User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Obesity pegged as diabetes cause in almost half of U.S. cases

Roughly 40% of all U.S. cases of incident diabetes during 2013-2016 were directly attributable to obesity, a finding that further solidifies the major etiologic role for obesity in the current American diabetes epidemic.

Researchers used data from a diverse cohort of 4,200 American adults in the MESA study during 2000-2017 to calculate a relative risk for developing diabetes of 2.7 in people with obesity compared with similar participants without obesity.

They then applied this relative risk estimate to obesity prevalence rates during serial iterations of NHANES, the recurring U.S.-wide survey of vital statistics in a representative cross-sectional population.

Their calculations showed that, during 2013-2016, 41% of U.S. adults who developed new onset diabetes did so because of obesity, after the researchers adjusted for potential confounders.

This “population attributable fraction,” or disease burden attributable to obesity, varied somewhat by sex, and by racial and ethnic subgrouping. Obesity was linked with the highest attributable rate among non-Hispanic White women, a rate of 53%, and with the lowest rate among non-Hispanic Black men, with an attributable fraction of 30%, Natalie A. Cameron, MD, and colleagues reported in their study, published online Feb. 10 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Potential for “meaningful impact” by reducing obesity

“Our study highlights the meaningful impact that reducing obesity could have on type 2 diabetes prevention in the United States. Decreasing obesity needs to be a priority,” Dr. Cameron, of the McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University in Chicago, said in a statement issued by the American Heart Association.

“Public health efforts that support healthy lifestyles, such as increasing access to nutritious foods, promoting physical activity, and developing community programs to prevent obesity, could substantially reduce new cases of type 2 diabetes,” she added.

MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) enrolled adults aged 45-84 years and free from clinical cardiovascular disease at six U.S. sites during 2000-2002, and then followed them with four additional examinations through 2017.

For the current study, researchers narrowed the cohort down to 4,200 participants who were aged 45-79 years and free from diabetes at entry, and also restricted this subgroup to participants classified as non-Hispanic White (54% of the cohort), non-Hispanic Black (33%), or Mexican American (13%). At entry, 34% of the cohort had obesity, with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2.

During a median follow-up of just over 9 years, 12% of the cohort developed incident diabetes. After adjustment for possible confounders, a hazard ratio model showed an overall 2.7-fold higher rate of incident diabetes among people with obesity compared to those without.

The researchers then applied this hazard ratio to obesity prevalence statistics from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) during the same time period, with data from the biennial NHANES project collapsed into four time strata: 2001-2004, 2005-2008, 2009-2012, and 2013-2016. They again limited their analysis to NHANES data collected from people aged 45-79 years who self-reported categorization as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or Mexican American.

During the period from 2001-2004 to 2013-2016, overall obesity prevalence tallied by NHANES data rose from 34% to 41%. Among people with type 2 diabetes during 2013-2016, obesity prevalence was 65%.

To calculate the population attributable fraction researchers combined the MESA and NHANES estimates and adjusted for potential confounders and found that, overall, in 41% of people with incident diabetes during 2013-2016, the disease was attributable to obesity.

The study received no commercial funding, and none of the authors had disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Roughly 40% of all U.S. cases of incident diabetes during 2013-2016 were directly attributable to obesity, a finding that further solidifies the major etiologic role for obesity in the current American diabetes epidemic.

Researchers used data from a diverse cohort of 4,200 American adults in the MESA study during 2000-2017 to calculate a relative risk for developing diabetes of 2.7 in people with obesity compared with similar participants without obesity.

They then applied this relative risk estimate to obesity prevalence rates during serial iterations of NHANES, the recurring U.S.-wide survey of vital statistics in a representative cross-sectional population.

Their calculations showed that, during 2013-2016, 41% of U.S. adults who developed new onset diabetes did so because of obesity, after the researchers adjusted for potential confounders.

This “population attributable fraction,” or disease burden attributable to obesity, varied somewhat by sex, and by racial and ethnic subgrouping. Obesity was linked with the highest attributable rate among non-Hispanic White women, a rate of 53%, and with the lowest rate among non-Hispanic Black men, with an attributable fraction of 30%, Natalie A. Cameron, MD, and colleagues reported in their study, published online Feb. 10 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Potential for “meaningful impact” by reducing obesity

“Our study highlights the meaningful impact that reducing obesity could have on type 2 diabetes prevention in the United States. Decreasing obesity needs to be a priority,” Dr. Cameron, of the McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University in Chicago, said in a statement issued by the American Heart Association.

“Public health efforts that support healthy lifestyles, such as increasing access to nutritious foods, promoting physical activity, and developing community programs to prevent obesity, could substantially reduce new cases of type 2 diabetes,” she added.

MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) enrolled adults aged 45-84 years and free from clinical cardiovascular disease at six U.S. sites during 2000-2002, and then followed them with four additional examinations through 2017.

For the current study, researchers narrowed the cohort down to 4,200 participants who were aged 45-79 years and free from diabetes at entry, and also restricted this subgroup to participants classified as non-Hispanic White (54% of the cohort), non-Hispanic Black (33%), or Mexican American (13%). At entry, 34% of the cohort had obesity, with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2.

During a median follow-up of just over 9 years, 12% of the cohort developed incident diabetes. After adjustment for possible confounders, a hazard ratio model showed an overall 2.7-fold higher rate of incident diabetes among people with obesity compared to those without.

The researchers then applied this hazard ratio to obesity prevalence statistics from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) during the same time period, with data from the biennial NHANES project collapsed into four time strata: 2001-2004, 2005-2008, 2009-2012, and 2013-2016. They again limited their analysis to NHANES data collected from people aged 45-79 years who self-reported categorization as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or Mexican American.

During the period from 2001-2004 to 2013-2016, overall obesity prevalence tallied by NHANES data rose from 34% to 41%. Among people with type 2 diabetes during 2013-2016, obesity prevalence was 65%.

To calculate the population attributable fraction researchers combined the MESA and NHANES estimates and adjusted for potential confounders and found that, overall, in 41% of people with incident diabetes during 2013-2016, the disease was attributable to obesity.

The study received no commercial funding, and none of the authors had disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Roughly 40% of all U.S. cases of incident diabetes during 2013-2016 were directly attributable to obesity, a finding that further solidifies the major etiologic role for obesity in the current American diabetes epidemic.

Researchers used data from a diverse cohort of 4,200 American adults in the MESA study during 2000-2017 to calculate a relative risk for developing diabetes of 2.7 in people with obesity compared with similar participants without obesity.

They then applied this relative risk estimate to obesity prevalence rates during serial iterations of NHANES, the recurring U.S.-wide survey of vital statistics in a representative cross-sectional population.

Their calculations showed that, during 2013-2016, 41% of U.S. adults who developed new onset diabetes did so because of obesity, after the researchers adjusted for potential confounders.

This “population attributable fraction,” or disease burden attributable to obesity, varied somewhat by sex, and by racial and ethnic subgrouping. Obesity was linked with the highest attributable rate among non-Hispanic White women, a rate of 53%, and with the lowest rate among non-Hispanic Black men, with an attributable fraction of 30%, Natalie A. Cameron, MD, and colleagues reported in their study, published online Feb. 10 in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Potential for “meaningful impact” by reducing obesity

“Our study highlights the meaningful impact that reducing obesity could have on type 2 diabetes prevention in the United States. Decreasing obesity needs to be a priority,” Dr. Cameron, of the McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University in Chicago, said in a statement issued by the American Heart Association.

“Public health efforts that support healthy lifestyles, such as increasing access to nutritious foods, promoting physical activity, and developing community programs to prevent obesity, could substantially reduce new cases of type 2 diabetes,” she added.

MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) enrolled adults aged 45-84 years and free from clinical cardiovascular disease at six U.S. sites during 2000-2002, and then followed them with four additional examinations through 2017.

For the current study, researchers narrowed the cohort down to 4,200 participants who were aged 45-79 years and free from diabetes at entry, and also restricted this subgroup to participants classified as non-Hispanic White (54% of the cohort), non-Hispanic Black (33%), or Mexican American (13%). At entry, 34% of the cohort had obesity, with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2.

