User login

Is prescribing stimulants OK for comorbid opioid use disorder, ADHD?

A growing number of patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) have a diagnosis of comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), raising issues about whether it’s appropriate to prescribe stimulants in this patient population.

One new study showed that from 2007-2017, there was a threefold increase in OUD and comorbid ADHD and that a significant number of these patients received prescription stimulants.

“This is the beginning stages of looking at whether or not there are risks of prescribing stimulants to patients who are on medications for opioid use disorder,” investigator Tae Woo (Ted) Park, MD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told this news organization.

“More and more people are being identified with ADHD, and we need to do more research on the best way to manage this patient group,” Dr. Park added.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

Biological connection?

Dr. Park is not convinced there is “an actual biological connection” between ADHD and OUD, noting that there are many reasons why patients with ADHD may be more prone to developing such a disorder.

Perhaps they did not get an ADHD diagnosis as a child, “which led to impairment in their ability to be successful at school and then in a job,” which in turn predisposed them to having a substance use disorder, said Dr. Park.

From previous research and his own clinical experience, ADHD can significantly affect quality of life and “cause increased impairment” in patients with a substance use disorder, he added.

Interestingly, there’s evidence suggesting patients treated for ADHD early in life are less likely to develop a substance use disorder later on, he said.

The “gold standard” treatment for ADHD is a prescription stimulant, which carries its own addiction risks. “So the issue is about whether or not to prescribe risky medications and how to weigh the risks and benefits,” said Dr. Park.

From a private health insurance database, researchers examined records for patients aged 18-64 years who were receiving medication for OUD, including buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone, from 2007-2017.

In the study sample, about 17,000 individuals were receiving stimulants, and 156,000 were not receiving these drugs. The largest percentage of participants in both groups was in the age-18-to-25 category.

About 35% of those receiving stimulants had ADHD, and about the same percentage had a mood disorder diagnosis.

Percentage of co-occurring ADHD and OUD increased from more than 4% in 2007 to more than 14% in 2017. The prevalence of stimulant use plus medication for OUD also increased during that time.

The increase in ADHD diagnoses may reflect growing identification of the condition, Dr. Park noted. As the opioid problem became more apparent and additional treatments made available, “there were more health care contacts, more assessments, and more diagnoses, including of ADHD,” he said.

Risks versus benefits

Stimulants may also be risky in patients with OUD. Results from another study presented at the AAAP meeting showed these drugs were associated with an increased chance of poisoning in patients receiving buprenorphine.

However, Dr. Park is skeptical the combination of stimulants and buprenorphine “leads to a biological risk of overdose.” He used a hypothetical scenario where other factors play into the connection: A patient gets a prescription stimulant, becomes addicted, then starts using street or illicit stimulants, which leads to a relapse on opioids, and then to an overdose.

Dr. Park noted that the same study that found an increased poisoning risk in stimulant users also found that patients tend to stay on buprenorphine treatment, providing protection against overdose.

“So there are risks and benefits of prescribing these medications, and it becomes tricky to know whether to prescribe them or not,” he said.

While stimulants are by far the best treatment for ADHD, atomoxetine (Strattera), a nonstimulant medication with antidepressant effects is another option, Dr. Park said.

He added that a limitation of his study was that very few individuals in the database received methadone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A growing number of patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) have a diagnosis of comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), raising issues about whether it’s appropriate to prescribe stimulants in this patient population.

One new study showed that from 2007-2017, there was a threefold increase in OUD and comorbid ADHD and that a significant number of these patients received prescription stimulants.

“This is the beginning stages of looking at whether or not there are risks of prescribing stimulants to patients who are on medications for opioid use disorder,” investigator Tae Woo (Ted) Park, MD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told this news organization.

“More and more people are being identified with ADHD, and we need to do more research on the best way to manage this patient group,” Dr. Park added.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

Biological connection?

Dr. Park is not convinced there is “an actual biological connection” between ADHD and OUD, noting that there are many reasons why patients with ADHD may be more prone to developing such a disorder.

Perhaps they did not get an ADHD diagnosis as a child, “which led to impairment in their ability to be successful at school and then in a job,” which in turn predisposed them to having a substance use disorder, said Dr. Park.

From previous research and his own clinical experience, ADHD can significantly affect quality of life and “cause increased impairment” in patients with a substance use disorder, he added.

Interestingly, there’s evidence suggesting patients treated for ADHD early in life are less likely to develop a substance use disorder later on, he said.

The “gold standard” treatment for ADHD is a prescription stimulant, which carries its own addiction risks. “So the issue is about whether or not to prescribe risky medications and how to weigh the risks and benefits,” said Dr. Park.

From a private health insurance database, researchers examined records for patients aged 18-64 years who were receiving medication for OUD, including buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone, from 2007-2017.

In the study sample, about 17,000 individuals were receiving stimulants, and 156,000 were not receiving these drugs. The largest percentage of participants in both groups was in the age-18-to-25 category.

About 35% of those receiving stimulants had ADHD, and about the same percentage had a mood disorder diagnosis.

