User login

Tocilizumab + methotrexate vs. tocilizumab alone for preventing radiographic progression in RA

Key clinical point: Tocilizumab (TCZ) and methotrexate (MTX) combination therapy was generally more effective than TCZ monotherapy in preventing radiographic progression in patients with early and established rheumatoid arthritis. However, effect modifiers were more joint damage or lower disease activity score (DAS) in early RA and longer disease duration in established RA.

Major finding: Overall, TCZ monotherapy was less effective in preventing radiographic progression (relative risk; 95% confidence interval) than TCZ+MTX combination therapy in patients with early (0.96; 0.90 to –1.03) and established (0.96; 0.87 to –1.07) RA. These effects were modified by baseline joint damage (P less than .01), DAS assessing 28 joints (P = .04) in early RA, and disease duration (P = .04) in established RA.

Study details: Analysis of individual patient data from randomized controlled trials comparing TCZ monotherapy and TCZ+MTX combination therapy in patients with early (n=1,089) and established (n=417) RA.

Disclosures: No study sponsor was identified. Some of the investigators reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Verhoeven MMA et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Nov 30. doi: 10.1002/acr.24524.

Key clinical point: Tocilizumab (TCZ) and methotrexate (MTX) combination therapy was generally more effective than TCZ monotherapy in preventing radiographic progression in patients with early and established rheumatoid arthritis. However, effect modifiers were more joint damage or lower disease activity score (DAS) in early RA and longer disease duration in established RA.

Major finding: Overall, TCZ monotherapy was less effective in preventing radiographic progression (relative risk; 95% confidence interval) than TCZ+MTX combination therapy in patients with early (0.96; 0.90 to –1.03) and established (0.96; 0.87 to –1.07) RA. These effects were modified by baseline joint damage (P less than .01), DAS assessing 28 joints (P = .04) in early RA, and disease duration (P = .04) in established RA.

Study details: Analysis of individual patient data from randomized controlled trials comparing TCZ monotherapy and TCZ+MTX combination therapy in patients with early (n=1,089) and established (n=417) RA.

Disclosures: No study sponsor was identified. Some of the investigators reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Verhoeven MMA et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Nov 30. doi: 10.1002/acr.24524.

Key clinical point: Tocilizumab (TCZ) and methotrexate (MTX) combination therapy was generally more effective than TCZ monotherapy in preventing radiographic progression in patients with early and established rheumatoid arthritis. However, effect modifiers were more joint damage or lower disease activity score (DAS) in early RA and longer disease duration in established RA.

Major finding: Overall, TCZ monotherapy was less effective in preventing radiographic progression (relative risk; 95% confidence interval) than TCZ+MTX combination therapy in patients with early (0.96; 0.90 to –1.03) and established (0.96; 0.87 to –1.07) RA. These effects were modified by baseline joint damage (P less than .01), DAS assessing 28 joints (P = .04) in early RA, and disease duration (P = .04) in established RA.

Study details: Analysis of individual patient data from randomized controlled trials comparing TCZ monotherapy and TCZ+MTX combination therapy in patients with early (n=1,089) and established (n=417) RA.

Disclosures: No study sponsor was identified. Some of the investigators reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Verhoeven MMA et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Nov 30. doi: 10.1002/acr.24524.

Prognostic factors for short-term mortality in RA patients admitted to ICU

Key clinical point: Nonuse of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), high updated Charlson’s comorbidity index (CCI), elevated acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score, and coagulation abnormalities predicted poorer prognosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Major finding: The 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year mortality rates were 22%, 27%, and 37%, respectively. Factors associated with an increased mortality risk after ICU admission were nonuse of csDMARDs (hazard ratio [HR], 0.413; P = .0229), elevated updated CCI (HR, 1.522; P = .0007), high APACHE II score (HR, 1.045; P = .0008), and extended prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (HR, 2.670; P = .0051). The liver (P = .0004) and renal (P = .0009) disease scores were significantly higher in nonsurvivors vs. survivors.

Study details: The findings are based on a single-center retrospective study of 67 patients (mean age at admission, 68±13 years) with RA (median duration, 14±15 years) admitted to the ICU.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from JSPS KAKENHI. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fujiwara T et al. BMC Rheumatol. 2020 Dec 4. doi: 10.1186/s41927-020-00164-1.

Key clinical point: Nonuse of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), high updated Charlson’s comorbidity index (CCI), elevated acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score, and coagulation abnormalities predicted poorer prognosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Major finding: The 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year mortality rates were 22%, 27%, and 37%, respectively. Factors associated with an increased mortality risk after ICU admission were nonuse of csDMARDs (hazard ratio [HR], 0.413; P = .0229), elevated updated CCI (HR, 1.522; P = .0007), high APACHE II score (HR, 1.045; P = .0008), and extended prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (HR, 2.670; P = .0051). The liver (P = .0004) and renal (P = .0009) disease scores were significantly higher in nonsurvivors vs. survivors.

Study details: The findings are based on a single-center retrospective study of 67 patients (mean age at admission, 68±13 years) with RA (median duration, 14±15 years) admitted to the ICU.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from JSPS KAKENHI. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fujiwara T et al. BMC Rheumatol. 2020 Dec 4. doi: 10.1186/s41927-020-00164-1.