During a median follow-up of just over 9 years, 12% of the cohort developed incident diabetes. After adjustment for possible confounders, a hazard ratio model showed an overall 2.7-fold higher rate of incident diabetes among people with obesity compared to those without.

The researchers then applied this hazard ratio to obesity prevalence statistics from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) during the same time period, with data from the biennial NHANES project collapsed into four time strata: 2001-2004, 2005-2008, 2009-2012, and 2013-2016. They again limited their analysis to NHANES data collected from people aged 45-79 years who self-reported categorization as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or Mexican American.

During the period from 2001-2004 to 2013-2016, overall obesity prevalence tallied by NHANES data rose from 34% to 41%. Among people with type 2 diabetes during 2013-2016, obesity prevalence was 65%.

To calculate the population attributable fraction researchers combined the MESA and NHANES estimates and adjusted for potential confounders and found that, overall, in 41% of people with incident diabetes during 2013-2016, the disease was attributable to obesity.

The study received no commercial funding, and none of the authors had disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Home devices screen for atrial fibrillation

In an ad for one of these products, KardiaMobile, a cardiologist says this device “detects atrial fibrillation, one of the major causes of stroke.” You might also have heard that the Apple Watch has an opt-in feature that constantly screens for atrial fibrillation without any effort being made by the patient, or can check on-demand for AFib if a wearer experiences palpitations or an abnormal heart beat. Both of these devices generate a standard limb–lead ECG (essentially lead I) by connecting the device to both arms and producing a 30-second rhythm strip.

KardiaMobile recently introduced a newer device. When you place this device on a bare knee and touch one electrode with fingers from the right hand and another electrode with fingers from the left hand, the device produces a six-lead ECG. These small devices send an image of the ECG to a patient’s smartphone over Bluetooth, and the results can be easily read, printed out, or sent to the doctor for further analysis. Additionally, both of KardiaMobile’s devices utilize artificial intelligence to analyze a rhythm strip in real time and let the patient know if the ECG is normal, shows AFib, or is unable to be analyzed.

The electrocardiographic technology was formerly only available in a medical setting. It required an expensive machine and could only be interpreted by someone with expertise developed through years of training. Now it is readily available to patients in their homes. But how accurate is the technology and how are we going to use it?

How effective is KardiaMobile at detecting AFib?

Studies have looked at both KardiaMobile and the Apple Watch. One study of KardiaMobile in patients with Afib who were admitted for antiarrhythmic drug initiation showed that about a quarter of readings could not be classified because of artifact and other reasons. After exclusion of unclassified recordings, the KardiaMobile interpretation had 97% sensitivity and 94% specificity for AFib detection when compared with physician-interpreted ECGs.1 In a large review of the device’s accuracy, there was about 85% sensitivity and specificity of the automated readings.2

How does the Apple Watch find AFib?

Like the KardiaMobile device, the Apple Watch can be used whenever patients notice symptoms or whenever they and their physicians decide the device would be useful. In addition, though, the Apple Watch has a function where the wearer can opt in to have the watch screen for AFib in the background whenever the watch is worn.

The watch monitors heart rate using photoplethysmography, where light-sensitive photodiodes detect blood pulses to assess heart rate variability. When an irregular heart rate is detected, the AW alerts the user of possible AFib. Once alerted, the wearer can then utilize a second function to obtain a single-lead ECG. Heart rate, rhythm, and a 30-second ECG tracing are saved in the Bluetooth-linked iPhone’s health app and can be exported for review by a physician.

In a study of over 400,000 participants, among participants notified of an irregular pulse through screening there was a positive predictive value of 84%.3 Single-lead EKGs initiated by watch wearers had a specificity for AFib of 99.6% among tracings with good wave forms, indicating very few false positives. Only 1 individual of the 263 individuals who had normal sinus rhythm on 12-lead ECG was classified as having AFib, though in 7% sinus rhythm could not be confirmed because of poor tracings.4,5

What should we do with the results?

It’s impressive that these devices deliver accurate information with very good specificity. Our hope is that detecting AFib with one of these devices will lead to an intervention being made that will decrease a patient’s risk of stroke. But it is not clear if routine screening in asymptomatic adults will accomplish this.

While more data is needed, we must acknowledge that our patients will soon be bringing us results from home. Regardless of what we think of this technology, we need to decide what to do when patients call us with results from these devices.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. William A et al. Heart Rhythm. 2018 Oct;15(10):1561-5.

2. KardiaMobile for the ambulatory detection of atrial fibrillation. NICE Medtech innovation briefing. 29 October 2020 Oct 29. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mib232.

3. Perez MV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1909-17.

4. Using Apple Watch for Arrhythmia Detection, December 2018. Apple. https://www.apple.com/healthcare/site/docs/Apple_Watch_Arrhythmia_Detection.pdf. Accessed 2019 Apr 5.

5. De Novo Classification Request for ECG App. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/DEN180044.pdf. Accessed 2019 Apr 29.

In an ad for one of these products, KardiaMobile, a cardiologist says this device “detects atrial fibrillation, one of the major causes of stroke.” You might also have heard that the Apple Watch has an opt-in feature that constantly screens for atrial fibrillation without any effort being made by the patient, or can check on-demand for AFib if a wearer experiences palpitations or an abnormal heart beat. Both of these devices generate a standard limb–lead ECG (essentially lead I) by connecting the device to both arms and producing a 30-second rhythm strip.

KardiaMobile recently introduced a newer device. When you place this device on a bare knee and touch one electrode with fingers from the right hand and another electrode with fingers from the left hand, the device produces a six-lead ECG. These small devices send an image of the ECG to a patient’s smartphone over Bluetooth, and the results can be easily read, printed out, or sent to the doctor for further analysis. Additionally, both of KardiaMobile’s devices utilize artificial intelligence to analyze a rhythm strip in real time and let the patient know if the ECG is normal, shows AFib, or is unable to be analyzed.

The electrocardiographic technology was formerly only available in a medical setting. It required an expensive machine and could only be interpreted by someone with expertise developed through years of training. Now it is readily available to patients in their homes. But how accurate is the technology and how are we going to use it?

How effective is KardiaMobile at detecting AFib?

Studies have looked at both KardiaMobile and the Apple Watch. One study of KardiaMobile in patients with Afib who were admitted for antiarrhythmic drug initiation showed that about a quarter of readings could not be classified because of artifact and other reasons. After exclusion of unclassified recordings, the KardiaMobile interpretation had 97% sensitivity and 94% specificity for AFib detection when compared with physician-interpreted ECGs.1 In a large review of the device’s accuracy, there was about 85% sensitivity and specificity of the automated readings.2

How does the Apple Watch find AFib?

Like the KardiaMobile device, the Apple Watch can be used whenever patients notice symptoms or whenever they and their physicians decide the device would be useful. In addition, though, the Apple Watch has a function where the wearer can opt in to have the watch screen for AFib in the background whenever the watch is worn.

The watch monitors heart rate using photoplethysmography, where light-sensitive photodiodes detect blood pulses to assess heart rate variability. When an irregular heart rate is detected, the AW alerts the user of possible AFib. Once alerted, the wearer can then utilize a second function to obtain a single-lead ECG. Heart rate, rhythm, and a 30-second ECG tracing are saved in the Bluetooth-linked iPhone’s health app and can be exported for review by a physician.

In a study of over 400,000 participants, among participants notified of an irregular pulse through screening there was a positive predictive value of 84%.3 Single-lead EKGs initiated by watch wearers had a specificity for AFib of 99.6% among tracings with good wave forms, indicating very few false positives. Only 1 individual of the 263 individuals who had normal sinus rhythm on 12-lead ECG was classified as having AFib, though in 7% sinus rhythm could not be confirmed because of poor tracings.4,5

What should we do with the results?

It’s impressive that these devices deliver accurate information with very good specificity. Our hope is that detecting AFib with one of these devices will lead to an intervention being made that will decrease a patient’s risk of stroke. But it is not clear if routine screening in asymptomatic adults will accomplish this.

