User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Identifying the right database

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center will be converting to the most common electronic medical record (EMR) systems used today: Epic. Until that time, Vanderbilt used a homegrown system to keep track of patient data. The “system” was actual comprised of a few separate programs that integrated data, depending on the functions being accessed and who was accessing them.

For many research projects across the hospital, including my own, we are going to be limiting ourselves to data from the time period when our homegrown EMR was functioning. This is thinking a few steps ahead, but it would be interesting to see if our model, once validated, performed similarly in a new EMR environment. Unfortunately, this is thinking a few too many steps ahead for me, as I will have graduated (hopefully) by the time the new EMR is up and running reliably enough for EMR-based research like this project.

The first step in our study was identifying the right database to use, and now the next step will be extracting the data we need. Moving forward, I am continuing to work with my mentors, Dr. Eduard Vasilevskis and Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld closely. We resubmitted our IRB application now that we have identified how we can pull the data we need, and we identified a few specialized patient populations for whom a separate scoring tool might be useful (e.g., stroke patients). I am looking forward to learning the particulars how our dataset will be built. The potential for finding the answers to many patient-care questions probably lies in the EMR data we already have, but you need to know how to get them to study them.

Monisha Bhatia, a native of Nashville, Tenn., is a fourth-year medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. She is hoping to pursue either a residency in internal medicine or a combined internal medicine/emergency medicine program. Prior to medical school, she completed a JD/MPH program at Boston University, and she hopes to use her legal training in working with regulatory authorities to improve access to health care for all Americans.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center will be converting to the most common electronic medical record (EMR) systems used today: Epic. Until that time, Vanderbilt used a homegrown system to keep track of patient data. The “system” was actual comprised of a few separate programs that integrated data, depending on the functions being accessed and who was accessing them.

For many research projects across the hospital, including my own, we are going to be limiting ourselves to data from the time period when our homegrown EMR was functioning. This is thinking a few steps ahead, but it would be interesting to see if our model, once validated, performed similarly in a new EMR environment. Unfortunately, this is thinking a few too many steps ahead for me, as I will have graduated (hopefully) by the time the new EMR is up and running reliably enough for EMR-based research like this project.

The first step in our study was identifying the right database to use, and now the next step will be extracting the data we need. Moving forward, I am continuing to work with my mentors, Dr. Eduard Vasilevskis and Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld closely. We resubmitted our IRB application now that we have identified how we can pull the data we need, and we identified a few specialized patient populations for whom a separate scoring tool might be useful (e.g., stroke patients). I am looking forward to learning the particulars how our dataset will be built. The potential for finding the answers to many patient-care questions probably lies in the EMR data we already have, but you need to know how to get them to study them.

Monisha Bhatia, a native of Nashville, Tenn., is a fourth-year medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. She is hoping to pursue either a residency in internal medicine or a combined internal medicine/emergency medicine program. Prior to medical school, she completed a JD/MPH program at Boston University, and she hopes to use her legal training in working with regulatory authorities to improve access to health care for all Americans.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center will be converting to the most common electronic medical record (EMR) systems used today: Epic. Until that time, Vanderbilt used a homegrown system to keep track of patient data. The “system” was actual comprised of a few separate programs that integrated data, depending on the functions being accessed and who was accessing them.

For many research projects across the hospital, including my own, we are going to be limiting ourselves to data from the time period when our homegrown EMR was functioning. This is thinking a few steps ahead, but it would be interesting to see if our model, once validated, performed similarly in a new EMR environment. Unfortunately, this is thinking a few too many steps ahead for me, as I will have graduated (hopefully) by the time the new EMR is up and running reliably enough for EMR-based research like this project.

The first step in our study was identifying the right database to use, and now the next step will be extracting the data we need. Moving forward, I am continuing to work with my mentors, Dr. Eduard Vasilevskis and Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld closely. We resubmitted our IRB application now that we have identified how we can pull the data we need, and we identified a few specialized patient populations for whom a separate scoring tool might be useful (e.g., stroke patients). I am looking forward to learning the particulars how our dataset will be built. The potential for finding the answers to many patient-care questions probably lies in the EMR data we already have, but you need to know how to get them to study them.

Monisha Bhatia, a native of Nashville, Tenn., is a fourth-year medical student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. She is hoping to pursue either a residency in internal medicine or a combined internal medicine/emergency medicine program. Prior to medical school, she completed a JD/MPH program at Boston University, and she hopes to use her legal training in working with regulatory authorities to improve access to health care for all Americans.

Understanding people is complex, yet essential for effective leadership

Editor’s note: Each month, Society of Hospital Medicine puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients.

What are the requirements to become a Master in Hospital Medicine, and how has this designation been beneficial to your career?

I have been an SHM member since the early years (early 2000s, I think), and I became a Master in Hospital Medicine (MHM) in 2013. I see the MHM designation as recognizing accomplishments that have been critical in advancing the field of hospital medicine and SHM as a society.

I would guess that my contributions to the SHM Board, being SHM president, cofounding (with others) the Academic Hospitalist Academy, founding (with others) the Quality Safety Educators Academy, and being the founding chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine pathway were probably what led to my induction.

The salient question probably isn’t “How has this designation been beneficial to my career?” but, rather, “How, after receiving the MHM designation, has my career benefited hospital medicine and SHM?” To my mind, there are some awards in life that recognize excellence in the completion of a task. They herald the end of a finite game: a “best research project” award, for example. But then there are a special few recognitions that, while they recognize past contributions, focus more upon the future than the past. They are infinite recognitions, because implicitly, they are recognitions of “promise” as much as achievement. They convey the organization’s trust in, and high expectations for, the recipient. In sum, they are simultaneously an honor and an obligation … an obligation and an expectation that the recipient will continue to do even more. In academic parlance, being “tenured” is a good example; for the Society of Hospital Medicine, the equivalent is the MHM recognition. I have done a lot for SHM, but the MHM designation obligates me to do even more. Honoring that obligation is what I plan to do with my career.

How did you become involved with SHM’s Leadership Academy, and how has the program developed over the years?

I started doing a 1-hour talk when the Mastering Teamwork course started. I did that for a couple of years but, as my career was evolving into higher-level institutional and hospital leadership, there was much more to talk about than I could fit into 1 hour.

The core of my leadership message is based in the “character ethic” (being better than who you are) and not the popular “personality ethic” (looking better than you are). So it’s that … plus all of the leadership mistakes I have made along the way. And that’s a lot of mistakes … enough to fill 9 hours of Mastering Teamwork.

In your opinion, what are some of the main takeaways for those who participate in SHM’s Leadership Academy?

Two of the three core components of great leadership are having a mission and purpose and being sincere. Leadership Academy can’t deliver the first two, so participants do have to come prepared to be trained.

Understanding people is the third core component, and mastering that skill is really complex. It is not something you can do with a clever slogan and a new lapel pin. It comes in many forms: teamwork, communication, networking, dealing with crisis, orchestrating change, etc. But at its core, Leadership Academy is all about training future leaders in how to understand people … and to develop the skills to inspire, motivate, and move their team to greater heights. Because at its core, leadership is about getting people to go places they otherwise didn’t want to go and to do things that they didn’t already want to do. And, to do that, you have to understand people.

As an active SHM member of many years, what advice do you have for members who wish to get more involved?

You have to start somewhere, and you have to see the entry level years as investing in yourself. There will be sacrifice involved, so don’t expect immediate returns on the investment, and the first few years might not be that fun.

