User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

10 Recent paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and treatment of depression

Nowhere is that change in landscape more apparent than in major depression, the No. 1 disabling condition in all of medicine, according to the World Health Organization. The past decade has generated at least 10 paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and pharmacotherapeutics of depression.

Clinging to simplistic tradition

Most contemporary clinicians continue to practice the traditional model of depression, which is based on the assumption that depression is caused by a deficiency of monoamines: serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE). The entire antidepressant armamentarium approved for use by the FDA was designed according to the amine deficiency hypothesis. Depressed patients uniformly receive reuptake inhibitors of 5-HT and NE, but few achieve full remission, as the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study showed.1

As scientific paradigm shifts infiltrate clinical practice, however, the tired notion of “chemical imbalance” will yield to more complex and evidence-based models.

Usually, it would be remarkable to witness a single paradigm shift in the understanding of a brain disorder. Imagine the disruptive impact of multiple scientific shifts within the past decade! Consider the following departures from the old dogma about the simplistic old explanation of depression.

1. From neurotransmitters to neuroplasticity

For half a century, our field tenaciously held to the monoamine theory, which posits that depression is caused by a deficiency of 5-HT or NE, or both. All antidepressants in use today were developed to increase brain monoamines by inhibiting their reuptake at the synaptic cleft. Now, research points to other causes:

• impaired neuroplasticity

• a decrement of neurogenesis

• synaptic deficits

• decreased neurotrophins (such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor)

• dendritic pathology.2,3

2. From ‘chemical imbalance’ to neuroinflammation

The simplistic notion that depression is a chemical imbalance, so to speak, in the brain is giving way to rapidly emerging evidence that depression is associated with neuroinflammation.4

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated in the plasma of depressed patients, and subside when the acute episode is treated. Current antidepressants actually have anti-inflammatory effects that have gone unrecognized.5 A meta-analysis of the use of anti-inflammatory agents (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin) in depression shows promising efficacy.6 Some inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, already have been reported to predict response to some antidepressants, but not to others.7

3. From 5-HT and NE pathways to glutamate NMDA receptors

Recent landmark studies8 have, taken together, demonstrated that a single IV dose of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist ketamine (a psychotogenic drug of abuse FDA-approved only as an anesthetic) can produce clinical improvement of severe depression and even full remission for several days. Such studies demonstrate that the old dogma of 5-HT and NE deficiency might not be a valid overarching hypothesis of the depression syndrome.

Long-term maintenance studies of ketamine to document its safety and continued efficacy need to be conducted. The mechanism of action of ketamine is believed to be a rapid trigger for enhancing neuroplasticity.

4. From oral to parenteral administration

Several studies have been published showing the efficacy of IV or intranasal administration of new agents for depression. Ketamine studies, for example, were conducted using an IV infusion of a 150-mg dose over 1 hour. Other IV studies used the anticholinergic scopolamine.9

Intranasal ketamine also has been shown to be clinically efficacious.10 Inhalable nitrous oxide (laughing gas, an NMDA antagonist) recently was reported to improve depression as well.11

It is possible that parenteral administration of antidepressant agents may exert a different neurobiological effect and provide a more rapid response than oral medication.

5. From delayed efficacy (weeks) to immediate onset (1 or 2 hours)

The widely entrenched notion that depression takes several weeks to improve with an antidepressant has collapsed with emerging evidence that symptoms of the disorder (even suicidal ideation) can be reversed within 1 or 2 hours.12 IV ketamine isn’t the only example; IV scopolamine,9 inhalable nitrous oxide,11 and overnight sleep deprivation13 also exert a rapid therapeutic effect. This is a major rethinking of how quickly the curtain of severe depression can be lifted, and is great news for patients and their family.

6. From psychological symptoms to cortical or subcortical changes

Depression traditionally has been recognized as a clinical syndrome of sadness, self-deprecation, cognitive dulling, and vegetative symptoms. In recent studies, however, researchers report that low hippocampus volume14 in healthy young girls predicts future depression. Patients with unremitting depression have been reported to have an abnormally shaped hippocampus.15

In addition, gray-matter volume in the subgenual anterior cingulate (Brodmann area 24) is hypoplastic in depressed persons,16 making that area a target for deep-brain stimulation (DBS). Brain morphological changes such as a hypoplastic hippocampus might become useful biomarkers for identifying persons at risk of severe depression, and might become a useful adjunctive biomarker for making a clinical diagnosis.

7. From healing the mind to repairing the brain

It is well-established that depression is associated with loss of dendritic spines and arborizations, loss of synapses, and diminishment of glial cells, especially in the hippocampus17 and anterior cingulate.18 Treating depression, whether pharmaceutical or somatic, involves reversing these changes by increasing neurotrophic factors, enhancing neurogenesis and gliogenesis, and restoring synaptic and dendritic health and cell survival in the hippocampus and frontal cortex.19,20 Treating depression involves brain repair, which is reflected, ultimately, in healing the mind.

8. From pharmacotherapy to neuromodulation

Although drugs remain the predominant treatment modality for depression, there is palpable escalation in the use of neuromodulation methods.

