User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

AHA targets rising prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in children

Obstructive sleep apnea is becoming more common in children and adolescents as the prevalence of obesity increases, but it may also be a preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

The statement focuses on the links between OSA and CVD risk factors in children and adolescents, and reviews diagnostic strategies and treatments. The writing committee reported that 1%-6% of children and adolescents have OSA, as do up to 60% of adolescents considered obese.

The statement was created by the AHA’s Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young subcommittee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Carissa M. Baker-Smith, MD, chair of the writing group chair and director of pediatric preventive cardiology at Nemours Cardiac Center, Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del., explained the rationale for issuing the statement at this time, noting that the relationship between OSA and CVD in adults is well documented.

“There has been less focus on the importance of recognizing and treating sleep apnea in youth,” she said in an interview. “Thus, we felt that it was vitally important to get the word out to parents and to providers that paying attention to the quality and duration of your child’s sleep is vitally important to a child’s long-term heart health. Risk factors for heart disease, when present in childhood, can persist into adulthood.”

Clarity on polysomnography

For making the diagnosis of OSA in children, the statement provides clarity on the use of polysomnography and the role of the apnea-hypopnea index, which is lower in children with OSA than in adults. “One controversy, or at least as I saw it, was whether or not polysomnography testing is always required to make the diagnosis of OSA and before proceeding with tonsil and adenoid removal among children for whom enlarged tonsils and adenoids are present,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Polysomnography testing is not always needed before an ear, nose, and throat surgeon may recommend surgery.”

The statement also noted that history and physical examination may not yield enough reliable information to distinguish OSA from snoring.

In areas where sleep laboratories that work with children aren’t available, alternative tests such as daytime nap polysomnography, nocturnal oximetry, and nocturnal video recording may be used – with a caveat. “These alternative tests have weaker positive and negative predictive values when compared with polysomnography,” the writing committee noted. Home sleep apnea tests aren’t recommended in children. Questionnaires “are useful as screening, but not as diagnostic tools.”

Pediatric patients being evaluated for OSA should also be screened for hypertension and metabolic syndrome, as well as central nervous system and behavioral disorders. Diagnosing OSA in children and adolescents requires “a high index of suspicion,” the committee wrote.

Pediatricians and pediatric cardiologists should exercise that high index of suspicion when receiving referrals for cardiac evaluations for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication, Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Take the time to ask about a child’s sleep – snoring, apnea, etc. – especially if the child has obesity, difficulty focusing during the day, and if there is evidence of systemic hypertension or other signs of metabolic syndrome,” she said.

Risk factors for OSA in children

The statement also reviewed risk factors for OSA, among them obesity, particularly among children younger than 6 years. Other risk factors include upper and lower airway disease, hypotonia, parental history of hyperplasia of the adenoids and tonsils, craniofacial malformations, and neuromuscular disorders. However, the committee cited “limited data” to support that children with congenital heart disease may be at greater risk for OSA and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).

Black children are at significantly greater risk, and socioeconomic factors “may be potential confounders,” the committee stated. Other risk factors include allergic rhinitis and sickle cell disease.

But the statement underscores that “obesity is the main risk factor” for OSA in children and adolescents, and that the presence of increased inflammation may explain this relationship. Steroids may alleviate these symptoms, even in nonobese children, and removal of the adenoids or tonsils is an option to reduce inflammation in children with OSA.

“Obesity is a significant risk factor for sleep disturbances and obstructive sleep apnea, and the severity of sleep apnea may be improved by weight-loss interventions, which then improves metabolic syndrome factors such as insulin sensitivity,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “We need to increase awareness about how the rising prevalence of obesity may be impacting sleep quality in kids and recognize sleep-disordered breathing as something that could contribute to risks for hypertension and later cardiovascular disease.”

Children in whom OSA is suspected should also undergo screening for metabolic syndrome, and central nervous system and behavioral disorders.

Cardiovascular risks

The statement explores the connection between cardiovascular complications and SDB and OSA in depth.

“Inadequate sleep duration of < 5 hours per night in children and adolescents has been linked to an increased risk of hypertension and is also associated with an increased prevalence of obesity,” the committee wrote.

However, the statement left one question hanging: whether OSA alone or obesity cause higher BP in younger patients with OSA. But the committee concluded that BP levels increase with the severity of OSA, although the effects can vary with age. OSA in children peaks between ages 2 and 8, corresponding to the peak prevalence of hypertrophy of the tonsils and adenoids. Children aged 10-11 with more severe OSA may have BP dysregulation, while older adolescents develop higher sustained BP. Obesity may be a confounder for daytime BP elevations, while nighttime hypertension depends less on obesity and more on OSA severity.

“OSA is associated with abnormal BP in youth and, in particular, higher nighttime blood pressures and loss of the normal decline in BP that should occur during sleep,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Children with OSA appear to have higher BP than controls during both sleep and wake times, and BP levels increase with increasing severity of OSA.”

Nonetheless, children with OSA are at greater risk for other cardiovascular problems. Left ventricular hypertrophy may be a secondary outcome. “The presence of obstructive sleep apnea in children is associated with an 11-fold increased risk for LVH in children, a relationship not seen in the presence of primary snoring alone,” Dr. Baker-Smith said.

Dr. Baker-Smith had no relevant disclosures. Coauthor Amal Isaiah, MD, is coinventor of an imaging system for sleep apnea and receives royalties from the University of Maryland. The other coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Obstructive sleep apnea is becoming more common in children and adolescents as the prevalence of obesity increases, but it may also be a preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

The statement focuses on the links between OSA and CVD risk factors in children and adolescents, and reviews diagnostic strategies and treatments. The writing committee reported that 1%-6% of children and adolescents have OSA, as do up to 60% of adolescents considered obese.

The statement was created by the AHA’s Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young subcommittee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Carissa M. Baker-Smith, MD, chair of the writing group chair and director of pediatric preventive cardiology at Nemours Cardiac Center, Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del., explained the rationale for issuing the statement at this time, noting that the relationship between OSA and CVD in adults is well documented.

“There has been less focus on the importance of recognizing and treating sleep apnea in youth,” she said in an interview. “Thus, we felt that it was vitally important to get the word out to parents and to providers that paying attention to the quality and duration of your child’s sleep is vitally important to a child’s long-term heart health. Risk factors for heart disease, when present in childhood, can persist into adulthood.”

Clarity on polysomnography

For making the diagnosis of OSA in children, the statement provides clarity on the use of polysomnography and the role of the apnea-hypopnea index, which is lower in children with OSA than in adults. “One controversy, or at least as I saw it, was whether or not polysomnography testing is always required to make the diagnosis of OSA and before proceeding with tonsil and adenoid removal among children for whom enlarged tonsils and adenoids are present,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Polysomnography testing is not always needed before an ear, nose, and throat surgeon may recommend surgery.”

The statement also noted that history and physical examination may not yield enough reliable information to distinguish OSA from snoring.

In areas where sleep laboratories that work with children aren’t available, alternative tests such as daytime nap polysomnography, nocturnal oximetry, and nocturnal video recording may be used – with a caveat. “These alternative tests have weaker positive and negative predictive values when compared with polysomnography,” the writing committee noted. Home sleep apnea tests aren’t recommended in children. Questionnaires “are useful as screening, but not as diagnostic tools.”

Pediatric patients being evaluated for OSA should also be screened for hypertension and metabolic syndrome, as well as central nervous system and behavioral disorders. Diagnosing OSA in children and adolescents requires “a high index of suspicion,” the committee wrote.

Pediatricians and pediatric cardiologists should exercise that high index of suspicion when receiving referrals for cardiac evaluations for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication, Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Take the time to ask about a child’s sleep – snoring, apnea, etc. – especially if the child has obesity, difficulty focusing during the day, and if there is evidence of systemic hypertension or other signs of metabolic syndrome,” she said.

Risk factors for OSA in children

The statement also reviewed risk factors for OSA, among them obesity, particularly among children younger than 6 years. Other risk factors include upper and lower airway disease, hypotonia, parental history of hyperplasia of the adenoids and tonsils, craniofacial malformations, and neuromuscular disorders. However, the committee cited “limited data” to support that children with congenital heart disease may be at greater risk for OSA and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).

Black children are at significantly greater risk, and socioeconomic factors “may be potential confounders,” the committee stated. Other risk factors include allergic rhinitis and sickle cell disease.

But the statement underscores that “obesity is the main risk factor” for OSA in children and adolescents, and that the presence of increased inflammation may explain this relationship. Steroids may alleviate these symptoms, even in nonobese children, and removal of the adenoids or tonsils is an option to reduce inflammation in children with OSA.

“Obesity is a significant risk factor for sleep disturbances and obstructive sleep apnea, and the severity of sleep apnea may be improved by weight-loss interventions, which then improves metabolic syndrome factors such as insulin sensitivity,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “We need to increase awareness about how the rising prevalence of obesity may be impacting sleep quality in kids and recognize sleep-disordered breathing as something that could contribute to risks for hypertension and later cardiovascular disease.”

Children in whom OSA is suspected should also undergo screening for metabolic syndrome, and central nervous system and behavioral disorders.

Cardiovascular risks

The statement explores the connection between cardiovascular complications and SDB and OSA in depth.

“Inadequate sleep duration of < 5 hours per night in children and adolescents has been linked to an increased risk of hypertension and is also associated with an increased prevalence of obesity,” the committee wrote.

However, the statement left one question hanging: whether OSA alone or obesity cause higher BP in younger patients with OSA. But the committee concluded that BP levels increase with the severity of OSA, although the effects can vary with age. OSA in children peaks between ages 2 and 8, corresponding to the peak prevalence of hypertrophy of the tonsils and adenoids. Children aged 10-11 with more severe OSA may have BP dysregulation, while older adolescents develop higher sustained BP. Obesity may be a confounder for daytime BP elevations, while nighttime hypertension depends less on obesity and more on OSA severity.

“OSA is associated with abnormal BP in youth and, in particular, higher nighttime blood pressures and loss of the normal decline in BP that should occur during sleep,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Children with OSA appear to have higher BP than controls during both sleep and wake times, and BP levels increase with increasing severity of OSA.”

Nonetheless, children with OSA are at greater risk for other cardiovascular problems. Left ventricular hypertrophy may be a secondary outcome. “The presence of obstructive sleep apnea in children is associated with an 11-fold increased risk for LVH in children, a relationship not seen in the presence of primary snoring alone,” Dr. Baker-Smith said.

Dr. Baker-Smith had no relevant disclosures. Coauthor Amal Isaiah, MD, is coinventor of an imaging system for sleep apnea and receives royalties from the University of Maryland. The other coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Obstructive sleep apnea is becoming more common in children and adolescents as the prevalence of obesity increases, but it may also be a preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

The statement focuses on the links between OSA and CVD risk factors in children and adolescents, and reviews diagnostic strategies and treatments. The writing committee reported that 1%-6% of children and adolescents have OSA, as do up to 60% of adolescents considered obese.

The statement was created by the AHA’s Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young subcommittee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Carissa M. Baker-Smith, MD, chair of the writing group chair and director of pediatric preventive cardiology at Nemours Cardiac Center, Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del., explained the rationale for issuing the statement at this time, noting that the relationship between OSA and CVD in adults is well documented.

“There has been less focus on the importance of recognizing and treating sleep apnea in youth,” she said in an interview. “Thus, we felt that it was vitally important to get the word out to parents and to providers that paying attention to the quality and duration of your child’s sleep is vitally important to a child’s long-term heart health. Risk factors for heart disease, when present in childhood, can persist into adulthood.”

Clarity on polysomnography

For making the diagnosis of OSA in children, the statement provides clarity on the use of polysomnography and the role of the apnea-hypopnea index, which is lower in children with OSA than in adults. “One controversy, or at least as I saw it, was whether or not polysomnography testing is always required to make the diagnosis of OSA and before proceeding with tonsil and adenoid removal among children for whom enlarged tonsils and adenoids are present,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Polysomnography testing is not always needed before an ear, nose, and throat surgeon may recommend surgery.”

The statement also noted that history and physical examination may not yield enough reliable information to distinguish OSA from snoring.

In areas where sleep laboratories that work with children aren’t available, alternative tests such as daytime nap polysomnography, nocturnal oximetry, and nocturnal video recording may be used – with a caveat. “These alternative tests have weaker positive and negative predictive values when compared with polysomnography,” the writing committee noted. Home sleep apnea tests aren’t recommended in children. Questionnaires “are useful as screening, but not as diagnostic tools.”

Pediatric patients being evaluated for OSA should also be screened for hypertension and metabolic syndrome, as well as central nervous system and behavioral disorders. Diagnosing OSA in children and adolescents requires “a high index of suspicion,” the committee wrote.

Pediatricians and pediatric cardiologists should exercise that high index of suspicion when receiving referrals for cardiac evaluations for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication, Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Take the time to ask about a child’s sleep – snoring, apnea, etc. – especially if the child has obesity, difficulty focusing during the day, and if there is evidence of systemic hypertension or other signs of metabolic syndrome,” she said.

Risk factors for OSA in children

The statement also reviewed risk factors for OSA, among them obesity, particularly among children younger than 6 years. Other risk factors include upper and lower airway disease, hypotonia, parental history of hyperplasia of the adenoids and tonsils, craniofacial malformations, and neuromuscular disorders. However, the committee cited “limited data” to support that children with congenital heart disease may be at greater risk for OSA and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).

Black children are at significantly greater risk, and socioeconomic factors “may be potential confounders,” the committee stated. Other risk factors include allergic rhinitis and sickle cell disease.

But the statement underscores that “obesity is the main risk factor” for OSA in children and adolescents, and that the presence of increased inflammation may explain this relationship. Steroids may alleviate these symptoms, even in nonobese children, and removal of the adenoids or tonsils is an option to reduce inflammation in children with OSA.

“Obesity is a significant risk factor for sleep disturbances and obstructive sleep apnea, and the severity of sleep apnea may be improved by weight-loss interventions, which then improves metabolic syndrome factors such as insulin sensitivity,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “We need to increase awareness about how the rising prevalence of obesity may be impacting sleep quality in kids and recognize sleep-disordered breathing as something that could contribute to risks for hypertension and later cardiovascular disease.”

Children in whom OSA is suspected should also undergo screening for metabolic syndrome, and central nervous system and behavioral disorders.

Cardiovascular risks

The statement explores the connection between cardiovascular complications and SDB and OSA in depth.

“Inadequate sleep duration of < 5 hours per night in children and adolescents has been linked to an increased risk of hypertension and is also associated with an increased prevalence of obesity,” the committee wrote.

However, the statement left one question hanging: whether OSA alone or obesity cause higher BP in younger patients with OSA. But the committee concluded that BP levels increase with the severity of OSA, although the effects can vary with age. OSA in children peaks between ages 2 and 8, corresponding to the peak prevalence of hypertrophy of the tonsils and adenoids. Children aged 10-11 with more severe OSA may have BP dysregulation, while older adolescents develop higher sustained BP. Obesity may be a confounder for daytime BP elevations, while nighttime hypertension depends less on obesity and more on OSA severity.

“OSA is associated with abnormal BP in youth and, in particular, higher nighttime blood pressures and loss of the normal decline in BP that should occur during sleep,” Dr. Baker-Smith said. “Children with OSA appear to have higher BP than controls during both sleep and wake times, and BP levels increase with increasing severity of OSA.”

Nonetheless, children with OSA are at greater risk for other cardiovascular problems. Left ventricular hypertrophy may be a secondary outcome. “The presence of obstructive sleep apnea in children is associated with an 11-fold increased risk for LVH in children, a relationship not seen in the presence of primary snoring alone,” Dr. Baker-Smith said.

Dr. Baker-Smith had no relevant disclosures. Coauthor Amal Isaiah, MD, is coinventor of an imaging system for sleep apnea and receives royalties from the University of Maryland. The other coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

COVID booster may benefit active-treatment cancer patients

A COVID-19 booster shot may be beneficial for patients with cancer who are undergoing treatment, according to new findings from an Israeli case-control study.

The seropositivity rate among the patients with cancer remained high (87%) about 4 months after the patients had received the second BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) vaccination. However, the median IgG titer in the patients and the control persons who were without cancer decreased over time. Notably, in a previous analysis that the authors conducted and in the current one, the IgG titers were statistically significantly lower in the patients with cancer as compared to control persons.

The correlation between antibody levels following vaccination and clinical protection has yet to be proven, but the accumulating evidence supports antibody response as a possible correlate of disease protection.

“Our data can’t predict if a third booster dose is necessary,” said study author Salomon M. Stemmer, MD, professor at the Institute of Oncology of Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel. “It does seem quite logical that a booster dose will cause an increase in IgG levels.”

The findings were published Aug. 11, 2021, in a research letter in JAMA Oncology.

In their previous study, Dr. Stemmer and colleagues compared the rates of anti–spike antibody response to the initial shot of the BNT162b2 vaccine among 102 adults with solid-tumor cancers who were undergoing treatment with that of 78 healthy control persons. They found that a high percentage of patients undergoing treatment for cancer (90%) achieved a sufficient antibody response to the BNT162b2 vaccine.

Booster endorsed

Responses to COVID-19 vaccination have varied among patients with cancer. For patients with solid tumors, responses have been good even while the patients were receiving systemic therapy. However, among patients with blood cancers, particularly those receiving immunosuppressive therapies, responses have been poor. Studies have identified factors associated with a poor response, but it has been unclear whether to recommend booster shots.

In August the Food and Drug Administration authorized a third dose of either the Pfizer or the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for all individuals with compromised immune systems. Those eligible for a third dose include solid-organ transplant recipients, those undergoing cancer treatments, and people with autoimmune diseases that suppress their immune systems.

IgG titers lower in cancer patients

In the current analysis, the authors evaluated the anti-S response in the patients with cancer approximately 4 months after they had received the second vaccine dose. They compared the responses in those patients with the responses in a control group.

The cohort included 95 patients from the prior study and 66 control persons. The most common malignancies were gastrointestinal (26%), lung (25%), and breast (18%).

All patients were receiving systemic therapy. Chemotherapy was the most common (28%), followed by immunotherapy (21%) and combination chemotherapy/biological therapy (20%).

At a median of 123 days after the second vaccination, 83 patients with cancer (87%) and all of the control patients (100%) were seropositive for anti-S IgG antibodies. The median titer levels were significantly lower among case patients as compared with control patients (417 AU/mL [interquartile range, 136-895] vs. 1,220 AU/mL [IQR, 588-1,987]; P < .001)

There was a 3.6-fold range in median titer values across tumor types and an even wider range (8.8-fold) across the different types of treatment. The lowest titers were observed among patients who had received immunotherapy plus chemotherapy/biological therapy (median [IQR], 94.4 [49.4-191] AU/mL vs. 147 [62.8-339] AU/mL).

In an exploratory multivariable analysis, treatments with chemotherapy plus immunotherapy and immunotherapy plus biological therapy were significantly associated with lower IgG titers.

No downside for cancer patients

The Biden administration announced a plan to begin booster COVID-19 vaccinations for all American adults in September, with recommendations that the third vaccine be given at least 8 months after the second mRNA vaccine dose.

Jeremy M. Levin, DPhil, the chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics, explained that, concerning boosters, “it is inconceivable that we will have all data at this stage.

“Knowledge about how boosters work and don’t work and when you should ideally have them is imperfect,” he told this news organization. “However, we can have a lot of confidence in the fact that hundreds of millions of people have received the vaccine, so we know a lot about the safety and efficacy.”

Immunocompromised adults represent less than 5% of the total population, and most of the available data on vaccination are from patients who have undergone solid-organ transplant, Dr. Levin explained. Studies have shown that their response is less robust to vaccination in comparison with adults in the general population.

“Although it is still preliminary, the strongest data come from Israel,” he said, “where they found that the booster was highly effective and doubled the number of transplant patients who developed antibodies.”

But data are not yet available in the setting of cancer. “But even though we don’t have the data yet, the answer is that no matter, the booster process is essential,” he said. “The evidence we have is that boosters raise the immune response, and it is the best data we have now.”

Martin J. Edelman, MD, chair, department of hematology/oncology, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, noted that the current recommendation is that patients who are immunocompromised receive a booster immediately.

At his health system, this is interpreted to include patients who have undergone the following treatments: Transplant (solid-organ and bone marrow transplant), hemodialysis, hematologic malignancy treatment, active immunosuppressive (chemotherapy, chemoimmunotherapy, and nonhormonal or single-agent immunotherapy) treatment, rheumatology treatments, and high-dose steroids.

“As for cancer patients, we are making arrangements to vaccinate patients who meet the above criteria now,” he said. “There is no known downside to receiving booster immediately. While there may be less of a response than waiting for completion of treatment, we know that patients on active therapy are frequently able to mount a response, and any response is better than none.”

Dr. Edelman added that this area is changing very rapidly. “We will modify our approach as information and guidance from appropriate organizations, such as the FDA and CDC, become available.”

Dr. Stemmer has received institutional research grants from CAN-FITE, AstraZeneca, Bioline RX, BMS, Halozyme, Clovis Oncology, CTG Pharma, Exelixis, Geicam, Incyte, Lilly, Moderna, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Roche, and owns stocks and options in CTG Pharma, DocBoxMD, Tyrnovo, VYPE, Cytora, and CAN-FITE. Dr. Edelman has received personal fees and other compensation from Windmil, Biomarker Strategies, AstraZeneca, Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline, Apexigen, Nektar, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Armo, Bergen Bio, and Apexigen outside the submitted work. He has submitted a patent for epigenetic modifications to increase susceptibility to radiopharmaceuticals and is a paid adviser for Kanaph and Flame. Dr. Levin is chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A COVID-19 booster shot may be beneficial for patients with cancer who are undergoing treatment, according to new findings from an Israeli case-control study.

The seropositivity rate among the patients with cancer remained high (87%) about 4 months after the patients had received the second BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) vaccination. However, the median IgG titer in the patients and the control persons who were without cancer decreased over time. Notably, in a previous analysis that the authors conducted and in the current one, the IgG titers were statistically significantly lower in the patients with cancer as compared to control persons.

The correlation between antibody levels following vaccination and clinical protection has yet to be proven, but the accumulating evidence supports antibody response as a possible correlate of disease protection.

“Our data can’t predict if a third booster dose is necessary,” said study author Salomon M. Stemmer, MD, professor at the Institute of Oncology of Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel. “It does seem quite logical that a booster dose will cause an increase in IgG levels.”

The findings were published Aug. 11, 2021, in a research letter in JAMA Oncology.

In their previous study, Dr. Stemmer and colleagues compared the rates of anti–spike antibody response to the initial shot of the BNT162b2 vaccine among 102 adults with solid-tumor cancers who were undergoing treatment with that of 78 healthy control persons. They found that a high percentage of patients undergoing treatment for cancer (90%) achieved a sufficient antibody response to the BNT162b2 vaccine.

Booster endorsed

Responses to COVID-19 vaccination have varied among patients with cancer. For patients with solid tumors, responses have been good even while the patients were receiving systemic therapy. However, among patients with blood cancers, particularly those receiving immunosuppressive therapies, responses have been poor. Studies have identified factors associated with a poor response, but it has been unclear whether to recommend booster shots.

In August the Food and Drug Administration authorized a third dose of either the Pfizer or the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for all individuals with compromised immune systems. Those eligible for a third dose include solid-organ transplant recipients, those undergoing cancer treatments, and people with autoimmune diseases that suppress their immune systems.

IgG titers lower in cancer patients

In the current analysis, the authors evaluated the anti-S response in the patients with cancer approximately 4 months after they had received the second vaccine dose. They compared the responses in those patients with the responses in a control group.

The cohort included 95 patients from the prior study and 66 control persons. The most common malignancies were gastrointestinal (26%), lung (25%), and breast (18%).

All patients were receiving systemic therapy. Chemotherapy was the most common (28%), followed by immunotherapy (21%) and combination chemotherapy/biological therapy (20%).

At a median of 123 days after the second vaccination, 83 patients with cancer (87%) and all of the control patients (100%) were seropositive for anti-S IgG antibodies. The median titer levels were significantly lower among case patients as compared with control patients (417 AU/mL [interquartile range, 136-895] vs. 1,220 AU/mL [IQR, 588-1,987]; P < .001)

There was a 3.6-fold range in median titer values across tumor types and an even wider range (8.8-fold) across the different types of treatment. The lowest titers were observed among patients who had received immunotherapy plus chemotherapy/biological therapy (median [IQR], 94.4 [49.4-191] AU/mL vs. 147 [62.8-339] AU/mL).

In an exploratory multivariable analysis, treatments with chemotherapy plus immunotherapy and immunotherapy plus biological therapy were significantly associated with lower IgG titers.

No downside for cancer patients

The Biden administration announced a plan to begin booster COVID-19 vaccinations for all American adults in September, with recommendations that the third vaccine be given at least 8 months after the second mRNA vaccine dose.

Jeremy M. Levin, DPhil, the chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics, explained that, concerning boosters, “it is inconceivable that we will have all data at this stage.

“Knowledge about how boosters work and don’t work and when you should ideally have them is imperfect,” he told this news organization. “However, we can have a lot of confidence in the fact that hundreds of millions of people have received the vaccine, so we know a lot about the safety and efficacy.”

Immunocompromised adults represent less than 5% of the total population, and most of the available data on vaccination are from patients who have undergone solid-organ transplant, Dr. Levin explained. Studies have shown that their response is less robust to vaccination in comparison with adults in the general population.

“Although it is still preliminary, the strongest data come from Israel,” he said, “where they found that the booster was highly effective and doubled the number of transplant patients who developed antibodies.”

But data are not yet available in the setting of cancer. “But even though we don’t have the data yet, the answer is that no matter, the booster process is essential,” he said. “The evidence we have is that boosters raise the immune response, and it is the best data we have now.”

Martin J. Edelman, MD, chair, department of hematology/oncology, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, noted that the current recommendation is that patients who are immunocompromised receive a booster immediately.

At his health system, this is interpreted to include patients who have undergone the following treatments: Transplant (solid-organ and bone marrow transplant), hemodialysis, hematologic malignancy treatment, active immunosuppressive (chemotherapy, chemoimmunotherapy, and nonhormonal or single-agent immunotherapy) treatment, rheumatology treatments, and high-dose steroids.

“As for cancer patients, we are making arrangements to vaccinate patients who meet the above criteria now,” he said. “There is no known downside to receiving booster immediately. While there may be less of a response than waiting for completion of treatment, we know that patients on active therapy are frequently able to mount a response, and any response is better than none.”

Dr. Edelman added that this area is changing very rapidly. “We will modify our approach as information and guidance from appropriate organizations, such as the FDA and CDC, become available.”

Dr. Stemmer has received institutional research grants from CAN-FITE, AstraZeneca, Bioline RX, BMS, Halozyme, Clovis Oncology, CTG Pharma, Exelixis, Geicam, Incyte, Lilly, Moderna, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Roche, and owns stocks and options in CTG Pharma, DocBoxMD, Tyrnovo, VYPE, Cytora, and CAN-FITE. Dr. Edelman has received personal fees and other compensation from Windmil, Biomarker Strategies, AstraZeneca, Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline, Apexigen, Nektar, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Armo, Bergen Bio, and Apexigen outside the submitted work. He has submitted a patent for epigenetic modifications to increase susceptibility to radiopharmaceuticals and is a paid adviser for Kanaph and Flame. Dr. Levin is chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A COVID-19 booster shot may be beneficial for patients with cancer who are undergoing treatment, according to new findings from an Israeli case-control study.

The seropositivity rate among the patients with cancer remained high (87%) about 4 months after the patients had received the second BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) vaccination. However, the median IgG titer in the patients and the control persons who were without cancer decreased over time. Notably, in a previous analysis that the authors conducted and in the current one, the IgG titers were statistically significantly lower in the patients with cancer as compared to control persons.

The correlation between antibody levels following vaccination and clinical protection has yet to be proven, but the accumulating evidence supports antibody response as a possible correlate of disease protection.

“Our data can’t predict if a third booster dose is necessary,” said study author Salomon M. Stemmer, MD, professor at the Institute of Oncology of Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel. “It does seem quite logical that a booster dose will cause an increase in IgG levels.”

The findings were published Aug. 11, 2021, in a research letter in JAMA Oncology.

In their previous study, Dr. Stemmer and colleagues compared the rates of anti–spike antibody response to the initial shot of the BNT162b2 vaccine among 102 adults with solid-tumor cancers who were undergoing treatment with that of 78 healthy control persons. They found that a high percentage of patients undergoing treatment for cancer (90%) achieved a sufficient antibody response to the BNT162b2 vaccine.

Booster endorsed

Responses to COVID-19 vaccination have varied among patients with cancer. For patients with solid tumors, responses have been good even while the patients were receiving systemic therapy. However, among patients with blood cancers, particularly those receiving immunosuppressive therapies, responses have been poor. Studies have identified factors associated with a poor response, but it has been unclear whether to recommend booster shots.

In August the Food and Drug Administration authorized a third dose of either the Pfizer or the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for all individuals with compromised immune systems. Those eligible for a third dose include solid-organ transplant recipients, those undergoing cancer treatments, and people with autoimmune diseases that suppress their immune systems.

IgG titers lower in cancer patients

In the current analysis, the authors evaluated the anti-S response in the patients with cancer approximately 4 months after they had received the second vaccine dose. They compared the responses in those patients with the responses in a control group.

The cohort included 95 patients from the prior study and 66 control persons. The most common malignancies were gastrointestinal (26%), lung (25%), and breast (18%).

All patients were receiving systemic therapy. Chemotherapy was the most common (28%), followed by immunotherapy (21%) and combination chemotherapy/biological therapy (20%).

At a median of 123 days after the second vaccination, 83 patients with cancer (87%) and all of the control patients (100%) were seropositive for anti-S IgG antibodies. The median titer levels were significantly lower among case patients as compared with control patients (417 AU/mL [interquartile range, 136-895] vs. 1,220 AU/mL [IQR, 588-1,987]; P < .001)

There was a 3.6-fold range in median titer values across tumor types and an even wider range (8.8-fold) across the different types of treatment. The lowest titers were observed among patients who had received immunotherapy plus chemotherapy/biological therapy (median [IQR], 94.4 [49.4-191] AU/mL vs. 147 [62.8-339] AU/mL).

In an exploratory multivariable analysis, treatments with chemotherapy plus immunotherapy and immunotherapy plus biological therapy were significantly associated with lower IgG titers.

No downside for cancer patients

The Biden administration announced a plan to begin booster COVID-19 vaccinations for all American adults in September, with recommendations that the third vaccine be given at least 8 months after the second mRNA vaccine dose.

Jeremy M. Levin, DPhil, the chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics, explained that, concerning boosters, “it is inconceivable that we will have all data at this stage.

“Knowledge about how boosters work and don’t work and when you should ideally have them is imperfect,” he told this news organization. “However, we can have a lot of confidence in the fact that hundreds of millions of people have received the vaccine, so we know a lot about the safety and efficacy.”

Immunocompromised adults represent less than 5% of the total population, and most of the available data on vaccination are from patients who have undergone solid-organ transplant, Dr. Levin explained. Studies have shown that their response is less robust to vaccination in comparison with adults in the general population.

“Although it is still preliminary, the strongest data come from Israel,” he said, “where they found that the booster was highly effective and doubled the number of transplant patients who developed antibodies.”

But data are not yet available in the setting of cancer. “But even though we don’t have the data yet, the answer is that no matter, the booster process is essential,” he said. “The evidence we have is that boosters raise the immune response, and it is the best data we have now.”

Martin J. Edelman, MD, chair, department of hematology/oncology, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, noted that the current recommendation is that patients who are immunocompromised receive a booster immediately.

At his health system, this is interpreted to include patients who have undergone the following treatments: Transplant (solid-organ and bone marrow transplant), hemodialysis, hematologic malignancy treatment, active immunosuppressive (chemotherapy, chemoimmunotherapy, and nonhormonal or single-agent immunotherapy) treatment, rheumatology treatments, and high-dose steroids.

“As for cancer patients, we are making arrangements to vaccinate patients who meet the above criteria now,” he said. “There is no known downside to receiving booster immediately. While there may be less of a response than waiting for completion of treatment, we know that patients on active therapy are frequently able to mount a response, and any response is better than none.”

Dr. Edelman added that this area is changing very rapidly. “We will modify our approach as information and guidance from appropriate organizations, such as the FDA and CDC, become available.”

