User login

Widespread Necrotizing Purpura and Lucio Phenomenon as the First Diagnostic Presentation of Diffuse Nonnodular Lepromatous Leprosy

Case Report

A 70-year-old man living in Esna, Luxor, Egypt presented to the Department of Rheumatology and Rehabilitation with widespread gangrenous skin lesions associated with ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration. One year prior, the patient had an insidious onset of nocturnal fever, bilateral leg edema, and numbness and a tingling sensation in both hands. He presented some laboratory and radiologic investigations that were performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, which revealed thrombocytopenia, mild splenomegaly, and generalized lymphadenopathy. An excisional left axillary lymph node biopsy was performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, and the pathology report provided by the patient described a reactive, foamy, histiocyte-rich lesion, suggesting a diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The patient had no diabetes or hypertension and no history of deep vein thrombosis, stroke, or unintentional weight loss. No medications were taken prior to the onset of the skin lesions, and his family history was irrelevant.

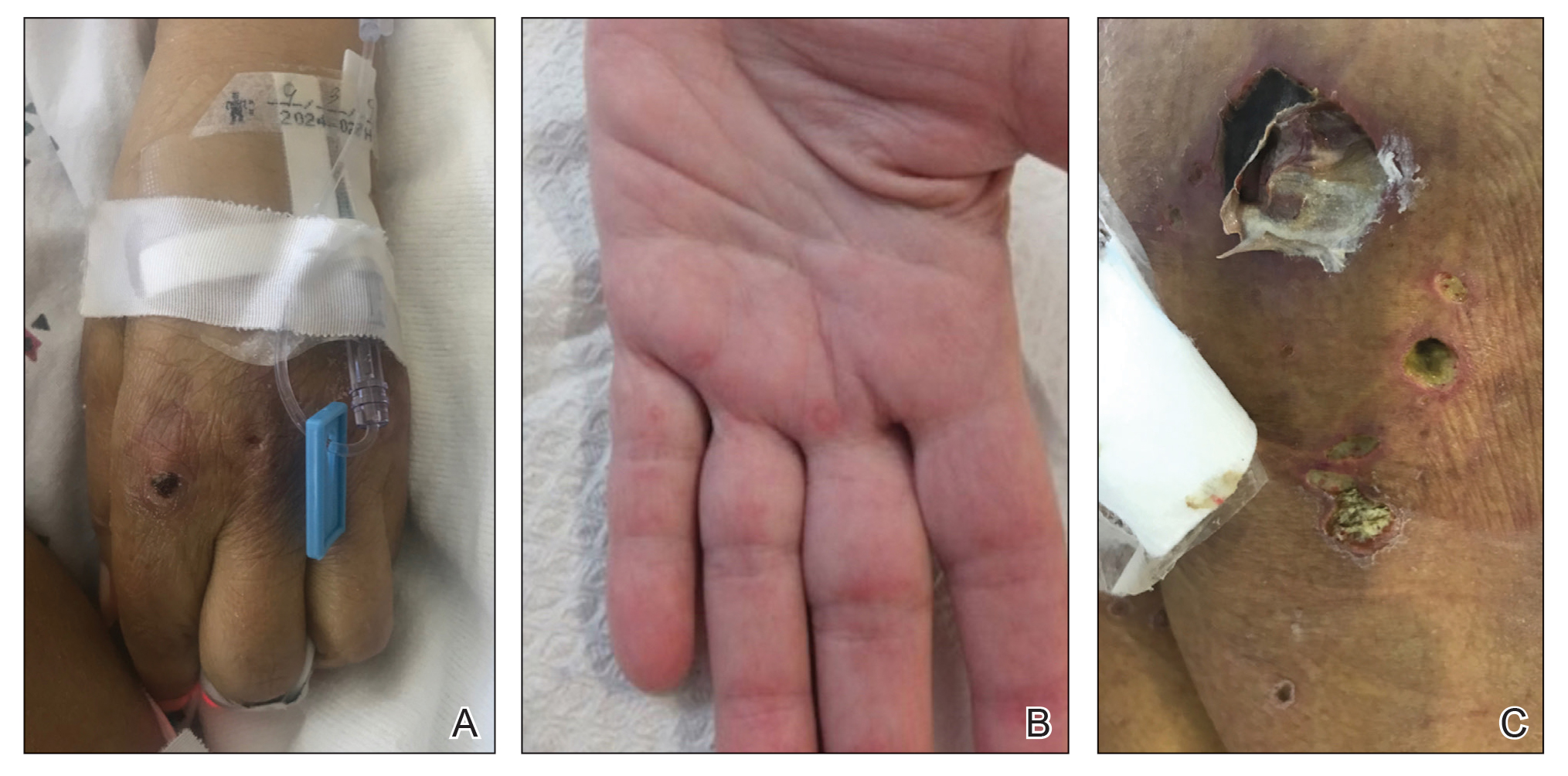

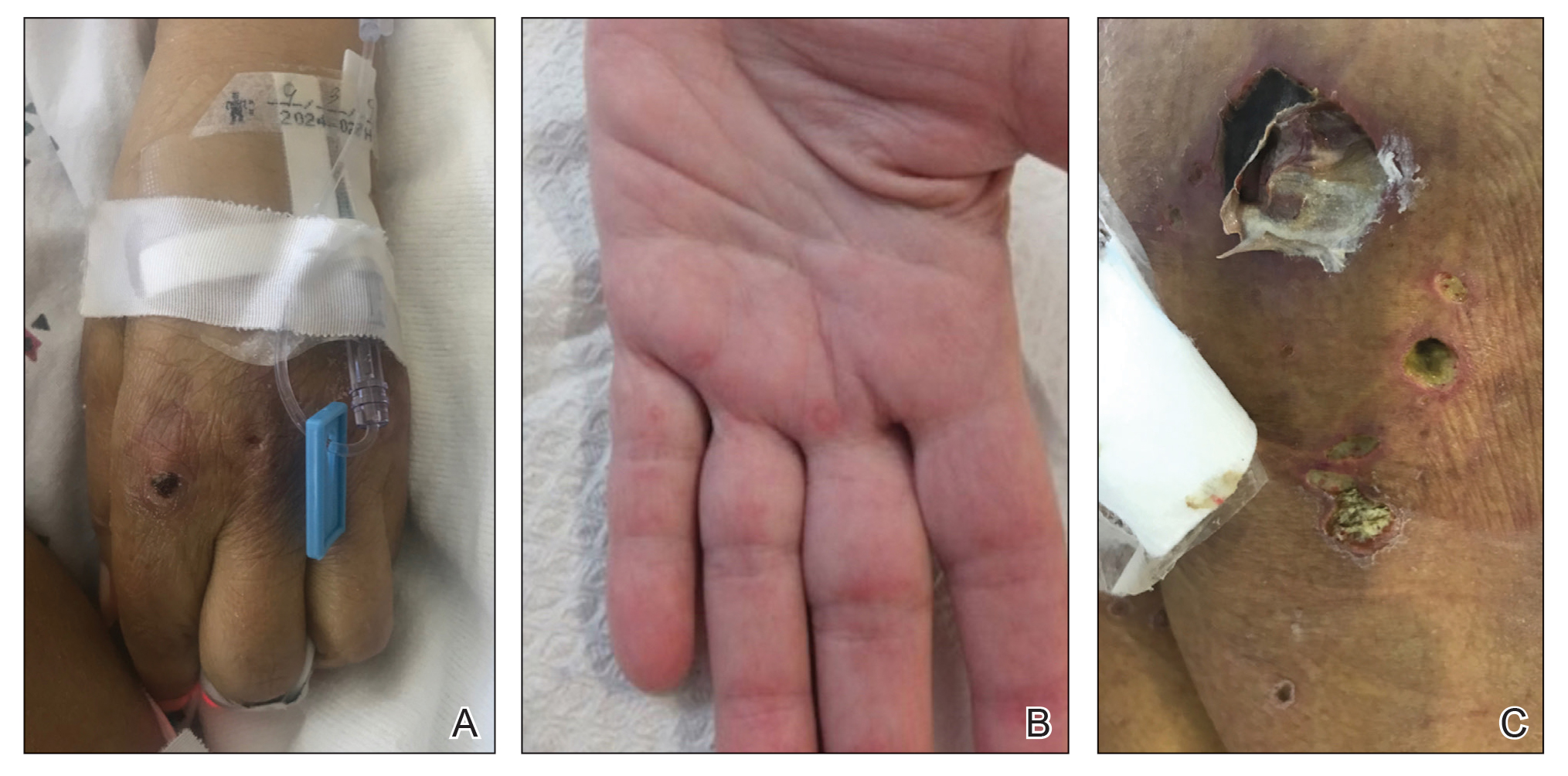

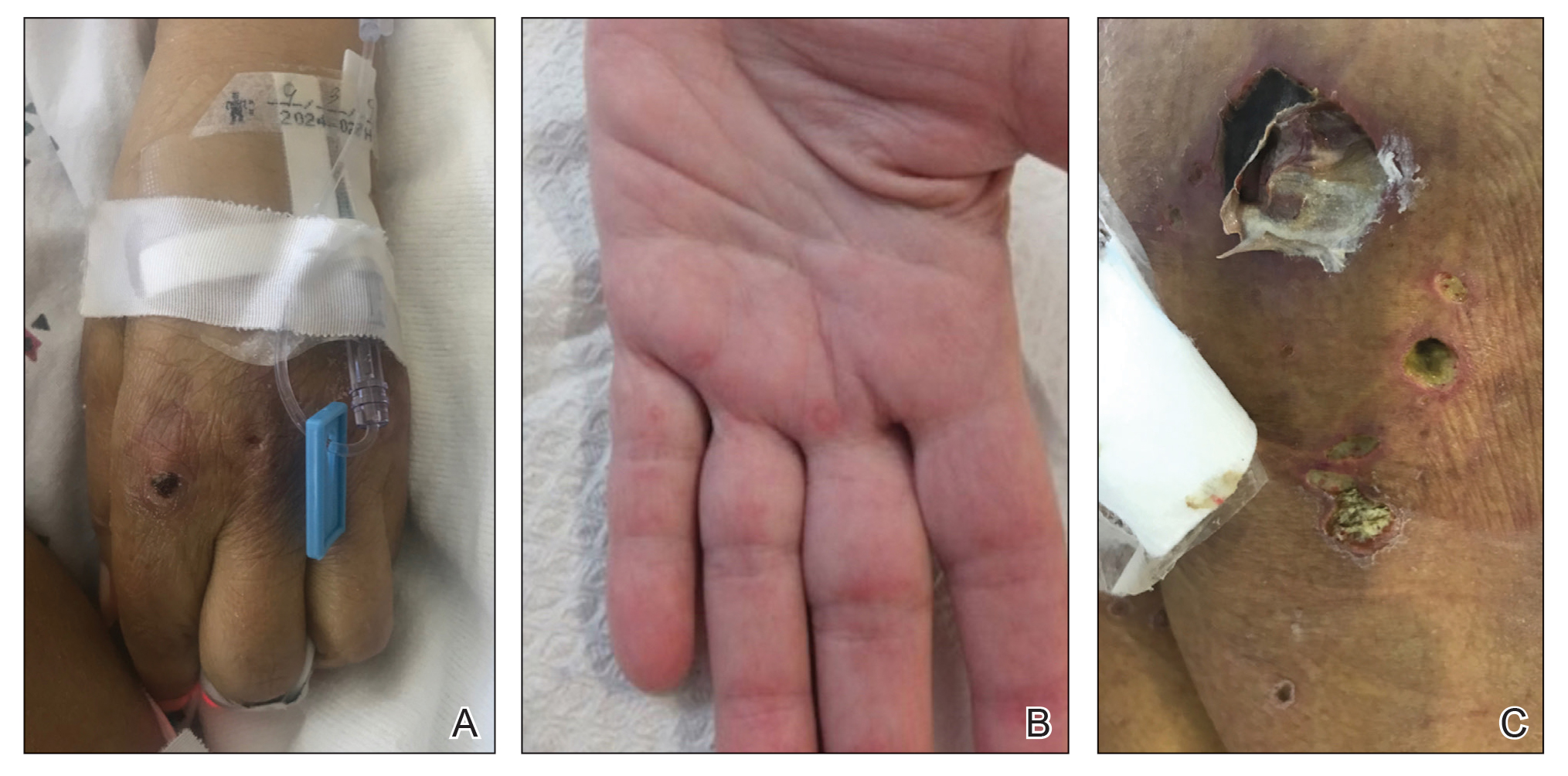

General examination at the current presentation revealed a fever (temperature, 101.3 °F [38.5 °C]), a normal heart rate (90 beats per minute), normal blood pressure (120/80 mmHg), normal respiratory rate (14 breaths per minute), accentuated heart sounds, and normal vesicular breathing without adventitious sounds. He had saddle nose, loss of the outer third of the eyebrows, and marked reduction in the density of the eyelashes (madarosis). Bilateral pitting edema of the legs also was present. Neurologic examination revealed hypoesthesia in a glove-and-stocking pattern, thickened peripheral nerves, and trophic changes over both hands; however, he had normal muscle power and deep reflexes. Joint examination revealed no abnormalities. Skin examination revealed widespread, reticulated, necrotizing, purpuric lesions on the arms, legs, abdomen, and ears, some associated with gangrenous ulcerations and hemorrhagic blisters. Scattered vasculitic ulcers and gangrenous patches were seen on the fingers. A gangrenous ulcer mimicking Fournier gangrene was seen involving the scrotal skin in addition to a gangrenous lesion on the glans penis (Figure 1–3). Unaffected skin appeared smooth, shiny, and edematous and showed no nodular lesions. Peripheral pulsations were intact.