While more data is needed, we must acknowledge that our patients will soon be bringing us results from home. Regardless of what we think of this technology, we need to decide what to do when patients call us with results from these devices.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. William A et al. Heart Rhythm. 2018 Oct;15(10):1561-5.

2. KardiaMobile for the ambulatory detection of atrial fibrillation. NICE Medtech innovation briefing. 29 October 2020 Oct 29. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mib232.

3. Perez MV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1909-17.

4. Using Apple Watch for Arrhythmia Detection, December 2018. Apple. https://www.apple.com/healthcare/site/docs/Apple_Watch_Arrhythmia_Detection.pdf. Accessed 2019 Apr 5.

5. De Novo Classification Request for ECG App. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/DEN180044.pdf. Accessed 2019 Apr 29.

In an ad for one of these products, KardiaMobile, a cardiologist says this device “detects atrial fibrillation, one of the major causes of stroke.” You might also have heard that the Apple Watch has an opt-in feature that constantly screens for atrial fibrillation without any effort being made by the patient, or can check on-demand for AFib if a wearer experiences palpitations or an abnormal heart beat. Both of these devices generate a standard limb–lead ECG (essentially lead I) by connecting the device to both arms and producing a 30-second rhythm strip.

KardiaMobile recently introduced a newer device. When you place this device on a bare knee and touch one electrode with fingers from the right hand and another electrode with fingers from the left hand, the device produces a six-lead ECG. These small devices send an image of the ECG to a patient’s smartphone over Bluetooth, and the results can be easily read, printed out, or sent to the doctor for further analysis. Additionally, both of KardiaMobile’s devices utilize artificial intelligence to analyze a rhythm strip in real time and let the patient know if the ECG is normal, shows AFib, or is unable to be analyzed.

The electrocardiographic technology was formerly only available in a medical setting. It required an expensive machine and could only be interpreted by someone with expertise developed through years of training. Now it is readily available to patients in their homes. But how accurate is the technology and how are we going to use it?

How effective is KardiaMobile at detecting AFib?

Studies have looked at both KardiaMobile and the Apple Watch. One study of KardiaMobile in patients with Afib who were admitted for antiarrhythmic drug initiation showed that about a quarter of readings could not be classified because of artifact and other reasons. After exclusion of unclassified recordings, the KardiaMobile interpretation had 97% sensitivity and 94% specificity for AFib detection when compared with physician-interpreted ECGs.1 In a large review of the device’s accuracy, there was about 85% sensitivity and specificity of the automated readings.2

How does the Apple Watch find AFib?

Like the KardiaMobile device, the Apple Watch can be used whenever patients notice symptoms or whenever they and their physicians decide the device would be useful. In addition, though, the Apple Watch has a function where the wearer can opt in to have the watch screen for AFib in the background whenever the watch is worn.

The watch monitors heart rate using photoplethysmography, where light-sensitive photodiodes detect blood pulses to assess heart rate variability. When an irregular heart rate is detected, the AW alerts the user of possible AFib. Once alerted, the wearer can then utilize a second function to obtain a single-lead ECG. Heart rate, rhythm, and a 30-second ECG tracing are saved in the Bluetooth-linked iPhone’s health app and can be exported for review by a physician.

In a study of over 400,000 participants, among participants notified of an irregular pulse through screening there was a positive predictive value of 84%.3 Single-lead EKGs initiated by watch wearers had a specificity for AFib of 99.6% among tracings with good wave forms, indicating very few false positives. Only 1 individual of the 263 individuals who had normal sinus rhythm on 12-lead ECG was classified as having AFib, though in 7% sinus rhythm could not be confirmed because of poor tracings.4,5

What should we do with the results?

It’s impressive that these devices deliver accurate information with very good specificity. Our hope is that detecting AFib with one of these devices will lead to an intervention being made that will decrease a patient’s risk of stroke. But it is not clear if routine screening in asymptomatic adults will accomplish this.

While more data is needed, we must acknowledge that our patients will soon be bringing us results from home. Regardless of what we think of this technology, we need to decide what to do when patients call us with results from these devices.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. William A et al. Heart Rhythm. 2018 Oct;15(10):1561-5.

2. KardiaMobile for the ambulatory detection of atrial fibrillation. NICE Medtech innovation briefing. 29 October 2020 Oct 29. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mib232.

3. Perez MV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381:1909-17.

4. Using Apple Watch for Arrhythmia Detection, December 2018. Apple. https://www.apple.com/healthcare/site/docs/Apple_Watch_Arrhythmia_Detection.pdf. Accessed 2019 Apr 5.

5. De Novo Classification Request for ECG App. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/reviews/DEN180044.pdf. Accessed 2019 Apr 29.

Variants spur new FDA guidance on COVID vaccines, tests, drugs

The United States is currently facing three main variant threats, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: B.1.1.7, which originated in the United Kingdom; B.1.351 from South Africa; and the P.1 variant, which originated in Brazil.

Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, said on a telephone press briefing call Feb. 22 that the FDA has already been communicating with individual manufacturers as they assess the variants’ effect on their products, but these guidelines are issued for the sake of transparency and to welcome scientific input.

Tailoring may be necessary

Dr. Woodcock emphasized that, “at this time, available data suggest the FDA-authorized vaccines are effective in protecting circulating strains of SARS-CoV-2.” However, in the event the strains start to show resistance, it may be necessary to tailor the vaccine to the variant.

In that case, effectiveness of a modified vaccine should be determined by data from clinical immunogenicity studies, which would compare a recipient’s immune response with virus variants induced by the modified vaccine against the immune response to the authorized vaccine, the guidance states.

Manufacturers should also study the vaccine in both nonvaccinated people and people fully vaccinated with the authorized vaccine, according to the guidance.

Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said on the call that the clinical immunogenicity data is needed to understand, for instance, whether a new vaccine strain is able to cover the new and old strain or whether it just covers the new strain. Information is also needed to understand whether the modified vaccine, when given to someone fully vaccinated, will still promote a positive response without introducing safety concerns.

Further discussions will be necessary to decide whether future modified vaccines may be authorized without the need for clinical studies.

Variants and testing

The FDA’s updated guidance for test developers, Policy for Evaluating Impact of Viral Mutations on COVID-19 Tests, includes information that test performance can be influenced by the sequence of the variant, prevalence of the variant in the population, or design of the test. For example, molecular tests designed to detect multiple SARS-CoV-2 genetic targets are less susceptible to genetic variants than tests designed to detect a single genetic target.

The FDA already issued a safety alert on Jan. 8 to caution that genetic mutations to the virus in a patient sample can potentially change the performance of a diagnostic test. The FDA identified three tests that had been granted emergency-use authorization (EUA) that are known to be affected.

However, Dr. Woodcock said on the call, “at this time the impact does not appear to be significant.”

Updated guidance for therapeutics

The FDA has issued new guidance on the effect of variants on monoclonal antibody treatments.

“The FDA is aware that some of the monoclonal antibodies that have been authorized are less active against some of the SARS-CoV-2 variants that have emerged,” the FDA noted in its press release. “This guidance provides recommendations on efficient approaches to the generation of ... manufacturing and controls data that could potentially support an EUA for monoclonal antibody products that may be effective against emerging variants.”

While the FDA is monitoring the effects of variants, manufacturers bear a lot of the responsibility as well.

The FDA added: “With these guidances, the FDA is encouraging developers of drugs or biological products targeting SARS-CoV-2 to continuously monitor genomic databases for emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants and evaluate phenotypically any specific variants in the product target that are becoming prevalent or could potentially impact its activity.”

Dr.Woodcock added that “we urge all Americans to continue to get tested, get their vaccines when available, and follow important heath measures such as handwashing, masking, and social distancing.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The United States is currently facing three main variant threats, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: B.1.1.7, which originated in the United Kingdom; B.1.351 from South Africa; and the P.1 variant, which originated in Brazil.

Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, said on a telephone press briefing call Feb. 22 that the FDA has already been communicating with individual manufacturers as they assess the variants’ effect on their products, but these guidelines are issued for the sake of transparency and to welcome scientific input.

Tailoring may be necessary

Dr. Woodcock emphasized that, “at this time, available data suggest the FDA-authorized vaccines are effective in protecting circulating strains of SARS-CoV-2.” However, in the event the strains start to show resistance, it may be necessary to tailor the vaccine to the variant.

In that case, effectiveness of a modified vaccine should be determined by data from clinical immunogenicity studies, which would compare a recipient’s immune response with virus variants induced by the modified vaccine against the immune response to the authorized vaccine, the guidance states.

Manufacturers should also study the vaccine in both nonvaccinated people and people fully vaccinated with the authorized vaccine, according to the guidance.

Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said on the call that the clinical immunogenicity data is needed to understand, for instance, whether a new vaccine strain is able to cover the new and old strain or whether it just covers the new strain. Information is also needed to understand whether the modified vaccine, when given to someone fully vaccinated, will still promote a positive response without introducing safety concerns.

Further discussions will be necessary to decide whether future modified vaccines may be authorized without the need for clinical studies.

Variants and testing

The FDA’s updated guidance for test developers, Policy for Evaluating Impact of Viral Mutations on COVID-19 Tests, includes information that test performance can be influenced by the sequence of the variant, prevalence of the variant in the population, or design of the test. For example, molecular tests designed to detect multiple SARS-CoV-2 genetic targets are less susceptible to genetic variants than tests designed to detect a single genetic target.

The FDA already issued a safety alert on Jan. 8 to caution that genetic mutations to the virus in a patient sample can potentially change the performance of a diagnostic test. The FDA identified three tests that had been granted emergency-use authorization (EUA) that are known to be affected.

However, Dr. Woodcock said on the call, “at this time the impact does not appear to be significant.”

Updated guidance for therapeutics

The FDA has issued new guidance on the effect of variants on monoclonal antibody treatments.

“The FDA is aware that some of the monoclonal antibodies that have been authorized are less active against some of the SARS-CoV-2 variants that have emerged,” the FDA noted in its press release. “This guidance provides recommendations on efficient approaches to the generation of ... manufacturing and controls data that could potentially support an EUA for monoclonal antibody products that may be effective against emerging variants.”

While the FDA is monitoring the effects of variants, manufacturers bear a lot of the responsibility as well.

The FDA added: “With these guidances, the FDA is encouraging developers of drugs or biological products targeting SARS-CoV-2 to continuously monitor genomic databases for emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants and evaluate phenotypically any specific variants in the product target that are becoming prevalent or could potentially impact its activity.”

Dr.Woodcock added that “we urge all Americans to continue to get tested, get their vaccines when available, and follow important heath measures such as handwashing, masking, and social distancing.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The United States is currently facing three main variant threats, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: B.1.1.7, which originated in the United Kingdom; B.1.351 from South Africa; and the P.1 variant, which originated in Brazil.

Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, said on a telephone press briefing call Feb. 22 that the FDA has already been communicating with individual manufacturers as they assess the variants’ effect on their products, but these guidelines are issued for the sake of transparency and to welcome scientific input.

Tailoring may be necessary

Dr. Woodcock emphasized that, “at this time, available data suggest the FDA-authorized vaccines are effective in protecting circulating strains of SARS-CoV-2.” However, in the event the strains start to show resistance, it may be necessary to tailor the vaccine to the variant.

In that case, effectiveness of a modified vaccine should be determined by data from clinical immunogenicity studies, which would compare a recipient’s immune response with virus variants induced by the modified vaccine against the immune response to the authorized vaccine, the guidance states.

Manufacturers should also study the vaccine in both nonvaccinated people and people fully vaccinated with the authorized vaccine, according to the guidance.

Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said on the call that the clinical immunogenicity data is needed to understand, for instance, whether a new vaccine strain is able to cover the new and old strain or whether it just covers the new strain. Information is also needed to understand whether the modified vaccine, when given to someone fully vaccinated, will still promote a positive response without introducing safety concerns.

Further discussions will be necessary to decide whether future modified vaccines may be authorized without the need for clinical studies.

Variants and testing

The FDA’s updated guidance for test developers, Policy for Evaluating Impact of Viral Mutations on COVID-19 Tests, includes information that test performance can be influenced by the sequence of the variant, prevalence of the variant in the population, or design of the test. For example, molecular tests designed to detect multiple SARS-CoV-2 genetic targets are less susceptible to genetic variants than tests designed to detect a single genetic target.

The FDA already issued a safety alert on Jan. 8 to caution that genetic mutations to the virus in a patient sample can potentially change the performance of a diagnostic test. The FDA identified three tests that had been granted emergency-use authorization (EUA) that are known to be affected.

However, Dr. Woodcock said on the call, “at this time the impact does not appear to be significant.”

Updated guidance for therapeutics

The FDA has issued new guidance on the effect of variants on monoclonal antibody treatments.

“The FDA is aware that some of the monoclonal antibodies that have been authorized are less active against some of the SARS-CoV-2 variants that have emerged,” the FDA noted in its press release. “This guidance provides recommendations on efficient approaches to the generation of ... manufacturing and controls data that could potentially support an EUA for monoclonal antibody products that may be effective against emerging variants.”

While the FDA is monitoring the effects of variants, manufacturers bear a lot of the responsibility as well.

The FDA added: “With these guidances, the FDA is encouraging developers of drugs or biological products targeting SARS-CoV-2 to continuously monitor genomic databases for emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants and evaluate phenotypically any specific variants in the product target that are becoming prevalent or could potentially impact its activity.”

Dr.Woodcock added that “we urge all Americans to continue to get tested, get their vaccines when available, and follow important heath measures such as handwashing, masking, and social distancing.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New light cast on type 2 MI aims to sharpen diagnosis, therapy

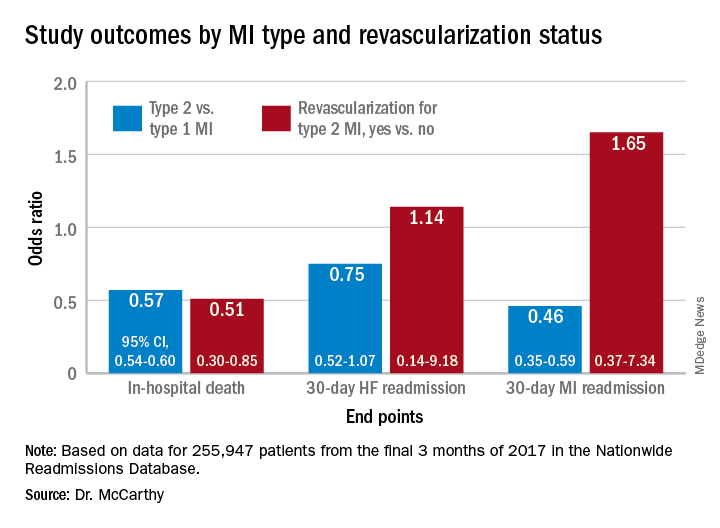

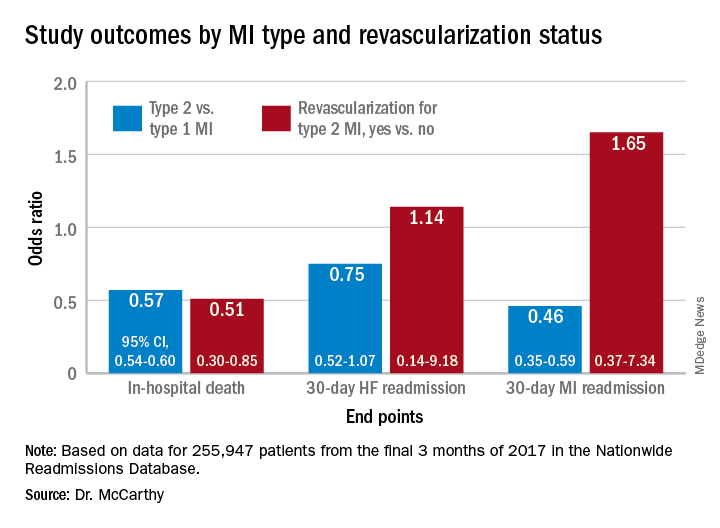

The hospital and postdischarge course of patients diagnosed with type 2 myocardial infarction, triggered when myocardial oxygen demand outstrips supply, differs in telling ways from those with the more common atherothrombotic type 1 MI, suggests a new registry analysis that aims to lift a cloud of confusion surrounding their management.

