User login

Low sexual desire: Appropriate use of testosterone in menopausal women

CASE Midlife woman with low libido causing distress

At her annual gynecologic visit, a 55-year-old woman notes that she has almost no interest in sex. In the past, her libido was good and relations were pleasurable. Since her mid-40s, she has noticed a gradual decline in libido and orgasmic response. Sexual frequency has declined from once or twice weekly to just a few times per month. She has been married for 25 years and describes the relationship as caring and strong. Her husband is healthy with a good libido; his intermittent erectile dysfunction is treated with a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor. The patient’s low libido is distressing, as the decline in sexual frequency is causing some conflict for the couple. She requests that her testosterone level be checked because she heard that treatment with testosterone cream will solve this problem.

Evaluating and treating low libido in menopausal women

Low libido is a very common sexual problem for women. When sexual problems are accompanied by distress, they are classified as sexual dysfunctions. Although ObGyns should discuss sexual concerns at every comprehensive visit, if the patient has no associated distress, treatment is not necessarily indicated. A woman with low libido or anorgasmia who is satisfied with her sex life and is not bothered by these issues does not require any intervention.

Currently, the only indication for testosterone therapy that is supported by clinical trial evidence is low sexual desire with associated distress, known as hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). Although other sexual problems also commonly occur in menopausal women, such as disorders of orgasm and pain, testosterone is not recommended for these problems. In addition, testosterone is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction.

Routinely inquire about sexual functioning

Ask your patients about sexual concerns at every comprehensive visit. You can easily incorporate into the review of systems a general question, such as, “Do you have any sexual concerns?” If the patient does mention a sexual problem, schedule a separate visit (given appointment time constraints) to address it. History and physical examination information you gather during the comprehensive visit will be helpful in the subsequent problem-focused visit.

Taking a thorough history is key when addressing a patient’s sexual problems, since identifying possible etiologies guides treatment. Often, the cause of female sexual dysfunction is multifactorial and includes physiologic, psychologic, and relationship issues.

- Evidence supports low-dose transdermal testosterone in carefully selected menopausal women with HSDD and no other identifiable reason for the sexual dysfunction

- Inform women considering testosterone for HSDD of the limited effectiveness and high placebo responses seen in clinical trials

- Women also must be informed that treatment is off-label (no testosterone formulations are FDA approved for women)

- Review with patients the limitations of compounded medications, and discuss possible adverse effects of androgens. Long-term safety is unknown and, as androgens are converted to estrogens

Explore potential causes, recommend standard therapies

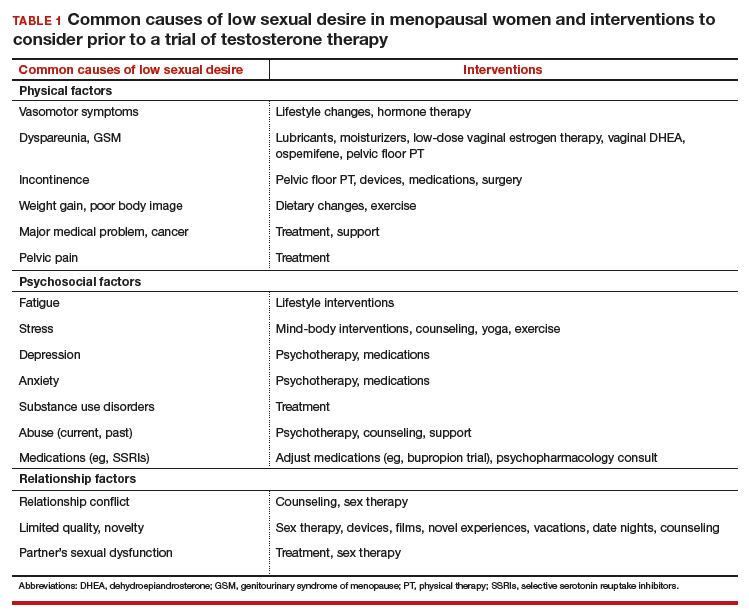

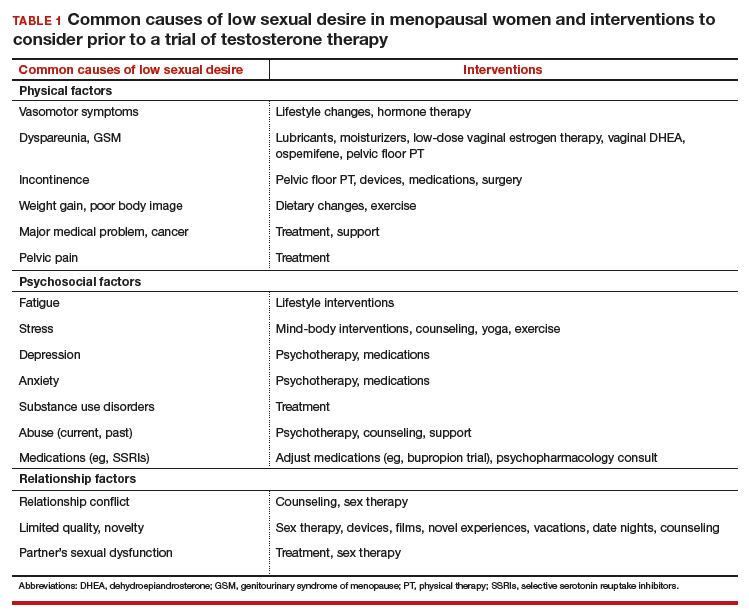

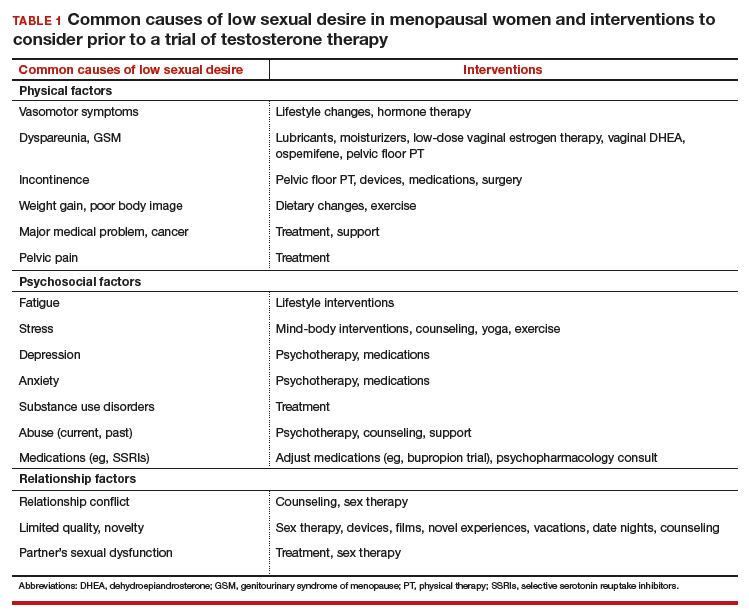

Common causes of low libido in menopausal women include vasomotor symptoms, insomnia, urinary incontinence, cancer or another major medical problem, weight gain, poor body image, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) with dyspareunia, fatigue, stress, aging, relationship duration, lack of novelty, relationship conflict, and a partner’s sexual problems. Other common etiologies include depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, as well as medications used to treat these disorders, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Continue to: There are many effective therapies...

There are many effective therapies for low sexual desire to consider prior to initiating a trial of testosterone, which should be considered for HSDD only if the disorder persists after addressing all other possible contributing factors (TABLE 1).

Sex therapy, for example, provides information on sexual functioning and helps improve communication and mutual pleasure and satisfaction. Strongly encourage—if not require—a consultation with a sex therapist before prescribing testosterone for low libido. Any testosterone-derived improvement in sexual functioning will be enhanced by improved communication and additional strategies to achieve mutual pleasure.

Hormone therapy. Vasomotor symptoms, with their associated sleep disruption, fatigue, and reduced quality of life (QOL), often adversely impact sexual desire. Estrogen therapy does not appear to improve libido in otherwise asymptomatic women; however, in women with bothersome vasomotor symptoms treated with estrogen, sexual interest may increase as a result of improved sleep, fatigue, and overall QOL. The benefits of systemic hormone therapy generally outweigh its risks for most healthy women younger than age 60 who have bothersome hot flashes and night sweats.1

Nonhormonal and other therapies. GSM with dyspareunia is a principal cause of sexual dysfunction in older women.2 Many safe and effective treatments are available, including low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy, nonhormonal moisturizers and lubricants, ospemifene, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone, and pelvic floor physical therapy.3 Urinary incontinence commonly occurs in midlife women and contributes to low libido.4

Lifestyle approaches. Address fatigue and stress by having the patient adjust her work and sleep schedules, obtain help with housework and meals, and engage in mind-body interventions, counseling, or yoga. Sexual function may benefit from yoga practice, likely as a result of the patient experiencing reduced stress and enhanced body image. Improving overall health and body image with regular exercise, optimal diet, and weight management may contribute to a more satisfying sex life after the onset of menopause.

Relationship refresh. Women’s sexual interest often declines with relationship duration, and both men and women who are in new relationships generally have increased libido, affirming the importance of novelty over the long term. Couples will benefit from “date nights,” weekends away from home, and trying novel positions, locations, and times for sex. Couple’s counseling may address relationship conflict.

Expert referral. Depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders are prevalent in menopausal women and contribute to sexual dysfunction. Effective therapy is available, although some pharmacologic treatments (including SSRIs) may be an additional cause of sexual dysfunction. In addition to recommending appropriate counseling and support, referring the patient to a psychopharmacologist with expertise in managing sexual adverse effects of medications may optimize care.

Continue to: Sexual function improves, but patient still wants to try testosterone

CASE Sexual function improves, but patient still wants to try testosterone

The patient returns for follow-up visits scheduled specifically to address her sexual concerns. Sex is more comfortable and pleasurable since initiating low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy. Having been on an SSRI since her mid-40s for mild depression, the patient switched to bupropion and notes improved libido and orgasmic response. She is exercising more regularly and working with a nutritionist to address a 15-lb weight gain after menopause. The couple saw a sex therapist and is communicating better about sex with more novelty in their repertoire. They are enjoying a regular date night. Although the patient’s sex life has improved with these interventions, she is still very interested in trying testosterone.

Testosterone’s effects on HSDD in menopausal women

After addressing the many factors that contribute to sexual disinterest, a trial of testosterone may be appropriate for a menopausal woman who continues to experience low libido with associated distress.

Testosterone levels decrease with aging in both men and women. Although testosterone levels decline by approximately 50% with bilateral oophorectomy, there is no decline in androgen levels with natural menopause.5 Testosterone circulates tightly bound to sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), so free or active testosterone will be reduced by oral estrogens, which increase SHBG levels.6 As most menopausal women will have a low testosterone level due to aging, measuring the testosterone level does not provide information about the etiology of the sexual problem.

Although some studies have identified an association between endogenous androgen levels and sexual function, the associations are modest and are of uncertain clinical significance.7-9 Not surprisingly, other factors, such as physical and psychologic health and the quality of the relationship, often are reported as more important predictors of sexual satisfaction than androgen levels.10

While endogenous testosterone levels may not correlate with sexual function, clinical trials of carefully selected menopausal women with HSDD have shown that androgen treatment generally results in improved sexual function.11 Studies demonstrate substantial improvements in sexual desire, orgasmic response, and frequency in menopausal women treated with high doses of intramuscular testosterone, which result in supraphysiologic androgen levels.12,13 While it is interesting that women with testosterone levels in the male low range have sizeable increases in sexual desire and response, long-term use of high-dose testosterone would result in unacceptable androgenic adverse effects and risks.

Continue to: Testosterone in low doses...

Testosterone in low doses. It is more relevant to consider the impact on female sexual function of low doses of testosterone, which raise the reduced testosterone levels seen in older women to the higher levels seen in reproductive-aged women.

A series of double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trials in menopausal women with HSDD examined the impact on sexual function of a transdermal testosterone patch (300 μg) that increased blood testosterone levels to the upper limit of normal for young women.14-17 In these studies, compared with placebo, women using testosterone reported significant improvements in sexual desire, arousal, orgasmic response, frequency, and sexually related distress. Findings were consistent in surgically and naturally menopausal women, with and without the use of concurrent estrogen therapy. Improvements were clinically limited, however. On average, testosterone-treated women experienced 1 to 1.5 additional satisfying sexual events in a 4-week period compared with those treated with placebo. The percentage of women reporting a clinically meaningful benefit from treatment was significantly greater in women treated with testosterone (52%) compared with the placebo-treated women (31%).18 An appreciable placebo response was seen, typical of most studies of therapies for sexual dysfunction.

Safety concerns

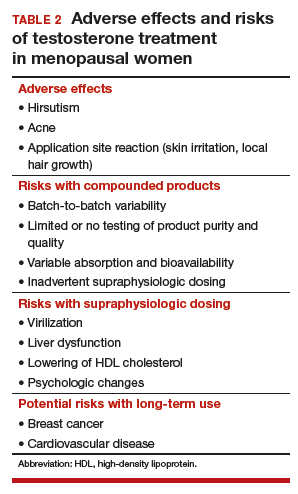

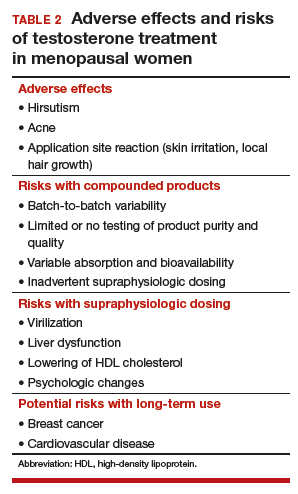

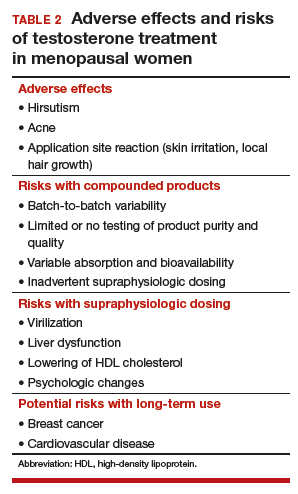

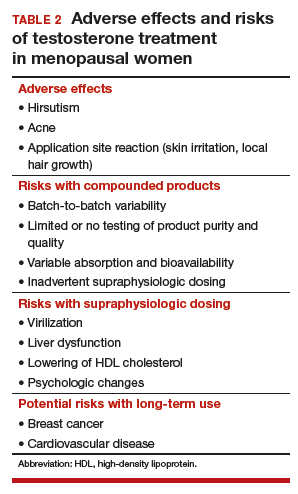

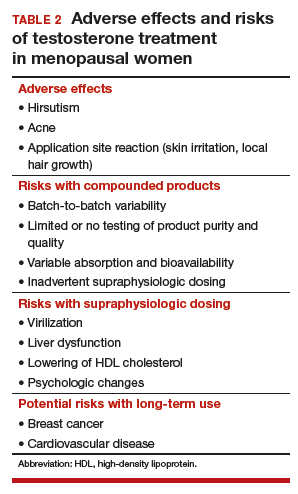

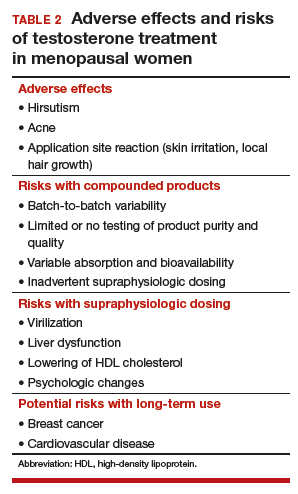

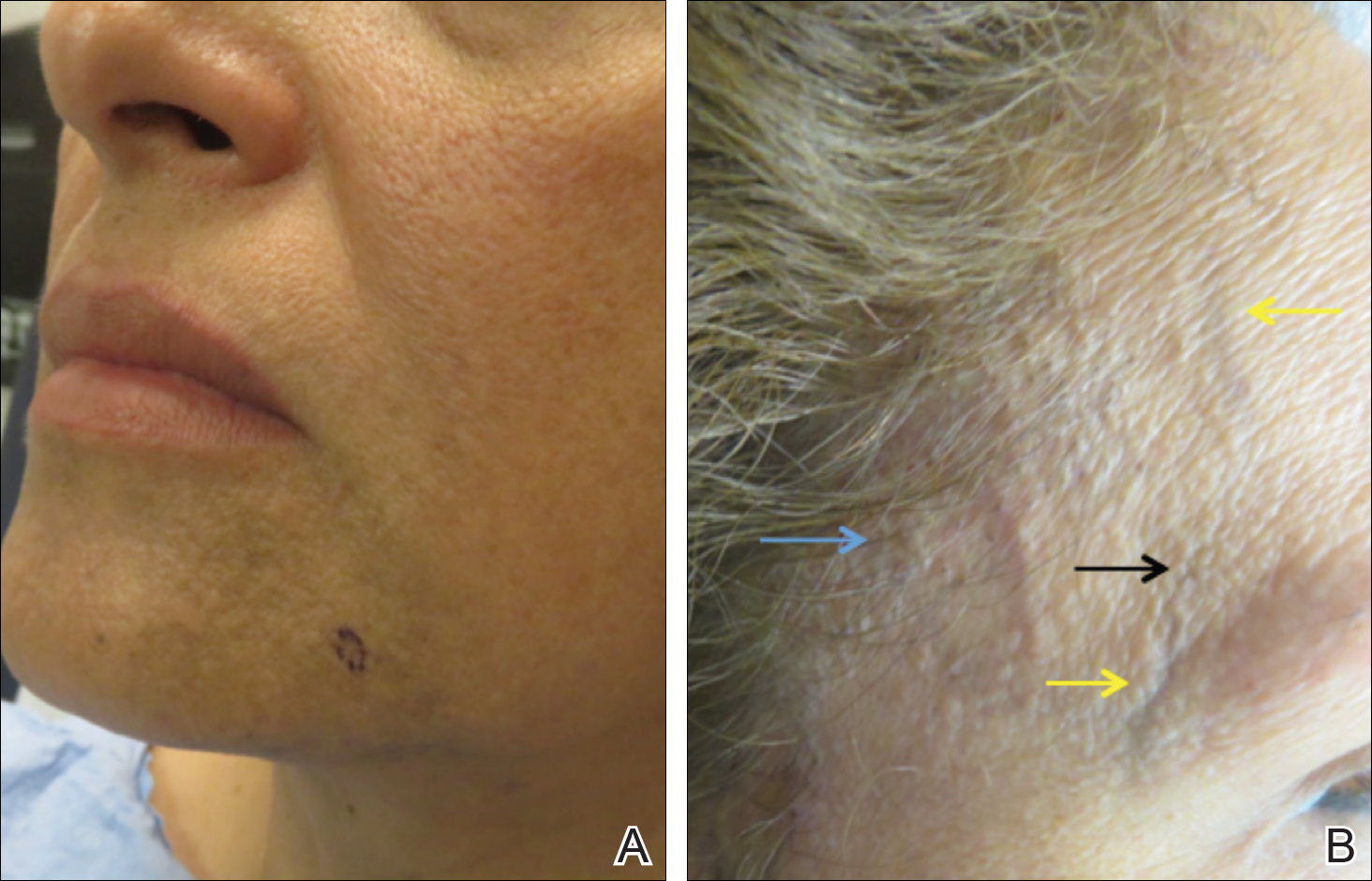

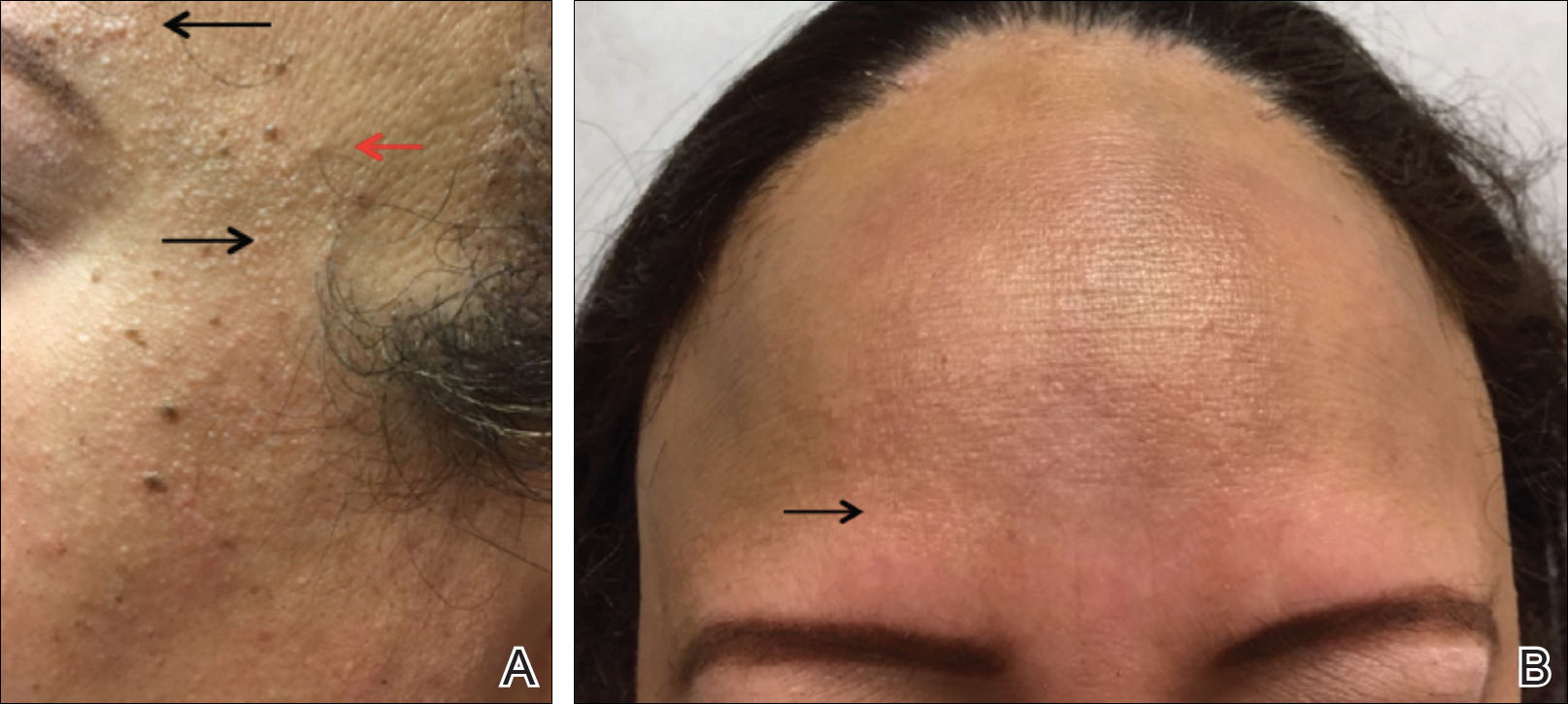

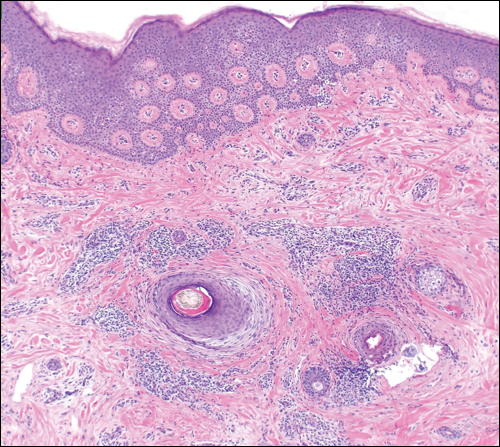

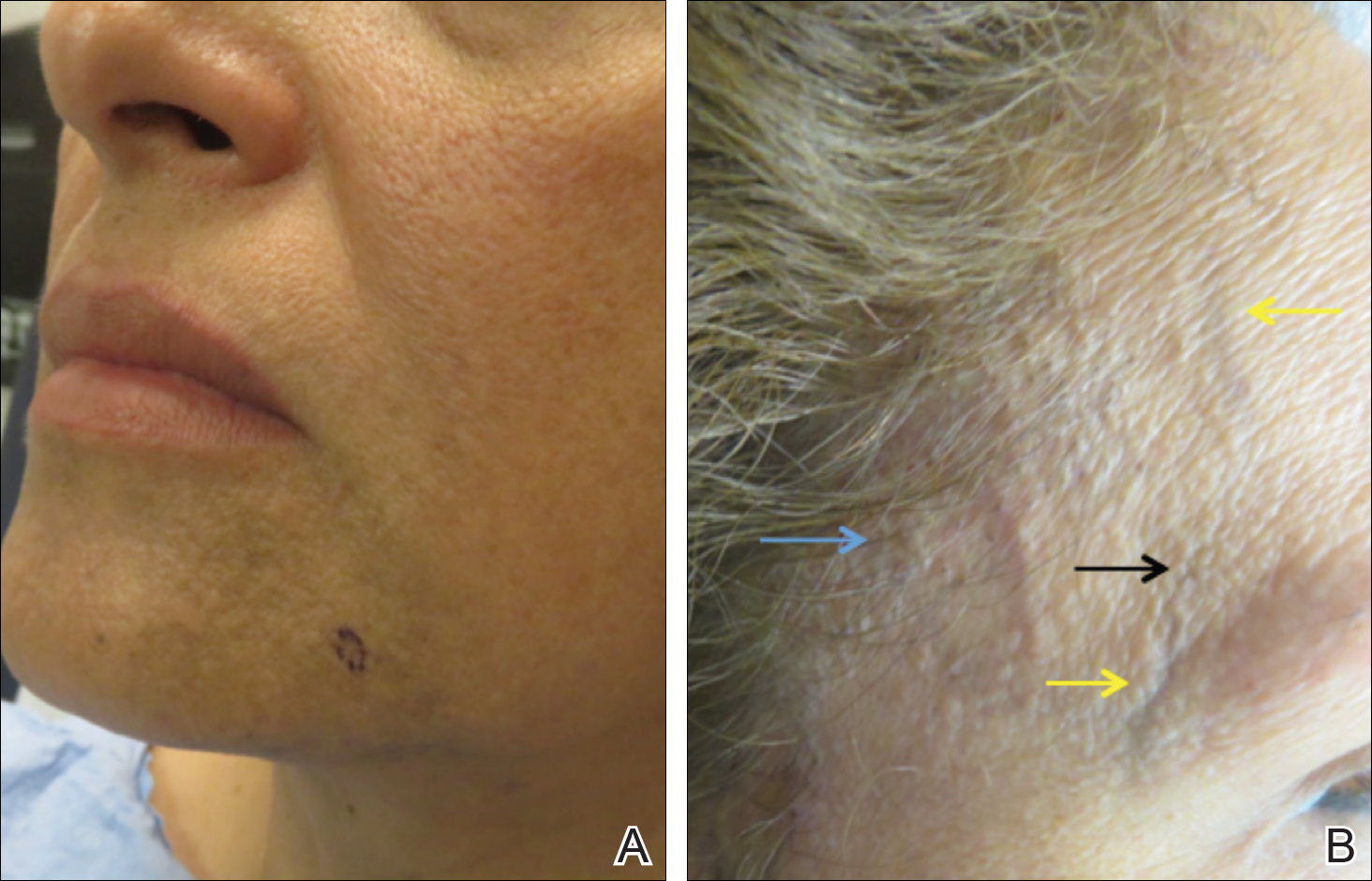

Potential risks of testosterone treatment include acne, hirsutism, irreversible deepening of the voice, and adverse changes in lipids and liver function (TABLE 2).19 Adverse effects are dose dependent and are unlikely with physiologically dosed testosterone.

A 1-year study of testosterone patches in approximately 800 menopausal women with HSDD (with a subgroup of women followed for an additional year) provides the most comprehensive safety data available.17 Unwanted hair growth occurred more often in women receiving testosterone, without significant differences in blood biochemistry,hematologic parameters, carbohydrate metabolism, or lipids. Breast cancer was diagnosed in more women receiving testosterone than placebo. Although this finding may have been due to chance, the investigators concluded that long-term effects of testosterone treatment remain uncertain.

The FDA reviewed the data from the testosterone patch studies and determined that testosterone patches were effective for the treatment of HSDD in menopausal women, but more information was needed on long-term safety before approval could be granted. Another company then developed a testosterone gel product that produced similar blood levels as the testosterone patch. It was presumed that there would be similar efficacy; the principal goal of these studies was to examine long-term safety, particularly with respect to breast cancer and cardiovascular disease. Unexpectedly, although it raised testosterone blood levels to the upper limit of normal for young women, the testosterone gel product was no more effective than placebo.20 The clinical trial was ended, with safety data never published.

Continue to: Availability of testosterone formulations

Availability of testosterone formulations

Currently, no androgen therapies are FDA approved for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Although the best evidence regarding testosterone efficacy and safety involves the use of testosterone patches (300 μg), appropriately dosed for women, these patches are not currently available. FDA-approved testosterone patches are approved for the treatment of male hypogonadism, but use of these patches in women is not recommended since they would result in very high circulating testosterone levels.

Testosterone subcutaneous implants, pellets, and intramuscular injections also are not recommended for women because of the risk of excessive dosing. Small trials of menopausal women taking oral estrogen with low sexual desire found that oral formulations of testosterone improved libido in this study population.21 The combination of esterified estrogens (0.625 mg) and methyltestosterone (1.25 mg) is available as a compounded, non-FDA approved product. Oral androgen formulations generally are not advised, due to potential adverse effects on lipids and liver function.22

Compounded testosterone products. Ointments and creams may be compounded by prescription (TABLE 3). Product purity, dose, bioavailability, and quality typically are untested, and substantial variability exists between formulations and batches.23 Applying 1% testosterone cream or gel (0.5 g/day) topically to the thigh or lower abdomen should increase the low testosterone levels typically seen in menopausal women to the higher levels seen in younger women.24,25 Application to the vulva or vagina is not advised, as it may cause local irritation and is unpredictably absorbed.

Adapting male testosterone products. High-quality FDA-approved testosterone gel formulations are available for male hypogonadism. However, since women have approximately one-tenth the circulating testosterone levels of men, supraphysiologic dosing is a risk when these products are prescribed for women. Most testosterone products approved for men are provided in pumps or packets, and they are difficult to dose-adjust for women. Applying one-tenth the male dose of 1% testosterone gel (Testim), which comes in a resealable unit-dose tube, is an alternative to compounding. For men, the dose is 1 tube per day, so women should make 1 tube last for 10 days by using 3 to 4 drops of testosterone gel per day. Close physical contact must be avoided immediately after application, as topical hormone creams and gels are easily transferred to others. The safety and efficacy of compounded or dose-adjusted male testosterone products used in women are unknown.

Follow treated women closely. Women who elect to use transdermal testosterone therapy should be seen at 8 to 12 weeks to assess treatment response. Regular follow-up visits are required to assess response, satisfaction, and adverse effects, including acne and hirsutism. Since there may be little correlation between serum testosterone levels and the prescribed dose of a compounded testosterone product, testosterone levels should be measured regularly as a safety measure. The goal is to keep serum testosterone concentrations within the normal range for reproductive-aged women to reduce the likelihood of adverse effects. Testosterone levels should not be tested as an efficacy measure, however, as there is no testosterone level that will assure a satisfactory sex life.

CASE Conclusion

After a thorough discussion of high placebo response rates, potential adverse effects, unknown long-term risks, and off-label nature of testosterone use, the patient elects a trial of compounded 1% testosterone cream. Her clinician informs her of the limitations of compounded formulations and the need for regular testing of testosterone levels to prevent supraphysiologic dosing. At a follow-up visit 8 weeks later, she reports improved sexual desire and elects to continue treatment and monitoring. After using testosterone for 2 years, the patient is uncertain that she still is experiencing a significant benefit, stops testosterone treatment, and remains satisfied with her sex life.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- The North American Menopause Society Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

- Simon JA, Nappi RE, Kingsberg SA, et al. Clarifying Vaginal Atrophy's Impact on Sex and Relationships (CLOSER) survey: emotional and physical impact of vaginal discomfort on North American postmenopausal women and their partners. Menopause. 2014;21:137-142.

- The North American Menopause Society. Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20:888-902.

- Shifren J, Monz B, Russo P, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970-978.

- Davison S, Bell R, Donath S, et al. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3847-3853.

- Shifren JL, Desindes S, McIlwain M, et al. A randomized, open-label, crossover study comparing the effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen therapy on serum androgens, thyroid hormones, and adrenal hormones in naturally menopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14:985-994.

- Davis SR, Davison SL, Donath S, et al. Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. JAMA. 2005;294:91-96.

- Wahlin-Jacobsen S, Pedersen AT, Kristensen E, et al. Is there a correlation between androgens and sexual desire in women? J Sex Med. 2015;12:358-373.

- Randolph JF Jr, Zheng H, Avis NE, et al. Masturbation frequency and sexual function domains are associated with serum reproductive hormone levels across the menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:258-266.

- Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger H. The relative effects of hormones and relationship factors on sexual function of women through the natural menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:174-180.

- Shifren JL, Davis SR. Androgens in postmenopausal women: a review. Menopause. 2017;24:970-979.

- Sherwin BB, Gelfand MM, Brender W. Androgen enhances sexual motivation in females: a prospective, crossover study of sex steroid administration in the surgical menopause. Psychosom Med. 1985;47:339-351.

- Huang G, Basaria S, Travison TG, et al. Testosterone dose-response relationships in hysterectomized women with or without oophorectomy: effects on sexual function, body composition, muscle performance and physical function in a randomized trial. Menopause. 2014;21:612-623.

- Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682-688.

- Simon J, Braunstein G, Nachtigall L, et al. Testosterone patch increases sexual activity and desire in surgically menopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5226-5233.

- Shifren JL, Davis SR, Moreau M, et al. Testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in naturally menopausal women: results from the INTIMATE NM1 study. Menopause. 2006;13:770-779.

- Davis SR, Moreau M, Kroll R, et al; APHRODITE Study Team. Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2005-2017.

- Kingsberg S, Shifren J, Wekselman K, et al. Evaluation of the clinical relevance of benefits associated with transdermal testosterone treatment in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1001-1008.

- Wierman ME, Arlt W, Basson R, et al. Androgen therapy in women: a reappraisal: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3489-3510.

- Snabes M, Zborowski J, Simes S. Libigel (testosterone gel) does not differentiate from placebo therapy in the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire in postmenopausal women (abstract). J Sex Med. 2012;9(suppl 3):171.

- Lobo RA, Rosen RC, Yang HM, et al. Comparative effects of oral esterified estrogens with and without methyltestosterone on endocrine profiles and dimensions of sexual function in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1341-1352.

- Somboonporn W, Davis S, Seif M, et al. Testsoterone for peri- and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;19:CD004509.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice and American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Committee opinion 532: compounded bioidentical menopausal hormone therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;(2 pt 1):411-415.

- Fooladi E, Reuter SE, Bell RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a transdermal testosterone cream in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22:44-49.

- Shifren JL. Testosterone for midlife women: the hormone of desire? Menopause. 2015;22:1147-1149.

CASE Midlife woman with low libido causing distress

At her annual gynecologic visit, a 55-year-old woman notes that she has almost no interest in sex. In the past, her libido was good and relations were pleasurable. Since her mid-40s, she has noticed a gradual decline in libido and orgasmic response. Sexual frequency has declined from once or twice weekly to just a few times per month. She has been married for 25 years and describes the relationship as caring and strong. Her husband is healthy with a good libido; his intermittent erectile dysfunction is treated with a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor. The patient’s low libido is distressing, as the decline in sexual frequency is causing some conflict for the couple. She requests that her testosterone level be checked because she heard that treatment with testosterone cream will solve this problem.

Evaluating and treating low libido in menopausal women

Low libido is a very common sexual problem for women. When sexual problems are accompanied by distress, they are classified as sexual dysfunctions. Although ObGyns should discuss sexual concerns at every comprehensive visit, if the patient has no associated distress, treatment is not necessarily indicated. A woman with low libido or anorgasmia who is satisfied with her sex life and is not bothered by these issues does not require any intervention.

Currently, the only indication for testosterone therapy that is supported by clinical trial evidence is low sexual desire with associated distress, known as hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). Although other sexual problems also commonly occur in menopausal women, such as disorders of orgasm and pain, testosterone is not recommended for these problems. In addition, testosterone is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction.

Routinely inquire about sexual functioning

Ask your patients about sexual concerns at every comprehensive visit. You can easily incorporate into the review of systems a general question, such as, “Do you have any sexual concerns?” If the patient does mention a sexual problem, schedule a separate visit (given appointment time constraints) to address it. History and physical examination information you gather during the comprehensive visit will be helpful in the subsequent problem-focused visit.

Taking a thorough history is key when addressing a patient’s sexual problems, since identifying possible etiologies guides treatment. Often, the cause of female sexual dysfunction is multifactorial and includes physiologic, psychologic, and relationship issues.

- Evidence supports low-dose transdermal testosterone in carefully selected menopausal women with HSDD and no other identifiable reason for the sexual dysfunction

- Inform women considering testosterone for HSDD of the limited effectiveness and high placebo responses seen in clinical trials

- Women also must be informed that treatment is off-label (no testosterone formulations are FDA approved for women)

- Review with patients the limitations of compounded medications, and discuss possible adverse effects of androgens. Long-term safety is unknown and, as androgens are converted to estrogens

Explore potential causes, recommend standard therapies

Common causes of low libido in menopausal women include vasomotor symptoms, insomnia, urinary incontinence, cancer or another major medical problem, weight gain, poor body image, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) with dyspareunia, fatigue, stress, aging, relationship duration, lack of novelty, relationship conflict, and a partner’s sexual problems. Other common etiologies include depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, as well as medications used to treat these disorders, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Continue to: There are many effective therapies...

There are many effective therapies for low sexual desire to consider prior to initiating a trial of testosterone, which should be considered for HSDD only if the disorder persists after addressing all other possible contributing factors (TABLE 1).

Sex therapy, for example, provides information on sexual functioning and helps improve communication and mutual pleasure and satisfaction. Strongly encourage—if not require—a consultation with a sex therapist before prescribing testosterone for low libido. Any testosterone-derived improvement in sexual functioning will be enhanced by improved communication and additional strategies to achieve mutual pleasure.

Hormone therapy. Vasomotor symptoms, with their associated sleep disruption, fatigue, and reduced quality of life (QOL), often adversely impact sexual desire. Estrogen therapy does not appear to improve libido in otherwise asymptomatic women; however, in women with bothersome vasomotor symptoms treated with estrogen, sexual interest may increase as a result of improved sleep, fatigue, and overall QOL. The benefits of systemic hormone therapy generally outweigh its risks for most healthy women younger than age 60 who have bothersome hot flashes and night sweats.1

Nonhormonal and other therapies. GSM with dyspareunia is a principal cause of sexual dysfunction in older women.2 Many safe and effective treatments are available, including low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy, nonhormonal moisturizers and lubricants, ospemifene, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone, and pelvic floor physical therapy.3 Urinary incontinence commonly occurs in midlife women and contributes to low libido.4

Lifestyle approaches. Address fatigue and stress by having the patient adjust her work and sleep schedules, obtain help with housework and meals, and engage in mind-body interventions, counseling, or yoga. Sexual function may benefit from yoga practice, likely as a result of the patient experiencing reduced stress and enhanced body image. Improving overall health and body image with regular exercise, optimal diet, and weight management may contribute to a more satisfying sex life after the onset of menopause.

Relationship refresh. Women’s sexual interest often declines with relationship duration, and both men and women who are in new relationships generally have increased libido, affirming the importance of novelty over the long term. Couples will benefit from “date nights,” weekends away from home, and trying novel positions, locations, and times for sex. Couple’s counseling may address relationship conflict.

Expert referral. Depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders are prevalent in menopausal women and contribute to sexual dysfunction. Effective therapy is available, although some pharmacologic treatments (including SSRIs) may be an additional cause of sexual dysfunction. In addition to recommending appropriate counseling and support, referring the patient to a psychopharmacologist with expertise in managing sexual adverse effects of medications may optimize care.

Continue to: Sexual function improves, but patient still wants to try testosterone

CASE Sexual function improves, but patient still wants to try testosterone

The patient returns for follow-up visits scheduled specifically to address her sexual concerns. Sex is more comfortable and pleasurable since initiating low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy. Having been on an SSRI since her mid-40s for mild depression, the patient switched to bupropion and notes improved libido and orgasmic response. She is exercising more regularly and working with a nutritionist to address a 15-lb weight gain after menopause. The couple saw a sex therapist and is communicating better about sex with more novelty in their repertoire. They are enjoying a regular date night. Although the patient’s sex life has improved with these interventions, she is still very interested in trying testosterone.

Testosterone’s effects on HSDD in menopausal women

After addressing the many factors that contribute to sexual disinterest, a trial of testosterone may be appropriate for a menopausal woman who continues to experience low libido with associated distress.

Testosterone levels decrease with aging in both men and women. Although testosterone levels decline by approximately 50% with bilateral oophorectomy, there is no decline in androgen levels with natural menopause.5 Testosterone circulates tightly bound to sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), so free or active testosterone will be reduced by oral estrogens, which increase SHBG levels.6 As most menopausal women will have a low testosterone level due to aging, measuring the testosterone level does not provide information about the etiology of the sexual problem.

Although some studies have identified an association between endogenous androgen levels and sexual function, the associations are modest and are of uncertain clinical significance.7-9 Not surprisingly, other factors, such as physical and psychologic health and the quality of the relationship, often are reported as more important predictors of sexual satisfaction than androgen levels.10

While endogenous testosterone levels may not correlate with sexual function, clinical trials of carefully selected menopausal women with HSDD have shown that androgen treatment generally results in improved sexual function.11 Studies demonstrate substantial improvements in sexual desire, orgasmic response, and frequency in menopausal women treated with high doses of intramuscular testosterone, which result in supraphysiologic androgen levels.12,13 While it is interesting that women with testosterone levels in the male low range have sizeable increases in sexual desire and response, long-term use of high-dose testosterone would result in unacceptable androgenic adverse effects and risks.

Continue to: Testosterone in low doses...

Testosterone in low doses. It is more relevant to consider the impact on female sexual function of low doses of testosterone, which raise the reduced testosterone levels seen in older women to the higher levels seen in reproductive-aged women.

A series of double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trials in menopausal women with HSDD examined the impact on sexual function of a transdermal testosterone patch (300 μg) that increased blood testosterone levels to the upper limit of normal for young women.14-17 In these studies, compared with placebo, women using testosterone reported significant improvements in sexual desire, arousal, orgasmic response, frequency, and sexually related distress. Findings were consistent in surgically and naturally menopausal women, with and without the use of concurrent estrogen therapy. Improvements were clinically limited, however. On average, testosterone-treated women experienced 1 to 1.5 additional satisfying sexual events in a 4-week period compared with those treated with placebo. The percentage of women reporting a clinically meaningful benefit from treatment was significantly greater in women treated with testosterone (52%) compared with the placebo-treated women (31%).18 An appreciable placebo response was seen, typical of most studies of therapies for sexual dysfunction.

Safety concerns

Potential risks of testosterone treatment include acne, hirsutism, irreversible deepening of the voice, and adverse changes in lipids and liver function (TABLE 2).19 Adverse effects are dose dependent and are unlikely with physiologically dosed testosterone.

A 1-year study of testosterone patches in approximately 800 menopausal women with HSDD (with a subgroup of women followed for an additional year) provides the most comprehensive safety data available.17 Unwanted hair growth occurred more often in women receiving testosterone, without significant differences in blood biochemistry,hematologic parameters, carbohydrate metabolism, or lipids. Breast cancer was diagnosed in more women receiving testosterone than placebo. Although this finding may have been due to chance, the investigators concluded that long-term effects of testosterone treatment remain uncertain.

The FDA reviewed the data from the testosterone patch studies and determined that testosterone patches were effective for the treatment of HSDD in menopausal women, but more information was needed on long-term safety before approval could be granted. Another company then developed a testosterone gel product that produced similar blood levels as the testosterone patch. It was presumed that there would be similar efficacy; the principal goal of these studies was to examine long-term safety, particularly with respect to breast cancer and cardiovascular disease. Unexpectedly, although it raised testosterone blood levels to the upper limit of normal for young women, the testosterone gel product was no more effective than placebo.20 The clinical trial was ended, with safety data never published.

Continue to: Availability of testosterone formulations

Availability of testosterone formulations

Currently, no androgen therapies are FDA approved for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Although the best evidence regarding testosterone efficacy and safety involves the use of testosterone patches (300 μg), appropriately dosed for women, these patches are not currently available. FDA-approved testosterone patches are approved for the treatment of male hypogonadism, but use of these patches in women is not recommended since they would result in very high circulating testosterone levels.

Testosterone subcutaneous implants, pellets, and intramuscular injections also are not recommended for women because of the risk of excessive dosing. Small trials of menopausal women taking oral estrogen with low sexual desire found that oral formulations of testosterone improved libido in this study population.21 The combination of esterified estrogens (0.625 mg) and methyltestosterone (1.25 mg) is available as a compounded, non-FDA approved product. Oral androgen formulations generally are not advised, due to potential adverse effects on lipids and liver function.22

Compounded testosterone products. Ointments and creams may be compounded by prescription (TABLE 3). Product purity, dose, bioavailability, and quality typically are untested, and substantial variability exists between formulations and batches.23 Applying 1% testosterone cream or gel (0.5 g/day) topically to the thigh or lower abdomen should increase the low testosterone levels typically seen in menopausal women to the higher levels seen in younger women.24,25 Application to the vulva or vagina is not advised, as it may cause local irritation and is unpredictably absorbed.

Adapting male testosterone products. High-quality FDA-approved testosterone gel formulations are available for male hypogonadism. However, since women have approximately one-tenth the circulating testosterone levels of men, supraphysiologic dosing is a risk when these products are prescribed for women. Most testosterone products approved for men are provided in pumps or packets, and they are difficult to dose-adjust for women. Applying one-tenth the male dose of 1% testosterone gel (Testim), which comes in a resealable unit-dose tube, is an alternative to compounding. For men, the dose is 1 tube per day, so women should make 1 tube last for 10 days by using 3 to 4 drops of testosterone gel per day. Close physical contact must be avoided immediately after application, as topical hormone creams and gels are easily transferred to others. The safety and efficacy of compounded or dose-adjusted male testosterone products used in women are unknown.

Follow treated women closely. Women who elect to use transdermal testosterone therapy should be seen at 8 to 12 weeks to assess treatment response. Regular follow-up visits are required to assess response, satisfaction, and adverse effects, including acne and hirsutism. Since there may be little correlation between serum testosterone levels and the prescribed dose of a compounded testosterone product, testosterone levels should be measured regularly as a safety measure. The goal is to keep serum testosterone concentrations within the normal range for reproductive-aged women to reduce the likelihood of adverse effects. Testosterone levels should not be tested as an efficacy measure, however, as there is no testosterone level that will assure a satisfactory sex life.

CASE Conclusion

After a thorough discussion of high placebo response rates, potential adverse effects, unknown long-term risks, and off-label nature of testosterone use, the patient elects a trial of compounded 1% testosterone cream. Her clinician informs her of the limitations of compounded formulations and the need for regular testing of testosterone levels to prevent supraphysiologic dosing. At a follow-up visit 8 weeks later, she reports improved sexual desire and elects to continue treatment and monitoring. After using testosterone for 2 years, the patient is uncertain that she still is experiencing a significant benefit, stops testosterone treatment, and remains satisfied with her sex life.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Midlife woman with low libido causing distress

At her annual gynecologic visit, a 55-year-old woman notes that she has almost no interest in sex. In the past, her libido was good and relations were pleasurable. Since her mid-40s, she has noticed a gradual decline in libido and orgasmic response. Sexual frequency has declined from once or twice weekly to just a few times per month. She has been married for 25 years and describes the relationship as caring and strong. Her husband is healthy with a good libido; his intermittent erectile dysfunction is treated with a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor. The patient’s low libido is distressing, as the decline in sexual frequency is causing some conflict for the couple. She requests that her testosterone level be checked because she heard that treatment with testosterone cream will solve this problem.

Evaluating and treating low libido in menopausal women

Low libido is a very common sexual problem for women. When sexual problems are accompanied by distress, they are classified as sexual dysfunctions. Although ObGyns should discuss sexual concerns at every comprehensive visit, if the patient has no associated distress, treatment is not necessarily indicated. A woman with low libido or anorgasmia who is satisfied with her sex life and is not bothered by these issues does not require any intervention.

Currently, the only indication for testosterone therapy that is supported by clinical trial evidence is low sexual desire with associated distress, known as hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). Although other sexual problems also commonly occur in menopausal women, such as disorders of orgasm and pain, testosterone is not recommended for these problems. In addition, testosterone is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction.

Routinely inquire about sexual functioning

Ask your patients about sexual concerns at every comprehensive visit. You can easily incorporate into the review of systems a general question, such as, “Do you have any sexual concerns?” If the patient does mention a sexual problem, schedule a separate visit (given appointment time constraints) to address it. History and physical examination information you gather during the comprehensive visit will be helpful in the subsequent problem-focused visit.

Taking a thorough history is key when addressing a patient’s sexual problems, since identifying possible etiologies guides treatment. Often, the cause of female sexual dysfunction is multifactorial and includes physiologic, psychologic, and relationship issues.

- Evidence supports low-dose transdermal testosterone in carefully selected menopausal women with HSDD and no other identifiable reason for the sexual dysfunction

- Inform women considering testosterone for HSDD of the limited effectiveness and high placebo responses seen in clinical trials

- Women also must be informed that treatment is off-label (no testosterone formulations are FDA approved for women)

- Review with patients the limitations of compounded medications, and discuss possible adverse effects of androgens. Long-term safety is unknown and, as androgens are converted to estrogens

Explore potential causes, recommend standard therapies

Common causes of low libido in menopausal women include vasomotor symptoms, insomnia, urinary incontinence, cancer or another major medical problem, weight gain, poor body image, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) with dyspareunia, fatigue, stress, aging, relationship duration, lack of novelty, relationship conflict, and a partner’s sexual problems. Other common etiologies include depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, as well as medications used to treat these disorders, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Continue to: There are many effective therapies...

There are many effective therapies for low sexual desire to consider prior to initiating a trial of testosterone, which should be considered for HSDD only if the disorder persists after addressing all other possible contributing factors (TABLE 1).

Sex therapy, for example, provides information on sexual functioning and helps improve communication and mutual pleasure and satisfaction. Strongly encourage—if not require—a consultation with a sex therapist before prescribing testosterone for low libido. Any testosterone-derived improvement in sexual functioning will be enhanced by improved communication and additional strategies to achieve mutual pleasure.

Hormone therapy. Vasomotor symptoms, with their associated sleep disruption, fatigue, and reduced quality of life (QOL), often adversely impact sexual desire. Estrogen therapy does not appear to improve libido in otherwise asymptomatic women; however, in women with bothersome vasomotor symptoms treated with estrogen, sexual interest may increase as a result of improved sleep, fatigue, and overall QOL. The benefits of systemic hormone therapy generally outweigh its risks for most healthy women younger than age 60 who have bothersome hot flashes and night sweats.1

Nonhormonal and other therapies. GSM with dyspareunia is a principal cause of sexual dysfunction in older women.2 Many safe and effective treatments are available, including low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy, nonhormonal moisturizers and lubricants, ospemifene, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone, and pelvic floor physical therapy.3 Urinary incontinence commonly occurs in midlife women and contributes to low libido.4

Lifestyle approaches. Address fatigue and stress by having the patient adjust her work and sleep schedules, obtain help with housework and meals, and engage in mind-body interventions, counseling, or yoga. Sexual function may benefit from yoga practice, likely as a result of the patient experiencing reduced stress and enhanced body image. Improving overall health and body image with regular exercise, optimal diet, and weight management may contribute to a more satisfying sex life after the onset of menopause.

Relationship refresh. Women’s sexual interest often declines with relationship duration, and both men and women who are in new relationships generally have increased libido, affirming the importance of novelty over the long term. Couples will benefit from “date nights,” weekends away from home, and trying novel positions, locations, and times for sex. Couple’s counseling may address relationship conflict.

Expert referral. Depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders are prevalent in menopausal women and contribute to sexual dysfunction. Effective therapy is available, although some pharmacologic treatments (including SSRIs) may be an additional cause of sexual dysfunction. In addition to recommending appropriate counseling and support, referring the patient to a psychopharmacologist with expertise in managing sexual adverse effects of medications may optimize care.

Continue to: Sexual function improves, but patient still wants to try testosterone

CASE Sexual function improves, but patient still wants to try testosterone

The patient returns for follow-up visits scheduled specifically to address her sexual concerns. Sex is more comfortable and pleasurable since initiating low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy. Having been on an SSRI since her mid-40s for mild depression, the patient switched to bupropion and notes improved libido and orgasmic response. She is exercising more regularly and working with a nutritionist to address a 15-lb weight gain after menopause. The couple saw a sex therapist and is communicating better about sex with more novelty in their repertoire. They are enjoying a regular date night. Although the patient’s sex life has improved with these interventions, she is still very interested in trying testosterone.

Testosterone’s effects on HSDD in menopausal women

After addressing the many factors that contribute to sexual disinterest, a trial of testosterone may be appropriate for a menopausal woman who continues to experience low libido with associated distress.

Testosterone levels decrease with aging in both men and women. Although testosterone levels decline by approximately 50% with bilateral oophorectomy, there is no decline in androgen levels with natural menopause.5 Testosterone circulates tightly bound to sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), so free or active testosterone will be reduced by oral estrogens, which increase SHBG levels.6 As most menopausal women will have a low testosterone level due to aging, measuring the testosterone level does not provide information about the etiology of the sexual problem.

Although some studies have identified an association between endogenous androgen levels and sexual function, the associations are modest and are of uncertain clinical significance.7-9 Not surprisingly, other factors, such as physical and psychologic health and the quality of the relationship, often are reported as more important predictors of sexual satisfaction than androgen levels.10

While endogenous testosterone levels may not correlate with sexual function, clinical trials of carefully selected menopausal women with HSDD have shown that androgen treatment generally results in improved sexual function.11 Studies demonstrate substantial improvements in sexual desire, orgasmic response, and frequency in menopausal women treated with high doses of intramuscular testosterone, which result in supraphysiologic androgen levels.12,13 While it is interesting that women with testosterone levels in the male low range have sizeable increases in sexual desire and response, long-term use of high-dose testosterone would result in unacceptable androgenic adverse effects and risks.

Continue to: Testosterone in low doses...

Testosterone in low doses. It is more relevant to consider the impact on female sexual function of low doses of testosterone, which raise the reduced testosterone levels seen in older women to the higher levels seen in reproductive-aged women.

A series of double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trials in menopausal women with HSDD examined the impact on sexual function of a transdermal testosterone patch (300 μg) that increased blood testosterone levels to the upper limit of normal for young women.14-17 In these studies, compared with placebo, women using testosterone reported significant improvements in sexual desire, arousal, orgasmic response, frequency, and sexually related distress. Findings were consistent in surgically and naturally menopausal women, with and without the use of concurrent estrogen therapy. Improvements were clinically limited, however. On average, testosterone-treated women experienced 1 to 1.5 additional satisfying sexual events in a 4-week period compared with those treated with placebo. The percentage of women reporting a clinically meaningful benefit from treatment was significantly greater in women treated with testosterone (52%) compared with the placebo-treated women (31%).18 An appreciable placebo response was seen, typical of most studies of therapies for sexual dysfunction.

Safety concerns

Potential risks of testosterone treatment include acne, hirsutism, irreversible deepening of the voice, and adverse changes in lipids and liver function (TABLE 2).19 Adverse effects are dose dependent and are unlikely with physiologically dosed testosterone.

A 1-year study of testosterone patches in approximately 800 menopausal women with HSDD (with a subgroup of women followed for an additional year) provides the most comprehensive safety data available.17 Unwanted hair growth occurred more often in women receiving testosterone, without significant differences in blood biochemistry,hematologic parameters, carbohydrate metabolism, or lipids. Breast cancer was diagnosed in more women receiving testosterone than placebo. Although this finding may have been due to chance, the investigators concluded that long-term effects of testosterone treatment remain uncertain.

The FDA reviewed the data from the testosterone patch studies and determined that testosterone patches were effective for the treatment of HSDD in menopausal women, but more information was needed on long-term safety before approval could be granted. Another company then developed a testosterone gel product that produced similar blood levels as the testosterone patch. It was presumed that there would be similar efficacy; the principal goal of these studies was to examine long-term safety, particularly with respect to breast cancer and cardiovascular disease. Unexpectedly, although it raised testosterone blood levels to the upper limit of normal for young women, the testosterone gel product was no more effective than placebo.20 The clinical trial was ended, with safety data never published.

Continue to: Availability of testosterone formulations

Availability of testosterone formulations

Currently, no androgen therapies are FDA approved for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Although the best evidence regarding testosterone efficacy and safety involves the use of testosterone patches (300 μg), appropriately dosed for women, these patches are not currently available. FDA-approved testosterone patches are approved for the treatment of male hypogonadism, but use of these patches in women is not recommended since they would result in very high circulating testosterone levels.

Testosterone subcutaneous implants, pellets, and intramuscular injections also are not recommended for women because of the risk of excessive dosing. Small trials of menopausal women taking oral estrogen with low sexual desire found that oral formulations of testosterone improved libido in this study population.21 The combination of esterified estrogens (0.625 mg) and methyltestosterone (1.25 mg) is available as a compounded, non-FDA approved product. Oral androgen formulations generally are not advised, due to potential adverse effects on lipids and liver function.22

Compounded testosterone products. Ointments and creams may be compounded by prescription (TABLE 3). Product purity, dose, bioavailability, and quality typically are untested, and substantial variability exists between formulations and batches.23 Applying 1% testosterone cream or gel (0.5 g/day) topically to the thigh or lower abdomen should increase the low testosterone levels typically seen in menopausal women to the higher levels seen in younger women.24,25 Application to the vulva or vagina is not advised, as it may cause local irritation and is unpredictably absorbed.

Adapting male testosterone products. High-quality FDA-approved testosterone gel formulations are available for male hypogonadism. However, since women have approximately one-tenth the circulating testosterone levels of men, supraphysiologic dosing is a risk when these products are prescribed for women. Most testosterone products approved for men are provided in pumps or packets, and they are difficult to dose-adjust for women. Applying one-tenth the male dose of 1% testosterone gel (Testim), which comes in a resealable unit-dose tube, is an alternative to compounding. For men, the dose is 1 tube per day, so women should make 1 tube last for 10 days by using 3 to 4 drops of testosterone gel per day. Close physical contact must be avoided immediately after application, as topical hormone creams and gels are easily transferred to others. The safety and efficacy of compounded or dose-adjusted male testosterone products used in women are unknown.

Follow treated women closely. Women who elect to use transdermal testosterone therapy should be seen at 8 to 12 weeks to assess treatment response. Regular follow-up visits are required to assess response, satisfaction, and adverse effects, including acne and hirsutism. Since there may be little correlation between serum testosterone levels and the prescribed dose of a compounded testosterone product, testosterone levels should be measured regularly as a safety measure. The goal is to keep serum testosterone concentrations within the normal range for reproductive-aged women to reduce the likelihood of adverse effects. Testosterone levels should not be tested as an efficacy measure, however, as there is no testosterone level that will assure a satisfactory sex life.

CASE Conclusion

After a thorough discussion of high placebo response rates, potential adverse effects, unknown long-term risks, and off-label nature of testosterone use, the patient elects a trial of compounded 1% testosterone cream. Her clinician informs her of the limitations of compounded formulations and the need for regular testing of testosterone levels to prevent supraphysiologic dosing. At a follow-up visit 8 weeks later, she reports improved sexual desire and elects to continue treatment and monitoring. After using testosterone for 2 years, the patient is uncertain that she still is experiencing a significant benefit, stops testosterone treatment, and remains satisfied with her sex life.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- The North American Menopause Society Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

- Simon JA, Nappi RE, Kingsberg SA, et al. Clarifying Vaginal Atrophy's Impact on Sex and Relationships (CLOSER) survey: emotional and physical impact of vaginal discomfort on North American postmenopausal women and their partners. Menopause. 2014;21:137-142.

- The North American Menopause Society. Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20:888-902.

- Shifren J, Monz B, Russo P, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970-978.

- Davison S, Bell R, Donath S, et al. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3847-3853.

- Shifren JL, Desindes S, McIlwain M, et al. A randomized, open-label, crossover study comparing the effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen therapy on serum androgens, thyroid hormones, and adrenal hormones in naturally menopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14:985-994.

- Davis SR, Davison SL, Donath S, et al. Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. JAMA. 2005;294:91-96.

- Wahlin-Jacobsen S, Pedersen AT, Kristensen E, et al. Is there a correlation between androgens and sexual desire in women? J Sex Med. 2015;12:358-373.

- Randolph JF Jr, Zheng H, Avis NE, et al. Masturbation frequency and sexual function domains are associated with serum reproductive hormone levels across the menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:258-266.

- Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger H. The relative effects of hormones and relationship factors on sexual function of women through the natural menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:174-180.

- Shifren JL, Davis SR. Androgens in postmenopausal women: a review. Menopause. 2017;24:970-979.

- Sherwin BB, Gelfand MM, Brender W. Androgen enhances sexual motivation in females: a prospective, crossover study of sex steroid administration in the surgical menopause. Psychosom Med. 1985;47:339-351.

- Huang G, Basaria S, Travison TG, et al. Testosterone dose-response relationships in hysterectomized women with or without oophorectomy: effects on sexual function, body composition, muscle performance and physical function in a randomized trial. Menopause. 2014;21:612-623.

- Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682-688.

- Simon J, Braunstein G, Nachtigall L, et al. Testosterone patch increases sexual activity and desire in surgically menopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5226-5233.

- Shifren JL, Davis SR, Moreau M, et al. Testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in naturally menopausal women: results from the INTIMATE NM1 study. Menopause. 2006;13:770-779.

- Davis SR, Moreau M, Kroll R, et al; APHRODITE Study Team. Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2005-2017.

- Kingsberg S, Shifren J, Wekselman K, et al. Evaluation of the clinical relevance of benefits associated with transdermal testosterone treatment in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1001-1008.

- Wierman ME, Arlt W, Basson R, et al. Androgen therapy in women: a reappraisal: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3489-3510.

- Snabes M, Zborowski J, Simes S. Libigel (testosterone gel) does not differentiate from placebo therapy in the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire in postmenopausal women (abstract). J Sex Med. 2012;9(suppl 3):171.

- Lobo RA, Rosen RC, Yang HM, et al. Comparative effects of oral esterified estrogens with and without methyltestosterone on endocrine profiles and dimensions of sexual function in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1341-1352.

- Somboonporn W, Davis S, Seif M, et al. Testsoterone for peri- and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;19:CD004509.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice and American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Committee opinion 532: compounded bioidentical menopausal hormone therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;(2 pt 1):411-415.

- Fooladi E, Reuter SE, Bell RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a transdermal testosterone cream in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22:44-49.

- Shifren JL. Testosterone for midlife women: the hormone of desire? Menopause. 2015;22:1147-1149.

- The North American Menopause Society Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

- Simon JA, Nappi RE, Kingsberg SA, et al. Clarifying Vaginal Atrophy's Impact on Sex and Relationships (CLOSER) survey: emotional and physical impact of vaginal discomfort on North American postmenopausal women and their partners. Menopause. 2014;21:137-142.

- The North American Menopause Society. Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20:888-902.

- Shifren J, Monz B, Russo P, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:970-978.

- Davison S, Bell R, Donath S, et al. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3847-3853.

- Shifren JL, Desindes S, McIlwain M, et al. A randomized, open-label, crossover study comparing the effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen therapy on serum androgens, thyroid hormones, and adrenal hormones in naturally menopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14:985-994.

- Davis SR, Davison SL, Donath S, et al. Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. JAMA. 2005;294:91-96.

- Wahlin-Jacobsen S, Pedersen AT, Kristensen E, et al. Is there a correlation between androgens and sexual desire in women? J Sex Med. 2015;12:358-373.

- Randolph JF Jr, Zheng H, Avis NE, et al. Masturbation frequency and sexual function domains are associated with serum reproductive hormone levels across the menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:258-266.

- Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger H. The relative effects of hormones and relationship factors on sexual function of women through the natural menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:174-180.

- Shifren JL, Davis SR. Androgens in postmenopausal women: a review. Menopause. 2017;24:970-979.

- Sherwin BB, Gelfand MM, Brender W. Androgen enhances sexual motivation in females: a prospective, crossover study of sex steroid administration in the surgical menopause. Psychosom Med. 1985;47:339-351.

- Huang G, Basaria S, Travison TG, et al. Testosterone dose-response relationships in hysterectomized women with or without oophorectomy: effects on sexual function, body composition, muscle performance and physical function in a randomized trial. Menopause. 2014;21:612-623.

- Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682-688.

- Simon J, Braunstein G, Nachtigall L, et al. Testosterone patch increases sexual activity and desire in surgically menopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5226-5233.

- Shifren JL, Davis SR, Moreau M, et al. Testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in naturally menopausal women: results from the INTIMATE NM1 study. Menopause. 2006;13:770-779.

- Davis SR, Moreau M, Kroll R, et al; APHRODITE Study Team. Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2005-2017.

- Kingsberg S, Shifren J, Wekselman K, et al. Evaluation of the clinical relevance of benefits associated with transdermal testosterone treatment in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1001-1008.

- Wierman ME, Arlt W, Basson R, et al. Androgen therapy in women: a reappraisal: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:3489-3510.

- Snabes M, Zborowski J, Simes S. Libigel (testosterone gel) does not differentiate from placebo therapy in the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire in postmenopausal women (abstract). J Sex Med. 2012;9(suppl 3):171.

- Lobo RA, Rosen RC, Yang HM, et al. Comparative effects of oral esterified estrogens with and without methyltestosterone on endocrine profiles and dimensions of sexual function in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1341-1352.

- Somboonporn W, Davis S, Seif M, et al. Testsoterone for peri- and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;19:CD004509.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice and American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Committee opinion 532: compounded bioidentical menopausal hormone therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;(2 pt 1):411-415.

- Fooladi E, Reuter SE, Bell RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a transdermal testosterone cream in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22:44-49.

- Shifren JL. Testosterone for midlife women: the hormone of desire? Menopause. 2015;22:1147-1149.

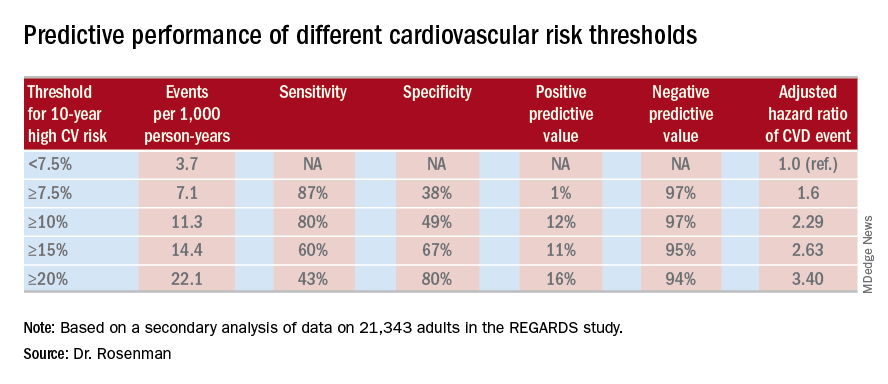

Data support revising ASCVD cardiovascular risk threshold

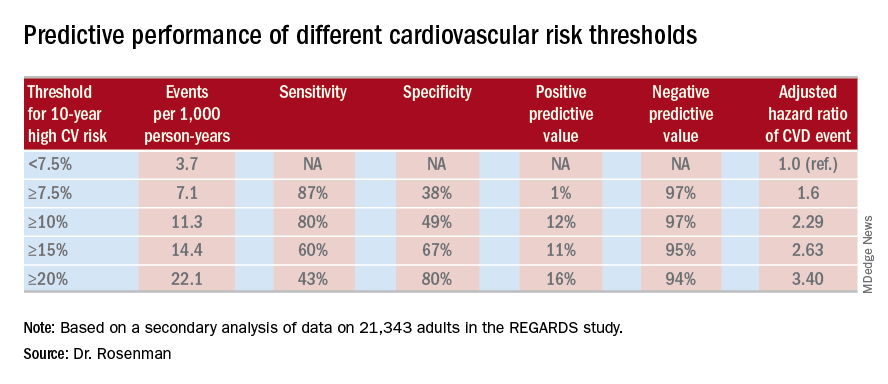

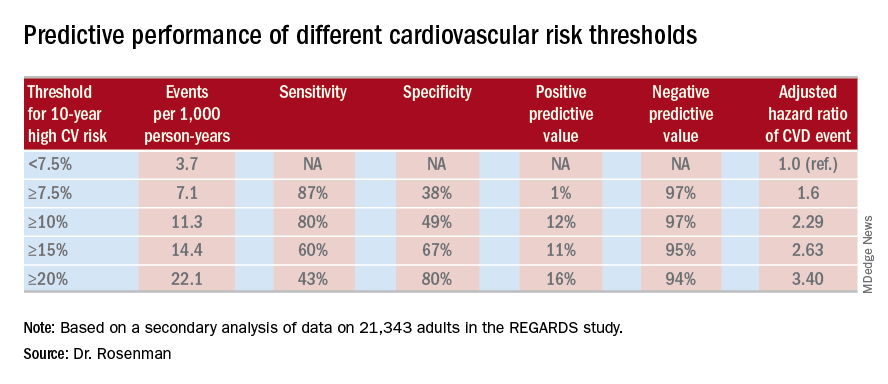

MUNICH – Revising the threshold for actionable high cardiovascular risk from the current 7.5% or greater risk of an event within 10 years as defined in American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines using the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD ) Risk Calculator to a 10% or greater 10-year risk would provide the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity for discriminating future risk of cardiovascular events, according to Robert S. Rosenman, MD.

“I think this is very important from a public health policy perspective,” Dr. Rosenman, a cardiologist who is professor of medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

He elaborated: “This would eliminate 11.4 million people who are currently candidates for a statin but may not be getting the benefits of statin therapy. We feel that this information is actually quite important for the primary prevention population because there’s been a lot of pushback from our primary care physician colleagues about the overtreatment of low-risk individuals” under the current guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129[25 Suppl 2]:S49-73).

Dr. Rosenman and his coinvestigators conducted a secondary analysis of data on 21,343 adults in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. All participants were free of a baseline history of heart disease or stroke. During a median 8.5 years of follow-up, 1,717 of them experienced adjudicated coronary heart disease or stroke events.

In multivariate analyses adjusted for standard cardiovascular risk factors, socioeconomic and demographic factors, and the use of statins and/or antihypertensive drugs, the higher the baseline 10-year predicted risk using the ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator based on the Pooled Cohort risk equations, the higher the incidence rate of cardiovascular events. No surprise there.

What was impressive, however, was that the optimal combination of sensitivity and specificity as captured in a statistic known as Youden’s index occurred at a 10-year predicted risk of 10%-12%. The biggest net improvement obtained through reclassification resulted from moving the threshold for elevated 10-year cardiovascular risk warranting statin therapy from 7.5% or greater to 10% or more, rather than using thresholds of 15% or 20%.

He cited data from the 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in support of his estimate that switching to a 10% threshold from the current 7.5% threshold would reduce the number of Americans deemed at high cardiovascular risk from 57.1 million to 45.8 million.

“This cutoff value of 10%, by the way, is the same cutoff value used in the recently published ACC/AHA guideline on hypertension. And it’s also the same cutoff value used for antiplatelet therapy in looking at the benefit/risk ratio. So this value of 10% is, I think, really the right number. Our study is the first effort that has been shown to validate that number, and it brings the cutoff values in the various guidelines in line,” the cardiologist observed.

Asked if these new findings are likely to result in a revision of the ACC/AHA cardiovascular risk assessment guidelines, Dr. Rosenman replied that the guidelines are under revision, with the draft update now circulating for comment. So the timing is dicey: His study is now in prepublication peer review, but hasn’t yet been published and thus may not carry persuasive weight.

“Hopefully, the guideline panel is going to make an adjustment to make the 10% figure in line with the blood pressure guidelines,” he said.

The new analysis of the REGARDS study was funded by a collaboration between Amgen, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and the University of Alabama. Dr. Rosenman reported receiving research funding from and serving as an advisor to Amgen and a handful of other companies.

MUNICH – Revising the threshold for actionable high cardiovascular risk from the current 7.5% or greater risk of an event within 10 years as defined in American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines using the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD ) Risk Calculator to a 10% or greater 10-year risk would provide the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity for discriminating future risk of cardiovascular events, according to Robert S. Rosenman, MD.

“I think this is very important from a public health policy perspective,” Dr. Rosenman, a cardiologist who is professor of medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

He elaborated: “This would eliminate 11.4 million people who are currently candidates for a statin but may not be getting the benefits of statin therapy. We feel that this information is actually quite important for the primary prevention population because there’s been a lot of pushback from our primary care physician colleagues about the overtreatment of low-risk individuals” under the current guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129[25 Suppl 2]:S49-73).

Dr. Rosenman and his coinvestigators conducted a secondary analysis of data on 21,343 adults in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. All participants were free of a baseline history of heart disease or stroke. During a median 8.5 years of follow-up, 1,717 of them experienced adjudicated coronary heart disease or stroke events.

In multivariate analyses adjusted for standard cardiovascular risk factors, socioeconomic and demographic factors, and the use of statins and/or antihypertensive drugs, the higher the baseline 10-year predicted risk using the ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator based on the Pooled Cohort risk equations, the higher the incidence rate of cardiovascular events. No surprise there.

What was impressive, however, was that the optimal combination of sensitivity and specificity as captured in a statistic known as Youden’s index occurred at a 10-year predicted risk of 10%-12%. The biggest net improvement obtained through reclassification resulted from moving the threshold for elevated 10-year cardiovascular risk warranting statin therapy from 7.5% or greater to 10% or more, rather than using thresholds of 15% or 20%.

He cited data from the 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in support of his estimate that switching to a 10% threshold from the current 7.5% threshold would reduce the number of Americans deemed at high cardiovascular risk from 57.1 million to 45.8 million.

“This cutoff value of 10%, by the way, is the same cutoff value used in the recently published ACC/AHA guideline on hypertension. And it’s also the same cutoff value used for antiplatelet therapy in looking at the benefit/risk ratio. So this value of 10% is, I think, really the right number. Our study is the first effort that has been shown to validate that number, and it brings the cutoff values in the various guidelines in line,” the cardiologist observed.

Asked if these new findings are likely to result in a revision of the ACC/AHA cardiovascular risk assessment guidelines, Dr. Rosenman replied that the guidelines are under revision, with the draft update now circulating for comment. So the timing is dicey: His study is now in prepublication peer review, but hasn’t yet been published and thus may not carry persuasive weight.

“Hopefully, the guideline panel is going to make an adjustment to make the 10% figure in line with the blood pressure guidelines,” he said.

The new analysis of the REGARDS study was funded by a collaboration between Amgen, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and the University of Alabama. Dr. Rosenman reported receiving research funding from and serving as an advisor to Amgen and a handful of other companies.

MUNICH – Revising the threshold for actionable high cardiovascular risk from the current 7.5% or greater risk of an event within 10 years as defined in American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines using the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD ) Risk Calculator to a 10% or greater 10-year risk would provide the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity for discriminating future risk of cardiovascular events, according to Robert S. Rosenman, MD.

“I think this is very important from a public health policy perspective,” Dr. Rosenman, a cardiologist who is professor of medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

He elaborated: “This would eliminate 11.4 million people who are currently candidates for a statin but may not be getting the benefits of statin therapy. We feel that this information is actually quite important for the primary prevention population because there’s been a lot of pushback from our primary care physician colleagues about the overtreatment of low-risk individuals” under the current guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129[25 Suppl 2]:S49-73).

Dr. Rosenman and his coinvestigators conducted a secondary analysis of data on 21,343 adults in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study. All participants were free of a baseline history of heart disease or stroke. During a median 8.5 years of follow-up, 1,717 of them experienced adjudicated coronary heart disease or stroke events.

In multivariate analyses adjusted for standard cardiovascular risk factors, socioeconomic and demographic factors, and the use of statins and/or antihypertensive drugs, the higher the baseline 10-year predicted risk using the ACC/AHA ASCVD Risk Calculator based on the Pooled Cohort risk equations, the higher the incidence rate of cardiovascular events. No surprise there.

What was impressive, however, was that the optimal combination of sensitivity and specificity as captured in a statistic known as Youden’s index occurred at a 10-year predicted risk of 10%-12%. The biggest net improvement obtained through reclassification resulted from moving the threshold for elevated 10-year cardiovascular risk warranting statin therapy from 7.5% or greater to 10% or more, rather than using thresholds of 15% or 20%.

He cited data from the 2011-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in support of his estimate that switching to a 10% threshold from the current 7.5% threshold would reduce the number of Americans deemed at high cardiovascular risk from 57.1 million to 45.8 million.

“This cutoff value of 10%, by the way, is the same cutoff value used in the recently published ACC/AHA guideline on hypertension. And it’s also the same cutoff value used for antiplatelet therapy in looking at the benefit/risk ratio. So this value of 10% is, I think, really the right number. Our study is the first effort that has been shown to validate that number, and it brings the cutoff values in the various guidelines in line,” the cardiologist observed.

Asked if these new findings are likely to result in a revision of the ACC/AHA cardiovascular risk assessment guidelines, Dr. Rosenman replied that the guidelines are under revision, with the draft update now circulating for comment. So the timing is dicey: His study is now in prepublication peer review, but hasn’t yet been published and thus may not carry persuasive weight.

“Hopefully, the guideline panel is going to make an adjustment to make the 10% figure in line with the blood pressure guidelines,” he said.

The new analysis of the REGARDS study was funded by a collaboration between Amgen, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and the University of Alabama. Dr. Rosenman reported receiving research funding from and serving as an advisor to Amgen and a handful of other companies.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Redefining the threshold for high 10-year cardiovascular risk from the current 7.5% to 10% would reduce the number of Americans warranting statin therapy by 11.4 million.

Study details: This was a secondary analysis of data on 21,343 adults in the REGARDS study, 1,717 of whom experienced coronary heart disease or stroke events during a median 8.5 years of prospective follow-up.

Disclosures: The new analysis of the REGARDS study was funded by a collaboration between Amgen, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and the University of Alabama. The presenter reported ties to Amgen and a handful of other companies.

FDA approves adalimumab biosimilar Hyrimoz