Positive findings from a wide panel of laboratory investigations included an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (103 mm for the first hour [reference range, 0–22 mm]), high C-reactive protein (50.7 mg/L [reference range, up to 6 mg/L]), anemia (hemoglobin count, 7.3 g/dL [reference range, 13.5–17.5 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (45×103/mm3 [reference range, 150×103/mm3), low serum albumin (2.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.4–5.4 g/dL]), elevated IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (IgG, 21.4 IgG phospholipid [GPL] units [reference range, <10 IgG phospholipid (GPL) units]; IgM, 59.4 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units [reference range, <7 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units]), positive lupus anticoagulant panel test, elevated anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies (IgG, 17.5

Nerve conduction velocity showed axonal sensory polyneuropathy. Motor nerve conduction studies for median and ulnar nerves were within normal range. Lower-limb nerves assessment was limited by the ulcerated areas and marked edema. Echocardiography was unremarkable. Arterial Doppler studies were only available for the upper limbs and were unremarkable.

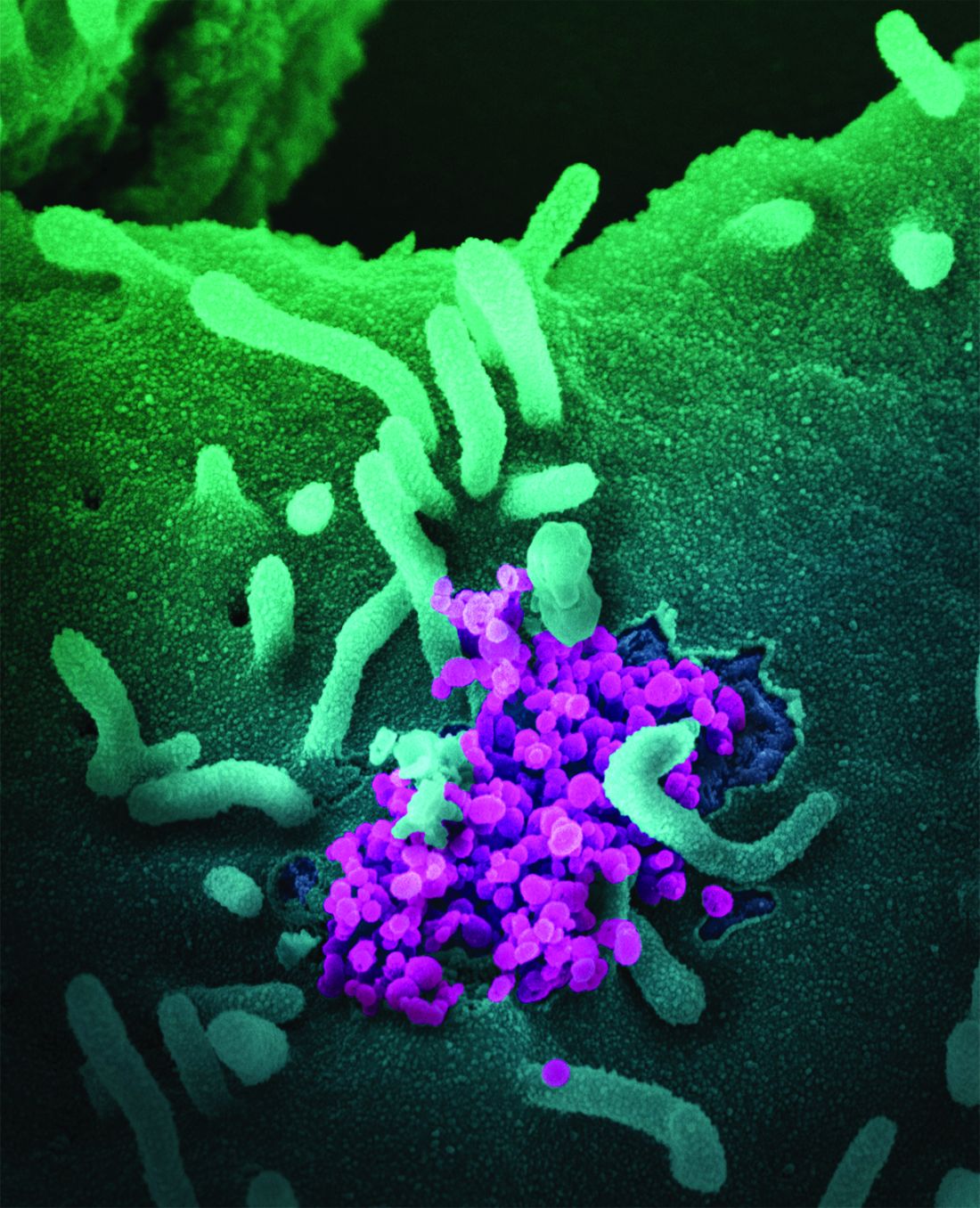

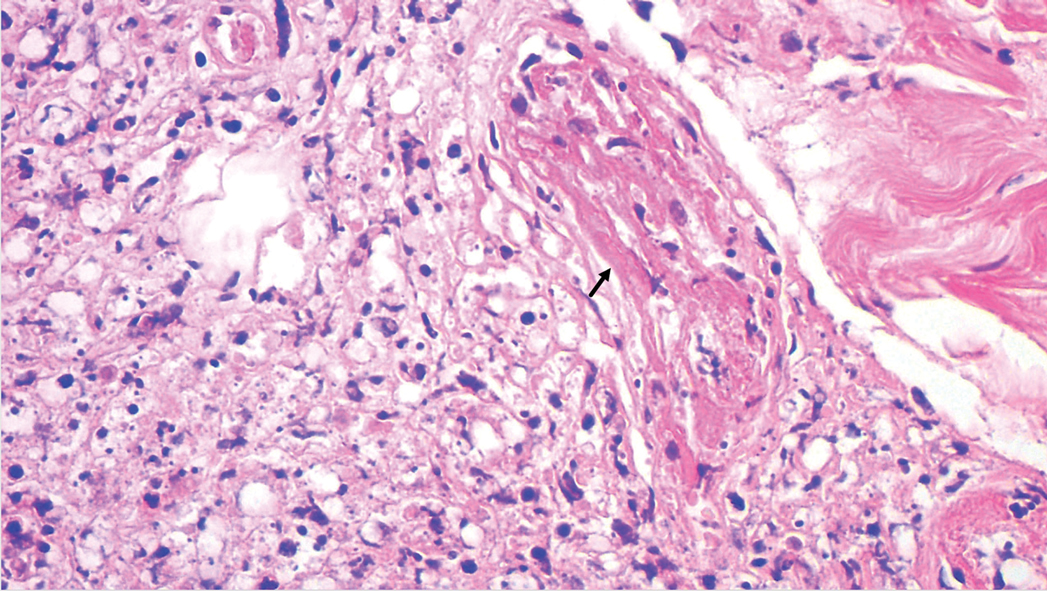

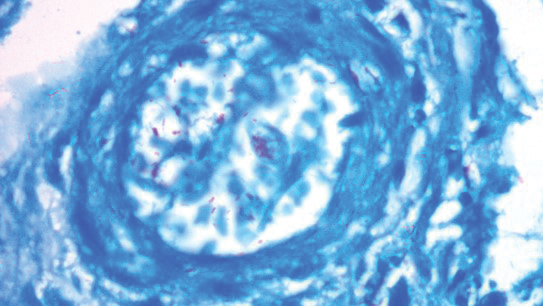

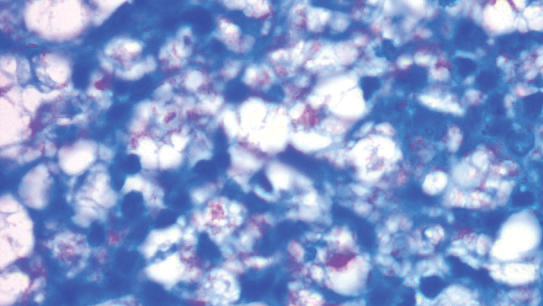

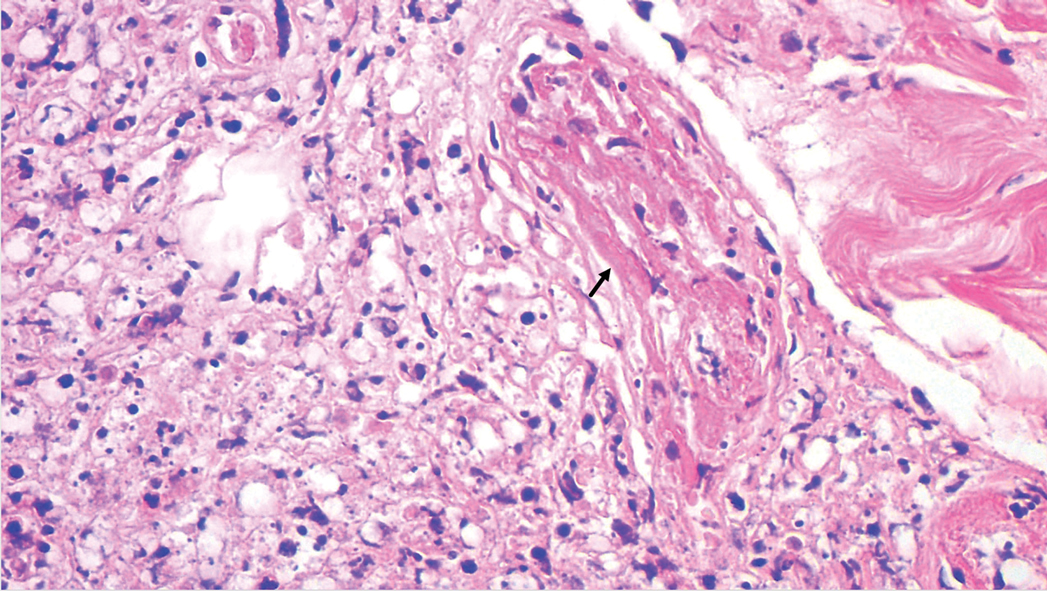

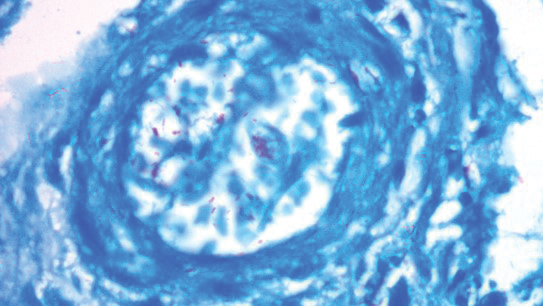

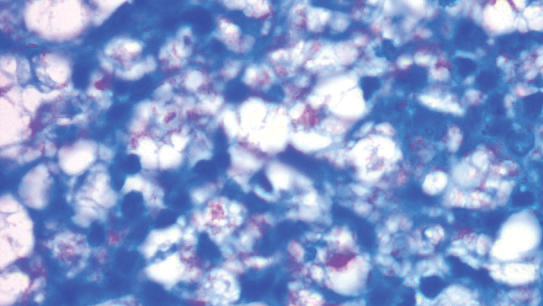

