User login

Screening and Treating Hepatitis C in the VA: Achieving Excellence Using Lean and System Redesign

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem in the US. Following the 2010 report of the Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) on hepatitis and liver cancer, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan in 2011 with subsequent action plan updates for 2014-2016 and 2017-2020.1-3 A NASEM phase 2 report and the 2017-2020 HHS action plan outline a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.3,4 The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the single largest HCV care provider in the US with about 165,000 veterans in care diagnosed with HCV in the beginning of 2014 and is a national leader in the testing and treatment of HCV.5,6

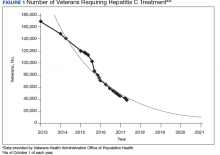

The VA’s recommendations for screening for HCV infection are in alignment with the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations to test all veterans born between 1945 and 1965 and anyone with risk factors such as injection drug use.7-9 As of January 1, 2018, the VA had screened more than 80% of veterans in care within this highest risk birth cohort. As of January 1, 2018, more than 100,000 veterans in VA care have initiated treatment for HCV with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) (Figure 1).

Several critical factors contributed to the VA success with HCV testing and treatment, including congressional appropriation of funding from fiscal year (FY) 2016 through FY 2018, unrestricted access to interferon-free DAA HCV treatments, and dedicated resources from the VA National Viral Hepatitis Program within the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs (HHRC) in the Office of Specialty Care Services.5 In 2014, HHRC created and supported the Hepatitis Innovation Team (HIT) Collaborative, a VA process improvement initiative enabling

Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) -based, multidisciplinary teams to increase veterans’ access to HCV testing and treatment.

As the VA makes consistent progress toward eliminating HCV in veterans in VA care, it has become clear that achieving a cure is only a starting point in improving HCV care. Many patients with HCV infection also have advanced liver disease (ALD), or cirrhosis, which is a condition of permanent liver fibrosis that remains after the patient has been cured of HCV infection. In addition to hepatitis C, ALD also can be caused by excessive alcohol use, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases, and several other inherited diseases. Advanced liver disease affects more than 80,000 veterans in VA care, and the HIT infrastructure provides an excellent framework to better understand and address facility-level and systemwide challenges in diagnosing, caring for, and treating veterans with ALD across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system.

This report will describe the elements that contributed to the success of the HIT Collaborative in redesigning care for patients affected by HCV in the VA and how these elements can be applied to improve the system of care for VHA ALD care.

Hepatitis Innovation Teams Collaborative Leadership

After the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved new DAA medications to treat HCV, the VA recognized the need to mobilize the health care system quickly and allocate resources for these new, minimally toxic, and highly effective medications. Early in 2014, HHRC established the National Hepatitis C Resource Center (NHCRC), a successor program to the 4 regional hepatitis C resource centers that had addressed HCV care across the system.10 The NHCRC was charged with developing an operational strategy for VA to respond rapidly to the availability of DAAs. In collaboration with representatives from the Office of Strategic Integration | Veterans Engineering Resource Center (OSI|VERC), the NHCRC formed the HIT Collaborative Leadership Team (CLT).

The HIT CLT is responsible for executing the HIT Collaborative and uses a Lean process improvement framework focused on eliminating waste and maximizing value. Members of the CLT with expertise in facilitation, Lean process improvement, leadership, clinical knowledge, and population health management act as coaches for the VISN HITs. The CLT works to build and support the VISN HITs, identify opportunities for individual teams to improve and assist in finding the right local mix of “players” to be successful. The HIT CLT ensures all teams are functioning and working toward achieving their goals. The CLT obtains data from VA national databases, which are provided to the VISN HITs to inform and encourage continuous improvement of their strategies. Annual VA-wide aspirational goals are developed and disseminated to encourage a unified mission.

Catchment areas for each VISN include between 6 and 10 medical centers as well as outpatient and ambulatory care centers. Multidisciplinary HITs are composed of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, social workers, mental health and substance use providers, peer support specialists, administrators, information technology experts, and systems redesign professionals from medical centers within each VISN. Teams develop strong relationships across medical centers, implement context-specific strategies applicable to rural

and urban centers, and share expertise. In addition to intra-VISN process improvement, HITs collaborate monthly across VISNs via a virtual platform. They share strong practices, seek advice from one another, and compare outcomes on an established set of goals.

The HITs use process improvement tools to systematically assess the current steps involved in care. At the close of each year, the HITs analyze the current state of operations and set goals to improve over the following year guided by a target state map. Seed funding is provided to every VISN HIT annually to launch change initiatives. Many VISN HITs use these funds to support a VISN HIT coordinator, and HITs also use this financial support to conduct 2- to 3-day process improvement workshops and to purchase supplies, such as point-of-care testing kits. The HIT communication and work are predominantly executed virtually.

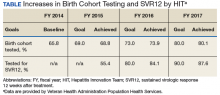

Each year, teams worked toward achieving goals set nationally. These included increasing HCV birth cohort testing and improving the percentage of patients who had SVR12 testing

(Table).

the percentage of patients who received SVR12 testing posttreatment completion was not included in the HIT Collaborative’s annual goals for the first year of the program. Recognizing this as a critical area for improvement, the HIT CLT set a goal to test 80% of all patients who completed treatment. The HITs applied Lean tools to identify and overcome gaps in the SVR12 testing process. By the end of the second year, 84% of all patients who completed treatment had been tested for SVR12.

The HITs also set specific local VISN and medical center goals, prioritizing projects that could have the greatest impact on local patient access and quality of care and build on existing strengths and address barriers. These projects encompass a wide range of areas that contribute to the overall national goals.

Focus on Lean

Lean process improvement is based on 2 key pillars: respect for people (those seeking service as customers and patients and those providing service as frontline staff and stakeholders) and continuous improvement. With Lean, personnel providing care should work to identify and eliminate waste in the system and to streamline care delivery to maximize process steps that are most valued by patients (eg, interaction with a clinical provider) and minimize those that are not valued (eg, time spent waiting to see a provider). With the knowledge that HHRC fully supports their work, HITs were encouraged to innovate based on local resources, context, and culture.

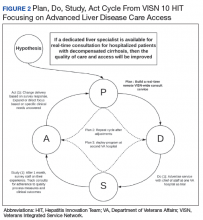

Teams receive basic training in Lean from the HIT CLT and local systems redesign specialists if available. The HITs apply the A3 structured approach to problem solving.11 The HITs follow prescribed problemsolving steps that help identify where to focus process improvement efforts, including analyzing the current state of care, outlining the target state, and prioritizing solution

approaches based on what will have the highest impact for patients.

to accommodate the outcomes they observe (Figure 2).

Innovations

Over the course of the HIT Collaborative, numerous innovations have emerged to address and mitigate barriers to HCV screening and treatment. Examples of successful innovations include the following:

- To address transportation issues, several teams developed programs specific to patients with HCV in rural locations or with limited mobility. Mobile vans and units traditionally used as mobile cardiology clinics were transformed into HCV clinics, bringing testing and treatment services directly to veterans;

- Pharmacists and social workers developed outreach strategies to locate homeless veterans, provide point-of-care testing and utilize mobile technology to concurrently enroll and link veterans to care; and

- Many liver care teams partnered with inpatient and outpatient substance use treatment clinics to provide patient education and coordinate HCV treatment.

Inter-VISN working groups developed systemwide tools to address common needs. In the program’s first year, a few medical facilities across a handful of VISNs shared local population health management systems, programming, and best practices. Over time, this working group combined the virtual networking capacity of the HIT Collaborative with technical expertise to promote rapid dissemination and uptake of a population health management system. Providers at medical centers across VA use the tools to identify veterans who should be screened and treated for HCV with the ability to continuously update information, identifying patients who do not respond to treatment or patients overdue for SVR12 testing.

Providers with experience using telehepatology formed another inter-VISN working group. These subject matter experts provided guidance to care teams interested in implementing telehealth in areas where limited local resources or knowledge had prevented them from moving forward. The ability to build a strong coalition across content areas fostered a collaborative learning environment, adaptable to implementing new processes and technologies.

In 2017, the VA made significant efforts to reach out to veterans eligible for VA care who had not yet been screened or remained untreated. In May, Hepatitis Awareness Month, HITs held HCV testing and community outreach events and participated in veteran stand-downs and veteran service organization activities.

Evaluation

Since 2014, the VA has increased its HCV treatment and screening rates. To assess the components contributing to these achievements and the role of the HIT Collaborative in driving this success, a team of implementation scientists have been working with the CLT to conduct a HIT program evaluation. The goal of the evaluation is to establish the impact of the HIT Collaborative. The evaluation team catalogs the activities of the Collaborative and the HITs and assesses implementation strategies (use of specific techniques) to increase the uptake of evidence-based practices specifically related to HCV treatment.12

At the close of each FY, HCV providers and members of the HIT Collaborative are queried through an online survey to determine which strategies have been used to improve HCV care and how these strategies were associated with the HIT Collaborative. The use of more strategies was associated with more HCV treatment initiations.13 All utilized strategies were identified whether or not they were associated with treatment starts. These data are being used to understand which combinations of strategies are most effective at increasing treatment for HCV in the VA and to inform future initiatives.

Expanding the Scope

Inspired by the successful results of the HIT work in HCV and in the spirit of continuously improving health care delivery, HHRC expanded the scope of the HIT Collaborative in FY 2018 to include ALD. There are about 80,000 veterans in VA care with advanced scarring of the liver and between 10,000 to 15,000 new diagnoses each year. In addition to HCV as an etiology for ALD, cases of cirrhosis are projected to increase among veterans in care due to metabolic syndrome and alcohol use. A recent review of VA data from fiscal year 2016 found that 88.6% of ALD patients had been seen in primary care within the past 2 years, with about half (51%) seen in a gastroenterology (GI) or hepatology clinic (Personal communication, HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Program Office March 16, 2018). For patients in VA care with ALD, GI visits are associated with a lower 5-year mortality.14 Annual mortality for all ALD patients in VA is 6.2%, and of those with a hospital admission, mortality rises to 31%.15 In FY 2016, there were about 52,000 ALD-related discharges (more than 2 per patient). Of those discharges, 24% were readmitted within 30 days, with an average length of stay of 1.9 days and an estimated cost per patient of $47,000 over 3 years.16

Hepatologists from across the VA convened to identify critical opportunities for improvement for patients with ALD. Base on available evidence presented in the literature and their clinical expertise, these subject matter experts identified several areas for quality improvement, with the overarching goal to improve identification of patients with early cirrhosis and ensure appropriate linkage to care for all cirrhotic patients, thus improving quality of life and reducing mortality. Although not finalized, candidate improvement targets include consistent linkage to care and treatment for HCV and HBV, comprehensive case management, post-discharge patient follow-up, and adherence to evidence-based standards of care.

Conclusion

The VA has made great strides in nearly eliminating HCV among veterans in VA care. The national effort to redesign hepatitis care using Lean management strategies and develop local and regional teams and centralized support allowed VA to maximize available resources to achieve higher rates of HCV birth cohort testing and treatment of patients infected with HCV than has any other health care system in the US.

The HIT Collaborative has been a unique and innovative mechanism to promote directed, patient-outcome driven change in a large and dynamic health care system. It has allowed rural and urban providers to work together to develop and spread quality improvement innovations and as an integrated system to achieve national priorities. The focus of this foundational HIT structure is expanding to identifying, treat, and care for VA’s ALD population.

1. Colvin HM, Mitchell AE, eds; and the Committee on the Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infections Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Combating the silent epidemic of viral hepatitis: action plan for the prevention, care and treatment of viral hepatitis. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/action-plan-viral-hepatitis-2011.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2018.

3. Wolitski R. National viral hepatitis action plan: 2017-2020. https://www.hhs.gov/hepatitis/action-plan/national-viralhepatitis-action-plan-overview/index.html. Updated February

21, 2018. Accessed May 8, 2018.

4. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017.

5. Belperio PS, Chartier M, Ross DB, Alaigh P, Shulkin D. Curing hepatitis C infection: best practices from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann of Intern Med. 2017;167(7):499-504.

6. Kushner T, Serper M, Kaplan DE. Delta hepatitis within the Veterans Affairs medical system in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes. J Hepatol. 2015;63(3):586-592.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Health Administration. National Clinical Preventive Service Guidance Statements: Screening for Hepatitis C. http://www.prevention.va.gov/CPS/Screening_for_Hepatitis_C.asp. Published on June 20, 2017. [Nonpubic document; source not verified.]

8. Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):349-357.

9. Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1-32.

10. Garrard J, Choudary V, Groom H, et al. Organizational change in management of hepatitis C: evaluation of a CME program. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(2):145-160.

11. Shook J. Managing to Learn: Using the A3 Management Process to Solve Problems, Gain Agreement, Mentor, and Lead. Cambridge, MA: Lean Enterprise Institute; 2010.

12. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21.

13. Rogal SS, Yakovchenko V, Waltz TJ, et al. The association between implementation strategy use and the uptake of hepatitis C treatment in a national sample. Implement Sci.

2017;12(1):60.

14. Mellinger JL, Moser S, Welsh DE, et al. Access to subspecialty care and survival among patients with liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(6):838-844.

15. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in the burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US Veterans from 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-1482.e5.

16. Kaplan DE, Chapko MK, Mehta R, et al; VOCAL Study Group. Healthcare costs related to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma among veterans with cirrhosis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(1):106-114.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem in the US. Following the 2010 report of the Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) on hepatitis and liver cancer, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan in 2011 with subsequent action plan updates for 2014-2016 and 2017-2020.1-3 A NASEM phase 2 report and the 2017-2020 HHS action plan outline a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.3,4 The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the single largest HCV care provider in the US with about 165,000 veterans in care diagnosed with HCV in the beginning of 2014 and is a national leader in the testing and treatment of HCV.5,6

The VA’s recommendations for screening for HCV infection are in alignment with the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations to test all veterans born between 1945 and 1965 and anyone with risk factors such as injection drug use.7-9 As of January 1, 2018, the VA had screened more than 80% of veterans in care within this highest risk birth cohort. As of January 1, 2018, more than 100,000 veterans in VA care have initiated treatment for HCV with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) (Figure 1).

Several critical factors contributed to the VA success with HCV testing and treatment, including congressional appropriation of funding from fiscal year (FY) 2016 through FY 2018, unrestricted access to interferon-free DAA HCV treatments, and dedicated resources from the VA National Viral Hepatitis Program within the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs (HHRC) in the Office of Specialty Care Services.5 In 2014, HHRC created and supported the Hepatitis Innovation Team (HIT) Collaborative, a VA process improvement initiative enabling

Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) -based, multidisciplinary teams to increase veterans’ access to HCV testing and treatment.

As the VA makes consistent progress toward eliminating HCV in veterans in VA care, it has become clear that achieving a cure is only a starting point in improving HCV care. Many patients with HCV infection also have advanced liver disease (ALD), or cirrhosis, which is a condition of permanent liver fibrosis that remains after the patient has been cured of HCV infection. In addition to hepatitis C, ALD also can be caused by excessive alcohol use, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases, and several other inherited diseases. Advanced liver disease affects more than 80,000 veterans in VA care, and the HIT infrastructure provides an excellent framework to better understand and address facility-level and systemwide challenges in diagnosing, caring for, and treating veterans with ALD across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system.

This report will describe the elements that contributed to the success of the HIT Collaborative in redesigning care for patients affected by HCV in the VA and how these elements can be applied to improve the system of care for VHA ALD care.

Hepatitis Innovation Teams Collaborative Leadership

After the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved new DAA medications to treat HCV, the VA recognized the need to mobilize the health care system quickly and allocate resources for these new, minimally toxic, and highly effective medications. Early in 2014, HHRC established the National Hepatitis C Resource Center (NHCRC), a successor program to the 4 regional hepatitis C resource centers that had addressed HCV care across the system.10 The NHCRC was charged with developing an operational strategy for VA to respond rapidly to the availability of DAAs. In collaboration with representatives from the Office of Strategic Integration | Veterans Engineering Resource Center (OSI|VERC), the NHCRC formed the HIT Collaborative Leadership Team (CLT).

The HIT CLT is responsible for executing the HIT Collaborative and uses a Lean process improvement framework focused on eliminating waste and maximizing value. Members of the CLT with expertise in facilitation, Lean process improvement, leadership, clinical knowledge, and population health management act as coaches for the VISN HITs. The CLT works to build and support the VISN HITs, identify opportunities for individual teams to improve and assist in finding the right local mix of “players” to be successful. The HIT CLT ensures all teams are functioning and working toward achieving their goals. The CLT obtains data from VA national databases, which are provided to the VISN HITs to inform and encourage continuous improvement of their strategies. Annual VA-wide aspirational goals are developed and disseminated to encourage a unified mission.

Catchment areas for each VISN include between 6 and 10 medical centers as well as outpatient and ambulatory care centers. Multidisciplinary HITs are composed of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, social workers, mental health and substance use providers, peer support specialists, administrators, information technology experts, and systems redesign professionals from medical centers within each VISN. Teams develop strong relationships across medical centers, implement context-specific strategies applicable to rural

and urban centers, and share expertise. In addition to intra-VISN process improvement, HITs collaborate monthly across VISNs via a virtual platform. They share strong practices, seek advice from one another, and compare outcomes on an established set of goals.

The HITs use process improvement tools to systematically assess the current steps involved in care. At the close of each year, the HITs analyze the current state of operations and set goals to improve over the following year guided by a target state map. Seed funding is provided to every VISN HIT annually to launch change initiatives. Many VISN HITs use these funds to support a VISN HIT coordinator, and HITs also use this financial support to conduct 2- to 3-day process improvement workshops and to purchase supplies, such as point-of-care testing kits. The HIT communication and work are predominantly executed virtually.

Each year, teams worked toward achieving goals set nationally. These included increasing HCV birth cohort testing and improving the percentage of patients who had SVR12 testing

(Table).

the percentage of patients who received SVR12 testing posttreatment completion was not included in the HIT Collaborative’s annual goals for the first year of the program. Recognizing this as a critical area for improvement, the HIT CLT set a goal to test 80% of all patients who completed treatment. The HITs applied Lean tools to identify and overcome gaps in the SVR12 testing process. By the end of the second year, 84% of all patients who completed treatment had been tested for SVR12.

The HITs also set specific local VISN and medical center goals, prioritizing projects that could have the greatest impact on local patient access and quality of care and build on existing strengths and address barriers. These projects encompass a wide range of areas that contribute to the overall national goals.

Focus on Lean

Lean process improvement is based on 2 key pillars: respect for people (those seeking service as customers and patients and those providing service as frontline staff and stakeholders) and continuous improvement. With Lean, personnel providing care should work to identify and eliminate waste in the system and to streamline care delivery to maximize process steps that are most valued by patients (eg, interaction with a clinical provider) and minimize those that are not valued (eg, time spent waiting to see a provider). With the knowledge that HHRC fully supports their work, HITs were encouraged to innovate based on local resources, context, and culture.

Teams receive basic training in Lean from the HIT CLT and local systems redesign specialists if available. The HITs apply the A3 structured approach to problem solving.11 The HITs follow prescribed problemsolving steps that help identify where to focus process improvement efforts, including analyzing the current state of care, outlining the target state, and prioritizing solution

approaches based on what will have the highest impact for patients.

to accommodate the outcomes they observe (Figure 2).

Innovations

Over the course of the HIT Collaborative, numerous innovations have emerged to address and mitigate barriers to HCV screening and treatment. Examples of successful innovations include the following:

- To address transportation issues, several teams developed programs specific to patients with HCV in rural locations or with limited mobility. Mobile vans and units traditionally used as mobile cardiology clinics were transformed into HCV clinics, bringing testing and treatment services directly to veterans;

- Pharmacists and social workers developed outreach strategies to locate homeless veterans, provide point-of-care testing and utilize mobile technology to concurrently enroll and link veterans to care; and

- Many liver care teams partnered with inpatient and outpatient substance use treatment clinics to provide patient education and coordinate HCV treatment.

Inter-VISN working groups developed systemwide tools to address common needs. In the program’s first year, a few medical facilities across a handful of VISNs shared local population health management systems, programming, and best practices. Over time, this working group combined the virtual networking capacity of the HIT Collaborative with technical expertise to promote rapid dissemination and uptake of a population health management system. Providers at medical centers across VA use the tools to identify veterans who should be screened and treated for HCV with the ability to continuously update information, identifying patients who do not respond to treatment or patients overdue for SVR12 testing.

Providers with experience using telehepatology formed another inter-VISN working group. These subject matter experts provided guidance to care teams interested in implementing telehealth in areas where limited local resources or knowledge had prevented them from moving forward. The ability to build a strong coalition across content areas fostered a collaborative learning environment, adaptable to implementing new processes and technologies.

In 2017, the VA made significant efforts to reach out to veterans eligible for VA care who had not yet been screened or remained untreated. In May, Hepatitis Awareness Month, HITs held HCV testing and community outreach events and participated in veteran stand-downs and veteran service organization activities.

Evaluation

Since 2014, the VA has increased its HCV treatment and screening rates. To assess the components contributing to these achievements and the role of the HIT Collaborative in driving this success, a team of implementation scientists have been working with the CLT to conduct a HIT program evaluation. The goal of the evaluation is to establish the impact of the HIT Collaborative. The evaluation team catalogs the activities of the Collaborative and the HITs and assesses implementation strategies (use of specific techniques) to increase the uptake of evidence-based practices specifically related to HCV treatment.12

At the close of each FY, HCV providers and members of the HIT Collaborative are queried through an online survey to determine which strategies have been used to improve HCV care and how these strategies were associated with the HIT Collaborative. The use of more strategies was associated with more HCV treatment initiations.13 All utilized strategies were identified whether or not they were associated with treatment starts. These data are being used to understand which combinations of strategies are most effective at increasing treatment for HCV in the VA and to inform future initiatives.

Expanding the Scope

Inspired by the successful results of the HIT work in HCV and in the spirit of continuously improving health care delivery, HHRC expanded the scope of the HIT Collaborative in FY 2018 to include ALD. There are about 80,000 veterans in VA care with advanced scarring of the liver and between 10,000 to 15,000 new diagnoses each year. In addition to HCV as an etiology for ALD, cases of cirrhosis are projected to increase among veterans in care due to metabolic syndrome and alcohol use. A recent review of VA data from fiscal year 2016 found that 88.6% of ALD patients had been seen in primary care within the past 2 years, with about half (51%) seen in a gastroenterology (GI) or hepatology clinic (Personal communication, HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Program Office March 16, 2018). For patients in VA care with ALD, GI visits are associated with a lower 5-year mortality.14 Annual mortality for all ALD patients in VA is 6.2%, and of those with a hospital admission, mortality rises to 31%.15 In FY 2016, there were about 52,000 ALD-related discharges (more than 2 per patient). Of those discharges, 24% were readmitted within 30 days, with an average length of stay of 1.9 days and an estimated cost per patient of $47,000 over 3 years.16

Hepatologists from across the VA convened to identify critical opportunities for improvement for patients with ALD. Base on available evidence presented in the literature and their clinical expertise, these subject matter experts identified several areas for quality improvement, with the overarching goal to improve identification of patients with early cirrhosis and ensure appropriate linkage to care for all cirrhotic patients, thus improving quality of life and reducing mortality. Although not finalized, candidate improvement targets include consistent linkage to care and treatment for HCV and HBV, comprehensive case management, post-discharge patient follow-up, and adherence to evidence-based standards of care.

Conclusion

The VA has made great strides in nearly eliminating HCV among veterans in VA care. The national effort to redesign hepatitis care using Lean management strategies and develop local and regional teams and centralized support allowed VA to maximize available resources to achieve higher rates of HCV birth cohort testing and treatment of patients infected with HCV than has any other health care system in the US.

The HIT Collaborative has been a unique and innovative mechanism to promote directed, patient-outcome driven change in a large and dynamic health care system. It has allowed rural and urban providers to work together to develop and spread quality improvement innovations and as an integrated system to achieve national priorities. The focus of this foundational HIT structure is expanding to identifying, treat, and care for VA’s ALD population.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health problem in the US. Following the 2010 report of the Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) on hepatitis and liver cancer, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan in 2011 with subsequent action plan updates for 2014-2016 and 2017-2020.1-3 A NASEM phase 2 report and the 2017-2020 HHS action plan outline a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.3,4 The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the single largest HCV care provider in the US with about 165,000 veterans in care diagnosed with HCV in the beginning of 2014 and is a national leader in the testing and treatment of HCV.5,6

The VA’s recommendations for screening for HCV infection are in alignment with the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations to test all veterans born between 1945 and 1965 and anyone with risk factors such as injection drug use.7-9 As of January 1, 2018, the VA had screened more than 80% of veterans in care within this highest risk birth cohort. As of January 1, 2018, more than 100,000 veterans in VA care have initiated treatment for HCV with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) (Figure 1).

Several critical factors contributed to the VA success with HCV testing and treatment, including congressional appropriation of funding from fiscal year (FY) 2016 through FY 2018, unrestricted access to interferon-free DAA HCV treatments, and dedicated resources from the VA National Viral Hepatitis Program within the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs (HHRC) in the Office of Specialty Care Services.5 In 2014, HHRC created and supported the Hepatitis Innovation Team (HIT) Collaborative, a VA process improvement initiative enabling

Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) -based, multidisciplinary teams to increase veterans’ access to HCV testing and treatment.

As the VA makes consistent progress toward eliminating HCV in veterans in VA care, it has become clear that achieving a cure is only a starting point in improving HCV care. Many patients with HCV infection also have advanced liver disease (ALD), or cirrhosis, which is a condition of permanent liver fibrosis that remains after the patient has been cured of HCV infection. In addition to hepatitis C, ALD also can be caused by excessive alcohol use, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases, and several other inherited diseases. Advanced liver disease affects more than 80,000 veterans in VA care, and the HIT infrastructure provides an excellent framework to better understand and address facility-level and systemwide challenges in diagnosing, caring for, and treating veterans with ALD across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system.

This report will describe the elements that contributed to the success of the HIT Collaborative in redesigning care for patients affected by HCV in the VA and how these elements can be applied to improve the system of care for VHA ALD care.

Hepatitis Innovation Teams Collaborative Leadership

After the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved new DAA medications to treat HCV, the VA recognized the need to mobilize the health care system quickly and allocate resources for these new, minimally toxic, and highly effective medications. Early in 2014, HHRC established the National Hepatitis C Resource Center (NHCRC), a successor program to the 4 regional hepatitis C resource centers that had addressed HCV care across the system.10 The NHCRC was charged with developing an operational strategy for VA to respond rapidly to the availability of DAAs. In collaboration with representatives from the Office of Strategic Integration | Veterans Engineering Resource Center (OSI|VERC), the NHCRC formed the HIT Collaborative Leadership Team (CLT).

The HIT CLT is responsible for executing the HIT Collaborative and uses a Lean process improvement framework focused on eliminating waste and maximizing value. Members of the CLT with expertise in facilitation, Lean process improvement, leadership, clinical knowledge, and population health management act as coaches for the VISN HITs. The CLT works to build and support the VISN HITs, identify opportunities for individual teams to improve and assist in finding the right local mix of “players” to be successful. The HIT CLT ensures all teams are functioning and working toward achieving their goals. The CLT obtains data from VA national databases, which are provided to the VISN HITs to inform and encourage continuous improvement of their strategies. Annual VA-wide aspirational goals are developed and disseminated to encourage a unified mission.

Catchment areas for each VISN include between 6 and 10 medical centers as well as outpatient and ambulatory care centers. Multidisciplinary HITs are composed of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, social workers, mental health and substance use providers, peer support specialists, administrators, information technology experts, and systems redesign professionals from medical centers within each VISN. Teams develop strong relationships across medical centers, implement context-specific strategies applicable to rural

and urban centers, and share expertise. In addition to intra-VISN process improvement, HITs collaborate monthly across VISNs via a virtual platform. They share strong practices, seek advice from one another, and compare outcomes on an established set of goals.

The HITs use process improvement tools to systematically assess the current steps involved in care. At the close of each year, the HITs analyze the current state of operations and set goals to improve over the following year guided by a target state map. Seed funding is provided to every VISN HIT annually to launch change initiatives. Many VISN HITs use these funds to support a VISN HIT coordinator, and HITs also use this financial support to conduct 2- to 3-day process improvement workshops and to purchase supplies, such as point-of-care testing kits. The HIT communication and work are predominantly executed virtually.

Each year, teams worked toward achieving goals set nationally. These included increasing HCV birth cohort testing and improving the percentage of patients who had SVR12 testing

(Table).

the percentage of patients who received SVR12 testing posttreatment completion was not included in the HIT Collaborative’s annual goals for the first year of the program. Recognizing this as a critical area for improvement, the HIT CLT set a goal to test 80% of all patients who completed treatment. The HITs applied Lean tools to identify and overcome gaps in the SVR12 testing process. By the end of the second year, 84% of all patients who completed treatment had been tested for SVR12.

The HITs also set specific local VISN and medical center goals, prioritizing projects that could have the greatest impact on local patient access and quality of care and build on existing strengths and address barriers. These projects encompass a wide range of areas that contribute to the overall national goals.

Focus on Lean

Lean process improvement is based on 2 key pillars: respect for people (those seeking service as customers and patients and those providing service as frontline staff and stakeholders) and continuous improvement. With Lean, personnel providing care should work to identify and eliminate waste in the system and to streamline care delivery to maximize process steps that are most valued by patients (eg, interaction with a clinical provider) and minimize those that are not valued (eg, time spent waiting to see a provider). With the knowledge that HHRC fully supports their work, HITs were encouraged to innovate based on local resources, context, and culture.

Teams receive basic training in Lean from the HIT CLT and local systems redesign specialists if available. The HITs apply the A3 structured approach to problem solving.11 The HITs follow prescribed problemsolving steps that help identify where to focus process improvement efforts, including analyzing the current state of care, outlining the target state, and prioritizing solution

approaches based on what will have the highest impact for patients.

to accommodate the outcomes they observe (Figure 2).

Innovations

Over the course of the HIT Collaborative, numerous innovations have emerged to address and mitigate barriers to HCV screening and treatment. Examples of successful innovations include the following:

- To address transportation issues, several teams developed programs specific to patients with HCV in rural locations or with limited mobility. Mobile vans and units traditionally used as mobile cardiology clinics were transformed into HCV clinics, bringing testing and treatment services directly to veterans;

- Pharmacists and social workers developed outreach strategies to locate homeless veterans, provide point-of-care testing and utilize mobile technology to concurrently enroll and link veterans to care; and

- Many liver care teams partnered with inpatient and outpatient substance use treatment clinics to provide patient education and coordinate HCV treatment.

Inter-VISN working groups developed systemwide tools to address common needs. In the program’s first year, a few medical facilities across a handful of VISNs shared local population health management systems, programming, and best practices. Over time, this working group combined the virtual networking capacity of the HIT Collaborative with technical expertise to promote rapid dissemination and uptake of a population health management system. Providers at medical centers across VA use the tools to identify veterans who should be screened and treated for HCV with the ability to continuously update information, identifying patients who do not respond to treatment or patients overdue for SVR12 testing.

Providers with experience using telehepatology formed another inter-VISN working group. These subject matter experts provided guidance to care teams interested in implementing telehealth in areas where limited local resources or knowledge had prevented them from moving forward. The ability to build a strong coalition across content areas fostered a collaborative learning environment, adaptable to implementing new processes and technologies.

In 2017, the VA made significant efforts to reach out to veterans eligible for VA care who had not yet been screened or remained untreated. In May, Hepatitis Awareness Month, HITs held HCV testing and community outreach events and participated in veteran stand-downs and veteran service organization activities.

Evaluation

Since 2014, the VA has increased its HCV treatment and screening rates. To assess the components contributing to these achievements and the role of the HIT Collaborative in driving this success, a team of implementation scientists have been working with the CLT to conduct a HIT program evaluation. The goal of the evaluation is to establish the impact of the HIT Collaborative. The evaluation team catalogs the activities of the Collaborative and the HITs and assesses implementation strategies (use of specific techniques) to increase the uptake of evidence-based practices specifically related to HCV treatment.12

At the close of each FY, HCV providers and members of the HIT Collaborative are queried through an online survey to determine which strategies have been used to improve HCV care and how these strategies were associated with the HIT Collaborative. The use of more strategies was associated with more HCV treatment initiations.13 All utilized strategies were identified whether or not they were associated with treatment starts. These data are being used to understand which combinations of strategies are most effective at increasing treatment for HCV in the VA and to inform future initiatives.

Expanding the Scope

Inspired by the successful results of the HIT work in HCV and in the spirit of continuously improving health care delivery, HHRC expanded the scope of the HIT Collaborative in FY 2018 to include ALD. There are about 80,000 veterans in VA care with advanced scarring of the liver and between 10,000 to 15,000 new diagnoses each year. In addition to HCV as an etiology for ALD, cases of cirrhosis are projected to increase among veterans in care due to metabolic syndrome and alcohol use. A recent review of VA data from fiscal year 2016 found that 88.6% of ALD patients had been seen in primary care within the past 2 years, with about half (51%) seen in a gastroenterology (GI) or hepatology clinic (Personal communication, HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Program Office March 16, 2018). For patients in VA care with ALD, GI visits are associated with a lower 5-year mortality.14 Annual mortality for all ALD patients in VA is 6.2%, and of those with a hospital admission, mortality rises to 31%.15 In FY 2016, there were about 52,000 ALD-related discharges (more than 2 per patient). Of those discharges, 24% were readmitted within 30 days, with an average length of stay of 1.9 days and an estimated cost per patient of $47,000 over 3 years.16

Hepatologists from across the VA convened to identify critical opportunities for improvement for patients with ALD. Base on available evidence presented in the literature and their clinical expertise, these subject matter experts identified several areas for quality improvement, with the overarching goal to improve identification of patients with early cirrhosis and ensure appropriate linkage to care for all cirrhotic patients, thus improving quality of life and reducing mortality. Although not finalized, candidate improvement targets include consistent linkage to care and treatment for HCV and HBV, comprehensive case management, post-discharge patient follow-up, and adherence to evidence-based standards of care.

Conclusion

The VA has made great strides in nearly eliminating HCV among veterans in VA care. The national effort to redesign hepatitis care using Lean management strategies and develop local and regional teams and centralized support allowed VA to maximize available resources to achieve higher rates of HCV birth cohort testing and treatment of patients infected with HCV than has any other health care system in the US.

The HIT Collaborative has been a unique and innovative mechanism to promote directed, patient-outcome driven change in a large and dynamic health care system. It has allowed rural and urban providers to work together to develop and spread quality improvement innovations and as an integrated system to achieve national priorities. The focus of this foundational HIT structure is expanding to identifying, treat, and care for VA’s ALD population.

1. Colvin HM, Mitchell AE, eds; and the Committee on the Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infections Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Combating the silent epidemic of viral hepatitis: action plan for the prevention, care and treatment of viral hepatitis. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/action-plan-viral-hepatitis-2011.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2018.

3. Wolitski R. National viral hepatitis action plan: 2017-2020. https://www.hhs.gov/hepatitis/action-plan/national-viralhepatitis-action-plan-overview/index.html. Updated February

21, 2018. Accessed May 8, 2018.

4. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017.

5. Belperio PS, Chartier M, Ross DB, Alaigh P, Shulkin D. Curing hepatitis C infection: best practices from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann of Intern Med. 2017;167(7):499-504.

6. Kushner T, Serper M, Kaplan DE. Delta hepatitis within the Veterans Affairs medical system in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes. J Hepatol. 2015;63(3):586-592.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Health Administration. National Clinical Preventive Service Guidance Statements: Screening for Hepatitis C. http://www.prevention.va.gov/CPS/Screening_for_Hepatitis_C.asp. Published on June 20, 2017. [Nonpubic document; source not verified.]

8. Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):349-357.

9. Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1-32.

10. Garrard J, Choudary V, Groom H, et al. Organizational change in management of hepatitis C: evaluation of a CME program. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(2):145-160.

11. Shook J. Managing to Learn: Using the A3 Management Process to Solve Problems, Gain Agreement, Mentor, and Lead. Cambridge, MA: Lean Enterprise Institute; 2010.

12. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21.

13. Rogal SS, Yakovchenko V, Waltz TJ, et al. The association between implementation strategy use and the uptake of hepatitis C treatment in a national sample. Implement Sci.

2017;12(1):60.

14. Mellinger JL, Moser S, Welsh DE, et al. Access to subspecialty care and survival among patients with liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(6):838-844.

15. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in the burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US Veterans from 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-1482.e5.

16. Kaplan DE, Chapko MK, Mehta R, et al; VOCAL Study Group. Healthcare costs related to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma among veterans with cirrhosis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(1):106-114.

1. Colvin HM, Mitchell AE, eds; and the Committee on the Prevention and Control of Viral Hepatitis Infections Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Combating the silent epidemic of viral hepatitis: action plan for the prevention, care and treatment of viral hepatitis. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/action-plan-viral-hepatitis-2011.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2018.

3. Wolitski R. National viral hepatitis action plan: 2017-2020. https://www.hhs.gov/hepatitis/action-plan/national-viralhepatitis-action-plan-overview/index.html. Updated February

21, 2018. Accessed May 8, 2018.

4. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017.

5. Belperio PS, Chartier M, Ross DB, Alaigh P, Shulkin D. Curing hepatitis C infection: best practices from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann of Intern Med. 2017;167(7):499-504.

6. Kushner T, Serper M, Kaplan DE. Delta hepatitis within the Veterans Affairs medical system in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes. J Hepatol. 2015;63(3):586-592.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Health Administration. National Clinical Preventive Service Guidance Statements: Screening for Hepatitis C. http://www.prevention.va.gov/CPS/Screening_for_Hepatitis_C.asp. Published on June 20, 2017. [Nonpubic document; source not verified.]

8. Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(5):349-357.

9. Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1-32.

10. Garrard J, Choudary V, Groom H, et al. Organizational change in management of hepatitis C: evaluation of a CME program. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(2):145-160.

11. Shook J. Managing to Learn: Using the A3 Management Process to Solve Problems, Gain Agreement, Mentor, and Lead. Cambridge, MA: Lean Enterprise Institute; 2010.

12. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21.

13. Rogal SS, Yakovchenko V, Waltz TJ, et al. The association between implementation strategy use and the uptake of hepatitis C treatment in a national sample. Implement Sci.

2017;12(1):60.

14. Mellinger JL, Moser S, Welsh DE, et al. Access to subspecialty care and survival among patients with liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(6):838-844.

15. Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in the burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US Veterans from 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-1482.e5.

16. Kaplan DE, Chapko MK, Mehta R, et al; VOCAL Study Group. Healthcare costs related to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma among veterans with cirrhosis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(1):106-114.

A ‘highly effective’ strategy for haplo-HSCT

STOCKHOLM—Researchers have identified a “highly effective” transplant strategy for pediatric patients with primary immunodeficiencies who lack a suitable HLA-compatible donor, according to a speaker at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA).

The strategy involves α/β T-cell- and B-cell-depleted haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant (haplo-HSCT) followed by infusion of the T-cell product BPX-501.

Children treated with this strategy in a phase 1/2 trial had disease-free and overall survival rates that compared favorably with rates observed in recipients of matched, unrelated transplants.

In addition, the incidence of severe acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GHVD) was low in this trial.

Daria Pagliara, MD, PhD, of Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesu in Rome, Italy, presented these results at the recent EHA Congress as abstract S871.

The research was sponsored by Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing BPX-501.

BPX-501 consists of genetically modified donor T cells incorporating the CaspaCIDe safety switch, which is designed to eliminate the T cells in the event of toxicity. Rimiducid is used to activate the CaspaCIDe safety switch, which consists of the CID-binding domain coupled to the signaling domain of caspase-9, an enzyme that is part of the apoptotic pathway.

Dr Pagliara explained that T cells are collected from donors via non-mobilized apheresis, the cells are modified to create the BPX-501 product, and the product is infused in HSCT recipients at day 14 after transplant (+/- 4 days).

The patients do not receive GVHD prophylaxis after transplant but are given rimiducid if they develop GVHD that does not respond to standard therapy.

Patients and transplant characteristics

Dr Pagliara reported results with BPX-501 in 59 patients. They had a median age of 1.85 years (range, 0.21 to 17.55), and 57.6% were male.

Patients had severe combined immune deficiency (32%), Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome (15%), chronic granulomatous disease (12%), hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (10%), combined immunodeficiency disease (7%), major histocompatibility complex class II deficiency (5%), and “other” immunodeficiencies (19%).

The patients received BPX-501 after an α/β T-cell-depleted, B-cell-depleted haplo-HSCT. Most patients had a parent donor (94.9%), and 5.1% had a sibling donor. The median donor age was 34 (range, 21-52).

About half of patients (49.2%) received treosulfan-based conditioning, 39% received busulfan-based conditioning, and 11.9% received other conditioning.

The median CD34 dose was 22.0 x 106/kg, and the median α/β T-cell dose was 0.4 x 105/kg.

The median time to BPX-501 infusion was 15 days (range, 11-56). The median time to discharge was 40 days (range, 18-204).

The median follow-up was 536 days (range, 32-1252).

Engraftment and survival

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 16 days, and the median time to platelet engraftment was 11 days.

Three patients had primary graft failure (5.1%), but 1 of these patients was successfully re-transplanted from the same donor.

The cumulative incidence of transplant-related mortality was 8.7%.

There were 5 cases of transplant-related mortality, which were due to graft failure/disseminated fungal infection, cytomegalovirus (CMV) encephalitis, worsening juvenile dermatomyositis/macrophage activation syndrome, bronchopulmonary hemorrhage, and CMV/adenovirus.

“I would like to underline that 3 of these 5 patients died of infectious complications that were present before the transplant—1 fungal invasive infection, 1 encephalitis due to CMV reactivation, and 1 pulmonary infection due to the presence of adenovirus and cytomegalovirus,” Dr Pagliara said.

The rate of disease-free survival and overall survival were both 87.6%.

GVHD and adverse events

Dr Pagliara said there were low rates of acute GVHD in the first 100 days.

The rate of grade 2-4 acute GVHD was 8.9%, and the rate of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was 1.8%. There were 4 cases of grade 2 GVHD—three stage 3 skin and one stage 1 upper gastrointestinal. There was a single case of grade 3 GVHD—stage 3 liver.

Of the 19 patients who developed acute GVHD, 7 received at least 1 dose of rimiducid. These patients had visceral involvement or GVHD that was not responsive to standard care.

Four patients had a complete response to rimiducid, and 1 had a partial response. One patient did not respond, and 1 was not evaluable. The non-evaluable patient was on corticosteroids and cyclosporine with controlled GVHD but was unable to be weaned off corticosteroids. Rimiducid was given in an attempt to wean the patient off corticosteroids.

“Most importantly, only 1 patient out of 59 developed chronic GVHD, with only mild involvement of the skin,” Dr Pagliara said. This patient did not receive rimiducid.

Nine patients (15.2%) had at least 1 adverse event (AE).

AEs occurring after BPX-501 administration were grade 1 or 2 in nature. They included diarrhea, vomiting, pyrexia, CMV viremia, rhinovirus infection, hypokalemia, pruritus, and rash.

There were no severe AEs attributed to BPX-501.

STOCKHOLM—Researchers have identified a “highly effective” transplant strategy for pediatric patients with primary immunodeficiencies who lack a suitable HLA-compatible donor, according to a speaker at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA).

The strategy involves α/β T-cell- and B-cell-depleted haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant (haplo-HSCT) followed by infusion of the T-cell product BPX-501.

Children treated with this strategy in a phase 1/2 trial had disease-free and overall survival rates that compared favorably with rates observed in recipients of matched, unrelated transplants.

In addition, the incidence of severe acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GHVD) was low in this trial.

Daria Pagliara, MD, PhD, of Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesu in Rome, Italy, presented these results at the recent EHA Congress as abstract S871.

The research was sponsored by Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing BPX-501.

BPX-501 consists of genetically modified donor T cells incorporating the CaspaCIDe safety switch, which is designed to eliminate the T cells in the event of toxicity. Rimiducid is used to activate the CaspaCIDe safety switch, which consists of the CID-binding domain coupled to the signaling domain of caspase-9, an enzyme that is part of the apoptotic pathway.

Dr Pagliara explained that T cells are collected from donors via non-mobilized apheresis, the cells are modified to create the BPX-501 product, and the product is infused in HSCT recipients at day 14 after transplant (+/- 4 days).

The patients do not receive GVHD prophylaxis after transplant but are given rimiducid if they develop GVHD that does not respond to standard therapy.

Patients and transplant characteristics

Dr Pagliara reported results with BPX-501 in 59 patients. They had a median age of 1.85 years (range, 0.21 to 17.55), and 57.6% were male.

Patients had severe combined immune deficiency (32%), Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome (15%), chronic granulomatous disease (12%), hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (10%), combined immunodeficiency disease (7%), major histocompatibility complex class II deficiency (5%), and “other” immunodeficiencies (19%).

The patients received BPX-501 after an α/β T-cell-depleted, B-cell-depleted haplo-HSCT. Most patients had a parent donor (94.9%), and 5.1% had a sibling donor. The median donor age was 34 (range, 21-52).

About half of patients (49.2%) received treosulfan-based conditioning, 39% received busulfan-based conditioning, and 11.9% received other conditioning.

The median CD34 dose was 22.0 x 106/kg, and the median α/β T-cell dose was 0.4 x 105/kg.

The median time to BPX-501 infusion was 15 days (range, 11-56). The median time to discharge was 40 days (range, 18-204).

The median follow-up was 536 days (range, 32-1252).

Engraftment and survival

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 16 days, and the median time to platelet engraftment was 11 days.

Three patients had primary graft failure (5.1%), but 1 of these patients was successfully re-transplanted from the same donor.

The cumulative incidence of transplant-related mortality was 8.7%.

There were 5 cases of transplant-related mortality, which were due to graft failure/disseminated fungal infection, cytomegalovirus (CMV) encephalitis, worsening juvenile dermatomyositis/macrophage activation syndrome, bronchopulmonary hemorrhage, and CMV/adenovirus.

“I would like to underline that 3 of these 5 patients died of infectious complications that were present before the transplant—1 fungal invasive infection, 1 encephalitis due to CMV reactivation, and 1 pulmonary infection due to the presence of adenovirus and cytomegalovirus,” Dr Pagliara said.

The rate of disease-free survival and overall survival were both 87.6%.

GVHD and adverse events

Dr Pagliara said there were low rates of acute GVHD in the first 100 days.

The rate of grade 2-4 acute GVHD was 8.9%, and the rate of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was 1.8%. There were 4 cases of grade 2 GVHD—three stage 3 skin and one stage 1 upper gastrointestinal. There was a single case of grade 3 GVHD—stage 3 liver.

Of the 19 patients who developed acute GVHD, 7 received at least 1 dose of rimiducid. These patients had visceral involvement or GVHD that was not responsive to standard care.

Four patients had a complete response to rimiducid, and 1 had a partial response. One patient did not respond, and 1 was not evaluable. The non-evaluable patient was on corticosteroids and cyclosporine with controlled GVHD but was unable to be weaned off corticosteroids. Rimiducid was given in an attempt to wean the patient off corticosteroids.

“Most importantly, only 1 patient out of 59 developed chronic GVHD, with only mild involvement of the skin,” Dr Pagliara said. This patient did not receive rimiducid.

Nine patients (15.2%) had at least 1 adverse event (AE).

AEs occurring after BPX-501 administration were grade 1 or 2 in nature. They included diarrhea, vomiting, pyrexia, CMV viremia, rhinovirus infection, hypokalemia, pruritus, and rash.

There were no severe AEs attributed to BPX-501.

STOCKHOLM—Researchers have identified a “highly effective” transplant strategy for pediatric patients with primary immunodeficiencies who lack a suitable HLA-compatible donor, according to a speaker at the 23rd Congress of the European Hematology Association (EHA).

The strategy involves α/β T-cell- and B-cell-depleted haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant (haplo-HSCT) followed by infusion of the T-cell product BPX-501.

Children treated with this strategy in a phase 1/2 trial had disease-free and overall survival rates that compared favorably with rates observed in recipients of matched, unrelated transplants.

In addition, the incidence of severe acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GHVD) was low in this trial.

Daria Pagliara, MD, PhD, of Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesu in Rome, Italy, presented these results at the recent EHA Congress as abstract S871.

The research was sponsored by Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing BPX-501.

BPX-501 consists of genetically modified donor T cells incorporating the CaspaCIDe safety switch, which is designed to eliminate the T cells in the event of toxicity. Rimiducid is used to activate the CaspaCIDe safety switch, which consists of the CID-binding domain coupled to the signaling domain of caspase-9, an enzyme that is part of the apoptotic pathway.

Dr Pagliara explained that T cells are collected from donors via non-mobilized apheresis, the cells are modified to create the BPX-501 product, and the product is infused in HSCT recipients at day 14 after transplant (+/- 4 days).

The patients do not receive GVHD prophylaxis after transplant but are given rimiducid if they develop GVHD that does not respond to standard therapy.

Patients and transplant characteristics

Dr Pagliara reported results with BPX-501 in 59 patients. They had a median age of 1.85 years (range, 0.21 to 17.55), and 57.6% were male.

Patients had severe combined immune deficiency (32%), Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome (15%), chronic granulomatous disease (12%), hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (10%), combined immunodeficiency disease (7%), major histocompatibility complex class II deficiency (5%), and “other” immunodeficiencies (19%).

The patients received BPX-501 after an α/β T-cell-depleted, B-cell-depleted haplo-HSCT. Most patients had a parent donor (94.9%), and 5.1% had a sibling donor. The median donor age was 34 (range, 21-52).

About half of patients (49.2%) received treosulfan-based conditioning, 39% received busulfan-based conditioning, and 11.9% received other conditioning.

The median CD34 dose was 22.0 x 106/kg, and the median α/β T-cell dose was 0.4 x 105/kg.

The median time to BPX-501 infusion was 15 days (range, 11-56). The median time to discharge was 40 days (range, 18-204).

The median follow-up was 536 days (range, 32-1252).

Engraftment and survival

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 16 days, and the median time to platelet engraftment was 11 days.

Three patients had primary graft failure (5.1%), but 1 of these patients was successfully re-transplanted from the same donor.

The cumulative incidence of transplant-related mortality was 8.7%.

There were 5 cases of transplant-related mortality, which were due to graft failure/disseminated fungal infection, cytomegalovirus (CMV) encephalitis, worsening juvenile dermatomyositis/macrophage activation syndrome, bronchopulmonary hemorrhage, and CMV/adenovirus.

“I would like to underline that 3 of these 5 patients died of infectious complications that were present before the transplant—1 fungal invasive infection, 1 encephalitis due to CMV reactivation, and 1 pulmonary infection due to the presence of adenovirus and cytomegalovirus,” Dr Pagliara said.

The rate of disease-free survival and overall survival were both 87.6%.

GVHD and adverse events

Dr Pagliara said there were low rates of acute GVHD in the first 100 days.

The rate of grade 2-4 acute GVHD was 8.9%, and the rate of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was 1.8%. There were 4 cases of grade 2 GVHD—three stage 3 skin and one stage 1 upper gastrointestinal. There was a single case of grade 3 GVHD—stage 3 liver.

Of the 19 patients who developed acute GVHD, 7 received at least 1 dose of rimiducid. These patients had visceral involvement or GVHD that was not responsive to standard care.

Four patients had a complete response to rimiducid, and 1 had a partial response. One patient did not respond, and 1 was not evaluable. The non-evaluable patient was on corticosteroids and cyclosporine with controlled GVHD but was unable to be weaned off corticosteroids. Rimiducid was given in an attempt to wean the patient off corticosteroids.

“Most importantly, only 1 patient out of 59 developed chronic GVHD, with only mild involvement of the skin,” Dr Pagliara said. This patient did not receive rimiducid.

Nine patients (15.2%) had at least 1 adverse event (AE).

AEs occurring after BPX-501 administration were grade 1 or 2 in nature. They included diarrhea, vomiting, pyrexia, CMV viremia, rhinovirus infection, hypokalemia, pruritus, and rash.

There were no severe AEs attributed to BPX-501.

Perioperative RBC transfusions linked to VTE

Patients who receive red blood cell (RBC) transfusions before, during, or immediately after surgery may have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), a new study suggests.

In this retrospective study, transfusion recipients had twice the risk of VTE as patients who did not receive RBC transfusions during the perioperative period.

Investigators say these findings require validation, but they suggest a need for physicians to consider non-transfusion alternatives to treat anemia in patients undergoing surgery.

“These findings reinforce the importance of following rigorous perioperative patient blood management practices for transfusions,” said Ruchika Goel, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

Dr Goel and her colleagues reported their findings in JAMA Surgery.

The investigators analyzed data on 750,937 patients who underwent surgery in 2014. In all, 6.3% (n=47,410) of patients received at least one RBC transfusion.

Within 30 days of surgery, 0.8% (n=6309) of all patients had a VTE. This included 0.6% (n=4336) with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 0.3% (n=2514) with pulmonary embolism (PE), and 0.1% (n=541) with DVT and PE.

Analyses showed that patients who received RBC transfusions were twice as likely to develop VTE as those who did not receive transfusions (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=2.1). This was true for both DVT (aOR=2.2) and PE (aOR=1.9).

“We also saw this risk across different surgical disciplines, ranging from neurosurgery to cardiac surgery,” said study author Aaron Tobian, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Furthermore, VTE risk increased with the number of RBC transfusions a patient received. The aORs were 2.1 for 1 transfusion, 3.1 for 2 transfusions, and 4.5 for 3 or more transfusions (compared to patients who did not receive any transfusions).

“This retrospective study demonstrates that there may be additional risks to blood transfusion that are not generally recognized in the community,” Dr Tobian said. “While additional research is needed to confirm these results, the findings reinforce the need to limit blood transfusions to only when necessary.”

Patients who receive red blood cell (RBC) transfusions before, during, or immediately after surgery may have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), a new study suggests.

In this retrospective study, transfusion recipients had twice the risk of VTE as patients who did not receive RBC transfusions during the perioperative period.

Investigators say these findings require validation, but they suggest a need for physicians to consider non-transfusion alternatives to treat anemia in patients undergoing surgery.

“These findings reinforce the importance of following rigorous perioperative patient blood management practices for transfusions,” said Ruchika Goel, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

Dr Goel and her colleagues reported their findings in JAMA Surgery.

The investigators analyzed data on 750,937 patients who underwent surgery in 2014. In all, 6.3% (n=47,410) of patients received at least one RBC transfusion.

Within 30 days of surgery, 0.8% (n=6309) of all patients had a VTE. This included 0.6% (n=4336) with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 0.3% (n=2514) with pulmonary embolism (PE), and 0.1% (n=541) with DVT and PE.

Analyses showed that patients who received RBC transfusions were twice as likely to develop VTE as those who did not receive transfusions (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=2.1). This was true for both DVT (aOR=2.2) and PE (aOR=1.9).

“We also saw this risk across different surgical disciplines, ranging from neurosurgery to cardiac surgery,” said study author Aaron Tobian, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Furthermore, VTE risk increased with the number of RBC transfusions a patient received. The aORs were 2.1 for 1 transfusion, 3.1 for 2 transfusions, and 4.5 for 3 or more transfusions (compared to patients who did not receive any transfusions).

“This retrospective study demonstrates that there may be additional risks to blood transfusion that are not generally recognized in the community,” Dr Tobian said. “While additional research is needed to confirm these results, the findings reinforce the need to limit blood transfusions to only when necessary.”

Patients who receive red blood cell (RBC) transfusions before, during, or immediately after surgery may have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), a new study suggests.

In this retrospective study, transfusion recipients had twice the risk of VTE as patients who did not receive RBC transfusions during the perioperative period.

Investigators say these findings require validation, but they suggest a need for physicians to consider non-transfusion alternatives to treat anemia in patients undergoing surgery.

“These findings reinforce the importance of following rigorous perioperative patient blood management practices for transfusions,” said Ruchika Goel, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

Dr Goel and her colleagues reported their findings in JAMA Surgery.

The investigators analyzed data on 750,937 patients who underwent surgery in 2014. In all, 6.3% (n=47,410) of patients received at least one RBC transfusion.

Within 30 days of surgery, 0.8% (n=6309) of all patients had a VTE. This included 0.6% (n=4336) with deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 0.3% (n=2514) with pulmonary embolism (PE), and 0.1% (n=541) with DVT and PE.

Analyses showed that patients who received RBC transfusions were twice as likely to develop VTE as those who did not receive transfusions (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]=2.1). This was true for both DVT (aOR=2.2) and PE (aOR=1.9).

“We also saw this risk across different surgical disciplines, ranging from neurosurgery to cardiac surgery,” said study author Aaron Tobian, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Furthermore, VTE risk increased with the number of RBC transfusions a patient received. The aORs were 2.1 for 1 transfusion, 3.1 for 2 transfusions, and 4.5 for 3 or more transfusions (compared to patients who did not receive any transfusions).

“This retrospective study demonstrates that there may be additional risks to blood transfusion that are not generally recognized in the community,” Dr Tobian said. “While additional research is needed to confirm these results, the findings reinforce the need to limit blood transfusions to only when necessary.”

Company stops development of eryaspase in ALL

Erytech Pharma said it plans to stop development of eryaspase for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

This means withdrawal of the European marketing authorization application for eryaspase as a treatment for relapsed and refractory ALL.

However, Erytech will continue development of eryaspase as a treatment for certain solid tumor malignancies.

Eryaspase consists of L-asparaginase encapsulated inside donor-derived red blood cells. These enzyme-loaded red blood cells function as bioreactors to eliminate circulating asparagine and “starve” cancer cells, thereby inducing their death.