User login

Most addiction specialists support legalized therapeutic psychedelics

The majority of addiction specialists, including psychiatrists, believe psychedelics are promising for the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs) and psychiatric illnesses and, with some caveats, support legalization of the substances for these indications, results of a new survey show.

This strong positive attitude is “a surprise” given previous wariness of addiction specialists regarding legalization of marijuana, noted study investigator Amanda Kim, MD, JD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We had hypothesized that addiction specialists would express more skepticism about psychedelics compared to nonaddiction specialists,” Dr. Kim said.

Instead, addiction experts who participated in the survey were very much in favor of psychedelics being legalized for therapeutic use, but only in a controlled setting.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

Growing interest

In recent years, there has been increased interest in the scientific community and among the general public in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, said Dr. Kim. Previous research has shown growing positivity about psychedelics and support for their legalization among psychiatrists, she added.

Psychedelics have been decriminalized and/or legalized in several jurisdictions. The Food and Drug Administration has granted breakthrough therapy designation for 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and has granted the same designation to psilocybin in the treatment of major depressive disorder.

“Despite psychedelics increasingly entering the mainstream, we are unaware of any studies specifically assessing the current attitudes of physicians specializing in addictions regarding psychedelics,” Dr. Kim said.

For the study, investigators identified prospective survey participants from the AAAP directory. They also reached out to program directors of addiction medicine and addiction psychiatry fellowships.

In the anonymous online survey, respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with 30 statements.

The analysis included 145 respondents (59% men; mean age, 46.2 years). Psychiatrists made up about two-thirds of the sample. The remainder specialized in internal and family medicine.

Most respondents had some clinical exposure to psychedelics.

Positive attitudes, concerns

Overall, participants expressed very positive attitudes regarding the therapeutic use of psychedelics. About 64% strongly agreed or agreed psychedelics show promise in treating SUDs, and 82% agreed they show promise in treating psychiatric disorders.

However, more than one-third of respondents (37.9%) expressed concern about the addictive potential of psychedelics. This is more than in previous research polling psychiatrists, possibly because the study’s “broad” definition of psychedelics included “nonclassic, nonserotonergic hallucinogens,” such as ketamine and MDMA, Dr. Kim noted.

Because ketamine and MDMA are both lumped into the hallucinogen category in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), “and both are known to have addictive potential, this may have obscured participant responses,” she added.

Some 28% of participants expressed concern about psychedelic use increasing the risk for subsequent psychiatric disorders and long-term cognitive impairment.

Almost three-quarters (74.5%) believe the therapeutic use of psychedelics should be legalized. However, most wanted legal therapeutic psychedelics to be highly regulated and administered only in controlled settings with specially trained providers.

Almost half of the sample believed therapeutic psychedelics should be legal in a variety of different contexts and by non-Western providers, in accordance with indigenous and/or spiritual traditions.

One surprising finding was that most respondents believed patients would be keen on using psychedelics to treat SUDs, said Dr. Kim.

“This may reflect evolving attitudes of both providers and patients about psychedelics, and it will be interesting to further study attitudes of patients toward the use of psychedelics to treat SUD in the future,” she added.

Attitudes toward psychedelics were generally similar for psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists; but psychiatrists expressed greater comfort in discussing them with patients and were more likely to have observed complications of psychedelics use in their practice.

Dr. Kim said the study’s limitations included the small sample size and possible selection bias, as those with more favorable views of psychedelics may have been more likely to respond.

The study was supported by the Source Research Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The majority of addiction specialists, including psychiatrists, believe psychedelics are promising for the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs) and psychiatric illnesses and, with some caveats, support legalization of the substances for these indications, results of a new survey show.

This strong positive attitude is “a surprise” given previous wariness of addiction specialists regarding legalization of marijuana, noted study investigator Amanda Kim, MD, JD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We had hypothesized that addiction specialists would express more skepticism about psychedelics compared to nonaddiction specialists,” Dr. Kim said.

Instead, addiction experts who participated in the survey were very much in favor of psychedelics being legalized for therapeutic use, but only in a controlled setting.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

Growing interest

In recent years, there has been increased interest in the scientific community and among the general public in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, said Dr. Kim. Previous research has shown growing positivity about psychedelics and support for their legalization among psychiatrists, she added.

Psychedelics have been decriminalized and/or legalized in several jurisdictions. The Food and Drug Administration has granted breakthrough therapy designation for 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and has granted the same designation to psilocybin in the treatment of major depressive disorder.

“Despite psychedelics increasingly entering the mainstream, we are unaware of any studies specifically assessing the current attitudes of physicians specializing in addictions regarding psychedelics,” Dr. Kim said.

For the study, investigators identified prospective survey participants from the AAAP directory. They also reached out to program directors of addiction medicine and addiction psychiatry fellowships.

In the anonymous online survey, respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with 30 statements.

The analysis included 145 respondents (59% men; mean age, 46.2 years). Psychiatrists made up about two-thirds of the sample. The remainder specialized in internal and family medicine.

Most respondents had some clinical exposure to psychedelics.

Positive attitudes, concerns

Overall, participants expressed very positive attitudes regarding the therapeutic use of psychedelics. About 64% strongly agreed or agreed psychedelics show promise in treating SUDs, and 82% agreed they show promise in treating psychiatric disorders.

However, more than one-third of respondents (37.9%) expressed concern about the addictive potential of psychedelics. This is more than in previous research polling psychiatrists, possibly because the study’s “broad” definition of psychedelics included “nonclassic, nonserotonergic hallucinogens,” such as ketamine and MDMA, Dr. Kim noted.

Because ketamine and MDMA are both lumped into the hallucinogen category in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), “and both are known to have addictive potential, this may have obscured participant responses,” she added.

Some 28% of participants expressed concern about psychedelic use increasing the risk for subsequent psychiatric disorders and long-term cognitive impairment.

Almost three-quarters (74.5%) believe the therapeutic use of psychedelics should be legalized. However, most wanted legal therapeutic psychedelics to be highly regulated and administered only in controlled settings with specially trained providers.

Almost half of the sample believed therapeutic psychedelics should be legal in a variety of different contexts and by non-Western providers, in accordance with indigenous and/or spiritual traditions.

One surprising finding was that most respondents believed patients would be keen on using psychedelics to treat SUDs, said Dr. Kim.

“This may reflect evolving attitudes of both providers and patients about psychedelics, and it will be interesting to further study attitudes of patients toward the use of psychedelics to treat SUD in the future,” she added.

Attitudes toward psychedelics were generally similar for psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists; but psychiatrists expressed greater comfort in discussing them with patients and were more likely to have observed complications of psychedelics use in their practice.

Dr. Kim said the study’s limitations included the small sample size and possible selection bias, as those with more favorable views of psychedelics may have been more likely to respond.

The study was supported by the Source Research Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The majority of addiction specialists, including psychiatrists, believe psychedelics are promising for the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs) and psychiatric illnesses and, with some caveats, support legalization of the substances for these indications, results of a new survey show.

This strong positive attitude is “a surprise” given previous wariness of addiction specialists regarding legalization of marijuana, noted study investigator Amanda Kim, MD, JD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“We had hypothesized that addiction specialists would express more skepticism about psychedelics compared to nonaddiction specialists,” Dr. Kim said.

Instead, addiction experts who participated in the survey were very much in favor of psychedelics being legalized for therapeutic use, but only in a controlled setting.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

Growing interest

In recent years, there has been increased interest in the scientific community and among the general public in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, said Dr. Kim. Previous research has shown growing positivity about psychedelics and support for their legalization among psychiatrists, she added.

Psychedelics have been decriminalized and/or legalized in several jurisdictions. The Food and Drug Administration has granted breakthrough therapy designation for 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and has granted the same designation to psilocybin in the treatment of major depressive disorder.

“Despite psychedelics increasingly entering the mainstream, we are unaware of any studies specifically assessing the current attitudes of physicians specializing in addictions regarding psychedelics,” Dr. Kim said.

For the study, investigators identified prospective survey participants from the AAAP directory. They also reached out to program directors of addiction medicine and addiction psychiatry fellowships.

In the anonymous online survey, respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with 30 statements.

The analysis included 145 respondents (59% men; mean age, 46.2 years). Psychiatrists made up about two-thirds of the sample. The remainder specialized in internal and family medicine.

Most respondents had some clinical exposure to psychedelics.

Positive attitudes, concerns

Overall, participants expressed very positive attitudes regarding the therapeutic use of psychedelics. About 64% strongly agreed or agreed psychedelics show promise in treating SUDs, and 82% agreed they show promise in treating psychiatric disorders.

However, more than one-third of respondents (37.9%) expressed concern about the addictive potential of psychedelics. This is more than in previous research polling psychiatrists, possibly because the study’s “broad” definition of psychedelics included “nonclassic, nonserotonergic hallucinogens,” such as ketamine and MDMA, Dr. Kim noted.

Because ketamine and MDMA are both lumped into the hallucinogen category in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), “and both are known to have addictive potential, this may have obscured participant responses,” she added.

Some 28% of participants expressed concern about psychedelic use increasing the risk for subsequent psychiatric disorders and long-term cognitive impairment.

Almost three-quarters (74.5%) believe the therapeutic use of psychedelics should be legalized. However, most wanted legal therapeutic psychedelics to be highly regulated and administered only in controlled settings with specially trained providers.

