User login

Use of ECMO in the management of influenza-associated ARDS

Now that we are in the midst of flu season, many discussions regarding the management of patients with influenza virus infections are ensuing. While prevention is always preferable, and we encourage everyone to get vaccinated, influenza remains a rapidly widespread infection. In the United States during last year’s flu season (2017-18), there was an estimated 49 million cases of influenza, 960,000 hospitalizations, and 79,000 deaths. Approximately 86% of all deaths were estimated to occur in those aged 65 and older (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webpage on Burden of Influenza).

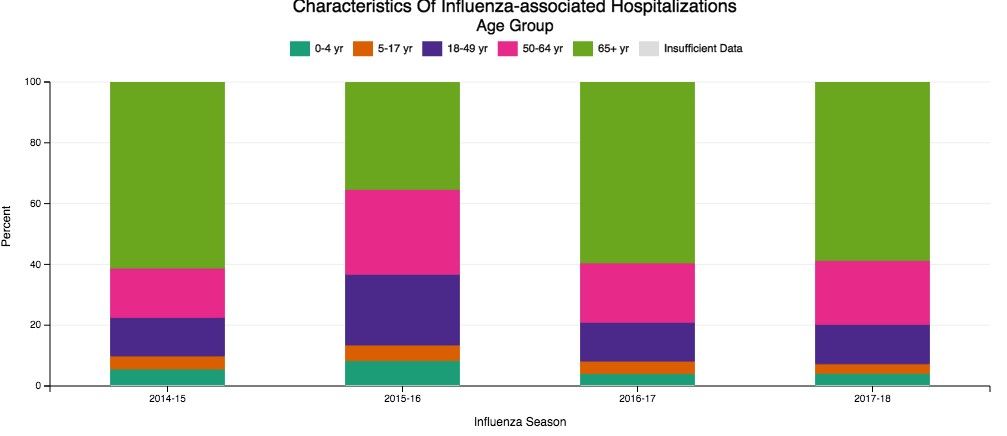

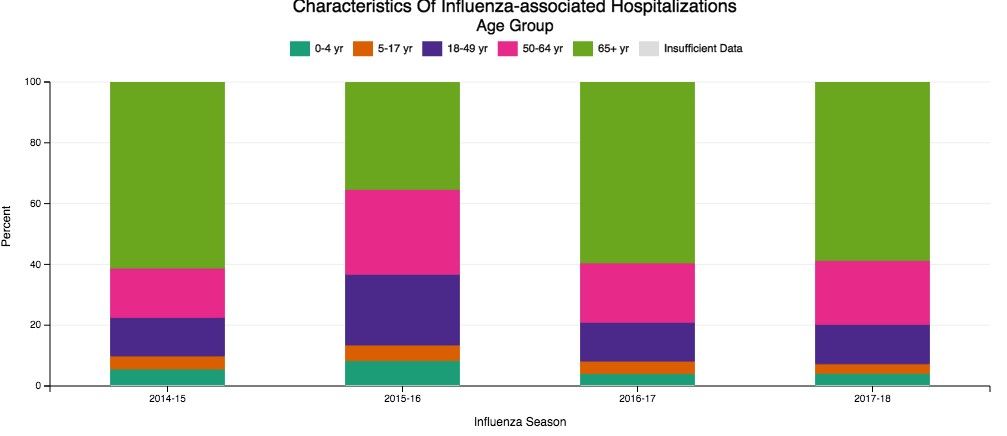

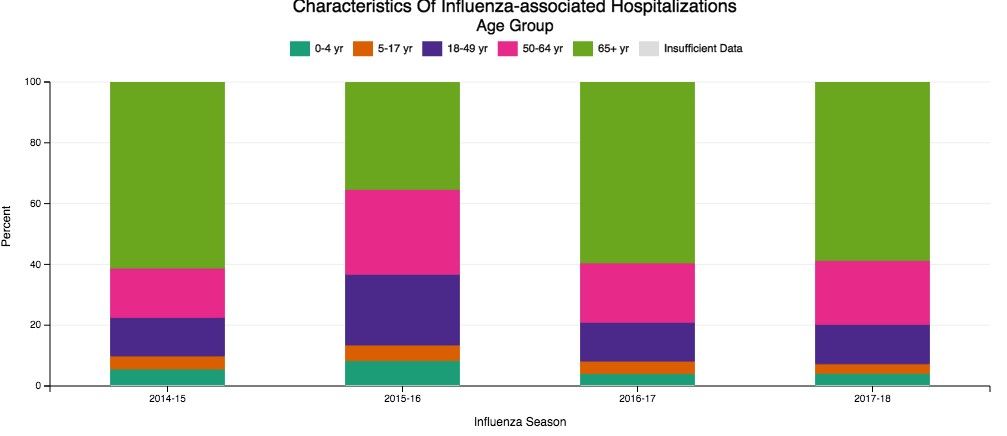

Despite our best efforts, there are inevitable times when some patients become ill enough to require hospitalization. Patients aged 65 and older make up the overwhelming majority of patients with influenza who eventually require hospitalization (Fig 1) (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FluView Database). Comorbidities also confer higher risk for more severe illness and potential hospitalization irrespective of age (Fig 2). In children with known medical conditions, asthma confers highest risk of hospitalization, as 27% of those with asthma were hospitalized after developing the flu. In adults, 52% of those with cardiovascular disease and 30% of adult patients with chronic lung disease who were confirmed to have influenza required hospitalization for treatment (Fig 2, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FluView Database).

The most severe cases of influenza can require ICU care and advanced management of respiratory failure as a result of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The lungs suffer significant injury due to the viral infection, and they lose their ability to effectively oxygenate the blood. Secondary bacterial infections can also occur as a complication, which compounds the injury. Given the fact that so many patients have significant comorbidities and are of advanced age, it is reasonable to expect that a fair proportion of those with influenza would develop respiratory failure as a consequence. For some of these patients, the hypoxemia that develops as a result of the lung injury can be exceptionally challenging to manage. In extreme cases, conventional ventilator management is insufficient, and the need for additional, advanced therapies arise.

Studies of VV ECMO in severe influenza

ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) is a treatment that has been employed to help support patients with severe hypoxemic respiratory failure while their lungs recover from acute injury. Venovenous (VV) ECMO requires peripheral insertion of large cannulae into the venous system to take deoxygenated blood, deliver it through the membrane oxygenator and return the oxygenated blood back to the venous system. In simplest terms, the membrane of ECMO circuit serves as a substitute for the gas exchange function of the lungs and provides the oxygenation that the injured alveoli of the lung are unable to provide. The overall intent is to have the external ECMO circuit do all of the gas exchange work while the lungs heal.

Much research has been done on VV ECMO as an adjunct or salvage therapy in patients with refractory hypoxemic respiratory failure due to ARDS. Historical and recent studies have shown that approximately 60% of patients with ARDS have viral (approximately 20%) or bacterial (approximately 40%) pneumonia as the underlying cause (Zapol, et al. JAMA. 1979; 242[20]:2193; Combes A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965). Naturally, given the frequency of infection as a cause for ARDS, and the severity of illness that can develop with influenza infection in particular, an interest has arisen in the applicability of ECMO in cases of severe influenza-related ARDS.

In 2009, during the H1N1 influenza pandemic, the ANZ ECMO investigators in Australia and New Zealand described a 78% survival rate for their patients with severe H1N1 associated ARDS treated with VV ECMO between June and August of that year (Davies A, et al. JAMA. 2009;302[17]:1888). The eagerly awaited results of the randomized, controlled CESAR trial (Peek G, et al. Lancet. 2009;374:1351) that studied patients aged 18 to 64 with severe, refractory respiratory failure transferred to a specialized center for ECMO care had additional impact in catalyzing interest in ECMO use. This trial showed improved survival with ECMO (63% in ECMO vs 47% control, RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.05-0.97 P=.03) with a gain of 0.03 QALY (quality-adjusted life years) with additional cost of 40,000 pounds sterling. However, a major critique is that 24% of patients transferred to the specialized center never were treated with ECMO. Significantly, there was incomplete follow-up data on nearly half of the patients, as well. Many conclude that the survival benefit seen in this study may be more reflective of the expertise in respiratory failure management (especially as it relates to lung protective ventilation) at this center than therapy with ECMO itself.

Additional cohort studies in the United Kingdom (Noah MA, et al. JAMA. 2011;306[15]:1659) and Italy (Pappalardo F, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39[2]:275) showed approximately 70% in-hospital survival rates for patients with H1N1 influenza transferred to a specialized ECMO center and treated with ECMO.

Nonetheless, the information gained from the observational data from ANZ ECMO, along with data published in European cohort studies and the randomized controlled CESAR trial after the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, greatly contributed to the rise in use of ECMO for refractory ARDS due to influenza. Subsequently, there has been a rapid establishment and expansion of ECMO centers over the past decade, primarily to meet the anticipated demands of treating severe influenza-related ARDS.

The recently published EOLIA trial (Combes A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965) was designed to study the benefit of VV ECMO vs conventional mechanical ventilation in ARDS and demonstrated an 11% absolute reduction in 60-day mortality, which did not reach statistical significance. Like the CESAR trial, there are critiques of the outcome, especially as it relates to stopping the trial early due to the inability to show a significant benefit of VV ECMO over mechanical ventilation.

All of the aforementioned studies evaluated adults under age 65. Interestingly, there are no specific age contraindications for the use of ECMO (ELSO Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Extracorporeal Life Support, Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, Version 1.4 August 2017), but many consider older age as a risk for poor outcome. Approximately 2,300 adult patients in the United States have been treated with ECMO for respiratory failure each year, and only 10% of those are over age 65 (CMS Changes in ECMO Reimbursements – ELSO Report). The outcome benefit of ECMO for a relatively healthy patient over age 65 is not known, as those patients have not been evaluated in studies thus far. When comparison to data from decades ago is made, one must keep in mind that populations worldwide are living longer, and a continued increase in number of adults over the age 65 is expected.

While the overall interpretation of the outcomes of studies of ECMO may be fraught with controversy, there is little debate that providing care for patients with refractory respiratory failure in centers that provide high-level skill and expertise in management of respiratory failure has a clear benefit, irrespective of whether the patient eventually receives therapy with ECMO. What is also clear is that ECMO is costly, with per-patient costs demonstrated to be at least double that of those receiving mechanical ventilation alone (Peek G, et al. Lancet. 2009;374:1351). This substantial cost associated with ECMO cannot be ignored in today’s era of value-based care.

Fortuitously, CMS recently released new DRG reimbursement scales for the use of ECMO effective Oct 1, 2018. VV ECMO could have as much as a 70% reduction in reimbursement, and many insurance companies are expected to follow suit (CMS Changes in ECMO Reimbursements –ELSO Report). Only time will tell what impact this, along with the current evidence, will have on long-term provision of ECMO care for our sickest of patients with influenza and associated respiratory illnesses.

Dr. Tatem is with the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan.

Now that we are in the midst of flu season, many discussions regarding the management of patients with influenza virus infections are ensuing. While prevention is always preferable, and we encourage everyone to get vaccinated, influenza remains a rapidly widespread infection. In the United States during last year’s flu season (2017-18), there was an estimated 49 million cases of influenza, 960,000 hospitalizations, and 79,000 deaths. Approximately 86% of all deaths were estimated to occur in those aged 65 and older (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webpage on Burden of Influenza).

Despite our best efforts, there are inevitable times when some patients become ill enough to require hospitalization. Patients aged 65 and older make up the overwhelming majority of patients with influenza who eventually require hospitalization (Fig 1) (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FluView Database). Comorbidities also confer higher risk for more severe illness and potential hospitalization irrespective of age (Fig 2). In children with known medical conditions, asthma confers highest risk of hospitalization, as 27% of those with asthma were hospitalized after developing the flu. In adults, 52% of those with cardiovascular disease and 30% of adult patients with chronic lung disease who were confirmed to have influenza required hospitalization for treatment (Fig 2, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FluView Database).

The most severe cases of influenza can require ICU care and advanced management of respiratory failure as a result of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The lungs suffer significant injury due to the viral infection, and they lose their ability to effectively oxygenate the blood. Secondary bacterial infections can also occur as a complication, which compounds the injury. Given the fact that so many patients have significant comorbidities and are of advanced age, it is reasonable to expect that a fair proportion of those with influenza would develop respiratory failure as a consequence. For some of these patients, the hypoxemia that develops as a result of the lung injury can be exceptionally challenging to manage. In extreme cases, conventional ventilator management is insufficient, and the need for additional, advanced therapies arise.

Studies of VV ECMO in severe influenza

ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) is a treatment that has been employed to help support patients with severe hypoxemic respiratory failure while their lungs recover from acute injury. Venovenous (VV) ECMO requires peripheral insertion of large cannulae into the venous system to take deoxygenated blood, deliver it through the membrane oxygenator and return the oxygenated blood back to the venous system. In simplest terms, the membrane of ECMO circuit serves as a substitute for the gas exchange function of the lungs and provides the oxygenation that the injured alveoli of the lung are unable to provide. The overall intent is to have the external ECMO circuit do all of the gas exchange work while the lungs heal.

Much research has been done on VV ECMO as an adjunct or salvage therapy in patients with refractory hypoxemic respiratory failure due to ARDS. Historical and recent studies have shown that approximately 60% of patients with ARDS have viral (approximately 20%) or bacterial (approximately 40%) pneumonia as the underlying cause (Zapol, et al. JAMA. 1979; 242[20]:2193; Combes A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965). Naturally, given the frequency of infection as a cause for ARDS, and the severity of illness that can develop with influenza infection in particular, an interest has arisen in the applicability of ECMO in cases of severe influenza-related ARDS.

In 2009, during the H1N1 influenza pandemic, the ANZ ECMO investigators in Australia and New Zealand described a 78% survival rate for their patients with severe H1N1 associated ARDS treated with VV ECMO between June and August of that year (Davies A, et al. JAMA. 2009;302[17]:1888). The eagerly awaited results of the randomized, controlled CESAR trial (Peek G, et al. Lancet. 2009;374:1351) that studied patients aged 18 to 64 with severe, refractory respiratory failure transferred to a specialized center for ECMO care had additional impact in catalyzing interest in ECMO use. This trial showed improved survival with ECMO (63% in ECMO vs 47% control, RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.05-0.97 P=.03) with a gain of 0.03 QALY (quality-adjusted life years) with additional cost of 40,000 pounds sterling. However, a major critique is that 24% of patients transferred to the specialized center never were treated with ECMO. Significantly, there was incomplete follow-up data on nearly half of the patients, as well. Many conclude that the survival benefit seen in this study may be more reflective of the expertise in respiratory failure management (especially as it relates to lung protective ventilation) at this center than therapy with ECMO itself.

Additional cohort studies in the United Kingdom (Noah MA, et al. JAMA. 2011;306[15]:1659) and Italy (Pappalardo F, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39[2]:275) showed approximately 70% in-hospital survival rates for patients with H1N1 influenza transferred to a specialized ECMO center and treated with ECMO.

Nonetheless, the information gained from the observational data from ANZ ECMO, along with data published in European cohort studies and the randomized controlled CESAR trial after the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, greatly contributed to the rise in use of ECMO for refractory ARDS due to influenza. Subsequently, there has been a rapid establishment and expansion of ECMO centers over the past decade, primarily to meet the anticipated demands of treating severe influenza-related ARDS.

The recently published EOLIA trial (Combes A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965) was designed to study the benefit of VV ECMO vs conventional mechanical ventilation in ARDS and demonstrated an 11% absolute reduction in 60-day mortality, which did not reach statistical significance. Like the CESAR trial, there are critiques of the outcome, especially as it relates to stopping the trial early due to the inability to show a significant benefit of VV ECMO over mechanical ventilation.

All of the aforementioned studies evaluated adults under age 65. Interestingly, there are no specific age contraindications for the use of ECMO (ELSO Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Extracorporeal Life Support, Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, Version 1.4 August 2017), but many consider older age as a risk for poor outcome. Approximately 2,300 adult patients in the United States have been treated with ECMO for respiratory failure each year, and only 10% of those are over age 65 (CMS Changes in ECMO Reimbursements – ELSO Report). The outcome benefit of ECMO for a relatively healthy patient over age 65 is not known, as those patients have not been evaluated in studies thus far. When comparison to data from decades ago is made, one must keep in mind that populations worldwide are living longer, and a continued increase in number of adults over the age 65 is expected.

While the overall interpretation of the outcomes of studies of ECMO may be fraught with controversy, there is little debate that providing care for patients with refractory respiratory failure in centers that provide high-level skill and expertise in management of respiratory failure has a clear benefit, irrespective of whether the patient eventually receives therapy with ECMO. What is also clear is that ECMO is costly, with per-patient costs demonstrated to be at least double that of those receiving mechanical ventilation alone (Peek G, et al. Lancet. 2009;374:1351). This substantial cost associated with ECMO cannot be ignored in today’s era of value-based care.

Fortuitously, CMS recently released new DRG reimbursement scales for the use of ECMO effective Oct 1, 2018. VV ECMO could have as much as a 70% reduction in reimbursement, and many insurance companies are expected to follow suit (CMS Changes in ECMO Reimbursements –ELSO Report). Only time will tell what impact this, along with the current evidence, will have on long-term provision of ECMO care for our sickest of patients with influenza and associated respiratory illnesses.

Dr. Tatem is with the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan.

Now that we are in the midst of flu season, many discussions regarding the management of patients with influenza virus infections are ensuing. While prevention is always preferable, and we encourage everyone to get vaccinated, influenza remains a rapidly widespread infection. In the United States during last year’s flu season (2017-18), there was an estimated 49 million cases of influenza, 960,000 hospitalizations, and 79,000 deaths. Approximately 86% of all deaths were estimated to occur in those aged 65 and older (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webpage on Burden of Influenza).

Despite our best efforts, there are inevitable times when some patients become ill enough to require hospitalization. Patients aged 65 and older make up the overwhelming majority of patients with influenza who eventually require hospitalization (Fig 1) (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FluView Database). Comorbidities also confer higher risk for more severe illness and potential hospitalization irrespective of age (Fig 2). In children with known medical conditions, asthma confers highest risk of hospitalization, as 27% of those with asthma were hospitalized after developing the flu. In adults, 52% of those with cardiovascular disease and 30% of adult patients with chronic lung disease who were confirmed to have influenza required hospitalization for treatment (Fig 2, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FluView Database).

The most severe cases of influenza can require ICU care and advanced management of respiratory failure as a result of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The lungs suffer significant injury due to the viral infection, and they lose their ability to effectively oxygenate the blood. Secondary bacterial infections can also occur as a complication, which compounds the injury. Given the fact that so many patients have significant comorbidities and are of advanced age, it is reasonable to expect that a fair proportion of those with influenza would develop respiratory failure as a consequence. For some of these patients, the hypoxemia that develops as a result of the lung injury can be exceptionally challenging to manage. In extreme cases, conventional ventilator management is insufficient, and the need for additional, advanced therapies arise.

Studies of VV ECMO in severe influenza

ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) is a treatment that has been employed to help support patients with severe hypoxemic respiratory failure while their lungs recover from acute injury. Venovenous (VV) ECMO requires peripheral insertion of large cannulae into the venous system to take deoxygenated blood, deliver it through the membrane oxygenator and return the oxygenated blood back to the venous system. In simplest terms, the membrane of ECMO circuit serves as a substitute for the gas exchange function of the lungs and provides the oxygenation that the injured alveoli of the lung are unable to provide. The overall intent is to have the external ECMO circuit do all of the gas exchange work while the lungs heal.

Much research has been done on VV ECMO as an adjunct or salvage therapy in patients with refractory hypoxemic respiratory failure due to ARDS. Historical and recent studies have shown that approximately 60% of patients with ARDS have viral (approximately 20%) or bacterial (approximately 40%) pneumonia as the underlying cause (Zapol, et al. JAMA. 1979; 242[20]:2193; Combes A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965). Naturally, given the frequency of infection as a cause for ARDS, and the severity of illness that can develop with influenza infection in particular, an interest has arisen in the applicability of ECMO in cases of severe influenza-related ARDS.

In 2009, during the H1N1 influenza pandemic, the ANZ ECMO investigators in Australia and New Zealand described a 78% survival rate for their patients with severe H1N1 associated ARDS treated with VV ECMO between June and August of that year (Davies A, et al. JAMA. 2009;302[17]:1888). The eagerly awaited results of the randomized, controlled CESAR trial (Peek G, et al. Lancet. 2009;374:1351) that studied patients aged 18 to 64 with severe, refractory respiratory failure transferred to a specialized center for ECMO care had additional impact in catalyzing interest in ECMO use. This trial showed improved survival with ECMO (63% in ECMO vs 47% control, RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.05-0.97 P=.03) with a gain of 0.03 QALY (quality-adjusted life years) with additional cost of 40,000 pounds sterling. However, a major critique is that 24% of patients transferred to the specialized center never were treated with ECMO. Significantly, there was incomplete follow-up data on nearly half of the patients, as well. Many conclude that the survival benefit seen in this study may be more reflective of the expertise in respiratory failure management (especially as it relates to lung protective ventilation) at this center than therapy with ECMO itself.

Additional cohort studies in the United Kingdom (Noah MA, et al. JAMA. 2011;306[15]:1659) and Italy (Pappalardo F, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39[2]:275) showed approximately 70% in-hospital survival rates for patients with H1N1 influenza transferred to a specialized ECMO center and treated with ECMO.

Nonetheless, the information gained from the observational data from ANZ ECMO, along with data published in European cohort studies and the randomized controlled CESAR trial after the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, greatly contributed to the rise in use of ECMO for refractory ARDS due to influenza. Subsequently, there has been a rapid establishment and expansion of ECMO centers over the past decade, primarily to meet the anticipated demands of treating severe influenza-related ARDS.

The recently published EOLIA trial (Combes A, et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965) was designed to study the benefit of VV ECMO vs conventional mechanical ventilation in ARDS and demonstrated an 11% absolute reduction in 60-day mortality, which did not reach statistical significance. Like the CESAR trial, there are critiques of the outcome, especially as it relates to stopping the trial early due to the inability to show a significant benefit of VV ECMO over mechanical ventilation.

All of the aforementioned studies evaluated adults under age 65. Interestingly, there are no specific age contraindications for the use of ECMO (ELSO Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Extracorporeal Life Support, Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, Version 1.4 August 2017), but many consider older age as a risk for poor outcome. Approximately 2,300 adult patients in the United States have been treated with ECMO for respiratory failure each year, and only 10% of those are over age 65 (CMS Changes in ECMO Reimbursements – ELSO Report). The outcome benefit of ECMO for a relatively healthy patient over age 65 is not known, as those patients have not been evaluated in studies thus far. When comparison to data from decades ago is made, one must keep in mind that populations worldwide are living longer, and a continued increase in number of adults over the age 65 is expected.

While the overall interpretation of the outcomes of studies of ECMO may be fraught with controversy, there is little debate that providing care for patients with refractory respiratory failure in centers that provide high-level skill and expertise in management of respiratory failure has a clear benefit, irrespective of whether the patient eventually receives therapy with ECMO. What is also clear is that ECMO is costly, with per-patient costs demonstrated to be at least double that of those receiving mechanical ventilation alone (Peek G, et al. Lancet. 2009;374:1351). This substantial cost associated with ECMO cannot be ignored in today’s era of value-based care.

Fortuitously, CMS recently released new DRG reimbursement scales for the use of ECMO effective Oct 1, 2018. VV ECMO could have as much as a 70% reduction in reimbursement, and many insurance companies are expected to follow suit (CMS Changes in ECMO Reimbursements –ELSO Report). Only time will tell what impact this, along with the current evidence, will have on long-term provision of ECMO care for our sickest of patients with influenza and associated respiratory illnesses.

Dr. Tatem is with the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan.

The 1-hour sepsis bundle is serious—serious like a heart attack

In 2002, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the International Sepsis Forum formed the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) aiming to reduce sepsis-related mortality by 25% within 5 years, mimicking the progress made in the management of STEMI (http://www.survivingsepsis.org/About-SSC/Pages/History.aspx).

SSC bundles: a historic perspective

The first guidelines were published in 2004. Recognizing that guidelines may not influence bedside practice for many years, the SSC partnered with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to apply performance improvement methodology to sepsis management, developing the “sepsis change bundles.” In addition to hospital resources for education, screening, and data collection, the 6-hour resuscitation and 24-hour management bundles were created. Subsequent data, collected as part of the initiative, demonstrated an association between bundle compliance and survival.

In 2008, the SSC guidelines were revised, and the National Quality Forum (NQF) adopted sepsis bundle compliance as a quality measure. NQF endorsement is often the first step toward the creation of mandates by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), but that did not occur at the time.

In 2012, the SSC guidelines were updated and published with new 3- and 6-hour bundles. That year, Rory Staunton, an otherwise healthy 12-year-old boy, died of septic shock in New York. The public discussion of this case, among other factors, prompted New York state to develop a sepsis care mandate that became state law in 2014. An annual public report details each hospital’s compliance with process measures and risk-adjusted mortality. The correlation between measure compliance and survival also holds true in this data set.

In 2015, CMS developed the SEP-1 measure. While the symbolic importance of a sepsis federal mandate and its potential to improve patient outcomes is recognized, concerns remain about the measure itself. The detailed and specific way data must be collected may disconnect clinical care provided from measured compliance. The time pressure and the “all-or-nothing” approach might incentivize interventions potentially harmful in some patients. No patient-centered outcomes are reported. This measure might be tied to reimbursement in the future.

The original version of SEP-1 was based on the 2012 SSC bundles, which reflected the best evidence available at the time (the 2001 Early Goal-Directed Therapy trial). By 2015, elements of that strategy had been challenged, and the PROCESS, PROMISE, and ARISE trials contested the notion that protcolized resuscitation decreased mortality. Moreover, new definitions of sepsis syndromes (Sepsis-3) were published in 2016 (Singer M, et al. JAMA. 2016;315[8]:801).

The 2016 SSC guidelines adopted the new definitions and recommended that patients with sepsis-induced hypoperfusion immediately receive a 30 mL/kg crystalloid bolus, followed by frequent reassessment. CMS did not adopt the Sepsis-3 definitions, but updates were made to allow the clinicians flexibility to demonstrate reassessment of the patient.

Comparing the 1-hour bundle to STEMI care

This year, the SSC published a 1-hour bundle to replace the 3- and 6-hour bundles (Levy MM et al. Crit Care Med. 2018;46[6]:997). Whereas previous bundles set time frames for completion of the elements, the 1-hour bundle focuses on the initiation of these components. The authors revisited the parallel between early management of sepsis and STEMI. The 1-hour bundle includes serum lactate, blood cultures prior to antibiotics, broad-spectrum antibiotics, a 30 mL/kg crystalloid bolus for patients with hypotension or lactate greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L, and vasopressors for persistent hypotension.

Elements of controversy after the publication of this bundle include:

1. One hour seems insufficient for complex clinical decision making and interventions for a syndrome with no specific diagnostic test: sepsis often mimics, or is mimicked by, other conditions.

2. Some bundle elements are not supported by high-quality evidence. No controlled studies exist regarding the appropriate volume of initial fluids or the impact of timing of antibiotics on outcomes.

3. The 1-hour time frame will encourage empiric delivery of fluids and antibiotics to patients who are not septic, potentially leading to harm.

4. While the 1-hour bundle is a quality improvement tool and not for public reporting, former bundles have been adopted as federally regulated measures.

Has the SSC gone too far? Are these concerns enough to abandon the 1-hour bundle? Or are the concerns regarding the 1-hour bundle an example of “perfect is the enemy of better”? To understand the potential for imperfect guidelines to drive tremendous patient-level improvements, one must consider the evolution of STEMI management.

Since the 1970s, the in-hospital mortality for STEMI has decreased from 25% to around 5%. The most significant factor in this achievement was the recognition that early reperfusion improves outcomes and that doing it consistently requires complex coordination. In 2004, a Door-to-Balloon (D2B) time of less than 90 minutes was included as a guideline recommendation (Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2004;110[5]:588). CMS started collecting performance data on this metric, made that data public, and later tied the performance to hospital reimbursement.

Initially, the 90-minute goal was achieved in only 44% of cases. In 2006, the D2B initiative was launched, providing recommendations for public education, coordination of care, and emergent management of STEMI. Compliance with these recommendations required significant education and changes to STEMI care at multiple levels. Data were collected and submitted to inform the process. Six years later, compliance with the D2B goal had increased from 44% to 91%. The median D2B dropped from 96 to 64 minutes. Based on high compliance, CMS discontinued the use of this metric for reimbursement as the variation between high and low performers was minimal. Put simply, the entire country had gotten better at treating STEMI. The “time-zero” for STEMI was pushed back further, and D2B has been replaced with first-medical-contact (FMC) to device time. The recommendation is to achieve this as quickly as possible, and in less than 90 minutes (O’Gara P, et al. JACC. 2013;61[4]:485).

Consider the complexity of getting a patient from their home to a catheterization lab within 90 minutes, even in ideal circumstances. This short time frame encourages, by design, a low threshold to activate the system. We accept that some patients will receive an unnecessary catheterization or systemic fibrinolysis although the recommendation is based on level B evidence.

Compliance with the STEMI guidelines is more labor-intensive and complex than compliance with the 1-hour sepsis bundle. So, is STEMI a fair comparison to sepsis? Both syndromes are common, potentially deadly, and time-sensitive. Both require early recognition, but neither has a definitive diagnostic test. Instead, diagnosis requires an integration of multiple complex clinical factors. Both are backed by imperfect science that continues to evolve. Over-diagnosis of either will expose the patient to potentially harmful therapies.

The early management of STEMI is a valid comparison to the early management of sepsis. We must consider this comparison as we ponder the 1-hour sepsis bundle.

Is triage time the appropriate time-zero? In either condition, triage time is too early in some cases and too late in others. Unfortunately, there is no better alternative, and STEMI guidelines have evolved to start the clock before triage. Using a point such as “recognition of sepsis” would fail to capture delayed recognition.

Is it possible to diagnose and initiate treatment for sepsis in such a short time frame? Consider the treatment received by the usual care group of the PROCESS trial (The ProCESS Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1683). Prior to meeting entry criteria, which occurred in less than 1 hour, patients in this group received an initial fluid bolus and had a lactate assessment. Prior to randomization, which occurred at around 90 minutes, this group completed 28 mL/kg of crystalloid fluid, and 76% received antibiotics. Thus, the usual-care group in this study nearly achieved the 1-hour bundle currently being contested.

Is it appropriate for a guideline to strongly recommend interventions not backed by level A evidence? The recommendation for FMC to catheterization within 90 minutes has not been studied in a controlled way. The precise dosing and timing of fibrinolysis is also not based on controlled data. Reperfusion devices and antiplatelet agents continue to be rigorously studied, sometimes with conflicting results.

Finally, should the 1-hour bundle be abandoned out of concern that it will be used as a national performance metric? First, there is currently no indication that the 1-hour bundle will be adopted as a performance metric. For the sake of argument, let’s assume the 1-hour bundle will be regulated and used to compare hospitals. Is there reason to think this bundle favors some hospitals over others and will lead to an unfair comparison? Is there significant inequity in the ability to draw blood cultures, send a lactate, start IV fluids, and initiate antibiotics?

Certainly, national compliance with such a metric would be very low at first. Therein lies the actual problem: a person who suffers a STEMI anywhere in the country is very likely to receive high-quality care. Currently, the same cannot be said about a patient with sepsis. Perhaps that should be the focus of our concern.

Dr. Uppal is Assistant Professor, NYU School of Medicine, Bellevue Hospital Center, New York, New York.

In 2002, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the International Sepsis Forum formed the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) aiming to reduce sepsis-related mortality by 25% within 5 years, mimicking the progress made in the management of STEMI (http://www.survivingsepsis.org/About-SSC/Pages/History.aspx).

SSC bundles: a historic perspective

The first guidelines were published in 2004. Recognizing that guidelines may not influence bedside practice for many years, the SSC partnered with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to apply performance improvement methodology to sepsis management, developing the “sepsis change bundles.” In addition to hospital resources for education, screening, and data collection, the 6-hour resuscitation and 24-hour management bundles were created. Subsequent data, collected as part of the initiative, demonstrated an association between bundle compliance and survival.

In 2008, the SSC guidelines were revised, and the National Quality Forum (NQF) adopted sepsis bundle compliance as a quality measure. NQF endorsement is often the first step toward the creation of mandates by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), but that did not occur at the time.

In 2012, the SSC guidelines were updated and published with new 3- and 6-hour bundles. That year, Rory Staunton, an otherwise healthy 12-year-old boy, died of septic shock in New York. The public discussion of this case, among other factors, prompted New York state to develop a sepsis care mandate that became state law in 2014. An annual public report details each hospital’s compliance with process measures and risk-adjusted mortality. The correlation between measure compliance and survival also holds true in this data set.

In 2015, CMS developed the SEP-1 measure. While the symbolic importance of a sepsis federal mandate and its potential to improve patient outcomes is recognized, concerns remain about the measure itself. The detailed and specific way data must be collected may disconnect clinical care provided from measured compliance. The time pressure and the “all-or-nothing” approach might incentivize interventions potentially harmful in some patients. No patient-centered outcomes are reported. This measure might be tied to reimbursement in the future.

The original version of SEP-1 was based on the 2012 SSC bundles, which reflected the best evidence available at the time (the 2001 Early Goal-Directed Therapy trial). By 2015, elements of that strategy had been challenged, and the PROCESS, PROMISE, and ARISE trials contested the notion that protcolized resuscitation decreased mortality. Moreover, new definitions of sepsis syndromes (Sepsis-3) were published in 2016 (Singer M, et al. JAMA. 2016;315[8]:801).

The 2016 SSC guidelines adopted the new definitions and recommended that patients with sepsis-induced hypoperfusion immediately receive a 30 mL/kg crystalloid bolus, followed by frequent reassessment. CMS did not adopt the Sepsis-3 definitions, but updates were made to allow the clinicians flexibility to demonstrate reassessment of the patient.

Comparing the 1-hour bundle to STEMI care

This year, the SSC published a 1-hour bundle to replace the 3- and 6-hour bundles (Levy MM et al. Crit Care Med. 2018;46[6]:997). Whereas previous bundles set time frames for completion of the elements, the 1-hour bundle focuses on the initiation of these components. The authors revisited the parallel between early management of sepsis and STEMI. The 1-hour bundle includes serum lactate, blood cultures prior to antibiotics, broad-spectrum antibiotics, a 30 mL/kg crystalloid bolus for patients with hypotension or lactate greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L, and vasopressors for persistent hypotension.

Elements of controversy after the publication of this bundle include:

1. One hour seems insufficient for complex clinical decision making and interventions for a syndrome with no specific diagnostic test: sepsis often mimics, or is mimicked by, other conditions.

2. Some bundle elements are not supported by high-quality evidence. No controlled studies exist regarding the appropriate volume of initial fluids or the impact of timing of antibiotics on outcomes.

3. The 1-hour time frame will encourage empiric delivery of fluids and antibiotics to patients who are not septic, potentially leading to harm.

4. While the 1-hour bundle is a quality improvement tool and not for public reporting, former bundles have been adopted as federally regulated measures.

Has the SSC gone too far? Are these concerns enough to abandon the 1-hour bundle? Or are the concerns regarding the 1-hour bundle an example of “perfect is the enemy of better”? To understand the potential for imperfect guidelines to drive tremendous patient-level improvements, one must consider the evolution of STEMI management.

Since the 1970s, the in-hospital mortality for STEMI has decreased from 25% to around 5%. The most significant factor in this achievement was the recognition that early reperfusion improves outcomes and that doing it consistently requires complex coordination. In 2004, a Door-to-Balloon (D2B) time of less than 90 minutes was included as a guideline recommendation (Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2004;110[5]:588). CMS started collecting performance data on this metric, made that data public, and later tied the performance to hospital reimbursement.

Initially, the 90-minute goal was achieved in only 44% of cases. In 2006, the D2B initiative was launched, providing recommendations for public education, coordination of care, and emergent management of STEMI. Compliance with these recommendations required significant education and changes to STEMI care at multiple levels. Data were collected and submitted to inform the process. Six years later, compliance with the D2B goal had increased from 44% to 91%. The median D2B dropped from 96 to 64 minutes. Based on high compliance, CMS discontinued the use of this metric for reimbursement as the variation between high and low performers was minimal. Put simply, the entire country had gotten better at treating STEMI. The “time-zero” for STEMI was pushed back further, and D2B has been replaced with first-medical-contact (FMC) to device time. The recommendation is to achieve this as quickly as possible, and in less than 90 minutes (O’Gara P, et al. JACC. 2013;61[4]:485).

Consider the complexity of getting a patient from their home to a catheterization lab within 90 minutes, even in ideal circumstances. This short time frame encourages, by design, a low threshold to activate the system. We accept that some patients will receive an unnecessary catheterization or systemic fibrinolysis although the recommendation is based on level B evidence.

Compliance with the STEMI guidelines is more labor-intensive and complex than compliance with the 1-hour sepsis bundle. So, is STEMI a fair comparison to sepsis? Both syndromes are common, potentially deadly, and time-sensitive. Both require early recognition, but neither has a definitive diagnostic test. Instead, diagnosis requires an integration of multiple complex clinical factors. Both are backed by imperfect science that continues to evolve. Over-diagnosis of either will expose the patient to potentially harmful therapies.

The early management of STEMI is a valid comparison to the early management of sepsis. We must consider this comparison as we ponder the 1-hour sepsis bundle.

Is triage time the appropriate time-zero? In either condition, triage time is too early in some cases and too late in others. Unfortunately, there is no better alternative, and STEMI guidelines have evolved to start the clock before triage. Using a point such as “recognition of sepsis” would fail to capture delayed recognition.

Is it possible to diagnose and initiate treatment for sepsis in such a short time frame? Consider the treatment received by the usual care group of the PROCESS trial (The ProCESS Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1683). Prior to meeting entry criteria, which occurred in less than 1 hour, patients in this group received an initial fluid bolus and had a lactate assessment. Prior to randomization, which occurred at around 90 minutes, this group completed 28 mL/kg of crystalloid fluid, and 76% received antibiotics. Thus, the usual-care group in this study nearly achieved the 1-hour bundle currently being contested.

Is it appropriate for a guideline to strongly recommend interventions not backed by level A evidence? The recommendation for FMC to catheterization within 90 minutes has not been studied in a controlled way. The precise dosing and timing of fibrinolysis is also not based on controlled data. Reperfusion devices and antiplatelet agents continue to be rigorously studied, sometimes with conflicting results.

Finally, should the 1-hour bundle be abandoned out of concern that it will be used as a national performance metric? First, there is currently no indication that the 1-hour bundle will be adopted as a performance metric. For the sake of argument, let’s assume the 1-hour bundle will be regulated and used to compare hospitals. Is there reason to think this bundle favors some hospitals over others and will lead to an unfair comparison? Is there significant inequity in the ability to draw blood cultures, send a lactate, start IV fluids, and initiate antibiotics?

Certainly, national compliance with such a metric would be very low at first. Therein lies the actual problem: a person who suffers a STEMI anywhere in the country is very likely to receive high-quality care. Currently, the same cannot be said about a patient with sepsis. Perhaps that should be the focus of our concern.

Dr. Uppal is Assistant Professor, NYU School of Medicine, Bellevue Hospital Center, New York, New York.

In 2002, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the International Sepsis Forum formed the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) aiming to reduce sepsis-related mortality by 25% within 5 years, mimicking the progress made in the management of STEMI (http://www.survivingsepsis.org/About-SSC/Pages/History.aspx).

SSC bundles: a historic perspective

The first guidelines were published in 2004. Recognizing that guidelines may not influence bedside practice for many years, the SSC partnered with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to apply performance improvement methodology to sepsis management, developing the “sepsis change bundles.” In addition to hospital resources for education, screening, and data collection, the 6-hour resuscitation and 24-hour management bundles were created. Subsequent data, collected as part of the initiative, demonstrated an association between bundle compliance and survival.

In 2008, the SSC guidelines were revised, and the National Quality Forum (NQF) adopted sepsis bundle compliance as a quality measure. NQF endorsement is often the first step toward the creation of mandates by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), but that did not occur at the time.

In 2012, the SSC guidelines were updated and published with new 3- and 6-hour bundles. That year, Rory Staunton, an otherwise healthy 12-year-old boy, died of septic shock in New York. The public discussion of this case, among other factors, prompted New York state to develop a sepsis care mandate that became state law in 2014. An annual public report details each hospital’s compliance with process measures and risk-adjusted mortality. The correlation between measure compliance and survival also holds true in this data set.

In 2015, CMS developed the SEP-1 measure. While the symbolic importance of a sepsis federal mandate and its potential to improve patient outcomes is recognized, concerns remain about the measure itself. The detailed and specific way data must be collected may disconnect clinical care provided from measured compliance. The time pressure and the “all-or-nothing” approach might incentivize interventions potentially harmful in some patients. No patient-centered outcomes are reported. This measure might be tied to reimbursement in the future.

The original version of SEP-1 was based on the 2012 SSC bundles, which reflected the best evidence available at the time (the 2001 Early Goal-Directed Therapy trial). By 2015, elements of that strategy had been challenged, and the PROCESS, PROMISE, and ARISE trials contested the notion that protcolized resuscitation decreased mortality. Moreover, new definitions of sepsis syndromes (Sepsis-3) were published in 2016 (Singer M, et al. JAMA. 2016;315[8]:801).

The 2016 SSC guidelines adopted the new definitions and recommended that patients with sepsis-induced hypoperfusion immediately receive a 30 mL/kg crystalloid bolus, followed by frequent reassessment. CMS did not adopt the Sepsis-3 definitions, but updates were made to allow the clinicians flexibility to demonstrate reassessment of the patient.

Comparing the 1-hour bundle to STEMI care

This year, the SSC published a 1-hour bundle to replace the 3- and 6-hour bundles (Levy MM et al. Crit Care Med. 2018;46[6]:997). Whereas previous bundles set time frames for completion of the elements, the 1-hour bundle focuses on the initiation of these components. The authors revisited the parallel between early management of sepsis and STEMI. The 1-hour bundle includes serum lactate, blood cultures prior to antibiotics, broad-spectrum antibiotics, a 30 mL/kg crystalloid bolus for patients with hypotension or lactate greater than or equal to 4 mmol/L, and vasopressors for persistent hypotension.

Elements of controversy after the publication of this bundle include:

1. One hour seems insufficient for complex clinical decision making and interventions for a syndrome with no specific diagnostic test: sepsis often mimics, or is mimicked by, other conditions.

2. Some bundle elements are not supported by high-quality evidence. No controlled studies exist regarding the appropriate volume of initial fluids or the impact of timing of antibiotics on outcomes.

3. The 1-hour time frame will encourage empiric delivery of fluids and antibiotics to patients who are not septic, potentially leading to harm.

4. While the 1-hour bundle is a quality improvement tool and not for public reporting, former bundles have been adopted as federally regulated measures.

Has the SSC gone too far? Are these concerns enough to abandon the 1-hour bundle? Or are the concerns regarding the 1-hour bundle an example of “perfect is the enemy of better”? To understand the potential for imperfect guidelines to drive tremendous patient-level improvements, one must consider the evolution of STEMI management.

Since the 1970s, the in-hospital mortality for STEMI has decreased from 25% to around 5%. The most significant factor in this achievement was the recognition that early reperfusion improves outcomes and that doing it consistently requires complex coordination. In 2004, a Door-to-Balloon (D2B) time of less than 90 minutes was included as a guideline recommendation (Antman EM, et al. Circulation. 2004;110[5]:588). CMS started collecting performance data on this metric, made that data public, and later tied the performance to hospital reimbursement.

Initially, the 90-minute goal was achieved in only 44% of cases. In 2006, the D2B initiative was launched, providing recommendations for public education, coordination of care, and emergent management of STEMI. Compliance with these recommendations required significant education and changes to STEMI care at multiple levels. Data were collected and submitted to inform the process. Six years later, compliance with the D2B goal had increased from 44% to 91%. The median D2B dropped from 96 to 64 minutes. Based on high compliance, CMS discontinued the use of this metric for reimbursement as the variation between high and low performers was minimal. Put simply, the entire country had gotten better at treating STEMI. The “time-zero” for STEMI was pushed back further, and D2B has been replaced with first-medical-contact (FMC) to device time. The recommendation is to achieve this as quickly as possible, and in less than 90 minutes (O’Gara P, et al. JACC. 2013;61[4]:485).

Consider the complexity of getting a patient from their home to a catheterization lab within 90 minutes, even in ideal circumstances. This short time frame encourages, by design, a low threshold to activate the system. We accept that some patients will receive an unnecessary catheterization or systemic fibrinolysis although the recommendation is based on level B evidence.

Compliance with the STEMI guidelines is more labor-intensive and complex than compliance with the 1-hour sepsis bundle. So, is STEMI a fair comparison to sepsis? Both syndromes are common, potentially deadly, and time-sensitive. Both require early recognition, but neither has a definitive diagnostic test. Instead, diagnosis requires an integration of multiple complex clinical factors. Both are backed by imperfect science that continues to evolve. Over-diagnosis of either will expose the patient to potentially harmful therapies.

The early management of STEMI is a valid comparison to the early management of sepsis. We must consider this comparison as we ponder the 1-hour sepsis bundle.

Is triage time the appropriate time-zero? In either condition, triage time is too early in some cases and too late in others. Unfortunately, there is no better alternative, and STEMI guidelines have evolved to start the clock before triage. Using a point such as “recognition of sepsis” would fail to capture delayed recognition.

Is it possible to diagnose and initiate treatment for sepsis in such a short time frame? Consider the treatment received by the usual care group of the PROCESS trial (The ProCESS Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1683). Prior to meeting entry criteria, which occurred in less than 1 hour, patients in this group received an initial fluid bolus and had a lactate assessment. Prior to randomization, which occurred at around 90 minutes, this group completed 28 mL/kg of crystalloid fluid, and 76% received antibiotics. Thus, the usual-care group in this study nearly achieved the 1-hour bundle currently being contested.

Is it appropriate for a guideline to strongly recommend interventions not backed by level A evidence? The recommendation for FMC to catheterization within 90 minutes has not been studied in a controlled way. The precise dosing and timing of fibrinolysis is also not based on controlled data. Reperfusion devices and antiplatelet agents continue to be rigorously studied, sometimes with conflicting results.

Finally, should the 1-hour bundle be abandoned out of concern that it will be used as a national performance metric? First, there is currently no indication that the 1-hour bundle will be adopted as a performance metric. For the sake of argument, let’s assume the 1-hour bundle will be regulated and used to compare hospitals. Is there reason to think this bundle favors some hospitals over others and will lead to an unfair comparison? Is there significant inequity in the ability to draw blood cultures, send a lactate, start IV fluids, and initiate antibiotics?

Certainly, national compliance with such a metric would be very low at first. Therein lies the actual problem: a person who suffers a STEMI anywhere in the country is very likely to receive high-quality care. Currently, the same cannot be said about a patient with sepsis. Perhaps that should be the focus of our concern.

Dr. Uppal is Assistant Professor, NYU School of Medicine, Bellevue Hospital Center, New York, New York.

Introducing CHEST’s new CEO/EVP

Greetings! My name is Robert Musacchio; I am proud to introduce myself as the new Chief Executive Officer and Executive Vice President of CHEST. I am honored to join this team of distinguished clinicians as we spearhead progress in the fight against lung disease.

I have had the pleasure of working at CHEST for the last 4 years, first joining CHEST Enterprises as Senior Vice President of Business Development. In that role, I focused on revenue growth and product diversification before becoming COO of CHEST. As COO, I dedicated myself to strengthening our team by mentoring staff and collaborating with senior leadership, a challenge that I have deeply enjoyed.

Before joining CHEST, I worked at the American Medical Association for 35 years in roles encompassing research, advocacy, membership, and publishing. I also worked with boards and membership groups as a member of the AMA’s CPT® Editorial Panel and as a publisher for JAMA.

As CEO, I hope to leverage those experiences to support CHEST in its mission, which is to improve lung health not just for 1 year but for the next 25 years. For that reason, our leadership team has outlined an organizational culture that fosters short-term success and long-term innovation, focusing on four key areas:

People: How do we attract and retain the right people?

Strategy: How do we create a truly differentiated strategy?

Execution: How do we improve our process to drive flawless execution?

Resources: How do we ensure that we have sufficient resources to invest in our mission?

Those questions in mind, we have established several standards that guide the way we work. We are focusing on leading with integrity, cultivating passion and innovation, honoring our team, and having fun while we deliver cutting-edge education and create community for our members. With these norms, we can continue to foster an environment that generates results. This, in turn, will enable CHEST to fulfill its core purpose of crushing lung disease.

We can crush lung disease by arming our members with industry-leading education offerings—including simulation experiences and live lab courses—and expanding them worldwide to Thailand and Greece in 2019. We can crush lung disease by using cutting-edge technologies—including interactive gaming platforms—to glean further insights. We can crush lung disease by connecting our membership of nearly 20,000 pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine professionals to innovative education tools, along with a network of prestigious colleagues to deliver the highest quality patient care.

Most importantly, we can crush lung disease by empowering our members in their work—if you care about lung disease, we care about you!

And, if you care about lung disease, I am excited to partner with you in this cause. I am thankful for this opportunity to lead CHEST and the CHEST Foundation into the future and look forward to working with you.

Greetings! My name is Robert Musacchio; I am proud to introduce myself as the new Chief Executive Officer and Executive Vice President of CHEST. I am honored to join this team of distinguished clinicians as we spearhead progress in the fight against lung disease.

I have had the pleasure of working at CHEST for the last 4 years, first joining CHEST Enterprises as Senior Vice President of Business Development. In that role, I focused on revenue growth and product diversification before becoming COO of CHEST. As COO, I dedicated myself to strengthening our team by mentoring staff and collaborating with senior leadership, a challenge that I have deeply enjoyed.

Before joining CHEST, I worked at the American Medical Association for 35 years in roles encompassing research, advocacy, membership, and publishing. I also worked with boards and membership groups as a member of the AMA’s CPT® Editorial Panel and as a publisher for JAMA.

As CEO, I hope to leverage those experiences to support CHEST in its mission, which is to improve lung health not just for 1 year but for the next 25 years. For that reason, our leadership team has outlined an organizational culture that fosters short-term success and long-term innovation, focusing on four key areas:

People: How do we attract and retain the right people?

Strategy: How do we create a truly differentiated strategy?

Execution: How do we improve our process to drive flawless execution?

Resources: How do we ensure that we have sufficient resources to invest in our mission?

Those questions in mind, we have established several standards that guide the way we work. We are focusing on leading with integrity, cultivating passion and innovation, honoring our team, and having fun while we deliver cutting-edge education and create community for our members. With these norms, we can continue to foster an environment that generates results. This, in turn, will enable CHEST to fulfill its core purpose of crushing lung disease.

We can crush lung disease by arming our members with industry-leading education offerings—including simulation experiences and live lab courses—and expanding them worldwide to Thailand and Greece in 2019. We can crush lung disease by using cutting-edge technologies—including interactive gaming platforms—to glean further insights. We can crush lung disease by connecting our membership of nearly 20,000 pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine professionals to innovative education tools, along with a network of prestigious colleagues to deliver the highest quality patient care.

Most importantly, we can crush lung disease by empowering our members in their work—if you care about lung disease, we care about you!

And, if you care about lung disease, I am excited to partner with you in this cause. I am thankful for this opportunity to lead CHEST and the CHEST Foundation into the future and look forward to working with you.

Greetings! My name is Robert Musacchio; I am proud to introduce myself as the new Chief Executive Officer and Executive Vice President of CHEST. I am honored to join this team of distinguished clinicians as we spearhead progress in the fight against lung disease.

I have had the pleasure of working at CHEST for the last 4 years, first joining CHEST Enterprises as Senior Vice President of Business Development. In that role, I focused on revenue growth and product diversification before becoming COO of CHEST. As COO, I dedicated myself to strengthening our team by mentoring staff and collaborating with senior leadership, a challenge that I have deeply enjoyed.

Before joining CHEST, I worked at the American Medical Association for 35 years in roles encompassing research, advocacy, membership, and publishing. I also worked with boards and membership groups as a member of the AMA’s CPT® Editorial Panel and as a publisher for JAMA.

As CEO, I hope to leverage those experiences to support CHEST in its mission, which is to improve lung health not just for 1 year but for the next 25 years. For that reason, our leadership team has outlined an organizational culture that fosters short-term success and long-term innovation, focusing on four key areas:

People: How do we attract and retain the right people?

Strategy: How do we create a truly differentiated strategy?

Execution: How do we improve our process to drive flawless execution?

Resources: How do we ensure that we have sufficient resources to invest in our mission?

Those questions in mind, we have established several standards that guide the way we work. We are focusing on leading with integrity, cultivating passion and innovation, honoring our team, and having fun while we deliver cutting-edge education and create community for our members. With these norms, we can continue to foster an environment that generates results. This, in turn, will enable CHEST to fulfill its core purpose of crushing lung disease.

We can crush lung disease by arming our members with industry-leading education offerings—including simulation experiences and live lab courses—and expanding them worldwide to Thailand and Greece in 2019. We can crush lung disease by using cutting-edge technologies—including interactive gaming platforms—to glean further insights. We can crush lung disease by connecting our membership of nearly 20,000 pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine professionals to innovative education tools, along with a network of prestigious colleagues to deliver the highest quality patient care.

Most importantly, we can crush lung disease by empowering our members in their work—if you care about lung disease, we care about you!

And, if you care about lung disease, I am excited to partner with you in this cause. I am thankful for this opportunity to lead CHEST and the CHEST Foundation into the future and look forward to working with you.

TOURMALINE-MM3: Ixazomib improves PFS after myeloma transplant

SAN DIEGO – Ixazomib improved progression-free survival following autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, according to results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial.

Treatment with the oral proteasome inhibitor for 24 months was well tolerated, had a low discontinuation rate, and improved progression-free survival by 39% versus placebo, according to Meletios A. Dimopoulos, MD, of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

These findings suggest ixazomib (Ninlaro) represents a “new treatment option for maintenance after transplantation,” Dr. Dimopoulos said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The trial, known as TOURMALINE-MM3, is the first-ever randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a proteasome inhibitor used as maintenance after ASCT, according to Dr. Dimopoulos. Lenalidomide is approved in that setting, but 29% of patients who start the treatment discontinue because of treatment-related adverse events.

“Proteasome inhibitors have a different mechanism of action and may provide an alternative to lenalidomide,” Dr. Dimopoulos said at an oral abstract session. Ixazomib has a manageable toxicity profile and “convenient” weekly oral dosing, making it “well suited” for maintenance.

When asked by an attendee whether ixazomib would become “the standard of care” for younger patients with myeloma in this setting, Dr. Dimopoulos replied the results show that ixazomib “is an option for patients, especially for those where a physician may believe that a proteasome inhibitor may be indicated.”

However, when pressed by an attendee to comment on how ixazomib compares with lenalidomide for maintenance, Dr. Dimopoulos remarked that current maintenance studies are moving in the direction of combining therapies.

“I think that instead of saying, ‘is ixazomib better than lenalidomide?’ or vice versa, it is better to see how one may combine those drugs in subsets of patients, or even combine these drugs with other agents,” he said.

The TOURMALINE-MM3 study included 656 patients randomized posttransplantation to receive weekly ixazomib or placebo for up to 2 years.

The median progression-free survival was 26.5 months for ixazomib versus 21.3 months for placebo (P = .002; hazard ratio, 0.720; 95% confidence interval, 0.582-0.890). Median overall survival had not been reached in either ixazomib or placebo arms as of this report, with a median follow-up of 31 months.

The discontinuation rate was 7% for ixazomib versus 5% for placebo, according to the investigator. Moreover, ixazomib was associated with “low toxicity” and no difference in the rates of new primary malignancies, at 3% in both arms.

A manuscript describing results of the TOURMALINE-MM3 study is in press in the Lancet, with an expected online publication date of Dec. 10, Dr. Dimopoulos told attendees. Other studies are ongoing to evaluate ixazomib combinations and treatment to progression in this setting.

TOURMALINE-MM3 is sponsored by Takeda (Millennium), the maker of ixazomib. Dr. Dimopoulos reported honoraria and consultancy with Janssen, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Celgene.

SOURCE: Dimopoulos MA et al. ASH 2018, Abstract 301.

SAN DIEGO – Ixazomib improved progression-free survival following autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, according to results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial.

Treatment with the oral proteasome inhibitor for 24 months was well tolerated, had a low discontinuation rate, and improved progression-free survival by 39% versus placebo, according to Meletios A. Dimopoulos, MD, of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

These findings suggest ixazomib (Ninlaro) represents a “new treatment option for maintenance after transplantation,” Dr. Dimopoulos said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The trial, known as TOURMALINE-MM3, is the first-ever randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a proteasome inhibitor used as maintenance after ASCT, according to Dr. Dimopoulos. Lenalidomide is approved in that setting, but 29% of patients who start the treatment discontinue because of treatment-related adverse events.

“Proteasome inhibitors have a different mechanism of action and may provide an alternative to lenalidomide,” Dr. Dimopoulos said at an oral abstract session. Ixazomib has a manageable toxicity profile and “convenient” weekly oral dosing, making it “well suited” for maintenance.

When asked by an attendee whether ixazomib would become “the standard of care” for younger patients with myeloma in this setting, Dr. Dimopoulos replied the results show that ixazomib “is an option for patients, especially for those where a physician may believe that a proteasome inhibitor may be indicated.”

However, when pressed by an attendee to comment on how ixazomib compares with lenalidomide for maintenance, Dr. Dimopoulos remarked that current maintenance studies are moving in the direction of combining therapies.

“I think that instead of saying, ‘is ixazomib better than lenalidomide?’ or vice versa, it is better to see how one may combine those drugs in subsets of patients, or even combine these drugs with other agents,” he said.

The TOURMALINE-MM3 study included 656 patients randomized posttransplantation to receive weekly ixazomib or placebo for up to 2 years.

The median progression-free survival was 26.5 months for ixazomib versus 21.3 months for placebo (P = .002; hazard ratio, 0.720; 95% confidence interval, 0.582-0.890). Median overall survival had not been reached in either ixazomib or placebo arms as of this report, with a median follow-up of 31 months.

The discontinuation rate was 7% for ixazomib versus 5% for placebo, according to the investigator. Moreover, ixazomib was associated with “low toxicity” and no difference in the rates of new primary malignancies, at 3% in both arms.

A manuscript describing results of the TOURMALINE-MM3 study is in press in the Lancet, with an expected online publication date of Dec. 10, Dr. Dimopoulos told attendees. Other studies are ongoing to evaluate ixazomib combinations and treatment to progression in this setting.

TOURMALINE-MM3 is sponsored by Takeda (Millennium), the maker of ixazomib. Dr. Dimopoulos reported honoraria and consultancy with Janssen, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Celgene.

SOURCE: Dimopoulos MA et al. ASH 2018, Abstract 301.

SAN DIEGO – Ixazomib improved progression-free survival following autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, according to results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial.

Treatment with the oral proteasome inhibitor for 24 months was well tolerated, had a low discontinuation rate, and improved progression-free survival by 39% versus placebo, according to Meletios A. Dimopoulos, MD, of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

These findings suggest ixazomib (Ninlaro) represents a “new treatment option for maintenance after transplantation,” Dr. Dimopoulos said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The trial, known as TOURMALINE-MM3, is the first-ever randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a proteasome inhibitor used as maintenance after ASCT, according to Dr. Dimopoulos. Lenalidomide is approved in that setting, but 29% of patients who start the treatment discontinue because of treatment-related adverse events.

“Proteasome inhibitors have a different mechanism of action and may provide an alternative to lenalidomide,” Dr. Dimopoulos said at an oral abstract session. Ixazomib has a manageable toxicity profile and “convenient” weekly oral dosing, making it “well suited” for maintenance.

When asked by an attendee whether ixazomib would become “the standard of care” for younger patients with myeloma in this setting, Dr. Dimopoulos replied the results show that ixazomib “is an option for patients, especially for those where a physician may believe that a proteasome inhibitor may be indicated.”

However, when pressed by an attendee to comment on how ixazomib compares with lenalidomide for maintenance, Dr. Dimopoulos remarked that current maintenance studies are moving in the direction of combining therapies.

“I think that instead of saying, ‘is ixazomib better than lenalidomide?’ or vice versa, it is better to see how one may combine those drugs in subsets of patients, or even combine these drugs with other agents,” he said.

The TOURMALINE-MM3 study included 656 patients randomized posttransplantation to receive weekly ixazomib or placebo for up to 2 years.

The median progression-free survival was 26.5 months for ixazomib versus 21.3 months for placebo (P = .002; hazard ratio, 0.720; 95% confidence interval, 0.582-0.890). Median overall survival had not been reached in either ixazomib or placebo arms as of this report, with a median follow-up of 31 months.

The discontinuation rate was 7% for ixazomib versus 5% for placebo, according to the investigator. Moreover, ixazomib was associated with “low toxicity” and no difference in the rates of new primary malignancies, at 3% in both arms.

A manuscript describing results of the TOURMALINE-MM3 study is in press in the Lancet, with an expected online publication date of Dec. 10, Dr. Dimopoulos told attendees. Other studies are ongoing to evaluate ixazomib combinations and treatment to progression in this setting.

TOURMALINE-MM3 is sponsored by Takeda (Millennium), the maker of ixazomib. Dr. Dimopoulos reported honoraria and consultancy with Janssen, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Celgene.

SOURCE: Dimopoulos MA et al. ASH 2018, Abstract 301.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2018

Key clinical point: The proteasome inhibitor ixazomib significantly improved progression-free survival following autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.

Major finding: The median progression-free survival was 26.5 months for ixazomib, versus 21.3 months for placebo (P = .002; hazard ratio, 0.720; 95% confidence interval, 0.582-0.890).

Study details: TOURMALINE-MM3, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, includes 656 patients with newly diagnosed myeloma who had undergone autologous stem cell transplantation.

Disclosures: TOURMALINE-MM3 is sponsored by Takeda (Millennium), the maker of ixazomib. Dr. Dimopoulos reported honoraria and consultancy with Janssen, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Celgene.

Source: Dimopoulos MA et al. ASH 2018, Abstract 301.

JULIET: CAR T cells go the distance in r/r DLBCL

SAN DIEGO – Two-thirds of adults with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who had early responses to chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapy with tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) remain in remission with no evidence of minimal residual disease, according to an updated analysis of the JULIET trial.

In the single-arm, open-label trial, the overall response rate after 19 months of follow-up was 54%, including 40% complete remissions and 14% partial remissions. The median duration of response had not been reached at the time of data cutoff, and the median overall survival had not been reached for patients with a complete remission. Overall survival in this heavily pretreated population as a whole (all patients who received CAR T-cell infusions) was 11.1 months.

Adverse events were similar to those previously reported and were manageable, according to investigator Richard Thomas Maziarz, MD, from the Oregon Health & Science Knight Cancer Institute in Portland.

In this video interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Dr. Maziarz discusses the promising results using CAR T cells in this difficult to treat population.

SAN DIEGO – Two-thirds of adults with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who had early responses to chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapy with tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) remain in remission with no evidence of minimal residual disease, according to an updated analysis of the JULIET trial.

In the single-arm, open-label trial, the overall response rate after 19 months of follow-up was 54%, including 40% complete remissions and 14% partial remissions. The median duration of response had not been reached at the time of data cutoff, and the median overall survival had not been reached for patients with a complete remission. Overall survival in this heavily pretreated population as a whole (all patients who received CAR T-cell infusions) was 11.1 months.

Adverse events were similar to those previously reported and were manageable, according to investigator Richard Thomas Maziarz, MD, from the Oregon Health & Science Knight Cancer Institute in Portland.

In this video interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Dr. Maziarz discusses the promising results using CAR T cells in this difficult to treat population.

SAN DIEGO – Two-thirds of adults with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who had early responses to chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapy with tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) remain in remission with no evidence of minimal residual disease, according to an updated analysis of the JULIET trial.

In the single-arm, open-label trial, the overall response rate after 19 months of follow-up was 54%, including 40% complete remissions and 14% partial remissions. The median duration of response had not been reached at the time of data cutoff, and the median overall survival had not been reached for patients with a complete remission. Overall survival in this heavily pretreated population as a whole (all patients who received CAR T-cell infusions) was 11.1 months.

Adverse events were similar to those previously reported and were manageable, according to investigator Richard Thomas Maziarz, MD, from the Oregon Health & Science Knight Cancer Institute in Portland.

In this video interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Dr. Maziarz discusses the promising results using CAR T cells in this difficult to treat population.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2018

Beat AML trial delivers genomic results in 7 days

SAN DIEGO – Investigators demonstrated the feasibility of delivering genomic results in 7 days in a population of older, newly diagnosed patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The Beat AML Master Trial is an ongoing umbrella study that harnesses cytogenetic information and next generation sequencing to match patients with targeted therapies across a number of substudies or outside of the trial’s multicenter network.