User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Beyond ‘selfies’: An epidemic of acquired narcissism

Narcissism has an evil reputation. But is it justified? A modicum of narcissism is actually healthy. It can bolster self-confidence, assertiveness, and success in business and in the sociobiology of mating. Perhaps that’s why narcissism as a trait has a survival value from an evolutionary perspective.

Taking an excessive number of “selfies” with a smartphone is probably the most common and relatively benign form of mild narcissism (and not in DSM-5, yet). Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), with a prevalence of 1%, is on the extreme end of the narcissism continuum. It has become tainted with such an intensely negative halo that it has become a despised trait, an insult, and even a vile epithet, like a 4-letter word. But as psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, we clinically relate to patients with NPD as being afflicted with a serious neuropsychiatric disorder, not as despicable individuals. Many people outside the mental health profession abhor persons with NPD because of their gargantuan hubris, insufferable selfishness, self-aggrandizement, emotional abuse of others, and irremediable vanity. Narcissistic personality disorder deprives its sufferers of the prosocial capacity for empathy, which leads them to belittle others or treat competent individuals with disdain, never as equals. They also seem to be incapable of experiencing shame as they inflate their self-importance and megalomania at the expense of those they degrade. They cannot tolerate any success by others because it threatens to overshadow their own exaggerated achievements. They can be mercilessly harsh towards their underlings. They are incapable of fostering warm, long-term loving relationships, where bidirectional respect is essential. Their lives often are replete with brief, broken-up relationships because they emotionally, physically, or sexually abuse their intimate partners.

Primary NPD has been shown in twin studies to be highly genetic, and more strongly heritable than 17 other personality dimensions.1 It is also resistant to any effective psychotherapeutic, pharmacologic, or somatic treatments. This is particularly relevant given the proclivity of individuals with NPD to experience a crushing disappointment, commonly known as “narcissistic injury,” following a real or imagined failure. This could lead to a painful depression or an outburst of “narcissistic rage” directed at anyone perceived as undermining them, and may even lead to violent behavior.2

Apart from heritable narcissism, there is also another form of narcissism that can develop in some individuals following life events. That hazardous condition, known as “acquired narcissism,” is most often associated with achieving the coveted status of an exalted celebrity. At risk for this acquired personality affliction are famous actors, singers, movie directors, TV anchors, or politicians (although some politicians are natural-born narcissists, driven to seek the powers of public office), and less frequently physicians (perhaps because the practice of medicine is not done in front of spectators) or scientists (because research, no matter how momentous, rarely procures the glamour or public adulation of the entertainment industry). The ardent fans of those “celebs” shower them with such intense attention and adulation that it malignantly transforms previously “normal” individuals into narcissists who start believing they are indeed “very special” and superior to the rest of us mortals (especially as their earning power balloons into the millions after growing up with humble social or economic roots).

Social media has become a catalyst for acquired narcissism, with millions of followers on Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube. Cable TV also caters to politicians, some of whom morph into narcissists, intoxicated with their newfound eminence and stature among their partisan followers, and become genuinely convinced that they have supreme power or influence over the masses. They get carried away with their own exaggerated self-importance as oracles of the “truth,” regardless of how extreme their views may be. Celebrity, politics, social media, and cable TV have converged into a combustible mix, a crucible for acquired narcissism.

An interesting feature of acquired narcissism is “collective narcissism,” in which celebrities coalesce to consolidate their imagined superhuman attributes that go beyond the technical skills of their professions such as acting, singing, sports, or politics. Thus, entertainers or star athletes believe they can enunciate radical statements about contemporary social, political, or environmental issues (at both ends of the debate) as though their artistic success renders them wise arbiters of the truth. What complicates matters is their delirious fans, who revere and mimic whatever their idols say (and their fashion or their tattoos), which further intensifies the grandiosity and megalomania of acquired narcissism. Celebrity triggers mindless idolatry, fueling the narcissism of individuals who are blessed (or cursed?) with runaway personal success. Neuroscientists should conduct research into how the brain is neurobiologically altered by fame, but there are many more urgent questions that demand their attention. It would be important to know if it is reversible or enduring, even as fame inevitably dims.

Continue to: The pursuit of wealth and fame...

The pursuit of wealth and fame is widely prevalent and can be healthy if it is not all-consuming. But if achieved beyond the aspirer’s wildest dreams, he/she may reach an inflection point conducive to a pathologic degree of acquired narcissism. That’s what the French refer to as “les risques du métier” (ie, occupational hazard). I recall reading about celebrities who became enraged when a policeman “dared” to stop their car for some driving violation, confronting the officer with “Do you know who I am?” That question may be a clinical biomarker of acquired narcissism.

Interestingly, several years ago, when the American Psychiatry Association last revised the DSM—sometimes referred to as the “bible” of psychiatric nosology—it came close to dropping NPD from its listed disorders, but then reverted and kept it as one of the 275 diagnostic categories included in DSM-5.3 Had the NPD diagnosis been discarded, one wonders if the mythical god of narcissism would have suffered a transcendental “narcissistic injury”…

1. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831

2. Malmquist CP. Homicide: a psychiatric perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2006:181-182.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Narcissism has an evil reputation. But is it justified? A modicum of narcissism is actually healthy. It can bolster self-confidence, assertiveness, and success in business and in the sociobiology of mating. Perhaps that’s why narcissism as a trait has a survival value from an evolutionary perspective.

Taking an excessive number of “selfies” with a smartphone is probably the most common and relatively benign form of mild narcissism (and not in DSM-5, yet). Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), with a prevalence of 1%, is on the extreme end of the narcissism continuum. It has become tainted with such an intensely negative halo that it has become a despised trait, an insult, and even a vile epithet, like a 4-letter word. But as psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, we clinically relate to patients with NPD as being afflicted with a serious neuropsychiatric disorder, not as despicable individuals. Many people outside the mental health profession abhor persons with NPD because of their gargantuan hubris, insufferable selfishness, self-aggrandizement, emotional abuse of others, and irremediable vanity. Narcissistic personality disorder deprives its sufferers of the prosocial capacity for empathy, which leads them to belittle others or treat competent individuals with disdain, never as equals. They also seem to be incapable of experiencing shame as they inflate their self-importance and megalomania at the expense of those they degrade. They cannot tolerate any success by others because it threatens to overshadow their own exaggerated achievements. They can be mercilessly harsh towards their underlings. They are incapable of fostering warm, long-term loving relationships, where bidirectional respect is essential. Their lives often are replete with brief, broken-up relationships because they emotionally, physically, or sexually abuse their intimate partners.

Primary NPD has been shown in twin studies to be highly genetic, and more strongly heritable than 17 other personality dimensions.1 It is also resistant to any effective psychotherapeutic, pharmacologic, or somatic treatments. This is particularly relevant given the proclivity of individuals with NPD to experience a crushing disappointment, commonly known as “narcissistic injury,” following a real or imagined failure. This could lead to a painful depression or an outburst of “narcissistic rage” directed at anyone perceived as undermining them, and may even lead to violent behavior.2

Apart from heritable narcissism, there is also another form of narcissism that can develop in some individuals following life events. That hazardous condition, known as “acquired narcissism,” is most often associated with achieving the coveted status of an exalted celebrity. At risk for this acquired personality affliction are famous actors, singers, movie directors, TV anchors, or politicians (although some politicians are natural-born narcissists, driven to seek the powers of public office), and less frequently physicians (perhaps because the practice of medicine is not done in front of spectators) or scientists (because research, no matter how momentous, rarely procures the glamour or public adulation of the entertainment industry). The ardent fans of those “celebs” shower them with such intense attention and adulation that it malignantly transforms previously “normal” individuals into narcissists who start believing they are indeed “very special” and superior to the rest of us mortals (especially as their earning power balloons into the millions after growing up with humble social or economic roots).

Social media has become a catalyst for acquired narcissism, with millions of followers on Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube. Cable TV also caters to politicians, some of whom morph into narcissists, intoxicated with their newfound eminence and stature among their partisan followers, and become genuinely convinced that they have supreme power or influence over the masses. They get carried away with their own exaggerated self-importance as oracles of the “truth,” regardless of how extreme their views may be. Celebrity, politics, social media, and cable TV have converged into a combustible mix, a crucible for acquired narcissism.

An interesting feature of acquired narcissism is “collective narcissism,” in which celebrities coalesce to consolidate their imagined superhuman attributes that go beyond the technical skills of their professions such as acting, singing, sports, or politics. Thus, entertainers or star athletes believe they can enunciate radical statements about contemporary social, political, or environmental issues (at both ends of the debate) as though their artistic success renders them wise arbiters of the truth. What complicates matters is their delirious fans, who revere and mimic whatever their idols say (and their fashion or their tattoos), which further intensifies the grandiosity and megalomania of acquired narcissism. Celebrity triggers mindless idolatry, fueling the narcissism of individuals who are blessed (or cursed?) with runaway personal success. Neuroscientists should conduct research into how the brain is neurobiologically altered by fame, but there are many more urgent questions that demand their attention. It would be important to know if it is reversible or enduring, even as fame inevitably dims.

Continue to: The pursuit of wealth and fame...

The pursuit of wealth and fame is widely prevalent and can be healthy if it is not all-consuming. But if achieved beyond the aspirer’s wildest dreams, he/she may reach an inflection point conducive to a pathologic degree of acquired narcissism. That’s what the French refer to as “les risques du métier” (ie, occupational hazard). I recall reading about celebrities who became enraged when a policeman “dared” to stop their car for some driving violation, confronting the officer with “Do you know who I am?” That question may be a clinical biomarker of acquired narcissism.

Interestingly, several years ago, when the American Psychiatry Association last revised the DSM—sometimes referred to as the “bible” of psychiatric nosology—it came close to dropping NPD from its listed disorders, but then reverted and kept it as one of the 275 diagnostic categories included in DSM-5.3 Had the NPD diagnosis been discarded, one wonders if the mythical god of narcissism would have suffered a transcendental “narcissistic injury”…

Narcissism has an evil reputation. But is it justified? A modicum of narcissism is actually healthy. It can bolster self-confidence, assertiveness, and success in business and in the sociobiology of mating. Perhaps that’s why narcissism as a trait has a survival value from an evolutionary perspective.

Taking an excessive number of “selfies” with a smartphone is probably the most common and relatively benign form of mild narcissism (and not in DSM-5, yet). Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), with a prevalence of 1%, is on the extreme end of the narcissism continuum. It has become tainted with such an intensely negative halo that it has become a despised trait, an insult, and even a vile epithet, like a 4-letter word. But as psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, we clinically relate to patients with NPD as being afflicted with a serious neuropsychiatric disorder, not as despicable individuals. Many people outside the mental health profession abhor persons with NPD because of their gargantuan hubris, insufferable selfishness, self-aggrandizement, emotional abuse of others, and irremediable vanity. Narcissistic personality disorder deprives its sufferers of the prosocial capacity for empathy, which leads them to belittle others or treat competent individuals with disdain, never as equals. They also seem to be incapable of experiencing shame as they inflate their self-importance and megalomania at the expense of those they degrade. They cannot tolerate any success by others because it threatens to overshadow their own exaggerated achievements. They can be mercilessly harsh towards their underlings. They are incapable of fostering warm, long-term loving relationships, where bidirectional respect is essential. Their lives often are replete with brief, broken-up relationships because they emotionally, physically, or sexually abuse their intimate partners.

Primary NPD has been shown in twin studies to be highly genetic, and more strongly heritable than 17 other personality dimensions.1 It is also resistant to any effective psychotherapeutic, pharmacologic, or somatic treatments. This is particularly relevant given the proclivity of individuals with NPD to experience a crushing disappointment, commonly known as “narcissistic injury,” following a real or imagined failure. This could lead to a painful depression or an outburst of “narcissistic rage” directed at anyone perceived as undermining them, and may even lead to violent behavior.2

Apart from heritable narcissism, there is also another form of narcissism that can develop in some individuals following life events. That hazardous condition, known as “acquired narcissism,” is most often associated with achieving the coveted status of an exalted celebrity. At risk for this acquired personality affliction are famous actors, singers, movie directors, TV anchors, or politicians (although some politicians are natural-born narcissists, driven to seek the powers of public office), and less frequently physicians (perhaps because the practice of medicine is not done in front of spectators) or scientists (because research, no matter how momentous, rarely procures the glamour or public adulation of the entertainment industry). The ardent fans of those “celebs” shower them with such intense attention and adulation that it malignantly transforms previously “normal” individuals into narcissists who start believing they are indeed “very special” and superior to the rest of us mortals (especially as their earning power balloons into the millions after growing up with humble social or economic roots).

Social media has become a catalyst for acquired narcissism, with millions of followers on Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube. Cable TV also caters to politicians, some of whom morph into narcissists, intoxicated with their newfound eminence and stature among their partisan followers, and become genuinely convinced that they have supreme power or influence over the masses. They get carried away with their own exaggerated self-importance as oracles of the “truth,” regardless of how extreme their views may be. Celebrity, politics, social media, and cable TV have converged into a combustible mix, a crucible for acquired narcissism.

An interesting feature of acquired narcissism is “collective narcissism,” in which celebrities coalesce to consolidate their imagined superhuman attributes that go beyond the technical skills of their professions such as acting, singing, sports, or politics. Thus, entertainers or star athletes believe they can enunciate radical statements about contemporary social, political, or environmental issues (at both ends of the debate) as though their artistic success renders them wise arbiters of the truth. What complicates matters is their delirious fans, who revere and mimic whatever their idols say (and their fashion or their tattoos), which further intensifies the grandiosity and megalomania of acquired narcissism. Celebrity triggers mindless idolatry, fueling the narcissism of individuals who are blessed (or cursed?) with runaway personal success. Neuroscientists should conduct research into how the brain is neurobiologically altered by fame, but there are many more urgent questions that demand their attention. It would be important to know if it is reversible or enduring, even as fame inevitably dims.

Continue to: The pursuit of wealth and fame...

The pursuit of wealth and fame is widely prevalent and can be healthy if it is not all-consuming. But if achieved beyond the aspirer’s wildest dreams, he/she may reach an inflection point conducive to a pathologic degree of acquired narcissism. That’s what the French refer to as “les risques du métier” (ie, occupational hazard). I recall reading about celebrities who became enraged when a policeman “dared” to stop their car for some driving violation, confronting the officer with “Do you know who I am?” That question may be a clinical biomarker of acquired narcissism.

Interestingly, several years ago, when the American Psychiatry Association last revised the DSM—sometimes referred to as the “bible” of psychiatric nosology—it came close to dropping NPD from its listed disorders, but then reverted and kept it as one of the 275 diagnostic categories included in DSM-5.3 Had the NPD diagnosis been discarded, one wonders if the mythical god of narcissism would have suffered a transcendental “narcissistic injury”…

1. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831

2. Malmquist CP. Homicide: a psychiatric perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2006:181-182.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

1. Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Jackson DN, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(12):1826-1831

2. Malmquist CP. Homicide: a psychiatric perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2006:181-182.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Backlash against using rating scales

I strongly disagree with the editorial by Ahmed A. Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, (“It’s time to implement measurement-based care in psychiatric practice,” From the Editor,

We do not have much more to lose before it’s a checklist, vital signs, and a script. I now refer to our profession as “McMedicine.” If you don’t have what is on the menu, you cannot get served. Diseases are rarely treated, symptoms are treated. This is not the profession of medicine. We are not fixing much; we are mostly providing consumers for pharmaceutical companies.

Few psychiatric disorders have been subjected to more measurement than depression. Quite a while ago, someone tried to compare depression scales. They correlated scale scores with the results of evaluations by board-certified psychiatrists. The best scale was a single question: “Are you depressed?” This had been included as a control. Can you do better?

Furthermore, the “paper and numbers” people can’t wait to get an “objective” wrench to tighten the screws and apply the principles of the industrial revolution to squeeze more money out of the system. They will find some way to turn patients into standardized products.

John L. Schenkel, MD

Retired psychiatrist

Peru, NY

With the use of an electronic medical record, what should be a simple 1-page note is transformed into a 5-page note of details. Doctors no longer attend to their patients but rather to their computers. Has this raised consciousness—the most important metric, according to Dr. David Hawkins? I doubt it.

In the words of my great professor, Dr. James Gustafson, I will continue to start my interview with what concerns the patient. Most of the time, they implicitly know.

Our focus should instead be on bringing down the cost of health care. This is what angers our patients most, and yet we do not make it a priority.

Psychiatrist

Glenbeigh Hospital

Rock Creek, Ohio

Signature Health

Ashtabula, Ohio

Behavioral Wellness Group

Mentor, Ohio

Continue to: The authors respond

The authors respond

We appreciate Drs. Schenkel’s and Primc’s comments on our editorial regarding measurement-based care (MBC). However, MBC will not increase the workload of psychiatrists; rather, it will streamline the evaluation of patients and measure the severity of their symptoms or adverse effects as well as the degree of their improvement. The proper use of scales with the appropriate patient populations may actually help clinicians to reduce the extensive amount of details that go into medical records.

The following quote, an excerpt from another article we wrote on MBC,1 speaks to Dr. Primc’s concerns:

“…measures in psychiatry could be considered the equivalent of a thermometer and a stethoscope to a physician.

Ahmed A. Aboraya, MD, DrPH

Assistant Professor

Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry

Chief of Psychiatry

Sharpe Hospital West Virginia University

Weston, West Virginia

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neuroscience

Medical Director: Neuropsychiatry

Director, Schizophrenia and Neuropsychiatry Programs

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

Cincinnati, Ohio

Professor Emeritus, Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

Reference

1. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick DE, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatry-past, present, and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

I strongly disagree with the editorial by Ahmed A. Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, (“It’s time to implement measurement-based care in psychiatric practice,” From the Editor,

We do not have much more to lose before it’s a checklist, vital signs, and a script. I now refer to our profession as “McMedicine.” If you don’t have what is on the menu, you cannot get served. Diseases are rarely treated, symptoms are treated. This is not the profession of medicine. We are not fixing much; we are mostly providing consumers for pharmaceutical companies.

Few psychiatric disorders have been subjected to more measurement than depression. Quite a while ago, someone tried to compare depression scales. They correlated scale scores with the results of evaluations by board-certified psychiatrists. The best scale was a single question: “Are you depressed?” This had been included as a control. Can you do better?

Furthermore, the “paper and numbers” people can’t wait to get an “objective” wrench to tighten the screws and apply the principles of the industrial revolution to squeeze more money out of the system. They will find some way to turn patients into standardized products.

John L. Schenkel, MD

Retired psychiatrist

Peru, NY

With the use of an electronic medical record, what should be a simple 1-page note is transformed into a 5-page note of details. Doctors no longer attend to their patients but rather to their computers. Has this raised consciousness—the most important metric, according to Dr. David Hawkins? I doubt it.

In the words of my great professor, Dr. James Gustafson, I will continue to start my interview with what concerns the patient. Most of the time, they implicitly know.

Our focus should instead be on bringing down the cost of health care. This is what angers our patients most, and yet we do not make it a priority.

Psychiatrist

Glenbeigh Hospital

Rock Creek, Ohio

Signature Health

Ashtabula, Ohio

Behavioral Wellness Group

Mentor, Ohio

Continue to: The authors respond

The authors respond

We appreciate Drs. Schenkel’s and Primc’s comments on our editorial regarding measurement-based care (MBC). However, MBC will not increase the workload of psychiatrists; rather, it will streamline the evaluation of patients and measure the severity of their symptoms or adverse effects as well as the degree of their improvement. The proper use of scales with the appropriate patient populations may actually help clinicians to reduce the extensive amount of details that go into medical records.

The following quote, an excerpt from another article we wrote on MBC,1 speaks to Dr. Primc’s concerns:

“…measures in psychiatry could be considered the equivalent of a thermometer and a stethoscope to a physician.

Ahmed A. Aboraya, MD, DrPH

Assistant Professor

Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry

Chief of Psychiatry

Sharpe Hospital West Virginia University

Weston, West Virginia

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neuroscience

Medical Director: Neuropsychiatry

Director, Schizophrenia and Neuropsychiatry Programs

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

Cincinnati, Ohio

Professor Emeritus, Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

Reference

1. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick DE, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatry-past, present, and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

I strongly disagree with the editorial by Ahmed A. Aboraya, MD, DrPH, and Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, (“It’s time to implement measurement-based care in psychiatric practice,” From the Editor,

We do not have much more to lose before it’s a checklist, vital signs, and a script. I now refer to our profession as “McMedicine.” If you don’t have what is on the menu, you cannot get served. Diseases are rarely treated, symptoms are treated. This is not the profession of medicine. We are not fixing much; we are mostly providing consumers for pharmaceutical companies.

Few psychiatric disorders have been subjected to more measurement than depression. Quite a while ago, someone tried to compare depression scales. They correlated scale scores with the results of evaluations by board-certified psychiatrists. The best scale was a single question: “Are you depressed?” This had been included as a control. Can you do better?

Furthermore, the “paper and numbers” people can’t wait to get an “objective” wrench to tighten the screws and apply the principles of the industrial revolution to squeeze more money out of the system. They will find some way to turn patients into standardized products.

John L. Schenkel, MD

Retired psychiatrist

Peru, NY

With the use of an electronic medical record, what should be a simple 1-page note is transformed into a 5-page note of details. Doctors no longer attend to their patients but rather to their computers. Has this raised consciousness—the most important metric, according to Dr. David Hawkins? I doubt it.

In the words of my great professor, Dr. James Gustafson, I will continue to start my interview with what concerns the patient. Most of the time, they implicitly know.

Our focus should instead be on bringing down the cost of health care. This is what angers our patients most, and yet we do not make it a priority.

Psychiatrist

Glenbeigh Hospital

Rock Creek, Ohio

Signature Health

Ashtabula, Ohio

Behavioral Wellness Group

Mentor, Ohio

Continue to: The authors respond

The authors respond

We appreciate Drs. Schenkel’s and Primc’s comments on our editorial regarding measurement-based care (MBC). However, MBC will not increase the workload of psychiatrists; rather, it will streamline the evaluation of patients and measure the severity of their symptoms or adverse effects as well as the degree of their improvement. The proper use of scales with the appropriate patient populations may actually help clinicians to reduce the extensive amount of details that go into medical records.

The following quote, an excerpt from another article we wrote on MBC,1 speaks to Dr. Primc’s concerns:

“…measures in psychiatry could be considered the equivalent of a thermometer and a stethoscope to a physician.

Ahmed A. Aboraya, MD, DrPH

Assistant Professor

Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry

Chief of Psychiatry

Sharpe Hospital West Virginia University

Weston, West Virginia

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neuroscience

Medical Director: Neuropsychiatry

Director, Schizophrenia and Neuropsychiatry Programs

University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

Cincinnati, Ohio

Professor Emeritus, Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

Reference

1. Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA, Elswick DE, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatry-past, present, and future. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11-12):13-26.

Seizure-like episodes, but is it really epilepsy?

CASE Increasingly frequent paroxysmal episodes

Ms. N, age 12, comes to the hospital for evaluation of paroxysmal episodes of pain, weakness, and muscle spasms. A neurologist who evaluated her as an outpatient had recommended a routine electroencephalogram (EEG); after those results were inconclusive, Ms. N’s mother brought her to the hospital for a 24-hour video EEG.

Ms. N has a history of asthma. She has no history of seizures or headache, but her mother has an unspecified seizure disorder that has been stable with antiepileptic medication for many years. Ms. N has no other family history of autoimmune or neurologic disorders.

Ms. N’s episodes began 6 months ago and have progressively increased in frequency from 5 to 12 episodes a day. She says that before she has an episode, she “ feels tingling in her fingers and mouth, and butterflies in her belly,” and then her “whole body clenches up.” She denies experiencing tongue biting, facial or extremity weakness, incontinence, or loss of consciousness during these episodes.

Shortly before her hospitalization, Ms. N had won a scholarship to attend an overnight art camp. Because her episodes were becoming more frequent and their etiology remained unclear, Ms. N and her mother decided it would be unsafe for her to attend, and that she should go to the hospital for evaluation instead.

EVALUATION Tough questions reveal answers

The pediatric team evaluates Ms. N. Her physical exam, laboratory values, and imaging are all within normal limits. Her neurologic exam demonstrates full strength, tone, and sensation in all extremities. All cranial nerves and reflexes are intact. No dysmorphic features or gait abnormalities are noted. All laboratory and imaging tests are normal, including complete blood cell count, electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, glucose, creatine kinase, liver enzymes, urine drug screen, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) urine test, and h

After the initial workup, the pediatric team consults the child and adolescent psychiatry team for a complete assessment of Ms. N due to concerns that a psychological component is contributing to her episodes. According to the psychosocial history obtained from Ms. N and her mother, Ms. N had experienced disrupted attachment, trauma, and loss. At age 5, Ms. N was temporarily removed from her mother’s custody after a fight between her mother and brother. At age 9, Ms. N’s stepfather, her primary father figure, died of a brain tumor.

Ms. N also has significant trauma stemming from her relationship with her biological father. Ms. N’s mother reports that her daughter was conceived during nonconsensual sexual intercourse. Ms. N did not have much contact with her biological father until 6 months ago, when he started picking her up at school and taking her to his home for several hours without permission or supervision. Afterwards, Ms. N confided to her mother and a teacher that her father sexually assaulted her during those visits.

Continue to: Ms. N and her mother...

Ms. N and her mother reported the assault to the police and were awaiting legal action.

During the interview with the psychiatry team, Ms. N denies that any thoughts or actions trigger the episodes and reports that she cannot control when they happen. Because she cannot anticipate the episodes, she says she is afraid to leave her house. She does not know why the episodes are happening and feels frustrated that they are getting worse. Ms. N says, “I have been feeling down lately,” but she denies hopelessness, worthlessness, suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, delusions, or hallucinations.

In the hospital, when the psychiatry team asks Ms. N about her visits with her father, she says that they are “too painful to talk about,” and fears that discussing them will trigger an episode. However, her mother suggests that her daughter’s sexual trauma, as well as ongoing frustrations with the legal system, are influencing her mood; she has had low energy, poor appetite, and is spending more time in bed. Her mother also reports that Ms. N “avoids going out in the sun and spending time with her friends outside. She doesn’t seem to enjoy shopping and art like she used to.” Ms. N told her mother that she was having nightmares about the trauma and “could not stop thinking about some of the bad stuff that happened during the day.”

Ten minutes into the interview, while being questioned about her father, Ms. N experiences a spastic episode. She curls up in bed on her left side, clenches her entire body, and shuts her eyes. Her mother quickly runs to her bedside and counts the seconds until the end of the episode. After 25 seconds, Ms. N awakes with full recollection of the episode. On review of the video EEG during the episode, no ictal patterns are seen.

[polldaddy:10375873]

The authors’ observations

Paroxysmal episodes of weakness, numbness, and muscle spasms in a young female are suggestive of either epilepsy or nonepileptic seizure (NES).1,2 The negative EEG and physical features are inconsistent with epileptiform seizure, and Ms. N’s history and evaluation are suggestive of NES. Nonepileptic seizures are a type of a conversion disorder, or functional neurologic symptom disorder, in which a patient experiences weakness, abnormal movements, or seizure-like episodes that are inconsistent with organic neurologic disease.3 When a diagnosis of conversion disorder is suspected, a clinician must always consider other pathology that can explain the symptoms, such as migraine, vasovagal syncope, or intracranial mass. If a patient has focal neurologic deficits, head imaging should be pursued. Additionally, the clinician must screen for malingering and factitious disorder before establishing a definitive diagnosis. However, conversion disorder is not a diagnosis of exclusion. For example, a negative EEG does not rule out epilepsy, and patients can have both epilepsy and concomitant NES.

Continue to: Although NES is a common...

Although NES is a common type of conversion disorder, it is often difficult to diagnose, manage, and treat. Patients often receive antiepileptic medications but continue to have worsening events that are refractory to treatment. Various clinical features can suggest NES instead of epilepsy. Forced eye closure on video recording is a specific finding suggestive of NES, yet this feature is not sufficient to make the diagnosis.4 A video EEG must be performed to assess for epilepsy. The diagnosis of NES does not exclude the possibility that a patient has epilepsy, as NES can occur in up to 40% of patients with epilepsy.5 A video EEG without ictal patterns before, during, and after an observed episode is diagnostic of NES.6

[polldaddy:10375874]

The authors’ observations

Conversion disorders such as NES are a presentation of neurologic symptoms that cannot be readily accounted for by other conditions and are often associated with antecedent trauma. Multiple factors in Ms. N’s history increase her risk of NES, including loss of multiple loved ones, ongoing legal involvement, and alleged sexual abuse by her father.

Victims of sexual abuse are more likely than the general population to demonstrate symptoms of conversion disorder, especially NES.7,8 The onset of paroxysmal episodes after incestuous abuse in a teenage girl is characteristic of NES. Compared with patients with complex partial epilepsy (CPE), patients with NES are 3 times more likely to report sexual trauma.9,10 Children who report sexual abuse that precedes NES are more likely to have been victimized by a first-degree relative than patients with CPE who report sexual abuse.11 Risk factors for victims developing NES may be related to the severity of adversity, stress sensitivity, and decreased hippocampal volume.12,13

Ms. N endorsed many psychiatric symptoms that accompany her paroxysmal episodes; this is similar to findings in other patients with NES.14 One study found that depression is 3 times more prevalent and PTSD is 8 times more prevalent in patients with NES.12 During the evaluation, Ms. N’s mother said her daughter had low energy, poor appetite, lethargy, and anhedonia for the preceding 5 months, which is consistent with adjustment disorder.3 Her flashbacks, nightmares, difficulty sleeping, and agoraphobia, along with her trouble engaging with the people and activities that used to bring her joy, are symptoms of PTSD. Nonepileptic seizure is often associated with PTSD and can be viewed as an expression of a dissociated subtype.15

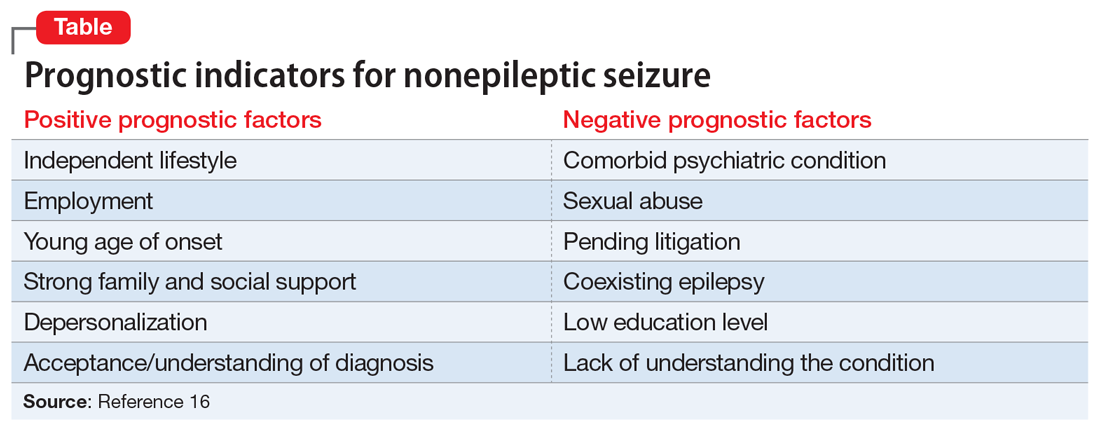

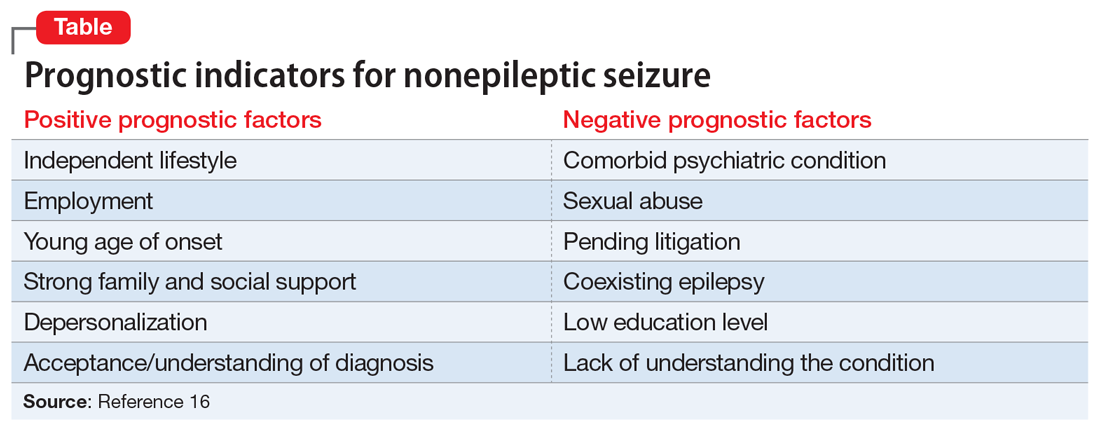

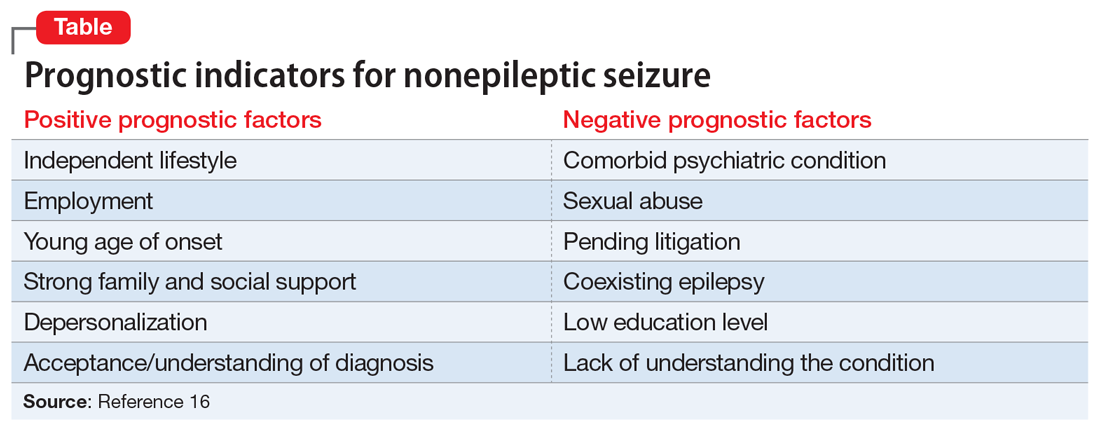

In a literature review, Durrant et al16 isolated prognostic indicators for NES (Table16). This study found that 70% of children and 40% of adults achieve remission from NES. Ms. N’s case has multiple concerning features, such as her comorbid psychiatric conditions, ongoing involvement in a legal case, and sexual trauma; this last factor is associated with the most severe symptoms and worse outcomes.16,17 Despite this somber reality, Ms. N has the support of her mother and is relatively young, which play a vital role in recovery.

Continue to: TREATMENT A strategy for minimizing the episodes

TREATMENT A strategy for minimizing the episodes

Ms. N’s medical workup remains unremarkable throughout the rest of her hospital stay. The psychiatry and pediatric teams discuss their assessments and agree that NES is the most likely diagnosis. The psychiatry team counsels Ms. N and her mother on the diagnosis and etiology of NES.

[polldaddy:10375876]

The authors’ observations

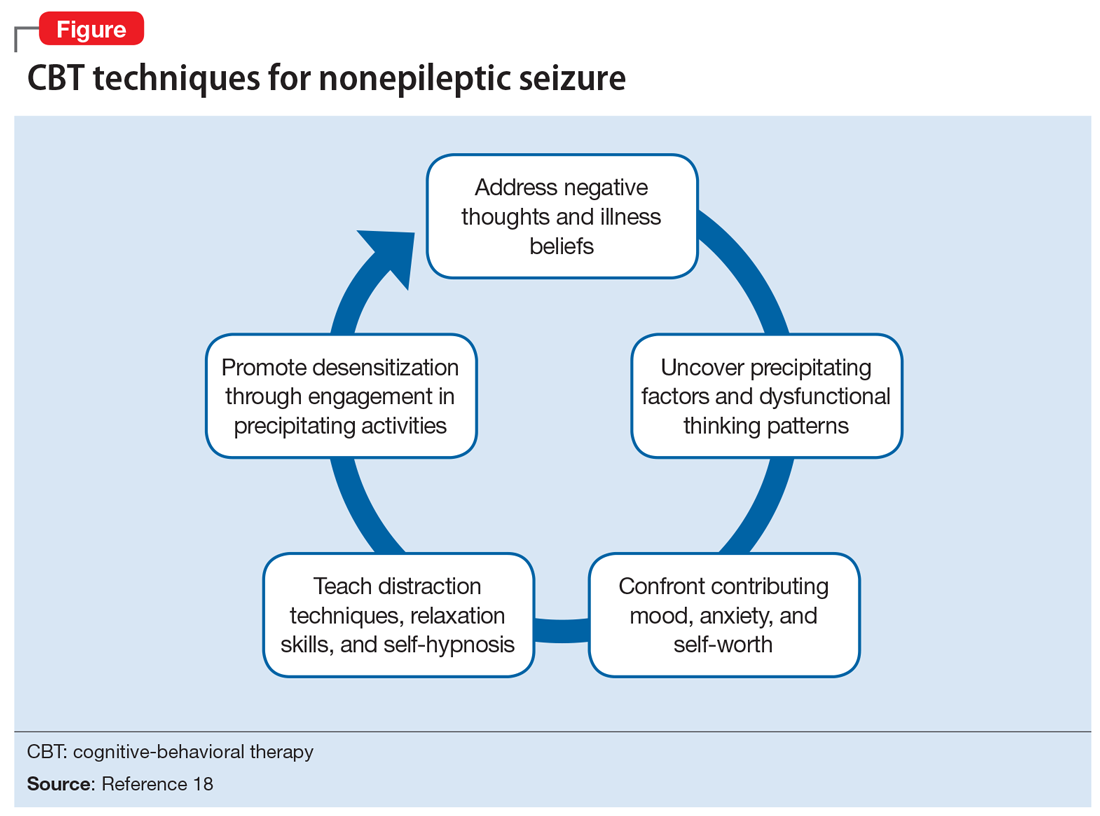

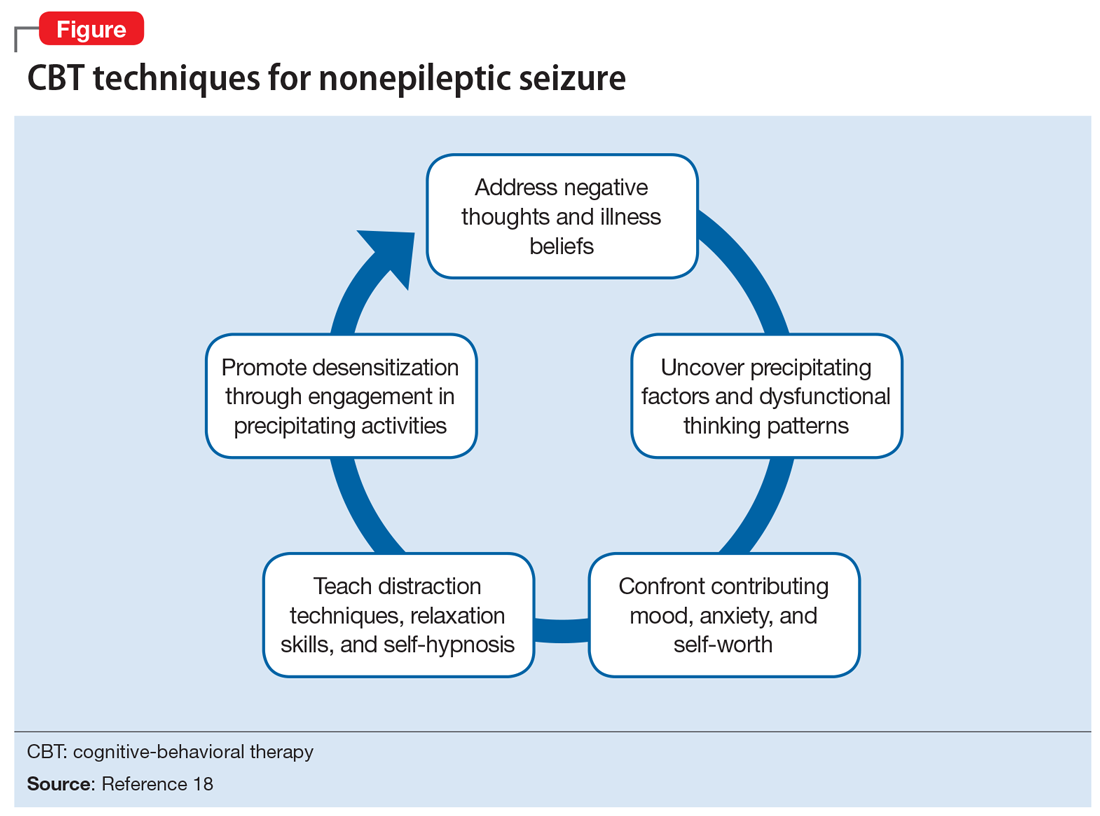

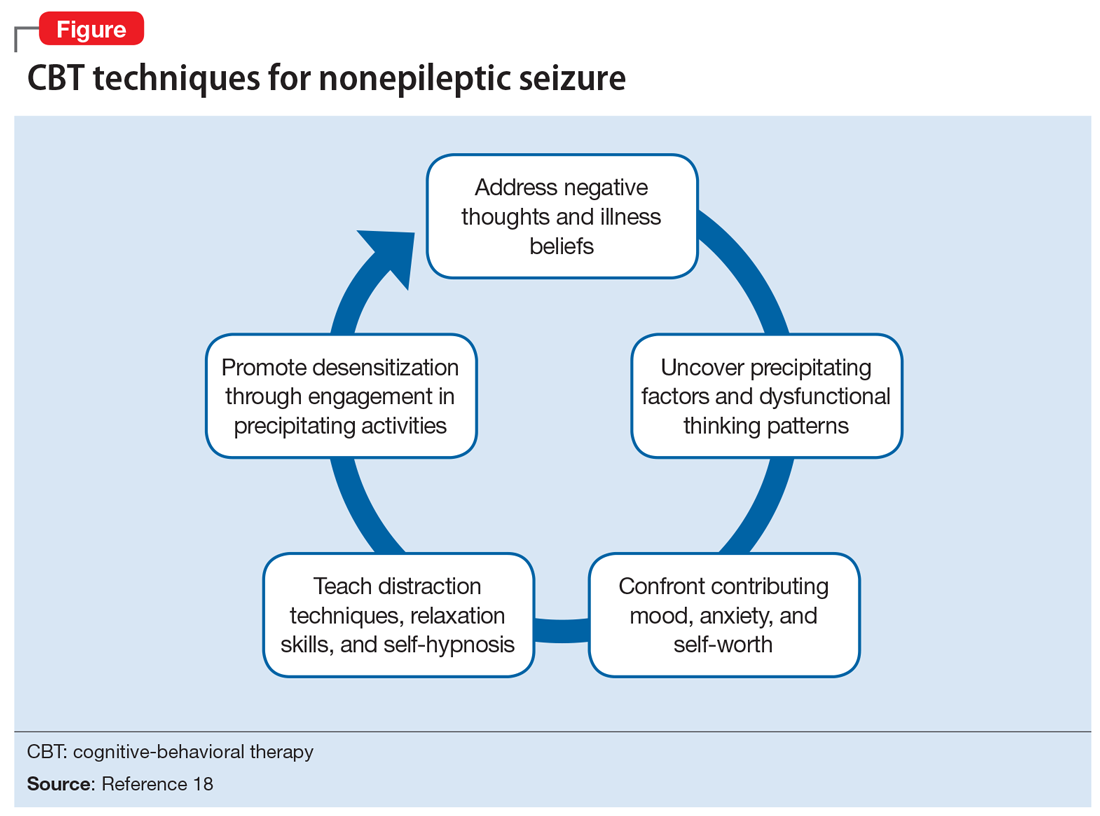

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is currently the treatment of choice for reducing seizure frequency in patients with NES.18,19 The use of CBT was suggested due to the theory that NES represents a dissociative response to trauma. Therapy focuses on changing a patient’s beliefs and perceptions associated with attacks.5 A randomized study of 66 patients with NES compared the use of CBT plus standard medical care with standard medical care alone.18 The standard medical care consisted of supportive treatment, an explanation of NES from a neuropsychiatrist, and supervised withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs. The CBT treatment group was offered weekly hour-long sessions for 12 weeks, accompanied by CBT homework and journaling the frequency and nature of seizure episodes (the CBT techniques are outlined in the Figure18). After 4 months, the CBT treatment group had fewer seizures, and after a 6-month follow-up, they were more likely to be seizure-free. However, in this study, CBT treatment did not improve mood or employment status.

A later investigation looked at using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to treat NES in adults.19 This study divided participants into 4 treatment groups: CBT with informed psychotherapy (CBT-ip), CBT-ip plus sertraline, sertraline alone, and treatment as usual. Sertraline was titrated up to a dose of 200 mg/d as tolerated. After 16 weeks of sertraline alone, seizure frequency did not decrease. Although both CBT groups showed a reduction in symptoms of up to 60%, the CBT-ip group reported fewer psychiatric symptoms with better social interactions, quality of life, and global functioning compared with patients treated with CBT-ip plus sertraline. The authors suggested that this may be due to the somatic adverse effects associated with sertraline. This study suggests that CBT without medication is the treatment of choice.

In addition to CBT, studies of psychodynamic psychotherapy for NES have had promising findings.20 Psychodynamic psychotherapy focuses on addressing conscious and unconscious anger, loss, feelings of isolation, and trauma. Through improving emotional processing, insight, coping skills and self-regulation, patients often benefit from an improvement in seizures, psychosocial functioning and health care utilization.

Metin et al21 found that group therapy alongside a family-centered approach elicited a strong and durable reduction in seizures in patients with NES. At enrollment, investigators distributed information on NES to patients and families. Psychoeducation and psychoanalysis with behavior modification techniques were provided in 90-minute weekly group sessions over 3 months. Participants also underwent monthly individualized sessions for standard psychiatric care for 9 months. During the group sessions, operant conditioning techniques were used to prevent secondary gain from seizure-like activity. Families met 4 times for 1 hour each to discuss seizures, receive psychoeducation on a subconscious etiology of NES, and learn behavior modification techniques. All 9 participants who completed group and individual therapy reported a significant and sustained reduction in seizure frequency by at least 50% at 12-month follow-up. Patients also demonstrated improvements in mood, anxiety, and quality of life.

Continue to: A meta-analysis...

A meta-analysis by Carlson and Perry22 that included 13 studies and 228 participants, examined different treatment modalities and their effectiveness for NES. They found that patients who received psychological intervention had a 47% remission rate and 82% improvement in seizure frequency compared with only 14% to 23% of those who did not receive therapy. They postulated that therapy for this illness must be flexible to properly address the socially, psychologically, and functionally heterogenous patient population. Although there are few randomized controlled trials for NES to determine the best evidence-based intervention, there is now consensus that NES has a favorable prognosis when barriers to psychological care are eliminated.

OUTCOME Referral for CBT

The treatment team advises Ms. N to engage in outpatient therapy after discharge from the hospital. Ms. N and her mother agree to the treatment plan, and leave the hospital with a referral for CBT the next day.

Bottom Line

Nonepileptic seizure (NES) is a type of conversion disorder characterized by seizure-like episodes without ictal qualities. Risk factors for NES include concomitant epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, unstable psychosocial situations, and antecedent trauma. Patients with a history of incestuous sexual abuse are most at risk for developing NES. A normal EEG that fully captures a seizure-like episode is diagnostic of NES. Cognitive-behavioral therapy can minimize seizure frequency and intensity.

Related Resources

- Marsh P, Benbadis S, Fernandez F. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: ways to win over skeptical patients. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):21-24, 32-35.

- LaFrance WC Jr. Eye-opening behaviors help diagnose nonepileptic seizures. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(11):121-122, 124, 130.

- LaFrance WC Jr, Kanner AM, Barry JJ. Treating patients with psychological nonepileptic seizures. In: Ettinger AB, Kanner AM, eds. Psychiatric issues in epilepsy: a practical guide to diagnosis and treatment. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/ Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:461-488.

Drug Brand Name

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Lesser R. Psychogenic seizures. Neurology. 1996;46(6):1499-1507.

2. Stone J, LaFrance W, Brown R, et al. Conversion disorder: current problems and potential solutions for DSM-5. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(6):369-376.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Syed T, Arozullah A, Suciu G, et al. Do observer and self-reports of ictal eye closure predict psychogenic nonepileptic seizures? Epilepsia. 2008;49(5):898-904.

5. Vega-Zelaya L, Alvarez M, Ezquiaga E, et al. Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures in a surgical epilepsy unit: experience and a comprehensive review. Epilepsy Topics. 2014. doi: 10.5772/57439.

6. LaFrance W, Baker G, Duncan R, et al. Minimum requirements for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a staged approach. Epilepsia. 2013;54(11):2005-2018.

7. Roeloes K, Pasman J. Stress, childhood trauma, and cognitive functions in functional neurologic disorders. In: Hallett M, Stone J, Carson A, eds. Handbook of clinical neurology: functional neurologic disorders. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:139-155.

8. Paras M, Murad M, Chen L, et al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of somatic disorders. JAMA. 2009;302(5):550.

9. Fiszman A, Alves-Leon SV, Nunes RG, et al. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a critical review. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5(6):818-825.

10. Sharpe D, Faye C. Non-epileptic seizures and child sexual abuse: a critical review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(8):1020-1040.

11. Alper K, Devinsky O, Perrine K, et al. Nonepileptic seizures and childhood sexual and physical abuse. Neurology. 1993;43(10):1950-1953.

12. Plioplys S, Doss J, Siddarth P et al. A multisite controlled study of risk factors in pediatric psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2014;55(11):1739-1747.

13. Andersen S, Tomada A, Vincow E, et al. Preliminary evidence for sensitive periods in the effect of childhood sexual abuse on regional brain development. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;20(3):292-301.

14. Sar V. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

15. Rosenberg HJ, Rosenberg SD, Williamson PD, et al. A comparative study of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence in epilepsy patients and psychogenic nonepileptic seizure patients. Epilepsia. 2000;41(4):447-452.

16. Durrant J, Rickards H, Cavanna A. Prognosis and outcome predictors in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2011;2011:1-7.

17. Selkirk M, Duncan R, Oto M, et al. Clinical differences between patients with nonepileptic seizures who report antecedent sexual abuse and those who do not. Epilepsia. 2008;49(8):1446-1450.

18. Goldstein L, Chalder T, Chigwedere C, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a pilot RCT. Neurology. 2010;74(24):1986-1994.

19. LaFrance W, Baird G, Barry J, et al. Multicenter pilot treatment trial for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(9):997.

20. Howlett S, Reuber M. An augmented model of brief psychodynamic interpersonal therapy for patients with nonepileptic seizures. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2009;46(1):125-138.

21. Metin SZ, Ozmen M, Metin B, et al. Treatment with group psychotherapy for chronic psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;28(1):91-94.

22. Carlson P, Perry KN. Psychological interventions for psychogenic non-epileptic seizures: a meta-analysis. Seizure. 2017;45:142-150.

CASE Increasingly frequent paroxysmal episodes

Ms. N, age 12, comes to the hospital for evaluation of paroxysmal episodes of pain, weakness, and muscle spasms. A neurologist who evaluated her as an outpatient had recommended a routine electroencephalogram (EEG); after those results were inconclusive, Ms. N’s mother brought her to the hospital for a 24-hour video EEG.

Ms. N has a history of asthma. She has no history of seizures or headache, but her mother has an unspecified seizure disorder that has been stable with antiepileptic medication for many years. Ms. N has no other family history of autoimmune or neurologic disorders.

Ms. N’s episodes began 6 months ago and have progressively increased in frequency from 5 to 12 episodes a day. She says that before she has an episode, she “ feels tingling in her fingers and mouth, and butterflies in her belly,” and then her “whole body clenches up.” She denies experiencing tongue biting, facial or extremity weakness, incontinence, or loss of consciousness during these episodes.

Shortly before her hospitalization, Ms. N had won a scholarship to attend an overnight art camp. Because her episodes were becoming more frequent and their etiology remained unclear, Ms. N and her mother decided it would be unsafe for her to attend, and that she should go to the hospital for evaluation instead.

EVALUATION Tough questions reveal answers

The pediatric team evaluates Ms. N. Her physical exam, laboratory values, and imaging are all within normal limits. Her neurologic exam demonstrates full strength, tone, and sensation in all extremities. All cranial nerves and reflexes are intact. No dysmorphic features or gait abnormalities are noted. All laboratory and imaging tests are normal, including complete blood cell count, electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, glucose, creatine kinase, liver enzymes, urine drug screen, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) urine test, and h

After the initial workup, the pediatric team consults the child and adolescent psychiatry team for a complete assessment of Ms. N due to concerns that a psychological component is contributing to her episodes. According to the psychosocial history obtained from Ms. N and her mother, Ms. N had experienced disrupted attachment, trauma, and loss. At age 5, Ms. N was temporarily removed from her mother’s custody after a fight between her mother and brother. At age 9, Ms. N’s stepfather, her primary father figure, died of a brain tumor.

Ms. N also has significant trauma stemming from her relationship with her biological father. Ms. N’s mother reports that her daughter was conceived during nonconsensual sexual intercourse. Ms. N did not have much contact with her biological father until 6 months ago, when he started picking her up at school and taking her to his home for several hours without permission or supervision. Afterwards, Ms. N confided to her mother and a teacher that her father sexually assaulted her during those visits.

Continue to: Ms. N and her mother...

Ms. N and her mother reported the assault to the police and were awaiting legal action.

During the interview with the psychiatry team, Ms. N denies that any thoughts or actions trigger the episodes and reports that she cannot control when they happen. Because she cannot anticipate the episodes, she says she is afraid to leave her house. She does not know why the episodes are happening and feels frustrated that they are getting worse. Ms. N says, “I have been feeling down lately,” but she denies hopelessness, worthlessness, suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, delusions, or hallucinations.

In the hospital, when the psychiatry team asks Ms. N about her visits with her father, she says that they are “too painful to talk about,” and fears that discussing them will trigger an episode. However, her mother suggests that her daughter’s sexual trauma, as well as ongoing frustrations with the legal system, are influencing her mood; she has had low energy, poor appetite, and is spending more time in bed. Her mother also reports that Ms. N “avoids going out in the sun and spending time with her friends outside. She doesn’t seem to enjoy shopping and art like she used to.” Ms. N told her mother that she was having nightmares about the trauma and “could not stop thinking about some of the bad stuff that happened during the day.”

Ten minutes into the interview, while being questioned about her father, Ms. N experiences a spastic episode. She curls up in bed on her left side, clenches her entire body, and shuts her eyes. Her mother quickly runs to her bedside and counts the seconds until the end of the episode. After 25 seconds, Ms. N awakes with full recollection of the episode. On review of the video EEG during the episode, no ictal patterns are seen.

[polldaddy:10375873]

The authors’ observations

Paroxysmal episodes of weakness, numbness, and muscle spasms in a young female are suggestive of either epilepsy or nonepileptic seizure (NES).1,2 The negative EEG and physical features are inconsistent with epileptiform seizure, and Ms. N’s history and evaluation are suggestive of NES. Nonepileptic seizures are a type of a conversion disorder, or functional neurologic symptom disorder, in which a patient experiences weakness, abnormal movements, or seizure-like episodes that are inconsistent with organic neurologic disease.3 When a diagnosis of conversion disorder is suspected, a clinician must always consider other pathology that can explain the symptoms, such as migraine, vasovagal syncope, or intracranial mass. If a patient has focal neurologic deficits, head imaging should be pursued. Additionally, the clinician must screen for malingering and factitious disorder before establishing a definitive diagnosis. However, conversion disorder is not a diagnosis of exclusion. For example, a negative EEG does not rule out epilepsy, and patients can have both epilepsy and concomitant NES.

Continue to: Although NES is a common...

Although NES is a common type of conversion disorder, it is often difficult to diagnose, manage, and treat. Patients often receive antiepileptic medications but continue to have worsening events that are refractory to treatment. Various clinical features can suggest NES instead of epilepsy. Forced eye closure on video recording is a specific finding suggestive of NES, yet this feature is not sufficient to make the diagnosis.4 A video EEG must be performed to assess for epilepsy. The diagnosis of NES does not exclude the possibility that a patient has epilepsy, as NES can occur in up to 40% of patients with epilepsy.5 A video EEG without ictal patterns before, during, and after an observed episode is diagnostic of NES.6

[polldaddy:10375874]

The authors’ observations

Conversion disorders such as NES are a presentation of neurologic symptoms that cannot be readily accounted for by other conditions and are often associated with antecedent trauma. Multiple factors in Ms. N’s history increase her risk of NES, including loss of multiple loved ones, ongoing legal involvement, and alleged sexual abuse by her father.

Victims of sexual abuse are more likely than the general population to demonstrate symptoms of conversion disorder, especially NES.7,8 The onset of paroxysmal episodes after incestuous abuse in a teenage girl is characteristic of NES. Compared with patients with complex partial epilepsy (CPE), patients with NES are 3 times more likely to report sexual trauma.9,10 Children who report sexual abuse that precedes NES are more likely to have been victimized by a first-degree relative than patients with CPE who report sexual abuse.11 Risk factors for victims developing NES may be related to the severity of adversity, stress sensitivity, and decreased hippocampal volume.12,13

Ms. N endorsed many psychiatric symptoms that accompany her paroxysmal episodes; this is similar to findings in other patients with NES.14 One study found that depression is 3 times more prevalent and PTSD is 8 times more prevalent in patients with NES.12 During the evaluation, Ms. N’s mother said her daughter had low energy, poor appetite, lethargy, and anhedonia for the preceding 5 months, which is consistent with adjustment disorder.3 Her flashbacks, nightmares, difficulty sleeping, and agoraphobia, along with her trouble engaging with the people and activities that used to bring her joy, are symptoms of PTSD. Nonepileptic seizure is often associated with PTSD and can be viewed as an expression of a dissociated subtype.15

In a literature review, Durrant et al16 isolated prognostic indicators for NES (Table16). This study found that 70% of children and 40% of adults achieve remission from NES. Ms. N’s case has multiple concerning features, such as her comorbid psychiatric conditions, ongoing involvement in a legal case, and sexual trauma; this last factor is associated with the most severe symptoms and worse outcomes.16,17 Despite this somber reality, Ms. N has the support of her mother and is relatively young, which play a vital role in recovery.

Continue to: TREATMENT A strategy for minimizing the episodes

TREATMENT A strategy for minimizing the episodes

Ms. N’s medical workup remains unremarkable throughout the rest of her hospital stay. The psychiatry and pediatric teams discuss their assessments and agree that NES is the most likely diagnosis. The psychiatry team counsels Ms. N and her mother on the diagnosis and etiology of NES.

[polldaddy:10375876]

The authors’ observations

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is currently the treatment of choice for reducing seizure frequency in patients with NES.18,19 The use of CBT was suggested due to the theory that NES represents a dissociative response to trauma. Therapy focuses on changing a patient’s beliefs and perceptions associated with attacks.5 A randomized study of 66 patients with NES compared the use of CBT plus standard medical care with standard medical care alone.18 The standard medical care consisted of supportive treatment, an explanation of NES from a neuropsychiatrist, and supervised withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs. The CBT treatment group was offered weekly hour-long sessions for 12 weeks, accompanied by CBT homework and journaling the frequency and nature of seizure episodes (the CBT techniques are outlined in the Figure18). After 4 months, the CBT treatment group had fewer seizures, and after a 6-month follow-up, they were more likely to be seizure-free. However, in this study, CBT treatment did not improve mood or employment status.

A later investigation looked at using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to treat NES in adults.19 This study divided participants into 4 treatment groups: CBT with informed psychotherapy (CBT-ip), CBT-ip plus sertraline, sertraline alone, and treatment as usual. Sertraline was titrated up to a dose of 200 mg/d as tolerated. After 16 weeks of sertraline alone, seizure frequency did not decrease. Although both CBT groups showed a reduction in symptoms of up to 60%, the CBT-ip group reported fewer psychiatric symptoms with better social interactions, quality of life, and global functioning compared with patients treated with CBT-ip plus sertraline. The authors suggested that this may be due to the somatic adverse effects associated with sertraline. This study suggests that CBT without medication is the treatment of choice.

In addition to CBT, studies of psychodynamic psychotherapy for NES have had promising findings.20 Psychodynamic psychotherapy focuses on addressing conscious and unconscious anger, loss, feelings of isolation, and trauma. Through improving emotional processing, insight, coping skills and self-regulation, patients often benefit from an improvement in seizures, psychosocial functioning and health care utilization.

Metin et al21 found that group therapy alongside a family-centered approach elicited a strong and durable reduction in seizures in patients with NES. At enrollment, investigators distributed information on NES to patients and families. Psychoeducation and psychoanalysis with behavior modification techniques were provided in 90-minute weekly group sessions over 3 months. Participants also underwent monthly individualized sessions for standard psychiatric care for 9 months. During the group sessions, operant conditioning techniques were used to prevent secondary gain from seizure-like activity. Families met 4 times for 1 hour each to discuss seizures, receive psychoeducation on a subconscious etiology of NES, and learn behavior modification techniques. All 9 participants who completed group and individual therapy reported a significant and sustained reduction in seizure frequency by at least 50% at 12-month follow-up. Patients also demonstrated improvements in mood, anxiety, and quality of life.

Continue to: A meta-analysis...

A meta-analysis by Carlson and Perry22 that included 13 studies and 228 participants, examined different treatment modalities and their effectiveness for NES. They found that patients who received psychological intervention had a 47% remission rate and 82% improvement in seizure frequency compared with only 14% to 23% of those who did not receive therapy. They postulated that therapy for this illness must be flexible to properly address the socially, psychologically, and functionally heterogenous patient population. Although there are few randomized controlled trials for NES to determine the best evidence-based intervention, there is now consensus that NES has a favorable prognosis when barriers to psychological care are eliminated.

OUTCOME Referral for CBT

The treatment team advises Ms. N to engage in outpatient therapy after discharge from the hospital. Ms. N and her mother agree to the treatment plan, and leave the hospital with a referral for CBT the next day.

Bottom Line

Nonepileptic seizure (NES) is a type of conversion disorder characterized by seizure-like episodes without ictal qualities. Risk factors for NES include concomitant epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, unstable psychosocial situations, and antecedent trauma. Patients with a history of incestuous sexual abuse are most at risk for developing NES. A normal EEG that fully captures a seizure-like episode is diagnostic of NES. Cognitive-behavioral therapy can minimize seizure frequency and intensity.

Related Resources

- Marsh P, Benbadis S, Fernandez F. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: ways to win over skeptical patients. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):21-24, 32-35.

- LaFrance WC Jr. Eye-opening behaviors help diagnose nonepileptic seizures. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(11):121-122, 124, 130.

- LaFrance WC Jr, Kanner AM, Barry JJ. Treating patients with psychological nonepileptic seizures. In: Ettinger AB, Kanner AM, eds. Psychiatric issues in epilepsy: a practical guide to diagnosis and treatment. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/ Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:461-488.

Drug Brand Name

Sertraline • Zoloft

CASE Increasingly frequent paroxysmal episodes

Ms. N, age 12, comes to the hospital for evaluation of paroxysmal episodes of pain, weakness, and muscle spasms. A neurologist who evaluated her as an outpatient had recommended a routine electroencephalogram (EEG); after those results were inconclusive, Ms. N’s mother brought her to the hospital for a 24-hour video EEG.

Ms. N has a history of asthma. She has no history of seizures or headache, but her mother has an unspecified seizure disorder that has been stable with antiepileptic medication for many years. Ms. N has no other family history of autoimmune or neurologic disorders.

Ms. N’s episodes began 6 months ago and have progressively increased in frequency from 5 to 12 episodes a day. She says that before she has an episode, she “ feels tingling in her fingers and mouth, and butterflies in her belly,” and then her “whole body clenches up.” She denies experiencing tongue biting, facial or extremity weakness, incontinence, or loss of consciousness during these episodes.

Shortly before her hospitalization, Ms. N had won a scholarship to attend an overnight art camp. Because her episodes were becoming more frequent and their etiology remained unclear, Ms. N and her mother decided it would be unsafe for her to attend, and that she should go to the hospital for evaluation instead.

EVALUATION Tough questions reveal answers

The pediatric team evaluates Ms. N. Her physical exam, laboratory values, and imaging are all within normal limits. Her neurologic exam demonstrates full strength, tone, and sensation in all extremities. All cranial nerves and reflexes are intact. No dysmorphic features or gait abnormalities are noted. All laboratory and imaging tests are normal, including complete blood cell count, electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, glucose, creatine kinase, liver enzymes, urine drug screen, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) urine test, and h

After the initial workup, the pediatric team consults the child and adolescent psychiatry team for a complete assessment of Ms. N due to concerns that a psychological component is contributing to her episodes. According to the psychosocial history obtained from Ms. N and her mother, Ms. N had experienced disrupted attachment, trauma, and loss. At age 5, Ms. N was temporarily removed from her mother’s custody after a fight between her mother and brother. At age 9, Ms. N’s stepfather, her primary father figure, died of a brain tumor.

Ms. N also has significant trauma stemming from her relationship with her biological father. Ms. N’s mother reports that her daughter was conceived during nonconsensual sexual intercourse. Ms. N did not have much contact with her biological father until 6 months ago, when he started picking her up at school and taking her to his home for several hours without permission or supervision. Afterwards, Ms. N confided to her mother and a teacher that her father sexually assaulted her during those visits.

Continue to: Ms. N and her mother...

Ms. N and her mother reported the assault to the police and were awaiting legal action.

During the interview with the psychiatry team, Ms. N denies that any thoughts or actions trigger the episodes and reports that she cannot control when they happen. Because she cannot anticipate the episodes, she says she is afraid to leave her house. She does not know why the episodes are happening and feels frustrated that they are getting worse. Ms. N says, “I have been feeling down lately,” but she denies hopelessness, worthlessness, suicidal ideation, homicidal ideation, delusions, or hallucinations.

In the hospital, when the psychiatry team asks Ms. N about her visits with her father, she says that they are “too painful to talk about,” and fears that discussing them will trigger an episode. However, her mother suggests that her daughter’s sexual trauma, as well as ongoing frustrations with the legal system, are influencing her mood; she has had low energy, poor appetite, and is spending more time in bed. Her mother also reports that Ms. N “avoids going out in the sun and spending time with her friends outside. She doesn’t seem to enjoy shopping and art like she used to.” Ms. N told her mother that she was having nightmares about the trauma and “could not stop thinking about some of the bad stuff that happened during the day.”

Ten minutes into the interview, while being questioned about her father, Ms. N experiences a spastic episode. She curls up in bed on her left side, clenches her entire body, and shuts her eyes. Her mother quickly runs to her bedside and counts the seconds until the end of the episode. After 25 seconds, Ms. N awakes with full recollection of the episode. On review of the video EEG during the episode, no ictal patterns are seen.

[polldaddy:10375873]

The authors’ observations

Paroxysmal episodes of weakness, numbness, and muscle spasms in a young female are suggestive of either epilepsy or nonepileptic seizure (NES).1,2 The negative EEG and physical features are inconsistent with epileptiform seizure, and Ms. N’s history and evaluation are suggestive of NES. Nonepileptic seizures are a type of a conversion disorder, or functional neurologic symptom disorder, in which a patient experiences weakness, abnormal movements, or seizure-like episodes that are inconsistent with organic neurologic disease.3 When a diagnosis of conversion disorder is suspected, a clinician must always consider other pathology that can explain the symptoms, such as migraine, vasovagal syncope, or intracranial mass. If a patient has focal neurologic deficits, head imaging should be pursued. Additionally, the clinician must screen for malingering and factitious disorder before establishing a definitive diagnosis. However, conversion disorder is not a diagnosis of exclusion. For example, a negative EEG does not rule out epilepsy, and patients can have both epilepsy and concomitant NES.

Continue to: Although NES is a common...

Although NES is a common type of conversion disorder, it is often difficult to diagnose, manage, and treat. Patients often receive antiepileptic medications but continue to have worsening events that are refractory to treatment. Various clinical features can suggest NES instead of epilepsy. Forced eye closure on video recording is a specific finding suggestive of NES, yet this feature is not sufficient to make the diagnosis.4 A video EEG must be performed to assess for epilepsy. The diagnosis of NES does not exclude the possibility that a patient has epilepsy, as NES can occur in up to 40% of patients with epilepsy.5 A video EEG without ictal patterns before, during, and after an observed episode is diagnostic of NES.6

[polldaddy:10375874]

The authors’ observations

Conversion disorders such as NES are a presentation of neurologic symptoms that cannot be readily accounted for by other conditions and are often associated with antecedent trauma. Multiple factors in Ms. N’s history increase her risk of NES, including loss of multiple loved ones, ongoing legal involvement, and alleged sexual abuse by her father.

Victims of sexual abuse are more likely than the general population to demonstrate symptoms of conversion disorder, especially NES.7,8 The onset of paroxysmal episodes after incestuous abuse in a teenage girl is characteristic of NES. Compared with patients with complex partial epilepsy (CPE), patients with NES are 3 times more likely to report sexual trauma.9,10 Children who report sexual abuse that precedes NES are more likely to have been victimized by a first-degree relative than patients with CPE who report sexual abuse.11 Risk factors for victims developing NES may be related to the severity of adversity, stress sensitivity, and decreased hippocampal volume.12,13

Ms. N endorsed many psychiatric symptoms that accompany her paroxysmal episodes; this is similar to findings in other patients with NES.14 One study found that depression is 3 times more prevalent and PTSD is 8 times more prevalent in patients with NES.12 During the evaluation, Ms. N’s mother said her daughter had low energy, poor appetite, lethargy, and anhedonia for the preceding 5 months, which is consistent with adjustment disorder.3 Her flashbacks, nightmares, difficulty sleeping, and agoraphobia, along with her trouble engaging with the people and activities that used to bring her joy, are symptoms of PTSD. Nonepileptic seizure is often associated with PTSD and can be viewed as an expression of a dissociated subtype.15

In a literature review, Durrant et al16 isolated prognostic indicators for NES (Table16). This study found that 70% of children and 40% of adults achieve remission from NES. Ms. N’s case has multiple concerning features, such as her comorbid psychiatric conditions, ongoing involvement in a legal case, and sexual trauma; this last factor is associated with the most severe symptoms and worse outcomes.16,17 Despite this somber reality, Ms. N has the support of her mother and is relatively young, which play a vital role in recovery.

Continue to: TREATMENT A strategy for minimizing the episodes

TREATMENT A strategy for minimizing the episodes

Ms. N’s medical workup remains unremarkable throughout the rest of her hospital stay. The psychiatry and pediatric teams discuss their assessments and agree that NES is the most likely diagnosis. The psychiatry team counsels Ms. N and her mother on the diagnosis and etiology of NES.

[polldaddy:10375876]

The authors’ observations

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is currently the treatment of choice for reducing seizure frequency in patients with NES.18,19 The use of CBT was suggested due to the theory that NES represents a dissociative response to trauma. Therapy focuses on changing a patient’s beliefs and perceptions associated with attacks.5 A randomized study of 66 patients with NES compared the use of CBT plus standard medical care with standard medical care alone.18 The standard medical care consisted of supportive treatment, an explanation of NES from a neuropsychiatrist, and supervised withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs. The CBT treatment group was offered weekly hour-long sessions for 12 weeks, accompanied by CBT homework and journaling the frequency and nature of seizure episodes (the CBT techniques are outlined in the Figure18). After 4 months, the CBT treatment group had fewer seizures, and after a 6-month follow-up, they were more likely to be seizure-free. However, in this study, CBT treatment did not improve mood or employment status.

A later investigation looked at using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to treat NES in adults.19 This study divided participants into 4 treatment groups: CBT with informed psychotherapy (CBT-ip), CBT-ip plus sertraline, sertraline alone, and treatment as usual. Sertraline was titrated up to a dose of 200 mg/d as tolerated. After 16 weeks of sertraline alone, seizure frequency did not decrease. Although both CBT groups showed a reduction in symptoms of up to 60%, the CBT-ip group reported fewer psychiatric symptoms with better social interactions, quality of life, and global functioning compared with patients treated with CBT-ip plus sertraline. The authors suggested that this may be due to the somatic adverse effects associated with sertraline. This study suggests that CBT without medication is the treatment of choice.