User login

Mood stabilizers: Balancing tolerability, serum levels, and dosage

Mr. B, age 32, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder 10 years ago after experiencing a manic episode that resulted in his first psychiatric hospitalization. He was prescribed quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and remained stable for the next several years. Unfortunately, Mr. B developed significant metabolic adverse effects, including diabetes and a 30-pound weight gain, so he was switched from quetiapine to lithium. Mr. B was unable to tolerate the sedation and cognitive effects of lithium, and the dose could not be titrated to within the therapeutic window. As a result, Mr. B experienced a moderate depressive episode. His current clinician would like to initiate lamotrigine at a starting dose of 25 mg/d. Mr. B has not had a manic episode since the index hospitalization, and this is his first depressive episode.

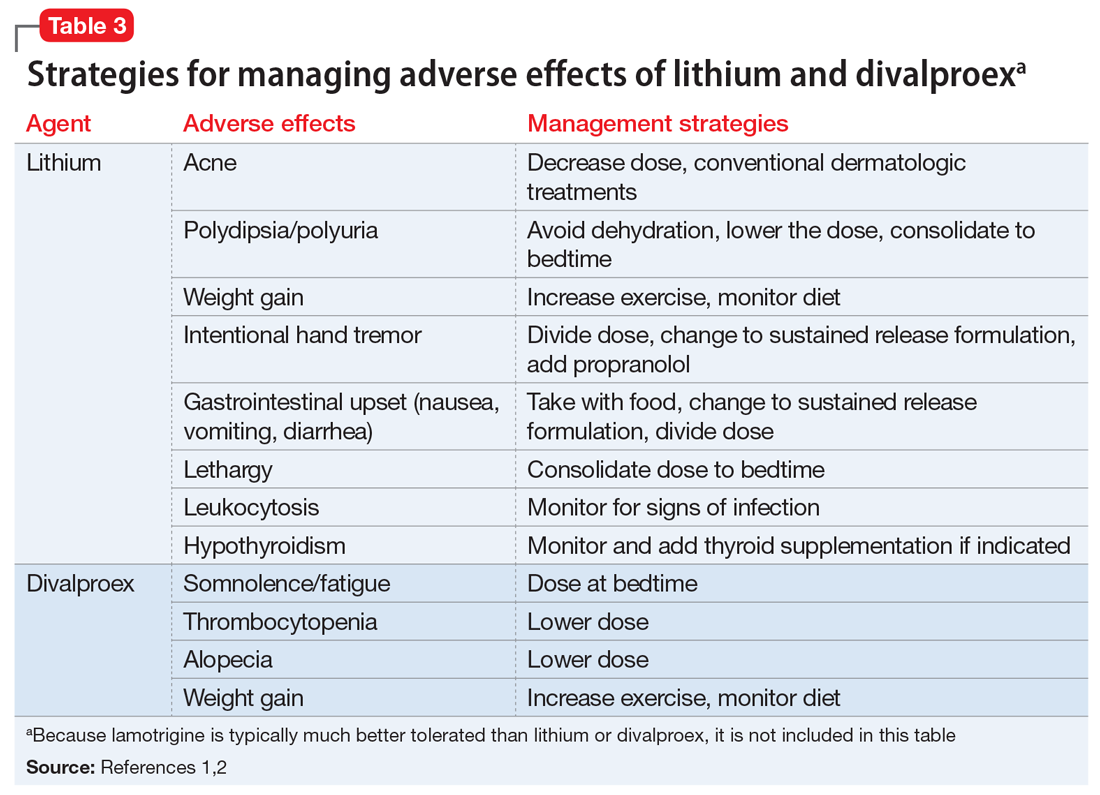

The term “mood stabilizer” has come to refer to medications that treat a depressive and/or manic episode without inducing the other. In conventional terms, it refers to non-antipsychotic medications such as lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine. Except for lithium, mood stabilizers are also antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). The role of AEDs for treating psychiatric conditions was discovered after they were originally FDA-approved for treating seizures. Following this discovery, the recommended doses and therapeutic ranges for these agents when applied to psychiatric treatment fell into a gray area.

Every patient is different and requires an individualized treatment plan, but this often leaves the clinician wondering, “How high is too high for this mood stabilizer?” or “My patient is responding well, but could a higher dose be even more effective?” In the case of Mr. B, who has trialed 2 medications with poor tolerability, how high can the lamotrigine dose be titrated to achieve a therapeutic response without adverse effects? The literature on this topic does not provide an exact answer, but does shed some light on key considerations for such decisions.

Which mood stabilizers are recommended?

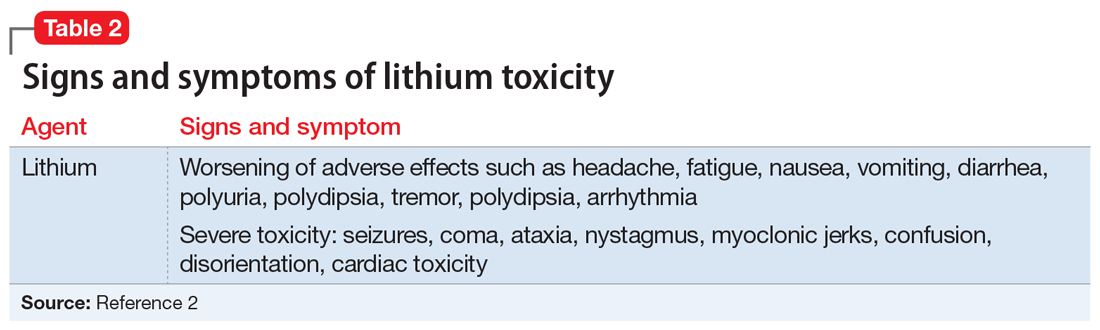

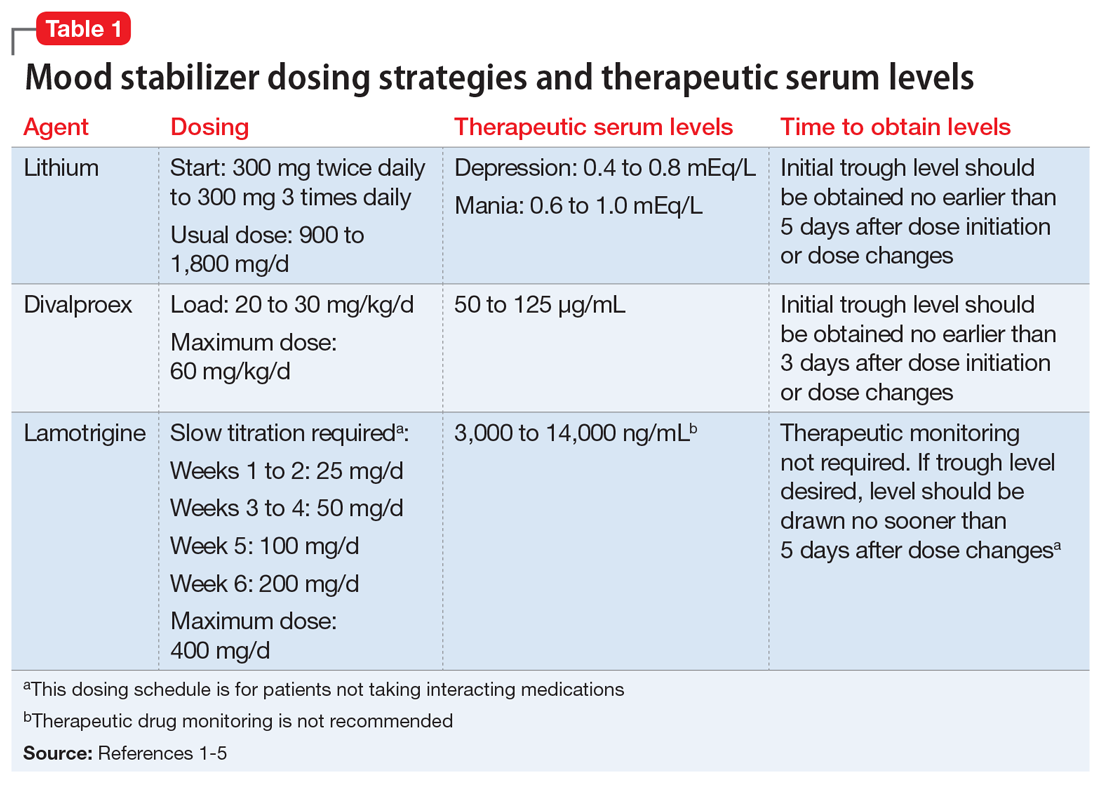

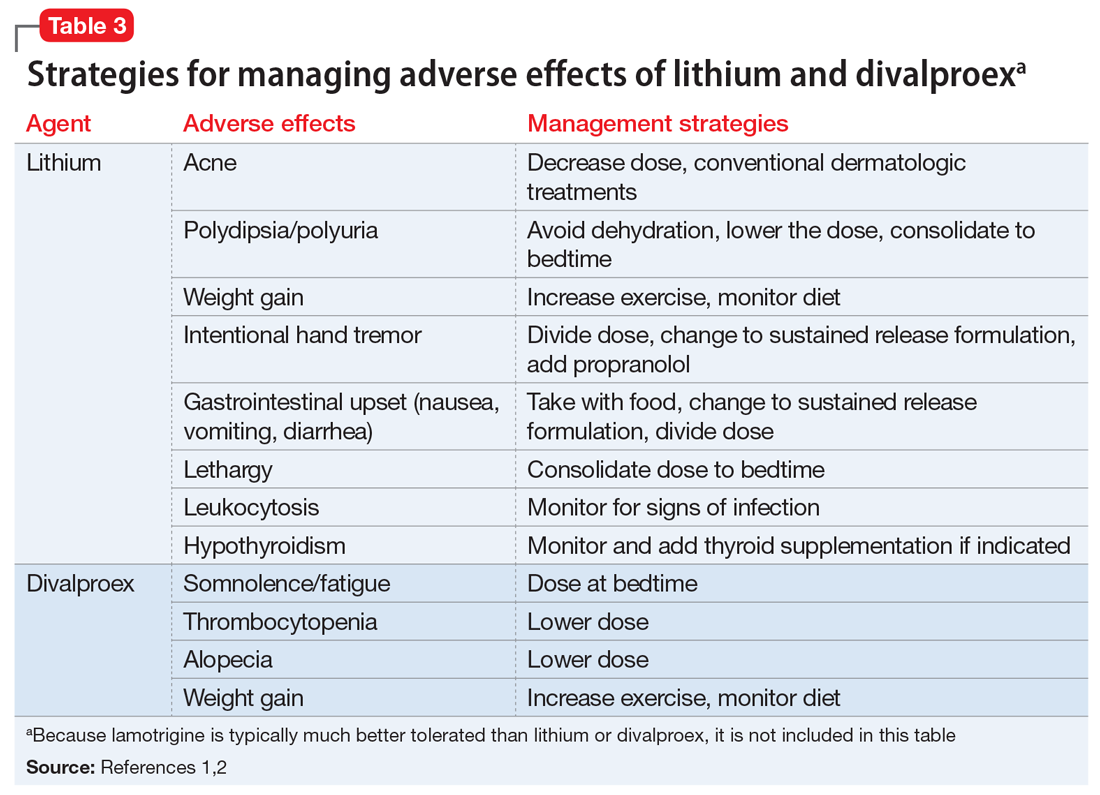

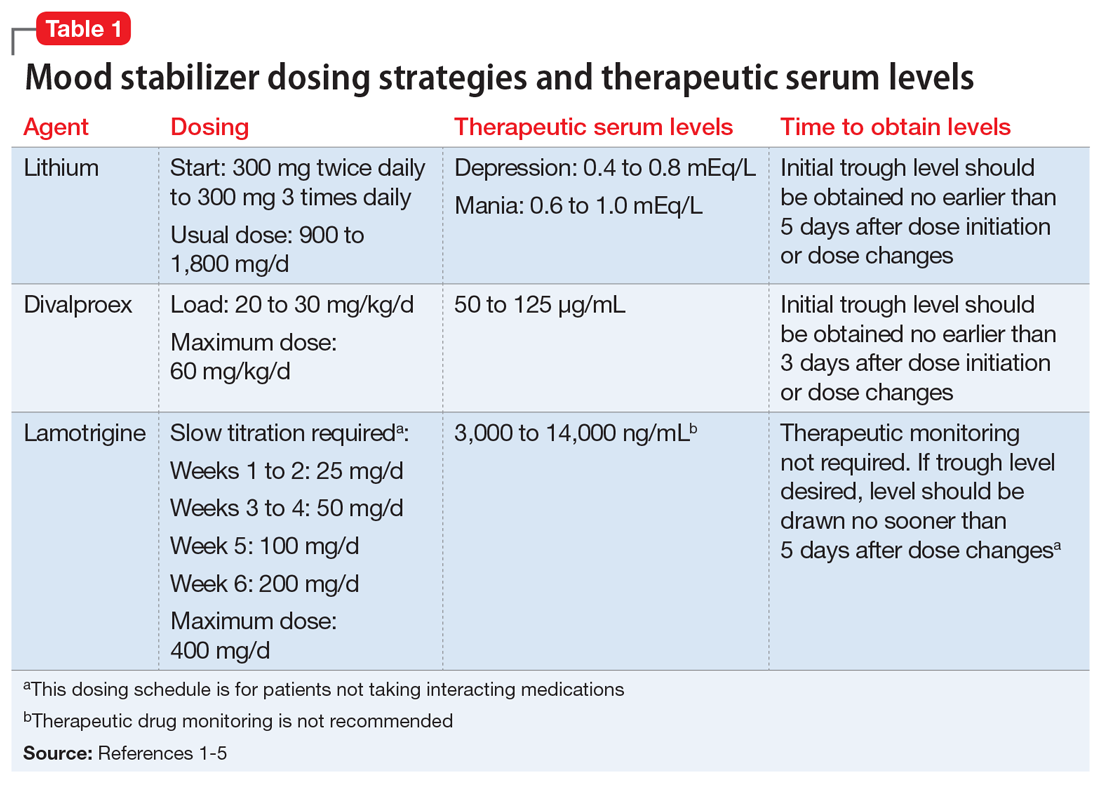

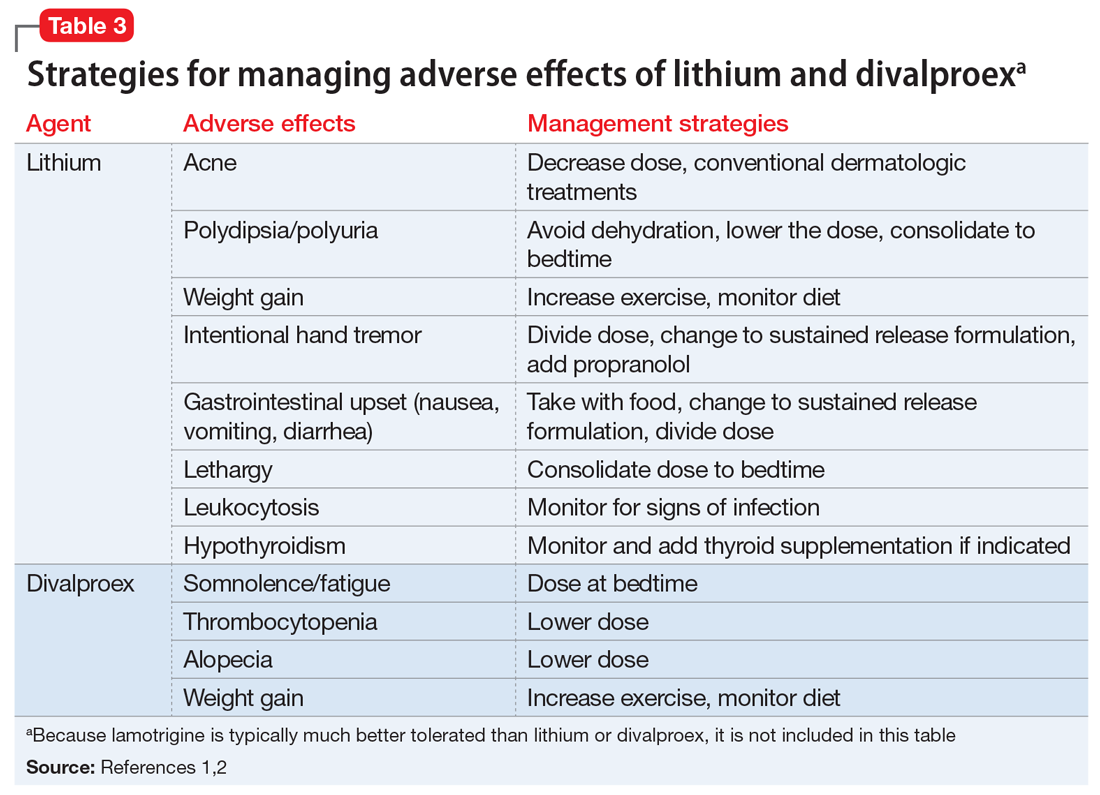

One of the most recently updated guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder was released in 2018 by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT).1 Lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine were each recommended as a first-line option for treating bipolar disorder. For lithium and divalproex, the CANMAT guidelines recommend serum level monitoring for efficacy and tolerability; however, they do not recommend serum level monitoring for lamotrigine. Lithium and divalproex each have safety and tolerability concerns, particularly when selected for maintenance therapy, whereas lamotrigine is typically much better tolerated.1 Divalproex and lithium can cause weight gain, gastrointestinal adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), and tremor. Additional tolerability concerns with lithium include renal toxicity, electrocardiogram abnormalities, hypothyroidism, cognitive impairment, and dermatologic reactions. Divalproex can produce greater levels of sedation and may impact reproductive function (oligomenorrhea or hyperandrogenism). One of the most common adverse effects of lamotrigine is a non-serious rash; however, slow dose titration is necessary to decrease the risk of a serious, life-threatening rash such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Lithium

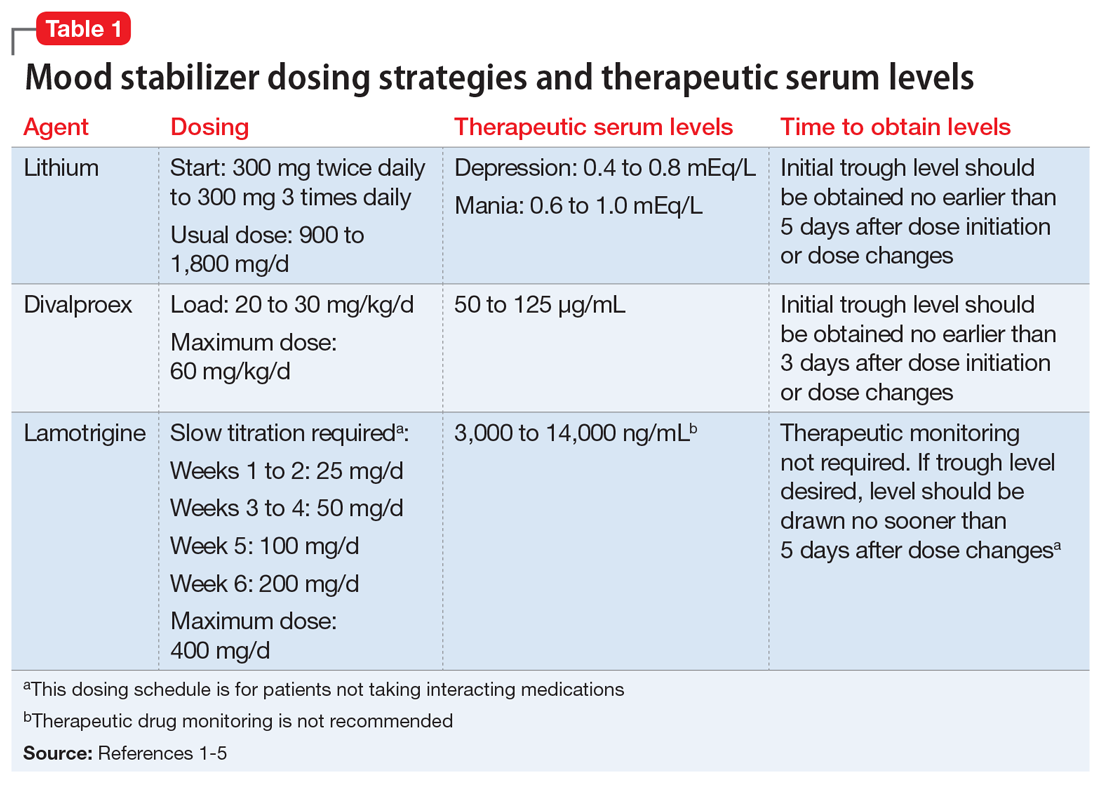

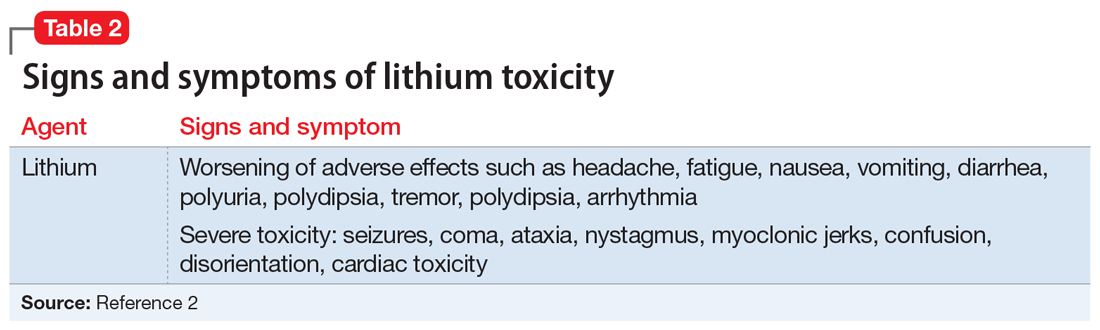

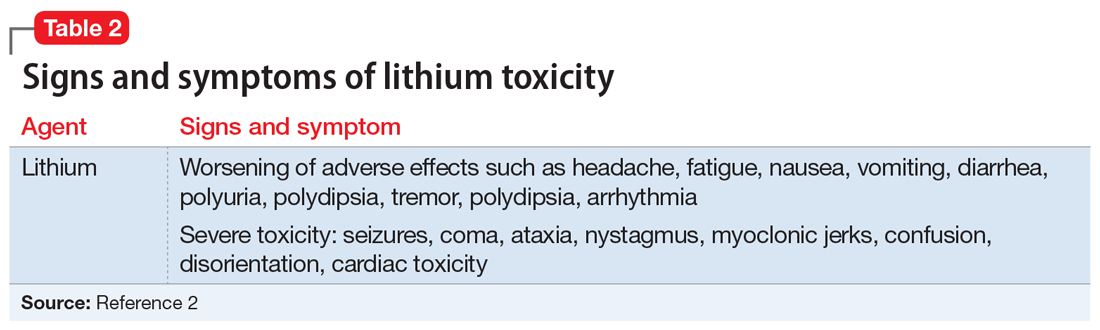

Lithium continues to be regarded as a gold-standard therapy for bipolar disorder. The exact serum levels corresponding to efficacy and tolerability vary. The Lithiumeter: Version 2.0 is a schematic that incorporates the various levels recommended by different clinical guidelines.2 The recommended serum levels range from 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for mania and 0.4 to 0.8 mEq/L for depression.2 One of the main issues with lithium dosing is balancing a therapeutic level with tolerability and toxicity. Toxicity may begin when lithium levels exceed 1.2 mEq/L, and levels >2.0 mEq/L can be lethal. Signs of acute toxicity include tremor, headache, arrhythmia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, polyuria, and polydipsia. Conversely, chronic lithium use may lead to chronic toxicity as patients age and their physical health changes. Signs of chronic toxicity include ataxia, confusion, renal dysfunction, and tremor. There is no “one size fits all” when it comes to lithium dosing. Individualized dosing is necessary to balance efficacy and tolerability.

Divalproex

Divalproex was initially studied for use as an AED, and its therapeutic levels as an AED are not the same as those indicated for bipolar disorder. Generally, patients with bipolar disorder require a divalproex serum level >50 µg/mL. Ranges closer to 100 µg/mL have been found to be most effective for treating acute mania.3 A loading dose of 20 to 30 mg/kg/d can be administered to help achieve mood stabilization. Again, efficacy must be balanced against toxicity. The maximum dose of divalproex is 60 mg/kg/d, which is rarely seen in psychiatric practice. Early studies of divalproex found adverse effects greatest in individuals with plasma levels >100 µg/mL. Reported adverse effects included alopecia, weight gain, tremor, and mental status changes.4

Lamotrigine

Unlike lithium and divalproex, lamotrigine therapeutic drug monitoring is not common. The accepted therapeutic reference range (TRR) for lamotrigine as an AED is 3,000 to 14,000 ng/mL. Unholzer et al5 evaluated the dose and TRR for individuals with bipolar disorder treated with lamotrigine. No statistically significant difference in lamotrigine serum levels was found in responders vs nonresponders.5 Most patients were prescribed ≤200 mg/d; however, some were prescribed higher doses. The maximum dose recommended when lamotrigine is used as an AED is 400 mg/d; however, this study furthered the evidence that lower doses tend to be effective in bipolar disorder.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

It has been 3 months since Mr. B was initiated on lamotrigine, and he has since been titrated to his current, stable dose of 100 mg/d. Mr. B is no longer experiencing the sedation he had with lithium and has the energy to commit to an exercise routine. This has allowed him to lose 15 pounds so far and greatly improve control of his diabetes.

Dosage summary

Most available evidence supports dosing lithium and divalproex to effect, typically seen between 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L and 50 to 125 µg/mL, respectively. Higher plasma levels tend to correspond to more adverse effects and toxicity. Lamotrigine does not have such a narrow therapeutic window. Lamotrigine for psychiatric treatment yields greatest efficacy at approximately 200 mg/d, but doses can be increased if warranted, which could be the case in Mr. B.

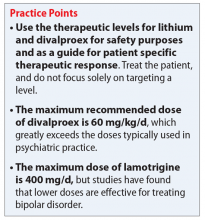

Table 11-5 outlines dosing strategies and therapeutic serum levels for lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine. Table 22 lists signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, and Table 31,2 describes strategies for managing adverse effects of lithium and divalproex.

1. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

2. Malhi GS, Gershon S, Outhred T. Lithiumeter: version 2.0. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(8):631-641.

3. Allen MH, Hirschfeld RM, Wozniak PJ, et al. Linear relationship of valproate serum concentration to response and optimal serum levels for acute mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):272-275.

4. Turnbull DM, Rawlins MD, Weightman D, et al. Plasma concentrations of sodium valproate: their clinical value. Ann Neurol. 1983;14(1):38-42.

5. Unholzer S, Haen E. Retrospective analysis of therapeutic drug monitoring data for treatment of bipolar disorder with lamotrigine. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(7):296.

Mr. B, age 32, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder 10 years ago after experiencing a manic episode that resulted in his first psychiatric hospitalization. He was prescribed quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and remained stable for the next several years. Unfortunately, Mr. B developed significant metabolic adverse effects, including diabetes and a 30-pound weight gain, so he was switched from quetiapine to lithium. Mr. B was unable to tolerate the sedation and cognitive effects of lithium, and the dose could not be titrated to within the therapeutic window. As a result, Mr. B experienced a moderate depressive episode. His current clinician would like to initiate lamotrigine at a starting dose of 25 mg/d. Mr. B has not had a manic episode since the index hospitalization, and this is his first depressive episode.

The term “mood stabilizer” has come to refer to medications that treat a depressive and/or manic episode without inducing the other. In conventional terms, it refers to non-antipsychotic medications such as lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine. Except for lithium, mood stabilizers are also antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). The role of AEDs for treating psychiatric conditions was discovered after they were originally FDA-approved for treating seizures. Following this discovery, the recommended doses and therapeutic ranges for these agents when applied to psychiatric treatment fell into a gray area.

Every patient is different and requires an individualized treatment plan, but this often leaves the clinician wondering, “How high is too high for this mood stabilizer?” or “My patient is responding well, but could a higher dose be even more effective?” In the case of Mr. B, who has trialed 2 medications with poor tolerability, how high can the lamotrigine dose be titrated to achieve a therapeutic response without adverse effects? The literature on this topic does not provide an exact answer, but does shed some light on key considerations for such decisions.

Which mood stabilizers are recommended?

One of the most recently updated guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder was released in 2018 by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT).1 Lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine were each recommended as a first-line option for treating bipolar disorder. For lithium and divalproex, the CANMAT guidelines recommend serum level monitoring for efficacy and tolerability; however, they do not recommend serum level monitoring for lamotrigine. Lithium and divalproex each have safety and tolerability concerns, particularly when selected for maintenance therapy, whereas lamotrigine is typically much better tolerated.1 Divalproex and lithium can cause weight gain, gastrointestinal adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), and tremor. Additional tolerability concerns with lithium include renal toxicity, electrocardiogram abnormalities, hypothyroidism, cognitive impairment, and dermatologic reactions. Divalproex can produce greater levels of sedation and may impact reproductive function (oligomenorrhea or hyperandrogenism). One of the most common adverse effects of lamotrigine is a non-serious rash; however, slow dose titration is necessary to decrease the risk of a serious, life-threatening rash such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Lithium

Lithium continues to be regarded as a gold-standard therapy for bipolar disorder. The exact serum levels corresponding to efficacy and tolerability vary. The Lithiumeter: Version 2.0 is a schematic that incorporates the various levels recommended by different clinical guidelines.2 The recommended serum levels range from 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for mania and 0.4 to 0.8 mEq/L for depression.2 One of the main issues with lithium dosing is balancing a therapeutic level with tolerability and toxicity. Toxicity may begin when lithium levels exceed 1.2 mEq/L, and levels >2.0 mEq/L can be lethal. Signs of acute toxicity include tremor, headache, arrhythmia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, polyuria, and polydipsia. Conversely, chronic lithium use may lead to chronic toxicity as patients age and their physical health changes. Signs of chronic toxicity include ataxia, confusion, renal dysfunction, and tremor. There is no “one size fits all” when it comes to lithium dosing. Individualized dosing is necessary to balance efficacy and tolerability.

Divalproex

Divalproex was initially studied for use as an AED, and its therapeutic levels as an AED are not the same as those indicated for bipolar disorder. Generally, patients with bipolar disorder require a divalproex serum level >50 µg/mL. Ranges closer to 100 µg/mL have been found to be most effective for treating acute mania.3 A loading dose of 20 to 30 mg/kg/d can be administered to help achieve mood stabilization. Again, efficacy must be balanced against toxicity. The maximum dose of divalproex is 60 mg/kg/d, which is rarely seen in psychiatric practice. Early studies of divalproex found adverse effects greatest in individuals with plasma levels >100 µg/mL. Reported adverse effects included alopecia, weight gain, tremor, and mental status changes.4

Lamotrigine

Unlike lithium and divalproex, lamotrigine therapeutic drug monitoring is not common. The accepted therapeutic reference range (TRR) for lamotrigine as an AED is 3,000 to 14,000 ng/mL. Unholzer et al5 evaluated the dose and TRR for individuals with bipolar disorder treated with lamotrigine. No statistically significant difference in lamotrigine serum levels was found in responders vs nonresponders.5 Most patients were prescribed ≤200 mg/d; however, some were prescribed higher doses. The maximum dose recommended when lamotrigine is used as an AED is 400 mg/d; however, this study furthered the evidence that lower doses tend to be effective in bipolar disorder.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

It has been 3 months since Mr. B was initiated on lamotrigine, and he has since been titrated to his current, stable dose of 100 mg/d. Mr. B is no longer experiencing the sedation he had with lithium and has the energy to commit to an exercise routine. This has allowed him to lose 15 pounds so far and greatly improve control of his diabetes.

Dosage summary

Most available evidence supports dosing lithium and divalproex to effect, typically seen between 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L and 50 to 125 µg/mL, respectively. Higher plasma levels tend to correspond to more adverse effects and toxicity. Lamotrigine does not have such a narrow therapeutic window. Lamotrigine for psychiatric treatment yields greatest efficacy at approximately 200 mg/d, but doses can be increased if warranted, which could be the case in Mr. B.

Table 11-5 outlines dosing strategies and therapeutic serum levels for lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine. Table 22 lists signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, and Table 31,2 describes strategies for managing adverse effects of lithium and divalproex.

Mr. B, age 32, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder 10 years ago after experiencing a manic episode that resulted in his first psychiatric hospitalization. He was prescribed quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and remained stable for the next several years. Unfortunately, Mr. B developed significant metabolic adverse effects, including diabetes and a 30-pound weight gain, so he was switched from quetiapine to lithium. Mr. B was unable to tolerate the sedation and cognitive effects of lithium, and the dose could not be titrated to within the therapeutic window. As a result, Mr. B experienced a moderate depressive episode. His current clinician would like to initiate lamotrigine at a starting dose of 25 mg/d. Mr. B has not had a manic episode since the index hospitalization, and this is his first depressive episode.

The term “mood stabilizer” has come to refer to medications that treat a depressive and/or manic episode without inducing the other. In conventional terms, it refers to non-antipsychotic medications such as lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine. Except for lithium, mood stabilizers are also antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). The role of AEDs for treating psychiatric conditions was discovered after they were originally FDA-approved for treating seizures. Following this discovery, the recommended doses and therapeutic ranges for these agents when applied to psychiatric treatment fell into a gray area.

Every patient is different and requires an individualized treatment plan, but this often leaves the clinician wondering, “How high is too high for this mood stabilizer?” or “My patient is responding well, but could a higher dose be even more effective?” In the case of Mr. B, who has trialed 2 medications with poor tolerability, how high can the lamotrigine dose be titrated to achieve a therapeutic response without adverse effects? The literature on this topic does not provide an exact answer, but does shed some light on key considerations for such decisions.

Which mood stabilizers are recommended?

One of the most recently updated guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder was released in 2018 by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT).1 Lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine were each recommended as a first-line option for treating bipolar disorder. For lithium and divalproex, the CANMAT guidelines recommend serum level monitoring for efficacy and tolerability; however, they do not recommend serum level monitoring for lamotrigine. Lithium and divalproex each have safety and tolerability concerns, particularly when selected for maintenance therapy, whereas lamotrigine is typically much better tolerated.1 Divalproex and lithium can cause weight gain, gastrointestinal adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), and tremor. Additional tolerability concerns with lithium include renal toxicity, electrocardiogram abnormalities, hypothyroidism, cognitive impairment, and dermatologic reactions. Divalproex can produce greater levels of sedation and may impact reproductive function (oligomenorrhea or hyperandrogenism). One of the most common adverse effects of lamotrigine is a non-serious rash; however, slow dose titration is necessary to decrease the risk of a serious, life-threatening rash such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Lithium

Lithium continues to be regarded as a gold-standard therapy for bipolar disorder. The exact serum levels corresponding to efficacy and tolerability vary. The Lithiumeter: Version 2.0 is a schematic that incorporates the various levels recommended by different clinical guidelines.2 The recommended serum levels range from 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for mania and 0.4 to 0.8 mEq/L for depression.2 One of the main issues with lithium dosing is balancing a therapeutic level with tolerability and toxicity. Toxicity may begin when lithium levels exceed 1.2 mEq/L, and levels >2.0 mEq/L can be lethal. Signs of acute toxicity include tremor, headache, arrhythmia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, polyuria, and polydipsia. Conversely, chronic lithium use may lead to chronic toxicity as patients age and their physical health changes. Signs of chronic toxicity include ataxia, confusion, renal dysfunction, and tremor. There is no “one size fits all” when it comes to lithium dosing. Individualized dosing is necessary to balance efficacy and tolerability.

Divalproex

Divalproex was initially studied for use as an AED, and its therapeutic levels as an AED are not the same as those indicated for bipolar disorder. Generally, patients with bipolar disorder require a divalproex serum level >50 µg/mL. Ranges closer to 100 µg/mL have been found to be most effective for treating acute mania.3 A loading dose of 20 to 30 mg/kg/d can be administered to help achieve mood stabilization. Again, efficacy must be balanced against toxicity. The maximum dose of divalproex is 60 mg/kg/d, which is rarely seen in psychiatric practice. Early studies of divalproex found adverse effects greatest in individuals with plasma levels >100 µg/mL. Reported adverse effects included alopecia, weight gain, tremor, and mental status changes.4

Lamotrigine

Unlike lithium and divalproex, lamotrigine therapeutic drug monitoring is not common. The accepted therapeutic reference range (TRR) for lamotrigine as an AED is 3,000 to 14,000 ng/mL. Unholzer et al5 evaluated the dose and TRR for individuals with bipolar disorder treated with lamotrigine. No statistically significant difference in lamotrigine serum levels was found in responders vs nonresponders.5 Most patients were prescribed ≤200 mg/d; however, some were prescribed higher doses. The maximum dose recommended when lamotrigine is used as an AED is 400 mg/d; however, this study furthered the evidence that lower doses tend to be effective in bipolar disorder.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

It has been 3 months since Mr. B was initiated on lamotrigine, and he has since been titrated to his current, stable dose of 100 mg/d. Mr. B is no longer experiencing the sedation he had with lithium and has the energy to commit to an exercise routine. This has allowed him to lose 15 pounds so far and greatly improve control of his diabetes.

Dosage summary

Most available evidence supports dosing lithium and divalproex to effect, typically seen between 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L and 50 to 125 µg/mL, respectively. Higher plasma levels tend to correspond to more adverse effects and toxicity. Lamotrigine does not have such a narrow therapeutic window. Lamotrigine for psychiatric treatment yields greatest efficacy at approximately 200 mg/d, but doses can be increased if warranted, which could be the case in Mr. B.

Table 11-5 outlines dosing strategies and therapeutic serum levels for lithium, divalproex, and lamotrigine. Table 22 lists signs and symptoms of lithium toxicity, and Table 31,2 describes strategies for managing adverse effects of lithium and divalproex.

1. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

2. Malhi GS, Gershon S, Outhred T. Lithiumeter: version 2.0. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(8):631-641.

3. Allen MH, Hirschfeld RM, Wozniak PJ, et al. Linear relationship of valproate serum concentration to response and optimal serum levels for acute mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):272-275.

4. Turnbull DM, Rawlins MD, Weightman D, et al. Plasma concentrations of sodium valproate: their clinical value. Ann Neurol. 1983;14(1):38-42.

5. Unholzer S, Haen E. Retrospective analysis of therapeutic drug monitoring data for treatment of bipolar disorder with lamotrigine. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(7):296.

1. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

2. Malhi GS, Gershon S, Outhred T. Lithiumeter: version 2.0. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(8):631-641.

3. Allen MH, Hirschfeld RM, Wozniak PJ, et al. Linear relationship of valproate serum concentration to response and optimal serum levels for acute mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):272-275.

4. Turnbull DM, Rawlins MD, Weightman D, et al. Plasma concentrations of sodium valproate: their clinical value. Ann Neurol. 1983;14(1):38-42.

5. Unholzer S, Haen E. Retrospective analysis of therapeutic drug monitoring data for treatment of bipolar disorder with lamotrigine. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2015;48(7):296.

COVID-19’s impact on internet gaming disorder among children and adolescents

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of youth has been significant. Its possible effects range from boredom, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation to potential increased rates of internet gaming disorder (IGD), which may have worsened during a nationwide shutdown and extended period of limited social interactions. Presently, there is a paucity of research on the impact of internet gaming on children and adolescents’ mental health and well-being during COVID-19. This article aims to bring awareness to the possible rising impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on IGD and mental health in youth.

Gaming offers benefits—and risks

The gaming industry has grown immensely over the past several years. While many businesses were impacted negatively during the pandemic, the gaming industry grew. It was estimated to be worth $159.3 billion in 2020, an increase of 9.3% from 2019.1

Stay-at-home orders and quarantine protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic have significantly disrupted normal activities, resulting in increased time for digital entertainment, including online gaming and related activities. Internet gaming offers some benefits for children and adolescents, including socialization and connection with peers, which was especially important for avoiding isolation during the pandemic. Empirical evidence of the positive effects of internet gaming can be seen in studies of youth undergoing chemotherapy, those receiving psychotherapy for anxiety or depression, and those having emotional and behavioral problems.2 Internet gaming also provides participants with a platform to communicate with the outside world while maintaining social distancing, and might reduce anxiety, and in some cases, depression.3

Despite these benefits, for some youth, excessive internet gaming can have adverse effects. Due to its addictive properties, internet gaming can be dangerous for vulnerable individuals and lead to unhealthy habits, such as disturbed sleep patterns and increased anxiety.4 In a cross-sectional study conducted in China, Yu et al5 examined the association between IGD and suicidal ideation. They concluded that IGD was positively associated with insomnia and then depression, which in turn contributed to suicide ideation.5 A study based on a survey conducted in Iran from May to August 2020 in individuals age 13 to 18 years found that depression, anxiety, and stress were significant mediators in the association between IGD and self-reported quality of life.2

Internet gaming disorder is included in DSM-5 as a “condition for further study” and in ICD-11.6 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, a study of 1,178 American youth age 8 to 18 years revealed that 8.5% of gamers met the criteria for IGD.7 In a meta-analysis that included 16 studies, the pooled prevalence of IGD among adolescents was 4.6%.8 Some countries, including China and South Korea, have developed treatment plans for IGD,6 but in the United States treatment guidelines have not been established due to insufficient evidence.9

The COVID-19 pandemic has likely led to an increased number of children and adolescents with IGD and its adverse effects on their mental health and well-being. It remains to be seen whether these youth will improve as the pandemic resolves and they resume normal activities, or if impairments will persist.

In conclusion, while internet gaming during the COVID-19 pandemic has provided benefits for many children and adolescents, the negative impact for those who develop IGD may be significant. We should be prepared to detect and address the needs of these youth and their families. Additional research is needed on the post-pandemic prevalence of IGD, its impact on youth mental health, and treatment strategies.

1. WePC. Video game industry statistics, trends and data in 2021. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://www.wepc.com/news/video-game-statistics/

2. Fazeli S, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Lin CY, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress mediate the associations between internet gaming disorder, insomnia, and quality of life during the COVID-19 outbreak. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;12:100307. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100307

3. Özçetin M, Gümüstas F, Çag˘ Y, et al. The relationships between video game experience and cognitive abilities in adolescents. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:1171-1180. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S206271

4. Männikkö N, Ruotsalainen H, Miettunen J, et al. Problematic gaming behaviour and health-related outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(1):67-81. doi: 10.1177/1359105317740414

5. Yu Y, Yang X, Wang S, et al. Serial multiple mediation of the association between internet gaming disorder and suicidal ideation by insomnia and depression in adolescents in Shanghai, China. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):460. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02870-zz

6. American Psychiatric Association. Internet gaming. Published June 2018. Accessed June 7, 2021. www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/internet-gaming

7. Gentile D. Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18: a national study. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(5):594-602. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02340.x

8. Fam JY. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in adolescents: A meta-analysis across three decades. Scand J Psychol. 2018;59(5):524-531. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12459

9. Gentile DA, Bailey K, Bavelier D, et al. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(suppl 2):S81-S85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1758H

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of youth has been significant. Its possible effects range from boredom, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation to potential increased rates of internet gaming disorder (IGD), which may have worsened during a nationwide shutdown and extended period of limited social interactions. Presently, there is a paucity of research on the impact of internet gaming on children and adolescents’ mental health and well-being during COVID-19. This article aims to bring awareness to the possible rising impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on IGD and mental health in youth.

Gaming offers benefits—and risks

The gaming industry has grown immensely over the past several years. While many businesses were impacted negatively during the pandemic, the gaming industry grew. It was estimated to be worth $159.3 billion in 2020, an increase of 9.3% from 2019.1

Stay-at-home orders and quarantine protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic have significantly disrupted normal activities, resulting in increased time for digital entertainment, including online gaming and related activities. Internet gaming offers some benefits for children and adolescents, including socialization and connection with peers, which was especially important for avoiding isolation during the pandemic. Empirical evidence of the positive effects of internet gaming can be seen in studies of youth undergoing chemotherapy, those receiving psychotherapy for anxiety or depression, and those having emotional and behavioral problems.2 Internet gaming also provides participants with a platform to communicate with the outside world while maintaining social distancing, and might reduce anxiety, and in some cases, depression.3

Despite these benefits, for some youth, excessive internet gaming can have adverse effects. Due to its addictive properties, internet gaming can be dangerous for vulnerable individuals and lead to unhealthy habits, such as disturbed sleep patterns and increased anxiety.4 In a cross-sectional study conducted in China, Yu et al5 examined the association between IGD and suicidal ideation. They concluded that IGD was positively associated with insomnia and then depression, which in turn contributed to suicide ideation.5 A study based on a survey conducted in Iran from May to August 2020 in individuals age 13 to 18 years found that depression, anxiety, and stress were significant mediators in the association between IGD and self-reported quality of life.2

Internet gaming disorder is included in DSM-5 as a “condition for further study” and in ICD-11.6 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, a study of 1,178 American youth age 8 to 18 years revealed that 8.5% of gamers met the criteria for IGD.7 In a meta-analysis that included 16 studies, the pooled prevalence of IGD among adolescents was 4.6%.8 Some countries, including China and South Korea, have developed treatment plans for IGD,6 but in the United States treatment guidelines have not been established due to insufficient evidence.9

The COVID-19 pandemic has likely led to an increased number of children and adolescents with IGD and its adverse effects on their mental health and well-being. It remains to be seen whether these youth will improve as the pandemic resolves and they resume normal activities, or if impairments will persist.

In conclusion, while internet gaming during the COVID-19 pandemic has provided benefits for many children and adolescents, the negative impact for those who develop IGD may be significant. We should be prepared to detect and address the needs of these youth and their families. Additional research is needed on the post-pandemic prevalence of IGD, its impact on youth mental health, and treatment strategies.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of youth has been significant. Its possible effects range from boredom, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation to potential increased rates of internet gaming disorder (IGD), which may have worsened during a nationwide shutdown and extended period of limited social interactions. Presently, there is a paucity of research on the impact of internet gaming on children and adolescents’ mental health and well-being during COVID-19. This article aims to bring awareness to the possible rising impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on IGD and mental health in youth.

Gaming offers benefits—and risks

The gaming industry has grown immensely over the past several years. While many businesses were impacted negatively during the pandemic, the gaming industry grew. It was estimated to be worth $159.3 billion in 2020, an increase of 9.3% from 2019.1

Stay-at-home orders and quarantine protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic have significantly disrupted normal activities, resulting in increased time for digital entertainment, including online gaming and related activities. Internet gaming offers some benefits for children and adolescents, including socialization and connection with peers, which was especially important for avoiding isolation during the pandemic. Empirical evidence of the positive effects of internet gaming can be seen in studies of youth undergoing chemotherapy, those receiving psychotherapy for anxiety or depression, and those having emotional and behavioral problems.2 Internet gaming also provides participants with a platform to communicate with the outside world while maintaining social distancing, and might reduce anxiety, and in some cases, depression.3

Despite these benefits, for some youth, excessive internet gaming can have adverse effects. Due to its addictive properties, internet gaming can be dangerous for vulnerable individuals and lead to unhealthy habits, such as disturbed sleep patterns and increased anxiety.4 In a cross-sectional study conducted in China, Yu et al5 examined the association between IGD and suicidal ideation. They concluded that IGD was positively associated with insomnia and then depression, which in turn contributed to suicide ideation.5 A study based on a survey conducted in Iran from May to August 2020 in individuals age 13 to 18 years found that depression, anxiety, and stress were significant mediators in the association between IGD and self-reported quality of life.2

Internet gaming disorder is included in DSM-5 as a “condition for further study” and in ICD-11.6 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, a study of 1,178 American youth age 8 to 18 years revealed that 8.5% of gamers met the criteria for IGD.7 In a meta-analysis that included 16 studies, the pooled prevalence of IGD among adolescents was 4.6%.8 Some countries, including China and South Korea, have developed treatment plans for IGD,6 but in the United States treatment guidelines have not been established due to insufficient evidence.9

The COVID-19 pandemic has likely led to an increased number of children and adolescents with IGD and its adverse effects on their mental health and well-being. It remains to be seen whether these youth will improve as the pandemic resolves and they resume normal activities, or if impairments will persist.

In conclusion, while internet gaming during the COVID-19 pandemic has provided benefits for many children and adolescents, the negative impact for those who develop IGD may be significant. We should be prepared to detect and address the needs of these youth and their families. Additional research is needed on the post-pandemic prevalence of IGD, its impact on youth mental health, and treatment strategies.

1. WePC. Video game industry statistics, trends and data in 2021. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://www.wepc.com/news/video-game-statistics/

2. Fazeli S, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Lin CY, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress mediate the associations between internet gaming disorder, insomnia, and quality of life during the COVID-19 outbreak. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;12:100307. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100307

3. Özçetin M, Gümüstas F, Çag˘ Y, et al. The relationships between video game experience and cognitive abilities in adolescents. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:1171-1180. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S206271

4. Männikkö N, Ruotsalainen H, Miettunen J, et al. Problematic gaming behaviour and health-related outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(1):67-81. doi: 10.1177/1359105317740414

5. Yu Y, Yang X, Wang S, et al. Serial multiple mediation of the association between internet gaming disorder and suicidal ideation by insomnia and depression in adolescents in Shanghai, China. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):460. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02870-zz

6. American Psychiatric Association. Internet gaming. Published June 2018. Accessed June 7, 2021. www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/internet-gaming

7. Gentile D. Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18: a national study. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(5):594-602. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02340.x

8. Fam JY. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in adolescents: A meta-analysis across three decades. Scand J Psychol. 2018;59(5):524-531. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12459

9. Gentile DA, Bailey K, Bavelier D, et al. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(suppl 2):S81-S85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1758H

1. WePC. Video game industry statistics, trends and data in 2021. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://www.wepc.com/news/video-game-statistics/

2. Fazeli S, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Lin CY, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress mediate the associations between internet gaming disorder, insomnia, and quality of life during the COVID-19 outbreak. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;12:100307. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100307

3. Özçetin M, Gümüstas F, Çag˘ Y, et al. The relationships between video game experience and cognitive abilities in adolescents. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:1171-1180. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S206271

4. Männikkö N, Ruotsalainen H, Miettunen J, et al. Problematic gaming behaviour and health-related outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(1):67-81. doi: 10.1177/1359105317740414

5. Yu Y, Yang X, Wang S, et al. Serial multiple mediation of the association between internet gaming disorder and suicidal ideation by insomnia and depression in adolescents in Shanghai, China. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):460. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02870-zz

6. American Psychiatric Association. Internet gaming. Published June 2018. Accessed June 7, 2021. www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/internet-gaming

7. Gentile D. Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18: a national study. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(5):594-602. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02340.x

8. Fam JY. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in adolescents: A meta-analysis across three decades. Scand J Psychol. 2018;59(5):524-531. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12459

9. Gentile DA, Bailey K, Bavelier D, et al. Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(suppl 2):S81-S85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1758H

Stuck in a rut with the wrong diagnosis

CASE Aggressive behaviors, psychosis

Ms. N, age 58, has a long history of bipolar disorder with psychotic features. She presents to our emergency department (ED) after an acute fall and frequent violent behaviors at her nursing home, where she had resided since being diagnosed with an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. For several weeks before her fall, she was physically aggressive, throwing objects at nursing home staff, and was unable to have her behavior redirected.

While in the ED, Ms. N rambles and appears to be responding to internal stimuli. Suddenly, she stops responding and begins to stare.

HISTORY Severe, chronic psychosis and hospitalization

Ms. N is well-known at our inpatient psychiatry and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) services. During the last 10 years, she has had worsening manic, psychotic, and catatonic (both excited and stuporous subtype) episodes. Three years ago, she had experienced a period of severe, chronic psychosis and excited catatonia that required extended inpatient treatment. While hospitalized, Ms. N had marginal responses to clozapine and benzodiazepines, but improved dramatically with ECT. After Ms. N left the hospital, she went to live with her boyfriend. She remained stable on monthly maintenance ECT treatments (bifrontal) before she was lost to follow-up 14 months prior to the current presentation. Ms. N’s family reports that she needed a cardiac clearance before continuing ECT treatment; however, she was hospitalized at another hospital with pneumonia and subsequent complications that interrupted the maintenance ECT treatments.

Approximately 3 months after medical issues requiring hospitalization began, Ms. N received a diagnosis of neurocognitive disorder due to difficulty with activities of daily living and cognitive decline. She was transferred to a nursing home by the outside hospital. When Ms. N’s symptoms of psychosis returned and she required inpatient psychiatric care, she was transferred to a nearby facility that did not have ECT available or knowledge of her history of catatonia resistant to pharmacologic management. Ms. N had a documented history of catatonia that spanned 10 years. During the last 4 years, Ms. N often required ECT treatment. Her current medication regimen prescribed by an outpatient psychiatrist includes clozapine, 300 mg twice daily, and clonazepam, 0.5 mg twice daily, both for bipolar disorder.

EVALUATION An unusual mix of symptoms

In the ED, Ms. N undergoes a CT of the head, which is found to be nonacute. Laboratory results show that her white blood cell count is 14.3 K/µL, which is mildly elevated. Results from a urinalysis and electrocardiogram (ECG) are unremarkable.

After Ms. N punches a radiology technician, she is administered IV lorazepam, 2 mg once, for her agitation. Twenty minutes after receiving IV lorazepam, she is calm and cooperative. However, approximately 4 hours later, Ms. N is yelling, tearful, and expressing delusions of grandeur—she believes she is God.

After she is admitted to the medical floor, Ms. N is seen by our consultation and liaison psychiatry service. She exhibits several signs of catatonia, including grasp reflex, gegenhalten (oppositional paratonia), waxy flexibility, and echolalia. Ms. N also has an episode of urinary incontinence. At some parts of the day, she is alert and oriented to self and location; at other times, she is somnolent and disoriented. The treatment team continues Ms. N’s previous medication regimen of clozapine, 300 mg twice daily, and clonazepam, 0.5 mg twice daily. Unfortunately, at times Ms. N spits out and hides her administered oral medications, which leads to the decision to discontinue clozapine. Once medically cleared, Ms. N is transferred to the psychiatric floor.

[polldaddy:10869949]

Continue to: TREATMENT

TREATMENT Bifrontal ECT initiated

On hospital Day 3 Ms. N is administered a trial of IM lorazepam, titrated up to 6 mg/d (maximum tolerated dose) while the treatment team initiates the legal process to conduct ECT because she is unable to give consent. Once Ms. N begins tolerating oral medications, amantadine, 100 mg twice daily, is added to treat her catatonia. As in prior hospitalizations, Ms. N is unresponsive to pharmacotherapy alone for her catatonic symptoms. On hospital Day 8, forced ECT is granted, which is 5 days after the process of filing paperwork was started. Bifrontal ECT is utilized with the following settings: frequency 70 Hz, pulse width 1.5 ms, 100% energy dose, 504 mC. Ms. N does not experience a significant improvement until she receives 10 ECT treatments as part of a 3-times-per-week acute series protocol. The Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) and the KANNER scale are used to monitor her progress. Her initial BFCRS score is 17 and initial KANNER scale, part 2 score is 26.

Ms. N spends a total of 61 days in the hospital, which is significantly longer than her previous hospital admissions on our psychiatric unit; these previous admissions were for treatment of both stuporous and excited subtypes of catatonia. This increased length of stay coincides with a significantly longer duration of untreated catatonia. Knowledge of her history of both the stuporous and excited subtypes of catatonia would have allowed for faster diagnosis and treatment.1

The authors’ observations

Originally conceptualized as a separate syndrome by Karl Kahlbaum, catatonia was considered only as a specifier for neuropsychiatric conditions (primarily schizophrenia) as recently as DSM-IV-TR.2 DSM-5 describes catatonia as a marked psychomotor disturbance and acknowledges its connection to schizophrenia by keeping it in the same chapter.3 DSM-5 includes separate diagnoses for catatonia, catatonia due to a general medical condition, and unspecified catatonia (for catatonia without a known underlying disorder).3 A recent meta-analysis found the prevalence of catatonia is higher in patients with medical/neurologic illness, bipolar disorder, and autism than in those with schizophrenia.4

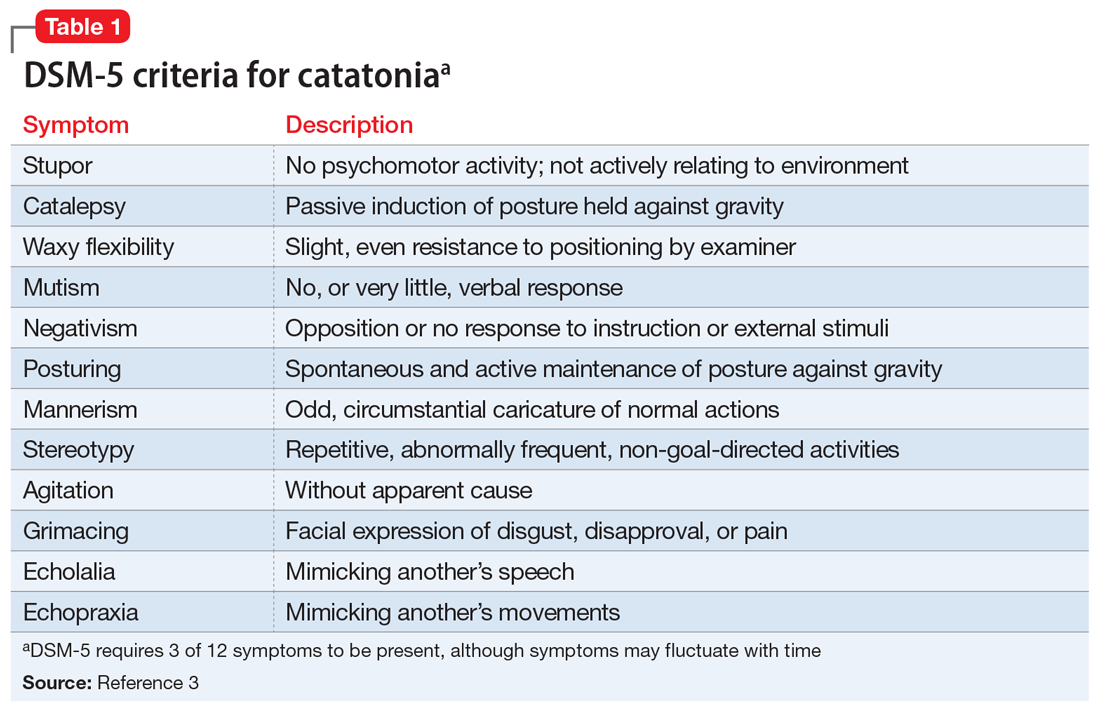

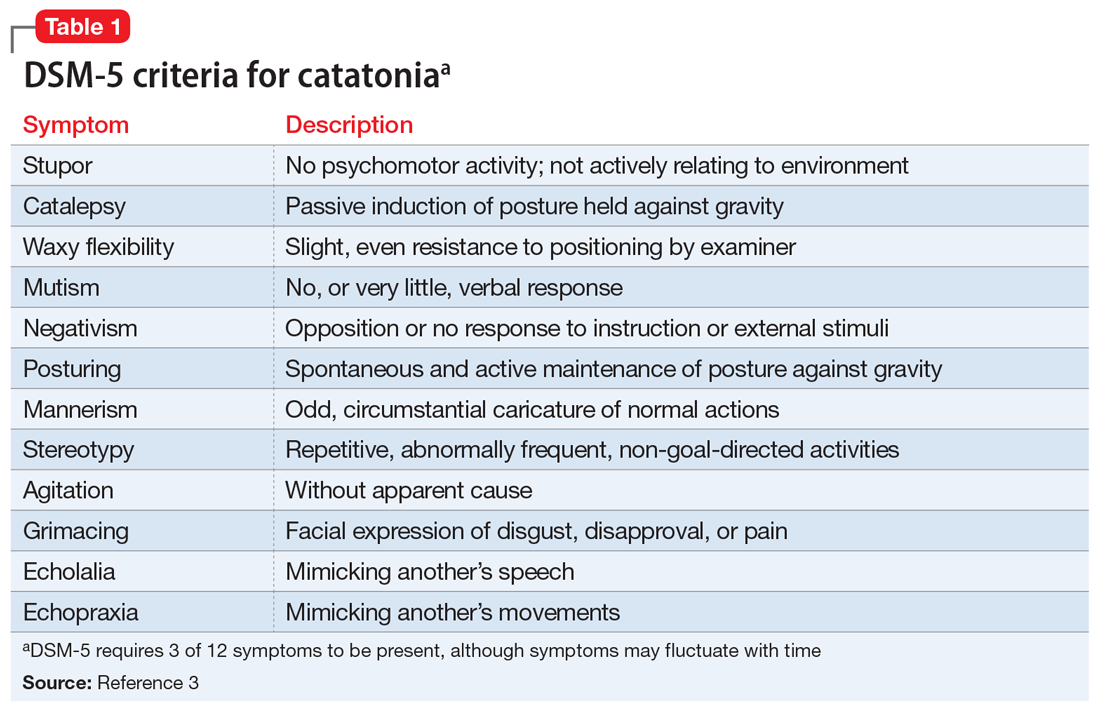

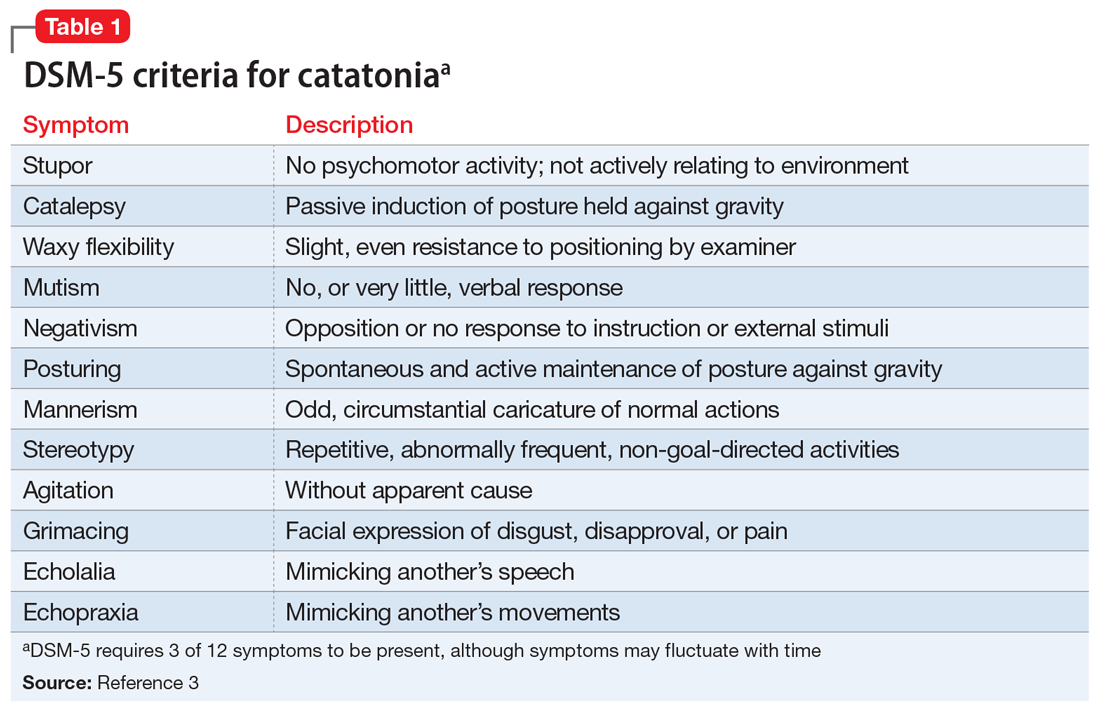

Table 13 highlights the DSM-5 criteria for catatonia. DSM-5 requires 3 of 12 symptoms to be present, although symptoms may fluctuate with time.3 If a clinician is not specifically looking for catatonia, it can be a difficult syndrome to diagnose. Does rigidity indicate catatonia, or excessive dopamine blockade from an antipsychotic? How can seemingly contradictory symptoms be part of the same syndrome? Many clinicians associate catatonia with the stuporous subtype (immobility, posturing, catalepsy), which is more prevalent, but the excited subtype, which may involve severe agitation, autonomic dysfunction, and impaired consciousness, can be lethal.2 The diversity in presentation of catatonia is not unlike the challenging variety of symptoms of heart attacks.

A retrospective study of all adults admitted to a hospital found that only 41% of patients who met criteria for catatonia received this diagnosis.5 Further complicating the diagnosis, delirium and catatonia can co-exist; one study found this was the case in 1 of 3 critically ill patients.6 DSM-5 criteria for catatonia due to another medical condition exclude the diagnosis if delirium is present, but this study and others suggest this needs to be reconsidered.3

Continue to: A standardized evaluation is key

A standardized evaluation is key

Just as a patient who presents with chest pain requires a standardized evaluation, including a pertinent history, laboratory workup, and ECG, psychiatrists may also use standardized diagnostic instruments to aid in the diagnosis of catatonia. One study of hospitalized patients with schizophrenia found that using a standardized diagnostic procedure for catatonia resulted in a 7-fold increase in the diagnosis.7 The BFCRS is the most common standardized instrument for catatonia, likely due to its high inter-rater reliability.8 Other scales include the KANNER scale and Northoff Catatonia Scale, which emphasize different aspects of the disease or for certain clinical populations (eg, the KANNER scale adjusts for patients who are nonverbal at baseline). One study suggested that BFCRS has lower reliability for less-severe illness.9 These differences emphasize that psychiatry does not have a thorough understanding of the intricacies of catatonia. However, using validated screening tools can lead to more consistent diagnoses and continue important research on this often-misunderstood illness.

Dangers of untreated catatonia

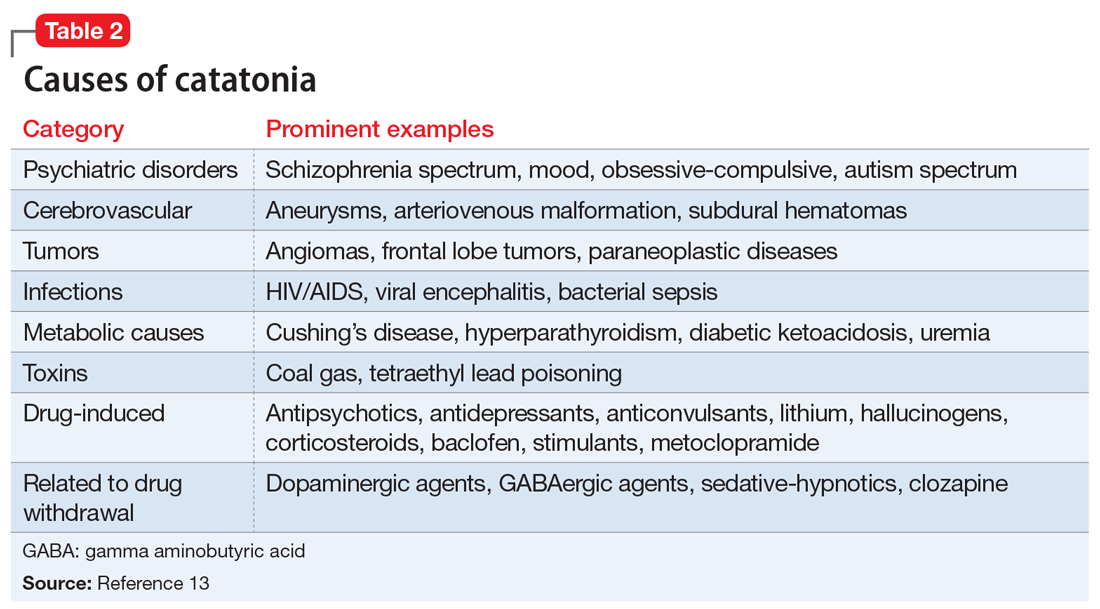

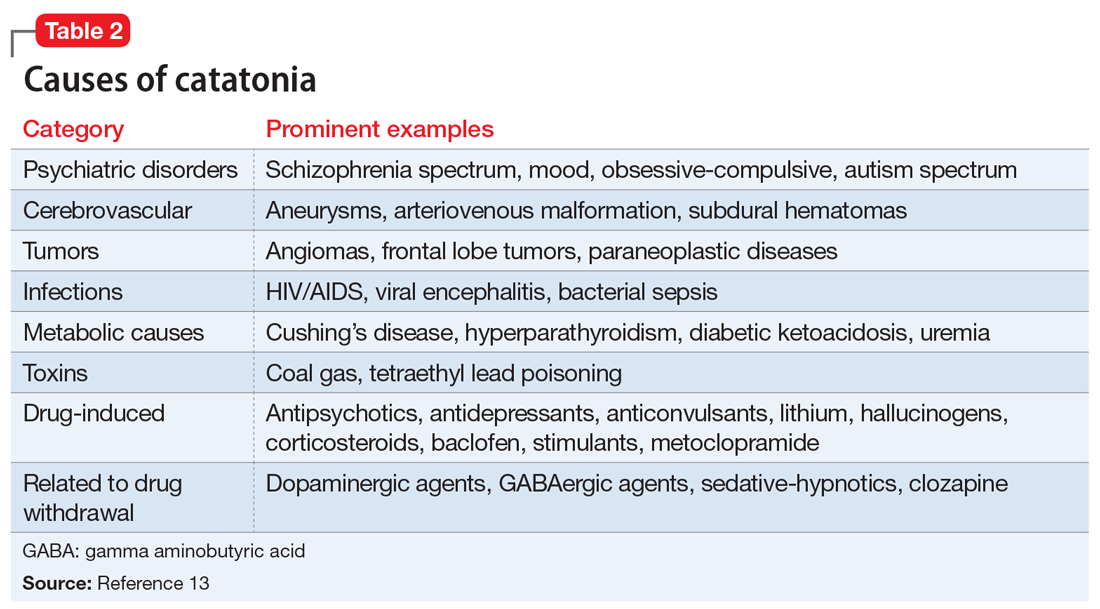

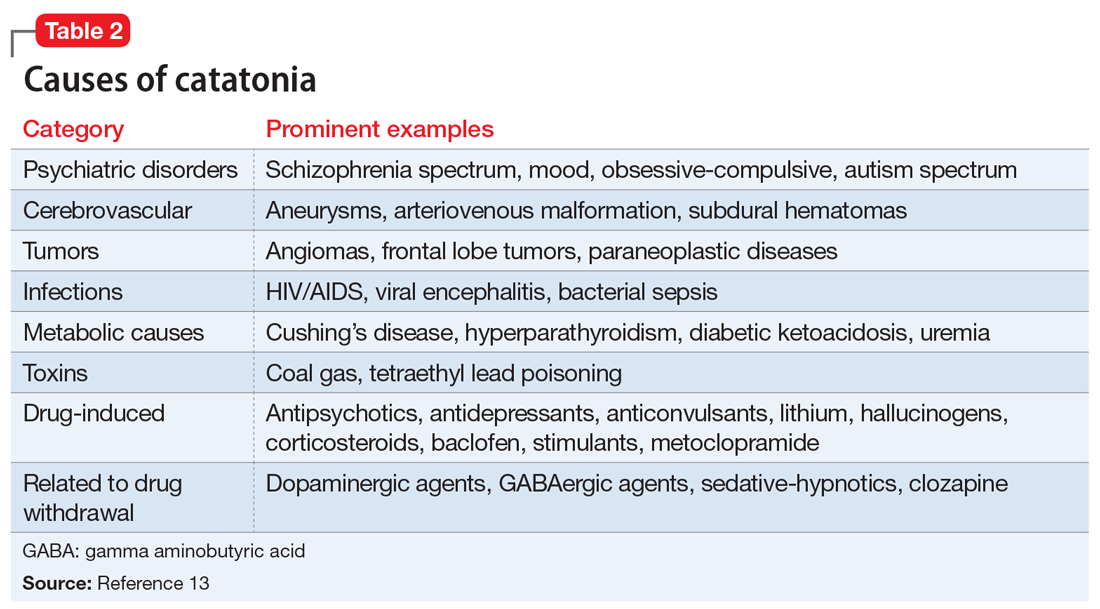

Rapid treatment of catatonia is necessary to prevent mortality. A study of patients in Kentucky’s state psychiatric hospitals found that untreated catatonia with resultant death from pulmonary embolism was the leading cause of preventable death.10 A 17-year retrospective study of patients with schizophrenia admitted to 1 hospital found that those with catatonia were >4 times as likely to die during hospitalization than those without catatonia.11 The significant morbidity and mortality from untreated catatonia are typically attributed to the consequences of poorly controlled movements, immobility, autonomic instability, and poor/no oral intake. Reduced oral intake can result in malnutrition, dehydration, arrhythmias, and increased risk of infections. Furthermore, chronic catatonic episodes are more difficult to treat.12 In addition to the aggressive management of neuropsychiatric symptoms, it is vital to evaluate relevant medical etiologies that may be contributing to the syndrome (Table 213). Tracking vital signs and laboratory values, such as creatine kinase, electrolytes, and complete blood count, is required to ensure the medical condition does not become life-threatening.

Treatment options

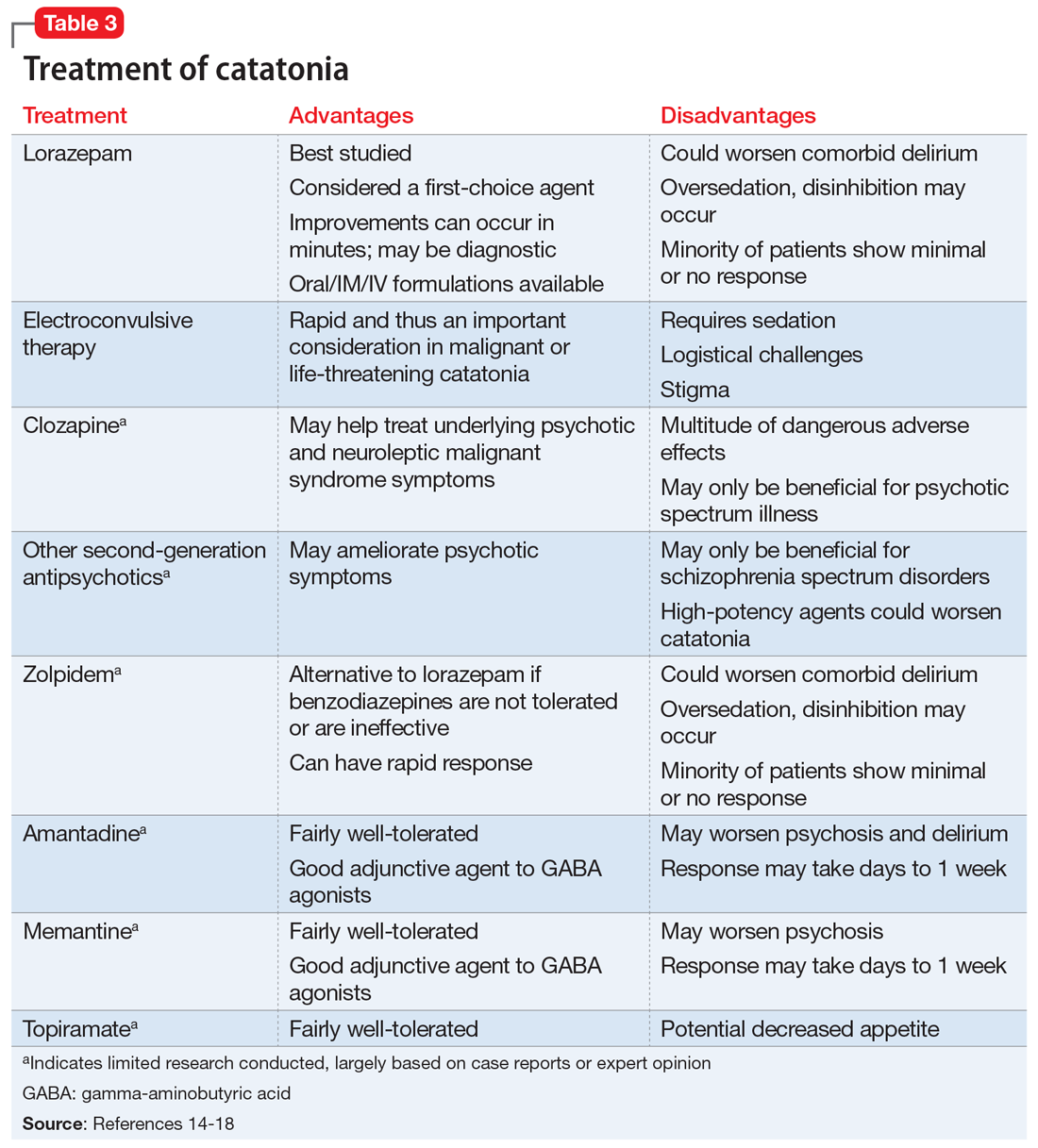

Studies and expert opinion suggest that benzodiazepines (specifically lorazepam, because it is the most studied agent) are the first-line treatment for catatonia. A lorazepam challenge test—providing 1 or 2 mg of IV lorazepam—is considered diagnostic and therapeutic given the high rate of response within 10 minutes.14 Patients with limited response to lorazepam or who are medically compromised should undergo ECT. Electroconvulsive therapy is considered the gold-standard treatment for catatonia; estimated response rates range from 59% to 100%, even in patients who fail to respond to pharmacotherapy.15 Although highly effective, ECT is often hindered by the time required to initiate treatment, stigma, lack of access, and other logistical challenges.

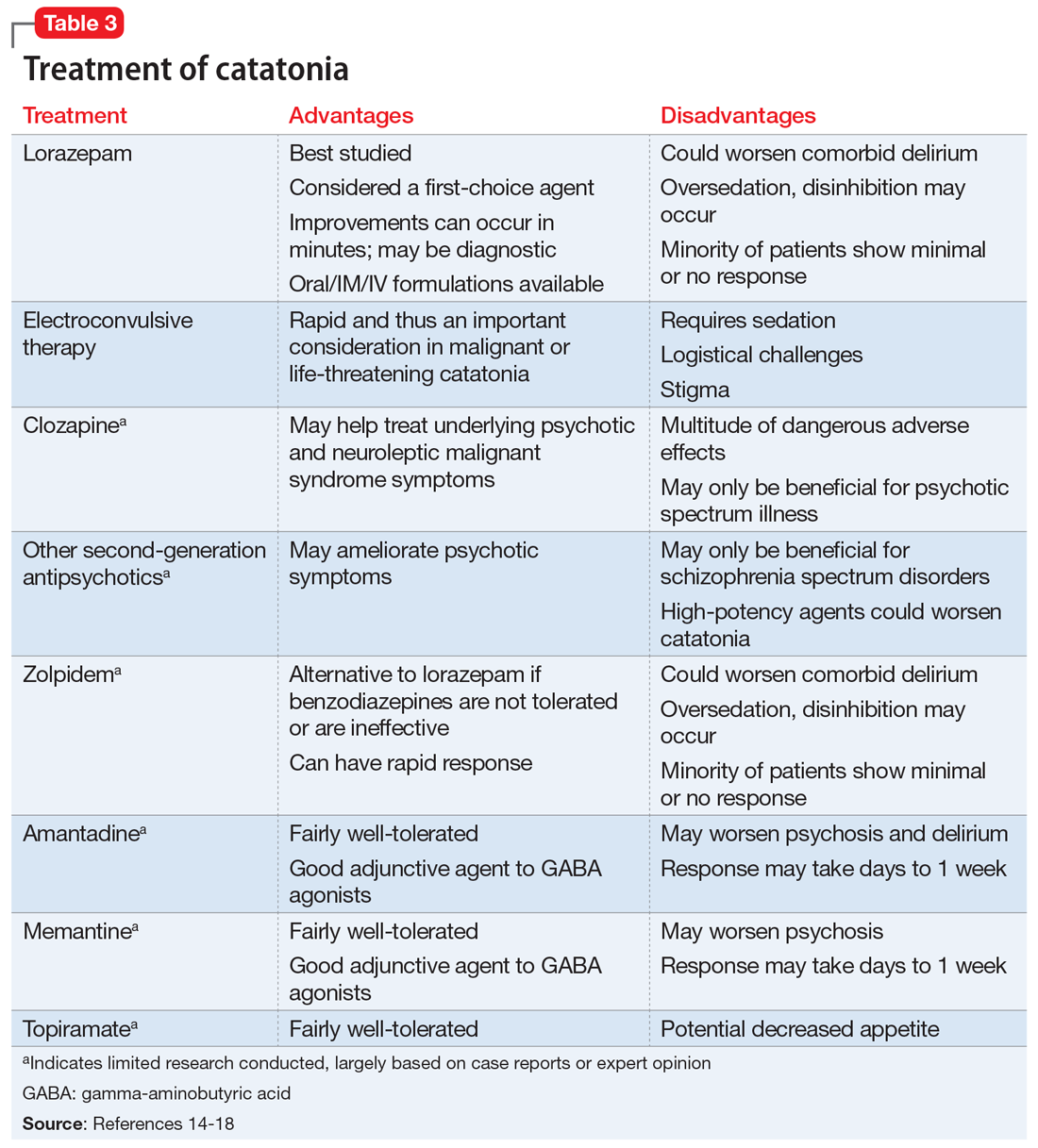

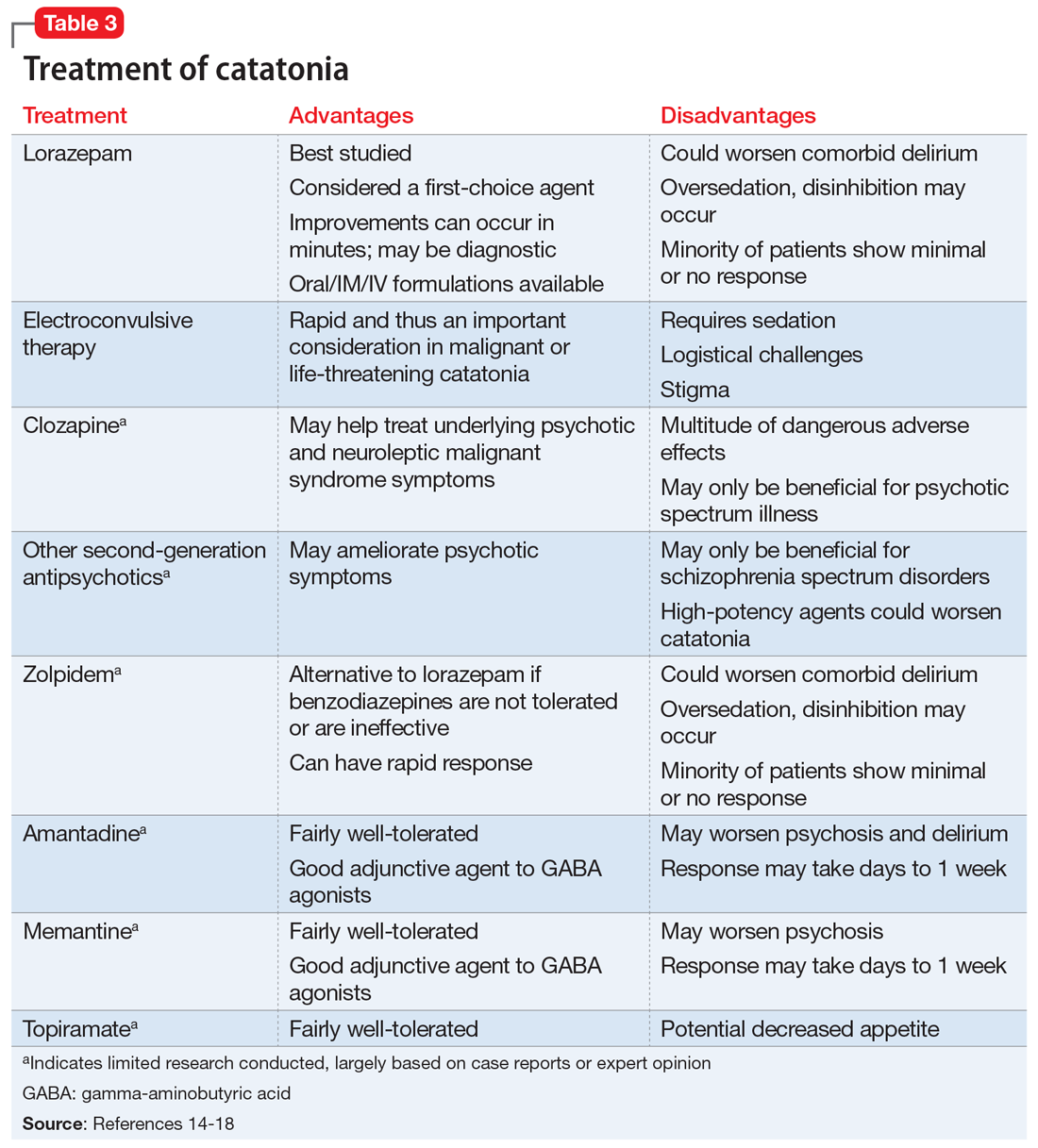

Table 314-18 highlights the advantages and disadvantages of treatment options for catatonia. Some researchers have suggested a zolpidem challenge test could augment lorazepam because some patients respond only to zolpidem.14 The efficacy of these medications along with some evidence of anti-N-methyl-

Ms. N was ultimately diagnosed with bipolar disorder, current episode mixed, with psychotic and catatonic features. Ms. N had symptoms of mania including grandiosity, periods of lack of sleep, delusions as well as depressive symptoms of tearfulness and low mood. The treatment team had considered that Ms. N had delirious mania because she had fluctuating sensorium, which included varying degrees of orientation and ability to answer questioning. However, the literature supporting the differentiation between delirious mania and excited catatonia is unclear, and both conditions may respond to ECT.18 A diagnosis of catatonia allowed the team to use rating scales to track Ms. N’s progress by monitoring for specific signs, such as grasp reflex and waxy flexibility.

Continue to: OUTCOME

OUTCOME Return to baseline

Before discharge, Ms. N’s BFCRS score decreases from the initial score of 17 to 0, and her KANNER scale score decreases from the initial score of 26 to 4, which correlates with vast improvement in clinical presentation. Once Ms. N completes the acute ECT treatment, she returns to her baseline level of functioning, and is discharged to live with her boyfriend. She is advised to continue weekly ECT for the first several months to ensure clinical stability. This regimen is later transitioned to biweekly and then monthly. Electroconvulsive therapy protocols from previous research were utilized in Ms. N’s case, but ultimately the lowest number of ECT treatments needed to maintain stability is determined clinically over many years.19 Ms. N is discharged on aripiprazole, 15 mg/d; bupropion ER, 300 mg/d (added after depressive symptoms emerge while catatonia symptoms improve midway through her lengthy hospitalization); and memantine, 10 mg/d. Ideally, clozapine would have been continued; however, due to her history of nonadherence and frequent restarting of the medication at a low dose, clozapine was discontinued and aripiprazole initiated.

More than 1 year later, Ms. N remains stable and continues to receive monthly ECT maintenance treatments.

Bottom Line

Catatonia should always be considered in a patient who presents with acute neuropsychiatric symptoms. Rapid diagnosis with standardized screening instruments and aggressive treatment are vital to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Related Resource

- Freudenreich O, Francis A, Fricchione GL. Chapter 9. Psychosis, mania, and catatonia. In: Levenson, James L, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine and consultation-liaison psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Baclofen • Ozobax

Bupropion ER • Wellbutrin XL

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Metoclopramide • Reglan

Memantine • Namenda

Topiramate • Topamax

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Carroll BT. The universal field hypothesis of catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. CNS Spectrums. 2000;5(7):26-33.

2. Rasmussen SA, Mazurek MF, Rosebush PI. Catatonia: our current understanding of its diagnosis, treatment and pathophysiology. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(4):391‐398.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. 119-121.

4. Solmi M, Pigato GG, Roiter B, et al. Prevalence of catatonia and its moderators in clinical samples: results from a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2017;44(5):1133-1150.

5. Llesuy JR, Medina M, Jacobson KC, et al. Catatonia under-diagnosis in the general hospital. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;30(2):145-151.

6. Wilson JE, Carlson R, Duggan MC, et al. Delirium and catatonia in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(11):1837-1844.

7. Heijden FVD, Tuinier S, Arts N, et al. Catatonia: disappeared or under-diagnosed? Psychopathology. 2005;38(1):3-8.

8. Sarkar S, Sakey S, Mathan K, et al. Assessing catatonia using four different instruments: inter-rater reliability and prevalence in inpatient clinical population. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;23:27-31.

9. Wilson JE, Niu K, Nicolson SE, et al. The diagnostic criteria and structure of catatonia. Schizophr Res. 2015;164(1-3):256-262.

10. Puentes R, Brenzel A, Leon JD. Pulmonary embolism during stuporous episodes of catatonia was found to be the most frequent cause of preventable death according to a state mortality review: 6 deaths in 15 years. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2017; doi:10.3371/csrp.rpab.071317

11. Funayama M, Takata T, Koreki A, et al. Catatonic stupor in schizophrenic disorders and subsequent medical complications and mortality. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2018:80(4):370-376.

12. Perugi G, Medda P, Toni C, et al. The role of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in bipolar disorder: effectiveness in 522 patients with bipolar depression, mixed-state, mania and catatonic features. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(3):359-371.

13. Freudenreich O, Francis A, Fricchione GL. Chapter 9. Psychosis, mania, and catatonia. In: Levenson, James L, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychosomatic medicine and Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

14. Sienaert P, Dhossche DM, Vancampfort D, et al. A clinical review of the treatment of catatonia. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:181.

15. Pelzer A, Heijden FVD, Boer ED. Systematic review of catatonia treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:317-326.

16. Carroll BT, Goforth HW, Thomas C, et al. Review of adjunctive glutamate antagonist therapy in the treatment of catatonic syndromes. J Neuropsychiatry and Clin Neurosci. 2007;19(4):406-412.

17. Fink M. Rediscovering catatonia: the biography of a treatable syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2013;(441):1-47.

18. Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: a clinician’s guide to diagnosis and treatment. Cambridge University Press; 2006.

19. Petrides G, Tobias KG, Kellner CH, et al. Continuation and maintenance electroconvulsive therapy for mood disorders: review of the literature. Neuropsychobiology. 2011;64(3):129-140.

CASE Aggressive behaviors, psychosis

Ms. N, age 58, has a long history of bipolar disorder with psychotic features. She presents to our emergency department (ED) after an acute fall and frequent violent behaviors at her nursing home, where she had resided since being diagnosed with an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. For several weeks before her fall, she was physically aggressive, throwing objects at nursing home staff, and was unable to have her behavior redirected.

While in the ED, Ms. N rambles and appears to be responding to internal stimuli. Suddenly, she stops responding and begins to stare.

HISTORY Severe, chronic psychosis and hospitalization

Ms. N is well-known at our inpatient psychiatry and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) services. During the last 10 years, she has had worsening manic, psychotic, and catatonic (both excited and stuporous subtype) episodes. Three years ago, she had experienced a period of severe, chronic psychosis and excited catatonia that required extended inpatient treatment. While hospitalized, Ms. N had marginal responses to clozapine and benzodiazepines, but improved dramatically with ECT. After Ms. N left the hospital, she went to live with her boyfriend. She remained stable on monthly maintenance ECT treatments (bifrontal) before she was lost to follow-up 14 months prior to the current presentation. Ms. N’s family reports that she needed a cardiac clearance before continuing ECT treatment; however, she was hospitalized at another hospital with pneumonia and subsequent complications that interrupted the maintenance ECT treatments.

Approximately 3 months after medical issues requiring hospitalization began, Ms. N received a diagnosis of neurocognitive disorder due to difficulty with activities of daily living and cognitive decline. She was transferred to a nursing home by the outside hospital. When Ms. N’s symptoms of psychosis returned and she required inpatient psychiatric care, she was transferred to a nearby facility that did not have ECT available or knowledge of her history of catatonia resistant to pharmacologic management. Ms. N had a documented history of catatonia that spanned 10 years. During the last 4 years, Ms. N often required ECT treatment. Her current medication regimen prescribed by an outpatient psychiatrist includes clozapine, 300 mg twice daily, and clonazepam, 0.5 mg twice daily, both for bipolar disorder.

EVALUATION An unusual mix of symptoms

In the ED, Ms. N undergoes a CT of the head, which is found to be nonacute. Laboratory results show that her white blood cell count is 14.3 K/µL, which is mildly elevated. Results from a urinalysis and electrocardiogram (ECG) are unremarkable.

After Ms. N punches a radiology technician, she is administered IV lorazepam, 2 mg once, for her agitation. Twenty minutes after receiving IV lorazepam, she is calm and cooperative. However, approximately 4 hours later, Ms. N is yelling, tearful, and expressing delusions of grandeur—she believes she is God.

After she is admitted to the medical floor, Ms. N is seen by our consultation and liaison psychiatry service. She exhibits several signs of catatonia, including grasp reflex, gegenhalten (oppositional paratonia), waxy flexibility, and echolalia. Ms. N also has an episode of urinary incontinence. At some parts of the day, she is alert and oriented to self and location; at other times, she is somnolent and disoriented. The treatment team continues Ms. N’s previous medication regimen of clozapine, 300 mg twice daily, and clonazepam, 0.5 mg twice daily. Unfortunately, at times Ms. N spits out and hides her administered oral medications, which leads to the decision to discontinue clozapine. Once medically cleared, Ms. N is transferred to the psychiatric floor.

[polldaddy:10869949]

Continue to: TREATMENT

TREATMENT Bifrontal ECT initiated

On hospital Day 3 Ms. N is administered a trial of IM lorazepam, titrated up to 6 mg/d (maximum tolerated dose) while the treatment team initiates the legal process to conduct ECT because she is unable to give consent. Once Ms. N begins tolerating oral medications, amantadine, 100 mg twice daily, is added to treat her catatonia. As in prior hospitalizations, Ms. N is unresponsive to pharmacotherapy alone for her catatonic symptoms. On hospital Day 8, forced ECT is granted, which is 5 days after the process of filing paperwork was started. Bifrontal ECT is utilized with the following settings: frequency 70 Hz, pulse width 1.5 ms, 100% energy dose, 504 mC. Ms. N does not experience a significant improvement until she receives 10 ECT treatments as part of a 3-times-per-week acute series protocol. The Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) and the KANNER scale are used to monitor her progress. Her initial BFCRS score is 17 and initial KANNER scale, part 2 score is 26.

Ms. N spends a total of 61 days in the hospital, which is significantly longer than her previous hospital admissions on our psychiatric unit; these previous admissions were for treatment of both stuporous and excited subtypes of catatonia. This increased length of stay coincides with a significantly longer duration of untreated catatonia. Knowledge of her history of both the stuporous and excited subtypes of catatonia would have allowed for faster diagnosis and treatment.1

The authors’ observations

Originally conceptualized as a separate syndrome by Karl Kahlbaum, catatonia was considered only as a specifier for neuropsychiatric conditions (primarily schizophrenia) as recently as DSM-IV-TR.2 DSM-5 describes catatonia as a marked psychomotor disturbance and acknowledges its connection to schizophrenia by keeping it in the same chapter.3 DSM-5 includes separate diagnoses for catatonia, catatonia due to a general medical condition, and unspecified catatonia (for catatonia without a known underlying disorder).3 A recent meta-analysis found the prevalence of catatonia is higher in patients with medical/neurologic illness, bipolar disorder, and autism than in those with schizophrenia.4

Table 13 highlights the DSM-5 criteria for catatonia. DSM-5 requires 3 of 12 symptoms to be present, although symptoms may fluctuate with time.3 If a clinician is not specifically looking for catatonia, it can be a difficult syndrome to diagnose. Does rigidity indicate catatonia, or excessive dopamine blockade from an antipsychotic? How can seemingly contradictory symptoms be part of the same syndrome? Many clinicians associate catatonia with the stuporous subtype (immobility, posturing, catalepsy), which is more prevalent, but the excited subtype, which may involve severe agitation, autonomic dysfunction, and impaired consciousness, can be lethal.2 The diversity in presentation of catatonia is not unlike the challenging variety of symptoms of heart attacks.

A retrospective study of all adults admitted to a hospital found that only 41% of patients who met criteria for catatonia received this diagnosis.5 Further complicating the diagnosis, delirium and catatonia can co-exist; one study found this was the case in 1 of 3 critically ill patients.6 DSM-5 criteria for catatonia due to another medical condition exclude the diagnosis if delirium is present, but this study and others suggest this needs to be reconsidered.3

Continue to: A standardized evaluation is key

A standardized evaluation is key

Just as a patient who presents with chest pain requires a standardized evaluation, including a pertinent history, laboratory workup, and ECG, psychiatrists may also use standardized diagnostic instruments to aid in the diagnosis of catatonia. One study of hospitalized patients with schizophrenia found that using a standardized diagnostic procedure for catatonia resulted in a 7-fold increase in the diagnosis.7 The BFCRS is the most common standardized instrument for catatonia, likely due to its high inter-rater reliability.8 Other scales include the KANNER scale and Northoff Catatonia Scale, which emphasize different aspects of the disease or for certain clinical populations (eg, the KANNER scale adjusts for patients who are nonverbal at baseline). One study suggested that BFCRS has lower reliability for less-severe illness.9 These differences emphasize that psychiatry does not have a thorough understanding of the intricacies of catatonia. However, using validated screening tools can lead to more consistent diagnoses and continue important research on this often-misunderstood illness.

Dangers of untreated catatonia

Rapid treatment of catatonia is necessary to prevent mortality. A study of patients in Kentucky’s state psychiatric hospitals found that untreated catatonia with resultant death from pulmonary embolism was the leading cause of preventable death.10 A 17-year retrospective study of patients with schizophrenia admitted to 1 hospital found that those with catatonia were >4 times as likely to die during hospitalization than those without catatonia.11 The significant morbidity and mortality from untreated catatonia are typically attributed to the consequences of poorly controlled movements, immobility, autonomic instability, and poor/no oral intake. Reduced oral intake can result in malnutrition, dehydration, arrhythmias, and increased risk of infections. Furthermore, chronic catatonic episodes are more difficult to treat.12 In addition to the aggressive management of neuropsychiatric symptoms, it is vital to evaluate relevant medical etiologies that may be contributing to the syndrome (Table 213). Tracking vital signs and laboratory values, such as creatine kinase, electrolytes, and complete blood count, is required to ensure the medical condition does not become life-threatening.

Treatment options

Studies and expert opinion suggest that benzodiazepines (specifically lorazepam, because it is the most studied agent) are the first-line treatment for catatonia. A lorazepam challenge test—providing 1 or 2 mg of IV lorazepam—is considered diagnostic and therapeutic given the high rate of response within 10 minutes.14 Patients with limited response to lorazepam or who are medically compromised should undergo ECT. Electroconvulsive therapy is considered the gold-standard treatment for catatonia; estimated response rates range from 59% to 100%, even in patients who fail to respond to pharmacotherapy.15 Although highly effective, ECT is often hindered by the time required to initiate treatment, stigma, lack of access, and other logistical challenges.

Table 314-18 highlights the advantages and disadvantages of treatment options for catatonia. Some researchers have suggested a zolpidem challenge test could augment lorazepam because some patients respond only to zolpidem.14 The efficacy of these medications along with some evidence of anti-N-methyl-

Ms. N was ultimately diagnosed with bipolar disorder, current episode mixed, with psychotic and catatonic features. Ms. N had symptoms of mania including grandiosity, periods of lack of sleep, delusions as well as depressive symptoms of tearfulness and low mood. The treatment team had considered that Ms. N had delirious mania because she had fluctuating sensorium, which included varying degrees of orientation and ability to answer questioning. However, the literature supporting the differentiation between delirious mania and excited catatonia is unclear, and both conditions may respond to ECT.18 A diagnosis of catatonia allowed the team to use rating scales to track Ms. N’s progress by monitoring for specific signs, such as grasp reflex and waxy flexibility.

Continue to: OUTCOME

OUTCOME Return to baseline

Before discharge, Ms. N’s BFCRS score decreases from the initial score of 17 to 0, and her KANNER scale score decreases from the initial score of 26 to 4, which correlates with vast improvement in clinical presentation. Once Ms. N completes the acute ECT treatment, she returns to her baseline level of functioning, and is discharged to live with her boyfriend. She is advised to continue weekly ECT for the first several months to ensure clinical stability. This regimen is later transitioned to biweekly and then monthly. Electroconvulsive therapy protocols from previous research were utilized in Ms. N’s case, but ultimately the lowest number of ECT treatments needed to maintain stability is determined clinically over many years.19 Ms. N is discharged on aripiprazole, 15 mg/d; bupropion ER, 300 mg/d (added after depressive symptoms emerge while catatonia symptoms improve midway through her lengthy hospitalization); and memantine, 10 mg/d. Ideally, clozapine would have been continued; however, due to her history of nonadherence and frequent restarting of the medication at a low dose, clozapine was discontinued and aripiprazole initiated.

More than 1 year later, Ms. N remains stable and continues to receive monthly ECT maintenance treatments.

Bottom Line

Catatonia should always be considered in a patient who presents with acute neuropsychiatric symptoms. Rapid diagnosis with standardized screening instruments and aggressive treatment are vital to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Related Resource

- Freudenreich O, Francis A, Fricchione GL. Chapter 9. Psychosis, mania, and catatonia. In: Levenson, James L, ed. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine and consultation-liaison psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Baclofen • Ozobax

Bupropion ER • Wellbutrin XL

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lorazepam • Ativan

Metoclopramide • Reglan

Memantine • Namenda

Topiramate • Topamax

Zolpidem • Ambien

CASE Aggressive behaviors, psychosis

Ms. N, age 58, has a long history of bipolar disorder with psychotic features. She presents to our emergency department (ED) after an acute fall and frequent violent behaviors at her nursing home, where she had resided since being diagnosed with an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. For several weeks before her fall, she was physically aggressive, throwing objects at nursing home staff, and was unable to have her behavior redirected.

While in the ED, Ms. N rambles and appears to be responding to internal stimuli. Suddenly, she stops responding and begins to stare.

HISTORY Severe, chronic psychosis and hospitalization

Ms. N is well-known at our inpatient psychiatry and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) services. During the last 10 years, she has had worsening manic, psychotic, and catatonic (both excited and stuporous subtype) episodes. Three years ago, she had experienced a period of severe, chronic psychosis and excited catatonia that required extended inpatient treatment. While hospitalized, Ms. N had marginal responses to clozapine and benzodiazepines, but improved dramatically with ECT. After Ms. N left the hospital, she went to live with her boyfriend. She remained stable on monthly maintenance ECT treatments (bifrontal) before she was lost to follow-up 14 months prior to the current presentation. Ms. N’s family reports that she needed a cardiac clearance before continuing ECT treatment; however, she was hospitalized at another hospital with pneumonia and subsequent complications that interrupted the maintenance ECT treatments.

Approximately 3 months after medical issues requiring hospitalization began, Ms. N received a diagnosis of neurocognitive disorder due to difficulty with activities of daily living and cognitive decline. She was transferred to a nursing home by the outside hospital. When Ms. N’s symptoms of psychosis returned and she required inpatient psychiatric care, she was transferred to a nearby facility that did not have ECT available or knowledge of her history of catatonia resistant to pharmacologic management. Ms. N had a documented history of catatonia that spanned 10 years. During the last 4 years, Ms. N often required ECT treatment. Her current medication regimen prescribed by an outpatient psychiatrist includes clozapine, 300 mg twice daily, and clonazepam, 0.5 mg twice daily, both for bipolar disorder.

EVALUATION An unusual mix of symptoms

In the ED, Ms. N undergoes a CT of the head, which is found to be nonacute. Laboratory results show that her white blood cell count is 14.3 K/µL, which is mildly elevated. Results from a urinalysis and electrocardiogram (ECG) are unremarkable.

After Ms. N punches a radiology technician, she is administered IV lorazepam, 2 mg once, for her agitation. Twenty minutes after receiving IV lorazepam, she is calm and cooperative. However, approximately 4 hours later, Ms. N is yelling, tearful, and expressing delusions of grandeur—she believes she is God.

After she is admitted to the medical floor, Ms. N is seen by our consultation and liaison psychiatry service. She exhibits several signs of catatonia, including grasp reflex, gegenhalten (oppositional paratonia), waxy flexibility, and echolalia. Ms. N also has an episode of urinary incontinence. At some parts of the day, she is alert and oriented to self and location; at other times, she is somnolent and disoriented. The treatment team continues Ms. N’s previous medication regimen of clozapine, 300 mg twice daily, and clonazepam, 0.5 mg twice daily. Unfortunately, at times Ms. N spits out and hides her administered oral medications, which leads to the decision to discontinue clozapine. Once medically cleared, Ms. N is transferred to the psychiatric floor.

[polldaddy:10869949]

Continue to: TREATMENT

TREATMENT Bifrontal ECT initiated

On hospital Day 3 Ms. N is administered a trial of IM lorazepam, titrated up to 6 mg/d (maximum tolerated dose) while the treatment team initiates the legal process to conduct ECT because she is unable to give consent. Once Ms. N begins tolerating oral medications, amantadine, 100 mg twice daily, is added to treat her catatonia. As in prior hospitalizations, Ms. N is unresponsive to pharmacotherapy alone for her catatonic symptoms. On hospital Day 8, forced ECT is granted, which is 5 days after the process of filing paperwork was started. Bifrontal ECT is utilized with the following settings: frequency 70 Hz, pulse width 1.5 ms, 100% energy dose, 504 mC. Ms. N does not experience a significant improvement until she receives 10 ECT treatments as part of a 3-times-per-week acute series protocol. The Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) and the KANNER scale are used to monitor her progress. Her initial BFCRS score is 17 and initial KANNER scale, part 2 score is 26.

Ms. N spends a total of 61 days in the hospital, which is significantly longer than her previous hospital admissions on our psychiatric unit; these previous admissions were for treatment of both stuporous and excited subtypes of catatonia. This increased length of stay coincides with a significantly longer duration of untreated catatonia. Knowledge of her history of both the stuporous and excited subtypes of catatonia would have allowed for faster diagnosis and treatment.1

The authors’ observations

Originally conceptualized as a separate syndrome by Karl Kahlbaum, catatonia was considered only as a specifier for neuropsychiatric conditions (primarily schizophrenia) as recently as DSM-IV-TR.2 DSM-5 describes catatonia as a marked psychomotor disturbance and acknowledges its connection to schizophrenia by keeping it in the same chapter.3 DSM-5 includes separate diagnoses for catatonia, catatonia due to a general medical condition, and unspecified catatonia (for catatonia without a known underlying disorder).3 A recent meta-analysis found the prevalence of catatonia is higher in patients with medical/neurologic illness, bipolar disorder, and autism than in those with schizophrenia.4

Table 13 highlights the DSM-5 criteria for catatonia. DSM-5 requires 3 of 12 symptoms to be present, although symptoms may fluctuate with time.3 If a clinician is not specifically looking for catatonia, it can be a difficult syndrome to diagnose. Does rigidity indicate catatonia, or excessive dopamine blockade from an antipsychotic? How can seemingly contradictory symptoms be part of the same syndrome? Many clinicians associate catatonia with the stuporous subtype (immobility, posturing, catalepsy), which is more prevalent, but the excited subtype, which may involve severe agitation, autonomic dysfunction, and impaired consciousness, can be lethal.2 The diversity in presentation of catatonia is not unlike the challenging variety of symptoms of heart attacks.

A retrospective study of all adults admitted to a hospital found that only 41% of patients who met criteria for catatonia received this diagnosis.5 Further complicating the diagnosis, delirium and catatonia can co-exist; one study found this was the case in 1 of 3 critically ill patients.6 DSM-5 criteria for catatonia due to another medical condition exclude the diagnosis if delirium is present, but this study and others suggest this needs to be reconsidered.3

Continue to: A standardized evaluation is key

A standardized evaluation is key