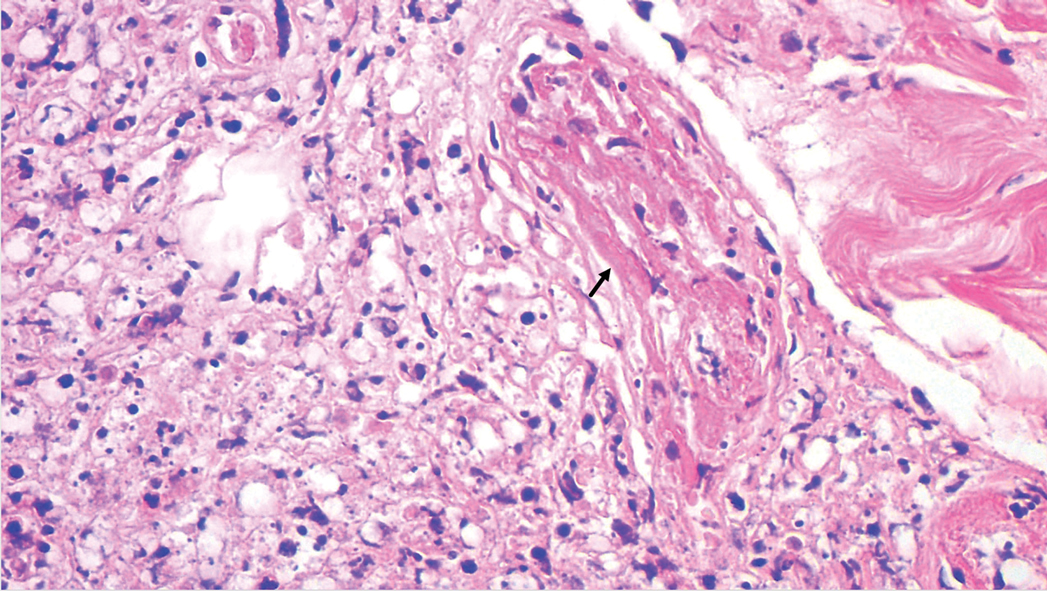

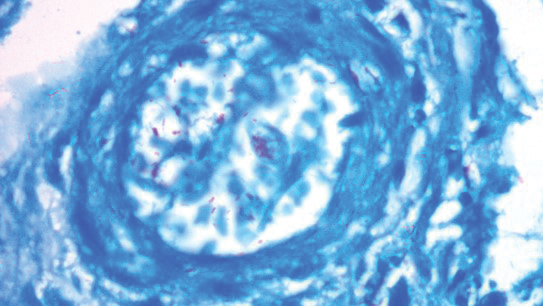

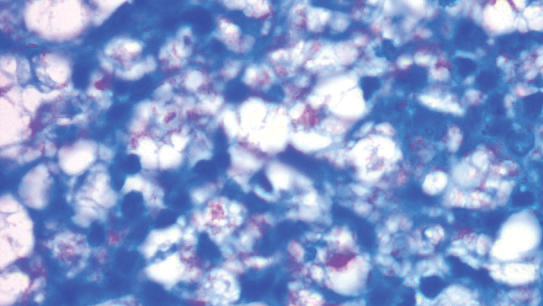

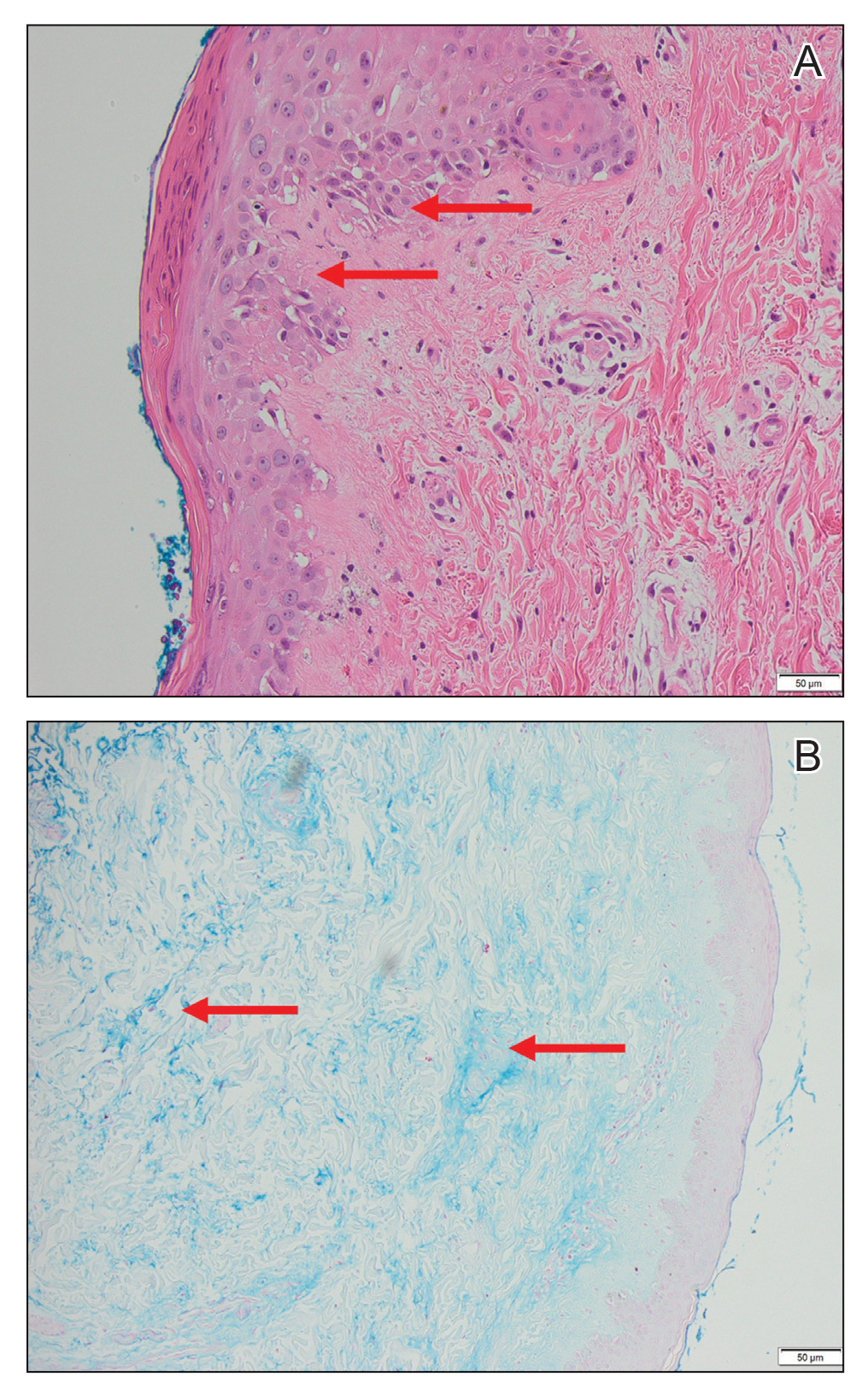

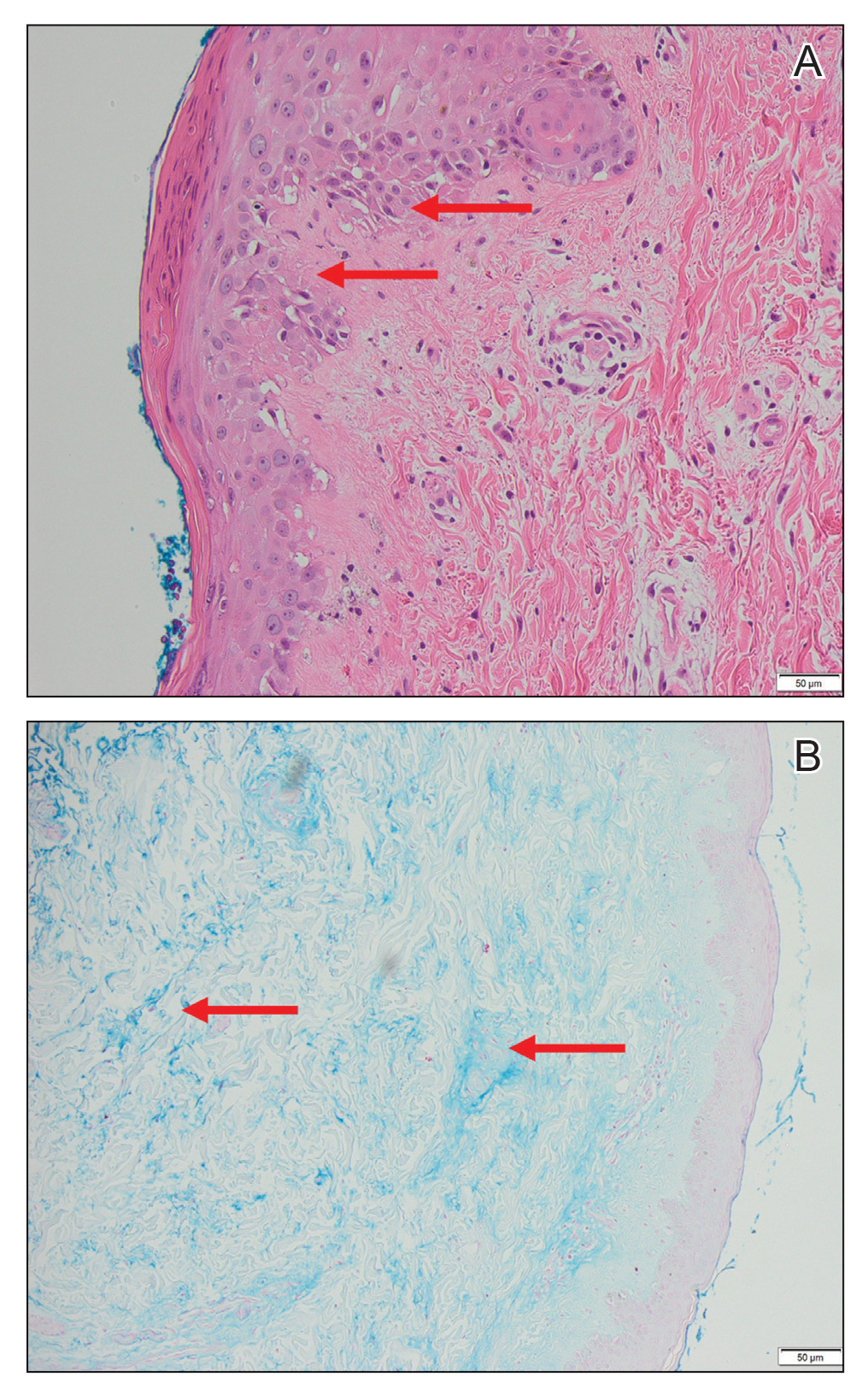

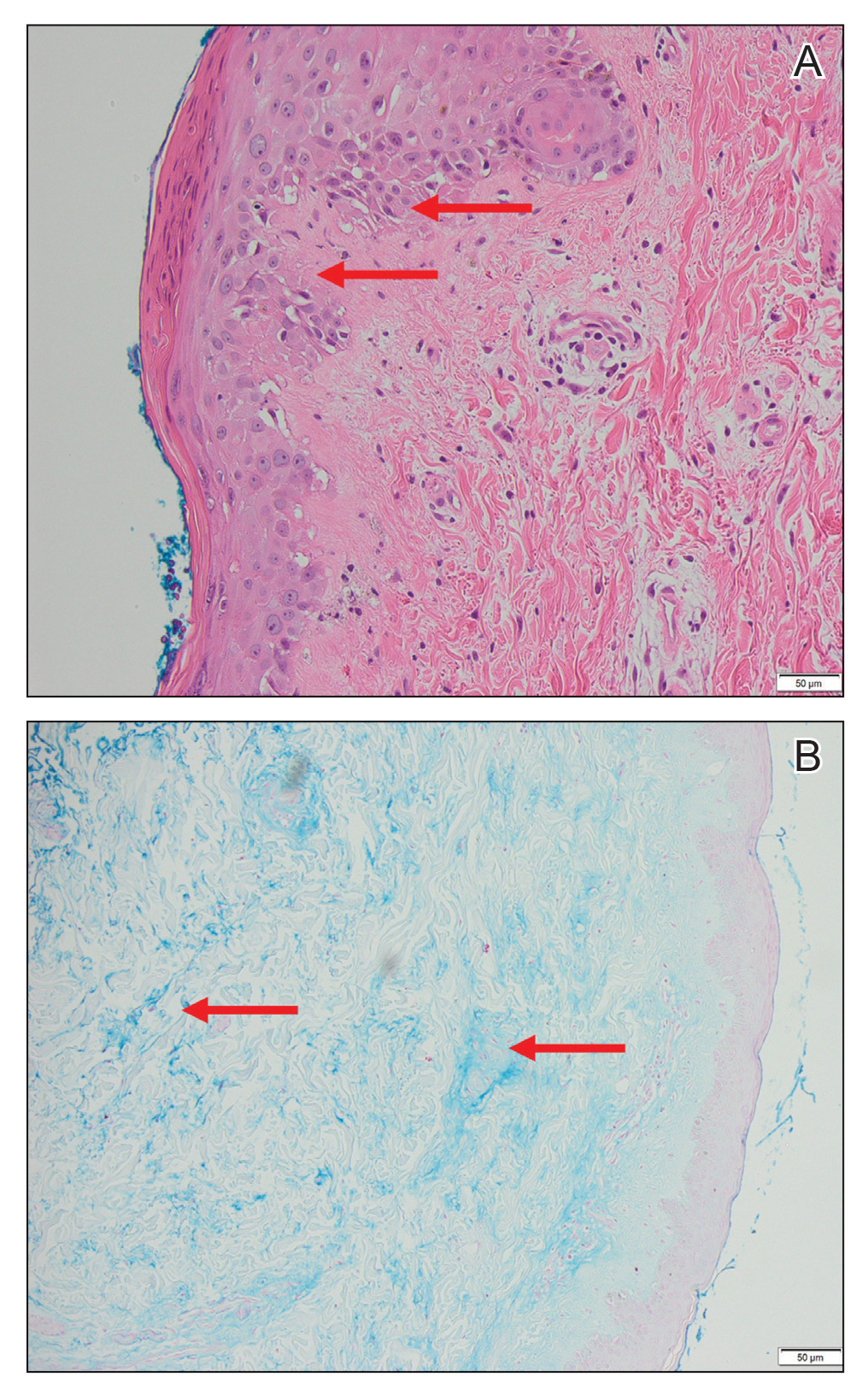

A punch biopsy was taken from one of the necrotizing purpuric lesions on the legs, and histopathologic examination revealed foci of epidermal necrosis and subepidermal separation and superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrates extending into the fat lobules. The infiltrates were mainly made up of foamy macrophages, and some contained globi (lepra cells), in addition to lymphocytes and many neutrophils with nuclear dust. Blood vessels in the superficial and deep dermis and in the subcutaneous fat showed fibrinoid necrosis in their walls with neutrophils infiltrating the walls and thrombi in the lumens (Figure 4). Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining revealed clumps of acid-fast lepra bacilli inside vascular lumina and endothelial cell lining and within the foamy macrophages (Figure 5). Slit-skin smear examination was performed twice and yielded negative results. The slide and paraffin block of the already performed lymph node biopsy were retrieved. Examination revealed aggregates of foamy histiocytes surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells replacing normal lymphoid follicles. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain was performed, and clusters of acid-fast bacilli were detected within the foamy histiocytic infiltrate (Figure 6).

According to the results of the skin biopsy, the revised result of the lymph node biopsy, and the pattern of neurologic deficit together with clinical and laboratory correlation, the patient was diagnosed with diffuse nonnodular lepromatous leprosy presenting with Lucio phenomenon (Lucio leprosy) and associated with lepromatous lymphadenitis.

The patient received the following treatment: methylprednisolone 500 mg (intravenous pulse therapy) followed by daily oral administration of prednisolone 10 mg, rifampicin 300 mg, dapsone 100 mg, clofazimine 100 mg, acetylsalicylic acid 150 mg, and enoxaparin sodium 80 mg. In addition, the scrotal Fournier gangrene–like lesion was treated by surgical debridement followed by vacuum therapy. By the second week after treatment, the gangrenous lesions of the fingers developed a line of demarcation, and the skin infarctions started to recede.

Comment

Despite a decrease in its prevalence through a World Health Organization (WHO)–empowered eradication program, leprosy still represents a health problem in endemic areas.1,2 It is characterized by a wide range of immune responses to Mycobacterium leprae, displaying a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic manifestations that vary from the tuberculoid or paucibacillary pole with a strong cell-mediated immune response and fewer organisms to the lepromatous or multibacillary pole with weaker cell-mediated immune response and higher loads of organisms.3 In addition to its well-known cutaneous and neurologic manifestations, leprosy can present with a variety of manifestations, including constitutional symptoms, musculoskeletal manifestations, and serologic abnormalities; thus, leprosy can mimic rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, and vasculitis—a pitfall that may result in misdiagnosis as a rheumatologic disorder.3-7

The chronic course of leprosy can be disrupted by acute, immunologically mediated reactions known as lepra reactions, of which there are 3 types.8 Type I lepra reactions are cell mediated and occur mainly in patients with borderline disease, often representing an upgrade toward the tuberculoid pole; less often they represent a downgrade reaction. Nerves become painful and swollen with possible loss of function, and skin lesions become edematous and tender; sometimes arthritis develops.9 Type II lepra reactions, also known as erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), occur in borderline lepromatous and lepromatous patients with a high bacillary load. They are characterized by fever, body aches, tender cutaneous/subcutaneous nodules that may ulcerate, possible bullous lesions, painful nerve swellings, swollen joints, iritis, lymphadenitis, glomerulonephritis, epididymo-orchitis, and hepatic affection. Both immune-complex and delayed hypersensitivity reactions play a role in ENL.8,10 The third reaction is a rare aggressive type known as Lucio phenomenon or Lucio leprosy, which presents with irregular-shaped, angulated, or stellar necrotizing purpuric lesions (hemorrhagic infacrtions) developing mainly on the extremities. The lesions evolve into ulcers that heal with atrophic scarring.2,11 Lucio phenomenon develops as a result of thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of vascular endothelial cells by lepra bacilli.2,11-14 Involvement of the scrotal skin, such as in our patient, is rare.

Lucio phenomenon mainly is seen in Mexico and Central America, and few cases have been documented in Cuba, South America, the United States, India, Polynesia, South Africa, and Southeast Asia.15-17 It specifically occurs in patients with untreated, diffuse, nonnodular lepromatous leprosy (pure and primitive diffuse lepromatous leprosy (DLL)/diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí). This type of leprosy was first described by Lucio and Alvarado18 in 1852 as a distinct form of lepromatous leprosy characterized by widespread and dense infiltration of the whole skin by lepra bacilli without the typical nodular lesions of leprosy, rendering its diagnosis challenging, especially in sporadic cases. Other manifestations of DLL include complete alopecia of the eyebrows and eyelashes, destructive rhinitis, and areas of anhidrosis and dyesthesia.2

Latapí and Chévez-Zomora19 defined Lucio phenomenon in 1948 as a form of histopathologic vasculitis restricted to patients with DLL. Histopathologically, in addition to the infiltration of the skin with acid-fast bacilli–laden foamy histiocytes, lesions of Lucio phenomenon show features of necrotizing (leukocytoclastic) vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis20 or vascular thrombi with minimal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and no evidence of vasculitis.11 Medium to large vessels in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue show infiltration of their walls with a large number of macrophages laden with acid-fast bacilli.11 Cases with histopathologic features mimicking antiphospholipid syndrome with endothelial cell proliferation, thrombosis, and mild mononuclear cell infiltrate also may be seen.20 In all cases, ischemic epidermal necrosis is seen, as well as acid-fast bacilli, both singly and in clusters (globi) within endothelial cells and inside blood vessel lumina.

Although Lucio phenomenon initially was thought to be immune-complex mediated like ENL, it has been suggested that the main trigger is thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of the vascular endothelial cells by the lepra bacilli, resulting in necrosis.14 Bacterial lipopolysaccharides promote the release of IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor α, which in turn stimulate the production of prostaglandins, IL-6, and coagulation factor III, leading to vascular thrombosis and tissue necrosis.21,22 Moreover, antiphospholipid antibodies, which have been found to be induced in response to certain infectious agents in genetically predisposed individuals,23 have been reported in patients with leprosy, mainly in association with lepromatous leprosy. The reported prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies ranged from 37% to 98%, whereas anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies ranged from 3% to 19%, and antiprothrombin antibodies ranged from 6% to 45%.24,25 Antiphospholipid antibodies have been reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of Lucio phenomenon.11,13,15,26 Our case supports this hypothesis with positive anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies, and positive lupus anticoagulant.

In accordance with Curi et al,2 who reported 5 cases of DLL with Lucio phenomenon, our patient showed a similar presentation with positive inflammatory markers in association with a negative autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) and negative venereal disease research laboratory test. It is important to mention that a positive autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) can be present in leprotic patients, causing possible diagnostic confusion with collagen diseases.27,28

An interesting finding in our case was the negative slit-skin smear results. Although the specificity of slit-skin smear is 100%, as it directly demonstrates the presence of acid-fast bacilli,29 its sensitivity is low and varies from 10% to 50%.30 The detection of acid-fast bacilli in tissue sections is reported to be a better method for confirming the diagnosis of leprosy.31

The provisional impression of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the lymph node biopsy in our patient was excluded upon detection of acid-fast bacilli in the foamy histiocytes infiltrating the lymph node; moreover, the normal serum lipids and serum ferritin argued against this diagnosis.32 Leprosy tends to involve the lymph nodes, particularly in borderline, borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous forms.33 The incidence of lymph node involvement accompanied by skin lesions with the presence of acid-fast bacilli in the lymph nodes is 92.2%.34

Our patient showed an excellent response to antileprotic treatment, which was administered according to the WHO multidrug therapy guidelines for multibacillary leprosy,35 combined with low-dose prednisolone, acetylsalicylic acid, and anticoagulant treatment. Thalidomide and high-dose prednisolone (60 mg/d) combined with antileprotic treatment also have been reported to be successful in managing recurrent infarctions in leprosy.36 The Fournier-like gangrenous ulcer of the scrotum was managed by surgical debridement and vacuum therapy.

It is noteworthy that the WHO elimination goal for leprosy was to reduce the prevalence to less than 1 case per 10,000 population. Egypt is among the first countries in North Africa and the Middle East regions to achieve this target supervised by the National Leprosy Control Program as early as 1994; this was further reduced to 0.33 cases per 10,000 population in 2004, and reduced again in 2009; however, certain foci showed a prevalence rate more than the elimination target, particularly in the cities of Qena (1.12) and Sohag (2.47).37 Esna, where our patient is from, is an endemic area in Egypt.38

Conclusion

1. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics: 2011. World Health Organization; 2011. https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2011_Full.pdf

2. Curi PF, Villaroel JS, Migliore N, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: report of five cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1397-1401.

3. Shrestha B, Li YQ, Fu P. Leprosy mimics adult onset Still’s disease in a Chinese patient. Egypt Rheumatol. 2018;40:217-220.

4. Prasad S, Misra R, Aggarwal A, et al. Leprosy revealed in a rheumatology clinic: a case series. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:129-133.

5. Chao G, Fang L, Lu C. Leprosy with ANA positive mistaken for connective tissue disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:645-648.

6. Chauhan S, Wakhlu A, Agarwal V. Arthritis in leprosy. Rheumatology. 2010;49:2237-2242.

7. Rath D, Bhargava S, Kundu BK. Leprosy mimicking common rheumatologic entities: a trial for the clinician in the era of biologics. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:429698.

8. Cuevas J, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Carrillo R, et al. Erythema nodosum leprosum: reactional leprosy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:126-130.

9. Henriques CC, Lopéz B, Mestre T, et al. Leprosy and rheumatoid arthritis: consequence or association? BMJ Case Rep. 2012;13:1-4.

10. Vázquez-Botet M, Sánchez JL. Erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:436-437.

11. Nunzie E, Ortega Cabrera LV, Macanchi Moncayo FM, et al. Lucio leprosy with Lucio’s phenomenon, digital gangrene and anticardiolipin antibodies. Lepr Rev. 2014;85:194-200.

12. Salvi S, Chopra A. Leprosy in a rheumatology setting: a challenging mimic to expose. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1557-1563.

13. Azulay-Abulafia L, Pereira SL, Hardmann D, et al. Lucio phenomenon. vasculitis or occlusive vasculopathy? Hautarzt. 2006;57:1101-1105.

14. Benard G, Sakai-Valente NY, Bianconcini Trindade MA. Concomittant Lucio phenomenon and erythema nodosum in a leprosy patient: clues for their distinct pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:288-292.

15. Rocha RH, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: exuberant case report and review of Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(suppl 5):S60-S63.

16. Costa IM, Kawano LB, Pereira CP, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:566-571.

17. Kumari R, Thappa DM, Basu D. A fatal case of Lucio phenomenon from India. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

18. Lucio R, Alvarado I. Opúsculo Sobre el Mal de San Lázaro o Elefantiasis de los Griegos. M. Murguía; 1852.

19. Latapí F, Chévez-Zamora A. The “spotted” leprosy of Lucio: an introduction to its clinical and histological study. Int J Lepr. 1948;16:421-437.

20. Vargas OF. Diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí: a histologic study. Lepr Rev. 2007;78:248-260.

21. Latapí FR, Chevez-Zamora A. La lepra manchada de Lucio. Rev Dermatol Mex. 1978;22:102-107.

22. Monteiro R, Abreu MA, Tiezzi MG, et al. Fenômeno de Lúcio: mais um caso relatado no Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:296-300.

23. Gharavi EE, Chaimovich H, Cucucrull E, et al. Induction of antiphospholipid antibodies by immunization with synthetic bacterial & viral peptides. Lupus. 1999;8:449-455.

24. de Larrañaga GF, Forastiero RR, Martinuzzo ME, et al. High prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in leprosy: evaluation of antigen reactivity. Lupus. 2000;9:594-600.

25. Loizou S, Singh S, Wypkema E, et al. Anticardiolipin, anti-beta(2)-glycoprotein I and antiprothrombin antibodies in black South African patients with infectious disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1106-1111.

26. Akerkar SM, Bichile LS. Leprosy & gangrene: a rare association; role of antiphospholipid antibodies. BMC Infect Dis. 2005,5:74.

27. Horta-Baas G, Hernández-Cabrera MF, Barile-Fabris LA, et al. Multibacillary leprosy mimicking systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and literature review. Lupus. 2015;24:1095-1102.

