User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

New panic disorder model flags risk for recurrence, persistence

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

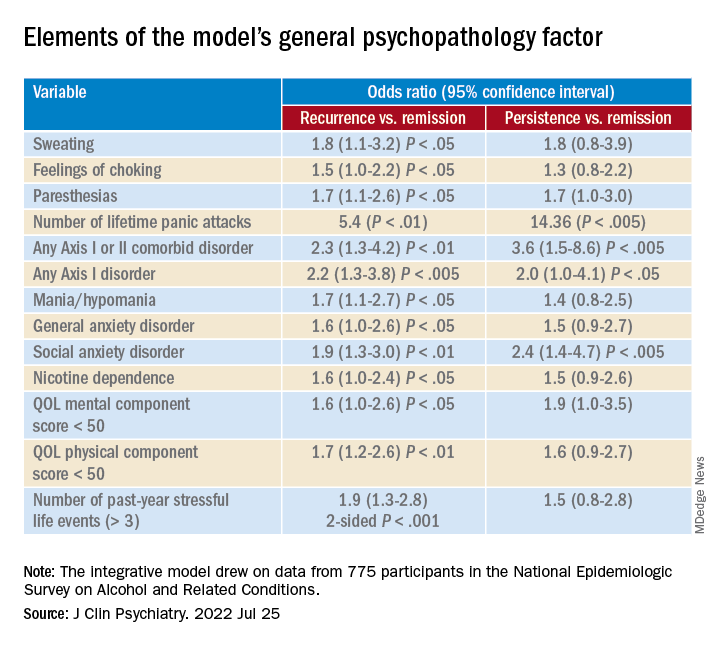

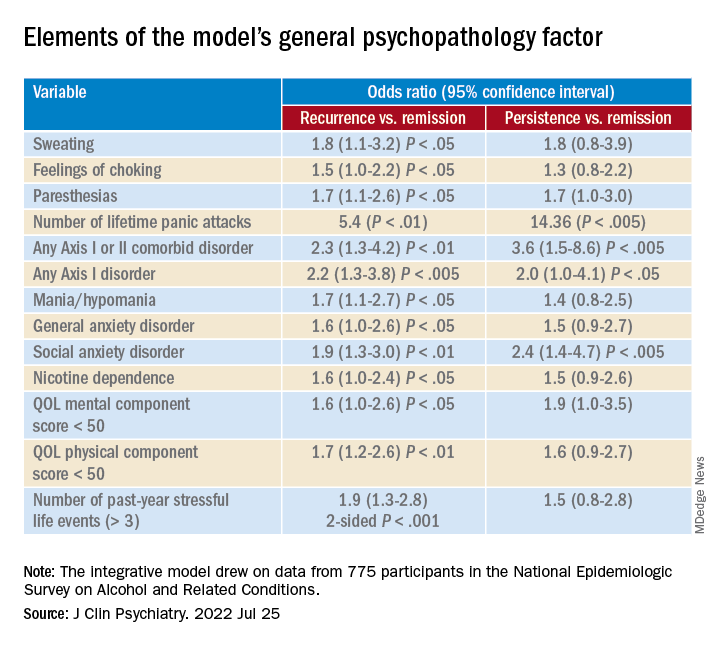

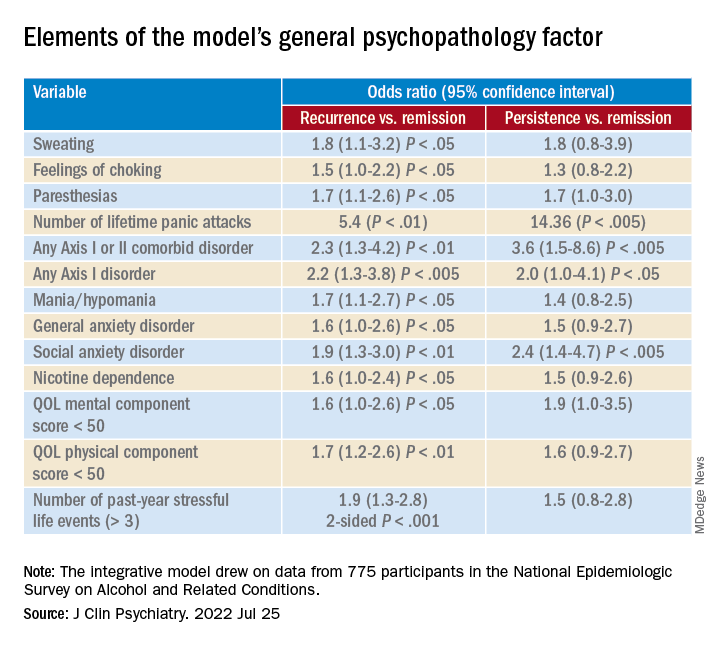

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Siblings of children with chronic health conditions may have increased mental health risks

Siblings of children with chronic health conditions could be at an increased risk for depression, according to a new report.

In a systematic review of 34 studies, siblings of children with chronic health conditions had significantly higher scores on depressive rating scales than individuals without a sibling with a chronic health condition (standardized mean difference = 0.53; P < .001). Findings related to other clinical health outcomes, such as physical health conditions or mortality, were inconsistent.

“We’ve known for a long time that siblings of kids with chronic conditions undergo stress, and there have been conflicting data on how that stress is manifested in terms of their own health,” senior study author Eyal Cohen, MD, program head for child health evaluative sciences at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, told this news organization.

“For some siblings, having the experience of being raised with a child with a chronic condition may be an asset and build resiliency, while other siblings may feel strong negative emotions, such as sadness, anger, and fear,” he said. “Although we know that this experience is stressful for many siblings, it is important to know whether it changes their health outcomes, so that appropriate support can be put in place for those who need it.”

