User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

The battle of egos behind the life-saving discovery of insulin

Leonard Thompson’s father was so desperate to save his 14-year-old child from certain death due to diabetes that, on Jan. 11, 1922, he took him to Toronto General Hospital to receive what is arguably the first dose of insulin given to a human. From an anticipated life expectancy of weeks – months at best – Thompson lived for an astonishing further 13 years, eventually dying from pneumonia unrelated to diabetes.

By all accounts, the story is a centenary celebration of a remarkable discovery. Insulin has changed what was once a death sentence to a near-normal life expectancy for the millions of people with type 1 diabetes over the past 100 years.

But behind the life-changing success of the discovery – and the Nobel Prize that went with it – lies a tale blighted by disputed claims, twisted truths, and likely injustices between the scientists involved, as they each vied for an honored place in medical history.

Kersten Hall, PhD, honorary fellow, religion and history of science, at the University of Leeds, England, has scoured archives and personal records held at the University of Toronto to uncover the personal stories behind insulin’s discovery.

Despite the wranglings, Dr. Hall asserts: “There’s a distinction between the science and the scientists. Scientists are wonderfully flawed and complex human beings with all their glorious virtues and vices, as we all are. It’s no surprise that they get greedy, jealous, and insecure.”

At death’s door: Diabetes before the 1920s

Prior to insulin’s discovery in 1921, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes placed someone at death’s door, with nothing but starvation – albeit a slightly slower death – to mitigate a fast-approaching departure from this world. At that time, most diabetes cases would have been type 1 diabetes because, with less obesogenic diets and shorter lifespans, people were much less likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Nowadays, it is widely recognized that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is on a steep upward curve, but so too is type 1 diabetes. In the United States alone, there are 1.5 million people diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a number expected to rise to around 5 million by 2050, according to JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization.

Interestingly, 100 years since the first treated patient, life-long insulin remains the only real effective therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes. Once pancreatic beta cells have ceased to function and insulin production has stopped, insulin replacement is the only way to keep blood glucose levels within the recommended range (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [6.5%]), according to the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), as well as numerous diabetes organizations, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Preliminary clinical trials have looked at stem cell transplantation, prematurely dubbed as a “cure” for type 1 diabetes, as an alternative to insulin therapy. The procedure involves transplanting stem cell–derived cells, which become functional beta cells when infused into humans, but requires immunosuppression, as reported by this news organization.

Today, the life expectancy of people with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin is close to those without the disease, although this is dependent on how tightly blood glucose is controlled. Some studies show life expectancy of those with type 1 diabetes is around 8-12 years lower than the general population but varies depending on where a person lives.

In some lower-income countries, many with type 1 diabetes still die prematurely either because they are undiagnosed or cannot access insulin. The high cost of insulin in the United States is well publicized, as featured in numerous articles by this news organization, and numerous patients in the United States have died because they cannot afford insulin.

Without insulin, young Leonard Thompson would have been lucky to have reached his 15th birthday.

“Such patients were cachectic and thin and would have weighed around 40-50 pounds (18-23 kg), which is very low for an older child. Survival was short and lasted weeks or months usually,” said Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist in Portland, Ore.

“The discovery of insulin was really a miracle because without it diabetes patients were facing certain death. Even nowadays, if people don’t get their insulin because they can’t afford it or for whatever reason, they can still die,” Dr. Stephens stressed.

Antidiabetic effects of pancreatic extract limited

Back in 1869, Paul Langerhans, MD, discovered pancreatic islet cells, or islets of Langerhans, as a medical student. Researchers tried to produce extracts that lowered blood glucose but they were too toxic for patient use.

In 1908, as detailed in his recent book, Insulin – the Crooked Timber, Dr. Hall also refers to the fact that a German researcher, Georg Zuelzer, MD, demonstrated in six patients that pancreatic extracts could reduce urinary levels of glucose and ketones, and that in one case, the treatment woke the patient from a coma. Dr. Zuelzer had purified the extract with alcohol but patients still experienced convulsions and coma; in fact, they were experiencing hypoglycemic shock, but Dr. Zuelzer had not identified it as such.

“He thought his preparation was full of impurities – and that’s the irony. He had in his hands an insulin prep that was so clean and so potent that it sent the test animals into hypoglycemic shock,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

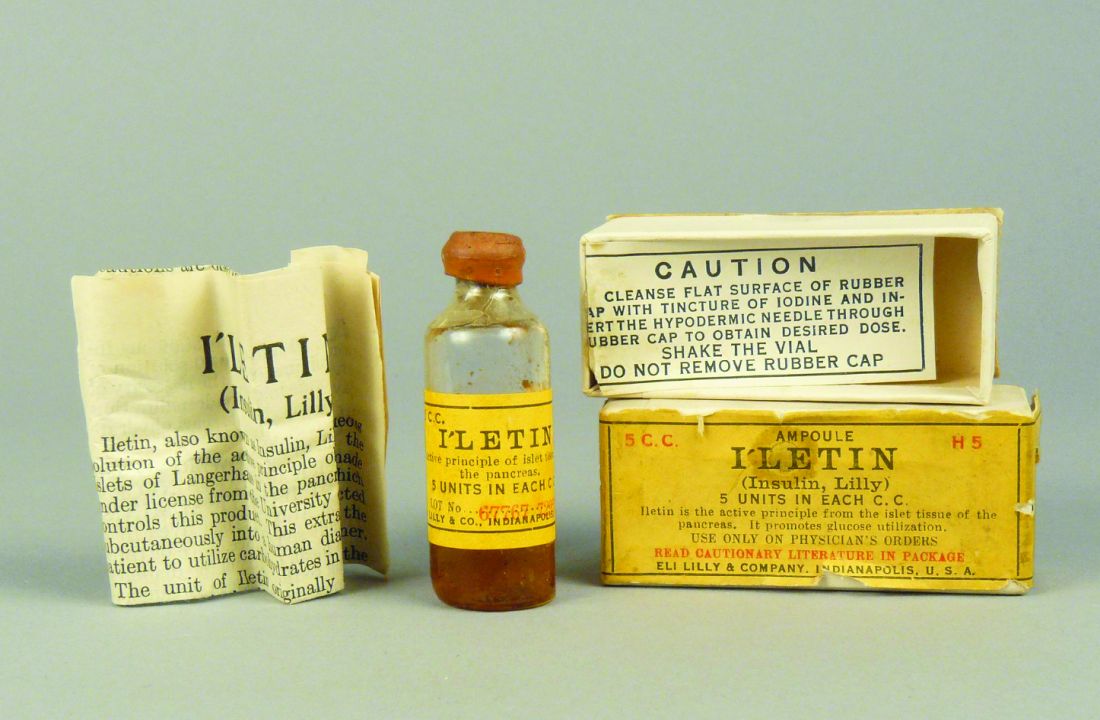

By 1921, two young researchers, Frederick G. Banting, MD, a practicing medical doctor in Toronto, together with a final year physiology student at the University of Toronto, Charles H. Best, MD, DSc, collaborated on the instruction of Dr. Best’s superior, John James Rickard Macleod, MBChB, professor of physiology at the University of Toronto, to make pancreatic extracts, first from dogs and then from cattle.

Over the months prior to treating Thompson, working together in the laboratory, Dr. Banting and Dr. Best prepared the pancreatic extract from cattle and tested it on dogs with diabetes.

Then, in what amounted to a phase 1 trial of its day, with an “n of one,” a frail and close-to-death Thompson was given 15 cc of pancreatic extract at Toronto General Hospital in January 1922. His blood glucose level dropped by 25%, but unfortunately, his body still produced ketones, indicating the antidiabetic effect was limited. He also experienced an adverse reaction at the injection site with an accumulation of abscesses.

So despite success with isolating the extract and administering it to Thompson, the product remained tainted with impurities.

At this point, colleague James Collip, MD, PhD, came to the rescue. He used his skills as a biochemist to purify the pancreatic extract enough to eliminate impurities.