The oldest of these neuromodulatory techniques is electroconvulsive therapy, an excellent treatment for severe depression (and one that enhances hippocampal neurogenesis). In addition, several novel neuromodulation methods have been approved (transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation) or are in development (transcranial direct-current stimulation, cranial electrotherapy stimulation, and DBS).21 These somatic approaches to treating the brain directly to alleviate depression target regions involved in depression and reduce the needless risks associated with exposing other organ systems to a drug.

9. From monotherapy to combination therapy

The use of combination therapy for depression has escalated with FDA approval of adjunctive use of atypical antipsychotics in unipolar and bipolar depression. In addition, the landmark STAR*D study1 demonstrated the value of augmentation therapy with a second antidepressant when 1 agent fails. Other controlled studies have shown that combining 2 antidepressants is superior to administering 1.22

Just as other serious medical disorders—such as cancer and hypertension—are treated with 2 or 3 medications, severe depression might require a similar strategy. The field gradually is adopting that approach.

10. From cortical folds to wrinkles on the face

Last, a new (and unexpected) paradigm shift recently emerged, which is genuinely intriguing—even baffling. Using placebo-controlled designs, several researchers have reported significant, persistent improvement of depressive symptoms after injection of onabotulinumtoxinA in the corrugator muscles of the glabellar region of the face, where the omega sign often appears in a depressed person.23,24

The longest of the studies25 was 6 months; investigators reported that improvement continued even after the effect of the botulinum toxin on the omega sign wore off. The proposed mechanism of action is the facial feedback hypothesis, which suggests that, biologically, facial expression has an impact on one’s emotional state.

Big payoffs coming from research in neuroscience

These 10 paradigm shifts in a single psychiatric syndrome are emblematic of exciting clinical and research advances in our field. Like all syndromes, depression is associated with multiple genetic and environmental causes; it isn’t surprising that myriad treatment approaches are emerging.

The days of clinging to monolithic, serendipity-generated models surely are over. Evidence-based psychiatric brain research is shattering aging dogmas that have, for decades, stifled innovation in psychiatric therapeutics that is now moving in novel directions.

Take note, however, that the only paradigm shift that matters to depressed patients is the one that transcends mere control of their symptoms and restores their wellness, functional capacity, and quality of life. With the explosive momentum of neuroscience discovery, psychiatry is, at last, poised to deliver—in splendid, even seismic, fashion.

1. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

2. Serafini G, Hayley S, Pompili M, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis, neurotrophic factors and depression: possible therapeutic targets [published online November 30, 2014]? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666141130223723.

3. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2012;338(6103):68-72.

4. Iwata M, Ota KT, Duman RS. The inflammasome: pathways linking psychological stress, depression, and systemic illnesses. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31:105-114.

5. Sacre S, Medghalichi M, Gregory B, et al. Fluoxetine and citalopram exhibit potent anti-inflammatory activity in human and murine models of rheumatoid arthritis and inhibit toll-like receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(3):683-693.

6. Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12): 1381-1391.

7. Uher R, Tansey KE, Dew T, et al. An inflammatory biomarker as a differential predictor of outcome of depression treatment with escitalopram and nortiptyline. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(14):1278-1286.

8. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics [published online October 17, 2014]. Annual Rev Med. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-053013-062946.

9. Furey ML, Khanna A, Hoffman EM, et al. Scopolamine produces larger antidepressant and antianxiety effects in women than in men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(12):2479-2488.

10. Lapidus KA, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2014; 76(12):970-976.

11. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial [published December 14, 2014]. Biol Psychiatry. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.016.

12. Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12): 1381-1391.

13. Bunney BG, Bunney WE. Mechanisms of rapid antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation therapy: clock genes and circadian rhythms. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1164-1171.

14. Chen MC, Hamilton JP, Gotlib IH. Decreased hippocampal volume in healthy girls at risk for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):270-276.

15. Tae WS, Kim SS, Lee KU, et al. Hippocampal shape deformation in female patients with unremitting major depressive disorder. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(4):671-676.

16. Hamani C, Mayberg H, Synder B, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subcallosal cingulate gyrus for depression: anatomical location of active contacts in clinical responders and a suggested guideline for targeting. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(6):1209-1215.

17. Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1516-1518.

18. Redlich R, Almeoda JJ, Grotegerd D, et al. Brain morphometric biomarkers distinguishing unipolar and bipolar depression. A voxel-based morphometry-pattern classification approach. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(11):1222-1230.

19. Mendez-David I, Hen R, Gardier AM, et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis: an actor in the antidepressant-like action. Ann Pharm Fr. 2013;71(3):143-149.

20. Serafini G. Neuroplasticity and major depression, the role of modern antidepressant drugs. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(3):49-57.

21. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

22. Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, et al. Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: a double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):281-288.

23. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(5):574-581.

24. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

25. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

Nowhere is that change in landscape more apparent than in major depression, the No. 1 disabling condition in all of medicine, according to the World Health Organization. The past decade has generated at least 10 paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and pharmacotherapeutics of depression.

Clinging to simplistic tradition

Most contemporary clinicians continue to practice the traditional model of depression, which is based on the assumption that depression is caused by a deficiency of monoamines: serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE). The entire antidepressant armamentarium approved for use by the FDA was designed according to the amine deficiency hypothesis. Depressed patients uniformly receive reuptake inhibitors of 5-HT and NE, but few achieve full remission, as the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study showed.1

As scientific paradigm shifts infiltrate clinical practice, however, the tired notion of “chemical imbalance” will yield to more complex and evidence-based models.