Percentage of co-occurring ADHD and OUD increased from more than 4% in 2007 to more than 14% in 2017. The prevalence of stimulant use plus medication for OUD also increased during that time.

The increase in ADHD diagnoses may reflect growing identification of the condition, Dr. Park noted. As the opioid problem became more apparent and additional treatments made available, “there were more health care contacts, more assessments, and more diagnoses, including of ADHD,” he said.

Risks versus benefits

Stimulants may also be risky in patients with OUD. Results from another study presented at the AAAP meeting showed these drugs were associated with an increased chance of poisoning in patients receiving buprenorphine.

However, Dr. Park is skeptical the combination of stimulants and buprenorphine “leads to a biological risk of overdose.” He used a hypothetical scenario where other factors play into the connection: A patient gets a prescription stimulant, becomes addicted, then starts using street or illicit stimulants, which leads to a relapse on opioids, and then to an overdose.

Dr. Park noted that the same study that found an increased poisoning risk in stimulant users also found that patients tend to stay on buprenorphine treatment, providing protection against overdose.

“So there are risks and benefits of prescribing these medications, and it becomes tricky to know whether to prescribe them or not,” he said.

While stimulants are by far the best treatment for ADHD, atomoxetine (Strattera), a nonstimulant medication with antidepressant effects is another option, Dr. Park said.

He added that a limitation of his study was that very few individuals in the database received methadone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A growing number of patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) have a diagnosis of comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), raising issues about whether it’s appropriate to prescribe stimulants in this patient population.

One new study showed that from 2007-2017, there was a threefold increase in OUD and comorbid ADHD and that a significant number of these patients received prescription stimulants.

“This is the beginning stages of looking at whether or not there are risks of prescribing stimulants to patients who are on medications for opioid use disorder,” investigator Tae Woo (Ted) Park, MD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told this news organization.

“More and more people are being identified with ADHD, and we need to do more research on the best way to manage this patient group,” Dr. Park added.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

Biological connection?

Dr. Park is not convinced there is “an actual biological connection” between ADHD and OUD, noting that there are many reasons why patients with ADHD may be more prone to developing such a disorder.

Perhaps they did not get an ADHD diagnosis as a child, “which led to impairment in their ability to be successful at school and then in a job,” which in turn predisposed them to having a substance use disorder, said Dr. Park.

From previous research and his own clinical experience, ADHD can significantly affect quality of life and “cause increased impairment” in patients with a substance use disorder, he added.

Interestingly, there’s evidence suggesting patients treated for ADHD early in life are less likely to develop a substance use disorder later on, he said.

The “gold standard” treatment for ADHD is a prescription stimulant, which carries its own addiction risks. “So the issue is about whether or not to prescribe risky medications and how to weigh the risks and benefits,” said Dr. Park.

From a private health insurance database, researchers examined records for patients aged 18-64 years who were receiving medication for OUD, including buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone, from 2007-2017.

In the study sample, about 17,000 individuals were receiving stimulants, and 156,000 were not receiving these drugs. The largest percentage of participants in both groups was in the age-18-to-25 category.

About 35% of those receiving stimulants had ADHD, and about the same percentage had a mood disorder diagnosis.

Percentage of co-occurring ADHD and OUD increased from more than 4% in 2007 to more than 14% in 2017. The prevalence of stimulant use plus medication for OUD also increased during that time.

The increase in ADHD diagnoses may reflect growing identification of the condition, Dr. Park noted. As the opioid problem became more apparent and additional treatments made available, “there were more health care contacts, more assessments, and more diagnoses, including of ADHD,” he said.

Risks versus benefits

Stimulants may also be risky in patients with OUD. Results from another study presented at the AAAP meeting showed these drugs were associated with an increased chance of poisoning in patients receiving buprenorphine.

However, Dr. Park is skeptical the combination of stimulants and buprenorphine “leads to a biological risk of overdose.” He used a hypothetical scenario where other factors play into the connection: A patient gets a prescription stimulant, becomes addicted, then starts using street or illicit stimulants, which leads to a relapse on opioids, and then to an overdose.

Dr. Park noted that the same study that found an increased poisoning risk in stimulant users also found that patients tend to stay on buprenorphine treatment, providing protection against overdose.

“So there are risks and benefits of prescribing these medications, and it becomes tricky to know whether to prescribe them or not,” he said.

While stimulants are by far the best treatment for ADHD, atomoxetine (Strattera), a nonstimulant medication with antidepressant effects is another option, Dr. Park said.

He added that a limitation of his study was that very few individuals in the database received methadone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAAP 2021

Average-risk women with dense breasts—What breast screening is appropriate?

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

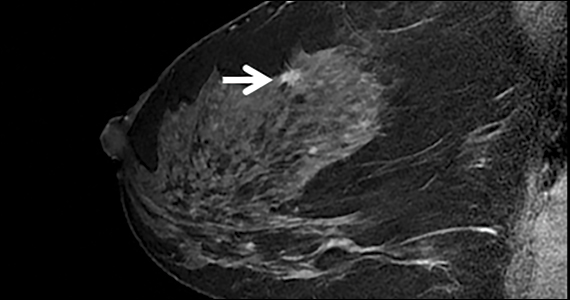

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

Quiz developed in collaboration with

Outrage over dapagliflozin withdrawal for type 1 diabetes in EU

In a shocking, yet low-key, announcement, the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Forxiga, AstraZeneca) has been withdrawn from the market in all EU countries for the indication of type 1 diabetes.

This includes withdrawal in the U.K., which was part of the EU when dapagliflozin was approved for type 1 diabetes in 2019, but following Brexit, is no longer.

AstraZeneca said the decision is not motivated by safety concerns but points nevertheless to an increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) associated with SGLT2 inhibitors in those with type 1 diabetes, which it said might cause “confusion” among physicians using the drug to treat numerous other indications for which this agent is now approved.

DKA is a potentially dangerous side effect resulting from acid build-up in the blood and is normally accompanied by very high glucose levels. DKA is flagged as a potential side effect in type 2 diabetes but is more common in those with type 1 diabetes. It can also occur as “euglycemic” DKA, which is ketosis but with relatively normal glucose levels (and therefore harder for patients to detect). Euglycemic DKA is thought to be more of a risk in those with type 1 diabetes than in those with type 2 diabetes.

One charity believes concerns around safety are the underlying factor for the withdrawal of dapagliflozin for type 1 diabetes in Europe, suggesting that AstraZeneca might not want to risk income from more lucrative indications – such as type 2 diabetes with much larger patient populations – because of potential concerns from doctors, who may be deterred from prescribing the drug due to concerns about DKA.

JDRF International, a leading global type 1 diabetes charity, called on AstraZeneca in a statement “to explain to people affected by type 1 diabetes why the drug has been withdrawn.”

It added that dapagliflozin is the “only other drug besides insulin” to be licensed in Europe for the treatment of type 1 diabetes and represents a “major advancement since the discovery of insulin 100 years ago.”

Karen Addington, U.K. Chief Executive of JDRF, said it is “appalling” that the drug has been withdrawn, as “many people with type 1 are finding it an effective and useful tool to help manage their glucose levels.”

SGLT2 inhibitors never approved for type 1 diabetes in U.S.

Dapagliflozin and other drugs from the SGLT2 inhibitor class had already been approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes for a number of years when dapagliflozin was approved in early 2019 for the treatment of adults with type 1 diabetes meeting certain criteria by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which at that time included the U.K. in its remit, based on data from the DEPICT series of phase 3 trials.

SGLT2 inhibitors have also recently shown benefit in other indications, such as heart failure and chronic kidney disease – even in the absence of diabetes – leaving some to label them a new class of wonder drugs.

Following the 2019 EU approval for type 1 diabetes, dapagliflozin was subsequently recommended for this use on the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Wales and was accompanied by guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which has now had to be withdrawn.

Of note, dapagliflozin was never approved for use in type 1 diabetes in the United States (where it is known as Farxiga), with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration turning it down in July 2019.

An advisory panel for the FDA also later turned down another SGLT2 inhibitor for type 1 diabetes, empagliflozin (Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim) in Nov. 2019, as reported by this news organization.

Discontinuation ‘not due to safety concerns,’ says AZ

The announcement to discontinue dapagliflozin for the indication of type 1 diabetes in certain adults just two and a half years after its approval in the EU comes as a big surprise, especially as it was made with little fanfare just last month.

In the U.K., AstraZeneca sent a letter to health care professionals on Nov. 2 stating that, from Oct. 25, dapagliflozin 5 mg was “no longer authorized” for the treatment of type 1 diabetes and “should no longer be used” in this patient population.

However, it underlined that other indications for dapagliflozin 5 mg and 10 mg were “not affected by this licensing change,” and it remains available for adults with type 2 diabetes, as well as for the management of symptomatic chronic heart feature with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

In the letter, sent by Tom Keith-Roach, country president of AstraZeneca UK, the company asserts that the removal of the type 1 diabetes indication from dapagliflozin is “not due to any safety concern” with the drug “in any indication, including type 1 diabetes.”

It nevertheless goes on to highlight that DKA is a known common side effect of dapagliflozin in type 1 diabetes and, following the announcement, “additional risk minimization measures ... will no longer be available.”

In a separate statement, AstraZeneca said that the decision to remove the indication was made “voluntarily” and had been “agreed” with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in Great Britain and the equivalent body in Northern Ireland.

“It follows discussions regarding product information changes needed post-approval for dapagliflozin 5 mg specific to type 1 diabetes,” the company said, “which might cause confusion” among physicians treating patients with type 2 diabetes, chronic heart feature with reduced ejection fraction, or CKD.

AstraZeneca told this news organization that similar communications about the withdrawal were issued to health care agencies and health care professionals in all countries of the EU.

‘Appalling, devastating, disappointing’ for patients

The announcement has been met with disappointment in some quarters and outrage in others, and questions have been raised as to the explanation given by AstraZeneca for the drug’s withdrawal.

“Although only a small number of people with type 1 diabetes have been using dapagliflozin, we know that those who have been using it will have been benefitting from tighter control of their condition,” Simon O’Neill, director of health intelligence and professional liaison at Diabetes UK, told this news organization.

“It’s disappointing that these people will now need to go back to the drawing board and will have to work with their clinical team to find other ways of better managing their condition.”

Mr. O’Neill said it was “disappointing that AstraZeneca and the MHRA were unable to find a workable solution to allow people living with type 1 diabetes to continue using the drug safely without leading to confusion for clinicians or people living with type 2 diabetes, who also use it.”

Sanjoy Dutta, JDRF International vice president of research, added that the news is “devastating.”

“The impending negative impact of removing a drug like dapagliflozin from any market can be detrimental in the potential for other national medical ruling boards to have confidence in approving it for their citizens,” he added.

“We stand with our type 1 diabetes communities across the globe in demanding an explanation to clarify this removal.”

Why not an educational campaign about DKA risk?

In an interview, Hilary Nathan, policy & communications director at JDRF International, explained that the charity has its theories as to why dapagliflozin has been withdrawn for type 1 diabetes.

What AstraZeneca is saying, “and what we don’t agree with them on,” is that the “black triangle” warning that has to be put onto the drug due to the increased risk of DKA in type 1 diabetes is “misunderstood by health care practitioners” outside of that specialty and that “by having that black triangle, it will inhibit take-up in those other markets.”

In other words, “there will be less desire to prescribe it,” ventured Ms. Nathan.

She continued: “For us, we feel that if a medicine is deemed safe and efficacious, it should not be withdrawn because of other patient constituencies.”

“We asked: ‘Why can’t you do an educational awareness campaign about the black triangle?’ And the might of AstraZeneca said it would be too big a task.”

Ms. Nathan was also surprised at how the drug could be withdrawn without any warning or real explanation.

“How is it possible that, when a drug is approved there are multiple stakeholders that are involved in putting forward views and experiences – both from the clinical and patient advocacy communities, as well as obviously the pharmaceutical community – yet [a drug] can be withdrawn by a ... company that may well have conflicts of interest around commercial take-up.”

She added: “I feel that there are potentially motives around the withdrawal that AstraZeneca are still not being clear about.”

Perhaps a further clue as to the real motives behind the withdrawal can be found in an announcement, just last week, by the British MHRA.

“The decision by the marketing authorization holder to voluntarily withdraw the indication in type 1 diabetes followed commercial considerations due to a specific European-wide regulatory requirement for this authorization,” it said.

“The decision was not driven by any new safety concerns, such as the already known increased risk of DKA in type 1 diabetes compared with type 2 diabetes.”

Separately, a new in-depth investigation into when Johnson & Johnson, which markets another SGLT2 inhibitor, canagliflozin (Invokana), first knew that its agent was associated with DKA has revealed multiple discrepancies in staff accounts. Some claim the company knew as early as 2010 that canagliflozin – first approved for type 2 diabetes in the United States in 2013 – could increase the risk of DKA. It was not until May 2015 that the FDA first issued a warning about the potential risk of DKA associated with use of SGLT2 inhibitors, with the EMA following suit a month later. In Dec. 2015, the FDA updated the labels for all SGLT2 inhibitors approved in the United States at that time – canagliflozin, empagliflozin, and dapagliflozin – to include the risks for ketoacidosis (and urinary tract infections).

Forxiga (dapagliflozin) is manufactured by AstraZeneca. No relevant financial relationships declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a shocking, yet low-key, announcement, the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Forxiga, AstraZeneca) has been withdrawn from the market in all EU countries for the indication of type 1 diabetes.

This includes withdrawal in the U.K., which was part of the EU when dapagliflozin was approved for type 1 diabetes in 2019, but following Brexit, is no longer.

AstraZeneca said the decision is not motivated by safety concerns but points nevertheless to an increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) associated with SGLT2 inhibitors in those with type 1 diabetes, which it said might cause “confusion” among physicians using the drug to treat numerous other indications for which this agent is now approved.

DKA is a potentially dangerous side effect resulting from acid build-up in the blood and is normally accompanied by very high glucose levels. DKA is flagged as a potential side effect in type 2 diabetes but is more common in those with type 1 diabetes. It can also occur as “euglycemic” DKA, which is ketosis but with relatively normal glucose levels (and therefore harder for patients to detect). Euglycemic DKA is thought to be more of a risk in those with type 1 diabetes than in those with type 2 diabetes.

One charity believes concerns around safety are the underlying factor for the withdrawal of dapagliflozin for type 1 diabetes in Europe, suggesting that AstraZeneca might not want to risk income from more lucrative indications – such as type 2 diabetes with much larger patient populations – because of potential concerns from doctors, who may be deterred from prescribing the drug due to concerns about DKA.

JDRF International, a leading global type 1 diabetes charity, called on AstraZeneca in a statement “to explain to people affected by type 1 diabetes why the drug has been withdrawn.”

It added that dapagliflozin is the “only other drug besides insulin” to be licensed in Europe for the treatment of type 1 diabetes and represents a “major advancement since the discovery of insulin 100 years ago.”

Karen Addington, U.K. Chief Executive of JDRF, said it is “appalling” that the drug has been withdrawn, as “many people with type 1 are finding it an effective and useful tool to help manage their glucose levels.”

SGLT2 inhibitors never approved for type 1 diabetes in U.S.

Dapagliflozin and other drugs from the SGLT2 inhibitor class had already been approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes for a number of years when dapagliflozin was approved in early 2019 for the treatment of adults with type 1 diabetes meeting certain criteria by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which at that time included the U.K. in its remit, based on data from the DEPICT series of phase 3 trials.

SGLT2 inhibitors have also recently shown benefit in other indications, such as heart failure and chronic kidney disease – even in the absence of diabetes – leaving some to label them a new class of wonder drugs.

Following the 2019 EU approval for type 1 diabetes, dapagliflozin was subsequently recommended for this use on the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Wales and was accompanied by guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which has now had to be withdrawn.

Of note, dapagliflozin was never approved for use in type 1 diabetes in the United States (where it is known as Farxiga), with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration turning it down in July 2019.

An advisory panel for the FDA also later turned down another SGLT2 inhibitor for type 1 diabetes, empagliflozin (Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim) in Nov. 2019, as reported by this news organization.

Discontinuation ‘not due to safety concerns,’ says AZ

The announcement to discontinue dapagliflozin for the indication of type 1 diabetes in certain adults just two and a half years after its approval in the EU comes as a big surprise, especially as it was made with little fanfare just last month.

In the U.K., AstraZeneca sent a letter to health care professionals on Nov. 2 stating that, from Oct. 25, dapagliflozin 5 mg was “no longer authorized” for the treatment of type 1 diabetes and “should no longer be used” in this patient population.

However, it underlined that other indications for dapagliflozin 5 mg and 10 mg were “not affected by this licensing change,” and it remains available for adults with type 2 diabetes, as well as for the management of symptomatic chronic heart feature with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

In the letter, sent by Tom Keith-Roach, country president of AstraZeneca UK, the company asserts that the removal of the type 1 diabetes indication from dapagliflozin is “not due to any safety concern” with the drug “in any indication, including type 1 diabetes.”

It nevertheless goes on to highlight that DKA is a known common side effect of dapagliflozin in type 1 diabetes and, following the announcement, “additional risk minimization measures ... will no longer be available.”

In a separate statement, AstraZeneca said that the decision to remove the indication was made “voluntarily” and had been “agreed” with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in Great Britain and the equivalent body in Northern Ireland.

“It follows discussions regarding product information changes needed post-approval for dapagliflozin 5 mg specific to type 1 diabetes,” the company said, “which might cause confusion” among physicians treating patients with type 2 diabetes, chronic heart feature with reduced ejection fraction, or CKD.

AstraZeneca told this news organization that similar communications about the withdrawal were issued to health care agencies and health care professionals in all countries of the EU.

‘Appalling, devastating, disappointing’ for patients

The announcement has been met with disappointment in some quarters and outrage in others, and questions have been raised as to the explanation given by AstraZeneca for the drug’s withdrawal.

“Although only a small number of people with type 1 diabetes have been using dapagliflozin, we know that those who have been using it will have been benefitting from tighter control of their condition,” Simon O’Neill, director of health intelligence and professional liaison at Diabetes UK, told this news organization.

“It’s disappointing that these people will now need to go back to the drawing board and will have to work with their clinical team to find other ways of better managing their condition.”

Mr. O’Neill said it was “disappointing that AstraZeneca and the MHRA were unable to find a workable solution to allow people living with type 1 diabetes to continue using the drug safely without leading to confusion for clinicians or people living with type 2 diabetes, who also use it.”

Sanjoy Dutta, JDRF International vice president of research, added that the news is “devastating.”

“The impending negative impact of removing a drug like dapagliflozin from any market can be detrimental in the potential for other national medical ruling boards to have confidence in approving it for their citizens,” he added.

“We stand with our type 1 diabetes communities across the globe in demanding an explanation to clarify this removal.”

Why not an educational campaign about DKA risk?

In an interview, Hilary Nathan, policy & communications director at JDRF International, explained that the charity has its theories as to why dapagliflozin has been withdrawn for type 1 diabetes.

What AstraZeneca is saying, “and what we don’t agree with them on,” is that the “black triangle” warning that has to be put onto the drug due to the increased risk of DKA in type 1 diabetes is “misunderstood by health care practitioners” outside of that specialty and that “by having that black triangle, it will inhibit take-up in those other markets.”

In other words, “there will be less desire to prescribe it,” ventured Ms. Nathan.

She continued: “For us, we feel that if a medicine is deemed safe and efficacious, it should not be withdrawn because of other patient constituencies.”

“We asked: ‘Why can’t you do an educational awareness campaign about the black triangle?’ And the might of AstraZeneca said it would be too big a task.”

Ms. Nathan was also surprised at how the drug could be withdrawn without any warning or real explanation.

“How is it possible that, when a drug is approved there are multiple stakeholders that are involved in putting forward views and experiences – both from the clinical and patient advocacy communities, as well as obviously the pharmaceutical community – yet [a drug] can be withdrawn by a ... company that may well have conflicts of interest around commercial take-up.”

She added: “I feel that there are potentially motives around the withdrawal that AstraZeneca are still not being clear about.”

Perhaps a further clue as to the real motives behind the withdrawal can be found in an announcement, just last week, by the British MHRA.

“The decision by the marketing authorization holder to voluntarily withdraw the indication in type 1 diabetes followed commercial considerations due to a specific European-wide regulatory requirement for this authorization,” it said.

“The decision was not driven by any new safety concerns, such as the already known increased risk of DKA in type 1 diabetes compared with type 2 diabetes.”

Separately, a new in-depth investigation into when Johnson & Johnson, which markets another SGLT2 inhibitor, canagliflozin (Invokana), first knew that its agent was associated with DKA has revealed multiple discrepancies in staff accounts. Some claim the company knew as early as 2010 that canagliflozin – first approved for type 2 diabetes in the United States in 2013 – could increase the risk of DKA. It was not until May 2015 that the FDA first issued a warning about the potential risk of DKA associated with use of SGLT2 inhibitors, with the EMA following suit a month later. In Dec. 2015, the FDA updated the labels for all SGLT2 inhibitors approved in the United States at that time – canagliflozin, empagliflozin, and dapagliflozin – to include the risks for ketoacidosis (and urinary tract infections).

Forxiga (dapagliflozin) is manufactured by AstraZeneca. No relevant financial relationships declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a shocking, yet low-key, announcement, the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Forxiga, AstraZeneca) has been withdrawn from the market in all EU countries for the indication of type 1 diabetes.

This includes withdrawal in the U.K., which was part of the EU when dapagliflozin was approved for type 1 diabetes in 2019, but following Brexit, is no longer.

AstraZeneca said the decision is not motivated by safety concerns but points nevertheless to an increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) associated with SGLT2 inhibitors in those with type 1 diabetes, which it said might cause “confusion” among physicians using the drug to treat numerous other indications for which this agent is now approved.

DKA is a potentially dangerous side effect resulting from acid build-up in the blood and is normally accompanied by very high glucose levels. DKA is flagged as a potential side effect in type 2 diabetes but is more common in those with type 1 diabetes. It can also occur as “euglycemic” DKA, which is ketosis but with relatively normal glucose levels (and therefore harder for patients to detect). Euglycemic DKA is thought to be more of a risk in those with type 1 diabetes than in those with type 2 diabetes.

One charity believes concerns around safety are the underlying factor for the withdrawal of dapagliflozin for type 1 diabetes in Europe, suggesting that AstraZeneca might not want to risk income from more lucrative indications – such as type 2 diabetes with much larger patient populations – because of potential concerns from doctors, who may be deterred from prescribing the drug due to concerns about DKA.

JDRF International, a leading global type 1 diabetes charity, called on AstraZeneca in a statement “to explain to people affected by type 1 diabetes why the drug has been withdrawn.”

It added that dapagliflozin is the “only other drug besides insulin” to be licensed in Europe for the treatment of type 1 diabetes and represents a “major advancement since the discovery of insulin 100 years ago.”

Karen Addington, U.K. Chief Executive of JDRF, said it is “appalling” that the drug has been withdrawn, as “many people with type 1 are finding it an effective and useful tool to help manage their glucose levels.”

SGLT2 inhibitors never approved for type 1 diabetes in U.S.

Dapagliflozin and other drugs from the SGLT2 inhibitor class had already been approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes for a number of years when dapagliflozin was approved in early 2019 for the treatment of adults with type 1 diabetes meeting certain criteria by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which at that time included the U.K. in its remit, based on data from the DEPICT series of phase 3 trials.

SGLT2 inhibitors have also recently shown benefit in other indications, such as heart failure and chronic kidney disease – even in the absence of diabetes – leaving some to label them a new class of wonder drugs.

Following the 2019 EU approval for type 1 diabetes, dapagliflozin was subsequently recommended for this use on the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Wales and was accompanied by guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which has now had to be withdrawn.

Of note, dapagliflozin was never approved for use in type 1 diabetes in the United States (where it is known as Farxiga), with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration turning it down in July 2019.

An advisory panel for the FDA also later turned down another SGLT2 inhibitor for type 1 diabetes, empagliflozin (Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim) in Nov. 2019, as reported by this news organization.

Discontinuation ‘not due to safety concerns,’ says AZ

The announcement to discontinue dapagliflozin for the indication of type 1 diabetes in certain adults just two and a half years after its approval in the EU comes as a big surprise, especially as it was made with little fanfare just last month.

In the U.K., AstraZeneca sent a letter to health care professionals on Nov. 2 stating that, from Oct. 25, dapagliflozin 5 mg was “no longer authorized” for the treatment of type 1 diabetes and “should no longer be used” in this patient population.

However, it underlined that other indications for dapagliflozin 5 mg and 10 mg were “not affected by this licensing change,” and it remains available for adults with type 2 diabetes, as well as for the management of symptomatic chronic heart feature with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

In the letter, sent by Tom Keith-Roach, country president of AstraZeneca UK, the company asserts that the removal of the type 1 diabetes indication from dapagliflozin is “not due to any safety concern” with the drug “in any indication, including type 1 diabetes.”

It nevertheless goes on to highlight that DKA is a known common side effect of dapagliflozin in type 1 diabetes and, following the announcement, “additional risk minimization measures ... will no longer be available.”

In a separate statement, AstraZeneca said that the decision to remove the indication was made “voluntarily” and had been “agreed” with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in Great Britain and the equivalent body in Northern Ireland.

“It follows discussions regarding product information changes needed post-approval for dapagliflozin 5 mg specific to type 1 diabetes,” the company said, “which might cause confusion” among physicians treating patients with type 2 diabetes, chronic heart feature with reduced ejection fraction, or CKD.

AstraZeneca told this news organization that similar communications about the withdrawal were issued to health care agencies and health care professionals in all countries of the EU.

‘Appalling, devastating, disappointing’ for patients

The announcement has been met with disappointment in some quarters and outrage in others, and questions have been raised as to the explanation given by AstraZeneca for the drug’s withdrawal.

“Although only a small number of people with type 1 diabetes have been using dapagliflozin, we know that those who have been using it will have been benefitting from tighter control of their condition,” Simon O’Neill, director of health intelligence and professional liaison at Diabetes UK, told this news organization.

“It’s disappointing that these people will now need to go back to the drawing board and will have to work with their clinical team to find other ways of better managing their condition.”

Mr. O’Neill said it was “disappointing that AstraZeneca and the MHRA were unable to find a workable solution to allow people living with type 1 diabetes to continue using the drug safely without leading to confusion for clinicians or people living with type 2 diabetes, who also use it.”

Sanjoy Dutta, JDRF International vice president of research, added that the news is “devastating.”

“The impending negative impact of removing a drug like dapagliflozin from any market can be detrimental in the potential for other national medical ruling boards to have confidence in approving it for their citizens,” he added.

“We stand with our type 1 diabetes communities across the globe in demanding an explanation to clarify this removal.”

Why not an educational campaign about DKA risk?

In an interview, Hilary Nathan, policy & communications director at JDRF International, explained that the charity has its theories as to why dapagliflozin has been withdrawn for type 1 diabetes.

What AstraZeneca is saying, “and what we don’t agree with them on,” is that the “black triangle” warning that has to be put onto the drug due to the increased risk of DKA in type 1 diabetes is “misunderstood by health care practitioners” outside of that specialty and that “by having that black triangle, it will inhibit take-up in those other markets.”

In other words, “there will be less desire to prescribe it,” ventured Ms. Nathan.

She continued: “For us, we feel that if a medicine is deemed safe and efficacious, it should not be withdrawn because of other patient constituencies.”

“We asked: ‘Why can’t you do an educational awareness campaign about the black triangle?’ And the might of AstraZeneca said it would be too big a task.”

Ms. Nathan was also surprised at how the drug could be withdrawn without any warning or real explanation.

“How is it possible that, when a drug is approved there are multiple stakeholders that are involved in putting forward views and experiences – both from the clinical and patient advocacy communities, as well as obviously the pharmaceutical community – yet [a drug] can be withdrawn by a ... company that may well have conflicts of interest around commercial take-up.”

She added: “I feel that there are potentially motives around the withdrawal that AstraZeneca are still not being clear about.”

Perhaps a further clue as to the real motives behind the withdrawal can be found in an announcement, just last week, by the British MHRA.

“The decision by the marketing authorization holder to voluntarily withdraw the indication in type 1 diabetes followed commercial considerations due to a specific European-wide regulatory requirement for this authorization,” it said.

“The decision was not driven by any new safety concerns, such as the already known increased risk of DKA in type 1 diabetes compared with type 2 diabetes.”

Separately, a new in-depth investigation into when Johnson & Johnson, which markets another SGLT2 inhibitor, canagliflozin (Invokana), first knew that its agent was associated with DKA has revealed multiple discrepancies in staff accounts. Some claim the company knew as early as 2010 that canagliflozin – first approved for type 2 diabetes in the United States in 2013 – could increase the risk of DKA. It was not until May 2015 that the FDA first issued a warning about the potential risk of DKA associated with use of SGLT2 inhibitors, with the EMA following suit a month later. In Dec. 2015, the FDA updated the labels for all SGLT2 inhibitors approved in the United States at that time – canagliflozin, empagliflozin, and dapagliflozin – to include the risks for ketoacidosis (and urinary tract infections).

Forxiga (dapagliflozin) is manufactured by AstraZeneca. No relevant financial relationships declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenges for the ObGyn

In this question-and-answer article (the second in a series), our objective is to reinforce for the clinician several practical points of management for common infectious diseases. The principal references for the answers to the questions are 2 textbook chapters written by Dr. Duff.1,2 Other pertinent references are included in the text.

9. For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin

500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

10. What are the characteristic mucocutaneous lesions of primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis?

The characteristic mucosal lesion of primary syphilis is the painless chancre. The usual mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis are maculopapular lesions (red or violet in color) on the palms and soles, mucous patches on the oral membranes, and condyloma lata on the genitalia. The classic mucocutaneous lesion of tertiary syphilis is the gumma.

Other serious manifestations of advanced syphilis include central nervous system abnormalities, such as tabes dorsalis, the Argyll Robertson pupil, and dementia, and cardiac abnormalities, such as aortitis, which can lead to a dissecting aneurysm of the aortic root. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

11. In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This

regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

Continue to: 12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?...

12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?

In patients with bacterial vaginosis, the vaginal pH typically is elevated in the range of 4.5. When a drop of potassium hydroxide solution is added to the vaginal secretions, a characteristic fishlike (amine) odor is liberated (positive “whiff test”). With saline microscopy, the key findings are a relative absence of lactobacilli in the background, an abundance of small cocci and bacilli, and the presence of clue cells, which are epithelial cells studded with bacteria along their

outer margin.

13. For a moderately ill pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate antibiotic combination for inpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia?

This patient should be treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours) plus oral or intravenous azithromycin. The appropriate oral dose of azithromycin is 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily for 4 doses. The appropriate intravenous dose of azithromycin is 500 mg every 24 hours. The goal is to provide appropriate coverage for the most likely pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and mycoplasmas. (Antibacterial drugs for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021:63:10-14. Postma DF, van Werkoven CH, van Eldin LJ, et al; CAP-START Study Group. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372: 1312-1323.)

14. What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying groundglass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

15. What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

16. What is the best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection?

The single best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)–specific antibody to the virus.

17. What are the best tests for identification of a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection?

Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection typically test positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and for IgG antibody to the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). In addition, they also may test positive for the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and their viral load can be quantified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when significant antigenemia is present. The presence of the e antigen indicates a high rate of viral replication and a corresponding high rate of infectivity.

18. What antenatal treatment is indicated in a pregnant woman at 28 weeks’ gestation who has a hepatitis B viral load of 2 million copies/mL?

This patient has a markedly elevated viral load and is at significantly increased risk of transmitting hepatitis B infection to her neonate even if the infant receives hepatitis B immune globulin immediately after birth and quickly begins the hepatitis B vaccine series. Daily antenatal treatment with tenofovir (300 mg daily) from 28 weeks until delivery will significantly reduce the risk of perinatal transmission.

19. Should a postpartum patient with chronic hepatitis C infection be discouraged from breastfeeding her infant?

Hepatitis C is not a contraindication to breastfeeding. Although the virus has been identified in breast milk, the risk of transmission to the infant is exceedingly low.

20. What are the principal microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis?

Staphylococci and Streptococcus viridans are the 2 dominant microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis. For the initial treatment of mastitis, the drug of choice is dicloxacillin sodium (500 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours for 7 to 10 days). If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, cephalexin (500 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours for 7 to 10 days) is an appropriate alternative. If the allergy to penicillin is severe or if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection is suspected, either clindamycin (300 mg orally twice daily for 7 to 10 days) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength orally twice daily for 7 to 10 days should be used. ●

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

In this question-and-answer article (the second in a series), our objective is to reinforce for the clinician several practical points of management for common infectious diseases. The principal references for the answers to the questions are 2 textbook chapters written by Dr. Duff.1,2 Other pertinent references are included in the text.

9. For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin

500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

10. What are the characteristic mucocutaneous lesions of primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis?

The characteristic mucosal lesion of primary syphilis is the painless chancre. The usual mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis are maculopapular lesions (red or violet in color) on the palms and soles, mucous patches on the oral membranes, and condyloma lata on the genitalia. The classic mucocutaneous lesion of tertiary syphilis is the gumma.

Other serious manifestations of advanced syphilis include central nervous system abnormalities, such as tabes dorsalis, the Argyll Robertson pupil, and dementia, and cardiac abnormalities, such as aortitis, which can lead to a dissecting aneurysm of the aortic root. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

11. In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This

regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

Continue to: 12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?...

12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?

In patients with bacterial vaginosis, the vaginal pH typically is elevated in the range of 4.5. When a drop of potassium hydroxide solution is added to the vaginal secretions, a characteristic fishlike (amine) odor is liberated (positive “whiff test”). With saline microscopy, the key findings are a relative absence of lactobacilli in the background, an abundance of small cocci and bacilli, and the presence of clue cells, which are epithelial cells studded with bacteria along their

outer margin.

13. For a moderately ill pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate antibiotic combination for inpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia?

This patient should be treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours) plus oral or intravenous azithromycin. The appropriate oral dose of azithromycin is 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily for 4 doses. The appropriate intravenous dose of azithromycin is 500 mg every 24 hours. The goal is to provide appropriate coverage for the most likely pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and mycoplasmas. (Antibacterial drugs for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021:63:10-14. Postma DF, van Werkoven CH, van Eldin LJ, et al; CAP-START Study Group. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372: 1312-1323.)

14. What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?