When Thompson was treated 2 weeks later with the purified extract, he experienced a more positive outcome. Gone was the injection site reaction, gone were the high blood glucose levels, and Thompson “became brighter, more active, looked better, and said he felt stronger,” according to a publication describing the treatment.

Dr. Collip also determined that by over-purifying the product, the animals he experimented on could overreact and experience convulsions, coma, and death due to hypoglycemia from too much insulin.

Fighting talk

Recalling an excerpt from Dr. Banting’s diary, Dr. Hall said that Dr. Banting had a mercurial temper and testified to his loss of patience with Dr. Collip when the chemist refused to share his formula of purification. His diary reads: “I grabbed him in one hand by the overcoat ... and almost lifting him I sat him down hard on the chair ... I remember telling him that it was a good job he was so much smaller – otherwise I would ‘knock hell out of him.’ ”

According to Dr. Hall, in 1923, when Dr. Banting and Dr. Macleod were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine, Dr. Best resented being excluded, and despite Dr. Banting’s sharing half his prize money with Dr. Best, animosity prevailed.

At one point, before leaving on a plane for a wartime mission to the United Kingdom, Dr. Banting noted that if he didn’t make it back alive, “and they give my [professorial] chair to that son-of-a-bitch Best, I’ll never rest in my grave.” In a cruel twist of fate, Dr. Banting’s plane crashed and all aboard died.

The Nobel Prize had also been a source of rivalry between Dr. Banting and his boss, Dr. Macleod. In late 1921, while presenting the findings from animal models at the American Physiological Society conference, Dr. Banting’s nerves got the better of him and Dr. Macleod took over at the podium to finish the talk. Dr. Banting perceived this as his boss stealing the limelight.

Only a few months later, at the Association of American Physicians annual conference, Dr. Macleod played to an audience for a second time by making the first formal announcement of the discovery to the scientific community. Notably, Dr. Banting was absent.

The Nobel Prize or a poisoned chalice?

Awarded annually for physics, chemistry, medicine/physiology, literature, peace, and economics, Nobel Prizes are usually considered the holy grail of achievement. In 1895, funds for the prizes were bequeathed by Alfred Nobel in his last will and testament, with each prize worth around $40,000 at the time (approximately $1,000,000 in today’s value).

Writing in 2001 in the journal Diabetes Voice, Professor Sir George Alberti, DPhil, BM BCh, former president of the UK Royal College of Physicians, summarized the burden that accompanies the Nobel Prize: “I personally believe that such prizes and awards do more harm than good and should be abolished. Many a scientist has gone to their grave feeling deeply aggrieved because they were not awarded a Nobel Prize.”

Such high stakes surround the prize that, in the case of insulin, the course of its discovery meant courtesies and truth were swept aside in hot pursuit of fame. After Dr. Macleod died in 1935 and Dr. Banting died in 1941, Dr. Best took the opportunity to try to revise history. There was the small obstacle of Dr. Collip, but Dr. Best managed to play down Dr. Collip’s contribution by focusing on the eureka moment as being the first insulin dose administered, despite the fact that a more complete recovery without side effects was later achieved only with Dr. Collip’s help.

Despite exclusion from the Nobel Prize, Dr. Best nevertheless became recognized as the “go-to-guy” for the discovery of insulin, said Dr. Hall. When Dr. Best spoke about the discovery of insulin at the New York Diabetes Association meeting in 1946, he was introduced as a speaker whose reputation was already so great that he did “not require much of an introduction.”

“And when a new research institute was opened in Toronto in 1953, it was named in his honor. The opening address, by Sir Henry Dale of the UK Medical Research Council, sang Best’s praises to the rafters, much to the disgruntlement of Best’s former colleague, James Collip, who was sitting in the audience,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

Both Dr. Hall and Dr. Stephens live with type 1 diabetes and have benefited from the efforts of Dr. Banting, Dr. Best, Dr. Collip, Dr. Zuelzer, and Dr. Macleod.

“The discovery of insulin was a miracle, it has allowed people to survive,” said Dr. Stephens. “Few medicines can reverse a death sentence like insulin can. It’s easy to forget how it was when insulin wasn’t there – and it wasn’t that long ago.”

Dr. Hall reflects that scientific progress and discovery are often portrayed as being the result of towering geniuses standing on each other’s shoulders.

“But I think that when German philosopher Immanuel Kant remarked that ‘Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing can ever be made,’ he offered us a much more accurate picture of how science works. And I think that there’s perhaps no more powerful example of this than the story of insulin,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Leonard Thompson’s father was so desperate to save his 14-year-old child from certain death due to diabetes that, on Jan. 11, 1922, he took him to Toronto General Hospital to receive what is arguably the first dose of insulin given to a human. From an anticipated life expectancy of weeks – months at best – Thompson lived for an astonishing further 13 years, eventually dying from pneumonia unrelated to diabetes.

By all accounts, the story is a centenary celebration of a remarkable discovery. Insulin has changed what was once a death sentence to a near-normal life expectancy for the millions of people with type 1 diabetes over the past 100 years.

But behind the life-changing success of the discovery – and the Nobel Prize that went with it – lies a tale blighted by disputed claims, twisted truths, and likely injustices between the scientists involved, as they each vied for an honored place in medical history.

Kersten Hall, PhD, honorary fellow, religion and history of science, at the University of Leeds, England, has scoured archives and personal records held at the University of Toronto to uncover the personal stories behind insulin’s discovery.

Despite the wranglings, Dr. Hall asserts: “There’s a distinction between the science and the scientists. Scientists are wonderfully flawed and complex human beings with all their glorious virtues and vices, as we all are. It’s no surprise that they get greedy, jealous, and insecure.”

At death’s door: Diabetes before the 1920s

Prior to insulin’s discovery in 1921, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes placed someone at death’s door, with nothing but starvation – albeit a slightly slower death – to mitigate a fast-approaching departure from this world. At that time, most diabetes cases would have been type 1 diabetes because, with less obesogenic diets and shorter lifespans, people were much less likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Nowadays, it is widely recognized that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is on a steep upward curve, but so too is type 1 diabetes. In the United States alone, there are 1.5 million people diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a number expected to rise to around 5 million by 2050, according to JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization.

Interestingly, 100 years since the first treated patient, life-long insulin remains the only real effective therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes. Once pancreatic beta cells have ceased to function and insulin production has stopped, insulin replacement is the only way to keep blood glucose levels within the recommended range (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [6.5%]), according to the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), as well as numerous diabetes organizations, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Preliminary clinical trials have looked at stem cell transplantation, prematurely dubbed as a “cure” for type 1 diabetes, as an alternative to insulin therapy. The procedure involves transplanting stem cell–derived cells, which become functional beta cells when infused into humans, but requires immunosuppression, as reported by this news organization.

Today, the life expectancy of people with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin is close to those without the disease, although this is dependent on how tightly blood glucose is controlled. Some studies show life expectancy of those with type 1 diabetes is around 8-12 years lower than the general population but varies depending on where a person lives.

In some lower-income countries, many with type 1 diabetes still die prematurely either because they are undiagnosed or cannot access insulin. The high cost of insulin in the United States is well publicized, as featured in numerous articles by this news organization, and numerous patients in the United States have died because they cannot afford insulin.

Without insulin, young Leonard Thompson would have been lucky to have reached his 15th birthday.

“Such patients were cachectic and thin and would have weighed around 40-50 pounds (18-23 kg), which is very low for an older child. Survival was short and lasted weeks or months usually,” said Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist in Portland, Ore.

“The discovery of insulin was really a miracle because without it diabetes patients were facing certain death. Even nowadays, if people don’t get their insulin because they can’t afford it or for whatever reason, they can still die,” Dr. Stephens stressed.

Antidiabetic effects of pancreatic extract limited

Back in 1869, Paul Langerhans, MD, discovered pancreatic islet cells, or islets of Langerhans, as a medical student. Researchers tried to produce extracts that lowered blood glucose but they were too toxic for patient use.

In 1908, as detailed in his recent book, Insulin – the Crooked Timber, Dr. Hall also refers to the fact that a German researcher, Georg Zuelzer, MD, demonstrated in six patients that pancreatic extracts could reduce urinary levels of glucose and ketones, and that in one case, the treatment woke the patient from a coma. Dr. Zuelzer had purified the extract with alcohol but patients still experienced convulsions and coma; in fact, they were experiencing hypoglycemic shock, but Dr. Zuelzer had not identified it as such.

“He thought his preparation was full of impurities – and that’s the irony. He had in his hands an insulin prep that was so clean and so potent that it sent the test animals into hypoglycemic shock,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

By 1921, two young researchers, Frederick G. Banting, MD, a practicing medical doctor in Toronto, together with a final year physiology student at the University of Toronto, Charles H. Best, MD, DSc, collaborated on the instruction of Dr. Best’s superior, John James Rickard Macleod, MBChB, professor of physiology at the University of Toronto, to make pancreatic extracts, first from dogs and then from cattle.

Over the months prior to treating Thompson, working together in the laboratory, Dr. Banting and Dr. Best prepared the pancreatic extract from cattle and tested it on dogs with diabetes.

Then, in what amounted to a phase 1 trial of its day, with an “n of one,” a frail and close-to-death Thompson was given 15 cc of pancreatic extract at Toronto General Hospital in January 1922. His blood glucose level dropped by 25%, but unfortunately, his body still produced ketones, indicating the antidiabetic effect was limited. He also experienced an adverse reaction at the injection site with an accumulation of abscesses.

So despite success with isolating the extract and administering it to Thompson, the product remained tainted with impurities.

At this point, colleague James Collip, MD, PhD, came to the rescue. He used his skills as a biochemist to purify the pancreatic extract enough to eliminate impurities.

When Thompson was treated 2 weeks later with the purified extract, he experienced a more positive outcome. Gone was the injection site reaction, gone were the high blood glucose levels, and Thompson “became brighter, more active, looked better, and said he felt stronger,” according to a publication describing the treatment.

Dr. Collip also determined that by over-purifying the product, the animals he experimented on could overreact and experience convulsions, coma, and death due to hypoglycemia from too much insulin.

Fighting talk

Recalling an excerpt from Dr. Banting’s diary, Dr. Hall said that Dr. Banting had a mercurial temper and testified to his loss of patience with Dr. Collip when the chemist refused to share his formula of purification. His diary reads: “I grabbed him in one hand by the overcoat ... and almost lifting him I sat him down hard on the chair ... I remember telling him that it was a good job he was so much smaller – otherwise I would ‘knock hell out of him.’ ”

According to Dr. Hall, in 1923, when Dr. Banting and Dr. Macleod were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine, Dr. Best resented being excluded, and despite Dr. Banting’s sharing half his prize money with Dr. Best, animosity prevailed.

At one point, before leaving on a plane for a wartime mission to the United Kingdom, Dr. Banting noted that if he didn’t make it back alive, “and they give my [professorial] chair to that son-of-a-bitch Best, I’ll never rest in my grave.” In a cruel twist of fate, Dr. Banting’s plane crashed and all aboard died.

The Nobel Prize had also been a source of rivalry between Dr. Banting and his boss, Dr. Macleod. In late 1921, while presenting the findings from animal models at the American Physiological Society conference, Dr. Banting’s nerves got the better of him and Dr. Macleod took over at the podium to finish the talk. Dr. Banting perceived this as his boss stealing the limelight.

Only a few months later, at the Association of American Physicians annual conference, Dr. Macleod played to an audience for a second time by making the first formal announcement of the discovery to the scientific community. Notably, Dr. Banting was absent.

The Nobel Prize or a poisoned chalice?

Awarded annually for physics, chemistry, medicine/physiology, literature, peace, and economics, Nobel Prizes are usually considered the holy grail of achievement. In 1895, funds for the prizes were bequeathed by Alfred Nobel in his last will and testament, with each prize worth around $40,000 at the time (approximately $1,000,000 in today’s value).

Writing in 2001 in the journal Diabetes Voice, Professor Sir George Alberti, DPhil, BM BCh, former president of the UK Royal College of Physicians, summarized the burden that accompanies the Nobel Prize: “I personally believe that such prizes and awards do more harm than good and should be abolished. Many a scientist has gone to their grave feeling deeply aggrieved because they were not awarded a Nobel Prize.”

Such high stakes surround the prize that, in the case of insulin, the course of its discovery meant courtesies and truth were swept aside in hot pursuit of fame. After Dr. Macleod died in 1935 and Dr. Banting died in 1941, Dr. Best took the opportunity to try to revise history. There was the small obstacle of Dr. Collip, but Dr. Best managed to play down Dr. Collip’s contribution by focusing on the eureka moment as being the first insulin dose administered, despite the fact that a more complete recovery without side effects was later achieved only with Dr. Collip’s help.

Despite exclusion from the Nobel Prize, Dr. Best nevertheless became recognized as the “go-to-guy” for the discovery of insulin, said Dr. Hall. When Dr. Best spoke about the discovery of insulin at the New York Diabetes Association meeting in 1946, he was introduced as a speaker whose reputation was already so great that he did “not require much of an introduction.”

“And when a new research institute was opened in Toronto in 1953, it was named in his honor. The opening address, by Sir Henry Dale of the UK Medical Research Council, sang Best’s praises to the rafters, much to the disgruntlement of Best’s former colleague, James Collip, who was sitting in the audience,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

Both Dr. Hall and Dr. Stephens live with type 1 diabetes and have benefited from the efforts of Dr. Banting, Dr. Best, Dr. Collip, Dr. Zuelzer, and Dr. Macleod.

“The discovery of insulin was a miracle, it has allowed people to survive,” said Dr. Stephens. “Few medicines can reverse a death sentence like insulin can. It’s easy to forget how it was when insulin wasn’t there – and it wasn’t that long ago.”

Dr. Hall reflects that scientific progress and discovery are often portrayed as being the result of towering geniuses standing on each other’s shoulders.

“But I think that when German philosopher Immanuel Kant remarked that ‘Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing can ever be made,’ he offered us a much more accurate picture of how science works. And I think that there’s perhaps no more powerful example of this than the story of insulin,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Leonard Thompson’s father was so desperate to save his 14-year-old child from certain death due to diabetes that, on Jan. 11, 1922, he took him to Toronto General Hospital to receive what is arguably the first dose of insulin given to a human. From an anticipated life expectancy of weeks – months at best – Thompson lived for an astonishing further 13 years, eventually dying from pneumonia unrelated to diabetes.

By all accounts, the story is a centenary celebration of a remarkable discovery. Insulin has changed what was once a death sentence to a near-normal life expectancy for the millions of people with type 1 diabetes over the past 100 years.

But behind the life-changing success of the discovery – and the Nobel Prize that went with it – lies a tale blighted by disputed claims, twisted truths, and likely injustices between the scientists involved, as they each vied for an honored place in medical history.

Kersten Hall, PhD, honorary fellow, religion and history of science, at the University of Leeds, England, has scoured archives and personal records held at the University of Toronto to uncover the personal stories behind insulin’s discovery.

Despite the wranglings, Dr. Hall asserts: “There’s a distinction between the science and the scientists. Scientists are wonderfully flawed and complex human beings with all their glorious virtues and vices, as we all are. It’s no surprise that they get greedy, jealous, and insecure.”

At death’s door: Diabetes before the 1920s

Prior to insulin’s discovery in 1921, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes placed someone at death’s door, with nothing but starvation – albeit a slightly slower death – to mitigate a fast-approaching departure from this world. At that time, most diabetes cases would have been type 1 diabetes because, with less obesogenic diets and shorter lifespans, people were much less likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Nowadays, it is widely recognized that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is on a steep upward curve, but so too is type 1 diabetes. In the United States alone, there are 1.5 million people diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a number expected to rise to around 5 million by 2050, according to JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization.

Interestingly, 100 years since the first treated patient, life-long insulin remains the only real effective therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes. Once pancreatic beta cells have ceased to function and insulin production has stopped, insulin replacement is the only way to keep blood glucose levels within the recommended range (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [6.5%]), according to the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), as well as numerous diabetes organizations, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Preliminary clinical trials have looked at stem cell transplantation, prematurely dubbed as a “cure” for type 1 diabetes, as an alternative to insulin therapy. The procedure involves transplanting stem cell–derived cells, which become functional beta cells when infused into humans, but requires immunosuppression, as reported by this news organization.

Today, the life expectancy of people with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin is close to those without the disease, although this is dependent on how tightly blood glucose is controlled. Some studies show life expectancy of those with type 1 diabetes is around 8-12 years lower than the general population but varies depending on where a person lives.

In some lower-income countries, many with type 1 diabetes still die prematurely either because they are undiagnosed or cannot access insulin. The high cost of insulin in the United States is well publicized, as featured in numerous articles by this news organization, and numerous patients in the United States have died because they cannot afford insulin.

Without insulin, young Leonard Thompson would have been lucky to have reached his 15th birthday.

“Such patients were cachectic and thin and would have weighed around 40-50 pounds (18-23 kg), which is very low for an older child. Survival was short and lasted weeks or months usually,” said Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist in Portland, Ore.

“The discovery of insulin was really a miracle because without it diabetes patients were facing certain death. Even nowadays, if people don’t get their insulin because they can’t afford it or for whatever reason, they can still die,” Dr. Stephens stressed.

Antidiabetic effects of pancreatic extract limited

Back in 1869, Paul Langerhans, MD, discovered pancreatic islet cells, or islets of Langerhans, as a medical student. Researchers tried to produce extracts that lowered blood glucose but they were too toxic for patient use.

In 1908, as detailed in his recent book, Insulin – the Crooked Timber, Dr. Hall also refers to the fact that a German researcher, Georg Zuelzer, MD, demonstrated in six patients that pancreatic extracts could reduce urinary levels of glucose and ketones, and that in one case, the treatment woke the patient from a coma. Dr. Zuelzer had purified the extract with alcohol but patients still experienced convulsions and coma; in fact, they were experiencing hypoglycemic shock, but Dr. Zuelzer had not identified it as such.

“He thought his preparation was full of impurities – and that’s the irony. He had in his hands an insulin prep that was so clean and so potent that it sent the test animals into hypoglycemic shock,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

By 1921, two young researchers, Frederick G. Banting, MD, a practicing medical doctor in Toronto, together with a final year physiology student at the University of Toronto, Charles H. Best, MD, DSc, collaborated on the instruction of Dr. Best’s superior, John James Rickard Macleod, MBChB, professor of physiology at the University of Toronto, to make pancreatic extracts, first from dogs and then from cattle.

Over the months prior to treating Thompson, working together in the laboratory, Dr. Banting and Dr. Best prepared the pancreatic extract from cattle and tested it on dogs with diabetes.

Then, in what amounted to a phase 1 trial of its day, with an “n of one,” a frail and close-to-death Thompson was given 15 cc of pancreatic extract at Toronto General Hospital in January 1922. His blood glucose level dropped by 25%, but unfortunately, his body still produced ketones, indicating the antidiabetic effect was limited. He also experienced an adverse reaction at the injection site with an accumulation of abscesses.

So despite success with isolating the extract and administering it to Thompson, the product remained tainted with impurities.

At this point, colleague James Collip, MD, PhD, came to the rescue. He used his skills as a biochemist to purify the pancreatic extract enough to eliminate impurities.

When Thompson was treated 2 weeks later with the purified extract, he experienced a more positive outcome. Gone was the injection site reaction, gone were the high blood glucose levels, and Thompson “became brighter, more active, looked better, and said he felt stronger,” according to a publication describing the treatment.

Dr. Collip also determined that by over-purifying the product, the animals he experimented on could overreact and experience convulsions, coma, and death due to hypoglycemia from too much insulin.

Fighting talk

Recalling an excerpt from Dr. Banting’s diary, Dr. Hall said that Dr. Banting had a mercurial temper and testified to his loss of patience with Dr. Collip when the chemist refused to share his formula of purification. His diary reads: “I grabbed him in one hand by the overcoat ... and almost lifting him I sat him down hard on the chair ... I remember telling him that it was a good job he was so much smaller – otherwise I would ‘knock hell out of him.’ ”

According to Dr. Hall, in 1923, when Dr. Banting and Dr. Macleod were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine, Dr. Best resented being excluded, and despite Dr. Banting’s sharing half his prize money with Dr. Best, animosity prevailed.

At one point, before leaving on a plane for a wartime mission to the United Kingdom, Dr. Banting noted that if he didn’t make it back alive, “and they give my [professorial] chair to that son-of-a-bitch Best, I’ll never rest in my grave.” In a cruel twist of fate, Dr. Banting’s plane crashed and all aboard died.

The Nobel Prize had also been a source of rivalry between Dr. Banting and his boss, Dr. Macleod. In late 1921, while presenting the findings from animal models at the American Physiological Society conference, Dr. Banting’s nerves got the better of him and Dr. Macleod took over at the podium to finish the talk. Dr. Banting perceived this as his boss stealing the limelight.

Only a few months later, at the Association of American Physicians annual conference, Dr. Macleod played to an audience for a second time by making the first formal announcement of the discovery to the scientific community. Notably, Dr. Banting was absent.

The Nobel Prize or a poisoned chalice?

Awarded annually for physics, chemistry, medicine/physiology, literature, peace, and economics, Nobel Prizes are usually considered the holy grail of achievement. In 1895, funds for the prizes were bequeathed by Alfred Nobel in his last will and testament, with each prize worth around $40,000 at the time (approximately $1,000,000 in today’s value).

Writing in 2001 in the journal Diabetes Voice, Professor Sir George Alberti, DPhil, BM BCh, former president of the UK Royal College of Physicians, summarized the burden that accompanies the Nobel Prize: “I personally believe that such prizes and awards do more harm than good and should be abolished. Many a scientist has gone to their grave feeling deeply aggrieved because they were not awarded a Nobel Prize.”

Such high stakes surround the prize that, in the case of insulin, the course of its discovery meant courtesies and truth were swept aside in hot pursuit of fame. After Dr. Macleod died in 1935 and Dr. Banting died in 1941, Dr. Best took the opportunity to try to revise history. There was the small obstacle of Dr. Collip, but Dr. Best managed to play down Dr. Collip’s contribution by focusing on the eureka moment as being the first insulin dose administered, despite the fact that a more complete recovery without side effects was later achieved only with Dr. Collip’s help.

Despite exclusion from the Nobel Prize, Dr. Best nevertheless became recognized as the “go-to-guy” for the discovery of insulin, said Dr. Hall. When Dr. Best spoke about the discovery of insulin at the New York Diabetes Association meeting in 1946, he was introduced as a speaker whose reputation was already so great that he did “not require much of an introduction.”

“And when a new research institute was opened in Toronto in 1953, it was named in his honor. The opening address, by Sir Henry Dale of the UK Medical Research Council, sang Best’s praises to the rafters, much to the disgruntlement of Best’s former colleague, James Collip, who was sitting in the audience,” Dr. Hall pointed out.

Both Dr. Hall and Dr. Stephens live with type 1 diabetes and have benefited from the efforts of Dr. Banting, Dr. Best, Dr. Collip, Dr. Zuelzer, and Dr. Macleod.

“The discovery of insulin was a miracle, it has allowed people to survive,” said Dr. Stephens. “Few medicines can reverse a death sentence like insulin can. It’s easy to forget how it was when insulin wasn’t there – and it wasn’t that long ago.”

Dr. Hall reflects that scientific progress and discovery are often portrayed as being the result of towering geniuses standing on each other’s shoulders.

“But I think that when German philosopher Immanuel Kant remarked that ‘Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing can ever be made,’ he offered us a much more accurate picture of how science works. And I think that there’s perhaps no more powerful example of this than the story of insulin,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical boards pressured to let it slide when doctors spread COVID misinformation

Tennessee’s Board of Medical Examiners unanimously adopted in September 2021 a statement that said doctors spreading COVID misinformation – such as suggesting that vaccines contain microchips – could jeopardize their license to practice.

“I’m very glad that we’re taking this step,” Dr. Stephen Loyd, MD, the panel’s vice president, said at the time. “If you’re spreading this willful misinformation, for me it’s going to be really hard to do anything other than put you on probation or take your license for a year. There has to be a message sent for this. It’s not okay.”

The board’s statement was posted on a government website.

The growing tension in Tennessee between conservative lawmakers and the state’s medical board may be the most prominent example in the country. But the Federation of State Medical Boards, which created the language adopted by at least 15 state boards, is tracking legislation introduced by Republicans in at least 14 states that would restrict a medical board’s authority to discipline doctors for their advice on COVID.

Humayun Chaudhry, DO, the federation’s CEO, called it “an unwelcome trend.” The nonprofit association, based in Euless, Tex., said the statement is merely a COVID-specific restatement of an existing rule: that doctors who engage in behavior that puts patients at risk could face disciplinary action.

Although doctors have leeway to decide which treatments to provide, the medical boards that oversee them have broad authority over licensing. Often, doctors are investigated for violating guidelines on prescribing high-powered drugs. But physicians are sometimes punished for other “unprofessional conduct.” In 2013, Tennessee’s board fined U.S. Rep. Scott DesJarlais for separately having sexual relations with two female patients more than a decade earlier.

Still, stopping doctors from sharing unsound medical advice has proved challenging. Even defining misinformation has been difficult. And during the pandemic, resistance from some state legislatures is complicating the effort.

A relatively small group of physicians peddle COVID misinformation, but many of them associate with America’s Frontline Doctors. Its founder, Simone Gold, MD, has claimed patients are dying from COVID treatments, not the virus itself. Sherri Tenpenny, DO, said in a legislative hearing in Ohio that the COVID vaccine could magnetize patients. Stella Immanuel, MD, has pushed hydroxychloroquine as a COVID cure in Texas, although clinical trials showed that it had no benefit. None of them agreed to requests for comment.

The Texas Medical Board fined Dr. Immanuel $500 for not informing a patient of the risks associated with using hydroxychloroquine as an off-label COVID treatment.

In Tennessee, state lawmakers called a special legislative session in October to address COVID restrictions, and Republican Gov. Bill Lee signed a sweeping package of bills that push back against pandemic rules. One included language directed at the medical board’s recent COVID policy statement, making it more difficult for the panel to investigate complaints about physicians’ advice on COVID vaccines or treatments.

In November, Republican state Rep. John Ragan sent the medical board a letter demanding that the statement be deleted from the state’s website. Rep. Ragan leads a legislative panel that had raised the prospect of defunding the state’s health department over its promotion of COVID vaccines to teens.

Among his demands, Rep. Ragan listed 20 questions he wanted the medical board to answer in writing, including why the misinformation “policy” was proposed nearly two years into the pandemic, which scholars would determine what constitutes misinformation, and how was the “policy” not an infringement on the doctor-patient relationship.

“If you fail to act promptly, your organization will be required to appear before the Joint Government Operations Committee to explain your inaction,” Rep. Ragan wrote in the letter, obtained by Kaiser Health News and Nashville Public Radio.

In response to a request for comment, Rep. Ragan said that “any executive agency, including Board of Medical Examiners, that refuses to follow the law is subject to dissolution.”

He set a deadline of Dec. 7.

In Florida, a Republican-sponsored bill making its way through the state legislature proposes to ban medical boards from revoking or threatening to revoke doctors’ licenses for what they say unless “direct physical harm” of a patient occurred. If the publicized complaint can’t be proved, the board could owe a doctor up to $1.5 million in damages.

Although Florida’s medical board has not adopted the Federation of State Medical Boards’ COVID misinformation statement, the panel has considered misinformation complaints against physicians, including the state’s surgeon general, Joseph Ladapo, MD, PhD.

Dr. Chaudhry said he’s surprised just how many COVID-related complaints are being filed across the country. Often, boards do not publicize investigations before a violation of ethics or standards is confirmed. But in response to a survey by the federation in late 2021, two-thirds of state boards reported an increase in misinformation complaints. And the federation said 12 boards had taken action against a licensed physician.

“At the end of the day, if a physician who is licensed engages in activity that causes harm, the state medical boards are the ones that historically have been set up to look into the situation and make a judgment about what happened or didn’t happen,” Dr. Chaudhry said. “And if you start to chip away at that, it becomes a slippery slope.”

The Georgia Composite Medical Board adopted a version of the federation’s misinformation guidance in early November and has been receiving 10-20 complaints each month, said Debi Dalton, MD, the chairperson. Two months in, no one had been sanctioned.

Dr. Dalton said that even putting out a misinformation policy leaves some “gray” area. Generally, physicians are expected to follow the “consensus,” rather than “the newest information that pops up on social media,” she said.

“We expect physicians to think ethically, professionally, and with the safety of patients in mind,” Dr. Dalton said.

A few physician groups are resisting attempts to root out misinformation, including the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, known for its stands against government regulation.

Some medical boards have opted against taking a public stand against misinformation.

The Alabama Board of Medical Examiners discussed signing on to the federation’s statement, according to the minutes from an October meeting. But after debating the potential legal ramifications in a private executive session, the board opted not to act.

In Tennessee, the Board of Medical Examiners met on the day Rep. Ragan had set as the deadline and voted to remove the misinformation statement from its website to avoid being called into a legislative hearing. But then, in late January, the board decided to stick with the policy – although it did not republish the statement online immediately – and more specifically defined misinformation, calling it “content that is false, inaccurate or misleading, even if spread unintentionally.”

Board members acknowledged they would likely get more pushback from lawmakers but said they wanted to protect their profession from interference.

“Doctors who are putting forth good evidence-based medicine deserve the protection of this board so they can actually say: ‘Hey, I’m in line with this guideline, and this is a source of truth,’” said Melanie Blake, MD, the board’s president. “We should be a source of truth.”

The medical board was looking into nearly 30 open complaints related to COVID when its misinformation statement came down from its website. As of early February, no Tennessee physician had faced disciplinary action.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation. This story is part of a partnership that includes Nashville Public Radio, NPR, and KHN.

Tennessee’s Board of Medical Examiners unanimously adopted in September 2021 a statement that said doctors spreading COVID misinformation – such as suggesting that vaccines contain microchips – could jeopardize their license to practice.

“I’m very glad that we’re taking this step,” Dr. Stephen Loyd, MD, the panel’s vice president, said at the time. “If you’re spreading this willful misinformation, for me it’s going to be really hard to do anything other than put you on probation or take your license for a year. There has to be a message sent for this. It’s not okay.”

The board’s statement was posted on a government website.

The growing tension in Tennessee between conservative lawmakers and the state’s medical board may be the most prominent example in the country. But the Federation of State Medical Boards, which created the language adopted by at least 15 state boards, is tracking legislation introduced by Republicans in at least 14 states that would restrict a medical board’s authority to discipline doctors for their advice on COVID.

Humayun Chaudhry, DO, the federation’s CEO, called it “an unwelcome trend.” The nonprofit association, based in Euless, Tex., said the statement is merely a COVID-specific restatement of an existing rule: that doctors who engage in behavior that puts patients at risk could face disciplinary action.

Although doctors have leeway to decide which treatments to provide, the medical boards that oversee them have broad authority over licensing. Often, doctors are investigated for violating guidelines on prescribing high-powered drugs. But physicians are sometimes punished for other “unprofessional conduct.” In 2013, Tennessee’s board fined U.S. Rep. Scott DesJarlais for separately having sexual relations with two female patients more than a decade earlier.

Still, stopping doctors from sharing unsound medical advice has proved challenging. Even defining misinformation has been difficult. And during the pandemic, resistance from some state legislatures is complicating the effort.

A relatively small group of physicians peddle COVID misinformation, but many of them associate with America’s Frontline Doctors. Its founder, Simone Gold, MD, has claimed patients are dying from COVID treatments, not the virus itself. Sherri Tenpenny, DO, said in a legislative hearing in Ohio that the COVID vaccine could magnetize patients. Stella Immanuel, MD, has pushed hydroxychloroquine as a COVID cure in Texas, although clinical trials showed that it had no benefit. None of them agreed to requests for comment.

The Texas Medical Board fined Dr. Immanuel $500 for not informing a patient of the risks associated with using hydroxychloroquine as an off-label COVID treatment.

In Tennessee, state lawmakers called a special legislative session in October to address COVID restrictions, and Republican Gov. Bill Lee signed a sweeping package of bills that push back against pandemic rules. One included language directed at the medical board’s recent COVID policy statement, making it more difficult for the panel to investigate complaints about physicians’ advice on COVID vaccines or treatments.

In November, Republican state Rep. John Ragan sent the medical board a letter demanding that the statement be deleted from the state’s website. Rep. Ragan leads a legislative panel that had raised the prospect of defunding the state’s health department over its promotion of COVID vaccines to teens.

Among his demands, Rep. Ragan listed 20 questions he wanted the medical board to answer in writing, including why the misinformation “policy” was proposed nearly two years into the pandemic, which scholars would determine what constitutes misinformation, and how was the “policy” not an infringement on the doctor-patient relationship.

“If you fail to act promptly, your organization will be required to appear before the Joint Government Operations Committee to explain your inaction,” Rep. Ragan wrote in the letter, obtained by Kaiser Health News and Nashville Public Radio.

In response to a request for comment, Rep. Ragan said that “any executive agency, including Board of Medical Examiners, that refuses to follow the law is subject to dissolution.”

He set a deadline of Dec. 7.

In Florida, a Republican-sponsored bill making its way through the state legislature proposes to ban medical boards from revoking or threatening to revoke doctors’ licenses for what they say unless “direct physical harm” of a patient occurred. If the publicized complaint can’t be proved, the board could owe a doctor up to $1.5 million in damages.

Although Florida’s medical board has not adopted the Federation of State Medical Boards’ COVID misinformation statement, the panel has considered misinformation complaints against physicians, including the state’s surgeon general, Joseph Ladapo, MD, PhD.

Dr. Chaudhry said he’s surprised just how many COVID-related complaints are being filed across the country. Often, boards do not publicize investigations before a violation of ethics or standards is confirmed. But in response to a survey by the federation in late 2021, two-thirds of state boards reported an increase in misinformation complaints. And the federation said 12 boards had taken action against a licensed physician.

“At the end of the day, if a physician who is licensed engages in activity that causes harm, the state medical boards are the ones that historically have been set up to look into the situation and make a judgment about what happened or didn’t happen,” Dr. Chaudhry said. “And if you start to chip away at that, it becomes a slippery slope.”

The Georgia Composite Medical Board adopted a version of the federation’s misinformation guidance in early November and has been receiving 10-20 complaints each month, said Debi Dalton, MD, the chairperson. Two months in, no one had been sanctioned.

Dr. Dalton said that even putting out a misinformation policy leaves some “gray” area. Generally, physicians are expected to follow the “consensus,” rather than “the newest information that pops up on social media,” she said.

“We expect physicians to think ethically, professionally, and with the safety of patients in mind,” Dr. Dalton said.

A few physician groups are resisting attempts to root out misinformation, including the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, known for its stands against government regulation.

Some medical boards have opted against taking a public stand against misinformation.

The Alabama Board of Medical Examiners discussed signing on to the federation’s statement, according to the minutes from an October meeting. But after debating the potential legal ramifications in a private executive session, the board opted not to act.

In Tennessee, the Board of Medical Examiners met on the day Rep. Ragan had set as the deadline and voted to remove the misinformation statement from its website to avoid being called into a legislative hearing. But then, in late January, the board decided to stick with the policy – although it did not republish the statement online immediately – and more specifically defined misinformation, calling it “content that is false, inaccurate or misleading, even if spread unintentionally.”

Board members acknowledged they would likely get more pushback from lawmakers but said they wanted to protect their profession from interference.

“Doctors who are putting forth good evidence-based medicine deserve the protection of this board so they can actually say: ‘Hey, I’m in line with this guideline, and this is a source of truth,’” said Melanie Blake, MD, the board’s president. “We should be a source of truth.”

The medical board was looking into nearly 30 open complaints related to COVID when its misinformation statement came down from its website. As of early February, no Tennessee physician had faced disciplinary action.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation. This story is part of a partnership that includes Nashville Public Radio, NPR, and KHN.

Tennessee’s Board of Medical Examiners unanimously adopted in September 2021 a statement that said doctors spreading COVID misinformation – such as suggesting that vaccines contain microchips – could jeopardize their license to practice.

“I’m very glad that we’re taking this step,” Dr. Stephen Loyd, MD, the panel’s vice president, said at the time. “If you’re spreading this willful misinformation, for me it’s going to be really hard to do anything other than put you on probation or take your license for a year. There has to be a message sent for this. It’s not okay.”

The board’s statement was posted on a government website.

The growing tension in Tennessee between conservative lawmakers and the state’s medical board may be the most prominent example in the country. But the Federation of State Medical Boards, which created the language adopted by at least 15 state boards, is tracking legislation introduced by Republicans in at least 14 states that would restrict a medical board’s authority to discipline doctors for their advice on COVID.

Humayun Chaudhry, DO, the federation’s CEO, called it “an unwelcome trend.” The nonprofit association, based in Euless, Tex., said the statement is merely a COVID-specific restatement of an existing rule: that doctors who engage in behavior that puts patients at risk could face disciplinary action.

Although doctors have leeway to decide which treatments to provide, the medical boards that oversee them have broad authority over licensing. Often, doctors are investigated for violating guidelines on prescribing high-powered drugs. But physicians are sometimes punished for other “unprofessional conduct.” In 2013, Tennessee’s board fined U.S. Rep. Scott DesJarlais for separately having sexual relations with two female patients more than a decade earlier.

Still, stopping doctors from sharing unsound medical advice has proved challenging. Even defining misinformation has been difficult. And during the pandemic, resistance from some state legislatures is complicating the effort.

A relatively small group of physicians peddle COVID misinformation, but many of them associate with America’s Frontline Doctors. Its founder, Simone Gold, MD, has claimed patients are dying from COVID treatments, not the virus itself. Sherri Tenpenny, DO, said in a legislative hearing in Ohio that the COVID vaccine could magnetize patients. Stella Immanuel, MD, has pushed hydroxychloroquine as a COVID cure in Texas, although clinical trials showed that it had no benefit. None of them agreed to requests for comment.

The Texas Medical Board fined Dr. Immanuel $500 for not informing a patient of the risks associated with using hydroxychloroquine as an off-label COVID treatment.

In Tennessee, state lawmakers called a special legislative session in October to address COVID restrictions, and Republican Gov. Bill Lee signed a sweeping package of bills that push back against pandemic rules. One included language directed at the medical board’s recent COVID policy statement, making it more difficult for the panel to investigate complaints about physicians’ advice on COVID vaccines or treatments.

In November, Republican state Rep. John Ragan sent the medical board a letter demanding that the statement be deleted from the state’s website. Rep. Ragan leads a legislative panel that had raised the prospect of defunding the state’s health department over its promotion of COVID vaccines to teens.

Among his demands, Rep. Ragan listed 20 questions he wanted the medical board to answer in writing, including why the misinformation “policy” was proposed nearly two years into the pandemic, which scholars would determine what constitutes misinformation, and how was the “policy” not an infringement on the doctor-patient relationship.

“If you fail to act promptly, your organization will be required to appear before the Joint Government Operations Committee to explain your inaction,” Rep. Ragan wrote in the letter, obtained by Kaiser Health News and Nashville Public Radio.

In response to a request for comment, Rep. Ragan said that “any executive agency, including Board of Medical Examiners, that refuses to follow the law is subject to dissolution.”

He set a deadline of Dec. 7.

In Florida, a Republican-sponsored bill making its way through the state legislature proposes to ban medical boards from revoking or threatening to revoke doctors’ licenses for what they say unless “direct physical harm” of a patient occurred. If the publicized complaint can’t be proved, the board could owe a doctor up to $1.5 million in damages.

Although Florida’s medical board has not adopted the Federation of State Medical Boards’ COVID misinformation statement, the panel has considered misinformation complaints against physicians, including the state’s surgeon general, Joseph Ladapo, MD, PhD.

Dr. Chaudhry said he’s surprised just how many COVID-related complaints are being filed across the country. Often, boards do not publicize investigations before a violation of ethics or standards is confirmed. But in response to a survey by the federation in late 2021, two-thirds of state boards reported an increase in misinformation complaints. And the federation said 12 boards had taken action against a licensed physician.

“At the end of the day, if a physician who is licensed engages in activity that causes harm, the state medical boards are the ones that historically have been set up to look into the situation and make a judgment about what happened or didn’t happen,” Dr. Chaudhry said. “And if you start to chip away at that, it becomes a slippery slope.”

The Georgia Composite Medical Board adopted a version of the federation’s misinformation guidance in early November and has been receiving 10-20 complaints each month, said Debi Dalton, MD, the chairperson. Two months in, no one had been sanctioned.

Dr. Dalton said that even putting out a misinformation policy leaves some “gray” area. Generally, physicians are expected to follow the “consensus,” rather than “the newest information that pops up on social media,” she said.

“We expect physicians to think ethically, professionally, and with the safety of patients in mind,” Dr. Dalton said.

A few physician groups are resisting attempts to root out misinformation, including the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, known for its stands against government regulation.

Some medical boards have opted against taking a public stand against misinformation.

The Alabama Board of Medical Examiners discussed signing on to the federation’s statement, according to the minutes from an October meeting. But after debating the potential legal ramifications in a private executive session, the board opted not to act.

In Tennessee, the Board of Medical Examiners met on the day Rep. Ragan had set as the deadline and voted to remove the misinformation statement from its website to avoid being called into a legislative hearing. But then, in late January, the board decided to stick with the policy – although it did not republish the statement online immediately – and more specifically defined misinformation, calling it “content that is false, inaccurate or misleading, even if spread unintentionally.”

Board members acknowledged they would likely get more pushback from lawmakers but said they wanted to protect their profession from interference.

“Doctors who are putting forth good evidence-based medicine deserve the protection of this board so they can actually say: ‘Hey, I’m in line with this guideline, and this is a source of truth,’” said Melanie Blake, MD, the board’s president. “We should be a source of truth.”

The medical board was looking into nearly 30 open complaints related to COVID when its misinformation statement came down from its website. As of early February, no Tennessee physician had faced disciplinary action.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation. This story is part of a partnership that includes Nashville Public Radio, NPR, and KHN.

16 toddlers with HIV at birth had no detectable virus 2 years later

Hours after their births, 34 infants began a three-drug combination HIV treatment. Now, 2 years later, a third of those toddlers have tested negative for HIV antibodies and have no detectable HIV DNA in their blood. The children aren’t cured of HIV, but as many as 16 of them may be candidates to stop treatment and see if they are in fact in HIV remission.

If one or more are,

At the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Deborah Persaud, MD, interim director of pediatric infectious diseases and professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Md., told this news organization that the evidence suggests that more U.S. clinicians should start infants at high risk for HIV on presumptive treatment – not only to potentially prevent transmission but also to set the child up for the lowest possible viral reservoir, the first step to HIV remission.

The three-drug preemptive treatment is “not uniformly practiced,” Dr. Persaud said in an interview. “We’re at a point now where we don’t have to wait to see if we have remission” to act on these findings, she said. “The question is, should this now become standard of care for in-utero infected infants?”

Every year, about 150 infants are born with HIV in the United States, according to the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation. Current U.S. perinatal treatment guidelines already suggest either treatment with one or more HIV drugs at birth to attempt preventing transmission or initiating three-drug regimens for infants at high risk for perinatally acquired HIV. In this case “high risk” is defined as infants born to:

- people who haven’t received any HIV treatment before delivery or during delivery,

- people who did receive treatment but failed to achieve undetectable viral loads, or

- people who acquire HIV during pregnancy, or who otherwise weren’t diagnosed until after birth.

Trying to replicate the Mississippi baby

The Mississippi baby did eventually relapse. But ever since Dr. Persaud reported the case of that 2-year-old who went into treatment-free remission in 2013, she has been trying to figure out how to duplicate that initial success. There were several factors in that remission, but one piece researchers could control was starting treatment very early – before HIV blood tests even come back positive. So, in this trial, researchers enrolled 440 infants in Africa and Asia at high risk for in utero HIV transmission.

All 440 of those infants received their first doses of the three-drug preemptive treatment within 24 hours of birth. Of those 440 infants, 34 tested positive for HIV and remained in the trial.*

Meanwhile, in North America, South America, and African countries, another 20 infants enrolled in the trial – not as part of the protocol but because their clinicians had been influenced by the news of the Mississippi baby, Dr. Persaud said, and decided on their own to start high-risk infants on three-drug regimens preemptively.

“We wanted to take advantage of those real-world situations of infants being treated outside the clinical trials,” Dr. Persaud said.

Now there were 54 infants trying this very early treatment. In Cohort One, they started their first drug cocktail 7 hours after delivery. In Cohort Two, their first antiretroviral combination treatment was at 32.8 hours of life, and they enrolled in the trial at 8 days. Then researchers followed the infants closely, adding on lopinavir and ritonavir when age-appropriate.

Meeting milestones

To continue in the trial and be considered for treatment interruption, infants had to meet certain milestones. At 24 weeks, HIV RNA needed to be below 200 copies per milliliter. Then their HIV RNA needed to stay below 200 copies consistently until week 48. At week 48, they had to have an HIV RNA that was even lower – below 20 or 40 copies – with “target not detected” in the test in HIV RNA. That’s a sign that there weren’t even any trace levels of viral nucleic acid RNA in the blood to indicate HIV. Then, from week 48 on, they had to maintain that level of viral suppression until age 2.

At that point, not only did they need to maintain that level of viral suppression, they also needed to have a negative HIV antibody test and a PCR test for total HIV DNA, which had to be undetectable down to the limit of 4 copies per 106 – that is, there were fewer than 4 copies of the virus out of 1 million cells tested. Only then would they be considered for treatment interruption.

“After week 28 there was no leeway,” Dr. Persaud said. Then “they had to have nothing detectable from the first year of age. We thought the best shot at remission were cases that achieved very good and strict virologic control.”

Criteria for consideration

Of the 34 infants in Cohort One, 24 infants made it past the first hurdle at 24 weeks and 6 had PCR tests that found no cell-associated HIV DNA. In Cohort Two, 15 made it past the week-24 hurdle and 4 had no detectable HIV DNA via PCR test.

Now, more than 2 years out from study initiation, Dr. Persaud and colleagues are evaluating each child to see if any still meet the requirements for treatment interruption. The COVID-19 pandemic has delayed their evaluations, and it’s possible that fewer children now meet the requirements. But Dr. Persaud said there are still candidates left. An analysis suggests that up to 30% of the children, or 16, were candidates at 2 years.

“We have kids who are eligible for [antiretroviral therapy] cessation years out from this, which I think is really important,” she said in an interview. “It’s not game over.”

And although 30% is not an overwhelming victory, Dr. Persaud said the team’s goal was “to identify an N of 1 to replicate the Mississippi baby.” The study team, led by Ellen Chadwick, MD, of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, and a member of the board that creates HIV perinatal treatment guidelines, is starting a new trial, using more modern, integrase inhibitor-based, three-drug regimens for infants and pairing them with broadly neutralizing antibodies. The combination used in this trial included zidovudine, or AZT.

If one of the children is able to go off treatment, it would be the first step toward creating a functional cure for HIV, starting with the youngest people affected by the virus.

“This trial convinces me that very early treatment was the key strategy that led to remission in the Mississippi baby,” Dr. Persaud said in an interview. “We’re confirming here that the first step toward remission and cure is reducing reservoirs. We’ve got that here. Whether we need more on top of that – therapeutic vaccines, immunotherapies, or a better regimen to start out with – needs to be determined.”

The presentation was met with excitement and questions. For instance, if very early treatment works, why does it work for just 30% of the children?

Were some of the children able to control HIV on their own because they were rare post-treatment controllers? And was 30% really a victory? Others were convinced of it.

“Amazing outcome to have 30% so well suppressed after 2 years with CA-DNA not detected,” commented Hermione Lyall, MBChB, a pediatric infectious disease doctor at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust in the United Kingdom, in the virtual chat.

As for whether the study should change practice, Elaine Abrams, MD, professor of epidemiology and pediatrics at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and CROI cochair, said that this study proves that the three-drug regimen is at the very least safe to start immediately.

Whether it should become standard of care everywhere is still up for discussion, she told this news organization.

“It very much depends on what you’re trying to achieve,” she said. “Postnatal prophylaxis is provided to reduce the risk of acquiring infection. That’s a different objective than early treatment. If you have 1,000 high-risk babies, how many are likely to turn out to have HIV infection? And how many of those will you be treating with three drugs and actually making this impact by doing so? And how many babies are going to be getting possibly extra treatment that they don’t need?”

Regardless, what’s clear is that treatment is essential – for mother and infant, said Carl Dieffenbach, PhD, director of the division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It needs to start, he said, by making sure all mothers know their HIV status and have access early in pregnancy to the treatment that can prevent transmission.

“So much of what’s wrong in the world is about implementation of health care,” he said in an interview. Still, “if you could demonstrate that early treatment to the mother plus early treatment to the babies [is efficacious], we could really talk about an HIV-free generation of kids.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Persaud, Dr. Dieffenbach, Dr. Abrams, and Dr. Lyall all report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Correction, 2/16/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the number that tested positive for HIV and remained in the trial.

This article was updated 2/16/22.

Hours after their births, 34 infants began a three-drug combination HIV treatment. Now, 2 years later, a third of those toddlers have tested negative for HIV antibodies and have no detectable HIV DNA in their blood. The children aren’t cured of HIV, but as many as 16 of them may be candidates to stop treatment and see if they are in fact in HIV remission.

If one or more are,

At the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Deborah Persaud, MD, interim director of pediatric infectious diseases and professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Md., told this news organization that the evidence suggests that more U.S. clinicians should start infants at high risk for HIV on presumptive treatment – not only to potentially prevent transmission but also to set the child up for the lowest possible viral reservoir, the first step to HIV remission.

The three-drug preemptive treatment is “not uniformly practiced,” Dr. Persaud said in an interview. “We’re at a point now where we don’t have to wait to see if we have remission” to act on these findings, she said. “The question is, should this now become standard of care for in-utero infected infants?”

Every year, about 150 infants are born with HIV in the United States, according to the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation. Current U.S. perinatal treatment guidelines already suggest either treatment with one or more HIV drugs at birth to attempt preventing transmission or initiating three-drug regimens for infants at high risk for perinatally acquired HIV. In this case “high risk” is defined as infants born to:

- people who haven’t received any HIV treatment before delivery or during delivery,

- people who did receive treatment but failed to achieve undetectable viral loads, or

- people who acquire HIV during pregnancy, or who otherwise weren’t diagnosed until after birth.

Trying to replicate the Mississippi baby

The Mississippi baby did eventually relapse. But ever since Dr. Persaud reported the case of that 2-year-old who went into treatment-free remission in 2013, she has been trying to figure out how to duplicate that initial success. There were several factors in that remission, but one piece researchers could control was starting treatment very early – before HIV blood tests even come back positive. So, in this trial, researchers enrolled 440 infants in Africa and Asia at high risk for in utero HIV transmission.

All 440 of those infants received their first doses of the three-drug preemptive treatment within 24 hours of birth. Of those 440 infants, 34 tested positive for HIV and remained in the trial.*

Meanwhile, in North America, South America, and African countries, another 20 infants enrolled in the trial – not as part of the protocol but because their clinicians had been influenced by the news of the Mississippi baby, Dr. Persaud said, and decided on their own to start high-risk infants on three-drug regimens preemptively.

“We wanted to take advantage of those real-world situations of infants being treated outside the clinical trials,” Dr. Persaud said.

Now there were 54 infants trying this very early treatment. In Cohort One, they started their first drug cocktail 7 hours after delivery. In Cohort Two, their first antiretroviral combination treatment was at 32.8 hours of life, and they enrolled in the trial at 8 days. Then researchers followed the infants closely, adding on lopinavir and ritonavir when age-appropriate.

Meeting milestones

To continue in the trial and be considered for treatment interruption, infants had to meet certain milestones. At 24 weeks, HIV RNA needed to be below 200 copies per milliliter. Then their HIV RNA needed to stay below 200 copies consistently until week 48. At week 48, they had to have an HIV RNA that was even lower – below 20 or 40 copies – with “target not detected” in the test in HIV RNA. That’s a sign that there weren’t even any trace levels of viral nucleic acid RNA in the blood to indicate HIV. Then, from week 48 on, they had to maintain that level of viral suppression until age 2.

At that point, not only did they need to maintain that level of viral suppression, they also needed to have a negative HIV antibody test and a PCR test for total HIV DNA, which had to be undetectable down to the limit of 4 copies per 106 – that is, there were fewer than 4 copies of the virus out of 1 million cells tested. Only then would they be considered for treatment interruption.

“After week 28 there was no leeway,” Dr. Persaud said. Then “they had to have nothing detectable from the first year of age. We thought the best shot at remission were cases that achieved very good and strict virologic control.”

Criteria for consideration

Of the 34 infants in Cohort One, 24 infants made it past the first hurdle at 24 weeks and 6 had PCR tests that found no cell-associated HIV DNA. In Cohort Two, 15 made it past the week-24 hurdle and 4 had no detectable HIV DNA via PCR test.

Now, more than 2 years out from study initiation, Dr. Persaud and colleagues are evaluating each child to see if any still meet the requirements for treatment interruption. The COVID-19 pandemic has delayed their evaluations, and it’s possible that fewer children now meet the requirements. But Dr. Persaud said there are still candidates left. An analysis suggests that up to 30% of the children, or 16, were candidates at 2 years.

“We have kids who are eligible for [antiretroviral therapy] cessation years out from this, which I think is really important,” she said in an interview. “It’s not game over.”

And although 30% is not an overwhelming victory, Dr. Persaud said the team’s goal was “to identify an N of 1 to replicate the Mississippi baby.” The study team, led by Ellen Chadwick, MD, of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, and a member of the board that creates HIV perinatal treatment guidelines, is starting a new trial, using more modern, integrase inhibitor-based, three-drug regimens for infants and pairing them with broadly neutralizing antibodies. The combination used in this trial included zidovudine, or AZT.

If one of the children is able to go off treatment, it would be the first step toward creating a functional cure for HIV, starting with the youngest people affected by the virus.

“This trial convinces me that very early treatment was the key strategy that led to remission in the Mississippi baby,” Dr. Persaud said in an interview. “We’re confirming here that the first step toward remission and cure is reducing reservoirs. We’ve got that here. Whether we need more on top of that – therapeutic vaccines, immunotherapies, or a better regimen to start out with – needs to be determined.”

The presentation was met with excitement and questions. For instance, if very early treatment works, why does it work for just 30% of the children?

Were some of the children able to control HIV on their own because they were rare post-treatment controllers? And was 30% really a victory? Others were convinced of it.