User login

ECTRIMS and EAN Publish Recommendations for Treating MS

The European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS) and the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) have published a guideline to offer up-to-date, evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of adult patients with MS. The guideline is intended to fill a perceived need for a comprehensive document that includes information about recently approved MS therapies and helps clinicians and patients resolve difficulties in everyday clinical practice. It was published in the February issue of Multiple Sclerosis.

Authors Addressed 10 Questions

Xavier Montalban, MD, PhD, Chair and Director of the Department of Neurology and Neuroimmunology at Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona, and colleagues agreed to investigate 10 questions related to treatment efficacy, response criteria, strategies to address suboptimal response and safety concerns, and treatment of MS in pregnancy. They developed the guideline following the recommendations of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group, along with EAN recommendations for writing a neurologic management guideline. Literature searches relied upon databases such as the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Excerpta Medica, and Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online.

The authors evaluated data for all disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) approved by the European Medicines Agency at the time of publication. They did not consider combination therapies, complementary or alternative medicine, or symptomatic treatment. Although focused on Europe, the guideline does not account for regulatory or organizational issues specific to any European country.

Strong Recommendations

Dr. Montalban and colleagues agreed upon 21 recommendations and consensus statements. The recommendations were categorized as strong or weak, according to the quality of evidence and the risk–benefit balance. The authors formulated consensus statements on questions for which evidence was insufficient to support a formal recommendation.

The first of the guideline’s three strong recommendations is that neurologists offer interferon or glatiramer acetate to patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) and an abnormal MRI with lesions suggestive of MS who do not fulfill criteria for MS. The second is to offer early treatment with DMTs to patients with active relapsing-remitting MS, as defined by clinical relapses or MRI activity. The authors defined active lesions as contrast-enhancing lesions or new or unequivocally enlarging T2 lesions assessed at least annually. This recommendation also applies to patients with CIS who fulfill current diagnostic criteria for MS. The third strong recommendation is to offer a more efficacious drug to patients treated with interferon or glatiramer acetate who show evidence of disease activity.

Weak Recommendations

Nine of the guideline’s recommendations are categorized as weak. For example, neurologists should consider treating patients with active secondary progressive MS with interferon beta-1a or -1b, taking into account the treatments’ “dubious efficacy,” as well as their safety and tolerability, according to the authors. Neurologists should consider mitoxantrone, ocrelizumab, and cladribine for this population. The authors recommend considering ocrelizumab as a treatment for patients with primary progressive MS.

As a way of monitoring treatment response, the authors recommend that neurologists consider combining MRI with clinical measures when evaluating disease evolution in treated patients. When making treatment decisions in the event of safety concerns, neurologists should consider the possibility that disease activity may resume or rebound if treatment is stopped, particularly with natalizumab, said Dr. Montalban and colleagues. Continuation of DMT treatment should be considered for patients who are clinically stable, who have stable MRI, and who have no problems with safety or tolerability, according to the guideline.

“For women planning a pregnancy, if there is a high risk of disease reactivation, consider using interferon or glatiramer acetate until pregnancy is confirmed,” said the authors. “In some very specific (active) cases, continuing this treatment during pregnancy could also be considered.” Delaying pregnancy is advisable for women with persistent high disease activity. If such a woman decides to become pregnant or has an unplanned pregnancy, neurologists may consider treatment with natalizumab throughout pregnancy after a full discussion with the patient of the potential implications. “Treatment with alemtuzumab could be an alternative therapeutic option for planned pregnancy in very active cases, provided that a four-month interval is strictly observed from the latest infusion until conception,” said Dr. Montalban and colleagues.

Consensus Statements

Several of the guideline’s consensus statements relate to the monitoring of treatment response. For patients treated with DMTs, the authors recommend performing a standardized reference brain MRI within six months of treatment onset, and comparing it with a subsequent brain MRI performed 12 months after starting treatment. The measurement of new or unequivocally enlarging T2 lesions is the preferred MRI method of gauging treatment response, supplemented by gadolinium-enhancing lesions. To monitor treatment safety, the authors recommend performing a standardized reference brain MRI every year in patients at low risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), and every three to six months in patients at high risk for PML.

If the neurologist and patient have decided to switch therapies, they should consider the patient’s characteristics and comorbidities, drug safety profiles, and disease severity when choosing a new DMT. If treatment of a highly efficacious drug is stopped because of safety or efficacy problems, the neurologist should consider starting another highly efficacious drug, according to the guideline. Disease activity, the drug’s half-life and biologic activity, and the potential for resumed disease activity or rebound should be considered when choosing a new therapy, said Dr. Montalban and colleagues.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24(2):96-120.

The European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS) and the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) have published a guideline to offer up-to-date, evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of adult patients with MS. The guideline is intended to fill a perceived need for a comprehensive document that includes information about recently approved MS therapies and helps clinicians and patients resolve difficulties in everyday clinical practice. It was published in the February issue of Multiple Sclerosis.

Authors Addressed 10 Questions

Xavier Montalban, MD, PhD, Chair and Director of the Department of Neurology and Neuroimmunology at Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona, and colleagues agreed to investigate 10 questions related to treatment efficacy, response criteria, strategies to address suboptimal response and safety concerns, and treatment of MS in pregnancy. They developed the guideline following the recommendations of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group, along with EAN recommendations for writing a neurologic management guideline. Literature searches relied upon databases such as the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Excerpta Medica, and Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online.

The authors evaluated data for all disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) approved by the European Medicines Agency at the time of publication. They did not consider combination therapies, complementary or alternative medicine, or symptomatic treatment. Although focused on Europe, the guideline does not account for regulatory or organizational issues specific to any European country.

Strong Recommendations

Dr. Montalban and colleagues agreed upon 21 recommendations and consensus statements. The recommendations were categorized as strong or weak, according to the quality of evidence and the risk–benefit balance. The authors formulated consensus statements on questions for which evidence was insufficient to support a formal recommendation.

The first of the guideline’s three strong recommendations is that neurologists offer interferon or glatiramer acetate to patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) and an abnormal MRI with lesions suggestive of MS who do not fulfill criteria for MS. The second is to offer early treatment with DMTs to patients with active relapsing-remitting MS, as defined by clinical relapses or MRI activity. The authors defined active lesions as contrast-enhancing lesions or new or unequivocally enlarging T2 lesions assessed at least annually. This recommendation also applies to patients with CIS who fulfill current diagnostic criteria for MS. The third strong recommendation is to offer a more efficacious drug to patients treated with interferon or glatiramer acetate who show evidence of disease activity.

Weak Recommendations

Nine of the guideline’s recommendations are categorized as weak. For example, neurologists should consider treating patients with active secondary progressive MS with interferon beta-1a or -1b, taking into account the treatments’ “dubious efficacy,” as well as their safety and tolerability, according to the authors. Neurologists should consider mitoxantrone, ocrelizumab, and cladribine for this population. The authors recommend considering ocrelizumab as a treatment for patients with primary progressive MS.

As a way of monitoring treatment response, the authors recommend that neurologists consider combining MRI with clinical measures when evaluating disease evolution in treated patients. When making treatment decisions in the event of safety concerns, neurologists should consider the possibility that disease activity may resume or rebound if treatment is stopped, particularly with natalizumab, said Dr. Montalban and colleagues. Continuation of DMT treatment should be considered for patients who are clinically stable, who have stable MRI, and who have no problems with safety or tolerability, according to the guideline.

“For women planning a pregnancy, if there is a high risk of disease reactivation, consider using interferon or glatiramer acetate until pregnancy is confirmed,” said the authors. “In some very specific (active) cases, continuing this treatment during pregnancy could also be considered.” Delaying pregnancy is advisable for women with persistent high disease activity. If such a woman decides to become pregnant or has an unplanned pregnancy, neurologists may consider treatment with natalizumab throughout pregnancy after a full discussion with the patient of the potential implications. “Treatment with alemtuzumab could be an alternative therapeutic option for planned pregnancy in very active cases, provided that a four-month interval is strictly observed from the latest infusion until conception,” said Dr. Montalban and colleagues.

Consensus Statements

Several of the guideline’s consensus statements relate to the monitoring of treatment response. For patients treated with DMTs, the authors recommend performing a standardized reference brain MRI within six months of treatment onset, and comparing it with a subsequent brain MRI performed 12 months after starting treatment. The measurement of new or unequivocally enlarging T2 lesions is the preferred MRI method of gauging treatment response, supplemented by gadolinium-enhancing lesions. To monitor treatment safety, the authors recommend performing a standardized reference brain MRI every year in patients at low risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), and every three to six months in patients at high risk for PML.

If the neurologist and patient have decided to switch therapies, they should consider the patient’s characteristics and comorbidities, drug safety profiles, and disease severity when choosing a new DMT. If treatment of a highly efficacious drug is stopped because of safety or efficacy problems, the neurologist should consider starting another highly efficacious drug, according to the guideline. Disease activity, the drug’s half-life and biologic activity, and the potential for resumed disease activity or rebound should be considered when choosing a new therapy, said Dr. Montalban and colleagues.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24(2):96-120.

The European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS) and the European Academy of Neurology (EAN) have published a guideline to offer up-to-date, evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of adult patients with MS. The guideline is intended to fill a perceived need for a comprehensive document that includes information about recently approved MS therapies and helps clinicians and patients resolve difficulties in everyday clinical practice. It was published in the February issue of Multiple Sclerosis.

