User login

MDedge Daily News: Why the barber’s chair can help hypertension

Why the barber’s chair can help hypertension, how family history affects colorectal cancer risk, a steroid shot could ease hip osteoarthritis pain, and why excessive daytime sleepiness could lead to dementia.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Why the barber’s chair can help hypertension, how family history affects colorectal cancer risk, a steroid shot could ease hip osteoarthritis pain, and why excessive daytime sleepiness could lead to dementia.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Why the barber’s chair can help hypertension, how family history affects colorectal cancer risk, a steroid shot could ease hip osteoarthritis pain, and why excessive daytime sleepiness could lead to dementia.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Incidence and Management of Asymptomatic Hypertensive Urgency at a VA Emergency Department

Hypertension affects more than 65 million individuals in the U.S., accounting for nearly 30% of the adult population.1 Less than 50% of those with hypertension are taking appropriate pharmacotherapy.2 Hypertension contributes to cardiovascular events, including cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, hypertensive retinopathy, renal failure, myocardial infarction, and heart failure.1 Chronic hypertension mainly is an asymptomatic condition, earning the nickname “the silent killer.”2 An acute, symptomatic elevation in blood pressure (BP) often is referred to as hypertensive emergency. Symptoms of end-organ damage can include headache, blurry vision, chest pain, shortness of breath, altered mental status, epistaxis, and oliguria.2 Although rare, hypertensive emergencies should be treated immediately. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee (JNC 7), and the more recent JNC 8, have published guidelines on managing chronic hypertension.3,4 However, neither report provides guidance on hypertensive emergency or the appropriate actions in cases of extremely elevated BP in an asymptomatic patient.3,4

Acute hypertensive episodes—often referred to as hypertensive crises—are responsible for nearly 8 million hospitalizations each year and 20 million visits to the emergency department (ED).5,6 Most of these visits are same-day “treat-and-release” events.5 There is no universally accepted BP value associated with a hypertensive crisis, but most resources state that a BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg requires attention.2,7 Without other symptoms, elevated BP is not an emergency, yet ED referral for acute management is common.7

Three terms fall under the umbrella of hypertensive crises: hypertensive emergency, hypertensive urgency, and asymptomatic hypertension (AH).2 In a 2007 article, the American College of Chest Physicians defined hypertensive emergency as BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg with evidence of end-organ damage.2 Symptoms are almost always present in true hypertensive emergencies, and immediate medical intervention is required to halt further organ damage. In the same article, hypertensive urgency is defined as BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg without end-organ damage.2 The definition of hypertensive urgency could be further refined to include the presence of cardiovascular and renal risk factors, although this additional point is not consistent across the literature. Asymptomatic hypertension is similar to hypertensive urgency; however, there is an absence of signs or symptoms of end-organ damage.2 There is ambiguity in the literature concerning managing hypertensive urgency and AH, but both share a basic tenet: Immediate BP reduction is not essential. Gradual dosage adjustment(s) of oral medications, preferably by a primary care provider (PCP), and follow-up within 7 days are recommended.7

Limited evidence exists to guide ED providers in managing AH. Long-term outcomes and guidelines intended for the primary care setting should not be extrapolated to acute management in the ED. With limited treatment guidelines, providers might be more likely to refer patients with AH to the ED for evaluation. In 2013, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) created a clinical policy concerning AH in the ED. The ACEP concluded that screening for target organ injury and medical intervention in the ED does not reduce rates of adverse events (AEs) and could lead to overtreatment and acute hypoperfusion.7 More recently, Patel and colleagues published findings on hypertensive urgency in the ambulatory care setting, which similarly found that referral to the ED was associated with increased use of health care resources and no change in short-term major AEs.8 The ACEP recommends that patients presenting with AH be referred to primary care clinics where long-term monitoring and medication adjustments can be achieved more cost-effectively.7

The objective of this retrospective evaluation was to assess the incidence and management of AH within a VA ED. The authors aimed to provide insight into how these patients are managed and discuss alternatives to ED use.

Methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted within the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS), which provides patient care at 2 medical centers in Gainesville and Lake City, Florida, as well as 11 outpatient clinics located throughout North Florida and South Georgia. The NFSGVHS serves rural and urban veteran populations. Study approval was granted by the NFSGVHS Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Adult patients who were ordered at least 1 antihypertensive medication in the ED from July 1, 2011 to July 1, 2014, in addition to being asymptomatic with BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg at ED triage were included. Based on clinical experience, the authors estimated that 3 years would provide a sample size of more than 100 patients. Patients were excluded if they presented with any acute symptoms or were hospitalized for further management.

Data Collection

Baseline demographics were collected for all participants. During the ED encounter, pre- and postintervention vital signs were recorded and prespecified laboratory data obtained. Interrater reliability was accounted for by performing random reviews of previously collected data to ensure consistency during the chart review process. Renal end-organ damage was defined using Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria, a serum creatinine 50% above baseline, or an absolute increase in baseline serum creatinine by 0.3 mg/dL.9 Additional laboratory markers of organ damage included cardiac troponin levels. Urinalysis results also were assessed to determine the presence of hematuria or proteinuria. Patient-reported nonadherence with medications was determined by reviewing ED provider and/or nurse documentation notes for the index ED encounter.

Investigators documented the route (IV or oral) and antihypertensive(s) medication selected for each patient. Adverse effects and any changes to patients’ outpatient medication regimens were noted. Investigators also assessed days to next medical contact after ED discharge to determine whether follow-up occurred according to the recommended standard of 7 days.9 Days to next medical contact was defined as any contact—in person or by telephone—that was documented in the electronic health record after the index ED visit.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean, median, and standard deviation, were used to analyze data.

Results

A total of 1,052 patients presented with BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg and for whom antihypertensive medication was ordered but not necessarily given in the ED. Of the total, 724 patients were excluded because of hospital admission for other primary diagnoses; however, 6 of these patients were admitted for hypertensive urgency. The final analysis included 132 patients who presented with the primary condition of elevated BP without any accompanying symptoms. Among these patients, 2 had repeat ED visits for AH during the specified time frame.

Most patients were male with an average age of 63 years and documented history of hypertension. Nearly all patients had established primary care within the NFSGVHS. The most common comorbidity was diabetes mellitus (36%), followed by coronary artery disease (27%) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (21%) (Table 1). About one-third of patients presented to the ED on their own volition, and slightly more than half were referred to the ED by primary care or specialty clinics.

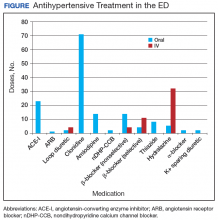

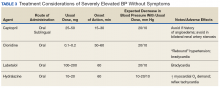

In the ED, 130 patients received BP treatment (Table 2). Medication was ordered for 2 patients who did not receive treatment. In total, 12 different medication classes were used for treating patients with AH in the ED (Figure).

Treatment in the ED resulted in an average BP and heart rate reduction of 27/20 mm Hg and 5 beats per minute, respectively. About 80% of patients had a basic metabolic panel drawn, and there were no instances of acute kidney injury. Of the patients in the study 38% had cardiac enzymes collected, and only 1 patient had a positive result, which was determined to be unrelated to acute coronary syndrome. Forty-one (31%) of patients had a urinalysis; 12 has positive results for hematuria, and 18 revealed proteinuria. Of note, the 6 patients who were hospitalized for hypertensive urgency had neither symptoms at presentation to the ED nor laboratory findings indicating end-organ damage. The reason these patients were admitted is unclear.

At discharge, ED providers made changes to 54% of patients’ outpatient antihypertensive regimens. These changes included adding a new medication (68%), increasing the dosage of an existing medication (24%), or multiple changes (8%). Refills were provided for 18% of prescriptions. Follow-up within 7 days from ED discharge was recorded for 34% of patients. One patient received follow-up outside the NFSGVHS and was not included in this analysis.

Discussion

The aim of this retrospective study was to determine the incidence of AH in a VA ED and describe how these patients were managed. Overall, the rate of patients presenting to the ED with AH during the study period was about 1 patient every 8 days or 45 patients per year. By comparison, more than 30,000 patients are seen at the NFSGVHS ED annually. Although AH seems to be an uncommon occurrence, study findings raise questions about the value of managing the condition in the ED.

This study found several management strategies as well as noteworthy trends. For example, laboratory tests were not ordered routinely for all patients, suggesting that some ED providers question their use for AH. There were no patients with acute elevations in serum creatinine that indicated acute kidney injury, and although hematuria and proteinuria were common findings, neither were specific for acute injury. However, there were findings typical of chronic hypertension, and urinalysis may provide little benefit when testing for acute kidney injury. Only 1 patient showed elevated cardiac enzymes, which was determined to be a result of CKD.

Although not included in the final analysis, the 6 patients who were hospitalized for hypertensive urgency were similar in that they had neither symptoms at presentation to the ED nor laboratory findings indicating end-organ damage. Collectively, these findings support existing literature that questions the utility of laboratory testing of patients with AH in the ED.10

Patients also were treated with a variety of antihypertensive agents in the ED. One explanation might be outpatient nonadherence with medications. In patients with AH, it is common to provide doses of chronic medications that the patient might have missed and should be taking on a regular basis. Therefore, assessing adherence with current medications before modifying chronic therapy is an important initial step when managing AH.

Although oral agents primarily were used, IV antihypertensives were administered to about one-third of patients. Preference for IV administration in the ED might be related to its ability to lower BP quickly. The practice of obtaining IV access for medication in a patient with AH is costly, unnecessary, and potentially harmful.7 The authors theorize that this practice is performed, in many cases, as an attempt to expedite ED discharge after an acceptable BP reading is documented.

Rapid reductions in BP can precipitate hypoperfusion inadvertently and are more likely to occur with IV agents than with oral ones. Therefore, the safety, convenience, and cost savings associated with oral administration make it the preferred route for managing AH.

Best Practices

Primary care clinics are best suited to manage AH because medication adjustments and long-term monitoring are easier to perform and at substantially lower costs when compared with that of the ED. Rather than immediately referring a patient to the ED, clinicians should consider factors that could elevate BP, such as medication nonadherence, anxiety, acute pain, recent tobacco or caffeine use, or white coat syndrome. Staff should be well educated on proper BP measurement and instructed to repeat the reading for confirmation. Before measuring BP, allow the patient to sit quietly for 5 minutes with the feet flat on the floor and arm supported.3 Ideally, the measurement used should be the average of 3 BP readings on an automated device.11 If BP readings are high, staff should ask the patient about medication adherence and missed medication(s) should be administered.

It also is reasonable to have the patient rest quietly for up to 30 minutes because rest has been shown to reduce BP in some patients.12 The drawback to the prolonged rest strategy is the potential to cause delays in care for other patients. However, it is important to remember that wait times in the ED often are measured in hours, which causes frustration for patients referred to the ED for AH management. Before completing the office visit, the provider should recheck BP using proper technique and confirm that the patient has antihypertensive medication(s) in his/her possession; a follow-up appointment should be scheduled for no later than 1 week.

Primary care providers might be concerned about taking on additional liability and could favor ED referral, but legislation makes it difficult for EDs to defer nonemergent issues to primary care clinics. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act states that hospitals are prohibited from denying a patient care during an emergency.13 Despite evidence that AH is not an emergency, many patients continue to be referred to the ED. One-third of patients presented to the ED on their own volition and more than one-half were referred by health care personnel. This strongly suggests that both patients and health care personnel consider AH an emergency medical condition requiring immediate attention. However, patients with AH rarely are found to have any acute end-organ damage; therefore, acute treatment and extensive laboratory or diagnostic testing in the ED provides little, if any, benefit.10 The authors believe the ACEP clinical policy should be adopted into mainstream practice to help reduce health care costs and preserve ED resources for patients with true emergencies.

Another pervasive issue that could contribute to inappropriate AH referrals to the ED is the shortage of PCPs and limited same-day appointments for nonemergent conditions. In a 2017 survey, the average wait time for a PCP appointment ranged between 12 and 109 days, depending on the metropolitan area. The national average wait time conducted by this survey was 29.3 days.14 When primary care appointments are unavailable, triage staff could recommend that patients seek care in the ED. Additionally, patients might choose to seek ED care rather than wait for the next available PCP appointment. Clinic proximity to an ED could influence referral rates. In other words, medical centers or health systems with primary care clinics and ED services under one roof could experience more frequent ED referrals.

A promising strategy to help overcome the challenges of addressing AH and avoiding ED referrals is increasing patient access to and use of qualified, nonphysician providers, such as clinical pharmacists and nurse practitioners. Large health systems such as the VA and Kaiser Permanente have employed clinical pharmacist providers to reduce follow-up times for patients in primary care settings.15 Furthermore, there is substantial evidence that supports the cost-effectiveness and clinical success of pharmacist-driven hypertension clinics.16-18 Nurse-driven efforts to improve hypertension control have been successfully implemented in health systems.19 Both clinical pharmacist and nurse-managed hypertension clinics are effective solutions to manage patients with AH who might otherwise use costly ED services.For example, the average cost of a single ED visit is $740 to $3,437.20 In comparison, a 2010 report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality showed the average annual cost of managing hypertension in ambulatory care clinics was $442 per adult, a cost considerably lower than that of the ED.21

Limitations

The retrospective and observational design of this study are inherent limitations. This study was not designed to evaluate cardiovascular outcomes after ED encounters. The sample size could have been larger if patients with BP < 180/110 mm Hg at ED triage were included; however, the 180/110 mm Hg threshold was chosen because it was the most widely agreed on BP value in the literature. This study did not capture patients who presented with AH and did not receive any acute treatment in the ED.Prescribing patterns based on provider training (eg, emergency medicine, family medicine, or internal medicine) were not tracked and might have accounted for differences in selection of diagnostic tests, laboratory ordering, and route of drug administration preference.

A small subset of patients reported positive pain scores at triage but did not describe acute pain. Pain scores are highly subjective, and few primary literature sources link chronic pain with increased BP.22,23 Nevertheless, patients who reported acute pain and elevated BP were excluded in order to identify truly asymptomatic patients. VA hospitals are unique health systems and data obtained from this study might not be applicable to other public or private facilities. Last, the study did not take into account patients’ psychosocial circumstances that might have fostered a disproportionate reliance on the ED for health care.

Conclusion

Asymptomatic patients with elevated BP are treated in the ED despite no evidence supporting improved outcomes after acute BP lowering in this population. Follow-up after ED encounters for AH did not occur consistently within guideline-recommended 7 days, a trend that also occurs in non-VA systems.8 Clinics and health care systems could establish policies to prevent or minimize management of AH in the ED. Ideally, AH should be managed in a clinic setting by a PCP, but growing clinician workload might lead to increasing wait times and difficultly obtaining same-day appointments. Nurse-led clinics and clinical pharmacists operating under a scope of practice and working closely with a PCP are a cost-effective solution to ensure timely treatment and appropriate follow-up of patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida South Georgia Veterans Health System in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(133):

1-8.

