User login

Adaptive therapy borrows from nature to keep rhabdomyosarcoma in check

In 1859, Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” which outlined his world-shaking theory of evolution and its core principle of natural selection caused by environmental pressures that may determine whether an organism adapts and survives, or remains static, languishes, and eventually dies out.

The same forces that have influenced the size and shape of the beaks of finches in the Galapagos Islands, the length of giraffe necks in Africa, and the intestinal microbiomes of the nearly 8 billion human inhabitants of this planet also control whether malignant cells thrive and multiply, wither and die when assaulted by chemotherapy, or go into hiding, mutating and waiting for their next opportunity to erupt again and metastasize.

The ability of malignant cells to adapt to environmental pressures is “cancer’s most lethal and sophisticated property,” said Damon R. Reed, MD, program leader of the adolescent/young adult program at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla.

Dr. Reed and colleagues are developing methods to meet cancer on its own terms, applying evolutionary principles to the treatment of childhood fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma in an innovative, and some would say audacious, clinical trial.

Adaptive versus conventional therapy

The trial, now recruiting, is designed to evaluate each of four different strategies for chemotherapy schedules in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma.

The trial contains four arms, three of which consist of either conventional chemotherapy based on published clinical trials, moving a second-line therapy to the first line, or adding maintenance therapy, all of which have the goal of inducing as many complete remissions as possible.

The remaining adaptive therapy arm, however, is entirely novel in approach, with therapy using a combination of chemotherapy drugs that will be started and interrupted based on tumor responses, with resumption of therapy on an adaptive schedule unique to each patient. The goal of treatment for patients enrolled in this arm will be prolongation of the time to disease progression, rather than complete remission.

Although some people might consider the adaptive therapy approach to be sacrificing the hope for a cure in exchange for palliation, the hard truth is that patients with fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma (in contrast to those with fusion-negative disease) have a dismal prognosis following relapse after up-front intensified therapy.

Instead, because a cure is exceedingly unlikely in patients with metastatic disease, the conventional idea of delivering the maximum tolerated dose of chemotherapy until disease progression could be replaced by an approach based on understanding of the evolution of cancer cells under selective pressures, Dr. Reed and colleagues contend.

“Although adaptive therapy would represent a major paradigm shift in pediatric oncology, this approach would exploit the chemotherapy-sensitive population to prevent the emergence of resistant populations, optimizing tumor control with less toxicity,” they wrote in a commentary published online in the journal Cancer.1

Poor survival with advanced disease

Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a form of soft tissue sarcoma of mesenchymal origin. Approximately 25% of cases are parameningeal, arising from sites adjacent to the meninges of the nasopharynx, middle ear, paranasal sinuses, orbit, and other regions of the head and neck. Approximately 31% of cases arise in the genitourinary tract and 13% in the extremities, and other tumors occur less commonly in the trunk, chest wall, perineal/anal region, and abdomen.

The overall 5-year survival rate is approximately 71%.1

However, for patients with high-risk disease, a group that includes children 10 years of age or older with widespread disease with or without an activating PAX/FOX01 gene fusion, 5-year survival ranges from just 20% to 30% (Cancer Facts & Figures 2020).

“Among patients with metastatic disease, there is a clear difference in overall survival between those who have fusion-positive disease, where the 5-year overall survival is about 19%, and patients with fusion-negative disease,” said Douglas S. Hawkins, MD, chair of the children’s oncology group and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and associate chief in the division of hematology/oncology at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Patients with fusion-negative disease can be further classified into those with multiple metastatic sites, with a 5-year overall survival rate of approximately 45%, and those with a single metastatic site, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 70%, he said in an interview.

“So when we talk about metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma, there actually is a diversity of outcomes, between really bad – those with fusion-positive disease – and not terrible – not great, but not terrible – for a selected group of patients with fusion-negative disease,” Dr. Hawkins said.

The poor prognosis for patients with metastatic fusion-positive disease prompted Dr. Reed and colleagues to rethink the entire approach to advanced cancers.

“If someone has a sarcoma, we know that we need to do surgery and radiation to the area, we know that localized disease does better than metastatic disease, and we generally hit it with some kind of chemotherapy that we call ‘standard of care,’ ” he said in an interview.

This approach is largely effective in some forms of cancer of bone and soft tissues, such as Ewing sarcoma, he notes, which has 5-year survival rates below 20% when treated with surgery and radiation only, but with the addition of chemotherapy has 5-year overall survival rates as high as 80%.

“At other times, with other sarcomas, the cure rate is abysmal, but we still call it standard of care,” Dr. Reed said.

For example, patients with metastatic fusion-positive RMS may have an initial response to chemotherapy, but most will eventually experience relapse and die of the disease.

“With some of the most common treatments, 70% of patients will have their cancers shrink by more than 50%, which is a major response, but the vast majority of them will have a recurrence later on,” Dr. Hawkins said.

He noted that the standard of care for patients with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma, both with and without the PAX/FOX01 fusion, is chemotherapy, generally with the VAC regimen (vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide), although other agents such as doxorubicin, ifosfamide, etoposide, or irinotecan have also been tried, with little effect on event-free survival or overall survival rates.

A life too brief

Ricky Huff and his family know the course that the disease can take only too well. In 2015, his 5-month-old son, Theo, was diagnosed with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma and put under the care of Damon Reed at Moffitt.

“During the whole course of treatment – I’m sure like many other parents – apart from relying on Damon and his treatment expertise to try to determine the best treatment options, I was reading everything under the sun to try to get a working knowledge of what Theo was up against, what his treatment and clinical trial options were, and what was the state of the science,” Mr. Huff says.

Unfortunately, the characteristics of Theo’s disease, including his very young age at onset and diagnosis of stage 4 metastatic disease, conspired against him, and despite undergoing 14 months of chemotherapy, Theo died of the disease in October 2016, 5 months shy of what would have been his second birthday.

In their grief, Mr. Huff, a real estate lawyer with a practice in Clearwater, Fla., and his wife, Leah, were determined to help other families of children with cancer and settled on the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation. Mr. Huff joined the board of directors of the foundation, which is collaborating with Moffitt Cancer Center on the adaptive therapy trial.

An evolutionary primer (cancer edition)

To get a better idea of just how adaptive therapy works, it is helpful to view cancer cells through the lens of species development, adaptation, extinction, and evolution.

“Cancer cells compete against each other in a dynamic environment. Their tumor ecosystems exhibit spatial and temporal fluctuations in blood-borne nutrients, oxygen, growth factors, immune cells, and hormones,” Dr. Reed and colleagues wrote.

These influences can affect genetically identical cancer cells, which may begin to diverge from one another depending on their location in a tumor and the availability of nutrients, which in turn can result in two once-identical cells exhibiting different transcription rates for growth factors.

“Ultimately, this may affect the rate of progression through the cell cycle, leading to distinct rates of proliferation and mutational acquisition,” they wrote.

The diverging subpopulations will begin to develop different methods for adapting to the tumor microenvironment, with unique strategies for both accelerating growth and avoiding hazards such as chemotherapy drugs or radiation, the investigators explained.

“By the time a cancer becomes clinically apparent, cancer cells have transformed from a single clone into a diverse community of cell types evolving in response to a spatially and temporally heterogeneous tumor environment. Theoretically, a 10-gram cancer may contain the same order of magnitude of cancer cells as there are humans on earth, with tremendous diversity of phenotypes and environments,” they wrote.

Survival of the fittest

The competition of individuals within and between species described by Darwin also applies to cancer cells, in their interactions both with each other and with stromal cells and immune cells resulting in “the progressive replacement of less fit phenotypes by those that are more fit,” Dr. Reed and colleagues explained.

And just like the old joke about two hikers trying to escape from a charging grizzly bear (one says, “This is futile – we can’t outrun a grizzly,” and the other says, “I only have to outrun you!”), cancer cells only need to be more resistant to therapeutic attack than normal cells that are critical to function.

“This may explain why initial responses in certain solid tumors (notably rhabdomyosarcoma) do not predict eventual survival. The sensitivities of the dominant cancer cell populations dictate the initial response, but it is the ecology and evolution of the rare and more resistant populations that determine cure or relapse,” they wrote.

The endangered species list

As with many types of cancer, the current approach to treating pediatric sarcomas with curative intent is with a “first strike” approach, treating patients with surgery, radiation, and cytotoxic chemotherapy at the maximum tolerated dose for as long as needed or until unacceptable toxicities occur, with the intention of wiping out all cancer cells without permanently injuring normal cells.

The evolutionary analogy to this approach is a mass extinction event such as the meteor strike that is believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs roughly 66 million years ago. Fossil evidence suggests that the cataclysmic event resulted in the atmosphere being blanketed with dust particles that blocked sunlight and caused massive die-off of plants that dinosaurs needed to survive and were ill-adapted to do without.

In contrast, populations of smaller, more adaptable species of microbes, insects, and animals, including our mammalian ancestors, were able to survive and eventually flourish.

Many patients with localized cancers may be cured with up-front therapy, but others will have residual disease from populations of cells that are intrinsically resistant to therapy or have developed new evasion strategies.

Strike two and the MVP

Dr. Reed and colleagues liken the approach of second-line therapy for treatment of relapsed or refractory disease to the concept of “background extinctions,” using the fate of the passenger pigeon as an example of how a second-strike therapeutic strategy works.

Although the popular conception is that the passenger pigeon was hunted to extinction by humans, the species in fact died out because of many different factors, including loss of habitat, isolation of populations leading to a loss of genetic diversity, and disruption of breeding habits.

“Once first strikes of deforestation and hunting reduced the birds to small, fragmented populations, a series of what would otherwise have been minor second strikes pushed the passenger pigeon below its extinction threshold, or minimum viable population,” they said.

The analogy, as it applies to cancer therapy, is the use of second-line or follow-on therapy with one or more agents that the residual cells are at least in theory not resistant to. In the case of fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma, the drug most commonly added in the second-strike approach is vinorelbine.2

“Second strikes should be timed to occur around the time when the first strike has achieved its greatest effect, presumably at the point when the disease becomes clinically undetectable or at a measurable nadir,” Dr. Reed and colleagues wrote. “Ideally, second-strike therapies should have modes of action that require different resistance strategies by the cancer cells than those needed for resistance to the first strike.”

Adaptive therapy

As Dr. Reed and colleagues note, despite optimal therapy, 94% of patients with metastatic fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma will experience a relapse within 3 years of diagnosis.1 Clearly the scorched earth or “throw everything you have it” approach no longer works, and that’s where adaptive therapy comes in.

Here again, the authors rely on nature, or rather human interaction with nature, to devise a strategy for keeping the disease at bay when extinction of all cancerous cells cannot be achieved.

They cite the example of agricultural integrated pest management, which seeks to keep harmful insects in check by treating them to suppress but not completely destroy a population, then stopping the use of pesticides, and resuming only when the insect population spikes and again becomes a threat to crops.

“The goal is to limit crop damage while retaining the sensitivity of the insects to the pesticides. Resistance most often comes at a cost. In the absence of the pesticide, sensitive individuals will outcompete resistant individuals,” they wrote.

Adaptive therapy uses the same approach to reduce selection pressures that foster resistance, with patients treated only until a specific, predetermined response is achieved in the dominant population of chemosensitive cells. The treatment is then interrupted and reintroduced only when the tumor rebounds to a certain predetermined size.

In this scenario, cells that retain sensitivity to chemotherapy will be able to reproduce and proliferate more rapidly than drug-resistant cells, and the therapy can then be reintroduced. This strategy is less likely to cause the development and proliferation of resistant cells than conventional intensified chemotherapy, Dr. Reed and colleagues contend.

Putting it to the test

The clinical trial that Dr. Reed and colleagues have initiated, officially titled “Evolutionary Inspired Therapy for Newly Diagnosed, Metastatic, Fusion Positive Rhabdomyosarcoma,” (NCT04388839) contains four arms: three experimental and one active comparator arm.

“We won’t randomize; we don’t feel that it would be fair to randomize patients, because these arms are so different from each other,” Dr. Reed said.

Arm A is the experimental first-strike arm, a 42-week course containing cyclophosphamide delivered intravenously over 60 minutes at a dose ranging from 220 mg to 1200 mg, vinorelbine delivered in an IV push over 6-10 minutes with a dose ranging from 4 mg to 25 mg, and actinomycin D administered via IV over 3-5 minutes at a dose ranging from 0.025 mg to 0.04 mg.

“The idea is that we take the standard of care, and we add a drug – vinorelbine – to make it stronger,” Dr. Reed said. “The idea is that the resistant cell, the cell that escapes, if we start hitting it on day 1 with vinorelbine, we might be able to drive it to extinction.”

Arm B, the second experimental arm, is the second-strike and maintenance arm, in which patients will receive conventional doses of vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide (VAC) until complete response (CR) for 12-42 weeks, and will then be switched to up to 2 years of maintenance with vinorelbine and oral cyclophosphamide.

“Vinorelbine will be added when the cancer is declining or first goes into remission. We try not to wait 42 weeks, which is too long we think, by which time the cancer may be fully adapted and resistant,” he explained.

Arm C is the adaptive therapy arm, in which patients will receive VAC that starts and stops based on response, with the goal of prolonging time to disease progression rather than achieving CR.

Arm D is the active comparator arm, consisting of conventional chemotherapy based on published clinical trials, such as VAC for 42 weeks, or other standard-of-care regimens that may include irinotecan, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and/or etoposide.

A change in thinking

Dr. Reed acknowledges that Arm C, the adaptive therapy arm, “definitely represents a change in thinking for pediatric oncology.”

“The idea is that if you could do this perfectly well, you would be able to take a patient who is diagnosed today and essentially ‘pause’ their disease for a while. Then 5 years from now, if there is a better medicine, you would have gotten that patient to that medicine.”

The optimal approach to treating metastatic fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma may be similar to that used for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, with induction, consolidation, and maintenance and the option of delayed intensification, he said.

“But we’re so far away from knowing which series to do that we just need to show that any series – any changing it up – is helpful.”

Dr. Reed said that when he started presenting the concept of adaptive therapy in clinical meetings in 2017, “I was told to come up with a better idea. There were several people who instantly got it, but most people would instantly get angry.”

The common refrain was that adaptive therapy was “giving up.”

But minds began to change in 2018, following presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology of a European study showing that adding 6 months of low-dose chemotherapy maintenance to standard therapy improved the 5-year overall survival rate of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma from 73.7% to 86.6%.2

Before presenting the idea of adaptive therapy to his colleagues, he ran it by the parents of children with advanced sarcomas, and many were on board with it, he said.

Ricky Huff said that had the option of adaptive therapy been available for Theo, he and his wife would have been willing to try it.

“Of course, everyone has the ability in hindsight to apply critical thinking to decisions that you made or could have made,” he said. “I think is true for many parents, who if they’re presented with information about options will say ‘well if there’s a 1 percent chance, I want that chance for my child, especially for a 5-month-old.”

The decision to choose adaptive therapy is a difficult decision to make, whether for oneself or for one’s son, because it isn’t curative.

“My wife and I have since had a conversation about this, and I do think we would have considered it, although through a lot of difficult conversations,” he said.

“After we got the pathology, knowing that it was metastatic, fusion-positive, and given his age, just doing a brief literature review on my own, I knew what we were up against using 20-year-old treatments, and that the chance of a cure was very, very small.”

If parents of children with metastatic, poor-prognosis rhabdomyosarcoma could be made to understand that adaptive therapy would entail shorter and fewer hospital stays, and cumulatively less toxic chemotherapy, and could prolong the lives of their children, the option might be more acceptable, he said.

And as Dr. Reed mentioned, prolonging time to progression offers hope of additional therapies to come.

“The whole time that my son was being treated, I hoped that there was going to be something else that came out, that a new trial would be launched because they found a way to drug a mutation, or treat it with immunotherapy – something that was going to give us a better option.”

Asked whether he would be willing to share his experiences in this article, Mr. Huff said that “I am willing to, in whatever small way I can, make an impact, and hopefully save another family from what we experienced.”

References

1. Reed DR et al. Cancer. 2020 Jun 1;126(11):2577-87 2. Bisogno G et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:18_suppl,LBA-2

In 1859, Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” which outlined his world-shaking theory of evolution and its core principle of natural selection caused by environmental pressures that may determine whether an organism adapts and survives, or remains static, languishes, and eventually dies out.

The same forces that have influenced the size and shape of the beaks of finches in the Galapagos Islands, the length of giraffe necks in Africa, and the intestinal microbiomes of the nearly 8 billion human inhabitants of this planet also control whether malignant cells thrive and multiply, wither and die when assaulted by chemotherapy, or go into hiding, mutating and waiting for their next opportunity to erupt again and metastasize.

The ability of malignant cells to adapt to environmental pressures is “cancer’s most lethal and sophisticated property,” said Damon R. Reed, MD, program leader of the adolescent/young adult program at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla.

Dr. Reed and colleagues are developing methods to meet cancer on its own terms, applying evolutionary principles to the treatment of childhood fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma in an innovative, and some would say audacious, clinical trial.

Adaptive versus conventional therapy

The trial, now recruiting, is designed to evaluate each of four different strategies for chemotherapy schedules in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma.

The trial contains four arms, three of which consist of either conventional chemotherapy based on published clinical trials, moving a second-line therapy to the first line, or adding maintenance therapy, all of which have the goal of inducing as many complete remissions as possible.

The remaining adaptive therapy arm, however, is entirely novel in approach, with therapy using a combination of chemotherapy drugs that will be started and interrupted based on tumor responses, with resumption of therapy on an adaptive schedule unique to each patient. The goal of treatment for patients enrolled in this arm will be prolongation of the time to disease progression, rather than complete remission.

Although some people might consider the adaptive therapy approach to be sacrificing the hope for a cure in exchange for palliation, the hard truth is that patients with fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma (in contrast to those with fusion-negative disease) have a dismal prognosis following relapse after up-front intensified therapy.

Instead, because a cure is exceedingly unlikely in patients with metastatic disease, the conventional idea of delivering the maximum tolerated dose of chemotherapy until disease progression could be replaced by an approach based on understanding of the evolution of cancer cells under selective pressures, Dr. Reed and colleagues contend.

“Although adaptive therapy would represent a major paradigm shift in pediatric oncology, this approach would exploit the chemotherapy-sensitive population to prevent the emergence of resistant populations, optimizing tumor control with less toxicity,” they wrote in a commentary published online in the journal Cancer.1

Poor survival with advanced disease

Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a form of soft tissue sarcoma of mesenchymal origin. Approximately 25% of cases are parameningeal, arising from sites adjacent to the meninges of the nasopharynx, middle ear, paranasal sinuses, orbit, and other regions of the head and neck. Approximately 31% of cases arise in the genitourinary tract and 13% in the extremities, and other tumors occur less commonly in the trunk, chest wall, perineal/anal region, and abdomen.

The overall 5-year survival rate is approximately 71%.1

However, for patients with high-risk disease, a group that includes children 10 years of age or older with widespread disease with or without an activating PAX/FOX01 gene fusion, 5-year survival ranges from just 20% to 30% (Cancer Facts & Figures 2020).

“Among patients with metastatic disease, there is a clear difference in overall survival between those who have fusion-positive disease, where the 5-year overall survival is about 19%, and patients with fusion-negative disease,” said Douglas S. Hawkins, MD, chair of the children’s oncology group and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and associate chief in the division of hematology/oncology at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Patients with fusion-negative disease can be further classified into those with multiple metastatic sites, with a 5-year overall survival rate of approximately 45%, and those with a single metastatic site, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 70%, he said in an interview.

“So when we talk about metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma, there actually is a diversity of outcomes, between really bad – those with fusion-positive disease – and not terrible – not great, but not terrible – for a selected group of patients with fusion-negative disease,” Dr. Hawkins said.

The poor prognosis for patients with metastatic fusion-positive disease prompted Dr. Reed and colleagues to rethink the entire approach to advanced cancers.

“If someone has a sarcoma, we know that we need to do surgery and radiation to the area, we know that localized disease does better than metastatic disease, and we generally hit it with some kind of chemotherapy that we call ‘standard of care,’ ” he said in an interview.

This approach is largely effective in some forms of cancer of bone and soft tissues, such as Ewing sarcoma, he notes, which has 5-year survival rates below 20% when treated with surgery and radiation only, but with the addition of chemotherapy has 5-year overall survival rates as high as 80%.

“At other times, with other sarcomas, the cure rate is abysmal, but we still call it standard of care,” Dr. Reed said.

For example, patients with metastatic fusion-positive RMS may have an initial response to chemotherapy, but most will eventually experience relapse and die of the disease.

“With some of the most common treatments, 70% of patients will have their cancers shrink by more than 50%, which is a major response, but the vast majority of them will have a recurrence later on,” Dr. Hawkins said.

He noted that the standard of care for patients with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma, both with and without the PAX/FOX01 fusion, is chemotherapy, generally with the VAC regimen (vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide), although other agents such as doxorubicin, ifosfamide, etoposide, or irinotecan have also been tried, with little effect on event-free survival or overall survival rates.

A life too brief

Ricky Huff and his family know the course that the disease can take only too well. In 2015, his 5-month-old son, Theo, was diagnosed with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma and put under the care of Damon Reed at Moffitt.

“During the whole course of treatment – I’m sure like many other parents – apart from relying on Damon and his treatment expertise to try to determine the best treatment options, I was reading everything under the sun to try to get a working knowledge of what Theo was up against, what his treatment and clinical trial options were, and what was the state of the science,” Mr. Huff says.

Unfortunately, the characteristics of Theo’s disease, including his very young age at onset and diagnosis of stage 4 metastatic disease, conspired against him, and despite undergoing 14 months of chemotherapy, Theo died of the disease in October 2016, 5 months shy of what would have been his second birthday.

In their grief, Mr. Huff, a real estate lawyer with a practice in Clearwater, Fla., and his wife, Leah, were determined to help other families of children with cancer and settled on the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation. Mr. Huff joined the board of directors of the foundation, which is collaborating with Moffitt Cancer Center on the adaptive therapy trial.

An evolutionary primer (cancer edition)

To get a better idea of just how adaptive therapy works, it is helpful to view cancer cells through the lens of species development, adaptation, extinction, and evolution.

“Cancer cells compete against each other in a dynamic environment. Their tumor ecosystems exhibit spatial and temporal fluctuations in blood-borne nutrients, oxygen, growth factors, immune cells, and hormones,” Dr. Reed and colleagues wrote.

These influences can affect genetically identical cancer cells, which may begin to diverge from one another depending on their location in a tumor and the availability of nutrients, which in turn can result in two once-identical cells exhibiting different transcription rates for growth factors.

“Ultimately, this may affect the rate of progression through the cell cycle, leading to distinct rates of proliferation and mutational acquisition,” they wrote.

The diverging subpopulations will begin to develop different methods for adapting to the tumor microenvironment, with unique strategies for both accelerating growth and avoiding hazards such as chemotherapy drugs or radiation, the investigators explained.

“By the time a cancer becomes clinically apparent, cancer cells have transformed from a single clone into a diverse community of cell types evolving in response to a spatially and temporally heterogeneous tumor environment. Theoretically, a 10-gram cancer may contain the same order of magnitude of cancer cells as there are humans on earth, with tremendous diversity of phenotypes and environments,” they wrote.

Survival of the fittest

The competition of individuals within and between species described by Darwin also applies to cancer cells, in their interactions both with each other and with stromal cells and immune cells resulting in “the progressive replacement of less fit phenotypes by those that are more fit,” Dr. Reed and colleagues explained.

And just like the old joke about two hikers trying to escape from a charging grizzly bear (one says, “This is futile – we can’t outrun a grizzly,” and the other says, “I only have to outrun you!”), cancer cells only need to be more resistant to therapeutic attack than normal cells that are critical to function.

“This may explain why initial responses in certain solid tumors (notably rhabdomyosarcoma) do not predict eventual survival. The sensitivities of the dominant cancer cell populations dictate the initial response, but it is the ecology and evolution of the rare and more resistant populations that determine cure or relapse,” they wrote.

The endangered species list

As with many types of cancer, the current approach to treating pediatric sarcomas with curative intent is with a “first strike” approach, treating patients with surgery, radiation, and cytotoxic chemotherapy at the maximum tolerated dose for as long as needed or until unacceptable toxicities occur, with the intention of wiping out all cancer cells without permanently injuring normal cells.

The evolutionary analogy to this approach is a mass extinction event such as the meteor strike that is believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs roughly 66 million years ago. Fossil evidence suggests that the cataclysmic event resulted in the atmosphere being blanketed with dust particles that blocked sunlight and caused massive die-off of plants that dinosaurs needed to survive and were ill-adapted to do without.

In contrast, populations of smaller, more adaptable species of microbes, insects, and animals, including our mammalian ancestors, were able to survive and eventually flourish.

Many patients with localized cancers may be cured with up-front therapy, but others will have residual disease from populations of cells that are intrinsically resistant to therapy or have developed new evasion strategies.

Strike two and the MVP

Dr. Reed and colleagues liken the approach of second-line therapy for treatment of relapsed or refractory disease to the concept of “background extinctions,” using the fate of the passenger pigeon as an example of how a second-strike therapeutic strategy works.

Although the popular conception is that the passenger pigeon was hunted to extinction by humans, the species in fact died out because of many different factors, including loss of habitat, isolation of populations leading to a loss of genetic diversity, and disruption of breeding habits.

“Once first strikes of deforestation and hunting reduced the birds to small, fragmented populations, a series of what would otherwise have been minor second strikes pushed the passenger pigeon below its extinction threshold, or minimum viable population,” they said.

The analogy, as it applies to cancer therapy, is the use of second-line or follow-on therapy with one or more agents that the residual cells are at least in theory not resistant to. In the case of fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma, the drug most commonly added in the second-strike approach is vinorelbine.2

“Second strikes should be timed to occur around the time when the first strike has achieved its greatest effect, presumably at the point when the disease becomes clinically undetectable or at a measurable nadir,” Dr. Reed and colleagues wrote. “Ideally, second-strike therapies should have modes of action that require different resistance strategies by the cancer cells than those needed for resistance to the first strike.”

Adaptive therapy

As Dr. Reed and colleagues note, despite optimal therapy, 94% of patients with metastatic fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma will experience a relapse within 3 years of diagnosis.1 Clearly the scorched earth or “throw everything you have it” approach no longer works, and that’s where adaptive therapy comes in.

Here again, the authors rely on nature, or rather human interaction with nature, to devise a strategy for keeping the disease at bay when extinction of all cancerous cells cannot be achieved.

They cite the example of agricultural integrated pest management, which seeks to keep harmful insects in check by treating them to suppress but not completely destroy a population, then stopping the use of pesticides, and resuming only when the insect population spikes and again becomes a threat to crops.

“The goal is to limit crop damage while retaining the sensitivity of the insects to the pesticides. Resistance most often comes at a cost. In the absence of the pesticide, sensitive individuals will outcompete resistant individuals,” they wrote.

Adaptive therapy uses the same approach to reduce selection pressures that foster resistance, with patients treated only until a specific, predetermined response is achieved in the dominant population of chemosensitive cells. The treatment is then interrupted and reintroduced only when the tumor rebounds to a certain predetermined size.

In this scenario, cells that retain sensitivity to chemotherapy will be able to reproduce and proliferate more rapidly than drug-resistant cells, and the therapy can then be reintroduced. This strategy is less likely to cause the development and proliferation of resistant cells than conventional intensified chemotherapy, Dr. Reed and colleagues contend.

Putting it to the test

The clinical trial that Dr. Reed and colleagues have initiated, officially titled “Evolutionary Inspired Therapy for Newly Diagnosed, Metastatic, Fusion Positive Rhabdomyosarcoma,” (NCT04388839) contains four arms: three experimental and one active comparator arm.

“We won’t randomize; we don’t feel that it would be fair to randomize patients, because these arms are so different from each other,” Dr. Reed said.

Arm A is the experimental first-strike arm, a 42-week course containing cyclophosphamide delivered intravenously over 60 minutes at a dose ranging from 220 mg to 1200 mg, vinorelbine delivered in an IV push over 6-10 minutes with a dose ranging from 4 mg to 25 mg, and actinomycin D administered via IV over 3-5 minutes at a dose ranging from 0.025 mg to 0.04 mg.

“The idea is that we take the standard of care, and we add a drug – vinorelbine – to make it stronger,” Dr. Reed said. “The idea is that the resistant cell, the cell that escapes, if we start hitting it on day 1 with vinorelbine, we might be able to drive it to extinction.”

Arm B, the second experimental arm, is the second-strike and maintenance arm, in which patients will receive conventional doses of vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide (VAC) until complete response (CR) for 12-42 weeks, and will then be switched to up to 2 years of maintenance with vinorelbine and oral cyclophosphamide.

“Vinorelbine will be added when the cancer is declining or first goes into remission. We try not to wait 42 weeks, which is too long we think, by which time the cancer may be fully adapted and resistant,” he explained.

Arm C is the adaptive therapy arm, in which patients will receive VAC that starts and stops based on response, with the goal of prolonging time to disease progression rather than achieving CR.

Arm D is the active comparator arm, consisting of conventional chemotherapy based on published clinical trials, such as VAC for 42 weeks, or other standard-of-care regimens that may include irinotecan, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and/or etoposide.

A change in thinking

Dr. Reed acknowledges that Arm C, the adaptive therapy arm, “definitely represents a change in thinking for pediatric oncology.”

“The idea is that if you could do this perfectly well, you would be able to take a patient who is diagnosed today and essentially ‘pause’ their disease for a while. Then 5 years from now, if there is a better medicine, you would have gotten that patient to that medicine.”

The optimal approach to treating metastatic fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma may be similar to that used for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, with induction, consolidation, and maintenance and the option of delayed intensification, he said.

“But we’re so far away from knowing which series to do that we just need to show that any series – any changing it up – is helpful.”

Dr. Reed said that when he started presenting the concept of adaptive therapy in clinical meetings in 2017, “I was told to come up with a better idea. There were several people who instantly got it, but most people would instantly get angry.”

The common refrain was that adaptive therapy was “giving up.”

But minds began to change in 2018, following presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology of a European study showing that adding 6 months of low-dose chemotherapy maintenance to standard therapy improved the 5-year overall survival rate of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma from 73.7% to 86.6%.2

Before presenting the idea of adaptive therapy to his colleagues, he ran it by the parents of children with advanced sarcomas, and many were on board with it, he said.

Ricky Huff said that had the option of adaptive therapy been available for Theo, he and his wife would have been willing to try it.

“Of course, everyone has the ability in hindsight to apply critical thinking to decisions that you made or could have made,” he said. “I think is true for many parents, who if they’re presented with information about options will say ‘well if there’s a 1 percent chance, I want that chance for my child, especially for a 5-month-old.”

The decision to choose adaptive therapy is a difficult decision to make, whether for oneself or for one’s son, because it isn’t curative.

“My wife and I have since had a conversation about this, and I do think we would have considered it, although through a lot of difficult conversations,” he said.

“After we got the pathology, knowing that it was metastatic, fusion-positive, and given his age, just doing a brief literature review on my own, I knew what we were up against using 20-year-old treatments, and that the chance of a cure was very, very small.”

If parents of children with metastatic, poor-prognosis rhabdomyosarcoma could be made to understand that adaptive therapy would entail shorter and fewer hospital stays, and cumulatively less toxic chemotherapy, and could prolong the lives of their children, the option might be more acceptable, he said.

And as Dr. Reed mentioned, prolonging time to progression offers hope of additional therapies to come.

“The whole time that my son was being treated, I hoped that there was going to be something else that came out, that a new trial would be launched because they found a way to drug a mutation, or treat it with immunotherapy – something that was going to give us a better option.”

Asked whether he would be willing to share his experiences in this article, Mr. Huff said that “I am willing to, in whatever small way I can, make an impact, and hopefully save another family from what we experienced.”

References

1. Reed DR et al. Cancer. 2020 Jun 1;126(11):2577-87 2. Bisogno G et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:18_suppl,LBA-2

In 1859, Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” which outlined his world-shaking theory of evolution and its core principle of natural selection caused by environmental pressures that may determine whether an organism adapts and survives, or remains static, languishes, and eventually dies out.

The same forces that have influenced the size and shape of the beaks of finches in the Galapagos Islands, the length of giraffe necks in Africa, and the intestinal microbiomes of the nearly 8 billion human inhabitants of this planet also control whether malignant cells thrive and multiply, wither and die when assaulted by chemotherapy, or go into hiding, mutating and waiting for their next opportunity to erupt again and metastasize.

The ability of malignant cells to adapt to environmental pressures is “cancer’s most lethal and sophisticated property,” said Damon R. Reed, MD, program leader of the adolescent/young adult program at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla.

Dr. Reed and colleagues are developing methods to meet cancer on its own terms, applying evolutionary principles to the treatment of childhood fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma in an innovative, and some would say audacious, clinical trial.

Adaptive versus conventional therapy

The trial, now recruiting, is designed to evaluate each of four different strategies for chemotherapy schedules in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma.

The trial contains four arms, three of which consist of either conventional chemotherapy based on published clinical trials, moving a second-line therapy to the first line, or adding maintenance therapy, all of which have the goal of inducing as many complete remissions as possible.

The remaining adaptive therapy arm, however, is entirely novel in approach, with therapy using a combination of chemotherapy drugs that will be started and interrupted based on tumor responses, with resumption of therapy on an adaptive schedule unique to each patient. The goal of treatment for patients enrolled in this arm will be prolongation of the time to disease progression, rather than complete remission.

Although some people might consider the adaptive therapy approach to be sacrificing the hope for a cure in exchange for palliation, the hard truth is that patients with fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma (in contrast to those with fusion-negative disease) have a dismal prognosis following relapse after up-front intensified therapy.

Instead, because a cure is exceedingly unlikely in patients with metastatic disease, the conventional idea of delivering the maximum tolerated dose of chemotherapy until disease progression could be replaced by an approach based on understanding of the evolution of cancer cells under selective pressures, Dr. Reed and colleagues contend.

“Although adaptive therapy would represent a major paradigm shift in pediatric oncology, this approach would exploit the chemotherapy-sensitive population to prevent the emergence of resistant populations, optimizing tumor control with less toxicity,” they wrote in a commentary published online in the journal Cancer.1

Poor survival with advanced disease

Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a form of soft tissue sarcoma of mesenchymal origin. Approximately 25% of cases are parameningeal, arising from sites adjacent to the meninges of the nasopharynx, middle ear, paranasal sinuses, orbit, and other regions of the head and neck. Approximately 31% of cases arise in the genitourinary tract and 13% in the extremities, and other tumors occur less commonly in the trunk, chest wall, perineal/anal region, and abdomen.

The overall 5-year survival rate is approximately 71%.1

However, for patients with high-risk disease, a group that includes children 10 years of age or older with widespread disease with or without an activating PAX/FOX01 gene fusion, 5-year survival ranges from just 20% to 30% (Cancer Facts & Figures 2020).

“Among patients with metastatic disease, there is a clear difference in overall survival between those who have fusion-positive disease, where the 5-year overall survival is about 19%, and patients with fusion-negative disease,” said Douglas S. Hawkins, MD, chair of the children’s oncology group and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and associate chief in the division of hematology/oncology at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Patients with fusion-negative disease can be further classified into those with multiple metastatic sites, with a 5-year overall survival rate of approximately 45%, and those with a single metastatic site, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 70%, he said in an interview.

“So when we talk about metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma, there actually is a diversity of outcomes, between really bad – those with fusion-positive disease – and not terrible – not great, but not terrible – for a selected group of patients with fusion-negative disease,” Dr. Hawkins said.

The poor prognosis for patients with metastatic fusion-positive disease prompted Dr. Reed and colleagues to rethink the entire approach to advanced cancers.

“If someone has a sarcoma, we know that we need to do surgery and radiation to the area, we know that localized disease does better than metastatic disease, and we generally hit it with some kind of chemotherapy that we call ‘standard of care,’ ” he said in an interview.

This approach is largely effective in some forms of cancer of bone and soft tissues, such as Ewing sarcoma, he notes, which has 5-year survival rates below 20% when treated with surgery and radiation only, but with the addition of chemotherapy has 5-year overall survival rates as high as 80%.

“At other times, with other sarcomas, the cure rate is abysmal, but we still call it standard of care,” Dr. Reed said.

For example, patients with metastatic fusion-positive RMS may have an initial response to chemotherapy, but most will eventually experience relapse and die of the disease.

“With some of the most common treatments, 70% of patients will have their cancers shrink by more than 50%, which is a major response, but the vast majority of them will have a recurrence later on,” Dr. Hawkins said.

He noted that the standard of care for patients with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma, both with and without the PAX/FOX01 fusion, is chemotherapy, generally with the VAC regimen (vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide), although other agents such as doxorubicin, ifosfamide, etoposide, or irinotecan have also been tried, with little effect on event-free survival or overall survival rates.

A life too brief

Ricky Huff and his family know the course that the disease can take only too well. In 2015, his 5-month-old son, Theo, was diagnosed with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma and put under the care of Damon Reed at Moffitt.

“During the whole course of treatment – I’m sure like many other parents – apart from relying on Damon and his treatment expertise to try to determine the best treatment options, I was reading everything under the sun to try to get a working knowledge of what Theo was up against, what his treatment and clinical trial options were, and what was the state of the science,” Mr. Huff says.

Unfortunately, the characteristics of Theo’s disease, including his very young age at onset and diagnosis of stage 4 metastatic disease, conspired against him, and despite undergoing 14 months of chemotherapy, Theo died of the disease in October 2016, 5 months shy of what would have been his second birthday.

In their grief, Mr. Huff, a real estate lawyer with a practice in Clearwater, Fla., and his wife, Leah, were determined to help other families of children with cancer and settled on the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation. Mr. Huff joined the board of directors of the foundation, which is collaborating with Moffitt Cancer Center on the adaptive therapy trial.

An evolutionary primer (cancer edition)

To get a better idea of just how adaptive therapy works, it is helpful to view cancer cells through the lens of species development, adaptation, extinction, and evolution.

“Cancer cells compete against each other in a dynamic environment. Their tumor ecosystems exhibit spatial and temporal fluctuations in blood-borne nutrients, oxygen, growth factors, immune cells, and hormones,” Dr. Reed and colleagues wrote.

These influences can affect genetically identical cancer cells, which may begin to diverge from one another depending on their location in a tumor and the availability of nutrients, which in turn can result in two once-identical cells exhibiting different transcription rates for growth factors.

“Ultimately, this may affect the rate of progression through the cell cycle, leading to distinct rates of proliferation and mutational acquisition,” they wrote.

The diverging subpopulations will begin to develop different methods for adapting to the tumor microenvironment, with unique strategies for both accelerating growth and avoiding hazards such as chemotherapy drugs or radiation, the investigators explained.

“By the time a cancer becomes clinically apparent, cancer cells have transformed from a single clone into a diverse community of cell types evolving in response to a spatially and temporally heterogeneous tumor environment. Theoretically, a 10-gram cancer may contain the same order of magnitude of cancer cells as there are humans on earth, with tremendous diversity of phenotypes and environments,” they wrote.

Survival of the fittest

The competition of individuals within and between species described by Darwin also applies to cancer cells, in their interactions both with each other and with stromal cells and immune cells resulting in “the progressive replacement of less fit phenotypes by those that are more fit,” Dr. Reed and colleagues explained.

And just like the old joke about two hikers trying to escape from a charging grizzly bear (one says, “This is futile – we can’t outrun a grizzly,” and the other says, “I only have to outrun you!”), cancer cells only need to be more resistant to therapeutic attack than normal cells that are critical to function.

“This may explain why initial responses in certain solid tumors (notably rhabdomyosarcoma) do not predict eventual survival. The sensitivities of the dominant cancer cell populations dictate the initial response, but it is the ecology and evolution of the rare and more resistant populations that determine cure or relapse,” they wrote.

The endangered species list

As with many types of cancer, the current approach to treating pediatric sarcomas with curative intent is with a “first strike” approach, treating patients with surgery, radiation, and cytotoxic chemotherapy at the maximum tolerated dose for as long as needed or until unacceptable toxicities occur, with the intention of wiping out all cancer cells without permanently injuring normal cells.

The evolutionary analogy to this approach is a mass extinction event such as the meteor strike that is believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs roughly 66 million years ago. Fossil evidence suggests that the cataclysmic event resulted in the atmosphere being blanketed with dust particles that blocked sunlight and caused massive die-off of plants that dinosaurs needed to survive and were ill-adapted to do without.

In contrast, populations of smaller, more adaptable species of microbes, insects, and animals, including our mammalian ancestors, were able to survive and eventually flourish.

Many patients with localized cancers may be cured with up-front therapy, but others will have residual disease from populations of cells that are intrinsically resistant to therapy or have developed new evasion strategies.

Strike two and the MVP

Dr. Reed and colleagues liken the approach of second-line therapy for treatment of relapsed or refractory disease to the concept of “background extinctions,” using the fate of the passenger pigeon as an example of how a second-strike therapeutic strategy works.

Although the popular conception is that the passenger pigeon was hunted to extinction by humans, the species in fact died out because of many different factors, including loss of habitat, isolation of populations leading to a loss of genetic diversity, and disruption of breeding habits.

“Once first strikes of deforestation and hunting reduced the birds to small, fragmented populations, a series of what would otherwise have been minor second strikes pushed the passenger pigeon below its extinction threshold, or minimum viable population,” they said.

The analogy, as it applies to cancer therapy, is the use of second-line or follow-on therapy with one or more agents that the residual cells are at least in theory not resistant to. In the case of fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma, the drug most commonly added in the second-strike approach is vinorelbine.2

“Second strikes should be timed to occur around the time when the first strike has achieved its greatest effect, presumably at the point when the disease becomes clinically undetectable or at a measurable nadir,” Dr. Reed and colleagues wrote. “Ideally, second-strike therapies should have modes of action that require different resistance strategies by the cancer cells than those needed for resistance to the first strike.”

Adaptive therapy

As Dr. Reed and colleagues note, despite optimal therapy, 94% of patients with metastatic fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma will experience a relapse within 3 years of diagnosis.1 Clearly the scorched earth or “throw everything you have it” approach no longer works, and that’s where adaptive therapy comes in.

Here again, the authors rely on nature, or rather human interaction with nature, to devise a strategy for keeping the disease at bay when extinction of all cancerous cells cannot be achieved.

They cite the example of agricultural integrated pest management, which seeks to keep harmful insects in check by treating them to suppress but not completely destroy a population, then stopping the use of pesticides, and resuming only when the insect population spikes and again becomes a threat to crops.

“The goal is to limit crop damage while retaining the sensitivity of the insects to the pesticides. Resistance most often comes at a cost. In the absence of the pesticide, sensitive individuals will outcompete resistant individuals,” they wrote.

Adaptive therapy uses the same approach to reduce selection pressures that foster resistance, with patients treated only until a specific, predetermined response is achieved in the dominant population of chemosensitive cells. The treatment is then interrupted and reintroduced only when the tumor rebounds to a certain predetermined size.

In this scenario, cells that retain sensitivity to chemotherapy will be able to reproduce and proliferate more rapidly than drug-resistant cells, and the therapy can then be reintroduced. This strategy is less likely to cause the development and proliferation of resistant cells than conventional intensified chemotherapy, Dr. Reed and colleagues contend.

Putting it to the test

The clinical trial that Dr. Reed and colleagues have initiated, officially titled “Evolutionary Inspired Therapy for Newly Diagnosed, Metastatic, Fusion Positive Rhabdomyosarcoma,” (NCT04388839) contains four arms: three experimental and one active comparator arm.

“We won’t randomize; we don’t feel that it would be fair to randomize patients, because these arms are so different from each other,” Dr. Reed said.

Arm A is the experimental first-strike arm, a 42-week course containing cyclophosphamide delivered intravenously over 60 minutes at a dose ranging from 220 mg to 1200 mg, vinorelbine delivered in an IV push over 6-10 minutes with a dose ranging from 4 mg to 25 mg, and actinomycin D administered via IV over 3-5 minutes at a dose ranging from 0.025 mg to 0.04 mg.

“The idea is that we take the standard of care, and we add a drug – vinorelbine – to make it stronger,” Dr. Reed said. “The idea is that the resistant cell, the cell that escapes, if we start hitting it on day 1 with vinorelbine, we might be able to drive it to extinction.”

Arm B, the second experimental arm, is the second-strike and maintenance arm, in which patients will receive conventional doses of vincristine, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide (VAC) until complete response (CR) for 12-42 weeks, and will then be switched to up to 2 years of maintenance with vinorelbine and oral cyclophosphamide.

“Vinorelbine will be added when the cancer is declining or first goes into remission. We try not to wait 42 weeks, which is too long we think, by which time the cancer may be fully adapted and resistant,” he explained.

Arm C is the adaptive therapy arm, in which patients will receive VAC that starts and stops based on response, with the goal of prolonging time to disease progression rather than achieving CR.

Arm D is the active comparator arm, consisting of conventional chemotherapy based on published clinical trials, such as VAC for 42 weeks, or other standard-of-care regimens that may include irinotecan, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and/or etoposide.

A change in thinking

Dr. Reed acknowledges that Arm C, the adaptive therapy arm, “definitely represents a change in thinking for pediatric oncology.”

“The idea is that if you could do this perfectly well, you would be able to take a patient who is diagnosed today and essentially ‘pause’ their disease for a while. Then 5 years from now, if there is a better medicine, you would have gotten that patient to that medicine.”

The optimal approach to treating metastatic fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma may be similar to that used for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, with induction, consolidation, and maintenance and the option of delayed intensification, he said.

“But we’re so far away from knowing which series to do that we just need to show that any series – any changing it up – is helpful.”

Dr. Reed said that when he started presenting the concept of adaptive therapy in clinical meetings in 2017, “I was told to come up with a better idea. There were several people who instantly got it, but most people would instantly get angry.”

The common refrain was that adaptive therapy was “giving up.”

But minds began to change in 2018, following presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology of a European study showing that adding 6 months of low-dose chemotherapy maintenance to standard therapy improved the 5-year overall survival rate of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma from 73.7% to 86.6%.2

Before presenting the idea of adaptive therapy to his colleagues, he ran it by the parents of children with advanced sarcomas, and many were on board with it, he said.

Ricky Huff said that had the option of adaptive therapy been available for Theo, he and his wife would have been willing to try it.

“Of course, everyone has the ability in hindsight to apply critical thinking to decisions that you made or could have made,” he said. “I think is true for many parents, who if they’re presented with information about options will say ‘well if there’s a 1 percent chance, I want that chance for my child, especially for a 5-month-old.”

The decision to choose adaptive therapy is a difficult decision to make, whether for oneself or for one’s son, because it isn’t curative.

“My wife and I have since had a conversation about this, and I do think we would have considered it, although through a lot of difficult conversations,” he said.

“After we got the pathology, knowing that it was metastatic, fusion-positive, and given his age, just doing a brief literature review on my own, I knew what we were up against using 20-year-old treatments, and that the chance of a cure was very, very small.”

If parents of children with metastatic, poor-prognosis rhabdomyosarcoma could be made to understand that adaptive therapy would entail shorter and fewer hospital stays, and cumulatively less toxic chemotherapy, and could prolong the lives of their children, the option might be more acceptable, he said.

And as Dr. Reed mentioned, prolonging time to progression offers hope of additional therapies to come.

“The whole time that my son was being treated, I hoped that there was going to be something else that came out, that a new trial would be launched because they found a way to drug a mutation, or treat it with immunotherapy – something that was going to give us a better option.”

Asked whether he would be willing to share his experiences in this article, Mr. Huff said that “I am willing to, in whatever small way I can, make an impact, and hopefully save another family from what we experienced.”

References

1. Reed DR et al. Cancer. 2020 Jun 1;126(11):2577-87 2. Bisogno G et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:18_suppl,LBA-2

Meeting the unmet need in multiple myeloma

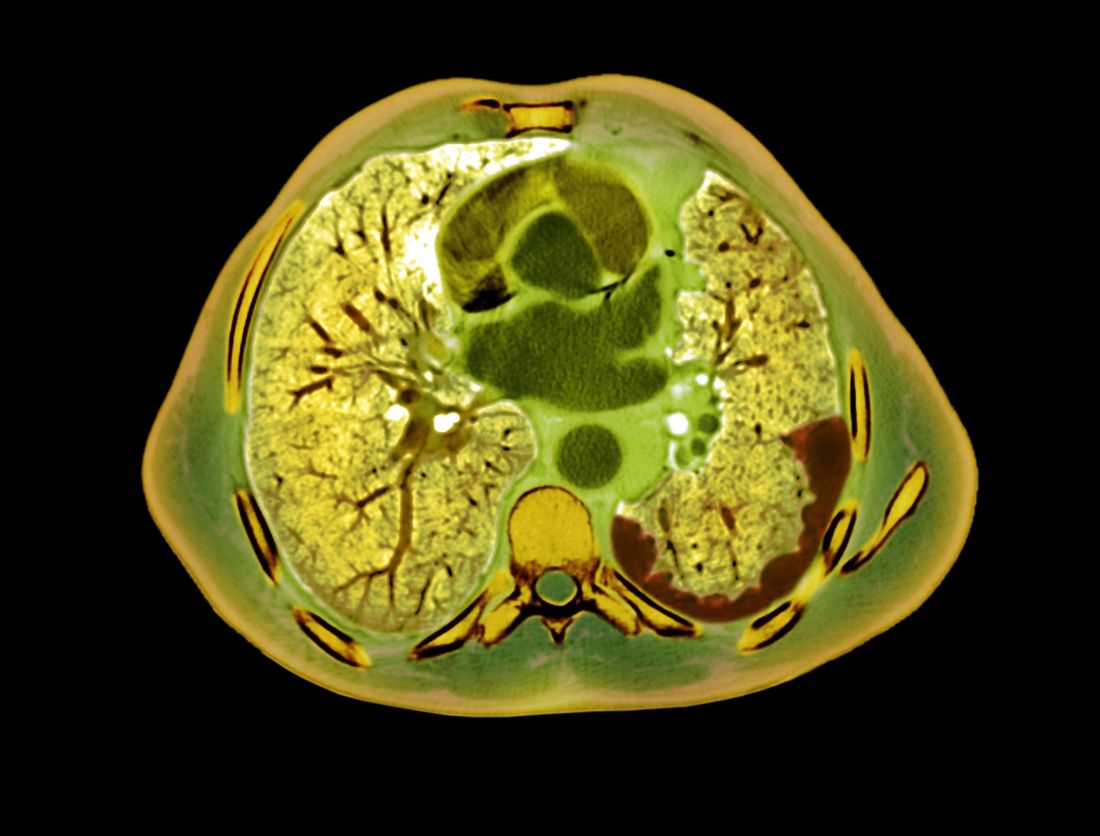

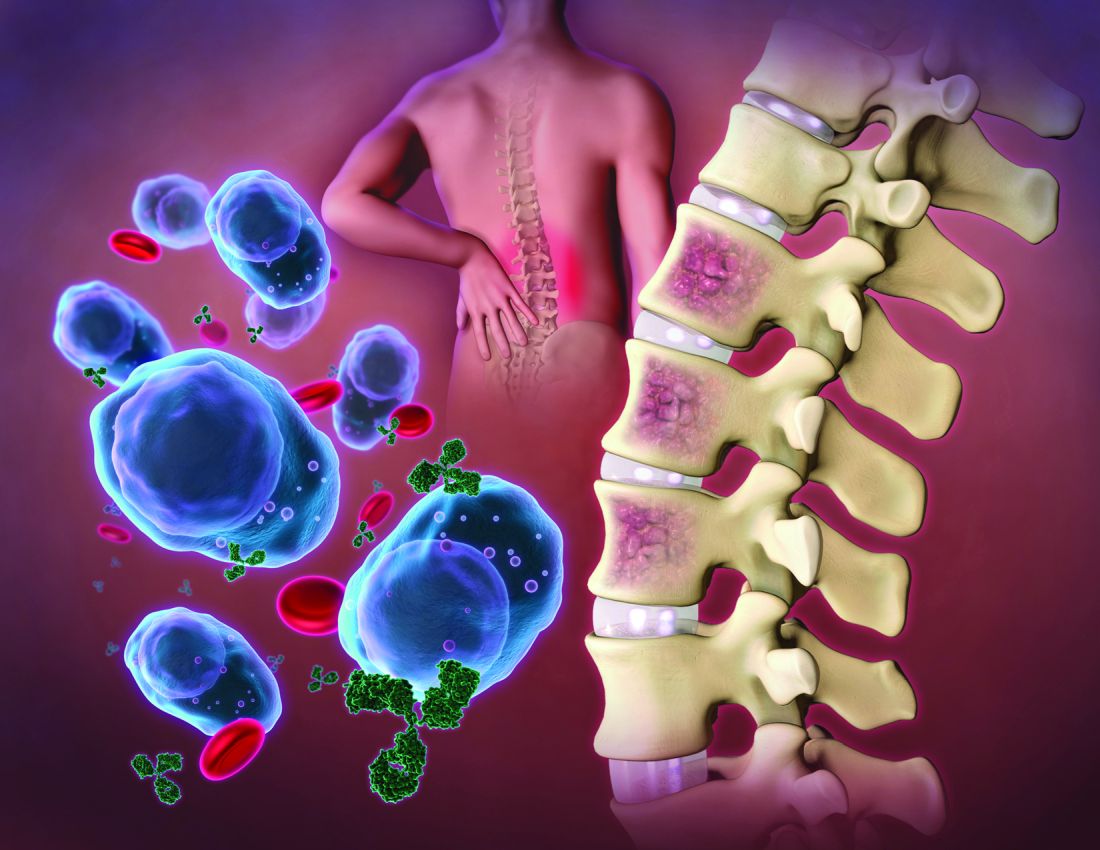

In multiple myeloma, survival has been very significantly improved by immunomodulatory drugs, proteasome inhibitors, and CD38-targeting antibodies. Despite these advances, multiple myeloma, which is characterized by malignant proliferation of clonal plasma cells in bone marrow, remains an incurable plasma cell disorder with near-certain relapse after successful treatment. Prognosis for patients who develop triple-class refractory disease is poor, with less than 1-year survival. The substantial unmet therapeutic need extends further to other poor survival multiple myeloma populations that include newly diagnosed patients with high cytogenic risk profiles and those with early relapse after first-line therapy. For all of these, interest in drugs with novel mechanisms of action is naturally high.

More specific, less toxic

Post allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation and donor lymphocyte infusion sustained remissions reflect a graft-versus-myeloma effect mediated by donor T cells.1 The substantial morbidity and mortality associated with graft-versus-host disease and opportunistic infections, however, have spurred searches for alternative, more specific, and less toxic T-cell therapies with stronger antitumor activity.

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs)

In CAR T-cell therapies for multiple myeloma, autologous T cells are harvested from the patient and reprogrammed to target multiple myeloma cells through the introduction of genes that encode CARs, which are fusion proteins coupling an antigen-recognition moiety and a transmembrane-spanning element to a T-cell activation domain (typically CD3 zeta [CD247]). The T cells are then expanded and reinfused to the patient following a lymphodepletion regimen. Five strategies using autologous CAR T cells are currently approved for diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma, and other hematologic malignancies. Notably, in patients with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma, CAR T cells have demonstrated impressive activity.

BCMA-targeting CAR T cells

The B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA; TNFRSF17), which plays an important role in the survival of long-lived plasma cells in bone marrow, is an attractive target for CAR T-cell therapy because it is expressed on normal and malignant plasma cell surfaces and by mature B cells. When ligands (TNFSF 13B/TNFSF13) bind to BCMA expressed on multiple myeloma cell surfaces, survival and proliferation pathways and drug resistance are activated.

High-quality responses have been demonstrated in several trials of anti-BCMA CAR T cells, which kill multiple myeloma cell lines and primary multiple myeloma cells through degranulation of T cells and lysis of tumor cells, even those with low BCMA expression. Based on efficacy in triple-class exposed multiple myeloma that compared favorably to conventional care with improved health-related quality of life, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave breakthrough designation to ciltacabtagene autoleucel in December 2019 and approval for idecabtagene vicleucel in March 2021.

Idecabtagene vicleucel

Idecabtagene vicleucel expresses a murine BCMA-targeting single-chain variable fragment with a 4-1BB costimulatory motif. The phase 2 KarMMa study2 evaluated idecabtagene vicleucel (target dose of 450 × 106 CAR T cells; range 150 × 106 to 450 × 106) activity in 128 patients with triple-class exposed multiple myeloma. Partial responses or better were observed in 94 of 128 patients (73%) (95% confidence interval, 66-81); 42 (33%) had a complete response or better (95% CI, 25-41), with a median progression-free survival of 8.8 months (95% CI, 5.6-11.6). Outcomes were improved in the highest fixed-dose group, with partial response or better in 81% (44 of 55), complete response or better in 39% (21), and median overall survival of 12.1 months (95% CI, 8.8-12.3). Patients with high-risk cytogenetic profiles, extramedullary disease, and high tumor burden also had deep and durable responses. Outcomes were less favorable in patients with revised International Staging System stage 3 disease.

Ciltacabtagene autoleucel

Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a 4-1BB–based CAR T-cell therapy with two BCMA-targeting domains, confers high-avidity binding. In the phase 1b/2 CARTITUDE-1 study, conducted in the United States and Europe, preliminary results in 97 patients showed a 97% response rate with ciltacabtagene autoleucel (target dose 0.75 × 106 CAR T cells per kg), and in 65 patients, a complete response (67%). Progression-free survival at 12 months was 77% (95% CI, 66-84) and overall survival was 89% (95% CI, 80-94).3

In the phase 1 LEGEND-2 study4 that was conducted at four sites in China among less heavily pretreated multiple myeloma patients, while all used the same CAR construct, sites used variable conditioning regimens (split versus single). In the site using cyclophosphamide as the lymphodepletion therapy and three split CAR T-cell infusions, partial response or better was achieved in 50 patients (88%) with a median of three prior therapy lines. The complete response rate was high (74%) and minimal residual disease negativity was reached in 39 patients (68%). Median progression-free survival was 19.9 months (95% CI, 9.6-31.0), but 28.2 months among those with complete responses (95% CI, 19.9-not estimable). Median overall survival was also favorable at 36.1 months (95% CI, 26.4-not estimable); it was 35.0 months-not estimable among patients with complete responses. Results from the other three sites were comparable.

Noteworthy among other BCMA-targeting CAR T-cell products in earlier stages of clinical development is orvacabtagene autoleucel, which has a fully human BCMA-specific binding domain. At higher doses (300 × 106 to 600 × 106 CAR T cells) among 62 patients with triple-class–exposed multiple myeloma in the EVOLVE trial, 92% had a partial or better response, with complete responses or better in 36%, all with an encouraging safety profile.

BCMA-targeting CAR T cell toxicity

While van de Donk, Usmani, and Yong, in their review1 note a lack of evidence of off-target toxicity with BCMA-targeting CAR T-cell therapy in clinical studies so far, they do point to several clinical syndromes (cytokine release syndrome, infections, respiratory failure, neurotoxicity, pulmonary aspergillosis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage) caused by cytokines produced during CAR T-cell expansion and to cytopenias and infections arising from prior treatment, bridging therapy, and lymphodepleting conditioning. Deaths attributed to treatment in the above-mentioned trials underscore the need for careful monitoring and early intervention.

Cytokine release syndrome

In the BCMA-targeting CAR T-cell therapy studies, the frequency of cytokine release syndrome varies widely from 17% to 95% but is generally attributed to CAR T-cell activation and is associated with increased serum ferritin concentrations, high c-reactive proteins, and proinflammatory cytokines. High tumor load, in multiple myeloma patients receiving CD19-targeting CAR T cells, was associated with a higher incidence of severe cytokine release syndrome. In a small number of patients, macrophage activation syndrome and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, the most aggressive variants of cytokine release syndrome, are caused by severe immune activation and lead to multiorgan dysfunction.

Neurotoxicity

Immune effector cell–-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) symptoms, in multiple myeloma patients treated with BCMA-targeting CAR T cells, may include delirium, transient confusion, aphasia, lethargy, tremor, dysgraphia, seizures, cerebral edema, and rarely, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.1 While the pathophysiology of CAR T cell–related neurotoxicity is not well understood, high tumor load, higher peak concentrations of CAR T cells, and more severe cytokine release syndrome are more common in patients with severe neurotoxicity. “The frequency of neurotoxicities,” Dr. Yong noted in an interview, “has been reduced by steps taken to mitigate these risk factors.”

High interest in phase I study

A phase I study presented in Blood has attracted interest because the novel BCMA-targeting CAR agent (CT103A) being tested is fully human.4 In an accompanying editorial, Lee and Yong note that doubt for any real potential for durable CAR T therapy responses in multiple myeloma is raised by the poor persistence of multiple myeloma CAR T cells in multiple myeloma patients.3

In the earliest trials of BCMA CARs, while reported rates of objective antimyeloma responses were in the approximately 33%-88% range among patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM), persistence was typically 6 months or less. Lee and Yong point out, however, that while correlation between persistence and duration of response (DOR) has been variable, median persistence was 308 days in the phase I study. Wang and colleagues, the phase I study authors, state that levels of CAR T-cell proliferation and duration of cellular persistence may be determinants of DOR in CAR T therapy for multiple myeloma. They observe that the multiple mechanisms potentially responsible for the inability of some CAR T cells to survive in vivo, may include antigen escape, T-cell intrinsic mechanisms, tumor microenvironment–mediated suppression, and host anti-CAR immunity. CARs with humanized or fully human single-chain variable fragments (scFvs), prior studies suggest, may retain antitumor activity through bypassing potential host anti-CAR immunogenicity.

In the study, CT103A, a fully human scFv, was tested in an open-label, single-arm design for safety and preliminary efficacy in 18 patients (8 female; median age 53.5 years) with RRMM (at least three lines of prior therapies including a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent) who had undergone leukapheresis and had received lymphodepletion chemotherapy with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide. Four patients (22.2%) had been treated previously with murine anti-BCMA CAR T cells. Safety and tolerability (including dose-limiting toxicity) were the primary endpoints, with efficacy and pharmacokinetics secondary.

Rapid responses

Two weeks after infusion, the overall response rate (ORR) was 77.8% (14 of 18) and by 1 month it was 88.9% (16 of 18). Eventually, all responded and 72.2% (13 of 18) achieved a complete response (CR) or stringent complete response (sCR). All 17 patients evaluated for minimum residual disease (MRD) in bone marrow were MRD-negative at 10-4 nucleated cells by flow cytometry within 1 month. Median DOR was 325 days (range, 7-573 days) for all patients and 412 days (range, 213-573 days) for the 13 with CR/sCR. CAR transgenes were detectable at the cutoff date in 77.8% of patients, with a median CAR transgene persistence of 307.5 days.

During follow-up, four deaths were reported, including one patient with persistent sCR (sudden severe infection). Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates at 1 year were 58.3% and 75%, respectively. Extramedullary myeloma was associated with a shortened PFS (79.1% versus 20.0%, P = .015), but not OS (79.1% versus 60.0%, P = .328) at 1 year.

All patients experienced grade 3 or higher adverse events, most of which were expected hematologic effects of lymphodepleting chemotherapy and CT103A infusions. Grade 1 and 2 cytokine release syndromes occurred in 70.6% patients (17 of 18), with 1 grade 4 event (5.9%). The patients receiving a dose of up to 3.0 × 106 CAR+ T cells/kg required less treatment of cytokine release syndrome than the patients who received a dose of 6.0 × 106 CAR+ T cells/kg. No immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome was observed. Antidrug antibody positivity occurred in only 1 patient.

Two characteristics of CT103A may contribute to its long persistence, stated study senior author Jianfeng Zhou, MD, PhD, chairman and professor of the department of hematology, Tongji Hospital in Wuhan, China. “One is the reduced immunogenicity achieved by the fully human construct; another is the relatively low binding affinity of the CAR binder. Notably, four patients who previously received murine BCMA CAR were included and still benefit from CT103A. It demonstrates the possibility of retreatment with a different CAR.” Dr. Zhou also emphasized that the lack of ICANS in the entire cohort reflects the excellent safety profile of CT103A.

The editorial commentary in Blood by Lydia Sarah Hui Lee, MD, and Kwee L. Yong, PhD, underscored impressive responses to CT103A, specifically to the median time to response of 15 days, the 100% ORR, and the not reached median progression-free survival at 394 days).5 The best results in other published nonhuman BCMA CAR T-cell trials, they note, were about 1 month (time to response), approximately 33%-88% (ORR), and median progression-free survival of 7-15 months.

Immune responses, Dr. Yong said in an interview, can guide subsequent treatment. “For example, if a patient previously exposed to BCMA CAR T cells in which the construct is either chimeric or humanized, but retains some murine elements, and had detectable antimurine antibodies, we may aim for a fully human one if we are considering treating with a different BCMA CAR T-cell product.” She added, “On the other hand, a similar patient whose serum did not contain such antibodies may be a candidate for a humanized product that retained some murine elements.”

Wang and colleagues concluded, “Altogether, CT103A is safe and highly active in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma and can be developed as a promising therapy for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.”4 An ongoing multicenter phase II trial with single-arm design is recruiting 100 patients. The infusion dosage, suggested by the phase I trial, is 1 × 106 cells/kg. Endpoints include efficacy and safety.

Improving CAR T

Optimizing CAR design and adapting manufacturing processes to generate cell products enriched for T-cell subsets, such as early memory cells, are among strategies being explored to improve CAR T effectiveness.1 Also, dual-antigen targeting to interdict antigen escape and rational combination treatments to enhance persistence are under investigation, along with efforts to improve CAR T-cell therapy safety (for example, incorporation of a suicide gene safety system). They note further that several groups are researching use of induced pluripotent stem cells to generate large quantities of off-the-shelf CAR T-cell immunotherapies that would circumvent the complex, costly, and time-consuming process of manufacturing patient-specific autologous CAR T cells.

References

1. van de Donk N et al. Lancet Haematol. 2021 June;8(6):e446-61.

2. Munshi NC et al. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:705-716.

3. Berdeja JG et al. The Lancet. 2021 July; 398:314-24.

4. Wang D et al. Blood. 2021 May;137(21):2890-901.

5. Lee L and Yong K. Blood. 2021 May;137(21):2859-60.

In multiple myeloma, survival has been very significantly improved by immunomodulatory drugs, proteasome inhibitors, and CD38-targeting antibodies. Despite these advances, multiple myeloma, which is characterized by malignant proliferation of clonal plasma cells in bone marrow, remains an incurable plasma cell disorder with near-certain relapse after successful treatment. Prognosis for patients who develop triple-class refractory disease is poor, with less than 1-year survival. The substantial unmet therapeutic need extends further to other poor survival multiple myeloma populations that include newly diagnosed patients with high cytogenic risk profiles and those with early relapse after first-line therapy. For all of these, interest in drugs with novel mechanisms of action is naturally high.

More specific, less toxic