User login

When the benchwarmer is a slugger

I still, on occasion, use Felbatol (felbamate).

Thirty years since its explosive entrance to the market, then even more explosive collapse, it remains, in my opinion, the most effective of the second generation of anti-seizure medications. Arguably, even more effective than any of the third generation, too.

That’s not to say I use a lot of it. I don’t. It’s like handling unstable dynamite. Tremendous power, but also an above-average degree of risk. Even after things hit the fan with it in the mid-90s, I remember one of my epilepsy clinic attendings telling me, “This is a home-run drug. In refractory patients you might see some benefit by adding another agent, but with this one, you could stop their seizures and hit it out of the park.”

Like most neurologists, I use other epilepsy options first and second line. But sometimes you get the patient who’s failed the usual ones. Then I start to think about Felbatol. I explain the situation to the patients and their families and let them make the final decision. I worry and watch labs very closely for a while. I probably have no more than three to five patients on it in the practice. But when it works, it’s amazing stuff.

Now, let’s jump ahead to 2021. The year of Aduhelm (and several similar agents racing up behind it).

None of these drugs are even close to hitting home runs. For that matter, I’m not convinced they’re even able to get a man on base. To stretch my baseball analogy a bit, imagine watching a game by looking only at the RBI and ERA stats changing. The numbers change slightly, but you have no evidence that either team is winning. Which is, after all, the whole point.

And, to some extent, that’s the basis of Aduhelm’s approval, and likely the same standards its competitors will be held to.

Although they treat different conditions, and are chemically unrelated, the similarities between Felbatol and the currently advancing bunch of monoclonal antibody (MAB) agents for Alzheimer’s disease make an interesting contrast.

Unlike Felbatol’s proven efficacy for epilepsy, the current MABs offer minimal statistically significant clinical benefit for Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time the risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) and its complications with them is significantly higher than that of either of Felbatol’s known, potentially lethal, idiosyncratic effects.

With those odds, In medicine, every day is an exercise in working through the risks and benefits of each patient’s individual situation.

As I’ve stated before, I’m not in the grandstand rooting for these Alzheimer’s drugs to fail. I’ve lost a few family members, and certainly my share of patients, to dementia. I’d be thrilled, and more than willing to prescribe it, if something truly effective came along for it.

Nor do I take any kind of pleasure in the recent news that, because of Aduhelm’s failings, around 1,000 Biogen employees will lose their jobs. I feel terrible for them, as most had nothing to do with the decision to forge ahead with the product. More may soon follow at other companies working with similar agents.

Here we are, though, going into 2022. I’m still, albeit rarely, writing for Felbatol 30 years after it came to market for one reason: It works. But it seems pretty unlikely that future neurologists in 2052 will say the same about the current crops of MABs for Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I still, on occasion, use Felbatol (felbamate).

Thirty years since its explosive entrance to the market, then even more explosive collapse, it remains, in my opinion, the most effective of the second generation of anti-seizure medications. Arguably, even more effective than any of the third generation, too.

That’s not to say I use a lot of it. I don’t. It’s like handling unstable dynamite. Tremendous power, but also an above-average degree of risk. Even after things hit the fan with it in the mid-90s, I remember one of my epilepsy clinic attendings telling me, “This is a home-run drug. In refractory patients you might see some benefit by adding another agent, but with this one, you could stop their seizures and hit it out of the park.”

Like most neurologists, I use other epilepsy options first and second line. But sometimes you get the patient who’s failed the usual ones. Then I start to think about Felbatol. I explain the situation to the patients and their families and let them make the final decision. I worry and watch labs very closely for a while. I probably have no more than three to five patients on it in the practice. But when it works, it’s amazing stuff.

Now, let’s jump ahead to 2021. The year of Aduhelm (and several similar agents racing up behind it).

None of these drugs are even close to hitting home runs. For that matter, I’m not convinced they’re even able to get a man on base. To stretch my baseball analogy a bit, imagine watching a game by looking only at the RBI and ERA stats changing. The numbers change slightly, but you have no evidence that either team is winning. Which is, after all, the whole point.

And, to some extent, that’s the basis of Aduhelm’s approval, and likely the same standards its competitors will be held to.

Although they treat different conditions, and are chemically unrelated, the similarities between Felbatol and the currently advancing bunch of monoclonal antibody (MAB) agents for Alzheimer’s disease make an interesting contrast.

Unlike Felbatol’s proven efficacy for epilepsy, the current MABs offer minimal statistically significant clinical benefit for Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time the risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) and its complications with them is significantly higher than that of either of Felbatol’s known, potentially lethal, idiosyncratic effects.

With those odds, In medicine, every day is an exercise in working through the risks and benefits of each patient’s individual situation.

As I’ve stated before, I’m not in the grandstand rooting for these Alzheimer’s drugs to fail. I’ve lost a few family members, and certainly my share of patients, to dementia. I’d be thrilled, and more than willing to prescribe it, if something truly effective came along for it.

Nor do I take any kind of pleasure in the recent news that, because of Aduhelm’s failings, around 1,000 Biogen employees will lose their jobs. I feel terrible for them, as most had nothing to do with the decision to forge ahead with the product. More may soon follow at other companies working with similar agents.

Here we are, though, going into 2022. I’m still, albeit rarely, writing for Felbatol 30 years after it came to market for one reason: It works. But it seems pretty unlikely that future neurologists in 2052 will say the same about the current crops of MABs for Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I still, on occasion, use Felbatol (felbamate).

Thirty years since its explosive entrance to the market, then even more explosive collapse, it remains, in my opinion, the most effective of the second generation of anti-seizure medications. Arguably, even more effective than any of the third generation, too.

That’s not to say I use a lot of it. I don’t. It’s like handling unstable dynamite. Tremendous power, but also an above-average degree of risk. Even after things hit the fan with it in the mid-90s, I remember one of my epilepsy clinic attendings telling me, “This is a home-run drug. In refractory patients you might see some benefit by adding another agent, but with this one, you could stop their seizures and hit it out of the park.”

Like most neurologists, I use other epilepsy options first and second line. But sometimes you get the patient who’s failed the usual ones. Then I start to think about Felbatol. I explain the situation to the patients and their families and let them make the final decision. I worry and watch labs very closely for a while. I probably have no more than three to five patients on it in the practice. But when it works, it’s amazing stuff.

Now, let’s jump ahead to 2021. The year of Aduhelm (and several similar agents racing up behind it).

None of these drugs are even close to hitting home runs. For that matter, I’m not convinced they’re even able to get a man on base. To stretch my baseball analogy a bit, imagine watching a game by looking only at the RBI and ERA stats changing. The numbers change slightly, but you have no evidence that either team is winning. Which is, after all, the whole point.

And, to some extent, that’s the basis of Aduhelm’s approval, and likely the same standards its competitors will be held to.

Although they treat different conditions, and are chemically unrelated, the similarities between Felbatol and the currently advancing bunch of monoclonal antibody (MAB) agents for Alzheimer’s disease make an interesting contrast.

Unlike Felbatol’s proven efficacy for epilepsy, the current MABs offer minimal statistically significant clinical benefit for Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time the risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) and its complications with them is significantly higher than that of either of Felbatol’s known, potentially lethal, idiosyncratic effects.

With those odds, In medicine, every day is an exercise in working through the risks and benefits of each patient’s individual situation.

As I’ve stated before, I’m not in the grandstand rooting for these Alzheimer’s drugs to fail. I’ve lost a few family members, and certainly my share of patients, to dementia. I’d be thrilled, and more than willing to prescribe it, if something truly effective came along for it.

Nor do I take any kind of pleasure in the recent news that, because of Aduhelm’s failings, around 1,000 Biogen employees will lose their jobs. I feel terrible for them, as most had nothing to do with the decision to forge ahead with the product. More may soon follow at other companies working with similar agents.

Here we are, though, going into 2022. I’m still, albeit rarely, writing for Felbatol 30 years after it came to market for one reason: It works. But it seems pretty unlikely that future neurologists in 2052 will say the same about the current crops of MABs for Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

