User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Clinical Updates on Osteoarthritis of the Hip

As primary care doctors, we diagnosis and treat many patients with osteoarthritis. In fact, according to World Health Organization statistics, approximately 528 million people around the world suffer from some form of this type of arthritis. With the aging of the population and the obesity epidemic, the rate of osteoarthritis has increased 113% since 1990 and is predicted to continue to rise.

While the knee is the most commonly affected joint, osteoarthritis also frequently affects the hands and hips. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons issued guidelines concerning the management of osteoarthritis of the hip. The clinical guidelines are aimed at orthopedists, but it is important for primary care doctors be aware of them as well since we are the physicians who usually diagnose the disease, manage it in its early stages, and follow the patients with and after the orthopedist has undertaken any procedures.

While the complete set of guidelines is 80 pages long, strong recommendations have been made that everyone should be aware of. The role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has been reconfirmed as a modality to improve pain and function. A recommendation against using intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the hip was made as the evidence shows it did not improve pain or function better than placebo. Conversely, intra-articular corticosteroids were shown to improve pain and function in the short-term and many primary care doctors provide this treatment in their practice.

These guidelines do a great job covering the totality of management of osteoarthritis of the hip, from conservation management to surgical and post-surgical treatments. Patients often come to us with their questions so not only is it important to know the evidence for what we do in our practices, we need to know what our orthopedic colleagues are doing. We will be the ones asked to do the pre-operative evaluations on these patients, so we need to understand the procedure and its risks. We will also manage these patients post-operatively and need to be aware of what the evidence shows.

Opioid use is also covered in the guidelines: they recommend against the use of opioids to control pain in these patients. In the age of the opioid epidemic, it is a good reminder to be cautious with these meds. It is also a good time to stress smoking cessation with patients.

The guidelines discuss adverse outcomes in patients with diabetes and/or obesity. As primary care physicians, we need to be aware of those risks and be sure our patients are medically optimized before signing that pre-operative form.

A new feature of these guidelines is a discussion on social detriments to health. This is important for many diseases that we treat and we often don’t realize the impact they can have on a patient’s health and recovery. Even if we know a patient would benefit from physical therapy, it doesn’t help them if the patient has no way to get to the appointment. Some patients have copays for every physical therapy session and just can’t afford it. Knowing what the patient needs medically is not enough. We need to understand how they can access that care. Some patients have no one to help them after hip surgery and may avoid doing it for that reason. As primary care doctors, we should be helping our patients access the care they need.

We need to be able to say that a procedure needs to be delayed in the face of poorly controlled disease, such as diabetes. As the rates of osteoarthritis continue to rise, we need to understand that it is not an inevitable age-based occurrence in a patient’s life but rather an inflammatory disease that causes great pain and dysfunction. Utilizing these guidelines and working with our orthopedic colleagues can help patients decrease pain, improve functioning, and enjoy life again.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, New Jersey, and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey. She was paid by Pfizer as a consultant on Paxlovid, paid by GlaxoSmithKline as a consultant for the Shingrix vaccine, and is the editor in chief of Physician’s Weekly.

As primary care doctors, we diagnosis and treat many patients with osteoarthritis. In fact, according to World Health Organization statistics, approximately 528 million people around the world suffer from some form of this type of arthritis. With the aging of the population and the obesity epidemic, the rate of osteoarthritis has increased 113% since 1990 and is predicted to continue to rise.

While the knee is the most commonly affected joint, osteoarthritis also frequently affects the hands and hips. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons issued guidelines concerning the management of osteoarthritis of the hip. The clinical guidelines are aimed at orthopedists, but it is important for primary care doctors be aware of them as well since we are the physicians who usually diagnose the disease, manage it in its early stages, and follow the patients with and after the orthopedist has undertaken any procedures.

While the complete set of guidelines is 80 pages long, strong recommendations have been made that everyone should be aware of. The role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has been reconfirmed as a modality to improve pain and function. A recommendation against using intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the hip was made as the evidence shows it did not improve pain or function better than placebo. Conversely, intra-articular corticosteroids were shown to improve pain and function in the short-term and many primary care doctors provide this treatment in their practice.

These guidelines do a great job covering the totality of management of osteoarthritis of the hip, from conservation management to surgical and post-surgical treatments. Patients often come to us with their questions so not only is it important to know the evidence for what we do in our practices, we need to know what our orthopedic colleagues are doing. We will be the ones asked to do the pre-operative evaluations on these patients, so we need to understand the procedure and its risks. We will also manage these patients post-operatively and need to be aware of what the evidence shows.

Opioid use is also covered in the guidelines: they recommend against the use of opioids to control pain in these patients. In the age of the opioid epidemic, it is a good reminder to be cautious with these meds. It is also a good time to stress smoking cessation with patients.

The guidelines discuss adverse outcomes in patients with diabetes and/or obesity. As primary care physicians, we need to be aware of those risks and be sure our patients are medically optimized before signing that pre-operative form.

A new feature of these guidelines is a discussion on social detriments to health. This is important for many diseases that we treat and we often don’t realize the impact they can have on a patient’s health and recovery. Even if we know a patient would benefit from physical therapy, it doesn’t help them if the patient has no way to get to the appointment. Some patients have copays for every physical therapy session and just can’t afford it. Knowing what the patient needs medically is not enough. We need to understand how they can access that care. Some patients have no one to help them after hip surgery and may avoid doing it for that reason. As primary care doctors, we should be helping our patients access the care they need.

We need to be able to say that a procedure needs to be delayed in the face of poorly controlled disease, such as diabetes. As the rates of osteoarthritis continue to rise, we need to understand that it is not an inevitable age-based occurrence in a patient’s life but rather an inflammatory disease that causes great pain and dysfunction. Utilizing these guidelines and working with our orthopedic colleagues can help patients decrease pain, improve functioning, and enjoy life again.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, New Jersey, and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey. She was paid by Pfizer as a consultant on Paxlovid, paid by GlaxoSmithKline as a consultant for the Shingrix vaccine, and is the editor in chief of Physician’s Weekly.

As primary care doctors, we diagnosis and treat many patients with osteoarthritis. In fact, according to World Health Organization statistics, approximately 528 million people around the world suffer from some form of this type of arthritis. With the aging of the population and the obesity epidemic, the rate of osteoarthritis has increased 113% since 1990 and is predicted to continue to rise.

While the knee is the most commonly affected joint, osteoarthritis also frequently affects the hands and hips. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons issued guidelines concerning the management of osteoarthritis of the hip. The clinical guidelines are aimed at orthopedists, but it is important for primary care doctors be aware of them as well since we are the physicians who usually diagnose the disease, manage it in its early stages, and follow the patients with and after the orthopedist has undertaken any procedures.

While the complete set of guidelines is 80 pages long, strong recommendations have been made that everyone should be aware of. The role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has been reconfirmed as a modality to improve pain and function. A recommendation against using intra-articular hyaluronic acid in the hip was made as the evidence shows it did not improve pain or function better than placebo. Conversely, intra-articular corticosteroids were shown to improve pain and function in the short-term and many primary care doctors provide this treatment in their practice.

These guidelines do a great job covering the totality of management of osteoarthritis of the hip, from conservation management to surgical and post-surgical treatments. Patients often come to us with their questions so not only is it important to know the evidence for what we do in our practices, we need to know what our orthopedic colleagues are doing. We will be the ones asked to do the pre-operative evaluations on these patients, so we need to understand the procedure and its risks. We will also manage these patients post-operatively and need to be aware of what the evidence shows.

Opioid use is also covered in the guidelines: they recommend against the use of opioids to control pain in these patients. In the age of the opioid epidemic, it is a good reminder to be cautious with these meds. It is also a good time to stress smoking cessation with patients.

The guidelines discuss adverse outcomes in patients with diabetes and/or obesity. As primary care physicians, we need to be aware of those risks and be sure our patients are medically optimized before signing that pre-operative form.

A new feature of these guidelines is a discussion on social detriments to health. This is important for many diseases that we treat and we often don’t realize the impact they can have on a patient’s health and recovery. Even if we know a patient would benefit from physical therapy, it doesn’t help them if the patient has no way to get to the appointment. Some patients have copays for every physical therapy session and just can’t afford it. Knowing what the patient needs medically is not enough. We need to understand how they can access that care. Some patients have no one to help them after hip surgery and may avoid doing it for that reason. As primary care doctors, we should be helping our patients access the care they need.

