User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

Early use of high-titer plasma may prevent severe COVID-19

Administering convalescent plasma that has high levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 within the first 3 days of symptoms was associated with significantly lower chances of progression to severe COVID-19, new evidence demonstrates.

In a trial of 160 older adults with COVID-19, half of whom were randomly assigned to receive plasma and half to receive placebo infusion, treatment with high-titer plasma lowered the relative risk for severe disease by 48% in an intent-to-treat analysis.

“We now have evidence, in the context of a small but well-designed study, that convalescent plasma with high titers of antibody against SARS-CoV-2 administered in the first 3 days of mild symptoms to infected elderly reduces progression of illness and the rate of severe presentations,” senior author Fernando Polack, MD, said in an interview.

“Not any plasma, not any time,” added Dr. Polack, an infectious disease specialist and scientific director at Fundacion INFANT and professor of pediatrics at the University of Buenos Aires. The key, he said, is to select plasma in the upper 28th percentile of IgG antibody concentrations and to administer therapy prior to disease progression.

The study was published online Jan. 6 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“It’s a very good study and approaches a different population from the PlasmAr study,” Ventura Simonovich, MD, chief of the clinical pharmacology section, Medical Clinic Service, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, said in an interview. “This is the first published randomized controlled trial that shows real benefit in this [older adult] population, the most vulnerable in this disease,” he said.

Dr. Simonovich, who was not affiliated with the current study, was lead author of the PlasmAr trial, which was published in The New England Journal of Medicine Nov. 24, 2020. In that trial, the researchers evaluated adults aged 18 years and older and found no significant benefit with convalescent plasma treatment over placebo for patients with COVID-19 and severe pneumonia.

“We know antibodies work best when given early and in high dose. This is one of the rare reports that validates it in the outpatient setting,” David Sullivan, MD, professor of molecular biology and immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

Dr. Sullivan pointed out that most previous studies on convalescent plasma focused on patients with COVID-19 who had severe cases late in the disease course.

Regarding the current study, he said, “The striking thing is treating people within 3 days of illness.”

A more cautious interpretation may be warranted, one expert said. “The study demonstrates the benefit of early intervention. There was a dose-dependent effect, with higher titers providing a greater benefit,” Manoj Menon, MD, MPH, a hematologist and oncologist at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“Taken together, the findings have biologic plausibility and produce more data on the role of convalescent plasma to a relevant age cohort,” he added.

However, Dr. Menon said: “Given the limited sample size, I do not think this study, although well conducted, definitively addresses the role of convalescent plasma for COVID-19. But it does merit additional study.”

A search for clear answers

Treatments that target the early stages of COVID-19 “remain elusive. Few strategies provide benefit, several have failed, and others are being evaluated,” the researchers noted. “In hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the infusion of convalescent plasma against SARS-CoV-2 late in the course of illness has not shown clear benefits and, consequently, the most appropriate antibody concentrations for effective treatment are unclear.”

To learn more, Dr. Polack and colleagues included patients with PCR-confirmed COVID-19 who were aged 75 years or older, regardless of comorbidities. They also included patients aged 65-74 years who had at least one underlying condition. Participants were enrolled at clinical sites or geriatric units in Argentina. The mean age was 77 years, and 62% were women.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, the primary outcome – severe respiratory disease – occurred in 16% of the plasma recipients, vs. 31% of the group that received placebo. The relative risk was 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.29-0.94; P = .03).

The number needed to treat to avoid a severe respiratory disease episode was 7 (95% CI, 4-50).

Life-threatening respiratory disease, a secondary outcome, occurred in four people in the plasma group, compared with 10 in the placebo group. Two patients in the treatment group and four patients in the placebo group died.

The researchers also ran a modified intent-to-treat analysis that excluded six participants who experienced severe respiratory disease prior to receiving plasma or placebo. In this analysis, efficacy of plasma therapy increased to 60%.

“Again, this finding suggests that early intervention is critical for efficacy,” the investigators noted.

The investigators, who are based in Argentina, defined their primary endpoint as a respiratory rate of 30 or more breaths per minute and/or an oxygen saturation of less than 93% while breathing ambient air.

Dr. Sullivan pointed out that this is equivalent to the threshold commonly used for hospitalizing people with COVID-19 in the United States. “So it’s equivalent to avoiding hospitalizations. The take-home is high-titer plasma prevents respiratory distress, which equals hospitalization for us.”

Dr. Sullivan is conducting similar research in the United States regarding the use of plasma for treatment or prevention. He and colleagues are evaluating adults aged 18-90 years, “not just the ones at highest risk for going to the hospital,” he said. Enrollment is ongoing.

An inexpensive therapy with global potential?

“Although our trial lacked the statistical power to discern long-term outcomes, the convalescent plasma group appeared to have better outcomes than the placebo group with respect to all secondary endpoints,” the researchers wrote. “Our findings underscore the need to return to the classic approach of treating acute viral infections early, and they define IgG targets that facilitate donor selection.”

Dr. Polack said, “This is an inexpensive solution to mitigate the burden of severe illness in the population most vulnerable to the virus: the elderly. And it has the attraction of being applicable not only in industrialized countries but in many areas of the developing world.”

Convalescent plasma “is a potentially inexpensive alternative to monoclonal antibodies,” the researchers added. Furthermore, “early infusions of convalescent plasma can provide a bridge to recovery for at-risk patients until vaccines become widely available.”

Dr. Polack said the study findings did not surprise him. “We always thought that, as it has been the case in the past with many therapeutic strategies against respiratory and other viral infections, the earlier you treat, the better.

“We just hoped that within 72 hours of symptoms we would be treating early enough – remember that there is a 4- to 5-day incubation period that the virus leverages before the first symptom – and with enough antibody,” he added.

“We are glad it worked,” he said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and by the Fundación INFANT Pandemic Fund. Dr. Polack, Dr. Simonovich, and Dr. Sullivan have disclosed various financial relationships industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Administering convalescent plasma that has high levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 within the first 3 days of symptoms was associated with significantly lower chances of progression to severe COVID-19, new evidence demonstrates.

In a trial of 160 older adults with COVID-19, half of whom were randomly assigned to receive plasma and half to receive placebo infusion, treatment with high-titer plasma lowered the relative risk for severe disease by 48% in an intent-to-treat analysis.

“We now have evidence, in the context of a small but well-designed study, that convalescent plasma with high titers of antibody against SARS-CoV-2 administered in the first 3 days of mild symptoms to infected elderly reduces progression of illness and the rate of severe presentations,” senior author Fernando Polack, MD, said in an interview.

“Not any plasma, not any time,” added Dr. Polack, an infectious disease specialist and scientific director at Fundacion INFANT and professor of pediatrics at the University of Buenos Aires. The key, he said, is to select plasma in the upper 28th percentile of IgG antibody concentrations and to administer therapy prior to disease progression.

The study was published online Jan. 6 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“It’s a very good study and approaches a different population from the PlasmAr study,” Ventura Simonovich, MD, chief of the clinical pharmacology section, Medical Clinic Service, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, said in an interview. “This is the first published randomized controlled trial that shows real benefit in this [older adult] population, the most vulnerable in this disease,” he said.

Dr. Simonovich, who was not affiliated with the current study, was lead author of the PlasmAr trial, which was published in The New England Journal of Medicine Nov. 24, 2020. In that trial, the researchers evaluated adults aged 18 years and older and found no significant benefit with convalescent plasma treatment over placebo for patients with COVID-19 and severe pneumonia.

“We know antibodies work best when given early and in high dose. This is one of the rare reports that validates it in the outpatient setting,” David Sullivan, MD, professor of molecular biology and immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

Dr. Sullivan pointed out that most previous studies on convalescent plasma focused on patients with COVID-19 who had severe cases late in the disease course.

Regarding the current study, he said, “The striking thing is treating people within 3 days of illness.”

A more cautious interpretation may be warranted, one expert said. “The study demonstrates the benefit of early intervention. There was a dose-dependent effect, with higher titers providing a greater benefit,” Manoj Menon, MD, MPH, a hematologist and oncologist at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“Taken together, the findings have biologic plausibility and produce more data on the role of convalescent plasma to a relevant age cohort,” he added.

However, Dr. Menon said: “Given the limited sample size, I do not think this study, although well conducted, definitively addresses the role of convalescent plasma for COVID-19. But it does merit additional study.”

A search for clear answers

Treatments that target the early stages of COVID-19 “remain elusive. Few strategies provide benefit, several have failed, and others are being evaluated,” the researchers noted. “In hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the infusion of convalescent plasma against SARS-CoV-2 late in the course of illness has not shown clear benefits and, consequently, the most appropriate antibody concentrations for effective treatment are unclear.”

To learn more, Dr. Polack and colleagues included patients with PCR-confirmed COVID-19 who were aged 75 years or older, regardless of comorbidities. They also included patients aged 65-74 years who had at least one underlying condition. Participants were enrolled at clinical sites or geriatric units in Argentina. The mean age was 77 years, and 62% were women.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, the primary outcome – severe respiratory disease – occurred in 16% of the plasma recipients, vs. 31% of the group that received placebo. The relative risk was 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.29-0.94; P = .03).

The number needed to treat to avoid a severe respiratory disease episode was 7 (95% CI, 4-50).

Life-threatening respiratory disease, a secondary outcome, occurred in four people in the plasma group, compared with 10 in the placebo group. Two patients in the treatment group and four patients in the placebo group died.

The researchers also ran a modified intent-to-treat analysis that excluded six participants who experienced severe respiratory disease prior to receiving plasma or placebo. In this analysis, efficacy of plasma therapy increased to 60%.

“Again, this finding suggests that early intervention is critical for efficacy,” the investigators noted.

The investigators, who are based in Argentina, defined their primary endpoint as a respiratory rate of 30 or more breaths per minute and/or an oxygen saturation of less than 93% while breathing ambient air.

Dr. Sullivan pointed out that this is equivalent to the threshold commonly used for hospitalizing people with COVID-19 in the United States. “So it’s equivalent to avoiding hospitalizations. The take-home is high-titer plasma prevents respiratory distress, which equals hospitalization for us.”

Dr. Sullivan is conducting similar research in the United States regarding the use of plasma for treatment or prevention. He and colleagues are evaluating adults aged 18-90 years, “not just the ones at highest risk for going to the hospital,” he said. Enrollment is ongoing.

An inexpensive therapy with global potential?

“Although our trial lacked the statistical power to discern long-term outcomes, the convalescent plasma group appeared to have better outcomes than the placebo group with respect to all secondary endpoints,” the researchers wrote. “Our findings underscore the need to return to the classic approach of treating acute viral infections early, and they define IgG targets that facilitate donor selection.”

Dr. Polack said, “This is an inexpensive solution to mitigate the burden of severe illness in the population most vulnerable to the virus: the elderly. And it has the attraction of being applicable not only in industrialized countries but in many areas of the developing world.”

Convalescent plasma “is a potentially inexpensive alternative to monoclonal antibodies,” the researchers added. Furthermore, “early infusions of convalescent plasma can provide a bridge to recovery for at-risk patients until vaccines become widely available.”

Dr. Polack said the study findings did not surprise him. “We always thought that, as it has been the case in the past with many therapeutic strategies against respiratory and other viral infections, the earlier you treat, the better.

“We just hoped that within 72 hours of symptoms we would be treating early enough – remember that there is a 4- to 5-day incubation period that the virus leverages before the first symptom – and with enough antibody,” he added.

“We are glad it worked,” he said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and by the Fundación INFANT Pandemic Fund. Dr. Polack, Dr. Simonovich, and Dr. Sullivan have disclosed various financial relationships industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Administering convalescent plasma that has high levels of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 within the first 3 days of symptoms was associated with significantly lower chances of progression to severe COVID-19, new evidence demonstrates.

In a trial of 160 older adults with COVID-19, half of whom were randomly assigned to receive plasma and half to receive placebo infusion, treatment with high-titer plasma lowered the relative risk for severe disease by 48% in an intent-to-treat analysis.

“We now have evidence, in the context of a small but well-designed study, that convalescent plasma with high titers of antibody against SARS-CoV-2 administered in the first 3 days of mild symptoms to infected elderly reduces progression of illness and the rate of severe presentations,” senior author Fernando Polack, MD, said in an interview.

“Not any plasma, not any time,” added Dr. Polack, an infectious disease specialist and scientific director at Fundacion INFANT and professor of pediatrics at the University of Buenos Aires. The key, he said, is to select plasma in the upper 28th percentile of IgG antibody concentrations and to administer therapy prior to disease progression.

The study was published online Jan. 6 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

“It’s a very good study and approaches a different population from the PlasmAr study,” Ventura Simonovich, MD, chief of the clinical pharmacology section, Medical Clinic Service, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, said in an interview. “This is the first published randomized controlled trial that shows real benefit in this [older adult] population, the most vulnerable in this disease,” he said.

Dr. Simonovich, who was not affiliated with the current study, was lead author of the PlasmAr trial, which was published in The New England Journal of Medicine Nov. 24, 2020. In that trial, the researchers evaluated adults aged 18 years and older and found no significant benefit with convalescent plasma treatment over placebo for patients with COVID-19 and severe pneumonia.

“We know antibodies work best when given early and in high dose. This is one of the rare reports that validates it in the outpatient setting,” David Sullivan, MD, professor of molecular biology and immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

Dr. Sullivan pointed out that most previous studies on convalescent plasma focused on patients with COVID-19 who had severe cases late in the disease course.

Regarding the current study, he said, “The striking thing is treating people within 3 days of illness.”

A more cautious interpretation may be warranted, one expert said. “The study demonstrates the benefit of early intervention. There was a dose-dependent effect, with higher titers providing a greater benefit,” Manoj Menon, MD, MPH, a hematologist and oncologist at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“Taken together, the findings have biologic plausibility and produce more data on the role of convalescent plasma to a relevant age cohort,” he added.