The study was published online in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Risk for psychological challenges

About a quarter of children in the United States have a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral condition, and more than a third have at least one current or lifelong health condition, the study authors write. A childhood chronic health condition can affect family members through worse mental health outcomes, increased stress, and poorer health-related quality of life.

Dr. Cohen and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the clinical mental and physical health outcomes of siblings of children with chronic health conditions in comparison with siblings of healthy children or normative data.

The research team included English-language studies that reported on clinically diagnosable mental or physical health outcomes among siblings of persons younger than 18 years who had a chronic health condition. They included a comparison group and used an experimental or observational design for their study. The researchers analyzed 34 studies, including 28 that reported on mental health, 3 that reported on physical health, and 3 that reported on mortality.

Overall, siblings of children with chronic health conditions had significantly higher scores on depression rating scales than their comparison groups. Siblings’ anxiety scores weren’t substantially higher, however (standard mean difference = 0.21; P = .07).

The effects for confirmed psychiatric diagnoses, physical health outcomes, and mortality could not be included in the meta-analysis, owing to the limited number of studies and the high level of heterogeneity among the studies.

Dr. Cohen noted that although the researchers weren’t surprised that siblings may be at increased risk of mental health challenges, they were surprised by the limited data regarding physical health.

“At a minimum, our findings support the importance of asking open-ended questions about how a family is doing during clinical encounters,” he said. “These siblings may also benefit from programs such as support groups or summer camps, which have been shown to improve mental health and behavioral outcomes in siblings of children with chronic health conditions, such as cancer and neurodevelopmental disabilities.”

Future studies should assess the specific risk factors for mental health problems in siblings of children with chronic health conditions, Dr. Cohen said. Additional research could also investigate the design and effectiveness of interventions that address these concerns.

Message of inclusiveness

“The message that resonates with me is about the interventions and resources needed to support siblings,” Linda Nguyen, a doctoral student in rehabilitation science and researcher with the CanChild Center for Childhood Disability Research at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., told this news organization.

Ms. Nguyen, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched the resources available to siblings in Canada and has found a lack of support options, particularly when it comes to specific health care management roles.

“Consistently throughout my research, I’ve seen the need for resources that go beyond a focus on siblings’ well-being and instead support them in their different roles,” she said. “Some want to be friends, mentors, supporters, and caregivers for their siblings in the future.”

Siblings often adopt different roles as they form their own identity, Ms. Nguyen noted, which becomes a larger part of the health care conversation as children with chronic conditions make the transition from pediatric to adult health care. Siblings want to be asked how they’d like to be involved, she said. Some would like to be involved with health care appointments, the chronic condition community, research, and policy making.

“At the societal level and public level, there’s also a message of inclusiveness and making sure that we’re welcoming youth with disabilities and chronic conditions,” Jan Willem Gorter, MD, PhD, a professor of pediatrics and scientist for CanChild at McMaster University, told this news organization.

Dr. Gorter, who also was not involved with this study, noted that children with chronic conditions often feel left behind, which can influence the involvement of their siblings as well.

“There are a lot of places in the world where children with disabilities go to special schools, and they spend a lot of time in a different world, with different experiences than their siblings,” he said. “At the public health level, we want to advocate for an inclusive society and support the whole family, which benefits everybody.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the CHILD-BRIGHT Network summer studentship, which is supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. Dr. Cohen, Ms. Nguyen, and Dr. Gorter have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Siblings of children with chronic health conditions could be at an increased risk for depression, according to a new report.

In a systematic review of 34 studies, siblings of children with chronic health conditions had significantly higher scores on depressive rating scales than individuals without a sibling with a chronic health condition (standardized mean difference = 0.53; P < .001). Findings related to other clinical health outcomes, such as physical health conditions or mortality, were inconsistent.

“We’ve known for a long time that siblings of kids with chronic conditions undergo stress, and there have been conflicting data on how that stress is manifested in terms of their own health,” senior study author Eyal Cohen, MD, program head for child health evaluative sciences at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, told this news organization.

“For some siblings, having the experience of being raised with a child with a chronic condition may be an asset and build resiliency, while other siblings may feel strong negative emotions, such as sadness, anger, and fear,” he said. “Although we know that this experience is stressful for many siblings, it is important to know whether it changes their health outcomes, so that appropriate support can be put in place for those who need it.”

The study was published online in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Risk for psychological challenges

About a quarter of children in the United States have a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral condition, and more than a third have at least one current or lifelong health condition, the study authors write. A childhood chronic health condition can affect family members through worse mental health outcomes, increased stress, and poorer health-related quality of life.

Dr. Cohen and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the clinical mental and physical health outcomes of siblings of children with chronic health conditions in comparison with siblings of healthy children or normative data.

The research team included English-language studies that reported on clinically diagnosable mental or physical health outcomes among siblings of persons younger than 18 years who had a chronic health condition. They included a comparison group and used an experimental or observational design for their study. The researchers analyzed 34 studies, including 28 that reported on mental health, 3 that reported on physical health, and 3 that reported on mortality.

Overall, siblings of children with chronic health conditions had significantly higher scores on depression rating scales than their comparison groups. Siblings’ anxiety scores weren’t substantially higher, however (standard mean difference = 0.21; P = .07).

The effects for confirmed psychiatric diagnoses, physical health outcomes, and mortality could not be included in the meta-analysis, owing to the limited number of studies and the high level of heterogeneity among the studies.

Dr. Cohen noted that although the researchers weren’t surprised that siblings may be at increased risk of mental health challenges, they were surprised by the limited data regarding physical health.

“At a minimum, our findings support the importance of asking open-ended questions about how a family is doing during clinical encounters,” he said. “These siblings may also benefit from programs such as support groups or summer camps, which have been shown to improve mental health and behavioral outcomes in siblings of children with chronic health conditions, such as cancer and neurodevelopmental disabilities.”

