on psoriasis and overall health. As previously discussed, the high intake of omega-3 acids in the MeD is one of the ways it may exert its anti-inflammatory benefits.7

Next Steps in Advising Psoriasis Patients

A major limitation of the data for MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets is limited randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of these diets on psoriasis. Thus, dietary recommendations for psoriasis are not as strong as for other diseases for which more conclusive data exist.8 Although the data on diet and psoriasis are not definitive, perhaps dermatologists should shift the question from “Does this diet definitely improve psoriasis?” to “Does this diet definitely improve my patient’s health as a whole and maybe also their psoriasis?” For instance, the MeD has been shown to reduce the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease as well as to slow cognitive decline.17 Vegan/vegetarian diets focusing on whole vs processed foods have been shown to be highly effective in combatting obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease including severe atherosclerosis, and hypertension.18 Psoriasis patients are at increased risk for many of the ailments that the MeD and plant-based diets protect against, making these diets potentially even more impactful than for someone without psoriasis.19 Dietary recommendations should still be made in conjunction with continuing traditional therapies for psoriasis and in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician and/or dietitian; however, rather than waiting for more randomized controlled trials before making health-promoting recommendations, what would be the downside of starting now? At worst, the dietary change decreases their risk for several metabolic conditions, and at best they may even see an improvement in their psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease for which several lifestyle factors—smoking, alcohol use, and psychological stress—are associated with higher incidence and more severe disease.1-3 Diet also has been implicated as a factor that can affect psoriasis,4 and many patients have shown interest in possible dietary interventions to help their disease.5

In 2018, the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) presented dietary recommendations for patients based on results from a systematic review. From the available literature, only dietary weight reduction with hypocaloric diets in overweight or obese patients could be strongly recommended, and it has been proven that obesity is associated with worse psoriasis severity.6 Other more recent studies have shown that dietary modifications such as intermittent fasting and the ketogenic diet also led to weight loss and improved psoriasis severity in overweight patients; however, it is difficult to discern if the improvement was due to weight loss alone or if the dietary patterns themselves played a role.7,8 The paucity of well-designed studies evaluating the effects of other dietary changes has prevented further guidelines from being written. We propose that dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet (MeD) and vegan/vegetarian diets—even without strong data showing benefits in skin disease—may help to decrease systemic inflammation, improve gut dysbiosis, and help decrease the risk for cardiometabolic comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis.

Mediterranean Diet

The MeD is based on the dietary tendencies of inhabitants from the regions surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and is centered around nutrient-rich foods such as vegetables, olive oil, and legumes while limiting meat and dairy.9 The NPF recommended considering a trial of the MeD based on low-quality evidence.6 Observational studies have indicated that psoriasis patients are less likely to adhere to the MeD, but those who do have less severe disease.8 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Mediterranean diet and psoriasis yielded no prospective interventional studies. Given the association of the MeD with less severe disease, it is important to understand which specific foods in the MeD could be beneficial. Intake of omega-3 fatty acids, such as those found in fatty fish, are important for modulation of systemic inflammation.7 High intake of polyphenols—found in fruits and vegetables, extra-virgin olive oil, and wine—also have been implicated in improving inflammatory diseases due to potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Individually, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and sea fish have been associated with lowering C-reactive protein levels, which also is indicative of the benefits of these foods on systemic inflammation.7

Vegan/Vegetarian Diets

Although fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains are a substantial component of the MeD, there are limited data on vegetarian or purely vegan plant-based diets. An observational study from the NPF found that only 48.4% (15/31) of patients on the MeD vs 69.0% (20/29) on a vegan diet reported a favorable skin response.5 Two case reports also have shown beneficial results of a strict vegan diet for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, where whole-food plant-based diets also improved joint symptoms.10-12 As with any diet, those who pursue a plant-based diet should strive to consume a variety of foods to avoid nutrient deficiencies. A recent systematic meta-analysis of 141 studies evaluated nutrient status of vegan and vegetarian diets compared to pescovegetarians and those who consume meat. All dietary patterns showed varying degrees of low levels of different nutrients.13 Of note, the researchers found that vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, and docosahexaenoic acid were lower in plant-based diets. In contrast, folate; vitamins B1, B6, C, and E; polyunsaturated fatty acids; α-linolenic acid; and magnesium intake were higher. Those who consumed meat were at risk for inadequate intake of fiber, polyunsaturated fatty acids, α-linolenic acid, folate, vitamin E, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D, though vitamin D intake was higher than in vegans/vegetarians.13 The results of this meta-analysis indicated the importance of educating patients on what constitutes a well-rounded, micronutrient-rich diet or appropriate supplementation for any diet.

Effects on Gut Microbiome

Any changes in diet can lead to alterations in the gut microbiome, which may impact skin disease, as evidence indicates a bidirectional relationship between gut and skin health.10 A metagenomic analysis of the gut microbiota in patients with untreated plaque psoriasis revealed a signature dysbiosis for which the researchers developed a psoriasis microbiota index, suggesting the gut microbiota may play a role in psoriasis pathophysiology.14 Research shows that both the MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets, which are relatively rich in fiber and omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated fat and animal protein compared to many diets, cause increases in dietary fiber–metabolizing bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids. These short-chain fatty acids improve gut epithelial integrity and alleviate both gut and systemic inflammation.10

The changes to the gut microbiome induced by a high-fat diet also are concerning. In contrast to the MeD or vegan/vegetarian diets, consumption of a high-fat diet induces alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota that in turn increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines and promote higher intestinal permeability.10 Similarly, high sugar consumption promotes increased intestinal permeability and shifts the gut microbiota to organisms that can rapidly utilize simple carbohydrates at the expense of other beneficial organisms, reducing bacterial diversity.15 The Western diet, which is notable for both high fat and high sugar content, is sometimes referred to as a proinflammatory diet and has been shown to worsen psoriasiformlike lesions in mice.16 Importantly, most research indicates that high fat and high sugar consumption appear to be more prevalent in psoriasis patients,8 but the type of fat consumed in the diet matters. The Western diet includes abundant saturated fat found in meat, dairy products, palm and coconut oils, and processed foods, as well as omega-6 fatty acids that are found in meat, poultry, and eggs. Saturated fat has been shown to promote helper T cell (TH17) accumulation in the skin, and omega-6 fatty acids serve as precursors to various inflammatory lipid mediators.4 This distinction of sources of fat between the Western diet and MeD is important in understanding the diets’ different effects on psoriasis and overall health. As previously discussed, the high intake of omega-3 acids in the MeD is one of the ways it may exert its anti-inflammatory benefits.7

Next Steps in Advising Psoriasis Patients

A major limitation of the data for MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets is limited randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of these diets on psoriasis. Thus, dietary recommendations for psoriasis are not as strong as for other diseases for which more conclusive data exist.8 Although the data on diet and psoriasis are not definitive, perhaps dermatologists should shift the question from “Does this diet definitely improve psoriasis?” to “Does this diet definitely improve my patient’s health as a whole and maybe also their psoriasis?” For instance, the MeD has been shown to reduce the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease as well as to slow cognitive decline.17 Vegan/vegetarian diets focusing on whole vs processed foods have been shown to be highly effective in combatting obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease including severe atherosclerosis, and hypertension.18 Psoriasis patients are at increased risk for many of the ailments that the MeD and plant-based diets protect against, making these diets potentially even more impactful than for someone without psoriasis.19 Dietary recommendations should still be made in conjunction with continuing traditional therapies for psoriasis and in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician and/or dietitian; however, rather than waiting for more randomized controlled trials before making health-promoting recommendations, what would be the downside of starting now? At worst, the dietary change decreases their risk for several metabolic conditions, and at best they may even see an improvement in their psoriasis.

- Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: results from an Italian case–control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:61-67. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23681.x

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, et al. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:304-314. doi:10.1111/bjd.12670

- Zhu K, Zhu C, Fan Y. Alcohol consumption and psoriatic risk: a meta‐analysis of case–control studies. J Dermatol. 2012;39:770-773. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01577.x

- Kanda N, Hoashi T, Saeki H. Nutrition and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5405. doi:10.3390/ijms21155405

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. national survey. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:227-242. doi:10.1007/s13555-017-0183-4

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al. Dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1412

- Duchnik E, Kruk J, Tuchowska A, et al. The impact of diet and physical activity on psoriasis: a narrative review of the current evidence. Nutrients. 2023;15:840. doi:10.3390/nu15040840

- Chung M, Bartholomew E, Yeroushalmi S, et al. Dietary intervention and supplements in the management of psoriasis: current perspectives. Psoriasis Targets Ther. 2022;12:151-176. doi:10.2147/PTT.S328581

- Mazza E, Ferro Y, Pujia R, et al. Mediterranean diet in healthy aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:1076-1083. doi:10.1007/s12603-021-1675-6

- Flores-Balderas X, Peña-Peña M, Rada KM, et al. Beneficial effects of plant-based diets on skin health and inflammatory skin diseases. Nutrients. 2023;15:2842. doi:10.3390/nu15132842

- Bonjour M, Gabriel S, Valencia A, et al. Challenging case in clinical practice: prolonged water-only fasting followed by an exclusively whole-plant-food diet in the management of severe plaque psoriasis. Integr Complement Ther. 2022;28:85-87. doi:10.1089/ict.2022.29010.mbo

- Lewandowska M, Dunbar K, Kassam S. Managing psoriatic arthritis with a whole food plant-based diet: a case study. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15:402-406. doi:10.1177/1559827621993435

- Neufingerl N, Eilander A. Nutrient intake and status in adults consuming plant-based diets compared to meat-eaters: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2021;14:29. doi:10.3390/nu14010029

- Dei-Cas I, Giliberto F, Luce L, et al. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota in non-treated plaque psoriasis patients stratified by disease severity: development of a new psoriasis-microbiome index. Sci Rep. 2020;10:12754. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69537-3

- Satokari R. High intake of sugar and the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory gut bacteria. Nutrients. 2020;12:1348. doi:10.3390/nu12051348

- Shi Z, Wu X, Santos Rocha C, et al. Short-term Western diet intake promotes IL-23–mediated skin and joint inflammation accompanied by changes to the gut microbiota in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:1780-1791. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.032

- Romagnolo DF, Selmin OI. Mediterranean diet and prevention of chronic diseases. Nutr Today. 2017;52:208-222. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000228

- Tuso PJ, Ismail MH, Ha BP, et al. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013;17:61-66. doi:10.7812/TPP/12-085

- Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

- Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: results from an Italian case–control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:61-67. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23681.x

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, et al. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:304-314. doi:10.1111/bjd.12670

- Zhu K, Zhu C, Fan Y. Alcohol consumption and psoriatic risk: a meta‐analysis of case–control studies. J Dermatol. 2012;39:770-773. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01577.x

- Kanda N, Hoashi T, Saeki H. Nutrition and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5405. doi:10.3390/ijms21155405

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. national survey. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:227-242. doi:10.1007/s13555-017-0183-4

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al. Dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1412

- Duchnik E, Kruk J, Tuchowska A, et al. The impact of diet and physical activity on psoriasis: a narrative review of the current evidence. Nutrients. 2023;15:840. doi:10.3390/nu15040840

- Chung M, Bartholomew E, Yeroushalmi S, et al. Dietary intervention and supplements in the management of psoriasis: current perspectives. Psoriasis Targets Ther. 2022;12:151-176. doi:10.2147/PTT.S328581

- Mazza E, Ferro Y, Pujia R, et al. Mediterranean diet in healthy aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:1076-1083. doi:10.1007/s12603-021-1675-6

- Flores-Balderas X, Peña-Peña M, Rada KM, et al. Beneficial effects of plant-based diets on skin health and inflammatory skin diseases. Nutrients. 2023;15:2842. doi:10.3390/nu15132842

- Bonjour M, Gabriel S, Valencia A, et al. Challenging case in clinical practice: prolonged water-only fasting followed by an exclusively whole-plant-food diet in the management of severe plaque psoriasis. Integr Complement Ther. 2022;28:85-87. doi:10.1089/ict.2022.29010.mbo

- Lewandowska M, Dunbar K, Kassam S. Managing psoriatic arthritis with a whole food plant-based diet: a case study. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15:402-406. doi:10.1177/1559827621993435

- Neufingerl N, Eilander A. Nutrient intake and status in adults consuming plant-based diets compared to meat-eaters: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2021;14:29. doi:10.3390/nu14010029

- Dei-Cas I, Giliberto F, Luce L, et al. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota in non-treated plaque psoriasis patients stratified by disease severity: development of a new psoriasis-microbiome index. Sci Rep. 2020;10:12754. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69537-3

- Satokari R. High intake of sugar and the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory gut bacteria. Nutrients. 2020;12:1348. doi:10.3390/nu12051348

- Shi Z, Wu X, Santos Rocha C, et al. Short-term Western diet intake promotes IL-23–mediated skin and joint inflammation accompanied by changes to the gut microbiota in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:1780-1791. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.032

- Romagnolo DF, Selmin OI. Mediterranean diet and prevention of chronic diseases. Nutr Today. 2017;52:208-222. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000228

- Tuso PJ, Ismail MH, Ha BP, et al. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013;17:61-66. doi:10.7812/TPP/12-085

- Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

Practice Points

- Psoriasis is affected by lifestyle factors such as diet, which is an area of interest for many patients.

- Low-calorie diets are strongly recommended for overweight/obese patients with psoriasis to improve their disease.

- Changes in dietary patterns, such as adopting a Mediterranean diet or a plant-based diet, also have shown promise.

