User login

Diffuse Annular Plaques in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

A review of the medical records of the patient’s mother from her first pregnancy revealed positive anti-Ro/SSA (Sjögren syndrome A) (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]) and anti-La/SSB (Sjögren syndrome B) antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]), which were reconfirmed during her pregnancy with our patient (the second child). The patient’s older brother was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) 2 years prior at 1 month of age; therefore, the mother took hydroxychloroquine during the pregnancy with the second child to help prevent heart block if the child was diagnosed with NLE. Given the family history, positive antibodies in the mother, and clinical presentation, our patient was diagnosed with NLE. He was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and pediatrician to continue the workup of systemic manifestations of NLE and to rule out the presence of congenital heart block. The rash resolved 6 months after the initial presentation, and he did not develop any systemic manifestations of NLE.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare acquired autoimmune disorder caused by the placental transfer of anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and less commonly anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antinuclear autoantibodies.1,2 Approximately 1% to 2% of mothers with these positive antibodies will have infants affected with NLE.2 The annual prevalence of NLE in the United States is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. Mothers of children with NLE most commonly have clinical Sjögren syndrome; however, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies may be present in 0.1% to 1.5% of healthy women, and 25% to 60% of women with autoimmune disease may be asymptomatic.1 As demonstrated in our case, when there is a family history of NLE in an infant from an earlier pregnancy, the risk for NLE increases to 17% to 20% in subsequent pregnancies1,3 and up to 25% in subsequent pregnancies if the initial child was diagnosed with a congenital heart block in the setting of NLE.1

Neonatal lupus erythematosus classically presents as annular erythematous macules and plaques with central scaling, telangictasia, atrophy, and pigmentary changes. It may start on the scalp and face and spread caudally.1,2 Patients may develop these lesions after UV exposure, and 80% of infants may not have dermatologic findings at birth. Importantly, 40% to 60% of mothers may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation of their child’s NLE.1 The diagnosis can be confirmed via antibody testing in the mother and/or infant. If performed, a punch biopsy shows interface dermatitis, vacuolar degeneration, and possible periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates on histopathology.1,2

Management of cutaneous NLE includes sun protection (eg, application of sunscreen) and topical corticosteroids. Most dermatologic manifestations of NLE are transient, resolving after clearance of maternal IgG antibodies in 6 to 9 months; however, some telangiectasia, dyspigmentation, and atrophic scarring may persist.1-3

Neonatal lupus erythematosus also may have hepatobiliary, cardiac, hematologic, and less commonly neurologic manifestations. Hepatobiliary manifestations usually present as hepatomegaly or asymptomatic elevated transaminases or γ-glutamyl transferase.1,3 Approximately 10% to 20% of infants with NLE may present with transient anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Cardiac manifestations are permanent and may require pacemaker implantation.1,3 The incidence of a congenital heart block in infants with NLE is 15% to 30%.3 Cardiac NLE most commonly injures the conductive tissue, leading to a congenital atrioventricular block. The development of a congenital heart block develops in the 18th to 24th week of gestation. Manifestations of a more advanced condition can include dilation of the ascending aorta and dilated cardiomyopathy.1 As such, patients need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist for monitoring and treatment of any cardiac manifestations.

The overall prognosis of infants affected with NLE varies. Cardiac involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, while isolated cutaneous involvement requires little treatment and portends a favorable prognosis. It is critical for dermatologists to recognize NLE to refer patients to appropriate specialists to investigate and further monitor possible extracutaneous manifestations. With an understanding of the increased risk for a congenital heart block and NLE in subsequent pregnancies, mothers with positive anti-Ro/La antibodies should receive timely counseling and screening. In expectant mothers with suspected autoimmune disease, testing for antinuclear antibodies and SSA and SSB antibodies can be considered, as administration of hydroxychloroquine or prenatal systemic corticosteroids has proven to be effective in preventing a congenital heart block.1 Our patient was followed by pediatric cardiology and was not found to have a congenital heart block.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of annular erythema in infants, as NLE can mimic several conditions. Tinea corporis may present as scaly annular plaques with central clearing; however, it rarely is encountered fulminantly in neonates.4 Erythema multiforme is a mucocutaneous hypersensitivy reaction distinguished by targetoid morphology.5 It is an exceedingly rare diagnosis in neonates; the average pediatric age of onset is 5.6 years.6 Erythema multiforme often is associated with an infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus,5 and mucosal involvement is common.6 Urticaria multiforme (also known as acute annular urticaria) is a benign disease that appears between 2 months to 3 years of age with blanchable urticarial plaques that likely are triggered by viral or bacterial infections, antibiotics, or vaccines.6 Specific lesions usually will resolve within 24 hours. Annular erythema of infancy is a benign and asymptomatic gyrate erythema that presents as annular plaques with palpable borders that spread centrifugally in patients younger than 1 year. Notably, lesions should periodically fade and may reappear cyclically for months to years. Evaluation for underlying disease usually is negative.6

- Derdulska JM, Rudnicka L, Szykut-Badaczewska A, et al. Neonatal lupus erythematosus—practical guidelines. J Perinat Med. 2021;49:529-538. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0543

- Wu J, Berk-Krauss J, Glick SA. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:590. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0041

- Hon KL, Leung AK. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:301274. doi:10.1155/2012/301274

- Khare AK, Gupta LK, Mittal A, et al. Neonatal tinea corporis. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:201. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.6274

- Ang-Tiu CU, Nicolas ME. Erythema multiforme in a 25-day old neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E118-E120. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2012.01873.x

- Agnihotri G, Tsoukas MM. Annular skin lesions in infancy [published online February 3, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:505-512. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.12.011

The Diagnosis: Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

A review of the medical records of the patient’s mother from her first pregnancy revealed positive anti-Ro/SSA (Sjögren syndrome A) (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]) and anti-La/SSB (Sjögren syndrome B) antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]), which were reconfirmed during her pregnancy with our patient (the second child). The patient’s older brother was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) 2 years prior at 1 month of age; therefore, the mother took hydroxychloroquine during the pregnancy with the second child to help prevent heart block if the child was diagnosed with NLE. Given the family history, positive antibodies in the mother, and clinical presentation, our patient was diagnosed with NLE. He was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and pediatrician to continue the workup of systemic manifestations of NLE and to rule out the presence of congenital heart block. The rash resolved 6 months after the initial presentation, and he did not develop any systemic manifestations of NLE.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare acquired autoimmune disorder caused by the placental transfer of anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and less commonly anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antinuclear autoantibodies.1,2 Approximately 1% to 2% of mothers with these positive antibodies will have infants affected with NLE.2 The annual prevalence of NLE in the United States is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. Mothers of children with NLE most commonly have clinical Sjögren syndrome; however, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies may be present in 0.1% to 1.5% of healthy women, and 25% to 60% of women with autoimmune disease may be asymptomatic.1 As demonstrated in our case, when there is a family history of NLE in an infant from an earlier pregnancy, the risk for NLE increases to 17% to 20% in subsequent pregnancies1,3 and up to 25% in subsequent pregnancies if the initial child was diagnosed with a congenital heart block in the setting of NLE.1