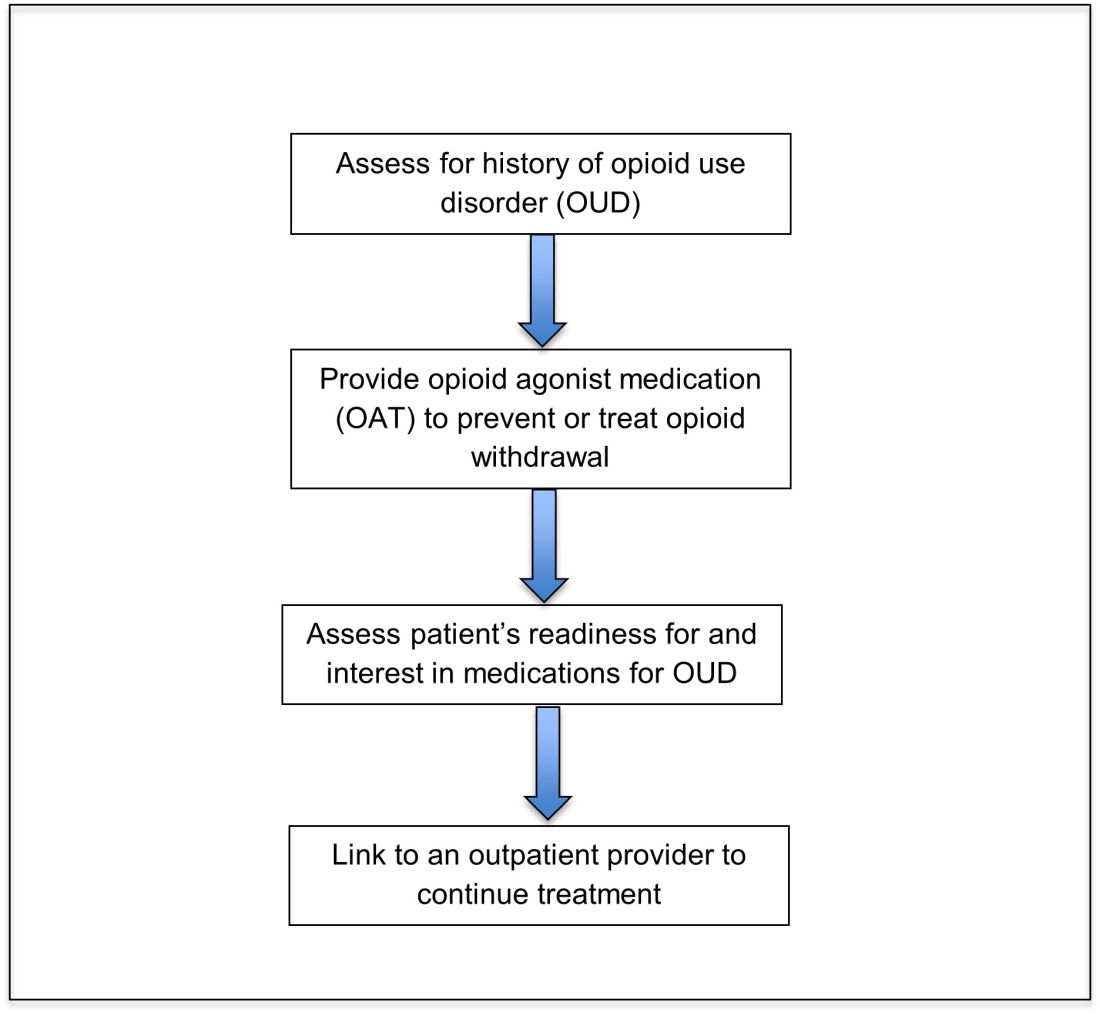

Treatment of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients

An opportunity for impact

Case

A 35-year-old woman with opioid use disorder (OUD) presents with fever, left arm redness, and swelling. She is admitted to the hospital for cellulitis treatment. On the day after admission she becomes agitated and develops nausea, diarrhea, and generalized pain. Opioid withdrawal is suspected. How should her opioid use be addressed while in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Since 1999, there have been more than 800,000 deaths related to drug overdose in the United States, and in 2019 more than 70% of drug overdose deaths involved an opioid.1,2 Although effective treatments for OUD exist, less than 20% of those with OUD are engaged in treatment.3

In America, 4%-11% of hospitalized patients have OUD. Hospitalized patients with OUD often experience stigma surrounding their disease, and many inpatient clinicians lack knowledge regarding the care of patients with OUD. As a result, withdrawal symptoms may go untreated, which can erode trust in the medical system and contribute to patients’ leaving the hospital before their primary medical issue is fully addressed. Therefore, it is essential that inpatient clinicians be familiar with the management of this complex and vulnerable patient population. Initiating treatment for OUD in the hospital setting is feasible and effective, and can lead to increased engagement in OUD treatment even after the hospital stay.

Overview of the data

Assessing patients with suspected OUD

Assessment for OUD starts with an in-depth opioid use history including frequency, amount, and method of administration. Clinicians should gather information regarding use of other substances or nonprescribed medications, and take thorough psychiatric and social histories. A formal diagnosis of OUD can be made using the Fifth Edition Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria.

Recognizing and managing opioid withdrawal

OUD in hospitalized patients often becomes apparent when patients develop signs and symptoms of withdrawal. Decreasing physical discomfort related to withdrawal can allow inpatient clinicians to address the condition for which the patient was hospitalized, help to strengthen the patient-clinician relationship, and provide an opportunity to discuss long-term OUD treatment.

Signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal include anxiety, restlessness, irritability, generalized pain, rhinorrhea, yawning, lacrimation, piloerection, anorexia, and nausea. Withdrawal can last days to weeks, depending on the half-life of the opioid that was used. Opioids with shorter half-lives, such as heroin or oxycodone, cause withdrawal with earlier onset and shorter duration than do opioids with longer half-lives, such as methadone. The degree of withdrawal can be quantified with validated tools, such as the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS).

Treatment of opioid withdrawal should generally include the use of an opioid agonist such as methadone or buprenorphine. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis found methadone or buprenorphine to be more effective than clonidine in alleviating symptoms of withdrawal and in retaining patients in treatment.4 Clonidine, an alpha2-adrenergic agonist that binds to receptors in the locus coeruleus, does not alleviate opioid cravings, but may be used as an adjunctive treatment for associated autonomic withdrawal symptoms. Other adjunctive medications include analgesics, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, and antihistamines.

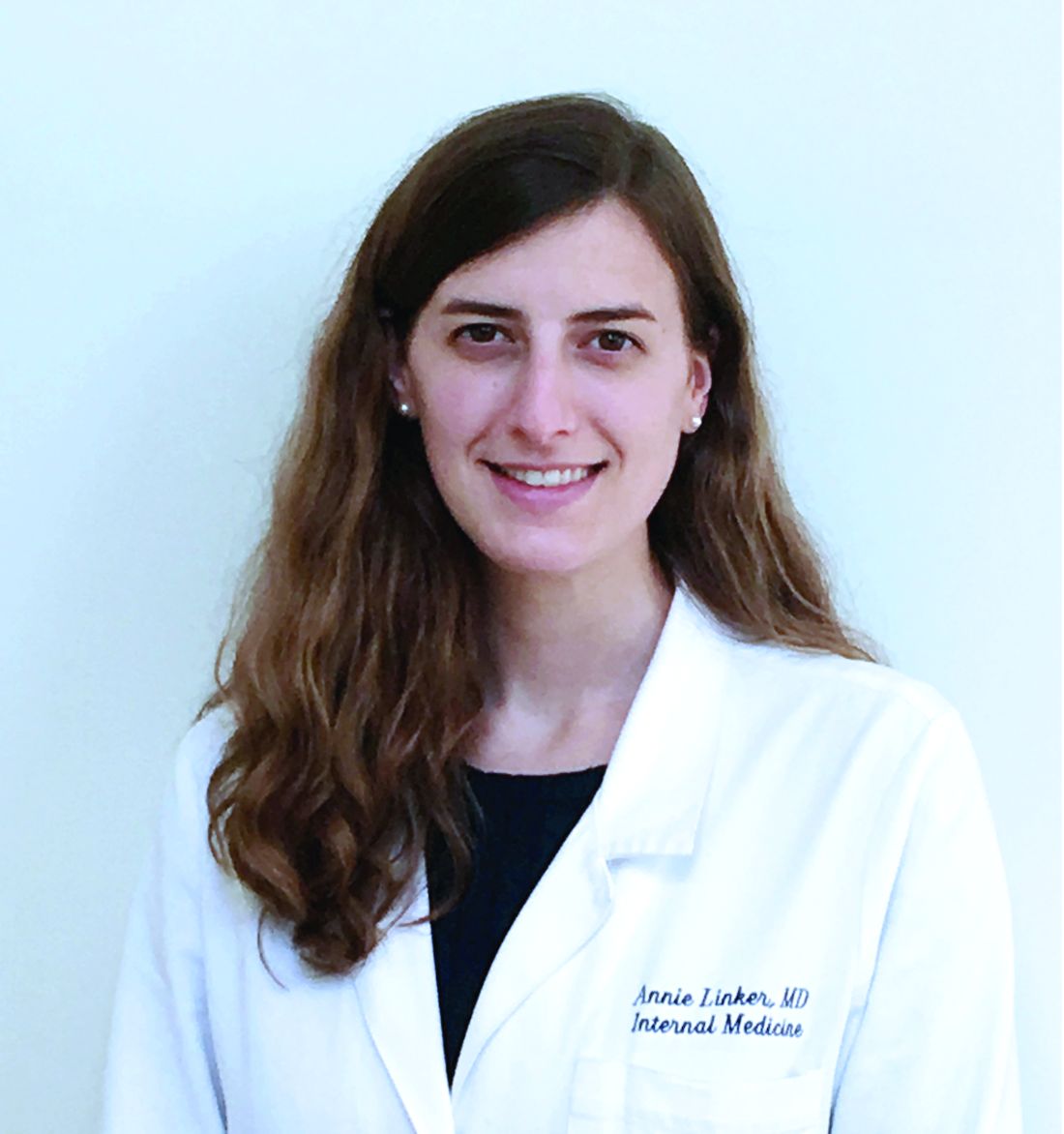

Opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine is associated with decreased mortality, opioid use, and infectious complications, but remains underutilized.5 Hospitalized patients with OUD are frequently managed with a rapid opioid detoxification and then discharged without continued OUD treatment. Detoxification alone can lead to a relapse rate as high as 90%.6 Patients are at increased risk for overdose after withdrawal due to loss of tolerance. Inpatient clinicians can close this OUD treatment gap by familiarizing themselves with OAT and offering to initiate OAT for maintenance treatment in interested patients. In one study, patients started on buprenorphine while hospitalized were more likely to be engaged in treatment and less likely to report drug use at follow-up, compared to patients who were referred without starting the medication.7

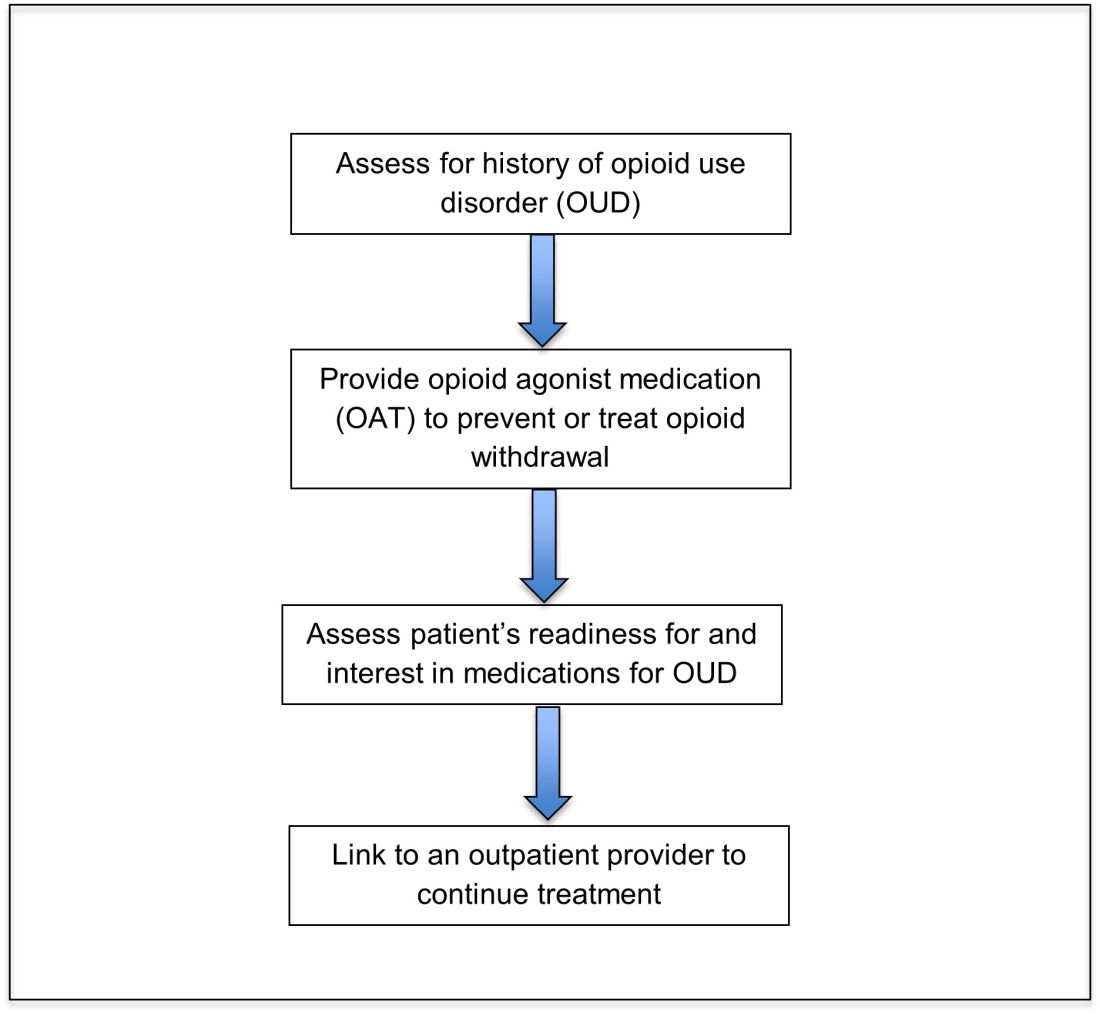

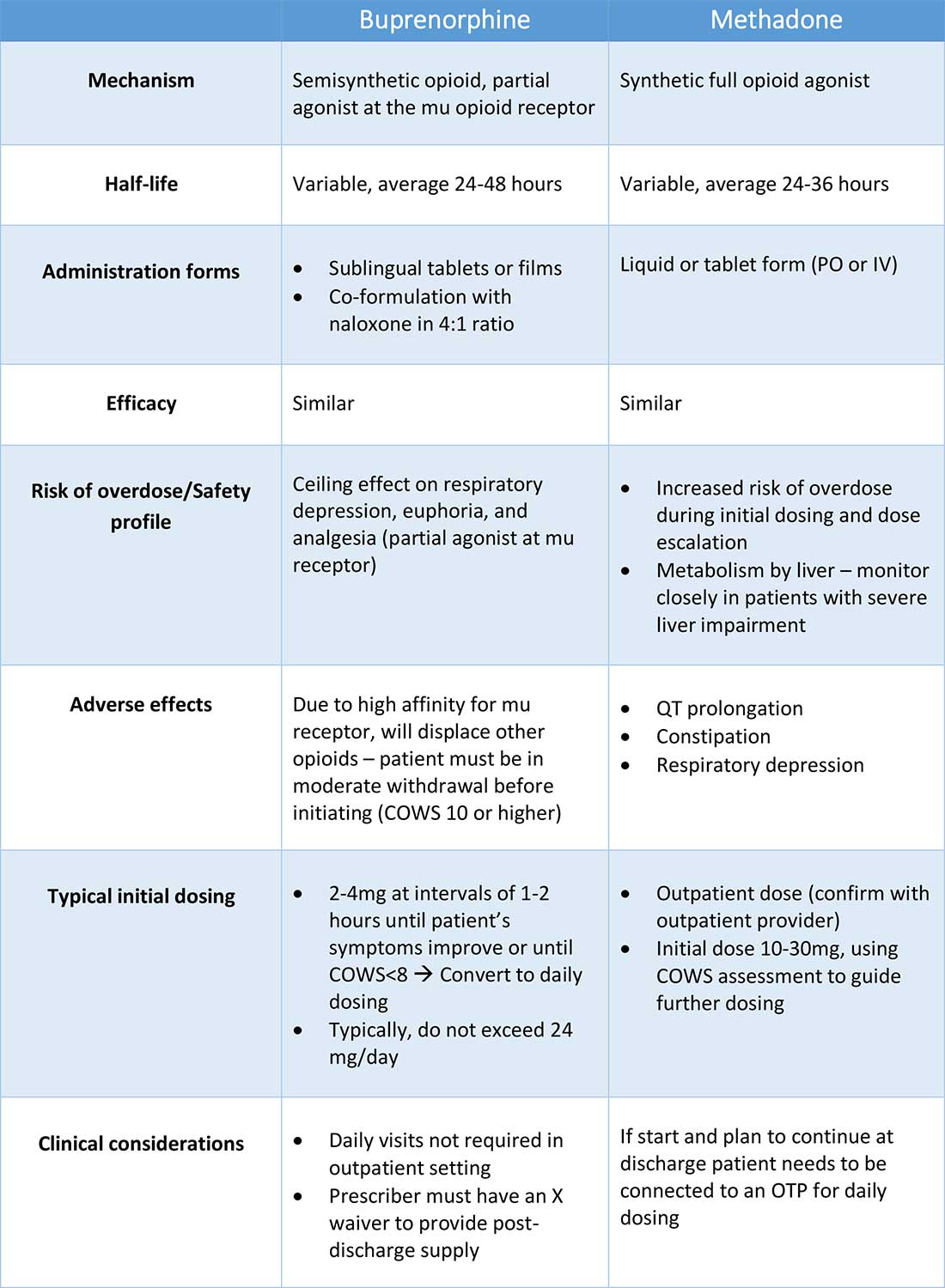

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the mu opioid receptor that can be ordered in the inpatient setting by any clinician. In the outpatient setting only DATA 2000 waivered clinicians can prescribe buprenorphine.8 Buprenorphine is most commonly coformulated with naloxone, an opioid antagonist, and is available in sublingual films or tablets. The naloxone component is not bioavailable when taken sublingually but becomes bioavailable if the drug is injected intravenously, leading to acute withdrawal.

Buprenorphine has a higher affinity for the mu opioid receptor than most opioids. If administered while other opioids are still present, it will displace the other opioid from the receptor but only partially stimulate the receptor, which can cause precipitated withdrawal. Buprenorphine initiation can start when the COWS score reflects moderate withdrawal. Many institutions use a threshold of 8-12 on the COWS scale. Typical dosing is 2-4 mg of buprenorphine at intervals of 1-2 hours as needed until the COWS score is less than 8, up to a maximum of 16 mg on day 1. The total dose from day 1 may be given as a daily dose beginning on day 2, up to a maximum total daily dose of 24 mg.

In recent years, a method of initiating buprenorphine called “micro-dosing” has gained traction. Very small doses of buprenorphine are given while a patient is receiving other opioids, thereby reducing the risk of precipitated withdrawal. This method can be helpful for patients who cannot tolerate withdrawal or who have recently taken long-acting opioids such as methadone. Such protocols should be utilized only at centers where consultation with an addiction specialist or experienced clinician is possible.

Despite evidence of buprenorphine’s efficacy, there are barriers to prescribing it. Physicians and advanced practitioners must be granted a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe buprenorphine to outpatients. As of 2017, less than 10% of primary care physicians had obtained waivers.9 However, inpatient clinicians without a waiver can order buprenorphine and initiate treatment. Best practice is to do so with a specific plan for continuation at discharge. We encourage inpatient clinicians to obtain a waiver, so that a prescription can be given at discharge to bridge the patient to a first appointment with a community clinician who can continue treatment. As of April 27, 2021, providers treating fewer than 30 patients with OUD at one time may obtain a waiver without additional training.10

Methadone

Methadone is a full agonist at the mu opioid receptor. In the hospital setting, methadone can be ordered by any clinician to prevent and treat withdrawal. Commonly, doses of 10 mg can be given using the COWS score to guide the need for additional dosing. The patient can be reassessed every 1-2 hours to ensure that symptoms are improving, and that there is no sign of oversedation before giving additional methadone. For most patients, withdrawal can be managed with 20-40 mg of methadone daily.

In contrast to buprenorphine, methadone will not precipitate withdrawal and can be initiated even when patients are not yet showing withdrawal symptoms. Outpatient methadone treatment for OUD is federally regulated and can be delivered only in opioid treatment programs (OTPs).

Choosing methadone or buprenorphine in the inpatient setting

The choice between buprenorphine and methadone should take into consideration several factors, including patient preference, treatment history, and available outpatient treatment programs, which may vary widely by geographic region. Some patients benefit from the higher level of support and counseling available at OTPs. Methadone is available at all OTPs, and the availability of buprenorphine in this setting is increasing. Other patients may prefer the convenience and flexibility of buprenorphine treatment in an outpatient office setting.

Some patients have prior negative experiences with OAT. These can include prior precipitated withdrawal with buprenorphine induction, or negative experiences with the structure of OTPs. Clinicians are encouraged to provide counseling if patients have a history of precipitated withdrawal to assure them that this can be avoided with proper dosing. Clinicians should be familiar with available treatment options in their community and can refer to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website to locate OTPs and buprenorphine prescribers.

Polypharmacy and safety

If combined with benzodiazepines, alcohol, or other sedating agents, methadone or buprenorphine can increase risk of overdose. However, OUD treatment should not be withheld because of other substance use. Clinicians initiating treatment should counsel patients on the risk of concomitant substance use and provide overdose prevention education.

A brief note on naltrexone

Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is used more commonly in outpatient addiction treatment than in the inpatient setting, but inpatient clinicians should be aware of its use. It is available in oral and long-acting injectable formulations. Its utility in the inpatient setting may be limited as safe administration requires 7-10 days of opioid abstinence.

Discharge planning

Patients with OUD or who are started on OAT during a hospitalization should be linked to continued outpatient treatment. Before discharge it is best to ensure vaccinations for HAV, HBV, pneumococcus, and tetanus are up to date, and perform screening for HIV, hepatitis C, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections if appropriate. All patients with OUD should be prescribed or provided with take-home naloxone for overdose reversal. Patients can also be referred to syringe service programs for additional harm reduction counseling and services.

Application of the data to our patient

For our patient, either methadone or buprenorphine could be used to treat her withdrawal. The COWS score should be used to assess withdrawal severity, and to guide appropriate timing of medication initiation. If she wishes to continue OAT after discharge, she should be linked to a clinician who can engage her in ongoing medical care. Prior to discharge she should also receive relevant vaccines and screening for infectious diseases as outlined above, as well as take-home naloxone (or a prescription).

Bottom line

Inpatient clinicians can play a pivotal role in patients’ lives by ensuring that patients with OUD receive OAT and are connected to outpatient care at discharge.

Dr. Linker is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Ms. Hirt, Mr. Fine, and Mr. Villasanivis are medical students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the division of general internal medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Herscher is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

1. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov.

2. Mattson CL et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202-7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4.

3. Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

4. Gowing L et al. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2017(2):CD002025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub5.

5. Sordo L et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017 Apr 26;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550.

6. Smyth BP et al. Lapse and relapse following inpatient treatment of opiate dependence. Ir Med J. 2010 Jun;103(6):176-9. Available at www.drugsandalcohol.ie/13405.

7. Liebschutz JM. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Aug;174(8):1369-76. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556.

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (Aug 20, 2020) Statutes, Regulations, and Guidelines.

9. McBain RK et al. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(7):504-6. doi: 10.7326/M19-2403.

10. HHS releases new buprenorphine practice guidelines, expanding access to treatment for opioid use disorder. Apr 27, 2021.

11. Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Additional reading

Winetsky D. Expanding treatment opportunities for hospitalized patients with opioid use disorders. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan;13(1):62-4. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2861.

Donroe JH. Caring for patients with opioid use disorder in the hospital. Can Med Assoc J. 2016 Dec 6;188(17-18):1232-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160290.

Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Key points

- Most patients with OUD are not engaged in evidence-based treatment. Clinicians have an opportunity to utilize the inpatient stay as a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

- Buprenorphine and methadone are effective opioid agonist medications used to treat OUD, and clinicians with the appropriate knowledge base can initiate either during the inpatient encounter, and link the patient to OUD treatment after the hospital stay.

Quiz

Caring for hospitalized patients with OUD

Most patients with OUD are not engaged in effective treatment. Hospitalization can be a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

1. Which is an effective and evidence-based medication for treating opioid withdrawal and OUD?

a) Naltrexone.

b) Buprenorphine.

c) Opioid detoxification.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Buprenorphine is effective for alleviating symptoms of withdrawal as well as for the long-term treatment of OUD. While naltrexone is also used to treat OUD, it is not useful for treating withdrawal. Clonidine can be a useful adjunctive medication for treating withdrawal but is not a long-term treatment for OUD. Nonpharmacologic detoxification is not an effective treatment for OUD and is associated with high relapse rates.

2. What scale can be used during a hospital stay to monitor patients with OUD at risk of opioid withdrawal, and to aid in buprenorphine initiation?

a) CIWA score.

b) PADUA score.

c) COWS score.

d) 4T score.

Explanation: COWS is the “clinical opiate withdrawal scale.” The COWS score should be calculated by a trained provider, and includes objective parameters (such as pulse) and subjective symptoms (such as GI upset, bone/joint aches.) It is recommended that agonist therapy be started when the COWS score is consistent with moderate withdrawal.

3. How can clinicians reliably find out if there are outpatient resources/clinics for patients with OUD in their area?

a) No way to find this out without personal knowledge.

b) Hospital providers and patients can visit www.samhsa.gov/find-help/national-helpline or call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) to find options for treatment for substance use disorders in their areas.

c) Dial “0” on any phone and ask.

d) Ask around at your hospital.

Explanation: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that is engaged in public health efforts to reduce the impact of substance abuse and mental illness on local communities. The agency’s website has helpful information about resources for substance use treatment.

4. Patients with OUD should be prescribed and given training about what medication that can be lifesaving when given during an opioid overdose?

a) Aspirin.

b) Naloxone.

c) Naltrexone.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Naloxone can be life-saving in the setting of an overdose. Best practice is to provide naloxone and training to patients with OUD.

5. When patients take buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids, there is concern for the development of which reaction:

a) Precipitated withdrawal.

b) Opioid overdose.

c) Allergic reaction.

d) Intoxication.

Explanation: Administering buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids can cause precipitated withdrawal, as buprenorphine binds with higher affinity to the mu receptor than many opioids. Precipitated withdrawal causes severe discomfort and can be dangerous for patients.

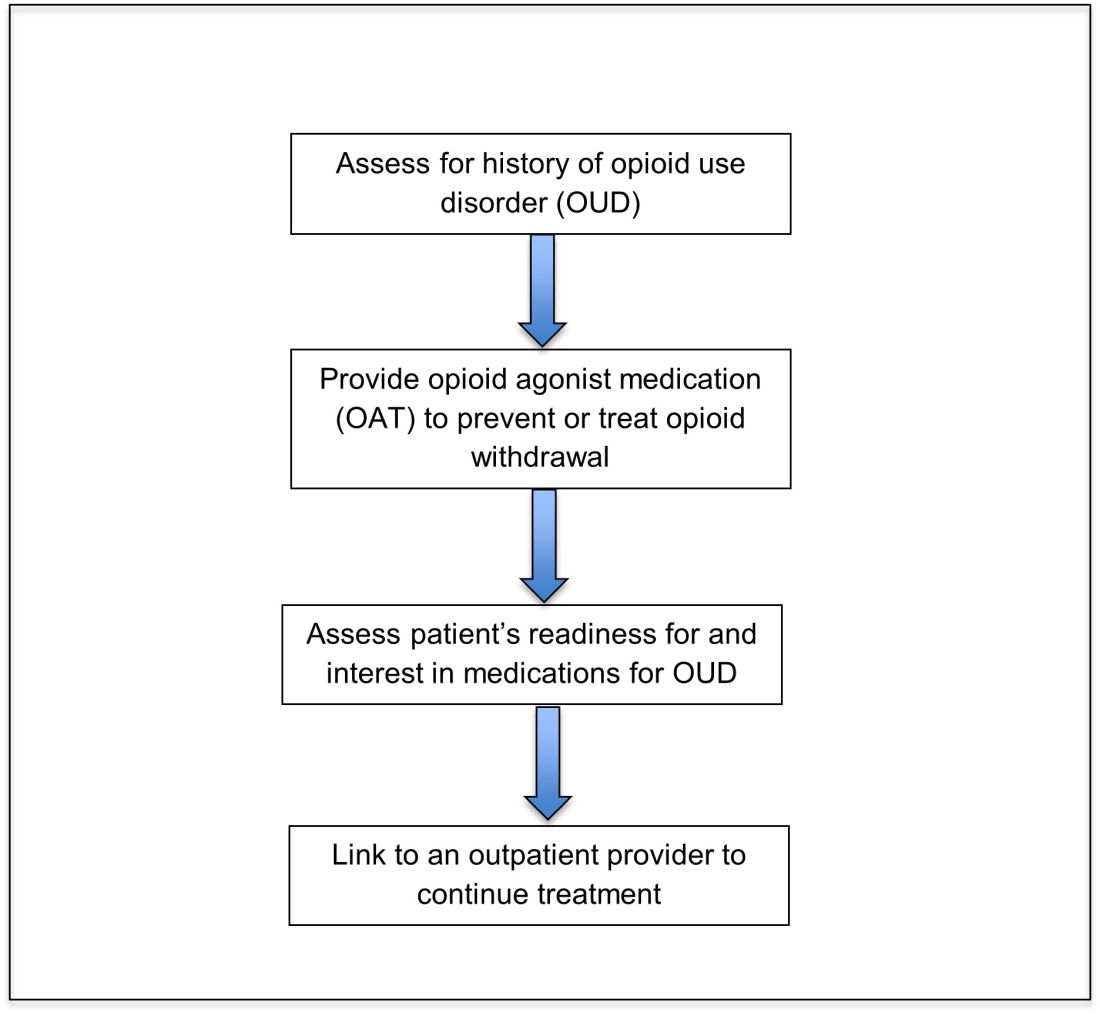

An opportunity for impact

An opportunity for impact

Case

A 35-year-old woman with opioid use disorder (OUD) presents with fever, left arm redness, and swelling. She is admitted to the hospital for cellulitis treatment. On the day after admission she becomes agitated and develops nausea, diarrhea, and generalized pain. Opioid withdrawal is suspected. How should her opioid use be addressed while in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Since 1999, there have been more than 800,000 deaths related to drug overdose in the United States, and in 2019 more than 70% of drug overdose deaths involved an opioid.1,2 Although effective treatments for OUD exist, less than 20% of those with OUD are engaged in treatment.3

In America, 4%-11% of hospitalized patients have OUD. Hospitalized patients with OUD often experience stigma surrounding their disease, and many inpatient clinicians lack knowledge regarding the care of patients with OUD. As a result, withdrawal symptoms may go untreated, which can erode trust in the medical system and contribute to patients’ leaving the hospital before their primary medical issue is fully addressed. Therefore, it is essential that inpatient clinicians be familiar with the management of this complex and vulnerable patient population. Initiating treatment for OUD in the hospital setting is feasible and effective, and can lead to increased engagement in OUD treatment even after the hospital stay.

Overview of the data

Assessing patients with suspected OUD

Assessment for OUD starts with an in-depth opioid use history including frequency, amount, and method of administration. Clinicians should gather information regarding use of other substances or nonprescribed medications, and take thorough psychiatric and social histories. A formal diagnosis of OUD can be made using the Fifth Edition Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria.

Recognizing and managing opioid withdrawal

OUD in hospitalized patients often becomes apparent when patients develop signs and symptoms of withdrawal. Decreasing physical discomfort related to withdrawal can allow inpatient clinicians to address the condition for which the patient was hospitalized, help to strengthen the patient-clinician relationship, and provide an opportunity to discuss long-term OUD treatment.

Signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal include anxiety, restlessness, irritability, generalized pain, rhinorrhea, yawning, lacrimation, piloerection, anorexia, and nausea. Withdrawal can last days to weeks, depending on the half-life of the opioid that was used. Opioids with shorter half-lives, such as heroin or oxycodone, cause withdrawal with earlier onset and shorter duration than do opioids with longer half-lives, such as methadone. The degree of withdrawal can be quantified with validated tools, such as the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS).

Treatment of opioid withdrawal should generally include the use of an opioid agonist such as methadone or buprenorphine. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis found methadone or buprenorphine to be more effective than clonidine in alleviating symptoms of withdrawal and in retaining patients in treatment.4 Clonidine, an alpha2-adrenergic agonist that binds to receptors in the locus coeruleus, does not alleviate opioid cravings, but may be used as an adjunctive treatment for associated autonomic withdrawal symptoms. Other adjunctive medications include analgesics, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, and antihistamines.

Opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine is associated with decreased mortality, opioid use, and infectious complications, but remains underutilized.5 Hospitalized patients with OUD are frequently managed with a rapid opioid detoxification and then discharged without continued OUD treatment. Detoxification alone can lead to a relapse rate as high as 90%.6 Patients are at increased risk for overdose after withdrawal due to loss of tolerance. Inpatient clinicians can close this OUD treatment gap by familiarizing themselves with OAT and offering to initiate OAT for maintenance treatment in interested patients. In one study, patients started on buprenorphine while hospitalized were more likely to be engaged in treatment and less likely to report drug use at follow-up, compared to patients who were referred without starting the medication.7

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the mu opioid receptor that can be ordered in the inpatient setting by any clinician. In the outpatient setting only DATA 2000 waivered clinicians can prescribe buprenorphine.8 Buprenorphine is most commonly coformulated with naloxone, an opioid antagonist, and is available in sublingual films or tablets. The naloxone component is not bioavailable when taken sublingually but becomes bioavailable if the drug is injected intravenously, leading to acute withdrawal.

Buprenorphine has a higher affinity for the mu opioid receptor than most opioids. If administered while other opioids are still present, it will displace the other opioid from the receptor but only partially stimulate the receptor, which can cause precipitated withdrawal. Buprenorphine initiation can start when the COWS score reflects moderate withdrawal. Many institutions use a threshold of 8-12 on the COWS scale. Typical dosing is 2-4 mg of buprenorphine at intervals of 1-2 hours as needed until the COWS score is less than 8, up to a maximum of 16 mg on day 1. The total dose from day 1 may be given as a daily dose beginning on day 2, up to a maximum total daily dose of 24 mg.

In recent years, a method of initiating buprenorphine called “micro-dosing” has gained traction. Very small doses of buprenorphine are given while a patient is receiving other opioids, thereby reducing the risk of precipitated withdrawal. This method can be helpful for patients who cannot tolerate withdrawal or who have recently taken long-acting opioids such as methadone. Such protocols should be utilized only at centers where consultation with an addiction specialist or experienced clinician is possible.

Despite evidence of buprenorphine’s efficacy, there are barriers to prescribing it. Physicians and advanced practitioners must be granted a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe buprenorphine to outpatients. As of 2017, less than 10% of primary care physicians had obtained waivers.9 However, inpatient clinicians without a waiver can order buprenorphine and initiate treatment. Best practice is to do so with a specific plan for continuation at discharge. We encourage inpatient clinicians to obtain a waiver, so that a prescription can be given at discharge to bridge the patient to a first appointment with a community clinician who can continue treatment. As of April 27, 2021, providers treating fewer than 30 patients with OUD at one time may obtain a waiver without additional training.10

Methadone

Methadone is a full agonist at the mu opioid receptor. In the hospital setting, methadone can be ordered by any clinician to prevent and treat withdrawal. Commonly, doses of 10 mg can be given using the COWS score to guide the need for additional dosing. The patient can be reassessed every 1-2 hours to ensure that symptoms are improving, and that there is no sign of oversedation before giving additional methadone. For most patients, withdrawal can be managed with 20-40 mg of methadone daily.

In contrast to buprenorphine, methadone will not precipitate withdrawal and can be initiated even when patients are not yet showing withdrawal symptoms. Outpatient methadone treatment for OUD is federally regulated and can be delivered only in opioid treatment programs (OTPs).

Choosing methadone or buprenorphine in the inpatient setting

The choice between buprenorphine and methadone should take into consideration several factors, including patient preference, treatment history, and available outpatient treatment programs, which may vary widely by geographic region. Some patients benefit from the higher level of support and counseling available at OTPs. Methadone is available at all OTPs, and the availability of buprenorphine in this setting is increasing. Other patients may prefer the convenience and flexibility of buprenorphine treatment in an outpatient office setting.

Some patients have prior negative experiences with OAT. These can include prior precipitated withdrawal with buprenorphine induction, or negative experiences with the structure of OTPs. Clinicians are encouraged to provide counseling if patients have a history of precipitated withdrawal to assure them that this can be avoided with proper dosing. Clinicians should be familiar with available treatment options in their community and can refer to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website to locate OTPs and buprenorphine prescribers.

Polypharmacy and safety

If combined with benzodiazepines, alcohol, or other sedating agents, methadone or buprenorphine can increase risk of overdose. However, OUD treatment should not be withheld because of other substance use. Clinicians initiating treatment should counsel patients on the risk of concomitant substance use and provide overdose prevention education.

A brief note on naltrexone

Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is used more commonly in outpatient addiction treatment than in the inpatient setting, but inpatient clinicians should be aware of its use. It is available in oral and long-acting injectable formulations. Its utility in the inpatient setting may be limited as safe administration requires 7-10 days of opioid abstinence.

Discharge planning

Patients with OUD or who are started on OAT during a hospitalization should be linked to continued outpatient treatment. Before discharge it is best to ensure vaccinations for HAV, HBV, pneumococcus, and tetanus are up to date, and perform screening for HIV, hepatitis C, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections if appropriate. All patients with OUD should be prescribed or provided with take-home naloxone for overdose reversal. Patients can also be referred to syringe service programs for additional harm reduction counseling and services.

Application of the data to our patient

For our patient, either methadone or buprenorphine could be used to treat her withdrawal. The COWS score should be used to assess withdrawal severity, and to guide appropriate timing of medication initiation. If she wishes to continue OAT after discharge, she should be linked to a clinician who can engage her in ongoing medical care. Prior to discharge she should also receive relevant vaccines and screening for infectious diseases as outlined above, as well as take-home naloxone (or a prescription).

Bottom line

Inpatient clinicians can play a pivotal role in patients’ lives by ensuring that patients with OUD receive OAT and are connected to outpatient care at discharge.

Dr. Linker is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Ms. Hirt, Mr. Fine, and Mr. Villasanivis are medical students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the division of general internal medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Herscher is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

1. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov.

2. Mattson CL et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202-7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4.

3. Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

4. Gowing L et al. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2017(2):CD002025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub5.

5. Sordo L et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017 Apr 26;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550.

6. Smyth BP et al. Lapse and relapse following inpatient treatment of opiate dependence. Ir Med J. 2010 Jun;103(6):176-9. Available at www.drugsandalcohol.ie/13405.

7. Liebschutz JM. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Aug;174(8):1369-76. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556.

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (Aug 20, 2020) Statutes, Regulations, and Guidelines.

9. McBain RK et al. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(7):504-6. doi: 10.7326/M19-2403.

10. HHS releases new buprenorphine practice guidelines, expanding access to treatment for opioid use disorder. Apr 27, 2021.

11. Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Additional reading

Winetsky D. Expanding treatment opportunities for hospitalized patients with opioid use disorders. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan;13(1):62-4. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2861.

Donroe JH. Caring for patients with opioid use disorder in the hospital. Can Med Assoc J. 2016 Dec 6;188(17-18):1232-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160290.

Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Key points

- Most patients with OUD are not engaged in evidence-based treatment. Clinicians have an opportunity to utilize the inpatient stay as a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

- Buprenorphine and methadone are effective opioid agonist medications used to treat OUD, and clinicians with the appropriate knowledge base can initiate either during the inpatient encounter, and link the patient to OUD treatment after the hospital stay.

Quiz

Caring for hospitalized patients with OUD

Most patients with OUD are not engaged in effective treatment. Hospitalization can be a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

1. Which is an effective and evidence-based medication for treating opioid withdrawal and OUD?

a) Naltrexone.

b) Buprenorphine.

c) Opioid detoxification.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Buprenorphine is effective for alleviating symptoms of withdrawal as well as for the long-term treatment of OUD. While naltrexone is also used to treat OUD, it is not useful for treating withdrawal. Clonidine can be a useful adjunctive medication for treating withdrawal but is not a long-term treatment for OUD. Nonpharmacologic detoxification is not an effective treatment for OUD and is associated with high relapse rates.

2. What scale can be used during a hospital stay to monitor patients with OUD at risk of opioid withdrawal, and to aid in buprenorphine initiation?

a) CIWA score.

b) PADUA score.

c) COWS score.

d) 4T score.

Explanation: COWS is the “clinical opiate withdrawal scale.” The COWS score should be calculated by a trained provider, and includes objective parameters (such as pulse) and subjective symptoms (such as GI upset, bone/joint aches.) It is recommended that agonist therapy be started when the COWS score is consistent with moderate withdrawal.

3. How can clinicians reliably find out if there are outpatient resources/clinics for patients with OUD in their area?

a) No way to find this out without personal knowledge.

b) Hospital providers and patients can visit www.samhsa.gov/find-help/national-helpline or call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) to find options for treatment for substance use disorders in their areas.

c) Dial “0” on any phone and ask.

d) Ask around at your hospital.

Explanation: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that is engaged in public health efforts to reduce the impact of substance abuse and mental illness on local communities. The agency’s website has helpful information about resources for substance use treatment.

4. Patients with OUD should be prescribed and given training about what medication that can be lifesaving when given during an opioid overdose?

a) Aspirin.

b) Naloxone.

c) Naltrexone.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Naloxone can be life-saving in the setting of an overdose. Best practice is to provide naloxone and training to patients with OUD.

5. When patients take buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids, there is concern for the development of which reaction:

a) Precipitated withdrawal.

b) Opioid overdose.

c) Allergic reaction.

d) Intoxication.

Explanation: Administering buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids can cause precipitated withdrawal, as buprenorphine binds with higher affinity to the mu receptor than many opioids. Precipitated withdrawal causes severe discomfort and can be dangerous for patients.

Case

A 35-year-old woman with opioid use disorder (OUD) presents with fever, left arm redness, and swelling. She is admitted to the hospital for cellulitis treatment. On the day after admission she becomes agitated and develops nausea, diarrhea, and generalized pain. Opioid withdrawal is suspected. How should her opioid use be addressed while in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Since 1999, there have been more than 800,000 deaths related to drug overdose in the United States, and in 2019 more than 70% of drug overdose deaths involved an opioid.1,2 Although effective treatments for OUD exist, less than 20% of those with OUD are engaged in treatment.3

In America, 4%-11% of hospitalized patients have OUD. Hospitalized patients with OUD often experience stigma surrounding their disease, and many inpatient clinicians lack knowledge regarding the care of patients with OUD. As a result, withdrawal symptoms may go untreated, which can erode trust in the medical system and contribute to patients’ leaving the hospital before their primary medical issue is fully addressed. Therefore, it is essential that inpatient clinicians be familiar with the management of this complex and vulnerable patient population. Initiating treatment for OUD in the hospital setting is feasible and effective, and can lead to increased engagement in OUD treatment even after the hospital stay.

Overview of the data

Assessing patients with suspected OUD

Assessment for OUD starts with an in-depth opioid use history including frequency, amount, and method of administration. Clinicians should gather information regarding use of other substances or nonprescribed medications, and take thorough psychiatric and social histories. A formal diagnosis of OUD can be made using the Fifth Edition Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria.

Recognizing and managing opioid withdrawal

OUD in hospitalized patients often becomes apparent when patients develop signs and symptoms of withdrawal. Decreasing physical discomfort related to withdrawal can allow inpatient clinicians to address the condition for which the patient was hospitalized, help to strengthen the patient-clinician relationship, and provide an opportunity to discuss long-term OUD treatment.

Signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal include anxiety, restlessness, irritability, generalized pain, rhinorrhea, yawning, lacrimation, piloerection, anorexia, and nausea. Withdrawal can last days to weeks, depending on the half-life of the opioid that was used. Opioids with shorter half-lives, such as heroin or oxycodone, cause withdrawal with earlier onset and shorter duration than do opioids with longer half-lives, such as methadone. The degree of withdrawal can be quantified with validated tools, such as the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS).

Treatment of opioid withdrawal should generally include the use of an opioid agonist such as methadone or buprenorphine. A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis found methadone or buprenorphine to be more effective than clonidine in alleviating symptoms of withdrawal and in retaining patients in treatment.4 Clonidine, an alpha2-adrenergic agonist that binds to receptors in the locus coeruleus, does not alleviate opioid cravings, but may be used as an adjunctive treatment for associated autonomic withdrawal symptoms. Other adjunctive medications include analgesics, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, and antihistamines.

Opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) with methadone or buprenorphine is associated with decreased mortality, opioid use, and infectious complications, but remains underutilized.5 Hospitalized patients with OUD are frequently managed with a rapid opioid detoxification and then discharged without continued OUD treatment. Detoxification alone can lead to a relapse rate as high as 90%.6 Patients are at increased risk for overdose after withdrawal due to loss of tolerance. Inpatient clinicians can close this OUD treatment gap by familiarizing themselves with OAT and offering to initiate OAT for maintenance treatment in interested patients. In one study, patients started on buprenorphine while hospitalized were more likely to be engaged in treatment and less likely to report drug use at follow-up, compared to patients who were referred without starting the medication.7

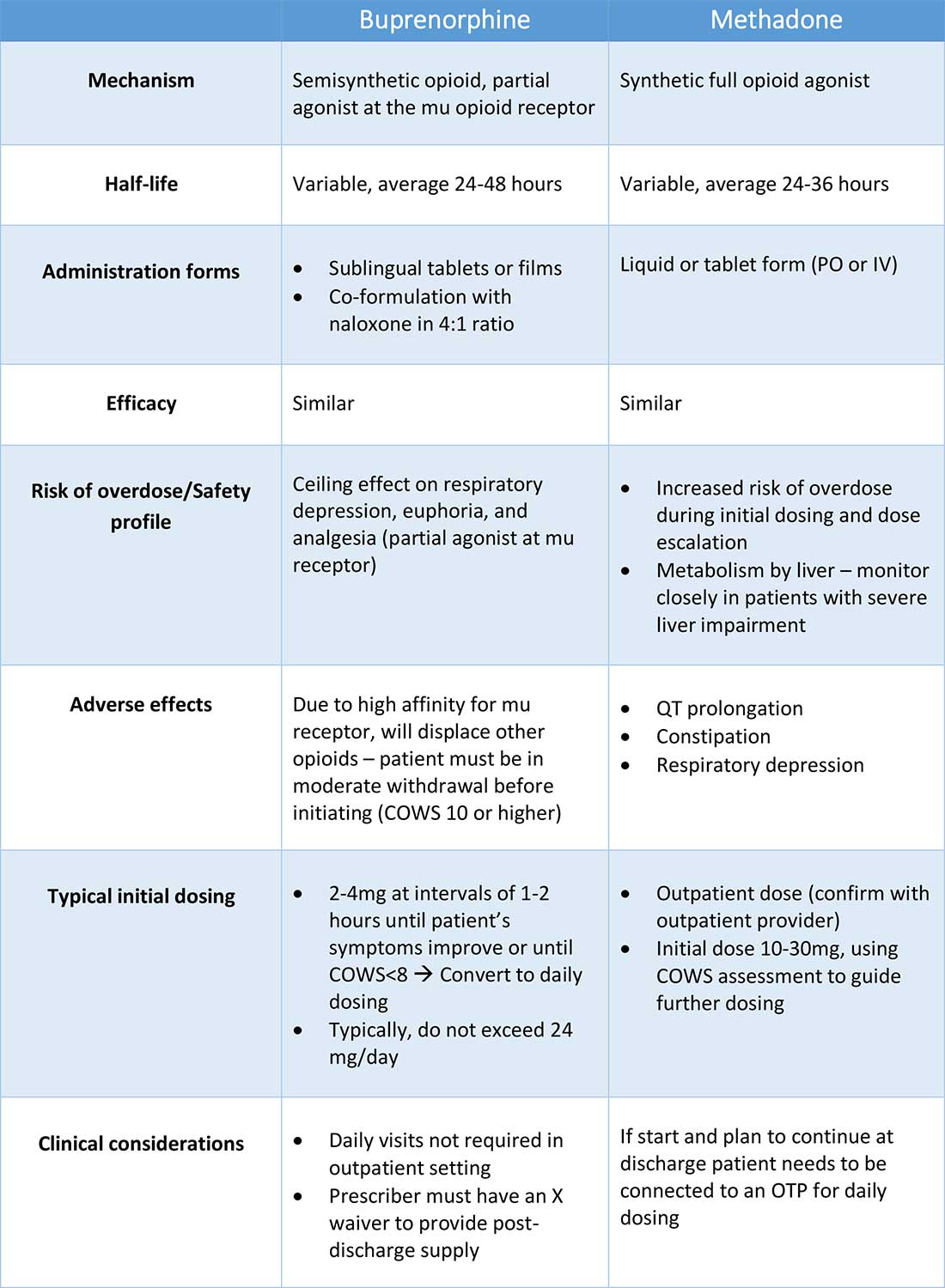

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial agonist at the mu opioid receptor that can be ordered in the inpatient setting by any clinician. In the outpatient setting only DATA 2000 waivered clinicians can prescribe buprenorphine.8 Buprenorphine is most commonly coformulated with naloxone, an opioid antagonist, and is available in sublingual films or tablets. The naloxone component is not bioavailable when taken sublingually but becomes bioavailable if the drug is injected intravenously, leading to acute withdrawal.

Buprenorphine has a higher affinity for the mu opioid receptor than most opioids. If administered while other opioids are still present, it will displace the other opioid from the receptor but only partially stimulate the receptor, which can cause precipitated withdrawal. Buprenorphine initiation can start when the COWS score reflects moderate withdrawal. Many institutions use a threshold of 8-12 on the COWS scale. Typical dosing is 2-4 mg of buprenorphine at intervals of 1-2 hours as needed until the COWS score is less than 8, up to a maximum of 16 mg on day 1. The total dose from day 1 may be given as a daily dose beginning on day 2, up to a maximum total daily dose of 24 mg.

In recent years, a method of initiating buprenorphine called “micro-dosing” has gained traction. Very small doses of buprenorphine are given while a patient is receiving other opioids, thereby reducing the risk of precipitated withdrawal. This method can be helpful for patients who cannot tolerate withdrawal or who have recently taken long-acting opioids such as methadone. Such protocols should be utilized only at centers where consultation with an addiction specialist or experienced clinician is possible.

Despite evidence of buprenorphine’s efficacy, there are barriers to prescribing it. Physicians and advanced practitioners must be granted a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe buprenorphine to outpatients. As of 2017, less than 10% of primary care physicians had obtained waivers.9 However, inpatient clinicians without a waiver can order buprenorphine and initiate treatment. Best practice is to do so with a specific plan for continuation at discharge. We encourage inpatient clinicians to obtain a waiver, so that a prescription can be given at discharge to bridge the patient to a first appointment with a community clinician who can continue treatment. As of April 27, 2021, providers treating fewer than 30 patients with OUD at one time may obtain a waiver without additional training.10

Methadone

Methadone is a full agonist at the mu opioid receptor. In the hospital setting, methadone can be ordered by any clinician to prevent and treat withdrawal. Commonly, doses of 10 mg can be given using the COWS score to guide the need for additional dosing. The patient can be reassessed every 1-2 hours to ensure that symptoms are improving, and that there is no sign of oversedation before giving additional methadone. For most patients, withdrawal can be managed with 20-40 mg of methadone daily.

In contrast to buprenorphine, methadone will not precipitate withdrawal and can be initiated even when patients are not yet showing withdrawal symptoms. Outpatient methadone treatment for OUD is federally regulated and can be delivered only in opioid treatment programs (OTPs).

Choosing methadone or buprenorphine in the inpatient setting

The choice between buprenorphine and methadone should take into consideration several factors, including patient preference, treatment history, and available outpatient treatment programs, which may vary widely by geographic region. Some patients benefit from the higher level of support and counseling available at OTPs. Methadone is available at all OTPs, and the availability of buprenorphine in this setting is increasing. Other patients may prefer the convenience and flexibility of buprenorphine treatment in an outpatient office setting.

Some patients have prior negative experiences with OAT. These can include prior precipitated withdrawal with buprenorphine induction, or negative experiences with the structure of OTPs. Clinicians are encouraged to provide counseling if patients have a history of precipitated withdrawal to assure them that this can be avoided with proper dosing. Clinicians should be familiar with available treatment options in their community and can refer to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website to locate OTPs and buprenorphine prescribers.

Polypharmacy and safety

If combined with benzodiazepines, alcohol, or other sedating agents, methadone or buprenorphine can increase risk of overdose. However, OUD treatment should not be withheld because of other substance use. Clinicians initiating treatment should counsel patients on the risk of concomitant substance use and provide overdose prevention education.

A brief note on naltrexone

Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is used more commonly in outpatient addiction treatment than in the inpatient setting, but inpatient clinicians should be aware of its use. It is available in oral and long-acting injectable formulations. Its utility in the inpatient setting may be limited as safe administration requires 7-10 days of opioid abstinence.

Discharge planning

Patients with OUD or who are started on OAT during a hospitalization should be linked to continued outpatient treatment. Before discharge it is best to ensure vaccinations for HAV, HBV, pneumococcus, and tetanus are up to date, and perform screening for HIV, hepatitis C, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections if appropriate. All patients with OUD should be prescribed or provided with take-home naloxone for overdose reversal. Patients can also be referred to syringe service programs for additional harm reduction counseling and services.

Application of the data to our patient

For our patient, either methadone or buprenorphine could be used to treat her withdrawal. The COWS score should be used to assess withdrawal severity, and to guide appropriate timing of medication initiation. If she wishes to continue OAT after discharge, she should be linked to a clinician who can engage her in ongoing medical care. Prior to discharge she should also receive relevant vaccines and screening for infectious diseases as outlined above, as well as take-home naloxone (or a prescription).

Bottom line

Inpatient clinicians can play a pivotal role in patients’ lives by ensuring that patients with OUD receive OAT and are connected to outpatient care at discharge.

Dr. Linker is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Ms. Hirt, Mr. Fine, and Mr. Villasanivis are medical students at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Wang is assistant professor in the division of general internal medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Herscher is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

1. Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. Available at http://wonder.cdc.gov.

2. Mattson CL et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths – United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:202-7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006a4.

3. Wakeman SE et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Feb 5;3(2):e1920622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622.

4. Gowing L et al. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb;2017(2):CD002025. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub5.

5. Sordo L et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017 Apr 26;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550.

6. Smyth BP et al. Lapse and relapse following inpatient treatment of opiate dependence. Ir Med J. 2010 Jun;103(6):176-9. Available at www.drugsandalcohol.ie/13405.

7. Liebschutz JM. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Aug;174(8):1369-76. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556.

8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (Aug 20, 2020) Statutes, Regulations, and Guidelines.

9. McBain RK et al. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(7):504-6. doi: 10.7326/M19-2403.

10. HHS releases new buprenorphine practice guidelines, expanding access to treatment for opioid use disorder. Apr 27, 2021.

11. Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Additional reading

Winetsky D. Expanding treatment opportunities for hospitalized patients with opioid use disorders. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan;13(1):62-4. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2861.

Donroe JH. Caring for patients with opioid use disorder in the hospital. Can Med Assoc J. 2016 Dec 6;188(17-18):1232-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160290.

Herscher M et al. Diagnosis and management of opioid use disorder in hospitalized patients. Med Clin North Am. 2020 Jul;104(4):695-708. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.03.003.

Key points

- Most patients with OUD are not engaged in evidence-based treatment. Clinicians have an opportunity to utilize the inpatient stay as a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

- Buprenorphine and methadone are effective opioid agonist medications used to treat OUD, and clinicians with the appropriate knowledge base can initiate either during the inpatient encounter, and link the patient to OUD treatment after the hospital stay.

Quiz

Caring for hospitalized patients with OUD

Most patients with OUD are not engaged in effective treatment. Hospitalization can be a ‘reachable moment’ to engage patients with OUD in evidence-based treatment.

1. Which is an effective and evidence-based medication for treating opioid withdrawal and OUD?

a) Naltrexone.

b) Buprenorphine.

c) Opioid detoxification.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Buprenorphine is effective for alleviating symptoms of withdrawal as well as for the long-term treatment of OUD. While naltrexone is also used to treat OUD, it is not useful for treating withdrawal. Clonidine can be a useful adjunctive medication for treating withdrawal but is not a long-term treatment for OUD. Nonpharmacologic detoxification is not an effective treatment for OUD and is associated with high relapse rates.

2. What scale can be used during a hospital stay to monitor patients with OUD at risk of opioid withdrawal, and to aid in buprenorphine initiation?

a) CIWA score.

b) PADUA score.

c) COWS score.

d) 4T score.

Explanation: COWS is the “clinical opiate withdrawal scale.” The COWS score should be calculated by a trained provider, and includes objective parameters (such as pulse) and subjective symptoms (such as GI upset, bone/joint aches.) It is recommended that agonist therapy be started when the COWS score is consistent with moderate withdrawal.

3. How can clinicians reliably find out if there are outpatient resources/clinics for patients with OUD in their area?

a) No way to find this out without personal knowledge.

b) Hospital providers and patients can visit www.samhsa.gov/find-help/national-helpline or call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) to find options for treatment for substance use disorders in their areas.

c) Dial “0” on any phone and ask.

d) Ask around at your hospital.

Explanation: The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that is engaged in public health efforts to reduce the impact of substance abuse and mental illness on local communities. The agency’s website has helpful information about resources for substance use treatment.

4. Patients with OUD should be prescribed and given training about what medication that can be lifesaving when given during an opioid overdose?

a) Aspirin.

b) Naloxone.

c) Naltrexone.

d) Clonidine.

Explanation: Naloxone can be life-saving in the setting of an overdose. Best practice is to provide naloxone and training to patients with OUD.

5. When patients take buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids, there is concern for the development of which reaction:

a) Precipitated withdrawal.

b) Opioid overdose.

c) Allergic reaction.

d) Intoxication.

Explanation: Administering buprenorphine soon after taking other opioids can cause precipitated withdrawal, as buprenorphine binds with higher affinity to the mu receptor than many opioids. Precipitated withdrawal causes severe discomfort and can be dangerous for patients.

Is it OK to just be satisfied?

It is possible to talk to a patient for a brief moment and just know if he or she is a satisficer or a maximizer. A “satisficer” when presented with treatment options will invariably say: “I’ll do whatever you say, Doctor.” A “maximizer,” in contrast, would like a printed copy of treatment choices, then would seek a second opinion before ultimately buying an UpToDate subscription to research treatments for him or herself.

.

This notion that we have tendencies toward maximizing or satisficing is thanks to Nobel Memorial Prize winner and all-around smart guy, Herbert A. Simon, PhD. Dr. Simon recognized that, although each person might be expected to make optimal decisions to benefit himself or herself, this is practically impossible. To do so would require an infinite amount of time and energy. He found therefore that we actually exhibit “bounded rationality;” that is, we make the best decision given the limits of time, the price of acquiring information, and even our cognitive abilities. The amount of effort we give to make a decision also depends on the situation: You might be very invested in choosing the right spouse, but not at all invested in choosing soup or salad. (Although, we all have friends who are: “Um, is there any thyme in the soup?”)

You’ll certainly recognize that people have different set points on the spectrum between being a satisficer, one who will take the first option that meets a standard, and a maximizer, one who will seek and accept only the best, even if choosing is at great cost. There are risks and benefits of each. In getting the best job, maximizers might be more successful, but satisficers seem to be happier.

