User login

Sexually Transmitted Infections Caused by Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Diagnosis and Treatment

From the Fargo Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Fargo, ND (Dr. Dietz, Dr. Hammer, Dr. Zegarra, and Dr. Lo), and the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong, China (Dr. Cho).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the management of patients with Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are organisms that cause urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. There is increasing antibiotic resistance to both organisms, which poses significant challenges to clinicians. Additionally, diagnostic tests for M. genitalium are not widely available, and commonly used tests for both organisms do not provide antibiotic sensitivity information. The increasing resistance of both M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae to currently used antimicrobial agents is alarming and warrants cautious monitoring.

- Conclusion: As the yield of new or effective antibiotic therapies has decreased over the past few years, increasing antibiotic resistance will lead to difficult treatment scenarios for sexually transmitted infections caused by these 2 organisms.

Keywords: Mycoplasma genitalium, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, antibiotic resistance, sexually transmitted infections, STIs.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 1 million cases of sexually transmitted Infections (STIs) are acquired every day worldwide,1 and that the majority of STIs have few or no symptoms, making diagnosis difficult. Two organisms of interest are Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In contrast to Chlamydia trachomatis, which is rarely resistant to treatment regimens, M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotic treatment and pose an impending threat. These bacteria can cause urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Whereas antibiotic resistance to M. genitalium is emerging, resistance to N. gonorrhea has been a continual problem for decades. Drug resistance, especially for N. gonorrhoeae, is listed as a major threat to efforts to reduce the impact of STIs worldwide.2 In 2013, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified N. gonorrhoeae drug resistance as an urgent threat.3 As the yield of new or effective antibiotic therapies has decreased over the past few years, increasing antibiotic resistance will lead to challenging treatment scenarios for STIs caused by these 2 organisms.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

M. genitalium

M. genitalium is an emerging pathogen that is an etiologic agent of upper and lower genital tract STIs, such as urethritis, cervicitis, and PID.4-13 In addition, it is thought to be involved in tubal infertility and acquisition of other sexually transmitted pathogens, including HIV.7,8,13 The prevalence of M. genitalium in the general U.S. population in 2016 was reported to be approximately 17.2% for males and 16.1% for females.14 Infections are more common in patients aged 30 years and younger than in older populations.15 Also, patients self-identifying as black were found to have a higher prevalence of M. genitalium.14 This organism was first reported as being isolated from the urethras of 2 men with non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) in London in 1980.15,16 It is a significant cause of acute and chronic NGU in males, and is estimated to account for 6% to 50% of cases of NGU.17,18M. genitalium in females has been associated with cervicitis4,9 and PID.8,10 A meta-analysis by Lis et al showed that M. genitalium infection was associated with an increased risk for preterm birth and spontaneous abortion.11 In addition, M. genitalium infections occur frequently in HIV-positive patients.19,20 M. genitalium increases susceptibility for passage of HIV across the epithelium by reducing epithelial barrier integrity.19

Beta lactams are ineffective against M. genitalium because mycoplasmas lack a cell wall and thus cell wall penicillin-binding proteins.21M. genitalium’s abilty to invade host epithelial cells is another mechanism that can protect the bacteria from antibiotic exposure.20 One of the first reports of antibiotic sensitivity testing for M. genitalium, published in 1997, noted that the organism was not susceptible to nalidixic acid, cephalosporins, penicillins, and rifampicin.22 In general, mycoplasmas are normally susceptible to antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis,23 and initial good sensitivity to doxycycline and erythromycin was noted but this has since decreased. New antibiotics are on the horizon, but they have not been extensively tested in vivo.23

N. gonorrhoeae

Gonorrhea is the second most common STI of bacterial origin following C. trachomatis,24-26 which is rarely resistant to conventional regimens. In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 106 million cases of N. gonorrhoeae infection were acquired annually and that 36.4 million adults were infected with N. gonorrhoeae.27 In the United States, the CDC estimates that gonorrhea cases are under-reported. An estimated 800,000 or more new cases are reported per year.28

The most common clinical presentations are urethritis in men and cervicitis in women.29 While urethritis is most likely to be symptomatic, only 50% of women with acute gonorrhea are symptomatic.29 In addition to lower urogenital tract infection, N. gonorrhoeae can also cause PID, ectopic pregnancy, infertility in women, and epididymitis in men.29,30 Rare complications can develop from the spread of N. gonorrhoeae to other parts of the body including the joints, eyes, cardiovascular system, and skin.29

N. gonorrhoeae can attach to the columnar epithelium and causes host innate immune-driven inflammation with neutrophil influx.29 It can avoid the immune response by varying its outer membrane protein expression. The organism is also able to acquire DNA from other Neisseria species30 and genera, which results in reduced susceptibility to therapies.

The Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), established in 1986, is a collaborative project involving the CDC and STI clinics in 26 cities in the United States along with 5 regional laboratories.31 The GISP monitors susceptibilities in N. gonorrhoeae isolates obtained from roughly 6000 symptomatic men each year.31 Data collected from the GISP allows clinicians to treat infections with the correct antibiotic. Just as they observed patterns of fluoroquinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae, there has been a geographic progression of decreasing susceptibility to cephalosporins in recent years.31

The ease with which N. gonorrhoeae can develop resistance is particularly alarming. Sulfonamide use began in the 1930s, but resistance developed within approximately 10 years.30,32N. gonorrhoeae has acquired resistance to each therapeutic agent used for treatment over the course of its lifetime. One hypothesis is that use of single-dose therapy to rapidly treat the infection has led to treatment failure and allows for selective pressure where organisms with decreased antibiotic susceptibility are more likely to survive.30 However, there is limited evidence to support monotherapy versus combination therapy in treating N. gonorrhoeae.33,34 It is no exaggeration to say gonorrhea is now at risk of becoming an untreatable disease because of the rapid emergence of multidrug resistant N. gonorrhoeae strains worldwide.35

Diagnosis

Whether the urethritis, cervicitis, or PID is caused by N. gonorrhoeae, M. genitalium, or other non-gonococcal microorganisms (eg, C. trachomatis), no symptoms are specific to any of the microorganisms. Therefore, clinicians rely on laboratory tests to diagnose STIs caused by N. gonorrhoeae or M. genitalium.

M. genitalium

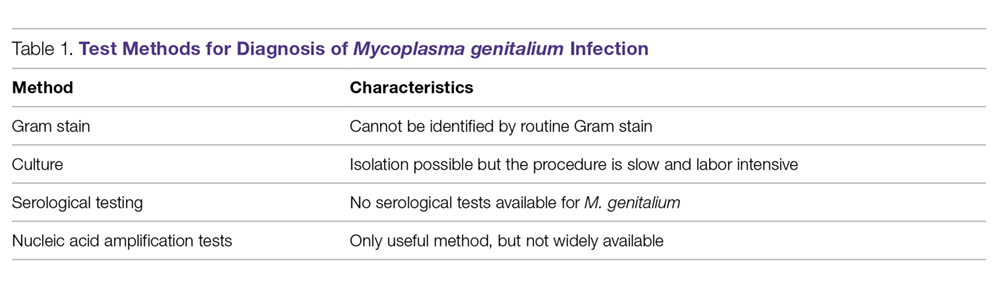

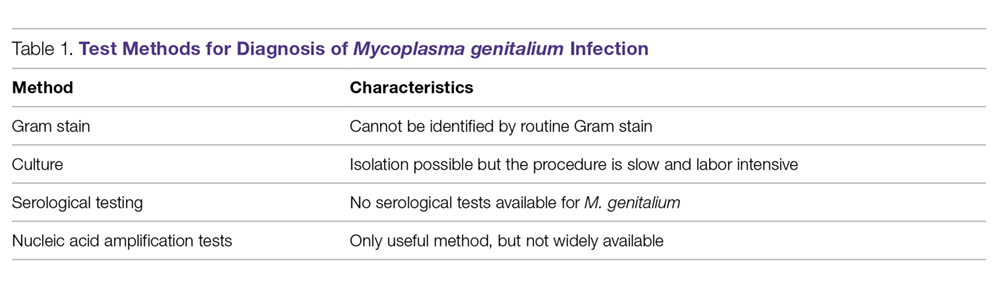

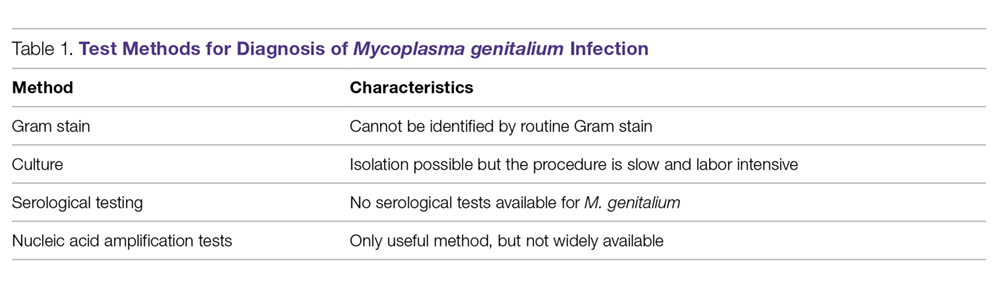

Gram Stain. Because M. genitalium lacks a cell wall, it cannot be identified by routine Gram stain.

Culture. Culturing of this fastidious bacterium might offer the advantage of assessing antibiotic susceptibility;36 however, the procedure is labor intensive and time consuming, and only a few labs in the world have the capability to perform this culture.12 Thus, this testing method is primarily undertaken for research purposes.

Serological Testing. Because of serologic cross-reactions between Mycoplasma pneumoniae and M. genitalium, there are no standardized serological tests for M. genitalium.37

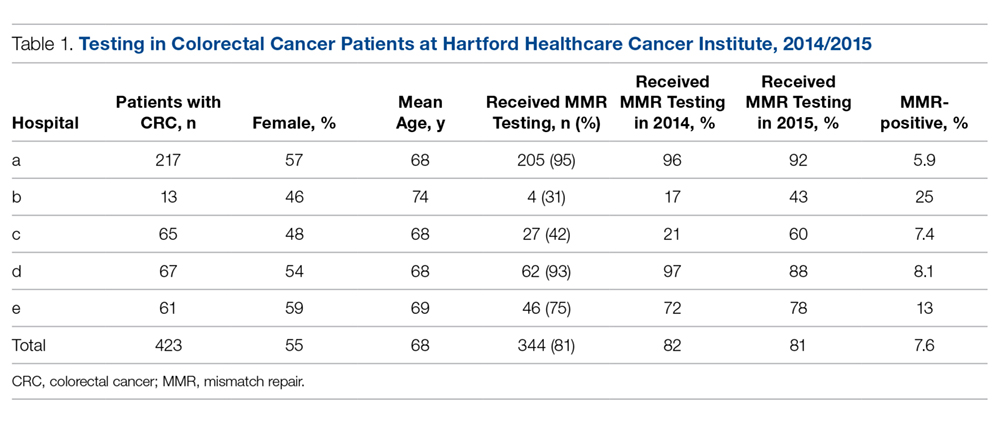

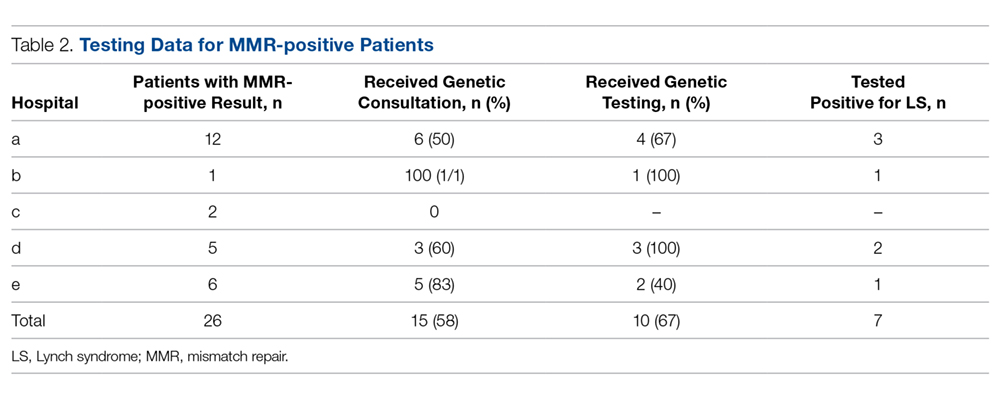

Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests. M. genitalium diagnosis currently is made based exclusively on nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) methodology (polymerase chain reaction [PCR] or transcription-mediated amplification [TMA]), which is the only clinically useful method to detect M. genitalium. TMA for M. genitalium is commercially available in an analyte-specific reagent (ASR) format, but this has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).38 A study analyzing urogenital specimens from female patients via this TMA product found a 98.7% true-positive result when confirmed with repeat testing or alternative-target TMA, and only a 0.5% false-negative rate.38 There is evidence that this TMA product can be used to identify M. genitalium in urine, stool, and pharyngeal samples.39 These assays are currently available in some reference labs and large medical centers but are not widely available. Table 1 summarizes the diagnostic methods for M. genitalium.

N. gonorrhoeae

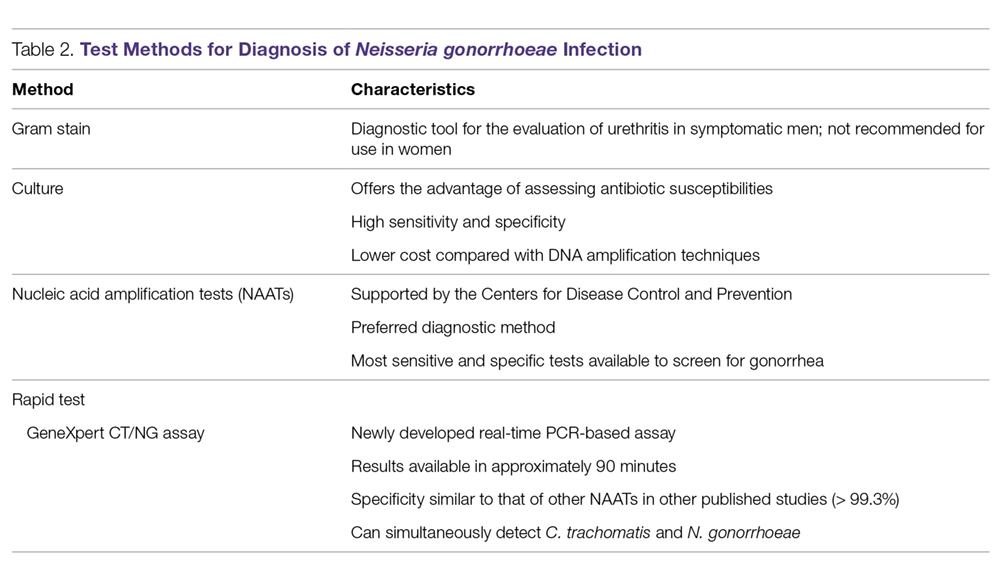

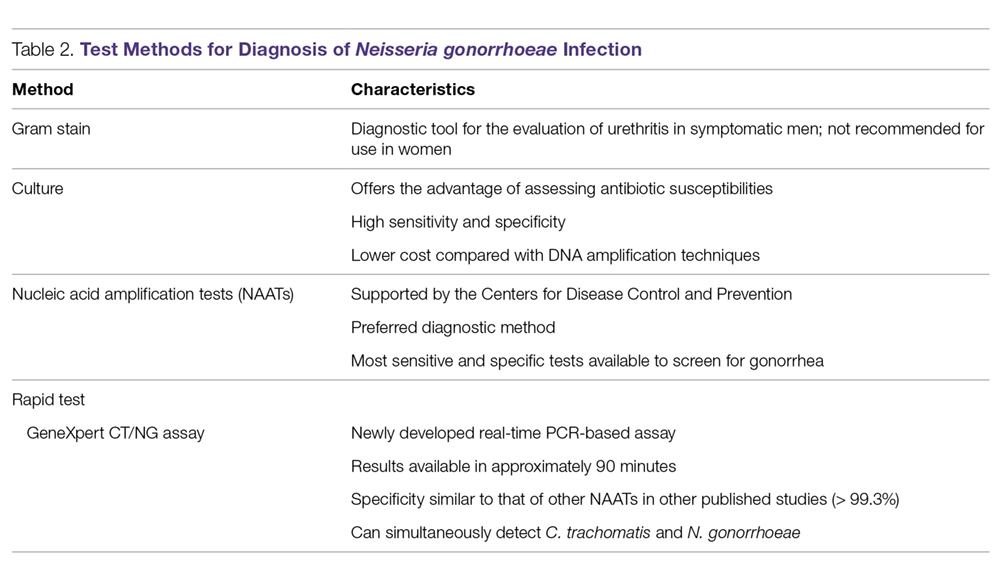

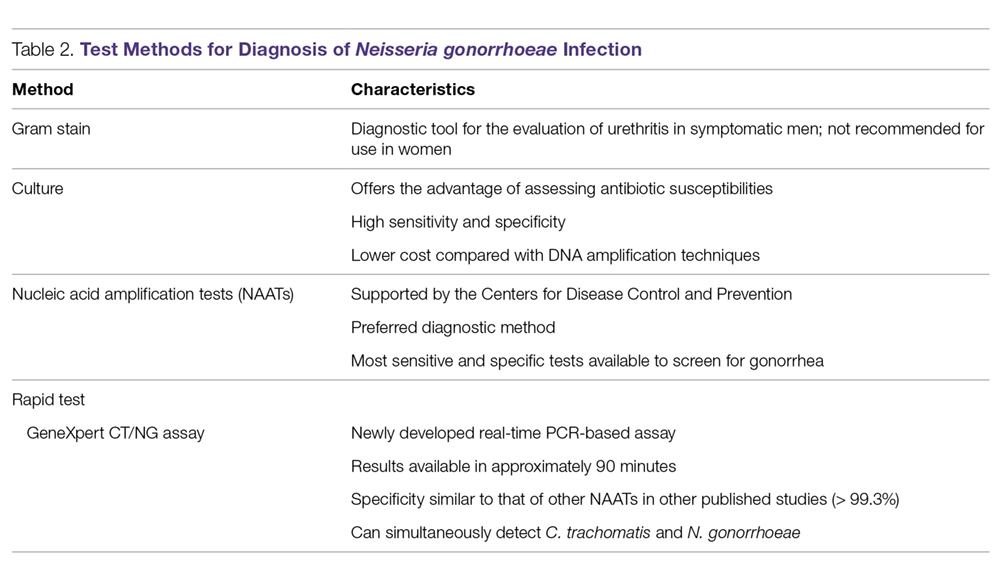

Gonococcal infection can involve the urogenital tract, but can also be extra-urogenital. The method of diagnoses of urogenital infections has expanded from Gram stain of urethral or cervical discharge and the use of selective media culture (usually Thayer-Martin media)40 to molecular methods such as NAATs, which have a higher sensitivity than cultures.41,42

Gram Stain. A Gram stain that shows polymorphonuclear leukocytes with intracellular gram-negative diplococci can be considered diagnostic for N. gonorrhoeae urethritis infection in symptomatic men when samples are obtained from the urethra.43 A retrospective study of 1148 women with gonorrhea revealed that of 1049 cases of cervical gonorrhea, only 6.4% were positive by smear alone; and of 841 cases of urethral gonorrhea, only 5.1% were positive by smear alone; therefore, other diagnostic methods are generally preferred in women.44 Because Gram stain of vaginal specimens is positive in only 50% to 60% of females, its use in women and in suspected extragenital gonococcal infections is not recommended.43-45 When Gram stain was performed in asymptomatic men, the sensitivity was around 80%.39 Thus, in asymptomatic men with a high pre-test probability of having the infection, the use of other additional testing would increase the rate of detection.43

Culture. Urethral swab specimens from males with symptomatic urethritis and cervical swab samples from females with endocervical infection must be inoculated onto both a selective medium (eg, modified Thayer-Martin medium or Martin Lewis medium) and a nonselective medium (eg, chocolate agar). A selective medium is used because it can suppress the growth of contaminating organisms, and a nonselective medium is used because some strains of N. gonorrhoeae are inhibited by the vancomycin present in the selective medium.40 Specimens collected from sterile sites, such as blood, synovial fluid, and cerebrospinal fluid, should be streaked on nonselective medium such as chocolate agar. The material used for collection is critical; the preferred swabs should have plastic or wire shafts and rayon, Dacron, or calcium alginate tips. Materials such as wooden shafts or cotton tips can be toxic to N. gonorrhoeae.40 The specimen should be inoculated immediately onto the appropriate medium and transported rapidly to the laboratory, where it should be incubated at 35º to 37ºC with 5% CO2 and examined at 24 and 48 hours post collection.40 If the specimens cannot be inoculated immediately onto the appropriate medium, the specimen swab should be delivered to the lab in a special transport system that can keep the N. gonorrhoeae viable for up to 48 hours at room temperature.46

The following specimen collection techniques are recommended by the CDC:40

- In males, the cotton swab should be inserted about 2 to 3 cm into the urethral meatus and rotated 360° degrees 2 or 3 times.

- In females, collection of cervical specimens requires inserting the tip of the swab 1 to 2 centimeters into the cervical os and rotating 360° 2 or 3 times.

- Samples obtained outside of the urogenital tract: rectal specimens may be obtained by inserting the swab 3 to 4 cm into the rectal vault. Pharyngeal specimens are to be obtained from the posterior pharynx with a swab.

Culture tests allow the clinician to assess antimicrobial susceptibility and are relatively low cost when compared with nucleic acid detection tests. The sensitivity of culture ranges from 72% to 95% for symptomatic patients, but drops to 65% to 85% for asymptomatic patients.45-47 This low sensitivity is a major disadvantage of culture tests when compared to NAATs. Other disadvantages are the need for the specimens to be transported under conditions adequate to maintain the viability of organisms and the fact that 24 to 72 hours is required to report presumptive culture results.42 Antimicrobial sensitivity testing generally is not recommended; however, it is advisable to perform antimicrobial sensitivity in cases of treatment failure or disseminated gonococcal infection.12

Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests. NAATs use techniques that allow the amplification and detection of N. gonorrhoeae DNA or RNA sequences through various methods, which include assays such as PCR (eg, Amplicor; Roche, Nutley, NJ), TMA (eg, APTIMA; Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA), and strand-displacement amplification (SDA; Probe-Tec; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lake, NJ). While PCR and SDA methods amplify bacterial DNA, TMA amplifies bacterial rRNA.41

The FDA has cleared NAATs to test endocervical, vaginal, and urethral (men) swab specimens and urine for both men and women. There are several NAATs available to test rectal, oropharyngeal, and conjunctival specimens; however, none of them are FDA-cleared. Some local and commercial laboratories have validated the reliability of these extra-urogenital NAATs.12,48 Compared to cultures, NAATs have the advantages of being more sensitive and requiring less strict collection and transport conditions. However, they are costlier than cultures, do not provide any antimicrobial susceptibility information, and have varying specificity.49,50

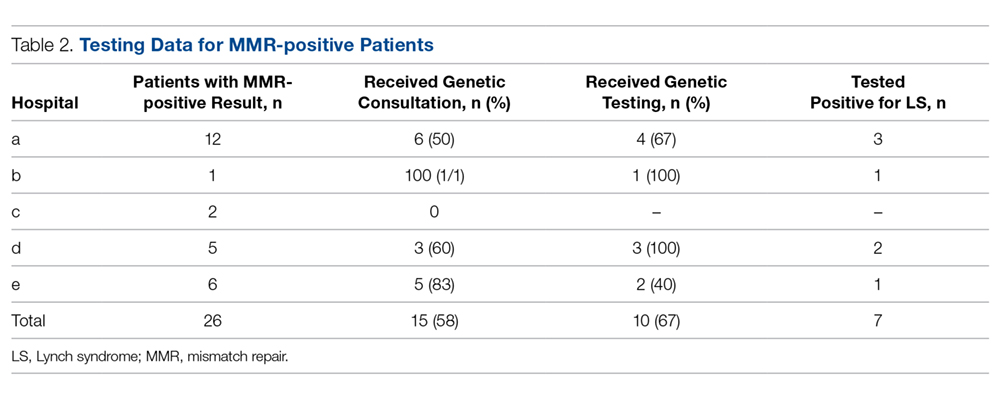

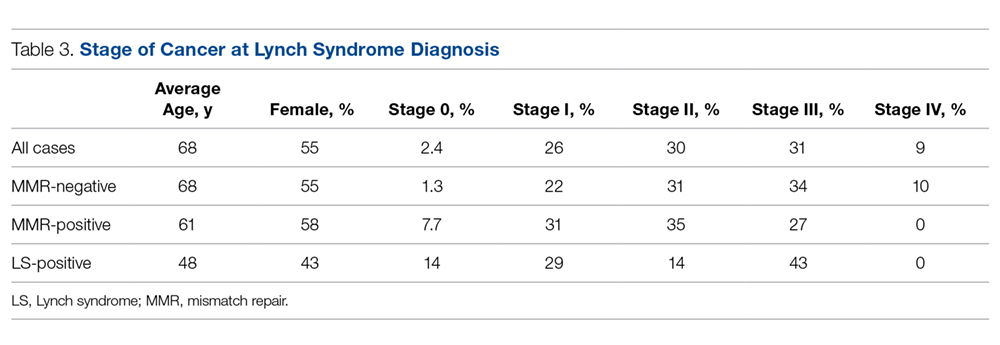

Rapid Tests. NAAT results are usually available in approximately 1 to 2 days, so there has been significant interest in creating technologies that would allow for a more rapid turnaround time. The GeneXpert CT/NG is a newly developed real-time PCR-based assay that can simultaneously detect C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae. The advantage of this technique is the 90-minute turnaround time and its ability to process more than 90 samples at a time. The specificity of this test for N. gonorrhoeae is similar to that of other NAATs (> 99.3%), suggesting that cross-reactivity is not a significant problem.51 Table 2 summarizes the test methods used for diagnosing N. gonorrhoeae.

Treatment

M. genitalium

M. genitalium, Mycoplasma hominis, and the ureaplasmas (U. urealyticum and U. parvum) are generally transmitted sexually, and the natural habitat of this Mycoplasmataceae family of bacteria is the genitourinary tract. All the mycoplasmas can cause NGU, cervicitis, and PID. Presently, multiple-drug resistant M. hominis and ureaplasmas remain uncommon, but the prevalence of M. genitalium resistant to multiple antibiotics has increased significantly in recent years.23,52

In the 1990s, M. genitalium was highly sensitive to the tetracyclines in vitro,53 and doxycycline was the drug of choice for treating NGU. However, it later became apparent that doxycycline was largely ineffective in treating urethritis caused by M. genitalium.54,55

Subsequently, azithromycin, a macrolide, became popular in treating urethritis in males and cervicitis in females because it was highly active against C. trachomatis54 and M. genitalium56 and it can be given orally as a single 1-g dose, thus increasing patients’ compliance. However, azithromycin-resistant M. genitalium has rapidly emerged and rates of treatment failure with azithromycin as high as 40% have been reported in recent studies.57,58 The resistance was found to be mediated by mutations in the 23S rRNA gene upon exposure of M. genitalium to azithromycin.15,57-59 Multiple studies conducted in various countries (including the United States, Netherlands, England, and France) all found high rates of 23S rRNA gene mutations.15,57-59M. genitalium samples were analyzed using reverse transcription-PCR and Sanger sequencing of the 23S tRNA to assess rates of macrolide resistance markers. The study found that 50.8% of female participants and 42% of male participants harbored mutations indicating macrolide resistance.15

An in vitro study conducted in France showed that the respiratory fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin was highly active against mycoplasmas, including M. genitalium.60 This study and others led to the use of moxifloxacin in treating infections caused by azithromycin-resistant M. genitalium. Moxifloxacin initially was successful in treating previous treatment failure cases.61 Unfortunately, the success has been short-lived, as researchers from Japan and Australia have reported moxifloxacin treament failures.62-64 These treatment failures were related to mutations in the parC and gyrA genes.62

Because M. genitalium exhibits significantly increased resistance to the tetracyclines, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones, leading to treatment failures associated with the resistance, the recently published CDC sexually transmitted diseases guidelines (2015) do not specifically recommend or endorse one class of antibiotics over another to treat M. genitalium infections; this contrasts with their approach for other infections in which they make specific recommendations for treatment.12 The lack of clear recommendations from the CDC makes standardized treatment for this pathogen difficult. The CDC guidelines do identify M. genitalium as an emerging issue, and mention that a single 1-g dose of azithromycin should likely be recommended over doxycycline due to the low cure rate of 31% seen with doxycycline. Moxifloxacin is mentioned as a possible alternative, but it is noted that the medication has not been evaluated in clinical trials and several studies have shown failures.12

Although the existing antibiotics to treat M. genitalium infections are far from desirable, treatment approaches have been recommended:65

- Azithromycin or doxycycline should be considered for empiric treatment without documented M. genitalium infection.

- Azithromycin is suggested as the first choice in documented M. genitalium infections.

- In patients with urethritis, azithromycin is recommended over doxycycline based on multiple studies. A single 1-g dose of azithromycin is preferred to an extended regimen due to increased compliance despite the extended regimen being slightly superior in effectiveness. The single-dose regimen is associated with selection of macrolide-resistant strains.65

- Women with cervicitis and PID with documented M. genitalium infection should receive an azithromycin-containing regimen.

Although the existing antibiotics on the market could not keep up with the rapid mutations of M. genitalium, a few recent studies have provided a glimmer of hope to tackle this wily microorganism. Two recent studies from Japan demonstrated that sitafloxacin, a novel fluoroquinolone, administered 100 mg twice a day to patients with M. genitalium was superior to other older fluoroquinolones.66,67 This fluoroquinolone could turn out to be a promising first-line antibiotic for treatment of STIs caused by M. genitalium. Bissessor and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study of M. genitalium-infected male and female patients attending a STI clinic in Melbourne, Australia, and found that oral pristinamycin is highly effective in treating the M. genitalium strains that are resistant to azithromycin and moxifloxacin.68 Jensen et al reported on the novel fluoroketolide solithromycin, which demonstrated superior in vitro activity against M. genitalium compared with doxycycline, fluoroquinolones, and other macrolides.69 Solithromycin could potentially become a new antibiotic to treat infection caused by multi-drug resistant M. genitalium.

N. gonorrhoeae

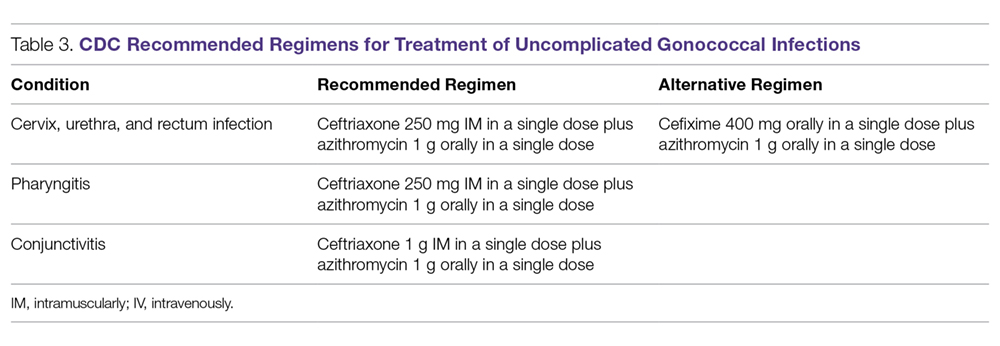

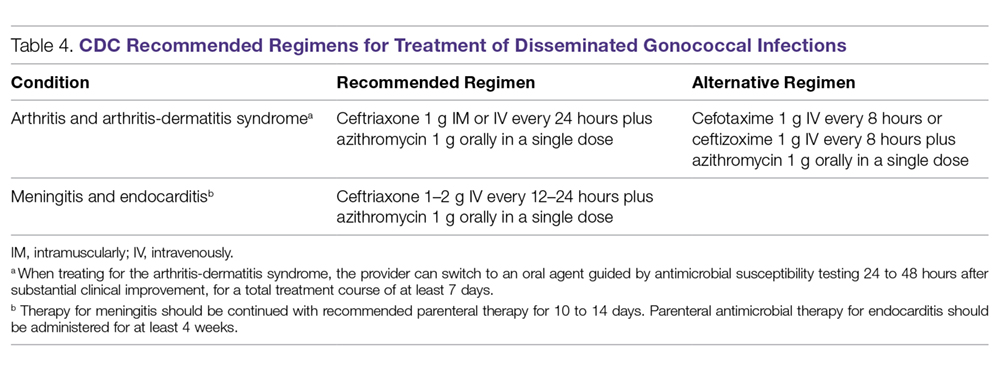

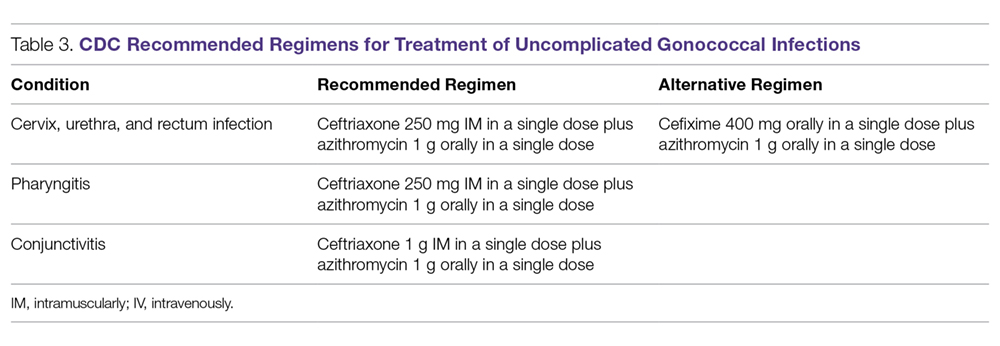

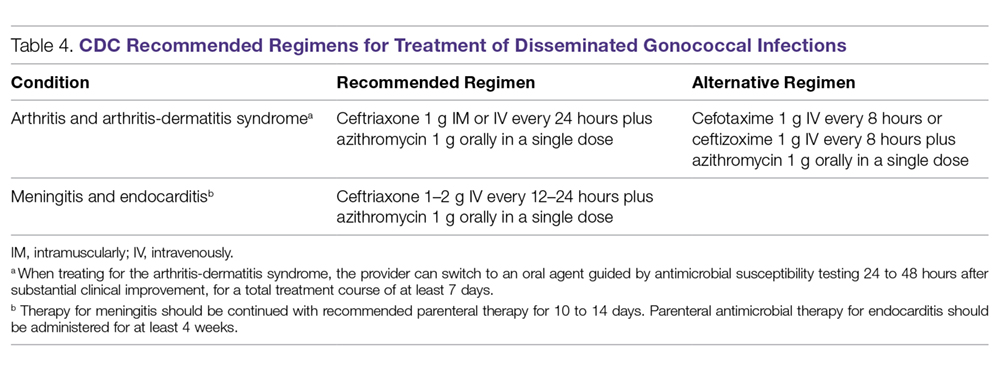

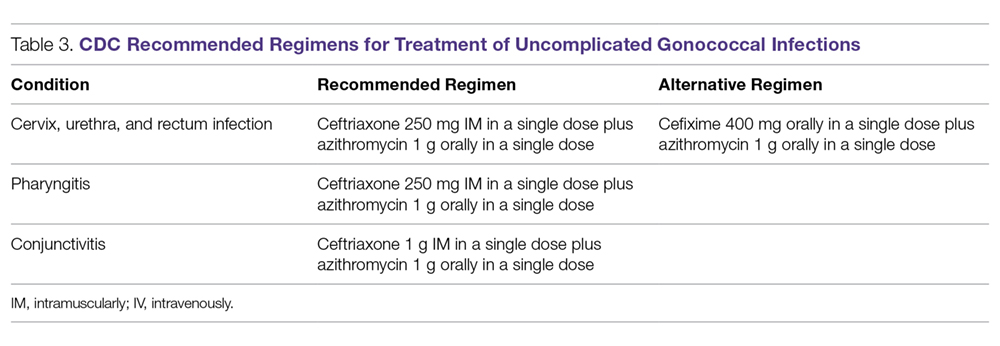

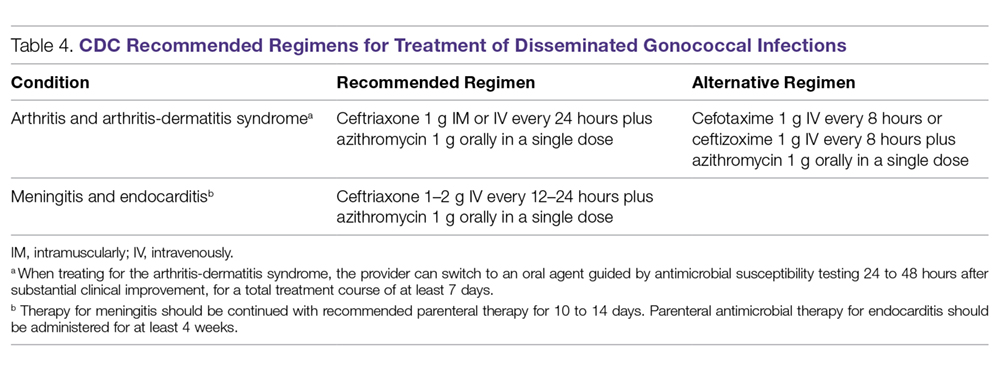

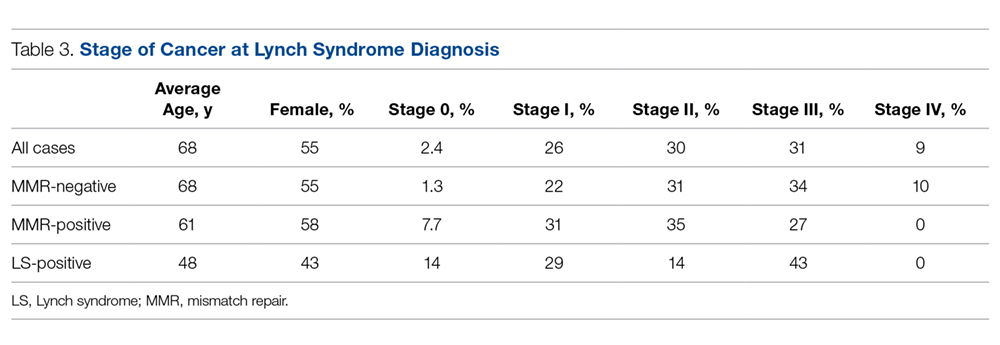

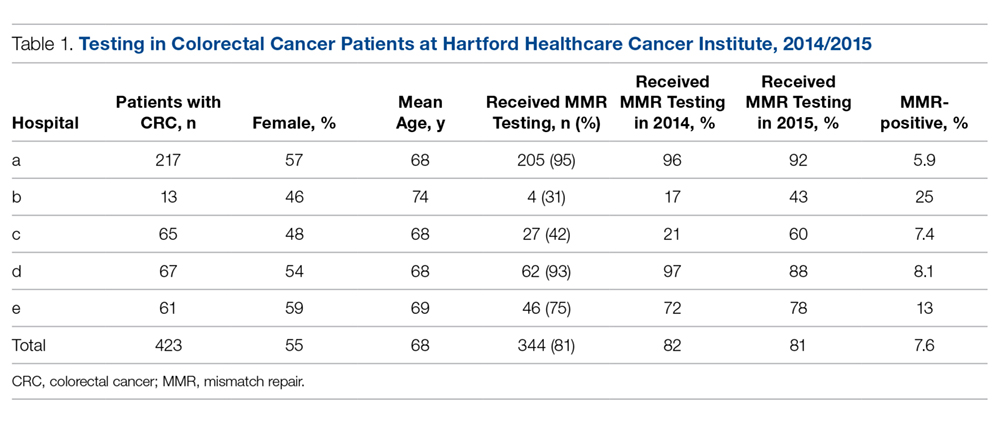

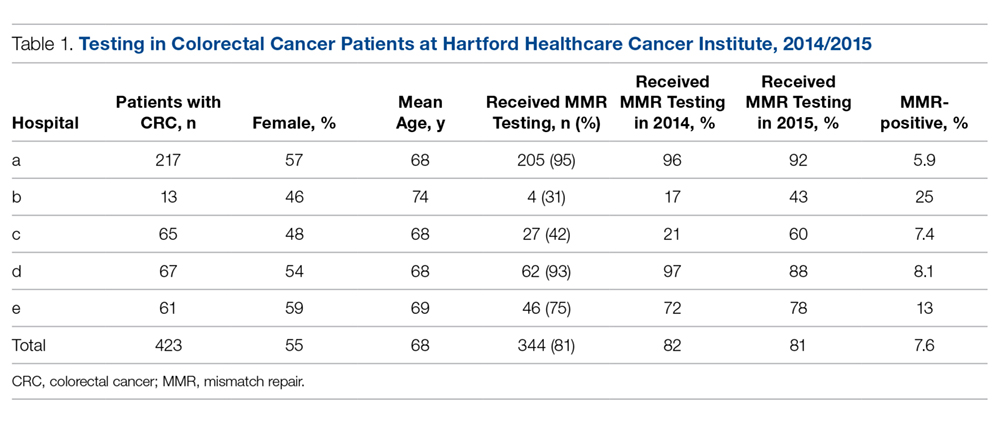

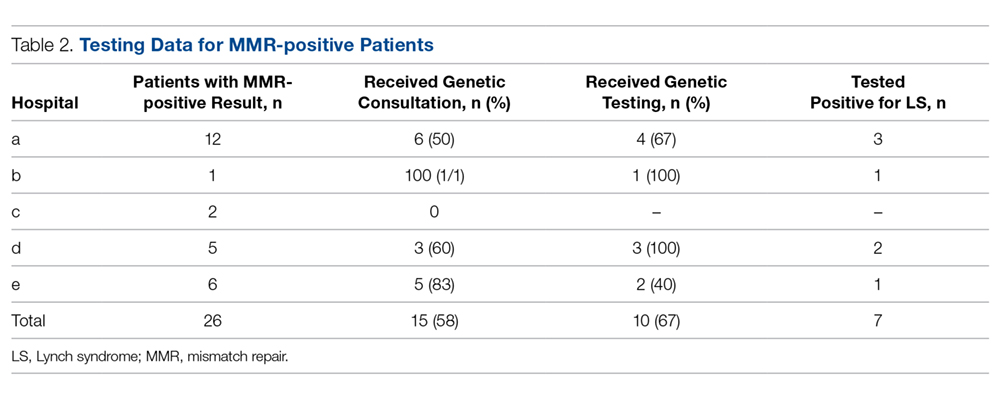

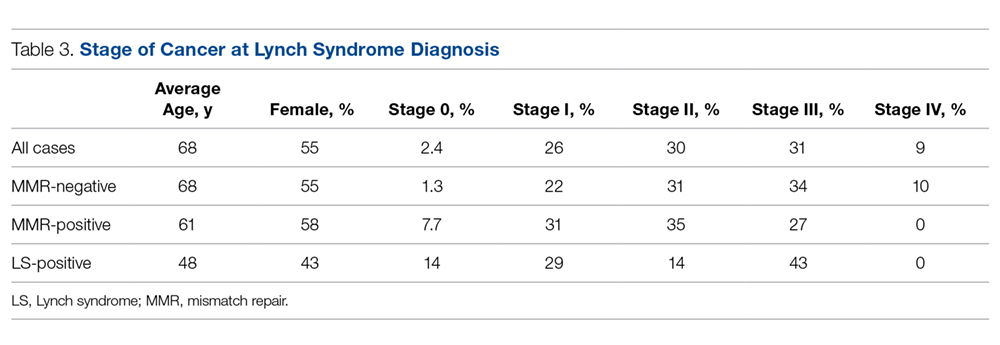

Because of increasing resistance of N. gonorrhoeae to fluoroquinolones in the United States, the CDC recommended against their routine use for all cases of gonorrhea in August 2007.70 In some countries, penicillin-, tetracycline-, and ciprofloxacin-resistance rates could be as high as 100%, and these antibacterial agents are no longer treatment options for gonorrhea. The WHO released new N. gonorrhoeae treatment guidelines in 2016 due to high-level of resistance to previously recommended fluoroquinolones and decreased susceptibility to the third-generation cephalosporins, which were a first-line recommendation in the 2003 guidelines.45 The CDC’s currently recommended regimens for the treatment of uncomplicated and disseminated gonorrheal infections are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.12 Recommendations from the WHO guidelines are very similar to the CDC recommendations.45

In light of the increasing resistance of N. gonorrhoeae to cephalosporins, 1 g of oral azithromycin should be added to ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly in treating all cases of gonorrhea. The rationale for adding azithromycin to ceftriaxone is that azithromycin is active against N. gonorrhoeae at a different molecular target at a high dose, and it can also cover other co-pathogens.71 Unfortunately, susceptibility to cephalosporins has been decreasing rapidly.72 The greatest concern is the potential worldwide spread of the strain isolated in Kyoto, Japan, in 2009 from a patient with pharyngeal gonorrhea that was highly resistant to ceftriaxone (minimum inhibitory concentration of 2.0 to 4.0 µg/mL).73 At this time, N. gonorrhoeae isolates that are highly resistant to ceftriaxone are still rare globally.

Although cefixime is listed as an alternative treatment if ceftriaxone is not available, the 2015 CDC gonorrhea treatment guidelines note that N. gonorrhoeae is becoming more resistant to this oral third-generation cephalosporin; this increasing resistance is due in part to the genetic exchange between N. gonorrhoeae and other oral commensals actively taking place in the oral cavity, creating more resistant species. Another possible reason for cefixime resistance is that the concentration of cefixime used in treating gonococcal pharyngeal infection is subtherapeutic.74 A recent randomized multicenter trial in the United States compared 2 non-cephalosporin regimens: a single 240-mg dose of intramuscular gentamicin plus a single 2-g dose of oral azithromycin, and a single 320-mg dose of oral gemifloxacin plus a single 2-g dose of oral azithromycin. These combinations achieved 100% and 99.5% microbiological cure rates, respectively, in 401 patients with urogenital gonorrhea.75 Thus, these combination regimens can be considered as alternatives when the N. gonorrhoeae is resistant to cephalosporins or the patient is intolerant or allergic to cephalosporins.

Because N. gonorrhoeae has evolved into a “superbug,” becoming resistant to all currently available antimicrobial agents, it is important to focus on developing new agents with unique mechanisms of action to treat N. gonorrhoeae–related infections. Zoliflodacin (ETX0914), a novel topoisomerase II inhibitor, has the potential to become an effective agent to treat multi-drug resistant N. gonorrhoeae. A recent phase 2 trial demonstrated that a single oral 2000-mg dose of zoliflodacin microbiologically cleared 98% of gonorrhea patients, and some of the trial participants were infected with ciprofloxacin- or azithromycin-resistant strains.76 An additional phase 2 clinical trial compared oral zoliflodacin and intramuscular ceftriaxone. For uncomplicated urogential infections, 96% of patients in the zoliflodacin group achieved microbiologic cure versus 100% in the ceftriaxone group; however, zoliflodacin was less efficacious for pharyngeal infections.77 Gepotidacin (GSK2140944) is another new antimicrobial agent in the pipeline that looks promising. It is a novel first-in-class triazaacenaphthylene that inhibits bacterial DNA replication. A recent phase 2 clinical trial demonstrated that 1.5-g and 3-g single oral doses eradicated urogenital N. gonorrhoeae with microbiological success rates of 97% and 95%, respectively.78

Test of Cure

Because of the decreasing susceptibility of M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae to recommended treatment regimens, the European Guidelines consider test of cure essential in STIs caused by these 2 organisms to ensure eradication of infection and identify emerging resistance.79 However, test of cure is not routinely recommended by the CDC for these organisms in asymptomatic patients.12

Sexual Risk-Reduction Counseling

Besides aggressive treatment with appropriate antimicrobial agents, it is also essential that patients and their partners receive counseling to reduce the risk of STI. A recently published systematic review demonstrated that high-intensity counseling could decrease STI incidents in adolescents and adults.80

Conclusion

It is clear that these 2 sexually transmitted ”superbugs” are increasingly resistant to antibiotics and pose an increasing threat. Future epidemiological research and drug development studies need to be devoted to these 2 organisms, as well as to the potential development of a vaccine. This is especially important considering that antimicrobials may no longer be recommended when the prevalence of resistance to a particular antimicrobial reaches 5%, as is the case with WHO and other agencies that set the standard of ≥ 95% effectiveness for an antimicrobial to be considered as a recommended treatment.32 With current resistance rates for penicillin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline at close to 100% for N. gonorrhoeae in some countries,30,79 it is important to remain cognizant about current and future treatment options.

Because screening methods for M. genitalium are not available in most countries and there is not an FDA-approved screening method in the United States, M. genitalium poses a significant challenge for clinicians treating urethritis, cervicitis, and PID. Thus, the development of an effective screening method and established screening guidelines for M. genitalium is urgently needed. Better surveillance, prudent use of available antibiotics, and development of novel compounds are necessary to eliminate the impending threat caused by M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae.

This article is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Fargo VA Health Care System. The contents of this manuscript do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Corresponding author: Tze Shien Lo, MD, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 2101 Elm Street N, Fargo, ND 58102.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. World Health Organization. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs110/en/. Fact Sheet #110. Updated August 2016. Accessed December 16, 2017.

2. World Health Organization. Growing antibiotic resistance forces updates to recommended treatment for sexually transmitted infections www.who.int/en/news-room/detail/30-08-2016-growing-antibiotic-resistance-forces-updates-to-recommended-treatment-for-sexually-transmitted-infections. Released August 30, 2016.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance biggest threats. www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest_threats.html. Released February 27, 2018.

4. Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: From chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:498-514.

5. Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: The aetiological agent of urethritis and other sexually transmitted diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:1-11.

6. Jaiyeoba O, Lazenby G, Soper DE. Recommendations and rationale for the treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9:61-70.

7. McGowin CL, Anderson-Smits C. Mycoplasma genitalium: An emerging cause of sexually transmitted disease in women. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001324.

8. Manhart LE, Broad JM, Golden MR. Mycoplasma genitalium: Should we treat and how? Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53 Suppl 3:S129-42.

9. Gaydos C, Maldeis NE, Hardick A, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium as a contributor to the multiple etiologies of cervicitis in women attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(1SE0):598-606.

10. Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Meyn L, et al. O04.6 Mycoplasma genitalium-Is it a pathogen in acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)? Sex Transm Infect. 2013 89:A34 http://sti.bmj.com/content/89/Suppl_1/A34.2. Accessed February 1, 2018.

11. Lis R, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Manhart LE. Mycoplasma genitalium infection and female reproductive tract disease: A meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:418-426.

12. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

13. Davies N. Mycoplasma genitalium: The need for testing and emerging diagnostic options. MLO Med Lab Obs. 2015;47:8,10-11.

14. Getman D, Jiang A, O’Donnell M, Cohen S. Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence, coinfection, and macrolide antibiotic resistance frequency in a multicenter clinical study cohort in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:2278-2283.

15. Tully JG, Taylor-Robinson D, Cole RM, Rose DL. A newly discovered mycoplasma in the human urogenital tract. Lancet. 1981;1(8233):1288-1291.

16. Taylor-Robinson D. The Harrison Lecture. The history and role of Mycoplasma genitalium in sexually transmitted diseases. Genitourin Med. 1995;71:1-8.

17. Horner P, Thomas B, Gilroy CB, Egger M, Taylor-Robinson D. Role of Mycoplasma genitalium and ureaplasma urealyticum in acute and chronic nongonococcal urethritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:995-1003.

18. Horner P, Blee K, O’Mahony C, et al. Clinical Effectiveness Group of the British Association of Sexual Health and HIV. 2015 UK National Guideline on the management of non-gonococcal urethritis. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27:85-96.

19. Das K, De la Garza G, Siwak EB, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium promotes epithelial crossing and peripheral blood mononuclear cell infection by HIV-1. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;23:31-38.

20. McGowin CL, Annan RS, Quayle AJ, et al. Persistent Mycoplasma genitalium infection of human endocervical epithelial cells elicits chronic inflammatory cytokine secretion. Infect Immun. 2012;80:3842-3849.

21. Salado-Rasmussen K, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium testing pattern and macrolide resistance: A Danish nationwide retrospective survey. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:24-30.

22. Taylor-Robinson D, Bebear C. Antibiotic susceptibilities of mycoplasmas and treatment of mycoplasmal infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:622-630.

23. Taylor-Robinson D. Diagnosis and antimicrobial treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium infection: Sobering thoughts. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12:715-722.

24. Ison CA. Biology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and the clinical picture of infection. In: Gross G, Tyring SK, eds. Sexually Transmitted Infections and Sexually Transmitted Diseases.1st ed. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2011:77-90.

25. Criss AK, Seifert HS. A bacterial siren song: Intimate interactions between neisseria and neutrophils. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:178-190.

26. Urban CF, Lourido S, Zychlinsky A. How do microbes evade neutrophil killing? Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1687-1696.

27. World Health Organization, Dept. of Reproductive Health and Research. Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections - 2008. www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/stisestimates/en/. Published 2012. Accessed February 6, 2018.

28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/emerging.htm. Updated June 4, 2015.

29. Skerlev M, Culav-Koscak I. Gonorrhea: New challenges. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:275-281.

30. Kirkcaldy RD, Ballard RC, Dowell D. Gonococcal resistance: Are cephalosporins next? Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13:196-204.

31. Kidd S, Kirkcaldy R, Weinstock H, Bolan G. Tackling multidrug-resistant gonorrhea: How should we prepare for the untreatable? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012;10:831-833.

32. Wang SA, Harvey AB, Conner SM, et al. Antimicrobial resistance for Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United States, 1988 to 2003: The spread of fluoroquinolone resistance. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:81-88.

33. Barbee LA, Kerani RP, Dombrowski JC, et al. A retrospective comparative study of 2-drug oral and intramuscular cephalosporin treatment regimens for pharyngeal gonorrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1539-434.

34. Sathia L, Ellis B, Phillip S, et al. Pharyngeal gonorrhoea - is dual therapy the way forward? Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:647–8.

35. Tanaka M. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains circulating worldwide. Int J Urol. 2012;19:98-99.

36. Hamasuna R, Osada Y, Jensen JS. Isolation of Mycoplasma genitalium from first-void urine specimens by coculture with vero cells. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:847-850.

37. Razin S. Mycoplasma. In: Boricello SP, Murray PR, Funke G, eds. Topley & Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbial Infections. London, UK: Hodder Arnold; 2005:1957-2005.

38. Munson E, Bykowski H, Munson K, et al. Clinical laboratory assessment of Mycoplasma genitalium transcription-medicated ampliflication using primary female urogenital specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:432-437.

39. Munson E, Wenten D, Jhansale S, et al. Expansion of comprehensive screening of male-sexually transmitted infection clinic attendees with Mycoplasma genitalium and Trichomonas vaginalis molecule assessment: a restrospective analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;55:321-325.

40. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae--2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-02):1-19.

41. Boyadzhyan B, Yashina T, Yatabe JH, et al. Comparison of the APTIMA CT and GC assays with the APTIMA combo 2 assay, the Abbott LCx assay, and direct fluorescent-antibody and culture assays for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3089-3093.

42. Graseck AS, Shih SL, Peipert JF. Home versus clinic-based specimen collection for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9:183-194.

43. Sherrard J, Barlow D. Gonorrhoea in men: Clinical and diagnostic aspects. Genitourin Med. 1996;72:422-426.

44. Goh BT, Varia KB, Ayliffe PF, Lim FK Diagnosis of gonorrhea by gram-stained smears and cultures in men and women: role of the urethral smear. Sex Transm Dis. 1985;12:135-139.

45. World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/rtis/gonorrhoea-treatment-guidelines/en/. Published 2016. Accessed December 16, 2017.

46. Arbique JC, Forward KR, LeBlanc J. Evaluation of four commercial transport media for the survival of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;36:163-168.

47. Schink JC, Keith LG. Problems in the culture diagnosis of gonorrhea. J Reprod Med. 1985;30(3 Suppl):244-249.

48. Marrazzo JM, Apicella MA. Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhea). In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015:2446-2462.

49. Barry PM, Klausner JD. The use of cephalosporins for gonorrhea: The impending problem of resistance. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:555-577.

50. Tabrizi SN, Unemo M, Limnios AE, et al. Evaluation of six commercial nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and other Neisseria species. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3610-3615.

51. Goldenberg SD, Finn J, Sedudzi E, et al. Performance of the GeneXpert CT/NG assay compared to that of the Aptima AC2 assay for detection of rectal Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by use of residual Aptima Samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3867-3869.

52. Martin D. Mycoplasma genitalium, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma species. In: Bennet J, Dolin R, Blaser M, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Sauders; 2015:2190-2193.

53. Hannan PC. Comparative susceptibilities of various AIDS-associated and human urogenital tract mycoplasmas and strains of Mycoplasma pneumoniae to 10 classes of antimicrobial agent in vitro. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:1115-1122.

54. Mena LA, Mroczkowski TF, Nsuami M, Martin DH. A randomized comparison of azithromycin and doxycycline for the treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium-positive urethritis in men. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1649-1654.

55. Schwebke JR, Rompalo A, Taylor S, et al. Re-evaluating the treatment of nongonococcal urethritis: Emphasizing emerging pathogens--a randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:163-170.

56. Bjornelius E, Anagrius C, Bojs G, et al. Antibiotic treatment of symptomatic Mycoplasma genitalium infection in Scandinavia: A controlled clinical trial. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:72-76.

57. Nijhuis RH, Severs TT, Van der Vegt DS, et al. High levels of macrolide resistance-associated mutations in Mycoplasma genitalium warrant antibiotic susceptibility-guided treatment. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2515-2518.

58. Pond MJ, Nori AV, Witney AA, et al. High prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in nongonococcal urethritis: The need for routine testing and the inadequacy of current treatment options. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:631-637.

59. Touati A, Peuchant O, Jensen JS, et al. Direct detection of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium isolates from clinical specimens from France by use of real-time PCR and melting curve analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1549-1555.

60. Bebear CM, de Barbeyrac B, Pereyre S, et al. Activity of moxifloxacin against the urogenital Mycoplasmas ureaplasma spp., Mycoplasma hominis and Mycoplasma genitalium and Chlamydia trachomatis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:801-805.

61. Jernberg E, Moghaddam A, Moi H. Azithromycin and moxifloxacin for microbiological cure of Mycoplasma genitalium infection: An open study. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:676-679.

62. Tagg KA, Jeoffreys NJ, Couldwell DL, et al. Fluoroquinolone and macrolide resistance-associated mutations in Mycoplasma genitalium. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2245-2249.

63. Couldwell DL, Tagg KA, Jeoffreys NJ, Gilbert GL. Failure of moxifloxacin treatment in Mycoplasma genitalium infections due to macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:822-828.

64. Shimada Y, Deguchi T, Nakane K, et al. Emergence of clinical strains of Mycoplasma genitalium harbouring alterations in ParC associated with fluoroquinolone resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36:255-258.

65. Mobley V, Seña A. Mycoplasma genitalium infection in men and women. In: UpToDate. www.uptodate.com. Last updated March 8, 2017. Accessed February 13, 2018.

66. Takahashi S, Hamasuna R, Yasuda M, et al. Clinical efficacy of sitafloxacin 100 mg twice daily for 7 days for patients with non-gonococcal urethritis. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19:941-945.

67. Ito S, Yasuda M, Seike K, et al. Clinical and microbiological outcomes in treatment of men with non-gonococcal urethritis with a 100-mg twice-daily dose regimen of sitafloxacin. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18:414-418.

68. Bissessor M, Tabrizi SN, Twin J, et al. Macrolide resistance and azithromycin failure in a Mycoplasma genitalium-infected cohort, and response of azithromycin failures to alternative antibiotic regimens. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;60:1228-1236.

69. Jensen JS, Fernandes P, Unemo M. In vitro activity of the new fluoroketolide solithromycin (CEM-101) against macrolide-resistant and -susceptible Mycoplasma genitalium strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3151-3156.

70. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: Fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:332-336.

71. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/default.htm. Published 2015. Accessed February13, 2016.

72. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cephalosporin susceptibility among Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates--United States, 2000-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:873-877.

73. Ohnishi M, Saika T, Hoshina S, et al. Ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:148-149.

74. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: Oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:590-594.

75. Kirkcaldy RD, Weinstock HS, Moore PC, et al. The efficacy and safety of gentamicin plus azithromycin and gemifloxacin plus azithromycin as treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1083-1091.

76. Seña AC, Taylor SN, Marrazzo J, et al. Microbiological cure rates and antimicrobial susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to ETX0914 (AZD0914) in a phase II treatment trial for urogenital gonorrhea. (Poster 1308) Program and Abstract of ID Week 2016. New Orleans, LA, . October 25-30, 2016.

77. Taylor S, Marrazzo J, Batteiger B, et al. Single-dose zoliflodacin (ETX0914) for treatment of urogential gonorrhea. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1835-1845.

78. Perry C, Dumont E, Raychaudhuri A. O05.3 A phase II, randomised, stdy in adults subjects evaluating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of single doses of gepotidacin (GSK2140944) for treatment of uncomplicated urogenital gonorrhea. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(Suppl 2).

79. Bignell C, Unemo M, European STI Guidelines Editorial Board. 2012 European guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of gonorrhoea in adults. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:85-92.

80. O’Connor EA, Lin JS, Burda BU, et al. Behavioral sexual risk-reduction counseling in primary care to prevent sexually transmitted infections: A systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:874-883.

From the Fargo Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Fargo, ND (Dr. Dietz, Dr. Hammer, Dr. Zegarra, and Dr. Lo), and the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong, China (Dr. Cho).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the management of patients with Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are organisms that cause urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. There is increasing antibiotic resistance to both organisms, which poses significant challenges to clinicians. Additionally, diagnostic tests for M. genitalium are not widely available, and commonly used tests for both organisms do not provide antibiotic sensitivity information. The increasing resistance of both M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae to currently used antimicrobial agents is alarming and warrants cautious monitoring.

- Conclusion: As the yield of new or effective antibiotic therapies has decreased over the past few years, increasing antibiotic resistance will lead to difficult treatment scenarios for sexually transmitted infections caused by these 2 organisms.

Keywords: Mycoplasma genitalium, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, antibiotic resistance, sexually transmitted infections, STIs.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 1 million cases of sexually transmitted Infections (STIs) are acquired every day worldwide,1 and that the majority of STIs have few or no symptoms, making diagnosis difficult. Two organisms of interest are Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In contrast to Chlamydia trachomatis, which is rarely resistant to treatment regimens, M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotic treatment and pose an impending threat. These bacteria can cause urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Whereas antibiotic resistance to M. genitalium is emerging, resistance to N. gonorrhea has been a continual problem for decades. Drug resistance, especially for N. gonorrhoeae, is listed as a major threat to efforts to reduce the impact of STIs worldwide.2 In 2013, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified N. gonorrhoeae drug resistance as an urgent threat.3 As the yield of new or effective antibiotic therapies has decreased over the past few years, increasing antibiotic resistance will lead to challenging treatment scenarios for STIs caused by these 2 organisms.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

M. genitalium

M. genitalium is an emerging pathogen that is an etiologic agent of upper and lower genital tract STIs, such as urethritis, cervicitis, and PID.4-13 In addition, it is thought to be involved in tubal infertility and acquisition of other sexually transmitted pathogens, including HIV.7,8,13 The prevalence of M. genitalium in the general U.S. population in 2016 was reported to be approximately 17.2% for males and 16.1% for females.14 Infections are more common in patients aged 30 years and younger than in older populations.15 Also, patients self-identifying as black were found to have a higher prevalence of M. genitalium.14 This organism was first reported as being isolated from the urethras of 2 men with non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) in London in 1980.15,16 It is a significant cause of acute and chronic NGU in males, and is estimated to account for 6% to 50% of cases of NGU.17,18M. genitalium in females has been associated with cervicitis4,9 and PID.8,10 A meta-analysis by Lis et al showed that M. genitalium infection was associated with an increased risk for preterm birth and spontaneous abortion.11 In addition, M. genitalium infections occur frequently in HIV-positive patients.19,20 M. genitalium increases susceptibility for passage of HIV across the epithelium by reducing epithelial barrier integrity.19

Beta lactams are ineffective against M. genitalium because mycoplasmas lack a cell wall and thus cell wall penicillin-binding proteins.21M. genitalium’s abilty to invade host epithelial cells is another mechanism that can protect the bacteria from antibiotic exposure.20 One of the first reports of antibiotic sensitivity testing for M. genitalium, published in 1997, noted that the organism was not susceptible to nalidixic acid, cephalosporins, penicillins, and rifampicin.22 In general, mycoplasmas are normally susceptible to antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis,23 and initial good sensitivity to doxycycline and erythromycin was noted but this has since decreased. New antibiotics are on the horizon, but they have not been extensively tested in vivo.23

N. gonorrhoeae

Gonorrhea is the second most common STI of bacterial origin following C. trachomatis,24-26 which is rarely resistant to conventional regimens. In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 106 million cases of N. gonorrhoeae infection were acquired annually and that 36.4 million adults were infected with N. gonorrhoeae.27 In the United States, the CDC estimates that gonorrhea cases are under-reported. An estimated 800,000 or more new cases are reported per year.28

The most common clinical presentations are urethritis in men and cervicitis in women.29 While urethritis is most likely to be symptomatic, only 50% of women with acute gonorrhea are symptomatic.29 In addition to lower urogenital tract infection, N. gonorrhoeae can also cause PID, ectopic pregnancy, infertility in women, and epididymitis in men.29,30 Rare complications can develop from the spread of N. gonorrhoeae to other parts of the body including the joints, eyes, cardiovascular system, and skin.29

N. gonorrhoeae can attach to the columnar epithelium and causes host innate immune-driven inflammation with neutrophil influx.29 It can avoid the immune response by varying its outer membrane protein expression. The organism is also able to acquire DNA from other Neisseria species30 and genera, which results in reduced susceptibility to therapies.

The Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), established in 1986, is a collaborative project involving the CDC and STI clinics in 26 cities in the United States along with 5 regional laboratories.31 The GISP monitors susceptibilities in N. gonorrhoeae isolates obtained from roughly 6000 symptomatic men each year.31 Data collected from the GISP allows clinicians to treat infections with the correct antibiotic. Just as they observed patterns of fluoroquinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae, there has been a geographic progression of decreasing susceptibility to cephalosporins in recent years.31

The ease with which N. gonorrhoeae can develop resistance is particularly alarming. Sulfonamide use began in the 1930s, but resistance developed within approximately 10 years.30,32N. gonorrhoeae has acquired resistance to each therapeutic agent used for treatment over the course of its lifetime. One hypothesis is that use of single-dose therapy to rapidly treat the infection has led to treatment failure and allows for selective pressure where organisms with decreased antibiotic susceptibility are more likely to survive.30 However, there is limited evidence to support monotherapy versus combination therapy in treating N. gonorrhoeae.33,34 It is no exaggeration to say gonorrhea is now at risk of becoming an untreatable disease because of the rapid emergence of multidrug resistant N. gonorrhoeae strains worldwide.35

Diagnosis

Whether the urethritis, cervicitis, or PID is caused by N. gonorrhoeae, M. genitalium, or other non-gonococcal microorganisms (eg, C. trachomatis), no symptoms are specific to any of the microorganisms. Therefore, clinicians rely on laboratory tests to diagnose STIs caused by N. gonorrhoeae or M. genitalium.

M. genitalium

Gram Stain. Because M. genitalium lacks a cell wall, it cannot be identified by routine Gram stain.

Culture. Culturing of this fastidious bacterium might offer the advantage of assessing antibiotic susceptibility;36 however, the procedure is labor intensive and time consuming, and only a few labs in the world have the capability to perform this culture.12 Thus, this testing method is primarily undertaken for research purposes.

Serological Testing. Because of serologic cross-reactions between Mycoplasma pneumoniae and M. genitalium, there are no standardized serological tests for M. genitalium.37

Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests. M. genitalium diagnosis currently is made based exclusively on nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) methodology (polymerase chain reaction [PCR] or transcription-mediated amplification [TMA]), which is the only clinically useful method to detect M. genitalium. TMA for M. genitalium is commercially available in an analyte-specific reagent (ASR) format, but this has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).38 A study analyzing urogenital specimens from female patients via this TMA product found a 98.7% true-positive result when confirmed with repeat testing or alternative-target TMA, and only a 0.5% false-negative rate.38 There is evidence that this TMA product can be used to identify M. genitalium in urine, stool, and pharyngeal samples.39 These assays are currently available in some reference labs and large medical centers but are not widely available. Table 1 summarizes the diagnostic methods for M. genitalium.

N. gonorrhoeae

Gonococcal infection can involve the urogenital tract, but can also be extra-urogenital. The method of diagnoses of urogenital infections has expanded from Gram stain of urethral or cervical discharge and the use of selective media culture (usually Thayer-Martin media)40 to molecular methods such as NAATs, which have a higher sensitivity than cultures.41,42

Gram Stain. A Gram stain that shows polymorphonuclear leukocytes with intracellular gram-negative diplococci can be considered diagnostic for N. gonorrhoeae urethritis infection in symptomatic men when samples are obtained from the urethra.43 A retrospective study of 1148 women with gonorrhea revealed that of 1049 cases of cervical gonorrhea, only 6.4% were positive by smear alone; and of 841 cases of urethral gonorrhea, only 5.1% were positive by smear alone; therefore, other diagnostic methods are generally preferred in women.44 Because Gram stain of vaginal specimens is positive in only 50% to 60% of females, its use in women and in suspected extragenital gonococcal infections is not recommended.43-45 When Gram stain was performed in asymptomatic men, the sensitivity was around 80%.39 Thus, in asymptomatic men with a high pre-test probability of having the infection, the use of other additional testing would increase the rate of detection.43

Culture. Urethral swab specimens from males with symptomatic urethritis and cervical swab samples from females with endocervical infection must be inoculated onto both a selective medium (eg, modified Thayer-Martin medium or Martin Lewis medium) and a nonselective medium (eg, chocolate agar). A selective medium is used because it can suppress the growth of contaminating organisms, and a nonselective medium is used because some strains of N. gonorrhoeae are inhibited by the vancomycin present in the selective medium.40 Specimens collected from sterile sites, such as blood, synovial fluid, and cerebrospinal fluid, should be streaked on nonselective medium such as chocolate agar. The material used for collection is critical; the preferred swabs should have plastic or wire shafts and rayon, Dacron, or calcium alginate tips. Materials such as wooden shafts or cotton tips can be toxic to N. gonorrhoeae.40 The specimen should be inoculated immediately onto the appropriate medium and transported rapidly to the laboratory, where it should be incubated at 35º to 37ºC with 5% CO2 and examined at 24 and 48 hours post collection.40 If the specimens cannot be inoculated immediately onto the appropriate medium, the specimen swab should be delivered to the lab in a special transport system that can keep the N. gonorrhoeae viable for up to 48 hours at room temperature.46

The following specimen collection techniques are recommended by the CDC:40

- In males, the cotton swab should be inserted about 2 to 3 cm into the urethral meatus and rotated 360° degrees 2 or 3 times.

- In females, collection of cervical specimens requires inserting the tip of the swab 1 to 2 centimeters into the cervical os and rotating 360° 2 or 3 times.

- Samples obtained outside of the urogenital tract: rectal specimens may be obtained by inserting the swab 3 to 4 cm into the rectal vault. Pharyngeal specimens are to be obtained from the posterior pharynx with a swab.

Culture tests allow the clinician to assess antimicrobial susceptibility and are relatively low cost when compared with nucleic acid detection tests. The sensitivity of culture ranges from 72% to 95% for symptomatic patients, but drops to 65% to 85% for asymptomatic patients.45-47 This low sensitivity is a major disadvantage of culture tests when compared to NAATs. Other disadvantages are the need for the specimens to be transported under conditions adequate to maintain the viability of organisms and the fact that 24 to 72 hours is required to report presumptive culture results.42 Antimicrobial sensitivity testing generally is not recommended; however, it is advisable to perform antimicrobial sensitivity in cases of treatment failure or disseminated gonococcal infection.12

Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests. NAATs use techniques that allow the amplification and detection of N. gonorrhoeae DNA or RNA sequences through various methods, which include assays such as PCR (eg, Amplicor; Roche, Nutley, NJ), TMA (eg, APTIMA; Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA), and strand-displacement amplification (SDA; Probe-Tec; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lake, NJ). While PCR and SDA methods amplify bacterial DNA, TMA amplifies bacterial rRNA.41

The FDA has cleared NAATs to test endocervical, vaginal, and urethral (men) swab specimens and urine for both men and women. There are several NAATs available to test rectal, oropharyngeal, and conjunctival specimens; however, none of them are FDA-cleared. Some local and commercial laboratories have validated the reliability of these extra-urogenital NAATs.12,48 Compared to cultures, NAATs have the advantages of being more sensitive and requiring less strict collection and transport conditions. However, they are costlier than cultures, do not provide any antimicrobial susceptibility information, and have varying specificity.49,50

Rapid Tests. NAAT results are usually available in approximately 1 to 2 days, so there has been significant interest in creating technologies that would allow for a more rapid turnaround time. The GeneXpert CT/NG is a newly developed real-time PCR-based assay that can simultaneously detect C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae. The advantage of this technique is the 90-minute turnaround time and its ability to process more than 90 samples at a time. The specificity of this test for N. gonorrhoeae is similar to that of other NAATs (> 99.3%), suggesting that cross-reactivity is not a significant problem.51 Table 2 summarizes the test methods used for diagnosing N. gonorrhoeae.

Treatment

M. genitalium

M. genitalium, Mycoplasma hominis, and the ureaplasmas (U. urealyticum and U. parvum) are generally transmitted sexually, and the natural habitat of this Mycoplasmataceae family of bacteria is the genitourinary tract. All the mycoplasmas can cause NGU, cervicitis, and PID. Presently, multiple-drug resistant M. hominis and ureaplasmas remain uncommon, but the prevalence of M. genitalium resistant to multiple antibiotics has increased significantly in recent years.23,52

In the 1990s, M. genitalium was highly sensitive to the tetracyclines in vitro,53 and doxycycline was the drug of choice for treating NGU. However, it later became apparent that doxycycline was largely ineffective in treating urethritis caused by M. genitalium.54,55

Subsequently, azithromycin, a macrolide, became popular in treating urethritis in males and cervicitis in females because it was highly active against C. trachomatis54 and M. genitalium56 and it can be given orally as a single 1-g dose, thus increasing patients’ compliance. However, azithromycin-resistant M. genitalium has rapidly emerged and rates of treatment failure with azithromycin as high as 40% have been reported in recent studies.57,58 The resistance was found to be mediated by mutations in the 23S rRNA gene upon exposure of M. genitalium to azithromycin.15,57-59 Multiple studies conducted in various countries (including the United States, Netherlands, England, and France) all found high rates of 23S rRNA gene mutations.15,57-59M. genitalium samples were analyzed using reverse transcription-PCR and Sanger sequencing of the 23S tRNA to assess rates of macrolide resistance markers. The study found that 50.8% of female participants and 42% of male participants harbored mutations indicating macrolide resistance.15

An in vitro study conducted in France showed that the respiratory fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin was highly active against mycoplasmas, including M. genitalium.60 This study and others led to the use of moxifloxacin in treating infections caused by azithromycin-resistant M. genitalium. Moxifloxacin initially was successful in treating previous treatment failure cases.61 Unfortunately, the success has been short-lived, as researchers from Japan and Australia have reported moxifloxacin treament failures.62-64 These treatment failures were related to mutations in the parC and gyrA genes.62

Because M. genitalium exhibits significantly increased resistance to the tetracyclines, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones, leading to treatment failures associated with the resistance, the recently published CDC sexually transmitted diseases guidelines (2015) do not specifically recommend or endorse one class of antibiotics over another to treat M. genitalium infections; this contrasts with their approach for other infections in which they make specific recommendations for treatment.12 The lack of clear recommendations from the CDC makes standardized treatment for this pathogen difficult. The CDC guidelines do identify M. genitalium as an emerging issue, and mention that a single 1-g dose of azithromycin should likely be recommended over doxycycline due to the low cure rate of 31% seen with doxycycline. Moxifloxacin is mentioned as a possible alternative, but it is noted that the medication has not been evaluated in clinical trials and several studies have shown failures.12

Although the existing antibiotics to treat M. genitalium infections are far from desirable, treatment approaches have been recommended:65

- Azithromycin or doxycycline should be considered for empiric treatment without documented M. genitalium infection.

- Azithromycin is suggested as the first choice in documented M. genitalium infections.

- In patients with urethritis, azithromycin is recommended over doxycycline based on multiple studies. A single 1-g dose of azithromycin is preferred to an extended regimen due to increased compliance despite the extended regimen being slightly superior in effectiveness. The single-dose regimen is associated with selection of macrolide-resistant strains.65

- Women with cervicitis and PID with documented M. genitalium infection should receive an azithromycin-containing regimen.

Although the existing antibiotics on the market could not keep up with the rapid mutations of M. genitalium, a few recent studies have provided a glimmer of hope to tackle this wily microorganism. Two recent studies from Japan demonstrated that sitafloxacin, a novel fluoroquinolone, administered 100 mg twice a day to patients with M. genitalium was superior to other older fluoroquinolones.66,67 This fluoroquinolone could turn out to be a promising first-line antibiotic for treatment of STIs caused by M. genitalium. Bissessor and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study of M. genitalium-infected male and female patients attending a STI clinic in Melbourne, Australia, and found that oral pristinamycin is highly effective in treating the M. genitalium strains that are resistant to azithromycin and moxifloxacin.68 Jensen et al reported on the novel fluoroketolide solithromycin, which demonstrated superior in vitro activity against M. genitalium compared with doxycycline, fluoroquinolones, and other macrolides.69 Solithromycin could potentially become a new antibiotic to treat infection caused by multi-drug resistant M. genitalium.

N. gonorrhoeae

Because of increasing resistance of N. gonorrhoeae to fluoroquinolones in the United States, the CDC recommended against their routine use for all cases of gonorrhea in August 2007.70 In some countries, penicillin-, tetracycline-, and ciprofloxacin-resistance rates could be as high as 100%, and these antibacterial agents are no longer treatment options for gonorrhea. The WHO released new N. gonorrhoeae treatment guidelines in 2016 due to high-level of resistance to previously recommended fluoroquinolones and decreased susceptibility to the third-generation cephalosporins, which were a first-line recommendation in the 2003 guidelines.45 The CDC’s currently recommended regimens for the treatment of uncomplicated and disseminated gonorrheal infections are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.12 Recommendations from the WHO guidelines are very similar to the CDC recommendations.45

In light of the increasing resistance of N. gonorrhoeae to cephalosporins, 1 g of oral azithromycin should be added to ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly in treating all cases of gonorrhea. The rationale for adding azithromycin to ceftriaxone is that azithromycin is active against N. gonorrhoeae at a different molecular target at a high dose, and it can also cover other co-pathogens.71 Unfortunately, susceptibility to cephalosporins has been decreasing rapidly.72 The greatest concern is the potential worldwide spread of the strain isolated in Kyoto, Japan, in 2009 from a patient with pharyngeal gonorrhea that was highly resistant to ceftriaxone (minimum inhibitory concentration of 2.0 to 4.0 µg/mL).73 At this time, N. gonorrhoeae isolates that are highly resistant to ceftriaxone are still rare globally.

Although cefixime is listed as an alternative treatment if ceftriaxone is not available, the 2015 CDC gonorrhea treatment guidelines note that N. gonorrhoeae is becoming more resistant to this oral third-generation cephalosporin; this increasing resistance is due in part to the genetic exchange between N. gonorrhoeae and other oral commensals actively taking place in the oral cavity, creating more resistant species. Another possible reason for cefixime resistance is that the concentration of cefixime used in treating gonococcal pharyngeal infection is subtherapeutic.74 A recent randomized multicenter trial in the United States compared 2 non-cephalosporin regimens: a single 240-mg dose of intramuscular gentamicin plus a single 2-g dose of oral azithromycin, and a single 320-mg dose of oral gemifloxacin plus a single 2-g dose of oral azithromycin. These combinations achieved 100% and 99.5% microbiological cure rates, respectively, in 401 patients with urogenital gonorrhea.75 Thus, these combination regimens can be considered as alternatives when the N. gonorrhoeae is resistant to cephalosporins or the patient is intolerant or allergic to cephalosporins.

Because N. gonorrhoeae has evolved into a “superbug,” becoming resistant to all currently available antimicrobial agents, it is important to focus on developing new agents with unique mechanisms of action to treat N. gonorrhoeae–related infections. Zoliflodacin (ETX0914), a novel topoisomerase II inhibitor, has the potential to become an effective agent to treat multi-drug resistant N. gonorrhoeae. A recent phase 2 trial demonstrated that a single oral 2000-mg dose of zoliflodacin microbiologically cleared 98% of gonorrhea patients, and some of the trial participants were infected with ciprofloxacin- or azithromycin-resistant strains.76 An additional phase 2 clinical trial compared oral zoliflodacin and intramuscular ceftriaxone. For uncomplicated urogential infections, 96% of patients in the zoliflodacin group achieved microbiologic cure versus 100% in the ceftriaxone group; however, zoliflodacin was less efficacious for pharyngeal infections.77 Gepotidacin (GSK2140944) is another new antimicrobial agent in the pipeline that looks promising. It is a novel first-in-class triazaacenaphthylene that inhibits bacterial DNA replication. A recent phase 2 clinical trial demonstrated that 1.5-g and 3-g single oral doses eradicated urogenital N. gonorrhoeae with microbiological success rates of 97% and 95%, respectively.78

Test of Cure

Because of the decreasing susceptibility of M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae to recommended treatment regimens, the European Guidelines consider test of cure essential in STIs caused by these 2 organisms to ensure eradication of infection and identify emerging resistance.79 However, test of cure is not routinely recommended by the CDC for these organisms in asymptomatic patients.12

Sexual Risk-Reduction Counseling

Besides aggressive treatment with appropriate antimicrobial agents, it is also essential that patients and their partners receive counseling to reduce the risk of STI. A recently published systematic review demonstrated that high-intensity counseling could decrease STI incidents in adolescents and adults.80

Conclusion

It is clear that these 2 sexually transmitted ”superbugs” are increasingly resistant to antibiotics and pose an increasing threat. Future epidemiological research and drug development studies need to be devoted to these 2 organisms, as well as to the potential development of a vaccine. This is especially important considering that antimicrobials may no longer be recommended when the prevalence of resistance to a particular antimicrobial reaches 5%, as is the case with WHO and other agencies that set the standard of ≥ 95% effectiveness for an antimicrobial to be considered as a recommended treatment.32 With current resistance rates for penicillin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline at close to 100% for N. gonorrhoeae in some countries,30,79 it is important to remain cognizant about current and future treatment options.

Because screening methods for M. genitalium are not available in most countries and there is not an FDA-approved screening method in the United States, M. genitalium poses a significant challenge for clinicians treating urethritis, cervicitis, and PID. Thus, the development of an effective screening method and established screening guidelines for M. genitalium is urgently needed. Better surveillance, prudent use of available antibiotics, and development of novel compounds are necessary to eliminate the impending threat caused by M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae.

This article is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Fargo VA Health Care System. The contents of this manuscript do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Corresponding author: Tze Shien Lo, MD, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 2101 Elm Street N, Fargo, ND 58102.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Fargo Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Fargo, ND (Dr. Dietz, Dr. Hammer, Dr. Zegarra, and Dr. Lo), and the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong, China (Dr. Cho).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the management of patients with Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are organisms that cause urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. There is increasing antibiotic resistance to both organisms, which poses significant challenges to clinicians. Additionally, diagnostic tests for M. genitalium are not widely available, and commonly used tests for both organisms do not provide antibiotic sensitivity information. The increasing resistance of both M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae to currently used antimicrobial agents is alarming and warrants cautious monitoring.

- Conclusion: As the yield of new or effective antibiotic therapies has decreased over the past few years, increasing antibiotic resistance will lead to difficult treatment scenarios for sexually transmitted infections caused by these 2 organisms.

Keywords: Mycoplasma genitalium, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, antibiotic resistance, sexually transmitted infections, STIs.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 1 million cases of sexually transmitted Infections (STIs) are acquired every day worldwide,1 and that the majority of STIs have few or no symptoms, making diagnosis difficult. Two organisms of interest are Mycoplasma genitalium and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In contrast to Chlamydia trachomatis, which is rarely resistant to treatment regimens, M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae are becoming increasingly resistant to antibiotic treatment and pose an impending threat. These bacteria can cause urethritis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Whereas antibiotic resistance to M. genitalium is emerging, resistance to N. gonorrhea has been a continual problem for decades. Drug resistance, especially for N. gonorrhoeae, is listed as a major threat to efforts to reduce the impact of STIs worldwide.2 In 2013, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified N. gonorrhoeae drug resistance as an urgent threat.3 As the yield of new or effective antibiotic therapies has decreased over the past few years, increasing antibiotic resistance will lead to challenging treatment scenarios for STIs caused by these 2 organisms.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

M. genitalium

M. genitalium is an emerging pathogen that is an etiologic agent of upper and lower genital tract STIs, such as urethritis, cervicitis, and PID.4-13 In addition, it is thought to be involved in tubal infertility and acquisition of other sexually transmitted pathogens, including HIV.7,8,13 The prevalence of M. genitalium in the general U.S. population in 2016 was reported to be approximately 17.2% for males and 16.1% for females.14 Infections are more common in patients aged 30 years and younger than in older populations.15 Also, patients self-identifying as black were found to have a higher prevalence of M. genitalium.14 This organism was first reported as being isolated from the urethras of 2 men with non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) in London in 1980.15,16 It is a significant cause of acute and chronic NGU in males, and is estimated to account for 6% to 50% of cases of NGU.17,18M. genitalium in females has been associated with cervicitis4,9 and PID.8,10 A meta-analysis by Lis et al showed that M. genitalium infection was associated with an increased risk for preterm birth and spontaneous abortion.11 In addition, M. genitalium infections occur frequently in HIV-positive patients.19,20 M. genitalium increases susceptibility for passage of HIV across the epithelium by reducing epithelial barrier integrity.19

Beta lactams are ineffective against M. genitalium because mycoplasmas lack a cell wall and thus cell wall penicillin-binding proteins.21M. genitalium’s abilty to invade host epithelial cells is another mechanism that can protect the bacteria from antibiotic exposure.20 One of the first reports of antibiotic sensitivity testing for M. genitalium, published in 1997, noted that the organism was not susceptible to nalidixic acid, cephalosporins, penicillins, and rifampicin.22 In general, mycoplasmas are normally susceptible to antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis,23 and initial good sensitivity to doxycycline and erythromycin was noted but this has since decreased. New antibiotics are on the horizon, but they have not been extensively tested in vivo.23

N. gonorrhoeae

Gonorrhea is the second most common STI of bacterial origin following C. trachomatis,24-26 which is rarely resistant to conventional regimens. In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 106 million cases of N. gonorrhoeae infection were acquired annually and that 36.4 million adults were infected with N. gonorrhoeae.27 In the United States, the CDC estimates that gonorrhea cases are under-reported. An estimated 800,000 or more new cases are reported per year.28

The most common clinical presentations are urethritis in men and cervicitis in women.29 While urethritis is most likely to be symptomatic, only 50% of women with acute gonorrhea are symptomatic.29 In addition to lower urogenital tract infection, N. gonorrhoeae can also cause PID, ectopic pregnancy, infertility in women, and epididymitis in men.29,30 Rare complications can develop from the spread of N. gonorrhoeae to other parts of the body including the joints, eyes, cardiovascular system, and skin.29

N. gonorrhoeae can attach to the columnar epithelium and causes host innate immune-driven inflammation with neutrophil influx.29 It can avoid the immune response by varying its outer membrane protein expression. The organism is also able to acquire DNA from other Neisseria species30 and genera, which results in reduced susceptibility to therapies.

The Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP), established in 1986, is a collaborative project involving the CDC and STI clinics in 26 cities in the United States along with 5 regional laboratories.31 The GISP monitors susceptibilities in N. gonorrhoeae isolates obtained from roughly 6000 symptomatic men each year.31 Data collected from the GISP allows clinicians to treat infections with the correct antibiotic. Just as they observed patterns of fluoroquinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae, there has been a geographic progression of decreasing susceptibility to cephalosporins in recent years.31

The ease with which N. gonorrhoeae can develop resistance is particularly alarming. Sulfonamide use began in the 1930s, but resistance developed within approximately 10 years.30,32N. gonorrhoeae has acquired resistance to each therapeutic agent used for treatment over the course of its lifetime. One hypothesis is that use of single-dose therapy to rapidly treat the infection has led to treatment failure and allows for selective pressure where organisms with decreased antibiotic susceptibility are more likely to survive.30 However, there is limited evidence to support monotherapy versus combination therapy in treating N. gonorrhoeae.33,34 It is no exaggeration to say gonorrhea is now at risk of becoming an untreatable disease because of the rapid emergence of multidrug resistant N. gonorrhoeae strains worldwide.35

Diagnosis

Whether the urethritis, cervicitis, or PID is caused by N. gonorrhoeae, M. genitalium, or other non-gonococcal microorganisms (eg, C. trachomatis), no symptoms are specific to any of the microorganisms. Therefore, clinicians rely on laboratory tests to diagnose STIs caused by N. gonorrhoeae or M. genitalium.

M. genitalium

Gram Stain. Because M. genitalium lacks a cell wall, it cannot be identified by routine Gram stain.

Culture. Culturing of this fastidious bacterium might offer the advantage of assessing antibiotic susceptibility;36 however, the procedure is labor intensive and time consuming, and only a few labs in the world have the capability to perform this culture.12 Thus, this testing method is primarily undertaken for research purposes.

Serological Testing. Because of serologic cross-reactions between Mycoplasma pneumoniae and M. genitalium, there are no standardized serological tests for M. genitalium.37