2. Marik PE, Varon J. Hypertensive crises: challenges and management. Chest. 2007;131(6):1949-1962.

3. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-1252.

4. James, PA, Oparil, S, Carter, BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

5. American Heart Association. High blood pressure ER visits jumped 25 percent in 2006-11. http://newsroom.heart.org/news/high-blood-pressure-er-visits-jumped-25-percent-in-2006-11. Published September 9, 2014. Accessed January 19, 2018.

6. Owens P, Mutter R. Statistical brief #100: emergency department visits for adults in community hospitals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb100.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed January 19, 2018.

7. Wolf SJ, Lo B, Shih RD, Smith MD, Fesmire FM; American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients in the emergency department with asymptomatic elevated blood pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(1):59-68.

8. Patel KK, Young L, Howell EH, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting with hypertensive urgency in the office setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):981-988.

9. Acute Kidney Injury Network. AKIN studies. http://www.akinet.org/akinstudies.php. Updated 2017. Accessed January 19, 2018.

10. Karras DJ, Kruus LK, Cienki JJ, et al. Utility of routine testing for patients with asymptomatic severe blood pressure elevation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(3):231-239.

11. The SPRINT Research Group. A Randomized trial of Intensive versus standard blood pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

12. Grassi D, O’Flaherty M, Pellizzari M, et al; Group of Investigators of the REHASE Program. Hypertensive urgencies in the emergency department: evaluating blood pressure response to rest and to antihypertensive drugs with different profiles. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(9):662-667.

13. Canters for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Emergency medical treatment & labor act (EMTALA). https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EMTALA/index.html. Updated March 26, 2012. Accessed January 19, 2018.

14. Merritt Hawkins. 2017 Survey of physician appointment wait times and Medicare and Medicaid acceptance rates. https://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/Merritt-Hawkins/Pdf/mha2017waittimesurveyPDF.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed January 19, 2018.

15. Galewitz P. VA treats patients’ impatience with clinical pharmacists. USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/10/24/kaiser-va-treats-patients-impatience-clinical-pharmacists/92479132/. Published October 24, 2016. Accessed January 19, 2018.

16. Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, et al. Physician and pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1996-2002.

17. Borenstein JE, Graber G, Saltiel E, et al. Physician-pharmacist comanagement of hypertension: a randomized comparative trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(2):209-216.

18. Okamoto MP, Nakahiro RK. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of a pharmacist-managed hypertension clinic. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(11):1337-1344.

19. Brown VM. Managing patients with hypertension in nurse-led clinics. Nursing. 2017;47(4):16-19.

20. Caldwell N, Srebotnjak T, Wang T, Hsia R. “How Much Will I Get Charged for This?” Patient charges for top ten diagnoses in the emergency department. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2): e55491.

21. Davis KE. Expenditures for hypertension among adults age 18 and older, 2010: estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st404/stat404.shtml. Published April 2013. Accessed January 19, 2018.

22. Marco CA, Plewa MC, Buderer N, et al. Self-reported pain scores in the emergency department: lack of association with vital signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(9):974-979.

23. Wood D, Goodnight S, Haig AJ, Nasari T. Body mass index, but not blood pressure is related to the level of pain in persons with chronic pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2011;24(2):

111-115.

Hypertension affects more than 65 million individuals in the U.S., accounting for nearly 30% of the adult population.1 Less than 50% of those with hypertension are taking appropriate pharmacotherapy.2 Hypertension contributes to cardiovascular events, including cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, hypertensive retinopathy, renal failure, myocardial infarction, and heart failure.1 Chronic hypertension mainly is an asymptomatic condition, earning the nickname “the silent killer.”2 An acute, symptomatic elevation in blood pressure (BP) often is referred to as hypertensive emergency. Symptoms of end-organ damage can include headache, blurry vision, chest pain, shortness of breath, altered mental status, epistaxis, and oliguria.2 Although rare, hypertensive emergencies should be treated immediately. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee (JNC 7), and the more recent JNC 8, have published guidelines on managing chronic hypertension.3,4 However, neither report provides guidance on hypertensive emergency or the appropriate actions in cases of extremely elevated BP in an asymptomatic patient.3,4

Acute hypertensive episodes—often referred to as hypertensive crises—are responsible for nearly 8 million hospitalizations each year and 20 million visits to the emergency department (ED).5,6 Most of these visits are same-day “treat-and-release” events.5 There is no universally accepted BP value associated with a hypertensive crisis, but most resources state that a BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg requires attention.2,7 Without other symptoms, elevated BP is not an emergency, yet ED referral for acute management is common.7

Three terms fall under the umbrella of hypertensive crises: hypertensive emergency, hypertensive urgency, and asymptomatic hypertension (AH).2 In a 2007 article, the American College of Chest Physicians defined hypertensive emergency as BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg with evidence of end-organ damage.2 Symptoms are almost always present in true hypertensive emergencies, and immediate medical intervention is required to halt further organ damage. In the same article, hypertensive urgency is defined as BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg without end-organ damage.2 The definition of hypertensive urgency could be further refined to include the presence of cardiovascular and renal risk factors, although this additional point is not consistent across the literature. Asymptomatic hypertension is similar to hypertensive urgency; however, there is an absence of signs or symptoms of end-organ damage.2 There is ambiguity in the literature concerning managing hypertensive urgency and AH, but both share a basic tenet: Immediate BP reduction is not essential. Gradual dosage adjustment(s) of oral medications, preferably by a primary care provider (PCP), and follow-up within 7 days are recommended.7

Limited evidence exists to guide ED providers in managing AH. Long-term outcomes and guidelines intended for the primary care setting should not be extrapolated to acute management in the ED. With limited treatment guidelines, providers might be more likely to refer patients with AH to the ED for evaluation. In 2013, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) created a clinical policy concerning AH in the ED. The ACEP concluded that screening for target organ injury and medical intervention in the ED does not reduce rates of adverse events (AEs) and could lead to overtreatment and acute hypoperfusion.7 More recently, Patel and colleagues published findings on hypertensive urgency in the ambulatory care setting, which similarly found that referral to the ED was associated with increased use of health care resources and no change in short-term major AEs.8 The ACEP recommends that patients presenting with AH be referred to primary care clinics where long-term monitoring and medication adjustments can be achieved more cost-effectively.7

The objective of this retrospective evaluation was to assess the incidence and management of AH within a VA ED. The authors aimed to provide insight into how these patients are managed and discuss alternatives to ED use.

Methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted within the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS), which provides patient care at 2 medical centers in Gainesville and Lake City, Florida, as well as 11 outpatient clinics located throughout North Florida and South Georgia. The NFSGVHS serves rural and urban veteran populations. Study approval was granted by the NFSGVHS Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Adult patients who were ordered at least 1 antihypertensive medication in the ED from July 1, 2011 to July 1, 2014, in addition to being asymptomatic with BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg at ED triage were included. Based on clinical experience, the authors estimated that 3 years would provide a sample size of more than 100 patients. Patients were excluded if they presented with any acute symptoms or were hospitalized for further management.