We need to be able to say that a procedure needs to be delayed in the face of poorly controlled disease, such as diabetes. As the rates of osteoarthritis continue to rise, we need to understand that it is not an inevitable age-based occurrence in a patient’s life but rather an inflammatory disease that causes great pain and dysfunction. Utilizing these guidelines and working with our orthopedic colleagues can help patients decrease pain, improve functioning, and enjoy life again.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, New Jersey, and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey. She was paid by Pfizer as a consultant on Paxlovid, paid by GlaxoSmithKline as a consultant for the Shingrix vaccine, and is the editor in chief of Physician’s Weekly.

More Evidence Ties Semaglutide to Reduced Alzheimer’s Risk

Adults with type 2 diabetes who were prescribed the GLP-1 RA semaglutide had a significantly lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease compared with their peers who were prescribed any of seven other antidiabetic medications, including other types of GLP-1 receptor–targeting medications.

“These findings support further clinical trials to assess semaglutide’s potential in delaying or preventing Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote the investigators, led by Rong Xu, PhD, with Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

The study was published online on October 24 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Real-World Data

Semaglutide has shown neuroprotective effects in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. In animal models of Alzheimer’s disease, the drug reduced beta-amyloid deposition and improved spatial learning and memory, as well as glucose metabolism in the brain.

In a real-world analysis, Xu and colleagues used electronic health record data to identify 17,104 new users of semaglutide and 1,077,657 new users of seven other antidiabetic medications, including other GLP-1 RAs, insulin, metformin, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, sulfonylurea, and thiazolidinedione.

Over 3 years, treatment with semaglutide was associated with significantly reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, most strongly compared with insulin (hazard ratio [HR], 0.33) and most weakly compared with other GLP-1 RAs (HR, 0.59).

Compared with the other medications, semaglutide was associated with a 40%-70% reduced risk for first-time diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in patients with type 2 diabetes, with similar reductions seen across obesity status and gender and age groups, the authors reported.

The findings align with recent evidence suggesting GLP-1 RAs may protect cognitive function.

For example, as previously reported, in the phase 2b ELAD clinical trial, adults with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease taking the GLP-1 RA liraglutide exhibited slower decline in memory and thinking and experienced less brain atrophy over 12 months compared with placebo.

Promising, but Preliminary

Reached for comment, Courtney Kloske, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association director of scientific engagement, noted that diabetes is a known risk factor for AD and managing diabetes with drugs such as semaglutide “could benefit brain health simply by managing diabetes.”

“However, we still need large clinical trials in representative populations to determine if semaglutide specifically lowers the risk of Alzheimer’s, so it is too early to recommend it for prevention,” Kloske said.

She noted that some research suggests that GLP-1 RAs “may help reduce inflammation and positively impact brain energy use. However, more research is needed to fully understand how these processes might contribute to preventing cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s,” Kloske cautioned.

The Alzheimer’s Association’s “Part the Cloud” initiative has invested more than $68 million to advance 65 clinical trials targeting a variety of compounds, including repurposed drugs that may address known and potential new aspects of the disease, Kloske said.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Xu and Kloske have no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Adults with type 2 diabetes who were prescribed the GLP-1 RA semaglutide had a significantly lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease compared with their peers who were prescribed any of seven other antidiabetic medications, including other types of GLP-1 receptor–targeting medications.

“These findings support further clinical trials to assess semaglutide’s potential in delaying or preventing Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote the investigators, led by Rong Xu, PhD, with Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

The study was published online on October 24 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Real-World Data

Semaglutide has shown neuroprotective effects in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. In animal models of Alzheimer’s disease, the drug reduced beta-amyloid deposition and improved spatial learning and memory, as well as glucose metabolism in the brain.

In a real-world analysis, Xu and colleagues used electronic health record data to identify 17,104 new users of semaglutide and 1,077,657 new users of seven other antidiabetic medications, including other GLP-1 RAs, insulin, metformin, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, sulfonylurea, and thiazolidinedione.

Over 3 years, treatment with semaglutide was associated with significantly reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, most strongly compared with insulin (hazard ratio [HR], 0.33) and most weakly compared with other GLP-1 RAs (HR, 0.59).

Compared with the other medications, semaglutide was associated with a 40%-70% reduced risk for first-time diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in patients with type 2 diabetes, with similar reductions seen across obesity status and gender and age groups, the authors reported.

The findings align with recent evidence suggesting GLP-1 RAs may protect cognitive function.

For example, as previously reported, in the phase 2b ELAD clinical trial, adults with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease taking the GLP-1 RA liraglutide exhibited slower decline in memory and thinking and experienced less brain atrophy over 12 months compared with placebo.

Promising, but Preliminary

Reached for comment, Courtney Kloske, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association director of scientific engagement, noted that diabetes is a known risk factor for AD and managing diabetes with drugs such as semaglutide “could benefit brain health simply by managing diabetes.”

“However, we still need large clinical trials in representative populations to determine if semaglutide specifically lowers the risk of Alzheimer’s, so it is too early to recommend it for prevention,” Kloske said.

She noted that some research suggests that GLP-1 RAs “may help reduce inflammation and positively impact brain energy use. However, more research is needed to fully understand how these processes might contribute to preventing cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s,” Kloske cautioned.

The Alzheimer’s Association’s “Part the Cloud” initiative has invested more than $68 million to advance 65 clinical trials targeting a variety of compounds, including repurposed drugs that may address known and potential new aspects of the disease, Kloske said.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Xu and Kloske have no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Adults with type 2 diabetes who were prescribed the GLP-1 RA semaglutide had a significantly lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease compared with their peers who were prescribed any of seven other antidiabetic medications, including other types of GLP-1 receptor–targeting medications.

“These findings support further clinical trials to assess semaglutide’s potential in delaying or preventing Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote the investigators, led by Rong Xu, PhD, with Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

The study was published online on October 24 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

Real-World Data

Semaglutide has shown neuroprotective effects in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. In animal models of Alzheimer’s disease, the drug reduced beta-amyloid deposition and improved spatial learning and memory, as well as glucose metabolism in the brain.

In a real-world analysis, Xu and colleagues used electronic health record data to identify 17,104 new users of semaglutide and 1,077,657 new users of seven other antidiabetic medications, including other GLP-1 RAs, insulin, metformin, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, sulfonylurea, and thiazolidinedione.

Over 3 years, treatment with semaglutide was associated with significantly reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, most strongly compared with insulin (hazard ratio [HR], 0.33) and most weakly compared with other GLP-1 RAs (HR, 0.59).

Compared with the other medications, semaglutide was associated with a 40%-70% reduced risk for first-time diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in patients with type 2 diabetes, with similar reductions seen across obesity status and gender and age groups, the authors reported.

The findings align with recent evidence suggesting GLP-1 RAs may protect cognitive function.

For example, as previously reported, in the phase 2b ELAD clinical trial, adults with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease taking the GLP-1 RA liraglutide exhibited slower decline in memory and thinking and experienced less brain atrophy over 12 months compared with placebo.

Promising, but Preliminary

Reached for comment, Courtney Kloske, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association director of scientific engagement, noted that diabetes is a known risk factor for AD and managing diabetes with drugs such as semaglutide “could benefit brain health simply by managing diabetes.”

“However, we still need large clinical trials in representative populations to determine if semaglutide specifically lowers the risk of Alzheimer’s, so it is too early to recommend it for prevention,” Kloske said.

She noted that some research suggests that GLP-1 RAs “may help reduce inflammation and positively impact brain energy use. However, more research is needed to fully understand how these processes might contribute to preventing cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s,” Kloske cautioned.

The Alzheimer’s Association’s “Part the Cloud” initiative has invested more than $68 million to advance 65 clinical trials targeting a variety of compounds, including repurposed drugs that may address known and potential new aspects of the disease, Kloske said.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Xu and Kloske have no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ALZHEIMER’S & DEMENTIA

How Old Are You? Stand on One Leg and I’ll Tell You

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

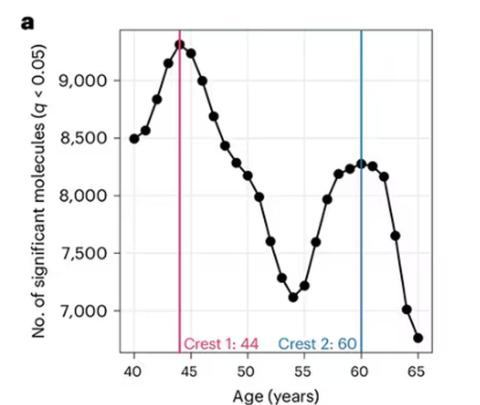

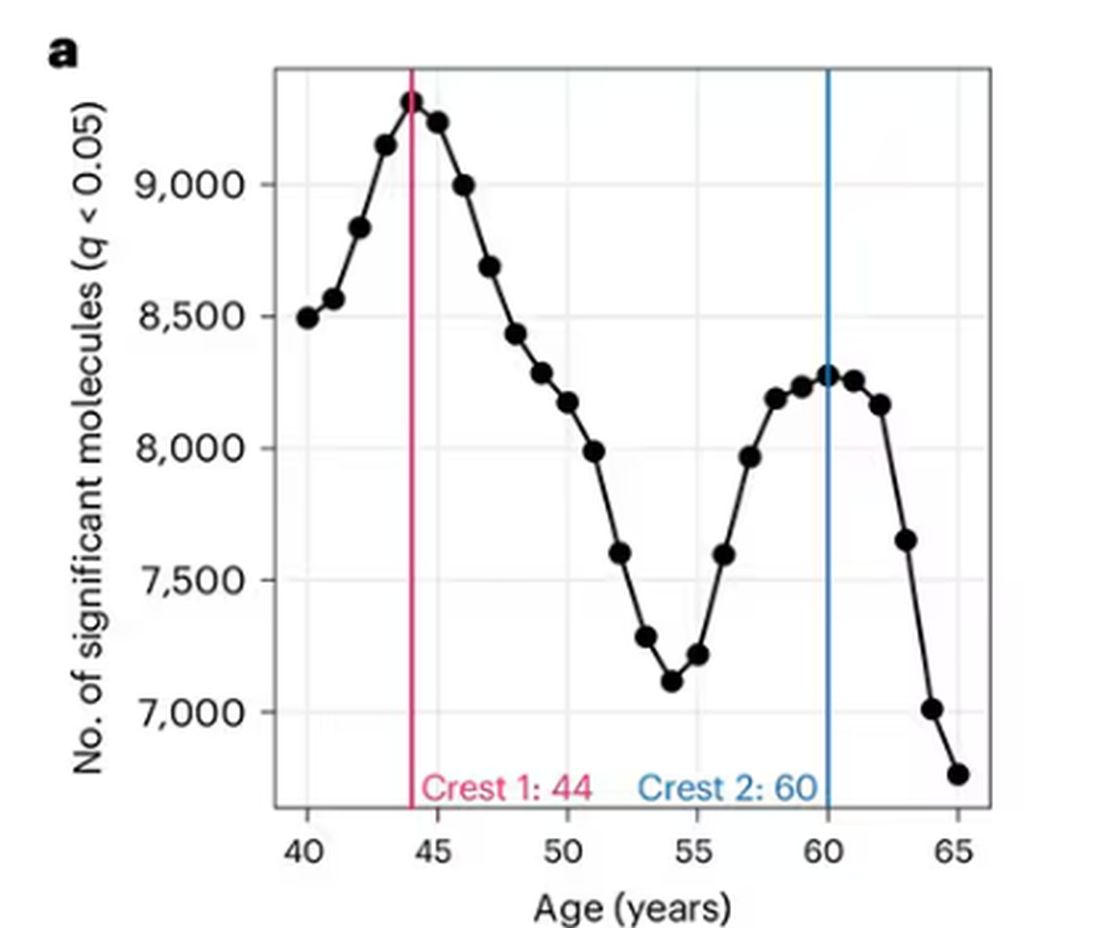

So I was lying in bed the other night, trying to read my phone, and started complaining to my wife about how my vision keeps getting worse, and then how stiff I feel when I wake up in the morning, and how a recent injury is taking too long to heal, and she said, “Well, yeah. You’re 44. That’s when things start to head downhill.”

And I was like, “Forty-four? That seems very specific. I thought 50 was what people complain about.” And she said, “No, it’s a thing — 44 years old and 60 years old. There’s a drop-off there.”

And you know what? She was right.

A study, “Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging,” published in Nature Aging in August 2024, analyzed a ton of proteins and metabolites in people of various ages and found, when you put it all together, that I should know better than to doubt my brilliant spouse.

But deep down, I believe the cliché that age is just a number. I don’t particularly care about being 44, or turning 50 or 60. I care about how my body and brain are aging. If I can be a happy, healthy, 80-year-old in full command of my faculties, I would consider that a major win no matter what the calendar says.

So I’m always interested in ways to quantify how my body is aging, independent of how many birthdays I have passed. And, according to a new study, there’s actually a really easy way to do this: Just stand on one leg.

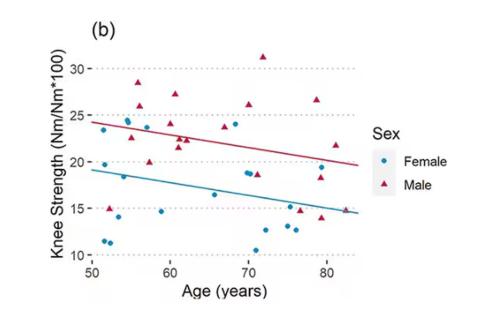

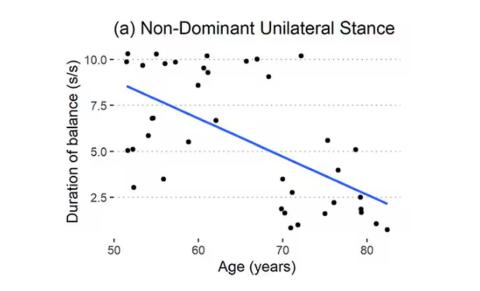

The surprising results come from “Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study,” appearing in PLOS One, which analyzed 40 individuals — half under age 65 and half over age 65 — across a variety of domains of strength, balance, and gait. The conceit of the study? We all know that things like strength and balance worsen over time, but what worsens fastest? What might be the best metric to tell us how our bodies are aging?

To that end, you have a variety of correlations between various metrics and calendar age.

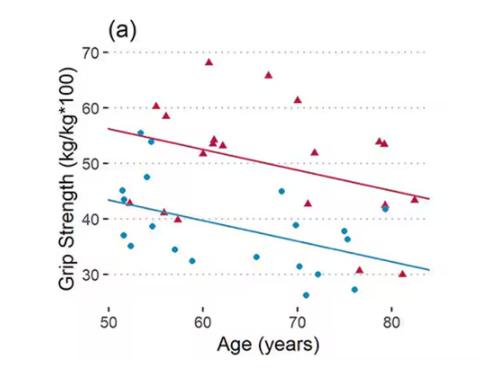

As age increases, grip strength goes down. Men (inexplicably in pink) have higher grip strength overall, and women (confusingly in blue) lower. Somewhat less strong correlations were seen for knee strength.

