User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

The state of hospital medicine in 2018

Productivity, pay, and roles remain center stage

In a national health care environment undergoing unprecedented transformation, the specialty of hospital medicine appears to be an island of relative stability, a conclusion that is supported by the principal findings from SHM’s 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report.

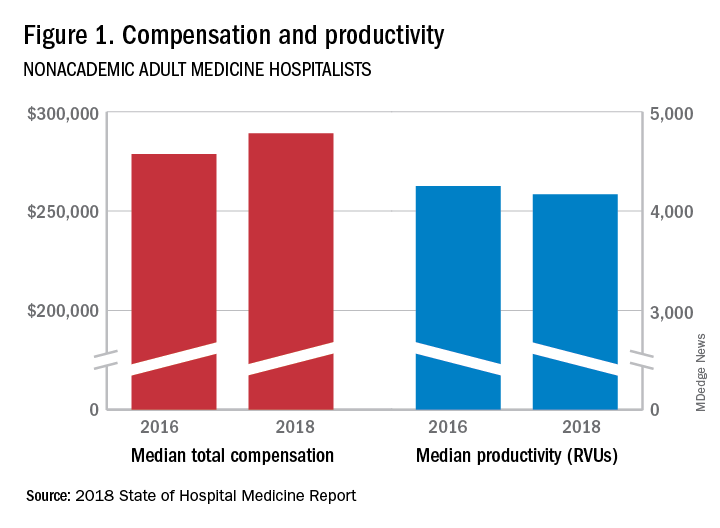

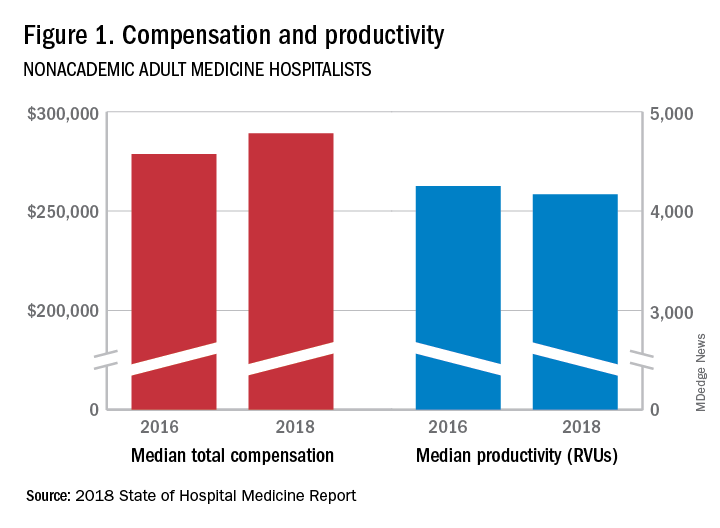

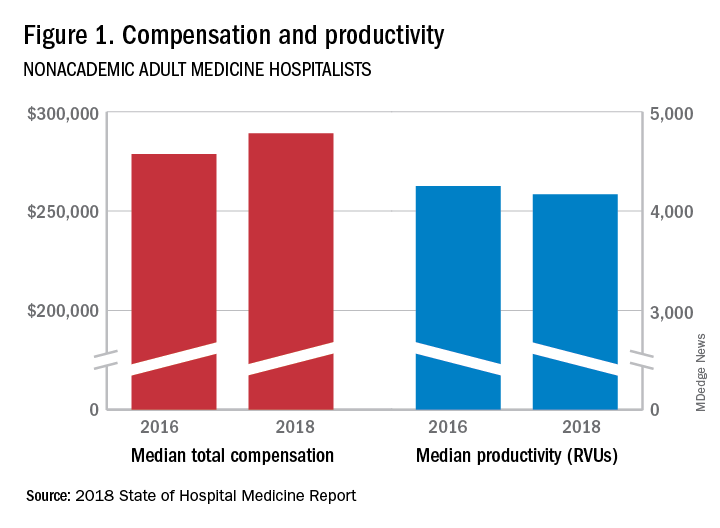

The report of hospitalist group practice characteristics, as well as other key data defining the field’s current status, that the Society of Hospital Medicine puts out every 2 years reveals that overall salaries for hospitalist physicians are up by 3.8% since 2016. Although productivity, as measured by work relative value units (RVUs), remained largely flat over the same period, financial support per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician position to hospitalist groups from their hospitals and health systems is up significantly.

Total support per FTE averaged $176,657 in 2018, 12% higher than in 2016, noted Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which oversees the biennial survey. Compensation and productivity data were collected by the Medical Group Management Association and licensed by SHM for inclusion in its report.

These findings – particularly the flat productivity – raise questions about long-term sustainability, Ms. Flores said. “What is going on? Do hospital administrators still recognize the value hospitalists bring to the operations and the quality of their hospitals? Or is paying the subsidy just a cost of doing business – a necessity for most hospitals in a setting where demand for hospitalist positions remains high?”

Andrew White, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee and director of the hospital medicine service at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, said basic market forces dictate that it is “pretty much inconceivable” to run a modern hospital of any size without hospitalists.

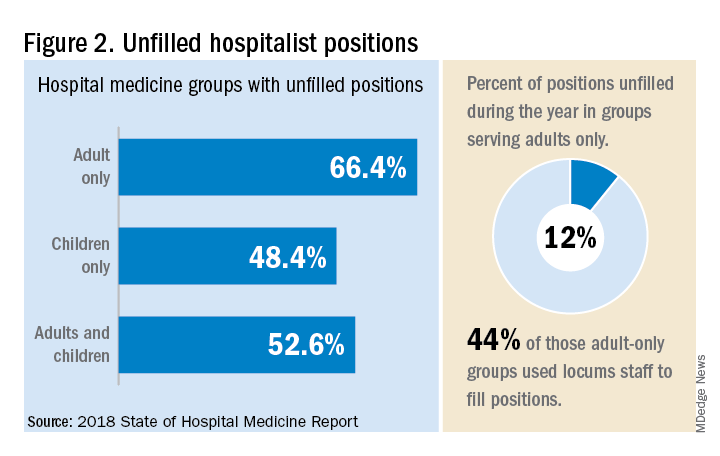

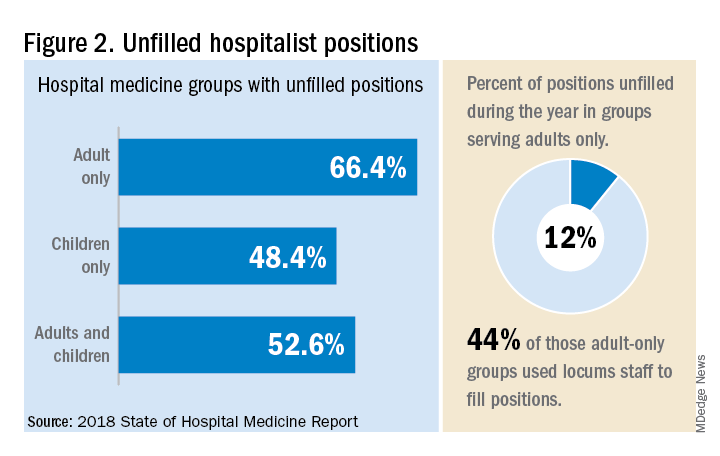

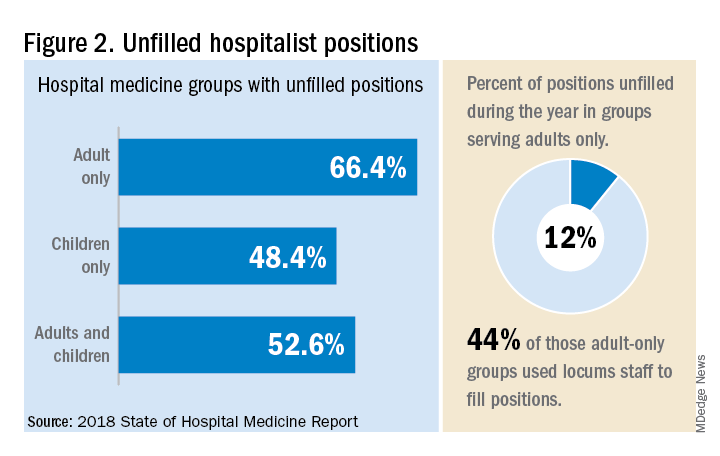

“Clearly, demand outstrips supply, which drives up salaries and support, whether CEOs feel that the hospitalist group is earning that support or not,” Dr. White said. “The unfilled hospitalist positions we identified speak to ongoing projected greater demand than supply. That said, hospitalists and group leaders can’t be complacent and must collaborate effectively with hospitals to provide highly valuable services.” Turnover of hospitalist positions was up slightly, he noted, at 7.4% in 2018, from 6.9% in 2016, reversing a trend of previous years.

But will these trends continue at a time when hospitals face continued pressure to cut costs, as the hospital medicine subsidy may represent one of their largest cost centers? Because the size of hospitalist groups continues to grow, hospitals’ total subsidy for hospital medicine is going up faster than the percentage increase in support per FTE.

How do hospitalists use the SoHM report?

Dr. White called the 2018 SoHM report the “most representative and balanced sample to date” of hospitalist group practices, with some of the highest quality data, thanks to more robust participation in the survey by pediatric groups and improved distribution among hospitalist management companies and academic programs.

“Not that past reports had major flaws, but this version is more authoritative, reflecting an intentional effort by our Practice Analysis Committee to bring in more participants from key groups,” he said.

The biennial report has been around long enough to achieve brand recognition in the field as the most authoritative source of information regarding hospitalist practice, he added. “We worked hard this year to balance the participants, with more of our responses than in the past coming from multi-hospital groups, whether 4 to 5 sites, or 20 to 30.”

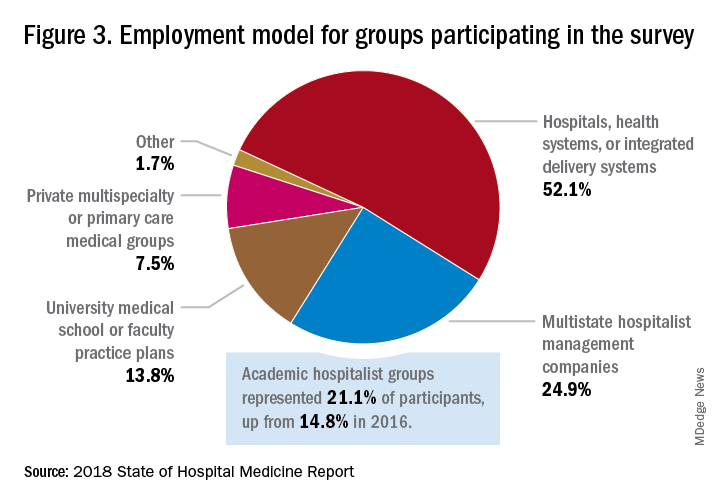

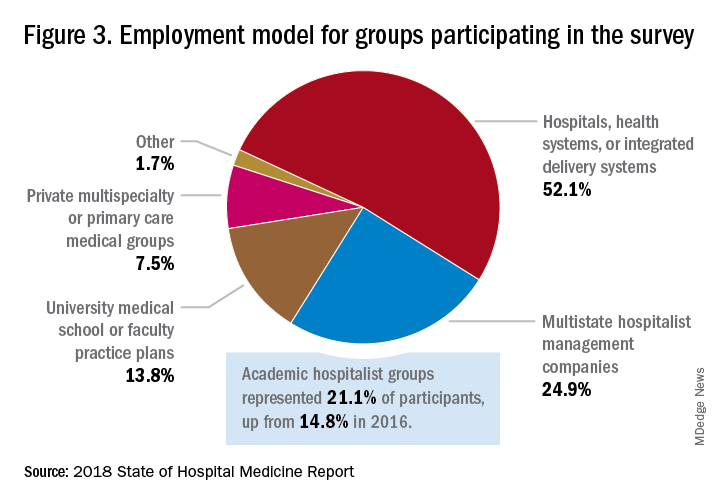

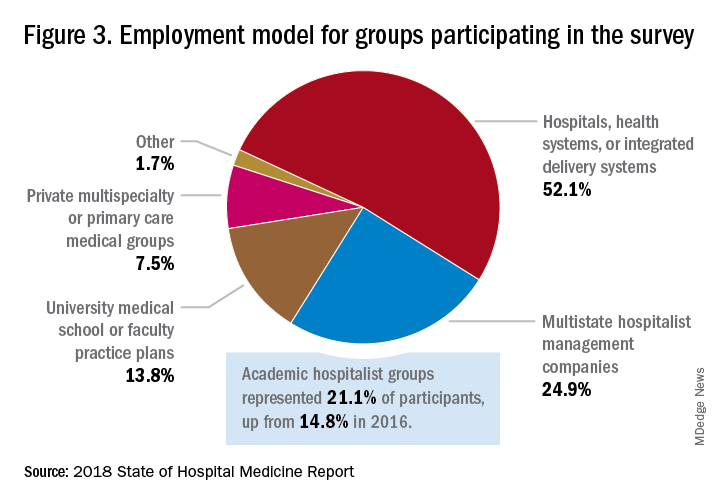

Surveys were conducted online in January and February of 2018 in response to invitations mailed and emailed to targeted hospital medicine group leaders. A total of 569 groups completed the survey, representing 8,889 hospitalist FTEs, approximately 16% of the total hospitalist workforce. Responses were presented in several categories, including by size of program, region and employment model. Groups that care for adults only represented 87.9% of the surveys, while groups that care for children only were 6.7% and groups that care for both adults and children were 5.4%.

“This survey doesn’t tell us what should be best practice in hospital medicine,” Dr. White said, only what is actual current practice. He uses it in his own health system to not only contextualize and justify his group’s performance metrics for hospital administrators – relative to national and categorical averages – but also to see if the direction his group is following is consistent with what’s going on in the larger field.

“These data offer a very powerful resource regarding the trends in hospital medicine,” said Romil Chadha, MD, MPH, FACP, SFHM, associate division chief for operations in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky and UK Healthcare, Lexington. “It is my repository of data to go before my administrators for decisions that need to be made or to pilot new programs.”

Dr. Chadha also uses the data to help answer compensation, scheduling, and support questions from his group’s members.

Thomas McIlraith, MD, immediate past chairman of the hospital medicine department at Mercy Medical Group, Sacramento, Calif., said the report’s value is that it allows comparisons of salaries in different settings, and to see, for example, how night staffing is structured. “A lot of leaders I spoke to at SHM’s 2018 Leadership Academy in Vancouver were saying they didn’t feel up to parity with the national standards. You can use the report to look at the state of hospital medicine nationally and make comparisons,” he said.

Calls for more productivity

Roberta Himebaugh, MBA, SFHM, senior vice president of acute care services for the national hospitalist management company TeamHealth, and cochair of the SHM Practice Administrators Special Interest Group, said her company’s clients have traditionally asked for greater productivity from their hospitalist contracts as a way to decrease overall costs. Some markets are starting to see a change in that approach, she noted.

“Recently there’s been an increased focus on paying hospitalists to focus on quality rather than just productivity. Some of our clients are willing to pay for that, and we are trying to assign value to this non-billable time or adjust our productivity standards appropriately. I think hospitals definitely understand the value of non-billable services from hospitalists, but still will push us on the productivity targets,” Ms. Himebaugh said.

“I don’t believe hospital medicine can be sustainable long term on flat productivity or flat RVUs,” she added. “Yet the costs of burnout associated with pushing higher productivity are not sustainable, either.” So what are the answers? She said many inefficiencies are involved in responding to inquiries on the floor that could have been addressed another way, or waiting for the turnaround of diagnostic tests.

“Maybe we don’t need physicians to be in the hospital 24/7 if we have access to telehealth, or a partnership with the emergency department, or greater use of advanced care practice providers,” Ms. Himebaugh said. “Our hospitals are examining those options, and we have to look at how we can become more efficient and less costly. At TeamHealth, we are trying to staff for value – looking at patient flow patterns and adjusting our schedules accordingly. Is there a bolus of admissions tied to emergency department shift changes, or to certain days of the week? How can we move from the 12-hour shift that begins at 7 a.m. and ends at 7 p.m., and instead provide coverage for when the patients are there?”

Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, said he appreciates the volume of data in the report but wishes for even more survey participants, which could make the breakouts for subgroups such as academic hospitalists more robust. Other current sources of hospitalist salary data include the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), which produces compensation reports to help medical schools and teaching hospitals with benchmarking, and the Faculty Practice Solution Center developed jointly by AAMC and Vizient to provide faculty practice plans with analytic tools. The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) is another valuable source of information, some of which was licensed for inclusion in the SoHM report.

“There is no source of absolute truth that hospitalists can point to,” Dr. Williams said. “I will present my data and my administrators will reply: ‘We have our own data.’ Our institution has consistently ranked first or second nationwide for the sickest patients. We take more Medicaid and dually eligible patients, who have a lot of social issues. They take a lot of time to manage medically and the RVUs don’t reflect that. And yet I’m still judged by my RVUs generated per hospitalist. Hospital administrators understandably want to get the most productivity, and they are looking for their own data for average productivity numbers.”

Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that hospital medicine’s flat productivity trends would be difficult to sustain in the business world. But there aren’t easy or obvious ways to increase hospitalists’ productivity. The SoHM report also shows that as productivity increases, total compensation increases but at a lower rate, resulting in a gradual decrease in compensation per RVU.

Pressures to increase productivity can be a double-edged sword, Dr. Williams added. Demanding that doctors make more billable visits faster to generate more RVUs can be a recipe for burnout and turnover, with huge costs associated with recruiting replacements.

“If there was recent turnover of hospitalists at the hospital, with the need to find replacements, there may be institutional memory about that,” he said. “But where are hospitals spending their money? Bottom line, we still need to learn to cut our costs.”

How is hospitalist practice evolving?

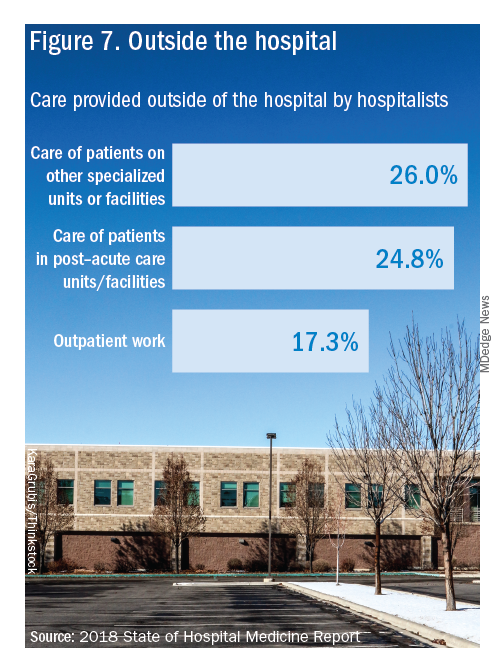

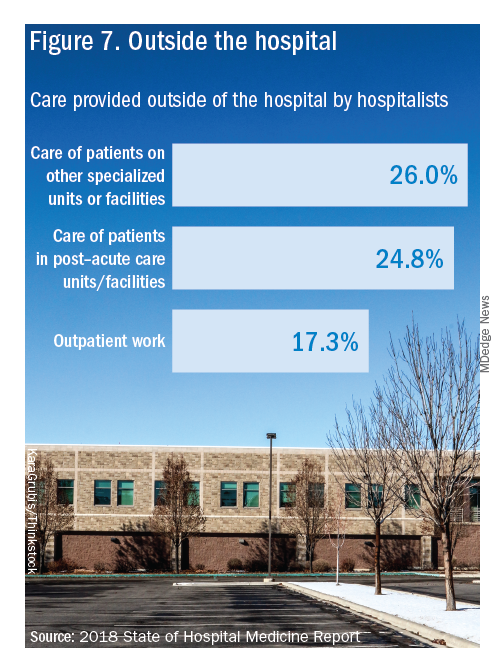

In addition to payment and productivity data, the SoHM report provides a current picture of the evolving state of hospitalist group practices. A key thread is how the work hospitalists are doing, and the way they do it, is changing, with new information about comanagement roles, dedicated admitters, night coverage, geographic rounding, and the like.

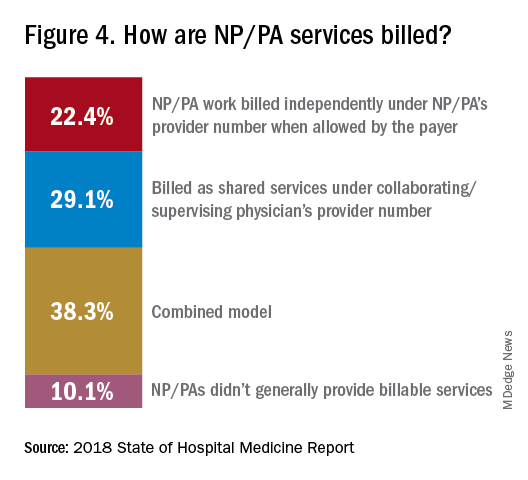

Making greater use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPs/PAs), may be one way to change the flat productivity trends, Dr. Brown said. With a cost per RVU that’s roughly half that of a doctor’s, NPs/PAs could contribute to the bottom line. But he sees surprisingly large variation in how hospitalist groups are using them. Typically, they are deployed at a ratio of four doctors to one NP/PA, but that ratio could be two to one or even one to one, he said.

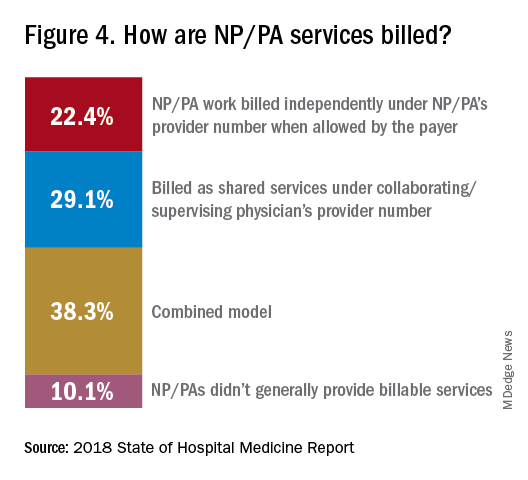

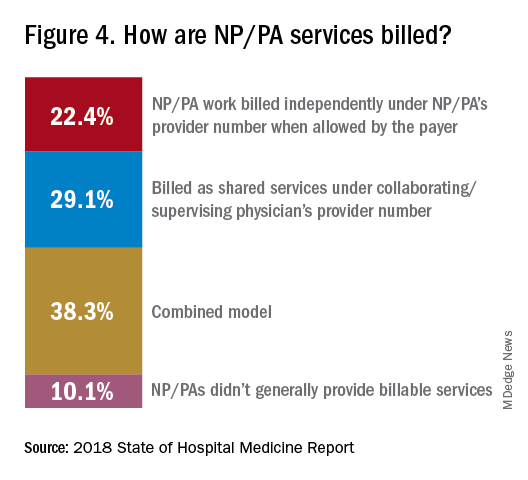

Use of NPs/PAs by academic hospitalist groups is up, from 52.1% in 2016 to 75.7% in 2018. For adult-only groups, 76.8% had NPs/PAs, with higher rates in hospitals and health systems and lower rates in the West region. But a lot of groups are using these practitioners for nonproductive work, and some are failing to generate any billing income, Dr. Brown said.

“The rate at which NPs/PAs performed billable services was higher in physician-owned practices, resulting in a lower cost per RVU, suggesting that many practices may be underutilizing their NPs/PAs or not sharing the work.” Not every NP or PA wants to or is able to care for very complex patients, Dr. Brown said, “but you want a system where the NP and PA can work at the highest level permitted by state law.”

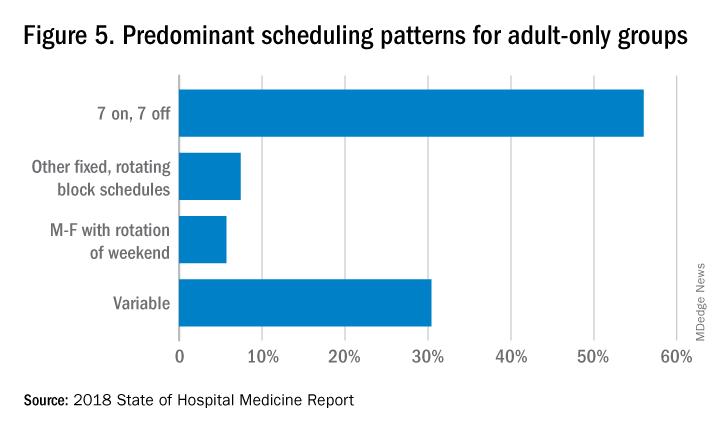

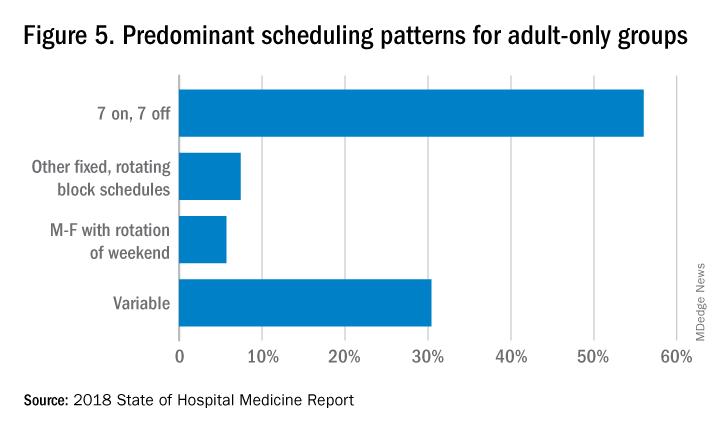

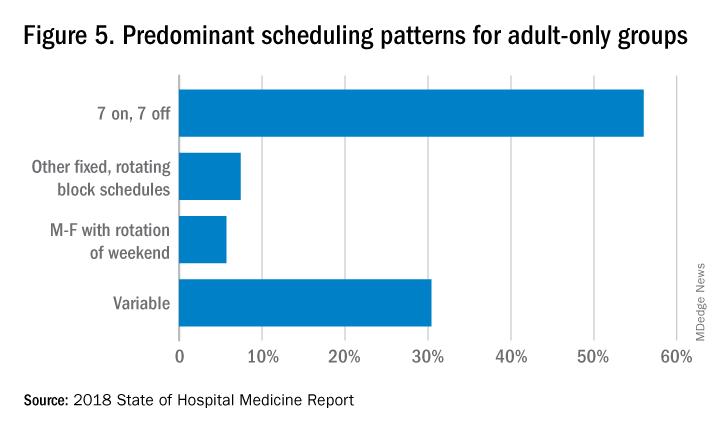

The predominant scheduling model of hospital medicine, 7 days on duty followed by 7 days off, has diminished somewhat in recent years. There appears to be some fluctuation and a gradual move away from 7 on/7 off toward some kind of variable approach, since the former may not be physically sustainable for the doctor over the long haul, Dr. Brown said. Some groups are experimenting with a combined approach.

“I think balancing workload with manpower has always been a challenge for our field. Maybe we should be working shorter shifts or fewer days and making sure our hospitalists aren’t ever sitting around idle,” he said. “And could we come in on nonclinical days to do administrative tasks? I think the solution is out there, but we haven’t created the algorithms to define that yet. If you could somehow use the data for volume, number of beds, nurse staffing, etc., by year and seasonally, you might be able to reliably predict census. This is about applying data hospitals already have in their electronic health records, but utilizing the data in ways that are more helpful.”

Dr. McIlraith added that a big driver of the future of hospital medicine will be the evolution of the EHR and the digitalization of health care, as hospitals learn how to leverage more of what’s in their EHRs. “The impact will grow for hospitalists through the creation and maturation of big data systems – and the learning that can be extracted from what’s contained in the electronic health record.”

Another important question for hospitalist groups is their model of backup scheduling, to make sure there is a replacement available if a scheduled doctor calls in sick or if demand is unexpectedly high.

“In today’s world, this is how we have traditionally managed unpredictability,” Dr. Brown said. “You don’t know when you will need it, but if you need it, you want it immediately. So how do you pay for it – only when the doctor comes in, or also an amount just for being on call?” Some groups pay for both, he said, others for neither.

“We are a group of 70 hospitalists, and if someone is sick you can’t just shut down the service,” said Dr. Chadha. “We are one of the few to use incentives for both, which could include a 1-week decrease in clinical shifts in exchange for 2 weeks of backup. We have times with 25% usage of backup number 1, and 10% usage of backup number 2,” he noted. “But the goal is for our hospitalists to have assurances that there is a backup system and that it works.”

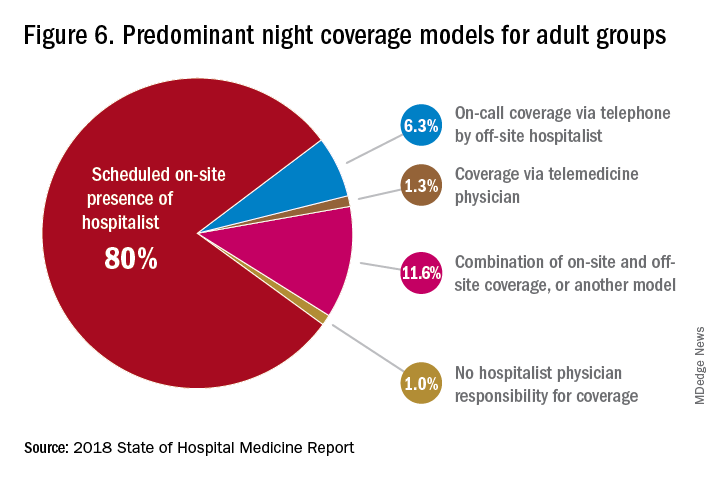

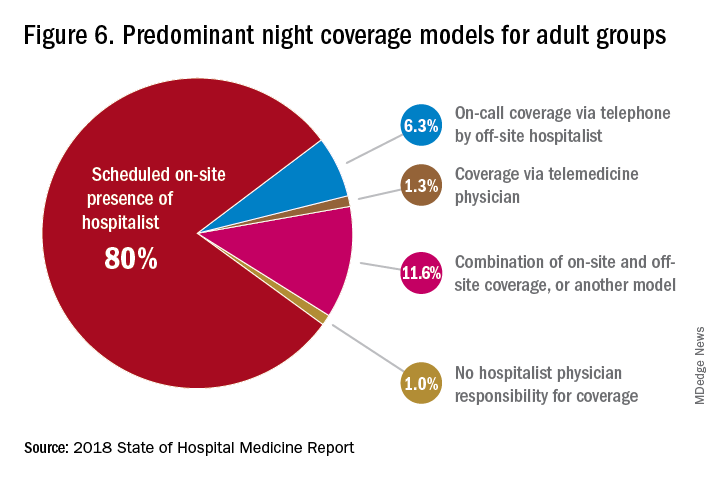

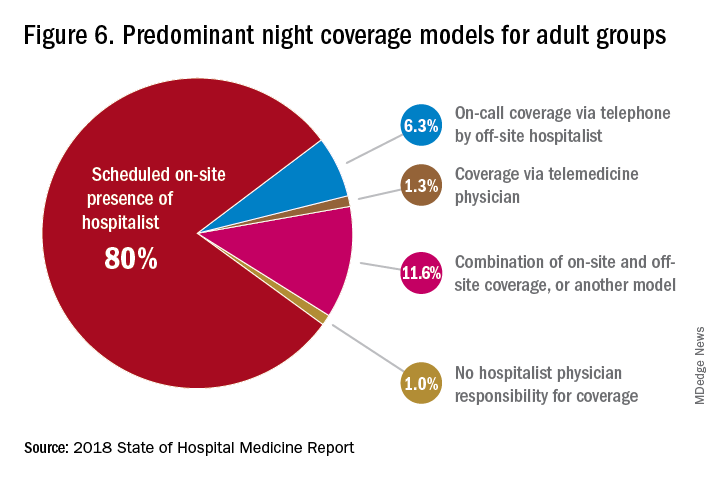

The presence of nocturnists in hospitals continues to rise, with 76.1% of adults-only groups having nocturnists, 27.6% of children-only groups, and 68.2% of adults and children groups. Geographic or unit-based hospital assignments have grown to 36.4% of adult-only groups.

What are hospitalists’ other new roles?

“We have a large group of 50 doctors, with about 40 FTEs, and we are evolving from the traditional generalist role toward more subspecialty comanagement,” said Bryan Huang, MD, physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California–San Diego. “Our hospitalists are asking what it means to be an academic hospitalist as our teaching roles have shrunk.”

Dr. Huang recently took on a new role as physician adviser for his hospital in such areas as utilization review, patient flow, and length of stay. “I’m spearheading a work group to address quality issues – all of which involve collaboration with other professionals. We also developed an admitting role here for a hospitalist whose sole role for the day is to admit patients.” Nationally up to 51.2% of hospitalist groups utilize a dedicated daytime admitter.

The report found that hospital services for which hospitalists are more likely to be attendings than consultants include GI/liver, 78.4%; palliative care, 77.3%; neurology/stroke, 73.6%; oncology, 67.8%; cardiology, 56.9%; and critical care, 50.7%. Conditions where hospitalists are more likely to consult rather than admit and attend include neurosurgery, orthopedics, general surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and other surgical subspecialties.

Other hospital services routinely provided by adult-only hospitalists include care of patients in an ICU setting (62.7%); primary responsibility for observation units (54.6%); primary clinical responsibility for rapid response teams (48.8%); primary responsibility for code blue or cardiac arrest teams (43.8%); nighttime admissions or tuck-in services (33.9%); and medical procedures (31.5%). For pediatric hospital medicine groups, care of healthy newborns and medical procedures were among the most common services provided, while for hospitalists serving adults and children, rapid response teams, ICUs, and specialty units were most common.

New models of payment for health care

As the larger health care system is being transformed by new payment models and benefit structures, including accountable care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing, bundled payments, and other forms of population-based coverage – which is described as a volume-to-value shift in health care – how are these new models affecting hospitalists?

Observers say penetration of these new models varies widely by locality but they haven’t had much direct impact on hospitalists’ practices – at least not yet. However, as hospitals and health systems find themselves needing to learn new ways to invest their resources differently in response to these trends, what matters to the hospital should be of great importance to the hospitalist group.

“I haven’t seen a lot of dramatic changes in how hospitalists engage with value-based purchasing,” Dr. White said. “If we know that someone is part of an ACO, the instinctual – and right – response is to treat them like any other patient. But we still need to be committed to not waste resources.”

Hospitalists are the best people to understand the intricacies of how the health care system works under value-based approaches, Dr. Huang said. “That’s why so many hospitalists have taken leadership positions in their hospitals. I think all of this translates to the practical, day-to-day work of hospitalists, reflected in our focus on readmissions and length of stay.”

Dr. Williams said the health care system still hasn’t turned the corner from fee-for-service to value-based purchasing. “It still represents a tiny fraction of the income of hospitalists. Hospitals still have to focus on the bottom line, as fee-for-service reimbursement for hospitalized patients continues to get squeezed, and ACOs aren’t exactly paying premium rates either. Ask almost any hospital CEO what drives their bottom line today and the answer is volume – along with optimizing productivity. Pretty much every place I look, the future does not look terribly rosy for hospitals.”

Ms. Himebaugh said she is bullish on hospital medicine, in the sense that it’s unlikely to go away anytime soon. “Hospitalists are needed and provide value. But I don’t think we have devised the right model yet. I’m not sure our current model is sustainable. We need to find new models we can afford that don’t require squeezing our providers.”

For more information about the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report, contact SHM’s Practice Management Department at: [email protected] or call 800-843-3360. See also: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/.

Productivity, pay, and roles remain center stage

Productivity, pay, and roles remain center stage

In a national health care environment undergoing unprecedented transformation, the specialty of hospital medicine appears to be an island of relative stability, a conclusion that is supported by the principal findings from SHM’s 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report.

The report of hospitalist group practice characteristics, as well as other key data defining the field’s current status, that the Society of Hospital Medicine puts out every 2 years reveals that overall salaries for hospitalist physicians are up by 3.8% since 2016. Although productivity, as measured by work relative value units (RVUs), remained largely flat over the same period, financial support per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician position to hospitalist groups from their hospitals and health systems is up significantly.

Total support per FTE averaged $176,657 in 2018, 12% higher than in 2016, noted Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which oversees the biennial survey. Compensation and productivity data were collected by the Medical Group Management Association and licensed by SHM for inclusion in its report.

These findings – particularly the flat productivity – raise questions about long-term sustainability, Ms. Flores said. “What is going on? Do hospital administrators still recognize the value hospitalists bring to the operations and the quality of their hospitals? Or is paying the subsidy just a cost of doing business – a necessity for most hospitals in a setting where demand for hospitalist positions remains high?”

Andrew White, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee and director of the hospital medicine service at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, said basic market forces dictate that it is “pretty much inconceivable” to run a modern hospital of any size without hospitalists.

“Clearly, demand outstrips supply, which drives up salaries and support, whether CEOs feel that the hospitalist group is earning that support or not,” Dr. White said. “The unfilled hospitalist positions we identified speak to ongoing projected greater demand than supply. That said, hospitalists and group leaders can’t be complacent and must collaborate effectively with hospitals to provide highly valuable services.” Turnover of hospitalist positions was up slightly, he noted, at 7.4% in 2018, from 6.9% in 2016, reversing a trend of previous years.

But will these trends continue at a time when hospitals face continued pressure to cut costs, as the hospital medicine subsidy may represent one of their largest cost centers? Because the size of hospitalist groups continues to grow, hospitals’ total subsidy for hospital medicine is going up faster than the percentage increase in support per FTE.

How do hospitalists use the SoHM report?

Dr. White called the 2018 SoHM report the “most representative and balanced sample to date” of hospitalist group practices, with some of the highest quality data, thanks to more robust participation in the survey by pediatric groups and improved distribution among hospitalist management companies and academic programs.

“Not that past reports had major flaws, but this version is more authoritative, reflecting an intentional effort by our Practice Analysis Committee to bring in more participants from key groups,” he said.

The biennial report has been around long enough to achieve brand recognition in the field as the most authoritative source of information regarding hospitalist practice, he added. “We worked hard this year to balance the participants, with more of our responses than in the past coming from multi-hospital groups, whether 4 to 5 sites, or 20 to 30.”

Surveys were conducted online in January and February of 2018 in response to invitations mailed and emailed to targeted hospital medicine group leaders. A total of 569 groups completed the survey, representing 8,889 hospitalist FTEs, approximately 16% of the total hospitalist workforce. Responses were presented in several categories, including by size of program, region and employment model. Groups that care for adults only represented 87.9% of the surveys, while groups that care for children only were 6.7% and groups that care for both adults and children were 5.4%.

“This survey doesn’t tell us what should be best practice in hospital medicine,” Dr. White said, only what is actual current practice. He uses it in his own health system to not only contextualize and justify his group’s performance metrics for hospital administrators – relative to national and categorical averages – but also to see if the direction his group is following is consistent with what’s going on in the larger field.

“These data offer a very powerful resource regarding the trends in hospital medicine,” said Romil Chadha, MD, MPH, FACP, SFHM, associate division chief for operations in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky and UK Healthcare, Lexington. “It is my repository of data to go before my administrators for decisions that need to be made or to pilot new programs.”

Dr. Chadha also uses the data to help answer compensation, scheduling, and support questions from his group’s members.

Thomas McIlraith, MD, immediate past chairman of the hospital medicine department at Mercy Medical Group, Sacramento, Calif., said the report’s value is that it allows comparisons of salaries in different settings, and to see, for example, how night staffing is structured. “A lot of leaders I spoke to at SHM’s 2018 Leadership Academy in Vancouver were saying they didn’t feel up to parity with the national standards. You can use the report to look at the state of hospital medicine nationally and make comparisons,” he said.

Calls for more productivity

Roberta Himebaugh, MBA, SFHM, senior vice president of acute care services for the national hospitalist management company TeamHealth, and cochair of the SHM Practice Administrators Special Interest Group, said her company’s clients have traditionally asked for greater productivity from their hospitalist contracts as a way to decrease overall costs. Some markets are starting to see a change in that approach, she noted.

“Recently there’s been an increased focus on paying hospitalists to focus on quality rather than just productivity. Some of our clients are willing to pay for that, and we are trying to assign value to this non-billable time or adjust our productivity standards appropriately. I think hospitals definitely understand the value of non-billable services from hospitalists, but still will push us on the productivity targets,” Ms. Himebaugh said.

“I don’t believe hospital medicine can be sustainable long term on flat productivity or flat RVUs,” she added. “Yet the costs of burnout associated with pushing higher productivity are not sustainable, either.” So what are the answers? She said many inefficiencies are involved in responding to inquiries on the floor that could have been addressed another way, or waiting for the turnaround of diagnostic tests.

“Maybe we don’t need physicians to be in the hospital 24/7 if we have access to telehealth, or a partnership with the emergency department, or greater use of advanced care practice providers,” Ms. Himebaugh said. “Our hospitals are examining those options, and we have to look at how we can become more efficient and less costly. At TeamHealth, we are trying to staff for value – looking at patient flow patterns and adjusting our schedules accordingly. Is there a bolus of admissions tied to emergency department shift changes, or to certain days of the week? How can we move from the 12-hour shift that begins at 7 a.m. and ends at 7 p.m., and instead provide coverage for when the patients are there?”

Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, said he appreciates the volume of data in the report but wishes for even more survey participants, which could make the breakouts for subgroups such as academic hospitalists more robust. Other current sources of hospitalist salary data include the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), which produces compensation reports to help medical schools and teaching hospitals with benchmarking, and the Faculty Practice Solution Center developed jointly by AAMC and Vizient to provide faculty practice plans with analytic tools. The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) is another valuable source of information, some of which was licensed for inclusion in the SoHM report.

“There is no source of absolute truth that hospitalists can point to,” Dr. Williams said. “I will present my data and my administrators will reply: ‘We have our own data.’ Our institution has consistently ranked first or second nationwide for the sickest patients. We take more Medicaid and dually eligible patients, who have a lot of social issues. They take a lot of time to manage medically and the RVUs don’t reflect that. And yet I’m still judged by my RVUs generated per hospitalist. Hospital administrators understandably want to get the most productivity, and they are looking for their own data for average productivity numbers.”

Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that hospital medicine’s flat productivity trends would be difficult to sustain in the business world. But there aren’t easy or obvious ways to increase hospitalists’ productivity. The SoHM report also shows that as productivity increases, total compensation increases but at a lower rate, resulting in a gradual decrease in compensation per RVU.

Pressures to increase productivity can be a double-edged sword, Dr. Williams added. Demanding that doctors make more billable visits faster to generate more RVUs can be a recipe for burnout and turnover, with huge costs associated with recruiting replacements.

“If there was recent turnover of hospitalists at the hospital, with the need to find replacements, there may be institutional memory about that,” he said. “But where are hospitals spending their money? Bottom line, we still need to learn to cut our costs.”

How is hospitalist practice evolving?

In addition to payment and productivity data, the SoHM report provides a current picture of the evolving state of hospitalist group practices. A key thread is how the work hospitalists are doing, and the way they do it, is changing, with new information about comanagement roles, dedicated admitters, night coverage, geographic rounding, and the like.

Making greater use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPs/PAs), may be one way to change the flat productivity trends, Dr. Brown said. With a cost per RVU that’s roughly half that of a doctor’s, NPs/PAs could contribute to the bottom line. But he sees surprisingly large variation in how hospitalist groups are using them. Typically, they are deployed at a ratio of four doctors to one NP/PA, but that ratio could be two to one or even one to one, he said.

Use of NPs/PAs by academic hospitalist groups is up, from 52.1% in 2016 to 75.7% in 2018. For adult-only groups, 76.8% had NPs/PAs, with higher rates in hospitals and health systems and lower rates in the West region. But a lot of groups are using these practitioners for nonproductive work, and some are failing to generate any billing income, Dr. Brown said.

“The rate at which NPs/PAs performed billable services was higher in physician-owned practices, resulting in a lower cost per RVU, suggesting that many practices may be underutilizing their NPs/PAs or not sharing the work.” Not every NP or PA wants to or is able to care for very complex patients, Dr. Brown said, “but you want a system where the NP and PA can work at the highest level permitted by state law.”

The predominant scheduling model of hospital medicine, 7 days on duty followed by 7 days off, has diminished somewhat in recent years. There appears to be some fluctuation and a gradual move away from 7 on/7 off toward some kind of variable approach, since the former may not be physically sustainable for the doctor over the long haul, Dr. Brown said. Some groups are experimenting with a combined approach.

“I think balancing workload with manpower has always been a challenge for our field. Maybe we should be working shorter shifts or fewer days and making sure our hospitalists aren’t ever sitting around idle,” he said. “And could we come in on nonclinical days to do administrative tasks? I think the solution is out there, but we haven’t created the algorithms to define that yet. If you could somehow use the data for volume, number of beds, nurse staffing, etc., by year and seasonally, you might be able to reliably predict census. This is about applying data hospitals already have in their electronic health records, but utilizing the data in ways that are more helpful.”

Dr. McIlraith added that a big driver of the future of hospital medicine will be the evolution of the EHR and the digitalization of health care, as hospitals learn how to leverage more of what’s in their EHRs. “The impact will grow for hospitalists through the creation and maturation of big data systems – and the learning that can be extracted from what’s contained in the electronic health record.”

Another important question for hospitalist groups is their model of backup scheduling, to make sure there is a replacement available if a scheduled doctor calls in sick or if demand is unexpectedly high.

“In today’s world, this is how we have traditionally managed unpredictability,” Dr. Brown said. “You don’t know when you will need it, but if you need it, you want it immediately. So how do you pay for it – only when the doctor comes in, or also an amount just for being on call?” Some groups pay for both, he said, others for neither.

“We are a group of 70 hospitalists, and if someone is sick you can’t just shut down the service,” said Dr. Chadha. “We are one of the few to use incentives for both, which could include a 1-week decrease in clinical shifts in exchange for 2 weeks of backup. We have times with 25% usage of backup number 1, and 10% usage of backup number 2,” he noted. “But the goal is for our hospitalists to have assurances that there is a backup system and that it works.”

The presence of nocturnists in hospitals continues to rise, with 76.1% of adults-only groups having nocturnists, 27.6% of children-only groups, and 68.2% of adults and children groups. Geographic or unit-based hospital assignments have grown to 36.4% of adult-only groups.

What are hospitalists’ other new roles?

“We have a large group of 50 doctors, with about 40 FTEs, and we are evolving from the traditional generalist role toward more subspecialty comanagement,” said Bryan Huang, MD, physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California–San Diego. “Our hospitalists are asking what it means to be an academic hospitalist as our teaching roles have shrunk.”

Dr. Huang recently took on a new role as physician adviser for his hospital in such areas as utilization review, patient flow, and length of stay. “I’m spearheading a work group to address quality issues – all of which involve collaboration with other professionals. We also developed an admitting role here for a hospitalist whose sole role for the day is to admit patients.” Nationally up to 51.2% of hospitalist groups utilize a dedicated daytime admitter.

The report found that hospital services for which hospitalists are more likely to be attendings than consultants include GI/liver, 78.4%; palliative care, 77.3%; neurology/stroke, 73.6%; oncology, 67.8%; cardiology, 56.9%; and critical care, 50.7%. Conditions where hospitalists are more likely to consult rather than admit and attend include neurosurgery, orthopedics, general surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and other surgical subspecialties.

Other hospital services routinely provided by adult-only hospitalists include care of patients in an ICU setting (62.7%); primary responsibility for observation units (54.6%); primary clinical responsibility for rapid response teams (48.8%); primary responsibility for code blue or cardiac arrest teams (43.8%); nighttime admissions or tuck-in services (33.9%); and medical procedures (31.5%). For pediatric hospital medicine groups, care of healthy newborns and medical procedures were among the most common services provided, while for hospitalists serving adults and children, rapid response teams, ICUs, and specialty units were most common.

New models of payment for health care

As the larger health care system is being transformed by new payment models and benefit structures, including accountable care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing, bundled payments, and other forms of population-based coverage – which is described as a volume-to-value shift in health care – how are these new models affecting hospitalists?

Observers say penetration of these new models varies widely by locality but they haven’t had much direct impact on hospitalists’ practices – at least not yet. However, as hospitals and health systems find themselves needing to learn new ways to invest their resources differently in response to these trends, what matters to the hospital should be of great importance to the hospitalist group.

“I haven’t seen a lot of dramatic changes in how hospitalists engage with value-based purchasing,” Dr. White said. “If we know that someone is part of an ACO, the instinctual – and right – response is to treat them like any other patient. But we still need to be committed to not waste resources.”

Hospitalists are the best people to understand the intricacies of how the health care system works under value-based approaches, Dr. Huang said. “That’s why so many hospitalists have taken leadership positions in their hospitals. I think all of this translates to the practical, day-to-day work of hospitalists, reflected in our focus on readmissions and length of stay.”

Dr. Williams said the health care system still hasn’t turned the corner from fee-for-service to value-based purchasing. “It still represents a tiny fraction of the income of hospitalists. Hospitals still have to focus on the bottom line, as fee-for-service reimbursement for hospitalized patients continues to get squeezed, and ACOs aren’t exactly paying premium rates either. Ask almost any hospital CEO what drives their bottom line today and the answer is volume – along with optimizing productivity. Pretty much every place I look, the future does not look terribly rosy for hospitals.”

Ms. Himebaugh said she is bullish on hospital medicine, in the sense that it’s unlikely to go away anytime soon. “Hospitalists are needed and provide value. But I don’t think we have devised the right model yet. I’m not sure our current model is sustainable. We need to find new models we can afford that don’t require squeezing our providers.”

For more information about the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report, contact SHM’s Practice Management Department at: [email protected] or call 800-843-3360. See also: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/.

In a national health care environment undergoing unprecedented transformation, the specialty of hospital medicine appears to be an island of relative stability, a conclusion that is supported by the principal findings from SHM’s 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report.

The report of hospitalist group practice characteristics, as well as other key data defining the field’s current status, that the Society of Hospital Medicine puts out every 2 years reveals that overall salaries for hospitalist physicians are up by 3.8% since 2016. Although productivity, as measured by work relative value units (RVUs), remained largely flat over the same period, financial support per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician position to hospitalist groups from their hospitals and health systems is up significantly.

Total support per FTE averaged $176,657 in 2018, 12% higher than in 2016, noted Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM, of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, which oversees the biennial survey. Compensation and productivity data were collected by the Medical Group Management Association and licensed by SHM for inclusion in its report.

These findings – particularly the flat productivity – raise questions about long-term sustainability, Ms. Flores said. “What is going on? Do hospital administrators still recognize the value hospitalists bring to the operations and the quality of their hospitals? Or is paying the subsidy just a cost of doing business – a necessity for most hospitals in a setting where demand for hospitalist positions remains high?”

Andrew White, MD, FACP, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee and director of the hospital medicine service at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, said basic market forces dictate that it is “pretty much inconceivable” to run a modern hospital of any size without hospitalists.

“Clearly, demand outstrips supply, which drives up salaries and support, whether CEOs feel that the hospitalist group is earning that support or not,” Dr. White said. “The unfilled hospitalist positions we identified speak to ongoing projected greater demand than supply. That said, hospitalists and group leaders can’t be complacent and must collaborate effectively with hospitals to provide highly valuable services.” Turnover of hospitalist positions was up slightly, he noted, at 7.4% in 2018, from 6.9% in 2016, reversing a trend of previous years.

But will these trends continue at a time when hospitals face continued pressure to cut costs, as the hospital medicine subsidy may represent one of their largest cost centers? Because the size of hospitalist groups continues to grow, hospitals’ total subsidy for hospital medicine is going up faster than the percentage increase in support per FTE.

How do hospitalists use the SoHM report?

Dr. White called the 2018 SoHM report the “most representative and balanced sample to date” of hospitalist group practices, with some of the highest quality data, thanks to more robust participation in the survey by pediatric groups and improved distribution among hospitalist management companies and academic programs.

“Not that past reports had major flaws, but this version is more authoritative, reflecting an intentional effort by our Practice Analysis Committee to bring in more participants from key groups,” he said.

The biennial report has been around long enough to achieve brand recognition in the field as the most authoritative source of information regarding hospitalist practice, he added. “We worked hard this year to balance the participants, with more of our responses than in the past coming from multi-hospital groups, whether 4 to 5 sites, or 20 to 30.”

Surveys were conducted online in January and February of 2018 in response to invitations mailed and emailed to targeted hospital medicine group leaders. A total of 569 groups completed the survey, representing 8,889 hospitalist FTEs, approximately 16% of the total hospitalist workforce. Responses were presented in several categories, including by size of program, region and employment model. Groups that care for adults only represented 87.9% of the surveys, while groups that care for children only were 6.7% and groups that care for both adults and children were 5.4%.

“This survey doesn’t tell us what should be best practice in hospital medicine,” Dr. White said, only what is actual current practice. He uses it in his own health system to not only contextualize and justify his group’s performance metrics for hospital administrators – relative to national and categorical averages – but also to see if the direction his group is following is consistent with what’s going on in the larger field.

“These data offer a very powerful resource regarding the trends in hospital medicine,” said Romil Chadha, MD, MPH, FACP, SFHM, associate division chief for operations in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky and UK Healthcare, Lexington. “It is my repository of data to go before my administrators for decisions that need to be made or to pilot new programs.”

Dr. Chadha also uses the data to help answer compensation, scheduling, and support questions from his group’s members.

Thomas McIlraith, MD, immediate past chairman of the hospital medicine department at Mercy Medical Group, Sacramento, Calif., said the report’s value is that it allows comparisons of salaries in different settings, and to see, for example, how night staffing is structured. “A lot of leaders I spoke to at SHM’s 2018 Leadership Academy in Vancouver were saying they didn’t feel up to parity with the national standards. You can use the report to look at the state of hospital medicine nationally and make comparisons,” he said.

Calls for more productivity

Roberta Himebaugh, MBA, SFHM, senior vice president of acute care services for the national hospitalist management company TeamHealth, and cochair of the SHM Practice Administrators Special Interest Group, said her company’s clients have traditionally asked for greater productivity from their hospitalist contracts as a way to decrease overall costs. Some markets are starting to see a change in that approach, she noted.

“Recently there’s been an increased focus on paying hospitalists to focus on quality rather than just productivity. Some of our clients are willing to pay for that, and we are trying to assign value to this non-billable time or adjust our productivity standards appropriately. I think hospitals definitely understand the value of non-billable services from hospitalists, but still will push us on the productivity targets,” Ms. Himebaugh said.

“I don’t believe hospital medicine can be sustainable long term on flat productivity or flat RVUs,” she added. “Yet the costs of burnout associated with pushing higher productivity are not sustainable, either.” So what are the answers? She said many inefficiencies are involved in responding to inquiries on the floor that could have been addressed another way, or waiting for the turnaround of diagnostic tests.

“Maybe we don’t need physicians to be in the hospital 24/7 if we have access to telehealth, or a partnership with the emergency department, or greater use of advanced care practice providers,” Ms. Himebaugh said. “Our hospitals are examining those options, and we have to look at how we can become more efficient and less costly. At TeamHealth, we are trying to staff for value – looking at patient flow patterns and adjusting our schedules accordingly. Is there a bolus of admissions tied to emergency department shift changes, or to certain days of the week? How can we move from the 12-hour shift that begins at 7 a.m. and ends at 7 p.m., and instead provide coverage for when the patients are there?”

Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, said he appreciates the volume of data in the report but wishes for even more survey participants, which could make the breakouts for subgroups such as academic hospitalists more robust. Other current sources of hospitalist salary data include the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), which produces compensation reports to help medical schools and teaching hospitals with benchmarking, and the Faculty Practice Solution Center developed jointly by AAMC and Vizient to provide faculty practice plans with analytic tools. The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) is another valuable source of information, some of which was licensed for inclusion in the SoHM report.

“There is no source of absolute truth that hospitalists can point to,” Dr. Williams said. “I will present my data and my administrators will reply: ‘We have our own data.’ Our institution has consistently ranked first or second nationwide for the sickest patients. We take more Medicaid and dually eligible patients, who have a lot of social issues. They take a lot of time to manage medically and the RVUs don’t reflect that. And yet I’m still judged by my RVUs generated per hospitalist. Hospital administrators understandably want to get the most productivity, and they are looking for their own data for average productivity numbers.”

Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., said that hospital medicine’s flat productivity trends would be difficult to sustain in the business world. But there aren’t easy or obvious ways to increase hospitalists’ productivity. The SoHM report also shows that as productivity increases, total compensation increases but at a lower rate, resulting in a gradual decrease in compensation per RVU.

Pressures to increase productivity can be a double-edged sword, Dr. Williams added. Demanding that doctors make more billable visits faster to generate more RVUs can be a recipe for burnout and turnover, with huge costs associated with recruiting replacements.

“If there was recent turnover of hospitalists at the hospital, with the need to find replacements, there may be institutional memory about that,” he said. “But where are hospitals spending their money? Bottom line, we still need to learn to cut our costs.”

How is hospitalist practice evolving?

In addition to payment and productivity data, the SoHM report provides a current picture of the evolving state of hospitalist group practices. A key thread is how the work hospitalists are doing, and the way they do it, is changing, with new information about comanagement roles, dedicated admitters, night coverage, geographic rounding, and the like.

Making greater use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPs/PAs), may be one way to change the flat productivity trends, Dr. Brown said. With a cost per RVU that’s roughly half that of a doctor’s, NPs/PAs could contribute to the bottom line. But he sees surprisingly large variation in how hospitalist groups are using them. Typically, they are deployed at a ratio of four doctors to one NP/PA, but that ratio could be two to one or even one to one, he said.

Use of NPs/PAs by academic hospitalist groups is up, from 52.1% in 2016 to 75.7% in 2018. For adult-only groups, 76.8% had NPs/PAs, with higher rates in hospitals and health systems and lower rates in the West region. But a lot of groups are using these practitioners for nonproductive work, and some are failing to generate any billing income, Dr. Brown said.

“The rate at which NPs/PAs performed billable services was higher in physician-owned practices, resulting in a lower cost per RVU, suggesting that many practices may be underutilizing their NPs/PAs or not sharing the work.” Not every NP or PA wants to or is able to care for very complex patients, Dr. Brown said, “but you want a system where the NP and PA can work at the highest level permitted by state law.”

The predominant scheduling model of hospital medicine, 7 days on duty followed by 7 days off, has diminished somewhat in recent years. There appears to be some fluctuation and a gradual move away from 7 on/7 off toward some kind of variable approach, since the former may not be physically sustainable for the doctor over the long haul, Dr. Brown said. Some groups are experimenting with a combined approach.

“I think balancing workload with manpower has always been a challenge for our field. Maybe we should be working shorter shifts or fewer days and making sure our hospitalists aren’t ever sitting around idle,” he said. “And could we come in on nonclinical days to do administrative tasks? I think the solution is out there, but we haven’t created the algorithms to define that yet. If you could somehow use the data for volume, number of beds, nurse staffing, etc., by year and seasonally, you might be able to reliably predict census. This is about applying data hospitals already have in their electronic health records, but utilizing the data in ways that are more helpful.”

Dr. McIlraith added that a big driver of the future of hospital medicine will be the evolution of the EHR and the digitalization of health care, as hospitals learn how to leverage more of what’s in their EHRs. “The impact will grow for hospitalists through the creation and maturation of big data systems – and the learning that can be extracted from what’s contained in the electronic health record.”

Another important question for hospitalist groups is their model of backup scheduling, to make sure there is a replacement available if a scheduled doctor calls in sick or if demand is unexpectedly high.

“In today’s world, this is how we have traditionally managed unpredictability,” Dr. Brown said. “You don’t know when you will need it, but if you need it, you want it immediately. So how do you pay for it – only when the doctor comes in, or also an amount just for being on call?” Some groups pay for both, he said, others for neither.

“We are a group of 70 hospitalists, and if someone is sick you can’t just shut down the service,” said Dr. Chadha. “We are one of the few to use incentives for both, which could include a 1-week decrease in clinical shifts in exchange for 2 weeks of backup. We have times with 25% usage of backup number 1, and 10% usage of backup number 2,” he noted. “But the goal is for our hospitalists to have assurances that there is a backup system and that it works.”

The presence of nocturnists in hospitals continues to rise, with 76.1% of adults-only groups having nocturnists, 27.6% of children-only groups, and 68.2% of adults and children groups. Geographic or unit-based hospital assignments have grown to 36.4% of adult-only groups.

What are hospitalists’ other new roles?

“We have a large group of 50 doctors, with about 40 FTEs, and we are evolving from the traditional generalist role toward more subspecialty comanagement,” said Bryan Huang, MD, physician adviser and associate clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California–San Diego. “Our hospitalists are asking what it means to be an academic hospitalist as our teaching roles have shrunk.”

Dr. Huang recently took on a new role as physician adviser for his hospital in such areas as utilization review, patient flow, and length of stay. “I’m spearheading a work group to address quality issues – all of which involve collaboration with other professionals. We also developed an admitting role here for a hospitalist whose sole role for the day is to admit patients.” Nationally up to 51.2% of hospitalist groups utilize a dedicated daytime admitter.

The report found that hospital services for which hospitalists are more likely to be attendings than consultants include GI/liver, 78.4%; palliative care, 77.3%; neurology/stroke, 73.6%; oncology, 67.8%; cardiology, 56.9%; and critical care, 50.7%. Conditions where hospitalists are more likely to consult rather than admit and attend include neurosurgery, orthopedics, general surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and other surgical subspecialties.

Other hospital services routinely provided by adult-only hospitalists include care of patients in an ICU setting (62.7%); primary responsibility for observation units (54.6%); primary clinical responsibility for rapid response teams (48.8%); primary responsibility for code blue or cardiac arrest teams (43.8%); nighttime admissions or tuck-in services (33.9%); and medical procedures (31.5%). For pediatric hospital medicine groups, care of healthy newborns and medical procedures were among the most common services provided, while for hospitalists serving adults and children, rapid response teams, ICUs, and specialty units were most common.

New models of payment for health care

As the larger health care system is being transformed by new payment models and benefit structures, including accountable care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing, bundled payments, and other forms of population-based coverage – which is described as a volume-to-value shift in health care – how are these new models affecting hospitalists?

Observers say penetration of these new models varies widely by locality but they haven’t had much direct impact on hospitalists’ practices – at least not yet. However, as hospitals and health systems find themselves needing to learn new ways to invest their resources differently in response to these trends, what matters to the hospital should be of great importance to the hospitalist group.

“I haven’t seen a lot of dramatic changes in how hospitalists engage with value-based purchasing,” Dr. White said. “If we know that someone is part of an ACO, the instinctual – and right – response is to treat them like any other patient. But we still need to be committed to not waste resources.”

Hospitalists are the best people to understand the intricacies of how the health care system works under value-based approaches, Dr. Huang said. “That’s why so many hospitalists have taken leadership positions in their hospitals. I think all of this translates to the practical, day-to-day work of hospitalists, reflected in our focus on readmissions and length of stay.”

Dr. Williams said the health care system still hasn’t turned the corner from fee-for-service to value-based purchasing. “It still represents a tiny fraction of the income of hospitalists. Hospitals still have to focus on the bottom line, as fee-for-service reimbursement for hospitalized patients continues to get squeezed, and ACOs aren’t exactly paying premium rates either. Ask almost any hospital CEO what drives their bottom line today and the answer is volume – along with optimizing productivity. Pretty much every place I look, the future does not look terribly rosy for hospitals.”

Ms. Himebaugh said she is bullish on hospital medicine, in the sense that it’s unlikely to go away anytime soon. “Hospitalists are needed and provide value. But I don’t think we have devised the right model yet. I’m not sure our current model is sustainable. We need to find new models we can afford that don’t require squeezing our providers.”

For more information about the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report, contact SHM’s Practice Management Department at: [email protected] or call 800-843-3360. See also: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/.

Appropriate use criteria for imaging in nonvalvular heart disease released

The American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and other groups have jointly released an appropriate use criteria (AUC) document regarding the use of imaging modalities in diagnosing nonvalvular (that is, structural) heart disease.

Imaging plays an important role in diagnosing both valvular and nonvalvular heart diseases, so the goal of the document was to help clinicians provide high-quality care by standardizing the decision-making process. To do so, a committee was formed to devise scenarios that reflected situations in real-world practice; these scenarios were considered within categories to prevent the list from being too exhaustive. The scenarios were then reviewed by a rating panel in terms of how appropriate certain modalities were in each situation. The panel members first evaluated the scenarios independently then face to face as a panel before giving their final scores (from 1 to 9) independently.

For example, for the indication of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, the panelists rated transthoracic echocardiography with or without 3-D and with contrast as needed as a 8, which means it’s an “appropriate test,” whereas they gave CT for the same indication a 3, which means “rarely appropriate.” For sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, they gave a 9 and a 6, respectively; this latter score indicates the test “may be appropriate.” These scenarios and the respective scores for any given test are organized into tables, such as initial evaluation or follow-up.

This AUC document “signals a shift from documents evaluating a single modality in various disease states to documents evaluating multiple imaging modalities and focusing on evidence and clinical experience within a given disease category,” the authors wrote. “We believe this approach better reflects clinical decision making in real-world scenarios and offers the diagnostic choices available to the clinician.”

The full document can be viewed in JACC.

The American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and other groups have jointly released an appropriate use criteria (AUC) document regarding the use of imaging modalities in diagnosing nonvalvular (that is, structural) heart disease.

Imaging plays an important role in diagnosing both valvular and nonvalvular heart diseases, so the goal of the document was to help clinicians provide high-quality care by standardizing the decision-making process. To do so, a committee was formed to devise scenarios that reflected situations in real-world practice; these scenarios were considered within categories to prevent the list from being too exhaustive. The scenarios were then reviewed by a rating panel in terms of how appropriate certain modalities were in each situation. The panel members first evaluated the scenarios independently then face to face as a panel before giving their final scores (from 1 to 9) independently.

For example, for the indication of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, the panelists rated transthoracic echocardiography with or without 3-D and with contrast as needed as a 8, which means it’s an “appropriate test,” whereas they gave CT for the same indication a 3, which means “rarely appropriate.” For sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, they gave a 9 and a 6, respectively; this latter score indicates the test “may be appropriate.” These scenarios and the respective scores for any given test are organized into tables, such as initial evaluation or follow-up.

This AUC document “signals a shift from documents evaluating a single modality in various disease states to documents evaluating multiple imaging modalities and focusing on evidence and clinical experience within a given disease category,” the authors wrote. “We believe this approach better reflects clinical decision making in real-world scenarios and offers the diagnostic choices available to the clinician.”

The full document can be viewed in JACC.

The American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and other groups have jointly released an appropriate use criteria (AUC) document regarding the use of imaging modalities in diagnosing nonvalvular (that is, structural) heart disease.

Imaging plays an important role in diagnosing both valvular and nonvalvular heart diseases, so the goal of the document was to help clinicians provide high-quality care by standardizing the decision-making process. To do so, a committee was formed to devise scenarios that reflected situations in real-world practice; these scenarios were considered within categories to prevent the list from being too exhaustive. The scenarios were then reviewed by a rating panel in terms of how appropriate certain modalities were in each situation. The panel members first evaluated the scenarios independently then face to face as a panel before giving their final scores (from 1 to 9) independently.

For example, for the indication of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, the panelists rated transthoracic echocardiography with or without 3-D and with contrast as needed as a 8, which means it’s an “appropriate test,” whereas they gave CT for the same indication a 3, which means “rarely appropriate.” For sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, they gave a 9 and a 6, respectively; this latter score indicates the test “may be appropriate.” These scenarios and the respective scores for any given test are organized into tables, such as initial evaluation or follow-up.

This AUC document “signals a shift from documents evaluating a single modality in various disease states to documents evaluating multiple imaging modalities and focusing on evidence and clinical experience within a given disease category,” the authors wrote. “We believe this approach better reflects clinical decision making in real-world scenarios and offers the diagnostic choices available to the clinician.”

The full document can be viewed in JACC.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

SHM announces National Hospitalist Day

Inaugural day of recognition to honor hospital medicine care team

The Society of Hospital Medicine is proud to announce the inaugural National Hospitalist Day, to be held on Thursday, March 7, 2019. Occurring the first Thursday in March annually, National Hospitalist Day will serve to celebrate the fastest-growing specialty in modern medicine and hospitalists’ enduring contributions to the evolving health care landscape.

National Hospitalist Day was recently approved by the National Day Calendar and was one of approximately 30 national days to be approved for the year out of an applicant pool of more than 18,000.

“As the only society dedicated to the specialty of hospital medicine, it is appropriate that SHM spearhead a national day to recognize the countless contributions of hospitalists to health care, from clinical, academic, and leadership perspectives and more,” said Larry Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “We look forward to hospitalists across the nation contributing to the festivities and making this a tradition for years to come.”

In addition to celebrating hospitalists’ contributions to patient care, SHM will also be highlighting the diverse career paths of hospital medicine professionals, from frontline hospitalist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants to practice administrators, C-suite executives, and academic hospitalists.

Highlights of SHM’s campaign include the following:

- Downloadable customizable posters and assets for hospitals and individuals’ offices to celebrate their hospital medicine team, available on SHM’s website, hospitalmedicine.org.

- A series of spotlights of hospitalists at all stages of their careers in The Hospitalist, SHM’s monthly newsmagazine.

- A social media campaign inviting hospitalists and their employers to share their success stories using the hashtag #HowWeHospitalist, including banner graphics, profile photo overlays, and more.

- A social media contest to determine the most creative ways of celebrating use of the hashtag.

- A Twitter chat for hospitalists to celebrate virtually with their colleagues and peers from around the world.

“Hospitalists innovate, lead, and push the boundaries of clinical care and deserve to be recognized for their transformative contributions to health care,” said Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief operating officer of SHM. “We hope this is the beginning of a long-standing tradition in honoring hospitalists and the noteworthy work they do.”

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/hospitalistday.

Mr. Radler is marketing communications manager at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Inaugural day of recognition to honor hospital medicine care team

Inaugural day of recognition to honor hospital medicine care team

The Society of Hospital Medicine is proud to announce the inaugural National Hospitalist Day, to be held on Thursday, March 7, 2019. Occurring the first Thursday in March annually, National Hospitalist Day will serve to celebrate the fastest-growing specialty in modern medicine and hospitalists’ enduring contributions to the evolving health care landscape.

National Hospitalist Day was recently approved by the National Day Calendar and was one of approximately 30 national days to be approved for the year out of an applicant pool of more than 18,000.

“As the only society dedicated to the specialty of hospital medicine, it is appropriate that SHM spearhead a national day to recognize the countless contributions of hospitalists to health care, from clinical, academic, and leadership perspectives and more,” said Larry Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “We look forward to hospitalists across the nation contributing to the festivities and making this a tradition for years to come.”

In addition to celebrating hospitalists’ contributions to patient care, SHM will also be highlighting the diverse career paths of hospital medicine professionals, from frontline hospitalist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants to practice administrators, C-suite executives, and academic hospitalists.

Highlights of SHM’s campaign include the following:

- Downloadable customizable posters and assets for hospitals and individuals’ offices to celebrate their hospital medicine team, available on SHM’s website, hospitalmedicine.org.

- A series of spotlights of hospitalists at all stages of their careers in The Hospitalist, SHM’s monthly newsmagazine.

- A social media campaign inviting hospitalists and their employers to share their success stories using the hashtag #HowWeHospitalist, including banner graphics, profile photo overlays, and more.

- A social media contest to determine the most creative ways of celebrating use of the hashtag.

- A Twitter chat for hospitalists to celebrate virtually with their colleagues and peers from around the world.

“Hospitalists innovate, lead, and push the boundaries of clinical care and deserve to be recognized for their transformative contributions to health care,” said Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief operating officer of SHM. “We hope this is the beginning of a long-standing tradition in honoring hospitalists and the noteworthy work they do.”

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/hospitalistday.

Mr. Radler is marketing communications manager at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

The Society of Hospital Medicine is proud to announce the inaugural National Hospitalist Day, to be held on Thursday, March 7, 2019. Occurring the first Thursday in March annually, National Hospitalist Day will serve to celebrate the fastest-growing specialty in modern medicine and hospitalists’ enduring contributions to the evolving health care landscape.

National Hospitalist Day was recently approved by the National Day Calendar and was one of approximately 30 national days to be approved for the year out of an applicant pool of more than 18,000.

“As the only society dedicated to the specialty of hospital medicine, it is appropriate that SHM spearhead a national day to recognize the countless contributions of hospitalists to health care, from clinical, academic, and leadership perspectives and more,” said Larry Wellikson, MD, MHM, chief executive officer of SHM. “We look forward to hospitalists across the nation contributing to the festivities and making this a tradition for years to come.”

In addition to celebrating hospitalists’ contributions to patient care, SHM will also be highlighting the diverse career paths of hospital medicine professionals, from frontline hospitalist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants to practice administrators, C-suite executives, and academic hospitalists.

Highlights of SHM’s campaign include the following:

- Downloadable customizable posters and assets for hospitals and individuals’ offices to celebrate their hospital medicine team, available on SHM’s website, hospitalmedicine.org.

- A series of spotlights of hospitalists at all stages of their careers in The Hospitalist, SHM’s monthly newsmagazine.

- A social media campaign inviting hospitalists and their employers to share their success stories using the hashtag #HowWeHospitalist, including banner graphics, profile photo overlays, and more.

- A social media contest to determine the most creative ways of celebrating use of the hashtag.

- A Twitter chat for hospitalists to celebrate virtually with their colleagues and peers from around the world.

“Hospitalists innovate, lead, and push the boundaries of clinical care and deserve to be recognized for their transformative contributions to health care,” said Eric E. Howell, MD, MHM, chief operating officer of SHM. “We hope this is the beginning of a long-standing tradition in honoring hospitalists and the noteworthy work they do.”

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/hospitalistday.

Mr. Radler is marketing communications manager at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

New diabetes drugs solidify their cardiovascular and renal benefits

CHICAGO – When the first results from a large trial that showed profound and unexpected benefits for preventing heart failure hospitalizations associated with use of the antihyperglycemic sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor empagliflozin came out – a little over 3 years ago – the general reaction from clinicians was some variant of “Could this be real?”

Since then, as results from some five other large, international trials have come out showing both similar benefits from two other drugs in the same SGLT2 inhibitor class, canagliflozin and dapagliflozin, as well as results showing clear cardiovascular disease benefits from three drugs in a second class of antihyperglycemics, the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), the general consensus among cardiologists became: “The cardiovascular and renal benefits are real. How can we now best use these drugs to help patients?”

This change increasingly forces cardiologists, as well as the primary care physicians who often manage patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, to become more comfortable prescribing these two classes of antihyperglycemic drugs. During a talk at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, Eugene Braunwald, MD, arguably the top thought leader in cardiology, coined a new name for the medical subspecialty that he foresees navigating this overlap between diabetes care and cardiovascular disease prevention: diabetocardiology (although a more euphonic alternative might be cardiodiabetology, while the more comprehensive name could be cardionephrodiabetology).

“I was certainly surprised” by the first report in 2015 from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28), said Dr. Braunwald, who is professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston. A lot of his colleagues were surprised and said, “It’s just one trial.”

“Now we have three trials,” with the addition of the CANVAS trial for canagliflozin (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377[7]:644-57) and the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 10. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1812389) for dapagliflozin reported at the AHA meeting in November.

“We are in the midst of two pandemics: heart failure and type 2 diabetes. As cardiologists, we have to learn how to deal with this,” said Dr. Braunwald, and the evidence now clearly shows that these drugs can help with that.

As another speaker at the meeting, Javed Butler, MD, a heart failure specialist, observed in a separate talk at the meeting, “Heart failure is one of the most common, if not the most common complication, of patients with diabetes.” This tight link between heart failure and diabetes helps make cardiovascular mortality “the number one cause of death” in patients with diabetes, said Dr. Butler, professor and chairman of medicine at the University of Mississippi in Jackson.

“Thanks to the cardiovascular outcome trials, we now have a much broader and deeper appreciation of heart failure and renal disease as integral components of the cardiovascular-renal spectrum in people with diabetes,” said Subodh Verma, MD, a professor at the University of Toronto and cardiac surgeon at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto. Dr. Braunwald spelled out in his talk some of the interrelationships of diabetes, heart failure, and renal dysfunction that together produce a downward-spiraling vicious circle for patients, a pathophysiological process that clinicians can now short-circuit by treatment with a SGLT2 inhibitor.

Cardiovascular outcome trials show the way

In the context of antihyperglycemic drugs, the “cardiovascular outcome trials” refers to a series of large trials mandated by the Food and Drug Administration in 2008 to assess the cardiovascular disease effects of new agents coming onto the U.S. market to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). By the time Dr. Verma spoke at the AHA meeting, he could cite reported results from 12 of these trials: 5 different drugs in the GLP-1 RA class, 4 drugs in the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor class, and 3 drugs from the SGLT2 inhibitor class. Dr. Verma summed what the findings have shown.

The four tested DDP-4 inhibitors (alogliptin, linagliptin, saxagliptin, and sitagliptin) consistently showed neutrality for the primary outcome of major adverse cardiovascular disease events (MACE), constituted by cardiovascular disease death, MI, or stroke.

The five tested GLP-1 RAs (albiglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, and semaglutide) showed a mixed pattern of MACE results that seemed to be linked with the subclass the drug fell into. The two exedin-4–based drugs, exenatide and lixisenatide, each showed a statistically neutral effect for MACE, as well as collectively in a combined analysis. In contrast, three human GLP-1–based drugs, albiglutide, liraglutide, and semaglutide, each showed a consistent, statistically-significant MACE reduction in their respective outcome trials, and collectively they showed a highly significant 18% reduction in MACE, compared with placebo, Dr. Verma said. Further, recent analysis by Dr. Verma that used data from liraglutide treatment in the LEADER trial showed the MACE benefit occurred only among enrolled patients treated with liraglutide who had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Patients enrolled in the trial with only multiple risk factors (in addition to having T2DM) but without established ASCVD showed no significant benefit from liraglutide treatment for the MACE endpoint, compared with control patients.