The observational study of more than 250,000 patients with either form of MI, said to be the largest of its kind, points to widespread unfamiliarity with distinctions between the two, and the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of misclassification. It suggests, in particular, that type 2 MI may be grossly underdiagnosed and undertreated.

The minority of patients with type 2 MI were more likely female and to have heart failure (HF), renal disease, valve disease, or atrial fibrillation, and less likely to have a lipid disorder, compared with those with type 1 MI. They were one-fifth as likely to be referred for coronary angiography and 20 times less likely to undergo revascularization.

Indeed, only about 2% of the type 2 cohort ultimately underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery (CABG). Yet the analysis suggests that cardiovascular risk climbs regardless of MI type and that in patients with type 2 MI, coronary revascularization might well cut the risk of death in half over the short term.

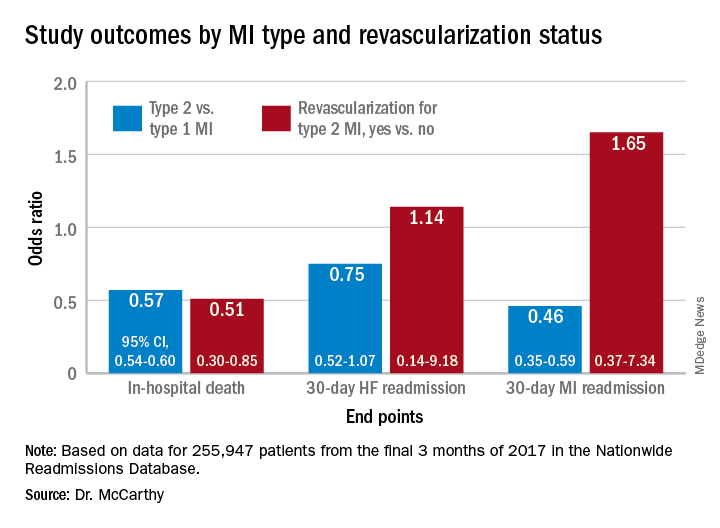

There were also disparities in clinical outcomes in the analysis, based on data from the final 3 months of 2017 in the Nationwide Readmissions Database, which reportedly documents almost 60% of hospitalizations in the United States.

For example, those with type 1 or type 2 MI – as characterized in the then-current third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction and today’s UDMI-4 – were comparably at risk for both 30-day all-cause readmission and HF readmission. But type 2 patients were less likely to die in the hospital or be readmitted within 30 days for recurrent MI.

Revascularization uncertainty

Importantly, the study’s 3-month observation period immediately followed the debut of a code specifically for type 2 MI in the ICD-10-CM system.

Type 2 accounted for about 15% of MIs during that period, the percentage climbing sharply from the first to the third month. That suggests clinicians were still getting used to the code during the early weeks, “undercoding” for type-2 MI at first but less so after some experience, Cian P. McCarthy, MB, BCh, BAO, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“I can imagine that as people become more aware of the coding, using it more often, the proportion of type 2 MI relative to the total MI cases will probably be much higher,” said McCarthy, lead author on the study published online Feb. 15, 2021, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

What had been understood about type 2 MI came largely from single-center studies, he said. This “first national study of type-2 MI in the United States” sought to determine whether such findings are hospital specific or “representative of what people are doing nationally.”

The new analysis largely confirms that patients with type 2 MI are typically burdened with multiple comorbidities, Dr. McCarthy said, but also suggests that type 2 often was, and likely still is, incorrectly classified as type 1. So, it was “surprising” that they were rarely referred for angiography. “Only 1 in 50 received revascularization.”

Those diagnosed with type-2 MI were far less likely to receive coronary angiography (10.9% vs. 57.3%), PCI (1.7% vs. 38.5%), or CABG (0.4% vs. 7.8%) (P < .001 for all three differences), the report noted.

That, Dr. McCarthy said, “clearly shows that clinicians are uncertain about whether revascularization is beneficial” in type 2 MI.

Coding not in sync with UDMI

If there is confusion in practice about differentiating type 2 from type 1 MI, it likely has multiple sources, and one may be inconsistencies in how the UDMI and relevant ICD codes are applied in practice.

For example, the coding mandate is always to classify ST-segment elevation MI and non-STEMI as type 1, yet UDMI-4 itself states that a type 2 MI may be either STEMI or non-STEMI, noted Dr. McCarthy, as well as an editorial accompanying the report.

“It also can be difficult at times to distinguish type 2 MI from the diagnosis of myocardial injury,” both of which are partly defined by elevated cardiac troponin (cTn), adds the editorial, from Kristian Thygesen, MD, DSc, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark, and Allan S. Jaffe, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Crucially, but potentially sometimes overlooked, a diagnosis of infarction requires evidence of ischemia along with the biomarker elevation, whereas myocardial injury is defined by raised cTn without evidence of ischemia. Yet there is no ICD-10-CM code for “nonischemic myocardial injury,” Dr. Thygesen and Dr. Jaffe observed.

“Instead, the new ICD-10-CM coding includes a proxy called ‘non-MI troponin elevation due to an underlying cause,’ ” they wrote. “Unfortunately, although some have advocated using this code for myocardial injury, it is not specific for an elevated cTn value and could represent any abnormal laboratory measurements.” The code could be “misleading” and thus worsen the potential for miscoding and “misattribution of MI diagnoses.”

In the current study, 84.6% of the cohort were classified with type 1 MI, 14.8% with type 2, and 0.6% with both types. Of those with type 1 MI, 22.1% had STEMI, 76.4% had non-STEMI with the remainder “unspecified.”

“I think the introduction of ICD codes for type-2 MI is helpful in that we can study type 2 MI more broadly, across institutions, and try and get a better sense of its outcomes and how these patients are treated,” Dr. McCarthy said. But the coding system’s deficiencies may often lead to misclassification of patients. Especially, patients with type 2 STEMI may be miscoded as having type-1 STEMI, and those with only myocardial injury may be miscoded as having type 2 MI.

Most type 2 MI is a complication

A profile of patients with type 2 MI may be helpful for making distinctions. The analysis showed that, compared with patients with type 1 MI, they were slightly but significantly older and more likely to have clinical depression, alcohol or other substance abuse disorder, and to be female. They also had more heart failure (27.9% vs. 10.9%), kidney disease (35.7% vs. 25.7%), atrial fibrillation (31% vs. 21%), and anemia (26% vs. 18.9%) (P < .001 for all differences).

Type 2 patients were less likely to have CV risk factors usually associated with plaque instability and atherothrombosis, including a history of smoking, dyslipidemia, MI, PCI, or CABG (P < .001 for all differences), the group noted.

Of the 37,765 patients with type 2 MI, 91% received the diagnosis as secondary to another condition, including sepsis in 24.5%, hypertension in 16.9%, arrhythmias in 6.1%, respiratory failure in 4.3%, and pneumonia in 2.8% of cases.

In multivariate analyses, patients with type 2 MI, compared with type 1, showed lower risks of in-hospital death and readmission for MI within 30 days. Their 30-day risks of readmission from any cause and from MI were similar.

In-hospital mortality was lower for patients with type 2 MI who underwent revascularization, compared with those who did not, “but they were a very select, small proportion of the patient group. I would say there are probably unmeasured confounders,” Dr. McCarthy said.

“There’s a real kind of equipoise, so I think we desperately need a trial to guide us on whether revascularization is beneficial.”

Dr. McCarthy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Thygesen disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jaffe disclosed serving as a consultant for Abbott, Roche, Siemens, Beckman-Coulter, Radiometer, ET Healthcare, Sphingotec, Brava, Quidel, Amgen, Novartis, and Medscape for educational activities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The hospital and postdischarge course of patients diagnosed with type 2 myocardial infarction, triggered when myocardial oxygen demand outstrips supply, differs in telling ways from those with the more common atherothrombotic type 1 MI, suggests a new registry analysis that aims to lift a cloud of confusion surrounding their management.

