User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

Fecal transplant linked to reduced C. difficile mortality

Vancomycin followed by fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) was associated with reduced Clostridioides difficile (C. diff)-related mortality in patients hospitalized with refractory severe or fulminant C. diff infection (CDI) at a single center. The improvements came after Indiana University implemented an FMT option in 2013.

About 8% of C. diff patients develop severe or fulminant CDI (SFCDI), which can lead to toxic colon and multiorgan failure. Surgery is the current recommended treatment for these patients if they are refractory to vancomycin, but 30-day mortality is above 40%. FMT is recommended for recurrent CDI, and it achieves cure rates greater than 80%, along with fewer relapses compared with anti-CDI antibiotic therapy.

FMT has been shown to be effective for SFCDI, with a 91% cure rate for serious CDI and 66% for fulminant CDI.

In the study published in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, researchers led by Yao-Wen Cheng, MD, and Monika Fischer, MD, of Indiana University, assessed the effect of FMT on SFCDI after their institution adopted it as a treatment protocol for SFCDI. Patients could receive FMT if there was evidence that their SFCDI was refractory, or if they had two or more CDI recurrences. The treatment includes oral vancomycin and pseudomembrane-driven sequential FMT.

Two hundred five patients were admitted before FMT implementation, 225 after. Fifty patients received FMT because of refractory SFCDI. A median of two FMTs was conducted per patient. 21 other patients received FMT for nonrefractory SFCDI or other conditions, including 18 patients with multiple recurrent CDI.

Thirty-day CDI-related mortality dropped after FMT implementation (4.4% versus 10.2%; P =.02). This was true in both the fulminant subset (9.1% versus 21.3%; P =.015) and the refractory group (12.1% versus 43.2%; P < .001).

The researchers used segmented logistic regression to determine if the improved outcomes could be due to nontreatment factors that varied over time, and found that the difference in CDI-related mortality was eliminated except for refractory SFCDI patients (odds of mortality after FMT implementation, 0.09; P =.023). There was no significant difference between those receiving non-CDI antibiotics (4.8%) and those who did not (6.9%; P =.75).

FMT was associated with lower frequency of CDI-related colectomy overall (2.7% versus 6.8%; P =.041), as well as in the fulminant (5.5% versus 15.7%; P =.017) and refractory subgroups (7.6% versus 31.8%; P =.001).

The findings follow another study that showed improved 3-month mortality for FMT among patients hospitalized with severe CDI (12.1% versus 42.2%; P < .003).

The results underscore the utility of FMT for SFCDI, and suggest it might have the most benefit in refractory SFCDI. The authors believe that FMT should be an alternative to colectomy when first-line anti-CDI antibiotics are partially or completely ineffective. In the absence of FMT, patients who go on to fail vancomycin or fidaxomicin will likely continue to be managed medically, with up to 80% mortality, or through salvage colectomy, with postsurgical morality rates of 30-40%.

Although a randomized trial could answer the question of FMT efficacy more definitively, it is unlikely to be conducted for ethical reasons.

“Further investigation is required to clearly define FMT’s role and timing in the clinical course of severe and fulminant CDI. However, our study suggests that FMT should be offered to patients with severe and fulminant CDI who do not respond to a 5-day course of anti-CDI antibiotics and may be considered in lieu of or before colectomy,” the researchers wrote.

No source of funding was disclosed.

SOURCE: Cheng YW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2234-43. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.029.

Vancomycin followed by fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) was associated with reduced Clostridioides difficile (C. diff)-related mortality in patients hospitalized with refractory severe or fulminant C. diff infection (CDI) at a single center. The improvements came after Indiana University implemented an FMT option in 2013.

About 8% of C. diff patients develop severe or fulminant CDI (SFCDI), which can lead to toxic colon and multiorgan failure. Surgery is the current recommended treatment for these patients if they are refractory to vancomycin, but 30-day mortality is above 40%. FMT is recommended for recurrent CDI, and it achieves cure rates greater than 80%, along with fewer relapses compared with anti-CDI antibiotic therapy.

FMT has been shown to be effective for SFCDI, with a 91% cure rate for serious CDI and 66% for fulminant CDI.

In the study published in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, researchers led by Yao-Wen Cheng, MD, and Monika Fischer, MD, of Indiana University, assessed the effect of FMT on SFCDI after their institution adopted it as a treatment protocol for SFCDI. Patients could receive FMT if there was evidence that their SFCDI was refractory, or if they had two or more CDI recurrences. The treatment includes oral vancomycin and pseudomembrane-driven sequential FMT.

Two hundred five patients were admitted before FMT implementation, 225 after. Fifty patients received FMT because of refractory SFCDI. A median of two FMTs was conducted per patient. 21 other patients received FMT for nonrefractory SFCDI or other conditions, including 18 patients with multiple recurrent CDI.

Thirty-day CDI-related mortality dropped after FMT implementation (4.4% versus 10.2%; P =.02). This was true in both the fulminant subset (9.1% versus 21.3%; P =.015) and the refractory group (12.1% versus 43.2%; P < .001).

The researchers used segmented logistic regression to determine if the improved outcomes could be due to nontreatment factors that varied over time, and found that the difference in CDI-related mortality was eliminated except for refractory SFCDI patients (odds of mortality after FMT implementation, 0.09; P =.023). There was no significant difference between those receiving non-CDI antibiotics (4.8%) and those who did not (6.9%; P =.75).

FMT was associated with lower frequency of CDI-related colectomy overall (2.7% versus 6.8%; P =.041), as well as in the fulminant (5.5% versus 15.7%; P =.017) and refractory subgroups (7.6% versus 31.8%; P =.001).

The findings follow another study that showed improved 3-month mortality for FMT among patients hospitalized with severe CDI (12.1% versus 42.2%; P < .003).

The results underscore the utility of FMT for SFCDI, and suggest it might have the most benefit in refractory SFCDI. The authors believe that FMT should be an alternative to colectomy when first-line anti-CDI antibiotics are partially or completely ineffective. In the absence of FMT, patients who go on to fail vancomycin or fidaxomicin will likely continue to be managed medically, with up to 80% mortality, or through salvage colectomy, with postsurgical morality rates of 30-40%.

Although a randomized trial could answer the question of FMT efficacy more definitively, it is unlikely to be conducted for ethical reasons.

“Further investigation is required to clearly define FMT’s role and timing in the clinical course of severe and fulminant CDI. However, our study suggests that FMT should be offered to patients with severe and fulminant CDI who do not respond to a 5-day course of anti-CDI antibiotics and may be considered in lieu of or before colectomy,” the researchers wrote.

No source of funding was disclosed.

SOURCE: Cheng YW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2234-43. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.029.

Vancomycin followed by fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) was associated with reduced Clostridioides difficile (C. diff)-related mortality in patients hospitalized with refractory severe or fulminant C. diff infection (CDI) at a single center. The improvements came after Indiana University implemented an FMT option in 2013.

About 8% of C. diff patients develop severe or fulminant CDI (SFCDI), which can lead to toxic colon and multiorgan failure. Surgery is the current recommended treatment for these patients if they are refractory to vancomycin, but 30-day mortality is above 40%. FMT is recommended for recurrent CDI, and it achieves cure rates greater than 80%, along with fewer relapses compared with anti-CDI antibiotic therapy.