Neonatal lupus erythematosus classically presents as annular erythematous macules and plaques with central scaling, telangictasia, atrophy, and pigmentary changes. It may start on the scalp and face and spread caudally.1,2 Patients may develop these lesions after UV exposure, and 80% of infants may not have dermatologic findings at birth. Importantly, 40% to 60% of mothers may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation of their child’s NLE.1 The diagnosis can be confirmed via antibody testing in the mother and/or infant. If performed, a punch biopsy shows interface dermatitis, vacuolar degeneration, and possible periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates on histopathology.1,2

Management of cutaneous NLE includes sun protection (eg, application of sunscreen) and topical corticosteroids. Most dermatologic manifestations of NLE are transient, resolving after clearance of maternal IgG antibodies in 6 to 9 months; however, some telangiectasia, dyspigmentation, and atrophic scarring may persist.1-3

Neonatal lupus erythematosus also may have hepatobiliary, cardiac, hematologic, and less commonly neurologic manifestations. Hepatobiliary manifestations usually present as hepatomegaly or asymptomatic elevated transaminases or γ-glutamyl transferase.1,3 Approximately 10% to 20% of infants with NLE may present with transient anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Cardiac manifestations are permanent and may require pacemaker implantation.1,3 The incidence of a congenital heart block in infants with NLE is 15% to 30%.3 Cardiac NLE most commonly injures the conductive tissue, leading to a congenital atrioventricular block. The development of a congenital heart block develops in the 18th to 24th week of gestation. Manifestations of a more advanced condition can include dilation of the ascending aorta and dilated cardiomyopathy.1 As such, patients need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist for monitoring and treatment of any cardiac manifestations.

The overall prognosis of infants affected with NLE varies. Cardiac involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, while isolated cutaneous involvement requires little treatment and portends a favorable prognosis. It is critical for dermatologists to recognize NLE to refer patients to appropriate specialists to investigate and further monitor possible extracutaneous manifestations. With an understanding of the increased risk for a congenital heart block and NLE in subsequent pregnancies, mothers with positive anti-Ro/La antibodies should receive timely counseling and screening. In expectant mothers with suspected autoimmune disease, testing for antinuclear antibodies and SSA and SSB antibodies can be considered, as administration of hydroxychloroquine or prenatal systemic corticosteroids has proven to be effective in preventing a congenital heart block.1 Our patient was followed by pediatric cardiology and was not found to have a congenital heart block.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of annular erythema in infants, as NLE can mimic several conditions. Tinea corporis may present as scaly annular plaques with central clearing; however, it rarely is encountered fulminantly in neonates.4 Erythema multiforme is a mucocutaneous hypersensitivy reaction distinguished by targetoid morphology.5 It is an exceedingly rare diagnosis in neonates; the average pediatric age of onset is 5.6 years.6 Erythema multiforme often is associated with an infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus,5 and mucosal involvement is common.6 Urticaria multiforme (also known as acute annular urticaria) is a benign disease that appears between 2 months to 3 years of age with blanchable urticarial plaques that likely are triggered by viral or bacterial infections, antibiotics, or vaccines.6 Specific lesions usually will resolve within 24 hours. Annular erythema of infancy is a benign and asymptomatic gyrate erythema that presents as annular plaques with palpable borders that spread centrifugally in patients younger than 1 year. Notably, lesions should periodically fade and may reappear cyclically for months to years. Evaluation for underlying disease usually is negative.6

The Diagnosis: Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus

A review of the medical records of the patient’s mother from her first pregnancy revealed positive anti-Ro/SSA (Sjögren syndrome A) (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]) and anti-La/SSB (Sjögren syndrome B) antibodies (>8.0 U [reference range <1.0 U]), which were reconfirmed during her pregnancy with our patient (the second child). The patient’s older brother was diagnosed with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE) 2 years prior at 1 month of age; therefore, the mother took hydroxychloroquine during the pregnancy with the second child to help prevent heart block if the child was diagnosed with NLE. Given the family history, positive antibodies in the mother, and clinical presentation, our patient was diagnosed with NLE. He was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and pediatrician to continue the workup of systemic manifestations of NLE and to rule out the presence of congenital heart block. The rash resolved 6 months after the initial presentation, and he did not develop any systemic manifestations of NLE.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus is a rare acquired autoimmune disorder caused by the placental transfer of anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies and less commonly anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein antinuclear autoantibodies.1,2 Approximately 1% to 2% of mothers with these positive antibodies will have infants affected with NLE.2 The annual prevalence of NLE in the United States is approximately 1 in 20,000 live births. Mothers of children with NLE most commonly have clinical Sjögren syndrome; however, anti-Ro/SSA and anti-LA/SSB antibodies may be present in 0.1% to 1.5% of healthy women, and 25% to 60% of women with autoimmune disease may be asymptomatic.1 As demonstrated in our case, when there is a family history of NLE in an infant from an earlier pregnancy, the risk for NLE increases to 17% to 20% in subsequent pregnancies1,3 and up to 25% in subsequent pregnancies if the initial child was diagnosed with a congenital heart block in the setting of NLE.1

Neonatal lupus erythematosus classically presents as annular erythematous macules and plaques with central scaling, telangictasia, atrophy, and pigmentary changes. It may start on the scalp and face and spread caudally.1,2 Patients may develop these lesions after UV exposure, and 80% of infants may not have dermatologic findings at birth. Importantly, 40% to 60% of mothers may be asymptomatic at the time of presentation of their child’s NLE.1 The diagnosis can be confirmed via antibody testing in the mother and/or infant. If performed, a punch biopsy shows interface dermatitis, vacuolar degeneration, and possible periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates on histopathology.1,2