Authors Addressed 10 Questions

Xavier Montalban, MD, PhD, Chair and Director of the Department of Neurology and Neuroimmunology at Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona, and colleagues agreed to investigate 10 questions related to treatment efficacy, response criteria, strategies to address suboptimal response and safety concerns, and treatment of MS in pregnancy. They developed the guideline following the recommendations of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group, along with EAN recommendations for writing a neurologic management guideline. Literature searches relied upon databases such as the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Excerpta Medica, and Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online.

The authors evaluated data for all disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) approved by the European Medicines Agency at the time of publication. They did not consider combination therapies, complementary or alternative medicine, or symptomatic treatment. Although focused on Europe, the guideline does not account for regulatory or organizational issues specific to any European country.

Strong Recommendations

Dr. Montalban and colleagues agreed upon 21 recommendations and consensus statements. The recommendations were categorized as strong or weak, according to the quality of evidence and the risk–benefit balance. The authors formulated consensus statements on questions for which evidence was insufficient to support a formal recommendation.

The first of the guideline’s three strong recommendations is that neurologists offer interferon or glatiramer acetate to patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) and an abnormal MRI with lesions suggestive of MS who do not fulfill criteria for MS. The second is to offer early treatment with DMTs to patients with active relapsing-remitting MS, as defined by clinical relapses or MRI activity. The authors defined active lesions as contrast-enhancing lesions or new or unequivocally enlarging T2 lesions assessed at least annually. This recommendation also applies to patients with CIS who fulfill current diagnostic criteria for MS. The third strong recommendation is to offer a more efficacious drug to patients treated with interferon or glatiramer acetate who show evidence of disease activity.

Weak Recommendations

Nine of the guideline’s recommendations are categorized as weak. For example, neurologists should consider treating patients with active secondary progressive MS with interferon beta-1a or -1b, taking into account the treatments’ “dubious efficacy,” as well as their safety and tolerability, according to the authors. Neurologists should consider mitoxantrone, ocrelizumab, and cladribine for this population. The authors recommend considering ocrelizumab as a treatment for patients with primary progressive MS.

As a way of monitoring treatment response, the authors recommend that neurologists consider combining MRI with clinical measures when evaluating disease evolution in treated patients. When making treatment decisions in the event of safety concerns, neurologists should consider the possibility that disease activity may resume or rebound if treatment is stopped, particularly with natalizumab, said Dr. Montalban and colleagues. Continuation of DMT treatment should be considered for patients who are clinically stable, who have stable MRI, and who have no problems with safety or tolerability, according to the guideline.

“For women planning a pregnancy, if there is a high risk of disease reactivation, consider using interferon or glatiramer acetate until pregnancy is confirmed,” said the authors. “In some very specific (active) cases, continuing this treatment during pregnancy could also be considered.” Delaying pregnancy is advisable for women with persistent high disease activity. If such a woman decides to become pregnant or has an unplanned pregnancy, neurologists may consider treatment with natalizumab throughout pregnancy after a full discussion with the patient of the potential implications. “Treatment with alemtuzumab could be an alternative therapeutic option for planned pregnancy in very active cases, provided that a four-month interval is strictly observed from the latest infusion until conception,” said Dr. Montalban and colleagues.

Consensus Statements

Several of the guideline’s consensus statements relate to the monitoring of treatment response. For patients treated with DMTs, the authors recommend performing a standardized reference brain MRI within six months of treatment onset, and comparing it with a subsequent brain MRI performed 12 months after starting treatment. The measurement of new or unequivocally enlarging T2 lesions is the preferred MRI method of gauging treatment response, supplemented by gadolinium-enhancing lesions. To monitor treatment safety, the authors recommend performing a standardized reference brain MRI every year in patients at low risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), and every three to six months in patients at high risk for PML.

If the neurologist and patient have decided to switch therapies, they should consider the patient’s characteristics and comorbidities, drug safety profiles, and disease severity when choosing a new DMT. If treatment of a highly efficacious drug is stopped because of safety or efficacy problems, the neurologist should consider starting another highly efficacious drug, according to the guideline. Disease activity, the drug’s half-life and biologic activity, and the potential for resumed disease activity or rebound should be considered when choosing a new therapy, said Dr. Montalban and colleagues.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24(2):96-120.

Guidelines update best practices for hemorrhoid treatment

Each year, more than 2.2 million patients in the United States undergo evaluations for symptoms of hemorrhoids, according to updated guidelines on the management of hemorrhoids issued by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

“As a result, it is important to identify symptomatic hemorrhoids as the underlying source of the anorectal symptom and to have a clear understanding of the evaluation and management of this disease process,” wrote Bradley R. Davis, MD, FACS, chief of colon and rectal surgery at the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C., and the fellow members of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the ASCRS.

The guidelines recommend evaluation of hemorrhoids based on a disease-specific history, and a physical that emphasizes the degree and duration of symptoms and identifies risk factors. But the guideline writers note that the recommendation is a grade 1C because the supporting data mainly come from observational or case studies.

“The cardinal signs of internal hemorrhoids are painless bleeding with bowel movements with intermittent protrusion,” the committee said, also emphasizing that patients should be evaluated for fecal incontinence, which could inform surgical decision making.

In addition, the guidelines call for a complete endoscopic evaluation of the colon for patients who present with symptomatic hemorrhoids and rectal bleeding; this recommendation is based on moderately strong evidence, and presented with a grade of 1B.

Medical management of hemorrhoids may include office-based procedures or surgery, according to the guidelines.

“Most patients with grade I and II and select patients with grade III internal hemorrhoidal disease who fail medical treatment can be effectively treated with office-based procedures, such as banding, sclerotherapy, and infrared coagulation,” the committee wrote, and medical office treatment received a strong grade 1A recommendation based on high-quality evidence. Although office procedures are generally well tolerated, the condition can recur. Bleeding is the most common complication, and it is more likely after rubber-band ligation than other office-based options, the guidelines state.

The guidelines offer a weak recommendation of 2C, based on the lack of quality evidence, for the use of early surgical excision to treat patients with thrombosed external hemorrhoids. “Although most patients treated nonoperatively will experience eventual resolution of their symptoms, excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoids may result in more rapid symptom resolution, lower incidence of recurrence, and longer remission intervals,” the committee noted.

Surgical hemorrhoidectomy received the strongest possible recommendation (1A, based on high-quality evidence) for the treatment of patients with external hemorrhoids or a combination of internal and external hemorrhoids with prolapse.

Surgical options described in the recommendations include surgical excision (hemorrhoidectomy), hemorrhoidopexy, and Doppler-guided hemorrhoidectomy, with citations of studies on each procedure. Data from a meta-analysis of 18 randomized prospective studies comparing hemorrhoidectomy with office-based procedures showed that hemorrhoidectomy was “the most effective treatment for patients with grade III hemorrhoids,” but it was associated with greater pain and complication rates, according to the guidelines.

However, complications in general are low after surgical hemorrhoidectomy, with reported complication rates of 1%-2% for the most common complication of postprocedure hemorrhage, the guidelines state. After surgery, the guidelines recommend with a 1B grade (moderate quality evidence) that patients use “a multimodality pain regimen to reduce narcotic usage and promote a faster recovery.”

The committee members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Davis BR et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018; 61:284-92.

Each year, more than 2.2 million patients in the United States undergo evaluations for symptoms of hemorrhoids, according to updated guidelines on the management of hemorrhoids issued by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

“As a result, it is important to identify symptomatic hemorrhoids as the underlying source of the anorectal symptom and to have a clear understanding of the evaluation and management of this disease process,” wrote Bradley R. Davis, MD, FACS, chief of colon and rectal surgery at the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C., and the fellow members of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the ASCRS.

The guidelines recommend evaluation of hemorrhoids based on a disease-specific history, and a physical that emphasizes the degree and duration of symptoms and identifies risk factors. But the guideline writers note that the recommendation is a grade 1C because the supporting data mainly come from observational or case studies.

“The cardinal signs of internal hemorrhoids are painless bleeding with bowel movements with intermittent protrusion,” the committee said, also emphasizing that patients should be evaluated for fecal incontinence, which could inform surgical decision making.

In addition, the guidelines call for a complete endoscopic evaluation of the colon for patients who present with symptomatic hemorrhoids and rectal bleeding; this recommendation is based on moderately strong evidence, and presented with a grade of 1B.

Medical management of hemorrhoids may include office-based procedures or surgery, according to the guidelines.

“Most patients with grade I and II and select patients with grade III internal hemorrhoidal disease who fail medical treatment can be effectively treated with office-based procedures, such as banding, sclerotherapy, and infrared coagulation,” the committee wrote, and medical office treatment received a strong grade 1A recommendation based on high-quality evidence. Although office procedures are generally well tolerated, the condition can recur. Bleeding is the most common complication, and it is more likely after rubber-band ligation than other office-based options, the guidelines state.

The guidelines offer a weak recommendation of 2C, based on the lack of quality evidence, for the use of early surgical excision to treat patients with thrombosed external hemorrhoids. “Although most patients treated nonoperatively will experience eventual resolution of their symptoms, excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoids may result in more rapid symptom resolution, lower incidence of recurrence, and longer remission intervals,” the committee noted.