FMT has been shown to be effective for SFCDI, with a 91% cure rate for serious CDI and 66% for fulminant CDI.

In the study published in the September issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, researchers led by Yao-Wen Cheng, MD, and Monika Fischer, MD, of Indiana University, assessed the effect of FMT on SFCDI after their institution adopted it as a treatment protocol for SFCDI. Patients could receive FMT if there was evidence that their SFCDI was refractory, or if they had two or more CDI recurrences. The treatment includes oral vancomycin and pseudomembrane-driven sequential FMT.

Two hundred five patients were admitted before FMT implementation, 225 after. Fifty patients received FMT because of refractory SFCDI. A median of two FMTs was conducted per patient. 21 other patients received FMT for nonrefractory SFCDI or other conditions, including 18 patients with multiple recurrent CDI.

Thirty-day CDI-related mortality dropped after FMT implementation (4.4% versus 10.2%; P =.02). This was true in both the fulminant subset (9.1% versus 21.3%; P =.015) and the refractory group (12.1% versus 43.2%; P < .001).

The researchers used segmented logistic regression to determine if the improved outcomes could be due to nontreatment factors that varied over time, and found that the difference in CDI-related mortality was eliminated except for refractory SFCDI patients (odds of mortality after FMT implementation, 0.09; P =.023). There was no significant difference between those receiving non-CDI antibiotics (4.8%) and those who did not (6.9%; P =.75).

FMT was associated with lower frequency of CDI-related colectomy overall (2.7% versus 6.8%; P =.041), as well as in the fulminant (5.5% versus 15.7%; P =.017) and refractory subgroups (7.6% versus 31.8%; P =.001).

The findings follow another study that showed improved 3-month mortality for FMT among patients hospitalized with severe CDI (12.1% versus 42.2%; P < .003).

The results underscore the utility of FMT for SFCDI, and suggest it might have the most benefit in refractory SFCDI. The authors believe that FMT should be an alternative to colectomy when first-line anti-CDI antibiotics are partially or completely ineffective. In the absence of FMT, patients who go on to fail vancomycin or fidaxomicin will likely continue to be managed medically, with up to 80% mortality, or through salvage colectomy, with postsurgical morality rates of 30-40%.

Although a randomized trial could answer the question of FMT efficacy more definitively, it is unlikely to be conducted for ethical reasons.

“Further investigation is required to clearly define FMT’s role and timing in the clinical course of severe and fulminant CDI. However, our study suggests that FMT should be offered to patients with severe and fulminant CDI who do not respond to a 5-day course of anti-CDI antibiotics and may be considered in lieu of or before colectomy,” the researchers wrote.

No source of funding was disclosed.

SOURCE: Cheng YW et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2234-43. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.12.029.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Medicare faces calls to stop physician pay cuts in E/M overhaul

A planned overhaul of reimbursement for evaluation and management (E/M) services emerged as perhaps the most contentious issue connected to Medicare’s 2021 payment policies for clinicians.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included the planned E/M overhaul — and accompanying offsets — in the draft 2021 physician fee schedule, released in August. The draft fee schedule drew at least 45,675 responses by October 5, the deadline for offering comments, with many of the responses addressing the E/M overhaul.

The influential Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) “strongly” endorsed the “budget-neutral” approach taken with the E/M overhaul. This planned reshuffling of payments is a step toward addressing a shortfall of primary care clinicians, inasmuch as it would help make this field more financially appealing, MedPAC said in an October 2 letter to CMS.

In contrast, physician organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), asked CMS to waive or revise the budget-neutral aspect of the E/M overhaul. Among the specialties slated for reductions are those deeply involved with the response to the pandemic, wrote James L. Madara, AMA’s chief executive officer, in an October 5 comment to CMS. Emergency medicine as a field would see a 6% cut, and infectious disease specialists, a 4% reduction.

“Payment reductions of this magnitude would be a major problem at any time, but to impose cuts of this magnitude during or immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic, including steep cuts to many of the specialties that have been on the front lines in efforts to treat patients in places with widespread infection, is unconscionable,” Madara wrote.

Madara also said specialties scheduled for payment reductions include those least able to make up for the lack of in-person care as a result of the uptick in telehealth during the pandemic.

A chart in the draft physician fee schedule (Table 90) shows reductions for many specialties that do not routinely bill for office visits. The table shows an 8% cut for anesthesiologists, a 7% cut for general surgeons, and a 6% cut for ophthalmologists. Table 90 also shows an estimated 11% reduction for radiologists and a 9% drop for pathologists.

The draft rule notes that these figures are based upon estimates of aggregate allowed charges across all services, so they may not reflect what any particular clinician might receive.

In total, Table 90 shows how the E/M changes and connected offsets would affect more than 50 fields of medicine. The proposal includes a 17% expected increase for endocrinologists and a 14% bump for those in hematology/oncology. There are expected increases of 13% for family practice and 4% for internal medicine.

This reshuffling of payments among specialties is only part of the 2021 E/M overhaul. There’s strong support for other aspects, making it unlikely that CMS would consider dropping the plan entirely.

“CMS’ new office visit policy will lead to significant administrative burden reduction and will better describe and recognize the resources involved in clinical office visits as they are performed today,” AMA’s Madara wrote in his comment.

Changes for the billing framework for E/M slated to start in 2021 are the result of substantial collaboration by an AMA-convened work group, which brought together more than 170 state medical and specialty societies, Madara said in his comment.

CMS has been developing this plan for several years. It outlined this 2021 E/M overhaul in the 2020 Medicare physician fee schedule finalized last year.

Madara urged CMS to proceed with the E/M changes but also “exercise the full breadth and depth of its administrative authority” to avoid or minimize the planned cuts.

“To be clear, we are not asking CMS to phase in implementation of the E/M changes but rather to phase in the payment reductions for certain specialties and health professionals in 2021 due to budget neutrality,” he wrote.

Other groups asking CMS to waive the budget-neutrality requirement include the American College of Physicians, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) asked CMS to temporarily waive the budget-neutrality requirement and pressed the agency to maintain the underlying principle of the E/M overhaul.

“Should HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] use its authority to waive budget neutrality, we also recommend that CMS finalize a reinstatement plan for the conversion factor reductions that provides physician practices with ample time to prepare and does not result in a financial cliff,” wrote John S. Cullen, MD, board chair for AAFP, in a September 28 comment to CMS.

Owing to the declaration of a public health emergency, HHS could use a special provision known as 1135 waiver authority to waive budget-neutrality requirements, Cullen wrote.

“The AAFP understands that HHS’ authority is limited by the timing of the end of the public health emergency, but we believe that this approach will provide Congress with needed time to enact an accompanying legislative solution,” he wrote.

Lawmakers weigh in

Lawmakers in both political parties have asked CMS to reconsider the offsets in the E/M overhaul.

Rep. Michael C. Burgess, MD (R-TX), who practiced as an obstetrician before joining Congress, in October introduced a bill with Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) that would provide for a 1-year waiver of budget-neutrality adjustments under the Medicare physician fee schedule.

