User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

How should you use the lab to monitor patients taking a mood stabilizer?

Ms. W, age 27, presents with a chief concern of “depression.” She describes a history of several hypomanic episodes as well as the current depressive episode, prompting a bipolar II disorder diagnosis. She is naïve to all psychotropics. You plan to initiate a mood-stabilizing agent. What would you include in your initial workup before starting treatment and how would you monitor her as she continues treatment?

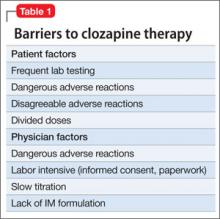

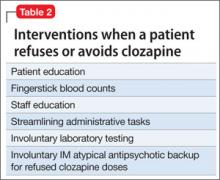

Mood stabilizers are employed to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder) and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. Some evidence suggests that mood stabilizers also can be used for treatment-resistant depressive disorders and borderline personality disorder.1 Mood stabilizers include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and lamotrigine.2-5

This review focuses on applications and monitoring of mood stabilizers for bipolar I and II disorders. We also will briefly review atypical antipsychotics because they also are used to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (see the September 2013 issue of Current Psychiatry at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a more detailed article on monitoring of antipsychotics).6

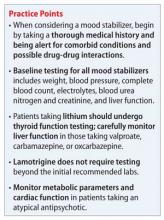

There are several well-researched guidelines used to guide clinical practice.2-5 Many guidelines recommend baseline and routine monitoring parameters based on the characteristics of the agent used. However, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) guidelines highlight the importance of monitoring medical comorbidities, which are common among patients with bipolar disorder and can affect pharmacotherapy and clinical outcomes. These recommendations are similar to metabolic monitoring guidelines for antipsychotics.5

Reviews of therapeutic monitoring show that only one-third to one-half of patien

taking a mood stabilizer are appropriately monitored. Poor adherence to guideline recommendations often is observed because of patients’ lack of insight or medication adherence and because psychiatric care generally is segregated from other medical care.7-9

Baseline testing

The ISBD guidelines recommend an initial workup for all patients that includes:

• waist circumference or body mass index (BMI), or both

• blood pressure

• complete blood count (CBC)

• electrolytes

• blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine

• liver function tests (LFTs)

• fasting glucose

• fasting lipid profile.

In addition, medical history, cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake, and family history of cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus should be documented. Rule out pregnancy in women of childbearing potential.2 The Figure describes monitoring parameters based on selected agent.

Agent-specific monitoring

Lithium. Patients beginning lithium therapy should undergo thyroid function testing and, for patients age >40, ECG monitoring. Educate patients about potential side effects of lithium, signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, and the importance of avoiding dehydration. Adding or changing certain medications could elevate the serum lithium level (eg, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE]-inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], COX-2 inhibitors).

Lithium can cause weight gain and adverse effects in several organ systems, including:

• gastrointestinal (GI) (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, diarrhea)

• renal (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, tubulointerstitial renal disease)

• neurologic (tremors, cognitive dulling, raised intracranial pressure)

• endocrine (thyroid and parathyroid dysfunction)

• cardiac (benign electrocardiographic changes, conduction abnormalities)

• dermatologic (acne, psoriasis, hair loss)

• hematologic (benign leukocytosis).

Lithium has a narrow therapeutic index (0.5 to 1.2 mEq/L), which means that small changes in the serum level can result in therapeutic inefficacy or toxicity. Lithium toxicity can cause irreversible organ damage or death. Serum lithium levels, symptomatic response, emergence and evolution of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and the recognition of patient risk factors for toxicity can help guide dosing. From a safety monitoring viewpoint, lithium toxicity, renal and endocrine adverse effects, and potential drug interactions are foremost concerns.

Lithium usually is started at a low, divided dosages to minimize side effects, and titrated according to response. Check lithium levels before and after each dose increase. Serum levels reach steady state 5 days after dosage adjustment, but might need to be checked sooner if a rapid increase is necessary, such as when treating acute mania, or if you suspect toxicity.

If the patient has renal insufficiency, it may take longer for the lithium to reach steady state; therefore, delaying a blood level beyond 5 days may be necessary to gauge a true steady state. Also, anytime a medication that interferes with lithium renal elimination, such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, is added or the dosage is changed, a new lithium level will need to be obtained to reassess the level in 5 days, assuming adequate renal function. In general, renal function and thyroid function should be evaluated once or twice during the first 6 months of lithium treatment.

Subsequently, renal and thyroid function can be checked every 6 months to 1 year in stable patients or when clinically indicated. Check a patient’s weight after 6 months of therapy, then at least annually.2

Valproic acid (VPA) and its derivatives. The most important initial monitoring for VPA therapy includes LFTs and CBC. Before initiating VPA treatment, take a medical history, with special attention to hepatic, hematologic, and bleeding abnormalities. Therapeutic blood monitoring can be conducted once steady state is achieved and as clinically necessary thereafter.

VPA can be administered at an initial starting dosage of 20 to 30 mg/kg/d in inpatients. In outpatients it is given in low, divided doses or as once-daily dosing using an extended-release formulation to minimize GI and neurologic toxicity and titrated every few days. Target serum level is 50 to 125 μg/mL.

Side effects of VPA include GI distress (eg, anorexia, nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, diarrhea), hematologic effects (reversible leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), hair loss, weight gain, tremor, hepatic effects (benign LFT elevations, hepatotoxicity), osteoporosis, and sedation. Patients with prior or current hepatic disease may be at greater risk for hepatotoxicity. There is an association between VPA and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Rare, idiosyncratic, but potentially fatal adverse events with valproate include irreversible hepatic failure, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, and agranulocytosis.

Older monitoring standards indicated taking LFTs and CBC every 6 months and serum VPA level as clinically indicated. According to ISBD guidelines, weight, CBC, LFTs, and menstrual history should be monitored every 3 months for the first year and then annually; blood pressure, bone status (densitometry), fasting glucose, and fasting lipids should be monitored only in patients with related risk factors. Routine ammonia levels are not recommended but might be indicated if a patient has sudden mental status changes or change in condition.2

Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. The most important initial monitoring for carbamazepine therapy includes LFTs, renal function, electrolytes, and CBC. Before treatment, take a medical history, with special emphasis on history of blood dyscrasias or liver disease. After initiating carbamazepine, CBC, LFTs, electrolytes, and renal function should be done monthly for 3 months, then repeated annually.

Carbamazepine is a substrate and an inducer of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, so it can reduce levels of many other drugs including other antiepileptics, warfarin, and oral contraceptives. Serum level of carbamazepine can be measured at trough after 5 days, with a target level of 4 to 12 μg/mL. Two levels should be drawn, 4 weeks apart, to establish therapeutic dosage secondary to autoinduction of the CYP450 system.2

As many as one-half of patients experience side effects with carbamazepine. The most common side effects include fatigue, nausea, and neurologic symptoms (diplopia, blurred vision, and ataxia). Less frequent side effects include skin rashes, leukopenia, liver enzyme elevations, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, and hypo-osmolality. Rare, potentially fatal side effects include agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatic failure, and exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome).