28. Pradhan V, Badakere SS, Shankar KU. Increased incidence of cytoplasmic ANCA (cANCA) and other auto antibodies in leprosy patients from western India. Lepr Rev. 2004;75:50-56.

29. Oskam L. Diagnosis and classification of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2002;73:17-26.

30. Rao PN. Recent advances in the control programs and therapy of leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:269-276.

31. Rao PN, Pratap D, Ramana Reddy AV, et al. Evaluation of leprosy patients with 1 to 5 skin lesions with relevance to their grouping into paucibacillary or multibacillary disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:207-210.

32. Rosado FGN, Kim AS. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. an update on diagnosis and pathogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:713-727.

33. Kar HK, Mohanty HC, Mohanty GN, et al. Clinicopathological study of lymph node involvement in leprosy. Lepr India. 1983;55:725-738.

34. Gupta JC, Panda PK, Shrivastava KK, et al. A histopathologic study of lymph nodes in 43 cases of leprosy. Lepr India. 1978;50:196-203.

35. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Seventh Report. World Health Organization; 1998. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42060/WHO_TRS_874.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

36. Misra DP, Parida JR, Chowdhury AC, et al. Lepra reaction with Lucio phenomenon mimicking cutaneous vasculitis. Case Rep Immunol. 2014;2014:641989.

37. Amer A, Mansour A. Epidemiological study of leprosy in Egypt: 2005-2009. Egypt J Dermatol Venereol. 2014;34:70-73.

38. World Health Organization. Screening campaign aims to eliminate leprosy in Egypt. Published May 9, 2018. Accessed September 8, 2021. http://www.emro.who.int/egy/egypt-events/last-miless-activities-on-eliminating-leprosy-from-egypt.html

Case Report

A 70-year-old man living in Esna, Luxor, Egypt presented to the Department of Rheumatology and Rehabilitation with widespread gangrenous skin lesions associated with ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration. One year prior, the patient had an insidious onset of nocturnal fever, bilateral leg edema, and numbness and a tingling sensation in both hands. He presented some laboratory and radiologic investigations that were performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, which revealed thrombocytopenia, mild splenomegaly, and generalized lymphadenopathy. An excisional left axillary lymph node biopsy was performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, and the pathology report provided by the patient described a reactive, foamy, histiocyte-rich lesion, suggesting a diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The patient had no diabetes or hypertension and no history of deep vein thrombosis, stroke, or unintentional weight loss. No medications were taken prior to the onset of the skin lesions, and his family history was irrelevant.

General examination at the current presentation revealed a fever (temperature, 101.3 °F [38.5 °C]), a normal heart rate (90 beats per minute), normal blood pressure (120/80 mmHg), normal respiratory rate (14 breaths per minute), accentuated heart sounds, and normal vesicular breathing without adventitious sounds. He had saddle nose, loss of the outer third of the eyebrows, and marked reduction in the density of the eyelashes (madarosis). Bilateral pitting edema of the legs also was present. Neurologic examination revealed hypoesthesia in a glove-and-stocking pattern, thickened peripheral nerves, and trophic changes over both hands; however, he had normal muscle power and deep reflexes. Joint examination revealed no abnormalities. Skin examination revealed widespread, reticulated, necrotizing, purpuric lesions on the arms, legs, abdomen, and ears, some associated with gangrenous ulcerations and hemorrhagic blisters. Scattered vasculitic ulcers and gangrenous patches were seen on the fingers. A gangrenous ulcer mimicking Fournier gangrene was seen involving the scrotal skin in addition to a gangrenous lesion on the glans penis (Figure 1–3). Unaffected skin appeared smooth, shiny, and edematous and showed no nodular lesions. Peripheral pulsations were intact.

Positive findings from a wide panel of laboratory investigations included an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (103 mm for the first hour [reference range, 0–22 mm]), high C-reactive protein (50.7 mg/L [reference range, up to 6 mg/L]), anemia (hemoglobin count, 7.3 g/dL [reference range, 13.5–17.5 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (45×103/mm3 [reference range, 150×103/mm3), low serum albumin (2.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.4–5.4 g/dL]), elevated IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (IgG, 21.4 IgG phospholipid [GPL] units [reference range, <10 IgG phospholipid (GPL) units]; IgM, 59.4 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units [reference range, <7 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units]), positive lupus anticoagulant panel test, elevated anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies (IgG, 17.5

Nerve conduction velocity showed axonal sensory polyneuropathy. Motor nerve conduction studies for median and ulnar nerves were within normal range. Lower-limb nerves assessment was limited by the ulcerated areas and marked edema. Echocardiography was unremarkable. Arterial Doppler studies were only available for the upper limbs and were unremarkable.

A punch biopsy was taken from one of the necrotizing purpuric lesions on the legs, and histopathologic examination revealed foci of epidermal necrosis and subepidermal separation and superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrates extending into the fat lobules. The infiltrates were mainly made up of foamy macrophages, and some contained globi (lepra cells), in addition to lymphocytes and many neutrophils with nuclear dust. Blood vessels in the superficial and deep dermis and in the subcutaneous fat showed fibrinoid necrosis in their walls with neutrophils infiltrating the walls and thrombi in the lumens (Figure 4). Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining revealed clumps of acid-fast lepra bacilli inside vascular lumina and endothelial cell lining and within the foamy macrophages (Figure 5). Slit-skin smear examination was performed twice and yielded negative results. The slide and paraffin block of the already performed lymph node biopsy were retrieved. Examination revealed aggregates of foamy histiocytes surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells replacing normal lymphoid follicles. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain was performed, and clusters of acid-fast bacilli were detected within the foamy histiocytic infiltrate (Figure 6).

According to the results of the skin biopsy, the revised result of the lymph node biopsy, and the pattern of neurologic deficit together with clinical and laboratory correlation, the patient was diagnosed with diffuse nonnodular lepromatous leprosy presenting with Lucio phenomenon (Lucio leprosy) and associated with lepromatous lymphadenitis.

The patient received the following treatment: methylprednisolone 500 mg (intravenous pulse therapy) followed by daily oral administration of prednisolone 10 mg, rifampicin 300 mg, dapsone 100 mg, clofazimine 100 mg, acetylsalicylic acid 150 mg, and enoxaparin sodium 80 mg. In addition, the scrotal Fournier gangrene–like lesion was treated by surgical debridement followed by vacuum therapy. By the second week after treatment, the gangrenous lesions of the fingers developed a line of demarcation, and the skin infarctions started to recede.

Comment

Despite a decrease in its prevalence through a World Health Organization (WHO)–empowered eradication program, leprosy still represents a health problem in endemic areas.1,2 It is characterized by a wide range of immune responses to Mycobacterium leprae, displaying a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic manifestations that vary from the tuberculoid or paucibacillary pole with a strong cell-mediated immune response and fewer organisms to the lepromatous or multibacillary pole with weaker cell-mediated immune response and higher loads of organisms.3 In addition to its well-known cutaneous and neurologic manifestations, leprosy can present with a variety of manifestations, including constitutional symptoms, musculoskeletal manifestations, and serologic abnormalities; thus, leprosy can mimic rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, and vasculitis—a pitfall that may result in misdiagnosis as a rheumatologic disorder.3-7

The chronic course of leprosy can be disrupted by acute, immunologically mediated reactions known as lepra reactions, of which there are 3 types.8 Type I lepra reactions are cell mediated and occur mainly in patients with borderline disease, often representing an upgrade toward the tuberculoid pole; less often they represent a downgrade reaction. Nerves become painful and swollen with possible loss of function, and skin lesions become edematous and tender; sometimes arthritis develops.9 Type II lepra reactions, also known as erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), occur in borderline lepromatous and lepromatous patients with a high bacillary load. They are characterized by fever, body aches, tender cutaneous/subcutaneous nodules that may ulcerate, possible bullous lesions, painful nerve swellings, swollen joints, iritis, lymphadenitis, glomerulonephritis, epididymo-orchitis, and hepatic affection. Both immune-complex and delayed hypersensitivity reactions play a role in ENL.8,10 The third reaction is a rare aggressive type known as Lucio phenomenon or Lucio leprosy, which presents with irregular-shaped, angulated, or stellar necrotizing purpuric lesions (hemorrhagic infacrtions) developing mainly on the extremities. The lesions evolve into ulcers that heal with atrophic scarring.2,11 Lucio phenomenon develops as a result of thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of vascular endothelial cells by lepra bacilli.2,11-14 Involvement of the scrotal skin, such as in our patient, is rare.

Lucio phenomenon mainly is seen in Mexico and Central America, and few cases have been documented in Cuba, South America, the United States, India, Polynesia, South Africa, and Southeast Asia.15-17 It specifically occurs in patients with untreated, diffuse, nonnodular lepromatous leprosy (pure and primitive diffuse lepromatous leprosy (DLL)/diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí). This type of leprosy was first described by Lucio and Alvarado18 in 1852 as a distinct form of lepromatous leprosy characterized by widespread and dense infiltration of the whole skin by lepra bacilli without the typical nodular lesions of leprosy, rendering its diagnosis challenging, especially in sporadic cases. Other manifestations of DLL include complete alopecia of the eyebrows and eyelashes, destructive rhinitis, and areas of anhidrosis and dyesthesia.2

Latapí and Chévez-Zomora19 defined Lucio phenomenon in 1948 as a form of histopathologic vasculitis restricted to patients with DLL. Histopathologically, in addition to the infiltration of the skin with acid-fast bacilli–laden foamy histiocytes, lesions of Lucio phenomenon show features of necrotizing (leukocytoclastic) vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis20 or vascular thrombi with minimal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and no evidence of vasculitis.11 Medium to large vessels in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue show infiltration of their walls with a large number of macrophages laden with acid-fast bacilli.11 Cases with histopathologic features mimicking antiphospholipid syndrome with endothelial cell proliferation, thrombosis, and mild mononuclear cell infiltrate also may be seen.20 In all cases, ischemic epidermal necrosis is seen, as well as acid-fast bacilli, both singly and in clusters (globi) within endothelial cells and inside blood vessel lumina.

Although Lucio phenomenon initially was thought to be immune-complex mediated like ENL, it has been suggested that the main trigger is thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of the vascular endothelial cells by the lepra bacilli, resulting in necrosis.14 Bacterial lipopolysaccharides promote the release of IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor α, which in turn stimulate the production of prostaglandins, IL-6, and coagulation factor III, leading to vascular thrombosis and tissue necrosis.21,22 Moreover, antiphospholipid antibodies, which have been found to be induced in response to certain infectious agents in genetically predisposed individuals,23 have been reported in patients with leprosy, mainly in association with lepromatous leprosy. The reported prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies ranged from 37% to 98%, whereas anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies ranged from 3% to 19%, and antiprothrombin antibodies ranged from 6% to 45%.24,25 Antiphospholipid antibodies have been reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of Lucio phenomenon.11,13,15,26 Our case supports this hypothesis with positive anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies, and positive lupus anticoagulant.

In accordance with Curi et al,2 who reported 5 cases of DLL with Lucio phenomenon, our patient showed a similar presentation with positive inflammatory markers in association with a negative autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) and negative venereal disease research laboratory test. It is important to mention that a positive autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) can be present in leprotic patients, causing possible diagnostic confusion with collagen diseases.27,28

An interesting finding in our case was the negative slit-skin smear results. Although the specificity of slit-skin smear is 100%, as it directly demonstrates the presence of acid-fast bacilli,29 its sensitivity is low and varies from 10% to 50%.30 The detection of acid-fast bacilli in tissue sections is reported to be a better method for confirming the diagnosis of leprosy.31

The provisional impression of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the lymph node biopsy in our patient was excluded upon detection of acid-fast bacilli in the foamy histiocytes infiltrating the lymph node; moreover, the normal serum lipids and serum ferritin argued against this diagnosis.32 Leprosy tends to involve the lymph nodes, particularly in borderline, borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous forms.33 The incidence of lymph node involvement accompanied by skin lesions with the presence of acid-fast bacilli in the lymph nodes is 92.2%.34

Our patient showed an excellent response to antileprotic treatment, which was administered according to the WHO multidrug therapy guidelines for multibacillary leprosy,35 combined with low-dose prednisolone, acetylsalicylic acid, and anticoagulant treatment. Thalidomide and high-dose prednisolone (60 mg/d) combined with antileprotic treatment also have been reported to be successful in managing recurrent infarctions in leprosy.36 The Fournier-like gangrenous ulcer of the scrotum was managed by surgical debridement and vacuum therapy.

It is noteworthy that the WHO elimination goal for leprosy was to reduce the prevalence to less than 1 case per 10,000 population. Egypt is among the first countries in North Africa and the Middle East regions to achieve this target supervised by the National Leprosy Control Program as early as 1994; this was further reduced to 0.33 cases per 10,000 population in 2004, and reduced again in 2009; however, certain foci showed a prevalence rate more than the elimination target, particularly in the cities of Qena (1.12) and Sohag (2.47).37 Esna, where our patient is from, is an endemic area in Egypt.38

Conclusion

Case Report

A 70-year-old man living in Esna, Luxor, Egypt presented to the Department of Rheumatology and Rehabilitation with widespread gangrenous skin lesions associated with ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration. One year prior, the patient had an insidious onset of nocturnal fever, bilateral leg edema, and numbness and a tingling sensation in both hands. He presented some laboratory and radiologic investigations that were performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, which revealed thrombocytopenia, mild splenomegaly, and generalized lymphadenopathy. An excisional left axillary lymph node biopsy was performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, and the pathology report provided by the patient described a reactive, foamy, histiocyte-rich lesion, suggesting a diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The patient had no diabetes or hypertension and no history of deep vein thrombosis, stroke, or unintentional weight loss. No medications were taken prior to the onset of the skin lesions, and his family history was irrelevant.

General examination at the current presentation revealed a fever (temperature, 101.3 °F [38.5 °C]), a normal heart rate (90 beats per minute), normal blood pressure (120/80 mmHg), normal respiratory rate (14 breaths per minute), accentuated heart sounds, and normal vesicular breathing without adventitious sounds. He had saddle nose, loss of the outer third of the eyebrows, and marked reduction in the density of the eyelashes (madarosis). Bilateral pitting edema of the legs also was present. Neurologic examination revealed hypoesthesia in a glove-and-stocking pattern, thickened peripheral nerves, and trophic changes over both hands; however, he had normal muscle power and deep reflexes. Joint examination revealed no abnormalities. Skin examination revealed widespread, reticulated, necrotizing, purpuric lesions on the arms, legs, abdomen, and ears, some associated with gangrenous ulcerations and hemorrhagic blisters. Scattered vasculitic ulcers and gangrenous patches were seen on the fingers. A gangrenous ulcer mimicking Fournier gangrene was seen involving the scrotal skin in addition to a gangrenous lesion on the glans penis (Figure 1–3). Unaffected skin appeared smooth, shiny, and edematous and showed no nodular lesions. Peripheral pulsations were intact.

Positive findings from a wide panel of laboratory investigations included an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (103 mm for the first hour [reference range, 0–22 mm]), high C-reactive protein (50.7 mg/L [reference range, up to 6 mg/L]), anemia (hemoglobin count, 7.3 g/dL [reference range, 13.5–17.5 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (45×103/mm3 [reference range, 150×103/mm3), low serum albumin (2.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.4–5.4 g/dL]), elevated IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (IgG, 21.4 IgG phospholipid [GPL] units [reference range, <10 IgG phospholipid (GPL) units]; IgM, 59.4 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units [reference range, <7 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units]), positive lupus anticoagulant panel test, elevated anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies (IgG, 17.5

Nerve conduction velocity showed axonal sensory polyneuropathy. Motor nerve conduction studies for median and ulnar nerves were within normal range. Lower-limb nerves assessment was limited by the ulcerated areas and marked edema. Echocardiography was unremarkable. Arterial Doppler studies were only available for the upper limbs and were unremarkable.

A punch biopsy was taken from one of the necrotizing purpuric lesions on the legs, and histopathologic examination revealed foci of epidermal necrosis and subepidermal separation and superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrates extending into the fat lobules. The infiltrates were mainly made up of foamy macrophages, and some contained globi (lepra cells), in addition to lymphocytes and many neutrophils with nuclear dust. Blood vessels in the superficial and deep dermis and in the subcutaneous fat showed fibrinoid necrosis in their walls with neutrophils infiltrating the walls and thrombi in the lumens (Figure 4). Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining revealed clumps of acid-fast lepra bacilli inside vascular lumina and endothelial cell lining and within the foamy macrophages (Figure 5). Slit-skin smear examination was performed twice and yielded negative results. The slide and paraffin block of the already performed lymph node biopsy were retrieved. Examination revealed aggregates of foamy histiocytes surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells replacing normal lymphoid follicles. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain was performed, and clusters of acid-fast bacilli were detected within the foamy histiocytic infiltrate (Figure 6).

According to the results of the skin biopsy, the revised result of the lymph node biopsy, and the pattern of neurologic deficit together with clinical and laboratory correlation, the patient was diagnosed with diffuse nonnodular lepromatous leprosy presenting with Lucio phenomenon (Lucio leprosy) and associated with lepromatous lymphadenitis.

The patient received the following treatment: methylprednisolone 500 mg (intravenous pulse therapy) followed by daily oral administration of prednisolone 10 mg, rifampicin 300 mg, dapsone 100 mg, clofazimine 100 mg, acetylsalicylic acid 150 mg, and enoxaparin sodium 80 mg. In addition, the scrotal Fournier gangrene–like lesion was treated by surgical debridement followed by vacuum therapy. By the second week after treatment, the gangrenous lesions of the fingers developed a line of demarcation, and the skin infarctions started to recede.

Comment

Despite a decrease in its prevalence through a World Health Organization (WHO)–empowered eradication program, leprosy still represents a health problem in endemic areas.1,2 It is characterized by a wide range of immune responses to Mycobacterium leprae, displaying a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic manifestations that vary from the tuberculoid or paucibacillary pole with a strong cell-mediated immune response and fewer organisms to the lepromatous or multibacillary pole with weaker cell-mediated immune response and higher loads of organisms.3 In addition to its well-known cutaneous and neurologic manifestations, leprosy can present with a variety of manifestations, including constitutional symptoms, musculoskeletal manifestations, and serologic abnormalities; thus, leprosy can mimic rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, and vasculitis—a pitfall that may result in misdiagnosis as a rheumatologic disorder.3-7

The chronic course of leprosy can be disrupted by acute, immunologically mediated reactions known as lepra reactions, of which there are 3 types.8 Type I lepra reactions are cell mediated and occur mainly in patients with borderline disease, often representing an upgrade toward the tuberculoid pole; less often they represent a downgrade reaction. Nerves become painful and swollen with possible loss of function, and skin lesions become edematous and tender; sometimes arthritis develops.9 Type II lepra reactions, also known as erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), occur in borderline lepromatous and lepromatous patients with a high bacillary load. They are characterized by fever, body aches, tender cutaneous/subcutaneous nodules that may ulcerate, possible bullous lesions, painful nerve swellings, swollen joints, iritis, lymphadenitis, glomerulonephritis, epididymo-orchitis, and hepatic affection. Both immune-complex and delayed hypersensitivity reactions play a role in ENL.8,10 The third reaction is a rare aggressive type known as Lucio phenomenon or Lucio leprosy, which presents with irregular-shaped, angulated, or stellar necrotizing purpuric lesions (hemorrhagic infacrtions) developing mainly on the extremities. The lesions evolve into ulcers that heal with atrophic scarring.2,11 Lucio phenomenon develops as a result of thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of vascular endothelial cells by lepra bacilli.2,11-14 Involvement of the scrotal skin, such as in our patient, is rare.

Lucio phenomenon mainly is seen in Mexico and Central America, and few cases have been documented in Cuba, South America, the United States, India, Polynesia, South Africa, and Southeast Asia.15-17 It specifically occurs in patients with untreated, diffuse, nonnodular lepromatous leprosy (pure and primitive diffuse lepromatous leprosy (DLL)/diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí). This type of leprosy was first described by Lucio and Alvarado18 in 1852 as a distinct form of lepromatous leprosy characterized by widespread and dense infiltration of the whole skin by lepra bacilli without the typical nodular lesions of leprosy, rendering its diagnosis challenging, especially in sporadic cases. Other manifestations of DLL include complete alopecia of the eyebrows and eyelashes, destructive rhinitis, and areas of anhidrosis and dyesthesia.2

Latapí and Chévez-Zomora19 defined Lucio phenomenon in 1948 as a form of histopathologic vasculitis restricted to patients with DLL. Histopathologically, in addition to the infiltration of the skin with acid-fast bacilli–laden foamy histiocytes, lesions of Lucio phenomenon show features of necrotizing (leukocytoclastic) vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis20 or vascular thrombi with minimal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and no evidence of vasculitis.11 Medium to large vessels in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue show infiltration of their walls with a large number of macrophages laden with acid-fast bacilli.11 Cases with histopathologic features mimicking antiphospholipid syndrome with endothelial cell proliferation, thrombosis, and mild mononuclear cell infiltrate also may be seen.20 In all cases, ischemic epidermal necrosis is seen, as well as acid-fast bacilli, both singly and in clusters (globi) within endothelial cells and inside blood vessel lumina.

Although Lucio phenomenon initially was thought to be immune-complex mediated like ENL, it has been suggested that the main trigger is thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of the vascular endothelial cells by the lepra bacilli, resulting in necrosis.14 Bacterial lipopolysaccharides promote the release of IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor α, which in turn stimulate the production of prostaglandins, IL-6, and coagulation factor III, leading to vascular thrombosis and tissue necrosis.21,22 Moreover, antiphospholipid antibodies, which have been found to be induced in response to certain infectious agents in genetically predisposed individuals,23 have been reported in patients with leprosy, mainly in association with lepromatous leprosy. The reported prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies ranged from 37% to 98%, whereas anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies ranged from 3% to 19%, and antiprothrombin antibodies ranged from 6% to 45%.24,25 Antiphospholipid antibodies have been reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of Lucio phenomenon.11,13,15,26 Our case supports this hypothesis with positive anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies, and positive lupus anticoagulant.

In accordance with Curi et al,2 who reported 5 cases of DLL with Lucio phenomenon, our patient showed a similar presentation with positive inflammatory markers in association with a negative autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) and negative venereal disease research laboratory test. It is important to mention that a positive autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) can be present in leprotic patients, causing possible diagnostic confusion with collagen diseases.27,28

An interesting finding in our case was the negative slit-skin smear results. Although the specificity of slit-skin smear is 100%, as it directly demonstrates the presence of acid-fast bacilli,29 its sensitivity is low and varies from 10% to 50%.30 The detection of acid-fast bacilli in tissue sections is reported to be a better method for confirming the diagnosis of leprosy.31

The provisional impression of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the lymph node biopsy in our patient was excluded upon detection of acid-fast bacilli in the foamy histiocytes infiltrating the lymph node; moreover, the normal serum lipids and serum ferritin argued against this diagnosis.32 Leprosy tends to involve the lymph nodes, particularly in borderline, borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous forms.33 The incidence of lymph node involvement accompanied by skin lesions with the presence of acid-fast bacilli in the lymph nodes is 92.2%.34

Our patient showed an excellent response to antileprotic treatment, which was administered according to the WHO multidrug therapy guidelines for multibacillary leprosy,35 combined with low-dose prednisolone, acetylsalicylic acid, and anticoagulant treatment. Thalidomide and high-dose prednisolone (60 mg/d) combined with antileprotic treatment also have been reported to be successful in managing recurrent infarctions in leprosy.36 The Fournier-like gangrenous ulcer of the scrotum was managed by surgical debridement and vacuum therapy.

It is noteworthy that the WHO elimination goal for leprosy was to reduce the prevalence to less than 1 case per 10,000 population. Egypt is among the first countries in North Africa and the Middle East regions to achieve this target supervised by the National Leprosy Control Program as early as 1994; this was further reduced to 0.33 cases per 10,000 population in 2004, and reduced again in 2009; however, certain foci showed a prevalence rate more than the elimination target, particularly in the cities of Qena (1.12) and Sohag (2.47).37 Esna, where our patient is from, is an endemic area in Egypt.38

Conclusion

1. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics: 2011. World Health Organization; 2011. https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2011_Full.pdf

2. Curi PF, Villaroel JS, Migliore N, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: report of five cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1397-1401.

3. Shrestha B, Li YQ, Fu P. Leprosy mimics adult onset Still’s disease in a Chinese patient. Egypt Rheumatol. 2018;40:217-220.

4. Prasad S, Misra R, Aggarwal A, et al. Leprosy revealed in a rheumatology clinic: a case series. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:129-133.

5. Chao G, Fang L, Lu C. Leprosy with ANA positive mistaken for connective tissue disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:645-648.

6. Chauhan S, Wakhlu A, Agarwal V. Arthritis in leprosy. Rheumatology. 2010;49:2237-2242.

7. Rath D, Bhargava S, Kundu BK. Leprosy mimicking common rheumatologic entities: a trial for the clinician in the era of biologics. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:429698.

8. Cuevas J, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Carrillo R, et al. Erythema nodosum leprosum: reactional leprosy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:126-130.

9. Henriques CC, Lopéz B, Mestre T, et al. Leprosy and rheumatoid arthritis: consequence or association? BMJ Case Rep. 2012;13:1-4.

10. Vázquez-Botet M, Sánchez JL. Erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:436-437.

11. Nunzie E, Ortega Cabrera LV, Macanchi Moncayo FM, et al. Lucio leprosy with Lucio’s phenomenon, digital gangrene and anticardiolipin antibodies. Lepr Rev. 2014;85:194-200.

12. Salvi S, Chopra A. Leprosy in a rheumatology setting: a challenging mimic to expose. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1557-1563.

13. Azulay-Abulafia L, Pereira SL, Hardmann D, et al. Lucio phenomenon. vasculitis or occlusive vasculopathy? Hautarzt. 2006;57:1101-1105.

14. Benard G, Sakai-Valente NY, Bianconcini Trindade MA. Concomittant Lucio phenomenon and erythema nodosum in a leprosy patient: clues for their distinct pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:288-292.

15. Rocha RH, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: exuberant case report and review of Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(suppl 5):S60-S63.

16. Costa IM, Kawano LB, Pereira CP, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:566-571.

17. Kumari R, Thappa DM, Basu D. A fatal case of Lucio phenomenon from India. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

18. Lucio R, Alvarado I. Opúsculo Sobre el Mal de San Lázaro o Elefantiasis de los Griegos. M. Murguía; 1852.

19. Latapí F, Chévez-Zamora A. The “spotted” leprosy of Lucio: an introduction to its clinical and histological study. Int J Lepr. 1948;16:421-437.

20. Vargas OF. Diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí: a histologic study. Lepr Rev. 2007;78:248-260.

21. Latapí FR, Chevez-Zamora A. La lepra manchada de Lucio. Rev Dermatol Mex. 1978;22:102-107.

22. Monteiro R, Abreu MA, Tiezzi MG, et al. Fenômeno de Lúcio: mais um caso relatado no Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:296-300.

23. Gharavi EE, Chaimovich H, Cucucrull E, et al. Induction of antiphospholipid antibodies by immunization with synthetic bacterial & viral peptides. Lupus. 1999;8:449-455.

24. de Larrañaga GF, Forastiero RR, Martinuzzo ME, et al. High prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in leprosy: evaluation of antigen reactivity. Lupus. 2000;9:594-600.

25. Loizou S, Singh S, Wypkema E, et al. Anticardiolipin, anti-beta(2)-glycoprotein I and antiprothrombin antibodies in black South African patients with infectious disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1106-1111.

26. Akerkar SM, Bichile LS. Leprosy & gangrene: a rare association; role of antiphospholipid antibodies. BMC Infect Dis. 2005,5:74.

27. Horta-Baas G, Hernández-Cabrera MF, Barile-Fabris LA, et al. Multibacillary leprosy mimicking systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and literature review. Lupus. 2015;24:1095-1102.

28. Pradhan V, Badakere SS, Shankar KU. Increased incidence of cytoplasmic ANCA (cANCA) and other auto antibodies in leprosy patients from western India. Lepr Rev. 2004;75:50-56.

29. Oskam L. Diagnosis and classification of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2002;73:17-26.

30. Rao PN. Recent advances in the control programs and therapy of leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:269-276.

31. Rao PN, Pratap D, Ramana Reddy AV, et al. Evaluation of leprosy patients with 1 to 5 skin lesions with relevance to their grouping into paucibacillary or multibacillary disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:207-210.

32. Rosado FGN, Kim AS. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. an update on diagnosis and pathogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:713-727.

33. Kar HK, Mohanty HC, Mohanty GN, et al. Clinicopathological study of lymph node involvement in leprosy. Lepr India. 1983;55:725-738.

34. Gupta JC, Panda PK, Shrivastava KK, et al. A histopathologic study of lymph nodes in 43 cases of leprosy. Lepr India. 1978;50:196-203.

35. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Seventh Report. World Health Organization; 1998. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42060/WHO_TRS_874.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

36. Misra DP, Parida JR, Chowdhury AC, et al. Lepra reaction with Lucio phenomenon mimicking cutaneous vasculitis. Case Rep Immunol. 2014;2014:641989.

37. Amer A, Mansour A. Epidemiological study of leprosy in Egypt: 2005-2009. Egypt J Dermatol Venereol. 2014;34:70-73.

38. World Health Organization. Screening campaign aims to eliminate leprosy in Egypt. Published May 9, 2018. Accessed September 8, 2021. http://www.emro.who.int/egy/egypt-events/last-miless-activities-on-eliminating-leprosy-from-egypt.html

1. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics: 2011. World Health Organization; 2011. https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2011_Full.pdf

2. Curi PF, Villaroel JS, Migliore N, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: report of five cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1397-1401.

3. Shrestha B, Li YQ, Fu P. Leprosy mimics adult onset Still’s disease in a Chinese patient. Egypt Rheumatol. 2018;40:217-220.

4. Prasad S, Misra R, Aggarwal A, et al. Leprosy revealed in a rheumatology clinic: a case series. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:129-133.

5. Chao G, Fang L, Lu C. Leprosy with ANA positive mistaken for connective tissue disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:645-648.

6. Chauhan S, Wakhlu A, Agarwal V. Arthritis in leprosy. Rheumatology. 2010;49:2237-2242.

7. Rath D, Bhargava S, Kundu BK. Leprosy mimicking common rheumatologic entities: a trial for the clinician in the era of biologics. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:429698.

8. Cuevas J, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Carrillo R, et al. Erythema nodosum leprosum: reactional leprosy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:126-130.

9. Henriques CC, Lopéz B, Mestre T, et al. Leprosy and rheumatoid arthritis: consequence or association? BMJ Case Rep. 2012;13:1-4.

10. Vázquez-Botet M, Sánchez JL. Erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:436-437.

11. Nunzie E, Ortega Cabrera LV, Macanchi Moncayo FM, et al. Lucio leprosy with Lucio’s phenomenon, digital gangrene and anticardiolipin antibodies. Lepr Rev. 2014;85:194-200.

12. Salvi S, Chopra A. Leprosy in a rheumatology setting: a challenging mimic to expose. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1557-1563.

13. Azulay-Abulafia L, Pereira SL, Hardmann D, et al. Lucio phenomenon. vasculitis or occlusive vasculopathy? Hautarzt. 2006;57:1101-1105.

14. Benard G, Sakai-Valente NY, Bianconcini Trindade MA. Concomittant Lucio phenomenon and erythema nodosum in a leprosy patient: clues for their distinct pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:288-292.

15. Rocha RH, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: exuberant case report and review of Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(suppl 5):S60-S63.

16. Costa IM, Kawano LB, Pereira CP, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:566-571.

17. Kumari R, Thappa DM, Basu D. A fatal case of Lucio phenomenon from India. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

18. Lucio R, Alvarado I. Opúsculo Sobre el Mal de San Lázaro o Elefantiasis de los Griegos. M. Murguía; 1852.

19. Latapí F, Chévez-Zamora A. The “spotted” leprosy of Lucio: an introduction to its clinical and histological study. Int J Lepr. 1948;16:421-437.

20. Vargas OF. Diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí: a histologic study. Lepr Rev. 2007;78:248-260.

21. Latapí FR, Chevez-Zamora A. La lepra manchada de Lucio. Rev Dermatol Mex. 1978;22:102-107.

22. Monteiro R, Abreu MA, Tiezzi MG, et al. Fenômeno de Lúcio: mais um caso relatado no Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:296-300.

23. Gharavi EE, Chaimovich H, Cucucrull E, et al. Induction of antiphospholipid antibodies by immunization with synthetic bacterial & viral peptides. Lupus. 1999;8:449-455.

24. de Larrañaga GF, Forastiero RR, Martinuzzo ME, et al. High prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in leprosy: evaluation of antigen reactivity. Lupus. 2000;9:594-600.

25. Loizou S, Singh S, Wypkema E, et al. Anticardiolipin, anti-beta(2)-glycoprotein I and antiprothrombin antibodies in black South African patients with infectious disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1106-1111.

26. Akerkar SM, Bichile LS. Leprosy & gangrene: a rare association; role of antiphospholipid antibodies. BMC Infect Dis. 2005,5:74.

27. Horta-Baas G, Hernández-Cabrera MF, Barile-Fabris LA, et al. Multibacillary leprosy mimicking systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and literature review. Lupus. 2015;24:1095-1102.

28. Pradhan V, Badakere SS, Shankar KU. Increased incidence of cytoplasmic ANCA (cANCA) and other auto antibodies in leprosy patients from western India. Lepr Rev. 2004;75:50-56.

29. Oskam L. Diagnosis and classification of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2002;73:17-26.

30. Rao PN. Recent advances in the control programs and therapy of leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:269-276.

31. Rao PN, Pratap D, Ramana Reddy AV, et al. Evaluation of leprosy patients with 1 to 5 skin lesions with relevance to their grouping into paucibacillary or multibacillary disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:207-210.

32. Rosado FGN, Kim AS. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. an update on diagnosis and pathogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:713-727.

33. Kar HK, Mohanty HC, Mohanty GN, et al. Clinicopathological study of lymph node involvement in leprosy. Lepr India. 1983;55:725-738.

34. Gupta JC, Panda PK, Shrivastava KK, et al. A histopathologic study of lymph nodes in 43 cases of leprosy. Lepr India. 1978;50:196-203.

35. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Seventh Report. World Health Organization; 1998. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42060/WHO_TRS_874.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

36. Misra DP, Parida JR, Chowdhury AC, et al. Lepra reaction with Lucio phenomenon mimicking cutaneous vasculitis. Case Rep Immunol. 2014;2014:641989.

37. Amer A, Mansour A. Epidemiological study of leprosy in Egypt: 2005-2009. Egypt J Dermatol Venereol. 2014;34:70-73.

38. World Health Organization. Screening campaign aims to eliminate leprosy in Egypt. Published May 9, 2018. Accessed September 8, 2021. http://www.emro.who.int/egy/egypt-events/last-miless-activities-on-eliminating-leprosy-from-egypt.html

Practice Points

- Leprosy is a great mimicker of many connective tissue diseases, including vasculitis.

- Antiphospholipid antibodies are involved in Lucio phenomenon.

- Prompt treatment is important in Lucio phenomenon to avoid morbidity and mortality.

Electrocuted by 11,000 volts, now a triple amputee ... and an MD

Bruce “BJ” Miller Jr., a 19-year-old Princeton (N.J.) University sophomore, was horsing around with friends near a train track in 1990 when they spotted a parked commuter train. They decided to climb over the train, and Mr. Miller was first up the ladder.

An explosion ripped through the air, and Mr. Miller was thrown on top of the train, his body smoking. His petrified friends called for an ambulance.

Clinging to life, Mr. Miller was airlifted to the burn unit at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, N.J..

Physicians saved Mr. Miller’s life, but they had to amputate both of his legs below the knees and his left arm below the elbow.

“With electricity, you burn from the inside out,” said Mr. Miller, now 50. “The voltage enters your body – in my case, the wrist – and runs around internally until it finds a way out. That is often the lower extremities as the ground tends to ground the current, but not always. In my case, the current tried to come through my chest – which is also burned and required skin grafting – but not enough to spare my legs. I think I had a half-dozen or so surgeries over the first month or 2 at the hospital.”

Waking up to a new body

Mr. Miller doesn’t remember much about the accident, but he recalls waking up a few days later in the ICU and feeling the need to use the bathroom. Disoriented, Mr. Miller pulled off his ventilator, climbed out of bed, and tried to walk forward, unaware of his injuries. His feet and legs had not yet been amputated. When the catheter line ran out of slack, he collapsed.

“Eventually, a nurse came rushing in, responding to the ventilator alarm bells going off,” Mr. Miller said. “My dad wasn’t far behind. It became clear to me then that this was not a dream and [I realized] what had happened and why I was in the hospital.”

For months, Mr. Miller lived in the burn unit, undergoing countless skin grafts and surgeries. Because viable and nonviable tissue take time to be revealed after burns, surgeons take the minimum amount of tissue during each operation to give damaged tissue a chance to heal, he explained. In Mr. Miller’s case, his feet were amputated first, and later, his legs.

“In those early days from the hospital bed, my mind turned to issues related to identity,” he said. “What do I do with myself?

Mr. Miller eventually moved to the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (now called The Shirley Ryan AbilityLab), where he started the grueling process of rebuilding his strength and learning to walk on prosthetic legs.

“Any one day was filled with a mix of optimism and good fight and 5 minutes later, exasperation, frustration, tons of pain, and insecurity about my body,” he said. “My family and friends held the gate for me in a way, but a lot of the work was up to me. I had to believe that I deserved this love, that I wanted to be alive, and that there was still something here for me.”

Mr. Miller didn’t have to look far for inspiration. His mom had lived with polio for most of her life and acquired post-polio syndrome as she grew older, he said. When he was a child, his mom walked with crutches, and she became wheelchair-dependent by the time he was a teenager.

After the first surgery to amputate his feet, Mr. Miller and his mom shared a deep discussion about his joining the ranks of “the disabled,” and how their connection was now even stronger.

“In this way, the injuries unlocked even more experiences to share between us, and more love to feel, and therefore some early sense of gain to complement all the losses happening,” he said. “She had taught me so much about living with disability and had given me all the tools I needed to refashion my sense of self.”