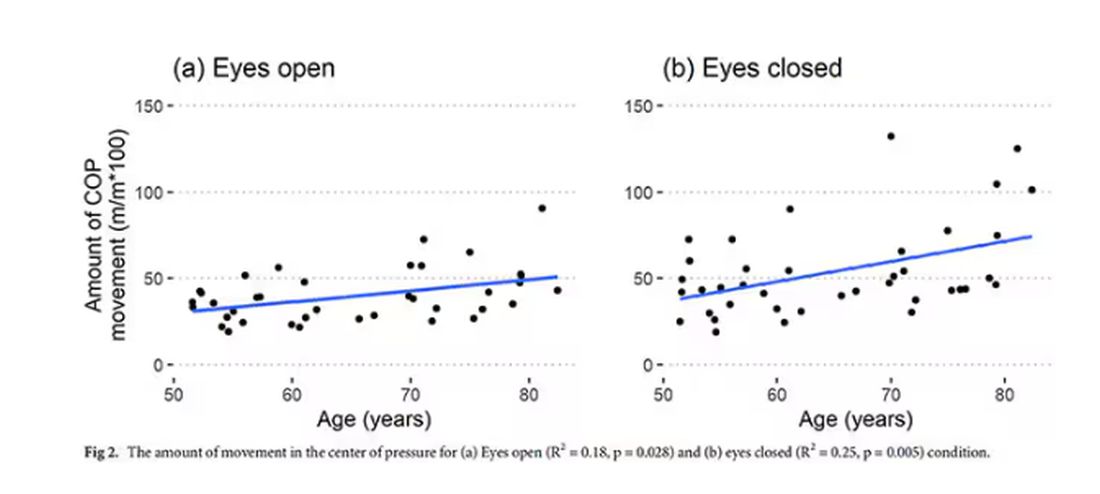

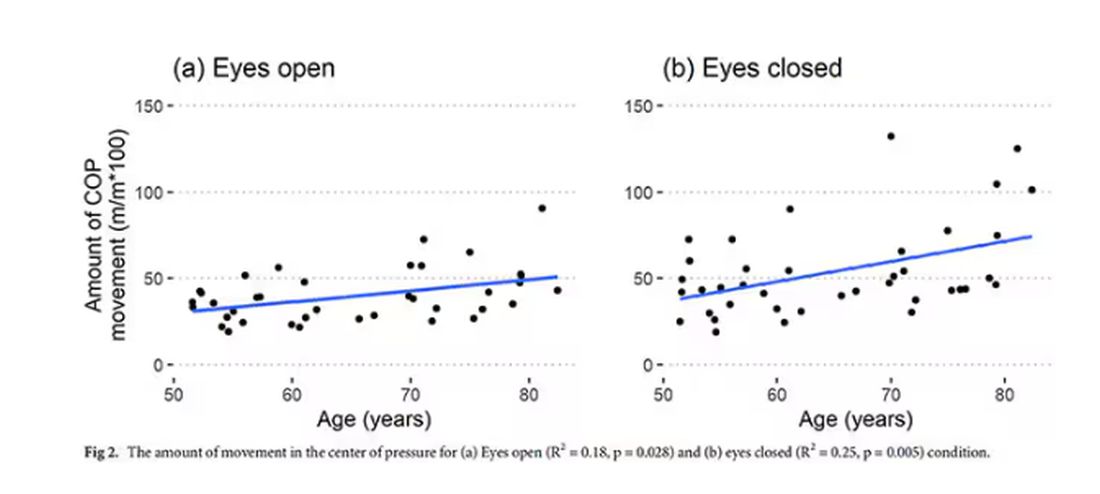

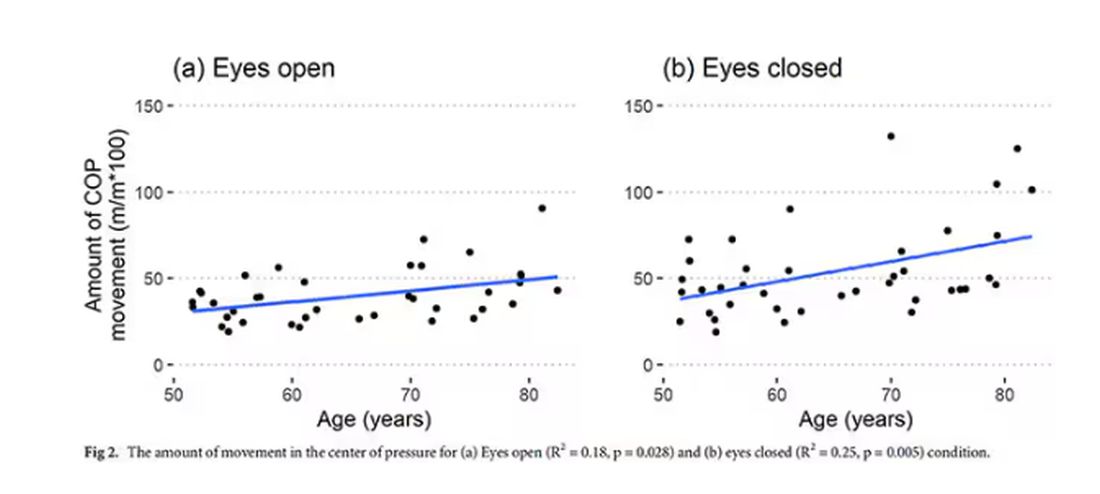

What about balance?

To assess this, the researchers had the participants stand on a pressure plate. In one scenario, they did this with eyes open, and the next with eyes closed. They then measured how much the pressure varied around the center of the individual on the plate — basically, how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

Sway increased as age increased. Sway increased a bit more with eyes closed than with eyes open.

But the strongest correlation between any of these metrics and age was a simple one: How long can you stand on one leg?

Particularly for the nondominant leg, what you see here is a pretty dramatic drop-off in balance time around age 65, with younger people able to do 10 seconds with ease and some older people barely being able to make it to 2.

Of course, I had to try this for myself. And as I was standing around on one leg, it became clear to me exactly why this might be a good metric. It really integrates balance and strength in a way that the other tests don’t: balance, clearly, since you have to stay vertical over a relatively small base; but strength as well, because, well, one leg is holding up all the rest of you. You do feel it after a while.

So this metric passes the smell test to me, at least as a potential proxy for age-related physical decline.

But I should be careful to note that this was a cross-sectional study; the researchers looked at various people who were all different ages, not the same people over time to watch how these things change as they aged.

Also, the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs like this implies a certain linear relationship between age and standing-on-one-foot time. The raw data — the points on this graph — don’t appear that linear to me. As I mentioned above, it seems like there might be a bit of a sharp drop-off somewhere in the mid-60s. That means that we may not be able to use this as a sensitive test for aging that slowly changes as your body gets older. It might be that you’re able to essentially stand on one leg as long as you want until, one day, you can’t. That gives us less warning and less to act on.

And finally, we don’t know that changing this metric will change your health for the better. I’m sure a good physiatrist or physical therapist could design some exercises to increase any of our standing-on-one leg times. And no doubt, with practice, you could get your numbers way up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re healthier. It’s like “teaching to the test”; you might score better on the standardized exam but you didn’t really learn the material.

So I am not adding one-leg standing to my daily exercise routine. But I won’t lie and tell you that, from time to time, and certainly on my 60th birthday, you may find me standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

So I was lying in bed the other night, trying to read my phone, and started complaining to my wife about how my vision keeps getting worse, and then how stiff I feel when I wake up in the morning, and how a recent injury is taking too long to heal, and she said, “Well, yeah. You’re 44. That’s when things start to head downhill.”

And I was like, “Forty-four? That seems very specific. I thought 50 was what people complain about.” And she said, “No, it’s a thing — 44 years old and 60 years old. There’s a drop-off there.”

And you know what? She was right.

A study, “Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging,” published in Nature Aging in August 2024, analyzed a ton of proteins and metabolites in people of various ages and found, when you put it all together, that I should know better than to doubt my brilliant spouse.

But deep down, I believe the cliché that age is just a number. I don’t particularly care about being 44, or turning 50 or 60. I care about how my body and brain are aging. If I can be a happy, healthy, 80-year-old in full command of my faculties, I would consider that a major win no matter what the calendar says.

So I’m always interested in ways to quantify how my body is aging, independent of how many birthdays I have passed. And, according to a new study, there’s actually a really easy way to do this: Just stand on one leg.

The surprising results come from “Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study,” appearing in PLOS One, which analyzed 40 individuals — half under age 65 and half over age 65 — across a variety of domains of strength, balance, and gait. The conceit of the study? We all know that things like strength and balance worsen over time, but what worsens fastest? What might be the best metric to tell us how our bodies are aging?

To that end, you have a variety of correlations between various metrics and calendar age.

As age increases, grip strength goes down. Men (inexplicably in pink) have higher grip strength overall, and women (confusingly in blue) lower. Somewhat less strong correlations were seen for knee strength.

What about balance?

To assess this, the researchers had the participants stand on a pressure plate. In one scenario, they did this with eyes open, and the next with eyes closed. They then measured how much the pressure varied around the center of the individual on the plate — basically, how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

Sway increased as age increased. Sway increased a bit more with eyes closed than with eyes open.

But the strongest correlation between any of these metrics and age was a simple one: How long can you stand on one leg?

Particularly for the nondominant leg, what you see here is a pretty dramatic drop-off in balance time around age 65, with younger people able to do 10 seconds with ease and some older people barely being able to make it to 2.