Management of cutaneous NLE includes sun protection (eg, application of sunscreen) and topical corticosteroids. Most dermatologic manifestations of NLE are transient, resolving after clearance of maternal IgG antibodies in 6 to 9 months; however, some telangiectasia, dyspigmentation, and atrophic scarring may persist.1-3

Neonatal lupus erythematosus also may have hepatobiliary, cardiac, hematologic, and less commonly neurologic manifestations. Hepatobiliary manifestations usually present as hepatomegaly or asymptomatic elevated transaminases or γ-glutamyl transferase.1,3 Approximately 10% to 20% of infants with NLE may present with transient anemia and thrombocytopenia.1 Cardiac manifestations are permanent and may require pacemaker implantation.1,3 The incidence of a congenital heart block in infants with NLE is 15% to 30%.3 Cardiac NLE most commonly injures the conductive tissue, leading to a congenital atrioventricular block. The development of a congenital heart block develops in the 18th to 24th week of gestation. Manifestations of a more advanced condition can include dilation of the ascending aorta and dilated cardiomyopathy.1 As such, patients need to be followed by a pediatric cardiologist for monitoring and treatment of any cardiac manifestations.

The overall prognosis of infants affected with NLE varies. Cardiac involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, while isolated cutaneous involvement requires little treatment and portends a favorable prognosis. It is critical for dermatologists to recognize NLE to refer patients to appropriate specialists to investigate and further monitor possible extracutaneous manifestations. With an understanding of the increased risk for a congenital heart block and NLE in subsequent pregnancies, mothers with positive anti-Ro/La antibodies should receive timely counseling and screening. In expectant mothers with suspected autoimmune disease, testing for antinuclear antibodies and SSA and SSB antibodies can be considered, as administration of hydroxychloroquine or prenatal systemic corticosteroids has proven to be effective in preventing a congenital heart block.1 Our patient was followed by pediatric cardiology and was not found to have a congenital heart block.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of annular erythema in infants, as NLE can mimic several conditions. Tinea corporis may present as scaly annular plaques with central clearing; however, it rarely is encountered fulminantly in neonates.4 Erythema multiforme is a mucocutaneous hypersensitivy reaction distinguished by targetoid morphology.5 It is an exceedingly rare diagnosis in neonates; the average pediatric age of onset is 5.6 years.6 Erythema multiforme often is associated with an infection, most commonly herpes simplex virus,5 and mucosal involvement is common.6 Urticaria multiforme (also known as acute annular urticaria) is a benign disease that appears between 2 months to 3 years of age with blanchable urticarial plaques that likely are triggered by viral or bacterial infections, antibiotics, or vaccines.6 Specific lesions usually will resolve within 24 hours. Annular erythema of infancy is a benign and asymptomatic gyrate erythema that presents as annular plaques with palpable borders that spread centrifugally in patients younger than 1 year. Notably, lesions should periodically fade and may reappear cyclically for months to years. Evaluation for underlying disease usually is negative.6

- Derdulska JM, Rudnicka L, Szykut-Badaczewska A, et al. Neonatal lupus erythematosus—practical guidelines. J Perinat Med. 2021;49:529-538. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0543

- Wu J, Berk-Krauss J, Glick SA. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:590. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0041

- Hon KL, Leung AK. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:301274. doi:10.1155/2012/301274

- Khare AK, Gupta LK, Mittal A, et al. Neonatal tinea corporis. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:201. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.6274

- Ang-Tiu CU, Nicolas ME. Erythema multiforme in a 25-day old neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E118-E120. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2012.01873.x

- Agnihotri G, Tsoukas MM. Annular skin lesions in infancy [published online February 3, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:505-512. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.12.011

- Derdulska JM, Rudnicka L, Szykut-Badaczewska A, et al. Neonatal lupus erythematosus—practical guidelines. J Perinat Med. 2021;49:529-538. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0543

- Wu J, Berk-Krauss J, Glick SA. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:590. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0041

- Hon KL, Leung AK. Neonatal lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:301274. doi:10.1155/2012/301274

- Khare AK, Gupta LK, Mittal A, et al. Neonatal tinea corporis. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:201. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.6274

- Ang-Tiu CU, Nicolas ME. Erythema multiforme in a 25-day old neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E118-E120. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2012.01873.x

- Agnihotri G, Tsoukas MM. Annular skin lesions in infancy [published online February 3, 2022]. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:505-512. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.12.011

A 5-week-old infant boy presented with a rash at birth (left). The pregnancy was full term without complications, and he was otherwise healthy. A family history revealed that his older brother developed a similar rash 2 weeks after birth (right). Physical examination revealed polycyclic annular patches with an erythematous border and central clearing diffusely located on the trunk, extremities, scalp, and face with periorbital edema.

Dupilumab-Induced Facial Flushing After Alcohol Consumption

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

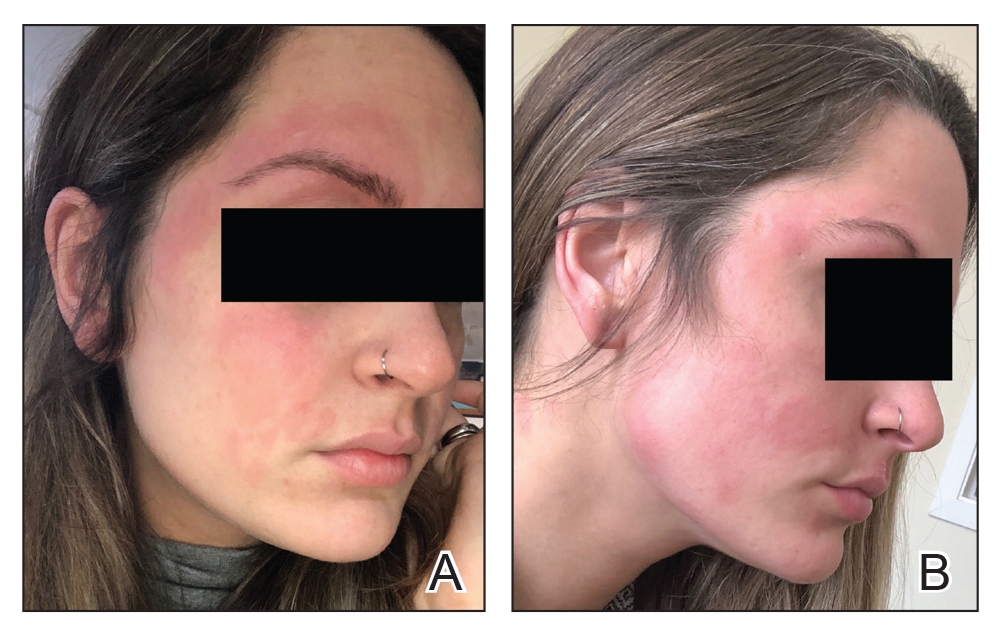

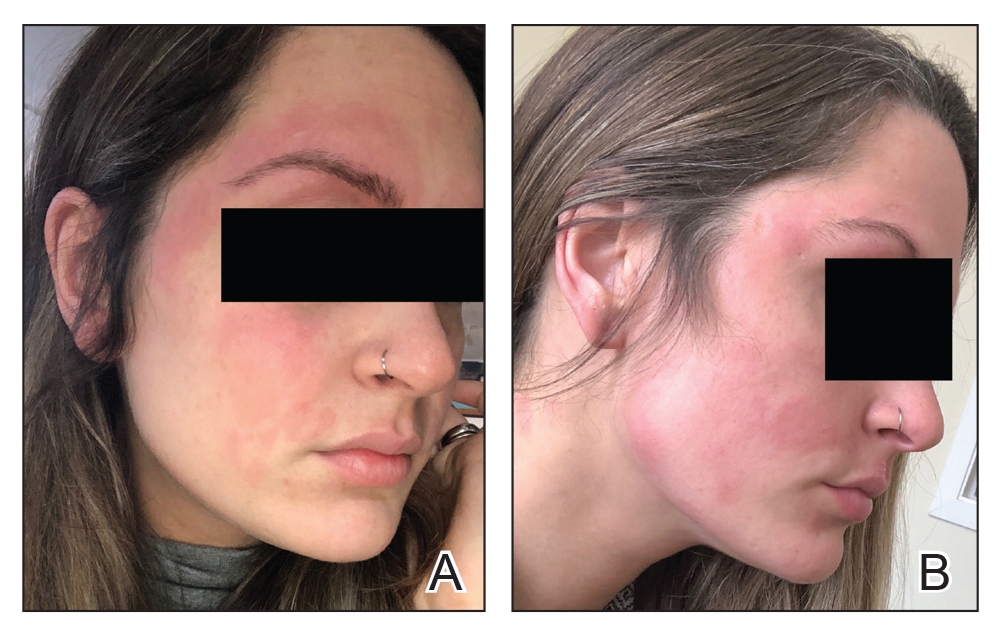

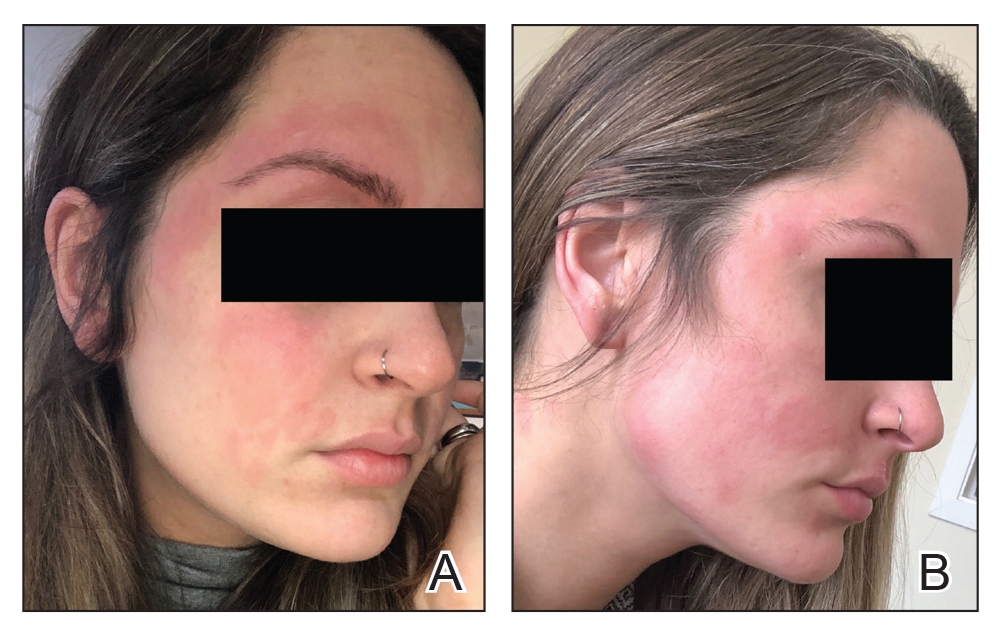

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor that inhibits the action of helper T cell (TH2)–type cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. Dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). We report 2 patients with AD who were treated with dupilumab and subsequently developed facial flushing after consuming alcohol.

Case Report

Patient 1

A 24-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lifelong history of moderate to severe AD. She had a medical history of asthma and seasonal allergies, which were treated with fexofenadine and an inhaler, as needed. The patient had an affected body surface area of approximately 70% and had achieved only partial relief with topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Because her disease was severe, the patient was started on dupilumab at FDA-approved dosing for AD: a 600-mg subcutaneous (SC) loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. She reported rapid skin clearance within 2 weeks of the start of treatment. Her course was complicated by mild head and neck dermatitis.

Seven months after starting treatment, the patient began to acutely experience erythema and warmth over the entire face that was triggered by drinking alcohol (Figure). Before starting dupilumab, she had consumed alcohol on multiple occasions without a flushing effect. This new finding was distinguishable from her facial dermatitis. Onset was within a few minutes after drinking alcohol; flushing self-resolved in 15 to 30 minutes. Although diffuse, erythema and warmth were concentrated around the jawline, eyebrows, and ears and occurred every time the patient drank alcohol. Moreover, she reported that consumption of hard (ie, distilled) liquor, specifically tequila, caused a more severe presentation. She denied other symptoms associated with dupilumab.

Patient 2

A 32-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a 10-year history of moderate to severe AD. He had a medical history of asthma (treated with albuterol, montelukast, and fluticasone); allergic rhinitis; and severe environmental allergies, including sensitivity to dust mites, dogs, trees, and grass.

For AD, the patient had been treated with topical corticosteroids and the Goeckerman regimen (a combination of phototherapy and crude coal tar). He experienced only partial relief with topical corticosteroids; the Goeckerman regimen cleared his skin, but he had quick recurrence after approximately 1 month. Given his work schedule, the patient was unable to resume phototherapy.

