User login

Depression biomarkers: Which ones matter most?

Multiple biomarkers of depression involved in several brain circuits are altered in patients with unipolar depression.

because they suggest neuroimmunological alterations, disturbances in the blood-brain-barrier, hyperactivity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and impaired neuroplasticity as factors in depression pathophysiology.

However, said study investigator Michael E. Benros, MD, PhD, professor and head of research at Mental Health Centre Copenhagen and University of Copenhagen, this is on a group level. “So in order to be relevant in a clinical context, the results need to be validated by further high-quality studies identifying subgroups with different biological underpinnings,” he told this news organization.

Identification of potential subgroups of depression with different biomarkers might help explain the diverse symptomatology and variability in treatment response observed in patients with depression, he noted.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Multiple pathways to depression

The systematic review and meta-analysis included 97 studies investigating 165 CSF biomarkers.

Of the 42 biomarkers investigated in at least two studies, patients with unipolar depression had higher CSF levels of interleukin 6, a marker of chronic inflammation; total protein, which signals blood-brain barrier dysfunction and increased permeability; and cortisol, which is linked to psychological stress, compared with healthy controls.

Depression was also associated with:

- Lower CSF levels of homovanillic acid, the major terminal metabolite of dopamine.

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS thought to play a vital role in the control of stress and depression.

- Somatostatin, a neuropeptide often coexpressed with GABA.

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein involved in neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmission.

- Amyloid-β 40, implicated in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Transthyretin, involved in transport of thyroxine across the blood-brain barrier.

Collectively, the findings point toward a “dysregulated dopaminergic system, a compromised inhibitory system, HPA axis hyperactivity, increased neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier permeability, and impaired neuroplasticity as important factors in depression pathophysiology,” the investigators wrote.

“It is notable that we did not find significant difference in the metabolite levels of serotonin and noradrenalin, which are the most targeted neurotransmitters in modern antidepressant treatment,” said Dr. Benros.

However, this could be explained by substantial heterogeneity between studies and the fact that quantification of total CSF biomarker concentrations does not reflect local alteration within the brain, he explained.

Many of the studies had small cohorts and most quantified only a few biomarkers, making it hard to examine potential interactions between biomarkers or identify specific phenotypes of depression.

“Novel high-quality studies including larger cohorts with an integrative approach and extensive numbers of biomarkers are needed to validate these potential biomarkers of depression and set the stage for the development of more effective and precise treatments,” the researchers noted.

Which ones hold water?

Reached for comment, Dean MacKinnon, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, noted that this analysis “extracts the vast amount of knowledge” gained from different studies on biomarkers in the CSF for depression.

“They were able to identify 97 papers that have enough information in them that they could sort of lump them together and see which ones still hold water. It’s always useful to be able to look at patterns in the research and see if you can find some consistent trends,” he told this news organization.

Dr. MacKinnon, who was not part of the research team, also noted that “nonreplicability” is a problem in psychiatry and psychology research, “so being able to show that at least some studies were sufficiently well done, to get a good result, and that they could be replicated in at least one other good study is useful information.”

When it comes to depression, Dr. MacKinnon said, “We just don’t know enough to really pin down a physiologic pathway to explain it. The fact that some people seem to have high cortisol and some people seem to have high permeability of blood-brain barrier, and others have abnormalities in dopamine, is interesting and suggests that depression is likely not a unitary disease with a single cause.”

He cautioned, however, that the findings don’t have immediate clinical implications for individual patients with depression.

“Theoretically, down the road, if you extrapolate from what they found, and if it’s truly the case that this research maps to something that could suggest a different clinical approach, you might be able to determine whether one patient might respond better to an SSRI or an SNRI or something like that,” Dr. MacKinnon said.

Dr. Benros reported grants from Lundbeck Foundation during the conduct of the study. Dr. MacKinnon has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Multiple biomarkers of depression involved in several brain circuits are altered in patients with unipolar depression.

because they suggest neuroimmunological alterations, disturbances in the blood-brain-barrier, hyperactivity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and impaired neuroplasticity as factors in depression pathophysiology.

However, said study investigator Michael E. Benros, MD, PhD, professor and head of research at Mental Health Centre Copenhagen and University of Copenhagen, this is on a group level. “So in order to be relevant in a clinical context, the results need to be validated by further high-quality studies identifying subgroups with different biological underpinnings,” he told this news organization.

Identification of potential subgroups of depression with different biomarkers might help explain the diverse symptomatology and variability in treatment response observed in patients with depression, he noted.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Multiple pathways to depression

The systematic review and meta-analysis included 97 studies investigating 165 CSF biomarkers.

Of the 42 biomarkers investigated in at least two studies, patients with unipolar depression had higher CSF levels of interleukin 6, a marker of chronic inflammation; total protein, which signals blood-brain barrier dysfunction and increased permeability; and cortisol, which is linked to psychological stress, compared with healthy controls.

Depression was also associated with:

- Lower CSF levels of homovanillic acid, the major terminal metabolite of dopamine.

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS thought to play a vital role in the control of stress and depression.

- Somatostatin, a neuropeptide often coexpressed with GABA.

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein involved in neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmission.

- Amyloid-β 40, implicated in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Transthyretin, involved in transport of thyroxine across the blood-brain barrier.

Collectively, the findings point toward a “dysregulated dopaminergic system, a compromised inhibitory system, HPA axis hyperactivity, increased neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier permeability, and impaired neuroplasticity as important factors in depression pathophysiology,” the investigators wrote.

“It is notable that we did not find significant difference in the metabolite levels of serotonin and noradrenalin, which are the most targeted neurotransmitters in modern antidepressant treatment,” said Dr. Benros.