Association Between Atopic Dermatitis and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among US Adults in the 1999-2006 NHANES Survey

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 16.5 million adults in the United States.1 Atopic dermatitis is associated with skin barrier dysfunction and the activation of type 2 inflammatory cytokines. Multiorgan involvement of AD has been demonstrated, as patients with AD are more prone to asthma, allergic rhinitis, and other systemic diseases.2 In 2020, Smirnova et al3 reported a significant association (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.30-1.92) between AD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in a large Swedish population. Currently, there is a lack of research evaluating the association between AD and COPD in a population of US adults. Therefore, we explored the association between AD and COPD (chronic bronchitis or emphysema) in a population of US adults utilizing the 1999-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), as these were the latest data for AD available in NHANES.4

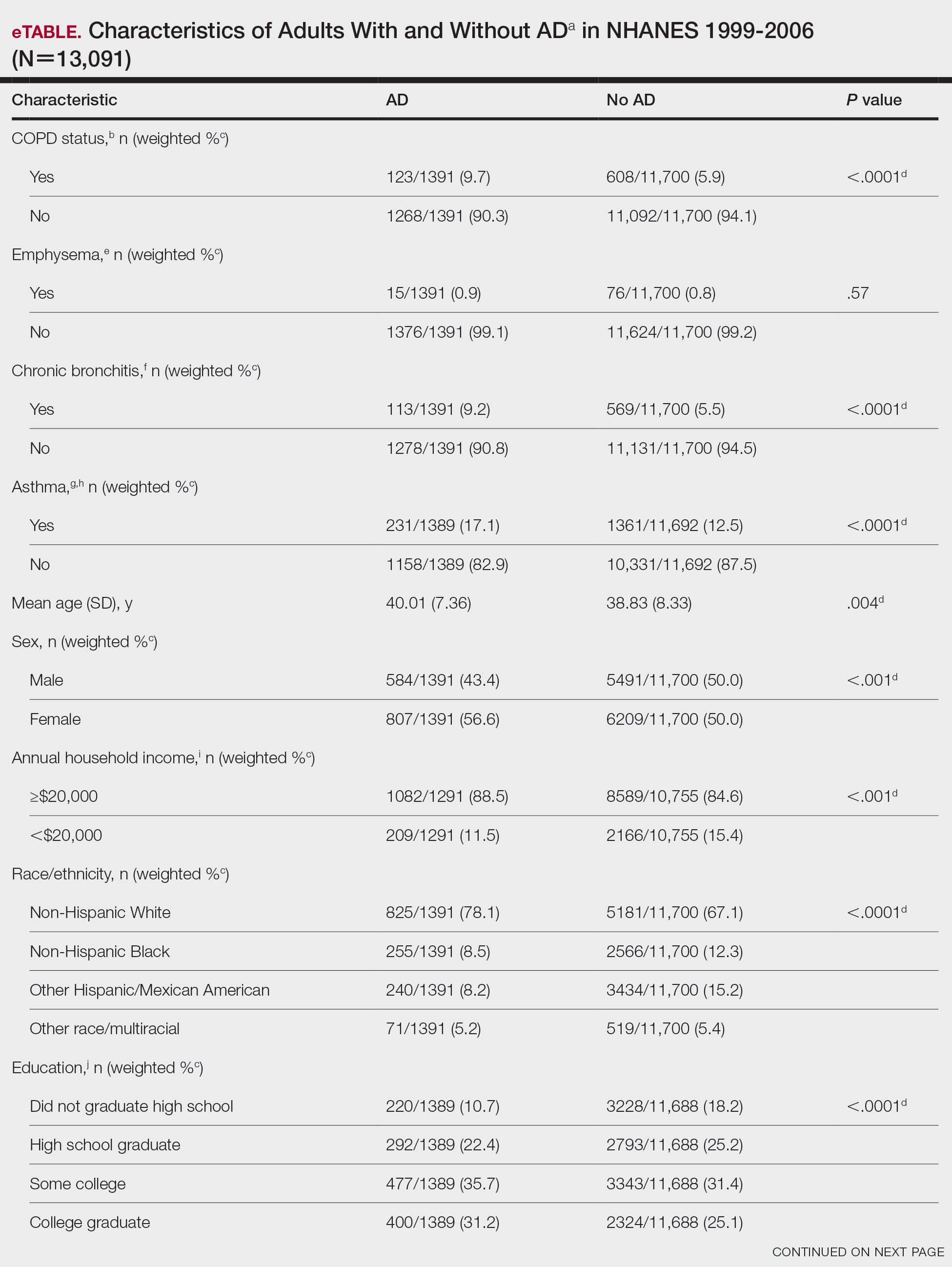

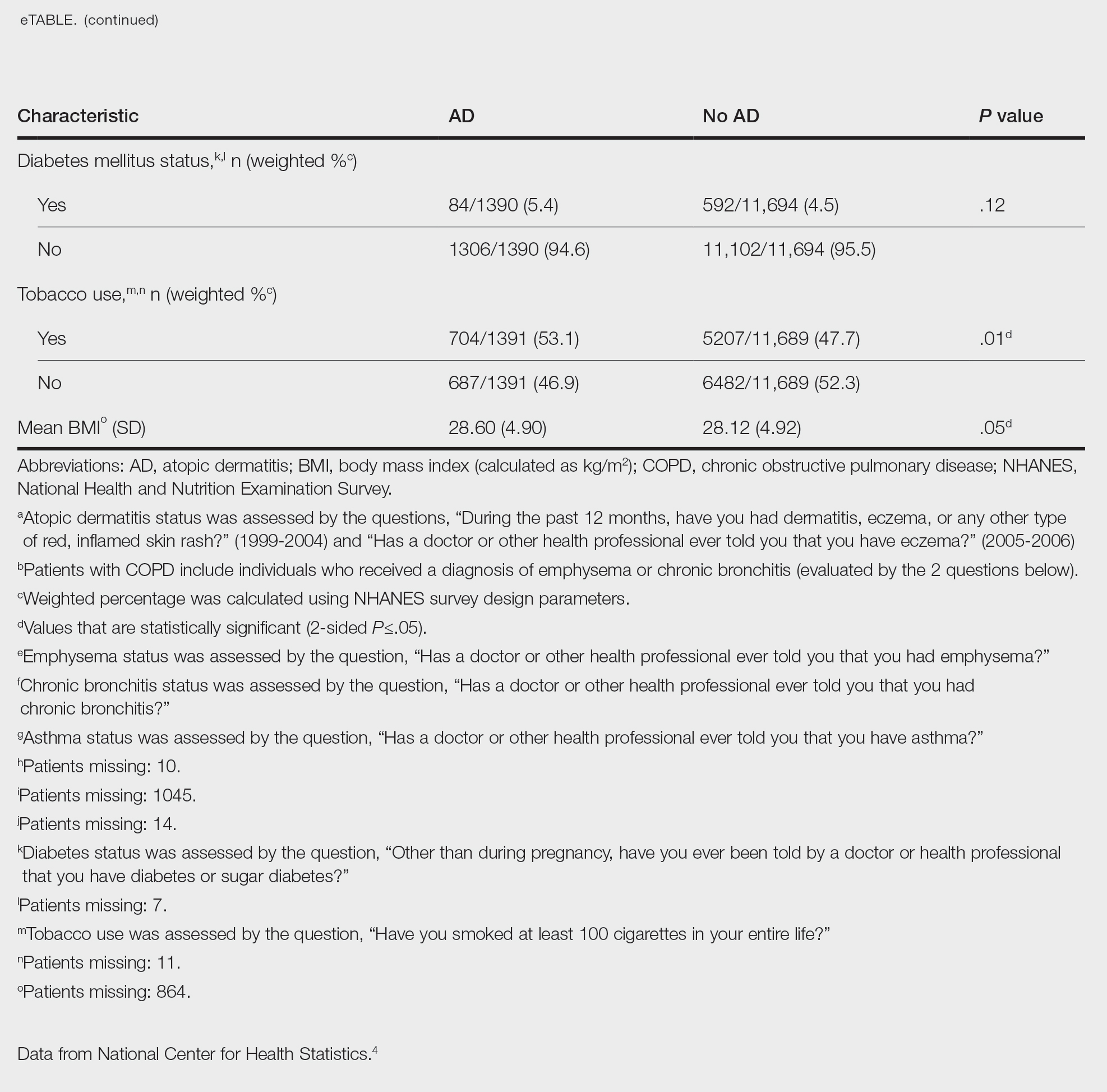

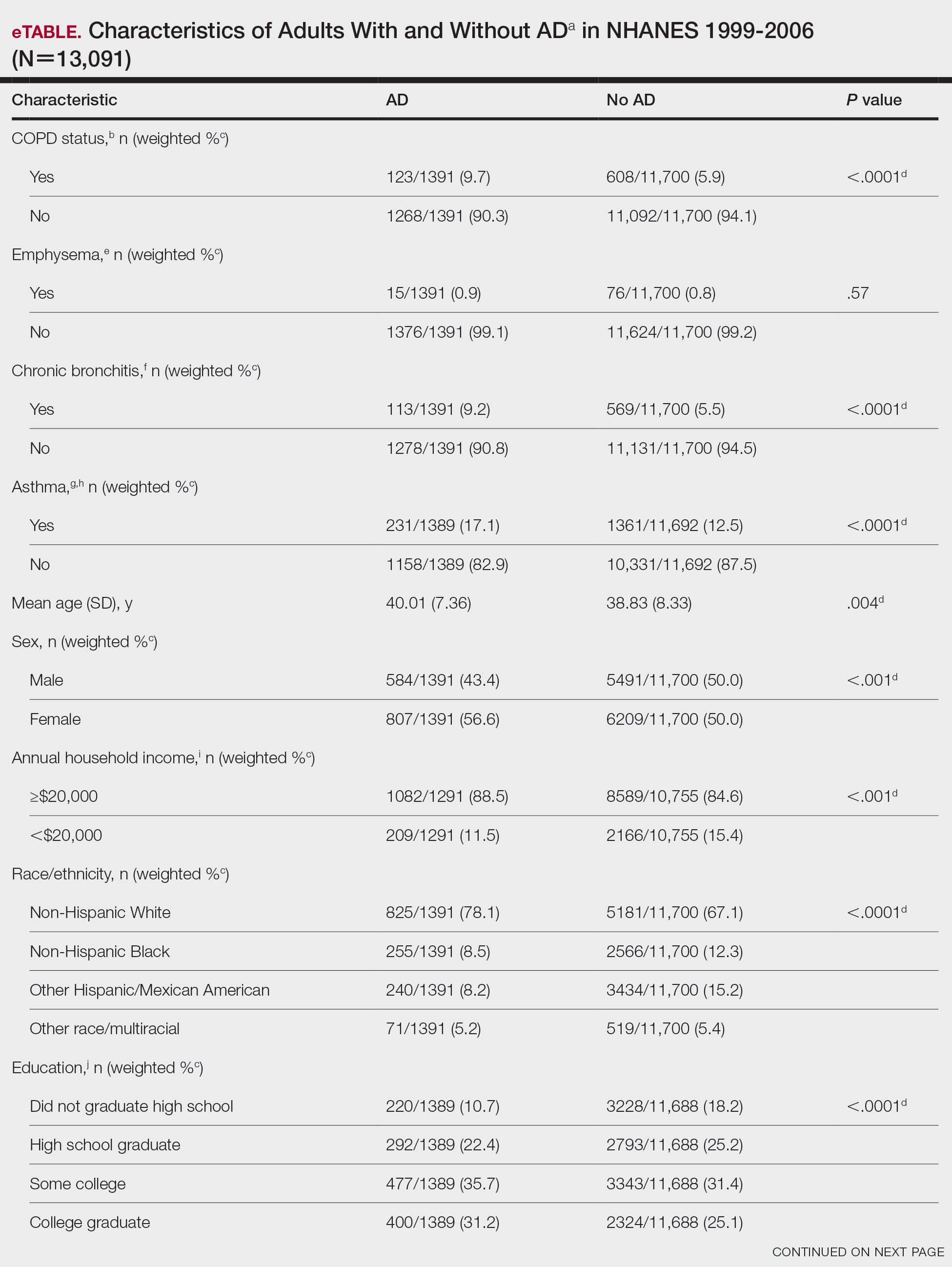

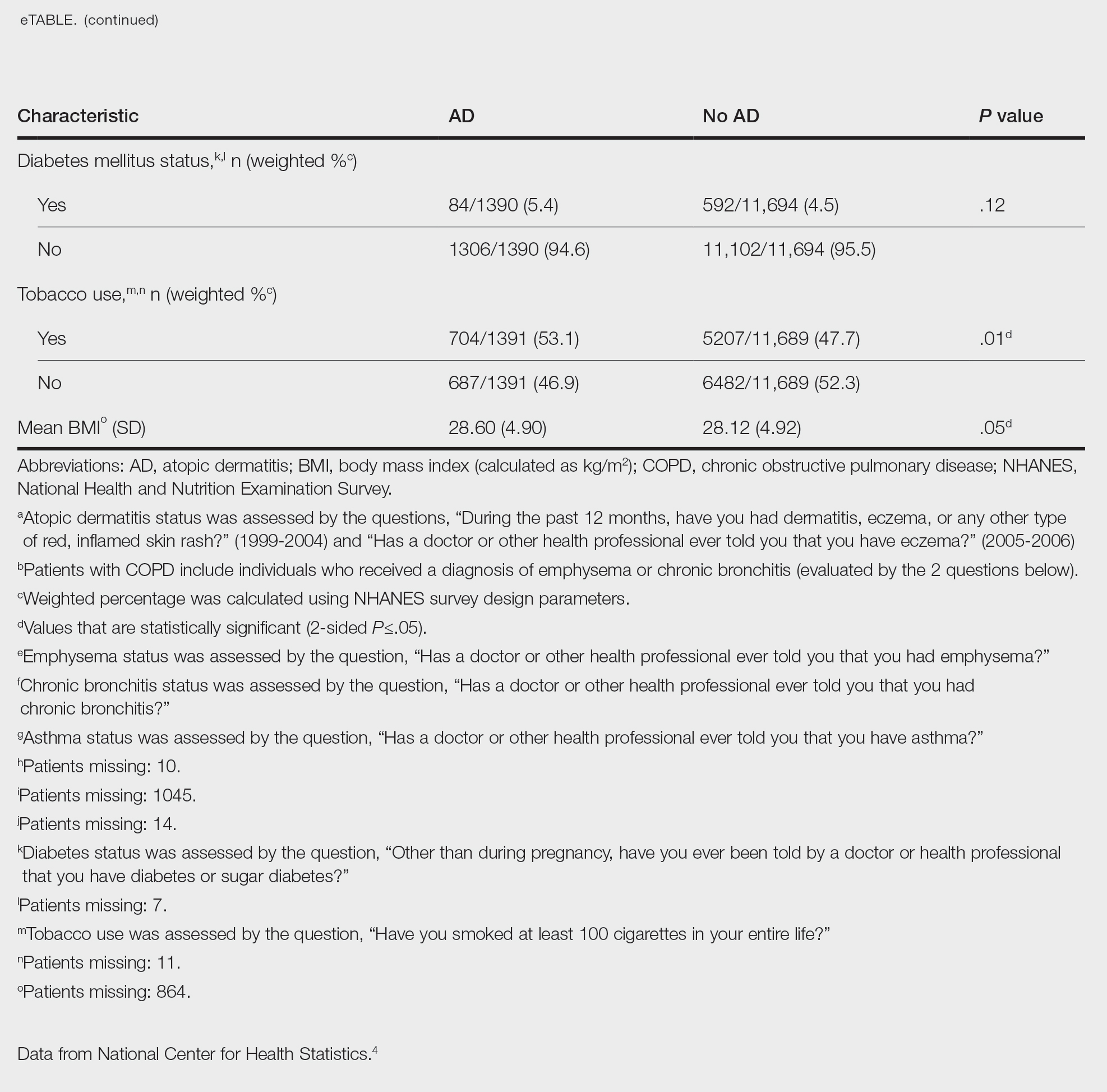

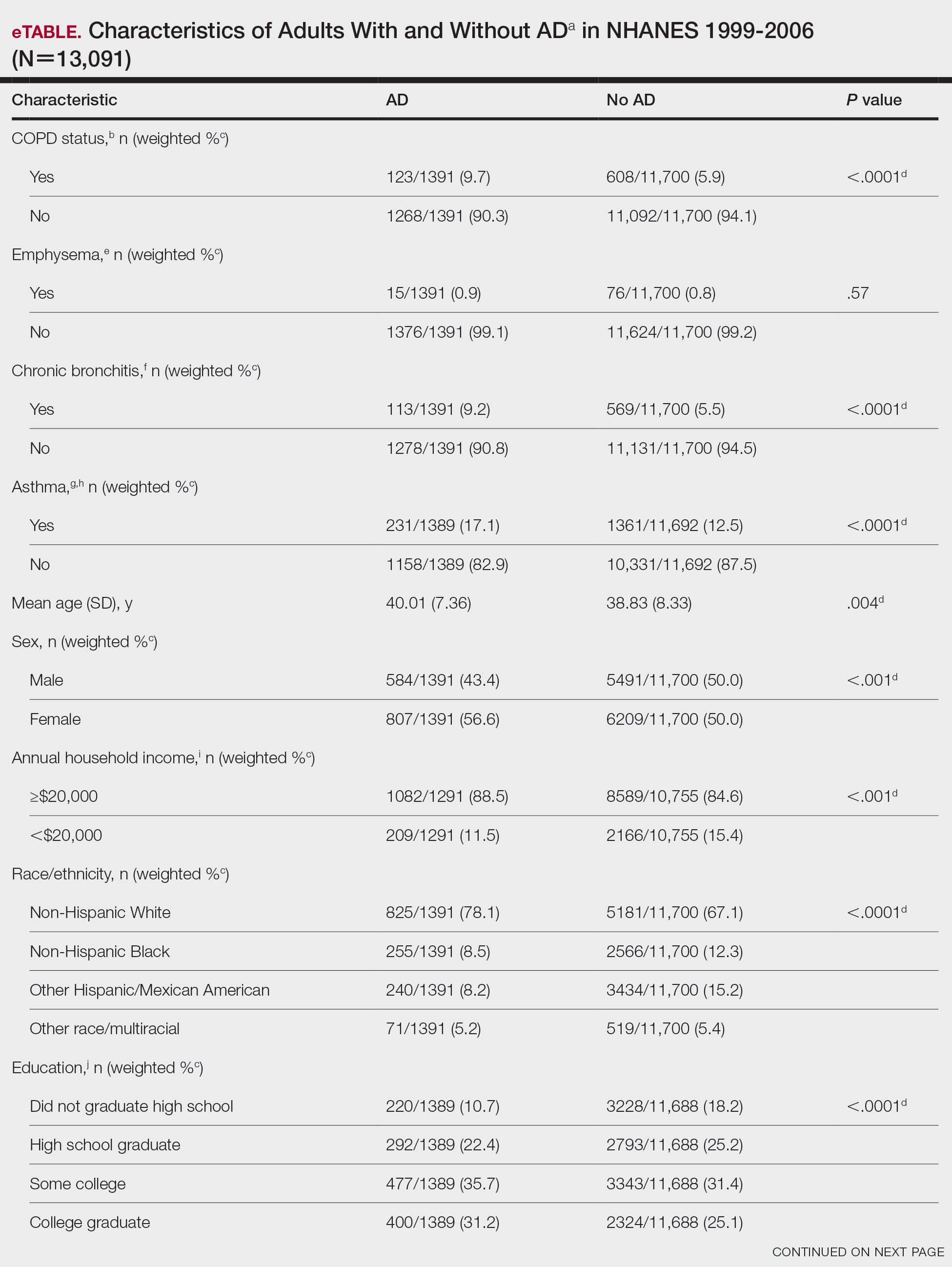

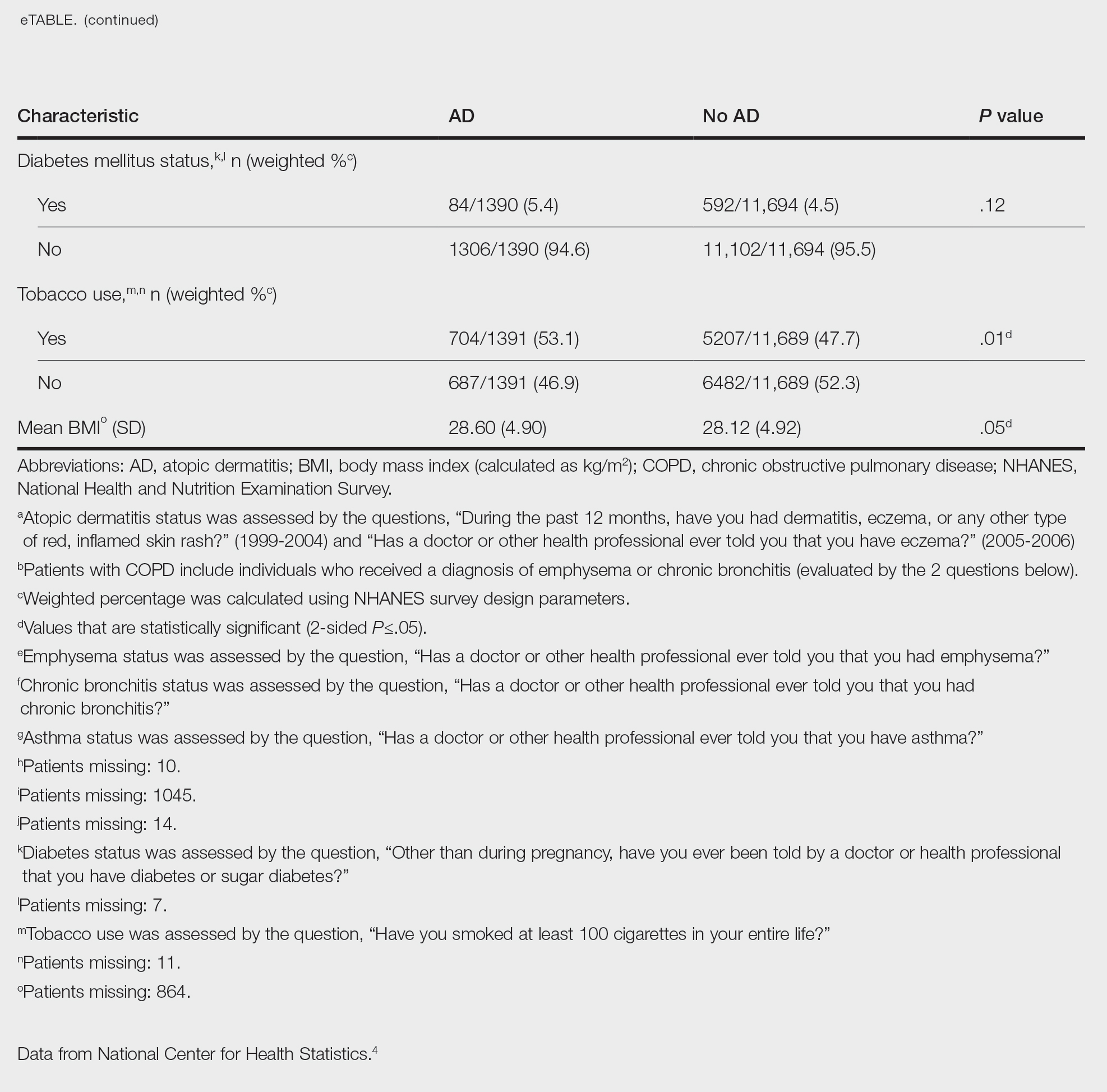

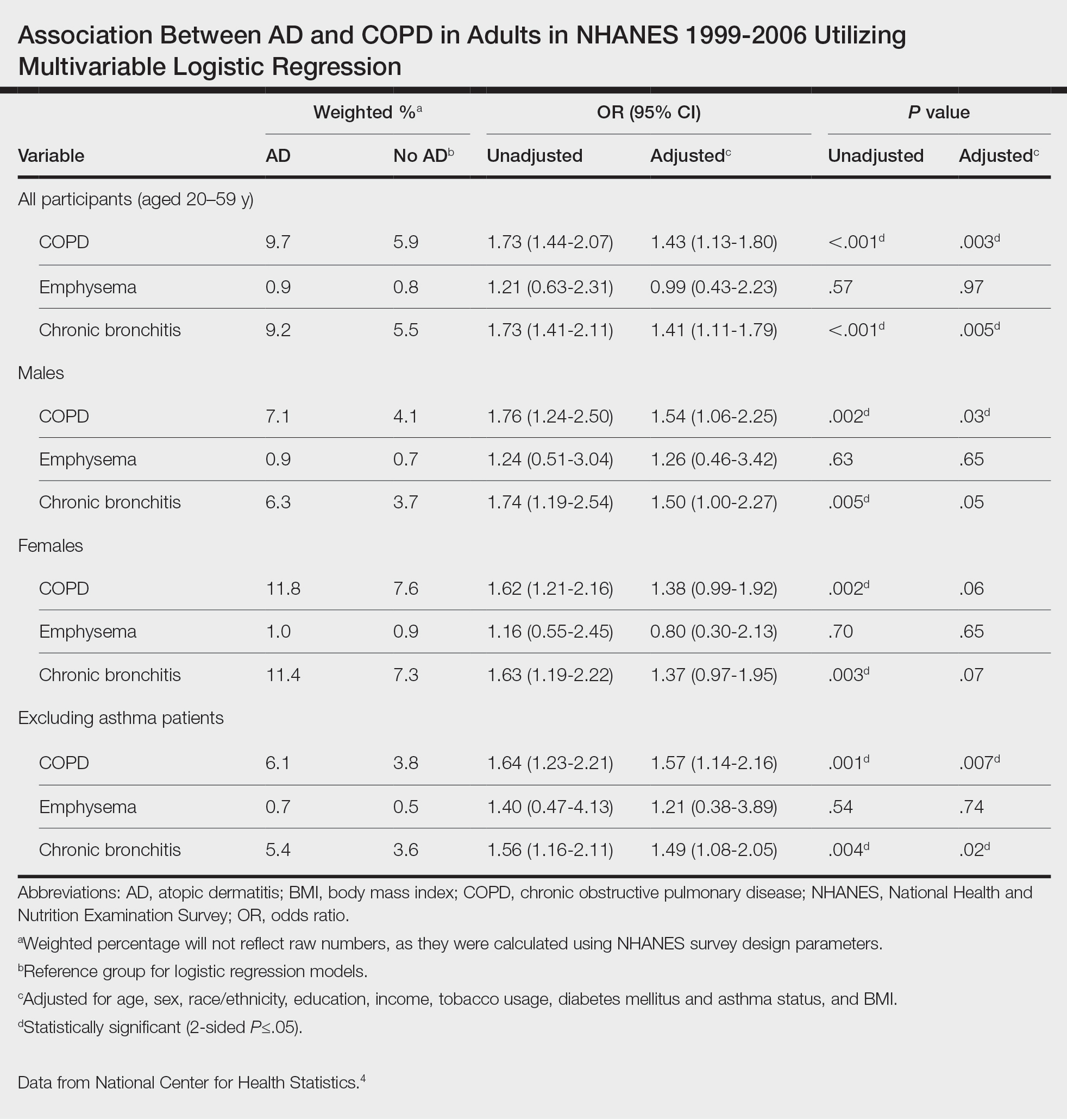

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 1999-2006 NHANES database. Three outcome variables—emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and COPD—and numerous confounding variables for each participant were extracted from the NHANES database. The original cohort consisted of 13,134 participants, and 43 patients were excluded from our analysis owing to the lack of response to survey questions regarding AD and COPD status. The relationship between AD and COPD was evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analyses utilizing Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our logistic regression models, we controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, tobacco usage, diabetes mellitus and asthma status, and body mass index (eTable).

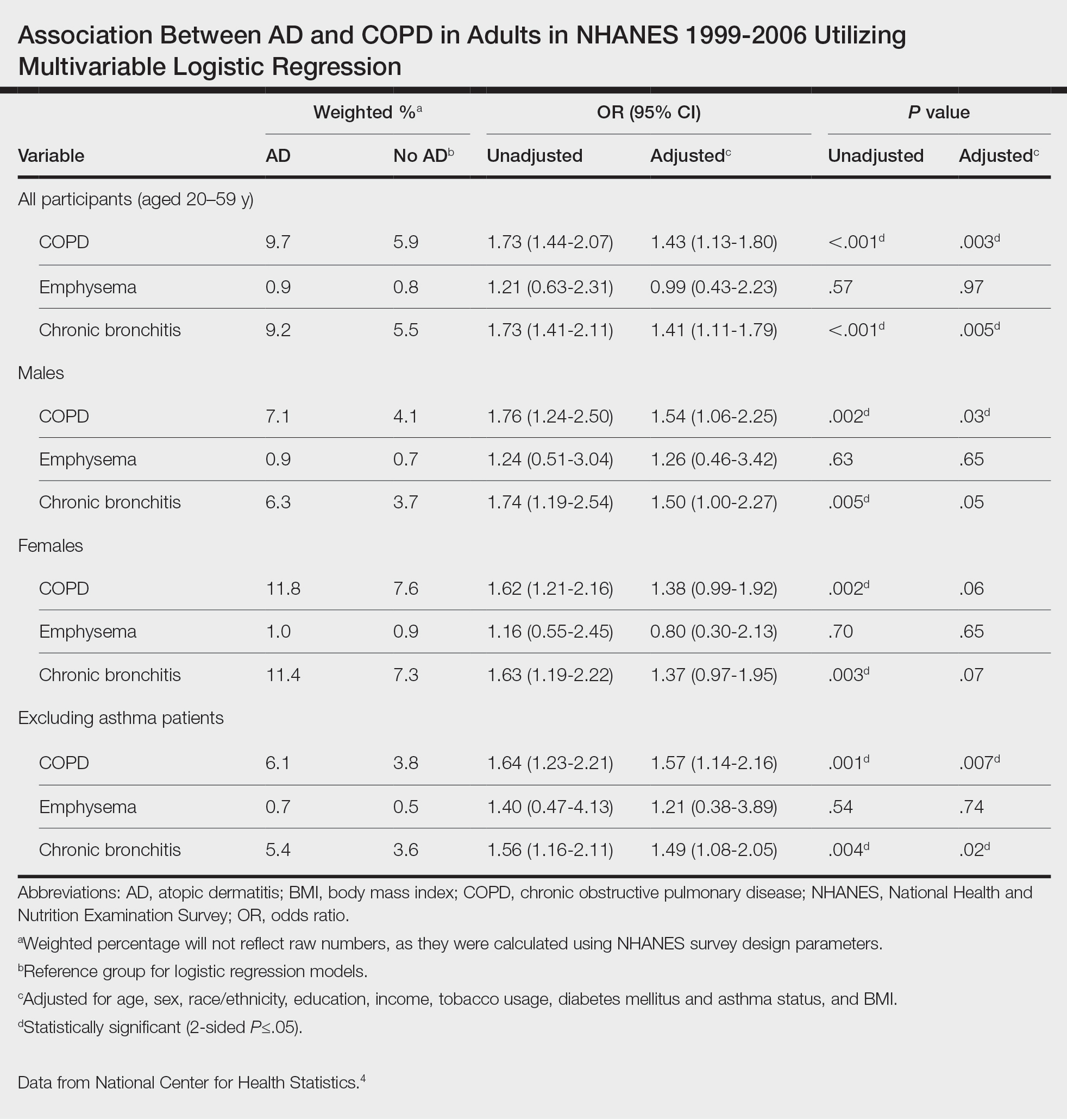

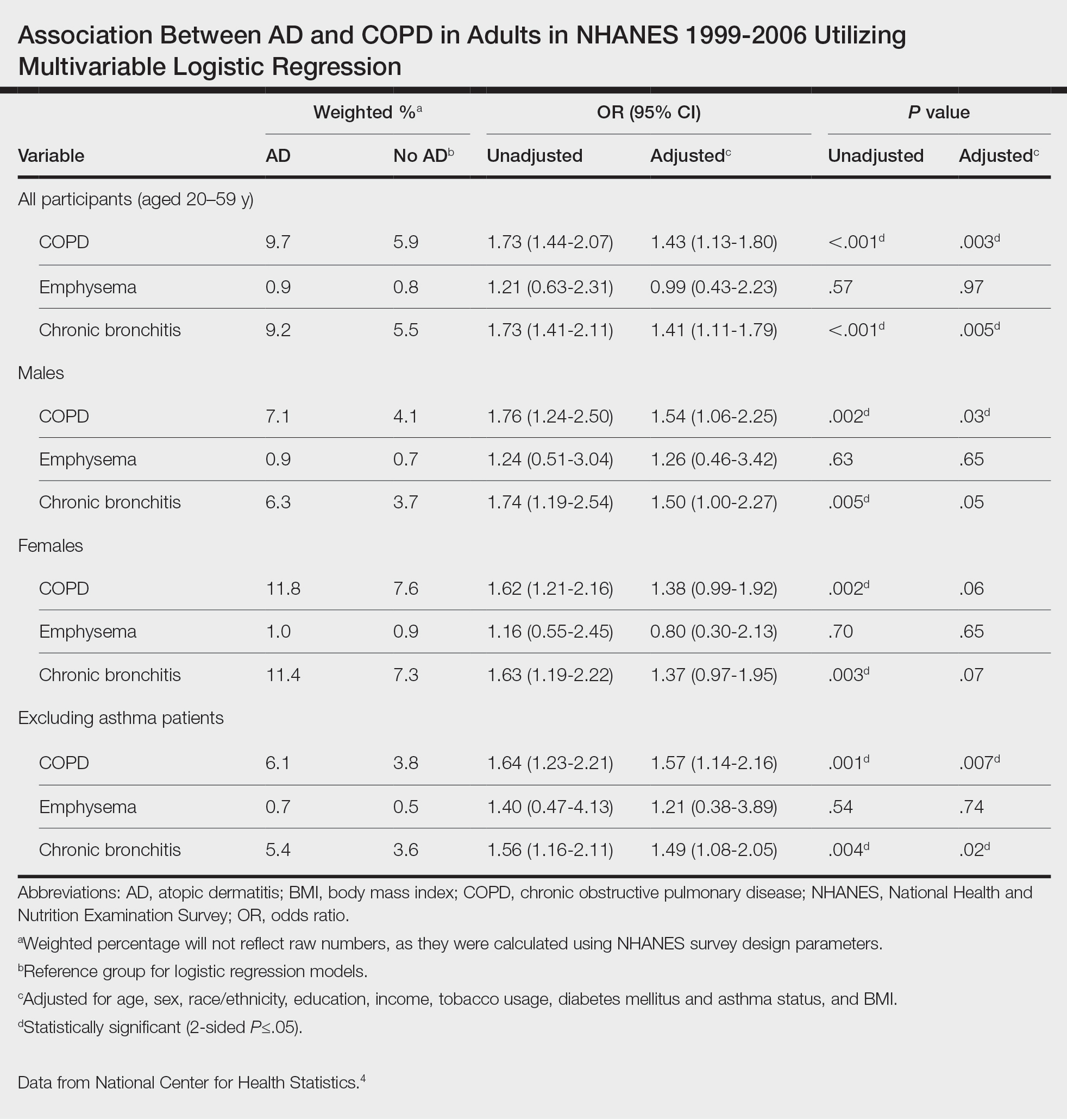

Our study consisted of 13,091 participants. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between AD and COPD (Table). Approximately 12.5% (weighted) of the patients in our analysis had AD. Additionally, 9.7% (weighted) of patients with AD had received a diagnosis of COPD; conversely, 5.9% (weighted) of patients without AD had received a diagnosis of COPD. More patients with AD reported a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis (9.2%) rather than emphysema (0.9%). Our analysis revealed a significant association between AD and COPD among adults aged 20 to 59 years (AOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.13-1.80; P=.003) after controlling for potential confounding variables. Subsequently, we performed subgroup analyses, including exclusion of patients with an asthma diagnosis, to further explore the association between AD and COPD. After excluding participants with asthma, there was still a significant association between AD and COPD (AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.14-2.16; P=.007). Moreover, the odds of receiving a COPD diagnosis were significantly higher among male patients with AD (AOR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.06-2.25; P=.03).

Our results support the association between AD and COPD, more specifically chronic bronchitis. This finding may be due to similar pathogenic mechanisms in both conditions, including overlapping cytokine production and immune pathways.5 Additionally, Harazin et al6 discussed the role of a novel gene, collagen 29A1 (COL29A1), in the pathogenesis of AD, COPD, and asthma. Variations in this gene may predispose patients to not only atopic diseases but also COPD.6

Limitations of our study include self-reported diagnoses and lack of patients older than 59 years. Self-reported diagnoses could have resulted in some misclassification of COPD, as some individuals may have reported a diagnosis of COPD rather than their true diagnosis of asthma. We mitigated this limitation by constructing a subpopulation model with exclusion of individuals with asthma. Further studies with spirometry-diagnosed COPD are needed to explore this relationship and the potential contributory pathophysiologic mechanisms. Understanding this association may increase awareness of potential comorbidities and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028

- Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, Hristakieva E, et al. Atopic dermatitis as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:409-413. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.007

- Smirnova J, Montgomery S, Lindberg M, et al. Associations of self-reported atopic dermatitis with comorbid conditions in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20:23. doi:10.1186/s12895-020-00117-8

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Kawayama T, Okamoto M, Imaoka H, et al. Interleukin-18 in pulmonary inflammatory diseases. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32:443-449. doi:10.1089/jir.2012.0029

- Harazin M, Parwez Q, Petrasch-Parwez E, et al. Variation in the COL29A1 gene in German patients with atopic dermatitis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:740-742. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00923.x

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 16.5 million adults in the United States.1 Atopic dermatitis is associated with skin barrier dysfunction and the activation of type 2 inflammatory cytokines. Multiorgan involvement of AD has been demonstrated, as patients with AD are more prone to asthma, allergic rhinitis, and other systemic diseases.2 In 2020, Smirnova et al3 reported a significant association (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.30-1.92) between AD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in a large Swedish population. Currently, there is a lack of research evaluating the association between AD and COPD in a population of US adults. Therefore, we explored the association between AD and COPD (chronic bronchitis or emphysema) in a population of US adults utilizing the 1999-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), as these were the latest data for AD available in NHANES.4

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 1999-2006 NHANES database. Three outcome variables—emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and COPD—and numerous confounding variables for each participant were extracted from the NHANES database. The original cohort consisted of 13,134 participants, and 43 patients were excluded from our analysis owing to the lack of response to survey questions regarding AD and COPD status. The relationship between AD and COPD was evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analyses utilizing Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our logistic regression models, we controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, tobacco usage, diabetes mellitus and asthma status, and body mass index (eTable).

Our study consisted of 13,091 participants. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between AD and COPD (Table). Approximately 12.5% (weighted) of the patients in our analysis had AD. Additionally, 9.7% (weighted) of patients with AD had received a diagnosis of COPD; conversely, 5.9% (weighted) of patients without AD had received a diagnosis of COPD. More patients with AD reported a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis (9.2%) rather than emphysema (0.9%). Our analysis revealed a significant association between AD and COPD among adults aged 20 to 59 years (AOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.13-1.80; P=.003) after controlling for potential confounding variables. Subsequently, we performed subgroup analyses, including exclusion of patients with an asthma diagnosis, to further explore the association between AD and COPD. After excluding participants with asthma, there was still a significant association between AD and COPD (AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.14-2.16; P=.007). Moreover, the odds of receiving a COPD diagnosis were significantly higher among male patients with AD (AOR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.06-2.25; P=.03).

Our results support the association between AD and COPD, more specifically chronic bronchitis. This finding may be due to similar pathogenic mechanisms in both conditions, including overlapping cytokine production and immune pathways.5 Additionally, Harazin et al6 discussed the role of a novel gene, collagen 29A1 (COL29A1), in the pathogenesis of AD, COPD, and asthma. Variations in this gene may predispose patients to not only atopic diseases but also COPD.6

Limitations of our study include self-reported diagnoses and lack of patients older than 59 years. Self-reported diagnoses could have resulted in some misclassification of COPD, as some individuals may have reported a diagnosis of COPD rather than their true diagnosis of asthma. We mitigated this limitation by constructing a subpopulation model with exclusion of individuals with asthma. Further studies with spirometry-diagnosed COPD are needed to explore this relationship and the potential contributory pathophysiologic mechanisms. Understanding this association may increase awareness of potential comorbidities and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 16.5 million adults in the United States.1 Atopic dermatitis is associated with skin barrier dysfunction and the activation of type 2 inflammatory cytokines. Multiorgan involvement of AD has been demonstrated, as patients with AD are more prone to asthma, allergic rhinitis, and other systemic diseases.2 In 2020, Smirnova et al3 reported a significant association (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.30-1.92) between AD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in a large Swedish population. Currently, there is a lack of research evaluating the association between AD and COPD in a population of US adults. Therefore, we explored the association between AD and COPD (chronic bronchitis or emphysema) in a population of US adults utilizing the 1999-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), as these were the latest data for AD available in NHANES.4

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 1999-2006 NHANES database. Three outcome variables—emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and COPD—and numerous confounding variables for each participant were extracted from the NHANES database. The original cohort consisted of 13,134 participants, and 43 patients were excluded from our analysis owing to the lack of response to survey questions regarding AD and COPD status. The relationship between AD and COPD was evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analyses utilizing Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our logistic regression models, we controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, tobacco usage, diabetes mellitus and asthma status, and body mass index (eTable).

Our study consisted of 13,091 participants. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between AD and COPD (Table). Approximately 12.5% (weighted) of the patients in our analysis had AD. Additionally, 9.7% (weighted) of patients with AD had received a diagnosis of COPD; conversely, 5.9% (weighted) of patients without AD had received a diagnosis of COPD. More patients with AD reported a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis (9.2%) rather than emphysema (0.9%). Our analysis revealed a significant association between AD and COPD among adults aged 20 to 59 years (AOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.13-1.80; P=.003) after controlling for potential confounding variables. Subsequently, we performed subgroup analyses, including exclusion of patients with an asthma diagnosis, to further explore the association between AD and COPD. After excluding participants with asthma, there was still a significant association between AD and COPD (AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.14-2.16; P=.007). Moreover, the odds of receiving a COPD diagnosis were significantly higher among male patients with AD (AOR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.06-2.25; P=.03).

Our results support the association between AD and COPD, more specifically chronic bronchitis. This finding may be due to similar pathogenic mechanisms in both conditions, including overlapping cytokine production and immune pathways.5 Additionally, Harazin et al6 discussed the role of a novel gene, collagen 29A1 (COL29A1), in the pathogenesis of AD, COPD, and asthma. Variations in this gene may predispose patients to not only atopic diseases but also COPD.6

Limitations of our study include self-reported diagnoses and lack of patients older than 59 years. Self-reported diagnoses could have resulted in some misclassification of COPD, as some individuals may have reported a diagnosis of COPD rather than their true diagnosis of asthma. We mitigated this limitation by constructing a subpopulation model with exclusion of individuals with asthma. Further studies with spirometry-diagnosed COPD are needed to explore this relationship and the potential contributory pathophysiologic mechanisms. Understanding this association may increase awareness of potential comorbidities and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028

- Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, Hristakieva E, et al. Atopic dermatitis as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:409-413. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.007

- Smirnova J, Montgomery S, Lindberg M, et al. Associations of self-reported atopic dermatitis with comorbid conditions in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20:23. doi:10.1186/s12895-020-00117-8

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Kawayama T, Okamoto M, Imaoka H, et al. Interleukin-18 in pulmonary inflammatory diseases. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32:443-449. doi:10.1089/jir.2012.0029

- Harazin M, Parwez Q, Petrasch-Parwez E, et al. Variation in the COL29A1 gene in German patients with atopic dermatitis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:740-742. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00923.x

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028

- Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, Hristakieva E, et al. Atopic dermatitis as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:409-413. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.007

- Smirnova J, Montgomery S, Lindberg M, et al. Associations of self-reported atopic dermatitis with comorbid conditions in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20:23. doi:10.1186/s12895-020-00117-8

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Kawayama T, Okamoto M, Imaoka H, et al. Interleukin-18 in pulmonary inflammatory diseases. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32:443-449. doi:10.1089/jir.2012.0029

- Harazin M, Parwez Q, Petrasch-Parwez E, et al. Variation in the COL29A1 gene in German patients with atopic dermatitis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:740-742. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00923.x

Practice Points

- Various comorbidities are associated with atopic dermatitis (AD). Currently, research exploring the association between AD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is limited.

- Understanding the systemic diseases associated with inflammatory skin diseases can assist with adequate patient management.

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis: A Review of the Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Acute generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare severe variant of psoriasis characterized by the sudden widespread eruption of sterile pustules.1,2 The cutaneous manifestations of GPP also may be accompanied by signs of systemic inflammation, including fever, malaise, and leukocytosis.2 Complications are common and may be life-threatening, especially in older patients with comorbid diseases.3 Generalized pustular psoriasis most commonly occurs in patients with a preceding history of psoriasis, but it also may occur de novo.4 Generalized pustular psoriasis is associated with notable morbidity and mortality, and relapses are common.3,4 Many triggers of GPP have been identified, including initiation and withdrawal of various medications, infections, pregnancy, and other conditions.5,6 Although GPP most often occurs in adults, it also may arise in children and infants.3 In pregnancy, GPP is referred to as impetigo herpetiformis, despite having no etiologic ties with either herpes simplex virus or staphylococcal or streptococcal infection. Impetigo herpetiformis is considered one of the most dangerous dermatoses of pregnancy because of high rates of associated maternal and fetal morbidity.6,7

Acute GPP has proven to be a challenging disease to treat due to the rarity and relapsing-remitting nature of the disease; additionally, there are relatively few randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments for GPP. This review summarizes the features of GPP, including the pathophysiology of the disease, clinical and histological manifestations, and recommendations for management based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using MeSH terms pertaining to the disease, including generalized pustular psoriasis, impetigo herpetiformis, and von Zumbusch psoriasis.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GPP is only partially understood, but it is thought to have a distinct pattern of immune activation compared with plaque psoriasis.8 Although there is a considerable amount of overlap and cross-talk among cytokine pathways, GPP generally is driven by innate immunity and unrestrained IL-36 cytokine activity. In contrast, adaptive immune responses—namely the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, IL-23, IL-17, and IL-22 axes—underlie plaque psoriasis.8-10

Proinflammatory IL-36 cytokines α, β, and γ, which are all part of the IL-1 superfamily, bind to the IL-36 receptor (IL-36R) to recruit and activate immune cells via various mediators, including IL-1β; IL-8; and chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8.3 The IL-36 receptor antagonist (IL-36ra) acts to inhibit this inflammatory cascade.3,8 Microarray analyses of skin biopsy samples have shown that overexpression of IL-17A, TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-36 are seen in both GPP and plaque psoriasis lesions, but GPP lesions had higher expression of IL-1β, IL-36α, and IL-36γ and elevated neutrophil chemokines—CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8—compared with plaque psoriasis lesions.8

Gene Mutations Associated With GPP

There are 3 gene mutations that have been associated with pustular variants of psoriasis, though these mutations account for a minority of cases of GPP.4 Genetic screenings are not routinely indicated in patients with GPP, but they may be warranted in severe cases when a familial pattern of inheritance is suspected.4

IL36RN—The gene IL36RN codes the anti-inflammatory IL-36ra. Loss-of-function mutations in IL36RN lead to impairment of IL-36ra and consequently hyperactivity of the proinflammatory responses triggered by IL-36.3 Homozygous and heterozygous mutations in IL36RN have been observed in both familial and sporadic cases of GPP.11-13 Subsequent retrospective analyses have identified the presence of IL36RN mutations in patients with GPP with frequencies ranging from 23% to 37%.14-17IL36RN mutations are thought to be more common in patients without concomitant plaque psoriasis and have been associated with severe disease and early disease onset.15

CARD14—A gain-of-function mutation in CARD14 results in overactivation of the proinflammatory nuclear factor κB pathway and has been implicated in cases of GPP with concurrent psoriasis vulgaris. Interestingly, this may suggest distinct etiologies underlying GPP de novo and GPP in patients with a history of psoriasis.18,19

AP1S3—A loss-of-function mutation in AP1S3 results in abnormal endosomal trafficking and autophagy as well as increased expression of IL-36α.20,21

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis Cutaneous Manifestations of GPP

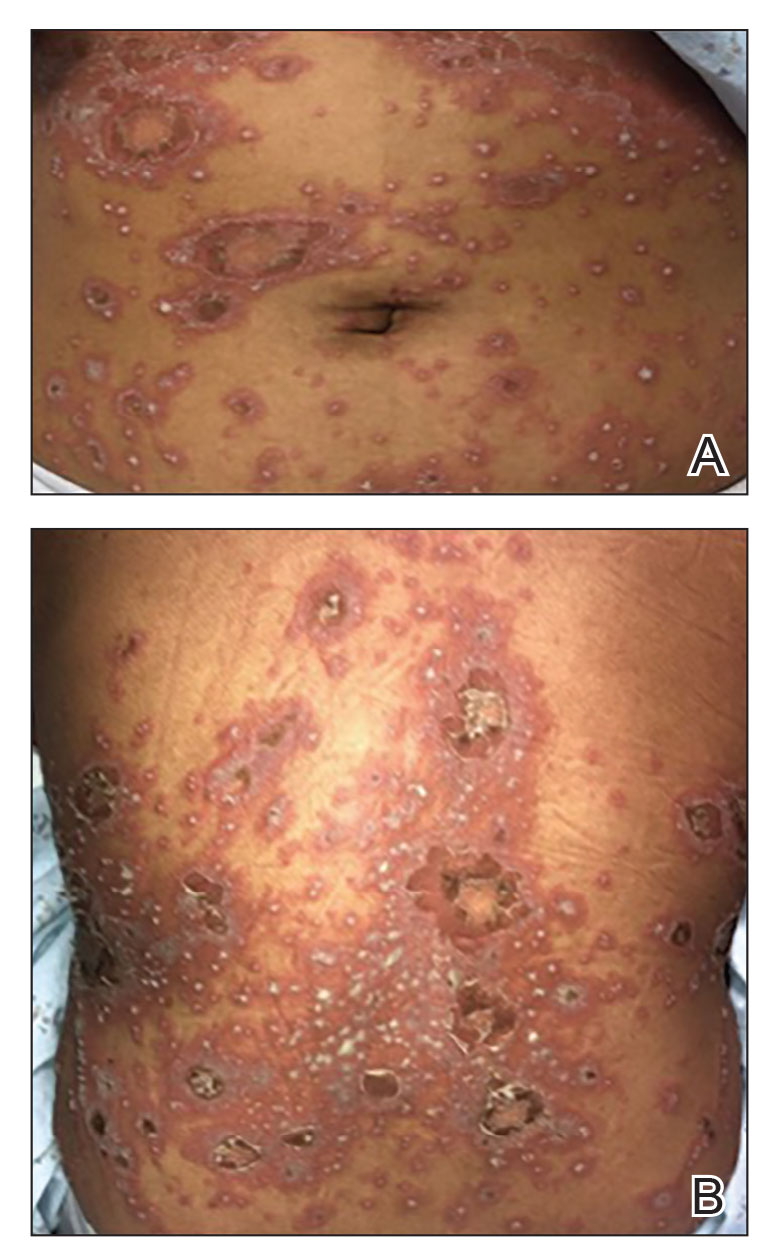

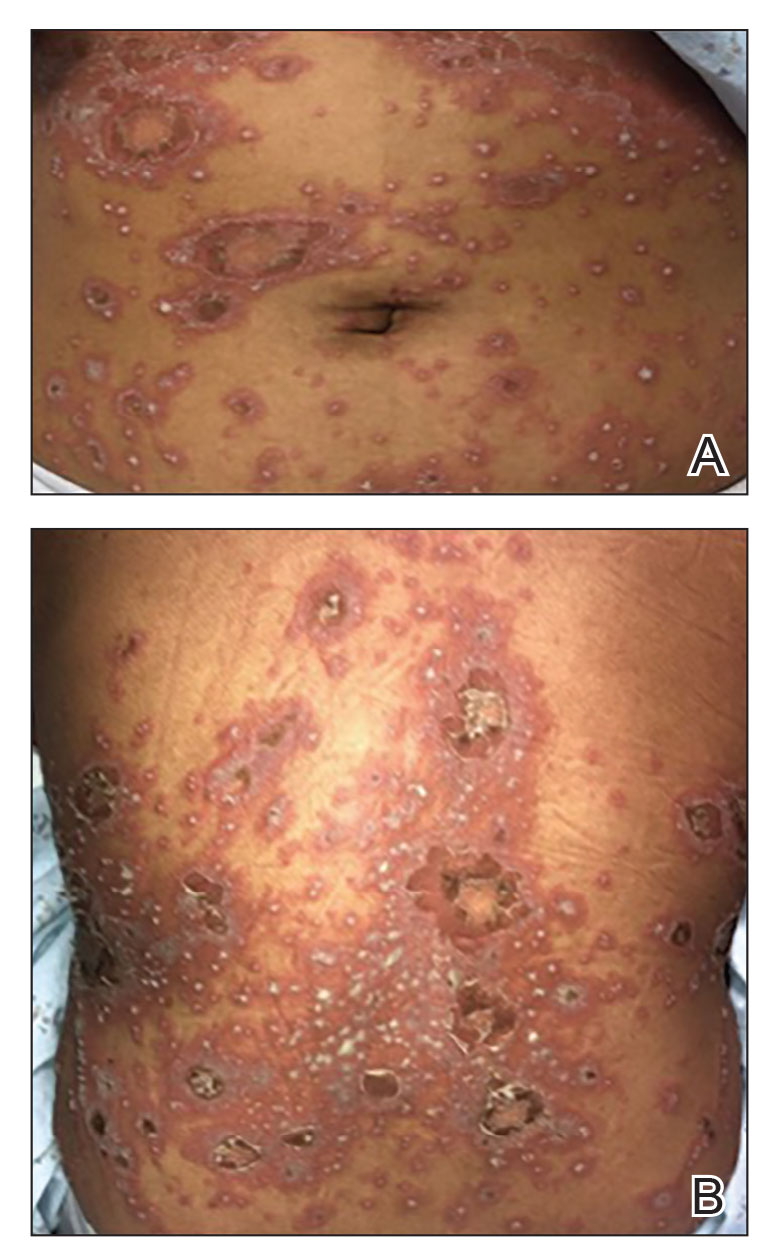

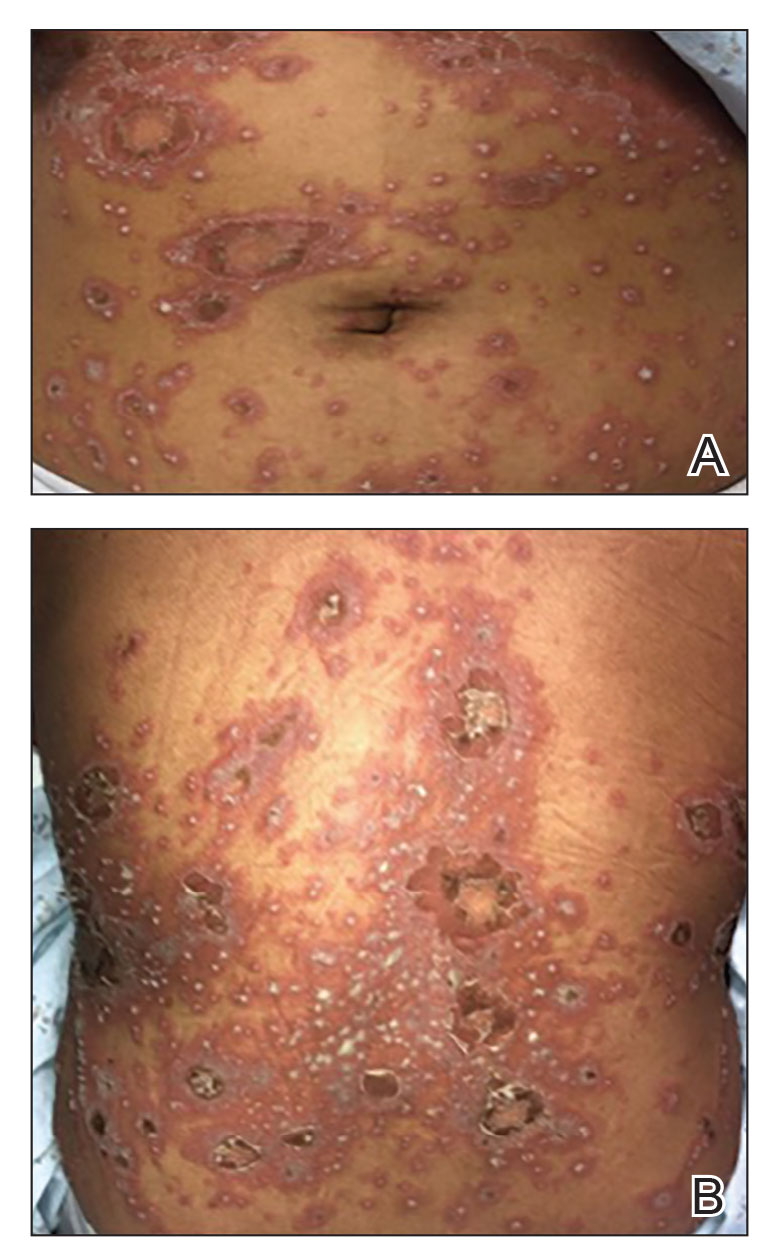

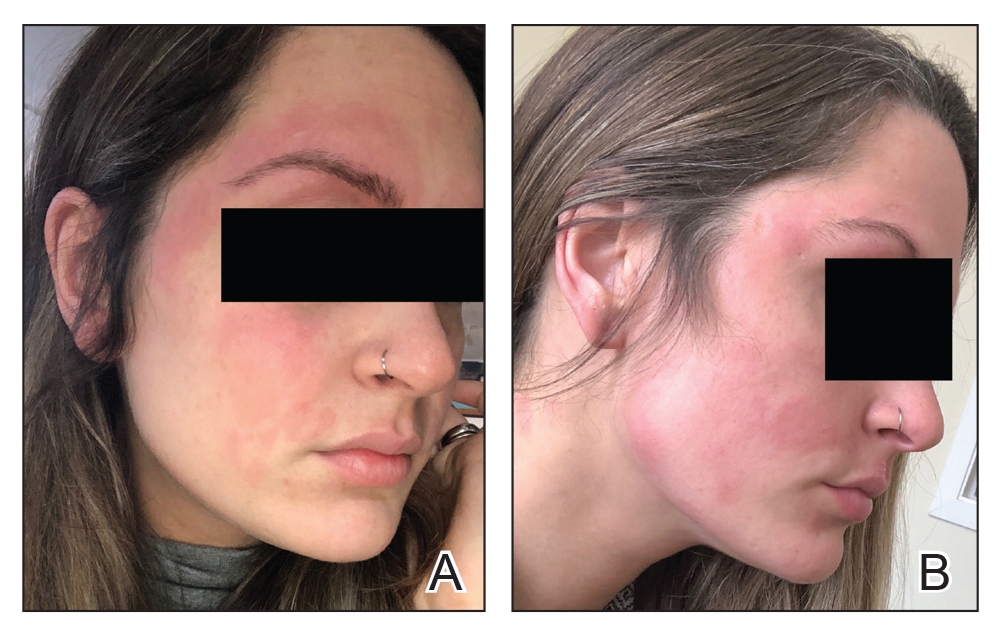

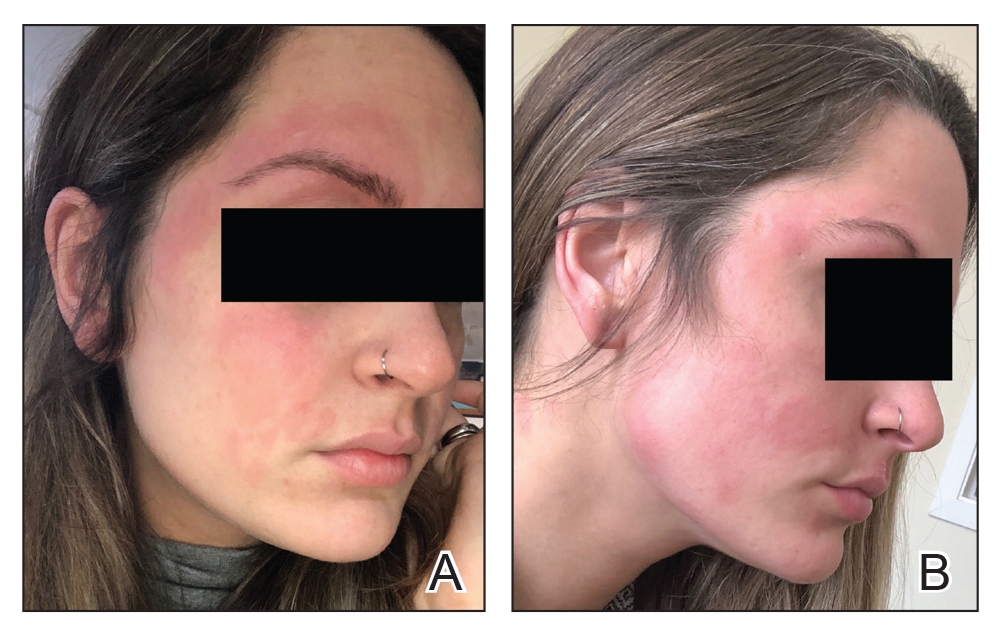

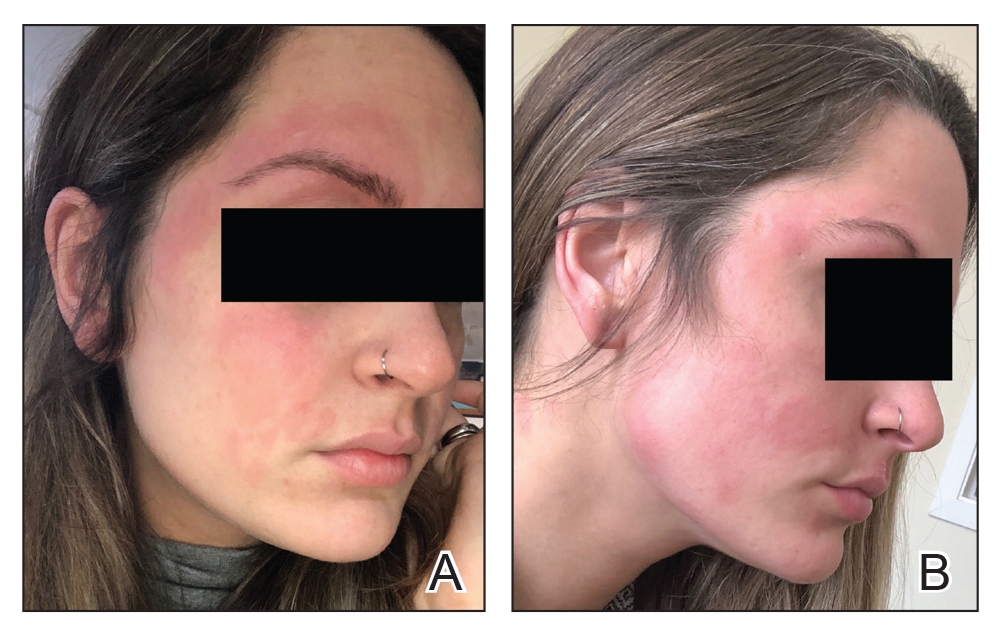

Generalized pustular psoriasis is characterized by the onset of widespread 2- to 3-mm sterile pustules on erythematous skin or within psoriasiform plaques4 (Figure). In patients with skin of color, the erythema may appear less obvious or perhaps slightly violaceous compared to White skin. Pustules may coalesce to form “lakes” of pus.5 Cutaneous symptoms include pain, burning, and pruritus. Associated mucosal findings may include cheilitis, geographic tongue, conjunctivitis, and uveitis.4

The severity of symptoms can vary greatly among patients as well as between flares within the same patient.2,3 Four distinct patterns of GPP have been described. The von Zumbusch pattern is characterized by a rapid, generalized, painful, erythematous and pustular eruption accompanied by fever and asthenia. The pustules usually resolve after several days with extensive scaling. The annular pattern is characterized by annular, erythematous, scaly lesions with pustules present centrifugally. The lesions enlarge by centrifugal expansion over a period of hours to days, while healing occurs centrally. The exanthematic type is an acute eruption of small pustules that abruptly appear and disappear within a few days, usually from infection or medication initiation. Sometimes pustules appear within or at the edge of existing psoriatic plaques in a localized pattern—the fourth pattern—often following the exposure to irritants (eg, tars, anthralin).5

Impetigo Herpetiformis—Impetigo herpetiformis is a form of GPP associated with pregnancy. It generally presents early in the third trimester with symmetric erythematous plaques in flexural and intertriginous areas with pustules present at lesion margins. Lesions expand centrifugally, with pustulation present at the advancing edge.6,7 Patients often are acutely ill with fever, delirium, vomiting, and tetany. Mucous membranes, including the tongue, mouth, and esophagus, also may be involved. The eruption typically resolves after delivery, though it often recurs with subsequent pregnancies, with the morbidity risk rising with each successive pregnancy.7

Systemic and Extracutaneous Manifestations of GPP

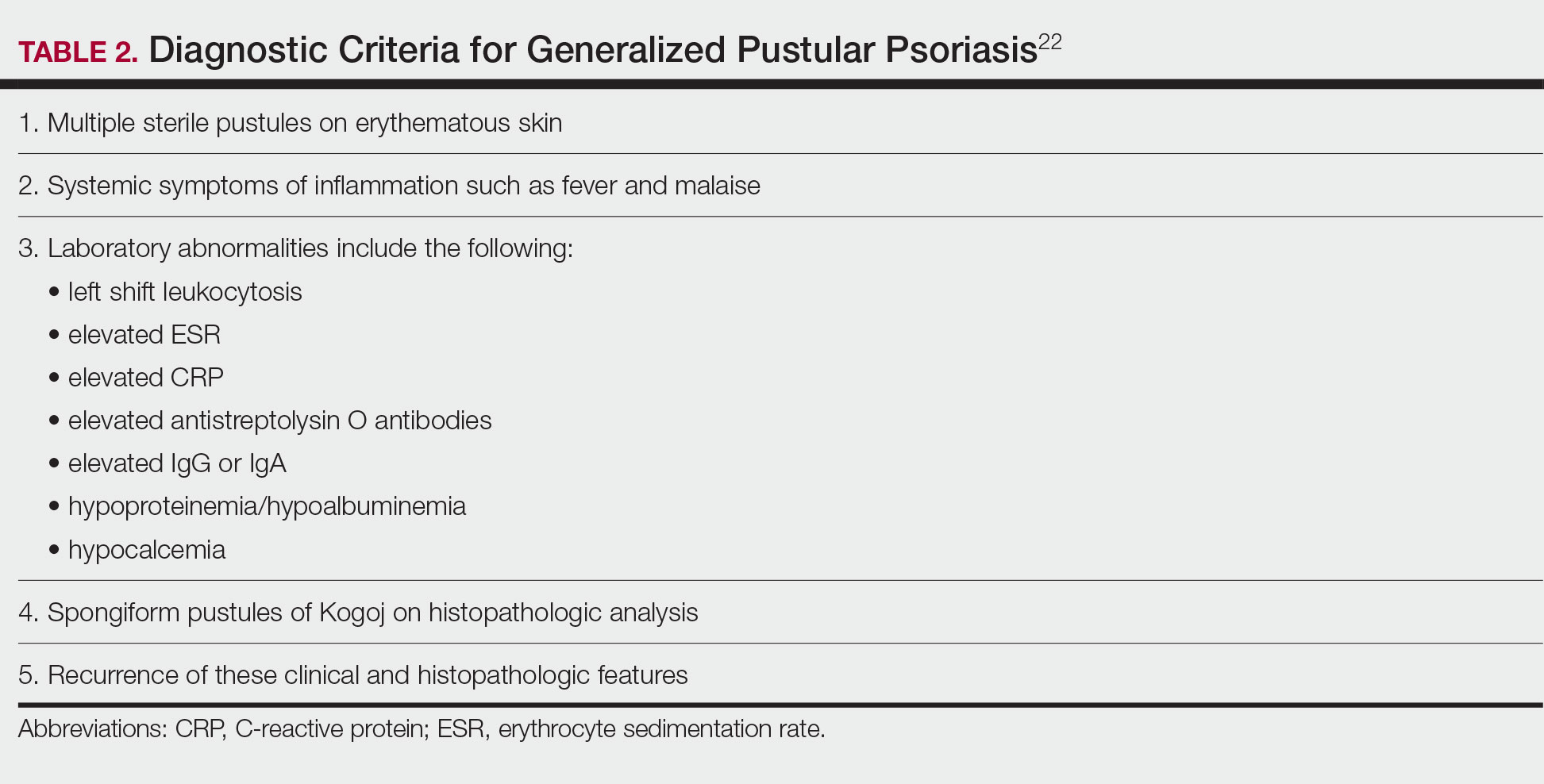

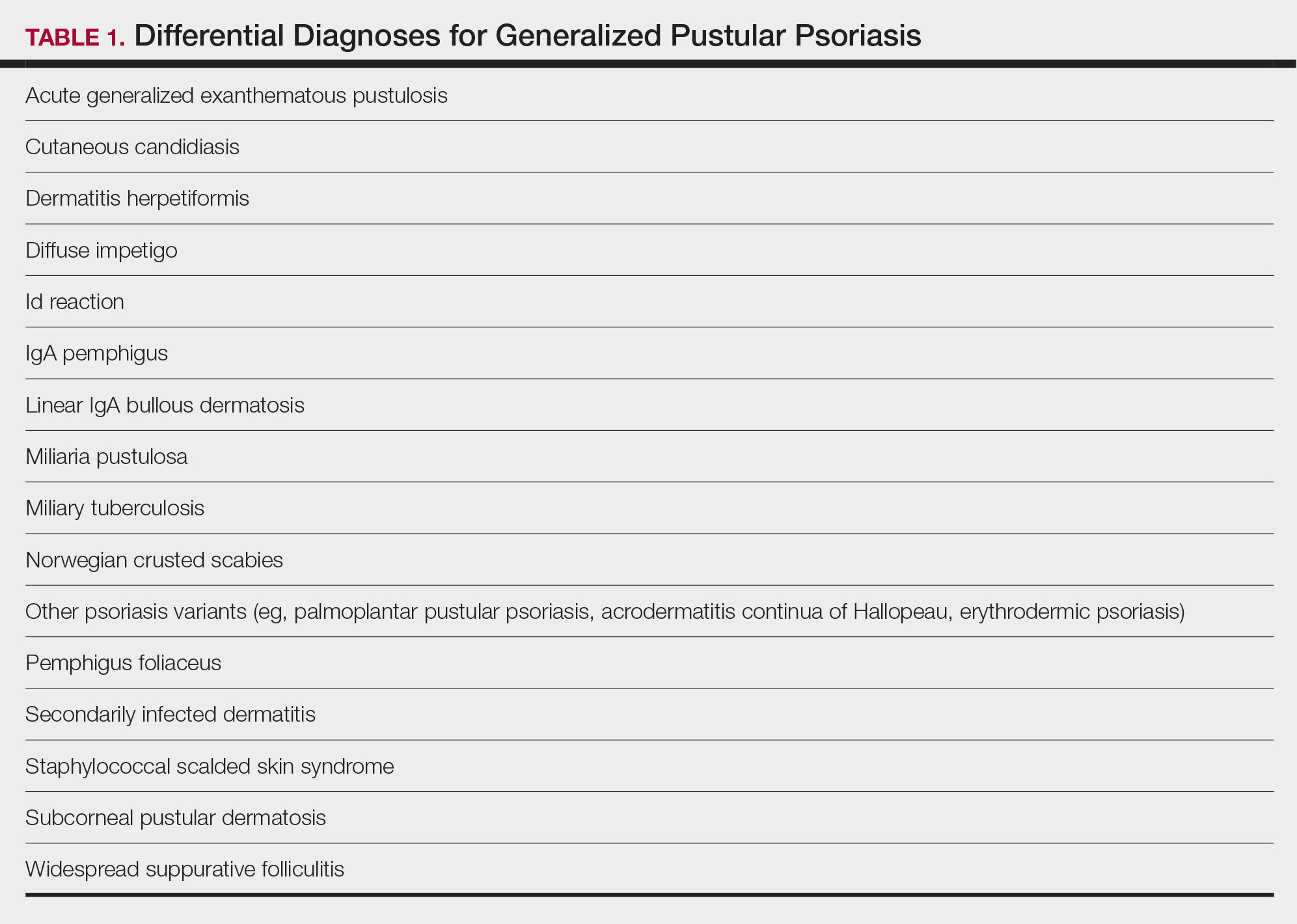

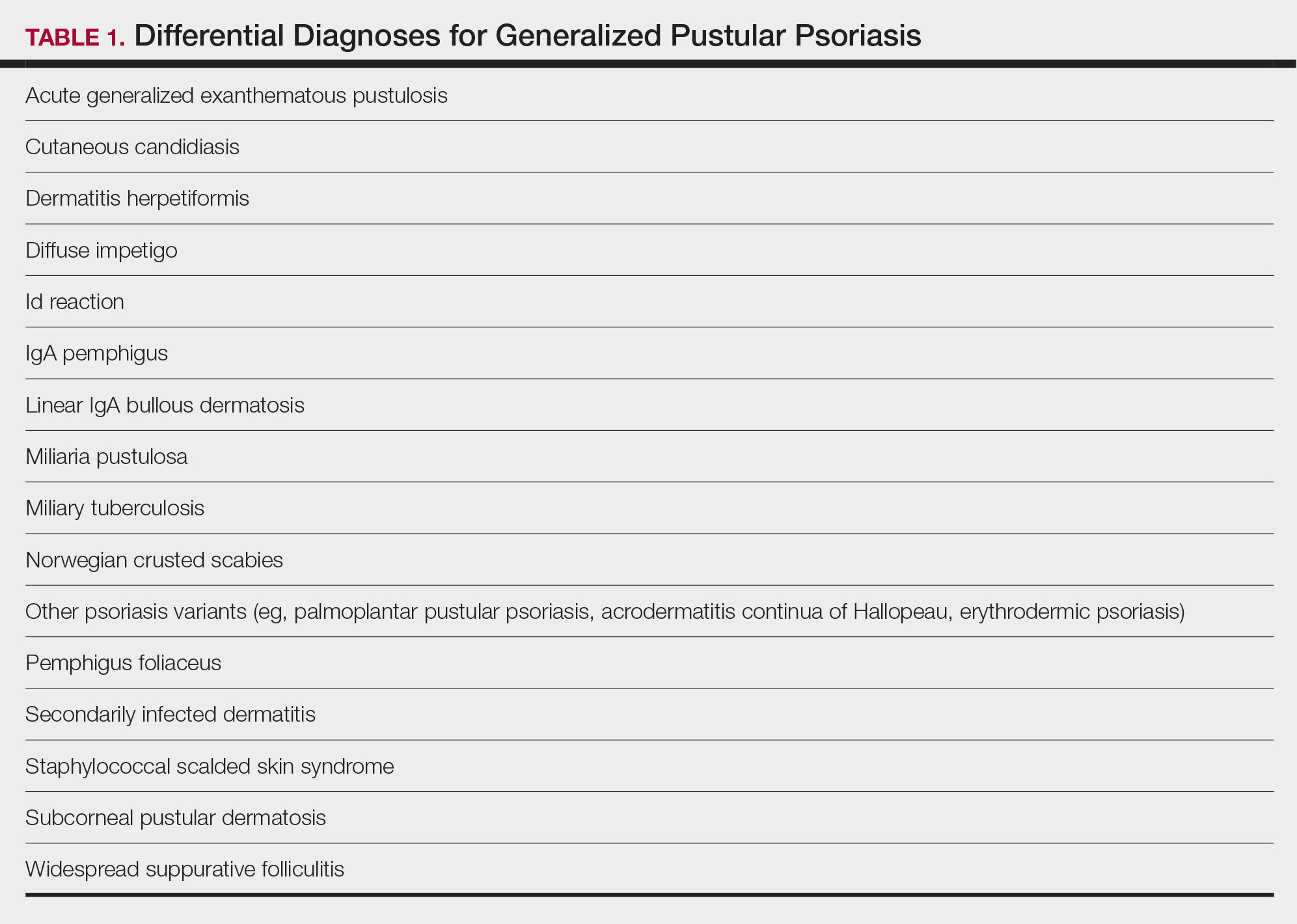

Although the severity of GPP is highly variable, skin manifestations often are accompanied by systemic manifestations of inflammation, including fever and malaise. Common laboratory abnormalities include leukocytosis with peripheral neutrophilia, a high serum C-reactive protein level, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.22 Abnormal liver enzymes often are present and result from neutrophilic cholangitis, with alternating strictures and dilations of biliary ducts observed on magnetic resonance imaging.23 Additional laboratory abnormalities are provided in Table 2. Other extracutaneous findings associated with GPP include arthralgia, edema, and characteristic psoriatic nail changes.4 Fatal complications include acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal dysfunction, cardiovascular shock, and sepsis.24,25

Histologic Features

Given the potential for the skin manifestations of GPP to mimic other disorders, a skin biopsy is warranted to confirm the diagnosis. Generalized pustular psoriasis is histologically characterized by the presence of subcorneal macropustules (ie, spongiform pustules of Kogoj) formed by neutrophil infiltration into the spongelike network of the epidermis.6 Otherwise, the architecture of the epithelium in GPP is similar to that seen with plaque psoriasis, with parakeratosis, acanthosis, rete-ridge elongation, diminished stratum granulosum, and thinning of the suprapapillary epidermis, though the inflammatory cell infiltrate and edema are markedly more severe in GPP than plaque psoriasis.3,4

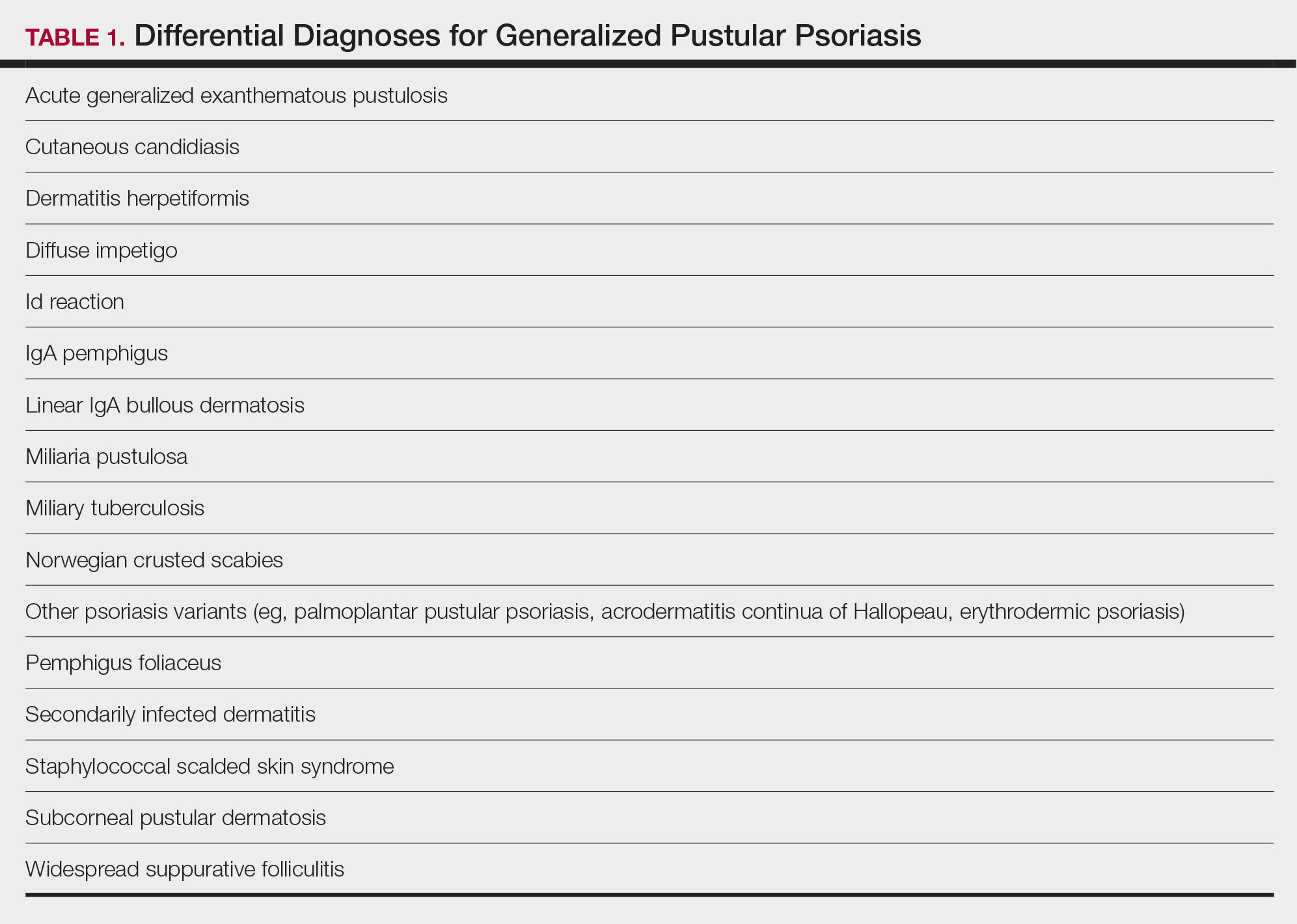

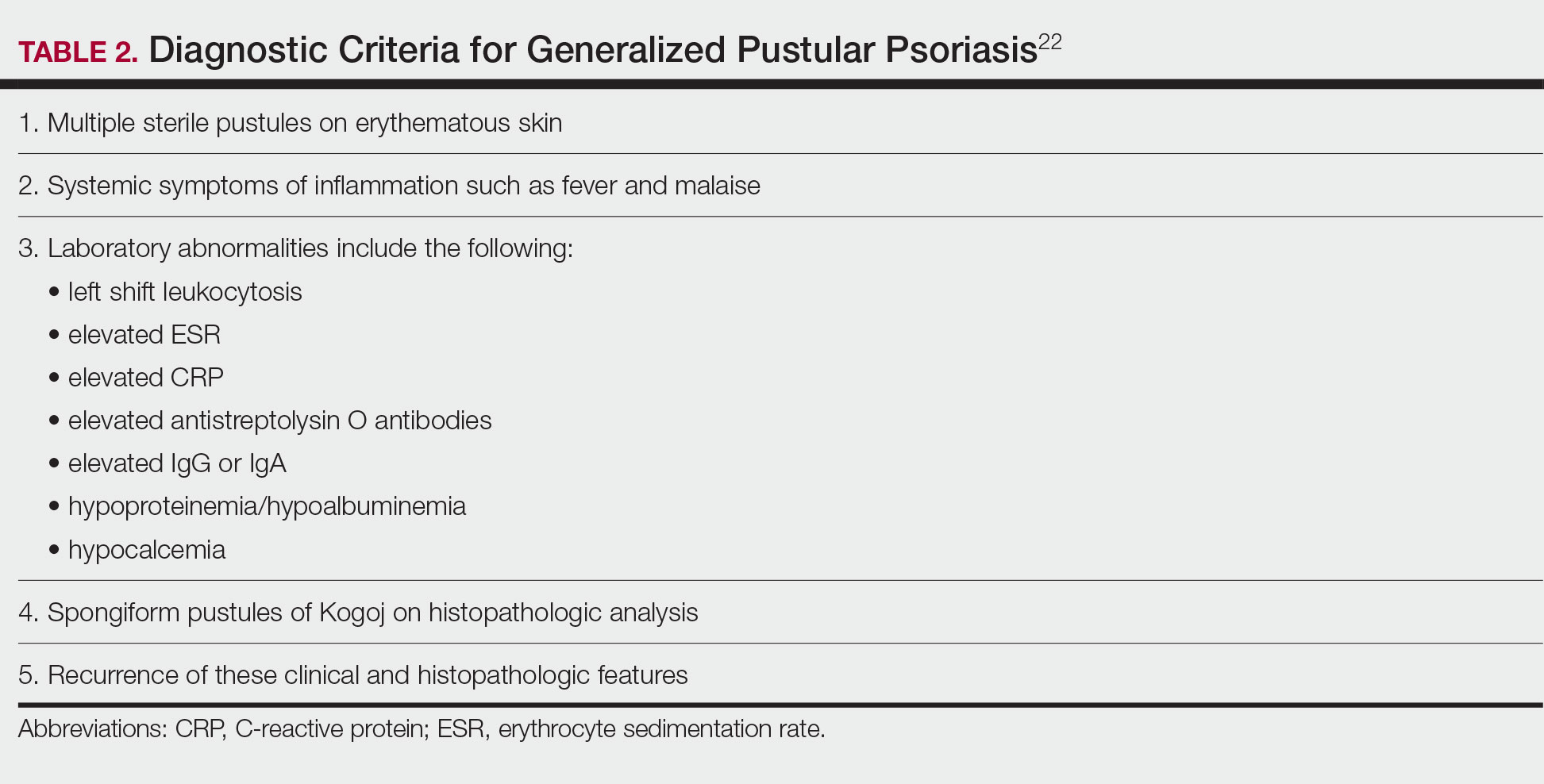

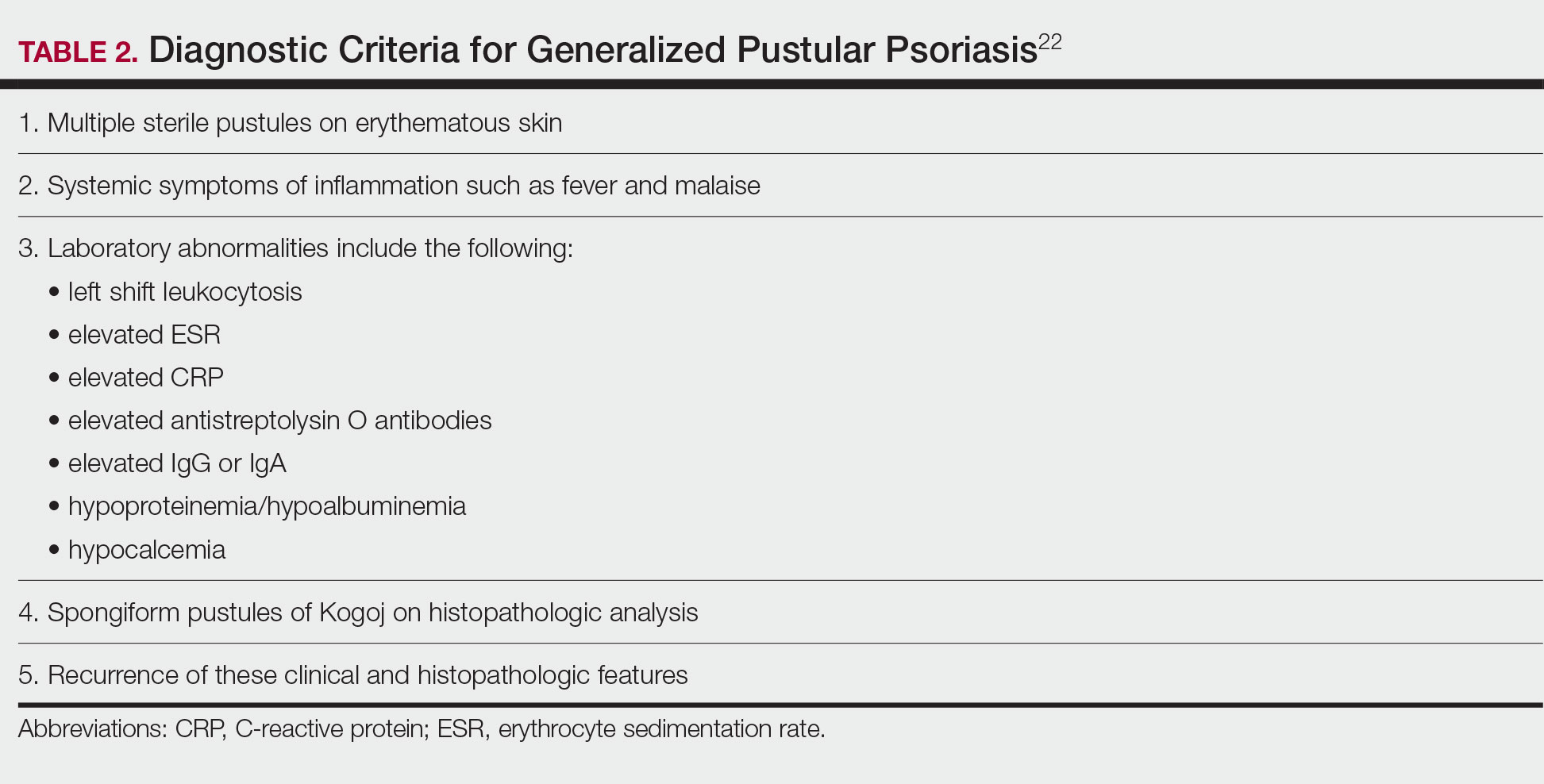

Differential Diagnosis

There are many other cutaneous pustular diagnoses that must be ruled out when evaluating a patient with GPP (Table 1).26 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a common mimicker of GPP that is differentiated histologically by the presence of eosinophils and necrotic keratinocytes.4 In addition to its distinct histopathologic findings, AGEP is classically associated with recent initiation of certain medications, most commonly penicillins, macrolides, quinolones, sulfonamides, terbinafine, and diltiazem.27 In contrast, GPP more commonly is related to withdrawal of corticosteroids as well as initiation of some biologic medications, including anti-TNF agents.3 Generalized pustular psoriasis should be suspected over AGEP in patients with a personal or family history of psoriasis, though GPP may arise in patients with or without a history of psoriasis. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually is more abrupt in both onset and resolution compared with GPP, with clearance of pustules within a few days to weeks following cessation of the triggering factor.4

Other pustular variants of psoriasis (eg, palmoplantar pustular psoriasis, acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau) are differentiated from GPP by their chronicity and localization to palmoplantar and/or ungual surfaces.5 Other differential diagnoses are listed in Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for GPP

Diagnostic criteria have been proposed for GPP (Table 2), including (1) the presence of sterile pustules, (2) systemic signs of inflammation, (3) laboratory abnormalities, (4) histopathologic confirmation of spongiform pustules of Kogoj, and (5) recurrence of symptoms.22 To definitively diagnose GPP, all 5 criteria must be met. To rule out mimickers, it may be worthwhile to perform Gram staining, potassium hydroxide preparation, in vitro cultures, and/or immunofluorescence testing.6

Treatment

Given the high potential for mortality associated with GPP, the most essential component of management is to ensure adequate supportive care. Any temperature, fluid, or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected as they arise. Secondary infections also must be identified and treated, if present, to reduce the risk for fatal complications, including systemic infection and sepsis. Precautions must be taken to ensure that serious end-organ damage, including hepatic, renal, and respiratory dysfunction, is avoided.

Adjunctive topical intervention often is initiated with bland emollients, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and/or vitamin D derivatives to help soothe skin symptoms, but treatment with systemic therapies usually is warranted to achieve symptom control.2,25 Importantly, there are no systemic or topical agents that have specifically been approved for the treatment of GPP in Europe or the United States.3 Given the absence of universally accepted treatment guidelines, therapeutic agents for GPP usually are selected based on clinical experience while also taking the extent of involvement and disease severity into consideration.3

Treatment Recommendations for Adults

Oral Systemic Agents—Treatment guidelines set forth by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) in 2012 proposed that first-line therapies for GPP should be acitretin, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and infliximab.28 However, since those guidelines were established, many new biologic therapies have been approved for the treatment of psoriasis and often are considered in the treatment of psoriasis subtypes, including GPP.29 Although retinoids previously were considered to be a preferred first-line therapy, they are associated with a high incidence of adverse effects and must be used with caution in women of childbearing age.6 Oral acitretin at a dosage of 0.75 to 1.0 mg/kg/d has been shown to result in clinical improvement within 1 to 2 weeks, and a maintenance dosage of 0.125 to 0.25 mg/kg/d is required for several months to prevent recurrence.30 Methotrexate—5.0 to 15.0 mg/wk, or perhaps higher in patients with refractory disease, increased by 2.5-mg intervals until symptoms improve—is recommended by the NPF in patients who are unresponsive or cannot tolerate retinoids, though close monitoring for hematologic abnormalities is required. Cyclosporine 2.5 to 5.0 mg/kg/d is considered an alternative to methotrexate and retinoids; it has a faster onset of action, with improvement reported as early as 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.1,28 Although cyclosporine may be effective in the acute phase, especially in severe cases of GPP, long-term use of cyclosporine is not recommended because of the potential for renal dysfunction and hypertension.31

Biologic Agents—More recent evidence has accumulated supporting the efficacy of anti-TNF agents in the treatment of GPP, suggesting the positioning of these agents as first line. A number of case series have shown dramatic and rapid improvement of GPP with intravenous infliximab 3 to 5 mg/kg, with results observed hours to days after the first infusion.32-37 Thus, infliximab is recommended as first-line treatment in severe acute cases, though its efficacy as a maintenance therapy has not been sufficiently investigated.6 Case reports and case series document the safety and efficacy of adalimumab 40 to 80 mg every 1 to 2 weeks38,39 and etanercept 25 to 50 mg twice weekly40-42 in patients with recalcitrantGPP. Therefore, these anti-TNF agents may be considered in patients who are nonresponsive to treatment with infliximab.

Rarely, there have been reports of paradoxical induction of GPP with the use of some anti-TNF agents,43-45 which may be due to a cytokine imbalance characterized by unopposed IFN-α activation.6 In patients with a history of GPP after initiation of a biologic, treatment with agents from within the offending class should be avoided.

The IL-17A monoclonal antibodies secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab have been shown in open-label phase 3 studies to result in disease remission at 12 weeks.46-48 Treatment with guselkumab, an IL-23 monoclonal antibody, also has demonstrated efficacy in patients with GPP.49 Ustekinumab, an IL-12/23 inhibitor, in combination with acitretin also has been shown to be successful in achieving disease remission after a few weeks of treatment.50

More recent case reports have shown the efficacy of IL-1 inhibitors including gevokizumab, canakinumab, and anakinra in achieving GPP clearance, though more prospective studies are needed to evaluate their efficacy.51-53 Given the etiologic association between IL-1 disinhibition and GPP, future investigations of these therapies as well as those that target the IL-36 pathway may prove to be particularly interesting.

Phototherapy and Combination Therapies—Phototherapy may be considered as maintenance therapy after disease control is achieved, though it is not considered appropriate for acute cases.28 Combination therapies with a biologic plus a nonbiologic systemic agent or alternating among various biologics may allow physicians to maximize benefits and minimize adverse effects in the long term, though there is insufficient evidence to suggest any specific combination treatment algorithm for GPP.28

Treatment Recommendations for Pediatric Patients

Based on a small number of case series and case reports, the first-line treatment strategy for children with GPP is similar to adults. Given the notable adverse events of most oral systemic agents, biologic therapies may emerge as first-line therapy in the pediatric population as more evidence accumulates.28

Treatment Recommendations for Pregnant Patients

Systemic corticosteroids are widely considered to be the first-line treatments for the management of impetigo herpetiformis.7 Low-dose prednisone (15–30 mg/d) usually is effective, but severe cases may require increasing the dosage to 60 mg/d.6 Given the potential for rebound flares upon withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids, these agents must be gradually tapered after the resolution of symptoms.

Certolizumab pegol also is an attractive option in pregnant patients with impetigo herpetiformis because of its favorable safety profile and negligible mother-to-infant transfer through the placenta or breast milk. It has been shown to be effective in treating GPP and impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy in recently published case reports.54,55 In refractory cases, other TNF-α inhibitors (eg, adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept) or cyclosporine may be considered. However, cautious medical monitoring is warranted, as little is known about the potential adverse effects of these agents to the mother and fetus.28,56 Data from transplant recipients along with several case reports indicate that cyclosporine is not associated with an increased risk for adverse effects during pregnancy at a dose of 2 to 3 mg/kg.57-59 Both methotrexate and retinoids are known teratogens and are therefore contraindicated in pregnant patients.56

If pustules do not resolve in the postpartum period, patients should be treated with standard GPP therapies. However, long-term and population studies are lacking regarding the potential for infant exposure to systemic agents in breast milk. Therefore, the NPF recommends avoiding breastfeeding while taking systemic medications, if possible.56

Limitations of Treatment Recommendations

The ability to generate an evidence-based treatment strategy for GPP is limited by a lack of high-quality studies investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments in patients with GPP due to the rarity and relapsing-remitting nature of the disease, which makes randomized controlled trials difficult to conduct. The quality of the available research is further limited by the lack of validated outcome measures to specifically assess improvements in patients with GPP, such that results are difficult to synthesize and compare among studies.31

Conclusion

Although limited, the available research suggests that treatment with various biologics, especially infliximab, is effective in achieving rapid clearance in patients with GPP. In general, biologics may be the most appropriate treatment option in patients with GPP given their relatively favorable safety profiles. Other oral systemic agents, including acitretin, cyclosporine, and methotrexate, have limited evidence to support their use in the acute phase, but their safety profiles often limit their utility in the long-term. Emerging evidence regarding the association of GPP with IL36RN mutations suggests a unique role for agents targeting the IL-36 or IL-1 pathways, though this has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

- Benjegerdes KE, Hyde K, Kivelevitch D, et al. Pustular psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:131‐144.

- Bachelez H. Pustular psoriasis and related pustular skin diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:614‐618.

- Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:907‐919.

- Ly K, Beck KM, Smith MP, et al. Diagnosis and screening of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2019;9:37‐42.

- van de Kerkhof PCM, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012:138-160.

- Hoegler KM, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review and update on treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1645‐1651.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101‐104.

- Johnston A, Xing X, Wolterink L, et al. IL-1 and IL-36 are dominant cytokines in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:109-120.

- Furue K, Yamamura K, Tsuji G, et al. Highlighting interleukin-36 signalling in plaque psoriasis and pustular psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:5-13.

- Ogawa E, Sato Y, Minagawa A, et al. Pathogenesis of psoriasis and development of treatment. J Dermatol. 2018;45:264-272.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620-628.

- Onoufriadis A, Simpson MA, Pink AE, et al. Mutations in IL36RN/IL1F5 are associated with the severe episodic inflammatory skin disease known as generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:432-437.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366-1369.

- Sugiura K, Takemoto A, Yamaguchi M, et al. The majority of generalized pustular psoriasis without psoriasis vulgaris is caused by deficiency of interleukin-36 receptor antagonist. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2514-2521.

- Hussain S, Berki DM, Choon SE, et al. IL36RN mutations define a severe autoinflammatory phenotype of generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1067-1070.e9.

- Körber A, Mossner R, Renner R, et al. Mutations in IL36RN in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2634-2637.

- Twelves S, Mostafa A, Dand N, et al. Clinical and genetic differences between pustular psoriasis subtypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:1021-1026.

- Sugiura K. The genetic background of generalized pustular psoriasis: IL36RN mutations and CARD14 gain-of-function variants. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:187-192

- Wang Y, Cheng R, Lu Z, et al. Clinical profiles of pediatric patients with GPP alone and with different IL36RN genotypes. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;85:235-240.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Simpson MA, Navarini AA, et al. AP1S3 mutations are associated with pustular psoriasis and impaired Toll-like receptor 3 trafficking. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:790-797.

- Mahil SK, Twelves S, Farkas K, et al. AP1S3 mutations cause skin autoinflammation by disrupting keratinocyte autophagy and upregulating IL-36 production. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:2251-2259.

- Umezawa Y, Ozawa A, Kawasima T, et al. Therapeutic guidelines for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) based on a proposed classification of disease severity. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295(suppl 1):S43-S54.

- Viguier M, Allez M, Zagdanski AM, et al. High frequency of cholestasis in generalized pustular psoriasis: evidence for neutrophilic involvement of the biliary tract. Hepatology. 2004;40:452-458.

- Ryan TJ, Baker H. The prognosis of generalized pustular psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:407-411.

- Kalb RE. Pustular psoriasis: management. In: Ofori AO, Duffin KC, eds. UpToDate. UpToDate; 2014. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pustular-psoriasis-management/print

- Naik HB, Cowen EW. Autoinflammatory pustular neutrophilic diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:405-425.

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case-control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:989-996.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279‐288.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Mengesha YM, Bennett ML. Pustular skin disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002;3:389-400.

- Zhou LL, Georgakopoulos JR, Ighani A, et al. Systemic monotherapy treatments for generalized pustular psoriasis: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:591‐601.

- Elewski BE. Infliximab for the treatment of severe pustular psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:796-797.

- Kim HS, You HS, Cho HH, et al. Two cases of generalized pustular psoriasis: successful treatment with infliximab. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:787-788.

- Trent JT, Kerdel FA. Successful treatment of Von Zumbusch pustular psoriasis with infliximab. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:224-228.

- Poulalhon N, Begon E, Lebbé C, et al. A follow-up study in 28 patients treated with infliximab for severe recalcitrant psoriasis: evidence for efficacy and high incidence of biological autoimmunity. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:329-336.

- Routhouska S, Sheth PB, Korman NJ. Long-term management of generalized pustular psoriasis with infliximab: case series. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:184-188.

- Lisby S, Gniadecki R. Infliximab (Remicade) for acute, severe pustular and erythrodermic psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:247-248.

- Zangrilli A, Papoutsaki M, Talamonti M, et al. Long-term efficacy of adalimumab in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2008;19:185-187.

- Matsumoto A, Komine M, Karakawa M, et al. Adalimumab administration after infliximab therapy is a successful treatment strategy for generalized pustular psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2017;44:202-204.