User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

How to assess an Antimicrobial Stewardship Program

A study compares the merits of DOT and DOTA

The currently recommended method for hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) to measure antibiotic use is Days of Therapy/1,000 patient-days, but there are a few disadvantages of using the DOT, said Maryrose Laguio-Vila, MD, coauthor of a recent study on stewardship.

“For accurate measurement, it requires information technology (IT) support to assist an ASP in generating reports of antibiotic prescriptions and administrations to patients, often from an electronic medical record (EMR). In hospitals where there is no EMR, DOT is probably not easily done and would have to be manually extracted (a herculean task),” she said. “Second, DOT tends to be an aggregate measurement of antibiotics used at an institution or hospital location; if an ASP does a specific intervention targeting a group of antibiotics or infectious indication, changes in the hospital-wide DOT or drug-class DOT may not accurately reflect the exact impact of an ASP’s intervention.”

The paper offers an alternative/supplemental method for ASPs to quantify their impact on antibiotic use without using an EMR or needing IT support: Days of Therapy Avoided. “DOTA can be tracked prospectively (or retrospectively) with each intervention an ASP makes, and calculates an exact amount of antibiotic use avoided,” Dr. Laguio-Vila said. “If the ASP also tracks the types of antibiotic recommendations made according to infectious indication, comparison of DOTA between indications – such as pneumonia versus UTI [urinary tract infection] – can lead to ideas of which type of indication needs clinical guidelines development, or order set revision, or which type of infection the ASP should target to reduce high-risk antibiotics.”

Also, she added, because most ASPs have several types of interventions at once (such as education on pneumonia guidelines, as well as penicillin-allergy assessment), aggregate assessments of institutional antibiotic use like the DOT cannot quantify how much impact a specific intervention has accomplished. DOTA may offer a fairer assessment of the direct changes in antibiotic use resulting from specific ASP activities, because tracking DOTA is extracted from each specific patient intervention.

“Now that the Joint Commission has a requirement that all hospitals seeking JC accreditation have some form of an ASP in place and measure antibiotic use in some way at their institution, there may be numerous hospitals facing the same challenges with calculating a DOT. DOTA would meet these requirements, but in a ‘low tech’ way,” Dr. Laguio-Vila said. “For hospitalists with interests in being the antibiotic steward or champion for their institution, DOTA is an option for measuring antibiotic use.”

Reference

Datta S et al. Days of therapy avoided: A novel method for measuring the impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program to stop antibiotics. J Hosp Med. 2018 Feb 8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2927.

A study compares the merits of DOT and DOTA

A study compares the merits of DOT and DOTA

The currently recommended method for hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) to measure antibiotic use is Days of Therapy/1,000 patient-days, but there are a few disadvantages of using the DOT, said Maryrose Laguio-Vila, MD, coauthor of a recent study on stewardship.

“For accurate measurement, it requires information technology (IT) support to assist an ASP in generating reports of antibiotic prescriptions and administrations to patients, often from an electronic medical record (EMR). In hospitals where there is no EMR, DOT is probably not easily done and would have to be manually extracted (a herculean task),” she said. “Second, DOT tends to be an aggregate measurement of antibiotics used at an institution or hospital location; if an ASP does a specific intervention targeting a group of antibiotics or infectious indication, changes in the hospital-wide DOT or drug-class DOT may not accurately reflect the exact impact of an ASP’s intervention.”

The paper offers an alternative/supplemental method for ASPs to quantify their impact on antibiotic use without using an EMR or needing IT support: Days of Therapy Avoided. “DOTA can be tracked prospectively (or retrospectively) with each intervention an ASP makes, and calculates an exact amount of antibiotic use avoided,” Dr. Laguio-Vila said. “If the ASP also tracks the types of antibiotic recommendations made according to infectious indication, comparison of DOTA between indications – such as pneumonia versus UTI [urinary tract infection] – can lead to ideas of which type of indication needs clinical guidelines development, or order set revision, or which type of infection the ASP should target to reduce high-risk antibiotics.”

Also, she added, because most ASPs have several types of interventions at once (such as education on pneumonia guidelines, as well as penicillin-allergy assessment), aggregate assessments of institutional antibiotic use like the DOT cannot quantify how much impact a specific intervention has accomplished. DOTA may offer a fairer assessment of the direct changes in antibiotic use resulting from specific ASP activities, because tracking DOTA is extracted from each specific patient intervention.

“Now that the Joint Commission has a requirement that all hospitals seeking JC accreditation have some form of an ASP in place and measure antibiotic use in some way at their institution, there may be numerous hospitals facing the same challenges with calculating a DOT. DOTA would meet these requirements, but in a ‘low tech’ way,” Dr. Laguio-Vila said. “For hospitalists with interests in being the antibiotic steward or champion for their institution, DOTA is an option for measuring antibiotic use.”

Reference

Datta S et al. Days of therapy avoided: A novel method for measuring the impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program to stop antibiotics. J Hosp Med. 2018 Feb 8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2927.

The currently recommended method for hospital antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) to measure antibiotic use is Days of Therapy/1,000 patient-days, but there are a few disadvantages of using the DOT, said Maryrose Laguio-Vila, MD, coauthor of a recent study on stewardship.

“For accurate measurement, it requires information technology (IT) support to assist an ASP in generating reports of antibiotic prescriptions and administrations to patients, often from an electronic medical record (EMR). In hospitals where there is no EMR, DOT is probably not easily done and would have to be manually extracted (a herculean task),” she said. “Second, DOT tends to be an aggregate measurement of antibiotics used at an institution or hospital location; if an ASP does a specific intervention targeting a group of antibiotics or infectious indication, changes in the hospital-wide DOT or drug-class DOT may not accurately reflect the exact impact of an ASP’s intervention.”

The paper offers an alternative/supplemental method for ASPs to quantify their impact on antibiotic use without using an EMR or needing IT support: Days of Therapy Avoided. “DOTA can be tracked prospectively (or retrospectively) with each intervention an ASP makes, and calculates an exact amount of antibiotic use avoided,” Dr. Laguio-Vila said. “If the ASP also tracks the types of antibiotic recommendations made according to infectious indication, comparison of DOTA between indications – such as pneumonia versus UTI [urinary tract infection] – can lead to ideas of which type of indication needs clinical guidelines development, or order set revision, or which type of infection the ASP should target to reduce high-risk antibiotics.”

Also, she added, because most ASPs have several types of interventions at once (such as education on pneumonia guidelines, as well as penicillin-allergy assessment), aggregate assessments of institutional antibiotic use like the DOT cannot quantify how much impact a specific intervention has accomplished. DOTA may offer a fairer assessment of the direct changes in antibiotic use resulting from specific ASP activities, because tracking DOTA is extracted from each specific patient intervention.

“Now that the Joint Commission has a requirement that all hospitals seeking JC accreditation have some form of an ASP in place and measure antibiotic use in some way at their institution, there may be numerous hospitals facing the same challenges with calculating a DOT. DOTA would meet these requirements, but in a ‘low tech’ way,” Dr. Laguio-Vila said. “For hospitalists with interests in being the antibiotic steward or champion for their institution, DOTA is an option for measuring antibiotic use.”

Reference

Datta S et al. Days of therapy avoided: A novel method for measuring the impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program to stop antibiotics. J Hosp Med. 2018 Feb 8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2927.

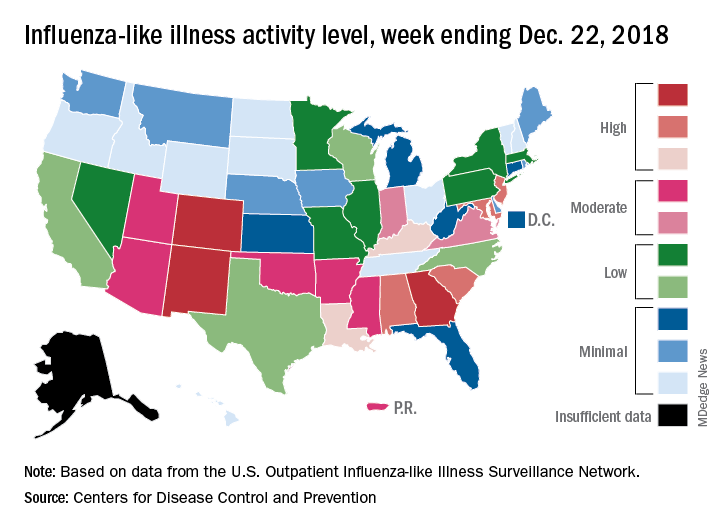

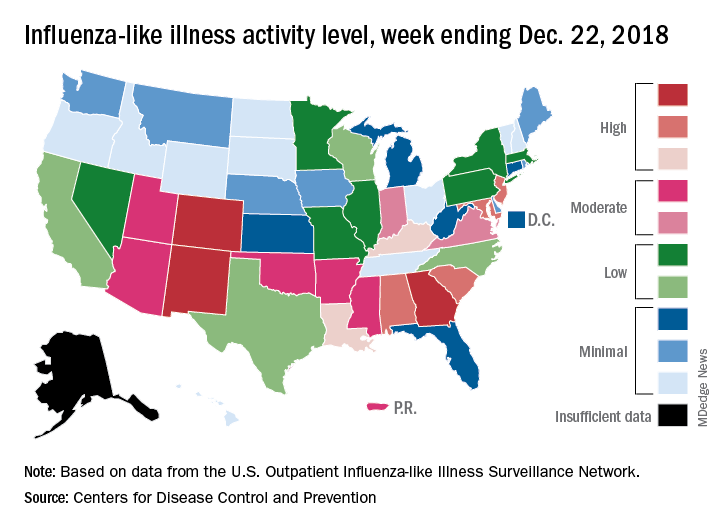

CDC: Flu activity ‘high’ in nine states

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Patients with ILI made up an estimated 3.3% of outpatient visits for the week, which is up from 2.7% the previous week and well above the baseline rate of 2.2%, which the 2018-2019 flu season has now exceeded for the past 3 weeks, the CDC reported Dec. 28. ILI is defined “as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.”

Three states – Colorado, Georgia, and New Mexico – are now at the highest level of flu activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, and nine states are in the “high” range (8-10), compared with two states in high range (both at level 10) for the week ending Dec. 15. Another seven states and Puerto Rico are now in the “moderate” range of 6-7, data from the CDC’s Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network show.

Four flu-related deaths in children were reported during the week ending Dec. 22, two of which occurred in previous weeks, which brings the total to 11 for the 2018-2019 season, the CDC reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Patients with ILI made up an estimated 3.3% of outpatient visits for the week, which is up from 2.7% the previous week and well above the baseline rate of 2.2%, which the 2018-2019 flu season has now exceeded for the past 3 weeks, the CDC reported Dec. 28. ILI is defined “as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.”

Three states – Colorado, Georgia, and New Mexico – are now at the highest level of flu activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, and nine states are in the “high” range (8-10), compared with two states in high range (both at level 10) for the week ending Dec. 15. Another seven states and Puerto Rico are now in the “moderate” range of 6-7, data from the CDC’s Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network show.

Four flu-related deaths in children were reported during the week ending Dec. 22, two of which occurred in previous weeks, which brings the total to 11 for the 2018-2019 season, the CDC reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Patients with ILI made up an estimated 3.3% of outpatient visits for the week, which is up from 2.7% the previous week and well above the baseline rate of 2.2%, which the 2018-2019 flu season has now exceeded for the past 3 weeks, the CDC reported Dec. 28. ILI is defined “as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.”

Three states – Colorado, Georgia, and New Mexico – are now at the highest level of flu activity on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, and nine states are in the “high” range (8-10), compared with two states in high range (both at level 10) for the week ending Dec. 15. Another seven states and Puerto Rico are now in the “moderate” range of 6-7, data from the CDC’s Outpatient ILI Surveillance Network show.

Four flu-related deaths in children were reported during the week ending Dec. 22, two of which occurred in previous weeks, which brings the total to 11 for the 2018-2019 season, the CDC reported.

No change in postoperative pain with restrictive opioid protocol

Opioid prescriptions after gynecologic surgery can be significantly reduced without impacting postoperative pain scores or complication rates, according to a paper published in JAMA Network Open.

A tertiary care comprehensive care center implemented an ultrarestrictive opioid prescription protocol (UROPP) then evaluated the outcomes in a case-control study involving 605 women undergoing gynecologic surgery, compared with 626 controls treated before implementation of the new protocol.

The ultrarestrictive protocol was prompted by frequent inquiries from patients who had used very little of their prescribed opioids after surgery and wanted to know what to do with the unused pills.

The new protocol involved a short preoperative counseling session about postoperative pain management. Following that, ambulatory surgery, minimally invasive surgery, or laparotomy patients were prescribed a 7-day supply of nonopioid pain relief. Laparotomy patients were also prescribed a 3-day supply of an oral opioid.

Any patients who required more than five opioid doses in the 24 hours before discharge were also prescribed a 3-day supply of opioid pain medication as needed, and all patients had the option of requesting an additional 3-day opioid refill.

Researchers saw no significant differences between the two groups in mean postoperative pain scores 2 weeks after surgery, and a similar number of patients in each group requested an opioid refill. There was also no significant difference in the number of postoperative complications between groups.

Implementation of the ultrarestrictive protocol was associated with significant declines in the mean number of opioid pills prescribed dropped from 31.7 to 3.5 in all surgical cases, from 43.6 to 12.1 in the laparotomy group, from 38.4 to 1.3 in the minimally invasive surgery group, and from 13.9 to 0.2 in patients who underwent ambulatory surgery.

“These data suggest that the implementation of a UROPP in a large surgical service is feasible and safe and was associated with a significantly decreased number of opioids dispensed during the perioperative period, particularly among opioid-naive patients,” wrote Jaron Mark, MD, of the department of gynecologic oncology at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y., and his coauthors. “The opioid-sparing effect was also marked and statistically significant in the laparotomy group, where most patients remained physically active and recovered well with no negative sequelae or elevated pain score after surgery.”

The researchers also noted that patients who were discharged home with an opioid prescription were more likely to call and request a refill within 30 days, compared with patients who did not receive opioids at discharge.

The study was supported by the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, the National Cancer Institute and the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation. Two authors reported receiving fees and nonfinancial support from the private sector unrelated to the study.

SOURCE: Mark J et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5452.

The ultrarestrictive postoperative opioid prescribing protocol described in this study is a promising strategy for reducing opioid prescribing without increasing pain and limiting the potential for diversion and misuse of opioids. An important element of this protocol is the preoperative counseling, because setting patient expectations is likely to be an important factor in improving postoperative outcomes.

It is also worth noting that this study focused on patients undergoing major and minor gynecologic surgery, so more research is needed to explore these outcomes particularly among patients undergoing procedures that may be associated with a higher risk of persistent postoperative pain and/or opioid use. It is also a management strategy explored in patients at low risk of chronic postoperative opioid use, but a similar pathway should be developed and explored in more high-risk patients.

Dr. Jennifer M. Hah is from the department of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain management at Stanford University (Calif.). These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Network Open. 2018 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5432). No conflicts of interest were reported.

The ultrarestrictive postoperative opioid prescribing protocol described in this study is a promising strategy for reducing opioid prescribing without increasing pain and limiting the potential for diversion and misuse of opioids. An important element of this protocol is the preoperative counseling, because setting patient expectations is likely to be an important factor in improving postoperative outcomes.

It is also worth noting that this study focused on patients undergoing major and minor gynecologic surgery, so more research is needed to explore these outcomes particularly among patients undergoing procedures that may be associated with a higher risk of persistent postoperative pain and/or opioid use. It is also a management strategy explored in patients at low risk of chronic postoperative opioid use, but a similar pathway should be developed and explored in more high-risk patients.

Dr. Jennifer M. Hah is from the department of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain management at Stanford University (Calif.). These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Network Open. 2018 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5432). No conflicts of interest were reported.

The ultrarestrictive postoperative opioid prescribing protocol described in this study is a promising strategy for reducing opioid prescribing without increasing pain and limiting the potential for diversion and misuse of opioids. An important element of this protocol is the preoperative counseling, because setting patient expectations is likely to be an important factor in improving postoperative outcomes.

It is also worth noting that this study focused on patients undergoing major and minor gynecologic surgery, so more research is needed to explore these outcomes particularly among patients undergoing procedures that may be associated with a higher risk of persistent postoperative pain and/or opioid use. It is also a management strategy explored in patients at low risk of chronic postoperative opioid use, but a similar pathway should be developed and explored in more high-risk patients.

Dr. Jennifer M. Hah is from the department of anesthesiology, perioperative, and pain management at Stanford University (Calif.). These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Network Open. 2018 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5432). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Opioid prescriptions after gynecologic surgery can be significantly reduced without impacting postoperative pain scores or complication rates, according to a paper published in JAMA Network Open.

A tertiary care comprehensive care center implemented an ultrarestrictive opioid prescription protocol (UROPP) then evaluated the outcomes in a case-control study involving 605 women undergoing gynecologic surgery, compared with 626 controls treated before implementation of the new protocol.

The ultrarestrictive protocol was prompted by frequent inquiries from patients who had used very little of their prescribed opioids after surgery and wanted to know what to do with the unused pills.

The new protocol involved a short preoperative counseling session about postoperative pain management. Following that, ambulatory surgery, minimally invasive surgery, or laparotomy patients were prescribed a 7-day supply of nonopioid pain relief. Laparotomy patients were also prescribed a 3-day supply of an oral opioid.

Any patients who required more than five opioid doses in the 24 hours before discharge were also prescribed a 3-day supply of opioid pain medication as needed, and all patients had the option of requesting an additional 3-day opioid refill.

Researchers saw no significant differences between the two groups in mean postoperative pain scores 2 weeks after surgery, and a similar number of patients in each group requested an opioid refill. There was also no significant difference in the number of postoperative complications between groups.

Implementation of the ultrarestrictive protocol was associated with significant declines in the mean number of opioid pills prescribed dropped from 31.7 to 3.5 in all surgical cases, from 43.6 to 12.1 in the laparotomy group, from 38.4 to 1.3 in the minimally invasive surgery group, and from 13.9 to 0.2 in patients who underwent ambulatory surgery.

“These data suggest that the implementation of a UROPP in a large surgical service is feasible and safe and was associated with a significantly decreased number of opioids dispensed during the perioperative period, particularly among opioid-naive patients,” wrote Jaron Mark, MD, of the department of gynecologic oncology at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y., and his coauthors. “The opioid-sparing effect was also marked and statistically significant in the laparotomy group, where most patients remained physically active and recovered well with no negative sequelae or elevated pain score after surgery.”

The researchers also noted that patients who were discharged home with an opioid prescription were more likely to call and request a refill within 30 days, compared with patients who did not receive opioids at discharge.

The study was supported by the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, the National Cancer Institute and the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation. Two authors reported receiving fees and nonfinancial support from the private sector unrelated to the study.

SOURCE: Mark J et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5452.

Opioid prescriptions after gynecologic surgery can be significantly reduced without impacting postoperative pain scores or complication rates, according to a paper published in JAMA Network Open.

A tertiary care comprehensive care center implemented an ultrarestrictive opioid prescription protocol (UROPP) then evaluated the outcomes in a case-control study involving 605 women undergoing gynecologic surgery, compared with 626 controls treated before implementation of the new protocol.

The ultrarestrictive protocol was prompted by frequent inquiries from patients who had used very little of their prescribed opioids after surgery and wanted to know what to do with the unused pills.

The new protocol involved a short preoperative counseling session about postoperative pain management. Following that, ambulatory surgery, minimally invasive surgery, or laparotomy patients were prescribed a 7-day supply of nonopioid pain relief. Laparotomy patients were also prescribed a 3-day supply of an oral opioid.

Any patients who required more than five opioid doses in the 24 hours before discharge were also prescribed a 3-day supply of opioid pain medication as needed, and all patients had the option of requesting an additional 3-day opioid refill.

Researchers saw no significant differences between the two groups in mean postoperative pain scores 2 weeks after surgery, and a similar number of patients in each group requested an opioid refill. There was also no significant difference in the number of postoperative complications between groups.

Implementation of the ultrarestrictive protocol was associated with significant declines in the mean number of opioid pills prescribed dropped from 31.7 to 3.5 in all surgical cases, from 43.6 to 12.1 in the laparotomy group, from 38.4 to 1.3 in the minimally invasive surgery group, and from 13.9 to 0.2 in patients who underwent ambulatory surgery.

“These data suggest that the implementation of a UROPP in a large surgical service is feasible and safe and was associated with a significantly decreased number of opioids dispensed during the perioperative period, particularly among opioid-naive patients,” wrote Jaron Mark, MD, of the department of gynecologic oncology at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y., and his coauthors. “The opioid-sparing effect was also marked and statistically significant in the laparotomy group, where most patients remained physically active and recovered well with no negative sequelae or elevated pain score after surgery.”

The researchers also noted that patients who were discharged home with an opioid prescription were more likely to call and request a refill within 30 days, compared with patients who did not receive opioids at discharge.

The study was supported by the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, the National Cancer Institute and the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation. Two authors reported receiving fees and nonfinancial support from the private sector unrelated to the study.

SOURCE: Mark J et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5452.

Key clinical point: A ultrarestrictive postoperative opioid protocol is not associated with higher postoperative pain scores.

Major finding: The protocol achieves significant reductions in opioid use.

Study details: A case-control study in 1,231 women undergoing gynecologic surgery.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, the National Cancer Institute, and the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation. Two authors reported receiving fees and nonfinancial support from the private sector unrelated to the study.

Source: Mark J et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5452.

EHR stress linked to burnout

Physicians who experience stress related to the use of health information technology are twice as likely to experience burnout.

Rebekah Gardner, MD, of Brown University in Providence, R.I., and her colleagues surveyed all 4,197 Rhode Island physicians in 2017 to learn how the use of electronic health records affected their practices and their job satisfaction.

Just over a quarter (25.0%) of 1,792 respondents reported burnout. Among electronic health record users (91% of respondents), 70% reported health IT-related stress (J Am Med Inform Assoc. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy145).

“After adjustment, physicians reporting poor/marginal time for documentation had 2.8 times the odds of burnout (95% confidence interval, 2.0-4.1; P less than .0001) compared to those reporting sufficient time,” according to the researchers.

The team looked at three stress-related variables: whether the EHR adds to the frustration of one’s day; whether physicians felt they had sufficient time for documentation; and the amount of time spent on the EHR at home. Variables were measured on a four- or five-point scale depending on the question related to the specific stress variable.

Almost two-thirds (64.2%) of respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that EHRs add to the frustration of their day.

“It was the most commonly cited HIT-related stress measure in almost every specialty, with the highest prevalence among emergency physicians (77.6%),” the investigators wrote.

More than a third of physicians (37.7%) reported “moderately high” or “excessive” time spent on EHRs at home; this metric was the most commonly cited stress measure among pediatricians (63.6%).

Nearly half (46.4%) of physicians reported “poor” or “marginal” sufficiency of time for documentation.

“Presence of any 1 of the HIT-related stress measures was associated with approximately twice the odds of burnout among physician respondents,” Dr. Gardner and her colleagues noted, adding that “measuring and addressing HIT-related stress is an important step in reducing workforce burden and improving the care of our patients.”

To alleviate burnout, the authors recommended increased use of scribes, use of medical assistants to help create a more team-based documentation function, improved EHR training, providing more time during the day for documentation, and streamlining documentation expectations, with certain culture shifts needed in some cases (i.e., banning work-related email and clinical tasks for vacationing physicians).

SOURCE: Gardner R et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy145.

Physicians who experience stress related to the use of health information technology are twice as likely to experience burnout.

Rebekah Gardner, MD, of Brown University in Providence, R.I., and her colleagues surveyed all 4,197 Rhode Island physicians in 2017 to learn how the use of electronic health records affected their practices and their job satisfaction.

Just over a quarter (25.0%) of 1,792 respondents reported burnout. Among electronic health record users (91% of respondents), 70% reported health IT-related stress (J Am Med Inform Assoc. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy145).

“After adjustment, physicians reporting poor/marginal time for documentation had 2.8 times the odds of burnout (95% confidence interval, 2.0-4.1; P less than .0001) compared to those reporting sufficient time,” according to the researchers.

The team looked at three stress-related variables: whether the EHR adds to the frustration of one’s day; whether physicians felt they had sufficient time for documentation; and the amount of time spent on the EHR at home. Variables were measured on a four- or five-point scale depending on the question related to the specific stress variable.

Almost two-thirds (64.2%) of respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that EHRs add to the frustration of their day.

“It was the most commonly cited HIT-related stress measure in almost every specialty, with the highest prevalence among emergency physicians (77.6%),” the investigators wrote.

More than a third of physicians (37.7%) reported “moderately high” or “excessive” time spent on EHRs at home; this metric was the most commonly cited stress measure among pediatricians (63.6%).

Nearly half (46.4%) of physicians reported “poor” or “marginal” sufficiency of time for documentation.

“Presence of any 1 of the HIT-related stress measures was associated with approximately twice the odds of burnout among physician respondents,” Dr. Gardner and her colleagues noted, adding that “measuring and addressing HIT-related stress is an important step in reducing workforce burden and improving the care of our patients.”

To alleviate burnout, the authors recommended increased use of scribes, use of medical assistants to help create a more team-based documentation function, improved EHR training, providing more time during the day for documentation, and streamlining documentation expectations, with certain culture shifts needed in some cases (i.e., banning work-related email and clinical tasks for vacationing physicians).

SOURCE: Gardner R et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy145.

Physicians who experience stress related to the use of health information technology are twice as likely to experience burnout.

Rebekah Gardner, MD, of Brown University in Providence, R.I., and her colleagues surveyed all 4,197 Rhode Island physicians in 2017 to learn how the use of electronic health records affected their practices and their job satisfaction.

Just over a quarter (25.0%) of 1,792 respondents reported burnout. Among electronic health record users (91% of respondents), 70% reported health IT-related stress (J Am Med Inform Assoc. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy145).

“After adjustment, physicians reporting poor/marginal time for documentation had 2.8 times the odds of burnout (95% confidence interval, 2.0-4.1; P less than .0001) compared to those reporting sufficient time,” according to the researchers.

The team looked at three stress-related variables: whether the EHR adds to the frustration of one’s day; whether physicians felt they had sufficient time for documentation; and the amount of time spent on the EHR at home. Variables were measured on a four- or five-point scale depending on the question related to the specific stress variable.

Almost two-thirds (64.2%) of respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that EHRs add to the frustration of their day.

“It was the most commonly cited HIT-related stress measure in almost every specialty, with the highest prevalence among emergency physicians (77.6%),” the investigators wrote.

More than a third of physicians (37.7%) reported “moderately high” or “excessive” time spent on EHRs at home; this metric was the most commonly cited stress measure among pediatricians (63.6%).

Nearly half (46.4%) of physicians reported “poor” or “marginal” sufficiency of time for documentation.

“Presence of any 1 of the HIT-related stress measures was associated with approximately twice the odds of burnout among physician respondents,” Dr. Gardner and her colleagues noted, adding that “measuring and addressing HIT-related stress is an important step in reducing workforce burden and improving the care of our patients.”

To alleviate burnout, the authors recommended increased use of scribes, use of medical assistants to help create a more team-based documentation function, improved EHR training, providing more time during the day for documentation, and streamlining documentation expectations, with certain culture shifts needed in some cases (i.e., banning work-related email and clinical tasks for vacationing physicians).

SOURCE: Gardner R et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy145.

FROM JAMIA

Key clinical point: EHR-related stress is a measurable predictor of physician burnout.

Major finding: Seventy percent of EHR users who responded to a survey reported stress related to the use of health information technology.

Study details: Survey of all 4,197 physicians in Rhode Island; 1,792 (43%) responded.

Disclosures: The Rhode Island Department of Health funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Gardner R et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy145.

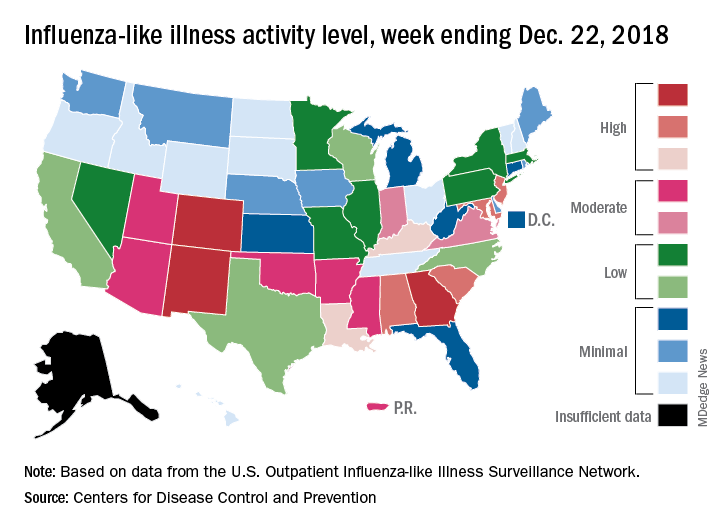

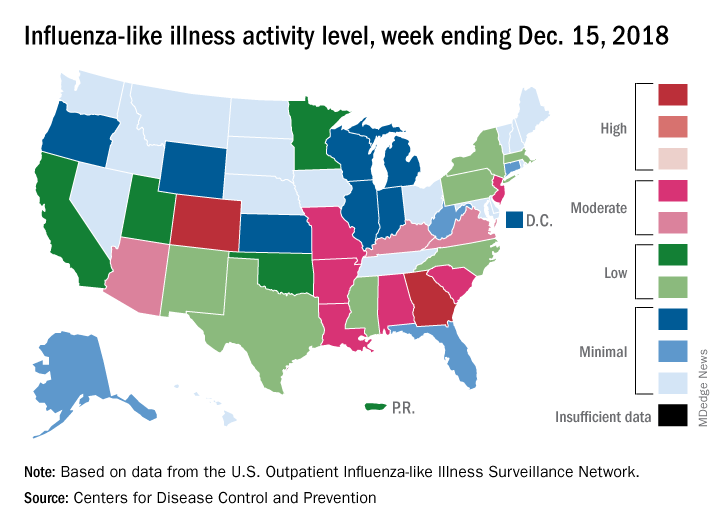

2018-2019 flu season starts in earnest

National flu activity moved solidly into above-average territory during the week ending Dec. 15, as Colorado and Georgia took the lead with the highest activity levels in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.7% for the week, which was up from 2.3% the previous week and above the national baseline of 2.2%, the CDC reported. ILI is defined “as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.”

Colorado and Georgia both reported ILI activity of 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, making them the only states in the “high” range (8-10). Nine states and New York City had activity levels in the “moderate” range (6-7), Puerto Rico and 11 states were in the “low” range (4-5), and 28 states and the District of Columbia were in the “minimal” range (1-3), the CDC said.

During the comparable period of last year’s high-severity flu season, which ultimately resulted in 900,000 flu-related hospitalizations and 80,000 deaths (185 pediatric), nine states were already at level 10. For the 2018-2019 season so far, there have been seven ILI-related pediatric deaths, CDC data show.

National flu activity moved solidly into above-average territory during the week ending Dec. 15, as Colorado and Georgia took the lead with the highest activity levels in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.7% for the week, which was up from 2.3% the previous week and above the national baseline of 2.2%, the CDC reported. ILI is defined “as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.”

Colorado and Georgia both reported ILI activity of 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, making them the only states in the “high” range (8-10). Nine states and New York City had activity levels in the “moderate” range (6-7), Puerto Rico and 11 states were in the “low” range (4-5), and 28 states and the District of Columbia were in the “minimal” range (1-3), the CDC said.

During the comparable period of last year’s high-severity flu season, which ultimately resulted in 900,000 flu-related hospitalizations and 80,000 deaths (185 pediatric), nine states were already at level 10. For the 2018-2019 season so far, there have been seven ILI-related pediatric deaths, CDC data show.

National flu activity moved solidly into above-average territory during the week ending Dec. 15, as Colorado and Georgia took the lead with the highest activity levels in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.7% for the week, which was up from 2.3% the previous week and above the national baseline of 2.2%, the CDC reported. ILI is defined “as fever (temperature of 100°F [37.8°C] or greater) and cough and/or sore throat.”

Colorado and Georgia both reported ILI activity of 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, making them the only states in the “high” range (8-10). Nine states and New York City had activity levels in the “moderate” range (6-7), Puerto Rico and 11 states were in the “low” range (4-5), and 28 states and the District of Columbia were in the “minimal” range (1-3), the CDC said.

During the comparable period of last year’s high-severity flu season, which ultimately resulted in 900,000 flu-related hospitalizations and 80,000 deaths (185 pediatric), nine states were already at level 10. For the 2018-2019 season so far, there have been seven ILI-related pediatric deaths, CDC data show.

Can higher MAP post cardiac arrest improve neurologic outcomes?

CHICAGO – A European clinical trial that targeted a mean arterial blood pressure after cardiac arrest higher than what the existing guidelines recommend found that the approach was safe, improved blood flow and oxygen to the brain, helped patients recover quicker, and reduced the number of adverse cardiac events, although it did not reduce the extent of anoxic brain damage or improve functional outcomes, the lead investigator reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The Neuroprotect trial randomly assigned 112 adult survivors of an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who were unconscious upon admission to two study groups: early goal-directed hemodynamic optimization (EGDHO), in which researchers used a targeted mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 85-100 mm Hg and mixed venous oxygen saturation between 65% and 75% during the first 36 hours after ICU admission; and the standard care group, in which they used the guideline-recommended MAP target of 65 mm Hg, said Koen Ameloot, MD, of East Limburg Hospital in Genk, Belgium.

“EGDHO clearly improved cerebral perfusion and oxygenation, thereby for the first time providing the proof of concept for this new hemodynamic target,” Dr. Ameloot said. “However, this did not result in the reduction of the extent of anoxic brain hemorrhage or effusion rate on MRI or an improvement in functional outcome at 180 days.”

He noted the trial was predicated on improving upon the so-called “two-hit” model of cardiac arrest sequelae: the first hit being the no-flow and low-flow period before achieving restoration of spontaneous circulation; the second hit being hypoperfusion and reperfusion injury during ICU stay.

Dr. Ameloot referenced a study in which he and other coauthors reported that patients with a MAP target of 65 mm Hg “experience a profound drop of cerebral oxygen saturation during the first 12 hours of ICU stay that may cause additional brain damage” (Resuscitation. 2018;123:92-7).

The researchers explored the question of what is the optimal MAP if a target of 65 mm Hg is too low, Dr. Ameloot said. “We showed that maximal brain oxygenation is achieved with a MAP of 100 mm Hg, while lower MAPs were associated with submaximal brain perfusion and higher MAPs with excessive after-load, a reduction in stroke volume, and suboptimal cerebral oxygenation.”

During the 36-hour intervention period, the EGDHO patients received higher doses of norepinephrine, Dr. Ameloot said. “This resulted in significant improvement of cerebral oxygenation during the first 12 hours and was paralleled by significantly higher cerebral perfusion in the subset of patients in whom Doppler measurements were performed,” he said. “While patients allocated to the MAP 65 mm Hg target experienced a profound drop of cerebral oxygenation during the critical first 6-12 hours of ICU stay, cerebral oxygenation was maintained at 67% in patients assigned to EGDHO.”

However, the rate of anoxic brain damage, measured as the percentage of irreversibly damaged anoxic voxels on diffusion-weighted MRI – the primary endpoint of the study – was actually higher in the EGDHO group, 16% vs. 12%, Dr. Ameloot said. “The percentage of anoxic voxels was only a poor predictor of favorable neurological outcome at 180 days, questioning the validity of the primary endpoint,” he said. He also noted that 23% of the trial participants did not have an MRI scan because of higher than expected 5-day rates of death.

“The percentage of patients with favorable neurological outcome tended to be somewhat higher in the intervention arm, although this did not reach statistical significance at ICU discharge and at 180 days,” Dr. Ameloot said. He noted that 42% of the intervention group and 33% of controls in the full-analysis set (P = .30) and 43% and 27%, respectively, in the per-protocol set (P = .15) had a favorable neurological outcome, as calculated using the Glasgow-Pittsburgh Cerebral Performance Category scores of 1 or 2, at 180 days.

The study did not reveal any noteworthy differences in ICU stay (7 vs. 8 days, P = .13) or days on mechanical ventilation (5 vs. 7, P = .31), although fewer patients in the EGDHO group required a tracheostomy (4% vs. 18%, P = .02). The intervention group also had lower rates of cardiac events, including recurrent cardiac arrest, limb ischemia, new atrial fibrillation, and pulmonary edema (13% vs. 33%; P = .02), Dr. Ameloot said.

Future post-hoc analyses of the data will explore the hypothesis that higher blood pressure leads to improved coronary perfusion and reduced infarct size, thus improving prognosis, he added.

“Should this trial therefore be the definite end to the promising hypothesis that improving brain oxygenation might reduce the second hit in post–cardiac arrest patients? I don’t think so,” Dr. Ameloot said. He noted a few limits to the study: that the perfusion rate on MRI was a poor predictor of 180-day outcome; that more patients than expected entered the trial without receiving basic life support and with nonshockable rhythms; and that there was possibly less extensive brain damage among controls at baseline. “Only an adequately powered clinical trial can provide an answer about the effects of EGDHO in post–cardiac arrest patients,” Dr. Ameloot said.

Dr. Ameloot had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Ameloot K et al. AHA 2018, Abstract 18620

CHICAGO – A European clinical trial that targeted a mean arterial blood pressure after cardiac arrest higher than what the existing guidelines recommend found that the approach was safe, improved blood flow and oxygen to the brain, helped patients recover quicker, and reduced the number of adverse cardiac events, although it did not reduce the extent of anoxic brain damage or improve functional outcomes, the lead investigator reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The Neuroprotect trial randomly assigned 112 adult survivors of an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who were unconscious upon admission to two study groups: early goal-directed hemodynamic optimization (EGDHO), in which researchers used a targeted mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 85-100 mm Hg and mixed venous oxygen saturation between 65% and 75% during the first 36 hours after ICU admission; and the standard care group, in which they used the guideline-recommended MAP target of 65 mm Hg, said Koen Ameloot, MD, of East Limburg Hospital in Genk, Belgium.

“EGDHO clearly improved cerebral perfusion and oxygenation, thereby for the first time providing the proof of concept for this new hemodynamic target,” Dr. Ameloot said. “However, this did not result in the reduction of the extent of anoxic brain hemorrhage or effusion rate on MRI or an improvement in functional outcome at 180 days.”

He noted the trial was predicated on improving upon the so-called “two-hit” model of cardiac arrest sequelae: the first hit being the no-flow and low-flow period before achieving restoration of spontaneous circulation; the second hit being hypoperfusion and reperfusion injury during ICU stay.

Dr. Ameloot referenced a study in which he and other coauthors reported that patients with a MAP target of 65 mm Hg “experience a profound drop of cerebral oxygen saturation during the first 12 hours of ICU stay that may cause additional brain damage” (Resuscitation. 2018;123:92-7).

The researchers explored the question of what is the optimal MAP if a target of 65 mm Hg is too low, Dr. Ameloot said. “We showed that maximal brain oxygenation is achieved with a MAP of 100 mm Hg, while lower MAPs were associated with submaximal brain perfusion and higher MAPs with excessive after-load, a reduction in stroke volume, and suboptimal cerebral oxygenation.”

During the 36-hour intervention period, the EGDHO patients received higher doses of norepinephrine, Dr. Ameloot said. “This resulted in significant improvement of cerebral oxygenation during the first 12 hours and was paralleled by significantly higher cerebral perfusion in the subset of patients in whom Doppler measurements were performed,” he said. “While patients allocated to the MAP 65 mm Hg target experienced a profound drop of cerebral oxygenation during the critical first 6-12 hours of ICU stay, cerebral oxygenation was maintained at 67% in patients assigned to EGDHO.”

However, the rate of anoxic brain damage, measured as the percentage of irreversibly damaged anoxic voxels on diffusion-weighted MRI – the primary endpoint of the study – was actually higher in the EGDHO group, 16% vs. 12%, Dr. Ameloot said. “The percentage of anoxic voxels was only a poor predictor of favorable neurological outcome at 180 days, questioning the validity of the primary endpoint,” he said. He also noted that 23% of the trial participants did not have an MRI scan because of higher than expected 5-day rates of death.

“The percentage of patients with favorable neurological outcome tended to be somewhat higher in the intervention arm, although this did not reach statistical significance at ICU discharge and at 180 days,” Dr. Ameloot said. He noted that 42% of the intervention group and 33% of controls in the full-analysis set (P = .30) and 43% and 27%, respectively, in the per-protocol set (P = .15) had a favorable neurological outcome, as calculated using the Glasgow-Pittsburgh Cerebral Performance Category scores of 1 or 2, at 180 days.

The study did not reveal any noteworthy differences in ICU stay (7 vs. 8 days, P = .13) or days on mechanical ventilation (5 vs. 7, P = .31), although fewer patients in the EGDHO group required a tracheostomy (4% vs. 18%, P = .02). The intervention group also had lower rates of cardiac events, including recurrent cardiac arrest, limb ischemia, new atrial fibrillation, and pulmonary edema (13% vs. 33%; P = .02), Dr. Ameloot said.

Future post-hoc analyses of the data will explore the hypothesis that higher blood pressure leads to improved coronary perfusion and reduced infarct size, thus improving prognosis, he added.

“Should this trial therefore be the definite end to the promising hypothesis that improving brain oxygenation might reduce the second hit in post–cardiac arrest patients? I don’t think so,” Dr. Ameloot said. He noted a few limits to the study: that the perfusion rate on MRI was a poor predictor of 180-day outcome; that more patients than expected entered the trial without receiving basic life support and with nonshockable rhythms; and that there was possibly less extensive brain damage among controls at baseline. “Only an adequately powered clinical trial can provide an answer about the effects of EGDHO in post–cardiac arrest patients,” Dr. Ameloot said.

Dr. Ameloot had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Ameloot K et al. AHA 2018, Abstract 18620

CHICAGO – A European clinical trial that targeted a mean arterial blood pressure after cardiac arrest higher than what the existing guidelines recommend found that the approach was safe, improved blood flow and oxygen to the brain, helped patients recover quicker, and reduced the number of adverse cardiac events, although it did not reduce the extent of anoxic brain damage or improve functional outcomes, the lead investigator reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The Neuroprotect trial randomly assigned 112 adult survivors of an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest who were unconscious upon admission to two study groups: early goal-directed hemodynamic optimization (EGDHO), in which researchers used a targeted mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 85-100 mm Hg and mixed venous oxygen saturation between 65% and 75% during the first 36 hours after ICU admission; and the standard care group, in which they used the guideline-recommended MAP target of 65 mm Hg, said Koen Ameloot, MD, of East Limburg Hospital in Genk, Belgium.

“EGDHO clearly improved cerebral perfusion and oxygenation, thereby for the first time providing the proof of concept for this new hemodynamic target,” Dr. Ameloot said. “However, this did not result in the reduction of the extent of anoxic brain hemorrhage or effusion rate on MRI or an improvement in functional outcome at 180 days.”

He noted the trial was predicated on improving upon the so-called “two-hit” model of cardiac arrest sequelae: the first hit being the no-flow and low-flow period before achieving restoration of spontaneous circulation; the second hit being hypoperfusion and reperfusion injury during ICU stay.

Dr. Ameloot referenced a study in which he and other coauthors reported that patients with a MAP target of 65 mm Hg “experience a profound drop of cerebral oxygen saturation during the first 12 hours of ICU stay that may cause additional brain damage” (Resuscitation. 2018;123:92-7).

The researchers explored the question of what is the optimal MAP if a target of 65 mm Hg is too low, Dr. Ameloot said. “We showed that maximal brain oxygenation is achieved with a MAP of 100 mm Hg, while lower MAPs were associated with submaximal brain perfusion and higher MAPs with excessive after-load, a reduction in stroke volume, and suboptimal cerebral oxygenation.”

During the 36-hour intervention period, the EGDHO patients received higher doses of norepinephrine, Dr. Ameloot said. “This resulted in significant improvement of cerebral oxygenation during the first 12 hours and was paralleled by significantly higher cerebral perfusion in the subset of patients in whom Doppler measurements were performed,” he said. “While patients allocated to the MAP 65 mm Hg target experienced a profound drop of cerebral oxygenation during the critical first 6-12 hours of ICU stay, cerebral oxygenation was maintained at 67% in patients assigned to EGDHO.”

However, the rate of anoxic brain damage, measured as the percentage of irreversibly damaged anoxic voxels on diffusion-weighted MRI – the primary endpoint of the study – was actually higher in the EGDHO group, 16% vs. 12%, Dr. Ameloot said. “The percentage of anoxic voxels was only a poor predictor of favorable neurological outcome at 180 days, questioning the validity of the primary endpoint,” he said. He also noted that 23% of the trial participants did not have an MRI scan because of higher than expected 5-day rates of death.

“The percentage of patients with favorable neurological outcome tended to be somewhat higher in the intervention arm, although this did not reach statistical significance at ICU discharge and at 180 days,” Dr. Ameloot said. He noted that 42% of the intervention group and 33% of controls in the full-analysis set (P = .30) and 43% and 27%, respectively, in the per-protocol set (P = .15) had a favorable neurological outcome, as calculated using the Glasgow-Pittsburgh Cerebral Performance Category scores of 1 or 2, at 180 days.

The study did not reveal any noteworthy differences in ICU stay (7 vs. 8 days, P = .13) or days on mechanical ventilation (5 vs. 7, P = .31), although fewer patients in the EGDHO group required a tracheostomy (4% vs. 18%, P = .02). The intervention group also had lower rates of cardiac events, including recurrent cardiac arrest, limb ischemia, new atrial fibrillation, and pulmonary edema (13% vs. 33%; P = .02), Dr. Ameloot said.

Future post-hoc analyses of the data will explore the hypothesis that higher blood pressure leads to improved coronary perfusion and reduced infarct size, thus improving prognosis, he added.

“Should this trial therefore be the definite end to the promising hypothesis that improving brain oxygenation might reduce the second hit in post–cardiac arrest patients? I don’t think so,” Dr. Ameloot said. He noted a few limits to the study: that the perfusion rate on MRI was a poor predictor of 180-day outcome; that more patients than expected entered the trial without receiving basic life support and with nonshockable rhythms; and that there was possibly less extensive brain damage among controls at baseline. “Only an adequately powered clinical trial can provide an answer about the effects of EGDHO in post–cardiac arrest patients,” Dr. Ameloot said.

Dr. Ameloot had no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Ameloot K et al. AHA 2018, Abstract 18620

REPORTING FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Forty-three percent of patients in the intervention group had a favorable neurological outcome vs. 27% of controls (P = .15).

Study details: The Neuroprotect trial was a multicenter, randomized, open-label, assessor-blinded trial of 112 post–cardiac arrest patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Ameloot had no financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Ameloot K et al. AHA 2018, Abstract 18620

Hospital medicine fellowships

Is it the right choice for me?

As Dr. Melanie Schaffer neared the end of her family medicine residency in the spring of 2015, she found herself considering a hospital medicine fellowship. Unsure if she could get a hospitalist job in an urban market given the outpatient focus of her training, Dr. Schaffer began searching for fellowships on the Society of Hospital Medicine website.1

Likewise, in 2014 Dr. Micah Prochaska was seriously contemplating a hospital medicine fellowship. He was about to graduate from internal medicine residency at the University of Chicago and was eager to gain skills and experience in clinical research.

In 2006, there were a total of 16 HM fellowship programs in the United States, catering to graduates of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatric residencies.2 Since that time, the number of hospital medicine fellowships has grown considerably, paralleling the explosive growth of hospital medicine as a specialty. For example, at one point in the summer of 2018, the SHM website listed 13 clinical family practice fellowships, 29 internal medicine fellowships, and 26 pediatric fellowships. Each fellowship emphasized different aspects of hospital medicine including clinical practice, research, quality improvement, and leadership.

Now more than ever, residents interested in hospital medicine may get overwhelmed by the multitude of options for fellowship training. And the question remains: why pursue fellowship training in the first place?

“I learned that as a family physician it is harder to get a job as a hospitalist outside of smaller communities, and I wanted to have extra training and credentials,” Dr. Schaffer said. “I pursued a fellowship in hospital medicine to hone my inpatient skills, obtain more ICU exposure, and work on procedures.”

Dr. Schaffer’s online search eventually led her to the Advanced Hospital Medicine Fellowship at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle. This 1-year hospital medicine fellowship started in 2008 with an intentional clinical focus, aiming to provide additional training opportunities in hospital medicine primarily to family medicine residency graduates.

“The goal of our program is to bridge the gap between the training of family medicine and internal medicine so our trainees can refine and develop their inpatient skills,” said Dr. David Wilson, program director of the Swedish Hospitalist Fellowship.

During her fellowship year, Dr. Schaffer was caring for hospitalized adult patients on a general medical ward, with supervision from a dedicated group of teaching hospitalists. She also completed rotations in the ICU, on subspecialty services, and received advanced training in point-of-care ultrasound.

Now in her second year of practice as a full time adult hospitalist at Swedish Medical Center, Dr. Schaffer believes her year of hospital medicine fellowship prepared her well for her current position.

“I am constantly using the tools and knowledge I acquired during my fellowship year,” she said. “I would encourage anyone who has an interest in working on procedural skills and gaining more ICU exposure to pursue a similar fellowship.”

In contrast to Dr. Schaffer, Dr. Prochaska was satisfied with his clinical training but chose to pursue a hospital medicine fellowship to develop research skills. Prior to starting the 2-year Hospitalist Scholars Training Program at the University of Chicago in 2014, Dr. Prochaska had a clear vision of becoming a hospital medicine health outcomes investigator, and believed this career would not be possible without the additional training offered by a research-focused fellowship program.

The Hospitalist Scholars Program at the University of Chicago, one of the first programs of its kind, offers a built-in master’s degree to all participants. At the conclusion of his fellowship training in 2016, Dr. Prochaska completed his Master’s in Health Sciences, which gives considerable attention to biostatistics and epidemiology. According to Dr. Prochaska, the key to becoming a successful academic researcher lies in one’s ability to write grants and receive funding, a skill he honed during this fellowship.

Now on faculty at the University of Chicago in the Section of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Prochaska devotes approximately 75% of his time to research and 25% to patient care.

Beyond the research training and experience he gained during his hospital medicine fellowship, Dr. Prochaska said he values the mentorship afforded to him. He noted that one of the most meaningful experiences during his 2 years of fellowship was having the opportunity to sit down with his program directors, Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. David Meltzer, to discuss the trajectory of his career in academic medicine.

“It is hard to find senior mentors in hospital medicine,” Dr. Prochaska said. “You could get a master’s degree on your own, but with the fellowship program, your mentors can help you think about the next steps in your career.”

For Dr. Schaffer and Dr. Prochaska, fellowship provided training and experience well-matched to their individual goals and helped foster their careers in hospital medicine. For some, however, a fellowship may not be a necessary step on the path to becoming a hospitalist. Many leaders in the field of hospital medicine have advanced in their careers without further training. In addition, receiving little more than a resident’s salary for an additional year or more during fellowship may not be financially tenable for some. Given the ongoing demand for hospitalists across the country, the lack of a fellowship on your resume may not significantly diminish your chances of securing a position, especially in the community setting.

In the end, the decision of whether to pursue a hospital medicine fellowship is a personal one, and the programs available are as varied as the individuals completing them. “Any hospitalist interested in more than simply patient care – potentially QI, medical education, policy, or administration – should consider a fellowship,” Dr. Prochaska said. “Hospitalists have a unique opportunity to be involved in all these areas, but there are absolutely critical skills you need to develop beyond your clinical skills to succeed.” Fellowships are one way to enhance these nonclinical skills.

The best advice to those considering a hospital medicine fellowship? Dedicate some time to engage in self-assessment and goal setting, before jumping to SHM’s online list of programs.

Ask yourself: “Where do I see myself in 10 years? What do I wish to accomplish in my career as a hospitalist? What additional training (clinical, research, quality improvement, leadership) might I need to achieve these goals? Will completion of a hospital medicine fellowship help me make this vision a reality?”

For Dr. Schaffer, a clinical practice–focused hospital medicine fellowship served as a necessary bridge between her family medicine residency and her current position as an adult hospitalist. While for Dr. Prochaska, a research-intensive hospital medicine fellowship was a key step in launching his academic career.

Of course, for many trainees at the end of residency, your self-assessment may lead you in the opposite direction. In that case it is time to find your first “real job” as an attending physician. But if you feel you need more training to meet your personal goals you should rest assured – whether now or in the future, there is almost certainly a hospital medicine fellowship that is right for you.

Dr. Schouten is a hospitalist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and serves on the Society of Hospital Medicine Physicians in Training Committee. Dr. Sundar is a hospitalist at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital in Sandy Springs, Ga., and serves as the Site Assistant Director for Education.

References

1. www.hospitalmedicine.org/membership/hospitalist-fellowships/

2. Ranji et al. “Hospital medicine fellowships: Works in progress.” American J Med. 2006 Jan;119(1):72.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.061.

Is it the right choice for me?

Is it the right choice for me?

As Dr. Melanie Schaffer neared the end of her family medicine residency in the spring of 2015, she found herself considering a hospital medicine fellowship. Unsure if she could get a hospitalist job in an urban market given the outpatient focus of her training, Dr. Schaffer began searching for fellowships on the Society of Hospital Medicine website.1

Likewise, in 2014 Dr. Micah Prochaska was seriously contemplating a hospital medicine fellowship. He was about to graduate from internal medicine residency at the University of Chicago and was eager to gain skills and experience in clinical research.

In 2006, there were a total of 16 HM fellowship programs in the United States, catering to graduates of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatric residencies.2 Since that time, the number of hospital medicine fellowships has grown considerably, paralleling the explosive growth of hospital medicine as a specialty. For example, at one point in the summer of 2018, the SHM website listed 13 clinical family practice fellowships, 29 internal medicine fellowships, and 26 pediatric fellowships. Each fellowship emphasized different aspects of hospital medicine including clinical practice, research, quality improvement, and leadership.

Now more than ever, residents interested in hospital medicine may get overwhelmed by the multitude of options for fellowship training. And the question remains: why pursue fellowship training in the first place?

“I learned that as a family physician it is harder to get a job as a hospitalist outside of smaller communities, and I wanted to have extra training and credentials,” Dr. Schaffer said. “I pursued a fellowship in hospital medicine to hone my inpatient skills, obtain more ICU exposure, and work on procedures.”

Dr. Schaffer’s online search eventually led her to the Advanced Hospital Medicine Fellowship at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle. This 1-year hospital medicine fellowship started in 2008 with an intentional clinical focus, aiming to provide additional training opportunities in hospital medicine primarily to family medicine residency graduates.

“The goal of our program is to bridge the gap between the training of family medicine and internal medicine so our trainees can refine and develop their inpatient skills,” said Dr. David Wilson, program director of the Swedish Hospitalist Fellowship.

During her fellowship year, Dr. Schaffer was caring for hospitalized adult patients on a general medical ward, with supervision from a dedicated group of teaching hospitalists. She also completed rotations in the ICU, on subspecialty services, and received advanced training in point-of-care ultrasound.

Now in her second year of practice as a full time adult hospitalist at Swedish Medical Center, Dr. Schaffer believes her year of hospital medicine fellowship prepared her well for her current position.

“I am constantly using the tools and knowledge I acquired during my fellowship year,” she said. “I would encourage anyone who has an interest in working on procedural skills and gaining more ICU exposure to pursue a similar fellowship.”

In contrast to Dr. Schaffer, Dr. Prochaska was satisfied with his clinical training but chose to pursue a hospital medicine fellowship to develop research skills. Prior to starting the 2-year Hospitalist Scholars Training Program at the University of Chicago in 2014, Dr. Prochaska had a clear vision of becoming a hospital medicine health outcomes investigator, and believed this career would not be possible without the additional training offered by a research-focused fellowship program.

The Hospitalist Scholars Program at the University of Chicago, one of the first programs of its kind, offers a built-in master’s degree to all participants. At the conclusion of his fellowship training in 2016, Dr. Prochaska completed his Master’s in Health Sciences, which gives considerable attention to biostatistics and epidemiology. According to Dr. Prochaska, the key to becoming a successful academic researcher lies in one’s ability to write grants and receive funding, a skill he honed during this fellowship.

Now on faculty at the University of Chicago in the Section of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Prochaska devotes approximately 75% of his time to research and 25% to patient care.

Beyond the research training and experience he gained during his hospital medicine fellowship, Dr. Prochaska said he values the mentorship afforded to him. He noted that one of the most meaningful experiences during his 2 years of fellowship was having the opportunity to sit down with his program directors, Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. David Meltzer, to discuss the trajectory of his career in academic medicine.

“It is hard to find senior mentors in hospital medicine,” Dr. Prochaska said. “You could get a master’s degree on your own, but with the fellowship program, your mentors can help you think about the next steps in your career.”

For Dr. Schaffer and Dr. Prochaska, fellowship provided training and experience well-matched to their individual goals and helped foster their careers in hospital medicine. For some, however, a fellowship may not be a necessary step on the path to becoming a hospitalist. Many leaders in the field of hospital medicine have advanced in their careers without further training. In addition, receiving little more than a resident’s salary for an additional year or more during fellowship may not be financially tenable for some. Given the ongoing demand for hospitalists across the country, the lack of a fellowship on your resume may not significantly diminish your chances of securing a position, especially in the community setting.

In the end, the decision of whether to pursue a hospital medicine fellowship is a personal one, and the programs available are as varied as the individuals completing them. “Any hospitalist interested in more than simply patient care – potentially QI, medical education, policy, or administration – should consider a fellowship,” Dr. Prochaska said. “Hospitalists have a unique opportunity to be involved in all these areas, but there are absolutely critical skills you need to develop beyond your clinical skills to succeed.” Fellowships are one way to enhance these nonclinical skills.

The best advice to those considering a hospital medicine fellowship? Dedicate some time to engage in self-assessment and goal setting, before jumping to SHM’s online list of programs.

Ask yourself: “Where do I see myself in 10 years? What do I wish to accomplish in my career as a hospitalist? What additional training (clinical, research, quality improvement, leadership) might I need to achieve these goals? Will completion of a hospital medicine fellowship help me make this vision a reality?”

For Dr. Schaffer, a clinical practice–focused hospital medicine fellowship served as a necessary bridge between her family medicine residency and her current position as an adult hospitalist. While for Dr. Prochaska, a research-intensive hospital medicine fellowship was a key step in launching his academic career.

Of course, for many trainees at the end of residency, your self-assessment may lead you in the opposite direction. In that case it is time to find your first “real job” as an attending physician. But if you feel you need more training to meet your personal goals you should rest assured – whether now or in the future, there is almost certainly a hospital medicine fellowship that is right for you.

Dr. Schouten is a hospitalist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and serves on the Society of Hospital Medicine Physicians in Training Committee. Dr. Sundar is a hospitalist at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital in Sandy Springs, Ga., and serves as the Site Assistant Director for Education.

References

1. www.hospitalmedicine.org/membership/hospitalist-fellowships/

2. Ranji et al. “Hospital medicine fellowships: Works in progress.” American J Med. 2006 Jan;119(1):72.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.061.

As Dr. Melanie Schaffer neared the end of her family medicine residency in the spring of 2015, she found herself considering a hospital medicine fellowship. Unsure if she could get a hospitalist job in an urban market given the outpatient focus of her training, Dr. Schaffer began searching for fellowships on the Society of Hospital Medicine website.1

Likewise, in 2014 Dr. Micah Prochaska was seriously contemplating a hospital medicine fellowship. He was about to graduate from internal medicine residency at the University of Chicago and was eager to gain skills and experience in clinical research.

In 2006, there were a total of 16 HM fellowship programs in the United States, catering to graduates of internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatric residencies.2 Since that time, the number of hospital medicine fellowships has grown considerably, paralleling the explosive growth of hospital medicine as a specialty. For example, at one point in the summer of 2018, the SHM website listed 13 clinical family practice fellowships, 29 internal medicine fellowships, and 26 pediatric fellowships. Each fellowship emphasized different aspects of hospital medicine including clinical practice, research, quality improvement, and leadership.

Now more than ever, residents interested in hospital medicine may get overwhelmed by the multitude of options for fellowship training. And the question remains: why pursue fellowship training in the first place?

“I learned that as a family physician it is harder to get a job as a hospitalist outside of smaller communities, and I wanted to have extra training and credentials,” Dr. Schaffer said. “I pursued a fellowship in hospital medicine to hone my inpatient skills, obtain more ICU exposure, and work on procedures.”

Dr. Schaffer’s online search eventually led her to the Advanced Hospital Medicine Fellowship at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle. This 1-year hospital medicine fellowship started in 2008 with an intentional clinical focus, aiming to provide additional training opportunities in hospital medicine primarily to family medicine residency graduates.

“The goal of our program is to bridge the gap between the training of family medicine and internal medicine so our trainees can refine and develop their inpatient skills,” said Dr. David Wilson, program director of the Swedish Hospitalist Fellowship.

During her fellowship year, Dr. Schaffer was caring for hospitalized adult patients on a general medical ward, with supervision from a dedicated group of teaching hospitalists. She also completed rotations in the ICU, on subspecialty services, and received advanced training in point-of-care ultrasound.

Now in her second year of practice as a full time adult hospitalist at Swedish Medical Center, Dr. Schaffer believes her year of hospital medicine fellowship prepared her well for her current position.

“I am constantly using the tools and knowledge I acquired during my fellowship year,” she said. “I would encourage anyone who has an interest in working on procedural skills and gaining more ICU exposure to pursue a similar fellowship.”

In contrast to Dr. Schaffer, Dr. Prochaska was satisfied with his clinical training but chose to pursue a hospital medicine fellowship to develop research skills. Prior to starting the 2-year Hospitalist Scholars Training Program at the University of Chicago in 2014, Dr. Prochaska had a clear vision of becoming a hospital medicine health outcomes investigator, and believed this career would not be possible without the additional training offered by a research-focused fellowship program.

The Hospitalist Scholars Program at the University of Chicago, one of the first programs of its kind, offers a built-in master’s degree to all participants. At the conclusion of his fellowship training in 2016, Dr. Prochaska completed his Master’s in Health Sciences, which gives considerable attention to biostatistics and epidemiology. According to Dr. Prochaska, the key to becoming a successful academic researcher lies in one’s ability to write grants and receive funding, a skill he honed during this fellowship.

Now on faculty at the University of Chicago in the Section of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Prochaska devotes approximately 75% of his time to research and 25% to patient care.

Beyond the research training and experience he gained during his hospital medicine fellowship, Dr. Prochaska said he values the mentorship afforded to him. He noted that one of the most meaningful experiences during his 2 years of fellowship was having the opportunity to sit down with his program directors, Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. David Meltzer, to discuss the trajectory of his career in academic medicine.

“It is hard to find senior mentors in hospital medicine,” Dr. Prochaska said. “You could get a master’s degree on your own, but with the fellowship program, your mentors can help you think about the next steps in your career.”

For Dr. Schaffer and Dr. Prochaska, fellowship provided training and experience well-matched to their individual goals and helped foster their careers in hospital medicine. For some, however, a fellowship may not be a necessary step on the path to becoming a hospitalist. Many leaders in the field of hospital medicine have advanced in their careers without further training. In addition, receiving little more than a resident’s salary for an additional year or more during fellowship may not be financially tenable for some. Given the ongoing demand for hospitalists across the country, the lack of a fellowship on your resume may not significantly diminish your chances of securing a position, especially in the community setting.

In the end, the decision of whether to pursue a hospital medicine fellowship is a personal one, and the programs available are as varied as the individuals completing them. “Any hospitalist interested in more than simply patient care – potentially QI, medical education, policy, or administration – should consider a fellowship,” Dr. Prochaska said. “Hospitalists have a unique opportunity to be involved in all these areas, but there are absolutely critical skills you need to develop beyond your clinical skills to succeed.” Fellowships are one way to enhance these nonclinical skills.

The best advice to those considering a hospital medicine fellowship? Dedicate some time to engage in self-assessment and goal setting, before jumping to SHM’s online list of programs.

Ask yourself: “Where do I see myself in 10 years? What do I wish to accomplish in my career as a hospitalist? What additional training (clinical, research, quality improvement, leadership) might I need to achieve these goals? Will completion of a hospital medicine fellowship help me make this vision a reality?”

For Dr. Schaffer, a clinical practice–focused hospital medicine fellowship served as a necessary bridge between her family medicine residency and her current position as an adult hospitalist. While for Dr. Prochaska, a research-intensive hospital medicine fellowship was a key step in launching his academic career.