However, this could be explained by substantial heterogeneity between studies and the fact that quantification of total CSF biomarker concentrations does not reflect local alteration within the brain, he explained.

Many of the studies had small cohorts and most quantified only a few biomarkers, making it hard to examine potential interactions between biomarkers or identify specific phenotypes of depression.

“Novel high-quality studies including larger cohorts with an integrative approach and extensive numbers of biomarkers are needed to validate these potential biomarkers of depression and set the stage for the development of more effective and precise treatments,” the researchers noted.

Which ones hold water?

Reached for comment, Dean MacKinnon, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, noted that this analysis “extracts the vast amount of knowledge” gained from different studies on biomarkers in the CSF for depression.

“They were able to identify 97 papers that have enough information in them that they could sort of lump them together and see which ones still hold water. It’s always useful to be able to look at patterns in the research and see if you can find some consistent trends,” he told this news organization.

Dr. MacKinnon, who was not part of the research team, also noted that “nonreplicability” is a problem in psychiatry and psychology research, “so being able to show that at least some studies were sufficiently well done, to get a good result, and that they could be replicated in at least one other good study is useful information.”

When it comes to depression, Dr. MacKinnon said, “We just don’t know enough to really pin down a physiologic pathway to explain it. The fact that some people seem to have high cortisol and some people seem to have high permeability of blood-brain barrier, and others have abnormalities in dopamine, is interesting and suggests that depression is likely not a unitary disease with a single cause.”

He cautioned, however, that the findings don’t have immediate clinical implications for individual patients with depression.

“Theoretically, down the road, if you extrapolate from what they found, and if it’s truly the case that this research maps to something that could suggest a different clinical approach, you might be able to determine whether one patient might respond better to an SSRI or an SNRI or something like that,” Dr. MacKinnon said.

Dr. Benros reported grants from Lundbeck Foundation during the conduct of the study. Dr. MacKinnon has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Multiple biomarkers of depression involved in several brain circuits are altered in patients with unipolar depression.

because they suggest neuroimmunological alterations, disturbances in the blood-brain-barrier, hyperactivity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and impaired neuroplasticity as factors in depression pathophysiology.

However, said study investigator Michael E. Benros, MD, PhD, professor and head of research at Mental Health Centre Copenhagen and University of Copenhagen, this is on a group level. “So in order to be relevant in a clinical context, the results need to be validated by further high-quality studies identifying subgroups with different biological underpinnings,” he told this news organization.

Identification of potential subgroups of depression with different biomarkers might help explain the diverse symptomatology and variability in treatment response observed in patients with depression, he noted.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Multiple pathways to depression

The systematic review and meta-analysis included 97 studies investigating 165 CSF biomarkers.

Of the 42 biomarkers investigated in at least two studies, patients with unipolar depression had higher CSF levels of interleukin 6, a marker of chronic inflammation; total protein, which signals blood-brain barrier dysfunction and increased permeability; and cortisol, which is linked to psychological stress, compared with healthy controls.

Depression was also associated with:

- Lower CSF levels of homovanillic acid, the major terminal metabolite of dopamine.

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS thought to play a vital role in the control of stress and depression.

- Somatostatin, a neuropeptide often coexpressed with GABA.

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein involved in neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmission.

- Amyloid-β 40, implicated in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Transthyretin, involved in transport of thyroxine across the blood-brain barrier.

Collectively, the findings point toward a “dysregulated dopaminergic system, a compromised inhibitory system, HPA axis hyperactivity, increased neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier permeability, and impaired neuroplasticity as important factors in depression pathophysiology,” the investigators wrote.

“It is notable that we did not find significant difference in the metabolite levels of serotonin and noradrenalin, which are the most targeted neurotransmitters in modern antidepressant treatment,” said Dr. Benros.

However, this could be explained by substantial heterogeneity between studies and the fact that quantification of total CSF biomarker concentrations does not reflect local alteration within the brain, he explained.

Many of the studies had small cohorts and most quantified only a few biomarkers, making it hard to examine potential interactions between biomarkers or identify specific phenotypes of depression.

“Novel high-quality studies including larger cohorts with an integrative approach and extensive numbers of biomarkers are needed to validate these potential biomarkers of depression and set the stage for the development of more effective and precise treatments,” the researchers noted.

Which ones hold water?

Reached for comment, Dean MacKinnon, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, noted that this analysis “extracts the vast amount of knowledge” gained from different studies on biomarkers in the CSF for depression.

“They were able to identify 97 papers that have enough information in them that they could sort of lump them together and see which ones still hold water. It’s always useful to be able to look at patterns in the research and see if you can find some consistent trends,” he told this news organization.

Dr. MacKinnon, who was not part of the research team, also noted that “nonreplicability” is a problem in psychiatry and psychology research, “so being able to show that at least some studies were sufficiently well done, to get a good result, and that they could be replicated in at least one other good study is useful information.”

When it comes to depression, Dr. MacKinnon said, “We just don’t know enough to really pin down a physiologic pathway to explain it. The fact that some people seem to have high cortisol and some people seem to have high permeability of blood-brain barrier, and others have abnormalities in dopamine, is interesting and suggests that depression is likely not a unitary disease with a single cause.”

He cautioned, however, that the findings don’t have immediate clinical implications for individual patients with depression.

“Theoretically, down the road, if you extrapolate from what they found, and if it’s truly the case that this research maps to something that could suggest a different clinical approach, you might be able to determine whether one patient might respond better to an SSRI or an SNRI or something like that,” Dr. MacKinnon said.