Almost half of the sample believed therapeutic psychedelics should be legal in a variety of different contexts and by non-Western providers, in accordance with indigenous and/or spiritual traditions.

One surprising finding was that most respondents believed patients would be keen on using psychedelics to treat SUDs, said Dr. Kim.

“This may reflect evolving attitudes of both providers and patients about psychedelics, and it will be interesting to further study attitudes of patients toward the use of psychedelics to treat SUD in the future,” she added.

Attitudes toward psychedelics were generally similar for psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists; but psychiatrists expressed greater comfort in discussing them with patients and were more likely to have observed complications of psychedelics use in their practice.

Dr. Kim said the study’s limitations included the small sample size and possible selection bias, as those with more favorable views of psychedelics may have been more likely to respond.

The study was supported by the Source Research Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAAP 2021

COVID-19 interrupted global poliovirus surveillance and immunization

Most (86%) of these outbreaks were caused by cVDPV2 (circulating VDPV type 2 poliovirus, which originated with the vaccine), and most occurred in Africa, according to a new study of vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreaks between Jan. 2020 and June 2021 published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was launched in 1988 and used live attenuated oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV). Since then, cases of wild poliovirus have declined more than 99.99%.

The cVDPV2 likely originated among children born in areas with poor vaccine coverage. Jay Wenger, MD, director, Polio, at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, told this news organization that “the inactivated vaccines that we give in most developed countries now are good in that they provide humoral immunity, the antibodies in the bloodstream. They don’t necessarily provide mucosal immunity. They don’t make the kid’s gut immune to getting reinfected or actually immune to reproducing the virus if they get it in their gut. So we could still have a situation where everybody was vaccinated with IPV [inactivated poliovirus], but the virus could still be transmitting around because kids’ guts would still be producing the virus and there will still be transmission in your population, probably without much or any paralysis because of the IPV. As soon as that virus hit a population that was not vaccinated, they would get paralyzed.”

Dr. Wenger added, “The ideal vaccine would be an oral vaccine that didn’t mutate back and couldn’t cause these VDPVs.” Scientists developed such a vaccine, approved by the World Health Organization last year under an Emergency Use Authorization. This nOPV2 (novel oral poliovirus type 2) vaccine has been given since March 2021 in areas with the VDPD2 outbreaks. The nOPV2 should allow them to “basically stamp out the outbreaks.”

The world had almost eradicated the disease, with the last cases of polio from wild virus occurring in Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan as of 2014. Africa was declared free of wild polio in 2020 after it had been eradicated from Nigeria, which accounted for more than half of the world’s cases only a decade earlier. Now cVDPV outbreaks affect 28 African countries, plus Iran, Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia. And there was also one case in China. Globally, there were 1,335 cases of cVDPV causing paralysis during the reporting period.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on polio, accounting for much of this year’s increase in cases. Dr. Wenger said, “We couldn’t do any campaigns. We pretty much stopped doing outbreak response campaigns in the middle of the year because of COVID.”

The CDC report notes that many of the supplementary immunizations in response to cVDPV2 outbreaks were of “poor quality,” and prolonged delays enabled geographically expanding cVDPV2 transmission.

Steve Wassilak, MD, chief coauthor of the CDC study, told this news organization that, because of COVID, “what we’ve been lacking is a rapid response for the most part. Some of that is due to laboratory delays and shipment because of COVID’s effect on international travel.” He noted, however, that there has been good recovery in surveillance and immunization activities despite COVID. And, he added, eradication “can be done, and many outbreaks have closed even during the [COVID] outbreak.”

Dr. Wassilak said that in Nigeria, “the face of the campaign became national.” In Pakistan, much of the work is done by national and international partners.

Dr. Wenger said that in Nigeria and other challenging areas, “the approach was essentially to make direct contact with the traditional leaders and the religious leaders and the local actors in each of these populations. So, it’s really getting down to the grassroots level.” Infectious disease officials send teams to speak with individuals in the “local, traditional leader system.”

“Just talking to them actually got us a long way and giving them the information that they need. In most cases, I mean, people want to do things to help their kids,” said Dr. Wenger.

For now, the initial plan, per the CDC, is to “initiate prompt and high coverage outbreak responses with available type 2 OPV to interrupt transmission” until a better supply of nOPV2 is available, then switch to IPVs.

Dr. Wenger and Dr. Wassilak report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most (86%) of these outbreaks were caused by cVDPV2 (circulating VDPV type 2 poliovirus, which originated with the vaccine), and most occurred in Africa, according to a new study of vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreaks between Jan. 2020 and June 2021 published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was launched in 1988 and used live attenuated oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV). Since then, cases of wild poliovirus have declined more than 99.99%.

The cVDPV2 likely originated among children born in areas with poor vaccine coverage. Jay Wenger, MD, director, Polio, at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, told this news organization that “the inactivated vaccines that we give in most developed countries now are good in that they provide humoral immunity, the antibodies in the bloodstream. They don’t necessarily provide mucosal immunity. They don’t make the kid’s gut immune to getting reinfected or actually immune to reproducing the virus if they get it in their gut. So we could still have a situation where everybody was vaccinated with IPV [inactivated poliovirus], but the virus could still be transmitting around because kids’ guts would still be producing the virus and there will still be transmission in your population, probably without much or any paralysis because of the IPV. As soon as that virus hit a population that was not vaccinated, they would get paralyzed.”

Dr. Wenger added, “The ideal vaccine would be an oral vaccine that didn’t mutate back and couldn’t cause these VDPVs.” Scientists developed such a vaccine, approved by the World Health Organization last year under an Emergency Use Authorization. This nOPV2 (novel oral poliovirus type 2) vaccine has been given since March 2021 in areas with the VDPD2 outbreaks. The nOPV2 should allow them to “basically stamp out the outbreaks.”

The world had almost eradicated the disease, with the last cases of polio from wild virus occurring in Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan as of 2014. Africa was declared free of wild polio in 2020 after it had been eradicated from Nigeria, which accounted for more than half of the world’s cases only a decade earlier. Now cVDPV outbreaks affect 28 African countries, plus Iran, Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia. And there was also one case in China. Globally, there were 1,335 cases of cVDPV causing paralysis during the reporting period.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on polio, accounting for much of this year’s increase in cases. Dr. Wenger said, “We couldn’t do any campaigns. We pretty much stopped doing outbreak response campaigns in the middle of the year because of COVID.”

The CDC report notes that many of the supplementary immunizations in response to cVDPV2 outbreaks were of “poor quality,” and prolonged delays enabled geographically expanding cVDPV2 transmission.

Steve Wassilak, MD, chief coauthor of the CDC study, told this news organization that, because of COVID, “what we’ve been lacking is a rapid response for the most part. Some of that is due to laboratory delays and shipment because of COVID’s effect on international travel.” He noted, however, that there has been good recovery in surveillance and immunization activities despite COVID. And, he added, eradication “can be done, and many outbreaks have closed even during the [COVID] outbreak.”

Dr. Wassilak said that in Nigeria, “the face of the campaign became national.” In Pakistan, much of the work is done by national and international partners.

Dr. Wenger said that in Nigeria and other challenging areas, “the approach was essentially to make direct contact with the traditional leaders and the religious leaders and the local actors in each of these populations. So, it’s really getting down to the grassroots level.” Infectious disease officials send teams to speak with individuals in the “local, traditional leader system.”

“Just talking to them actually got us a long way and giving them the information that they need. In most cases, I mean, people want to do things to help their kids,” said Dr. Wenger.

For now, the initial plan, per the CDC, is to “initiate prompt and high coverage outbreak responses with available type 2 OPV to interrupt transmission” until a better supply of nOPV2 is available, then switch to IPVs.

Dr. Wenger and Dr. Wassilak report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most (86%) of these outbreaks were caused by cVDPV2 (circulating VDPV type 2 poliovirus, which originated with the vaccine), and most occurred in Africa, according to a new study of vaccine-derived poliovirus outbreaks between Jan. 2020 and June 2021 published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was launched in 1988 and used live attenuated oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV). Since then, cases of wild poliovirus have declined more than 99.99%.

The cVDPV2 likely originated among children born in areas with poor vaccine coverage. Jay Wenger, MD, director, Polio, at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, told this news organization that “the inactivated vaccines that we give in most developed countries now are good in that they provide humoral immunity, the antibodies in the bloodstream. They don’t necessarily provide mucosal immunity. They don’t make the kid’s gut immune to getting reinfected or actually immune to reproducing the virus if they get it in their gut. So we could still have a situation where everybody was vaccinated with IPV [inactivated poliovirus], but the virus could still be transmitting around because kids’ guts would still be producing the virus and there will still be transmission in your population, probably without much or any paralysis because of the IPV. As soon as that virus hit a population that was not vaccinated, they would get paralyzed.”

Dr. Wenger added, “The ideal vaccine would be an oral vaccine that didn’t mutate back and couldn’t cause these VDPVs.” Scientists developed such a vaccine, approved by the World Health Organization last year under an Emergency Use Authorization. This nOPV2 (novel oral poliovirus type 2) vaccine has been given since March 2021 in areas with the VDPD2 outbreaks. The nOPV2 should allow them to “basically stamp out the outbreaks.”

