User login

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis a ‘robust diagnosis’

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Very few patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have connective tissue disease antibodies, suggesting that IPF is a “robust diagnosis” when made on the basis of standard diagnostic tests, it was reported at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

“The results were perhaps not what we’d expected,” said Caroline V. Cotton, PhD, of the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease at the University of Liverpool, England.

This means that chest physicians are getting the diagnosis right in the majority of cases, based on currently available methods, such as patients’ clinical history and examination, the results of high resolution–computed tomography, and widely available serology. “Which is good news,” Dr. Cotton observed.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) comprises a huge spectrum of disorders. The main groups of ILDs are idiopathic, granulomatous, connective tissue disease–associated environmental, or medication exposure–associated; and the rare causes of ILD, each of which contain multiple subgroups of which IPF is one.

Sometimes it is obvious to respiratory physicians what the cause is, such as environmental exposure to asbestos or sarcoidosis for the granulomatous ILD, Dr. Cotton noted. Identifying connective tissue disease (CTD)–associated ILD can be more diagnostically challenging, however, and there are a large number of rheumatic conditions associated with CTD-associated ILD, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, and Sjögren’s syndrome, to name a few.

One of the problems is that signs and symptoms of CTD may be absent at the time ILD starts to manifest and, even if signs are present, they may too subtle to be picked up in a general chest clinic. There also is a large number of antibodies for CTDs, but not all are widely available.

Dr. Cotton and her associates, therefore, wondered if there was a chance that patients being diagnosed with IPF actually could have covert CTD-associated ILD; this is an important distinction to make because the treatment differs for the two conditions. While ILD associated with CTD has a strong inflammatory component and is treated with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, steroids can be harmful and increase mortality in IPF-ILD. The latter is treated with antifibrotic medications, such as pirfenidone and nintedanib.

For the study, serum samples from 250 patients with a definite diagnosis of IPF who were participating in the UK-BILD study were obtained and screened for known CTD antibodies using immunoprecipitation. Antibodies could be detected in just five (2%) patients – these included one patient each with anti-KS and anti-OJ antibodies, which are antisynthetase antibodies that are associated with myositis. Anti-Ku, another myositis-associated antibody, was identified in another patient, and one patient had an anti-RNA polymerase II antibody, which is associated with systemic sclerosis. Antimitochondrial autoantibodies were observed in one patient, and these are linked to primary biliary cirrhosis, which the patient was known to have.

There was nothing remarkable between the patients who did and did not have CTD antibodies in terms of their demographics, 76% and 80% were male, the mean ages were 73 and 70 years, respectively, and all were white.

However, 40% of patients did have unknown strong bands on immunoprecipitation, Dr. Cotton reported. This could suggest that there is an underlying immunological component to IPF, she added, but they had no recognized antibodies.

“A very small number of patients with IPF actually have the presence of autoantibodies strongly associated with CTDs. This suggests IPF is a very robust diagnosis; chest physicians are diagnosing it correctly most of the time, and they are really good at good at weeding out those who have got IPF and those who have potentially got connective tissue disease.” Dr. Cotton concluded.

Dr. Cotton had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Cotton CV et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.206.

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Very few patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have connective tissue disease antibodies, suggesting that IPF is a “robust diagnosis” when made on the basis of standard diagnostic tests, it was reported at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

“The results were perhaps not what we’d expected,” said Caroline V. Cotton, PhD, of the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease at the University of Liverpool, England.

This means that chest physicians are getting the diagnosis right in the majority of cases, based on currently available methods, such as patients’ clinical history and examination, the results of high resolution–computed tomography, and widely available serology. “Which is good news,” Dr. Cotton observed.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) comprises a huge spectrum of disorders. The main groups of ILDs are idiopathic, granulomatous, connective tissue disease–associated environmental, or medication exposure–associated; and the rare causes of ILD, each of which contain multiple subgroups of which IPF is one.

Sometimes it is obvious to respiratory physicians what the cause is, such as environmental exposure to asbestos or sarcoidosis for the granulomatous ILD, Dr. Cotton noted. Identifying connective tissue disease (CTD)–associated ILD can be more diagnostically challenging, however, and there are a large number of rheumatic conditions associated with CTD-associated ILD, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, and Sjögren’s syndrome, to name a few.

One of the problems is that signs and symptoms of CTD may be absent at the time ILD starts to manifest and, even if signs are present, they may too subtle to be picked up in a general chest clinic. There also is a large number of antibodies for CTDs, but not all are widely available.

Dr. Cotton and her associates, therefore, wondered if there was a chance that patients being diagnosed with IPF actually could have covert CTD-associated ILD; this is an important distinction to make because the treatment differs for the two conditions. While ILD associated with CTD has a strong inflammatory component and is treated with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, steroids can be harmful and increase mortality in IPF-ILD. The latter is treated with antifibrotic medications, such as pirfenidone and nintedanib.

For the study, serum samples from 250 patients with a definite diagnosis of IPF who were participating in the UK-BILD study were obtained and screened for known CTD antibodies using immunoprecipitation. Antibodies could be detected in just five (2%) patients – these included one patient each with anti-KS and anti-OJ antibodies, which are antisynthetase antibodies that are associated with myositis. Anti-Ku, another myositis-associated antibody, was identified in another patient, and one patient had an anti-RNA polymerase II antibody, which is associated with systemic sclerosis. Antimitochondrial autoantibodies were observed in one patient, and these are linked to primary biliary cirrhosis, which the patient was known to have.

There was nothing remarkable between the patients who did and did not have CTD antibodies in terms of their demographics, 76% and 80% were male, the mean ages were 73 and 70 years, respectively, and all were white.

However, 40% of patients did have unknown strong bands on immunoprecipitation, Dr. Cotton reported. This could suggest that there is an underlying immunological component to IPF, she added, but they had no recognized antibodies.

“A very small number of patients with IPF actually have the presence of autoantibodies strongly associated with CTDs. This suggests IPF is a very robust diagnosis; chest physicians are diagnosing it correctly most of the time, and they are really good at good at weeding out those who have got IPF and those who have potentially got connective tissue disease.” Dr. Cotton concluded.

Dr. Cotton had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Cotton CV et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.206.

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Very few patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have connective tissue disease antibodies, suggesting that IPF is a “robust diagnosis” when made on the basis of standard diagnostic tests, it was reported at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference.

“The results were perhaps not what we’d expected,” said Caroline V. Cotton, PhD, of the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease at the University of Liverpool, England.

This means that chest physicians are getting the diagnosis right in the majority of cases, based on currently available methods, such as patients’ clinical history and examination, the results of high resolution–computed tomography, and widely available serology. “Which is good news,” Dr. Cotton observed.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) comprises a huge spectrum of disorders. The main groups of ILDs are idiopathic, granulomatous, connective tissue disease–associated environmental, or medication exposure–associated; and the rare causes of ILD, each of which contain multiple subgroups of which IPF is one.

Sometimes it is obvious to respiratory physicians what the cause is, such as environmental exposure to asbestos or sarcoidosis for the granulomatous ILD, Dr. Cotton noted. Identifying connective tissue disease (CTD)–associated ILD can be more diagnostically challenging, however, and there are a large number of rheumatic conditions associated with CTD-associated ILD, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, and Sjögren’s syndrome, to name a few.

One of the problems is that signs and symptoms of CTD may be absent at the time ILD starts to manifest and, even if signs are present, they may too subtle to be picked up in a general chest clinic. There also is a large number of antibodies for CTDs, but not all are widely available.

Dr. Cotton and her associates, therefore, wondered if there was a chance that patients being diagnosed with IPF actually could have covert CTD-associated ILD; this is an important distinction to make because the treatment differs for the two conditions. While ILD associated with CTD has a strong inflammatory component and is treated with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, steroids can be harmful and increase mortality in IPF-ILD. The latter is treated with antifibrotic medications, such as pirfenidone and nintedanib.

For the study, serum samples from 250 patients with a definite diagnosis of IPF who were participating in the UK-BILD study were obtained and screened for known CTD antibodies using immunoprecipitation. Antibodies could be detected in just five (2%) patients – these included one patient each with anti-KS and anti-OJ antibodies, which are antisynthetase antibodies that are associated with myositis. Anti-Ku, another myositis-associated antibody, was identified in another patient, and one patient had an anti-RNA polymerase II antibody, which is associated with systemic sclerosis. Antimitochondrial autoantibodies were observed in one patient, and these are linked to primary biliary cirrhosis, which the patient was known to have.

There was nothing remarkable between the patients who did and did not have CTD antibodies in terms of their demographics, 76% and 80% were male, the mean ages were 73 and 70 years, respectively, and all were white.

However, 40% of patients did have unknown strong bands on immunoprecipitation, Dr. Cotton reported. This could suggest that there is an underlying immunological component to IPF, she added, but they had no recognized antibodies.

“A very small number of patients with IPF actually have the presence of autoantibodies strongly associated with CTDs. This suggests IPF is a very robust diagnosis; chest physicians are diagnosing it correctly most of the time, and they are really good at good at weeding out those who have got IPF and those who have potentially got connective tissue disease.” Dr. Cotton concluded.

Dr. Cotton had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Cotton CV et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57[Suppl. 3]:key075.206.

REPORTING FROM RHEUMATOLOGY 2018

Key clinical point: Few patients diagnosed as having idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) are likely to have connective tissue disorders (CTD).

Major finding: Only 2% of patients had a recognized CTD antibody present.

Study details: 250 patients with IPF participating in the UK-BILD multicenter study.

Disclosures: Dr. Cotton stated she had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Cotton CV et al. Rheumatology. 2018;57(Suppl. 3):key075.206.

Delayed Cutaneous Reactions to Iodinated Contrast

Case Report

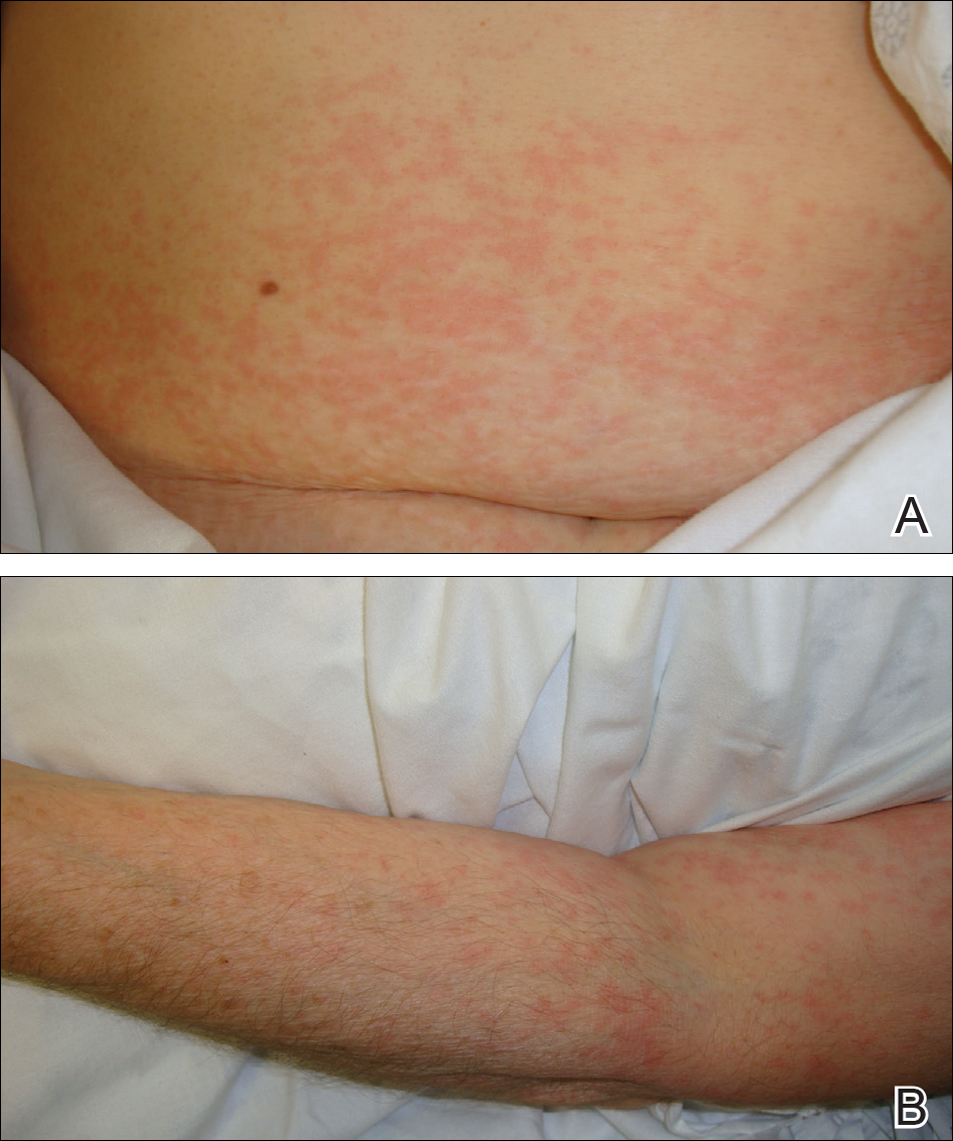

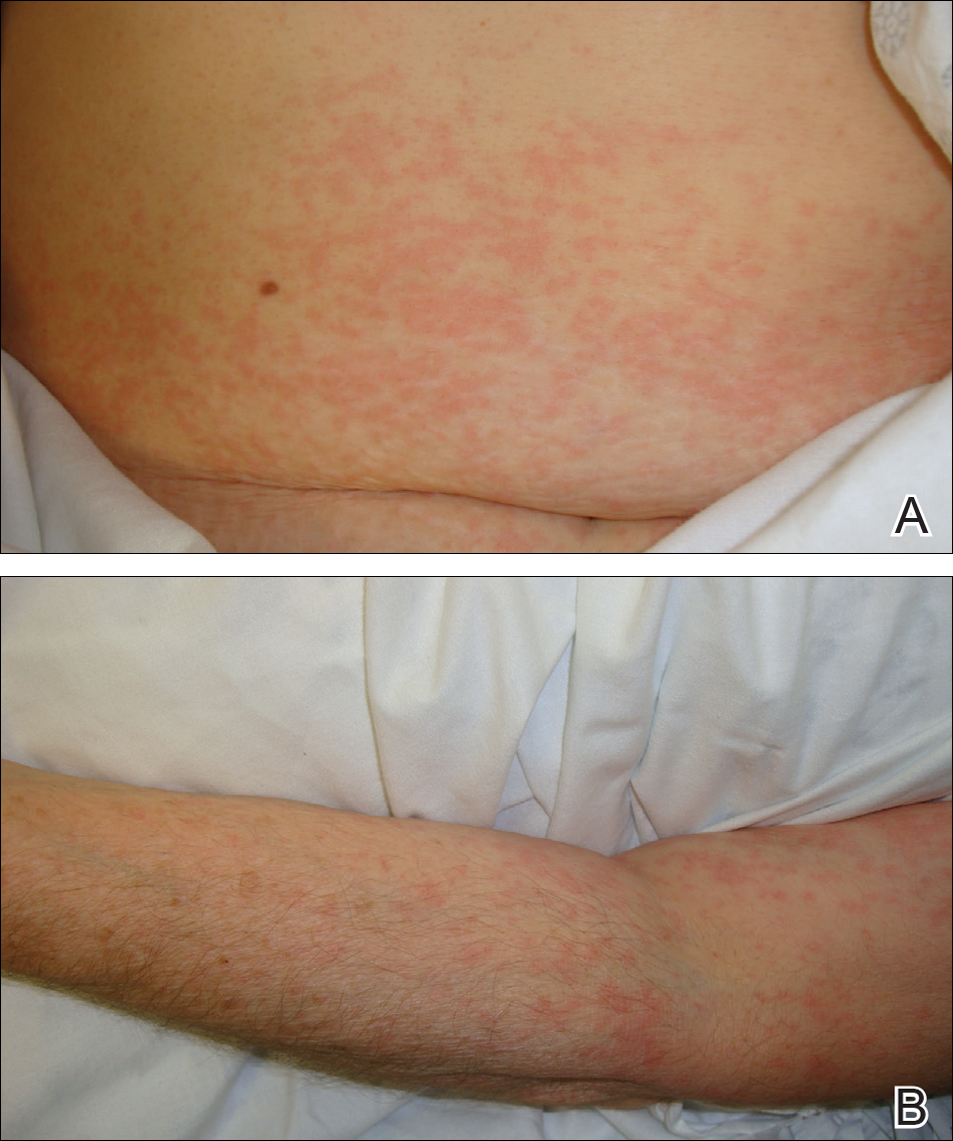

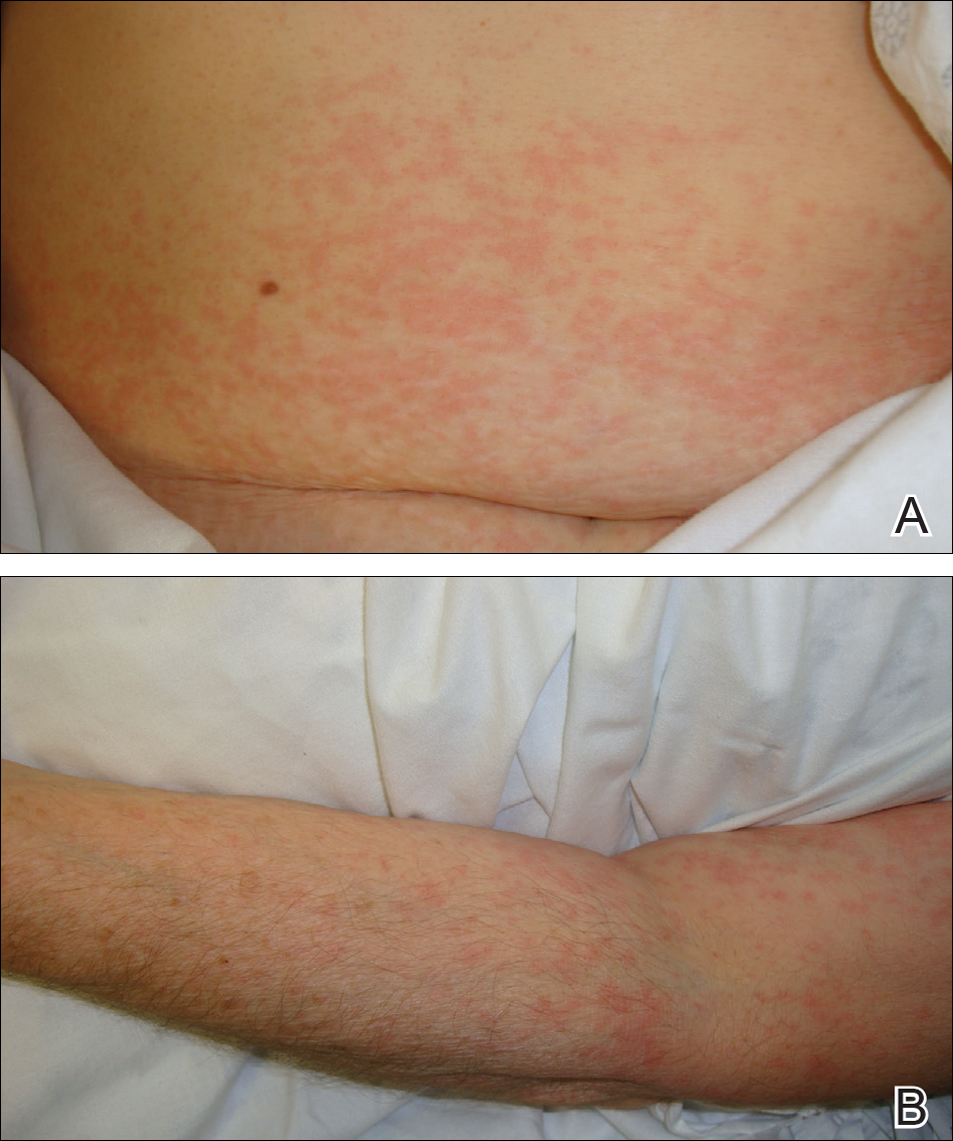

A 67-year-old woman with a history of allergic rhinitis presented in the spring with a pruritic eruption of 2 days’ duration that began on the abdomen and spread to the chest, back, and bilateral arms. Six days prior to the onset of the symptoms she underwent computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate abdominal pain and peripheral eosinophilia. Two iodinated contrast (IC) agents were used: intravenous iohexol and oral diatrizoate meglumine–diatrizoate sodium. The eruption was not preceded by fever, malaise, sore throat, rhinorrhea, cough, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, or new medication or supplement use. The patient denied any history of drug allergy or cutaneous eruptions. Her current medications, which she had been taking long-term, were aspirin, lisinopril, diltiazem, levothyroxine, esomeprazole, paroxetine, gabapentin, and diphenhydramine.

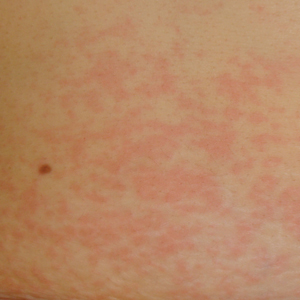

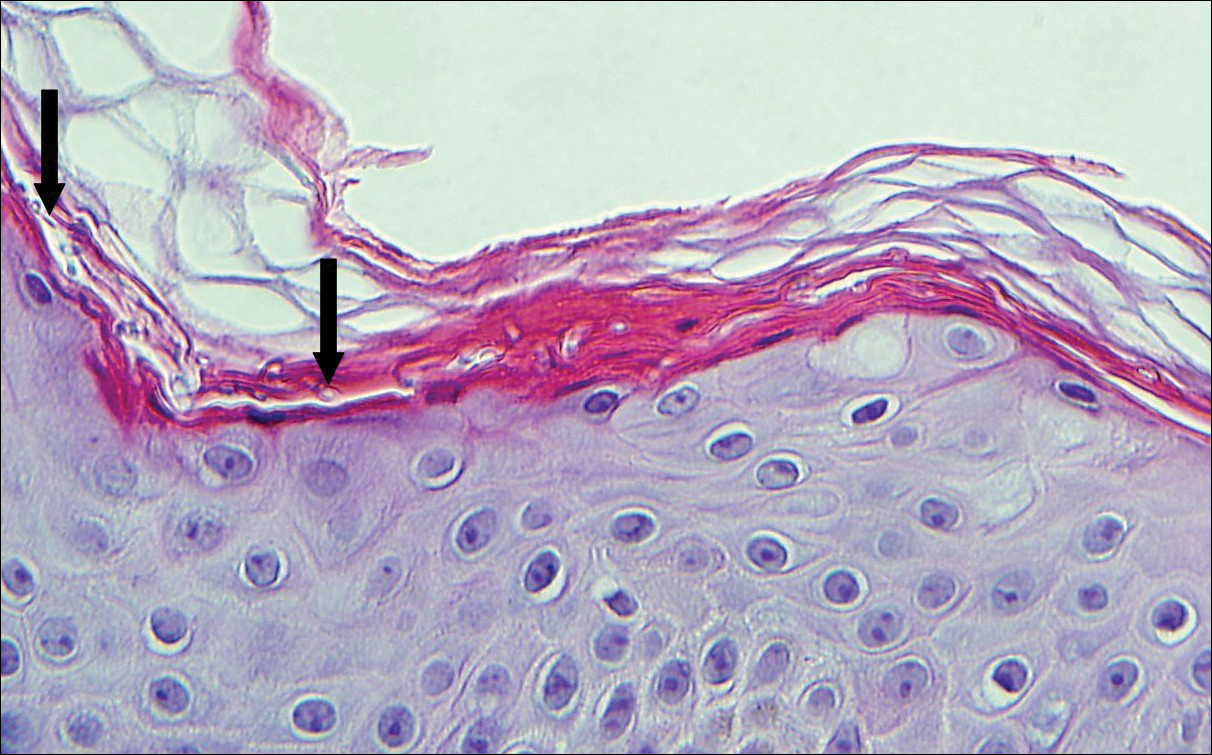

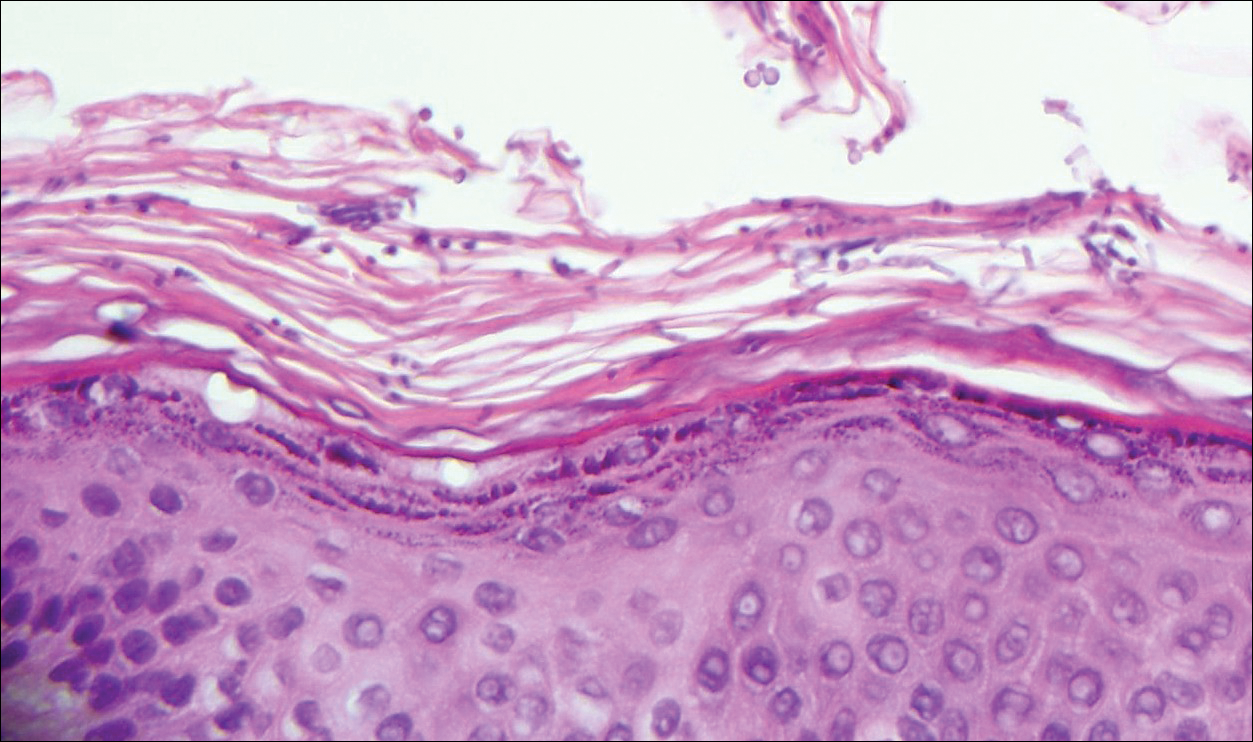

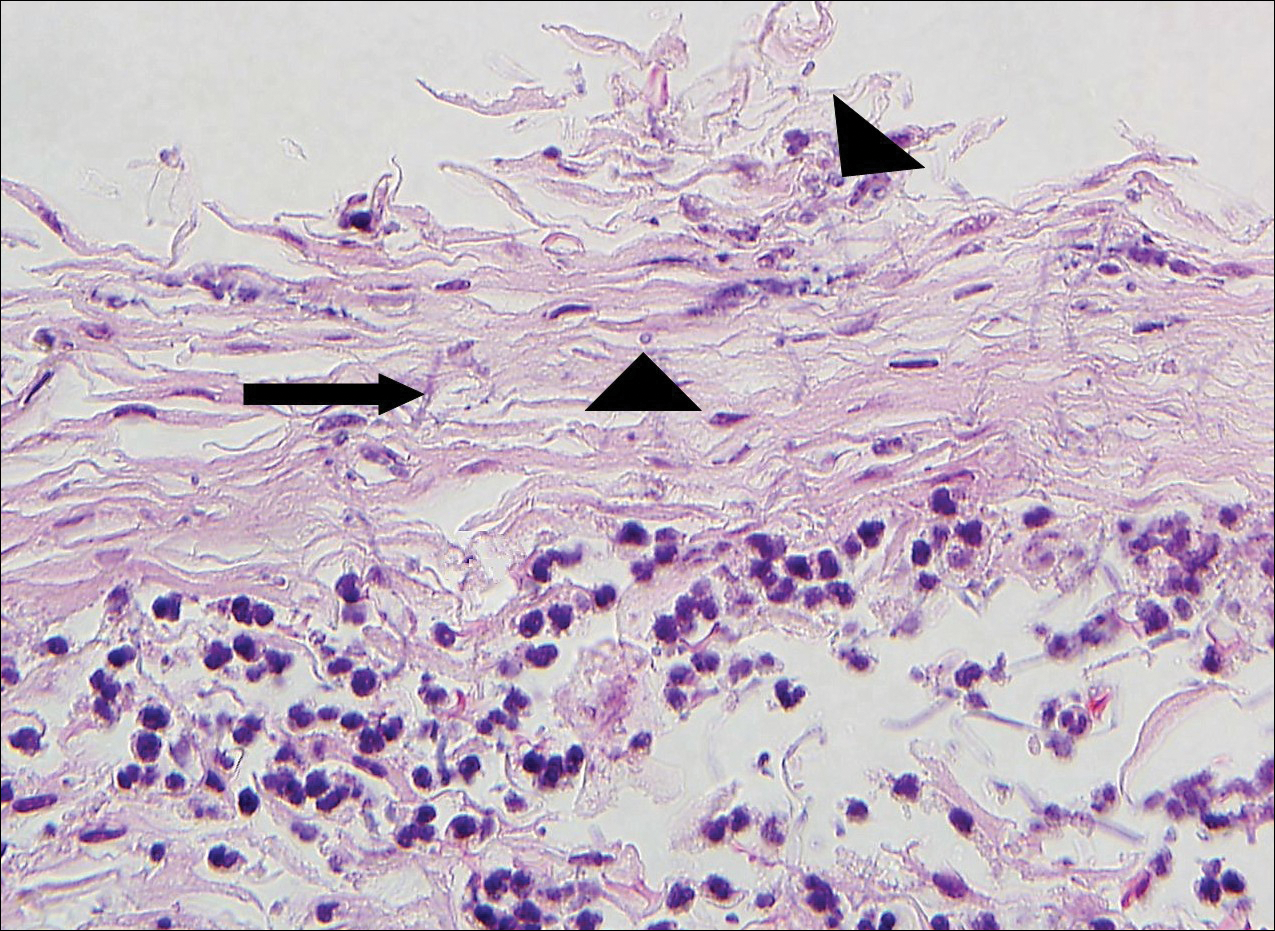

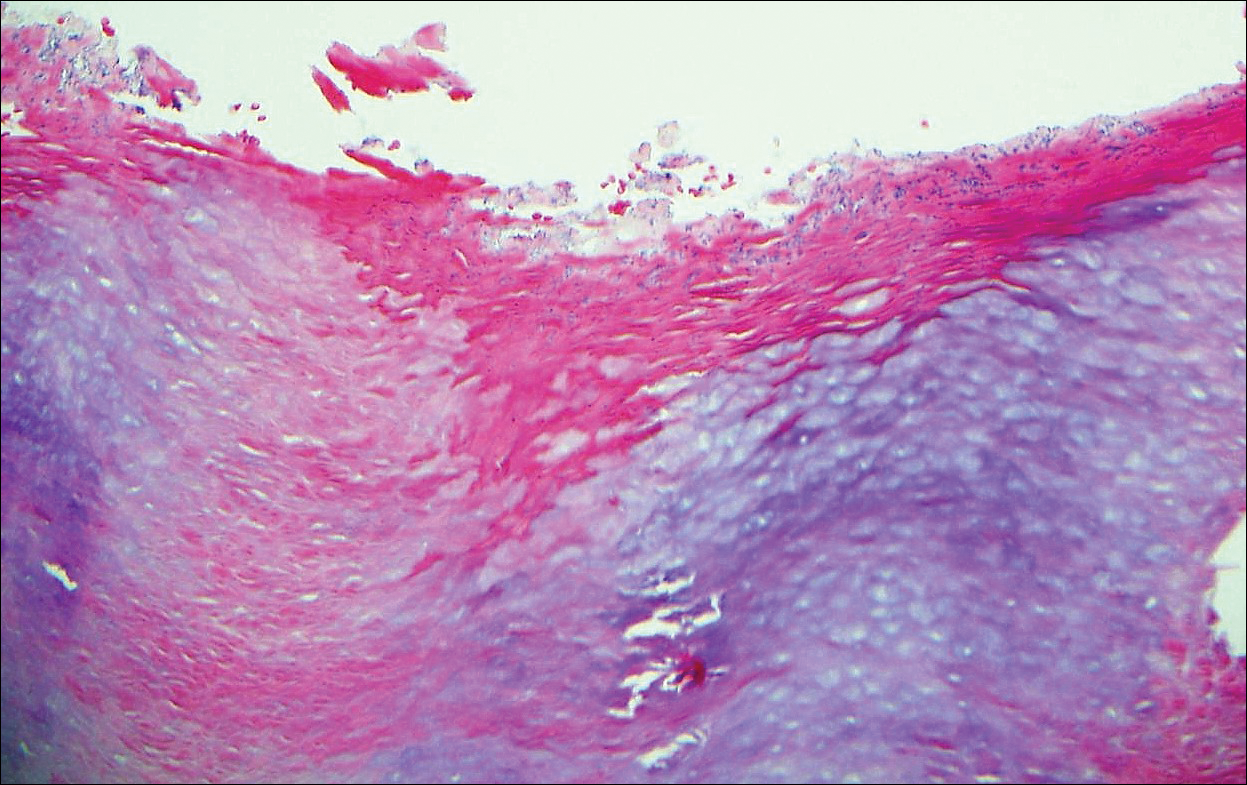

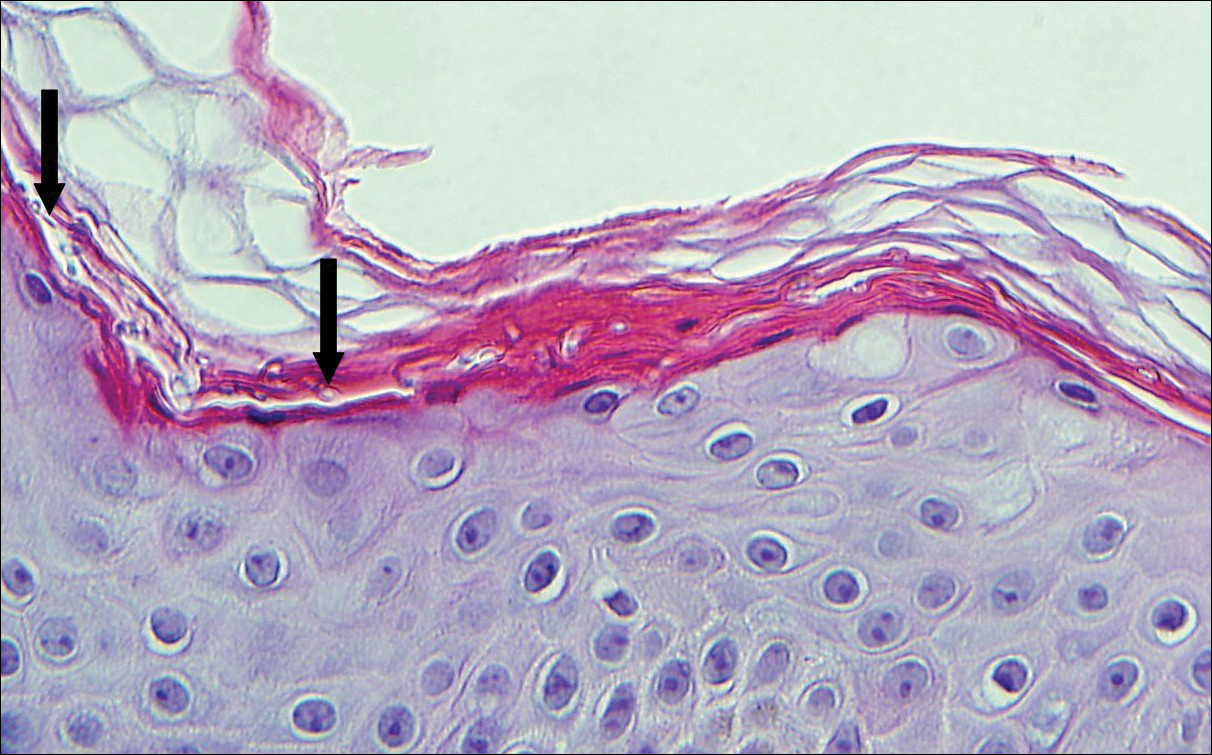

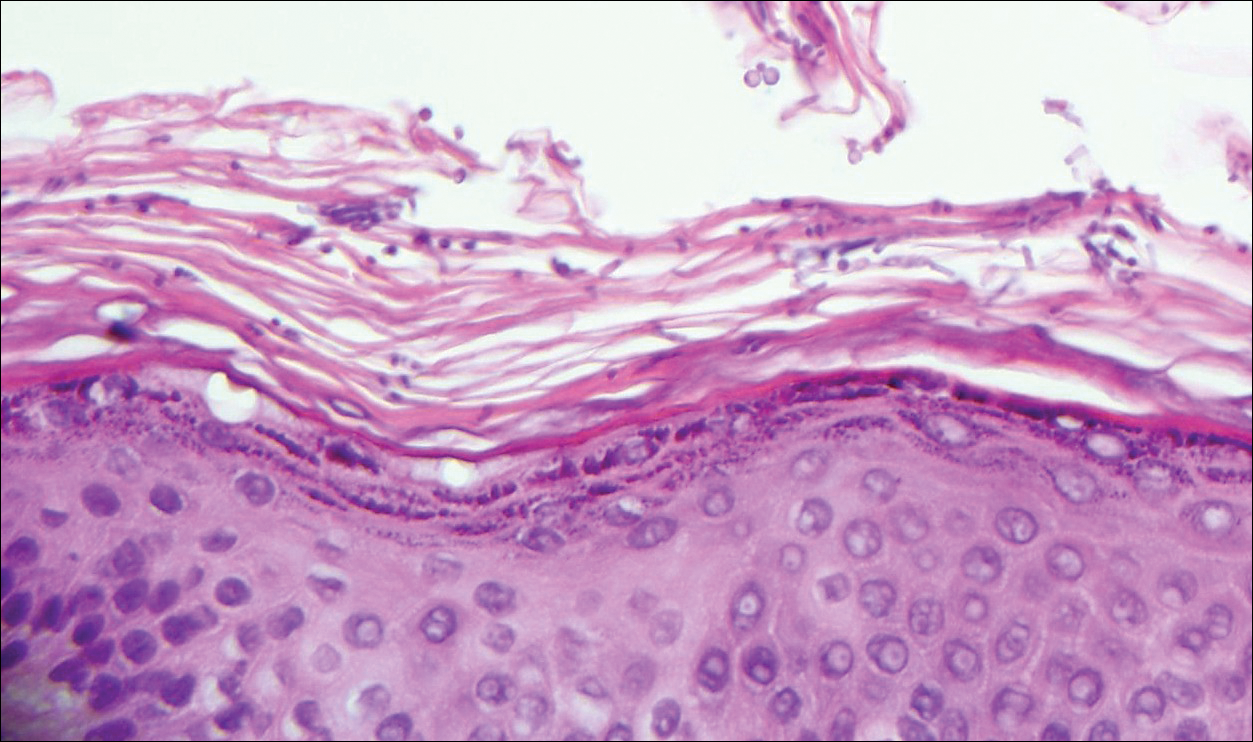

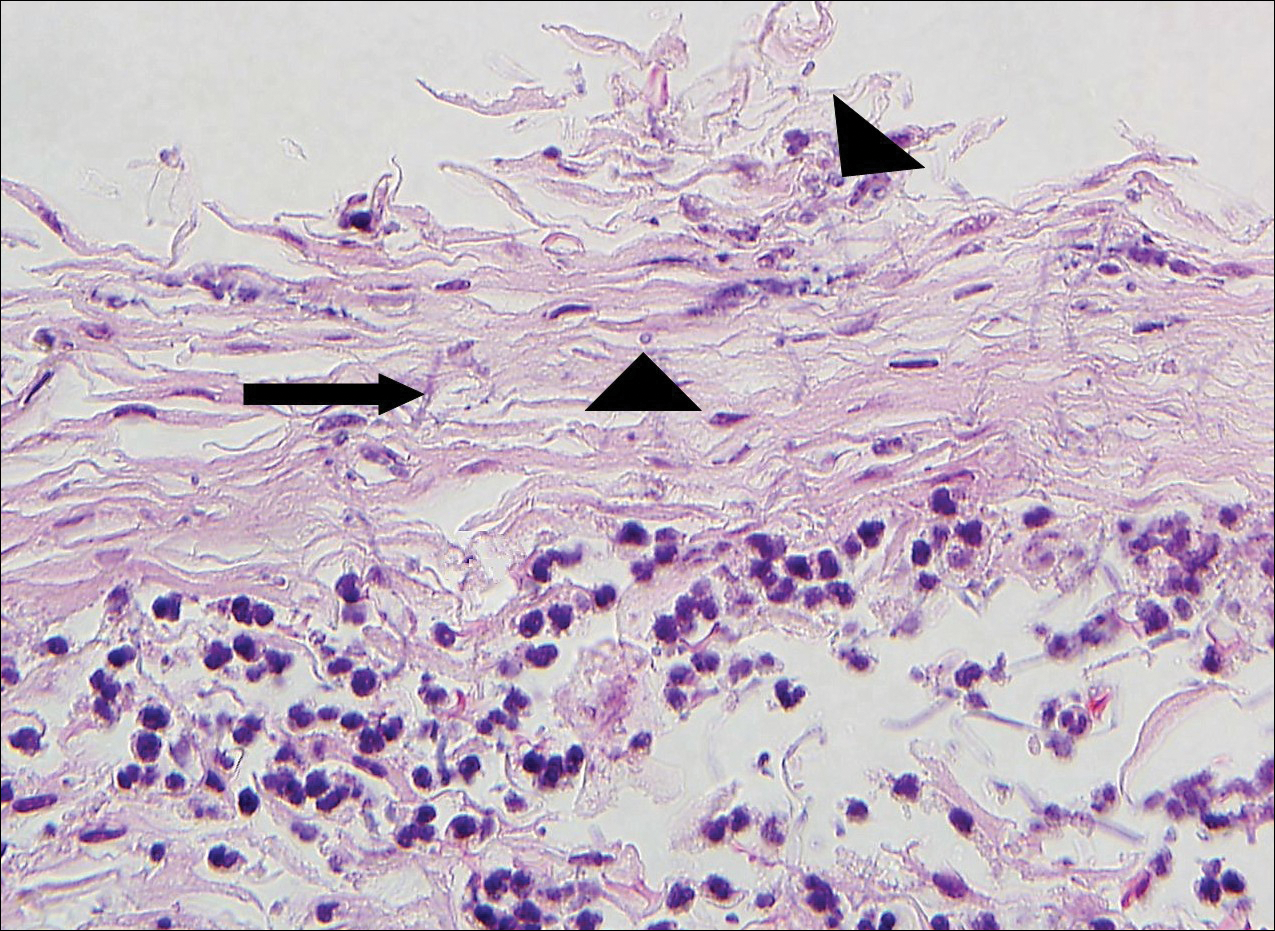

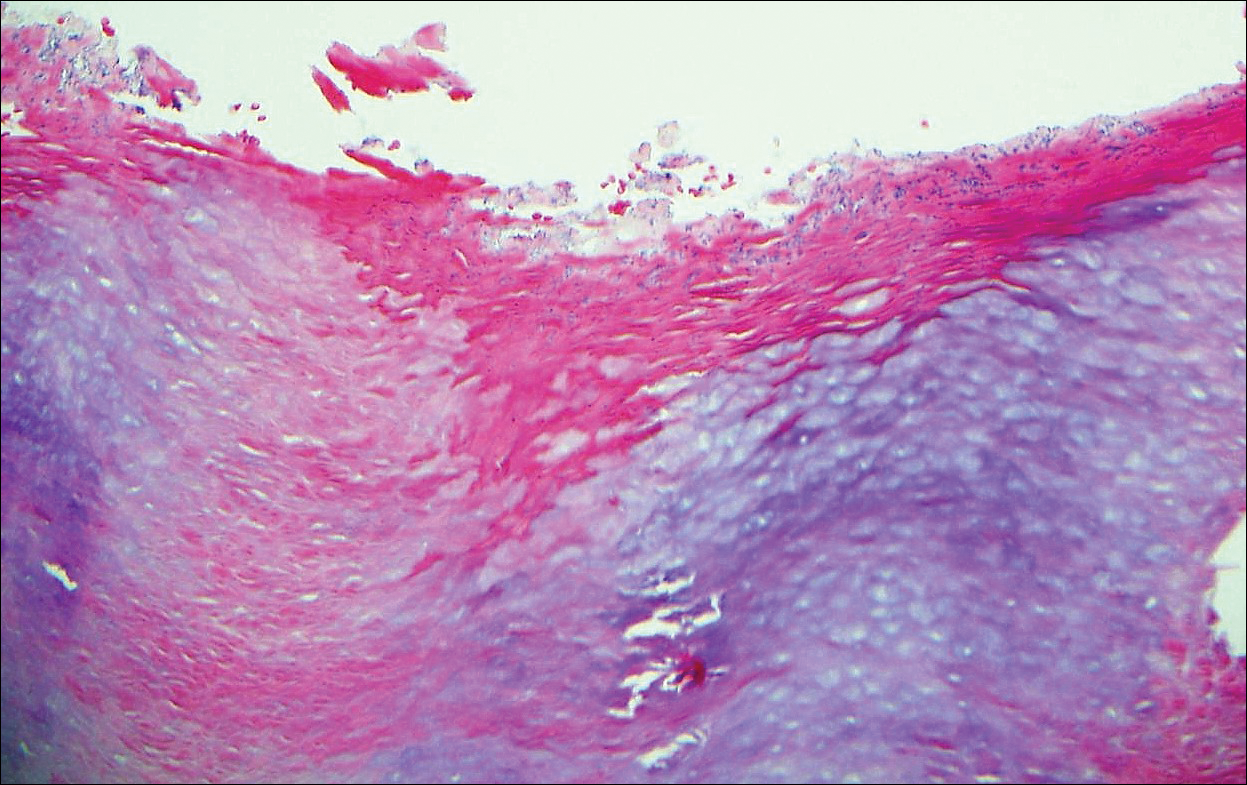

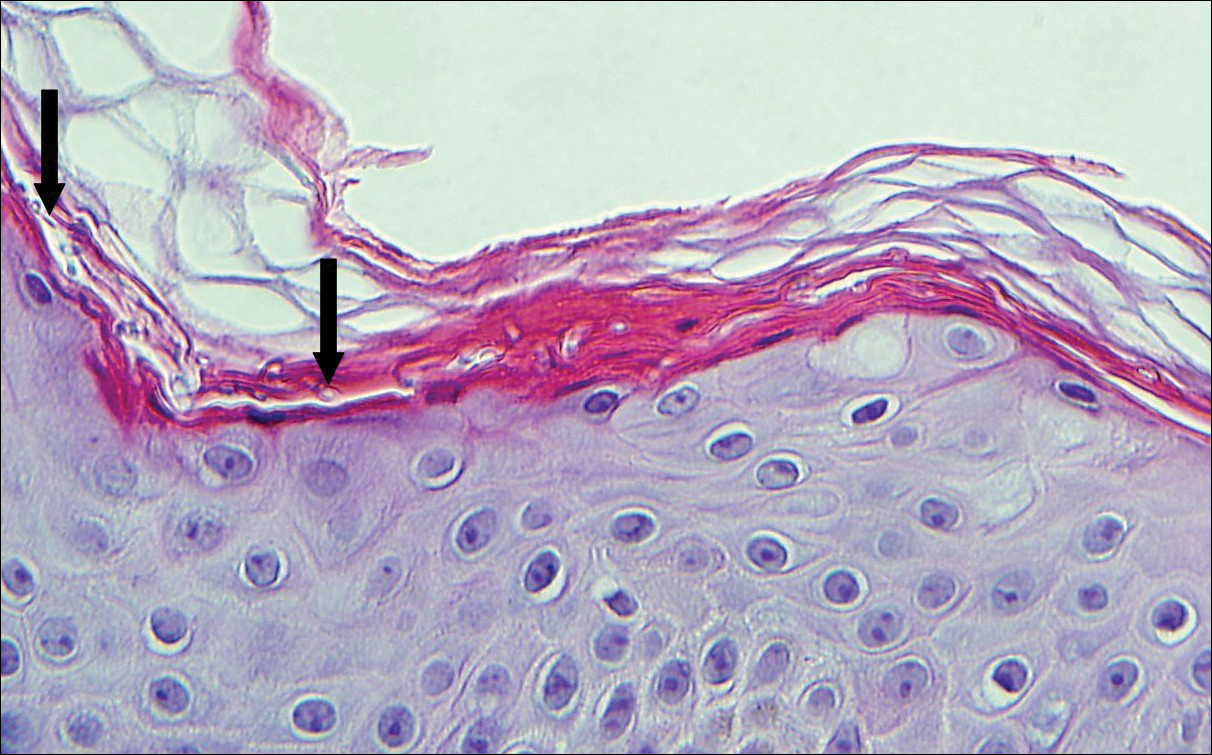

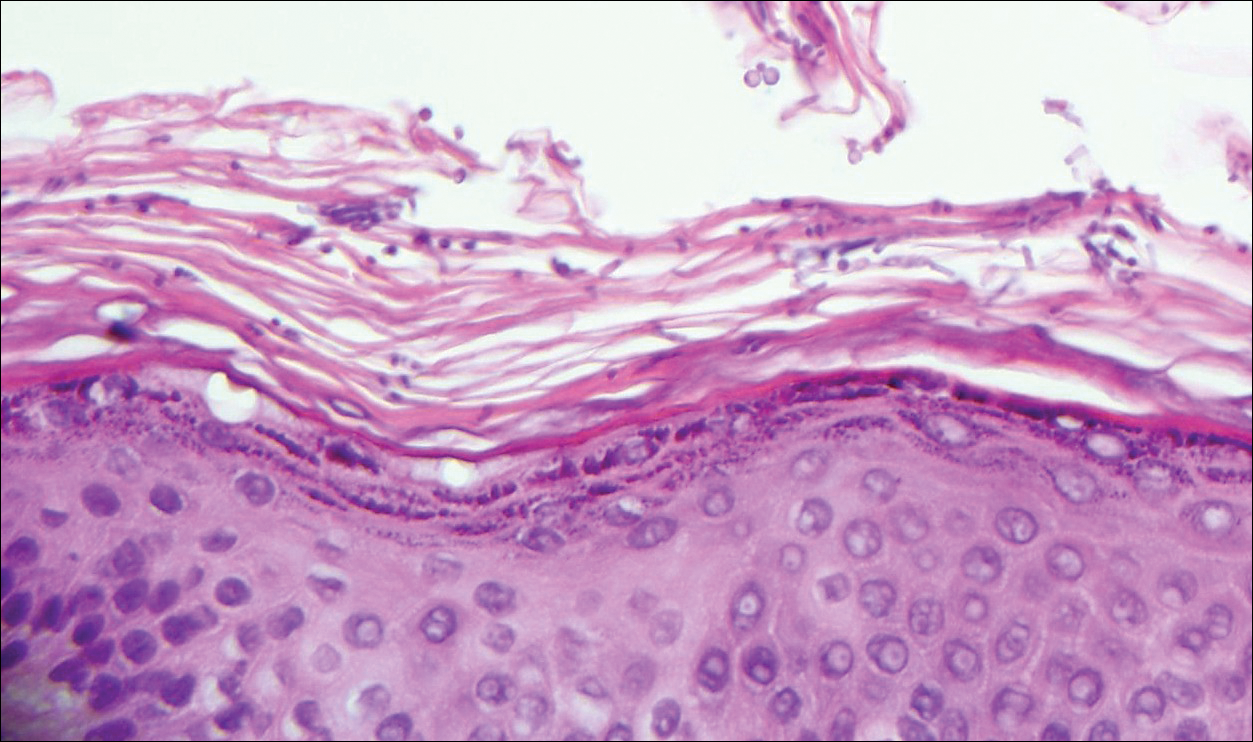

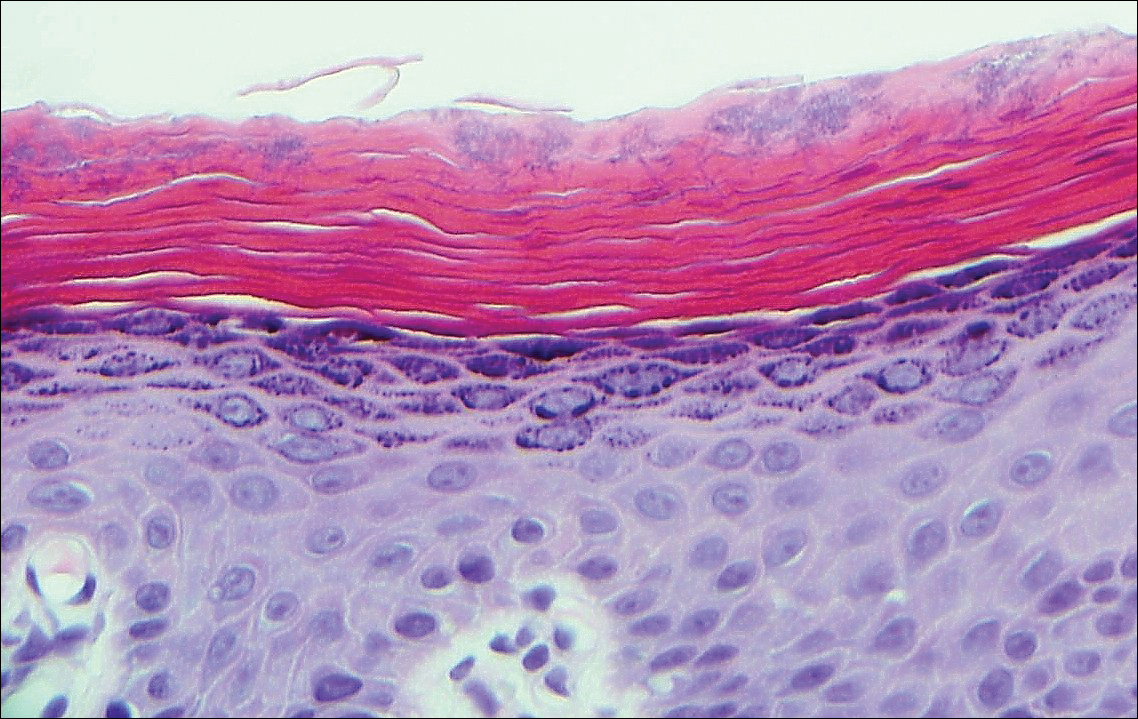

Physical examination was notable for erythematous, blanchable, nontender macules coalescing into patches on the trunk and bilateral arms (Figure). There was slight erythema on the nasolabial folds and ears. The mucosal surfaces and distal legs were clear. The patient was afebrile. Her white blood cell count was 12.5×109/L with 32.3% eosinophils (baseline: white blood cell count, 14.8×109/L; 22% eosinophils)(reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L; 1%–4% eosinophils). Her comprehensive metabolic panel was within reference range. The human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antibody immunoassay was nonreactive.

The patient was diagnosed with an exanthematous eruption caused by IC and was treated with oral hydroxyzine and triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%. The eruption resolved within 2 weeks without recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

Comment

Del

Clinical Presentation of Delayed Reactions

Most delayed cutaneous reactions to IC present as exanthematous eruptions in the week following a contrast-enhanced CT scan or coronary angiogram.2,12 The reactions tend to resolve within 2 weeks of onset, and the treatment is largely supportive with antihistamines and/or corticosteroids for the associated pruritus.2,5,6 In a study of 98 patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC, delayed-onset urticaria and angioedema also have been reported with incidence rates of 19% and 24%, respectively.2 Other reactions are less common. In the same study, 7% of patients developed palpable purpura; acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; bullous, flexural, or psoriasislike exanthema; exfoliative eruptions; or purpura and a maculopapular eruption combined with eosinophilia.2 There also have been reports of IC-induced erythema multiforme,3 fixed drug eruptions,10,11 symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema,13 cutaneous vasculitis,14 drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms,15 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN,7,8,16,17 and iododerma.18

IC Agents

Virtually all delayed cutaneous reactions to IC reportedly are due to intravascular rather than oral agents,1,2,19 with the exception of iododerma18 and 1 reported case of TEN.17 Intravenous iohexol was most likely the offending drug in our case. In a prospective cohort study of 539 patients undergoing CT scans, the absolute risk for developing a delayed cutaneous reaction (defined as rash, itching, or skin redness or swelling) to intravascular iohexol was 9.4%.20 Randomized, double-blind studies have found that the risk for delayed cutaneous eruptions is similar among various types of IC, except for iodixanol, which confers a higher risk.5,6,21

Risk Factors

Interestingly, analyses have shown that delayed reactions to IC are more common in atopic patients and during high pollen season.22 Our patient displayed these risk factors, as she had allergic rhinitis and presented for evaluation in late spring when local pollen counts were high. Additionally, patients who develop delayed reactions to IC are notably more likely than controls to have a history of other cutaneous drug reactions, serum creatinine levels greater than 2.0 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL),3 or history of treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.19

Patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC are not at increased risk for immediate reactions and vice versa.2,3 This finding is consistent with the evidence that delayed and immediate reactions to IC are mechanistically unrelated.23 Additionally, seafood allergy is not a risk factor for either immediate or delayed reactions to IC, despite a common misconception among physicians and patients because seafood is iodinated.24,25

Reexposure to IC

Patients who have had delayed cutaneous reactions to IC are at risk for similar eruptions upon reexposure. Although the reactions are believed to be cell mediated, skin testing with IC is not sensitive enough to reliably identify tolerable alternatives.12 Consequently, gadolinium-based agents have been recommended in patients with a history of reactions to IC if additional contrast-enhanced studies are needed.13,26 Iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents do not cross-react, and gadolinium is compatible with studies other than magnetic resonance imaging.1,27

Premedication

Despite the absence of cross-reactivity, the American College of Radiology considers patients with hypersensitivity reactions to IC to be at increased risk for reactions to gadolinium but does not make specific recommendations regarding premedication given the dearth of data.1 As a result, premedication may be considered prior to gadolinium administration depending on the severity of the delayed reaction to IC. Additionally, premedication may be beneficial in cases in which gadolinium is contraindicated and IC must be reused. In a retrospective study, all patients with suspected delayed reactions to IC tolerated IC or gadolinium contrast when pretreated with corticosteroids with or without antihistamines.28 Regimens with corticosteroids and either cyclosporine or intravenous immunoglobulin also have prevented the recurrence of IC-induced exanthematous eruptions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.29,30 Despite these reports, delayed cutaneous reactions to IC have recurred in other patients receiving corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or cyclosporine for premedication or concurrent treatment of an underlying condition.16,29-31

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to recognize IC as a cause of delayed drug reactions. Current awareness is limited, and as a result, patients often are reexposed to the offending contrast agents unsuspectingly. In addition to diagnosing these eruptions, dermatologists may help prevent their recurrence if future contrast-enhanced studies are required by recommending gadolinium-based agents and/or premedication.

- Cohan RH, Davenport MS, Dillman JR, et al; ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media. 9th ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

- Brockow K, Romano A, Aberer W, et al; European Network of Drug Allergy and the EAACI Interest Group on Drug Hypersensitivity. Skin testing in patients with hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media—a European multicenter study. Allergy. 2009;64:234-241.

Hosoya T, Yamaguchi K, Akutsu T, et al. Delayed adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media and their risk factors. Radiat Med. 2000;18:39-45. - Rydberg J, Charles J, Aspelin P. Frequency of late allergy-like adverse reactions following injection of intravascular non-ionic contrast media: a retrospective study comparing a non-ionic monomeric contrast medium with a non-ionic dimeric contrast medium. Acta Radiol. 1998;39:219-222.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Grech ED, et al. Early and late reactions after the use of iopamidol 340, ioxaglate 320, and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J. 2001;141:677-683.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Campbell PG, et al. Early and late reactions following the use of iopamidol 340, iomeprol 350 and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:133-138.

- Brown M, Yowler C, Brandt C. Recurrent toxic epidermal necrolysis secondary to iopromide contrast. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34:E53-E56.

- Rosado A, Canto G, Veleiro B, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after repeated injections of iohexol. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:262-263.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W198-W201.

- Good AE, Novak E, Sonda LP III. Fixed eruption and fever after urography. South Med J. 1980;73:948-949.

- Benson PM, Giblin WJ, Douglas DM. Transient, nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption caused by radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2, pt 2):379-381.

- Torres MJ, Gomez F, Doña I, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with nonimmediate cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy. 2012;67:929-935.

- Scherer K, Harr T, Bach S, et al. The role of iodine in hypersensitivity reactions to radio contrast media. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:468-475.

- Reynolds NJ, Wallington TB, Burton JL. Hydralazine predisposes to acute cutaneous vasculitis following urography with iopamidol. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:82-85.

- Belhadjali H, Bouzgarrou L, Youssef M, et al. DRESS syndrome induced by sodium meglumine ioxitalamate. Allergy. 2008;63:786-787.

- Baldwin BT, Lien MH, Khan H, et al. Case of fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis due to cardiac catheterization dye. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:837-840.

- Schmidt BJ, Foley WD, Bohorfoush AG. Toxic epidermal necrolysis related to oral administration of diluted diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1215-1216.

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379.

- Choyke PL, Miller DL, Lotze MT, et al. Delayed reactions to contrast media after interleukin-2 immunotherapy. Radiology. 1992;183:111-114.

- Loh S, Bagheri S, Katzberg RW, et al. Delayed adverse reaction to contrast-enhanced CT: a prospective single-center study comparison to control group without enhancement. Radiology. 2010;255:764-771.

- Bertrand P, Delhommais A, Alison D, et al. Immediate and delayed tolerance of iohexol and ioxaglate in lower limb phlebography: a double-blind comparative study in humans. Acad Radiol. 1995;2:683-686.

- Munechika H, Hiramatsu Y, Kudo S, et al. A prospective survey of delayed adverse reactions to iohexol in urography and computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:185-194.

- Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Romano A, Barbaud A, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3359-3372.

- H

uang SW. Seafood and iodine: an analysis of a medical myth. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:468-469. - B

aig M, Farag A, Sajid J, et al. Shellfish allergy and relation to iodinated contrast media: United Kingdom survey. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:107-111. - B

öhm I, Schild HH. A practical guide to diagnose lesser-known immediate and delayed contrast media-induced adverse cutaneous reactions. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1570-1579. - Ose K, Doue T, Zen K, et al. “Gadolinium” as an alternative to iodinated contrast media for X-ray angiography in patients with severe allergy. Circ J. 2005;69:507-509.

- Ji

ngu A, Fukuda J, Taketomi-Takahashi A, et al. Breakthrough reactions of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media after oral steroid premedication protocol. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:34. - Ro

mano A, Artesani MC, Andriolo M, et al. Effective prophylactic protocol in delayed hypersensitivity to contrast media: report of a case involving lymphocyte transformation studies with different compounds. Radiology. 2002;225:466-470. - He

bert AA, Bogle MA. Intravenous immunoglobulin prophylaxis for recurrent Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:286-288. - Ha

sdenteufel F, Waton J, Cordebar V, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions caused by iodixanol: an assessment of cross-reactivity in 22 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1356-1357.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of allergic rhinitis presented in the spring with a pruritic eruption of 2 days’ duration that began on the abdomen and spread to the chest, back, and bilateral arms. Six days prior to the onset of the symptoms she underwent computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate abdominal pain and peripheral eosinophilia. Two iodinated contrast (IC) agents were used: intravenous iohexol and oral diatrizoate meglumine–diatrizoate sodium. The eruption was not preceded by fever, malaise, sore throat, rhinorrhea, cough, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, or new medication or supplement use. The patient denied any history of drug allergy or cutaneous eruptions. Her current medications, which she had been taking long-term, were aspirin, lisinopril, diltiazem, levothyroxine, esomeprazole, paroxetine, gabapentin, and diphenhydramine.

Physical examination was notable for erythematous, blanchable, nontender macules coalescing into patches on the trunk and bilateral arms (Figure). There was slight erythema on the nasolabial folds and ears. The mucosal surfaces and distal legs were clear. The patient was afebrile. Her white blood cell count was 12.5×109/L with 32.3% eosinophils (baseline: white blood cell count, 14.8×109/L; 22% eosinophils)(reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L; 1%–4% eosinophils). Her comprehensive metabolic panel was within reference range. The human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antibody immunoassay was nonreactive.

The patient was diagnosed with an exanthematous eruption caused by IC and was treated with oral hydroxyzine and triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%. The eruption resolved within 2 weeks without recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

Comment

Del

Clinical Presentation of Delayed Reactions

Most delayed cutaneous reactions to IC present as exanthematous eruptions in the week following a contrast-enhanced CT scan or coronary angiogram.2,12 The reactions tend to resolve within 2 weeks of onset, and the treatment is largely supportive with antihistamines and/or corticosteroids for the associated pruritus.2,5,6 In a study of 98 patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC, delayed-onset urticaria and angioedema also have been reported with incidence rates of 19% and 24%, respectively.2 Other reactions are less common. In the same study, 7% of patients developed palpable purpura; acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; bullous, flexural, or psoriasislike exanthema; exfoliative eruptions; or purpura and a maculopapular eruption combined with eosinophilia.2 There also have been reports of IC-induced erythema multiforme,3 fixed drug eruptions,10,11 symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema,13 cutaneous vasculitis,14 drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms,15 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN,7,8,16,17 and iododerma.18

IC Agents

Virtually all delayed cutaneous reactions to IC reportedly are due to intravascular rather than oral agents,1,2,19 with the exception of iododerma18 and 1 reported case of TEN.17 Intravenous iohexol was most likely the offending drug in our case. In a prospective cohort study of 539 patients undergoing CT scans, the absolute risk for developing a delayed cutaneous reaction (defined as rash, itching, or skin redness or swelling) to intravascular iohexol was 9.4%.20 Randomized, double-blind studies have found that the risk for delayed cutaneous eruptions is similar among various types of IC, except for iodixanol, which confers a higher risk.5,6,21

Risk Factors

Interestingly, analyses have shown that delayed reactions to IC are more common in atopic patients and during high pollen season.22 Our patient displayed these risk factors, as she had allergic rhinitis and presented for evaluation in late spring when local pollen counts were high. Additionally, patients who develop delayed reactions to IC are notably more likely than controls to have a history of other cutaneous drug reactions, serum creatinine levels greater than 2.0 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL),3 or history of treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.19

Patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC are not at increased risk for immediate reactions and vice versa.2,3 This finding is consistent with the evidence that delayed and immediate reactions to IC are mechanistically unrelated.23 Additionally, seafood allergy is not a risk factor for either immediate or delayed reactions to IC, despite a common misconception among physicians and patients because seafood is iodinated.24,25

Reexposure to IC

Patients who have had delayed cutaneous reactions to IC are at risk for similar eruptions upon reexposure. Although the reactions are believed to be cell mediated, skin testing with IC is not sensitive enough to reliably identify tolerable alternatives.12 Consequently, gadolinium-based agents have been recommended in patients with a history of reactions to IC if additional contrast-enhanced studies are needed.13,26 Iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents do not cross-react, and gadolinium is compatible with studies other than magnetic resonance imaging.1,27

Premedication

Despite the absence of cross-reactivity, the American College of Radiology considers patients with hypersensitivity reactions to IC to be at increased risk for reactions to gadolinium but does not make specific recommendations regarding premedication given the dearth of data.1 As a result, premedication may be considered prior to gadolinium administration depending on the severity of the delayed reaction to IC. Additionally, premedication may be beneficial in cases in which gadolinium is contraindicated and IC must be reused. In a retrospective study, all patients with suspected delayed reactions to IC tolerated IC or gadolinium contrast when pretreated with corticosteroids with or without antihistamines.28 Regimens with corticosteroids and either cyclosporine or intravenous immunoglobulin also have prevented the recurrence of IC-induced exanthematous eruptions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.29,30 Despite these reports, delayed cutaneous reactions to IC have recurred in other patients receiving corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or cyclosporine for premedication or concurrent treatment of an underlying condition.16,29-31

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to recognize IC as a cause of delayed drug reactions. Current awareness is limited, and as a result, patients often are reexposed to the offending contrast agents unsuspectingly. In addition to diagnosing these eruptions, dermatologists may help prevent their recurrence if future contrast-enhanced studies are required by recommending gadolinium-based agents and/or premedication.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of allergic rhinitis presented in the spring with a pruritic eruption of 2 days’ duration that began on the abdomen and spread to the chest, back, and bilateral arms. Six days prior to the onset of the symptoms she underwent computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate abdominal pain and peripheral eosinophilia. Two iodinated contrast (IC) agents were used: intravenous iohexol and oral diatrizoate meglumine–diatrizoate sodium. The eruption was not preceded by fever, malaise, sore throat, rhinorrhea, cough, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, or new medication or supplement use. The patient denied any history of drug allergy or cutaneous eruptions. Her current medications, which she had been taking long-term, were aspirin, lisinopril, diltiazem, levothyroxine, esomeprazole, paroxetine, gabapentin, and diphenhydramine.

Physical examination was notable for erythematous, blanchable, nontender macules coalescing into patches on the trunk and bilateral arms (Figure). There was slight erythema on the nasolabial folds and ears. The mucosal surfaces and distal legs were clear. The patient was afebrile. Her white blood cell count was 12.5×109/L with 32.3% eosinophils (baseline: white blood cell count, 14.8×109/L; 22% eosinophils)(reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L; 1%–4% eosinophils). Her comprehensive metabolic panel was within reference range. The human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antibody immunoassay was nonreactive.

The patient was diagnosed with an exanthematous eruption caused by IC and was treated with oral hydroxyzine and triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%. The eruption resolved within 2 weeks without recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

Comment

Del

Clinical Presentation of Delayed Reactions

Most delayed cutaneous reactions to IC present as exanthematous eruptions in the week following a contrast-enhanced CT scan or coronary angiogram.2,12 The reactions tend to resolve within 2 weeks of onset, and the treatment is largely supportive with antihistamines and/or corticosteroids for the associated pruritus.2,5,6 In a study of 98 patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC, delayed-onset urticaria and angioedema also have been reported with incidence rates of 19% and 24%, respectively.2 Other reactions are less common. In the same study, 7% of patients developed palpable purpura; acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; bullous, flexural, or psoriasislike exanthema; exfoliative eruptions; or purpura and a maculopapular eruption combined with eosinophilia.2 There also have been reports of IC-induced erythema multiforme,3 fixed drug eruptions,10,11 symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema,13 cutaneous vasculitis,14 drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms,15 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN,7,8,16,17 and iododerma.18

IC Agents

Virtually all delayed cutaneous reactions to IC reportedly are due to intravascular rather than oral agents,1,2,19 with the exception of iododerma18 and 1 reported case of TEN.17 Intravenous iohexol was most likely the offending drug in our case. In a prospective cohort study of 539 patients undergoing CT scans, the absolute risk for developing a delayed cutaneous reaction (defined as rash, itching, or skin redness or swelling) to intravascular iohexol was 9.4%.20 Randomized, double-blind studies have found that the risk for delayed cutaneous eruptions is similar among various types of IC, except for iodixanol, which confers a higher risk.5,6,21

Risk Factors

Interestingly, analyses have shown that delayed reactions to IC are more common in atopic patients and during high pollen season.22 Our patient displayed these risk factors, as she had allergic rhinitis and presented for evaluation in late spring when local pollen counts were high. Additionally, patients who develop delayed reactions to IC are notably more likely than controls to have a history of other cutaneous drug reactions, serum creatinine levels greater than 2.0 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL),3 or history of treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.19

Patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC are not at increased risk for immediate reactions and vice versa.2,3 This finding is consistent with the evidence that delayed and immediate reactions to IC are mechanistically unrelated.23 Additionally, seafood allergy is not a risk factor for either immediate or delayed reactions to IC, despite a common misconception among physicians and patients because seafood is iodinated.24,25

Reexposure to IC

Patients who have had delayed cutaneous reactions to IC are at risk for similar eruptions upon reexposure. Although the reactions are believed to be cell mediated, skin testing with IC is not sensitive enough to reliably identify tolerable alternatives.12 Consequently, gadolinium-based agents have been recommended in patients with a history of reactions to IC if additional contrast-enhanced studies are needed.13,26 Iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents do not cross-react, and gadolinium is compatible with studies other than magnetic resonance imaging.1,27

Premedication

Despite the absence of cross-reactivity, the American College of Radiology considers patients with hypersensitivity reactions to IC to be at increased risk for reactions to gadolinium but does not make specific recommendations regarding premedication given the dearth of data.1 As a result, premedication may be considered prior to gadolinium administration depending on the severity of the delayed reaction to IC. Additionally, premedication may be beneficial in cases in which gadolinium is contraindicated and IC must be reused. In a retrospective study, all patients with suspected delayed reactions to IC tolerated IC or gadolinium contrast when pretreated with corticosteroids with or without antihistamines.28 Regimens with corticosteroids and either cyclosporine or intravenous immunoglobulin also have prevented the recurrence of IC-induced exanthematous eruptions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.29,30 Despite these reports, delayed cutaneous reactions to IC have recurred in other patients receiving corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or cyclosporine for premedication or concurrent treatment of an underlying condition.16,29-31

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to recognize IC as a cause of delayed drug reactions. Current awareness is limited, and as a result, patients often are reexposed to the offending contrast agents unsuspectingly. In addition to diagnosing these eruptions, dermatologists may help prevent their recurrence if future contrast-enhanced studies are required by recommending gadolinium-based agents and/or premedication.

- Cohan RH, Davenport MS, Dillman JR, et al; ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media. 9th ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

- Brockow K, Romano A, Aberer W, et al; European Network of Drug Allergy and the EAACI Interest Group on Drug Hypersensitivity. Skin testing in patients with hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media—a European multicenter study. Allergy. 2009;64:234-241.

Hosoya T, Yamaguchi K, Akutsu T, et al. Delayed adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media and their risk factors. Radiat Med. 2000;18:39-45. - Rydberg J, Charles J, Aspelin P. Frequency of late allergy-like adverse reactions following injection of intravascular non-ionic contrast media: a retrospective study comparing a non-ionic monomeric contrast medium with a non-ionic dimeric contrast medium. Acta Radiol. 1998;39:219-222.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Grech ED, et al. Early and late reactions after the use of iopamidol 340, ioxaglate 320, and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J. 2001;141:677-683.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Campbell PG, et al. Early and late reactions following the use of iopamidol 340, iomeprol 350 and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:133-138.

- Brown M, Yowler C, Brandt C. Recurrent toxic epidermal necrolysis secondary to iopromide contrast. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34:E53-E56.

- Rosado A, Canto G, Veleiro B, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after repeated injections of iohexol. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:262-263.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W198-W201.

- Good AE, Novak E, Sonda LP III. Fixed eruption and fever after urography. South Med J. 1980;73:948-949.

- Benson PM, Giblin WJ, Douglas DM. Transient, nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption caused by radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2, pt 2):379-381.

- Torres MJ, Gomez F, Doña I, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with nonimmediate cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy. 2012;67:929-935.

- Scherer K, Harr T, Bach S, et al. The role of iodine in hypersensitivity reactions to radio contrast media. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:468-475.

- Reynolds NJ, Wallington TB, Burton JL. Hydralazine predisposes to acute cutaneous vasculitis following urography with iopamidol. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:82-85.

- Belhadjali H, Bouzgarrou L, Youssef M, et al. DRESS syndrome induced by sodium meglumine ioxitalamate. Allergy. 2008;63:786-787.

- Baldwin BT, Lien MH, Khan H, et al. Case of fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis due to cardiac catheterization dye. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:837-840.

- Schmidt BJ, Foley WD, Bohorfoush AG. Toxic epidermal necrolysis related to oral administration of diluted diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1215-1216.

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379.

- Choyke PL, Miller DL, Lotze MT, et al. Delayed reactions to contrast media after interleukin-2 immunotherapy. Radiology. 1992;183:111-114.

- Loh S, Bagheri S, Katzberg RW, et al. Delayed adverse reaction to contrast-enhanced CT: a prospective single-center study comparison to control group without enhancement. Radiology. 2010;255:764-771.

- Bertrand P, Delhommais A, Alison D, et al. Immediate and delayed tolerance of iohexol and ioxaglate in lower limb phlebography: a double-blind comparative study in humans. Acad Radiol. 1995;2:683-686.

- Munechika H, Hiramatsu Y, Kudo S, et al. A prospective survey of delayed adverse reactions to iohexol in urography and computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:185-194.

- Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Romano A, Barbaud A, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3359-3372.

- H

uang SW. Seafood and iodine: an analysis of a medical myth. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:468-469. - B

aig M, Farag A, Sajid J, et al. Shellfish allergy and relation to iodinated contrast media: United Kingdom survey. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:107-111. - B

öhm I, Schild HH. A practical guide to diagnose lesser-known immediate and delayed contrast media-induced adverse cutaneous reactions. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1570-1579. - Ose K, Doue T, Zen K, et al. “Gadolinium” as an alternative to iodinated contrast media for X-ray angiography in patients with severe allergy. Circ J. 2005;69:507-509.

- Ji

ngu A, Fukuda J, Taketomi-Takahashi A, et al. Breakthrough reactions of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media after oral steroid premedication protocol. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:34. - Ro

mano A, Artesani MC, Andriolo M, et al. Effective prophylactic protocol in delayed hypersensitivity to contrast media: report of a case involving lymphocyte transformation studies with different compounds. Radiology. 2002;225:466-470. - He

bert AA, Bogle MA. Intravenous immunoglobulin prophylaxis for recurrent Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:286-288. - Ha

sdenteufel F, Waton J, Cordebar V, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions caused by iodixanol: an assessment of cross-reactivity in 22 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1356-1357.

- Cohan RH, Davenport MS, Dillman JR, et al; ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media. 9th ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

- Brockow K, Romano A, Aberer W, et al; European Network of Drug Allergy and the EAACI Interest Group on Drug Hypersensitivity. Skin testing in patients with hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media—a European multicenter study. Allergy. 2009;64:234-241.

Hosoya T, Yamaguchi K, Akutsu T, et al. Delayed adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media and their risk factors. Radiat Med. 2000;18:39-45. - Rydberg J, Charles J, Aspelin P. Frequency of late allergy-like adverse reactions following injection of intravascular non-ionic contrast media: a retrospective study comparing a non-ionic monomeric contrast medium with a non-ionic dimeric contrast medium. Acta Radiol. 1998;39:219-222.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Grech ED, et al. Early and late reactions after the use of iopamidol 340, ioxaglate 320, and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J. 2001;141:677-683.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Campbell PG, et al. Early and late reactions following the use of iopamidol 340, iomeprol 350 and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:133-138.

- Brown M, Yowler C, Brandt C. Recurrent toxic epidermal necrolysis secondary to iopromide contrast. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34:E53-E56.

- Rosado A, Canto G, Veleiro B, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after repeated injections of iohexol. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:262-263.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W198-W201.

- Good AE, Novak E, Sonda LP III. Fixed eruption and fever after urography. South Med J. 1980;73:948-949.

- Benson PM, Giblin WJ, Douglas DM. Transient, nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption caused by radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2, pt 2):379-381.

- Torres MJ, Gomez F, Doña I, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with nonimmediate cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy. 2012;67:929-935.

- Scherer K, Harr T, Bach S, et al. The role of iodine in hypersensitivity reactions to radio contrast media. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:468-475.

- Reynolds NJ, Wallington TB, Burton JL. Hydralazine predisposes to acute cutaneous vasculitis following urography with iopamidol. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:82-85.

- Belhadjali H, Bouzgarrou L, Youssef M, et al. DRESS syndrome induced by sodium meglumine ioxitalamate. Allergy. 2008;63:786-787.

- Baldwin BT, Lien MH, Khan H, et al. Case of fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis due to cardiac catheterization dye. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:837-840.

- Schmidt BJ, Foley WD, Bohorfoush AG. Toxic epidermal necrolysis related to oral administration of diluted diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1215-1216.

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379.

- Choyke PL, Miller DL, Lotze MT, et al. Delayed reactions to contrast media after interleukin-2 immunotherapy. Radiology. 1992;183:111-114.

- Loh S, Bagheri S, Katzberg RW, et al. Delayed adverse reaction to contrast-enhanced CT: a prospective single-center study comparison to control group without enhancement. Radiology. 2010;255:764-771.

- Bertrand P, Delhommais A, Alison D, et al. Immediate and delayed tolerance of iohexol and ioxaglate in lower limb phlebography: a double-blind comparative study in humans. Acad Radiol. 1995;2:683-686.

- Munechika H, Hiramatsu Y, Kudo S, et al. A prospective survey of delayed adverse reactions to iohexol in urography and computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:185-194.

- Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Romano A, Barbaud A, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3359-3372.

- H

uang SW. Seafood and iodine: an analysis of a medical myth. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:468-469. - B

aig M, Farag A, Sajid J, et al. Shellfish allergy and relation to iodinated contrast media: United Kingdom survey. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:107-111. - B

öhm I, Schild HH. A practical guide to diagnose lesser-known immediate and delayed contrast media-induced adverse cutaneous reactions. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1570-1579. - Ose K, Doue T, Zen K, et al. “Gadolinium” as an alternative to iodinated contrast media for X-ray angiography in patients with severe allergy. Circ J. 2005;69:507-509.

- Ji

ngu A, Fukuda J, Taketomi-Takahashi A, et al. Breakthrough reactions of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media after oral steroid premedication protocol. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:34. - Ro

mano A, Artesani MC, Andriolo M, et al. Effective prophylactic protocol in delayed hypersensitivity to contrast media: report of a case involving lymphocyte transformation studies with different compounds. Radiology. 2002;225:466-470. - He

bert AA, Bogle MA. Intravenous immunoglobulin prophylaxis for recurrent Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:286-288. - Ha

sdenteufel F, Waton J, Cordebar V, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions caused by iodixanol: an assessment of cross-reactivity in 22 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1356-1357.

Practice Points

- Delayed cutaneous reactions to iodinated contrast (IC) are common, but patients frequently are misdiagnosed and inadvertently readministered the offending agent.

- The most common IC-induced delayed reactions are self-limited exanthematous eruptions that develop within 1 week of exposure.

- Risk factors for delayed reactions to IC include atopy, contrast exposure during high pollen season, use of the agent iodixanol, a history of other cutaneous drug eruptions, elevated serum creatinine levels, and treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.

- Dermatologists can help prevent recurrent reactions in patients who require repeated exposure to IC by recommending gadolinium-based contrast agents and/or premedication.

Smoking tied to localized prostate cancer recurrence, metastasis, death

Patients with localized prostate cancer who were smokers at the time of local therapy had a higher risk of experiencing adverse outcomes and death related to the disease, a systematic review and meta-analysis has shown.

Current smokers in the study had a higher risk of biochemical recurrence, metastasis, and cancer-specific mortality after undergoing primary radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

“Our findings encourage radiation oncologists and urologists to counsel patients to stop smoking, using primary prostate cancer treatment as a teachable moment,” wrote Dr. Foerster and coauthors. The report was published in JAMA Oncology.

The investigators performed a database search of studies published from January 2000 to March 2017 and selected 11 articles for quantitative analysis. Those studies, which were all observational and not randomized, comprised 22,549 patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy. Of those patients, 4,202 (18.6%) were current smokers.

Current smokers had a higher risk of cancer-specific mortality, the investigators found based on analysis of five studies (hazard ratio, 1.89; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-2.69; P less than .001).

They also had a significantly higher risk of biochemical recurrence, based on 10 studies (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.18-1.66; P less than .001), and high risk of metastasis based on 3 studies (HR, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.80-3.51; P less than .001), the report shows.

Future studies need to more closely examine the link between smoking cessation and longer-term oncologic outcomes, as well as a more precise assessment of smoking exposure, the researchers concluded.

In the current study, results were inconclusive as to whether former smoking and time to cessation had any relationship to outcomes after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

“Available data were sparse and heterogenous,” they noted.

Dr. Foerster is supported by the Scholarship Foundation of Swiss Urology. One coauthor reported disclosures related to Astellas, Cepheid, Ipsen, Jansen, Lilly, Olympus, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanochemia, Sanofi, and Wolff.

SOURCE: Foerster B et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1071.

While previous studies have linked smoking to adverse outcomes in prostate cancer, including death, this study argues that the higher rate of prostate cancer–related death among smokers is a real effect with a biological cause, Stephen J. Freedland, MD, said in an editorial.

The current study included only men healthy enough to undergo aggressive treatment, which is an “important and necessary step to level the playing field,” Dr. Freedland wrote.

In that context, current smokers in this study had an 89% increased risk of prostate cancer–related death. “This finding shows that when we treat patients equally and minimize deaths from other causes, there is a stronger link between smoking and death from prostate cancer,” Dr. Freedland noted.

The finding also supports the notion that many smokers won’t live long enough to die from prostate cancer, given its slow-growing nature and the effects of smoking on competing causes of death, he added.

A scenario in which smokers did not live long enough to die of prostate cancer would predict a lower risk of prostate cancer–related death among smokers, he explained.

Because smoking has such clear adverse effects, physicians of all specialties should be hypervigilant about urging patients to quit smoking, Dr. Freedland concluded.

“If all of us remembered we are physicians first and oncologists and/or prostate cancer experts second, we will realize we are uniquely poised to help our patients, as the time of a new cancer diagnosis is a teachable moment when patients are very receptive to overall health advice,” he wrote.

Dr. Freedland is with the Center for Integrated Research on Cancer and Lifestyle, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. These comments are derived from his editorial in JAMA Oncology. Dr. Freeland had no reported conflict of interest disclosures.

While previous studies have linked smoking to adverse outcomes in prostate cancer, including death, this study argues that the higher rate of prostate cancer–related death among smokers is a real effect with a biological cause, Stephen J. Freedland, MD, said in an editorial.

The current study included only men healthy enough to undergo aggressive treatment, which is an “important and necessary step to level the playing field,” Dr. Freedland wrote.

In that context, current smokers in this study had an 89% increased risk of prostate cancer–related death. “This finding shows that when we treat patients equally and minimize deaths from other causes, there is a stronger link between smoking and death from prostate cancer,” Dr. Freedland noted.

The finding also supports the notion that many smokers won’t live long enough to die from prostate cancer, given its slow-growing nature and the effects of smoking on competing causes of death, he added.

A scenario in which smokers did not live long enough to die of prostate cancer would predict a lower risk of prostate cancer–related death among smokers, he explained.

Because smoking has such clear adverse effects, physicians of all specialties should be hypervigilant about urging patients to quit smoking, Dr. Freedland concluded.

“If all of us remembered we are physicians first and oncologists and/or prostate cancer experts second, we will realize we are uniquely poised to help our patients, as the time of a new cancer diagnosis is a teachable moment when patients are very receptive to overall health advice,” he wrote.

Dr. Freedland is with the Center for Integrated Research on Cancer and Lifestyle, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. These comments are derived from his editorial in JAMA Oncology. Dr. Freeland had no reported conflict of interest disclosures.

While previous studies have linked smoking to adverse outcomes in prostate cancer, including death, this study argues that the higher rate of prostate cancer–related death among smokers is a real effect with a biological cause, Stephen J. Freedland, MD, said in an editorial.

The current study included only men healthy enough to undergo aggressive treatment, which is an “important and necessary step to level the playing field,” Dr. Freedland wrote.

In that context, current smokers in this study had an 89% increased risk of prostate cancer–related death. “This finding shows that when we treat patients equally and minimize deaths from other causes, there is a stronger link between smoking and death from prostate cancer,” Dr. Freedland noted.

The finding also supports the notion that many smokers won’t live long enough to die from prostate cancer, given its slow-growing nature and the effects of smoking on competing causes of death, he added.

A scenario in which smokers did not live long enough to die of prostate cancer would predict a lower risk of prostate cancer–related death among smokers, he explained.

Because smoking has such clear adverse effects, physicians of all specialties should be hypervigilant about urging patients to quit smoking, Dr. Freedland concluded.

“If all of us remembered we are physicians first and oncologists and/or prostate cancer experts second, we will realize we are uniquely poised to help our patients, as the time of a new cancer diagnosis is a teachable moment when patients are very receptive to overall health advice,” he wrote.

Dr. Freedland is with the Center for Integrated Research on Cancer and Lifestyle, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. These comments are derived from his editorial in JAMA Oncology. Dr. Freeland had no reported conflict of interest disclosures.

Patients with localized prostate cancer who were smokers at the time of local therapy had a higher risk of experiencing adverse outcomes and death related to the disease, a systematic review and meta-analysis has shown.

Current smokers in the study had a higher risk of biochemical recurrence, metastasis, and cancer-specific mortality after undergoing primary radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

“Our findings encourage radiation oncologists and urologists to counsel patients to stop smoking, using primary prostate cancer treatment as a teachable moment,” wrote Dr. Foerster and coauthors. The report was published in JAMA Oncology.

The investigators performed a database search of studies published from January 2000 to March 2017 and selected 11 articles for quantitative analysis. Those studies, which were all observational and not randomized, comprised 22,549 patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy. Of those patients, 4,202 (18.6%) were current smokers.

Current smokers had a higher risk of cancer-specific mortality, the investigators found based on analysis of five studies (hazard ratio, 1.89; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-2.69; P less than .001).

They also had a significantly higher risk of biochemical recurrence, based on 10 studies (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.18-1.66; P less than .001), and high risk of metastasis based on 3 studies (HR, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.80-3.51; P less than .001), the report shows.

Future studies need to more closely examine the link between smoking cessation and longer-term oncologic outcomes, as well as a more precise assessment of smoking exposure, the researchers concluded.

In the current study, results were inconclusive as to whether former smoking and time to cessation had any relationship to outcomes after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

“Available data were sparse and heterogenous,” they noted.

Dr. Foerster is supported by the Scholarship Foundation of Swiss Urology. One coauthor reported disclosures related to Astellas, Cepheid, Ipsen, Jansen, Lilly, Olympus, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanochemia, Sanofi, and Wolff.

SOURCE: Foerster B et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1071.

Patients with localized prostate cancer who were smokers at the time of local therapy had a higher risk of experiencing adverse outcomes and death related to the disease, a systematic review and meta-analysis has shown.

Current smokers in the study had a higher risk of biochemical recurrence, metastasis, and cancer-specific mortality after undergoing primary radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

“Our findings encourage radiation oncologists and urologists to counsel patients to stop smoking, using primary prostate cancer treatment as a teachable moment,” wrote Dr. Foerster and coauthors. The report was published in JAMA Oncology.

The investigators performed a database search of studies published from January 2000 to March 2017 and selected 11 articles for quantitative analysis. Those studies, which were all observational and not randomized, comprised 22,549 patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy. Of those patients, 4,202 (18.6%) were current smokers.

Current smokers had a higher risk of cancer-specific mortality, the investigators found based on analysis of five studies (hazard ratio, 1.89; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-2.69; P less than .001).

They also had a significantly higher risk of biochemical recurrence, based on 10 studies (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.18-1.66; P less than .001), and high risk of metastasis based on 3 studies (HR, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.80-3.51; P less than .001), the report shows.

Future studies need to more closely examine the link between smoking cessation and longer-term oncologic outcomes, as well as a more precise assessment of smoking exposure, the researchers concluded.

In the current study, results were inconclusive as to whether former smoking and time to cessation had any relationship to outcomes after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

“Available data were sparse and heterogenous,” they noted.

Dr. Foerster is supported by the Scholarship Foundation of Swiss Urology. One coauthor reported disclosures related to Astellas, Cepheid, Ipsen, Jansen, Lilly, Olympus, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanochemia, Sanofi, and Wolff.

SOURCE: Foerster B et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1071.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Patients with localized prostate cancer should be encouraged to quit smoking because of the risk of potentially worse oncologic outcomes.

Major finding: Current smokers had a higher risk of biochemical recurrence, metastasis, and cancer-specific mortality, with hazard ratios of 1.40, 2.51, and 1.89, respectively.

Study details: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 studies involving 22,549 patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

Disclosures: The first author is supported by the Scholarship Foundation of Swiss Urology. One coauthor reported disclosures related to Astellas, Cepheid, Ipsen, Jansen, Lilly, Olympus, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Sanochemia, Sanofi, and Wolff.

Source: Foerster B et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 May 24. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1071.

Web portal does not reduce phone encounters or office visits for IBD patients

WASHINGTON – Inflammatory bowel disease patients may love web-based portals that allow them to interact with their doctors and records, but it does not seem to reduce their trips to the doctor.

“There was actually no decrease in office visits or phone encounters with patients that are utilizing MyChart [a web-based patient portal],” said Alexander Hristov, MD, a resident at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, in a video interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week®. “So in fact, the patients that had MyChart use were also the patients that were calling in more frequently and visiting the clinic more frequently, which is interesting because we did not see that there was an offset for emergency room visits or hospitalizations.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Out of the 616 total patients with either Crohn’s disease (355 patients) or ulcerative colitis (261 patients) analyzed in the study, 28% used MyChart. MyChart users also had higher number of prednisone prescriptions, compared with nonusers (51.9% vs. 40.8%, P = .01). There was no difference between MyChart users and nonusers for emergency room visits (P = .11) or hospitalizations (P = .16).

Interestingly, most messages sent via MyChart were for administrative reasons (54%), with both symptoms (28%) and education (18%) lagging behind.

Even though patients seem to like the portal, there is no billable time set aside for physicians to add the data for patients to access or respond to patient comments and requests through the portal. Unless MyChart can be shown to improve outcomes in some way, it is only an added burden for physicians.

Dr. Hristov mentioned that further work should be done to understand how web-based portals like MyChart can help both doctors and patients utilize this technology.

“We want to see the actual, measurable clinical outcomes of MyChart use,” he said. “So we want to set up a protocol where we can actually have measurable statistics looking at disease activity, inflammatory markers, and is there an impact that we are having on the patients disease course.”

Dr. Hristov had no financial disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Hristov A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May. doi: 0.1016/S0016-5085(18)32737-9.

WASHINGTON – Inflammatory bowel disease patients may love web-based portals that allow them to interact with their doctors and records, but it does not seem to reduce their trips to the doctor.

“There was actually no decrease in office visits or phone encounters with patients that are utilizing MyChart [a web-based patient portal],” said Alexander Hristov, MD, a resident at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, in a video interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week®. “So in fact, the patients that had MyChart use were also the patients that were calling in more frequently and visiting the clinic more frequently, which is interesting because we did not see that there was an offset for emergency room visits or hospitalizations.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Out of the 616 total patients with either Crohn’s disease (355 patients) or ulcerative colitis (261 patients) analyzed in the study, 28% used MyChart. MyChart users also had higher number of prednisone prescriptions, compared with nonusers (51.9% vs. 40.8%, P = .01). There was no difference between MyChart users and nonusers for emergency room visits (P = .11) or hospitalizations (P = .16).

Interestingly, most messages sent via MyChart were for administrative reasons (54%), with both symptoms (28%) and education (18%) lagging behind.

Even though patients seem to like the portal, there is no billable time set aside for physicians to add the data for patients to access or respond to patient comments and requests through the portal. Unless MyChart can be shown to improve outcomes in some way, it is only an added burden for physicians.

Dr. Hristov mentioned that further work should be done to understand how web-based portals like MyChart can help both doctors and patients utilize this technology.

“We want to see the actual, measurable clinical outcomes of MyChart use,” he said. “So we want to set up a protocol where we can actually have measurable statistics looking at disease activity, inflammatory markers, and is there an impact that we are having on the patients disease course.”

Dr. Hristov had no financial disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Hristov A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May. doi: 0.1016/S0016-5085(18)32737-9.

WASHINGTON – Inflammatory bowel disease patients may love web-based portals that allow them to interact with their doctors and records, but it does not seem to reduce their trips to the doctor.

“There was actually no decrease in office visits or phone encounters with patients that are utilizing MyChart [a web-based patient portal],” said Alexander Hristov, MD, a resident at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, in a video interview at the annual Digestive Disease Week®. “So in fact, the patients that had MyChart use were also the patients that were calling in more frequently and visiting the clinic more frequently, which is interesting because we did not see that there was an offset for emergency room visits or hospitalizations.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Out of the 616 total patients with either Crohn’s disease (355 patients) or ulcerative colitis (261 patients) analyzed in the study, 28% used MyChart. MyChart users also had higher number of prednisone prescriptions, compared with nonusers (51.9% vs. 40.8%, P = .01). There was no difference between MyChart users and nonusers for emergency room visits (P = .11) or hospitalizations (P = .16).

Interestingly, most messages sent via MyChart were for administrative reasons (54%), with both symptoms (28%) and education (18%) lagging behind.

Even though patients seem to like the portal, there is no billable time set aside for physicians to add the data for patients to access or respond to patient comments and requests through the portal. Unless MyChart can be shown to improve outcomes in some way, it is only an added burden for physicians.

Dr. Hristov mentioned that further work should be done to understand how web-based portals like MyChart can help both doctors and patients utilize this technology.

“We want to see the actual, measurable clinical outcomes of MyChart use,” he said. “So we want to set up a protocol where we can actually have measurable statistics looking at disease activity, inflammatory markers, and is there an impact that we are having on the patients disease course.”

Dr. Hristov had no financial disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Hristov A et al. Gastroenterology. 2018 May. doi: 0.1016/S0016-5085(18)32737-9.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2018

Key clinical point: Inflammatory bowel disease patients had more office visits and phone calls with physicians, and had worse outcomes.

Major finding: MyChart patients averaged 7.2 office visits and 19.2 phone encounters, compared with 5.6 office visits and 13.7 phone encounters in nonusers.

Study details: A review of patient electronic health records from Jan. 1, 2012, to December 31, 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Hristov had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

Source: Hristov A et al Gastroenterology. 2018 May. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(18)32737-9.

Liver enzyme a marker of disease progression in primary biliary cholangitis

The liver enzyme autotaxin may be a useful noninvasive marker of disease progression in people with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), new research has suggested.

Satoru Joshita, MD, from the gastroenterology and hepatology department at Shinshu University in Matsumoto, Japan, and colleagues noted that the liver-specific autoimmune disease PBC is characterized by the destruction of bile ducts, leading to cirrhosis and liver failure, and is more often seen in women.

Symptoms at diagnosis, a lack of response to gold standard treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid, and more advanced histologic phase are linked to worse patient outcomes, the research team explained in Scientific Reports.

While liver biopsy could give vital information on the severity of disease, it is an invasive procedure that is limited by sampling error and interobserver disparity. “As advanced histological stage is associated with a worse prognosis in PBC patients, it is important for clinicians to know clinical stage noninvasively when deciding appropriate therapies,” they wrote.

Noninvasive measures of liver fibrosis and PBC progression are available, such as Wisteria floribunda agglutinin–positive Mac-2 binding protein, hyaluronic acid, and type IV collagen 7S, but the authors said their “diagnostic abilities remain under scrutiny” because of their “moderate” accuracy.

Previous research had described autotaxin (ATX), a secreted enzyme metabolized by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, as a prognostic factor for overall survival in cirrhosis patients, which suggested “an important role of ATX in the progression of liver disease,” the researchers noted.

They therefore set out to assess its utility as a marker of primary biliary cholangitis disease progression by measuring the serum ATX values of 128 treatment-naive, histologically assessed PBC patients, 108 of whom were female and 20 were male. Their ATX levels were then compared with 80 healthy controls.

Results showed that the ATX levels of patients with PBC were significantly higher than those of controls (median, 0.97 mg/L vs. 0.76 mg/L, respectively; P less than .0001).

Autotaxin results were validated by biopsy-proven histologic assessment: Patients with PBC that was classified as Nakanuma’s stage I, II, III, and IV had median ATX concentrations of 0.70, 0.80, 0.87, 1.03, and 1.70 mg/L, respectively, which demonstrated significant increases in concentration of ATX with disease stage (r = 0.53; P less than .0001). The researchers confirmed this finding using Scheuer’s classification of the disease (r = 0.43; P less than .0001).

The researchers noted that their findings were also “well correlated with other established noninvasive fibrosis markers, indicating ATX to be a reliable clinical surrogate marker to predict disease progression in patients with PBC.”

For example, autotaxin levels correlated with W. floribunda agglutinin–positive Mac-2 binding protein (r = 0.51; P less than .0001) and the fibrosis index based on four factors index (r = 0.51; P less than .0001).

Interestingly, the researchers found a sex difference in ATX levels: Not only were ATX values in female patients significantly higher than those in female controls (median, 1.00 mg/L vs. 0.82 mg/L, respectively; P less than .001) but they also were higher than those of male patients (median, 0.78 mg/L; P = .005).

According to the authors, these findings highlighted a need for sex-specific benchmarks, as well as more research to clarify why the sex disparity existed.

A further longitudinal study conducted by the authors involving 29 patients seen at their clinic showed that ATX levels increased slowly but significantly over an 18-year period, with a median increase rate of 0.03 mg/L per year (P less than .00001).

Patients who died from their disease had a significantly higher autotaxin increase rate than did survivors (0.05 mg/L per year vs. 0.02 mg/L per year, respectively; P less than .01).

Based on their findings, the researchers concluded that serum ATX levels “represent an accurate, noninvasive biomarker for estimating disease progression in patients with PBC.”

However, they said a longer longitudinal study of patients with PBC looking at ATX levels and clinical features, as well as long-term prognosis and complicating hepatocellular carcinoma, was warranted.

Two coauthors are employees of TOSOH corporation and Inova Diagnostics. The remaining authors had no conflicts to declare related to this study.

SOURCE: Joshita S et al. Scientific Reports. 2018 May 25. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26531-0.

The liver enzyme autotaxin may be a useful noninvasive marker of disease progression in people with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), new research has suggested.

Satoru Joshita, MD, from the gastroenterology and hepatology department at Shinshu University in Matsumoto, Japan, and colleagues noted that the liver-specific autoimmune disease PBC is characterized by the destruction of bile ducts, leading to cirrhosis and liver failure, and is more often seen in women.

Symptoms at diagnosis, a lack of response to gold standard treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid, and more advanced histologic phase are linked to worse patient outcomes, the research team explained in Scientific Reports.

While liver biopsy could give vital information on the severity of disease, it is an invasive procedure that is limited by sampling error and interobserver disparity. “As advanced histological stage is associated with a worse prognosis in PBC patients, it is important for clinicians to know clinical stage noninvasively when deciding appropriate therapies,” they wrote.

Noninvasive measures of liver fibrosis and PBC progression are available, such as Wisteria floribunda agglutinin–positive Mac-2 binding protein, hyaluronic acid, and type IV collagen 7S, but the authors said their “diagnostic abilities remain under scrutiny” because of their “moderate” accuracy.

Previous research had described autotaxin (ATX), a secreted enzyme metabolized by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, as a prognostic factor for overall survival in cirrhosis patients, which suggested “an important role of ATX in the progression of liver disease,” the researchers noted.

They therefore set out to assess its utility as a marker of primary biliary cholangitis disease progression by measuring the serum ATX values of 128 treatment-naive, histologically assessed PBC patients, 108 of whom were female and 20 were male. Their ATX levels were then compared with 80 healthy controls.

Results showed that the ATX levels of patients with PBC were significantly higher than those of controls (median, 0.97 mg/L vs. 0.76 mg/L, respectively; P less than .0001).

Autotaxin results were validated by biopsy-proven histologic assessment: Patients with PBC that was classified as Nakanuma’s stage I, II, III, and IV had median ATX concentrations of 0.70, 0.80, 0.87, 1.03, and 1.70 mg/L, respectively, which demonstrated significant increases in concentration of ATX with disease stage (r = 0.53; P less than .0001). The researchers confirmed this finding using Scheuer’s classification of the disease (r = 0.43; P less than .0001).

The researchers noted that their findings were also “well correlated with other established noninvasive fibrosis markers, indicating ATX to be a reliable clinical surrogate marker to predict disease progression in patients with PBC.”

For example, autotaxin levels correlated with W. floribunda agglutinin–positive Mac-2 binding protein (r = 0.51; P less than .0001) and the fibrosis index based on four factors index (r = 0.51; P less than .0001).

Interestingly, the researchers found a sex difference in ATX levels: Not only were ATX values in female patients significantly higher than those in female controls (median, 1.00 mg/L vs. 0.82 mg/L, respectively; P less than .001) but they also were higher than those of male patients (median, 0.78 mg/L; P = .005).