User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

ABIM to allow do-overs for all subspecialties with Knowledge Check-In

ABIM previously announced that, beginning in 2018, physicians taking the Knowledge Check-In in 2018 would get another chance to take it in 2 years if they were unsuccessful, even if they were due to pass the maintenance of certification (MOC) exam later that year. In 2018, Knowledge Check-Ins will be offered in internal medicine and nephrology.

“Based on feedback ABIM has received from the physician community, we are happy to let you know that we are extending this policy to include all other internal medicine subspecialties in the future,” ABIM said in a Dec. 4 announcement on its website. “This means that if a physician takes the Knowledge Check-In in the first year it is offered in their subspecialty and is unsuccessful, they will get at least one additional opportunity to take and pass it 2 years later.”

The Knowledge Check-In is an alternative to the traditional MOC process, and is administered every 2 years rather than the standard decade between MOC exams. ABIM noted that a single failure on a Knowledge Check-In will not result in a status change to a physician’s certification status.

Separately, ABIM also announced that it will continue to make practice assessment activities (part IV of the MOC program) a part of the portfolio of options that can be used to satisfy MOC requirements.

“Our intent is to support physicians completing MOC activities that are most meaningful to their practice, including those that enhance and improve medical knowledge, as well as many existing quality improvement activities, and those that blend both,” ABIM said in its announcement.

ABIM previously announced that, beginning in 2018, physicians taking the Knowledge Check-In in 2018 would get another chance to take it in 2 years if they were unsuccessful, even if they were due to pass the maintenance of certification (MOC) exam later that year. In 2018, Knowledge Check-Ins will be offered in internal medicine and nephrology.

“Based on feedback ABIM has received from the physician community, we are happy to let you know that we are extending this policy to include all other internal medicine subspecialties in the future,” ABIM said in a Dec. 4 announcement on its website. “This means that if a physician takes the Knowledge Check-In in the first year it is offered in their subspecialty and is unsuccessful, they will get at least one additional opportunity to take and pass it 2 years later.”

The Knowledge Check-In is an alternative to the traditional MOC process, and is administered every 2 years rather than the standard decade between MOC exams. ABIM noted that a single failure on a Knowledge Check-In will not result in a status change to a physician’s certification status.

Separately, ABIM also announced that it will continue to make practice assessment activities (part IV of the MOC program) a part of the portfolio of options that can be used to satisfy MOC requirements.

“Our intent is to support physicians completing MOC activities that are most meaningful to their practice, including those that enhance and improve medical knowledge, as well as many existing quality improvement activities, and those that blend both,” ABIM said in its announcement.

ABIM previously announced that, beginning in 2018, physicians taking the Knowledge Check-In in 2018 would get another chance to take it in 2 years if they were unsuccessful, even if they were due to pass the maintenance of certification (MOC) exam later that year. In 2018, Knowledge Check-Ins will be offered in internal medicine and nephrology.

“Based on feedback ABIM has received from the physician community, we are happy to let you know that we are extending this policy to include all other internal medicine subspecialties in the future,” ABIM said in a Dec. 4 announcement on its website. “This means that if a physician takes the Knowledge Check-In in the first year it is offered in their subspecialty and is unsuccessful, they will get at least one additional opportunity to take and pass it 2 years later.”

The Knowledge Check-In is an alternative to the traditional MOC process, and is administered every 2 years rather than the standard decade between MOC exams. ABIM noted that a single failure on a Knowledge Check-In will not result in a status change to a physician’s certification status.

Separately, ABIM also announced that it will continue to make practice assessment activities (part IV of the MOC program) a part of the portfolio of options that can be used to satisfy MOC requirements.

“Our intent is to support physicians completing MOC activities that are most meaningful to their practice, including those that enhance and improve medical knowledge, as well as many existing quality improvement activities, and those that blend both,” ABIM said in its announcement.

Alarm reductions don’t improve ICU response times

TORONTO – It will take more than a reduction in alarms to address the issue of alarm fatigue in the ICU; a change in the ICU staff culture is needed, suggests new research.

“It may take years to recondition clinicians [to realize] that alarms are actionable and must get a response,” Afua Kunadu, MD, said during her presentation on the study at the CHEST annual meeting. Results from prior studies had suggested that as many as 99% of clinical alarms do not result in clinical intervention, noted Dr. Kunadu, an internal medicine physician at Harlem Hospital Center in New York.

She described the program, which started in the 20-bed adult ICU of Harlem Hospital Center, following a 2014 National Patient Safety Goal issued by The Joint Commission to improve the safety of clinical alarm systems by reducing unneeded alarms and alarm fatigue. The Harlem Hospital task force that ran the program began with an audit of alarms that went off in the ICU and used the results to identify the three most common alarms: bedside cardiac monitors, infusion pumps, and mechanical ventilators. The task force arranged to reset the default settings on these devices to decrease alarm frequency and boost the clinical importance of each alarm that still sounded. Concurrently, they ran educational sessions about the new alarm thresholds, the anticipated drop in alarm number, and the increased urgency to respond to the remaining alarms very quickly for the ICU staff.

The raised thresholds effectively cut the number of alarms. The average number of alarms per patient per hour fell from 4.5 at baseline during September 2016 to about 2 after 1 month, during December 2016. Then the rate further declined to reach a steady nadir that stayed at about 1.3 alarms per patient per hour 4 months into the program.

But timely responses, measured as the percentage of alarm responses occurring within 60 seconds after the alarm went off, fell from 60% at 1 month into the program down to 12% after 4 months, Dr. Kunadu reported.

She had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TORONTO – It will take more than a reduction in alarms to address the issue of alarm fatigue in the ICU; a change in the ICU staff culture is needed, suggests new research.

“It may take years to recondition clinicians [to realize] that alarms are actionable and must get a response,” Afua Kunadu, MD, said during her presentation on the study at the CHEST annual meeting. Results from prior studies had suggested that as many as 99% of clinical alarms do not result in clinical intervention, noted Dr. Kunadu, an internal medicine physician at Harlem Hospital Center in New York.

She described the program, which started in the 20-bed adult ICU of Harlem Hospital Center, following a 2014 National Patient Safety Goal issued by The Joint Commission to improve the safety of clinical alarm systems by reducing unneeded alarms and alarm fatigue. The Harlem Hospital task force that ran the program began with an audit of alarms that went off in the ICU and used the results to identify the three most common alarms: bedside cardiac monitors, infusion pumps, and mechanical ventilators. The task force arranged to reset the default settings on these devices to decrease alarm frequency and boost the clinical importance of each alarm that still sounded. Concurrently, they ran educational sessions about the new alarm thresholds, the anticipated drop in alarm number, and the increased urgency to respond to the remaining alarms very quickly for the ICU staff.

The raised thresholds effectively cut the number of alarms. The average number of alarms per patient per hour fell from 4.5 at baseline during September 2016 to about 2 after 1 month, during December 2016. Then the rate further declined to reach a steady nadir that stayed at about 1.3 alarms per patient per hour 4 months into the program.

But timely responses, measured as the percentage of alarm responses occurring within 60 seconds after the alarm went off, fell from 60% at 1 month into the program down to 12% after 4 months, Dr. Kunadu reported.

She had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TORONTO – It will take more than a reduction in alarms to address the issue of alarm fatigue in the ICU; a change in the ICU staff culture is needed, suggests new research.

“It may take years to recondition clinicians [to realize] that alarms are actionable and must get a response,” Afua Kunadu, MD, said during her presentation on the study at the CHEST annual meeting. Results from prior studies had suggested that as many as 99% of clinical alarms do not result in clinical intervention, noted Dr. Kunadu, an internal medicine physician at Harlem Hospital Center in New York.

She described the program, which started in the 20-bed adult ICU of Harlem Hospital Center, following a 2014 National Patient Safety Goal issued by The Joint Commission to improve the safety of clinical alarm systems by reducing unneeded alarms and alarm fatigue. The Harlem Hospital task force that ran the program began with an audit of alarms that went off in the ICU and used the results to identify the three most common alarms: bedside cardiac monitors, infusion pumps, and mechanical ventilators. The task force arranged to reset the default settings on these devices to decrease alarm frequency and boost the clinical importance of each alarm that still sounded. Concurrently, they ran educational sessions about the new alarm thresholds, the anticipated drop in alarm number, and the increased urgency to respond to the remaining alarms very quickly for the ICU staff.