Because of symptoms related to the patient’s severe allergies, his allergist prescribed dupilumab: a 600-mg SC loading dose, followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks. The patient reported near-complete resolution of AD symptoms approximately 2 months after initiating treatment. He reported a few episodes of mild conjunctivitis that self-resolved after the first month of treatment.

Three weeks after initiating dupilumab, the patient noticed new-onset facial flushing in response to consuming alcohol. He described flushing as sudden immediate redness and warmth concentrated around the forehead, eyes, and cheeks. He reported that flushing was worse with hard liquor than with beer. Flushing would slowly subside over approximately 30 minutes despite continued alcohol consumption.

Comment

Two other single-patient case reports have discussed similar findings of alcohol-induced flushing associated with dupilumab.1,2 Both of those patients—a 19-year-old woman and a 26-year-old woman—had not experienced flushing before beginning treatment with dupilumab for AD. Both experienced onset of facial flushing months after beginning dupilumab even though both had consumed alcohol before starting dupilumab, similar to the cases presented here. One patient had a history of asthma; the other had a history of seasonal and environmental allergies.

Possible Mechanism of Action

Acute alcohol ingestion causes dermal vasodilation of the skin (ie, flushing).3 A proposed mechanism is that flushing results from direct action on central vascular-control mechanisms. This theory results from observations that individuals with quadriplegia lack notable ethanol-induced vasodilation, suggesting that ethanol has a central neural site of action.Although some research has indicated that ethanol might induce these effects by altering the action of certain hormones (eg, angiotensin, vasopressin, and catecholamines), the precise mechanism by which ethanol alters vascular function in humans remains unexplained.3

Deficiencies in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, and certain cytochrome P450 enzymes also might contribute to facial flushing. People of Asian, especially East Asian, descent often respond to an acute dose of ethanol with symptoms of facial flushing—predominantly the result of an elevated blood level of acetaldehyde caused by an inherited deficiency of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2,4 which is downstream from ADH in the metabolic pathway of alcohol. The major enzyme system responsible for metabolism of ethanol is ADH; however, the cytochrome P450–dependent ethanol-oxidizing system—including major CYP450 isoforms CYP3A, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, as well as minor CYP450 isoforms, such as CYP2E1— also are involved, to a lesser extent.5

A Role for Dupilumab?

A recent pharmacokinetic study found that dupilumab appears to have little effect on the activity of the major CYP450 isoforms. However, the drug’s effect on ADH and minor CYP450 minor isoforms is unknown. Prior drug-drug interaction studies have shown that certain cytokines and cytokine modulators can markedly influence the expression, stability, and activity of specific CYP450 enzymes.6 For example, IL-6 causes a reduction in messenger RNA for CYP3A4 and, to a lesser extent, for other isoforms.7 Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Conclusion

We describe 2 cases of dupilumab-induced facial flushing after alcohol consumption. The mechanism of this dupilumab-associated flushing is unknown and requires further research.

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

- Herz S, Petri M, Sondermann W. New alcohol flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis under therapy with dupilumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12762. doi:10.1111/dth.12762

- Igelman SJ, Na C, Simpson EL. Alcohol-induced facial flushing in a patient with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:139-140. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.002

- Malpas SC, Robinson BJ, Maling TJ. Mechanism of ethanol-induced vasodilation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1990;68:731-734. doi:10.1152/jappl.1990.68.2.731

- Brooks PJ, Enoch M-A, Goldman D, et al. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050

- Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:667-685. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2012.08.002

- Davis JD, Bansal A, Hassman D, et al. Evaluation of potential disease-mediated drug-drug interaction in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis receiving dupilumab. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1146-1154. doi:10.1002/cpt.1058

- Mimura H, Kobayashi K, Xu L, et al. Effects of cytokines on CYP3A4 expression and reversal of the effects by anti-cytokine agents in the three-dimensionally cultured human hepatoma cell line FLC-4. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2015;30:105-110. doi:10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.09.004

Practice Points

- Dupilumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits the action of IL-4 and IL-13. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

- Facial flushing after alcohol consumption may be an emerging side effect of dupilumab.

- Whether dupilumab influences enzymes involved in processing alcohol requires further study.

Recent Developments in Psychodermatology and Psychopharmacology for Delusional Patients

The management of delusional infestation (DI), also known as Morgellons disease or delusional parasitosis, can lead to some of the most difficult and stressful patient encounters in dermatology. As a specialty, dermatology providers are trained to respect scientific objectivity and pride themselves on their visual diagnostic acumen. Therefore, having to accommodate a patient’s erroneous ideations and potentially treat a psychiatric pathology poses a challenge for many dermatology providers because it requires shifting their mindset to where the subjective reality becomes the primary issue during the visit. This disconnect may lead to strife between the patient and the provider. All of these issues may make it difficult for dermatologists to connect with DI patients with the usual courtesy and consideration given to other patients. Moreover, some dermatologists find it difficult to respect the chief concern, which often is seen as purely psychological because there may be some lingering bias where psychological concerns perhaps are not seen as bona fide or legitimate disorders.

Is There a Biologic Basis for DI? A New Theory on the Etiology of Delusional Parasitosis

It is important to distinguish DI phenomenology into primary and secondary causes. Primary DI refers to cases where the delusion and formication occur spontaneously. In contrast, in secondary DI the delusion and other manifestations (eg, formication) happen secondarily to underlying broader diagnoses such as illicit substance abuse, primary psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia, organic brain syndrome, and vitamin B12 deficiency.

It is well known that primary DI overwhelmingly occurs in older women, whereas secondary DI does not show this same predilection. It has been a big unanswered question as to why primary DI so often occurs not only in women but specifically in older women. The latest theory that has been advancing in Europe and is supported by some data, including magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, involves the dopamine transporter (DAT) system, which is important in making sure the dopamine level in the intersynaptic space is not excessive.1 The DAT system is much more prominent in woman vs men and deteriorates with age due to declining estrogen levels. This age-related loss of striatal DAT is thought to be one possible etiology of DI. It has been hypothesized that decreased DAT functioning may cause an increase in extracellular striatal dopamine levels in the synapse that can lead to tactile hallucinations and delusions, which are hallmark symptoms seen in DI. Given that women experience a greater age-related DAT decline in striatal subregions than men, it is thought that primary DI mainly affects older women due to the decline of neuroprotective effects of estrogen on DAT activity with age.2 Further studies should evaluate the possibility of estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of DI.

Improving Care of Psychodermatology Patients in Clinic

There are several medications that are known to be effective for the treatment of DI, including pimozide, risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine, among others. Pimozide is uniquely accepted by DI patients because it has no official psychiatric indication from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); it is only indicated in the United States for Tourette syndrome, which is a neurologic disorder. Therefore, pimozide arguably can be disregarded as a true antipsychotic agent. The fact that its chemical structure is similar to those of bona fide antipsychotic medications does not necessarily put it in this same category, as there also are antiemetic and antitussive medications (eg, prochlorperazine, promethazine) with chemical structures similar to antipsychotics, but clinicians generally do not think of these drugs as antipsychotics despite the similarities. This nuanced and admittedly somewhat arbitrary categorization is critical to patient care; in our clinic, we have found that patients who categorically refuse to consider all psychiatric medications are much more willing to try pimozide for this very reason, that this medication can uniquely be presented to the DI patient as an agent not used in psychiatry. We have found great success in treatment with pimozide, even with relatively low doses.3,4

One of the main reasons dermatologists are reluctant to prescribe antipsychotic medications or even pimozide is the concern for side effects, especially tardive dyskinesia (TD), which is thought to be irreversible and untreatable. However, after a half century of worldwide use of pimozide in dermatology, a PubMed search of English-language articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pimozide and tardive dyskinesia, tardive dyskinesia and delusions of parasitosis, tardive dyskinesia and dermatology, and tardive dyskinesia and delusional infestation/Morgellons disease yielded only 1 known case of TD reported in dermatologic use for DI.5 In this particular case, TD-like symptoms did not appear until after pimozide had been discontinued for 1 month. Therefore, it is not clear if this case was true TD or a condition known as withdrawal dyskinesia, which mimics TD and usually is self-limiting.5

The senior author (J.K.) has been using pimozide for treatment of DI for more than 30 years and has not encountered TD or any other notable side effects. The reason for this extremely low incidence of side effects may be due to its high efficacy in treating DI; hence, only a low dose of pimozide usually is needed. At the University of California, San Francisco, Psychodermatology Clinic, pimozide typically is used to treat DI at a low dose of 3 mg or less daily, starting with 0.5 or 1 mg and slowly titrating upward until a clinically effective dose is reached. Pimozide rarely is used long-term; after the resolution of symptoms, the dose usually is continued at the clinically effective dose for a few months and then is slowly tapered off. In contrast, for a condition such as schizophrenia, an antipsychotic medication often is needed at high doses for life, resulting in higher TD occurrences being reported. Therefore, even though the newer antipsychotic agents are preferable to pimozide because of their somewhat lower risk for TD, in actual clinical practice many, if not most, DI patients detest any suggestion of taking a medication for “crazy people.” Thus, we find that pimozide’s inherent superior acceptability among DI patients often is critical to enabling any effective treatment to occur at all due to the fact that the provider can honestly say that pimozide has no FDA psychiatric indication.

Still, one of the biggest apprehensions with initiating and continuing these medications in dermatology is fear of TD. Now, dermatologists can be made aware that if this very rare side effect occurs, there are medications approved to treat TD, even if the anti-TD therapy is administered by a neurologist. For the first time, 2 medications were approved by the FDA for treatment of TD in 2017, namely valbenazine and deutetrabenazine. These medications represent a class known as vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitors and function by ultimately reducing the amount of dopamine released from the presynaptic dopaminergic neurons. In phase 3 trials for valbenazine and deutetrabenazine, 40% (N=234) and 34% (N=222) of patients, respectively, achieved a response, which was defined as at least a 50% decrease from baseline on the abnormal involuntary movement scale dyskinesia score in 6 to 12 weeks compared to 9% and 12%, respectively, with placebo.Discontinuation because of an adverse event was seldom encountered with both medications.6

Conclusion

The recent developments in psychodermatology with regard to DI are encouraging. The advent of new evidence and theories suggestive of an organic basis for DI could help this condition become more respected in the eyes of the dermatologist as a bona fide disorder. Moreover, the new developments and availability of medications that can treat TD can further make it easier for dermatologists to consider offering DI patients truly meaningful treatment that they desperately need. Therefore, both of these developments are welcomed for our specialty.

- Huber M, Kirchler E, Karner M, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the dopamine transporter. a new insight of etiology? Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:1351-1358.

- Chan SY, Koo J. Sex differences in primary delusional infestation: an insight into etiology and potential novel therapy. Int J Women Dermatol. 2020;6:226.

- Lorenzo CR, Koo J. Pimozide in dermatologic practice: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:339-349.

- Brownstone ND, Beck K, Sekhon S, et al. Morgellons Disease. 2nd ed. Kindle Direct Publishing; 2020.

- Thomson AM, Wallace J, Kobylecki C. Tardive dyskinesia after drug withdrawal in two older adults: clinical features, complications and management. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19:563-564.

- Citrome L. Tardive dyskinesia: placing vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors into clinical perspective. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18:323-332.

The management of delusional infestation (DI), also known as Morgellons disease or delusional parasitosis, can lead to some of the most difficult and stressful patient encounters in dermatology. As a specialty, dermatology providers are trained to respect scientific objectivity and pride themselves on their visual diagnostic acumen. Therefore, having to accommodate a patient’s erroneous ideations and potentially treat a psychiatric pathology poses a challenge for many dermatology providers because it requires shifting their mindset to where the subjective reality becomes the primary issue during the visit. This disconnect may lead to strife between the patient and the provider. All of these issues may make it difficult for dermatologists to connect with DI patients with the usual courtesy and consideration given to other patients. Moreover, some dermatologists find it difficult to respect the chief concern, which often is seen as purely psychological because there may be some lingering bias where psychological concerns perhaps are not seen as bona fide or legitimate disorders.

Is There a Biologic Basis for DI? A New Theory on the Etiology of Delusional Parasitosis

It is important to distinguish DI phenomenology into primary and secondary causes. Primary DI refers to cases where the delusion and formication occur spontaneously. In contrast, in secondary DI the delusion and other manifestations (eg, formication) happen secondarily to underlying broader diagnoses such as illicit substance abuse, primary psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia, organic brain syndrome, and vitamin B12 deficiency.

It is well known that primary DI overwhelmingly occurs in older women, whereas secondary DI does not show this same predilection. It has been a big unanswered question as to why primary DI so often occurs not only in women but specifically in older women. The latest theory that has been advancing in Europe and is supported by some data, including magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, involves the dopamine transporter (DAT) system, which is important in making sure the dopamine level in the intersynaptic space is not excessive.1 The DAT system is much more prominent in woman vs men and deteriorates with age due to declining estrogen levels. This age-related loss of striatal DAT is thought to be one possible etiology of DI. It has been hypothesized that decreased DAT functioning may cause an increase in extracellular striatal dopamine levels in the synapse that can lead to tactile hallucinations and delusions, which are hallmark symptoms seen in DI. Given that women experience a greater age-related DAT decline in striatal subregions than men, it is thought that primary DI mainly affects older women due to the decline of neuroprotective effects of estrogen on DAT activity with age.2 Further studies should evaluate the possibility of estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of DI.

Improving Care of Psychodermatology Patients in Clinic

There are several medications that are known to be effective for the treatment of DI, including pimozide, risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine, among others. Pimozide is uniquely accepted by DI patients because it has no official psychiatric indication from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); it is only indicated in the United States for Tourette syndrome, which is a neurologic disorder. Therefore, pimozide arguably can be disregarded as a true antipsychotic agent. The fact that its chemical structure is similar to those of bona fide antipsychotic medications does not necessarily put it in this same category, as there also are antiemetic and antitussive medications (eg, prochlorperazine, promethazine) with chemical structures similar to antipsychotics, but clinicians generally do not think of these drugs as antipsychotics despite the similarities. This nuanced and admittedly somewhat arbitrary categorization is critical to patient care; in our clinic, we have found that patients who categorically refuse to consider all psychiatric medications are much more willing to try pimozide for this very reason, that this medication can uniquely be presented to the DI patient as an agent not used in psychiatry. We have found great success in treatment with pimozide, even with relatively low doses.3,4

One of the main reasons dermatologists are reluctant to prescribe antipsychotic medications or even pimozide is the concern for side effects, especially tardive dyskinesia (TD), which is thought to be irreversible and untreatable. However, after a half century of worldwide use of pimozide in dermatology, a PubMed search of English-language articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pimozide and tardive dyskinesia, tardive dyskinesia and delusions of parasitosis, tardive dyskinesia and dermatology, and tardive dyskinesia and delusional infestation/Morgellons disease yielded only 1 known case of TD reported in dermatologic use for DI.5 In this particular case, TD-like symptoms did not appear until after pimozide had been discontinued for 1 month. Therefore, it is not clear if this case was true TD or a condition known as withdrawal dyskinesia, which mimics TD and usually is self-limiting.5

The senior author (J.K.) has been using pimozide for treatment of DI for more than 30 years and has not encountered TD or any other notable side effects. The reason for this extremely low incidence of side effects may be due to its high efficacy in treating DI; hence, only a low dose of pimozide usually is needed. At the University of California, San Francisco, Psychodermatology Clinic, pimozide typically is used to treat DI at a low dose of 3 mg or less daily, starting with 0.5 or 1 mg and slowly titrating upward until a clinically effective dose is reached. Pimozide rarely is used long-term; after the resolution of symptoms, the dose usually is continued at the clinically effective dose for a few months and then is slowly tapered off. In contrast, for a condition such as schizophrenia, an antipsychotic medication often is needed at high doses for life, resulting in higher TD occurrences being reported. Therefore, even though the newer antipsychotic agents are preferable to pimozide because of their somewhat lower risk for TD, in actual clinical practice many, if not most, DI patients detest any suggestion of taking a medication for “crazy people.” Thus, we find that pimozide’s inherent superior acceptability among DI patients often is critical to enabling any effective treatment to occur at all due to the fact that the provider can honestly say that pimozide has no FDA psychiatric indication.

Still, one of the biggest apprehensions with initiating and continuing these medications in dermatology is fear of TD. Now, dermatologists can be made aware that if this very rare side effect occurs, there are medications approved to treat TD, even if the anti-TD therapy is administered by a neurologist. For the first time, 2 medications were approved by the FDA for treatment of TD in 2017, namely valbenazine and deutetrabenazine. These medications represent a class known as vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitors and function by ultimately reducing the amount of dopamine released from the presynaptic dopaminergic neurons. In phase 3 trials for valbenazine and deutetrabenazine, 40% (N=234) and 34% (N=222) of patients, respectively, achieved a response, which was defined as at least a 50% decrease from baseline on the abnormal involuntary movement scale dyskinesia score in 6 to 12 weeks compared to 9% and 12%, respectively, with placebo.Discontinuation because of an adverse event was seldom encountered with both medications.6

Conclusion

The recent developments in psychodermatology with regard to DI are encouraging. The advent of new evidence and theories suggestive of an organic basis for DI could help this condition become more respected in the eyes of the dermatologist as a bona fide disorder. Moreover, the new developments and availability of medications that can treat TD can further make it easier for dermatologists to consider offering DI patients truly meaningful treatment that they desperately need. Therefore, both of these developments are welcomed for our specialty.

The management of delusional infestation (DI), also known as Morgellons disease or delusional parasitosis, can lead to some of the most difficult and stressful patient encounters in dermatology. As a specialty, dermatology providers are trained to respect scientific objectivity and pride themselves on their visual diagnostic acumen. Therefore, having to accommodate a patient’s erroneous ideations and potentially treat a psychiatric pathology poses a challenge for many dermatology providers because it requires shifting their mindset to where the subjective reality becomes the primary issue during the visit. This disconnect may lead to strife between the patient and the provider. All of these issues may make it difficult for dermatologists to connect with DI patients with the usual courtesy and consideration given to other patients. Moreover, some dermatologists find it difficult to respect the chief concern, which often is seen as purely psychological because there may be some lingering bias where psychological concerns perhaps are not seen as bona fide or legitimate disorders.

Is There a Biologic Basis for DI? A New Theory on the Etiology of Delusional Parasitosis

It is important to distinguish DI phenomenology into primary and secondary causes. Primary DI refers to cases where the delusion and formication occur spontaneously. In contrast, in secondary DI the delusion and other manifestations (eg, formication) happen secondarily to underlying broader diagnoses such as illicit substance abuse, primary psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia, organic brain syndrome, and vitamin B12 deficiency.