Of course, I had to try this for myself. And as I was standing around on one leg, it became clear to me exactly why this might be a good metric. It really integrates balance and strength in a way that the other tests don’t: balance, clearly, since you have to stay vertical over a relatively small base; but strength as well, because, well, one leg is holding up all the rest of you. You do feel it after a while.

So this metric passes the smell test to me, at least as a potential proxy for age-related physical decline.

But I should be careful to note that this was a cross-sectional study; the researchers looked at various people who were all different ages, not the same people over time to watch how these things change as they aged.

Also, the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs like this implies a certain linear relationship between age and standing-on-one-foot time. The raw data — the points on this graph — don’t appear that linear to me. As I mentioned above, it seems like there might be a bit of a sharp drop-off somewhere in the mid-60s. That means that we may not be able to use this as a sensitive test for aging that slowly changes as your body gets older. It might be that you’re able to essentially stand on one leg as long as you want until, one day, you can’t. That gives us less warning and less to act on.

And finally, we don’t know that changing this metric will change your health for the better. I’m sure a good physiatrist or physical therapist could design some exercises to increase any of our standing-on-one leg times. And no doubt, with practice, you could get your numbers way up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re healthier. It’s like “teaching to the test”; you might score better on the standardized exam but you didn’t really learn the material.

So I am not adding one-leg standing to my daily exercise routine. But I won’t lie and tell you that, from time to time, and certainly on my 60th birthday, you may find me standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

So I was lying in bed the other night, trying to read my phone, and started complaining to my wife about how my vision keeps getting worse, and then how stiff I feel when I wake up in the morning, and how a recent injury is taking too long to heal, and she said, “Well, yeah. You’re 44. That’s when things start to head downhill.”

And I was like, “Forty-four? That seems very specific. I thought 50 was what people complain about.” And she said, “No, it’s a thing — 44 years old and 60 years old. There’s a drop-off there.”

And you know what? She was right.

A study, “Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging,” published in Nature Aging in August 2024, analyzed a ton of proteins and metabolites in people of various ages and found, when you put it all together, that I should know better than to doubt my brilliant spouse.

But deep down, I believe the cliché that age is just a number. I don’t particularly care about being 44, or turning 50 or 60. I care about how my body and brain are aging. If I can be a happy, healthy, 80-year-old in full command of my faculties, I would consider that a major win no matter what the calendar says.

So I’m always interested in ways to quantify how my body is aging, independent of how many birthdays I have passed. And, according to a new study, there’s actually a really easy way to do this: Just stand on one leg.

The surprising results come from “Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study,” appearing in PLOS One, which analyzed 40 individuals — half under age 65 and half over age 65 — across a variety of domains of strength, balance, and gait. The conceit of the study? We all know that things like strength and balance worsen over time, but what worsens fastest? What might be the best metric to tell us how our bodies are aging?

To that end, you have a variety of correlations between various metrics and calendar age.

As age increases, grip strength goes down. Men (inexplicably in pink) have higher grip strength overall, and women (confusingly in blue) lower. Somewhat less strong correlations were seen for knee strength.

What about balance?

To assess this, the researchers had the participants stand on a pressure plate. In one scenario, they did this with eyes open, and the next with eyes closed. They then measured how much the pressure varied around the center of the individual on the plate — basically, how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

Sway increased as age increased. Sway increased a bit more with eyes closed than with eyes open.

But the strongest correlation between any of these metrics and age was a simple one: How long can you stand on one leg?

Particularly for the nondominant leg, what you see here is a pretty dramatic drop-off in balance time around age 65, with younger people able to do 10 seconds with ease and some older people barely being able to make it to 2.

Of course, I had to try this for myself. And as I was standing around on one leg, it became clear to me exactly why this might be a good metric. It really integrates balance and strength in a way that the other tests don’t: balance, clearly, since you have to stay vertical over a relatively small base; but strength as well, because, well, one leg is holding up all the rest of you. You do feel it after a while.

So this metric passes the smell test to me, at least as a potential proxy for age-related physical decline.

But I should be careful to note that this was a cross-sectional study; the researchers looked at various people who were all different ages, not the same people over time to watch how these things change as they aged.

Also, the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs like this implies a certain linear relationship between age and standing-on-one-foot time. The raw data — the points on this graph — don’t appear that linear to me. As I mentioned above, it seems like there might be a bit of a sharp drop-off somewhere in the mid-60s. That means that we may not be able to use this as a sensitive test for aging that slowly changes as your body gets older. It might be that you’re able to essentially stand on one leg as long as you want until, one day, you can’t. That gives us less warning and less to act on.

And finally, we don’t know that changing this metric will change your health for the better. I’m sure a good physiatrist or physical therapist could design some exercises to increase any of our standing-on-one leg times. And no doubt, with practice, you could get your numbers way up. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re healthier. It’s like “teaching to the test”; you might score better on the standardized exam but you didn’t really learn the material.

So I am not adding one-leg standing to my daily exercise routine. But I won’t lie and tell you that, from time to time, and certainly on my 60th birthday, you may find me standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Is CGM the New CBT?

Lauren is a 45-year-old corporate lawyer who managed to excel in every aspect of her life, including parenting her three children while working full-time as a corporate lawyer. A math major at Harvard, she loves data.

Suffice it to say, given that I was treating her for a thyroid condition rather than diabetes, I was a little surprised when she requested I prescribe her a FreeStyle Libre (Abbott) monitor. She explained she was struggling to lose 10 pounds, and she thought continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) would help her determine which foods were impeding her weight loss journey.

While I didn’t see much downside to acquiescing, I felt she had probably been spending too much time on Reddit. What information could CGM give someone without diabetes that couldn’t be gleaned from a food label? Nevertheless, Lauren filled the prescription and began her foray into this relatively uncharted world. When she returned for a follow-up visit several months later, I was shocked to see that she had lost her intended weight. With my tail between my legs, I decided to review the theories and science behind the use of CGM in patients without insulin resistance.

Although it’s not rocket science, CGM can help patients through a “carrot and stick” approach to dieting. Lean proteins, nonstarchy vegetables, and monounsaturated fats such as nuts and avocado all support weight loss and tend to keep blood glucose levels stable. In contrast, foods known to cause weight gain (eg, sugary foods, refined starches, and processed foods) cause sugar spikes in real time. Similarly, large portion sizes are more likely to result in sugar spikes, and pairing proteins with carbohydrates minimizes blood glucose excursions.

Though all of this is basic common sense, . And because blood glucose is influenced by myriad factors including stress, genetics and metabolism, CGM can also potentially help create personal guidance for food choices.

In addition, CGM can reveal the effect of poor sleep and stress on blood glucose levels, thereby encouraging healthier lifestyle choices. The data collected also may provide information on how different modalities of physical activity affect blood glucose levels. A recent study compared the effect of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and continuous moderate-intensity exercise on postmeal blood glucose in overweight individuals without diabetes. CGM revealed that HIIT is more advantageous for preventing postmeal spikes.

Although CGM appears to be a sophisticated form of cognitive-behavioral therapy, I do worry that the incessant stream of information can lead to worsening anxiety, obsessive compulsive behaviors, or restrictive eating tendencies. Still, thanks to Lauren, I now believe that real-time CGM may lead to behavior modification in food selection and physical activity.

Dr. Messer, Clinical Assistant Professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Associate Professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, New York, NY, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Lauren is a 45-year-old corporate lawyer who managed to excel in every aspect of her life, including parenting her three children while working full-time as a corporate lawyer. A math major at Harvard, she loves data.

Suffice it to say, given that I was treating her for a thyroid condition rather than diabetes, I was a little surprised when she requested I prescribe her a FreeStyle Libre (Abbott) monitor. She explained she was struggling to lose 10 pounds, and she thought continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) would help her determine which foods were impeding her weight loss journey.

While I didn’t see much downside to acquiescing, I felt she had probably been spending too much time on Reddit. What information could CGM give someone without diabetes that couldn’t be gleaned from a food label? Nevertheless, Lauren filled the prescription and began her foray into this relatively uncharted world. When she returned for a follow-up visit several months later, I was shocked to see that she had lost her intended weight. With my tail between my legs, I decided to review the theories and science behind the use of CGM in patients without insulin resistance.

Although it’s not rocket science, CGM can help patients through a “carrot and stick” approach to dieting. Lean proteins, nonstarchy vegetables, and monounsaturated fats such as nuts and avocado all support weight loss and tend to keep blood glucose levels stable. In contrast, foods known to cause weight gain (eg, sugary foods, refined starches, and processed foods) cause sugar spikes in real time. Similarly, large portion sizes are more likely to result in sugar spikes, and pairing proteins with carbohydrates minimizes blood glucose excursions.

Though all of this is basic common sense, . And because blood glucose is influenced by myriad factors including stress, genetics and metabolism, CGM can also potentially help create personal guidance for food choices.

In addition, CGM can reveal the effect of poor sleep and stress on blood glucose levels, thereby encouraging healthier lifestyle choices. The data collected also may provide information on how different modalities of physical activity affect blood glucose levels. A recent study compared the effect of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and continuous moderate-intensity exercise on postmeal blood glucose in overweight individuals without diabetes. CGM revealed that HIIT is more advantageous for preventing postmeal spikes.

Although CGM appears to be a sophisticated form of cognitive-behavioral therapy, I do worry that the incessant stream of information can lead to worsening anxiety, obsessive compulsive behaviors, or restrictive eating tendencies. Still, thanks to Lauren, I now believe that real-time CGM may lead to behavior modification in food selection and physical activity.

Dr. Messer, Clinical Assistant Professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Associate Professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, New York, NY, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Lauren is a 45-year-old corporate lawyer who managed to excel in every aspect of her life, including parenting her three children while working full-time as a corporate lawyer. A math major at Harvard, she loves data.

Suffice it to say, given that I was treating her for a thyroid condition rather than diabetes, I was a little surprised when she requested I prescribe her a FreeStyle Libre (Abbott) monitor. She explained she was struggling to lose 10 pounds, and she thought continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) would help her determine which foods were impeding her weight loss journey.

While I didn’t see much downside to acquiescing, I felt she had probably been spending too much time on Reddit. What information could CGM give someone without diabetes that couldn’t be gleaned from a food label? Nevertheless, Lauren filled the prescription and began her foray into this relatively uncharted world. When she returned for a follow-up visit several months later, I was shocked to see that she had lost her intended weight. With my tail between my legs, I decided to review the theories and science behind the use of CGM in patients without insulin resistance.

Although it’s not rocket science, CGM can help patients through a “carrot and stick” approach to dieting. Lean proteins, nonstarchy vegetables, and monounsaturated fats such as nuts and avocado all support weight loss and tend to keep blood glucose levels stable. In contrast, foods known to cause weight gain (eg, sugary foods, refined starches, and processed foods) cause sugar spikes in real time. Similarly, large portion sizes are more likely to result in sugar spikes, and pairing proteins with carbohydrates minimizes blood glucose excursions.

Though all of this is basic common sense, . And because blood glucose is influenced by myriad factors including stress, genetics and metabolism, CGM can also potentially help create personal guidance for food choices.

In addition, CGM can reveal the effect of poor sleep and stress on blood glucose levels, thereby encouraging healthier lifestyle choices. The data collected also may provide information on how different modalities of physical activity affect blood glucose levels. A recent study compared the effect of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and continuous moderate-intensity exercise on postmeal blood glucose in overweight individuals without diabetes. CGM revealed that HIIT is more advantageous for preventing postmeal spikes.

Although CGM appears to be a sophisticated form of cognitive-behavioral therapy, I do worry that the incessant stream of information can lead to worsening anxiety, obsessive compulsive behaviors, or restrictive eating tendencies. Still, thanks to Lauren, I now believe that real-time CGM may lead to behavior modification in food selection and physical activity.

Dr. Messer, Clinical Assistant Professor, Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Associate Professor, Hofstra School of Medicine, New York, NY, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How Much Does Long COVID Cost Society? New Data Shed Light

Long COVID, a major public health crisis, is also becoming a significant economic crisis. A new study in Nature reports that the global annual economic impact of long COVID has hit $1 trillion — or about 1% of the global economy.

Long COVID is estimated to affect 6%-7% of adults. Those afflicted are often unable to work for extended periods, and some simply stop working altogether.

Besides damaging individual lives, long COVID is having wide-ranging impacts on health systems and economies worldwide, as those who suffer from it have large absences from work, leading to lower productivity. Even those who return to work after weeks, months, or even up to a year out of work may come back with worse productivity and some functional impairment — as a few of the condition’s common symptoms include fatigue and brain fog.

Experts say more is needed not only in terms of scientific research into new treatments for long COVID but also from a public policy perspective.

Long COVID’s impact on the labor force is already having ripple effects throughout the economy of the United States and other countries. Earlier this year, the US Government Accountability Office stated long COVID potentially affects up to 23 million Americans, with as many as a million people out of work. The healthcare industry is particularly hard hit.

The latest survey from the National Center for Health Statistics estimated 17.3%-18.6% of adults have experienced long COVID. This isn’t the same as those who have it now, only a broad indicator of people who’ve ever experienced symptoms.

Public health experts, economists, researchers, and physicians say they are only beginning to focus on ways to reduce long COVID’s impact.

They suggest a range of potential solutions to address the public health crisis and the economic impacts — including implementing a more thorough surveillance system to track long COVID cases, building better ventilation systems in hospitals and buildings to reduce the spread of the virus, increasing vaccination efforts as new viral strains continuously emerge, and more funding for long COVID research to better quantify and qualify the disease’s impact.

Shaky Statistics, Inconsistent Surveillance

David Smith, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Diego, said more needs to be done to survey, quantify, and qualify the impacts of long COVID on the economy before practical solutions can be identified.

“Our surveillance system sucks,” Smith said. “I can see how many people test positive for COVID, but how many of those people have long COVID?”

Long COVID also doesn’t have a true definition or standard diagnosis, which complicates surveillance efforts. It includes a spectrum of symptoms such as shortness of breath, chronic fatigue, and brain fog that linger for 2-3 months after an acute infection. But there’s no “concrete case definition,” Smith said. “And not everybody’s long COVID is exactly the same as everybody else’s.”

As a result, epidemiologists can’t effectively characterize the disease, and health economists can’t measure its exact economic impact.

Few countries have established comprehensive surveillance systems to estimate the burden of long COVID at the population level.

The United States currently tracks new cases by measuring wastewater levels, which isn’t as comprehensive as the tracking that was done during the pandemic. But positive wastewater samples can’t tell us who is infected in an area, nor can it distinguish whether a visitor/tourist or resident is mostly contributing to the wastewater analysis — an important distinction in public health studies.

Wastewater surveillance is an excellent complement to traditional disease surveillance with advantages and disadvantages, but it shouldn’t be the sole way to measure disease.

What Research Best Informs the Debate?

A study by Economist Impact — a think tank that partners with corporations, foundations, NGOs, and governments to help drive policy — estimated between a 0.5% and 2.3% gross domestic product (GDP) loss across eight separate countries in 2024. The study included the United Kingdom and United States.

Meanwhile, Australian researchers recently detailed how long COVID-related reductions in labor supply affected its productivity and GDP from 2022 to 2024. The study found that long COVID could be costing the Australian economy about 0.5% of its GDP, which researchers deemed a conservative estimate.

Public health researchers in New Zealand used the estimate of GDP loss in Australia to measure their own potential losses and advocated for strengthening occupational support across all sectors to protect health.

But these studies can’t quite compare with what would have to be done for the United States economy.

“New Zealand is small ... and has an excellent public health system with good delivery of vaccines and treatments…so how do we compare that to us?” Smith said. “They do better in all of their public health metrics than we do.”

Measuring the Economic Impact

Gopi Shah Goda, PhD, a health economist and senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution, co-authored a 2023 study that found COVID-19 reduced the US labor force by about 500,000 people.

Plus, workers who missed a full week due to COVID-19 absences became 7% less likely to return to the labor force a year later compared with workers who didn’t miss work for health reasons. That amounts to 0.2% of the labor force, a significant number.

“Even a small percent of the labor force is a big number…it’s like an extra year of populating aging,” Goda said.

“Some people who get long COVID might have dropped out of the labor force anyway,” Goda added.

The study concluded that average individual earnings lost from long COVID were $9000, and the total lost labor supply amounted to $62 billion annually — about half the estimated productivity losses from cancer or diabetes.

But research into long COVID research continues to be underfunded compared with other health conditions, experts noted.

Cancer and diabetes both receive billions of research dollars annually from the National Institutes of Health. Long COVID research gets only a few million, according to Goda.

Informing Public Health Policy

When it comes to caring for patients with long COVID, the big issue facing every nation’s public policy leaders is how best to allocate limited health resources.

“Public health never has enough money ... Do they buy more vaccines? Do they do educational programs? Who do they target the most?” Smith said.

Though Smith thinks the best preventative measure is increased vaccination, vaccination rates remain low in the United States.

“Unfortunately, as last fall demonstrated, there’s a lot of vaccine indifference and skepticism,” said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee.

Over the past year, only 14% of eligible children and 22% of adults received the 2023-2024 COVID vaccine boosters.

Schaffner said public health experts wrestle with ways to assure the public vaccines are safe and effective.

“They’re trying to provide a level of comfort that [getting vaccinated] is the socially appropriate thing to do,” which remains a significant challenge, Schaffner said.

Some people don’t have access to vaccines and comprehensive medical services because they lack insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare. And the United States still doesn’t distribute vaccines as well as other countries, Schaffner added.

“In other countries, every doctor’s office gets vaccines for free ... here, we have a large commercial enterprise that basically runs it…there are still populations who aren’t reached,” he said.

Long COVID clinics that have opened around the country have offered help to some patients with long COVID. A year and a half ago, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, established its Long COVID Care Center. Stanford University, Stanford, California, opened its Long COVID Clinic back in 2021. Vanderbilt University now has its own, as well — the Adult Post-COVID Clinic.

But these clinics have faced declining federal resources, forcing some to close and others to face questions about whether they will be able to continue to operate without more aggressive federal direction and policy planning.

“With some central direction, we could provide better supportive care for the many patients with long COVID out there,” Schaffner said.

For countries with universal healthcare systems, services such as occupational health, extended sick leave, extended time for disability, and workers’ compensation benefits are readily available.

But in the United States, it’s often left to the physicians and their patients to figure out a plan.

“I think we could make physicians more aware of options for their patients…for example, regularly check eligibility for workers compensation,” Schaffner said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID, a major public health crisis, is also becoming a significant economic crisis. A new study in Nature reports that the global annual economic impact of long COVID has hit $1 trillion — or about 1% of the global economy.

Long COVID is estimated to affect 6%-7% of adults. Those afflicted are often unable to work for extended periods, and some simply stop working altogether.

Besides damaging individual lives, long COVID is having wide-ranging impacts on health systems and economies worldwide, as those who suffer from it have large absences from work, leading to lower productivity. Even those who return to work after weeks, months, or even up to a year out of work may come back with worse productivity and some functional impairment — as a few of the condition’s common symptoms include fatigue and brain fog.

Experts say more is needed not only in terms of scientific research into new treatments for long COVID but also from a public policy perspective.

Long COVID’s impact on the labor force is already having ripple effects throughout the economy of the United States and other countries. Earlier this year, the US Government Accountability Office stated long COVID potentially affects up to 23 million Americans, with as many as a million people out of work. The healthcare industry is particularly hard hit.

The latest survey from the National Center for Health Statistics estimated 17.3%-18.6% of adults have experienced long COVID. This isn’t the same as those who have it now, only a broad indicator of people who’ve ever experienced symptoms.

Public health experts, economists, researchers, and physicians say they are only beginning to focus on ways to reduce long COVID’s impact.

They suggest a range of potential solutions to address the public health crisis and the economic impacts — including implementing a more thorough surveillance system to track long COVID cases, building better ventilation systems in hospitals and buildings to reduce the spread of the virus, increasing vaccination efforts as new viral strains continuously emerge, and more funding for long COVID research to better quantify and qualify the disease’s impact.

Shaky Statistics, Inconsistent Surveillance

David Smith, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Diego, said more needs to be done to survey, quantify, and qualify the impacts of long COVID on the economy before practical solutions can be identified.

“Our surveillance system sucks,” Smith said. “I can see how many people test positive for COVID, but how many of those people have long COVID?”

Long COVID also doesn’t have a true definition or standard diagnosis, which complicates surveillance efforts. It includes a spectrum of symptoms such as shortness of breath, chronic fatigue, and brain fog that linger for 2-3 months after an acute infection. But there’s no “concrete case definition,” Smith said. “And not everybody’s long COVID is exactly the same as everybody else’s.”

As a result, epidemiologists can’t effectively characterize the disease, and health economists can’t measure its exact economic impact.

Few countries have established comprehensive surveillance systems to estimate the burden of long COVID at the population level.

The United States currently tracks new cases by measuring wastewater levels, which isn’t as comprehensive as the tracking that was done during the pandemic. But positive wastewater samples can’t tell us who is infected in an area, nor can it distinguish whether a visitor/tourist or resident is mostly contributing to the wastewater analysis — an important distinction in public health studies.

Wastewater surveillance is an excellent complement to traditional disease surveillance with advantages and disadvantages, but it shouldn’t be the sole way to measure disease.

What Research Best Informs the Debate?

A study by Economist Impact — a think tank that partners with corporations, foundations, NGOs, and governments to help drive policy — estimated between a 0.5% and 2.3% gross domestic product (GDP) loss across eight separate countries in 2024. The study included the United Kingdom and United States.

Meanwhile, Australian researchers recently detailed how long COVID-related reductions in labor supply affected its productivity and GDP from 2022 to 2024. The study found that long COVID could be costing the Australian economy about 0.5% of its GDP, which researchers deemed a conservative estimate.

Public health researchers in New Zealand used the estimate of GDP loss in Australia to measure their own potential losses and advocated for strengthening occupational support across all sectors to protect health.

But these studies can’t quite compare with what would have to be done for the United States economy.

“New Zealand is small ... and has an excellent public health system with good delivery of vaccines and treatments…so how do we compare that to us?” Smith said. “They do better in all of their public health metrics than we do.”

Measuring the Economic Impact

Gopi Shah Goda, PhD, a health economist and senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution, co-authored a 2023 study that found COVID-19 reduced the US labor force by about 500,000 people.

Plus, workers who missed a full week due to COVID-19 absences became 7% less likely to return to the labor force a year later compared with workers who didn’t miss work for health reasons. That amounts to 0.2% of the labor force, a significant number.

“Even a small percent of the labor force is a big number…it’s like an extra year of populating aging,” Goda said.

“Some people who get long COVID might have dropped out of the labor force anyway,” Goda added.

The study concluded that average individual earnings lost from long COVID were $9000, and the total lost labor supply amounted to $62 billion annually — about half the estimated productivity losses from cancer or diabetes.

But research into long COVID research continues to be underfunded compared with other health conditions, experts noted.

Cancer and diabetes both receive billions of research dollars annually from the National Institutes of Health. Long COVID research gets only a few million, according to Goda.

Informing Public Health Policy

When it comes to caring for patients with long COVID, the big issue facing every nation’s public policy leaders is how best to allocate limited health resources.

“Public health never has enough money ... Do they buy more vaccines? Do they do educational programs? Who do they target the most?” Smith said.

Though Smith thinks the best preventative measure is increased vaccination, vaccination rates remain low in the United States.

“Unfortunately, as last fall demonstrated, there’s a lot of vaccine indifference and skepticism,” said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee.

Over the past year, only 14% of eligible children and 22% of adults received the 2023-2024 COVID vaccine boosters.

Schaffner said public health experts wrestle with ways to assure the public vaccines are safe and effective.

“They’re trying to provide a level of comfort that [getting vaccinated] is the socially appropriate thing to do,” which remains a significant challenge, Schaffner said.

Some people don’t have access to vaccines and comprehensive medical services because they lack insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare. And the United States still doesn’t distribute vaccines as well as other countries, Schaffner added.

“In other countries, every doctor’s office gets vaccines for free ... here, we have a large commercial enterprise that basically runs it…there are still populations who aren’t reached,” he said.

Long COVID clinics that have opened around the country have offered help to some patients with long COVID. A year and a half ago, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, established its Long COVID Care Center. Stanford University, Stanford, California, opened its Long COVID Clinic back in 2021. Vanderbilt University now has its own, as well — the Adult Post-COVID Clinic.

But these clinics have faced declining federal resources, forcing some to close and others to face questions about whether they will be able to continue to operate without more aggressive federal direction and policy planning.

“With some central direction, we could provide better supportive care for the many patients with long COVID out there,” Schaffner said.

For countries with universal healthcare systems, services such as occupational health, extended sick leave, extended time for disability, and workers’ compensation benefits are readily available.

But in the United States, it’s often left to the physicians and their patients to figure out a plan.

“I think we could make physicians more aware of options for their patients…for example, regularly check eligibility for workers compensation,” Schaffner said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID, a major public health crisis, is also becoming a significant economic crisis. A new study in Nature reports that the global annual economic impact of long COVID has hit $1 trillion — or about 1% of the global economy.

Long COVID is estimated to affect 6%-7% of adults. Those afflicted are often unable to work for extended periods, and some simply stop working altogether.

Besides damaging individual lives, long COVID is having wide-ranging impacts on health systems and economies worldwide, as those who suffer from it have large absences from work, leading to lower productivity. Even those who return to work after weeks, months, or even up to a year out of work may come back with worse productivity and some functional impairment — as a few of the condition’s common symptoms include fatigue and brain fog.

Experts say more is needed not only in terms of scientific research into new treatments for long COVID but also from a public policy perspective.

Long COVID’s impact on the labor force is already having ripple effects throughout the economy of the United States and other countries. Earlier this year, the US Government Accountability Office stated long COVID potentially affects up to 23 million Americans, with as many as a million people out of work. The healthcare industry is particularly hard hit.

The latest survey from the National Center for Health Statistics estimated 17.3%-18.6% of adults have experienced long COVID. This isn’t the same as those who have it now, only a broad indicator of people who’ve ever experienced symptoms.

Public health experts, economists, researchers, and physicians say they are only beginning to focus on ways to reduce long COVID’s impact.

They suggest a range of potential solutions to address the public health crisis and the economic impacts — including implementing a more thorough surveillance system to track long COVID cases, building better ventilation systems in hospitals and buildings to reduce the spread of the virus, increasing vaccination efforts as new viral strains continuously emerge, and more funding for long COVID research to better quantify and qualify the disease’s impact.

Shaky Statistics, Inconsistent Surveillance

David Smith, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Diego, said more needs to be done to survey, quantify, and qualify the impacts of long COVID on the economy before practical solutions can be identified.

“Our surveillance system sucks,” Smith said. “I can see how many people test positive for COVID, but how many of those people have long COVID?”

Long COVID also doesn’t have a true definition or standard diagnosis, which complicates surveillance efforts. It includes a spectrum of symptoms such as shortness of breath, chronic fatigue, and brain fog that linger for 2-3 months after an acute infection. But there’s no “concrete case definition,” Smith said. “And not everybody’s long COVID is exactly the same as everybody else’s.”

As a result, epidemiologists can’t effectively characterize the disease, and health economists can’t measure its exact economic impact.

Few countries have established comprehensive surveillance systems to estimate the burden of long COVID at the population level.

The United States currently tracks new cases by measuring wastewater levels, which isn’t as comprehensive as the tracking that was done during the pandemic. But positive wastewater samples can’t tell us who is infected in an area, nor can it distinguish whether a visitor/tourist or resident is mostly contributing to the wastewater analysis — an important distinction in public health studies.

Wastewater surveillance is an excellent complement to traditional disease surveillance with advantages and disadvantages, but it shouldn’t be the sole way to measure disease.

What Research Best Informs the Debate?

A study by Economist Impact — a think tank that partners with corporations, foundations, NGOs, and governments to help drive policy — estimated between a 0.5% and 2.3% gross domestic product (GDP) loss across eight separate countries in 2024. The study included the United Kingdom and United States.

Meanwhile, Australian researchers recently detailed how long COVID-related reductions in labor supply affected its productivity and GDP from 2022 to 2024. The study found that long COVID could be costing the Australian economy about 0.5% of its GDP, which researchers deemed a conservative estimate.

Public health researchers in New Zealand used the estimate of GDP loss in Australia to measure their own potential losses and advocated for strengthening occupational support across all sectors to protect health.

But these studies can’t quite compare with what would have to be done for the United States economy.

“New Zealand is small ... and has an excellent public health system with good delivery of vaccines and treatments…so how do we compare that to us?” Smith said. “They do better in all of their public health metrics than we do.”

Measuring the Economic Impact

Gopi Shah Goda, PhD, a health economist and senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution, co-authored a 2023 study that found COVID-19 reduced the US labor force by about 500,000 people.

Plus, workers who missed a full week due to COVID-19 absences became 7% less likely to return to the labor force a year later compared with workers who didn’t miss work for health reasons. That amounts to 0.2% of the labor force, a significant number.

“Even a small percent of the labor force is a big number…it’s like an extra year of populating aging,” Goda said.

“Some people who get long COVID might have dropped out of the labor force anyway,” Goda added.

The study concluded that average individual earnings lost from long COVID were $9000, and the total lost labor supply amounted to $62 billion annually — about half the estimated productivity losses from cancer or diabetes.

But research into long COVID research continues to be underfunded compared with other health conditions, experts noted.

Cancer and diabetes both receive billions of research dollars annually from the National Institutes of Health. Long COVID research gets only a few million, according to Goda.

Informing Public Health Policy

When it comes to caring for patients with long COVID, the big issue facing every nation’s public policy leaders is how best to allocate limited health resources.

“Public health never has enough money ... Do they buy more vaccines? Do they do educational programs? Who do they target the most?” Smith said.

Though Smith thinks the best preventative measure is increased vaccination, vaccination rates remain low in the United States.

“Unfortunately, as last fall demonstrated, there’s a lot of vaccine indifference and skepticism,” said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee.

Over the past year, only 14% of eligible children and 22% of adults received the 2023-2024 COVID vaccine boosters.

Schaffner said public health experts wrestle with ways to assure the public vaccines are safe and effective.

“They’re trying to provide a level of comfort that [getting vaccinated] is the socially appropriate thing to do,” which remains a significant challenge, Schaffner said.

Some people don’t have access to vaccines and comprehensive medical services because they lack insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare. And the United States still doesn’t distribute vaccines as well as other countries, Schaffner added.

“In other countries, every doctor’s office gets vaccines for free ... here, we have a large commercial enterprise that basically runs it…there are still populations who aren’t reached,” he said.

Long COVID clinics that have opened around the country have offered help to some patients with long COVID. A year and a half ago, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, established its Long COVID Care Center. Stanford University, Stanford, California, opened its Long COVID Clinic back in 2021. Vanderbilt University now has its own, as well — the Adult Post-COVID Clinic.

But these clinics have faced declining federal resources, forcing some to close and others to face questions about whether they will be able to continue to operate without more aggressive federal direction and policy planning.

“With some central direction, we could provide better supportive care for the many patients with long COVID out there,” Schaffner said.

For countries with universal healthcare systems, services such as occupational health, extended sick leave, extended time for disability, and workers’ compensation benefits are readily available.

But in the United States, it’s often left to the physicians and their patients to figure out a plan.

“I think we could make physicians more aware of options for their patients…for example, regularly check eligibility for workers compensation,” Schaffner said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE

Dry Eye Linked to Increased Risk for Mental Health Disorders

TOPLINE:

Patients with dry eye disease are more than three times as likely to have mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, as those without the condition.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used a database from the National Institutes of Health to investigate the association between dry eye disease and mental health disorders in a large and diverse nationwide population of American adults.

- They identified 18,257 patients (mean age, 64.9 years; 67% women) with dry eye disease who were propensity score–matched with 54,765 participants without the condition.

- The cases of dry eye disease were identified using Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine codes for dry eyes, meibomian gland dysfunction, and tear film insufficiency.

- The outcome measures for mental health conditions were clinical diagnoses of depressive disorders, anxiety-related disorders, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients with dry eye disease had more than triple the risk for mental health conditions than participants without the condition (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.21; P < .001).

- Patients with dry eye disease had a higher risk for a depressive disorder (aOR, 3.47), anxiety-related disorder (aOR, 2.74), bipolar disorder (aOR, 2.23), and schizophrenia spectrum disorder (aOR, 2.48; P < .001 for all) than participants without the condition.

- The associations between dry eye disease and mental health conditions were significantly stronger among Black individuals than among White individuals, except for bipolar disorder.

- Dry eye disease was associated with two- to threefold higher odds of depressive disorders, anxiety-related disorders, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders even in participants who never used medications for mental health (P < .001 for all).

IN PRACTICE: