User login

Second COVID booster: Who should receive it and when?

The more boosters the better? Data from Israel show that immune protection in elderly people is strengthened even further after a fourth dose. Karl Lauterbach, MD, German minister of health, recently pleaded for a second booster for those aged 18 years and older, and he pushed for a European Union–wide recommendation. He has not been able to implement this yet.

Just as before, Germany’s Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) is only recommending the second booster for people aged 70 years and older, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is recommending the fourth vaccination for everyone aged 80 years and older, and the United States has set the general age limit at 50 years.

Specialists remain skeptical about expanding the availability of the second booster. “From an immunologic perspective, people under the age of 70 with a healthy immune system do not need this fourth vaccination,” said Christiane Falk, PhD, head of the Institute for Transplantation Immunology of the Hannover Medical School (Germany) and member of the German Federal Government COVID Expert Panel, at a Science Media Center press briefing.

After the second vaccination, young healthy people are sufficiently protected against a severe course of the disease. Dr. Falk sees the STIKO recommendation as feasible, since it can be worked with. People in nursing facilities or those with additional underlying conditions would be considered for a fourth vaccination, explained Dr. Falk.

Complete protection unrealistic

Achieving complete protection against infection through multiple boosters is not realistic, said Christoph Neumann-Haefelin, MD, head of the Working Group for Translational Virus Immunology at the Clinic for Internal Medicine II, University Hospital Freiburg, Germany. Therefore, this should not be pursued when discussing boosters. “The aim of the booster vaccination should be to protect different groups of people against severe courses of the disease,” said Dr. Neumann-Haefelin.

Neutralizing antibodies that are only present in high concentrations for a few weeks after infection or vaccination are sometimes able to prevent the infection on their own. The immunologic memory of B cells and T cells, which ensures long-lasting protection against severe courses of the disease, is at a high level after two doses, and a third dose increases the protection more.

While people with a weak immune system need significantly more vaccinations in a shorter period to receive the same protection, too many booster vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 are not sensible for young healthy people.

Immune saturation effect

A recent study in macaques showed that an adjusted Omicron booster did not lead to higher antibody titers, compared with a usual booster. In January 2022, the EMA warned against frequent consecutive boosters that may no longer produce the desired immune response.

If someone receives a booster too early, a saturation effect can occur, warned Andreas Radbruch, PhD, scientific director of the German Rheumatism Research Center Berlin. “We know this from lots of experimental studies but also from lots of other vaccinations. For example, you cannot be vaccinated against tetanus twice at 3- or 4-week intervals. Nothing at all will happen the second time,” explained Dr. Radbruch.

If the same antigen is applied again and again at the same dose, the immune system is made so active that the antigen is directly intercepted and cannot have any new effect on the immune system. This mechanism has been known for a long time, said Dr. Radbruch.

‘Original antigenic sin’

Premature boosting could even be a handicap in the competition between immune response and virus, said Dr. Radbruch. This is due to the principle of “original antigenic sin.” If the immune system has already come into contact with a virus, contact with a new virus variant will cause it to form antibodies predominantly against those epitopes that were already present in the original virus. As a result of this, too many boosters can weaken protection against different variants.

“We have not actually observed this with SARS-CoV-2, however,” said Dr. Radbruch. “Immunity is always extremely broad. With a double or triple vaccination, all previously existing variants are covered by an affinity-matured immune system.”

Dr. Neumann-Haefelin confirmed this and added that all virus mutations, including Omicron, have different epitopes that affect the antibody response, but the T-cell response does not differ.

Dr. Radbruch said that the vaccine protection probably lasts for decades. Following an infection or vaccination, the antibody concentration in the bone marrow is similar to that achieved after a measles or tetanus vaccination. “The vaccination is already extremely efficient. You have protection at the same magnitude as for other infectious diseases or vaccinations, which is expected to last decades,” said Dr. Radbruch.

He clarified that the decrease in antibodies after vaccination and infection is normal and does not indicate a drop in protection. “Quantity and quality must not be confused here. There is simply less mass, but the grade of remaining antibody increases.”

In the competition around the virus antigens (referred to as affinity maturation), antibodies develop that bind 10 to 100 times better and are particularly protective against the virus. The immune system is thereby sustainably effective.

For whom and when?

Since the immune response is age dependent, it makes more sense to administer an additional booster to elderly people than to young people. Also included in this group, however, are people whose immune system still does not provide the same level of protection after the second or even third vaccination as that of younger, healthy people.

Dr. Radbruch noted that 4% of people older than 70 years exhibited autoantibodies against interferons. The effects are huge. “That is 20% of patients in an intensive care unit – and they all have a very poor prognosis,” said Dr. Radbruch. These people are extremely threatened by the virus. Multiple vaccinations are sensible for them.

Even people with a weak immune response benefit from multiple vaccinations, confirmed Dr. Neumann-Haefelin. “We are not seeing the antibody responses here that we see in young people with healthy immune systems until the third or fourth vaccination sometimes.”

Although for young healthy people, it is particularly important to ensure a sufficient period between vaccinations so that the affinity maturation is not impaired, those with a weak immune response can be vaccinated again as soon as after 3 months.

The “optimum minimum period of time” for people with healthy immune systems is 6 months, according to Dr. Neumann-Haefelin. “This is true for everyone in whom a proper response is expected.” The vaccine protection probably lasts significantly longer, and therefore, frequent boosting may not be necessary in the future, he said. The time separation also applies for medical personnel, for whom the Robert Koch Institute also recommends a second booster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The more boosters the better? Data from Israel show that immune protection in elderly people is strengthened even further after a fourth dose. Karl Lauterbach, MD, German minister of health, recently pleaded for a second booster for those aged 18 years and older, and he pushed for a European Union–wide recommendation. He has not been able to implement this yet.

Just as before, Germany’s Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) is only recommending the second booster for people aged 70 years and older, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is recommending the fourth vaccination for everyone aged 80 years and older, and the United States has set the general age limit at 50 years.

Specialists remain skeptical about expanding the availability of the second booster. “From an immunologic perspective, people under the age of 70 with a healthy immune system do not need this fourth vaccination,” said Christiane Falk, PhD, head of the Institute for Transplantation Immunology of the Hannover Medical School (Germany) and member of the German Federal Government COVID Expert Panel, at a Science Media Center press briefing.

After the second vaccination, young healthy people are sufficiently protected against a severe course of the disease. Dr. Falk sees the STIKO recommendation as feasible, since it can be worked with. People in nursing facilities or those with additional underlying conditions would be considered for a fourth vaccination, explained Dr. Falk.

Complete protection unrealistic

Achieving complete protection against infection through multiple boosters is not realistic, said Christoph Neumann-Haefelin, MD, head of the Working Group for Translational Virus Immunology at the Clinic for Internal Medicine II, University Hospital Freiburg, Germany. Therefore, this should not be pursued when discussing boosters. “The aim of the booster vaccination should be to protect different groups of people against severe courses of the disease,” said Dr. Neumann-Haefelin.

Neutralizing antibodies that are only present in high concentrations for a few weeks after infection or vaccination are sometimes able to prevent the infection on their own. The immunologic memory of B cells and T cells, which ensures long-lasting protection against severe courses of the disease, is at a high level after two doses, and a third dose increases the protection more.

While people with a weak immune system need significantly more vaccinations in a shorter period to receive the same protection, too many booster vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 are not sensible for young healthy people.

Immune saturation effect

A recent study in macaques showed that an adjusted Omicron booster did not lead to higher antibody titers, compared with a usual booster. In January 2022, the EMA warned against frequent consecutive boosters that may no longer produce the desired immune response.

If someone receives a booster too early, a saturation effect can occur, warned Andreas Radbruch, PhD, scientific director of the German Rheumatism Research Center Berlin. “We know this from lots of experimental studies but also from lots of other vaccinations. For example, you cannot be vaccinated against tetanus twice at 3- or 4-week intervals. Nothing at all will happen the second time,” explained Dr. Radbruch.

If the same antigen is applied again and again at the same dose, the immune system is made so active that the antigen is directly intercepted and cannot have any new effect on the immune system. This mechanism has been known for a long time, said Dr. Radbruch.

‘Original antigenic sin’

Premature boosting could even be a handicap in the competition between immune response and virus, said Dr. Radbruch. This is due to the principle of “original antigenic sin.” If the immune system has already come into contact with a virus, contact with a new virus variant will cause it to form antibodies predominantly against those epitopes that were already present in the original virus. As a result of this, too many boosters can weaken protection against different variants.

“We have not actually observed this with SARS-CoV-2, however,” said Dr. Radbruch. “Immunity is always extremely broad. With a double or triple vaccination, all previously existing variants are covered by an affinity-matured immune system.”

Dr. Neumann-Haefelin confirmed this and added that all virus mutations, including Omicron, have different epitopes that affect the antibody response, but the T-cell response does not differ.

Dr. Radbruch said that the vaccine protection probably lasts for decades. Following an infection or vaccination, the antibody concentration in the bone marrow is similar to that achieved after a measles or tetanus vaccination. “The vaccination is already extremely efficient. You have protection at the same magnitude as for other infectious diseases or vaccinations, which is expected to last decades,” said Dr. Radbruch.

He clarified that the decrease in antibodies after vaccination and infection is normal and does not indicate a drop in protection. “Quantity and quality must not be confused here. There is simply less mass, but the grade of remaining antibody increases.”

In the competition around the virus antigens (referred to as affinity maturation), antibodies develop that bind 10 to 100 times better and are particularly protective against the virus. The immune system is thereby sustainably effective.

For whom and when?

Since the immune response is age dependent, it makes more sense to administer an additional booster to elderly people than to young people. Also included in this group, however, are people whose immune system still does not provide the same level of protection after the second or even third vaccination as that of younger, healthy people.

Dr. Radbruch noted that 4% of people older than 70 years exhibited autoantibodies against interferons. The effects are huge. “That is 20% of patients in an intensive care unit – and they all have a very poor prognosis,” said Dr. Radbruch. These people are extremely threatened by the virus. Multiple vaccinations are sensible for them.

Even people with a weak immune response benefit from multiple vaccinations, confirmed Dr. Neumann-Haefelin. “We are not seeing the antibody responses here that we see in young people with healthy immune systems until the third or fourth vaccination sometimes.”

Although for young healthy people, it is particularly important to ensure a sufficient period between vaccinations so that the affinity maturation is not impaired, those with a weak immune response can be vaccinated again as soon as after 3 months.

The “optimum minimum period of time” for people with healthy immune systems is 6 months, according to Dr. Neumann-Haefelin. “This is true for everyone in whom a proper response is expected.” The vaccine protection probably lasts significantly longer, and therefore, frequent boosting may not be necessary in the future, he said. The time separation also applies for medical personnel, for whom the Robert Koch Institute also recommends a second booster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The more boosters the better? Data from Israel show that immune protection in elderly people is strengthened even further after a fourth dose. Karl Lauterbach, MD, German minister of health, recently pleaded for a second booster for those aged 18 years and older, and he pushed for a European Union–wide recommendation. He has not been able to implement this yet.

Just as before, Germany’s Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) is only recommending the second booster for people aged 70 years and older, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is recommending the fourth vaccination for everyone aged 80 years and older, and the United States has set the general age limit at 50 years.

Specialists remain skeptical about expanding the availability of the second booster. “From an immunologic perspective, people under the age of 70 with a healthy immune system do not need this fourth vaccination,” said Christiane Falk, PhD, head of the Institute for Transplantation Immunology of the Hannover Medical School (Germany) and member of the German Federal Government COVID Expert Panel, at a Science Media Center press briefing.

After the second vaccination, young healthy people are sufficiently protected against a severe course of the disease. Dr. Falk sees the STIKO recommendation as feasible, since it can be worked with. People in nursing facilities or those with additional underlying conditions would be considered for a fourth vaccination, explained Dr. Falk.

Complete protection unrealistic

Achieving complete protection against infection through multiple boosters is not realistic, said Christoph Neumann-Haefelin, MD, head of the Working Group for Translational Virus Immunology at the Clinic for Internal Medicine II, University Hospital Freiburg, Germany. Therefore, this should not be pursued when discussing boosters. “The aim of the booster vaccination should be to protect different groups of people against severe courses of the disease,” said Dr. Neumann-Haefelin.

Neutralizing antibodies that are only present in high concentrations for a few weeks after infection or vaccination are sometimes able to prevent the infection on their own. The immunologic memory of B cells and T cells, which ensures long-lasting protection against severe courses of the disease, is at a high level after two doses, and a third dose increases the protection more.

While people with a weak immune system need significantly more vaccinations in a shorter period to receive the same protection, too many booster vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 are not sensible for young healthy people.

Immune saturation effect

A recent study in macaques showed that an adjusted Omicron booster did not lead to higher antibody titers, compared with a usual booster. In January 2022, the EMA warned against frequent consecutive boosters that may no longer produce the desired immune response.

If someone receives a booster too early, a saturation effect can occur, warned Andreas Radbruch, PhD, scientific director of the German Rheumatism Research Center Berlin. “We know this from lots of experimental studies but also from lots of other vaccinations. For example, you cannot be vaccinated against tetanus twice at 3- or 4-week intervals. Nothing at all will happen the second time,” explained Dr. Radbruch.

If the same antigen is applied again and again at the same dose, the immune system is made so active that the antigen is directly intercepted and cannot have any new effect on the immune system. This mechanism has been known for a long time, said Dr. Radbruch.

‘Original antigenic sin’

Premature boosting could even be a handicap in the competition between immune response and virus, said Dr. Radbruch. This is due to the principle of “original antigenic sin.” If the immune system has already come into contact with a virus, contact with a new virus variant will cause it to form antibodies predominantly against those epitopes that were already present in the original virus. As a result of this, too many boosters can weaken protection against different variants.

“We have not actually observed this with SARS-CoV-2, however,” said Dr. Radbruch. “Immunity is always extremely broad. With a double or triple vaccination, all previously existing variants are covered by an affinity-matured immune system.”

Dr. Neumann-Haefelin confirmed this and added that all virus mutations, including Omicron, have different epitopes that affect the antibody response, but the T-cell response does not differ.

Dr. Radbruch said that the vaccine protection probably lasts for decades. Following an infection or vaccination, the antibody concentration in the bone marrow is similar to that achieved after a measles or tetanus vaccination. “The vaccination is already extremely efficient. You have protection at the same magnitude as for other infectious diseases or vaccinations, which is expected to last decades,” said Dr. Radbruch.

He clarified that the decrease in antibodies after vaccination and infection is normal and does not indicate a drop in protection. “Quantity and quality must not be confused here. There is simply less mass, but the grade of remaining antibody increases.”

In the competition around the virus antigens (referred to as affinity maturation), antibodies develop that bind 10 to 100 times better and are particularly protective against the virus. The immune system is thereby sustainably effective.

For whom and when?

Since the immune response is age dependent, it makes more sense to administer an additional booster to elderly people than to young people. Also included in this group, however, are people whose immune system still does not provide the same level of protection after the second or even third vaccination as that of younger, healthy people.

Dr. Radbruch noted that 4% of people older than 70 years exhibited autoantibodies against interferons. The effects are huge. “That is 20% of patients in an intensive care unit – and they all have a very poor prognosis,” said Dr. Radbruch. These people are extremely threatened by the virus. Multiple vaccinations are sensible for them.

Even people with a weak immune response benefit from multiple vaccinations, confirmed Dr. Neumann-Haefelin. “We are not seeing the antibody responses here that we see in young people with healthy immune systems until the third or fourth vaccination sometimes.”

Although for young healthy people, it is particularly important to ensure a sufficient period between vaccinations so that the affinity maturation is not impaired, those with a weak immune response can be vaccinated again as soon as after 3 months.

The “optimum minimum period of time” for people with healthy immune systems is 6 months, according to Dr. Neumann-Haefelin. “This is true for everyone in whom a proper response is expected.” The vaccine protection probably lasts significantly longer, and therefore, frequent boosting may not be necessary in the future, he said. The time separation also applies for medical personnel, for whom the Robert Koch Institute also recommends a second booster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vagus nerve stimulation: A little-known option for depression

Standard therapies for depression are antidepressants and psychotherapy. In particularly severe cases, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) may also be indicated. VNS is an approved, effective, well-tolerated, long-term therapy for chronic and therapy-resistant depression, wrote Christine Reif-Leonhardt, MD, and associates from the University Hospital Frankfurt am Main (Germany), in a recent journal article. The cost of VNS is covered by health insurance funds in Germany.

Available since 1994

As the authors reported, invasive VNS was approved in the European Union in 1994 and in the United States in 1997 for the treatment of children with medicinal therapy–refractory epilepsy. Because positive and lasting effects on mood could be seen in adults after around 3 months of VNS, irrespective of the effectiveness of anticonvulsive medication, “a genuinely antidepressant effect of VNS [was] postulated,” and therefore it was further developed as an antidepressant therapy.

A VNS system first received a CE certification in 2001 in the European Union for the treatment of patients with chronic or relapsing depression who had therapy-resistant depression or who were intolerant of the current depression therapy. In 2005, VNS was approved in the United States for the treatment of patients aged 18 years or older with therapy-resistant major depression for which at least four antidepressant therapies had not helped sufficiently.

Few sham-controlled studies

According to Dr. Reif-Leonhardt and colleagues, there have been multiple studies and case series on VNS in patients with therapy-resistant depression in the past 20 years. Many of the studies highlighted the additional benefits of VNS as an adjuvant procedure, but they were observational studies. Sham-controlled studies are in short supply because of methodologic difficulties and ethical problems.

The largest long-term study is a registry study in which 494 patients with therapy-resistant depression received the combination of the usual antidepressant therapy and VNS. The study lasted 5 years; 301 patients served as a control group and received the usual therapy. The cumulative response to the therapy (68% vs. 41%) and the remission rate (43% vs. 26%) were significantly greater in the group that received VNS, according to the authors. Patients who underwent at least one ECT series of at least seven sessions responded particularly well to VNS. The combined therapy was also more effective in ECT nonresponders than the usual therapy alone.

To date, only one sham-controlled study of VNS treatment for therapy-resistant depression has been conducted. In it, VNS was not significantly superior to a sham stimulation over an observation period of 10 weeks. However, observational studies have provided evidence that the antidepressant effect of VNS only develops after at least 12 months of treatment. According to Dr. Reif-Leonhardt and colleagues, the data indicate that differences in response rate and therapy effect can only be observed in the longer term after 3-12 months and that as the therapy duration increases, so do the effects of VNS. From this, it can be assumed “that the VNS mechanism of action can be attributed to neuroplastic and adaptive phenomena.”

The typical, common side effects of surgery are pain and paresthesia. Through irritation of the nerve, approximately every third patient experiences postoperative hoarseness and a voice change. Serious side effects and complications, such as temporary swallowing disorders, are rare. By reducing the stimulation intensity or lowering the stimulation frequency or impulse width, the side effects associated with stimulation can be alleviated or even eliminated. A second small surgical intervention may become necessary to replace broken cables or the battery (life span, 3-8 years).

Criteria for VNS therapy

When should VNS be considered? The authors specified the following criteria:

- An insufficient response to at least two antidepressants from different substance classes (ideally including one tricyclic) at a sufficient dosage and duration, as well as to two augmentation agents (such as lithium and quetiapine) in combination with guideline psychotherapy

- Intolerable side effects from pharmacotherapy or contraindications to medicinal therapy

- For patients who respond to ECT, the occurrence of relapses or residual symptoms after cessation of (maintenance) ECT, intolerable ECT side effects, or the need for maintenance ECT

- Repeated or long hospital treatments because of depression

This article is a translation of an article from Univadis Germany and first appeared on Medscape.com.

Standard therapies for depression are antidepressants and psychotherapy. In particularly severe cases, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) may also be indicated. VNS is an approved, effective, well-tolerated, long-term therapy for chronic and therapy-resistant depression, wrote Christine Reif-Leonhardt, MD, and associates from the University Hospital Frankfurt am Main (Germany), in a recent journal article. The cost of VNS is covered by health insurance funds in Germany.

Available since 1994

As the authors reported, invasive VNS was approved in the European Union in 1994 and in the United States in 1997 for the treatment of children with medicinal therapy–refractory epilepsy. Because positive and lasting effects on mood could be seen in adults after around 3 months of VNS, irrespective of the effectiveness of anticonvulsive medication, “a genuinely antidepressant effect of VNS [was] postulated,” and therefore it was further developed as an antidepressant therapy.

A VNS system first received a CE certification in 2001 in the European Union for the treatment of patients with chronic or relapsing depression who had therapy-resistant depression or who were intolerant of the current depression therapy. In 2005, VNS was approved in the United States for the treatment of patients aged 18 years or older with therapy-resistant major depression for which at least four antidepressant therapies had not helped sufficiently.

Few sham-controlled studies

According to Dr. Reif-Leonhardt and colleagues, there have been multiple studies and case series on VNS in patients with therapy-resistant depression in the past 20 years. Many of the studies highlighted the additional benefits of VNS as an adjuvant procedure, but they were observational studies. Sham-controlled studies are in short supply because of methodologic difficulties and ethical problems.

The largest long-term study is a registry study in which 494 patients with therapy-resistant depression received the combination of the usual antidepressant therapy and VNS. The study lasted 5 years; 301 patients served as a control group and received the usual therapy. The cumulative response to the therapy (68% vs. 41%) and the remission rate (43% vs. 26%) were significantly greater in the group that received VNS, according to the authors. Patients who underwent at least one ECT series of at least seven sessions responded particularly well to VNS. The combined therapy was also more effective in ECT nonresponders than the usual therapy alone.

To date, only one sham-controlled study of VNS treatment for therapy-resistant depression has been conducted. In it, VNS was not significantly superior to a sham stimulation over an observation period of 10 weeks. However, observational studies have provided evidence that the antidepressant effect of VNS only develops after at least 12 months of treatment. According to Dr. Reif-Leonhardt and colleagues, the data indicate that differences in response rate and therapy effect can only be observed in the longer term after 3-12 months and that as the therapy duration increases, so do the effects of VNS. From this, it can be assumed “that the VNS mechanism of action can be attributed to neuroplastic and adaptive phenomena.”

The typical, common side effects of surgery are pain and paresthesia. Through irritation of the nerve, approximately every third patient experiences postoperative hoarseness and a voice change. Serious side effects and complications, such as temporary swallowing disorders, are rare. By reducing the stimulation intensity or lowering the stimulation frequency or impulse width, the side effects associated with stimulation can be alleviated or even eliminated. A second small surgical intervention may become necessary to replace broken cables or the battery (life span, 3-8 years).

Criteria for VNS therapy

When should VNS be considered? The authors specified the following criteria:

- An insufficient response to at least two antidepressants from different substance classes (ideally including one tricyclic) at a sufficient dosage and duration, as well as to two augmentation agents (such as lithium and quetiapine) in combination with guideline psychotherapy

- Intolerable side effects from pharmacotherapy or contraindications to medicinal therapy

- For patients who respond to ECT, the occurrence of relapses or residual symptoms after cessation of (maintenance) ECT, intolerable ECT side effects, or the need for maintenance ECT

- Repeated or long hospital treatments because of depression

This article is a translation of an article from Univadis Germany and first appeared on Medscape.com.

Standard therapies for depression are antidepressants and psychotherapy. In particularly severe cases, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) may also be indicated. VNS is an approved, effective, well-tolerated, long-term therapy for chronic and therapy-resistant depression, wrote Christine Reif-Leonhardt, MD, and associates from the University Hospital Frankfurt am Main (Germany), in a recent journal article. The cost of VNS is covered by health insurance funds in Germany.

Available since 1994

As the authors reported, invasive VNS was approved in the European Union in 1994 and in the United States in 1997 for the treatment of children with medicinal therapy–refractory epilepsy. Because positive and lasting effects on mood could be seen in adults after around 3 months of VNS, irrespective of the effectiveness of anticonvulsive medication, “a genuinely antidepressant effect of VNS [was] postulated,” and therefore it was further developed as an antidepressant therapy.

A VNS system first received a CE certification in 2001 in the European Union for the treatment of patients with chronic or relapsing depression who had therapy-resistant depression or who were intolerant of the current depression therapy. In 2005, VNS was approved in the United States for the treatment of patients aged 18 years or older with therapy-resistant major depression for which at least four antidepressant therapies had not helped sufficiently.

Few sham-controlled studies

According to Dr. Reif-Leonhardt and colleagues, there have been multiple studies and case series on VNS in patients with therapy-resistant depression in the past 20 years. Many of the studies highlighted the additional benefits of VNS as an adjuvant procedure, but they were observational studies. Sham-controlled studies are in short supply because of methodologic difficulties and ethical problems.

The largest long-term study is a registry study in which 494 patients with therapy-resistant depression received the combination of the usual antidepressant therapy and VNS. The study lasted 5 years; 301 patients served as a control group and received the usual therapy. The cumulative response to the therapy (68% vs. 41%) and the remission rate (43% vs. 26%) were significantly greater in the group that received VNS, according to the authors. Patients who underwent at least one ECT series of at least seven sessions responded particularly well to VNS. The combined therapy was also more effective in ECT nonresponders than the usual therapy alone.

To date, only one sham-controlled study of VNS treatment for therapy-resistant depression has been conducted. In it, VNS was not significantly superior to a sham stimulation over an observation period of 10 weeks. However, observational studies have provided evidence that the antidepressant effect of VNS only develops after at least 12 months of treatment. According to Dr. Reif-Leonhardt and colleagues, the data indicate that differences in response rate and therapy effect can only be observed in the longer term after 3-12 months and that as the therapy duration increases, so do the effects of VNS. From this, it can be assumed “that the VNS mechanism of action can be attributed to neuroplastic and adaptive phenomena.”

The typical, common side effects of surgery are pain and paresthesia. Through irritation of the nerve, approximately every third patient experiences postoperative hoarseness and a voice change. Serious side effects and complications, such as temporary swallowing disorders, are rare. By reducing the stimulation intensity or lowering the stimulation frequency or impulse width, the side effects associated with stimulation can be alleviated or even eliminated. A second small surgical intervention may become necessary to replace broken cables or the battery (life span, 3-8 years).

Criteria for VNS therapy

When should VNS be considered? The authors specified the following criteria:

- An insufficient response to at least two antidepressants from different substance classes (ideally including one tricyclic) at a sufficient dosage and duration, as well as to two augmentation agents (such as lithium and quetiapine) in combination with guideline psychotherapy

- Intolerable side effects from pharmacotherapy or contraindications to medicinal therapy

- For patients who respond to ECT, the occurrence of relapses or residual symptoms after cessation of (maintenance) ECT, intolerable ECT side effects, or the need for maintenance ECT

- Repeated or long hospital treatments because of depression

This article is a translation of an article from Univadis Germany and first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DER NERVENARZT

BRAF V600E Expression in Primary Melanoma and Its Association With Death: A Population-Based, Retrospective, Cross-Sectional Study

Approximately 50% of melanomas contain BRAF mutations, which occur in a greater proportion of melanomas found on sites of intermittent sun exposure.1BRAF-mutated melanomas have been associated with high levels of early-life ambient UV exposure, especially between ages 0 and 20 years.2 In addition, studies have shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas commonly are found on the trunk and extremities.1-3BRAF mutations also have been associated with younger age, superficial spreading subtype and low tumor thickness, absence of dermal melanocyte mitosis, low Ki-67 score, low phospho-histone H3 score, pigmented melanoma, advanced melanoma stage, and conjunctival melanoma.4-7BRAF mutations are found more frequently in metastatic melanoma lesions than primary melanomas, suggesting that BRAF mutations may be acquired during metastasis.8 Studies have shown different conclusions on the effect of BRAF mutation on melanoma-related death.5,9,10

The aim of this study was to identify trends in BRAF V600E–mutated melanoma according to age, sex, and melanoma-specific survival among Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents with a first diagnosis of melanoma at 18 to 60 years of age.

Methods

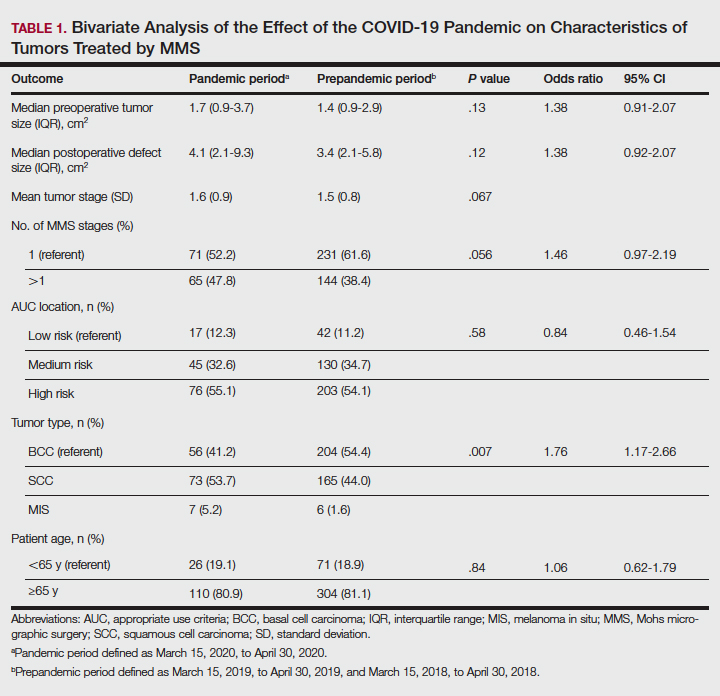

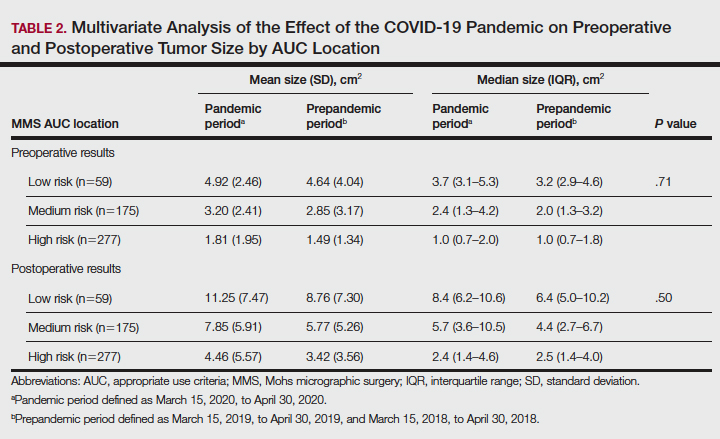

In total, 638 patients aged 18 to 60 years who resided in Olmsted County and had a first lifetime diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma between 1970 and 2009 were retrospectively identified as a part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP is a health records linkage system that encompasses almost all sources of medical care available to the local population of Olmsted County.11 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minnesota).

Of the 638 individuals identified in the REP, 536 had been seen at Mayo Clinic and thus potentially had tissue blocks available for the study of BRAF mutation expression. Of these 536 patients, 156 did not have sufficient residual tissue available. As a result, 380 (60%) of the original 638 patients had available blocks with sufficient tissue for immunohistochemical analysis of BRAF expression. Only primary cutaneous melanomas were included in the present study.

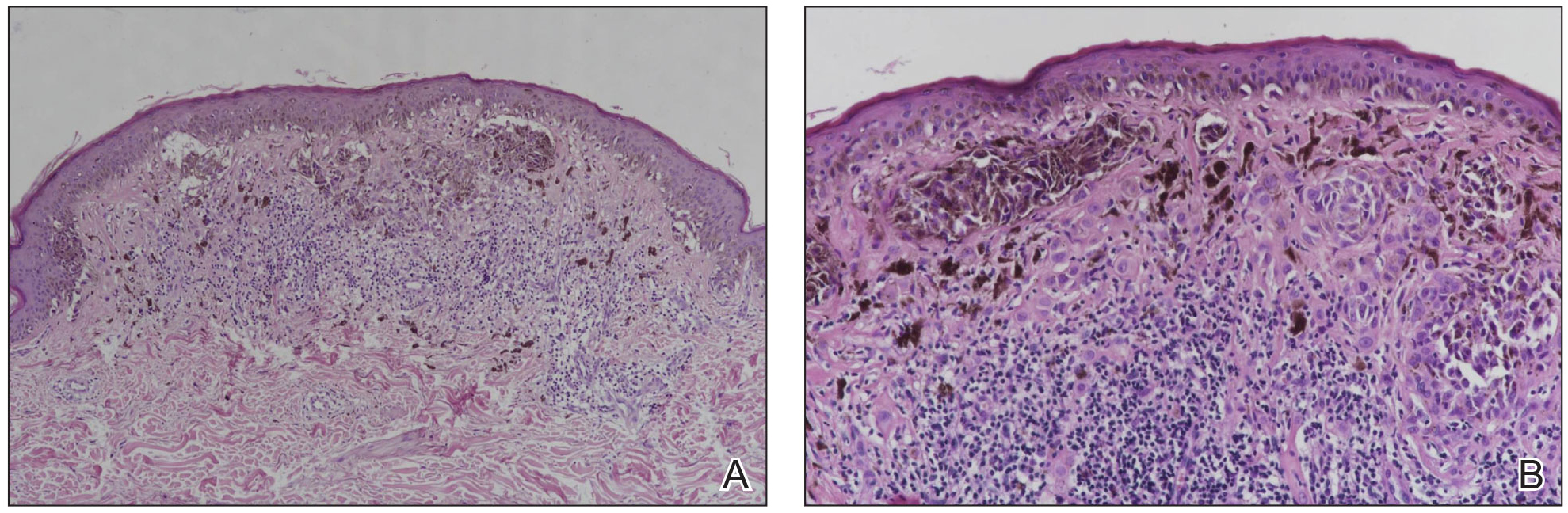

All specimens were reviewed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (J.S.L.) for appropriateness of inclusion, which involved confirmation of the diagnosis of melanoma, histologic type of melanoma, and presence of sufficient residual tissue for immunohistochemical stains.

All specimens were originally diagnosed as malignant melanoma at the time of clinical care by at least 2 board-certified dermatopathologists. For the purposes of this study, all specimens were rereviewed for diagnostic accuracy. We required that specimens exhibit severe cytologic and architectural atypia as well as other features favoring melanoma, such as consumption of rete pegs, pagetosis, confluence of junctional melanocytes, evidence of regression, lack of maturation of melanocytes with descent into the dermis, or mitotic figures among the dermal melanocyte population.

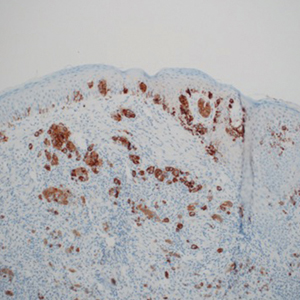

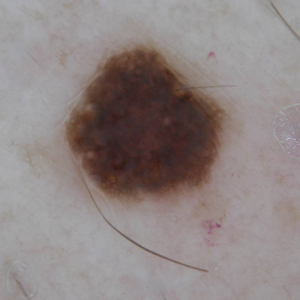

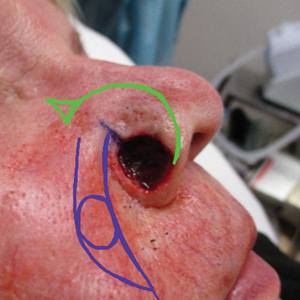

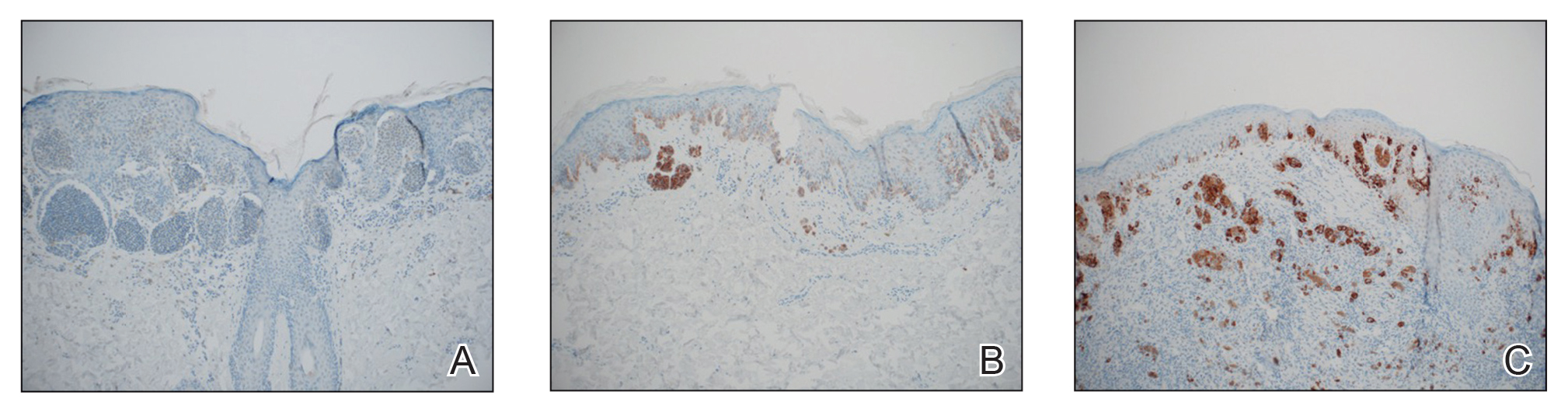

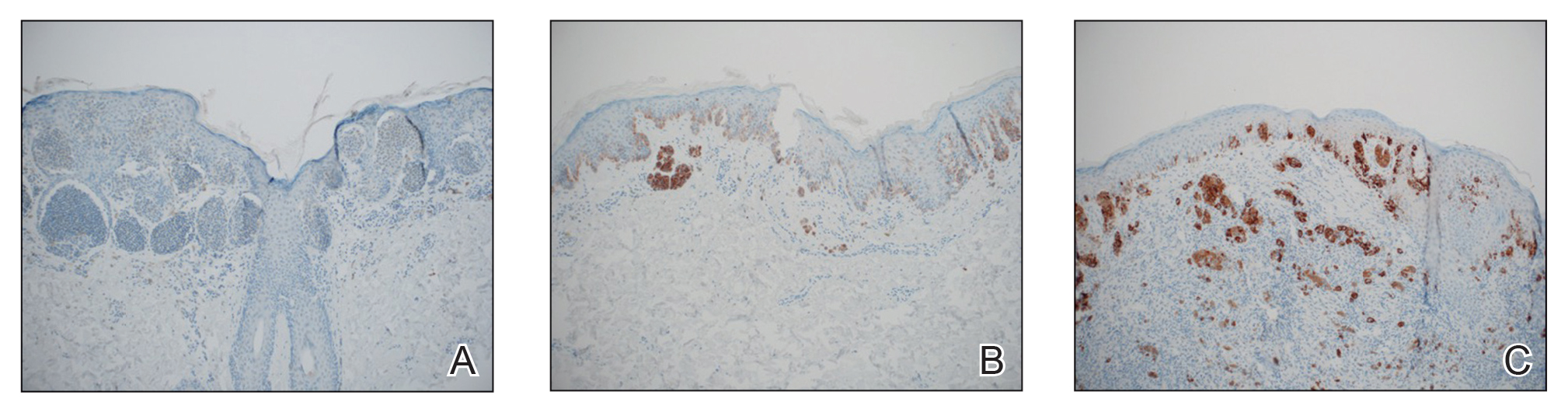

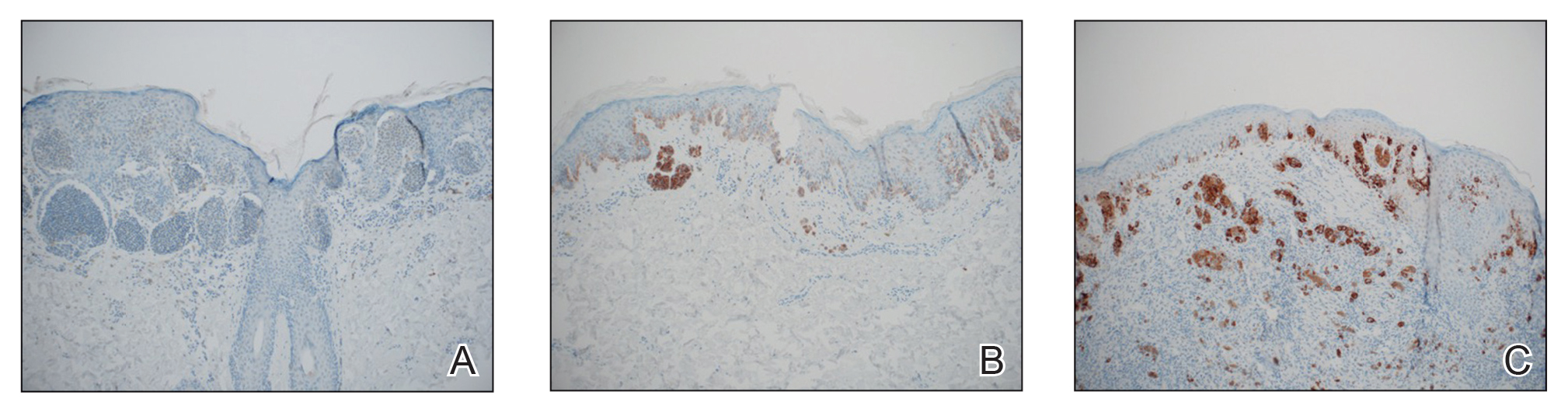

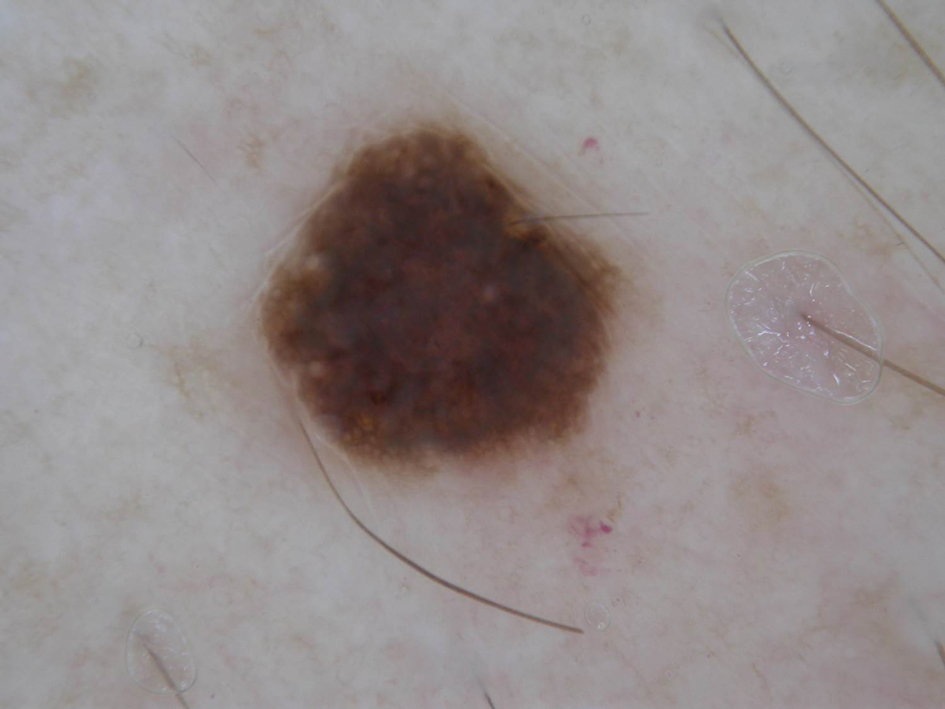

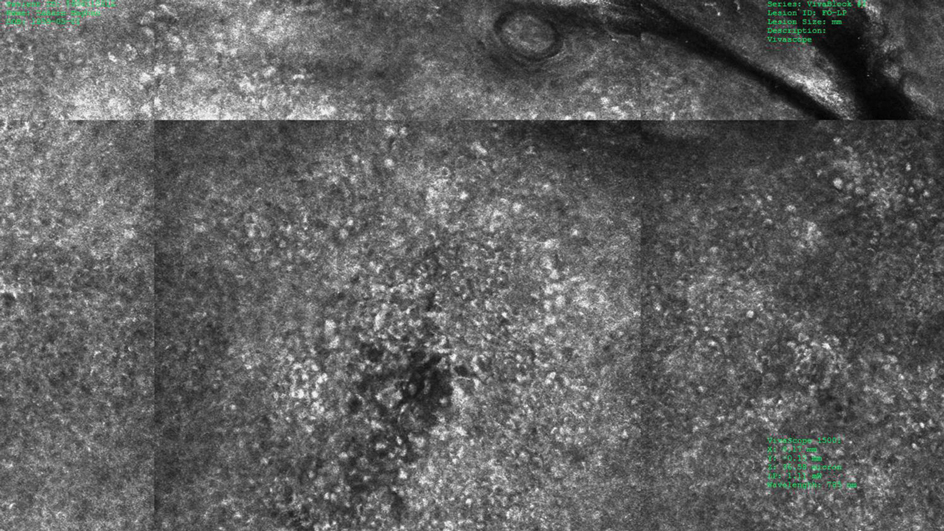

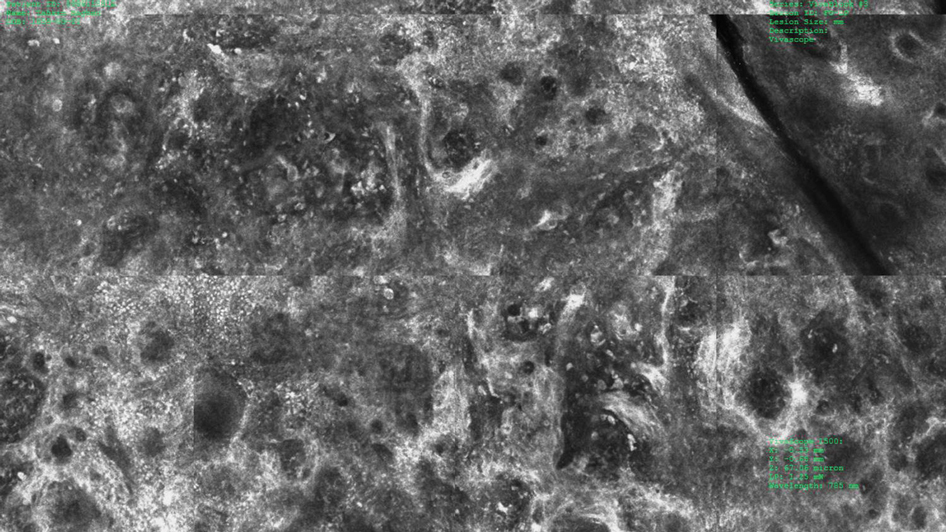

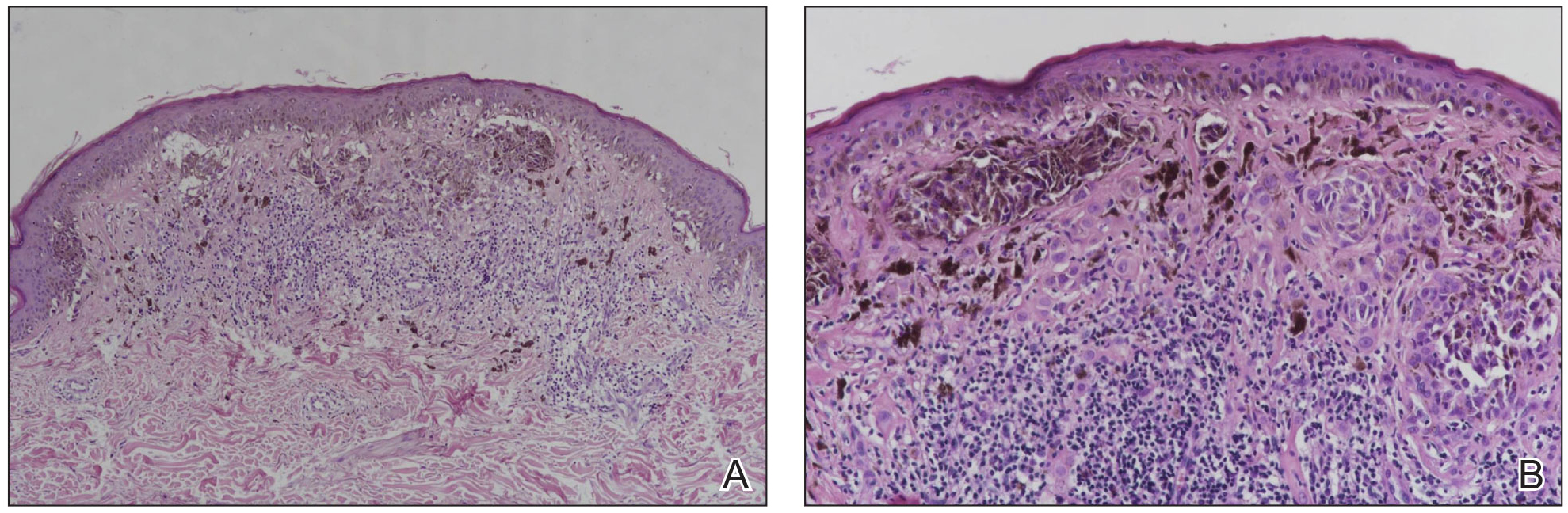

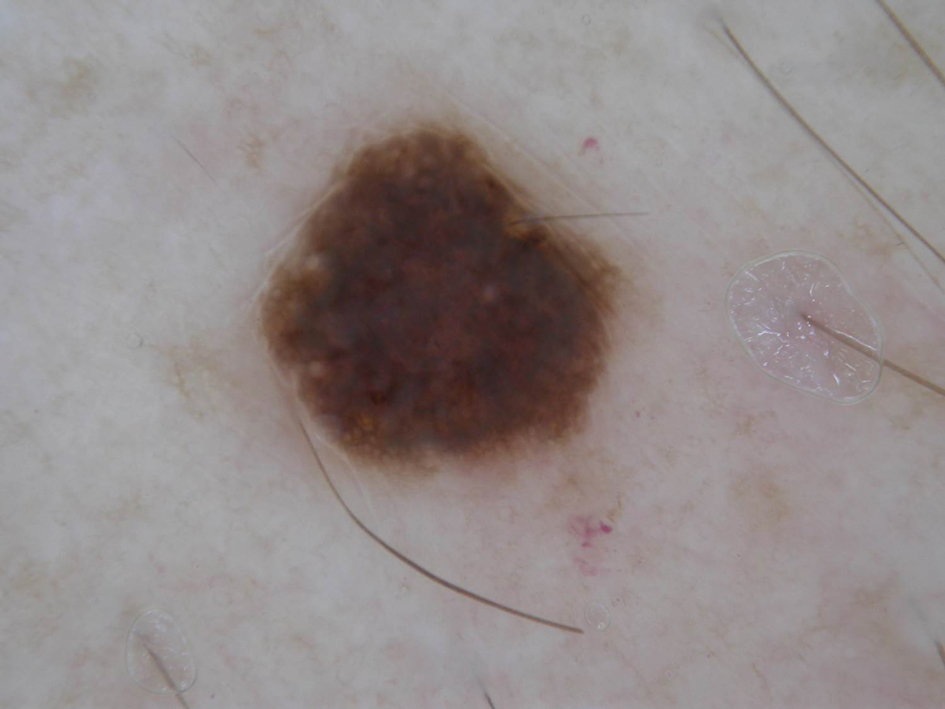

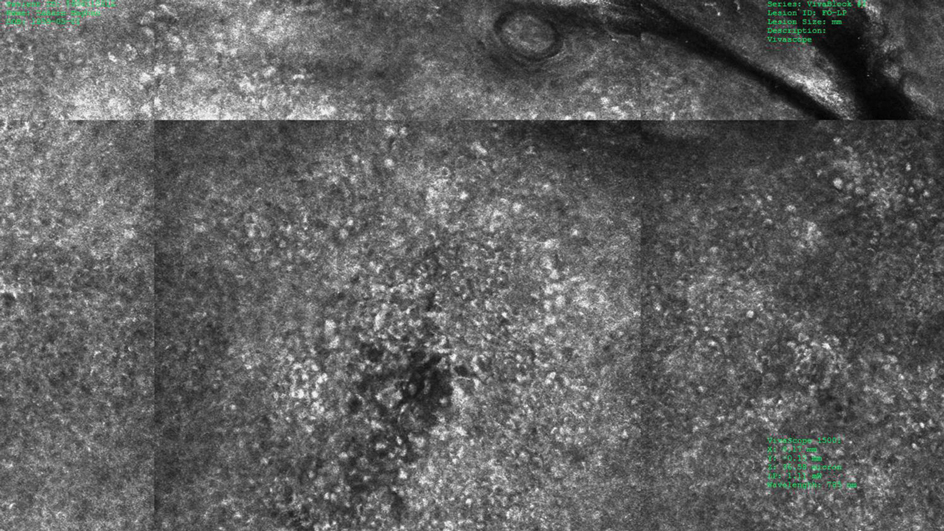

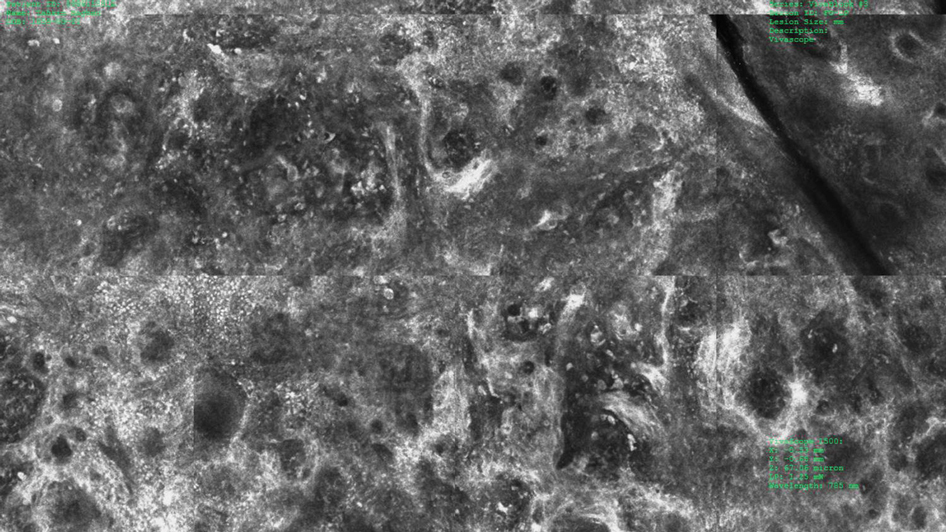

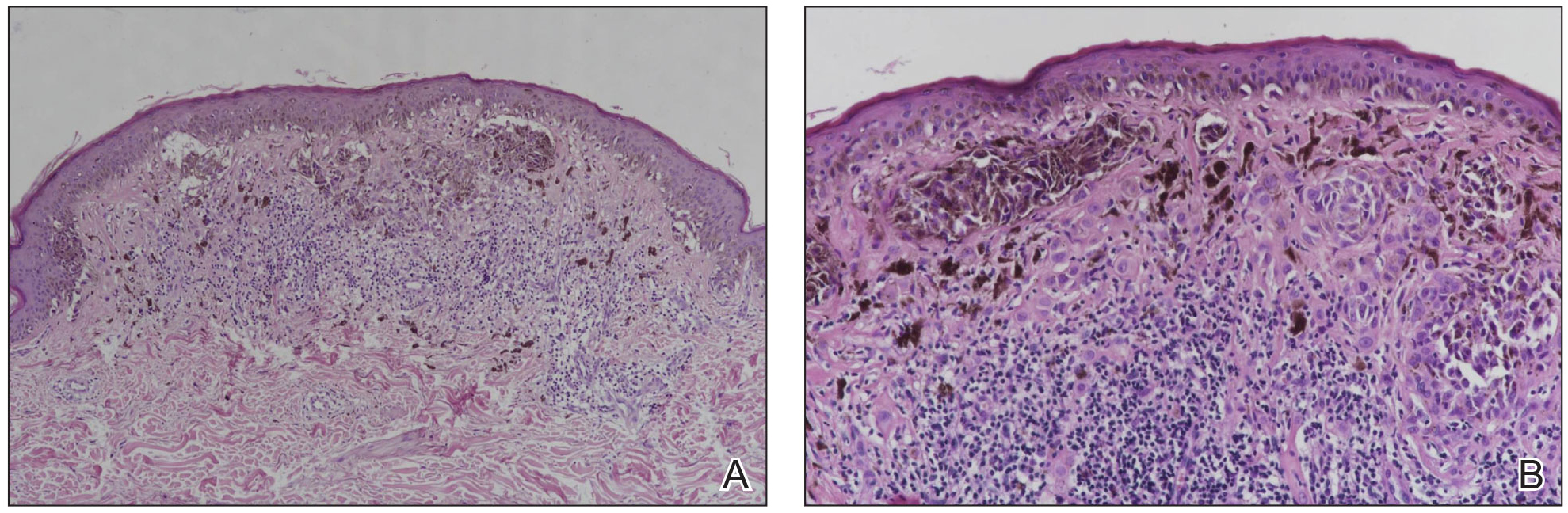

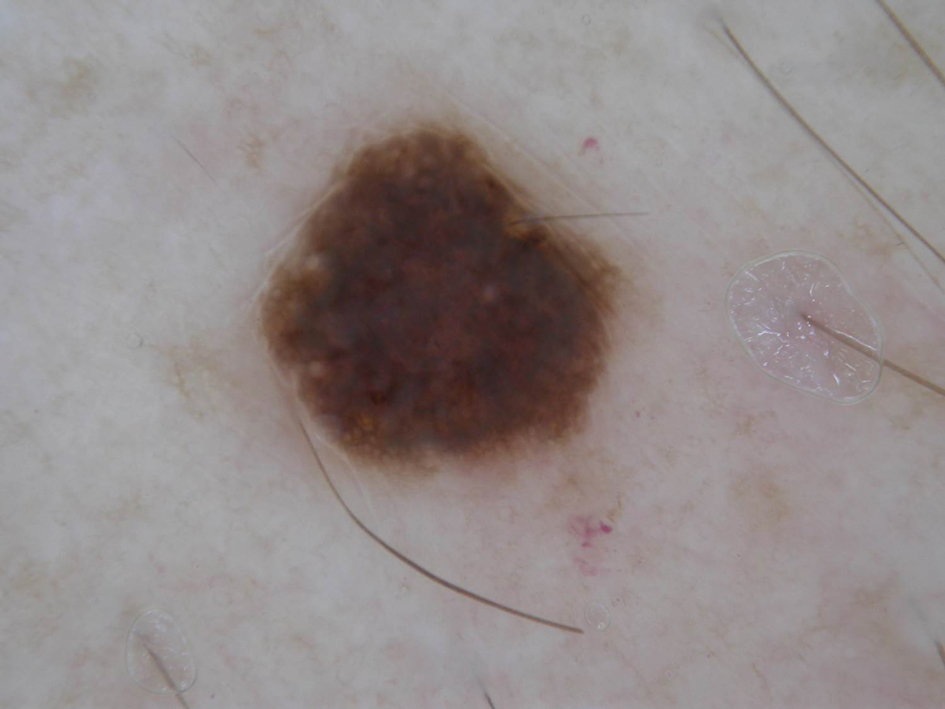

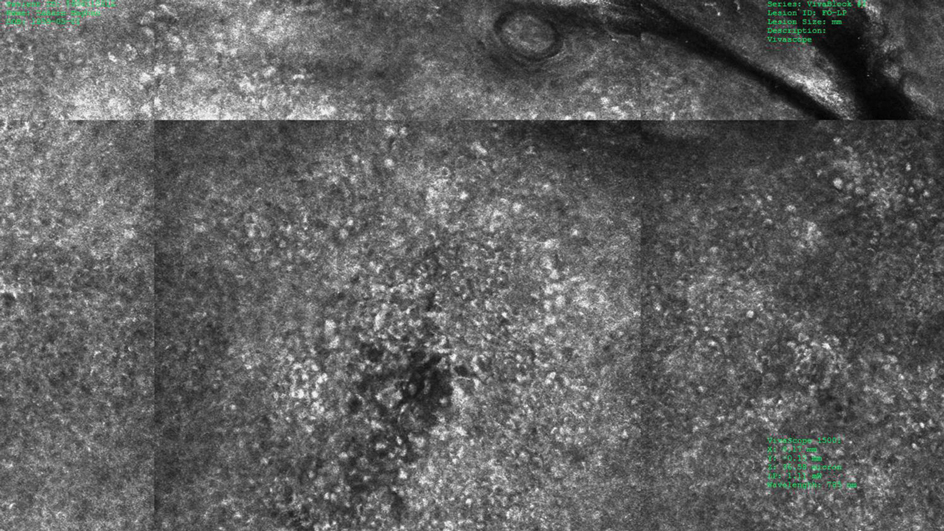

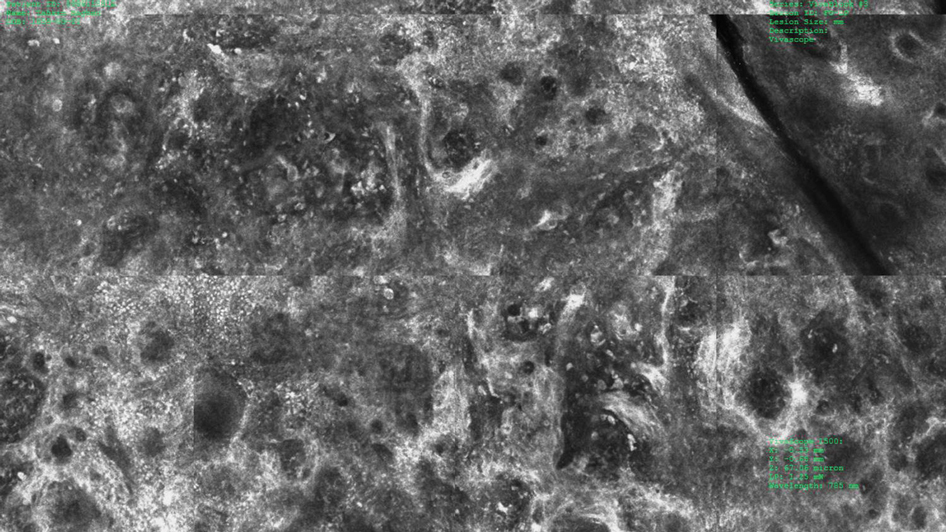

The available tissue blocks were retrieved, sectioned, confirmed as melanoma, and stained with a mouse antihuman BRAF V600E monoclonal antibody (clone VE1; Spring Bioscience) to determine the presence of a BRAF V600E mutation. BRAF staining was evaluated in conjunction with a review of the associated slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Cytoplasmic staining of melanocytes for BRAF was graded as negative, focal or partial positive (<50% of tumor), or diffuse positive (>50% of tumor)(Figure 1). When a melanoma arose in association with a nevus, we considered only the melanoma component for BRAF staining. We categorized the histologic type as superficial spreading, nodular, or lentigo maligna, and the location as head and neck, trunk, or extremities.

Patient characteristics and survival outcomes were gathered through the health record and included age, Breslow thickness, location, decade of diagnosis, histologic type, stage (ie, noninvasive, invasive, or advanced), and follow-up. Pathologic stage 0 was considered noninvasive; stages IA and IB, invasive; and stages IIA or higher, advanced.

Statistical Analysis—Comparisons between the group of patients in the study (n=380) and the group of patients excluded for the reasons stated above (n=258) as well as associations of mutant BRAF status (positive [partial positive and diffuse positive] vs negative) with patient age (young adults [age range, 18–39 years] and middle-aged adults [age range, 40–60 years]), sex, decade of diagnosis, location, histologic type, and stage were evaluated with Wilcoxon rank sum, χ2, Fisher exact, or Cochran-Armitage trend tests. Disease-specific survival and overall survival rates were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of melanoma diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow-up. Associations of mutant BRAF expression status with death from melanoma and death from any cause were evaluated with Cox proportional hazard regression models and summarized with hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. Survival analyses were limited to patients with invasive or advanced disease. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS version 9.4). All tests were 2-sided, and P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and Tumor Characteristics—Of the 380 tissue specimens that underwent BRAF V600E analysis, 247 had negative staining; 106 had diffuse strong staining; and 27 had focal or partial staining. In total, 133 (35%) were positive, either partially or diffusely. The median age for patients who had negative staining was 45 years; for those with positive staining, it was 41 years (P=.07).

The patients who met inclusion criteria (n=380) were compared with those who were excluded (n=258)(eTable 1). The groups were similar on the basis of sex; age; and melanoma location, stage, and histologic subtype. However, some evidence showed that patients included in the study received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently (1970-1989, 13.2%; 1990-1999, 28.7%; 2000-2009, 58.2%) than those who were excluded (1970-1989, 24.7%; 1990-1999, 23.5%; 2000-2009, 51.8%)(P=.02).

BRAF V600E expression was more commonly found in superficial spreading (37.7%) and nodular melanomas (35.0%) than in situ melanomas (17.1%)(P=.01). Other characteristics of BRAF V600E expression are described in eTable 2. Overall, invasive and advanced melanomas were significantly more likely to harbor BRAF V600E expression than noninvasive melanomas (39.6% and 37.9%, respectively, vs 17.9%; P=.003). However, advanced melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among women, and invasive melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among men (eTable 2).

Survival—Survival analyses were limited to 297 patients with confirmed invasive or advanced disease. Of these, 180 (61%) had no BRAF V600E staining; 25 (8%) had partial staining; and 92 (31%) had diffuse positive staining. In total, 117 patients (39%) had a BRAF-mutated melanoma.

Among the patients still alive, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of follow-up was 10.2 (7.0-16.8) years. Thirty-nine patients with invasive or advanced disease had died of any cause at a median (IQR) of 3.0 (1.3-10.2) years after diagnosis. In total, 26 patients died of melanoma at a median (IQR) follow-up of 2.5 (1.3-7.4) years after diagnosis. Eight women and 18 men died of malignant melanoma. Five deaths occurred because of malignant melanoma among patients aged 18 to 39 years, and 21 occurred among patients aged 40 to 60 years. In the 18- to 39-year-old group, all 5 deaths were among patients with a BRAF-positive melanoma. Estimated disease-specific survival rate (95% CI; number still at risk) at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after diagnosis was 94% (91%-97%; 243), 91% (87%-95%; 142), 89% (85%-94%; 87), and 88% (83%-93%; 45), respectively.

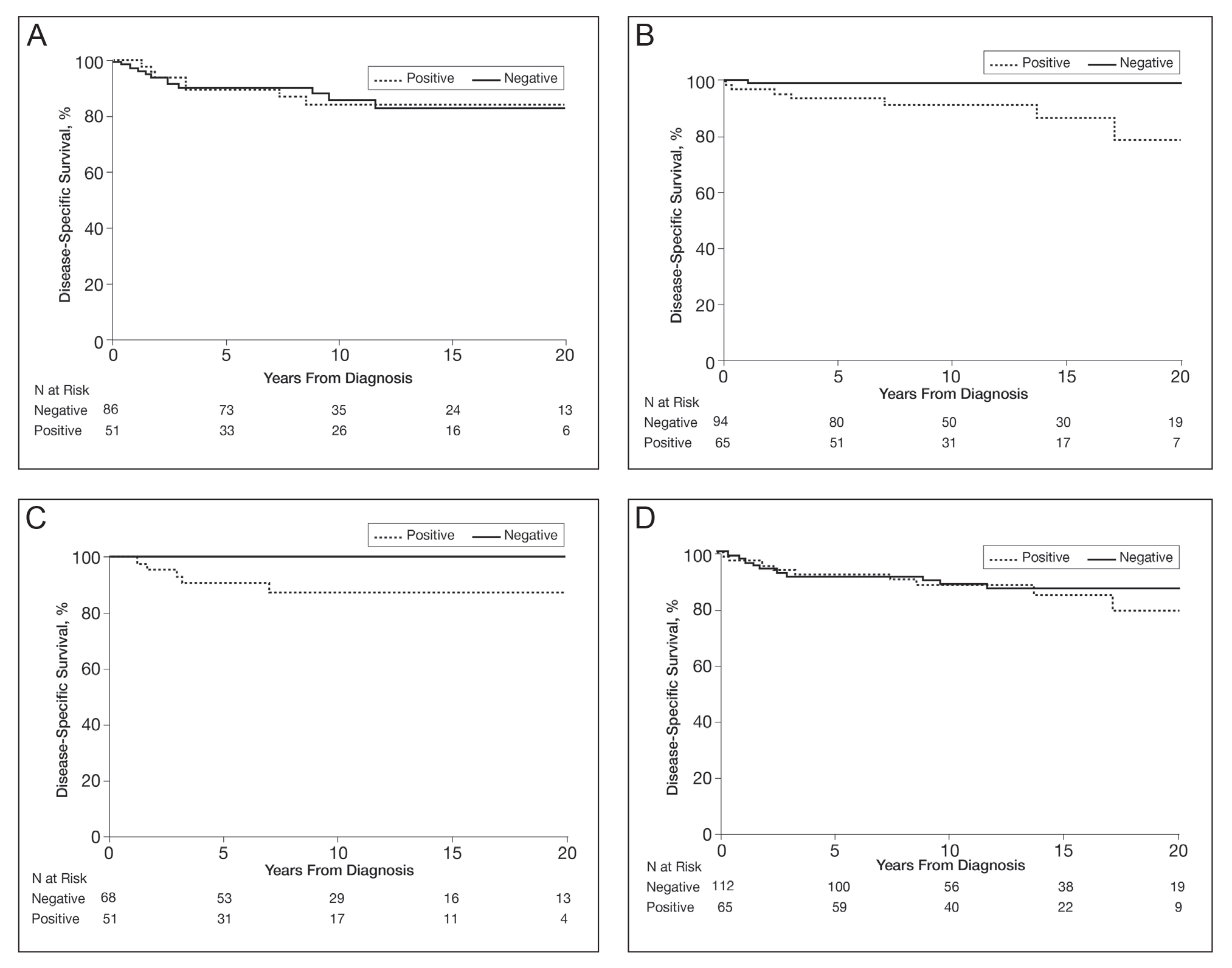

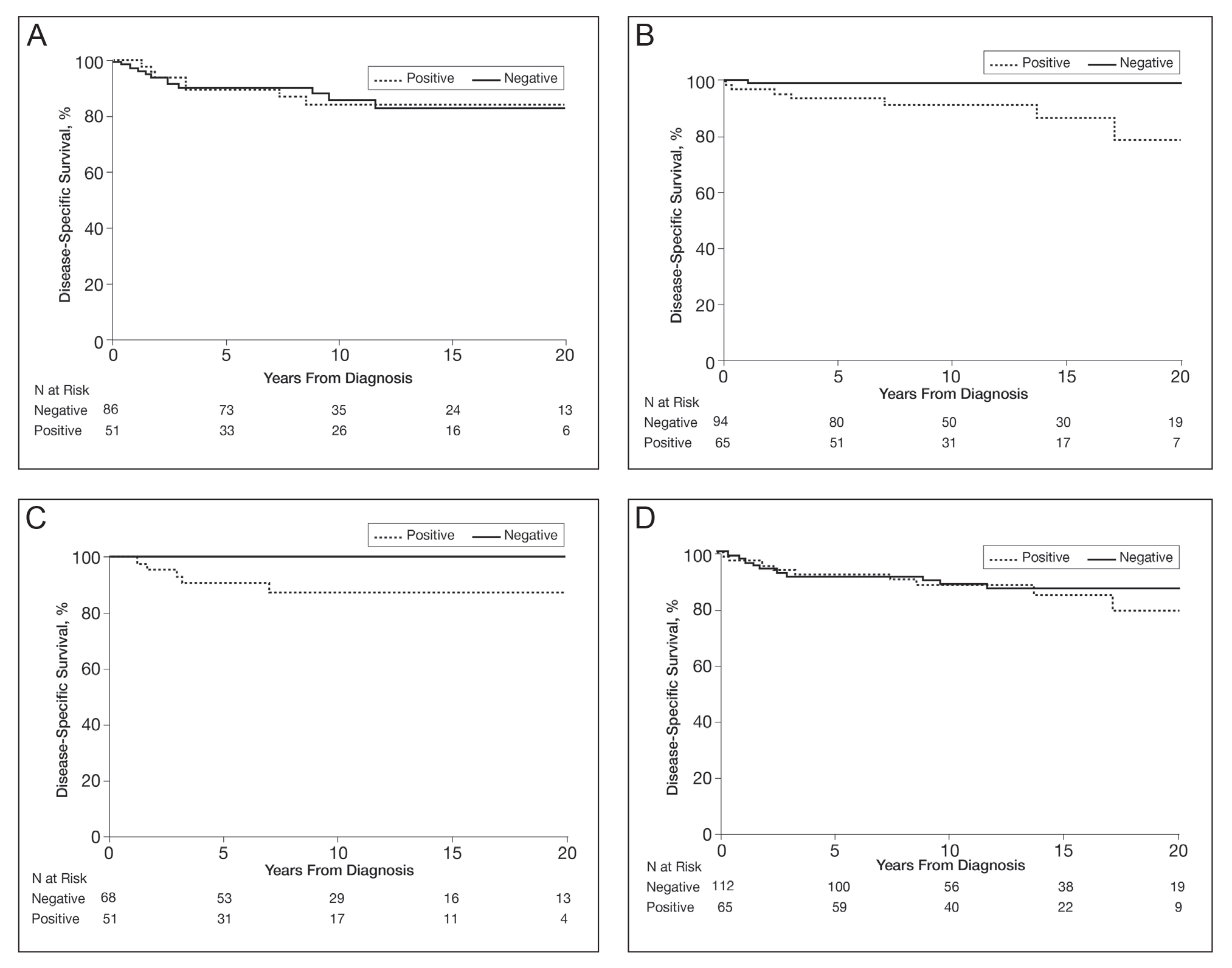

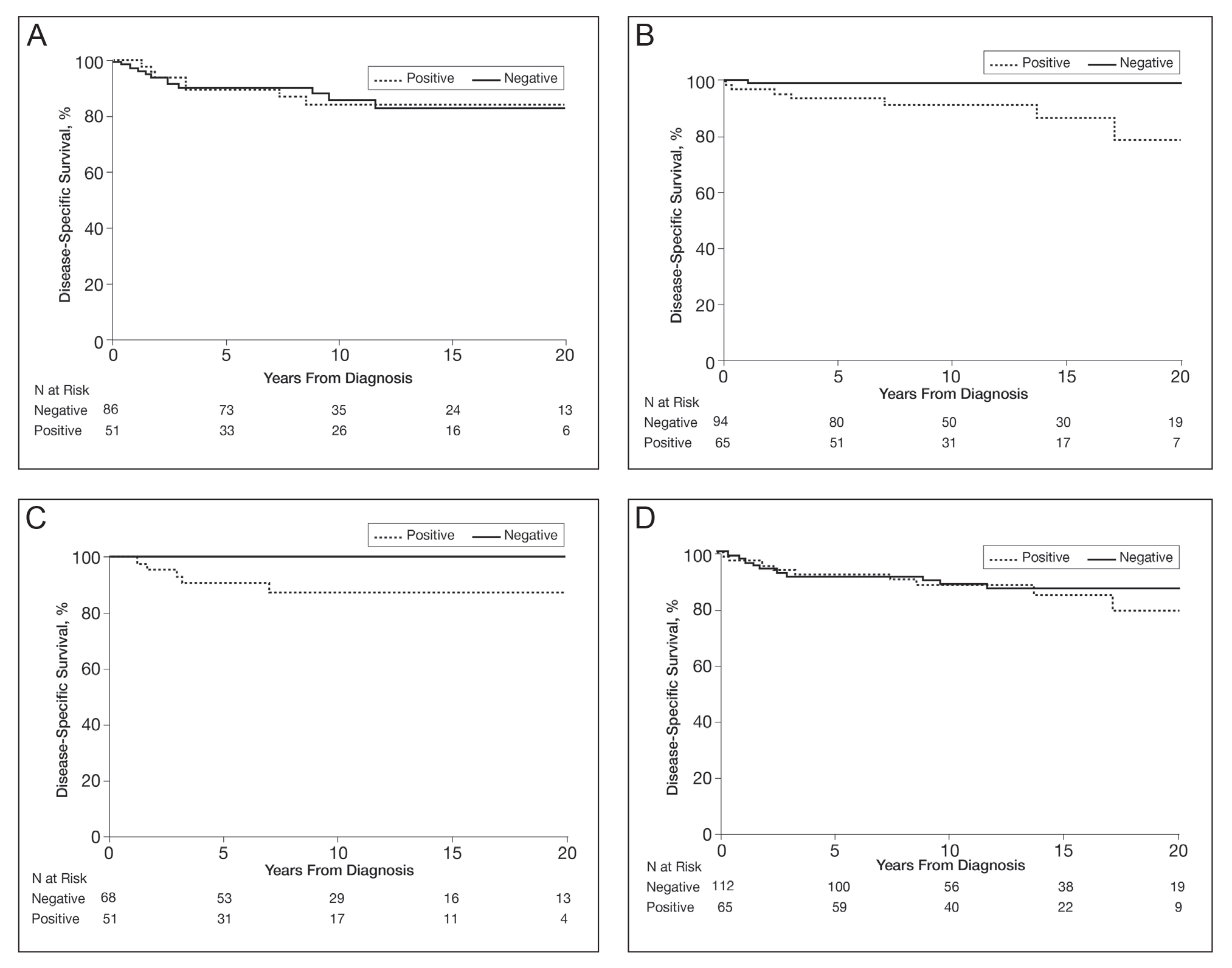

In a univariable analysis, the HR for association of positive mutant BRAF expression with death of malignant melanoma was 1.84 (95% CI, 0.85-3.98; P=.12). No statistically significant interaction was observed between decade of diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.60). However, the interaction between sex and BRAF expression was significant (P=.04), with increased risk of death from melanoma among women with BRAF-mutated melanoma (HR, 10.88; 95% CI, 1.34-88.41; P=.026) but not among men (HR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.40-2.64; P=.97)(Figures 2A and 2B). The HR for death from malignant melanoma among young adults aged 18 to 39 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 16.4 (95% CI, 0.81-330.10; P=.068), whereas the HR among adults aged 40 to 60 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.52-2.98; P=.63)(Figures 2C and 2D).

BRAF V600E expression was not significantly associated with death from any cause (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.74-2.61; P=.31) or with decade of diagnosis (P=.13). Similarly, BRAF expression was not associated with death from any cause according to sex (P=.31). However, a statistically significant interaction was seen between age at diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.003). BRAF expression was significantly associated with death from any cause for adults aged 18 to 39 years (HR, 9.60; 95% CI, 1.15-80.00; P=.04). In comparison, no association of BRAF expression with death was observed for adults aged 40 to 60 years (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.48-2.03; P=.98).

Comment

We found that melanomas with BRAF mutations were more likely in advanced and invasive melanoma. The frequency of BRAF mutations among melanomas that were considered advanced was higher in women than men. Although the number of deaths was limited, women with a melanoma with BRAF expression were more likely to die of melanoma, young adults with a BRAF-mutated melanoma had an almost 10-fold increased risk of dying from any cause, and middle-aged adults showed no increased risk of death. These findings suggest that young adults who are genetically prone to a BRAF-mutated melanoma could be at a disadvantage for all-cause mortality. Although this finding was significant, the 95% CI was large, and further studies would be warranted before sound conclusions could be made.

Melanoma has been increasing in incidence across all age groups in Olmsted County over the last 4 decades.12-14 However, our results show that the percentage of BRAF-mutated melanomas in this population has been stable over time, with no statistically significant difference by age or sex. Other confounding factors may have an influence, such as increased rates of early detection and diagnosis of melanoma in contemporary times. Our data suggest that patients included in the BRAF-mutation analysis study had received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently than those who were excluded from the study, which could be due to older melanomas being less likely to have adequate tissue specimens available for immunohistochemical staining/evaluation.

Prior research has shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas typically occur on the trunk and are more likely in individuals with more than 14 nevi on the back.2 In the present cohort, BRAF-positive melanomas had a predisposition toward the trunk but also were found on the head, neck, and extremities—areas that are more likely to have long-term sun damage. One suggestion is that 2 distinct pathways for melanoma development exist: one associated with a large number of melanocytic nevi (that is more prone to genetic mutations in melanocytes) and the other associated with long-term sun exposure.15,16 The combination of these hypotheses suggests that individuals who are prone to the development of large numbers of nevi may require sun exposure for the initial insult, but the development of melanoma may be carried out by other factors after this initial sun exposure insult, whereas individuals without large numbers of nevi who may have less genetic risk may require continued long-term sun exposure for melanoma to develop.17

Our study had limitations, including the small numbers of deaths overall and cause-specific deaths of metastatic melanoma, which limited our ability to conduct more extensive multivariable modeling. Also, the retrospective nature and time frame of looking back 4 decades did not allow us to have information sufficient to categorize some patients as having dysplastic nevus syndrome or not, which would be a potentially interesting variable to include in the analysis. Because the number of deaths in the 18- to 39-year-old cohort was only 5, further statistical comparison regarding tumor type and other variables pertaining to BRAF positivity were not possible. In addition, our data were collected from patients residing in a single geographic county (Olmsted County, Minnesota), which may limit generalizability. Lastly, BRAF V600E mutations were identified through immunostaining only, not molecular data, so it is possible some patients had false-negative immunohistochemistry findings and thus were not identified.

Conclusion

BRAF-mutated melanomas were found in 35% of our cohort, with no significant change in the percentage of melanomas with BRAF V600E mutations over the last 4 decades in this population. In addition, no differences or significant trends existed according to sex and BRAF-mutated melanoma development. Women with BRAF-mutated melanomas were more likely to die of metastatic melanoma than men, and young adults with BRAF-mutated melanomas had a higher all-cause mortality risk. Further research is needed to decipher what effect BRAF-mutated melanomas have on metastasis and cause-specific death in women as well as all-cause mortality in young adults.

Acknowledgment—The authors are indebted to Scientific Publications, Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota).

- Grimaldi AM, Cassidy PB, Leachmann S, et al. Novel approaches in melanoma prevention and therapy. Cancer Treat Res. 2014;159: 443-455.

- Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, et al. Number of nevi and early-life ambient UV exposure are associated with BRAF-mutant melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:991-997.

- Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135-2147.

- Thomas NE, Edmiston SN, Alexander A, et al. Association between NRAS and BRAF mutational status and melanoma-specific survival among patients with higher-risk primary melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:359-368.

- Liu W, Kelly JW, Trivett M, et al. Distinct clinical and pathological features are associated with the BRAF(T1799A(V600E)) mutation in primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:900-905.

- Kim SY, Kim SN, Hahn HJ, et al. Metaanalysis of BRAF mutations and clinicopathologic characteristics in primary melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1036-1046.e2.

- Larsen AC, Dahl C, Dahmcke CM, et al. BRAF mutations in conjunctival melanoma: investigation of incidence, clinicopathological features, prognosis and paired premalignant lesions. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:463-470.

- Shinozaki M, Fujimoto A, Morton DL, et al. Incidence of BRAF oncogene mutation and clinical relevance for primary cutaneous melanomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1753-1757.

- Heppt MV, Siepmann T, Engel J, et al. Prognostic significance of BRAF and NRAS mutations in melanoma: a German study from routine care. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:536.

- Mar VJ, Liu W, Devitt B, et al. The role of BRAF mutations in primary melanoma growth rate and survival. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:76-82.

- Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, et al. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1202-1213.

- Reed KB, Brewer JD, Lohse CM, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma among young adults: an epidemiological study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:328-334.

- Olazagasti Lourido JM, Ma JE, Lohse CM, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma in the elderly: an epidemiological study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1555-1562.

- Lowe GC, Saavedra A, Reed KB, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma among middle-aged adults: an epidemiologic study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:52-59.

- Whiteman DC, Parsons PG, Green AC. p53 expression and risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:843-848.

- Whiteman DC, Watt P, Purdie DM, et al. Melanocytic nevi, solar keratoses, and divergent pathways to cutaneous melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:806-812.

- Olsen CM, Zens MS, Green AC, et al. Biologic markers of sun exposure and melanoma risk in women: pooled case-control analysis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:713-723.

Approximately 50% of melanomas contain BRAF mutations, which occur in a greater proportion of melanomas found on sites of intermittent sun exposure.1BRAF-mutated melanomas have been associated with high levels of early-life ambient UV exposure, especially between ages 0 and 20 years.2 In addition, studies have shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas commonly are found on the trunk and extremities.1-3BRAF mutations also have been associated with younger age, superficial spreading subtype and low tumor thickness, absence of dermal melanocyte mitosis, low Ki-67 score, low phospho-histone H3 score, pigmented melanoma, advanced melanoma stage, and conjunctival melanoma.4-7BRAF mutations are found more frequently in metastatic melanoma lesions than primary melanomas, suggesting that BRAF mutations may be acquired during metastasis.8 Studies have shown different conclusions on the effect of BRAF mutation on melanoma-related death.5,9,10

The aim of this study was to identify trends in BRAF V600E–mutated melanoma according to age, sex, and melanoma-specific survival among Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents with a first diagnosis of melanoma at 18 to 60 years of age.

Methods

In total, 638 patients aged 18 to 60 years who resided in Olmsted County and had a first lifetime diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma between 1970 and 2009 were retrospectively identified as a part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP is a health records linkage system that encompasses almost all sources of medical care available to the local population of Olmsted County.11 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minnesota).

Of the 638 individuals identified in the REP, 536 had been seen at Mayo Clinic and thus potentially had tissue blocks available for the study of BRAF mutation expression. Of these 536 patients, 156 did not have sufficient residual tissue available. As a result, 380 (60%) of the original 638 patients had available blocks with sufficient tissue for immunohistochemical analysis of BRAF expression. Only primary cutaneous melanomas were included in the present study.

All specimens were reviewed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (J.S.L.) for appropriateness of inclusion, which involved confirmation of the diagnosis of melanoma, histologic type of melanoma, and presence of sufficient residual tissue for immunohistochemical stains.

All specimens were originally diagnosed as malignant melanoma at the time of clinical care by at least 2 board-certified dermatopathologists. For the purposes of this study, all specimens were rereviewed for diagnostic accuracy. We required that specimens exhibit severe cytologic and architectural atypia as well as other features favoring melanoma, such as consumption of rete pegs, pagetosis, confluence of junctional melanocytes, evidence of regression, lack of maturation of melanocytes with descent into the dermis, or mitotic figures among the dermal melanocyte population.

The available tissue blocks were retrieved, sectioned, confirmed as melanoma, and stained with a mouse antihuman BRAF V600E monoclonal antibody (clone VE1; Spring Bioscience) to determine the presence of a BRAF V600E mutation. BRAF staining was evaluated in conjunction with a review of the associated slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Cytoplasmic staining of melanocytes for BRAF was graded as negative, focal or partial positive (<50% of tumor), or diffuse positive (>50% of tumor)(Figure 1). When a melanoma arose in association with a nevus, we considered only the melanoma component for BRAF staining. We categorized the histologic type as superficial spreading, nodular, or lentigo maligna, and the location as head and neck, trunk, or extremities.

Patient characteristics and survival outcomes were gathered through the health record and included age, Breslow thickness, location, decade of diagnosis, histologic type, stage (ie, noninvasive, invasive, or advanced), and follow-up. Pathologic stage 0 was considered noninvasive; stages IA and IB, invasive; and stages IIA or higher, advanced.

Statistical Analysis—Comparisons between the group of patients in the study (n=380) and the group of patients excluded for the reasons stated above (n=258) as well as associations of mutant BRAF status (positive [partial positive and diffuse positive] vs negative) with patient age (young adults [age range, 18–39 years] and middle-aged adults [age range, 40–60 years]), sex, decade of diagnosis, location, histologic type, and stage were evaluated with Wilcoxon rank sum, χ2, Fisher exact, or Cochran-Armitage trend tests. Disease-specific survival and overall survival rates were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of melanoma diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow-up. Associations of mutant BRAF expression status with death from melanoma and death from any cause were evaluated with Cox proportional hazard regression models and summarized with hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. Survival analyses were limited to patients with invasive or advanced disease. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS version 9.4). All tests were 2-sided, and P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and Tumor Characteristics—Of the 380 tissue specimens that underwent BRAF V600E analysis, 247 had negative staining; 106 had diffuse strong staining; and 27 had focal or partial staining. In total, 133 (35%) were positive, either partially or diffusely. The median age for patients who had negative staining was 45 years; for those with positive staining, it was 41 years (P=.07).

The patients who met inclusion criteria (n=380) were compared with those who were excluded (n=258)(eTable 1). The groups were similar on the basis of sex; age; and melanoma location, stage, and histologic subtype. However, some evidence showed that patients included in the study received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently (1970-1989, 13.2%; 1990-1999, 28.7%; 2000-2009, 58.2%) than those who were excluded (1970-1989, 24.7%; 1990-1999, 23.5%; 2000-2009, 51.8%)(P=.02).

BRAF V600E expression was more commonly found in superficial spreading (37.7%) and nodular melanomas (35.0%) than in situ melanomas (17.1%)(P=.01). Other characteristics of BRAF V600E expression are described in eTable 2. Overall, invasive and advanced melanomas were significantly more likely to harbor BRAF V600E expression than noninvasive melanomas (39.6% and 37.9%, respectively, vs 17.9%; P=.003). However, advanced melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among women, and invasive melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among men (eTable 2).

Survival—Survival analyses were limited to 297 patients with confirmed invasive or advanced disease. Of these, 180 (61%) had no BRAF V600E staining; 25 (8%) had partial staining; and 92 (31%) had diffuse positive staining. In total, 117 patients (39%) had a BRAF-mutated melanoma.

Among the patients still alive, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of follow-up was 10.2 (7.0-16.8) years. Thirty-nine patients with invasive or advanced disease had died of any cause at a median (IQR) of 3.0 (1.3-10.2) years after diagnosis. In total, 26 patients died of melanoma at a median (IQR) follow-up of 2.5 (1.3-7.4) years after diagnosis. Eight women and 18 men died of malignant melanoma. Five deaths occurred because of malignant melanoma among patients aged 18 to 39 years, and 21 occurred among patients aged 40 to 60 years. In the 18- to 39-year-old group, all 5 deaths were among patients with a BRAF-positive melanoma. Estimated disease-specific survival rate (95% CI; number still at risk) at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after diagnosis was 94% (91%-97%; 243), 91% (87%-95%; 142), 89% (85%-94%; 87), and 88% (83%-93%; 45), respectively.

In a univariable analysis, the HR for association of positive mutant BRAF expression with death of malignant melanoma was 1.84 (95% CI, 0.85-3.98; P=.12). No statistically significant interaction was observed between decade of diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.60). However, the interaction between sex and BRAF expression was significant (P=.04), with increased risk of death from melanoma among women with BRAF-mutated melanoma (HR, 10.88; 95% CI, 1.34-88.41; P=.026) but not among men (HR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.40-2.64; P=.97)(Figures 2A and 2B). The HR for death from malignant melanoma among young adults aged 18 to 39 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 16.4 (95% CI, 0.81-330.10; P=.068), whereas the HR among adults aged 40 to 60 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.52-2.98; P=.63)(Figures 2C and 2D).

BRAF V600E expression was not significantly associated with death from any cause (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.74-2.61; P=.31) or with decade of diagnosis (P=.13). Similarly, BRAF expression was not associated with death from any cause according to sex (P=.31). However, a statistically significant interaction was seen between age at diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.003). BRAF expression was significantly associated with death from any cause for adults aged 18 to 39 years (HR, 9.60; 95% CI, 1.15-80.00; P=.04). In comparison, no association of BRAF expression with death was observed for adults aged 40 to 60 years (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.48-2.03; P=.98).

Comment

We found that melanomas with BRAF mutations were more likely in advanced and invasive melanoma. The frequency of BRAF mutations among melanomas that were considered advanced was higher in women than men. Although the number of deaths was limited, women with a melanoma with BRAF expression were more likely to die of melanoma, young adults with a BRAF-mutated melanoma had an almost 10-fold increased risk of dying from any cause, and middle-aged adults showed no increased risk of death. These findings suggest that young adults who are genetically prone to a BRAF-mutated melanoma could be at a disadvantage for all-cause mortality. Although this finding was significant, the 95% CI was large, and further studies would be warranted before sound conclusions could be made.

Melanoma has been increasing in incidence across all age groups in Olmsted County over the last 4 decades.12-14 However, our results show that the percentage of BRAF-mutated melanomas in this population has been stable over time, with no statistically significant difference by age or sex. Other confounding factors may have an influence, such as increased rates of early detection and diagnosis of melanoma in contemporary times. Our data suggest that patients included in the BRAF-mutation analysis study had received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently than those who were excluded from the study, which could be due to older melanomas being less likely to have adequate tissue specimens available for immunohistochemical staining/evaluation.

Prior research has shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas typically occur on the trunk and are more likely in individuals with more than 14 nevi on the back.2 In the present cohort, BRAF-positive melanomas had a predisposition toward the trunk but also were found on the head, neck, and extremities—areas that are more likely to have long-term sun damage. One suggestion is that 2 distinct pathways for melanoma development exist: one associated with a large number of melanocytic nevi (that is more prone to genetic mutations in melanocytes) and the other associated with long-term sun exposure.15,16 The combination of these hypotheses suggests that individuals who are prone to the development of large numbers of nevi may require sun exposure for the initial insult, but the development of melanoma may be carried out by other factors after this initial sun exposure insult, whereas individuals without large numbers of nevi who may have less genetic risk may require continued long-term sun exposure for melanoma to develop.17

Our study had limitations, including the small numbers of deaths overall and cause-specific deaths of metastatic melanoma, which limited our ability to conduct more extensive multivariable modeling. Also, the retrospective nature and time frame of looking back 4 decades did not allow us to have information sufficient to categorize some patients as having dysplastic nevus syndrome or not, which would be a potentially interesting variable to include in the analysis. Because the number of deaths in the 18- to 39-year-old cohort was only 5, further statistical comparison regarding tumor type and other variables pertaining to BRAF positivity were not possible. In addition, our data were collected from patients residing in a single geographic county (Olmsted County, Minnesota), which may limit generalizability. Lastly, BRAF V600E mutations were identified through immunostaining only, not molecular data, so it is possible some patients had false-negative immunohistochemistry findings and thus were not identified.

Conclusion

BRAF-mutated melanomas were found in 35% of our cohort, with no significant change in the percentage of melanomas with BRAF V600E mutations over the last 4 decades in this population. In addition, no differences or significant trends existed according to sex and BRAF-mutated melanoma development. Women with BRAF-mutated melanomas were more likely to die of metastatic melanoma than men, and young adults with BRAF-mutated melanomas had a higher all-cause mortality risk. Further research is needed to decipher what effect BRAF-mutated melanomas have on metastasis and cause-specific death in women as well as all-cause mortality in young adults.

Acknowledgment—The authors are indebted to Scientific Publications, Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota).

Approximately 50% of melanomas contain BRAF mutations, which occur in a greater proportion of melanomas found on sites of intermittent sun exposure.1BRAF-mutated melanomas have been associated with high levels of early-life ambient UV exposure, especially between ages 0 and 20 years.2 In addition, studies have shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas commonly are found on the trunk and extremities.1-3BRAF mutations also have been associated with younger age, superficial spreading subtype and low tumor thickness, absence of dermal melanocyte mitosis, low Ki-67 score, low phospho-histone H3 score, pigmented melanoma, advanced melanoma stage, and conjunctival melanoma.4-7BRAF mutations are found more frequently in metastatic melanoma lesions than primary melanomas, suggesting that BRAF mutations may be acquired during metastasis.8 Studies have shown different conclusions on the effect of BRAF mutation on melanoma-related death.5,9,10

The aim of this study was to identify trends in BRAF V600E–mutated melanoma according to age, sex, and melanoma-specific survival among Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents with a first diagnosis of melanoma at 18 to 60 years of age.

Methods

In total, 638 patients aged 18 to 60 years who resided in Olmsted County and had a first lifetime diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma between 1970 and 2009 were retrospectively identified as a part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP). The REP is a health records linkage system that encompasses almost all sources of medical care available to the local population of Olmsted County.11 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, Minnesota).

Of the 638 individuals identified in the REP, 536 had been seen at Mayo Clinic and thus potentially had tissue blocks available for the study of BRAF mutation expression. Of these 536 patients, 156 did not have sufficient residual tissue available. As a result, 380 (60%) of the original 638 patients had available blocks with sufficient tissue for immunohistochemical analysis of BRAF expression. Only primary cutaneous melanomas were included in the present study.

All specimens were reviewed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (J.S.L.) for appropriateness of inclusion, which involved confirmation of the diagnosis of melanoma, histologic type of melanoma, and presence of sufficient residual tissue for immunohistochemical stains.

All specimens were originally diagnosed as malignant melanoma at the time of clinical care by at least 2 board-certified dermatopathologists. For the purposes of this study, all specimens were rereviewed for diagnostic accuracy. We required that specimens exhibit severe cytologic and architectural atypia as well as other features favoring melanoma, such as consumption of rete pegs, pagetosis, confluence of junctional melanocytes, evidence of regression, lack of maturation of melanocytes with descent into the dermis, or mitotic figures among the dermal melanocyte population.

The available tissue blocks were retrieved, sectioned, confirmed as melanoma, and stained with a mouse antihuman BRAF V600E monoclonal antibody (clone VE1; Spring Bioscience) to determine the presence of a BRAF V600E mutation. BRAF staining was evaluated in conjunction with a review of the associated slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Cytoplasmic staining of melanocytes for BRAF was graded as negative, focal or partial positive (<50% of tumor), or diffuse positive (>50% of tumor)(Figure 1). When a melanoma arose in association with a nevus, we considered only the melanoma component for BRAF staining. We categorized the histologic type as superficial spreading, nodular, or lentigo maligna, and the location as head and neck, trunk, or extremities.

Patient characteristics and survival outcomes were gathered through the health record and included age, Breslow thickness, location, decade of diagnosis, histologic type, stage (ie, noninvasive, invasive, or advanced), and follow-up. Pathologic stage 0 was considered noninvasive; stages IA and IB, invasive; and stages IIA or higher, advanced.

Statistical Analysis—Comparisons between the group of patients in the study (n=380) and the group of patients excluded for the reasons stated above (n=258) as well as associations of mutant BRAF status (positive [partial positive and diffuse positive] vs negative) with patient age (young adults [age range, 18–39 years] and middle-aged adults [age range, 40–60 years]), sex, decade of diagnosis, location, histologic type, and stage were evaluated with Wilcoxon rank sum, χ2, Fisher exact, or Cochran-Armitage trend tests. Disease-specific survival and overall survival rates were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of melanoma diagnosis to the date of death or the last follow-up. Associations of mutant BRAF expression status with death from melanoma and death from any cause were evaluated with Cox proportional hazard regression models and summarized with hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI. Survival analyses were limited to patients with invasive or advanced disease. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS version 9.4). All tests were 2-sided, and P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and Tumor Characteristics—Of the 380 tissue specimens that underwent BRAF V600E analysis, 247 had negative staining; 106 had diffuse strong staining; and 27 had focal or partial staining. In total, 133 (35%) were positive, either partially or diffusely. The median age for patients who had negative staining was 45 years; for those with positive staining, it was 41 years (P=.07).

The patients who met inclusion criteria (n=380) were compared with those who were excluded (n=258)(eTable 1). The groups were similar on the basis of sex; age; and melanoma location, stage, and histologic subtype. However, some evidence showed that patients included in the study received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently (1970-1989, 13.2%; 1990-1999, 28.7%; 2000-2009, 58.2%) than those who were excluded (1970-1989, 24.7%; 1990-1999, 23.5%; 2000-2009, 51.8%)(P=.02).

BRAF V600E expression was more commonly found in superficial spreading (37.7%) and nodular melanomas (35.0%) than in situ melanomas (17.1%)(P=.01). Other characteristics of BRAF V600E expression are described in eTable 2. Overall, invasive and advanced melanomas were significantly more likely to harbor BRAF V600E expression than noninvasive melanomas (39.6% and 37.9%, respectively, vs 17.9%; P=.003). However, advanced melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among women, and invasive melanomas more commonly expressed BRAF positivity among men (eTable 2).

Survival—Survival analyses were limited to 297 patients with confirmed invasive or advanced disease. Of these, 180 (61%) had no BRAF V600E staining; 25 (8%) had partial staining; and 92 (31%) had diffuse positive staining. In total, 117 patients (39%) had a BRAF-mutated melanoma.

Among the patients still alive, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) duration of follow-up was 10.2 (7.0-16.8) years. Thirty-nine patients with invasive or advanced disease had died of any cause at a median (IQR) of 3.0 (1.3-10.2) years after diagnosis. In total, 26 patients died of melanoma at a median (IQR) follow-up of 2.5 (1.3-7.4) years after diagnosis. Eight women and 18 men died of malignant melanoma. Five deaths occurred because of malignant melanoma among patients aged 18 to 39 years, and 21 occurred among patients aged 40 to 60 years. In the 18- to 39-year-old group, all 5 deaths were among patients with a BRAF-positive melanoma. Estimated disease-specific survival rate (95% CI; number still at risk) at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after diagnosis was 94% (91%-97%; 243), 91% (87%-95%; 142), 89% (85%-94%; 87), and 88% (83%-93%; 45), respectively.

In a univariable analysis, the HR for association of positive mutant BRAF expression with death of malignant melanoma was 1.84 (95% CI, 0.85-3.98; P=.12). No statistically significant interaction was observed between decade of diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.60). However, the interaction between sex and BRAF expression was significant (P=.04), with increased risk of death from melanoma among women with BRAF-mutated melanoma (HR, 10.88; 95% CI, 1.34-88.41; P=.026) but not among men (HR 1.02; 95% CI, 0.40-2.64; P=.97)(Figures 2A and 2B). The HR for death from malignant melanoma among young adults aged 18 to 39 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 16.4 (95% CI, 0.81-330.10; P=.068), whereas the HR among adults aged 40 to 60 years with a BRAF-mutated melanoma was 1.24 (95% CI, 0.52-2.98; P=.63)(Figures 2C and 2D).

BRAF V600E expression was not significantly associated with death from any cause (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.74-2.61; P=.31) or with decade of diagnosis (P=.13). Similarly, BRAF expression was not associated with death from any cause according to sex (P=.31). However, a statistically significant interaction was seen between age at diagnosis and BRAF expression (P=.003). BRAF expression was significantly associated with death from any cause for adults aged 18 to 39 years (HR, 9.60; 95% CI, 1.15-80.00; P=.04). In comparison, no association of BRAF expression with death was observed for adults aged 40 to 60 years (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.48-2.03; P=.98).

Comment

We found that melanomas with BRAF mutations were more likely in advanced and invasive melanoma. The frequency of BRAF mutations among melanomas that were considered advanced was higher in women than men. Although the number of deaths was limited, women with a melanoma with BRAF expression were more likely to die of melanoma, young adults with a BRAF-mutated melanoma had an almost 10-fold increased risk of dying from any cause, and middle-aged adults showed no increased risk of death. These findings suggest that young adults who are genetically prone to a BRAF-mutated melanoma could be at a disadvantage for all-cause mortality. Although this finding was significant, the 95% CI was large, and further studies would be warranted before sound conclusions could be made.

Melanoma has been increasing in incidence across all age groups in Olmsted County over the last 4 decades.12-14 However, our results show that the percentage of BRAF-mutated melanomas in this population has been stable over time, with no statistically significant difference by age or sex. Other confounding factors may have an influence, such as increased rates of early detection and diagnosis of melanoma in contemporary times. Our data suggest that patients included in the BRAF-mutation analysis study had received the diagnosis of melanoma more recently than those who were excluded from the study, which could be due to older melanomas being less likely to have adequate tissue specimens available for immunohistochemical staining/evaluation.

Prior research has shown that BRAF-mutated melanomas typically occur on the trunk and are more likely in individuals with more than 14 nevi on the back.2 In the present cohort, BRAF-positive melanomas had a predisposition toward the trunk but also were found on the head, neck, and extremities—areas that are more likely to have long-term sun damage. One suggestion is that 2 distinct pathways for melanoma development exist: one associated with a large number of melanocytic nevi (that is more prone to genetic mutations in melanocytes) and the other associated with long-term sun exposure.15,16 The combination of these hypotheses suggests that individuals who are prone to the development of large numbers of nevi may require sun exposure for the initial insult, but the development of melanoma may be carried out by other factors after this initial sun exposure insult, whereas individuals without large numbers of nevi who may have less genetic risk may require continued long-term sun exposure for melanoma to develop.17