Patients of Asian descent who are taking carbamazepine should undergo genetic testing for the HLA-B*1502 enzyme because persons with this allele are at higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Also, patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of these rare adverse reactions so that medical treatment is not delayed should these adverse events present.

Lamotrigine does not require further laboratory monitoring beyond the initial recommended workup. The most important variables to consider are interactions with other medications (especially other antiepileptics, such as VPA and carbamazepine) and observing for rash. Titration takes several weeks to minimize risk of developing a rash.2 Similar to carbamazepine, the patient should be educated on the signs and symptoms of exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome) so that medical treatment is sought out should this reaction occur.

Atypical antipsychotics. Baseline workup includes the general monitoring parameters described above. Atypical antipsychotics have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects than typical antipsychotics, but are associated with an increased risk of metabolic complications. Other major ADRs to consider are cardiac effects and hyperprolactinemia; clinicians should therefore inquire about a personal or family history of cardiac problems, including congenital long QT syndrome. Patients should be screened for any medications that can prolong the QTc interval or interact with the metabolism of medications known to cause QTc prolongation.

Measure weight monthly for the first 3 months, then every 3 months to monitor for metabolic side effects during ongoing treatment. Obtain blood pressure and fasting glucose every 3 months for the first year, then annually. Repeat a fasting lipid profile 3 months after initiating treatment, then annually. Cardiac effects and prolactin levels can be monitored as needed if clinically indicated.2

CASE CONTINUED

You discuss with Ms. W choices of a mood stabilizing agent to treat her bipolar II disorder; she agrees to start lithium. Before initiating treatment, you obtain her weight (and calculate her BMI), blood pressure, CBC, electrolyte levels, BUN and creatinine levels, liver function tests, fasting glucose, fasting lipid profile, and thyroid panel. You also review her medical history, lifestyle factors (cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake), and family history. A urine pregnancy screen is negative. The pharmacist assists in screening for potential drug-drug interactions, including over-the-counter medications that Ms. W occasionally takes as needed. She is counseled on the use of NSAIDS because these drugs can increase the lithium level.

Ms. W tolerates and responds well to lithium. No further dosing recommendations are made, based on clinical response. You measure her weight at 6 months, then annually. Renal function and thyroid function are monitored at 3 and 6 months after lithium is initiated, and then annually. One year after starting lithium, she continues to tolerate the medication and has minimal metabolic side effects.

Related Resources

• McInnis MG. Lithium for bipolar disorder: A re-emerging treatment for mood instability. Current Psychiatry. 2014; 13(6):38-44.

• Stahl SM. Stahl’s illustrated mood stabilizers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Valproic acid • Depacon, Depakote

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Warfarin • Coumadin

Lithium • Lithobid, Eskalith

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Maglione M, Ruelaz Maher A, Hu J, et al. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 43. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/150/778/CER43_Off-LabelAntipsychotics_20110928.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed June 6, 2014.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

3. Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al; International Society for Bipolar Disorders. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559-595.

4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder (CG38). The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG038. Updated February 13, 2014. Accessed June 6, 2014.

5. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(6):721-739.

6. Zeier K, Connell R, Resch W, et al. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2013; 12(9):51-54.

7. Krishnan KR. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):1-8.

8. Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, et al. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):145-151.

9. Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of mood stabilizers in Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1014-1018.

Ms. W, age 27, presents with a chief concern of “depression.” She describes a history of several hypomanic episodes as well as the current depressive episode, prompting a bipolar II disorder diagnosis. She is naïve to all psychotropics. You plan to initiate a mood-stabilizing agent. What would you include in your initial workup before starting treatment and how would you monitor her as she continues treatment?

Mood stabilizers are employed to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder) and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. Some evidence suggests that mood stabilizers also can be used for treatment-resistant depressive disorders and borderline personality disorder.1 Mood stabilizers include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and lamotrigine.2-5

This review focuses on applications and monitoring of mood stabilizers for bipolar I and II disorders. We also will briefly review atypical antipsychotics because they also are used to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (see the September 2013 issue of Current Psychiatry at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a more detailed article on monitoring of antipsychotics).6

There are several well-researched guidelines used to guide clinical practice.2-5 Many guidelines recommend baseline and routine monitoring parameters based on the characteristics of the agent used. However, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) guidelines highlight the importance of monitoring medical comorbidities, which are common among patients with bipolar disorder and can affect pharmacotherapy and clinical outcomes. These recommendations are similar to metabolic monitoring guidelines for antipsychotics.5

Reviews of therapeutic monitoring show that only one-third to one-half of patien

taking a mood stabilizer are appropriately monitored. Poor adherence to guideline recommendations often is observed because of patients’ lack of insight or medication adherence and because psychiatric care generally is segregated from other medical care.7-9

Baseline testing

The ISBD guidelines recommend an initial workup for all patients that includes:

• waist circumference or body mass index (BMI), or both

• blood pressure

• complete blood count (CBC)

• electrolytes

• blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine

• liver function tests (LFTs)

• fasting glucose

• fasting lipid profile.

In addition, medical history, cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake, and family history of cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus should be documented. Rule out pregnancy in women of childbearing potential.2 The Figure describes monitoring parameters based on selected agent.

Agent-specific monitoring

Lithium. Patients beginning lithium therapy should undergo thyroid function testing and, for patients age >40, ECG monitoring. Educate patients about potential side effects of lithium, signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, and the importance of avoiding dehydration. Adding or changing certain medications could elevate the serum lithium level (eg, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE]-inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], COX-2 inhibitors).

Lithium can cause weight gain and adverse effects in several organ systems, including:

• gastrointestinal (GI) (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, diarrhea)

• renal (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, tubulointerstitial renal disease)

• neurologic (tremors, cognitive dulling, raised intracranial pressure)

• endocrine (thyroid and parathyroid dysfunction)

• cardiac (benign electrocardiographic changes, conduction abnormalities)

• dermatologic (acne, psoriasis, hair loss)

• hematologic (benign leukocytosis).

Lithium has a narrow therapeutic index (0.5 to 1.2 mEq/L), which means that small changes in the serum level can result in therapeutic inefficacy or toxicity. Lithium toxicity can cause irreversible organ damage or death. Serum lithium levels, symptomatic response, emergence and evolution of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and the recognition of patient risk factors for toxicity can help guide dosing. From a safety monitoring viewpoint, lithium toxicity, renal and endocrine adverse effects, and potential drug interactions are foremost concerns.

Lithium usually is started at a low, divided dosages to minimize side effects, and titrated according to response. Check lithium levels before and after each dose increase. Serum levels reach steady state 5 days after dosage adjustment, but might need to be checked sooner if a rapid increase is necessary, such as when treating acute mania, or if you suspect toxicity.

If the patient has renal insufficiency, it may take longer for the lithium to reach steady state; therefore, delaying a blood level beyond 5 days may be necessary to gauge a true steady state. Also, anytime a medication that interferes with lithium renal elimination, such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, is added or the dosage is changed, a new lithium level will need to be obtained to reassess the level in 5 days, assuming adequate renal function. In general, renal function and thyroid function should be evaluated once or twice during the first 6 months of lithium treatment.