Future studies should assess the specific risk factors for mental health problems in siblings of children with chronic health conditions, Dr. Cohen said. Additional research could also investigate the design and effectiveness of interventions that address these concerns.

Message of inclusiveness

“The message that resonates with me is about the interventions and resources needed to support siblings,” Linda Nguyen, a doctoral student in rehabilitation science and researcher with the CanChild Center for Childhood Disability Research at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., told this news organization.

Ms. Nguyen, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched the resources available to siblings in Canada and has found a lack of support options, particularly when it comes to specific health care management roles.

“Consistently throughout my research, I’ve seen the need for resources that go beyond a focus on siblings’ well-being and instead support them in their different roles,” she said. “Some want to be friends, mentors, supporters, and caregivers for their siblings in the future.”

Siblings often adopt different roles as they form their own identity, Ms. Nguyen noted, which becomes a larger part of the health care conversation as children with chronic conditions make the transition from pediatric to adult health care. Siblings want to be asked how they’d like to be involved, she said. Some would like to be involved with health care appointments, the chronic condition community, research, and policy making.

“At the societal level and public level, there’s also a message of inclusiveness and making sure that we’re welcoming youth with disabilities and chronic conditions,” Jan Willem Gorter, MD, PhD, a professor of pediatrics and scientist for CanChild at McMaster University, told this news organization.

Dr. Gorter, who also was not involved with this study, noted that children with chronic conditions often feel left behind, which can influence the involvement of their siblings as well.

“There are a lot of places in the world where children with disabilities go to special schools, and they spend a lot of time in a different world, with different experiences than their siblings,” he said. “At the public health level, we want to advocate for an inclusive society and support the whole family, which benefits everybody.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the CHILD-BRIGHT Network summer studentship, which is supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. Dr. Cohen, Ms. Nguyen, and Dr. Gorter have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Siblings of children with chronic health conditions could be at an increased risk for depression, according to a new report.

In a systematic review of 34 studies, siblings of children with chronic health conditions had significantly higher scores on depressive rating scales than individuals without a sibling with a chronic health condition (standardized mean difference = 0.53; P < .001). Findings related to other clinical health outcomes, such as physical health conditions or mortality, were inconsistent.

“We’ve known for a long time that siblings of kids with chronic conditions undergo stress, and there have been conflicting data on how that stress is manifested in terms of their own health,” senior study author Eyal Cohen, MD, program head for child health evaluative sciences at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, told this news organization.

“For some siblings, having the experience of being raised with a child with a chronic condition may be an asset and build resiliency, while other siblings may feel strong negative emotions, such as sadness, anger, and fear,” he said. “Although we know that this experience is stressful for many siblings, it is important to know whether it changes their health outcomes, so that appropriate support can be put in place for those who need it.”

The study was published online in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Risk for psychological challenges

About a quarter of children in the United States have a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral condition, and more than a third have at least one current or lifelong health condition, the study authors write. A childhood chronic health condition can affect family members through worse mental health outcomes, increased stress, and poorer health-related quality of life.

Dr. Cohen and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the clinical mental and physical health outcomes of siblings of children with chronic health conditions in comparison with siblings of healthy children or normative data.

The research team included English-language studies that reported on clinically diagnosable mental or physical health outcomes among siblings of persons younger than 18 years who had a chronic health condition. They included a comparison group and used an experimental or observational design for their study. The researchers analyzed 34 studies, including 28 that reported on mental health, 3 that reported on physical health, and 3 that reported on mortality.

Overall, siblings of children with chronic health conditions had significantly higher scores on depression rating scales than their comparison groups. Siblings’ anxiety scores weren’t substantially higher, however (standard mean difference = 0.21; P = .07).

The effects for confirmed psychiatric diagnoses, physical health outcomes, and mortality could not be included in the meta-analysis, owing to the limited number of studies and the high level of heterogeneity among the studies.

Dr. Cohen noted that although the researchers weren’t surprised that siblings may be at increased risk of mental health challenges, they were surprised by the limited data regarding physical health.

“At a minimum, our findings support the importance of asking open-ended questions about how a family is doing during clinical encounters,” he said. “These siblings may also benefit from programs such as support groups or summer camps, which have been shown to improve mental health and behavioral outcomes in siblings of children with chronic health conditions, such as cancer and neurodevelopmental disabilities.”

Future studies should assess the specific risk factors for mental health problems in siblings of children with chronic health conditions, Dr. Cohen said. Additional research could also investigate the design and effectiveness of interventions that address these concerns.

Message of inclusiveness

“The message that resonates with me is about the interventions and resources needed to support siblings,” Linda Nguyen, a doctoral student in rehabilitation science and researcher with the CanChild Center for Childhood Disability Research at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., told this news organization.

Ms. Nguyen, who wasn’t involved with this study, has researched the resources available to siblings in Canada and has found a lack of support options, particularly when it comes to specific health care management roles.

“Consistently throughout my research, I’ve seen the need for resources that go beyond a focus on siblings’ well-being and instead support them in their different roles,” she said. “Some want to be friends, mentors, supporters, and caregivers for their siblings in the future.”

Siblings often adopt different roles as they form their own identity, Ms. Nguyen noted, which becomes a larger part of the health care conversation as children with chronic conditions make the transition from pediatric to adult health care. Siblings want to be asked how they’d like to be involved, she said. Some would like to be involved with health care appointments, the chronic condition community, research, and policy making.

“At the societal level and public level, there’s also a message of inclusiveness and making sure that we’re welcoming youth with disabilities and chronic conditions,” Jan Willem Gorter, MD, PhD, a professor of pediatrics and scientist for CanChild at McMaster University, told this news organization.

Dr. Gorter, who also was not involved with this study, noted that children with chronic conditions often feel left behind, which can influence the involvement of their siblings as well.

“There are a lot of places in the world where children with disabilities go to special schools, and they spend a lot of time in a different world, with different experiences than their siblings,” he said. “At the public health level, we want to advocate for an inclusive society and support the whole family, which benefits everybody.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the CHILD-BRIGHT Network summer studentship, which is supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. Dr. Cohen, Ms. Nguyen, and Dr. Gorter have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Postpartum depression risk higher with family psych history

Mothers who have a family history of any psychiatric disorder have almost two times the risk of postpartum depression as do mothers without such history, according to a new study.

Mette-Marie Zacher Kjeldsen, MSc, with the National Centre for Register-based Research at Aarhus (Denmark) University, led the study, a meta-analysis that included 26 studies with information on 100,877 women.

Findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

When mothers had a family history of psychiatric disorders, the odds ratio for PPD was 2.08 (95% confidence interval, 1.67-2.59). That corresponds to a risk ratio of 1.79 (95% CI, 1.52-2.09), assuming a 15% postpartum depression prevalence in the general population.

Not doomed to develop PPD

Polina Teslyar, MD, a perinatal psychiatrist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston told this news organization it’s important to point out that though the risk is higher, women with a family psychiatric history should not feel as though they are destined to develop PPD.

“You are still more likely to not have postpartum depression, but it is important to be aware of personal risk factors so that if a person is experiencing that, they ask for help quickly rather than suffering and not knowing something is amiss,” she emphasized. Dr. Teslyar says she does see the higher risk for PPD, which is preventable and treatable, in her own practice when women have had a family history of psychiatric disorders.

The association makes sense, but literature on why that is has been varied, she said, and likely involves both genetics and socioeconomic factors. It’s difficult to tease apart how big a part each plays.

In her perinatal practice she sees women even before they are pregnant to discuss risk factors for PPD so she does ask about family history of psychiatric disorders, specifically about history of PPD and anxiety.

The researchers suggest routine perinatal care should include an easy low-cost, two-part question about both personal and family history of psychiatric disorders.

“As the assessment is possible even prior to conception, this would leave time for planning preventive efforts, such as psychosocial and psychological interventions targeting these at-risk women,” the authors write.

Asking about family history a challenge

Dr. Teslyar noted though that one of the challenges in asking about family history is that families may not have openly shared psychiatric history details with offspring. Family members may also report conditions they suspect a family member had rather than having a documented diagnosis.

In places where there is universal health care, she noted, finding documented diagnoses is easier, but otherwise “you’re really taking a subjective interpretation.”

The researchers found that subgroup, sensitivity, and meta–regression analyses aligned with the primary findings. The overall certainty of evidence was graded as moderate.

This study was not able to make clear how the specific diagnoses of family members affect the risk of developing PPD because much of the data from the studies came from self-report and questions were not consistent across the studies.

For instance, only 7 studies asked specifically about first-degree family members and 10 asked about specific diagnoses. Diagnoses ranged from mild affective disorders to more intrusive disorders, such as schizophrenia.

And while this study doesn’t seek to determine why the family history and risk of PPD appear to be connected, the authors offer some possible explanations.

“Growing up in an environment with parents struggling with mental health problems potentially influences the social support received from these parents when going into motherhood,” the authors write. “This particular explanation is supported by umbrella reviews concluding that lack of social support is a significant PPD risk factor.”

Screening, extraction, and assessment of studies included was done independently by two reviewers, increasing validity, the authors note.

The authors state that approximately 10%-15% of new mothers experience PPD, but Dr. Teslyar points out the numbers in the United States are typically quoted at up to 20%-30%. PPD ranges from mild to severe episodes and includes symptoms like those for major depression outside the postpartum period.

Study authors received funding from The Lundbeck Foundation and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. A coauthor, Vibe G. Frokjaer, MD, PhD, has served as consultant and lecturer for H. Lundbeck and Sage Therapeutics. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Teslyar reports no relevant financial relationships.

Mothers who have a family history of any psychiatric disorder have almost two times the risk of postpartum depression as do mothers without such history, according to a new study.

Mette-Marie Zacher Kjeldsen, MSc, with the National Centre for Register-based Research at Aarhus (Denmark) University, led the study, a meta-analysis that included 26 studies with information on 100,877 women.

Findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

When mothers had a family history of psychiatric disorders, the odds ratio for PPD was 2.08 (95% confidence interval, 1.67-2.59). That corresponds to a risk ratio of 1.79 (95% CI, 1.52-2.09), assuming a 15% postpartum depression prevalence in the general population.

Not doomed to develop PPD

Polina Teslyar, MD, a perinatal psychiatrist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston told this news organization it’s important to point out that though the risk is higher, women with a family psychiatric history should not feel as though they are destined to develop PPD.

“You are still more likely to not have postpartum depression, but it is important to be aware of personal risk factors so that if a person is experiencing that, they ask for help quickly rather than suffering and not knowing something is amiss,” she emphasized. Dr. Teslyar says she does see the higher risk for PPD, which is preventable and treatable, in her own practice when women have had a family history of psychiatric disorders.

The association makes sense, but literature on why that is has been varied, she said, and likely involves both genetics and socioeconomic factors. It’s difficult to tease apart how big a part each plays.

In her perinatal practice she sees women even before they are pregnant to discuss risk factors for PPD so she does ask about family history of psychiatric disorders, specifically about history of PPD and anxiety.

The researchers suggest routine perinatal care should include an easy low-cost, two-part question about both personal and family history of psychiatric disorders.

“As the assessment is possible even prior to conception, this would leave time for planning preventive efforts, such as psychosocial and psychological interventions targeting these at-risk women,” the authors write.

Asking about family history a challenge

Dr. Teslyar noted though that one of the challenges in asking about family history is that families may not have openly shared psychiatric history details with offspring. Family members may also report conditions they suspect a family member had rather than having a documented diagnosis.

In places where there is universal health care, she noted, finding documented diagnoses is easier, but otherwise “you’re really taking a subjective interpretation.”

The researchers found that subgroup, sensitivity, and meta–regression analyses aligned with the primary findings. The overall certainty of evidence was graded as moderate.

This study was not able to make clear how the specific diagnoses of family members affect the risk of developing PPD because much of the data from the studies came from self-report and questions were not consistent across the studies.

For instance, only 7 studies asked specifically about first-degree family members and 10 asked about specific diagnoses. Diagnoses ranged from mild affective disorders to more intrusive disorders, such as schizophrenia.

And while this study doesn’t seek to determine why the family history and risk of PPD appear to be connected, the authors offer some possible explanations.

“Growing up in an environment with parents struggling with mental health problems potentially influences the social support received from these parents when going into motherhood,” the authors write. “This particular explanation is supported by umbrella reviews concluding that lack of social support is a significant PPD risk factor.”

Screening, extraction, and assessment of studies included was done independently by two reviewers, increasing validity, the authors note.

The authors state that approximately 10%-15% of new mothers experience PPD, but Dr. Teslyar points out the numbers in the United States are typically quoted at up to 20%-30%. PPD ranges from mild to severe episodes and includes symptoms like those for major depression outside the postpartum period.

Study authors received funding from The Lundbeck Foundation and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. A coauthor, Vibe G. Frokjaer, MD, PhD, has served as consultant and lecturer for H. Lundbeck and Sage Therapeutics. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Teslyar reports no relevant financial relationships.

Mothers who have a family history of any psychiatric disorder have almost two times the risk of postpartum depression as do mothers without such history, according to a new study.

Mette-Marie Zacher Kjeldsen, MSc, with the National Centre for Register-based Research at Aarhus (Denmark) University, led the study, a meta-analysis that included 26 studies with information on 100,877 women.

Findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

When mothers had a family history of psychiatric disorders, the odds ratio for PPD was 2.08 (95% confidence interval, 1.67-2.59). That corresponds to a risk ratio of 1.79 (95% CI, 1.52-2.09), assuming a 15% postpartum depression prevalence in the general population.

Not doomed to develop PPD

Polina Teslyar, MD, a perinatal psychiatrist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston told this news organization it’s important to point out that though the risk is higher, women with a family psychiatric history should not feel as though they are destined to develop PPD.

“You are still more likely to not have postpartum depression, but it is important to be aware of personal risk factors so that if a person is experiencing that, they ask for help quickly rather than suffering and not knowing something is amiss,” she emphasized. Dr. Teslyar says she does see the higher risk for PPD, which is preventable and treatable, in her own practice when women have had a family history of psychiatric disorders.

The association makes sense, but literature on why that is has been varied, she said, and likely involves both genetics and socioeconomic factors. It’s difficult to tease apart how big a part each plays.

In her perinatal practice she sees women even before they are pregnant to discuss risk factors for PPD so she does ask about family history of psychiatric disorders, specifically about history of PPD and anxiety.

The researchers suggest routine perinatal care should include an easy low-cost, two-part question about both personal and family history of psychiatric disorders.

“As the assessment is possible even prior to conception, this would leave time for planning preventive efforts, such as psychosocial and psychological interventions targeting these at-risk women,” the authors write.

Asking about family history a challenge

Dr. Teslyar noted though that one of the challenges in asking about family history is that families may not have openly shared psychiatric history details with offspring. Family members may also report conditions they suspect a family member had rather than having a documented diagnosis.

In places where there is universal health care, she noted, finding documented diagnoses is easier, but otherwise “you’re really taking a subjective interpretation.”

The researchers found that subgroup, sensitivity, and meta–regression analyses aligned with the primary findings. The overall certainty of evidence was graded as moderate.

This study was not able to make clear how the specific diagnoses of family members affect the risk of developing PPD because much of the data from the studies came from self-report and questions were not consistent across the studies.

For instance, only 7 studies asked specifically about first-degree family members and 10 asked about specific diagnoses. Diagnoses ranged from mild affective disorders to more intrusive disorders, such as schizophrenia.

And while this study doesn’t seek to determine why the family history and risk of PPD appear to be connected, the authors offer some possible explanations.

“Growing up in an environment with parents struggling with mental health problems potentially influences the social support received from these parents when going into motherhood,” the authors write. “This particular explanation is supported by umbrella reviews concluding that lack of social support is a significant PPD risk factor.”

Screening, extraction, and assessment of studies included was done independently by two reviewers, increasing validity, the authors note.

The authors state that approximately 10%-15% of new mothers experience PPD, but Dr. Teslyar points out the numbers in the United States are typically quoted at up to 20%-30%. PPD ranges from mild to severe episodes and includes symptoms like those for major depression outside the postpartum period.

Study authors received funding from The Lundbeck Foundation and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. A coauthor, Vibe G. Frokjaer, MD, PhD, has served as consultant and lecturer for H. Lundbeck and Sage Therapeutics. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Teslyar reports no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

COVID-19 may trigger irritable bowel syndrome

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common with long COVID, also known as post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, according to Walter Chan, MD, MPH, and Madhusudan Grover, MBBS.

Dr. Chan, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Dr. Grover, an associate professor of medicine and physiology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., conducted a review of the literature on COVID-19’s long-term gastrointestinal effects. Their review was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Estimates of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms with COVID-19 have ranged as high as 60%, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover report, and the symptoms may be present in patients with long COVID, a syndrome that continues 4 weeks or longer.

