User login

What’s Eating You? The South African Fattail Scorpion Revisited

Identification

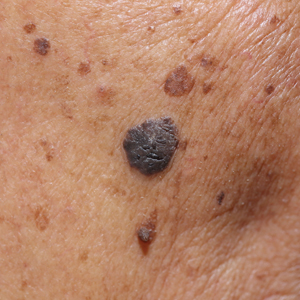

The South African fattail scorpion (Parabuthus transvaalicus)(Figure) is one of the most poisonous scorpions in southern Africa.1 A member of the Buthidae scorpion family, it can grow as long as 15 cm and is dark brown-black with lighter red-brown pincers. Similar to other fattail scorpions, it has slender pincers (pedipalps) and a thick square tail (the telson). Parabuthus transvaalicus inhabits hot dry deserts, scrublands, and semiarid regions.1,2 It also is popular in exotic pet collections, the most common source of stings in the United States.

Stings and Envenomation

Scorpions with thicker tails generally have more potent venom than those with slender tails and thick pincers. Venom is injected by a stinger at the tip of the telson1; P transvaalicus also can spray venom as far as 3 m.1,2 Venom is not known to cause toxicity through skin contact but could represent a hazard if sprayed in the eye.

Scorpion toxins are a group of complex neurotoxins that act on sodium channels, either retarding inactivation (α toxin) or enhancing activation (β toxin), causing massive depolarization of excitable cells.1,3 The toxin causes neurons to fire repetitively.4 Neurotransmitters—noradrenaline, adrenaline, and acetylcholine—cause the observed sympathetic, parasympathetic, and skeletal muscle effects.1

Incidence

Worldwide, more than 1.2 million individuals are stung by a scorpion annually, causing more than 3250 deaths a year.5 Adults are stung more often, but children experience more severe envenomation, are more likely to develop severe illness requiring intensive supportive care, and have a higher mortality.4

As many as one-third of patients stung by a Parabuthus scorpion develop neuromuscular toxicity, which can be life-threatening.6 In a study of 277 envenomations by P transvaalicus, 10% of patients developed severe symptoms and 5 died. Children younger than 10 years and adults older than 50 years are at greatest risk for

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of scorpion envenomation varies with the species involved, the amount of venom injected, and the victim’s weight and baseline health.1 Scorpion envenomation is divided into 4 grades based on the severity of a sting:

• Grade I: pain and paresthesia at the envenomation site; usually, no local inflammation

• Grade II: local symptoms as well as more remote pain and paresthesia; pain can radiate up the affected limb

• Grade III: cranial nerve or somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction; either presentation can have associated autonomic dysfunction

• Grade IV: both cranial nerve and somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction, with associated auto-nomic dysfunction

The initial symptom of a scorpion sting is intense burning pain. The sting site might be unimpressive, with only a mild local reaction. Symptoms usually progress to maximum severity within 5 hours.1 Muscle pain, cramps, and weakness are prominent. The patient might have difficulty walking and swallowing, with increased salivation and drooling, and visual disturbance with abnormal eye movements. Pulse, blood pressure, and temperature often are elevated. The patient might be hyperreflexic with clonus.1,6

Symptoms of increased sympathetic activity are hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac dysrhythmia, perspiration, hyperglycemia, and restlessness.1,2 Parasympathetic effects are increased salivation, hypotension, bradycardia, and gastric distension. Skeletal muscle effects include tremors and involuntary muscle movement, which can be severe. Cranial nerve dysfunction may manifest as dysphagia, drooling, abnormal eye movements, blurred vision, slurred speech, and tongue fasciculations. Subsequent development of muscle weakness, bulbar paralysis, and difficulty breathing may be caused by depletion of neurotransmitters after prolonged excessive neuronal activity.1

Distinctive Signs in Younger Patients

A child who is stung by a scorpion might have symptoms similar to those seen in an adult victim but can also experience an extreme form of restlessness that indicates severe envenomation characterized by inability to lay still, violent muscle twitching, and uncontrollable flailing of extremities. The child might have facial grimacing, with lip-smacking and chewing motions. In addition, bulbar paralysis and respiratory distress are more likely in children who have been stung than in adults.1,2

Management

Treatment of a P transvaalicus sting is directed at “scorpionism,” envenomation that is associated with systemic symptoms that can be life-threatening. Treatment comprises support of vital functions, symptomatic measures, and injection of antivenin.8

Support of Vital Functions

In adults, systemic symptoms can be delayed as long as 8 hours after the sting. However, most severe cases usually are evident within 60 minutes; infants can reach grade IV as quickly as 15 to 30 minutes.9,10 Loss of pharyngeal reflexes and development of respiratory distress are ominous warning signs requiring immediate respiratory support. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death.1 An asymptomatic child should be admitted to a hospital for observation for a minimum of 12 hours if the species of scorpion was not identified.2

Pain Relief

Most patients cannot tolerate an ice pack because of severe hyperesthesia. Infiltration of the local sting site with an anesthetic generally is safe and can provide some local pain relief. Intravenous fentanyl has been used in closely monitored patients because the drug is not associated with histamine release. Medications that cause release of histamine, such as morphine, can exacerbate or confuse the clinical picture.

Antivenin

Scorpion antivenin contains purified IgG fragments; allergic reactions are now rare. The sooner antivenin is administered, the greater the benefit. When administered early, it can prevent many of the most serious complications.7 In a randomized, double-blind study of critically ill children with clinically significant signs of scorpion envenomation, intravenous administration of scorpion-specific fragment antigen-binding 2 (F[(ab’]2) antivenin resulted in resolution of clinical symptoms within 4 hours.11

When managing grade III or IV scorpion envenomation, all patients should be admitted to a medical facility equipped to provide intensive supportive care; consider consultation with a regional poison control center. The World Health Organization maintains an international poison control center (at https://www.who.int/ipcs/poisons/centre/en/) with regional telephone numbers; alternatively, in the United States, call the nationwide telephone number of the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222).

The World Health Organization has identified declining production of antivenin as a crisis.12

Resolution

Symptoms of envenomation typically resolve 9 to 30 hours after a sting in a patient with grade III or IV envenomation not treated with antivenin.4 However, pain and paresthesia occasionally last as long as 2 weeks. In rare cases, more long-term sequelae of burning paresthesia persist for months.4

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to be aware of the potential for life-threatening envenomation by certain scorpion species native to southern Africa. In the United States, stings of these species most often are seen in patients with a pet collection, but late sequelae also can be seen in travelers returning from an endemic region. The site of a sting often appears unimpressive initially, but severe hyperesthesia is common. Patients with cardiac, neurologic, or respiratory symptoms require intensive supportive care. Proper care can be lifesaving.

- Müller GJ, Modler H, Wium CA, et al. Scorpion sting in southern Africa: diagnosis and management. Continuing Medical Education. 2012;30:356-361.

- Müller GJ. Scorpionism in South Africa. a report of 42 serious scorpion envenomations. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:405-411.

- Quintero-Hernández V, Jiménez-Vargas JM, Gurrola GB, et al. Scorpion venom components that affect ion-channels function. Toxicon. 2013;76:328-342.

- LoVecchio F, McBride C. Scorpion envenomations in young children in central Arizona. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:937-940.

- Chippaux JP, Goyffon M. Epidemiology of scorpionism: a global appraisal. Acta Trop. 2008;107:71-79.

- Bergman NJ. Clinical description of Parabuthus transvaalicus scorpionism in Zimbabwe. Toxicon. 1997;35:759-771.

- Chippaux JP. Emerging options for the management of scorpion stings. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2012;6:165-173.

- Santos MS, Silva CG, Neto BS, et al. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of scorpionism in the world: a systematic review. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27:504-518.

- Amaral CF, Rezende NA. Both cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of pulmonary oedema after scorpion envenoming. Toxicon. 1997;35:997-998.

- Bergman NJ. Scorpion sting in Zimbabwe. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:163-167.

- Boyer LV, Theodorou AA, Berg RA, et al; Arizona Envenomation Investigators. antivenom for critically ill children with neurotoxicity from scorpion stings. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2090-2098.

- Theakston RD, Warrell DA, Griffiths E. Report of a WHO workshop on the standardization and control of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2003;41:541-557.

Identification

The South African fattail scorpion (Parabuthus transvaalicus)(Figure) is one of the most poisonous scorpions in southern Africa.1 A member of the Buthidae scorpion family, it can grow as long as 15 cm and is dark brown-black with lighter red-brown pincers. Similar to other fattail scorpions, it has slender pincers (pedipalps) and a thick square tail (the telson). Parabuthus transvaalicus inhabits hot dry deserts, scrublands, and semiarid regions.1,2 It also is popular in exotic pet collections, the most common source of stings in the United States.

Stings and Envenomation

Scorpions with thicker tails generally have more potent venom than those with slender tails and thick pincers. Venom is injected by a stinger at the tip of the telson1; P transvaalicus also can spray venom as far as 3 m.1,2 Venom is not known to cause toxicity through skin contact but could represent a hazard if sprayed in the eye.

Scorpion toxins are a group of complex neurotoxins that act on sodium channels, either retarding inactivation (α toxin) or enhancing activation (β toxin), causing massive depolarization of excitable cells.1,3 The toxin causes neurons to fire repetitively.4 Neurotransmitters—noradrenaline, adrenaline, and acetylcholine—cause the observed sympathetic, parasympathetic, and skeletal muscle effects.1

Incidence

Worldwide, more than 1.2 million individuals are stung by a scorpion annually, causing more than 3250 deaths a year.5 Adults are stung more often, but children experience more severe envenomation, are more likely to develop severe illness requiring intensive supportive care, and have a higher mortality.4

As many as one-third of patients stung by a Parabuthus scorpion develop neuromuscular toxicity, which can be life-threatening.6 In a study of 277 envenomations by P transvaalicus, 10% of patients developed severe symptoms and 5 died. Children younger than 10 years and adults older than 50 years are at greatest risk for

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of scorpion envenomation varies with the species involved, the amount of venom injected, and the victim’s weight and baseline health.1 Scorpion envenomation is divided into 4 grades based on the severity of a sting:

• Grade I: pain and paresthesia at the envenomation site; usually, no local inflammation

• Grade II: local symptoms as well as more remote pain and paresthesia; pain can radiate up the affected limb

• Grade III: cranial nerve or somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction; either presentation can have associated autonomic dysfunction

• Grade IV: both cranial nerve and somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction, with associated auto-nomic dysfunction

The initial symptom of a scorpion sting is intense burning pain. The sting site might be unimpressive, with only a mild local reaction. Symptoms usually progress to maximum severity within 5 hours.1 Muscle pain, cramps, and weakness are prominent. The patient might have difficulty walking and swallowing, with increased salivation and drooling, and visual disturbance with abnormal eye movements. Pulse, blood pressure, and temperature often are elevated. The patient might be hyperreflexic with clonus.1,6

Symptoms of increased sympathetic activity are hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac dysrhythmia, perspiration, hyperglycemia, and restlessness.1,2 Parasympathetic effects are increased salivation, hypotension, bradycardia, and gastric distension. Skeletal muscle effects include tremors and involuntary muscle movement, which can be severe. Cranial nerve dysfunction may manifest as dysphagia, drooling, abnormal eye movements, blurred vision, slurred speech, and tongue fasciculations. Subsequent development of muscle weakness, bulbar paralysis, and difficulty breathing may be caused by depletion of neurotransmitters after prolonged excessive neuronal activity.1

Distinctive Signs in Younger Patients

A child who is stung by a scorpion might have symptoms similar to those seen in an adult victim but can also experience an extreme form of restlessness that indicates severe envenomation characterized by inability to lay still, violent muscle twitching, and uncontrollable flailing of extremities. The child might have facial grimacing, with lip-smacking and chewing motions. In addition, bulbar paralysis and respiratory distress are more likely in children who have been stung than in adults.1,2

Management

Treatment of a P transvaalicus sting is directed at “scorpionism,” envenomation that is associated with systemic symptoms that can be life-threatening. Treatment comprises support of vital functions, symptomatic measures, and injection of antivenin.8

Support of Vital Functions

In adults, systemic symptoms can be delayed as long as 8 hours after the sting. However, most severe cases usually are evident within 60 minutes; infants can reach grade IV as quickly as 15 to 30 minutes.9,10 Loss of pharyngeal reflexes and development of respiratory distress are ominous warning signs requiring immediate respiratory support. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death.1 An asymptomatic child should be admitted to a hospital for observation for a minimum of 12 hours if the species of scorpion was not identified.2

Pain Relief

Most patients cannot tolerate an ice pack because of severe hyperesthesia. Infiltration of the local sting site with an anesthetic generally is safe and can provide some local pain relief. Intravenous fentanyl has been used in closely monitored patients because the drug is not associated with histamine release. Medications that cause release of histamine, such as morphine, can exacerbate or confuse the clinical picture.

Antivenin

Scorpion antivenin contains purified IgG fragments; allergic reactions are now rare. The sooner antivenin is administered, the greater the benefit. When administered early, it can prevent many of the most serious complications.7 In a randomized, double-blind study of critically ill children with clinically significant signs of scorpion envenomation, intravenous administration of scorpion-specific fragment antigen-binding 2 (F[(ab’]2) antivenin resulted in resolution of clinical symptoms within 4 hours.11

When managing grade III or IV scorpion envenomation, all patients should be admitted to a medical facility equipped to provide intensive supportive care; consider consultation with a regional poison control center. The World Health Organization maintains an international poison control center (at https://www.who.int/ipcs/poisons/centre/en/) with regional telephone numbers; alternatively, in the United States, call the nationwide telephone number of the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222).

The World Health Organization has identified declining production of antivenin as a crisis.12

Resolution

Symptoms of envenomation typically resolve 9 to 30 hours after a sting in a patient with grade III or IV envenomation not treated with antivenin.4 However, pain and paresthesia occasionally last as long as 2 weeks. In rare cases, more long-term sequelae of burning paresthesia persist for months.4

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to be aware of the potential for life-threatening envenomation by certain scorpion species native to southern Africa. In the United States, stings of these species most often are seen in patients with a pet collection, but late sequelae also can be seen in travelers returning from an endemic region. The site of a sting often appears unimpressive initially, but severe hyperesthesia is common. Patients with cardiac, neurologic, or respiratory symptoms require intensive supportive care. Proper care can be lifesaving.

Identification

The South African fattail scorpion (Parabuthus transvaalicus)(Figure) is one of the most poisonous scorpions in southern Africa.1 A member of the Buthidae scorpion family, it can grow as long as 15 cm and is dark brown-black with lighter red-brown pincers. Similar to other fattail scorpions, it has slender pincers (pedipalps) and a thick square tail (the telson). Parabuthus transvaalicus inhabits hot dry deserts, scrublands, and semiarid regions.1,2 It also is popular in exotic pet collections, the most common source of stings in the United States.

Stings and Envenomation

Scorpions with thicker tails generally have more potent venom than those with slender tails and thick pincers. Venom is injected by a stinger at the tip of the telson1; P transvaalicus also can spray venom as far as 3 m.1,2 Venom is not known to cause toxicity through skin contact but could represent a hazard if sprayed in the eye.

Scorpion toxins are a group of complex neurotoxins that act on sodium channels, either retarding inactivation (α toxin) or enhancing activation (β toxin), causing massive depolarization of excitable cells.1,3 The toxin causes neurons to fire repetitively.4 Neurotransmitters—noradrenaline, adrenaline, and acetylcholine—cause the observed sympathetic, parasympathetic, and skeletal muscle effects.1

Incidence

Worldwide, more than 1.2 million individuals are stung by a scorpion annually, causing more than 3250 deaths a year.5 Adults are stung more often, but children experience more severe envenomation, are more likely to develop severe illness requiring intensive supportive care, and have a higher mortality.4

As many as one-third of patients stung by a Parabuthus scorpion develop neuromuscular toxicity, which can be life-threatening.6 In a study of 277 envenomations by P transvaalicus, 10% of patients developed severe symptoms and 5 died. Children younger than 10 years and adults older than 50 years are at greatest risk for

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of scorpion envenomation varies with the species involved, the amount of venom injected, and the victim’s weight and baseline health.1 Scorpion envenomation is divided into 4 grades based on the severity of a sting:

• Grade I: pain and paresthesia at the envenomation site; usually, no local inflammation

• Grade II: local symptoms as well as more remote pain and paresthesia; pain can radiate up the affected limb

• Grade III: cranial nerve or somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction; either presentation can have associated autonomic dysfunction

• Grade IV: both cranial nerve and somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction, with associated auto-nomic dysfunction

The initial symptom of a scorpion sting is intense burning pain. The sting site might be unimpressive, with only a mild local reaction. Symptoms usually progress to maximum severity within 5 hours.1 Muscle pain, cramps, and weakness are prominent. The patient might have difficulty walking and swallowing, with increased salivation and drooling, and visual disturbance with abnormal eye movements. Pulse, blood pressure, and temperature often are elevated. The patient might be hyperreflexic with clonus.1,6

Symptoms of increased sympathetic activity are hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac dysrhythmia, perspiration, hyperglycemia, and restlessness.1,2 Parasympathetic effects are increased salivation, hypotension, bradycardia, and gastric distension. Skeletal muscle effects include tremors and involuntary muscle movement, which can be severe. Cranial nerve dysfunction may manifest as dysphagia, drooling, abnormal eye movements, blurred vision, slurred speech, and tongue fasciculations. Subsequent development of muscle weakness, bulbar paralysis, and difficulty breathing may be caused by depletion of neurotransmitters after prolonged excessive neuronal activity.1

Distinctive Signs in Younger Patients

A child who is stung by a scorpion might have symptoms similar to those seen in an adult victim but can also experience an extreme form of restlessness that indicates severe envenomation characterized by inability to lay still, violent muscle twitching, and uncontrollable flailing of extremities. The child might have facial grimacing, with lip-smacking and chewing motions. In addition, bulbar paralysis and respiratory distress are more likely in children who have been stung than in adults.1,2

Management

Treatment of a P transvaalicus sting is directed at “scorpionism,” envenomation that is associated with systemic symptoms that can be life-threatening. Treatment comprises support of vital functions, symptomatic measures, and injection of antivenin.8

Support of Vital Functions

In adults, systemic symptoms can be delayed as long as 8 hours after the sting. However, most severe cases usually are evident within 60 minutes; infants can reach grade IV as quickly as 15 to 30 minutes.9,10 Loss of pharyngeal reflexes and development of respiratory distress are ominous warning signs requiring immediate respiratory support. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death.1 An asymptomatic child should be admitted to a hospital for observation for a minimum of 12 hours if the species of scorpion was not identified.2

Pain Relief

Most patients cannot tolerate an ice pack because of severe hyperesthesia. Infiltration of the local sting site with an anesthetic generally is safe and can provide some local pain relief. Intravenous fentanyl has been used in closely monitored patients because the drug is not associated with histamine release. Medications that cause release of histamine, such as morphine, can exacerbate or confuse the clinical picture.

Antivenin

Scorpion antivenin contains purified IgG fragments; allergic reactions are now rare. The sooner antivenin is administered, the greater the benefit. When administered early, it can prevent many of the most serious complications.7 In a randomized, double-blind study of critically ill children with clinically significant signs of scorpion envenomation, intravenous administration of scorpion-specific fragment antigen-binding 2 (F[(ab’]2) antivenin resulted in resolution of clinical symptoms within 4 hours.11

When managing grade III or IV scorpion envenomation, all patients should be admitted to a medical facility equipped to provide intensive supportive care; consider consultation with a regional poison control center. The World Health Organization maintains an international poison control center (at https://www.who.int/ipcs/poisons/centre/en/) with regional telephone numbers; alternatively, in the United States, call the nationwide telephone number of the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222).

The World Health Organization has identified declining production of antivenin as a crisis.12

Resolution

Symptoms of envenomation typically resolve 9 to 30 hours after a sting in a patient with grade III or IV envenomation not treated with antivenin.4 However, pain and paresthesia occasionally last as long as 2 weeks. In rare cases, more long-term sequelae of burning paresthesia persist for months.4

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to be aware of the potential for life-threatening envenomation by certain scorpion species native to southern Africa. In the United States, stings of these species most often are seen in patients with a pet collection, but late sequelae also can be seen in travelers returning from an endemic region. The site of a sting often appears unimpressive initially, but severe hyperesthesia is common. Patients with cardiac, neurologic, or respiratory symptoms require intensive supportive care. Proper care can be lifesaving.

- Müller GJ, Modler H, Wium CA, et al. Scorpion sting in southern Africa: diagnosis and management. Continuing Medical Education. 2012;30:356-361.

- Müller GJ. Scorpionism in South Africa. a report of 42 serious scorpion envenomations. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:405-411.

- Quintero-Hernández V, Jiménez-Vargas JM, Gurrola GB, et al. Scorpion venom components that affect ion-channels function. Toxicon. 2013;76:328-342.

- LoVecchio F, McBride C. Scorpion envenomations in young children in central Arizona. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:937-940.

- Chippaux JP, Goyffon M. Epidemiology of scorpionism: a global appraisal. Acta Trop. 2008;107:71-79.

- Bergman NJ. Clinical description of Parabuthus transvaalicus scorpionism in Zimbabwe. Toxicon. 1997;35:759-771.

- Chippaux JP. Emerging options for the management of scorpion stings. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2012;6:165-173.

- Santos MS, Silva CG, Neto BS, et al. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of scorpionism in the world: a systematic review. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27:504-518.

- Amaral CF, Rezende NA. Both cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of pulmonary oedema after scorpion envenoming. Toxicon. 1997;35:997-998.

- Bergman NJ. Scorpion sting in Zimbabwe. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:163-167.

- Boyer LV, Theodorou AA, Berg RA, et al; Arizona Envenomation Investigators. antivenom for critically ill children with neurotoxicity from scorpion stings. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2090-2098.

- Theakston RD, Warrell DA, Griffiths E. Report of a WHO workshop on the standardization and control of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2003;41:541-557.

- Müller GJ, Modler H, Wium CA, et al. Scorpion sting in southern Africa: diagnosis and management. Continuing Medical Education. 2012;30:356-361.

- Müller GJ. Scorpionism in South Africa. a report of 42 serious scorpion envenomations. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:405-411.

- Quintero-Hernández V, Jiménez-Vargas JM, Gurrola GB, et al. Scorpion venom components that affect ion-channels function. Toxicon. 2013;76:328-342.

- LoVecchio F, McBride C. Scorpion envenomations in young children in central Arizona. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:937-940.

- Chippaux JP, Goyffon M. Epidemiology of scorpionism: a global appraisal. Acta Trop. 2008;107:71-79.

- Bergman NJ. Clinical description of Parabuthus transvaalicus scorpionism in Zimbabwe. Toxicon. 1997;35:759-771.

- Chippaux JP. Emerging options for the management of scorpion stings. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2012;6:165-173.

- Santos MS, Silva CG, Neto BS, et al. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of scorpionism in the world: a systematic review. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27:504-518.

- Amaral CF, Rezende NA. Both cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of pulmonary oedema after scorpion envenoming. Toxicon. 1997;35:997-998.

- Bergman NJ. Scorpion sting in Zimbabwe. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:163-167.

- Boyer LV, Theodorou AA, Berg RA, et al; Arizona Envenomation Investigators. antivenom for critically ill children with neurotoxicity from scorpion stings. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2090-2098.

- Theakston RD, Warrell DA, Griffiths E. Report of a WHO workshop on the standardization and control of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2003;41:541-557.

Practice Points

- Exotic and dangerous pets are becoming more popular. Scorpion stings cause potentially life-threatening neurotoxicity, with children particularly susceptible.

- Fattail scorpions are particularly dangerous and physicians should be aware that their stings may be encountered worldwide.

- Symptoms present 1 to 8 hours after envenomation, with severe cases showing hyperreflexia, clonus, difficulty swallowing, and respiratory distress. The sting site may be unimpressive.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy to Facilitate Knifeless Skin Cancer Management

Practice Gap

Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in elderly patients can cause morbidity because these patients frequently struggle to care for their biopsy sites and experience biopsy- and surgery-related complications. To minimize this treatment-related morbidity, we designed a knifeless treatment approach that employs reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) in lieu of skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis of NMSC, then uses either intralesional or topical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (as appropriate, depending on depth of invasion) to cure the NMSC. With this approach, the patient is spared both biopsy- and surgery-related difficulties, though both intralesional and topical chemotherapy are accompanied by their own risks for adverse effects.

The Technique

Elderly patients, diabetic patients, and patients with lesions suspicious for NMSC on areas prone to poor wound healing or to notable treatment-related morbidity (eg, lower legs, genitals, the face of younger patients) are offered skin biopsy or RCM; the latter is performed during the appointment by an RC

When resolution is uncertain, RCM is repeated to assess for tumor clearance. Repeat RCM is performed at least 4 weeks after termination of treatment to avoid misinterpretation caused by treatment-related tissue inflammation. Patients who are not cured using this management approach are offered appropriate surgical management.

Practice Implications

Reflectance confocal microscopy has emerged as an effective modality for confirming the diagnosis of NMSC with high sensitivity and specificity.1,2 Emergence of this technology presents an opportunity for improving the way the NMSC is managed because RCM allows dermatologists to confirm the diagnosis of BCC and SCC by interpretation of RCM mosaics rather than by histopathologic examination of biopsied tissue. Our knifeless approach to skin cancer management is especially beneficial when biopsy and dermatologic surgery are likely to confer notable morbidity, such as managing NMSC on the face of a young adult, in the frail elderly population, or in diabetic patients, and when treating sites on the lower extremity prone to poor wound healing.

- Song E, Grant-Kels JM, Swede H, et al. Paired comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis and reflectance confocal microscopy in the detection of melanoma in vivo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1187-1192.

- Ferrari B, Salgarelli AC, Mandel VD, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: the aid of reflectance confocal microscopy for the accurate diagnosis and management. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:169-177.

Practice Gap

Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in elderly patients can cause morbidity because these patients frequently struggle to care for their biopsy sites and experience biopsy- and surgery-related complications. To minimize this treatment-related morbidity, we designed a knifeless treatment approach that employs reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) in lieu of skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis of NMSC, then uses either intralesional or topical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (as appropriate, depending on depth of invasion) to cure the NMSC. With this approach, the patient is spared both biopsy- and surgery-related difficulties, though both intralesional and topical chemotherapy are accompanied by their own risks for adverse effects.

The Technique

Elderly patients, diabetic patients, and patients with lesions suspicious for NMSC on areas prone to poor wound healing or to notable treatment-related morbidity (eg, lower legs, genitals, the face of younger patients) are offered skin biopsy or RCM; the latter is performed during the appointment by an RC

When resolution is uncertain, RCM is repeated to assess for tumor clearance. Repeat RCM is performed at least 4 weeks after termination of treatment to avoid misinterpretation caused by treatment-related tissue inflammation. Patients who are not cured using this management approach are offered appropriate surgical management.

Practice Implications

Reflectance confocal microscopy has emerged as an effective modality for confirming the diagnosis of NMSC with high sensitivity and specificity.1,2 Emergence of this technology presents an opportunity for improving the way the NMSC is managed because RCM allows dermatologists to confirm the diagnosis of BCC and SCC by interpretation of RCM mosaics rather than by histopathologic examination of biopsied tissue. Our knifeless approach to skin cancer management is especially beneficial when biopsy and dermatologic surgery are likely to confer notable morbidity, such as managing NMSC on the face of a young adult, in the frail elderly population, or in diabetic patients, and when treating sites on the lower extremity prone to poor wound healing.

Practice Gap

Management of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in elderly patients can cause morbidity because these patients frequently struggle to care for their biopsy sites and experience biopsy- and surgery-related complications. To minimize this treatment-related morbidity, we designed a knifeless treatment approach that employs reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) in lieu of skin biopsy to establish the diagnosis of NMSC, then uses either intralesional or topical chemotherapy or immunotherapy (as appropriate, depending on depth of invasion) to cure the NMSC. With this approach, the patient is spared both biopsy- and surgery-related difficulties, though both intralesional and topical chemotherapy are accompanied by their own risks for adverse effects.

The Technique

Elderly patients, diabetic patients, and patients with lesions suspicious for NMSC on areas prone to poor wound healing or to notable treatment-related morbidity (eg, lower legs, genitals, the face of younger patients) are offered skin biopsy or RCM; the latter is performed during the appointment by an RC

When resolution is uncertain, RCM is repeated to assess for tumor clearance. Repeat RCM is performed at least 4 weeks after termination of treatment to avoid misinterpretation caused by treatment-related tissue inflammation. Patients who are not cured using this management approach are offered appropriate surgical management.

Practice Implications

Reflectance confocal microscopy has emerged as an effective modality for confirming the diagnosis of NMSC with high sensitivity and specificity.1,2 Emergence of this technology presents an opportunity for improving the way the NMSC is managed because RCM allows dermatologists to confirm the diagnosis of BCC and SCC by interpretation of RCM mosaics rather than by histopathologic examination of biopsied tissue. Our knifeless approach to skin cancer management is especially beneficial when biopsy and dermatologic surgery are likely to confer notable morbidity, such as managing NMSC on the face of a young adult, in the frail elderly population, or in diabetic patients, and when treating sites on the lower extremity prone to poor wound healing.

- Song E, Grant-Kels JM, Swede H, et al. Paired comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis and reflectance confocal microscopy in the detection of melanoma in vivo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1187-1192.

- Ferrari B, Salgarelli AC, Mandel VD, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: the aid of reflectance confocal microscopy for the accurate diagnosis and management. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:169-177.

- Song E, Grant-Kels JM, Swede H, et al. Paired comparison of the sensitivity and specificity of multispectral digital skin lesion analysis and reflectance confocal microscopy in the detection of melanoma in vivo: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1187-1192.

- Ferrari B, Salgarelli AC, Mandel VD, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck: the aid of reflectance confocal microscopy for the accurate diagnosis and management. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017;152:169-177.

What Neglected Tropical Diseases Teach Us About Stigma

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of 20 diseases that typically are chronic and cause long-term disability, which negatively impacts work productivity, child survival, and school performance and attendance with adverse effect on future earnings.1 Data from the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study revealed that half of the world’s NTDs occur in poor populations living in wealthy countries.2 Neglected tropical diseases with skin manifestations include parasitic infections (eg, American trypanosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, scabies and other ectoparasites, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, taeniasis/cysticercosis), bacterial infections (eg, Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws), fungal infections (eg, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, deep mycoses), and viral infections (eg, dengue, chikungunya). Rabies and snakebite envenomization involve the skin through inoculation. Within the larger group of NTDs, the World Health Organization has identified “skin NTDs” as a subgroup of NTDs that present primarily with changes in the skin.3 In the absence of early diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, chronic and lifelong disfigurement, disability, stigma, and socioeconomic losses ensue.

The Department of Health of the Government of Western Australia stated:

Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others. When a person is labeled by their illness they are no longer seen as an individual but as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes and beliefs toward this group create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination.4

Stigma associated with skin NTDs exemplifies how skin diseases can have enduring impact on individuals.5 For example, scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis carries heavy psychosocial burden. Young women reported that facial scarring from cutaneous leishmaniasis led to marriage rejections.6 Some even reported extreme suicidal ideations.7 Recently, major depressive disorder associated with scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis has been recognized as a notable contributor to disease burden from cutaneous leishmaniasis.8

Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of leg and scrotal lymphedema worldwide. Even when the condition is treated, lymphedema often persists due to chronic irreversible lymphatic damage. A systematic review of 18 stigma studies in lymphatic filariasis found common themes related to the deleterious consequences of stigma on social relationships; work and education opportunities; health outcomes from reduced treatment-seeking behavior; and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.9 In one subdistrict in India, implementation of a community-based lymphedema management program that consisted of teaching hygiene and limb care for more than 20,000 lymphedema patients and performing community outreach activities (eg, street plays, radio programs, informational brochures) to teach people about lymphatic filariasis and lymphedema care was associated with community members being accepting of patients and an improvement in their understanding of disease etiology.10

Skin involvement from onchocerciasis infection (onchocercal skin disease) is another condition associated with notable stigma.9 Through the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, annual mass drug administration of ivermectin in onchocerciasis-endemic communities has reduced the rate of onchocercal skin disease in these communities. In looking at perception of stigma in onchocercal skin diseases before community-directed ivermectin therapy and 7 to 10 years after, avoidance of people with onchocercal skin disease decreased from 32.7% to 4.3%. There also was an improvement in relationships between healthy people and those with onchocercal skin disease.11

One of the most stigmatizing conditions is leprosy, often referred to as Hansen disease to give credit to the person who discovered that leprosy was caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not from sin, being cursed, or genetic inheritance. Even with this knowledge, stigma persists that can lead to family abandonment and social isolation, which further impacts afflicted individuals’ willingness to seek care, thus leading to disease progression. More recently, there has been research looking at interventions to reduce the stigma that individuals afflicted with leprosy face. In a study from Indonesia where individuals with leprosy were randomized to counseling, socioeconomic development, or contact between community members and affected people, all interventions were associated with a reduction in stigma.12 A rights-based counseling module integrated individual, family, and group forms of counseling and consisted of 5 sessions that focused on medical knowledge of leprosy and rights of individuals with leprosy, along with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy. Socioeconomic development involved opportunities for business training, creation of community groups through which microfinance services were administered, and other assistance to improve livelihood. Informed by evidence from the field of human immunodeficiency virus and mental health that co

Although steps are being taken to address the psychosocial burden of skin NTDs, there is still much work to be done. From the public health lens that largely governs the policies and approaches toward addressing NTDs, the focus often is on interrupting and eliminating disease transmission. Morbidity management, including reduction in stigma and functional impairment, is not always the priority. It is in this space that dermatologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for management approaches that address the morbidity associated with skin NTDs. We have an intimate understanding of how impactful skin diseases can be, even if they are not commonly fatal. Globally, skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden,14 yet dermatology lacks effective evidence-based interventions for reducing stigma in our patients with visible chronic diseases.15

Every day, we see firsthand how skin diseases affect not only our patients but also their families, friends, and caregivers. Although we may not see skin NTDs on a regular basis in our clinics, we can understand almost intuitively how devastating skin NTDs could be on individuals, families, and communities. For patients with skin NTDs, receiving medical therapy is only one component of treatment. In addition to optimizing early diagnosis and treatment, interventions taken to educate families and communities affected by skin NTDs are vitally important. Stigma reduction is possible, as we have seen from the aforementioned interventions used in communities with lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. We call upon our fellow dermatologists to take interest in creating, evaluating, and promoting interventions that address stigma in skin NTDs; it is critical in achieving and maintaining health and well-being for our patients.

- Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ, Damania A, Naghavi M. Blue Marble Health and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004744.

- Skin NTDs. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/skin-ntds/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Stigma, discrimination and mental illness. February 2009. http://www.health.wa.gov.au/docreg/Education/Population/Health_Problems/Mental_Illness/Mentalhealth_stigma_fact.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:E230.

- Bennis I, Belaid L, De Brouwere V, et al. “The mosquitoes that destroy your face.” social impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Morocco, a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:E0189906.

- Bennis I, Thys S, Filali H, et al. Psychosocial impact of scars due to cutaneous leishmaniasis on high school students in Errachidia province, Morocco. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:46.

- Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Haines LR, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and co-morbid major depressive disorder: a systematic review with burden estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:E0007092.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl 1):I53-I70.

- Cassidy T, Worrell CM, Little K, et al. Experiences of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India: an analysis of focus group discussions with patients, families, community members and program volunteers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004424.

- Tchounkeu YF, Onyeneho NG, Wanji S, et al. Changes in stigma and discrimination of onchocerciasis in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:340-347.

- Dadun D, Van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:2-22.

- Kumar A, Lambert S, Lockwood DNJ. Picturing health: a new face for leprosy. Lancet. 2019;393:629-638.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review [published online June 8, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15734.

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of 20 diseases that typically are chronic and cause long-term disability, which negatively impacts work productivity, child survival, and school performance and attendance with adverse effect on future earnings.1 Data from the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study revealed that half of the world’s NTDs occur in poor populations living in wealthy countries.2 Neglected tropical diseases with skin manifestations include parasitic infections (eg, American trypanosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, scabies and other ectoparasites, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, taeniasis/cysticercosis), bacterial infections (eg, Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws), fungal infections (eg, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, deep mycoses), and viral infections (eg, dengue, chikungunya). Rabies and snakebite envenomization involve the skin through inoculation. Within the larger group of NTDs, the World Health Organization has identified “skin NTDs” as a subgroup of NTDs that present primarily with changes in the skin.3 In the absence of early diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, chronic and lifelong disfigurement, disability, stigma, and socioeconomic losses ensue.

The Department of Health of the Government of Western Australia stated:

Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others. When a person is labeled by their illness they are no longer seen as an individual but as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes and beliefs toward this group create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination.4

Stigma associated with skin NTDs exemplifies how skin diseases can have enduring impact on individuals.5 For example, scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis carries heavy psychosocial burden. Young women reported that facial scarring from cutaneous leishmaniasis led to marriage rejections.6 Some even reported extreme suicidal ideations.7 Recently, major depressive disorder associated with scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis has been recognized as a notable contributor to disease burden from cutaneous leishmaniasis.8

Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of leg and scrotal lymphedema worldwide. Even when the condition is treated, lymphedema often persists due to chronic irreversible lymphatic damage. A systematic review of 18 stigma studies in lymphatic filariasis found common themes related to the deleterious consequences of stigma on social relationships; work and education opportunities; health outcomes from reduced treatment-seeking behavior; and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.9 In one subdistrict in India, implementation of a community-based lymphedema management program that consisted of teaching hygiene and limb care for more than 20,000 lymphedema patients and performing community outreach activities (eg, street plays, radio programs, informational brochures) to teach people about lymphatic filariasis and lymphedema care was associated with community members being accepting of patients and an improvement in their understanding of disease etiology.10

Skin involvement from onchocerciasis infection (onchocercal skin disease) is another condition associated with notable stigma.9 Through the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, annual mass drug administration of ivermectin in onchocerciasis-endemic communities has reduced the rate of onchocercal skin disease in these communities. In looking at perception of stigma in onchocercal skin diseases before community-directed ivermectin therapy and 7 to 10 years after, avoidance of people with onchocercal skin disease decreased from 32.7% to 4.3%. There also was an improvement in relationships between healthy people and those with onchocercal skin disease.11

One of the most stigmatizing conditions is leprosy, often referred to as Hansen disease to give credit to the person who discovered that leprosy was caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not from sin, being cursed, or genetic inheritance. Even with this knowledge, stigma persists that can lead to family abandonment and social isolation, which further impacts afflicted individuals’ willingness to seek care, thus leading to disease progression. More recently, there has been research looking at interventions to reduce the stigma that individuals afflicted with leprosy face. In a study from Indonesia where individuals with leprosy were randomized to counseling, socioeconomic development, or contact between community members and affected people, all interventions were associated with a reduction in stigma.12 A rights-based counseling module integrated individual, family, and group forms of counseling and consisted of 5 sessions that focused on medical knowledge of leprosy and rights of individuals with leprosy, along with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy. Socioeconomic development involved opportunities for business training, creation of community groups through which microfinance services were administered, and other assistance to improve livelihood. Informed by evidence from the field of human immunodeficiency virus and mental health that co

Although steps are being taken to address the psychosocial burden of skin NTDs, there is still much work to be done. From the public health lens that largely governs the policies and approaches toward addressing NTDs, the focus often is on interrupting and eliminating disease transmission. Morbidity management, including reduction in stigma and functional impairment, is not always the priority. It is in this space that dermatologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for management approaches that address the morbidity associated with skin NTDs. We have an intimate understanding of how impactful skin diseases can be, even if they are not commonly fatal. Globally, skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden,14 yet dermatology lacks effective evidence-based interventions for reducing stigma in our patients with visible chronic diseases.15

Every day, we see firsthand how skin diseases affect not only our patients but also their families, friends, and caregivers. Although we may not see skin NTDs on a regular basis in our clinics, we can understand almost intuitively how devastating skin NTDs could be on individuals, families, and communities. For patients with skin NTDs, receiving medical therapy is only one component of treatment. In addition to optimizing early diagnosis and treatment, interventions taken to educate families and communities affected by skin NTDs are vitally important. Stigma reduction is possible, as we have seen from the aforementioned interventions used in communities with lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. We call upon our fellow dermatologists to take interest in creating, evaluating, and promoting interventions that address stigma in skin NTDs; it is critical in achieving and maintaining health and well-being for our patients.

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a group of 20 diseases that typically are chronic and cause long-term disability, which negatively impacts work productivity, child survival, and school performance and attendance with adverse effect on future earnings.1 Data from the 2013 Global Burden of Disease study revealed that half of the world’s NTDs occur in poor populations living in wealthy countries.2 Neglected tropical diseases with skin manifestations include parasitic infections (eg, American trypanosomiasis, African trypanosomiasis, dracunculiasis, echinococcosis, foodborne trematodiases, leishmaniasis, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, scabies and other ectoparasites, schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, taeniasis/cysticercosis), bacterial infections (eg, Buruli ulcer, leprosy, yaws), fungal infections (eg, mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, deep mycoses), and viral infections (eg, dengue, chikungunya). Rabies and snakebite envenomization involve the skin through inoculation. Within the larger group of NTDs, the World Health Organization has identified “skin NTDs” as a subgroup of NTDs that present primarily with changes in the skin.3 In the absence of early diagnosis and treatment of these diseases, chronic and lifelong disfigurement, disability, stigma, and socioeconomic losses ensue.

The Department of Health of the Government of Western Australia stated:

Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart from others. When a person is labeled by their illness they are no longer seen as an individual but as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes and beliefs toward this group create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination.4

Stigma associated with skin NTDs exemplifies how skin diseases can have enduring impact on individuals.5 For example, scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis carries heavy psychosocial burden. Young women reported that facial scarring from cutaneous leishmaniasis led to marriage rejections.6 Some even reported extreme suicidal ideations.7 Recently, major depressive disorder associated with scarring from inactive cutaneous leishmaniasis has been recognized as a notable contributor to disease burden from cutaneous leishmaniasis.8

Lymphatic filariasis is a major cause of leg and scrotal lymphedema worldwide. Even when the condition is treated, lymphedema often persists due to chronic irreversible lymphatic damage. A systematic review of 18 stigma studies in lymphatic filariasis found common themes related to the deleterious consequences of stigma on social relationships; work and education opportunities; health outcomes from reduced treatment-seeking behavior; and mental health, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies.9 In one subdistrict in India, implementation of a community-based lymphedema management program that consisted of teaching hygiene and limb care for more than 20,000 lymphedema patients and performing community outreach activities (eg, street plays, radio programs, informational brochures) to teach people about lymphatic filariasis and lymphedema care was associated with community members being accepting of patients and an improvement in their understanding of disease etiology.10

Skin involvement from onchocerciasis infection (onchocercal skin disease) is another condition associated with notable stigma.9 Through the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, annual mass drug administration of ivermectin in onchocerciasis-endemic communities has reduced the rate of onchocercal skin disease in these communities. In looking at perception of stigma in onchocercal skin diseases before community-directed ivermectin therapy and 7 to 10 years after, avoidance of people with onchocercal skin disease decreased from 32.7% to 4.3%. There also was an improvement in relationships between healthy people and those with onchocercal skin disease.11

One of the most stigmatizing conditions is leprosy, often referred to as Hansen disease to give credit to the person who discovered that leprosy was caused by Mycobacterium leprae and not from sin, being cursed, or genetic inheritance. Even with this knowledge, stigma persists that can lead to family abandonment and social isolation, which further impacts afflicted individuals’ willingness to seek care, thus leading to disease progression. More recently, there has been research looking at interventions to reduce the stigma that individuals afflicted with leprosy face. In a study from Indonesia where individuals with leprosy were randomized to counseling, socioeconomic development, or contact between community members and affected people, all interventions were associated with a reduction in stigma.12 A rights-based counseling module integrated individual, family, and group forms of counseling and consisted of 5 sessions that focused on medical knowledge of leprosy and rights of individuals with leprosy, along with elements of cognitive behavioral therapy. Socioeconomic development involved opportunities for business training, creation of community groups through which microfinance services were administered, and other assistance to improve livelihood. Informed by evidence from the field of human immunodeficiency virus and mental health that co

Although steps are being taken to address the psychosocial burden of skin NTDs, there is still much work to be done. From the public health lens that largely governs the policies and approaches toward addressing NTDs, the focus often is on interrupting and eliminating disease transmission. Morbidity management, including reduction in stigma and functional impairment, is not always the priority. It is in this space that dermatologists are uniquely positioned to advocate for management approaches that address the morbidity associated with skin NTDs. We have an intimate understanding of how impactful skin diseases can be, even if they are not commonly fatal. Globally, skin diseases are the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden,14 yet dermatology lacks effective evidence-based interventions for reducing stigma in our patients with visible chronic diseases.15

Every day, we see firsthand how skin diseases affect not only our patients but also their families, friends, and caregivers. Although we may not see skin NTDs on a regular basis in our clinics, we can understand almost intuitively how devastating skin NTDs could be on individuals, families, and communities. For patients with skin NTDs, receiving medical therapy is only one component of treatment. In addition to optimizing early diagnosis and treatment, interventions taken to educate families and communities affected by skin NTDs are vitally important. Stigma reduction is possible, as we have seen from the aforementioned interventions used in communities with lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. We call upon our fellow dermatologists to take interest in creating, evaluating, and promoting interventions that address stigma in skin NTDs; it is critical in achieving and maintaining health and well-being for our patients.

- Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ, Damania A, Naghavi M. Blue Marble Health and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004744.

- Skin NTDs. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/skin-ntds/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Stigma, discrimination and mental illness. February 2009. http://www.health.wa.gov.au/docreg/Education/Population/Health_Problems/Mental_Illness/Mentalhealth_stigma_fact.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:E230.

- Bennis I, Belaid L, De Brouwere V, et al. “The mosquitoes that destroy your face.” social impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Morocco, a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:E0189906.

- Bennis I, Thys S, Filali H, et al. Psychosocial impact of scars due to cutaneous leishmaniasis on high school students in Errachidia province, Morocco. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:46.

- Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Haines LR, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and co-morbid major depressive disorder: a systematic review with burden estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:E0007092.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl 1):I53-I70.

- Cassidy T, Worrell CM, Little K, et al. Experiences of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India: an analysis of focus group discussions with patients, families, community members and program volunteers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004424.

- Tchounkeu YF, Onyeneho NG, Wanji S, et al. Changes in stigma and discrimination of onchocerciasis in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:340-347.

- Dadun D, Van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:2-22.

- Kumar A, Lambert S, Lockwood DNJ. Picturing health: a new face for leprosy. Lancet. 2019;393:629-638.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review [published online June 8, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15734.

- Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ, Damania A, Naghavi M. Blue Marble Health and the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004744.

- Skin NTDs. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/skin-ntds/en/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Government of Western Australia Department of Health. Stigma, discrimination and mental illness. February 2009. http://www.health.wa.gov.au/docreg/Education/Population/Health_Problems/Mental_Illness/Mentalhealth_stigma_fact.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Hotez PJ. Stigma: the stealth weapon of the NTD. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:E230.

- Bennis I, Belaid L, De Brouwere V, et al. “The mosquitoes that destroy your face.” social impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Morocco, a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:E0189906.

- Bennis I, Thys S, Filali H, et al. Psychosocial impact of scars due to cutaneous leishmaniasis on high school students in Errachidia province, Morocco. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:46.

- Bailey F, Mondragon-Shem K, Haines LR, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and co-morbid major depressive disorder: a systematic review with burden estimates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:E0007092.

- Hofstraat K, van Brakel WH. Social stigma towards neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. Int Health. 2016;8(suppl 1):I53-I70.

- Cassidy T, Worrell CM, Little K, et al. Experiences of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India: an analysis of focus group discussions with patients, families, community members and program volunteers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:E0004424.

- Tchounkeu YF, Onyeneho NG, Wanji S, et al. Changes in stigma and discrimination of onchocerciasis in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:340-347.

- Dadun D, Van Brakel WH, Peters RMH, et al. Impact of socio-economic development, contact and peer counselling on stigma against persons affected by leprosy in Cirebon, Indonesia—a randomised controlled trial. Lepr Rev. 2017;88:2-22.

- Kumar A, Lambert S, Lockwood DNJ. Picturing health: a new face for leprosy. Lancet. 2019;393:629-638.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce stigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review [published online June 8, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15734.

GRECC Connect: Geriatrics Telehealth to Empower Health Care Providers and Improve Management of Older Veterans in Rural Communities

Nearly 2.7 million veterans who rely on the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for their health care live in rural communities.1 Of these, more than half are aged ≥ 65 years. Rural veterans have greater rates of service-related disability and chronic medical conditions than do their urban counterparts.1,2 Yet because of their rural location, they face unique challenges, including long travel times and distances to health care services, lack of public transportation options, and limited availability of specialized medical and social support services.

Compounding these geographic barriers is a more general lack of workforce infrastructure and a dearth of clinical health care providers (HCPs) skilled in geriatric medicine. The demand for geriatricians is projected to outpace supply and result in a national shortage of nearly 27 000 geriatricians by 2025.3 Moreover, the overwhelming majority (90%) of HCPs identifying as geriatric specialists reside in urban areas.4 This creates tremendous pressure on the health care system to provide remote care for older veterans contending with complex conditions, and ultimately these veterans may not receive the specialized care they need.

Telehealth modalities bridge these gaps by bringing health care to veterans in rural communities. They may also hold promise for strengthening community care in rural areas through workforce development and dissemination of educational resources. The VHA has been recognized as a leader in the field of telehealth since it began offering telehealth services to veterans in 19775-8 and served more than 677 000 Veterans via telehealth in fiscal year (FY) 2015.9 The VHA currently employs multiple modes of telehealth to increase veterans’ access to health care, including: (1) synchronous technology like clinical video telehealth (CVT), which provides live encounters between HCPs and patients using videoconferencing software; and (2) asynchronous technology, such as store-and-forward communication that offers remote transmission and clinical interpretation of veteran health data. The VHA has also strengthened its broad telehealth infrastructure by staffing VHA clinical sites with telehealth clinical technicians and providing telehealth hardware throughout.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) and Office of Rural Health (ORH) established the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers (GRECC) Connect project in 2014 to leverage the existing telehealth technologies at the VA to meet the health care needs of older veterans. GRECC Connect builds on the VHA network of geriatrics expertise in GRECCs by providing telehealth-based consultative support for rural primary care provider (PCP) teams, older veterans, and their families. This program profile describes this project’s mission, structure, and activities.

Program Overview

GRECC Connect leverages the clinical expertise and administrative infrastructure of participating GRECCs in order to reach clinicians and veterans in primarily rural communities.10 GRECCs are VA centers of excellence focused on aging and comprise a large network of interdisciplinary geriatrics expertise. All GRECCs have strong affiliations with local universities and are located in urban VA medical centers (VAMCs). GRECC Connect is based on a hub-and-spoke model in which urban GRECC hub sites are connected to community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) and VAMC spokes that primarily serve veterans in other communities. CBOCs are stand-alone clinics that are geographically separate from a related VA medical center and provide outpatient primary care, mental health care services, and some specialty care services such as cardiology or neurology. They range in size from small, mainly telehealth clinics with 1 technician to large clinics with several specialty providers. Each GRECC hub site partners with an average of 6 CBOCs (range 3-16), each of which is an average distance of 92.8 miles from the related VA medical center (range 20-406 miles).

GRECC Connect was established under the umbrella of the VA Geriatric Scholars Program, which since 2008 integrates geriatrics into rural primary care practices through tailored education for continuing professional development.11 Through intensive courses in geriatrics and quality improvement methods and through participation in local quality improvement projects benefiting older veterans, the Geriatric Scholars Program trains rural PCPs so that they can more effectively and independently diagnose and manage common geriatric syndromes.12 The network of clinician scholars developed by the Geriatric Scholars Program, all rural frontline clinicians at VA clinics, has given the GRECC Connect project a well-prepared, geriatrics-trained workforce to act as project champions at rural CBOCs and VAMCs. The GRECC Connect project’s goals are to enhance access to geriatric specialty care among older veterans with complex medical problems, geriatric syndromes, and increased risk for institutionalization, and to provide geriatrics-focused educational support to rural HCP teams.

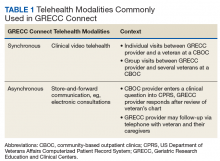

Geriatric Provider Consultations

The first overarching goal of the GRECC Connect project is to improve access to geriatrics specialty care by facilitating linkages between GRECC hub sites and the CBOCs and VAMCs that primarily serve veterans in rural communities. GRECC hub sites offer consultative support from geriatrics specialty team members (eg, geriatricians, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, gero- or neuropsychologists, registered nurses [RNs], and social workers) to rural PCP in their catchment area. This support is offered through a variety of telehealth modalities readily available in the VA (Table 1). These include CVT, in which a veteran located at a rural CBOC is seen using videoconferencing software by a geriatrics specialty provider who is located at a GRECC hub site. At some GRECC hub sites, CVT has also been used to conduct group visits between a GRECC provider at the hub site and several veterans who participate from a rural CBOC. Electronic consultations, or e-consults, involve a rural provider entering a clinical question in the VA Computerized Patient Record System. The question is then triaged, and a geriatrics provider at a GRECC responds, based on review of that veteran’s chart. At some GRECC hub sites, the e-consults are more extensive and may include telephone contact with the veteran or their caregiver.

Consultations between GRECC-based teams and rural PCPs may cover any aspect of geriatrics care, ranging from broad concerns to subspecialty areas of geriatric medicine. For instance, general geriatrics consultation may address polypharmacy, during either care transitions or ongoing care. Consultation may also reflect the specific focus area of a particular GRECC, such as cognitive assessment (eg, Pittsburgh GRECC), management of osteoporosis to address falls (eg, Durham GRECC, Miami GRECC), and continence care (eg, Birmingham/Atlanta GRECC).13 Most consultations are initiated by a remote HCP who is seeking geriatrics expertise from the GRECC team.

Some GRECC hub sites, however, employ case finding strategies, or detailed chart reviews, in order to identify older veterans who may benefit from geriatrics consultation. For veterans identified through those mechanisms, the GRECC clinicians suggest that the rural HCP either request or allow an e-consult or evaluation via CVT for those veterans. The geriatric consultations may help identify additional care needs for older veterans and lead to recommendations, orders, or remote provision of a variety of other actions, including VA or non-VA services (eg, home-based primary care, home nursing service, respite service, social support services such as Meals on Wheels); neuropsychological testing; physical or occupational therapy; audiology or optometry referral; falls and fracture risk assessment and interventions to reduce falls (eg, home safety evaluation, physical therapy); osteoporosis risk assessments (eg, densitometry, recommendations for pharmacologic therapy) to reduce the risk of injury or nontraumatic fractures from falls; palliative care for incontinence and hospice; and counseling on geriatric issues such as dementia caregiving, advanced directives, and driving cessation.

More recently, the Miami GRECC has begun evaluating rural veterans at risk for hypoglycemia, providing patient education and counseling about hypoglycemia, and making recommendations to the veterans’ primary care teams.14 Consultations may also lead to the appropriate use or discontinuation of medications, related to polypharmacy. GRECC-based teams, for example, have helped rural HCPs modify medication doses, start appropriate medications for dementia and depression, and identify and stop potentially inappropriate medications (eg, those that increase fall risk or that have significant anticholinergic properties).15

GRECC Connect Geriatric Case Conference Series

The second overarching goal of the GRECC Connect project is to provide geriatrics-focused educational support to equip PCPs to better serve their aging veteran patients. This is achieved through twice-monthly, case-based conferences supported by the VA Employee Education System (EES) and delivered through a webinar interface. Case conferences are targeted to members of the health care team who may provide care for rural older adults, including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, RNs, psychologists, social workers, physical and occupational therapists, and pharmacists. The format of these sessions includes a clinical case presentation, a didactic portion to enhance knowledge of participants, and an open question/answer period. The conferences focus on discussions of challenging clinical cases, addressing common problems (eg, driving concerns), and the assessment/management of geriatric syndromes (eg, cognitive decline, falls, polypharmacy). These conferences aim to improve the knowledge and skills of rural clinical teams in taking care of older veterans and to disseminate best practices in geriatric medicine, using case discussions to highlight practical applications of practices to clinical care. Recent GRECC Connect geriatric case conferences are listed in Table 2 and are recorded and archived to ensure that busy clinicians may access these trainings at the time of their choosing. These materials are catalogued and archived on the EES server.

Early Experience

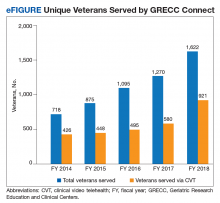

GRECC Connect tracks on an annual basis the number of unique veterans served, number of participating GRECC hub sites and CBOCs, mileage from veteran homes to teleconsultation sites, and number of clinicians and staff engaged in GRECC Connect education programs.16 Since its inception in 2014, the GRECC Connect project has provided direct clinical support to more than 4000 unique veterans (eFigure), of whom half were seen for a cognition-related issue. Consultations were made on behalf of 1,622 veterans in FY 2018, of whom 60% were from rural or highly rural communities and 56.8% were served by CVT visits. The number of GRECC hub sites has increased from 4 in FY 2014 to 12 (of 20 total GRECCs) in FY 2018. The locations of current GRECC hub sites can be found on the Geriatric Scholars website: www.gerischolars.org. Through this expansion, GRECC Connect provides geriatric consultative and educational support to > 70 rural VA clinics in 10 of the 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs).

To assess the reduction in commute times from teleconsultation, we calculated the difference between the mileage from veteran homes to teleconsultation sites (ie, rural clinics) and the mileage from veteran homes to VAMCs where geriatric teams are located. We estimate that the 1622 veterans served in FY 2018 saved a total of 179 121 miles in travel through GRECC Connect. Veterans traveled 106 fewer miles and on average saved $58 in out-of-pocket savings (based on US General Services Administration 2018 standard mileage reimbursement rate of $0.545 per mile). However, many of the veterans have reported anecdotally that the reduction in mileage traveled was less important than the elimination of stress involved in urban navigating, driving, and parking.