Subsequently, renal and thyroid function can be checked every 6 months to 1 year in stable patients or when clinically indicated. Check a patient’s weight after 6 months of therapy, then at least annually.2

Valproic acid (VPA) and its derivatives. The most important initial monitoring for VPA therapy includes LFTs and CBC. Before initiating VPA treatment, take a medical history, with special attention to hepatic, hematologic, and bleeding abnormalities. Therapeutic blood monitoring can be conducted once steady state is achieved and as clinically necessary thereafter.

VPA can be administered at an initial starting dosage of 20 to 30 mg/kg/d in inpatients. In outpatients it is given in low, divided doses or as once-daily dosing using an extended-release formulation to minimize GI and neurologic toxicity and titrated every few days. Target serum level is 50 to 125 μg/mL.

Side effects of VPA include GI distress (eg, anorexia, nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, diarrhea), hematologic effects (reversible leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), hair loss, weight gain, tremor, hepatic effects (benign LFT elevations, hepatotoxicity), osteoporosis, and sedation. Patients with prior or current hepatic disease may be at greater risk for hepatotoxicity. There is an association between VPA and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Rare, idiosyncratic, but potentially fatal adverse events with valproate include irreversible hepatic failure, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, and agranulocytosis.

Older monitoring standards indicated taking LFTs and CBC every 6 months and serum VPA level as clinically indicated. According to ISBD guidelines, weight, CBC, LFTs, and menstrual history should be monitored every 3 months for the first year and then annually; blood pressure, bone status (densitometry), fasting glucose, and fasting lipids should be monitored only in patients with related risk factors. Routine ammonia levels are not recommended but might be indicated if a patient has sudden mental status changes or change in condition.2

Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. The most important initial monitoring for carbamazepine therapy includes LFTs, renal function, electrolytes, and CBC. Before treatment, take a medical history, with special emphasis on history of blood dyscrasias or liver disease. After initiating carbamazepine, CBC, LFTs, electrolytes, and renal function should be done monthly for 3 months, then repeated annually.

Carbamazepine is a substrate and an inducer of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, so it can reduce levels of many other drugs including other antiepileptics, warfarin, and oral contraceptives. Serum level of carbamazepine can be measured at trough after 5 days, with a target level of 4 to 12 μg/mL. Two levels should be drawn, 4 weeks apart, to establish therapeutic dosage secondary to autoinduction of the CYP450 system.2

As many as one-half of patients experience side effects with carbamazepine. The most common side effects include fatigue, nausea, and neurologic symptoms (diplopia, blurred vision, and ataxia). Less frequent side effects include skin rashes, leukopenia, liver enzyme elevations, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, and hypo-osmolality. Rare, potentially fatal side effects include agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatic failure, and exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome).

Patients of Asian descent who are taking carbamazepine should undergo genetic testing for the HLA-B*1502 enzyme because persons with this allele are at higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Also, patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of these rare adverse reactions so that medical treatment is not delayed should these adverse events present.

Lamotrigine does not require further laboratory monitoring beyond the initial recommended workup. The most important variables to consider are interactions with other medications (especially other antiepileptics, such as VPA and carbamazepine) and observing for rash. Titration takes several weeks to minimize risk of developing a rash.2 Similar to carbamazepine, the patient should be educated on the signs and symptoms of exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome) so that medical treatment is sought out should this reaction occur.

Atypical antipsychotics. Baseline workup includes the general monitoring parameters described above. Atypical antipsychotics have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects than typical antipsychotics, but are associated with an increased risk of metabolic complications. Other major ADRs to consider are cardiac effects and hyperprolactinemia; clinicians should therefore inquire about a personal or family history of cardiac problems, including congenital long QT syndrome. Patients should be screened for any medications that can prolong the QTc interval or interact with the metabolism of medications known to cause QTc prolongation.

Measure weight monthly for the first 3 months, then every 3 months to monitor for metabolic side effects during ongoing treatment. Obtain blood pressure and fasting glucose every 3 months for the first year, then annually. Repeat a fasting lipid profile 3 months after initiating treatment, then annually. Cardiac effects and prolactin levels can be monitored as needed if clinically indicated.2

CASE CONTINUED

You discuss with Ms. W choices of a mood stabilizing agent to treat her bipolar II disorder; she agrees to start lithium. Before initiating treatment, you obtain her weight (and calculate her BMI), blood pressure, CBC, electrolyte levels, BUN and creatinine levels, liver function tests, fasting glucose, fasting lipid profile, and thyroid panel. You also review her medical history, lifestyle factors (cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake), and family history. A urine pregnancy screen is negative. The pharmacist assists in screening for potential drug-drug interactions, including over-the-counter medications that Ms. W occasionally takes as needed. She is counseled on the use of NSAIDS because these drugs can increase the lithium level.

Ms. W tolerates and responds well to lithium. No further dosing recommendations are made, based on clinical response. You measure her weight at 6 months, then annually. Renal function and thyroid function are monitored at 3 and 6 months after lithium is initiated, and then annually. One year after starting lithium, she continues to tolerate the medication and has minimal metabolic side effects.

Related Resources

• McInnis MG. Lithium for bipolar disorder: A re-emerging treatment for mood instability. Current Psychiatry. 2014; 13(6):38-44.

• Stahl SM. Stahl’s illustrated mood stabilizers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Valproic acid • Depacon, Depakote

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Warfarin • Coumadin

Lithium • Lithobid, Eskalith

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Ms. W, age 27, presents with a chief concern of “depression.” She describes a history of several hypomanic episodes as well as the current depressive episode, prompting a bipolar II disorder diagnosis. She is naïve to all psychotropics. You plan to initiate a mood-stabilizing agent. What would you include in your initial workup before starting treatment and how would you monitor her as she continues treatment?

Mood stabilizers are employed to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (bipolar I, bipolar II, and cyclothymic disorder) and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. Some evidence suggests that mood stabilizers also can be used for treatment-resistant depressive disorders and borderline personality disorder.1 Mood stabilizers include lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and lamotrigine.2-5

This review focuses on applications and monitoring of mood stabilizers for bipolar I and II disorders. We also will briefly review atypical antipsychotics because they also are used to treat bipolar spectrum disorders (see the September 2013 issue of Current Psychiatry at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a more detailed article on monitoring of antipsychotics).6

There are several well-researched guidelines used to guide clinical practice.2-5 Many guidelines recommend baseline and routine monitoring parameters based on the characteristics of the agent used. However, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) guidelines highlight the importance of monitoring medical comorbidities, which are common among patients with bipolar disorder and can affect pharmacotherapy and clinical outcomes. These recommendations are similar to metabolic monitoring guidelines for antipsychotics.5

Reviews of therapeutic monitoring show that only one-third to one-half of patien

taking a mood stabilizer are appropriately monitored. Poor adherence to guideline recommendations often is observed because of patients’ lack of insight or medication adherence and because psychiatric care generally is segregated from other medical care.7-9

Baseline testing

The ISBD guidelines recommend an initial workup for all patients that includes:

• waist circumference or body mass index (BMI), or both

• blood pressure

• complete blood count (CBC)

• electrolytes

• blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine

• liver function tests (LFTs)

• fasting glucose

• fasting lipid profile.