The world had almost eradicated the disease, with the last cases of polio from wild virus occurring in Nigeria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan as of 2014. Africa was declared free of wild polio in 2020 after it had been eradicated from Nigeria, which accounted for more than half of the world’s cases only a decade earlier. Now cVDPV outbreaks affect 28 African countries, plus Iran, Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia. And there was also one case in China. Globally, there were 1,335 cases of cVDPV causing paralysis during the reporting period.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on polio, accounting for much of this year’s increase in cases. Dr. Wenger said, “We couldn’t do any campaigns. We pretty much stopped doing outbreak response campaigns in the middle of the year because of COVID.”

The CDC report notes that many of the supplementary immunizations in response to cVDPV2 outbreaks were of “poor quality,” and prolonged delays enabled geographically expanding cVDPV2 transmission.

Steve Wassilak, MD, chief coauthor of the CDC study, told this news organization that, because of COVID, “what we’ve been lacking is a rapid response for the most part. Some of that is due to laboratory delays and shipment because of COVID’s effect on international travel.” He noted, however, that there has been good recovery in surveillance and immunization activities despite COVID. And, he added, eradication “can be done, and many outbreaks have closed even during the [COVID] outbreak.”

Dr. Wassilak said that in Nigeria, “the face of the campaign became national.” In Pakistan, much of the work is done by national and international partners.

Dr. Wenger said that in Nigeria and other challenging areas, “the approach was essentially to make direct contact with the traditional leaders and the religious leaders and the local actors in each of these populations. So, it’s really getting down to the grassroots level.” Infectious disease officials send teams to speak with individuals in the “local, traditional leader system.”

“Just talking to them actually got us a long way and giving them the information that they need. In most cases, I mean, people want to do things to help their kids,” said Dr. Wenger.

For now, the initial plan, per the CDC, is to “initiate prompt and high coverage outbreak responses with available type 2 OPV to interrupt transmission” until a better supply of nOPV2 is available, then switch to IPVs.

Dr. Wenger and Dr. Wassilak report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular effects of breast cancer treatment vary based on weight, menopausal status

For example, certain chemotherapy drugs may confer higher risk in breast cancer survivors of normal weight, whereas they may lower stroke risk in those who are obese, according to Heather Greenlee, ND, PhD, a public health researcher and naturopathic physician with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

In postmenopausal women with breast cancer, aromatase inhibitors may increase cardiovascular risk, while tamoxifen appears to reduce the risk of incident dyslipidemia, she said.

The findings are from separate analyses of data from studies presented during a poster discussion session at the symposium.

Breast cancer treatment and cardiovascular effects: The role of weight

In one analysis, Dr. Greenlee and colleagues examined outcomes in 13,582 breast cancer survivors with a median age of 60 years and median follow-up of 7 years to assess whether cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk associated with specific breast cancer therapies varies by body mass index (BMI) category at diagnosis.

Many routinely used breast cancer therapies are cardiotoxic, and being overweight or obese are known risk factors for CVD, but few studies have assessed whether BMI modifies the effect of these treatment on cardiovascular risk, Dr. Greenlee explained.

After adjusting for baseline demographic and health-related factors, and other breast cancer treatment, they found that:

- Ischemic heart disease risk was higher among normal-weight women who received anthracyclines, compared with those who did not (hazard ratio, 4.2). No other risk associations were observed for other breast cancer therapies and BMI groups.

- Heart failure/cardiomyopathy risk was higher among women with normal weight who received anthracyclines, cyclophosphamides, or left-sided radiation, compared with those who did not (HRs, 5.24, 3.27, and 2.05, respectively), and among overweight women who received anthracyclines, compared with those who did not (HR, 2.18). No risk associations were observed for women who received trastuzumab, taxanes, endocrine therapy, or radiation on any side, and no risk associations were observed for women who were obese.

- Stroke risk was higher in normal-weight women who received taxanes, cyclophosphamides, or left-sided radiation versus those who did not (HRs, 2.14, 2.35, and 1.31, respectively), and stroke risk was lower in obese women who received anthracyclines, taxanes, or cyclophosphamide, compared with those who did not (HRs, 0.32, 0.41, and 0.29, respectively). No risk associations were observed for trastuzumab, endocrine therapy, or radiation on any side, and no risk associations were observed for women who were overweight.

The lack of associations noted between treatments and heart failure risk among obese patients could be caused by the “obesity paradox” observed in prior obese populations, the investigators noted, adding that additional analyses are planned to “examine whether different dosage and duration of breast cancer therapy exposures across the BMI groups contributed to these risk associations.”

Breast cancer treatment and cardiometabolic effects: The role of menopausal status

In a separate analysis, Dr. Greenlee and colleagues looked at the association between endocrine therapies and cardiometabolic risk based on menopausal status.

Endocrine therapy is associated with CVD in breast cancer survivors and may be associated with developing cardiometabolic risk factors like diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, they noted, explaining that tamoxifen has mixed estrogenic and antiestrogenic activity, while aromatase inhibitors deplete endogenous estrogen.

Since most studies have compared tamoxifen with aromatase inhibitor use, it has been a challenge challenging to discern the effects of each, Dr. Greenlee said.

She and her colleagues reviewed records for 14,942 breast cancer survivors who were diagnosed between 2005 and 2013. The patients had a mean age of 61 years at baseline, and 24.9% were premenopausal at the time of diagnosis. Of the premenopausal women, 27.3% used tamoxifen, 19.2% used aromatase inhibitors, and 53.5% did not use endocrine therapy, and of the postmenopausal women, 6.6% used tamoxifen, 47.7% used aromatase inhibitors, and 45.7% did not use endocrine therapy.

After adjusting for baseline demographics and health factors, the investigators found that:

- The use of tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors was not associated with a risk of developing diabetes, dyslipidemia, or hypertension in premenopausal women, or with a risk of developing diabetes or hypertension in postmenopausal women.

- The risk of dyslipidemia was higher in postmenopausal aromatase inhibitor users, and lower in postmenopausal tamoxifen users, compared with postmenopausal non-users of endocrine therapy (HRs, 1.15 and 0.75, respectively).

The lack of associations between endocrine therapy and CVD risk in premenopausal women may be from low power, Dr. Greenlee said, noting that analyses in larger sample sizes are needed.

She and her colleagues plan to conduct further analyses looking at treatment dosage and duration, and comparing steroidal versus nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors.

Future studies should examine the implications of these associations on long-term CVD and how best to manage lipid profiles in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors who have a history of endocrine therapy treatment, they concluded.

This research was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute.

For example, certain chemotherapy drugs may confer higher risk in breast cancer survivors of normal weight, whereas they may lower stroke risk in those who are obese, according to Heather Greenlee, ND, PhD, a public health researcher and naturopathic physician with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

In postmenopausal women with breast cancer, aromatase inhibitors may increase cardiovascular risk, while tamoxifen appears to reduce the risk of incident dyslipidemia, she said.

The findings are from separate analyses of data from studies presented during a poster discussion session at the symposium.

Breast cancer treatment and cardiovascular effects: The role of weight

In one analysis, Dr. Greenlee and colleagues examined outcomes in 13,582 breast cancer survivors with a median age of 60 years and median follow-up of 7 years to assess whether cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk associated with specific breast cancer therapies varies by body mass index (BMI) category at diagnosis.

Many routinely used breast cancer therapies are cardiotoxic, and being overweight or obese are known risk factors for CVD, but few studies have assessed whether BMI modifies the effect of these treatment on cardiovascular risk, Dr. Greenlee explained.

After adjusting for baseline demographic and health-related factors, and other breast cancer treatment, they found that:

- Ischemic heart disease risk was higher among normal-weight women who received anthracyclines, compared with those who did not (hazard ratio, 4.2). No other risk associations were observed for other breast cancer therapies and BMI groups.

- Heart failure/cardiomyopathy risk was higher among women with normal weight who received anthracyclines, cyclophosphamides, or left-sided radiation, compared with those who did not (HRs, 5.24, 3.27, and 2.05, respectively), and among overweight women who received anthracyclines, compared with those who did not (HR, 2.18). No risk associations were observed for women who received trastuzumab, taxanes, endocrine therapy, or radiation on any side, and no risk associations were observed for women who were obese.

- Stroke risk was higher in normal-weight women who received taxanes, cyclophosphamides, or left-sided radiation versus those who did not (HRs, 2.14, 2.35, and 1.31, respectively), and stroke risk was lower in obese women who received anthracyclines, taxanes, or cyclophosphamide, compared with those who did not (HRs, 0.32, 0.41, and 0.29, respectively). No risk associations were observed for trastuzumab, endocrine therapy, or radiation on any side, and no risk associations were observed for women who were overweight.

The lack of associations noted between treatments and heart failure risk among obese patients could be caused by the “obesity paradox” observed in prior obese populations, the investigators noted, adding that additional analyses are planned to “examine whether different dosage and duration of breast cancer therapy exposures across the BMI groups contributed to these risk associations.”

Breast cancer treatment and cardiometabolic effects: The role of menopausal status

In a separate analysis, Dr. Greenlee and colleagues looked at the association between endocrine therapies and cardiometabolic risk based on menopausal status.

Endocrine therapy is associated with CVD in breast cancer survivors and may be associated with developing cardiometabolic risk factors like diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, they noted, explaining that tamoxifen has mixed estrogenic and antiestrogenic activity, while aromatase inhibitors deplete endogenous estrogen.

Since most studies have compared tamoxifen with aromatase inhibitor use, it has been a challenge challenging to discern the effects of each, Dr. Greenlee said.

She and her colleagues reviewed records for 14,942 breast cancer survivors who were diagnosed between 2005 and 2013. The patients had a mean age of 61 years at baseline, and 24.9% were premenopausal at the time of diagnosis. Of the premenopausal women, 27.3% used tamoxifen, 19.2% used aromatase inhibitors, and 53.5% did not use endocrine therapy, and of the postmenopausal women, 6.6% used tamoxifen, 47.7% used aromatase inhibitors, and 45.7% did not use endocrine therapy.

After adjusting for baseline demographics and health factors, the investigators found that:

- The use of tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors was not associated with a risk of developing diabetes, dyslipidemia, or hypertension in premenopausal women, or with a risk of developing diabetes or hypertension in postmenopausal women.

- The risk of dyslipidemia was higher in postmenopausal aromatase inhibitor users, and lower in postmenopausal tamoxifen users, compared with postmenopausal non-users of endocrine therapy (HRs, 1.15 and 0.75, respectively).

The lack of associations between endocrine therapy and CVD risk in premenopausal women may be from low power, Dr. Greenlee said, noting that analyses in larger sample sizes are needed.

She and her colleagues plan to conduct further analyses looking at treatment dosage and duration, and comparing steroidal versus nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors.

Future studies should examine the implications of these associations on long-term CVD and how best to manage lipid profiles in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors who have a history of endocrine therapy treatment, they concluded.

This research was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute.

For example, certain chemotherapy drugs may confer higher risk in breast cancer survivors of normal weight, whereas they may lower stroke risk in those who are obese, according to Heather Greenlee, ND, PhD, a public health researcher and naturopathic physician with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

In postmenopausal women with breast cancer, aromatase inhibitors may increase cardiovascular risk, while tamoxifen appears to reduce the risk of incident dyslipidemia, she said.

The findings are from separate analyses of data from studies presented during a poster discussion session at the symposium.

Breast cancer treatment and cardiovascular effects: The role of weight

In one analysis, Dr. Greenlee and colleagues examined outcomes in 13,582 breast cancer survivors with a median age of 60 years and median follow-up of 7 years to assess whether cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk associated with specific breast cancer therapies varies by body mass index (BMI) category at diagnosis.

Many routinely used breast cancer therapies are cardiotoxic, and being overweight or obese are known risk factors for CVD, but few studies have assessed whether BMI modifies the effect of these treatment on cardiovascular risk, Dr. Greenlee explained.

After adjusting for baseline demographic and health-related factors, and other breast cancer treatment, they found that:

- Ischemic heart disease risk was higher among normal-weight women who received anthracyclines, compared with those who did not (hazard ratio, 4.2). No other risk associations were observed for other breast cancer therapies and BMI groups.

- Heart failure/cardiomyopathy risk was higher among women with normal weight who received anthracyclines, cyclophosphamides, or left-sided radiation, compared with those who did not (HRs, 5.24, 3.27, and 2.05, respectively), and among overweight women who received anthracyclines, compared with those who did not (HR, 2.18). No risk associations were observed for women who received trastuzumab, taxanes, endocrine therapy, or radiation on any side, and no risk associations were observed for women who were obese.

- Stroke risk was higher in normal-weight women who received taxanes, cyclophosphamides, or left-sided radiation versus those who did not (HRs, 2.14, 2.35, and 1.31, respectively), and stroke risk was lower in obese women who received anthracyclines, taxanes, or cyclophosphamide, compared with those who did not (HRs, 0.32, 0.41, and 0.29, respectively). No risk associations were observed for trastuzumab, endocrine therapy, or radiation on any side, and no risk associations were observed for women who were overweight.

The lack of associations noted between treatments and heart failure risk among obese patients could be caused by the “obesity paradox” observed in prior obese populations, the investigators noted, adding that additional analyses are planned to “examine whether different dosage and duration of breast cancer therapy exposures across the BMI groups contributed to these risk associations.”

Breast cancer treatment and cardiometabolic effects: The role of menopausal status

In a separate analysis, Dr. Greenlee and colleagues looked at the association between endocrine therapies and cardiometabolic risk based on menopausal status.

Endocrine therapy is associated with CVD in breast cancer survivors and may be associated with developing cardiometabolic risk factors like diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, they noted, explaining that tamoxifen has mixed estrogenic and antiestrogenic activity, while aromatase inhibitors deplete endogenous estrogen.

Since most studies have compared tamoxifen with aromatase inhibitor use, it has been a challenge challenging to discern the effects of each, Dr. Greenlee said.

She and her colleagues reviewed records for 14,942 breast cancer survivors who were diagnosed between 2005 and 2013. The patients had a mean age of 61 years at baseline, and 24.9% were premenopausal at the time of diagnosis. Of the premenopausal women, 27.3% used tamoxifen, 19.2% used aromatase inhibitors, and 53.5% did not use endocrine therapy, and of the postmenopausal women, 6.6% used tamoxifen, 47.7% used aromatase inhibitors, and 45.7% did not use endocrine therapy.

After adjusting for baseline demographics and health factors, the investigators found that:

- The use of tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors was not associated with a risk of developing diabetes, dyslipidemia, or hypertension in premenopausal women, or with a risk of developing diabetes or hypertension in postmenopausal women.

- The risk of dyslipidemia was higher in postmenopausal aromatase inhibitor users, and lower in postmenopausal tamoxifen users, compared with postmenopausal non-users of endocrine therapy (HRs, 1.15 and 0.75, respectively).

The lack of associations between endocrine therapy and CVD risk in premenopausal women may be from low power, Dr. Greenlee said, noting that analyses in larger sample sizes are needed.

She and her colleagues plan to conduct further analyses looking at treatment dosage and duration, and comparing steroidal versus nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors.

Future studies should examine the implications of these associations on long-term CVD and how best to manage lipid profiles in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors who have a history of endocrine therapy treatment, they concluded.

This research was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute.

FROM SABCS 2021

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Overlap in a Pregnant Patient

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old pregnant woman at 5 weeks’ gestation was transferred to dermatology from an outside hospital with a full-body rash. Three days after noting a fever and generalized body aches, she developed a painful rash on the legs that had gradually spread to the arms, trunk, and face. Symptoms of eyelid pruritus and edema initially were improved with intravenous (IV) steroids at an emergency department visit, but they started to flare soon thereafter with worsening mucosal involvement and dysphagia. After a second visit to the emergency department and repeat treatment with IV steroids, she was transferred to our institution for a higher level of care.

