User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Oregon Physician Assistants Get Name Change

On April 4, Oregon’s Governor Tina Kotek signed a bill into law that officially changed the title of “physician assistants” to “physician associates” in the state.

In the Medscape Physician Assistant Career Satisfaction Report 2023, a diverse range of opinions on the title switch was reflected. Only 40% of PAs favored the name change at the time, 45% neither opposed nor favored it, and 15% opposed the name change, reflecting the complexity of the issue.

According to the AAPA, the change came about to better reflect the work PAs do in not just “assisting” physicians but in working independently with patients. Some also felt that the word “assistant” implies dependence. However, despite associate’s more accurate reflection of the job, PAs mostly remain split on whether they want the new moniker.

Many say that the name change will be confusing for the public and their patients, while others say that physician assistant was already not well understood, as patients often thought of the profession as a doctor’s helper or an assistant, like a medical assistant.

Yet many long-time PAs say that they prefer the title they’ve always had and that explaining to patients the new associate title will be equally confusing. Some mentioned patients may think they’re a business associate of the physician.

Oregon PAs won’t immediately switch to the new name. The new law takes effect on June 6, 2024. The Oregon Medical Board will establish regulations and guidance before PAs adopt the new name in their practices.

The law only changes the name of PAs in Oregon, not in other states. In fact, prematurely using the title of physician associate could subject a PA to regulatory challenges or disciplinary actions.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

On April 4, Oregon’s Governor Tina Kotek signed a bill into law that officially changed the title of “physician assistants” to “physician associates” in the state.

In the Medscape Physician Assistant Career Satisfaction Report 2023, a diverse range of opinions on the title switch was reflected. Only 40% of PAs favored the name change at the time, 45% neither opposed nor favored it, and 15% opposed the name change, reflecting the complexity of the issue.

According to the AAPA, the change came about to better reflect the work PAs do in not just “assisting” physicians but in working independently with patients. Some also felt that the word “assistant” implies dependence. However, despite associate’s more accurate reflection of the job, PAs mostly remain split on whether they want the new moniker.

Many say that the name change will be confusing for the public and their patients, while others say that physician assistant was already not well understood, as patients often thought of the profession as a doctor’s helper or an assistant, like a medical assistant.

Yet many long-time PAs say that they prefer the title they’ve always had and that explaining to patients the new associate title will be equally confusing. Some mentioned patients may think they’re a business associate of the physician.

Oregon PAs won’t immediately switch to the new name. The new law takes effect on June 6, 2024. The Oregon Medical Board will establish regulations and guidance before PAs adopt the new name in their practices.

The law only changes the name of PAs in Oregon, not in other states. In fact, prematurely using the title of physician associate could subject a PA to regulatory challenges or disciplinary actions.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

On April 4, Oregon’s Governor Tina Kotek signed a bill into law that officially changed the title of “physician assistants” to “physician associates” in the state.

In the Medscape Physician Assistant Career Satisfaction Report 2023, a diverse range of opinions on the title switch was reflected. Only 40% of PAs favored the name change at the time, 45% neither opposed nor favored it, and 15% opposed the name change, reflecting the complexity of the issue.

According to the AAPA, the change came about to better reflect the work PAs do in not just “assisting” physicians but in working independently with patients. Some also felt that the word “assistant” implies dependence. However, despite associate’s more accurate reflection of the job, PAs mostly remain split on whether they want the new moniker.

Many say that the name change will be confusing for the public and their patients, while others say that physician assistant was already not well understood, as patients often thought of the profession as a doctor’s helper or an assistant, like a medical assistant.

Yet many long-time PAs say that they prefer the title they’ve always had and that explaining to patients the new associate title will be equally confusing. Some mentioned patients may think they’re a business associate of the physician.

Oregon PAs won’t immediately switch to the new name. The new law takes effect on June 6, 2024. The Oregon Medical Board will establish regulations and guidance before PAs adopt the new name in their practices.

The law only changes the name of PAs in Oregon, not in other states. In fact, prematurely using the title of physician associate could subject a PA to regulatory challenges or disciplinary actions.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Evening May Be the Best Time for Exercise

TOPLINE:

Moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity performed in the evening is associated with the lowest risk for mortality, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and microvascular disease (MVD) in adults with obesity, including those with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

METHODOLOGY:

- Bouts of moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity are widely recognized to improve cardiometabolic risk factors, but whether morning, afternoon, or evening timing may lead to greater improvements is unclear.

- Researchers analyzed UK Biobank data of 29,836 participants with obesity (body mass index, › 30; mean age, 62.2 years; 53.2% women), including 2995 also diagnosed with T2D, all enrolled in 2006-2010.

- Aerobic activity was defined as bouts lasting ≥ 3 minutes, and the intensity of activity was classified as light, moderate, or vigorous using accelerometer data collected from participants.

- Participants were stratified into the morning (6 a.m. to < 12 p.m.), afternoon (12 p.m. to < 6 p.m.), and evening (6 p.m. to < 12 a.m.) groups based on when > 50% of their total moderate to vigorous activity occurred, and those with no aerobic bouts were considered the reference group.

- The association between the timing of aerobic physical activity and risk for all-cause mortality, CVD (defined as circulatory, such as hypertension), and MVD (neuropathy, nephropathy, or retinopathy) was evaluated over a median follow-up of 7.9 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Mortality risk was lower in the afternoon (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.51-0.71) and morning (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56-0.79) activity groups than in the reference group, but this association was weaker than that observed in the evening activity group.

- The evening moderate to vigorous activity group had a lower risk for CVD (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.54-0.75) and MVD (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.63-0.92) than the reference group.

- Among participants with obesity and T2D, moderate to vigorous physical activity in the evening was associated with a lower risk for mortality, CVD, and MVD.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “The results of this study emphasize that beyond the total volume of MVPA [moderate to vigorous physical activity], its timing, particularly in the evening, was consistently associated with the lowest risk of mortality relative to other timing windows.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Angelo Sabag, PhD, Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney, Australia, was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

Because this was an observational study, the possibility of reverse causation from prodromal disease and unaccounted confounding factors could not have been ruled out. There was a lag of a median of 5.5 years between the UK Biobank baseline, when covariate measurements were taken, and the accelerometry study. Moreover, the response rate of the UK Biobank was low.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant and the National Heart Foundation of Australia Postdoctoral Fellowship. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity performed in the evening is associated with the lowest risk for mortality, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and microvascular disease (MVD) in adults with obesity, including those with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

METHODOLOGY:

- Bouts of moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity are widely recognized to improve cardiometabolic risk factors, but whether morning, afternoon, or evening timing may lead to greater improvements is unclear.

- Researchers analyzed UK Biobank data of 29,836 participants with obesity (body mass index, › 30; mean age, 62.2 years; 53.2% women), including 2995 also diagnosed with T2D, all enrolled in 2006-2010.

- Aerobic activity was defined as bouts lasting ≥ 3 minutes, and the intensity of activity was classified as light, moderate, or vigorous using accelerometer data collected from participants.

- Participants were stratified into the morning (6 a.m. to < 12 p.m.), afternoon (12 p.m. to < 6 p.m.), and evening (6 p.m. to < 12 a.m.) groups based on when > 50% of their total moderate to vigorous activity occurred, and those with no aerobic bouts were considered the reference group.

- The association between the timing of aerobic physical activity and risk for all-cause mortality, CVD (defined as circulatory, such as hypertension), and MVD (neuropathy, nephropathy, or retinopathy) was evaluated over a median follow-up of 7.9 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Mortality risk was lower in the afternoon (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.51-0.71) and morning (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56-0.79) activity groups than in the reference group, but this association was weaker than that observed in the evening activity group.

- The evening moderate to vigorous activity group had a lower risk for CVD (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.54-0.75) and MVD (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.63-0.92) than the reference group.

- Among participants with obesity and T2D, moderate to vigorous physical activity in the evening was associated with a lower risk for mortality, CVD, and MVD.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “The results of this study emphasize that beyond the total volume of MVPA [moderate to vigorous physical activity], its timing, particularly in the evening, was consistently associated with the lowest risk of mortality relative to other timing windows.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Angelo Sabag, PhD, Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney, Australia, was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

Because this was an observational study, the possibility of reverse causation from prodromal disease and unaccounted confounding factors could not have been ruled out. There was a lag of a median of 5.5 years between the UK Biobank baseline, when covariate measurements were taken, and the accelerometry study. Moreover, the response rate of the UK Biobank was low.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant and the National Heart Foundation of Australia Postdoctoral Fellowship. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity performed in the evening is associated with the lowest risk for mortality, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and microvascular disease (MVD) in adults with obesity, including those with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

METHODOLOGY:

- Bouts of moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity are widely recognized to improve cardiometabolic risk factors, but whether morning, afternoon, or evening timing may lead to greater improvements is unclear.

- Researchers analyzed UK Biobank data of 29,836 participants with obesity (body mass index, › 30; mean age, 62.2 years; 53.2% women), including 2995 also diagnosed with T2D, all enrolled in 2006-2010.

- Aerobic activity was defined as bouts lasting ≥ 3 minutes, and the intensity of activity was classified as light, moderate, or vigorous using accelerometer data collected from participants.

- Participants were stratified into the morning (6 a.m. to < 12 p.m.), afternoon (12 p.m. to < 6 p.m.), and evening (6 p.m. to < 12 a.m.) groups based on when > 50% of their total moderate to vigorous activity occurred, and those with no aerobic bouts were considered the reference group.

- The association between the timing of aerobic physical activity and risk for all-cause mortality, CVD (defined as circulatory, such as hypertension), and MVD (neuropathy, nephropathy, or retinopathy) was evaluated over a median follow-up of 7.9 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Mortality risk was lower in the afternoon (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.51-0.71) and morning (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56-0.79) activity groups than in the reference group, but this association was weaker than that observed in the evening activity group.

- The evening moderate to vigorous activity group had a lower risk for CVD (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.54-0.75) and MVD (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.63-0.92) than the reference group.

- Among participants with obesity and T2D, moderate to vigorous physical activity in the evening was associated with a lower risk for mortality, CVD, and MVD.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “The results of this study emphasize that beyond the total volume of MVPA [moderate to vigorous physical activity], its timing, particularly in the evening, was consistently associated with the lowest risk of mortality relative to other timing windows.”

SOURCE:

The study, led by Angelo Sabag, PhD, Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney, Australia, was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

Because this was an observational study, the possibility of reverse causation from prodromal disease and unaccounted confounding factors could not have been ruled out. There was a lag of a median of 5.5 years between the UK Biobank baseline, when covariate measurements were taken, and the accelerometry study. Moreover, the response rate of the UK Biobank was low.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant and the National Heart Foundation of Australia Postdoctoral Fellowship. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How These Young MDs Impressed the Hell Out of Their Bosses

Safe to say that anyone undertaking the physician journey does so with intense motivation and book smarts. Still, it can be incredibly hard to stand out. Everyone’s a go-getter, but what’s the X factor?

Here’s what they said ...

Lesson #1: Never Be Scared to Ask

Brien Barnewolt, MD, chairman and chief of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Tufts Medical Center, was very much surprised when a resident named Scott G. Weiner did something unexpected: Go after a job in the fall of his junior year residency instead of following the typical senior year trajectory.

“It’s very unusual for a trainee to apply for a job virtually a year ahead of schedule. But he knew what he wanted,” said Dr. Barnewolt. “I’d never had anybody come to me in that same scenario, and I’ve been doing this a long time.”

Under normal circumstances it would’ve been easy for Dr. Barnewolt to say no. But the unexpected request made him and his colleagues take a closer look, and they were impressed with Dr. Weiner’s skills. That, paired with his ambition and demeanor, compelled them to offer him an early job. But there’s more.

As the next year approached, Dr. Weiner explained he had an opportunity to work in emergency medicine in Tuscany and asked if he could take a 1-year delayed start for the position he applied a year early for.

The department held his position, and upon his return, Dr. Weiner made a lasting impact at Tufts before eventually moving on. “He outgrew us, which is nice to see,” Dr. Barnewolt said. (Dr. Weiner is currently McGraw Distinguished Chair in Emergency Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and associate professor at Harvard Medical School.)

Bottom line: Why did Dr. Barnewolt and his colleagues do so much to accommodate a young candidate? Yes, Dr. Weiner was talented, but he was also up-front about his ambitions from the get-go. Dr. Barnewolt said that kind of initiative can only be looked at positively.

“My advice would be, if you see an opportunity or a potential place where you might want to work, put out those feelers, start those conversations,” he said. “It’s not too early, especially in certain specialties, where the job market is very tight. Then, when circumstances change, be open about it and have that conversation. The worst that somebody can say is no, so it never hurts to be honest and open about where you want to go and what you want to be.”

Lesson #2: Chase Your Passion ‘Relentlessly’

Vance G. Fowler, MD, MHS, an infectious disease specialist at Duke University School of Medicine, runs a laboratory that researches methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Over the years, he’s mentored many doctors but understands the ambitions of young trainees don’t always align with the little free time that they have. “Many of them drop away when you give them a [side] project,” he said.

So when Tori Kinamon asked him to work on an MRSA project — in her first year — he gave her one that focused on researching vertebral osteomyelitis, a bone infection that can coincide with S aureus. What Dr. Fowler didn’t know: Kinamon (now MD) had been a competitive gymnast at Brown and battled her own life-threatening infection with MRSA.

“To my absolute astonishment, not only did she stick to it, but she was able to compile a presentation on the science and gave an oral presentation within a year of walking in the door,” said Dr. Fowler.

She went on to lead an initiative between the National Institutes of Health and US Food and Drug Administration to create endpoints for clinical drug trials, all of which occurred before starting her residency, which she’s about to embark upon.

Dr. Kinamon’s a good example, he said, of what happens when you add genuine passion to book smarts. Those who do always stand out because you can’t fake that. “Find your passion, and then chase it down relentlessly,” he said. “Once you’ve found your passion, things get easy because it stops being work and it starts being something else.”

If you haven’t identified a focus area, Dr. Fowler said to “be agnostic and observant. Keep your eyes open and your options open because you may surprise yourself. It may turn out that you end up liking something a whole lot more than you thought you did.”

Lesson #3: When You Say You’ve Always Wanted to Do Something, Do Something

As the chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the Northwestern Medicine Canning Thoracic Institute, Scott Budinger, MD, often hears lip service from doctors who want to put their skills to use in their local communities. One of his students actually did it.

Justin Fiala, MD, a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep specialist at Northwestern Medicine, joined Northwestern as a pulmonary fellow with a big interest in addressing health equity issues.

Dr. Fiala began volunteering with CommunityHealth during his fellowship and saw that many patients of the free Chicago-area clinic needed help with sleep disorders. He launched the organization’s first sleep clinic and its Patient-Centered Apnea Protocols Initiative.

“He developed a plan with some of the partners of the sleep apnea equipment to do home sleep testing for these patients that’s free of cost,” said Dr. Budinger.

Dr. Fiala goes in on Saturdays and runs a free clinic conducting sleep studies for patients and outfits them with devices that they need to improve their conditions, said Dr. Budinger.

“And these patients are the severest of the severe patients,” he said. “These are people that have severe sleep apnea that are driving around the roads, oftentimes don’t have insurance because they’re also precluded from having auto insurance. So, this is really something that not just benefits these patients but benefits our whole community.”

The fact that Dr. Fiala followed through on something that all doctors aspire to do — and in the middle of a very busy training program — is something that Dr. Budinger said makes him stand out in a big way.

“If you talk to any of our trainees or young faculty, everybody’s interested in addressing the issue of health disparities,” said Dr. Budinger. “Justin looked at that and said, ‘Well, you know, I’m not interested in talking about it. What can I do about this problem? And how can I actually get boots on the ground and help?’ That requires a big activation energy that many people don’t have.”

Lesson #4: Be a People-Person and a Patient-Person

When hiring employees at American Family Care in Portland, Oregon, Andrew Miller, MD, director of provider training, is always on the lookout for young MDs with emotional intelligence and a good bedside manner. He has been recently blown away, however, by a young physician’s assistant named Joseph Van Bindsbergen, PA-C, who was described as “all-around wonderful” during his reference check.

“Having less than 6 months of experience out of school, he is our highest ranked provider, whether it’s a nurse practitioner, PA, or doctor, in terms of patient satisfaction,” said Dr. Miller. The young PA has an “unprecedented perfect score” on his NPS rating.

Why? Patients said they’ve never felt as heard as they felt with Van Bindsbergen.

“That’s the thing I think that the up-and-coming providers should be focusing on is making your patients feel heard,” explained Dr. Miller. Van Bindsbergen is great at building rapport with a patient, whether they are 6 or 96. “He doesn’t just ask about sore throat symptoms. He asks, ‘what is the impact on your life of the sore throat? How does it affect your family or your work? What do you think this could be besides just strep? What are your concerns?’ ”

Dr. Miller said the magic of Van Bindsbergen is that he has an innate ability to look at patients “not just as a diagnosis but as a person, which they love.”

Lesson #5: Remember to Make That Difference With Each Patient

Doctors are used to swooping in and seeing a patient, ordering further testing if needed, and then moving on to the next patient. But one young intern at the start of his medical career broke this mold by giving a very anxious patient some much-needed support.

“There was a resident who was working overnight, and this poor young woman came in who had a new diagnosis of an advanced illness and a lot of anxiety around her condition, the newness of it, and the impact this is going to have on her family and her life,” said Elizabeth Horn Prsic, MD, assistant professor at Yale School of Medicine and firm chief for medical oncology and the director of Adult Inpatient Palliative Care.

Dr. Prsic found out the next morning that this trainee accompanied the patient to the MRI and held her hand as much as he was allowed to throughout the entire experience. “I was like, ‘wait you went down with her to radiology?’ And he’s like, ‘Yes, I was there the whole time,’ ” she recalled.

This gesture not only helped the patient feel calmer after receiving a potentially life-altering diagnosis but also helped ensure the test results were as clear as possible.

“If the study is not done well and a patient is moving or uncomfortable, it has to be stopped early or paused,” said Dr. Prsic. “Then the study is not very useful. In situations like these, medical decisions may be made based on imperfect data. The fact that we had this full complete good quality scan helped us get the care that she needed in a much timelier manner to help her and to move along the care that she that was medically appropriate for her.”

Dr. Prsic got emotional reflecting on the experience. Working at Yale, she saw a ton of intelligent doctors come through the ranks. But this gesture, she said, should serve as a reminder that “you don’t need to be the smartest person in the room to just be there for a patient. It was pure empathic presence and human connection. It gave me hope in the next generation of physicians.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Safe to say that anyone undertaking the physician journey does so with intense motivation and book smarts. Still, it can be incredibly hard to stand out. Everyone’s a go-getter, but what’s the X factor?

Here’s what they said ...

Lesson #1: Never Be Scared to Ask

Brien Barnewolt, MD, chairman and chief of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Tufts Medical Center, was very much surprised when a resident named Scott G. Weiner did something unexpected: Go after a job in the fall of his junior year residency instead of following the typical senior year trajectory.

“It’s very unusual for a trainee to apply for a job virtually a year ahead of schedule. But he knew what he wanted,” said Dr. Barnewolt. “I’d never had anybody come to me in that same scenario, and I’ve been doing this a long time.”

Under normal circumstances it would’ve been easy for Dr. Barnewolt to say no. But the unexpected request made him and his colleagues take a closer look, and they were impressed with Dr. Weiner’s skills. That, paired with his ambition and demeanor, compelled them to offer him an early job. But there’s more.

As the next year approached, Dr. Weiner explained he had an opportunity to work in emergency medicine in Tuscany and asked if he could take a 1-year delayed start for the position he applied a year early for.

The department held his position, and upon his return, Dr. Weiner made a lasting impact at Tufts before eventually moving on. “He outgrew us, which is nice to see,” Dr. Barnewolt said. (Dr. Weiner is currently McGraw Distinguished Chair in Emergency Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and associate professor at Harvard Medical School.)

Bottom line: Why did Dr. Barnewolt and his colleagues do so much to accommodate a young candidate? Yes, Dr. Weiner was talented, but he was also up-front about his ambitions from the get-go. Dr. Barnewolt said that kind of initiative can only be looked at positively.

“My advice would be, if you see an opportunity or a potential place where you might want to work, put out those feelers, start those conversations,” he said. “It’s not too early, especially in certain specialties, where the job market is very tight. Then, when circumstances change, be open about it and have that conversation. The worst that somebody can say is no, so it never hurts to be honest and open about where you want to go and what you want to be.”

Lesson #2: Chase Your Passion ‘Relentlessly’

Vance G. Fowler, MD, MHS, an infectious disease specialist at Duke University School of Medicine, runs a laboratory that researches methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Over the years, he’s mentored many doctors but understands the ambitions of young trainees don’t always align with the little free time that they have. “Many of them drop away when you give them a [side] project,” he said.

So when Tori Kinamon asked him to work on an MRSA project — in her first year — he gave her one that focused on researching vertebral osteomyelitis, a bone infection that can coincide with S aureus. What Dr. Fowler didn’t know: Kinamon (now MD) had been a competitive gymnast at Brown and battled her own life-threatening infection with MRSA.

“To my absolute astonishment, not only did she stick to it, but she was able to compile a presentation on the science and gave an oral presentation within a year of walking in the door,” said Dr. Fowler.

She went on to lead an initiative between the National Institutes of Health and US Food and Drug Administration to create endpoints for clinical drug trials, all of which occurred before starting her residency, which she’s about to embark upon.

Dr. Kinamon’s a good example, he said, of what happens when you add genuine passion to book smarts. Those who do always stand out because you can’t fake that. “Find your passion, and then chase it down relentlessly,” he said. “Once you’ve found your passion, things get easy because it stops being work and it starts being something else.”

If you haven’t identified a focus area, Dr. Fowler said to “be agnostic and observant. Keep your eyes open and your options open because you may surprise yourself. It may turn out that you end up liking something a whole lot more than you thought you did.”

Lesson #3: When You Say You’ve Always Wanted to Do Something, Do Something

As the chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the Northwestern Medicine Canning Thoracic Institute, Scott Budinger, MD, often hears lip service from doctors who want to put their skills to use in their local communities. One of his students actually did it.

Justin Fiala, MD, a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep specialist at Northwestern Medicine, joined Northwestern as a pulmonary fellow with a big interest in addressing health equity issues.

Dr. Fiala began volunteering with CommunityHealth during his fellowship and saw that many patients of the free Chicago-area clinic needed help with sleep disorders. He launched the organization’s first sleep clinic and its Patient-Centered Apnea Protocols Initiative.

“He developed a plan with some of the partners of the sleep apnea equipment to do home sleep testing for these patients that’s free of cost,” said Dr. Budinger.

Dr. Fiala goes in on Saturdays and runs a free clinic conducting sleep studies for patients and outfits them with devices that they need to improve their conditions, said Dr. Budinger.

“And these patients are the severest of the severe patients,” he said. “These are people that have severe sleep apnea that are driving around the roads, oftentimes don’t have insurance because they’re also precluded from having auto insurance. So, this is really something that not just benefits these patients but benefits our whole community.”

The fact that Dr. Fiala followed through on something that all doctors aspire to do — and in the middle of a very busy training program — is something that Dr. Budinger said makes him stand out in a big way.

“If you talk to any of our trainees or young faculty, everybody’s interested in addressing the issue of health disparities,” said Dr. Budinger. “Justin looked at that and said, ‘Well, you know, I’m not interested in talking about it. What can I do about this problem? And how can I actually get boots on the ground and help?’ That requires a big activation energy that many people don’t have.”

Lesson #4: Be a People-Person and a Patient-Person

When hiring employees at American Family Care in Portland, Oregon, Andrew Miller, MD, director of provider training, is always on the lookout for young MDs with emotional intelligence and a good bedside manner. He has been recently blown away, however, by a young physician’s assistant named Joseph Van Bindsbergen, PA-C, who was described as “all-around wonderful” during his reference check.

“Having less than 6 months of experience out of school, he is our highest ranked provider, whether it’s a nurse practitioner, PA, or doctor, in terms of patient satisfaction,” said Dr. Miller. The young PA has an “unprecedented perfect score” on his NPS rating.

Why? Patients said they’ve never felt as heard as they felt with Van Bindsbergen.

“That’s the thing I think that the up-and-coming providers should be focusing on is making your patients feel heard,” explained Dr. Miller. Van Bindsbergen is great at building rapport with a patient, whether they are 6 or 96. “He doesn’t just ask about sore throat symptoms. He asks, ‘what is the impact on your life of the sore throat? How does it affect your family or your work? What do you think this could be besides just strep? What are your concerns?’ ”

Dr. Miller said the magic of Van Bindsbergen is that he has an innate ability to look at patients “not just as a diagnosis but as a person, which they love.”

Lesson #5: Remember to Make That Difference With Each Patient

Doctors are used to swooping in and seeing a patient, ordering further testing if needed, and then moving on to the next patient. But one young intern at the start of his medical career broke this mold by giving a very anxious patient some much-needed support.

“There was a resident who was working overnight, and this poor young woman came in who had a new diagnosis of an advanced illness and a lot of anxiety around her condition, the newness of it, and the impact this is going to have on her family and her life,” said Elizabeth Horn Prsic, MD, assistant professor at Yale School of Medicine and firm chief for medical oncology and the director of Adult Inpatient Palliative Care.

Dr. Prsic found out the next morning that this trainee accompanied the patient to the MRI and held her hand as much as he was allowed to throughout the entire experience. “I was like, ‘wait you went down with her to radiology?’ And he’s like, ‘Yes, I was there the whole time,’ ” she recalled.

This gesture not only helped the patient feel calmer after receiving a potentially life-altering diagnosis but also helped ensure the test results were as clear as possible.

“If the study is not done well and a patient is moving or uncomfortable, it has to be stopped early or paused,” said Dr. Prsic. “Then the study is not very useful. In situations like these, medical decisions may be made based on imperfect data. The fact that we had this full complete good quality scan helped us get the care that she needed in a much timelier manner to help her and to move along the care that she that was medically appropriate for her.”

Dr. Prsic got emotional reflecting on the experience. Working at Yale, she saw a ton of intelligent doctors come through the ranks. But this gesture, she said, should serve as a reminder that “you don’t need to be the smartest person in the room to just be there for a patient. It was pure empathic presence and human connection. It gave me hope in the next generation of physicians.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Safe to say that anyone undertaking the physician journey does so with intense motivation and book smarts. Still, it can be incredibly hard to stand out. Everyone’s a go-getter, but what’s the X factor?

Here’s what they said ...

Lesson #1: Never Be Scared to Ask

Brien Barnewolt, MD, chairman and chief of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Tufts Medical Center, was very much surprised when a resident named Scott G. Weiner did something unexpected: Go after a job in the fall of his junior year residency instead of following the typical senior year trajectory.

“It’s very unusual for a trainee to apply for a job virtually a year ahead of schedule. But he knew what he wanted,” said Dr. Barnewolt. “I’d never had anybody come to me in that same scenario, and I’ve been doing this a long time.”

Under normal circumstances it would’ve been easy for Dr. Barnewolt to say no. But the unexpected request made him and his colleagues take a closer look, and they were impressed with Dr. Weiner’s skills. That, paired with his ambition and demeanor, compelled them to offer him an early job. But there’s more.

As the next year approached, Dr. Weiner explained he had an opportunity to work in emergency medicine in Tuscany and asked if he could take a 1-year delayed start for the position he applied a year early for.

The department held his position, and upon his return, Dr. Weiner made a lasting impact at Tufts before eventually moving on. “He outgrew us, which is nice to see,” Dr. Barnewolt said. (Dr. Weiner is currently McGraw Distinguished Chair in Emergency Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and associate professor at Harvard Medical School.)

Bottom line: Why did Dr. Barnewolt and his colleagues do so much to accommodate a young candidate? Yes, Dr. Weiner was talented, but he was also up-front about his ambitions from the get-go. Dr. Barnewolt said that kind of initiative can only be looked at positively.

“My advice would be, if you see an opportunity or a potential place where you might want to work, put out those feelers, start those conversations,” he said. “It’s not too early, especially in certain specialties, where the job market is very tight. Then, when circumstances change, be open about it and have that conversation. The worst that somebody can say is no, so it never hurts to be honest and open about where you want to go and what you want to be.”

Lesson #2: Chase Your Passion ‘Relentlessly’

Vance G. Fowler, MD, MHS, an infectious disease specialist at Duke University School of Medicine, runs a laboratory that researches methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Over the years, he’s mentored many doctors but understands the ambitions of young trainees don’t always align with the little free time that they have. “Many of them drop away when you give them a [side] project,” he said.

So when Tori Kinamon asked him to work on an MRSA project — in her first year — he gave her one that focused on researching vertebral osteomyelitis, a bone infection that can coincide with S aureus. What Dr. Fowler didn’t know: Kinamon (now MD) had been a competitive gymnast at Brown and battled her own life-threatening infection with MRSA.

“To my absolute astonishment, not only did she stick to it, but she was able to compile a presentation on the science and gave an oral presentation within a year of walking in the door,” said Dr. Fowler.

She went on to lead an initiative between the National Institutes of Health and US Food and Drug Administration to create endpoints for clinical drug trials, all of which occurred before starting her residency, which she’s about to embark upon.

Dr. Kinamon’s a good example, he said, of what happens when you add genuine passion to book smarts. Those who do always stand out because you can’t fake that. “Find your passion, and then chase it down relentlessly,” he said. “Once you’ve found your passion, things get easy because it stops being work and it starts being something else.”

If you haven’t identified a focus area, Dr. Fowler said to “be agnostic and observant. Keep your eyes open and your options open because you may surprise yourself. It may turn out that you end up liking something a whole lot more than you thought you did.”

Lesson #3: When You Say You’ve Always Wanted to Do Something, Do Something

As the chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the Northwestern Medicine Canning Thoracic Institute, Scott Budinger, MD, often hears lip service from doctors who want to put their skills to use in their local communities. One of his students actually did it.

Justin Fiala, MD, a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep specialist at Northwestern Medicine, joined Northwestern as a pulmonary fellow with a big interest in addressing health equity issues.

Dr. Fiala began volunteering with CommunityHealth during his fellowship and saw that many patients of the free Chicago-area clinic needed help with sleep disorders. He launched the organization’s first sleep clinic and its Patient-Centered Apnea Protocols Initiative.

“He developed a plan with some of the partners of the sleep apnea equipment to do home sleep testing for these patients that’s free of cost,” said Dr. Budinger.

Dr. Fiala goes in on Saturdays and runs a free clinic conducting sleep studies for patients and outfits them with devices that they need to improve their conditions, said Dr. Budinger.

“And these patients are the severest of the severe patients,” he said. “These are people that have severe sleep apnea that are driving around the roads, oftentimes don’t have insurance because they’re also precluded from having auto insurance. So, this is really something that not just benefits these patients but benefits our whole community.”

The fact that Dr. Fiala followed through on something that all doctors aspire to do — and in the middle of a very busy training program — is something that Dr. Budinger said makes him stand out in a big way.

“If you talk to any of our trainees or young faculty, everybody’s interested in addressing the issue of health disparities,” said Dr. Budinger. “Justin looked at that and said, ‘Well, you know, I’m not interested in talking about it. What can I do about this problem? And how can I actually get boots on the ground and help?’ That requires a big activation energy that many people don’t have.”

Lesson #4: Be a People-Person and a Patient-Person

When hiring employees at American Family Care in Portland, Oregon, Andrew Miller, MD, director of provider training, is always on the lookout for young MDs with emotional intelligence and a good bedside manner. He has been recently blown away, however, by a young physician’s assistant named Joseph Van Bindsbergen, PA-C, who was described as “all-around wonderful” during his reference check.

“Having less than 6 months of experience out of school, he is our highest ranked provider, whether it’s a nurse practitioner, PA, or doctor, in terms of patient satisfaction,” said Dr. Miller. The young PA has an “unprecedented perfect score” on his NPS rating.

Why? Patients said they’ve never felt as heard as they felt with Van Bindsbergen.

“That’s the thing I think that the up-and-coming providers should be focusing on is making your patients feel heard,” explained Dr. Miller. Van Bindsbergen is great at building rapport with a patient, whether they are 6 or 96. “He doesn’t just ask about sore throat symptoms. He asks, ‘what is the impact on your life of the sore throat? How does it affect your family or your work? What do you think this could be besides just strep? What are your concerns?’ ”

Dr. Miller said the magic of Van Bindsbergen is that he has an innate ability to look at patients “not just as a diagnosis but as a person, which they love.”

Lesson #5: Remember to Make That Difference With Each Patient

Doctors are used to swooping in and seeing a patient, ordering further testing if needed, and then moving on to the next patient. But one young intern at the start of his medical career broke this mold by giving a very anxious patient some much-needed support.

“There was a resident who was working overnight, and this poor young woman came in who had a new diagnosis of an advanced illness and a lot of anxiety around her condition, the newness of it, and the impact this is going to have on her family and her life,” said Elizabeth Horn Prsic, MD, assistant professor at Yale School of Medicine and firm chief for medical oncology and the director of Adult Inpatient Palliative Care.

Dr. Prsic found out the next morning that this trainee accompanied the patient to the MRI and held her hand as much as he was allowed to throughout the entire experience. “I was like, ‘wait you went down with her to radiology?’ And he’s like, ‘Yes, I was there the whole time,’ ” she recalled.

This gesture not only helped the patient feel calmer after receiving a potentially life-altering diagnosis but also helped ensure the test results were as clear as possible.

“If the study is not done well and a patient is moving or uncomfortable, it has to be stopped early or paused,” said Dr. Prsic. “Then the study is not very useful. In situations like these, medical decisions may be made based on imperfect data. The fact that we had this full complete good quality scan helped us get the care that she needed in a much timelier manner to help her and to move along the care that she that was medically appropriate for her.”

Dr. Prsic got emotional reflecting on the experience. Working at Yale, she saw a ton of intelligent doctors come through the ranks. But this gesture, she said, should serve as a reminder that “you don’t need to be the smartest person in the room to just be there for a patient. It was pure empathic presence and human connection. It gave me hope in the next generation of physicians.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal Trade Commission Bans Noncompete Agreements, Urges More Protections for Healthcare Workers

But business groups have vowed to challenge the decision in court.

The proposed final rule passed on a 3-2 vote, with the dissenting commissioners disputing the FTC’s authority to broadly ban noncompetes.

Tensions around noncompetes have been building for years. In 2021, President Biden issued an executive order supporting measures to improve economic competition, in which he urged the FTC to consider its rulemaking authority to address noncompete clauses that unfairly limit workers’ mobility. In January 2023, per that directive, the agency proposed ending the restrictive covenants.

While the FTC estimates that the final rule will reduce healthcare costs by up to $194 billion over the next decade and increase worker earnings by $300 million annually, the ruling faces legal hurdles.

US Chamber of Commerce president and CEO Suzanne P. Clark said in a statement that the move is a “blatant power grab” that will undermine competitive business practices, adding that the Chamber will sue to block the measure.

The FTC received more than 26,000 comments on noncompetes during the public feedback period, with about 25,000 supporting the measure, said Benjamin Cady, JD, an FTC attorney.

Mr. Cady called the feedback “compelling,” citing instances of workers who were forced to commute long distances, uproot their families, or risk expensive litigation for wanting to pursue job opportunities.

For example, a comment from a physician working in Appalachia highlights the potential real-life implications of the agreements. “With hospital systems merging, providers with aggressive noncompetes must abandon the community that they serve if they [choose] to leave their employer. Healthcare providers feel trapped in their current employment situation, leading to significant burnout that can shorten their [career] longevity.”

Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya said physicians have had their lives upended by cumbersome noncompetes, often having to move out of state to practice. “A pandemic killed a million people in this country, and there are doctors who cannot work because of a noncompete,” he said.

It’s unclear whether physicians and others who work for nonprofit healthcare groups or hospitals will be covered by the new ban. FTC Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter acknowledged that the agency’s jurisdictional limitations mean that employees of “certain nonprofit organizations” may not benefit from the rule.

“We want to be transparent about the limitation and recognize there are workers, especially healthcare workers, who are bound by anticompetitive and unfair noncompete clauses, that our rule will struggle to reach,” she said. To cover nonprofit healthcare employees, Ms. Slaughter urged Congress to pass legislation banning noncompetes, such as the Workforce Mobility Act of 2021 and the Freedom to Compete Act of 2023.

The FTC final rule will take effect 120 days after it is published in the federal register, and new noncompete agreements will be banned as of this date. However, existing contracts for senior executives will remain in effect because these individuals are less likely to experience “acute harm” due to their ability to negotiate accordingly, said Mr. Cady.

States, AMA Take Aim at Noncompetes

Before the federal ban, several states had already passed legislation limiting the reach of noncompetes. According to a recent article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 12 states prohibit noncompete clauses for physicians: Alabama, California, Colorado, Delaware, Massachusetts, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and South Dakota.

The remaining states allow noncompetes in some form, often excluding them for employees earning below a certain threshold. For example, in Oregon, noncompete agreements may apply to employees earning more than $113,241. Most states have provisions to adjust the threshold annually. The District of Columbia permits 2-year noncompetes for “medical specialists” earning over $250,000 annually.

Indiana employers can no longer enter into noncompete agreements with primary care providers. Other specialties may be subject to the clauses, except when the physician terminates the contract for cause or when an employer terminates the contract without cause.

Rachel Marcus, MD, a cardiologist in Washington, DC, found out how limiting her employment contract’s noncompete clause was when she wanted to leave a former position. Due to the restrictions, she told this news organization that she couldn’t work locally for a competitor for 2 years. The closest location she could seek employment without violating the agreement was Baltimore, approximately 40 miles away.

Dr. Marcus ultimately moved to another position within the same organization because of the company’s reputation for being “aggressive” in their enforcement actions.

Although the American Medical Association (AMA) does not support a total ban, its House of Delegates adopted policies last year to support the prohibition of noncompete contracts for physicians employed by for-profit or nonprofit hospitals, hospital systems, or staffing companies.

Challenges Await

The American Hospital Association, which opposed the proposed rule, called it “bad policy.” The decision “will likely be short-lived, with courts almost certain to stop it before it can do damage to hospitals’ ability to care for their patients and communities,” the association said in a statement.

To ease the transition to the new rule, the FTC also released a model language for employers to use when discussing the changes with their employees. “All employers need to do to comply with the rule is to stop enforcing existing noncompetes with workers other than senior executives and provide notice to such workers,” he said.

Dr. Marcus hopes the ban improves doctors’ lives. “Your employer is going to have to treat you better because they know that you can easily go across town to a place that has a higher salary, and your patient can go with you.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

But business groups have vowed to challenge the decision in court.

The proposed final rule passed on a 3-2 vote, with the dissenting commissioners disputing the FTC’s authority to broadly ban noncompetes.

Tensions around noncompetes have been building for years. In 2021, President Biden issued an executive order supporting measures to improve economic competition, in which he urged the FTC to consider its rulemaking authority to address noncompete clauses that unfairly limit workers’ mobility. In January 2023, per that directive, the agency proposed ending the restrictive covenants.

While the FTC estimates that the final rule will reduce healthcare costs by up to $194 billion over the next decade and increase worker earnings by $300 million annually, the ruling faces legal hurdles.

US Chamber of Commerce president and CEO Suzanne P. Clark said in a statement that the move is a “blatant power grab” that will undermine competitive business practices, adding that the Chamber will sue to block the measure.

The FTC received more than 26,000 comments on noncompetes during the public feedback period, with about 25,000 supporting the measure, said Benjamin Cady, JD, an FTC attorney.

Mr. Cady called the feedback “compelling,” citing instances of workers who were forced to commute long distances, uproot their families, or risk expensive litigation for wanting to pursue job opportunities.

For example, a comment from a physician working in Appalachia highlights the potential real-life implications of the agreements. “With hospital systems merging, providers with aggressive noncompetes must abandon the community that they serve if they [choose] to leave their employer. Healthcare providers feel trapped in their current employment situation, leading to significant burnout that can shorten their [career] longevity.”

Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya said physicians have had their lives upended by cumbersome noncompetes, often having to move out of state to practice. “A pandemic killed a million people in this country, and there are doctors who cannot work because of a noncompete,” he said.

It’s unclear whether physicians and others who work for nonprofit healthcare groups or hospitals will be covered by the new ban. FTC Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter acknowledged that the agency’s jurisdictional limitations mean that employees of “certain nonprofit organizations” may not benefit from the rule.

“We want to be transparent about the limitation and recognize there are workers, especially healthcare workers, who are bound by anticompetitive and unfair noncompete clauses, that our rule will struggle to reach,” she said. To cover nonprofit healthcare employees, Ms. Slaughter urged Congress to pass legislation banning noncompetes, such as the Workforce Mobility Act of 2021 and the Freedom to Compete Act of 2023.

The FTC final rule will take effect 120 days after it is published in the federal register, and new noncompete agreements will be banned as of this date. However, existing contracts for senior executives will remain in effect because these individuals are less likely to experience “acute harm” due to their ability to negotiate accordingly, said Mr. Cady.

States, AMA Take Aim at Noncompetes

Before the federal ban, several states had already passed legislation limiting the reach of noncompetes. According to a recent article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 12 states prohibit noncompete clauses for physicians: Alabama, California, Colorado, Delaware, Massachusetts, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and South Dakota.

The remaining states allow noncompetes in some form, often excluding them for employees earning below a certain threshold. For example, in Oregon, noncompete agreements may apply to employees earning more than $113,241. Most states have provisions to adjust the threshold annually. The District of Columbia permits 2-year noncompetes for “medical specialists” earning over $250,000 annually.

Indiana employers can no longer enter into noncompete agreements with primary care providers. Other specialties may be subject to the clauses, except when the physician terminates the contract for cause or when an employer terminates the contract without cause.

Rachel Marcus, MD, a cardiologist in Washington, DC, found out how limiting her employment contract’s noncompete clause was when she wanted to leave a former position. Due to the restrictions, she told this news organization that she couldn’t work locally for a competitor for 2 years. The closest location she could seek employment without violating the agreement was Baltimore, approximately 40 miles away.

Dr. Marcus ultimately moved to another position within the same organization because of the company’s reputation for being “aggressive” in their enforcement actions.

Although the American Medical Association (AMA) does not support a total ban, its House of Delegates adopted policies last year to support the prohibition of noncompete contracts for physicians employed by for-profit or nonprofit hospitals, hospital systems, or staffing companies.

Challenges Await

The American Hospital Association, which opposed the proposed rule, called it “bad policy.” The decision “will likely be short-lived, with courts almost certain to stop it before it can do damage to hospitals’ ability to care for their patients and communities,” the association said in a statement.

To ease the transition to the new rule, the FTC also released a model language for employers to use when discussing the changes with their employees. “All employers need to do to comply with the rule is to stop enforcing existing noncompetes with workers other than senior executives and provide notice to such workers,” he said.

Dr. Marcus hopes the ban improves doctors’ lives. “Your employer is going to have to treat you better because they know that you can easily go across town to a place that has a higher salary, and your patient can go with you.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

But business groups have vowed to challenge the decision in court.

The proposed final rule passed on a 3-2 vote, with the dissenting commissioners disputing the FTC’s authority to broadly ban noncompetes.

Tensions around noncompetes have been building for years. In 2021, President Biden issued an executive order supporting measures to improve economic competition, in which he urged the FTC to consider its rulemaking authority to address noncompete clauses that unfairly limit workers’ mobility. In January 2023, per that directive, the agency proposed ending the restrictive covenants.

While the FTC estimates that the final rule will reduce healthcare costs by up to $194 billion over the next decade and increase worker earnings by $300 million annually, the ruling faces legal hurdles.

US Chamber of Commerce president and CEO Suzanne P. Clark said in a statement that the move is a “blatant power grab” that will undermine competitive business practices, adding that the Chamber will sue to block the measure.

The FTC received more than 26,000 comments on noncompetes during the public feedback period, with about 25,000 supporting the measure, said Benjamin Cady, JD, an FTC attorney.

Mr. Cady called the feedback “compelling,” citing instances of workers who were forced to commute long distances, uproot their families, or risk expensive litigation for wanting to pursue job opportunities.

For example, a comment from a physician working in Appalachia highlights the potential real-life implications of the agreements. “With hospital systems merging, providers with aggressive noncompetes must abandon the community that they serve if they [choose] to leave their employer. Healthcare providers feel trapped in their current employment situation, leading to significant burnout that can shorten their [career] longevity.”

Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya said physicians have had their lives upended by cumbersome noncompetes, often having to move out of state to practice. “A pandemic killed a million people in this country, and there are doctors who cannot work because of a noncompete,” he said.

It’s unclear whether physicians and others who work for nonprofit healthcare groups or hospitals will be covered by the new ban. FTC Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter acknowledged that the agency’s jurisdictional limitations mean that employees of “certain nonprofit organizations” may not benefit from the rule.

“We want to be transparent about the limitation and recognize there are workers, especially healthcare workers, who are bound by anticompetitive and unfair noncompete clauses, that our rule will struggle to reach,” she said. To cover nonprofit healthcare employees, Ms. Slaughter urged Congress to pass legislation banning noncompetes, such as the Workforce Mobility Act of 2021 and the Freedom to Compete Act of 2023.

The FTC final rule will take effect 120 days after it is published in the federal register, and new noncompete agreements will be banned as of this date. However, existing contracts for senior executives will remain in effect because these individuals are less likely to experience “acute harm” due to their ability to negotiate accordingly, said Mr. Cady.

States, AMA Take Aim at Noncompetes

Before the federal ban, several states had already passed legislation limiting the reach of noncompetes. According to a recent article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 12 states prohibit noncompete clauses for physicians: Alabama, California, Colorado, Delaware, Massachusetts, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and South Dakota.

The remaining states allow noncompetes in some form, often excluding them for employees earning below a certain threshold. For example, in Oregon, noncompete agreements may apply to employees earning more than $113,241. Most states have provisions to adjust the threshold annually. The District of Columbia permits 2-year noncompetes for “medical specialists” earning over $250,000 annually.

Indiana employers can no longer enter into noncompete agreements with primary care providers. Other specialties may be subject to the clauses, except when the physician terminates the contract for cause or when an employer terminates the contract without cause.

Rachel Marcus, MD, a cardiologist in Washington, DC, found out how limiting her employment contract’s noncompete clause was when she wanted to leave a former position. Due to the restrictions, she told this news organization that she couldn’t work locally for a competitor for 2 years. The closest location she could seek employment without violating the agreement was Baltimore, approximately 40 miles away.

Dr. Marcus ultimately moved to another position within the same organization because of the company’s reputation for being “aggressive” in their enforcement actions.

Although the American Medical Association (AMA) does not support a total ban, its House of Delegates adopted policies last year to support the prohibition of noncompete contracts for physicians employed by for-profit or nonprofit hospitals, hospital systems, or staffing companies.

Challenges Await

The American Hospital Association, which opposed the proposed rule, called it “bad policy.” The decision “will likely be short-lived, with courts almost certain to stop it before it can do damage to hospitals’ ability to care for their patients and communities,” the association said in a statement.

To ease the transition to the new rule, the FTC also released a model language for employers to use when discussing the changes with their employees. “All employers need to do to comply with the rule is to stop enforcing existing noncompetes with workers other than senior executives and provide notice to such workers,” he said.

Dr. Marcus hopes the ban improves doctors’ lives. “Your employer is going to have to treat you better because they know that you can easily go across town to a place that has a higher salary, and your patient can go with you.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Are Women Better Doctors Than Men?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s a battle of the sexes today as we dive into a paper that makes you say, “Wow, what an interesting study” and also “Boy, am I glad I didn’t do that study.” That’s because studies like this are always somewhat fraught; they say something about medicine but also something about society — and that makes this a bit precarious. But that’s never stopped us before. So, let’s go ahead and try to answer the question: Do women make better doctors than men?

On the surface, this question seems nearly impossible to answer. It’s too broad; what does it mean to be a “better” doctor? At first blush it seems that there are just too many variables to control for here: the type of doctor, the type of patient, the clinical scenario, and so on.

But this study, “Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates by physician and patient sex,” which appears in Annals of Internal Medicine, uses a fairly ingenious method to cut through all the bias by leveraging two simple facts: First, hospital medicine is largely conducted by hospitalists these days; second, due to the shift-based nature of hospitalist work, the hospitalist you get when you are admitted to the hospital is pretty much random.

In other words, if you are admitted to the hospital for an acute illness and get a hospitalist as your attending, you have no control over whether it is a man or a woman. Is this a randomized trial? No, but it’s not bad.

Researchers used Medicare claims data to identify adults over age 65 who had nonelective hospital admissions throughout the United States. The claims revealed the sex of the patient and the name of the attending physician. By linking to a medical provider database, they could determine the sex of the provider.

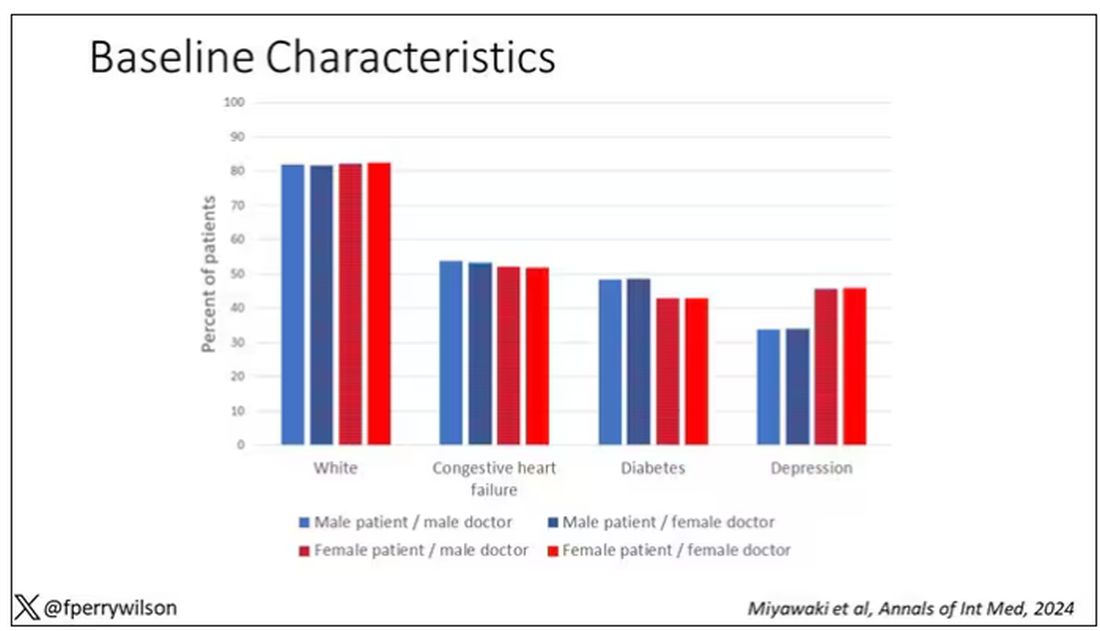

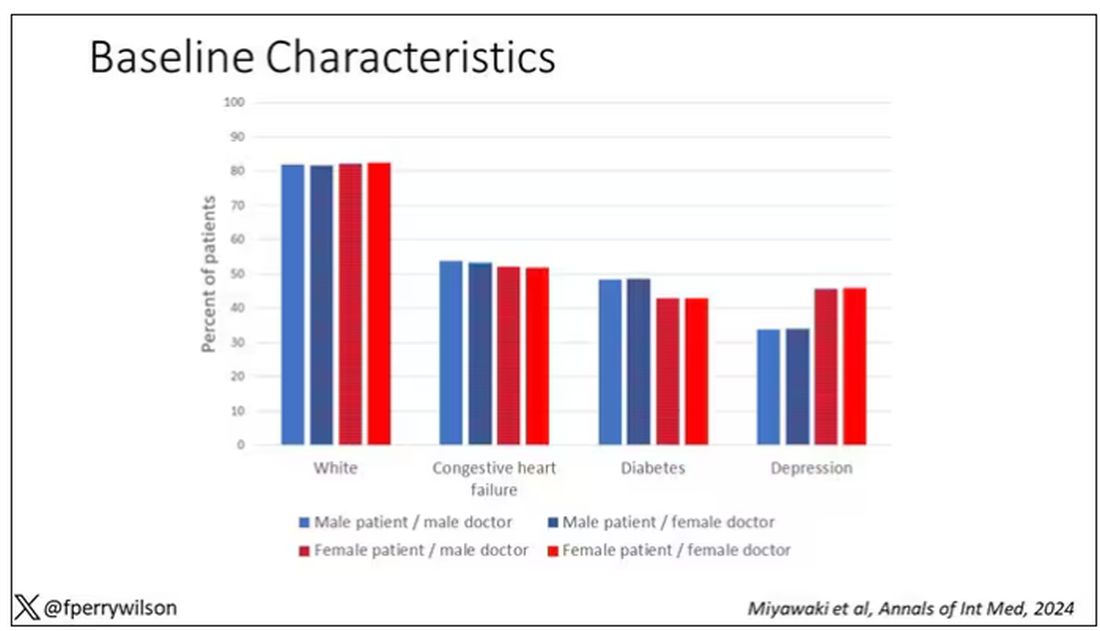

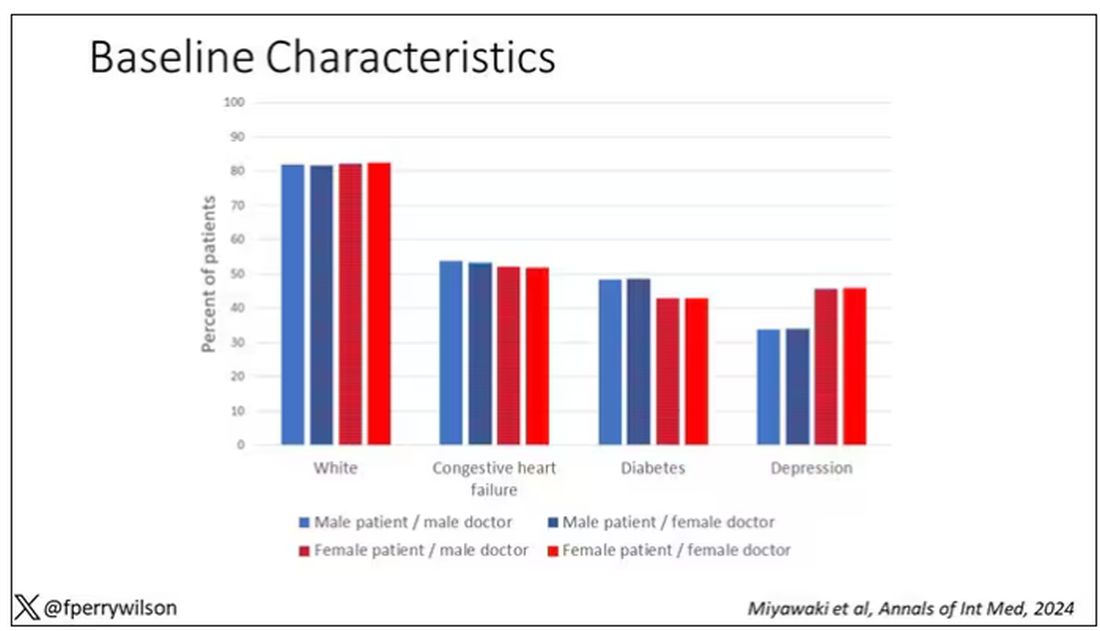

The goal was to look at outcomes across four dyads:

- Male patient – male doctor

- Male patient – female doctor

- Female patient – male doctor

- Female patient – female doctor

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality.

I told you that focusing on hospitalists produces some pseudorandomization, but let’s look at the data to be sure. Just under a million patients were treated by approximately 50,000 physicians, 30% of whom were female. And, though female patients and male patients differed, they did not differ with respect to the sex of their hospitalist. So, by physician sex, patients were similar in mean age, race, ethnicity, household income, eligibility for Medicaid, and comorbid conditions. The authors even created a “predicted mortality” score which was similar across the groups as well.

Now, the female physicians were a bit different from the male physicians. The female hospitalists were slightly more likely to have an osteopathic degree, had slightly fewer admissions per year, and were a bit younger.

So, we have broadly similar patients regardless of who their hospitalist was, but hospitalists differ by factors other than their sex. Fine.

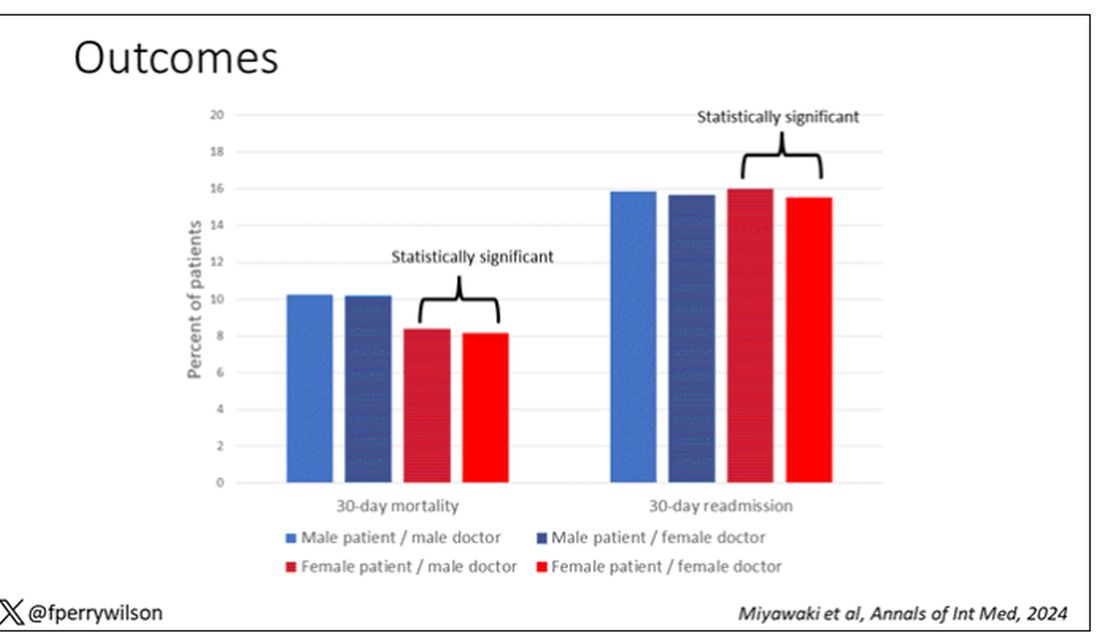

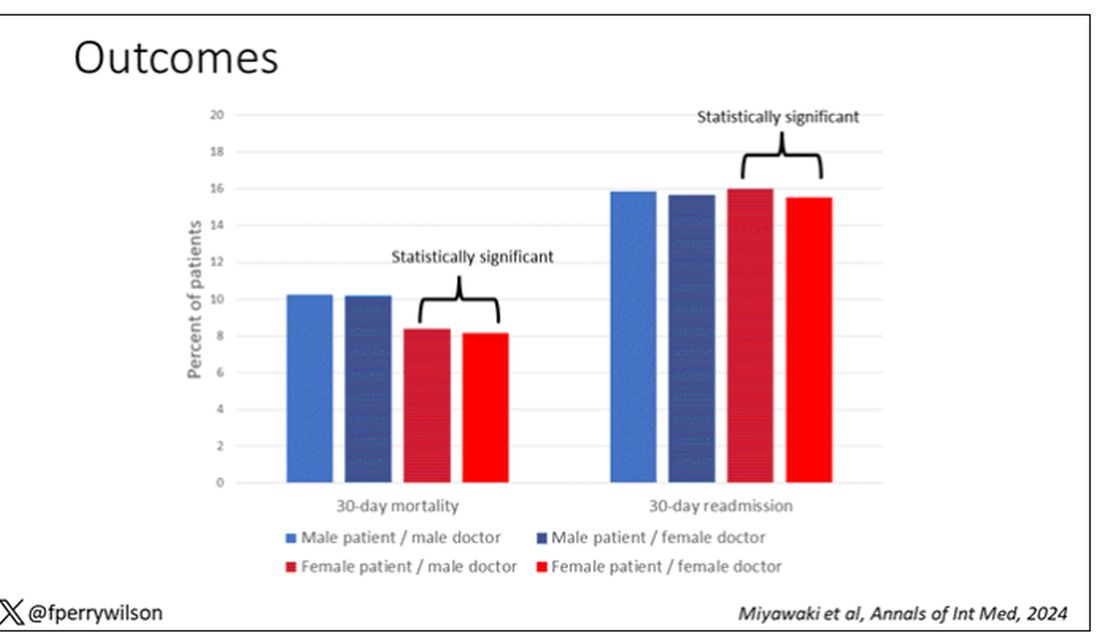

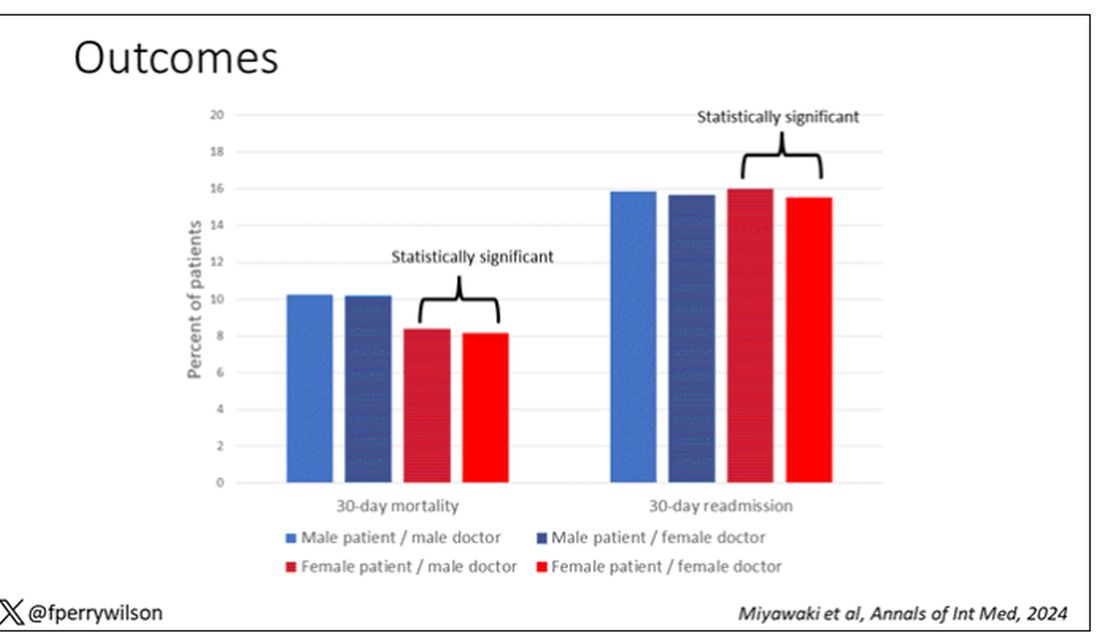

I’ve graphed the results here.

This is a relatively small effect, to be sure, but if you multiply it across the millions of hospitalist admissions per year, you can start to put up some real numbers.

So, what is going on here? I see four broad buckets of possibilities.

Let’s start with the obvious explanation: Women, on average, are better doctors than men. I am married to a woman doctor, and based on my personal experience, this explanation is undoubtedly true. But why would that be?

The authors cite data that suggest that female physicians are less likely than male physicians to dismiss patient concerns — and in particular, the concerns of female patients — perhaps leading to fewer missed diagnoses. But this is impossible to measure with administrative data, so this study can no more tell us whether these female hospitalists are more attentive than their male counterparts than it can suggest that the benefit is mediated by the shorter average height of female physicians. Perhaps the key is being closer to the patient?

The second possibility here is that this has nothing to do with the sex of the physician at all; it has to do with those other things that associate with the sex of the physician. We know, for example, that the female physicians saw fewer patients per year than the male physicians, but the study authors adjusted for this in the statistical models. Still, other unmeasured factors (confounders) could be present. By the way, confounders wouldn’t necessarily change the primary finding — you are better off being cared for by female physicians. It’s just not because they are female; it’s a convenient marker for some other quality, such as age.

The third possibility is that the study represents a phenomenon called collider bias. The idea here is that physicians only get into the study if they are hospitalists, and the quality of physicians who choose to become a hospitalist may differ by sex. When deciding on a specialty, a talented resident considering certain lifestyle issues may find hospital medicine particularly attractive — and that draw toward a more lifestyle-friendly specialty may differ by sex, as some prior studies have shown. If true, the pool of women hospitalists may be better than their male counterparts because male physicians of that caliber don’t become hospitalists.

Okay, don’t write in. I’m just trying to cite examples of how to think about collider bias. I can’t prove that this is the case, and in fact the authors do a sensitivity analysis of all physicians, not just hospitalists, and show the same thing. So this is probably not true, but epidemiology is fun, right?

And the fourth possibility: This is nothing but statistical noise. The effect size is incredibly small and just on the border of statistical significance. Especially when you’re working with very large datasets like this, you’ve got to be really careful about overinterpreting statistically significant findings that are nevertheless of small magnitude.

Regardless, it’s an interesting study, one that made me think and, of course, worry a bit about how I would present it. Forgive me if I’ve been indelicate in handling the complex issues of sex, gender, and society here. But I’m not sure what you expect; after all, I’m only a male doctor.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s a battle of the sexes today as we dive into a paper that makes you say, “Wow, what an interesting study” and also “Boy, am I glad I didn’t do that study.” That’s because studies like this are always somewhat fraught; they say something about medicine but also something about society — and that makes this a bit precarious. But that’s never stopped us before. So, let’s go ahead and try to answer the question: Do women make better doctors than men?

On the surface, this question seems nearly impossible to answer. It’s too broad; what does it mean to be a “better” doctor? At first blush it seems that there are just too many variables to control for here: the type of doctor, the type of patient, the clinical scenario, and so on.

But this study, “Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates by physician and patient sex,” which appears in Annals of Internal Medicine, uses a fairly ingenious method to cut through all the bias by leveraging two simple facts: First, hospital medicine is largely conducted by hospitalists these days; second, due to the shift-based nature of hospitalist work, the hospitalist you get when you are admitted to the hospital is pretty much random.

In other words, if you are admitted to the hospital for an acute illness and get a hospitalist as your attending, you have no control over whether it is a man or a woman. Is this a randomized trial? No, but it’s not bad.

Researchers used Medicare claims data to identify adults over age 65 who had nonelective hospital admissions throughout the United States. The claims revealed the sex of the patient and the name of the attending physician. By linking to a medical provider database, they could determine the sex of the provider.

The goal was to look at outcomes across four dyads:

- Male patient – male doctor

- Male patient – female doctor

- Female patient – male doctor

- Female patient – female doctor

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality.

I told you that focusing on hospitalists produces some pseudorandomization, but let’s look at the data to be sure. Just under a million patients were treated by approximately 50,000 physicians, 30% of whom were female. And, though female patients and male patients differed, they did not differ with respect to the sex of their hospitalist. So, by physician sex, patients were similar in mean age, race, ethnicity, household income, eligibility for Medicaid, and comorbid conditions. The authors even created a “predicted mortality” score which was similar across the groups as well.

Now, the female physicians were a bit different from the male physicians. The female hospitalists were slightly more likely to have an osteopathic degree, had slightly fewer admissions per year, and were a bit younger.

So, we have broadly similar patients regardless of who their hospitalist was, but hospitalists differ by factors other than their sex. Fine.

I’ve graphed the results here.

This is a relatively small effect, to be sure, but if you multiply it across the millions of hospitalist admissions per year, you can start to put up some real numbers.

So, what is going on here? I see four broad buckets of possibilities.

Let’s start with the obvious explanation: Women, on average, are better doctors than men. I am married to a woman doctor, and based on my personal experience, this explanation is undoubtedly true. But why would that be?

The authors cite data that suggest that female physicians are less likely than male physicians to dismiss patient concerns — and in particular, the concerns of female patients — perhaps leading to fewer missed diagnoses. But this is impossible to measure with administrative data, so this study can no more tell us whether these female hospitalists are more attentive than their male counterparts than it can suggest that the benefit is mediated by the shorter average height of female physicians. Perhaps the key is being closer to the patient?

The second possibility here is that this has nothing to do with the sex of the physician at all; it has to do with those other things that associate with the sex of the physician. We know, for example, that the female physicians saw fewer patients per year than the male physicians, but the study authors adjusted for this in the statistical models. Still, other unmeasured factors (confounders) could be present. By the way, confounders wouldn’t necessarily change the primary finding — you are better off being cared for by female physicians. It’s just not because they are female; it’s a convenient marker for some other quality, such as age.

The third possibility is that the study represents a phenomenon called collider bias. The idea here is that physicians only get into the study if they are hospitalists, and the quality of physicians who choose to become a hospitalist may differ by sex. When deciding on a specialty, a talented resident considering certain lifestyle issues may find hospital medicine particularly attractive — and that draw toward a more lifestyle-friendly specialty may differ by sex, as some prior studies have shown. If true, the pool of women hospitalists may be better than their male counterparts because male physicians of that caliber don’t become hospitalists.

Okay, don’t write in. I’m just trying to cite examples of how to think about collider bias. I can’t prove that this is the case, and in fact the authors do a sensitivity analysis of all physicians, not just hospitalists, and show the same thing. So this is probably not true, but epidemiology is fun, right?

And the fourth possibility: This is nothing but statistical noise. The effect size is incredibly small and just on the border of statistical significance. Especially when you’re working with very large datasets like this, you’ve got to be really careful about overinterpreting statistically significant findings that are nevertheless of small magnitude.

Regardless, it’s an interesting study, one that made me think and, of course, worry a bit about how I would present it. Forgive me if I’ve been indelicate in handling the complex issues of sex, gender, and society here. But I’m not sure what you expect; after all, I’m only a male doctor.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s a battle of the sexes today as we dive into a paper that makes you say, “Wow, what an interesting study” and also “Boy, am I glad I didn’t do that study.” That’s because studies like this are always somewhat fraught; they say something about medicine but also something about society — and that makes this a bit precarious. But that’s never stopped us before. So, let’s go ahead and try to answer the question: Do women make better doctors than men?

On the surface, this question seems nearly impossible to answer. It’s too broad; what does it mean to be a “better” doctor? At first blush it seems that there are just too many variables to control for here: the type of doctor, the type of patient, the clinical scenario, and so on.

But this study, “Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates by physician and patient sex,” which appears in Annals of Internal Medicine, uses a fairly ingenious method to cut through all the bias by leveraging two simple facts: First, hospital medicine is largely conducted by hospitalists these days; second, due to the shift-based nature of hospitalist work, the hospitalist you get when you are admitted to the hospital is pretty much random.

In other words, if you are admitted to the hospital for an acute illness and get a hospitalist as your attending, you have no control over whether it is a man or a woman. Is this a randomized trial? No, but it’s not bad.

Researchers used Medicare claims data to identify adults over age 65 who had nonelective hospital admissions throughout the United States. The claims revealed the sex of the patient and the name of the attending physician. By linking to a medical provider database, they could determine the sex of the provider.

The goal was to look at outcomes across four dyads:

- Male patient – male doctor