The observational study of more than 250,000 patients with either form of MI, said to be the largest of its kind, points to widespread unfamiliarity with distinctions between the two, and the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of misclassification. It suggests, in particular, that type 2 MI may be grossly underdiagnosed and undertreated.

The minority of patients with type 2 MI were more likely female and to have heart failure (HF), renal disease, valve disease, or atrial fibrillation, and less likely to have a lipid disorder, compared with those with type 1 MI. They were one-fifth as likely to be referred for coronary angiography and 20 times less likely to undergo revascularization.

Indeed, only about 2% of the type 2 cohort ultimately underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery (CABG). Yet the analysis suggests that cardiovascular risk climbs regardless of MI type and that in patients with type 2 MI, coronary revascularization might well cut the risk of death in half over the short term.

There were also disparities in clinical outcomes in the analysis, based on data from the final 3 months of 2017 in the Nationwide Readmissions Database, which reportedly documents almost 60% of hospitalizations in the United States.

For example, those with type 1 or type 2 MI – as characterized in the then-current third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction and today’s UDMI-4 – were comparably at risk for both 30-day all-cause readmission and HF readmission. But type 2 patients were less likely to die in the hospital or be readmitted within 30 days for recurrent MI.

Revascularization uncertainty

Importantly, the study’s 3-month observation period immediately followed the debut of a code specifically for type 2 MI in the ICD-10-CM system.

Type 2 accounted for about 15% of MIs during that period, the percentage climbing sharply from the first to the third month. That suggests clinicians were still getting used to the code during the early weeks, “undercoding” for type-2 MI at first but less so after some experience, Cian P. McCarthy, MB, BCh, BAO, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“I can imagine that as people become more aware of the coding, using it more often, the proportion of type 2 MI relative to the total MI cases will probably be much higher,” said McCarthy, lead author on the study published online Feb. 15, 2021, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

What had been understood about type 2 MI came largely from single-center studies, he said. This “first national study of type-2 MI in the United States” sought to determine whether such findings are hospital specific or “representative of what people are doing nationally.”

The new analysis largely confirms that patients with type 2 MI are typically burdened with multiple comorbidities, Dr. McCarthy said, but also suggests that type 2 often was, and likely still is, incorrectly classified as type 1. So, it was “surprising” that they were rarely referred for angiography. “Only 1 in 50 received revascularization.”

Those diagnosed with type-2 MI were far less likely to receive coronary angiography (10.9% vs. 57.3%), PCI (1.7% vs. 38.5%), or CABG (0.4% vs. 7.8%) (P < .001 for all three differences), the report noted.

That, Dr. McCarthy said, “clearly shows that clinicians are uncertain about whether revascularization is beneficial” in type 2 MI.

Coding not in sync with UDMI

If there is confusion in practice about differentiating type 2 from type 1 MI, it likely has multiple sources, and one may be inconsistencies in how the UDMI and relevant ICD codes are applied in practice.

For example, the coding mandate is always to classify ST-segment elevation MI and non-STEMI as type 1, yet UDMI-4 itself states that a type 2 MI may be either STEMI or non-STEMI, noted Dr. McCarthy, as well as an editorial accompanying the report.

“It also can be difficult at times to distinguish type 2 MI from the diagnosis of myocardial injury,” both of which are partly defined by elevated cardiac troponin (cTn), adds the editorial, from Kristian Thygesen, MD, DSc, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark, and Allan S. Jaffe, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Crucially, but potentially sometimes overlooked, a diagnosis of infarction requires evidence of ischemia along with the biomarker elevation, whereas myocardial injury is defined by raised cTn without evidence of ischemia. Yet there is no ICD-10-CM code for “nonischemic myocardial injury,” Dr. Thygesen and Dr. Jaffe observed.

“Instead, the new ICD-10-CM coding includes a proxy called ‘non-MI troponin elevation due to an underlying cause,’ ” they wrote. “Unfortunately, although some have advocated using this code for myocardial injury, it is not specific for an elevated cTn value and could represent any abnormal laboratory measurements.” The code could be “misleading” and thus worsen the potential for miscoding and “misattribution of MI diagnoses.”

In the current study, 84.6% of the cohort were classified with type 1 MI, 14.8% with type 2, and 0.6% with both types. Of those with type 1 MI, 22.1% had STEMI, 76.4% had non-STEMI with the remainder “unspecified.”

“I think the introduction of ICD codes for type-2 MI is helpful in that we can study type 2 MI more broadly, across institutions, and try and get a better sense of its outcomes and how these patients are treated,” Dr. McCarthy said. But the coding system’s deficiencies may often lead to misclassification of patients. Especially, patients with type 2 STEMI may be miscoded as having type-1 STEMI, and those with only myocardial injury may be miscoded as having type 2 MI.

Most type 2 MI is a complication

A profile of patients with type 2 MI may be helpful for making distinctions. The analysis showed that, compared with patients with type 1 MI, they were slightly but significantly older and more likely to have clinical depression, alcohol or other substance abuse disorder, and to be female. They also had more heart failure (27.9% vs. 10.9%), kidney disease (35.7% vs. 25.7%), atrial fibrillation (31% vs. 21%), and anemia (26% vs. 18.9%) (P < .001 for all differences).

Type 2 patients were less likely to have CV risk factors usually associated with plaque instability and atherothrombosis, including a history of smoking, dyslipidemia, MI, PCI, or CABG (P < .001 for all differences), the group noted.

Of the 37,765 patients with type 2 MI, 91% received the diagnosis as secondary to another condition, including sepsis in 24.5%, hypertension in 16.9%, arrhythmias in 6.1%, respiratory failure in 4.3%, and pneumonia in 2.8% of cases.

In multivariate analyses, patients with type 2 MI, compared with type 1, showed lower risks of in-hospital death and readmission for MI within 30 days. Their 30-day risks of readmission from any cause and from MI were similar.

In-hospital mortality was lower for patients with type 2 MI who underwent revascularization, compared with those who did not, “but they were a very select, small proportion of the patient group. I would say there are probably unmeasured confounders,” Dr. McCarthy said.

“There’s a real kind of equipoise, so I think we desperately need a trial to guide us on whether revascularization is beneficial.”

Dr. McCarthy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Thygesen disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jaffe disclosed serving as a consultant for Abbott, Roche, Siemens, Beckman-Coulter, Radiometer, ET Healthcare, Sphingotec, Brava, Quidel, Amgen, Novartis, and Medscape for educational activities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The hospital and postdischarge course of patients diagnosed with type 2 myocardial infarction, triggered when myocardial oxygen demand outstrips supply, differs in telling ways from those with the more common atherothrombotic type 1 MI, suggests a new registry analysis that aims to lift a cloud of confusion surrounding their management.

The observational study of more than 250,000 patients with either form of MI, said to be the largest of its kind, points to widespread unfamiliarity with distinctions between the two, and the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of misclassification. It suggests, in particular, that type 2 MI may be grossly underdiagnosed and undertreated.

The minority of patients with type 2 MI were more likely female and to have heart failure (HF), renal disease, valve disease, or atrial fibrillation, and less likely to have a lipid disorder, compared with those with type 1 MI. They were one-fifth as likely to be referred for coronary angiography and 20 times less likely to undergo revascularization.

Indeed, only about 2% of the type 2 cohort ultimately underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery (CABG). Yet the analysis suggests that cardiovascular risk climbs regardless of MI type and that in patients with type 2 MI, coronary revascularization might well cut the risk of death in half over the short term.

There were also disparities in clinical outcomes in the analysis, based on data from the final 3 months of 2017 in the Nationwide Readmissions Database, which reportedly documents almost 60% of hospitalizations in the United States.

For example, those with type 1 or type 2 MI – as characterized in the then-current third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction and today’s UDMI-4 – were comparably at risk for both 30-day all-cause readmission and HF readmission. But type 2 patients were less likely to die in the hospital or be readmitted within 30 days for recurrent MI.

Revascularization uncertainty

Importantly, the study’s 3-month observation period immediately followed the debut of a code specifically for type 2 MI in the ICD-10-CM system.

Type 2 accounted for about 15% of MIs during that period, the percentage climbing sharply from the first to the third month. That suggests clinicians were still getting used to the code during the early weeks, “undercoding” for type-2 MI at first but less so after some experience, Cian P. McCarthy, MB, BCh, BAO, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“I can imagine that as people become more aware of the coding, using it more often, the proportion of type 2 MI relative to the total MI cases will probably be much higher,” said McCarthy, lead author on the study published online Feb. 15, 2021, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

What had been understood about type 2 MI came largely from single-center studies, he said. This “first national study of type-2 MI in the United States” sought to determine whether such findings are hospital specific or “representative of what people are doing nationally.”

The new analysis largely confirms that patients with type 2 MI are typically burdened with multiple comorbidities, Dr. McCarthy said, but also suggests that type 2 often was, and likely still is, incorrectly classified as type 1. So, it was “surprising” that they were rarely referred for angiography. “Only 1 in 50 received revascularization.”

Those diagnosed with type-2 MI were far less likely to receive coronary angiography (10.9% vs. 57.3%), PCI (1.7% vs. 38.5%), or CABG (0.4% vs. 7.8%) (P < .001 for all three differences), the report noted.

That, Dr. McCarthy said, “clearly shows that clinicians are uncertain about whether revascularization is beneficial” in type 2 MI.

Coding not in sync with UDMI

If there is confusion in practice about differentiating type 2 from type 1 MI, it likely has multiple sources, and one may be inconsistencies in how the UDMI and relevant ICD codes are applied in practice.

For example, the coding mandate is always to classify ST-segment elevation MI and non-STEMI as type 1, yet UDMI-4 itself states that a type 2 MI may be either STEMI or non-STEMI, noted Dr. McCarthy, as well as an editorial accompanying the report.

“It also can be difficult at times to distinguish type 2 MI from the diagnosis of myocardial injury,” both of which are partly defined by elevated cardiac troponin (cTn), adds the editorial, from Kristian Thygesen, MD, DSc, Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark, and Allan S. Jaffe, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Crucially, but potentially sometimes overlooked, a diagnosis of infarction requires evidence of ischemia along with the biomarker elevation, whereas myocardial injury is defined by raised cTn without evidence of ischemia. Yet there is no ICD-10-CM code for “nonischemic myocardial injury,” Dr. Thygesen and Dr. Jaffe observed.

“Instead, the new ICD-10-CM coding includes a proxy called ‘non-MI troponin elevation due to an underlying cause,’ ” they wrote. “Unfortunately, although some have advocated using this code for myocardial injury, it is not specific for an elevated cTn value and could represent any abnormal laboratory measurements.” The code could be “misleading” and thus worsen the potential for miscoding and “misattribution of MI diagnoses.”

In the current study, 84.6% of the cohort were classified with type 1 MI, 14.8% with type 2, and 0.6% with both types. Of those with type 1 MI, 22.1% had STEMI, 76.4% had non-STEMI with the remainder “unspecified.”

“I think the introduction of ICD codes for type-2 MI is helpful in that we can study type 2 MI more broadly, across institutions, and try and get a better sense of its outcomes and how these patients are treated,” Dr. McCarthy said. But the coding system’s deficiencies may often lead to misclassification of patients. Especially, patients with type 2 STEMI may be miscoded as having type-1 STEMI, and those with only myocardial injury may be miscoded as having type 2 MI.

Most type 2 MI is a complication

A profile of patients with type 2 MI may be helpful for making distinctions. The analysis showed that, compared with patients with type 1 MI, they were slightly but significantly older and more likely to have clinical depression, alcohol or other substance abuse disorder, and to be female. They also had more heart failure (27.9% vs. 10.9%), kidney disease (35.7% vs. 25.7%), atrial fibrillation (31% vs. 21%), and anemia (26% vs. 18.9%) (P < .001 for all differences).

Type 2 patients were less likely to have CV risk factors usually associated with plaque instability and atherothrombosis, including a history of smoking, dyslipidemia, MI, PCI, or CABG (P < .001 for all differences), the group noted.

Of the 37,765 patients with type 2 MI, 91% received the diagnosis as secondary to another condition, including sepsis in 24.5%, hypertension in 16.9%, arrhythmias in 6.1%, respiratory failure in 4.3%, and pneumonia in 2.8% of cases.

In multivariate analyses, patients with type 2 MI, compared with type 1, showed lower risks of in-hospital death and readmission for MI within 30 days. Their 30-day risks of readmission from any cause and from MI were similar.

In-hospital mortality was lower for patients with type 2 MI who underwent revascularization, compared with those who did not, “but they were a very select, small proportion of the patient group. I would say there are probably unmeasured confounders,” Dr. McCarthy said.

“There’s a real kind of equipoise, so I think we desperately need a trial to guide us on whether revascularization is beneficial.”

Dr. McCarthy has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Thygesen disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jaffe disclosed serving as a consultant for Abbott, Roche, Siemens, Beckman-Coulter, Radiometer, ET Healthcare, Sphingotec, Brava, Quidel, Amgen, Novartis, and Medscape for educational activities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term CPAP use linked with more physical activity

in new research.

“The aim of this study was to determine whether long-term CPAP treatment affects self-reported physical activity among participants with moderate-severe OSA and comorbid CV disease,” wrote David Stevens, PhD, of Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia, and his colleagues. The findings were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

Researchers conducted a secondary analysis of the Sleep apnea cardiovascular endpoints (SAVE) trial that enrolled 2,687 adults aged 45-75 years old with OSA and confirmed CVD. In the study, participants were randomized to receive either CPAP plus usual care or usual care alone.

Physical activity levels were self-reported using the Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (LTEQ) at baseline and at 6-, 24-, and 48-month follow-up intervals. The physical functioning subscale of the 36-item short form questionnaire (SF-36) was used to determine if activity levels were consistent with expert recommendations and to evaluate the effects on any self-perceived limitation of physical activity.

Moderate physical activity was higher among CPAP users

After a mean follow-up duration of 3.7 years, participants in the CPAP arm had approximately 20% higher levels of moderate physical activity, compared with the control arm (adjusted mean scores]: 8.7 points vs. 7.3 points; 95% confidence interval, 7.5-9.9 vs. 6.1-8.5; P = .003).

However, no significant difference was observed between treatment arms for mild physical activity (adjusted mean scores, 14.4 points vs. 14.2 points; 95% CI, 13.5-15.3 vs. 13.3-15.1; P = 0.599) or vigorous physical activity (adjusted mean scores, 3.4 points vs. 2.9 points; 95% CI 2.6-4.2 vs. 2.1-3.7; P = .125).

In addition, participants in the CPAP group reported less limitation in physical activity (adjusted between-group difference in SF-36 physical functioning subscale score = 1.66; 95% CI, 0.87-2.45; P < .001) and were more likely to report activity levels consistent with guideline recommendations.

“We were pleasantly surprised to find that people assigned to CPAP reported more physical activity than their counterparts who received usual care, despite being given no specific exercise instructions,” Kelly A. Loffler, PhD, a coauthor of the study, said in an interview.

“While I don’t think this will result in any immediate changes to guidelines, it is a helpful reminder to clinicians who are treating such patients, that the symptomatic benefits people experience with CPAP present a window of opportunity to improve health more holistically,” Dr. Loffler explained.

The researchers acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the use of self-reported outcome measures. In future studies, they recommended that recent technological innovations, such as the availability of activity tracking devices, should be used to measure physical activity.

They also noted that patients with excessive sleepiness and severe hypoxemia were excluded from the SAVE trial; thus, the findings may not be generalizable to all patients.

Study reinforces CPAP’s health benefits

Emerson M. Wickwire, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, explained that CPAP treatment is associated with well-documented health benefits among patients with CVD, as well as enhanced quality of life.

“These results provide further evidence that treating OSA can provide direct and indirect health benefits, suggesting that increased physical activity can be a vital pathway to improved cardiovascular health and enjoyment of life,” Dr. Wickwire, who is also director of the Insomnia Program at the University of Maryland Midtown Medical Center, Baltimore, said in an interview.

Steven M. Scharf, MD, a pulmonologist who is director of the Sleep Disorders Center (Adults) at the University of Maryland, also said the study findings were consistent with previous research involving patients treated for OSA.

“It is no surprise that treatment of OSA improves patient’s daily physical functioning,” explained Dr. Scharf, who is also a clinical professor, in an interview. “These results are expected, but very welcome, and I was glad to see them.”

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Respironics Sleep and Respiratory Research Foundation, and Philips Respironics. Some authors reported financial affiliations with medical device and pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Loffler, Dr. Wickwire, and Dr. Scharf reported no conflicts of interest related to this work.

in new research.

“The aim of this study was to determine whether long-term CPAP treatment affects self-reported physical activity among participants with moderate-severe OSA and comorbid CV disease,” wrote David Stevens, PhD, of Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia, and his colleagues. The findings were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

Researchers conducted a secondary analysis of the Sleep apnea cardiovascular endpoints (SAVE) trial that enrolled 2,687 adults aged 45-75 years old with OSA and confirmed CVD. In the study, participants were randomized to receive either CPAP plus usual care or usual care alone.

Physical activity levels were self-reported using the Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (LTEQ) at baseline and at 6-, 24-, and 48-month follow-up intervals. The physical functioning subscale of the 36-item short form questionnaire (SF-36) was used to determine if activity levels were consistent with expert recommendations and to evaluate the effects on any self-perceived limitation of physical activity.

Moderate physical activity was higher among CPAP users

After a mean follow-up duration of 3.7 years, participants in the CPAP arm had approximately 20% higher levels of moderate physical activity, compared with the control arm (adjusted mean scores]: 8.7 points vs. 7.3 points; 95% confidence interval, 7.5-9.9 vs. 6.1-8.5; P = .003).

However, no significant difference was observed between treatment arms for mild physical activity (adjusted mean scores, 14.4 points vs. 14.2 points; 95% CI, 13.5-15.3 vs. 13.3-15.1; P = 0.599) or vigorous physical activity (adjusted mean scores, 3.4 points vs. 2.9 points; 95% CI 2.6-4.2 vs. 2.1-3.7; P = .125).

In addition, participants in the CPAP group reported less limitation in physical activity (adjusted between-group difference in SF-36 physical functioning subscale score = 1.66; 95% CI, 0.87-2.45; P < .001) and were more likely to report activity levels consistent with guideline recommendations.

“We were pleasantly surprised to find that people assigned to CPAP reported more physical activity than their counterparts who received usual care, despite being given no specific exercise instructions,” Kelly A. Loffler, PhD, a coauthor of the study, said in an interview.

“While I don’t think this will result in any immediate changes to guidelines, it is a helpful reminder to clinicians who are treating such patients, that the symptomatic benefits people experience with CPAP present a window of opportunity to improve health more holistically,” Dr. Loffler explained.

The researchers acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the use of self-reported outcome measures. In future studies, they recommended that recent technological innovations, such as the availability of activity tracking devices, should be used to measure physical activity.

They also noted that patients with excessive sleepiness and severe hypoxemia were excluded from the SAVE trial; thus, the findings may not be generalizable to all patients.

Study reinforces CPAP’s health benefits

Emerson M. Wickwire, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, explained that CPAP treatment is associated with well-documented health benefits among patients with CVD, as well as enhanced quality of life.

“These results provide further evidence that treating OSA can provide direct and indirect health benefits, suggesting that increased physical activity can be a vital pathway to improved cardiovascular health and enjoyment of life,” Dr. Wickwire, who is also director of the Insomnia Program at the University of Maryland Midtown Medical Center, Baltimore, said in an interview.

Steven M. Scharf, MD, a pulmonologist who is director of the Sleep Disorders Center (Adults) at the University of Maryland, also said the study findings were consistent with previous research involving patients treated for OSA.

“It is no surprise that treatment of OSA improves patient’s daily physical functioning,” explained Dr. Scharf, who is also a clinical professor, in an interview. “These results are expected, but very welcome, and I was glad to see them.”

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Respironics Sleep and Respiratory Research Foundation, and Philips Respironics. Some authors reported financial affiliations with medical device and pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Loffler, Dr. Wickwire, and Dr. Scharf reported no conflicts of interest related to this work.

in new research.

“The aim of this study was to determine whether long-term CPAP treatment affects self-reported physical activity among participants with moderate-severe OSA and comorbid CV disease,” wrote David Stevens, PhD, of Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia, and his colleagues. The findings were recently published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

Researchers conducted a secondary analysis of the Sleep apnea cardiovascular endpoints (SAVE) trial that enrolled 2,687 adults aged 45-75 years old with OSA and confirmed CVD. In the study, participants were randomized to receive either CPAP plus usual care or usual care alone.

Physical activity levels were self-reported using the Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (LTEQ) at baseline and at 6-, 24-, and 48-month follow-up intervals. The physical functioning subscale of the 36-item short form questionnaire (SF-36) was used to determine if activity levels were consistent with expert recommendations and to evaluate the effects on any self-perceived limitation of physical activity.

Moderate physical activity was higher among CPAP users

After a mean follow-up duration of 3.7 years, participants in the CPAP arm had approximately 20% higher levels of moderate physical activity, compared with the control arm (adjusted mean scores]: 8.7 points vs. 7.3 points; 95% confidence interval, 7.5-9.9 vs. 6.1-8.5; P = .003).

However, no significant difference was observed between treatment arms for mild physical activity (adjusted mean scores, 14.4 points vs. 14.2 points; 95% CI, 13.5-15.3 vs. 13.3-15.1; P = 0.599) or vigorous physical activity (adjusted mean scores, 3.4 points vs. 2.9 points; 95% CI 2.6-4.2 vs. 2.1-3.7; P = .125).

In addition, participants in the CPAP group reported less limitation in physical activity (adjusted between-group difference in SF-36 physical functioning subscale score = 1.66; 95% CI, 0.87-2.45; P < .001) and were more likely to report activity levels consistent with guideline recommendations.

“We were pleasantly surprised to find that people assigned to CPAP reported more physical activity than their counterparts who received usual care, despite being given no specific exercise instructions,” Kelly A. Loffler, PhD, a coauthor of the study, said in an interview.

“While I don’t think this will result in any immediate changes to guidelines, it is a helpful reminder to clinicians who are treating such patients, that the symptomatic benefits people experience with CPAP present a window of opportunity to improve health more holistically,” Dr. Loffler explained.

The researchers acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the use of self-reported outcome measures. In future studies, they recommended that recent technological innovations, such as the availability of activity tracking devices, should be used to measure physical activity.

They also noted that patients with excessive sleepiness and severe hypoxemia were excluded from the SAVE trial; thus, the findings may not be generalizable to all patients.

Study reinforces CPAP’s health benefits

Emerson M. Wickwire, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, explained that CPAP treatment is associated with well-documented health benefits among patients with CVD, as well as enhanced quality of life.

“These results provide further evidence that treating OSA can provide direct and indirect health benefits, suggesting that increased physical activity can be a vital pathway to improved cardiovascular health and enjoyment of life,” Dr. Wickwire, who is also director of the Insomnia Program at the University of Maryland Midtown Medical Center, Baltimore, said in an interview.

Steven M. Scharf, MD, a pulmonologist who is director of the Sleep Disorders Center (Adults) at the University of Maryland, also said the study findings were consistent with previous research involving patients treated for OSA.

“It is no surprise that treatment of OSA improves patient’s daily physical functioning,” explained Dr. Scharf, who is also a clinical professor, in an interview. “These results are expected, but very welcome, and I was glad to see them.”

The study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Respironics Sleep and Respiratory Research Foundation, and Philips Respironics. Some authors reported financial affiliations with medical device and pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Loffler, Dr. Wickwire, and Dr. Scharf reported no conflicts of interest related to this work.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL SLEEP MEDICINE

Large study finds trans men on testosterone at risk for blood clots