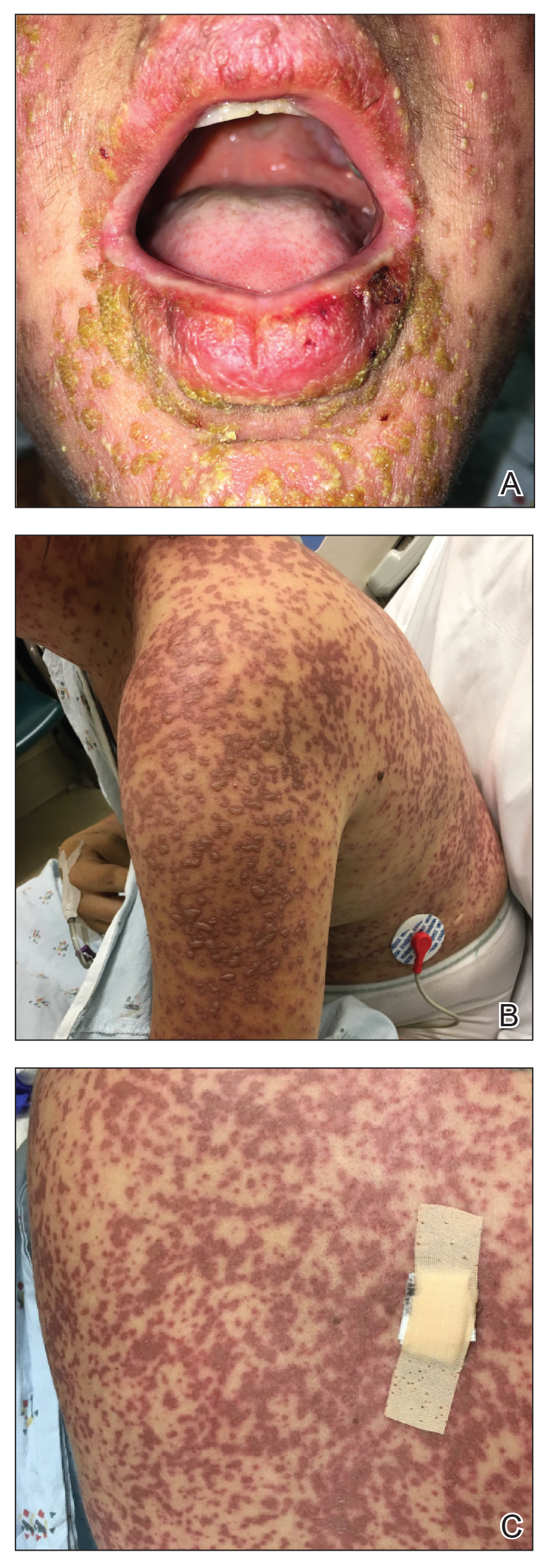

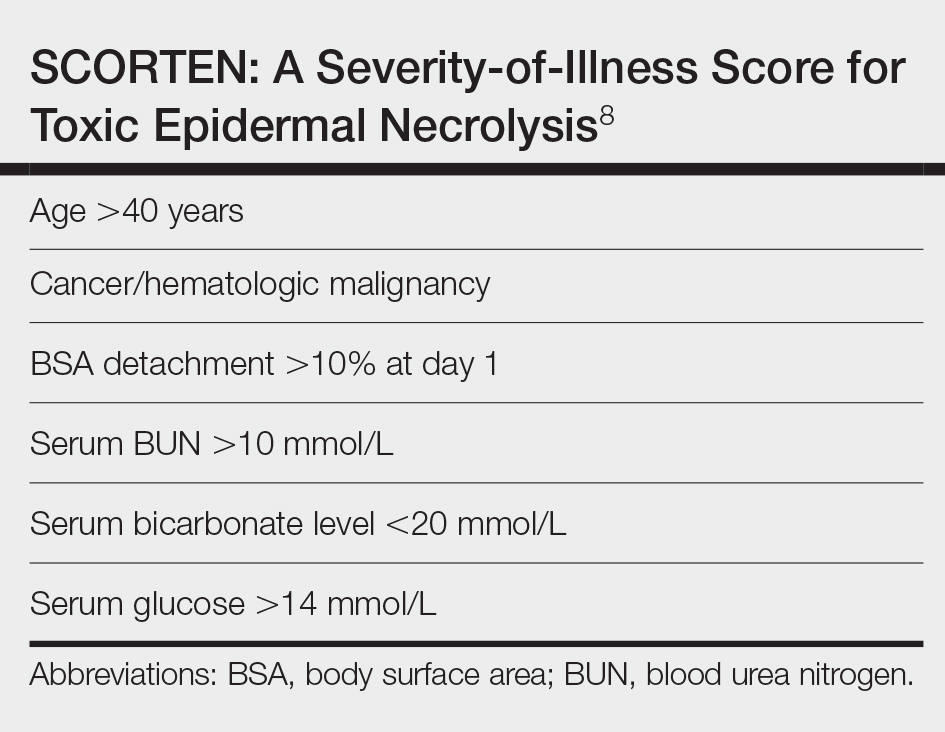

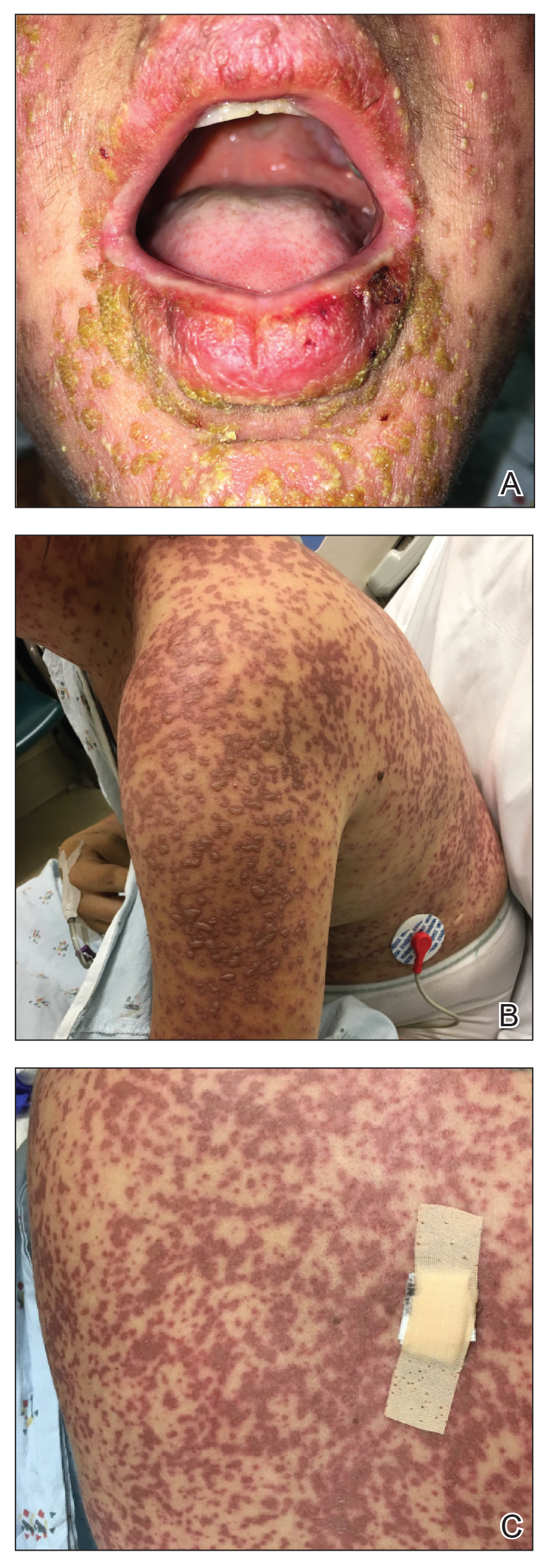

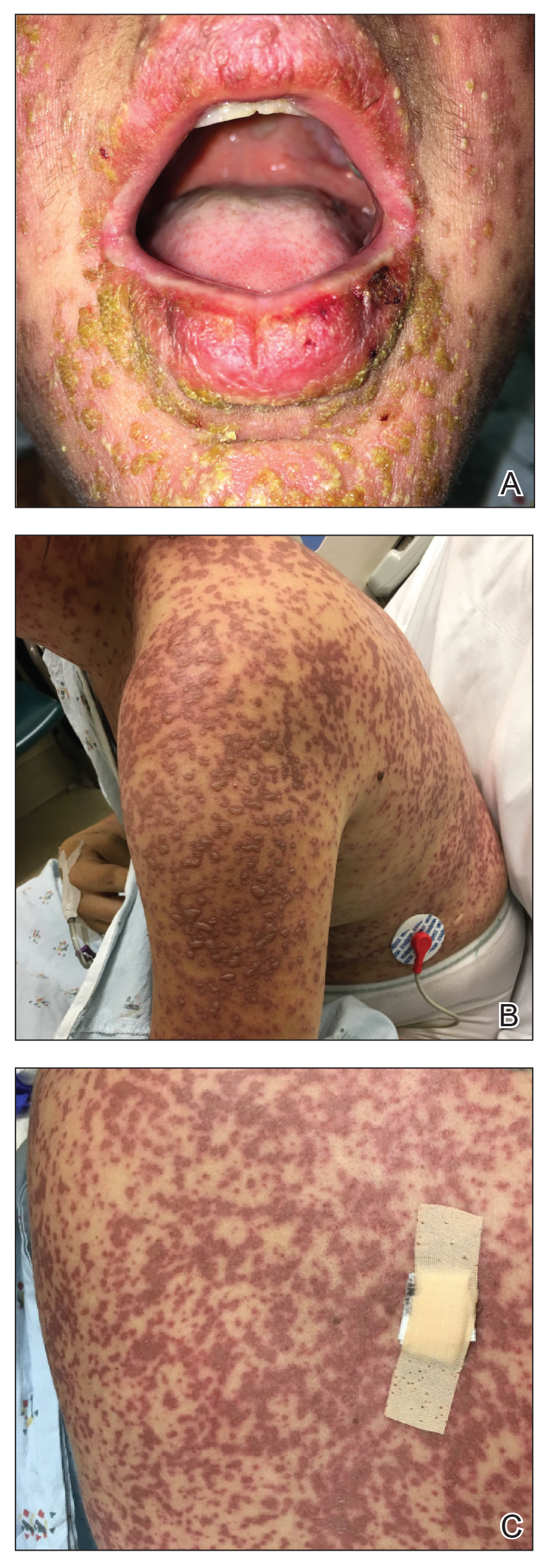

The patient denied taking any new medications in the 2 months prior to the onset of the rash. Her medication history only consisted of over-the-counter prenatal vitamins, a single use of over-the-counter migraine medication (containing acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine as active ingredients), and a possible use of ibuprofen or acetaminophen separately. She reported ocular discomfort and blurriness, dysphagia, dysuria, and vaginal discomfort. Physical examination revealed dusky red to violaceous macules and patches that involved approximately 65% of the body surface area (BSA), with bullae involving approximately 10% BSA. The face was diffusely red and edematous with crusted erosions and scattered bullae on the cheeks. Mucosal involvement was notable for injected conjunctivae and erosions present on the upper hard palate of the mouth and lips (Figure, A). Erythematous macules with dusky centers coalescing into patches with overlying vesicles and bullae were scattered on the arms (Figure, B), hands, trunk (Figure, C), and legs. The Nikolsky sign was positive. The vulva was swollen and covered with erythematous macules with dusky centers.

A biopsy from the upper back revealed a vacuolar interface with subepidermal bullae and confluent keratinocyte necrosis with many CD8+ cells and scattered granzyme B. Given these results in conjunction with the clinical findings, a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) overlap was made. In addition to providing supportive care, the patient was started on a 4-day course of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG)(3g/kg total) and prednisone 60 mg daily, tapered over several weeks with a good clinical response. At outpatient follow-up she was found to have postinflammatory hypopigmentation on the face, trunk, and extremities, as well as tear duct scarring, but she had no vulvovaginal scarring or stenosis. She was progressing well in her pregnancy with no serious complications for 4 months after admission, at which point she was lost to follow-up.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN represent a spectrum of severe mucocutaneous reactions with high morbidity and mortality. Medications are the leading trigger, followed by infection. The most common inciting medications include antibacterial sulfonamides, antiepileptics such as carbamazepine and lamotrigine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nevirapine, and allopurinol. The onset of symptoms from 1 to 4 weeks combined with characteristic morphologic features helps distinguish SJS/TEN from other drug eruptions. The initial presentation classically consists of a flulike prodrome followed by mucocutaneous eruption. Skin lesions often present as a diffuse erythema or ill-defined, coalescing, erythematous macules with purpuric centers that may evolve into vesicles and bullae with sloughing of the skin. Histopathology reveals full-thickness epidermal necrosis with detachment.1

Erythema multiforme and Mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) are high on the differential diagnosis. Distinguishing features of erythema multiforme include the morphology of targetoid lesions and a common distribution on the extremities, in addition to the limited bullae and epidermal detachment in comparison with SJS/TEN. In MIRM, mucositis often is more severe and extensive, with multiple mucosal surfaces affected. It typically has less cutaneous involvement than SJS/TEN, though clinical variants can include diffuse rash and affect fewer than 2 mucosal sites.2 Depending on the timing of rash onset, Mycoplasma IgM/IgG titers may be drawn to further support the diagnosis. A diagnosis of MIRM was not favored in our patient due to lack of respiratory symptoms, normal chest radiography, and negative Mycoplasma IgM and IgG titers.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap has been reported in pregnant patients, typically in association with HIV infection or new medication exposure.3 A combination of genetic susceptibility and an altered immune system during pregnancy may contribute to the pathogenesis, involving a cytotoxic T-cell mediated reaction with release of inflammatory cytokines.1 Interestingly, these factors that may predispose a patient to developing SJS/TEN may not pass on to the neonate, evidenced by a few cases that showed no reaction in the newborn when given the same offending drug.4

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis more frequently presents in the second or third trimester, with no increase in maternal mortality and an equally high survival rate of the fetus.1,5 Unique sequelae in pregnant patients may include vaginal stenosis, vulvar swelling, and postpartum sepsis. Fetal complications can include low birth weight, preterm delivery, and respiratory distress. The fetus rarely exhibits cutaneous manifestations of the disease.6

A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of SJS/TEN overlap in special patient populations such as pregnant women is vital. Supportive measures consisting of wound care, fluid and electrolyte management, infection monitoring, and nutritional support have sufficed in treating SJS/TEN in pregnant patients.3 Although adjunctive therapy with systemic corticosteroids, IVIG, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors commonly are used in clinical practice, the safety of these treatments in pregnant patients affected by SJS/TEN has not been established. However, use of these medications for other indications, primarily rheumatologic diseases, has been reported to be safe in the pregnant population.7 If necessary, glucocorticoids should be used in the lowest effective dose to avoid complications such as premature rupture of membranes; intrauterine growth restriction; and increased risk for pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, osteoporosis, and infection. Little is known about IVIG use in pregnancy. While it has not been associated with increased risk of fetal malformations, it may cross the placenta in a notable amount when administered after 30 weeks’ gestation.7

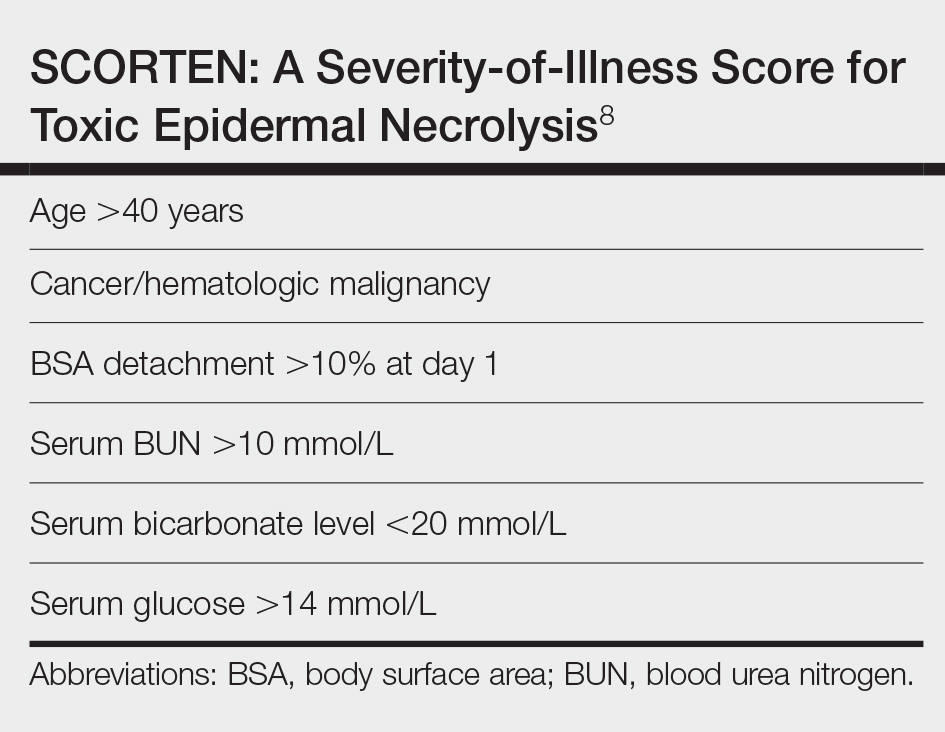

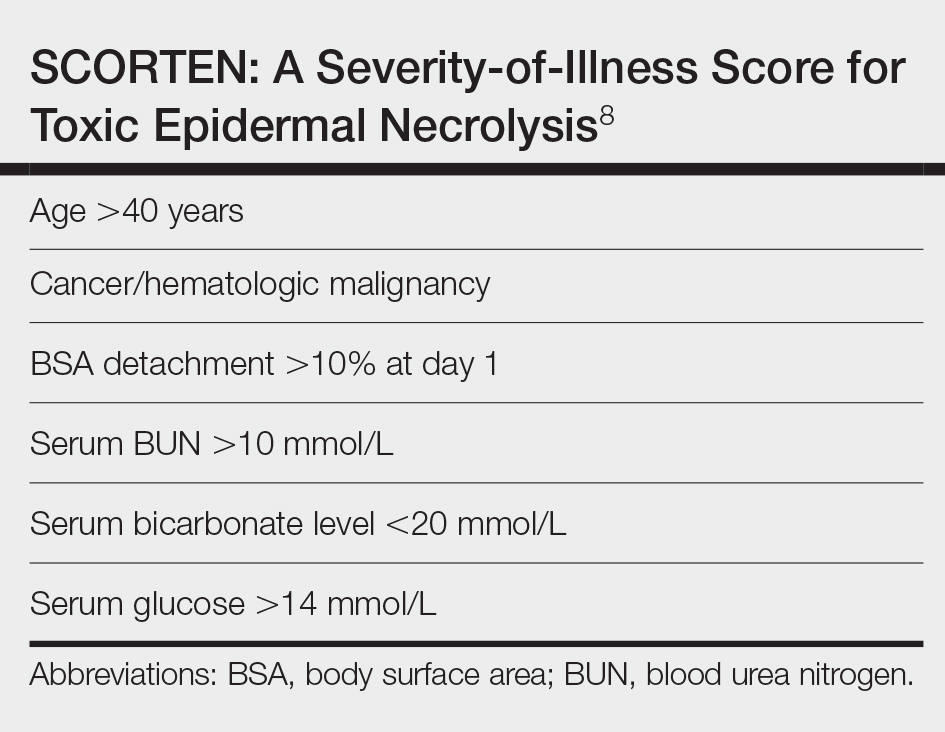

Unlike most cases of SJS/TEN in pregnancy that largely were associated with HIV infection or drug exposure, primarily antiretrovirals such as nevirapine or antiepileptics, our case is a rare incidence of SJS/TEN in a pregnant patient with no clear medication or infectious trigger. Although the causative drug was unclear, we suspected it was secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. The patient had a SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) of 0, which portends a relatively good prognosis with an estimated mortality rate of approximately 3% (Table).8 However, the large BSA involvement of the morbilliform rash warranted aggressive management to prevent the involved skin from fully detaching.

1. Struck MF, Illert T, Liss Y, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:816-821. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181eed441

2. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

3. Knight L, Todd G, Muloiwa R, et al. Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: maternal and foetal outcomes in twenty-two consecutive pregnant HIV infected women. PLoS One. 2015;10:1-11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135501

4. Velter C, Hotz C, Ingen-Housz-Oro S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome during pregnancy: case report of a newborn treated with the culprit drug. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:224-225. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4607

5. El Daief SG, Das S, Ekekwe G, et al. A successful pregnancy outcome after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2014;34:445-446. doi:10.3109/01443615.2014.914897

6. Rodriguez G, Trent JT, Mirzabeigi M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a mother and fetus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):96-98. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.023

7. Bermas BL. Safety of rheumatic disease medication use during pregnancy and lactation. UptoDate website. Updated March 24, 2021. Accessed December 16, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/safety-of-rheumatic-disease-medication-use-during-pregnancy-and-lactation#H11

8. Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old pregnant woman at 5 weeks’ gestation was transferred to dermatology from an outside hospital with a full-body rash. Three days after noting a fever and generalized body aches, she developed a painful rash on the legs that had gradually spread to the arms, trunk, and face. Symptoms of eyelid pruritus and edema initially were improved with intravenous (IV) steroids at an emergency department visit, but they started to flare soon thereafter with worsening mucosal involvement and dysphagia. After a second visit to the emergency department and repeat treatment with IV steroids, she was transferred to our institution for a higher level of care.

The patient denied taking any new medications in the 2 months prior to the onset of the rash. Her medication history only consisted of over-the-counter prenatal vitamins, a single use of over-the-counter migraine medication (containing acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine as active ingredients), and a possible use of ibuprofen or acetaminophen separately. She reported ocular discomfort and blurriness, dysphagia, dysuria, and vaginal discomfort. Physical examination revealed dusky red to violaceous macules and patches that involved approximately 65% of the body surface area (BSA), with bullae involving approximately 10% BSA. The face was diffusely red and edematous with crusted erosions and scattered bullae on the cheeks. Mucosal involvement was notable for injected conjunctivae and erosions present on the upper hard palate of the mouth and lips (Figure, A). Erythematous macules with dusky centers coalescing into patches with overlying vesicles and bullae were scattered on the arms (Figure, B), hands, trunk (Figure, C), and legs. The Nikolsky sign was positive. The vulva was swollen and covered with erythematous macules with dusky centers.

A biopsy from the upper back revealed a vacuolar interface with subepidermal bullae and confluent keratinocyte necrosis with many CD8+ cells and scattered granzyme B. Given these results in conjunction with the clinical findings, a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) overlap was made. In addition to providing supportive care, the patient was started on a 4-day course of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG)(3g/kg total) and prednisone 60 mg daily, tapered over several weeks with a good clinical response. At outpatient follow-up she was found to have postinflammatory hypopigmentation on the face, trunk, and extremities, as well as tear duct scarring, but she had no vulvovaginal scarring or stenosis. She was progressing well in her pregnancy with no serious complications for 4 months after admission, at which point she was lost to follow-up.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN represent a spectrum of severe mucocutaneous reactions with high morbidity and mortality. Medications are the leading trigger, followed by infection. The most common inciting medications include antibacterial sulfonamides, antiepileptics such as carbamazepine and lamotrigine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nevirapine, and allopurinol. The onset of symptoms from 1 to 4 weeks combined with characteristic morphologic features helps distinguish SJS/TEN from other drug eruptions. The initial presentation classically consists of a flulike prodrome followed by mucocutaneous eruption. Skin lesions often present as a diffuse erythema or ill-defined, coalescing, erythematous macules with purpuric centers that may evolve into vesicles and bullae with sloughing of the skin. Histopathology reveals full-thickness epidermal necrosis with detachment.1

Erythema multiforme and Mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) are high on the differential diagnosis. Distinguishing features of erythema multiforme include the morphology of targetoid lesions and a common distribution on the extremities, in addition to the limited bullae and epidermal detachment in comparison with SJS/TEN. In MIRM, mucositis often is more severe and extensive, with multiple mucosal surfaces affected. It typically has less cutaneous involvement than SJS/TEN, though clinical variants can include diffuse rash and affect fewer than 2 mucosal sites.2 Depending on the timing of rash onset, Mycoplasma IgM/IgG titers may be drawn to further support the diagnosis. A diagnosis of MIRM was not favored in our patient due to lack of respiratory symptoms, normal chest radiography, and negative Mycoplasma IgM and IgG titers.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap has been reported in pregnant patients, typically in association with HIV infection or new medication exposure.3 A combination of genetic susceptibility and an altered immune system during pregnancy may contribute to the pathogenesis, involving a cytotoxic T-cell mediated reaction with release of inflammatory cytokines.1 Interestingly, these factors that may predispose a patient to developing SJS/TEN may not pass on to the neonate, evidenced by a few cases that showed no reaction in the newborn when given the same offending drug.4

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis more frequently presents in the second or third trimester, with no increase in maternal mortality and an equally high survival rate of the fetus.1,5 Unique sequelae in pregnant patients may include vaginal stenosis, vulvar swelling, and postpartum sepsis. Fetal complications can include low birth weight, preterm delivery, and respiratory distress. The fetus rarely exhibits cutaneous manifestations of the disease.6

A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of SJS/TEN overlap in special patient populations such as pregnant women is vital. Supportive measures consisting of wound care, fluid and electrolyte management, infection monitoring, and nutritional support have sufficed in treating SJS/TEN in pregnant patients.3 Although adjunctive therapy with systemic corticosteroids, IVIG, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors commonly are used in clinical practice, the safety of these treatments in pregnant patients affected by SJS/TEN has not been established. However, use of these medications for other indications, primarily rheumatologic diseases, has been reported to be safe in the pregnant population.7 If necessary, glucocorticoids should be used in the lowest effective dose to avoid complications such as premature rupture of membranes; intrauterine growth restriction; and increased risk for pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, osteoporosis, and infection. Little is known about IVIG use in pregnancy. While it has not been associated with increased risk of fetal malformations, it may cross the placenta in a notable amount when administered after 30 weeks’ gestation.7

Unlike most cases of SJS/TEN in pregnancy that largely were associated with HIV infection or drug exposure, primarily antiretrovirals such as nevirapine or antiepileptics, our case is a rare incidence of SJS/TEN in a pregnant patient with no clear medication or infectious trigger. Although the causative drug was unclear, we suspected it was secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. The patient had a SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) of 0, which portends a relatively good prognosis with an estimated mortality rate of approximately 3% (Table).8 However, the large BSA involvement of the morbilliform rash warranted aggressive management to prevent the involved skin from fully detaching.

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old pregnant woman at 5 weeks’ gestation was transferred to dermatology from an outside hospital with a full-body rash. Three days after noting a fever and generalized body aches, she developed a painful rash on the legs that had gradually spread to the arms, trunk, and face. Symptoms of eyelid pruritus and edema initially were improved with intravenous (IV) steroids at an emergency department visit, but they started to flare soon thereafter with worsening mucosal involvement and dysphagia. After a second visit to the emergency department and repeat treatment with IV steroids, she was transferred to our institution for a higher level of care.

The patient denied taking any new medications in the 2 months prior to the onset of the rash. Her medication history only consisted of over-the-counter prenatal vitamins, a single use of over-the-counter migraine medication (containing acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine as active ingredients), and a possible use of ibuprofen or acetaminophen separately. She reported ocular discomfort and blurriness, dysphagia, dysuria, and vaginal discomfort. Physical examination revealed dusky red to violaceous macules and patches that involved approximately 65% of the body surface area (BSA), with bullae involving approximately 10% BSA. The face was diffusely red and edematous with crusted erosions and scattered bullae on the cheeks. Mucosal involvement was notable for injected conjunctivae and erosions present on the upper hard palate of the mouth and lips (Figure, A). Erythematous macules with dusky centers coalescing into patches with overlying vesicles and bullae were scattered on the arms (Figure, B), hands, trunk (Figure, C), and legs. The Nikolsky sign was positive. The vulva was swollen and covered with erythematous macules with dusky centers.

A biopsy from the upper back revealed a vacuolar interface with subepidermal bullae and confluent keratinocyte necrosis with many CD8+ cells and scattered granzyme B. Given these results in conjunction with the clinical findings, a diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) overlap was made. In addition to providing supportive care, the patient was started on a 4-day course of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG)(3g/kg total) and prednisone 60 mg daily, tapered over several weeks with a good clinical response. At outpatient follow-up she was found to have postinflammatory hypopigmentation on the face, trunk, and extremities, as well as tear duct scarring, but she had no vulvovaginal scarring or stenosis. She was progressing well in her pregnancy with no serious complications for 4 months after admission, at which point she was lost to follow-up.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and TEN represent a spectrum of severe mucocutaneous reactions with high morbidity and mortality. Medications are the leading trigger, followed by infection. The most common inciting medications include antibacterial sulfonamides, antiepileptics such as carbamazepine and lamotrigine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nevirapine, and allopurinol. The onset of symptoms from 1 to 4 weeks combined with characteristic morphologic features helps distinguish SJS/TEN from other drug eruptions. The initial presentation classically consists of a flulike prodrome followed by mucocutaneous eruption. Skin lesions often present as a diffuse erythema or ill-defined, coalescing, erythematous macules with purpuric centers that may evolve into vesicles and bullae with sloughing of the skin. Histopathology reveals full-thickness epidermal necrosis with detachment.1

Erythema multiforme and Mycoplasma-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) are high on the differential diagnosis. Distinguishing features of erythema multiforme include the morphology of targetoid lesions and a common distribution on the extremities, in addition to the limited bullae and epidermal detachment in comparison with SJS/TEN. In MIRM, mucositis often is more severe and extensive, with multiple mucosal surfaces affected. It typically has less cutaneous involvement than SJS/TEN, though clinical variants can include diffuse rash and affect fewer than 2 mucosal sites.2 Depending on the timing of rash onset, Mycoplasma IgM/IgG titers may be drawn to further support the diagnosis. A diagnosis of MIRM was not favored in our patient due to lack of respiratory symptoms, normal chest radiography, and negative Mycoplasma IgM and IgG titers.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap has been reported in pregnant patients, typically in association with HIV infection or new medication exposure.3 A combination of genetic susceptibility and an altered immune system during pregnancy may contribute to the pathogenesis, involving a cytotoxic T-cell mediated reaction with release of inflammatory cytokines.1 Interestingly, these factors that may predispose a patient to developing SJS/TEN may not pass on to the neonate, evidenced by a few cases that showed no reaction in the newborn when given the same offending drug.4

Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis more frequently presents in the second or third trimester, with no increase in maternal mortality and an equally high survival rate of the fetus.1,5 Unique sequelae in pregnant patients may include vaginal stenosis, vulvar swelling, and postpartum sepsis. Fetal complications can include low birth weight, preterm delivery, and respiratory distress. The fetus rarely exhibits cutaneous manifestations of the disease.6

A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of SJS/TEN overlap in special patient populations such as pregnant women is vital. Supportive measures consisting of wound care, fluid and electrolyte management, infection monitoring, and nutritional support have sufficed in treating SJS/TEN in pregnant patients.3 Although adjunctive therapy with systemic corticosteroids, IVIG, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors commonly are used in clinical practice, the safety of these treatments in pregnant patients affected by SJS/TEN has not been established. However, use of these medications for other indications, primarily rheumatologic diseases, has been reported to be safe in the pregnant population.7 If necessary, glucocorticoids should be used in the lowest effective dose to avoid complications such as premature rupture of membranes; intrauterine growth restriction; and increased risk for pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, osteoporosis, and infection. Little is known about IVIG use in pregnancy. While it has not been associated with increased risk of fetal malformations, it may cross the placenta in a notable amount when administered after 30 weeks’ gestation.7

Unlike most cases of SJS/TEN in pregnancy that largely were associated with HIV infection or drug exposure, primarily antiretrovirals such as nevirapine or antiepileptics, our case is a rare incidence of SJS/TEN in a pregnant patient with no clear medication or infectious trigger. Although the causative drug was unclear, we suspected it was secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. The patient had a SCORTEN (SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis) of 0, which portends a relatively good prognosis with an estimated mortality rate of approximately 3% (Table).8 However, the large BSA involvement of the morbilliform rash warranted aggressive management to prevent the involved skin from fully detaching.

1. Struck MF, Illert T, Liss Y, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:816-821. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181eed441

2. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

3. Knight L, Todd G, Muloiwa R, et al. Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: maternal and foetal outcomes in twenty-two consecutive pregnant HIV infected women. PLoS One. 2015;10:1-11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135501

4. Velter C, Hotz C, Ingen-Housz-Oro S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome during pregnancy: case report of a newborn treated with the culprit drug. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:224-225. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4607

5. El Daief SG, Das S, Ekekwe G, et al. A successful pregnancy outcome after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2014;34:445-446. doi:10.3109/01443615.2014.914897

6. Rodriguez G, Trent JT, Mirzabeigi M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a mother and fetus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):96-98. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.023

7. Bermas BL. Safety of rheumatic disease medication use during pregnancy and lactation. UptoDate website. Updated March 24, 2021. Accessed December 16, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/safety-of-rheumatic-disease-medication-use-during-pregnancy-and-lactation#H11

8. Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x

1. Struck MF, Illert T, Liss Y, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:816-821. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181eed441

2. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-245.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

3. Knight L, Todd G, Muloiwa R, et al. Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: maternal and foetal outcomes in twenty-two consecutive pregnant HIV infected women. PLoS One. 2015;10:1-11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135501

4. Velter C, Hotz C, Ingen-Housz-Oro S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome during pregnancy: case report of a newborn treated with the culprit drug. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:224-225. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4607

5. El Daief SG, Das S, Ekekwe G, et al. A successful pregnancy outcome after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2014;34:445-446. doi:10.3109/01443615.2014.914897

6. Rodriguez G, Trent JT, Mirzabeigi M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in a mother and fetus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):96-98. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.09.023

7. Bermas BL. Safety of rheumatic disease medication use during pregnancy and lactation. UptoDate website. Updated March 24, 2021. Accessed December 16, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/safety-of-rheumatic-disease-medication-use-during-pregnancy-and-lactation#H11

8. Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, et al. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149-153. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x

Practice Points

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) represent a spectrum of severe mucocutaneous reactions commonly presenting as drug eruptions.

- Pregnant patients affected by SJS/TEN represent a special patient population that requires a multidisciplinary approach for management and treatment.

- The rates of adverse outcomes for pregnant patients with SJS/TEN are low with timely diagnosis, removal of the offending agent, and supportive care as mainstays of treatment.

Don’t panic over lamotrigine, but beware of cardiac risks

New York University neurologist Jacqueline A. French, MD, told colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. But it’s now crucial to take special precautions in high-risk groups such as older people and heart patients.

“We need to plan more carefully when we use it, which we hate to do, as we know. But we’ve still got to do it,” said Dr. French, former president of the AES. “The risks are very small, but keep in mind that they’re not zero.”

In October 2020, the Food and Drug Administration added a warning to the lamotrigine label that said the drug “could slow ventricular conduction (widen QRS) and induce proarrhythmia, including sudden death, in patients with structural heart disease or myocardial ischemia.”

The FDA recommended avoiding the sodium channel blocker’s use “in patients who have cardiac conduction disorders (e.g., second- or third-degree heart block), ventricular arrhythmias, or cardiac disease or abnormality (e.g., myocardial ischemia, heart failure, structural heart disease, Brugada syndrome, or other sodium channelopathies). Concomitant use of other sodium channel blockers may increase the risk of proarrhythmia.”

Later, in March 2021, the FDA announced that a review of in vitro findings “showed a potential increased risk of heart rhythm problems.”

As Dr. French noted, lamotrigine remains widely prescribed even though there’s “no pharmaceutical company out there pushing [it].” It’s an especially beneficial drug for certain groups such as the elderly and women of child-bearing age, she said.

But older people are also at higher risk of drug-related heart complications because of the fact that many already have cardiac disease, Dr. French said. She highlighted a 2005 trial of lamotrigine that found 48% of 593 patients aged 60 years and older had cardiac disease.

Special precautions

So what should neurologists know about prescribing lamotrigine in light of the new warning? Dr. French recommended guidelines that she cowrote with the AES and International League Against Epilepsy.

- Prescribe as normal in patients under 60 with no cardiac risk factors. In patients older than 60, or younger with risk factors, consider an EKG before prescribing lamotrigine.

- “Nonspecific EKG abnormalities (e.g., nonspecific ST and T wave abnormalities) are not concerning, and should not preclude these individuals from being prescribed lamotrigine.”

- Beware of higher risk and consider consulting a cardiologist before starting treatment in patients with second- or third-degree heart block, Brugada syndrome, arrhythmogenic ventricular cardiomyopathy, left bundle branch block, and right bundle branch block with left anterior or posterior fascicular block.

- “In most cases the initial EKG can be obtained while titrating, mainly when the individual is at the first dose of 25 mg/day because lamotrigine must be titrated slowly, and because cardiac adverse events are dose related.”

- “Clinicians should consider obtaining an EKG and/or cardiology consultation in people on lamotrigine with sudden-onset syncope or presyncope with loss of muscular tone without a clear vasovagal or orthostatic cause.”

Dr. French cautioned colleagues that they shouldn’t assume that lamotrigine stands alone among sodium channel blockers in terms of cardiac risk. As she noted, the FDA is asking manufacturers of other drugs in that class to provide data. “At some point, maybe sometime in the near future, we are going to hear in this particular in vitro sense how the other sodium channel blockers do stack up, compared with lamotrigine. At presence, in the absence of the availability of all of the rest of the data, it would be incorrect to presume that lamotrigine has more cardiac effects than other sodium channel blocking antiseizure medicines or all antiseizure medicines.”

For now, she said, although the guidelines are for lamotrigine, it’s “prudent” to follow them for all sodium channel blockers.

Dr. French reported no disclosures.

New York University neurologist Jacqueline A. French, MD, told colleagues at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. But it’s now crucial to take special precautions in high-risk groups such as older people and heart patients.

“We need to plan more carefully when we use it, which we hate to do, as we know. But we’ve still got to do it,” said Dr. French, former president of the AES. “The risks are very small, but keep in mind that they’re not zero.”

In October 2020, the Food and Drug Administration added a warning to the lamotrigine label that said the drug “could slow ventricular conduction (widen QRS) and induce proarrhythmia, including sudden death, in patients with structural heart disease or myocardial ischemia.”

The FDA recommended avoiding the sodium channel blocker’s use “in patients who have cardiac conduction disorders (e.g., second- or third-degree heart block), ventricular arrhythmias, or cardiac disease or abnormality (e.g., myocardial ischemia, heart failure, structural heart disease, Brugada syndrome, or other sodium channelopathies). Concomitant use of other sodium channel blockers may increase the risk of proarrhythmia.”

Later, in March 2021, the FDA announced that a review of in vitro findings “showed a potential increased risk of heart rhythm problems.”

As Dr. French noted, lamotrigine remains widely prescribed even though there’s “no pharmaceutical company out there pushing [it].” It’s an especially beneficial drug for certain groups such as the elderly and women of child-bearing age, she said.