Surgical hemorrhoidectomy received the strongest possible recommendation (1A, based on high-quality evidence) for the treatment of patients with external hemorrhoids or a combination of internal and external hemorrhoids with prolapse.

Surgical options described in the recommendations include surgical excision (hemorrhoidectomy), hemorrhoidopexy, and Doppler-guided hemorrhoidectomy, with citations of studies on each procedure. Data from a meta-analysis of 18 randomized prospective studies comparing hemorrhoidectomy with office-based procedures showed that hemorrhoidectomy was “the most effective treatment for patients with grade III hemorrhoids,” but it was associated with greater pain and complication rates, according to the guidelines.

However, complications in general are low after surgical hemorrhoidectomy, with reported complication rates of 1%-2% for the most common complication of postprocedure hemorrhage, the guidelines state. After surgery, the guidelines recommend with a 1B grade (moderate quality evidence) that patients use “a multimodality pain regimen to reduce narcotic usage and promote a faster recovery.”

The committee members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Davis BR et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018; 61:284-92.

Each year, more than 2.2 million patients in the United States undergo evaluations for symptoms of hemorrhoids, according to updated guidelines on the management of hemorrhoids issued by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.

“As a result, it is important to identify symptomatic hemorrhoids as the underlying source of the anorectal symptom and to have a clear understanding of the evaluation and management of this disease process,” wrote Bradley R. Davis, MD, FACS, chief of colon and rectal surgery at the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C., and the fellow members of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the ASCRS.

The guidelines recommend evaluation of hemorrhoids based on a disease-specific history, and a physical that emphasizes the degree and duration of symptoms and identifies risk factors. But the guideline writers note that the recommendation is a grade 1C because the supporting data mainly come from observational or case studies.

“The cardinal signs of internal hemorrhoids are painless bleeding with bowel movements with intermittent protrusion,” the committee said, also emphasizing that patients should be evaluated for fecal incontinence, which could inform surgical decision making.

In addition, the guidelines call for a complete endoscopic evaluation of the colon for patients who present with symptomatic hemorrhoids and rectal bleeding; this recommendation is based on moderately strong evidence, and presented with a grade of 1B.

Medical management of hemorrhoids may include office-based procedures or surgery, according to the guidelines.

“Most patients with grade I and II and select patients with grade III internal hemorrhoidal disease who fail medical treatment can be effectively treated with office-based procedures, such as banding, sclerotherapy, and infrared coagulation,” the committee wrote, and medical office treatment received a strong grade 1A recommendation based on high-quality evidence. Although office procedures are generally well tolerated, the condition can recur. Bleeding is the most common complication, and it is more likely after rubber-band ligation than other office-based options, the guidelines state.

The guidelines offer a weak recommendation of 2C, based on the lack of quality evidence, for the use of early surgical excision to treat patients with thrombosed external hemorrhoids. “Although most patients treated nonoperatively will experience eventual resolution of their symptoms, excision of thrombosed external hemorrhoids may result in more rapid symptom resolution, lower incidence of recurrence, and longer remission intervals,” the committee noted.

Surgical hemorrhoidectomy received the strongest possible recommendation (1A, based on high-quality evidence) for the treatment of patients with external hemorrhoids or a combination of internal and external hemorrhoids with prolapse.

Surgical options described in the recommendations include surgical excision (hemorrhoidectomy), hemorrhoidopexy, and Doppler-guided hemorrhoidectomy, with citations of studies on each procedure. Data from a meta-analysis of 18 randomized prospective studies comparing hemorrhoidectomy with office-based procedures showed that hemorrhoidectomy was “the most effective treatment for patients with grade III hemorrhoids,” but it was associated with greater pain and complication rates, according to the guidelines.

However, complications in general are low after surgical hemorrhoidectomy, with reported complication rates of 1%-2% for the most common complication of postprocedure hemorrhage, the guidelines state. After surgery, the guidelines recommend with a 1B grade (moderate quality evidence) that patients use “a multimodality pain regimen to reduce narcotic usage and promote a faster recovery.”

The committee members had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Davis BR et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018; 61:284-92.

FROM DISEASES OF THE COLON & RECTUM

Screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has issued recommendations on screening for idiopathic scoliosis in asymptomatic children and adolescents aged 10-18 years.1 This recommendation concluded that the current evidence on the benefits and harms of screening is insufficient (I statement) and updated its 2004 recommendation against routine screening, in which it had concluded that the harms of screening exceeded the potential benefits (D recommendation).

Importance

Screening methods

The USPSTF concluded that currently available screening tests can accurately detect adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Screening methods include visual inspection using the forward bend test, use of scoliometer measurement of the angle of trunk rotation during forward bend test with a rotation of 5 degrees–7 degrees recommended to be referred for radiography, and Moiré topography that enumerates asymmetric contour lines on the back (values greater than 2 are referred to radiography).

The USPSTF reviewed seven fair-quality observational studies (n = 447,243) and concluded that screening with a combination of forward bend test, scoliometer measurement and that Moiré topography had the highest sensitivity (93.8%) and specificity (99.2%), a low false-negative rate (6.2%), the lowest false-positive rate (0.8%), and the highest positive predictive value (81%). Sensitivity was lower when screening programs used only one or two screening tests, and single screening tests were associated with highest false-positive rates.

In general, the potential harms associated with false-positive results include psychological harm, chest radiation exposure, and other unnecessary treatment, but the USPSTF did not find evidence on the direct harms of screening.

Effectiveness of intervention or treatment

Bracing: The USPSTF found five studies (n = 651) that evaluated the effectiveness of treatment with three different types of braces. The average ages of participants ranged from 12 to 13 years, and their curvature severity varied from Cobb angle of 20 degrees to 30 degrees. The largest study (n = 242) was a good-quality, international, controlled clinical trial known as the Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial; it demonstrated significant benefit and quality-of-life outcomes associated with bracing for 18 hours/day. In this study, the rate of treatment success in the as-treated analysis was 72% in the intervention group and 48% in the control group. The rate of treatment success in the intention-to-treat analysis was 75% in the intervention group and 42% in the control group. The number needed to treat was three to prevent one case of curvature progression past 50%.

Exercise: The USPSTF found just two trials (n = 184) that evaluated the effectiveness of tailored physiotherapeutic, scoliosis-specific exercise treatments. The participants were older than 10 years and had Cobb angles ranging from 10 degrees to 25 degrees. At the 12-month follow-up, the studies showed significant improvement, including those in quality-of-life measures. In one of the trials, the intervention group had a Cobb angle reduction of 4.9 degrees while the control group had an increase of 2.8 degrees.

Harms: Only one good-quality study (n = 242) reported harms of bracing, which include skin problems, body pain, physical limitations, anxiety, and depression. The USPSTF did not find any studies that assessed the harms of treatment with exercise or surgery.

Association between spinal curvature severity and adult health outcomes

The USPSTF did not find any studies that directly addressed whether changes in the severity of spinal curvature in adolescence resulted in changes in adult health outcomes. The USPSTF did review two fair-quality retrospective, observational, long-term, follow-up analyses (n = 339) of adults diagnosed with idiopathic scoliosis in adolescence and treated with either bracing or surgery. Quality of life measurements, pulmonary consequences, and pregnancy outcomes were not significantly different between the two treatment groups or between those treated and those simply observed. However, those treated with bracing did report more negative treatment experience and body distortion.

Recommendation of others

The Scoliosis Research Society, American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America, and American Academy of Pediatrics issued a joint position statement in September 2015 recommending that screening examinations for scoliosis should be performed for females at ages 10 and 12 years and for males at either 13 or 14 years.2

Their rationale, articulated in the statement and in an editorial in JAMA accompanying the publication of the USPSTF statement, is primarily based on findings in the Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial that showed a 56% decrease in the rate of progression of moderate curves to greater than 50 degrees. The evidence that intervention works – along with concerns about costs, family burden, loss of school time, risks of surgical complications, and the 22% need for long-term revision surgery – makes avoidance of progression of curves in scoliosis a high-value issue. In addition, they reasoned, the screening trials from which the false-positive values were derived were primarily school-based screening and not done in physician offices.

The Bottom Line

Although the joint statement made by pediatric orthopedic societies and the American Academy of Pediatrics had recommended screening examinations, the USPSTF concluded that the current evidence is insufficient and that the balance of benefits and harms of screening for adolescent (aged 10-18 years) idiopathic scoliosis (Cobb angle greater than 10 degrees) cannot be determined, giving an “I” recommendation.

Dr. Aarisha Shrestha is a first-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

References

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(2):165–72.

2. HreskoMT et al. SRS/POSNA/AAOS/AAP position statement: Screening for the early detection for idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents. 2015. Accessed December 8, 2017.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has issued recommendations on screening for idiopathic scoliosis in asymptomatic children and adolescents aged 10-18 years.1 This recommendation concluded that the current evidence on the benefits and harms of screening is insufficient (I statement) and updated its 2004 recommendation against routine screening, in which it had concluded that the harms of screening exceeded the potential benefits (D recommendation).

Importance

Screening methods

The USPSTF concluded that currently available screening tests can accurately detect adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Screening methods include visual inspection using the forward bend test, use of scoliometer measurement of the angle of trunk rotation during forward bend test with a rotation of 5 degrees–7 degrees recommended to be referred for radiography, and Moiré topography that enumerates asymmetric contour lines on the back (values greater than 2 are referred to radiography).

The USPSTF reviewed seven fair-quality observational studies (n = 447,243) and concluded that screening with a combination of forward bend test, scoliometer measurement and that Moiré topography had the highest sensitivity (93.8%) and specificity (99.2%), a low false-negative rate (6.2%), the lowest false-positive rate (0.8%), and the highest positive predictive value (81%). Sensitivity was lower when screening programs used only one or two screening tests, and single screening tests were associated with highest false-positive rates.

In general, the potential harms associated with false-positive results include psychological harm, chest radiation exposure, and other unnecessary treatment, but the USPSTF did not find evidence on the direct harms of screening.

Effectiveness of intervention or treatment

Bracing: The USPSTF found five studies (n = 651) that evaluated the effectiveness of treatment with three different types of braces. The average ages of participants ranged from 12 to 13 years, and their curvature severity varied from Cobb angle of 20 degrees to 30 degrees. The largest study (n = 242) was a good-quality, international, controlled clinical trial known as the Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial; it demonstrated significant benefit and quality-of-life outcomes associated with bracing for 18 hours/day. In this study, the rate of treatment success in the as-treated analysis was 72% in the intervention group and 48% in the control group. The rate of treatment success in the intention-to-treat analysis was 75% in the intervention group and 42% in the control group. The number needed to treat was three to prevent one case of curvature progression past 50%.

Exercise: The USPSTF found just two trials (n = 184) that evaluated the effectiveness of tailored physiotherapeutic, scoliosis-specific exercise treatments. The participants were older than 10 years and had Cobb angles ranging from 10 degrees to 25 degrees. At the 12-month follow-up, the studies showed significant improvement, including those in quality-of-life measures. In one of the trials, the intervention group had a Cobb angle reduction of 4.9 degrees while the control group had an increase of 2.8 degrees.

Harms: Only one good-quality study (n = 242) reported harms of bracing, which include skin problems, body pain, physical limitations, anxiety, and depression. The USPSTF did not find any studies that assessed the harms of treatment with exercise or surgery.

Association between spinal curvature severity and adult health outcomes

The USPSTF did not find any studies that directly addressed whether changes in the severity of spinal curvature in adolescence resulted in changes in adult health outcomes. The USPSTF did review two fair-quality retrospective, observational, long-term, follow-up analyses (n = 339) of adults diagnosed with idiopathic scoliosis in adolescence and treated with either bracing or surgery. Quality of life measurements, pulmonary consequences, and pregnancy outcomes were not significantly different between the two treatment groups or between those treated and those simply observed. However, those treated with bracing did report more negative treatment experience and body distortion.

Recommendation of others

The Scoliosis Research Society, American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America, and American Academy of Pediatrics issued a joint position statement in September 2015 recommending that screening examinations for scoliosis should be performed for females at ages 10 and 12 years and for males at either 13 or 14 years.2

Their rationale, articulated in the statement and in an editorial in JAMA accompanying the publication of the USPSTF statement, is primarily based on findings in the Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial that showed a 56% decrease in the rate of progression of moderate curves to greater than 50 degrees. The evidence that intervention works – along with concerns about costs, family burden, loss of school time, risks of surgical complications, and the 22% need for long-term revision surgery – makes avoidance of progression of curves in scoliosis a high-value issue. In addition, they reasoned, the screening trials from which the false-positive values were derived were primarily school-based screening and not done in physician offices.

The Bottom Line

Although the joint statement made by pediatric orthopedic societies and the American Academy of Pediatrics had recommended screening examinations, the USPSTF concluded that the current evidence is insufficient and that the balance of benefits and harms of screening for adolescent (aged 10-18 years) idiopathic scoliosis (Cobb angle greater than 10 degrees) cannot be determined, giving an “I” recommendation.

Dr. Aarisha Shrestha is a first-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

References

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(2):165–72.

2. HreskoMT et al. SRS/POSNA/AAOS/AAP position statement: Screening for the early detection for idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents. 2015. Accessed December 8, 2017.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has issued recommendations on screening for idiopathic scoliosis in asymptomatic children and adolescents aged 10-18 years.1 This recommendation concluded that the current evidence on the benefits and harms of screening is insufficient (I statement) and updated its 2004 recommendation against routine screening, in which it had concluded that the harms of screening exceeded the potential benefits (D recommendation).

Importance

Screening methods

The USPSTF concluded that currently available screening tests can accurately detect adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Screening methods include visual inspection using the forward bend test, use of scoliometer measurement of the angle of trunk rotation during forward bend test with a rotation of 5 degrees–7 degrees recommended to be referred for radiography, and Moiré topography that enumerates asymmetric contour lines on the back (values greater than 2 are referred to radiography).

The USPSTF reviewed seven fair-quality observational studies (n = 447,243) and concluded that screening with a combination of forward bend test, scoliometer measurement and that Moiré topography had the highest sensitivity (93.8%) and specificity (99.2%), a low false-negative rate (6.2%), the lowest false-positive rate (0.8%), and the highest positive predictive value (81%). Sensitivity was lower when screening programs used only one or two screening tests, and single screening tests were associated with highest false-positive rates.

In general, the potential harms associated with false-positive results include psychological harm, chest radiation exposure, and other unnecessary treatment, but the USPSTF did not find evidence on the direct harms of screening.

Effectiveness of intervention or treatment

Bracing: The USPSTF found five studies (n = 651) that evaluated the effectiveness of treatment with three different types of braces. The average ages of participants ranged from 12 to 13 years, and their curvature severity varied from Cobb angle of 20 degrees to 30 degrees. The largest study (n = 242) was a good-quality, international, controlled clinical trial known as the Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial; it demonstrated significant benefit and quality-of-life outcomes associated with bracing for 18 hours/day. In this study, the rate of treatment success in the as-treated analysis was 72% in the intervention group and 48% in the control group. The rate of treatment success in the intention-to-treat analysis was 75% in the intervention group and 42% in the control group. The number needed to treat was three to prevent one case of curvature progression past 50%.

Exercise: The USPSTF found just two trials (n = 184) that evaluated the effectiveness of tailored physiotherapeutic, scoliosis-specific exercise treatments. The participants were older than 10 years and had Cobb angles ranging from 10 degrees to 25 degrees. At the 12-month follow-up, the studies showed significant improvement, including those in quality-of-life measures. In one of the trials, the intervention group had a Cobb angle reduction of 4.9 degrees while the control group had an increase of 2.8 degrees.

Harms: Only one good-quality study (n = 242) reported harms of bracing, which include skin problems, body pain, physical limitations, anxiety, and depression. The USPSTF did not find any studies that assessed the harms of treatment with exercise or surgery.

Association between spinal curvature severity and adult health outcomes

The USPSTF did not find any studies that directly addressed whether changes in the severity of spinal curvature in adolescence resulted in changes in adult health outcomes. The USPSTF did review two fair-quality retrospective, observational, long-term, follow-up analyses (n = 339) of adults diagnosed with idiopathic scoliosis in adolescence and treated with either bracing or surgery. Quality of life measurements, pulmonary consequences, and pregnancy outcomes were not significantly different between the two treatment groups or between those treated and those simply observed. However, those treated with bracing did report more negative treatment experience and body distortion.

Recommendation of others

The Scoliosis Research Society, American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America, and American Academy of Pediatrics issued a joint position statement in September 2015 recommending that screening examinations for scoliosis should be performed for females at ages 10 and 12 years and for males at either 13 or 14 years.2

Their rationale, articulated in the statement and in an editorial in JAMA accompanying the publication of the USPSTF statement, is primarily based on findings in the Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial that showed a 56% decrease in the rate of progression of moderate curves to greater than 50 degrees. The evidence that intervention works – along with concerns about costs, family burden, loss of school time, risks of surgical complications, and the 22% need for long-term revision surgery – makes avoidance of progression of curves in scoliosis a high-value issue. In addition, they reasoned, the screening trials from which the false-positive values were derived were primarily school-based screening and not done in physician offices.

The Bottom Line

Although the joint statement made by pediatric orthopedic societies and the American Academy of Pediatrics had recommended screening examinations, the USPSTF concluded that the current evidence is insufficient and that the balance of benefits and harms of screening for adolescent (aged 10-18 years) idiopathic scoliosis (Cobb angle greater than 10 degrees) cannot be determined, giving an “I” recommendation.

Dr. Aarisha Shrestha is a first-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is a professor of family and community medicine at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

References

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;319(2):165–72.

2. HreskoMT et al. SRS/POSNA/AAOS/AAP position statement: Screening for the early detection for idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents. 2015. Accessed December 8, 2017.

AAN Recommends Exercise for People With MCI

Neurologists should recommend twice-weekly exercise to patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) as part of an overall approach to management, according to a practice guideline update from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN). The Level B recommendation is based on six-month studies that suggest that such exercise possibly improves cognition. The update was published online ahead of print December 27, 2017, in Neurology.

“Regular physical exercise has long been shown to have heart health benefits, and now we can say exercise also may help improve memory for people with MCI,” said Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD, Director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and lead author of the update. “What is good for your heart can be good for your brain.”

The update also states that clinicians may recommend cognitive training for people with MCI (Level C). The evidence, however, is insufficient “to support or refute the use of any individual cognitive intervention strategy,” according to the guideline. “When various cognitive interventions are considered as a group, for patients with MCI, cognitive interventions may improve select measures of cognitive function.”

Document Updates 2001 Practice Parameter

The current practice guideline update revises the AAN’s 2001 practice parameter that provided recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of MCI. Dr. Petersen and colleagues based the update on a systematic review of articles about MCI prevalence, prognosis, and treatment. They classified evidence according to AAN criteria and based recommendations on modified Delphi consensus.

The authors found that the prevalence of MCI is 6.7% for people between ages 60 and 64, 8.4% for people between ages 65 and 69, 10.1% for people between ages 70 and 74, 14.8% for people between ages 75 and 79, and 25.2% for people between ages 80 and 84. Approximately 15% of people with MCI who are older than 65 develop dementia during two years of follow-up.

No Evidence for Pharmacologic Treatment

Evidence does not support a symptomatic cognitive benefit in MCI for any pharmacologic or dietary agents, according to the authors. The FDA has not approved any medication for treating MCI. If clinicians offer cholinesterase inhibitors to their patients with MCI, they must first discuss the fact that the treatment is off label and not backed by empirical evidence, according to the update. Gastrointestinal symptoms and cardiac concerns are common side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors.

Assessment for MCI is appropriate for patients who complain of impaired memory or cognition, as well as those who present for a Medicare Annual Wellness Visit, according to the update. Clinicians should evaluate patients with MCI for risk factors that are potentially modifiable. Patients with MCI also should undergo serial assessments over time so that clinicians can monitor them for changes in cognitive status.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Langa KM, Levine DA. The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;312(23):2551-2561.

Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2017 Dec 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Vega JN, Newhouse PA. Mild cognitive impairment: diagnosis, longitudinal course, and emerging treatments. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(10):490.

Neurologists should recommend twice-weekly exercise to patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) as part of an overall approach to management, according to a practice guideline update from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN). The Level B recommendation is based on six-month studies that suggest that such exercise possibly improves cognition. The update was published online ahead of print December 27, 2017, in Neurology.

“Regular physical exercise has long been shown to have heart health benefits, and now we can say exercise also may help improve memory for people with MCI,” said Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD, Director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and lead author of the update. “What is good for your heart can be good for your brain.”

The update also states that clinicians may recommend cognitive training for people with MCI (Level C). The evidence, however, is insufficient “to support or refute the use of any individual cognitive intervention strategy,” according to the guideline. “When various cognitive interventions are considered as a group, for patients with MCI, cognitive interventions may improve select measures of cognitive function.”

Document Updates 2001 Practice Parameter

The current practice guideline update revises the AAN’s 2001 practice parameter that provided recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of MCI. Dr. Petersen and colleagues based the update on a systematic review of articles about MCI prevalence, prognosis, and treatment. They classified evidence according to AAN criteria and based recommendations on modified Delphi consensus.

The authors found that the prevalence of MCI is 6.7% for people between ages 60 and 64, 8.4% for people between ages 65 and 69, 10.1% for people between ages 70 and 74, 14.8% for people between ages 75 and 79, and 25.2% for people between ages 80 and 84. Approximately 15% of people with MCI who are older than 65 develop dementia during two years of follow-up.

No Evidence for Pharmacologic Treatment

Evidence does not support a symptomatic cognitive benefit in MCI for any pharmacologic or dietary agents, according to the authors. The FDA has not approved any medication for treating MCI. If clinicians offer cholinesterase inhibitors to their patients with MCI, they must first discuss the fact that the treatment is off label and not backed by empirical evidence, according to the update. Gastrointestinal symptoms and cardiac concerns are common side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors.

Assessment for MCI is appropriate for patients who complain of impaired memory or cognition, as well as those who present for a Medicare Annual Wellness Visit, according to the update. Clinicians should evaluate patients with MCI for risk factors that are potentially modifiable. Patients with MCI also should undergo serial assessments over time so that clinicians can monitor them for changes in cognitive status.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Langa KM, Levine DA. The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;312(23):2551-2561.

Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2017 Dec 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Vega JN, Newhouse PA. Mild cognitive impairment: diagnosis, longitudinal course, and emerging treatments. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(10):490.

Neurologists should recommend twice-weekly exercise to patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) as part of an overall approach to management, according to a practice guideline update from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN). The Level B recommendation is based on six-month studies that suggest that such exercise possibly improves cognition. The update was published online ahead of print December 27, 2017, in Neurology.

“Regular physical exercise has long been shown to have heart health benefits, and now we can say exercise also may help improve memory for people with MCI,” said Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD, Director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and lead author of the update. “What is good for your heart can be good for your brain.”

The update also states that clinicians may recommend cognitive training for people with MCI (Level C). The evidence, however, is insufficient “to support or refute the use of any individual cognitive intervention strategy,” according to the guideline. “When various cognitive interventions are considered as a group, for patients with MCI, cognitive interventions may improve select measures of cognitive function.”

Document Updates 2001 Practice Parameter

The current practice guideline update revises the AAN’s 2001 practice parameter that provided recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of MCI. Dr. Petersen and colleagues based the update on a systematic review of articles about MCI prevalence, prognosis, and treatment. They classified evidence according to AAN criteria and based recommendations on modified Delphi consensus.

The authors found that the prevalence of MCI is 6.7% for people between ages 60 and 64, 8.4% for people between ages 65 and 69, 10.1% for people between ages 70 and 74, 14.8% for people between ages 75 and 79, and 25.2% for people between ages 80 and 84. Approximately 15% of people with MCI who are older than 65 develop dementia during two years of follow-up.

No Evidence for Pharmacologic Treatment

Evidence does not support a symptomatic cognitive benefit in MCI for any pharmacologic or dietary agents, according to the authors. The FDA has not approved any medication for treating MCI. If clinicians offer cholinesterase inhibitors to their patients with MCI, they must first discuss the fact that the treatment is off label and not backed by empirical evidence, according to the update. Gastrointestinal symptoms and cardiac concerns are common side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors.

Assessment for MCI is appropriate for patients who complain of impaired memory or cognition, as well as those who present for a Medicare Annual Wellness Visit, according to the update. Clinicians should evaluate patients with MCI for risk factors that are potentially modifiable. Patients with MCI also should undergo serial assessments over time so that clinicians can monitor them for changes in cognitive status.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Langa KM, Levine DA. The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;312(23):2551-2561.

Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2017 Dec 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Vega JN, Newhouse PA. Mild cognitive impairment: diagnosis, longitudinal course, and emerging treatments. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(10):490.

nPEP for HIV: Updated CDC guidelines available for primary care physicians

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided health care providers with updated recommendations for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) with antiretroviral drugs to prevent transmission of HIV following sexual interaction, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposures.1 The new recommendations include the use of more effective and more tolerable drug regimens that employ antiretroviral medications that were approved since the previous guidelines came out in 2005; they also provide updated guidance on exposure assessment, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and longer-term prevention measures, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Screening for HIV infection has been expanding broadly in all health care settings over the past decade, so primary care physicians play an increasingly vital role in preventing HIV infection. Today, primary care physicians are also often the most likely “go-to” health care provider when patients think they may have been exposed to HIV. Clinically, this is an emergency situation, so time is of the essence: Treatment with three powerful antiretrovirals must be initiated within a few hours of – but no later than 72 hours after – an isolated exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious body fluids that may contain HIV.

The key issue for primary care physicians, especially those who have never prescribed PEP before, is advance planning. What you do up front, in terms of organizing materials and training staff, is worth the effort because there is so much at stake – for your patients and for society. The good news is that once you have an established nPEP protocol in place, it stays in place. When a patient asks for help, the protocol kicks in automatically.

Getting ready for nPEP

Prepare your staff:

- Educate your whole staff about the urgency of seeing potential nPEP patients immediately.

- Choose the staff person in your office who will submit requests for PEP medications to the pharmacy and/or pharmaceutical companies; your financial reimbursement staff person is likely a good candidate for this job.

- Learn about patient assistance programs (for uninsured or underinsured patients) and crime victims compensation programs (reimbursement or emergency awards for victims of violent crimes, including rape, for various out-of-pocket expenses including medical expenses).

Keep paperwork and materials on hand:

- Have information and forms for patient assistance programs for pharmaceutical companies supplying the drugs. Pharmaceutical companies are aware of the urgency for nPEP medications and are ready to respond immediately. They may mail the medication so it arrives the next day or, more likely, fax a voucher or other information for the patient to present to a local pharmacist who will fill the prescription.

- Have information on your state’s crime victims compensation program available.

- Consider keeping nPEP Starter Packs (with an initial 3-7 days’ worth of medication) readily available in your office.

Rapid evaluation of patients seeking care after potential exposure to HIV

Effective delivery of nPEP requires prompt initial evaluation of patients and assessment of HIV transmission risk. Take a methodical, step-by-step history of the exposure to address the following basic questions:

- Date and time of exposure? nPEP should be initiated as soon as possible after HIV exposure; it is unlikely to be effective if not initiated within 72 hours or less.

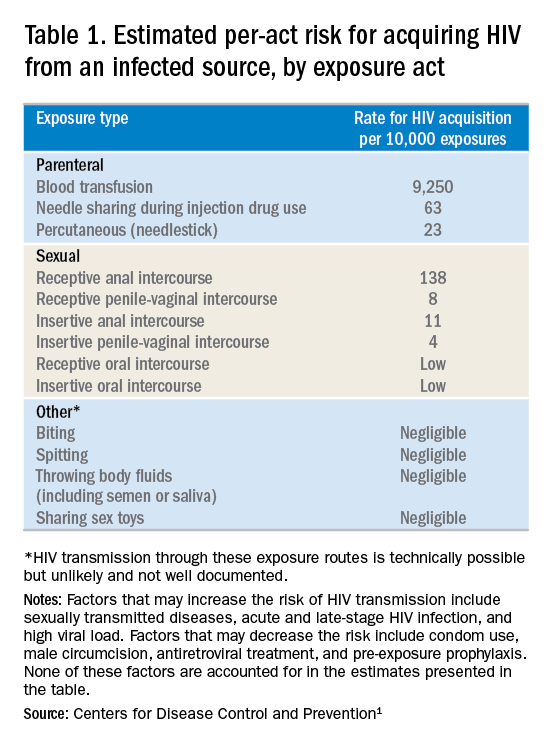

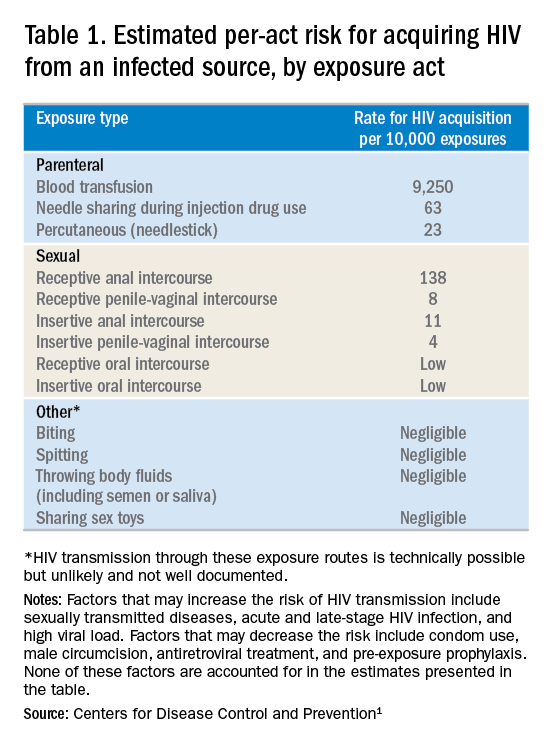

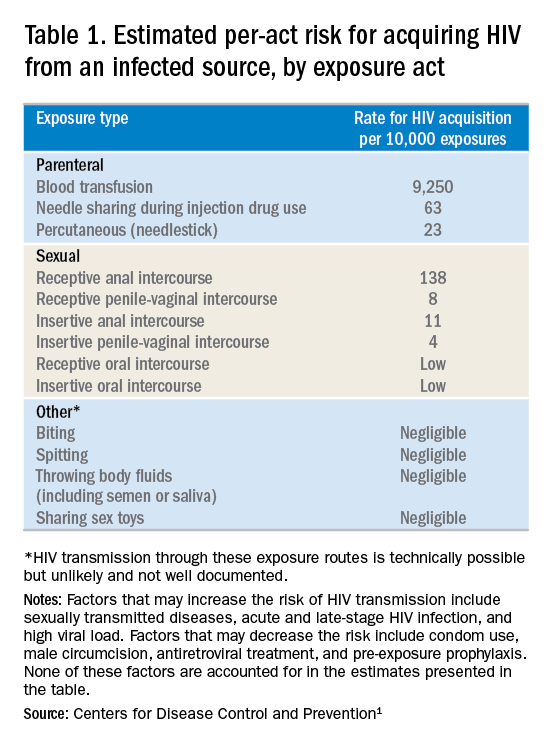

- Frequency of exposure? Type/route of exposure? nPEP is generally reserved for isolated or infrequent exposures that present a substantial risk for HIV acquisition (see Table 1 on HIV acquisition risk below).

- HIV status of exposure source? If the source is positive, is the source person on HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy? If unknown, is the source person an injecting drug user or a man who has sex with men (MSM)?

Based on the initial evaluation, is nPEP recommended?

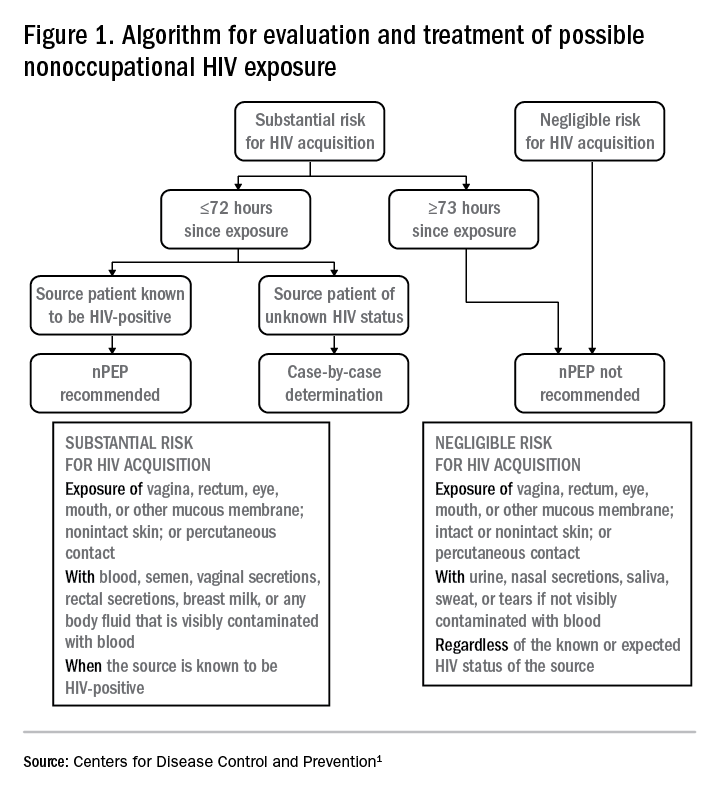

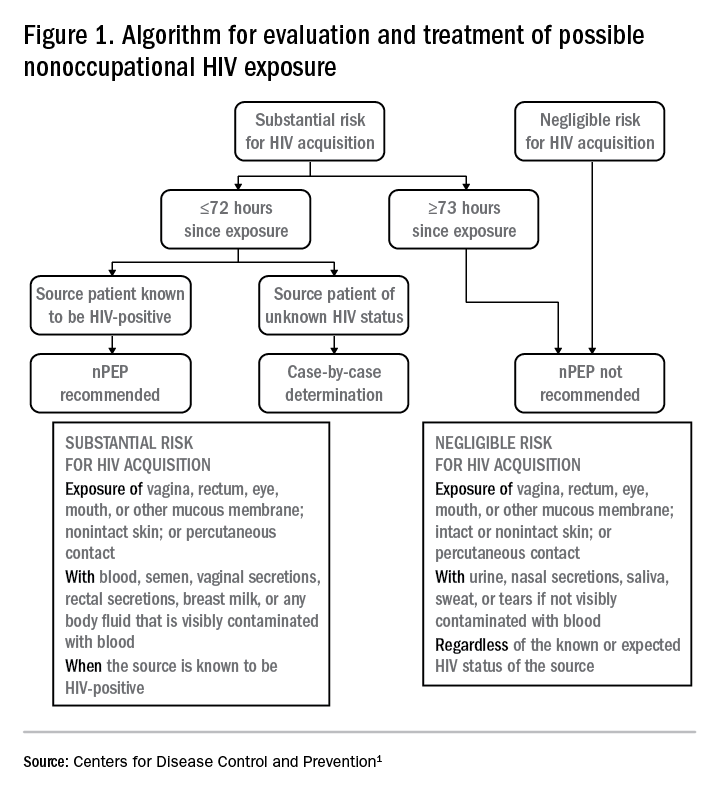

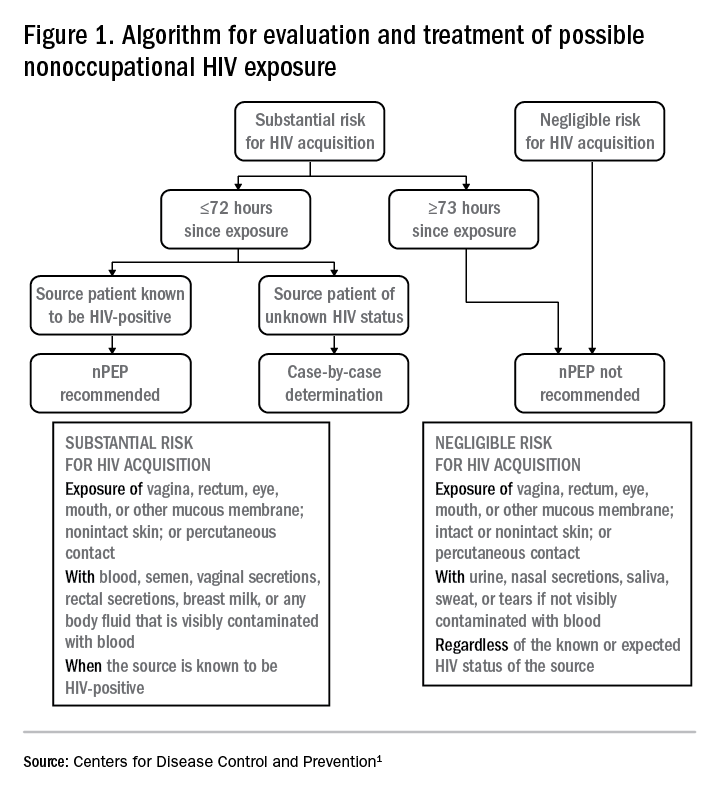

Answers to the questions asked during the initial evaluation of the patient will determine whether nPEP is indicated. Along with its updated recommendations, the CDC provided an algorithm to help guide evaluation and treatment.

Preferred HIV test

Administer an HIV test to all patients considered for nPEP, preferably the rapid combined antigen and antibody test (Ag/Ab), or just the antibody test if the Ag/Ab test is not available. nPEP is indicated only for persons without HIV infections. However, if results are not available during the initial evaluation, assume the patient is not infected. If indicated and started, nPEP can be discontinued if tests later shown the patient already has an HIV infection.

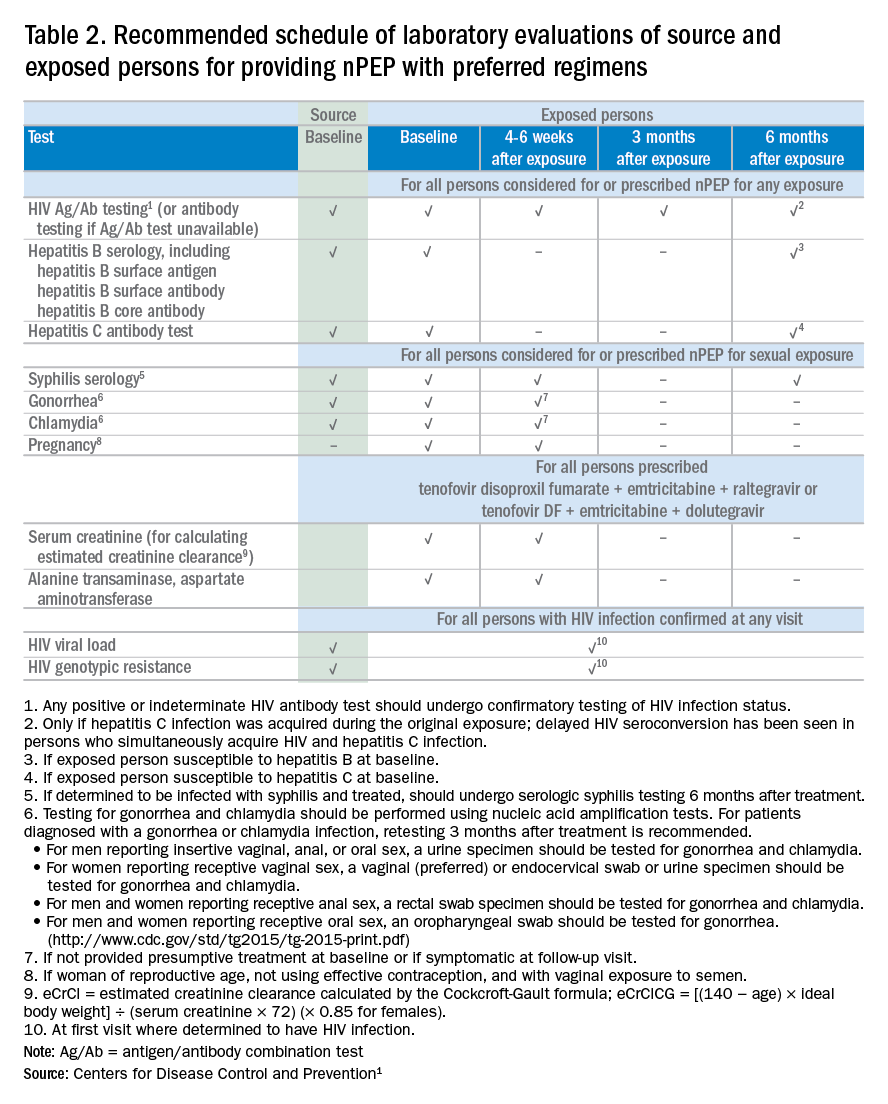

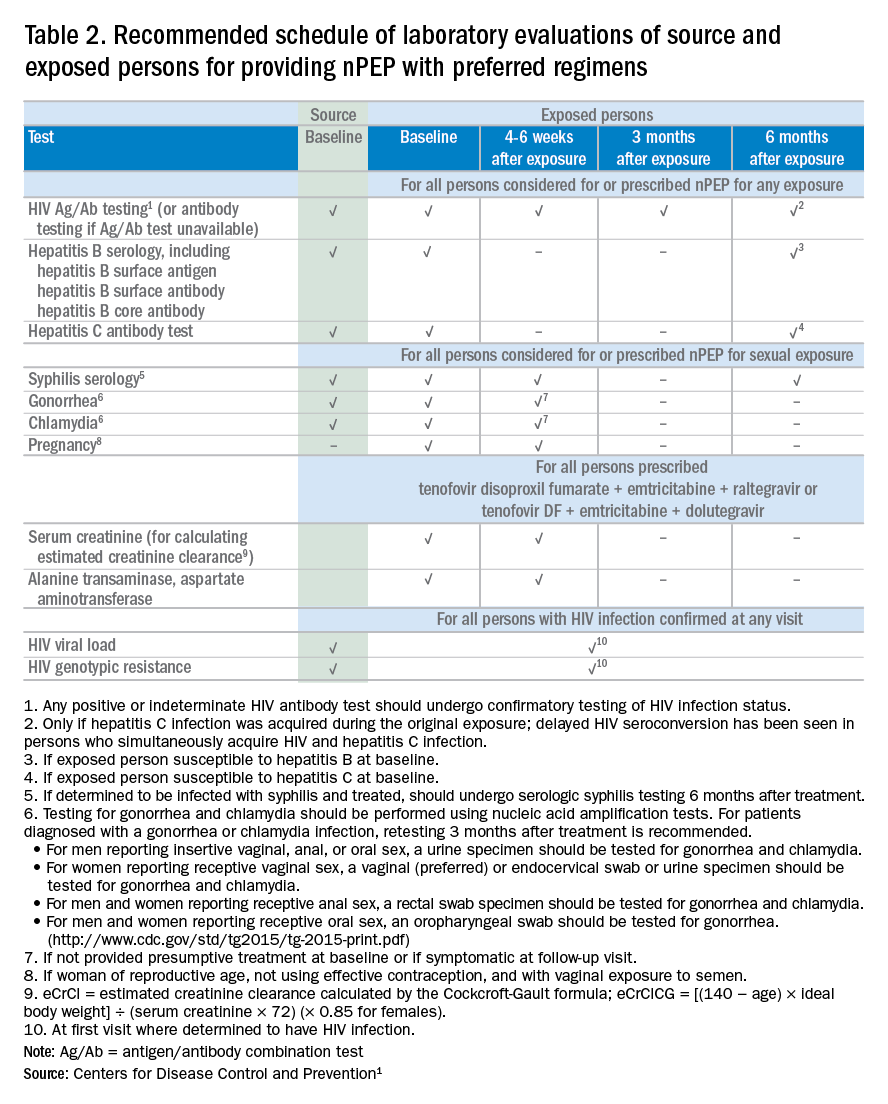

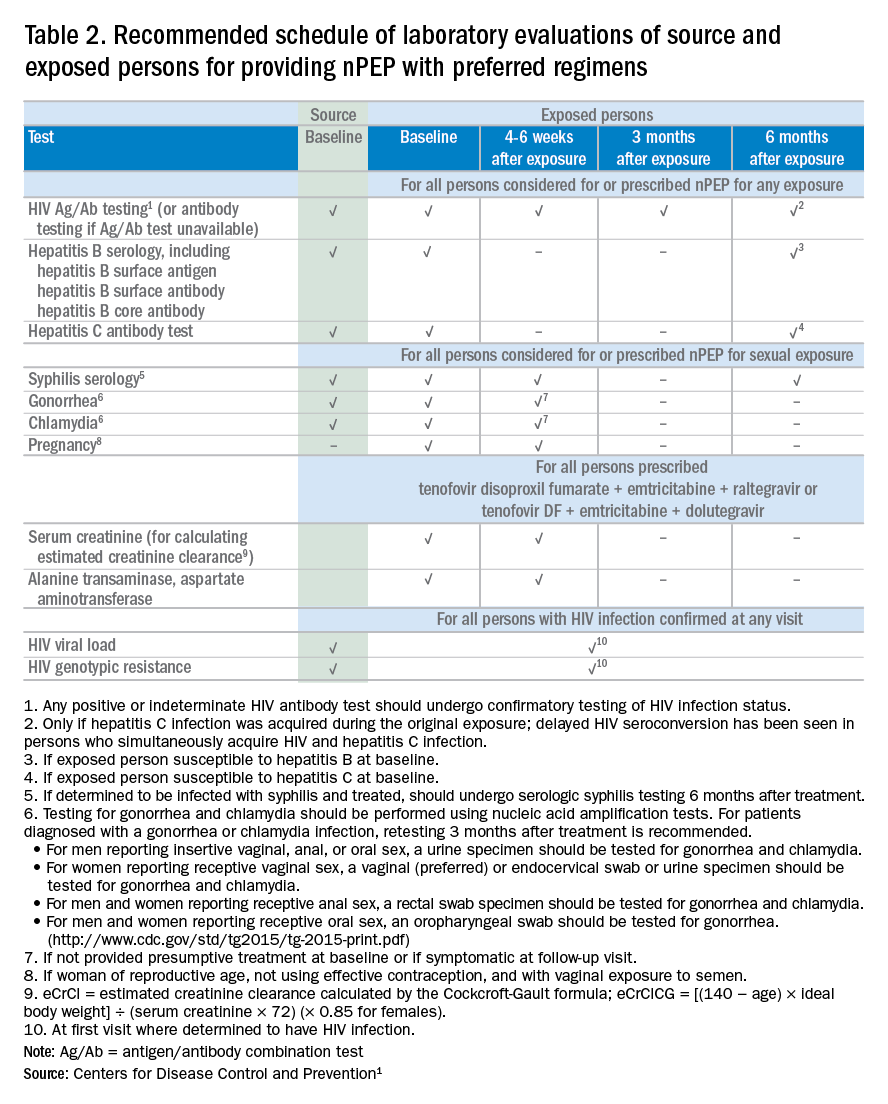

Laboratory testing

If nPEP is indicated, conduct laboratory testing. Lab testing is required to document the patient’s HIV status (and that of the source person, when available), identify and manage other conditions potentially resulting from exposure, identify conditions that may affect the nPEP medication regimen, and monitor safety or toxicities to the prescribed regimen.