Dr. Benros reported grants from Lundbeck Foundation during the conduct of the study. Dr. MacKinnon has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Burnout ‘highly prevalent’ in psychiatrists across the globe

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

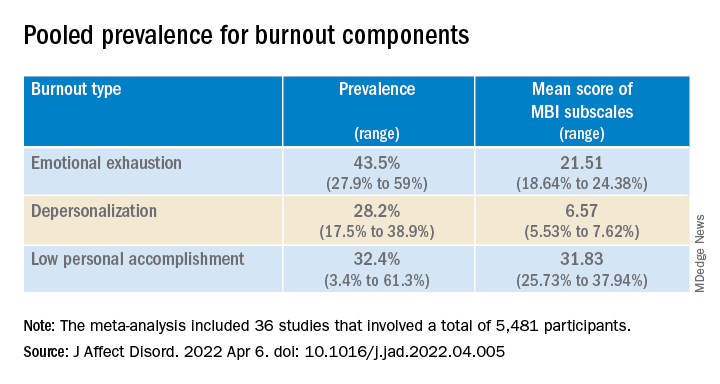

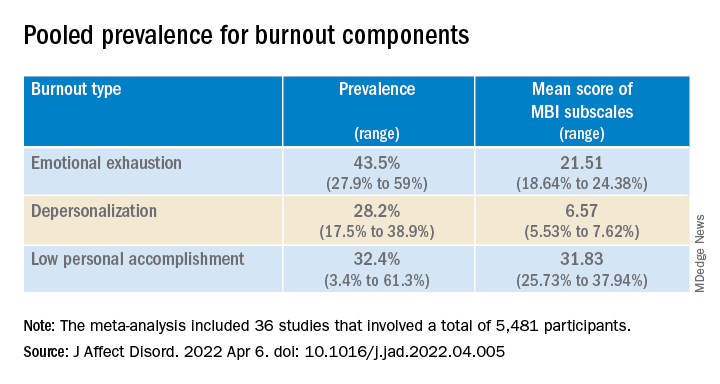

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

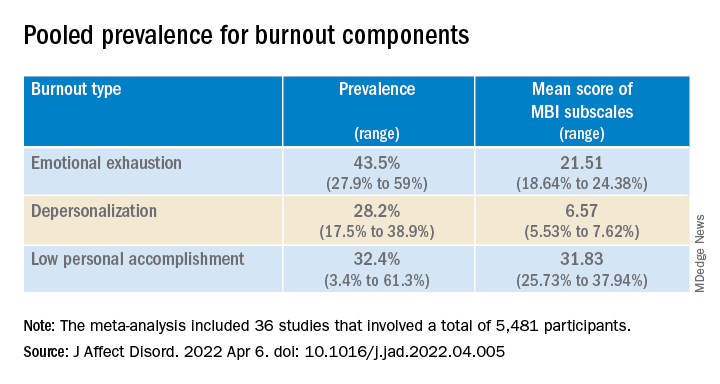

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Cellular gene profiling may predict IBD treatment response

Transcriptomic profiling of phagocytes in the lamina propria of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may guide future treatment selection, according to investigators.

Mucosal gut biopsies revealed that phagocytic gene expression correlated with inflammatory states, types of IBD, and responses to therapy, lead author Gillian E. Jacobsen a MD/PhD candidate at the University of Miami and colleagues reported.

In an article in Gastro Hep Advances, the investigators wrote that “lamina propria phagocytes along with epithelial cells represent a first line of defense and play a balancing act between tolerance toward commensal microbes and generation of immune responses toward pathogenic microorganisms. ... Inappropriate responses by lamina propria phagocytes have been linked to IBD.”

To better understand these responses, the researchers collected 111 gut mucosal biopsies from 54 patients with IBD, among whom 59% were taking biologics, 72% had inflammation in at least one biopsy site, and 41% had previously used at least one other biologic. Samples were analyzed to determine cell phenotypes, gene expression, and cytokine responses to in vitro Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor exposure.

Ms. Jacobsen and colleagues noted that most reports that address the function of phagocytes focus on circulating dendritic cells, monocytes, or monocyte-derived macrophages, rather than on resident phagocyte populations located in the lamina propria. However, these circulating cells “do not reflect intestinal inflammation, or whole tissue biopsies.”

Phagocytes based on CD11b expression and phenotyped CD11b+-enriched cells using flow cytometry were identified. In samples with active inflammation, cells were most often granulocytes (45.5%), followed by macrophages (22.6%) and monocytes (9.4%). Uninflamed samples had a slightly lower proportion of granulocytes (33.6%), about the same proportion of macrophages (22.7%), and a higher rate of B cells (15.6% vs. 9.0%).

Ms. Jacobsen and colleagues highlighted the absolute uptick in granulocytes, including neutrophils.

“Neutrophilic infiltration is a major indicator of IBD activity and may be critically linked to ongoing inflammation,” they wrote. “These data demonstrate that CD11b+ enrichment reflects the inflammatory state of the biopsies.”

The investigators also showed that transcriptional profiles of lamina propria CD11b+ cells differed “greatly” between colon and ileum, which suggested that “the location or cellular environment plays a marked role in determining the gene expression of phagocytes.”

CD11b+ cell gene expression profiles also correlated with ulcerative colitis versus Crohn’s disease, although the researchers noted that these patterns were less pronounced than correlations with inflammatory states

“There are pathways common to inflammation regardless of the IBD type that could be used as markers of inflammation or targets for therapy.”

Comparing colon samples from patients who responded to anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy with those who were refractory to anti-TNF therapy revealed significant associations between response type and 52 differentially expressed genes.

“These genes were mostly immunoglobulin genes up-regulated in the anti–TNF-treated inflamed colon, suggesting that CD11b+ B cells may play a role in medication refractoriness.”

Evaluating inflamed colon and anti-TNF refractory ileum revealed differential expression of OSM, a known marker of TNF-resistant disease, as well as TREM1, a proinflammatory marker. In contrast, NTS genes showed high expression in uninflamed samples on anti-TNF therapy. The researchers noted that these findings “may be used to build precision medicine approaches in IBD.”

Further experiments showed that in vitro exposure of anti-TNF refractory samples to JAK inhibitors resulted in significantly reduced secretion of interleukin-8 and TNF-alpha.

“Our study provides functional data that JAK inhibition with tofacitinib (JAK1/JAK3) or ruxolitinib (JAK1/JAK2) inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production even in TNF-refractory samples,” the researchers wrote. “These data inform the response of patients to JAK inhibitors, including those refractory to other treatments.”

The study was supported by Pfizer, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Micky & Madeleine Arison Family Foundation Crohn’s & Colitis Discovery Laboratory, and Martin Kalser Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Miami. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Takeda, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, and others.

Inflammatory bowel diseases are complex and heterogenous disorders driven by inappropriate immune responses to luminal substances, including diet and microbes, resulting in chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Therapies for IBD largely center around suppressing immune responses; however, given the complexity and heterogeneity of these diseases, consensus on which aspect of the immune response to suppress and which cell type to target in a given patient is unclear.

Sreeram Udayan, PhD, and Rodney D. Newberry, MD, are with the division of gastroenterology in the department of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

Inflammatory bowel diseases are complex and heterogenous disorders driven by inappropriate immune responses to luminal substances, including diet and microbes, resulting in chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Therapies for IBD largely center around suppressing immune responses; however, given the complexity and heterogeneity of these diseases, consensus on which aspect of the immune response to suppress and which cell type to target in a given patient is unclear.

Sreeram Udayan, PhD, and Rodney D. Newberry, MD, are with the division of gastroenterology in the department of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

Inflammatory bowel diseases are complex and heterogenous disorders driven by inappropriate immune responses to luminal substances, including diet and microbes, resulting in chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Therapies for IBD largely center around suppressing immune responses; however, given the complexity and heterogeneity of these diseases, consensus on which aspect of the immune response to suppress and which cell type to target in a given patient is unclear.

Sreeram Udayan, PhD, and Rodney D. Newberry, MD, are with the division of gastroenterology in the department of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

Transcriptomic profiling of phagocytes in the lamina propria of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may guide future treatment selection, according to investigators.

Mucosal gut biopsies revealed that phagocytic gene expression correlated with inflammatory states, types of IBD, and responses to therapy, lead author Gillian E. Jacobsen a MD/PhD candidate at the University of Miami and colleagues reported.

In an article in Gastro Hep Advances, the investigators wrote that “lamina propria phagocytes along with epithelial cells represent a first line of defense and play a balancing act between tolerance toward commensal microbes and generation of immune responses toward pathogenic microorganisms. ... Inappropriate responses by lamina propria phagocytes have been linked to IBD.”

To better understand these responses, the researchers collected 111 gut mucosal biopsies from 54 patients with IBD, among whom 59% were taking biologics, 72% had inflammation in at least one biopsy site, and 41% had previously used at least one other biologic. Samples were analyzed to determine cell phenotypes, gene expression, and cytokine responses to in vitro Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor exposure.

Ms. Jacobsen and colleagues noted that most reports that address the function of phagocytes focus on circulating dendritic cells, monocytes, or monocyte-derived macrophages, rather than on resident phagocyte populations located in the lamina propria. However, these circulating cells “do not reflect intestinal inflammation, or whole tissue biopsies.”

Phagocytes based on CD11b expression and phenotyped CD11b+-enriched cells using flow cytometry were identified. In samples with active inflammation, cells were most often granulocytes (45.5%), followed by macrophages (22.6%) and monocytes (9.4%). Uninflamed samples had a slightly lower proportion of granulocytes (33.6%), about the same proportion of macrophages (22.7%), and a higher rate of B cells (15.6% vs. 9.0%).

Ms. Jacobsen and colleagues highlighted the absolute uptick in granulocytes, including neutrophils.

“Neutrophilic infiltration is a major indicator of IBD activity and may be critically linked to ongoing inflammation,” they wrote. “These data demonstrate that CD11b+ enrichment reflects the inflammatory state of the biopsies.”

The investigators also showed that transcriptional profiles of lamina propria CD11b+ cells differed “greatly” between colon and ileum, which suggested that “the location or cellular environment plays a marked role in determining the gene expression of phagocytes.”

CD11b+ cell gene expression profiles also correlated with ulcerative colitis versus Crohn’s disease, although the researchers noted that these patterns were less pronounced than correlations with inflammatory states

“There are pathways common to inflammation regardless of the IBD type that could be used as markers of inflammation or targets for therapy.”

Comparing colon samples from patients who responded to anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy with those who were refractory to anti-TNF therapy revealed significant associations between response type and 52 differentially expressed genes.

“These genes were mostly immunoglobulin genes up-regulated in the anti–TNF-treated inflamed colon, suggesting that CD11b+ B cells may play a role in medication refractoriness.”

Evaluating inflamed colon and anti-TNF refractory ileum revealed differential expression of OSM, a known marker of TNF-resistant disease, as well as TREM1, a proinflammatory marker. In contrast, NTS genes showed high expression in uninflamed samples on anti-TNF therapy. The researchers noted that these findings “may be used to build precision medicine approaches in IBD.”

Further experiments showed that in vitro exposure of anti-TNF refractory samples to JAK inhibitors resulted in significantly reduced secretion of interleukin-8 and TNF-alpha.

“Our study provides functional data that JAK inhibition with tofacitinib (JAK1/JAK3) or ruxolitinib (JAK1/JAK2) inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production even in TNF-refractory samples,” the researchers wrote. “These data inform the response of patients to JAK inhibitors, including those refractory to other treatments.”

The study was supported by Pfizer, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Micky & Madeleine Arison Family Foundation Crohn’s & Colitis Discovery Laboratory, and Martin Kalser Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Miami. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Takeda, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, and others.

Transcriptomic profiling of phagocytes in the lamina propria of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may guide future treatment selection, according to investigators.

Mucosal gut biopsies revealed that phagocytic gene expression correlated with inflammatory states, types of IBD, and responses to therapy, lead author Gillian E. Jacobsen a MD/PhD candidate at the University of Miami and colleagues reported.

In an article in Gastro Hep Advances, the investigators wrote that “lamina propria phagocytes along with epithelial cells represent a first line of defense and play a balancing act between tolerance toward commensal microbes and generation of immune responses toward pathogenic microorganisms. ... Inappropriate responses by lamina propria phagocytes have been linked to IBD.”

To better understand these responses, the researchers collected 111 gut mucosal biopsies from 54 patients with IBD, among whom 59% were taking biologics, 72% had inflammation in at least one biopsy site, and 41% had previously used at least one other biologic. Samples were analyzed to determine cell phenotypes, gene expression, and cytokine responses to in vitro Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor exposure.

Ms. Jacobsen and colleagues noted that most reports that address the function of phagocytes focus on circulating dendritic cells, monocytes, or monocyte-derived macrophages, rather than on resident phagocyte populations located in the lamina propria. However, these circulating cells “do not reflect intestinal inflammation, or whole tissue biopsies.”

Phagocytes based on CD11b expression and phenotyped CD11b+-enriched cells using flow cytometry were identified. In samples with active inflammation, cells were most often granulocytes (45.5%), followed by macrophages (22.6%) and monocytes (9.4%). Uninflamed samples had a slightly lower proportion of granulocytes (33.6%), about the same proportion of macrophages (22.7%), and a higher rate of B cells (15.6% vs. 9.0%).

Ms. Jacobsen and colleagues highlighted the absolute uptick in granulocytes, including neutrophils.

“Neutrophilic infiltration is a major indicator of IBD activity and may be critically linked to ongoing inflammation,” they wrote. “These data demonstrate that CD11b+ enrichment reflects the inflammatory state of the biopsies.”

The investigators also showed that transcriptional profiles of lamina propria CD11b+ cells differed “greatly” between colon and ileum, which suggested that “the location or cellular environment plays a marked role in determining the gene expression of phagocytes.”

CD11b+ cell gene expression profiles also correlated with ulcerative colitis versus Crohn’s disease, although the researchers noted that these patterns were less pronounced than correlations with inflammatory states

“There are pathways common to inflammation regardless of the IBD type that could be used as markers of inflammation or targets for therapy.”

Comparing colon samples from patients who responded to anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy with those who were refractory to anti-TNF therapy revealed significant associations between response type and 52 differentially expressed genes.

“These genes were mostly immunoglobulin genes up-regulated in the anti–TNF-treated inflamed colon, suggesting that CD11b+ B cells may play a role in medication refractoriness.”

Evaluating inflamed colon and anti-TNF refractory ileum revealed differential expression of OSM, a known marker of TNF-resistant disease, as well as TREM1, a proinflammatory marker. In contrast, NTS genes showed high expression in uninflamed samples on anti-TNF therapy. The researchers noted that these findings “may be used to build precision medicine approaches in IBD.”

Further experiments showed that in vitro exposure of anti-TNF refractory samples to JAK inhibitors resulted in significantly reduced secretion of interleukin-8 and TNF-alpha.

“Our study provides functional data that JAK inhibition with tofacitinib (JAK1/JAK3) or ruxolitinib (JAK1/JAK2) inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production even in TNF-refractory samples,” the researchers wrote. “These data inform the response of patients to JAK inhibitors, including those refractory to other treatments.”

The study was supported by Pfizer, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Micky & Madeleine Arison Family Foundation Crohn’s & Colitis Discovery Laboratory, and Martin Kalser Chair in Gastroenterology at the University of Miami. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Takeda, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, and others.

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

Reading Chekhov on the Cancer Ward

Burnout and other forms of psychosocial distress are common among health care professionals necessitating measures to promote well-being and reduce burnout.1 Studies have shown that nonmedical reading is associated with low burnout and that small group study sections can promote wellness.2,3 Narrative medicine, which proposes a model for humane and effective medical practice, advocates for the necessity of narrative competence.

Short Story Club

Narrative competence is the ability to acknowledge, interpret, and act on the stories of others. The narrative skill of close reading also encourages reflective practice, equipping practitioners to better weather the tides of illness.4 In our case, we formed a short story club intervention to closely read, or read and reflect, on literary fiction. We explored how reading and reflecting would result in profound changes in thinking and feeling and noted different ways by which they can cause such well-being. We describe here the 7 ways in which stories led us to increase bonding, improve empathy, and promote meaning in medicine.

Slowing Down

The short story club helped to bond us together and increase our sense of meaning in medicine by slowing us down. One member of the group likened the experience to increasing the pixels in a painting, thereby improving the resolution and seeing more clearly. Another member mentioned the experience as a form of meditation in slowing down the brain, breathing in the story, and breathing out impressions. One story by Anatole Broyard emphasized the importance of slowing down and “brooding” over a patient.5 The author describes his experience as a prostate cancer patient, in which his body was treated but his story was ignored. He begged his doctors to pay more attention to his story to listen and to brood over him. This story was enlightening to us; we saw how desperate our patients are to tell their stories, and for us to hear their stories.

Mirrors and Windows

Another way reading and reflecting on short stories helped was by reflecting our practices to ourselves, as though looking into a mirror to see ourselves and out of a window to see others. We found that stories mirrored our own world and allowed us to discuss issues close to us without the embarrassment or stigma of owning the story. In one session we read “The Doctor’s Visit” by Anton Chekhov.6 Some of the members resonated with the doctor of this story who awkwardly attended to his lady patient whose son was dying of a brain tumor. The doctor was nervous, insecure, and unable to express any empathy. He was also the father of the child who was dying and refused to admit any responsibility. One member of the group stated that he could relate to the doctor’s insecurities and mentioned that he too felt insecure and even sometimes felt like an imposter. This led to a discussion of insecurities, ways to bolster self-confidence, and ways to accept and respect limitations. This was a conversation that may not have taken place without the story as anchor to discuss insecurities that we individually may not have been willing to admit to the group.

In a different session, we discussed the story “Interpreter of Maladies” by Jhumpa Lahiri in which a settled Indian American family returns to India to tour and learn about their heritage from a guide (the interpreter of maladies) who interpreted the culture for them.7 The family professed to be interested in knowing about the culture but could not concentrate: the wife stayed busy flirting with the guide and revealing outrageous secrets to him, the children were engrossed in their squabbles, and the father was essentially absent taking photographs as souvenirs instead of seeing the sites firsthand. Some of the members of the group were Indian American and could relate to the alienation from their home and nostalgia for their country, while others could relate to the same alienation, albeit from other cultures and countries. This allowed us to talk about deeply personal topics, without having to own the topic or reveal personal issues. The discussion led to a deep understanding and empathy for us and our colleagues knowing the pain of alienation that some of them felt but could not discuss.

The stories also served as windows into the world of others which enabled us to see and become the other. For example, in one session we reflected on “Babylon Revisited” by F. Scott Fitzgerald.8 In this story, an American man returns to Paris after the Great Depression and recalls his life as a young artist in the American artist expatriate community of Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. During that time, he partied, drank in excess, lost his wife to pneumonia (for which he was at least partially responsible), lost custody of his daughter, and lost his fortune. As he returned to Paris to try to reclaim his daughter, we feel his pain as he tries but fails to overcome chronic alcoholism, sexual indiscretions, and losses. This gave rise to discussion of losses in general as we became one with the main character. This increased our empathy for others in a way that could not have been possible without this short story as anchor.

In another session we reflected on “Hills Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway, in which a man is waiting for a train while proposing his girlfriend get an abortion.9 She agonizes over her choices and makes no decision in this story. Yet, we the reader could “become” the woman in the story faced with hard choices of having a baby but losing the man she loves, or having an abortion and maybe losing him anyway. In becoming this woman, we could experience the complex emotions and feel an experience of the other.

Exploring the Taboo

A third aspect of the club was enabling discussion of controversial topics. There were topics that arose in the group which never would have arisen in clinical practice discussions. These had to do with the taboo topics such as romantic attachments to patients. We read “The Caves of Lascaux” and reflected on the story of a young doctor who becomes enamored and obsessed with his beautiful but dying patient.10 He becomes so obsessed with her that he almost abandons his wife, family, and stable livelihood to descend with her into the caves. This story gave rise to discussions about romantic attachment to patients and how to handle and extricate one from the situation. The senior doctors explained some of their relevant experiences and how they either transferred care or sought counseling to extricate themselves from a potentially dangerous situation, especially when they too fell under the spell of forbidden romance.

Moral Grounding

These sessions also served to define the moral basis of our own practice. Much of health care psychosocial distress is related to moral injury in which health care professionals do the wrong thing or fail to do the right thing at the right time, due to external pressures related to financial or other gains. Reading and reflecting put us face-to-face with moral dilemmas and let us find our moral grounding. In reading “The Haircut” by Ring Lardner, we explored the disruptive town scoundrel who harassed and tortured his friends and neighbors but in such outrageous ways that he was considered a comedian rather than an abuser.11 Despite his hurtful acts, the townspeople (including the narrator) considered him a clown and laughed at his racist and sexist statements as well as his tricks.He faced no consequences such as confrontation, until the end when fate caught up. This story gave rise to a discussion of how we handle unkind, racist, sexist, or other comments which are disguised as humor, and to what extent we tolerate such controversial behavior. Do we go along with the scoundrel and laugh, or do we confront such people and insist that they respect and honor other people? The story sensitized the group to the ways in which prejudice and racism or sexism can be masked as humor, and to consider our moral responsibilities in society.

In another session we read and reflected on “Three Questions” by Leo Tolstoy.12 In this story, a king travels to another territory but gets distracted by helping a neighbor in need, and thereby inadvertently and fortunately avoids the trap that had been devised to kill him. The author gives us his moral basis by asking and answering 3 questions: Who is the most important person? What is the most important thing to do? What is the most important thing to do now? His answers provided his moral grounding. We discussed our answers and the basis of our moral grounding, whether it be the injunction do no harm, the more complex religious backgrounds of our childhood, or otherwise.

Symbols and Metaphors

The practice of reading and reflecting also taught us symbols and metaphors. Symbols and metaphors are the essence of storytelling, and they provide keys to understanding people. We sought out and studied the metaphors and symbols in each of the stories we read. In “I Stood There Ironing”, a woman is ironing as she is being questioned by a social worker on the upbringing of her first daughter, and its impact on her psychosocial distress.13 The woman remembers the hardships in raising her daughter and her neglect and abuse of the child due to circumstances beyond her control. She keeps ironing back and forth as she recounts the ways in which she neglected her child. The ironing provides a metaphor for attempting to straighten out her life and for recognizing finally at the end of the story that the daughter should not be the dress, under which her iron is pressing. This gave rise to a discussion of metaphors in our lives and the meanings they carry.

Problem-solving Guide

A sixth way the reflections helped was by serving as a guide to solving our problems. Some of the stories we read resonated deeply with members of the group and provided guides to solving problems. In one meeting we discussed “Those Are as Brothers” by Nancy Hale, a story in which a Nazi concentration camp survivor finds refuge in a country home and develops a friendship with a survivor of an abusive marriage.14 Reading and reflecting on this story enabled us to see the impact of trauma on ourselves, our life choices, professions, ways of being, philosophies, and even on our next generation. The story was personal for several members of the group, some of whom were second-generation Holocaust survivors, and for one who admitted to severe trauma as a child. Discussing our backgrounds together, we empathized with each other and helped each other heal. The story also provided a guide to healing from trauma, as its title indicates: sharing stories together can be a way to heal. The solidarity of standing together, as brothers, heals. The concentration camp survivor was mistreated in his job, but the abuse trauma victim rushes to his defense and vows her friendship and support. This soothed his soul and healed his mind. The guidance is clear: we can do the same, find friends, treat them like brothers, support each other and heal.

Bonding Through Shared Experience

The final and possibly most important way in which the club helped was by serving as an adventure to bond group members together through shared experience. We believe that literature can capture imagination in extraordinary ways and provide an opportunity to undertake remarkable journeys. As such, together we traveled to the ends of the earth from the beginning to the end of time and beyond. We traveled through the hills of Africa, meandered in the streets of Russia and Poland, watched the racetracks in Italy, toured the Taj Mahal in India, and descended into the caves of Lascaux, all while working in Little Rock, Arkansas. We shared a wide array of experiences together, which allowed us to know ourselves and others better, to share stories, and to develop a common vision, common ground, and common culture.

Conclusions

Through reading and reflecting on stories, we bonded as a group, increased our empathy for each other and others, and found meaning in medicine. Other studies have shown that participation in small study groups promote physician well-being, improve job satisfaction, and decrease burnout.3 We synergized this effort by reading nonmedical stories on a consistent basis, hoping to gain resilience to psychosocial distress.3 We chose short stories rather than novels to minimize any stress from excess reading. Combining these interventions, small group studies and nonmedical reading, into a single intervention as is typical in the practice of narrative medicine may provide a way to improve team functioning.

This pilot study showed that it is possible to form short story clubs even in a busy oncology program and that such programs benefit participants in a variety of ways with no apparent adverse effects. Further research is needed to study the impact of reading and reflecting on medical work in small study groups in larger numbers of subjects and to evaluate their impact on burnout. Further study is also needed to develop narrative medicine curricula that best address the needs of particular subspecialties and to determine the optimal conditions for implementation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Erick Messias for inspiring and encouraging this project at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences where he was Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs. He is presently Chair of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience at the St. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

1. Messias E, Gathright MM, Freeman ES, et al. Differences in burnout prevalence between clinical professionals and biomedical scientists in an academic medical centre: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e023506. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023506

2. Marchalik D, Rodriguez A, Namath A, et al. The impact of non-medical reading on clinical burnout: a national survey of palliative care providers. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8(4):428-435. doi:10.21037/apm.2019.05.02

3. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387

4. Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and tust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

5. Broyard A. Doctor Talk to Me. August 26, 1990. Accessed September 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/26/magazine/doctor-talk-to-me.html

6. Chekhov A. A Doctor’s Visit,. In: Reynolds R, Stone J, eds. On Doctoring. Simon and Shuster;1995:50-59.

7. Lahiri J. Interpreter of Maladies. In: Lahiri J. Interpreter of Maladies. Mariner Books;2019.

8. Fitzgerald FS. Babylon Revisited. In: Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:62-81.

9. Hemingway E. Hills like White Elephants. In: Reynolds R, Stone J, eds. On Doctoring. Simon and Shuster;1995:108-111.

10. Karmel M. Caves of Lascaux. In: Ofri D, Staff of the Bellavue Literary Review, eds. The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review. Bellevue Literary Press;2008:168-174.

11. Lardner R. The Haircut. In Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:48-61.

12. Tolstoy L. The Three Questions. Accessed September 2021. https://www.plough.com/en/topics/culture/short-stories/the-three-questions

13. Olsen T. I Stand Here Ironing. In Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:173-180.

14. Hale N. Those Are as Brothers. In: Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:132-141.

Burnout and other forms of psychosocial distress are common among health care professionals necessitating measures to promote well-being and reduce burnout.1 Studies have shown that nonmedical reading is associated with low burnout and that small group study sections can promote wellness.2,3 Narrative medicine, which proposes a model for humane and effective medical practice, advocates for the necessity of narrative competence.

Short Story Club

Narrative competence is the ability to acknowledge, interpret, and act on the stories of others. The narrative skill of close reading also encourages reflective practice, equipping practitioners to better weather the tides of illness.4 In our case, we formed a short story club intervention to closely read, or read and reflect, on literary fiction. We explored how reading and reflecting would result in profound changes in thinking and feeling and noted different ways by which they can cause such well-being. We describe here the 7 ways in which stories led us to increase bonding, improve empathy, and promote meaning in medicine.

Slowing Down

The short story club helped to bond us together and increase our sense of meaning in medicine by slowing us down. One member of the group likened the experience to increasing the pixels in a painting, thereby improving the resolution and seeing more clearly. Another member mentioned the experience as a form of meditation in slowing down the brain, breathing in the story, and breathing out impressions. One story by Anatole Broyard emphasized the importance of slowing down and “brooding” over a patient.5 The author describes his experience as a prostate cancer patient, in which his body was treated but his story was ignored. He begged his doctors to pay more attention to his story to listen and to brood over him. This story was enlightening to us; we saw how desperate our patients are to tell their stories, and for us to hear their stories.

Mirrors and Windows

Another way reading and reflecting on short stories helped was by reflecting our practices to ourselves, as though looking into a mirror to see ourselves and out of a window to see others. We found that stories mirrored our own world and allowed us to discuss issues close to us without the embarrassment or stigma of owning the story. In one session we read “The Doctor’s Visit” by Anton Chekhov.6 Some of the members resonated with the doctor of this story who awkwardly attended to his lady patient whose son was dying of a brain tumor. The doctor was nervous, insecure, and unable to express any empathy. He was also the father of the child who was dying and refused to admit any responsibility. One member of the group stated that he could relate to the doctor’s insecurities and mentioned that he too felt insecure and even sometimes felt like an imposter. This led to a discussion of insecurities, ways to bolster self-confidence, and ways to accept and respect limitations. This was a conversation that may not have taken place without the story as anchor to discuss insecurities that we individually may not have been willing to admit to the group.

In a different session, we discussed the story “Interpreter of Maladies” by Jhumpa Lahiri in which a settled Indian American family returns to India to tour and learn about their heritage from a guide (the interpreter of maladies) who interpreted the culture for them.7 The family professed to be interested in knowing about the culture but could not concentrate: the wife stayed busy flirting with the guide and revealing outrageous secrets to him, the children were engrossed in their squabbles, and the father was essentially absent taking photographs as souvenirs instead of seeing the sites firsthand. Some of the members of the group were Indian American and could relate to the alienation from their home and nostalgia for their country, while others could relate to the same alienation, albeit from other cultures and countries. This allowed us to talk about deeply personal topics, without having to own the topic or reveal personal issues. The discussion led to a deep understanding and empathy for us and our colleagues knowing the pain of alienation that some of them felt but could not discuss.

The stories also served as windows into the world of others which enabled us to see and become the other. For example, in one session we reflected on “Babylon Revisited” by F. Scott Fitzgerald.8 In this story, an American man returns to Paris after the Great Depression and recalls his life as a young artist in the American artist expatriate community of Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. During that time, he partied, drank in excess, lost his wife to pneumonia (for which he was at least partially responsible), lost custody of his daughter, and lost his fortune. As he returned to Paris to try to reclaim his daughter, we feel his pain as he tries but fails to overcome chronic alcoholism, sexual indiscretions, and losses. This gave rise to discussion of losses in general as we became one with the main character. This increased our empathy for others in a way that could not have been possible without this short story as anchor.

In another session we reflected on “Hills Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway, in which a man is waiting for a train while proposing his girlfriend get an abortion.9 She agonizes over her choices and makes no decision in this story. Yet, we the reader could “become” the woman in the story faced with hard choices of having a baby but losing the man she loves, or having an abortion and maybe losing him anyway. In becoming this woman, we could experience the complex emotions and feel an experience of the other.

Exploring the Taboo

A third aspect of the club was enabling discussion of controversial topics. There were topics that arose in the group which never would have arisen in clinical practice discussions. These had to do with the taboo topics such as romantic attachments to patients. We read “The Caves of Lascaux” and reflected on the story of a young doctor who becomes enamored and obsessed with his beautiful but dying patient.10 He becomes so obsessed with her that he almost abandons his wife, family, and stable livelihood to descend with her into the caves. This story gave rise to discussions about romantic attachment to patients and how to handle and extricate one from the situation. The senior doctors explained some of their relevant experiences and how they either transferred care or sought counseling to extricate themselves from a potentially dangerous situation, especially when they too fell under the spell of forbidden romance.

Moral Grounding

These sessions also served to define the moral basis of our own practice. Much of health care psychosocial distress is related to moral injury in which health care professionals do the wrong thing or fail to do the right thing at the right time, due to external pressures related to financial or other gains. Reading and reflecting put us face-to-face with moral dilemmas and let us find our moral grounding. In reading “The Haircut” by Ring Lardner, we explored the disruptive town scoundrel who harassed and tortured his friends and neighbors but in such outrageous ways that he was considered a comedian rather than an abuser.11 Despite his hurtful acts, the townspeople (including the narrator) considered him a clown and laughed at his racist and sexist statements as well as his tricks.He faced no consequences such as confrontation, until the end when fate caught up. This story gave rise to a discussion of how we handle unkind, racist, sexist, or other comments which are disguised as humor, and to what extent we tolerate such controversial behavior. Do we go along with the scoundrel and laugh, or do we confront such people and insist that they respect and honor other people? The story sensitized the group to the ways in which prejudice and racism or sexism can be masked as humor, and to consider our moral responsibilities in society.

In another session we read and reflected on “Three Questions” by Leo Tolstoy.12 In this story, a king travels to another territory but gets distracted by helping a neighbor in need, and thereby inadvertently and fortunately avoids the trap that had been devised to kill him. The author gives us his moral basis by asking and answering 3 questions: Who is the most important person? What is the most important thing to do? What is the most important thing to do now? His answers provided his moral grounding. We discussed our answers and the basis of our moral grounding, whether it be the injunction do no harm, the more complex religious backgrounds of our childhood, or otherwise.

Symbols and Metaphors

The practice of reading and reflecting also taught us symbols and metaphors. Symbols and metaphors are the essence of storytelling, and they provide keys to understanding people. We sought out and studied the metaphors and symbols in each of the stories we read. In “I Stood There Ironing”, a woman is ironing as she is being questioned by a social worker on the upbringing of her first daughter, and its impact on her psychosocial distress.13 The woman remembers the hardships in raising her daughter and her neglect and abuse of the child due to circumstances beyond her control. She keeps ironing back and forth as she recounts the ways in which she neglected her child. The ironing provides a metaphor for attempting to straighten out her life and for recognizing finally at the end of the story that the daughter should not be the dress, under which her iron is pressing. This gave rise to a discussion of metaphors in our lives and the meanings they carry.

Problem-solving Guide