In addition, medical history, cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake, and family history of cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus should be documented. Rule out pregnancy in women of childbearing potential.2 The Figure describes monitoring parameters based on selected agent.

Agent-specific monitoring

Lithium. Patients beginning lithium therapy should undergo thyroid function testing and, for patients age >40, ECG monitoring. Educate patients about potential side effects of lithium, signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, and the importance of avoiding dehydration. Adding or changing certain medications could elevate the serum lithium level (eg, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE]-inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], COX-2 inhibitors).

Lithium can cause weight gain and adverse effects in several organ systems, including:

• gastrointestinal (GI) (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, diarrhea)

• renal (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, tubulointerstitial renal disease)

• neurologic (tremors, cognitive dulling, raised intracranial pressure)

• endocrine (thyroid and parathyroid dysfunction)

• cardiac (benign electrocardiographic changes, conduction abnormalities)

• dermatologic (acne, psoriasis, hair loss)

• hematologic (benign leukocytosis).

Lithium has a narrow therapeutic index (0.5 to 1.2 mEq/L), which means that small changes in the serum level can result in therapeutic inefficacy or toxicity. Lithium toxicity can cause irreversible organ damage or death. Serum lithium levels, symptomatic response, emergence and evolution of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and the recognition of patient risk factors for toxicity can help guide dosing. From a safety monitoring viewpoint, lithium toxicity, renal and endocrine adverse effects, and potential drug interactions are foremost concerns.

Lithium usually is started at a low, divided dosages to minimize side effects, and titrated according to response. Check lithium levels before and after each dose increase. Serum levels reach steady state 5 days after dosage adjustment, but might need to be checked sooner if a rapid increase is necessary, such as when treating acute mania, or if you suspect toxicity.

If the patient has renal insufficiency, it may take longer for the lithium to reach steady state; therefore, delaying a blood level beyond 5 days may be necessary to gauge a true steady state. Also, anytime a medication that interferes with lithium renal elimination, such as diuretics, ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, is added or the dosage is changed, a new lithium level will need to be obtained to reassess the level in 5 days, assuming adequate renal function. In general, renal function and thyroid function should be evaluated once or twice during the first 6 months of lithium treatment.

Subsequently, renal and thyroid function can be checked every 6 months to 1 year in stable patients or when clinically indicated. Check a patient’s weight after 6 months of therapy, then at least annually.2

Valproic acid (VPA) and its derivatives. The most important initial monitoring for VPA therapy includes LFTs and CBC. Before initiating VPA treatment, take a medical history, with special attention to hepatic, hematologic, and bleeding abnormalities. Therapeutic blood monitoring can be conducted once steady state is achieved and as clinically necessary thereafter.

VPA can be administered at an initial starting dosage of 20 to 30 mg/kg/d in inpatients. In outpatients it is given in low, divided doses or as once-daily dosing using an extended-release formulation to minimize GI and neurologic toxicity and titrated every few days. Target serum level is 50 to 125 μg/mL.

Side effects of VPA include GI distress (eg, anorexia, nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, diarrhea), hematologic effects (reversible leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), hair loss, weight gain, tremor, hepatic effects (benign LFT elevations, hepatotoxicity), osteoporosis, and sedation. Patients with prior or current hepatic disease may be at greater risk for hepatotoxicity. There is an association between VPA and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Rare, idiosyncratic, but potentially fatal adverse events with valproate include irreversible hepatic failure, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, and agranulocytosis.

Older monitoring standards indicated taking LFTs and CBC every 6 months and serum VPA level as clinically indicated. According to ISBD guidelines, weight, CBC, LFTs, and menstrual history should be monitored every 3 months for the first year and then annually; blood pressure, bone status (densitometry), fasting glucose, and fasting lipids should be monitored only in patients with related risk factors. Routine ammonia levels are not recommended but might be indicated if a patient has sudden mental status changes or change in condition.2

Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. The most important initial monitoring for carbamazepine therapy includes LFTs, renal function, electrolytes, and CBC. Before treatment, take a medical history, with special emphasis on history of blood dyscrasias or liver disease. After initiating carbamazepine, CBC, LFTs, electrolytes, and renal function should be done monthly for 3 months, then repeated annually.

Carbamazepine is a substrate and an inducer of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, so it can reduce levels of many other drugs including other antiepileptics, warfarin, and oral contraceptives. Serum level of carbamazepine can be measured at trough after 5 days, with a target level of 4 to 12 μg/mL. Two levels should be drawn, 4 weeks apart, to establish therapeutic dosage secondary to autoinduction of the CYP450 system.2

As many as one-half of patients experience side effects with carbamazepine. The most common side effects include fatigue, nausea, and neurologic symptoms (diplopia, blurred vision, and ataxia). Less frequent side effects include skin rashes, leukopenia, liver enzyme elevations, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, and hypo-osmolality. Rare, potentially fatal side effects include agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatic failure, and exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome).

Patients of Asian descent who are taking carbamazepine should undergo genetic testing for the HLA-B*1502 enzyme because persons with this allele are at higher risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Also, patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of these rare adverse reactions so that medical treatment is not delayed should these adverse events present.

Lamotrigine does not require further laboratory monitoring beyond the initial recommended workup. The most important variables to consider are interactions with other medications (especially other antiepileptics, such as VPA and carbamazepine) and observing for rash. Titration takes several weeks to minimize risk of developing a rash.2 Similar to carbamazepine, the patient should be educated on the signs and symptoms of exfoliative dermatitis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome) so that medical treatment is sought out should this reaction occur.

Atypical antipsychotics. Baseline workup includes the general monitoring parameters described above. Atypical antipsychotics have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects than typical antipsychotics, but are associated with an increased risk of metabolic complications. Other major ADRs to consider are cardiac effects and hyperprolactinemia; clinicians should therefore inquire about a personal or family history of cardiac problems, including congenital long QT syndrome. Patients should be screened for any medications that can prolong the QTc interval or interact with the metabolism of medications known to cause QTc prolongation.

Measure weight monthly for the first 3 months, then every 3 months to monitor for metabolic side effects during ongoing treatment. Obtain blood pressure and fasting glucose every 3 months for the first year, then annually. Repeat a fasting lipid profile 3 months after initiating treatment, then annually. Cardiac effects and prolactin levels can be monitored as needed if clinically indicated.2

CASE CONTINUED

You discuss with Ms. W choices of a mood stabilizing agent to treat her bipolar II disorder; she agrees to start lithium. Before initiating treatment, you obtain her weight (and calculate her BMI), blood pressure, CBC, electrolyte levels, BUN and creatinine levels, liver function tests, fasting glucose, fasting lipid profile, and thyroid panel. You also review her medical history, lifestyle factors (cigarette smoking status, alcohol intake), and family history. A urine pregnancy screen is negative. The pharmacist assists in screening for potential drug-drug interactions, including over-the-counter medications that Ms. W occasionally takes as needed. She is counseled on the use of NSAIDS because these drugs can increase the lithium level.

Ms. W tolerates and responds well to lithium. No further dosing recommendations are made, based on clinical response. You measure her weight at 6 months, then annually. Renal function and thyroid function are monitored at 3 and 6 months after lithium is initiated, and then annually. One year after starting lithium, she continues to tolerate the medication and has minimal metabolic side effects.

Related Resources

• McInnis MG. Lithium for bipolar disorder: A re-emerging treatment for mood instability. Current Psychiatry. 2014; 13(6):38-44.

• Stahl SM. Stahl’s illustrated mood stabilizers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol Valproic acid • Depacon, Depakote

Lamotrigine • Lamictal Warfarin • Coumadin

Lithium • Lithobid, Eskalith

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Maglione M, Ruelaz Maher A, Hu J, et al. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 43. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/150/778/CER43_Off-LabelAntipsychotics_20110928.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed June 6, 2014.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

3. Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al; International Society for Bipolar Disorders. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559-595.

4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder (CG38). The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG038. Updated February 13, 2014. Accessed June 6, 2014.

5. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(6):721-739.

6. Zeier K, Connell R, Resch W, et al. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2013; 12(9):51-54.

7. Krishnan KR. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):1-8.

8. Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, et al. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):145-151.

9. Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of mood stabilizers in Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1014-1018.

1. Maglione M, Ruelaz Maher A, Hu J, et al. Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 43. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/150/778/CER43_Off-LabelAntipsychotics_20110928.pdf. Published September 2011. Accessed June 6, 2014.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(suppl 4):1-50.

3. Ng F, Mammen OK, Wilting I, et al; International Society for Bipolar Disorders. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) consensus guidelines for the safety monitoring of bipolar disorder treatments. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(6):559-595.

4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Bipolar disorder (CG38). The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG038. Updated February 13, 2014. Accessed June 6, 2014.

5. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2007. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(6):721-739.

6. Zeier K, Connell R, Resch W, et al. Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics. Current Psychiatry. 2013; 12(9):51-54.

7. Krishnan KR. Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of bipolar disorder. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):1-8.

8. Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, et al. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1-3):145-151.

9. Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of mood stabilizers in Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1014-1018.

Post-World War II psychiatry: 70 years of momentous change

A large percentage of psychiatrists practicing today are Boomers, and have experienced the tumultuous change in their profession since the end of World War II. At a recent Grand Rounds presentation in the Department of Neurology & Psychiatry at Saint Louis University, participants examined major changes and paradigm shifts that have reshaped psychiatry since 1946. The audience, which included me, contributed historical observations to the list of those changes and shifts, which I’ve classified here for your benefit, whether or not you are a Boomer.

Medical advances

Consider these discoveries and developments:

• Penicillin in 1947, which led to a reduction in cases of psychosis caused by tertiary syphilis, a disease that accounted for 10% to 15% of state hospital admissions.

• Lithium in 1948, the first pharmaceutical treatment for mania.

• Chlorpromazine, the first antipsychotic drug, in 1952, launching the psychopharmacology era and ending lifetime institutional sequestration as the only “treatment” for serious mental disorders.

• Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in 1959, from observations that iproniazid, a drug used in tuberculosis sanitariums, improved the mood of tuberculosis patients. This was the first pharmacotherapy for depression, which had been treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), developed in the 1930s.

• Tricyclic antidepressants, starting with imipramine in the late 1950s, during attempts to synthesize additional phenothiazine antipsychotics.

• Diazepam, introduced in 1963 for its anti-anxiety effects, became the most widely used drug in the world over the next 2 decades.

• Pre-frontal lobotomy to treat severe psychiatric disorders. The neurosurgeon-inventor of this so-called medical advance won the 1949 Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology. The procedure was rapidly discredited after the development of antipsychotic drugs.

• Fluoxetine, the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, in 1987, revolutionized the treatment of depression, especially in primary care settings.

• Clozapine, as an effective treatment for refractory and suicidal schizophrenia, and the spawning of second-generation antipsychotics. These newer agents shifted focus from neurologic adverse effects (extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia) to cardio-metabolic side effects (obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension).

Changes to the landscape of health care

Three noteworthy developments made the list:

• The Community Mental Health Act of 1963, signed into law by President John F. Kennedy, revolutionized psychiatric care by shifting delivery of care from inpatient, hospital-based facilities to outpatient, clinic-based centers. There are now close to 800 community mental health centers in the United States, where care is dominated by non-physician mental health providers—in contrast to the era of state hospitals, during which physicians and nurses provided care for mentally ill patients.

• Deinstitutionalization. This move-ment gathered momentum in the 1970s and 1980s, leading to closing of the majority of state hospitals, with tragic consequences for the seriously mentally ill—including early demise, homelessness, substance abuse, and incarceration. In fact, the large percentage of mentally ill people in U.S. jails and prisons, instead of in a hospital, represents what has been labeled trans-institutionalization (see my March 2008 editorial, “Bring back the asylums?,” available at CurrentPsychiatry.com).

• Managed care, emerging in the late 1980s and early 1990s, caused a seismic disturbance in the delivery of, and reimbursement for, psychiatric care. The result was a significant decline in access to, and quality of, care—especially the so-called carve-out model that reduced payment for psychiatric care even more drastically than for general medical care. Under managed care, the priority became saving money, rather than saving lives. Average hospital stay for patients who had a psychiatric disorder, which was years in the pre-pharmacotherapy era, and weeks or months after that, shrunk to a few days under managed care.

Changes in professional direction

Two major shifts in the complexion of the specialty were identified:

• The decline of psychoanalysis, which had dominated psychiatry for decades (the 1940s through the 1970s), was a major shift in the conceptualization, training, and delivery of care in psychiatry. The rise of biological psychiatry and the medical model of psychiatric brain disorders, as well as the emergence of evidence-based (and briefer) psychotherapies (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and interpersonal therapy), gradually replaced the Freudian model of mental illness.

As a result, it became no longer necessary to be a certified psychoanalyst to be named chair of a department of psychiatry. The impact of this change on psychiatric training has been profound, because medical management by psychiatrists superseded psychotherapy— given the brief hospitalization that is required and the diminishing coverage for psychotherapy by insurers.

• Delegation of psychosocial treatments to non-psychiatrists. The unintended consequences of psychiatrists’ change of focus to 1) consultation on medical/surgical patients and 2) the medical evaluation, diagnosis, and pharmacotherapy of mental disorders led to the so-called “dual treatment model” for the most seriously mentally ill patients: The physician provides medical management and non-physician mental health professionals provide counseling, psychosocial therapy, and rehabilitation.

Disruptive breakthroughs

Several are notable:

• National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Establishment of NIMH in April 1949 was a major step toward funding research into psychiatric disorders. Billions of dollars have been invested to generate knowledge about the causes, treatment, course, and prevention of mental illness. No other country has spent as much on psychiatric research. It would have been nearly impossible to discover what we know today without the work of NIMH.