Every year, there is a call for committee membership, and you need to get involved in one or more of those committees. Find the most senior hospitalist, who is the most involved in SHM, and tell her that you want to be on an SHM committee, and could she nominate you? If you do not have that luxury, then pay attention at the SHM annual conference. The SHM president-elect is responsible for building out the SHM committee nominees; as president, you are always looking to find enthusiastic people to be on the committees. Receiving emails from enthusiastic members is more welcome than you might think. As soon as that person is announced, find her email and start making the request to be on a committee. Be open to the assignment: Even if it is not your favorite committee, being there is more important than not.

But remember, networking and reputation are “two tailed.” You can improve your reputation by meaningful and consistent participation on a committee (leading to higher and better leadership opportunities), but you can also tarnish it by being assigned to a committee and not doing anything. You do that once, and there is a high probability that you will not be asked back again.

Great strategy, at the end of the day, is always putting yourself in a position with the maximum number of options. The key to personal development strategy is networking. The more people you know, the higher the probability that your email box will light up with the “Hey, do you want to collaborate on this project together?” sort of emails. Attend the annual conferences, attend the SHM Academies (Leadership, Quality and Safety Educators Academy, Academic Hospitalist Academy, etc.). Build genuine relationships with the people you meet there, and the rest will work out just fine.

Ms. Steele is the marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: Each month, Society of Hospital Medicine puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients.

What are the requirements to become a Master in Hospital Medicine, and how has this designation been beneficial to your career?

I have been an SHM member since the early years (early 2000s, I think), and I became a Master in Hospital Medicine (MHM) in 2013. I see the MHM designation as recognizing accomplishments that have been critical in advancing the field of hospital medicine and SHM as a society.

I would guess that my contributions to the SHM Board, being SHM president, cofounding (with others) the Academic Hospitalist Academy, founding (with others) the Quality Safety Educators Academy, and being the founding chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine pathway were probably what led to my induction.

The salient question probably isn’t “How has this designation been beneficial to my career?” but, rather, “How, after receiving the MHM designation, has my career benefited hospital medicine and SHM?” To my mind, there are some awards in life that recognize excellence in the completion of a task. They herald the end of a finite game: a “best research project” award, for example. But then there are a special few recognitions that, while they recognize past contributions, focus more upon the future than the past. They are infinite recognitions, because implicitly, they are recognitions of “promise” as much as achievement. They convey the organization’s trust in, and high expectations for, the recipient. In sum, they are simultaneously an honor and an obligation … an obligation and an expectation that the recipient will continue to do even more. In academic parlance, being “tenured” is a good example; for the Society of Hospital Medicine, the equivalent is the MHM recognition. I have done a lot for SHM, but the MHM designation obligates me to do even more. Honoring that obligation is what I plan to do with my career.

How did you become involved with SHM’s Leadership Academy, and how has the program developed over the years?

I started doing a 1-hour talk when the Mastering Teamwork course started. I did that for a couple of years but, as my career was evolving into higher-level institutional and hospital leadership, there was much more to talk about than I could fit into 1 hour.

The core of my leadership message is based in the “character ethic” (being better than who you are) and not the popular “personality ethic” (looking better than you are). So it’s that … plus all of the leadership mistakes I have made along the way. And that’s a lot of mistakes … enough to fill 9 hours of Mastering Teamwork.

In your opinion, what are some of the main takeaways for those who participate in SHM’s Leadership Academy?

Two of the three core components of great leadership are having a mission and purpose and being sincere. Leadership Academy can’t deliver the first two, so participants do have to come prepared to be trained.

Understanding people is the third core component, and mastering that skill is really complex. It is not something you can do with a clever slogan and a new lapel pin. It comes in many forms: teamwork, communication, networking, dealing with crisis, orchestrating change, etc. But at its core, Leadership Academy is all about training future leaders in how to understand people … and to develop the skills to inspire, motivate, and move their team to greater heights. Because at its core, leadership is about getting people to go places they otherwise didn’t want to go and to do things that they didn’t already want to do. And, to do that, you have to understand people.

As an active SHM member of many years, what advice do you have for members who wish to get more involved?

You have to start somewhere, and you have to see the entry level years as investing in yourself. There will be sacrifice involved, so don’t expect immediate returns on the investment, and the first few years might not be that fun.

Every year, there is a call for committee membership, and you need to get involved in one or more of those committees. Find the most senior hospitalist, who is the most involved in SHM, and tell her that you want to be on an SHM committee, and could she nominate you? If you do not have that luxury, then pay attention at the SHM annual conference. The SHM president-elect is responsible for building out the SHM committee nominees; as president, you are always looking to find enthusiastic people to be on the committees. Receiving emails from enthusiastic members is more welcome than you might think. As soon as that person is announced, find her email and start making the request to be on a committee. Be open to the assignment: Even if it is not your favorite committee, being there is more important than not.

But remember, networking and reputation are “two tailed.” You can improve your reputation by meaningful and consistent participation on a committee (leading to higher and better leadership opportunities), but you can also tarnish it by being assigned to a committee and not doing anything. You do that once, and there is a high probability that you will not be asked back again.

Great strategy, at the end of the day, is always putting yourself in a position with the maximum number of options. The key to personal development strategy is networking. The more people you know, the higher the probability that your email box will light up with the “Hey, do you want to collaborate on this project together?” sort of emails. Attend the annual conferences, attend the SHM Academies (Leadership, Quality and Safety Educators Academy, Academic Hospitalist Academy, etc.). Build genuine relationships with the people you meet there, and the rest will work out just fine.

Ms. Steele is the marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: Each month, Society of Hospital Medicine puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients.

What are the requirements to become a Master in Hospital Medicine, and how has this designation been beneficial to your career?

I have been an SHM member since the early years (early 2000s, I think), and I became a Master in Hospital Medicine (MHM) in 2013. I see the MHM designation as recognizing accomplishments that have been critical in advancing the field of hospital medicine and SHM as a society.

I would guess that my contributions to the SHM Board, being SHM president, cofounding (with others) the Academic Hospitalist Academy, founding (with others) the Quality Safety Educators Academy, and being the founding chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine pathway were probably what led to my induction.

The salient question probably isn’t “How has this designation been beneficial to my career?” but, rather, “How, after receiving the MHM designation, has my career benefited hospital medicine and SHM?” To my mind, there are some awards in life that recognize excellence in the completion of a task. They herald the end of a finite game: a “best research project” award, for example. But then there are a special few recognitions that, while they recognize past contributions, focus more upon the future than the past. They are infinite recognitions, because implicitly, they are recognitions of “promise” as much as achievement. They convey the organization’s trust in, and high expectations for, the recipient. In sum, they are simultaneously an honor and an obligation … an obligation and an expectation that the recipient will continue to do even more. In academic parlance, being “tenured” is a good example; for the Society of Hospital Medicine, the equivalent is the MHM recognition. I have done a lot for SHM, but the MHM designation obligates me to do even more. Honoring that obligation is what I plan to do with my career.

How did you become involved with SHM’s Leadership Academy, and how has the program developed over the years?

I started doing a 1-hour talk when the Mastering Teamwork course started. I did that for a couple of years but, as my career was evolving into higher-level institutional and hospital leadership, there was much more to talk about than I could fit into 1 hour.

The core of my leadership message is based in the “character ethic” (being better than who you are) and not the popular “personality ethic” (looking better than you are). So it’s that … plus all of the leadership mistakes I have made along the way. And that’s a lot of mistakes … enough to fill 9 hours of Mastering Teamwork.

In your opinion, what are some of the main takeaways for those who participate in SHM’s Leadership Academy?

Two of the three core components of great leadership are having a mission and purpose and being sincere. Leadership Academy can’t deliver the first two, so participants do have to come prepared to be trained.

Understanding people is the third core component, and mastering that skill is really complex. It is not something you can do with a clever slogan and a new lapel pin. It comes in many forms: teamwork, communication, networking, dealing with crisis, orchestrating change, etc. But at its core, Leadership Academy is all about training future leaders in how to understand people … and to develop the skills to inspire, motivate, and move their team to greater heights. Because at its core, leadership is about getting people to go places they otherwise didn’t want to go and to do things that they didn’t already want to do. And, to do that, you have to understand people.

As an active SHM member of many years, what advice do you have for members who wish to get more involved?

You have to start somewhere, and you have to see the entry level years as investing in yourself. There will be sacrifice involved, so don’t expect immediate returns on the investment, and the first few years might not be that fun.

Every year, there is a call for committee membership, and you need to get involved in one or more of those committees. Find the most senior hospitalist, who is the most involved in SHM, and tell her that you want to be on an SHM committee, and could she nominate you? If you do not have that luxury, then pay attention at the SHM annual conference. The SHM president-elect is responsible for building out the SHM committee nominees; as president, you are always looking to find enthusiastic people to be on the committees. Receiving emails from enthusiastic members is more welcome than you might think. As soon as that person is announced, find her email and start making the request to be on a committee. Be open to the assignment: Even if it is not your favorite committee, being there is more important than not.

But remember, networking and reputation are “two tailed.” You can improve your reputation by meaningful and consistent participation on a committee (leading to higher and better leadership opportunities), but you can also tarnish it by being assigned to a committee and not doing anything. You do that once, and there is a high probability that you will not be asked back again.

Great strategy, at the end of the day, is always putting yourself in a position with the maximum number of options. The key to personal development strategy is networking. The more people you know, the higher the probability that your email box will light up with the “Hey, do you want to collaborate on this project together?” sort of emails. Attend the annual conferences, attend the SHM Academies (Leadership, Quality and Safety Educators Academy, Academic Hospitalist Academy, etc.). Build genuine relationships with the people you meet there, and the rest will work out just fine.

Ms. Steele is the marketing communications specialist at the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Atrial fibrillation boosts VTE risk

BARCELONA – Atrial fibrillation is at least as strong a risk factor for venous thromboembolism as for ischemic stroke, Bjorn Hornestam, MD, asserted at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This novel finding from a Swedish national registry study suggests it’s time for thoughtful consideration of a revision of risk scores in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), according to Dr. Hornestam, director of cardiology at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden.

“VTE risk is not included as an outcome in the CHA2DS2-VASc score, so we underestimate the total thromboembolic risk in AF patients,” he said.

Dr. Hornestam presented a Swedish registry study of 1.36 million patients, including 470,738 patients with new-onset AF and no previous diagnosis of VTE or ischemic stroke and twice as many controls without AF who were matched to the AF patients by age, gender, and county.

The VTE risk was highest during the first 30 days after diagnosis of AF. Women with new-onset AF had an 8.3-fold increased risk of VTE compared with controls during this early period, by a margin of 55.8 versus 6.4 cases per 1,000 person-years. Men with newly diagnosed AF had a 7.2-fold increased risk of VTE in the first 30 days, reflecting a rate of 40.1 per 1,000 person-years compared to 5.6 per 1,000 in controls.

The VTE risk dropped off precipitously in men after the first month. The rate was cut in half by 2 months after AF diagnosis and was no different from that of controls by 9 months.

In women, too, the early elevated VTE risk was halved by 2 months out, but thereafter the rate of decline in VTE risk slowed. Even 10 years after AF diagnosis, women had a 21% greater VTE risk than did matched controls.

Of note, the risk of VTE during the first 12 months after diagnosis of AF was nearly twice as great in both men and women under age 65 than in those older than 75.

These data raise the question of whether standard therapy in AF patients needs to be modified, especially during what now appears to be the critical time frame of the first 3-6 months after diagnosis of the arrhythmia, Dr. Hornestam said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

BARCELONA – Atrial fibrillation is at least as strong a risk factor for venous thromboembolism as for ischemic stroke, Bjorn Hornestam, MD, asserted at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This novel finding from a Swedish national registry study suggests it’s time for thoughtful consideration of a revision of risk scores in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), according to Dr. Hornestam, director of cardiology at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden.

“VTE risk is not included as an outcome in the CHA2DS2-VASc score, so we underestimate the total thromboembolic risk in AF patients,” he said.

Dr. Hornestam presented a Swedish registry study of 1.36 million patients, including 470,738 patients with new-onset AF and no previous diagnosis of VTE or ischemic stroke and twice as many controls without AF who were matched to the AF patients by age, gender, and county.

The VTE risk was highest during the first 30 days after diagnosis of AF. Women with new-onset AF had an 8.3-fold increased risk of VTE compared with controls during this early period, by a margin of 55.8 versus 6.4 cases per 1,000 person-years. Men with newly diagnosed AF had a 7.2-fold increased risk of VTE in the first 30 days, reflecting a rate of 40.1 per 1,000 person-years compared to 5.6 per 1,000 in controls.

The VTE risk dropped off precipitously in men after the first month. The rate was cut in half by 2 months after AF diagnosis and was no different from that of controls by 9 months.

In women, too, the early elevated VTE risk was halved by 2 months out, but thereafter the rate of decline in VTE risk slowed. Even 10 years after AF diagnosis, women had a 21% greater VTE risk than did matched controls.

Of note, the risk of VTE during the first 12 months after diagnosis of AF was nearly twice as great in both men and women under age 65 than in those older than 75.

These data raise the question of whether standard therapy in AF patients needs to be modified, especially during what now appears to be the critical time frame of the first 3-6 months after diagnosis of the arrhythmia, Dr. Hornestam said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

BARCELONA – Atrial fibrillation is at least as strong a risk factor for venous thromboembolism as for ischemic stroke, Bjorn Hornestam, MD, asserted at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

This novel finding from a Swedish national registry study suggests it’s time for thoughtful consideration of a revision of risk scores in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), according to Dr. Hornestam, director of cardiology at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden.

“VTE risk is not included as an outcome in the CHA2DS2-VASc score, so we underestimate the total thromboembolic risk in AF patients,” he said.

Dr. Hornestam presented a Swedish registry study of 1.36 million patients, including 470,738 patients with new-onset AF and no previous diagnosis of VTE or ischemic stroke and twice as many controls without AF who were matched to the AF patients by age, gender, and county.

The VTE risk was highest during the first 30 days after diagnosis of AF. Women with new-onset AF had an 8.3-fold increased risk of VTE compared with controls during this early period, by a margin of 55.8 versus 6.4 cases per 1,000 person-years. Men with newly diagnosed AF had a 7.2-fold increased risk of VTE in the first 30 days, reflecting a rate of 40.1 per 1,000 person-years compared to 5.6 per 1,000 in controls.

The VTE risk dropped off precipitously in men after the first month. The rate was cut in half by 2 months after AF diagnosis and was no different from that of controls by 9 months.

In women, too, the early elevated VTE risk was halved by 2 months out, but thereafter the rate of decline in VTE risk slowed. Even 10 years after AF diagnosis, women had a 21% greater VTE risk than did matched controls.

Of note, the risk of VTE during the first 12 months after diagnosis of AF was nearly twice as great in both men and women under age 65 than in those older than 75.

These data raise the question of whether standard therapy in AF patients needs to be modified, especially during what now appears to be the critical time frame of the first 3-6 months after diagnosis of the arrhythmia, Dr. Hornestam said.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The risk of a first venous thromboembolism is increased 7.2- to 8.3-fold during the first 30 days following diagnosis of AF and remains moderately elevated in women even 10 years later.

Data source: An observational Swedish national registry study of more than 1.3 million patients, including 470,738 with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation and their matched controls.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Quick Byte: Telemental health visits on the rise

Telemental health visits are on the rise.

In 2014, there were 5.3 and 11.8 telemental health visits per 100 rural beneficiaries with any mental illness or serious mental illness, respectively.

Reference

Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, et al. Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural Medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Aff. 2017 May 1;36(5):909-17. Accessed May 24, 2017.

Telemental health visits are on the rise.

In 2014, there were 5.3 and 11.8 telemental health visits per 100 rural beneficiaries with any mental illness or serious mental illness, respectively.

Reference

Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, et al. Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural Medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Aff. 2017 May 1;36(5):909-17. Accessed May 24, 2017.

Telemental health visits are on the rise.

In 2014, there were 5.3 and 11.8 telemental health visits per 100 rural beneficiaries with any mental illness or serious mental illness, respectively.

Reference

Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, et al. Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural Medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Aff. 2017 May 1;36(5):909-17. Accessed May 24, 2017.

Sneak Peek: The Hospital Leader blog – Oct. 2017

You Have Lowered Length of Stay. Congratulations: You’re Fired.

For several decades, providers working within hospitals have had incentives to reduce stay durations and keep patient flow tip-top. Diagnosis Related Group (DRG)–based and capitated payments expedited that shift.

Accompanying the change, physicians became more aware of the potential repercussions of sicker and quicker discharges. They began to monitor their care and, as best as possible, use what measures they could as a proxy for quality (readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions). Providers balanced the harms of a continued stay with the benefits of added days, not to mention the need for cost savings.

I recognize this because of the cognitive dissonance providers now experience because of the mixed messages delivered by hospital leaders.

On the one hand, the DRG-driven system that we have binds the hospital’s bottom line – and that is not going away. On the other, we are paying more attention to excessive costs in post-acute settings, that is, subacute facilities when home health will do or more intense acute rehabilitation rather than the subacute route.

Making determinations as to whether a certain course is proper, whether a patient will be safe, whether families can provide adequate agency and backing, and whether we can avail community services takes time. Sicker and quicker; mindful of short-term outcomes; worked when we had postdischarge blinders on. As we remove such obstacles, and payment incentives change to cover broader intervals of time, we have to adapt. And that means leadership must realize that the practices that held hospitals in sound financial stead in years past are heading toward extinction – or, at best, falling out of favor.

Compare the costs of routine hospital care with the added expense of post-acute care, then multiply that extra expense times an aging, dependent population, and you add billions of dollars to the recovery tab. Some of these expenses are necessary, and some are not; a stay at a skilled nursing facility, for example, doubles the cost of an episode.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

- Why 7 On/7 Off Doesn’t Meet the Needs of Long-Stay Hospital Patients by Lauren Doctoroff, MD, FHM

- Is It Time for Health Policy M&Ms? by Chris Moriates, MD

- George Carlin Predicts Hospital Planning Strategy by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

- Many Paths to a Richer Job by Leslie Flores, MHA, MPH, SFHM

- A New Face for Online Modules by Chris Moriates, MD

You Have Lowered Length of Stay. Congratulations: You’re Fired.

For several decades, providers working within hospitals have had incentives to reduce stay durations and keep patient flow tip-top. Diagnosis Related Group (DRG)–based and capitated payments expedited that shift.

Accompanying the change, physicians became more aware of the potential repercussions of sicker and quicker discharges. They began to monitor their care and, as best as possible, use what measures they could as a proxy for quality (readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions). Providers balanced the harms of a continued stay with the benefits of added days, not to mention the need for cost savings.

I recognize this because of the cognitive dissonance providers now experience because of the mixed messages delivered by hospital leaders.

On the one hand, the DRG-driven system that we have binds the hospital’s bottom line – and that is not going away. On the other, we are paying more attention to excessive costs in post-acute settings, that is, subacute facilities when home health will do or more intense acute rehabilitation rather than the subacute route.

Making determinations as to whether a certain course is proper, whether a patient will be safe, whether families can provide adequate agency and backing, and whether we can avail community services takes time. Sicker and quicker; mindful of short-term outcomes; worked when we had postdischarge blinders on. As we remove such obstacles, and payment incentives change to cover broader intervals of time, we have to adapt. And that means leadership must realize that the practices that held hospitals in sound financial stead in years past are heading toward extinction – or, at best, falling out of favor.

Compare the costs of routine hospital care with the added expense of post-acute care, then multiply that extra expense times an aging, dependent population, and you add billions of dollars to the recovery tab. Some of these expenses are necessary, and some are not; a stay at a skilled nursing facility, for example, doubles the cost of an episode.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

- Why 7 On/7 Off Doesn’t Meet the Needs of Long-Stay Hospital Patients by Lauren Doctoroff, MD, FHM

- Is It Time for Health Policy M&Ms? by Chris Moriates, MD

- George Carlin Predicts Hospital Planning Strategy by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

- Many Paths to a Richer Job by Leslie Flores, MHA, MPH, SFHM

- A New Face for Online Modules by Chris Moriates, MD

You Have Lowered Length of Stay. Congratulations: You’re Fired.

For several decades, providers working within hospitals have had incentives to reduce stay durations and keep patient flow tip-top. Diagnosis Related Group (DRG)–based and capitated payments expedited that shift.

Accompanying the change, physicians became more aware of the potential repercussions of sicker and quicker discharges. They began to monitor their care and, as best as possible, use what measures they could as a proxy for quality (readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions). Providers balanced the harms of a continued stay with the benefits of added days, not to mention the need for cost savings.

I recognize this because of the cognitive dissonance providers now experience because of the mixed messages delivered by hospital leaders.

On the one hand, the DRG-driven system that we have binds the hospital’s bottom line – and that is not going away. On the other, we are paying more attention to excessive costs in post-acute settings, that is, subacute facilities when home health will do or more intense acute rehabilitation rather than the subacute route.

Making determinations as to whether a certain course is proper, whether a patient will be safe, whether families can provide adequate agency and backing, and whether we can avail community services takes time. Sicker and quicker; mindful of short-term outcomes; worked when we had postdischarge blinders on. As we remove such obstacles, and payment incentives change to cover broader intervals of time, we have to adapt. And that means leadership must realize that the practices that held hospitals in sound financial stead in years past are heading toward extinction – or, at best, falling out of favor.

Compare the costs of routine hospital care with the added expense of post-acute care, then multiply that extra expense times an aging, dependent population, and you add billions of dollars to the recovery tab. Some of these expenses are necessary, and some are not; a stay at a skilled nursing facility, for example, doubles the cost of an episode.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

- Why 7 On/7 Off Doesn’t Meet the Needs of Long-Stay Hospital Patients by Lauren Doctoroff, MD, FHM

- Is It Time for Health Policy M&Ms? by Chris Moriates, MD

- George Carlin Predicts Hospital Planning Strategy by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

- Many Paths to a Richer Job by Leslie Flores, MHA, MPH, SFHM

- A New Face for Online Modules by Chris Moriates, MD

Scheduling patterns in hospital medicine

For years, the Society of Hospital Medicine has been asking hospital medicine programs about operational metrics in order to understand and catalog how they are functioning and evolving. After compensation, the scheduling patterns that hospital medicine groups (HMGs) are using is the most reviewed item in the report.

When hospital medicine first started, 7 days working followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) quickly became vogue. No one really knows how this happened, but it was most likely due to the fact that hospital medicine most closely resembled emergency medicine and scheduling similar to emergency medicine seemed to make sense (that is, 14 shifts per month). That along with the assumption that continuity of care was critical in inpatient care and would improve quality most likely resulted in the popularity of the 7-on-7-off schedule.

In the most recent survey in 2016, HMGs were once again asked to comment on how they schedule. Groups were able to choose from five scheduling options:

1. Seven days on followed by 7 days off

2. Other fixed rotation block schedules (such as 5-on 5-off; or 10-on 5-off)

3. Monday to Friday with rotating weekend coverage

4. Variable schedule

5. Other

Looking at HMG programs that serve only adult populations, a majority of them (48%) follow a fixed rotating schedule either 7 days on followed by 7 days off, or some other fixed schedule, while 31% of programs that responded stated that they used a Monday to Friday schedule. Looking at the programs as a whole, it would seem that the 7-on-7-off schedule was quickly losing popularity while the Monday to Friday schedule was increasingly being used. However, this broad generalization doesn’t really give you the full picture.

Upon analyzing the data further, we see some distinct differences arise based on program size. Small programs (fewer than 10 full-time employees [FTEs]) are much more likely to schedule a Monday to Friday schedule than any other model, whereas only a handful of large programs (greater than 20 FTEs) schedule in this way, rather choosing to use a 7-on-7-off schedule.

The last survey was done in 2014 and a lot has changed since then. Significantly more programs responded in 2016, compared with 2014 (530 vs. 355) and the majority of this increase was made of up smaller programs (fewer than 10 FTEs). Programs with four or fewer FTEs, compared with the prior survey, increased by over 400% (37 programs in 2014 vs. 151 programs in 2016). Overall, programs with fewer than 10 FTEs constituted over 50% of the total programs that responded in 2016 (whereas they made up only a third in 2014). This was particularly significant since size of the program was the one variable that determined how a program might schedule – other factors like geographic region, academic status, or primary hospital GME status did not show significant variance in how groups scheduled.

The second major change that occurred is that these same small programs (those with fewer than 10 FTEs) moved overwhelmingly to a Monday to Friday schedule. In 2014, only 3% of small programs scheduled using a Monday to Friday pattern, but in 2016 almost 50% of small programs reported scheduling in this way. This change in the overall composition of programs, with small programs now making up over 50% of the programs that reported, and the specific change in how small programs schedule results in a noteworthy decrease of programs using a 7 days on followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) schedule (53.8% in 2014 and only 38.1% in 2016), and a corresponding increase in the number of programs that schedule using a Monday to Friday schedule (4% in 2014 to 31% in 2016).

In distinct contrast to programs with fewer than 10 FTEs, a very similar number of programs with greater than 20 FTEs reported in 2016 as in 2014 – there was no increase in this subgroup. I’m not clear at this time if this is because there is truly no increase in the number of large programs nationally, or if there is another factor causing larger programs to under-report. The large programs that did report data in 2016 continue to utilize a 7-on-7-off schedule or another fixed rotating block schedule more than 50% of the time. In fact, the utilization of one of these two scheduling patterns increased slightly from 2014 to 2016 (from 52% to 58%). Those that did not use one of the prior mentioned scheduling patterns were most likely to schedule with a variable schedule. A Monday to Friday schedule was almost never used in programs of this size and showed no significant change from 2014 to 2016.

This snapshot highlights the changing landscape in hospital medicine. Hospital medicine is penetrating more and more into smaller and smaller hospitals, and has even made it into critical access hospitals. As recently as 5-10 years ago, it was felt that these hospitals were too small to have a hospital medicine program. This is likely one of the reasons for the increase in programs with four or fewer FTEs. There has also been increasing discontent with the 7-on-7-off schedule, which many feel is leading to burnout. Dr. Bob Wachter famously said during the closing plenary of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting that the 7-on-7-off schedule was “a mistake.” Despite this brewing discontent, larger programs have not changed their scheduling patterns, likely because finding a another scheduling pattern that is effective, supports high-quality care, and is sustainable for such a large group is challenging.

Many people will say that there are as many different types of hospital medicine programs as there are hospital medicine programs. This is true for scheduling as for other aspects of hospital medicine operations. As we continue to grow and evolve as an industry, scheduling patterns will continue to change and evolve as well. For now, two patterns are emerging – smaller programs are utilizing a Monday to Friday schedule and larger programs are utilizing a 7-on-7-off schedule. Only time will tell if these scheduling patterns persist or continue to evolve.

Dr. George is a board certified internal medicine physician and practicing hospitalist with over 15 years of experience in hospital medicine. She has been actively involved in the Society of Hospital Medicine and has participated in and chaired multiple committees and task forces. She is currently executive vice president and chief medical officer of Hospital Medicine at Schumacher Clinical Partners, a national provider of emergency medicine and hospital medicine services. She lives in the northwest suburbs of Chicago with her family.

For years, the Society of Hospital Medicine has been asking hospital medicine programs about operational metrics in order to understand and catalog how they are functioning and evolving. After compensation, the scheduling patterns that hospital medicine groups (HMGs) are using is the most reviewed item in the report.

When hospital medicine first started, 7 days working followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) quickly became vogue. No one really knows how this happened, but it was most likely due to the fact that hospital medicine most closely resembled emergency medicine and scheduling similar to emergency medicine seemed to make sense (that is, 14 shifts per month). That along with the assumption that continuity of care was critical in inpatient care and would improve quality most likely resulted in the popularity of the 7-on-7-off schedule.

In the most recent survey in 2016, HMGs were once again asked to comment on how they schedule. Groups were able to choose from five scheduling options:

1. Seven days on followed by 7 days off

2. Other fixed rotation block schedules (such as 5-on 5-off; or 10-on 5-off)

3. Monday to Friday with rotating weekend coverage

4. Variable schedule

5. Other

Looking at HMG programs that serve only adult populations, a majority of them (48%) follow a fixed rotating schedule either 7 days on followed by 7 days off, or some other fixed schedule, while 31% of programs that responded stated that they used a Monday to Friday schedule. Looking at the programs as a whole, it would seem that the 7-on-7-off schedule was quickly losing popularity while the Monday to Friday schedule was increasingly being used. However, this broad generalization doesn’t really give you the full picture.

Upon analyzing the data further, we see some distinct differences arise based on program size. Small programs (fewer than 10 full-time employees [FTEs]) are much more likely to schedule a Monday to Friday schedule than any other model, whereas only a handful of large programs (greater than 20 FTEs) schedule in this way, rather choosing to use a 7-on-7-off schedule.

The last survey was done in 2014 and a lot has changed since then. Significantly more programs responded in 2016, compared with 2014 (530 vs. 355) and the majority of this increase was made of up smaller programs (fewer than 10 FTEs). Programs with four or fewer FTEs, compared with the prior survey, increased by over 400% (37 programs in 2014 vs. 151 programs in 2016). Overall, programs with fewer than 10 FTEs constituted over 50% of the total programs that responded in 2016 (whereas they made up only a third in 2014). This was particularly significant since size of the program was the one variable that determined how a program might schedule – other factors like geographic region, academic status, or primary hospital GME status did not show significant variance in how groups scheduled.

The second major change that occurred is that these same small programs (those with fewer than 10 FTEs) moved overwhelmingly to a Monday to Friday schedule. In 2014, only 3% of small programs scheduled using a Monday to Friday pattern, but in 2016 almost 50% of small programs reported scheduling in this way. This change in the overall composition of programs, with small programs now making up over 50% of the programs that reported, and the specific change in how small programs schedule results in a noteworthy decrease of programs using a 7 days on followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) schedule (53.8% in 2014 and only 38.1% in 2016), and a corresponding increase in the number of programs that schedule using a Monday to Friday schedule (4% in 2014 to 31% in 2016).

In distinct contrast to programs with fewer than 10 FTEs, a very similar number of programs with greater than 20 FTEs reported in 2016 as in 2014 – there was no increase in this subgroup. I’m not clear at this time if this is because there is truly no increase in the number of large programs nationally, or if there is another factor causing larger programs to under-report. The large programs that did report data in 2016 continue to utilize a 7-on-7-off schedule or another fixed rotating block schedule more than 50% of the time. In fact, the utilization of one of these two scheduling patterns increased slightly from 2014 to 2016 (from 52% to 58%). Those that did not use one of the prior mentioned scheduling patterns were most likely to schedule with a variable schedule. A Monday to Friday schedule was almost never used in programs of this size and showed no significant change from 2014 to 2016.

This snapshot highlights the changing landscape in hospital medicine. Hospital medicine is penetrating more and more into smaller and smaller hospitals, and has even made it into critical access hospitals. As recently as 5-10 years ago, it was felt that these hospitals were too small to have a hospital medicine program. This is likely one of the reasons for the increase in programs with four or fewer FTEs. There has also been increasing discontent with the 7-on-7-off schedule, which many feel is leading to burnout. Dr. Bob Wachter famously said during the closing plenary of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting that the 7-on-7-off schedule was “a mistake.” Despite this brewing discontent, larger programs have not changed their scheduling patterns, likely because finding a another scheduling pattern that is effective, supports high-quality care, and is sustainable for such a large group is challenging.

Many people will say that there are as many different types of hospital medicine programs as there are hospital medicine programs. This is true for scheduling as for other aspects of hospital medicine operations. As we continue to grow and evolve as an industry, scheduling patterns will continue to change and evolve as well. For now, two patterns are emerging – smaller programs are utilizing a Monday to Friday schedule and larger programs are utilizing a 7-on-7-off schedule. Only time will tell if these scheduling patterns persist or continue to evolve.

Dr. George is a board certified internal medicine physician and practicing hospitalist with over 15 years of experience in hospital medicine. She has been actively involved in the Society of Hospital Medicine and has participated in and chaired multiple committees and task forces. She is currently executive vice president and chief medical officer of Hospital Medicine at Schumacher Clinical Partners, a national provider of emergency medicine and hospital medicine services. She lives in the northwest suburbs of Chicago with her family.

For years, the Society of Hospital Medicine has been asking hospital medicine programs about operational metrics in order to understand and catalog how they are functioning and evolving. After compensation, the scheduling patterns that hospital medicine groups (HMGs) are using is the most reviewed item in the report.

When hospital medicine first started, 7 days working followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) quickly became vogue. No one really knows how this happened, but it was most likely due to the fact that hospital medicine most closely resembled emergency medicine and scheduling similar to emergency medicine seemed to make sense (that is, 14 shifts per month). That along with the assumption that continuity of care was critical in inpatient care and would improve quality most likely resulted in the popularity of the 7-on-7-off schedule.

In the most recent survey in 2016, HMGs were once again asked to comment on how they schedule. Groups were able to choose from five scheduling options:

1. Seven days on followed by 7 days off

2. Other fixed rotation block schedules (such as 5-on 5-off; or 10-on 5-off)

3. Monday to Friday with rotating weekend coverage

4. Variable schedule

5. Other

Looking at HMG programs that serve only adult populations, a majority of them (48%) follow a fixed rotating schedule either 7 days on followed by 7 days off, or some other fixed schedule, while 31% of programs that responded stated that they used a Monday to Friday schedule. Looking at the programs as a whole, it would seem that the 7-on-7-off schedule was quickly losing popularity while the Monday to Friday schedule was increasingly being used. However, this broad generalization doesn’t really give you the full picture.

Upon analyzing the data further, we see some distinct differences arise based on program size. Small programs (fewer than 10 full-time employees [FTEs]) are much more likely to schedule a Monday to Friday schedule than any other model, whereas only a handful of large programs (greater than 20 FTEs) schedule in this way, rather choosing to use a 7-on-7-off schedule.

The last survey was done in 2014 and a lot has changed since then. Significantly more programs responded in 2016, compared with 2014 (530 vs. 355) and the majority of this increase was made of up smaller programs (fewer than 10 FTEs). Programs with four or fewer FTEs, compared with the prior survey, increased by over 400% (37 programs in 2014 vs. 151 programs in 2016). Overall, programs with fewer than 10 FTEs constituted over 50% of the total programs that responded in 2016 (whereas they made up only a third in 2014). This was particularly significant since size of the program was the one variable that determined how a program might schedule – other factors like geographic region, academic status, or primary hospital GME status did not show significant variance in how groups scheduled.

The second major change that occurred is that these same small programs (those with fewer than 10 FTEs) moved overwhelmingly to a Monday to Friday schedule. In 2014, only 3% of small programs scheduled using a Monday to Friday pattern, but in 2016 almost 50% of small programs reported scheduling in this way. This change in the overall composition of programs, with small programs now making up over 50% of the programs that reported, and the specific change in how small programs schedule results in a noteworthy decrease of programs using a 7 days on followed by 7 days off (7-on-7-off) schedule (53.8% in 2014 and only 38.1% in 2016), and a corresponding increase in the number of programs that schedule using a Monday to Friday schedule (4% in 2014 to 31% in 2016).

In distinct contrast to programs with fewer than 10 FTEs, a very similar number of programs with greater than 20 FTEs reported in 2016 as in 2014 – there was no increase in this subgroup. I’m not clear at this time if this is because there is truly no increase in the number of large programs nationally, or if there is another factor causing larger programs to under-report. The large programs that did report data in 2016 continue to utilize a 7-on-7-off schedule or another fixed rotating block schedule more than 50% of the time. In fact, the utilization of one of these two scheduling patterns increased slightly from 2014 to 2016 (from 52% to 58%). Those that did not use one of the prior mentioned scheduling patterns were most likely to schedule with a variable schedule. A Monday to Friday schedule was almost never used in programs of this size and showed no significant change from 2014 to 2016.

This snapshot highlights the changing landscape in hospital medicine. Hospital medicine is penetrating more and more into smaller and smaller hospitals, and has even made it into critical access hospitals. As recently as 5-10 years ago, it was felt that these hospitals were too small to have a hospital medicine program. This is likely one of the reasons for the increase in programs with four or fewer FTEs. There has also been increasing discontent with the 7-on-7-off schedule, which many feel is leading to burnout. Dr. Bob Wachter famously said during the closing plenary of the 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting that the 7-on-7-off schedule was “a mistake.” Despite this brewing discontent, larger programs have not changed their scheduling patterns, likely because finding a another scheduling pattern that is effective, supports high-quality care, and is sustainable for such a large group is challenging.

Many people will say that there are as many different types of hospital medicine programs as there are hospital medicine programs. This is true for scheduling as for other aspects of hospital medicine operations. As we continue to grow and evolve as an industry, scheduling patterns will continue to change and evolve as well. For now, two patterns are emerging – smaller programs are utilizing a Monday to Friday schedule and larger programs are utilizing a 7-on-7-off schedule. Only time will tell if these scheduling patterns persist or continue to evolve.

Dr. George is a board certified internal medicine physician and practicing hospitalist with over 15 years of experience in hospital medicine. She has been actively involved in the Society of Hospital Medicine and has participated in and chaired multiple committees and task forces. She is currently executive vice president and chief medical officer of Hospital Medicine at Schumacher Clinical Partners, a national provider of emergency medicine and hospital medicine services. She lives in the northwest suburbs of Chicago with her family.

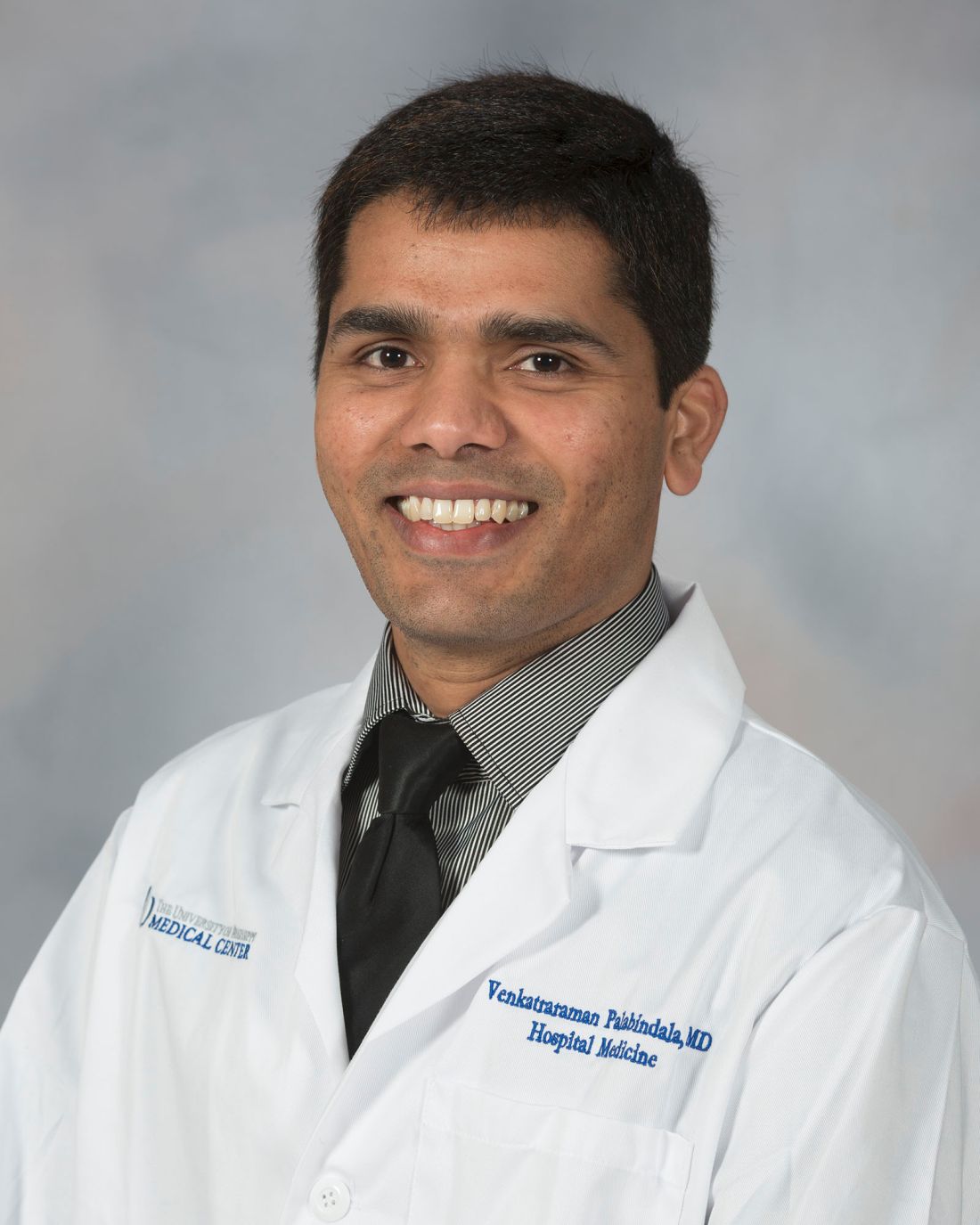

Emphasizing an entrepreneurial spirit: Raman Palabindala, MD

Venkatraraman “Raman” Palabindala, MD, FACP, SFHM, was destined to be a doctor since his first breath. Born in India, his father decided Dr. Palabindala would take the mantle as the doctor of the family, while his siblings took to other professions like engineering.

Eager to be in the thick of things, Dr. Palabindala has voraciously pursued leadership positions, leading to his current role as chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson.

Dr. Palabindala is enthusiastic about his role as one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, and took time to tell us more about himself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you get into medicine?

A: It’s all because of my dad’s motivation. My father believed in education, so when I was born, he said, “He’s going to be a doctor,” and as I grew up, I just worked towards being a physician and nothing else. I didn’t even have an option of choosing anything else. My dad said that I would be a doctor, and I am a doctor. I feel like that was the best thing that happened to me, though; it worked out well.

Q: How and when did you decide to go into hospital medicine?

A: After I came to the U.S., I joined residency in internal medicine at GBMC – that’s Greater Baltimore Medical Center – it’s affiliated with Johns Hopkins. I always wanted to be an internist, but my experiences in the clinic world were not so great. But I really enjoyed inpatient medicine, so in my 3rd year, when I was doing my chief residency year, I did get opportunities to join a fellowship, but I decided just to be a hospitalist at that time.

Q: What do you find to be rewarding about hospital medicine?

Q: What is one of the biggest challenges in hospital medicine?

A: I think talking about the business aspect of medicine, because it is like a taboo. We don’t really want to talk about whether the patient is covered or not covered by insurance, how much we are billing, and why we must discuss business issues while we are trying to focus on patient care, but these things are going to indirectly affect patient care, too. If you didn’t note the patient status accurately, they are going to get an inappropriate bill.

Q: What’s the best advice you have received that you try to pass on to your students?

A: Do the rounds at the bedside. We have the tendency of doing everything outside and then going in the room and just telling the patient what we are going to do. Instead, I encourage everyone to be at the bedside. Even without students, I go and sit at the bedside and then review the data in terms the patient can understand, and then explain the care plan, so they actually feel like we are at the bedside for a longer time. We are with the patient for at least 10 to 15 minutes, but at the same time, we are getting things done. I encourage my students and residents to do this.

Q: What is the worst advice you’ve received?

A: I don’t know if this is the “worst” advice, but in my second year, I was trying to take some leadership positions and was told I should wait, that leadership skills come with experience. I do think that’s a bad piece of advice. It’s all about learning how hard you work and then how fast you learn, and then how fast you implement. People who work, learn, and implement quickly can make a difference.

Q: Outside of patient care, what other career interests do you have?

A: I’m interested in smart clinics, and I actually have a patent for smart clinic chains. I’m a big fan of primary care, because, like hospitalists revolutionized inpatient care, I think we can revolutionize the outpatient care experience as well. I don’t think we are being very efficient with outpatient care.

But if I was not practicing medicine, I probably would be a chef. I like to cook, and I would open up my own restaurant if I was not doing this.

Q: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

A: I want to be a consultant, evaluating hospitalist programs and guiding programs to grow and be more efficient. That, I think, would be the primary job that I would like to be doing, along with giving lectures and teaching about patient safety and quality, and educating younger physicians about the business of medicine.

Q: What experience with SHM has made the most lasting impact on you?

A: I would say the best impression was from the Academic Hospitalist Academy meeting I attended in Denver. I think that was helpful, because it was like a boot camp where you have only a limited number of attendees with a dedicated mentor. That was amazing, and I learned a lot. It helped me in redesigning my approach to where I would like to be both short- and long-term. I implemented at least 50 percent of what I learned at that meeting.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently and why was it the best?

A: Being Mortal by Atul Gawande. It’s a really beautiful book.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Venkatraraman “Raman” Palabindala, MD, FACP, SFHM, was destined to be a doctor since his first breath. Born in India, his father decided Dr. Palabindala would take the mantle as the doctor of the family, while his siblings took to other professions like engineering.

Eager to be in the thick of things, Dr. Palabindala has voraciously pursued leadership positions, leading to his current role as chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson.

Dr. Palabindala is enthusiastic about his role as one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, and took time to tell us more about himself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you get into medicine?

A: It’s all because of my dad’s motivation. My father believed in education, so when I was born, he said, “He’s going to be a doctor,” and as I grew up, I just worked towards being a physician and nothing else. I didn’t even have an option of choosing anything else. My dad said that I would be a doctor, and I am a doctor. I feel like that was the best thing that happened to me, though; it worked out well.

Q: How and when did you decide to go into hospital medicine?

A: After I came to the U.S., I joined residency in internal medicine at GBMC – that’s Greater Baltimore Medical Center – it’s affiliated with Johns Hopkins. I always wanted to be an internist, but my experiences in the clinic world were not so great. But I really enjoyed inpatient medicine, so in my 3rd year, when I was doing my chief residency year, I did get opportunities to join a fellowship, but I decided just to be a hospitalist at that time.

Q: What do you find to be rewarding about hospital medicine?

Q: What is one of the biggest challenges in hospital medicine?

A: I think talking about the business aspect of medicine, because it is like a taboo. We don’t really want to talk about whether the patient is covered or not covered by insurance, how much we are billing, and why we must discuss business issues while we are trying to focus on patient care, but these things are going to indirectly affect patient care, too. If you didn’t note the patient status accurately, they are going to get an inappropriate bill.

Q: What’s the best advice you have received that you try to pass on to your students?

A: Do the rounds at the bedside. We have the tendency of doing everything outside and then going in the room and just telling the patient what we are going to do. Instead, I encourage everyone to be at the bedside. Even without students, I go and sit at the bedside and then review the data in terms the patient can understand, and then explain the care plan, so they actually feel like we are at the bedside for a longer time. We are with the patient for at least 10 to 15 minutes, but at the same time, we are getting things done. I encourage my students and residents to do this.

Q: What is the worst advice you’ve received?

A: I don’t know if this is the “worst” advice, but in my second year, I was trying to take some leadership positions and was told I should wait, that leadership skills come with experience. I do think that’s a bad piece of advice. It’s all about learning how hard you work and then how fast you learn, and then how fast you implement. People who work, learn, and implement quickly can make a difference.

Q: Outside of patient care, what other career interests do you have?

A: I’m interested in smart clinics, and I actually have a patent for smart clinic chains. I’m a big fan of primary care, because, like hospitalists revolutionized inpatient care, I think we can revolutionize the outpatient care experience as well. I don’t think we are being very efficient with outpatient care.

But if I was not practicing medicine, I probably would be a chef. I like to cook, and I would open up my own restaurant if I was not doing this.

Q: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

A: I want to be a consultant, evaluating hospitalist programs and guiding programs to grow and be more efficient. That, I think, would be the primary job that I would like to be doing, along with giving lectures and teaching about patient safety and quality, and educating younger physicians about the business of medicine.

Q: What experience with SHM has made the most lasting impact on you?

A: I would say the best impression was from the Academic Hospitalist Academy meeting I attended in Denver. I think that was helpful, because it was like a boot camp where you have only a limited number of attendees with a dedicated mentor. That was amazing, and I learned a lot. It helped me in redesigning my approach to where I would like to be both short- and long-term. I implemented at least 50 percent of what I learned at that meeting.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently and why was it the best?

A: Being Mortal by Atul Gawande. It’s a really beautiful book.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Venkatraraman “Raman” Palabindala, MD, FACP, SFHM, was destined to be a doctor since his first breath. Born in India, his father decided Dr. Palabindala would take the mantle as the doctor of the family, while his siblings took to other professions like engineering.

Eager to be in the thick of things, Dr. Palabindala has voraciously pursued leadership positions, leading to his current role as chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson.

Dr. Palabindala is enthusiastic about his role as one of the eight new members of The Hospitalist editorial advisory board, and took time to tell us more about himself in a recent interview.

Q: How did you get into medicine?

A: It’s all because of my dad’s motivation. My father believed in education, so when I was born, he said, “He’s going to be a doctor,” and as I grew up, I just worked towards being a physician and nothing else. I didn’t even have an option of choosing anything else. My dad said that I would be a doctor, and I am a doctor. I feel like that was the best thing that happened to me, though; it worked out well.

Q: How and when did you decide to go into hospital medicine?

A: After I came to the U.S., I joined residency in internal medicine at GBMC – that’s Greater Baltimore Medical Center – it’s affiliated with Johns Hopkins. I always wanted to be an internist, but my experiences in the clinic world were not so great. But I really enjoyed inpatient medicine, so in my 3rd year, when I was doing my chief residency year, I did get opportunities to join a fellowship, but I decided just to be a hospitalist at that time.

Q: What do you find to be rewarding about hospital medicine?

Q: What is one of the biggest challenges in hospital medicine?

A: I think talking about the business aspect of medicine, because it is like a taboo. We don’t really want to talk about whether the patient is covered or not covered by insurance, how much we are billing, and why we must discuss business issues while we are trying to focus on patient care, but these things are going to indirectly affect patient care, too. If you didn’t note the patient status accurately, they are going to get an inappropriate bill.

Q: What’s the best advice you have received that you try to pass on to your students?

A: Do the rounds at the bedside. We have the tendency of doing everything outside and then going in the room and just telling the patient what we are going to do. Instead, I encourage everyone to be at the bedside. Even without students, I go and sit at the bedside and then review the data in terms the patient can understand, and then explain the care plan, so they actually feel like we are at the bedside for a longer time. We are with the patient for at least 10 to 15 minutes, but at the same time, we are getting things done. I encourage my students and residents to do this.

Q: What is the worst advice you’ve received?

A: I don’t know if this is the “worst” advice, but in my second year, I was trying to take some leadership positions and was told I should wait, that leadership skills come with experience. I do think that’s a bad piece of advice. It’s all about learning how hard you work and then how fast you learn, and then how fast you implement. People who work, learn, and implement quickly can make a difference.

Q: Outside of patient care, what other career interests do you have?

A: I’m interested in smart clinics, and I actually have a patent for smart clinic chains. I’m a big fan of primary care, because, like hospitalists revolutionized inpatient care, I think we can revolutionize the outpatient care experience as well. I don’t think we are being very efficient with outpatient care.

But if I was not practicing medicine, I probably would be a chef. I like to cook, and I would open up my own restaurant if I was not doing this.

Q: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

A: I want to be a consultant, evaluating hospitalist programs and guiding programs to grow and be more efficient. That, I think, would be the primary job that I would like to be doing, along with giving lectures and teaching about patient safety and quality, and educating younger physicians about the business of medicine.

Q: What experience with SHM has made the most lasting impact on you?

A: I would say the best impression was from the Academic Hospitalist Academy meeting I attended in Denver. I think that was helpful, because it was like a boot camp where you have only a limited number of attendees with a dedicated mentor. That was amazing, and I learned a lot. It helped me in redesigning my approach to where I would like to be both short- and long-term. I implemented at least 50 percent of what I learned at that meeting.

Q: What’s the best book that you’ve read recently and why was it the best?

A: Being Mortal by Atul Gawande. It’s a really beautiful book.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Caprini score is not a good predictor of PE in patients with DVT