User login

Things We Do for No Reason™: Fluid Restriction for the Management of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure in Patients With Reduced Ejection Fraction

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

The hospitalist enters admission orders for an 80-year-old woman with hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who presented to the emergency department with weight gain, lower extremity edema, and dyspnea on exertion. She has an elevated jugular venous pressure, crackles on pulmonary exam, and bilateral pitting edema with warm extremities. Labs show a sodium of 140 mmol/L and creatinine of 1.4 mg/dL. After ordering intravenous furosemide for management of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), the hospitalist arrives at the nutrition section of the CHF Admission Order Set and reflexively picks an option for a fluid-restricted diet.

BACKGROUND

Patients with ADHF, the leading cause of hospitalization for patients older than 65 years,1 may present with signs and symptoms of volume overload: shortness of breath, lower-extremity swelling, and end-organ dysfunction. Before the 1980s, treatment of ADHF relied on loop diuretics, bedrest, and fluid restriction to minimize congestive symptoms.2 Clinicians based this practice on early theories framing heart failure as primarily an issue of salt and water retention that could be counterbalanced by sodium and fluid restriction.2

Today, hospitalists understand heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) as a heterogenous disease with a shared pathophysiology in which reduced cardiac output, elevated systemic venous pressures, and/or shunting of blood away from the kidneys may all lead to decreased renal perfusion. These phenomena trigger the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), leading to sodium and water retention and fluid redistribution.2 As part of the modern day treatment regimen, providers continue to place patients on fluid-restricted diets. Guidelines support this practice.3,4

Since most of the existing literature on the topic of fluid restriction in ADHF relates to HFrEF (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] <40%), as opposed to heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, LVEF ≥50%), this review will focus on HFrEF patients. Limited existing data support extrapolating these arguments to HFpEF patients as well.5

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK FLUID RESTRICTION IS IMPORTANT IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ADHF IN HFREF PATIENTS

Longstanding conventional wisdom and data extrapolation from the chronic heart failure population has undergirded the practice of fluid restriction for ADHF. Current iterations of the American and European heart failure guidelines recommend fluid restriction of 1.5 to 2.0 L/day in severe ADHF as a management strategy.3,4 The American guidelines recommend considering restricting fluid intake to 2 L/day for most hospitalized ADHF patients without hyponatremia or diuretic resistance. The guidelines base the recommendation on clinical experience and data from a single randomized trial evaluating the effects of sodium restriction on heart failure outcomes in outpatients recently admitted for ADHF.4,6 This trial randomly assigned 232 patients with compensated HFrEF to either a normal or low-sodium diet plus oral furosemide. Researchers instructed both groups to adhere to a 1000 mL/day fluid restriction. The authors found a high incidence of readmissions for worsening congestive heart failure among a cohort of patients (n = 54) with a normal sodium diet who were excluded from randomization due to inability to adhere to the prescribed fluid restriction.6 Notably, this study did not evaluate patients receiving treatment for ADHF and was not designed to investigate the role of fluid restriction for the treatment of ADHF.

A subsequent study by the same investigators looked more deliberately, although not singularly, at outpatient fluid restriction. This study randomly assigned 410 patients with compensated HFrEF into eight groups by fluid intake (1 L vs 2 L), salt intake (80 mmol vs 120 mmol), and furosemide dose (125 mg twice daily vs 250 mg twice daily). At 180 days, the group receiving the fluid-restricted diet with higher sodium intake and higher diuretic dose had the lowest risk of hospital readmission.7Results from these studies of the chronic, compensated heart failure population, in conjunction with longstanding conventional wisdom, have influenced the management of patients hospitalized with ADHF.

WHY FLUID RESTRICTION IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ADHF IN HFREF PATIENTS MIGHT NOT BE HELPFUL

From a pathophysiologic perspective, fluid restriction in ADHF may counterproductively lead to RAAS activation.8 Congestion develops when arterial underfilling leads to RAAS activation, triggering sodium and water retention.2 Furthermore, RAAS activation, as measured by plasma levels of renin, angiotensin II, and aldosterone, correlates with prognosis and mortality in chronic HFrEF.9 Analyses from one of the largest databases of biomarkers from ADHF suggest that RAAS is further upregulated during decongestive therapy.10 While researchers have not studied the effects of fluid restriction on RAAS activation in ADHF patients, extrapolating from these data one may question whether fluid restriction in ADHF patients may further drive RAAS activation. Further activation may contribute to adverse incident outcomes such as worsening renal function.

The most relevant and compelling evidence against fluid restriction to date comes from Travers et al,11 who conducted the first randomized controlled trial examining fluid restriction in ADHF patients. Their small study compared restricted (1 L fluid restriction) vs liberal (free fluid) intake in hospitalized patients with ADHF and demonstrated no difference in duration or daily dose of intravenous diuretics, time to symptomatic improvement, total daily fluid output, or average hospitalization weight loss between the two arms. Furthermore, researchers withdrew more patients in the fluid-restricted arm due to a sustained rise in serum creatinine, suggesting potential harm of this intervention.11 The sample size (N = 67) and fluid-intake difference of only 400 mL between the two groups limited the study results.

In a subsequent randomized controlled trial, Aliti et al12 examined the clinical outcomes of even more aggressive fluid restriction (800 mL/day) and sodium restriction (800 mg/day) versus liberal intake (at least 2.5 L fluid/day and approximately 3-5 g sodium/day) in hospitalized patients with ADHF (N = 75). While this study evaluated both fluid and sodium restriction, it produced relevant results. The study demonstrated no significant difference in weight loss, use of diuretics, or rehospitalization between the study arms.12 At 30-day follow-up, researchers found that patients in the intervention group had more congestion and an increased likelihood of having a B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level greater than 700 pg/mL. In the subset of all patients with an elevated BNP level greater than 700 pg/mL at the end of the study, patients in the intervention group had a significantly higher rate of readmission (7 out of 22) compared with controls (1 of 20). Moreover, the fluid-restricted group had 50% higher perceived thirst values compared to the control group.12 The sensation of thirst not only reduces quality of life, but, given that angiotensin II stimulates thirst, it may reflect RAAS activation.13 For these reasons, clinicians should consider this side effect seriously, especially when the literature lacks evidence of the benefits from fluid restriction.

WHEN FLUID RESTRICTION IS HELPFUL IN THE MANAGEMENT OF DECOMPENSATED HEART FAILURE IN HFREF PATIENTS

Fluid-restrict patients who have chronic hyponatremia (Na <135 mmol/L) due to end-stage HFrEF in select circumstances. Hyponatremia develops in heart failure primarily because of the body’s inability to excrete free water due to non-osmotic arginine vasopressin secretion.4 Other processes contribute to hyponatremia, including increased free water intake due to angiotensin II stimulating thirst and decreased glomerular filtration rate limiting the kidney’s ability to excrete free water. Since hyponatremia in heart failure primarily occurs due to derangements of free water regulation, limiting free water intake may help; the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European heart failure guidelines explicitly recommend this strategy for patients with stage D heart failure.3,4 However, no available randomized data support this practice, and observational data suggest that fluid restriction has limited impact on hyponatremia in ADHF.14 Guidelines also suggest employing fluid restriction in patients with diuretic resistance as an adjunctive therapy.

Twenty-nine percent of patients with ADHF have comorbid chronic kidney disease (CKD).15 Providers often prescribe patients with advanced CKD salt- and fluid-restrictive diets due to more limited abilities in sodium and free water excretion. However, no studies have examined the effects of fluid restriction alone without salt restriction in the CKD/ADHF population.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

In the present day of evidence-based pharmacologic therapies, research indicates that fluid-restriction does not help and potentially may harm. Instead, treat hospitalized HFrEF patients with ADHF with modern, evidence-based pharmacologic therapies and allow the patients to drink when thirsty.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Treat patients with ADHF and reduced ejection fraction with evidence-based neurohormonal blockade and initiate loop diuretics to alleviate congestion.

- Allow patients with ADHF and reduced ejection fraction to drink when thirsty in the absence of hyponatremia.

