User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Dramatic Increase in College Student Suicide Rates

TOPLINE:

, a new study by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators analyzed deaths between 2002 and 2022, using Poisson regression models to assess changes in incidence rates over time.

- Data were drawn from the NCAA death database, which includes death from any cause, and included demographic characteristics such as age and race and sporting discipline.

- They utilized linear and quadratic fits between year and suicide incidence for men and women.

- Given the low incidence of suicide deaths per year, the incidence rate was multiplied by 100,000 to calculate the incidence per 100,000 athlete-years (AYs).

TAKEAWAY:

- Of 1102 total deaths, 11.6% were due to suicide (98 men, 30 women).

- Athletes who died by suicide ranged in age from 17 to 24 years (mean, 20 years) were predominantly men (77%) and White (59%), with the highest suicide incidence rate among male cross-country athletes (1:29 per 815 AYs).

- The overall incidence of suicide was 1:71 per 145 AYs.

- Over the last 10 years, suicide was the second most common cause of death after accidents, with the proportion of deaths by suicide doubling from the first to the second decades (7.6% to 15.3%).

- Among men, the suicide incidence rate increased in a linear fashion (5-year incidence rate ratio, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.14-1.53), while among women, a quadratic association was identified (P = .002), with the incidence rate reaching its lowest point in women from 2010 to 2011 and increasing thereafter.

IN PRACTICE:

“Athletes are generally thought of as one of the healthiest populations in our society, yet the pressures of school, internal and external performance expectations, time demands, injury, athletic identity, and physical fatigue can lead to depression, mental health problems, and suicide,” the authors wrote. “Although the rate of suicide among collegiate athletes remains lower than the general population, it is important to recognize the parallel increase to ensure this population is not overlooked when assessing for risk factors and implementing prevention strategies.”

SOURCE:

Bridget M. Whelan, MPH, research scientist in the Department of Family Medicine, Sports Medicine Section, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, was the lead and corresponding author on the study, which was published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

There is no mandatory reporting system for athlete deaths in the United States, and investigators’ search identified 16 deaths with unknown causes, suggesting reported suicide incidence rates may be underestimated. Additionally, in cases of overdose that were not clearly intentional, the death was listed as “overdose,” possibly resulting in underreporting of suicide.

DISCLOSURES:

No source of study funding was listed. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, a new study by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators analyzed deaths between 2002 and 2022, using Poisson regression models to assess changes in incidence rates over time.

- Data were drawn from the NCAA death database, which includes death from any cause, and included demographic characteristics such as age and race and sporting discipline.

- They utilized linear and quadratic fits between year and suicide incidence for men and women.

- Given the low incidence of suicide deaths per year, the incidence rate was multiplied by 100,000 to calculate the incidence per 100,000 athlete-years (AYs).

TAKEAWAY:

- Of 1102 total deaths, 11.6% were due to suicide (98 men, 30 women).

- Athletes who died by suicide ranged in age from 17 to 24 years (mean, 20 years) were predominantly men (77%) and White (59%), with the highest suicide incidence rate among male cross-country athletes (1:29 per 815 AYs).

- The overall incidence of suicide was 1:71 per 145 AYs.

- Over the last 10 years, suicide was the second most common cause of death after accidents, with the proportion of deaths by suicide doubling from the first to the second decades (7.6% to 15.3%).

- Among men, the suicide incidence rate increased in a linear fashion (5-year incidence rate ratio, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.14-1.53), while among women, a quadratic association was identified (P = .002), with the incidence rate reaching its lowest point in women from 2010 to 2011 and increasing thereafter.

IN PRACTICE:

“Athletes are generally thought of as one of the healthiest populations in our society, yet the pressures of school, internal and external performance expectations, time demands, injury, athletic identity, and physical fatigue can lead to depression, mental health problems, and suicide,” the authors wrote. “Although the rate of suicide among collegiate athletes remains lower than the general population, it is important to recognize the parallel increase to ensure this population is not overlooked when assessing for risk factors and implementing prevention strategies.”

SOURCE:

Bridget M. Whelan, MPH, research scientist in the Department of Family Medicine, Sports Medicine Section, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, was the lead and corresponding author on the study, which was published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

There is no mandatory reporting system for athlete deaths in the United States, and investigators’ search identified 16 deaths with unknown causes, suggesting reported suicide incidence rates may be underestimated. Additionally, in cases of overdose that were not clearly intentional, the death was listed as “overdose,” possibly resulting in underreporting of suicide.

DISCLOSURES:

No source of study funding was listed. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, a new study by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) found.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators analyzed deaths between 2002 and 2022, using Poisson regression models to assess changes in incidence rates over time.

- Data were drawn from the NCAA death database, which includes death from any cause, and included demographic characteristics such as age and race and sporting discipline.

- They utilized linear and quadratic fits between year and suicide incidence for men and women.

- Given the low incidence of suicide deaths per year, the incidence rate was multiplied by 100,000 to calculate the incidence per 100,000 athlete-years (AYs).

TAKEAWAY:

- Of 1102 total deaths, 11.6% were due to suicide (98 men, 30 women).

- Athletes who died by suicide ranged in age from 17 to 24 years (mean, 20 years) were predominantly men (77%) and White (59%), with the highest suicide incidence rate among male cross-country athletes (1:29 per 815 AYs).

- The overall incidence of suicide was 1:71 per 145 AYs.

- Over the last 10 years, suicide was the second most common cause of death after accidents, with the proportion of deaths by suicide doubling from the first to the second decades (7.6% to 15.3%).

- Among men, the suicide incidence rate increased in a linear fashion (5-year incidence rate ratio, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.14-1.53), while among women, a quadratic association was identified (P = .002), with the incidence rate reaching its lowest point in women from 2010 to 2011 and increasing thereafter.

IN PRACTICE:

“Athletes are generally thought of as one of the healthiest populations in our society, yet the pressures of school, internal and external performance expectations, time demands, injury, athletic identity, and physical fatigue can lead to depression, mental health problems, and suicide,” the authors wrote. “Although the rate of suicide among collegiate athletes remains lower than the general population, it is important to recognize the parallel increase to ensure this population is not overlooked when assessing for risk factors and implementing prevention strategies.”

SOURCE:

Bridget M. Whelan, MPH, research scientist in the Department of Family Medicine, Sports Medicine Section, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, was the lead and corresponding author on the study, which was published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

There is no mandatory reporting system for athlete deaths in the United States, and investigators’ search identified 16 deaths with unknown causes, suggesting reported suicide incidence rates may be underestimated. Additionally, in cases of overdose that were not clearly intentional, the death was listed as “overdose,” possibly resulting in underreporting of suicide.

DISCLOSURES:

No source of study funding was listed. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Girls Catching Up With Boys in Substance Use

, warned the authors of a new report detailing trends across several regions between 2018 and 2022. The latest 4-yearly Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study, in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe, concluded that substance use remains “a crucial public health problem among adolescents” despite overall declines in smoking, alcohol, and cannabis use.

The new report: A focus on adolescent substance use in Europe, central Asia, and Canada, detailed substance use among adolescents aged 11, 13, and 15 years across 44 countries and regions in Europe, Central Asia, and Canada in the 2021-2022 school-based survey.

Principal findings included:

- Cigarette smoking: Lifetime smoking declined between 2018 and 2022, particularly among 13-year-old boys and 15-year-old boys and girls. There was also a small but significant decrease in current smoking among 15-year-old boys.

- Alcohol use: Lifetime use decreased overall in boys between 2018 and 2022, particularly among 15-year-olds. An increase was observed among 11- and 13-year-old girls but not 15-year-old girls. There was a small but significant decrease in the proportion of current drinkers among 15-year-old boys, with no change among 11- and 13-year-old boys. Current alcohol use increased among girls in all age groups.

- Cannabis use: Lifetime use among 15-year-olds decreased slightly from 14% to 12% between 2018 and 2022, while 6% of 15-year-olds reported having used cannabis in the previous 30 days.

- Vaping: In 2022 vapes (e-cigarettes) were more popular among adolescents than conventional tobacco cigarettes.

Traditional Gender Gap Narrowing or Reversing

Report coauthor Judith Brown from the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, and a project manager for the Scottish survey, said that “there was an overall increase in current alcohol use and drunkenness among older girls” despite the overall decrease in boys’ alcohol use.

She explained: “Substance use has traditionally been more prevalent among boys, and the survey findings confirm a well-established gender difference, with higher prevalence in boys than in girls among 11-year-olds. By the age of 13, however, gender differences diminish or even disappear in many countries and regions.”

“Among 15-year-olds, girls often reported more frequent substance use than boys. While this pattern has been known for cigarette smoking in many countries and regions for about two decades, especially among 15-year-olds, it is a new phenomenon for behaviors related to other substances (such as alcohol consumption and drunkenness) in most countries and regions. Historically, prevalence for these behaviors has been higher among boys than girls.”

The new survey results highlight this gender reversal for several substances, she said. “Cannabis is the only substance for which both lifetime and current use is consistently higher in boys.”

Vaping Is an Emerging Public Health Concern

Dr. Brown added that the 2022 survey was the first time that vaping data had been collected from all countries. Although this is against the background of continuing decreases in smoking rates, “researchers suggest the transition to e-cigarettes, as a more popular choice than conventional cigarettes, highlights an urgent need for more targeted interventions to address this emerging public health concern.”

The report authors commented that because young people’s brains are still developing, they are “very sensitive to substances such as nicotine,” making it “easier for them to get hooked.”

Margreet de Looze, PhD, assistant professor of interdisciplinary social science at Utrecht University in Utrecht, the Netherlands, agreed with the authors’ concerns. “Vaping is extremely attractive for young people,” she said, “because the taste is more attractive than that of traditional cigarettes.” Until recently, many people were not aware of health hazards attached to vaping. “While more research is needed, vaping may function as a first step toward tobacco use and is hazardous for young people’s health. Therefore, it should be strongly discouraged.”

Substance Use Trends May Be Stabilizing or Rising Again

Increased awareness of the harmful effects of alcohol for adolescent development is also one postulated reason for declining adolescent alcohol consumption in both Europe and North America over the past two decades, which Dr. de Looze’s research has explored. Her work has also noted the “growing trend” of young people abstaining from alcohol altogether and some evidence of reductions in adolescent risk behaviors more generally, including early sexual initiation and juvenile crime.

“It may be good to realize that, in fact, the current generation of youth in many respects is healthier and reports less risky health behaviors as compared to previous generations,” she said.

However, “The declining trend in adolescent substance use that took place in many countries since the beginning of the 21st century seems to have stabilized, and moreover, in some countries and subgroups of adolescents, substance use appears to be on the rise again.” She cited particularly an overall increase in current alcohol use and drunkenness among older girls between 2018 and 2022. “It appears that, especially for girls, recent trends over time are less favorable as compared with boys.”

Multiple Influences on Adolescent Substance Abuse

Peer group influences are known to come to the fore during adolescence, and Dr. de Looze added that the early 21st century saw marked reductions in adolescent face-to-face contacts with their peers due to the rise in digital communications. “Adolescents typically use substances in the presence of peers (and in the absence of adults/parents), as it increases their status in their peer group.” Reduced in person interactions with friends may therefore have contributed to the earlier decline in substance use.

However, her team had found that adolescents who spend much time online with friends often also spend much time with friends offline. “They are what you could call the ‘social’ youth, who just spend much time with peers, be it offline or online,” she said. “More research is needed to disentangle exactly how, what kind, for whom the digital environment may be related to young people’s substance use,” she said.

“We also see that young people actively select their friends. So, if you are curious and a bit of a sensation-seeker yourself, you are more likely to become friends with youth who are just like you, and together, you may be more likely to try out substances.”

Factors underlying adolescent substance use and differences between countries are influenced by a complex interplay of factors, said Carina Ferreira-Borges, PhD, regional adviser for alcohol, illicit drugs, and prison health at the WHO Regional Office for Europe.

“Prevention measures definitely play a critical role in reducing substance use,” she said, “but other factors, such as cultural norms and socioeconomic conditions, also significantly impact these patterns.”

“Variations in substance use among countries can be attributed to different levels of implemented polices, public health initiatives, and the extent to which substance use is normalized or stigmatized within each society.”

Policy Efforts Must Be Targeted

“To address these disparities effectively, interventions and population-level policies need to be culturally adapted and target the specific environments where substance use is normalized among adolescents. By understanding and modifying the broader context in which young people make choices about substance use, we can better influence their behavior and health outcomes.”

Dr. de Looze cautioned, “In the past two decades, public health efforts in many countries have focused on reducing young people’s engagement in substance use. It is important that these efforts continue, as every year a new generation of youth is born. If public health efforts do not continue to focus on supporting a healthy lifestyle among young people, it should not come as a surprise that rates start or continue to rise again.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, warned the authors of a new report detailing trends across several regions between 2018 and 2022. The latest 4-yearly Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study, in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe, concluded that substance use remains “a crucial public health problem among adolescents” despite overall declines in smoking, alcohol, and cannabis use.

The new report: A focus on adolescent substance use in Europe, central Asia, and Canada, detailed substance use among adolescents aged 11, 13, and 15 years across 44 countries and regions in Europe, Central Asia, and Canada in the 2021-2022 school-based survey.

Principal findings included:

- Cigarette smoking: Lifetime smoking declined between 2018 and 2022, particularly among 13-year-old boys and 15-year-old boys and girls. There was also a small but significant decrease in current smoking among 15-year-old boys.

- Alcohol use: Lifetime use decreased overall in boys between 2018 and 2022, particularly among 15-year-olds. An increase was observed among 11- and 13-year-old girls but not 15-year-old girls. There was a small but significant decrease in the proportion of current drinkers among 15-year-old boys, with no change among 11- and 13-year-old boys. Current alcohol use increased among girls in all age groups.

- Cannabis use: Lifetime use among 15-year-olds decreased slightly from 14% to 12% between 2018 and 2022, while 6% of 15-year-olds reported having used cannabis in the previous 30 days.

- Vaping: In 2022 vapes (e-cigarettes) were more popular among adolescents than conventional tobacco cigarettes.

Traditional Gender Gap Narrowing or Reversing

Report coauthor Judith Brown from the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, and a project manager for the Scottish survey, said that “there was an overall increase in current alcohol use and drunkenness among older girls” despite the overall decrease in boys’ alcohol use.

She explained: “Substance use has traditionally been more prevalent among boys, and the survey findings confirm a well-established gender difference, with higher prevalence in boys than in girls among 11-year-olds. By the age of 13, however, gender differences diminish or even disappear in many countries and regions.”

“Among 15-year-olds, girls often reported more frequent substance use than boys. While this pattern has been known for cigarette smoking in many countries and regions for about two decades, especially among 15-year-olds, it is a new phenomenon for behaviors related to other substances (such as alcohol consumption and drunkenness) in most countries and regions. Historically, prevalence for these behaviors has been higher among boys than girls.”

The new survey results highlight this gender reversal for several substances, she said. “Cannabis is the only substance for which both lifetime and current use is consistently higher in boys.”

Vaping Is an Emerging Public Health Concern

Dr. Brown added that the 2022 survey was the first time that vaping data had been collected from all countries. Although this is against the background of continuing decreases in smoking rates, “researchers suggest the transition to e-cigarettes, as a more popular choice than conventional cigarettes, highlights an urgent need for more targeted interventions to address this emerging public health concern.”

The report authors commented that because young people’s brains are still developing, they are “very sensitive to substances such as nicotine,” making it “easier for them to get hooked.”

Margreet de Looze, PhD, assistant professor of interdisciplinary social science at Utrecht University in Utrecht, the Netherlands, agreed with the authors’ concerns. “Vaping is extremely attractive for young people,” she said, “because the taste is more attractive than that of traditional cigarettes.” Until recently, many people were not aware of health hazards attached to vaping. “While more research is needed, vaping may function as a first step toward tobacco use and is hazardous for young people’s health. Therefore, it should be strongly discouraged.”

Substance Use Trends May Be Stabilizing or Rising Again

Increased awareness of the harmful effects of alcohol for adolescent development is also one postulated reason for declining adolescent alcohol consumption in both Europe and North America over the past two decades, which Dr. de Looze’s research has explored. Her work has also noted the “growing trend” of young people abstaining from alcohol altogether and some evidence of reductions in adolescent risk behaviors more generally, including early sexual initiation and juvenile crime.

“It may be good to realize that, in fact, the current generation of youth in many respects is healthier and reports less risky health behaviors as compared to previous generations,” she said.

However, “The declining trend in adolescent substance use that took place in many countries since the beginning of the 21st century seems to have stabilized, and moreover, in some countries and subgroups of adolescents, substance use appears to be on the rise again.” She cited particularly an overall increase in current alcohol use and drunkenness among older girls between 2018 and 2022. “It appears that, especially for girls, recent trends over time are less favorable as compared with boys.”

Multiple Influences on Adolescent Substance Abuse

Peer group influences are known to come to the fore during adolescence, and Dr. de Looze added that the early 21st century saw marked reductions in adolescent face-to-face contacts with their peers due to the rise in digital communications. “Adolescents typically use substances in the presence of peers (and in the absence of adults/parents), as it increases their status in their peer group.” Reduced in person interactions with friends may therefore have contributed to the earlier decline in substance use.

However, her team had found that adolescents who spend much time online with friends often also spend much time with friends offline. “They are what you could call the ‘social’ youth, who just spend much time with peers, be it offline or online,” she said. “More research is needed to disentangle exactly how, what kind, for whom the digital environment may be related to young people’s substance use,” she said.

“We also see that young people actively select their friends. So, if you are curious and a bit of a sensation-seeker yourself, you are more likely to become friends with youth who are just like you, and together, you may be more likely to try out substances.”

Factors underlying adolescent substance use and differences between countries are influenced by a complex interplay of factors, said Carina Ferreira-Borges, PhD, regional adviser for alcohol, illicit drugs, and prison health at the WHO Regional Office for Europe.

“Prevention measures definitely play a critical role in reducing substance use,” she said, “but other factors, such as cultural norms and socioeconomic conditions, also significantly impact these patterns.”

“Variations in substance use among countries can be attributed to different levels of implemented polices, public health initiatives, and the extent to which substance use is normalized or stigmatized within each society.”

Policy Efforts Must Be Targeted

“To address these disparities effectively, interventions and population-level policies need to be culturally adapted and target the specific environments where substance use is normalized among adolescents. By understanding and modifying the broader context in which young people make choices about substance use, we can better influence their behavior and health outcomes.”

Dr. de Looze cautioned, “In the past two decades, public health efforts in many countries have focused on reducing young people’s engagement in substance use. It is important that these efforts continue, as every year a new generation of youth is born. If public health efforts do not continue to focus on supporting a healthy lifestyle among young people, it should not come as a surprise that rates start or continue to rise again.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, warned the authors of a new report detailing trends across several regions between 2018 and 2022. The latest 4-yearly Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study, in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe, concluded that substance use remains “a crucial public health problem among adolescents” despite overall declines in smoking, alcohol, and cannabis use.

The new report: A focus on adolescent substance use in Europe, central Asia, and Canada, detailed substance use among adolescents aged 11, 13, and 15 years across 44 countries and regions in Europe, Central Asia, and Canada in the 2021-2022 school-based survey.

Principal findings included:

- Cigarette smoking: Lifetime smoking declined between 2018 and 2022, particularly among 13-year-old boys and 15-year-old boys and girls. There was also a small but significant decrease in current smoking among 15-year-old boys.

- Alcohol use: Lifetime use decreased overall in boys between 2018 and 2022, particularly among 15-year-olds. An increase was observed among 11- and 13-year-old girls but not 15-year-old girls. There was a small but significant decrease in the proportion of current drinkers among 15-year-old boys, with no change among 11- and 13-year-old boys. Current alcohol use increased among girls in all age groups.

- Cannabis use: Lifetime use among 15-year-olds decreased slightly from 14% to 12% between 2018 and 2022, while 6% of 15-year-olds reported having used cannabis in the previous 30 days.

- Vaping: In 2022 vapes (e-cigarettes) were more popular among adolescents than conventional tobacco cigarettes.

Traditional Gender Gap Narrowing or Reversing

Report coauthor Judith Brown from the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, and a project manager for the Scottish survey, said that “there was an overall increase in current alcohol use and drunkenness among older girls” despite the overall decrease in boys’ alcohol use.

She explained: “Substance use has traditionally been more prevalent among boys, and the survey findings confirm a well-established gender difference, with higher prevalence in boys than in girls among 11-year-olds. By the age of 13, however, gender differences diminish or even disappear in many countries and regions.”

“Among 15-year-olds, girls often reported more frequent substance use than boys. While this pattern has been known for cigarette smoking in many countries and regions for about two decades, especially among 15-year-olds, it is a new phenomenon for behaviors related to other substances (such as alcohol consumption and drunkenness) in most countries and regions. Historically, prevalence for these behaviors has been higher among boys than girls.”

The new survey results highlight this gender reversal for several substances, she said. “Cannabis is the only substance for which both lifetime and current use is consistently higher in boys.”

Vaping Is an Emerging Public Health Concern

Dr. Brown added that the 2022 survey was the first time that vaping data had been collected from all countries. Although this is against the background of continuing decreases in smoking rates, “researchers suggest the transition to e-cigarettes, as a more popular choice than conventional cigarettes, highlights an urgent need for more targeted interventions to address this emerging public health concern.”

The report authors commented that because young people’s brains are still developing, they are “very sensitive to substances such as nicotine,” making it “easier for them to get hooked.”

Margreet de Looze, PhD, assistant professor of interdisciplinary social science at Utrecht University in Utrecht, the Netherlands, agreed with the authors’ concerns. “Vaping is extremely attractive for young people,” she said, “because the taste is more attractive than that of traditional cigarettes.” Until recently, many people were not aware of health hazards attached to vaping. “While more research is needed, vaping may function as a first step toward tobacco use and is hazardous for young people’s health. Therefore, it should be strongly discouraged.”

Substance Use Trends May Be Stabilizing or Rising Again

Increased awareness of the harmful effects of alcohol for adolescent development is also one postulated reason for declining adolescent alcohol consumption in both Europe and North America over the past two decades, which Dr. de Looze’s research has explored. Her work has also noted the “growing trend” of young people abstaining from alcohol altogether and some evidence of reductions in adolescent risk behaviors more generally, including early sexual initiation and juvenile crime.

“It may be good to realize that, in fact, the current generation of youth in many respects is healthier and reports less risky health behaviors as compared to previous generations,” she said.

However, “The declining trend in adolescent substance use that took place in many countries since the beginning of the 21st century seems to have stabilized, and moreover, in some countries and subgroups of adolescents, substance use appears to be on the rise again.” She cited particularly an overall increase in current alcohol use and drunkenness among older girls between 2018 and 2022. “It appears that, especially for girls, recent trends over time are less favorable as compared with boys.”

Multiple Influences on Adolescent Substance Abuse

Peer group influences are known to come to the fore during adolescence, and Dr. de Looze added that the early 21st century saw marked reductions in adolescent face-to-face contacts with their peers due to the rise in digital communications. “Adolescents typically use substances in the presence of peers (and in the absence of adults/parents), as it increases their status in their peer group.” Reduced in person interactions with friends may therefore have contributed to the earlier decline in substance use.

However, her team had found that adolescents who spend much time online with friends often also spend much time with friends offline. “They are what you could call the ‘social’ youth, who just spend much time with peers, be it offline or online,” she said. “More research is needed to disentangle exactly how, what kind, for whom the digital environment may be related to young people’s substance use,” she said.

“We also see that young people actively select their friends. So, if you are curious and a bit of a sensation-seeker yourself, you are more likely to become friends with youth who are just like you, and together, you may be more likely to try out substances.”

Factors underlying adolescent substance use and differences between countries are influenced by a complex interplay of factors, said Carina Ferreira-Borges, PhD, regional adviser for alcohol, illicit drugs, and prison health at the WHO Regional Office for Europe.

“Prevention measures definitely play a critical role in reducing substance use,” she said, “but other factors, such as cultural norms and socioeconomic conditions, also significantly impact these patterns.”

“Variations in substance use among countries can be attributed to different levels of implemented polices, public health initiatives, and the extent to which substance use is normalized or stigmatized within each society.”

Policy Efforts Must Be Targeted

“To address these disparities effectively, interventions and population-level policies need to be culturally adapted and target the specific environments where substance use is normalized among adolescents. By understanding and modifying the broader context in which young people make choices about substance use, we can better influence their behavior and health outcomes.”

Dr. de Looze cautioned, “In the past two decades, public health efforts in many countries have focused on reducing young people’s engagement in substance use. It is important that these efforts continue, as every year a new generation of youth is born. If public health efforts do not continue to focus on supporting a healthy lifestyle among young people, it should not come as a surprise that rates start or continue to rise again.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Antidepressants and Dementia Risk: Reassuring Data

TOPLINE:

, new research suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators studied 5511 individuals (58% women; mean age, 71 years) from the Rotterdam study, an ongoing prospective population-based cohort study.

- Participants were free from dementia at baseline, and incident dementia was monitored from baseline until 2018 with repeated cognitive assessments using the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) and the Geriatric Mental Schedule, as well as MRIs.

- Information on participants’ antidepressant use was extracted from pharmacy records from 1992 until baseline (2002-2008).

- During a mean follow-up of 10 years, 12% of participants developed dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 17% of participants had used antidepressants during the roughly 10-year period prior to baseline, and 4.1% were still using antidepressants at baseline.

- Medication use at baseline was more common in women than in men (21% vs 18%), and use increased with age: From 2.1% in participants aged between 45 and 50 years to 4.5% in those older than 80 years.

- After adjustment for confounders, there was no association between antidepressant use and dementia risk (hazard ratio [HR], 1.14; 95% CI, 0.92-1.41), accelerated cognitive decline, or atrophy of white and gray matter.

- However, tricyclic antidepressant use was associated with increased dementia risk (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.01-1.83) compared with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.81-1.54).

IN PRACTICE:

“Although prescription of antidepressant medication in older individuals, in particular those with some cognitive impairment, may have acute symptomatic anticholinergic effects that warrant consideration in clinical practice, our results show that long-term antidepressant use does not have lasting effects on cognition or brain health in older adults without indication of cognitive impairment,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Frank J. Wolters, MD, of the Department of Epidemiology and the Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine and Alzheimer Center, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, was the senior author on this study that was published online in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included the concern that although exclusion of participants with MMSE < 26 at baseline prevented reversed causation (ie, antidepressant use in response to depression during the prodromal phase of dementia), it may have introduced selection bias by disregarding the effects of antidepressant use prior to baseline and excluding participants with lower education.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was conducted as part of the Netherlands Consortium of Dementia Cohorts, which receives funding in the context of Deltaplan Dementie from ZonMW Memorabel and Alzheimer Nederland. Further funding was also obtained from the Stichting Erasmus Trustfonds. This study was further supported by a 2020 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest or relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, new research suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators studied 5511 individuals (58% women; mean age, 71 years) from the Rotterdam study, an ongoing prospective population-based cohort study.

- Participants were free from dementia at baseline, and incident dementia was monitored from baseline until 2018 with repeated cognitive assessments using the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) and the Geriatric Mental Schedule, as well as MRIs.

- Information on participants’ antidepressant use was extracted from pharmacy records from 1992 until baseline (2002-2008).

- During a mean follow-up of 10 years, 12% of participants developed dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 17% of participants had used antidepressants during the roughly 10-year period prior to baseline, and 4.1% were still using antidepressants at baseline.

- Medication use at baseline was more common in women than in men (21% vs 18%), and use increased with age: From 2.1% in participants aged between 45 and 50 years to 4.5% in those older than 80 years.

- After adjustment for confounders, there was no association between antidepressant use and dementia risk (hazard ratio [HR], 1.14; 95% CI, 0.92-1.41), accelerated cognitive decline, or atrophy of white and gray matter.

- However, tricyclic antidepressant use was associated with increased dementia risk (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.01-1.83) compared with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.81-1.54).

IN PRACTICE:

“Although prescription of antidepressant medication in older individuals, in particular those with some cognitive impairment, may have acute symptomatic anticholinergic effects that warrant consideration in clinical practice, our results show that long-term antidepressant use does not have lasting effects on cognition or brain health in older adults without indication of cognitive impairment,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Frank J. Wolters, MD, of the Department of Epidemiology and the Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine and Alzheimer Center, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, was the senior author on this study that was published online in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included the concern that although exclusion of participants with MMSE < 26 at baseline prevented reversed causation (ie, antidepressant use in response to depression during the prodromal phase of dementia), it may have introduced selection bias by disregarding the effects of antidepressant use prior to baseline and excluding participants with lower education.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was conducted as part of the Netherlands Consortium of Dementia Cohorts, which receives funding in the context of Deltaplan Dementie from ZonMW Memorabel and Alzheimer Nederland. Further funding was also obtained from the Stichting Erasmus Trustfonds. This study was further supported by a 2020 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest or relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, new research suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators studied 5511 individuals (58% women; mean age, 71 years) from the Rotterdam study, an ongoing prospective population-based cohort study.

- Participants were free from dementia at baseline, and incident dementia was monitored from baseline until 2018 with repeated cognitive assessments using the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) and the Geriatric Mental Schedule, as well as MRIs.

- Information on participants’ antidepressant use was extracted from pharmacy records from 1992 until baseline (2002-2008).

- During a mean follow-up of 10 years, 12% of participants developed dementia.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, 17% of participants had used antidepressants during the roughly 10-year period prior to baseline, and 4.1% were still using antidepressants at baseline.

- Medication use at baseline was more common in women than in men (21% vs 18%), and use increased with age: From 2.1% in participants aged between 45 and 50 years to 4.5% in those older than 80 years.

- After adjustment for confounders, there was no association between antidepressant use and dementia risk (hazard ratio [HR], 1.14; 95% CI, 0.92-1.41), accelerated cognitive decline, or atrophy of white and gray matter.

- However, tricyclic antidepressant use was associated with increased dementia risk (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.01-1.83) compared with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.81-1.54).

IN PRACTICE:

“Although prescription of antidepressant medication in older individuals, in particular those with some cognitive impairment, may have acute symptomatic anticholinergic effects that warrant consideration in clinical practice, our results show that long-term antidepressant use does not have lasting effects on cognition or brain health in older adults without indication of cognitive impairment,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Frank J. Wolters, MD, of the Department of Epidemiology and the Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine and Alzheimer Center, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, was the senior author on this study that was published online in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included the concern that although exclusion of participants with MMSE < 26 at baseline prevented reversed causation (ie, antidepressant use in response to depression during the prodromal phase of dementia), it may have introduced selection bias by disregarding the effects of antidepressant use prior to baseline and excluding participants with lower education.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was conducted as part of the Netherlands Consortium of Dementia Cohorts, which receives funding in the context of Deltaplan Dementie from ZonMW Memorabel and Alzheimer Nederland. Further funding was also obtained from the Stichting Erasmus Trustfonds. This study was further supported by a 2020 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. The authors reported no conflicts of interest or relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Mandatory DMV Reporting Tied to Dementia Underdiagnosis

, new research suggests.

Investigators found that primary care physicians (PCPs) in states with clinician reporting mandates had a 59% higher probability of underdiagnosing dementia compared with their counterparts in states that require patients to self-report or that have no reporting mandates.

“Our findings in this cross-sectional study raise concerns about potential adverse effects of mandatory clinician reporting for dementia diagnosis and underscore the need for careful consideration of the effect of such policies,” wrote the investigators, led by Soeren Mattke, MD, DSc, director of the USC Brain Health Observatory and research professor of economics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Lack of Guidance

As the US population ages, the number of older drivers is increasing, with 55.8 million drivers 65 years old or older. Approximately 7 million people in this age group have dementia — an estimate that is expected to increase to nearly 12 million by 2040.

The aging population raises a “critical policy question” about how to ensure road safety. Although the American Medical Association’s Code of Ethics outlines a physician’s obligation to identify drivers with medical impairments that impede safe driving, guidance restricting cognitively impaired drivers from driving is lacking.

In addition, evidence as to whether cognitive impairment indeed poses a threat to driving safety is mixed and has led to a lack of uniform policies with respect to reporting dementia.

Four states explicitly require clinicians to report dementia diagnoses to the DMV, which will then determine the patient’s fitness to drive, whereas 14 states require people with dementia to self-report. The remaining states have no explicit reporting requirements.

The issue of mandatory reporting is controversial, the researchers noted. On the one hand, physicians could protect patients and others by reporting potentially unsafe drivers.

On the other hand, evidence of an association with lower accident risks in patients with dementia is sparse and mandatory reporting may adversely affect physician-patient relationships. Empirical evidence for unintended consequences of reporting laws is lacking.

To examine the potential link between dementia underdiagnosis and mandatory reporting policies, the investigators analyzed the 100% data from the Medicare fee-for-service program and Medicare Advantage plans from 2017 to 2019, which included 223,036 PCPs with a panel of 25 or more Medicare patients.

The researchers examined dementia diagnosis rates in the patient panel of PCPs, rather than neurologists or gerontologists, regardless of who documented the diagnosis. Dr. Mattke said that it is possible that the diagnosis was established after referral to a specialist.

Each physician’s expected number of dementia cases was estimated using a predictive model based on patient characteristics. The researchers then compared the estimate with observed dementia diagnoses, thereby identifying clinicians who underdiagnosed dementia after sampling errors were accounted for.

‘Heavy-Handed Interference’

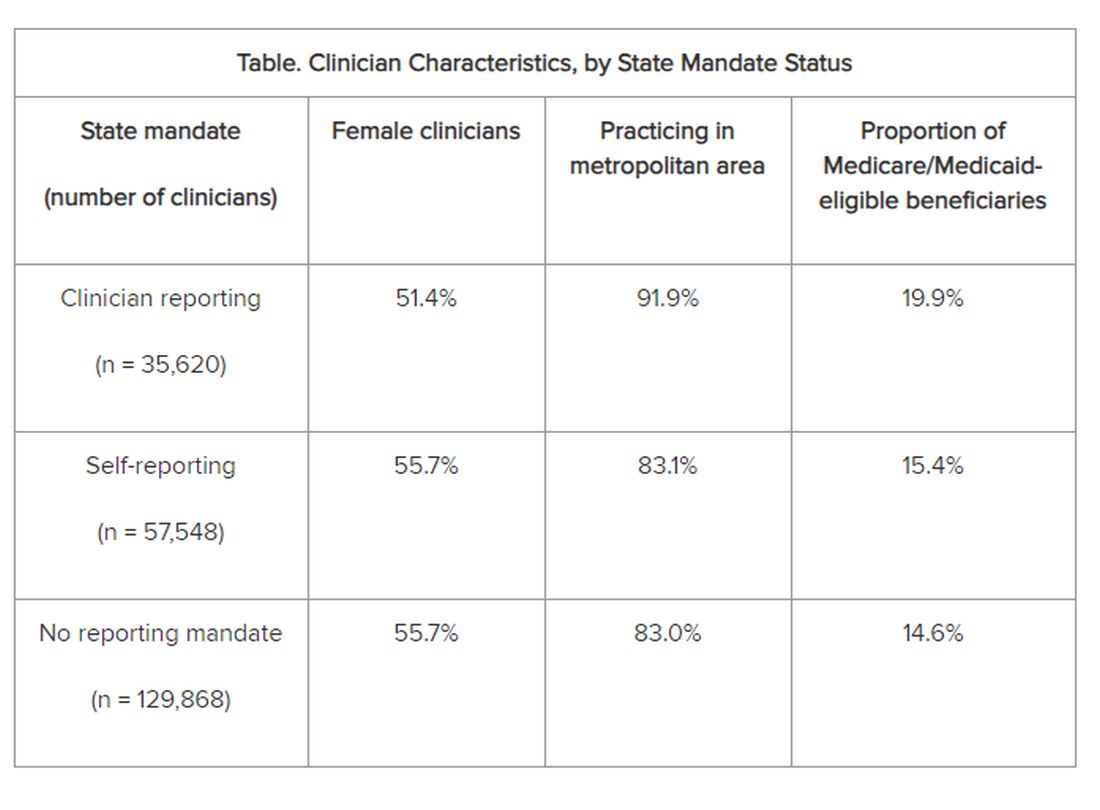

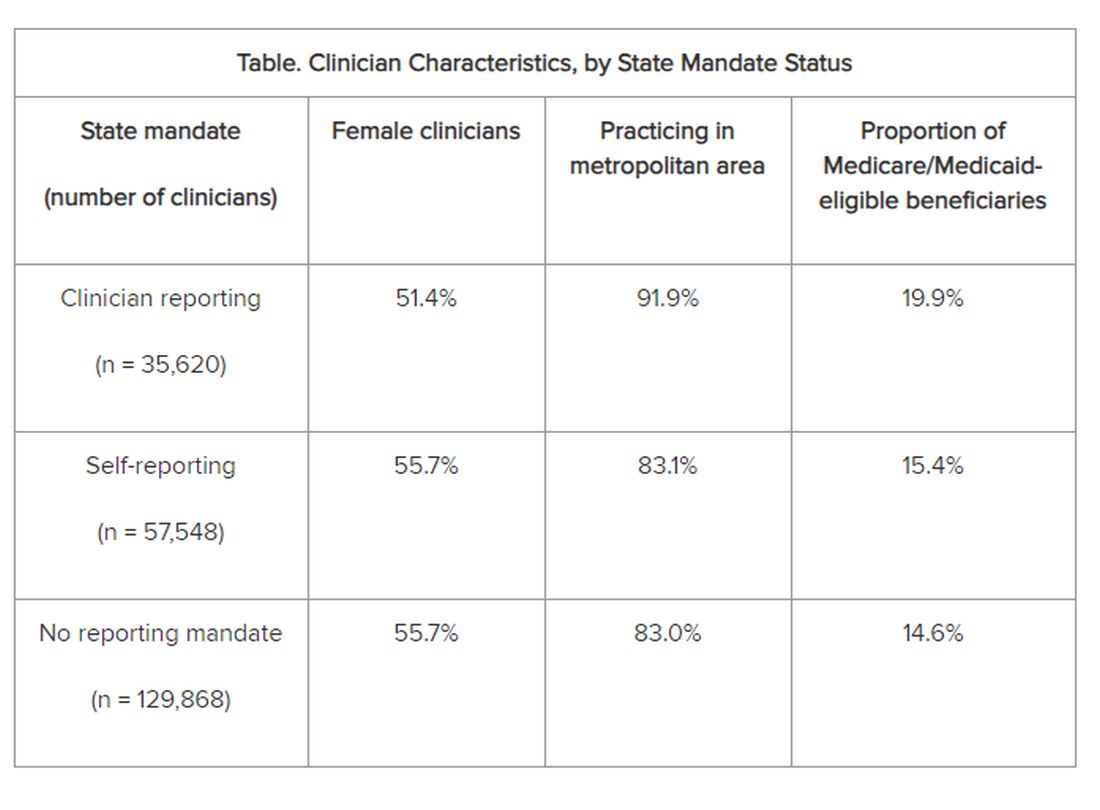

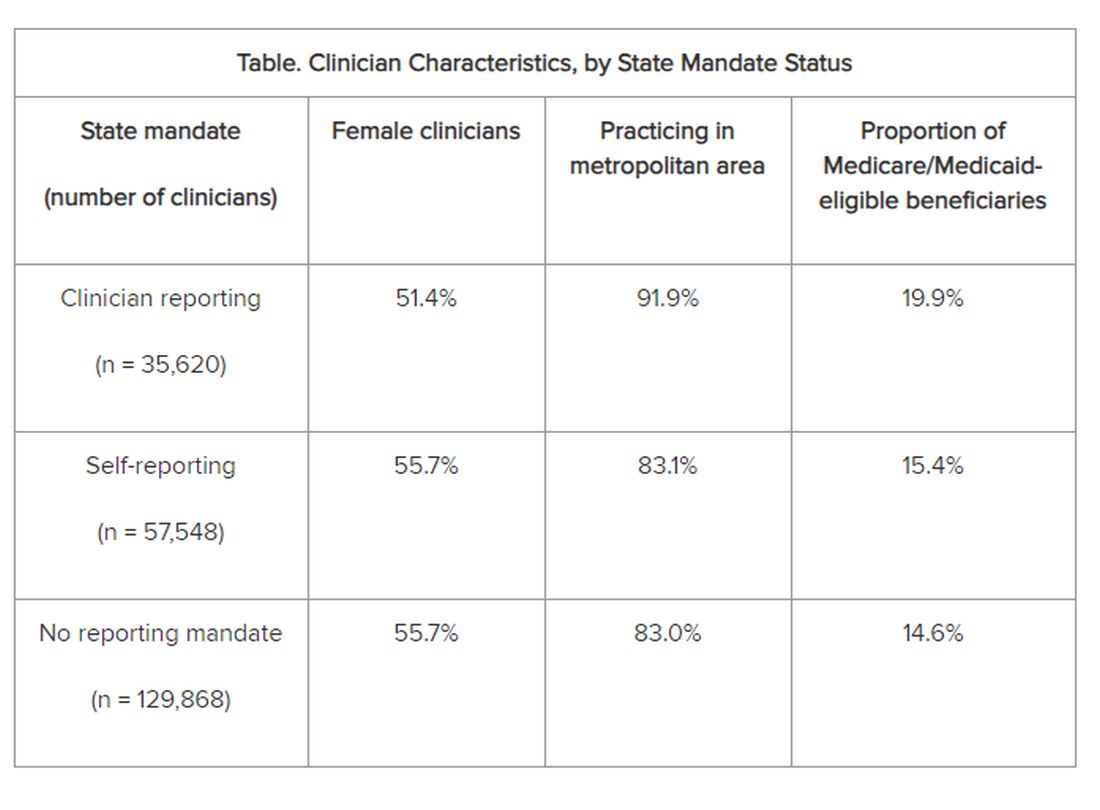

The researchers adjusted for several covariates potentially associated with a clinician’s probability of underdiagnosing dementia. These included sex, office location, practice specialty, racial/ethnic composition of the patient panel, and percentage of patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. The table shows PCP characteristics.

Adjusted results showed that PCPs practicing in states with clinician reporting mandates had a 12.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 10.5%-14.2%) probability of underdiagnosing dementia versus 7.8% (95% CI, 6.9%-8.7%) in states with self-reporting and 7.7% (95% CI, 6.9%-8.4%) in states with no mandates, translating into a 4–percentage point difference (P < .001).

“Our study is the first to provide empirical evidence for the potential adverse effects of reporting policies,” the researchers noted. “Although we found that some clinicians underdiagnosed dementia regardless of state mandates, the key finding of this study reveals that primary care clinicians who practice in states with clinician reporting mandates were 59% more likely to do so…compared with those states with no reporting requirements…or driver self-reporting requirements.”

The investigators suggested that one potential explanation for underdiagnosis is patient resistance to cognitive testing. If patients were aware that the clinician was obligated by law to report their dementia diagnosis to the DMV, “they might be more inclined to conceal their symptoms or refuse further assessments, in addition to the general stigma and resistance to a formal assessment after a positive dementia screening result.”

“The findings suggest that policymakers might want to rethink those physician reporting mandates, since we also could not find conclusive evidence that they improve road safety,” Dr. Mattke said. “Maybe patients and their physicians can arrive at a sensible approach to determine driving fitness without such heavy-handed interference.”

However, he cautioned that the findings are not definitive and further study is needed before firm recommendations either for or against mandatory reporting.

In addition, the researchers noted several study limitations. One is that dementia underdiagnosis may also be associated with factors not captured in their model, including physician-patient relationships, health literacy, or language barriers.

However, Dr. Mattke noted, “ my sense is that those unobservable factors are not systematically related to state reporting policies and having omitted them would therefore not bias our results.”

Experts Weigh In

Commenting on the research, Morgan Daven, MA, the Alzheimer’s Association vice president of health systems, said that dementia is widely and significantly underdiagnosed, and not only in the states with dementia reporting mandates. Many factors may contribute to underdiagnosis, and although the study shows an association between reporting mandates and underdiagnosis, it does not demonstrate causation.

That said, Mr. Daven added, “fear and stigma related to dementia may inhibit the clinician, the patient, and their family from pursuing detection and diagnosis for dementia. As a society, we need to address dementia fear and stigma for all parties.”

He noted that useful tools include healthcare policies, workforce training, public awareness and education, and public policies to mitigate fear and stigma and their negative effects on diagnosis, care, support, and communication.

A potential study limitation is that it relied only on diagnoses by PCPs. Mr. Daven noted that the diagnosis of Alzheimer’ disease — the most common cause of dementia — is confirmation of amyloid buildup via a biomarker test, using PET or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

“Both of these tests are extremely limited in their use and accessibility in a primary care setting. Inclusion of diagnoses by dementia specialists would provide a more complete picture,” he said.

Mr. Daven added that the Alzheimer’s Association encourages families to proactively discuss driving and other disease-related safety concerns as soon as possible. The Alzheimer’s Association Dementia and Driving webpage offers tips and strategies to discuss driving concerns with a family member.

In an accompanying editorial, Donald Redelmeier, MD, MS(HSR), and Vidhi Bhatt, BSc, both of the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, differentiate the mandate for physicians to warn patients with dementia about traffic safety from the mandate for reporting child maltreatment, gunshot victims, or communicable diseases. They noted that mandated warnings “are not easy, can engender patient dissatisfaction, and need to be handled with tact.”

Yet, they pointed out, “breaking bad news is what practicing medicine entails.” They emphasized that, regardless of government mandates, “counseling patients for more road safety is an essential skill for clinicians in diverse states who hope to help their patients avoid becoming more traffic statistics.”

Research reported in this publication was supported by Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, and a grant from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Mattke reported receiving grants from Genentech for a research contract with USC during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Eisai, Biogen, C2N, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, and Roche Genentech; and serving on the Senscio Systems board of directors, ALZpath scientific advisory board, AiCure scientific advisory board, and Boston Millennia Partners scientific advisory board outside the submitted work. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. The editorial was supported by the Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Kimel-Schatzky Traumatic Brain Injury Research Fund, and the Graduate Diploma Program in Health Research at the University of Toronto. The editorial authors report no other relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Investigators found that primary care physicians (PCPs) in states with clinician reporting mandates had a 59% higher probability of underdiagnosing dementia compared with their counterparts in states that require patients to self-report or that have no reporting mandates.

“Our findings in this cross-sectional study raise concerns about potential adverse effects of mandatory clinician reporting for dementia diagnosis and underscore the need for careful consideration of the effect of such policies,” wrote the investigators, led by Soeren Mattke, MD, DSc, director of the USC Brain Health Observatory and research professor of economics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Lack of Guidance

As the US population ages, the number of older drivers is increasing, with 55.8 million drivers 65 years old or older. Approximately 7 million people in this age group have dementia — an estimate that is expected to increase to nearly 12 million by 2040.

The aging population raises a “critical policy question” about how to ensure road safety. Although the American Medical Association’s Code of Ethics outlines a physician’s obligation to identify drivers with medical impairments that impede safe driving, guidance restricting cognitively impaired drivers from driving is lacking.

In addition, evidence as to whether cognitive impairment indeed poses a threat to driving safety is mixed and has led to a lack of uniform policies with respect to reporting dementia.

Four states explicitly require clinicians to report dementia diagnoses to the DMV, which will then determine the patient’s fitness to drive, whereas 14 states require people with dementia to self-report. The remaining states have no explicit reporting requirements.

The issue of mandatory reporting is controversial, the researchers noted. On the one hand, physicians could protect patients and others by reporting potentially unsafe drivers.

On the other hand, evidence of an association with lower accident risks in patients with dementia is sparse and mandatory reporting may adversely affect physician-patient relationships. Empirical evidence for unintended consequences of reporting laws is lacking.

To examine the potential link between dementia underdiagnosis and mandatory reporting policies, the investigators analyzed the 100% data from the Medicare fee-for-service program and Medicare Advantage plans from 2017 to 2019, which included 223,036 PCPs with a panel of 25 or more Medicare patients.

The researchers examined dementia diagnosis rates in the patient panel of PCPs, rather than neurologists or gerontologists, regardless of who documented the diagnosis. Dr. Mattke said that it is possible that the diagnosis was established after referral to a specialist.

Each physician’s expected number of dementia cases was estimated using a predictive model based on patient characteristics. The researchers then compared the estimate with observed dementia diagnoses, thereby identifying clinicians who underdiagnosed dementia after sampling errors were accounted for.

‘Heavy-Handed Interference’

The researchers adjusted for several covariates potentially associated with a clinician’s probability of underdiagnosing dementia. These included sex, office location, practice specialty, racial/ethnic composition of the patient panel, and percentage of patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. The table shows PCP characteristics.

Adjusted results showed that PCPs practicing in states with clinician reporting mandates had a 12.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 10.5%-14.2%) probability of underdiagnosing dementia versus 7.8% (95% CI, 6.9%-8.7%) in states with self-reporting and 7.7% (95% CI, 6.9%-8.4%) in states with no mandates, translating into a 4–percentage point difference (P < .001).

“Our study is the first to provide empirical evidence for the potential adverse effects of reporting policies,” the researchers noted. “Although we found that some clinicians underdiagnosed dementia regardless of state mandates, the key finding of this study reveals that primary care clinicians who practice in states with clinician reporting mandates were 59% more likely to do so…compared with those states with no reporting requirements…or driver self-reporting requirements.”

The investigators suggested that one potential explanation for underdiagnosis is patient resistance to cognitive testing. If patients were aware that the clinician was obligated by law to report their dementia diagnosis to the DMV, “they might be more inclined to conceal their symptoms or refuse further assessments, in addition to the general stigma and resistance to a formal assessment after a positive dementia screening result.”

“The findings suggest that policymakers might want to rethink those physician reporting mandates, since we also could not find conclusive evidence that they improve road safety,” Dr. Mattke said. “Maybe patients and their physicians can arrive at a sensible approach to determine driving fitness without such heavy-handed interference.”

However, he cautioned that the findings are not definitive and further study is needed before firm recommendations either for or against mandatory reporting.

In addition, the researchers noted several study limitations. One is that dementia underdiagnosis may also be associated with factors not captured in their model, including physician-patient relationships, health literacy, or language barriers.

However, Dr. Mattke noted, “ my sense is that those unobservable factors are not systematically related to state reporting policies and having omitted them would therefore not bias our results.”

Experts Weigh In

Commenting on the research, Morgan Daven, MA, the Alzheimer’s Association vice president of health systems, said that dementia is widely and significantly underdiagnosed, and not only in the states with dementia reporting mandates. Many factors may contribute to underdiagnosis, and although the study shows an association between reporting mandates and underdiagnosis, it does not demonstrate causation.

That said, Mr. Daven added, “fear and stigma related to dementia may inhibit the clinician, the patient, and their family from pursuing detection and diagnosis for dementia. As a society, we need to address dementia fear and stigma for all parties.”

He noted that useful tools include healthcare policies, workforce training, public awareness and education, and public policies to mitigate fear and stigma and their negative effects on diagnosis, care, support, and communication.

A potential study limitation is that it relied only on diagnoses by PCPs. Mr. Daven noted that the diagnosis of Alzheimer’ disease — the most common cause of dementia — is confirmation of amyloid buildup via a biomarker test, using PET or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

“Both of these tests are extremely limited in their use and accessibility in a primary care setting. Inclusion of diagnoses by dementia specialists would provide a more complete picture,” he said.

Mr. Daven added that the Alzheimer’s Association encourages families to proactively discuss driving and other disease-related safety concerns as soon as possible. The Alzheimer’s Association Dementia and Driving webpage offers tips and strategies to discuss driving concerns with a family member.

In an accompanying editorial, Donald Redelmeier, MD, MS(HSR), and Vidhi Bhatt, BSc, both of the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, differentiate the mandate for physicians to warn patients with dementia about traffic safety from the mandate for reporting child maltreatment, gunshot victims, or communicable diseases. They noted that mandated warnings “are not easy, can engender patient dissatisfaction, and need to be handled with tact.”

Yet, they pointed out, “breaking bad news is what practicing medicine entails.” They emphasized that, regardless of government mandates, “counseling patients for more road safety is an essential skill for clinicians in diverse states who hope to help their patients avoid becoming more traffic statistics.”

Research reported in this publication was supported by Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, and a grant from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Mattke reported receiving grants from Genentech for a research contract with USC during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Eisai, Biogen, C2N, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, and Roche Genentech; and serving on the Senscio Systems board of directors, ALZpath scientific advisory board, AiCure scientific advisory board, and Boston Millennia Partners scientific advisory board outside the submitted work. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. The editorial was supported by the Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Kimel-Schatzky Traumatic Brain Injury Research Fund, and the Graduate Diploma Program in Health Research at the University of Toronto. The editorial authors report no other relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research suggests.

Investigators found that primary care physicians (PCPs) in states with clinician reporting mandates had a 59% higher probability of underdiagnosing dementia compared with their counterparts in states that require patients to self-report or that have no reporting mandates.

“Our findings in this cross-sectional study raise concerns about potential adverse effects of mandatory clinician reporting for dementia diagnosis and underscore the need for careful consideration of the effect of such policies,” wrote the investigators, led by Soeren Mattke, MD, DSc, director of the USC Brain Health Observatory and research professor of economics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Lack of Guidance

As the US population ages, the number of older drivers is increasing, with 55.8 million drivers 65 years old or older. Approximately 7 million people in this age group have dementia — an estimate that is expected to increase to nearly 12 million by 2040.

The aging population raises a “critical policy question” about how to ensure road safety. Although the American Medical Association’s Code of Ethics outlines a physician’s obligation to identify drivers with medical impairments that impede safe driving, guidance restricting cognitively impaired drivers from driving is lacking.

In addition, evidence as to whether cognitive impairment indeed poses a threat to driving safety is mixed and has led to a lack of uniform policies with respect to reporting dementia.

Four states explicitly require clinicians to report dementia diagnoses to the DMV, which will then determine the patient’s fitness to drive, whereas 14 states require people with dementia to self-report. The remaining states have no explicit reporting requirements.

The issue of mandatory reporting is controversial, the researchers noted. On the one hand, physicians could protect patients and others by reporting potentially unsafe drivers.

On the other hand, evidence of an association with lower accident risks in patients with dementia is sparse and mandatory reporting may adversely affect physician-patient relationships. Empirical evidence for unintended consequences of reporting laws is lacking.

To examine the potential link between dementia underdiagnosis and mandatory reporting policies, the investigators analyzed the 100% data from the Medicare fee-for-service program and Medicare Advantage plans from 2017 to 2019, which included 223,036 PCPs with a panel of 25 or more Medicare patients.

The researchers examined dementia diagnosis rates in the patient panel of PCPs, rather than neurologists or gerontologists, regardless of who documented the diagnosis. Dr. Mattke said that it is possible that the diagnosis was established after referral to a specialist.

Each physician’s expected number of dementia cases was estimated using a predictive model based on patient characteristics. The researchers then compared the estimate with observed dementia diagnoses, thereby identifying clinicians who underdiagnosed dementia after sampling errors were accounted for.

‘Heavy-Handed Interference’

The researchers adjusted for several covariates potentially associated with a clinician’s probability of underdiagnosing dementia. These included sex, office location, practice specialty, racial/ethnic composition of the patient panel, and percentage of patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. The table shows PCP characteristics.

Adjusted results showed that PCPs practicing in states with clinician reporting mandates had a 12.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 10.5%-14.2%) probability of underdiagnosing dementia versus 7.8% (95% CI, 6.9%-8.7%) in states with self-reporting and 7.7% (95% CI, 6.9%-8.4%) in states with no mandates, translating into a 4–percentage point difference (P < .001).

“Our study is the first to provide empirical evidence for the potential adverse effects of reporting policies,” the researchers noted. “Although we found that some clinicians underdiagnosed dementia regardless of state mandates, the key finding of this study reveals that primary care clinicians who practice in states with clinician reporting mandates were 59% more likely to do so…compared with those states with no reporting requirements…or driver self-reporting requirements.”

The investigators suggested that one potential explanation for underdiagnosis is patient resistance to cognitive testing. If patients were aware that the clinician was obligated by law to report their dementia diagnosis to the DMV, “they might be more inclined to conceal their symptoms or refuse further assessments, in addition to the general stigma and resistance to a formal assessment after a positive dementia screening result.”

“The findings suggest that policymakers might want to rethink those physician reporting mandates, since we also could not find conclusive evidence that they improve road safety,” Dr. Mattke said. “Maybe patients and their physicians can arrive at a sensible approach to determine driving fitness without such heavy-handed interference.”

However, he cautioned that the findings are not definitive and further study is needed before firm recommendations either for or against mandatory reporting.

In addition, the researchers noted several study limitations. One is that dementia underdiagnosis may also be associated with factors not captured in their model, including physician-patient relationships, health literacy, or language barriers.

However, Dr. Mattke noted, “ my sense is that those unobservable factors are not systematically related to state reporting policies and having omitted them would therefore not bias our results.”

Experts Weigh In

Commenting on the research, Morgan Daven, MA, the Alzheimer’s Association vice president of health systems, said that dementia is widely and significantly underdiagnosed, and not only in the states with dementia reporting mandates. Many factors may contribute to underdiagnosis, and although the study shows an association between reporting mandates and underdiagnosis, it does not demonstrate causation.

That said, Mr. Daven added, “fear and stigma related to dementia may inhibit the clinician, the patient, and their family from pursuing detection and diagnosis for dementia. As a society, we need to address dementia fear and stigma for all parties.”

He noted that useful tools include healthcare policies, workforce training, public awareness and education, and public policies to mitigate fear and stigma and their negative effects on diagnosis, care, support, and communication.

A potential study limitation is that it relied only on diagnoses by PCPs. Mr. Daven noted that the diagnosis of Alzheimer’ disease — the most common cause of dementia — is confirmation of amyloid buildup via a biomarker test, using PET or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

“Both of these tests are extremely limited in their use and accessibility in a primary care setting. Inclusion of diagnoses by dementia specialists would provide a more complete picture,” he said.

Mr. Daven added that the Alzheimer’s Association encourages families to proactively discuss driving and other disease-related safety concerns as soon as possible. The Alzheimer’s Association Dementia and Driving webpage offers tips and strategies to discuss driving concerns with a family member.

In an accompanying editorial, Donald Redelmeier, MD, MS(HSR), and Vidhi Bhatt, BSc, both of the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, differentiate the mandate for physicians to warn patients with dementia about traffic safety from the mandate for reporting child maltreatment, gunshot victims, or communicable diseases. They noted that mandated warnings “are not easy, can engender patient dissatisfaction, and need to be handled with tact.”

Yet, they pointed out, “breaking bad news is what practicing medicine entails.” They emphasized that, regardless of government mandates, “counseling patients for more road safety is an essential skill for clinicians in diverse states who hope to help their patients avoid becoming more traffic statistics.”

Research reported in this publication was supported by Genentech, a member of the Roche Group, and a grant from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Mattke reported receiving grants from Genentech for a research contract with USC during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Eisai, Biogen, C2N, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, and Roche Genentech; and serving on the Senscio Systems board of directors, ALZpath scientific advisory board, AiCure scientific advisory board, and Boston Millennia Partners scientific advisory board outside the submitted work. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. The editorial was supported by the Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Kimel-Schatzky Traumatic Brain Injury Research Fund, and the Graduate Diploma Program in Health Research at the University of Toronto. The editorial authors report no other relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

From JAMA Network Open

Does ‘Brain Training’ Really Improve Cognition and Forestall Cognitive Decline?

The concept that cognitive health can be preserved or improved is often expressed as “use it or lose it.” Numerous modifiable risk factors are associated with “losing” cognitive abilities with age, and a cognitively active lifestyle may have a protective effect.

But what is a “cognitively active lifestyle” — do crosswords and Sudoku count?

One popular approach is “brain training.” While not a scientific term with an established definition, it “typically refers to tasks or drills that are designed to strengthen specific aspects of one’s cognitive function,” explained Yuko Hara, PhD, director of Aging and Alzheimer’s Prevention at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation.

Manuel Montero-Odasso, MD, PhD, director of the Gait and Brain Lab, Parkwood Institute, London, Ontario, Canada, elaborated: “Cognitive training involves performing a definitive task or set of tasks where you increase attentional demands to improve focus and concentration and memory. You try to execute the new things that you’ve learned and to remember them.”

In a commentary published by this news organization in 2022, neuroscientist Michael Merzenich, PhD, professor emeritus at University of California San Francisco, said that growing a person’s cognitive reserve and actively managing brain health can play an important role in preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s disease. Important components of this include brain training and physical exercise.

Brain Training: Mechanism of Action

Dr. Montero-Odasso, team leader at the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging and team co-leader at the Ontario Neurodegenerative Research Initiative, explained that cognitive training creates new synapses in the brain, thus stimulating neuroplasticity.

“When we try to activate networks mainly in the frontal lobe, the prefrontal cortex, a key mechanism underlying this process is enhancement of the synaptic plasticity at excitatory synapses, which connect neurons into networks; in other words, we generate new synapses, and that’s how we enhance brain health and cognitive abilities.”

The more neural connections, the greater the processing speed of the brain, he continued. “Cognitive training creates an anatomical change in the brain.”

Executive functions, which include attention, inhibition, planning, and multitasking, are regulated predominantly by the prefrontal cortex. Damage in this region of the brain is also implicated in dementia. Alterations in the connectivity of this area are associated with cognitive impairment, independent of other structural pathological aberrations (eg, gray matter atrophy). These patterns may precede structural pathological changes associated with cognitive impairment and dementia.

Neuroplasticity changes have been corroborated through neuroimaging, which has demonstrated that after cognitive training, there is more activation in the prefrontal cortex that correlates with new synapses, Dr. Montero-Odasso said.

Henry Mahncke, PhD, CEO of the brain training company Posit Science/BrainHQ, explained that early research was conducted on rodents and monkeys, with Dr. Merzenich as one of the leading pioneers in developing the concept of brain plasticity. Dr. Merzenich cofounded Posit Science and is currently its chief scientific officer.

Dr. Mahncke recounted that as a graduate student, he had worked with Dr. Merzenich researching brain plasticity. When Dr. Merzenich founded Posit Science, he asked Dr. Mahncke to join the company to help develop approaches to enhance brain plasticity — building the brain-training exercises and running the clinical trials.

“It’s now well understood that the brain can rewire itself at any age and in almost any condition,” Dr. Mahncke said. “In kids and in younger and older adults, whether with healthy or unhealthy brains, the fundamental way the brain works is by continually rewiring and rebuilding itself, based on what we ask it to do.”

Dr. Mahncke said.

Unsubstantiated Claims and Controversy

Brain training is not without controversy, Dr. Hara pointed out. “Some manufacturers of brain games have been criticized and even fined for making unsubstantiated claims,” she said.

A 2016 review found that brain-training interventions do improve performance on specific trained tasks, but there is less evidence that they improve performance on closely related tasks and little evidence that training improves everyday cognitive performance. A 2017 review reached similar conclusions, calling evidence regarding prevention or delay of cognitive decline or dementia through brain games “insufficient,” although cognitive training could “improve cognition in the domain trained.”

“The general consensus is that for most brain-training programs, people may get better at specific tasks through practice, but these improvements don’t necessarily translate into improvement in other tasks that require other cognitive domains or prevention of dementia or age-related cognitive decline,” Dr. Hara said.

She noted that most brain-training programs “have not been rigorously tested in clinical trials” — although some, such as those featured in the ACTIVE trial, did show evidence of effectiveness.