How much this extends into other spheres of life is unclear. It is clear, though, that the work of choosing can come at a cost.

The psychologist Barry Schwartz, PhD, believes that, in general, having more choices leads to more anxiety, not more contentment. For example, which Christmas tree lot would you rather visit: One with hundreds of trees of half a dozen varieties? Or one with just a few trees each of Balsam and Douglas Firs? Dr. Schwartz would argue that you might waste an entire afternoon in the first lot only to bring it home and have remorse when you realize it’s a little lopsided. Or let’s say your child applied to all the Ivy League and Public Ivy schools and also threw in all the top liberal arts colleges. The anxiety of selecting the best and the terror that the “best one” might not choose him or her could be overwhelming. A key lesson is that more in life is by chance than we realize, including how straight your tree is and who gets into Princeton this year. Yet, our expectation that things will work out perfectly if only we maximize is ubiquitous. That confidence in our ability to choose correctly is, however, unwarranted. Better to do your best and know that your tree will be festive and there are many colleges which would lead to a happy life than to fret in choosing and then suffer from dashed expectations. Sometimes good enough is good enough.

Being a satisficer or maximizer is probably somewhat fixed, a personality trait, like being extroverted or conscientious. Yet, having insight can be helpful. If choosing a restaurant in Manhattan becomes an actual project for you with spreadsheets and your own statistical analysis, then go for it! Just know that if that process causes you angst and apprehension, then there is another way. Go to Eleven Madison Park, just because I say so. You might have the best dinner of your life or maybe not. At least by not choosing you’ll have the gift of time to spend picking out a tree instead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

It is possible to talk to a patient for a brief moment and just know if he or she is a satisficer or a maximizer. A “satisficer” when presented with treatment options will invariably say: “I’ll do whatever you say, Doctor.” A “maximizer,” in contrast, would like a printed copy of treatment choices, then would seek a second opinion before ultimately buying an UpToDate subscription to research treatments for him or herself.

.

This notion that we have tendencies toward maximizing or satisficing is thanks to Nobel Memorial Prize winner and all-around smart guy, Herbert A. Simon, PhD. Dr. Simon recognized that, although each person might be expected to make optimal decisions to benefit himself or herself, this is practically impossible. To do so would require an infinite amount of time and energy. He found therefore that we actually exhibit “bounded rationality;” that is, we make the best decision given the limits of time, the price of acquiring information, and even our cognitive abilities. The amount of effort we give to make a decision also depends on the situation: You might be very invested in choosing the right spouse, but not at all invested in choosing soup or salad. (Although, we all have friends who are: “Um, is there any thyme in the soup?”)

You’ll certainly recognize that people have different set points on the spectrum between being a satisficer, one who will take the first option that meets a standard, and a maximizer, one who will seek and accept only the best, even if choosing is at great cost. There are risks and benefits of each. In getting the best job, maximizers might be more successful, but satisficers seem to be happier.

How much this extends into other spheres of life is unclear. It is clear, though, that the work of choosing can come at a cost.

The psychologist Barry Schwartz, PhD, believes that, in general, having more choices leads to more anxiety, not more contentment. For example, which Christmas tree lot would you rather visit: One with hundreds of trees of half a dozen varieties? Or one with just a few trees each of Balsam and Douglas Firs? Dr. Schwartz would argue that you might waste an entire afternoon in the first lot only to bring it home and have remorse when you realize it’s a little lopsided. Or let’s say your child applied to all the Ivy League and Public Ivy schools and also threw in all the top liberal arts colleges. The anxiety of selecting the best and the terror that the “best one” might not choose him or her could be overwhelming. A key lesson is that more in life is by chance than we realize, including how straight your tree is and who gets into Princeton this year. Yet, our expectation that things will work out perfectly if only we maximize is ubiquitous. That confidence in our ability to choose correctly is, however, unwarranted. Better to do your best and know that your tree will be festive and there are many colleges which would lead to a happy life than to fret in choosing and then suffer from dashed expectations. Sometimes good enough is good enough.

Being a satisficer or maximizer is probably somewhat fixed, a personality trait, like being extroverted or conscientious. Yet, having insight can be helpful. If choosing a restaurant in Manhattan becomes an actual project for you with spreadsheets and your own statistical analysis, then go for it! Just know that if that process causes you angst and apprehension, then there is another way. Go to Eleven Madison Park, just because I say so. You might have the best dinner of your life or maybe not. At least by not choosing you’ll have the gift of time to spend picking out a tree instead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

It is possible to talk to a patient for a brief moment and just know if he or she is a satisficer or a maximizer. A “satisficer” when presented with treatment options will invariably say: “I’ll do whatever you say, Doctor.” A “maximizer,” in contrast, would like a printed copy of treatment choices, then would seek a second opinion before ultimately buying an UpToDate subscription to research treatments for him or herself.

.

This notion that we have tendencies toward maximizing or satisficing is thanks to Nobel Memorial Prize winner and all-around smart guy, Herbert A. Simon, PhD. Dr. Simon recognized that, although each person might be expected to make optimal decisions to benefit himself or herself, this is practically impossible. To do so would require an infinite amount of time and energy. He found therefore that we actually exhibit “bounded rationality;” that is, we make the best decision given the limits of time, the price of acquiring information, and even our cognitive abilities. The amount of effort we give to make a decision also depends on the situation: You might be very invested in choosing the right spouse, but not at all invested in choosing soup or salad. (Although, we all have friends who are: “Um, is there any thyme in the soup?”)

You’ll certainly recognize that people have different set points on the spectrum between being a satisficer, one who will take the first option that meets a standard, and a maximizer, one who will seek and accept only the best, even if choosing is at great cost. There are risks and benefits of each. In getting the best job, maximizers might be more successful, but satisficers seem to be happier.

How much this extends into other spheres of life is unclear. It is clear, though, that the work of choosing can come at a cost.

The psychologist Barry Schwartz, PhD, believes that, in general, having more choices leads to more anxiety, not more contentment. For example, which Christmas tree lot would you rather visit: One with hundreds of trees of half a dozen varieties? Or one with just a few trees each of Balsam and Douglas Firs? Dr. Schwartz would argue that you might waste an entire afternoon in the first lot only to bring it home and have remorse when you realize it’s a little lopsided. Or let’s say your child applied to all the Ivy League and Public Ivy schools and also threw in all the top liberal arts colleges. The anxiety of selecting the best and the terror that the “best one” might not choose him or her could be overwhelming. A key lesson is that more in life is by chance than we realize, including how straight your tree is and who gets into Princeton this year. Yet, our expectation that things will work out perfectly if only we maximize is ubiquitous. That confidence in our ability to choose correctly is, however, unwarranted. Better to do your best and know that your tree will be festive and there are many colleges which would lead to a happy life than to fret in choosing and then suffer from dashed expectations. Sometimes good enough is good enough.

Being a satisficer or maximizer is probably somewhat fixed, a personality trait, like being extroverted or conscientious. Yet, having insight can be helpful. If choosing a restaurant in Manhattan becomes an actual project for you with spreadsheets and your own statistical analysis, then go for it! Just know that if that process causes you angst and apprehension, then there is another way. Go to Eleven Madison Park, just because I say so. You might have the best dinner of your life or maybe not. At least by not choosing you’ll have the gift of time to spend picking out a tree instead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

ADHD Pathophysiology

When surgery is the next step in treating endometriosis—know your patient’s priorities and how to optimize long-term pain relief

Cara R. King, DO, MS, is a member of the Cleveland Clinic Section of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery (MIGS). She is the Director of Benign Gynecologic Surgery, and Associate Program Director of the MIGS Fellowship, and Director of Innovation for the Women’s Health Institute. She is a member of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL), the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS), American College of Surgeons (ACS), and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

Q: How much of your surgical practice is dedicated to patients with endometriosis?

Dr. King: The majority of my practice is dedicated to treating women with endometriosis. I practice at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio, which is a high-volume referral center, so many of my patients are coming to me for endometriosis or pelvic pain-type symptoms. For most of my patients, I serve as a consultant, which means it's not their initial visit for this issue. I'm often seeing patients who have not found relief through alternate medical or surgical treatments and typically, have more deeply infiltrating or complex endometriosis disease.

Q: How do you make the treatment decision with patients that surgery is the next or proper needed step?

Dr. King: This decision depends on the goals and priorities of each of my patients. I don't have a one-size-fits-all type approach as every patient's journey and unique experiences vary. Ultimately, deciding on the available options and order of treatment depends on the patient's symptoms and priorities. I always start with a thorough history, including a detailed physical exam. The pelvic exam includes evaluation of the bladder, bowel, pelvic floor muscles, nerves, as well as the gynecologic organs including vagina, uterus, cervix and adnexa. If I palpate a nodule on the uterosacral ligaments or behind the cervix, I will sometimes perform a rectovaginal exam to assess for deeply infiltrating bowel disease. Various imaging modalities, including a transvaginal ultrasound or an MRI, can be helpful to further characterize the disease. This allows us to create a treatment plan that best aligns with the patients’ priorities and goals. As a general rule, surgery is usually indicated if empiric options have failed or if they desire definitive diagnosis; meaning the patient is still having pain symptoms despite conservative options or if they have failed or are intolerant to medical options. Some patients are not candidates for medical therapy, such as those who desire pregnancy or who are trying to conceive, so medical options wouldn't be an option for these patients. For patients who prefer an immediate diagnosis, surgical intervention may also be the best option. When I see initial consults for patients who haven't previously seen an endometriosis specialist, if they're not trying to conceive and if they are candidates for medical therapy, I think that's a reasonable first step. We must understand that medications are not curative, they are merely suppressive for endometriosis, so when patients come to me that have been on medical therapy for more than 3 months without pain improvement, and they haven't been offered a surgical approach, diagnostic laparoscopy is often the next best step.

Q: Please detail the presurgical discussion, or the consent process, that would allow you to go beyond the agreed-to procedure, if necessary?