- Consider initiating fluid restriction in patients with ADHF and concurrent hyponatremia and/or diuretic resistance. There is little evidence to guide setting specific limits on fluid intake.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist starts the patient admitted for ADHF on an intravenous loop diuretic, continues her home beta blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and does not impose any fluid restriction. Her symptoms of congestion resolve, and she is discharged.

Hospitalists often treat patients with ADHF and reduced ejection fraction with fluid restriction. However, limited evidence supports this practice as part of the management of ADHF. Fluid restriction may have unintended adverse effects of increasing thirst and worsening renal function and quality of life.

What do you do? Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29-322. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000152

2. Arrigo M, Parissis JT, Akiyama E, Mebazaa A. Understanding acute heart failure: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2016;18(Suppl G):G11-G18. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/suw044

3. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8):891-975. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.592

4. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147-e239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019

5. Machado d’Almeida KS, Rabelo-Silva ER, Souza GC, et al. Aggressive fluid and sodium restriction in decompensated heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results from a randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2018;54:111-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2018.02.007

6. Paterna S, Gaspare P, Fasullo S, Sarullo FM, Di Pasquale P. Normal-sodium diet compared with low-sodium diet in compensated congestive heart failure: is sodium an old enemy or a new friend? Clin Sci (Lond). 2008;114(3):221-230. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20070193

7. Paterna S, Parrinello G, Cannizzaro S, et al. Medium term effects of different dosage of diuretic, sodium, and fluid administration on neurohormonal and clinical outcome in patients with recently compensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(1):93-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.043

8. Shore AC, Markandu ND, Sagnella GA, et al. Endocrine and renal response to water loading and water restriction in normal man. Clin Sci (Lond). 1988;75(2):171-177. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs0750171

9. Oliveros E, Oni ET, Shahzad A, et al. Benefits and risks of continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists during hospitalizations for acute heart failure. Cardiorenal Med. 2020;10(2):69-84. https://doi.org/10.1159/000504167

10. Mentz RJ, Stevens SR, DeVore AD, et al. Decongestion strategies and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation in acute heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(2):97-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2014.09.003

11. Travers B, O’Loughlin C, Murphy NF, et al. Fluid restriction in the management of decompensated heart failure: no impact on time to clinical stability. J Card Fail. 2007;13(2):128-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.10.012

12. Aliti GB, Rabelo ER, Clausell N, Rohde LE, Biolo A, Beck-da-Silva L. Aggressive fluid and sodium restriction in acute decompensated heart failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1058-1064. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.552

13. Jao GT, Chiong JR. Hyponatremia in acute decompensated heart failure: mechanisms, prognosis, and treatment options. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(11):666-671. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.20822

14. Nagler EV, Haller MC, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R, Craig JC, Webster AC. Interventions for chronic non-hypovolaemic hypotonic hyponatraemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;28(6):CD010965. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd010965.pub2

15. Fonarow GC; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4(Suppl 7):S21-S30.

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

The hospitalist enters admission orders for an 80-year-old woman with hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who presented to the emergency department with weight gain, lower extremity edema, and dyspnea on exertion. She has an elevated jugular venous pressure, crackles on pulmonary exam, and bilateral pitting edema with warm extremities. Labs show a sodium of 140 mmol/L and creatinine of 1.4 mg/dL. After ordering intravenous furosemide for management of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), the hospitalist arrives at the nutrition section of the CHF Admission Order Set and reflexively picks an option for a fluid-restricted diet.

BACKGROUND

Patients with ADHF, the leading cause of hospitalization for patients older than 65 years,1 may present with signs and symptoms of volume overload: shortness of breath, lower-extremity swelling, and end-organ dysfunction. Before the 1980s, treatment of ADHF relied on loop diuretics, bedrest, and fluid restriction to minimize congestive symptoms.2 Clinicians based this practice on early theories framing heart failure as primarily an issue of salt and water retention that could be counterbalanced by sodium and fluid restriction.2

Today, hospitalists understand heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) as a heterogenous disease with a shared pathophysiology in which reduced cardiac output, elevated systemic venous pressures, and/or shunting of blood away from the kidneys may all lead to decreased renal perfusion. These phenomena trigger the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), leading to sodium and water retention and fluid redistribution.2 As part of the modern day treatment regimen, providers continue to place patients on fluid-restricted diets. Guidelines support this practice.3,4

Since most of the existing literature on the topic of fluid restriction in ADHF relates to HFrEF (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] <40%), as opposed to heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, LVEF ≥50%), this review will focus on HFrEF patients. Limited existing data support extrapolating these arguments to HFpEF patients as well.5

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK FLUID RESTRICTION IS IMPORTANT IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ADHF IN HFREF PATIENTS

Longstanding conventional wisdom and data extrapolation from the chronic heart failure population has undergirded the practice of fluid restriction for ADHF. Current iterations of the American and European heart failure guidelines recommend fluid restriction of 1.5 to 2.0 L/day in severe ADHF as a management strategy.3,4 The American guidelines recommend considering restricting fluid intake to 2 L/day for most hospitalized ADHF patients without hyponatremia or diuretic resistance. The guidelines base the recommendation on clinical experience and data from a single randomized trial evaluating the effects of sodium restriction on heart failure outcomes in outpatients recently admitted for ADHF.4,6 This trial randomly assigned 232 patients with compensated HFrEF to either a normal or low-sodium diet plus oral furosemide. Researchers instructed both groups to adhere to a 1000 mL/day fluid restriction. The authors found a high incidence of readmissions for worsening congestive heart failure among a cohort of patients (n = 54) with a normal sodium diet who were excluded from randomization due to inability to adhere to the prescribed fluid restriction.6 Notably, this study did not evaluate patients receiving treatment for ADHF and was not designed to investigate the role of fluid restriction for the treatment of ADHF.

A subsequent study by the same investigators looked more deliberately, although not singularly, at outpatient fluid restriction. This study randomly assigned 410 patients with compensated HFrEF into eight groups by fluid intake (1 L vs 2 L), salt intake (80 mmol vs 120 mmol), and furosemide dose (125 mg twice daily vs 250 mg twice daily). At 180 days, the group receiving the fluid-restricted diet with higher sodium intake and higher diuretic dose had the lowest risk of hospital readmission.7Results from these studies of the chronic, compensated heart failure population, in conjunction with longstanding conventional wisdom, have influenced the management of patients hospitalized with ADHF.

WHY FLUID RESTRICTION IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ADHF IN HFREF PATIENTS MIGHT NOT BE HELPFUL

From a pathophysiologic perspective, fluid restriction in ADHF may counterproductively lead to RAAS activation.8 Congestion develops when arterial underfilling leads to RAAS activation, triggering sodium and water retention.2 Furthermore, RAAS activation, as measured by plasma levels of renin, angiotensin II, and aldosterone, correlates with prognosis and mortality in chronic HFrEF.9 Analyses from one of the largest databases of biomarkers from ADHF suggest that RAAS is further upregulated during decongestive therapy.10 While researchers have not studied the effects of fluid restriction on RAAS activation in ADHF patients, extrapolating from these data one may question whether fluid restriction in ADHF patients may further drive RAAS activation. Further activation may contribute to adverse incident outcomes such as worsening renal function.

The most relevant and compelling evidence against fluid restriction to date comes from Travers et al,11 who conducted the first randomized controlled trial examining fluid restriction in ADHF patients. Their small study compared restricted (1 L fluid restriction) vs liberal (free fluid) intake in hospitalized patients with ADHF and demonstrated no difference in duration or daily dose of intravenous diuretics, time to symptomatic improvement, total daily fluid output, or average hospitalization weight loss between the two arms. Furthermore, researchers withdrew more patients in the fluid-restricted arm due to a sustained rise in serum creatinine, suggesting potential harm of this intervention.11 The sample size (N = 67) and fluid-intake difference of only 400 mL between the two groups limited the study results.

In a subsequent randomized controlled trial, Aliti et al12 examined the clinical outcomes of even more aggressive fluid restriction (800 mL/day) and sodium restriction (800 mg/day) versus liberal intake (at least 2.5 L fluid/day and approximately 3-5 g sodium/day) in hospitalized patients with ADHF (N = 75). While this study evaluated both fluid and sodium restriction, it produced relevant results. The study demonstrated no significant difference in weight loss, use of diuretics, or rehospitalization between the study arms.12 At 30-day follow-up, researchers found that patients in the intervention group had more congestion and an increased likelihood of having a B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level greater than 700 pg/mL. In the subset of all patients with an elevated BNP level greater than 700 pg/mL at the end of the study, patients in the intervention group had a significantly higher rate of readmission (7 out of 22) compared with controls (1 of 20). Moreover, the fluid-restricted group had 50% higher perceived thirst values compared to the control group.12 The sensation of thirst not only reduces quality of life, but, given that angiotensin II stimulates thirst, it may reflect RAAS activation.13 For these reasons, clinicians should consider this side effect seriously, especially when the literature lacks evidence of the benefits from fluid restriction.

WHEN FLUID RESTRICTION IS HELPFUL IN THE MANAGEMENT OF DECOMPENSATED HEART FAILURE IN HFREF PATIENTS

Fluid-restrict patients who have chronic hyponatremia (Na <135 mmol/L) due to end-stage HFrEF in select circumstances. Hyponatremia develops in heart failure primarily because of the body’s inability to excrete free water due to non-osmotic arginine vasopressin secretion.4 Other processes contribute to hyponatremia, including increased free water intake due to angiotensin II stimulating thirst and decreased glomerular filtration rate limiting the kidney’s ability to excrete free water. Since hyponatremia in heart failure primarily occurs due to derangements of free water regulation, limiting free water intake may help; the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European heart failure guidelines explicitly recommend this strategy for patients with stage D heart failure.3,4 However, no available randomized data support this practice, and observational data suggest that fluid restriction has limited impact on hyponatremia in ADHF.14 Guidelines also suggest employing fluid restriction in patients with diuretic resistance as an adjunctive therapy.

Twenty-nine percent of patients with ADHF have comorbid chronic kidney disease (CKD).15 Providers often prescribe patients with advanced CKD salt- and fluid-restrictive diets due to more limited abilities in sodium and free water excretion. However, no studies have examined the effects of fluid restriction alone without salt restriction in the CKD/ADHF population.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

In the present day of evidence-based pharmacologic therapies, research indicates that fluid-restriction does not help and potentially may harm. Instead, treat hospitalized HFrEF patients with ADHF with modern, evidence-based pharmacologic therapies and allow the patients to drink when thirsty.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Treat patients with ADHF and reduced ejection fraction with evidence-based neurohormonal blockade and initiate loop diuretics to alleviate congestion.

- Allow patients with ADHF and reduced ejection fraction to drink when thirsty in the absence of hyponatremia.

- Consider initiating fluid restriction in patients with ADHF and concurrent hyponatremia and/or diuretic resistance. There is little evidence to guide setting specific limits on fluid intake.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist starts the patient admitted for ADHF on an intravenous loop diuretic, continues her home beta blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and does not impose any fluid restriction. Her symptoms of congestion resolve, and she is discharged.

Hospitalists often treat patients with ADHF and reduced ejection fraction with fluid restriction. However, limited evidence supports this practice as part of the management of ADHF. Fluid restriction may have unintended adverse effects of increasing thirst and worsening renal function and quality of life.

What do you do? Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

The hospitalist enters admission orders for an 80-year-old woman with hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who presented to the emergency department with weight gain, lower extremity edema, and dyspnea on exertion. She has an elevated jugular venous pressure, crackles on pulmonary exam, and bilateral pitting edema with warm extremities. Labs show a sodium of 140 mmol/L and creatinine of 1.4 mg/dL. After ordering intravenous furosemide for management of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), the hospitalist arrives at the nutrition section of the CHF Admission Order Set and reflexively picks an option for a fluid-restricted diet.

BACKGROUND

Patients with ADHF, the leading cause of hospitalization for patients older than 65 years,1 may present with signs and symptoms of volume overload: shortness of breath, lower-extremity swelling, and end-organ dysfunction. Before the 1980s, treatment of ADHF relied on loop diuretics, bedrest, and fluid restriction to minimize congestive symptoms.2 Clinicians based this practice on early theories framing heart failure as primarily an issue of salt and water retention that could be counterbalanced by sodium and fluid restriction.2

Today, hospitalists understand heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) as a heterogenous disease with a shared pathophysiology in which reduced cardiac output, elevated systemic venous pressures, and/or shunting of blood away from the kidneys may all lead to decreased renal perfusion. These phenomena trigger the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), leading to sodium and water retention and fluid redistribution.2 As part of the modern day treatment regimen, providers continue to place patients on fluid-restricted diets. Guidelines support this practice.3,4

Since most of the existing literature on the topic of fluid restriction in ADHF relates to HFrEF (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] <40%), as opposed to heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, LVEF ≥50%), this review will focus on HFrEF patients. Limited existing data support extrapolating these arguments to HFpEF patients as well.5

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK FLUID RESTRICTION IS IMPORTANT IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ADHF IN HFREF PATIENTS

Longstanding conventional wisdom and data extrapolation from the chronic heart failure population has undergirded the practice of fluid restriction for ADHF. Current iterations of the American and European heart failure guidelines recommend fluid restriction of 1.5 to 2.0 L/day in severe ADHF as a management strategy.3,4 The American guidelines recommend considering restricting fluid intake to 2 L/day for most hospitalized ADHF patients without hyponatremia or diuretic resistance. The guidelines base the recommendation on clinical experience and data from a single randomized trial evaluating the effects of sodium restriction on heart failure outcomes in outpatients recently admitted for ADHF.4,6 This trial randomly assigned 232 patients with compensated HFrEF to either a normal or low-sodium diet plus oral furosemide. Researchers instructed both groups to adhere to a 1000 mL/day fluid restriction. The authors found a high incidence of readmissions for worsening congestive heart failure among a cohort of patients (n = 54) with a normal sodium diet who were excluded from randomization due to inability to adhere to the prescribed fluid restriction.6 Notably, this study did not evaluate patients receiving treatment for ADHF and was not designed to investigate the role of fluid restriction for the treatment of ADHF.

A subsequent study by the same investigators looked more deliberately, although not singularly, at outpatient fluid restriction. This study randomly assigned 410 patients with compensated HFrEF into eight groups by fluid intake (1 L vs 2 L), salt intake (80 mmol vs 120 mmol), and furosemide dose (125 mg twice daily vs 250 mg twice daily). At 180 days, the group receiving the fluid-restricted diet with higher sodium intake and higher diuretic dose had the lowest risk of hospital readmission.7Results from these studies of the chronic, compensated heart failure population, in conjunction with longstanding conventional wisdom, have influenced the management of patients hospitalized with ADHF.

WHY FLUID RESTRICTION IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ADHF IN HFREF PATIENTS MIGHT NOT BE HELPFUL

From a pathophysiologic perspective, fluid restriction in ADHF may counterproductively lead to RAAS activation.8 Congestion develops when arterial underfilling leads to RAAS activation, triggering sodium and water retention.2 Furthermore, RAAS activation, as measured by plasma levels of renin, angiotensin II, and aldosterone, correlates with prognosis and mortality in chronic HFrEF.9 Analyses from one of the largest databases of biomarkers from ADHF suggest that RAAS is further upregulated during decongestive therapy.10 While researchers have not studied the effects of fluid restriction on RAAS activation in ADHF patients, extrapolating from these data one may question whether fluid restriction in ADHF patients may further drive RAAS activation. Further activation may contribute to adverse incident outcomes such as worsening renal function.

The most relevant and compelling evidence against fluid restriction to date comes from Travers et al,11 who conducted the first randomized controlled trial examining fluid restriction in ADHF patients. Their small study compared restricted (1 L fluid restriction) vs liberal (free fluid) intake in hospitalized patients with ADHF and demonstrated no difference in duration or daily dose of intravenous diuretics, time to symptomatic improvement, total daily fluid output, or average hospitalization weight loss between the two arms. Furthermore, researchers withdrew more patients in the fluid-restricted arm due to a sustained rise in serum creatinine, suggesting potential harm of this intervention.11 The sample size (N = 67) and fluid-intake difference of only 400 mL between the two groups limited the study results.

In a subsequent randomized controlled trial, Aliti et al12 examined the clinical outcomes of even more aggressive fluid restriction (800 mL/day) and sodium restriction (800 mg/day) versus liberal intake (at least 2.5 L fluid/day and approximately 3-5 g sodium/day) in hospitalized patients with ADHF (N = 75). While this study evaluated both fluid and sodium restriction, it produced relevant results. The study demonstrated no significant difference in weight loss, use of diuretics, or rehospitalization between the study arms.12 At 30-day follow-up, researchers found that patients in the intervention group had more congestion and an increased likelihood of having a B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level greater than 700 pg/mL. In the subset of all patients with an elevated BNP level greater than 700 pg/mL at the end of the study, patients in the intervention group had a significantly higher rate of readmission (7 out of 22) compared with controls (1 of 20). Moreover, the fluid-restricted group had 50% higher perceived thirst values compared to the control group.12 The sensation of thirst not only reduces quality of life, but, given that angiotensin II stimulates thirst, it may reflect RAAS activation.13 For these reasons, clinicians should consider this side effect seriously, especially when the literature lacks evidence of the benefits from fluid restriction.

WHEN FLUID RESTRICTION IS HELPFUL IN THE MANAGEMENT OF DECOMPENSATED HEART FAILURE IN HFREF PATIENTS

Fluid-restrict patients who have chronic hyponatremia (Na <135 mmol/L) due to end-stage HFrEF in select circumstances. Hyponatremia develops in heart failure primarily because of the body’s inability to excrete free water due to non-osmotic arginine vasopressin secretion.4 Other processes contribute to hyponatremia, including increased free water intake due to angiotensin II stimulating thirst and decreased glomerular filtration rate limiting the kidney’s ability to excrete free water. Since hyponatremia in heart failure primarily occurs due to derangements of free water regulation, limiting free water intake may help; the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European heart failure guidelines explicitly recommend this strategy for patients with stage D heart failure.3,4 However, no available randomized data support this practice, and observational data suggest that fluid restriction has limited impact on hyponatremia in ADHF.14 Guidelines also suggest employing fluid restriction in patients with diuretic resistance as an adjunctive therapy.

Twenty-nine percent of patients with ADHF have comorbid chronic kidney disease (CKD).15 Providers often prescribe patients with advanced CKD salt- and fluid-restrictive diets due to more limited abilities in sodium and free water excretion. However, no studies have examined the effects of fluid restriction alone without salt restriction in the CKD/ADHF population.

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

In the present day of evidence-based pharmacologic therapies, research indicates that fluid-restriction does not help and potentially may harm. Instead, treat hospitalized HFrEF patients with ADHF with modern, evidence-based pharmacologic therapies and allow the patients to drink when thirsty.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Treat patients with ADHF and reduced ejection fraction with evidence-based neurohormonal blockade and initiate loop diuretics to alleviate congestion.

- Allow patients with ADHF and reduced ejection fraction to drink when thirsty in the absence of hyponatremia.

- Consider initiating fluid restriction in patients with ADHF and concurrent hyponatremia and/or diuretic resistance. There is little evidence to guide setting specific limits on fluid intake.

CONCLUSION

The hospitalist starts the patient admitted for ADHF on an intravenous loop diuretic, continues her home beta blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, and does not impose any fluid restriction. Her symptoms of congestion resolve, and she is discharged.

Hospitalists often treat patients with ADHF and reduced ejection fraction with fluid restriction. However, limited evidence supports this practice as part of the management of ADHF. Fluid restriction may have unintended adverse effects of increasing thirst and worsening renal function and quality of life.

What do you do? Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter.

1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29-322. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000152

2. Arrigo M, Parissis JT, Akiyama E, Mebazaa A. Understanding acute heart failure: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2016;18(Suppl G):G11-G18. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/suw044

3. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8):891-975. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.592

4. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147-e239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019

5. Machado d’Almeida KS, Rabelo-Silva ER, Souza GC, et al. Aggressive fluid and sodium restriction in decompensated heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results from a randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2018;54:111-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2018.02.007

6. Paterna S, Gaspare P, Fasullo S, Sarullo FM, Di Pasquale P. Normal-sodium diet compared with low-sodium diet in compensated congestive heart failure: is sodium an old enemy or a new friend? Clin Sci (Lond). 2008;114(3):221-230. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20070193

7. Paterna S, Parrinello G, Cannizzaro S, et al. Medium term effects of different dosage of diuretic, sodium, and fluid administration on neurohormonal and clinical outcome in patients with recently compensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(1):93-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.043

8. Shore AC, Markandu ND, Sagnella GA, et al. Endocrine and renal response to water loading and water restriction in normal man. Clin Sci (Lond). 1988;75(2):171-177. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs0750171

9. Oliveros E, Oni ET, Shahzad A, et al. Benefits and risks of continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists during hospitalizations for acute heart failure. Cardiorenal Med. 2020;10(2):69-84. https://doi.org/10.1159/000504167

10. Mentz RJ, Stevens SR, DeVore AD, et al. Decongestion strategies and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation in acute heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(2):97-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2014.09.003

11. Travers B, O’Loughlin C, Murphy NF, et al. Fluid restriction in the management of decompensated heart failure: no impact on time to clinical stability. J Card Fail. 2007;13(2):128-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.10.012

12. Aliti GB, Rabelo ER, Clausell N, Rohde LE, Biolo A, Beck-da-Silva L. Aggressive fluid and sodium restriction in acute decompensated heart failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1058-1064. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.552

13. Jao GT, Chiong JR. Hyponatremia in acute decompensated heart failure: mechanisms, prognosis, and treatment options. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(11):666-671. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.20822

14. Nagler EV, Haller MC, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R, Craig JC, Webster AC. Interventions for chronic non-hypovolaemic hypotonic hyponatraemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;28(6):CD010965. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd010965.pub2

15. Fonarow GC; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4(Suppl 7):S21-S30.

1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29-322. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000152

2. Arrigo M, Parissis JT, Akiyama E, Mebazaa A. Understanding acute heart failure: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2016;18(Suppl G):G11-G18. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/suw044

3. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(8):891-975. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.592

4. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147-e239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019

5. Machado d’Almeida KS, Rabelo-Silva ER, Souza GC, et al. Aggressive fluid and sodium restriction in decompensated heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results from a randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2018;54:111-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2018.02.007

6. Paterna S, Gaspare P, Fasullo S, Sarullo FM, Di Pasquale P. Normal-sodium diet compared with low-sodium diet in compensated congestive heart failure: is sodium an old enemy or a new friend? Clin Sci (Lond). 2008;114(3):221-230. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs20070193

7. Paterna S, Parrinello G, Cannizzaro S, et al. Medium term effects of different dosage of diuretic, sodium, and fluid administration on neurohormonal and clinical outcome in patients with recently compensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103(1):93-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.043

8. Shore AC, Markandu ND, Sagnella GA, et al. Endocrine and renal response to water loading and water restriction in normal man. Clin Sci (Lond). 1988;75(2):171-177. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs0750171

9. Oliveros E, Oni ET, Shahzad A, et al. Benefits and risks of continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists during hospitalizations for acute heart failure. Cardiorenal Med. 2020;10(2):69-84. https://doi.org/10.1159/000504167

10. Mentz RJ, Stevens SR, DeVore AD, et al. Decongestion strategies and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation in acute heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(2):97-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2014.09.003

11. Travers B, O’Loughlin C, Murphy NF, et al. Fluid restriction in the management of decompensated heart failure: no impact on time to clinical stability. J Card Fail. 2007;13(2):128-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.10.012

12. Aliti GB, Rabelo ER, Clausell N, Rohde LE, Biolo A, Beck-da-Silva L. Aggressive fluid and sodium restriction in acute decompensated heart failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1058-1064. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.552

13. Jao GT, Chiong JR. Hyponatremia in acute decompensated heart failure: mechanisms, prognosis, and treatment options. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(11):666-671. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.20822

14. Nagler EV, Haller MC, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R, Craig JC, Webster AC. Interventions for chronic non-hypovolaemic hypotonic hyponatraemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;28(6):CD010965. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd010965.pub2

15. Fonarow GC; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4(Suppl 7):S21-S30.

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Improving Healthcare Value: Managing Length of Stay and Improving the Hospital Medicine Value Proposition

Healthcare payment model reform has increased pressure on healthcare systems and hospitalists to improve efficiency and reduce the cost of care. These pressures on the healthcare system have been exacerbated by a global pandemic and an aging patient population straining hospital capacity and resources. Hospital capacity constraints may contribute to hospital crowding and can compromise patient outcomes.1 Increasing hospital capacity also contributes to an increase in hospitalist census. This increase in census is accompanied by proportional increases in hospitalist burnout, cost of care, and prolonged length of stay (LOS).2 Managing LOS reduces “waste” (or non–value-added inpatient days) and can improve outcomes and efficiency within the hospital system.

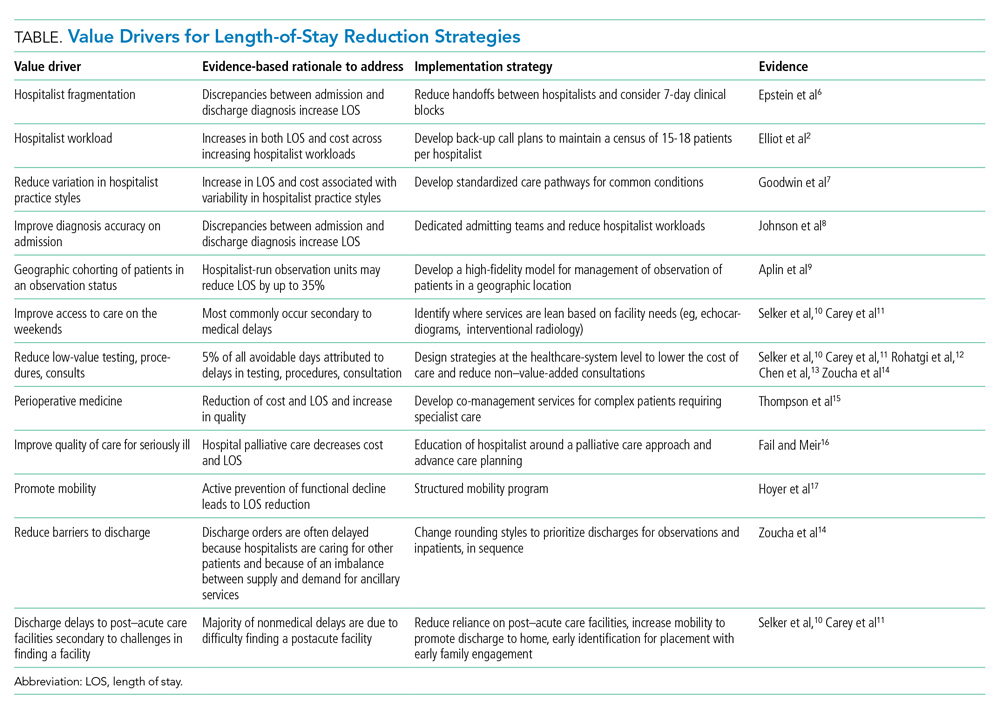

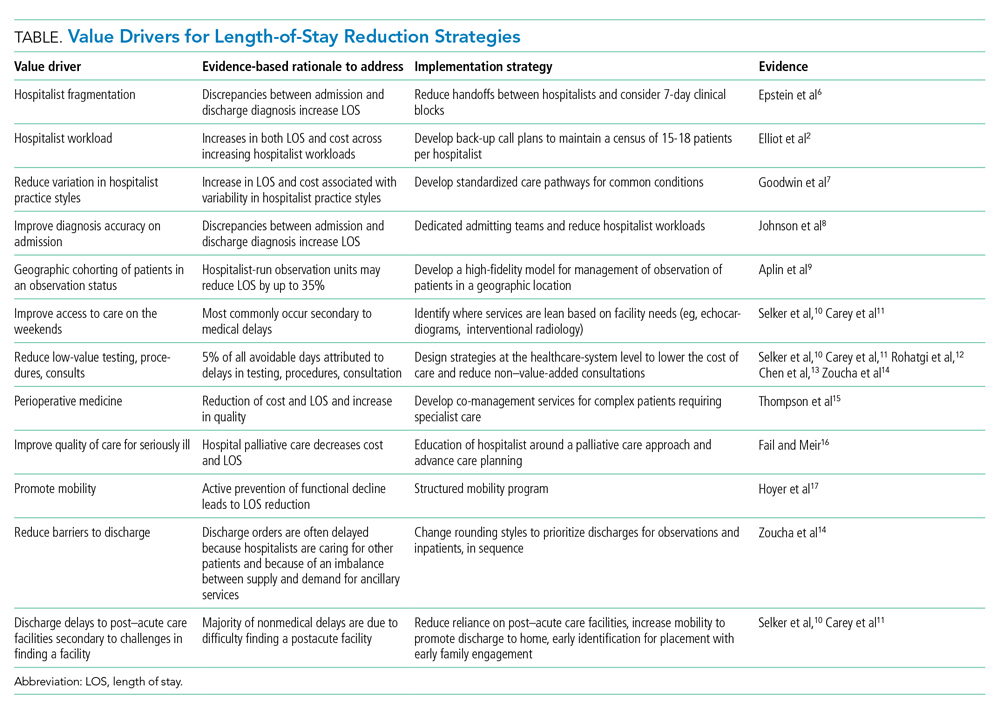

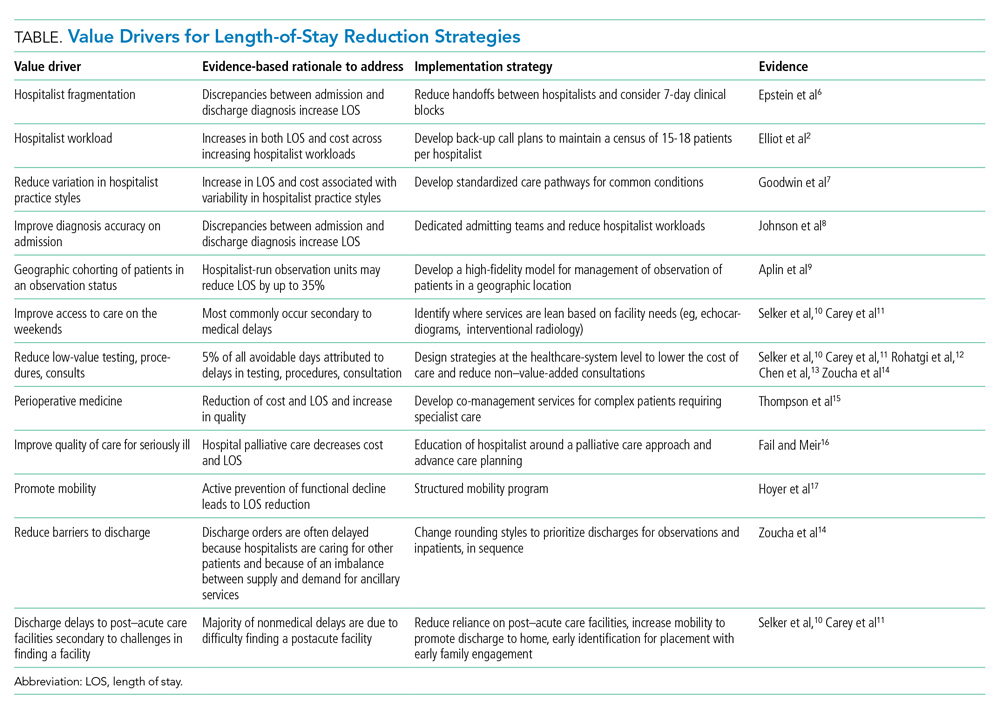

The benefits for LOS reduction when patients are managed by hospitalists compared with primary care practitioners are well described and are associated with decreases in average LOS and cost.3-5 The shorter LOS with hospitalist care is most pronounced in older patients with more complex disease processes, which has temporal importance. The Department of Health and Human Services expects the number of American adults aged >65 years to approach 72 million (20% of the US population) by 2030. Hospitalists are positioned to drive evidence-based care pathways and improve the quality of patient care in this growing patient population. We examine the reasons for managing LOS, summarize factors that contribute to an increased LOS (“waste”), and propose a list of evidence-based value drivers for LOS reduction (Table).2,6-17 Our experience utilizing this approach within Cleveland Clinic Florida following implementation of many of these evidence-based strategies to reduce non–value-added hospital days is also described in the Appendix Figure.

WHY MANAGE LOS?

Barriers to sustainable LOS-reduction strategies have evolved, in part, since the introduction of the Medicare Prospective Payment System, which moved hospital Medicare payments to a predetermined fixed rate for each diagnosis-related group. This led to financial pressures on healthcare systems to identify methods to reduce cost and, in turn, contributed to an increase in postacute facility utilization, with alternative payment models developing in parallel.18,19 These changes along with disaggregated payments between hospitals and postacute facilities have created a formidable challenge to LOS and cost-reduction plans.19

The usual “why” for reducing LOS includes improving constraints on hospital capacity, strains on resources, and deleterious outcomes. In our experience, an evidence-based approach to LOS management should focus on: (1) reduction in patient hospital days through decreased care variation; (2) stabilizing hospitalist workloads; (3) minimizing the fragmentation inherent to the hospitalist care delivery model; and (4) developing service lines to manage patients hospitalized in an observation status and for those patients undergoing procedures deemed medically complex. The literature is mixed on the impact of LOS reductions on other clinical end points, such as readmissions or mortality, with the preponderance indicating no deleterious impact.20-22 Managing LOS using an evidence-based approach that addresses the variability of individual patients is essential to the LOS strategies employed. These strategies should focus on process improvements to drive LOS reduction and utilize metrics under the individual hospitalist control to support their contribution to the hospitalist groups’ overall LOS.23

IMPROVING HOSPITALIST VALUE AROUND LOS MANAGEMENT

Intrinsic factors such as hospitalist staffing fragmentation, high rounding census, failing to prioritize patients ready to be discharged, variability in practice, number of consultants per patient, and hospitalist behaviors contribute to increased LOS.2,6,8 A first precept to management of LOS at the group level is to recognize all hospitalist services are not created equal, and “lumping” hospitalists into a single efficiency metric would not yield actionable information.

The literature is rife with examples of the significant variation in practice styles among hospitalists. A large study including more than 1000 hospitalists identified practice variation as the strongest predictor of variations in mean LOS.7 While Goodwin et al7 identified significant variation among hospitalists’ LOS and the discharge destination of patients, much of the variation could be attributable to the hospitals where they practice. These findings ostensibly highlight the importance of LOS strategies being developed collaboratively among hospitalist groups and the healthcare systems they serve. Similar variation exists among hospitalists on teaching services versus nonteaching services. Our experience parallels that of other studies with regard to teaching services that have found that hospitalists on teaching services often have additional responsibilities and are less able to gain the efficiency of nonresident hospitalists services.3 The impact of teaching services on hospitalist efficiencies is an important component when setting expectations at the hospitalist group level for providers on academic services.

Workload and staffing models for hospitalists have a significant impact on hospitalist efficiency and LOS management. As workload increased, Elliot and colleagues2 identified a proportional increase in LOS. For occupancies of 75% to 85%, LOS increased exponentially above a daily relative value unit of approximately 25 and a census value of approximately 15. The magnitude of this difference in LOS and cost across the range of hospitalist workloads was $262, with an average increase in LOS of 2 days for every unit increase in census. Higher workloads contributed to inferior discussion of treatment options with patients; delays in discharges; delays in placing discharge orders; and unnecessary testing, procedures, and consults.14 To mitigate inefficiency and adverse impacts of higher workloads, hospitalist groups should develop mechanisms to absorb surges in census and unanticipated changes to staffing maintaining the workload within a range appropriate to the patient population.

Decreasing fragmentation, when multiple hospitalists care for the patient during hospitalization, is a necessary component of any LOS-reduction strategy. Studies of pneumonia and heart failure have demonstrated that a 10% increase in hosptialist fragmentation is associated with significant increases in LOS.24 Schedules with hospitalists on 7-day rotating rounding blocks have the intuitive advantage of improving care continuity for patients compared with schedules with a shorter number of consecutive rounding days, resulting in fewer hospitalists caring for each patient and decreased “fragmentation.” Additional value drivers for LOS reduction strategies for hospitalists are listed in the Table.

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report highlighted that, among patients discharged by hospitalist groups, 80.8% were inpatient and 19.2% were outpatient. With nearly one in five patients discharged in observation status, it behooves hospitalist programs to work to effectively manage these patients. Indeed, hospitalist-run observation units have been shown to decrease LOS significantly without an increase in return rates to the emergency department or hospital compared with patients managed prior to the introduction of a dedicated observation unit.9

Although an in-depth discussion is beyond the scope of the present article, it is worth noting the value of hospitalist comanagement (HCoM) strategies. The impact of HCoM teams is demonstrated by reductions in LOS and cost of care resulting from decreases in medical complications, number of consultants per patient, and a decrease in 30-day readmsissions.12 The Society of Hospital Medicine Perioperative Care Work Group has outlined a collaborative framework for hospitalists and healthcare systems to draw from.15

THE CLEVELAND CLINIC INDIAN RIVER HOSPITAL EXPERIENCE

Within the Cleveland Clinic Indian River Hospital (CCIRH) medicine department, many of the aforementioned strategies and tactics were standardized among hospitalist providers. Hospitalists at CCIRH are scheduled on 7-day rotating blocks to reduce fragmentation. In 2019, we targeted a range of 15 to 18 patient contacts per rounding hospitalist per day and utilized a back-up call system to stabilize the hospitalist census. The hospitalist service lines are enhanced through HCoM services with patients cohorted on dedicated HCoM teams. The follow-up to discharge ratio is used to provide feedback at the provider level as both a management and assessment tool.23 The rounding and admitting teams are dedicated to their responsibility (with the occasional exception necessitating the rounding team assist with admissions when the volumes are high). Direct admissions and transfers from outside hospitals are managed by a dedicated hospital medicine “quarterback” to minimize disruption of the admitting and rounding teams. Barriers to discharge are identified at the time of admission by care management and aggressively managed. Prolonged LOS reports are generated daily and disseminated to care managers and physician leadership. In January 2019, the average LOS for inpatients at CCIRH was 4.4 days. In December 2019, the average LOS for the calendar year to-date at CCIRH was 3.9 days (Appendix Figure).

The value proposition for managing LOS should be viewed in the context of the total cost of care over an extended period of time and not viewed in isolation. Readmission rates serve as a counterbalance to LOS-reduction strategies and contribute to higher costs of care when increased. The 30-day readmission rate for this cohort over this same time period was down slightly compared with the previous year to 12.1%. In addition, observation patients at CCIRH are managed in a closed, geographically cohorted unit, staffed by dedicated advanced-practice providers and physicians dedicated to observation medicine. Over this same time period, more than 5500 patients were managed in the observation unit. These patients had an average LOS of 19.2 hours, with approximately four out of every five patients being discharged to home from an observation status.

The impact of COVID-19 and higher hospital volumes are best visualized in the Appendix Figure. Increases in LOS were observed during periods of COVID-19–related “surges” in hospital volume. These reversals in LOS trends during periods of high occupancy echo earlier findings by Elliot et al2 showing that external factors that are not directly under the control of the hospitalist drive LOS and must be considered when developing LOS reduction strategies.

CONCLUSION

The shift toward value-based payment models provides a strong tailwind for healthcare systems to manage LOS. Hospitalists are well positioned to drive LOS-reduction strategies for the healthcare systems they serve and provide value by driving both quality and efficiency. A complete realization of the value proposition of hospitalist programs in driving LOS-reduction initiatives requires the healthcare systems they serve to provide these teams with the appropriate resources and tools.

1. Eriksson CO, Stoner RC, Eden KB, Newgard CD, Guise J-M. The association between hospital capacity strain and inpatient outcomes in highly developed countries: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):686-696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3936-3

2. Elliott DJ, Young RS, Brice J, Aguiar R, Kolm P. Effect of hospitalist workload on the quality and efficiency of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):786-793. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.300

3. Rachoin JS, Skaf J, Cerceo E, et al. The impact of hospitalists on length of stay and costs: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(1):e23-30.

4. Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Effect of hospitalists on length of stay in the medicare population: variation according to hospital and patient characteristics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1649-1657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03007.x

5. Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Kenwood C, Benjamin EM, Auerbach AD. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2589-2600. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa067735

6. Epstein K, Juarez E, Epstein A, Loya K, Singer A. The impact of fragmentation of hospitalist care on length of stay. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):335-338. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.675

7. Goodwin JS, Lin Y-L, Singh S, Kuo Y-F. Variation in length of stay and outcomes among hospitalized patients attributable to hospitals and hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):370-376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2255-6

8. Johnson T, McNutt R, Odwazny R, Patel D, Baker S. Discrepancy between admission and discharge diagnoses as a predictor of hospital length of stay. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):234-239. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.453

9. Aplin KS, Coutinho McAllister S, Kupersmith E, Rachoin JS. Caring for patients in a hospitalist-run clinical decision unit is associated with decreased length of stay without increasing revisit rates. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(6):391-395. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2188

10. Selker HP, Beshansky JR, Pauker SG, Kassirer JP. The epidemiology of delays in a teaching hospital. The development and use of a tool that detects unnecessary hospital days. Med Care. 1989;27(2):112-129. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198902000-00003

11. Carey MR, Sheth H, Braithwaite RS. A prospective study of reasons for prolonged hospitalizations on a general medicine teaching service. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):108-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40269.x

12. Rohatgi N, Loftus P, Grujic O, Cullen M, Hopkins J, Ahuja N. Surgical comanagement by hospitalists improves patient outcomes: a propensity score analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):275-282. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001629

13. Chen LM, Freitag MH, Franco M, Sullivan CD, Dickson C, Brancati FL. Natural history of late discharges from a general medical ward. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):226-233. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.413

14. Zoucha J, Hull M, Keniston A, et al. Barriers to early hospital discharge: a cross-sectional study at five academic hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):816-822. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3074

15. Thompson RE, Pfeifer K, Grant PJ, et al. Hospital medicine and perioperative care: a framework for high-quality, high-value collaborative care. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):277-282. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2717

16. Fail RE, Meier DE. Improving quality of care for seriously ill patients: opportunities for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(3):194-197. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2896

17. Hoyer EH, Friedman M, Lavezza A, et al. Promoting mobility and reducing length of stay in hospitalized general medicine patients: a quality-improvement project. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):341-347. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2546

18. Davis C, Rhodes DJ. The impact of DRGs on the cost and quality of health care in the United States. Health Policy. 1988;9(2):117-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(88)90029-2

19. Rothberg M, Lee N. Reducing readmissions or length of stay-Which is more important? J Hosp Med. 2017;12(8):685-686. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2790

20. Kaboli PJ, Go JT, Hockenberry J, et al. Associations between reduced hospital length of stay and 30-day readmission rate and mortality: 14-year experience in 129 Veterans Affairs hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(12):837-845. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00003

21. Rinne ST, Graves MC, Bastian LA, et al. Association between length of stay and readmission for COPD. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8):e253-e258.

22. Sud M, Yu B, Wijeysundera HC, et al. Associations between short or long length of stay and 30-day readmission and mortality in hospitalized patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(8):578-588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2017.03.012

23. Rothman RD, Whinney CM, Pappas MA, Zoller DM, Rosencrance JG, Peter DJ. The relationship between the follow-up to discharge ratio and length of stay. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(9):396-399. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.88490

24. Epstein K, Juarez E, Epstein A, Loya K, Singer A. The impact of fragmentation of hospitalist care on length of stay. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):335-338. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.675

Healthcare payment model reform has increased pressure on healthcare systems and hospitalists to improve efficiency and reduce the cost of care. These pressures on the healthcare system have been exacerbated by a global pandemic and an aging patient population straining hospital capacity and resources. Hospital capacity constraints may contribute to hospital crowding and can compromise patient outcomes.1 Increasing hospital capacity also contributes to an increase in hospitalist census. This increase in census is accompanied by proportional increases in hospitalist burnout, cost of care, and prolonged length of stay (LOS).2 Managing LOS reduces “waste” (or non–value-added inpatient days) and can improve outcomes and efficiency within the hospital system.

The benefits for LOS reduction when patients are managed by hospitalists compared with primary care practitioners are well described and are associated with decreases in average LOS and cost.3-5 The shorter LOS with hospitalist care is most pronounced in older patients with more complex disease processes, which has temporal importance. The Department of Health and Human Services expects the number of American adults aged >65 years to approach 72 million (20% of the US population) by 2030. Hospitalists are positioned to drive evidence-based care pathways and improve the quality of patient care in this growing patient population. We examine the reasons for managing LOS, summarize factors that contribute to an increased LOS (“waste”), and propose a list of evidence-based value drivers for LOS reduction (Table).2,6-17 Our experience utilizing this approach within Cleveland Clinic Florida following implementation of many of these evidence-based strategies to reduce non–value-added hospital days is also described in the Appendix Figure.

WHY MANAGE LOS?

Barriers to sustainable LOS-reduction strategies have evolved, in part, since the introduction of the Medicare Prospective Payment System, which moved hospital Medicare payments to a predetermined fixed rate for each diagnosis-related group. This led to financial pressures on healthcare systems to identify methods to reduce cost and, in turn, contributed to an increase in postacute facility utilization, with alternative payment models developing in parallel.18,19 These changes along with disaggregated payments between hospitals and postacute facilities have created a formidable challenge to LOS and cost-reduction plans.19

The usual “why” for reducing LOS includes improving constraints on hospital capacity, strains on resources, and deleterious outcomes. In our experience, an evidence-based approach to LOS management should focus on: (1) reduction in patient hospital days through decreased care variation; (2) stabilizing hospitalist workloads; (3) minimizing the fragmentation inherent to the hospitalist care delivery model; and (4) developing service lines to manage patients hospitalized in an observation status and for those patients undergoing procedures deemed medically complex. The literature is mixed on the impact of LOS reductions on other clinical end points, such as readmissions or mortality, with the preponderance indicating no deleterious impact.20-22 Managing LOS using an evidence-based approach that addresses the variability of individual patients is essential to the LOS strategies employed. These strategies should focus on process improvements to drive LOS reduction and utilize metrics under the individual hospitalist control to support their contribution to the hospitalist groups’ overall LOS.23

IMPROVING HOSPITALIST VALUE AROUND LOS MANAGEMENT

Intrinsic factors such as hospitalist staffing fragmentation, high rounding census, failing to prioritize patients ready to be discharged, variability in practice, number of consultants per patient, and hospitalist behaviors contribute to increased LOS.2,6,8 A first precept to management of LOS at the group level is to recognize all hospitalist services are not created equal, and “lumping” hospitalists into a single efficiency metric would not yield actionable information.

The literature is rife with examples of the significant variation in practice styles among hospitalists. A large study including more than 1000 hospitalists identified practice variation as the strongest predictor of variations in mean LOS.7 While Goodwin et al7 identified significant variation among hospitalists’ LOS and the discharge destination of patients, much of the variation could be attributable to the hospitals where they practice. These findings ostensibly highlight the importance of LOS strategies being developed collaboratively among hospitalist groups and the healthcare systems they serve. Similar variation exists among hospitalists on teaching services versus nonteaching services. Our experience parallels that of other studies with regard to teaching services that have found that hospitalists on teaching services often have additional responsibilities and are less able to gain the efficiency of nonresident hospitalists services.3 The impact of teaching services on hospitalist efficiencies is an important component when setting expectations at the hospitalist group level for providers on academic services.

Workload and staffing models for hospitalists have a significant impact on hospitalist efficiency and LOS management. As workload increased, Elliot and colleagues2 identified a proportional increase in LOS. For occupancies of 75% to 85%, LOS increased exponentially above a daily relative value unit of approximately 25 and a census value of approximately 15. The magnitude of this difference in LOS and cost across the range of hospitalist workloads was $262, with an average increase in LOS of 2 days for every unit increase in census. Higher workloads contributed to inferior discussion of treatment options with patients; delays in discharges; delays in placing discharge orders; and unnecessary testing, procedures, and consults.14 To mitigate inefficiency and adverse impacts of higher workloads, hospitalist groups should develop mechanisms to absorb surges in census and unanticipated changes to staffing maintaining the workload within a range appropriate to the patient population.

Decreasing fragmentation, when multiple hospitalists care for the patient during hospitalization, is a necessary component of any LOS-reduction strategy. Studies of pneumonia and heart failure have demonstrated that a 10% increase in hosptialist fragmentation is associated with significant increases in LOS.24 Schedules with hospitalists on 7-day rotating rounding blocks have the intuitive advantage of improving care continuity for patients compared with schedules with a shorter number of consecutive rounding days, resulting in fewer hospitalists caring for each patient and decreased “fragmentation.” Additional value drivers for LOS reduction strategies for hospitalists are listed in the Table.

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report highlighted that, among patients discharged by hospitalist groups, 80.8% were inpatient and 19.2% were outpatient. With nearly one in five patients discharged in observation status, it behooves hospitalist programs to work to effectively manage these patients. Indeed, hospitalist-run observation units have been shown to decrease LOS significantly without an increase in return rates to the emergency department or hospital compared with patients managed prior to the introduction of a dedicated observation unit.9

Although an in-depth discussion is beyond the scope of the present article, it is worth noting the value of hospitalist comanagement (HCoM) strategies. The impact of HCoM teams is demonstrated by reductions in LOS and cost of care resulting from decreases in medical complications, number of consultants per patient, and a decrease in 30-day readmsissions.12 The Society of Hospital Medicine Perioperative Care Work Group has outlined a collaborative framework for hospitalists and healthcare systems to draw from.15

THE CLEVELAND CLINIC INDIAN RIVER HOSPITAL EXPERIENCE

Within the Cleveland Clinic Indian River Hospital (CCIRH) medicine department, many of the aforementioned strategies and tactics were standardized among hospitalist providers. Hospitalists at CCIRH are scheduled on 7-day rotating blocks to reduce fragmentation. In 2019, we targeted a range of 15 to 18 patient contacts per rounding hospitalist per day and utilized a back-up call system to stabilize the hospitalist census. The hospitalist service lines are enhanced through HCoM services with patients cohorted on dedicated HCoM teams. The follow-up to discharge ratio is used to provide feedback at the provider level as both a management and assessment tool.23 The rounding and admitting teams are dedicated to their responsibility (with the occasional exception necessitating the rounding team assist with admissions when the volumes are high). Direct admissions and transfers from outside hospitals are managed by a dedicated hospital medicine “quarterback” to minimize disruption of the admitting and rounding teams. Barriers to discharge are identified at the time of admission by care management and aggressively managed. Prolonged LOS reports are generated daily and disseminated to care managers and physician leadership. In January 2019, the average LOS for inpatients at CCIRH was 4.4 days. In December 2019, the average LOS for the calendar year to-date at CCIRH was 3.9 days (Appendix Figure).

The value proposition for managing LOS should be viewed in the context of the total cost of care over an extended period of time and not viewed in isolation. Readmission rates serve as a counterbalance to LOS-reduction strategies and contribute to higher costs of care when increased. The 30-day readmission rate for this cohort over this same time period was down slightly compared with the previous year to 12.1%. In addition, observation patients at CCIRH are managed in a closed, geographically cohorted unit, staffed by dedicated advanced-practice providers and physicians dedicated to observation medicine. Over this same time period, more than 5500 patients were managed in the observation unit. These patients had an average LOS of 19.2 hours, with approximately four out of every five patients being discharged to home from an observation status.

The impact of COVID-19 and higher hospital volumes are best visualized in the Appendix Figure. Increases in LOS were observed during periods of COVID-19–related “surges” in hospital volume. These reversals in LOS trends during periods of high occupancy echo earlier findings by Elliot et al2 showing that external factors that are not directly under the control of the hospitalist drive LOS and must be considered when developing LOS reduction strategies.

CONCLUSION

The shift toward value-based payment models provides a strong tailwind for healthcare systems to manage LOS. Hospitalists are well positioned to drive LOS-reduction strategies for the healthcare systems they serve and provide value by driving both quality and efficiency. A complete realization of the value proposition of hospitalist programs in driving LOS-reduction initiatives requires the healthcare systems they serve to provide these teams with the appropriate resources and tools.

Healthcare payment model reform has increased pressure on healthcare systems and hospitalists to improve efficiency and reduce the cost of care. These pressures on the healthcare system have been exacerbated by a global pandemic and an aging patient population straining hospital capacity and resources. Hospital capacity constraints may contribute to hospital crowding and can compromise patient outcomes.1 Increasing hospital capacity also contributes to an increase in hospitalist census. This increase in census is accompanied by proportional increases in hospitalist burnout, cost of care, and prolonged length of stay (LOS).2 Managing LOS reduces “waste” (or non–value-added inpatient days) and can improve outcomes and efficiency within the hospital system.

The benefits for LOS reduction when patients are managed by hospitalists compared with primary care practitioners are well described and are associated with decreases in average LOS and cost.3-5 The shorter LOS with hospitalist care is most pronounced in older patients with more complex disease processes, which has temporal importance. The Department of Health and Human Services expects the number of American adults aged >65 years to approach 72 million (20% of the US population) by 2030. Hospitalists are positioned to drive evidence-based care pathways and improve the quality of patient care in this growing patient population. We examine the reasons for managing LOS, summarize factors that contribute to an increased LOS (“waste”), and propose a list of evidence-based value drivers for LOS reduction (Table).2,6-17 Our experience utilizing this approach within Cleveland Clinic Florida following implementation of many of these evidence-based strategies to reduce non–value-added hospital days is also described in the Appendix Figure.

WHY MANAGE LOS?

Barriers to sustainable LOS-reduction strategies have evolved, in part, since the introduction of the Medicare Prospective Payment System, which moved hospital Medicare payments to a predetermined fixed rate for each diagnosis-related group. This led to financial pressures on healthcare systems to identify methods to reduce cost and, in turn, contributed to an increase in postacute facility utilization, with alternative payment models developing in parallel.18,19 These changes along with disaggregated payments between hospitals and postacute facilities have created a formidable challenge to LOS and cost-reduction plans.19

The usual “why” for reducing LOS includes improving constraints on hospital capacity, strains on resources, and deleterious outcomes. In our experience, an evidence-based approach to LOS management should focus on: (1) reduction in patient hospital days through decreased care variation; (2) stabilizing hospitalist workloads; (3) minimizing the fragmentation inherent to the hospitalist care delivery model; and (4) developing service lines to manage patients hospitalized in an observation status and for those patients undergoing procedures deemed medically complex. The literature is mixed on the impact of LOS reductions on other clinical end points, such as readmissions or mortality, with the preponderance indicating no deleterious impact.20-22 Managing LOS using an evidence-based approach that addresses the variability of individual patients is essential to the LOS strategies employed. These strategies should focus on process improvements to drive LOS reduction and utilize metrics under the individual hospitalist control to support their contribution to the hospitalist groups’ overall LOS.23

IMPROVING HOSPITALIST VALUE AROUND LOS MANAGEMENT

Intrinsic factors such as hospitalist staffing fragmentation, high rounding census, failing to prioritize patients ready to be discharged, variability in practice, number of consultants per patient, and hospitalist behaviors contribute to increased LOS.2,6,8 A first precept to management of LOS at the group level is to recognize all hospitalist services are not created equal, and “lumping” hospitalists into a single efficiency metric would not yield actionable information.

The literature is rife with examples of the significant variation in practice styles among hospitalists. A large study including more than 1000 hospitalists identified practice variation as the strongest predictor of variations in mean LOS.7 While Goodwin et al7 identified significant variation among hospitalists’ LOS and the discharge destination of patients, much of the variation could be attributable to the hospitals where they practice. These findings ostensibly highlight the importance of LOS strategies being developed collaboratively among hospitalist groups and the healthcare systems they serve. Similar variation exists among hospitalists on teaching services versus nonteaching services. Our experience parallels that of other studies with regard to teaching services that have found that hospitalists on teaching services often have additional responsibilities and are less able to gain the efficiency of nonresident hospitalists services.3 The impact of teaching services on hospitalist efficiencies is an important component when setting expectations at the hospitalist group level for providers on academic services.