• Neuroscience. The meteoric rise of neuroscience from the 1960s to the present has had a dramatic effect, transforming old psychiatry and the study and therapy of the mind to a focus on the brain-mind continuum and the prospects of brain repair and neuroplasticity. Psychiatry is now regarded as a clinical neuroscience specialty of brain disorders that manifest as changes in thought, affect, mood, cognition, and behavior.

• Brain imaging. Techniques developed since the 1970s—the veritable alphabet soup of CT, PET, SPECT, MRI, MRS, fMRI, and DTI— has revolutionized understanding of brain structure and function in all psychiatric disorders but especially in psychotic and mood disorders.

• Molecular genetics. Advances over the past 2 decades have shed unprecedented light on the complex genetics of psychiatric disorders. It is becoming apparent that most psychiatric disorders are caused via gene-by-environment interaction; etiology is therefore a consequence of genetic and non-genetic variables. Risk genes, copy number variants, and de novo mutations are being discovered almost weekly, and progress in epigenetics holds promise for preventing medical disorders, including psychiatric illness.

• Neuromodulation. Advances represent an important paradigm shift, from pharmacotherapy to brain stimulation. Several techniques have been approved by the FDA, including transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, and deep brain stimulation, to supplement, and perhaps eventually supplant, ECT.

Legal intrusiveness

No other medical specialty has been subject to laws governing clinical practice as psychiatry has been. Progressive intrusion of laws (ostensibly, enacted to protect the civil rights of “the disabled”) ends up hurting patients who refuse admission and then often harm themselves or others or decline urgent treatment, which can be associated with loss of brain tissue in acute psychotic, manic, and depressed states. No legal shackles apply to treating unconscious stroke patients, delirious geriatric patients, or semiconscious myocardial infarction patients when they are admitted to a hospital.

Distortions of the anti-psychiatry movement

The antipsychiatry movement preceded the Baby Boomer era by a century but has continued unabated. The movement gained momentum and became more defamatory after release of the movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1975, which portrayed psychiatry in a purely negative light. Despite progress in public understanding of psychiatry, and tangible improvements in practice, the stigma of mental illness persists. Media portrayals, including motion pictures, continue to distort the good that psychiatrists do for their patients.

Gender and sexuality

• Gender distribution of psychiatrists. A major shift occurred over the past 7 decades, reflecting the same pattern that has been documented in other medical specialties. At least one-half of psychiatry residents are now women—a welcome change from the pre-1946 era, when nearly all psychiatrists were men. This demographic transformation has had an impact on the dynamics of psychiatric practice.

• Acceptance and depathologization of homosexuality. Until 1974, homosexuality was considered a psychiatric disorder, and many homosexual persons sought treatment. That year, membership of the American Psychiatric Association voted to remove homosexuality from DSM-II and to no longer regard it as a behavioral abnormality. This was a huge step toward de-pathologizing same-sex orientation and love, and might have been the major impetus for the progressive social acceptance of gay, lesbian, and transgendered people over the past 4 decades.

The DSM paradigm shift in psychiatric diagnosis

• DSM-III. Perhaps the most radical change in the diagnostic criteria of psychiatric disorders occurred in 1980, with introduction of DSM-III to replace DSM-I and DSM-II, which were absurdly vague, unreliable, and with poor validity.

The move toward more operational and reliable diagnostic requirements began with the Research Diagnostic Criteria, developed by the Department of Psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. DSM-III represented a complete paradigm shift in psychiatric diagnosis. Subsequent editions maintained the same methodology, with relatively modest changes. The field expects continued evolution in DSM diagnostic criteria, including the future inclusion of biomarkers, based on sound, controlled studies.

• Recognizing PTSD. Develop-ment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a diagnostic entity, and its inclusion in DSM-III, were major changes in psychiatric nosology. At last, the old terms—shell shock, battle fatigue, neurasthenia—were legitimized as a recognizable syndrome secondary to major life trauma, including war and rape. That legitimacy has instigated substantial clinical and research interest in identifying how serious psychopathology can be triggered by life events.

Pharmaceutical industry debacle

Few industries have fallen so far from grace in the eyes of psychiatric professionals and the public as the manufacturers of psychotropic drugs.

At the dawn of the psychopharmacology era (the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s) pharmaceutical companies were respected and regarded by physicians and patients as a vital partner in health care for their discovery and development of medications to treat psychiatric disorders. That image was tarnished in the 1990s, however, with the approval and release of several atypical antipsychotics. Cutthroat competition, questionable publication methods, concealment of negative findings, and excessive spending on marketing, including FDA-approved educational programs for clinicians on efficacy, safety, and dosing, all contributed to escalating cynicism about the industry. Academic faculty who received research grants to conduct FDA-required clinical trials of new agents were painted with the same brush.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest became a mandatory procedure at universities and for NIMH grant applicants and journal publishers. Class-action lawsuits against companies that manufacture second-generation antipsychotics—filed for lack of transparency about metabolic side effects—exacerbated the intensity of criticism and condemnation.

Although new drug development has become measurably more rigorous and ethical because of self-regulation, combined with vigorous government scrutiny and regulation, demonization of the pharmaceutical industry remains unabated. That might be the reason why several major pharmaceutical companies have abandoned research and development of psychotropic drugs. That is likely to impede progress in psychopharmacotherapeutics; after all, no other private or government entity develops drugs for patients who have a psychiatric illness. The need for such agents is great: There is no FDA-indicated drug for the majority of DSM-5 diagnoses.

We entrust the future to next generations

Momentous events have transformed psychiatry during the lifespan of Baby Boomers like me and many of you. Because the cohort of 80 million Baby Boomers has comprised a significant percentage of the nation’s scientists, media representatives, members of the American Psychiatric Association, academicians, and community leaders over the past few decades, it is conceivable that the Baby Boomer generation helped trigger most of the transformative changes in psychiatry we have seen over the past 70 years.

I can only wonder: What direction will psychiatry take in the age of Generation X, Generation Y, and the Millennials? Only this is certain: Psychiatry will continue to evolve— long after Baby Boomers are gone.

A large percentage of psychiatrists practicing today are Boomers, and have experienced the tumultuous change in their profession since the end of World War II. At a recent Grand Rounds presentation in the Department of Neurology & Psychiatry at Saint Louis University, participants examined major changes and paradigm shifts that have reshaped psychiatry since 1946. The audience, which included me, contributed historical observations to the list of those changes and shifts, which I’ve classified here for your benefit, whether or not you are a Boomer.

Medical advances

Consider these discoveries and developments:

• Penicillin in 1947, which led to a reduction in cases of psychosis caused by tertiary syphilis, a disease that accounted for 10% to 15% of state hospital admissions.

• Lithium in 1948, the first pharmaceutical treatment for mania.

• Chlorpromazine, the first antipsychotic drug, in 1952, launching the psychopharmacology era and ending lifetime institutional sequestration as the only “treatment” for serious mental disorders.

• Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in 1959, from observations that iproniazid, a drug used in tuberculosis sanitariums, improved the mood of tuberculosis patients. This was the first pharmacotherapy for depression, which had been treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), developed in the 1930s.

• Tricyclic antidepressants, starting with imipramine in the late 1950s, during attempts to synthesize additional phenothiazine antipsychotics.

• Diazepam, introduced in 1963 for its anti-anxiety effects, became the most widely used drug in the world over the next 2 decades.

• Pre-frontal lobotomy to treat severe psychiatric disorders. The neurosurgeon-inventor of this so-called medical advance won the 1949 Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology. The procedure was rapidly discredited after the development of antipsychotic drugs.

• Fluoxetine, the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, in 1987, revolutionized the treatment of depression, especially in primary care settings.

• Clozapine, as an effective treatment for refractory and suicidal schizophrenia, and the spawning of second-generation antipsychotics. These newer agents shifted focus from neurologic adverse effects (extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia) to cardio-metabolic side effects (obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension).

Changes to the landscape of health care

Three noteworthy developments made the list:

• The Community Mental Health Act of 1963, signed into law by President John F. Kennedy, revolutionized psychiatric care by shifting delivery of care from inpatient, hospital-based facilities to outpatient, clinic-based centers. There are now close to 800 community mental health centers in the United States, where care is dominated by non-physician mental health providers—in contrast to the era of state hospitals, during which physicians and nurses provided care for mentally ill patients.

• Deinstitutionalization. This move-ment gathered momentum in the 1970s and 1980s, leading to closing of the majority of state hospitals, with tragic consequences for the seriously mentally ill—including early demise, homelessness, substance abuse, and incarceration. In fact, the large percentage of mentally ill people in U.S. jails and prisons, instead of in a hospital, represents what has been labeled trans-institutionalization (see my March 2008 editorial, “Bring back the asylums?,” available at CurrentPsychiatry.com).

• Managed care, emerging in the late 1980s and early 1990s, caused a seismic disturbance in the delivery of, and reimbursement for, psychiatric care. The result was a significant decline in access to, and quality of, care—especially the so-called carve-out model that reduced payment for psychiatric care even more drastically than for general medical care. Under managed care, the priority became saving money, rather than saving lives. Average hospital stay for patients who had a psychiatric disorder, which was years in the pre-pharmacotherapy era, and weeks or months after that, shrunk to a few days under managed care.

Changes in professional direction

Two major shifts in the complexion of the specialty were identified:

• The decline of psychoanalysis, which had dominated psychiatry for decades (the 1940s through the 1970s), was a major shift in the conceptualization, training, and delivery of care in psychiatry. The rise of biological psychiatry and the medical model of psychiatric brain disorders, as well as the emergence of evidence-based (and briefer) psychotherapies (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and interpersonal therapy), gradually replaced the Freudian model of mental illness.

As a result, it became no longer necessary to be a certified psychoanalyst to be named chair of a department of psychiatry. The impact of this change on psychiatric training has been profound, because medical management by psychiatrists superseded psychotherapy— given the brief hospitalization that is required and the diminishing coverage for psychotherapy by insurers.

• Delegation of psychosocial treatments to non-psychiatrists. The unintended consequences of psychiatrists’ change of focus to 1) consultation on medical/surgical patients and 2) the medical evaluation, diagnosis, and pharmacotherapy of mental disorders led to the so-called “dual treatment model” for the most seriously mentally ill patients: The physician provides medical management and non-physician mental health professionals provide counseling, psychosocial therapy, and rehabilitation.

Disruptive breakthroughs

Several are notable:

• National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Establishment of NIMH in April 1949 was a major step toward funding research into psychiatric disorders. Billions of dollars have been invested to generate knowledge about the causes, treatment, course, and prevention of mental illness. No other country has spent as much on psychiatric research. It would have been nearly impossible to discover what we know today without the work of NIMH.

• Neuroscience. The meteoric rise of neuroscience from the 1960s to the present has had a dramatic effect, transforming old psychiatry and the study and therapy of the mind to a focus on the brain-mind continuum and the prospects of brain repair and neuroplasticity. Psychiatry is now regarded as a clinical neuroscience specialty of brain disorders that manifest as changes in thought, affect, mood, cognition, and behavior.

• Brain imaging. Techniques developed since the 1970s—the veritable alphabet soup of CT, PET, SPECT, MRI, MRS, fMRI, and DTI— has revolutionized understanding of brain structure and function in all psychiatric disorders but especially in psychotic and mood disorders.

• Molecular genetics. Advances over the past 2 decades have shed unprecedented light on the complex genetics of psychiatric disorders. It is becoming apparent that most psychiatric disorders are caused via gene-by-environment interaction; etiology is therefore a consequence of genetic and non-genetic variables. Risk genes, copy number variants, and de novo mutations are being discovered almost weekly, and progress in epigenetics holds promise for preventing medical disorders, including psychiatric illness.

• Neuromodulation. Advances represent an important paradigm shift, from pharmacotherapy to brain stimulation. Several techniques have been approved by the FDA, including transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, and deep brain stimulation, to supplement, and perhaps eventually supplant, ECT.

Legal intrusiveness

No other medical specialty has been subject to laws governing clinical practice as psychiatry has been. Progressive intrusion of laws (ostensibly, enacted to protect the civil rights of “the disabled”) ends up hurting patients who refuse admission and then often harm themselves or others or decline urgent treatment, which can be associated with loss of brain tissue in acute psychotic, manic, and depressed states. No legal shackles apply to treating unconscious stroke patients, delirious geriatric patients, or semiconscious myocardial infarction patients when they are admitted to a hospital.

Distortions of the anti-psychiatry movement

The antipsychiatry movement preceded the Baby Boomer era by a century but has continued unabated. The movement gained momentum and became more defamatory after release of the movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1975, which portrayed psychiatry in a purely negative light. Despite progress in public understanding of psychiatry, and tangible improvements in practice, the stigma of mental illness persists. Media portrayals, including motion pictures, continue to distort the good that psychiatrists do for their patients.

Gender and sexuality

• Gender distribution of psychiatrists. A major shift occurred over the past 7 decades, reflecting the same pattern that has been documented in other medical specialties. At least one-half of psychiatry residents are now women—a welcome change from the pre-1946 era, when nearly all psychiatrists were men. This demographic transformation has had an impact on the dynamics of psychiatric practice.

• Acceptance and depathologization of homosexuality. Until 1974, homosexuality was considered a psychiatric disorder, and many homosexual persons sought treatment. That year, membership of the American Psychiatric Association voted to remove homosexuality from DSM-II and to no longer regard it as a behavioral abnormality. This was a huge step toward de-pathologizing same-sex orientation and love, and might have been the major impetus for the progressive social acceptance of gay, lesbian, and transgendered people over the past 4 decades.

The DSM paradigm shift in psychiatric diagnosis

• DSM-III. Perhaps the most radical change in the diagnostic criteria of psychiatric disorders occurred in 1980, with introduction of DSM-III to replace DSM-I and DSM-II, which were absurdly vague, unreliable, and with poor validity.

The move toward more operational and reliable diagnostic requirements began with the Research Diagnostic Criteria, developed by the Department of Psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. DSM-III represented a complete paradigm shift in psychiatric diagnosis. Subsequent editions maintained the same methodology, with relatively modest changes. The field expects continued evolution in DSM diagnostic criteria, including the future inclusion of biomarkers, based on sound, controlled studies.

• Recognizing PTSD. Develop-ment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a diagnostic entity, and its inclusion in DSM-III, were major changes in psychiatric nosology. At last, the old terms—shell shock, battle fatigue, neurasthenia—were legitimized as a recognizable syndrome secondary to major life trauma, including war and rape. That legitimacy has instigated substantial clinical and research interest in identifying how serious psychopathology can be triggered by life events.

Pharmaceutical industry debacle

Few industries have fallen so far from grace in the eyes of psychiatric professionals and the public as the manufacturers of psychotropic drugs.

At the dawn of the psychopharmacology era (the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s) pharmaceutical companies were respected and regarded by physicians and patients as a vital partner in health care for their discovery and development of medications to treat psychiatric disorders. That image was tarnished in the 1990s, however, with the approval and release of several atypical antipsychotics. Cutthroat competition, questionable publication methods, concealment of negative findings, and excessive spending on marketing, including FDA-approved educational programs for clinicians on efficacy, safety, and dosing, all contributed to escalating cynicism about the industry. Academic faculty who received research grants to conduct FDA-required clinical trials of new agents were painted with the same brush.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest became a mandatory procedure at universities and for NIMH grant applicants and journal publishers. Class-action lawsuits against companies that manufacture second-generation antipsychotics—filed for lack of transparency about metabolic side effects—exacerbated the intensity of criticism and condemnation.

Although new drug development has become measurably more rigorous and ethical because of self-regulation, combined with vigorous government scrutiny and regulation, demonization of the pharmaceutical industry remains unabated. That might be the reason why several major pharmaceutical companies have abandoned research and development of psychotropic drugs. That is likely to impede progress in psychopharmacotherapeutics; after all, no other private or government entity develops drugs for patients who have a psychiatric illness. The need for such agents is great: There is no FDA-indicated drug for the majority of DSM-5 diagnoses.

We entrust the future to next generations

Momentous events have transformed psychiatry during the lifespan of Baby Boomers like me and many of you. Because the cohort of 80 million Baby Boomers has comprised a significant percentage of the nation’s scientists, media representatives, members of the American Psychiatric Association, academicians, and community leaders over the past few decades, it is conceivable that the Baby Boomer generation helped trigger most of the transformative changes in psychiatry we have seen over the past 70 years.

I can only wonder: What direction will psychiatry take in the age of Generation X, Generation Y, and the Millennials? Only this is certain: Psychiatry will continue to evolve— long after Baby Boomers are gone.

A large percentage of psychiatrists practicing today are Boomers, and have experienced the tumultuous change in their profession since the end of World War II. At a recent Grand Rounds presentation in the Department of Neurology & Psychiatry at Saint Louis University, participants examined major changes and paradigm shifts that have reshaped psychiatry since 1946. The audience, which included me, contributed historical observations to the list of those changes and shifts, which I’ve classified here for your benefit, whether or not you are a Boomer.

Medical advances

Consider these discoveries and developments:

• Penicillin in 1947, which led to a reduction in cases of psychosis caused by tertiary syphilis, a disease that accounted for 10% to 15% of state hospital admissions.

• Lithium in 1948, the first pharmaceutical treatment for mania.

• Chlorpromazine, the first antipsychotic drug, in 1952, launching the psychopharmacology era and ending lifetime institutional sequestration as the only “treatment” for serious mental disorders.

• Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in 1959, from observations that iproniazid, a drug used in tuberculosis sanitariums, improved the mood of tuberculosis patients. This was the first pharmacotherapy for depression, which had been treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), developed in the 1930s.

• Tricyclic antidepressants, starting with imipramine in the late 1950s, during attempts to synthesize additional phenothiazine antipsychotics.

• Diazepam, introduced in 1963 for its anti-anxiety effects, became the most widely used drug in the world over the next 2 decades.

• Pre-frontal lobotomy to treat severe psychiatric disorders. The neurosurgeon-inventor of this so-called medical advance won the 1949 Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology. The procedure was rapidly discredited after the development of antipsychotic drugs.

• Fluoxetine, the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, in 1987, revolutionized the treatment of depression, especially in primary care settings.

• Clozapine, as an effective treatment for refractory and suicidal schizophrenia, and the spawning of second-generation antipsychotics. These newer agents shifted focus from neurologic adverse effects (extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia) to cardio-metabolic side effects (obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension).

Changes to the landscape of health care

Three noteworthy developments made the list:

• The Community Mental Health Act of 1963, signed into law by President John F. Kennedy, revolutionized psychiatric care by shifting delivery of care from inpatient, hospital-based facilities to outpatient, clinic-based centers. There are now close to 800 community mental health centers in the United States, where care is dominated by non-physician mental health providers—in contrast to the era of state hospitals, during which physicians and nurses provided care for mentally ill patients.

• Deinstitutionalization. This move-ment gathered momentum in the 1970s and 1980s, leading to closing of the majority of state hospitals, with tragic consequences for the seriously mentally ill—including early demise, homelessness, substance abuse, and incarceration. In fact, the large percentage of mentally ill people in U.S. jails and prisons, instead of in a hospital, represents what has been labeled trans-institutionalization (see my March 2008 editorial, “Bring back the asylums?,” available at CurrentPsychiatry.com).

• Managed care, emerging in the late 1980s and early 1990s, caused a seismic disturbance in the delivery of, and reimbursement for, psychiatric care. The result was a significant decline in access to, and quality of, care—especially the so-called carve-out model that reduced payment for psychiatric care even more drastically than for general medical care. Under managed care, the priority became saving money, rather than saving lives. Average hospital stay for patients who had a psychiatric disorder, which was years in the pre-pharmacotherapy era, and weeks or months after that, shrunk to a few days under managed care.

Changes in professional direction

Two major shifts in the complexion of the specialty were identified:

• The decline of psychoanalysis, which had dominated psychiatry for decades (the 1940s through the 1970s), was a major shift in the conceptualization, training, and delivery of care in psychiatry. The rise of biological psychiatry and the medical model of psychiatric brain disorders, as well as the emergence of evidence-based (and briefer) psychotherapies (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and interpersonal therapy), gradually replaced the Freudian model of mental illness.

As a result, it became no longer necessary to be a certified psychoanalyst to be named chair of a department of psychiatry. The impact of this change on psychiatric training has been profound, because medical management by psychiatrists superseded psychotherapy— given the brief hospitalization that is required and the diminishing coverage for psychotherapy by insurers.

• Delegation of psychosocial treatments to non-psychiatrists. The unintended consequences of psychiatrists’ change of focus to 1) consultation on medical/surgical patients and 2) the medical evaluation, diagnosis, and pharmacotherapy of mental disorders led to the so-called “dual treatment model” for the most seriously mentally ill patients: The physician provides medical management and non-physician mental health professionals provide counseling, psychosocial therapy, and rehabilitation.

Disruptive breakthroughs

Several are notable: