User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Treatment Stacking: Optimizing Therapeutic Regimens for Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating chronic condition that often is recalcitrant to first-line treatments, and mechanisms underlying its pathology remain unclear. Existing data suggest a multifactorial etiology with different pathophysiologic contributors, including genetic, hormonal, and immune dysregulation factors. At this time, only one medication (adalimumab) is US Food and Drug Administration approved for HS, but multiple medical and procedural therapies are available.1 Herein, we discuss the concept of treatment stacking, or the combination of unique therapeutic modalities—an approach we believe is key to optimizing management of HS patients.

Stacking Treatments for HS

Unlike psoriasis, in which a single biologic agent may provide 100% clearance (psoriasis area and severity index 100 [PASI 100]) without adjuvant treatment,2,3 the field of HS currently lacks medications that are efficacious to that degree of success as monotherapy. In HS, the benchmark for a positive treatment outcome is Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response 50 (HiSCR50),4 a 50% reduction in inflammatory lesion count—a far less stringent marker for disease improvement. Thus, providers should design HS treatment regimens with a model of combining therapies and shift away from monotherapy. Targeting different pathophysiologic pathways by stacking multiple treatments may provide synergistic benefits for HS patients. Treatment stacking is a familiar concept in acne; for instance, patients who benefit tremendously from isotretinoin may still require a hormone-modulating treatment (eg, spironolactone) to attain optimal results.

Adherence to a rigid treatment algorithm based on disease severity limits the potential to create comprehensive regimens that account for unique patient characteristics and clinical manifestations. When evaluating an HS patient, providers should systematically consider each pathophysiologic factor and target the ones that appear to be most involved in that particular patient. The North American HS guidelines illustrate this point by supporting use of several treatments across different Hurley stages, such as recommending hormonal treatment in patients with Hurley stages 1, 2, or 3.1 Of note, treatment stacking also includes procedural therapies. Surgeons typically prefer a patient’s disease management to be optimized prior to surgery, including reduced drainage and inflammation. In addition, even after surgery, patients often still require medical management to prevent continued disease worsening.

Treatment Pathways for HS

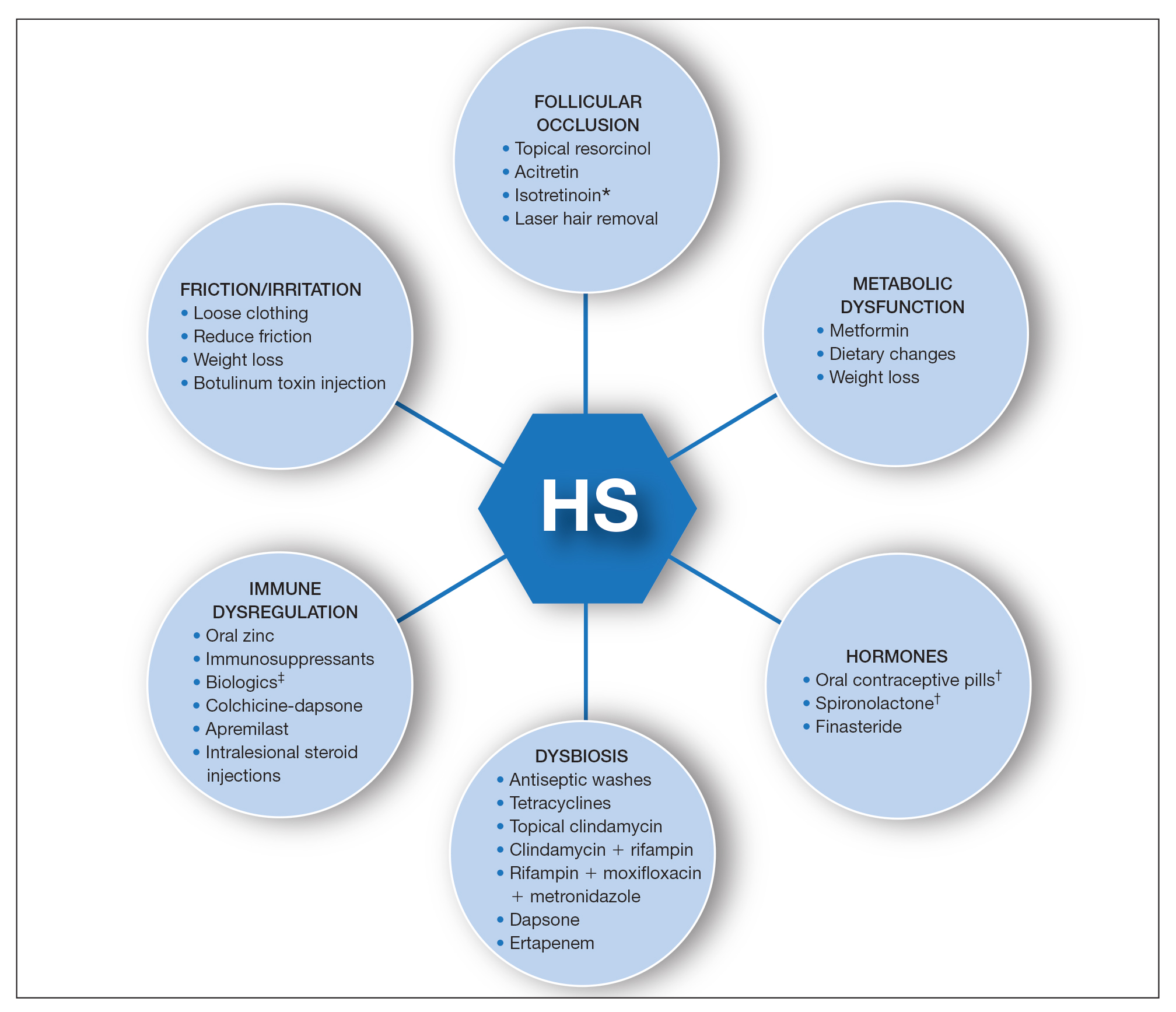

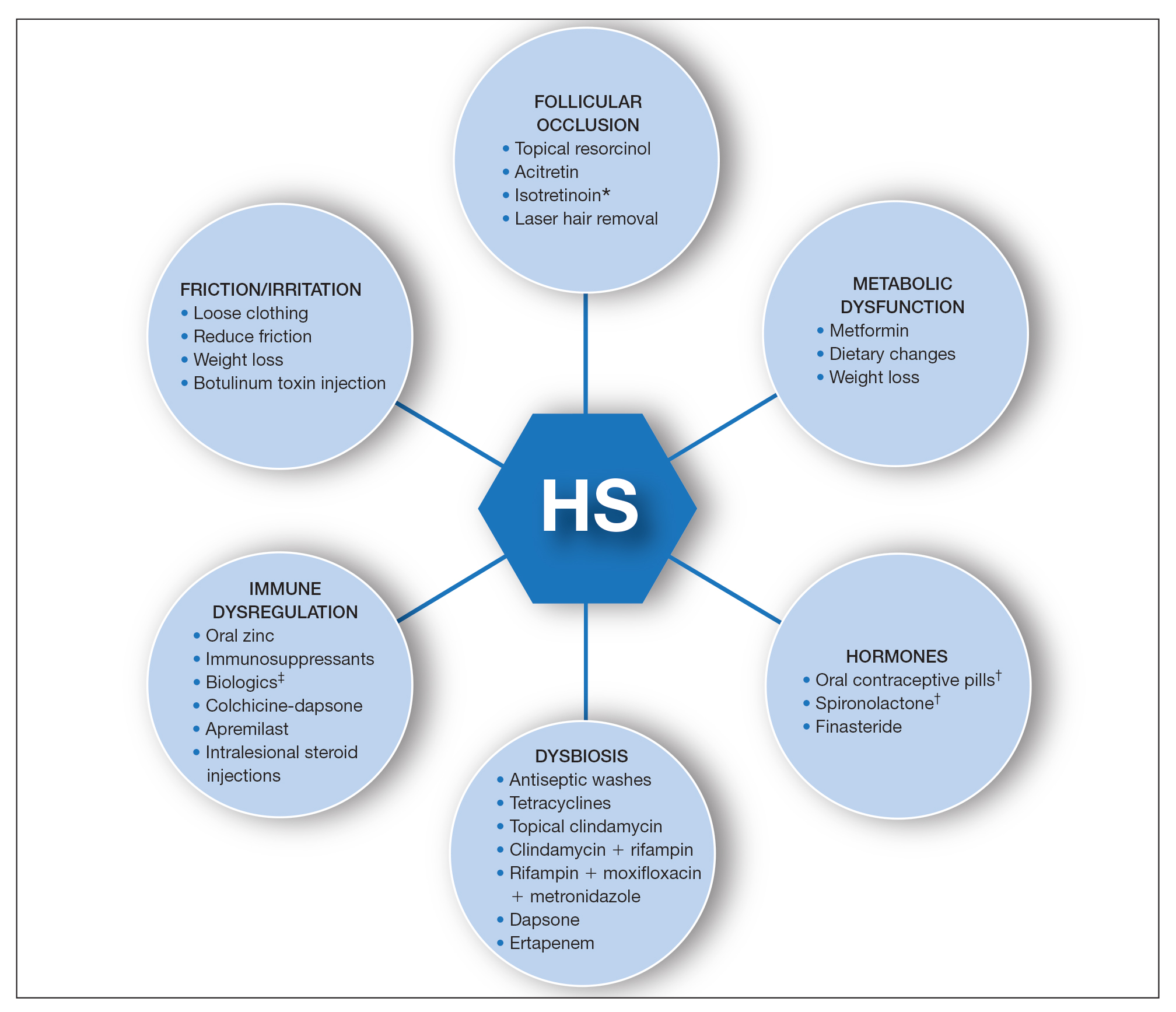

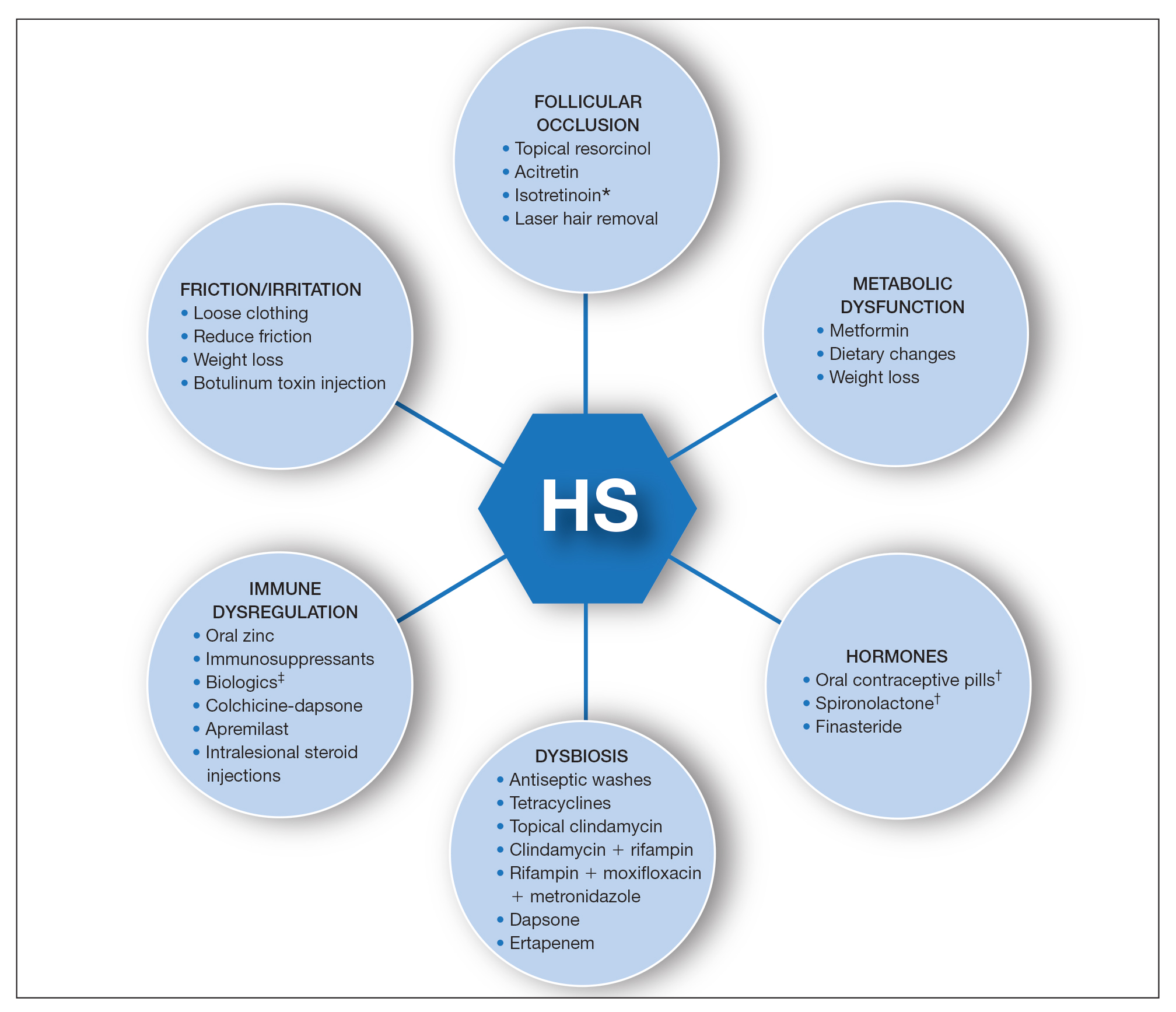

A multimodal approach with treatment stacking (Figure) can be useful to all HS patients, from those with the mildest to the most severe disease. Modifiable pathophysiologic factors and examples of their targeted treatments include (1) follicular occlusion (eg, oral retinoids), (2) metabolic dysfunction (eg, metformin), (3) hormones (eg, oral contraceptive pills, spironolactone, finasteride), (4) dysbiosis (eg, antibiotics such as clindamycin and rifampin combination therapy), (5) immune dysregulation (eg, biologic agents), and (6) friction/irritation (eg, weight loss, clothing recommendations).

Combining treatments from different pathways enables potentiation of individual treatment efficacies. A female patient with only a few HS nodules that flare with menses may be well controlled with spironolactone as her only systemic agent; however, she still may benefit from use of an antiseptic wash, topical clindamycin, and lifestyle changes such as weight loss and reduction of mechanical irritation. A patient with severe recalcitrant HS could notably benefit from concomitant biologic, systemic antibiotic, and hormonal/metabolic treatments. If disease control is still inadequate, agents within the same class can be switched (eg, choosing a different biologic) or other disease-modifying agents such as colchicine also can be added. The goal is to create an effective treatment toolbox with therapies targeting different pathophysiologic arms of HS and working together in synergy. Each tool can be refined by modifying dosing frequency and duration of use to strive for optimal response. At this time, the literature on HS combination therapy is sparse. A retrospective study of 31 patients reported promising combinations, including isotretinoin with spironolactone for mild disease, isotretinoin or doxycycline with adalimumab for moderate disease, and cyclosporine with adalimumab for severe disease.5 Larger prospective studies on clinical response to different combination regimens are warranted.

Optimizing Therapy for HS and Its Comorbidities

Additional considerations may further optimize treatment plans. Some therapies benefit all patients; for example, providers should counsel all HS patients on healthy weight management, optimized clothing choices,6 and friction reduction in the intertriginous folds. Providers also may consider adding therapies with faster onset of efficacy as a bridge to long-term, slower-onset therapies. For instance, female HS patients with menstrual flares who are prescribed spironolactone also may benefit from a course of systemic antibiotics, which typically provides more prompt relief. Treatment regimens also can concomitantly treat HS and its comorbidities.7 For example, metformin serves a dual purpose in HS patients with diabetes mellitus, and adalimumab in patients with both HS and inflammatory bowel disease.

Final Thoughts

The last decade has seen tremendous growth in HS research8 coupled with a remarkable expansion in the therapeutic pipeline.9 However, currently no single therapy for HS can guarantee satisfactory disease remission or durability of remission. The contrast between clinical trials and real-world practice should be acknowledged; the former often is restrictive in design with monotherapy and allowance of very limited concomitant treatments, such as topical or oral antibiotics. This limits our ability to draw conclusions regarding the additive synergistic potential of different therapeutics in combination. In clinical practice, we are not restricted by monotherapy trial protocols. As we await new tools, treatment stacking allows for creating a framework to best utilize the tools that are available to us.

Although HS has continued to affect the lives of many patients, improved understanding of underlying pathophysiology and a well-placed sense of urgency from all stakeholders (ie, patients, clinicians, researchers, industry partners) has pushed this field forward. Until our therapeutic armamentarium has expanded to include highly efficacious monotherapy options, providers should consider treatment stacking for every HS patient.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

- Reich K, Warren RB, Lebwohl M, et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:142-152. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2102383

- Imafuku S, Nakagawa H, Igarashi A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from a 5-year extension of a phase 3 study (reSURFACE 1). J Dermatol. 2021;48:844-852. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15763

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504370

- McPhie ML, Bridgman AC, Kirchhof MG. Combination therapies for hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review of 31 patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:270-276. doi:10.1177/1203475418823529

- Loh TY, Hendricks AJ, Hsiao JL, et al. Undergarment and fabric selection in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Basel Switz. 2021;237:119-124. doi:10.1159/000501611

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations [published online January 23, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Savage KT, Brant EG, Flood KS, et al. Publication trends in hidradenitis suppurativa from 2008 to 2018. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1885-1889. doi:10.1111/jdv.16213

- van Straalen KR, Schneider-Burrus S, Prens EP. Current and future treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:E178-E187. doi:10.1111/bjd.16768

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating chronic condition that often is recalcitrant to first-line treatments, and mechanisms underlying its pathology remain unclear. Existing data suggest a multifactorial etiology with different pathophysiologic contributors, including genetic, hormonal, and immune dysregulation factors. At this time, only one medication (adalimumab) is US Food and Drug Administration approved for HS, but multiple medical and procedural therapies are available.1 Herein, we discuss the concept of treatment stacking, or the combination of unique therapeutic modalities—an approach we believe is key to optimizing management of HS patients.

Stacking Treatments for HS

Unlike psoriasis, in which a single biologic agent may provide 100% clearance (psoriasis area and severity index 100 [PASI 100]) without adjuvant treatment,2,3 the field of HS currently lacks medications that are efficacious to that degree of success as monotherapy. In HS, the benchmark for a positive treatment outcome is Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response 50 (HiSCR50),4 a 50% reduction in inflammatory lesion count—a far less stringent marker for disease improvement. Thus, providers should design HS treatment regimens with a model of combining therapies and shift away from monotherapy. Targeting different pathophysiologic pathways by stacking multiple treatments may provide synergistic benefits for HS patients. Treatment stacking is a familiar concept in acne; for instance, patients who benefit tremendously from isotretinoin may still require a hormone-modulating treatment (eg, spironolactone) to attain optimal results.

Adherence to a rigid treatment algorithm based on disease severity limits the potential to create comprehensive regimens that account for unique patient characteristics and clinical manifestations. When evaluating an HS patient, providers should systematically consider each pathophysiologic factor and target the ones that appear to be most involved in that particular patient. The North American HS guidelines illustrate this point by supporting use of several treatments across different Hurley stages, such as recommending hormonal treatment in patients with Hurley stages 1, 2, or 3.1 Of note, treatment stacking also includes procedural therapies. Surgeons typically prefer a patient’s disease management to be optimized prior to surgery, including reduced drainage and inflammation. In addition, even after surgery, patients often still require medical management to prevent continued disease worsening.

Treatment Pathways for HS

A multimodal approach with treatment stacking (Figure) can be useful to all HS patients, from those with the mildest to the most severe disease. Modifiable pathophysiologic factors and examples of their targeted treatments include (1) follicular occlusion (eg, oral retinoids), (2) metabolic dysfunction (eg, metformin), (3) hormones (eg, oral contraceptive pills, spironolactone, finasteride), (4) dysbiosis (eg, antibiotics such as clindamycin and rifampin combination therapy), (5) immune dysregulation (eg, biologic agents), and (6) friction/irritation (eg, weight loss, clothing recommendations).

Combining treatments from different pathways enables potentiation of individual treatment efficacies. A female patient with only a few HS nodules that flare with menses may be well controlled with spironolactone as her only systemic agent; however, she still may benefit from use of an antiseptic wash, topical clindamycin, and lifestyle changes such as weight loss and reduction of mechanical irritation. A patient with severe recalcitrant HS could notably benefit from concomitant biologic, systemic antibiotic, and hormonal/metabolic treatments. If disease control is still inadequate, agents within the same class can be switched (eg, choosing a different biologic) or other disease-modifying agents such as colchicine also can be added. The goal is to create an effective treatment toolbox with therapies targeting different pathophysiologic arms of HS and working together in synergy. Each tool can be refined by modifying dosing frequency and duration of use to strive for optimal response. At this time, the literature on HS combination therapy is sparse. A retrospective study of 31 patients reported promising combinations, including isotretinoin with spironolactone for mild disease, isotretinoin or doxycycline with adalimumab for moderate disease, and cyclosporine with adalimumab for severe disease.5 Larger prospective studies on clinical response to different combination regimens are warranted.

Optimizing Therapy for HS and Its Comorbidities

Additional considerations may further optimize treatment plans. Some therapies benefit all patients; for example, providers should counsel all HS patients on healthy weight management, optimized clothing choices,6 and friction reduction in the intertriginous folds. Providers also may consider adding therapies with faster onset of efficacy as a bridge to long-term, slower-onset therapies. For instance, female HS patients with menstrual flares who are prescribed spironolactone also may benefit from a course of systemic antibiotics, which typically provides more prompt relief. Treatment regimens also can concomitantly treat HS and its comorbidities.7 For example, metformin serves a dual purpose in HS patients with diabetes mellitus, and adalimumab in patients with both HS and inflammatory bowel disease.

Final Thoughts

The last decade has seen tremendous growth in HS research8 coupled with a remarkable expansion in the therapeutic pipeline.9 However, currently no single therapy for HS can guarantee satisfactory disease remission or durability of remission. The contrast between clinical trials and real-world practice should be acknowledged; the former often is restrictive in design with monotherapy and allowance of very limited concomitant treatments, such as topical or oral antibiotics. This limits our ability to draw conclusions regarding the additive synergistic potential of different therapeutics in combination. In clinical practice, we are not restricted by monotherapy trial protocols. As we await new tools, treatment stacking allows for creating a framework to best utilize the tools that are available to us.

Although HS has continued to affect the lives of many patients, improved understanding of underlying pathophysiology and a well-placed sense of urgency from all stakeholders (ie, patients, clinicians, researchers, industry partners) has pushed this field forward. Until our therapeutic armamentarium has expanded to include highly efficacious monotherapy options, providers should consider treatment stacking for every HS patient.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating chronic condition that often is recalcitrant to first-line treatments, and mechanisms underlying its pathology remain unclear. Existing data suggest a multifactorial etiology with different pathophysiologic contributors, including genetic, hormonal, and immune dysregulation factors. At this time, only one medication (adalimumab) is US Food and Drug Administration approved for HS, but multiple medical and procedural therapies are available.1 Herein, we discuss the concept of treatment stacking, or the combination of unique therapeutic modalities—an approach we believe is key to optimizing management of HS patients.

Stacking Treatments for HS

Unlike psoriasis, in which a single biologic agent may provide 100% clearance (psoriasis area and severity index 100 [PASI 100]) without adjuvant treatment,2,3 the field of HS currently lacks medications that are efficacious to that degree of success as monotherapy. In HS, the benchmark for a positive treatment outcome is Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response 50 (HiSCR50),4 a 50% reduction in inflammatory lesion count—a far less stringent marker for disease improvement. Thus, providers should design HS treatment regimens with a model of combining therapies and shift away from monotherapy. Targeting different pathophysiologic pathways by stacking multiple treatments may provide synergistic benefits for HS patients. Treatment stacking is a familiar concept in acne; for instance, patients who benefit tremendously from isotretinoin may still require a hormone-modulating treatment (eg, spironolactone) to attain optimal results.

Adherence to a rigid treatment algorithm based on disease severity limits the potential to create comprehensive regimens that account for unique patient characteristics and clinical manifestations. When evaluating an HS patient, providers should systematically consider each pathophysiologic factor and target the ones that appear to be most involved in that particular patient. The North American HS guidelines illustrate this point by supporting use of several treatments across different Hurley stages, such as recommending hormonal treatment in patients with Hurley stages 1, 2, or 3.1 Of note, treatment stacking also includes procedural therapies. Surgeons typically prefer a patient’s disease management to be optimized prior to surgery, including reduced drainage and inflammation. In addition, even after surgery, patients often still require medical management to prevent continued disease worsening.

Treatment Pathways for HS

A multimodal approach with treatment stacking (Figure) can be useful to all HS patients, from those with the mildest to the most severe disease. Modifiable pathophysiologic factors and examples of their targeted treatments include (1) follicular occlusion (eg, oral retinoids), (2) metabolic dysfunction (eg, metformin), (3) hormones (eg, oral contraceptive pills, spironolactone, finasteride), (4) dysbiosis (eg, antibiotics such as clindamycin and rifampin combination therapy), (5) immune dysregulation (eg, biologic agents), and (6) friction/irritation (eg, weight loss, clothing recommendations).

Combining treatments from different pathways enables potentiation of individual treatment efficacies. A female patient with only a few HS nodules that flare with menses may be well controlled with spironolactone as her only systemic agent; however, she still may benefit from use of an antiseptic wash, topical clindamycin, and lifestyle changes such as weight loss and reduction of mechanical irritation. A patient with severe recalcitrant HS could notably benefit from concomitant biologic, systemic antibiotic, and hormonal/metabolic treatments. If disease control is still inadequate, agents within the same class can be switched (eg, choosing a different biologic) or other disease-modifying agents such as colchicine also can be added. The goal is to create an effective treatment toolbox with therapies targeting different pathophysiologic arms of HS and working together in synergy. Each tool can be refined by modifying dosing frequency and duration of use to strive for optimal response. At this time, the literature on HS combination therapy is sparse. A retrospective study of 31 patients reported promising combinations, including isotretinoin with spironolactone for mild disease, isotretinoin or doxycycline with adalimumab for moderate disease, and cyclosporine with adalimumab for severe disease.5 Larger prospective studies on clinical response to different combination regimens are warranted.

Optimizing Therapy for HS and Its Comorbidities

Additional considerations may further optimize treatment plans. Some therapies benefit all patients; for example, providers should counsel all HS patients on healthy weight management, optimized clothing choices,6 and friction reduction in the intertriginous folds. Providers also may consider adding therapies with faster onset of efficacy as a bridge to long-term, slower-onset therapies. For instance, female HS patients with menstrual flares who are prescribed spironolactone also may benefit from a course of systemic antibiotics, which typically provides more prompt relief. Treatment regimens also can concomitantly treat HS and its comorbidities.7 For example, metformin serves a dual purpose in HS patients with diabetes mellitus, and adalimumab in patients with both HS and inflammatory bowel disease.

Final Thoughts

The last decade has seen tremendous growth in HS research8 coupled with a remarkable expansion in the therapeutic pipeline.9 However, currently no single therapy for HS can guarantee satisfactory disease remission or durability of remission. The contrast between clinical trials and real-world practice should be acknowledged; the former often is restrictive in design with monotherapy and allowance of very limited concomitant treatments, such as topical or oral antibiotics. This limits our ability to draw conclusions regarding the additive synergistic potential of different therapeutics in combination. In clinical practice, we are not restricted by monotherapy trial protocols. As we await new tools, treatment stacking allows for creating a framework to best utilize the tools that are available to us.

Although HS has continued to affect the lives of many patients, improved understanding of underlying pathophysiology and a well-placed sense of urgency from all stakeholders (ie, patients, clinicians, researchers, industry partners) has pushed this field forward. Until our therapeutic armamentarium has expanded to include highly efficacious monotherapy options, providers should consider treatment stacking for every HS patient.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

- Reich K, Warren RB, Lebwohl M, et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:142-152. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2102383

- Imafuku S, Nakagawa H, Igarashi A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from a 5-year extension of a phase 3 study (reSURFACE 1). J Dermatol. 2021;48:844-852. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15763

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504370

- McPhie ML, Bridgman AC, Kirchhof MG. Combination therapies for hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review of 31 patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:270-276. doi:10.1177/1203475418823529

- Loh TY, Hendricks AJ, Hsiao JL, et al. Undergarment and fabric selection in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Basel Switz. 2021;237:119-124. doi:10.1159/000501611

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations [published online January 23, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Savage KT, Brant EG, Flood KS, et al. Publication trends in hidradenitis suppurativa from 2008 to 2018. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1885-1889. doi:10.1111/jdv.16213

- van Straalen KR, Schneider-Burrus S, Prens EP. Current and future treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:E178-E187. doi:10.1111/bjd.16768

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

- Reich K, Warren RB, Lebwohl M, et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:142-152. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2102383

- Imafuku S, Nakagawa H, Igarashi A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results from a 5-year extension of a phase 3 study (reSURFACE 1). J Dermatol. 2021;48:844-852. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15763

- Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504370

- McPhie ML, Bridgman AC, Kirchhof MG. Combination therapies for hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review of 31 patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:270-276. doi:10.1177/1203475418823529

- Loh TY, Hendricks AJ, Hsiao JL, et al. Undergarment and fabric selection in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Basel Switz. 2021;237:119-124. doi:10.1159/000501611

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations [published online January 23, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Savage KT, Brant EG, Flood KS, et al. Publication trends in hidradenitis suppurativa from 2008 to 2018. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1885-1889. doi:10.1111/jdv.16213

- van Straalen KR, Schneider-Burrus S, Prens EP. Current and future treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:E178-E187. doi:10.1111/bjd.16768

Bullous Amyloidosis Masquerading as Pseudoporphyria

Cutaneous amyloidosis encompasses a variety of clinical presentations. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises lichen amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis result from keratin deposits, while nodular amyloidosis results from cutaneous infiltration of plasma cells.2 Primary systemic amyloidosis is due to a plasma cell dyscrasia, particularly multiple myeloma, while secondary systemic amyloidosis occurs in the setting of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, renal dysfunction, or chronic inflammation, as seen with rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, and various autoinflammatory disorders.2 Plasma cell proliferative disorders are associated with various skin disorders, which may result from aggregated misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins, indicating light chain–related systemic amyloidosis. Mucocutaneous lesions can occur in 30% to 40% of cases of primary systemic amyloidosis and may present as purpura, ecchymoses, waxy thickening, plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and/or bullae.3,4 When blistering is present, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes autoimmune bullous disease, drug eruptions, enoxaparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, deposition diseases, allergic contact dermatitis, bullous cellulitis, bullous bite reactions, neutrophilic dermatosis, and bullous lichen sclerosus.5 Herein, we present a case of a woman with a bullous skin eruption who eventually was diagnosed with bullous amyloidosis subsequent to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of well-demarcated, hemorrhagic, flaccid vesicles and focal erosions with a rim of erythema on the distal forearms and hands. A shave biopsy from the right forearm showed cell-poor subepidermal vesicular dermatitis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 as well as urinary porphyrins were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed granular IgM at the basement membrane zone around vessels and cytoid bodies. At this time, a preliminary diagnosis of pseudoporphyria was suspected, though no classic medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, furosemide, antibiotics) or exogenous trigger factors (eg, UV light exposure, dialysis) were temporally related. Three months later, the patient presented with a large hemorrhagic bulla on the distal left forearm (Figure 1) and healing erosions on the dorsal fingers and upper back. Clobetasol ointment was initiated, as an autoimmune bullous dermatosis was suspected.

Approximately 1 year after she was first seen in our outpatient clinic, the patient was hospitalized for induction of chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone—for a new diagnosis of stage III multiple myeloma. A workup for back pain revealed multiple compression fractures and a plasma cell neoplasm with elevated λ light chains, which was confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy. During an inpatient dermatology consultation, we noted the development of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and worsening generalization of the hemorrhagic bullae, with healing erosions and intact hemorrhagic bullae on the dorsal hands, fingers (Figure 2), and upper back.

A repeat biopsy displayed bullous amyloidosis. Histopathologic examination revealed an ulcerated subepidermal blister with fibrin deposition at the ulcer base. A periadnexal, scant, eosinophilic deposition with extravasated red blood cells was appreciated. Amorphous eosinophilic deposits were found within the detached fragment of the epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate. A Congo red stain highlighted these areas with a salmon pink–colored material. Congo red staining showed a moderate amount of pale, apple green, birefringent deposit within these areas on polarized light examination.

A few months later, the patient was re-admitted, and the amount of skin detachment prompted the primary team to ask for another consultation. Although the extensive skin sloughing resembled toxic epidermal necrolysis, a repeat biopsy confirmed bullous amyloidosis.

Comment

Amyloidosis Histopathology—Amyloidoses represent a wide array of disorders with deposition of β-pleated sheets or amyloid fibrils, often with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 Primary systemic amyloidosis has been associated with underlying dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.6 In such cases, the skin lesions of multiple myeloma may result from a collection of misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins or their fragments, as in light chain–related systemic amyloidosis.3 Histopathologically, both systemic and cutaneous amyloidosis appear similar and display deposition of amorphous, eosinophilic, fissured amyloid material in the dermis. Congo red stains the material orange-red and will display a characteristic apple green birefringence under polarized light.4 Although bullous amyloid lesions are rare, the cutaneous forms of these lesions can be an important sign of plasma cell dyscrasia.7

Presentation of Bullous Amyloidosis—Bullous manifestations rarely have been noted in the primary cutaneous forms of amyloidosis.5,8,9 Importantly, cutaneous blistering more often is linked to systemic forms of amyloidosis with multiorgan involvement, including primary systemic and myeloma-associated amyloidosis.5,10 However, patients with localized bullous cutaneous amyloidosis without systemic involvement also have been seen.10,11 Bullae may occur at any time, with contents that frequently are hemorrhagic due to capillary fragility.12,13 Bullous manifestations raise the differential diagnoses of bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, linear IgA disease, porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, bullous drug eruption, bullous eruption of renal dialysis, or bullous lupus erythematosus.5,13-17

In our patient, the acral distribution of bullae, presence of hemorrhage, chronicity of symptoms, and negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay initially suggested a diagnosis of pseudoporphyria. However, the presence of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and subsequent confirmatory pathology aided in differentiating bullous amyloidosis from pseudoporphyria. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare form of skin-restricted amyloidoses, can coexist with bullous lesions. Of note, reported cases of nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis did not result in development of multiple myeloma.5,10

Bullae are located either subepidermally or intradermally, and bullous lesions of cutaneous amyloidosis typically demonstrate subepidermal or superficial intradermal clefting on light microscopy.5,10,12 Histopathology of bullous amyloidosis shows intradermal or subepidermal blister formation and amorphous eosinophilic material showing apple green birefringence with Congo red staining deposited in the dermis and/or around the adipocytes and blood vessel walls.12,18-20 In prior cases, direct immunofluorescence of bullous amyloidosis revealed absent immunoglobulin (IgG, IgA, IgM) or complement (C3 and C9) deposits in the basement membrane zone or dermis.13,21,22 In these cases, electron microscopy was useful in diagnosis, as it showed the presence of amyloid deposits.21,22

Cause of Bullae—Various mechanisms are thought to trigger the blister formation in amyloidosis. Bullae created from trauma or friction often present as tense painful blisters that commonly are hemorrhagic.10,23 Amyloid deposits in the walls of blood vessels and the affinity of dermal amyloid in blood vessel walls to surrounding collagen likely leads to increased fragility of capillaries and the dermal matrix, hemorrhagic tendency, and infrapapillary blisters, thus creating hemorrhagic bullous eruptions.24,25 Specifically, close proximity of immunoglobulin-derived amyloid oligomers to epidermal keratinocytes may be toxic and therefore could trigger subepidermal bullous change.5 Additionally, alteration in the physicochemical properties of the amyloidal protein might explain bullous eruption.9 Trauma or rubbing of the hands and feet may precipitate the acral blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.5,11

Due to deposition of these amyloid fibrils, skin bleeding in these patients is called amyloid or pinch purpura. Vessel wall fragility and damage by amyloid are the principal causes of periorbital and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.26 Destruction of the lamina densa and widening of the intercellular space between keratinocytes by amyloid globules induce skin fragility.11

Although uncommon, various cases of bullous amyloidosis have been reported in the literature. Multiple myeloma patients represent the majority of those reported to have bullous amyloidosis.6,7,13,24,27-30 Plasmacytoma-associated bullous amyloid purpura and paraproteinemia also have been noted.25 Multiple myeloma with secondary AL amyloidosis has been seen with amyloid purpura and atraumatic ecchymoses of the face, highlighting the hemorrhage noted in these patients.26

Management of Amyloidosis—Various treatment options have been attempted for primary cutaneous amyloidosis, including oral retinoids, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, amitriptyline, colchicine, cepharanthin, tacrolimus, dimethyl sulfoxide, vitamin D3 analogs, capsaicin, menthol, hydrocolloid dressings, surgical modalities, laser treatment, and phototherapy.1 There is no clear consensus for therapeutic modalities except for treating the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia in primary systemic amyloidosis.

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient displaying signs of pseudoporphyria that ultimately proved to be bullous amyloidosis, or what we termed pseudopseudoporphyria. Bullous amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnoses of hemorrhagic bullous skin eruptions. Particular attention should be given to a systemic workup for multiple myeloma when hemorrhagic vesicles/bullae are chronic and coexist with purpura, angina bullosa hemorrhagica, fatigue/weight loss, and/or macroglossia.

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Amyloidosis. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:341-345.

- Bhutani M, Shahid Z, Schnebelen A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell proliferative disorders. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:395-400.

- Terushkin V, Boyd KP, Patel RR, et al. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20711.

- LaChance A, Phelps A, Finch J, et al. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:344-347.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

- Kanoh T. Bullous amyloidosis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34:1050-1052.

- Johnson TM, Rapini RP, Hebert AA, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Cutis. 1989;43:346-352.

- Houman MH, Smiti KM, Ben Ghorbel I, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129:299-302.

- Sanusi T, Li Y, Qian Y, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis with bullous lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:400-402.

- Ochiai T, Morishima T, Hao T, et al. Bullous amyloidosis: the mechanism of blister formation revealed by electron microscopy. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:407-411.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Wang XD, Shen H, Liu ZH. Diffuse haemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis with multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:94-96.

- Biswas P, Aggarwal I, Sen D, et al. Bullous pemphigoid clinically presenting as lichen amyloidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:544-546.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous dermatosis vs amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:252.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous amyloidosis vs epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. JAMA. 1981;245:32.

- Murphy GM, Wright J, Nicholls DS, et al. Sunbed-induced pseudoporphyria. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:555-562.

- Pramatarov K, Lazarova A, Mateev G, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic primary systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:211-213.

- Bieber T, Ruzicka T, Linke RP, et al. Hemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis. a histologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study of two patients. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1683-1686.

- Khoo BP, Tay YK. Lichen amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:105-107.

- Asahina A, Hasegawa K, Ishiyama M, et al. Bullous amyloidosis mimicking bullous pemphigoid: usefulness of electron microscopic examination. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:427-428.

- Schmutz JL, Barbaud A, Cuny JF, et al. Bullous amyloidosis [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:295-301.

- Lachmann HJ, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis of the skin. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:1574-1583.

- Grundmann JU, Bonnekoh B, Gollnick H. Extensive haemorrhagic-bullous skin manifestation of systemic AA-amyloidosis associated with IgG lambda-myeloma. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:139-142.

- Hödl S, Turek TD, Kerl H. Plasmocytoma-associated bullous hemorrhagic amyloidosis of the skin [in German]. Hautarzt. 1982;33:556-558.

- Colucci G, Alberio L, Demarmels Biasiutti F, et al. Bilateral periorbital ecchymoses. an often missed sign of amyloid purpura. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:249-252.

- Behera B, Pattnaik M, Sahu B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:668-671.

- Fujita Y, Tsuji-Abe Y, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Nail dystrophy and blisters as sole manifestations in myeloma-associated amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:712-714.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Winzer M, Ruppert M, Baretton G, et al. Bullous poikilodermatitic amyloidosis of the skin with junctional bulla development in IgG light chain plasmacytoma of the lambda type. histology, immunohistology and electron microscopy [in German]. Hautarzt. 1992;43:199-204.

Cutaneous amyloidosis encompasses a variety of clinical presentations. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises lichen amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis result from keratin deposits, while nodular amyloidosis results from cutaneous infiltration of plasma cells.2 Primary systemic amyloidosis is due to a plasma cell dyscrasia, particularly multiple myeloma, while secondary systemic amyloidosis occurs in the setting of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, renal dysfunction, or chronic inflammation, as seen with rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, and various autoinflammatory disorders.2 Plasma cell proliferative disorders are associated with various skin disorders, which may result from aggregated misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins, indicating light chain–related systemic amyloidosis. Mucocutaneous lesions can occur in 30% to 40% of cases of primary systemic amyloidosis and may present as purpura, ecchymoses, waxy thickening, plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and/or bullae.3,4 When blistering is present, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes autoimmune bullous disease, drug eruptions, enoxaparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, deposition diseases, allergic contact dermatitis, bullous cellulitis, bullous bite reactions, neutrophilic dermatosis, and bullous lichen sclerosus.5 Herein, we present a case of a woman with a bullous skin eruption who eventually was diagnosed with bullous amyloidosis subsequent to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of well-demarcated, hemorrhagic, flaccid vesicles and focal erosions with a rim of erythema on the distal forearms and hands. A shave biopsy from the right forearm showed cell-poor subepidermal vesicular dermatitis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 as well as urinary porphyrins were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed granular IgM at the basement membrane zone around vessels and cytoid bodies. At this time, a preliminary diagnosis of pseudoporphyria was suspected, though no classic medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, furosemide, antibiotics) or exogenous trigger factors (eg, UV light exposure, dialysis) were temporally related. Three months later, the patient presented with a large hemorrhagic bulla on the distal left forearm (Figure 1) and healing erosions on the dorsal fingers and upper back. Clobetasol ointment was initiated, as an autoimmune bullous dermatosis was suspected.

Approximately 1 year after she was first seen in our outpatient clinic, the patient was hospitalized for induction of chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone—for a new diagnosis of stage III multiple myeloma. A workup for back pain revealed multiple compression fractures and a plasma cell neoplasm with elevated λ light chains, which was confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy. During an inpatient dermatology consultation, we noted the development of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and worsening generalization of the hemorrhagic bullae, with healing erosions and intact hemorrhagic bullae on the dorsal hands, fingers (Figure 2), and upper back.

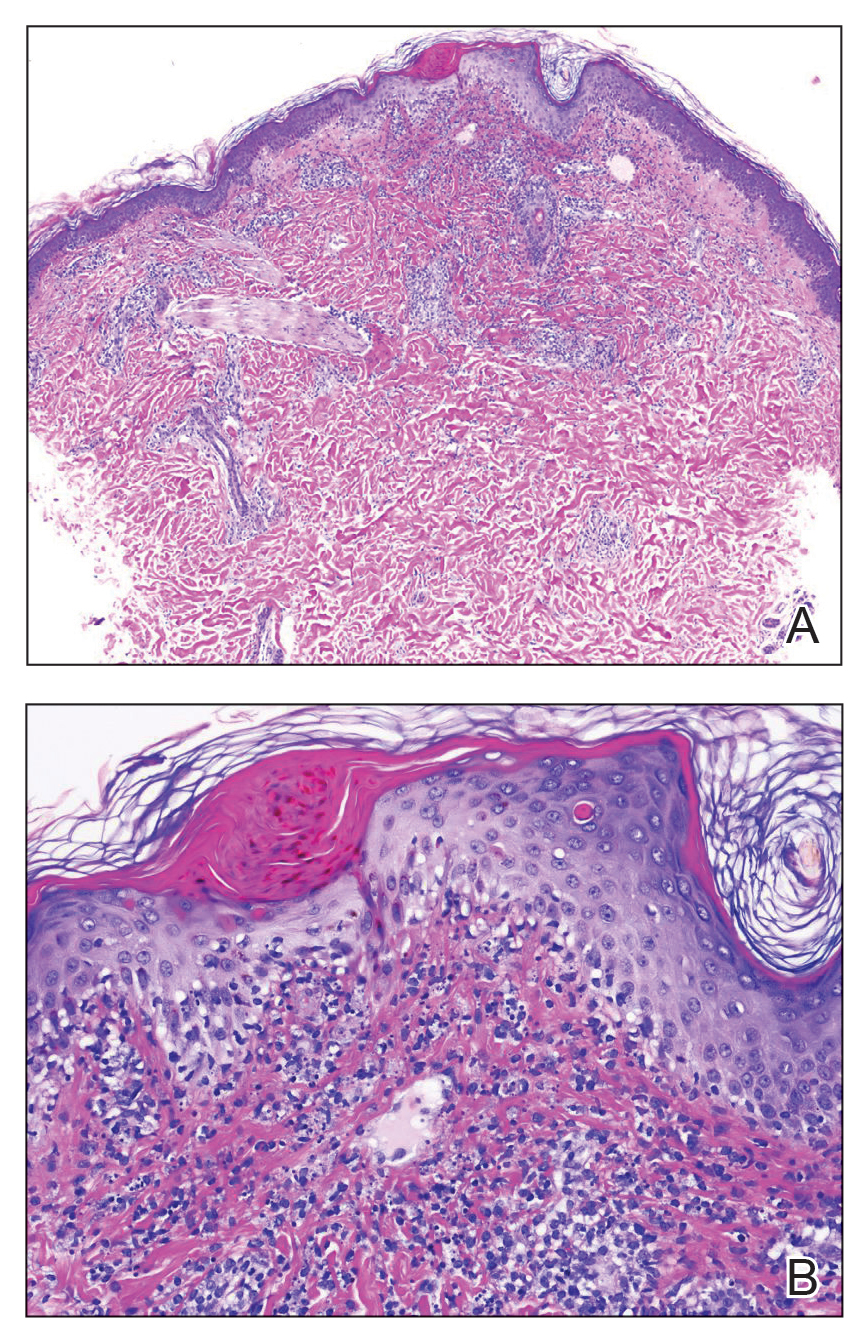

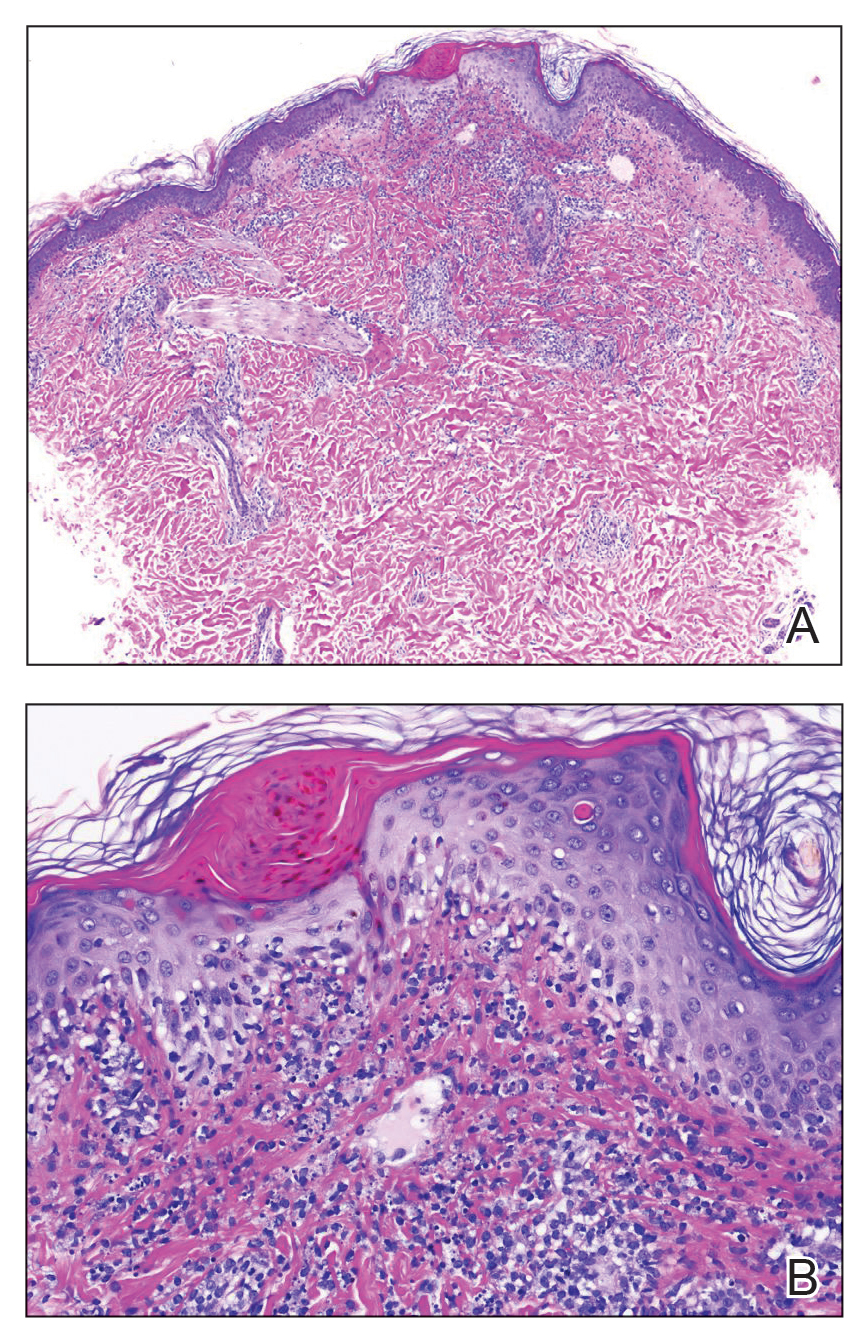

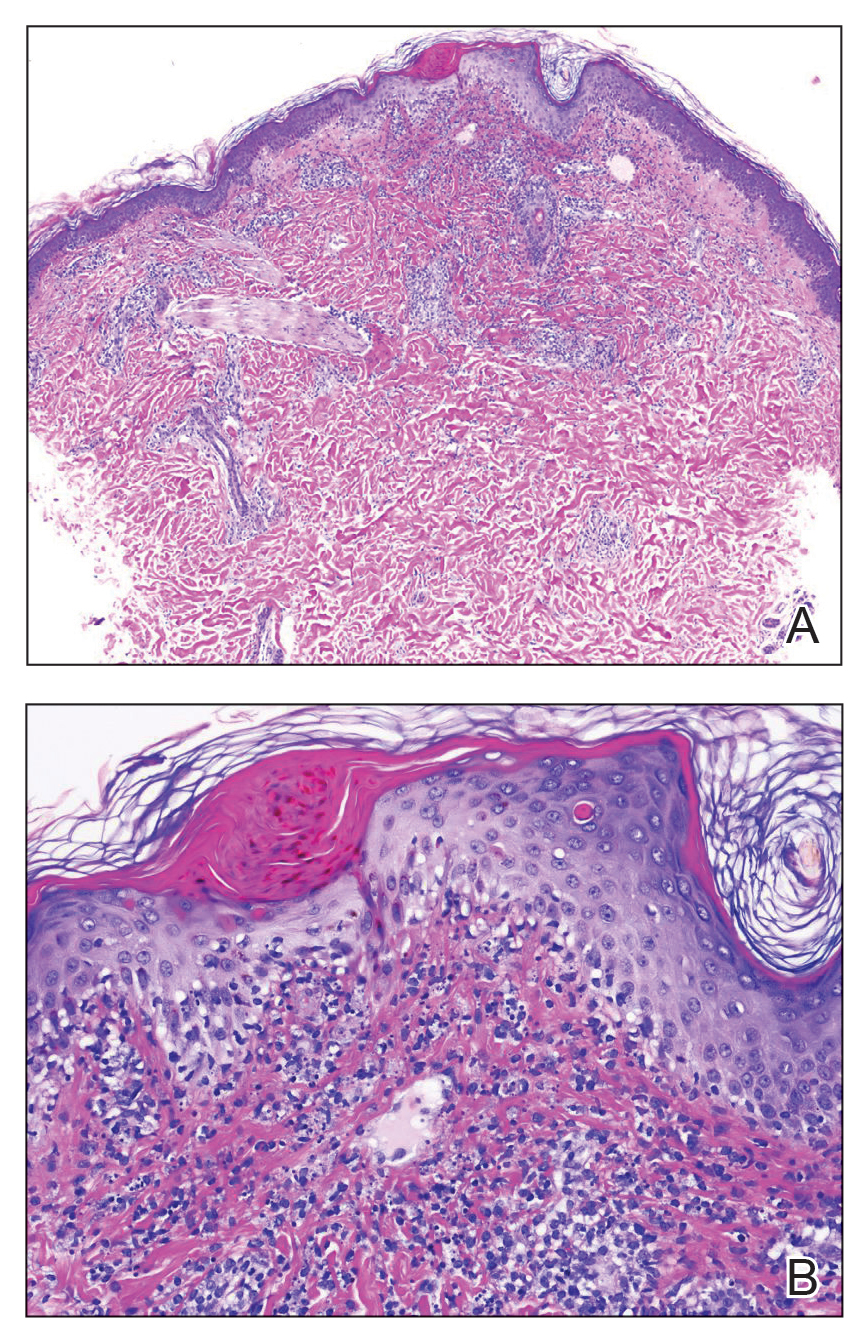

A repeat biopsy displayed bullous amyloidosis. Histopathologic examination revealed an ulcerated subepidermal blister with fibrin deposition at the ulcer base. A periadnexal, scant, eosinophilic deposition with extravasated red blood cells was appreciated. Amorphous eosinophilic deposits were found within the detached fragment of the epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate. A Congo red stain highlighted these areas with a salmon pink–colored material. Congo red staining showed a moderate amount of pale, apple green, birefringent deposit within these areas on polarized light examination.

A few months later, the patient was re-admitted, and the amount of skin detachment prompted the primary team to ask for another consultation. Although the extensive skin sloughing resembled toxic epidermal necrolysis, a repeat biopsy confirmed bullous amyloidosis.

Comment

Amyloidosis Histopathology—Amyloidoses represent a wide array of disorders with deposition of β-pleated sheets or amyloid fibrils, often with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 Primary systemic amyloidosis has been associated with underlying dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.6 In such cases, the skin lesions of multiple myeloma may result from a collection of misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins or their fragments, as in light chain–related systemic amyloidosis.3 Histopathologically, both systemic and cutaneous amyloidosis appear similar and display deposition of amorphous, eosinophilic, fissured amyloid material in the dermis. Congo red stains the material orange-red and will display a characteristic apple green birefringence under polarized light.4 Although bullous amyloid lesions are rare, the cutaneous forms of these lesions can be an important sign of plasma cell dyscrasia.7

Presentation of Bullous Amyloidosis—Bullous manifestations rarely have been noted in the primary cutaneous forms of amyloidosis.5,8,9 Importantly, cutaneous blistering more often is linked to systemic forms of amyloidosis with multiorgan involvement, including primary systemic and myeloma-associated amyloidosis.5,10 However, patients with localized bullous cutaneous amyloidosis without systemic involvement also have been seen.10,11 Bullae may occur at any time, with contents that frequently are hemorrhagic due to capillary fragility.12,13 Bullous manifestations raise the differential diagnoses of bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, linear IgA disease, porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, bullous drug eruption, bullous eruption of renal dialysis, or bullous lupus erythematosus.5,13-17

In our patient, the acral distribution of bullae, presence of hemorrhage, chronicity of symptoms, and negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay initially suggested a diagnosis of pseudoporphyria. However, the presence of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and subsequent confirmatory pathology aided in differentiating bullous amyloidosis from pseudoporphyria. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare form of skin-restricted amyloidoses, can coexist with bullous lesions. Of note, reported cases of nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis did not result in development of multiple myeloma.5,10

Bullae are located either subepidermally or intradermally, and bullous lesions of cutaneous amyloidosis typically demonstrate subepidermal or superficial intradermal clefting on light microscopy.5,10,12 Histopathology of bullous amyloidosis shows intradermal or subepidermal blister formation and amorphous eosinophilic material showing apple green birefringence with Congo red staining deposited in the dermis and/or around the adipocytes and blood vessel walls.12,18-20 In prior cases, direct immunofluorescence of bullous amyloidosis revealed absent immunoglobulin (IgG, IgA, IgM) or complement (C3 and C9) deposits in the basement membrane zone or dermis.13,21,22 In these cases, electron microscopy was useful in diagnosis, as it showed the presence of amyloid deposits.21,22

Cause of Bullae—Various mechanisms are thought to trigger the blister formation in amyloidosis. Bullae created from trauma or friction often present as tense painful blisters that commonly are hemorrhagic.10,23 Amyloid deposits in the walls of blood vessels and the affinity of dermal amyloid in blood vessel walls to surrounding collagen likely leads to increased fragility of capillaries and the dermal matrix, hemorrhagic tendency, and infrapapillary blisters, thus creating hemorrhagic bullous eruptions.24,25 Specifically, close proximity of immunoglobulin-derived amyloid oligomers to epidermal keratinocytes may be toxic and therefore could trigger subepidermal bullous change.5 Additionally, alteration in the physicochemical properties of the amyloidal protein might explain bullous eruption.9 Trauma or rubbing of the hands and feet may precipitate the acral blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.5,11

Due to deposition of these amyloid fibrils, skin bleeding in these patients is called amyloid or pinch purpura. Vessel wall fragility and damage by amyloid are the principal causes of periorbital and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.26 Destruction of the lamina densa and widening of the intercellular space between keratinocytes by amyloid globules induce skin fragility.11

Although uncommon, various cases of bullous amyloidosis have been reported in the literature. Multiple myeloma patients represent the majority of those reported to have bullous amyloidosis.6,7,13,24,27-30 Plasmacytoma-associated bullous amyloid purpura and paraproteinemia also have been noted.25 Multiple myeloma with secondary AL amyloidosis has been seen with amyloid purpura and atraumatic ecchymoses of the face, highlighting the hemorrhage noted in these patients.26

Management of Amyloidosis—Various treatment options have been attempted for primary cutaneous amyloidosis, including oral retinoids, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, amitriptyline, colchicine, cepharanthin, tacrolimus, dimethyl sulfoxide, vitamin D3 analogs, capsaicin, menthol, hydrocolloid dressings, surgical modalities, laser treatment, and phototherapy.1 There is no clear consensus for therapeutic modalities except for treating the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia in primary systemic amyloidosis.

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient displaying signs of pseudoporphyria that ultimately proved to be bullous amyloidosis, or what we termed pseudopseudoporphyria. Bullous amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnoses of hemorrhagic bullous skin eruptions. Particular attention should be given to a systemic workup for multiple myeloma when hemorrhagic vesicles/bullae are chronic and coexist with purpura, angina bullosa hemorrhagica, fatigue/weight loss, and/or macroglossia.

Cutaneous amyloidosis encompasses a variety of clinical presentations. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis comprises lichen amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis, and nodular amyloidosis.1 Macular and lichen amyloidosis result from keratin deposits, while nodular amyloidosis results from cutaneous infiltration of plasma cells.2 Primary systemic amyloidosis is due to a plasma cell dyscrasia, particularly multiple myeloma, while secondary systemic amyloidosis occurs in the setting of restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, renal dysfunction, or chronic inflammation, as seen with rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, and various autoinflammatory disorders.2 Plasma cell proliferative disorders are associated with various skin disorders, which may result from aggregated misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins, indicating light chain–related systemic amyloidosis. Mucocutaneous lesions can occur in 30% to 40% of cases of primary systemic amyloidosis and may present as purpura, ecchymoses, waxy thickening, plaques, subcutaneous nodules, and/or bullae.3,4 When blistering is present, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes autoimmune bullous disease, drug eruptions, enoxaparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis, deposition diseases, allergic contact dermatitis, bullous cellulitis, bullous bite reactions, neutrophilic dermatosis, and bullous lichen sclerosus.5 Herein, we present a case of a woman with a bullous skin eruption who eventually was diagnosed with bullous amyloidosis subsequent to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Case Report

A 70-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of well-demarcated, hemorrhagic, flaccid vesicles and focal erosions with a rim of erythema on the distal forearms and hands. A shave biopsy from the right forearm showed cell-poor subepidermal vesicular dermatitis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for bullous pemphigoid antigens 1 and 2 as well as urinary porphyrins were negative. Direct immunofluorescence showed granular IgM at the basement membrane zone around vessels and cytoid bodies. At this time, a preliminary diagnosis of pseudoporphyria was suspected, though no classic medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, furosemide, antibiotics) or exogenous trigger factors (eg, UV light exposure, dialysis) were temporally related. Three months later, the patient presented with a large hemorrhagic bulla on the distal left forearm (Figure 1) and healing erosions on the dorsal fingers and upper back. Clobetasol ointment was initiated, as an autoimmune bullous dermatosis was suspected.

Approximately 1 year after she was first seen in our outpatient clinic, the patient was hospitalized for induction of chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone—for a new diagnosis of stage III multiple myeloma. A workup for back pain revealed multiple compression fractures and a plasma cell neoplasm with elevated λ light chains, which was confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy. During an inpatient dermatology consultation, we noted the development of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and worsening generalization of the hemorrhagic bullae, with healing erosions and intact hemorrhagic bullae on the dorsal hands, fingers (Figure 2), and upper back.

A repeat biopsy displayed bullous amyloidosis. Histopathologic examination revealed an ulcerated subepidermal blister with fibrin deposition at the ulcer base. A periadnexal, scant, eosinophilic deposition with extravasated red blood cells was appreciated. Amorphous eosinophilic deposits were found within the detached fragment of the epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate. A Congo red stain highlighted these areas with a salmon pink–colored material. Congo red staining showed a moderate amount of pale, apple green, birefringent deposit within these areas on polarized light examination.

A few months later, the patient was re-admitted, and the amount of skin detachment prompted the primary team to ask for another consultation. Although the extensive skin sloughing resembled toxic epidermal necrolysis, a repeat biopsy confirmed bullous amyloidosis.

Comment

Amyloidosis Histopathology—Amyloidoses represent a wide array of disorders with deposition of β-pleated sheets or amyloid fibrils, often with cutaneous manifestations.2,3 Primary systemic amyloidosis has been associated with underlying dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.6 In such cases, the skin lesions of multiple myeloma may result from a collection of misfolded monoclonal immunoglobulins or their fragments, as in light chain–related systemic amyloidosis.3 Histopathologically, both systemic and cutaneous amyloidosis appear similar and display deposition of amorphous, eosinophilic, fissured amyloid material in the dermis. Congo red stains the material orange-red and will display a characteristic apple green birefringence under polarized light.4 Although bullous amyloid lesions are rare, the cutaneous forms of these lesions can be an important sign of plasma cell dyscrasia.7

Presentation of Bullous Amyloidosis—Bullous manifestations rarely have been noted in the primary cutaneous forms of amyloidosis.5,8,9 Importantly, cutaneous blistering more often is linked to systemic forms of amyloidosis with multiorgan involvement, including primary systemic and myeloma-associated amyloidosis.5,10 However, patients with localized bullous cutaneous amyloidosis without systemic involvement also have been seen.10,11 Bullae may occur at any time, with contents that frequently are hemorrhagic due to capillary fragility.12,13 Bullous manifestations raise the differential diagnoses of bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, linear IgA disease, porphyria cutanea tarda, pseudoporphyria, bullous drug eruption, bullous eruption of renal dialysis, or bullous lupus erythematosus.5,13-17

In our patient, the acral distribution of bullae, presence of hemorrhage, chronicity of symptoms, and negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay initially suggested a diagnosis of pseudoporphyria. However, the presence of intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and subsequent confirmatory pathology aided in differentiating bullous amyloidosis from pseudoporphyria. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis, a rare form of skin-restricted amyloidoses, can coexist with bullous lesions. Of note, reported cases of nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis did not result in development of multiple myeloma.5,10

Bullae are located either subepidermally or intradermally, and bullous lesions of cutaneous amyloidosis typically demonstrate subepidermal or superficial intradermal clefting on light microscopy.5,10,12 Histopathology of bullous amyloidosis shows intradermal or subepidermal blister formation and amorphous eosinophilic material showing apple green birefringence with Congo red staining deposited in the dermis and/or around the adipocytes and blood vessel walls.12,18-20 In prior cases, direct immunofluorescence of bullous amyloidosis revealed absent immunoglobulin (IgG, IgA, IgM) or complement (C3 and C9) deposits in the basement membrane zone or dermis.13,21,22 In these cases, electron microscopy was useful in diagnosis, as it showed the presence of amyloid deposits.21,22

Cause of Bullae—Various mechanisms are thought to trigger the blister formation in amyloidosis. Bullae created from trauma or friction often present as tense painful blisters that commonly are hemorrhagic.10,23 Amyloid deposits in the walls of blood vessels and the affinity of dermal amyloid in blood vessel walls to surrounding collagen likely leads to increased fragility of capillaries and the dermal matrix, hemorrhagic tendency, and infrapapillary blisters, thus creating hemorrhagic bullous eruptions.24,25 Specifically, close proximity of immunoglobulin-derived amyloid oligomers to epidermal keratinocytes may be toxic and therefore could trigger subepidermal bullous change.5 Additionally, alteration in the physicochemical properties of the amyloidal protein might explain bullous eruption.9 Trauma or rubbing of the hands and feet may precipitate the acral blister formation in bullous amyloidosis.5,11

Due to deposition of these amyloid fibrils, skin bleeding in these patients is called amyloid or pinch purpura. Vessel wall fragility and damage by amyloid are the principal causes of periorbital and gastrointestinal tract bleeding.26 Destruction of the lamina densa and widening of the intercellular space between keratinocytes by amyloid globules induce skin fragility.11

Although uncommon, various cases of bullous amyloidosis have been reported in the literature. Multiple myeloma patients represent the majority of those reported to have bullous amyloidosis.6,7,13,24,27-30 Plasmacytoma-associated bullous amyloid purpura and paraproteinemia also have been noted.25 Multiple myeloma with secondary AL amyloidosis has been seen with amyloid purpura and atraumatic ecchymoses of the face, highlighting the hemorrhage noted in these patients.26

Management of Amyloidosis—Various treatment options have been attempted for primary cutaneous amyloidosis, including oral retinoids, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, amitriptyline, colchicine, cepharanthin, tacrolimus, dimethyl sulfoxide, vitamin D3 analogs, capsaicin, menthol, hydrocolloid dressings, surgical modalities, laser treatment, and phototherapy.1 There is no clear consensus for therapeutic modalities except for treating the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia in primary systemic amyloidosis.

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient displaying signs of pseudoporphyria that ultimately proved to be bullous amyloidosis, or what we termed pseudopseudoporphyria. Bullous amyloidosis should be considered in the differential diagnoses of hemorrhagic bullous skin eruptions. Particular attention should be given to a systemic workup for multiple myeloma when hemorrhagic vesicles/bullae are chronic and coexist with purpura, angina bullosa hemorrhagica, fatigue/weight loss, and/or macroglossia.

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Amyloidosis. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:341-345.

- Bhutani M, Shahid Z, Schnebelen A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell proliferative disorders. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:395-400.

- Terushkin V, Boyd KP, Patel RR, et al. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20711.

- LaChance A, Phelps A, Finch J, et al. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:344-347.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

- Kanoh T. Bullous amyloidosis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34:1050-1052.

- Johnson TM, Rapini RP, Hebert AA, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Cutis. 1989;43:346-352.

- Houman MH, Smiti KM, Ben Ghorbel I, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129:299-302.

- Sanusi T, Li Y, Qian Y, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis with bullous lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:400-402.

- Ochiai T, Morishima T, Hao T, et al. Bullous amyloidosis: the mechanism of blister formation revealed by electron microscopy. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:407-411.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Wang XD, Shen H, Liu ZH. Diffuse haemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis with multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:94-96.

- Biswas P, Aggarwal I, Sen D, et al. Bullous pemphigoid clinically presenting as lichen amyloidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:544-546.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous dermatosis vs amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:252.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous amyloidosis vs epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. JAMA. 1981;245:32.

- Murphy GM, Wright J, Nicholls DS, et al. Sunbed-induced pseudoporphyria. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:555-562.

- Pramatarov K, Lazarova A, Mateev G, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic primary systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:211-213.

- Bieber T, Ruzicka T, Linke RP, et al. Hemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis. a histologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study of two patients. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1683-1686.

- Khoo BP, Tay YK. Lichen amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:105-107.

- Asahina A, Hasegawa K, Ishiyama M, et al. Bullous amyloidosis mimicking bullous pemphigoid: usefulness of electron microscopic examination. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:427-428.

- Schmutz JL, Barbaud A, Cuny JF, et al. Bullous amyloidosis [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:295-301.

- Lachmann HJ, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis of the skin. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:1574-1583.

- Grundmann JU, Bonnekoh B, Gollnick H. Extensive haemorrhagic-bullous skin manifestation of systemic AA-amyloidosis associated with IgG lambda-myeloma. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:139-142.

- Hödl S, Turek TD, Kerl H. Plasmocytoma-associated bullous hemorrhagic amyloidosis of the skin [in German]. Hautarzt. 1982;33:556-558.

- Colucci G, Alberio L, Demarmels Biasiutti F, et al. Bilateral periorbital ecchymoses. an often missed sign of amyloid purpura. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:249-252.

- Behera B, Pattnaik M, Sahu B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:668-671.

- Fujita Y, Tsuji-Abe Y, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Nail dystrophy and blisters as sole manifestations in myeloma-associated amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:712-714.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Winzer M, Ruppert M, Baretton G, et al. Bullous poikilodermatitic amyloidosis of the skin with junctional bulla development in IgG light chain plasmacytoma of the lambda type. histology, immunohistology and electron microscopy [in German]. Hautarzt. 1992;43:199-204.

- Weidner T, Illing T, Elsner P. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: a systematic treatment review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:629-642.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Amyloidosis. Dermatology Essentials. Elsevier Saunders; 2014:341-345.

- Bhutani M, Shahid Z, Schnebelen A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell proliferative disorders. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:395-400.

- Terushkin V, Boyd KP, Patel RR, et al. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20711.

- LaChance A, Phelps A, Finch J, et al. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:344-347.

- Gonzalez-Ramos J, Garrido-Gutiérrez C, González-Silva Y, et al. Relapsing bullous amyloidosis of the oral mucosa and acquired cutis laxa in a patient with multiple myeloma: a rare triple association. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:410-412.

- Kanoh T. Bullous amyloidosis [in Japanese]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34:1050-1052.

- Johnson TM, Rapini RP, Hebert AA, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Cutis. 1989;43:346-352.

- Houman MH, Smiti KM, Ben Ghorbel I, et al. Bullous amyloidosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2002;129:299-302.

- Sanusi T, Li Y, Qian Y, et al. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis with bullous lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:400-402.

- Ochiai T, Morishima T, Hao T, et al. Bullous amyloidosis: the mechanism of blister formation revealed by electron microscopy. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:407-411.

- Chu CH, Chan JY, Hsieh SW, et al. Diffuse ecchymoses and blisters on a yellowish waxy base: a case of bullous amyloidosis. J Dermatol. 2016;43:713-714.

- Wang XD, Shen H, Liu ZH. Diffuse haemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis with multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:94-96.

- Biswas P, Aggarwal I, Sen D, et al. Bullous pemphigoid clinically presenting as lichen amyloidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:544-546.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous dermatosis vs amyloidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:252.

- Bluhm JF 3rd. Bullous amyloidosis vs epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. JAMA. 1981;245:32.

- Murphy GM, Wright J, Nicholls DS, et al. Sunbed-induced pseudoporphyria. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:555-562.

- Pramatarov K, Lazarova A, Mateev G, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic primary systemic amyloidosis. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:211-213.

- Bieber T, Ruzicka T, Linke RP, et al. Hemorrhagic bullous amyloidosis. a histologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study of two patients. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1683-1686.

- Khoo BP, Tay YK. Lichen amyloidosis: a bullous variant. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2000;29:105-107.

- Asahina A, Hasegawa K, Ishiyama M, et al. Bullous amyloidosis mimicking bullous pemphigoid: usefulness of electron microscopic examination. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:427-428.

- Schmutz JL, Barbaud A, Cuny JF, et al. Bullous amyloidosis [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:295-301.

- Lachmann HJ, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis of the skin. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012:1574-1583.

- Grundmann JU, Bonnekoh B, Gollnick H. Extensive haemorrhagic-bullous skin manifestation of systemic AA-amyloidosis associated with IgG lambda-myeloma. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:139-142.

- Hödl S, Turek TD, Kerl H. Plasmocytoma-associated bullous hemorrhagic amyloidosis of the skin [in German]. Hautarzt. 1982;33:556-558.

- Colucci G, Alberio L, Demarmels Biasiutti F, et al. Bilateral periorbital ecchymoses. an often missed sign of amyloid purpura. Hamostaseologie. 2014;34:249-252.

- Behera B, Pattnaik M, Sahu B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of multiple myeloma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:668-671.

- Fujita Y, Tsuji-Abe Y, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Nail dystrophy and blisters as sole manifestations in myeloma-associated amyloidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:712-714.

- Chang SL, Lai PC, Cheng CJ, et al. Bullous amyloidosis in a hemodialysis patient is myeloma-associated rather than hemodialysis-associated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2007;14:153-156.

- Winzer M, Ruppert M, Baretton G, et al. Bullous poikilodermatitic amyloidosis of the skin with junctional bulla development in IgG light chain plasmacytoma of the lambda type. histology, immunohistology and electron microscopy [in German]. Hautarzt. 1992;43:199-204.

Practice Points

- Primary systemic amyloidosis, including the rare cutaneous bullous amyloidosis, often is difficult to diagnose and has been associated with underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or multiple myeloma.

- When evaluating patients with initially convincing signs of pseudoporphyria, it is imperative to consider the diagnosis of bullous amyloidosis, which additionally can present with intraoral hemorrhagic vesicles and have confirmatory histopathologic features.

- Further investigation for multiple myeloma is warranted when patients with a chronic hemorrhagic bullous condition also present with symptoms of purpura, angina bullosa hemorrhagica, fatigue, weight loss, and/or macroglossia. Accurate diagnosis of bullous amyloidosis and timely treatment of its underlying cause will contribute to better, more proactive patient care.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease in an Adolescent Boy

To the Editor:

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease, also called histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, was described in 1972 by both Kikuchi1 and Fujimoto et al.2 Most cases are reported in Asia, with limited reports in the United States.3-5 Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare, self-limiting condition consisting of benign lymphadenopathy and oftentimes fever and systemic symptoms. Lymph node involvement may mimic non-Hodgkin lymphoma or other reactive lymphadenopathy, rendering diagnostic accuracy challenging.5 Cutaneous manifestations are reported in only 16% to 40% of patients.6,7 Herein, we describe the clinical and pathologic features of a case of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease with cutaneous involvement in an adolescent boy.

A 13-year-old adolescent boy with no notable medical history presented to the pediatric emergency department with cervical lymphadenopathy, weight loss, intermittent fever, and an evolving rash on the face, ears, arms, and thighs of 6 weeks’ duration. The illness began with enlarged lymph nodes and erythematous macules on the face and was diagnosed by his primary care physician as lymphadenitis that was unresponsive to clindamycin. Over the subsequent weeks, the rash worsened, and he developed intermittent fevers, night sweats, abdominal pain, and nausea with a 20-pound weight loss. He presented to the emergency department 3 weeks prior to the current admission and was noted to have elevated cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgM and IgG in addition to lymphopenia and anemia. He was discharged with outpatient follow-up. The rash progressed to involve the face, ears, arms, and thighs. One day prior to the current admission, the patient’s abdominal pain worsened acutely, and he experienced several episodes of emesis. He presented to the pediatric emergency department for further evaluation, and a dermatology consultation was requested at that time.

The patient’s rash was asymptomatic. In addition to the above symptoms, he also noted frequent nosebleeds, gingival bleeding, and diffuse myalgia that was most prominent on the hands and feet; he denied diarrhea, sick contacts, recent travel, or insect bites. His vital signs were normal, and he remained afebrile throughout the hospitalization. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing patient with sunken eyes and dry lips. He had pink, oval, scaly plaques on the cheeks, ears, and arms (Figure 1). The thighs exhibited folliculocentric erythematous papules. The ocular conjunctivae were clear, but white exudative plaques were noted on the tongue. Tender, bilateral, cervical lymphadenopathy and diffuse abdominal tenderness with guarding and hepatosplenomegaly also were present. The fingers and toes were tender upon palpation.

Laboratory workup at admission revealed the following: low white blood cell count, 2700/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL); low hemoglobin, 9.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL); elevated aspartate aminotransferase, 91 U/L (reference range, 10–30 U/L); and elevated alanine aminotransferase, 118 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase (582 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]), ferritin (1681 ng/mL [reference range, 15–200 ng/mL]), and C-reactive protein (6.0 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]) also were elevated. A respiratory viral panel was unremarkable. Blood cultures were negative, and an HIV 1/2 assay was nonreactive. A chest radiograph demonstrated clear lung fields. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed prominent mesenteric, ileocolic, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

The differential diagnoses at this time included acute connective tissue disease, a paraneoplastic phenomenon, cutaneous lymphoma, or an infectious etiology. A punch biopsy of the skin as well as tissue cultures were performed from a lesion on the right arm. Quantitative immunoglobulin (IgA, IgG, IgM) levels were checked, all of which were within reference range. An antinuclear antibody (ANA) assay and rheumatoid factor were normal.

The tissue cultures were negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Microscopic examination of the skin biopsy revealed a moderate perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of predominantly histiocytes and lymphocytes with prominent karyorrhectic debris (nuclear dust) in the upper dermis as well as focal vacuolar interface changes with scattered necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis (Figure 2). Based on these histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease was considered. To confirm the diagnosis and to rule out the possibility of lymphoma, an excisional biopsy of the cervical lymph node was performed, which showed typical histopathologic features of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis.

Given the patient’s clinical presentation with arthralgia, anorexia, lymphadenitis, and hepatosplenomegaly along with histopathologic findings from both the skin and lymph node biopsies, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease was made. The patient was conservatively managed with acetaminophen and was discharged with improvement in his appetite and systemic symptoms.

He was seen for follow-up 3 months later in the outpatient clinic. He denied any recurrence of systemic symptoms but endorsed a recent shedding of hair consistent with telogen effluvium. The rash had substantially improved, though residual asymptomatic erythematous plaques remained on the right forehead and right cheek (Figure 3). He was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% to apply to the active area twice daily for the following 2 to 3 weeks.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease presents with a wide clinical spectrum, classically with benign lymphadenopathy and fever of unknown etiology.5,6 Lymphadenopathy most often is cervical (55%–99%)8 and unilateral,4,7 but patients can present with polyadenopathy (52%).7,8 Constitutional signs commonly include fever (35%–76%), weight loss, arthritis (5%–34%), and leukopenia (25%–74%).4,8,9

Cutaneous findings have been described in up to 40% of cases, of which clinical presentation is variable.6 Lesions may include blanchable, erythematous, painful, and/or indurated plaques, nodules, or maculopapules with confluence into patches, urticaria, morbilliform lesions, erythema multiforme, eyelid edema, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, papulopustules, ulcerated gingivae, and mucositis.6,7,10-13 Patients with skin lesions may be at an increased risk for developing systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).8 Our patient presented with erythematous scaly plaques with a predominance of lesions in photodistributed locations, which clinically mimicked an underlying connective tissue disease process such as SLE.

Infectious agents such as CMV, parvovirus B19, human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 8 and human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1, HIV, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Toxoplasma have all been implicated as possible causes of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease, but studies have failed to provide convincing causal evidence.9,14,15 Our patient had positive IgM and IgG for CMV, which may have incited his disease.

Definitive diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is made by lymph node excisional biopsy, which histologically exhibits a histiocytic cell proliferation with paracortical foci of necrosis and abundant karyorrhectic debris.5 Cutaneous histologic findings that support the diagnosis are variable and may include a dermal histiocytic infiltrate, epidermal change with necrotic keratinocytes, non-neutrophilic karyorrhectic debris, basal vacuolar change, papillary dermal edema, a nonspecific superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate, and a patchy infiltration of histiocytes and lymphocytes.6,13