It is well known that primary DI overwhelmingly occurs in older women, whereas secondary DI does not show this same predilection. It has been a big unanswered question as to why primary DI so often occurs not only in women but specifically in older women. The latest theory that has been advancing in Europe and is supported by some data, including magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, involves the dopamine transporter (DAT) system, which is important in making sure the dopamine level in the intersynaptic space is not excessive.1 The DAT system is much more prominent in woman vs men and deteriorates with age due to declining estrogen levels. This age-related loss of striatal DAT is thought to be one possible etiology of DI. It has been hypothesized that decreased DAT functioning may cause an increase in extracellular striatal dopamine levels in the synapse that can lead to tactile hallucinations and delusions, which are hallmark symptoms seen in DI. Given that women experience a greater age-related DAT decline in striatal subregions than men, it is thought that primary DI mainly affects older women due to the decline of neuroprotective effects of estrogen on DAT activity with age.2 Further studies should evaluate the possibility of estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of DI.

Improving Care of Psychodermatology Patients in Clinic

There are several medications that are known to be effective for the treatment of DI, including pimozide, risperidone, aripiprazole, and olanzapine, among others. Pimozide is uniquely accepted by DI patients because it has no official psychiatric indication from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); it is only indicated in the United States for Tourette syndrome, which is a neurologic disorder. Therefore, pimozide arguably can be disregarded as a true antipsychotic agent. The fact that its chemical structure is similar to those of bona fide antipsychotic medications does not necessarily put it in this same category, as there also are antiemetic and antitussive medications (eg, prochlorperazine, promethazine) with chemical structures similar to antipsychotics, but clinicians generally do not think of these drugs as antipsychotics despite the similarities. This nuanced and admittedly somewhat arbitrary categorization is critical to patient care; in our clinic, we have found that patients who categorically refuse to consider all psychiatric medications are much more willing to try pimozide for this very reason, that this medication can uniquely be presented to the DI patient as an agent not used in psychiatry. We have found great success in treatment with pimozide, even with relatively low doses.3,4

One of the main reasons dermatologists are reluctant to prescribe antipsychotic medications or even pimozide is the concern for side effects, especially tardive dyskinesia (TD), which is thought to be irreversible and untreatable. However, after a half century of worldwide use of pimozide in dermatology, a PubMed search of English-language articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms pimozide and tardive dyskinesia, tardive dyskinesia and delusions of parasitosis, tardive dyskinesia and dermatology, and tardive dyskinesia and delusional infestation/Morgellons disease yielded only 1 known case of TD reported in dermatologic use for DI.5 In this particular case, TD-like symptoms did not appear until after pimozide had been discontinued for 1 month. Therefore, it is not clear if this case was true TD or a condition known as withdrawal dyskinesia, which mimics TD and usually is self-limiting.5

The senior author (J.K.) has been using pimozide for treatment of DI for more than 30 years and has not encountered TD or any other notable side effects. The reason for this extremely low incidence of side effects may be due to its high efficacy in treating DI; hence, only a low dose of pimozide usually is needed. At the University of California, San Francisco, Psychodermatology Clinic, pimozide typically is used to treat DI at a low dose of 3 mg or less daily, starting with 0.5 or 1 mg and slowly titrating upward until a clinically effective dose is reached. Pimozide rarely is used long-term; after the resolution of symptoms, the dose usually is continued at the clinically effective dose for a few months and then is slowly tapered off. In contrast, for a condition such as schizophrenia, an antipsychotic medication often is needed at high doses for life, resulting in higher TD occurrences being reported. Therefore, even though the newer antipsychotic agents are preferable to pimozide because of their somewhat lower risk for TD, in actual clinical practice many, if not most, DI patients detest any suggestion of taking a medication for “crazy people.” Thus, we find that pimozide’s inherent superior acceptability among DI patients often is critical to enabling any effective treatment to occur at all due to the fact that the provider can honestly say that pimozide has no FDA psychiatric indication.

Still, one of the biggest apprehensions with initiating and continuing these medications in dermatology is fear of TD. Now, dermatologists can be made aware that if this very rare side effect occurs, there are medications approved to treat TD, even if the anti-TD therapy is administered by a neurologist. For the first time, 2 medications were approved by the FDA for treatment of TD in 2017, namely valbenazine and deutetrabenazine. These medications represent a class known as vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitors and function by ultimately reducing the amount of dopamine released from the presynaptic dopaminergic neurons. In phase 3 trials for valbenazine and deutetrabenazine, 40% (N=234) and 34% (N=222) of patients, respectively, achieved a response, which was defined as at least a 50% decrease from baseline on the abnormal involuntary movement scale dyskinesia score in 6 to 12 weeks compared to 9% and 12%, respectively, with placebo.Discontinuation because of an adverse event was seldom encountered with both medications.6

Conclusion

The recent developments in psychodermatology with regard to DI are encouraging. The advent of new evidence and theories suggestive of an organic basis for DI could help this condition become more respected in the eyes of the dermatologist as a bona fide disorder. Moreover, the new developments and availability of medications that can treat TD can further make it easier for dermatologists to consider offering DI patients truly meaningful treatment that they desperately need. Therefore, both of these developments are welcomed for our specialty.

- Huber M, Kirchler E, Karner M, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the dopamine transporter. a new insight of etiology? Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:1351-1358.

- Chan SY, Koo J. Sex differences in primary delusional infestation: an insight into etiology and potential novel therapy. Int J Women Dermatol. 2020;6:226.

- Lorenzo CR, Koo J. Pimozide in dermatologic practice: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:339-349.

- Brownstone ND, Beck K, Sekhon S, et al. Morgellons Disease. 2nd ed. Kindle Direct Publishing; 2020.

- Thomson AM, Wallace J, Kobylecki C. Tardive dyskinesia after drug withdrawal in two older adults: clinical features, complications and management. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19:563-564.

- Citrome L. Tardive dyskinesia: placing vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors into clinical perspective. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18:323-332.

- Huber M, Kirchler E, Karner M, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the dopamine transporter. a new insight of etiology? Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:1351-1358.

- Chan SY, Koo J. Sex differences in primary delusional infestation: an insight into etiology and potential novel therapy. Int J Women Dermatol. 2020;6:226.

- Lorenzo CR, Koo J. Pimozide in dermatologic practice: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:339-349.

- Brownstone ND, Beck K, Sekhon S, et al. Morgellons Disease. 2nd ed. Kindle Direct Publishing; 2020.

- Thomson AM, Wallace J, Kobylecki C. Tardive dyskinesia after drug withdrawal in two older adults: clinical features, complications and management. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19:563-564.

- Citrome L. Tardive dyskinesia: placing vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors into clinical perspective. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18:323-332.