In one survey of 749 COVID-19 survivors, 29% reported at least one new chronic gastrointestinal symptom. The most common were heartburn, constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Of those with abdominal pain, 39% had symptoms that met Rome IV criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

People who have gastrointestinal symptoms after their initial SARS-CoV-2 infection are more likely to have them with long COVID. Psychiatric diagnoses, hospitalization, and the loss of smell and taste are predictors of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Infectious gastroenteritis can increase the risk for disorders of gut-brain interaction, especially postinfection IBS, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

COVID-19 likely causes gastrointestinal symptoms through multiple mechanisms. It may suppress angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which protects intestinal cells. It can alter the microbiome. It can cause or worsen weight gain and diabetes. It may disrupt the immune system and trigger an autoimmune reaction. It can cause depression and anxiety, and it can alter dietary habits.

No specific treatments for gastrointestinal symptoms associated with long COVID have emerged, so clinicians should make use of established therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover recommend.

Beyond adequate sleep and exercise, these may include high-fiber, low FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols), gluten-free, low-carbohydrate, or elimination diets.

For diarrhea, they list loperamide, ondansetron, alosetron, eluxadoline, antispasmodics, rifaximin, and bile acid sequestrants.

For constipation, they mention fiber supplements, polyethylene glycol, linaclotide, plecanatide, lubiprostone, tenapanor, tegaserod, and prucalopride.

For modulating intestinal permeability, they recommend glutamine.

Neuromodulation may be achieved with tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, azaperones, and delta ligands, they write.

For psychological therapy, they recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy.

A handful of studies have suggested benefits from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pediococcus acidilactici as probiotic therapies. Additionally, one study showed positive results with a high-fiber formula, perhaps by nourishing short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

Dr. Chan reported financial relationships with Ironwood, Takeda, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Grover reported financial relationships with Takeda, Donga, Alexza Pharmaceuticals, and Alfasigma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common with long COVID, also known as post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, according to Walter Chan, MD, MPH, and Madhusudan Grover, MBBS.

Dr. Chan, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Dr. Grover, an associate professor of medicine and physiology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., conducted a review of the literature on COVID-19’s long-term gastrointestinal effects. Their review was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Estimates of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms with COVID-19 have ranged as high as 60%, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover report, and the symptoms may be present in patients with long COVID, a syndrome that continues 4 weeks or longer.

In one survey of 749 COVID-19 survivors, 29% reported at least one new chronic gastrointestinal symptom. The most common were heartburn, constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Of those with abdominal pain, 39% had symptoms that met Rome IV criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

People who have gastrointestinal symptoms after their initial SARS-CoV-2 infection are more likely to have them with long COVID. Psychiatric diagnoses, hospitalization, and the loss of smell and taste are predictors of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Infectious gastroenteritis can increase the risk for disorders of gut-brain interaction, especially postinfection IBS, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

COVID-19 likely causes gastrointestinal symptoms through multiple mechanisms. It may suppress angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which protects intestinal cells. It can alter the microbiome. It can cause or worsen weight gain and diabetes. It may disrupt the immune system and trigger an autoimmune reaction. It can cause depression and anxiety, and it can alter dietary habits.

No specific treatments for gastrointestinal symptoms associated with long COVID have emerged, so clinicians should make use of established therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover recommend.

Beyond adequate sleep and exercise, these may include high-fiber, low FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols), gluten-free, low-carbohydrate, or elimination diets.

For diarrhea, they list loperamide, ondansetron, alosetron, eluxadoline, antispasmodics, rifaximin, and bile acid sequestrants.

For constipation, they mention fiber supplements, polyethylene glycol, linaclotide, plecanatide, lubiprostone, tenapanor, tegaserod, and prucalopride.

For modulating intestinal permeability, they recommend glutamine.

Neuromodulation may be achieved with tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, azaperones, and delta ligands, they write.

For psychological therapy, they recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy.

A handful of studies have suggested benefits from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pediococcus acidilactici as probiotic therapies. Additionally, one study showed positive results with a high-fiber formula, perhaps by nourishing short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

Dr. Chan reported financial relationships with Ironwood, Takeda, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Grover reported financial relationships with Takeda, Donga, Alexza Pharmaceuticals, and Alfasigma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common with long COVID, also known as post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, according to Walter Chan, MD, MPH, and Madhusudan Grover, MBBS.

Dr. Chan, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Dr. Grover, an associate professor of medicine and physiology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., conducted a review of the literature on COVID-19’s long-term gastrointestinal effects. Their review was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Estimates of the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms with COVID-19 have ranged as high as 60%, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover report, and the symptoms may be present in patients with long COVID, a syndrome that continues 4 weeks or longer.

In one survey of 749 COVID-19 survivors, 29% reported at least one new chronic gastrointestinal symptom. The most common were heartburn, constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Of those with abdominal pain, 39% had symptoms that met Rome IV criteria for irritable bowel syndrome.

People who have gastrointestinal symptoms after their initial SARS-CoV-2 infection are more likely to have them with long COVID. Psychiatric diagnoses, hospitalization, and the loss of smell and taste are predictors of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Infectious gastroenteritis can increase the risk for disorders of gut-brain interaction, especially postinfection IBS, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

COVID-19 likely causes gastrointestinal symptoms through multiple mechanisms. It may suppress angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which protects intestinal cells. It can alter the microbiome. It can cause or worsen weight gain and diabetes. It may disrupt the immune system and trigger an autoimmune reaction. It can cause depression and anxiety, and it can alter dietary habits.

No specific treatments for gastrointestinal symptoms associated with long COVID have emerged, so clinicians should make use of established therapies for disorders of gut-brain interaction, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover recommend.

Beyond adequate sleep and exercise, these may include high-fiber, low FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols), gluten-free, low-carbohydrate, or elimination diets.

For diarrhea, they list loperamide, ondansetron, alosetron, eluxadoline, antispasmodics, rifaximin, and bile acid sequestrants.

For constipation, they mention fiber supplements, polyethylene glycol, linaclotide, plecanatide, lubiprostone, tenapanor, tegaserod, and prucalopride.

For modulating intestinal permeability, they recommend glutamine.

Neuromodulation may be achieved with tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, azaperones, and delta ligands, they write.

For psychological therapy, they recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy.

A handful of studies have suggested benefits from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pediococcus acidilactici as probiotic therapies. Additionally, one study showed positive results with a high-fiber formula, perhaps by nourishing short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria, Dr. Chan and Dr. Grover write.

Dr. Chan reported financial relationships with Ironwood, Takeda, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Grover reported financial relationships with Takeda, Donga, Alexza Pharmaceuticals, and Alfasigma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Early dementia but no specialists: Reinforcements needed?

Patients in rural areas are also less likely to see psychologists and undergo neuropsychological testing, according to the study, published in JAMA Network Open.

Patients who forgo such specialist visits and testing may be missing information about their condition that could help them prepare for changes in job responsibilities and future care decisions, said Wendy Yi Xu, PhD, of The Ohio State University, Columbus, who led the research.

“A lot of them are still in the workforce,” Dr. Xu said. Patients in the study were an average age of 56 years, well before the conventional age of retirement.

Location, location, location

To examine rural versus urban differences in the use of diagnostic tests and health care visits for early onset Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, Dr. Xu and colleagues analyzed commercial claims data from 2012-2018. They identified more than 71,000 patients aged 40-64 years with those conditions and focused on health care use by 7,311 patients in urban areas and 1,119 in rural areas within 90 days of a new dementia diagnosis.

The proportion who received neuropsychological testing was 19% among urban patients and 16% among rural patients. Psychological assessments, which are less specialized and detailed than neuropsychological testing, and brain imaging occurred at similar rates in both groups. Similar proportions of rural and urban patients visited neurologists (17.7% and 17.96%, respectively) and psychiatrists (6.02% and 6.47%).

But more urban patients than rural patients visited a psychologist, at 19% versus 15%, according to the researchers.

Approximately 18% of patients in rural areas saw a primary care provider without visiting other specialists, compared with 13% in urban areas.

The researchers found that rural patients were significantly less likely to undergo neuropsychological testing (odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.98) or see a psychologist (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60-0.85).

Similarly, rural patients had significantly higher odds of having only primary care providers involved in the diagnosis of dementia and symptom management (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.19-1.66).

Addressing workforce deficiencies

More primary care training in dementia care and collaboration with specialist colleagues could help address differences in care, Dr. Xu’s group writes. Such efforts are already underway.

In 2018, the Alzheimer’s Association launched telementoring programs focused on dementia care using the Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model. Researchers originally developed Project ECHO at the University of New Mexico in 2003 to teach primary care clinicians in remote settings how to treat patients infected with the hepatitis C virus.

With the Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care ECHO Program for Clinicians, primary care clinicians can participate in interactive case-based video conferencing sessions to better understand dementia and how to provide high-quality care in community settings, according to the association.

The program covers guidelines for diagnosis, disclosure, and follow-up; the initiation of care planning; managing disease-related challenges; and resources for patients and caregivers.

Since 2018, nearly 100 primary care practices in the United States have completed training in dementia care using Project ECHO, said Morgan Daven, vice president of health systems for the Alzheimer’s Association. Many cases featured in the program are challenging, he added.

“With primary care being on the front lines, it is really important that primary care physicians are equipped to do what they can to detect or diagnose and know when to refer,” Mr. Daven said.

The association has compiled other resources for clinicians as well.

A 2020 report from the association examined the role that primary care physicians play in dementia care. One survey found that 82% of primary care physicians consider themselves on the front lines of providing care for patients with dementia.

Meanwhile, about half say medical professionals are not prepared to meet rising demands associated with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia care.

Mr. Daven said the geographic disparities Dr. Xu and colleagues found are unsurprising. More than half of primary care physicians who care for people with Alzheimer’s disease say dementia specialists in their communities cannot meet demand. The problem is more urgent in rural areas. Roughly half of nonmetropolitan counties in the United States lack a practicing psychologist, according to a 2018 study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

“We really need to approach this on both sides – build the capacity in primary care, but we also need to address the dementia care specialty shortages,” Mr. Daven said.

The lack of obvious differences in access to neurologists in the new study “was surprising, given the more than fourfold difference between urban and rural areas in the supply of neurologists,” the researchers note. Health plans may maintain more access to neurologists than psychologists because of relatively higher reimbursement for neurologists, they observed.

One of the study coauthors disclosed ties to Aveanna Healthcare, a company that delivers home health and hospice care.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients in rural areas are also less likely to see psychologists and undergo neuropsychological testing, according to the study, published in JAMA Network Open.

Patients who forgo such specialist visits and testing may be missing information about their condition that could help them prepare for changes in job responsibilities and future care decisions, said Wendy Yi Xu, PhD, of The Ohio State University, Columbus, who led the research.

“A lot of them are still in the workforce,” Dr. Xu said. Patients in the study were an average age of 56 years, well before the conventional age of retirement.

Location, location, location

To examine rural versus urban differences in the use of diagnostic tests and health care visits for early onset Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, Dr. Xu and colleagues analyzed commercial claims data from 2012-2018. They identified more than 71,000 patients aged 40-64 years with those conditions and focused on health care use by 7,311 patients in urban areas and 1,119 in rural areas within 90 days of a new dementia diagnosis.

The proportion who received neuropsychological testing was 19% among urban patients and 16% among rural patients. Psychological assessments, which are less specialized and detailed than neuropsychological testing, and brain imaging occurred at similar rates in both groups. Similar proportions of rural and urban patients visited neurologists (17.7% and 17.96%, respectively) and psychiatrists (6.02% and 6.47%).

