User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

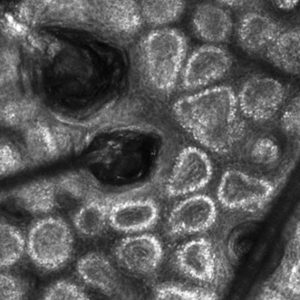

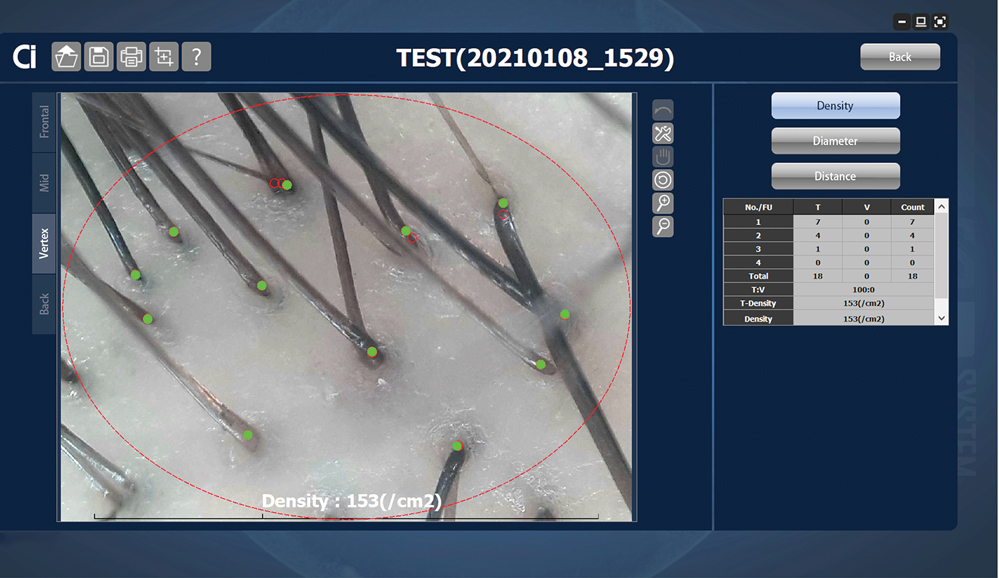

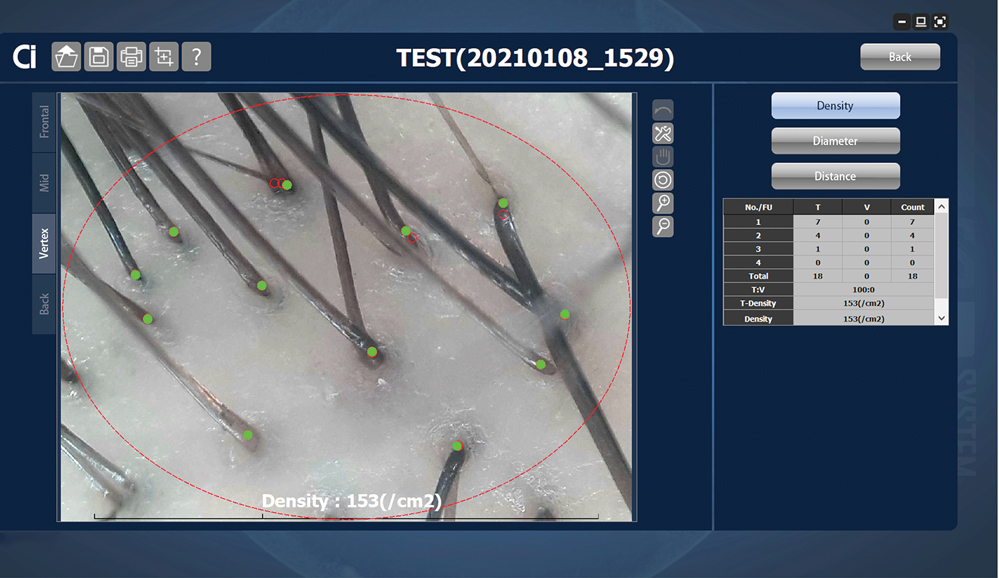

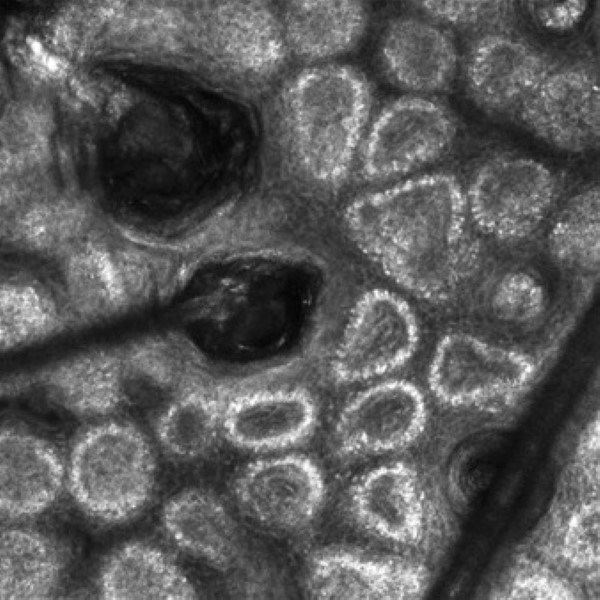

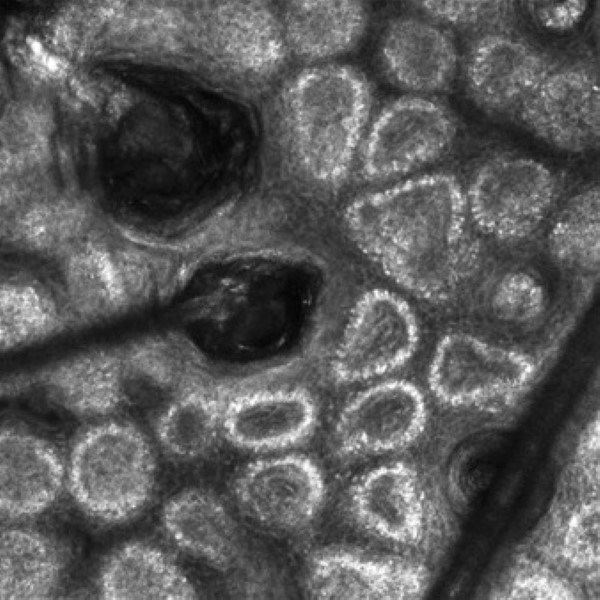

A 45-year-old White woman with no significant medical history presented with a 1-month history of lesions on the nose and right cheek

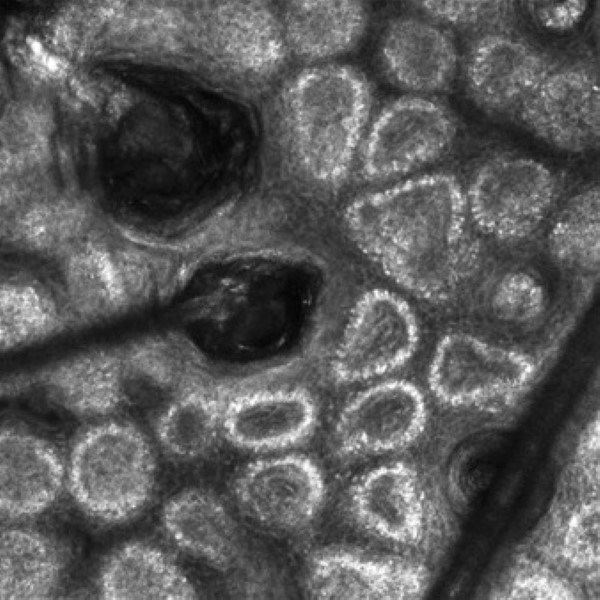

Cultures for bacteria, varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, and mpox virus were all negative. A biopsy revealed suprabasilar acantholysis with follicular involvement in association with blister formation and inflammation. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for suprabasilar IgG and C3 deposition, consistent with pemphigus vulgaris (PV).

. There is likely a genetic predisposition. Medications that may induce pemphigus include penicillamine, nifedipine, or captopril.

Clinically, flaccid blistering lesions are present that may be cutaneous and/or mucosal. Bullae can progress to erosions and crusting, which then heal with pigment alteration but not scarring. The most commonly affected sites are the mouth, intertriginous areas, face, and neck. Mucosal lesions may involve the lips, esophagus, conjunctiva, and genitals.

Biopsy for histology and direct immunofluorescence is important in distinguishing between PV and other blistering disorders. Up to 75% of patients with active disease also have a positive indirect immunofluorescence with circulating IgG.

Treatment is generally immunosuppressive. Systemic therapy usually begins with prednisone and then is transitioned to a steroid-sparing agent such as mycophenolate mofetil. Other steroid-sparing agents include azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Secondary infections are possible and should be treated. Topical therapies aimed at reducing pain, especially in mucosal lesions, can be beneficial.

This case and the photos are from Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Cultures for bacteria, varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, and mpox virus were all negative. A biopsy revealed suprabasilar acantholysis with follicular involvement in association with blister formation and inflammation. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for suprabasilar IgG and C3 deposition, consistent with pemphigus vulgaris (PV).

. There is likely a genetic predisposition. Medications that may induce pemphigus include penicillamine, nifedipine, or captopril.

Clinically, flaccid blistering lesions are present that may be cutaneous and/or mucosal. Bullae can progress to erosions and crusting, which then heal with pigment alteration but not scarring. The most commonly affected sites are the mouth, intertriginous areas, face, and neck. Mucosal lesions may involve the lips, esophagus, conjunctiva, and genitals.

Biopsy for histology and direct immunofluorescence is important in distinguishing between PV and other blistering disorders. Up to 75% of patients with active disease also have a positive indirect immunofluorescence with circulating IgG.

Treatment is generally immunosuppressive. Systemic therapy usually begins with prednisone and then is transitioned to a steroid-sparing agent such as mycophenolate mofetil. Other steroid-sparing agents include azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Secondary infections are possible and should be treated. Topical therapies aimed at reducing pain, especially in mucosal lesions, can be beneficial.

This case and the photos are from Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Cultures for bacteria, varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, and mpox virus were all negative. A biopsy revealed suprabasilar acantholysis with follicular involvement in association with blister formation and inflammation. Direct immunofluorescence was positive for suprabasilar IgG and C3 deposition, consistent with pemphigus vulgaris (PV).

. There is likely a genetic predisposition. Medications that may induce pemphigus include penicillamine, nifedipine, or captopril.

Clinically, flaccid blistering lesions are present that may be cutaneous and/or mucosal. Bullae can progress to erosions and crusting, which then heal with pigment alteration but not scarring. The most commonly affected sites are the mouth, intertriginous areas, face, and neck. Mucosal lesions may involve the lips, esophagus, conjunctiva, and genitals.

Biopsy for histology and direct immunofluorescence is important in distinguishing between PV and other blistering disorders. Up to 75% of patients with active disease also have a positive indirect immunofluorescence with circulating IgG.

Treatment is generally immunosuppressive. Systemic therapy usually begins with prednisone and then is transitioned to a steroid-sparing agent such as mycophenolate mofetil. Other steroid-sparing agents include azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Secondary infections are possible and should be treated. Topical therapies aimed at reducing pain, especially in mucosal lesions, can be beneficial.

This case and the photos are from Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Cigna accused of using AI, not doctors, to deny claims: Lawsuit

and forcing providers to bill patients in full.

In a complaint filed recently in California’s eastern district court, plaintiffs and Cigna health plan members Suzanne Kisting-Leung and Ayesha Smiley and their attorneys say that Cigna violates state insurance regulations by failing to conduct a “thorough, fair, and objective” review of their and other members’ claims.

The lawsuit says that, instead, Cigna relies on an algorithm, PxDx, to review and frequently deny medically necessary claims. According to court records, the system allows Cigna’s doctors to “instantly reject claims on medical grounds without ever opening patient files.” With use of the system, the average claims processing time is 1.2 seconds.

Cigna says it uses technology to verify coding on standard, low-cost procedures and to expedite physician reimbursement. In a statement to CBS News, the company called the lawsuit “highly questionable.”

The case highlights growing concerns about AI and its ability to replace humans for tasks and interactions in health care, business, and beyond. Public advocacy law firm Clarkson, which is representing the plaintiffs, has previously sued tech giants Google and ChatGPT creator OpenAI for harvesting Internet users’ personal and professional data to train their AI systems.

According to the complaint, Cigna denied the plaintiffs medically necessary tests, including blood work to screen for vitamin D deficiency and ultrasounds for patients suspected of having ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs’ attempts to appeal were unfruitful, and they were forced to pay out of pocket.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argue that the claims do not undergo more detailed reviews by physicians and employees, as mandated by California insurance laws, and that Cigna benefits by saving on labor costs.

Clarkson is demanding a jury trial and has asked the court to certify the Cigna case as a federal class action, potentially allowing the insurer’s other 2 million health plan members in California to join the lawsuit.

I. Glenn Cohen, JD, deputy dean and professor at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass., said in an interview that this is the first lawsuit he’s aware of in which AI was involved in denying health insurance claims and that it is probably an uphill battle for the plaintiffs.

“In the last 25 years, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions have made getting a class action approved more difficult. If allowed to go forward as a class action, which Cigna is likely to vigorously oppose, then the pressure on Cigna to settle the case becomes enormous,” he said.

The allegations come after a recent deep dive by the nonprofit ProPublica uncovered similar claim denial issues. One physician who worked for Cigna told the nonprofit that he and other company doctors essentially rubber-stamped the denials in batches, which took “all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

In 2022, the American Medical Association and two state physician groups joined another class action against Cigna stemming from allegations that the insurer’s intermediary, Multiplan, intentionally underpaid medical claims. And in March, Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, was accused of conspiring with other PBMs to drive up prescription drug prices for Ohio consumers, violating state antitrust laws.

Mr. Cohen said he expects Cigna to push back in court about the California class size, which the plaintiff’s attorneys hope will encompass all Cigna health plan members in the state.

“The injury is primarily to those whose claims were denied by AI, presumably a much smaller set of individuals and harder to identify,” said Mr. Cohen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and forcing providers to bill patients in full.

In a complaint filed recently in California’s eastern district court, plaintiffs and Cigna health plan members Suzanne Kisting-Leung and Ayesha Smiley and their attorneys say that Cigna violates state insurance regulations by failing to conduct a “thorough, fair, and objective” review of their and other members’ claims.

The lawsuit says that, instead, Cigna relies on an algorithm, PxDx, to review and frequently deny medically necessary claims. According to court records, the system allows Cigna’s doctors to “instantly reject claims on medical grounds without ever opening patient files.” With use of the system, the average claims processing time is 1.2 seconds.

Cigna says it uses technology to verify coding on standard, low-cost procedures and to expedite physician reimbursement. In a statement to CBS News, the company called the lawsuit “highly questionable.”

The case highlights growing concerns about AI and its ability to replace humans for tasks and interactions in health care, business, and beyond. Public advocacy law firm Clarkson, which is representing the plaintiffs, has previously sued tech giants Google and ChatGPT creator OpenAI for harvesting Internet users’ personal and professional data to train their AI systems.

According to the complaint, Cigna denied the plaintiffs medically necessary tests, including blood work to screen for vitamin D deficiency and ultrasounds for patients suspected of having ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs’ attempts to appeal were unfruitful, and they were forced to pay out of pocket.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argue that the claims do not undergo more detailed reviews by physicians and employees, as mandated by California insurance laws, and that Cigna benefits by saving on labor costs.

Clarkson is demanding a jury trial and has asked the court to certify the Cigna case as a federal class action, potentially allowing the insurer’s other 2 million health plan members in California to join the lawsuit.

I. Glenn Cohen, JD, deputy dean and professor at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass., said in an interview that this is the first lawsuit he’s aware of in which AI was involved in denying health insurance claims and that it is probably an uphill battle for the plaintiffs.

“In the last 25 years, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions have made getting a class action approved more difficult. If allowed to go forward as a class action, which Cigna is likely to vigorously oppose, then the pressure on Cigna to settle the case becomes enormous,” he said.

The allegations come after a recent deep dive by the nonprofit ProPublica uncovered similar claim denial issues. One physician who worked for Cigna told the nonprofit that he and other company doctors essentially rubber-stamped the denials in batches, which took “all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

In 2022, the American Medical Association and two state physician groups joined another class action against Cigna stemming from allegations that the insurer’s intermediary, Multiplan, intentionally underpaid medical claims. And in March, Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, was accused of conspiring with other PBMs to drive up prescription drug prices for Ohio consumers, violating state antitrust laws.

Mr. Cohen said he expects Cigna to push back in court about the California class size, which the plaintiff’s attorneys hope will encompass all Cigna health plan members in the state.

“The injury is primarily to those whose claims were denied by AI, presumably a much smaller set of individuals and harder to identify,” said Mr. Cohen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and forcing providers to bill patients in full.

In a complaint filed recently in California’s eastern district court, plaintiffs and Cigna health plan members Suzanne Kisting-Leung and Ayesha Smiley and their attorneys say that Cigna violates state insurance regulations by failing to conduct a “thorough, fair, and objective” review of their and other members’ claims.

The lawsuit says that, instead, Cigna relies on an algorithm, PxDx, to review and frequently deny medically necessary claims. According to court records, the system allows Cigna’s doctors to “instantly reject claims on medical grounds without ever opening patient files.” With use of the system, the average claims processing time is 1.2 seconds.

Cigna says it uses technology to verify coding on standard, low-cost procedures and to expedite physician reimbursement. In a statement to CBS News, the company called the lawsuit “highly questionable.”

The case highlights growing concerns about AI and its ability to replace humans for tasks and interactions in health care, business, and beyond. Public advocacy law firm Clarkson, which is representing the plaintiffs, has previously sued tech giants Google and ChatGPT creator OpenAI for harvesting Internet users’ personal and professional data to train their AI systems.

According to the complaint, Cigna denied the plaintiffs medically necessary tests, including blood work to screen for vitamin D deficiency and ultrasounds for patients suspected of having ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs’ attempts to appeal were unfruitful, and they were forced to pay out of pocket.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argue that the claims do not undergo more detailed reviews by physicians and employees, as mandated by California insurance laws, and that Cigna benefits by saving on labor costs.

Clarkson is demanding a jury trial and has asked the court to certify the Cigna case as a federal class action, potentially allowing the insurer’s other 2 million health plan members in California to join the lawsuit.

I. Glenn Cohen, JD, deputy dean and professor at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass., said in an interview that this is the first lawsuit he’s aware of in which AI was involved in denying health insurance claims and that it is probably an uphill battle for the plaintiffs.

“In the last 25 years, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions have made getting a class action approved more difficult. If allowed to go forward as a class action, which Cigna is likely to vigorously oppose, then the pressure on Cigna to settle the case becomes enormous,” he said.

The allegations come after a recent deep dive by the nonprofit ProPublica uncovered similar claim denial issues. One physician who worked for Cigna told the nonprofit that he and other company doctors essentially rubber-stamped the denials in batches, which took “all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

In 2022, the American Medical Association and two state physician groups joined another class action against Cigna stemming from allegations that the insurer’s intermediary, Multiplan, intentionally underpaid medical claims. And in March, Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, was accused of conspiring with other PBMs to drive up prescription drug prices for Ohio consumers, violating state antitrust laws.

Mr. Cohen said he expects Cigna to push back in court about the California class size, which the plaintiff’s attorneys hope will encompass all Cigna health plan members in the state.

“The injury is primarily to those whose claims were denied by AI, presumably a much smaller set of individuals and harder to identify,” said Mr. Cohen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Black women weigh emerging risks of ‘creamy crack’ hair straighteners

Deanna Denham Hughes was stunned when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022. She was only 32. She had no family history of cancer, and tests found no genetic link. Ms. Hughes wondered why she, an otherwise healthy Black mother of two, would develop a malignancy known as a “silent killer.”

After emergency surgery to remove the mass, along with her ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and appendix, Ms. Hughes said, she saw an Instagram post in which a woman with uterine cancer linked her condition to chemical hair straighteners.

“I almost fell over,” she said from her home in Smyrna, Ga.

When Ms. Hughes was about 4, her mother began applying a chemical straightener, or relaxer, to her hair every 6-8 weeks. “It burned, and it smelled awful,” Ms. Hughes recalled. “But it was just part of our routine to ‘deal with my hair.’ ”

The routine continued until she went to college and met other Black women who wore their hair naturally. Soon, Ms. Hughes quit relaxers.

Social and economic pressures have long compelled Black girls and women to straighten their hair to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards. But chemical straighteners are stinky and costly and sometimes cause painful scalp burns. Mounting evidence now shows they could be a health hazard.

Relaxers can contain carcinogens, such as formaldehyde-releasing agents, phthalates, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, according to National Institutes of Health studies. The compounds can mimic the body’s hormones and have been linked to breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, studies show.

African American women’s often frequent and lifelong application of chemical relaxers to their hair and scalp might explain why hormone-related cancers kill disproportionately more Black than White women, say researchers and cancer doctors.

“What’s in these products is harmful,” said Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, who has studied straightening products for the past 20 years.

She believes manufacturers, policymakers, and physicians should warn consumers that relaxers might cause cancer and other health problems.

But regulators have been slow to act, physicians have been reluctant to take up the cause, and racism continues to dictate fashion standards that make it tough for women to quit relaxers, products so addictive they’re known as “creamy crack.”

Michelle Obama straightened her hair when Barack Obama served as president because she believed Americans were “not ready” to see her in braids, the former first lady said after leaving the White House. The U.S. military still prohibited popular Black hairstyles such as dreadlocks and twists while the nation’s first Black president was in office.

California in 2019 became the first of nearly two dozen states to ban race-based hair discrimination. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed similar legislation, known as the CROWN Act, for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. But the bill failed in the Senate.

The need for legislation underscores the challenges Black girls and women face at school and in the workplace.

“You have to pick your struggles,” said Atlanta-based surgical oncologist Ryland J. Gore, MD. She informs her breast cancer patients about the increased cancer risk from relaxers. Despite her knowledge, however, Dr. Gore continues to use chemical straighteners on her own hair, as she has since she was about 7 years old.

“Your hair tells a story,” she said.

In conversations with patients, Dr. Gore sometimes talks about how African American women once wove messages into their braids about the route to take on the Underground Railroad as they sought freedom from slavery.

“It’s just a deep discussion,” one that touches on culture, history, and research into current hairstyling practices, she said. “The data is out there. So patients should be warned, and then they can make a decision.”

The first hint of a connection between hair products and health issues surfaced in the 1990s. Doctors began seeing signs of sexual maturation in Black babies and young girls who developed breasts and pubic hair after using shampoo containing estrogen or placental extract. When the girls stopped using the shampoo, the hair and breast development receded, according to a study published in the journal Clinical Pediatrics in 1998.

Since then, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers have linked chemicals in hair products to a variety of health issues more prevalent among Black women – from early puberty to preterm birth, obesity, and diabetes.

In recent years, researchers have focused on a possible connection between ingredients in chemical relaxers and hormone-related cancers, like the one Ms. Hughes developed, which tend to be more aggressive and deadly in Black women.

A 2017 study found White women who used chemical relaxers were nearly twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who did not use them. Because the vast majority of the Black study participants used relaxers, researchers could not effectively test the association in Black women, said lead author Adana Llanos, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York.

Researchers did test it in 2020.

The so-called Sister Study, a landmark National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences investigation into the causes of breast cancer and related diseases, followed 50,000 U.S. women whose sisters had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were cancer-free when they enrolled. Regardless of race, women who reported using relaxers in the prior year were 18% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Those who used relaxers at least every 5-8 weeks had a 31% higher breast cancer risk.

Nearly 75% of the Black sisters used relaxers in the prior year, compared with 3% of the non-Hispanic White sisters. Three-quarters of Black women self-reported using the straighteners as adolescents, and frequent use of chemical straighteners during adolescence raised the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, a 2021 NIH-funded study in the International Journal of Cancer found.

Another 2021 analysis of the Sister Study data showed sisters who self-reported that they frequently used relaxers or pressing products doubled their ovarian cancer risk. In 2022, another study found frequent use more than doubled uterine cancer risk.

After researchers discovered the link with uterine cancer, some called for policy changes and other measures to reduce exposure to chemical relaxers.

“It is time to intervene,” Dr. Llanos and her colleagues wrote in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute editorial accompanying the uterine cancer analysis. While acknowledging the need for more research, they issued a “call for action.”

No one can say that using permanent hair straighteners will give you cancer, Dr. Llanos said in an interview. “That’s not how cancer works,” she said, noting that some smokers never develop lung cancer, despite tobacco use being a known risk factor.

The body of research linking hair straighteners and cancer is more limited, said Dr. Llanos, who quit using chemical relaxers 15 years ago. But, she asked rhetorically, “Do we need to do the research for 50 more years to know that chemical relaxers are harmful?”

Charlotte R. Gamble, MD, a gynecological oncologist whose Washington, D.C., practice includes Black women with uterine and ovarian cancer, said she and her colleagues see the uterine cancer study findings as worthy of further exploration – but not yet worthy of discussion with patients.

“The jury’s out for me personally,” she said. “There’s so much more data that’s needed.”

Meanwhile, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers believe they have built a solid body of evidence.

“There are enough things we do know to begin taking action, developing interventions, providing useful information to clinicians and patients and the general public,” said Traci N. Bethea, PhD, assistant professor in the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research at Georgetown University.

Responsibility for regulating personal-care products, including chemical hair straighteners and hair dyes – which also have been linked to hormone-related cancers – lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But the FDA does not subject personal-care products to the same approval process it uses for food and drugs. The FDA restricts only 11 categories of chemicals used in cosmetics, while concerns about health effects have prompted the European Union to restrict the use of at least 2,400 substances.

In March, Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Shontel Brown (D-Ohio) asked the FDA to investigate the potential health threat posed by chemical relaxers. An FDA representative said the agency would look into it.

Natural hairstyles are enjoying a resurgence among Black girls and women, but many continue to rely on the creamy crack, said Dede Teteh, DrPH, assistant professor of public health at Chapman University, Irvine, Calif.

She had her first straightening perm at 8 and has struggled to withdraw from relaxers as an adult, said Dr. Teteh, who now wears locs. Not long ago, she considered chemically straightening her hair for an academic job interview because she didn’t want her hair to “be a hindrance” when she appeared before White professors.

Dr. Teteh led “The Cost of Beauty,” a hair-health research project published in 2017. She and her team interviewed 91 Black women in Southern California. Some became “combative” at the idea of quitting relaxers and claimed “everything can cause cancer.”

Their reactions speak to the challenges Black women face in America, Dr. Teteh said.

“It’s not that people do not want to hear the information related to their health,” she said. “But they want people to share the information in a way that it’s really empathetic to the plight of being Black here in the United States.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Deanna Denham Hughes was stunned when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022. She was only 32. She had no family history of cancer, and tests found no genetic link. Ms. Hughes wondered why she, an otherwise healthy Black mother of two, would develop a malignancy known as a “silent killer.”

After emergency surgery to remove the mass, along with her ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and appendix, Ms. Hughes said, she saw an Instagram post in which a woman with uterine cancer linked her condition to chemical hair straighteners.

“I almost fell over,” she said from her home in Smyrna, Ga.

When Ms. Hughes was about 4, her mother began applying a chemical straightener, or relaxer, to her hair every 6-8 weeks. “It burned, and it smelled awful,” Ms. Hughes recalled. “But it was just part of our routine to ‘deal with my hair.’ ”

The routine continued until she went to college and met other Black women who wore their hair naturally. Soon, Ms. Hughes quit relaxers.

Social and economic pressures have long compelled Black girls and women to straighten their hair to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards. But chemical straighteners are stinky and costly and sometimes cause painful scalp burns. Mounting evidence now shows they could be a health hazard.

Relaxers can contain carcinogens, such as formaldehyde-releasing agents, phthalates, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, according to National Institutes of Health studies. The compounds can mimic the body’s hormones and have been linked to breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, studies show.

African American women’s often frequent and lifelong application of chemical relaxers to their hair and scalp might explain why hormone-related cancers kill disproportionately more Black than White women, say researchers and cancer doctors.

“What’s in these products is harmful,” said Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, who has studied straightening products for the past 20 years.

She believes manufacturers, policymakers, and physicians should warn consumers that relaxers might cause cancer and other health problems.

But regulators have been slow to act, physicians have been reluctant to take up the cause, and racism continues to dictate fashion standards that make it tough for women to quit relaxers, products so addictive they’re known as “creamy crack.”

Michelle Obama straightened her hair when Barack Obama served as president because she believed Americans were “not ready” to see her in braids, the former first lady said after leaving the White House. The U.S. military still prohibited popular Black hairstyles such as dreadlocks and twists while the nation’s first Black president was in office.

California in 2019 became the first of nearly two dozen states to ban race-based hair discrimination. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed similar legislation, known as the CROWN Act, for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. But the bill failed in the Senate.

The need for legislation underscores the challenges Black girls and women face at school and in the workplace.

“You have to pick your struggles,” said Atlanta-based surgical oncologist Ryland J. Gore, MD. She informs her breast cancer patients about the increased cancer risk from relaxers. Despite her knowledge, however, Dr. Gore continues to use chemical straighteners on her own hair, as she has since she was about 7 years old.

“Your hair tells a story,” she said.

In conversations with patients, Dr. Gore sometimes talks about how African American women once wove messages into their braids about the route to take on the Underground Railroad as they sought freedom from slavery.

“It’s just a deep discussion,” one that touches on culture, history, and research into current hairstyling practices, she said. “The data is out there. So patients should be warned, and then they can make a decision.”

The first hint of a connection between hair products and health issues surfaced in the 1990s. Doctors began seeing signs of sexual maturation in Black babies and young girls who developed breasts and pubic hair after using shampoo containing estrogen or placental extract. When the girls stopped using the shampoo, the hair and breast development receded, according to a study published in the journal Clinical Pediatrics in 1998.

Since then, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers have linked chemicals in hair products to a variety of health issues more prevalent among Black women – from early puberty to preterm birth, obesity, and diabetes.

In recent years, researchers have focused on a possible connection between ingredients in chemical relaxers and hormone-related cancers, like the one Ms. Hughes developed, which tend to be more aggressive and deadly in Black women.

A 2017 study found White women who used chemical relaxers were nearly twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who did not use them. Because the vast majority of the Black study participants used relaxers, researchers could not effectively test the association in Black women, said lead author Adana Llanos, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York.

Researchers did test it in 2020.

The so-called Sister Study, a landmark National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences investigation into the causes of breast cancer and related diseases, followed 50,000 U.S. women whose sisters had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were cancer-free when they enrolled. Regardless of race, women who reported using relaxers in the prior year were 18% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Those who used relaxers at least every 5-8 weeks had a 31% higher breast cancer risk.

Nearly 75% of the Black sisters used relaxers in the prior year, compared with 3% of the non-Hispanic White sisters. Three-quarters of Black women self-reported using the straighteners as adolescents, and frequent use of chemical straighteners during adolescence raised the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, a 2021 NIH-funded study in the International Journal of Cancer found.

Another 2021 analysis of the Sister Study data showed sisters who self-reported that they frequently used relaxers or pressing products doubled their ovarian cancer risk. In 2022, another study found frequent use more than doubled uterine cancer risk.

After researchers discovered the link with uterine cancer, some called for policy changes and other measures to reduce exposure to chemical relaxers.

“It is time to intervene,” Dr. Llanos and her colleagues wrote in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute editorial accompanying the uterine cancer analysis. While acknowledging the need for more research, they issued a “call for action.”

No one can say that using permanent hair straighteners will give you cancer, Dr. Llanos said in an interview. “That’s not how cancer works,” she said, noting that some smokers never develop lung cancer, despite tobacco use being a known risk factor.

The body of research linking hair straighteners and cancer is more limited, said Dr. Llanos, who quit using chemical relaxers 15 years ago. But, she asked rhetorically, “Do we need to do the research for 50 more years to know that chemical relaxers are harmful?”

Charlotte R. Gamble, MD, a gynecological oncologist whose Washington, D.C., practice includes Black women with uterine and ovarian cancer, said she and her colleagues see the uterine cancer study findings as worthy of further exploration – but not yet worthy of discussion with patients.

“The jury’s out for me personally,” she said. “There’s so much more data that’s needed.”

Meanwhile, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers believe they have built a solid body of evidence.

“There are enough things we do know to begin taking action, developing interventions, providing useful information to clinicians and patients and the general public,” said Traci N. Bethea, PhD, assistant professor in the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research at Georgetown University.

Responsibility for regulating personal-care products, including chemical hair straighteners and hair dyes – which also have been linked to hormone-related cancers – lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But the FDA does not subject personal-care products to the same approval process it uses for food and drugs. The FDA restricts only 11 categories of chemicals used in cosmetics, while concerns about health effects have prompted the European Union to restrict the use of at least 2,400 substances.

In March, Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Shontel Brown (D-Ohio) asked the FDA to investigate the potential health threat posed by chemical relaxers. An FDA representative said the agency would look into it.

Natural hairstyles are enjoying a resurgence among Black girls and women, but many continue to rely on the creamy crack, said Dede Teteh, DrPH, assistant professor of public health at Chapman University, Irvine, Calif.

She had her first straightening perm at 8 and has struggled to withdraw from relaxers as an adult, said Dr. Teteh, who now wears locs. Not long ago, she considered chemically straightening her hair for an academic job interview because she didn’t want her hair to “be a hindrance” when she appeared before White professors.

Dr. Teteh led “The Cost of Beauty,” a hair-health research project published in 2017. She and her team interviewed 91 Black women in Southern California. Some became “combative” at the idea of quitting relaxers and claimed “everything can cause cancer.”

Their reactions speak to the challenges Black women face in America, Dr. Teteh said.

“It’s not that people do not want to hear the information related to their health,” she said. “But they want people to share the information in a way that it’s really empathetic to the plight of being Black here in the United States.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Deanna Denham Hughes was stunned when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022. She was only 32. She had no family history of cancer, and tests found no genetic link. Ms. Hughes wondered why she, an otherwise healthy Black mother of two, would develop a malignancy known as a “silent killer.”

After emergency surgery to remove the mass, along with her ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and appendix, Ms. Hughes said, she saw an Instagram post in which a woman with uterine cancer linked her condition to chemical hair straighteners.

“I almost fell over,” she said from her home in Smyrna, Ga.

When Ms. Hughes was about 4, her mother began applying a chemical straightener, or relaxer, to her hair every 6-8 weeks. “It burned, and it smelled awful,” Ms. Hughes recalled. “But it was just part of our routine to ‘deal with my hair.’ ”

The routine continued until she went to college and met other Black women who wore their hair naturally. Soon, Ms. Hughes quit relaxers.

Social and economic pressures have long compelled Black girls and women to straighten their hair to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards. But chemical straighteners are stinky and costly and sometimes cause painful scalp burns. Mounting evidence now shows they could be a health hazard.

Relaxers can contain carcinogens, such as formaldehyde-releasing agents, phthalates, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, according to National Institutes of Health studies. The compounds can mimic the body’s hormones and have been linked to breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, studies show.

African American women’s often frequent and lifelong application of chemical relaxers to their hair and scalp might explain why hormone-related cancers kill disproportionately more Black than White women, say researchers and cancer doctors.

“What’s in these products is harmful,” said Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, who has studied straightening products for the past 20 years.

She believes manufacturers, policymakers, and physicians should warn consumers that relaxers might cause cancer and other health problems.

But regulators have been slow to act, physicians have been reluctant to take up the cause, and racism continues to dictate fashion standards that make it tough for women to quit relaxers, products so addictive they’re known as “creamy crack.”

Michelle Obama straightened her hair when Barack Obama served as president because she believed Americans were “not ready” to see her in braids, the former first lady said after leaving the White House. The U.S. military still prohibited popular Black hairstyles such as dreadlocks and twists while the nation’s first Black president was in office.

California in 2019 became the first of nearly two dozen states to ban race-based hair discrimination. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed similar legislation, known as the CROWN Act, for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. But the bill failed in the Senate.

The need for legislation underscores the challenges Black girls and women face at school and in the workplace.

“You have to pick your struggles,” said Atlanta-based surgical oncologist Ryland J. Gore, MD. She informs her breast cancer patients about the increased cancer risk from relaxers. Despite her knowledge, however, Dr. Gore continues to use chemical straighteners on her own hair, as she has since she was about 7 years old.

“Your hair tells a story,” she said.

In conversations with patients, Dr. Gore sometimes talks about how African American women once wove messages into their braids about the route to take on the Underground Railroad as they sought freedom from slavery.

“It’s just a deep discussion,” one that touches on culture, history, and research into current hairstyling practices, she said. “The data is out there. So patients should be warned, and then they can make a decision.”

The first hint of a connection between hair products and health issues surfaced in the 1990s. Doctors began seeing signs of sexual maturation in Black babies and young girls who developed breasts and pubic hair after using shampoo containing estrogen or placental extract. When the girls stopped using the shampoo, the hair and breast development receded, according to a study published in the journal Clinical Pediatrics in 1998.

Since then, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers have linked chemicals in hair products to a variety of health issues more prevalent among Black women – from early puberty to preterm birth, obesity, and diabetes.

In recent years, researchers have focused on a possible connection between ingredients in chemical relaxers and hormone-related cancers, like the one Ms. Hughes developed, which tend to be more aggressive and deadly in Black women.

A 2017 study found White women who used chemical relaxers were nearly twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who did not use them. Because the vast majority of the Black study participants used relaxers, researchers could not effectively test the association in Black women, said lead author Adana Llanos, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York.

Researchers did test it in 2020.

The so-called Sister Study, a landmark National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences investigation into the causes of breast cancer and related diseases, followed 50,000 U.S. women whose sisters had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were cancer-free when they enrolled. Regardless of race, women who reported using relaxers in the prior year were 18% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Those who used relaxers at least every 5-8 weeks had a 31% higher breast cancer risk.

Nearly 75% of the Black sisters used relaxers in the prior year, compared with 3% of the non-Hispanic White sisters. Three-quarters of Black women self-reported using the straighteners as adolescents, and frequent use of chemical straighteners during adolescence raised the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, a 2021 NIH-funded study in the International Journal of Cancer found.

Another 2021 analysis of the Sister Study data showed sisters who self-reported that they frequently used relaxers or pressing products doubled their ovarian cancer risk. In 2022, another study found frequent use more than doubled uterine cancer risk.

After researchers discovered the link with uterine cancer, some called for policy changes and other measures to reduce exposure to chemical relaxers.

“It is time to intervene,” Dr. Llanos and her colleagues wrote in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute editorial accompanying the uterine cancer analysis. While acknowledging the need for more research, they issued a “call for action.”

No one can say that using permanent hair straighteners will give you cancer, Dr. Llanos said in an interview. “That’s not how cancer works,” she said, noting that some smokers never develop lung cancer, despite tobacco use being a known risk factor.

The body of research linking hair straighteners and cancer is more limited, said Dr. Llanos, who quit using chemical relaxers 15 years ago. But, she asked rhetorically, “Do we need to do the research for 50 more years to know that chemical relaxers are harmful?”

Charlotte R. Gamble, MD, a gynecological oncologist whose Washington, D.C., practice includes Black women with uterine and ovarian cancer, said she and her colleagues see the uterine cancer study findings as worthy of further exploration – but not yet worthy of discussion with patients.

“The jury’s out for me personally,” she said. “There’s so much more data that’s needed.”

Meanwhile, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers believe they have built a solid body of evidence.

“There are enough things we do know to begin taking action, developing interventions, providing useful information to clinicians and patients and the general public,” said Traci N. Bethea, PhD, assistant professor in the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research at Georgetown University.

Responsibility for regulating personal-care products, including chemical hair straighteners and hair dyes – which also have been linked to hormone-related cancers – lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But the FDA does not subject personal-care products to the same approval process it uses for food and drugs. The FDA restricts only 11 categories of chemicals used in cosmetics, while concerns about health effects have prompted the European Union to restrict the use of at least 2,400 substances.

In March, Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Shontel Brown (D-Ohio) asked the FDA to investigate the potential health threat posed by chemical relaxers. An FDA representative said the agency would look into it.

Natural hairstyles are enjoying a resurgence among Black girls and women, but many continue to rely on the creamy crack, said Dede Teteh, DrPH, assistant professor of public health at Chapman University, Irvine, Calif.

She had her first straightening perm at 8 and has struggled to withdraw from relaxers as an adult, said Dr. Teteh, who now wears locs. Not long ago, she considered chemically straightening her hair for an academic job interview because she didn’t want her hair to “be a hindrance” when she appeared before White professors.

Dr. Teteh led “The Cost of Beauty,” a hair-health research project published in 2017. She and her team interviewed 91 Black women in Southern California. Some became “combative” at the idea of quitting relaxers and claimed “everything can cause cancer.”

Their reactions speak to the challenges Black women face in America, Dr. Teteh said.

“It’s not that people do not want to hear the information related to their health,” she said. “But they want people to share the information in a way that it’s really empathetic to the plight of being Black here in the United States.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Many users of skin-lightening product unaware of risks

, a recent cross-sectional survey suggests.

Skin lightening – which uses chemicals to lighten dark areas of skin or to generally lighten skin tone – poses a health risk from potentially unsafe formulations, the authors write in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

Skin lightening is “influenced by colorism, the system of inequality that affords opportunities and privileges to lighter-skinned individuals across racial/ethnic groups,” they add. “Women, in particular, are vulnerable as media and popular culture propagate beauty standards that lighter skin can elevate physical appearance and social acceptance.”

“It is important to recognize that the primary motivator for skin lightening is most often dermatological disease but that, less frequently, it can be colorism,” senior study author Roopal V. Kundu, MD, professor of dermatology and founding director of the Northwestern Center for Ethnic Skin and Hair at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an email interview.

Skin lightening is a growing, multibillion-dollar, largely unregulated, global industry. Rates have been estimated at 27% in South Africa, 40% in China and South Korea, 77% in Nigeria, but U.S. rates are unknown.

To investigate skin-lightening habits and the role colorism plays in skin-lightening practices in the United States, Dr. Kundu and her colleagues sent an online survey to 578 adults with darker skin who participated in ResearchMatch, a national health registry supported by the National Institutes of Health that connects volunteers with research studies they choose to take part in.

Of the 455 people who completed the 19-item anonymous questionnaire, 238 (52.3%) identified as Black or African American, 83 (18.2%) as Asian, 84 (18.5%) as multiracial, 31 (6.8%) as Hispanic, 14 (3.1%) as American Indian or Alaska Native, and 5 (1.1%) as other. Overall, 364 (80.0%) were women.

The survey asked about demographics, colorism attitudes, skin tone satisfaction, and skin-lightening product use. To assess colorism attitudes, the researchers asked respondents to rate six colorism statements on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The statements included “Lighter skin tone increases one’s self-esteem,” and “Lighter skin tone increases one’s chance of having a romantic relationship or getting married.” The researchers also asked them to rate their skin satisfaction levels on a Likert scale from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

Used mostly to treat skin conditions

Despite a lack of medical input, about three-quarters of people who used skin-lightening products reported using them for medical conditions, and around one-quarter used them for general lightening, the researchers report.

Of all respondents, 97 (21.3%) reported using skin-lightening agents. Of them, 71 (73.2%) used them to treat a skin condition such as acne, melasma, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and 26 (26.8% of skin-lightening product users; 5.7% of all respondents) used them for generalized skin lightening.

The 97 users mostly obtained skin-lightening products from chain pharmacy and grocery stores, and also from community beauty stores, abroad, online, and medical providers, while two made them at home.

Skin-lightening product use did not differ with age, gender, race or ethnicity, education level, or immigration status.

Only 22 (22.7%) of the product users consulted a medical provider before using the products, and only 14 (14.4%) received skin-lightening products from medical providers.

In addition, 44 respondents (45.4%) could not identify the active ingredient in their skin-lightening products, but 34 (35.1%) reported using hydroquinone-based products. Other reported active ingredients included ascorbic acid, glycolic acid, salicylic acid, niacinamide, steroids, and mercury.

The face (86 people or 88.7%) and neck (37 or 38.1%) were the most common application sites.

Skin-lightening users were more likely to report that lighter skin was more beautiful and that it increased self-esteem and romantic prospects (P < .001 for all).

Elma Baron, MD, professor of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, advised doctors to remind patients to consult a dermatologist before they use skin-lightening agents. “A dermatologist can evaluate whether there is a true indication for skin-lightening agents and explain the benefits, risks, and limitations of common skin-lightening formulations.

“When dealing with hyperpigmentation, clinicians should remember that ultraviolet light is a potent stimulus for melanogenesis,” added Dr. Baron by email. She was not involved in the study. “Wearing hats and other sun-protective clothing, using sunscreen, and avoiding sunlight during peak hours must always be emphasized.”

Amy J. McMichael, MD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., often sees patients who try products based on persuasive advertising, not scientific benefit, she said by email.

“The findings are important, because many primary care providers and dermatologists do not realize that patients will use skin-lightening agents simply to provide a glow and in an attempt to attain complexion blending,” added Dr. McMichael, also not involved in the study.

She encouraged doctors to understand what motivates their patients to use skin-lightening agents, so they can effectively communicate what works and what does not work for their condition, as well as inform them about potential risks.

Strengths of the study, Dr. McMichael said, are the number of people surveyed and the inclusion of colorism data not typically gathered in studies of skin-lightening product use. Limitations include whether the reported conditions were what people actually had, and that, with over 50% of respondents being Black, the results may not be generalizable to other groups.

“Colorism is complex,” Dr. Kundu noted. “Dermatologists need to recognize how colorism impacts their patients, so they can provide them with culturally mindful care and deter them from using potentially harmful products.”

Illegal products may still be available

Dr. McMichael would like to know how many of these patients used products containing > 4%-strength hydroquinone, because they “can be dangerous, and patients don’t understand how these higher-strength medications can damage the skin.”

“Following the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security [CARES] Act of 2020, over-the-counter hydroquinone sales were prohibited in the U.S.,” the authors write. In 2022, the Food and Drug Administration issued warning letters to 12 companies that sold products containing unsafe concentrations of hydroquinone, because of concerns about swelling, rashes, and discoloration. Hydroquinone has also been linked with skin cancer.

“However, this study demonstrates that consumers in the U.S. may still have access to hydroquinone formulations,” the authors caution.

At its Skin Facts! Resources website, the FDA warns about potentially harmful over-the-counter skin-lightening products containing hydroquinone or mercury and recommends using only prescribed products. The information site was created by the FDA Office of Minority Health and Health Equity.

The study authors, Dr. Baron, and Dr. McMichael report no relevant financial relationships. The study did not receive external funding. All experts commented by email.

, a recent cross-sectional survey suggests.

Skin lightening – which uses chemicals to lighten dark areas of skin or to generally lighten skin tone – poses a health risk from potentially unsafe formulations, the authors write in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

Skin lightening is “influenced by colorism, the system of inequality that affords opportunities and privileges to lighter-skinned individuals across racial/ethnic groups,” they add. “Women, in particular, are vulnerable as media and popular culture propagate beauty standards that lighter skin can elevate physical appearance and social acceptance.”

“It is important to recognize that the primary motivator for skin lightening is most often dermatological disease but that, less frequently, it can be colorism,” senior study author Roopal V. Kundu, MD, professor of dermatology and founding director of the Northwestern Center for Ethnic Skin and Hair at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an email interview.

Skin lightening is a growing, multibillion-dollar, largely unregulated, global industry. Rates have been estimated at 27% in South Africa, 40% in China and South Korea, 77% in Nigeria, but U.S. rates are unknown.

To investigate skin-lightening habits and the role colorism plays in skin-lightening practices in the United States, Dr. Kundu and her colleagues sent an online survey to 578 adults with darker skin who participated in ResearchMatch, a national health registry supported by the National Institutes of Health that connects volunteers with research studies they choose to take part in.

Of the 455 people who completed the 19-item anonymous questionnaire, 238 (52.3%) identified as Black or African American, 83 (18.2%) as Asian, 84 (18.5%) as multiracial, 31 (6.8%) as Hispanic, 14 (3.1%) as American Indian or Alaska Native, and 5 (1.1%) as other. Overall, 364 (80.0%) were women.

The survey asked about demographics, colorism attitudes, skin tone satisfaction, and skin-lightening product use. To assess colorism attitudes, the researchers asked respondents to rate six colorism statements on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The statements included “Lighter skin tone increases one’s self-esteem,” and “Lighter skin tone increases one’s chance of having a romantic relationship or getting married.” The researchers also asked them to rate their skin satisfaction levels on a Likert scale from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

Used mostly to treat skin conditions

Despite a lack of medical input, about three-quarters of people who used skin-lightening products reported using them for medical conditions, and around one-quarter used them for general lightening, the researchers report.

Of all respondents, 97 (21.3%) reported using skin-lightening agents. Of them, 71 (73.2%) used them to treat a skin condition such as acne, melasma, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and 26 (26.8% of skin-lightening product users; 5.7% of all respondents) used them for generalized skin lightening.

The 97 users mostly obtained skin-lightening products from chain pharmacy and grocery stores, and also from community beauty stores, abroad, online, and medical providers, while two made them at home.

Skin-lightening product use did not differ with age, gender, race or ethnicity, education level, or immigration status.

Only 22 (22.7%) of the product users consulted a medical provider before using the products, and only 14 (14.4%) received skin-lightening products from medical providers.

In addition, 44 respondents (45.4%) could not identify the active ingredient in their skin-lightening products, but 34 (35.1%) reported using hydroquinone-based products. Other reported active ingredients included ascorbic acid, glycolic acid, salicylic acid, niacinamide, steroids, and mercury.

The face (86 people or 88.7%) and neck (37 or 38.1%) were the most common application sites.

Skin-lightening users were more likely to report that lighter skin was more beautiful and that it increased self-esteem and romantic prospects (P < .001 for all).

Elma Baron, MD, professor of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, advised doctors to remind patients to consult a dermatologist before they use skin-lightening agents. “A dermatologist can evaluate whether there is a true indication for skin-lightening agents and explain the benefits, risks, and limitations of common skin-lightening formulations.

“When dealing with hyperpigmentation, clinicians should remember that ultraviolet light is a potent stimulus for melanogenesis,” added Dr. Baron by email. She was not involved in the study. “Wearing hats and other sun-protective clothing, using sunscreen, and avoiding sunlight during peak hours must always be emphasized.”

Amy J. McMichael, MD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., often sees patients who try products based on persuasive advertising, not scientific benefit, she said by email.

“The findings are important, because many primary care providers and dermatologists do not realize that patients will use skin-lightening agents simply to provide a glow and in an attempt to attain complexion blending,” added Dr. McMichael, also not involved in the study.

She encouraged doctors to understand what motivates their patients to use skin-lightening agents, so they can effectively communicate what works and what does not work for their condition, as well as inform them about potential risks.

Strengths of the study, Dr. McMichael said, are the number of people surveyed and the inclusion of colorism data not typically gathered in studies of skin-lightening product use. Limitations include whether the reported conditions were what people actually had, and that, with over 50% of respondents being Black, the results may not be generalizable to other groups.

“Colorism is complex,” Dr. Kundu noted. “Dermatologists need to recognize how colorism impacts their patients, so they can provide them with culturally mindful care and deter them from using potentially harmful products.”

Illegal products may still be available

Dr. McMichael would like to know how many of these patients used products containing > 4%-strength hydroquinone, because they “can be dangerous, and patients don’t understand how these higher-strength medications can damage the skin.”

“Following the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security [CARES] Act of 2020, over-the-counter hydroquinone sales were prohibited in the U.S.,” the authors write. In 2022, the Food and Drug Administration issued warning letters to 12 companies that sold products containing unsafe concentrations of hydroquinone, because of concerns about swelling, rashes, and discoloration. Hydroquinone has also been linked with skin cancer.

“However, this study demonstrates that consumers in the U.S. may still have access to hydroquinone formulations,” the authors caution.

At its Skin Facts! Resources website, the FDA warns about potentially harmful over-the-counter skin-lightening products containing hydroquinone or mercury and recommends using only prescribed products. The information site was created by the FDA Office of Minority Health and Health Equity.

The study authors, Dr. Baron, and Dr. McMichael report no relevant financial relationships. The study did not receive external funding. All experts commented by email.

, a recent cross-sectional survey suggests.

Skin lightening – which uses chemicals to lighten dark areas of skin or to generally lighten skin tone – poses a health risk from potentially unsafe formulations, the authors write in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

Skin lightening is “influenced by colorism, the system of inequality that affords opportunities and privileges to lighter-skinned individuals across racial/ethnic groups,” they add. “Women, in particular, are vulnerable as media and popular culture propagate beauty standards that lighter skin can elevate physical appearance and social acceptance.”

“It is important to recognize that the primary motivator for skin lightening is most often dermatological disease but that, less frequently, it can be colorism,” senior study author Roopal V. Kundu, MD, professor of dermatology and founding director of the Northwestern Center for Ethnic Skin and Hair at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an email interview.

Skin lightening is a growing, multibillion-dollar, largely unregulated, global industry. Rates have been estimated at 27% in South Africa, 40% in China and South Korea, 77% in Nigeria, but U.S. rates are unknown.

To investigate skin-lightening habits and the role colorism plays in skin-lightening practices in the United States, Dr. Kundu and her colleagues sent an online survey to 578 adults with darker skin who participated in ResearchMatch, a national health registry supported by the National Institutes of Health that connects volunteers with research studies they choose to take part in.

Of the 455 people who completed the 19-item anonymous questionnaire, 238 (52.3%) identified as Black or African American, 83 (18.2%) as Asian, 84 (18.5%) as multiracial, 31 (6.8%) as Hispanic, 14 (3.1%) as American Indian or Alaska Native, and 5 (1.1%) as other. Overall, 364 (80.0%) were women.

The survey asked about demographics, colorism attitudes, skin tone satisfaction, and skin-lightening product use. To assess colorism attitudes, the researchers asked respondents to rate six colorism statements on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The statements included “Lighter skin tone increases one’s self-esteem,” and “Lighter skin tone increases one’s chance of having a romantic relationship or getting married.” The researchers also asked them to rate their skin satisfaction levels on a Likert scale from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

Used mostly to treat skin conditions

Despite a lack of medical input, about three-quarters of people who used skin-lightening products reported using them for medical conditions, and around one-quarter used them for general lightening, the researchers report.

Of all respondents, 97 (21.3%) reported using skin-lightening agents. Of them, 71 (73.2%) used them to treat a skin condition such as acne, melasma, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and 26 (26.8% of skin-lightening product users; 5.7% of all respondents) used them for generalized skin lightening.

The 97 users mostly obtained skin-lightening products from chain pharmacy and grocery stores, and also from community beauty stores, abroad, online, and medical providers, while two made them at home.

Skin-lightening product use did not differ with age, gender, race or ethnicity, education level, or immigration status.

Only 22 (22.7%) of the product users consulted a medical provider before using the products, and only 14 (14.4%) received skin-lightening products from medical providers.

In addition, 44 respondents (45.4%) could not identify the active ingredient in their skin-lightening products, but 34 (35.1%) reported using hydroquinone-based products. Other reported active ingredients included ascorbic acid, glycolic acid, salicylic acid, niacinamide, steroids, and mercury.

The face (86 people or 88.7%) and neck (37 or 38.1%) were the most common application sites.

Skin-lightening users were more likely to report that lighter skin was more beautiful and that it increased self-esteem and romantic prospects (P < .001 for all).

Elma Baron, MD, professor of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, advised doctors to remind patients to consult a dermatologist before they use skin-lightening agents. “A dermatologist can evaluate whether there is a true indication for skin-lightening agents and explain the benefits, risks, and limitations of common skin-lightening formulations.

“When dealing with hyperpigmentation, clinicians should remember that ultraviolet light is a potent stimulus for melanogenesis,” added Dr. Baron by email. She was not involved in the study. “Wearing hats and other sun-protective clothing, using sunscreen, and avoiding sunlight during peak hours must always be emphasized.”

Amy J. McMichael, MD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., often sees patients who try products based on persuasive advertising, not scientific benefit, she said by email.

“The findings are important, because many primary care providers and dermatologists do not realize that patients will use skin-lightening agents simply to provide a glow and in an attempt to attain complexion blending,” added Dr. McMichael, also not involved in the study.

She encouraged doctors to understand what motivates their patients to use skin-lightening agents, so they can effectively communicate what works and what does not work for their condition, as well as inform them about potential risks.

Strengths of the study, Dr. McMichael said, are the number of people surveyed and the inclusion of colorism data not typically gathered in studies of skin-lightening product use. Limitations include whether the reported conditions were what people actually had, and that, with over 50% of respondents being Black, the results may not be generalizable to other groups.

“Colorism is complex,” Dr. Kundu noted. “Dermatologists need to recognize how colorism impacts their patients, so they can provide them with culturally mindful care and deter them from using potentially harmful products.”

Illegal products may still be available

Dr. McMichael would like to know how many of these patients used products containing > 4%-strength hydroquinone, because they “can be dangerous, and patients don’t understand how these higher-strength medications can damage the skin.”

“Following the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security [CARES] Act of 2020, over-the-counter hydroquinone sales were prohibited in the U.S.,” the authors write. In 2022, the Food and Drug Administration issued warning letters to 12 companies that sold products containing unsafe concentrations of hydroquinone, because of concerns about swelling, rashes, and discoloration. Hydroquinone has also been linked with skin cancer.

“However, this study demonstrates that consumers in the U.S. may still have access to hydroquinone formulations,” the authors caution.

At its Skin Facts! Resources website, the FDA warns about potentially harmful over-the-counter skin-lightening products containing hydroquinone or mercury and recommends using only prescribed products. The information site was created by the FDA Office of Minority Health and Health Equity.

The study authors, Dr. Baron, and Dr. McMichael report no relevant financial relationships. The study did not receive external funding. All experts commented by email.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S DERMATOLOGY

Autoantibodies could help predict cancer risk in scleroderma

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Included patients from the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center Research Registry and the University of Pittsburgh Scleroderma Center, Pittsburgh.

- A total of 676 patients with scleroderma and a history of cancer were compared with 687 control patients with scleroderma but without a history of cancer.

- Serum tested via line blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for an array of scleroderma autoantibodies.

- Examined association between autoantibodies and overall cancer risk.

TAKEAWAYS:

- Anti-POLR3 and monospecific anti-Ro52 were associated with significantly increased overall cancer risk.

- Anti-centromere and anti-U1RNP were associated with a decreased cancer risk.

- These associations remained when looking specifically at cancer-associated scleroderma.

- Patients positive for anti-Ro52 in combination with either anti-U1RNP or anti-Th/To had a decreased risk of cancer, compared with those who had anti-Ro52 alone.

IN PRACTICE:

This study is too preliminary to have practice application.

SOURCE:

Ji Soo Kim, PhD, of John Hopkins University, Baltimore, was the first author of the study, published in Arthritis & Rheumatology on July 24, 2023. Fellow Johns Hopkins researchers Livia Casciola-Rosen, PhD, and Ami A. Shah, MD, were joint senior authors.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the Donald B. and Dorothy L. Stabler Foundation, the Jerome L. Greene Foundation, the Chresanthe Staurulakis Memorial Discovery Fund, the Martha McCrory Professorship, and the Johns Hopkins inHealth initiative. The authors disclosed the following patents or patent applications: Autoimmune Antigens and Cancer, Materials and Methods for Assessing Cancer Risk and Treating Cancer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Included patients from the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center Research Registry and the University of Pittsburgh Scleroderma Center, Pittsburgh.

- A total of 676 patients with scleroderma and a history of cancer were compared with 687 control patients with scleroderma but without a history of cancer.

- Serum tested via line blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for an array of scleroderma autoantibodies.

- Examined association between autoantibodies and overall cancer risk.

TAKEAWAYS:

- Anti-POLR3 and monospecific anti-Ro52 were associated with significantly increased overall cancer risk.

- Anti-centromere and anti-U1RNP were associated with a decreased cancer risk.

- These associations remained when looking specifically at cancer-associated scleroderma.

- Patients positive for anti-Ro52 in combination with either anti-U1RNP or anti-Th/To had a decreased risk of cancer, compared with those who had anti-Ro52 alone.

IN PRACTICE:

This study is too preliminary to have practice application.

SOURCE:

Ji Soo Kim, PhD, of John Hopkins University, Baltimore, was the first author of the study, published in Arthritis & Rheumatology on July 24, 2023. Fellow Johns Hopkins researchers Livia Casciola-Rosen, PhD, and Ami A. Shah, MD, were joint senior authors.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the Donald B. and Dorothy L. Stabler Foundation, the Jerome L. Greene Foundation, the Chresanthe Staurulakis Memorial Discovery Fund, the Martha McCrory Professorship, and the Johns Hopkins inHealth initiative. The authors disclosed the following patents or patent applications: Autoimmune Antigens and Cancer, Materials and Methods for Assessing Cancer Risk and Treating Cancer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Included patients from the Johns Hopkins Scleroderma Center Research Registry and the University of Pittsburgh Scleroderma Center, Pittsburgh.

- A total of 676 patients with scleroderma and a history of cancer were compared with 687 control patients with scleroderma but without a history of cancer.

- Serum tested via line blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for an array of scleroderma autoantibodies.

- Examined association between autoantibodies and overall cancer risk.

TAKEAWAYS:

- Anti-POLR3 and monospecific anti-Ro52 were associated with significantly increased overall cancer risk.

- Anti-centromere and anti-U1RNP were associated with a decreased cancer risk.

- These associations remained when looking specifically at cancer-associated scleroderma.

- Patients positive for anti-Ro52 in combination with either anti-U1RNP or anti-Th/To had a decreased risk of cancer, compared with those who had anti-Ro52 alone.

IN PRACTICE:

This study is too preliminary to have practice application.

SOURCE:

Ji Soo Kim, PhD, of John Hopkins University, Baltimore, was the first author of the study, published in Arthritis & Rheumatology on July 24, 2023. Fellow Johns Hopkins researchers Livia Casciola-Rosen, PhD, and Ami A. Shah, MD, were joint senior authors.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the Donald B. and Dorothy L. Stabler Foundation, the Jerome L. Greene Foundation, the Chresanthe Staurulakis Memorial Discovery Fund, the Martha McCrory Professorship, and the Johns Hopkins inHealth initiative. The authors disclosed the following patents or patent applications: Autoimmune Antigens and Cancer, Materials and Methods for Assessing Cancer Risk and Treating Cancer.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Medical students are skipping class lectures: Does it matter?

New technologies, including online lectures and guided-lesson websites, along with alternative teaching methods, such as the flipped classroom model, in which med students complete before-class assignments and participate in group projects, are helping to train future physicians for their medical careers.

So though students may not be attending in-person lectures like they did in the past, proponents of online learning say the education students receive and the subsequent care they deliver remains the same.

The Association of American Medical Colleges’ most recent annual survey of 2nd-year medical students found that 25% “almost never” attended their in-person lectures in 2022. The figure has steadily improved since 2020 but mirrors what AAMC recorded in 2017.

“The pandemic may have exacerbated the trend, but it’s a long-standing issue,” said Katherine McOwen, senior director of educational and student affairs at AAMC. She said in an interview that she’s witnessed the pattern for 24 years in her work with medical schools.

“I know it sounds alarming that students aren’t attending lectures. But that doesn’t mean they’re not learning,” said Ahmed Ahmed, MD, MPP, MSc, a recent graduate of Harvard Medical School and now a resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Today’s generation of medical students grew up in the age of technology. They are comfortable in front of the screen, so it makes sense for them to learn certain aspects of medical sciences and public health in the same way, Dr. Ahmed told this news organization.

Dr. Ahmed said that at Harvard he participated in one or two case-based classes per week that followed a flipped classroom model, which allows students to study topics on their own before discussing in a lecture format as a group. “We had to come up with a diagnostic plan and walk through the case slide by slide,” he said. “It got us to think like a clinician.”

The flipped classroom allows students to study at their own pace using their preferred learning style, leading to more collaboration in the classroom and between students, according to a 2022 article on the “new standard in medical education” published in Trends in Anaesthesia & Critical Care.