User login

Formerly Skin & Allergy News

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')]

The leading independent newspaper covering dermatology news and commentary.

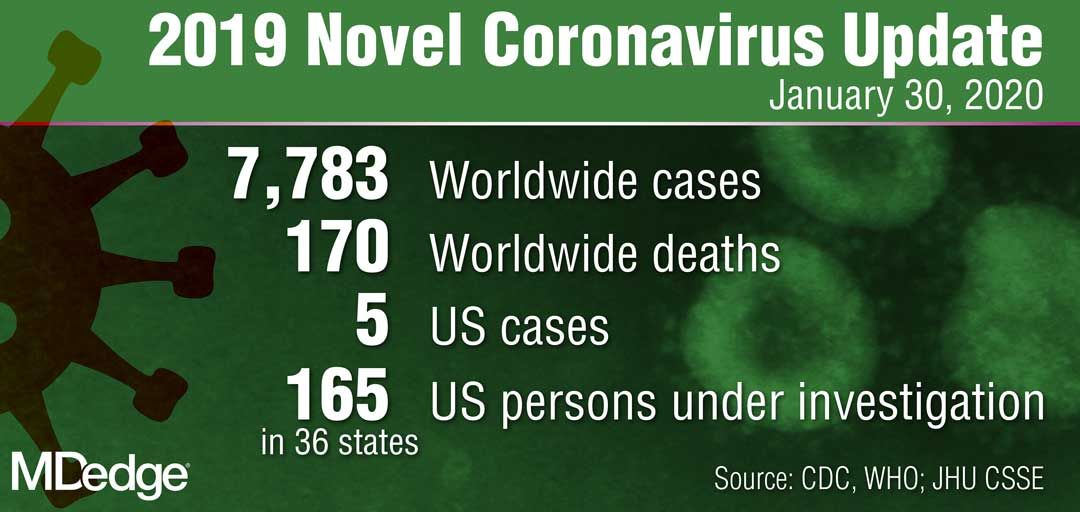

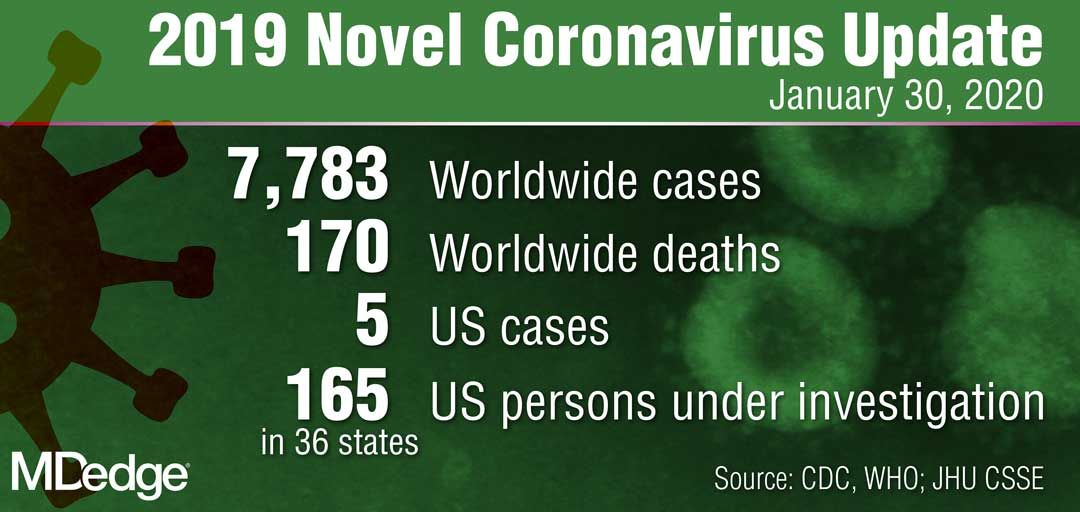

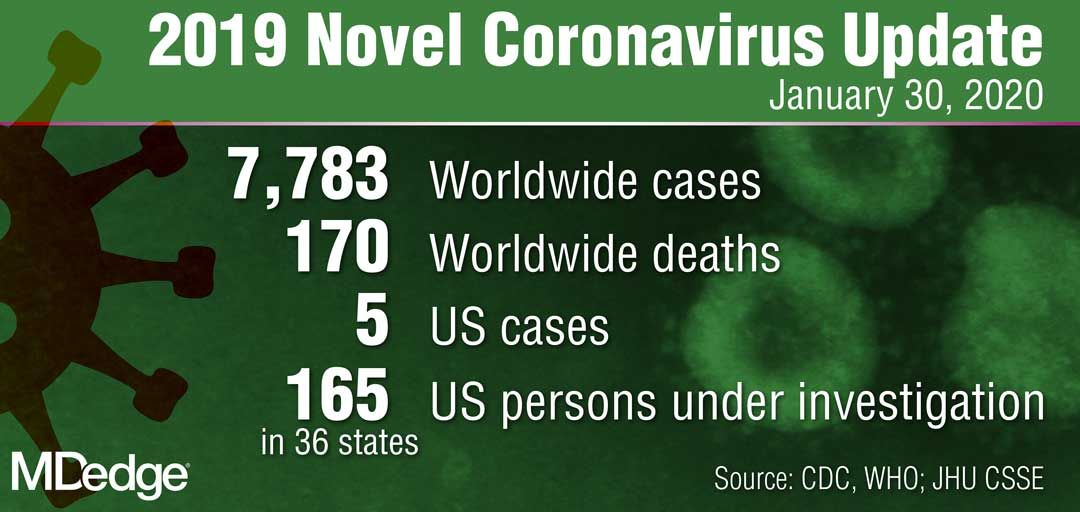

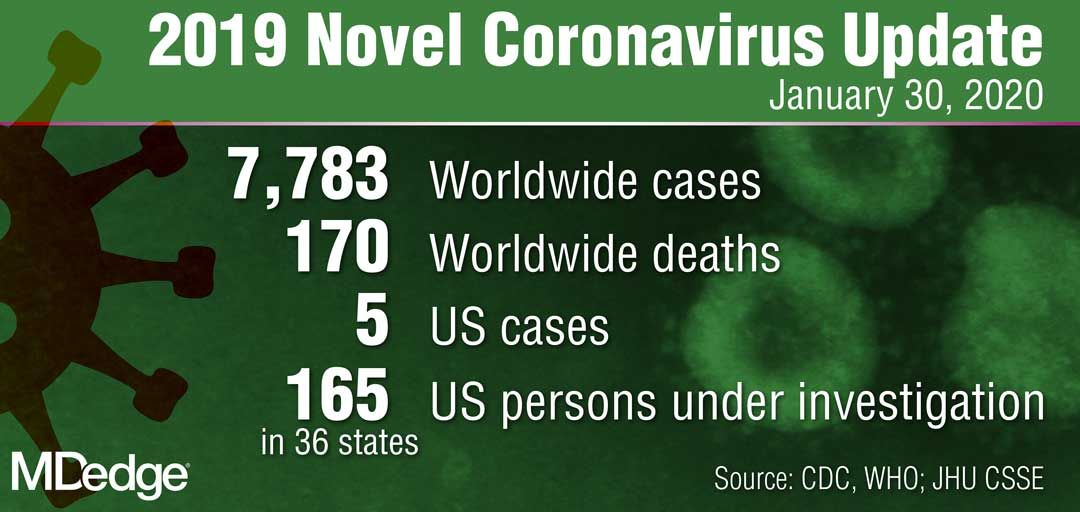

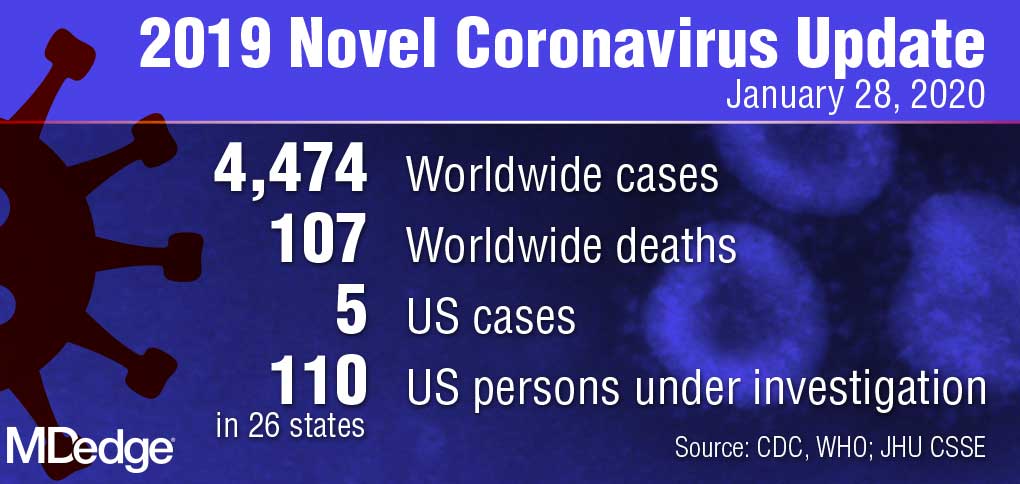

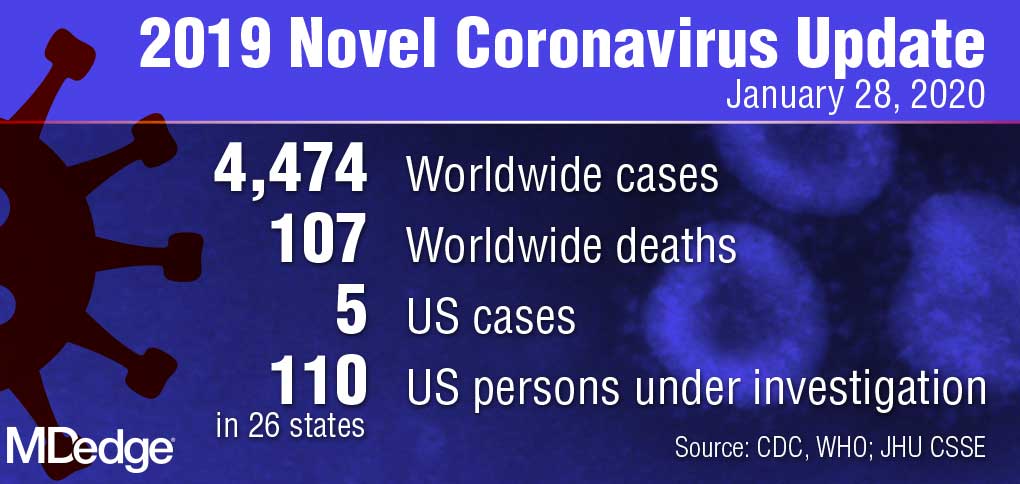

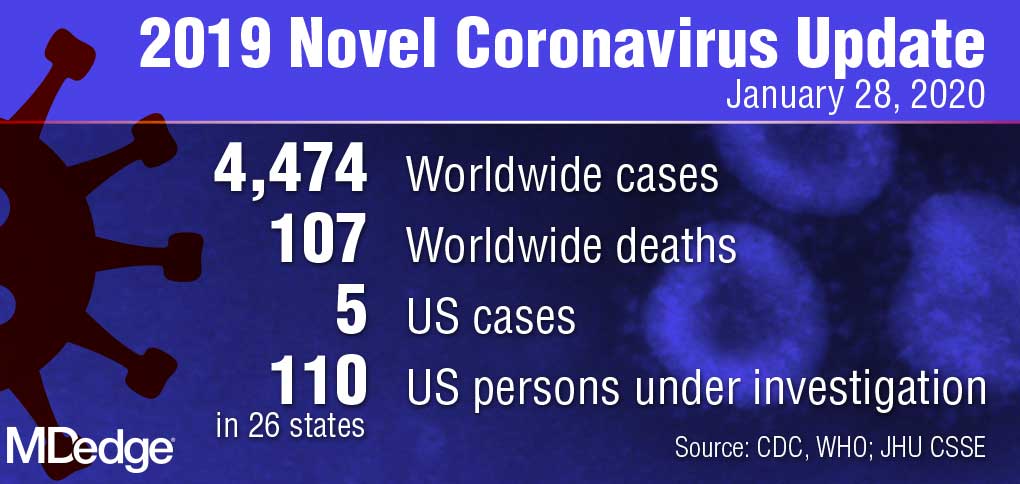

CDC: Risk in U.S. from 2019-nCoV remains low

A total of 165 persons in the United States are under investigation for infection with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), with 68 testing negative and only 5 confirming positive, according to data presented Jan. 29 during a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) briefing.

The remaining samples are in transit or are being processed at the CDC for testing, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during the briefing.

“The genetic sequence for all five viruses detected in the United States to date has been uploaded to the CDC website,” she said. “We are working quickly through the process to get the CDC-developed test into the hands of public health partners in the U.S. and internationally.”

Dr. Messonnier reported that the CDC is expanding screening efforts to U.S. ports of entry that house CDC quarantine stations. Also, in collaboration with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency is expanding distribution of travel health education materials to all travelers from China.

“The good news here is that, despite an aggressive public health investigation to find new cases [of 2019-nCoV], we have not,” she said. “The situation in China is concerning, however, we are looking hard here in the U.S. We will continue to be proactive. I still expect that we will find additional cases.”

In another development, the federal government facilitated the return of a plane full of U.S. citizens living in Wuhan, China, to March Air Reserve Force Base in Riverside County, Calif. “We have taken every precaution to ensure their safety while also continuing to protect the health of our nation and the people around them,” Dr. Messonnier said.

All 195 passengers have been screened, monitored, and evaluated by medical personnel “every step of the way,” including before takeoff, during the flight, during a refueling stop in Alaska, and again upon landing at March Air Reserve Force Base on Jan. 28. “All 195 patients are without the symptoms of the novel coronavirus, and all have been assigned living quarters at the Air Force base,” Dr. Messonnier said.

The CDC has launched a second stage of further screening and information gathering from the passengers, who will be offered testing as part of a thorough risk assessment.

“I understand that many people in the U.S. are worried about this virus and whether it will affect them,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Outbreaks like this are always concerning, particularly when a new virus is emerging. But we are well prepared and working closely with federal, state, and local partners to protect our communities and others nationwide from this public health threat. At this time, we continue to believe that the immediate health risk from this new virus to the general American public is low.”

A total of 165 persons in the United States are under investigation for infection with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), with 68 testing negative and only 5 confirming positive, according to data presented Jan. 29 during a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) briefing.

The remaining samples are in transit or are being processed at the CDC for testing, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during the briefing.

“The genetic sequence for all five viruses detected in the United States to date has been uploaded to the CDC website,” she said. “We are working quickly through the process to get the CDC-developed test into the hands of public health partners in the U.S. and internationally.”

Dr. Messonnier reported that the CDC is expanding screening efforts to U.S. ports of entry that house CDC quarantine stations. Also, in collaboration with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency is expanding distribution of travel health education materials to all travelers from China.

“The good news here is that, despite an aggressive public health investigation to find new cases [of 2019-nCoV], we have not,” she said. “The situation in China is concerning, however, we are looking hard here in the U.S. We will continue to be proactive. I still expect that we will find additional cases.”

In another development, the federal government facilitated the return of a plane full of U.S. citizens living in Wuhan, China, to March Air Reserve Force Base in Riverside County, Calif. “We have taken every precaution to ensure their safety while also continuing to protect the health of our nation and the people around them,” Dr. Messonnier said.

All 195 passengers have been screened, monitored, and evaluated by medical personnel “every step of the way,” including before takeoff, during the flight, during a refueling stop in Alaska, and again upon landing at March Air Reserve Force Base on Jan. 28. “All 195 patients are without the symptoms of the novel coronavirus, and all have been assigned living quarters at the Air Force base,” Dr. Messonnier said.

The CDC has launched a second stage of further screening and information gathering from the passengers, who will be offered testing as part of a thorough risk assessment.

“I understand that many people in the U.S. are worried about this virus and whether it will affect them,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Outbreaks like this are always concerning, particularly when a new virus is emerging. But we are well prepared and working closely with federal, state, and local partners to protect our communities and others nationwide from this public health threat. At this time, we continue to believe that the immediate health risk from this new virus to the general American public is low.”

A total of 165 persons in the United States are under investigation for infection with the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), with 68 testing negative and only 5 confirming positive, according to data presented Jan. 29 during a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) briefing.

The remaining samples are in transit or are being processed at the CDC for testing, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during the briefing.

“The genetic sequence for all five viruses detected in the United States to date has been uploaded to the CDC website,” she said. “We are working quickly through the process to get the CDC-developed test into the hands of public health partners in the U.S. and internationally.”

Dr. Messonnier reported that the CDC is expanding screening efforts to U.S. ports of entry that house CDC quarantine stations. Also, in collaboration with U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the agency is expanding distribution of travel health education materials to all travelers from China.

“The good news here is that, despite an aggressive public health investigation to find new cases [of 2019-nCoV], we have not,” she said. “The situation in China is concerning, however, we are looking hard here in the U.S. We will continue to be proactive. I still expect that we will find additional cases.”

In another development, the federal government facilitated the return of a plane full of U.S. citizens living in Wuhan, China, to March Air Reserve Force Base in Riverside County, Calif. “We have taken every precaution to ensure their safety while also continuing to protect the health of our nation and the people around them,” Dr. Messonnier said.

All 195 passengers have been screened, monitored, and evaluated by medical personnel “every step of the way,” including before takeoff, during the flight, during a refueling stop in Alaska, and again upon landing at March Air Reserve Force Base on Jan. 28. “All 195 patients are without the symptoms of the novel coronavirus, and all have been assigned living quarters at the Air Force base,” Dr. Messonnier said.

The CDC has launched a second stage of further screening and information gathering from the passengers, who will be offered testing as part of a thorough risk assessment.

“I understand that many people in the U.S. are worried about this virus and whether it will affect them,” Dr. Messonnier said. “Outbreaks like this are always concerning, particularly when a new virus is emerging. But we are well prepared and working closely with federal, state, and local partners to protect our communities and others nationwide from this public health threat. At this time, we continue to believe that the immediate health risk from this new virus to the general American public is low.”

Costs are keeping Americans out of the doctor’s office

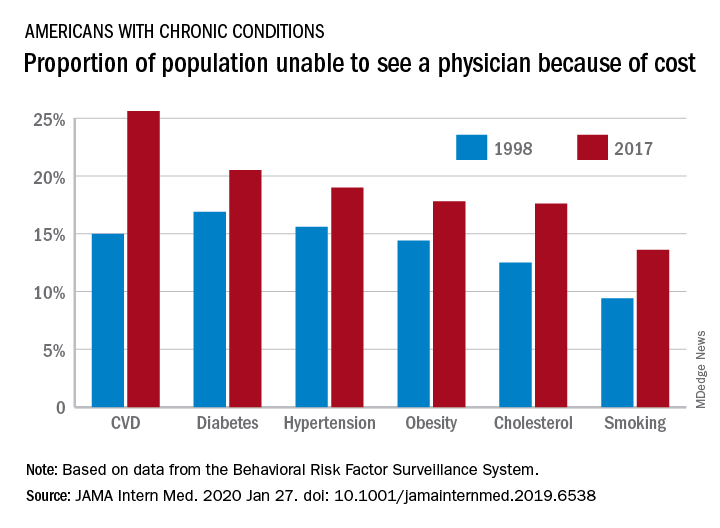

The cost of health care is keeping more Americans from seeing a doctor, even as the number of individuals with insurance coverage increases, according to a new study.

“Despite short-term gains owing to the [Affordable Care Act], over the past 20 years the portion of adults aged 18-64 years unable to see a physician owing to the cost increased, mostly because of an increase among persons with insurance,” Laura Hawks, MD, of Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance and Harvard Medical School in Boston and colleagues wrote in a new research report published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In 2017, nearly one-fifth of individuals with any chronic condition (diabetes, obesity, or cardiovascular disease) said they were unable to see a physician owing to cost,” they continued.

Researchers examined 20 years of data (January 1998 through December 2017) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to identify trends in unmet need for physician and preventive services.

Among adults aged 18-64 years who responded to the survey in 1998 and 2017, uninsurance decreased by 2.1 percentage points, falling from 16.9% to 14.8%. But at the same time, the portion of adults who were unable to see a physician because of cost rose by 2.7 percentage points, from 11.4% to 15.7%. Looking specifically at adults who had insurance coverage, the researchers found that cost was a barrier for 11.5% of them in 2017, up from 7.1% in 1998.

These results come against a backdrop of growing medical costs, increasing deductibles and copayments, an increasing use of cost containment measures like prior authorization, and narrow provider networks in the wake of the transition to value-based payment structures, the authors noted.

“Our finding that financial access to physician care worsened is concerning,” Dr. Hawks and her colleagues wrote. “Persons with conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and poor health status risk substantial harms if they forgo physician care. Financial barriers to care have been associated with increased hospitalizations and worse health outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease and hypertension and increased morbidity among patients with diabetes.”

One of the trends highlighted by the study authors is the growing number of employers offering plans with a high deductible.

“Enrollment in a high-deductible health plan, which has become increasingly common in the last decade, a trend uninterrupted by the ACA, is associated with forgoing needed care, especially among those of lower socioeconomic status,” the authors wrote. “Other changes in insurance benefit design, such as imposing tiered copayments and coinsurance obligations, eliminating coverage for some services (e.g., eyeglasses) and narrowing provider networks (which can force some patients to go out-of-network for care) may also have undermined the affordability of care.”

There was some positive news among the findings, however.

“The main encouraging finding from our analysis is the increase in the proportion of persons – both insured and uninsured – receiving cholesterol checks and flu shots,” Dr. Hawk and her colleagues wrote, adding that this increase “may be attributable to the increasing implementation of quality metrics, financial incentives, and improved systems for the delivery of these services.”

However, not all preventive services that had cost barriers eliminated under the ACA saw improvement, such as cancer screening. They note that the proportion of women who did not receive mammography increased during the study period and then plateaued, but did not improve following the implementation of the ACA. The authors described the reasons for this as “unclear.”

Dr. Hawks received funding support from an Institutional National Research Service award and from Cambridge Health Alliance, her employer. Other authors reported membership in Physicians for a National Health Program.

SOURCE: Hawks L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6538.

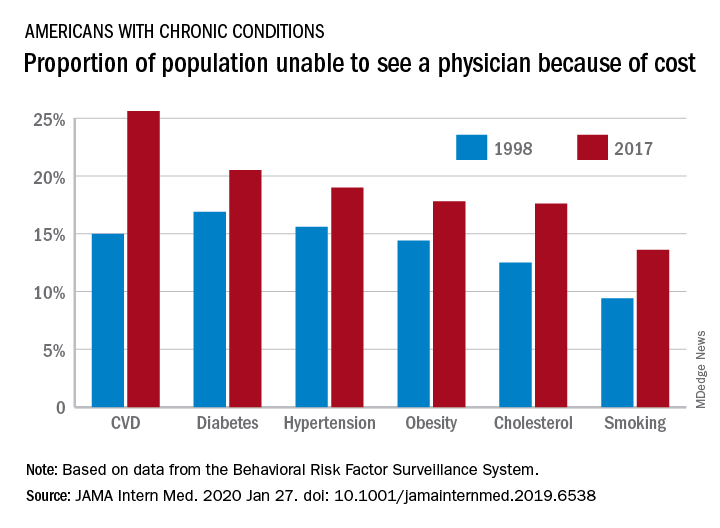

The cost of health care is keeping more Americans from seeing a doctor, even as the number of individuals with insurance coverage increases, according to a new study.

“Despite short-term gains owing to the [Affordable Care Act], over the past 20 years the portion of adults aged 18-64 years unable to see a physician owing to the cost increased, mostly because of an increase among persons with insurance,” Laura Hawks, MD, of Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance and Harvard Medical School in Boston and colleagues wrote in a new research report published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In 2017, nearly one-fifth of individuals with any chronic condition (diabetes, obesity, or cardiovascular disease) said they were unable to see a physician owing to cost,” they continued.

Researchers examined 20 years of data (January 1998 through December 2017) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to identify trends in unmet need for physician and preventive services.

Among adults aged 18-64 years who responded to the survey in 1998 and 2017, uninsurance decreased by 2.1 percentage points, falling from 16.9% to 14.8%. But at the same time, the portion of adults who were unable to see a physician because of cost rose by 2.7 percentage points, from 11.4% to 15.7%. Looking specifically at adults who had insurance coverage, the researchers found that cost was a barrier for 11.5% of them in 2017, up from 7.1% in 1998.

These results come against a backdrop of growing medical costs, increasing deductibles and copayments, an increasing use of cost containment measures like prior authorization, and narrow provider networks in the wake of the transition to value-based payment structures, the authors noted.

“Our finding that financial access to physician care worsened is concerning,” Dr. Hawks and her colleagues wrote. “Persons with conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and poor health status risk substantial harms if they forgo physician care. Financial barriers to care have been associated with increased hospitalizations and worse health outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease and hypertension and increased morbidity among patients with diabetes.”

One of the trends highlighted by the study authors is the growing number of employers offering plans with a high deductible.

“Enrollment in a high-deductible health plan, which has become increasingly common in the last decade, a trend uninterrupted by the ACA, is associated with forgoing needed care, especially among those of lower socioeconomic status,” the authors wrote. “Other changes in insurance benefit design, such as imposing tiered copayments and coinsurance obligations, eliminating coverage for some services (e.g., eyeglasses) and narrowing provider networks (which can force some patients to go out-of-network for care) may also have undermined the affordability of care.”

There was some positive news among the findings, however.

“The main encouraging finding from our analysis is the increase in the proportion of persons – both insured and uninsured – receiving cholesterol checks and flu shots,” Dr. Hawk and her colleagues wrote, adding that this increase “may be attributable to the increasing implementation of quality metrics, financial incentives, and improved systems for the delivery of these services.”

However, not all preventive services that had cost barriers eliminated under the ACA saw improvement, such as cancer screening. They note that the proportion of women who did not receive mammography increased during the study period and then plateaued, but did not improve following the implementation of the ACA. The authors described the reasons for this as “unclear.”

Dr. Hawks received funding support from an Institutional National Research Service award and from Cambridge Health Alliance, her employer. Other authors reported membership in Physicians for a National Health Program.

SOURCE: Hawks L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6538.

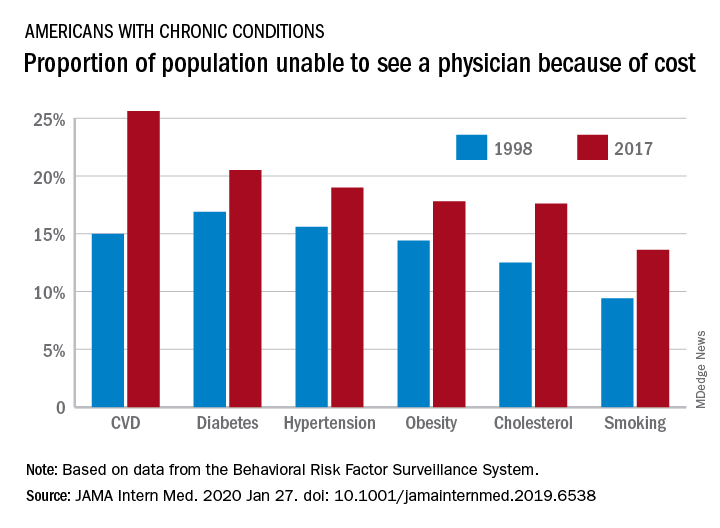

The cost of health care is keeping more Americans from seeing a doctor, even as the number of individuals with insurance coverage increases, according to a new study.

“Despite short-term gains owing to the [Affordable Care Act], over the past 20 years the portion of adults aged 18-64 years unable to see a physician owing to the cost increased, mostly because of an increase among persons with insurance,” Laura Hawks, MD, of Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance and Harvard Medical School in Boston and colleagues wrote in a new research report published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In 2017, nearly one-fifth of individuals with any chronic condition (diabetes, obesity, or cardiovascular disease) said they were unable to see a physician owing to cost,” they continued.

Researchers examined 20 years of data (January 1998 through December 2017) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to identify trends in unmet need for physician and preventive services.

Among adults aged 18-64 years who responded to the survey in 1998 and 2017, uninsurance decreased by 2.1 percentage points, falling from 16.9% to 14.8%. But at the same time, the portion of adults who were unable to see a physician because of cost rose by 2.7 percentage points, from 11.4% to 15.7%. Looking specifically at adults who had insurance coverage, the researchers found that cost was a barrier for 11.5% of them in 2017, up from 7.1% in 1998.

These results come against a backdrop of growing medical costs, increasing deductibles and copayments, an increasing use of cost containment measures like prior authorization, and narrow provider networks in the wake of the transition to value-based payment structures, the authors noted.

“Our finding that financial access to physician care worsened is concerning,” Dr. Hawks and her colleagues wrote. “Persons with conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and poor health status risk substantial harms if they forgo physician care. Financial barriers to care have been associated with increased hospitalizations and worse health outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease and hypertension and increased morbidity among patients with diabetes.”

One of the trends highlighted by the study authors is the growing number of employers offering plans with a high deductible.

“Enrollment in a high-deductible health plan, which has become increasingly common in the last decade, a trend uninterrupted by the ACA, is associated with forgoing needed care, especially among those of lower socioeconomic status,” the authors wrote. “Other changes in insurance benefit design, such as imposing tiered copayments and coinsurance obligations, eliminating coverage for some services (e.g., eyeglasses) and narrowing provider networks (which can force some patients to go out-of-network for care) may also have undermined the affordability of care.”

There was some positive news among the findings, however.

“The main encouraging finding from our analysis is the increase in the proportion of persons – both insured and uninsured – receiving cholesterol checks and flu shots,” Dr. Hawk and her colleagues wrote, adding that this increase “may be attributable to the increasing implementation of quality metrics, financial incentives, and improved systems for the delivery of these services.”

However, not all preventive services that had cost barriers eliminated under the ACA saw improvement, such as cancer screening. They note that the proportion of women who did not receive mammography increased during the study period and then plateaued, but did not improve following the implementation of the ACA. The authors described the reasons for this as “unclear.”

Dr. Hawks received funding support from an Institutional National Research Service award and from Cambridge Health Alliance, her employer. Other authors reported membership in Physicians for a National Health Program.

SOURCE: Hawks L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6538.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Psoriasis: A look back over the past 50 years, and forward to next steps

Imagine a patient suffering with horrible psoriasis for decades having failed “every available treatment.” Imagine him living all that time with “flaking, cracking, painful, itchy skin,” only to develop cirrhosis after exposure to toxic therapies.

Then imagine the experience for that patient when, 2 weeks after initiating treatment with a new interleukin-17 inhibitor, his skin clears completely.

“Two weeks later it’s all gone – it was a moment to behold,” said Joel M. Gelfand, MD, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who had cared for the man for many years before a psoriasis treatment revolution of sorts took the field of dermatology by storm.

“The progress has been breathtaking – there’s no other way to describe it – and it feels like a miracle every time I see a new patient who has tough disease and I have all these things to offer them,” he continued. “For most patients, I can really help them and make a major difference in their life.”

said Mark Lebwohl, MD, Waldman professor of dermatology and chair of the Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Dr. Lebwohl recounted some of his own experiences with psoriasis patients before the advent of treatments – particularly biologics – that have transformed practice.

There was a time when psoriasis patients had little more to turn to than the effective – but “disgusting” – Goeckerman Regimen involving cycles of UVB light exposure and topical crude coal tar application. Initially, the regimen, which was introduced in the 1920s, was used around the clock on an inpatient basis until the skin cleared, Dr. Lebwohl said.

In the 1970s, the immunosuppressive chemotherapy drug methotrexate became the first oral systemic therapy approved for severe psoriasis. For those with disabling disease, it offered some hope for relief, but only about 40% of patients achieved at least a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75), he said, adding that they did so at the expense of the liver and bone marrow. “But it was the only thing we had for severe psoriasis other than light treatments.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, oral retinoids emerged as a treatment for psoriasis, and the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporine used to prevent organ rejection in some transplant patients was found to clear psoriasis in affected transplant recipients. Although they brought relief to some patients with severe, disabling disease, these also came with a high price. “It’s not that effective, and it has lots of side effects ... and causes kidney damage in essentially 100% of patients,” Dr. Lebwohl said of cyclosporine.

“So we had treatments that worked, but because the side effects were sufficiently severe, a lot of patients were not treated,” he said.

Enter the biologics era

The early 2000s brought the first two approvals for psoriasis: alefacept (Amevive), a “modestly effective, but quite safe” immunosuppressive dimeric fusion protein approved in early 2003 for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, and efalizumab (Raptiva), a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody approved in October 2003; both were T-cell–targeted therapies. The former was withdrawn from the market voluntarily as newer agents became available, and the latter was withdrawn in 2009 because of a link with development of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, which had been used effectively for RA and Crohn’s disease, emerged next, and were highly effective, much safer than the systemic treatments, and gained “very widespread use,” Dr. Lebwohl said.

His colleague Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, was among the pioneers in the development of TNF blockers for the treatment of psoriasis. Her seminal, investigator-initiated paper on the efficacy and safety of infliximab (Remicade) monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis published in the Lancet in 2001 helped launch the current era in which many psoriasis patients achieve 100% PASI responses with limited side effects, he said, explaining that subsequent research elucidated the role of IL-12 and -23 – leading to effective treatments like ustekinumab (Stelara), and later IL-17, which is, “in fact, the molecule closest to the pathogenesis of psoriasis.”

“If you block IL-17, you get rid of psoriasis,” he said, noting that there are now several companies with approved antibodies to IL-17. “Taltz [ixekizumab] and Cosentyx [secukinumab] are the leading ones, and Siliq [brodalumab] blocks the receptor for IL-17, so it is very effective.”

Another novel biologic – bimekizumab – is on the horizon. It blocks both IL-17a and IL-17f, and appears highly effective in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). “Biologics were the real start of the [psoriasis treatment] revolution,” he said. “When I started out I would speak at patient meetings and the patients were angry at their physicians; they thought they weren’t aggressive enough, they were very frustrated.”

Dr. Lebwohl described patients he would see at annual National Psoriasis Foundation meetings: “There were patients in wheel chairs, because they couldn’t walk. They would be red and scaly all over ... you could have literally swept up scale like it was snow after one of those meetings.

“You go forward to around 2010 – nobody’s in wheelchairs anymore, everybody has clear skin, and it’s become a party; patients are no longer angry – they are thrilled with the results they are getting from much safer and much more effective drugs,” he said. “So it’s been a pleasure taking care of those patients and going from a very difficult time of treating them, to a time where we’ve done a great job treating them.”

Dr. Lebwohl noted that a “large number of dermatologists have been involved with the development of these drugs and making sure they succeed, and that has also been a pleasure to see.”

Dr. Gottlieb, who Dr. Lebwohl has described as “a superstar” in the fields of dermatology and rheumatology, is one such researcher. In an interview, she looked back on her work and the ways that her work “opened the field,” led to many of her trainees also doing “great work,” and changed the lives of patients.

“It’s nice to feel that I really did change, fundamentally, how psoriasis patients are treated,” said Dr. Gottlieb, who is a clinical professor in the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “That obviously feels great.”

She recalled a patient – “a 6-foot-5 biker with bad psoriasis” – who “literally, the minute the door closed, he was crying about how horrible his disease was.”

“And I cleared him ... and then you get big hugs – it just feels extremely good ... giving somebody their life back,” she said.

Dr. Gottlieb has been involved in much of the work in developing biologics for psoriasis, including the ongoing work with bimekizumab for PsA as mentioned by Dr. Lebwohl.

If the phase 2 data with bimekizumab are replicated in the ongoing phase 3 trials now underway at her center, “that can really raise the bar ... so if it’s reproducible, it’s very exciting.”

“It’s exciting to have an IL-23 blocker that, at least in clinical trials, showed inhibition of radiographic progression [in PsA],” she said. “That’s guselkumab those data are already out, and I was involved with that.”

The early work of Dr. Gottlieb and others has also “spread to other diseases,” like hidradenitis suppurativa and atopic dermatitis, she said, noting that numerous studies are underway.

Aside from curing all patients, her ultimate goal is getting to a point where psoriasis has no effect on patients’ quality of life.

“And I see it already,” she said. “It’s happening, and it’s nice to see that it’s happening in children now, too; several of the drugs are approved in kids.”

Alan Menter, MD, chairman of the division of dermatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, also a prolific researcher – and chair of the guidelines committee that published two new sets of guidelines for psoriasis treatment in 2019 – said that the field of dermatology was “late to the biologic evolution,” as many of the early biologics were first approved for PsA.

“But over the last 10 years, things have changed dramatically,” he said. “After that we suddenly leapt ahead of everybody. ... We now have 11 biologic drugs approved for psoriasis, which is more than any other disease has available.”

It’s been “highly exciting” to see this “evolution and revolution,” he commented, adding that one of the next challenges is to address the comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, associated with psoriasis.

“The big question now ... is if you improve skin and you improve joints, can you potentially reduce the risk of coronary artery disease,” he said. “Everybody is looking at that, and to me it’s one of the most exciting things that we’re doing.”

Work is ongoing to look at whether the IL-17s and IL-23s have “other indications outside of the skin and joints,” both within and outside of dermatology.

Like Dr. Gottlieb, Dr. Menter also mentioned the potential for hidradenitis suppurativa, and also for a condition that is rarely discussed or studied: genital psoriasis. Ixekizumab has recently been shown to work in about 75% of patients with genital psoriasis, he noted.

Another important area of research is the identification of biomarkers for predicting response and relapse, he said. For now, biomarker research has disappointed, he added, predicting that it will take at least 3-5 years before biomarkers to help guide treatment are identified.

Indeed, Dr. Gelfand, who also is director of the Psoriasis and Phototherapy Treatment Center, vice chair of clinical research, and medical director of the dermatology clinical studies unit at the University of Pennsylvania, agreed there is a need for research to improve treatment selection.

Advances are being made in genetics – with more than 80 different genes now identified as being related to psoriasis – and in medical informatics – which allow thousands of patients to be followed for years, he said, noting that this could elucidate immunopathological features that can improve treatments, predict and prevent comorbidity, and further improve outcomes.

“We also need care that is more patient centered,” he said, describing the ongoing pragmatic LITE trial of home- or office-based phototherapy for which he is the lead investigator, and other studies that he hopes will expand access to care.

Kenneth Brian Gordon, MD, chair and professor of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, whose career started in the basic science immunology arena, added the need for expanding benefit to patients with more-moderate disease. Like Dr. Menter, he identified psoriasis as the area in medicine that has had the greatest degree of advancement, except perhaps for hepatitis C.

He described the process not as a “bench-to-bedside” story, but as a bedside-to-bench, then “back-to-bedside” story.

It was really about taking those early T-cell–targeted biologics and anti-TNF agents from bedside to bench with the realization of the importance of the IL-23 and IL-17 pathways, and that understanding led back to the bedside with the development of the newest agents – and to a “huge difference in patient’s lives.”

“But we’ve gotten so good at treating patients with severe disease ... the question now is how to take care of those with more-moderate disease,” he said, noting that a focus on cost and better delivery systems will be needed for that population.

That research is underway, and the future looks bright – and clear.

“I think with psoriasis therapy and where we’ve come in the last 20 years ... we have a hard time remembering what it was like before we had biologic agents” he said. “Our perspective has changed a lot, and sometimes we forget that.”

In fact, “psoriasis has sort of dragged dermatology into the world of modern clinical trial science, and we can now apply that to all sorts of other diseases,” he said. “The psoriasis trials were the first really well-done large-scale trials in dermatology, and I think that has given dermatology a real leg up in how we do clinical research and how we do evidence-based medicine.”

All of the doctors interviewed for this story have received funds and/or honoraria from, consulted with, are employed with, or served on the advisory boards of manufacturers of biologics. Dr. Gelfand is a copatent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is deputy editor of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

Imagine a patient suffering with horrible psoriasis for decades having failed “every available treatment.” Imagine him living all that time with “flaking, cracking, painful, itchy skin,” only to develop cirrhosis after exposure to toxic therapies.

Then imagine the experience for that patient when, 2 weeks after initiating treatment with a new interleukin-17 inhibitor, his skin clears completely.

“Two weeks later it’s all gone – it was a moment to behold,” said Joel M. Gelfand, MD, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who had cared for the man for many years before a psoriasis treatment revolution of sorts took the field of dermatology by storm.

“The progress has been breathtaking – there’s no other way to describe it – and it feels like a miracle every time I see a new patient who has tough disease and I have all these things to offer them,” he continued. “For most patients, I can really help them and make a major difference in their life.”

said Mark Lebwohl, MD, Waldman professor of dermatology and chair of the Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Dr. Lebwohl recounted some of his own experiences with psoriasis patients before the advent of treatments – particularly biologics – that have transformed practice.

There was a time when psoriasis patients had little more to turn to than the effective – but “disgusting” – Goeckerman Regimen involving cycles of UVB light exposure and topical crude coal tar application. Initially, the regimen, which was introduced in the 1920s, was used around the clock on an inpatient basis until the skin cleared, Dr. Lebwohl said.

In the 1970s, the immunosuppressive chemotherapy drug methotrexate became the first oral systemic therapy approved for severe psoriasis. For those with disabling disease, it offered some hope for relief, but only about 40% of patients achieved at least a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75), he said, adding that they did so at the expense of the liver and bone marrow. “But it was the only thing we had for severe psoriasis other than light treatments.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, oral retinoids emerged as a treatment for psoriasis, and the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporine used to prevent organ rejection in some transplant patients was found to clear psoriasis in affected transplant recipients. Although they brought relief to some patients with severe, disabling disease, these also came with a high price. “It’s not that effective, and it has lots of side effects ... and causes kidney damage in essentially 100% of patients,” Dr. Lebwohl said of cyclosporine.

“So we had treatments that worked, but because the side effects were sufficiently severe, a lot of patients were not treated,” he said.

Enter the biologics era

The early 2000s brought the first two approvals for psoriasis: alefacept (Amevive), a “modestly effective, but quite safe” immunosuppressive dimeric fusion protein approved in early 2003 for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, and efalizumab (Raptiva), a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody approved in October 2003; both were T-cell–targeted therapies. The former was withdrawn from the market voluntarily as newer agents became available, and the latter was withdrawn in 2009 because of a link with development of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, which had been used effectively for RA and Crohn’s disease, emerged next, and were highly effective, much safer than the systemic treatments, and gained “very widespread use,” Dr. Lebwohl said.

His colleague Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, was among the pioneers in the development of TNF blockers for the treatment of psoriasis. Her seminal, investigator-initiated paper on the efficacy and safety of infliximab (Remicade) monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis published in the Lancet in 2001 helped launch the current era in which many psoriasis patients achieve 100% PASI responses with limited side effects, he said, explaining that subsequent research elucidated the role of IL-12 and -23 – leading to effective treatments like ustekinumab (Stelara), and later IL-17, which is, “in fact, the molecule closest to the pathogenesis of psoriasis.”

“If you block IL-17, you get rid of psoriasis,” he said, noting that there are now several companies with approved antibodies to IL-17. “Taltz [ixekizumab] and Cosentyx [secukinumab] are the leading ones, and Siliq [brodalumab] blocks the receptor for IL-17, so it is very effective.”

Another novel biologic – bimekizumab – is on the horizon. It blocks both IL-17a and IL-17f, and appears highly effective in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). “Biologics were the real start of the [psoriasis treatment] revolution,” he said. “When I started out I would speak at patient meetings and the patients were angry at their physicians; they thought they weren’t aggressive enough, they were very frustrated.”

Dr. Lebwohl described patients he would see at annual National Psoriasis Foundation meetings: “There were patients in wheel chairs, because they couldn’t walk. They would be red and scaly all over ... you could have literally swept up scale like it was snow after one of those meetings.

“You go forward to around 2010 – nobody’s in wheelchairs anymore, everybody has clear skin, and it’s become a party; patients are no longer angry – they are thrilled with the results they are getting from much safer and much more effective drugs,” he said. “So it’s been a pleasure taking care of those patients and going from a very difficult time of treating them, to a time where we’ve done a great job treating them.”

Dr. Lebwohl noted that a “large number of dermatologists have been involved with the development of these drugs and making sure they succeed, and that has also been a pleasure to see.”

Dr. Gottlieb, who Dr. Lebwohl has described as “a superstar” in the fields of dermatology and rheumatology, is one such researcher. In an interview, she looked back on her work and the ways that her work “opened the field,” led to many of her trainees also doing “great work,” and changed the lives of patients.

“It’s nice to feel that I really did change, fundamentally, how psoriasis patients are treated,” said Dr. Gottlieb, who is a clinical professor in the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “That obviously feels great.”

She recalled a patient – “a 6-foot-5 biker with bad psoriasis” – who “literally, the minute the door closed, he was crying about how horrible his disease was.”

“And I cleared him ... and then you get big hugs – it just feels extremely good ... giving somebody their life back,” she said.

Dr. Gottlieb has been involved in much of the work in developing biologics for psoriasis, including the ongoing work with bimekizumab for PsA as mentioned by Dr. Lebwohl.

If the phase 2 data with bimekizumab are replicated in the ongoing phase 3 trials now underway at her center, “that can really raise the bar ... so if it’s reproducible, it’s very exciting.”

“It’s exciting to have an IL-23 blocker that, at least in clinical trials, showed inhibition of radiographic progression [in PsA],” she said. “That’s guselkumab those data are already out, and I was involved with that.”

The early work of Dr. Gottlieb and others has also “spread to other diseases,” like hidradenitis suppurativa and atopic dermatitis, she said, noting that numerous studies are underway.

Aside from curing all patients, her ultimate goal is getting to a point where psoriasis has no effect on patients’ quality of life.

“And I see it already,” she said. “It’s happening, and it’s nice to see that it’s happening in children now, too; several of the drugs are approved in kids.”

Alan Menter, MD, chairman of the division of dermatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, also a prolific researcher – and chair of the guidelines committee that published two new sets of guidelines for psoriasis treatment in 2019 – said that the field of dermatology was “late to the biologic evolution,” as many of the early biologics were first approved for PsA.

“But over the last 10 years, things have changed dramatically,” he said. “After that we suddenly leapt ahead of everybody. ... We now have 11 biologic drugs approved for psoriasis, which is more than any other disease has available.”

It’s been “highly exciting” to see this “evolution and revolution,” he commented, adding that one of the next challenges is to address the comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, associated with psoriasis.

“The big question now ... is if you improve skin and you improve joints, can you potentially reduce the risk of coronary artery disease,” he said. “Everybody is looking at that, and to me it’s one of the most exciting things that we’re doing.”

Work is ongoing to look at whether the IL-17s and IL-23s have “other indications outside of the skin and joints,” both within and outside of dermatology.

Like Dr. Gottlieb, Dr. Menter also mentioned the potential for hidradenitis suppurativa, and also for a condition that is rarely discussed or studied: genital psoriasis. Ixekizumab has recently been shown to work in about 75% of patients with genital psoriasis, he noted.

Another important area of research is the identification of biomarkers for predicting response and relapse, he said. For now, biomarker research has disappointed, he added, predicting that it will take at least 3-5 years before biomarkers to help guide treatment are identified.

Indeed, Dr. Gelfand, who also is director of the Psoriasis and Phototherapy Treatment Center, vice chair of clinical research, and medical director of the dermatology clinical studies unit at the University of Pennsylvania, agreed there is a need for research to improve treatment selection.

Advances are being made in genetics – with more than 80 different genes now identified as being related to psoriasis – and in medical informatics – which allow thousands of patients to be followed for years, he said, noting that this could elucidate immunopathological features that can improve treatments, predict and prevent comorbidity, and further improve outcomes.

“We also need care that is more patient centered,” he said, describing the ongoing pragmatic LITE trial of home- or office-based phototherapy for which he is the lead investigator, and other studies that he hopes will expand access to care.

Kenneth Brian Gordon, MD, chair and professor of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, whose career started in the basic science immunology arena, added the need for expanding benefit to patients with more-moderate disease. Like Dr. Menter, he identified psoriasis as the area in medicine that has had the greatest degree of advancement, except perhaps for hepatitis C.

He described the process not as a “bench-to-bedside” story, but as a bedside-to-bench, then “back-to-bedside” story.

It was really about taking those early T-cell–targeted biologics and anti-TNF agents from bedside to bench with the realization of the importance of the IL-23 and IL-17 pathways, and that understanding led back to the bedside with the development of the newest agents – and to a “huge difference in patient’s lives.”

“But we’ve gotten so good at treating patients with severe disease ... the question now is how to take care of those with more-moderate disease,” he said, noting that a focus on cost and better delivery systems will be needed for that population.

That research is underway, and the future looks bright – and clear.

“I think with psoriasis therapy and where we’ve come in the last 20 years ... we have a hard time remembering what it was like before we had biologic agents” he said. “Our perspective has changed a lot, and sometimes we forget that.”

In fact, “psoriasis has sort of dragged dermatology into the world of modern clinical trial science, and we can now apply that to all sorts of other diseases,” he said. “The psoriasis trials were the first really well-done large-scale trials in dermatology, and I think that has given dermatology a real leg up in how we do clinical research and how we do evidence-based medicine.”

All of the doctors interviewed for this story have received funds and/or honoraria from, consulted with, are employed with, or served on the advisory boards of manufacturers of biologics. Dr. Gelfand is a copatent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is deputy editor of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

Imagine a patient suffering with horrible psoriasis for decades having failed “every available treatment.” Imagine him living all that time with “flaking, cracking, painful, itchy skin,” only to develop cirrhosis after exposure to toxic therapies.

Then imagine the experience for that patient when, 2 weeks after initiating treatment with a new interleukin-17 inhibitor, his skin clears completely.

“Two weeks later it’s all gone – it was a moment to behold,” said Joel M. Gelfand, MD, professor of dermatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who had cared for the man for many years before a psoriasis treatment revolution of sorts took the field of dermatology by storm.

“The progress has been breathtaking – there’s no other way to describe it – and it feels like a miracle every time I see a new patient who has tough disease and I have all these things to offer them,” he continued. “For most patients, I can really help them and make a major difference in their life.”

said Mark Lebwohl, MD, Waldman professor of dermatology and chair of the Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Dr. Lebwohl recounted some of his own experiences with psoriasis patients before the advent of treatments – particularly biologics – that have transformed practice.

There was a time when psoriasis patients had little more to turn to than the effective – but “disgusting” – Goeckerman Regimen involving cycles of UVB light exposure and topical crude coal tar application. Initially, the regimen, which was introduced in the 1920s, was used around the clock on an inpatient basis until the skin cleared, Dr. Lebwohl said.

In the 1970s, the immunosuppressive chemotherapy drug methotrexate became the first oral systemic therapy approved for severe psoriasis. For those with disabling disease, it offered some hope for relief, but only about 40% of patients achieved at least a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75), he said, adding that they did so at the expense of the liver and bone marrow. “But it was the only thing we had for severe psoriasis other than light treatments.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, oral retinoids emerged as a treatment for psoriasis, and the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporine used to prevent organ rejection in some transplant patients was found to clear psoriasis in affected transplant recipients. Although they brought relief to some patients with severe, disabling disease, these also came with a high price. “It’s not that effective, and it has lots of side effects ... and causes kidney damage in essentially 100% of patients,” Dr. Lebwohl said of cyclosporine.

“So we had treatments that worked, but because the side effects were sufficiently severe, a lot of patients were not treated,” he said.

Enter the biologics era

The early 2000s brought the first two approvals for psoriasis: alefacept (Amevive), a “modestly effective, but quite safe” immunosuppressive dimeric fusion protein approved in early 2003 for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, and efalizumab (Raptiva), a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody approved in October 2003; both were T-cell–targeted therapies. The former was withdrawn from the market voluntarily as newer agents became available, and the latter was withdrawn in 2009 because of a link with development of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, which had been used effectively for RA and Crohn’s disease, emerged next, and were highly effective, much safer than the systemic treatments, and gained “very widespread use,” Dr. Lebwohl said.

His colleague Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, was among the pioneers in the development of TNF blockers for the treatment of psoriasis. Her seminal, investigator-initiated paper on the efficacy and safety of infliximab (Remicade) monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis published in the Lancet in 2001 helped launch the current era in which many psoriasis patients achieve 100% PASI responses with limited side effects, he said, explaining that subsequent research elucidated the role of IL-12 and -23 – leading to effective treatments like ustekinumab (Stelara), and later IL-17, which is, “in fact, the molecule closest to the pathogenesis of psoriasis.”

“If you block IL-17, you get rid of psoriasis,” he said, noting that there are now several companies with approved antibodies to IL-17. “Taltz [ixekizumab] and Cosentyx [secukinumab] are the leading ones, and Siliq [brodalumab] blocks the receptor for IL-17, so it is very effective.”

Another novel biologic – bimekizumab – is on the horizon. It blocks both IL-17a and IL-17f, and appears highly effective in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). “Biologics were the real start of the [psoriasis treatment] revolution,” he said. “When I started out I would speak at patient meetings and the patients were angry at their physicians; they thought they weren’t aggressive enough, they were very frustrated.”

Dr. Lebwohl described patients he would see at annual National Psoriasis Foundation meetings: “There were patients in wheel chairs, because they couldn’t walk. They would be red and scaly all over ... you could have literally swept up scale like it was snow after one of those meetings.

“You go forward to around 2010 – nobody’s in wheelchairs anymore, everybody has clear skin, and it’s become a party; patients are no longer angry – they are thrilled with the results they are getting from much safer and much more effective drugs,” he said. “So it’s been a pleasure taking care of those patients and going from a very difficult time of treating them, to a time where we’ve done a great job treating them.”

Dr. Lebwohl noted that a “large number of dermatologists have been involved with the development of these drugs and making sure they succeed, and that has also been a pleasure to see.”

Dr. Gottlieb, who Dr. Lebwohl has described as “a superstar” in the fields of dermatology and rheumatology, is one such researcher. In an interview, she looked back on her work and the ways that her work “opened the field,” led to many of her trainees also doing “great work,” and changed the lives of patients.

“It’s nice to feel that I really did change, fundamentally, how psoriasis patients are treated,” said Dr. Gottlieb, who is a clinical professor in the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “That obviously feels great.”

She recalled a patient – “a 6-foot-5 biker with bad psoriasis” – who “literally, the minute the door closed, he was crying about how horrible his disease was.”

“And I cleared him ... and then you get big hugs – it just feels extremely good ... giving somebody their life back,” she said.

Dr. Gottlieb has been involved in much of the work in developing biologics for psoriasis, including the ongoing work with bimekizumab for PsA as mentioned by Dr. Lebwohl.

If the phase 2 data with bimekizumab are replicated in the ongoing phase 3 trials now underway at her center, “that can really raise the bar ... so if it’s reproducible, it’s very exciting.”

“It’s exciting to have an IL-23 blocker that, at least in clinical trials, showed inhibition of radiographic progression [in PsA],” she said. “That’s guselkumab those data are already out, and I was involved with that.”

The early work of Dr. Gottlieb and others has also “spread to other diseases,” like hidradenitis suppurativa and atopic dermatitis, she said, noting that numerous studies are underway.

Aside from curing all patients, her ultimate goal is getting to a point where psoriasis has no effect on patients’ quality of life.

“And I see it already,” she said. “It’s happening, and it’s nice to see that it’s happening in children now, too; several of the drugs are approved in kids.”

Alan Menter, MD, chairman of the division of dermatology at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, also a prolific researcher – and chair of the guidelines committee that published two new sets of guidelines for psoriasis treatment in 2019 – said that the field of dermatology was “late to the biologic evolution,” as many of the early biologics were first approved for PsA.

“But over the last 10 years, things have changed dramatically,” he said. “After that we suddenly leapt ahead of everybody. ... We now have 11 biologic drugs approved for psoriasis, which is more than any other disease has available.”

It’s been “highly exciting” to see this “evolution and revolution,” he commented, adding that one of the next challenges is to address the comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, associated with psoriasis.

“The big question now ... is if you improve skin and you improve joints, can you potentially reduce the risk of coronary artery disease,” he said. “Everybody is looking at that, and to me it’s one of the most exciting things that we’re doing.”

Work is ongoing to look at whether the IL-17s and IL-23s have “other indications outside of the skin and joints,” both within and outside of dermatology.

Like Dr. Gottlieb, Dr. Menter also mentioned the potential for hidradenitis suppurativa, and also for a condition that is rarely discussed or studied: genital psoriasis. Ixekizumab has recently been shown to work in about 75% of patients with genital psoriasis, he noted.

Another important area of research is the identification of biomarkers for predicting response and relapse, he said. For now, biomarker research has disappointed, he added, predicting that it will take at least 3-5 years before biomarkers to help guide treatment are identified.

Indeed, Dr. Gelfand, who also is director of the Psoriasis and Phototherapy Treatment Center, vice chair of clinical research, and medical director of the dermatology clinical studies unit at the University of Pennsylvania, agreed there is a need for research to improve treatment selection.

Advances are being made in genetics – with more than 80 different genes now identified as being related to psoriasis – and in medical informatics – which allow thousands of patients to be followed for years, he said, noting that this could elucidate immunopathological features that can improve treatments, predict and prevent comorbidity, and further improve outcomes.

“We also need care that is more patient centered,” he said, describing the ongoing pragmatic LITE trial of home- or office-based phototherapy for which he is the lead investigator, and other studies that he hopes will expand access to care.

Kenneth Brian Gordon, MD, chair and professor of dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, whose career started in the basic science immunology arena, added the need for expanding benefit to patients with more-moderate disease. Like Dr. Menter, he identified psoriasis as the area in medicine that has had the greatest degree of advancement, except perhaps for hepatitis C.

He described the process not as a “bench-to-bedside” story, but as a bedside-to-bench, then “back-to-bedside” story.

It was really about taking those early T-cell–targeted biologics and anti-TNF agents from bedside to bench with the realization of the importance of the IL-23 and IL-17 pathways, and that understanding led back to the bedside with the development of the newest agents – and to a “huge difference in patient’s lives.”

“But we’ve gotten so good at treating patients with severe disease ... the question now is how to take care of those with more-moderate disease,” he said, noting that a focus on cost and better delivery systems will be needed for that population.

That research is underway, and the future looks bright – and clear.

“I think with psoriasis therapy and where we’ve come in the last 20 years ... we have a hard time remembering what it was like before we had biologic agents” he said. “Our perspective has changed a lot, and sometimes we forget that.”

In fact, “psoriasis has sort of dragged dermatology into the world of modern clinical trial science, and we can now apply that to all sorts of other diseases,” he said. “The psoriasis trials were the first really well-done large-scale trials in dermatology, and I think that has given dermatology a real leg up in how we do clinical research and how we do evidence-based medicine.”

All of the doctors interviewed for this story have received funds and/or honoraria from, consulted with, are employed with, or served on the advisory boards of manufacturers of biologics. Dr. Gelfand is a copatent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is deputy editor of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

ID Blog: Wuhan coronavirus – just a stop on the zoonotic highway

Emerging viruses that spread to humans from an animal host are commonplace and represent some of the deadliest diseases known. Given the details of the Wuhan coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, including the genetic profile of the disease agent, the hypothesis of a snake origin was the first raised in the peer-reviewed literature.

It is a highly controversial origin story, however, given that mammals have been the sources of all other such zoonotic coronaviruses, as well as a host of other zoonotic diseases.

An animal source for emerging infections such as the 2019-nCoV is the default hypothesis, because “around 60% of all infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, as are 75% of all emerging infectious diseases,” according to a United Nations report. The report goes on to say that, “on average, one new infectious disease emerges in humans every 4 months.”

To appreciate the emergence and nature of 2019-nCoV, it is important to examine the history of zoonotic outbreaks of other such diseases, especially with regard to the “mixing-vessel” phenomenon, which has been noted in closely related coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS, as well as the widely disparate HIV, Ebola, and influenza viruses.

Mutants in the mixing vessel

The mixing-vessel phenomenon is conceptually easy but molecularly complex. A single animal is coinfected with two related viruses; the virus genomes recombine together (virus “sex”) in that animal to form a new variant of virus. Such new mutant viruses can be more or less infective, more or less deadly, and more or less able to jump the species or even genus barrier. An emerging viral zoonosis can occur when a human being is exposed to one of these new viruses (either from the origin species or another species intermediate) that is capable of also infecting a human cell. Such exposure can occur from close proximity to animal waste or body fluids, as in the farm environment, or from wildlife pets or the capturing and slaughtering of wildlife for food, as is proposed in the case of the Wuhan seafood market scenario. In fact, the scientists who postulated a snake intermediary as the potential mixing vessel also stated that 2019‐nCoV appears to be a recombinant virus between a bat coronavirus and an origin‐unknown coronavirus.

Coronaviruses in particular have a history of moving from animal to human hosts (and even back again), and their detailed genetic pattern and taxonomy can reveal the animal origin of these diseases.

Going batty

Bats, in particular, have been shown to be a reservoir species for both alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. Given their ecology and behavior, they have been found to play a key role in transmitting coronaviruses between species. A highly pertinent example of this is the SARS coronavirus, which was shown to have likely originated in Chinese horseshoe bats. The SARS virus, which is genetically closely related to the new Wuhan coronavirus, first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002.

Scientists speculate that the virus was then either transmitted directly to humans from bats, or passed through an intermediate host species, with SARS-like viruses isolated from Himalayan palm civets found in a live-animal market in Guangdong. The virus infection was also detected in other animals (including a raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides) and in humans working at the market.

The MERS coronavirus is a betacoronavirus that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It turned out to be far more deadly than either SARS or the Wuhan virus (at least as far as current estimates of the new coronavirus’s behavior). The MERS genotype was found to be closely related to MERS-like viruses in bats in Saudi Arabia, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Studies done on the cell receptor for MERS showed an apparently conserved viral receptor in both bats and humans. And an identical strain of MERS was found in bats in a nearby cave and near the workplace of the first known human patient.

However, in many of the other locations of the outbreak in the Middle East, there appeared to be limited contact between bats and humans, so scientists looked for another vector species, perhaps one that was acting as an intermediate. A high seroprevalence of MERS-CoV or a closely related virus was found in camels across the Arabian Peninsula and parts of eastern and northern Africa, while tests for MERS antibodies were negative in the most-likely other species of livestock or pet animals, including chickens, cows, goats, horses, and sheep.

In addition, the MERS-related CoV carried by camels was genetically highly similar to that detected in humans, as demonstrated in one particular outbreak on a farm in Qatar where the genetic sequences of MERS-CoV in the nasal swabs from 3 of 14 seropositive camels were similar to those of 2 human cases on the same farm. Similar genomic results were found in MERS-CoV from nasal swabs from camels in Saudi Arabia.

Other mixing-vessel zoonoses

HIV, the viral cause of AIDS, provides an almost-textbook origin story of the rise of a zoonotic supervillain. The virus was genetically traced to have a chimpanzee-to-human origin, but it was found to be more complicated than that. The virus first emerged in the 1920s in Africa in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, well before its rise to a global pandemic in the 1980s.

Researchers believe the chimpanzee virus is a hybrid of the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) naturally infecting two different monkey species: the red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) and the greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Chimpanzees kill and eat monkeys, which is likely how they acquired the monkey viruses. The viruses hybridized in a chimpanzee; the hybrid virus then spread through the chimpanzee population and was later transmitted to humans who captured and slaughtered chimps for meat (becoming exposed to their blood). This was the most likely origin of HIV-1.

HIV-1 also shows one of the major risks of zoonotic infections. They can continue to mutate in its human host, increasing the risk of greater virulence, but also interfering with the production of a universally effective vaccine. Since its transmission to humans, for example, many subtypes of the HIV-1 strain have developed, with genetic differences even in the same subtypes found to be up to 20%.

Ebolavirus, first detected in 1976, is another case of bats being the potential culprit. Genetic analysis has shown that African fruit bats are likely involved in the spread of the virus and may be its reservoir host. Further evidence of this was found in the most recent human-infecting Bombali variant of the virus, which was identified in samples from bats collected from Sierra Leone.

It was also found that pigs can also become infected with Zaire ebolavirus, leading to the fear that pigs could serve as a mixing vessel for it and other filoviruses. Pigs have their own forms of Ebola-like disease viruses, which are not currently transmissible to humans, but could provide a potential mixing-vessel reservoir.

Emergent influenzas

The Western world has been most affected by these highly mutable, multispecies zoonotic viruses. The 1957 and 1968 flu pandemics contained a mixture of gene segments from human and avian influenza viruses. “What is clear from genetic analysis of the viruses that caused these past pandemics is that reassortment (gene swapping) occurred to produce novel influenza viruses that caused the pandemics. In both of these cases, the new viruses that emerged showed major differences from the parent viruses,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza is, however, a good example that all zoonoses are not the result of a mixing-vessel phenomenon, with evidence showing that the origin of the catastrophic 1918 virus pandemic likely resulted from a bird influenza virus directly infecting humans and pigs at about the same time without reassortment, according to the CDC.

Building a protective infrastructure

The first 2 decades of the 21st century saw a huge increase in efforts to develop an infrastructure to monitor and potentially prevent the spread of new zoonoses. As part of a global effort led by the United Nations, the U.S. Agency for International AID developed the PREDICT program in 2009 “to strengthen global capacity for detection and discovery of zoonotic viruses with pandemic potential. Those include coronaviruses, the family to which SARS and MERS belong; paramyxoviruses, like Nipah virus; influenza viruses; and filoviruses, like the ebolavirus.”

PREDICT funding to the EcoHealth Alliance led to discovery of the likely bat origins of the Zaire ebolavirus during the 2013-2016 outbreak. And throughout the existence of PREDICT, more than 145,000 animals and people were surveyed in areas of likely zoonotic outbreaks, leading to the detection of more than “1,100 unique viruses, including zoonotic diseases of public health concern such as Bombali ebolavirus, Zaire ebolavirus, Marburg virus, and MERS- and SARS-like coronaviruses,” according to PREDICT partner, the University of California, Davis.

PREDICT-2 was launched in 2014 with the continuing goals of “identifying and better characterizing pathogens of known epidemic and unknown pandemic potential; recognizing animal reservoirs and amplification hosts of human-infectious viruses; and efficiently targeting intervention action at human behaviors which amplify disease transmission at critical animal-animal and animal-human interfaces in hotspots of viral evolution, spillover, amplification, and spread.”

However, in October 2019, the Trump administration cut all funding to the PREDICT program, leading to its shutdown. In a New York Times interview, Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, stated: “PREDICT was an approach to heading off pandemics, instead of sitting there waiting for them to emerge and then mobilizing.”

Ultimately, in addition to its human cost, the current Wuhan coronavirus outbreak can be looked at an object lesson – a test of the pandemic surveillance and control systems currently in place, and a practice run for the next and potentially deadlier zoonotic outbreaks to come. Perhaps it is also a reminder that cutting resources to detect zoonoses at their source in their animal hosts – before they enter the human chain– is perhaps not the most prudent of ideas.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Emerging viruses that spread to humans from an animal host are commonplace and represent some of the deadliest diseases known. Given the details of the Wuhan coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, including the genetic profile of the disease agent, the hypothesis of a snake origin was the first raised in the peer-reviewed literature.

It is a highly controversial origin story, however, given that mammals have been the sources of all other such zoonotic coronaviruses, as well as a host of other zoonotic diseases.

An animal source for emerging infections such as the 2019-nCoV is the default hypothesis, because “around 60% of all infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, as are 75% of all emerging infectious diseases,” according to a United Nations report. The report goes on to say that, “on average, one new infectious disease emerges in humans every 4 months.”

To appreciate the emergence and nature of 2019-nCoV, it is important to examine the history of zoonotic outbreaks of other such diseases, especially with regard to the “mixing-vessel” phenomenon, which has been noted in closely related coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS, as well as the widely disparate HIV, Ebola, and influenza viruses.

Mutants in the mixing vessel

The mixing-vessel phenomenon is conceptually easy but molecularly complex. A single animal is coinfected with two related viruses; the virus genomes recombine together (virus “sex”) in that animal to form a new variant of virus. Such new mutant viruses can be more or less infective, more or less deadly, and more or less able to jump the species or even genus barrier. An emerging viral zoonosis can occur when a human being is exposed to one of these new viruses (either from the origin species or another species intermediate) that is capable of also infecting a human cell. Such exposure can occur from close proximity to animal waste or body fluids, as in the farm environment, or from wildlife pets or the capturing and slaughtering of wildlife for food, as is proposed in the case of the Wuhan seafood market scenario. In fact, the scientists who postulated a snake intermediary as the potential mixing vessel also stated that 2019‐nCoV appears to be a recombinant virus between a bat coronavirus and an origin‐unknown coronavirus.

Coronaviruses in particular have a history of moving from animal to human hosts (and even back again), and their detailed genetic pattern and taxonomy can reveal the animal origin of these diseases.

Going batty

Bats, in particular, have been shown to be a reservoir species for both alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. Given their ecology and behavior, they have been found to play a key role in transmitting coronaviruses between species. A highly pertinent example of this is the SARS coronavirus, which was shown to have likely originated in Chinese horseshoe bats. The SARS virus, which is genetically closely related to the new Wuhan coronavirus, first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002.

Scientists speculate that the virus was then either transmitted directly to humans from bats, or passed through an intermediate host species, with SARS-like viruses isolated from Himalayan palm civets found in a live-animal market in Guangdong. The virus infection was also detected in other animals (including a raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides) and in humans working at the market.

The MERS coronavirus is a betacoronavirus that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It turned out to be far more deadly than either SARS or the Wuhan virus (at least as far as current estimates of the new coronavirus’s behavior). The MERS genotype was found to be closely related to MERS-like viruses in bats in Saudi Arabia, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Studies done on the cell receptor for MERS showed an apparently conserved viral receptor in both bats and humans. And an identical strain of MERS was found in bats in a nearby cave and near the workplace of the first known human patient.

However, in many of the other locations of the outbreak in the Middle East, there appeared to be limited contact between bats and humans, so scientists looked for another vector species, perhaps one that was acting as an intermediate. A high seroprevalence of MERS-CoV or a closely related virus was found in camels across the Arabian Peninsula and parts of eastern and northern Africa, while tests for MERS antibodies were negative in the most-likely other species of livestock or pet animals, including chickens, cows, goats, horses, and sheep.

In addition, the MERS-related CoV carried by camels was genetically highly similar to that detected in humans, as demonstrated in one particular outbreak on a farm in Qatar where the genetic sequences of MERS-CoV in the nasal swabs from 3 of 14 seropositive camels were similar to those of 2 human cases on the same farm. Similar genomic results were found in MERS-CoV from nasal swabs from camels in Saudi Arabia.

Other mixing-vessel zoonoses

HIV, the viral cause of AIDS, provides an almost-textbook origin story of the rise of a zoonotic supervillain. The virus was genetically traced to have a chimpanzee-to-human origin, but it was found to be more complicated than that. The virus first emerged in the 1920s in Africa in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, well before its rise to a global pandemic in the 1980s.

Researchers believe the chimpanzee virus is a hybrid of the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) naturally infecting two different monkey species: the red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) and the greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Chimpanzees kill and eat monkeys, which is likely how they acquired the monkey viruses. The viruses hybridized in a chimpanzee; the hybrid virus then spread through the chimpanzee population and was later transmitted to humans who captured and slaughtered chimps for meat (becoming exposed to their blood). This was the most likely origin of HIV-1.

HIV-1 also shows one of the major risks of zoonotic infections. They can continue to mutate in its human host, increasing the risk of greater virulence, but also interfering with the production of a universally effective vaccine. Since its transmission to humans, for example, many subtypes of the HIV-1 strain have developed, with genetic differences even in the same subtypes found to be up to 20%.

Ebolavirus, first detected in 1976, is another case of bats being the potential culprit. Genetic analysis has shown that African fruit bats are likely involved in the spread of the virus and may be its reservoir host. Further evidence of this was found in the most recent human-infecting Bombali variant of the virus, which was identified in samples from bats collected from Sierra Leone.

It was also found that pigs can also become infected with Zaire ebolavirus, leading to the fear that pigs could serve as a mixing vessel for it and other filoviruses. Pigs have their own forms of Ebola-like disease viruses, which are not currently transmissible to humans, but could provide a potential mixing-vessel reservoir.

Emergent influenzas

The Western world has been most affected by these highly mutable, multispecies zoonotic viruses. The 1957 and 1968 flu pandemics contained a mixture of gene segments from human and avian influenza viruses. “What is clear from genetic analysis of the viruses that caused these past pandemics is that reassortment (gene swapping) occurred to produce novel influenza viruses that caused the pandemics. In both of these cases, the new viruses that emerged showed major differences from the parent viruses,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.