Dr. Stemmer has received institutional research grants from CAN-FITE, AstraZeneca, Bioline RX, BMS, Halozyme, Clovis Oncology, CTG Pharma, Exelixis, Geicam, Incyte, Lilly, Moderna, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Roche, and owns stocks and options in CTG Pharma, DocBoxMD, Tyrnovo, VYPE, Cytora, and CAN-FITE. Dr. Edelman has received personal fees and other compensation from Windmil, Biomarker Strategies, AstraZeneca, Takeda, GlaxoSmithKline, Apexigen, Nektar, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Armo, Bergen Bio, and Apexigen outside the submitted work. He has submitted a patent for epigenetic modifications to increase susceptibility to radiopharmaceuticals and is a paid adviser for Kanaph and Flame. Dr. Levin is chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: New cases soar to near-record level

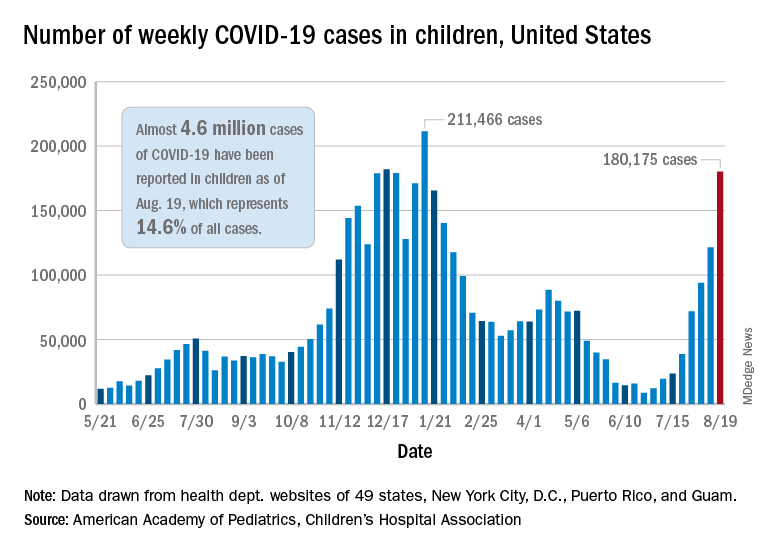

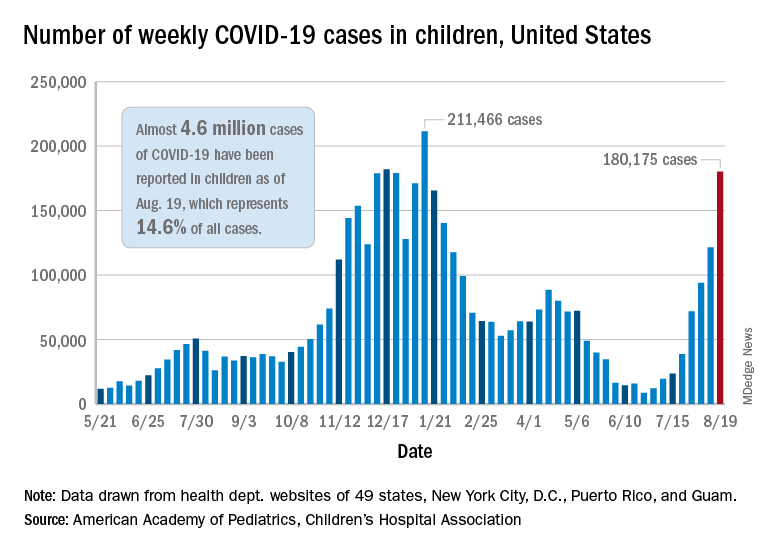

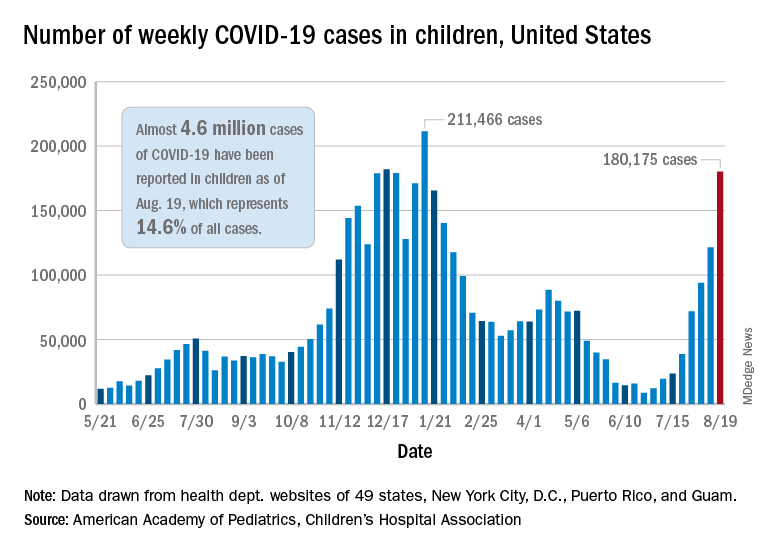

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children jumped by nearly 50% in the United States, posting the highest count since hitting a pandemic high back in mid-January, a new report shows.

The latest weekly figure represents a 48% increase over the previous week and an increase of over 2,000% in the 8 weeks since the national count dropped to a low of 8,500 cases for the week of June 18-24, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID report.

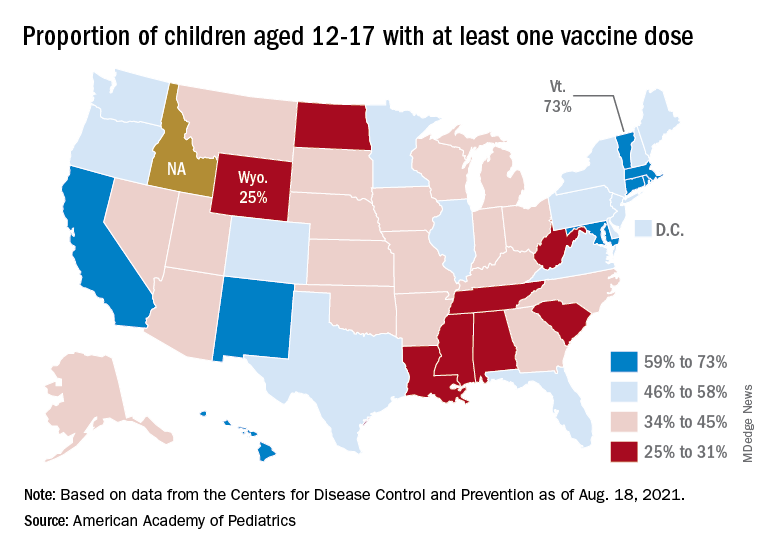

Vaccinations, in the meantime, appear to be headed in the opposite direction. Vaccine initiations were down for the second consecutive week, falling by 18% among 12- to 15-year-olds and by 15% in those aged 16-17 years, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, about 47% of children aged 12-15 and 56% of those aged 16-17 have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of Aug. 23, with 34% and 44%, respectively, reaching full vaccination. The total number of children with at least one dose is 11.6 million, including a relatively small number (about 200,000) of children under age 12 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

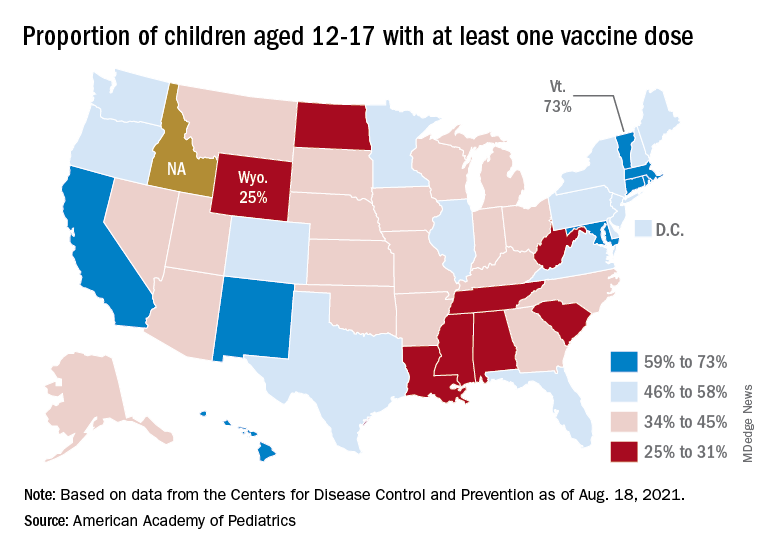

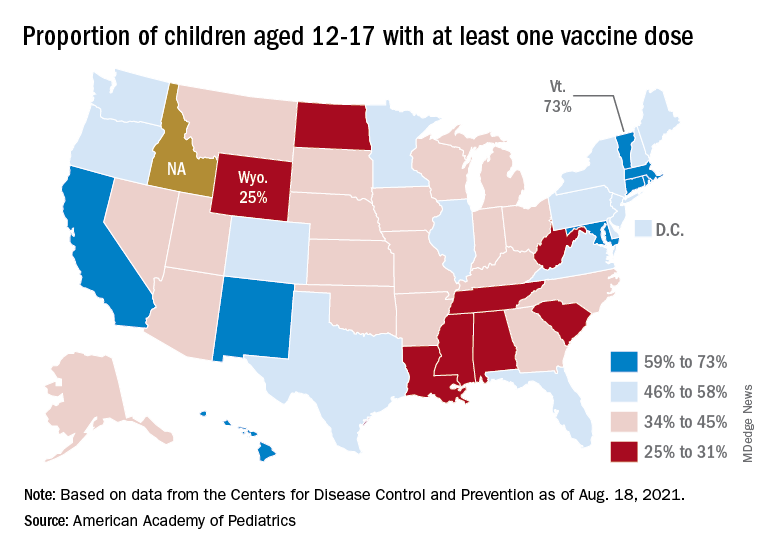

At the state level, vaccination is a source of considerable disparity. In Vermont, 73% of children aged 12-17 had received at least one dose by Aug. 18, and 63% were fully vaccinated. In Wyoming, however, just 25% of children had received at least one dose (17% are fully vaccinated), while Alabama has a lowest-in-the-nation full vaccination rate of 14%, based on a separate AAP analysis of CDC data.

There are seven states in which over 60% of 12- to 17-year-olds have at least started the vaccine regimen and five states where less than 30% have received at least one dose, the AAP noted.

Back on the incidence side of the pandemic, Mississippi and Hawaii had the largest increases in new cases over the past 2 weeks, followed by Florida and West Virginia. Cumulative figures show that California has had the most cases overall in children (550,337), Vermont has the highest proportion of all cases in children (22.9%), and Rhode Island has the highest rate of cases per 100,000 (10,636), the AAP and CHA said in the joint report based on data from 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Add up all those jurisdictions, and it works out to 4.6 million children infected with SARS-CoV-2 as of Aug. 19, with children representing 14.6% of all cases since the start of the pandemic. There have been over 18,000 hospitalizations so far, which is just 2.3% of the total for all ages in the 23 states (and New York City) that are reporting such data on their health department websites, the AAP and CHA said.

The number of COVID-related deaths in children is now 402 after the largest 1-week increase (24) since late May of 2020, when the AAP/CHA coverage began. Mortality data by age are available from 44 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children jumped by nearly 50% in the United States, posting the highest count since hitting a pandemic high back in mid-January, a new report shows.

The latest weekly figure represents a 48% increase over the previous week and an increase of over 2,000% in the 8 weeks since the national count dropped to a low of 8,500 cases for the week of June 18-24, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID report.

Vaccinations, in the meantime, appear to be headed in the opposite direction. Vaccine initiations were down for the second consecutive week, falling by 18% among 12- to 15-year-olds and by 15% in those aged 16-17 years, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, about 47% of children aged 12-15 and 56% of those aged 16-17 have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of Aug. 23, with 34% and 44%, respectively, reaching full vaccination. The total number of children with at least one dose is 11.6 million, including a relatively small number (about 200,000) of children under age 12 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

At the state level, vaccination is a source of considerable disparity. In Vermont, 73% of children aged 12-17 had received at least one dose by Aug. 18, and 63% were fully vaccinated. In Wyoming, however, just 25% of children had received at least one dose (17% are fully vaccinated), while Alabama has a lowest-in-the-nation full vaccination rate of 14%, based on a separate AAP analysis of CDC data.

There are seven states in which over 60% of 12- to 17-year-olds have at least started the vaccine regimen and five states where less than 30% have received at least one dose, the AAP noted.

Back on the incidence side of the pandemic, Mississippi and Hawaii had the largest increases in new cases over the past 2 weeks, followed by Florida and West Virginia. Cumulative figures show that California has had the most cases overall in children (550,337), Vermont has the highest proportion of all cases in children (22.9%), and Rhode Island has the highest rate of cases per 100,000 (10,636), the AAP and CHA said in the joint report based on data from 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Add up all those jurisdictions, and it works out to 4.6 million children infected with SARS-CoV-2 as of Aug. 19, with children representing 14.6% of all cases since the start of the pandemic. There have been over 18,000 hospitalizations so far, which is just 2.3% of the total for all ages in the 23 states (and New York City) that are reporting such data on their health department websites, the AAP and CHA said.

The number of COVID-related deaths in children is now 402 after the largest 1-week increase (24) since late May of 2020, when the AAP/CHA coverage began. Mortality data by age are available from 44 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children jumped by nearly 50% in the United States, posting the highest count since hitting a pandemic high back in mid-January, a new report shows.

The latest weekly figure represents a 48% increase over the previous week and an increase of over 2,000% in the 8 weeks since the national count dropped to a low of 8,500 cases for the week of June 18-24, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID report.

Vaccinations, in the meantime, appear to be headed in the opposite direction. Vaccine initiations were down for the second consecutive week, falling by 18% among 12- to 15-year-olds and by 15% in those aged 16-17 years, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, about 47% of children aged 12-15 and 56% of those aged 16-17 have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of Aug. 23, with 34% and 44%, respectively, reaching full vaccination. The total number of children with at least one dose is 11.6 million, including a relatively small number (about 200,000) of children under age 12 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

At the state level, vaccination is a source of considerable disparity. In Vermont, 73% of children aged 12-17 had received at least one dose by Aug. 18, and 63% were fully vaccinated. In Wyoming, however, just 25% of children had received at least one dose (17% are fully vaccinated), while Alabama has a lowest-in-the-nation full vaccination rate of 14%, based on a separate AAP analysis of CDC data.

There are seven states in which over 60% of 12- to 17-year-olds have at least started the vaccine regimen and five states where less than 30% have received at least one dose, the AAP noted.

Back on the incidence side of the pandemic, Mississippi and Hawaii had the largest increases in new cases over the past 2 weeks, followed by Florida and West Virginia. Cumulative figures show that California has had the most cases overall in children (550,337), Vermont has the highest proportion of all cases in children (22.9%), and Rhode Island has the highest rate of cases per 100,000 (10,636), the AAP and CHA said in the joint report based on data from 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Add up all those jurisdictions, and it works out to 4.6 million children infected with SARS-CoV-2 as of Aug. 19, with children representing 14.6% of all cases since the start of the pandemic. There have been over 18,000 hospitalizations so far, which is just 2.3% of the total for all ages in the 23 states (and New York City) that are reporting such data on their health department websites, the AAP and CHA said.

The number of COVID-related deaths in children is now 402 after the largest 1-week increase (24) since late May of 2020, when the AAP/CHA coverage began. Mortality data by age are available from 44 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

U.S. kidney transplants grow in number and success

During 2016-2019, U.S. centers performed kidney transplants in nearly 77,000 patients, a jump of almost 25% compared with 4-year averages of about 62,000 patients throughout 2004-2015. That works out to about 15,000 more patients receiving donor kidneys, Sundaram Hariharan, MD, and associates reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in a review of all U.S. renal transplantations performed during 1996-2019.

Coupled with the volume uptick during this 24-year period were new lows in graft losses and patient deaths. By 2018, mortality during the first year following transplantation occurred at about a 1% rate among patients who had received a kidney from a living donor, and at about a 3% rate when the organ came from a deceased donor, nearly half the rate of 2 decades earlier, in 1996. Rates of first-year graft loss during 2017 were also about half of what they had been in 1996, occurring in about 2% of patients who received a living donor organ and in about 6% of those who got a kidney from a deceased donor during 2017.

“Twenty years ago, kidney transplantation was the preferred option compared with dialysis, and even more so now,” summed up Dr. Hariharan, a senior transplant nephrologist and professor of medicine and surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and first author of the report. Kidney transplantation survival at U.S. centers “improved steadily over the past 24 years, despite patient variables becoming worse,” he said in an interview.

Kidney recipients are older, more obese, and have more prevalent diabetes

During the period studied, kidney transplant recipients became on average older and more obese, and had a higher prevalence of diabetes; the age of organ donors grew as well. The prevalence of diabetes among patients who received a kidney from a deceased donor increased from 24% during 1996-1999 to 36% during 2016-2019, while diabetes prevalence among recipients of an organ from a living donor rose from 25% in 1996-1999 to 29% during 2016-2019.

The improved graft and patient survival numbers “are very encouraging trends,” said Michelle A. Josephson, MD, professor and medical director of kidney transplantation at the University of Chicago, who was not involved with the report. “We have been hearing for a number of years that short-term graft survival had improved, but I’m thrilled to learn that long-term survival has also improved.”

The report documented 10-year survival of graft recipients during 2008-2011 of 67%, up from 61% during 1996-1999, and a 10-year overall graft survival rate of 54% in the 2008-2011 cohort, an improvement from the 42% rate in patients who received their organs in 1996-1999, changes Dr. Hariharan characterized as “modest.”

These improvements in long-term graft and patient survival are “meaningful, and particularly notable that outcomes improved despite increased complexity of the transplant population,” said Krista L. Lentine, MD, PhD, professor and medical director of living donation at Saint Louis University. But “despite these improvements, long-term graft survival remains limited,” she cautioned, especially because of risks for substantial complications from chronic immunosuppressive treatment including infection, cancer, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia.

The analysis reported by Dr. Hariharan and his associates used data collected by the Scientific Registry of Transplant Patients, run under contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which has tracked all patients who have had kidney transplants at U.S. centers since the late 1980s, said Dr. Hariharan. The database included just over 362,000 total transplants during the 24-year period studied, with 36% of all transplants involving organs from living donors with the remaining patients receiving kidneys from deceased donors.

Living donations still stagnant; deceased-donor kidneys rise

The data showed that the rate of transplants from living donors was stagnant for 2 decades, with 22,525 patients transplanted during 2000-2003, and 23,746 transplanted during 2016-2019, with very similar rates during the intervening years. The recent spurt in transplants during 2016-2019 compared with the preceding decade depended almost entirely on kidneys from deceased donors. This rate jumped from the steady, slow rise it showed during 1996-2015, when deceased-donor transplants rose from about 30,000 during 1996-1999 to about 41,000 during 2012-2015, to a more dramatic increase of about 12,000 additional transplants during the most recent period, adding up to a total of more than 53,000 transplants from deceased donors during 2016-2019.

“I strongly recommend organs from living donors” when feasible, said Dr. Hariharan. “At some centers, a high proportion of transplants use living donors, but not at other centers,” he said.

It’s unknown why transplants using organs from deceased donors has shown this growth, but Dr. Hariharan suggested a multifactorial explanation. Those factors include growth in the number of patients with end-stage renal disease who require dialysis, increased numbers of patients listed for kidney transplant, new approaches that allow organs from older donors and those infected with pathogens such as hepatitis C virus or HIV, greater numbers of people and families agreeing to donate organs, and possibly the opioid crisis that may have led to increased organ donation. The number of U.S. centers performing kidney transplants rose from fewer than 200 about a quarter of a century ago to about 250 today, he added.

‘Immuno Bill’ guarantees Medicare coverage for immunosuppression

Dr. Hariharan voiced optimism that graft and patient survival rates will continue to improve going forward. One factor will likely be the passage in late 2020 of the “Immuno Bill” by the U.S. Congress, which among other things mandated ongoing coverage starting in 2023 for immunosuppressive drugs for all Medicare beneficiaries with a kidney transplant. Until then, Medicare provides coverage for only 36 months, a time limit that has resulted in nearly 400 kidney recipients annually losing coverage of their immunosuppression medications.

Dr. Hariharan and coauthors called the existing potential for discontinuation of immunosuppressive drug an “unnecessary impediment to long-term survival for which patients and society paid a heavy price.”

“Kidney transplantation, especially from living donors, offers patients with kidney failure the best chance for long-term survival and improved quality of life, with lower cost to the health care system,” Dr. Lentine said in an interview. Despite the many positive trends detailed in the report from Dr. Hariharan and coauthors, “the vast majority of the more than 700,000 people in the United States with kidney failure will not have an opportunity to receive a transplant due to limitations in organ supply.” And many patients who receive a kidney transplant eventually must resume dialysis because of “limited long-term graft survival resulting from allograft nephropathy, recurrent native disease, medication nonadherence, or other causes.” Plus many potentially transplantable organs go unused.

Dr. Lentine cited a position statement issued in July 2021 by the National Kidney Foundation that made several recommendations on how to improve access to kidney transplants and improve outcomes. “Expanding opportunities for safe living donation, eliminating racial disparities in living-donor access, improving wait-list access and transport readiness, maximizing use of deceased-donor organs, and extending graft longevity are critical priorities,” said Dr. Lentine, lead author on the statement.

“For many or even most patients with kidney failure transplantation is the optimal form of renal replacement. The better recent outcomes and evolving management strategies make transplantation an even more attractive option,” said Dr. Josephson. Improved outcomes among U.S. transplant patients also highlights the “importance of increasing access to kidney transplantation” for all people with kidney failure who could benefit from this treatment, she added.

Dr. Hariharan and Dr. Lentine had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Josephson has been a consultant to UCB and has an ownership interest in Seagen.

During 2016-2019, U.S. centers performed kidney transplants in nearly 77,000 patients, a jump of almost 25% compared with 4-year averages of about 62,000 patients throughout 2004-2015. That works out to about 15,000 more patients receiving donor kidneys, Sundaram Hariharan, MD, and associates reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in a review of all U.S. renal transplantations performed during 1996-2019.

Coupled with the volume uptick during this 24-year period were new lows in graft losses and patient deaths. By 2018, mortality during the first year following transplantation occurred at about a 1% rate among patients who had received a kidney from a living donor, and at about a 3% rate when the organ came from a deceased donor, nearly half the rate of 2 decades earlier, in 1996. Rates of first-year graft loss during 2017 were also about half of what they had been in 1996, occurring in about 2% of patients who received a living donor organ and in about 6% of those who got a kidney from a deceased donor during 2017.

“Twenty years ago, kidney transplantation was the preferred option compared with dialysis, and even more so now,” summed up Dr. Hariharan, a senior transplant nephrologist and professor of medicine and surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and first author of the report. Kidney transplantation survival at U.S. centers “improved steadily over the past 24 years, despite patient variables becoming worse,” he said in an interview.

Kidney recipients are older, more obese, and have more prevalent diabetes

During the period studied, kidney transplant recipients became on average older and more obese, and had a higher prevalence of diabetes; the age of organ donors grew as well. The prevalence of diabetes among patients who received a kidney from a deceased donor increased from 24% during 1996-1999 to 36% during 2016-2019, while diabetes prevalence among recipients of an organ from a living donor rose from 25% in 1996-1999 to 29% during 2016-2019.

The improved graft and patient survival numbers “are very encouraging trends,” said Michelle A. Josephson, MD, professor and medical director of kidney transplantation at the University of Chicago, who was not involved with the report. “We have been hearing for a number of years that short-term graft survival had improved, but I’m thrilled to learn that long-term survival has also improved.”

The report documented 10-year survival of graft recipients during 2008-2011 of 67%, up from 61% during 1996-1999, and a 10-year overall graft survival rate of 54% in the 2008-2011 cohort, an improvement from the 42% rate in patients who received their organs in 1996-1999, changes Dr. Hariharan characterized as “modest.”

These improvements in long-term graft and patient survival are “meaningful, and particularly notable that outcomes improved despite increased complexity of the transplant population,” said Krista L. Lentine, MD, PhD, professor and medical director of living donation at Saint Louis University. But “despite these improvements, long-term graft survival remains limited,” she cautioned, especially because of risks for substantial complications from chronic immunosuppressive treatment including infection, cancer, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia.

The analysis reported by Dr. Hariharan and his associates used data collected by the Scientific Registry of Transplant Patients, run under contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which has tracked all patients who have had kidney transplants at U.S. centers since the late 1980s, said Dr. Hariharan. The database included just over 362,000 total transplants during the 24-year period studied, with 36% of all transplants involving organs from living donors with the remaining patients receiving kidneys from deceased donors.

Living donations still stagnant; deceased-donor kidneys rise

The data showed that the rate of transplants from living donors was stagnant for 2 decades, with 22,525 patients transplanted during 2000-2003, and 23,746 transplanted during 2016-2019, with very similar rates during the intervening years. The recent spurt in transplants during 2016-2019 compared with the preceding decade depended almost entirely on kidneys from deceased donors. This rate jumped from the steady, slow rise it showed during 1996-2015, when deceased-donor transplants rose from about 30,000 during 1996-1999 to about 41,000 during 2012-2015, to a more dramatic increase of about 12,000 additional transplants during the most recent period, adding up to a total of more than 53,000 transplants from deceased donors during 2016-2019.

“I strongly recommend organs from living donors” when feasible, said Dr. Hariharan. “At some centers, a high proportion of transplants use living donors, but not at other centers,” he said.

It’s unknown why transplants using organs from deceased donors has shown this growth, but Dr. Hariharan suggested a multifactorial explanation. Those factors include growth in the number of patients with end-stage renal disease who require dialysis, increased numbers of patients listed for kidney transplant, new approaches that allow organs from older donors and those infected with pathogens such as hepatitis C virus or HIV, greater numbers of people and families agreeing to donate organs, and possibly the opioid crisis that may have led to increased organ donation. The number of U.S. centers performing kidney transplants rose from fewer than 200 about a quarter of a century ago to about 250 today, he added.

‘Immuno Bill’ guarantees Medicare coverage for immunosuppression

Dr. Hariharan voiced optimism that graft and patient survival rates will continue to improve going forward. One factor will likely be the passage in late 2020 of the “Immuno Bill” by the U.S. Congress, which among other things mandated ongoing coverage starting in 2023 for immunosuppressive drugs for all Medicare beneficiaries with a kidney transplant. Until then, Medicare provides coverage for only 36 months, a time limit that has resulted in nearly 400 kidney recipients annually losing coverage of their immunosuppression medications.

Dr. Hariharan and coauthors called the existing potential for discontinuation of immunosuppressive drug an “unnecessary impediment to long-term survival for which patients and society paid a heavy price.”

“Kidney transplantation, especially from living donors, offers patients with kidney failure the best chance for long-term survival and improved quality of life, with lower cost to the health care system,” Dr. Lentine said in an interview. Despite the many positive trends detailed in the report from Dr. Hariharan and coauthors, “the vast majority of the more than 700,000 people in the United States with kidney failure will not have an opportunity to receive a transplant due to limitations in organ supply.” And many patients who receive a kidney transplant eventually must resume dialysis because of “limited long-term graft survival resulting from allograft nephropathy, recurrent native disease, medication nonadherence, or other causes.” Plus many potentially transplantable organs go unused.

Dr. Lentine cited a position statement issued in July 2021 by the National Kidney Foundation that made several recommendations on how to improve access to kidney transplants and improve outcomes. “Expanding opportunities for safe living donation, eliminating racial disparities in living-donor access, improving wait-list access and transport readiness, maximizing use of deceased-donor organs, and extending graft longevity are critical priorities,” said Dr. Lentine, lead author on the statement.

“For many or even most patients with kidney failure transplantation is the optimal form of renal replacement. The better recent outcomes and evolving management strategies make transplantation an even more attractive option,” said Dr. Josephson. Improved outcomes among U.S. transplant patients also highlights the “importance of increasing access to kidney transplantation” for all people with kidney failure who could benefit from this treatment, she added.

Dr. Hariharan and Dr. Lentine had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Josephson has been a consultant to UCB and has an ownership interest in Seagen.

During 2016-2019, U.S. centers performed kidney transplants in nearly 77,000 patients, a jump of almost 25% compared with 4-year averages of about 62,000 patients throughout 2004-2015. That works out to about 15,000 more patients receiving donor kidneys, Sundaram Hariharan, MD, and associates reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in a review of all U.S. renal transplantations performed during 1996-2019.

Coupled with the volume uptick during this 24-year period were new lows in graft losses and patient deaths. By 2018, mortality during the first year following transplantation occurred at about a 1% rate among patients who had received a kidney from a living donor, and at about a 3% rate when the organ came from a deceased donor, nearly half the rate of 2 decades earlier, in 1996. Rates of first-year graft loss during 2017 were also about half of what they had been in 1996, occurring in about 2% of patients who received a living donor organ and in about 6% of those who got a kidney from a deceased donor during 2017.

“Twenty years ago, kidney transplantation was the preferred option compared with dialysis, and even more so now,” summed up Dr. Hariharan, a senior transplant nephrologist and professor of medicine and surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and first author of the report. Kidney transplantation survival at U.S. centers “improved steadily over the past 24 years, despite patient variables becoming worse,” he said in an interview.

Kidney recipients are older, more obese, and have more prevalent diabetes

During the period studied, kidney transplant recipients became on average older and more obese, and had a higher prevalence of diabetes; the age of organ donors grew as well. The prevalence of diabetes among patients who received a kidney from a deceased donor increased from 24% during 1996-1999 to 36% during 2016-2019, while diabetes prevalence among recipients of an organ from a living donor rose from 25% in 1996-1999 to 29% during 2016-2019.

The improved graft and patient survival numbers “are very encouraging trends,” said Michelle A. Josephson, MD, professor and medical director of kidney transplantation at the University of Chicago, who was not involved with the report. “We have been hearing for a number of years that short-term graft survival had improved, but I’m thrilled to learn that long-term survival has also improved.”

The report documented 10-year survival of graft recipients during 2008-2011 of 67%, up from 61% during 1996-1999, and a 10-year overall graft survival rate of 54% in the 2008-2011 cohort, an improvement from the 42% rate in patients who received their organs in 1996-1999, changes Dr. Hariharan characterized as “modest.”

These improvements in long-term graft and patient survival are “meaningful, and particularly notable that outcomes improved despite increased complexity of the transplant population,” said Krista L. Lentine, MD, PhD, professor and medical director of living donation at Saint Louis University. But “despite these improvements, long-term graft survival remains limited,” she cautioned, especially because of risks for substantial complications from chronic immunosuppressive treatment including infection, cancer, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidemia.

The analysis reported by Dr. Hariharan and his associates used data collected by the Scientific Registry of Transplant Patients, run under contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which has tracked all patients who have had kidney transplants at U.S. centers since the late 1980s, said Dr. Hariharan. The database included just over 362,000 total transplants during the 24-year period studied, with 36% of all transplants involving organs from living donors with the remaining patients receiving kidneys from deceased donors.

Living donations still stagnant; deceased-donor kidneys rise

The data showed that the rate of transplants from living donors was stagnant for 2 decades, with 22,525 patients transplanted during 2000-2003, and 23,746 transplanted during 2016-2019, with very similar rates during the intervening years. The recent spurt in transplants during 2016-2019 compared with the preceding decade depended almost entirely on kidneys from deceased donors. This rate jumped from the steady, slow rise it showed during 1996-2015, when deceased-donor transplants rose from about 30,000 during 1996-1999 to about 41,000 during 2012-2015, to a more dramatic increase of about 12,000 additional transplants during the most recent period, adding up to a total of more than 53,000 transplants from deceased donors during 2016-2019.

“I strongly recommend organs from living donors” when feasible, said Dr. Hariharan. “At some centers, a high proportion of transplants use living donors, but not at other centers,” he said.

It’s unknown why transplants using organs from deceased donors has shown this growth, but Dr. Hariharan suggested a multifactorial explanation. Those factors include growth in the number of patients with end-stage renal disease who require dialysis, increased numbers of patients listed for kidney transplant, new approaches that allow organs from older donors and those infected with pathogens such as hepatitis C virus or HIV, greater numbers of people and families agreeing to donate organs, and possibly the opioid crisis that may have led to increased organ donation. The number of U.S. centers performing kidney transplants rose from fewer than 200 about a quarter of a century ago to about 250 today, he added.

‘Immuno Bill’ guarantees Medicare coverage for immunosuppression

Dr. Hariharan voiced optimism that graft and patient survival rates will continue to improve going forward. One factor will likely be the passage in late 2020 of the “Immuno Bill” by the U.S. Congress, which among other things mandated ongoing coverage starting in 2023 for immunosuppressive drugs for all Medicare beneficiaries with a kidney transplant. Until then, Medicare provides coverage for only 36 months, a time limit that has resulted in nearly 400 kidney recipients annually losing coverage of their immunosuppression medications.

Dr. Hariharan and coauthors called the existing potential for discontinuation of immunosuppressive drug an “unnecessary impediment to long-term survival for which patients and society paid a heavy price.”

“Kidney transplantation, especially from living donors, offers patients with kidney failure the best chance for long-term survival and improved quality of life, with lower cost to the health care system,” Dr. Lentine said in an interview. Despite the many positive trends detailed in the report from Dr. Hariharan and coauthors, “the vast majority of the more than 700,000 people in the United States with kidney failure will not have an opportunity to receive a transplant due to limitations in organ supply.” And many patients who receive a kidney transplant eventually must resume dialysis because of “limited long-term graft survival resulting from allograft nephropathy, recurrent native disease, medication nonadherence, or other causes.” Plus many potentially transplantable organs go unused.

Dr. Lentine cited a position statement issued in July 2021 by the National Kidney Foundation that made several recommendations on how to improve access to kidney transplants and improve outcomes. “Expanding opportunities for safe living donation, eliminating racial disparities in living-donor access, improving wait-list access and transport readiness, maximizing use of deceased-donor organs, and extending graft longevity are critical priorities,” said Dr. Lentine, lead author on the statement.

“For many or even most patients with kidney failure transplantation is the optimal form of renal replacement. The better recent outcomes and evolving management strategies make transplantation an even more attractive option,” said Dr. Josephson. Improved outcomes among U.S. transplant patients also highlights the “importance of increasing access to kidney transplantation” for all people with kidney failure who could benefit from this treatment, she added.