Key clinical point: Nonuse of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), high updated Charlson’s comorbidity index (CCI), elevated acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score, and coagulation abnormalities predicted poorer prognosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Major finding: The 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year mortality rates were 22%, 27%, and 37%, respectively. Factors associated with an increased mortality risk after ICU admission were nonuse of csDMARDs (hazard ratio [HR], 0.413; P = .0229), elevated updated CCI (HR, 1.522; P = .0007), high APACHE II score (HR, 1.045; P = .0008), and extended prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (HR, 2.670; P = .0051). The liver (P = .0004) and renal (P = .0009) disease scores were significantly higher in nonsurvivors vs. survivors.

Study details: The findings are based on a single-center retrospective study of 67 patients (mean age at admission, 68±13 years) with RA (median duration, 14±15 years) admitted to the ICU.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from JSPS KAKENHI. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fujiwara T et al. BMC Rheumatol. 2020 Dec 4. doi: 10.1186/s41927-020-00164-1.

Gut microbiome influences response to methotrexate in new-onset RA patients

Key clinical point: Nonresponse to methotrexate (MTX) therapy can be predicted based on the gut microbiome of an individual patient newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis.

Major finding: A model developed using machine learning predicted 83.3% of patients who did not respond to MTX and 78% of MTX responders.

Study details: An analysis of DNA from fecal samples obtained from a training cohort of 26 patients with new-onset RA (NORA), a validation cohort of 21 patients with NORA, and a control group of 20 patients with RA.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Searle Scholars Program, various funds from the Spanish government, the UCSF Breakthrough Program for Rheumatoid Arthritis-related Research, and the Arthritis Foundation Center for Excellence. Four authors report consultancies and memberships on scientific advisory boards with pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies that do not overlap with the current study.

Source: Artacho A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Dec 13. doi: 10.1002/art.41622.

Key clinical point: Nonresponse to methotrexate (MTX) therapy can be predicted based on the gut microbiome of an individual patient newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis.

Major finding: A model developed using machine learning predicted 83.3% of patients who did not respond to MTX and 78% of MTX responders.

Study details: An analysis of DNA from fecal samples obtained from a training cohort of 26 patients with new-onset RA (NORA), a validation cohort of 21 patients with NORA, and a control group of 20 patients with RA.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Searle Scholars Program, various funds from the Spanish government, the UCSF Breakthrough Program for Rheumatoid Arthritis-related Research, and the Arthritis Foundation Center for Excellence. Four authors report consultancies and memberships on scientific advisory boards with pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies that do not overlap with the current study.

Source: Artacho A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Dec 13. doi: 10.1002/art.41622.

Key clinical point: Nonresponse to methotrexate (MTX) therapy can be predicted based on the gut microbiome of an individual patient newly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis.

Major finding: A model developed using machine learning predicted 83.3% of patients who did not respond to MTX and 78% of MTX responders.

Study details: An analysis of DNA from fecal samples obtained from a training cohort of 26 patients with new-onset RA (NORA), a validation cohort of 21 patients with NORA, and a control group of 20 patients with RA.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Searle Scholars Program, various funds from the Spanish government, the UCSF Breakthrough Program for Rheumatoid Arthritis-related Research, and the Arthritis Foundation Center for Excellence. Four authors report consultancies and memberships on scientific advisory boards with pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies that do not overlap with the current study.

Source: Artacho A et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Dec 13. doi: 10.1002/art.41622.

Perceived distress linked to inflammatory arthritis among at-risk individuals

Key clinical point: Higher perceived distress was associated with elevated risk of developing inflammatory arthritis (IA) in an at-risk population having either positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-related autoantibodies or inherent genetic risk based on family history.

Major finding: A 1-point increase in the perceived distress score was significantly associated with a 10% increase in the risk of incident IA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-1.19). Total perceived stress (aHR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.99-1.10) and self-efficacy (aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.91-1.18) scores were not significantly associated with the risk of incident IA.

Study details: This prospective cohort study evaluated 448 participants at an increased risk of developing future RA (either first-degree relatives of RA probands or positive for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies) from the Studies of the Etiologies of Rheumatoid Arthritis cohort.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Polinski KJ et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Nov 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.24085.

Key clinical point: Higher perceived distress was associated with elevated risk of developing inflammatory arthritis (IA) in an at-risk population having either positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-related autoantibodies or inherent genetic risk based on family history.

Major finding: A 1-point increase in the perceived distress score was significantly associated with a 10% increase in the risk of incident IA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-1.19). Total perceived stress (aHR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.99-1.10) and self-efficacy (aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.91-1.18) scores were not significantly associated with the risk of incident IA.

Study details: This prospective cohort study evaluated 448 participants at an increased risk of developing future RA (either first-degree relatives of RA probands or positive for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies) from the Studies of the Etiologies of Rheumatoid Arthritis cohort.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Polinski KJ et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Nov 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.24085.

Key clinical point: Higher perceived distress was associated with elevated risk of developing inflammatory arthritis (IA) in an at-risk population having either positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-related autoantibodies or inherent genetic risk based on family history.

Major finding: A 1-point increase in the perceived distress score was significantly associated with a 10% increase in the risk of incident IA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-1.19). Total perceived stress (aHR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.99-1.10) and self-efficacy (aHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.91-1.18) scores were not significantly associated with the risk of incident IA.