Usually, it would be remarkable to witness a single paradigm shift in the understanding of a brain disorder. Imagine the disruptive impact of multiple scientific shifts within the past decade! Consider the following departures from the old dogma about the simplistic old explanation of depression.

1. From neurotransmitters to neuroplasticity

For half a century, our field tenaciously held to the monoamine theory, which posits that depression is caused by a deficiency of 5-HT or NE, or both. All antidepressants in use today were developed to increase brain monoamines by inhibiting their reuptake at the synaptic cleft. Now, research points to other causes:

• impaired neuroplasticity

• a decrement of neurogenesis

• synaptic deficits

• decreased neurotrophins (such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor)

• dendritic pathology.2,3

2. From ‘chemical imbalance’ to neuroinflammation

The simplistic notion that depression is a chemical imbalance, so to speak, in the brain is giving way to rapidly emerging evidence that depression is associated with neuroinflammation.4

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated in the plasma of depressed patients, and subside when the acute episode is treated. Current antidepressants actually have anti-inflammatory effects that have gone unrecognized.5 A meta-analysis of the use of anti-inflammatory agents (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin) in depression shows promising efficacy.6 Some inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, already have been reported to predict response to some antidepressants, but not to others.7

3. From 5-HT and NE pathways to glutamate NMDA receptors

Recent landmark studies8 have, taken together, demonstrated that a single IV dose of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist ketamine (a psychotogenic drug of abuse FDA-approved only as an anesthetic) can produce clinical improvement of severe depression and even full remission for several days. Such studies demonstrate that the old dogma of 5-HT and NE deficiency might not be a valid overarching hypothesis of the depression syndrome.

Long-term maintenance studies of ketamine to document its safety and continued efficacy need to be conducted. The mechanism of action of ketamine is believed to be a rapid trigger for enhancing neuroplasticity.

4. From oral to parenteral administration

Several studies have been published showing the efficacy of IV or intranasal administration of new agents for depression. Ketamine studies, for example, were conducted using an IV infusion of a 150-mg dose over 1 hour. Other IV studies used the anticholinergic scopolamine.9

Intranasal ketamine also has been shown to be clinically efficacious.10 Inhalable nitrous oxide (laughing gas, an NMDA antagonist) recently was reported to improve depression as well.11

It is possible that parenteral administration of antidepressant agents may exert a different neurobiological effect and provide a more rapid response than oral medication.

5. From delayed efficacy (weeks) to immediate onset (1 or 2 hours)

The widely entrenched notion that depression takes several weeks to improve with an antidepressant has collapsed with emerging evidence that symptoms of the disorder (even suicidal ideation) can be reversed within 1 or 2 hours.12 IV ketamine isn’t the only example; IV scopolamine,9 inhalable nitrous oxide,11 and overnight sleep deprivation13 also exert a rapid therapeutic effect. This is a major rethinking of how quickly the curtain of severe depression can be lifted, and is great news for patients and their family.

6. From psychological symptoms to cortical or subcortical changes

Depression traditionally has been recognized as a clinical syndrome of sadness, self-deprecation, cognitive dulling, and vegetative symptoms. In recent studies, however, researchers report that low hippocampus volume14 in healthy young girls predicts future depression. Patients with unremitting depression have been reported to have an abnormally shaped hippocampus.15

In addition, gray-matter volume in the subgenual anterior cingulate (Brodmann area 24) is hypoplastic in depressed persons,16 making that area a target for deep-brain stimulation (DBS). Brain morphological changes such as a hypoplastic hippocampus might become useful biomarkers for identifying persons at risk of severe depression, and might become a useful adjunctive biomarker for making a clinical diagnosis.

7. From healing the mind to repairing the brain

It is well-established that depression is associated with loss of dendritic spines and arborizations, loss of synapses, and diminishment of glial cells, especially in the hippocampus17 and anterior cingulate.18 Treating depression, whether pharmaceutical or somatic, involves reversing these changes by increasing neurotrophic factors, enhancing neurogenesis and gliogenesis, and restoring synaptic and dendritic health and cell survival in the hippocampus and frontal cortex.19,20 Treating depression involves brain repair, which is reflected, ultimately, in healing the mind.

8. From pharmacotherapy to neuromodulation

Although drugs remain the predominant treatment modality for depression, there is palpable escalation in the use of neuromodulation methods.

The oldest of these neuromodulatory techniques is electroconvulsive therapy, an excellent treatment for severe depression (and one that enhances hippocampal neurogenesis). In addition, several novel neuromodulation methods have been approved (transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation) or are in development (transcranial direct-current stimulation, cranial electrotherapy stimulation, and DBS).21 These somatic approaches to treating the brain directly to alleviate depression target regions involved in depression and reduce the needless risks associated with exposing other organ systems to a drug.

9. From monotherapy to combination therapy

The use of combination therapy for depression has escalated with FDA approval of adjunctive use of atypical antipsychotics in unipolar and bipolar depression. In addition, the landmark STAR*D study1 demonstrated the value of augmentation therapy with a second antidepressant when 1 agent fails. Other controlled studies have shown that combining 2 antidepressants is superior to administering 1.22

Just as other serious medical disorders—such as cancer and hypertension—are treated with 2 or 3 medications, severe depression might require a similar strategy. The field gradually is adopting that approach.

10. From cortical folds to wrinkles on the face

Last, a new (and unexpected) paradigm shift recently emerged, which is genuinely intriguing—even baffling. Using placebo-controlled designs, several researchers have reported significant, persistent improvement of depressive symptoms after injection of onabotulinumtoxinA in the corrugator muscles of the glabellar region of the face, where the omega sign often appears in a depressed person.23,24

The longest of the studies25 was 6 months; investigators reported that improvement continued even after the effect of the botulinum toxin on the omega sign wore off. The proposed mechanism of action is the facial feedback hypothesis, which suggests that, biologically, facial expression has an impact on one’s emotional state.

Big payoffs coming from research in neuroscience

These 10 paradigm shifts in a single psychiatric syndrome are emblematic of exciting clinical and research advances in our field. Like all syndromes, depression is associated with multiple genetic and environmental causes; it isn’t surprising that myriad treatment approaches are emerging.

The days of clinging to monolithic, serendipity-generated models surely are over. Evidence-based psychiatric brain research is shattering aging dogmas that have, for decades, stifled innovation in psychiatric therapeutics that is now moving in novel directions.

Take note, however, that the only paradigm shift that matters to depressed patients is the one that transcends mere control of their symptoms and restores their wellness, functional capacity, and quality of life. With the explosive momentum of neuroscience discovery, psychiatry is, at last, poised to deliver—in splendid, even seismic, fashion.

Nowhere is that change in landscape more apparent than in major depression, the No. 1 disabling condition in all of medicine, according to the World Health Organization. The past decade has generated at least 10 paradigm shifts in the neurobiology and pharmacotherapeutics of depression.

Clinging to simplistic tradition

Most contemporary clinicians continue to practice the traditional model of depression, which is based on the assumption that depression is caused by a deficiency of monoamines: serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE). The entire antidepressant armamentarium approved for use by the FDA was designed according to the amine deficiency hypothesis. Depressed patients uniformly receive reuptake inhibitors of 5-HT and NE, but few achieve full remission, as the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study showed.1

As scientific paradigm shifts infiltrate clinical practice, however, the tired notion of “chemical imbalance” will yield to more complex and evidence-based models.

Usually, it would be remarkable to witness a single paradigm shift in the understanding of a brain disorder. Imagine the disruptive impact of multiple scientific shifts within the past decade! Consider the following departures from the old dogma about the simplistic old explanation of depression.

1. From neurotransmitters to neuroplasticity

For half a century, our field tenaciously held to the monoamine theory, which posits that depression is caused by a deficiency of 5-HT or NE, or both. All antidepressants in use today were developed to increase brain monoamines by inhibiting their reuptake at the synaptic cleft. Now, research points to other causes:

• impaired neuroplasticity

• a decrement of neurogenesis

• synaptic deficits

• decreased neurotrophins (such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor)

• dendritic pathology.2,3

2. From ‘chemical imbalance’ to neuroinflammation

The simplistic notion that depression is a chemical imbalance, so to speak, in the brain is giving way to rapidly emerging evidence that depression is associated with neuroinflammation.4

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are elevated in the plasma of depressed patients, and subside when the acute episode is treated. Current antidepressants actually have anti-inflammatory effects that have gone unrecognized.5 A meta-analysis of the use of anti-inflammatory agents (such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin) in depression shows promising efficacy.6 Some inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, already have been reported to predict response to some antidepressants, but not to others.7

3. From 5-HT and NE pathways to glutamate NMDA receptors

Recent landmark studies8 have, taken together, demonstrated that a single IV dose of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist ketamine (a psychotogenic drug of abuse FDA-approved only as an anesthetic) can produce clinical improvement of severe depression and even full remission for several days. Such studies demonstrate that the old dogma of 5-HT and NE deficiency might not be a valid overarching hypothesis of the depression syndrome.

Long-term maintenance studies of ketamine to document its safety and continued efficacy need to be conducted. The mechanism of action of ketamine is believed to be a rapid trigger for enhancing neuroplasticity.

4. From oral to parenteral administration

Several studies have been published showing the efficacy of IV or intranasal administration of new agents for depression. Ketamine studies, for example, were conducted using an IV infusion of a 150-mg dose over 1 hour. Other IV studies used the anticholinergic scopolamine.9

Intranasal ketamine also has been shown to be clinically efficacious.10 Inhalable nitrous oxide (laughing gas, an NMDA antagonist) recently was reported to improve depression as well.11

It is possible that parenteral administration of antidepressant agents may exert a different neurobiological effect and provide a more rapid response than oral medication.

5. From delayed efficacy (weeks) to immediate onset (1 or 2 hours)

The widely entrenched notion that depression takes several weeks to improve with an antidepressant has collapsed with emerging evidence that symptoms of the disorder (even suicidal ideation) can be reversed within 1 or 2 hours.12 IV ketamine isn’t the only example; IV scopolamine,9 inhalable nitrous oxide,11 and overnight sleep deprivation13 also exert a rapid therapeutic effect. This is a major rethinking of how quickly the curtain of severe depression can be lifted, and is great news for patients and their family.

6. From psychological symptoms to cortical or subcortical changes

Depression traditionally has been recognized as a clinical syndrome of sadness, self-deprecation, cognitive dulling, and vegetative symptoms. In recent studies, however, researchers report that low hippocampus volume14 in healthy young girls predicts future depression. Patients with unremitting depression have been reported to have an abnormally shaped hippocampus.15

In addition, gray-matter volume in the subgenual anterior cingulate (Brodmann area 24) is hypoplastic in depressed persons,16 making that area a target for deep-brain stimulation (DBS). Brain morphological changes such as a hypoplastic hippocampus might become useful biomarkers for identifying persons at risk of severe depression, and might become a useful adjunctive biomarker for making a clinical diagnosis.

7. From healing the mind to repairing the brain

It is well-established that depression is associated with loss of dendritic spines and arborizations, loss of synapses, and diminishment of glial cells, especially in the hippocampus17 and anterior cingulate.18 Treating depression, whether pharmaceutical or somatic, involves reversing these changes by increasing neurotrophic factors, enhancing neurogenesis and gliogenesis, and restoring synaptic and dendritic health and cell survival in the hippocampus and frontal cortex.19,20 Treating depression involves brain repair, which is reflected, ultimately, in healing the mind.

8. From pharmacotherapy to neuromodulation

Although drugs remain the predominant treatment modality for depression, there is palpable escalation in the use of neuromodulation methods.

The oldest of these neuromodulatory techniques is electroconvulsive therapy, an excellent treatment for severe depression (and one that enhances hippocampal neurogenesis). In addition, several novel neuromodulation methods have been approved (transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagus nerve stimulation) or are in development (transcranial direct-current stimulation, cranial electrotherapy stimulation, and DBS).21 These somatic approaches to treating the brain directly to alleviate depression target regions involved in depression and reduce the needless risks associated with exposing other organ systems to a drug.

9. From monotherapy to combination therapy

The use of combination therapy for depression has escalated with FDA approval of adjunctive use of atypical antipsychotics in unipolar and bipolar depression. In addition, the landmark STAR*D study1 demonstrated the value of augmentation therapy with a second antidepressant when 1 agent fails. Other controlled studies have shown that combining 2 antidepressants is superior to administering 1.22

Just as other serious medical disorders—such as cancer and hypertension—are treated with 2 or 3 medications, severe depression might require a similar strategy. The field gradually is adopting that approach.

10. From cortical folds to wrinkles on the face

Last, a new (and unexpected) paradigm shift recently emerged, which is genuinely intriguing—even baffling. Using placebo-controlled designs, several researchers have reported significant, persistent improvement of depressive symptoms after injection of onabotulinumtoxinA in the corrugator muscles of the glabellar region of the face, where the omega sign often appears in a depressed person.23,24

The longest of the studies25 was 6 months; investigators reported that improvement continued even after the effect of the botulinum toxin on the omega sign wore off. The proposed mechanism of action is the facial feedback hypothesis, which suggests that, biologically, facial expression has an impact on one’s emotional state.

Big payoffs coming from research in neuroscience

These 10 paradigm shifts in a single psychiatric syndrome are emblematic of exciting clinical and research advances in our field. Like all syndromes, depression is associated with multiple genetic and environmental causes; it isn’t surprising that myriad treatment approaches are emerging.

The days of clinging to monolithic, serendipity-generated models surely are over. Evidence-based psychiatric brain research is shattering aging dogmas that have, for decades, stifled innovation in psychiatric therapeutics that is now moving in novel directions.

Take note, however, that the only paradigm shift that matters to depressed patients is the one that transcends mere control of their symptoms and restores their wellness, functional capacity, and quality of life. With the explosive momentum of neuroscience discovery, psychiatry is, at last, poised to deliver—in splendid, even seismic, fashion.

1. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

2. Serafini G, Hayley S, Pompili M, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis, neurotrophic factors and depression: possible therapeutic targets [published online November 30, 2014]? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666141130223723.

3. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2012;338(6103):68-72.

4. Iwata M, Ota KT, Duman RS. The inflammasome: pathways linking psychological stress, depression, and systemic illnesses. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31:105-114.

5. Sacre S, Medghalichi M, Gregory B, et al. Fluoxetine and citalopram exhibit potent anti-inflammatory activity in human and murine models of rheumatoid arthritis and inhibit toll-like receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(3):683-693.

6. Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12): 1381-1391.

7. Uher R, Tansey KE, Dew T, et al. An inflammatory biomarker as a differential predictor of outcome of depression treatment with escitalopram and nortiptyline. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(14):1278-1286.

8. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics [published online October 17, 2014]. Annual Rev Med. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-053013-062946.

9. Furey ML, Khanna A, Hoffman EM, et al. Scopolamine produces larger antidepressant and antianxiety effects in women than in men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(12):2479-2488.

10. Lapidus KA, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2014; 76(12):970-976.

11. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial [published December 14, 2014]. Biol Psychiatry. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.016.

12. Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12): 1381-1391.

13. Bunney BG, Bunney WE. Mechanisms of rapid antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation therapy: clock genes and circadian rhythms. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1164-1171.

14. Chen MC, Hamilton JP, Gotlib IH. Decreased hippocampal volume in healthy girls at risk for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):270-276.

15. Tae WS, Kim SS, Lee KU, et al. Hippocampal shape deformation in female patients with unremitting major depressive disorder. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(4):671-676.