But more urban patients than rural patients visited a psychologist, at 19% versus 15%, according to the researchers.

Approximately 18% of patients in rural areas saw a primary care provider without visiting other specialists, compared with 13% in urban areas.

The researchers found that rural patients were significantly less likely to undergo neuropsychological testing (odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.98) or see a psychologist (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60-0.85).

Similarly, rural patients had significantly higher odds of having only primary care providers involved in the diagnosis of dementia and symptom management (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.19-1.66).

Addressing workforce deficiencies

More primary care training in dementia care and collaboration with specialist colleagues could help address differences in care, Dr. Xu’s group writes. Such efforts are already underway.

In 2018, the Alzheimer’s Association launched telementoring programs focused on dementia care using the Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model. Researchers originally developed Project ECHO at the University of New Mexico in 2003 to teach primary care clinicians in remote settings how to treat patients infected with the hepatitis C virus.

With the Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care ECHO Program for Clinicians, primary care clinicians can participate in interactive case-based video conferencing sessions to better understand dementia and how to provide high-quality care in community settings, according to the association.

The program covers guidelines for diagnosis, disclosure, and follow-up; the initiation of care planning; managing disease-related challenges; and resources for patients and caregivers.

Since 2018, nearly 100 primary care practices in the United States have completed training in dementia care using Project ECHO, said Morgan Daven, vice president of health systems for the Alzheimer’s Association. Many cases featured in the program are challenging, he added.

“With primary care being on the front lines, it is really important that primary care physicians are equipped to do what they can to detect or diagnose and know when to refer,” Mr. Daven said.

The association has compiled other resources for clinicians as well.

A 2020 report from the association examined the role that primary care physicians play in dementia care. One survey found that 82% of primary care physicians consider themselves on the front lines of providing care for patients with dementia.

Meanwhile, about half say medical professionals are not prepared to meet rising demands associated with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia care.

Mr. Daven said the geographic disparities Dr. Xu and colleagues found are unsurprising. More than half of primary care physicians who care for people with Alzheimer’s disease say dementia specialists in their communities cannot meet demand. The problem is more urgent in rural areas. Roughly half of nonmetropolitan counties in the United States lack a practicing psychologist, according to a 2018 study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

“We really need to approach this on both sides – build the capacity in primary care, but we also need to address the dementia care specialty shortages,” Mr. Daven said.

The lack of obvious differences in access to neurologists in the new study “was surprising, given the more than fourfold difference between urban and rural areas in the supply of neurologists,” the researchers note. Health plans may maintain more access to neurologists than psychologists because of relatively higher reimbursement for neurologists, they observed.

One of the study coauthors disclosed ties to Aveanna Healthcare, a company that delivers home health and hospice care.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients in rural areas are also less likely to see psychologists and undergo neuropsychological testing, according to the study, published in JAMA Network Open.

Patients who forgo such specialist visits and testing may be missing information about their condition that could help them prepare for changes in job responsibilities and future care decisions, said Wendy Yi Xu, PhD, of The Ohio State University, Columbus, who led the research.

“A lot of them are still in the workforce,” Dr. Xu said. Patients in the study were an average age of 56 years, well before the conventional age of retirement.

Location, location, location

To examine rural versus urban differences in the use of diagnostic tests and health care visits for early onset Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, Dr. Xu and colleagues analyzed commercial claims data from 2012-2018. They identified more than 71,000 patients aged 40-64 years with those conditions and focused on health care use by 7,311 patients in urban areas and 1,119 in rural areas within 90 days of a new dementia diagnosis.

The proportion who received neuropsychological testing was 19% among urban patients and 16% among rural patients. Psychological assessments, which are less specialized and detailed than neuropsychological testing, and brain imaging occurred at similar rates in both groups. Similar proportions of rural and urban patients visited neurologists (17.7% and 17.96%, respectively) and psychiatrists (6.02% and 6.47%).

But more urban patients than rural patients visited a psychologist, at 19% versus 15%, according to the researchers.

Approximately 18% of patients in rural areas saw a primary care provider without visiting other specialists, compared with 13% in urban areas.

The researchers found that rural patients were significantly less likely to undergo neuropsychological testing (odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.98) or see a psychologist (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60-0.85).

Similarly, rural patients had significantly higher odds of having only primary care providers involved in the diagnosis of dementia and symptom management (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.19-1.66).

Addressing workforce deficiencies

More primary care training in dementia care and collaboration with specialist colleagues could help address differences in care, Dr. Xu’s group writes. Such efforts are already underway.

In 2018, the Alzheimer’s Association launched telementoring programs focused on dementia care using the Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model. Researchers originally developed Project ECHO at the University of New Mexico in 2003 to teach primary care clinicians in remote settings how to treat patients infected with the hepatitis C virus.

With the Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care ECHO Program for Clinicians, primary care clinicians can participate in interactive case-based video conferencing sessions to better understand dementia and how to provide high-quality care in community settings, according to the association.

The program covers guidelines for diagnosis, disclosure, and follow-up; the initiation of care planning; managing disease-related challenges; and resources for patients and caregivers.

Since 2018, nearly 100 primary care practices in the United States have completed training in dementia care using Project ECHO, said Morgan Daven, vice president of health systems for the Alzheimer’s Association. Many cases featured in the program are challenging, he added.

“With primary care being on the front lines, it is really important that primary care physicians are equipped to do what they can to detect or diagnose and know when to refer,” Mr. Daven said.

The association has compiled other resources for clinicians as well.

A 2020 report from the association examined the role that primary care physicians play in dementia care. One survey found that 82% of primary care physicians consider themselves on the front lines of providing care for patients with dementia.

Meanwhile, about half say medical professionals are not prepared to meet rising demands associated with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia care.