Burgess and Rush were among the more than 160 members of Congress who signed a September letter to CMS asking the agency to act on its own to drop the budget-neutrality requirement. In the letter, led by Rep. Roger Marshall, MD (R-KS), the lawmakers acknowledge the usual legal requirements for CMS to offset payment increases in the physician fee schedule with cuts. But the lawmakers said the national public health emergency allows CMS to work around this.

“Given the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe you have the regulatory authority to immediately address these inequities,” the lawmakers wrote. “There is also the need to consider how the outbreak will be in the fall/winter months and if postponing certain elective procedures will go back into effect, per CMS’ recommendations.

“While we understand that legislative action may also be required to address this issue, given the January 1, 2021 effective date, we would ask you to take immediate actions to delay or mitigate these cuts while allowing the scheduled increases to go into effect,” the lawmakers said in closing their letter. “This approach will give Congress sufficient time to develop a meaningful solution and to address these looming needs.”

Another option might be for CMS to preserve the budget-neutrality claim for the 2021 physician fee schedule but soften the blow on specialties, Brian Fortune, president of the consulting firm Farragut Square Group, told Medscape Medical News. A former staffer for Republican leadership in the House of Representatives, Fortune has for more than 20 years followed Medicare policy.

The agency could redo some of the assumptions used in estimating the offsets, he said, adding that in the draft rule, CMS appears to be seeking feedback that could help it with new calculations.

“CMS has been looking for a way out,” Fortune said. “CMS could remodel the assumptions, and the cuts could drop by half or more.

“The agency has several options to get creative as the need arises,” he said.

“Overvalued” vs “devalued”

In its comment to CMS, though, MedPAC argued strongly for maintaining the offsets. The commission has for several years been investigating ways to use Medicare’s payment policies as a tool to boost the ranks of clinicians who provide primary care.

A reshuffling of payments among specialties is needed to address a known imbalance in which Medicare for many years has “overvalued” procedures at the expense of other medical care, wrote Michael E. Chernew, PhD, the chairman of MedPAC, in an October 2 comment to CMS.

“Some types of services — such as procedures, imaging, and tests — experience efficiency gains over time, as advances in technology, technique, and clinical practice enable clinicians to deliver them faster,” he wrote. “However, E&M office/outpatient visits do not lend themselves to such efficiency gains because they consist largely of activities that require the clinician’s time.”

Medicare’s payment policies have thus “passively devalued” the time many clinicians spend on office visits, helping to skew the decisions of young physicians toward specialties, according to Chernew.

Reshuffling payment away from specialties that are now “overvalued” is needed to “remedy several years of passive devaluation,” he wrote.

The median income in 2018 for primary care physicians was $243,000 in 2018, whereas that of specialists such as surgeons was $426,000, Chernew said in the letter, citing MedPAC research.

These figures echo the findings of Medscape’s most recent annual physician compensation report.

As one of the largest buyers of medical services, Medicare has significant influence on the practice of medicine in the United States. In 2018 alone, Medicare directly paid $70.5 billion for clinician services. Its payment policies already may have shaped the pool of clinicians available to treat people enrolled in Medicare, which covers those aged 65 years and older, Chernew said.

“The US has over three times as many specialists as primary care physicians, which could explain why MedPAC’s annual survey of Medicare beneficiaries has repeatedly found that beneficiaries who are looking for a new physician report having an easier time finding a new specialist than a new primary care provider,” he wrote.

“Access to primary care physicians could worsen in the future as the number of primary care physicians in the US, after remaining flat for several years, has actually started to decline,” Chernew said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A planned overhaul of reimbursement for evaluation and management (E/M) services emerged as perhaps the most contentious issue connected to Medicare’s 2021 payment policies for clinicians.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included the planned E/M overhaul — and accompanying offsets — in the draft 2021 physician fee schedule, released in August. The draft fee schedule drew at least 45,675 responses by October 5, the deadline for offering comments, with many of the responses addressing the E/M overhaul.

The influential Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) “strongly” endorsed the “budget-neutral” approach taken with the E/M overhaul. This planned reshuffling of payments is a step toward addressing a shortfall of primary care clinicians, inasmuch as it would help make this field more financially appealing, MedPAC said in an October 2 letter to CMS.

In contrast, physician organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), asked CMS to waive or revise the budget-neutral aspect of the E/M overhaul. Among the specialties slated for reductions are those deeply involved with the response to the pandemic, wrote James L. Madara, AMA’s chief executive officer, in an October 5 comment to CMS. Emergency medicine as a field would see a 6% cut, and infectious disease specialists, a 4% reduction.

“Payment reductions of this magnitude would be a major problem at any time, but to impose cuts of this magnitude during or immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic, including steep cuts to many of the specialties that have been on the front lines in efforts to treat patients in places with widespread infection, is unconscionable,” Madara wrote.

Madara also said specialties scheduled for payment reductions include those least able to make up for the lack of in-person care as a result of the uptick in telehealth during the pandemic.

A chart in the draft physician fee schedule (Table 90) shows reductions for many specialties that do not routinely bill for office visits. The table shows an 8% cut for anesthesiologists, a 7% cut for general surgeons, and a 6% cut for ophthalmologists. Table 90 also shows an estimated 11% reduction for radiologists and a 9% drop for pathologists.

The draft rule notes that these figures are based upon estimates of aggregate allowed charges across all services, so they may not reflect what any particular clinician might receive.

In total, Table 90 shows how the E/M changes and connected offsets would affect more than 50 fields of medicine. The proposal includes a 17% expected increase for endocrinologists and a 14% bump for those in hematology/oncology. There are expected increases of 13% for family practice and 4% for internal medicine.

This reshuffling of payments among specialties is only part of the 2021 E/M overhaul. There’s strong support for other aspects, making it unlikely that CMS would consider dropping the plan entirely.

“CMS’ new office visit policy will lead to significant administrative burden reduction and will better describe and recognize the resources involved in clinical office visits as they are performed today,” AMA’s Madara wrote in his comment.

Changes for the billing framework for E/M slated to start in 2021 are the result of substantial collaboration by an AMA-convened work group, which brought together more than 170 state medical and specialty societies, Madara said in his comment.

CMS has been developing this plan for several years. It outlined this 2021 E/M overhaul in the 2020 Medicare physician fee schedule finalized last year.

Madara urged CMS to proceed with the E/M changes but also “exercise the full breadth and depth of its administrative authority” to avoid or minimize the planned cuts.

“To be clear, we are not asking CMS to phase in implementation of the E/M changes but rather to phase in the payment reductions for certain specialties and health professionals in 2021 due to budget neutrality,” he wrote.

Other groups asking CMS to waive the budget-neutrality requirement include the American College of Physicians, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) asked CMS to temporarily waive the budget-neutrality requirement and pressed the agency to maintain the underlying principle of the E/M overhaul.

“Should HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] use its authority to waive budget neutrality, we also recommend that CMS finalize a reinstatement plan for the conversion factor reductions that provides physician practices with ample time to prepare and does not result in a financial cliff,” wrote John S. Cullen, MD, board chair for AAFP, in a September 28 comment to CMS.

Owing to the declaration of a public health emergency, HHS could use a special provision known as 1135 waiver authority to waive budget-neutrality requirements, Cullen wrote.

“The AAFP understands that HHS’ authority is limited by the timing of the end of the public health emergency, but we believe that this approach will provide Congress with needed time to enact an accompanying legislative solution,” he wrote.

Lawmakers weigh in

Lawmakers in both political parties have asked CMS to reconsider the offsets in the E/M overhaul.

Rep. Michael C. Burgess, MD (R-TX), who practiced as an obstetrician before joining Congress, in October introduced a bill with Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) that would provide for a 1-year waiver of budget-neutrality adjustments under the Medicare physician fee schedule.

Burgess and Rush were among the more than 160 members of Congress who signed a September letter to CMS asking the agency to act on its own to drop the budget-neutrality requirement. In the letter, led by Rep. Roger Marshall, MD (R-KS), the lawmakers acknowledge the usual legal requirements for CMS to offset payment increases in the physician fee schedule with cuts. But the lawmakers said the national public health emergency allows CMS to work around this.

“Given the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe you have the regulatory authority to immediately address these inequities,” the lawmakers wrote. “There is also the need to consider how the outbreak will be in the fall/winter months and if postponing certain elective procedures will go back into effect, per CMS’ recommendations.

“While we understand that legislative action may also be required to address this issue, given the January 1, 2021 effective date, we would ask you to take immediate actions to delay or mitigate these cuts while allowing the scheduled increases to go into effect,” the lawmakers said in closing their letter. “This approach will give Congress sufficient time to develop a meaningful solution and to address these looming needs.”

Another option might be for CMS to preserve the budget-neutrality claim for the 2021 physician fee schedule but soften the blow on specialties, Brian Fortune, president of the consulting firm Farragut Square Group, told Medscape Medical News. A former staffer for Republican leadership in the House of Representatives, Fortune has for more than 20 years followed Medicare policy.

The agency could redo some of the assumptions used in estimating the offsets, he said, adding that in the draft rule, CMS appears to be seeking feedback that could help it with new calculations.

“CMS has been looking for a way out,” Fortune said. “CMS could remodel the assumptions, and the cuts could drop by half or more.

“The agency has several options to get creative as the need arises,” he said.

“Overvalued” vs “devalued”

In its comment to CMS, though, MedPAC argued strongly for maintaining the offsets. The commission has for several years been investigating ways to use Medicare’s payment policies as a tool to boost the ranks of clinicians who provide primary care.

A reshuffling of payments among specialties is needed to address a known imbalance in which Medicare for many years has “overvalued” procedures at the expense of other medical care, wrote Michael E. Chernew, PhD, the chairman of MedPAC, in an October 2 comment to CMS.

“Some types of services — such as procedures, imaging, and tests — experience efficiency gains over time, as advances in technology, technique, and clinical practice enable clinicians to deliver them faster,” he wrote. “However, E&M office/outpatient visits do not lend themselves to such efficiency gains because they consist largely of activities that require the clinician’s time.”

Medicare’s payment policies have thus “passively devalued” the time many clinicians spend on office visits, helping to skew the decisions of young physicians toward specialties, according to Chernew.

Reshuffling payment away from specialties that are now “overvalued” is needed to “remedy several years of passive devaluation,” he wrote.

The median income in 2018 for primary care physicians was $243,000 in 2018, whereas that of specialists such as surgeons was $426,000, Chernew said in the letter, citing MedPAC research.

These figures echo the findings of Medscape’s most recent annual physician compensation report.

As one of the largest buyers of medical services, Medicare has significant influence on the practice of medicine in the United States. In 2018 alone, Medicare directly paid $70.5 billion for clinician services. Its payment policies already may have shaped the pool of clinicians available to treat people enrolled in Medicare, which covers those aged 65 years and older, Chernew said.

“The US has over three times as many specialists as primary care physicians, which could explain why MedPAC’s annual survey of Medicare beneficiaries has repeatedly found that beneficiaries who are looking for a new physician report having an easier time finding a new specialist than a new primary care provider,” he wrote.

“Access to primary care physicians could worsen in the future as the number of primary care physicians in the US, after remaining flat for several years, has actually started to decline,” Chernew said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A planned overhaul of reimbursement for evaluation and management (E/M) services emerged as perhaps the most contentious issue connected to Medicare’s 2021 payment policies for clinicians.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included the planned E/M overhaul — and accompanying offsets — in the draft 2021 physician fee schedule, released in August. The draft fee schedule drew at least 45,675 responses by October 5, the deadline for offering comments, with many of the responses addressing the E/M overhaul.

The influential Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) “strongly” endorsed the “budget-neutral” approach taken with the E/M overhaul. This planned reshuffling of payments is a step toward addressing a shortfall of primary care clinicians, inasmuch as it would help make this field more financially appealing, MedPAC said in an October 2 letter to CMS.

In contrast, physician organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), asked CMS to waive or revise the budget-neutral aspect of the E/M overhaul. Among the specialties slated for reductions are those deeply involved with the response to the pandemic, wrote James L. Madara, AMA’s chief executive officer, in an October 5 comment to CMS. Emergency medicine as a field would see a 6% cut, and infectious disease specialists, a 4% reduction.

“Payment reductions of this magnitude would be a major problem at any time, but to impose cuts of this magnitude during or immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic, including steep cuts to many of the specialties that have been on the front lines in efforts to treat patients in places with widespread infection, is unconscionable,” Madara wrote.

Madara also said specialties scheduled for payment reductions include those least able to make up for the lack of in-person care as a result of the uptick in telehealth during the pandemic.

A chart in the draft physician fee schedule (Table 90) shows reductions for many specialties that do not routinely bill for office visits. The table shows an 8% cut for anesthesiologists, a 7% cut for general surgeons, and a 6% cut for ophthalmologists. Table 90 also shows an estimated 11% reduction for radiologists and a 9% drop for pathologists.

The draft rule notes that these figures are based upon estimates of aggregate allowed charges across all services, so they may not reflect what any particular clinician might receive.

In total, Table 90 shows how the E/M changes and connected offsets would affect more than 50 fields of medicine. The proposal includes a 17% expected increase for endocrinologists and a 14% bump for those in hematology/oncology. There are expected increases of 13% for family practice and 4% for internal medicine.

This reshuffling of payments among specialties is only part of the 2021 E/M overhaul. There’s strong support for other aspects, making it unlikely that CMS would consider dropping the plan entirely.

“CMS’ new office visit policy will lead to significant administrative burden reduction and will better describe and recognize the resources involved in clinical office visits as they are performed today,” AMA’s Madara wrote in his comment.

Changes for the billing framework for E/M slated to start in 2021 are the result of substantial collaboration by an AMA-convened work group, which brought together more than 170 state medical and specialty societies, Madara said in his comment.

CMS has been developing this plan for several years. It outlined this 2021 E/M overhaul in the 2020 Medicare physician fee schedule finalized last year.

Madara urged CMS to proceed with the E/M changes but also “exercise the full breadth and depth of its administrative authority” to avoid or minimize the planned cuts.

“To be clear, we are not asking CMS to phase in implementation of the E/M changes but rather to phase in the payment reductions for certain specialties and health professionals in 2021 due to budget neutrality,” he wrote.

Other groups asking CMS to waive the budget-neutrality requirement include the American College of Physicians, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) asked CMS to temporarily waive the budget-neutrality requirement and pressed the agency to maintain the underlying principle of the E/M overhaul.

“Should HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] use its authority to waive budget neutrality, we also recommend that CMS finalize a reinstatement plan for the conversion factor reductions that provides physician practices with ample time to prepare and does not result in a financial cliff,” wrote John S. Cullen, MD, board chair for AAFP, in a September 28 comment to CMS.

Owing to the declaration of a public health emergency, HHS could use a special provision known as 1135 waiver authority to waive budget-neutrality requirements, Cullen wrote.

“The AAFP understands that HHS’ authority is limited by the timing of the end of the public health emergency, but we believe that this approach will provide Congress with needed time to enact an accompanying legislative solution,” he wrote.

Lawmakers weigh in

Lawmakers in both political parties have asked CMS to reconsider the offsets in the E/M overhaul.

Rep. Michael C. Burgess, MD (R-TX), who practiced as an obstetrician before joining Congress, in October introduced a bill with Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) that would provide for a 1-year waiver of budget-neutrality adjustments under the Medicare physician fee schedule.

Burgess and Rush were among the more than 160 members of Congress who signed a September letter to CMS asking the agency to act on its own to drop the budget-neutrality requirement. In the letter, led by Rep. Roger Marshall, MD (R-KS), the lawmakers acknowledge the usual legal requirements for CMS to offset payment increases in the physician fee schedule with cuts. But the lawmakers said the national public health emergency allows CMS to work around this.

“Given the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe you have the regulatory authority to immediately address these inequities,” the lawmakers wrote. “There is also the need to consider how the outbreak will be in the fall/winter months and if postponing certain elective procedures will go back into effect, per CMS’ recommendations.

“While we understand that legislative action may also be required to address this issue, given the January 1, 2021 effective date, we would ask you to take immediate actions to delay or mitigate these cuts while allowing the scheduled increases to go into effect,” the lawmakers said in closing their letter. “This approach will give Congress sufficient time to develop a meaningful solution and to address these looming needs.”

Another option might be for CMS to preserve the budget-neutrality claim for the 2021 physician fee schedule but soften the blow on specialties, Brian Fortune, president of the consulting firm Farragut Square Group, told Medscape Medical News. A former staffer for Republican leadership in the House of Representatives, Fortune has for more than 20 years followed Medicare policy.

The agency could redo some of the assumptions used in estimating the offsets, he said, adding that in the draft rule, CMS appears to be seeking feedback that could help it with new calculations.

“CMS has been looking for a way out,” Fortune said. “CMS could remodel the assumptions, and the cuts could drop by half or more.

“The agency has several options to get creative as the need arises,” he said.

“Overvalued” vs “devalued”

In its comment to CMS, though, MedPAC argued strongly for maintaining the offsets. The commission has for several years been investigating ways to use Medicare’s payment policies as a tool to boost the ranks of clinicians who provide primary care.

A reshuffling of payments among specialties is needed to address a known imbalance in which Medicare for many years has “overvalued” procedures at the expense of other medical care, wrote Michael E. Chernew, PhD, the chairman of MedPAC, in an October 2 comment to CMS.

“Some types of services — such as procedures, imaging, and tests — experience efficiency gains over time, as advances in technology, technique, and clinical practice enable clinicians to deliver them faster,” he wrote. “However, E&M office/outpatient visits do not lend themselves to such efficiency gains because they consist largely of activities that require the clinician’s time.”

Medicare’s payment policies have thus “passively devalued” the time many clinicians spend on office visits, helping to skew the decisions of young physicians toward specialties, according to Chernew.

Reshuffling payment away from specialties that are now “overvalued” is needed to “remedy several years of passive devaluation,” he wrote.

The median income in 2018 for primary care physicians was $243,000 in 2018, whereas that of specialists such as surgeons was $426,000, Chernew said in the letter, citing MedPAC research.

These figures echo the findings of Medscape’s most recent annual physician compensation report.

As one of the largest buyers of medical services, Medicare has significant influence on the practice of medicine in the United States. In 2018 alone, Medicare directly paid $70.5 billion for clinician services. Its payment policies already may have shaped the pool of clinicians available to treat people enrolled in Medicare, which covers those aged 65 years and older, Chernew said.

“The US has over three times as many specialists as primary care physicians, which could explain why MedPAC’s annual survey of Medicare beneficiaries has repeatedly found that beneficiaries who are looking for a new physician report having an easier time finding a new specialist than a new primary care provider,” he wrote.

“Access to primary care physicians could worsen in the future as the number of primary care physicians in the US, after remaining flat for several years, has actually started to decline,” Chernew said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

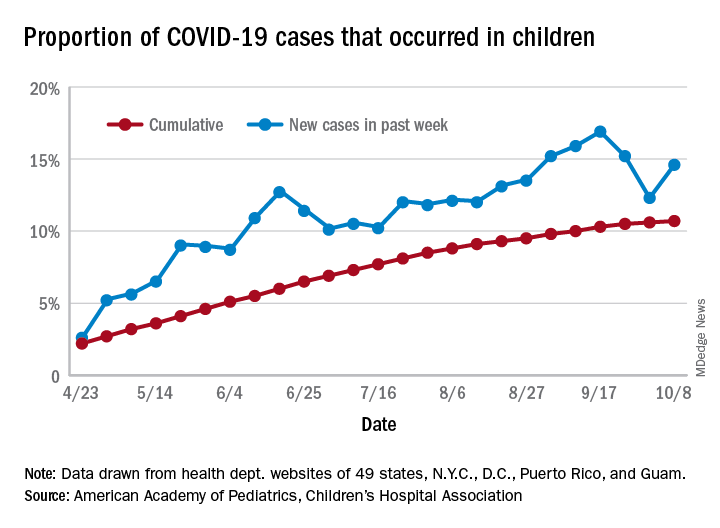

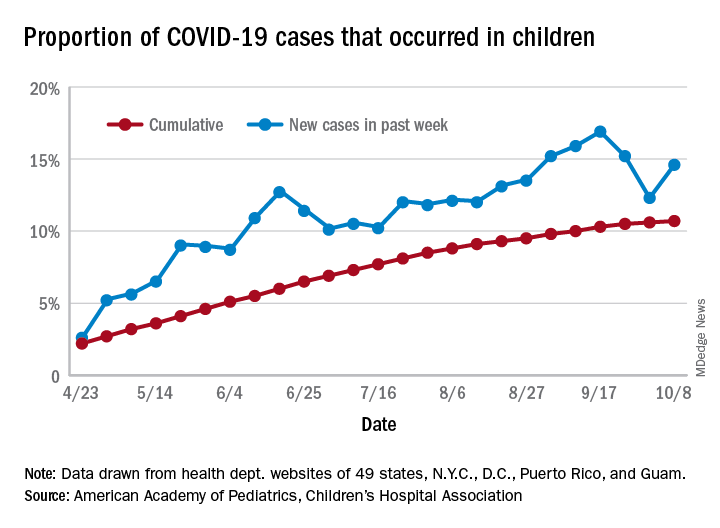

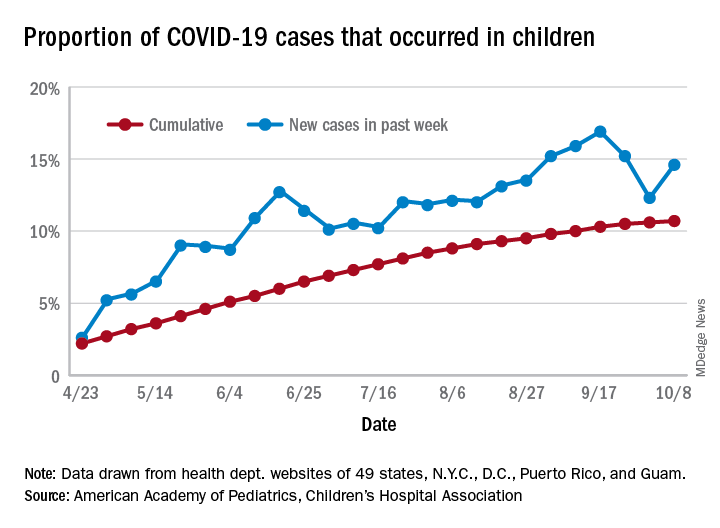

What’s in a number? 697,633 children with COVID-19

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

For the week, 14.6% of all COVID-19 cases reported in the United States occurred in children, after 2 consecutive weeks of declines that saw the proportion drop from 16.9% to 12.3%. The cumulative rate of child cases for the entire pandemic is 10.7%, with total child cases in the United States now up to 697,633 and cases among all ages at just over 6.5 million, the AAP and the CHA said Oct. 12 in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Nationally, there were 927 cases reported per 100,000 children as of Oct. 8, with rates at the state level varying from 176 per 100,000 in Vermont to 2,221 per 100,000 in North Dakota. Two other states were over 2,000 cases per 100,000 children: Tennessee (2,155) and South Carolina (2,116), based on data from the health departments of 49 states (New York does not report age distribution), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Severe illness continues to be rare in children, and national (25 states and New York City) hospitalization rates dropped in the last week. The proportion of hospitalizations occurring in children slipped from a pandemic high of 1.8% the previous week to 1.7% during the week of Oct. 8, and the rate of hospitalizations for children with COVID-19 was down to 1.4% from 1.6% the week before and 1.9% on Sept. 3, the AAP and the CHA said.

Mortality data from 42 states and New York City also show a decline. For the third consecutive week, children represented just 0.06% of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States, down from a high of 0.07% on Sept. 17. Only 0.02% of all cases in children have resulted in death, and that figure has been dropping since early June, when it reached 0.06%, according to the AAP/CHA report. As of Oct. 8, there have been 115 total deaths reported in children.

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

For the week, 14.6% of all COVID-19 cases reported in the United States occurred in children, after 2 consecutive weeks of declines that saw the proportion drop from 16.9% to 12.3%. The cumulative rate of child cases for the entire pandemic is 10.7%, with total child cases in the United States now up to 697,633 and cases among all ages at just over 6.5 million, the AAP and the CHA said Oct. 12 in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Nationally, there were 927 cases reported per 100,000 children as of Oct. 8, with rates at the state level varying from 176 per 100,000 in Vermont to 2,221 per 100,000 in North Dakota. Two other states were over 2,000 cases per 100,000 children: Tennessee (2,155) and South Carolina (2,116), based on data from the health departments of 49 states (New York does not report age distribution), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Severe illness continues to be rare in children, and national (25 states and New York City) hospitalization rates dropped in the last week. The proportion of hospitalizations occurring in children slipped from a pandemic high of 1.8% the previous week to 1.7% during the week of Oct. 8, and the rate of hospitalizations for children with COVID-19 was down to 1.4% from 1.6% the week before and 1.9% on Sept. 3, the AAP and the CHA said.

Mortality data from 42 states and New York City also show a decline. For the third consecutive week, children represented just 0.06% of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States, down from a high of 0.07% on Sept. 17. Only 0.02% of all cases in children have resulted in death, and that figure has been dropping since early June, when it reached 0.06%, according to the AAP/CHA report. As of Oct. 8, there have been 115 total deaths reported in children.

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

For the week, 14.6% of all COVID-19 cases reported in the United States occurred in children, after 2 consecutive weeks of declines that saw the proportion drop from 16.9% to 12.3%. The cumulative rate of child cases for the entire pandemic is 10.7%, with total child cases in the United States now up to 697,633 and cases among all ages at just over 6.5 million, the AAP and the CHA said Oct. 12 in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Nationally, there were 927 cases reported per 100,000 children as of Oct. 8, with rates at the state level varying from 176 per 100,000 in Vermont to 2,221 per 100,000 in North Dakota. Two other states were over 2,000 cases per 100,000 children: Tennessee (2,155) and South Carolina (2,116), based on data from the health departments of 49 states (New York does not report age distribution), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Severe illness continues to be rare in children, and national (25 states and New York City) hospitalization rates dropped in the last week. The proportion of hospitalizations occurring in children slipped from a pandemic high of 1.8% the previous week to 1.7% during the week of Oct. 8, and the rate of hospitalizations for children with COVID-19 was down to 1.4% from 1.6% the week before and 1.9% on Sept. 3, the AAP and the CHA said.

Mortality data from 42 states and New York City also show a decline. For the third consecutive week, children represented just 0.06% of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States, down from a high of 0.07% on Sept. 17. Only 0.02% of all cases in children have resulted in death, and that figure has been dropping since early June, when it reached 0.06%, according to the AAP/CHA report. As of Oct. 8, there have been 115 total deaths reported in children.

Flu vaccine significantly cuts pediatric hospitalizations

Unlike previous studies focused on vaccine effectiveness (VE) in ambulatory care office visits, Angela P. Campbell, MD, MPH, and associates have uncovered evidence of the overall benefit influenza vaccines play in reducing hospitalizations and emergency department visits in pediatric influenza patients.

“Our data provide important VE estimates against severe influenza in children,” the researchers noted in Pediatrics, adding that the findings “provide important evidence supporting the annual recommendation that all children 6 months and older should receive influenza vaccination.”

Dr. Campbell and colleagues collected ongoing surveillance data from the New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN), which is a network of pediatric hospitals across seven cities, including Kansas City, Mo.; Rochester, N.Y.; Cincinnati; Pittsburgh; Nashville, Tenn.; Houston; and Seattle. The influenza season encompassed the period Nov. 7, 2018 to June 21, 2019.

A total of 2,748 hospitalized children and 2,676 children who had completed ED visits that did not lead to hospitalization were included. Once those under 6 months were excluded, 1,792 hospitalized children were included in the VE analysis; of these, 226 (13%) tested positive for influenza infection, including 211 (93%) with influenza A viruses and 15 (7%) with influenza B viruses. Fully 1,611 of the patients (90%), had verified vaccine status, while 181 (10%) had solely parental reported vaccine status. The researchers reported 88 (5%) of the patients received mechanical ventilation and 7 (<1%) died.

Most noteworthy, They further estimated a significant reduction in hospitalizations linked to A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, even in the presence of circulating A(H3N2) viruses that differed from the A(H3N2) vaccine component.

Studies from other countries during the same time period showed that while “significant protection against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits and hospitalizations among children infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses” was observed, the same could not be said for protection against A(H3N2) viruses, which varied among pediatric outpatients in the United States (24%), in England (17% outpatient; 31% inpatient), Europe (46%), and Canada (48%). They explained that such variation in vaccine protection is multifactorial, and includes virus-, host-, and environment-related factors. They also noted that regional variations in circulating viruses, host factors including age, imprinting, and previous vaccination could explain the study’s finding of vaccine protection against both A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses.

When comparing VE estimates between ED visits and hospitalizations, the researchers observed one significant difference, that “hospitalized children likely represent more medically complex patients, with 58% having underlying medical conditions and 38% reporting at lease one hospitalization in the past year, compared with 28% and 14% respectively, among ED participants.”

Strengths of the study included the prospective multisite enrollment that provided data across diverse locations and representation from pediatric hospitalizations and ED care, which were not previously strongly represented in the literature. The single-season study with small sample size was considered a limitation, as was the inability to evaluate full and partial vaccine status. Vaccine data also were limited for many of the ED patients observed.

Dr. Campbell and colleagues did caution that while they consider their test-negative design optimal for evaluating both hospitalized and ED patients, they feel their results should not be “interpreted as VE against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits or infections that are not medically attended.”

In a separate interview, Michael E. Pichichero, MD, director of the Rochester General Hospital Research Institute and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), observed: “There are really no surprises here. A well done contemporary study confirms again the benefits of annual influenza vaccinations for children. Viral coinfections involving SARS-CoV-2 and influenza have been reported from Australia to cause heightened illnesses. That observation provides further impetus for parents to have their children receive influenza vaccinations.”

The researchers cited multiple sources of financial support for their ongoing work, including Sanofi, Quidel, Moderna, Karius, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. Funding for this study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Pichichero said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Campbell AP et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1368.

Unlike previous studies focused on vaccine effectiveness (VE) in ambulatory care office visits, Angela P. Campbell, MD, MPH, and associates have uncovered evidence of the overall benefit influenza vaccines play in reducing hospitalizations and emergency department visits in pediatric influenza patients.

“Our data provide important VE estimates against severe influenza in children,” the researchers noted in Pediatrics, adding that the findings “provide important evidence supporting the annual recommendation that all children 6 months and older should receive influenza vaccination.”

Dr. Campbell and colleagues collected ongoing surveillance data from the New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN), which is a network of pediatric hospitals across seven cities, including Kansas City, Mo.; Rochester, N.Y.; Cincinnati; Pittsburgh; Nashville, Tenn.; Houston; and Seattle. The influenza season encompassed the period Nov. 7, 2018 to June 21, 2019.

A total of 2,748 hospitalized children and 2,676 children who had completed ED visits that did not lead to hospitalization were included. Once those under 6 months were excluded, 1,792 hospitalized children were included in the VE analysis; of these, 226 (13%) tested positive for influenza infection, including 211 (93%) with influenza A viruses and 15 (7%) with influenza B viruses. Fully 1,611 of the patients (90%), had verified vaccine status, while 181 (10%) had solely parental reported vaccine status. The researchers reported 88 (5%) of the patients received mechanical ventilation and 7 (<1%) died.

Most noteworthy, They further estimated a significant reduction in hospitalizations linked to A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, even in the presence of circulating A(H3N2) viruses that differed from the A(H3N2) vaccine component.

Studies from other countries during the same time period showed that while “significant protection against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits and hospitalizations among children infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses” was observed, the same could not be said for protection against A(H3N2) viruses, which varied among pediatric outpatients in the United States (24%), in England (17% outpatient; 31% inpatient), Europe (46%), and Canada (48%). They explained that such variation in vaccine protection is multifactorial, and includes virus-, host-, and environment-related factors. They also noted that regional variations in circulating viruses, host factors including age, imprinting, and previous vaccination could explain the study’s finding of vaccine protection against both A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses.

When comparing VE estimates between ED visits and hospitalizations, the researchers observed one significant difference, that “hospitalized children likely represent more medically complex patients, with 58% having underlying medical conditions and 38% reporting at lease one hospitalization in the past year, compared with 28% and 14% respectively, among ED participants.”

Strengths of the study included the prospective multisite enrollment that provided data across diverse locations and representation from pediatric hospitalizations and ED care, which were not previously strongly represented in the literature. The single-season study with small sample size was considered a limitation, as was the inability to evaluate full and partial vaccine status. Vaccine data also were limited for many of the ED patients observed.

Dr. Campbell and colleagues did caution that while they consider their test-negative design optimal for evaluating both hospitalized and ED patients, they feel their results should not be “interpreted as VE against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits or infections that are not medically attended.”

In a separate interview, Michael E. Pichichero, MD, director of the Rochester General Hospital Research Institute and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), observed: “There are really no surprises here. A well done contemporary study confirms again the benefits of annual influenza vaccinations for children. Viral coinfections involving SARS-CoV-2 and influenza have been reported from Australia to cause heightened illnesses. That observation provides further impetus for parents to have their children receive influenza vaccinations.”

The researchers cited multiple sources of financial support for their ongoing work, including Sanofi, Quidel, Moderna, Karius, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. Funding for this study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Pichichero said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Campbell AP et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1368.

Unlike previous studies focused on vaccine effectiveness (VE) in ambulatory care office visits, Angela P. Campbell, MD, MPH, and associates have uncovered evidence of the overall benefit influenza vaccines play in reducing hospitalizations and emergency department visits in pediatric influenza patients.

“Our data provide important VE estimates against severe influenza in children,” the researchers noted in Pediatrics, adding that the findings “provide important evidence supporting the annual recommendation that all children 6 months and older should receive influenza vaccination.”

Dr. Campbell and colleagues collected ongoing surveillance data from the New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN), which is a network of pediatric hospitals across seven cities, including Kansas City, Mo.; Rochester, N.Y.; Cincinnati; Pittsburgh; Nashville, Tenn.; Houston; and Seattle. The influenza season encompassed the period Nov. 7, 2018 to June 21, 2019.

A total of 2,748 hospitalized children and 2,676 children who had completed ED visits that did not lead to hospitalization were included. Once those under 6 months were excluded, 1,792 hospitalized children were included in the VE analysis; of these, 226 (13%) tested positive for influenza infection, including 211 (93%) with influenza A viruses and 15 (7%) with influenza B viruses. Fully 1,611 of the patients (90%), had verified vaccine status, while 181 (10%) had solely parental reported vaccine status. The researchers reported 88 (5%) of the patients received mechanical ventilation and 7 (<1%) died.

Most noteworthy, They further estimated a significant reduction in hospitalizations linked to A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, even in the presence of circulating A(H3N2) viruses that differed from the A(H3N2) vaccine component.

Studies from other countries during the same time period showed that while “significant protection against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits and hospitalizations among children infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses” was observed, the same could not be said for protection against A(H3N2) viruses, which varied among pediatric outpatients in the United States (24%), in England (17% outpatient; 31% inpatient), Europe (46%), and Canada (48%). They explained that such variation in vaccine protection is multifactorial, and includes virus-, host-, and environment-related factors. They also noted that regional variations in circulating viruses, host factors including age, imprinting, and previous vaccination could explain the study’s finding of vaccine protection against both A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses.

When comparing VE estimates between ED visits and hospitalizations, the researchers observed one significant difference, that “hospitalized children likely represent more medically complex patients, with 58% having underlying medical conditions and 38% reporting at lease one hospitalization in the past year, compared with 28% and 14% respectively, among ED participants.”

Strengths of the study included the prospective multisite enrollment that provided data across diverse locations and representation from pediatric hospitalizations and ED care, which were not previously strongly represented in the literature. The single-season study with small sample size was considered a limitation, as was the inability to evaluate full and partial vaccine status. Vaccine data also were limited for many of the ED patients observed.

Dr. Campbell and colleagues did caution that while they consider their test-negative design optimal for evaluating both hospitalized and ED patients, they feel their results should not be “interpreted as VE against influenza-associated ambulatory care visits or infections that are not medically attended.”

In a separate interview, Michael E. Pichichero, MD, director of the Rochester General Hospital Research Institute and a clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), observed: “There are really no surprises here. A well done contemporary study confirms again the benefits of annual influenza vaccinations for children. Viral coinfections involving SARS-CoV-2 and influenza have been reported from Australia to cause heightened illnesses. That observation provides further impetus for parents to have their children receive influenza vaccinations.”

The researchers cited multiple sources of financial support for their ongoing work, including Sanofi, Quidel, Moderna, Karius, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. Funding for this study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Pichichero said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Campbell AP et al. Pediatrics. 2020. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1368.

FROM PEDIATRICS

‘Profound human toll’ in excess deaths from COVID-19 calculated in two studies

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.

“These deaths reflect a true measure of the human cost of the Great Pandemic of 2020,” they add.

The study from Emanuel and Bilinski was notable for calculating the excess COVID-19 and all-cause mortality to Sept. 2020, they note. “After the initial peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than rates in countries with high COVID-19 mortality.”

“Few people will forget the Great Pandemic of 2020, where and how they lived, how it substantially changed their lives, and for many, the profound human toll it has taken,” Bauchner and Fontanarosa write.

The study by Woolf and colleagues was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The study by Bilinski and Emanuel was partially funded by the Colton Foundation. Woolf, Emanuel, Fineberg, Bauchner, and Fontanarosa have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, additional deaths could be indirectly related because people avoided emergency care during the pandemic, new research shows.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 varied by state and phase of the pandemic, as reported in a study from researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University and Yale University that was published online October 12 in JAMA.

Another study published online simultaneously in JAMA took more of an international perspective. Investigators from the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University found that in America there were more excess deaths and there was higher all-cause mortality during the pandemic than in 18 other countries.

Although the ongoing number of deaths attributable to COVID-19 continues to garner attention, there can be a lag of weeks or months in how long it takes some public health agencies to update their figures.

“For the public at large, the take-home message is twofold: that the number of deaths caused by the pandemic exceeds publicly reported COVID-19 death counts by 20% and that states that reopened or lifted restrictions early suffered a protracted surge in excess deaths that extended into the summer,” lead author of the US-focused study, Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH, told Medscape Medical News.

The take-away for physicians is in the bigger picture – it is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic is responsible for deaths from other conditions as well. “Surges in COVID-19 were accompanied by an increase in deaths attributed to other causes, such as heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease and dementia,” said Woolf, director emeritus and senior adviser at the Center on Society and Health and professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia.

The investigators identified 225,530 excess US deaths in the 5 months from March to July. They report that 67% were directly attributable to COVID-19.

Deaths linked to COVID-19 included those in which the disease was listed as an underlying or contributing cause. US total death rates are “remarkably consistent” year after year, and the investigators calculated a 20% overall jump in mortality.

The study included data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the US Census Bureau for 48 states and the District of Columbia. Connecticut and North Carolina were excluded because of missing data.

Woolf and colleagues also found statistically higher rates of deaths from two other causes, heart disease and Alzheimer’s disease/dementia.

Altered states

New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Arizona, Mississippi, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, and Michigan had the highest per capita excess death rates. Three states experienced the shortest epidemics during the study period: New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

Some lessons could be learned by looking at how individual states managed large numbers of people with COVID-19. “Although we suspected that states that reopened early might have put themselves at risk of a pandemic surge, the consistency with which that occurred and the devastating numbers of deaths they suffered was a surprise,” Woolf said.

“The goal of our study is not to look in the rearview mirror and lament what happened months ago but to learn the lesson going forward: Our country will be unable to take control of this pandemic without more robust efforts to control community spread,” Woolf said. “Our study found that states that did this well, such as New York and New Jersey, experienced large surges but bent the curve and were back to baseline in less than 10 weeks.

“If we could do this as a country, countless lives could be saved.”

A global perspective

The United States experienced high mortality linked to COVID-19, as well as high all-cause mortality, compared with 18 other countries, as reported in the study by University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University researchers.

The United States ranked third, with 72 deaths per 100,000 people, among countries with moderate or high mortality. Although perhaps not surprising given the state of SARS-CoV-2 infection across the United States, a question remains as to what extent the relatively high mortality rate is linked to early outbreaks vs “poor long-term response,” the researchers note.

Alyssa Bilinski, MSc, and lead author Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia, calculated the difference in COVID-19 deaths among countries through Sept. 19, 2020. On this date, the United States reported a total 198,589 COVID-19 deaths.

They calculated that, if the US death rates were similar to those in Australia, the United States would have experienced 187,661 fewer COVID-19 deaths. If similar to those of Canada, there would have been 117,622 fewer deaths in the United States.

The US death rate was lower than six other countries with high COVID-19 mortality in the early spring, including Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. However, after May 10, the per capita mortality rate in the United States exceeded the others.

Between May 10 and Sept. 19, the death rate in Italy was 9.1 per 100,000, vs 36.9 per 100,000.

“After the first peak in early spring, US death rates from COVID-19 and from all causes remained higher than even countries with high COVID-19 mortality,” the researchers note. “This may have been a result of several factors, including weak public health infrastructure and a decentralized, inconsistent US response to the pandemic.”

“Mortifying and motivating”

Woolf and colleagues estimate that more than 225,000 excess deaths occurred in recent months; this represents a 20% increase over expected deaths, note Harvey V. Fineberg, MD, PhD, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, in an accompanying editorial in JAMA.

“Importantly, a condition such as COVID-19 can contribute both directly and indirectly to excess mortality,” he writes.

Although the direct contribution to the mortality rates by those infected is straightforward, “the indirect contribution may relate to circumstances or choices due to the COVID-19 pandemic: for example, a patient who develops symptoms of a stroke is too concerned about COVID-19 to go to the emergency department, and a potentially reversible condition becomes fatal.”

Fineberg notes that “a general indication of the death toll from COVID-19 and the excess deaths related to the pandemic, as presented by Woolf et al, are sufficiently mortifying and motivating.”

“Profound human toll”

“The importance of the estimate by Woolf et al – which suggests that for the entirety of 2020, more than 400,000 excess deaths will occur – cannot be overstated, because it accounts for what could be declines in some causes of death, like motor vehicle crashes, but increases in others, like myocardial infarction,” write Howard Bauchner, MD, editor in chief of JAMA, and Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, executive editor of JAMA, in another accompanying editorial.