Study details: This prospective cohort study evaluated 448 participants at an increased risk of developing future RA (either first-degree relatives of RA probands or positive for anti-citrullinated protein antibodies) from the Studies of the Etiologies of Rheumatoid Arthritis cohort.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Polinski KJ et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Nov 6. doi: 10.1002/acr.24085.

ANA measurement before TNFi therapy could help predict treatment failure in RA

Key clinical point: The appearance of total antinuclear antibodies (ANA) before administration of TNF-α inhibitors (TNFi) is a risk factor for the appearance of antidrug antibodies (ADrA) and treatment failure.

Major finding: ADrA appeared in 36.8% and 30.2% of patients treated with infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA), respectively; all being positive for total ANA before TNFi administration. High titers of total ANA before IFX treatment were significantly associated with inefficacy and discontinuation of treatment.

Study details: The data come from observational study of 121 patients with RA newly introduced to 3 classes of TNFi.

Disclosures: The study did not receive any funding. S Kumagai reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mori A et al. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243729.

Key clinical point: The appearance of total antinuclear antibodies (ANA) before administration of TNF-α inhibitors (TNFi) is a risk factor for the appearance of antidrug antibodies (ADrA) and treatment failure.

Major finding: ADrA appeared in 36.8% and 30.2% of patients treated with infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA), respectively; all being positive for total ANA before TNFi administration. High titers of total ANA before IFX treatment were significantly associated with inefficacy and discontinuation of treatment.

Study details: The data come from observational study of 121 patients with RA newly introduced to 3 classes of TNFi.

Disclosures: The study did not receive any funding. S Kumagai reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mori A et al. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243729.

Key clinical point: The appearance of total antinuclear antibodies (ANA) before administration of TNF-α inhibitors (TNFi) is a risk factor for the appearance of antidrug antibodies (ADrA) and treatment failure.

Major finding: ADrA appeared in 36.8% and 30.2% of patients treated with infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADA), respectively; all being positive for total ANA before TNFi administration. High titers of total ANA before IFX treatment were significantly associated with inefficacy and discontinuation of treatment.

Study details: The data come from observational study of 121 patients with RA newly introduced to 3 classes of TNFi.

Disclosures: The study did not receive any funding. S Kumagai reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Mori A et al. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243729.

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Medical management of colonic diverticulitis

A new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association seeks to provide gastroenterologists with practical and evidence-based advice for management of colonic diverticulitis.

For example, clinicians should consider lower endoscopy and CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast to rule out chronic diverticular inflammation, diverticular stricture or fistula, ischemic colitis, constipation, and inflammatory bowel disease, Anne F. Peery, MD, MSCR, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and associates wrote in Gastroenterology.

“In our practice, patients are reassured to know that ongoing symptoms are common and often attributable to visceral hypersensitivity,” they wrote. “This conversation is particularly important after a negative workup. If needed, ongoing abdominal pain can be treated with a low to modest dose of a tricyclic antidepressant.”

The update from the AGA includes 13 other recommendations, with noteworthy advice to use antibiotics selectively, rather than routinely, in cases of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis in immunocompetent patients. In a recent large meta-analysis, antibiotics did not shorten symptom duration or reduce rates of hospitalization, complications, or surgery in this setting. The clinical practice update advises using antibiotics if patients are frail or have comorbidities, vomiting or refractory symptoms, a C-reactive protein level above 140 mg/L, a baseline white blood cell count above 15 × 109 cells/L, or fluid collection or a longer segment of inflammation on CT scan. Antibiotics also are strongly advised for immunocompromised patients, who are at greater risk for complications and severe diverticulitis. Because of this risk, clinicians should have “a low threshold” for cross-sectional imaging, antibiotic treatment, and consultation with a colorectal surgeon, according to the update.

The authors recommend CT if patients have severe symptoms or have not previously been diagnosed with diverticulitis based on imaging. Clinicians also should consider imaging if patients have had multiple recurrences, are not responding to treatment, are immunocompromised, or are considering prophylactic surgery (in which case imaging is used to pinpoint areas of disease).

Colonoscopy is advised after episodes of complicated diverticulitis or after a first episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis if no high-quality colonoscopy has been performed in the past year. This colonoscopy is advised to rule out malignancy, which can be misdiagnosed as diverticulitis, and because diverticulitis (particularly complicated diverticulitis) has been associated with colon cancer in some studies, the update notes. Unless patients have “alarm symptoms” – that is, a change in stool caliber, iron deficiency anemia, bloody stools, weight loss, or abdominal pain – colonoscopy should be delayed until 6-8 weeks after the diverticulitis episode or until the acute symptoms resolve, whichever occurs later.

The decision to discuss elective segmental resection should be based on disease severity, not the prior number of episodes. Although elective surgery for diverticulitis has become increasingly common, patients should be aware that surgery often does not improve chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, and that surgery reduces but does not eliminate the risk for recurrence. The authors recommended against surgery to prevent complicated diverticulitis in immunocompetent patients with a history of uncomplicated episodes. “In this population, complicated diverticulitis is most often the first presentation of diverticulitis and is less likely with recurrences,” the update states. For acute complicated diverticulitis that has been effectively managed without surgery, patients are at heightened risk for recurrence, but “a growing literature suggest[s] a more conservative and personalized approach” rather than the routine use of interval elective resection, the authors noted. For all patients, counseling regarding surgery should incorporate thoughtful discussions of immune status, values and preferences, and operative risks versus benefits, including effects on quality of life.

Dr. Peery and another author were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Peery AF et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Dec 3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.059.

This article was updated Feb. 10, 2021.

A new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association seeks to provide gastroenterologists with practical and evidence-based advice for management of colonic diverticulitis.

For example, clinicians should consider lower endoscopy and CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast to rule out chronic diverticular inflammation, diverticular stricture or fistula, ischemic colitis, constipation, and inflammatory bowel disease, Anne F. Peery, MD, MSCR, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and associates wrote in Gastroenterology.

“In our practice, patients are reassured to know that ongoing symptoms are common and often attributable to visceral hypersensitivity,” they wrote. “This conversation is particularly important after a negative workup. If needed, ongoing abdominal pain can be treated with a low to modest dose of a tricyclic antidepressant.”

The update from the AGA includes 13 other recommendations, with noteworthy advice to use antibiotics selectively, rather than routinely, in cases of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis in immunocompetent patients. In a recent large meta-analysis, antibiotics did not shorten symptom duration or reduce rates of hospitalization, complications, or surgery in this setting. The clinical practice update advises using antibiotics if patients are frail or have comorbidities, vomiting or refractory symptoms, a C-reactive protein level above 140 mg/L, a baseline white blood cell count above 15 × 109 cells/L, or fluid collection or a longer segment of inflammation on CT scan. Antibiotics also are strongly advised for immunocompromised patients, who are at greater risk for complications and severe diverticulitis. Because of this risk, clinicians should have “a low threshold” for cross-sectional imaging, antibiotic treatment, and consultation with a colorectal surgeon, according to the update.

The authors recommend CT if patients have severe symptoms or have not previously been diagnosed with diverticulitis based on imaging. Clinicians also should consider imaging if patients have had multiple recurrences, are not responding to treatment, are immunocompromised, or are considering prophylactic surgery (in which case imaging is used to pinpoint areas of disease).

Colonoscopy is advised after episodes of complicated diverticulitis or after a first episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis if no high-quality colonoscopy has been performed in the past year. This colonoscopy is advised to rule out malignancy, which can be misdiagnosed as diverticulitis, and because diverticulitis (particularly complicated diverticulitis) has been associated with colon cancer in some studies, the update notes. Unless patients have “alarm symptoms” – that is, a change in stool caliber, iron deficiency anemia, bloody stools, weight loss, or abdominal pain – colonoscopy should be delayed until 6-8 weeks after the diverticulitis episode or until the acute symptoms resolve, whichever occurs later.

The decision to discuss elective segmental resection should be based on disease severity, not the prior number of episodes. Although elective surgery for diverticulitis has become increasingly common, patients should be aware that surgery often does not improve chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, and that surgery reduces but does not eliminate the risk for recurrence. The authors recommended against surgery to prevent complicated diverticulitis in immunocompetent patients with a history of uncomplicated episodes. “In this population, complicated diverticulitis is most often the first presentation of diverticulitis and is less likely with recurrences,” the update states. For acute complicated diverticulitis that has been effectively managed without surgery, patients are at heightened risk for recurrence, but “a growing literature suggest[s] a more conservative and personalized approach” rather than the routine use of interval elective resection, the authors noted. For all patients, counseling regarding surgery should incorporate thoughtful discussions of immune status, values and preferences, and operative risks versus benefits, including effects on quality of life.

Dr. Peery and another author were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Peery AF et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Dec 3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.059.

This article was updated Feb. 10, 2021.

A new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association seeks to provide gastroenterologists with practical and evidence-based advice for management of colonic diverticulitis.

For example, clinicians should consider lower endoscopy and CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast to rule out chronic diverticular inflammation, diverticular stricture or fistula, ischemic colitis, constipation, and inflammatory bowel disease, Anne F. Peery, MD, MSCR, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and associates wrote in Gastroenterology.

“In our practice, patients are reassured to know that ongoing symptoms are common and often attributable to visceral hypersensitivity,” they wrote. “This conversation is particularly important after a negative workup. If needed, ongoing abdominal pain can be treated with a low to modest dose of a tricyclic antidepressant.”

The update from the AGA includes 13 other recommendations, with noteworthy advice to use antibiotics selectively, rather than routinely, in cases of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis in immunocompetent patients. In a recent large meta-analysis, antibiotics did not shorten symptom duration or reduce rates of hospitalization, complications, or surgery in this setting. The clinical practice update advises using antibiotics if patients are frail or have comorbidities, vomiting or refractory symptoms, a C-reactive protein level above 140 mg/L, a baseline white blood cell count above 15 × 109 cells/L, or fluid collection or a longer segment of inflammation on CT scan. Antibiotics also are strongly advised for immunocompromised patients, who are at greater risk for complications and severe diverticulitis. Because of this risk, clinicians should have “a low threshold” for cross-sectional imaging, antibiotic treatment, and consultation with a colorectal surgeon, according to the update.

The authors recommend CT if patients have severe symptoms or have not previously been diagnosed with diverticulitis based on imaging. Clinicians also should consider imaging if patients have had multiple recurrences, are not responding to treatment, are immunocompromised, or are considering prophylactic surgery (in which case imaging is used to pinpoint areas of disease).

Colonoscopy is advised after episodes of complicated diverticulitis or after a first episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis if no high-quality colonoscopy has been performed in the past year. This colonoscopy is advised to rule out malignancy, which can be misdiagnosed as diverticulitis, and because diverticulitis (particularly complicated diverticulitis) has been associated with colon cancer in some studies, the update notes. Unless patients have “alarm symptoms” – that is, a change in stool caliber, iron deficiency anemia, bloody stools, weight loss, or abdominal pain – colonoscopy should be delayed until 6-8 weeks after the diverticulitis episode or until the acute symptoms resolve, whichever occurs later.

The decision to discuss elective segmental resection should be based on disease severity, not the prior number of episodes. Although elective surgery for diverticulitis has become increasingly common, patients should be aware that surgery often does not improve chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, and that surgery reduces but does not eliminate the risk for recurrence. The authors recommended against surgery to prevent complicated diverticulitis in immunocompetent patients with a history of uncomplicated episodes. “In this population, complicated diverticulitis is most often the first presentation of diverticulitis and is less likely with recurrences,” the update states. For acute complicated diverticulitis that has been effectively managed without surgery, patients are at heightened risk for recurrence, but “a growing literature suggest[s] a more conservative and personalized approach” rather than the routine use of interval elective resection, the authors noted. For all patients, counseling regarding surgery should incorporate thoughtful discussions of immune status, values and preferences, and operative risks versus benefits, including effects on quality of life.

Dr. Peery and another author were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Peery AF et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Dec 3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.059.

This article was updated Feb. 10, 2021.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Baricitinib favorable for long-term treatment of moderate to severe RA

Key clinical point: Baricitinib 4 mg may be considered for long-term treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who were either naïve to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or had inadequate response (IR) to methotrexate (MTX).

Major finding: At week 148, low disease activity was achieved in up to 61% of DMARD-naïve patients and 59% of MTX-IR patients initially treated with baricitinib. Baricitinib was well-tolerated.

Study details: Analysis of data from 2 completed (RA-BEGIN [n = 584] and RA-BEAM [n = 1,305]) and 1 ongoing long-term extension (RA-BEYOND) phase 3 trials involving either DMARD-naïve or MTX-IR patients.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Eli Lilly and Company. L Xie, B Jia, A Elias, A Cardoso, R Ortmann and C Walls are full-time employees of Eli Lilly and Company and may own stock or stock options in the company.

Source: Smolen JS et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 Nov 17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa576.

Key clinical point: Baricitinib 4 mg may be considered for long-term treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who were either naïve to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or had inadequate response (IR) to methotrexate (MTX).

Major finding: At week 148, low disease activity was achieved in up to 61% of DMARD-naïve patients and 59% of MTX-IR patients initially treated with baricitinib. Baricitinib was well-tolerated.

Study details: Analysis of data from 2 completed (RA-BEGIN [n = 584] and RA-BEAM [n = 1,305]) and 1 ongoing long-term extension (RA-BEYOND) phase 3 trials involving either DMARD-naïve or MTX-IR patients.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Eli Lilly and Company. L Xie, B Jia, A Elias, A Cardoso, R Ortmann and C Walls are full-time employees of Eli Lilly and Company and may own stock or stock options in the company.

Source: Smolen JS et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 Nov 17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa576.

Key clinical point: Baricitinib 4 mg may be considered for long-term treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who were either naïve to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or had inadequate response (IR) to methotrexate (MTX).

Major finding: At week 148, low disease activity was achieved in up to 61% of DMARD-naïve patients and 59% of MTX-IR patients initially treated with baricitinib. Baricitinib was well-tolerated.

Study details: Analysis of data from 2 completed (RA-BEGIN [n = 584] and RA-BEAM [n = 1,305]) and 1 ongoing long-term extension (RA-BEYOND) phase 3 trials involving either DMARD-naïve or MTX-IR patients.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Eli Lilly and Company. L Xie, B Jia, A Elias, A Cardoso, R Ortmann and C Walls are full-time employees of Eli Lilly and Company and may own stock or stock options in the company.

Source: Smolen JS et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020 Nov 17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa576.

Early treatment response may predict sustained DMARD-free remission in RA

Key clinical point: In anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA)-negative rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a significant decline in the disease activity score (DAS) within the first 4 months after diagnosis was associated with a higher probability of achieving sustained disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)-free remission (SDFR).

Major finding: In patients with ACPA-negative RA, the decline in DAS within the first 4 months was stronger in the SDFR vs. non-SDFR group (−1.73 vs. −1.07 units; P less than .001). SDFR incidence was high (70.2%) and rare (7.1%) when absolute DAS level at 4 months was less than 1.6 and 3.6 or greater, respectively.

Study details: The study cohort included 772 consecutive patients with RA promptly treated with conventional DMARDs. Patients were classified into SDFR (n=149) and non-SDFR (n=623) groups.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Verstappen M et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020 Nov 23. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02368-9.

Key clinical point: In anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA)-negative rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a significant decline in the disease activity score (DAS) within the first 4 months after diagnosis was associated with a higher probability of achieving sustained disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)-free remission (SDFR).

Major finding: In patients with ACPA-negative RA, the decline in DAS within the first 4 months was stronger in the SDFR vs. non-SDFR group (−1.73 vs. −1.07 units; P less than .001). SDFR incidence was high (70.2%) and rare (7.1%) when absolute DAS level at 4 months was less than 1.6 and 3.6 or greater, respectively.

Study details: The study cohort included 772 consecutive patients with RA promptly treated with conventional DMARDs. Patients were classified into SDFR (n=149) and non-SDFR (n=623) groups.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Verstappen M et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020 Nov 23. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02368-9.

Key clinical point: In anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA)-negative rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a significant decline in the disease activity score (DAS) within the first 4 months after diagnosis was associated with a higher probability of achieving sustained disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)-free remission (SDFR).

Major finding: In patients with ACPA-negative RA, the decline in DAS within the first 4 months was stronger in the SDFR vs. non-SDFR group (−1.73 vs. −1.07 units; P less than .001). SDFR incidence was high (70.2%) and rare (7.1%) when absolute DAS level at 4 months was less than 1.6 and 3.6 or greater, respectively.

Study details: The study cohort included 772 consecutive patients with RA promptly treated with conventional DMARDs. Patients were classified into SDFR (n=149) and non-SDFR (n=623) groups.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Verstappen M et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020 Nov 23. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02368-9.

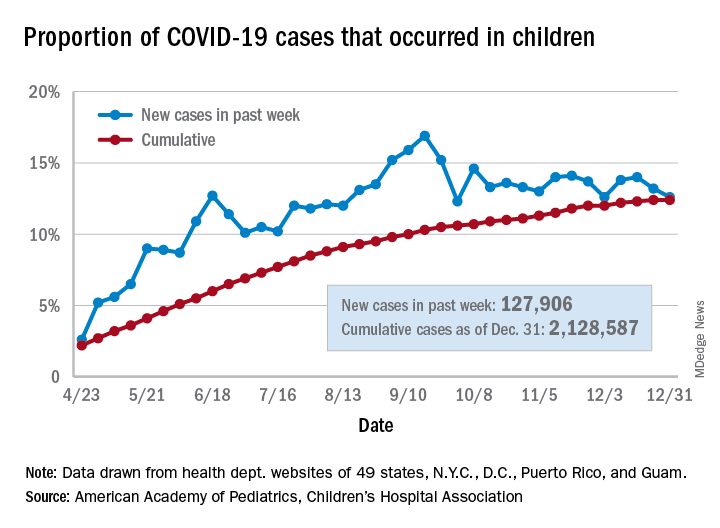

No increase seen in children’s cumulative COVID-19 burden

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

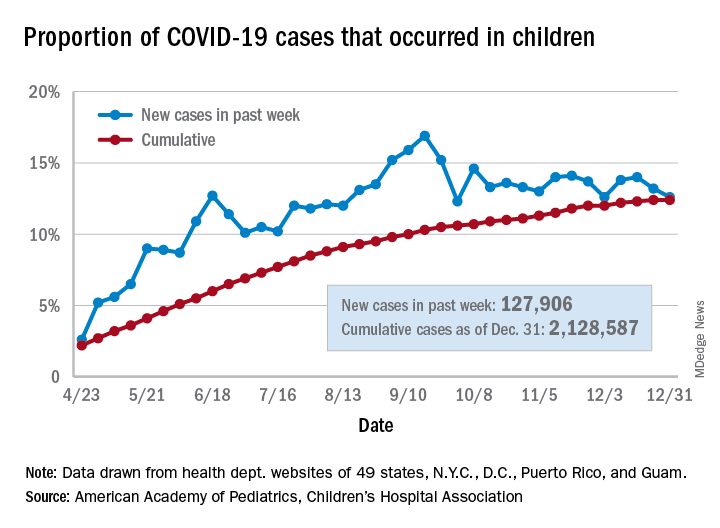

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

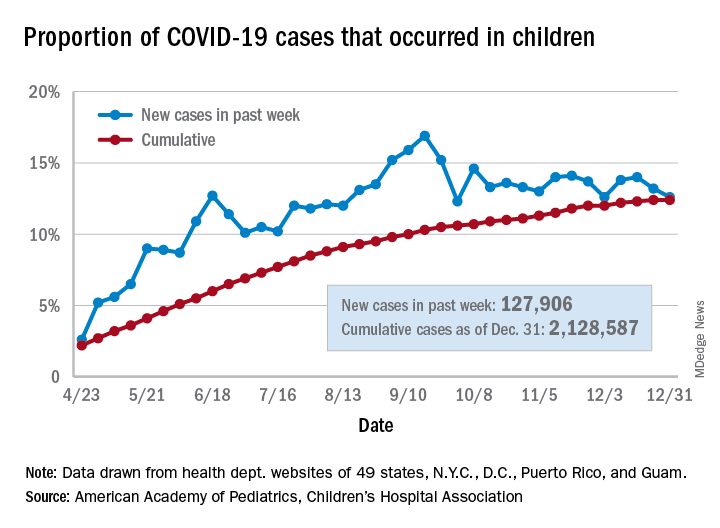

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

PDAC: Tumor reduction after neoadjuvant therapy may predict postsurgical survival

In patients who undergo resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) after neoadjuvant therapy, reduction in tumor size between diagnosis and surgery is associated with improved survival, according to a new single-center, retrospective analysis. The researchers compared tumor size as measured by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and found that a threshold of 47% or greater reduction in tumor size at resection was associated with a doubling in the 3-year survival rate.

The study, led by Rohit Das, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The research represents only a small percentage of patients since most diagnosed with PDAC have locally advanced or metastatic disease that rules out surgery. Still, the work puts more emphasis on measuring tumor size while performing EUS, according to Robert Jay Sealock, MD, who is an assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

“This is some helpful information that you can relay to the patient, saying that you have a significant decrease in the size of the tumor based on your initial EUS, and your chance of 3- to 5-year survival is going to be a lot higher, compared to somebody that didn’t have that tumor regression. Most of these patients will undergo an EUS anyway, and you’ll commonly if not always measure the tumor size while you’re in there. Now you can apply this information that you already have to give the patients some additional information if they do undergo surgery,” said Dr. Sealock, who was not involved in the research.

Previous efforts to prognosticate postsurgical survival focused on overall tumor burden using multidetector CT (MDCT), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels, and histologic examination following surgery, but all suffer from various limitations. MDCT is not always accurate in its measurement of tumor size, other conditions can also raise CA19-9 levels, and pathologic findings are subjective because sometimes the amount of tumor before neoadjuvant therapy is uncertain.

The researchers mapped survival statistics to EUS and pathologic findings for 340 treatment-naive and 365 neoadjuvant-treated PDAC patients at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. They used a 200 patient cohort from the same center who had been treated with neoadjuvant therapy for validation.

Pathology examination revealed that, in the treatment-naive group, 71% of tumors were larger than the size determined during EUS. In 9% of cases there was no change in size (EUS versus pathology T-staging Pearson correlation coefficient, 0.586; P < .001). A similar analysis of MDCT showed a weaker correlation. There was no correlation between preoperative EUS/MDCT findings and postoperative pathology among patients who received neoadjuvant therapy.

In the neoadjuvant therapy group, tumor size was reduced in 31%, was unchanged in 53%, and actually grew in 16%. Three-year overall survival was highest in the reduced group (50%), and lower in the unchanged (37%) and tumor-growth (34%) groups. At 5 years, overall survival was 31%, 19%, and 16%, respectively (P = .003). Compared with those whose tumor size remained the same or grew, those with reduced tumor size had higher 3-year overall survival (50% vs. 33%) and 5-year overall survival (31% vs. 18%; P < .001).

The researchers used recursive positioning to identify the optimal threshold for tumor reduction, and found that a 47% or greater reduction was associated with 67% overall survival at 3 years and 47% at 5 years, compared with 32% and 16% for those with smaller reduction or tumors that maintained or increased in size (P < .001).

The researchers noted that, although their study is large, it remains retrospective in design. Another limitation they cited was that not all patients received the same neoadjuvant therapy. Furthermore, both EUS and pathologic evaluation can be subjective, and it can be difficult to correct for that.

“While additional studies are required, incorporating preoperative EUS and postoperative pathologic tumor size measurements into the standard evaluation of neoadjuvant-treated PDAC patients may guide subsequent management in the adjuvant setting,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded in part by the National Pancreas Foundation, Sky Foundation, and the Pittsburgh Liver Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh. One author disclosed receiving an honorarium from Foundation Medicine, but the rest reported having nothing to disclose. Dr. Sealock has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Das R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec 2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.11.041.

In patients who undergo resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) after neoadjuvant therapy, reduction in tumor size between diagnosis and surgery is associated with improved survival, according to a new single-center, retrospective analysis. The researchers compared tumor size as measured by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and found that a threshold of 47% or greater reduction in tumor size at resection was associated with a doubling in the 3-year survival rate.

The study, led by Rohit Das, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The research represents only a small percentage of patients since most diagnosed with PDAC have locally advanced or metastatic disease that rules out surgery. Still, the work puts more emphasis on measuring tumor size while performing EUS, according to Robert Jay Sealock, MD, who is an assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

“This is some helpful information that you can relay to the patient, saying that you have a significant decrease in the size of the tumor based on your initial EUS, and your chance of 3- to 5-year survival is going to be a lot higher, compared to somebody that didn’t have that tumor regression. Most of these patients will undergo an EUS anyway, and you’ll commonly if not always measure the tumor size while you’re in there. Now you can apply this information that you already have to give the patients some additional information if they do undergo surgery,” said Dr. Sealock, who was not involved in the research.

Previous efforts to prognosticate postsurgical survival focused on overall tumor burden using multidetector CT (MDCT), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels, and histologic examination following surgery, but all suffer from various limitations. MDCT is not always accurate in its measurement of tumor size, other conditions can also raise CA19-9 levels, and pathologic findings are subjective because sometimes the amount of tumor before neoadjuvant therapy is uncertain.

The researchers mapped survival statistics to EUS and pathologic findings for 340 treatment-naive and 365 neoadjuvant-treated PDAC patients at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. They used a 200 patient cohort from the same center who had been treated with neoadjuvant therapy for validation.

Pathology examination revealed that, in the treatment-naive group, 71% of tumors were larger than the size determined during EUS. In 9% of cases there was no change in size (EUS versus pathology T-staging Pearson correlation coefficient, 0.586; P < .001). A similar analysis of MDCT showed a weaker correlation. There was no correlation between preoperative EUS/MDCT findings and postoperative pathology among patients who received neoadjuvant therapy.

In the neoadjuvant therapy group, tumor size was reduced in 31%, was unchanged in 53%, and actually grew in 16%. Three-year overall survival was highest in the reduced group (50%), and lower in the unchanged (37%) and tumor-growth (34%) groups. At 5 years, overall survival was 31%, 19%, and 16%, respectively (P = .003). Compared with those whose tumor size remained the same or grew, those with reduced tumor size had higher 3-year overall survival (50% vs. 33%) and 5-year overall survival (31% vs. 18%; P < .001).

The researchers used recursive positioning to identify the optimal threshold for tumor reduction, and found that a 47% or greater reduction was associated with 67% overall survival at 3 years and 47% at 5 years, compared with 32% and 16% for those with smaller reduction or tumors that maintained or increased in size (P < .001).

The researchers noted that, although their study is large, it remains retrospective in design. Another limitation they cited was that not all patients received the same neoadjuvant therapy. Furthermore, both EUS and pathologic evaluation can be subjective, and it can be difficult to correct for that.

“While additional studies are required, incorporating preoperative EUS and postoperative pathologic tumor size measurements into the standard evaluation of neoadjuvant-treated PDAC patients may guide subsequent management in the adjuvant setting,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded in part by the National Pancreas Foundation, Sky Foundation, and the Pittsburgh Liver Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh. One author disclosed receiving an honorarium from Foundation Medicine, but the rest reported having nothing to disclose. Dr. Sealock has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Das R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec 2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.11.041.

In patients who undergo resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) after neoadjuvant therapy, reduction in tumor size between diagnosis and surgery is associated with improved survival, according to a new single-center, retrospective analysis. The researchers compared tumor size as measured by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and found that a threshold of 47% or greater reduction in tumor size at resection was associated with a doubling in the 3-year survival rate.

The study, led by Rohit Das, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The research represents only a small percentage of patients since most diagnosed with PDAC have locally advanced or metastatic disease that rules out surgery. Still, the work puts more emphasis on measuring tumor size while performing EUS, according to Robert Jay Sealock, MD, who is an assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

“This is some helpful information that you can relay to the patient, saying that you have a significant decrease in the size of the tumor based on your initial EUS, and your chance of 3- to 5-year survival is going to be a lot higher, compared to somebody that didn’t have that tumor regression. Most of these patients will undergo an EUS anyway, and you’ll commonly if not always measure the tumor size while you’re in there. Now you can apply this information that you already have to give the patients some additional information if they do undergo surgery,” said Dr. Sealock, who was not involved in the research.

Previous efforts to prognosticate postsurgical survival focused on overall tumor burden using multidetector CT (MDCT), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels, and histologic examination following surgery, but all suffer from various limitations. MDCT is not always accurate in its measurement of tumor size, other conditions can also raise CA19-9 levels, and pathologic findings are subjective because sometimes the amount of tumor before neoadjuvant therapy is uncertain.

The researchers mapped survival statistics to EUS and pathologic findings for 340 treatment-naive and 365 neoadjuvant-treated PDAC patients at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. They used a 200 patient cohort from the same center who had been treated with neoadjuvant therapy for validation.

Pathology examination revealed that, in the treatment-naive group, 71% of tumors were larger than the size determined during EUS. In 9% of cases there was no change in size (EUS versus pathology T-staging Pearson correlation coefficient, 0.586; P < .001). A similar analysis of MDCT showed a weaker correlation. There was no correlation between preoperative EUS/MDCT findings and postoperative pathology among patients who received neoadjuvant therapy.

In the neoadjuvant therapy group, tumor size was reduced in 31%, was unchanged in 53%, and actually grew in 16%. Three-year overall survival was highest in the reduced group (50%), and lower in the unchanged (37%) and tumor-growth (34%) groups. At 5 years, overall survival was 31%, 19%, and 16%, respectively (P = .003). Compared with those whose tumor size remained the same or grew, those with reduced tumor size had higher 3-year overall survival (50% vs. 33%) and 5-year overall survival (31% vs. 18%; P < .001).

The researchers used recursive positioning to identify the optimal threshold for tumor reduction, and found that a 47% or greater reduction was associated with 67% overall survival at 3 years and 47% at 5 years, compared with 32% and 16% for those with smaller reduction or tumors that maintained or increased in size (P < .001).

The researchers noted that, although their study is large, it remains retrospective in design. Another limitation they cited was that not all patients received the same neoadjuvant therapy. Furthermore, both EUS and pathologic evaluation can be subjective, and it can be difficult to correct for that.

“While additional studies are required, incorporating preoperative EUS and postoperative pathologic tumor size measurements into the standard evaluation of neoadjuvant-treated PDAC patients may guide subsequent management in the adjuvant setting,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded in part by the National Pancreas Foundation, Sky Foundation, and the Pittsburgh Liver Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh. One author disclosed receiving an honorarium from Foundation Medicine, but the rest reported having nothing to disclose. Dr. Sealock has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Das R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Dec 2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.11.041.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY