User login

Racial, ethnic disparities in maternal mortality, morbidity persist

Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal and infant outcomes persist in the United States, with Black women being 3-4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes, compared with Latina and non-Latina white women, Elizabeth Howell, MD, said in a presentation at the 2020 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Location matters, too, and ethnic disparities appear to transcend class, said Dr. Howell of Penn Medicine, Philadelphia. In New York City, for example, Black women are 8-12 times more likely to die than white women regardless of educational attainment.

Dr. Howell cited the definitions of health equity and health disparities as defined by Paula Braveman, MD, in 2014 in the journal Public Health Reports, as follows: “Health equity means social justice in health (i.e., no one is denied the possibility to be healthy for belonging to a group that has historically been economically/socially disadvantaged. Health disparities are the metric we use to measure progress toward achieving health equity.”

Structural racism and discrimination contribute to disparities in maternal and infant morbidity and mortality in several ways, she said. Patient factors include sociodemographics, age, education, poverty, insurance, marital status, language, and literacy. In addition, a patient’s knowledge, beliefs, and health behaviors, as well as stress and self-efficacy are involved. Community factors such as crime, poverty, and community support play a role.

“These factors contribute to the health status of a woman when she becomes pregnant,” Dr. Howell said. “These factors contribute as the woman goes through the health system.”

Then provider factors that impact maternal and infant morbidity and mortality include knowledge, experience, implicit bias, cultural humility, and communication; these factors affect the quality and delivery of neonatal care, and can impact outcomes, Dr. Howell said.

“It is really important to note that many of these pregnancy-related deaths are thought to be preventable,” she said. “They are often caused by delays in diagnosis, problems with communication, and other system failures. Site care has received a great deal of attention” in recent years, the ob.gyn. noted.

How hospital quality contributes to health disparities

Dr. Howell shared data from a pair of National Institutes of Health–funded parallel group studies she conducted at New York City hospitals to investigate the contribution of hospital quality to health disparities in severe maternal morbidity and very preterm birth (prior to 32 weeks).

The researchers used vital statistics linked with discharge abstracts for all New York City deliveries between 2011-2013 and 2010-2014. They conducted a logistic regression analysis and ranked hospitals based on metrics of severe maternal morbidity and very preterm birth, and assessed differences by race in each delivery location.

Overall, Black women were almost three times as likely and Latina women were almost twice as likely as White women to experience some type of severe maternal morbidity, with rates of 4.2%, 2.7%, and 1.5%, respectively.

The researchers also ranked hospitals, and found a wide variation; women delivering in the lowest-ranked hospitals had six times the rate of severe maternal morbidity. They also conducted a simulation/thought exercise and determined that the hospital of delivery accounted for approximately 48% of the disparity in severe maternal morbidity between Black and White women.

Results were similar in the parallel study of very preterm birth rates in New York City hospitals, which were 32%, 28%, and 23% for Black, Latina, and White women, respectively.

The researchers also conducted interviews with personnel including chief medical officers, neonatal ICU directors, nurses, and respiratory therapists. The final phase of the research, which is ongoing, is the dissemination of the information, said Dr. Howell.

Overall, the high-performing hospitals were more likely to focus on standards and standardized care, stronger nurse/physician communication, greater awareness of the potential impact of racism on care, and greater sharing of performance data.

Women who participated in focus groups reported a range of experiences, but women of color were likely to report poor communication, feeling traumatized, and not being heard.

Study implications

Dr. Howell discussed the implications of her study in a question and answer session. “It is incredibly important for us to think about all the levers that we have to address disparities.”

“It is a complex web of factors, but quality of care is one of those mechanisms, and it is something we can do something about,” she noted.

In response to a question about whether women should know the rates of adverse outcomes at various hospitals, she said, “I think we have a responsibility to come up with quality of care measures that are informative to the women we care for.”

Much of obstetric quality issues focus on overuse of resources, “but that doesn’t help us reduce disparities,” she said.

Dr. Howell had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal and infant outcomes persist in the United States, with Black women being 3-4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes, compared with Latina and non-Latina white women, Elizabeth Howell, MD, said in a presentation at the 2020 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Location matters, too, and ethnic disparities appear to transcend class, said Dr. Howell of Penn Medicine, Philadelphia. In New York City, for example, Black women are 8-12 times more likely to die than white women regardless of educational attainment.

Dr. Howell cited the definitions of health equity and health disparities as defined by Paula Braveman, MD, in 2014 in the journal Public Health Reports, as follows: “Health equity means social justice in health (i.e., no one is denied the possibility to be healthy for belonging to a group that has historically been economically/socially disadvantaged. Health disparities are the metric we use to measure progress toward achieving health equity.”

Structural racism and discrimination contribute to disparities in maternal and infant morbidity and mortality in several ways, she said. Patient factors include sociodemographics, age, education, poverty, insurance, marital status, language, and literacy. In addition, a patient’s knowledge, beliefs, and health behaviors, as well as stress and self-efficacy are involved. Community factors such as crime, poverty, and community support play a role.

“These factors contribute to the health status of a woman when she becomes pregnant,” Dr. Howell said. “These factors contribute as the woman goes through the health system.”

Then provider factors that impact maternal and infant morbidity and mortality include knowledge, experience, implicit bias, cultural humility, and communication; these factors affect the quality and delivery of neonatal care, and can impact outcomes, Dr. Howell said.

“It is really important to note that many of these pregnancy-related deaths are thought to be preventable,” she said. “They are often caused by delays in diagnosis, problems with communication, and other system failures. Site care has received a great deal of attention” in recent years, the ob.gyn. noted.

How hospital quality contributes to health disparities

Dr. Howell shared data from a pair of National Institutes of Health–funded parallel group studies she conducted at New York City hospitals to investigate the contribution of hospital quality to health disparities in severe maternal morbidity and very preterm birth (prior to 32 weeks).

The researchers used vital statistics linked with discharge abstracts for all New York City deliveries between 2011-2013 and 2010-2014. They conducted a logistic regression analysis and ranked hospitals based on metrics of severe maternal morbidity and very preterm birth, and assessed differences by race in each delivery location.

Overall, Black women were almost three times as likely and Latina women were almost twice as likely as White women to experience some type of severe maternal morbidity, with rates of 4.2%, 2.7%, and 1.5%, respectively.

The researchers also ranked hospitals, and found a wide variation; women delivering in the lowest-ranked hospitals had six times the rate of severe maternal morbidity. They also conducted a simulation/thought exercise and determined that the hospital of delivery accounted for approximately 48% of the disparity in severe maternal morbidity between Black and White women.

Results were similar in the parallel study of very preterm birth rates in New York City hospitals, which were 32%, 28%, and 23% for Black, Latina, and White women, respectively.

The researchers also conducted interviews with personnel including chief medical officers, neonatal ICU directors, nurses, and respiratory therapists. The final phase of the research, which is ongoing, is the dissemination of the information, said Dr. Howell.

Overall, the high-performing hospitals were more likely to focus on standards and standardized care, stronger nurse/physician communication, greater awareness of the potential impact of racism on care, and greater sharing of performance data.

Women who participated in focus groups reported a range of experiences, but women of color were likely to report poor communication, feeling traumatized, and not being heard.

Study implications

Dr. Howell discussed the implications of her study in a question and answer session. “It is incredibly important for us to think about all the levers that we have to address disparities.”

“It is a complex web of factors, but quality of care is one of those mechanisms, and it is something we can do something about,” she noted.

In response to a question about whether women should know the rates of adverse outcomes at various hospitals, she said, “I think we have a responsibility to come up with quality of care measures that are informative to the women we care for.”

Much of obstetric quality issues focus on overuse of resources, “but that doesn’t help us reduce disparities,” she said.

Dr. Howell had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal and infant outcomes persist in the United States, with Black women being 3-4 times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes, compared with Latina and non-Latina white women, Elizabeth Howell, MD, said in a presentation at the 2020 virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Location matters, too, and ethnic disparities appear to transcend class, said Dr. Howell of Penn Medicine, Philadelphia. In New York City, for example, Black women are 8-12 times more likely to die than white women regardless of educational attainment.

Dr. Howell cited the definitions of health equity and health disparities as defined by Paula Braveman, MD, in 2014 in the journal Public Health Reports, as follows: “Health equity means social justice in health (i.e., no one is denied the possibility to be healthy for belonging to a group that has historically been economically/socially disadvantaged. Health disparities are the metric we use to measure progress toward achieving health equity.”

Structural racism and discrimination contribute to disparities in maternal and infant morbidity and mortality in several ways, she said. Patient factors include sociodemographics, age, education, poverty, insurance, marital status, language, and literacy. In addition, a patient’s knowledge, beliefs, and health behaviors, as well as stress and self-efficacy are involved. Community factors such as crime, poverty, and community support play a role.

“These factors contribute to the health status of a woman when she becomes pregnant,” Dr. Howell said. “These factors contribute as the woman goes through the health system.”

Then provider factors that impact maternal and infant morbidity and mortality include knowledge, experience, implicit bias, cultural humility, and communication; these factors affect the quality and delivery of neonatal care, and can impact outcomes, Dr. Howell said.

“It is really important to note that many of these pregnancy-related deaths are thought to be preventable,” she said. “They are often caused by delays in diagnosis, problems with communication, and other system failures. Site care has received a great deal of attention” in recent years, the ob.gyn. noted.

How hospital quality contributes to health disparities

Dr. Howell shared data from a pair of National Institutes of Health–funded parallel group studies she conducted at New York City hospitals to investigate the contribution of hospital quality to health disparities in severe maternal morbidity and very preterm birth (prior to 32 weeks).

The researchers used vital statistics linked with discharge abstracts for all New York City deliveries between 2011-2013 and 2010-2014. They conducted a logistic regression analysis and ranked hospitals based on metrics of severe maternal morbidity and very preterm birth, and assessed differences by race in each delivery location.

Overall, Black women were almost three times as likely and Latina women were almost twice as likely as White women to experience some type of severe maternal morbidity, with rates of 4.2%, 2.7%, and 1.5%, respectively.

The researchers also ranked hospitals, and found a wide variation; women delivering in the lowest-ranked hospitals had six times the rate of severe maternal morbidity. They also conducted a simulation/thought exercise and determined that the hospital of delivery accounted for approximately 48% of the disparity in severe maternal morbidity between Black and White women.

Results were similar in the parallel study of very preterm birth rates in New York City hospitals, which were 32%, 28%, and 23% for Black, Latina, and White women, respectively.

The researchers also conducted interviews with personnel including chief medical officers, neonatal ICU directors, nurses, and respiratory therapists. The final phase of the research, which is ongoing, is the dissemination of the information, said Dr. Howell.

Overall, the high-performing hospitals were more likely to focus on standards and standardized care, stronger nurse/physician communication, greater awareness of the potential impact of racism on care, and greater sharing of performance data.

Women who participated in focus groups reported a range of experiences, but women of color were likely to report poor communication, feeling traumatized, and not being heard.

Study implications

Dr. Howell discussed the implications of her study in a question and answer session. “It is incredibly important for us to think about all the levers that we have to address disparities.”

“It is a complex web of factors, but quality of care is one of those mechanisms, and it is something we can do something about,” she noted.

In response to a question about whether women should know the rates of adverse outcomes at various hospitals, she said, “I think we have a responsibility to come up with quality of care measures that are informative to the women we care for.”

Much of obstetric quality issues focus on overuse of resources, “but that doesn’t help us reduce disparities,” she said.

Dr. Howell had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM ACOG 2020

TRANSforming gynecology: An introduction to hormone therapy for the obstetrician/gynecologist

Incorporating gender-nonconforming patients into practice can seem like a daunting task at first. However, obstetricians/gynecologists, midwives, and other advanced women’s health care practitioners can provide quality care for both transgender men and women. Basic preventative services such as routine health and cancer screening and testing for sexually transmitted infections does not require specialized training in transgender health. In fact, administration of hormonal therapy and some surgical interventions are well within the scope of practice of the general obstetrician/gynecologist, as long as the provider has undergone appropriate training to achieve expertise. For example, organizations such as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) not only provides standards of care regarding the treatment of transgender individuals, but they also have training and educational opportunities targeted at providers who wish to become certified in more advanced care of the transgender patient. If an obstetrician/gynecologist is interested in prescribing hormone therapy, seeking further training within the field is a must.

It is important to remember that the process by which transgender individuals express their gender is a spectrum. Not all patients who identify as transgender will seek hormone therapy or surgical procedures. However, even if a provider has not undergone more specific training to administer hormone therapy, it is still very important to have a basic understanding of the hormones, routes of administration, and side effects.

While cross-sex hormone therapy does differ in practice, compared with hormone replacement therapy in cisgender counterparts, the principles are relatively similar. Testosterone therapy is the mainstay treatment for transgender men who desire medical transition.1,2 The overall goal of therapy is to achieve testosterone levels within the cisgender male physiologic range (300-1000 ng/dL). While the most common route of administration is subcutaneous or intramuscular injections in weekly, biweekly, or quarterly intervals, other routes may include daily transdermal patches and gels or oral formulations.1 Within the first few months of use, patients will notice signs of masculinization such as increased facial and body hair, increased muscle mass, increased libido, and amenorrhea. Other changes include male-pattern hair loss, clitoromegaly, redistribution of fat, voice deepening, and mood changes.1

Hormone therapy for transgender women is a bit more complicated as estrogen alone will often not achieve feminizing characteristics that are satisfying for patients.3 Estrogen therapy can include oral formulations of 17-beta estradiol or conjugated estrogens, although the latter is typically avoided because of the marked increase in thromboembolic events. Estrogens can also be administered in sublingual, intramuscular, or transdermal forms. Antiandrogens are often required to help decrease endogenous testosterone levels to cisgender female levels (30-100 ng/dL).3 Spironolactone is most commonly prescribed as an adjunct to estrogen therapy. Finasteride and GnRH agonists like leuprolide acetate can also be added if spironolactone is not effective or not tolerated by the patient. Feminizing effects of estrogen can take several months and most commonly include decreased spontaneous erections, decreased libido, breast growth, redistribution of fat to the waist and hips, decreased skin oiliness, and softening of the skin.3

Overall, hormone therapy for both transgender men and women is considered effective, safe, and well tolerated.4 Monitoring is typically performed every 3 months within the first year after initiating hormone therapy, and then continued every 6-12 months thereafter. Routine screening for all organs and tissues present (e.g. prostate, breast) should be undertaken.3 While this simply highlights the therapy and surveillance for patients, it is important to remember that many transgender men and women will see an obstetrician/gynecologist at some interval during their transition. Ultimately, it is paramount that we as obstetricians/gynecologists have a basic understanding of the treatments available so we can provide our patients with competent and compassionate care.

Dr. Brandt is an obstetrician/gynecologist and a plastic surgeon at Reading Hospital/Tower Health System in West Reading, Pa., where she has developed a gender-affirming medical and surgical clinic for ob.gyn. residents and plastic surgeon fellows.

References

1. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people. 7th version. Accessed 10/15/20.

2. Joint meeting of the International Society of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society 2014; ICE/ENDO 2014, Paper 14354. Accessed 01/08/16.

3. Qian R, Safer JD. Hormone treatment for the adult transgender patient, in “Comprehensive Care of the Transgender Patient,” 1st ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020, pp. 34-6.

4. Weinand JD and Safer JD. Hormone therapy in transgender adults is safe with provider supervision: A review of hormone therapy sequelae for transgender individuals. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015;2(2):55-60.

Incorporating gender-nonconforming patients into practice can seem like a daunting task at first. However, obstetricians/gynecologists, midwives, and other advanced women’s health care practitioners can provide quality care for both transgender men and women. Basic preventative services such as routine health and cancer screening and testing for sexually transmitted infections does not require specialized training in transgender health. In fact, administration of hormonal therapy and some surgical interventions are well within the scope of practice of the general obstetrician/gynecologist, as long as the provider has undergone appropriate training to achieve expertise. For example, organizations such as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) not only provides standards of care regarding the treatment of transgender individuals, but they also have training and educational opportunities targeted at providers who wish to become certified in more advanced care of the transgender patient. If an obstetrician/gynecologist is interested in prescribing hormone therapy, seeking further training within the field is a must.

It is important to remember that the process by which transgender individuals express their gender is a spectrum. Not all patients who identify as transgender will seek hormone therapy or surgical procedures. However, even if a provider has not undergone more specific training to administer hormone therapy, it is still very important to have a basic understanding of the hormones, routes of administration, and side effects.

While cross-sex hormone therapy does differ in practice, compared with hormone replacement therapy in cisgender counterparts, the principles are relatively similar. Testosterone therapy is the mainstay treatment for transgender men who desire medical transition.1,2 The overall goal of therapy is to achieve testosterone levels within the cisgender male physiologic range (300-1000 ng/dL). While the most common route of administration is subcutaneous or intramuscular injections in weekly, biweekly, or quarterly intervals, other routes may include daily transdermal patches and gels or oral formulations.1 Within the first few months of use, patients will notice signs of masculinization such as increased facial and body hair, increased muscle mass, increased libido, and amenorrhea. Other changes include male-pattern hair loss, clitoromegaly, redistribution of fat, voice deepening, and mood changes.1

Hormone therapy for transgender women is a bit more complicated as estrogen alone will often not achieve feminizing characteristics that are satisfying for patients.3 Estrogen therapy can include oral formulations of 17-beta estradiol or conjugated estrogens, although the latter is typically avoided because of the marked increase in thromboembolic events. Estrogens can also be administered in sublingual, intramuscular, or transdermal forms. Antiandrogens are often required to help decrease endogenous testosterone levels to cisgender female levels (30-100 ng/dL).3 Spironolactone is most commonly prescribed as an adjunct to estrogen therapy. Finasteride and GnRH agonists like leuprolide acetate can also be added if spironolactone is not effective or not tolerated by the patient. Feminizing effects of estrogen can take several months and most commonly include decreased spontaneous erections, decreased libido, breast growth, redistribution of fat to the waist and hips, decreased skin oiliness, and softening of the skin.3

Overall, hormone therapy for both transgender men and women is considered effective, safe, and well tolerated.4 Monitoring is typically performed every 3 months within the first year after initiating hormone therapy, and then continued every 6-12 months thereafter. Routine screening for all organs and tissues present (e.g. prostate, breast) should be undertaken.3 While this simply highlights the therapy and surveillance for patients, it is important to remember that many transgender men and women will see an obstetrician/gynecologist at some interval during their transition. Ultimately, it is paramount that we as obstetricians/gynecologists have a basic understanding of the treatments available so we can provide our patients with competent and compassionate care.

Dr. Brandt is an obstetrician/gynecologist and a plastic surgeon at Reading Hospital/Tower Health System in West Reading, Pa., where she has developed a gender-affirming medical and surgical clinic for ob.gyn. residents and plastic surgeon fellows.

References

1. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people. 7th version. Accessed 10/15/20.

2. Joint meeting of the International Society of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society 2014; ICE/ENDO 2014, Paper 14354. Accessed 01/08/16.

3. Qian R, Safer JD. Hormone treatment for the adult transgender patient, in “Comprehensive Care of the Transgender Patient,” 1st ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020, pp. 34-6.

4. Weinand JD and Safer JD. Hormone therapy in transgender adults is safe with provider supervision: A review of hormone therapy sequelae for transgender individuals. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015;2(2):55-60.

Incorporating gender-nonconforming patients into practice can seem like a daunting task at first. However, obstetricians/gynecologists, midwives, and other advanced women’s health care practitioners can provide quality care for both transgender men and women. Basic preventative services such as routine health and cancer screening and testing for sexually transmitted infections does not require specialized training in transgender health. In fact, administration of hormonal therapy and some surgical interventions are well within the scope of practice of the general obstetrician/gynecologist, as long as the provider has undergone appropriate training to achieve expertise. For example, organizations such as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) not only provides standards of care regarding the treatment of transgender individuals, but they also have training and educational opportunities targeted at providers who wish to become certified in more advanced care of the transgender patient. If an obstetrician/gynecologist is interested in prescribing hormone therapy, seeking further training within the field is a must.

It is important to remember that the process by which transgender individuals express their gender is a spectrum. Not all patients who identify as transgender will seek hormone therapy or surgical procedures. However, even if a provider has not undergone more specific training to administer hormone therapy, it is still very important to have a basic understanding of the hormones, routes of administration, and side effects.

While cross-sex hormone therapy does differ in practice, compared with hormone replacement therapy in cisgender counterparts, the principles are relatively similar. Testosterone therapy is the mainstay treatment for transgender men who desire medical transition.1,2 The overall goal of therapy is to achieve testosterone levels within the cisgender male physiologic range (300-1000 ng/dL). While the most common route of administration is subcutaneous or intramuscular injections in weekly, biweekly, or quarterly intervals, other routes may include daily transdermal patches and gels or oral formulations.1 Within the first few months of use, patients will notice signs of masculinization such as increased facial and body hair, increased muscle mass, increased libido, and amenorrhea. Other changes include male-pattern hair loss, clitoromegaly, redistribution of fat, voice deepening, and mood changes.1

Hormone therapy for transgender women is a bit more complicated as estrogen alone will often not achieve feminizing characteristics that are satisfying for patients.3 Estrogen therapy can include oral formulations of 17-beta estradiol or conjugated estrogens, although the latter is typically avoided because of the marked increase in thromboembolic events. Estrogens can also be administered in sublingual, intramuscular, or transdermal forms. Antiandrogens are often required to help decrease endogenous testosterone levels to cisgender female levels (30-100 ng/dL).3 Spironolactone is most commonly prescribed as an adjunct to estrogen therapy. Finasteride and GnRH agonists like leuprolide acetate can also be added if spironolactone is not effective or not tolerated by the patient. Feminizing effects of estrogen can take several months and most commonly include decreased spontaneous erections, decreased libido, breast growth, redistribution of fat to the waist and hips, decreased skin oiliness, and softening of the skin.3

Overall, hormone therapy for both transgender men and women is considered effective, safe, and well tolerated.4 Monitoring is typically performed every 3 months within the first year after initiating hormone therapy, and then continued every 6-12 months thereafter. Routine screening for all organs and tissues present (e.g. prostate, breast) should be undertaken.3 While this simply highlights the therapy and surveillance for patients, it is important to remember that many transgender men and women will see an obstetrician/gynecologist at some interval during their transition. Ultimately, it is paramount that we as obstetricians/gynecologists have a basic understanding of the treatments available so we can provide our patients with competent and compassionate care.

Dr. Brandt is an obstetrician/gynecologist and a plastic surgeon at Reading Hospital/Tower Health System in West Reading, Pa., where she has developed a gender-affirming medical and surgical clinic for ob.gyn. residents and plastic surgeon fellows.

References

1. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people. 7th version. Accessed 10/15/20.

2. Joint meeting of the International Society of Endocrinology and the Endocrine Society 2014; ICE/ENDO 2014, Paper 14354. Accessed 01/08/16.

3. Qian R, Safer JD. Hormone treatment for the adult transgender patient, in “Comprehensive Care of the Transgender Patient,” 1st ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020, pp. 34-6.

4. Weinand JD and Safer JD. Hormone therapy in transgender adults is safe with provider supervision: A review of hormone therapy sequelae for transgender individuals. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015;2(2):55-60.

Reproductive Rounds: Understanding antimüllerian hormone in ovarian-age testing

In reproductive medicine, there are few, if any, more pressing concerns from our patients than the biological clock, i.e., ovarian aging. While addressing this issue with women can be challenging, particularly for those who are anxious regarding their advanced maternal age, gynecologists must possess a thorough understanding of available diagnostic testing. This article will review the various methods to assess ovarian age and appropriate clinical management.

Ovarian reserve tests

Ovarian reserve represents the quality and quantity of oocytes. The former is defined by the woman’s chronologic age, which is the greatest predictor of fertility. From a peak monthly fecundity rate at age 30 of approximately 20%, the slow and steady decline of fertility ensues. Quantity represents the number of oocytes remaining from the original cohort.

Ovarian reserve is most provocatively gauged by the follicle response to gonadotropin stimulation, typically during an in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle.

Several biomarkers have been used to assess ovarian age. These include FSH, estradiol, and inhibin B. In general, these tests are more specific than sensitive, i.e., “normal” results do not necessarily exclude decreased ovarian reserve. But as a screening tool for decreased ovarian reserve, the most important factor is the positive predictive value (PPV). Statistically, in a population of women at low risk for decreased ovarian reserve, the PPV will be low despite sensitivity and specificity.

While inhibin B is a more direct and earlier reflection of ovarian function produced by granulose cells, assays lacked consistent results and a standardized cut-off value. FSH is the last biomarker to be affected by decreased ovarian reserve so elevations reflect more “end-stage” ovarian aging.

Additional tests for decreased ovarian reserve include antral follicle count (AFC) and the clomiphene citrate challenge test (CCCT). AFC is determined by using transvaginal ultrasound to count the number of follicular cysts in the 2- to 9-mm range. While AFC can be performed on any day of the cycle, the ovary is most optimally measured on menses because of less cystic activity. A combined AFC of 3-6 is considered severe decreased ovarian reserve. The CCCT involves prescribing clomiphene citrate 100 mg daily from cycle day 5-9 to measure FSH on cycle days 3 and 10. An FSH level greater than 10 IU/L or any elevation in FSH following CCCT is considered decreased ovarian reserve.

FSH had been the standard but levels may dramatically change monthly, making testing only valuable if it is elevated. Consequently, antimüllerian hormone (AMH) and AFC are considered the most useful tools to determine decreased ovarian reserve because of less variability. The other distinct advantage is the ability to obtain AMH any day in the menstrual cycle. Recently, in women undergoing IVF, AMH was superior to FSH in predicting live birth, particularly when their values were discordant (J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:60). While there is no established consensus, the ideal interval for repeating AMH appears to be approximately 3 months (Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:65S-6S).

AMH

AMH is expressed in the embryo at 8 weeks by the Sertoli cells of the testis causing the female reproductive internal system (müllerian) to regress. Without AMH expression, the müllerian system remains and the male (woffian duct system) regresses. The discovery of AMH production by the granulosa cells of the ovary launched a new era in the evaluation and management of infertile women. First reported in Fertility & Sterility in 2002 as a much earlier potential marker of ovarian aging, low levels of AMH predict a lower number of eggs in IVF.

AMH levels are produced in the embryo at 36 weeks’ gestation and increase up to the age of 24.5 years, decreasing thereafter. AMH reflects primordial (early) follicles that are FSH independent. The median AMH level decreases per year according to age groups are: 0.25 ng/mL in ages 26-30; 0.2 ng/mL in ages 31-36 years; and 0.1 ng/mL above age 36. (PLOS ONE 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125216).

AMH has also been studied as a potential biomarker to diagnose PCOS. While many women with PCOS have elevated AMH levels (typically greater than 3 ng/mL), there is no consensus on an AMH value that would be a criterion.

Many women, particularly those electing to defer fertility, express interest in obtaining their AMH level to consider planned oocyte cryopreservation, AKA, social egg freezing. While it is possible the results of AMH screening may compel women to electively freeze their eggs, extensive counseling on the implications and pitfalls of AMH levels is essential. Further, AMH cannot be used to accurately predict menopause.

Predicting outcomes

No biomarker is necessarily predictive of pregnancy but more a gauge of gonadotropin dosage to induce multifollicular development. AMH is a great predictor of oocyte yield with IVF (J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26[7]:383-9). However, in women older than 35 undergoing IVF, low AMH levels have been shown to reduce pregnancy rates (J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017;10:24–30). During IVF cycle attempts, an ultra-low AMH (≤0.4) resulted in high cancellation rates, reduced the number of oocytes retrieved and embryos developed, and lowered pregnancy rates in women of advanced reproductive age.

Alternatively, a study of 750 women who were not infertile and were actively trying to conceive demonstrated no difference in natural pregnancy rates in women aged 30-44 irrespective of AMH levels (JAMA. 2017;318[14]:1367-76).

A special consideration is for cancer patients who are status postgonadotoxic chemotherapy. Their oocyte attrition can be accelerated and AMH levels can become profoundly low. In those patients, current data suggest there is a modest recovery of postchemotherapy AMH levels up to 1 year. Further, oocyte yield following stimulation may be higher than expected despite a poor AMH level.

Conclusion

Ovarian aging is currently best measured by combining chronologic age, AFC, and AMH. There is no current evidence that AMH levels should be used to exclude patients from undergoing IVF or to recommend egg donation. Random screening of AMH levels in a low-risk population for decreased ovarian reserve may result in unnecessary alarm.

Dr. Trolice is director of Fertility CARE - The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

In reproductive medicine, there are few, if any, more pressing concerns from our patients than the biological clock, i.e., ovarian aging. While addressing this issue with women can be challenging, particularly for those who are anxious regarding their advanced maternal age, gynecologists must possess a thorough understanding of available diagnostic testing. This article will review the various methods to assess ovarian age and appropriate clinical management.

Ovarian reserve tests

Ovarian reserve represents the quality and quantity of oocytes. The former is defined by the woman’s chronologic age, which is the greatest predictor of fertility. From a peak monthly fecundity rate at age 30 of approximately 20%, the slow and steady decline of fertility ensues. Quantity represents the number of oocytes remaining from the original cohort.

Ovarian reserve is most provocatively gauged by the follicle response to gonadotropin stimulation, typically during an in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle.

Several biomarkers have been used to assess ovarian age. These include FSH, estradiol, and inhibin B. In general, these tests are more specific than sensitive, i.e., “normal” results do not necessarily exclude decreased ovarian reserve. But as a screening tool for decreased ovarian reserve, the most important factor is the positive predictive value (PPV). Statistically, in a population of women at low risk for decreased ovarian reserve, the PPV will be low despite sensitivity and specificity.

While inhibin B is a more direct and earlier reflection of ovarian function produced by granulose cells, assays lacked consistent results and a standardized cut-off value. FSH is the last biomarker to be affected by decreased ovarian reserve so elevations reflect more “end-stage” ovarian aging.

Additional tests for decreased ovarian reserve include antral follicle count (AFC) and the clomiphene citrate challenge test (CCCT). AFC is determined by using transvaginal ultrasound to count the number of follicular cysts in the 2- to 9-mm range. While AFC can be performed on any day of the cycle, the ovary is most optimally measured on menses because of less cystic activity. A combined AFC of 3-6 is considered severe decreased ovarian reserve. The CCCT involves prescribing clomiphene citrate 100 mg daily from cycle day 5-9 to measure FSH on cycle days 3 and 10. An FSH level greater than 10 IU/L or any elevation in FSH following CCCT is considered decreased ovarian reserve.

FSH had been the standard but levels may dramatically change monthly, making testing only valuable if it is elevated. Consequently, antimüllerian hormone (AMH) and AFC are considered the most useful tools to determine decreased ovarian reserve because of less variability. The other distinct advantage is the ability to obtain AMH any day in the menstrual cycle. Recently, in women undergoing IVF, AMH was superior to FSH in predicting live birth, particularly when their values were discordant (J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:60). While there is no established consensus, the ideal interval for repeating AMH appears to be approximately 3 months (Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:65S-6S).

AMH

AMH is expressed in the embryo at 8 weeks by the Sertoli cells of the testis causing the female reproductive internal system (müllerian) to regress. Without AMH expression, the müllerian system remains and the male (woffian duct system) regresses. The discovery of AMH production by the granulosa cells of the ovary launched a new era in the evaluation and management of infertile women. First reported in Fertility & Sterility in 2002 as a much earlier potential marker of ovarian aging, low levels of AMH predict a lower number of eggs in IVF.

AMH levels are produced in the embryo at 36 weeks’ gestation and increase up to the age of 24.5 years, decreasing thereafter. AMH reflects primordial (early) follicles that are FSH independent. The median AMH level decreases per year according to age groups are: 0.25 ng/mL in ages 26-30; 0.2 ng/mL in ages 31-36 years; and 0.1 ng/mL above age 36. (PLOS ONE 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125216).

AMH has also been studied as a potential biomarker to diagnose PCOS. While many women with PCOS have elevated AMH levels (typically greater than 3 ng/mL), there is no consensus on an AMH value that would be a criterion.

Many women, particularly those electing to defer fertility, express interest in obtaining their AMH level to consider planned oocyte cryopreservation, AKA, social egg freezing. While it is possible the results of AMH screening may compel women to electively freeze their eggs, extensive counseling on the implications and pitfalls of AMH levels is essential. Further, AMH cannot be used to accurately predict menopause.

Predicting outcomes

No biomarker is necessarily predictive of pregnancy but more a gauge of gonadotropin dosage to induce multifollicular development. AMH is a great predictor of oocyte yield with IVF (J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26[7]:383-9). However, in women older than 35 undergoing IVF, low AMH levels have been shown to reduce pregnancy rates (J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017;10:24–30). During IVF cycle attempts, an ultra-low AMH (≤0.4) resulted in high cancellation rates, reduced the number of oocytes retrieved and embryos developed, and lowered pregnancy rates in women of advanced reproductive age.

Alternatively, a study of 750 women who were not infertile and were actively trying to conceive demonstrated no difference in natural pregnancy rates in women aged 30-44 irrespective of AMH levels (JAMA. 2017;318[14]:1367-76).

A special consideration is for cancer patients who are status postgonadotoxic chemotherapy. Their oocyte attrition can be accelerated and AMH levels can become profoundly low. In those patients, current data suggest there is a modest recovery of postchemotherapy AMH levels up to 1 year. Further, oocyte yield following stimulation may be higher than expected despite a poor AMH level.

Conclusion

Ovarian aging is currently best measured by combining chronologic age, AFC, and AMH. There is no current evidence that AMH levels should be used to exclude patients from undergoing IVF or to recommend egg donation. Random screening of AMH levels in a low-risk population for decreased ovarian reserve may result in unnecessary alarm.

Dr. Trolice is director of Fertility CARE - The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

In reproductive medicine, there are few, if any, more pressing concerns from our patients than the biological clock, i.e., ovarian aging. While addressing this issue with women can be challenging, particularly for those who are anxious regarding their advanced maternal age, gynecologists must possess a thorough understanding of available diagnostic testing. This article will review the various methods to assess ovarian age and appropriate clinical management.

Ovarian reserve tests

Ovarian reserve represents the quality and quantity of oocytes. The former is defined by the woman’s chronologic age, which is the greatest predictor of fertility. From a peak monthly fecundity rate at age 30 of approximately 20%, the slow and steady decline of fertility ensues. Quantity represents the number of oocytes remaining from the original cohort.

Ovarian reserve is most provocatively gauged by the follicle response to gonadotropin stimulation, typically during an in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle.

Several biomarkers have been used to assess ovarian age. These include FSH, estradiol, and inhibin B. In general, these tests are more specific than sensitive, i.e., “normal” results do not necessarily exclude decreased ovarian reserve. But as a screening tool for decreased ovarian reserve, the most important factor is the positive predictive value (PPV). Statistically, in a population of women at low risk for decreased ovarian reserve, the PPV will be low despite sensitivity and specificity.

While inhibin B is a more direct and earlier reflection of ovarian function produced by granulose cells, assays lacked consistent results and a standardized cut-off value. FSH is the last biomarker to be affected by decreased ovarian reserve so elevations reflect more “end-stage” ovarian aging.

Additional tests for decreased ovarian reserve include antral follicle count (AFC) and the clomiphene citrate challenge test (CCCT). AFC is determined by using transvaginal ultrasound to count the number of follicular cysts in the 2- to 9-mm range. While AFC can be performed on any day of the cycle, the ovary is most optimally measured on menses because of less cystic activity. A combined AFC of 3-6 is considered severe decreased ovarian reserve. The CCCT involves prescribing clomiphene citrate 100 mg daily from cycle day 5-9 to measure FSH on cycle days 3 and 10. An FSH level greater than 10 IU/L or any elevation in FSH following CCCT is considered decreased ovarian reserve.

FSH had been the standard but levels may dramatically change monthly, making testing only valuable if it is elevated. Consequently, antimüllerian hormone (AMH) and AFC are considered the most useful tools to determine decreased ovarian reserve because of less variability. The other distinct advantage is the ability to obtain AMH any day in the menstrual cycle. Recently, in women undergoing IVF, AMH was superior to FSH in predicting live birth, particularly when their values were discordant (J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:60). While there is no established consensus, the ideal interval for repeating AMH appears to be approximately 3 months (Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:65S-6S).

AMH

AMH is expressed in the embryo at 8 weeks by the Sertoli cells of the testis causing the female reproductive internal system (müllerian) to regress. Without AMH expression, the müllerian system remains and the male (woffian duct system) regresses. The discovery of AMH production by the granulosa cells of the ovary launched a new era in the evaluation and management of infertile women. First reported in Fertility & Sterility in 2002 as a much earlier potential marker of ovarian aging, low levels of AMH predict a lower number of eggs in IVF.

AMH levels are produced in the embryo at 36 weeks’ gestation and increase up to the age of 24.5 years, decreasing thereafter. AMH reflects primordial (early) follicles that are FSH independent. The median AMH level decreases per year according to age groups are: 0.25 ng/mL in ages 26-30; 0.2 ng/mL in ages 31-36 years; and 0.1 ng/mL above age 36. (PLOS ONE 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125216).

AMH has also been studied as a potential biomarker to diagnose PCOS. While many women with PCOS have elevated AMH levels (typically greater than 3 ng/mL), there is no consensus on an AMH value that would be a criterion.

Many women, particularly those electing to defer fertility, express interest in obtaining their AMH level to consider planned oocyte cryopreservation, AKA, social egg freezing. While it is possible the results of AMH screening may compel women to electively freeze their eggs, extensive counseling on the implications and pitfalls of AMH levels is essential. Further, AMH cannot be used to accurately predict menopause.

Predicting outcomes

No biomarker is necessarily predictive of pregnancy but more a gauge of gonadotropin dosage to induce multifollicular development. AMH is a great predictor of oocyte yield with IVF (J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26[7]:383-9). However, in women older than 35 undergoing IVF, low AMH levels have been shown to reduce pregnancy rates (J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017;10:24–30). During IVF cycle attempts, an ultra-low AMH (≤0.4) resulted in high cancellation rates, reduced the number of oocytes retrieved and embryos developed, and lowered pregnancy rates in women of advanced reproductive age.

Alternatively, a study of 750 women who were not infertile and were actively trying to conceive demonstrated no difference in natural pregnancy rates in women aged 30-44 irrespective of AMH levels (JAMA. 2017;318[14]:1367-76).

A special consideration is for cancer patients who are status postgonadotoxic chemotherapy. Their oocyte attrition can be accelerated and AMH levels can become profoundly low. In those patients, current data suggest there is a modest recovery of postchemotherapy AMH levels up to 1 year. Further, oocyte yield following stimulation may be higher than expected despite a poor AMH level.

Conclusion

Ovarian aging is currently best measured by combining chronologic age, AFC, and AMH. There is no current evidence that AMH levels should be used to exclude patients from undergoing IVF or to recommend egg donation. Random screening of AMH levels in a low-risk population for decreased ovarian reserve may result in unnecessary alarm.

Dr. Trolice is director of Fertility CARE - The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

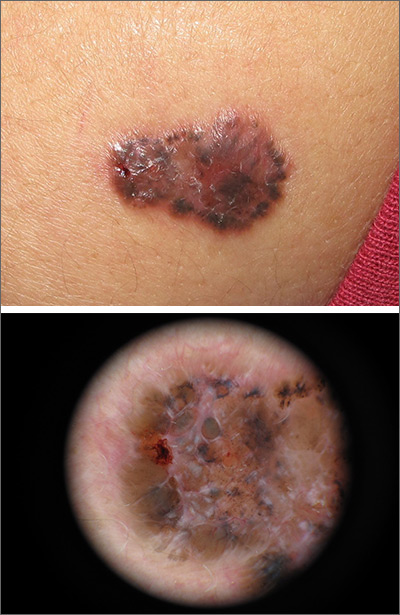

Growing brown and pink plaque

A shave biopsy of the lesion confirmed a nodular and pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC). In the United States, BCC is the most common cancer and accounts for 80% of all skin cancer diagnoses. BCC is also the most widespread cancer in White, Hispanic, and Asian patients and the second most common skin cancer in Black patients.

In all patients, BCC presents as a shiny growing macule, papule, or plaque, usually in areas of sun exposure. Much less is known about the role of UV exposure in skin of color because of the lack of high-quality studies in this population. Despite this, BCC in skin of color most often presents on the head and neck, as it does in non-Hispanic White patients. There is a correlation between lighter skin tones in Black patients and increased numbers of BCC diagnoses.

When assessing a suspicious skin lesion in skin of color, be on the lookout for the following visual cues. Pigmentation, clinically and on dermoscopy, is a more common feature of BCCs in non-White patients—occurring in more than half of all BCCs in skin of color.1 While pigmentation in a skin tumor may be mistaken for melanoma, the blue ovoid nests, brown dots in focus, and brown leaf-like areas on dermoscopy are BCC-specific clues that can alert the clinician to the diagnosis. In all patients, telangiectasias are another hallmark of BCC but may be the only feature in White patients and just one of many features in non-White patients.

In small data sets, there is no difference in tumor-related morbidity and prognosis between White and Black patients with BCC. Additionally, BCCs in White, Asian, and Hispanic patients have had no differences in preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs stages, and outcome.1

In this case, the patient underwent a complete excision with a 5-mm margin. She remained free of new or recurrent BCCs over the next 2 years, with surveillance exams twice a year.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

1. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526.

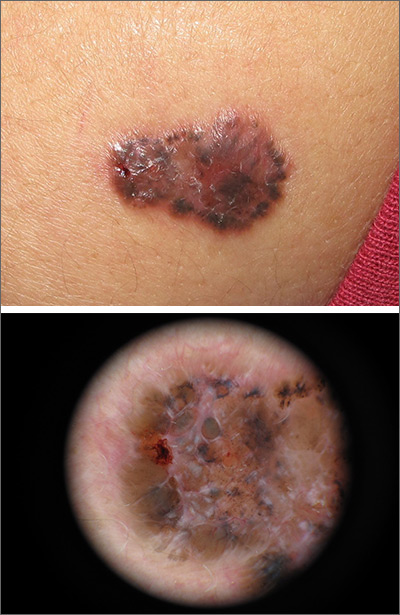

A shave biopsy of the lesion confirmed a nodular and pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC). In the United States, BCC is the most common cancer and accounts for 80% of all skin cancer diagnoses. BCC is also the most widespread cancer in White, Hispanic, and Asian patients and the second most common skin cancer in Black patients.

In all patients, BCC presents as a shiny growing macule, papule, or plaque, usually in areas of sun exposure. Much less is known about the role of UV exposure in skin of color because of the lack of high-quality studies in this population. Despite this, BCC in skin of color most often presents on the head and neck, as it does in non-Hispanic White patients. There is a correlation between lighter skin tones in Black patients and increased numbers of BCC diagnoses.

When assessing a suspicious skin lesion in skin of color, be on the lookout for the following visual cues. Pigmentation, clinically and on dermoscopy, is a more common feature of BCCs in non-White patients—occurring in more than half of all BCCs in skin of color.1 While pigmentation in a skin tumor may be mistaken for melanoma, the blue ovoid nests, brown dots in focus, and brown leaf-like areas on dermoscopy are BCC-specific clues that can alert the clinician to the diagnosis. In all patients, telangiectasias are another hallmark of BCC but may be the only feature in White patients and just one of many features in non-White patients.

In small data sets, there is no difference in tumor-related morbidity and prognosis between White and Black patients with BCC. Additionally, BCCs in White, Asian, and Hispanic patients have had no differences in preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs stages, and outcome.1

In this case, the patient underwent a complete excision with a 5-mm margin. She remained free of new or recurrent BCCs over the next 2 years, with surveillance exams twice a year.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

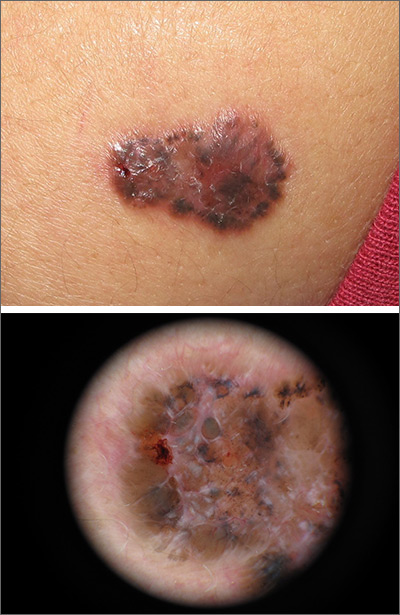

A shave biopsy of the lesion confirmed a nodular and pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC). In the United States, BCC is the most common cancer and accounts for 80% of all skin cancer diagnoses. BCC is also the most widespread cancer in White, Hispanic, and Asian patients and the second most common skin cancer in Black patients.

In all patients, BCC presents as a shiny growing macule, papule, or plaque, usually in areas of sun exposure. Much less is known about the role of UV exposure in skin of color because of the lack of high-quality studies in this population. Despite this, BCC in skin of color most often presents on the head and neck, as it does in non-Hispanic White patients. There is a correlation between lighter skin tones in Black patients and increased numbers of BCC diagnoses.

When assessing a suspicious skin lesion in skin of color, be on the lookout for the following visual cues. Pigmentation, clinically and on dermoscopy, is a more common feature of BCCs in non-White patients—occurring in more than half of all BCCs in skin of color.1 While pigmentation in a skin tumor may be mistaken for melanoma, the blue ovoid nests, brown dots in focus, and brown leaf-like areas on dermoscopy are BCC-specific clues that can alert the clinician to the diagnosis. In all patients, telangiectasias are another hallmark of BCC but may be the only feature in White patients and just one of many features in non-White patients.

In small data sets, there is no difference in tumor-related morbidity and prognosis between White and Black patients with BCC. Additionally, BCCs in White, Asian, and Hispanic patients have had no differences in preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs stages, and outcome.1

In this case, the patient underwent a complete excision with a 5-mm margin. She remained free of new or recurrent BCCs over the next 2 years, with surveillance exams twice a year.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

1. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526.

1. Hogue L, Harvey VM. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous melanoma in skin of color patients. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:519-526.

High hydroxychloroquine blood level may lower thrombosis risk in lupus

Maintaining an average hydroxychloroquine whole blood level above 1,068 ng/mL significantly reduced the risk of thrombosis in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus, based on data from 739 patients.

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is a common treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); studies suggest that it may protect against thrombosis, but the optimal dosing for this purpose remains unknown, wrote Michelle Petri, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers examined data on HCQ levels from 739 adults with SLE who were part of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, a longitudinal study of outcomes in SLE patients. Of these, 38 (5.1%) developed thrombosis during 2,330 person-years of follow-up.

Overall, the average HCQ blood level was significantly lower in patients who experienced thrombosis, compared to those who did not (720 ng/mL vs. 935 ng/mL; P = .025). “Prescribed hydroxychloroquine doses did not predict hydroxychloroquine blood levels,” the researchers noted.

In addition, Dr. Petri and associates found a dose-response relationship in which the thrombosis rate declined approximately 13% for every 200-ng/mL increase in the mean HCQ blood level measurement and for the most recent HCQ blood level measurement after controlling for factors that included age, ethnicity, lupus anticoagulant, low C3, and hypertension.

In a multivariate analysis, thrombotic events decreased by 69% in patients with mean HCQ blood levels greater than 1,068 ng/mL, compared to those with average HCQ blood levels less than 648 ng/mL.

The average age of the patients at the time HCQ measurements began was 43 years, 93% were female, and 46% were White. Patients visited a clinic every 3 months, and HCQ levels were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

“Between-person and within-person correlation coefficients were used to measure the strength of the linear association between HCQ blood levels and commonly prescribed HCQ doses from 4.5 to 6.5 mg/kg,” the researchers said.

Higher doses of HCQ have been associated with increased risk for retinopathy, and current guidelines recommend using less than 5 mg/kg of ideal body weight, the researchers said. “Importantly, there was no correlation between the prescribed dose and the hydroxychloroquine blood level over the range (4.5 to 6.5 mg/kg) used in clinical practice, highlighting the need for personalized hydroxychloroquine drug level-guided therapy and dose adjustment,” they emphasized.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design and potential confounding from variables not included in the model, as well as the small sample size, single site, and single rheumatologist involved in the study, the researchers noted.

The results suggest that aiming for a blood HCQ level of 1,068 ng/mL can be done safely to help prevent thrombosis in patients with SLE, the researchers said. “Routine clinical integration of hydroxychloroquine blood level measurement offers an opportunity for personalized drug dosing and risk management beyond rigid empirical dosing recommendations in patients with SLE,” they concluded.

The study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The researchers had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Petri M et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Jan 6. doi: 10.1002/ART.41621.

Maintaining an average hydroxychloroquine whole blood level above 1,068 ng/mL significantly reduced the risk of thrombosis in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus, based on data from 739 patients.

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is a common treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); studies suggest that it may protect against thrombosis, but the optimal dosing for this purpose remains unknown, wrote Michelle Petri, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers examined data on HCQ levels from 739 adults with SLE who were part of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, a longitudinal study of outcomes in SLE patients. Of these, 38 (5.1%) developed thrombosis during 2,330 person-years of follow-up.

Overall, the average HCQ blood level was significantly lower in patients who experienced thrombosis, compared to those who did not (720 ng/mL vs. 935 ng/mL; P = .025). “Prescribed hydroxychloroquine doses did not predict hydroxychloroquine blood levels,” the researchers noted.

In addition, Dr. Petri and associates found a dose-response relationship in which the thrombosis rate declined approximately 13% for every 200-ng/mL increase in the mean HCQ blood level measurement and for the most recent HCQ blood level measurement after controlling for factors that included age, ethnicity, lupus anticoagulant, low C3, and hypertension.

In a multivariate analysis, thrombotic events decreased by 69% in patients with mean HCQ blood levels greater than 1,068 ng/mL, compared to those with average HCQ blood levels less than 648 ng/mL.

The average age of the patients at the time HCQ measurements began was 43 years, 93% were female, and 46% were White. Patients visited a clinic every 3 months, and HCQ levels were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

“Between-person and within-person correlation coefficients were used to measure the strength of the linear association between HCQ blood levels and commonly prescribed HCQ doses from 4.5 to 6.5 mg/kg,” the researchers said.

Higher doses of HCQ have been associated with increased risk for retinopathy, and current guidelines recommend using less than 5 mg/kg of ideal body weight, the researchers said. “Importantly, there was no correlation between the prescribed dose and the hydroxychloroquine blood level over the range (4.5 to 6.5 mg/kg) used in clinical practice, highlighting the need for personalized hydroxychloroquine drug level-guided therapy and dose adjustment,” they emphasized.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design and potential confounding from variables not included in the model, as well as the small sample size, single site, and single rheumatologist involved in the study, the researchers noted.

The results suggest that aiming for a blood HCQ level of 1,068 ng/mL can be done safely to help prevent thrombosis in patients with SLE, the researchers said. “Routine clinical integration of hydroxychloroquine blood level measurement offers an opportunity for personalized drug dosing and risk management beyond rigid empirical dosing recommendations in patients with SLE,” they concluded.

The study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The researchers had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Petri M et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Jan 6. doi: 10.1002/ART.41621.

Maintaining an average hydroxychloroquine whole blood level above 1,068 ng/mL significantly reduced the risk of thrombosis in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus, based on data from 739 patients.

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is a common treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); studies suggest that it may protect against thrombosis, but the optimal dosing for this purpose remains unknown, wrote Michelle Petri, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. In a study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology, the researchers examined data on HCQ levels from 739 adults with SLE who were part of the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, a longitudinal study of outcomes in SLE patients. Of these, 38 (5.1%) developed thrombosis during 2,330 person-years of follow-up.

Overall, the average HCQ blood level was significantly lower in patients who experienced thrombosis, compared to those who did not (720 ng/mL vs. 935 ng/mL; P = .025). “Prescribed hydroxychloroquine doses did not predict hydroxychloroquine blood levels,” the researchers noted.

In addition, Dr. Petri and associates found a dose-response relationship in which the thrombosis rate declined approximately 13% for every 200-ng/mL increase in the mean HCQ blood level measurement and for the most recent HCQ blood level measurement after controlling for factors that included age, ethnicity, lupus anticoagulant, low C3, and hypertension.

In a multivariate analysis, thrombotic events decreased by 69% in patients with mean HCQ blood levels greater than 1,068 ng/mL, compared to those with average HCQ blood levels less than 648 ng/mL.

The average age of the patients at the time HCQ measurements began was 43 years, 93% were female, and 46% were White. Patients visited a clinic every 3 months, and HCQ levels were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

“Between-person and within-person correlation coefficients were used to measure the strength of the linear association between HCQ blood levels and commonly prescribed HCQ doses from 4.5 to 6.5 mg/kg,” the researchers said.

Higher doses of HCQ have been associated with increased risk for retinopathy, and current guidelines recommend using less than 5 mg/kg of ideal body weight, the researchers said. “Importantly, there was no correlation between the prescribed dose and the hydroxychloroquine blood level over the range (4.5 to 6.5 mg/kg) used in clinical practice, highlighting the need for personalized hydroxychloroquine drug level-guided therapy and dose adjustment,” they emphasized.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design and potential confounding from variables not included in the model, as well as the small sample size, single site, and single rheumatologist involved in the study, the researchers noted.

The results suggest that aiming for a blood HCQ level of 1,068 ng/mL can be done safely to help prevent thrombosis in patients with SLE, the researchers said. “Routine clinical integration of hydroxychloroquine blood level measurement offers an opportunity for personalized drug dosing and risk management beyond rigid empirical dosing recommendations in patients with SLE,” they concluded.

The study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The researchers had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Petri M et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Jan 6. doi: 10.1002/ART.41621.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Higher blood levels of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) were protective against thrombosis in adults with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Major finding: The average HCQ in SLE patients who developed thrombosis was 720 ng/mL, compared to 935 ng/mL in those without thrombosis (P = .025).

Study details: The data come from an observational study of 739 adults with SLE; 5.1% developed thrombosis during the study period.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The researchers had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Petri M et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Jan 6. doi: 10.1002/ART.41621.

Flow cytometry identifies rare combination of lymphoma and MDS

Key clinical point: Researchers used flow cytometry and genomic assessment to identify a shared DNMT3A mutation in a rare case of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and myelodysplastic syndrome.

Major finding: DNMT3A N612Rfs*36 was identified as the common mutation for AITL and myeloid neoplasm using both cytogenetic analysis (karyotype), which showed deletion of the long arm of chromosome 20 in 14 of 20 metaphases and also fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), which showed the same deletion in 36.3% of cells.

Study details: The data come from a case report of a 75-year-old man with a history of lung adenocarcinoma who was diagnosed with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and concomitant myelodysplastic syndrome.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Naganuma had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Naganuma K et al. J Hematol. 2020 Nov 6. doi: 10.14740/jh760.

Key clinical point: Researchers used flow cytometry and genomic assessment to identify a shared DNMT3A mutation in a rare case of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and myelodysplastic syndrome.

Major finding: DNMT3A N612Rfs*36 was identified as the common mutation for AITL and myeloid neoplasm using both cytogenetic analysis (karyotype), which showed deletion of the long arm of chromosome 20 in 14 of 20 metaphases and also fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), which showed the same deletion in 36.3% of cells.

Study details: The data come from a case report of a 75-year-old man with a history of lung adenocarcinoma who was diagnosed with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and concomitant myelodysplastic syndrome.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Naganuma had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Naganuma K et al. J Hematol. 2020 Nov 6. doi: 10.14740/jh760.

Key clinical point: Researchers used flow cytometry and genomic assessment to identify a shared DNMT3A mutation in a rare case of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and myelodysplastic syndrome.

Major finding: DNMT3A N612Rfs*36 was identified as the common mutation for AITL and myeloid neoplasm using both cytogenetic analysis (karyotype), which showed deletion of the long arm of chromosome 20 in 14 of 20 metaphases and also fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), which showed the same deletion in 36.3% of cells.

Study details: The data come from a case report of a 75-year-old man with a history of lung adenocarcinoma who was diagnosed with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and concomitant myelodysplastic syndrome.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Naganuma had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Naganuma K et al. J Hematol. 2020 Nov 6. doi: 10.14740/jh760.

Poor outcomes persist for MDS, ALL, AML patients who relapse after cell transplants

Key clinical point: Outcomes remain poor for patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome who suffer relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; factors associated with mortality included acute graft vs. host disease grade II-IV.

Major finding: The cumulative incidence of morphologic relapse in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation was 19%, 24%, and 26%, respectively at 12 months; the estimated median survival after relapse across all diseases was 2.9 months.

Study details: The data come from 420 adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Hong S et al. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2020 Dec 5. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2020.11.006.

Key clinical point: Outcomes remain poor for patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome who suffer relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; factors associated with mortality included acute graft vs. host disease grade II-IV.

Major finding: The cumulative incidence of morphologic relapse in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation was 19%, 24%, and 26%, respectively at 12 months; the estimated median survival after relapse across all diseases was 2.9 months.

Study details: The data come from 420 adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Hong S et al. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2020 Dec 5. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2020.11.006.

Key clinical point: Outcomes remain poor for patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome who suffer relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; factors associated with mortality included acute graft vs. host disease grade II-IV.

Major finding: The cumulative incidence of morphologic relapse in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation was 19%, 24%, and 26%, respectively at 12 months; the estimated median survival after relapse across all diseases was 2.9 months.

Study details: The data come from 420 adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Hong S et al. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2020 Dec 5. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2020.11.006.

Revised scoring system enhances prognostic value for MDS patients treated with 5-AZA

Key clinical point: Use of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) added to the International Prognostic Scoring System, revised (IPSS-R) could identify low, intermediate, and high-risk groups of patients with patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia.

Major finding: Serum ferritin levels < 520 ng/mL, ECOG PS scores of 0 or 1, and IPSS-R independently predicted stronger response to 5-AZA in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia.

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study of 687 consecutive patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia who were treated with 5-azacytidine (5-AZA).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Papageorgiou SG et al. Ther Adv Hematol. 2020 Dec 8. doi: 10.1177/2040620720966121.

Key clinical point: Use of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) added to the International Prognostic Scoring System, revised (IPSS-R) could identify low, intermediate, and high-risk groups of patients with patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia.

Major finding: Serum ferritin levels < 520 ng/mL, ECOG PS scores of 0 or 1, and IPSS-R independently predicted stronger response to 5-AZA in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia.

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study of 687 consecutive patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia who were treated with 5-azacytidine (5-AZA).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Papageorgiou SG et al. Ther Adv Hematol. 2020 Dec 8. doi: 10.1177/2040620720966121.

Key clinical point: Use of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) added to the International Prognostic Scoring System, revised (IPSS-R) could identify low, intermediate, and high-risk groups of patients with patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia.

Major finding: Serum ferritin levels < 520 ng/mL, ECOG PS scores of 0 or 1, and IPSS-R independently predicted stronger response to 5-AZA in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia.

Study details: The data come from a retrospective study of 687 consecutive patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia who were treated with 5-azacytidine (5-AZA).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Papageorgiou SG et al. Ther Adv Hematol. 2020 Dec 8. doi: 10.1177/2040620720966121.

MDS patients who responded to azacytidine showed low levels of Wilms’ tumor 1

Key clinical point: Myelodysplastic syndrome patients who responded to treatment with azacytidine showed significantly reduced peripheral blood levels of Wilms’ tumour 1 mRNA (WT-1) compared to nonresponders.

Major finding: A total of 20 patients (63%) showed a response to azacytidine; 7 patients (22%) achieved complete response and 19 patients (59%) achieved hematologic improvement. Responders had an average peripheral blood WT-A mRNA of 2,050 copies per micrograms of RNA vs. 7,550 copies per micrograms of RNA for nonresponders (P = 0.03).