nPEP treatment regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents

In the absence of randomized clinical trials, data from a case/control study demonstrating an 81% reduction of HIV transmission after use of occupational PEP among hospital workers remains the strongest evidence for the benefit of nPEP.1,2 For patients offered nPEP, recommended treatment includes prescribing either of the following regimens for 28 days:

- Preferred regimen: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (300 mg) with emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg) once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg daily.

- Alternative regimen: TDF (300 mg) with FTC (200 mg) once daily plus darunavir (DRV) (800 mg) and ritonavir (RTV) (100 mg) once daily.

Additional considerations and nPEP treatment regimens for children, patients with decreased renal function, and pregnant women are included in the CDC guidelines.

Crucial Information for Patients on nPEP

Emphasize the importance of proper dosing and adherence.

Review the patient information for each drug in the regimen, specifically the black boxes, warnings, and side effects, and counsel your patients accordingly.

Transitioning from nPEP to PrEP or from PrEP to nPEP

If you have a patient who engages in behavior that places them at risk for frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV, consider transitioning them to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) following their 28-day course of nPEP.3 PrEP is a two-drug regimen taken daily on an ongoing basis.

Additionally, for patients who are already on PrEP but who have not taken their medications within a week before the possible exposure, consider initiating nPEP for 28 days and then reintroducing PrEP if their HIV status is negative and the problems with adherence can be addressed moving forward.

Raising Awareness About nPEP

Many people never expect to be exposed to HIV and may not know about the availability of PEP in an emergency situation. You can help raise awareness by making educational materials available in your waiting rooms and exam rooms. Brochures and other HIV/AIDS educational materials for patients are available from the CDC Act Against AIDS campaign.

Summary

Dr. Dominguez is a Captain, U.S. Public Health Service, epidemiology branch, division of HIV/AIDS prevention, CDC.

Additional resources

- The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. As part of its Act Against AIDS initiative, the CDC developed the HIV Screening Standard Care program, which provides free tools and resources to help clinicians and nurses incorporate routine HIV screening into primary care settings.

- HIV guidelines and recommendations .

- Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV. United States, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. Cardo DM et al. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed March 6, 2017.

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided health care providers with updated recommendations for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) with antiretroviral drugs to prevent transmission of HIV following sexual interaction, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposures.1 The new recommendations include the use of more effective and more tolerable drug regimens that employ antiretroviral medications that were approved since the previous guidelines came out in 2005; they also provide updated guidance on exposure assessment, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and longer-term prevention measures, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Screening for HIV infection has been expanding broadly in all health care settings over the past decade, so primary care physicians play an increasingly vital role in preventing HIV infection. Today, primary care physicians are also often the most likely “go-to” health care provider when patients think they may have been exposed to HIV. Clinically, this is an emergency situation, so time is of the essence: Treatment with three powerful antiretrovirals must be initiated within a few hours of – but no later than 72 hours after – an isolated exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious body fluids that may contain HIV.

The key issue for primary care physicians, especially those who have never prescribed PEP before, is advance planning. What you do up front, in terms of organizing materials and training staff, is worth the effort because there is so much at stake – for your patients and for society. The good news is that once you have an established nPEP protocol in place, it stays in place. When a patient asks for help, the protocol kicks in automatically.

Getting ready for nPEP

Prepare your staff:

- Educate your whole staff about the urgency of seeing potential nPEP patients immediately.

- Choose the staff person in your office who will submit requests for PEP medications to the pharmacy and/or pharmaceutical companies; your financial reimbursement staff person is likely a good candidate for this job.

- Learn about patient assistance programs (for uninsured or underinsured patients) and crime victims compensation programs (reimbursement or emergency awards for victims of violent crimes, including rape, for various out-of-pocket expenses including medical expenses).

Keep paperwork and materials on hand:

- Have information and forms for patient assistance programs for pharmaceutical companies supplying the drugs. Pharmaceutical companies are aware of the urgency for nPEP medications and are ready to respond immediately. They may mail the medication so it arrives the next day or, more likely, fax a voucher or other information for the patient to present to a local pharmacist who will fill the prescription.

- Have information on your state’s crime victims compensation program available.

- Consider keeping nPEP Starter Packs (with an initial 3-7 days’ worth of medication) readily available in your office.

Rapid evaluation of patients seeking care after potential exposure to HIV

Effective delivery of nPEP requires prompt initial evaluation of patients and assessment of HIV transmission risk. Take a methodical, step-by-step history of the exposure to address the following basic questions:

- Date and time of exposure? nPEP should be initiated as soon as possible after HIV exposure; it is unlikely to be effective if not initiated within 72 hours or less.

- Frequency of exposure? Type/route of exposure? nPEP is generally reserved for isolated or infrequent exposures that present a substantial risk for HIV acquisition (see Table 1 on HIV acquisition risk below).

- HIV status of exposure source? If the source is positive, is the source person on HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy? If unknown, is the source person an injecting drug user or a man who has sex with men (MSM)?

Based on the initial evaluation, is nPEP recommended?

Answers to the questions asked during the initial evaluation of the patient will determine whether nPEP is indicated. Along with its updated recommendations, the CDC provided an algorithm to help guide evaluation and treatment.

Preferred HIV test

Administer an HIV test to all patients considered for nPEP, preferably the rapid combined antigen and antibody test (Ag/Ab), or just the antibody test if the Ag/Ab test is not available. nPEP is indicated only for persons without HIV infections. However, if results are not available during the initial evaluation, assume the patient is not infected. If indicated and started, nPEP can be discontinued if tests later shown the patient already has an HIV infection.

Laboratory testing

If nPEP is indicated, conduct laboratory testing. Lab testing is required to document the patient’s HIV status (and that of the source person, when available), identify and manage other conditions potentially resulting from exposure, identify conditions that may affect the nPEP medication regimen, and monitor safety or toxicities to the prescribed regimen.

nPEP treatment regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents

In the absence of randomized clinical trials, data from a case/control study demonstrating an 81% reduction of HIV transmission after use of occupational PEP among hospital workers remains the strongest evidence for the benefit of nPEP.1,2 For patients offered nPEP, recommended treatment includes prescribing either of the following regimens for 28 days:

- Preferred regimen: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (300 mg) with emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg) once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg daily.

- Alternative regimen: TDF (300 mg) with FTC (200 mg) once daily plus darunavir (DRV) (800 mg) and ritonavir (RTV) (100 mg) once daily.

Additional considerations and nPEP treatment regimens for children, patients with decreased renal function, and pregnant women are included in the CDC guidelines.

Crucial Information for Patients on nPEP

Emphasize the importance of proper dosing and adherence.

Review the patient information for each drug in the regimen, specifically the black boxes, warnings, and side effects, and counsel your patients accordingly.

Transitioning from nPEP to PrEP or from PrEP to nPEP

If you have a patient who engages in behavior that places them at risk for frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV, consider transitioning them to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) following their 28-day course of nPEP.3 PrEP is a two-drug regimen taken daily on an ongoing basis.

Additionally, for patients who are already on PrEP but who have not taken their medications within a week before the possible exposure, consider initiating nPEP for 28 days and then reintroducing PrEP if their HIV status is negative and the problems with adherence can be addressed moving forward.

Raising Awareness About nPEP

Many people never expect to be exposed to HIV and may not know about the availability of PEP in an emergency situation. You can help raise awareness by making educational materials available in your waiting rooms and exam rooms. Brochures and other HIV/AIDS educational materials for patients are available from the CDC Act Against AIDS campaign.

Summary

Dr. Dominguez is a Captain, U.S. Public Health Service, epidemiology branch, division of HIV/AIDS prevention, CDC.

Additional resources

- The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. As part of its Act Against AIDS initiative, the CDC developed the HIV Screening Standard Care program, which provides free tools and resources to help clinicians and nurses incorporate routine HIV screening into primary care settings.

- HIV guidelines and recommendations .

- Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV. United States, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. Cardo DM et al. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed March 6, 2017.