From burn patient to medical student

After returning to Princeton University and finishing his undergraduate degree, Mr. Miller decided to go into medicine. He wanted to use his experience to help patients and find ways to improve weaknesses in the health care system, he said. But he made a deal with himself that he wouldn’t become a doctor for the sake of becoming one; he would enter the vocation only if he could do the work and enjoy the job.

“I wasn’t sure if I could do it,” he said. “There weren’t a lot of triple amputees to point to, to say whether this was even mechanically possible, to get through the training. The medical institutions I spoke with knew they had some obligation by law to protect me, but there’s also an obligation that I need to be able to fulfill the competencies. This was uncharted water.”

Because his greatest physical challenge was standing for long periods, instructors at the University of California, San Francisco, made accommodations to alleviate the strain. His clinical rotations for example, were organized near his home to limit the need for travel. On surgical rotations, he was allowed to sit on a stool.

Medical training progressed smoothly until Mr. Miller completed a rotation in his chosen specialty, rehabilitation medicine. He didn’t enjoy it. The passion and meaning he hoped to find was missing. Disillusioned, and with his final year in medical school coming to an end, Mr. Miller dropped out of the Match program. Around the same time, his sister, Lisa, died by suicide.

“My whole family life was in shambles,” he said. “I felt like, ‘I can’t even help my sister, how am I going to help other people?’ ”

Mr. Miller earned his MD and moved to his parents’ home in Milwaukee after his sister’s death. He was close to giving up on medicine, but his deans convinced him to do a post-doc internship. It was as an intern at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, that he completed an elective in palliative care.

“I fell immediately in love with it the first day,” he said. “This was a field devoted to working with things you can’t change and dealing with a lack of control, what it’s like to live with these diagnoses. This was a place where I could dig into my experience and share that with patients and families. This was a place where my life story had something to offer.”

Creating a new form of palliative care

Dr. Miller went on to complete a fellowship at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in hospice and palliative medicine. He became a palliative care physician at UCSF Health, and later directed the Zen Hospice Project, a nonprofit dedicated to teaching mindfulness-based caregiving for professionals, family members, and caregivers.

Gayle Kojimoto, a program manager who worked with Dr. Miller at UCSF’s outpatient palliative care clinic for cancer patients, said Miller was a favorite among patients because of his authenticity and his ability to make them feel understood.

“Patients love him because he is 100% present with them,” said Ms. Kojimoto. “They feel like he can understand their suffering better than other docs. He’s open to hearing about their suffering, when others may not be, and he doesn’t judge them. Many patients have said that seeing him is better than seeing a therapist.”

In 2020, Dr. Miller cofounded Mettle Health, a first-of-its-kind company that aims to reframe the way people think about their well-being as it relates to chronic and serious illness. Mettle Health’s care team provides consultations on a range of topics, including practical, emotional, and existential issues. No physician referrals are needed.

When the pandemic started, Dr. Miller said he and his colleagues felt the moment was ripe for bringing palliative care online to increase access, while decreasing caregiver and clinician burnout.

“We set up Mettle Health as an online palliative care counseling and coaching business and we pulled it out of the healthcare system so that whether you’re a patient or a caregiver you don’t need to satisfy some insurance need to get this kind of care,” he said. “We also realized there are enough people writing prescriptions. The medical piece is relatively well tended to; it’s the psychosocial and spiritual issues, and the existential issues, that are so underdeveloped. We are a social service, not a medical service, and this allows us to complement existing structures of care rather than compete with them.”

Having Dr. Miller as a leader for Mettle Health is a huge driver for why people seek out the company, said Sonya Dolan, director of operations and cofounder of Mettle Health.

“His approach to working with patients, caregivers, and clinicians is something I think sets us apart and makes us special,” she said. “His way of thinking about serious illness and death and dying is incredibly unique and he has a way of talking about and humanizing something that’s scary for a lot of us.”

‘Surprised by how much I can still do’

Since the accident, Dr. Miller has come a long way in navigating his physical limitations. In the early years, Dr. Miller said he was determined to do as many activities as he still could. He skied, biked, and pushed himself to stand for long periods on his prosthetic legs.

“For years, I would force myself to do these things just to prove I could, but not really enjoy them,” he said. “I’d get out on the dance floor or put myself out in vulnerable social situations where I might fall. It was kind of brutal and difficult. But at about year 5 or so, I became much more at ease with myself and more at peace with myself.”

Today, Dr. Miller’s prosthetics make nearly all ambulatory activities possible, but he concentrates on the activities that bring him joy.

“Probably the thing I can still do that surprises people most, including myself, is riding a motorcycle,” he said. “As for my upper body, I’m thoroughly used to living with only one hand and I continue to be surprised at how much I can still do. With enough time and experimentation, I can usually find a way to do what I need/want to do. It took me awhile to figure out how to clap! Now I just pound my chest for the same effect!”

Dr. Miller is an animal-lover and said his pets and nature are a large part of his self-care. His dog Maysie travels nearly everywhere with him and his cats, the Muffin Man and Darkness, enjoy making guest appearances on his Zoom calls. The physician frequently visits the desert in southern Utah and said he loves the arts, architecture, and design.

Dr. Miller’s advice for others who are disabled and want to go into medicine? Live out loud with your truths and be open about your disabilities. Too often, disabled individuals hide their disabilities, lie about them, or shield the world from their story, he said.

“These are rich, ripe experiences that are incredibly valuable to someone who wants to go out and be of service in the world,” he said. “We should be proud of our experiences as disabled people. The creativity we’ve had to exercise, the workarounds we’ve had to employ, these should not be points of embarrassment, but points of pride. Anyone who wants to pursue clinical training of any kind should use these experiences explicitly. These are sources of strength, not something to be forgiven or tolerated or accommodated.”

The same goes for physicians who do not have disabilities but who have lived through hardship, pain, struggle, or adversity, he emphasized.

“Find a way to learn from them, find a way to own them,” he said. “Use them as a source of strength and the rest of the world will respond to you differently.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Bruce “BJ” Miller Jr., a 19-year-old Princeton (N.J.) University sophomore, was horsing around with friends near a train track in 1990 when they spotted a parked commuter train. They decided to climb over the train, and Mr. Miller was first up the ladder.

An explosion ripped through the air, and Mr. Miller was thrown on top of the train, his body smoking. His petrified friends called for an ambulance.

Clinging to life, Mr. Miller was airlifted to the burn unit at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, N.J..

Physicians saved Mr. Miller’s life, but they had to amputate both of his legs below the knees and his left arm below the elbow.

“With electricity, you burn from the inside out,” said Mr. Miller, now 50. “The voltage enters your body – in my case, the wrist – and runs around internally until it finds a way out. That is often the lower extremities as the ground tends to ground the current, but not always. In my case, the current tried to come through my chest – which is also burned and required skin grafting – but not enough to spare my legs. I think I had a half-dozen or so surgeries over the first month or 2 at the hospital.”

Waking up to a new body

Mr. Miller doesn’t remember much about the accident, but he recalls waking up a few days later in the ICU and feeling the need to use the bathroom. Disoriented, Mr. Miller pulled off his ventilator, climbed out of bed, and tried to walk forward, unaware of his injuries. His feet and legs had not yet been amputated. When the catheter line ran out of slack, he collapsed.

“Eventually, a nurse came rushing in, responding to the ventilator alarm bells going off,” Mr. Miller said. “My dad wasn’t far behind. It became clear to me then that this was not a dream and [I realized] what had happened and why I was in the hospital.”

For months, Mr. Miller lived in the burn unit, undergoing countless skin grafts and surgeries. Because viable and nonviable tissue take time to be revealed after burns, surgeons take the minimum amount of tissue during each operation to give damaged tissue a chance to heal, he explained. In Mr. Miller’s case, his feet were amputated first, and later, his legs.

“In those early days from the hospital bed, my mind turned to issues related to identity,” he said. “What do I do with myself?

Mr. Miller eventually moved to the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (now called The Shirley Ryan AbilityLab), where he started the grueling process of rebuilding his strength and learning to walk on prosthetic legs.

“Any one day was filled with a mix of optimism and good fight and 5 minutes later, exasperation, frustration, tons of pain, and insecurity about my body,” he said. “My family and friends held the gate for me in a way, but a lot of the work was up to me. I had to believe that I deserved this love, that I wanted to be alive, and that there was still something here for me.”

Mr. Miller didn’t have to look far for inspiration. His mom had lived with polio for most of her life and acquired post-polio syndrome as she grew older, he said. When he was a child, his mom walked with crutches, and she became wheelchair-dependent by the time he was a teenager.

After the first surgery to amputate his feet, Mr. Miller and his mom shared a deep discussion about his joining the ranks of “the disabled,” and how their connection was now even stronger.

“In this way, the injuries unlocked even more experiences to share between us, and more love to feel, and therefore some early sense of gain to complement all the losses happening,” he said. “She had taught me so much about living with disability and had given me all the tools I needed to refashion my sense of self.”

From burn patient to medical student

After returning to Princeton University and finishing his undergraduate degree, Mr. Miller decided to go into medicine. He wanted to use his experience to help patients and find ways to improve weaknesses in the health care system, he said. But he made a deal with himself that he wouldn’t become a doctor for the sake of becoming one; he would enter the vocation only if he could do the work and enjoy the job.

“I wasn’t sure if I could do it,” he said. “There weren’t a lot of triple amputees to point to, to say whether this was even mechanically possible, to get through the training. The medical institutions I spoke with knew they had some obligation by law to protect me, but there’s also an obligation that I need to be able to fulfill the competencies. This was uncharted water.”

Because his greatest physical challenge was standing for long periods, instructors at the University of California, San Francisco, made accommodations to alleviate the strain. His clinical rotations for example, were organized near his home to limit the need for travel. On surgical rotations, he was allowed to sit on a stool.

Medical training progressed smoothly until Mr. Miller completed a rotation in his chosen specialty, rehabilitation medicine. He didn’t enjoy it. The passion and meaning he hoped to find was missing. Disillusioned, and with his final year in medical school coming to an end, Mr. Miller dropped out of the Match program. Around the same time, his sister, Lisa, died by suicide.

“My whole family life was in shambles,” he said. “I felt like, ‘I can’t even help my sister, how am I going to help other people?’ ”

Mr. Miller earned his MD and moved to his parents’ home in Milwaukee after his sister’s death. He was close to giving up on medicine, but his deans convinced him to do a post-doc internship. It was as an intern at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, that he completed an elective in palliative care.

“I fell immediately in love with it the first day,” he said. “This was a field devoted to working with things you can’t change and dealing with a lack of control, what it’s like to live with these diagnoses. This was a place where I could dig into my experience and share that with patients and families. This was a place where my life story had something to offer.”

Creating a new form of palliative care

Dr. Miller went on to complete a fellowship at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in hospice and palliative medicine. He became a palliative care physician at UCSF Health, and later directed the Zen Hospice Project, a nonprofit dedicated to teaching mindfulness-based caregiving for professionals, family members, and caregivers.

Gayle Kojimoto, a program manager who worked with Dr. Miller at UCSF’s outpatient palliative care clinic for cancer patients, said Miller was a favorite among patients because of his authenticity and his ability to make them feel understood.

“Patients love him because he is 100% present with them,” said Ms. Kojimoto. “They feel like he can understand their suffering better than other docs. He’s open to hearing about their suffering, when others may not be, and he doesn’t judge them. Many patients have said that seeing him is better than seeing a therapist.”

In 2020, Dr. Miller cofounded Mettle Health, a first-of-its-kind company that aims to reframe the way people think about their well-being as it relates to chronic and serious illness. Mettle Health’s care team provides consultations on a range of topics, including practical, emotional, and existential issues. No physician referrals are needed.

When the pandemic started, Dr. Miller said he and his colleagues felt the moment was ripe for bringing palliative care online to increase access, while decreasing caregiver and clinician burnout.

“We set up Mettle Health as an online palliative care counseling and coaching business and we pulled it out of the healthcare system so that whether you’re a patient or a caregiver you don’t need to satisfy some insurance need to get this kind of care,” he said. “We also realized there are enough people writing prescriptions. The medical piece is relatively well tended to; it’s the psychosocial and spiritual issues, and the existential issues, that are so underdeveloped. We are a social service, not a medical service, and this allows us to complement existing structures of care rather than compete with them.”

Having Dr. Miller as a leader for Mettle Health is a huge driver for why people seek out the company, said Sonya Dolan, director of operations and cofounder of Mettle Health.

“His approach to working with patients, caregivers, and clinicians is something I think sets us apart and makes us special,” she said. “His way of thinking about serious illness and death and dying is incredibly unique and he has a way of talking about and humanizing something that’s scary for a lot of us.”

‘Surprised by how much I can still do’

Since the accident, Dr. Miller has come a long way in navigating his physical limitations. In the early years, Dr. Miller said he was determined to do as many activities as he still could. He skied, biked, and pushed himself to stand for long periods on his prosthetic legs.