16. Hamani C, Mayberg H, Synder B, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subcallosal cingulate gyrus for depression: anatomical location of active contacts in clinical responders and a suggested guideline for targeting. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(6):1209-1215.

17. Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1516-1518.

18. Redlich R, Almeoda JJ, Grotegerd D, et al. Brain morphometric biomarkers distinguishing unipolar and bipolar depression. A voxel-based morphometry-pattern classification approach. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(11):1222-1230.

19. Mendez-David I, Hen R, Gardier AM, et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis: an actor in the antidepressant-like action. Ann Pharm Fr. 2013;71(3):143-149.

20. Serafini G. Neuroplasticity and major depression, the role of modern antidepressant drugs. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(3):49-57.

21. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

22. Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, et al. Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: a double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):281-288.

23. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(5):574-581.

24. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

25. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

1. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Eng J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

2. Serafini G, Hayley S, Pompili M, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis, neurotrophic factors and depression: possible therapeutic targets [published online November 30, 2014]? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666141130223723.

3. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2012;338(6103):68-72.

4. Iwata M, Ota KT, Duman RS. The inflammasome: pathways linking psychological stress, depression, and systemic illnesses. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;31:105-114.

5. Sacre S, Medghalichi M, Gregory B, et al. Fluoxetine and citalopram exhibit potent anti-inflammatory activity in human and murine models of rheumatoid arthritis and inhibit toll-like receptors. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(3):683-693.

6. Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12): 1381-1391.

7. Uher R, Tansey KE, Dew T, et al. An inflammatory biomarker as a differential predictor of outcome of depression treatment with escitalopram and nortiptyline. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(14):1278-1286.

8. Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, et al. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics [published online October 17, 2014]. Annual Rev Med. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-053013-062946.

9. Furey ML, Khanna A, Hoffman EM, et al. Scopolamine produces larger antidepressant and antianxiety effects in women than in men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(12):2479-2488.

10. Lapidus KA, Levitch CF, Perez AM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2014; 76(12):970-976.

11. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial [published December 14, 2014]. Biol Psychiatry. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.11.016.

12. Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12): 1381-1391.

13. Bunney BG, Bunney WE. Mechanisms of rapid antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation therapy: clock genes and circadian rhythms. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1164-1171.

14. Chen MC, Hamilton JP, Gotlib IH. Decreased hippocampal volume in healthy girls at risk for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):270-276.

15. Tae WS, Kim SS, Lee KU, et al. Hippocampal shape deformation in female patients with unremitting major depressive disorder. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(4):671-676.

16. Hamani C, Mayberg H, Synder B, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subcallosal cingulate gyrus for depression: anatomical location of active contacts in clinical responders and a suggested guideline for targeting. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(6):1209-1215.

17. Sheline YI, Gado MH, Kraemer HC. Untreated depression and hippocampal volume loss. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1516-1518.

18. Redlich R, Almeoda JJ, Grotegerd D, et al. Brain morphometric biomarkers distinguishing unipolar and bipolar depression. A voxel-based morphometry-pattern classification approach. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(11):1222-1230.

19. Mendez-David I, Hen R, Gardier AM, et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis: an actor in the antidepressant-like action. Ann Pharm Fr. 2013;71(3):143-149.

20. Serafini G. Neuroplasticity and major depression, the role of modern antidepressant drugs. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(3):49-57.

21. Rosa MA, Lisanby SH. Somatic treatments for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):102-116.

22. Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, et al. Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: a double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):281-288.

23. Wollmer MA, de Boer C, Kalak N, et al. Facing depression with botulinum toxin: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(5):574-581.

24. Finzi E, Rosenthal NE. Treatment of depression with onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;52:1-6.

25. Magid M, Reichenberg JS, Poth PE, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder using botulinum toxin A: a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(8):837-844.

Beware of methylmercury during pregnancy!

Dr. Henry A. Nasrallah is correct that wild salmon is a good choice for pregnant women who want to boost intake of omega-3 fatty acids (Current Psychiatry, Comments & Controversies, December 2014; pg 33 [http://bit.ly/1wQoXdP]). The main concern about fish intake during pregnancy is exposure to methylmercury, and much of this concern is derived from the tragic results of epic mercury poisonings of food sources in the past.

The FDA advises that pregnant women and children avoid eating shark, tilefish, king mackerel, and swordfish because these fish have a relatively high level of mercury.1 Fish that are low in methyl-mercury include salmon and canned light tuna. (More information is available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/HealthEducators/ucm083324.htm.)

Although wild fish tend to be higher in omega-3 fatty acids than farm-raised fish, farmed fish can be an excellent source of omega-3 fatty acids. This is analogous to eating farm-produced livestock vs free-range, grass-fed livestock: Animals in their natural environment eat healthier and have more omega-3 fatty acids, whereas farmed livestock generally eat cheap and less healthy feed. Because wild fish can be pricey, it’s important that women understand that farm-raised fish are a good source of protein and other nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids.

Research has been inconclusive regarding the antidepressant benefits of omega-3 fatty acids, with some, but not all, studies demonstrating an add-on benefit of omega-3 fatty acid supplements for mood disorders. However, several epidemiological studies have reported that the low quality of dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids is associated with psychiatric illness, and fish and seafood are sources of essential fatty acids and other nutrients.2

1. Food safety for moms-to-be: while you’re pregnant–methylmercury. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/Food/ ResourcesForYou/HealthEducators/ucm083324. htm. Updated October 30, 2014. Accessed January 5, 2015.

2. Quirk SE, Williams LJ, O’Neil A, et al. The association between diet quality, dietary patterns and depression in adults: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:175.

Dr. Henry A. Nasrallah is correct that wild salmon is a good choice for pregnant women who want to boost intake of omega-3 fatty acids (Current Psychiatry, Comments & Controversies, December 2014; pg 33 [http://bit.ly/1wQoXdP]). The main concern about fish intake during pregnancy is exposure to methylmercury, and much of this concern is derived from the tragic results of epic mercury poisonings of food sources in the past.

The FDA advises that pregnant women and children avoid eating shark, tilefish, king mackerel, and swordfish because these fish have a relatively high level of mercury.1 Fish that are low in methyl-mercury include salmon and canned light tuna. (More information is available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/HealthEducators/ucm083324.htm.)

Although wild fish tend to be higher in omega-3 fatty acids than farm-raised fish, farmed fish can be an excellent source of omega-3 fatty acids. This is analogous to eating farm-produced livestock vs free-range, grass-fed livestock: Animals in their natural environment eat healthier and have more omega-3 fatty acids, whereas farmed livestock generally eat cheap and less healthy feed. Because wild fish can be pricey, it’s important that women understand that farm-raised fish are a good source of protein and other nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids.

Research has been inconclusive regarding the antidepressant benefits of omega-3 fatty acids, with some, but not all, studies demonstrating an add-on benefit of omega-3 fatty acid supplements for mood disorders. However, several epidemiological studies have reported that the low quality of dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids is associated with psychiatric illness, and fish and seafood are sources of essential fatty acids and other nutrients.2

Dr. Henry A. Nasrallah is correct that wild salmon is a good choice for pregnant women who want to boost intake of omega-3 fatty acids (Current Psychiatry, Comments & Controversies, December 2014; pg 33 [http://bit.ly/1wQoXdP]). The main concern about fish intake during pregnancy is exposure to methylmercury, and much of this concern is derived from the tragic results of epic mercury poisonings of food sources in the past.

The FDA advises that pregnant women and children avoid eating shark, tilefish, king mackerel, and swordfish because these fish have a relatively high level of mercury.1 Fish that are low in methyl-mercury include salmon and canned light tuna. (More information is available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/HealthEducators/ucm083324.htm.)

Although wild fish tend to be higher in omega-3 fatty acids than farm-raised fish, farmed fish can be an excellent source of omega-3 fatty acids. This is analogous to eating farm-produced livestock vs free-range, grass-fed livestock: Animals in their natural environment eat healthier and have more omega-3 fatty acids, whereas farmed livestock generally eat cheap and less healthy feed. Because wild fish can be pricey, it’s important that women understand that farm-raised fish are a good source of protein and other nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids.

Research has been inconclusive regarding the antidepressant benefits of omega-3 fatty acids, with some, but not all, studies demonstrating an add-on benefit of omega-3 fatty acid supplements for mood disorders. However, several epidemiological studies have reported that the low quality of dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids is associated with psychiatric illness, and fish and seafood are sources of essential fatty acids and other nutrients.2

1. Food safety for moms-to-be: while you’re pregnant–methylmercury. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/Food/ ResourcesForYou/HealthEducators/ucm083324. htm. Updated October 30, 2014. Accessed January 5, 2015.

2. Quirk SE, Williams LJ, O’Neil A, et al. The association between diet quality, dietary patterns and depression in adults: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:175.

1. Food safety for moms-to-be: while you’re pregnant–methylmercury. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/Food/ ResourcesForYou/HealthEducators/ucm083324. htm. Updated October 30, 2014. Accessed January 5, 2015.

2. Quirk SE, Williams LJ, O’Neil A, et al. The association between diet quality, dietary patterns and depression in adults: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:175.

More on insomnia disorders in older patients

Regarding Drs. Irene S. Hong’s and Jeffrey R. Bishop’s article, “Sedative-hypnotics for sleepless geriatric patients: Choose wisely” (Current Psychiatry, 2014;13(10):36-39, 46-50, 52 [http://bit.ly/1ApmcoO]), which undertook a comprehensive review of current therapies for insomnia in geriatric patients, here are 3 clarifications.

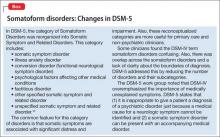

• I want to reinforce the latest thinking about the nature and pathophysiology of insomnia. DSM-5 classifies insomnia as a disorder, not as a symptom of other problems; the concept of “secondary insomnia” is rejected in DSM-5. Insomnia typically is seen as comorbid with other medical and psychiatric disorders. Often, insomnia predates the comorbid disorder (eg, depression), but rarely is it resolved by treating the comorbid condition.

• Good clinical practice, therefore, requires treating the comorbid condition and the insomnia each directly.

• The insomnia disorder manifests itself, in part, by a report of difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep. The authors use the example of sleep-onset insomnia as typical in older adults. However, sleep maintenance and early morning awakenings are the most common symptoms among geriatric insomnia patients.

• The authors mention only in passing an important medication for sleep maintenance in adults and in the geriatric patient specifically: doxepin. Low-dose doxepin, at 3 mg (for the geriatric patient) and 6 mg, is FDA-approved as a nonscheduled hypnotic for sleep maintenance insomnia. This formulationa is the only hypnotic classified as safe for geriatric patients in the 2012 Beers Criteria Update of the American Geriatrics Society.1 Unlike higher dosages of doxepin, the action of low-dose doxepin is, essentially, selective H1 antagonism.

aSold as Silenor.

Reference

1. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

Regarding Drs. Irene S. Hong’s and Jeffrey R. Bishop’s article, “Sedative-hypnotics for sleepless geriatric patients: Choose wisely” (Current Psychiatry, 2014;13(10):36-39, 46-50, 52 [http://bit.ly/1ApmcoO]), which undertook a comprehensive review of current therapies for insomnia in geriatric patients, here are 3 clarifications.

• I want to reinforce the latest thinking about the nature and pathophysiology of insomnia. DSM-5 classifies insomnia as a disorder, not as a symptom of other problems; the concept of “secondary insomnia” is rejected in DSM-5. Insomnia typically is seen as comorbid with other medical and psychiatric disorders. Often, insomnia predates the comorbid disorder (eg, depression), but rarely is it resolved by treating the comorbid condition.

• Good clinical practice, therefore, requires treating the comorbid condition and the insomnia each directly.

• The insomnia disorder manifests itself, in part, by a report of difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep. The authors use the example of sleep-onset insomnia as typical in older adults. However, sleep maintenance and early morning awakenings are the most common symptoms among geriatric insomnia patients.

• The authors mention only in passing an important medication for sleep maintenance in adults and in the geriatric patient specifically: doxepin. Low-dose doxepin, at 3 mg (for the geriatric patient) and 6 mg, is FDA-approved as a nonscheduled hypnotic for sleep maintenance insomnia. This formulationa is the only hypnotic classified as safe for geriatric patients in the 2012 Beers Criteria Update of the American Geriatrics Society.1 Unlike higher dosages of doxepin, the action of low-dose doxepin is, essentially, selective H1 antagonism.

aSold as Silenor.

Regarding Drs. Irene S. Hong’s and Jeffrey R. Bishop’s article, “Sedative-hypnotics for sleepless geriatric patients: Choose wisely” (Current Psychiatry, 2014;13(10):36-39, 46-50, 52 [http://bit.ly/1ApmcoO]), which undertook a comprehensive review of current therapies for insomnia in geriatric patients, here are 3 clarifications.

• I want to reinforce the latest thinking about the nature and pathophysiology of insomnia. DSM-5 classifies insomnia as a disorder, not as a symptom of other problems; the concept of “secondary insomnia” is rejected in DSM-5. Insomnia typically is seen as comorbid with other medical and psychiatric disorders. Often, insomnia predates the comorbid disorder (eg, depression), but rarely is it resolved by treating the comorbid condition.

• Good clinical practice, therefore, requires treating the comorbid condition and the insomnia each directly.

• The insomnia disorder manifests itself, in part, by a report of difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep. The authors use the example of sleep-onset insomnia as typical in older adults. However, sleep maintenance and early morning awakenings are the most common symptoms among geriatric insomnia patients.

• The authors mention only in passing an important medication for sleep maintenance in adults and in the geriatric patient specifically: doxepin. Low-dose doxepin, at 3 mg (for the geriatric patient) and 6 mg, is FDA-approved as a nonscheduled hypnotic for sleep maintenance insomnia. This formulationa is the only hypnotic classified as safe for geriatric patients in the 2012 Beers Criteria Update of the American Geriatrics Society.1 Unlike higher dosages of doxepin, the action of low-dose doxepin is, essentially, selective H1 antagonism.

aSold as Silenor.

Reference

1. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

Reference

1. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

Should the use of ‘endorse’ be endorsed in writing in psychiatry?

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

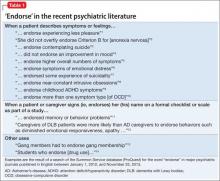

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

‘Acting out’ or pathological?

Mental illness during pregnancy

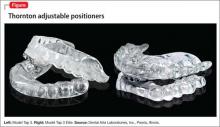

Consider a mandibular positioning device to alleviate sleep-disordered breathing

Snoring, snorting, gasping, and obstructive sleep apnea are caused by collapse of the pharyngeal airway during sleep.1 Pathophysiology includes a combination of anatomical and physiological variables.1 Common anatomical predisposing conditions include abnormalities of pharyngeal, lingual, and dental arches; physiological concerns are advancing age, male sex, obesity, use of sedatives, body positioning, and reduced muscle tone during rapid eye movement sleep. Coexistence of anatomic and physiological elements can produce significant narrowing of the upper airway.

Comorbidities include vascular, metabolic, and psychiatric conditions. As many as one-third of people with symptoms of sleep apnea report depressed mood; approximately 10% of these patients meet criteria for moderate or severe depression.2

In short, sleep-disordered breathing has a globally negative effect on mental health.

When should you consider obtaining a sleep apnea study?

Refer patients for a sleep study when snoring, snorting, gasping, or pauses in breathing occur during sleep, or in the case of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or unrefreshing sleep that cannot be explained by another medical or psychiatric illness.2 A sleep specialist can determine the most appropriate intervention for sleep-disordered breathing.