The raised thresholds effectively cut the number of alarms. The average number of alarms per patient per hour fell from 4.5 at baseline during September 2016 to about 2 after 1 month, during December 2016. Then the rate further declined to reach a steady nadir that stayed at about 1.3 alarms per patient per hour 4 months into the program.

But timely responses, measured as the percentage of alarm responses occurring within 60 seconds after the alarm went off, fell from 60% at 1 month into the program down to 12% after 4 months, Dr. Kunadu reported.

She had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT CHEST 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Average alarms/patient/hour fell from 4.5 to 1.3, but the percentage of responses in less than 60 seconds fell from 60% to 12%.

Data source: An observational study at a single adult ICU in the United States.

Disclosures: Dr. Kunadu had no disclosures.

Underlying peripheral arterial or venous disease in patients with lower extremity SSTIs

Clinical case

A 56-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes, morbid obesity, and hypertension presents with right lower extremity erythema, weeping, and exquisite tenderness associated with chills. She reports a 2-year history of chronic lower extremity swelling and cramps with a more recent development of scaling and two superficial ulcers on lower third of her leg. For 1 month, she has noted significant pain circumferentially around the ankles with focal tautness and pallor of the skin. She has tried acetaminophen and oxycodone with little relief.

Over the past week, she noted foul smelling discharge from one of the superficial ulcers with redness extending up to the knee prompting presentation to the emergency department. She had a fever to 101.2° F, tachycardia to 105 beats per minute, and leukocytosis to 14.7. She is admitted to the hospitalist service for sepsis secondary to right lower extremity cellulitis.

Introduction

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) remain among the most common inpatient diagnoses cared for by hospitalists. Most patients admitted to a hospitalist service with an SSTI meet the criteria for either moderate or severe infection as outlined by the Infectious Disease Society of America – systemic signs of infection by SIRS criteria or a high likelihood of an immunocompromised state, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection, trauma, or wounds.1

Often these patients have several comorbid conditions such as diabetes, morbid obesity, or peripheral arterial and venous disease. Though most hospitalists are adept at managing diabetes, blood pressure, and other comorbidities, the ability to recognize and manage peripheral vascular disease can be challenging. This article will discuss ways to help providers better identify and manage underlying peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and/or chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) in patients admitted with lower extremity SSTIs.

1. In addition to an infection, could there also be underlying peripheral arterial or venous disease?

Patients with peripheral edema and vascular disease are predisposed to recurrent lower extremity SSTIs. When assessing for vascular disease, it is important to consider PAD and CVI separately.

CVI refers to the spectrum of syndromes caused by venous valvular incompetency, venous obstruction, or decreased muscle contraction. Veins cannot maximally deliver venous blood back to the heart resulting in venous pooling in the lower extremities. The exact mechanism of the skin changes that accompany venous insufficiency is unknown but may be related to cytokine cascades that result in perivascular inflammation and a weakening of the dermal barrier. Over time, this can develop into spontaneous ulceration of the skin.2,3

PAD refers to atherosclerosis of the noncerebral, noncoronary arteries, which leads to ischemic symptoms and atrophy of the supplied territory. Ulceration usually results from mild trauma due to poor wound healing.4,5 A thorough history, assessment of risk factors, and physical exam are essential to identifying these two potential diagnoses in patients admitted with SSTIs.

First, the provider should assess risk factors for underlying vascular disease. For PAD, these include risk factors similar to those of coronary artery disease (CAD): hypertension, hyperlipidemia, history of smoking, and poorly-controlled diabetes. Chronic kidney disease and family history are also associated with PAD. Since PAD and CAD share similar risk factors, it is often common for patients with CAD (as well as patients with cerebrovascular disease) to have PAD. Risk factors for CVI include obesity, chronic sedentary lifestyle, multiple pregnancies, family history, and prior superficial or deep venous thrombosis.2,4

Next, the provider should ask the patient about symptoms experienced prior to the onset of the current SSTI. Patients with either arterial or venous disease will typically report lower extremity symptoms that have been occurring for months to years, long before the acute SSTI. The classic symptom for PAD is claudication – leg pain or cramping that occurs on exertion and improves with rest. This is due to decreased arterial blood flow to the affected limb, felt most acutely during exercise. Other symptoms include numbness, a cool lower extremity, and lower extremity hair loss. As PAD progresses, a patient may also have rest pain, which may indicate more critical ischemia, as well nonhealing wounds after mild trauma.

In contrast, symptoms of CVI present more variably. CVI can be associated with heaviness, cramping, and pain that are usually worse in the dependent position and relieved with elevation. Patients may also report dry skin, edema, pruritus, scaling, skin tightness, and indolent ulcers at advanced stages.2-6

The physical exam can help the provider distinguish between venous and arterial disease. Patients with PAD often have diminished or nonpalpable distal pulses, bruits in proximal arteries, pallor, hair loss, nail thickening, decreased capillary refill time, and ulceration of the toes. CVI shares some common characteristics but can be distinguished by evidence of varicose veins, telangiectasia, edema (which spares the foot), lipodermatosclerosis, and atrophie blanche (white scarring around the ankle). Patients with venous disease tend to have warm lower extremities and palpable pulses. Often, there is hyperpigmentation, especially around the ankles, and associated eczematous changes with scaling, erythema, and weeping. CVI can also present with ulcers. In addition, if the SSTI is not responding to appropriate antibiotics in the typical time frame, this may be a clue that there is an underlying vascular issue.2-6

Ulcers, whether arterial or venous, comprise a break in the skin’s protective barrier and give bacteria a point of entry. Thus, ulcers often get superinfected, leading to an SSTI rather than SSTIs causing ulcers. The anatomic location can help differentiate between venous and arterial ulcers. Arterial ulcers tend to occur on the toes, heels, and lateral and medial malleoli. Venous ulcers are classically present above the medial malleolus but can occur anywhere on the medial lower third of the leg. Venous ulcers are more superficial and have an irregular shape, while arterial ulcers are deeper, have smoother edges and a “punched-out” shape. Both arterial and venous ulcers can be exudative though venous ulcers are rarely necrotic. Both arterial and venous ulcers can be painful.7-9

2. There are signs and symptoms of underlying vascular disease in a patient with a lower extremity SSTI. Now what?

Neither PAD nor CVI is a clinical diagnosis, thus further work-up is required to confirm the diagnosis and accurately classify disease severity. The timing of this work-up is of unique interest to hospitalists.

Most patients who are hospitalized with cellulitis or a superficial wound infection do not need urgent inpatient work-up of suspected peripheral arterial or venous disease. The one notable exception to this is patients with diabetic foot infections or infected arterial ulcers that need prompt evaluation for possible critical limb ischemia. Barring cases of critical limb ischemia, the main objective of identifying PAD or CVI in patients hospitalized for SSTIs is to appropriately arrange testing and follow-up after discharge.

To address specific management strategies, it is useful to stratify patients by symptom and exam severity as follows: mild/moderate PAD symptoms without ulcer; infected ulcer with PAD features; mild/moderate CVI symptoms without ulcer; and infected ulcer with CVI features. As specific guidelines for the inpatient work-up and management of suspected peripheral arterial and venous disease are sparse, we rely on guidelines and best practices used in the outpatient setting and adapt them to these potential inpatient presentations.

Mild/Moderate PAD symptoms with superimposed cellulitis but no ulceration

In a patient admitted for cellulitis without open wounds, history and review of systems might reveal the presence of claudication or other symptoms suspicious for PAD. While the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force and American College of Cardiology discourages the routine screening of asymptomatic patients for PAD, patients with risk factors who endorse symptoms should undergo initial testing for PAD with an ankle-brachial index (ABI).10

The ABI is the ratio of ankle blood pressure to arm blood pressure, and is measured via sphygmomanometry with a Doppler probe. The ABI remains the simplest, most inexpensive first-line test for PAD. An ABI value of less than 0.9 is considered diagnostic for PAD and has been found to be more than 95% specific for arterial stenoses of greater than 50% on angiography across multiple studies.11

In an inpatient with risk factors for PAD and claudication symptoms, referral for outpatient ABIs with subsequent follow-up by a primary care physician should be arranged. If a diagnosis of PAD is made via ABI, the PCP should reinforce risk factor modification (tobacco cessation, diet, exercise, and aggressive lipid, blood pressure and blood glucose control) and start medical management with a single anti-platelet agent to reduce the risk of MI, stroke, or “vascular death.” The most recent ACC guidelines recommend either aspirin or clopidogrel as an acceptable anti-platelet agent (grade 1A).12 Cilostazol may be considered if claudication symptoms are significantly interfering with lifestyle. If this management fails, the patient may be referred to a vascular specialist for consideration of revascularization.

Infected ulcer with PAD features

Unlike cellulitis, arterial ulcers are a direct sequela of arterial insufficiency and represent the far end of the spectrum of disease severity and in certain cases treatment failure. Patients who present with advanced ischemic and/or diabetic foot ulcers may have never been evaluated for PAD as an outpatient. Prompt work-up and management is required given the high degree of morbidity and mortality associated with arterial ulcers. Whether an urgent inpatient evaluation is indicated depends on the clinical evaluation.

The first step is to determine the depth of the ulceration. Critical limb ischemia may be present if the ulcer is deep, gangrenous, overlies a bony prominence, or is associated with systemic signs of sepsis. A physical exam should include an assessment of the pulses including femoral, popliteal, PT and DP, preferably with bedside Doppler ultrasound. If pulses are absent, urgent vascular surgery evaluation is warranted to prevent loss of limb; the work-up generally involves imaging such as computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography to identify culprit lesions, or if sufficiently suspicious, immediate invasive angiogram with the potential for endovascular intervention.

While palpable pulses can be reassuring and raise the possibility of a nonarterial etiology of ulceration – such as a microvascular, neuropathic or venous disease – it is important to remember that pulse exams are often unreliable and provider dependent.13 Moreover, the presence of pulses does not effectively exclude severe PAD or critical limb ischemia in patients with a high pretest probability.14 Thus, in cases of deep, complex lower extremity and foot ulcers, it is prudent to obtain urgent evaluation by a surgical wound specialist, which depending on the institution may be podiatry, vascular surgery, or wound care. This may lead to a better clinical assessment of the wound and clearer recommendations regarding the need for additional testing, such as imaging, to rule out osteomyelitis, surgical debridement, or amputation.

Inpatient ABIs in this situation may help diagnose and quantify the severity of PAD. Newer classification schemes such as the Society of Vascular Surgery Wound Ischemia Foot Infection score take into account clinical findings as well as ABI scores to better prognosticate limb loss and select patients for intervention.15 If the clinical picture is deemed sufficiently suspicious for critical limb ischemia, the patient may be taken directly for invasive testing with possible intervention.

If an infected ulcer is superficial, shows no signs of gangrene, and has been present for less than 30 days, further work-up for suspected PAD can generally be deferred to an outpatient setting after resolution of the acute infection. Management of the wound is highly institution dependent. When available, a wound care specialist (physician or nurse) or a plastic surgeon can be consulted as an inpatient to give specific recommendations that can range anywhere from enzymatic debridement to simple dressing. If this service is unavailable, we recommend dressing the wound with moist nonocclusive dressings with frequent changes. Referrals for ABI testing and follow up in podiatry, wound care, or vascular clinic should be arranged. Finally, educating the patient on what to expect can increase compliance with the outpatient treatment plan.

Mild to moderate CVI symptoms with superimposed cellulitis but no ulceration

Chronic venous insufficiency is a syndrome that has variable presentations based on the location and degree of valvular incompetence in the superficial or, less commonly, deep venous systems. For a patient with cellulitis and CVI, the clinical exam findings may be associated with venous hypertension syndrome – in which there is deep axial reflux and possible obstruction – and could also represent complex varicose disease which is usually caused by superficial reflux of the greater saphenous vein.3 The lack of advanced skin changes and ulceration raises the suspicion of mild to moderate CVI.

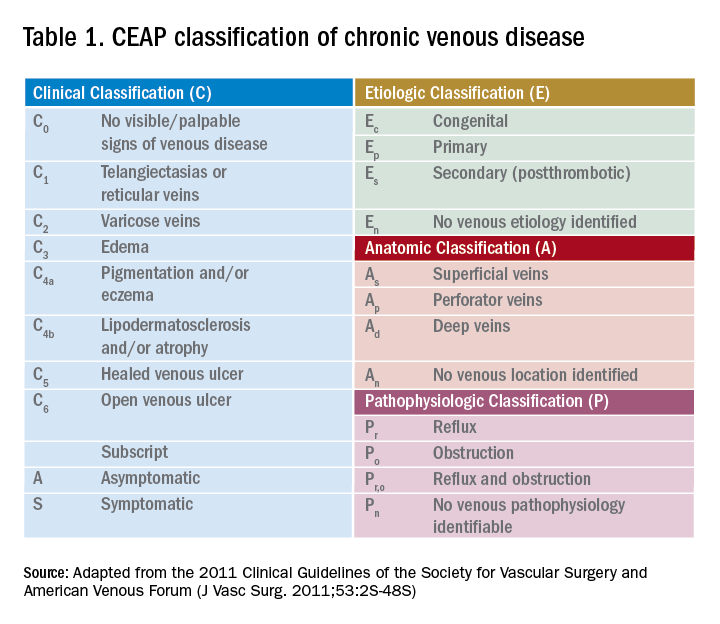

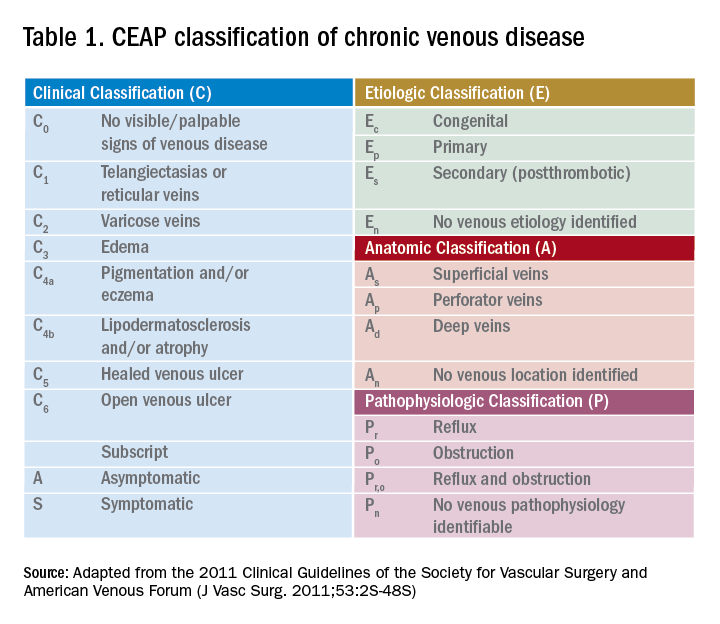

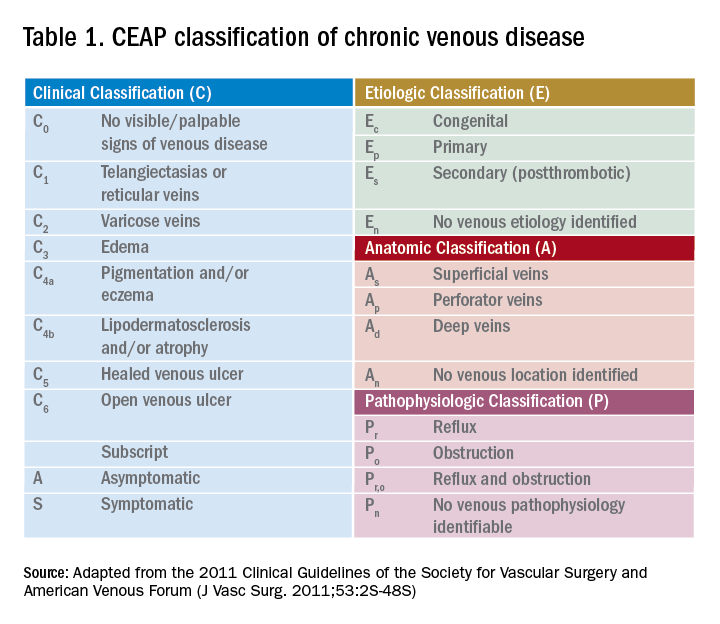

Guidelines from the American Venous Forum and the Society for Vascular Surgery recommend that all patients with suspected CVI, regardless of severity, undergo venous duplex ultrasound scanning as a first diagnostic test (grade 1A) to accurately classify the disease according to the Clinical Etiological Anatomical Pathophysiology (CEAP) system (Table 1).16

Compression therapy is commonly accepted as a noninvasive treatment option for all levels of CVI, yet most of the evidence comes from secondary prevention studies in patients with advanced CVI with venous ulcers.18 Strong evidence for the role of compression stockings in mild to moderate CVI is lacking. In fact, recent guidelines from the Society of Vascular Surgery, reviewed by the American Heart Association, do not recommend compression therapy as a primary treatment modality in patients with symptomatic varicose veins (without ulcers) if the patient is a candidate for saphenous vein ablation.19 This recommendation is based on clinical trial data that showed greater efficacy and cost-effectiveness of surgery versus conservative management in patients with CEAP2 (low severity) CVI as well as studies noting noncompliance with compression therapy as high as 75%.20-21

However, determining a patient’s candidacy for ablative or surgical therapy requires ultrasound data for accurate CEAP scoring, which is often not achieved as an inpatient. Given the potential benefit and lack of severe adverse effects, hospitalists can consider initiating compression therapy at the time of discharge in a patient with mild to moderate signs of CVI and a low risk profile for severe PAD. The prescription should specify knee-length elastic stockings with graduated compression between 20 to 30 mm Hg.22 The patient should also be encouraged to complete the outpatient duplex ultrasound testing prior to the PCP visit so that he or she can be referred to a vascular specialist appropriately.

Infected ulcer with CVI features

If the patient’s exam is suspicious for advanced venous disease with ulceration, the clinician should evaluate for the presence of scarring. This would indicate that there has been long-standing venous disease with recurrent ulceration. This patient should be asked about a previous diagnosis of CVI, prior compression therapy, and barriers to compliance with compression therapy such as poor fit or difficulty of use due to obesity or immobility. It is important to note that mixed ulcers are present in up to 20% of patients; a careful assessment of risk factors for PAD, pulse exam, and referral for outpatient ABI testing is warranted to rule out arterial insufficiency in this patient with likely venous ulcer.23

The AHA recommends prompt specialist evaluation for CEAP scores greater than or equal to 4; based on physical exam alone, this patient’s active venous ulcer yields the highest possible score of 6.2 If not previously done, this patient with advanced CVI and ulceration should be referred for an outpatient venous duplex ultrasound as well as urgent follow-up with a vascular specialist soon after discharge.

There is significant consensus in the literature that multilayer compression therapy between 30 and 40 mm Hg is the first-line treatment in patients with venous ulcers as it has been shown to promote ulcer healing and prevent recurrence.24-25 In addition, superficial venous surgery, including minimally invasive ablation, can reduce the recurrence of ulcers if used as adjunctive therapy in selected patients.26 However, compressive therapy should generally not be prescribed in patients with venous ulcers until PAD has been ruled out.

If ABI results are available, the clinician can consider compression at 30-40 mm Hg for ABI values greater than 0.8 and reduced compression at 20-30 mm Hg for values of 0.5-0.8; compression is contraindicated if the ABI is less than 0.5. Prompt follow-up with a vascular specialist can help direct compressive and/or surgical therapy. Wound care consultation as an inpatient can assist with dressing recommendations, though the evidence has not shown that dressings of any type worn under compressive garments improve ulcer healing.27

Bottom line

Hospitalists are in a unique position to identify patients with underlying peripheral arterial and venous disease when they are admitted for lower extremity skin and soft tissue infections. A focused history and physical exam can yield significant clinical clues and should prompt either inpatient or outpatient work-up.

In patients with deep ulcers and concern for critical limb ischemia, inpatient consultation should be sought. In patients with superficial venous or arterial ulcers, referral for outpatient ABI, color duplex ultrasound, or both should be made; most of these patients should also be directly referred to a vascular and/or wound specialist. Patients with more benign forms of disease who endorse chronic symptoms suspicious for mild to moderate PAD or CVI can be seen by a PCP for further management. All patients should be educated about the importance of follow-up as it remains their best chance to curb the progression of disease, reduce the risks for recurrent infection, and improve overall quality of life.

Back to the original case

Our patient’s lower extremity erythema, fever, and leukocytosis improved with 3 days of IV vancomycin treatment. Her wound was kept clean with moist dressings and showed no signs of deep infection; with elevation, her bilateral lower extremity edema also improved. Her physical exam findings and clinical history were highly suspicious for long-standing CVI. She was discharged with oral antibiotics and a referral to wound care for ongoing management of her superficial ulcers. An outpatient venous duplex ultrasound and ABI were scheduled prior to her vascular surgery appointment to effectively rule out PAD before consideration of further therapy for severe CVI.

Key Points

- Hospitalists are in a unique position to identify patients with peripheral vascular disease when they are admitted with SSTIs.

- When assessing patients, it is important to consider peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) separately.

- The classic symptom for PAD is claudication. In contrast, symptoms of CVI present more variably.

- Barring cases of critical limb ischemia, the main objective of identifying PAD or CVI is to arrange testing and follow-up after discharge.

References

1. Stevens, DL, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):147-59.

2. Eberhardt, RT, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency. Circulation. 2014;130:333-46.

3. Raju, S, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2319-27.

4. Kullo, IJ, et al. Peripheral artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):861-71.

5. Hennion D, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial disease. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Sep 1;88(5):306-10.

6. Henke P, et al. ACP Observer Extra: Peripheral arterial disease. June 2007.

7. Vivas A. Venous leg ulcers. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(3):ITC17-32.

8. Sumpio BE. Foot ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(11):787-93.

9. Bazari H, et al. Case 7–2007. 59-year-old woman with diabetic renal disease and nonhealing skin ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2007 Mar 8; 356(10):1049-57.

10. Moyer VA. Screening for peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular disease risk assessment with the ankle-brachial index in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Sep 3.159(5):342-8.

11. Khan TH, et al. Critical review of the ankle brachial index. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2008 May;4(2):101-6.

12. Gerhard-Herman MD, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2016.

13. Brearley S, et al. Peripheral pulse palpation: An unreliable physical sign. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1992;74:169-71.

14. Khan NA, et al. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? JAMA. 2006;295(5):536-46.

15. Mills JL Sr., et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Threatened Limb Classification System: Risk stratification based on wound, ischemia, and foot infection (WIfI). J Vasc Surg. 2014 Jan;59(1):220-34.e1-2.

16. Gloviczki P, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5, Suppl):2S-48S.

17. Hamper UM,et al. Ultrasound evaluation of the lower extremity veins. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007 May;45(3):525-47.

18. Vivas A. Venous leg ulcers. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(3):ITC17-32.

19. Gloviczki P, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5, Suppl):2S-48S.

20. Michaels JA, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing surgery with conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2006 Feb;93(2):175-81.

21. Raju S, et al. Use of compression stockings in chronic venous disease: Patient compliance and efficacy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007 Nov;21(6):790-5.

22. Gloviczki P, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5, Suppl):2S-48S.

23. Humphreys ML, et al. Management of mixed arterial and venous leg ulcers. Br J Surg. 2007 Sep;94(9):1104-7.

24. O’Meara S, et al. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11:CD000265.

25. Dolibog P, et al. A comparative clinical study on five types of compression therapy in patients with venous leg ulcers. Int J Med Sci. 2013;11(1):34-43.

26. Gohel MS, et al. Long term results of compression therapy alone versus compression plus surgery in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR): Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007 Jul 14;335(7610):83.

27. Palfreyman S, et al. Dressings for venous leg ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007 Aug 4;335(7613):244.

Clinical case

A 56-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes, morbid obesity, and hypertension presents with right lower extremity erythema, weeping, and exquisite tenderness associated with chills. She reports a 2-year history of chronic lower extremity swelling and cramps with a more recent development of scaling and two superficial ulcers on lower third of her leg. For 1 month, she has noted significant pain circumferentially around the ankles with focal tautness and pallor of the skin. She has tried acetaminophen and oxycodone with little relief.

Over the past week, she noted foul smelling discharge from one of the superficial ulcers with redness extending up to the knee prompting presentation to the emergency department. She had a fever to 101.2° F, tachycardia to 105 beats per minute, and leukocytosis to 14.7. She is admitted to the hospitalist service for sepsis secondary to right lower extremity cellulitis.

Introduction

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) remain among the most common inpatient diagnoses cared for by hospitalists. Most patients admitted to a hospitalist service with an SSTI meet the criteria for either moderate or severe infection as outlined by the Infectious Disease Society of America – systemic signs of infection by SIRS criteria or a high likelihood of an immunocompromised state, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection, trauma, or wounds.1

Often these patients have several comorbid conditions such as diabetes, morbid obesity, or peripheral arterial and venous disease. Though most hospitalists are adept at managing diabetes, blood pressure, and other comorbidities, the ability to recognize and manage peripheral vascular disease can be challenging. This article will discuss ways to help providers better identify and manage underlying peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and/or chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) in patients admitted with lower extremity SSTIs.

1. In addition to an infection, could there also be underlying peripheral arterial or venous disease?

Patients with peripheral edema and vascular disease are predisposed to recurrent lower extremity SSTIs. When assessing for vascular disease, it is important to consider PAD and CVI separately.

CVI refers to the spectrum of syndromes caused by venous valvular incompetency, venous obstruction, or decreased muscle contraction. Veins cannot maximally deliver venous blood back to the heart resulting in venous pooling in the lower extremities. The exact mechanism of the skin changes that accompany venous insufficiency is unknown but may be related to cytokine cascades that result in perivascular inflammation and a weakening of the dermal barrier. Over time, this can develop into spontaneous ulceration of the skin.2,3

PAD refers to atherosclerosis of the noncerebral, noncoronary arteries, which leads to ischemic symptoms and atrophy of the supplied territory. Ulceration usually results from mild trauma due to poor wound healing.4,5 A thorough history, assessment of risk factors, and physical exam are essential to identifying these two potential diagnoses in patients admitted with SSTIs.

First, the provider should assess risk factors for underlying vascular disease. For PAD, these include risk factors similar to those of coronary artery disease (CAD): hypertension, hyperlipidemia, history of smoking, and poorly-controlled diabetes. Chronic kidney disease and family history are also associated with PAD. Since PAD and CAD share similar risk factors, it is often common for patients with CAD (as well as patients with cerebrovascular disease) to have PAD. Risk factors for CVI include obesity, chronic sedentary lifestyle, multiple pregnancies, family history, and prior superficial or deep venous thrombosis.2,4

Next, the provider should ask the patient about symptoms experienced prior to the onset of the current SSTI. Patients with either arterial or venous disease will typically report lower extremity symptoms that have been occurring for months to years, long before the acute SSTI. The classic symptom for PAD is claudication – leg pain or cramping that occurs on exertion and improves with rest. This is due to decreased arterial blood flow to the affected limb, felt most acutely during exercise. Other symptoms include numbness, a cool lower extremity, and lower extremity hair loss. As PAD progresses, a patient may also have rest pain, which may indicate more critical ischemia, as well nonhealing wounds after mild trauma.

In contrast, symptoms of CVI present more variably. CVI can be associated with heaviness, cramping, and pain that are usually worse in the dependent position and relieved with elevation. Patients may also report dry skin, edema, pruritus, scaling, skin tightness, and indolent ulcers at advanced stages.2-6

The physical exam can help the provider distinguish between venous and arterial disease. Patients with PAD often have diminished or nonpalpable distal pulses, bruits in proximal arteries, pallor, hair loss, nail thickening, decreased capillary refill time, and ulceration of the toes. CVI shares some common characteristics but can be distinguished by evidence of varicose veins, telangiectasia, edema (which spares the foot), lipodermatosclerosis, and atrophie blanche (white scarring around the ankle). Patients with venous disease tend to have warm lower extremities and palpable pulses. Often, there is hyperpigmentation, especially around the ankles, and associated eczematous changes with scaling, erythema, and weeping. CVI can also present with ulcers. In addition, if the SSTI is not responding to appropriate antibiotics in the typical time frame, this may be a clue that there is an underlying vascular issue.2-6

Ulcers, whether arterial or venous, comprise a break in the skin’s protective barrier and give bacteria a point of entry. Thus, ulcers often get superinfected, leading to an SSTI rather than SSTIs causing ulcers. The anatomic location can help differentiate between venous and arterial ulcers. Arterial ulcers tend to occur on the toes, heels, and lateral and medial malleoli. Venous ulcers are classically present above the medial malleolus but can occur anywhere on the medial lower third of the leg. Venous ulcers are more superficial and have an irregular shape, while arterial ulcers are deeper, have smoother edges and a “punched-out” shape. Both arterial and venous ulcers can be exudative though venous ulcers are rarely necrotic. Both arterial and venous ulcers can be painful.7-9

2. There are signs and symptoms of underlying vascular disease in a patient with a lower extremity SSTI. Now what?

Neither PAD nor CVI is a clinical diagnosis, thus further work-up is required to confirm the diagnosis and accurately classify disease severity. The timing of this work-up is of unique interest to hospitalists.

Most patients who are hospitalized with cellulitis or a superficial wound infection do not need urgent inpatient work-up of suspected peripheral arterial or venous disease. The one notable exception to this is patients with diabetic foot infections or infected arterial ulcers that need prompt evaluation for possible critical limb ischemia. Barring cases of critical limb ischemia, the main objective of identifying PAD or CVI in patients hospitalized for SSTIs is to appropriately arrange testing and follow-up after discharge.

To address specific management strategies, it is useful to stratify patients by symptom and exam severity as follows: mild/moderate PAD symptoms without ulcer; infected ulcer with PAD features; mild/moderate CVI symptoms without ulcer; and infected ulcer with CVI features. As specific guidelines for the inpatient work-up and management of suspected peripheral arterial and venous disease are sparse, we rely on guidelines and best practices used in the outpatient setting and adapt them to these potential inpatient presentations.

Mild/Moderate PAD symptoms with superimposed cellulitis but no ulceration

In a patient admitted for cellulitis without open wounds, history and review of systems might reveal the presence of claudication or other symptoms suspicious for PAD. While the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force and American College of Cardiology discourages the routine screening of asymptomatic patients for PAD, patients with risk factors who endorse symptoms should undergo initial testing for PAD with an ankle-brachial index (ABI).10

The ABI is the ratio of ankle blood pressure to arm blood pressure, and is measured via sphygmomanometry with a Doppler probe. The ABI remains the simplest, most inexpensive first-line test for PAD. An ABI value of less than 0.9 is considered diagnostic for PAD and has been found to be more than 95% specific for arterial stenoses of greater than 50% on angiography across multiple studies.11

In an inpatient with risk factors for PAD and claudication symptoms, referral for outpatient ABIs with subsequent follow-up by a primary care physician should be arranged. If a diagnosis of PAD is made via ABI, the PCP should reinforce risk factor modification (tobacco cessation, diet, exercise, and aggressive lipid, blood pressure and blood glucose control) and start medical management with a single anti-platelet agent to reduce the risk of MI, stroke, or “vascular death.” The most recent ACC guidelines recommend either aspirin or clopidogrel as an acceptable anti-platelet agent (grade 1A).12 Cilostazol may be considered if claudication symptoms are significantly interfering with lifestyle. If this management fails, the patient may be referred to a vascular specialist for consideration of revascularization.

Infected ulcer with PAD features

Unlike cellulitis, arterial ulcers are a direct sequela of arterial insufficiency and represent the far end of the spectrum of disease severity and in certain cases treatment failure. Patients who present with advanced ischemic and/or diabetic foot ulcers may have never been evaluated for PAD as an outpatient. Prompt work-up and management is required given the high degree of morbidity and mortality associated with arterial ulcers. Whether an urgent inpatient evaluation is indicated depends on the clinical evaluation.

The first step is to determine the depth of the ulceration. Critical limb ischemia may be present if the ulcer is deep, gangrenous, overlies a bony prominence, or is associated with systemic signs of sepsis. A physical exam should include an assessment of the pulses including femoral, popliteal, PT and DP, preferably with bedside Doppler ultrasound. If pulses are absent, urgent vascular surgery evaluation is warranted to prevent loss of limb; the work-up generally involves imaging such as computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography to identify culprit lesions, or if sufficiently suspicious, immediate invasive angiogram with the potential for endovascular intervention.

While palpable pulses can be reassuring and raise the possibility of a nonarterial etiology of ulceration – such as a microvascular, neuropathic or venous disease – it is important to remember that pulse exams are often unreliable and provider dependent.13 Moreover, the presence of pulses does not effectively exclude severe PAD or critical limb ischemia in patients with a high pretest probability.14 Thus, in cases of deep, complex lower extremity and foot ulcers, it is prudent to obtain urgent evaluation by a surgical wound specialist, which depending on the institution may be podiatry, vascular surgery, or wound care. This may lead to a better clinical assessment of the wound and clearer recommendations regarding the need for additional testing, such as imaging, to rule out osteomyelitis, surgical debridement, or amputation.

Inpatient ABIs in this situation may help diagnose and quantify the severity of PAD. Newer classification schemes such as the Society of Vascular Surgery Wound Ischemia Foot Infection score take into account clinical findings as well as ABI scores to better prognosticate limb loss and select patients for intervention.15 If the clinical picture is deemed sufficiently suspicious for critical limb ischemia, the patient may be taken directly for invasive testing with possible intervention.

If an infected ulcer is superficial, shows no signs of gangrene, and has been present for less than 30 days, further work-up for suspected PAD can generally be deferred to an outpatient setting after resolution of the acute infection. Management of the wound is highly institution dependent. When available, a wound care specialist (physician or nurse) or a plastic surgeon can be consulted as an inpatient to give specific recommendations that can range anywhere from enzymatic debridement to simple dressing. If this service is unavailable, we recommend dressing the wound with moist nonocclusive dressings with frequent changes. Referrals for ABI testing and follow up in podiatry, wound care, or vascular clinic should be arranged. Finally, educating the patient on what to expect can increase compliance with the outpatient treatment plan.

Mild to moderate CVI symptoms with superimposed cellulitis but no ulceration

Chronic venous insufficiency is a syndrome that has variable presentations based on the location and degree of valvular incompetence in the superficial or, less commonly, deep venous systems. For a patient with cellulitis and CVI, the clinical exam findings may be associated with venous hypertension syndrome – in which there is deep axial reflux and possible obstruction – and could also represent complex varicose disease which is usually caused by superficial reflux of the greater saphenous vein.3 The lack of advanced skin changes and ulceration raises the suspicion of mild to moderate CVI.

Guidelines from the American Venous Forum and the Society for Vascular Surgery recommend that all patients with suspected CVI, regardless of severity, undergo venous duplex ultrasound scanning as a first diagnostic test (grade 1A) to accurately classify the disease according to the Clinical Etiological Anatomical Pathophysiology (CEAP) system (Table 1).16

Compression therapy is commonly accepted as a noninvasive treatment option for all levels of CVI, yet most of the evidence comes from secondary prevention studies in patients with advanced CVI with venous ulcers.18 Strong evidence for the role of compression stockings in mild to moderate CVI is lacking. In fact, recent guidelines from the Society of Vascular Surgery, reviewed by the American Heart Association, do not recommend compression therapy as a primary treatment modality in patients with symptomatic varicose veins (without ulcers) if the patient is a candidate for saphenous vein ablation.19 This recommendation is based on clinical trial data that showed greater efficacy and cost-effectiveness of surgery versus conservative management in patients with CEAP2 (low severity) CVI as well as studies noting noncompliance with compression therapy as high as 75%.20-21

However, determining a patient’s candidacy for ablative or surgical therapy requires ultrasound data for accurate CEAP scoring, which is often not achieved as an inpatient. Given the potential benefit and lack of severe adverse effects, hospitalists can consider initiating compression therapy at the time of discharge in a patient with mild to moderate signs of CVI and a low risk profile for severe PAD. The prescription should specify knee-length elastic stockings with graduated compression between 20 to 30 mm Hg.22 The patient should also be encouraged to complete the outpatient duplex ultrasound testing prior to the PCP visit so that he or she can be referred to a vascular specialist appropriately.

Infected ulcer with CVI features

If the patient’s exam is suspicious for advanced venous disease with ulceration, the clinician should evaluate for the presence of scarring. This would indicate that there has been long-standing venous disease with recurrent ulceration. This patient should be asked about a previous diagnosis of CVI, prior compression therapy, and barriers to compliance with compression therapy such as poor fit or difficulty of use due to obesity or immobility. It is important to note that mixed ulcers are present in up to 20% of patients; a careful assessment of risk factors for PAD, pulse exam, and referral for outpatient ABI testing is warranted to rule out arterial insufficiency in this patient with likely venous ulcer.23

The AHA recommends prompt specialist evaluation for CEAP scores greater than or equal to 4; based on physical exam alone, this patient’s active venous ulcer yields the highest possible score of 6.2 If not previously done, this patient with advanced CVI and ulceration should be referred for an outpatient venous duplex ultrasound as well as urgent follow-up with a vascular specialist soon after discharge.

There is significant consensus in the literature that multilayer compression therapy between 30 and 40 mm Hg is the first-line treatment in patients with venous ulcers as it has been shown to promote ulcer healing and prevent recurrence.24-25 In addition, superficial venous surgery, including minimally invasive ablation, can reduce the recurrence of ulcers if used as adjunctive therapy in selected patients.26 However, compressive therapy should generally not be prescribed in patients with venous ulcers until PAD has been ruled out.

If ABI results are available, the clinician can consider compression at 30-40 mm Hg for ABI values greater than 0.8 and reduced compression at 20-30 mm Hg for values of 0.5-0.8; compression is contraindicated if the ABI is less than 0.5. Prompt follow-up with a vascular specialist can help direct compressive and/or surgical therapy. Wound care consultation as an inpatient can assist with dressing recommendations, though the evidence has not shown that dressings of any type worn under compressive garments improve ulcer healing.27

Bottom line

Hospitalists are in a unique position to identify patients with underlying peripheral arterial and venous disease when they are admitted for lower extremity skin and soft tissue infections. A focused history and physical exam can yield significant clinical clues and should prompt either inpatient or outpatient work-up.

In patients with deep ulcers and concern for critical limb ischemia, inpatient consultation should be sought. In patients with superficial venous or arterial ulcers, referral for outpatient ABI, color duplex ultrasound, or both should be made; most of these patients should also be directly referred to a vascular and/or wound specialist. Patients with more benign forms of disease who endorse chronic symptoms suspicious for mild to moderate PAD or CVI can be seen by a PCP for further management. All patients should be educated about the importance of follow-up as it remains their best chance to curb the progression of disease, reduce the risks for recurrent infection, and improve overall quality of life.

Back to the original case

Our patient’s lower extremity erythema, fever, and leukocytosis improved with 3 days of IV vancomycin treatment. Her wound was kept clean with moist dressings and showed no signs of deep infection; with elevation, her bilateral lower extremity edema also improved. Her physical exam findings and clinical history were highly suspicious for long-standing CVI. She was discharged with oral antibiotics and a referral to wound care for ongoing management of her superficial ulcers. An outpatient venous duplex ultrasound and ABI were scheduled prior to her vascular surgery appointment to effectively rule out PAD before consideration of further therapy for severe CVI.

Key Points

- Hospitalists are in a unique position to identify patients with peripheral vascular disease when they are admitted with SSTIs.

- When assessing patients, it is important to consider peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) separately.

- The classic symptom for PAD is claudication. In contrast, symptoms of CVI present more variably.

- Barring cases of critical limb ischemia, the main objective of identifying PAD or CVI is to arrange testing and follow-up after discharge.

References

1. Stevens, DL, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):147-59.

2. Eberhardt, RT, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency. Circulation. 2014;130:333-46.

3. Raju, S, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2319-27.

4. Kullo, IJ, et al. Peripheral artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):861-71.

5. Hennion D, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial disease. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Sep 1;88(5):306-10.

6. Henke P, et al. ACP Observer Extra: Peripheral arterial disease. June 2007.

7. Vivas A. Venous leg ulcers. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(3):ITC17-32.

8. Sumpio BE. Foot ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(11):787-93.

9. Bazari H, et al. Case 7–2007. 59-year-old woman with diabetic renal disease and nonhealing skin ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2007 Mar 8; 356(10):1049-57.

10. Moyer VA. Screening for peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular disease risk assessment with the ankle-brachial index in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Sep 3.159(5):342-8.

11. Khan TH, et al. Critical review of the ankle brachial index. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2008 May;4(2):101-6.

12. Gerhard-Herman MD, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2016.

13. Brearley S, et al. Peripheral pulse palpation: An unreliable physical sign. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1992;74:169-71.

14. Khan NA, et al. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? JAMA. 2006;295(5):536-46.

15. Mills JL Sr., et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Threatened Limb Classification System: Risk stratification based on wound, ischemia, and foot infection (WIfI). J Vasc Surg. 2014 Jan;59(1):220-34.e1-2.

16. Gloviczki P, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5, Suppl):2S-48S.

17. Hamper UM,et al. Ultrasound evaluation of the lower extremity veins. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007 May;45(3):525-47.

18. Vivas A. Venous leg ulcers. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(3):ITC17-32.

19. Gloviczki P, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5, Suppl):2S-48S.

20. Michaels JA, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing surgery with conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2006 Feb;93(2):175-81.

21. Raju S, et al. Use of compression stockings in chronic venous disease: Patient compliance and efficacy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007 Nov;21(6):790-5.

22. Gloviczki P, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5, Suppl):2S-48S.

23. Humphreys ML, et al. Management of mixed arterial and venous leg ulcers. Br J Surg. 2007 Sep;94(9):1104-7.

24. O’Meara S, et al. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11:CD000265.

25. Dolibog P, et al. A comparative clinical study on five types of compression therapy in patients with venous leg ulcers. Int J Med Sci. 2013;11(1):34-43.

26. Gohel MS, et al. Long term results of compression therapy alone versus compression plus surgery in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR): Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007 Jul 14;335(7610):83.

27. Palfreyman S, et al. Dressings for venous leg ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007 Aug 4;335(7613):244.

Clinical case

A 56-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes, morbid obesity, and hypertension presents with right lower extremity erythema, weeping, and exquisite tenderness associated with chills. She reports a 2-year history of chronic lower extremity swelling and cramps with a more recent development of scaling and two superficial ulcers on lower third of her leg. For 1 month, she has noted significant pain circumferentially around the ankles with focal tautness and pallor of the skin. She has tried acetaminophen and oxycodone with little relief.

Over the past week, she noted foul smelling discharge from one of the superficial ulcers with redness extending up to the knee prompting presentation to the emergency department. She had a fever to 101.2° F, tachycardia to 105 beats per minute, and leukocytosis to 14.7. She is admitted to the hospitalist service for sepsis secondary to right lower extremity cellulitis.

Introduction

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) remain among the most common inpatient diagnoses cared for by hospitalists. Most patients admitted to a hospitalist service with an SSTI meet the criteria for either moderate or severe infection as outlined by the Infectious Disease Society of America – systemic signs of infection by SIRS criteria or a high likelihood of an immunocompromised state, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection, trauma, or wounds.1

Often these patients have several comorbid conditions such as diabetes, morbid obesity, or peripheral arterial and venous disease. Though most hospitalists are adept at managing diabetes, blood pressure, and other comorbidities, the ability to recognize and manage peripheral vascular disease can be challenging. This article will discuss ways to help providers better identify and manage underlying peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and/or chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) in patients admitted with lower extremity SSTIs.

1. In addition to an infection, could there also be underlying peripheral arterial or venous disease?

Patients with peripheral edema and vascular disease are predisposed to recurrent lower extremity SSTIs. When assessing for vascular disease, it is important to consider PAD and CVI separately.

CVI refers to the spectrum of syndromes caused by venous valvular incompetency, venous obstruction, or decreased muscle contraction. Veins cannot maximally deliver venous blood back to the heart resulting in venous pooling in the lower extremities. The exact mechanism of the skin changes that accompany venous insufficiency is unknown but may be related to cytokine cascades that result in perivascular inflammation and a weakening of the dermal barrier. Over time, this can develop into spontaneous ulceration of the skin.2,3

PAD refers to atherosclerosis of the noncerebral, noncoronary arteries, which leads to ischemic symptoms and atrophy of the supplied territory. Ulceration usually results from mild trauma due to poor wound healing.4,5 A thorough history, assessment of risk factors, and physical exam are essential to identifying these two potential diagnoses in patients admitted with SSTIs.

First, the provider should assess risk factors for underlying vascular disease. For PAD, these include risk factors similar to those of coronary artery disease (CAD): hypertension, hyperlipidemia, history of smoking, and poorly-controlled diabetes. Chronic kidney disease and family history are also associated with PAD. Since PAD and CAD share similar risk factors, it is often common for patients with CAD (as well as patients with cerebrovascular disease) to have PAD. Risk factors for CVI include obesity, chronic sedentary lifestyle, multiple pregnancies, family history, and prior superficial or deep venous thrombosis.2,4

Next, the provider should ask the patient about symptoms experienced prior to the onset of the current SSTI. Patients with either arterial or venous disease will typically report lower extremity symptoms that have been occurring for months to years, long before the acute SSTI. The classic symptom for PAD is claudication – leg pain or cramping that occurs on exertion and improves with rest. This is due to decreased arterial blood flow to the affected limb, felt most acutely during exercise. Other symptoms include numbness, a cool lower extremity, and lower extremity hair loss. As PAD progresses, a patient may also have rest pain, which may indicate more critical ischemia, as well nonhealing wounds after mild trauma.

In contrast, symptoms of CVI present more variably. CVI can be associated with heaviness, cramping, and pain that are usually worse in the dependent position and relieved with elevation. Patients may also report dry skin, edema, pruritus, scaling, skin tightness, and indolent ulcers at advanced stages.2-6

The physical exam can help the provider distinguish between venous and arterial disease. Patients with PAD often have diminished or nonpalpable distal pulses, bruits in proximal arteries, pallor, hair loss, nail thickening, decreased capillary refill time, and ulceration of the toes. CVI shares some common characteristics but can be distinguished by evidence of varicose veins, telangiectasia, edema (which spares the foot), lipodermatosclerosis, and atrophie blanche (white scarring around the ankle). Patients with venous disease tend to have warm lower extremities and palpable pulses. Often, there is hyperpigmentation, especially around the ankles, and associated eczematous changes with scaling, erythema, and weeping. CVI can also present with ulcers. In addition, if the SSTI is not responding to appropriate antibiotics in the typical time frame, this may be a clue that there is an underlying vascular issue.2-6

Ulcers, whether arterial or venous, comprise a break in the skin’s protective barrier and give bacteria a point of entry. Thus, ulcers often get superinfected, leading to an SSTI rather than SSTIs causing ulcers. The anatomic location can help differentiate between venous and arterial ulcers. Arterial ulcers tend to occur on the toes, heels, and lateral and medial malleoli. Venous ulcers are classically present above the medial malleolus but can occur anywhere on the medial lower third of the leg. Venous ulcers are more superficial and have an irregular shape, while arterial ulcers are deeper, have smoother edges and a “punched-out” shape. Both arterial and venous ulcers can be exudative though venous ulcers are rarely necrotic. Both arterial and venous ulcers can be painful.7-9

2. There are signs and symptoms of underlying vascular disease in a patient with a lower extremity SSTI. Now what?

Neither PAD nor CVI is a clinical diagnosis, thus further work-up is required to confirm the diagnosis and accurately classify disease severity. The timing of this work-up is of unique interest to hospitalists.

Most patients who are hospitalized with cellulitis or a superficial wound infection do not need urgent inpatient work-up of suspected peripheral arterial or venous disease. The one notable exception to this is patients with diabetic foot infections or infected arterial ulcers that need prompt evaluation for possible critical limb ischemia. Barring cases of critical limb ischemia, the main objective of identifying PAD or CVI in patients hospitalized for SSTIs is to appropriately arrange testing and follow-up after discharge.

To address specific management strategies, it is useful to stratify patients by symptom and exam severity as follows: mild/moderate PAD symptoms without ulcer; infected ulcer with PAD features; mild/moderate CVI symptoms without ulcer; and infected ulcer with CVI features. As specific guidelines for the inpatient work-up and management of suspected peripheral arterial and venous disease are sparse, we rely on guidelines and best practices used in the outpatient setting and adapt them to these potential inpatient presentations.

Mild/Moderate PAD symptoms with superimposed cellulitis but no ulceration

In a patient admitted for cellulitis without open wounds, history and review of systems might reveal the presence of claudication or other symptoms suspicious for PAD. While the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force and American College of Cardiology discourages the routine screening of asymptomatic patients for PAD, patients with risk factors who endorse symptoms should undergo initial testing for PAD with an ankle-brachial index (ABI).10

The ABI is the ratio of ankle blood pressure to arm blood pressure, and is measured via sphygmomanometry with a Doppler probe. The ABI remains the simplest, most inexpensive first-line test for PAD. An ABI value of less than 0.9 is considered diagnostic for PAD and has been found to be more than 95% specific for arterial stenoses of greater than 50% on angiography across multiple studies.11

In an inpatient with risk factors for PAD and claudication symptoms, referral for outpatient ABIs with subsequent follow-up by a primary care physician should be arranged. If a diagnosis of PAD is made via ABI, the PCP should reinforce risk factor modification (tobacco cessation, diet, exercise, and aggressive lipid, blood pressure and blood glucose control) and start medical management with a single anti-platelet agent to reduce the risk of MI, stroke, or “vascular death.” The most recent ACC guidelines recommend either aspirin or clopidogrel as an acceptable anti-platelet agent (grade 1A).12 Cilostazol may be considered if claudication symptoms are significantly interfering with lifestyle. If this management fails, the patient may be referred to a vascular specialist for consideration of revascularization.

Infected ulcer with PAD features

Unlike cellulitis, arterial ulcers are a direct sequela of arterial insufficiency and represent the far end of the spectrum of disease severity and in certain cases treatment failure. Patients who present with advanced ischemic and/or diabetic foot ulcers may have never been evaluated for PAD as an outpatient. Prompt work-up and management is required given the high degree of morbidity and mortality associated with arterial ulcers. Whether an urgent inpatient evaluation is indicated depends on the clinical evaluation.

The first step is to determine the depth of the ulceration. Critical limb ischemia may be present if the ulcer is deep, gangrenous, overlies a bony prominence, or is associated with systemic signs of sepsis. A physical exam should include an assessment of the pulses including femoral, popliteal, PT and DP, preferably with bedside Doppler ultrasound. If pulses are absent, urgent vascular surgery evaluation is warranted to prevent loss of limb; the work-up generally involves imaging such as computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography to identify culprit lesions, or if sufficiently suspicious, immediate invasive angiogram with the potential for endovascular intervention.

While palpable pulses can be reassuring and raise the possibility of a nonarterial etiology of ulceration – such as a microvascular, neuropathic or venous disease – it is important to remember that pulse exams are often unreliable and provider dependent.13 Moreover, the presence of pulses does not effectively exclude severe PAD or critical limb ischemia in patients with a high pretest probability.14 Thus, in cases of deep, complex lower extremity and foot ulcers, it is prudent to obtain urgent evaluation by a surgical wound specialist, which depending on the institution may be podiatry, vascular surgery, or wound care. This may lead to a better clinical assessment of the wound and clearer recommendations regarding the need for additional testing, such as imaging, to rule out osteomyelitis, surgical debridement, or amputation.

Inpatient ABIs in this situation may help diagnose and quantify the severity of PAD. Newer classification schemes such as the Society of Vascular Surgery Wound Ischemia Foot Infection score take into account clinical findings as well as ABI scores to better prognosticate limb loss and select patients for intervention.15 If the clinical picture is deemed sufficiently suspicious for critical limb ischemia, the patient may be taken directly for invasive testing with possible intervention.

If an infected ulcer is superficial, shows no signs of gangrene, and has been present for less than 30 days, further work-up for suspected PAD can generally be deferred to an outpatient setting after resolution of the acute infection. Management of the wound is highly institution dependent. When available, a wound care specialist (physician or nurse) or a plastic surgeon can be consulted as an inpatient to give specific recommendations that can range anywhere from enzymatic debridement to simple dressing. If this service is unavailable, we recommend dressing the wound with moist nonocclusive dressings with frequent changes. Referrals for ABI testing and follow up in podiatry, wound care, or vascular clinic should be arranged. Finally, educating the patient on what to expect can increase compliance with the outpatient treatment plan.

Mild to moderate CVI symptoms with superimposed cellulitis but no ulceration

Chronic venous insufficiency is a syndrome that has variable presentations based on the location and degree of valvular incompetence in the superficial or, less commonly, deep venous systems. For a patient with cellulitis and CVI, the clinical exam findings may be associated with venous hypertension syndrome – in which there is deep axial reflux and possible obstruction – and could also represent complex varicose disease which is usually caused by superficial reflux of the greater saphenous vein.3 The lack of advanced skin changes and ulceration raises the suspicion of mild to moderate CVI.

Guidelines from the American Venous Forum and the Society for Vascular Surgery recommend that all patients with suspected CVI, regardless of severity, undergo venous duplex ultrasound scanning as a first diagnostic test (grade 1A) to accurately classify the disease according to the Clinical Etiological Anatomical Pathophysiology (CEAP) system (Table 1).16

Compression therapy is commonly accepted as a noninvasive treatment option for all levels of CVI, yet most of the evidence comes from secondary prevention studies in patients with advanced CVI with venous ulcers.18 Strong evidence for the role of compression stockings in mild to moderate CVI is lacking. In fact, recent guidelines from the Society of Vascular Surgery, reviewed by the American Heart Association, do not recommend compression therapy as a primary treatment modality in patients with symptomatic varicose veins (without ulcers) if the patient is a candidate for saphenous vein ablation.19 This recommendation is based on clinical trial data that showed greater efficacy and cost-effectiveness of surgery versus conservative management in patients with CEAP2 (low severity) CVI as well as studies noting noncompliance with compression therapy as high as 75%.20-21

However, determining a patient’s candidacy for ablative or surgical therapy requires ultrasound data for accurate CEAP scoring, which is often not achieved as an inpatient. Given the potential benefit and lack of severe adverse effects, hospitalists can consider initiating compression therapy at the time of discharge in a patient with mild to moderate signs of CVI and a low risk profile for severe PAD. The prescription should specify knee-length elastic stockings with graduated compression between 20 to 30 mm Hg.22 The patient should also be encouraged to complete the outpatient duplex ultrasound testing prior to the PCP visit so that he or she can be referred to a vascular specialist appropriately.

Infected ulcer with CVI features

If the patient’s exam is suspicious for advanced venous disease with ulceration, the clinician should evaluate for the presence of scarring. This would indicate that there has been long-standing venous disease with recurrent ulceration. This patient should be asked about a previous diagnosis of CVI, prior compression therapy, and barriers to compliance with compression therapy such as poor fit or difficulty of use due to obesity or immobility. It is important to note that mixed ulcers are present in up to 20% of patients; a careful assessment of risk factors for PAD, pulse exam, and referral for outpatient ABI testing is warranted to rule out arterial insufficiency in this patient with likely venous ulcer.23

The AHA recommends prompt specialist evaluation for CEAP scores greater than or equal to 4; based on physical exam alone, this patient’s active venous ulcer yields the highest possible score of 6.2 If not previously done, this patient with advanced CVI and ulceration should be referred for an outpatient venous duplex ultrasound as well as urgent follow-up with a vascular specialist soon after discharge.

There is significant consensus in the literature that multilayer compression therapy between 30 and 40 mm Hg is the first-line treatment in patients with venous ulcers as it has been shown to promote ulcer healing and prevent recurrence.24-25 In addition, superficial venous surgery, including minimally invasive ablation, can reduce the recurrence of ulcers if used as adjunctive therapy in selected patients.26 However, compressive therapy should generally not be prescribed in patients with venous ulcers until PAD has been ruled out.

If ABI results are available, the clinician can consider compression at 30-40 mm Hg for ABI values greater than 0.8 and reduced compression at 20-30 mm Hg for values of 0.5-0.8; compression is contraindicated if the ABI is less than 0.5. Prompt follow-up with a vascular specialist can help direct compressive and/or surgical therapy. Wound care consultation as an inpatient can assist with dressing recommendations, though the evidence has not shown that dressings of any type worn under compressive garments improve ulcer healing.27

Bottom line