Data Collection

Baseline demographics were collected for all participants. During the ED encounter, pre- and postintervention vital signs were recorded and prespecified laboratory data obtained. Interrater reliability was accounted for by performing random reviews of previously collected data to ensure consistency during the chart review process. Renal end-organ damage was defined using Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria, a serum creatinine 50% above baseline, or an absolute increase in baseline serum creatinine by 0.3 mg/dL.9 Additional laboratory markers of organ damage included cardiac troponin levels. Urinalysis results also were assessed to determine the presence of hematuria or proteinuria. Patient-reported nonadherence with medications was determined by reviewing ED provider and/or nurse documentation notes for the index ED encounter.

Investigators documented the route (IV or oral) and antihypertensive(s) medication selected for each patient. Adverse effects and any changes to patients’ outpatient medication regimens were noted. Investigators also assessed days to next medical contact after ED discharge to determine whether follow-up occurred according to the recommended standard of 7 days.9 Days to next medical contact was defined as any contact—in person or by telephone—that was documented in the electronic health record after the index ED visit.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean, median, and standard deviation, were used to analyze data.

Results

A total of 1,052 patients presented with BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg and for whom antihypertensive medication was ordered but not necessarily given in the ED. Of the total, 724 patients were excluded because of hospital admission for other primary diagnoses; however, 6 of these patients were admitted for hypertensive urgency. The final analysis included 132 patients who presented with the primary condition of elevated BP without any accompanying symptoms. Among these patients, 2 had repeat ED visits for AH during the specified time frame.

Most patients were male with an average age of 63 years and documented history of hypertension. Nearly all patients had established primary care within the NFSGVHS. The most common comorbidity was diabetes mellitus (36%), followed by coronary artery disease (27%) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (21%) (Table 1). About one-third of patients presented to the ED on their own volition, and slightly more than half were referred to the ED by primary care or specialty clinics.

In the ED, 130 patients received BP treatment (Table 2). Medication was ordered for 2 patients who did not receive treatment. In total, 12 different medication classes were used for treating patients with AH in the ED (Figure).

Treatment in the ED resulted in an average BP and heart rate reduction of 27/20 mm Hg and 5 beats per minute, respectively. About 80% of patients had a basic metabolic panel drawn, and there were no instances of acute kidney injury. Of the patients in the study 38% had cardiac enzymes collected, and only 1 patient had a positive result, which was determined to be unrelated to acute coronary syndrome. Forty-one (31%) of patients had a urinalysis; 12 has positive results for hematuria, and 18 revealed proteinuria. Of note, the 6 patients who were hospitalized for hypertensive urgency had neither symptoms at presentation to the ED nor laboratory findings indicating end-organ damage. The reason these patients were admitted is unclear.

At discharge, ED providers made changes to 54% of patients’ outpatient antihypertensive regimens. These changes included adding a new medication (68%), increasing the dosage of an existing medication (24%), or multiple changes (8%). Refills were provided for 18% of prescriptions. Follow-up within 7 days from ED discharge was recorded for 34% of patients. One patient received follow-up outside the NFSGVHS and was not included in this analysis.

Discussion

The aim of this retrospective study was to determine the incidence of AH in a VA ED and describe how these patients were managed. Overall, the rate of patients presenting to the ED with AH during the study period was about 1 patient every 8 days or 45 patients per year. By comparison, more than 30,000 patients are seen at the NFSGVHS ED annually. Although AH seems to be an uncommon occurrence, study findings raise questions about the value of managing the condition in the ED.

This study found several management strategies as well as noteworthy trends. For example, laboratory tests were not ordered routinely for all patients, suggesting that some ED providers question their use for AH. There were no patients with acute elevations in serum creatinine that indicated acute kidney injury, and although hematuria and proteinuria were common findings, neither were specific for acute injury. However, there were findings typical of chronic hypertension, and urinalysis may provide little benefit when testing for acute kidney injury. Only 1 patient showed elevated cardiac enzymes, which was determined to be a result of CKD.

Although not included in the final analysis, the 6 patients who were hospitalized for hypertensive urgency were similar in that they had neither symptoms at presentation to the ED nor laboratory findings indicating end-organ damage. Collectively, these findings support existing literature that questions the utility of laboratory testing of patients with AH in the ED.10

Patients also were treated with a variety of antihypertensive agents in the ED. One explanation might be outpatient nonadherence with medications. In patients with AH, it is common to provide doses of chronic medications that the patient might have missed and should be taking on a regular basis. Therefore, assessing adherence with current medications before modifying chronic therapy is an important initial step when managing AH.

Although oral agents primarily were used, IV antihypertensives were administered to about one-third of patients. Preference for IV administration in the ED might be related to its ability to lower BP quickly. The practice of obtaining IV access for medication in a patient with AH is costly, unnecessary, and potentially harmful.7 The authors theorize that this practice is performed, in many cases, as an attempt to expedite ED discharge after an acceptable BP reading is documented.

Rapid reductions in BP can precipitate hypoperfusion inadvertently and are more likely to occur with IV agents than with oral ones. Therefore, the safety, convenience, and cost savings associated with oral administration make it the preferred route for managing AH.

Best Practices

Primary care clinics are best suited to manage AH because medication adjustments and long-term monitoring are easier to perform and at substantially lower costs when compared with that of the ED. Rather than immediately referring a patient to the ED, clinicians should consider factors that could elevate BP, such as medication nonadherence, anxiety, acute pain, recent tobacco or caffeine use, or white coat syndrome. Staff should be well educated on proper BP measurement and instructed to repeat the reading for confirmation. Before measuring BP, allow the patient to sit quietly for 5 minutes with the feet flat on the floor and arm supported.3 Ideally, the measurement used should be the average of 3 BP readings on an automated device.11 If BP readings are high, staff should ask the patient about medication adherence and missed medication(s) should be administered.

It also is reasonable to have the patient rest quietly for up to 30 minutes because rest has been shown to reduce BP in some patients.12 The drawback to the prolonged rest strategy is the potential to cause delays in care for other patients. However, it is important to remember that wait times in the ED often are measured in hours, which causes frustration for patients referred to the ED for AH management. Before completing the office visit, the provider should recheck BP using proper technique and confirm that the patient has antihypertensive medication(s) in his/her possession; a follow-up appointment should be scheduled for no later than 1 week.

Primary care providers might be concerned about taking on additional liability and could favor ED referral, but legislation makes it difficult for EDs to defer nonemergent issues to primary care clinics. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act states that hospitals are prohibited from denying a patient care during an emergency.13 Despite evidence that AH is not an emergency, many patients continue to be referred to the ED. One-third of patients presented to the ED on their own volition and more than one-half were referred by health care personnel. This strongly suggests that both patients and health care personnel consider AH an emergency medical condition requiring immediate attention. However, patients with AH rarely are found to have any acute end-organ damage; therefore, acute treatment and extensive laboratory or diagnostic testing in the ED provides little, if any, benefit.10 The authors believe the ACEP clinical policy should be adopted into mainstream practice to help reduce health care costs and preserve ED resources for patients with true emergencies.

Another pervasive issue that could contribute to inappropriate AH referrals to the ED is the shortage of PCPs and limited same-day appointments for nonemergent conditions. In a 2017 survey, the average wait time for a PCP appointment ranged between 12 and 109 days, depending on the metropolitan area. The national average wait time conducted by this survey was 29.3 days.14 When primary care appointments are unavailable, triage staff could recommend that patients seek care in the ED. Additionally, patients might choose to seek ED care rather than wait for the next available PCP appointment. Clinic proximity to an ED could influence referral rates. In other words, medical centers or health systems with primary care clinics and ED services under one roof could experience more frequent ED referrals.

A promising strategy to help overcome the challenges of addressing AH and avoiding ED referrals is increasing patient access to and use of qualified, nonphysician providers, such as clinical pharmacists and nurse practitioners. Large health systems such as the VA and Kaiser Permanente have employed clinical pharmacist providers to reduce follow-up times for patients in primary care settings.15 Furthermore, there is substantial evidence that supports the cost-effectiveness and clinical success of pharmacist-driven hypertension clinics.16-18 Nurse-driven efforts to improve hypertension control have been successfully implemented in health systems.19 Both clinical pharmacist and nurse-managed hypertension clinics are effective solutions to manage patients with AH who might otherwise use costly ED services.For example, the average cost of a single ED visit is $740 to $3,437.20 In comparison, a 2010 report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality showed the average annual cost of managing hypertension in ambulatory care clinics was $442 per adult, a cost considerably lower than that of the ED.21

Limitations

The retrospective and observational design of this study are inherent limitations. This study was not designed to evaluate cardiovascular outcomes after ED encounters. The sample size could have been larger if patients with BP < 180/110 mm Hg at ED triage were included; however, the 180/110 mm Hg threshold was chosen because it was the most widely agreed on BP value in the literature. This study did not capture patients who presented with AH and did not receive any acute treatment in the ED.Prescribing patterns based on provider training (eg, emergency medicine, family medicine, or internal medicine) were not tracked and might have accounted for differences in selection of diagnostic tests, laboratory ordering, and route of drug administration preference.

A small subset of patients reported positive pain scores at triage but did not describe acute pain. Pain scores are highly subjective, and few primary literature sources link chronic pain with increased BP.22,23 Nevertheless, patients who reported acute pain and elevated BP were excluded in order to identify truly asymptomatic patients. VA hospitals are unique health systems and data obtained from this study might not be applicable to other public or private facilities. Last, the study did not take into account patients’ psychosocial circumstances that might have fostered a disproportionate reliance on the ED for health care.

Conclusion

Asymptomatic patients with elevated BP are treated in the ED despite no evidence supporting improved outcomes after acute BP lowering in this population. Follow-up after ED encounters for AH did not occur consistently within guideline-recommended 7 days, a trend that also occurs in non-VA systems.8 Clinics and health care systems could establish policies to prevent or minimize management of AH in the ED. Ideally, AH should be managed in a clinic setting by a PCP, but growing clinician workload might lead to increasing wait times and difficultly obtaining same-day appointments. Nurse-led clinics and clinical pharmacists operating under a scope of practice and working closely with a PCP are a cost-effective solution to ensure timely treatment and appropriate follow-up of patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida South Georgia Veterans Health System in Gainesville, Florida.

Hypertension affects more than 65 million individuals in the U.S., accounting for nearly 30% of the adult population.1 Less than 50% of those with hypertension are taking appropriate pharmacotherapy.2 Hypertension contributes to cardiovascular events, including cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, hypertensive retinopathy, renal failure, myocardial infarction, and heart failure.1 Chronic hypertension mainly is an asymptomatic condition, earning the nickname “the silent killer.”2 An acute, symptomatic elevation in blood pressure (BP) often is referred to as hypertensive emergency. Symptoms of end-organ damage can include headache, blurry vision, chest pain, shortness of breath, altered mental status, epistaxis, and oliguria.2 Although rare, hypertensive emergencies should be treated immediately. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee (JNC 7), and the more recent JNC 8, have published guidelines on managing chronic hypertension.3,4 However, neither report provides guidance on hypertensive emergency or the appropriate actions in cases of extremely elevated BP in an asymptomatic patient.3,4

Acute hypertensive episodes—often referred to as hypertensive crises—are responsible for nearly 8 million hospitalizations each year and 20 million visits to the emergency department (ED).5,6 Most of these visits are same-day “treat-and-release” events.5 There is no universally accepted BP value associated with a hypertensive crisis, but most resources state that a BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg requires attention.2,7 Without other symptoms, elevated BP is not an emergency, yet ED referral for acute management is common.7

Three terms fall under the umbrella of hypertensive crises: hypertensive emergency, hypertensive urgency, and asymptomatic hypertension (AH).2 In a 2007 article, the American College of Chest Physicians defined hypertensive emergency as BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg with evidence of end-organ damage.2 Symptoms are almost always present in true hypertensive emergencies, and immediate medical intervention is required to halt further organ damage. In the same article, hypertensive urgency is defined as BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg without end-organ damage.2 The definition of hypertensive urgency could be further refined to include the presence of cardiovascular and renal risk factors, although this additional point is not consistent across the literature. Asymptomatic hypertension is similar to hypertensive urgency; however, there is an absence of signs or symptoms of end-organ damage.2 There is ambiguity in the literature concerning managing hypertensive urgency and AH, but both share a basic tenet: Immediate BP reduction is not essential. Gradual dosage adjustment(s) of oral medications, preferably by a primary care provider (PCP), and follow-up within 7 days are recommended.7

Limited evidence exists to guide ED providers in managing AH. Long-term outcomes and guidelines intended for the primary care setting should not be extrapolated to acute management in the ED. With limited treatment guidelines, providers might be more likely to refer patients with AH to the ED for evaluation. In 2013, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) created a clinical policy concerning AH in the ED. The ACEP concluded that screening for target organ injury and medical intervention in the ED does not reduce rates of adverse events (AEs) and could lead to overtreatment and acute hypoperfusion.7 More recently, Patel and colleagues published findings on hypertensive urgency in the ambulatory care setting, which similarly found that referral to the ED was associated with increased use of health care resources and no change in short-term major AEs.8 The ACEP recommends that patients presenting with AH be referred to primary care clinics where long-term monitoring and medication adjustments can be achieved more cost-effectively.7

The objective of this retrospective evaluation was to assess the incidence and management of AH within a VA ED. The authors aimed to provide insight into how these patients are managed and discuss alternatives to ED use.

Methods

This retrospective observational study was conducted within the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS), which provides patient care at 2 medical centers in Gainesville and Lake City, Florida, as well as 11 outpatient clinics located throughout North Florida and South Georgia. The NFSGVHS serves rural and urban veteran populations. Study approval was granted by the NFSGVHS Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Adult patients who were ordered at least 1 antihypertensive medication in the ED from July 1, 2011 to July 1, 2014, in addition to being asymptomatic with BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg at ED triage were included. Based on clinical experience, the authors estimated that 3 years would provide a sample size of more than 100 patients. Patients were excluded if they presented with any acute symptoms or were hospitalized for further management.

Data Collection

Baseline demographics were collected for all participants. During the ED encounter, pre- and postintervention vital signs were recorded and prespecified laboratory data obtained. Interrater reliability was accounted for by performing random reviews of previously collected data to ensure consistency during the chart review process. Renal end-organ damage was defined using Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria, a serum creatinine 50% above baseline, or an absolute increase in baseline serum creatinine by 0.3 mg/dL.9 Additional laboratory markers of organ damage included cardiac troponin levels. Urinalysis results also were assessed to determine the presence of hematuria or proteinuria. Patient-reported nonadherence with medications was determined by reviewing ED provider and/or nurse documentation notes for the index ED encounter.

Investigators documented the route (IV or oral) and antihypertensive(s) medication selected for each patient. Adverse effects and any changes to patients’ outpatient medication regimens were noted. Investigators also assessed days to next medical contact after ED discharge to determine whether follow-up occurred according to the recommended standard of 7 days.9 Days to next medical contact was defined as any contact—in person or by telephone—that was documented in the electronic health record after the index ED visit.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean, median, and standard deviation, were used to analyze data.

Results

A total of 1,052 patients presented with BP ≥ 180/110 mm Hg and for whom antihypertensive medication was ordered but not necessarily given in the ED. Of the total, 724 patients were excluded because of hospital admission for other primary diagnoses; however, 6 of these patients were admitted for hypertensive urgency. The final analysis included 132 patients who presented with the primary condition of elevated BP without any accompanying symptoms. Among these patients, 2 had repeat ED visits for AH during the specified time frame.

Most patients were male with an average age of 63 years and documented history of hypertension. Nearly all patients had established primary care within the NFSGVHS. The most common comorbidity was diabetes mellitus (36%), followed by coronary artery disease (27%) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (21%) (Table 1). About one-third of patients presented to the ED on their own volition, and slightly more than half were referred to the ED by primary care or specialty clinics.

In the ED, 130 patients received BP treatment (Table 2). Medication was ordered for 2 patients who did not receive treatment. In total, 12 different medication classes were used for treating patients with AH in the ED (Figure).

Treatment in the ED resulted in an average BP and heart rate reduction of 27/20 mm Hg and 5 beats per minute, respectively. About 80% of patients had a basic metabolic panel drawn, and there were no instances of acute kidney injury. Of the patients in the study 38% had cardiac enzymes collected, and only 1 patient had a positive result, which was determined to be unrelated to acute coronary syndrome. Forty-one (31%) of patients had a urinalysis; 12 has positive results for hematuria, and 18 revealed proteinuria. Of note, the 6 patients who were hospitalized for hypertensive urgency had neither symptoms at presentation to the ED nor laboratory findings indicating end-organ damage. The reason these patients were admitted is unclear.

At discharge, ED providers made changes to 54% of patients’ outpatient antihypertensive regimens. These changes included adding a new medication (68%), increasing the dosage of an existing medication (24%), or multiple changes (8%). Refills were provided for 18% of prescriptions. Follow-up within 7 days from ED discharge was recorded for 34% of patients. One patient received follow-up outside the NFSGVHS and was not included in this analysis.

Discussion

The aim of this retrospective study was to determine the incidence of AH in a VA ED and describe how these patients were managed. Overall, the rate of patients presenting to the ED with AH during the study period was about 1 patient every 8 days or 45 patients per year. By comparison, more than 30,000 patients are seen at the NFSGVHS ED annually. Although AH seems to be an uncommon occurrence, study findings raise questions about the value of managing the condition in the ED.

This study found several management strategies as well as noteworthy trends. For example, laboratory tests were not ordered routinely for all patients, suggesting that some ED providers question their use for AH. There were no patients with acute elevations in serum creatinine that indicated acute kidney injury, and although hematuria and proteinuria were common findings, neither were specific for acute injury. However, there were findings typical of chronic hypertension, and urinalysis may provide little benefit when testing for acute kidney injury. Only 1 patient showed elevated cardiac enzymes, which was determined to be a result of CKD.

Although not included in the final analysis, the 6 patients who were hospitalized for hypertensive urgency were similar in that they had neither symptoms at presentation to the ED nor laboratory findings indicating end-organ damage. Collectively, these findings support existing literature that questions the utility of laboratory testing of patients with AH in the ED.10

Patients also were treated with a variety of antihypertensive agents in the ED. One explanation might be outpatient nonadherence with medications. In patients with AH, it is common to provide doses of chronic medications that the patient might have missed and should be taking on a regular basis. Therefore, assessing adherence with current medications before modifying chronic therapy is an important initial step when managing AH.

Although oral agents primarily were used, IV antihypertensives were administered to about one-third of patients. Preference for IV administration in the ED might be related to its ability to lower BP quickly. The practice of obtaining IV access for medication in a patient with AH is costly, unnecessary, and potentially harmful.7 The authors theorize that this practice is performed, in many cases, as an attempt to expedite ED discharge after an acceptable BP reading is documented.

Rapid reductions in BP can precipitate hypoperfusion inadvertently and are more likely to occur with IV agents than with oral ones. Therefore, the safety, convenience, and cost savings associated with oral administration make it the preferred route for managing AH.

Best Practices

Primary care clinics are best suited to manage AH because medication adjustments and long-term monitoring are easier to perform and at substantially lower costs when compared with that of the ED. Rather than immediately referring a patient to the ED, clinicians should consider factors that could elevate BP, such as medication nonadherence, anxiety, acute pain, recent tobacco or caffeine use, or white coat syndrome. Staff should be well educated on proper BP measurement and instructed to repeat the reading for confirmation. Before measuring BP, allow the patient to sit quietly for 5 minutes with the feet flat on the floor and arm supported.3 Ideally, the measurement used should be the average of 3 BP readings on an automated device.11 If BP readings are high, staff should ask the patient about medication adherence and missed medication(s) should be administered.

It also is reasonable to have the patient rest quietly for up to 30 minutes because rest has been shown to reduce BP in some patients.12 The drawback to the prolonged rest strategy is the potential to cause delays in care for other patients. However, it is important to remember that wait times in the ED often are measured in hours, which causes frustration for patients referred to the ED for AH management. Before completing the office visit, the provider should recheck BP using proper technique and confirm that the patient has antihypertensive medication(s) in his/her possession; a follow-up appointment should be scheduled for no later than 1 week.

Primary care providers might be concerned about taking on additional liability and could favor ED referral, but legislation makes it difficult for EDs to defer nonemergent issues to primary care clinics. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act states that hospitals are prohibited from denying a patient care during an emergency.13 Despite evidence that AH is not an emergency, many patients continue to be referred to the ED. One-third of patients presented to the ED on their own volition and more than one-half were referred by health care personnel. This strongly suggests that both patients and health care personnel consider AH an emergency medical condition requiring immediate attention. However, patients with AH rarely are found to have any acute end-organ damage; therefore, acute treatment and extensive laboratory or diagnostic testing in the ED provides little, if any, benefit.10 The authors believe the ACEP clinical policy should be adopted into mainstream practice to help reduce health care costs and preserve ED resources for patients with true emergencies.

Another pervasive issue that could contribute to inappropriate AH referrals to the ED is the shortage of PCPs and limited same-day appointments for nonemergent conditions. In a 2017 survey, the average wait time for a PCP appointment ranged between 12 and 109 days, depending on the metropolitan area. The national average wait time conducted by this survey was 29.3 days.14 When primary care appointments are unavailable, triage staff could recommend that patients seek care in the ED. Additionally, patients might choose to seek ED care rather than wait for the next available PCP appointment. Clinic proximity to an ED could influence referral rates. In other words, medical centers or health systems with primary care clinics and ED services under one roof could experience more frequent ED referrals.

A promising strategy to help overcome the challenges of addressing AH and avoiding ED referrals is increasing patient access to and use of qualified, nonphysician providers, such as clinical pharmacists and nurse practitioners. Large health systems such as the VA and Kaiser Permanente have employed clinical pharmacist providers to reduce follow-up times for patients in primary care settings.15 Furthermore, there is substantial evidence that supports the cost-effectiveness and clinical success of pharmacist-driven hypertension clinics.16-18 Nurse-driven efforts to improve hypertension control have been successfully implemented in health systems.19 Both clinical pharmacist and nurse-managed hypertension clinics are effective solutions to manage patients with AH who might otherwise use costly ED services.For example, the average cost of a single ED visit is $740 to $3,437.20 In comparison, a 2010 report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality showed the average annual cost of managing hypertension in ambulatory care clinics was $442 per adult, a cost considerably lower than that of the ED.21

Limitations

The retrospective and observational design of this study are inherent limitations. This study was not designed to evaluate cardiovascular outcomes after ED encounters. The sample size could have been larger if patients with BP < 180/110 mm Hg at ED triage were included; however, the 180/110 mm Hg threshold was chosen because it was the most widely agreed on BP value in the literature. This study did not capture patients who presented with AH and did not receive any acute treatment in the ED.Prescribing patterns based on provider training (eg, emergency medicine, family medicine, or internal medicine) were not tracked and might have accounted for differences in selection of diagnostic tests, laboratory ordering, and route of drug administration preference.

A small subset of patients reported positive pain scores at triage but did not describe acute pain. Pain scores are highly subjective, and few primary literature sources link chronic pain with increased BP.22,23 Nevertheless, patients who reported acute pain and elevated BP were excluded in order to identify truly asymptomatic patients. VA hospitals are unique health systems and data obtained from this study might not be applicable to other public or private facilities. Last, the study did not take into account patients’ psychosocial circumstances that might have fostered a disproportionate reliance on the ED for health care.

Conclusion

Asymptomatic patients with elevated BP are treated in the ED despite no evidence supporting improved outcomes after acute BP lowering in this population. Follow-up after ED encounters for AH did not occur consistently within guideline-recommended 7 days, a trend that also occurs in non-VA systems.8 Clinics and health care systems could establish policies to prevent or minimize management of AH in the ED. Ideally, AH should be managed in a clinic setting by a PCP, but growing clinician workload might lead to increasing wait times and difficultly obtaining same-day appointments. Nurse-led clinics and clinical pharmacists operating under a scope of practice and working closely with a PCP are a cost-effective solution to ensure timely treatment and appropriate follow-up of patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida South Georgia Veterans Health System in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(133):

1-8.

2. Marik PE, Varon J. Hypertensive crises: challenges and management. Chest. 2007;131(6):1949-1962.

3. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-1252.

4. James, PA, Oparil, S, Carter, BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

5. American Heart Association. High blood pressure ER visits jumped 25 percent in 2006-11. http://newsroom.heart.org/news/high-blood-pressure-er-visits-jumped-25-percent-in-2006-11. Published September 9, 2014. Accessed January 19, 2018.

6. Owens P, Mutter R. Statistical brief #100: emergency department visits for adults in community hospitals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb100.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed January 19, 2018.

7. Wolf SJ, Lo B, Shih RD, Smith MD, Fesmire FM; American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients in the emergency department with asymptomatic elevated blood pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(1):59-68.

8. Patel KK, Young L, Howell EH, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting with hypertensive urgency in the office setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):981-988.

9. Acute Kidney Injury Network. AKIN studies. http://www.akinet.org/akinstudies.php. Updated 2017. Accessed January 19, 2018.

10. Karras DJ, Kruus LK, Cienki JJ, et al. Utility of routine testing for patients with asymptomatic severe blood pressure elevation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(3):231-239.

11. The SPRINT Research Group. A Randomized trial of Intensive versus standard blood pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

12. Grassi D, O’Flaherty M, Pellizzari M, et al; Group of Investigators of the REHASE Program. Hypertensive urgencies in the emergency department: evaluating blood pressure response to rest and to antihypertensive drugs with different profiles. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(9):662-667.

13. Canters for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Emergency medical treatment & labor act (EMTALA). https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EMTALA/index.html. Updated March 26, 2012. Accessed January 19, 2018.

14. Merritt Hawkins. 2017 Survey of physician appointment wait times and Medicare and Medicaid acceptance rates. https://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/Merritt-Hawkins/Pdf/mha2017waittimesurveyPDF.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed January 19, 2018.

15. Galewitz P. VA treats patients’ impatience with clinical pharmacists. USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/10/24/kaiser-va-treats-patients-impatience-clinical-pharmacists/92479132/. Published October 24, 2016. Accessed January 19, 2018.

16. Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, et al. Physician and pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1996-2002.

17. Borenstein JE, Graber G, Saltiel E, et al. Physician-pharmacist comanagement of hypertension: a randomized comparative trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(2):209-216.

18. Okamoto MP, Nakahiro RK. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of a pharmacist-managed hypertension clinic. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(11):1337-1344.

19. Brown VM. Managing patients with hypertension in nurse-led clinics. Nursing. 2017;47(4):16-19.

20. Caldwell N, Srebotnjak T, Wang T, Hsia R. “How Much Will I Get Charged for This?” Patient charges for top ten diagnoses in the emergency department. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2): e55491.

21. Davis KE. Expenditures for hypertension among adults age 18 and older, 2010: estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st404/stat404.shtml. Published April 2013. Accessed January 19, 2018.

22. Marco CA, Plewa MC, Buderer N, et al. Self-reported pain scores in the emergency department: lack of association with vital signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(9):974-979.

23. Wood D, Goodnight S, Haig AJ, Nasari T. Body mass index, but not blood pressure is related to the level of pain in persons with chronic pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2011;24(2):

111-115.

1. Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(133):

1-8.

2. Marik PE, Varon J. Hypertensive crises: challenges and management. Chest. 2007;131(6):1949-1962.

3. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-1252.

4. James, PA, Oparil, S, Carter, BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

5. American Heart Association. High blood pressure ER visits jumped 25 percent in 2006-11. http://newsroom.heart.org/news/high-blood-pressure-er-visits-jumped-25-percent-in-2006-11. Published September 9, 2014. Accessed January 19, 2018.

6. Owens P, Mutter R. Statistical brief #100: emergency department visits for adults in community hospitals. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb100.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed January 19, 2018.

7. Wolf SJ, Lo B, Shih RD, Smith MD, Fesmire FM; American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients in the emergency department with asymptomatic elevated blood pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(1):59-68.

8. Patel KK, Young L, Howell EH, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting with hypertensive urgency in the office setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):981-988.

9. Acute Kidney Injury Network. AKIN studies. http://www.akinet.org/akinstudies.php. Updated 2017. Accessed January 19, 2018.

10. Karras DJ, Kruus LK, Cienki JJ, et al. Utility of routine testing for patients with asymptomatic severe blood pressure elevation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(3):231-239.

11. The SPRINT Research Group. A Randomized trial of Intensive versus standard blood pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

12. Grassi D, O’Flaherty M, Pellizzari M, et al; Group of Investigators of the REHASE Program. Hypertensive urgencies in the emergency department: evaluating blood pressure response to rest and to antihypertensive drugs with different profiles. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10(9):662-667.

13. Canters for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Emergency medical treatment & labor act (EMTALA). https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EMTALA/index.html. Updated March 26, 2012. Accessed January 19, 2018.

14. Merritt Hawkins. 2017 Survey of physician appointment wait times and Medicare and Medicaid acceptance rates. https://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/Merritt-Hawkins/Pdf/mha2017waittimesurveyPDF.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed January 19, 2018.

15. Galewitz P. VA treats patients’ impatience with clinical pharmacists. USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/10/24/kaiser-va-treats-patients-impatience-clinical-pharmacists/92479132/. Published October 24, 2016. Accessed January 19, 2018.

16. Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, et al. Physician and pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1996-2002.

17. Borenstein JE, Graber G, Saltiel E, et al. Physician-pharmacist comanagement of hypertension: a randomized comparative trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(2):209-216.

18. Okamoto MP, Nakahiro RK. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of a pharmacist-managed hypertension clinic. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(11):1337-1344.

19. Brown VM. Managing patients with hypertension in nurse-led clinics. Nursing. 2017;47(4):16-19.

20. Caldwell N, Srebotnjak T, Wang T, Hsia R. “How Much Will I Get Charged for This?” Patient charges for top ten diagnoses in the emergency department. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2): e55491.

21. Davis KE. Expenditures for hypertension among adults age 18 and older, 2010: estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st404/stat404.shtml. Published April 2013. Accessed January 19, 2018.

22. Marco CA, Plewa MC, Buderer N, et al. Self-reported pain scores in the emergency department: lack of association with vital signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(9):974-979.

23. Wood D, Goodnight S, Haig AJ, Nasari T. Body mass index, but not blood pressure is related to the level of pain in persons with chronic pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2011;24(2):

111-115.

How US healthcare compares to other countries

The US has similar healthcare utilization as other high-income countries but spends more and tends to have worse health outcomes, according to a new study.

In 2016, the US spent 17.8% of its gross domestic product on healthcare. For 10 other high-income countries, spending ranged from 9.6% to 12.4%.

However, sizes of physician and nursing workforces were comparable between the countries, numbers of hospital discharges were similar, and lengths of hospital stay were lower in the US than in most other countries.

Meanwhile, the US had the lowest life expectancy and the highest rate of infant mortality.

This research was published in JAMA.

“There’s been a lot of interest in international comparisons between America and other high-income countries, and there’s been a lot of vagueness about why exactly our [US] spending is so much higher and our health outcomes are not necessarily better and often worse,” said study author Ashish K. Jha, MD, of Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts.

“This study really tries to fill in gaps, I think, across a wide range of issues, from structural capacity to utilization to prices to outcomes.”

For this study, Dr Jha and his colleagues analyzed recent healthcare data, primarily from 2013 to 2016. The team compared differences in healthcare spending, performance, and structural features between the US and 10 high-income countries—UK, Canada, Germany, Australia, Japan, Sweden, France, Netherlands, Switzerland, and Denmark.

Spending

In 2016, healthcare spending, as a percentage of gross domestic product, was as follows:

US—17.8%

Switzerland—12.4%

Sweden—11.9%

Germany—11.3%

France—11%

Japan—10.9%

Denmark—10.8%

Netherlands—10.5%

Canada—10.3%

UK—9.7%

Australia—9.6%.

“The big differences in spending really seem to be driven by prices,” Dr Jha said, noting that salaries for doctors and nurses, administrative expenditures, and pharmaceutical costs are “much higher” in the US.

The total spending on pharmaceuticals per capita was $1443 in the US but ranged from $466 (Netherlands) to $939 (Switzerland) in the other countries.

Administrative costs accounted for 8% of the total national health expenditure in the US but 1% (France, Japan) to 3% (Germany) in the other countries.

Outpatient care expenditures ranged from 22% (Netherlands) to 42% (US). Inpatient care expenditures ranged from 17% (Canada) to 32% (Netherlands), with 19% for the US. And expenditures for medical goods ranged from 10% (Denmark) to 20% (Germany), with the US at 14%.

Physicians’ and nurses’ salaries were higher in the US than other countries. For example, generalist physicians earned $218,173 in the US in 2016 but anywhere from $86,607 (Sweden) to $154,126 (Germany) in the other countries.

Utilization

Although US doctors and nurses earned more than their counterparts in comparator countries, there were no substantial between-country differences in the size of the physician and nursing workforces.

The number of working physicians for every 1000 people ranged from 2.1 (UK) to 4.3 (Switzerland), with the US at 2.6. The number of working nurses for every 1000 people ranged from 8.2 (UK) to 17.4 (Switzerland), with 11.1 for the US.

The US had comparable numbers of hospital beds as some of the other countries. The range was 2.5 (Sweden) to 13.2 (Japan) beds per 1000 people, with the US at 2.8.

The US ranked 6th when it came to hospital discharges for acute myocardial infarction (AMI, 192 per 100,000 people; range, 89 to 287), mental and behavioral issues (679 per 100,000 people; range, 119 to 1719), pneumonia (365 per 100,000 people; range, 187 to 567), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (230 per 100,000 people; range, 45 to 352).

The US had greater utilization of computed tomography than the other countries, with 245 examinations per 1000 people (range for other countries, 79 to 231). And US utilization of magnetic resonance imaging was higher than most countries, with 118 examinations per 1000 people (range, 41 to 131).

However, the US ranked on the lower end of the spectrum for length of hospital stay. The length of stay for a “normal delivery” childbirth ranged from a median of 1.5 days (UK) to 5.7 days (Japan), with the US clocking in at 2 days. The median length of stay for AMI ranged from a median of 3.9 days (Netherlands) to 10.3 days (Germany), with the US at 5.4 days.

“So much of the debate about healthcare these days is about over-utilization—that somehow our health system is uniquely bad at avoiding unnecessary services,” Dr Jha said. “I think these data really put that argument to rest. Except for a few pockets, utilization is not really different between us and these high-income Northern European countries, so maybe we need to spend a little less time focusing on that and a little bit more time focusing on prices of our healthcare system.”

Outcomes

The US ranked on the lower end of the spectrum for some mortality outcomes. Thirty-day stroke mortality per 1000 patients ranged from 4.2 in the US to 10 in Canada. Thirty-day AMI mortality per 1000 ranged from 4.1 (Australia) to 8.7 (Germany), with the US at 5.5.

However, infant mortality was highest in the US, at 5.8 deaths per 1000 live births (range for other countries, 2.1 to 5.1). And life expectancy was lowest in the US, at 78.8 years (range for other countries, 80.7 to 83.9).

The researchers noted that the US had the highest percentage of overweight or obese individuals age 15 and older, at 70.1% (range for other countries, 23.8% to 63.4%), but a low percentage of smokers (11.4%; range, 11.2% to 22.4%) and moderate alcohol consumption (8.8 L per capita; range, 7.2 to 11.9).

Limitations of this study include some differences in approaches to collecting and standardizing data across countries, as well as missing data for some countries.

The US has similar healthcare utilization as other high-income countries but spends more and tends to have worse health outcomes, according to a new study.

In 2016, the US spent 17.8% of its gross domestic product on healthcare. For 10 other high-income countries, spending ranged from 9.6% to 12.4%.

However, sizes of physician and nursing workforces were comparable between the countries, numbers of hospital discharges were similar, and lengths of hospital stay were lower in the US than in most other countries.

Meanwhile, the US had the lowest life expectancy and the highest rate of infant mortality.

This research was published in JAMA.

“There’s been a lot of interest in international comparisons between America and other high-income countries, and there’s been a lot of vagueness about why exactly our [US] spending is so much higher and our health outcomes are not necessarily better and often worse,” said study author Ashish K. Jha, MD, of Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts.

“This study really tries to fill in gaps, I think, across a wide range of issues, from structural capacity to utilization to prices to outcomes.”