User login

News and Views that Matter to Physicians

Docs to CMS: MACRA is too complex and should be delayed

The proposed federal regulations to implement the MACRA health care reforms are too complex, too onerous on small and solo practices, lack opportunities for many to participate in alternative payment models, and should be delayed for a full year, at least.

That was the message that emerged from hundreds of comments regarding the proposed rule that were submitted by physician organizations and other stakeholders.

“The intent of [the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015] was not to merely move the current incentive program into [the Merit-based Incentive Payment System], but to improve and simplify these programs into a single more unified approach,” the American Medical Association said in its comments, noting that “numerous changes” will be needed in the way cost and quality are measured.

AMA also called for a better, faster way for physicians to develop alternative payment models. “We strongly urge CMS to vigorously pursue this objective and establish a much more progressive and welcoming environment for the development and implementation of specialty-defined APMs than proposed in the [proposed rule].”

AMA also suggested that CMS provide more flexibility for solo and small practices, align the four components of MIPS so it operates as a single program, simplifying and lowering the financial risk for advanced APMs, and providing more timely feedback to physicians.

The organization also called for CMS to “create an initial transitional performance period from July 1, 2017, to December 31, 2017, to ensure the successful and appropriate implementation of the MACRA program. In future years, for all reporting requirements, CMS should allow physicians to select periods of less than a full calendar year to provide flexibility.”

In its comments, the American Medical Group Association questioned whether the proposed rule actually would lead to improved quality of care and reward value.

In the proposed rule, “CMS will measure and score quality and resource use or spending separately,” AMGA wrote in its comments. “CMS will not measure outcomes in relation to spending. CMS will not measure for value. If value is left unaddressed in the final rule, it will be difficult at best for the agency to meet MACRA and the [HHS] secretary’s overarching goals.”

While expressing support for MACRA conceptually, officials with the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote that they “see a strong and definite need and opportunity for CMS to step back and reconsider the approach to this proposed rule which we view as overly complex and burdensome to our members and indeed for all physicians. Given the significant complexity of the rule, we strongly encourage CMS to issue an interim final rule with comment period rather than to issue a final rule.”

Specifically, AAFP criticized the proposed rule for allowing small and solo practices to form “virtual groups” in order to earn bonuses, despite it being mandated by law.

Solo and small group practices who participate in MIPS to should “be eligible for positive payment updates if their performance yields such payments, but would be exempt from any negative payment update until such a time that the virtual group option is available,” AAFP officials wrote.

They also called for medical home delivery models to be included in APMs, in an effort to improve on the limited opportunities for family practices in particular to participate in alternative payment models.

The American College of Physicians also called for safe harbors for small and solo practices until virtual group options can be established.

ACP, like other groups, questioned that medical homes are not recognized as alternative payment models and argued that Congress intended medical homes to qualify as APMs “without bearing more than nominal financial risk.”

Despite the flexible approach to the overall quality payment program, CMS has “created a degree of complexity” and must “continue to seek ways to further streamline and simplify” the move to quality payments, according to comments from the American College of Cardiology.

The ACC also expressed concerns that the reporting requirements under MIPS and some of the APMs will limit the ability for cardiologists to report the most meaningful measures, particularly if they are part of a multi-specialty group, and suggested changes in scoring methodology or to allow more than one data file to be submitted in multi-specialty situations.

It also expressed concerns that the rule as proposed could adversely effect small practices, rural practices, and practices in health professional shortage areas, and “in the absence of other solutions such as virtual groups in 2017, CMS should monitor policies and provide effective practice assistance to these practices.”

The proposed rule provides no support for small practices, according to the American Gastroenterological Association.

“Upon release of the proposed rule, we were disappointed to see that not only will APMs be essentially closed off to small practices in the first years of implementation, but the MIPS program will significantly harm practices with less than 25 eligible clinicians,” AGA noted, citing data presented by CMS that 87% of solo practitioners will receive a negative adjustment with an aggregate negative impact of $300 million and for all practices with less than 25 eligible clinicians, the aggregate negative adjustment will total $649 million.

“Any system in which smaller practices are so heavily disadvantaged is unacceptable,” AGA said. CMS has previously stated that the regulatory impact statement would likely change and reflect a smaller impact for small and solo practices once more updated information can be modeled when the rule is final.

Additionally, AGA expressed concern over the limited engagement in APMs that will be possible under the proposed rule. “Given the importance of APM participation to both the practice and reimbursement of Medicare physicians, access to advanced APMs should be provided to all physicians.”

The association also expressed concern that the definition of APM is not broad enough and suggested that it be widened in scope so that it can capture payment models that have been created using the AGA’s Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice. It recommended a number of models be classified as APMs, including the colonoscopy bundled payment, gastroesophageal reflux disease episode payment, obesity bundled payment, Project Sonar (a chronic disease management program for IBD), and the Medical Home Neighbor.

The American College of Rheumatology called for a delay in the implementation of any final MACRA regulations, noting in its comments that with requirements set to begin in 2017, the current implementation schedule “does not provide enough time for providers to implement the required changes,” though ACR does not recommend a specific start time.

ACR also questioned how the criteria for APMs was set up, noting expressly that Physician Focused Payment Models may not meet the APM requirements. The group is seeking clarification on whether these models will qualify as an APM.

“Medical home APMs should also permit specialty physicians to participate, including small group and multispeciality groups, in keeping with the need for APMs to be flexible with their criteria and the role of specialty physicians in providing chronic care.

The American Academy of Dermatology Association echoed a number of concerns voiced across the medical profession and is calling for a delay in the implementation of MACRA’s regulations.

In particular, AADA noted that the regulations are not friendly for small and solo practices in general and little is contained within the proposal to “meaningfully engage specialist physicians in APMs.”

The association also is calling for broader mechanisms to allow for the development and recognition of APMs, including recognizing specialty-focused medical homes.

The group also is calling for pilot programs to test the validity of the measures that will form the basis of quality payment incentives and penalties.

In an effort to protect small and solo practices, AADA is calling for an exemption from MIPS or APM requirements until a virtual group option is developed, tested, and is fully operational.

The American Psychiatric Association echoed a number of broad concerns raised across the physician spectrum, including calling for a to the first year of implementation to July 1, 2017, and lasting through Dec. 31, 2017, as well as enabling the formation of virtual groups at the onset of implementation in its comments.

But APA also noted that mental health presents a variety of unique issues that need to be addressed.

For example, the association notes that psychiatrists work across a number of practice settings, including academic health centers, hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and private practices, as well as offering services via telemedicine.

“This makes it difficult for psychiatrists to capture all the work they do, because of the combination of settings that utilize multiple, and potentially differing reporting programs and methods,” APA noted.

It added that psychiatrists generally have limited time and resources that can be devoted to Medicare quality reporting, which would make participation in MIPS and APMs more challenging, particularly because many operate in small or solo practices that do not own electronic health record systems, which would complicate reporting requirements to qualify for MIPS or APMs.

In addition to concerns with reporting in general, APA said that psychiatrists “also have limited choices in outcome quality measures.”

The proposed federal regulations to implement the MACRA health care reforms are too complex, too onerous on small and solo practices, lack opportunities for many to participate in alternative payment models, and should be delayed for a full year, at least.

That was the message that emerged from hundreds of comments regarding the proposed rule that were submitted by physician organizations and other stakeholders.

“The intent of [the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015] was not to merely move the current incentive program into [the Merit-based Incentive Payment System], but to improve and simplify these programs into a single more unified approach,” the American Medical Association said in its comments, noting that “numerous changes” will be needed in the way cost and quality are measured.

AMA also called for a better, faster way for physicians to develop alternative payment models. “We strongly urge CMS to vigorously pursue this objective and establish a much more progressive and welcoming environment for the development and implementation of specialty-defined APMs than proposed in the [proposed rule].”

AMA also suggested that CMS provide more flexibility for solo and small practices, align the four components of MIPS so it operates as a single program, simplifying and lowering the financial risk for advanced APMs, and providing more timely feedback to physicians.

The organization also called for CMS to “create an initial transitional performance period from July 1, 2017, to December 31, 2017, to ensure the successful and appropriate implementation of the MACRA program. In future years, for all reporting requirements, CMS should allow physicians to select periods of less than a full calendar year to provide flexibility.”

In its comments, the American Medical Group Association questioned whether the proposed rule actually would lead to improved quality of care and reward value.

In the proposed rule, “CMS will measure and score quality and resource use or spending separately,” AMGA wrote in its comments. “CMS will not measure outcomes in relation to spending. CMS will not measure for value. If value is left unaddressed in the final rule, it will be difficult at best for the agency to meet MACRA and the [HHS] secretary’s overarching goals.”

While expressing support for MACRA conceptually, officials with the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote that they “see a strong and definite need and opportunity for CMS to step back and reconsider the approach to this proposed rule which we view as overly complex and burdensome to our members and indeed for all physicians. Given the significant complexity of the rule, we strongly encourage CMS to issue an interim final rule with comment period rather than to issue a final rule.”

Specifically, AAFP criticized the proposed rule for allowing small and solo practices to form “virtual groups” in order to earn bonuses, despite it being mandated by law.

Solo and small group practices who participate in MIPS to should “be eligible for positive payment updates if their performance yields such payments, but would be exempt from any negative payment update until such a time that the virtual group option is available,” AAFP officials wrote.

They also called for medical home delivery models to be included in APMs, in an effort to improve on the limited opportunities for family practices in particular to participate in alternative payment models.

The American College of Physicians also called for safe harbors for small and solo practices until virtual group options can be established.

ACP, like other groups, questioned that medical homes are not recognized as alternative payment models and argued that Congress intended medical homes to qualify as APMs “without bearing more than nominal financial risk.”

Despite the flexible approach to the overall quality payment program, CMS has “created a degree of complexity” and must “continue to seek ways to further streamline and simplify” the move to quality payments, according to comments from the American College of Cardiology.

The ACC also expressed concerns that the reporting requirements under MIPS and some of the APMs will limit the ability for cardiologists to report the most meaningful measures, particularly if they are part of a multi-specialty group, and suggested changes in scoring methodology or to allow more than one data file to be submitted in multi-specialty situations.

It also expressed concerns that the rule as proposed could adversely effect small practices, rural practices, and practices in health professional shortage areas, and “in the absence of other solutions such as virtual groups in 2017, CMS should monitor policies and provide effective practice assistance to these practices.”

The proposed rule provides no support for small practices, according to the American Gastroenterological Association.

“Upon release of the proposed rule, we were disappointed to see that not only will APMs be essentially closed off to small practices in the first years of implementation, but the MIPS program will significantly harm practices with less than 25 eligible clinicians,” AGA noted, citing data presented by CMS that 87% of solo practitioners will receive a negative adjustment with an aggregate negative impact of $300 million and for all practices with less than 25 eligible clinicians, the aggregate negative adjustment will total $649 million.

“Any system in which smaller practices are so heavily disadvantaged is unacceptable,” AGA said. CMS has previously stated that the regulatory impact statement would likely change and reflect a smaller impact for small and solo practices once more updated information can be modeled when the rule is final.

Additionally, AGA expressed concern over the limited engagement in APMs that will be possible under the proposed rule. “Given the importance of APM participation to both the practice and reimbursement of Medicare physicians, access to advanced APMs should be provided to all physicians.”

The association also expressed concern that the definition of APM is not broad enough and suggested that it be widened in scope so that it can capture payment models that have been created using the AGA’s Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice. It recommended a number of models be classified as APMs, including the colonoscopy bundled payment, gastroesophageal reflux disease episode payment, obesity bundled payment, Project Sonar (a chronic disease management program for IBD), and the Medical Home Neighbor.

The American College of Rheumatology called for a delay in the implementation of any final MACRA regulations, noting in its comments that with requirements set to begin in 2017, the current implementation schedule “does not provide enough time for providers to implement the required changes,” though ACR does not recommend a specific start time.

ACR also questioned how the criteria for APMs was set up, noting expressly that Physician Focused Payment Models may not meet the APM requirements. The group is seeking clarification on whether these models will qualify as an APM.

“Medical home APMs should also permit specialty physicians to participate, including small group and multispeciality groups, in keeping with the need for APMs to be flexible with their criteria and the role of specialty physicians in providing chronic care.

The American Academy of Dermatology Association echoed a number of concerns voiced across the medical profession and is calling for a delay in the implementation of MACRA’s regulations.

In particular, AADA noted that the regulations are not friendly for small and solo practices in general and little is contained within the proposal to “meaningfully engage specialist physicians in APMs.”

The association also is calling for broader mechanisms to allow for the development and recognition of APMs, including recognizing specialty-focused medical homes.

The group also is calling for pilot programs to test the validity of the measures that will form the basis of quality payment incentives and penalties.

In an effort to protect small and solo practices, AADA is calling for an exemption from MIPS or APM requirements until a virtual group option is developed, tested, and is fully operational.

The American Psychiatric Association echoed a number of broad concerns raised across the physician spectrum, including calling for a to the first year of implementation to July 1, 2017, and lasting through Dec. 31, 2017, as well as enabling the formation of virtual groups at the onset of implementation in its comments.

But APA also noted that mental health presents a variety of unique issues that need to be addressed.

For example, the association notes that psychiatrists work across a number of practice settings, including academic health centers, hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and private practices, as well as offering services via telemedicine.

“This makes it difficult for psychiatrists to capture all the work they do, because of the combination of settings that utilize multiple, and potentially differing reporting programs and methods,” APA noted.

It added that psychiatrists generally have limited time and resources that can be devoted to Medicare quality reporting, which would make participation in MIPS and APMs more challenging, particularly because many operate in small or solo practices that do not own electronic health record systems, which would complicate reporting requirements to qualify for MIPS or APMs.

In addition to concerns with reporting in general, APA said that psychiatrists “also have limited choices in outcome quality measures.”

The proposed federal regulations to implement the MACRA health care reforms are too complex, too onerous on small and solo practices, lack opportunities for many to participate in alternative payment models, and should be delayed for a full year, at least.

That was the message that emerged from hundreds of comments regarding the proposed rule that were submitted by physician organizations and other stakeholders.

“The intent of [the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015] was not to merely move the current incentive program into [the Merit-based Incentive Payment System], but to improve and simplify these programs into a single more unified approach,” the American Medical Association said in its comments, noting that “numerous changes” will be needed in the way cost and quality are measured.

AMA also called for a better, faster way for physicians to develop alternative payment models. “We strongly urge CMS to vigorously pursue this objective and establish a much more progressive and welcoming environment for the development and implementation of specialty-defined APMs than proposed in the [proposed rule].”

AMA also suggested that CMS provide more flexibility for solo and small practices, align the four components of MIPS so it operates as a single program, simplifying and lowering the financial risk for advanced APMs, and providing more timely feedback to physicians.

The organization also called for CMS to “create an initial transitional performance period from July 1, 2017, to December 31, 2017, to ensure the successful and appropriate implementation of the MACRA program. In future years, for all reporting requirements, CMS should allow physicians to select periods of less than a full calendar year to provide flexibility.”

In its comments, the American Medical Group Association questioned whether the proposed rule actually would lead to improved quality of care and reward value.

In the proposed rule, “CMS will measure and score quality and resource use or spending separately,” AMGA wrote in its comments. “CMS will not measure outcomes in relation to spending. CMS will not measure for value. If value is left unaddressed in the final rule, it will be difficult at best for the agency to meet MACRA and the [HHS] secretary’s overarching goals.”

While expressing support for MACRA conceptually, officials with the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote that they “see a strong and definite need and opportunity for CMS to step back and reconsider the approach to this proposed rule which we view as overly complex and burdensome to our members and indeed for all physicians. Given the significant complexity of the rule, we strongly encourage CMS to issue an interim final rule with comment period rather than to issue a final rule.”

Specifically, AAFP criticized the proposed rule for allowing small and solo practices to form “virtual groups” in order to earn bonuses, despite it being mandated by law.

Solo and small group practices who participate in MIPS to should “be eligible for positive payment updates if their performance yields such payments, but would be exempt from any negative payment update until such a time that the virtual group option is available,” AAFP officials wrote.

They also called for medical home delivery models to be included in APMs, in an effort to improve on the limited opportunities for family practices in particular to participate in alternative payment models.

The American College of Physicians also called for safe harbors for small and solo practices until virtual group options can be established.

ACP, like other groups, questioned that medical homes are not recognized as alternative payment models and argued that Congress intended medical homes to qualify as APMs “without bearing more than nominal financial risk.”

Despite the flexible approach to the overall quality payment program, CMS has “created a degree of complexity” and must “continue to seek ways to further streamline and simplify” the move to quality payments, according to comments from the American College of Cardiology.

The ACC also expressed concerns that the reporting requirements under MIPS and some of the APMs will limit the ability for cardiologists to report the most meaningful measures, particularly if they are part of a multi-specialty group, and suggested changes in scoring methodology or to allow more than one data file to be submitted in multi-specialty situations.

It also expressed concerns that the rule as proposed could adversely effect small practices, rural practices, and practices in health professional shortage areas, and “in the absence of other solutions such as virtual groups in 2017, CMS should monitor policies and provide effective practice assistance to these practices.”

The proposed rule provides no support for small practices, according to the American Gastroenterological Association.

“Upon release of the proposed rule, we were disappointed to see that not only will APMs be essentially closed off to small practices in the first years of implementation, but the MIPS program will significantly harm practices with less than 25 eligible clinicians,” AGA noted, citing data presented by CMS that 87% of solo practitioners will receive a negative adjustment with an aggregate negative impact of $300 million and for all practices with less than 25 eligible clinicians, the aggregate negative adjustment will total $649 million.

“Any system in which smaller practices are so heavily disadvantaged is unacceptable,” AGA said. CMS has previously stated that the regulatory impact statement would likely change and reflect a smaller impact for small and solo practices once more updated information can be modeled when the rule is final.

Additionally, AGA expressed concern over the limited engagement in APMs that will be possible under the proposed rule. “Given the importance of APM participation to both the practice and reimbursement of Medicare physicians, access to advanced APMs should be provided to all physicians.”

The association also expressed concern that the definition of APM is not broad enough and suggested that it be widened in scope so that it can capture payment models that have been created using the AGA’s Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice. It recommended a number of models be classified as APMs, including the colonoscopy bundled payment, gastroesophageal reflux disease episode payment, obesity bundled payment, Project Sonar (a chronic disease management program for IBD), and the Medical Home Neighbor.

The American College of Rheumatology called for a delay in the implementation of any final MACRA regulations, noting in its comments that with requirements set to begin in 2017, the current implementation schedule “does not provide enough time for providers to implement the required changes,” though ACR does not recommend a specific start time.

ACR also questioned how the criteria for APMs was set up, noting expressly that Physician Focused Payment Models may not meet the APM requirements. The group is seeking clarification on whether these models will qualify as an APM.

“Medical home APMs should also permit specialty physicians to participate, including small group and multispeciality groups, in keeping with the need for APMs to be flexible with their criteria and the role of specialty physicians in providing chronic care.

The American Academy of Dermatology Association echoed a number of concerns voiced across the medical profession and is calling for a delay in the implementation of MACRA’s regulations.

In particular, AADA noted that the regulations are not friendly for small and solo practices in general and little is contained within the proposal to “meaningfully engage specialist physicians in APMs.”

The association also is calling for broader mechanisms to allow for the development and recognition of APMs, including recognizing specialty-focused medical homes.

The group also is calling for pilot programs to test the validity of the measures that will form the basis of quality payment incentives and penalties.

In an effort to protect small and solo practices, AADA is calling for an exemption from MIPS or APM requirements until a virtual group option is developed, tested, and is fully operational.

The American Psychiatric Association echoed a number of broad concerns raised across the physician spectrum, including calling for a to the first year of implementation to July 1, 2017, and lasting through Dec. 31, 2017, as well as enabling the formation of virtual groups at the onset of implementation in its comments.

But APA also noted that mental health presents a variety of unique issues that need to be addressed.

For example, the association notes that psychiatrists work across a number of practice settings, including academic health centers, hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, and private practices, as well as offering services via telemedicine.

“This makes it difficult for psychiatrists to capture all the work they do, because of the combination of settings that utilize multiple, and potentially differing reporting programs and methods,” APA noted.

It added that psychiatrists generally have limited time and resources that can be devoted to Medicare quality reporting, which would make participation in MIPS and APMs more challenging, particularly because many operate in small or solo practices that do not own electronic health record systems, which would complicate reporting requirements to qualify for MIPS or APMs.

In addition to concerns with reporting in general, APA said that psychiatrists “also have limited choices in outcome quality measures.”

Opioid overdose epidemic now felt in the ICU

SAN FRANCISCO – The opioid overdose crisis in the United States is now plainly evident in intensive care units (ICUs), finds a study of hospitals in 44 states conducted between 2009 and 2015.

During the study period, ICU admissions for opioid overdoses increased by almost half, investigators reported in a session and related press briefing an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Furthermore, ICU deaths from this cause roughly doubled.

“This means the opioid use epidemic has probably reached a new level of crisis,” said lead investigator Jennifer P. Stevens, MD, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an adult intensive care physician at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. “And this means that in spite of everything that we can do in the ICU – keeping them alive on ventilators, doing life support, doing acute dialysis, doing round-the-clock care, round-the-clock board-certified intensivist care – we are still not able to make a difference in that mortality.”

Dr. Stevens added that any ICU admission for overdose from opioids is a preventable admission. “So if we have an increase in mortality of this population, we have a number of patients who have preventable deaths in our ICU,” she said.

Efforts to track this epidemic on a national level are important, she said, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been investigating opioid overdoses in some cities, including Boston, as they would any epidemic.

The factors driving the observed trends could not be determined from the study data, Dr. Stevens said. But state-specific patterns that show, for example, higher baseline rates and greater increases over time in ICU admissions for opioid overdose in Massachusetts and Indiana may be a starting point for investigation.

Certain practices in the ICU may also be inadvertently contributing. “I imagine that a patient who comes in with an opioid overdose can cause harm to themselves in a number of ways, and the things that we try to do to help them might cause harm in other ways as well,” she said. “So in an effort to try to maintain them in a safe, ventilated state, we might give them a ton of sedation that then prolongs their time on the ventilator. That’s sort of a simple example of how the two could intersect to have a multiplicative effect of harm.”

The idea for the study arose because ICU staff anecdotally noticed an uptick in admissions for opioid use disorder. “Not only were we seeing more people coming in, but we were seeing sicker people coming in, and with the associated tragedy that comes with a lot of young people coming in with opioid use disorder,” Dr. Stevens said. “We wanted to see if this was happening nationally... We asked, is this epidemic now reaching the most technologically advanced parts of our health care system?”

The investigators studied hospitals providing data to Vizient (formerly the University HealthSystem Consortium) between 2009 and 2015. The included hospitals – about 200 for each study year – were predominantly urban and university affiliated, but representation of community hospitals increased during the study period.

Ultimately, analyses were based on a total of 28.2 million hospital discharges of patients aged 18 years or older, which included 4.9 million ICU admissions.

Results reported at the meeting showed that 27,325 patients were admitted to the study hospitals’ ICUs with opioid overdose during the study period, as ascertained from billing codes.

Opioid overdose was seen in 45 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2009 but rose to 65 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2015, a 46% increase.

Furthermore, ICU deaths due to opioid overdose rose by 87% during the same time period, and mortality among patients admitted to the unit with overdose rose at a pace of 0.5% per month.

“This is somewhat unusual because a lot of times, when we are admitting more people to our ICUs or examining [a trend] further, mortality actually goes down. This is partly because maybe we are doing more for them and we are taking care of them in an aggressive way. But it’s also because we are admitting less sick people because we are more aware of the issue,” Dr. Stevens said. “And we saw the opposite of this – we saw that the mortality was going up.”

The use of billing data was a specific means but not a sensitive means of identifying opioid overdoses, she noted. Therefore, the observed values are likely underestimates of these outcomes.

Addressing the opioid overdose epidemic will require a multifaceted approach, according to Dr. Stevens, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

“Folks are doing very impressive work in the community trying to make sure EMTs and other first responders have access to the tools that they need in those settings,” she said. “But one thing we haven’t approached before is the care that we provide in the ICU, and maybe that’s a space that we need to think more prospectively about.”

SAN FRANCISCO – The opioid overdose crisis in the United States is now plainly evident in intensive care units (ICUs), finds a study of hospitals in 44 states conducted between 2009 and 2015.

During the study period, ICU admissions for opioid overdoses increased by almost half, investigators reported in a session and related press briefing an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Furthermore, ICU deaths from this cause roughly doubled.

“This means the opioid use epidemic has probably reached a new level of crisis,” said lead investigator Jennifer P. Stevens, MD, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an adult intensive care physician at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. “And this means that in spite of everything that we can do in the ICU – keeping them alive on ventilators, doing life support, doing acute dialysis, doing round-the-clock care, round-the-clock board-certified intensivist care – we are still not able to make a difference in that mortality.”

Dr. Stevens added that any ICU admission for overdose from opioids is a preventable admission. “So if we have an increase in mortality of this population, we have a number of patients who have preventable deaths in our ICU,” she said.

Efforts to track this epidemic on a national level are important, she said, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been investigating opioid overdoses in some cities, including Boston, as they would any epidemic.

The factors driving the observed trends could not be determined from the study data, Dr. Stevens said. But state-specific patterns that show, for example, higher baseline rates and greater increases over time in ICU admissions for opioid overdose in Massachusetts and Indiana may be a starting point for investigation.

Certain practices in the ICU may also be inadvertently contributing. “I imagine that a patient who comes in with an opioid overdose can cause harm to themselves in a number of ways, and the things that we try to do to help them might cause harm in other ways as well,” she said. “So in an effort to try to maintain them in a safe, ventilated state, we might give them a ton of sedation that then prolongs their time on the ventilator. That’s sort of a simple example of how the two could intersect to have a multiplicative effect of harm.”

The idea for the study arose because ICU staff anecdotally noticed an uptick in admissions for opioid use disorder. “Not only were we seeing more people coming in, but we were seeing sicker people coming in, and with the associated tragedy that comes with a lot of young people coming in with opioid use disorder,” Dr. Stevens said. “We wanted to see if this was happening nationally... We asked, is this epidemic now reaching the most technologically advanced parts of our health care system?”

The investigators studied hospitals providing data to Vizient (formerly the University HealthSystem Consortium) between 2009 and 2015. The included hospitals – about 200 for each study year – were predominantly urban and university affiliated, but representation of community hospitals increased during the study period.

Ultimately, analyses were based on a total of 28.2 million hospital discharges of patients aged 18 years or older, which included 4.9 million ICU admissions.

Results reported at the meeting showed that 27,325 patients were admitted to the study hospitals’ ICUs with opioid overdose during the study period, as ascertained from billing codes.

Opioid overdose was seen in 45 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2009 but rose to 65 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2015, a 46% increase.

Furthermore, ICU deaths due to opioid overdose rose by 87% during the same time period, and mortality among patients admitted to the unit with overdose rose at a pace of 0.5% per month.

“This is somewhat unusual because a lot of times, when we are admitting more people to our ICUs or examining [a trend] further, mortality actually goes down. This is partly because maybe we are doing more for them and we are taking care of them in an aggressive way. But it’s also because we are admitting less sick people because we are more aware of the issue,” Dr. Stevens said. “And we saw the opposite of this – we saw that the mortality was going up.”

The use of billing data was a specific means but not a sensitive means of identifying opioid overdoses, she noted. Therefore, the observed values are likely underestimates of these outcomes.

Addressing the opioid overdose epidemic will require a multifaceted approach, according to Dr. Stevens, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

“Folks are doing very impressive work in the community trying to make sure EMTs and other first responders have access to the tools that they need in those settings,” she said. “But one thing we haven’t approached before is the care that we provide in the ICU, and maybe that’s a space that we need to think more prospectively about.”

SAN FRANCISCO – The opioid overdose crisis in the United States is now plainly evident in intensive care units (ICUs), finds a study of hospitals in 44 states conducted between 2009 and 2015.

During the study period, ICU admissions for opioid overdoses increased by almost half, investigators reported in a session and related press briefing an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Furthermore, ICU deaths from this cause roughly doubled.

“This means the opioid use epidemic has probably reached a new level of crisis,” said lead investigator Jennifer P. Stevens, MD, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an adult intensive care physician at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, both in Boston. “And this means that in spite of everything that we can do in the ICU – keeping them alive on ventilators, doing life support, doing acute dialysis, doing round-the-clock care, round-the-clock board-certified intensivist care – we are still not able to make a difference in that mortality.”

Dr. Stevens added that any ICU admission for overdose from opioids is a preventable admission. “So if we have an increase in mortality of this population, we have a number of patients who have preventable deaths in our ICU,” she said.

Efforts to track this epidemic on a national level are important, she said, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been investigating opioid overdoses in some cities, including Boston, as they would any epidemic.

The factors driving the observed trends could not be determined from the study data, Dr. Stevens said. But state-specific patterns that show, for example, higher baseline rates and greater increases over time in ICU admissions for opioid overdose in Massachusetts and Indiana may be a starting point for investigation.

Certain practices in the ICU may also be inadvertently contributing. “I imagine that a patient who comes in with an opioid overdose can cause harm to themselves in a number of ways, and the things that we try to do to help them might cause harm in other ways as well,” she said. “So in an effort to try to maintain them in a safe, ventilated state, we might give them a ton of sedation that then prolongs their time on the ventilator. That’s sort of a simple example of how the two could intersect to have a multiplicative effect of harm.”

The idea for the study arose because ICU staff anecdotally noticed an uptick in admissions for opioid use disorder. “Not only were we seeing more people coming in, but we were seeing sicker people coming in, and with the associated tragedy that comes with a lot of young people coming in with opioid use disorder,” Dr. Stevens said. “We wanted to see if this was happening nationally... We asked, is this epidemic now reaching the most technologically advanced parts of our health care system?”

The investigators studied hospitals providing data to Vizient (formerly the University HealthSystem Consortium) between 2009 and 2015. The included hospitals – about 200 for each study year – were predominantly urban and university affiliated, but representation of community hospitals increased during the study period.

Ultimately, analyses were based on a total of 28.2 million hospital discharges of patients aged 18 years or older, which included 4.9 million ICU admissions.

Results reported at the meeting showed that 27,325 patients were admitted to the study hospitals’ ICUs with opioid overdose during the study period, as ascertained from billing codes.

Opioid overdose was seen in 45 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2009 but rose to 65 patients per 10,000 ICU admissions in 2015, a 46% increase.

Furthermore, ICU deaths due to opioid overdose rose by 87% during the same time period, and mortality among patients admitted to the unit with overdose rose at a pace of 0.5% per month.

“This is somewhat unusual because a lot of times, when we are admitting more people to our ICUs or examining [a trend] further, mortality actually goes down. This is partly because maybe we are doing more for them and we are taking care of them in an aggressive way. But it’s also because we are admitting less sick people because we are more aware of the issue,” Dr. Stevens said. “And we saw the opposite of this – we saw that the mortality was going up.”

The use of billing data was a specific means but not a sensitive means of identifying opioid overdoses, she noted. Therefore, the observed values are likely underestimates of these outcomes.

Addressing the opioid overdose epidemic will require a multifaceted approach, according to Dr. Stevens, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

“Folks are doing very impressive work in the community trying to make sure EMTs and other first responders have access to the tools that they need in those settings,” she said. “But one thing we haven’t approached before is the care that we provide in the ICU, and maybe that’s a space that we need to think more prospectively about.”

AT ATS 2016

Key clinical point: Opioid-related ICU admissions and mortality have risen sharply in recent years.

Major finding: ICU admissions for opioid overdose increased by 46%, and ICU deaths from this cause increased by 87%.

Data source: A cohort study of 28.2 million U.S. hospital discharges and 4.9 million ICU admissions between 2009 and 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Stevens disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

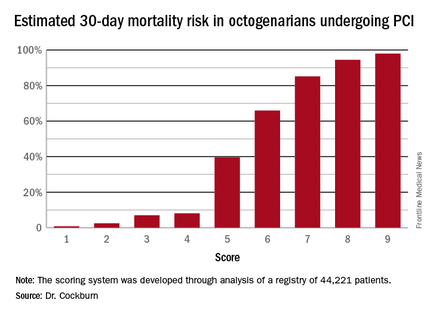

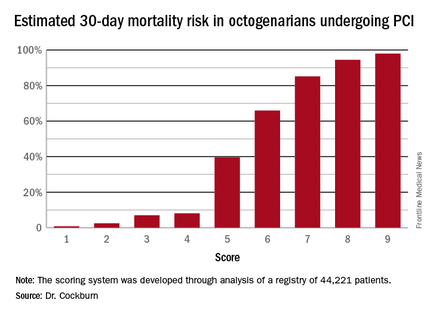

New risk score predicts PCI outcomes in octogenarians

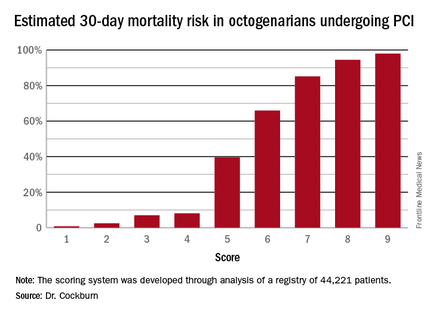

PARIS – A fast and simple clinically based scoring system enables physicians to determine the chance of a successful outcome for octogenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, James Cockburn, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

All six elements of the scoring system are readily available either at the time the very elderly patient presents or at diagnostic angiography, noted Dr. Cockburn of Brighton and Sussex University Hospital in Brighton, England.

He and his coworkers developed the risk score through analysis of a registry of 44,221 patients aged 80 or older who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The procedural success rate – defined as less than a 30% residual stenosis and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) 3 antegrade blood flow – was 92.3%. The 30-day mortality rate was 3.9%. The investigators teased out a set of easily accessible clinical factors associated with 30-day mortality and came up with a novel risk scoring system using a 9-point scale.

The clinical factors and scoring system are as follows:

• Age. 1 point for being 80-89, and 2 points at age 90 or older.

• Indication for PCI. 1 point for unstable angina/non–ST segment elevation MI, 2 points for STEMI, 0 points for other indications.

• Ventilated preprocedure. 1 point if yes.

• Creatinine level above 200 umol/L. 1 point for yes.

• Preprocedural cardiogenic shock. 2 points for yes.

• Poor left ventricular ejection fraction. If less than 30%, 1 point.

Thus, scores can range from 1 to 9. Dr. Cockburn and his coworkers calculated the risk of 30-day mortality for each possible score. They validated the score by performing a receiver operator curve analysis that showed an area under the curve of 0.83, suggestive of relatively high sensitivity and specificity.

A score of 4 or less suggests a very good chance of survival at 30 days. In contrast, a score of 6 was associated with a two in three chance of death by 30 days. And it’s not hard to reach a 6: A patient who is 90 years old (2 points), presents with STEMI (2 points), and is in cardiogenic shock (2 points) is already there. But if a 90-year-old patient presents with unstable angina and none of the other risk factors, that’s a score of 3 points, with an estimated probability of death at 30 days of only 7%, he noted.

Dr. Cockburn stressed that this risk score should not be used to base decisions on whether to take very elderly patients to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. “It enables you to have a useful conversation with relatives in which you can explain that this is a very high-risk intervention, or perhaps a low-risk intervention,” according to the cardiologist.

Discussants were emphatic in their agreement with Dr. Cockburn that this risk score shouldn’t be utilized to decide who does or doesn’t get PCI. One panelist said that what’s really lacking now in clinical practice – and where that huge British registry database could be helpful – is a scoring system that would predict which patients who don’t present in cardiogenic shock are going to develop it post PCI.

Dr. Cockburn reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

PARIS – A fast and simple clinically based scoring system enables physicians to determine the chance of a successful outcome for octogenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, James Cockburn, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

All six elements of the scoring system are readily available either at the time the very elderly patient presents or at diagnostic angiography, noted Dr. Cockburn of Brighton and Sussex University Hospital in Brighton, England.

He and his coworkers developed the risk score through analysis of a registry of 44,221 patients aged 80 or older who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The procedural success rate – defined as less than a 30% residual stenosis and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) 3 antegrade blood flow – was 92.3%. The 30-day mortality rate was 3.9%. The investigators teased out a set of easily accessible clinical factors associated with 30-day mortality and came up with a novel risk scoring system using a 9-point scale.

The clinical factors and scoring system are as follows:

• Age. 1 point for being 80-89, and 2 points at age 90 or older.

• Indication for PCI. 1 point for unstable angina/non–ST segment elevation MI, 2 points for STEMI, 0 points for other indications.

• Ventilated preprocedure. 1 point if yes.

• Creatinine level above 200 umol/L. 1 point for yes.

• Preprocedural cardiogenic shock. 2 points for yes.

• Poor left ventricular ejection fraction. If less than 30%, 1 point.

Thus, scores can range from 1 to 9. Dr. Cockburn and his coworkers calculated the risk of 30-day mortality for each possible score. They validated the score by performing a receiver operator curve analysis that showed an area under the curve of 0.83, suggestive of relatively high sensitivity and specificity.

A score of 4 or less suggests a very good chance of survival at 30 days. In contrast, a score of 6 was associated with a two in three chance of death by 30 days. And it’s not hard to reach a 6: A patient who is 90 years old (2 points), presents with STEMI (2 points), and is in cardiogenic shock (2 points) is already there. But if a 90-year-old patient presents with unstable angina and none of the other risk factors, that’s a score of 3 points, with an estimated probability of death at 30 days of only 7%, he noted.

Dr. Cockburn stressed that this risk score should not be used to base decisions on whether to take very elderly patients to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. “It enables you to have a useful conversation with relatives in which you can explain that this is a very high-risk intervention, or perhaps a low-risk intervention,” according to the cardiologist.

Discussants were emphatic in their agreement with Dr. Cockburn that this risk score shouldn’t be utilized to decide who does or doesn’t get PCI. One panelist said that what’s really lacking now in clinical practice – and where that huge British registry database could be helpful – is a scoring system that would predict which patients who don’t present in cardiogenic shock are going to develop it post PCI.

Dr. Cockburn reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

PARIS – A fast and simple clinically based scoring system enables physicians to determine the chance of a successful outcome for octogenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, James Cockburn, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

All six elements of the scoring system are readily available either at the time the very elderly patient presents or at diagnostic angiography, noted Dr. Cockburn of Brighton and Sussex University Hospital in Brighton, England.

He and his coworkers developed the risk score through analysis of a registry of 44,221 patients aged 80 or older who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The procedural success rate – defined as less than a 30% residual stenosis and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) 3 antegrade blood flow – was 92.3%. The 30-day mortality rate was 3.9%. The investigators teased out a set of easily accessible clinical factors associated with 30-day mortality and came up with a novel risk scoring system using a 9-point scale.

The clinical factors and scoring system are as follows:

• Age. 1 point for being 80-89, and 2 points at age 90 or older.

• Indication for PCI. 1 point for unstable angina/non–ST segment elevation MI, 2 points for STEMI, 0 points for other indications.

• Ventilated preprocedure. 1 point if yes.

• Creatinine level above 200 umol/L. 1 point for yes.

• Preprocedural cardiogenic shock. 2 points for yes.

• Poor left ventricular ejection fraction. If less than 30%, 1 point.

Thus, scores can range from 1 to 9. Dr. Cockburn and his coworkers calculated the risk of 30-day mortality for each possible score. They validated the score by performing a receiver operator curve analysis that showed an area under the curve of 0.83, suggestive of relatively high sensitivity and specificity.

A score of 4 or less suggests a very good chance of survival at 30 days. In contrast, a score of 6 was associated with a two in three chance of death by 30 days. And it’s not hard to reach a 6: A patient who is 90 years old (2 points), presents with STEMI (2 points), and is in cardiogenic shock (2 points) is already there. But if a 90-year-old patient presents with unstable angina and none of the other risk factors, that’s a score of 3 points, with an estimated probability of death at 30 days of only 7%, he noted.

Dr. Cockburn stressed that this risk score should not be used to base decisions on whether to take very elderly patients to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. “It enables you to have a useful conversation with relatives in which you can explain that this is a very high-risk intervention, or perhaps a low-risk intervention,” according to the cardiologist.

Discussants were emphatic in their agreement with Dr. Cockburn that this risk score shouldn’t be utilized to decide who does or doesn’t get PCI. One panelist said that what’s really lacking now in clinical practice – and where that huge British registry database could be helpful – is a scoring system that would predict which patients who don’t present in cardiogenic shock are going to develop it post PCI.

Dr. Cockburn reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: Six readily obtainable clinical factors can be added up to allow accurate estimates of 30-day mortality risk after PCI.

Major finding: Very elderly patients with a score of 3 out of a possible 9 had an estimated 30-day mortality risk of 7%, while at a score of 5, the risk jumped to 40%, and at 6 to 66%.

Data source: This novel 30-day risk scoring system for octogenarians undergoing PCI was derived from a registry of 44,221 such patients.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

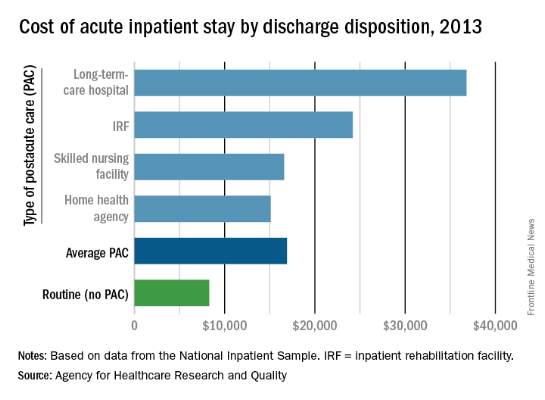

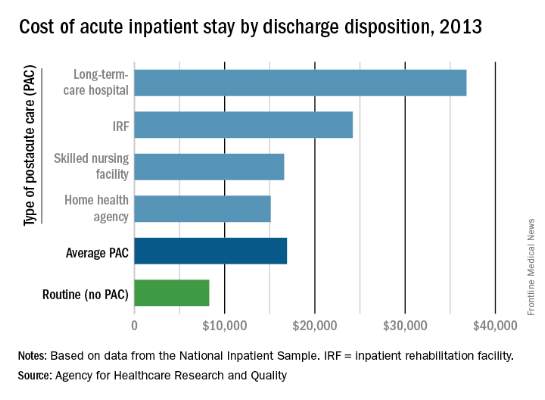

Hospital costs higher for patients discharged to postacute care

The average cost of U.S. hospital stays for injury or illness in patients discharged to postacute care is more than double that of visits with routine discharges, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For patients who were discharged from hospitals to PAC, the average cost of an inpatient visit in 2013 was $16,900, compared with $8,300 for patients with routine discharges. The inpatient visits with PAC were almost twice as long as those with routine discharge – 7.0 days vs. 3.6 days – and patients with PAC-discharge visits were much older – 69.5% were aged 65 years or older, compared with 22.4% of visits with routine discharges, the AHRQ reported.

The AHRQ used data from the 2013 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) to estimates discharges to PAC for all types of payers and describe these discharges from the perspective of payers, patients, hospitals, conditions/procedures, and geographic regions.

The cost of stays varied considerably among the various PAC settings in 2013. Inpatient stays with discharge to home health agencies had the lowest average cost at $15,100, with skilled nursing facilities next at $16,600, followed by inpatient rehabilitation facilities at $24,200 and long-term-care hospitals at $36,800. Length of stays by PAC setting showed the same trend: those with discharge to home health agencies were shortest (6.2 days) and those with discharge to long-term-care hospitals were longest (13.5 days), the AHRQ said in the report.

Inpatient stays with discharge to PAC made up 22.3% of all hospital discharges in 2013, with the bulk being discharges to home health agencies (50.1%) and skilled nursing facilities (40.5%). Discharges to inpatient rehabilitation facilities made up 7.2% of all PAC visits, while those to long-term-care hospitals were just 2.2%, the data from the NIS show.

The average cost of U.S. hospital stays for injury or illness in patients discharged to postacute care is more than double that of visits with routine discharges, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For patients who were discharged from hospitals to PAC, the average cost of an inpatient visit in 2013 was $16,900, compared with $8,300 for patients with routine discharges. The inpatient visits with PAC were almost twice as long as those with routine discharge – 7.0 days vs. 3.6 days – and patients with PAC-discharge visits were much older – 69.5% were aged 65 years or older, compared with 22.4% of visits with routine discharges, the AHRQ reported.

The AHRQ used data from the 2013 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) to estimates discharges to PAC for all types of payers and describe these discharges from the perspective of payers, patients, hospitals, conditions/procedures, and geographic regions.

The cost of stays varied considerably among the various PAC settings in 2013. Inpatient stays with discharge to home health agencies had the lowest average cost at $15,100, with skilled nursing facilities next at $16,600, followed by inpatient rehabilitation facilities at $24,200 and long-term-care hospitals at $36,800. Length of stays by PAC setting showed the same trend: those with discharge to home health agencies were shortest (6.2 days) and those with discharge to long-term-care hospitals were longest (13.5 days), the AHRQ said in the report.

Inpatient stays with discharge to PAC made up 22.3% of all hospital discharges in 2013, with the bulk being discharges to home health agencies (50.1%) and skilled nursing facilities (40.5%). Discharges to inpatient rehabilitation facilities made up 7.2% of all PAC visits, while those to long-term-care hospitals were just 2.2%, the data from the NIS show.

The average cost of U.S. hospital stays for injury or illness in patients discharged to postacute care is more than double that of visits with routine discharges, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For patients who were discharged from hospitals to PAC, the average cost of an inpatient visit in 2013 was $16,900, compared with $8,300 for patients with routine discharges. The inpatient visits with PAC were almost twice as long as those with routine discharge – 7.0 days vs. 3.6 days – and patients with PAC-discharge visits were much older – 69.5% were aged 65 years or older, compared with 22.4% of visits with routine discharges, the AHRQ reported.

The AHRQ used data from the 2013 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) to estimates discharges to PAC for all types of payers and describe these discharges from the perspective of payers, patients, hospitals, conditions/procedures, and geographic regions.

The cost of stays varied considerably among the various PAC settings in 2013. Inpatient stays with discharge to home health agencies had the lowest average cost at $15,100, with skilled nursing facilities next at $16,600, followed by inpatient rehabilitation facilities at $24,200 and long-term-care hospitals at $36,800. Length of stays by PAC setting showed the same trend: those with discharge to home health agencies were shortest (6.2 days) and those with discharge to long-term-care hospitals were longest (13.5 days), the AHRQ said in the report.

Inpatient stays with discharge to PAC made up 22.3% of all hospital discharges in 2013, with the bulk being discharges to home health agencies (50.1%) and skilled nursing facilities (40.5%). Discharges to inpatient rehabilitation facilities made up 7.2% of all PAC visits, while those to long-term-care hospitals were just 2.2%, the data from the NIS show.

Hospital costs higher for patients discharged to postacute care

The average cost of U.S. hospital stays for injury or illness in patients discharged to postacute care is more than double that of visits with routine discharges, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For patients who were discharged from hospitals to PAC, the average cost of an inpatient visit in 2013 was $16,900, compared with $8,300 for patients with routine discharges. The inpatient visits with PAC were almost twice as long as those with routine discharge – 7.0 days vs. 3.6 days – and patients with PAC-discharge visits were much older – 69.5% were aged 65 years or older, compared with 22.4% of visits with routine discharges, the AHRQ reported.

The AHRQ used data from the 2013 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) to estimates discharges to PAC for all types of payers and describe these discharges from the perspective of payers, patients, hospitals, conditions/procedures, and geographic regions.

The cost of stays varied considerably among the various PAC settings in 2013. Inpatient stays with discharge to home health agencies had the lowest average cost at $15,100, with skilled nursing facilities next at $16,600, followed by inpatient rehabilitation facilities at $24,200 and long-term-care hospitals at $36,800. Length of stays by PAC setting showed the same trend: those with discharge to home health agencies were shortest (6.2 days) and those with discharge to long-term-care hospitals were longest (13.5 days), the AHRQ said in the report.

Inpatient stays with discharge to PAC made up 22.3% of all hospital discharges in 2013, with the bulk being discharges to home health agencies (50.1%) and skilled nursing facilities (40.5%). Discharges to inpatient rehabilitation facilities made up 7.2% of all PAC visits, while those to long-term-care hospitals were just 2.2%, the data from the NIS show.

The average cost of U.S. hospital stays for injury or illness in patients discharged to postacute care is more than double that of visits with routine discharges, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For patients who were discharged from hospitals to PAC, the average cost of an inpatient visit in 2013 was $16,900, compared with $8,300 for patients with routine discharges. The inpatient visits with PAC were almost twice as long as those with routine discharge – 7.0 days vs. 3.6 days – and patients with PAC-discharge visits were much older – 69.5% were aged 65 years or older, compared with 22.4% of visits with routine discharges, the AHRQ reported.

The AHRQ used data from the 2013 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) to estimates discharges to PAC for all types of payers and describe these discharges from the perspective of payers, patients, hospitals, conditions/procedures, and geographic regions.

The cost of stays varied considerably among the various PAC settings in 2013. Inpatient stays with discharge to home health agencies had the lowest average cost at $15,100, with skilled nursing facilities next at $16,600, followed by inpatient rehabilitation facilities at $24,200 and long-term-care hospitals at $36,800. Length of stays by PAC setting showed the same trend: those with discharge to home health agencies were shortest (6.2 days) and those with discharge to long-term-care hospitals were longest (13.5 days), the AHRQ said in the report.

Inpatient stays with discharge to PAC made up 22.3% of all hospital discharges in 2013, with the bulk being discharges to home health agencies (50.1%) and skilled nursing facilities (40.5%). Discharges to inpatient rehabilitation facilities made up 7.2% of all PAC visits, while those to long-term-care hospitals were just 2.2%, the data from the NIS show.

The average cost of U.S. hospital stays for injury or illness in patients discharged to postacute care is more than double that of visits with routine discharges, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For patients who were discharged from hospitals to PAC, the average cost of an inpatient visit in 2013 was $16,900, compared with $8,300 for patients with routine discharges. The inpatient visits with PAC were almost twice as long as those with routine discharge – 7.0 days vs. 3.6 days – and patients with PAC-discharge visits were much older – 69.5% were aged 65 years or older, compared with 22.4% of visits with routine discharges, the AHRQ reported.

The AHRQ used data from the 2013 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) to estimates discharges to PAC for all types of payers and describe these discharges from the perspective of payers, patients, hospitals, conditions/procedures, and geographic regions.

The cost of stays varied considerably among the various PAC settings in 2013. Inpatient stays with discharge to home health agencies had the lowest average cost at $15,100, with skilled nursing facilities next at $16,600, followed by inpatient rehabilitation facilities at $24,200 and long-term-care hospitals at $36,800. Length of stays by PAC setting showed the same trend: those with discharge to home health agencies were shortest (6.2 days) and those with discharge to long-term-care hospitals were longest (13.5 days), the AHRQ said in the report.

Inpatient stays with discharge to PAC made up 22.3% of all hospital discharges in 2013, with the bulk being discharges to home health agencies (50.1%) and skilled nursing facilities (40.5%). Discharges to inpatient rehabilitation facilities made up 7.2% of all PAC visits, while those to long-term-care hospitals were just 2.2%, the data from the NIS show.

MPT64 rapid test may miss TB caused by M. africanum strain

Tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium africanum West Africa 2 is significantly less likely to be detected by a MPT64 rapid antigen test than is M. tuberculosis, according to a research team based in the Gambia.

A total of 173 MGIT culture-positive sputum samples were included in the study, and the initial MPT64 test was negative in 23 samples. Just over 90% of M. tuberculosis (MTB) samples converted to positive on day 0, while only 78.4% of M. africanum West Africa 2 (MAF2) samples converted. After 10 days, 97.5% of MTB samples were positive, while conversion of MAF2 samples remained low at 84.3%.

In a comparison of the mRNA transcript from samples of six MTB and five MAF2 patients who had not been treated for TB, the MTP64 gene was about 2.5 times more abundant in the MTB samples than the MAF2 samples. No association was found between conversion to positivity and sex, age, therapy, or mycobacterial growth units.

“Given the relatively low cost, limited technical expertise, and shorter turnaround time associated with using rapid speciation tests, compared to alternative speciation methods, MPT64 rapid tests will likely remain one of the preferred options for timely diagnosis of suspected TB despite the possibility of false negative results. Therefore, a negative MPT64 result would require confirmation by an alternative method, such as molecular tests or culture on p-nitrobenzoic acid, depending on laboratory infrastructure and resources,” the investigators noted.

Read the full study in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004801).

Tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium africanum West Africa 2 is significantly less likely to be detected by a MPT64 rapid antigen test than is M. tuberculosis, according to a research team based in the Gambia.

A total of 173 MGIT culture-positive sputum samples were included in the study, and the initial MPT64 test was negative in 23 samples. Just over 90% of M. tuberculosis (MTB) samples converted to positive on day 0, while only 78.4% of M. africanum West Africa 2 (MAF2) samples converted. After 10 days, 97.5% of MTB samples were positive, while conversion of MAF2 samples remained low at 84.3%.

In a comparison of the mRNA transcript from samples of six MTB and five MAF2 patients who had not been treated for TB, the MTP64 gene was about 2.5 times more abundant in the MTB samples than the MAF2 samples. No association was found between conversion to positivity and sex, age, therapy, or mycobacterial growth units.

“Given the relatively low cost, limited technical expertise, and shorter turnaround time associated with using rapid speciation tests, compared to alternative speciation methods, MPT64 rapid tests will likely remain one of the preferred options for timely diagnosis of suspected TB despite the possibility of false negative results. Therefore, a negative MPT64 result would require confirmation by an alternative method, such as molecular tests or culture on p-nitrobenzoic acid, depending on laboratory infrastructure and resources,” the investigators noted.

Read the full study in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004801).

Tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium africanum West Africa 2 is significantly less likely to be detected by a MPT64 rapid antigen test than is M. tuberculosis, according to a research team based in the Gambia.

A total of 173 MGIT culture-positive sputum samples were included in the study, and the initial MPT64 test was negative in 23 samples. Just over 90% of M. tuberculosis (MTB) samples converted to positive on day 0, while only 78.4% of M. africanum West Africa 2 (MAF2) samples converted. After 10 days, 97.5% of MTB samples were positive, while conversion of MAF2 samples remained low at 84.3%.

In a comparison of the mRNA transcript from samples of six MTB and five MAF2 patients who had not been treated for TB, the MTP64 gene was about 2.5 times more abundant in the MTB samples than the MAF2 samples. No association was found between conversion to positivity and sex, age, therapy, or mycobacterial growth units.

“Given the relatively low cost, limited technical expertise, and shorter turnaround time associated with using rapid speciation tests, compared to alternative speciation methods, MPT64 rapid tests will likely remain one of the preferred options for timely diagnosis of suspected TB despite the possibility of false negative results. Therefore, a negative MPT64 result would require confirmation by an alternative method, such as molecular tests or culture on p-nitrobenzoic acid, depending on laboratory infrastructure and resources,” the investigators noted.

Read the full study in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004801).

FROM PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES

MPT64 rapid test may miss TB caused by M. africanum strain

Tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium africanum West Africa 2 is significantly less likely to be detected by a MPT64 rapid antigen test than is M. tuberculosis, according to a research team based in the Gambia.

A total of 173 MGIT culture-positive sputum samples were included in the study, and the initial MPT64 test was negative in 23 samples. Just over 90% of M. tuberculosis (MTB) samples converted to positive on day 0, while only 78.4% of M. africanum West Africa 2 (MAF2) samples converted. After 10 days, 97.5% of MTB samples were positive, while conversion of MAF2 samples remained low at 84.3%.

In a comparison of the mRNA transcript from samples of six MTB and five MAF2 patients who had not been treated for TB, the MTP64 gene was about 2.5 times more abundant in the MTB samples than the MAF2 samples. No association was found between conversion to positivity and sex, age, therapy, or mycobacterial growth units.

“Given the relatively low cost, limited technical expertise, and shorter turnaround time associated with using rapid speciation tests, compared to alternative speciation methods, MPT64 rapid tests will likely remain one of the preferred options for timely diagnosis of suspected TB despite the possibility of false negative results. Therefore, a negative MPT64 result would require confirmation by an alternative method, such as molecular tests or culture on p-nitrobenzoic acid, depending on laboratory infrastructure and resources,” the investigators noted.

Read the full study in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004801).

Tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium africanum West Africa 2 is significantly less likely to be detected by a MPT64 rapid antigen test than is M. tuberculosis, according to a research team based in the Gambia.

A total of 173 MGIT culture-positive sputum samples were included in the study, and the initial MPT64 test was negative in 23 samples. Just over 90% of M. tuberculosis (MTB) samples converted to positive on day 0, while only 78.4% of M. africanum West Africa 2 (MAF2) samples converted. After 10 days, 97.5% of MTB samples were positive, while conversion of MAF2 samples remained low at 84.3%.

In a comparison of the mRNA transcript from samples of six MTB and five MAF2 patients who had not been treated for TB, the MTP64 gene was about 2.5 times more abundant in the MTB samples than the MAF2 samples. No association was found between conversion to positivity and sex, age, therapy, or mycobacterial growth units.

“Given the relatively low cost, limited technical expertise, and shorter turnaround time associated with using rapid speciation tests, compared to alternative speciation methods, MPT64 rapid tests will likely remain one of the preferred options for timely diagnosis of suspected TB despite the possibility of false negative results. Therefore, a negative MPT64 result would require confirmation by an alternative method, such as molecular tests or culture on p-nitrobenzoic acid, depending on laboratory infrastructure and resources,” the investigators noted.

Read the full study in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004801).

Tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium africanum West Africa 2 is significantly less likely to be detected by a MPT64 rapid antigen test than is M. tuberculosis, according to a research team based in the Gambia.

A total of 173 MGIT culture-positive sputum samples were included in the study, and the initial MPT64 test was negative in 23 samples. Just over 90% of M. tuberculosis (MTB) samples converted to positive on day 0, while only 78.4% of M. africanum West Africa 2 (MAF2) samples converted. After 10 days, 97.5% of MTB samples were positive, while conversion of MAF2 samples remained low at 84.3%.

In a comparison of the mRNA transcript from samples of six MTB and five MAF2 patients who had not been treated for TB, the MTP64 gene was about 2.5 times more abundant in the MTB samples than the MAF2 samples. No association was found between conversion to positivity and sex, age, therapy, or mycobacterial growth units.

“Given the relatively low cost, limited technical expertise, and shorter turnaround time associated with using rapid speciation tests, compared to alternative speciation methods, MPT64 rapid tests will likely remain one of the preferred options for timely diagnosis of suspected TB despite the possibility of false negative results. Therefore, a negative MPT64 result would require confirmation by an alternative method, such as molecular tests or culture on p-nitrobenzoic acid, depending on laboratory infrastructure and resources,” the investigators noted.

Read the full study in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases (doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004801).

FROM PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES

The nightmare of opioid addiction

You start your day refreshed, enthusiastic, and ready to take on every challenge that comes your way.

You print your list of patients for the day – not too bad, a mere 15; quite doable for a seasoned hospitalist. You scan your list: a hypertensive crisis – piece of cake; 3 patients with acute systolic heart failure – just follow the guidelines; 2 with a COPD exacerbation – no worries. You know how to treat these conditions, almost with your eyes closed. But, of course, all conditions do not have such straightforward treatments.

The next patient on your list is a 35-year-old on a methadone maintenance program admitted with an accidental heroin overdose. So sad. Then there is a 59-year-old with chronic back pain and known drug-seeking behavior, well known to you and your entire team. So frustrating. Next, you read about a healthy 24-year-old mother of two who slipped on a baby bottle and tumbled down two flights of stairs, breaking both femurs, a clavicle, and nine ribs.

As you mull over your approach to the first two, you cannot help but be concerned about the likelihood that this young mother will require strong narcotics to manage her pain for a considerable time, long after discharge. She has a legitimate reason to receive opioid analgesics, but how can you minimize her chances of becoming another statistic?

In 2012, an estimated 2.1 million Americans suffered from substance use disorders due to prescription opioid pain relievers while close to 467,000 were addicted to heroin.

To complicate matters, many who were legitimately prescribed painkillers go on to abuse heroin when they can no longer get prescription opiates from their health care providers. Naturally, we want to take away our patients’ pain, but in 2016 we must be keenly aware that every time we prescribe opiates for our patients there is a risk, whether great or small, that individual may some day suffer from a substance abuse disorder.

Evidence shows that the way the human brain deals with opiates, and subsequent opiate dependence, necessitates that we rethink how we view addiction. Addicts simply cannot be stereotyped as derelicts, always looking for their next high. They have a real disease.

According to the American Society of Addiction Medicine, addiction is a primary, chronic, and relapsing disease of the brain. When one thinks of addiction as a true disease, and not simply as a weakness of pleasure seekers with morals we deem beneath our own, it paints the addict in a completely different light.