However, Dr. Menon said: “Given the limited sample size, I do not think this study, although well conducted, definitively addresses the role of convalescent plasma for COVID-19. But it does merit additional study.”

A search for clear answers

Treatments that target the early stages of COVID-19 “remain elusive. Few strategies provide benefit, several have failed, and others are being evaluated,” the researchers noted. “In hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the infusion of convalescent plasma against SARS-CoV-2 late in the course of illness has not shown clear benefits and, consequently, the most appropriate antibody concentrations for effective treatment are unclear.”

To learn more, Dr. Polack and colleagues included patients with PCR-confirmed COVID-19 who were aged 75 years or older, regardless of comorbidities. They also included patients aged 65-74 years who had at least one underlying condition. Participants were enrolled at clinical sites or geriatric units in Argentina. The mean age was 77 years, and 62% were women.

In an intent-to-treat analysis, the primary outcome – severe respiratory disease – occurred in 16% of the plasma recipients, vs. 31% of the group that received placebo. The relative risk was 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.29-0.94; P = .03).

The number needed to treat to avoid a severe respiratory disease episode was 7 (95% CI, 4-50).

Life-threatening respiratory disease, a secondary outcome, occurred in four people in the plasma group, compared with 10 in the placebo group. Two patients in the treatment group and four patients in the placebo group died.

The researchers also ran a modified intent-to-treat analysis that excluded six participants who experienced severe respiratory disease prior to receiving plasma or placebo. In this analysis, efficacy of plasma therapy increased to 60%.

“Again, this finding suggests that early intervention is critical for efficacy,” the investigators noted.

The investigators, who are based in Argentina, defined their primary endpoint as a respiratory rate of 30 or more breaths per minute and/or an oxygen saturation of less than 93% while breathing ambient air.

Dr. Sullivan pointed out that this is equivalent to the threshold commonly used for hospitalizing people with COVID-19 in the United States. “So it’s equivalent to avoiding hospitalizations. The take-home is high-titer plasma prevents respiratory distress, which equals hospitalization for us.”

Dr. Sullivan is conducting similar research in the United States regarding the use of plasma for treatment or prevention. He and colleagues are evaluating adults aged 18-90 years, “not just the ones at highest risk for going to the hospital,” he said. Enrollment is ongoing.

An inexpensive therapy with global potential?

“Although our trial lacked the statistical power to discern long-term outcomes, the convalescent plasma group appeared to have better outcomes than the placebo group with respect to all secondary endpoints,” the researchers wrote. “Our findings underscore the need to return to the classic approach of treating acute viral infections early, and they define IgG targets that facilitate donor selection.”

Dr. Polack said, “This is an inexpensive solution to mitigate the burden of severe illness in the population most vulnerable to the virus: the elderly. And it has the attraction of being applicable not only in industrialized countries but in many areas of the developing world.”

Convalescent plasma “is a potentially inexpensive alternative to monoclonal antibodies,” the researchers added. Furthermore, “early infusions of convalescent plasma can provide a bridge to recovery for at-risk patients until vaccines become widely available.”

Dr. Polack said the study findings did not surprise him. “We always thought that, as it has been the case in the past with many therapeutic strategies against respiratory and other viral infections, the earlier you treat, the better.

“We just hoped that within 72 hours of symptoms we would be treating early enough – remember that there is a 4- to 5-day incubation period that the virus leverages before the first symptom – and with enough antibody,” he added.

“We are glad it worked,” he said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and by the Fundación INFANT Pandemic Fund. Dr. Polack, Dr. Simonovich, and Dr. Sullivan have disclosed various financial relationships industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Guidance issued on COVID vaccine use in patients with dermal fillers

outlining the potential risk and clinical relevance.

The association is not surprising, since other vaccines, including the influenza vaccine, have also been associated with inflammatory reactions in patients with dermal fillers. A warning about inflammatory events from these and other immunologic triggers should be part of routine informed consent, according to Sue Ellen Cox, MD, a coauthor of the guidance and the ASDS president-elect.

“Patients who have had dermal filler should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine, and those who have received the vaccine should not be discouraged from receiving dermal filler,” Dr. Cox, who practices in Chapel Hill, N.C., said in an interview.

The only available data to assess the risk came from the trial of the Moderna vaccine. Of a total of 15,184 participants who received at least one dose of mRNA-1273, three developed facial or lip swelling that was presumably related to dermal filler. In the placebo group, there were no comparable inflammatory events.

“This is a very small number, but there is no reliable information about the number of patients in either group who had dermal filler, so we do not know the denominator,” Dr. Cox said.

In all three cases, the swelling at the site of dermal filler was observed within 2 days of the vaccination. None were considered a serious adverse event and all resolved. The filler had been administered 2 weeks prior to vaccination in one case, 6 months prior in a second, and time of administration was unknown in the third.

The resolution of the inflammatory reactions associated with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is similar to those related to dermal fillers following other immunologic triggers, which not only include other vaccines, but viral or bacterial illnesses and dental procedures. Typically, they are readily controlled with oral corticosteroids, but also typically resolve even in the absence of treatment, according to Dr. Cox.

“The good news is that these will go away,” Dr. Cox said.

The ASDS guidance is meant to alert clinicians and patients to the potential association between inflammatory events and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with dermal filler, but Dr. Cox said that it will ultimately have very little effect on her own practice. She already employs an informed consent that includes language warning about the potential risk of local reactions to immunological triggers that include vaccines. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination can now be added to examples of potential triggers, but it does not change the importance of informing patients of such triggers, Dr. Cox explained.

Asked if patients should be informed specifically about the association between dermal filler inflammatory reactions and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the current ASDS president and first author of the guidance, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, suggested that they should. Although he emphasized that the side effect is clearly rare, he believes it deserves attention.

“We wanted dermatologists and other physicians to be aware of the potential. We focused on the available data but specifically decided not to provide any treatment recommendations at this time,” he said in an interview.

As new data become available, the Soft-Tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

“Our guidance was based only on the trial data, but there will soon be tens of millions of patients exposed to several different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. We may learn things we do not know now, and we plan to communicate to our membership and others any new information as events unfold,” said Dr. Avram, who is director of dermatologic surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston,

Based on her own expertise in the field, Dr. Cox suggested that administration of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and administration of dermal filler should be separated by at least 2 weeks regardless of which comes first. Her recommendation is not based on controlled data, but she considers this a prudent interval even if it has not been tested in a controlled study.

The full ASDS guidance is scheduled to appear in an upcoming issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

As new data become available, the Soft-tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other types of vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

This article was updated 1/7/21.

outlining the potential risk and clinical relevance.

The association is not surprising, since other vaccines, including the influenza vaccine, have also been associated with inflammatory reactions in patients with dermal fillers. A warning about inflammatory events from these and other immunologic triggers should be part of routine informed consent, according to Sue Ellen Cox, MD, a coauthor of the guidance and the ASDS president-elect.

“Patients who have had dermal filler should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine, and those who have received the vaccine should not be discouraged from receiving dermal filler,” Dr. Cox, who practices in Chapel Hill, N.C., said in an interview.

The only available data to assess the risk came from the trial of the Moderna vaccine. Of a total of 15,184 participants who received at least one dose of mRNA-1273, three developed facial or lip swelling that was presumably related to dermal filler. In the placebo group, there were no comparable inflammatory events.

“This is a very small number, but there is no reliable information about the number of patients in either group who had dermal filler, so we do not know the denominator,” Dr. Cox said.

In all three cases, the swelling at the site of dermal filler was observed within 2 days of the vaccination. None were considered a serious adverse event and all resolved. The filler had been administered 2 weeks prior to vaccination in one case, 6 months prior in a second, and time of administration was unknown in the third.

The resolution of the inflammatory reactions associated with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is similar to those related to dermal fillers following other immunologic triggers, which not only include other vaccines, but viral or bacterial illnesses and dental procedures. Typically, they are readily controlled with oral corticosteroids, but also typically resolve even in the absence of treatment, according to Dr. Cox.

“The good news is that these will go away,” Dr. Cox said.

The ASDS guidance is meant to alert clinicians and patients to the potential association between inflammatory events and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with dermal filler, but Dr. Cox said that it will ultimately have very little effect on her own practice. She already employs an informed consent that includes language warning about the potential risk of local reactions to immunological triggers that include vaccines. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination can now be added to examples of potential triggers, but it does not change the importance of informing patients of such triggers, Dr. Cox explained.

Asked if patients should be informed specifically about the association between dermal filler inflammatory reactions and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the current ASDS president and first author of the guidance, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, suggested that they should. Although he emphasized that the side effect is clearly rare, he believes it deserves attention.

“We wanted dermatologists and other physicians to be aware of the potential. We focused on the available data but specifically decided not to provide any treatment recommendations at this time,” he said in an interview.

As new data become available, the Soft-Tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

“Our guidance was based only on the trial data, but there will soon be tens of millions of patients exposed to several different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. We may learn things we do not know now, and we plan to communicate to our membership and others any new information as events unfold,” said Dr. Avram, who is director of dermatologic surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston,

Based on her own expertise in the field, Dr. Cox suggested that administration of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and administration of dermal filler should be separated by at least 2 weeks regardless of which comes first. Her recommendation is not based on controlled data, but she considers this a prudent interval even if it has not been tested in a controlled study.

The full ASDS guidance is scheduled to appear in an upcoming issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

As new data become available, the Soft-tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other types of vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

This article was updated 1/7/21.

outlining the potential risk and clinical relevance.

The association is not surprising, since other vaccines, including the influenza vaccine, have also been associated with inflammatory reactions in patients with dermal fillers. A warning about inflammatory events from these and other immunologic triggers should be part of routine informed consent, according to Sue Ellen Cox, MD, a coauthor of the guidance and the ASDS president-elect.

“Patients who have had dermal filler should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine, and those who have received the vaccine should not be discouraged from receiving dermal filler,” Dr. Cox, who practices in Chapel Hill, N.C., said in an interview.

The only available data to assess the risk came from the trial of the Moderna vaccine. Of a total of 15,184 participants who received at least one dose of mRNA-1273, three developed facial or lip swelling that was presumably related to dermal filler. In the placebo group, there were no comparable inflammatory events.

“This is a very small number, but there is no reliable information about the number of patients in either group who had dermal filler, so we do not know the denominator,” Dr. Cox said.

In all three cases, the swelling at the site of dermal filler was observed within 2 days of the vaccination. None were considered a serious adverse event and all resolved. The filler had been administered 2 weeks prior to vaccination in one case, 6 months prior in a second, and time of administration was unknown in the third.

The resolution of the inflammatory reactions associated with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is similar to those related to dermal fillers following other immunologic triggers, which not only include other vaccines, but viral or bacterial illnesses and dental procedures. Typically, they are readily controlled with oral corticosteroids, but also typically resolve even in the absence of treatment, according to Dr. Cox.

“The good news is that these will go away,” Dr. Cox said.

The ASDS guidance is meant to alert clinicians and patients to the potential association between inflammatory events and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with dermal filler, but Dr. Cox said that it will ultimately have very little effect on her own practice. She already employs an informed consent that includes language warning about the potential risk of local reactions to immunological triggers that include vaccines. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination can now be added to examples of potential triggers, but it does not change the importance of informing patients of such triggers, Dr. Cox explained.

Asked if patients should be informed specifically about the association between dermal filler inflammatory reactions and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the current ASDS president and first author of the guidance, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, suggested that they should. Although he emphasized that the side effect is clearly rare, he believes it deserves attention.

“We wanted dermatologists and other physicians to be aware of the potential. We focused on the available data but specifically decided not to provide any treatment recommendations at this time,” he said in an interview.

As new data become available, the Soft-Tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

“Our guidance was based only on the trial data, but there will soon be tens of millions of patients exposed to several different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. We may learn things we do not know now, and we plan to communicate to our membership and others any new information as events unfold,” said Dr. Avram, who is director of dermatologic surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston,

Based on her own expertise in the field, Dr. Cox suggested that administration of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and administration of dermal filler should be separated by at least 2 weeks regardless of which comes first. Her recommendation is not based on controlled data, but she considers this a prudent interval even if it has not been tested in a controlled study.

The full ASDS guidance is scheduled to appear in an upcoming issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

As new data become available, the Soft-tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other types of vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

This article was updated 1/7/21.

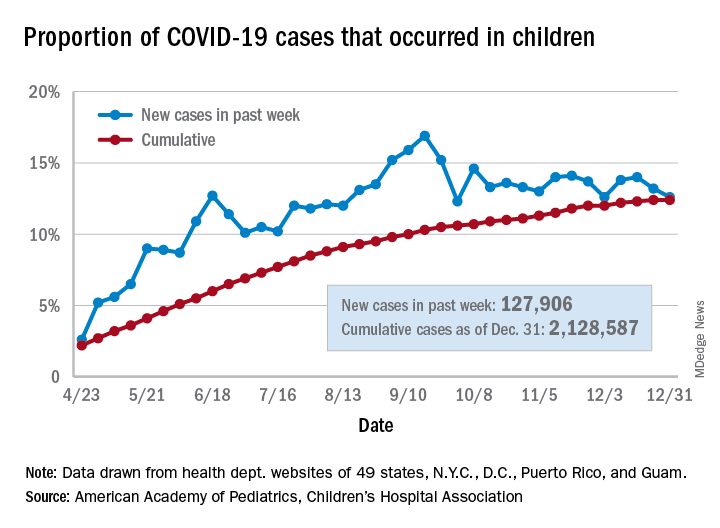

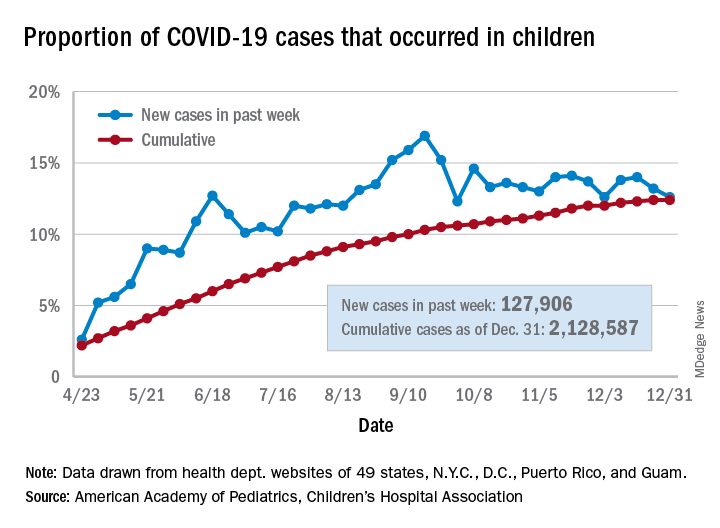

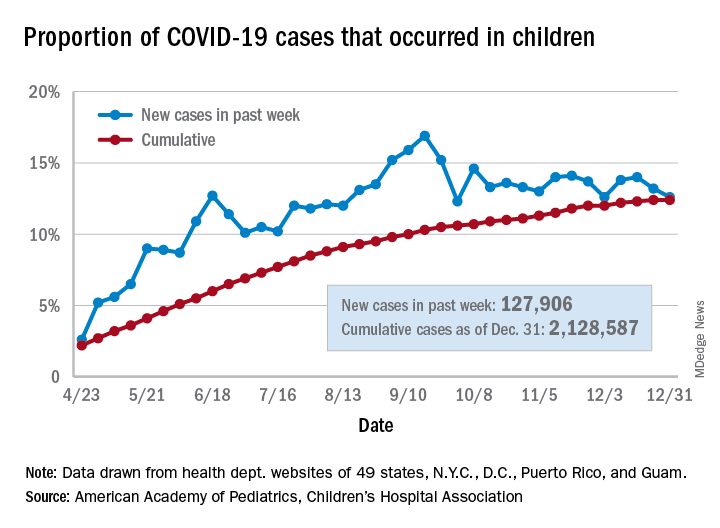

No increase seen in children’s cumulative COVID-19 burden

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

FDA warns about risk for false negatives from Curative COVID test

which is being used in Los Angeles and other large metropolitan areas in the United States.

The real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was developed by Menlo Park, Calif.–based health care start-up Curative. Results are analyzed by the company’s clinical lab, KorvaLabs. The test, which is authorized for prescription use only, received emergency-use authorization from the FDA on April 16, 2020. By Nov. 9, the company had processed 6 million test results, according to the company.

The FDA alert cautions that false negative results from any COVID-19 test can lead to delays in or the lack of supportive treatment and increase the risk for viral spread.

To mitigate the risk for false negatives, the agency advises clinicians to perform the Curative test as described in the product’s Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers. This includes limiting its use to people who have had COVID-19 symptoms for 14 days or less. “Consider retesting your patients using a different test if you suspect an inaccurate result was given recently by the Curative SARS-Cov-2 test,” the FDA alert stated. “If testing was performed more than 2 weeks ago, and there is no reason to suspect current SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is not necessary to retest.”

The alert also notes that a negative result from the Curative PCR test “does not rule out COVID-19 and should not be used as the sole basis for treatment or patient management decisions. A negative result does not exclude the possibility of COVID-19.”

According to a press release issued by Curative on Oct. 7, its PCR test is being used by the Department of Defense, as well as the states of Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia (Atlanta and Savannah), Illinois (Chicago), Louisiana, Texas, and Wyoming. The company also operates Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratories in San Dimas, Calif.; Washington, D.C.; and Pflugerville, Tex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

which is being used in Los Angeles and other large metropolitan areas in the United States.

The real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was developed by Menlo Park, Calif.–based health care start-up Curative. Results are analyzed by the company’s clinical lab, KorvaLabs. The test, which is authorized for prescription use only, received emergency-use authorization from the FDA on April 16, 2020. By Nov. 9, the company had processed 6 million test results, according to the company.

The FDA alert cautions that false negative results from any COVID-19 test can lead to delays in or the lack of supportive treatment and increase the risk for viral spread.

To mitigate the risk for false negatives, the agency advises clinicians to perform the Curative test as described in the product’s Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers. This includes limiting its use to people who have had COVID-19 symptoms for 14 days or less. “Consider retesting your patients using a different test if you suspect an inaccurate result was given recently by the Curative SARS-Cov-2 test,” the FDA alert stated. “If testing was performed more than 2 weeks ago, and there is no reason to suspect current SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is not necessary to retest.”

The alert also notes that a negative result from the Curative PCR test “does not rule out COVID-19 and should not be used as the sole basis for treatment or patient management decisions. A negative result does not exclude the possibility of COVID-19.”

According to a press release issued by Curative on Oct. 7, its PCR test is being used by the Department of Defense, as well as the states of Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia (Atlanta and Savannah), Illinois (Chicago), Louisiana, Texas, and Wyoming. The company also operates Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratories in San Dimas, Calif.; Washington, D.C.; and Pflugerville, Tex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

which is being used in Los Angeles and other large metropolitan areas in the United States.

The real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was developed by Menlo Park, Calif.–based health care start-up Curative. Results are analyzed by the company’s clinical lab, KorvaLabs. The test, which is authorized for prescription use only, received emergency-use authorization from the FDA on April 16, 2020. By Nov. 9, the company had processed 6 million test results, according to the company.

The FDA alert cautions that false negative results from any COVID-19 test can lead to delays in or the lack of supportive treatment and increase the risk for viral spread.

To mitigate the risk for false negatives, the agency advises clinicians to perform the Curative test as described in the product’s Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers. This includes limiting its use to people who have had COVID-19 symptoms for 14 days or less. “Consider retesting your patients using a different test if you suspect an inaccurate result was given recently by the Curative SARS-Cov-2 test,” the FDA alert stated. “If testing was performed more than 2 weeks ago, and there is no reason to suspect current SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is not necessary to retest.”

The alert also notes that a negative result from the Curative PCR test “does not rule out COVID-19 and should not be used as the sole basis for treatment or patient management decisions. A negative result does not exclude the possibility of COVID-19.”

According to a press release issued by Curative on Oct. 7, its PCR test is being used by the Department of Defense, as well as the states of Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia (Atlanta and Savannah), Illinois (Chicago), Louisiana, Texas, and Wyoming. The company also operates Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratories in San Dimas, Calif.; Washington, D.C.; and Pflugerville, Tex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many health plans now must cover full cost of expensive HIV prevention drugs

Ted Howard started taking Truvada a few years ago because he wanted to protect himself against HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. But the daily pill was so pricey he was seriously thinking about giving it up.

Under his insurance plan, the former flight attendant and customer service instructor owed $500 in copayments every month for the drug and an additional $250 every three months for lab work and clinic visits.

Luckily for Howard, his doctor at Las Vegas’ Huntridge Family Clinic, which specializes in LGBTQ care, enrolled him in a clinical trial that covered his medication and other costs in full.

“If I hadn’t been able to get into the trial, I wouldn’t have kept taking PrEP,” said Howard, 68, using the shorthand term for “preexposure prophylaxis.” Taken daily, these drugs — like Truvada — are more than 90% effective at preventing infection with HIV.

(some plans already began doing so last year).

Drugs in this category — Truvada, Descovy and, newly available, a generic version of Truvada — received an “A” recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Under the Affordable Care Act, preventive services that receive an “A” or “B” rating by the task force, a group of medical experts in prevention and primary care, must be covered by most private health plans without making members share the cost, usually through copayments or deductibles. Only plans that are grandfathered under the health law are exempt.

The task force recommended PrEP for people at high risk of HIV infection, including men who have sex with men and injection drug users.

In the United States, more than 1 million people live with HIV, and nearly 40,000 new HIV cases are diagnosed every year. Yet fewer than 10% of people who could benefit from PrEP are taking it. One key reason is that out-of-pocket costs can exceed $1,000 annually, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health last year. Required periodic blood tests and doctor visits can add hundreds of dollars to the cost of the drug, and it’s not clear if insurers are required to pick up all those costs.

“Cost sharing has been a problem,” said Michael Crews, policy director at One Colorado, an advocacy group for the LGBTQ community. “It’s not just getting on PrEP and taking a pill. It’s the lab and clinical services. That’s a huge barrier for folks.”

Whether you’re shopping for a new plan during open enrollment or want to check out what your current plan covers, here are answers to questions you may have about the new preventive coverage requirement.

Q: How can people find out whether their health plan covers PrEP medications without charge?

The plan’s list of covered drugs, called a formulary, should spell out which drugs are covered, along with details about which drug tier they fall into. Drugs placed in higher tiers generally have higher cost sharing. That list should be online with the plan documents that give coverage details.

Sorting out coverage and cost sharing can be tricky. Both Truvada and Descovy can also be used to treat HIV, and if they are taken for that purpose, a plan may require members to pay some of the cost. But if the drugs are taken to prevent HIV infection, patients shouldn’t owe anything out-of-pocket, no matter which tier they are on.

In a recent analysis of online formularies for plans sold on the ACA marketplaces, Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute, found that many plans seemed out of compliance with the requirement to cover PrEP without cost sharing this year.

But representatives for Oscar and Kaiser Permanente, two insurers that were called out in the analysis for lack of compliance, said the drugs are covered without cost sharing in plans nationwide if they are taken to prevent HIV. Schmid later revised his analysis to reflect Oscar’s coverage.

Coverage and cost-sharing information needs to be transparent and easy to find, Schmid said.

“I acted like a shopper of insurance, just like any person would do,” he said. “Even when the information is correct, [it’s so] difficult to find [and there’s] no uniformity.”

It may be necessary to call the insurer directly to confirm coverage details if information on the website is unclear.

Q: Are all three drugs covered without cost sharing?

Health plans have to cover at least one of the drugs in this category — Descovy and the brand and generic versions of Truvada — without cost sharing. People may have to jump through some hoops to get approval for a specific drug, however. For example, Oscar plans sold in 18 states cover the three PrEP options without cost sharing. The generic version of Truvada doesn’t require prior authorization by the insurer. But if someone wants to take the name-brand drug, that person has to go through an approval process. Descovy, a newer drug, is available without cost sharing only if people are unable to use Truvada or its generic version because of clinical intolerance or other issues.

Q: What about the lab work and clinical visits that are necessary while taking PrEP? Are those services also covered without cost sharing?

That is the thousand-dollar question. People who are taking drugs to prevent HIV infection need to meet with a clinician and have blood work every three months to test for HIV, hepatitis B and sexually transmitted infections, and to check their kidney function.

The task force recommendation doesn’t specify whether these services must also be covered without cost sharing, and advocates say federal guidance is necessary to ensure they are free.

“If you’ve got a high-deductible plan and you’ve got to meet it before those services are covered, that’s going to add up,” said Amy Killelea, senior director of health systems and policy at the National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors. “We’re trying to emphasize that it’s integral to the intervention itself.”

A handful of states have programs that help people cover their out-of-pocket costs for lab and clinical visits, generally based on income.

There is precedent for including free ancillary care as part of a recommended preventive service. After consumers and advocates complained, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) clarified that under the ACA removing a polyp during a screening colonoscopy is considered an integral part of the procedure and patients shouldn’t be charged for it.

CMS officials declined to clarify whether PrEP services such as lab work and clinical visits are to be covered without cost sharing as part of the preventive service and noted that states generally enforce such insurance requirements. “CMS intends to contact state regulators, as appropriate, to discuss issuer’s compliance with the federal requirements and whether issuers need further guidance on which services associated with PrEP must be covered without cost sharing,” the agency said in a statement.

Q: What if someone runs into roadblocks getting a plan to cover PrEP or related services without cost sharing?

If an insurer charges for the medication or a follow-up visit, people may have to go through an appeals process to fight it.

“They’d have to appeal to the insurance company and then to the state if they don’t succeed,” said Nadeen Israel, vice president of policy and advocacy at the AIDS Foundation of Chicago. “Most people don’t know to do that.”

Q: Are uninsured people also protected by this new cost-sharing change for PrEP?

Unfortunately, no. The ACA requirement to cover recommended preventive services without charging patients applies only to private insurance plans. People without insurance don’t benefit. Gilead, which makes both Truvada and Descovy, has a patient assistance program for the uninsured.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Ted Howard started taking Truvada a few years ago because he wanted to protect himself against HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. But the daily pill was so pricey he was seriously thinking about giving it up.

Under his insurance plan, the former flight attendant and customer service instructor owed $500 in copayments every month for the drug and an additional $250 every three months for lab work and clinic visits.

Luckily for Howard, his doctor at Las Vegas’ Huntridge Family Clinic, which specializes in LGBTQ care, enrolled him in a clinical trial that covered his medication and other costs in full.

“If I hadn’t been able to get into the trial, I wouldn’t have kept taking PrEP,” said Howard, 68, using the shorthand term for “preexposure prophylaxis.” Taken daily, these drugs — like Truvada — are more than 90% effective at preventing infection with HIV.

(some plans already began doing so last year).

Drugs in this category — Truvada, Descovy and, newly available, a generic version of Truvada — received an “A” recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Under the Affordable Care Act, preventive services that receive an “A” or “B” rating by the task force, a group of medical experts in prevention and primary care, must be covered by most private health plans without making members share the cost, usually through copayments or deductibles. Only plans that are grandfathered under the health law are exempt.

The task force recommended PrEP for people at high risk of HIV infection, including men who have sex with men and injection drug users.

In the United States, more than 1 million people live with HIV, and nearly 40,000 new HIV cases are diagnosed every year. Yet fewer than 10% of people who could benefit from PrEP are taking it. One key reason is that out-of-pocket costs can exceed $1,000 annually, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health last year. Required periodic blood tests and doctor visits can add hundreds of dollars to the cost of the drug, and it’s not clear if insurers are required to pick up all those costs.

“Cost sharing has been a problem,” said Michael Crews, policy director at One Colorado, an advocacy group for the LGBTQ community. “It’s not just getting on PrEP and taking a pill. It’s the lab and clinical services. That’s a huge barrier for folks.”

Whether you’re shopping for a new plan during open enrollment or want to check out what your current plan covers, here are answers to questions you may have about the new preventive coverage requirement.

Q: How can people find out whether their health plan covers PrEP medications without charge?

The plan’s list of covered drugs, called a formulary, should spell out which drugs are covered, along with details about which drug tier they fall into. Drugs placed in higher tiers generally have higher cost sharing. That list should be online with the plan documents that give coverage details.

Sorting out coverage and cost sharing can be tricky. Both Truvada and Descovy can also be used to treat HIV, and if they are taken for that purpose, a plan may require members to pay some of the cost. But if the drugs are taken to prevent HIV infection, patients shouldn’t owe anything out-of-pocket, no matter which tier they are on.

In a recent analysis of online formularies for plans sold on the ACA marketplaces, Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute, found that many plans seemed out of compliance with the requirement to cover PrEP without cost sharing this year.

But representatives for Oscar and Kaiser Permanente, two insurers that were called out in the analysis for lack of compliance, said the drugs are covered without cost sharing in plans nationwide if they are taken to prevent HIV. Schmid later revised his analysis to reflect Oscar’s coverage.

Coverage and cost-sharing information needs to be transparent and easy to find, Schmid said.

“I acted like a shopper of insurance, just like any person would do,” he said. “Even when the information is correct, [it’s so] difficult to find [and there’s] no uniformity.”

It may be necessary to call the insurer directly to confirm coverage details if information on the website is unclear.

Q: Are all three drugs covered without cost sharing?

Health plans have to cover at least one of the drugs in this category — Descovy and the brand and generic versions of Truvada — without cost sharing. People may have to jump through some hoops to get approval for a specific drug, however. For example, Oscar plans sold in 18 states cover the three PrEP options without cost sharing. The generic version of Truvada doesn’t require prior authorization by the insurer. But if someone wants to take the name-brand drug, that person has to go through an approval process. Descovy, a newer drug, is available without cost sharing only if people are unable to use Truvada or its generic version because of clinical intolerance or other issues.

Q: What about the lab work and clinical visits that are necessary while taking PrEP? Are those services also covered without cost sharing?

That is the thousand-dollar question. People who are taking drugs to prevent HIV infection need to meet with a clinician and have blood work every three months to test for HIV, hepatitis B and sexually transmitted infections, and to check their kidney function.

The task force recommendation doesn’t specify whether these services must also be covered without cost sharing, and advocates say federal guidance is necessary to ensure they are free.

“If you’ve got a high-deductible plan and you’ve got to meet it before those services are covered, that’s going to add up,” said Amy Killelea, senior director of health systems and policy at the National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors. “We’re trying to emphasize that it’s integral to the intervention itself.”

A handful of states have programs that help people cover their out-of-pocket costs for lab and clinical visits, generally based on income.

There is precedent for including free ancillary care as part of a recommended preventive service. After consumers and advocates complained, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) clarified that under the ACA removing a polyp during a screening colonoscopy is considered an integral part of the procedure and patients shouldn’t be charged for it.

CMS officials declined to clarify whether PrEP services such as lab work and clinical visits are to be covered without cost sharing as part of the preventive service and noted that states generally enforce such insurance requirements. “CMS intends to contact state regulators, as appropriate, to discuss issuer’s compliance with the federal requirements and whether issuers need further guidance on which services associated with PrEP must be covered without cost sharing,” the agency said in a statement.

Q: What if someone runs into roadblocks getting a plan to cover PrEP or related services without cost sharing?

If an insurer charges for the medication or a follow-up visit, people may have to go through an appeals process to fight it.

“They’d have to appeal to the insurance company and then to the state if they don’t succeed,” said Nadeen Israel, vice president of policy and advocacy at the AIDS Foundation of Chicago. “Most people don’t know to do that.”

Q: Are uninsured people also protected by this new cost-sharing change for PrEP?

Unfortunately, no. The ACA requirement to cover recommended preventive services without charging patients applies only to private insurance plans. People without insurance don’t benefit. Gilead, which makes both Truvada and Descovy, has a patient assistance program for the uninsured.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Ted Howard started taking Truvada a few years ago because he wanted to protect himself against HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. But the daily pill was so pricey he was seriously thinking about giving it up.

Under his insurance plan, the former flight attendant and customer service instructor owed $500 in copayments every month for the drug and an additional $250 every three months for lab work and clinic visits.

Luckily for Howard, his doctor at Las Vegas’ Huntridge Family Clinic, which specializes in LGBTQ care, enrolled him in a clinical trial that covered his medication and other costs in full.

“If I hadn’t been able to get into the trial, I wouldn’t have kept taking PrEP,” said Howard, 68, using the shorthand term for “preexposure prophylaxis.” Taken daily, these drugs — like Truvada — are more than 90% effective at preventing infection with HIV.

(some plans already began doing so last year).

Drugs in this category — Truvada, Descovy and, newly available, a generic version of Truvada — received an “A” recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Under the Affordable Care Act, preventive services that receive an “A” or “B” rating by the task force, a group of medical experts in prevention and primary care, must be covered by most private health plans without making members share the cost, usually through copayments or deductibles. Only plans that are grandfathered under the health law are exempt.

The task force recommended PrEP for people at high risk of HIV infection, including men who have sex with men and injection drug users.

In the United States, more than 1 million people live with HIV, and nearly 40,000 new HIV cases are diagnosed every year. Yet fewer than 10% of people who could benefit from PrEP are taking it. One key reason is that out-of-pocket costs can exceed $1,000 annually, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health last year. Required periodic blood tests and doctor visits can add hundreds of dollars to the cost of the drug, and it’s not clear if insurers are required to pick up all those costs.

“Cost sharing has been a problem,” said Michael Crews, policy director at One Colorado, an advocacy group for the LGBTQ community. “It’s not just getting on PrEP and taking a pill. It’s the lab and clinical services. That’s a huge barrier for folks.”

Whether you’re shopping for a new plan during open enrollment or want to check out what your current plan covers, here are answers to questions you may have about the new preventive coverage requirement.

Q: How can people find out whether their health plan covers PrEP medications without charge?

The plan’s list of covered drugs, called a formulary, should spell out which drugs are covered, along with details about which drug tier they fall into. Drugs placed in higher tiers generally have higher cost sharing. That list should be online with the plan documents that give coverage details.

Sorting out coverage and cost sharing can be tricky. Both Truvada and Descovy can also be used to treat HIV, and if they are taken for that purpose, a plan may require members to pay some of the cost. But if the drugs are taken to prevent HIV infection, patients shouldn’t owe anything out-of-pocket, no matter which tier they are on.

In a recent analysis of online formularies for plans sold on the ACA marketplaces, Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute, found that many plans seemed out of compliance with the requirement to cover PrEP without cost sharing this year.

But representatives for Oscar and Kaiser Permanente, two insurers that were called out in the analysis for lack of compliance, said the drugs are covered without cost sharing in plans nationwide if they are taken to prevent HIV. Schmid later revised his analysis to reflect Oscar’s coverage.

Coverage and cost-sharing information needs to be transparent and easy to find, Schmid said.

“I acted like a shopper of insurance, just like any person would do,” he said. “Even when the information is correct, [it’s so] difficult to find [and there’s] no uniformity.”

It may be necessary to call the insurer directly to confirm coverage details if information on the website is unclear.

Q: Are all three drugs covered without cost sharing?

Health plans have to cover at least one of the drugs in this category — Descovy and the brand and generic versions of Truvada — without cost sharing. People may have to jump through some hoops to get approval for a specific drug, however. For example, Oscar plans sold in 18 states cover the three PrEP options without cost sharing. The generic version of Truvada doesn’t require prior authorization by the insurer. But if someone wants to take the name-brand drug, that person has to go through an approval process. Descovy, a newer drug, is available without cost sharing only if people are unable to use Truvada or its generic version because of clinical intolerance or other issues.

Q: What about the lab work and clinical visits that are necessary while taking PrEP? Are those services also covered without cost sharing?

That is the thousand-dollar question. People who are taking drugs to prevent HIV infection need to meet with a clinician and have blood work every three months to test for HIV, hepatitis B and sexually transmitted infections, and to check their kidney function.

The task force recommendation doesn’t specify whether these services must also be covered without cost sharing, and advocates say federal guidance is necessary to ensure they are free.

“If you’ve got a high-deductible plan and you’ve got to meet it before those services are covered, that’s going to add up,” said Amy Killelea, senior director of health systems and policy at the National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors. “We’re trying to emphasize that it’s integral to the intervention itself.”

A handful of states have programs that help people cover their out-of-pocket costs for lab and clinical visits, generally based on income.

There is precedent for including free ancillary care as part of a recommended preventive service. After consumers and advocates complained, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) clarified that under the ACA removing a polyp during a screening colonoscopy is considered an integral part of the procedure and patients shouldn’t be charged for it.

CMS officials declined to clarify whether PrEP services such as lab work and clinical visits are to be covered without cost sharing as part of the preventive service and noted that states generally enforce such insurance requirements. “CMS intends to contact state regulators, as appropriate, to discuss issuer’s compliance with the federal requirements and whether issuers need further guidance on which services associated with PrEP must be covered without cost sharing,” the agency said in a statement.

Q: What if someone runs into roadblocks getting a plan to cover PrEP or related services without cost sharing?

If an insurer charges for the medication or a follow-up visit, people may have to go through an appeals process to fight it.

“They’d have to appeal to the insurance company and then to the state if they don’t succeed,” said Nadeen Israel, vice president of policy and advocacy at the AIDS Foundation of Chicago. “Most people don’t know to do that.”

Q: Are uninsured people also protected by this new cost-sharing change for PrEP?

Unfortunately, no. The ACA requirement to cover recommended preventive services without charging patients applies only to private insurance plans. People without insurance don’t benefit. Gilead, which makes both Truvada and Descovy, has a patient assistance program for the uninsured.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Microvascular injury of brain, olfactory bulb seen in COVID-19

new research suggests.

Postmortem MRI brain scans of 13 patients who died from COVID-19 showed abnormalities in 10 of the participants. Of these, nine showed punctate hyperintensities, “which represented areas of microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage,” the investigators reported. Immunostaining also showed a thinning of the basal lamina in five of these patients.

Further analyses showed punctate hypointensities linked to congested blood vessels in 10 patients. These areas were “interpreted as microhemorrhages,” the researchers noted.

There was no evidence of viral infection, including SARS-CoV-2.

“These findings may inform the interpretation of changes observed on [MRI] of punctate hyperintensities and linear hypointensities in patients with COVID-19,” wrote Myoung-Hwa Lee, PhD, a research fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and colleagues. The findings were published online Dec. 30 in a “correspondence” piece in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Interpret with caution

The investigators examined brains from a convenience sample of 19 patients (mean age, 50 years), all of whom died from COVID-19 between March and July 2020.

An 11.7-tesla scanner was used to obtain magnetic resonance microscopy images for 13 of the patients. In order to scan the olfactory bulb, the scanner was set at a resolution of 25 mcm; for the brain, it was set at 100 mcm.

Chromogenic immunostaining was used to assess brain abnormalities found in 10 of the patients. Multiplex fluorescence imaging was also used for some of the patients.

For 18 study participants, a histopathological brain examination was performed. In the patients who also had medical histories available to the researchers, five had mild respiratory syndrome, four had acute respiratory distress syndrome, two had pulmonary embolism, one had delirium, and three had unknown symptoms.

The punctate hyperintensities found on magnetic resonance microscopy were also found on histopathological exam. Collagen IV immunostaining showed a thinning in the basal lamina of endothelial cells in these areas.

In addition to congested blood vessels, punctate hypointensities were linked to areas of fibrinogen leakage – but also to “relatively intact vasculature,” the investigators reported.

“There was minimal perivascular inflammation in the specimens examined, but there was no vascular occlusion,” they added.

SARS-CoV-2 was also not found in any of the participants. “It is possible that the virus was cleared by the time of death or that viral copy numbers were below the level of detection by our assays,” the researchers noted.

In 13 of the patients, hypertrophic astrocytes, macrophage infiltrates, and perivascular-activated microglia were found. Eight patients showed CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in spaces and lumens next to endothelial cells.

Finally, five patients showed activated microglia next to neurons. This is “suggestive of neuronophagia in the olfactory bulb, substantial nigra, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve, and the pre-Bötzinger complex in the medulla, which is involved in the generation of spontaneous rhythmic breathing,” wrote the investigators.

In summary, vascular pathology was found in 10 cases, perivascular infiltrates were present in 13 cases, acute ischemic hypoxic neurons were present in 6 cases, and changes suggestive of neuronophagia were present in 5 cases.

The researchers noted that, although the study findings may be helpful when interpreting brain changes on MRI scan in this patient population, availability of clinical information for the participants was limited.

Therefore, “no conclusions can be drawn in relation to neurologic features of COVID-19,” they wrote.

The study was funded by NINDS. Dr. Lee and all but one of the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships; the remaining investigator reported having received grants from NINDS during the conduct of this study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Postmortem MRI brain scans of 13 patients who died from COVID-19 showed abnormalities in 10 of the participants. Of these, nine showed punctate hyperintensities, “which represented areas of microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage,” the investigators reported. Immunostaining also showed a thinning of the basal lamina in five of these patients.

Further analyses showed punctate hypointensities linked to congested blood vessels in 10 patients. These areas were “interpreted as microhemorrhages,” the researchers noted.

There was no evidence of viral infection, including SARS-CoV-2.

“These findings may inform the interpretation of changes observed on [MRI] of punctate hyperintensities and linear hypointensities in patients with COVID-19,” wrote Myoung-Hwa Lee, PhD, a research fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and colleagues. The findings were published online Dec. 30 in a “correspondence” piece in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Interpret with caution